Как правильно пишется словосочетание «крепостное право»

- Как правильно пишется слово «крепостной»

- Как правильно пишется слово «право»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: потреба — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к словосочетанию «крепостное право»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «крепостное право»

Предложения со словосочетанием «крепостное право»

- За многие годы, прошедшие со временем отмены крепостного права, дворянство в значительной степени утратило свои экономические позиции, оно постепенно сходило с исторической арены.

- Она не забывает, что ещё недавно хотела отменить крепостное право.

- Было это во времена крепостного права, когда помещики могли продавать и покупать людей, как вещи.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «крепостное право»

- — Кабы стояло крепостное право да был бы я твой барин — я бы те, дармоеда, каждую неделю по семи раз порол!

- Санина точно что в бок кольнуло. Он вспомнил, что, разговаривая с г-жой Розелли и ее дочерью о крепостном праве, которое, по его словам, возбуждало в нем глубокое негодование, он неоднократно заверял их, что никогда и ни за что своих крестьян продавать не станет, ибо считает подобную продажу безнравственным делом.

- — А у меня щуку люди не станут есть. При крепостном праве ели, а теперь — баста! Попы — те и сейчас щук едят.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Сочетаемость слова «право»

- международное право

гражданские права

крепостное право - права человека

право собственности

право выбора - нормы права

защита прав

нарушение прав человека - право принадлежит

право является

право возникает - иметь право

получить права

оказаться права - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение словосочетания «крепостное право»

-

Крепостно́е пра́во — совокупность юридических норм, закрепляющих наиболее полную и суровую форму феодальной зависимости. Включает запрет крестьянам уходить со своих земельных наделов (то есть прикрепление крестьян к земле или «крепость» крестьян земле; беглые подлежат принудительному возврату), наследственное подчинение административной и судебной власти определённого феодала, лишение крестьян права отчуждать земельные наделы и приобретать недвижимость, иногда — возможность для феодала отчуждать крестьян без земли. (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания КРЕПОСТНОЕ ПРАВО

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «право»

- Прав не дают, права — берут… Человек должен сам себе завоевать права, если не хочет быть раздавленным грудой обязанностей…

- Почему вообще вы берете себе право решать за другого человека? Ведь это — страшное право, оно редко ведет к добру. Бойтесь его!

- Гласность — это не только право общественности критиковать, но и право дождаться вразумительного ответа, объяснения сверху.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

Крепостно́е пра́во — совокупность юридических норм, закрепляющих наиболее полную и суровую форму феодальной зависимости. Включает запрет крестьянам уходить со своих земельных наделов (то есть прикрепление крестьян к земле или «крепость» крестьян земле; беглые подлежат принудительному возврату), наследственное подчинение административной и судебной власти определённого феодала, лишение крестьян права отчуждать земельные наделы и приобретать недвижимость, иногда — возможность для феодала отчуждать крестьян без земли.

Все значения словосочетания «крепостное право»

-

За многие годы, прошедшие со временем отмены крепостного права, дворянство в значительной степени утратило свои экономические позиции, оно постепенно сходило с исторической арены.

-

Она не забывает, что ещё недавно хотела отменить крепостное право.

-

Было это во времена крепостного права, когда помещики могли продавать и покупать людей, как вещи.

- (все предложения)

- крепостной гнёт

- ликвидация крепостного права

- отменить крепостное право

- уничтожение крепостного права

- крепостная зависимость

- (ещё синонимы…)

- крестьянин

- крепость

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- беглый крепостной

- освобождать своих крепостных

- крепостные стены

- отмена крепостного права

- стали крепостными

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- международное право

- права человека

- нормы права

- право принадлежит

- иметь право

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- Разбор по составу слова «крепостной»

- Разбор по составу слова «правый»

- Как правильно пишется слово «крепостной»

- Как правильно пишется слово «право»

«Serf» redirects here. For the saint, see Saint Serf. For the type of magnetometer, see SERF. For the film, see Serf (film).

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed during the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.[1]

Unlike slaves, serfs could not be bought, sold, or traded individually though they could, depending on the area, be sold together with land. The kholops in Russia, by contrast, could be traded like regular slaves, could be abused with no rights over their own bodies, could not leave the land they were bound to, and could marry only with their lord’s permission.[citation needed] Serfs who occupied a plot of land were required to work for the lord of the manor who owned that land. In return, they were entitled to protection, justice, and the right to cultivate certain fields within the manor to maintain their own subsistence. Serfs were often required not only to work on the lord’s fields, but also in his mines and forests and to labour to maintain roads. The manor formed the basic unit of feudal society, and the lord of the manor and the villeins, and to a certain extent the serfs, were bound legally: by taxation in the case of the former, and economically and socially in the latter.

The decline of serfdom in Western Europe has sometimes been attributed to the widespread plague epidemic of the Black Death, which reached Europe in 1347 and caused massive fatalities, disrupting society.[2] Conversely, serfdom grew stronger in Central and Eastern Europe, where it had previously been less common (this phenomenon was known as «later serfdom»).

In Eastern Europe, the institution persisted until the mid-19th century. In the Austrian Empire, serfdom was abolished by the 1781 Serfdom Patent; corvées continued to exist until 1848. Serfdom was abolished in Russia in 1861.[3] Prussia declared serfdom unacceptable in its General State Laws for the Prussian States in 1792 and finally abolished it in October 1807, in the wake of the Prussian Reform Movement.[4] In Finland, Norway, and Sweden, feudalism was never fully established, and serfdom did not exist; in Denmark, serfdom-like institutions did exist in both stavns (the stavnsbånd, from 1733 to 1788) and its vassal Iceland (the more restrictive vistarband, from 1490 until 1894).

According to medievalist historian Joseph R. Strayer, the concept of feudalism can also be applied to the societies of ancient Persia, ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt (Sixth to Twelfth dynasty), Islamic-ruled Northern and Central India, China (Zhou dynasty and end of Han dynasty) and Japan during the Shogunate. Wu Ta-k’un argued that the Shang-Zhou fengjian were kinship estates, quite distinct from feudalism.[5] James Lee and Cameron Campbell describe the Chinese Qing dynasty (1644–1912) as also maintaining a form of serfdom.[6]

Melvyn Goldstein described Tibet as having had serfdom until 1959,[7][8] but whether or not the Tibetan form of peasant tenancy that qualified as serfdom was widespread is contested by other scholars.[9][10] Bhutan is described by Tashi Wangchuk, a Bhutanese civil servant, as having officially abolished serfdom by 1959, but he believes that less than or about 10% of poor peasants were in copyhold situations.[11]

The United Nations 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery also prohibits serfdom as a practice similar to slavery.[12]

History

Galician slaughter in 1846 was a revolt against serfdom, directed against manorial property and oppression.

Social institutions similar to serfdom were known in ancient times. The status of the helots in the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta resembled that of the medieval serfs. By the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire faced a labour shortage. Large Roman landowners increasingly relied on Roman freemen, acting as tenant farmers, instead of slaves to provide labour.[13]

These tenant farmers, eventually known as coloni, saw their condition steadily erode. Because the tax system implemented by Diocletian assessed taxes based on both land and the inhabitants of that land, it became administratively inconvenient for peasants to leave the land where they were counted in the census.[13]

Medieval serfdom really began with the breakup of the Carolingian Empire around the 10th century.[citation needed] During this period, powerful feudal lords encouraged the establishment of serfdom as a source of agricultural labour. Serfdom, indeed, was an institution that reflected a fairly common practice whereby great landlords were assured that others worked to feed them and were held down, legally and economically, while doing so.

This arrangement provided most of the agricultural labour throughout the Middle Ages. Slavery persisted right through the Middle Ages,[14] but it was rare.

In the later Middle Ages serfdom began to disappear west of the Rhine even as it spread through eastern Europe. Serfdom reached Eastern Europe centuries later than Western Europe – it became dominant around the 15th century. In many of these countries serfdom was abolished during the Napoleonic invasions of the early 19th century, though in some it persisted until mid- or late- 19th century.[citation needed]

Etymology

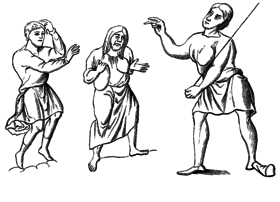

Costumes of slaves or serfs, from the sixth to the twelfth centuries, collected by H. de Vielcastel from original documents in European libraries

The word serf originated from the Middle French serf and was derived from the Latin servus («slave»). In Late Antiquity and most of the Middle Ages, what are now called serfs were usually designated in Latin as coloni. As slavery gradually disappeared and the legal status of servi became nearly identical to that of the coloni, the term changed meaning into the modern concept of «serf». The word «serf» is first recorded in English in the late 15th century, and came to its current definition in the 17th century. Serfdom was coined in 1850.[citation needed]

Dependency and the lower orders

Serfs had a specific place in feudal society, as did barons and knights: in return for protection, a serf would reside upon and work a parcel of land within the manor of his lord. Thus, the manorial system exhibited a degree of reciprocity.

One rationale held that serfs and freemen «worked for all» while a knight or baron «fought for all» and a churchman «prayed for all»; thus everyone had a place. The serf was the worst fed and rewarded however, although unlike slaves had certain rights in land and property.

A lord of the manor could not sell his serfs as a Roman might sell his slaves. On the other hand, if he chose to dispose of a parcel of land, the serfs associated with that land stayed with it to serve their new lord; simply speaking, they were implicitly sold in mass and as a part of a lot. This unified system preserved for the lord long-acquired knowledge of practices suited to the land. Further, a serf could not abandon his lands without permission,[15] nor did he possess a saleable title in them.[16]

Initiation

A freeman became a serf usually through force or necessity. Sometimes the greater physical and legal force of a local magnate intimidated freeholders or allodial owners into dependency. Often a few years of crop failure, a war, or brigandage might leave a person unable to make his own way. In such a case, he could strike a bargain with a lord of a manor. In exchange for gaining protection, his service was required: in labour, produce, or cash, or a combination of all. These bargains became formalised in a ceremony known as «bondage», in which a serf placed his head in the lord’s hands, akin to the ceremony of homage where a vassal placed his hands between those of his overlord. These oaths bound the lord and his new serf in a feudal contract and defined the terms of their agreement.[17] Often these bargains were severe.

A 7th-century Anglo Saxon «Oath of Fealty» states:

By the Lord before whom this sanctuary is holy, I will to N. be true and faithful, and love all which he loves and shun all which he shuns, according to the laws of God and the order of the world. Nor will I ever with will or action, through word or deed, do anything which is unpleasing to him, on condition that he will hold to me as I shall deserve it, and that he will perform everything as it was in our agreement when I submitted myself to him and chose his will.

To become a serf was a commitment that encompassed all aspects of the serf’s life. The children born to serfs inherited their status, and were considered born into serfdom. By taking on the duties of serfdom, people bound themselves and their progeny.

Class system

The social class of the peasantry can be differentiated into smaller categories. These distinctions were often less clear than suggested by their different names. Most often, there were two types of peasants:

- freemen, workers whose tenure within the manor was freehold

- villein

Lower classes of peasants, known as cottars or bordars, generally comprising the younger sons of villeins;[18][19] vagabonds; and slaves, made up the lower class of workers.

Coloni

The colonus system of the late Roman Empire can be considered the predecessor of Western European feudal serfdom.[20][21]

Freemen

Freemen, or free tenants held their land by one of a variety of contracts of feudal land-tenure and were essentially rent-paying tenant farmers who owed little or no service to the lord, and had a good degree of security of tenure and independence. In parts of 11th-century England freemen made up only 10% of the peasant population, and in most of the rest of Europe their numbers were also small.

Ministeriales

Ministeriales were hereditary unfree knights tied to their lord, that formed the lowest rung of nobility in the Holy Roman Empire.

Villeins

A villein (or villain) represented the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages.[dubious – discuss] Villeins had more rights and higher status than the lowest serf, but existed under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from freemen. Villeins generally rented small homes, with a patch of land. As part of the contract with the landlord, the lord of the manor, they were expected to spend some of their time working on the lord’s fields. The requirement often was not greatly onerous, contrary to popular belief, and was often only seasonal, for example the duty to help at harvest-time.[citation needed] The rest of their time was spent farming their own land for their own profit. Villeins were tied to their lord’s land and couldn’t leave it without his permission. Their lord also often decided whom they could marry.[22]

Like other types of serfs, villeins had to provide other services, possibly in addition to paying rent of money or produce. Villeins were somehow retained on their land and by unmentioned manners could not move away without their lord’s consent and the acceptance of the lord to whose manor they proposed to migrate to. Villeins were generally able to hold their own property, unlike slaves. Villeinage, as opposed to other forms of serfdom, was most common in Continental European feudalism, where land ownership had developed from roots in Roman law.

A variety of kinds of villeinage existed in Europe in the Middle Ages. Half-villeins received only half as many strips of land for their own use and owed a full complement of labour to the lord, often forcing them to rent out their services to other serfs to make up for this hardship. Villeinage was not a purely uni-directional exploitative relationship. In the Middle Ages, land within a lord’s manor provided sustenance and survival, and being a villein guaranteed access to land, and crops secure from theft by marauding robbers. Landlords, even where legally entitled to do so, rarely evicted villeins because of the value of their labour. Villeinage was much preferable to being a vagabond, a slave, or an unlanded labourer.

In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping from a manor to a city or borough and living there for more than a year; but this action involved the loss of land rights and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult.

In medieval England, two types of villeins existed–villeins regardant that were tied to land and villeins in gross that could be traded separately from land.[20]

Bordars and cottagers

In England, the Domesday Book, of 1086, uses bordarii (bordar) and cottarii (cottar) as interchangeable terms, cottar deriving from the native Anglo-Saxon tongue whereas bordar derived from the French.[23]

Status-wise, the bordar or cottar ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of a manor, holding a cottage, garden and just enough land to feed a family. In England, at the time of the Domesday Survey, this would have comprised between about 1 and 5 acres (0.4 and 2.0 hectares).[25] Under an Elizabethan statute, the Erection of Cottages Act 1588, the cottage had to be built with at least 4 acres (0.02 km2; 0.01 sq mi) of land.[26] The later Enclosures Acts (1604 onwards) removed the cottars’ right to any land: «before the Enclosures Act the cottager was a farm labourer with land and after the Enclosures Act the cottager was a farm labourer without land».[27]

The bordars and cottars did not own their draught oxen or horses. The Domesday Book showed that England comprised 12% freeholders, 35% serfs or villeins, 30% cotters and bordars, and 9% slaves.[25]

Smerd

Smerdy were a type of serfs above kholops in Medieval Poland and Kievan Rus’.

Kholops

Kholops were the lowest class of serfs in the medieval and early modern Russia. They had status similar to slaves, and could be freely traded.

Slaves

The last type of serf was the slave.[28] Slaves had the fewest rights and benefits from the manor. They owned no tenancy in land, worked for the lord exclusively and survived on donations from the landlord. It was always in the interest of the lord to prove that a servile arrangement existed, as this provided him with greater rights to fees and taxes. The status of a man was a primary issue in determining a person’s rights and obligations in many of the manorial court-cases of the period. Also, runaway slaves could be beaten if caught.

Serfdom was significantly more common than slavery throughout the feudal period. The villein was the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages. Villeins had more rights and status than those held as slaves, but were under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from the freeman. Within his constraints, a serf had some freedom. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned “only his belly”—even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lord—a serf might still accumulate personal property and wealth, and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbors, although this was rather an exception to the general rule. A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom.[29]

Duties

The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his fees and taxes in the form of seasonally appropriate labour. Usually, a portion of the week was devoted to ploughing his lord’s fields held in demesne, harvesting crops, digging ditches, repairing fences, and often working in the manor house. The remainder of the serf’s time he spent tending his own fields, crops and animals in order to provide for his family. Most manorial work was segregated by gender during the regular times of the year. During the harvest, the whole family was expected to work the fields.

A major difficulty of a serf’s life was that his work for his lord coincided with, and took precedence over, the work he had to perform on his own lands: when the lord’s crops were ready to be harvested, so were his own. On the other hand, the serf of a benign lord could look forward to being well fed during his service; it was a lord without foresight who did not provide a substantial meal for his serfs during the harvest and planting times.[citation needed] In exchange for this work on the lord’s demesne, the serfs had certain privileges and rights, including for example the right to gather deadwood – an essential source of fuel – from their lord’s forests.

In addition to service, a serf was required to pay certain taxes and fees. Taxes were based on the assessed value of his lands and holdings. Fees were usually paid in the form of agricultural produce rather than cash. The best ration of wheat from the serf’s harvest often went to the landlord. Generally hunting and trapping of wild game by the serfs on the lord’s property was prohibited. On Easter Sunday the peasant family perhaps might owe an extra dozen eggs, and at Christmas, a goose was perhaps required, too. When a family member died, extra taxes were paid to the lord as a form of feudal relief to enable the heir to keep the right to till what land he had. Any young woman who wished to marry a serf outside of her manor was forced to pay a fee for the right to leave her lord, and in compensation for her lost labour.

Often there were arbitrary tests to judge the worthiness of their tax payments. A chicken, for example, might be required to be able to jump over a fence of a given height to be considered old enough or well enough to be valued for tax purposes. The restraints of serfdom on personal and economic choice were enforced through various forms of manorial customary law and the manorial administration and court baron.

It was also a matter of discussion whether serfs could be required by law in times of war or conflict to fight for their lord’s land and property. In the case of their lord’s defeat, their own fate might be uncertain, so the serf certainly had an interest in supporting his lord.

Rights

Within his constraints, a serf had some freedoms. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned «only his belly» – even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lord – a serf might still accumulate personal property and wealth, and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbours, although this happened rarely.[30] A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom.[31]

A serf could grow what crop he saw fit on his lands, although a serf’s taxes often had to be paid in wheat. The surplus he would sell at market.

The landlord could not dispossess his serfs without legal cause and was supposed to protect them from the depredations of robbers or other lords, and he was expected to support them by charity in times of famine. Many such rights were enforceable by the serf in the manorial court.[citation needed]

Variations

Forms of serfdom varied greatly through time and regions. In some places, serfdom was merged with or exchanged for various forms of taxation.

The amount of labour required varied. In Poland, for example, it was commonly a few days per year per household in the 13th century, one day per week per household in the 14th century, four days per week per household in the 17th century, and six days per week per household in the 18th century. Early serfdom in Poland was mostly limited to the royal territories (królewszczyzny).

«Per household» means that every dwelling had to give a worker for the required number of days.[32] For example, in the 18th century, six people: a peasant, his wife, three children and a hired worker might be required to work for their lord one day a week, which would be counted as six days of labour.

Serfs served on occasion as soldiers in the event of conflict and could earn freedom or even ennoblement for valour in combat.[clarification needed] Serfs could purchase their freedom, be manumitted by generous owners, or flee to towns or to newly settled land where few questions were asked. Laws varied from country to country: in England a serf who made his way to a chartered town (i.e. a borough) and evaded recapture for a year and a day obtained his freedom and became a burgher of the town.

Serfdom by country and location

Americas

Aztec Empire

In the Aztec Empire, the Tlacotin class held similarities to serfdom. Even at its height, slaves only ever made up 2% of the population.[33]

Byzantine Empire

The paroikoi were the Byzantine equivalent of serfs.[34]

France

Serfdom in France started to diminish after the Black Death in France, when the lack of work force made manumission more common from that point onward, and by the 18th-century, serfdom had become relatively rare in most of France.

In 1779, the reforms of Jacques Necker abolished serfdom in all Crown lands in France. On the outbreak of the French Revolution of 1789, between 140.000[35] and 1,500,000[36] serfs remained in France, most of them on clerical lands[37] in Franche-Comté, Berry, Burgundy and Marche.[38][39]

However, although formal serfdom no longer existed in most of France, the feudal seigneurial laws still granted noble landlords many of the rights previously exercised over serfs, and the peasants of Auvergne, Nivernais and Champagne, though formally not serfs, could still not move freely.[40][41]

Serfdom was formally abolished in France on 4 August 1789,[42] and the remaining feudal rights that gave landlords control rights over peasants were abolished in 1789-93.[43]

Ireland

Gaelic Ireland

In Gaelic Ireland, a political and social system existing in Ireland from the prehistoric period (500 BC or earlier) up until the Norman conquest (12th century AD), the bothach («hut-dweller»), fuidir (perhaps linked to fot, «soil»)[44] and sencléithe («old dwelling-house»)[45] were low-ranked semi-free servile tenants similar to serfs.[46][47] According to Laurence Ginnell, the sencléithe and bothach «were not free to leave the territory except with permission, and in practice they usually served the flaith [prince]. They had no political or clan rights, could neither sue nor appear as witnesses, and were not free in the matter of entering into contracts. They could appear in a court of justice only in the name of the flaith or other person to whom they belonged, or whom they served, or by obtaining from an aire of the tuath to which they belonged permission to sue in his name.»[48][49] A fuidir was defined by D. A. Binchy as «a ‘tenant at will,’ settled by the lord (flaith) on a portion of the latter’s land; his services to the lord are always undefined. Although his condition is servile, he retains the right to abandon his holding on giving due notice to the lord and surrendering to him two thirds of the products of his husbandry.»[50][51]

Poland

Serfdom in Poland became the dominant form of relationship between peasants and nobility in the 17th century, and was a major feature of the economy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, although its origins can be traced back to the 12th century.

The first steps towards abolition of serfdom were enacted in the Constitution of 3 May 1791, and it was essentially eliminated by the Połaniec Manifesto. However, these reforms were partly nullified by the partition of Poland. Frederick the Great had abolished serfdom in the territories he gained from the first partition of Poland. Over the course of the 19th century, it was gradually abolished on Polish and Lithuanian territories under foreign control, as the region began to industrialize.

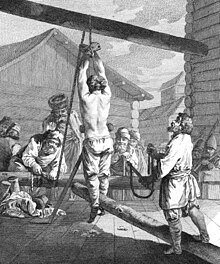

Russia

Serfdom became the dominant form of relation between Russian peasants and nobility in the 17th century. Serfdom only existed in central and southern areas of the Russian Empire. It was never established in the North, in the Urals, and in Siberia. According to the Encyclopedia of Human Rights:

In 1649 up to three-quarters of Muscovy’s peasants, or 13 to 14 million people, were serfs whose material lives were barely distinguishable from slaves. Perhaps another 1.5 million were formally enslaved, with Russian slaves serving Russian masters.[52]

Russia’s over 23 million (about 38% of the total population[53]) privately held serfs were freed from their lords by an edict of Alexander II in 1861. The owners were compensated through taxes on the freed serfs. State serfs were emancipated in 1866.[54]

Emancipation dates by country

|

|

See also

- Alipin

- Birkarls

- Colonus – early Medieval serfs

- Coolie

- Cottar

- Encomienda Spanish serfdom transplanted to the Americas

- Feudalism

- Fiefdom

- Folwark

- Freeholder

- Fugitive peasants

- Hacienda – Spanish manors

- Helot – ancient Greek serfs

- Indentured servant

- Josephinism

- Kholop

- Kolkhoz

- Maenor – Welsh manors

- Manorialism

- Ministerialis

- Peonage

- Russian serfdom

- Serfdom Patent

- Serfdom in Tibet controversy

- Serfs Emancipation Day

- Sharecropping

- Shōen – Japanese serfdom

- Slavery

- Smerd

- Subjugate

- Taeog – Welsh serfs

- Taxation as theft

- Thrall

- Yeoman – English freeholders

- Ritsuryō

- Fengjian

References

- ^ «Villeins in the Middle Ages | Middle Ages». 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8263-2871-7. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ «Serf. A Dictionary of World History«. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Edikt den erleichterten Besitz und den freien Gebrauch des Grundeigentums so wie die persönlichen Verhältnisse der Land-Bewohner betreffend Archived 12 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wu, Ta-k’un (February 1952). «An Interpretation of Chinese Economic History». Past & Present. 1 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1093/past/1.1.1.

- ^ Lee, James; Campbell, Cameron (1998). «Headship succession and household division in three Chinese banner serf populations, 1789–1909». Continuity and Change. 13 (1): 117–141. doi:10.1017/s0268416098003063. S2CID 144755944.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1986). «Re-examining Choice, Dependency and Command in the Tibetan Social System-‘Tax Appendages’ and Other Landless Serfs». Tibet Journal. 11 (4): 79–112.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1988). «On the Nature of Tibetan Peasantry». Tibet Journal. 13 (1): 61–65.

- ^ a b Barnett, Robert (2008) «What were the conditions regarding human rights in Tibet before democratic reform?» in: Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China’s 100 Questions, pp. 81–83. Eds. Anne-Marie Blondeau and Katia Buffetrille. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24464-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-520-24928-8 (paper)

- ^ a b Samuel, Geoffrey (1982). «Tibet as a Stateless Society and Some Islamic Parallels». Journal of Asian Studies. 41 (2): 215–229. doi:10.2307/2054940. JSTOR 2054940. S2CID 163321743.

- ^ a b BhutanStudies.org.bt Archived 27 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, T Wangchuk Change in the land use system in Bhutan: Ecology, History, Culture, and Power Nature Conservation Section. DoF, MoA

- ^ «Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery». United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commission. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b Mackay, Christopher (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 0521809185.

- ^ «Ways of ending slavery». Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ «serfdom». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ «Serfdom in Europe». Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Marc Bloch, Feudal Society: The Growth of the Ties of Dependence.

- ^ Studies of field systems in the British Isles, by Alan R. H. Baker, Robin Alan Butlin

- ^ An Economic History of the British Isles, by Arthur Birnie. P. 218

- ^ a b Craik, George Lillie (1846). «The Pictorial History of England: Being a History of the People, as Well as … — George Lillie Craik, Charles MacFarlane — Google Książki». Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ «The Edinburgh Review, Or Critical Journal: … To Be Continued Quarterly — Google Książki». 1842. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ «White Slavery in Colonial America: and Other Documented Facts Suppressed … — Google Książki». Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Hallam, H.E.; Finberg; Thirsk, Joan, eds. (1988). The Agrarian History of England and Wales: 1042–1350. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-521-20073-3.

- ^ Chapman, Tim (2001). Imperial Russia, 1801–1905 Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge. p.83. ISBN 0-415-23110-8

- ^ a b Daniel D. McGarry, Medieval History and Civilization (1976) p 242

- ^ Elmes, James (1827). On Architectural Jurisprudence; in which the Constitutions, Canons, Laws and Customs etc. London: W.Benning. pp. 178–179.

- ^ Hammond, J L; Barbara Hammond (1912). The Village Labourer 1760–1832. London: Longman Green & Co. p. 100.

- ^ McIntosh, Matthew (4 December 2018). «A History of Serfdom». Brewminate. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ McIntosh, Matthew (4 December 2018). «A History of Serfdom». Brewminate. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Hollister, Charles Warren; Bennett, Judith M. (2002). Medieval Europe: A Short History. McGraw-Hill. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-07-112109-5. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Bailey, Mark (2014). The Decline of Serfdom in Late Medieval England: From Bondage to Freedom. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-84383-890-6. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Maria Bogucka, Białogłowa w dawnej Polsce, Warsaw, 1998, ISBN 83-85660-78-X, p. 72

- ^ Bray, Warwick. «Everyday Life of the Aztecs» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Gregory, Timothy E. (11 January 2010). A History of Byzantium. John Wiley & Sons. p. 425. ISBN 978-1-4051-8471-7. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ The French Revolution, Napoleon, and the Republic: Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite

- ^ L.C.A. Knowles: Economic Development in the Nineteenth Century: France, Germany, Russia and …, s. 47

- ^ Jean Brissaud: A History of French Public Law, s. 327

- ^ L.C.A. Knowles: Economic Development in the Nineteenth Century: France, Germany, Russia and …, s. 47

- ^ Amy S. Wyngaard, From Savage to Citizen: The Invention of the Peasant in the French Enlightenment, s. 159

- ^ L.C.A. Knowles: Economic Development in the Nineteenth Century: France, Germany, Russia and …, s. 47

- ^ Amy S. Wyngaard, From Savage to Citizen: The Invention of the Peasant in the French Enlightenment, p. 159

- ^ Jean Brissaud: A History of French Public Law, p. 327

- ^ Christopher Thornhill, Democratic Crisis and Global Constitutional Law, p. 93

- ^ «eDIL — Irish Language Dictionary». www.dil.ie. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «eDIL — Irish Language Dictionary». www.dil.ie. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ MacManus, Seumas (1 April 2005). The Story of the Irish Race. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9781596050631. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ «An interesting life through the eyes of a slave driver». Independent. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «Bothachs and Sen-Cleithes — Brehon Laws». www.libraryireland.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «bothach». Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «fuidir». Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ «fuidir». téarma.ie. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ David P. Forsythe, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of Human Rights: Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780195334029. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Donald Mackenzie Wallace (1905). «CHAPTER XXVIII. THE SERFS». Russia. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009.

- ^ David Moon, Abolition of Serfdom in Russia: 1762–1907 (2002)

- ^ Richard Oram, ‘Rural society: 1. medieval’, in Michael Lynch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: University Press, 2005), p. 549.

- ^ a b J. A. Cannon, ‘Serfdom’, in John Cannon (ed.), The Oxford Companion to British History (Oxford: University Press, 2002), p. 852.

- ^ The Colliers (Scotland) Act 1799 (text) Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Hood family and coalmining)

- ^ a b Djuvara, Neagu (2009). Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne. Humanitas publishing house. p. 276. ISBN 978-973-50-2490-1.

- ^ [1] Archived 3 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Croatian encyclopedia, 1780 queen Maria Theresa introduced the regulations in Royal Croatia. 1785. king Joseph II introduced the Patent of freedom of movement of Serfs which gave them the right of movement, education and property, also ended their dependence to feudal lords.

- ^ Kfunigraz.ac.at Archived 29 October 2004 at archive.today

- ^ Emancipation of the Serfs Archived 7 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Backman, Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Blum, Jerome. The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe (Princeton UP, 1978)

- Coulborn, Rushton, ed. Feudalism in History. Princeton University Press, 1956.

- Bonnassie, Pierre. From Slavery to Feudalism in South-Western Europe Cambridge University Press, 1991 excerpt and text search Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Freedman, Paul, and Monique Bourin, eds. Forms of Servitude in Northern and Central Europe. Decline, Resistance and Expansion Brepols, 2005.

- Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat, eds. The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England. Glasgow: Cruithne P, 1994.

- Gorshkov, Boris B. «Serfdom: Eastern Europe» in Peter N. Stearns, ed, Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000 (2001) volume 2 pp. 379–88

- Hoch, Steven L. Serfdom and social control in Russia: Petrovskoe, a village in Tambov (1989)

- Kahan, Arcadius. «Notes on Serfdom in Western and Eastern Europe,» Journal of Economic History March 1973 33:86–99 in JSTOR Archived 12 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Kolchin, Peter. Unfree labor: American slavery and Russian serfdom (2009)

- Moon, David. The abolition of serfdom in Russia 1762–1907 (Longman, 2001)

- Scott, Tom, ed. The Peasantries of Europe (1998)

- Vadey, Liana. «Serfdom: Western Europe» in Peter N. Stearns, ed, Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000 (2001) volume 2 pp. 369–78

- White, Stephen D. Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe (2nd ed. Ashgate Variorum, 2000)

- Wirtschafter, Elise Kimerling. Russia’s age of serfdom 1649–1861 (2008)

- Wright, William E. Serf, Seigneur, and Sovereign: Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-century Bohemia (U of Minnesota Press, 1966).

- Wunder, Heide. «Serfdom in later medieval and early modern Germany» in T. H. Aston et al., Social Relations and Ideas: Essays in Honour of R. H. Hilton (Cambridge UP, 1983), 249–72

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serfdom.

- Serfdom, Encyclopædia Britannica (on-line edition).

- The Hull Project, Hull University

- Vinogradoff, Paul (1911). «Serfdom» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- Peasantry (social class), Encyclopædia Britannica.

- An excerpt from the book Serfdom to Self-Government: Memoirs of a Polish Village Mayor, 1842–1927.

- The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis, discussion and full online text of Evsey Domar (1970), «The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis», Economic History Review 30:1 (March), pp. 18–32.

«Serf» redirects here. For the saint, see Saint Serf. For the type of magnetometer, see SERF. For the film, see Serf (film).

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed during the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.[1]

Unlike slaves, serfs could not be bought, sold, or traded individually though they could, depending on the area, be sold together with land. The kholops in Russia, by contrast, could be traded like regular slaves, could be abused with no rights over their own bodies, could not leave the land they were bound to, and could marry only with their lord’s permission.[citation needed] Serfs who occupied a plot of land were required to work for the lord of the manor who owned that land. In return, they were entitled to protection, justice, and the right to cultivate certain fields within the manor to maintain their own subsistence. Serfs were often required not only to work on the lord’s fields, but also in his mines and forests and to labour to maintain roads. The manor formed the basic unit of feudal society, and the lord of the manor and the villeins, and to a certain extent the serfs, were bound legally: by taxation in the case of the former, and economically and socially in the latter.

The decline of serfdom in Western Europe has sometimes been attributed to the widespread plague epidemic of the Black Death, which reached Europe in 1347 and caused massive fatalities, disrupting society.[2] Conversely, serfdom grew stronger in Central and Eastern Europe, where it had previously been less common (this phenomenon was known as «later serfdom»).

In Eastern Europe, the institution persisted until the mid-19th century. In the Austrian Empire, serfdom was abolished by the 1781 Serfdom Patent; corvées continued to exist until 1848. Serfdom was abolished in Russia in 1861.[3] Prussia declared serfdom unacceptable in its General State Laws for the Prussian States in 1792 and finally abolished it in October 1807, in the wake of the Prussian Reform Movement.[4] In Finland, Norway, and Sweden, feudalism was never fully established, and serfdom did not exist; in Denmark, serfdom-like institutions did exist in both stavns (the stavnsbånd, from 1733 to 1788) and its vassal Iceland (the more restrictive vistarband, from 1490 until 1894).

According to medievalist historian Joseph R. Strayer, the concept of feudalism can also be applied to the societies of ancient Persia, ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt (Sixth to Twelfth dynasty), Islamic-ruled Northern and Central India, China (Zhou dynasty and end of Han dynasty) and Japan during the Shogunate. Wu Ta-k’un argued that the Shang-Zhou fengjian were kinship estates, quite distinct from feudalism.[5] James Lee and Cameron Campbell describe the Chinese Qing dynasty (1644–1912) as also maintaining a form of serfdom.[6]

Melvyn Goldstein described Tibet as having had serfdom until 1959,[7][8] but whether or not the Tibetan form of peasant tenancy that qualified as serfdom was widespread is contested by other scholars.[9][10] Bhutan is described by Tashi Wangchuk, a Bhutanese civil servant, as having officially abolished serfdom by 1959, but he believes that less than or about 10% of poor peasants were in copyhold situations.[11]

The United Nations 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery also prohibits serfdom as a practice similar to slavery.[12]

History

Galician slaughter in 1846 was a revolt against serfdom, directed against manorial property and oppression.

Social institutions similar to serfdom were known in ancient times. The status of the helots in the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta resembled that of the medieval serfs. By the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire faced a labour shortage. Large Roman landowners increasingly relied on Roman freemen, acting as tenant farmers, instead of slaves to provide labour.[13]

These tenant farmers, eventually known as coloni, saw their condition steadily erode. Because the tax system implemented by Diocletian assessed taxes based on both land and the inhabitants of that land, it became administratively inconvenient for peasants to leave the land where they were counted in the census.[13]

Medieval serfdom really began with the breakup of the Carolingian Empire around the 10th century.[citation needed] During this period, powerful feudal lords encouraged the establishment of serfdom as a source of agricultural labour. Serfdom, indeed, was an institution that reflected a fairly common practice whereby great landlords were assured that others worked to feed them and were held down, legally and economically, while doing so.

This arrangement provided most of the agricultural labour throughout the Middle Ages. Slavery persisted right through the Middle Ages,[14] but it was rare.

In the later Middle Ages serfdom began to disappear west of the Rhine even as it spread through eastern Europe. Serfdom reached Eastern Europe centuries later than Western Europe – it became dominant around the 15th century. In many of these countries serfdom was abolished during the Napoleonic invasions of the early 19th century, though in some it persisted until mid- or late- 19th century.[citation needed]

Etymology

Costumes of slaves or serfs, from the sixth to the twelfth centuries, collected by H. de Vielcastel from original documents in European libraries

The word serf originated from the Middle French serf and was derived from the Latin servus («slave»). In Late Antiquity and most of the Middle Ages, what are now called serfs were usually designated in Latin as coloni. As slavery gradually disappeared and the legal status of servi became nearly identical to that of the coloni, the term changed meaning into the modern concept of «serf». The word «serf» is first recorded in English in the late 15th century, and came to its current definition in the 17th century. Serfdom was coined in 1850.[citation needed]

Dependency and the lower orders

Serfs had a specific place in feudal society, as did barons and knights: in return for protection, a serf would reside upon and work a parcel of land within the manor of his lord. Thus, the manorial system exhibited a degree of reciprocity.

One rationale held that serfs and freemen «worked for all» while a knight or baron «fought for all» and a churchman «prayed for all»; thus everyone had a place. The serf was the worst fed and rewarded however, although unlike slaves had certain rights in land and property.

A lord of the manor could not sell his serfs as a Roman might sell his slaves. On the other hand, if he chose to dispose of a parcel of land, the serfs associated with that land stayed with it to serve their new lord; simply speaking, they were implicitly sold in mass and as a part of a lot. This unified system preserved for the lord long-acquired knowledge of practices suited to the land. Further, a serf could not abandon his lands without permission,[15] nor did he possess a saleable title in them.[16]

Initiation

A freeman became a serf usually through force or necessity. Sometimes the greater physical and legal force of a local magnate intimidated freeholders or allodial owners into dependency. Often a few years of crop failure, a war, or brigandage might leave a person unable to make his own way. In such a case, he could strike a bargain with a lord of a manor. In exchange for gaining protection, his service was required: in labour, produce, or cash, or a combination of all. These bargains became formalised in a ceremony known as «bondage», in which a serf placed his head in the lord’s hands, akin to the ceremony of homage where a vassal placed his hands between those of his overlord. These oaths bound the lord and his new serf in a feudal contract and defined the terms of their agreement.[17] Often these bargains were severe.

A 7th-century Anglo Saxon «Oath of Fealty» states:

By the Lord before whom this sanctuary is holy, I will to N. be true and faithful, and love all which he loves and shun all which he shuns, according to the laws of God and the order of the world. Nor will I ever with will or action, through word or deed, do anything which is unpleasing to him, on condition that he will hold to me as I shall deserve it, and that he will perform everything as it was in our agreement when I submitted myself to him and chose his will.

To become a serf was a commitment that encompassed all aspects of the serf’s life. The children born to serfs inherited their status, and were considered born into serfdom. By taking on the duties of serfdom, people bound themselves and their progeny.

Class system

The social class of the peasantry can be differentiated into smaller categories. These distinctions were often less clear than suggested by their different names. Most often, there were two types of peasants:

- freemen, workers whose tenure within the manor was freehold

- villein

Lower classes of peasants, known as cottars or bordars, generally comprising the younger sons of villeins;[18][19] vagabonds; and slaves, made up the lower class of workers.

Coloni

The colonus system of the late Roman Empire can be considered the predecessor of Western European feudal serfdom.[20][21]

Freemen

Freemen, or free tenants held their land by one of a variety of contracts of feudal land-tenure and were essentially rent-paying tenant farmers who owed little or no service to the lord, and had a good degree of security of tenure and independence. In parts of 11th-century England freemen made up only 10% of the peasant population, and in most of the rest of Europe their numbers were also small.

Ministeriales

Ministeriales were hereditary unfree knights tied to their lord, that formed the lowest rung of nobility in the Holy Roman Empire.

Villeins

A villein (or villain) represented the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages.[dubious – discuss] Villeins had more rights and higher status than the lowest serf, but existed under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from freemen. Villeins generally rented small homes, with a patch of land. As part of the contract with the landlord, the lord of the manor, they were expected to spend some of their time working on the lord’s fields. The requirement often was not greatly onerous, contrary to popular belief, and was often only seasonal, for example the duty to help at harvest-time.[citation needed] The rest of their time was spent farming their own land for their own profit. Villeins were tied to their lord’s land and couldn’t leave it without his permission. Their lord also often decided whom they could marry.[22]

Like other types of serfs, villeins had to provide other services, possibly in addition to paying rent of money or produce. Villeins were somehow retained on their land and by unmentioned manners could not move away without their lord’s consent and the acceptance of the lord to whose manor they proposed to migrate to. Villeins were generally able to hold their own property, unlike slaves. Villeinage, as opposed to other forms of serfdom, was most common in Continental European feudalism, where land ownership had developed from roots in Roman law.

A variety of kinds of villeinage existed in Europe in the Middle Ages. Half-villeins received only half as many strips of land for their own use and owed a full complement of labour to the lord, often forcing them to rent out their services to other serfs to make up for this hardship. Villeinage was not a purely uni-directional exploitative relationship. In the Middle Ages, land within a lord’s manor provided sustenance and survival, and being a villein guaranteed access to land, and crops secure from theft by marauding robbers. Landlords, even where legally entitled to do so, rarely evicted villeins because of the value of their labour. Villeinage was much preferable to being a vagabond, a slave, or an unlanded labourer.

In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping from a manor to a city or borough and living there for more than a year; but this action involved the loss of land rights and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult.

In medieval England, two types of villeins existed–villeins regardant that were tied to land and villeins in gross that could be traded separately from land.[20]

Bordars and cottagers

In England, the Domesday Book, of 1086, uses bordarii (bordar) and cottarii (cottar) as interchangeable terms, cottar deriving from the native Anglo-Saxon tongue whereas bordar derived from the French.[23]

Status-wise, the bordar or cottar ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of a manor, holding a cottage, garden and just enough land to feed a family. In England, at the time of the Domesday Survey, this would have comprised between about 1 and 5 acres (0.4 and 2.0 hectares).[25] Under an Elizabethan statute, the Erection of Cottages Act 1588, the cottage had to be built with at least 4 acres (0.02 km2; 0.01 sq mi) of land.[26] The later Enclosures Acts (1604 onwards) removed the cottars’ right to any land: «before the Enclosures Act the cottager was a farm labourer with land and after the Enclosures Act the cottager was a farm labourer without land».[27]

The bordars and cottars did not own their draught oxen or horses. The Domesday Book showed that England comprised 12% freeholders, 35% serfs or villeins, 30% cotters and bordars, and 9% slaves.[25]

Smerd

Smerdy were a type of serfs above kholops in Medieval Poland and Kievan Rus’.

Kholops

Kholops were the lowest class of serfs in the medieval and early modern Russia. They had status similar to slaves, and could be freely traded.

Slaves

The last type of serf was the slave.[28] Slaves had the fewest rights and benefits from the manor. They owned no tenancy in land, worked for the lord exclusively and survived on donations from the landlord. It was always in the interest of the lord to prove that a servile arrangement existed, as this provided him with greater rights to fees and taxes. The status of a man was a primary issue in determining a person’s rights and obligations in many of the manorial court-cases of the period. Also, runaway slaves could be beaten if caught.

Serfdom was significantly more common than slavery throughout the feudal period. The villein was the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages. Villeins had more rights and status than those held as slaves, but were under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from the freeman. Within his constraints, a serf had some freedom. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned “only his belly”—even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lord—a serf might still accumulate personal property and wealth, and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbors, although this was rather an exception to the general rule. A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom.[29]

Duties

The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his fees and taxes in the form of seasonally appropriate labour. Usually, a portion of the week was devoted to ploughing his lord’s fields held in demesne, harvesting crops, digging ditches, repairing fences, and often working in the manor house. The remainder of the serf’s time he spent tending his own fields, crops and animals in order to provide for his family. Most manorial work was segregated by gender during the regular times of the year. During the harvest, the whole family was expected to work the fields.

A major difficulty of a serf’s life was that his work for his lord coincided with, and took precedence over, the work he had to perform on his own lands: when the lord’s crops were ready to be harvested, so were his own. On the other hand, the serf of a benign lord could look forward to being well fed during his service; it was a lord without foresight who did not provide a substantial meal for his serfs during the harvest and planting times.[citation needed] In exchange for this work on the lord’s demesne, the serfs had certain privileges and rights, including for example the right to gather deadwood – an essential source of fuel – from their lord’s forests.

In addition to service, a serf was required to pay certain taxes and fees. Taxes were based on the assessed value of his lands and holdings. Fees were usually paid in the form of agricultural produce rather than cash. The best ration of wheat from the serf’s harvest often went to the landlord. Generally hunting and trapping of wild game by the serfs on the lord’s property was prohibited. On Easter Sunday the peasant family perhaps might owe an extra dozen eggs, and at Christmas, a goose was perhaps required, too. When a family member died, extra taxes were paid to the lord as a form of feudal relief to enable the heir to keep the right to till what land he had. Any young woman who wished to marry a serf outside of her manor was forced to pay a fee for the right to leave her lord, and in compensation for her lost labour.

Often there were arbitrary tests to judge the worthiness of their tax payments. A chicken, for example, might be required to be able to jump over a fence of a given height to be considered old enough or well enough to be valued for tax purposes. The restraints of serfdom on personal and economic choice were enforced through various forms of manorial customary law and the manorial administration and court baron.

It was also a matter of discussion whether serfs could be required by law in times of war or conflict to fight for their lord’s land and property. In the case of their lord’s defeat, their own fate might be uncertain, so the serf certainly had an interest in supporting his lord.

Rights

Within his constraints, a serf had some freedoms. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned «only his belly» – even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lord – a serf might still accumulate personal property and wealth, and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbours, although this happened rarely.[30] A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom.[31]

A serf could grow what crop he saw fit on his lands, although a serf’s taxes often had to be paid in wheat. The surplus he would sell at market.

The landlord could not dispossess his serfs without legal cause and was supposed to protect them from the depredations of robbers or other lords, and he was expected to support them by charity in times of famine. Many such rights were enforceable by the serf in the manorial court.[citation needed]

Variations

Forms of serfdom varied greatly through time and regions. In some places, serfdom was merged with or exchanged for various forms of taxation.

The amount of labour required varied. In Poland, for example, it was commonly a few days per year per household in the 13th century, one day per week per household in the 14th century, four days per week per household in the 17th century, and six days per week per household in the 18th century. Early serfdom in Poland was mostly limited to the royal territories (królewszczyzny).

«Per household» means that every dwelling had to give a worker for the required number of days.[32] For example, in the 18th century, six people: a peasant, his wife, three children and a hired worker might be required to work for their lord one day a week, which would be counted as six days of labour.

Serfs served on occasion as soldiers in the event of conflict and could earn freedom or even ennoblement for valour in combat.[clarification needed] Serfs could purchase their freedom, be manumitted by generous owners, or flee to towns or to newly settled land where few questions were asked. Laws varied from country to country: in England a serf who made his way to a chartered town (i.e. a borough) and evaded recapture for a year and a day obtained his freedom and became a burgher of the town.

Serfdom by country and location

Americas

Aztec Empire

In the Aztec Empire, the Tlacotin class held similarities to serfdom. Even at its height, slaves only ever made up 2% of the population.[33]

Byzantine Empire

The paroikoi were the Byzantine equivalent of serfs.[34]

France

Serfdom in France started to diminish after the Black Death in France, when the lack of work force made manumission more common from that point onward, and by the 18th-century, serfdom had become relatively rare in most of France.

In 1779, the reforms of Jacques Necker abolished serfdom in all Crown lands in France. On the outbreak of the French Revolution of 1789, between 140.000[35] and 1,500,000[36] serfs remained in France, most of them on clerical lands[37] in Franche-Comté, Berry, Burgundy and Marche.[38][39]

However, although formal serfdom no longer existed in most of France, the feudal seigneurial laws still granted noble landlords many of the rights previously exercised over serfs, and the peasants of Auvergne, Nivernais and Champagne, though formally not serfs, could still not move freely.[40][41]

Serfdom was formally abolished in France on 4 August 1789,[42] and the remaining feudal rights that gave landlords control rights over peasants were abolished in 1789-93.[43]

Ireland

Gaelic Ireland

In Gaelic Ireland, a political and social system existing in Ireland from the prehistoric period (500 BC or earlier) up until the Norman conquest (12th century AD), the bothach («hut-dweller»), fuidir (perhaps linked to fot, «soil»)[44] and sencléithe («old dwelling-house»)[45] were low-ranked semi-free servile tenants similar to serfs.[46][47] According to Laurence Ginnell, the sencléithe and bothach «were not free to leave the territory except with permission, and in practice they usually served the flaith [prince]. They had no political or clan rights, could neither sue nor appear as witnesses, and were not free in the matter of entering into contracts. They could appear in a court of justice only in the name of the flaith or other person to whom they belonged, or whom they served, or by obtaining from an aire of the tuath to which they belonged permission to sue in his name.»[48][49] A fuidir was defined by D. A. Binchy as «a ‘tenant at will,’ settled by the lord (flaith) on a portion of the latter’s land; his services to the lord are always undefined. Although his condition is servile, he retains the right to abandon his holding on giving due notice to the lord and surrendering to him two thirds of the products of his husbandry.»[50][51]

Poland

Serfdom in Poland became the dominant form of relationship between peasants and nobility in the 17th century, and was a major feature of the economy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, although its origins can be traced back to the 12th century.

The first steps towards abolition of serfdom were enacted in the Constitution of 3 May 1791, and it was essentially eliminated by the Połaniec Manifesto. However, these reforms were partly nullified by the partition of Poland. Frederick the Great had abolished serfdom in the territories he gained from the first partition of Poland. Over the course of the 19th century, it was gradually abolished on Polish and Lithuanian territories under foreign control, as the region began to industrialize.

Russia

Serfdom became the dominant form of relation between Russian peasants and nobility in the 17th century. Serfdom only existed in central and southern areas of the Russian Empire. It was never established in the North, in the Urals, and in Siberia. According to the Encyclopedia of Human Rights:

In 1649 up to three-quarters of Muscovy’s peasants, or 13 to 14 million people, were serfs whose material lives were barely distinguishable from slaves. Perhaps another 1.5 million were formally enslaved, with Russian slaves serving Russian masters.[52]

Russia’s over 23 million (about 38% of the total population[53]) privately held serfs were freed from their lords by an edict of Alexander II in 1861. The owners were compensated through taxes on the freed serfs. State serfs were emancipated in 1866.[54]

Emancipation dates by country

|

|

See also

- Alipin

- Birkarls

- Colonus – early Medieval serfs

- Coolie

- Cottar

- Encomienda Spanish serfdom transplanted to the Americas

- Feudalism

- Fiefdom

- Folwark

- Freeholder

- Fugitive peasants

- Hacienda – Spanish manors

- Helot – ancient Greek serfs

- Indentured servant

- Josephinism

- Kholop

- Kolkhoz

- Maenor – Welsh manors

- Manorialism

- Ministerialis

- Peonage

- Russian serfdom

- Serfdom Patent

- Serfdom in Tibet controversy

- Serfs Emancipation Day

- Sharecropping

- Shōen – Japanese serfdom

- Slavery

- Smerd

- Subjugate

- Taeog – Welsh serfs

- Taxation as theft

- Thrall

- Yeoman – English freeholders

- Ritsuryō

- Fengjian

References

- ^ «Villeins in the Middle Ages | Middle Ages». 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8263-2871-7. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ «Serf. A Dictionary of World History«. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Edikt den erleichterten Besitz und den freien Gebrauch des Grundeigentums so wie die persönlichen Verhältnisse der Land-Bewohner betreffend Archived 12 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wu, Ta-k’un (February 1952). «An Interpretation of Chinese Economic History». Past & Present. 1 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1093/past/1.1.1.

- ^ Lee, James; Campbell, Cameron (1998). «Headship succession and household division in three Chinese banner serf populations, 1789–1909». Continuity and Change. 13 (1): 117–141. doi:10.1017/s0268416098003063. S2CID 144755944.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1986). «Re-examining Choice, Dependency and Command in the Tibetan Social System-‘Tax Appendages’ and Other Landless Serfs». Tibet Journal. 11 (4): 79–112.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1988). «On the Nature of Tibetan Peasantry». Tibet Journal. 13 (1): 61–65.

- ^ a b Barnett, Robert (2008) «What were the conditions regarding human rights in Tibet before democratic reform?» in: Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China’s 100 Questions, pp. 81–83. Eds. Anne-Marie Blondeau and Katia Buffetrille. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24464-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-520-24928-8 (paper)

- ^ a b Samuel, Geoffrey (1982). «Tibet as a Stateless Society and Some Islamic Parallels». Journal of Asian Studies. 41 (2): 215–229. doi:10.2307/2054940. JSTOR 2054940. S2CID 163321743.

- ^ a b BhutanStudies.org.bt Archived 27 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, T Wangchuk Change in the land use system in Bhutan: Ecology, History, Culture, and Power Nature Conservation Section. DoF, MoA

- ^ «Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery». United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commission. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b Mackay, Christopher (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 0521809185.

- ^ «Ways of ending slavery». Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ «serfdom». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ «Serfdom in Europe». Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Marc Bloch, Feudal Society: The Growth of the Ties of Dependence.

- ^ Studies of field systems in the British Isles, by Alan R. H. Baker, Robin Alan Butlin

- ^ An Economic History of the British Isles, by Arthur Birnie. P. 218

- ^ a b Craik, George Lillie (1846). «The Pictorial History of England: Being a History of the People, as Well as … — George Lillie Craik, Charles MacFarlane — Google Książki». Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ «The Edinburgh Review, Or Critical Journal: … To Be Continued Quarterly — Google Książki». 1842. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ «White Slavery in Colonial America: and Other Documented Facts Suppressed … — Google Książki». Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Hallam, H.E.; Finberg; Thirsk, Joan, eds. (1988). The Agrarian History of England and Wales: 1042–1350. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-521-20073-3.

- ^ Chapman, Tim (2001). Imperial Russia, 1801–1905 Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge. p.83. ISBN 0-415-23110-8

- ^ a b Daniel D. McGarry, Medieval History and Civilization (1976) p 242

- ^ Elmes, James (1827). On Architectural Jurisprudence; in which the Constitutions, Canons, Laws and Customs etc. London: W.Benning. pp. 178–179.

- ^ Hammond, J L; Barbara Hammond (1912). The Village Labourer 1760–1832. London: Longman Green & Co. p. 100.

- ^ McIntosh, Matthew (4 December 2018). «A History of Serfdom». Brewminate. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ McIntosh, Matthew (4 December 2018). «A History of Serfdom». Brewminate. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Hollister, Charles Warren; Bennett, Judith M. (2002). Medieval Europe: A Short History. McGraw-Hill. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-07-112109-5. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Bailey, Mark (2014). The Decline of Serfdom in Late Medieval England: From Bondage to Freedom. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-84383-890-6. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Maria Bogucka, Białogłowa w dawnej Polsce, Warsaw, 1998, ISBN 83-85660-78-X, p. 72

- ^ Bray, Warwick. «Everyday Life of the Aztecs» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Gregory, Timothy E. (11 January 2010). A History of Byzantium. John Wiley & Sons. p. 425. ISBN 978-1-4051-8471-7. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ The French Revolution, Napoleon, and the Republic: Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite

- ^ L.C.A. Knowles: Economic Development in the Nineteenth Century: France, Germany, Russia and …, s. 47

- ^ Jean Brissaud: A History of French Public Law, s. 327

- ^ L.C.A. Knowles: Economic Development in the Nineteenth Century: France, Germany, Russia and …, s. 47

- ^ Amy S. Wyngaard, From Savage to Citizen: The Invention of the Peasant in the French Enlightenment, s. 159

- ^ L.C.A. Knowles: Economic Development in the Nineteenth Century: France, Germany, Russia and …, s. 47

- ^ Amy S. Wyngaard, From Savage to Citizen: The Invention of the Peasant in the French Enlightenment, p. 159

- ^ Jean Brissaud: A History of French Public Law, p. 327

- ^ Christopher Thornhill, Democratic Crisis and Global Constitutional Law, p. 93

- ^ «eDIL — Irish Language Dictionary». www.dil.ie. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «eDIL — Irish Language Dictionary». www.dil.ie. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ MacManus, Seumas (1 April 2005). The Story of the Irish Race. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9781596050631. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ «An interesting life through the eyes of a slave driver». Independent. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «Bothachs and Sen-Cleithes — Brehon Laws». www.libraryireland.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «bothach». Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ «fuidir». Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ «fuidir». téarma.ie. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ David P. Forsythe, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of Human Rights: Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780195334029. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Donald Mackenzie Wallace (1905). «CHAPTER XXVIII. THE SERFS». Russia. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009.

- ^ David Moon, Abolition of Serfdom in Russia: 1762–1907 (2002)

- ^ Richard Oram, ‘Rural society: 1. medieval’, in Michael Lynch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: University Press, 2005), p. 549.

- ^ a b J. A. Cannon, ‘Serfdom’, in John Cannon (ed.), The Oxford Companion to British History (Oxford: University Press, 2002), p. 852.

- ^ The Colliers (Scotland) Act 1799 (text) Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Hood family and coalmining)

- ^ a b Djuvara, Neagu (2009). Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne. Humanitas publishing house. p. 276. ISBN 978-973-50-2490-1.

- ^ [1] Archived 3 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Croatian encyclopedia, 1780 queen Maria Theresa introduced the regulations in Royal Croatia. 1785. king Joseph II introduced the Patent of freedom of movement of Serfs which gave them the right of movement, education and property, also ended their dependence to feudal lords.

- ^ Kfunigraz.ac.at Archived 29 October 2004 at archive.today

- ^ Emancipation of the Serfs Archived 7 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Backman, Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Blum, Jerome. The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe (Princeton UP, 1978)

- Coulborn, Rushton, ed. Feudalism in History. Princeton University Press, 1956.

- Bonnassie, Pierre. From Slavery to Feudalism in South-Western Europe Cambridge University Press, 1991 excerpt and text search Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Freedman, Paul, and Monique Bourin, eds. Forms of Servitude in Northern and Central Europe. Decline, Resistance and Expansion Brepols, 2005.

- Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat, eds. The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England. Glasgow: Cruithne P, 1994.

- Gorshkov, Boris B. «Serfdom: Eastern Europe» in Peter N. Stearns, ed, Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000 (2001) volume 2 pp. 379–88

- Hoch, Steven L. Serfdom and social control in Russia: Petrovskoe, a village in Tambov (1989)

- Kahan, Arcadius. «Notes on Serfdom in Western and Eastern Europe,» Journal of Economic History March 1973 33:86–99 in JSTOR Archived 12 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Kolchin, Peter. Unfree labor: American slavery and Russian serfdom (2009)

- Moon, David. The abolition of serfdom in Russia 1762–1907 (Longman, 2001)

- Scott, Tom, ed. The Peasantries of Europe (1998)

- Vadey, Liana. «Serfdom: Western Europe» in Peter N. Stearns, ed, Encyclopedia of European Social History: from 1352–2000 (2001) volume 2 pp. 369–78

- White, Stephen D. Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe (2nd ed. Ashgate Variorum, 2000)

- Wirtschafter, Elise Kimerling. Russia’s age of serfdom 1649–1861 (2008)

- Wright, William E. Serf, Seigneur, and Sovereign: Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-century Bohemia (U of Minnesota Press, 1966).

- Wunder, Heide. «Serfdom in later medieval and early modern Germany» in T. H. Aston et al., Social Relations and Ideas: Essays in Honour of R. H. Hilton (Cambridge UP, 1983), 249–72

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serfdom.

- Serfdom, Encyclopædia Britannica (on-line edition).

- The Hull Project, Hull University

- Vinogradoff, Paul (1911). «Serfdom» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- Peasantry (social class), Encyclopædia Britannica.

- An excerpt from the book Serfdom to Self-Government: Memoirs of a Polish Village Mayor, 1842–1927.