Ответ:

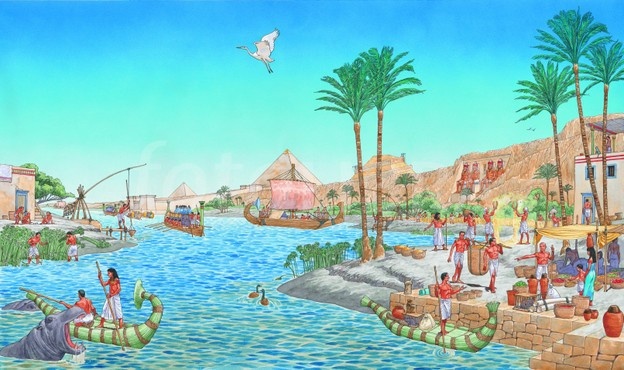

Разлив Нила был важным природным циклом в Египте с древних времен. Он отмечался египтянами как ежегодный праздник в течение двух недель, начиная с 15 августа, известный как Вафа Эль-Нил. Древние египтяне верили, что Нил наводняется каждый год из-за слез скорби Изиды по ее умершему мужу Осирису.

Объяснение:

Разлив Нила является результатом ежегодного муссона в период с мая по август, вызывающего огромные осадки на Эфиопском нагорье, вершины которого достигают высоты до 4550 м. Большая часть этой дождевой воды забирается Голубым Нилом и рекой Атбара в Нил, в то время как менее значительная часть течет через Собат и Белый Нил в Нил. В течение этого короткого периода эти реки вносят до девяноста процентов воды Нила, и большая часть отложений переносится им, но после сезона дождей истощается до малых рек.

Эти факты были неизвестны древним египтянам, которые могли наблюдать только подъем и падение вод Нила. Наводнение как таковое было предсказуемо, хотя его точные даты и уровни можно было прогнозировать только на краткосрочной основе, передавая показания манометра в Асуане в нижние районы королевства, где данные должны были быть преобразованы в местные условия. Конечно, нельзя было предвидеть степень наводнения и его общий сток.

Египетский год был разделен на три сезона: Ахет (Потоп), Перет (Рост) и Шему (Сбор урожая). Ахет охватил египетский цикл наводнения. Этот цикл был настолько последовательным, что египтяне рассчитывали его начало, используя гелиакическое восхождение Сириуса, ключевое событие, используемое для установки их календаря.

Если бы не река Нил, египетская цивилизация не могла бы развиваться, поскольку она является единственным значительным источником воды в этом пустынном регионе.

Другой его важностью была функция ворот в неизвестный мир. Нил течет с юга на север, к его дельте в Средиземном море. Наводнения считались ежегодным пришествием бога. Возможно, египетская мифология была основана на этом понимании, создавая истории богов или природы, чтобы придать дополнительное значение процессам и циклам, которые поддерживали Египет.

The flooding of the Nile has been an important natural cycle in Egypt since ancient times. It is celebrated by Egyptians as an annual holiday for two weeks starting August 15, known as Wafaa El-Nil. It is also celebrated in the Coptic Church by ceremonially throwing a martyr’s relic into the river, hence the name, The Martyr’s Finger (Coptic: ⲡⲓⲧⲏⲃ ⲛⲙⲁⲣⲧⲏⲣⲟⲥ, Arabic: Esba` al-shahīd). The flooding of the Nile was poetically described in myth as Isis’s tears of sorrow for Osiris when killed by their brother Set.

Flooding cycle[edit]

The flooding of the Nile is the result of the yearly monsoon between May and August causing enormous precipitations on the Ethiopian Highlands whose summits reach heights of up to 4550 m (14,928 ft). Most of this rainwater is taken by the Blue Nile and by the Atbarah River into the Nile, while a less important amount flows through the Sobat and the White Nile into the Nile. During this short period, those rivers contribute up to ninety percent of the water of the Nile and most of the sedimentation carried by it, but after the rainy season, dwindle to minor rivers.

The flooding as such was foreseeable, though its exact dates and levels could only be forecast on a short term basis by transmitting the gauge readings at Aswan to the lower parts of the kingdom where the data had to be converted to the local circumstances. What was not foreseeable, of course, was the extent of flooding and its total discharge.

The Egyptian year was divided into the three seasons of Akhet (Inundation), Peret (Growth), and Shemu (Harvest). Akhet covered the Egyptian flood cycle. This cycle was so consistent that the Egyptians timed its onset using the heliacal rising of Sirius, the key event used to set their calendar.

The first indications of the rise of the river could be seen at the first of the cataracts of the Nile (at Aswan) as early as the beginning of June, and a steady increase went on until the middle of July, when the increase of water became very great. The Nile continued to rise until the beginning of September, when the level remained stationary for a period of about three weeks, sometimes a little less. In October, it often rose again and reached its highest level. From this period, it began to subside and usually sank steadily until the month of June, when it reached its lowest level again. Flooding reached Aswan about a week earlier than Cairo, and Luxor five to six days earlier than Cairo. Typical heights of flood were 45 feet (13.7 metres) at Aswan, 38 feet (11.6 metres) at Luxor (and Thebes) and 25 feet (7.6 metres) at Cairo.[1]

Agriculture[edit]

Basin irrigation[edit]

Whilst the earliest Egyptians simply laboured those areas which were inundated by the floods, some 7000 years ago, they started to develop the basin irrigation method. Agricultural land was divided into large fields surrounded by dams and dykes and equipped with intake and exit canals. The basins were flooded and then closed for about 45 days to saturate the soil with moisture and allow the silt to deposit. Then the water was discharged to lower fields or back into the Nile. Immediately thereafter, sowing started, and harvesting followed some three or four months later. In the dry season thereafter, farming was not possible. Thus, all crops had to fit into this tight scheme of irrigation and timing.

In case of a small flood, the upper basins could not be filled with water which would mean famine. If a flood was too large, it would damage villages, dykes and canals.

The basin irrigation method did not exact too much of the soils, and their fertility was sustained by the annual silt deposit. Salinisation did not occur, since, in summer, the groundwater level was well below the surface, and any salinity which might have accrued was washed away by the next flood.

It is estimated that by this method, in ancient Egypt, some 2 million up to a maximum of 12 million inhabitants could be nourished. By the end of Late Antiquity, the methods and infrastructure slowly decayed, and the population diminished accordingly; by 1800, Egypt had a population of some 2.5 million inhabitants.

Perennial irrigation[edit]

Muhammad Ali Pasha, Khedive of Egypt (r. 1805–1848), attempted to modernize various aspects of Egypt. He endeavoured to extend arable land and achieve additional revenue by introducing cotton cultivation, a crop with a longer growing season and requiring sufficient water at all times. To this end, the Delta Barrages and wide systems of new canals were built, changing the irrigation system from the traditional basin irrigation to perennial irrigation whereby farmland could by irrigated throughout the year. Thereby, many crops could be harvested twice or even three times a year and agricultural output was increased dramatically.

In 1873, Isma’il Pasha commissioned the construction of the Ibrahimiya Canal, thereby greatly extending perennial irrigation.

End of flooding[edit]

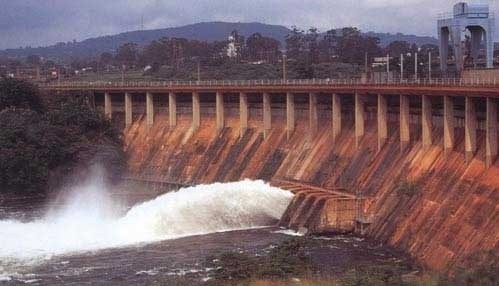

Although the British, during their first period in Egypt, improved and extended this system, it was not able to store large amounts of water and to fully retain the annual flooding. In order to further improve irrigation, Sir William Willcocks, in his role as director general of reservoirs for Egypt, planned and supervised the construction of the Aswan Low Dam, the first true storage reservoir, and the Assiut Barrage, both completed in 1902. However, they were still not able to retain sufficient water to cope with the driest summers, despite the Aswan Low Dam being raised twice, in 1907–1912 and in 1929–1933.

During the 1920s, the Sennar Dam was constructed on the Blue Nile as a reservoir in order to supply water to the huge Gezira Scheme on a regular basis. It was the first dam on the Nile to retain large amounts of sedimentation (and to divert a large quantity of it into the irrigation canals) and in spite of opening the sluice gates during the flooding in order to flush the sediments, the reservoir is assumed to have lost about a third of its storage capacity.[2][page needed] In 1966, the Roseires Dam was added to help irrigating the Gezira Scheme. The Jebel Aulia Dam on the White Nile south of Khartoum was completed in 1937 in order to compensate for the Blue Nile’s low waters in winter, but it was still not possible to overcome a period of very low waters in the Nile and thus avoid occasional drought, which had plagued Egypt since ancient times.

In order to overcome these problems, Harold Edwin Hurst, a British hydrologist in the Egyptian Public Works from 1906 until many years after his retirement age, studied the fluctuations of the water levels in the Nile, and already in 1946 submitted an elaborate plan for how a «century storage» could be achieved to cope with exceptional dry seasons occurring statistically once in a hundred years. His ideas of further reservoirs using Lake Victoria, Lake Albert and Lake Tana and of reducing the evaporation in the Sudd by digging the Jonglei Canal were opposed by the states concerned.

Eventually, Gamal Abdel Nasser, President of Egypt from 1956 to 1970, opted for the idea of the Aswan High Dam at Aswan in Egypt instead of having to deal with many foreign countries. The required size of the reservoir was calculated using Hurst’s figures and mathematical methods. In 1970, with the completion of the Aswan High Dam which was able to store the highest floods, the annual flooding cycle in Egypt came to an end in Lake Nasser.

Egypt’s population rose to 92.5 million (2016 estimate).[3][page needed]

Religious beliefs[edit]

The Nile was also an important part of ancient Egyptian spiritual life. In the Ancient Egyptian religion, Hapi was the god of the Nile and the annual flooding of it. Both he and the pharaoh were thought to control the flooding. The annual flooding of the Nile occasionally was said to be the Arrival of Hapi.[4] Since this flooding provided fertile soil in an area that was otherwise desert, Hapi symbolised fertility.

The god Osiris was also closely associated with the Nile and the fertility of the land. During inundation festivals, mud figures of Osiris were planted with barley.

[5]

See also[edit]

- Nilometer

- Egyptian Public Works

- Aswan Dam#Irrigation scheme

- Water supply and sanitation in Egypt

- Water resources management in modern Egypt

- The National Water Research Center (Egypt)

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Budge, Wallis E A (1895). The Nile Notes for Travellers in Egypt. Thos. Cook & Son (Egypt), Ltd, Ludgate Circus, London.

- ^ Eyasu Yazew Hagos: Development and Management of Irrigated Lands in Tigray, Ethiopia Dissertation 2005, Delft

- ^ «Population Clock». Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. 27 April 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson, p.106

- ^ Baines, John. «The Story of the Nile.» http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/nile_01.shtml

Bibliography[edit]

- Gill, Anton (2003). Ancient Egyptians: The Kingdom of the Pharaohs brought to Life. Harper Collins Entertainment.

- William Willcocks, James Ireland Craig: Egyptian Irrigation. Volume I; Egyptian Irrigation. Volume II. 3rd edition. Spon, London/ New York 1913.

- Greg Shapland: Rivers of Discord: International Water Disputes in the Middle East. C. Hurst & Co., London 1997, ISBN 1-85065-214-7, p. 57. (preview on Google books).

- John V. Sutcliffe, Yvonne P. Parks: The Hydrology of the Nile. International Association of Hydrological Sciences, Wallingford 1999, ISBN 978-1-901502-75-6, p. 151. (PDF Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine).

The flooding of the Nile has been an important natural cycle in Egypt since ancient times. It is celebrated by Egyptians as an annual holiday for two weeks starting August 15, known as Wafaa El-Nil. It is also celebrated in the Coptic Church by ceremonially throwing a martyr’s relic into the river, hence the name, The Martyr’s Finger (Coptic: ⲡⲓⲧⲏⲃ ⲛⲙⲁⲣⲧⲏⲣⲟⲥ, Arabic: Esba` al-shahīd). The flooding of the Nile was poetically described in myth as Isis’s tears of sorrow for Osiris when killed by their brother Set.

Flooding cycle[edit]

The flooding of the Nile is the result of the yearly monsoon between May and August causing enormous precipitations on the Ethiopian Highlands whose summits reach heights of up to 4550 m (14,928 ft). Most of this rainwater is taken by the Blue Nile and by the Atbarah River into the Nile, while a less important amount flows through the Sobat and the White Nile into the Nile. During this short period, those rivers contribute up to ninety percent of the water of the Nile and most of the sedimentation carried by it, but after the rainy season, dwindle to minor rivers.

The flooding as such was foreseeable, though its exact dates and levels could only be forecast on a short term basis by transmitting the gauge readings at Aswan to the lower parts of the kingdom where the data had to be converted to the local circumstances. What was not foreseeable, of course, was the extent of flooding and its total discharge.

The Egyptian year was divided into the three seasons of Akhet (Inundation), Peret (Growth), and Shemu (Harvest). Akhet covered the Egyptian flood cycle. This cycle was so consistent that the Egyptians timed its onset using the heliacal rising of Sirius, the key event used to set their calendar.

The first indications of the rise of the river could be seen at the first of the cataracts of the Nile (at Aswan) as early as the beginning of June, and a steady increase went on until the middle of July, when the increase of water became very great. The Nile continued to rise until the beginning of September, when the level remained stationary for a period of about three weeks, sometimes a little less. In October, it often rose again and reached its highest level. From this period, it began to subside and usually sank steadily until the month of June, when it reached its lowest level again. Flooding reached Aswan about a week earlier than Cairo, and Luxor five to six days earlier than Cairo. Typical heights of flood were 45 feet (13.7 metres) at Aswan, 38 feet (11.6 metres) at Luxor (and Thebes) and 25 feet (7.6 metres) at Cairo.[1]

Agriculture[edit]

Basin irrigation[edit]

Whilst the earliest Egyptians simply laboured those areas which were inundated by the floods, some 7000 years ago, they started to develop the basin irrigation method. Agricultural land was divided into large fields surrounded by dams and dykes and equipped with intake and exit canals. The basins were flooded and then closed for about 45 days to saturate the soil with moisture and allow the silt to deposit. Then the water was discharged to lower fields or back into the Nile. Immediately thereafter, sowing started, and harvesting followed some three or four months later. In the dry season thereafter, farming was not possible. Thus, all crops had to fit into this tight scheme of irrigation and timing.

In case of a small flood, the upper basins could not be filled with water which would mean famine. If a flood was too large, it would damage villages, dykes and canals.

The basin irrigation method did not exact too much of the soils, and their fertility was sustained by the annual silt deposit. Salinisation did not occur, since, in summer, the groundwater level was well below the surface, and any salinity which might have accrued was washed away by the next flood.

It is estimated that by this method, in ancient Egypt, some 2 million up to a maximum of 12 million inhabitants could be nourished. By the end of Late Antiquity, the methods and infrastructure slowly decayed, and the population diminished accordingly; by 1800, Egypt had a population of some 2.5 million inhabitants.

Perennial irrigation[edit]

Muhammad Ali Pasha, Khedive of Egypt (r. 1805–1848), attempted to modernize various aspects of Egypt. He endeavoured to extend arable land and achieve additional revenue by introducing cotton cultivation, a crop with a longer growing season and requiring sufficient water at all times. To this end, the Delta Barrages and wide systems of new canals were built, changing the irrigation system from the traditional basin irrigation to perennial irrigation whereby farmland could by irrigated throughout the year. Thereby, many crops could be harvested twice or even three times a year and agricultural output was increased dramatically.

In 1873, Isma’il Pasha commissioned the construction of the Ibrahimiya Canal, thereby greatly extending perennial irrigation.

End of flooding[edit]

Although the British, during their first period in Egypt, improved and extended this system, it was not able to store large amounts of water and to fully retain the annual flooding. In order to further improve irrigation, Sir William Willcocks, in his role as director general of reservoirs for Egypt, planned and supervised the construction of the Aswan Low Dam, the first true storage reservoir, and the Assiut Barrage, both completed in 1902. However, they were still not able to retain sufficient water to cope with the driest summers, despite the Aswan Low Dam being raised twice, in 1907–1912 and in 1929–1933.

During the 1920s, the Sennar Dam was constructed on the Blue Nile as a reservoir in order to supply water to the huge Gezira Scheme on a regular basis. It was the first dam on the Nile to retain large amounts of sedimentation (and to divert a large quantity of it into the irrigation canals) and in spite of opening the sluice gates during the flooding in order to flush the sediments, the reservoir is assumed to have lost about a third of its storage capacity.[2][page needed] In 1966, the Roseires Dam was added to help irrigating the Gezira Scheme. The Jebel Aulia Dam on the White Nile south of Khartoum was completed in 1937 in order to compensate for the Blue Nile’s low waters in winter, but it was still not possible to overcome a period of very low waters in the Nile and thus avoid occasional drought, which had plagued Egypt since ancient times.

In order to overcome these problems, Harold Edwin Hurst, a British hydrologist in the Egyptian Public Works from 1906 until many years after his retirement age, studied the fluctuations of the water levels in the Nile, and already in 1946 submitted an elaborate plan for how a «century storage» could be achieved to cope with exceptional dry seasons occurring statistically once in a hundred years. His ideas of further reservoirs using Lake Victoria, Lake Albert and Lake Tana and of reducing the evaporation in the Sudd by digging the Jonglei Canal were opposed by the states concerned.

Eventually, Gamal Abdel Nasser, President of Egypt from 1956 to 1970, opted for the idea of the Aswan High Dam at Aswan in Egypt instead of having to deal with many foreign countries. The required size of the reservoir was calculated using Hurst’s figures and mathematical methods. In 1970, with the completion of the Aswan High Dam which was able to store the highest floods, the annual flooding cycle in Egypt came to an end in Lake Nasser.

Egypt’s population rose to 92.5 million (2016 estimate).[3][page needed]

Religious beliefs[edit]

The Nile was also an important part of ancient Egyptian spiritual life. In the Ancient Egyptian religion, Hapi was the god of the Nile and the annual flooding of it. Both he and the pharaoh were thought to control the flooding. The annual flooding of the Nile occasionally was said to be the Arrival of Hapi.[4] Since this flooding provided fertile soil in an area that was otherwise desert, Hapi symbolised fertility.

The god Osiris was also closely associated with the Nile and the fertility of the land. During inundation festivals, mud figures of Osiris were planted with barley.

[5]

See also[edit]

- Nilometer

- Egyptian Public Works

- Aswan Dam#Irrigation scheme

- Water supply and sanitation in Egypt

- Water resources management in modern Egypt

- The National Water Research Center (Egypt)

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Budge, Wallis E A (1895). The Nile Notes for Travellers in Egypt. Thos. Cook & Son (Egypt), Ltd, Ludgate Circus, London.

- ^ Eyasu Yazew Hagos: Development and Management of Irrigated Lands in Tigray, Ethiopia Dissertation 2005, Delft

- ^ «Population Clock». Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. 27 April 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson, p.106

- ^ Baines, John. «The Story of the Nile.» http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/nile_01.shtml

Bibliography[edit]

- Gill, Anton (2003). Ancient Egyptians: The Kingdom of the Pharaohs brought to Life. Harper Collins Entertainment.

- William Willcocks, James Ireland Craig: Egyptian Irrigation. Volume I; Egyptian Irrigation. Volume II. 3rd edition. Spon, London/ New York 1913.

- Greg Shapland: Rivers of Discord: International Water Disputes in the Middle East. C. Hurst & Co., London 1997, ISBN 1-85065-214-7, p. 57. (preview on Google books).

- John V. Sutcliffe, Yvonne P. Parks: The Hydrology of the Nile. International Association of Hydrological Sciences, Wallingford 1999, ISBN 978-1-901502-75-6, p. 151. (PDF Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine).

История и культура Древнего Египта не перестает привлекать своей таинственностью и многообразием. Ученые изучают древнейшую в мире цивилизацию на основе памятников архитектуры, культуры, письменности, особенностей религии и духовной жизни, традиций и записей древних историков. Судьба этого государства всегда зависела от главного источника воды – Нила. Поэтому в первую очередь ученые пытались понять, какую роль играла главная водная артерия в жизни египтян, как возникла река Нил в Древнем Египте, разлив Нила и все, что с ним связано.

«Айгюптос и Нейлос»

Великий Геродот указывал, что Египет – это «Дар реки». Почему? Древний историк и философ объяснял, что разливаясь, Нил образовал часть суши (Геродот ее называет Дельтой), которую впоследствии заселили люди. Поэтому его определение «Дар реки» можно понимать буквально.

Однако, до сих пор истоки Нила не известны. Геродот считал, что он «зародился» от снегов, которые таяли в его верховьях. Моряки египетского царя Птолемея II намекали, что разливался Нил в период ливней на Эфиопском нагорье. А мореплаватели проникли дальше, чем кто-либо другой из путешественников древности – в южную часть страны. Во всяком случае, Птолемей утверждал, что исток Нила расположен в Лунных горах, и так считалось до Нового времени или Новой истории, которая началась в эпоху Возрождения.

Покровителем Нила у древних египтян считался бог Хапи. В классической же живописи и скульптуре Нил было принято изображать, как божество с закрытой тканью головой. Ткань была задрапирована, что означало «неведомость» происхождения.

У самой знаменитой статуи божества, которая была найдена в начале XVI века, на голове был венок из цветов лотоса и пшеничных колосьев. В руке возлежащий бог держал рог изобилия, тем самым олицетворяя Нил, как источник благ и хлеба для египтян. Скульптуру создал мастер эпохи Флавиев – династии римских императоров, которые правили Римской Империей в I столетии нашей эры.

«Ахет»

Нил разливался в июле, и длился этот период почти четыре месяца. Четырехмесячный разлив реки стоял в древнеегипетском календаре, как первое время года — «ахет». Жизнь египтян, которая в первую очередь зависела от разлива Нила и уровня его воды, и определила существующий тогда календарь, состоящий всего из трех времен года.

Когда наступал «ахет», то сельскохозяйственные и земледельческие работы прекращались. Это было время религиозных праздников. Разлившийся Нил представлял собой красочную картину: по его водам плыли праздничные суда и грузовые корабли.

Во время «ахета» велись строительные работы по восстановлению и возведению пирамид и гробниц повелителей, а также великолепных храмов. По одной из теорий, на такие работы пригоняли тысячи крестьян, фермеров и пахарей, которые вынуждены были гнуть спины, чтобы не угодить под кнут надсмотрщиков. Эта версия имеет место быть, но не однозначна: есть еще версии о наемных рабочих. А также об исполинах-атлантах, которые построили пирамиды намного раньше зарождения Египта. А во время «ахета» местные жители только реконструировали постройки, используя в качестве строительного материала обломки и глыбы от древних строений.

«Перет и Шему»

Наконец, начиналась уборка урожая – «шему». Этому сезону сопутствовала «засуха», когда с пустыни дул сильный ветер «хамсин». Он дул пятьдесят дней подряд и приносил с собой песчаные бури. Хамсин начинался в мае, а заканчивался как раз к следующему «ахет».

Наступлению «нового» года египтяне приписывали появление Сириуса («Сопдет» по-египетски). Самая яркая звезда на небе сияла в восточной части небосклона, как раз в тот момент, когда солнце должно было восходить из-за горизонта. Появление Сириуса всегда совпадало с подъемом уровня воды Нила.

Система усовершенствования

Суэцкий канал, построенный в 1869 году, усилил зависимость Египетского государства от других держав. Когда из-за низководья Нила в 1878 году случился неурожай, повлекший за собой голод, произошли народные восстания. Многие европейцы, жившие в Египте, были убиты. Как следствие, развязалась война, которую начала Великобритания и Египет фактически превратился в английскую колонию.

Для английской промышленности начался новый этап – расширение плантаций хлопка. Для этого надо было провести ряд работ по изменению водного режима главной египетской артерии. Сначала были построены три плотины:

- Асуанская;

- Асиутская;

- Калиубская.

Однако в 1936 году Асуанскую плотину пришлось надстроить, чтобы расширить сеть каналов. Правда, в нильской долине стали выращивать сахарный тростник и пальмы. Но урбанизация и сельские поселения постепенно стали оттеснять «зеленую» полосу.

В 1971 году была построена новая Асуанская плотина, кстати, не без участия специалистов из СССР. В связи с новшеством уровень воды в реке стабилизировался. Перед плотиной возникло водохранилище, которое вмещает всю массу нильской воды в период его разлива.

Благодать Нила

Ил со дна великой реки содержал много полезных веществ и минералов, благодаря чему почва была благодатной для засева многих культур. Земля, «напитанная» илом, была рыхлой и отлично поддавалась обработке. В связи с этим в Египте рано развилось земледелие, и затем сельскохозяйственное производство. Жители Египта держали домашний скот: овец, коз, быков. Скотоводством занимались и на общегосударственном уровне.

Кроме того, что в Ниле водилось множество рыбы, а также священные гиппопотамы и крокодилы, он давал жизнь буквально всему: и деревьям, и растениям, и животным, и птицам. Около Мемфиса был парк, в котором птиц и зверей было так много, что здесь устраивали охоту. В заводях реки рос лотос и папирус, а в ее долине произрастали пальмы: кокосовые, финиковые, а также виноградные и фруктовые деревья. Даже в пустыне обитали дикие животные: гепарды, шакалы, львы и страусы.

Итак, Нил и в древности, и сегодня имеет огромное значение для страны и ее жителей. Помимо того, что это транспортная артерия, река является еще и главным источником пресной воды. К тому же, Нил необычайно красив. Ежегодно посмотреть на его великолепие приезжают тысячи туристов.

Экскурсия по Нилу – одна из самых запоминающихся и интересных. Путешествие на теплоходе по священной реке оставит массу незабываемых впечатлений от древнейшей страны, полной загадок, легенд и мифов. Страны вечных песков и вечных пирамид, имя которой – Египет!

Специально для Лилия-Тревел.РУ — Анна Лазарева

Разлив Нила: яркие фото и видео, подробное описание и отзывы о событии Разлив Нила в 2023 году.

- Туры на Новый год в Египет

- Горящие туры по всему миру

Разлив Нила в древнем Египте всегда был одним из главных праздников. Дело в том, что река всегда была единственным источником пресной воды в этом засушливом регионе. Разлив Нила отмечался ежегодно в течение 2 недель, начиная с 15 августа. Интересно, что египтяне праздновали в это время Новый год, который был напрямую связан с восходом священной звезды Сириус.

В середине августа местные жители как раз заканчивали посев и ждали разлива Нила. Без прилива воды они бы просто не выжили из-за неурожая. Когда река возвращалась в свои берега, на полях оставалось много ила, благодаря которому почва получала удобрения.

Сегодня египтяне празднуют разлив Нила не так широко и торжественно. В 1971 году был построен Асуанский гидроузел, и Нил перестал разливаться. Тем не менее местные жители не забывают о традициях и обычаях предков.

К празднику готовились заранее — откармливали скотину и птицу, чтобы принести в жертву, шили новые наряды. Даже очень бедные египтяне старались хоть как-то преобразить свое жилище и одежду в преддверии Нового года. Жрицы вычисляли день, когда Нил должен был разлиться. В назначенный час весь народ ждал этого события на набережной. В огромную лодку помещали статуи бога Амона, его жены и сына и спускали в реку. В течение месяца лодка находилась в воде, и лишь потом скульптуры возвращали в храм. Все это время египтяне праздновали разлив Нила, благо все были освобождены от работы.

Египтяне были уверены, что Нил разливается в связи с тем, что богиня Исида льет слезы из-за гибели мужа Осириса.

В течение 2 недель египтяне отмечают этот древний праздник. Правда, массовые гуляния теперь больше рассчитаны на туристов, а также в эти дни обязательно проводятся спортивные состязания. Чаще всего команды соревнуются в водных видах спорта: виндсерфинге, плавании, гребле. Непременный пункт программы — выставки цветов. Кроме того, египтяне устраивают представления, на которых показывают, как праздник отмечался много лет назад.