Футбол

Футбол (от англ. foot — ступня, ball — мяч) — самый популярный командный вид спорта в мире, целью в котором является забить мяч в ворота соперника большее число раз, чем это сделает команда соперника в установленное время. Мяч в ворота можно забивать ногами или любыми другими частями тела (кроме рук).

Содержание

- История возникновения и развития футбола (кратко)

- Основные правила футбола (кратко)

- Размер футбольного поля и линии разметки

- Мяч для футбола

- Футбольная форма

- Стандартные положения в футболе

- Судейство в футболе

- Соревнования

- Футбольные структуры

История возникновения и развития футбола (кратко)

Точной даты возникновения футбола не известно, но можно с уверенностью сказать, что история футбола насчитывает не одно столетие и затронула немало стран. Игры с мячом были популярны на всех континентах, об этом говорят повсеместные находки археологов.

В Древнем Китае существовала игра, известная как «Цуцзюй», упоминания о которой были датированы вторым веком до нашей эры. По заявлению ФИФА в 2004 году, именно она считается наиболее древней из предшественников современного футбола.

В Японии подобная игра носила название «Кемари» (в некоторых источниках «Кенатт»). Первое упоминание о Кемари встречается в 644 году нашей эры. В Кэмари играют и в наше время в синтоистских святилищах во время фестивалей.

В Австралии мячи делали из шкур крыс, мочевых пузырей крупных животных, из скрученных волос. К сожалению, правил игры не сохранилось.

В Северной Америке тоже был предок футбола, игра называлась «pasuckuakohowog», что означает «они собрались, чтобы поиграть в мяч ногами». Обычно игры проходили на пляжах, мяч пытались забить в ворота шириной около полумили, само же поле было в два раз длиннее. Число участников игры доходило до 1000 человек.

Основные правила футбола (кратко)

Первые правила игры в футбол были введены 7 декабря 1863 года Футбольной ассоциацией Англии. Сегодня правила футбола устанавливает Международный совет футбольных ассоциаций (IFAB), в который входят ФИФА (4 голоса), а также представители английской, шотландской, североирландской и валлийской футбольных ассоциаций. Последняя редакция официальных футбольных правил датирована 1 июня 2013 года и состоит из 17 правил, вот краткое содержание:

- Правило 1: Судья

- Правило 2: Помощники судьи

- Правило 3: Продолжительность игры

- Правило 4: Начало и возобновление игры

- Правило 5: Мяч в игре и не в игре

- Правило 6: Определение взятия ворот

- Правило 11: Положение «Вне игры»

- Правило 12: Нарушения и недисциплинированное поведение игроков

- Правило 13: Штрафной и свободный удары

- Правило 14: 11-метровый удар

- Правило 15: Выбрасывание мяча

- Правило 16: Удар от ворот

- Правило 17: Угловой удар

Каждая футбольная команда должна состоять максимум из одиннадцати игроков (именно столько может находиться одновременно на поле), один из которых вратарь и он же единственный игрок, которому разрешено играть руками в рамках штрафной площади у своих ворот.

Футбольный матч состоит из двух таймов длительностью по 45 минут каждый. Между таймами предусмотрен 15 минутный перерыв на отдых, после которого команды меняются воротами. Это делается для того, чтобы команды были в равных условиях.

Футбольную игру выигрывает команда, забившая большее количество голов в ворота соперника.

Если команды закончили матч с одинаковым счетом голов, то фиксируется ничья, или назначаются два дополнительных тайма по 15 минут. Если дополнительное время закончилось ничьей, то назначается серия послематчевых пенальти.

Правила пенальти в футболе

Одиннадцатиметровый удар или пенальти является самым серьезным наказанием в футболе и выполняется с соответствующей отметки. При выполнении 11-метрового удара в воротах обязательно должен стоять вратарь.

Пробитие послематчевых пенальти в футболе проходит по следующим правилам: команды проводят по 5 ударов по воротам соперника с расстояния 11 метров, все удары должны проводиться разными игроками. Если после 5 ударов счет по пенальти равный, то команды продолжают пробивать по одной паре пенальти, пока не будет выявлен победитель.

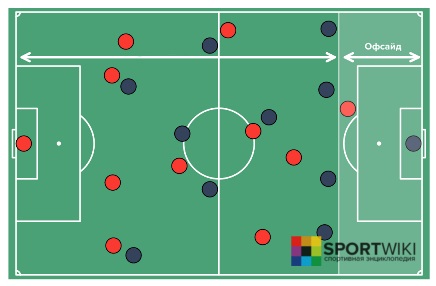

Положение «вне игры» в футболе

Считается, что игрок находится в положении «вне игры» или в офсайде, если он находится ближе к линии ворот соперника, чем мяч и предпоследний игрок соперника, включая вратаря.

Для того чтобы не оказаться в офсайде, игрокам необходимо придерживаться следующих правил:

- запрещается вмешиваться в игру (касание мяча, который ему передали или который коснулся партнёра по команде);

- запрещается мешать сопернику;

- запрещается получать преимущество благодаря своей позиции (касание мяча, который отскакивает от стойки или перекладины ворот или от соперника).

Игра рукой в футболе

Футбольные правила позволяют полевым игрокам касаться мяча любой частью тела, кроме рук. За игру рукой команде назначается штрафной удар или 11-метровый удар, который выполняет игрок команды соперника.

К правилам игры рукой в футболе относятся ещё два очень важных пункта:

- случайное попадание мяча в руку не является нарушением правил;

- инстинктивная защита от мяча не является нарушением правил.

Желтая и красная карточки

Желтая и красная карточки представляют собой знаки, который демонстрирует судья игрокам за нарушение правил и неспортивное поведение.

Желтая карточка носит предупредительный характер и дается игроку в следующих случаях:

- за умышленную игру рукой;

- за затяжку времени;

- за срыв атаки;

- за удар до свистка / выход из стенки (штрафной удар);

- за удар после свистка;

- за грубую игру;

- за неспортивное поведение;

- за споры с арбитром;

- за симуляцию;

- за уход или вход в игру без разрешения арбитра.

Красная карточка в футболе демонстрируется судьей за особо грубые нарушения или неспортивное поведение. Игрок, получивший красную карточку, должен покинуть поле до конца матча.

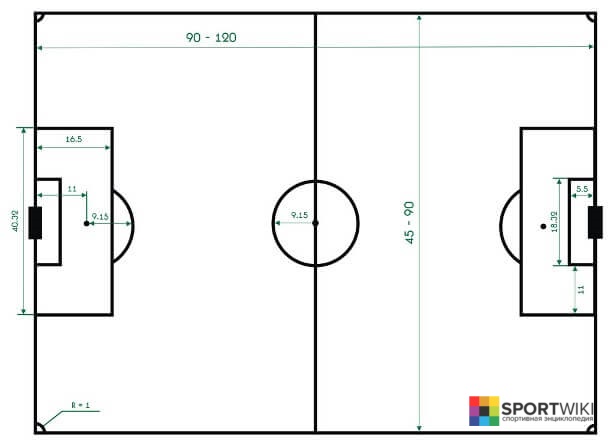

Размер футбольного поля и линии разметки

Стандартное поле для большого футбола представляет собой прямоугольную площадку, в которой линии ворот (лицевые линии) обязательно короче боковых линий. Далее мы рассмотрим параметры футбольного поля.

Размер футбольного поля в метрах четко не регламентирован, но есть определенные граничные показатели. Для проведения матчей национального уровня стандартная длина футбольного поля от ворот до ворот должна быть в пределах 90-120 метров, а ширина 45-90 метров. Площадь футбольного поля колеблется в пределах от 4050 м2 до 10800 м2. Для сравнения 1 гектар = 10 000 м2. Для международных матчей длина боковых линий не должна выходить за пределы интервала 100-110 метров, а линий ворот за пределы 64-75 метров. Существуют рекомендованные FIFA габариты футбольного поля 105 на 68 метров (площадь 7140 квадратных метров).

Разметку поля выполняют одинаковыми линиями, ширина разметки не должна превышать 12 сантиметров (линии входят в площади, которые они ограничивают). Боковую линию или край футбольного поля принято называть «бровкой».

Разметка футбольного поля

- Средняя линия – линия, которая делит поле на две равные половины. Посередине средней линии находится центр поля диаметром 0,3 метра. Окружность вокруг центра поля равняется 9,15 метров. Ударом или передачей с центра поля начинаются оба тайма матча, а также дополнительное время. После каждого забитого гола, мяч также устанавливается на центр поля.

- Линия ворот в футболе – проводится на газоне параллельно перекладине.

- Площадь футбольных ворот – линия, которая проводится на расстоянии 5,5 метров от внешней стороны стойки ворот. Перпендикулярно линии ворот проводятся две полосы длиной 5,5 метров, направленные вглубь поля. Их конечные точки соединяются линией, параллельной линии ворот.

- Штрафная площадь – из точек на расстоянии 16,5 м от внутренней стороны каждой стойки ворот, под прямым углом к линии ворот, вглубь поля проводятся две линии. На расстоянии 16,5 м эти линии соединены другой линией, параллельной линии ворот. По центру линии ворот и на расстоянии 11 метра от неё, наносится одиннадцатиметровая отметка, размечается она сплошным кругом диаметром 0,3 метра. В пределах штрафной площади вратарь может играть руками.

- Угловые секторы – дуги радиусом 1 метр с центром в углах футбольного поля. Данная линия образует ограниченную площадь для выполнения угловых ударов. В углах поля устанавливаются флаги высотой не менее 1,5 метра и размером полотнища 35х45 сантиметров.

Разметку поля осуществляют с помощью линий, ширина которых должна быть одинакова и не превышать 12 сантиметров. На изображении ниже схема разметки футбольного поля.

Ворота для футбола

Ворота располагаются точно посередине линии ворот. Стандартный размер ворот в футболе следующий:

- длина или ширина ворот в большом футболе – расстояние между вертикальными стойками (штангами) – 7,73 метра;

- высота ворот – расстояние от газона до перекладины – 2,44 метра.

Диаметр стоек и перекладины не должен превышать 12 сантиметров. Ворота изготавливаются из дерева или металла и выкрашены в белый цвет, а также имеют в поперечном сечении форму прямоугольника, эллипса, квадрата или круга.

Сетка для ворот в футболе должна соответствовать размерам ворот и должна быть прочной. Принято использовать футбольные сетки следующего размера 2,50 х 7,50 х 1,00 х 2,00 м.

Конструкция футбольного поля

Эталон конструкции футбольного поля выглядит следующим образом:

- Травяной газон.

- Подложка из песка и щебня.

- Трубы обогрева.

- Трубы дренажа.

- Трубы аэрации.

Покрытие для футбольного поля может быть натуральным или искусственным. Травяное покрытие требует дополнительного ухода, а именно полива и удобрения. Травяное покрытие не позволяет проводить более двух игр в неделю. Траву на поле привозят в специальных рулонах дёрна. Очень часто на футбольном поле можно видеть траву двух цветов (полосатое поле), так получается, из-за особенностей ухода за газоном. При стрижке газона машина сначала едет в одну сторону, а затем в другую и трава ложится в разные стороны (разнонаправленная стрижка газона). Делается это для удобства определения расстояний и офсайдов, а также для красоты. Высота травы на футбольном поле обычно составляет 2,5 – 3,5 см. Максимальная скорость мяча в футболе на текущий момент – 214 км/ч.

Искусственное покрытие для футбольного поля представляет собой ковёр из синтетического материала. Каждая травинка — это не просто полоска пластмассы, а изделие сложной формы. Для того чтобы искусственный газон был пригоден для игры, его засыпают наполнителем из песка и резиновой крошки.

Мяч для футбола

Каким же мячом играют в футбол? Профессиональный футбольный мяч состоит из трёх основных компонентов: камеры, подкладки и покрышки. Камера обычно изготавливается из синтетического бутила или натурального латекса. Подкладка – это внутренняя прослойка между покрышкой и камерой. Подкладка напрямую влияет на качество мяча. Чем она толще, тем мяч качественнее. Обычно подкладку делают из полиэстера или спрессованного хлопка. Покрышка состоит из 32 синтетических водонепроницаемых кусков, 12 из которых имеют пятиугольную форму, 20 – шестиугольную.

Размер мяча для футбола:

- длина окружности – 68-70 см;

- вес – не более 450 гр.

Скорость полета мяча в футболе достигает 200 км/ч.

Футбольная форма

Обязательными элементами комплекта спортивной футбольной формы игрока являются:

- Рубашка или футболка с рукавами.

- Трусы. Если используются подтрусники, то они должны быть такого же цвета.

- Гетры.

- Щитки. Должны быть полностью закрыты гетрами и обеспечивать должный уровень защиты.

- Бутсы.

Зачем футболистам гетры?

Гетры выполняют защитную функцию, поддерживая ногу и защищая от мелких травм. Благодаря им держатся щитки.

Вратарская футбольная форма должна отличаться по цвету от формы других игроков и судей.

Игроки не имеют права надевать никакой экипировки, которая может быть опасной для них или для других игроков, например ювелирные изделия и наручные часы.

Что футболисты одевают под шорты?

Подтрусники – плотно облегающие тело компрессионные трусы. Цвет и длина подтрусников не должны отличаться от цвета и длины трусов.

Стандартные положения в футболе

- Начальный удар. Розыгрыш мяча в футболе производится в трех случаях: в начале встречи, в начале второго тайма и после забитого гола. Все игроки команды, производящей начальный удар, должны находиться на своей половине поля, а их соперники — на расстоянии не меньше девяти метров от мяча. Игрок производящий начальный удар не имеет права повторно коснуться мяча раньше, чем это сделают другие игроки.

- Удар от ворот и введение мяча в игру вратарем. Ввод мяча в игру после его ухода за линию ворот (сбоку от стойки или над перекладиной), по вине игрока атакующей команды.

- Вбрасывание мяча из-за боковой линии. Производится полевым игроком после того, как мяч пересек боковую линию и покинул пределы поля. Вбрасывать мяч надо с того места, где он оказался в «ауте». Игрок, выполняющий прием, должен стоять лицом к полю на боковой линии или за ней. В момент броска, обе ступни игрока должны касаться земли. Мяч вводится в игру без сигнала судьи.

- Угловой удар. Ввод мяча в игру из углового сектора. Является наказанием для игроков обороняющейся команды, выбивших мяч за линию ворот.

- Штрафной и свободный удары. Наказание за умышленное касание мяча рукой или применение грубых приемов против игроков команды соперника.

- Одиннадцатиметровый удар (пенальти).

- Положение «вне игры» (офсайд).

Судейство в футболе

Судьи следят за соблюдением установленных правил на футбольном поле. На каждый матч назначается основной судья и два помощника.

В обязанности судьи входит:

- Хронометраж матча.

- Запись событий матча.

- Обеспечение соответствия мяча требованиям.

- Обеспечение экипировки игроков требованиям.

- Обеспечение отсутствия на поле посторонних лиц.

- Обеспечение ухода/выноса за пределы поля травмированных игроков.

- Предоставление соответствующим органам рапорт о матче, включающий информацию по всем принятым дисциплинарным мерам в отношении игроков и/или официальных лиц команд, а также по всем прочим инцидентам, произошедшим до, во время или после матча.

Права судьи:

- Остановить, временно прервать или прекратить матч при любом нарушении правил, постороннем вмешательстве, травмировании игроков;

- Принимать меры в отношении официальных лиц команд, ведущих себя некорректно;

- Продолжить игру до момента, когда мяч выйдет из игры в случае, если игрок, по его мнению, получил лишь незначительную травму;

- Продолжить игру, когда команда, против которой было совершено нарушение, получает выгоду от такого преимущества (осталась с мячом), и наказать за первоначальное нарушение, если предполагавшимся преимуществом команда не воспользовалась;

- Наказать игрока за более серьёзное нарушение Правил в случае, когда он одновременно совершает более одного нарушения;

- Действовать на основании рекомендации своих помощников и резервного судьи.

Соревнования

Соревнования организуются федерацией, для каждого турнира составляется собственный регламент, в котором обычно прописывается состав участников, схема турнира, правила определения победителей.

ФИФА

Национальные сборные

- Чемпионат мира – главное международное соревнование по футболу. Чемпионат проводится один раз в четыре года, участие в турнире могут принимать мужские национальные сборные стран-членов FIFA всех континентов.

- Кубок конфедераций – футбольное соревнование среди национальных сборных, которое проводится за год до Чемпионата мира. Проводится в стране-организаторе Чемпионата мира. В чемпионате принимают участие 8 команд: победители континентальных чемпионатов, победитель чемпионата мира и команда страны-организатора.

- Олимпийские игры

Клубные

- Клубный чемпионат мира по футболу – ежегодное соревнование между сильнейшими представителями шести континентальных конфедераций.

УЕФА

Национальные сборные

- Чемпионат Европы – главное соревнование национальных сборных под руководством УЕФА. Чемпионат проводится раз в четыре года.

Клубные

- Лига чемпионов УЕФА – самый престижный ежегодный европейский клубный футбольный турнир.

- Лига Европы УЕФА – второй по значимости турнир для европейских футбольных клубов, входящих в УЕФА.

- Суперкубок УЕФА – чемпионат из одного матча, в котором встречаются победители Лиги чемпионов УЕФА и Лиги Европы УЕФА предыдущего сезона.

КОНМЕБОЛ

Национальные сборные

- Кубок Америки – чемпионат, проводимый под эгидой КОНМЕБОЛ среди национальных сборных стран региона.

Клубные

- Кубок Либертадорес – кубок назван в честь исторических лидеров войны за независимость испанских колоний в Америке. Проводится среди лучших клубов стран региона.

- Южноамериканский кубок – второй по значимости клубный турнир Южной Америки после Кубка Либертадорес.

- Рекопа Южной Америки – аналог континентального Суперкубка. В турнире участвуют победители двух важнейших клубных турниров — Кубка Либертадорес и Южноамериканского кубка предыдущего сезона.

КОНКАКАФ

Национальные сборные

- Золотой кубок КОНКАКАФ – футбольный турнир для стран Северной, Центральной Америки и Карибского бассейна.

Клубные

- Лига чемпионов КОНКАКАФ – ежегодный футбольный чемпионат среди лучших клубов стран Северной и Центральной Америки и Карибского бассейна.

Футбольные структуры

Основной футбольной структурой является FIFA (Fédération internationale de football association), расположенная в Цюрихе, Швейцария. Она занимается организацией международных турниров мирового масштаба.

Континентальные организации:

- CONCACAF (СОnfederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football) – конфедерация футбола Северной и Центральной Америки и стран Карибского бассейна ,

- CONMEFBOL (CONfederacion sudaMEricana de FutBOL) – Южноамериканская конфедерация футбола,

- UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) – союз европейских футбольных ассоциаций,

- CAF (Confederation of African Football) – Африканская конфедерация футбола,

- AFC (Asian Football Confederation) – Азиатская конфедерация футбола,

- OFC (Oceania Football Confederation) – конфедерация футбола Океании.

FAQ

🚩 Кто придумал футбол?

Современный футбол был придуман в Англии в 1860-х годах.

🚩 Cколько футболистов в команде?

Команда состоит из 11 футболистов: десять полевых игроков и один вратарь.

🚩 Сколько футбольное поле в длину?

Длина футбольного поля от ворот до ворот должна быть в пределах 90-120 метров.

Мы постарались максимально полно охватить тему, поэтому данную информацию можно смело использовать при подготовке сообщений, докладов по физкультуре и рефератов на тему «Футбол».

Футбол (термин происходит от английского football, от foot — нога и ball — мяч) — это спортивная игра на травяном поле, в которой две противоборствующие команды (по 11 человек в каждой), используя ведение и передачи мяча ногами или другой частью тела (кроме рук), стремятся забить его в ворота соперника и не пропустить в свои. Футбольное поле — 90-120×45-90 м, продолжительность игры — 90 минут (2 тайма по 45 мин с перерывом 15 мин). Международная федерация футбольных ассоциаций (ФИФА (FIFA — Federation Internationale de Footbal Association) — международная федерация футбола. Основана 21 мая 1904 в Париже.

На учредительном конгрессе, состоявшемся 23 мая 1904 года, первым президентом ФИФА был избран француз Робер Герен. С 8 июня 1998 президентом стал Йозеф Зепп Блаттер (Швейцария). В составе ФИФА 204 национальные федерации (2000).)) основана в 1904 году, объединяет 204 национальных федерации (2002).

27 марта 1928 года в Голландии была выпущена первая в мире почтовая марка на футбольную тему.

Правила игры в футбол

Спортсмены, используя индивидуальное ведение и передачи мяча партнёрам ногами или любой другой частью тела, кроме рук, стараются забить его в ворота соперника наибольшее количество раз в установленное время. В команде 11 человек, в том числе вратарь. Игровая специально размеченная прямоугольная площадка — поле (110 — 100 х 75 — 69 м — для официальных матчей) имеет обычно травяной покров. Длина окружности мяча по диаметральному сечению 680 — 710 мм, масса 396 — 453 г.

Время игры 90 минут (2 периода-тайма по 45 мин с 10 — 15-минутным перерывом). В отличие от других игр с мячом прикасаться к нему руками разрешается только вратарю (в пределах штрафной площадки), остальным игрокам — при вбрасывании мяча в игру из-за боковой линии.

Существенно влияет на тактику футбольное правило «положение вне игры» — спортсмен, находящийся на половине поля соперника, имеет право принимать мяч от партнёра при условии, что между ними и линией ворот находится не менее двух игроков противника, включая вратаря. За нарушение правил назначаются штрафные удары по свободно лежащему мячу (при отдалении от него игроков команды-соперника не менее чем на 9 м); за нарушение в штрафной площади — 11-метровый удар (пенальти) по воротам, защищаемым только вратарём, стоящим на их линии. Регламент некоторых соревнований по футболу предусматривает при ничейном результате встречи дополнительное время или серии пенальти для выявления победителей; для матчей детей[en] и молодёжи — сокращение времени игры и размеров поля.

10 июля 1878 года на одном из футбольных матчей в Лондоне судить игру доверили полицейскому, и когда на игре возникла драка, он, не задумываясь, засвистел в свисток. Напуганные и ошеломленные игроки тотчас же прекратили драку. С тех пор арбитры на поле пользуются свистком.

23 марта 1891 года в матче английских команд Севера и Юга на футбольных воротах появилась сетка, годом ранее запатентованная ливерпульским инженером Джоном Броди.

История возникновения игры в футбол

Футбол — самая популярная командная игра в мире. История «ножного мяча» насчитывает немало столетий. В различные игры с мячом, похожие на футбол, играли в странахстран[en] Древнего Востока (Египет, Китай), в античном мире (Греция, Рим), во Франции («ла суль»), в Италии («кальчио»), в Англии. В Древнем Египте похожая на футбол игра была известна в 1900 до нашей эры. В Древней Греции игра в мяч была популярна в различных проявлениях в 4 веке до н. э., о чем свидетельствует изображение жонглирующего мячом юноши на древнегреческой амфоре, хранящейся в музее в Афинах. Среди воинов Спарты была популярна игра в мяч «эпискирос», в которую играли и руками, и ногами.

Непосредственным предшественником европейского футбола был, по всей вероятности, римский «гарпастум». В этой игре, которая была одним из видов военной тренировки легионеров, следовало провести мяч между двумя стойками. Их игра отличалась жестокостью. Именно благодаря римским завоевателям игра в мяч в 1 в. н. э. стала известна на Британских островах, быстро получив признание среди коренных жителей бриттов и кельтов. Бритты оказались достойными учениками — в 217 н. э. в г. Дерби они впервые победили команду римских легионеров.

Примерно в 5 в. эта игра исчезла вместе с римской империей, но память о ней осталась у европейцев, особенно в Италии. Даже великий Леонардо да Винчи[en], состязался в излюбленной флорентийскими юношами игре в ножной мяч. Когда в 17 веке сторонники казненного английского короля Карла I бежали в Италию, они познакомились там с этой игрой, а после восшествия на престол в 1660 Карла II завезли ее в Англию, где она стала игрой придворных. Средневековый футбол в Англии носил чрезвычайно азартный и грубый характер, и сама игра представляла собой, в сущности, дикую свалку на улицах. Англичане и шотландцы играли не на жизнь[en], а на смерть[en]. Неудивительно, что власти вели упорную войну с футболом; были изданы даже запретительные королевские указы Эдуарда II (под страхом тюремного заключения запрещалось играть в городе), Эдуарда III (запрещал футбол из-за того, что войска предпочитали эту игру совершенствованию в стрельбе из лука), Ричарда II, который вместе с футболом запретил теннис и игру в кости. Футбол не нравился и последующим английским монархам — от Генриха IV до Якова II.

Но популярность футбола в Англии была столь велика, что ей не могли помешать и королевские указы. Именно в Англии эта игра была названа «футболом», хотя это и произошло не при официальном признании игры, а при ее запрещении. В начале 19 в. в Великобритании произошел переход от «футбола толпы» к организованному футболу, первые правила которого были разработаны в 1846 году в Регби-скул и два года спустя уточнены в Кембридже. А в 1857 г. в Шеффилде был организован первый в мире футбольный клуб (Клуб (английское club) — общественная организация, объединяющая группы людей в целях общения, связанного с политическими, научными, художественными, спортивными, досуговыми и другими интересами.).

В 1863 году представители уже 7 клубов собрались в Лондоне, чтобы выработать единые правила игры и организовать Национальную футбольную ассоциацию. Были разработаны первые в мире официальные правила игры, получившие спустя несколько десятилетий всеобщее признание. С тех пор в правила неоднократно вносились изменения, которые, безусловно, влияли на тактику и технику игры. В 1873 состоялась первая международная встреча сборных команд Англии и Шотландии, закончившаяся со счетом 0:0. С 1884 на Британских островах начали разыгрываться первые международные турниры с участием футболистов Англии, Шотландии, Уэльса и Ирландии (такие турниры проводятся ежегодно и сейчас).

В конце 19 века футбол начал быстро завоевывать популярность в Европе и Латинской Америке[en]. В 1904 году по инициативе Бельгии, Дании, Нидерландов и Швейцарии была создана Международная федерация футбольных ассоциаций (ФИФА).

Футбол — олимпийский вид спорта

В олимпийском турнире участвуют 16 команд: 14 вакансий разыгрывается в отборочных соревнованиях: чемпион предыдущих Олимпийских игр и команда страны-организатора Олимпиады допускаются к соревнованиям без отборочных матчей. На первом этапе турнира матчи проводятся в четырех группах по круговой системе (каждый с каждым), затем команды, занявшие первое и второе места в подгруппах, разбиваются на пары и продолжают борьбу с выбыванием. С 1996 в программу Олимпийских игр включен женский турнир.

Полноправным олимпийским видом спорта футбол стал в 1900 году, на Олимпиаде в Афинах (1896) проводились только показательные соревнования по футболу. На Олимпийских играх в Париже (1900) участвовали всего три команды — Бельгии, Великобритании и Франции, чемпионами стали британцы (до Первой мировой войны[en] они еще два раза завоевывали золотые олимпийские медали в 1908 и 1912. В 1924 и 1928 олимпийское золото досталось сборной Уругвая, многие игроки которой стали первыми чемпионами мира в 1930. На Олимпийских играх в Берлине (1936) победила сборная Италии, которая через два года завоевала Кубок мира. В послевоенный период на Олимпийских играх блистали команды Швеции (1948), Венгрии (1952), СССР[en] (1956).

В 1960 году в Риме победила сборная Югославии. В последующие годы олимпийскими чемпионами становились: в 1964 Токио, в 1968 в Мехико — Венгрия, в 1972 в Мюнхене — Польша, в 1976 в Монреале — ГДР, в 1980 в Москве — Чехословакия, в 1984 в Лос-Анджелесе — Франция, в 1988 в Сеуле — СССР, в 1992 в Барселоне — Испания, в 1996 в Атланте — Нигерия, в 2000 в Сиднее — Камерун.

Чемпионаты мира

С 1930 года проводятся чемпионаты мира по футболу (так же, как и олимпийские турниры один раз в четырехлетие, в четные годы между високосными). В них принимают участие, в основном, профессиональные футболисты, чье мастерство оплачивается клубами. Футбол принадлежит к тем видам спорта (их совсем немного), в которых самым престижным состязанием является чемпионат мира, а не Олимпийские игры.

Первым чемпионом мира стала сборная Уругвая, в которой играли многие олимпийские чемпионы 1924 и 1928 годах. В 1934 и 1938 два раза подряд Кубок мира завоевывали итальянцы. Во время Второй мировой войны[en] турниры за мировое первенство не проводились. В 1950 году чемпионами во второй раз стали уругвайцы. В 1954 все прочили победу сборной Венгрии, которая на пути к финалу одержала верх не только над Южной Кореей и ФРГ, но и над лучшими командами чемпионата мира 1950 — Бразилией и Уругваем. Однако в финале, вновь играя с ФРГ, венгры, забив два гола, пропустили три. Золото досталось сборной Западной Германии. Чемпионом мира 1958 впервые стала сборная Бразилии — непременный участник предыдущих турниров. Бразильцы поочередно победили сборные Австрии (третий призер чемпионата мира 1954), СССР (олимпийский чемпион 1956), Уэльса, Франции и Швеции (олимпийский чемпион 1948) и лишь в матче (в группе) с Англией сыграла вничью.

В составе чемпионов команды играли ставшие знаменитыми футболистами Пеле, Гарринша Гарринча, Эдвальдо Изидио Нето Вава, Валдир Перейра Диди, Джалма дос Сантос. Спустя четыре года (1962) сборная Бразилии повторила свой успех, в третий раз бразильцы стали чемпионам мира в 1970, в бразильской сборной блистали Роберто Ривелино, Жаир Вентуро Фильо Жаирзиньо, Тостао.

В 1966 чемпионами мира (единственный раз) стали родоначальники футбола англичане — цвета сборной Англии защищали выдающиеся футболисты Б. Мур, Роберт Чарлтон, Джеффри Чарльз Херст, Джеймс Петер Гривс и другие. Выступление советской сборной стало ее высшим достижением за все годы участия в турнирах на Кубок мира. Сборная СССР дошла до полуфинала и заняла четвертое место. В 1974 сборная ФРГ стала чемпионом мира во второй раз. В ее составе играли легендарные Франц Беккенбауэр и Герд Мюллер.

В 1978 Кубок мира впервые выиграла молодая динамичная команда Аргентины, через восемь лет она повторила этот успех во многом благодаря своему лидеру Диего Марадоне (родился[en] 30 октября 1960 года в городе Ланус).

Итальянцы догнали бразильцев в 1989 году, став трехкратными чемпионами мира. В 1990 достижение бразильцев и итальянцев повторили футболисты ФРГ, также выигравшие чемпионат мира в третий раз. В 1994 Бразилия вновь вышла вперед, победив в четвертый раз, в команде выделялись Бебето, Ромарио де Соуза Фариа, Бранко.

Чемпионат 1998, который проводился во Франции, внес в летопись футбола имя нового победителя — сборную Франции, в рядах которой были Ф. Бартез, Ю. Джоркаефф, Зинеддин Зидан, Тьерри Анри, П. Вьейра и др.

Чемпионат мира 2002 года, состоявшийся в Корее и Японии, утвердил во главе футбольной элиты сборную Бразилии, которая завоевала пятый высший титул (сильнейшие игроки — Луис Назарио де Лима Роналдо, Ривалдо, Рональдиньо). Серебряным призером стала команда Германии, сенсацией турнира — сборная Турции, занявшая третье место. Четвертое место (и это тоже сенсация) досталось молодой и напористой сборной Южной Кореи.

За время проведения чемпионатов мира обнаружилась одна показательная особенность — очень часто на выступление команды, страна которой принимала мировой чемпионат, самым позитивным образом влияло место его проведения. Так было в Уругвае (1930), Англии (1966), Аргентине (1978), Франции (1998), Корее и Японии (2002).

Чемпионат мира 2006, проводившийся в Германии, окончился триумфом европейского футбола. В полуфинал вышли только лучшие команды Еропы — Германия, Португалия, Франция (победившая в четверть финале бразильцев), Италия. В финальном матче между сборными Италии и Франции в упорнейшей борьбе (по пенальти) победили итальянцы. Третье место досталось сильной команде Германии.

Кубок Европы

В 1958-1960 годах был проведен розыгрыш первого Кубка Европы (впоследствии всегда финалы Кубка и заменившего его чемпионата Европы проводятся в високосные годы). В первом финале 1960 сборная СССР победила сборную Югославии (2:1), в составе сборной СССР играли Лев Иванович Яшин, Г. Чохели, А. Масленкин, А. Крутиков, Ю. Войнов, Игорь Александрович Нетто, Слава Калистратович Метревели, Валентин Козьмич Иванов, Виктор Владимирович Понедельник, В. Бубукин, Михаил Шалвович Месхи (начиная с 1/8 финала также В. Беляев, В. Кесарев, В. Царев, Н. Симонян, А. Мамедов, А. Ильин, А. Исаев). Это высшее достижение советской сборной за все годы ее выступления на международной арене.

Второй Кубок Европы (1962-1964) выиграла сборная Испании (в финале у команды СССР со счетом 2:1).

В следующих турнирах (чемпионатах Европы) побеждали сборные: Италии (1968), ФРГ (1972, 1980), Чехословакии (1976), Франции (1984, 2000), Нидерландов (1988), Дании (1992), Германии (1996), Франции (2008), Греции (2004), Испании (2008). В 1988 сборная СССР пробилась в финал чемпионата Европы и, проиграв голландской сборной, заняла второе место. В 2004 сенсационную победу одержала не считавшаяся фаворитом команда Греции, обыгравшая в финале команду Португалии. Следует отметить, что единственной командой, победившей греческую сборную, стала команда России[en], которая не смогла пробиться в четвертьфинал. В 2008 сборная России, впервые возглавляемая иностранным тренером — голландским специалистом Гусом Хиддинком, — завоевала бронзовые награды, выиграв в блестящем четвертьфинале у сборной Голландии и уступив в полуфинале будущим чемпионам — испанцам.

Кубок европейских чемпионов

В сезоне 1955-56 впервые был разыгран Кубок европейских чемпионов (ныне — Лига чемпионов). Чаще всего победителем этого турнира становились мадридский «Реал» (Испания) (1956-1960, 1966, 1998, 2002), «Милан» (Италия) (1963, 1969, 1989, 1990, 1994, 2003), «Аякс» (Амстердам, Нидерланды) (1971-1973, 1995), «Ливерпуль» (Англия) (1977, 1978, 1981, 1984).

С сезона 1960-1961 по 1999 года (был слит с Кубком УЕФА) разыгрывался Кубок обладателей кубков европейских стран. Первым победителем турнира в 1961 стала «Фиорентина» (Флоренция, Италия). Первым дважды выиграл приз «Милан» (Италия) (1968 и 1973). «Барселона» (Испания) стала победителем турнира в 1979, 1982, 1989, 1997. Трижды этот трофей выигрывали советские команды: в 1975 и 1986 — «Динамо» (Киев, Украина[en]), в 1981 — «Динамо» (Тбилиси, Грузия).

Кубок УЕФА

Кубок УЕФА (для призеров национальных чемпионатов) разыгрывается с 1958 (до 1971 носил название Кубок Ярмарок). «Барселона» (Испания) побеждала в 1958, 1960, 1966, «Ювентус» (Турин, Италия) — в 1977, 1990, 1993, «Интер» (Милан, Италия) — в 1991, 1994, 1998. Российские команды дважды завоевывали этот трофей: в 2005 — ЦСКА, а в 2008 — «Зенит» (Санкт-Петербург).

Кубок Либертадорес

Сильнейшие южноамериканские команды разыгрывают Кубок Либертадорес с сезона 1959-1960. В 1960 и 1961 победил «Пеньяроль» (Монтевидео, Уругвай). В 1962 и 1963 — «Сантос» (Сан-Паулу, Бразилия), в 1964 и 1965 — «Индепендьенте» (Буэнос-Айрес, Аргентина). В 1966 «Пеньяроль» стал трехкратным обладателем кубка. В 1968-1970 трижды побеждал «Эстудиантес» (Ла-Плата, Аргентина).

Межконтинентальный кубок

С 1960 года сильнейшие клубы Европы и Южной Америки (не всегда регулярно и не всегда победители главных кубков) встречаются в матчах за Межконтинентальный кубок (с 2005 был заменен Кубком мира стран ФИФА). Победителями кубка, в частности, становились: испанский «Реал» (1960, 1966, 1998), уругвайский «Пеньяроль» (1961, 1966, 1982), бразильский «Сантос» (1962, 1963), итальянские «Интер» (1964, 1965) и «Милан» (1969, 1989, 1990, 2007), уругвайский «Насьональ» (1971, 1981, 1988), бразильский «Сан-Паулу» (1992, 1993, 2005). С 1981 встречи проводились в Токио и состояли из одного матча; с 2005 игры проходят по круговой системе. Чаще обладателями кубка становились южноамериканцы.

«Золотой мяч»

В 1956 был учрежден популярный личный приз лучшему футболисту Европы — «Золотой мяч». Его получали и футболисты других континентов, выступающие за европейские клубы (например, либериец Дж. Веа в в 1995, бразилец Роналдо в 1996 и 1997 и т.д.).

Первыми обладателями «Золотого мяча» были: Стэнли Мэтьюз (Англия, «Блэкпул», 1956); Лауте Альфредо ди Стефано (Испания, «Реал»,1957, 1959); Раймон Копа (Франция, «Реал», 1958); Луис Мирамонтес Суарес (Испания, «Барселона», 1960); О. Сивори (Италия, «Ювентус», 1961); Йозеф Масопуст (Чехословакия, «Дукла», 1962); Лев Яшин (СССР, «Динамо» Москва, 1963); Деннис Лоу (Шотландия, «Манчестер Юнайтед», 1964); Фаррейра Да Сильва Эйсебио (Португалия, «Бенфика», 1965); Роберт Чарлтон (Англия, «Манчестер Юнайтед», 1966). Среди других советских футболистов обладателями «Золотого мяча» были также Олег Владимирович Блохин (СССР, «Динамо», Киев, 1975) и Игорь Иванович Беланов (СССР, «Динамо», Киев, 1986).

Футбол в России

24 сентября 1893 года в Петербурге на ипподроме на Семёновском плацу (ныне Пионерская площадь) между командами «Спорт» и петербургским кружком спортсменов состоялась одна из первых в России игр в «ножной мяч» — футбол.

В Россию футбол был завезен англичанами в конце 19 века. В 1897 году петербургский «Кружок любителей спорта» создал первую русскую футбольную команду. Количество команд постоянно росло. В 1901 была образована Петербургская футбольная лига. Московская футбольная лига начала свою деятельность в 1911. По примеру Петербурга и Москвы футбольные клубы многих городов страны объединялись в футбольные лиги (Одесса, Харьков, Киев, Донбасс и др.). В общей массе это был еще совсем «зеленый» футбол. Игра носила ярко выраженный атлетический характер. Форварды ценились по напористости, а защитники — по габаритности. Соревнования возникали мгновенно, неожиданно. Играли в сапогах, ботинках, босиком. Нередко матчи кончались потасовкой.

Большинство выдающихся мастеров футбола начинало свою футбольную жизнь именно в «диких» командах. Такие популярные игроки первого поколения, как П. Канунников, Федор Ильич Селин, Н. Соколов, М. Бутусов приобрели первые футбольные навыки в рядах этих «диких» команд.

Первая игра сборных команд Петербурга и Москвы состоялась в 1907 году и закончилась победой Петербурга со счетом 2:0. В 1911 был организован Всероссийский футбольный союз. В 1913 было разыграно второе первенство России. Результат был сенсационным. Команда Петербурга, бесспорный фаворит, проиграла одесситам в финальном матче со счетом 2:4. В 1914 начавшиеся встречи на первенстве России доведены до конца не были. Их прервала Первая мировая война. На международную арену русские футболисты вышли впервые в 1910, когда Россию посетила команда пражского клуба «Коринтианс». Русские футболисты не могли оказать иностранцам должного сопротивления и большей частью проигрывали. История его только начиналась.

Футбол в России до 1917 не получил массового распространения. Подлинно массовым он стал в годы Советской власти. С 1923 начали разыгрываться чемпионаты страны, вначале для сборных команд городов (наибольших успехов добилась сборная Москвы). С 1936 разыгрывались чемпионаты и Кубок СССР для клубных команд. В 1930-х годах гремели имена братьев Старостиных, выступавших за московский «Спартак».

Чемпионами СССР были: тринадцать раз становилось «Динамо» (Киев), двенадцать раз — «Спартак» (Москва), одиннадцать — Динамо» (Москва), семь раз — ЦДКА-ЦСКА, три раза «Торпедо» (Москва), дважды — «Динамо» (Тбилиси), дважды — «Днепр» (Днепропетровск), по одному разу — «Арарат» (Ереван), «Динамо » (Минск) и «Зенит» (Ленинград).

Обладателями Кубка СССР были: десятикратным — Спартак» (Москва), девятикратным — «Динамо» (Киев), шестикратным — «Динамо» (Москва), шестикратным — Торпедо» (Москва), пятикратным — ЦДКА — ЦСКА, четырехкратным — «Шахтер» (Донецк), двукратными обладателями — «Арарат» (Ереван) и «Динамо» (Тбилиси), по одному разу Кубком владели «Зенит» (Ленинград), СКА (Ростов-на-Дону), «Металлист» (Харьков) и «Днепр» (Днепропетровск).

20 апреля 1960 года футболисты «Пахтакора» забили три мяча в собственные ворота, установив в истории чемпионатов СССР рекорд по автоголам.

После распада СССР в 1991 году в России и других союзных республиках стали проводиться собственные национальные чемпионаты. Безусловным лидером российского футбола является московский «Спартак». Команда становилась чемпионом в 1992-2001 годах (кроме 1995, когда высший титул завоевала команда «Спартак-Алания»). Обладателями Кубка России были: «Торпедо» (Москва) — 1993; «Спартак» (Москва) — 1994, 1998, 2003; «Динамо» (Москва) — 1995; «Локомотив» (Москва) — 1996, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2007; «Зенит» (Санкт-Петербург) — 1999, ЦСКА (Москва) — 2002, 2005, 2006, 2008; «Терек» (Грозный) — 2004.

Высшие достижения сборной в чемпионатах мира: четвертое место в 1966 году. Высшие достижения сборной в розыгрышах Кубка и чемпионатах Европы: первое место в 1960, вторые места в 1964, 1972 и 1988, третье место в 2008. Высшие достижения сборной в олимпийских турнирах: первые места в 1956 и 1988. Главные тренеры сборной СССР: в 1956 и в 1960 — Гавриил Дмитриевич Качалин, в 1964 — Константин Иванович Бесков, в 1972 — Н. Гуляев, в 1988 — Валерий Васильевич Лобановский и А. Бышовец. Тренеры сборной России — Олег Иванович Романцев, Г. Ярцев.

Высшие достижения клубов в еврокубках: первые места киевского «Динамо» в розыгрыше Кубка Кубков 1974-1975 и 1985-1986, тбилисского «Динамо» в 1980-1981, выигрыш европейского Суперкубка киевским «Динамо» в 1975. Киевлян тренировал Валерий Васильевич Лобановский, тбилисцев — Нодар Парсаданович Ахалкаци. Лучшими футболистами Европы были названы: в 1963 — вратарь московского «Динамо» Лев Яшин, в 1975 — нападающий киевского «Динамо» Олег Блохин, в 1986 — нападающий киевского «Динамо» Игорь Иванович Беланов. (В. И. Линдер)

20 апреля 2007 года футболист молдавского клуба «Дачия», выступающего в высшей лиге местного чемпионата, Сергей Потрымба покинул команду и отправился на заработки в Испанию, где он стал разнорабочим. Главная причина отъезда игрока из команды — низкая заработная плата, которая составляла 200-250 долларов в месяц.

Известные футбольные цитаты

Сэр Алекс Фергюсон однажды сказал о Филиппо Индзаги: Этот парень должен был родиться[en] в положении вне игры

.

При критике со стороны Джона Карью, Златан Ибрагимович ответил: То, что делает Карью с мячом, я могу сделать с апельсином.

Джордж Бест сказал: Я потратил много денег на выпивку, девчонок и быстрые автомобили. Остальное я просто промотал

, — когда его спросили о его образе жизни.

This article is about the family of sports. For specific sports and other uses, see Football (disambiguation).

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word football normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly called football include association football (known as soccer in North America and Australia); gridiron football (specifically American football or Canadian football); Australian rules football; rugby union and rugby league; and Gaelic football.[1] These various forms of football share to varying extent common origins and are known as «football codes».

There are a number of references to traditional, ancient, or prehistoric ball games played in many different parts of the world.[2][3][4] Contemporary codes of football can be traced back to the codification of these games at English public schools during the 19th century.[5][6] The expansion and cultural influence of the British Empire allowed these rules of football to spread to areas of British influence outside the directly controlled Empire.[7] By the end of the 19th century, distinct regional codes were already developing: Gaelic football, for example, deliberately incorporated the rules of local traditional football games in order to maintain their heritage.[8] In 1888, The Football League was founded in England, becoming the first of many professional football associations. During the 20th century, several of the various kinds of football grew to become some of the most popular team sports in the world.[9]

Common elements

The action of kicking in (clockwise from upper left) association, gridiron, rugby, and Australian football.

The various codes of football share certain common elements and can be grouped into two main classes of football: carrying codes like American football, Canadian football, Australian football, rugby union and rugby league, where the ball is moved about the field while being held in the hands or thrown, and kicking codes such as Association football and Gaelic football, where the ball is moved primarily with the feet, and where handling is strictly limited.[10]

Common rules among the sports include:[11]

- Two teams of usually between 11 and 18 players; some variations that have fewer players (five or more per team) are also popular.

- A clearly defined area in which to play the game.

- Scoring goals or points by moving the ball to an opposing team’s end of the field and either into a goal area, or over a line.

- Goals or points resulting from players putting the ball between two goalposts.

- The goal or line being defended by the opposing team.

- Players using only their body to move the ball, ie no additional equipment such as bats or sticks.

In all codes, common skills include passing, tackling, evasion of tackles, catching and kicking.[10] In most codes, there are rules restricting the movement of players offside, and players scoring a goal must put the ball either under or over a crossbar between the goalposts.

Etymology

There are conflicting explanations of the origin of the word «football». It is widely assumed that the word «football» (or the phrase «foot ball») refers to the action of the foot kicking a ball.[12] There is an alternative explanation, which is that football originally referred to a variety of games in medieval Europe, which were played on foot. There is no conclusive evidence for either explanation.

Early history

Ancient games

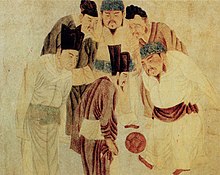

Ancient China

The Chinese competitive game cuju (蹴鞠) resembles modern association football (soccer),[13] descriptions appear in a military manual dated to the second and third centuries BC.[14] It existed during the Han dynasty and possibly the Qin dynasty, in the second and third centuries BC.[15] The Japanese version of cuju is kemari (蹴鞠), and was developed during the Asuka period.[16] This is known to have been played within the Japanese imperial court in Kyoto from about 600 AD. In kemari several people stand in a circle and kick a ball to each other, trying not to let the ball drop to the ground (much like keepie uppie).

Ancient Greece and Rome

The Ancient Greeks and Romans are known to have played many ball games, some of which involved the use of the feet. The Roman game harpastum is believed to have been adapted from a Greek team game known as «ἐπίσκυρος» (Episkyros)[17][18] or «φαινίνδα» (phaininda),[19] which is mentioned by a Greek playwright, Antiphanes (388–311 BC) and later referred to by the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215 AD). These games appear to have resembled rugby football.[20][21][22][23][24] The Roman politician Cicero (106–43 BC) describes the case of a man who was killed whilst having a shave when a ball was kicked into a barber’s shop. Roman ball games already knew the air-filled ball, the follis.[25][26] Episkyros is recognised as an early form of football by FIFA.[27]

Native Americans

There are a number of references to traditional, ancient, or prehistoric ball games, played by indigenous peoples in many different parts of the world. For example, in 1586, men from a ship commanded by an English explorer named John Davis, went ashore to play a form of football with Inuit in Greenland.[28] There are later accounts of an Inuit game played on ice, called Aqsaqtuk. Each match began with two teams facing each other in parallel lines, before attempting to kick the ball through each other team’s line and then at a goal. In 1610, William Strachey, a colonist at Jamestown, Virginia recorded a game played by Native Americans, called Pahsaheman.[citation needed] Pasuckuakohowog, a game similar to modern-day association football played amongst Amerindians, was also reported as early as the 17th century.

Games played in Mesoamerica with rubber balls by indigenous peoples are also well-documented as existing since before this time, but these had more similarities to basketball or volleyball, and no links have been found between such games and modern football sports. Northeastern American Indians, especially the Iroquois Confederation, played a game which made use of net racquets to throw and catch a small ball; however, although it is a ball-goal foot game, lacrosse (as its modern descendant is called) is likewise not usually classed as a form of «football.»[citation needed]

Oceania

On the Australian continent several tribes of indigenous people played kicking and catching games with stuffed balls which have been generalised by historians as Marn Grook (Djab Wurrung for «game ball»). The earliest historical account is an anecdote from the 1878 book by Robert Brough-Smyth, The Aborigines of Victoria, in which a man called Richard Thomas is quoted as saying, in about 1841 in Victoria, Australia, that he had witnessed Aboriginal people playing the game: «Mr Thomas describes how the foremost player will drop kick a ball made from the skin of a possum and how other players leap into the air in order to catch it.» Some historians have theorised that Marn Grook was one of the origins of Australian rules football.

The Māori in New Zealand played a game called Ki-o-rahi consisting of teams of seven players play on a circular field divided into zones, and score points by touching the ‘pou’ (boundary markers) and hitting a central ‘tupu’ or target.[citation needed]

These games and others may well go far back into antiquity. However, the main sources of modern football codes appear to lie in western Europe, especially England.

Turkic peoples

Mahmud al-Kashgari in his Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, described a game called «tepuk» among Turks in Central Asia. In the game, people try to attack each other’s castle by kicking a ball made of sheep leather.[29]

-

A Song dynasty painting by Su Hanchen (c. 1130-1160), depicting Chinese children playing cuju

-

A group of indigenous people playing a ball game in French Guiana

-

A revived version of kemari being played at the Tanzan Shrine, Japan, 2006

Medieval and early modern Europe

The Middle Ages saw a huge rise in popularity of annual Shrovetide football matches throughout Europe, particularly in England. An early reference to a ball game played in Britain comes from the 9th-century Historia Brittonum, attributed to Nennius, which describes «a party of boys … playing at ball».[30] References to a ball game played in northern France known as La Soule or Choule, in which the ball was propelled by hands, feet, and sticks,[31] date from the 12th century.[32]

The early forms of football played in England, sometimes referred to as «mob football», would be played in towns or between neighbouring villages, involving an unlimited number of players on opposing teams who would clash en masse,[33] struggling to move an item, such as inflated animal’s bladder[34] to particular geographical points, such as their opponents’ church, with play taking place in the open space between neighbouring parishes.[35] The game was played primarily during significant religious festivals, such as Shrovetide, Christmas, or Easter,[34] and Shrovetide games have survived into the modern era in a number of English towns (see below).

The first detailed description of what was almost certainly football in England was given by William FitzStephen in about 1174–1183. He described the activities of London youths during the annual festival of Shrove Tuesday:

After lunch all the youth of the city go out into the fields to take part in a ball game. The students of each school have their own ball; the workers from each city craft are also carrying their balls. Older citizens, fathers, and wealthy citizens come on horseback to watch their juniors competing, and to relive their own youth vicariously: you can see their inner passions aroused as they watch the action and get caught up in the fun being had by the carefree adolescents.[36]

Most of the very early references to the game speak simply of «ball play» or «playing at ball». This reinforces the idea that the games played at the time did not necessarily involve a ball being kicked.

An early reference to a ball game that was probably football comes from 1280 at Ulgham, Northumberland, England: «Henry… while playing at ball.. ran against David».[37] Football was played in Ireland in 1308, with a documented reference to John McCrocan, a spectator at a «football game» at Newcastle, County Down being charged with accidentally stabbing a player named William Bernard.[38] Another reference to a football game comes in 1321 at Shouldham, Norfolk, England: «[d]uring the game at ball as he kicked the ball, a lay friend of his… ran against him and wounded himself».[37]

In 1314, Nicholas de Farndone, Lord Mayor of the City of London issued a decree banning football in the French used by the English upper classes at the time. A translation reads: «[f]orasmuch as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large foot balls [rageries de grosses pelotes de pee][39] in the fields of the public from which many evils might arise which God forbid: we command and forbid on behalf of the king, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future.» This is the earliest reference to football.

In 1363, King Edward III of England issued a proclamation banning «…handball, football, or hockey; coursing and cock-fighting, or other such idle games»,[40] showing that «football» – whatever its exact form in this case – was being differentiated from games involving other parts of the body, such as handball.

«Football» in France, circa 1750

A game known as «football» was played in Scotland as early as the 15th century: it was prohibited by the Football Act 1424 and although the law fell into disuse it was not repealed until 1906. There is evidence for schoolboys playing a «football» ball game in Aberdeen in 1633 (some references cite 1636) which is notable as an early allusion to what some have considered to be passing the ball. The word «pass» in the most recent translation is derived from «huc percute» (strike it here) and later «repercute pilam» (strike the ball again) in the original Latin. It is not certain that the ball was being struck between members of the same team. The original word translated as «goal» is «metum», literally meaning the «pillar at each end of the circus course» in a Roman chariot race. There is a reference to «get hold of the ball before [another player] does» (Praeripe illi pilam si possis agere) suggesting that handling of the ball was allowed. One sentence states in the original 1930 translation «Throw yourself against him» (Age, objice te illi).

King Henry IV of England also presented one of the earliest documented uses of the English word «football», in 1409, when he issued a proclamation forbidding the levying of money for «foteball».[37][41]

There is also an account in Latin from the end of the 15th century of football being played at Caunton, Nottinghamshire. This is the first description of a «kicking game» and the first description of dribbling: «[t]he game at which they had met for common recreation is called by some the foot-ball game. It is one in which young men, in country sport, propel a huge ball not by throwing it into the air but by striking it and rolling it along the ground, and that not with their hands but with their feet… kicking in opposite directions.» The chronicler gives the earliest reference to a football pitch, stating that: «[t]he boundaries have been marked and the game had started.[37]

Oldest known painting of foot-ball in Scotland, by Alexander Carse, c. 1810

«Football» in Scotland, c. 1830

Other firsts in the medieval and early modern eras:

- «a football», in the sense of a ball rather than a game, was first mentioned in 1486.[41] This reference is in Dame Juliana Berners’ Book of St Albans. It states: «a certain rounde instrument to play with …it is an instrument for the foote and then it is calde in Latyn ‘pila pedalis’, a fotebal.»[37]

- a pair of football boots were ordered by King Henry VIII of England in 1526.[42]

- women playing a form of football was first described in 1580 by Sir Philip Sidney in one of his poems: «[a] tyme there is for all, my mother often sayes, When she, with skirts tuckt very hy, with girles at football playes.»[43]

- the first references to goals are in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In 1584 and 1602 respectively, John Norden and Richard Carew referred to «goals» in Cornish hurling. Carew described how goals were made: «they pitch two bushes in the ground, some eight or ten foote asunder; and directly against them, ten or twelue [twelve] score off, other twayne in like distance, which they terme their Goales».[44] He is also the first to describe goalkeepers and passing of the ball between players.

- the first direct reference to scoring a goal is in John Day’s play The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green (performed circa 1600; published 1659): «I’ll play a gole at camp-ball» (an extremely violent variety of football, which was popular in East Anglia). Similarly in a poem in 1613, Michael Drayton refers to «when the Ball to throw, And drive it to the Gole, in squadrons forth they goe».

Calcio Fiorentino

An illustration of the Calcio Fiorentino field and starting positions, from a 1688 book by Pietro di Lorenzo Bini

In the 16th century, the city of Florence celebrated the period between Epiphany and Lent by playing a game which today is known as «calcio storico» («historic kickball») in the Piazza Santa Croce.[45] The young aristocrats of the city would dress up in fine silk costumes and embroil themselves in a violent form of football. For example, calcio players could punch, shoulder charge, and kick opponents. Blows below the belt were allowed. The game is said to have originated as a military training exercise. In 1580, Count Giovanni de’ Bardi di Vernio wrote Discorso sopra ‘l giuoco del Calcio Fiorentino. This is sometimes said to be the earliest code of rules for any football game. The game was not played after January 1739 (until it was revived in May 1930).

Official disapproval and attempts to ban football

There have been many attempts to ban football, from the middle ages through to the modern day. The first such law was passed in England in 1314; it was followed by more than 30 in England alone between 1314 and 1667.[46]: 6 Women were banned from playing at English and Scottish Football League grounds in 1921, a ban that was only lifted in the 1970s. Female footballers still face similar problems in some parts of the world.

American football also faced pressures to ban the sport. The game played in the 19th century resembled mob football that developed in medieval Europe, including a version popular on university campuses known as Old division football, and several municipalities banned its play in the mid-19th century.[47][48] By the 20th century, the game had evolved to a more rugby style game. In 1905, there were calls to ban American football in the U.S. due to its violence; a meeting that year was hosted by American president Theodore Roosevelt led to sweeping rules changes that caused the sport to diverge significantly from its rugby roots to become more like the sport as it is played today.[49]

Establishment of modern codes

English public schools

While football continued to be played in various forms throughout Britain, its public schools (equivalent to private schools in other countries) are widely credited with four key achievements in the creation of modern football codes. First of all, the evidence suggests that they were important in taking football away from its «mob» form and turning it into an organised team sport. Second, many early descriptions of football and references to it were recorded by people who had studied at these schools. Third, it was teachers, students, and former students from these schools who first codified football games, to enable matches to be played between schools. Finally, it was at English public schools that the division between «kicking» and «running» (or «carrying») games first became clear.

The earliest evidence that games resembling football were being played at English public schools – mainly attended by boys from the upper, upper-middle and professional classes – comes from the Vulgaria by William Herman in 1519. Herman had been headmaster at Eton and Winchester colleges and his Latin textbook includes a translation exercise with the phrase «We wyll playe with a ball full of wynde».[50]

Richard Mulcaster, a student at Eton College in the early 16th century and later headmaster at other English schools, has been described as «the greatest sixteenth Century advocate of football».[51] Among his contributions are the earliest evidence of organised team football. Mulcaster’s writings refer to teams («sides» and «parties»), positions («standings»), a referee («judge over the parties») and a coach «(trayning maister)». Mulcaster’s «footeball» had evolved from the disordered and violent forms of traditional football:

[s]ome smaller number with such overlooking, sorted into sides and standings, not meeting with their bodies so boisterously to trie their strength: nor shouldring or shuffing one an other so barbarously … may use footeball for as much good to the body, by the chiefe use of the legges.[52]

In 1633, David Wedderburn, a teacher from Aberdeen, mentioned elements of modern football games in a short Latin textbook called Vocabula. Wedderburn refers to what has been translated into modern English as «keeping goal» and makes an allusion to passing the ball («strike it here»). There is a reference to «get hold of the ball», suggesting that some handling was allowed. It is clear that the tackles allowed included the charging and holding of opposing players («drive that man back»).[53]

A more detailed description of football is given in Francis Willughby’s Book of Games, written in about 1660.[54] Willughby, who had studied at Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School, Sutton Coldfield, is the first to describe goals and a distinct playing field: «a close that has a gate at either end. The gates are called Goals.» His book includes a diagram illustrating a football field. He also mentions tactics («leaving some of their best players to guard the goal»); scoring («they that can strike the ball through their opponents’ goal first win») and the way teams were selected («the players being equally divided according to their strength and nimbleness»). He is the first to describe a «law» of football: «they must not strike [an opponent’s leg] higher than the ball».[55][56]

English public schools were the first to codify football games. In particular, they devised the first offside rules, during the late 18th century.[57] In the earliest manifestations of these rules, players were «off their side» if they simply stood between the ball and the goal which was their objective. Players were not allowed to pass the ball forward, either by foot or by hand. They could only dribble with their feet, or advance the ball in a scrum or similar formation. However, offside laws began to diverge and develop differently at each school, as is shown by the rules of football from Winchester, Rugby, Harrow and Cheltenham, during between 1810 and 1850.[57] The first known codes – in the sense of a set of rules – were those of Eton in 1815[58] and Aldenham in 1825.[58])

During the early 19th century, most working-class people in Britain had to work six days a week, often for over twelve hours a day. They had neither the time nor the inclination to engage in sport for recreation and, at the time, many children were part of the labour force. Feast day football played on the streets was in decline. Public school boys, who enjoyed some freedom from work, became the inventors of organised football games with formal codes of rules.

Football was adopted by a number of public schools as a way of encouraging competitiveness and keeping youths fit. Each school drafted its own rules, which varied widely between different schools and were changed over time with each new intake of pupils. Two schools of thought developed regarding rules. Some schools favoured a game in which the ball could be carried (as at Rugby, Marlborough and Cheltenham), while others preferred a game where kicking and dribbling the ball was promoted (as at Eton, Harrow, Westminster and Charterhouse). The division into these two camps was partly the result of circumstances in which the games were played. For example, Charterhouse and Westminster at the time had restricted playing areas; the boys were confined to playing their ball game within the school cloisters, making it difficult for them to adopt rough and tumble running games.[citation needed]

Although the Rugby School (pictured) became famous due to a version that rugby football was invented there in 1823, most sports historians refuse this version stating it is apocryphal

William Webb Ellis, a pupil at Rugby School, is said to have «with a fine disregard for the rules of football, as played in his time [emphasis added], first took the ball in his arms and ran with it, thus creating the distinctive feature of the rugby game.» in 1823. This act is usually said to be the beginning of Rugby football, but there is little evidence that it occurred, and most sports historians believe the story to be apocryphal. The act of ‘taking the ball in his arms’ is often misinterpreted as ‘picking the ball up’ as it is widely believed that Webb Ellis’ ‘crime’ was handling the ball, as in modern association football, however handling the ball at the time was often permitted and in some cases compulsory,[59] the rule for which Webb Ellis showed disregard was running forward with it as the rules of his time only allowed a player to retreat backwards or kick forwards.

The boom in rail transport in Britain during the 1840s meant that people were able to travel further and with less inconvenience than they ever had before. Inter-school sporting competitions became possible. However, it was difficult for schools to play each other at football, as each school played by its own rules. The solution to this problem was usually that the match be divided into two halves, one half played by the rules of the host «home» school, and the other half by the visiting «away» school.

The modern rules of many football codes were formulated during the mid- or late- 19th century. This also applies to other sports such as lawn bowls, lawn tennis, etc. The major impetus for this was the patenting of the world’s first lawnmower in 1830. This allowed for the preparation of modern ovals, playing fields, pitches, grass courts, etc.[60]

Apart from Rugby football, the public school codes have barely been played beyond the confines of each school’s playing fields. However, many of them are still played at the schools which created them (see Surviving UK school games below).

Public schools’ dominance of sports in the UK began to wane after the Factory Act of 1850, which significantly increased the recreation time available to working class children. Before 1850, many British children had to work six days a week, for more than twelve hours a day. From 1850, they could not work before 6 a.m. (7 a.m. in winter) or after 6 p.m. on weekdays (7 p.m. in winter); on Saturdays they had to cease work at 2 p.m. These changes meant that working class children had more time for games, including various forms of football.

The earliest known matches between public schools are as follows:

- 9 December 1834: Eton School v. Harrow School.[61]

- 1840s: Old Rugbeians v. Old Salopians (played at Cambridge University).[62]

- 1840s: Old Rugbeians v. Old Salopians (played at Cambridge University the following year).[62]

- 1852: Harrow School v. Westminster School.[62]

- 1857: Haileybury School v. Westminster School.[62]

- 24 February 1858: Forest School v. Chigwell School.[63]

- 1858: Westminster School v. Winchester College.[62]

- 1859: Harrow School v. Westminster School.[62]

- 19 November 1859: Radley College v. Old Wykehamists.[62]

- 1 December 1859: Old Marlburians v. Old Rugbeians (played at Christ Church, Oxford).[62]

- 19 December 1859: Old Harrovians v. Old Wykehamists (played at Christ Church, Oxford).[62]

Firsts

Clubs

Sheffield F.C. (here pictured in 1857, the year of its foundation) is the oldest surviving association football club in the world

Notes about a Sheffield v. Hallam match, dated 29 December 1862

Sports clubs dedicated to playing football began in the 18th century, for example London’s Gymnastic Society which was founded in the mid-18th century and ceased playing matches in 1796.[64][62]

The first documented club to bear in the title a reference to being a ‘football club’ were called «The Foot-Ball Club» who were located in Edinburgh, Scotland, during the period 1824–41.[65][66] The club forbade tripping but allowed pushing and holding and the picking up of the ball.[66]

In 1845, three boys at Rugby school were tasked with codifying the rules then being used at the school. These were the first set of written rules (or code) for any form of football.[67] This further assisted the spread of the Rugby game.

The earliest known matches involving non-public school clubs or institutions are as follows:

- 13 February 1856: Charterhouse School v. St Bartholemew’s Hospital.[68]

- 7 November 1856: Bedford Grammar School v. Bedford Town Gentlemen.[69]

- 13 December 1856: Sunbury Military College v. Littleton Gentlemen.[70]

- December 1857: Edinburgh University v. Edinburgh Academical Club.[71]

- 24 November 1858: Westminster School v. Dingley Dell Club.[72]

- 12 May 1859: Tavistock School v. Princetown School.[73]

- 5 November 1859: Eton School v. Oxford University.[74]

- 22 February 1860: Charterhouse School v. Dingley Dell Club.[75]

- 21 July 1860: Melbourne v. Richmond.[76]

- 17 December 1860: 58th Regiment v. Sheffield.[77]

- 26 December 1860: Sheffield v. Hallam.[78]

Competitions

One of the longest running football fixture is the Cordner-Eggleston Cup, contested between Melbourne Grammar School and Scotch College, Melbourne every year since 1858. It is believed by many to also be the first match of Australian rules football, although it was played under experimental rules in its first year. The first football trophy tournament was the Caledonian Challenge Cup, donated by the Royal Caledonian Society of Melbourne, played in 1861 under the Melbourne Rules.[79] The oldest football league is a rugby football competition, the United Hospitals Challenge Cup (1874), while the oldest rugby trophy is the Yorkshire Cup, contested since 1878. The South Australian Football Association (30 April 1877) is the oldest surviving Australian rules football competition. The oldest surviving soccer trophy is the Youdan Cup (1867) and the oldest national football competition is the English FA Cup (1871). The Football League (1888) is recognised as the longest running Association Football league. The first ever international football match took place between sides representing England and Scotland on 5 March 1870 at the Oval under the authority of the FA. The first Rugby international took place in 1871.

Modern balls

Richard Lindon (seen in 1880) is believed to have invented the first footballs with rubber bladders

In Europe, early footballs were made out of animal bladders, more specifically pig’s bladders, which were inflated. Later leather coverings were introduced to allow the balls to keep their shape.[80] However, in 1851, Richard Lindon and William Gilbert, both shoemakers from the town of Rugby (near the school), exhibited both round and oval-shaped balls at the Great Exhibition in London. Richard Lindon’s wife is said to have died of lung disease caused by blowing up pig’s bladders.[81] Lindon also won medals for the invention of the «Rubber inflatable Bladder» and the «Brass Hand Pump».

In 1855, the U.S. inventor Charles Goodyear – who had patented vulcanised rubber – exhibited a spherical football, with an exterior of vulcanised rubber panels, at the Paris Exhibition Universelle. The ball was to prove popular in early forms of football in the U.S.[82]

The iconic ball with a regular pattern of hexagons and pentagons (see truncated icosahedron) did not become popular until the 1960s, and was first used in the World Cup in 1970.

Modern ball passing tactics

The earliest reference to a game of football involving players passing the ball and attempting to score past a goalkeeper was written in 1633 by David Wedderburn, a poet and teacher in Aberdeen, Scotland.[83] Nevertheless, the original text does not state whether the allusion to passing as ‘kick the ball back’ (‘Repercute pilam’) was in a forward or backward direction or between members of the same opposing teams (as was usual at this time)[84]

«Scientific» football is first recorded in 1839 from Lancashire[85] and in the modern game in Rugby football from 1862[86] and from Sheffield FC as early as 1865.[87][88] The first side to play a passing combination game was the Royal Engineers AFC in 1869/70[89][90] By 1869 they were «work[ing] well together», «backing up» and benefiting from «cooperation».[91] By 1870 the Engineers were passing the ball: «Lieut. Creswell, who having brought the ball up the side then kicked it into the middle to another of his side, who kicked it through the posts the minute before time was called».[92] Passing was a regular feature of their style.[93] By early 1872 the Engineers were the first football team renowned for «play[ing] beautifully together».[94] A double pass is first reported from Derby school against Nottingham Forest in March 1872, the first of which is irrefutably a short pass: «Mr Absey dribbling the ball half the length of the field delivered it to Wallis, who kicking it cleverly in front of the goal, sent it to the captain who drove it at once between the Nottingham posts».[95] The first side to have perfected the modern formation was Cambridge University AFC[96][97][98] and introduced the 2–3–5 «pyramid» formation.[99][100]

Rugby football

The Last Scrimmage by Edwin Buckman, depicting a rugby scrum in 1871

Rugby football was thought to have been started about 1845 at Rugby School in Rugby, Warwickshire, England although forms of football in which the ball was carried and tossed date to medieval times. In Britain, by 1870, there were 49 clubs playing variations of the Rugby school game.[101] There were also «rugby» clubs in Ireland, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. However, there was no generally accepted set of rules for rugby until 1871, when 21 clubs from London came together to form the Rugby Football Union (RFU). The first official RFU rules were adopted in June 1871.[102] These rules allowed passing the ball. They also included the try, where touching the ball over the line allowed an attempt at goal, though drop-goals from marks and general play, and penalty conversions were still the main form of contest. Regardless of any form of football, the first international match between the national team of England and Scotland took place at Raeburn Place on 27 March 1871.

Rugby football split into Rugby union, Rugby league, American football, and Canadian football. Tom Wills played Rugby football in England before founding Australian rules football.

Cambridge rules

During the nineteenth century, several codifications of the rules of football were made at the University of Cambridge, in order to enable students from different public schools to play each other. The Cambridge Rules of 1863 influenced the decision of Football Association to ban Rugby-style carrying of the ball in its own first set of laws.[103]

Sheffield rules

By the late 1850s, many football clubs had been formed throughout the English-speaking world, to play various codes of football. Sheffield Football Club, founded in 1857 in the English city of Sheffield by Nathaniel Creswick and William Prest, was later recognised as the world’s oldest club playing association football.[104]

However, the club initially played its own code of football: the Sheffield rules. The code was largely independent of the public school rules, the most significant difference being the lack of an offside rule.

The code was responsible for many innovations that later spread to association football. These included free kicks, corner kicks, handball, throw-ins and the crossbar.[105] By the 1870s they became the dominant code in the north and midlands of England. At this time a series of rule changes by both the London and Sheffield FAs gradually eroded the differences between the two games until the adoption of a common code in 1877.

Australian rules football

Tom Wills, major figure in the creation of Australian football

There is archival evidence of «foot-ball» games being played in various parts of Australia throughout the first half of the 19th century. The origins of an organised game of football known today as Australian rules football can be traced back to 1858 in Melbourne, the capital city of Victoria.

In July 1858, Tom Wills, an Australian-born cricketer educated at Rugby School in England, wrote a letter to Bell’s Life in Victoria & Sporting Chronicle, calling for a «foot-ball club» with a «code of laws» to keep cricketers fit during winter.[106] This is considered by historians to be a defining moment in the creation of Australian rules football. Through publicity and personal contacts Wills was able to co-ordinate football matches in Melbourne that experimented with various rules,[107] the first of which was played on 31 July 1858. One week later, Wills umpired a schoolboys match between Melbourne Grammar School and Scotch College. Following these matches, organised football in Melbourne rapidly increased in popularity.