Анубис – Древнеегипетский бог

Описание

Древнеегипетская мифология не менее интересна, нежели греческая: она наполнена множеством различных историй и фантастических героев.

Анубис – бог загробного мира, являющийся своеобразным проводником для душ: он встречал их и сопровождал до зала Двух Истин, где впоследствии решалась дальнейшая судьба умершего. В широком смысле, образ Анубиса связывают с самим словом «смерть». Некоторые описывают его, как карающего грешников судью или охраняющего места захоронения усопших. Можно заключить, что его роль, как божества Загробного мира, была неоспоримо одной из самых важных.

Образ Анубиса

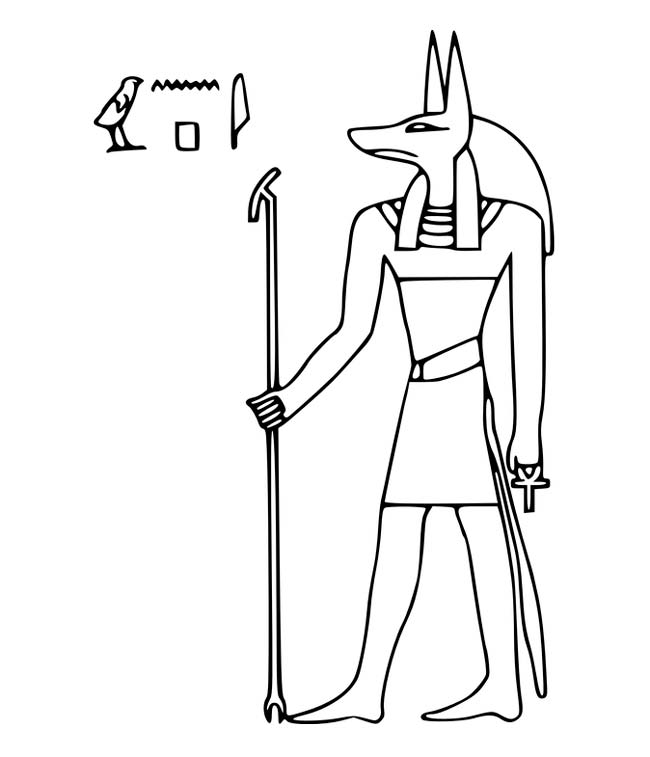

Абсолютно во всех источниках Анубис предстает в виде зооморфного человека с головой шакала или обычного чёрного шакала. На неприкрытых одеждой частях тела можно увидеть полностью чёрную кожу. Такой цвет был дан ей не просто так: ранее, при захоронении египетских фараонов, каждый из них проходил обряд мумификации. Суть этого обряда заключалась в специальном бальзамировании тела усопшего чёрной смолой и последующем его обматыванием белыми бинтами. Бинты также являются атрибутикой Анубиса, а обряд также ассоциируется с этим божеством.

Зал двух истин

Согласно мифологии Древнего Египта, прежде чем попасть на Небеса, душе предстояло пройти через зал Двух Истин, представлявший собой место проведения своеобразного суда над усопшим. Главным там являлся Осирис, помимо него, в зале находились ещё сорок два бога. Основным элементом процессии было взвешивание погружаемых Анубисом и Тотом на весы элементов: сердца умершего и пера богини истины Маат. В ходе суда душа должна была оправдаться перед каждым богом, лицезревшим тот или иной грех человека. Если чаша весов склонялась в сторону сердца, значит, оно было отягощено какими-либо грехами, в противоположной ситуации, душа человека признавалась чистой и безгрешной. Успешно пройдя проверку богов, усопшему открывался путь к тростниковым полям Иалу – аналогу Рая. Однако, если человек признавался грешным, его сердце поедала богиня-чудовище Аммат, а самого осужденного сбрасывали в бездну, кишащую крокодилами.

Легенда о появлении

Рождение Анубиса связывают с любовной историей, произошедшей между Осирисом и его сестрой – Нефтидой. Осирис был жента на её сестре, в то время как сама Нефтида была скована узами брака с Сетом – богом войны. Богиня плодородия была тайно влюблена в Осириса, не сумев совладать со своими чувствами, однажды она решилась на принятие облика своей сестры. С этим поступком она является перед Осирисом, после чего совращает его. Следствием произошедшего становится рождение младенца Анубиса. Испугавшаяся возможной жестокой кары со стороны Сета, Нефтида выбрасывает новорожденного в заросли, после чего его находит Исида – жена Осириса.

Сет, не прознавший о случившемся, однако завидовавший власти брата, вскоре разрывает тело Осириса на части и разбрасывает по разным частям мира. В дальнейшем взращённый богиней любви и уюта Анубис будет путешествовать с ней по миру в поисках частей тела отца.

В этой легенде также объясняется, каким образом Анубис получил такую роль среди богов. В конечном счёте, Анубису удается отыскать все части тела отца, но также их было необходимо ещё и соединить. Решением стала полная обмотка тела тканями, пропитанными специальной жидкостью и применение магии для воскрешения.

Заключение

Анубис – одно из самых почитаемых божеств Древнего Египта. Его имя было известно как в стране, где он родился, так и за её пределами. В наше время о нем часто можно услышать в туристической сфере, направленной на повествование о культурном достоянии Египта.

- Энциклопедия

- История

- Древнеегипетский Бог Анубис

Мир древнеегипетских богов — это мир тайн, удивительных историй с невероятными героями, в которых существует немало сюжетов как с положительными, так и с отрицательными персонажами.

Имя Бога Анубис связано с существованием загробного мира. Божество имело некоторые отличия в своем изображении. Однако в целом образ представлял собой животное — пса, либо это был человек с головой собаки. В любом случае он производил впечатление палача, взывая страх у всех вокруг.

Местом нахождения Анубиса было подземное царство, в котором он выполнял свою роль заведующего мертвыми. Несмотря на свои функции, ему поклонялись во все века, считая божеством, которое сопровождало умерших в царство мертвых.

Для некоторых Анубис был карателем, который своим внешним видом призван был нагонять страх на окружающих, наказывая за грехи и проступки в земной жизни. Таким образом, смерти и всему, что с ней было связано, привязывали образ Анубиса. В его власти было сопровождение и размещение душ умерших на весах в загробном мире. Тела были взвешены. Об отсутствии грехов при жизни говорил вес умершего, в таком случае он считался претендентом на обретение вечной жизни. Грешники же, не искупившие свою вину при жизни, были тяжелыми. Их судьба была в дальнейшем не легкой. Анубис справлялся со своими задачами, а после рассмотрения душ подводил итоги.

Нередко Анубис был изображен на фоне каменных глыб. Это было связано с тем, что он охранял могилы усопших, довольствуясь нахождением в подобных местах.

Еще одна роль, которая приписывалась с древних пор богу, состояла в бальзамировании. Черный цвет Анубиса связывают с тем, что после этого занятия умерший также становился темным.

Таким образом, Анубис — это известный в древнеегипетской мифологии бог, однако он не стал активным персонажем мифов. Любая тема, связанная с потусторонним миром, вызывает нередко мысли именно об этом божестве. Этот персонаж был защитником, однако всего того, что было связано с усопшими. Вся процедура подготовки мертвых к бальзамированию, установление вины при жизни с помощью весов, сопровождение их по загробному царству — все этого ложилось на плечи Анубиса.

Эта роль проведения подобных обрядов была не легкой, но он справлялся с ней, за что был почитаем всеми в Древнем Египте. В честь него стены храмов, гробницы, каменные глыбы хранили изображения существа с головой собаки и сохранились на века.

Вариант №2

Анубис является божеством, которое существовало еще в Древнем Египте. А вот жители Египта называли его Инпу. И для них он был с телом человека, а голова у него была либо собаки, либо шакала. Священным животным жители Египта считали шакала. Шерсть у него темно-рыжего цвета, именно поэтому напоминает золото. Несколько тысячелетий существовала цивилизация в Египте. Именно поэтому в разное время он занимался разными делами. Кроме этого он постоянно общался, а иногда даже и обращался к миру мертвых и они ему помогали. Сначала он провожал всех умерших в мир мертвых, а потом стал защитником. Вот именно поэтому он превратился в получеловека.

Раньше шакалов связывало кладбище, именно поэтому их обычно хоронили в маленьких по размеру могилах. После этого их разрывали хищники и съедали.

А теперь давайте разберемся, кто были его родители? Во многих источниках мать Анубиса не указывалась, указывался только отец. Немного попозже о нем стали слагать не только легенды, но еще и мифы и предания. Когда он стал замечательным проводником в мир мертвых, Исида решила принести ему останки мужа. Анубис сделал из него мумию и установил на берегу Нила.

Если вы посмотрите и почитаете Книгу мертвых, то там все подробно написано. Кроме этого там подробно описывается суд над Осирисом. У бога мудрости имеются весы, при помощи которых он взвешивает совесть умершего человека. Если человек всю жизнь жил правдиво и честно, то перо перевешивало и весы становились ровно. Если человек постоянно творил всем зло, то в этом случае он отправлялся в грешный мир. А возле весов находилось огромных размеров чудовище, которое этого грешника сразу же съедало. У данного животного было тело льва, а голова у него была крокодиловая.

Оказывается, все боги были зверобогами. Именно поэтому они носили головы различных животных. Кроме этого эти животные могли потом с ними общаться.

5 класс

Древнеегипетский Бог Анубис

Популярные темы сообщений

- Лось

Одним из самых крупных зверей проживающих в лесу является лось. У животного достаточно большой вес, а в росте он достигает до 2-х метров. Лоси чаще всего темно-бурого цвета, имеют огромное туловище и длинные ноги. Голова у животного круглая,

- Горох

Горох – это однолетнее растение с гибким вьющимся стеблем и светло — зелеными листочками. Его длинные стебли заканчиваются ветвистыми усами. Он цветет белыми или бледно — розовыми цветочками, а когда отцветает,

- Военно промышленный комплекс

Военно-промышленный комплекс, включает в себя научные и испытательные организации, а также предприятия по производству, которые занимаются разработкой военной и специальной техники для армии государства.

- Профессия электрик

Наверное, нет такой профессии, которая была бы не нужна человеку. А вот без помощи электрика вы не сможете включить ни один прибор, и придется сидеть в темноте. У него должно быть острое мышление, зоркий глаз и самое главное,

- Византия

Римская империя была огромным мощным государством, но когда умер император Феодосий, ее территории поделились на восточную и западную части. Римская Западная империя продержалась совсем недолго. Теперь же на карте осталась только

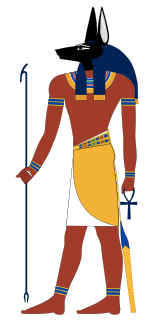

| Anubis | |

|---|---|

The Egyptian god Anubis (a modern rendition inspired by New Kingdom tomb paintings) |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Lycopolis, Cynopolis |

| Symbol | mummy gauze, fetish, jackal, flail |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Nepthys and Set, Osiris (Middle and New kingdom), or Ra (Old kingdom). |

| Siblings | Wepwawet |

| Consort | Anput, Nephthys[1] |

| Offspring | Kebechet |

| Greek equivalent | Hades or Hermes |

Anubis (;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις), also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian (Coptic: ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ, romanized: Anoup) is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also an embalmer. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced by Osiris in his role as lord of the underworld. One of his prominent roles was as a god who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the «Weighing of the Heart», in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in the Egyptian pantheon, however, no relevant myth involved him.[3]

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of the Nile River, and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with his brother Wepwawet, another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog’s head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[4] Anubis’ female counterpart is Anput. His daughter is the serpent goddess Kebechet.

Name

Anubis receiving offerings, hieroglyph name in third column from left, 14th century BC; painted limestone; from Saqqara (Egypt)

«Anubis» is a Greek rendering of this god’s Egyptian name.[5][6] Before the Greeks arrived in Egypt, around the 7th century BC, the god was known as Anpu or Inpu. The root of the name in ancient Egyptian language means «a royal child.» Inpu has a root to «inp», which means «to decay.» The god was also known as «First of the Westerners,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain,» «Ruler of the Nine Bows,» «The Dog who Swallows Millions,» «Master of Secrets,» «He Who is in the Place of Embalming,» and «Foremost of the Divine Booth.»[7] The positions that he had were also reflected in the titles he held such as «He Who Is upon His Mountain,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «Foremost of the Westerners,» and «He Who Is in the Place of Embalming.»[8]

In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name in hieroglyphs was composed of the sound signs inpw followed by a jackal[a] over a ḥtp sign:[10]

A new form with the jackal on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[10]

Anubis’ name jnpw was possibly pronounced [a.ˈna.pʰa(w)], based on Coptic Anoup and the Akkadian transcription 𒀀𒈾𒉺⟨a-na-pa⟩ in the name <ri-a-na-pa> «Reanapa» that appears in Amarna letter EA 315.[11][12] However, this transcription may also be interpreted as rˁ-nfr, a name similar to that of Prince Ranefer of the Fourth Dynasty.

History

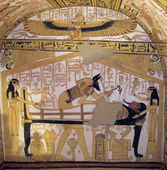

Anubis attending the mummy of the deceased.

In Egypt’s Early Dynastic period (c. 3100 – c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a «jackal» head and body.[13] A jackal god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns of Hor-Aha, Djer, and other pharaohs of the First Dynasty.[14] Since Predynastic Egypt, when the dead were buried in shallow graves, jackals had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[15] In the spirit of «fighting like with like,» a jackal was chosen to protect the dead, because «a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation.»[16]

In the Old Kingdom, Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC).[17] In the Roman era, which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[18]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son of Ra.[19] In the Coffin Texts, which were written in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddess Hesat or the cat-headed Bastet.[20] Another tradition depicted him as the son of Ra and Nephthys.[19] The Greek Plutarch (c. 40–120 AD) reported a tradition that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris’s wife Isis:[21]

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear of Seth; and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

George Hart sees this story as an «attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into the Osirian pantheon.»[20] An Egyptian papyrus from the Roman period (30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the «son of Isis.»[20] In Nubia, Anubis was seen as the husband of his mother Nephthys.[1]

In the Ptolemaic period (350–30 BC), when Egypt became a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with the Greek god Hermes, becoming Hermanubis.[23][24] The two gods were considered similar because they both guided souls to the afterlife.[25] The center of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name means «city of dogs.» In Book XI of The Golden Ass by Apuleius, there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued in Rome through at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egyptian animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens and Cerberus and Hades in the underworld.[26] In his dialogues, Plato often has Socrates utter oaths «by the dog» (Greek: kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt», and «by the dog, the god of the Egyptians», both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[27]

Roles

Embalmer

As jmy-wt (Imiut or the Imiut fetish) «He who is in the place of embalming», Anubis was associated with mummification. He was also called ḫnty zḥ-nṯr «He who presides over the god’s booth», in which «booth» could refer either to the place where embalming was carried out or the pharaoh’s burial chamber.[28][29]

In the Osiris myth, Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[17] Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris’s organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Protector of tombs

Anubis was a protector of graves and cemeteries. Several epithets attached to his name in Egyptian texts and inscriptions referred to that role. Khenty-Amentiu, which means «foremost of the westerners» and was also the name of a different canine funerary god, alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30] He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such as tpy-ḏw.f (Tepy-djuef) «He who is upon his mountain» (i.e. keeping guard over tombs from above) and nb-t3-ḏsr (Neb-ta-djeser) «Lord of the sacred land», which designates him as a god of the desert necropolis.[28][29]

The Jumilhac papyrus recounts another tale where Anubis protected the body of Osiris from Set. Set attempted to attack the body of Osiris by transforming himself into a leopard. Anubis stopped and subdued Set, however, and he branded Set’s skin with a hot iron rod. Anubis then flayed Set and wore his skin as a warning against evil-doers who would desecrate the tombs of the dead.[31] Priests who attended to the dead wore leopard skin in order to commemorate Anubis’ victory over Set. The legend of Anubis branding the hide of Set in leopard form was used to explain how the leopard got its spots.[32]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[33]

Guide of souls

By the late pharaonic era (664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to the afterlife.[34] Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headed Hathor, Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[35] Greek writers from the Roman period of Egyptian history designated that role as that of «psychopomp», a Greek term meaning «guide of souls» that they used to refer to their own god Hermes, who also played that role in Greek religion.[25] Funerary art from that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[36]

Weigher of hearts

The «weighing of the heart,» from the book of the dead of Hunefer. Anubis is portrayed as both guiding the deceased forward and manipulating the scales, under the scrutiny of the ibis-headed Thoth.

One of the roles of Anubis was as the «Guardian of the Scales.»[37] The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in the Book of the Dead, shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (the underworld, known as Duat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person against Ma’at (or «truth»), who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured by Ammit, and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[38][39]

Portrayal in art

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented deities in ancient Egyptian art.[3] He is depicted in royal tombs as early as the First Dynasty.[7] The god is typically treating a king’s corpse, providing sovereign to mummification rituals and funerals, or standing with fellow gods at the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul in the Hall of Two Truths.[8] One of his most popular representations is of him, with the body of a man and the head of a jackal with pointed ears, standing or kneeling, holding a gold scale while a heart of the soul is being weighed against Ma’at’s white truth feather.[7]

In the early dynastic period, he was depicted in animal form, as a black canine.[40] Anubis’s distinctive black color did not represent the animal, rather it had several symbolic meanings.[41] It represented «the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment with natron and the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification.»[41] Being the color of the fertile silt of the River Nile, to Egyptians, black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[42] In the Middle Kingdom, Anubis was often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal.[43] An extremely rare depiction of him in fully human form was found in a chapel of Ramesses II in Abydos.[41][6]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding a nḫ3ḫ3 «flail» in the crook of his arm.[43] Another of Anubis’s attributes was the jmy-wt or imiut fetish, named for his role in embalming.[44] In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person’s mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt.[45]

-

Isis, left, and Nephthys stand by as Anubis embalms the deceased, 13th century BC

-

The king with Anubis, from the tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BC; tempera on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Anubis amulet; 664–30 BC; faience; height: 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Recumbent Anubis; 664–30 BC; limestone, originally painted black; height: 38.1 cm, length: 64 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Worship

Although he does not appear in many myths, he was extremely popular with Egyptians and those of other cultures.[7] The Greeks linked him to their god Hermes, the god who guided the dead to the afterlife. The pairing was later known as Hermanubis. Anubis was heavily worshipped because, despite modern beliefs, he gave the people hope. People marveled in the guarantee that their body would be respected at death, their soul would be protected and justly judged.[7]

Anubis had male priests who sported wood masks with the god’s likeness when performing rituals.[7][8] His cult center was at Cynopolis in Upper Egypt but memorials were built everywhere and he was universally revered in every part of the nation.[7]

In popular culture

In popular and media culture, Anubis is often falsely portrayed as the sinister god of the dead. He gained popularity during the 20th and 21st centuries through books, video games, and movies where artists would give him evil powers and a dangerous army. Despite his nefarious reputation, his image is still the most recognizable of the Egyptian gods and replicas of his statues and paintings remain popular.

See also

- Abatur, Mandaean uthra who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate

- Animal mummy#Miscellaneous animals

- Anput

- Anubias

- Bhairava

- Egyptian mythology in popular culture

- Hades

Notes

- ^ The wild canine species in Egypt, long thought to have been a geographical variant of the golden jackal in older texts, was reclassified in 2015 as a separate species known as the African wolf, which was found to be more closely related to wolves and coyotes than to the jackal.[9] Nevertheless, ancient Greek texts about Anubis constantly refer to the deity as having a dog’s head, not a jackal or wolf’s, and there is still uncertainty as to what canid represents Anubis. Therefore the Name and History section uses the names the original sources used but in quotation marks.

References

- ^ a b Lévai, Jessica (2007). Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt. UMI.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 56

- ^ a b Johnston 2004, p. 579.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Coulter & Turner 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b «Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt – Anubis». Archived from the original on 27 December 2002. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Anubis». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c «Anubis». Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o’Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015). «Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species». Current Biology. 25 (#16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ a b Leprohon 1990, p. 164, citing Fischer 1968, p. 84 and Lapp 1986, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Conder 1894, p. 85.

- ^ «CDLI-Archival View». cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 (burials in shallow graves in Predynastic Egypt); Freeman 1997, p. 91 (rest of the information).

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 («fighting like with like» and «by jackals and other wild dogs»).

- ^ a b Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 166–67.

- ^ a b Hart 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Campbell, Price (2018). Ancient Egypt — Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Peacock 2000, pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ^ «Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon». Babylon.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b Riggs 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Hoerber 1963, p. 269 (for Cerberus and Hades).

- ^ E.g., Gorgias, 482b (Blackwood, Crossett & Long 1962, p. 318), or The Republic, 399e, 567e, 592a (Hoerber 1963, p. 268).

- ^ a b Hart 1986, pp. 23–24; Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

- ^ a b Vischak, Deborah (27 October 2014). Community and Identity in Ancient Egypt: The Old Kingdom Cemetery at Qubbet el-Hawa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107027602.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 23.

- ^ Armour 2001.

- ^ Zandee 1960, p. 255.

- ^ «The Gods of Ancient Egypt – Anubis». touregypt.net. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Kinsley 1989, p. 178; Riggs 2005, p. 166 («The motif of Anubis, or less frequently Hathor, leading the deceased to the afterlife was well-established in Egyptian art and thought by the end of the pharaonic era.»).

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127 and 166.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127–28 and 166–67.

- ^ Faulkner, Andrews & Wasserman 2008, p. 155.

- ^ «Museum Explorer / Death in Ancient Egypt – Weighing the heart». British Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ «Gods of Ancient Egypt: Anubis». Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 22; Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b «Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Anubis». Egyptianmyths.net. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

Bibliography

- Armour, Robert A. (2001), Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press

- Blackwood, Russell; Crossett, John; Long, Herbert (1962), «Gorgias 482b», The Classical Journal, 57 (7): 318–19, JSTOR 3295283.

- Conder, Claude Reignier (trans.) (1894) [1893], The Tell Amarna Tablets (Second ed.), London: Published for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund by A.P. Watt, ISBN 978-1-4147-0156-1.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Jefferson (NC) and London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-0317-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O.; Andrews, Carol; Wasserman, James (2008), The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day, Chronicle Books, ISBN 978-0-8118-6489-3.

- Fischer, Henry George (1968), Dendera in the Third Millennium B. C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt, London: J.J. Augustin.

- Freeman, Charles (1997), The Legacy of Ancient Egypt, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-816-03656-1.

- Gryglewski, Ryszard W. (2002), «Medical and Religious Aspects of Mummification in Ancient Egypt» (PDF), Organon, 31 (31): 128–48, PMID 15017968, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Hart, George (1986), A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-415-34495-1.

- Hoerber, Robert G. (1963), «The Socratic Oath ‘By the Dog’«, The Classical Journal, 58 (6): 268–69, JSTOR 3293989.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (general ed.) (2004), Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- Kinsley, David (1989), The Goddesses’ Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West, Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-835-5. (paperback).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lapp, Günther (1986), Die Opferformel des Alten Reiches: unter Berücksichtigung einiger späterer Formen [The offering formula of the Old Kingdom: considering a few later forms], Mainz am Rhein: Zabern, ISBN 978-3805308724.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1990), «The Offering Formula in the First Intermediate Period», The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 76: 163–64, doi:10.1177/030751339007600115, JSTOR 3822017, S2CID 192258122.

- Peacock, David (2000), «The Roman Period», in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Riggs, Christina (2005), The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London: Routledge

- Zandee, Jan (1960), Death as an Enemy: According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions, Brill Archive, GGKEY:A7N6PJCAF5Q

Further reading

- Duquesne, Terence (2005). The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I. Darengo Publications. ISBN 978-1-871266-24-5.

- El-Sadeek, Wafaa; Abdel Razek, Sabah (2007). Anubis, Upwawet, and Other Deities: Personal Worship and Official Religion in Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-437-231-5.

- Grenier, J.-C. (1977). Anubis alexandrin et romain (in French). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04917-8.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anubis.

Look up Anubis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

| Anubis | |

|---|---|

The Egyptian god Anubis (a modern rendition inspired by New Kingdom tomb paintings) |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Lycopolis, Cynopolis |

| Symbol | mummy gauze, fetish, jackal, flail |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Nepthys and Set, Osiris (Middle and New kingdom), or Ra (Old kingdom). |

| Siblings | Wepwawet |

| Consort | Anput, Nephthys[1] |

| Offspring | Kebechet |

| Greek equivalent | Hades or Hermes |

Anubis (;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις), also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian (Coptic: ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ, romanized: Anoup) is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also an embalmer. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced by Osiris in his role as lord of the underworld. One of his prominent roles was as a god who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the «Weighing of the Heart», in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in the Egyptian pantheon, however, no relevant myth involved him.[3]

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of the Nile River, and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with his brother Wepwawet, another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog’s head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[4] Anubis’ female counterpart is Anput. His daughter is the serpent goddess Kebechet.

Name

Anubis receiving offerings, hieroglyph name in third column from left, 14th century BC; painted limestone; from Saqqara (Egypt)

«Anubis» is a Greek rendering of this god’s Egyptian name.[5][6] Before the Greeks arrived in Egypt, around the 7th century BC, the god was known as Anpu or Inpu. The root of the name in ancient Egyptian language means «a royal child.» Inpu has a root to «inp», which means «to decay.» The god was also known as «First of the Westerners,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain,» «Ruler of the Nine Bows,» «The Dog who Swallows Millions,» «Master of Secrets,» «He Who is in the Place of Embalming,» and «Foremost of the Divine Booth.»[7] The positions that he had were also reflected in the titles he held such as «He Who Is upon His Mountain,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «Foremost of the Westerners,» and «He Who Is in the Place of Embalming.»[8]

In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name in hieroglyphs was composed of the sound signs inpw followed by a jackal[a] over a ḥtp sign:[10]

A new form with the jackal on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[10]

Anubis’ name jnpw was possibly pronounced [a.ˈna.pʰa(w)], based on Coptic Anoup and the Akkadian transcription 𒀀𒈾𒉺⟨a-na-pa⟩ in the name <ri-a-na-pa> «Reanapa» that appears in Amarna letter EA 315.[11][12] However, this transcription may also be interpreted as rˁ-nfr, a name similar to that of Prince Ranefer of the Fourth Dynasty.

History

Anubis attending the mummy of the deceased.

In Egypt’s Early Dynastic period (c. 3100 – c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a «jackal» head and body.[13] A jackal god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns of Hor-Aha, Djer, and other pharaohs of the First Dynasty.[14] Since Predynastic Egypt, when the dead were buried in shallow graves, jackals had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[15] In the spirit of «fighting like with like,» a jackal was chosen to protect the dead, because «a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation.»[16]

In the Old Kingdom, Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC).[17] In the Roman era, which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[18]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son of Ra.[19] In the Coffin Texts, which were written in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddess Hesat or the cat-headed Bastet.[20] Another tradition depicted him as the son of Ra and Nephthys.[19] The Greek Plutarch (c. 40–120 AD) reported a tradition that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris’s wife Isis:[21]

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear of Seth; and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

George Hart sees this story as an «attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into the Osirian pantheon.»[20] An Egyptian papyrus from the Roman period (30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the «son of Isis.»[20] In Nubia, Anubis was seen as the husband of his mother Nephthys.[1]

In the Ptolemaic period (350–30 BC), when Egypt became a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with the Greek god Hermes, becoming Hermanubis.[23][24] The two gods were considered similar because they both guided souls to the afterlife.[25] The center of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name means «city of dogs.» In Book XI of The Golden Ass by Apuleius, there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued in Rome through at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egyptian animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens and Cerberus and Hades in the underworld.[26] In his dialogues, Plato often has Socrates utter oaths «by the dog» (Greek: kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt», and «by the dog, the god of the Egyptians», both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[27]

Roles

Embalmer

As jmy-wt (Imiut or the Imiut fetish) «He who is in the place of embalming», Anubis was associated with mummification. He was also called ḫnty zḥ-nṯr «He who presides over the god’s booth», in which «booth» could refer either to the place where embalming was carried out or the pharaoh’s burial chamber.[28][29]

In the Osiris myth, Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[17] Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris’s organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Protector of tombs

Anubis was a protector of graves and cemeteries. Several epithets attached to his name in Egyptian texts and inscriptions referred to that role. Khenty-Amentiu, which means «foremost of the westerners» and was also the name of a different canine funerary god, alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30] He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such as tpy-ḏw.f (Tepy-djuef) «He who is upon his mountain» (i.e. keeping guard over tombs from above) and nb-t3-ḏsr (Neb-ta-djeser) «Lord of the sacred land», which designates him as a god of the desert necropolis.[28][29]

The Jumilhac papyrus recounts another tale where Anubis protected the body of Osiris from Set. Set attempted to attack the body of Osiris by transforming himself into a leopard. Anubis stopped and subdued Set, however, and he branded Set’s skin with a hot iron rod. Anubis then flayed Set and wore his skin as a warning against evil-doers who would desecrate the tombs of the dead.[31] Priests who attended to the dead wore leopard skin in order to commemorate Anubis’ victory over Set. The legend of Anubis branding the hide of Set in leopard form was used to explain how the leopard got its spots.[32]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[33]

Guide of souls

By the late pharaonic era (664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to the afterlife.[34] Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headed Hathor, Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[35] Greek writers from the Roman period of Egyptian history designated that role as that of «psychopomp», a Greek term meaning «guide of souls» that they used to refer to their own god Hermes, who also played that role in Greek religion.[25] Funerary art from that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[36]

Weigher of hearts

The «weighing of the heart,» from the book of the dead of Hunefer. Anubis is portrayed as both guiding the deceased forward and manipulating the scales, under the scrutiny of the ibis-headed Thoth.

One of the roles of Anubis was as the «Guardian of the Scales.»[37] The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in the Book of the Dead, shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (the underworld, known as Duat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person against Ma’at (or «truth»), who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured by Ammit, and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[38][39]

Portrayal in art

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented deities in ancient Egyptian art.[3] He is depicted in royal tombs as early as the First Dynasty.[7] The god is typically treating a king’s corpse, providing sovereign to mummification rituals and funerals, or standing with fellow gods at the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul in the Hall of Two Truths.[8] One of his most popular representations is of him, with the body of a man and the head of a jackal with pointed ears, standing or kneeling, holding a gold scale while a heart of the soul is being weighed against Ma’at’s white truth feather.[7]

In the early dynastic period, he was depicted in animal form, as a black canine.[40] Anubis’s distinctive black color did not represent the animal, rather it had several symbolic meanings.[41] It represented «the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment with natron and the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification.»[41] Being the color of the fertile silt of the River Nile, to Egyptians, black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[42] In the Middle Kingdom, Anubis was often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal.[43] An extremely rare depiction of him in fully human form was found in a chapel of Ramesses II in Abydos.[41][6]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding a nḫ3ḫ3 «flail» in the crook of his arm.[43] Another of Anubis’s attributes was the jmy-wt or imiut fetish, named for his role in embalming.[44] In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person’s mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt.[45]

-

Isis, left, and Nephthys stand by as Anubis embalms the deceased, 13th century BC

-

The king with Anubis, from the tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BC; tempera on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Anubis amulet; 664–30 BC; faience; height: 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Recumbent Anubis; 664–30 BC; limestone, originally painted black; height: 38.1 cm, length: 64 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Worship

Although he does not appear in many myths, he was extremely popular with Egyptians and those of other cultures.[7] The Greeks linked him to their god Hermes, the god who guided the dead to the afterlife. The pairing was later known as Hermanubis. Anubis was heavily worshipped because, despite modern beliefs, he gave the people hope. People marveled in the guarantee that their body would be respected at death, their soul would be protected and justly judged.[7]

Anubis had male priests who sported wood masks with the god’s likeness when performing rituals.[7][8] His cult center was at Cynopolis in Upper Egypt but memorials were built everywhere and he was universally revered in every part of the nation.[7]

In popular culture

In popular and media culture, Anubis is often falsely portrayed as the sinister god of the dead. He gained popularity during the 20th and 21st centuries through books, video games, and movies where artists would give him evil powers and a dangerous army. Despite his nefarious reputation, his image is still the most recognizable of the Egyptian gods and replicas of his statues and paintings remain popular.

See also

- Abatur, Mandaean uthra who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate

- Animal mummy#Miscellaneous animals

- Anput

- Anubias

- Bhairava

- Egyptian mythology in popular culture

- Hades

Notes

- ^ The wild canine species in Egypt, long thought to have been a geographical variant of the golden jackal in older texts, was reclassified in 2015 as a separate species known as the African wolf, which was found to be more closely related to wolves and coyotes than to the jackal.[9] Nevertheless, ancient Greek texts about Anubis constantly refer to the deity as having a dog’s head, not a jackal or wolf’s, and there is still uncertainty as to what canid represents Anubis. Therefore the Name and History section uses the names the original sources used but in quotation marks.

References

- ^ a b Lévai, Jessica (2007). Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt. UMI.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 56

- ^ a b Johnston 2004, p. 579.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Coulter & Turner 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b «Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt – Anubis». Archived from the original on 27 December 2002. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Anubis». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c «Anubis». Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o’Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015). «Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species». Current Biology. 25 (#16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ a b Leprohon 1990, p. 164, citing Fischer 1968, p. 84 and Lapp 1986, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Conder 1894, p. 85.

- ^ «CDLI-Archival View». cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 (burials in shallow graves in Predynastic Egypt); Freeman 1997, p. 91 (rest of the information).

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 («fighting like with like» and «by jackals and other wild dogs»).

- ^ a b Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 166–67.

- ^ a b Hart 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Campbell, Price (2018). Ancient Egypt — Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Peacock 2000, pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ^ «Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon». Babylon.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b Riggs 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Hoerber 1963, p. 269 (for Cerberus and Hades).

- ^ E.g., Gorgias, 482b (Blackwood, Crossett & Long 1962, p. 318), or The Republic, 399e, 567e, 592a (Hoerber 1963, p. 268).

- ^ a b Hart 1986, pp. 23–24; Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

- ^ a b Vischak, Deborah (27 October 2014). Community and Identity in Ancient Egypt: The Old Kingdom Cemetery at Qubbet el-Hawa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107027602.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 23.

- ^ Armour 2001.

- ^ Zandee 1960, p. 255.

- ^ «The Gods of Ancient Egypt – Anubis». touregypt.net. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Kinsley 1989, p. 178; Riggs 2005, p. 166 («The motif of Anubis, or less frequently Hathor, leading the deceased to the afterlife was well-established in Egyptian art and thought by the end of the pharaonic era.»).

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127 and 166.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127–28 and 166–67.

- ^ Faulkner, Andrews & Wasserman 2008, p. 155.

- ^ «Museum Explorer / Death in Ancient Egypt – Weighing the heart». British Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ «Gods of Ancient Egypt: Anubis». Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 22; Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b «Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Anubis». Egyptianmyths.net. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

Bibliography

- Armour, Robert A. (2001), Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press

- Blackwood, Russell; Crossett, John; Long, Herbert (1962), «Gorgias 482b», The Classical Journal, 57 (7): 318–19, JSTOR 3295283.

- Conder, Claude Reignier (trans.) (1894) [1893], The Tell Amarna Tablets (Second ed.), London: Published for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund by A.P. Watt, ISBN 978-1-4147-0156-1.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Jefferson (NC) and London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-0317-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O.; Andrews, Carol; Wasserman, James (2008), The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day, Chronicle Books, ISBN 978-0-8118-6489-3.

- Fischer, Henry George (1968), Dendera in the Third Millennium B. C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt, London: J.J. Augustin.

- Freeman, Charles (1997), The Legacy of Ancient Egypt, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-816-03656-1.

- Gryglewski, Ryszard W. (2002), «Medical and Religious Aspects of Mummification in Ancient Egypt» (PDF), Organon, 31 (31): 128–48, PMID 15017968, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Hart, George (1986), A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-415-34495-1.

- Hoerber, Robert G. (1963), «The Socratic Oath ‘By the Dog’«, The Classical Journal, 58 (6): 268–69, JSTOR 3293989.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (general ed.) (2004), Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- Kinsley, David (1989), The Goddesses’ Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West, Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-835-5. (paperback).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lapp, Günther (1986), Die Opferformel des Alten Reiches: unter Berücksichtigung einiger späterer Formen [The offering formula of the Old Kingdom: considering a few later forms], Mainz am Rhein: Zabern, ISBN 978-3805308724.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1990), «The Offering Formula in the First Intermediate Period», The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 76: 163–64, doi:10.1177/030751339007600115, JSTOR 3822017, S2CID 192258122.

- Peacock, David (2000), «The Roman Period», in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Riggs, Christina (2005), The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London: Routledge

- Zandee, Jan (1960), Death as an Enemy: According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions, Brill Archive, GGKEY:A7N6PJCAF5Q

Further reading

- Duquesne, Terence (2005). The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I. Darengo Publications. ISBN 978-1-871266-24-5.

- El-Sadeek, Wafaa; Abdel Razek, Sabah (2007). Anubis, Upwawet, and Other Deities: Personal Worship and Official Religion in Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-437-231-5.

- Grenier, J.-C. (1977). Anubis alexandrin et romain (in French). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04917-8.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anubis.

Look up Anubis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Доклады

- История

- Анубис Древнеегипетский Бог

Доклад Анубис — древнеегипетский Бог

По оценкам многих учёных пантеон древнеегипетских божеств насчитывал более 5 тысяч. Древние египтяне не скупились на количество богов, буквально каждое явление было связано с тем или иным божеством. Также это не давало поводов для возникновения религиозных и политических разногласий. Но, несмотря на такое огромное количество идолов, некоторым божествам поклонялись с особой силой и даже фанатизмом.

К этим богам, несомненно, относится Анубис – бог смерти, проводник в загробный мир и покровитель некрополей, кладбищ и могильников. В Древнем Египте вообще был распространён культ смерти, захоронения высшей знати и жрецов сопровождались целыми ритуалами, построением знаменитых пирамид. Конечно же, Анубис был окружён необычайным почитанием. Изображали его в виде человека с головой шакала, иногда он представал и в своей звериной ипостаси (шакала или дикой чёрной собаки Саб).

Анубис был сыном Осириса (бога растительности) и Нефтиды, сестры Исиды. Мать Анубиса, страшась Сета, отнесла сына на болота, где его обнаружила и вырастила богиня Исида. Позднее отец Анубиса Осирис был убит своим братом Сетом, пожелавшим отнять у него власть. Анубис сложил в одно целое разорванное на куски тело отца, и обернул тканью, которую смочил неким составом. Это положило начало мумифицированию в Египте, а Анубиса стали поклоняться ещё и как богу бальзамирования.

Самое первое упоминание об Анубисе встречается в XXIII веке до нашей эры, в Текстах пирамид во времена Древнего царства. Имя Анубис тоже имеет определенное значение. Сначала (с 2686 до 2181 года до нашей эры), оно изображалось парой иероглифов. В переводе имя бога значило «шакал» и «мир ему». Уже намного позже перевод стал звучать как «шакал на высокой подставке». Анубис неразрывно связан с чёрным цветом — цветом смерти, мрака и потустороннего мира, поэтому почти все изображения Анубиса выглядят именно чёрными.

В Древнем Египте имена умерших записывались в Книгу Мёртвых. По верованиям египтян, когда человек умирал, он попадал на суд Осириса. Именно Анубис взвешивал сердца умерших во время суда, узнавая сколько зла или добра находится в них. Люди особенно верили в справедливость божества.

Максимально популярен Анубис стал в Новом Царстве и Позднем времени. Древние египтяне тесно связывали его имя и с различными магическими ритуалами, изредка его представляли как « повелителя бау» — целого сонма магических сущностей, могущих быть как добрыми, так и злыми.

По свидетельству древнегреческого историка Страбона, местом концентрации почитателей культа Анубиса в Древнем Египте стала столица семнадцатого египетского нома Кинопль. Но, с усилением влияния Осириса, Анубис постепенно начал терять главенствующее положение, и часто его путали с Упуаутом, богом с волчьей внешностью.

Несомненно одно, культ Анубиса оказал огромное влияние на культурное, религиозное и политическое развитие страны.

Картинка к сообщению Анубис Древнеегипетский Бог

Популярные сегодня темы

- Древняя Греция

Древняя Греция – государство, занимавшее территории Пелопоннеса, южных Балкан и запада Ближнего Востока. Эта страна была образована в конце 3 тысячелетия до н.э. В 1 в. до н.э. она прекратила

- Сказки Пушкина

Произведения Александра Сергеевича Пушкина известны не только в России, но и во всём мире. Во многом свою популярность он получил из-за разнообразия в своих работах: он писал как серьёзные ро

- Профессия бухгалтер

Одной из самых распространенных и востребованных профессий в мире является профессия бухгалтера. Любое предприятие обязано вести расчет доходов и расходов.

- Творчество художника Михаила Нестерова

Михаил Васильевич Нестеров родился в 31 мая 1862 года, а умер 18 октября 1942 года. Михаилу Васильевичу Нестерову родители никогда не запрещали увлекаться творчеством

- Снегирь

Птицы, гнездящиеся в наших краях, с приближением зимних холодов улетают в южные страны. Но, несмотря на зимнюю стужу, некоторые пернатые остаются дома, а есть и такие, что прилетают к нам на

- Невесомость

Физика – это наука, которая изучает материальные явления вокруг нас. Одно из них — действие тела на опору или подвес, которое называется весом.

Бог смерти Анубис – одно из самых могущественных божеств древнеегипетского пантеона. Древние тексты называют его богом мумификации, бальзамирования, кладбища, гробниц, загробной жизни и подземного мира. Его изображение в виде собаки или человека с волчьей головой – это символ, широко используемый в поп-культуре.

Археологи определили африканского золотого волка как священного животного Анубиса. Его роли менялись в зависимости от контекста. Первая династия изображала его защитником могил. Позже его также признали бальзамировщиком. Однако в Поднебесной Осирис заменил Анубиса в качестве бога подземного мира. Несмотря на силу бога, он редко был неотъемлемой частью египетских мифологий.

Этимология

Имя Анубиса происходит от греческого перевода его египетского имени. Первоначально бог был известен как Анпу или Инпу. Корень его имени переводится как «царственное дитя». У бога есть несколько других эпитетов, таких как:

- Повелитель упаковки мумий.

- Начальник Некрополя.

- Князь Суда.

- Первый из жителей Запада.

- Вождь Западного нагорья.

- Счетчик червей.

- Мастер секретов.

- Собака, которая глотает миллионы.

- Тот, кто ест своего отца.

- Также, Повелитель Священной Земли.

Изображение и символизм Анубиса

Полная форма животного изображала Анубиса в ранний династический период. У него были голова и тело шакала. На наскальных рисунках времен правления Хор-Аха Джера изображен бог-шакал, которого мы можем принять за Анубиса.

С ранних времен додинастического Египта шакалы были прочно связаны с кладбищами, поскольку, как падальщики, они обнаруживали тела в неглубоких могилах. Возможно, шакал был выбран для защиты мертвых, чтобы противостоять этой проблеме.

Обычно бог изображался черной краской в сидячем положении. Еще одним известным качеством Анубиса была способность изменять форму. Рассказы утверждают, что он был настолько потрясен видом мертвого тела Осириса, что мгновенно превратился в ящерицу.

Со времен Древнего Королевства Анубис стал самым важным богом мертвых. Картины римской эпохи показывают, что он держит за руку мертвых людей, чтобы вести их к Осирису.

Отцовство Анубиса

Интересной частью мифологии бога являются различные версии его происхождения. Ранняя мифология изображает бога как сына Ра. Однако тексты гробов, написанные в первый промежуточный период, изображают Анубиса как сына либо Хесат (богини-коровы), либо Бастет. Более того, в другой сказке он изображен как сын Ра и Нефтиды.

Кроме того, греческий Плутарх утверждает, что Анубис был незаконнорожденным сыном Осириса и Нефтиды. Позже его удочерила Исида, жена Осириса. Согласно этой сказке, Нефтида соблазнила Осириса, притворившись Исизи. Позже она родила Анубиса и сразу же бросила его, опасаясь Сета, своего мужа.

Исида искала ребенка с помощью уловок и с огромными трудностями нашла Анубиса. Позже она вырастила его, и он стал ее союзником и стражем. Однако многие историки заявляют, что люди сформулировали эту историю, чтобы включить независимое божество Анубис в легенды об Осирисе. Более того, египетский папирус римского периода просто называет Анубиса «сыном Исиды». В период Птолемея люди объединили Анубиса с греческим богом Гермесом, называемым Германубисом. Они считали этих богов похожими, поскольку оба были проводниками в загробной жизни. Более того, Германубис постоянно появлялся в алхимической и герметической литературе Средневековья.

Роли Анубиса

Защитник могил и кладбищ – одна из главных ролей Анубиса. Папирус Джумилхака рассказывает историю о том, как Анубис защитил тело Осириса от Сета. Злой бог превратился в леопарда и попытался атаковать тело Сета. Однако Анубис остановился и успокоил Сета, прежде чем заклеймить его кожу раскаленным железным стержнем.

Позже Анубис содрал кожу Сета и надел его кожу в качестве предупреждения злодеям, которые очерняют могилу мертвых. Священники, сопровождающие мертвых, носили шкуры леопарда, чтобы отпраздновать победу Анубиса над Сетом. Более того, люди использовали легенду о брендовом наборе Анубиса, чтобы объяснить, как у леопарда появились пятна.

В текстах Анубис часто ассоциируется с мумификацией. Более того, в знаменитом мифе об Осирисе Анубис помог Исиде в бальзамировании Осириса. Некоторые версии также утверждают, что после того, как Сет убил Осириса, Анубису были переданы органы Осириса. Следовательно, с появлением этой сказки Анубис стал богом-покровителем бальзамировщиков. На картинах из «Книги мертвых» часто изображен священник в волчьей маске, поддерживающий мумию.

Поздняя эра фараонов (664–332 до н.э.) начала изображать Анубиса как бога, который руководил душами по всему миру жизни в загробную жизнь. Хатор с головой коровы выполняла аналогичную роль, но Анубис играл главную роль в этой функции. Искусство римского периода египетской истории изображает Анубиса, который ведет людей, одетых в греческую одежду, в загробную жизнь.

Страж чешуи – еще одна известная роль Анубиса. В «Книге мертвых» изображена жизненная сцена, в которой Анубис измеряет, взвешивая сердце на весах, чтобы определить, достоин ли человек войти в царство смерти. Анубис диктовал судьбу душ, сравнивая сердце мертвых с Маат/истиной (часто изображаемой как страусиное перо).

Аммит пожирал души тяжелее пера. А души легче пера взошли бы на небеса. Бог Тот часто внимательно следил за этим процессом.

Поклонение Анубису

Анубис не фигурирует в древнеегипетской мифологии. Однако бог был чрезвычайно популярен среди египтян и других культур. С Анубисом люди обрели надежду, что могущественное божество будет охранять даже их трупы. В его культовом центре в Кинополисе в Верхнем Египте было несколько изображений бога. Более того, у него также было несколько других мемориалов по всей стране.

Вывод

Анубис – один из самых узнаваемых богов Египта благодаря его постоянному изображению в поп-культуре. Однако популярная культура изображает его со злыми силами и опасной армией. Бог смерти остается популярной фигуркой и сегодня, согласно легендам, он пережил самого бога.