Троянская война – это одна из самых известных войн древности. Ведь в ней столкнулись интересы крупных государств, а также участвовало множество известных героев того времени. Троянская война преподносится нам в виде мифов и легенд, что требует от историков кропотливого анализа для создания картины тех событий.

Современные историки считают, что Троянская война произошла в период с 1240 по 1230 гг. до н.э. Хотя эта дата очень приблизительная. Мифы гласят, что причиной войны послужило похищение Парисом Елены, которая была замужем за царём Спарты Менелаем. Также Парис, кроме Елены, прихватил часть богатств у спартанского царя. Этот факт сподвигло Менелая идти войной на Трою. Остальные греки присоединились к нему, ведь при замужестве Елены был составлен договор, что все претенденты на ее руку будут защищать Елену и ее избранника, а претендовали на ее руку почти все цари Греции.

Другая версия начала войны звучит более правдоподобно. Троя мешала торговать греческим народам с остальным миром. Брала с их кораблей значительный налог, а недовольных просто топила. Грекам пришлось объединиться для защиты своих экономических интересов и пойти войной на Трою.

Было много разногласий между греками, не все хотели воевать. Начало войны было весьма неудачным. По ошибке вместо берегов Трои греки высадились в районе Мизии , где правил Телеф, дружественный им царь. Но не поняв этого, они напали на его владения. И лишь после кровопролитной битвы была понятна ошибка, и войско отправилось дальше к цели. Но на пути их ждали новые проблемы. Шторм раскидал по морю их корабли, что значительно затянуло время их прибытия к цели.

К берегам Трои добралось 1,186 кораблей и около 100 тысяч людей. Троянцы отважно защищали свою землю. В этом им помогали союзники и наемники, которых было великое множество. Про первые девять лет войны к нам дошла очень скудная информация. Ведь эти события были описаны в поэме «Киприада», которая, к сожалению, была потеряна. Но из мифов и легенд, которые до нас дошли, известно, что в этот период часто случались конфликты между греками, ведь некоторые командиры хотели покинуть эту войну и уехать. Другие желали продолжения. Также часто вспоминались давние конфликты. В этот период ведущую роль занимал Ахилл. Он совершал набеги на близкие города, разграбляя их. Ахиллом было уничтожено около двадцати городов возле берега и близко одиннадцати поселков вдали от берега.

В этот отрезок времени был проведен поединок между Парисом и Менелаем, в котором Менелай одержал победу. Побежденный Парис должен был отдать Елену и уплатить дань. Война должна быть окончена. Но остальных греков это не устраивало. Они хотели продолжения войны и уничтожения Трои.

Продолжение войны было весьма неудачным. Греков часто оттесняли к своим укреплениям. Их корабли сжигали. И лишь благодаря большому количеству солдат, они удерживали свои позиции. В боях погибли многие известные герои тех времен, такие как Ахилл, Патрокл и многие другие.

Все эти неудачи заставили греков пойти на хитрость. Мастером Эпеем был построен гигантский деревянный конь. Он был оставлен неподалеку возле стен, а в нем спрятались лучшие греческие воины. В это время основные греческие силы спалили свой лагерь и отплыли в море, давая понять, что война окончена. Троянцы, обнаружив деревянного коня, подумали, что это дары богов за их победу над греками и втянули его в город. В честь победы они устроили пир, охрана потеряла бдительность. В полночь греки вылезли из своего убежища, дали сигнал своим кораблям и отворили ворота.

Армия греков лавиной хлынула на спящий город, защитники ничего не смогли сделать, чтобы спасти город. Около двух дней греки грабили Трою. Жители были убиты или угнаны в рабство, а сам город был сожжен дотла.

- Энциклопедия

- История

- Троянская война

Троянская война краткое содержание для детей

Самой известной войной наполненной различными мифами и легендами, является Троянская война. Это событие имеет две пересказанные истории, первая, пожалуй, является более правдоподобной исторической информацией, а вторая скорее похожа на миф, наполненный романтизмом и героизмом.

И так, первая история гласит, что троянская война происходила в промежуток между 1240 и 1230 годах до нашей эры. Причиной развязывания такого продолжительного конфликта послужило то, что, Троя препятствовала прохождению торговых кораблей и взимала значительные налоги. Такое положение не устраивало греков, и они решили объединить усилия и оказать сопротивления Трои. Однако, Троянцы оказывали очень хорошее сопротивление и прочно удерживали свои границы.

Греки терпели поражения как в количестве воинов, так и в количестве сажённых троянцами кораблей. Также греки потеряли в сражениях своего главного героя Ахилла. Эти события очень вымотали их и тогда прибегнув к изощрённой хитрости, греками было придумано построить деревянного коня. Этот конь должен был выступить в качестве дара богов для троянцев.

И когда конь оказался внутри города, под покровом ночи из него выбрались самые лучшие греческие воины. Они открыли ворота и впустили армию, которая и одержала победу над потерявшими бдительность троянцами. Город был сожжен, люди были убиты, а некоторые взяты в плен.

По другой легенде, причиной конфликта послужила украденная Парисом жена царя Спарты Елена. Мифы также гласят, что Парис взял не только прекрасную царицу, но и ухватил некоторые ценные вещи царя. Это и стало причиной развязывания войны. Все греки объединили свои усилия, так как существовал такой контракт, который гласил, что все претенденты на руку Елены должны были защищать её и её мужа.

Сообщение Троянская война (вариант 2 доклада)

Троянская война – одно из наиболее легендарных событий, произошедших в 13-12 веках до нашей эры.

Сражения противоборствующих сторон происходили на полуострове Троада (ныне Бига). Все они нашли свое отражение в двух известных поэмах «Илиаде» и «Одиссее», и благодаря этому о Троянской войне имеет возможность узнать нынешнее поколение. Эпосы в словесной форме передавались из поколения в поколение, пока их не записал Гомер.

Сказать однозначно, являются ли события, описанные в источнике, достоверными, не представляется возможным. По мнению филологов, изучавших послание, прошедшее сквозь века, трактовали события, как длительный морской поход по морю, предводителями в котором были пелопонесские цари. При этом историки утверждают, что Троянская война была. Говорят они и о том, что противостояние длилось не меньше десяти лет. За это время сменилось много главнокомандующих и полегло бесчисленное количество доблестных воинов.

Итогом троянской войны стало падение Трои, которое произошло одним из самых интересных способов, получивших в дальнейшем нарицательное значение.

Причины начала противостояния

Основными причинами, побудившими начать противостояние сторон, являлось похищение Парисом (сыну троянского царя Приама) самой красивой женщины Древней Греции – Елены Прекрасной. На тот момент виновница сражений была супругой короля Спарты, но это не остановило вора. Причиной тому была любовь, которую питал вор к Елене.

Но это мифическое начало ученые не принимают, и говорят о том, что началом войны стали непомерные налоги, собираемые с торговцев, корабли которых проходили мимо Трои.

События Троянской войны

Первый этап войны ознаменовался позорным поражением, так как воины ошиблись местом и разрушили владения дружественного им правителя Телефа. Осознав свою ошибку, греки в количестве 100 тысяч человек, уместившихся на 1186 кораблях, отправились к берегам Трои.

Было много поражений и побед. Командиры конфликтовали между собой за первенство и регалии, а войска под их руководством грабили города. Наиболее известным и беспощадным полководцем был Ахилл.

Такая война длилась долгих девять лет. Переломным моментом стал бой между Парисом и Менелаем, в котором последний одержал победу. Итогом войны должно было стать освобождение Елены Прекрасной и выплата дани за разбой. Только в планы греков такой поворот событий не входил. Они жаждали продолжения войны и стремились разбить Трою.

Именно поэтому придумали способ проникнуть в город: самые сильные воины спрятались внутрь деревянного сооружения в форме коня. Любопытные жители приняли его за дар богов и собственноручно завели в город через главные ворота. Дождавшись ночи, греческие войска сожгли Трою дотла.

Вариант 3

Троянская война, несомненно, одно из самых масштабных событий Древнего мира, но в то же время самое загадочное, окутанное множеством мифов и легенд, воспетая великим Гомером в бессмертных поэмах «Илиада» и «Одиссея».

По приблизительным подсчетам историков данное событие длилось 10 лет с 1240 по 1230 года до н.э.

Причиной военного конфликта послужило вмешательство Трои в торговые отношения между греками и другими государствами. Троя облагала высокими налогами торговые суда, задерживала их, а те, кто выказывал недовольство или сопротивление, отправлялись на морское дно. В те времена Троя была сильным и прочно стоящим на ногах государством, ее непреступные стены выдерживали все нападки недовольных и оставались как всегда непреступными.

Согласно древнегреческим мифам, поводом к войне послужило похищение спартанской царицы – восхитительной красавицы Елены. Ее похитителем стал сын троянского царя Приама – молодой красавец Парис.

Спартанцы и остальные греки, связанные клятвой защищать царицу Спарты, объединились в 100 тысячное войско с долее 1000 кораблей и отправились войной к стенам Трои.

Долгие годы длилась осада непреступных и непреклонных троянских стен. Троя прочно стояла на своих позициях, в то время как греки несли колоссальные человеческие потери, как бумажные кораблики шел на дно их флот.

Измотанные долгими годами мелких побед и бесчисленных поражений, греки понимали, что сломить Трою можно только изнутри. Но поскольку силой взять город никак не удавалось, попасть в город можно только при помощи хитрости.

Такой хитростью стал знаменитый троянский конь – деревянное сооружение в форме животного, внутри которого спрятались самые смелые, сильные и могучие греческие воины.

Троянцы, однажды утром обнаружившие у своих ворот огромного коня, приняли его за дар богам и, возомнив себя великими победителями, занесли его как трофей за непреступные стены.

Дав волю гордыне, троянцы устроили большой пир, и когда их бдительность полностью утонула в бокалах с вином, греки нанесли смертоносный удар, в результате которого Троя пала на веки.

Эта война унесла много жизней, разрушила целое государство, но в то же время на тысячелетия прославила великих и могущественных воинов, сделав их бессмертными героями.

Кратко для детей 5, 6 класс

Троянская война

Интересные темы

- Жизнь и творчество Александра Грина

Одним из знаменитых русских писателей является Александр Грин. Около 400 произведений издали еще при жизни писателя. Им была придумана страна, в которой жили герои его произведений и эта страна получила название Гринландия.

- Доклад на тему Сергиев посад: Золотое кольцо России

Единственный город Московской области, включенный в 1969г. в туристический маршрут «Золотое кольцо» является город Сергиев Посад. Расположен город в северо-восточной части области в 52 км

- Хронологическая таблица жизни и творчества Маяковского

1893 г. в грузинском селе Багдати родился будущий поэт, редактор нескольких журналов, драматург, сатирик В. В. Маяковский. 1902-1906 учился в Кутаисской гимназии, где в 1905 году участвовал в революционном митинге и читал Запрещенные брошюры

- Планета Венера — сообщение оклад

Венера – вторая по счету планета в Солнечной системе. В чем ее особенности и почему она считается ядовитой? На все вопросы будут свои ответы.

- Белый медведь — сообщение доклад про Полярного медведя

Полярный медведь (Ursus maritimus), также называемый белым медведем и морским медведем, обитает на территориях арктического региона. Он проходит огромные расстояния на обширных пустынных просторах

История создания

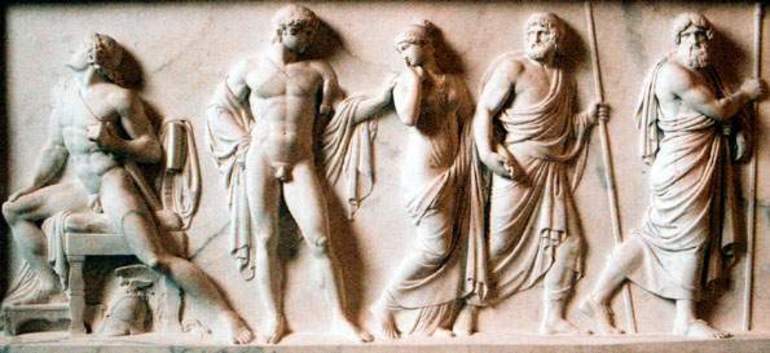

Сказания о взятии Трои были широко распространены в Древней Греции в XI—IX вв. до н. э. В них отражалась многовековая вражда между эллинами и жителями Малой Азии. Эти песни слагали странствующие певцы-рапсоды. Их приглашали во дворцы и простые дома, угощали ужином, а затем слушали их истории о богах и героях.

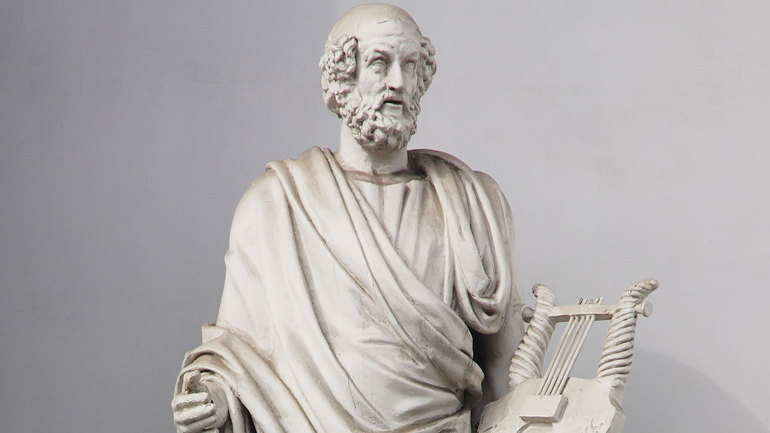

Певцы декламировали стихи-гекзаметры, подыгрывая себе на лире. Самым известным рапсодом был Гомер. Считается, что он создал 2 эпические поэмы о Троянской войне: «Илиаду» и «Одиссею». По мнению литературоведов, цикл песен и мифов о падении Трои, ставших основой этих произведений, сочинялся в течение нескольких веков. Так, автор «Илиады» предполагает, что его слушатели хорошо знакомые с основными событиями Троянской войны и ее героями: Гектором, Ахиллом, Атреем, Аяксом, Одиссеем и многими другими.

О самом Гомере мало что известно. По сведениям Геродота, он жил около 850 лет до н. э. Не сохранилось данных о его национальности и месте рождения, и за право зваться родиной Гомера спорят многие города на греческом побережье Малой Азии. Возможно, что Гомер — лишь псевдоним певца, так как по одной из версий это имя означает «слепой».

Похищение Елены

Ареной войны стала область на северо-западе Малой Азии. Ее жителей греки называли тевкрами, троянцами или дарданцами. Крупнейшим городом там была Троя, или Илион, где правил царь Приам. Он имел 49 сыновей, самые известные из которых — красавец Парис и отважный Гектор .

Краткое содержание поэмы «Илиада» состоит в следующем. Согласно Гомеру, завязкой истории стало происшествие на свадьбе аргонавта Пелея и нимфы Фетиды. На пир были приглашены все олимпийские боги, не пригласили лишь Эриду, богиню раздора. В отместку она подбросила яблоко с надписью «прекраснейшей», которое поднесли Гере, Афине и Афродите. Богини тут же стали спорить, кому оно предназначается. Судьей был выбран Парис. Он присудил яблоко Афродите, которая пообещала ему любовь самой прекрасной женщины на свете.

Красивейшей из смертных в то время считалась Елена, царица Спарты. Когда она была девушкой, ее руки добивались многие цари и герои. Чтобы не допустить распри, ее отец, спартанский царь, разрешил ей самой выбрать мужа. Елена выбрала Менелая, брата микенского царя Агамемнона. Все прочие женихи дали клятву, что они помогут ее избраннику, если кто-то попытается похитить у него жену.

Парис прибыл в Спарту, где был радушно встречен Менелаем. Афродита помогла гостю завоевать сердце Елены. Царь Спарты безоговорочно считал Париса своим другом и когда ему понадобилось срочно уехать, оставил жену на его попечении.

Влюбленные, прихватив с собой сокровища Менелая, сели на корабль и уехали в Трою. Это похищение, по Гомеру, стало причиной Троянской войны .

Возвратившийся домой спартанский царь был вне себя от горя. К нему приехал его друг, царь Итаки Одиссей, и мужчины отправились в Трою, чтобы вернуть Елену. Но ворота города остались перед ними закрытыми. Елена не захотела встречаться с оставленным мужем, а Парис — разговаривать с бывшим другом.

Начало войны

Менелай был возмущен этим грубым нарушением законов гостеприимства и надругательством над своей честью. Он обращается за поддержкой к брату, царю Микен Агамемнону. Тот согласился помочь отомстить «подлому тевкру», как они назвали Париса.

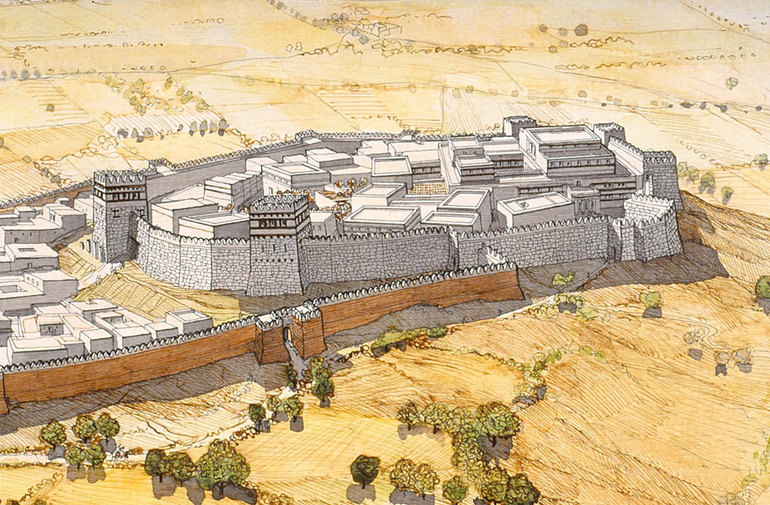

Но Троя — это хорошо защищенный город, укрепленный стенами и башнями, а тевкры — отважные и опытные воины. Чтобы захватить ее, не хватало сил ни у Менелая, ни у Агамемнона. Тогда они вспомнили о клятве, связывающей бывших женихов Елены, и обратились к греческим царям с просьбой о помощи. Те согласились, хотя и без особой охоты. Так, чтобы избежать участия в войне, недавно женившийся Одиссей даже притворился сумасшедшим, но его обман раскрыли.

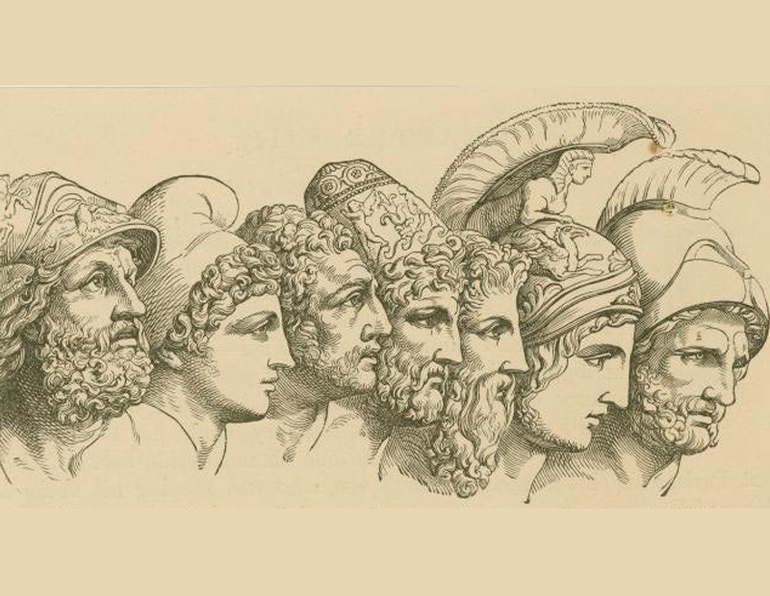

Слушатели Гомера хорошо знали имена отважных героев, участников войны на стороне ахейцев, как называли сторонников Менелая и Агамемнона. Они следующие:

- Ахилл, сын морской нимфы Фетиды;

- Нестор, правивший в Пилосе;

- Диомед, царь государства Аргос;

- Идонемей, критский правитель;

- Паламед из Эвбеи.

Перед отъездом прорицатель Калахант предрек, сколько что война будет продолжаться 9 лет и закончится победой лишь на десятом году. Услышавшие мрачное пророчество ахейцы печально побрели к кораблям, и армада двинулась в путь.

Поход на Трою начался неудачно. Суда отнесло к берегам Миссии, где правил царь Телефос. Местные жители напали на ахейцев, но Ахилл убил Телефоса, после чего его войско бежало с поля битвы.

Корабли отчалили от вражеского берега. Лишь после долгих злоключений войско Агамемнона смогло высадиться на берегах Илиона. Ахейцы двинулись на Трою. Им навстречу выступил отряд тевкров, которым руководил сын царя Гектор, могучий и отважный воин. Началась отчаянная сеча, в которой был убит царь Филаки Протесилай, первый погибший знатного рода. После этого троянцы отступили за городские стены.

Ахейцы собрались на военный совет, на котором выступил Менелай. Он сказал, что не хочет продолжения войны, и предложил вступить в переговоры с троянцами. Если они отдадут прекрасную Елену, то нужно возвратиться обратно. Это предложение было передано жителям Трои. Услышав предложение ахейцев, Елена тут же согласилась вернуться к Менелаю, чтобы прекратить кровопролитие. Ее поддержали мудрейшие члены совета, но остальные потребовали дать отпор захватчикам.

Осада города

Услышав ответ, ахейцы разбили укрепленный лагерь у стен Трои. Но город не был взят в кольцо, и осада могла продолжаться долго. Жители Трои выходили за его стены за водой и пропитанием, зато перед ахейцами остро встал продовольственный вопрос.

Чтобы решить его, греки стали грабить местных жителей, чем настроили против себя все население Троады. Так, царь Эней, правитель близлежащего города Дардан, сохранял нейтралитет, но отряд ахейцев захватил его стадо и погнал в лагерь. Эней с соратниками напал на мародеров и вступил в схватку с их предводителем Диомедом. Лишь покровительство богов спасло его от неминуемой смерти. После этого Эней укрылся в стенах Трои и стал одним из самых отважных его защитников.

Кроме него, на помощь Трое пришли другие племена и герои. В рядах защитников сражались следующие союзники :

- ликияне;

- мизийцы;

- пафлагоняне;

- лидяне;

- фригийцы;

- пеонийцы;

- фракийцы.

Среди них было много наемников, сражавшихся за плату. Чтобы заплатить им, царю Приаму пришлось опустошить свою сокровищницу.

Гомер рассказывает, сколько длилась Троянская война. Стычки между греками и жителями Малой Азии продолжались в течение 9 лет. Особенно в них отличился быстроногий Ахиллес. Он совершал набеги на окрестные селения и брал много добычи. Гомер писал, что он разрушил 12 городов возле Трои и 11 вдали от нее. Ахилл убил отца и братьев Андромахи, жены Гектора.

Но все попытки взять Трою окончились неудачей. Трижды греки ходили на приступ городских стен, и трижды были отброшены назад. Между тем корабли ахейцев начали уже гнить. Многие вожди требовали прекратить войну и возвратиться домой.

Гнев Ахилла

Греки не только грабили окрестных жителей, но и забирали в плен красивых девушек. Одной из них была Хрисеида, дочь Хриса, жрица Аполлона. Она приглянулась самому Агамемнону, и тот забрал ее себе. Несчастный отец пришел в лагерь ахейцев и умолял вернуть ему дочь за выкуп, но Агамемнон грубо прогнал его. Аполлон отомстил за обиду своего жреца. Он стал метать в греков золотые стрелы, отчего в лагере начался мор.

Прорицатель Калхас рассказал, что умилостивить Аполлона и прекратить мор можно, лишь отдав Хрисеиду отцу. Девушку вернули, и мор прекратился. Но Агамемнон потребовал, что вместо нее ему была отдана другая невольница — Брисеида, находившаяся у Ахилла. Ее забрали у героя и отдали Агамемнону.

Ахиллес, успевший полюбить девушку и возмущенный этим бесчестьем, объявил, что больше не будет участвовать в битве с троянцами. Его мать Фетида стала молить Зевса, чтобы тот покарал Агамемнона. После этого ход войны резко изменился. Троянцы стали брать верх.

Греческие воины были уже утомлены войной, и когда Агамемнон спросил, хотят ли они прекратить осаду, все радостно бросились к кораблям. Один из воинов, Терсит, кричал, что война выгодна лишь вождям, которые обогащаются от военной добычи. Соратников сумел удержать лишь хитроумный Одиссей, который побил Терсита и призвал продолжить войну во имя славы Эллады.

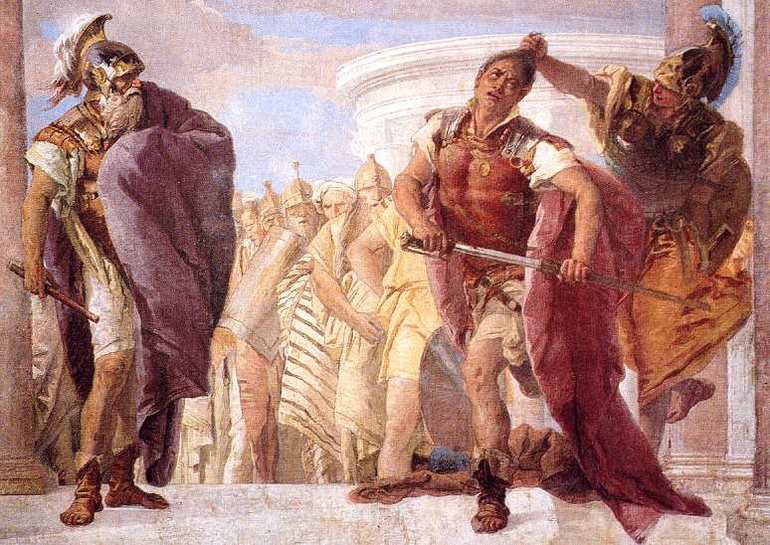

Греческое войско опять двинулась к Трое, откуда вышли ее защитники. Для прекращения войны был предложен было предложено провести поединок между Парисом и Менелаем. Могучий правитель Спарты победил противника, но Афродита спасла своего любимца от смерти и унесла его за стены Трои.

Исход поединка был уже ясен. По договору Менелаю должна была достаться Елена и богатый выкуп. Но вмешалась дела Афина, подговорившая пустить стрелу в победителя. Мир был нарушен, и битва началась вновь. Теперь победа встала склоняться на сторону троянцев, и греков оттеснили к кораблям. Тогда Агамемнон обратился к Ахиллу. Он просил его вернуться, обещал отдать Брисеиду и других пленниц. Но герой отказал послам.

Уговаривать Ахилла пришел его друг Патрокл, но он также отказал тому наотрез. Тогда Патрокл попросил героя хотя бы дать свои доспехи, чтобы вести в бой его войско. Он согласился при условии, что друг лишь оттеснит троянцев. Но тот нарушил уговор и погнался за врагами, после чего был убит Гектором. Греки с трудом отбили труп Патрокла, но доспехи Ахилла остались у троянцев.

Убийство Гектора и Троянский конь

Ахилл горько оплакивал своего друга и поклялся отомстить его убийце. Его мать Фетида попросила Гефеста сковать ему новые доспехи. Утром Ахиллес вызвал Гектора на бой. Он пронзил своего врага копьем, привязал за ноги к колеснице и отвез в лагерь греков.

Снова начались отчаянные битвы. В одной из них Ахилл пал от стрелы Париса. Она попала герою в пятку — единственное его уязвимое место. После гибели Гектора и Ахиллеса силы уравниваются. Греки приглашают героя Филоктета, обладающего стрелами Геракла. Это не дает военного перевеса, но одна из них убивает Париса.

Победить в войне помогает совет Одиссея. Он предложил сделать большого деревянного коня и поместить туда лучших воинов. Все прочие сядут на корабли и отплывут от берега. Ахейцы так и сделали. Утром жители Трои увидели, что враги покинули их побережье, а на морском берегу остался огромный деревянный конь. Друг Одиссея, переодетый в нищего, сообщил троянцам, что это дар ахейцев богине Палладе.

Громадного коня перетащили за стены Трои. Ночью греки выбрались наружу, разграбили город и устроили резню. Царь Приам был убит, вдова Гектора Андромаха была увезена как рабыня, ее сына сбросили со стены. Кассандру, дочь Приама, отдали в добычу Агамемнону. Елена, виновница Троянской войны, предстала перед Менелаем. Он хотел поразить изменницу, но его обезоружила ее красота. Из троянских вождей спасся лишь Эней, который по легенде впоследствии стал основателем Рима .

На этом приключении греческих героев не закончились. На обратном пути им пришлось испытать много бед:

- Корабль Менелая был застигнут бурей, после чего его отнесло в Египет.

- Возвратившийся домой Агамемнон был убит собственной женой.

- Дольше всех возвращался с войны Одиссей. О его странствиях была написана другая поэма Гомера — «Одиссея».

Из-за чего в реальности произошла Троянская война, сегодня судить трудно. Но сложенная о ней поэма стала первым художественным произведением, дошедшим до наших дней. На ней воспитаны многие поколения людей, и имена ее героев известны каждому.

Описанию осады Трои посвящено множество произведений греческой литературы и искусства. При этом не существует единого авторитетного источника, описывающего все события той войны. История разбросана по произведениям многих авторов, порой противоречащих друг другу. Важнейшими литературными источниками, повествующими о событиях, являются две эпические поэмы «Илиада» и «Одиссея», авторство которых традиционно приписывается Гомеру. Каждая поэма рассказывает лишь о части войны: «Илиада» освещает короткий период, предшествующий осаде Трои и саму войну, в то время как «Одиссея» повествует о возвращении одного из героев эпоса в родную Итаку, после взятия города.

О других событиях троянской войны сообщает так называемый «Циклический эпос» – целая группа поэм, авторство которых поначалу тоже приписывалось Гомеру. Однако позже выяснилось, что их авторами были последователи Гомера, использовавшие его язык и стилистику. Большая часть произведений хронологически завершает гомеровский эпос: «Эфиопида», «Малая Илиада», «Возвращения», «Телегония» и другие описывают судьбы гомеровских героев после завершения осады Трои. Исключение составляет лишь «Киприй», повествующих о довоенном периоде и событиях, которые стали причиной конфликта. Большая часть этих произведений дошла до наших дней лишь частично.

Предпосылки к войне

Считается, что причиной конфликта стало похищение троянским царевичем Парисом прекрасной Елены, которая была женой царя Спарты Менелая. Елена была настолько хороша собой, что отец царь Тиндарей никак не мог решиться выдать ее замуж, опасаясь мести отвергнутых женихов. Тогда было принято неслыханное по тем временам решение, разрешить девушке самой выбрать себе суженого. Дабы избежать возможного конфликта, все потенциальные женихи связали себя клятвой не преследовать счастливца, на которого падет выбор царевны, и в последующем всячески помогать ему при необходимости. Елена остановила свой выбор на Менелае, и стала его женой.

Однако еще раньше три самых могущественных богини Олимпа – Гера, Афина и Афродита – поспорили из-за золотого яблока, подкинутого богиней раздора Эридой. На яблоке было всего одно слово – «прекраснейшей», но именно оно стало причиной дальнейших событий. Каждая богиня считала, что яблоко по праву принадлежит ей и не желала уступить соперницам. Боги-мужчины отказались ввязываться в женскую распрю, а вот человеку мудрости не хватило. Богини обратились с просьбой рассудить их к Парису, сыну царя Приама, правившего Троей. Каждая обещала что-то взамен: Гера – власть, Афина – военную славу, а Афродита – любовь любой женщины, которую тот пожелает. Парис выбрал Афродиту, нажив при этом себе и народу Трои двух могущественнейших врагов.

Троянский царевич прибыл в Спарту, где в отсутствие Менелая, уговорил бежать Елену с ним (по другим источникам похитил). Возможно, дело и не дошло до столь масштабного конфликта, если бы беглецы не прихватили с собой сокровища Менелая. Этого оскорбленный муж снести уже не смог и бросил клич все бывшим женихам Елены, связавшим себя когда-то клятвой.

Осада Трои

Греческое войско общей численностью в 100 тысяч человек погрузилось на корабли и отправилось в Трою. Возглавляли ахейцев Менелай и микенский царь Агамемнон, приходившийся тому братом. После того как греки расположились лагерем под стенами города, было решено попытаться решить дело миром, для чего направить в Трою парламентеров. Однако троянцы не согласились на условия греков, рассчитывая на прочность крепостных стен и свое войско. Началась осада города.

Ссора Ахилла и Агамемнона

Согласно предсказанию, война должна была продлиться 9 лет, и только на 10-й год обещано падение Трои. Все эти годы ахейцы занимались мелким грабежом и набегами на близлежащие города. Во время одного из походов, добычей греков стали Хрисеида, дочь жреца Хриса, и Брисеида, дочь царя Брисея. Первая досталась царю Микен Агамемнону, а вторая Ахиллу – знаменитому греческому герою.

Вскоре в лагере греков начался мор, что было истолковано прорицателем Калхасом как гнев бога Аполлона, к которому обратился опечаленный отец Хрисеиды. Греки потребовали от Агамемнона вернуть пленницу отцу, и тот скрепя сердце согласился, но взамен начал требовать для себя Брисеиду, законную пленницу Ахилла. Завязалась словесная перепалка, в которой Ахилл обвинил Агамемнона в алчности, а тот в свою очередь обозвал великого героя трусом. В результате оскорбленный Ахилл отказался участвовать в дальнейшей осаде города, да к тому же попросил свою мать, морскую нимфу Фетиду, умолить Зевса даровать победу троянцам, чтобы наказать зарвавшегося Агамемнона.

Идя навстречу просьбе Фетиды, Зевс наслал микенского царя обманчивый сон, обещавший победу. Воодушевленные своим предводителем, греки устремились в бой. Троянское войско возглавлял Гектор, старший сын царя Приама. Сам царь был уже слишком стар, чтобы участвовать в сражении. Прежде чем начать битву, Гектор предложил провести поединок между Менелаем и своим братом Парисом. Победителю достанутся прекрасная Елена и похищенные сокровища, а греки и троянцы дадут священную клятву, что после поединка будет заключен мир.

Начало сражения

Обе стороны с радостью согласились – затянувшаяся война надоела многим. В поединке победил Менелай, а Парис остался жив лишь благодаря заступничеству богини Афродиты. Казалось, что война теперь должна окончиться, но это не входило в планы Геры и Афины, затаивших злобу на Париса. Гера поклялась уничтожить Трою и не собиралась отступать. Подосланная ею Афина приняла образ воина и обратилась к искусному лучнику Пандару, предлагая выстрелить в Менелая. Пандар не убил спартанского царя только потому, что сама же Афина немного отклонила его стрелу. Раненого Менелая унесли с поля, а греки, возмущенные вероломством троянцев устремились в бой.

В страшной битве сошлись люди, но и боги не остались в стороне – Афродита, Аполлон и бог войны Арес, поддерживали троянцев, а Гера и Афина Паллада греков. Множество народу погибло с обеих сторон, сама Афродита была ранена в руку одним из греков и вынуждена была вернуться на Олимп залечивать рану. Ни троянцы, ни ахейцы не могли взять вверх, и по совету мудрого греческого старца Нестора, было решено прервать сражение на один день, чтобы похоронить убитых.

Через день, памятуя обещание данное Фетиде, Зевс запретил кому-либо из богов вмешиваться в ход битвы. Чувствуя поддержку верховного божества, троянцы начали теснить греков, нанося огромный урон их войску. На все упреки Геры Зевс отвечал, что истребление ахейцев продлится до тех пор, пока на поле битвы не вернется Ахилл.

Опечаленные поражением греческие вожди собрались на совет, где по совету мудрого Нестора было решено отправить послов к Ахиллу с просьбой вернуться. Долго уговаривали послы, среди которых был Одиссей, великого героя, но тот оставался глух к их просьбам – слишком уж была велика обида на Агамемнона.

Гибель Патрокла и возвращение Ахилла

Пришлось и дальше грекам биться с троянцами без поддержки Ахилла. В страшном сражении троянцы истребили множество ахейцев, но и сами понесли большие потери. Грекам пришлось не только отойти от стен города, но и защищать свои корабли – так силен был натиск противника. Следивший за ходом битвы друг Ахилла Патрокл не мог сдержать слез, наблюдая за тем, как гибнут соплеменники. Обратившись к Ахиллу, Патрокл попросил отпустить его на помощь греческому войску, раз уж великий герой не желает сражаться сам. Получив разрешение, вместе со своими воинами Патрокл отправился на поле боя, где ему суждено было погибнуть от руки Гектора.

Опечаленный смертью ближайшего друга, Ахилл оплакал его тело, пообещав уничтожить Гектора. После примирения с Агамемноном герой вступил в битву с троянцами, нещадно их истребляя. Битва закипела с новой силой. До самых ворот города гнал Ахилл троянских воинов, которым едва удалось укрыться за стенами. Только Гектор остался на поле битвы, ожидая возможности сразиться с греческим героем. Ахилл убил Гектора, привязал его тело к колеснице и пустил коней вскачь. И только через несколько дней тело павшего троянского царевича вернули царю Приаму за большой выкуп. Сжалившись над несчастным отцом, Ахилл согласился прервать сражение на 11 дней, чтобы Троя могла оплакать и похоронить своего предводителя.

Гибель Ахилла и взятие Трои

Но со смертью Гектора не окончилась война. Вскоре погиб и сам Ахилл, сраженный стрелой Париса, которую направил бог Аполлон. В детстве, мать Ахилла богиня Фетида искупала сына в водах реки Стикс, разделяющей мир живых мертвых, после чего тело будущего героя стало неуязвимым. И только пятка, за которую держала его мать, осталась единственным незащищенным местом – именно в нее и попал Парис. Однако и сам он вскоре нашел смерть, погибнув от ядовитой стрелы, выпущенной одним из греков.

Множество троянских и греческих героев полегло, прежде чем хитроумный Одиссей придумал, как проникнуть в город. Греки соорудили огромного деревянного коня, а сами сделали вид, что отплывают восвояси. Лазутчик, подосланный к троянцам, убедил тех, что дивное сооружение это дар ахейцев богам. Заинтригованные жители Трои втащили коня в город, несмотря на предостережения жреца Лаокоонта и вещей Кассандры. Воодушевленные мнимым отплытием ахейцев, троянцы ликовали до глубокой ночи, а когда все уснули, из брюха деревянного коня выбрались греческие воины, которые открыли городские ворота огромному войску.

Эта ночь стала последней в истории Трои. Ахейцы уничтожили всех мужчин, не пощадив даже младенцев. Лишь Эней, потомкам которого суждено было основать Рим, с небольшим отрядом смог вырваться из захваченного города. Женщинам Трои была уготована горькая участь невольниц. Менелай разыскал неверную супругу, желая лишить ее жизни, но сраженный красотой Елены, простил измену. Несколько дней длилось разграбление Трои, а развалины города были преданы огню.

Троянская война в исторических фактах

Долгое время считалось, что Троянская война это всего лишь красивая легенда, не имеющая реальной основы. Однако во второй половине XIX века археологом-любителем Генрихом Шлиманом на холме Гиссарлык в западной Анатолии был обнаружен древний город. Шлиман объявил, что ему удалось найти руины Трои. Однако в дальнейшем выяснилось, что развалины найденного города гораздо древнее Трои, описанной в гомеровской «Илиаде».

Хотя точная датировка Троянской войны неизвестна, большинство исследователей считают, что она произошла в XIII-XII веке до н.э. Развалины, которые удалось обнаружить Шлиману, оказались старше как минимум на тысячу лет. Тем не менее раскопки на этом месте продолжались многими учеными в течение долгих лет. В результате было обнаружено 12 культурных слоев, один из которых вполне соотносится с периодом Троянской войны.

Однако, рассуждая логически, Троя не была изолированным городом. Еще раньше в Восточном Средиземноморье и на Ближнем Востоке возник целый ряд государств с высокоразвитым уровнем культуры: Вавилон, Хеттская империя, Финикия, Египет и другие. События такого масштаба, как их описывал Гомер, не могли не оставить следов в сказаниях народов, населявших эти государства, однако дело обстоит именно так. Никаких свидетельств о противостоянии ахейцев и Трои в легендах и мифах этих стран не найдено.

По все видимости, Гомер пересказал историю нескольких военных конфликтов и завоевательных походов, случившихся в разные временные промежутки, щедро приправив их своей фантазией. Реальность и вымысел переплетаются настолько причудливо, что не всегда удается отличить одно от другого.

Например, некоторые исследователи склонны считать вполне реальным эпизод с троянским конем. По предположениям части историков, под этим сооружением надо понимать стенобитную машину или таран, с помощью которого осаждающие разрушили крепостные стены.

Споры о реальности Троянской войны, по всей видимости, будут продолжаться еще долгое время. Однако не так уж важно, какими были реальные события, ведь именно они вдохновили Гомера на создание величайшего литературного памятника в истории человеческой цивилизации.

via

Движение «народов моря» привело и к знаменитой Троянской войне. Основные сведения о ней почерпнуты из поэм Гомера «Илиада» и «Одиссея». Считается, что она велась союзом ахейских государств (Фивами, Микенами, Тиринфом и другими) против государства Троя (Илион), расположенного в северо-западной части Малой Азии, на берегах Геллеспонта (Дарданелл) и Эгейского моря.

Блок: 1/3 | Кол-во символов: 372

Источник: http://grekoline.ru/drevnyaya-greciya/troyanskaya-vojna-kratko.html

Содержание

- 0.1 Сообщение о Троянской войне по истории

- 1 Троянская война кратко

- 1.1 Кратко о Троянской войне

- 1.1.1 Троянская война причина

- 1.1.2 Военные действия и сколько длилась Троянская война?

- 1.1.3 Последствия Троянской войны

- 1.2 Начало и причины Троянской войны

- 1.1 Кратко о Троянской войне

- 2 Троянская война

- 2.1 Результаты Троянской войны

Сообщение о Троянской войне по истории

Троянская война – это военный конфликт, возникший между греческими городами-государствами, возглавляемых Микеном и Спартой против Трои. Приблизительно это событие произошло в XIII-XII веке до нашей эры. Единственный источник, где содержатся сведенья о Троянской войне, это знаменитая поэма «Илиада» греческого автора Гомера.

Поскольку поэма является художественным произведением, то до раскопок Генриха Шлимана в начале XIX века никто не верил не то что в само военное действие, но и в существование Трои как таковой. Ее считали вымыслом и плодом воображения Гомера. Однако археологу удалось обнаружить целый город в месте, где по описанию Гомера была расположена Троя. Здесь и началась ее история.

Блок: 2/3 | Кол-во символов: 736

Источник: https://kratkoe.com/kratkoe-soobshhenie-o-troyanskoy-voyne/

Троянская война кратко

Если кратко, то согласно мифу, поводом к войне послужило похищением троянским царевичем Парисом жены царя Спарты Менелая. Греческие цари собрали большой флот из 1200 кораблей и подошли к берегам Трои. Возглавил союзную армию брат Менелая, царь Микен Агамемнон. Троянцы после короткого боя отступили к городу укрылись за его стенами. Войска Агамемнона высадились перед Троей на берегу моря лагерем, не блокировав ее со всех сторон. Этим воспользовались троянцы и с помощью союзников наладили снабжение осажденных. В результате осада Трои продлилась около десяти лет. Боевые действия в этот период практически не велись, и противники лишь изредка вступали в небольшие стычки.

Видя всю безнадежность дальнейшей осады, греки пустились на хитрость. Они сожгли свой лагерь, сели на корабли и сделали вид, что возвращаются по домам. На самом деле они обогнули остров Тенедос и встали на якорь с другой его стороны. Проснувшись утром, троянцы обнаружили у стен Трои лишь огромную деревянную фигуру коня. Поверив словам греческого перебежчика Синона, что владение этим конем принесет им победу, они втащили его в город.

Ночью из полой статуи коня вышли греческие воины, которых возглавлял царь Итаки Одиссей. Воины перебили охраняющую ворота стражу и впустили свое войско в город. С тех времен выражение «Троянский конь» стало нарицательным и обозначает обманные действия. Троя была разрушена до основания, а жители ее перебиты. Впоследствии город был восстановлен, но потерял свое значение, а к средним векам прекратил свое существование. Долгое время Троянскую войну считали древнегреческим мифом, но в конце XIX в. археолог Генрих Шлиман нашел остатки древнего города.

Фото:

Главная

ЛитРес — магазин электронных книг

Блок: 2/3 | Кол-во символов: 1749

Источник: http://grekoline.ru/drevnyaya-greciya/troyanskaya-vojna-kratko.html

Кратко о Троянской войне

-

Троянская война причина

В период Античности греческие города-государства (в особенности Микены) стремились стать владыками Эгейского моря. Но на их пути стояло одно из самых могущественных государств – Троя. Поэтому, чтобы подчинить себе торговые, богатые морские пути в Эгейское море, нужно было подчинить или уничтожить Трою.

- Повод к войне

Сегодня весь мир знает прекрасную историю о том, что дало грекам повод выступить войной на Трою. Ею послужила Елена Прекрасная – жена царя Спарты и союзника Микен. В легенде говорится, что Парис, молодой царевич Трои, влюбился в нее и похитил Елену, привезя к себе домой. Возмущенные греки тотчас же объявили Трое войну. Никто не знает, было ли так оно на самом деле.

-

Военные действия и сколько длилась Троянская война?

Греки огромной армией в 50 -100 тыс. человек из всех городов-государств выдвинулись в сторону Трои. С моря их поддерживал огромный флот, общим числом в 1 000 судов. Армия троянцев была значительно меньше, однако стены государства могли выдержать даже самую длительную осаду. После объявления войны прошел год, и греки высадили на берегах врага. Троянцы встретили врага на берегу, однако под их натиском и превосходством отступили за стены города. На протяжении долгих лет происходили кровавые столкновения, без видимого преимущества ни одной из сторон. Однако человеческие потери были большими у греков. Войска Трои возглавлял наследник престола и воин – Гектор, а греков — Ахиллес. В затяжной схватке этих великих воинов побеждает грек Ахиллес. А война продолжается. Целых 10 лет греки осаждали Трою безрезультатно, пока не поняли, что город нужно брать хитростью. Они построили из дерева знаменитого Троянского коня и подкатили его к городским воротам в знак того, что покидают Трою, признавая ее превосходство.

На самом деле, в коне сидели воины. Когда троянцы закатили подарок греков в город, те, с наступлением темноты вылезли с коня, и открыли ворота для своих соратников. Греческая армия ворвалась в спящий город, и к утру он уже вовсю полыхал в огне.

-

Последствия Троянской войны

Могущественная Троя была уничтожена. Микены, понеся серьезные человеческие и экономические потери, также вскоре пали.

Надеемся, что доклад о Троянской войне помог Вам подготовиться к занятию. А небольшое сообщение о Троянской войне Вы можете оставить через форму ниже.

Блок: 3/3 | Кол-во символов: 2338

Источник: https://kratkoe.com/kratkoe-soobshhenie-o-troyanskoy-voyne/

Начало и причины Троянской войны

Культура народов того времени тесно переплетена с мифами, поэтому изложенные в источниках причины довольно сказочные. Ученые же предполагают, что война была вызвана перемещениями «народов моря». Существует и мнение, что все наоборот – троянские баталии стали причиной переселения морских культур.

Мифическая причина такова. Богиня Эрида спровоцировала трех красивейших богинь Олимпа на спор, кто из них самая прекрасная. Зевс, уклонившись от такого выбора, оставил его красивейшему мужчине на земле, сыну царя Трои по имени Парис. Он выбрал ту богиню, которая пообещала влюбить в него красивейшую земную женщину. Это оказалась Елена, которая на тот момент была женой Менелая.

Вскоре Парис отправился в Спарту, где и правил Менелай. Последний радушно принял гостей и вскоре отбыл по срочному делу. Пока супруг был в отъезде, Елена сбежала с сокровищами и рабынями вместе с Парисом в Трою. Обнаружив пропажу, обманутый муж принялся собирать войска для военного похода.

Блок: 3/4 | Кол-во символов: 1002

Источник: https://www.istmira.com/drugoe-drevniy-mir/14462-kratkoe-soobschenie-na-temu-trojanskaja-vojna.html

Троянская война

Блок: 4/5 | Кол-во символов: 78

Источник: http://sochinite.ru/otvety/istoriya/troyanskaya-vojna-kratkoe-soderzhanie-dlya-detej

Результаты Троянской войны

Войско Менелая не сразу достигло Трои, они несколько раз ошибались и попадали в неприятности. В конце концов, добравшись до цели, начинается 41 день противостояния троянцев и греков, описанный в древней Илиаде.

Большинство этого времени было посвящено препирательству между Менелаем и Ахиллесом – самым сильным и знаменитым воином того времени. Его суть была в том, что греческий царь отобрал у Ахилла часть его награды – рабыню Брисеиду. Споры между людьми привели и к соперничеству между Богами, которые постоянно меняли свои пророчества и победителя войны.

В итоге, с помощью хитрого трюка – троянского коня, грекам удалось победить. Они смастерили большую деревянную статую бога и, оставив ее у ворот, скрылись. Троянцы приняли ее за дар в честь своей победы, внесли в город и устроили празднование. Когда наступила ночь, из коня выбрался отряд греков, открыл ворота изнутри и впустил основные силы нападающих. Они подчинили город за одну ночь, в которую пала знаменитая Троя.

Блок: 4/4 | Кол-во символов: 1017

Источник: https://www.istmira.com/drugoe-drevniy-mir/14462-kratkoe-soobschenie-na-temu-trojanskaja-vojna.html

Кол-во блоков: 12 | Общее кол-во символов: 12860

Количество использованных доноров: 4

Информация по каждому донору:

- https://kratkoe.com/kratkoe-soobshhenie-o-troyanskoy-voyne/: использовано 2 блоков из 3, кол-во символов 3074 (24%)

- http://sochinite.ru/otvety/istoriya/troyanskaya-vojna-kratkoe-soderzhanie-dlya-detej: использовано 3 блоков из 5, кол-во символов 5230 (41%)

- https://www.istmira.com/drugoe-drevniy-mir/14462-kratkoe-soobschenie-na-temu-trojanskaja-vojna.html: использовано 3 блоков из 4, кол-во символов 2435 (19%)

- http://grekoline.ru/drevnyaya-greciya/troyanskaya-vojna-kratko.html: использовано 2 блоков из 3, кол-во символов 2121 (16%)

|

Поделитесь в соц.сетях: |

Оцените статью:

|

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably Homer’s Iliad. The core of the Iliad (Books II – XXIII) describes a period of four days and two nights in the tenth year of the decade-long siege of Troy; the Odyssey describes the journey home of Odysseus, one of the war’s heroes. Other parts of the war are described in a cycle of epic poems, which have survived through fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets including Virgil and Ovid.

The ancient Greeks believed that Troy was located near the Dardanelles and that the Trojan War was a historical event of the 13th or 12th century BC, but by the mid-19th century AD, both the war and the city were widely seen as non-historical. In 1868, however, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann met Frank Calvert, who convinced Schliemann that Troy was at what is now Hisarlik in Turkey.[1] On the basis of excavations conducted by Schliemann and others, this claim is now accepted by most scholars.[2][3]

Whether there is any historical reality behind the Trojan War remains an open question. Many scholars believe that there is a historical core to the tale, though this may simply mean that the Homeric stories are a fusion of various tales of sieges and expeditions by Mycenaean Greeks during the Bronze Age. Those who believe that the stories of the Trojan War are derived from a specific historical conflict usually date it to the 12th or 11th century BC, often preferring the dates given by Eratosthenes, 1194–1184 BC, which roughly correspond to archaeological evidence of a catastrophic burning of Troy VII,[4] and the Late Bronze Age collapse.

Sources

The events of the Trojan War are found in many works of Greek literature and depicted in numerous works of Greek art. There is no single, authoritative text which tells the entire events of the war. Instead, the story is assembled from a variety of sources, some of which report contradictory versions of the events. The most important literary sources are the two epic poems traditionally credited to Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, composed sometime between the 9th and 6th centuries BC.[5] Each poem narrates only a part of the war. The Iliad covers a short period in the last year of the siege of Troy, while the Odyssey concerns Odysseus’s return to his home island of Ithaca following the sack of Troy and contains several flashbacks to particular episodes in the war.

Other parts of the Trojan War were told in the poems of the Epic Cycle, also known as the Cyclic Epics: the Cypria, Aethiopis, Little Iliad, Iliou Persis, Nostoi, and Telegony. Though these poems survive only in fragments, their content is known from a summary included in Proclus’ Chrestomathy.[6] The authorship of the Cyclic Epics is uncertain. It is generally thought that the poems were written down in the 7th and 6th century BC, after the composition of the Homeric poems, though it is widely believed that they were based on earlier traditions.[7]

Both the Homeric epics and the Epic Cycle take origin from oral tradition. Even after the composition of the Iliad, Odyssey, and the Cyclic Epics, the myths of the Trojan War were passed on orally in many genres of poetry and through non-poetic storytelling. Events and details of the story that are only found in later authors may have been passed on through oral tradition and could be as old as the Homeric poems. Visual art, such as vase painting, was another medium in which myths of the Trojan War circulated.[8]

In later ages playwrights, historians, and other intellectuals would create works inspired by the Trojan War. The three great tragedians of Athens—Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides—wrote a number of dramas that portray episodes from the Trojan War. Among Roman writers the most important is the 1st century BC poet Virgil; in Book 2 of his Aeneid, Aeneas narrates the sack of Troy.

Legend

Traditionally, the Trojan War arose from a sequence of events beginning with a quarrel between the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Eris, the goddess of discord, was not invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, and so arrived bearing a gift: a golden apple, inscribed «for the fairest». Each of the goddesses claimed to be the «fairest», and the rightful owner of the apple. They submitted the judgment to a shepherd they encountered tending his flock. Each of the goddesses promised the young man a boon in return for his favour: power, wisdom, or love. The youth—in fact Paris, a Trojan prince who had been raised in the countryside—chose love, and awarded the apple to Aphrodite. As his reward, Aphrodite caused Helen, the Queen of Sparta, and most beautiful of all women, to fall in love with Paris. But the judgement of Paris earned him the ire of both Hera and Athena, and when Helen left her husband, Menelaus, the Spartan king, for Paris of Troy, Menelaus called upon all the kings and princes of Greece to wage war upon Troy.

The Burning of Troy (1759/62), oil painting by Johann Georg Trautmann

Menelaus’ brother Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, led an expedition of Achaean troops to Troy and besieged the city for ten years because of Paris’ insult. After the deaths of many heroes, including the Achaeans Achilles and Ajax, and the Trojans Hector and Paris, the city fell to the ruse of the Trojan Horse. The Achaeans slaughtered the Trojans, except for some of the women and children whom they kept or sold as slaves and desecrated the temples, thus earning the gods’ wrath. Few of the Achaeans returned safely to their homes and many founded colonies in distant shores. The Romans later traced their origin to Aeneas, Aphrodite’s son and one of the Trojans, who was said to have led the surviving Trojans to modern-day Italy.

The following summary of the Trojan War follows the order of events as given in Proclus’ summary, along with the Iliad, Odyssey, and Aeneid, supplemented with details drawn from other authors.

Origins of the war

Musician figures from clay in Troy Museum.

Plan of Zeus

According to Greek mythology, Zeus had become king of the gods by overthrowing his father Cronus; Cronus in turn had overthrown his father Uranus. Zeus was not faithful to his wife and sister Hera, and had many relationships from which many children were born. Since Zeus believed that there were too many people populating the earth, he envisioned Momus[9] or Themis,[10] who was to use the Trojan War as a means to depopulate the Earth, especially of his demigod descendants.[11]

These can be supported by Hesiod’s account:

Now all the gods were divided through strife; for at that very time Zeus who thunders on high was meditating marvelous deeds, even to mingle storm and tempest over the boundless earth, and already he was hastening to make an utter end of the race of mortal men, declaring that he would destroy the lives of the demi-gods, that the children of the gods should not mate with wretched mortals, seeing their fate with their own eyes; but that the blessed gods henceforth even as aforetime should have their living and their habitations apart from men. But on those who were born of immortals and of mankind verily Zeus laid toil and sorrow upon sorrow.[12]

Judgement of Paris

Zeus came to learn from either Themis[13] or Prometheus, after Heracles had released him from Caucasus,[14] that, like his father Cronus, he would be overthrown by one of his sons. Another prophecy stated that a son of the sea-nymph Thetis, with whom Zeus fell in love after gazing upon her in the oceans off the Greek coast, would become greater than his father.[15] Possibly for one or both of these reasons,[16] Thetis was betrothed to an elderly human king, Peleus son of Aeacus, either upon Zeus’ orders,[17] or because she wished to please Hera, who had raised her.[18]

All of the gods were invited to Peleus and Thetis’ wedding and brought many gifts,[19] except Eris (the goddess of discord), who was stopped at the door by Hermes, on Zeus’ order.[20] Insulted, she threw from the door a gift of her own:[21] a golden apple (το μήλον της έριδος) on which was inscribed the word καλλίστῃ Kallistēi («To the fairest»).[22] The apple was claimed by Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. They quarreled bitterly over it, and none of the other gods would venture an opinion favoring one, for fear of earning the enmity of the other two. Eventually, Zeus ordered Hermes to lead the three goddesses to Paris, a prince of Troy, who, unaware of his ancestry, was being raised as a shepherd in Mount Ida,[23] because of a prophecy that he would be the downfall of Troy.[24] After bathing in the spring of Ida, the goddesses appeared to him naked, either for the sake of winning or at Paris’ request. Paris was unable to decide among them, so the goddesses resorted to bribes. Athena offered Paris wisdom, skill in battle, and the abilities of the greatest warriors; Hera offered him political power and control of all of Asia; and Aphrodite offered him the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta. Paris awarded the apple to Aphrodite, and, after several adventures, returned to Troy, where he was recognized by his royal family.

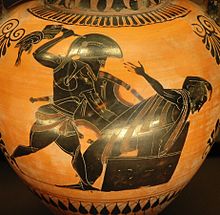

Thetis gives her son Achilles weapons forged by Hephaestus (detail of Attic black-figure hydria, 575–550 BC)

Peleus and Thetis bore a son, whom they named Achilles. It was foretold that he would either die of old age after an uneventful life, or die young in a battlefield and gain immortality through poetry.[25] Furthermore, when Achilles was nine years old, Calchas had prophesied that Troy could not again fall without his help.[26] A number of sources credit Thetis with attempting to make Achilles immortal when he was an infant. Some of these state that she held him over fire every night to burn away his mortal parts and rubbed him with ambrosia during the day, but Peleus discovered her actions and stopped her.[27]

According to some versions of this story, Thetis had already killed several sons in this manner, and Peleus’ action therefore saved his son’s life.[28] Other sources state that Thetis bathed Achilles in the Styx, the river that runs to the underworld, making him invulnerable wherever he was touched by the water.[29] Because she had held him by the heel, it was not immersed during the bathing and thus the heel remained mortal and vulnerable to injury (hence the expression «Achilles’ heel» for an isolated weakness). He grew up to be the greatest of all mortal warriors. After Calchas’ prophecy, Thetis hid Achilles in Skyros at the court of King Lycomedes, where he was disguised as a girl.[30] At a crucial point in the war, she assists her son by providing weapons divinely forged by Hephaestus (see below).

Elopement of Paris and Helen

The most beautiful woman in the world was Helen, one of the daughters of Tyndareus, King of Sparta. Her mother was Leda, who had been either raped or seduced by Zeus in the form of a swan.[31] Accounts differ over which of Leda’s four children, two pairs of twins, were fathered by Zeus and which by Tyndareus. However, Helen is usually credited as Zeus’ daughter,[32] and sometimes Nemesis is credited as her mother.[33] Helen had scores of suitors, and her father was unwilling to choose one for fear the others would retaliate violently.

Finally, one of the suitors, Odysseus of Ithaca, proposed a plan to solve the dilemma. In exchange for Tyndareus’ support of his own suit towards Penelope,[34] he suggested that Tyndareus require all of Helen’s suitors to promise that they would defend the marriage of Helen, regardless of whom he chose. The suitors duly swore the required oath on the severed pieces of a horse, although not without a certain amount of grumbling.[35]

Tyndareus chose Menelaus. Menelaus was a political choice on her father’s part. He had wealth and power. He had humbly not petitioned for her himself, but instead sent his brother Agamemnon on his behalf. He had promised Aphrodite a hecatomb, a sacrifice of 100 oxen, if he won Helen, but forgot about it and earned her wrath.[36] Menelaus inherited Tyndareus’ throne of Sparta with Helen as his queen when her brothers, Castor and Pollux, became gods,[37] and when Agamemnon married Helen’s sister Clytemnestra and took back the throne of Mycenae.[38]

Paris, under the guise of a supposed diplomatic mission, went to Sparta to get Helen and bring her back to Troy. Before Helen could look up to see him enter the palace, she was shot with an arrow from Eros, otherwise known as Cupid, and fell in love with Paris when she saw him, as promised by Aphrodite. Menelaus had left for Crete[39] to bury his uncle, Crateus.[40]

According to one account, Hera, still jealous over the judgement of Paris, sent a storm.[39] The storm caused the lovers to land in Egypt, where the gods replaced Helen with a likeness of her made of clouds, Nephele.[41] The myth of Helen being switched is attributed to the 6th century BC Sicilian poet Stesichorus, while for Homer the Helen in Troy was one and the same. The ship then landed in Sidon. Paris, fearful of getting caught, spent some time there and then sailed to Troy.[42]

Paris’ abduction of Helen had several precedents. Io was taken from Mycenae, Europa was taken from Phoenicia, Jason took Medea from Colchis,[43] and the Trojan princess Hesione had been taken by Heracles, who gave her to Telamon of Salamis.[44] According to Herodotus, Paris was emboldened by these examples to steal himself a wife from Greece, and expected no retribution, since there had been none in the other cases.[45]

Gathering of Achaean forces and the first expedition

According to Homer, Menelaus and his ally, Odysseus, traveled to Troy, where they unsuccessfully sought to recover Helen by diplomatic means.[46]

Menelaus then asked Agamemnon to uphold his oath, which, as one of Helen’s suitors, was to defend her marriage regardless of which suitor had been chosen. Agamemnon agreed and sent emissaries to all the Achaean kings and princes to call them to observe their oaths and retrieve Helen.[47]

Odysseus and Achilles

A scene from the Iliad where Odysseus (Ulysses) discovers Achilles dressed as a woman and hiding among the princesses at the royal court of Skyros. A late Roman mosaic from La Olmeda, Spain, 4th–5th centuries AD

Since Menelaus’s wedding, Odysseus had married Penelope and fathered a son, Telemachus. In order to avoid the war, he feigned madness and sowed his fields with salt. Palamedes outwitted him by placing Telemachus, then an infant, in front of the plough’s path. Odysseus turned aside, unwilling to kill his son, so revealing his sanity and forcing him to join the war.[39][48]

According to Homer, however, Odysseus supported the military adventure from the beginning, and traveled the region with Pylos’ king, Nestor, to recruit forces.[49]

At Skyros, Achilles had an affair with the king’s daughter Deidamia, resulting in a child, Neoptolemus.[50] Odysseus, Telamonian Ajax, and Achilles’ tutor Phoenix went to retrieve Achilles. Achilles’ mother disguised him as a woman so that he would not have to go to war, but, according to one story, they blew a horn, and Achilles revealed himself by seizing a spear to fight intruders, rather than fleeing.[26] According to another story, they disguised themselves as merchants bearing trinkets and weaponry, and Achilles was marked out from the other women for admiring weaponry instead of clothes and jewelry.[51]

Pausanias said that, according to Homer, Achilles did not hide in Skyros, but rather conquered the island, as part of the Trojan War.[52]

The Discovery of Achilles among the Daughters of Lycomedes (1664) by Jan de Bray

First gathering at Aulis

The Achaean forces first gathered at Aulis. All the suitors sent their forces except King Cinyras of Cyprus. Though he sent breastplates to Agamemnon and promised to send 50 ships, he sent only one real ship, led by the son of Mygdalion, and 49 ships made of clay.[53] Idomeneus was willing to lead the Cretan contingent in Mycenae’s war against Troy, but only as a co-commander, which he was granted.[54] The last commander to arrive was Achilles, who was then 15 years old.

Following a sacrifice to Apollo, a snake slithered from the altar to a sparrow’s nest in a plane tree nearby. It ate the mother and her nine chicks, then was turned to stone. Calchas interpreted this as a sign that Troy would fall in the tenth year of the war.[55]

Telephus

When the Achaeans left for the war, they did not know the way, and accidentally landed in Mysia, ruled by King Telephus, son of Heracles, who had led a contingent of Arcadians to settle there.[56] In the battle, Achilles wounded Telephus,[57] who had killed Thersander.[58] Because the wound would not heal, Telephus asked an oracle, «What will happen to the wound?». The oracle responded, «he that wounded shall heal». The Achaean fleet then set sail and was scattered by a storm. Achilles landed in Skyros and married Deidamia. A new gathering was set again in Aulis.[39]

Telephus went to Aulis, and either pretended to be a beggar, asking Agamemnon to help heal his wound,[59] or kidnapped Orestes and held him for ransom, demanding the wound be healed.[60] Achilles refused, claiming to have no medical knowledge. Odysseus reasoned that the spear that had inflicted the wound must be able to heal it. Pieces of the spear were scraped off onto the wound, and Telephus was healed.[61] Telephus then showed the Achaeans the route to Troy.[59]

Some scholars have regarded the expedition against Telephus and its resolution as a derivative reworking of elements from the main story of the Trojan War, but it has also been seen as fitting the story-pattern of the «preliminary adventure» that anticipates events and themes from the main narrative, and therefore as likely to be «early and integral».[62]

Second gathering

A map of the Troäd (Troas)

Eight years after the storm had scattered them,[63] the fleet of more than a thousand ships was gathered again. But when they had all reached Aulis, the winds ceased. The prophet Calchas stated that the goddess Artemis was punishing Agamemnon for killing either a sacred deer or a deer in a sacred grove, and boasting that he was a better hunter than she.[39] The only way to appease Artemis, he said, was to sacrifice Iphigenia, who was either the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra,[64] or of Helen and Theseus entrusted to Clytemnestra when Helen married Menelaus.[65]

Agamemnon refused, and the other commanders threatened to make Palamedes commander of the expedition.[66] According to some versions, Agamemnon relented and performed the sacrifice, but others claim that he sacrificed a deer in her place, or that at the last moment, Artemis took pity on the girl, and took her to be a maiden in one of her temples, substituting a lamb.[39] Hesiod says that Iphigenia became the goddess Hecate.[67]

The Achaean forces are described in detail in the Catalogue of Ships, in the second book of the Iliad. They consisted of 28 contingents from mainland Greece, the Peloponnese, the Dodecanese islands, Crete, and Ithaca, comprising 1186 pentekonters, ships with 50 rowers. Thucydides says[68] that according to tradition there were about 1200 ships, and that the Boeotian ships had 120 men, while Philoctetes’ ships only had the fifty rowers, these probably being maximum and minimum. These numbers would mean a total force of 70,000 to 130,000 men. Another catalogue of ships is given by the Bibliotheca that differs somewhat but agrees in numbers. Some scholars have claimed that Homer’s catalogue is an original Bronze Age document, possibly the Achaean commander’s order of operations.[69][70][71] Others believe it was a fabrication of Homer.

The second book of the Iliad also lists the Trojan allies, consisting of the Trojans themselves, led by Hector, and various allies listed as Dardanians led by Aeneas, Zeleians, Adrasteians, Percotians, Pelasgians, Thracians, Ciconian spearmen, Paionian archers, Halizones, Mysians, Phrygians, Maeonians, Miletians, Lycians led by Sarpedon and Carians. Nothing is said of the Trojan language; the Carians are specifically said to be barbarian-speaking, and the allied contingents are said to have spoken many languages, requiring orders to be translated by their individual commanders.[72] The Trojans and Achaeans in the Iliad share the same religion, same culture and the enemy heroes speak to each other in the same language, though this could be dramatic effect.

Nine years of war

Philoctetes

Philoctetes was Heracles’ friend, and because he lit Heracles’s funeral pyre when no one else would, he received Heracles’ bow and arrows.[73] He sailed with seven ships full of men to the Trojan War, where he was planning on fighting for the Achaeans. They stopped either at Chryse Island for supplies,[74] or in Tenedos, along with the rest of the fleet.[75] Philoctetes was then bitten by a snake. The wound festered and had a foul smell; on Odysseus’s advice, the Atreidae ordered Philoctetes to stay on Lemnos.[39]

Medon took control of Philoctetes’s men. While landing on Tenedos, Achilles killed king Tenes, son of Apollo, despite a warning by his mother that if he did so he would be killed himself by Apollo.[76] From Tenedos, Agamemnon sent an embassy to the Priam king of Troy composed of Menelaus and Odysseus, asking for Helen’s return. The embassy was refused.[77]

Philoctetes stayed on Lemnos for ten years, which was a deserted island according to Sophocles’ tragedy Philoctetes, but according to earlier tradition was populated by Minyans.[78]

Arrival

Calchas had prophesied that the first Achaean to walk on land after stepping off a ship would be the first to die.[79] Thus even the leading Greeks hesitated to land. Finally, Protesilaus, leader of the Phylaceans, landed first.[80] Odysseus had tricked him, in throwing his own shield down to land on, so that while he was first to leap off his ship, he was not the first to land on Trojan soil. Hector killed Protesilaus in single combat, though the Trojans conceded the beach. In the second wave of attacks, Achilles killed Cycnus, son of Poseidon. The Trojans then fled to the safety of the walls of their city.[81]

The walls served as sturdy fortifications for defense against the Greeks. The build of the walls was so impressive that legend held that they had been built by Poseidon and Apollo during a year of forced service to Trojan King Laomedon.[82] Protesilaus had killed many Trojans but was killed by Hector in most versions of the story,[83] though others list Aeneas, Achates, or Ephorbus as his slayer.[84] The Achaeans buried him as a god on the Thracian peninsula, across the Troäd.[85] After Protesilaus’ death, his brother, Podarces, took command of his troops.

Achilles’ campaigns

The Achaeans besieged Troy for nine years. This part of the war is the least developed among surviving sources, which prefer to talk about events in the last year of the war. After the initial landing the army was gathered in its entirety again only in the tenth year. Thucydides deduces that this was due to lack of money. They raided the Trojan allies and spent time farming the Thracian peninsula.[86] Troy was never completely besieged, thus it maintained communications with the interior of Asia Minor. Reinforcements continued to come until the very end. The Achaeans controlled only the entrance to the Dardanelles, and Troy and her allies controlled the shortest point at Abydos and Sestos and communicated with allies in Europe.[87]

Achilles and Ajax were the most active of the Achaeans, leading separate armies to raid lands of Trojan allies. According to Homer, Achilles conquered 11 cities and 12 islands.[88] According to Apollodorus, he raided the land of Aeneas in the Troäd region and stole his cattle.[89] He also captured Lyrnassus, Pedasus, and many of the neighbouring cities, and killed Troilus, son of Priam, who was still a youth; it was said that if he reached 20 years of age, Troy would not fall. According to Apollodorus,

He also took Lesbos and Phocaea, then Colophon, and Smyrna, and Clazomenae, and Cyme; and afterwards Aegialus and Tenos, the so-called Hundred Cities; then, in order, Adramytium and Side; then Endium, and Linaeum, and Colone. He took also Hypoplacian Thebes and Lyrnessus, and further Antandrus, and many other cities.[90]

Kakrides comments that the list is wrong in that it extends too far into the south.[91] Other sources talk of Achilles taking Pedasus, Monenia,[92] Mythemna (in Lesbos), and Peisidice.[93]

Among the loot from these cities was Briseis, from Lyrnessus, who was awarded to him, and Chryseis, from Hypoplacian Thebes, who was awarded to Agamemnon.[39] Achilles captured Lycaon, son of Priam,[94] while he was cutting branches in his father’s orchards. Patroclus sold him as a slave in Lemnos,[39] where he was bought by Eetion of Imbros and brought back to Troy. Only 12 days later Achilles slew him, after the death of Patroclus.[95]

Ajax and a game of petteia

Ajax son of Telamon laid waste the Thracian peninsula of which Polymestor, a son-in-law of Priam, was king. Polymestor surrendered Polydorus, one of Priam’s children, of whom he had custody. He then attacked the town of the Phrygian king Teleutas, killed him in single combat and carried off his daughter Tecmessa.[96] Ajax also hunted the Trojan flocks, both on Mount Ida and in the countryside.

Numerous paintings on pottery have suggested a tale not mentioned in the literary traditions. At some point in the war Achilles and Ajax were playing a board game (petteia).[97][98] They were absorbed in the game and oblivious to the surrounding battle.[99] The Trojans attacked and reached the heroes, who were only saved by an intervention of Athena.[100]

Death of Palamedes

Odysseus was sent to Thrace to return with grain, but came back empty-handed. When scorned by Palamedes, Odysseus challenged him to do better. Palamedes set out and returned with a shipload of grain.[101]

Odysseus had never forgiven Palamedes for threatening the life of his son. In revenge, Odysseus conceived a plot[102] where an incriminating letter was forged, from Priam to Palamedes,[103] and gold was planted in Palamedes’ quarters. The letter and gold were «discovered», and Agamemnon had Palamedes stoned to death for treason.

However, Pausanias, quoting the Cypria, says that Odysseus and Diomedes drowned Palamedes, while he was fishing, and Dictys says that Odysseus and Diomedes lured Palamedes into a well, which they said contained gold, then stoned him to death.[104]

Palamedes’ father Nauplius sailed to the Troäd and asked for justice, but was refused. In revenge, Nauplius traveled among the Achaean kingdoms and told the wives of the kings that they were bringing Trojan concubines to dethrone them. Many of the Greek wives were persuaded to betray their husbands, most significantly Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra, who was seduced by Aegisthus, son of Thyestes.[105]

Mutiny

Near the end of the ninth year since the landing, the Achaean army, tired from the fighting and from the lack of supplies, mutinied against their leaders and demanded to return to their homes. According to the Cypria, Achilles forced the army to stay.[39] According to Apollodorus, Agamemnon brought the Wine Growers, daughters of Anius, son of Apollo, who had the gift of producing by touch wine, wheat, and oil from the earth, in order to relieve the supply problem of the army.[106]

Iliad

Chryses pleading with Agamemnon for his daughter (360–350 BC)

Chryses, a priest of Apollo and father of Chryseis, came to Agamemnon to ask for the return of his daughter. Agamemnon refused, and insulted Chryses, who prayed to Apollo to avenge his ill-treatment. Enraged, Apollo afflicted the Achaean army with plague. Agamemnon was forced to return Chryseis to end the plague, and took Achilles’ concubine Briseis as his own. Enraged at the dishonour Agamemnon had inflicted upon him, Achilles decided he would no longer fight. He asked his mother, Thetis, to intercede with Zeus, who agreed to give the Trojans success in the absence of Achilles, the best warrior of the Achaeans.

After the withdrawal of Achilles, the Achaeans were initially successful. Both armies gathered in full for the first time since the landing. Menelaus and Paris fought a duel, which ended when Aphrodite snatched the beaten Paris from the field. With the truce broken, the armies began fighting again. Diomedes won great renown amongst the Achaeans, killing the Trojan hero Pandaros and nearly killing Aeneas, who was only saved by his mother, Aphrodite. With the assistance of Athena, Diomedes then wounded the gods Aphrodite and Ares. During the next days, however, the Trojans drove the Achaeans back to their camp and were stopped at the Achaean wall by Poseidon. The next day, though, with Zeus’ help, the Trojans broke into the Achaean camp and were on the verge of setting fire to the Achaean ships. An earlier appeal to Achilles to return was rejected, but after Hector burned Protesilaus’ ship, he allowed his relative and best friend Patroclus to go into battle wearing Achilles’ armour and lead his army. Patroclus drove the Trojans all the way back to the walls of Troy, and was only prevented from storming the city by the intervention of Apollo. Patroclus was then killed by Hector, who took Achilles’ armour from the body of Patroclus.

Triumphant Achilles dragging Hector’s body around Troy, from a panoramic fresco of the Achilleion

Achilles, maddened with grief over the death of Patroclus, swore to kill Hector in revenge. The exact nature of Achilles’ relationship to Patroclus is the subject of some debate.[107] Although certainly very close, Achilles and Patroclus are never explicitly cast as lovers by Homer,[108] but they were depicted as such in the archaic and classical periods of Greek literature, particularly in the works of Aeschylus, Aeschines and Plato.[109][110] He was reconciled with Agamemnon and received Briseis back, untouched by Agamemnon. He received a new set of arms, forged by the god Hephaestus, and returned to the battlefield. He slaughtered many Trojans, and nearly killed Aeneas, who was saved by Poseidon. Achilles fought with the river god Scamander, and a battle of the gods followed. The Trojan army returned to the city, except for Hector, who remained outside the walls because he was tricked by Athena. Achilles killed Hector, and afterwards he dragged Hector’s body from his chariot and refused to return the body to the Trojans for burial. The body nevertheless remained unscathed as it was preserved from all injury by Apollo and Aphrodite. The Achaeans then conducted funeral games for Patroclus. Afterwards, Priam came to Achilles’ tent, guided by Hermes, and asked Achilles to return Hector’s body. The armies made a temporary truce to allow the burial of the dead. The Iliad ends with the funeral of Hector.

After the Iliad

Penthesilea and the death of Achilles

Achilles killing the Amazon Penthesilea

Shortly after the burial of Hector, Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, arrived with her warriors.[111] Penthesilea, daughter of Otrera and Ares, had accidentally killed her sister Hippolyte. She was purified from this action by Priam,[112] and in exchange she fought for him and killed many, including Machaon[113] (according to Pausanias, Machaon was killed by Eurypylus),[114] and according to one version, Achilles himself, who was resurrected at the request of Thetis.[115] In another version, Penthesilia was killed by Achilles[116] who fell in love with her beauty after her death. Thersites, a simple soldier and the ugliest Achaean, taunted Achilles over his love[113] and gouged out Penthesilea’s eyes.[117] Achilles slew Thersites, and after a dispute sailed to Lesbos, where he was purified for his murder by Odysseus after sacrificing to Apollo, Artemis, and Leto.[116]

While they were away, Memnon of Ethiopia, son of Tithonus and Eos,[118] came with his host to help his stepbrother Priam.[119] He did not come directly from Ethiopia, but either from Susa in Persia, conquering all the peoples in between,[120] or from the Caucasus, leading an army of Ethiopians and Indians.[121] Like Achilles, he wore armour made by Hephaestus.[122] In the ensuing battle, Memnon killed Antilochus, who took one of Memnon’s blows to save his father Nestor.[123] Achilles and Memnon then fought. Zeus weighed the fate of the two heroes; the weight containing that of Memnon sank,[124] and he was slain by Achilles.[116][125] Achilles chased the Trojans to their city, which he entered. The gods, seeing that he had killed too many of their children, decided that it was his time to die. He was killed after Paris shot a poisoned arrow that was guided by Apollo.[116][118][126] In another version he was killed by a knife to the back (or heel) by Paris, while marrying Polyxena, daughter of Priam, in the temple of Thymbraean Apollo,[127] the site where he had earlier killed Troilus. Both versions conspicuously deny the killer any sort of valour, saying Achilles remained undefeated on the battlefield. His bones were mingled with those of Patroclus, and funeral games were held.[128] Like Ajax, he is represented as living after his death in the island of Leuke, at the mouth of the Danube River,[129] where he is married to Helen.[130]

Judgment of Arms