Христофор Колумб

Краткая биография

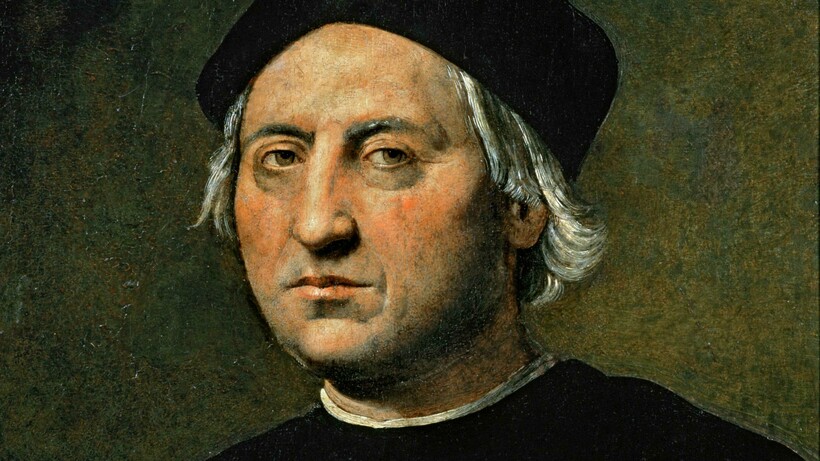

Выдающийся мореход и флотоводец, первооткрыватель Америки Христофор Колумб родился в 1451 г. в небогатой католической семье по одной из версий – в Генуе, по другим – на островах Мальорка или Корсика. На итальянском языке его фамилия звучит – Коломбо, на испанском – Колон.

Р. Гирландайо. Посмертный портрет Христофора Колумба. Около 1520 г.

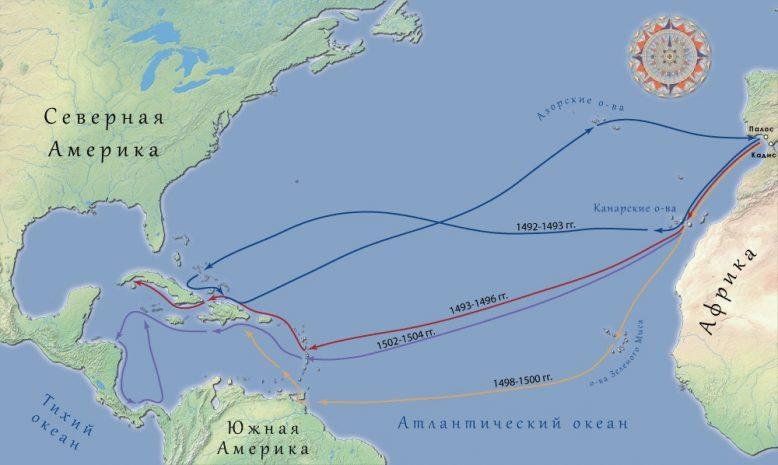

О юности Колумба сохранилось мало сведений, однако известно, что он говорил на четырех языках: итальянском, испанском, португальском и латинском. Несколько лет Колумб плавал на итальянских морских торговых судах, побывал на Британских островах, в Ирландии, Исландии, на западном побережье Африки. Однако главным делом его жизни можно считать четыре путешествия к берегам Америки: первое (1492–1493), второе (1493–1496), третье (1498–1500) и четвертое (1502–1504). Умер Колумб 20 мая 1506 г. и был похоронен в Севилье.

Величайшая ошибка, которая привела к величайшему открытию

К концу XV в. многих европейцев: монархов, купцов, банкиров и мореплавателей занимал вопрос о том, как можно достичь богатой пряностями и сокровищами Индии по морю. Сухопутный путь был труден и небезопасен. В то время идеи о шарообразности Земли становились все более популярными и многие всерьез задумывались над тем, что до индийских берегов можно доплыть не только восточным путем, обогнув Африку, но и западным – преодолев воды Атлантического океана. Христофор Колумб не был исключением. Получив совет флорентийского ученого (географа и астронома) Паолло дель Поццо Тосканелли, Колумб задумал предпринять такое дерзкое путешествие. В новых землях он мечтал найти жемчуг, драгоценные камни, золото, серебро и пряности. О размерах материков и океанов в XV в. еще не было точных сведений, поэтому ученый предполагал, что до азиатских берегов кораблям понадобится пройти около 5 тыс. км.

Герб Х. Колумба (Колона), пожалованный ему испанскими монархами за особые заслуги перед государством. В верхней части герба изображены замок и лев — символы королевства Кастилии и Леона. Внизу — очертания открытых Колумбом новых земель в Центральной Америке, а также якоря, символизирующие адмиральское звание. Вместе с гербом Колумбу был пожалован девиз «Кастилии и Леону новый мир был дан Колоном»

Прощание Колумба с испанскими монархами — Фердинандом и Изабеллой. Гравюра XIX в.

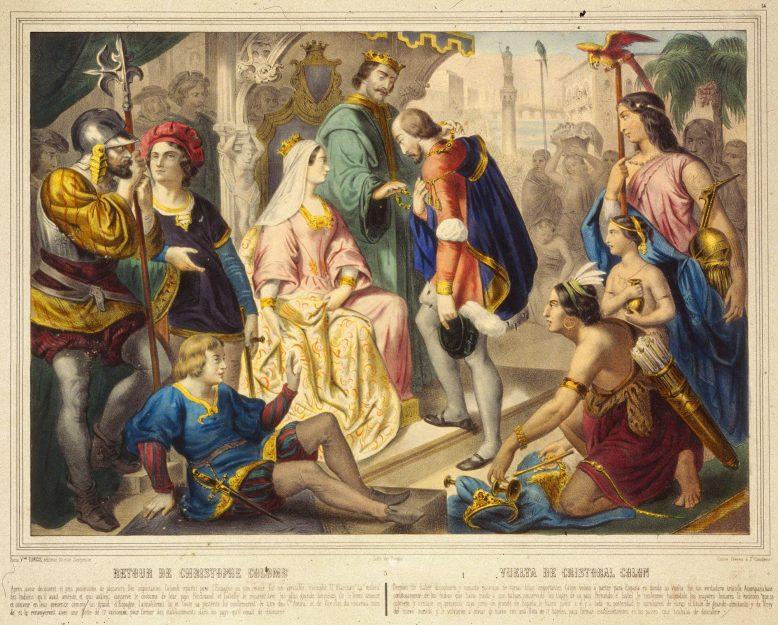

Колумб посвятил в свои планы сначала генуэзских купцов, затем португальского короля Жуана II, но не нашел у них поддержки. Тогда он обратился к испанской королеве Изабелле – она отказалась финансировать это сомнительное предприятие. В 1491 г. Колумбу удалось заинтересовать своим проектом испанских королевских финансистов, была созвана комиссия, но и она отвергла смелый проект, да и требования Колумба были признаны чрезмерными. В отчаянии он принял решение уехать во Францию, однако был возвращен с дороги – проект приняли. Испанские монархи (Фердинанд и Изабелла) пожаловали Колумбу и его наследникам дворянский титул «дон», произвели его в адмиралы и назначили своим вице-королем и главным правителем всех островов и материков, которые он лично откроет или приобретет. Колумбу была обещана десятая доля чистого дохода с новых земель и право разбора уголовных и гражданских дел. Экспедицию щедро финансировали испанские банкиры.

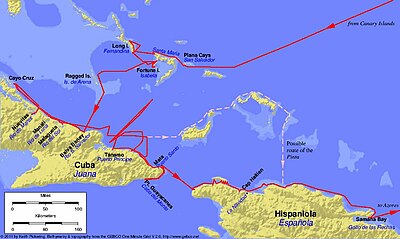

Колумб снарядил три корабля, названные «Санта-Мария», «Пинта» и «Нинья»; набрал команду – 90 человек. 3 августа 1492 г. корабли покинули Палос и взяли курс на Канарские острова, а оттуда, после короткой остановки, на запад. Путешествие оказалось неожиданно долгим, на кораблях назревал бунт, но наконец (через 33 дня) 12 октября 1492 г. матрос с «Пинты» увидел землю. Это был большой остров из архипелага Багамских островов, его жители – араваки – приветливо встретили испанцев, подплывали на лодках к их кораблям и обменивали свои вещи.

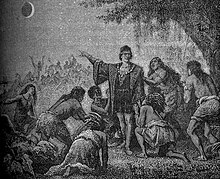

Дж. Вандерлин. Высадка Колумба на Гуанахани в 1492 г. Картина 1847 г.

Колумб со свитой высадился на берег и водрузил на острове знамя Кастилии, теперь он был адмиралом и вице-королем этих земель. Индейцы называли свой остров Гуанахани, адмирал дал ему христианское имя Сан-Сальвадор – «Святой спаситель» (в наши дни это остров Самана). Две недели испанцы обходили один за другим острова архипелага в поисках золота и пряностей, но ни того, ни другого там не оказалось. Однако у их жителей моряки увидели пластинки и слитки золота, которые те иногда меняли на стеклянные и глиняные черепки. Наконец флотилия достигла побережья очень крупного острова (Кубы), которое Колумб принял за один из полуостровов Восточной Азии. Его обитатели возделывали незнакомые европейцам растения: кукурузу, картофель, табак; лишь хлопок не удивил испанцев.

«Они шли с крестом в руке и с ненасытной жаждой золота в сердце». Бартоломео Лас Касас, испанский священник

25 декабря у берегов крупного острова «Санта-Мария» села на рифы. Колумб назвал его Эспаньола (совр. Гаити) и решил именно здесь основать первое европейское поселение. Из обломков корабля он приказал построить форт и дал ему имя Навидад (Рождество). Здесь добровольно остались 39 моряков, они надеялись больше разузнать о новых землях и найти много золота. Колумб снабдил их припасами на год, а сам на двух кораблях поспешил в Испанию. В середине февраля они добрались до Азорских островов, а 15 марта 1493 г. прибыли в Палос. Так завершилось первое путешествие Колумба.

Маршрут первой экспедиции Христофора Колумба в 1492-1493 гг.

Он привез в Испанию весть об открытых им на западе землях, немного золота, несколько невиданных еще в Европе островитян, которых стали называть индейцами, странные растения, плоды и перья диковинных птиц. Известие об открытии испанцами западного пути в Индию быстро облетело европейские страны. Римский папа предоставил Кастилии права на земли, которые она открыла в западных частях океана (к западу от островов Зеленого Мыса), тогда как за португальцами оставалось право на восточные земли. Колумб считал открытые земли Восточной Азией, поэтому европейцы стали именовать их Вест-Индией (Западной Индией), собственно Индия и Индонезия назывались в Европе Ост-Индией (Восточной Индией).

Обрадованные известием о новых обширных и богатых землях за океаном, принадлежащих теперь испанской короне, Фердинанд и Изабелла снарядили новую экспедицию к берегам Вест-Индии. Она состояла из 17 кораблей, флагманский парусник «Мария-Галанте» возглавлял Колумб. Экспедиция вышла из Кадиса 25 сентября 1493 г. Она доставила на Эспаньолу крупный рогатый скот, собак, виноградную лозу и семена сельскохозяйственных растений.

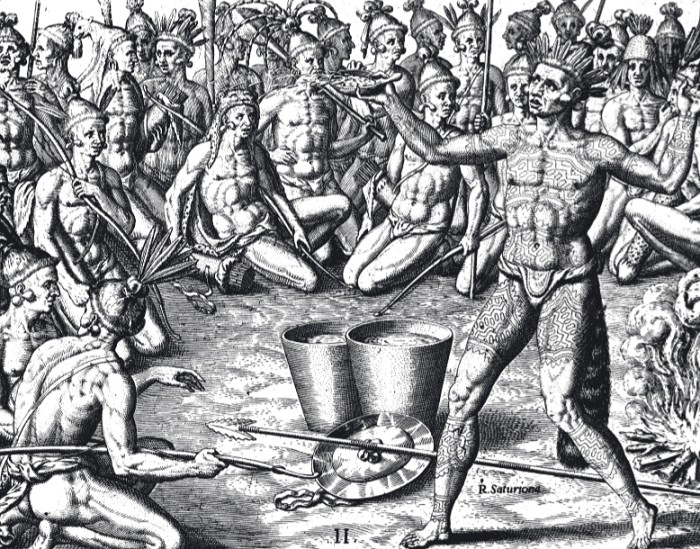

В опасное путешествие вместе с Колумбом отправились около 2 тыс. человек: идальго, придворные, монахи, священники и конечно моряки. Путь флотилии на этот раз проходил на 10° южнее, и, подгоняемые попутным северо-восточным пассатом, они через 20 дней достигли Малых Антильских островов. Это были Доминика, Гваделупа, Монтсеррат, Антигуа, Санта-Крус, Виргинские, Пуэрто-Рико и другие острова. Здесь жили воинственные карибы, которые на лодках, выдолбленных из одного ствола дерева, с луками и стрелами совершали набеги на мирных араваков, грабили, убивали их, увозили с собой женщин и возможно даже были людоедами.

Колумб на Эспаньоле. Раскрашенная гравюра. 1886 г.

Прибыв на Эспаньолу, испанцы обнаружили разрушенный, сожженный форт и останки моряков. Выяснилось, что колонисты грабили индейцев, уводили их жен, и взбунтовавшиеся араваки расправились с ними. К востоку от неудачного поселения Колумб основал новый город и дал ему имя Изабелла. В глубь острова отправилась экспедиция под руководством Алонсо Охеды, она обнаружила крупные поселения араваков, а также золотые россыпи у подножия гор (речной песок, содержащий золото). Тем временем в жарком климате запасы еды портились, содержать сотни колонистов на Эспаньоле стало невозможно, и Колумб принял решение отправить большую часть людей на 12 кораблях обратно в Испанию. С ними он передал испанским монархам «Памятную записку», в которой сообщал о найденных месторождениях золота и «следах пряностей». Он просил прислать скот, продукты, земледельческие орудия, а взамен предлагал индейцев, обращенных в рабство.

Дж. Г. Стедман. Женщина из племени араваков. 1818 г.

На гравюре изображены туземцы с островов Карибского моря. XV в.

В надежде открыть материковую часть Индии весной 1494 г. Колумб предпринял экспедицию на запад от Изабеллы. Обогнув юго-восточный берег Кубы, он достиг Сантьяго (Ямайки). Пройдя вдоль кубинских берегов более 1500 км, Колумб был уверен, что открыл берега нового континента.

Под руководством брата Колумба Бартоломео из Испании пришли три корабля с войском и провизией. Вновь прибывшие солдаты начали грабежи и насилия и были убиты индейцами, тогда Колумб предпринял военный поход в глубь острова. Его отряд из 200 солдат с лошадьми и собаками с немыслимой жестокостью убивал индейцев сотнями. Через девять месяцев Эспаньола была полностью покорена, оставшихся в живых индейцев Колумб обложил непосильной данью. Многие из них тысячами умирали от неизвестных, завезенных европейцами болезней или тяжелейшей работы на плантациях и золотых приисках. В 1496 г. Бартоломео Колумб заложил на южном берегу Эспаньолы новый город Санто-Доминго.

Резная каменная статуэтка «Старого бога» сапотекской цивилизации доколумбовой Америки. Монте-Альбан. Мексика. XIII–XV вв.

Золотая маска бога Шипе-Тотека. Из сокровищницы сапотекской цивилизации. Монте-Альбан. Мексика. XIII– XV вв.

Испанские монархи тем временем посчитали, что доходы, получаемые от новых земель, незначительны по сравнению с расходами на снаряжение экспедиций и содержание новых поселений, и решили расторгнуть договор с Колумбом. В 1495 г. они издали указ, разрешающий всем подданным Кастилии снаряжать экспедиции на запад для открытия новых земель и переселяться туда с условием, что две трети добытого золота будут отданы в испанскую казну. Взбешенный Колумб срочно вернулся в Испанию – так закончилось его второе путешествие. Он убеждал Изабеллу и Фердинанда, что достиг азиатского материка и что обнаружил во внутренних районах Эспаньолы загадочную страну Офир, откуда библейский царь Соломон получал золото. Колумб предложил в качестве новых поселенцев отправлять на Эспаньолу преступников, сократив им срок наказания. Ему поверили и на этот раз.

Епископ Б. Лас Касас в памфлете «Кратчайший рассказ о разрушении Западной Индии» с гневом писал о зверствах своих соотечественников: «Христиане своими конями, мечами и копьями стали учинять побоища среди индейцев и творить чрезвычайные жестокости. Вступая в селение, они не оставляли в живых никого – участи этой подвергался и стар и млад».

Весной 1498 г. Колумб снарядил третью экспедицию. Шесть кораблей 30 мая вышли из устья Гвадалквивира и взяли курс на юго-запад. Они достигли острова Тринидад и впервые увидели очертания побережья южноамериканского континента. Остановившись в дельте реки Ориноко, Колумб обнаружил, что вода в заливе пресная. Это могло быть только в том случае, если река протекала по обширному континенту. К испанским кораблям подходили на каноэ аборигены, у многих на груди были крупные украшения из золота и жемчуга. Открытые земли (около 400 км побережья) Колумб назвал «Земля Пария».

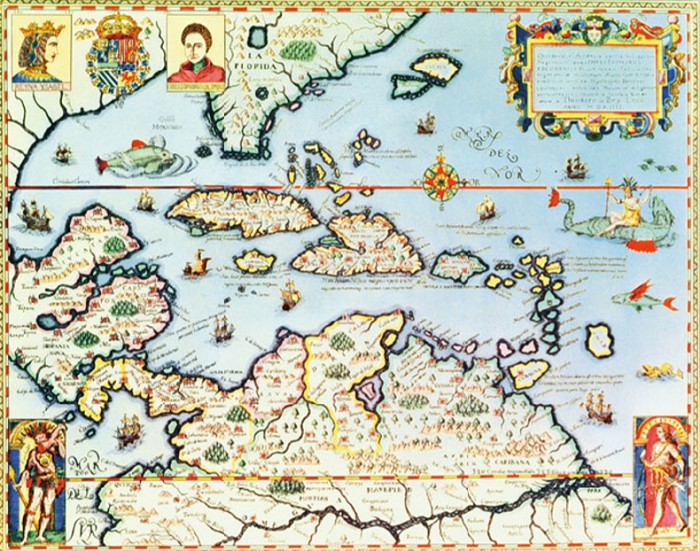

Карта Карибских островов и полуострова Флорида. Раскрашенная гравюра. XVI в.

В начале августа Адмирал тяжело заболел и приказал взять курс на Эспаньолу. Флотилия двинулась на север мимо островов Лос-Тестигос («Свидетели») и Маргарита («Жемчужная»). В Санто-Доминго тем временем против наместников Колумба восстали идальго. Жестоко эксплуатируя индейцев, издеваясь и убивая их сотнями, испанские завоеватели требовали еще большего. Колумбу пришлось согласиться на их условия – каждому идальго был выделен участок земли и индейцы для его обработки. За побег полагалось рабство или смерть. Продолжалось невиданное истребление коренных жителей острова.

Новая колония стала обузой для испанских монархов. Стало понятно, что открытая Колумбом земля не принесет сказочных богатств, и это не Индия. Адмирала начали обвинять в обмане и присвоении королевских доходов. Прибывший на Эспаньолу в 1500 г. Ф. Бовадилья арестовал Колумба и его братьев и в кандалах отправил их в Испанию. И хотя короли освободили Колумба, он был разжалован, унижен и оскорблен. Так закончилось его третье путешествие.

Т. де Бри. Арест Христофора Колумба. XVI в.

Колумб в цепях. Раскрашенная гравюра. 1875 г.

Р. Балака. Колумб перед испанской королевской четой. 1874 г.

Но все же Христофор Колумб не сдавался. В 1502 г. он предпринял еще одну попытку найти западный путь в Индию, теперь уже от открытых им новых земель. Колумб не имел представления о величине Тихого океана и надеялся, что, двигаясь на запад, достигнет через некоторое время берегов Восточной Азии. Четыре корабля с командой из 150 человек вышли в Атлантику 3 апреля. Минуя Малые Антильские острова, Колумб открыл остров Мартиника, остановился ненадолго на Эспаньоле, а затем двинулся на запад. Вскоре корабли подошли к берегам нового континента, это был полуостров Юкатан – земля индейцев племени майя.

Испанцы встретили индейцев, стоящих на гораздо более высокой ступени развития, чем жители Антильских островов. У них были цветные ткани и одежда, бронзовые топоры и колокольчики, бронзовая и деревянная посуда, деревянные мечи с острыми кремнями и бобы какао, которые они использовали в качестве денег. Но золота у них не было, и флотилия продолжила свой путь на восток, а затем на юг вдоль берегов Центральной Америки. Индейцы встречали испанцев дружелюбно, от них Колумб узнал, что к югу находится богатая страна, а за высокими горами – другое море (открытый позднее Тихий океан), но экспедиция, отправленная в глубь материка, не дошла до него. Шли дожди, корабли обветшали и начали гнить, два из них бросили, собрав команду на двух каравеллах, а Колумб продолжал искать пролив в западное море. Он прошел 2200 км, но все же вынужден был повернуть на север, к Ямайке. Потерпев кораблекрушение у ее берегов 25 июня 1503 г., команда и Колумб целый год дожидались помощи с Эспаньолы. Наконец оттуда пришло судно, снаряженное на деньги Колумба. Тяжелобольной капитан и измученные моряки добрались сначала до Эспаньолы, а затем вернулись в Испанию. Так закончилось четвертое плавание к берегам Вест-Индии.

Могила Колумба в кафедральном соборе Севильи. Испания

Вклад в географию

Христофор Колумб первым из европейцев пересек Атлантику в тропических широтах Северного полушария, он открыл побережье Южной и Центральной Америки, Большие Антильские и часть Малых Антильских и Багамских островов, остров Тринидад и несколько мелких островов в Карибском море.

По выражению французского географа XVIII в. Жана Анвиля, это была «величайшая ошибка, которая привела к величайшему открытию».

Поделиться ссылкой

Христофор Колумб совершил (4) путешествия через Атлантический океан. Главной идеей этих путешествий, которую Колумб вынашивал долгое время, было открытие западного морского пути в богатую пряностями Индию.

Христофор Колумб ((1451)–(1506)) — великий испанский мореплаватель итальянского происхождения.

Колумб первым из достоверно известных путешественников пересёк Атлантический океан в субтропической и тропической полосе северного полушария и первым из европейцев ходил в Карибском море. Он открыл и положил начало исследованию Южной и Центральной Америки, включая их континентальные части и близлежащие архипелаги — Большие Антильские (Куба, Гаити, Ямайка и Пуэрто-Рико), Малые Антильские (от Доминики до Виргинских островов, а также Тринидад) и Багамские острова.

В первом плавании Христофор Колумб достиг Багамских островов, Кубы и Гаити.

Первое плавание Христофора Колумба

(3) августа (1492) года Колумб отправился в своё первое плавание. В его распоряжении были (3) корабля: «Санта—Мария», «Нинья» и «Пинта». Чуть более двух месяцев понадобилось экспедиции, чтобы пересечь Атлантический океан и оказаться на Багамский островах. (12) октября (1492) года был открыт первый остров, который Колумб назвал Сан—Сальвадор. Колумб ошибочно считал, что смог открыть западный морской путь в Индию, поэтому назвал индейцами местных жителей.

|

|

|

Высадка Колумба в Америке |

Во время второго плавания Колумб открыл ряд других островов в Карибском море, в третьем — достиг побережья Южной Америки, в последнем — побережья Центральной Америки.

Карта второй, третьей и четвёртой экспедиций Христофора Колумба

В честь Христофора Колумба названа страна в Южной Америке, река в Северной Америке. Памятники отважному мореплавателю установлены в Италии, Испании, в некоторых странах Латинской Америки и в США.

Хотя Колумба в своё время называли «Адмирал моря—океана», умер он в бедности, так и не узнав, что открыл новый континент.

Америкой два материка назвали в честь Америго Веспуччи.

Источники:

Изображения:

Колумб. Автор: Себастьяно дель Пьомбо — Метрополитен-музей, Нью-Йорк — онлайн коллекция (The Met object ID 437645), Общественное достояние, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60077253.

Высадка Колумба в Америке. Автор: Джон Вандерлин — Architect of the Capitol, Общественное достояние, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1380997.

Христофор Колумб — легендарный путешественник-мореплаватель, считающийся первооткрывателем Американского континента. Кроме того, именно Колумб первым нанес на карты Саргассово и Карибское моря, Багамские и Антильские острова. Христофор Колумб является первым из известных путешественников, которому удалось пересечь Атлантический океан.

Биография Колумба по своему содержанию не может восприниматься как истина, так как реальных фактов о его происхождении и жизни вплоть до первой экспедиции найти крайне сложно. Так сложилась история, что даже судовой журнал, в который Христофор Колумб заносил сведения о путешествии в Новый свет, т.е. самый значительный исторический документ этого плавания, не сохранился. Биография Христофора Колумба кратко следующая…

Детство и юность

Итальянец по происхождению. Родился в Генуе между 25 августа и 31 октября 1451 в семье ткача-шерстянщика Доменико Коломбо (точная дата не установлена). Также в источниках встречается имя Кристобаль Колон, видимо итальянская транскрипция. В целом о детстве и юности известно очень мало. Право называться родиной мореплавателя на самом деле оспаривают 6 городов Италии и Испании, т.е. Генуя — это тоже не точно.

Мать Христофора, Сусанна Фонтанаросса, была дочерью ткача. У Христофора было 3 младших брата — Бартоломе (около 1460 г/р), Джакомо (около 1468 г/р), очень рано умерший Джованни Пеллегрино – и сестренка Бьянкинетта.

Документальные свидетельства того времени показывают, что финансовое положение семьи было плачевным. Особенно крупные финансовые проблемы возникли из-за дома, в который семейство переехало, когда Христофору было 4 года. Много позже на фундаменте того дома в Санто-Доминго, где Христофоро провел детство, было возведено здание, названное «Каса-ди-Коломбо» (исп. Casa di Colombo – «Дом Колумба»). На фасаде дома в 1887 г. появилась надпись: «Ни один родительский дом не может быть почитаем более этого».

Так как Коломбо-старший был уважаемым в городе ремесленником, в 1470 году его направили с важной миссией в Савону, чтобы обсудить с ткачами вопрос о введении единых цен на текстильную продукцию. Видимо, поэтому Доминико переселился с семьей в этот город, где после смерти супруги и младшего сына, а также после ухода из дома старших сыновей и замужества Бьянки, он все чаще стал искать утешение в чарке с вином.

Поскольку будущий первооткрыватель Америки рос возле моря, с детства его влекли морские просторы. Христофора с юности отличали вера в предзнаменования и божественное провидение, болезненное самолюбие и страсть к золоту. Он обладал недюжинным умом, разносторонними знаниями, талантом красноречия и даром убеждения. Известно, что поучившись немного в Павийском Университете, примерно в 1465 г. юноша поступил на службу в генуэзский флот и в довольно раннем возрасте стал плавать матросом по Средиземному морю на торговых судах. Через некоторое время он был тяжело ранен и временно оставил службу.

Жизнь в Португалии

В Португалии он выгодно женился на Фелипе Монис де Палестрелло, которая была дочерью губернатора этой страны. Бракосочетание состоялось в 1479 г., через год родился их сын, которого называли Диего. Колумб перевез жену в Геную, а сам и дальше продолжал путешествовать.

До 1485 г. Колумб «ходил» на португальских судах, занимался торговлей и самообразованием, увлекся составлением карт. В 1483 г. у него уже был готов новый проект морского торгового пути в Индию и Японию. Мысль о возможности такого плаванья выражали Аристотель и Сенека, Плиний Старший, Страбон и Плутарх, а в средние столетия теория Единого Океана была освящена церковью. Ее признавали арабский мир и его великие географы: Масуди, ал-Бируни, Идриси.

Колумбу удалось представить свой план королю Португалии Жуану II. Но, видно, его время еще не настало, или ему не удалось аргументированно убедить монарха в необходимости снаряжения экспедиции. После 2-х лет раздумий король отверг это предприятие, а дерзкий моряк попал в опалу. Тогда Колумб перешел на испанскую службу.

Переезд в Испанию

В Испании Колумб находит работу в монастыре, заводит роман с другой женщиной. Первая жена Колумба не прожила долго, хотя дата её смерти точно не установлена. Второй супругой Колумба стала Беатрис Энрикес де Арана. В этом браке также родился сын, получивший имя Фернандо.

Уже в 1486 г. Христофор Колумб сумел заинтриговать своим проектом влиятельного герцога Медина-Сели, который ввел небогатого, но одержимого мореплавателя в круг королевского окружения, банкиров и купцов.

В 1488 г. он получил от португальского короля приглашение к возвращению в Португалию, испанцы тоже хотели организовать экспедицию, но страна находилась в состоянии затянувшейся войны и не имела возможности выделить средства на плавание.

Прошло еще 4 года. В январе 1492 г. война завершилась, и вскоре Христофор Колумб добился разрешения от испанского короля на организацию экспедиции, но его в который раз подвел скверный характер! Требования мореплавателя были чрезмерными: назначение вице-королем всех новых земель, титул «главного адмирала океана» и большое количество денег. Король ему отказал, однако, королева Изабелла пообещала свою помощь и содействие. В итоге, 30 апреля 1492 г. король официально сделал Колумба дворянином, пожаловав ему титул «дон» и утвердив все выдвинутые требования.

Всего Колумб совершил к побережью Америки 4 плавания.

1-я экспедиция Колумба

Она состоялась 2 августа 1492 г. — 15 марта 1493 г. Целью первой испанской экспедиции, руководимой Христофором Колумбом, был поиск кратчайшего морского пути в Индию. Эта небольшая экспедиция, состоявшая из 90 человек на трех каравеллах «Санта-Мария» (исп. Santa María), «Пинта» (исп. Pinta) и «Нинья» (исп. La Niña). «Санта-Мария» — 3 августа 1492 г. отправилась в путь из Палоса (исп. Cabo de Palos). Дойдя до Канарских островов и повернув на запад, она пересекла Атлантику и открыла Саргассово море (англ. Sargasso Sea). Первой землей, увиденной среди волн, стал один из островов Багамского архипелага, названный Сан-Сальвадором (англ. San Salvador Island). На нем Колумб высадился 12 октября 1492 г. — этот день считается официальной датой открытия Америки. Далее были открыты еще ряд Багамских островов, Куба, Гаити.

В марте 1493 г. корабли вернулись в Кастилию, везя в трюмах некоторое количество золота, диковинные растения, яркие перья птиц и нескольких туземцев. Христофор Колумб объявил, что открыл западную Индию.

2-я экспедиция Колумба

25 сентября 1493 г — 11 июня 1496 г в подчинении адмирала находилось уже 17 кораблей. А численность экипажа достигала 2,5 тыс. человек. Экспедиция исследовала Гаити, где был проведен военный поход для поиска золота, а также открыты: Острова – Гваделупа, Доминикана, Малые Антильские, Поэрто-Рико, Ямайка, Хувентуд. Южные берега Кубы и Гаити.

Открыв остров Пуэрто-Рико, Колумб 22 ноября 1493 г. подплыл к Эспаньоле. Ночью суда подошли к месту, где стоял заложенный ими в первом плавании форт.

Все было тихо. На берегу не было ни одного огонька. Прибывшие дали залп из бомбард, но только эхо перекатилось вдали. Утром Колумб узнал, что испанцы своей жестокостью и жадностью так восстановили против себя индейцев, что однажды ночью те внезапно напали на крепость и сожгли ее, перебив насильников. Так новая земля встретила Колумба во время его второго плавания!

Вторая экспедиция Колумба была неудачной: открытия были незначительными; несмотря на тщательные поиски, золота нашли мало; в опять построенной колонии Изабелла свирепствовали болезни.

После второго плавания Колумб отчитывался перед государями Испании и утверждал, что нашел новый путь в Азию. Новые земли были провозглашены собственностью испанской короны. Началась их колонизация, на территории и острова перевозили уголовников, поскольку вольные поселенцы не хотели работать в колониях. Последствия были печальными – разрушены, разграблены, а потом и уничтожены древние империи ацтеков, инков, майя.

3-я экспедиция Колумба

Третья исследовательская экспедиция состоялась 30 мая 1498 г. — 25 ноября 1500 г. В плавание двинулось всего 6 судов. 31 июля был открыт остров Тринидад (исп. Trinidad), затем залив Пария (исп. Golfo de Paria), полуостров Пария и устье реки Ориноко (исп. Río Orinoco). 15 августа экипаж обнаружил остров Маргарита (исп. Isla Margarita).

Испанская королевская казна почти не получала доходов от своей новой колонии, а в это время португалец Васко да Гама открыл морской путь в настоящую Индию (1498) и вернулся с грузом пряностей, доказав таким образом, что земли, открытые Колумбом, — совсем не Индия, а сам он — обманщик.

В 1499 монопольное право Колумба на открытие новых земель было отменено. В 1500 королевская чета направила на Эспаньолу с неограниченными полномочиями своего представителя Франсиско де Бобадилью. Тот взял в свои руки всю власть на острове, арестовал Христофора Колумба вместе с братьями, заковал их в кандалы и отправил в Испанию.

В заключении Колумб просидел недолго, но, получив свободу, он лишился многих привилегий и большей части своих богатств — это стало самым большим разочарованием в жизни мореплавателя.

4-я, последняя экспедиция Колумба

9 мая 1502 г. — ноябрь 1504 г. Мореплавателю не давало покоя то, что в течение стольких лет, не был найден западный путь в Индию. Флотилия из четырех небольших каравелл (140–150 чел.) отплыла из Кадиса. Зайдя на Канарские острова, она 25 мая вышла в открытый океан и 15 июня достигла острова Матининьо, который Колумб переименовал в Мартинику. Пройдя мимо берегов Эспаньолы и обогнув Ямайку с юга, корабли подошли к островам Хардинес-де-ла-Рейна («Сады Королевы»), а затем круто повернули на юго-запад. За три дня (27–30 июля) они пересекли Карибское море и достигли архипелага Ислас-де-ла-Баия и земли, которой адмирал дал имя Гондурас («Глубины») из-за больших прибрежных глубин. Так была открыта Центральная Америка.

Взяв сначала курс на восток, Колумб обогнул м.Грасьяс-а-Дьос («Благодарение Богу») и поплыл на юг вдоль берегов Никарагуа, Коста-Рики и Панамы. Узнав от панамских индейцев о лежащей на западе богатейшей стране Сигуаре и большой реке, он решил, что это и Индия и река Ганг. 6 января 1503 корабли встали у устья р.Белен и в марте основали там небольшое поселение Санта-Мария. Однако уже в первой половине апреля им пришлось покинуть его из-за нападения индейцев. При отступлении они бросили одну каравеллу.

Двинувшись затем на восток вдоль панамского побережья, флотилия в конце апреля дошла до Дарьенского залива и берегов современной Колумбии, а 1 мая от мыса Пунта-де-Москитас повернула на север и 12 мая достигла о-вов Хардинес-де-ла-Рейна. Из-за плачевного состояния судов Колумб смог довести их только до северного берега Ямайки (25 июня). Затем мореплаватели были вынуждены провести целый год в бухте Санта-Глория (совр. Сент-Аннс).

От неминуемой гибели их спас волонтер Д.Мендес, которому удалось на двух каноэ добраться до Санто-Доминго и прислать оттуда каравеллу. 13 августа 1504 спасенные прибыли в столицу Эспаньолы. 12 сентября Колумб отплыл на родину и 7 ноября высадился в Сан-Лукаре.

Последние годы

В начале 1505 Колумб окончательно отказался от дальнейших планов морских экспедиций. Последние полтора года жизни он посвятил борьбе за восстановление его в должности вице-короля Индий и удовлетворение финансовых претензий, однако добился лишь частичной денежной компенсации.

До самой смерти он оставался в убеждении, что открытые им земли являлись частью Азиатского материка, а не новым континентом.

Колумб умер 20 мая 1506 в Вальядолиде, где и был похоронен. Интересной является судьба останков Колумба, которые из Испании перевезли на Гаити. Когда испанцы ушли с острова, то прах великого мореплавателя перевезли в Гавану, а оттуда – в Санта-Доминго, а затем – Севилью. Долгое время считалось, что останки покоятся в кафедральном соборе Севильи, но генетические исследование доказали обратное. Было установлено, что кости принадлежат другом человеку в возрасте 45 лет. Колумбу же на момент смерти было около 60 лет. Где находятся сейчас останки мореплавателя, никто из историков не знает.

Итоги жизни

Как оценивал Колумб свою жизнь -сложно предположить. Однако, он так и не сумел добраться до берегов сказочно богатой Индии, а ведь именно это было его сокровенной мечтой. Он даже не понял, что открыл. А континенты, увиденные впервые именно им, получили имя другого человека — Америго Веспуччи (итал. Amerigo Vespucci), который просто продлил проторенные великим генуэзцем тропы.

Христофор Колумб не был первооткрывателем Америки: острова и побережье Северной Америки посещались норманнами за сотни лет до него. Однако только открытия Колумба имели всемирно-историческое значение.

Имя Колумба носит государство Колумбия в Южной Америке, Колумбийское плато и река Колумбия в Северной Америке, федеральный округ Колумбия в США и провинция Британская Колумбия в Канаде; в США есть пять городов с названием Колумбус и четыре с названием Колумбия.

1-ый доклад (пример)

Короткая биография Христофора Колумба

Христофор Колумб родился в Республике Генуя, в нынешней северо-западной Италии. Его отец был торговцем шерстью среднего класса. Колумб научился плавать с раннего возраста, а затем работал бизнес-агентом, путешествуя из Европы в Англию, Ирландию, а затем вдоль западного побережья Африки. Он не был ученым, но был восторженным самообразованным человеком, который читал много трудов по астрономии, науке и навигации. Он свободно говорил на латинском, португальском и испанском языках.

Христофор Колумб был верующим в сферическую природу мира (некоторые христиане в то время по-прежнему придерживались мнения о том, что земля была плоской). Как амбициозный человек, Христофор Колумб надеялся найти западный торговый путь к прибыльным рынкам специй в Азии. Вместо того, чтобы плыть на восток, он надеялся, что путь на запад приведет его к таким странам, как Япония и Китай.

Чтобы получить необходимое финансирование и поддержку своих путешествий, он обратился к католическим монархам Испании. В рамках своего предложения он сказал, что надеется, что сможет распространять христианство на «языческих землях» востока. Испанские монархи согласились финансировать Колумба, частично и на миссионерские усилия, но больше делали ставку на прибыльные торговые рынки.

Молодость Колумба. Первые плавания

Христофор Колумб родился между 26 августа и 31 октября 1451 года на острове Корсика в Генуэзской республике. Образование будущий открыватель получил в Павийском университете.

Краткая биография Колумба не сохранила точных свидетельств о его первых плаваниях, однако известно, что в 1470-х годах он совершал морские экспедиции с торговыми целями. Уже тогда у Колумба возникла идея путешествия в Индию через запад. Мореплаватель много раз обращался к правителям европейских стран с просьбой помочь ему организовать экспедицию – к королю Жуану ІІ, герцогу Медина-Сели, королю Генриху VII и другим. Лишь в 1492 году путешествие Колумба было одобрено испанскими правителями, прежде всего, королевой Изабеллой. Ему был присвоен титул «дона», обещаны вознаграждения в случае удачного проведения проекта.

Путешествие в Америку

Первое путешествие Колумба было в 1492 году. Он намеревался отправиться в Японию, но оказался на Багамах, которые он назвал Сан-Сальвадором.

Колумб совершил в общей сложности четыре путешествия. Он плавал вдоль Карибских островов Кубы, Ямайки, Багам, а также дошел до материка Панамы.

Колумб не был первым человеком, который достиг Америки. Предыдущие успешные путешествия совершила туда норвежская экспедиция под руководством Лейфа Эриксона. Однако Колумб первым высадился в Америке и основал на ней постоянные поселения.

Доклады Колумба в течение следующих 400 лет побуждали все основные европейские державы стремиться колонизировать какую-либо часть этого континента.

В рамках заключенной сделки испанские монархи даровали Колумбу титул вице-короля и губернатора штатов на острове Эспаньола. Позже он делегировал губернаторство своим братьям. Однако в 1500 году, по приказу испанских короля и королевы, Колумб был арестован и помещен в цепи. Ему были предъявлены обвинения о некомпетентности и варварской практике при управлении новыми колониями. После нескольких недель в тюрьме Колумб и его братья были освобождены, но Колумбу больше не разрешалось быть губернатором Эспаньолы.

К концу своей жизни Колумб становился все более религиозным. В частности, он увлекся библейскими пророчествами и написал свою «Книгу пророчеств» (1505).

Колумб умер в 1506 году, в возрасте 54 лет от сердечного приступа, связанного с реактивным артритом. Несомненно, суровость путешествий по морю, стоила Колумбу здоровья. К концу своей жизни он часто болел.

Колумба почитают многие европейцы и американцы как человека, начертившего Америку на карте. День Колумба отмечается 12 октября в Испании и по всей Америке. Другие придерживаются более критического взгляда на него, утверждая, что его «открытие» на самом деле не было открытием, если земля уже была заселена, и что благодаря его действиям последующие европейские колонизации привели к жестокому обращению и геноциду коренных американцев.

Четыре экспедиции. Открытие Америки

В 1492 году было совершено первое плавание Колумба. Во время путешествия мореплавателем были открыты Багамские острова, Гаити, Куба, хотя сам он считал эти земли «Западной Индией».

Во время второй экспедиции помощников Колумба были такие известные личности как будущий завоеватель Кубы Диего Веласкес де Куэльяр, нотариус Родриго де Бастидас, первопроходец Хуан де ла Коса. Тогда открытия мореплавателя включали Виргинские, Малые Антильские острова, Ямайку, Пуэрто-Рико.

Третья экспедиция Христофора Колумба была совершена в 1498 году. Главным открытием мореплавателя был остров Тринидад. Однако в это же время Васко да Гама нашел настоящий путь в Индию, поэтому Колумб был объявлен обманщиком и отправлен под конвоем из Эспаньолы в Испанию. Тем не менее, по его прибытию местным финансистам удалось уговорить короля Фердинанда II снять обвинения.

Колумба не покидала надежда открыть новый краткий путь к Южной Азии. В 1502 году мореплаватель смог добиться разрешения короля на четвертое путешествие. Колумб достиг берега Центральной Америки, доказав, что между Атлантическим океаном и Южным морем лежит материк.

Пример короткого доклада на тему Христофор Колумб (по истории, 7 класс)

Родился Христофор Колумб между 25 августа и 31 октября 1451года в Италии. Он является одним из самых знаменитых мореплавателей и вписал свое имя в истории, как человек открывший миру Америку и по праву считается самой загадочной личностью того времени.

Историкам и по сей день не известна подлинная история великого мореплавателя, ведь подлинных материалов сохранилось очень мало и каждый новый биограф вносит новые выдуманные факты.

В истории не сохранилось достоверных сведений о его первых путешествиях, известно только, что уже в 70-х годах он совершал торговые плаванья к берегам Англии, вот тогда Колумба и посетила идея совершить плаванье в Индию через запад. И только лишь через 10 лет, ему удалось найти спонсоров для своей первой полноценной экспедиции в лице короля Фердинанда второго.

В первой же экспедиции им была открыта Куба, Багамские острова и Гаити, хотя он думал что это «Западная Индия».

Во второй экспедиции были открыты Венгерские и Малые Антильские острова, Пуэрто-Рико и Ямайка. После этой экспедиции Колумбу был дарован мраморный замок и его доход приближался к 200 000 франков, в то время ему уже можно было заканчивать карьеру мореплавателя и уходить на покой. Однако, короткий маршрут в Индию все еще не был открыт и он не остановился на достигнутом.

Очередная, третья по счету экспедиция, была совершена Колумбом в 1498 году. В этом плаванье был открыт остров Тринидад. Одновременно с этим, был открыт настоящий путь к берегам Индии и открыл его, мореплаватель Васко Да Гама. Колумба признали обманщиком и лгуном, все дарованные привилегии были отобраны.

В 1502 году Колумб чудом добивается разрешения короля на новое путешествие, с целью открыть более короткий путь к Южной Азии. Именно в этой экспедиции и была открыта Центральная Америка. Было доказано, что существует новый, поистине огромный материк. Однако, действительно первооткрывателем Америки, Колумба назвать сложно. Ведь еще в средние века, эти земли посещали исландские викинги, но из-за того, что сведения об их путешествиях не выходили за приделы Скандинавии, то первым стал Христофор Колумб.

За время последнего путешествия, Колумб серьезно заболел. По возвращению на родину, ему удается восстановить свои права и привилегии. Христофор Колумб скончался в 1506 году и был похоронен в Севилье. За свою жизнь он выучил множество языков, был дважды женат и имел двух детей, большую часть жизни он провел в море, открывая миру незнакомые земли.

Последние годы

Во время последнего путешествия Колумб тяжело заболел. По возвращению в Испанию ему не удалось восстановить дарованные ему привилегии и права. Умер Христофор Колумб 20 мая 1506 года в Севилье в Испании. Мореплаватель был сначала похоронен в Севилье, однако в 1540 году, по приказу императора Карла V останки Колумба были перевезены на остров Эспаньола (Гаити), а в 1899 году снова в Севилью.

Кротчайший доклад

Христофор Колумб родился 27 октября 1451 года в городке Генуя, Италия. Несмотря на то, что Христофор Колумб не ходил в школу, он знал, как и кто-либо другой, что Земля – круглая.Когда Колумб был подростком, он осознал, что для того, чтобы его мечта осуществилась, ему надо научиться как читать и писать так и считать, чтобы рассчитывать дистанцию и скорость кораблей. В то время как Христофор увлекся этой идеей, никто еще даже не предполагал, что на пути находится огромное препятствие -Северная и Южная Америка.

Колумб попросил королеву Испании Изабеллу и короля Фердинанда спонсировать его план, обещая при этом привезти золото, специи и шелк. В итоге ему выделили средства и 3 августа 1492 года он отправился в путь. 2 месяца спустя,12 октября, Христофор Колумб со своей командой сошли на берег острова, который сейчас известен как Багамы.

Христофор Колумб верил в то, что он был в Индии, что люди, которых он встретил были индийцами. Будучи до сих пор неосведомленным, Христофор Колумб заявил что они прибыли в Японию! Колумб 4 раза путешествовал в место, которое стало известным как “Новый Свет”, а позже – Америка. Но Христофор Колумб так и не узнал, что он открыл Америку. Перед смертью, 20 мая 1506 года, он был убежден что побывал в Азии.

Биография Христофора Колумба

26 Августа 1451 – 20 Мая 1506 гг. (54 года)

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 1694.

Христофор Колумб (1451–1506 гг.) – испанский мореплаватель, открывший Америку и близлежащие острова. Первый из путешественников, который пересек Атлантический океан. Совершил четыре экспедиции в тщетных попытках отыскать западный, более короткий путь в Индию. Его именем названа страна в Южной Америке — Колумбия.

Опыт работы учителем географии — 35 лет.

Молодость. Первые плавания

Христофор Колумб родился между 26 августа и 31 октября 1451 года на острове Корсика в Генуэзской республике. Образование будущий открыватель получил в Павийском университете.

Краткая биография Колумба не сохранила точных свидетельств о его первых плаваниях, однако известно, что в 1470-х годах он совершал морские экспедиции с торговыми целями. Уже тогда у Колумба возникла идея путешествия в Индию через запад. Мореплаватель много раз обращался к правителям европейских стран с просьбой помочь ему организовать экспедицию к королю Жуану ІІ, герцогу Медина-Сели, королю Генриху VII и другим. Лишь в 1492 году путешествие Колумба было одобрено испанскими правителями, прежде всего, королевой Изабеллой. Ему был присвоен титул «дона», обещаны вознаграждения в случае удачного проведения проекта.

Четыре экспедиции. Открытие Америки

В 1492 году было совершено первое плавание Колумба. Во время путешествия мореплавателем были открыты Багамские острова, Гаити, Куба, хотя сам он считал эти земли «Западной Индией».

Во время второй экспедиции среди помощников Колумба были такие известные личности как будущий завоеватель Кубы Диего Веласкес де Куэльяр, нотариус Родриго де Бастидас, первопроходец Хуан де ла Коса. Тогда открытия мореплавателя включали Виргинские, Малые Антильские острова, Ямайку, Пуэрто-Рико.

Третья экспедиция Христофора Колумба была совершена в 1498 году. Главным открытием мореплавателя был остров Тринидад. Однако в это же время Васко-да-Гама нашел настоящий путь в Индию, поэтому Колумб был объявлен обманщиком и отправлен под конвоем из Эспаньолы в Испанию. Тем не менее, по его прибытию местным финансистам удалось уговорить короля Фердинанда II снять обвинения.

Колумба не покидала надежда открыть новый краткий путь к Южной Азии. В 1502 году мореплаватель смог добиться разрешения короля на четвертое путешествие. Колумб достиг берега Центральной Америки, доказав, что между Атлантическим океаном и Южным морем лежит материк.

Последние годы

Во время последнего путешествия Колумб тяжело заболел. По возвращению в Испанию ему не удалось восстановить дарованные ему привилегии и права. Умер Христофор Колумб 20 мая 1506 года в Севилье в Испании. Мореплаватель был сначала похоронен в Севилье, однако в 1540 году, по приказу императора Карла V останки Колумба были перевезены на остров Эспаньола (Гаити), а в 1899 году снова в Севилью.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

- Историкам до сих пор не известна подлинная биография Христофора Колумба – фактических материалов о его судьбе и экспедициях так мало, что биографы мореплавателя вносят в его жизнеописание множество выдуманных утверждений.

- Вернувшись в Испанию после второй экспедиции, Колумб предложил селить на недавно открытые земли преступников.

- Предсмертными словами Колумба были: «In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum» («В твои руки, Господи, я вручаю мой дух»).

- Значение открытий мореплавателя было признано только в середине XVI века.

Тест по биографии

Биография запомнится лучше, если попытаетесь ответить на вопросы теста:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Мария Вощенко

10/11

-

Анна Полянская

11/11

-

Наталия Ворошилова

11/11

-

Ирина Стрелкова

11/11

-

Соня Коваль

9/11

-

Татьяна Коваль

7/11

-

Сергей Волков

8/11

-

Людмила Перес

11/11

-

Светик Жемчугова

11/11

-

Дмитрий Желтухин

9/11

Оценка по биографии

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 1694.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Христофор Колумб — это человек-легенда, знаменитый мореплаватель, флотоводец и картограф, открывший новый континент. В поисках морского пути в Индию он первым достиг берегов Америки. Его огромная трагедия в том, что до конца своих дней он даже не догадывался, что совершил величайшее открытие.

Биография Колумба

Точная дата рождения Христофора Колумба или, в испанском звучании, Кристобаля Коломбо не установлена. Известно только, что она приходится на период с 25 августа до октября 1451 года. В эти осенние дни в семье Доминико Коломбо и его жены Сусанны появился первенец. Проживали они в тот период в Генуе. Однако место рождения Колумба, как и дата, до сих пор остается предметом разногласий. Целых шесть итальянских и испанских городов по сей день оспаривают право называться родиной великого мореплавателя.

Родители Колумба были не очень состоятельными людьми. Отец, Доминико, был ткачом, попутно занимался торговлей. Он не оставлял попыток разбогатеть и в таких сферах, как виноградарство и устройство пастбищ. Мастерство и трудолюбие Доминико делали его одним из самых уважаемых горожан. Мать вела дом и воспитывала детей. Помимо Христофора, в семье было еще три сына и дочка. Один из сыновей, Доминик, умер в юном возрасте, а два других брата стали соратниками Христофора и сопровождали его в некоторых странствиях.

Обучение юного мореплавателя

По свидетельству многих историков, Христофор вместе со своими братьями и сестрой получал образование у приходящих преподавателей. Без посторонней помощи отец Колумба вряд ли мог оплатить частное обучение. Но, как утверждают исследователи, семейству помогали состоятельные единоверцы — мараны, или евреи, принявшие христианскую веру. Среди них еще в те времена встречалось много финансистов.

Благодаря полученным знаниям, а также финансовой поддержке благотворителей, Христофор смог поступить в университет города Падуя. Это учебное заведение считается одним из старейших в Европе. Университет славился высоким уровнем обучения, и Колумб еще в годы свирепствовавшей инквизиции знал, что Земля имеет форму шара, а не плоского блина.

В учебном заведении Христофор близко сошелся с астрономом Тосканелли, который и показал Колумбу другой, более короткий путь к Индии. Существовавший в те времена сухопутный способ перемещения к заветным землям был слишком долгим и опасным. Добраться до Индии по морю было гораздо легче и быстрее.

Личная жизнь

По свидетельствам исследователей, знаменитый путешественник был женат дважды. Он состоял в церковном браке с представительницей состоятельного семейства де Палестрелло, которую звали Фелипа Мониш. Отец девушки был известным мореплавателем. Так Христофор попал в семью, тесно связанную с морскими походами.

У молодой пары родился сын, которого назвали Диего. Уже в зрелом возрасте Диего станет знатным чиновником, вице-королем Новой Испании и обладателем различных высоких титулов.

Еще один мальчик у Колумба родился позднее. Христофор состоял в связи с женщиной по имени Беатрис, которая подарила ему наследника. Мальчика назвали Фернандо. К чести Колумба, он не делал различий между мальчиками. Оба сына получали внимание, помощь и поддержку в равной степени.

Еще подростком второй сын участвовал в экспедициях Колумба. Фернандо получил хорошее образование и стал ученым. Именно его перу принадлежит первая биография его отца. Фернандо, как и его брат, имел титулы и обладал солидным состоянием.

Экспедиции Колумба

Как многие люди, выросшие у моря, Колумб с юности мечтал о далеких странах и неизведанных землях. Больше всего его влекла Индия, полная несметных богатств. Золото, драгоценные камни, пряности — все это позволяло в короткий срок разбогатеть и подняться по социальной лестнице. После того, как Колумб получил от своего друга астронома информацию о другом, коротком, пути в Индию, он не переставал думать о воплощении своей мечты.

Помимо азарта исследователя, Колумбом двигала еще одна мощная сила — это желание обрести богатство, славу и общественное положение. Поэтому все свои усилия Христофор направил на то, чтобы сильные мира сего вложили средства в его экспедиции.

Всего известно о четырех экспедициях Христофора Колумба.

- Первое плавание. Продлилось более полугода, с августа 1492 г. по середину марта 1493 г.

- Вторая экспедиция. Самая масштабная и продолжительная. Длилась почти три года при участии семнадцати судов.

- Третье плавание. В нем принимали участие шесть кораблей. Проходило с 1498 г. по 1500 г.

- Четвертая экспедиция продлилась более двух лет, с мая 1502 г. по ноябрь 1504 г.

ЭТО ИНТЕРЕСНО. Примерно в 1492 году, поле того, как Колумб достиг Америки, в его заметках стало появляться упоминание о табаке — растении, которым индейцы набивали свои трубки.

Первое плавание Колумба

Своей первой экспедиции Колумб добивался почти десять лет. Сначала он обратился за содействием к генуэзским купцам. Не встретив поддержки, он попытал удачи у короля Португалии. Однако эта попытка тоже обернулась провалом. Немного позже, в 1885 году, Колумб просит аудиенции у короля и королевы Испании. Колумб пытается заинтересовать монархов несметными сокровищами, которые находятся в Индии. Положение осложнялось тем, что Колумб предлагал новый, кратчайший, путь в Индию. Его расчеты основывались на том, что Земля имеет форму шара. А в те времена подобные утверждения были чреваты судом инквизиции.

Заручившись покровительством испанских монархов, Колумб все же добивается снаряжения экспедиции.

В 1492 году в плавание на поиски пути в Индию отправилось три судна. В походе приняли участие две каравеллы — «Пинта» и «Нинья», а также четырехмачтовый парусник «Санта Мария».

Мореплаватели пересекли Атлантический океан, двигаясь на запад. В результате первой испанский экспедиции Колумбом были открыты:

- Саргассово море. Это уникальное море, которое не имеет берегов, ограничиваясь морскими течениями. Свое название море получило из-за скопления бурой водоросли саргассы.

- Багамские острова. Один из островов получил название Сан-Сальвадор, что в переводе с испанского значит «Святой Спаситель». Так Колумб окрестил остров, давший ему и его соратникам приют после 70-дневного морского путешествия.

- Гаити — цветущий остров, береговая линия которого изрезана бухтами и заливами. Он получил название Эспаньола, или Маленькая Испания. Это были земли, на которых появилась первая испанская колония.

- Куба. Этот тропический рай впервые увидел европейцев-завоевателей в октябре 1492 года.

Посмотрите следующее видео и ознакомьтесь с интересными фактами из жизни Христофора Колумба.

Из первой экспедиции Колумб привез незначительное количество золота, образцы неизвестных ранее растений, оперенье незнакомых птиц, а также несколько захваченных туземцев. Колумб объявил, что в результате похода открыл Западную Индию.

Второе плавание Колумба

Во второй экспедиции Колумб принимал участие уже в чине адмирала. Его сопровождали 2000 человек и 17 судов. Мореплаватели направились по тому же маршруту, через Атлантику. В результате были открыты:

- Остров Доминика. Его Колумб назвал в честь дня недели, в которую он был открыт. Dominicus — по латыни «воскресенье».

- Гваделупа, Санта-Мария Гваделупская, названная по имени монастыря в Испании.

- Антильские острова.

Берега, открытые во время первой экспедиции, были более тщательно исследованы. В результате второго похода была открыта эра колонизации. К найденным и описанным землям выдвинулись поселенцы и священнослужители. Некоторые отдаленные места стали использовать в качестве ссылки для опасных преступников.

ЭТО ИНТЕРЕСНО. В Барселоне, на том самом месте, куда ступил Колумб, вернувшись из первого похода, сейчас стоит памятник. Памятник представляет собой бронзовую скульптуру, расположенную на высокой металлической колонне.

Третья экспедиция Колумба

В 1498 году, всего на шести судах, Колумб направился на очередное исследование берегов Индии (как он считал). Итогом экспедиции стало открытие таких земель, как:

- Остров Тринидад. Колумб дал острову такое звучное имя, потому что он прибыл на него 31 июля, на день Святой Троицы. В честь этого праздника и были названы земли.

- Полуостров Пария и одноименный залив. Названы в честь крепкого местного дерева, которое служило сырьем для стрел аборигенов.

- Остров Маргарита — самый крупный из островов Карибского моря. Его названием Колумб увековечил принцессу Испании, Маргариту Австрийскую.

- Устье реки Ориноко.

По возвращении из плавания, в 1500 году, Колумба постигло большое разочарование. Он был направлен в Кастильскую тюрьму по ложному доносу. Выйдя на свободу, он лишился многих своих званий и привилегий, а также части своего состояния.

Четвертая экспедиция

Это предприятие стартовало в 1502 году. Цель Колумба была все та же — открытие западного пути в Индию. В результате были открыты:

- Остров Мартиника. Он не заинтересовал Колумба, так как на острове не было обнаружено золото.

- Гондурасский залив. На берегах залива Колумб, как утверждают, имел контакты с представителями Майя.

Во время последней экспедиции в районе Ямайки Колумба постигает большая неудача. Он потерпел крушение и в течение долгого года дожидался помощи и вызволения.

Знаменитый мореплаватель вернулся в Кастилию в 1504 году, морально сломленный и тяжело больной.

Закат жизни

К концу своей жизни Колумб потерял почти все, к чему так стремился. Он остался без денег и без полученных привилегий. Долгие и изнурительные переговоры с королем о возвращении прежнего статуса ни к чему не привели.

Главной своей неудачей Колумб считал то, что вожделенный морской путь в Индию он так и не проложил. Америка, по сути открытая им, получила название по имени совсем другого мореплавателя.

Умер великий путешественник в 1506 году. Даже после смерти ему не было суждено обрести покой. Его останки несколько раз перевозили по воле сына. Сейчас его прах покоится в испанской Севилье.

| Part of the Age of Discovery | |

The four voyages of Columbus (conjectural) |

|

| Date | 1492, 1493, 1498 & 1502 |

|---|---|

| Location | The Americas |

| Participants | Christopher Columbus and Castilian crew (among others) |

| Outcome | European rediscovery and colonization of the Americas |

Between 1492 and 1504, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus led four Spanish transatlantic maritime expeditions of discovery to the Americas. These voyages led to the widespread knowledge of the New World. This breakthrough inaugurated the period known as the Age of Discovery, which saw the colonization of the Americas, a related biological exchange, and trans-Atlantic trade. These events, the effects and consequences of which persist to the present, are often cited as the beginning of the modern era.

Born in the Republic of Genoa, Columbus was a navigator who sailed for the Crown of Castile (a predecessor to the modern Kingdom of Spain) in search of a westward route to the Indies, thought to be the East Asian source of spices and other precious oriental goods obtainable only through arduous overland routes. Columbus was partly inspired by 13th-century Italian explorer Marco Polo in his ambition to explore Asia and never admitted his failure in this, incessantly claiming and pointing to supposed evidence that he had reached the East Indies. Ever since, the Bahamas as well as the islands of the Caribbean have been referred to as the West Indies.

At the time of Columbus’s voyages, the Americas were inhabited by Indigenous Americans. Soon after first contact, Eurasian diseases such as smallpox began to devastate the indigenous populations. Columbus participated in the beginning of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, which involved brutally treating and enslaving the natives in the range of thousands.

Columbus died in 1506, and the next year, the New World was named «America» after Amerigo Vespucci, who realized that it was a unique landmass. The search for a westward route to Asia was completed in 1521, when another Spanish voyage, the Magellan-Elcano expedition sailed across the Pacific Ocean and reached Southeast Asia, before returning to Europe and completing the first circumnavigation of the world.

Background

Many Europeans of Columbus’s day assumed that a single, uninterrupted ocean surrounded Europe and Asia, although Norse explorers had colonized areas of North America beginning with Greenland c. 986.[1][2] The Norse maintained a presence in North America for hundreds of years, but contacts between their North American settlements and Europe had all but ceased by the early 15th century.[3][4][5]

Until the mid-15th century, Europe enjoyed a safe land passage to China and India—sources of valued goods such as silk, spices, and opiates—under the hegemony of the Mongol Empire (the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol Peace). With the Fall of Constantinople to the Turkish Ottoman Empire in 1453, the land route to Asia (the Silk Road) became more difficult as Christian traders were prohibited.[6]

Portugal was the main European power interested in pursuing trade routes overseas, with the neighboring kingdom of Castile—predecessor to Spain—having been somewhat slower to begin exploring the Atlantic because of the land area it had to reconquer from the Moors during the Reconquista. This remained unchanged until the late 15th century, following the dynastic union by marriage of Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon (together known as the Catholic Monarchs of Spain) in 1469, and the completion of the Reconquista in 1492, when the joint rulers conquered the Moorish kingdom of Granada, which had been providing Castile with African goods through tribute. The fledgling Spanish Empire decided to fund Columbus’s expedition in hopes of finding new trade routes and circumventing the lock Portugal had secured on Africa and the Indian Ocean with the 1481 papal bull Aeterni regis.[7]

Navigation plans

In response to the need for a new route to Asia, by the 1480s, Christopher and his brother Bartholomew had developed a plan to travel to the Indies (then construed roughly as all of southern and eastern Asia) by sailing directly west across what was believed to be the singular «Ocean Sea,» the Atlantic Ocean. By about 1481, Florentine cosmographer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli sent Columbus a map depicting such a route, with no intermediary landmass other than the mythical island of Antillia.[8] In 1484 on the island of La Gomera in the Canaries, then undergoing conquest by Castile, Columbus heard from some inhabitants of El Hierro that there was supposed to be a group of islands to the west.[9]

A popular misconception that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because Europeans thought the Earth was flat can be traced back to a 17th-century campaign of Protestants against Catholicism,[10] and was popularized in works such as Washington Irving’s 1828 biography of Columbus.[11] In fact, the knowledge that the Earth is spherical was widespread, having been the general opinion of Ancient Greek science, and gaining support throughout the Middle Ages (for example, Bede mentions it in The Reckoning of Time). The primitive maritime navigation of Columbus’s time relied on both the stars and the curvature of the Earth.[12][13]

Diameter of Earth and travel distance estimates

Columbus’s geographical conceptions (beige) compared to the known landmasses and their demarkation by Juan de la Cosa (black)

Eratosthenes had measured the diameter of the Earth with good precision in the 2nd century BC,[14] and the means of calculating its diameter using an astrolabe was known to both scholars and navigators.[12] Where Columbus differed from the generally accepted view of his time was in his incorrect assumption of a significantly smaller diameter for the Earth, claiming that Asia could be easily reached by sailing west across the Atlantic. Most scholars accepted Ptolemy’s correct assessment that the terrestrial landmass (for Europeans of the time, comprising Eurasia and Africa) occupied 180 degrees of the terrestrial sphere, and dismissed Columbus’s claim that the Earth was much smaller, and that Asia was only a few thousand nautical miles to the west of Europe.[15]

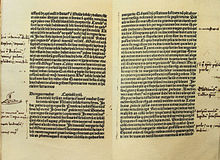

The «Columbus map», depicting only the Old World, was drawn c. 1490 in the workshop of Bartolomeo and Christopher Columbus in Lisbon.[16]

Handwritten notes by Christopher Columbus on the Latin edition of Marco Polo’s Le livre des merveilles

Columbus believed the incorrect calculations of Marinus of Tyre, putting the landmass at 225 degrees, leaving only 135 degrees of water.[17][15] Moreover, Columbus underestimated Alfraganus’s calculation of the length of a degree, reading the Arabic astronomer’s writings as if, rather than using the Arabic mile (about 1,830 m), he had used the Italian mile (about 1,480 meters). Alfraganus had calculated the length of a degree to be 56⅔ Arabic miles (66.2 nautical miles).[15] Columbus therefore estimated the size of the Earth to be about 75% of Eratosthenes’s calculation, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan as 2,400 nautical miles (about 23% of the real figure).[18]

Trade winds

There was a further element of key importance in the voyages of Columbus, the trade winds.[19] He planned to first sail to the Canary Islands before continuing west by utilizing the northeast trade wind.[20] Part of the return to Spain would require traveling against the wind using an arduous sailing technique called beating, during which almost no progress can be made.[21] To effectively make the return voyage, Columbus would need to follow the curving trade winds northeastward to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where he would be able to catch the «westerlies» that blow eastward to the coast of Western Europe.[22]

The navigational technique for travel in the Atlantic appears to have been exploited first by the Portuguese, who referred to it as the volta do mar (‘turn of the sea’). Columbus’s knowledge of the Atlantic wind patterns was, however, imperfect at the time of his first voyage. By sailing directly due west from the Canary Islands during hurricane season, skirting the so-called horse latitudes of the mid-Atlantic, Columbus risked either being becalmed or running into a tropical cyclone, both of which, by chance, he avoided.[23]

Funding campaign

Around 1484, King John II of Portugal submitted Columbus’s proposal to his experts, who rejected it on the basis that Columbus’s estimation of a travel distance of 2,400 nautical miles was about four times too low (which was accurate).[24]

In 1486, Columbus was granted an audience with the Catholic Monarchs, and he presented his plans to Isabella. She referred these to a committee, which determined that Columbus had grossly underestimated the distance to Asia. Pronouncing the idea impractical, they advised the monarchs not to support the proposed venture. To keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the Catholic Monarchs gave him an allowance, totaling about 14,000 maravedís for the year, or about the annual salary of a sailor.[25]

In 1488 Columbus again appealed to the court of Portugal, receiving a new invitation for an audience with John II. This again proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards Bartolomeu Dias returned to Portugal following a successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa. With an eastern sea route now under its control, Portugal was no longer interested in trailblazing a western trade route to Asia crossing unknown seas.[26]

In May 1489, Isabella sent Columbus another 10,000 maravedis, and the same year the Catholic Monarchs furnished him with a letter ordering all cities and towns under their domain to provide him food and lodging at no cost.[27]

As Queen Isabella’s forces neared victory over the Moorish Emirate of Granada for Castile, Columbus was summoned to the Spanish court for renewed discussions.[28] He waited at King Ferdinand’s camp until January 1492, when the monarchs conquered Granada. A council led by Isabella’s confessor, Hernando de Talavera, found Columbus’s proposal to reach the Indies implausible. Columbus had left for France when Ferdinand intervened,[a] first sending Talavera and Bishop Diego Deza to appeal to the queen.[29] Isabella was finally convinced by the king’s clerk Luis de Santángel, who argued that Columbus would bring his ideas elsewhere, and offered to help arrange the funding.[b] Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch Columbus, who had travelled several kilometers toward Córdoba.[29]

In the April 1492 «Capitulations of Santa Fe», Columbus was promised he would be given the title «Admiral of the Ocean Sea» and appointed viceroy and governor of the newly claimed and colonized for the Crown; he would also receive ten percent of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity if he was successful.[31] He had the right to nominate three people, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. The terms were unusually generous but, as his son later wrote, the monarchs were not confident of his return.

History

First voyage (1492–1493)

Captain’s ensign of Columbus’s ships

For his westward voyage to find a shorter route to the Orient, Columbus and his crew took three medium-sized ships, the largest of which was a carrack (Spanish: nao), the Santa María, which was owned and captained by Juan de la Cosa, and under Columbus’s direct command.[32][c] The other two were smaller caravels; the name of one is lost, but it is known by the Castilian nickname Pinta («painted one»). The other, the Santa Clara, was nicknamed the Niña («girl»), perhaps in reference to her owner, Juan Niño of Moguer.[33] The Pinta and the Niña were piloted by the Pinzón brothers (Martín Alonso and Vicente Yáñez, respectively).[32] On the morning of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera, going down the Rio Tinto and into the Atlantic.[34][35]

Three days into the journey, on 6 August 1492, the rudder of the Pinta broke.[36] Martín Alonso Pinzón suspected the owners of the ship of sabotage, as they were afraid to go on the journey. The crew was able to secure the rudder with ropes until they could reach the Canary Islands, where they arrived on 9 August.[37] The Pinta had its rudder replaced on the island of Gran Canaria, and by September 2 the ships rendezvoused at La Gomera, where the Niña‘s lateen sails were re-rigged to standard square sails.[38] Final provisions were secured, and on 6 September the ships departed San Sebastián de La Gomera[38][39] for what turned out to be a five-week-long westward voyage across the Atlantic.

As described in the abstract of his journal made by Bartolomé de las Casas, on the outward bound voyage Columbus recorded two sets of distances: one was in measurements he normally used, the other in the Portuguese maritime leagues used by his crew. Las Casas originally interpreted that he reported the shorter distances to his crew so they would not worry about sailing too far from Spain, but Oliver Dunn and James Kelley state that this was a misunderstanding.[40]

On 13 September 1492, Columbus observed that the needle of his compass no longer pointed to the North Star. It was once believed that Columbus had discovered magnetic declination, but it was later shown that the phenomenon was already known, both in Europe and in China.[41][d]

First Landing in the Americas

First voyage (conjectural):[e] modern place names in black, Columbus’s place names in blue

After 29 days out of sight of land, on 7 October 1492, the crew spotted «[i]mmense flocks of birds», some of which his sailors trapped and determined to be «field» birds (probably Eskimo curlews and American golden plovers). Columbus changed course to follow their flight.[45]

On 11 October, Columbus changed the fleet’s course to due west, and sailed through the night, believing land was soon to be found. At around 10:00 in the evening, Columbus thought he saw a light «like a little wax candle rising and falling».[46][f] Four hours later, land was sighted by a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodríguez Bermejo) aboard the Pinta.[47][g] Triana immediately alerted the rest of the crew with a shout, and the ship’s captain, Martín Alonso Pinzón, verified the land sighting and alerted Columbus by firing a lombard.[48][h] Columbus would later assert that he had first seen land, thus earning the promised annual reward of 10,000 maravedís.[49][50]

Columbus called this island San Salvador, in the present-day Bahamas; the indigenous name was Guanahani.[51] According to Samuel Eliot Morison, San Salvador Island[i] is the only island fitting the position indicated by Columbus’s journal.[44][j] Columbus wrote of the natives he first encountered in his journal entry of 12 October 1492:

Many of the men I have seen have scars on their bodies, and when I made signs to them to find out how this happened, they indicated that people from other nearby islands come to San Salvador to capture them; they defend themselves the best they can. I believe that people from the mainland come here to take them as slaves. They ought to make good and skilled servants, for they repeat very quickly whatever we say to them. I think they can very easily be made Christians, for they seem to have no religion. If it pleases our Lord, I will take six of them to Your Highnesses when I depart, in order that they may learn our language.[53]

A depiction of Columbus claiming possession of the land in caravels, the Niña and the Pinta

Columbus called the indigenous Americans indios (Spanish for ‘Indians’)[54][55][56] in the mistaken belief that he had reached the East Indies;[57] the islands of the Caribbean are termed the West Indies because of this error.

Columbus initially encountered the Lucayan, Taíno, and Arawak peoples.[k] Noting their gold ear ornaments, Columbus took some of the Arawaks prisoner and insisted that they guide him to the source of the gold.[59] Columbus noted that their primitive weapons and military tactics made the natives susceptible to easy conquest.[l]

Columbus observed the people and their cultural lifestyle. He also explored the northeast coast of Cuba, landing on 28 October 1492, and the north-western coast of Hispaniola, present day Haiti, by 5 December 1492. Here, the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas Day, 25 December 1492, and had to be abandoned. Columbus was received by the native cacique (chieftain) Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men, including the interpreter Luis de Torres,[60][m] and founded the settlement of La Navidad.[61] He kept sailing along the northern coast of Hispaniola with a single ship, until he encountered Pinzón and the Pinta on 6 January.

On 13 January 1493, Columbus made his last stop of this voyage in the Americas, in the Bay of Rincón at the eastern end of the Samaná Peninsula in northeast Hispaniola.[62] There he encountered the Ciguayos, the only natives who offered violent resistance during this first voyage.[63] The Ciguayos refused to trade the amount of bows and arrows that Columbus desired; in the ensuing clash one Ciguayo was stabbed in the buttocks and another wounded with an arrow in his chest.[64] Because of the Ciguayos’ use of arrows, Columbus named the inlet the Bay of Arrows (or Gulf of Arrows).[65]

Four natives who boarded the Niña at Samaná Peninsula told Columbus of what was possibly the Isla de Carib (probably Puerto Rico), which was supposed to be populated by cannibalistic Caribs, as well as Matinino, an island populated only by women, which Columbus associated with an island in the Indian Ocean described by Marco Polo.[66]

First return

On 16 January 1493, the homeward journey was begun.[67]

Columbus before the King (Ferdinand II) and Queen (Isabella I) of Spain upon returning from his first voyage

While returning to Spain, the Niña and Pinta encountered the roughest storm of their journey, and on the night of 13 February, lost contact with each other. All hands on the Niña vowed, if they were spared, to make a pilgrimage to the nearest church of Our Lady wherever they first made land.

On the morning of 15 February, land was spotted. Columbus believed they were approaching the Portuguese Azores Islands, but others felt that they were considerably north of the islands. Columbus turned out to be right. On the night of 17 February, the Niña laid anchor at Santa Maria Island, but the cable broke on sharp rocks, forcing Columbus to stay offshore until morning, when a safer location was found nearby. A few sailors took a boat to the island, where they were told by several islanders of a still safer place to land, so the Niña moved once again. At this spot, Columbus took aboard several islanders with food. When told of the vow to Our Lady, the islanders directed the crew to a small shrine nearby.[68]

Columbus sent half of the crew to the island to fulfill their vow, but he and the rest stayed on the Niña, planning to send the other half later. While the shore party were in prayer, they were taken prisoner by order of the island’s captain, João de Castanheira, ostensibly out of fear that they were pirates. Castanheira commandeered their shore boat, which he took with several armed men to the Niña, planning to arrest Columbus. When Columbus defied him, Castanheira said he did not believe or care about Columbus’ story, denounced Spaniards, and went back to the island. After another two days, Castanheira released the prisoners, having been unable to get confessions from them or to capture his real target, Columbus. Some claimed that Columbus was captured, but this is contradicted by Columbus’s log book.[68]

Leaving the island of Santa Maria in the Azores on 23 February, Columbus headed for Castilian Spain, but another storm forced him into Lisbon. He anchored next to a king’s harbor patrol ship on 4 March 1493, where he was told a fleet of 100 caravels had been lost in the storm. Astoundingly, both the Niña and the Pinta had been spared. Not finding King John II of Portugal in Lisbon, Columbus wrote to him and waited for a reply. The king agreed to meet Columbus at Vale do Paraíso, despite the poor relations between Portugal and Castile at the time. Upon learning of Columbus’s discoveries, the Portuguese king informed him that he believed the voyage to be in violation of the 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas.

After spending more than a week in Portugal, Columbus set sail for Spain. He arrived back in Palos on 15 March 1493 and later met with Ferdinand and Isabella in Barcelona to report his findings.[n][o]

Columbus showed off what he had brought back from his voyage to the monarchs, including a few small samples of gold, pearls, gold jewelry from the natives, a few Taíno he had kidnapped,[citation needed] flowers, and a hammock.[citation needed] He also brought the previously unknown tobacco plant, the pineapple fruit, and the turkey.[citation needed] He did not bring any of the precious East Indies spices such as black pepper, ginger or cloves. In his log, he wrote «there is also plenty of ‘ají’, which is their pepper, which is more valuable than black pepper, and all the people eat nothing else, it being very wholesome».[69][p]

Columbus brought captured Taínos to present to the sovereigns, never having met the infamous Caribs.[70] In Columbus’s letter on the first voyage, addressed to the Spanish court, he insisted he had reached Asia, describing the island of Hispaniola as being off the coast of China. He emphasized the potential riches of the land, exaggerating the abundance of gold, and that the natives seemed ready to convert to Christianity.[71] The letter was translated into multiple languages and widely distributed,[72] creating a sensation:

Hispaniola is a miracle. Mountains and hills, plains and pastures, are both fertile and beautiful … the harbors are unbelievably good and there are many wide rivers of which the majority contain gold. … There are many spices, and great mines of gold and other metals…[73]

Upon Columbus’s return, most people initially accepted that he had reached the East Indies, including the sovereigns and Pope Alexander VI,[57] though in a letter to the Vatican dated 1 November 1493, the historian Peter Martyr described Columbus as the discoverer of a Novi Orbis («New Globe»).[74] The pope issued four bulls (the first three of which are collectively known as the Bulls of Donation), to determine how Spain and Portugal would colonize and divide the spoils of the new lands. Inter caetera, issued 4 May 1493, divided the world outside Europe between Spain and Portugal along a north–south meridian 100 leagues west of either the Azores or Cape Verde Islands in the mid-Atlantic, thus granting Spain all the land discovered by Columbus.[75] The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, ratified in the next decade by Pope Julius II, moved the dividing line to 370 leagues west of the Azores or Cape Verde.[76]

Second voyage (1493–1496)

Columbus’s second voyage[q]

The stated purpose of the second voyage was to convert the indigenous Americans to Christianity. Before Columbus left Spain, he was directed by Ferdinand and Isabella to maintain friendly, even loving, relations with the natives.[78] He set sail from Cádiz, Spain, on 25 September 1493.[79]

The fleet for the second voyage was much larger: two naos and 15 caravels. The two naos were the flagship Marigalante («Gallant Mary»)[r] and the Gallega; the caravels were the Fraila (‘the nun’), San Juan, Colina (‘the hill’), Gallarda (‘the gallant’), Gutierre, Bonial, Rodriga, Triana, Vieja (‘the old’), Prieta (‘the brown’), Gorda (‘the fat’), Cardera, and Quintera.[80] The Niña returned for this expedition, which also included a ship named Pinta probably identical to that from the first expedition. In addition, the expedition saw the construction of the first ship in the Americas, the Santa Cruz or India.[81]

Caribbean exploration

On 3 November 1493, Christopher Columbus landed on a rugged shore on an island that he named Dominica. On the same day, he landed at Marie-Galante, which he named Santa María la Galante. After sailing past Les Saintes (Todos los Santos), he arrived at Guadeloupe (Santa María de Guadalupe), which he explored between 4 November and 10 November 1493. The exact course of his voyage through the Lesser Antilles is debated, but it seems likely that he turned north, sighting and naming many islands including Santa María de Montserrat (Montserrat), Santa María la Antigua (Antigua), Santa María la Redonda (Saint Martin), and Santa Cruz (Saint Croix, on 14 November).[82] He also sighted and named the island chain of the Santa Úrsula y las Once Mil Vírgenes (the Virgin Islands), and named the islands of Virgen Gorda.