Когда российские детишки достигают определённого возраста, им начинают читать русские народные сказки, например, «Курочка ряба», «Репка», «Колобок», «Лиса и заяц», «Петушок — золотой гребешок», «Сестрица Алёнушка и братец Иванушка», «Гуси-лебеди», «Мальчик с пальчик», «Царевна-лягушка», «Иван-царевич и серый волк», и многие другие.

И всем понятно — если сказки «русские народные», значит, написал их русский народ. Однако сразу весь народ писательством заниматься не может. Значит, у сказок должны быть конкретные авторы, или даже один автор. И такой автор есть.

Автором тех сказок, которые с начала 1940-х годов издавались в СССР и издаются сейчас в России и странах СНГ как «русские народные», был русский советский писатель Алексей Николаевич Толстой, более известный как автор таких романов, как «Пётр Первый», «Аэлита», «Гиперболоид инженера Гарина».

Если говорить более точно, граф Алексей Толстой был автором не сюжетов этих сказок, а их общепринятых в настоящее время текстов, их окончательной, «канонической» редакции.

Начиная со второй половины 1850-х годов отдельные энтузиасты из числа русских дворян и разночинцев стали записывать те сказки, которые рассказывали по деревням разные бабки и дедки, и впоследствии многие из этих записей издавались в виде сборников.

В 1860-х — 1930-х годах в Российской империи и в СССР были изданы такие сборники, как «Великорусские сказки» И.А. Худякова (1860-1862), «Народные русские сказки» А.Н. Афанасьева (1864), «Сказки и предания Самарского края» Д.Н. Садовникова (1884), «Красноярский сборник» (1902), «Северные сказки» Н.Е. Ончукова (1908), «Великорусские сказки Вятской губернии» Д.К. Зеленина (1914), «Великорусские сказки Пермской губернии» того же Д.К. Зеленина (1915), «Сборник великорусских сказок Архива русского географического общества» А.М. Смирнова (1917), «Сказки Верхнеленского края» М.К. Азадовского (1925), «Пятиречие» О.З. Озаровской, «Сказки и предания Северного края» И.В. Карнаухова (1934), «Сказки Куприянихи» (1937), «Сказки Саратовской области» (1937), «Сказки» М.М. Коргуева (1939).

Общий принцип построения всех русских народных сказок одинаков и понятен — добро побеждает зло, а вот сюжеты и даже интерпретации одного и того же сюжета в разных сборниках были совершенно разные. Даже простенькая 3-страничная сказка «Кот и лиса» была записана в десятках разных вариантов.

Поэтому издательства и даже профессиональные литературоведы и исследователи фольклора постоянно путались в этом множестве разных текстов об одном и том же, и нередко возникали споры и сомнения, какой же вариант сказки издавать.

В конце 1930-х годов А.Н. Толстой решил разобраться в этом хаотическом нагромождении записей русского фольклора, и подготовить для советских издательств единообразные, стандартные тексты русских народных сказок.

Каким методом он это делал? Вот что сам Алексей Николаевич Толстой написал об этом:

«Я поступаю так: из многочисленных вариантов народной сказки выбираю наиболее интересный, коренной, и обогащаю его из других вариантов яркими языковыми оборотами и сюжетными подробностями. Разумеется, мне приходится при таком собирании сказки из отдельных частей, или «реставрации» ее, дописывать кое-что самому, кое-что видоизменять, дополнять недостающее, но делаю я это в том же стиле».

А.Н. Толстой внимательно изучил все вышеперечисленные сборники русских сказок, а также неопубликованные записи из старых архивов; кроме того, он лично встречался с некоторыми народными сказителями, и записывал их варианты сказок.

На каждую сказку Алексей Толстой завёл специальную картотеку, в которой фиксировались достоинства и недостатки различных вариантов их текстов.

В конечном итоге все сказки ему пришлось писать заново, методом «собирания сказки из отдельных частей», то есть компиляции фрагментов, и при этом фрагменты сказок очень серьёзно редактировались и дополнялись текстами собственного сочинения.

В комментариях А.Н. Нечаева к 8-му тому Собрания сочинений А.Н. Толстого в десяти томах (М.: Государственное издательство художественной литературы, 1960, с. 537-562) приводятся конкретные примеры, как Алексей Николаевич Толстой очень существенно видоизменял «исходники» русских народных сказок, и как его авторские тексты довольно серьёзно отличаются от первоначальных вариантов соответствующих сказок в других сборниках.

Итогом авторской переработки А.Н. Толстым русских народных сказок стали два сборника, выпущенных в свет в 1940 и 1944 годах. В 1945 году писатель умер, поэтому некоторые сказки были опубликованы по рукописям уже посмертно, в 1953 году.

С тех пор почти во всех случаях, когда русские народные сказки издавались в СССР, а затем и в странах СНГ, они печатались по авторским текстам Алексея Толстого.

Как уже говорилось, от «народных» вариантов сказок авторская обработка А.Н. Толстого отличалась очень сильно.

Хорошо это или плохо? Безусловно, хорошо!

Алексей Толстой был непревзойдённым мастером художественного слова, на мой взгляд, это был самый лучший русский писатель первой половины XX века, и своим талантом он мог «довести до ума» даже очень слабые тексты.

Наиболее характерный и общеизвестный пример:

Алексей Николаевич Толстой взял весьма посредственную книжку итальянского писателя Карло Коллоди «Пиноккио, или Похождения деревянной куклы», и на базе этого сюжета написал совершенно гениальную сказку «Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино», которая оказалась многократно интереснее и увлекательнее оригинала.

Многие образы из «Приключений Буратино» прочно вошли в повседневную жизнь, в русский фольклор, и в русское массовое сознание. Вспомните, например, классическую поговорку «Работаю, как папа Карло», или телепередачу «Поле чудес» (а Поле чудес в сказе про Буратино, между прочим, было в Стране дураков), существует масса анекдотов про Буратино, словом, Алексею Толстому удалось превратить итальянский сюжет в подлинно русский, и любимый народом на протяжении многих поколений.

Точно так же и авторский вариант русских народных сказок А.Н. Толстого оказался значительно удачнее, чем варианты действительно «народные».

Ссылка.

Самые известные и популярные сказки русских и советских писателей, народные сказки.

Русские литературные сказки

Василий Андреевич Жуковский (1783–1852) стал одним из родоначальников русской авторской сказки.

В сказках А.С.Пушкина (1799–1837) отразилось знакомство с разнообразными текстами, от народных сказок из собрания братьев Гримм до высокой литературы. Несомненное влияние на пушкинские сказки оказало и знакомство автора с русским фольклором.

Одна из лучших русских авторских сказок Черная курица, или Подземные жители. Волшебная повесть для детей (1829) написана Антонием Погорельским (настоящие имя и фамилия – Алексей Алексеевич Перовский, 1787–1836).

Заметную роль в становлении русской литературной и авторской сказки сыграли Владимир Иванович Даль со своими вариациями на темы русской фольклорной сказки, Петр Павлович Ершов (1815–1869), автор стихотворной сказки Конек-Горбунок (1834), Михаил Евграфович Салтыков-Щедрин (1862–1889), создатель многочисленных сатирических сказок.

Корней Иванович Чуковский (настоящие имя и фамилия – Николай Васильевич Корнейчуков, 1882–1969). создал ряд сказок, ставших классическими – Мойдодыр (1923), Тараканище (1923), Муха-цокотуха (1924), Бармалей (1925), Айболит (1929).

Интересный авторские сказки в русле народной устной традиции создали отлично знавшие северный фольклор Борис Викторович Шергин (1896–1973,и Степан Григорьевич Писахов (1879–1960).

Этапной в развитии авторской сказки стала книга Юрия Карловича Олеши (1899–1960) Три толстяка (1924, выход в свет – 1928), его единственный опыт в детской литературе.

Произведения Евгения Львовича Шварца (1896–1958) Дракон (1944), Обыкновенное чудо (1954), демонстрируют прекрасное знание западноевропейской сказки, но являются неотъемлемой частью художественного мира драматурга.

Популярной стала Алексея Николаевича Толстого (1883–1945) Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино (1936)., где рассказывается о похождениях деревянного мальчика Буратино.

Лазарь Ильич Лагин (настоящая фамилия – Гинзбург, 1903–1979), создавая повесть Старик Хоттабыч (1938) строит повествование, описывая сказочное волшебство в социалистической стране, выработавшей новый тип человека..

С пересказа книги американского писателя Л.Ф.Баума «Мудрец из страны Оз» начинал Александр Мелентьевич Волков (1891–1977), написавший повесть «Волшебник Изумрудного города» (первое издание – 1939). Вышедшие впоследствии Урфин Джюс и его деревянные солдаты, Семь подземных королей, Огненный бог Марранов, Желтый туман и Тайна Заброшенного Замка – оригинальные сочинения автора.

Переходный между литературной и авторской сказкой жанр представлен в сборниках Финист – Ясный Сокол (1947) и Волшебное кольцо (1949), собранных Андреем Платоновичем Платоновым (1899–1951). Русские народные сказки преображены настолько, что вряд ли верно называть это «обработкой».

В 50-х годах большую известность получили книги Виталия Георгиевича Губарева (1912–1981) Королевство кривых зеркал (1951), В Тридевятом царстве (1956), Трое на острове (1959). Подлинную популярность книге принес одноименный кинофильм режиссера А.А.Роу, вышедший на экран в 1963.

Триология Николая Николаевича Носова (1908–1976) Приключения Незнайки и его друзей (отдельное издание – 1954), Незнайка в Солнечном городе (отдельное издание – 1958) и Незнайка на Луне (отдельное издание – 1971) соединила в себе различные стили, от утопии до памфлета.

Валерий Владимирович Медведев (род. 1923) в повести Баранкин, будь человеком! (1962) близок к жанру научной фантастики. Превосходную авторскую сказку Шел по городу волшебник…(1963) написал ленинградский прозаик Юрий Геннадьевич Томин (настоящая фамилия – Кокош, р. 1929).

Эдуард Николаевич Успенский (род. 1937). в книге «Крокодил Гена и его друзья» (1966) создает непривычную систему персонажей, делая главным героем изобретенное им существо. Его книга Вниз по волшебной реке (1979) построена на игре с формами и стереотипами народной сказки, в данном случае фольклорное произведение приобретает черты авторской.сказки

▤ Дополняющие материалы: 100 лучших сказок мира. Гид по сказкам

70 лучших сказок русских и советских писателей

| 1 | Александр Пушкин — Руслан и Людмила |

| 2 | Александр Пушкин — Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке |

| 3 | Александр Пушкин — Сказка о царе Салтане |

| 4 | Александр Пушкин — Сказка о попе и о работнике его Балде |

| 5 | Александр Пушкин — Сказка о золотом петушке |

| 6 | Александр Пушкин — Сказка о мёртвой царевне и о семи богатырях |

| 7 | Василий Жуковский — Сказка о царе Берендее, о сыне его Иване-царевиче, о хитростях Кощея Бессмертного и о премудрости Марьи-царевны, Кощеевой дочери |

| 8 | Василий Жуковский — Сказка о Иване-царевиче и сером волке |

| 9 | Иван Крылов — Ворона и Лисица |

| 10 | Иван Крылов — Мартышка и очки |

| 11 | Иван Крылов — Лебедь, Рак и Щука |

| 12 | Иван Крылов — Стрекоза и Муравей |

| 13 | Иван Крылов — Слон и Моська |

| 14 | Сергей Аксаков — Аленький цветочек |

| 15 | Петр Ершов — Конёк-Горбунок |

| 16 | Алексей Толстой — Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино |

| 17 | Алексей Толстой — Прожорливый башмак |

| 18 | Александр Островский — Снегурочка |

| 19 | Павел Бажов — Уральские сказы |

| 20 | Николай Некрасов — Генерал Топтыгин |

| 21 | Николай Некрасов — Сказка о добром царе, злом воеводе и бедном крестьянине |

| 22 | Николай Гоголь — Вий |

| 23 | Александр Грин — Бегущая по волнам |

| 24 | Самуил Маршак — Двенадцать месяцев |

| 25 | Николай Носов — Приключения Незнайки и его друзей |

| 26 | Николай Носов — Незнайка на Луне |

| 27 | Николай Носов — Незнайка в Солнечном городе |

| 28 | Алан Александр Милн — Винни-Пух |

| 29 | Эдуард Успенский — Дядя Фёдор, пёс и кот |

| 30 | Лазарь Лагин — Старик Хоттабыч |

| 31 | Корней Чуковский — Мойдодыр |

| 32 | Корней Чуковский — Доктор Айболит |

| 33 | Евгений Велтистов — Электроник — мальчик из чемодана |

| 34 | Аркадий Гайдар — Сказка о Военной тайне, о Мальчише-Кибальчише и его твёрдом слове |

| 35 | Сергей Козлов — Сказки о ёжике и медвежонке |

| 36 | Виталий Бианки — Рассказы и сказки |

| 37 | Юрий Олеша — Три толстяка |

| 38 | Константин Паустовский — Сказки |

| 39 | Виталий Губарев — Королевство кривых зеркал |

| 40 | Александр Волков — Урфин Джюс и его деревянные солдаты |

| 41 | Виталий Бианки — Синичкин календарь |

| 42 | Евгений Шварц — Голый король |

| 43 | Валентин Катаев — Цветик-семицветик |

| 44 | Александр Волков — Волшебник Изумрудного города |

| 45 | Александр Волков — Жёлтый Туман |

| 46 | Александр Волков — Огненный бог Марранов |

| 47 | Александр Волков — Семь подземных королей |

| 48 | Борис Шергин — Волшебное кольцо |

| 49 | Валерий Медведев — Баранкин, будь человеком |

| 50 | Юрий Томин — Шёл по городу волшебник |

| 51 | Лия Гераскина — В стране невыученных уроков |

| 52 | Сергей Абрамов — Выше радуги |

| 53 | Кир Булычев — Сто лет тому вперёд |

| 54 | Владимир Одоевский — Городок в табакерке |

| 55 | Владимир Одоевский — Мороз Иванович |

| 56 | Владимир Одоевский — Индийская сказка о четырех глухих |

| 57 | Вениамин Каверин — Песочные часы |

| 58 | Софья Прокофьева — Сказка о ветре в безветренный день (Пока бьют часы) |

| 59 | Всеволод Гаршин — Attalea princeps |

| 60 | Владимир Брагин — В Стране Дремучих Трав |

| 61 | Радий Погодин — Где ты, Гдетыгдеты? |

| 62 | Дмитрий Гайдук — Растаманские Сказки |

| 63 | Андрей Малышев — Елена Прекрасная |

| 64 | Софья Ролдугина — Ключ от всех дверей |

| 65 | Виталий Губарев — В Тридевятом царстве |

| 66 | Эдуард Веркин — Серия книг «Хроника Страны Мечты» |

| 67 | Тамара Крюкова — Кот на счастье |

| 68 | Елена Данько — Побеждённый Карабас |

| 69 | Степан Григорьевич Писахов — Соломбальска бывальщина |

| 70 | Ованес Туманян. Умный и глупый |

BOOK24. САМЫЕ ПОПУЛЯРНЫЕ КНИГИ СО СКАЗКАМИ

Русские народные сказки

Фольклористы обычно выделяют 3 основных вида русских народных сказок: сказки о животных, бытовые, и волшебные сказки.

Среди русских народных сказок присутствует достаточно много сказок о животных («Лиса и Журавль», «Лиса и волк», «Теремок» и т. п.), у которых обычно простая мораль, и они отражают чаще всего отношения, существующие между людьми. Затем идут бытовые сказки, в которых прослеживаются реальные черты народной жизни («Кашица из топора», «Жена-спорщица» и т. п). Наконец, самые интересные – волшебные сказки, с необычными сюжетами, героями, превращениями и всевозможными чудесами («Марья Моревна», «Сивка-бурка» и т. п.).

Всем хорошо известны традиционные персонажи русских сказок: Баба-яга, Василиса Премудрая, Иван-царевич, волшебные помощники (утка, заяц, медведь и другие).

В народных сказках с незапамятных времен идет яростная борьба между Добром и Злом: юный Иван-царевич храбро сражается со Змеем Горынычем и побеждает его, простой крестьянин ловко одурачивает жадного попа и чертей, а Василиса Прекрасная берет верх над жестокой Бабой-ягой.

В русских сказках частым персонажем оказываются волшебные животные, которые могут разговаривать и помогать главному герою. Иногда такими животными оказываются заколдованные люди, которых необходимо освободить от власти злых чар. Наиболее часто в русских сказках присутствуют следующие животные: лягушки (Царевна-Лягушка), птицы (Гуси-лебеди, Жар-Птица), лисы (Лиса Патрикеевна), медведи (Мишка Косолапый), кошки (Кот-Баюн), волки (Серый Волк), козы (Коза-дереза), лошади (Сивка-Бурка).

Нередко персонажами становятся демонические существа (Баба-Яга, Кощей Бессмертный, Чудо-юдо, Змей-Горыныч).

Люди представлены либо мужскими (Иван-дурак, Иван-царевич, Емеля, Солдат), либо женскими (Марья Искусница, Василиса Премудрая, Елена Прекрасная, Василиса Прекрасная) вымышленными персонажами.

Также персонажами могут стать ожившие артефакты (Терёшечка, Глиняный парень, Колобок).

Звери и птицы принимают активное участие в событиях народной сказки. Часто герой спасает их, а они, в свою очередь, ему помогают – так в сказках утверждается связь человека и природы. Каждый зверь имеет в сказке определенное символичное значение. Так, ворон – птица мудрая, волк всегда зол и коварен, лисица хитра, а медведь глуп. Кроме того, сказители любят давать своим героям необычные имена: Котофей Иваныч (кот), Михаил Потапыч (медведь), Лизавета Ивановна (лиса). Приключения животных похожи на людскую жизнь.

65 лучших русских народных сказок

| 1 | Гуси-лебеди | 33 | Два Ивана — солдатских сына |

| 2 | Иван-царевич и серый волк | 34 | Два Мороза |

| 3 | Сестрица Аленушка и братец Иванушка | 35 | Елена Премудрая |

| 4 | Василиса Прекрасная | 36 | Золотая рыбка |

| 5 | Царевна-Лягушка | 37 | Иван Бесталанный и Елена Премудрая |

| 6 | Иванушка-дурачок | 38 | Иван — коровий сын |

| 7 | Колобок | 39 | Казак и ведьма |

| 8 | Репка | 40 | Как лиса шила волку шубу |

| 9 | Курочка Ряба | 41 | Кашица из топора |

| 10 | Петушок – золотой гребешок | 42 | Коза — дереза |

| 11 | Баба-Яга | 43 | Кот — серый лоб, козел да баран |

| 12 | Сивка-Бурка | 44 | Кривая уточка |

| 13 | Теремок | 45 | Мальчик с пальчик |

| 14 | Морозко | 46 | Маша и медведь |

| 15 | Иван — крестьянский сын и чудо-юдо | 47 | Медведь и лиса |

| 16 | Финист — ясный сокол | 48 | Морской царь и Василиса Премудрая |

| 17 | Волк и коза | 49 | Мужик и медведь |

| 18 | Белая уточка | 50 | Никита Кожемяка |

| 19 | Бобовое зернышко | 51 | О Ерше Ершовиче, сыне Щетинникове |

| 20 | Волшебное кольцо | 52 | О молодильных яблоках и живой воде |

| 21 | Журавль и цапля | 53 | Пастушья дудочка |

| 22 | Зимовье зверей | 54 | По щучьему веленью |

| 23 | Каша из топора | 55 | Поди туда — не знаю куда, принеси то — не знаю что |

| 24 | Летучий корабль | 56 | Поп и батрак |

| 25 | Кот и лиса | 57 | Правда и Кривда |

| 26 | Лиса и волк | 58 | Семь Симеонов |

| 27 | Лиса и журавль | 59 | Фома и Ерема |

| 28 | Лиса и кувшин | 60 | Хаврошечка |

| 29 | Мужик и медведь | 61 | Хрустальная гора |

| 30 | Никита Кожемяка | 62 | Царевна — змея |

| 31 | Хаврошечка | 63 | Чернушка |

| 32 | Марья Моревна | 64 | Чудесная рубашка |

| 65 | Яичко |

Сказки. Купить книги

Русские народные сказки. Раздел в интернет-магазине Лабиринт

labirint.ru

Сказки отечественных писателей. Раздел в интернет-магазине Лабиринт

labirint.ru

Жанр «Сказки» в книжном магазине Литрес

litres.ru

Почитать русские народные сказки

Детская электронная библиотека «Пескарь»

peskarlib.ru/skazki

Сайт «Сказки»

l-skazki.ru

Мульфильмы по руским сказкам

А

А в этой сказке было так…

Алёнушка и солдат (мультфильм)

Б

Баба Яга. Начало (мультфильм)

Бабка Ёжка и другие

Бурёнушка

В

Вернулся служивый домой

Волк и семеро козлят (мультфильм)

Волк и семеро козлят на новый лад

В некотором царстве…

Василиса Прекрасная (мультфильм)

Верлиока (мультфильм)

Вершки и корешки

Волчище — серый хвостище

Волшебная птица (мультфильм)

Г

Горе — не беда

Гуси-лебеди (мультфильм)

Д

Двенадцать месяцев (аниме)

Девочка и медведь

Дереза (мультфильм)

Ж

Жар-птица (мультфильм)

Жил у бабушки козёл

Жихарка (мультфильм, 2006)

З

Зимовье зверей (мультфильм, 1981)

И

Ивашко и Баба-Яга

К

Как поймать перо Жар-Птицы

Как старик наседкой был

Колобок (мультфильм, 1936)

Краса ненаглядная

Крылатый, мохнатый да масленый

Как грибы с горохом воевали

Каша из топора

Колобок (мультфильм, 1956)

Кот и лиса (мультфильм)

Кот Котофеевич (мультфильм)

Л

Лиса и дрозд (мультфильм)

Летучий корабль (мультфильм)

Лиса и Волк (мультфильм, 1936)

Лиса и волк (мультфильм, 1958)

Лиса и заяц

Лиса и медведь (мультфильм)

Лиса Патрикеевна (мультфильм)

Лиса, заяц и петух (мультфильм)

М

Машенька (мультфильм)

Межа (мультфильм)

Мороз Иванович (мультфильм)

Мальчик-с-пальчик (мультфильм, 1977)

Машенька и медведь (мультфильм)

Медведь — липовая нога

Молодильные яблоки (мультфильм)

П

Петушок — золотой гребешок (мультфильм)

Поди туда, не знаю куда (мультфильм)

Последняя невеста Змея Горыныча

Про деда, бабу и курочку Рябу

Петух и боярин

По щучьему велению (мультфильм, 1984)

По щучьему велению (фильм, 1970)

С

Синеглазка (мультфильм)

Сказка о солдате (мультфильм)

Сказка сказывается

Снегурочка (мультфильм, 2006)

Старик и журавль (мультфильм)

Сестрица Алёнушка и братец Иванушка (мультфильм)

Сказка о глупом муже (мультфильм)

Сказка о Снегурочке (мультфильм)

Сказка про Емелю

Снегурка (мультфильм)

Т

Теремок (мультфильм, 1937)

Теремок (мультфильм, 1945)

Терем-теремок (мультфильм)

Три дровосека

У

Уважаемый леший

У страха глаза велики

Ц

Цапля и журавль (мультфильм)

Царевна-лягушка (мультфильм, 1954)

Царевна-лягушка (мультфильм, 1971)

Царь Дурандай

Ч

Чудесный колодец

Чудесный колокольчик

Чудо-мельница

ВИДЕО

Советские фильмы по мотивам литературных и народных сказок

www.ivi.ru

Советские и российские фильмы по мотивам сказок

www.youtube.com

60 любимых советских мультфильмов по мотивам сказок

kino.mail.ru

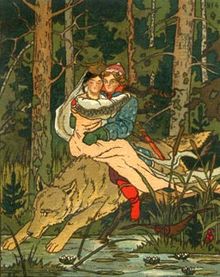

Ivan Tsarevich and the Grey Wolf (Zvorykin)

A Russian fairy tale or folktale (Russian: ска́зка; skazka; «story»; plural Russian: ска́зки, romanized: skazki) is a fairy tale from Russia.

Various sub-genres of skazka exist. A volshebnaya skazka [волше́бная ска́зка] (literally «magical tale») is considered a magical tale.[1][need quotation to verify] Skazki o zhivotnykh are tales about animals and bytovye skazki are tales about household life. These variations of skazki give the term more depth and detail different types of folktales.

Similarly to Western European traditions, especially the German-language collection published by the Brothers Grimm, Russian folklore was first collected by scholars and systematically studied in the 19th century. Russian fairy tales and folk tales were cataloged (compiled, grouped, numbered and published) by Alexander Afanasyev in his 1850s Narodnye russkie skazki. Scholars of folklore still refer to his collected texts when citing the number of a skazka plot. An exhaustive analysis of the stories, describing the stages of their plots and the classification of the characters based on their functions, was developed later, in the first half of the 20th century, by Vladimir Propp (1895-1970).

History[edit]

Appearing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fairy tales became widely popular as they spread throughout the country. Literature was considered an important factor in the education of Russian children who were meant to grow from the moral lessons in the tales. During the 18th Century Romanticism period, poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Pyotr Yershov began to define the Russian folk spirit with their stories. Throughout the 1860s, despite the rise of Realism, fairy tales still remained a beloved source of literature which drew inspiration from writers such as Hans Christian Andersen.[2] The messages in the fairy tales began to take a different shape once Joseph Stalin rose to power under the Communist movement.[3]

Popular fairy tale writer, Alexander Afanasyev

Effects of Communism[edit]

Fairy tales were thought to have a strong influence over children which is why Joseph Stalin decided to place restrictions upon the literature distributed under his rule. The tales created in the mid 1900s were used to impose Socialist beliefs and values as seen in numerous popular stories.[3] In comparison to stories from past centuries, fairy tales in the USSR had taken a more modern spin as seen in tales such as in Anatoliy Mityaev’s Grishka and the Astronaut. Past tales such as Alexander Afanasyev’s The Midnight Dance involved nobility and focused on romance.[4] Grishka and the Astronaut, though, examines modern Russian’s passion to travel through space as seen in reality with the Space Race between Russia and the United States.[5] The new tales included a focus on innovations and inventions that could help characters in place of magic which was often used as a device in past stories.

Influences[edit]

Russian kids listening to a new fairy tale

In Russia, the fairy tale is one sub-genre of folklore and is usually told in the form of a short story. They are used to express different aspects of the Russian culture. In Russia, fairy tales were propagated almost exclusively orally, until the 17th century, as written literature was reserved for religious purposes.[6] In their oral form, fairy tales allowed the freedom to explore the different methods of narration. The separation from written forms led Russians to develop techniques that were effective at creating dramatic and interesting stories. Such techniques have developed into consistent elements now found in popular literary works; They distinguish the genre of Russian fairy tales. Fairy tales were not confined to a particular socio-economic class and appealed to mass audiences, which resulted in them becoming a trademark of Russian culture.[7]

Cultural influences on Russian fairy tales have been unique and based on imagination. Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Polish-American author and Nobel Prize winner, claims that, “You don’t ask questions about a tale, and this is true for the folktales of all nations. They were not told as fact or history but as a means to entertain the listener, whether he was a child or an adult. Some contain a moral, others seem amoral or even antimoral, Some constitute fables on man’s follies and mistakes, others appear pointless.» They were created to entertain the reader.[8]

Russian fairy tales are extremely popular and are still used to inspire artistic works today. The Sleeping Beauty is still played in New York at the American Ballet Theater and has roots to original Russian fairy tales from 1890. Mr. Ratmansky’s, the artist-in-residence for the play, gained inspiration for the play’s choreography from its Russian background.[9]

Formalism[edit]

From the 1910s through the 1930s, a wave of literary criticism emerged in Russia, called Russian formalism by critics of the new school of thought.[10]

Analysis[edit]

Many different approaches of analyzing the morphology of the fairy tale have appeared in scholarly works. Differences in analyses can arise between synchronic and diachronic approaches.[11][12] Other differences can come from the relationship between story elements. After elements are identified, a structuralist can propose relationships between those elements. A paradigmatic relationship between elements is associative in nature whereas a syntagmatic relationship refers to the order and position of the elements relative to the other elements.[12]

A Russian Garland of Fairy Tales

Motif[edit]

Before the period of Russian formalism, beginning in 1910, Alexander Veselovksky called the motif the «simplest narrative unit.»[13] Veselovsky proposed that the different plots of a folktale arise from the unique combinations of motifs.

Motif analysis was also part of Stith Thompson’s approach to folkloristics.[14] Thompson’s research into the motifs of folklore culminated in the publication of the Motif-Index of Folk Literature.[15]

Structural[edit]

In 1919, Viktor Shklovsky published his essay titled «The Relationship Between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style».[13] As a major proponent during Russian formalism,[16] Shklovsky was one of the first scholars to criticize the failing methods of literary analysis and report on a syntagmatic approach to folktales. In his essay he claims, «It is my purpose to stress not so much the similarity of motifs, which I consider of little significance, as the similarity in the plot schemata.»[13]

Syntagmatic analysis, championed by Vladimir Propp, is the approach in which the elements of the fairy tale are analyzed in the order that they appear in the story. Wanting to overcome what he thought was arbitrary and subjective analysis of folklore by motif,[17] Propp published his book Morphology of the Folktale in 1928.[16] The book specifically states that Propp finds a dilemma in Veselovsky’s definition of a motif; it fails because it can be broken down into smaller units, contradicting its definition.[7] In response, Propp pioneered a specific breakdown that can be applied to most Aarne-Thompson type tales classified with numbers 300-749.[7][18] This methodology gives rise to Propp’s 31 functions, or actions, of the fairy tale.[18] Propp proposes that the functions are the fundamental units the story and that there are exactly 31 distinct functions. He observed in his analysis of 100 Russian fairy tales that tales almost always adhere to the order of the functions. The traits of the characters, or dramatis personae, involved in the actions are second to the action actually being carried out. This also follows his finding that while some functions may be missing between different stories, the order is kept the same for all the Russian fairy tales he analyzed.[7]

Alexander Nikiforov, like Shklovsky and Propp, was a folklorist in 1920s Soviet Russia. His early work also identified the benefits of a syntagmatic analysis of fairy tale elements. In his 1926 paper titled «The Morphological Study of Folklore», Nikiforov states that «Only the functions of the character, which constitute his dramatic role in the folk tale, are invariable.»[13] Since Nikiforov’s essay was written almost 2 years before Propp’s publication of Morphology of the Folktale[19], scholars have speculated that the idea of the function, widely attributed to Propp, could have first been recognized by Nikiforov.[20] One source claims that Nikiforov’s work was «not developed into a systematic analysis of syntagmatics» and failed to «keep apart structural principles and atomistic concepts».[17] Nikiforov’s work on folklore morphology was never pursued beyond his paper.[19]

Writers and collectors[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev began writing fairy tales at a time when folklore was viewed as simple entertainment. His interest in folklore stemmed from his interest in ancient Slavic mythology. During the 1850s, Afanasyev began to record part of his collection from tales dating to Boguchar, his birthplace. More of his collection came from the work of Vladimir Dhal and the Russian Geographical Society who collected tales from all around the Russian Empire.[21] Afanasyev was a part of the few who attempted to create a written collection of Russian folklore. This lack in collections of folklore was due to the control that the Church Slavonic had on printed literature in Russia, which allowed for only religious texts to be spread. To this, Afanasyev replied, “There is a million times more morality, truth and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness!”[22]

Between 1855 and 1863, Afanasyev edited Popular Russian Tales[Narodnye russkie skazki], which had been modeled after the Grimm’s Tales. This publication had a vast cultural impact over Russian scholars by establishing a desire for folklore studies in Russia. The rediscovery of Russian folklore through written text led to a generation of great Russian authors to come forth. Some of these authors include Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Folktales were quickly produced in written text and adapted. Since the production of this collection, Russian tales remain understood and recognized all over Russia.[21]

Alexander Pushkin[edit]

Alexander Pushkin is known as one of Russia’s leading writers and poets.[23] He is known for popularizing fairy tales in Russia and changed Russian literature by writing stories no one before him could.[24] Pushkin is considered Russia’s Shakespeare as, during a time when most of the Russian population was illiterate, he gave Russian’s the ability to desire in a less-strict Christian and a more pagan way through his fairy tales.[25]

Pushkin gained his love for Russian fairy tales from his childhood nurse, Ariana Rodionovna, who told him stories from her village when he was young.[26] His stories served importance to Russians past his death in 1837, especially during times political turmoil during the start of the 20th century, in which, “Pushkin’s verses gave children the Russian language in its most perfect magnificence, a language which they may never hear or speak again, but which will remain with them as an eternal treasure.”[27]

The value of his fairy tales was established a hundred years after Pushkin’s death when the Soviet Union declared him a national poet. Pushkin’s work was previously banned during the Czarist rule. During the Soviet Union, his tales were seen acceptable for education, since Pushkin’s fairy tales spoke of the poor class and had anti-clerical tones.[28]

Corpus[edit]

According to scholarship, some of «most popular or most significant» types of Russian Magic Tales (or Wonder Tales) are the following:[a][30]

| Tale number | Russian classification | Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index Grouping | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | The Winner of the Snake | The Dragon-Slayer | ||

| 301 | The Three Kingdoms | The Three Stolen Princesses | The Norka; Dawn, Midnight and Twilight | [b] |

| 302 | Kashchei’s Death in an Egg | Ogre’s (Devil’s) Heart in the Egg | The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

| 307 | The Girl Who Rose from the Grave | The Princess in the Coffin | Viy | [c] |

| 313 | Magic Escape | The Magic Flight | The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise | [d] |

| 315 | The Feigned Illness (beast’s milk) | The Faithless Sister | ||

| 325 | Crafty Knowledge | The Magician and his Pupil | [e] | |

| 327 | Children at Baba Yaga’s Hut | Children and the Ogre | ||

| 327C | Ivanusha and the Witch | The Devil (Witch) Carries the Hero Home in a Sack | [f] | |

| 400 | The husband looks for his wife, who has disappeared or been stolen (or a wife searches for her husband) | The Man on a Quest for The Lost Wife | The Maiden Tsar | |

| 461 | Mark the Rich | Three Hairs of the Devil’s Beard | The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars (Serbian); Vassili The Unlucky | [g] |

| 465 | The Beautiful Wife | The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | [h] |

| 480 | Stepmother and Stepdaughter | The Kind and Unkind Girls | Vasilissa the Beautiful | |

| 519 | The Blind Man and the Legless Man | The Strong Woman as Bride (Brunhilde) | [i][j][k] | |

| 531 | The Little Hunchback Horse | The Clever Horse | The Humpbacked Horse; The Firebird and Princess Vasilisa | [l] |

| 545B | Puss in Boots | The Cat as Helper | ||

| 555 | Kitten-Gold Forehead (a gold fish, a magical tree) | The Fisherman and His Wife | The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish | [m][n] |

| 560 | The Magic Ring | The Magic Ring | [o][p] | |

| 567 | The Marvelous Bird | The Magic Bird-Heart | ||

| 650A | Ivan the Bear’s Ear | Strong John | ||

| 706 | The Handless | The Maiden Without Hands | ||

| 707 | The Tale of Tsar Saltan [Marvelous Children] | The Three Golden Children | Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Wicked Sisters | [q] |

| 709 | The Dead Tsarina or The Dead Tsarevna | Snow White | The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights | [r] |

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Propp’s The Russian Folktale lists types 301, 302, 307, 315, 325, 327, 400, 461, 465, 519, 545B, 555, 560, 567 and 707.[29]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 301, «The Three Kingdoms and the Stolen Princesses», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 45 variants. The type was also the second «most frequently collected in Ukraine», with 31 texts.[31]

- ^ French folklorist Paul Delarue noticed that the tale type, despite existing «throughout Europe», is well known in Russia, where it found «its favorite soil».[32] Likewise, Jack Haney stated that type 307 was «most common» among East Slavs.[33]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 313, «The Magic Flight», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 41 variants. The type was also the «most frequently collected» in Ukraine, with 37 texts.[34]

- ^ Commenting on a Russian tale collected in the 20th century, Richard Dorson stated that the type was «one of the most widespread Russian Märchen».[35] In the East Slavic populations, scholarship registers 42 Russian variants, 25 Ukrainian and 10 Belarrussian.[36]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type of a fishing boy and a witch «[is] common among the various East European peoples.»[37]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type is popular among the East Slavs[38]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type, including previous type AaTh 465A, is «especially common in Russia».[39]

- ^ Russian researcher Dobrovolskaya Varvara Evgenievna stated that tale type ATU 519 (SUS 519) «belongs to the core of» the Russian tale corpus, due to «the presence of numerous variants».[40]

- ^ Following Löwis de Menar’s study, Walter Puchner concluded on its diffusion especially in the East Slavic area.[41]

- ^ Stith Thompson also located this tale type across Russia and the Baltic regions.[42]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type «is extremely popular in all three branches of East Slavic».[43]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type is «common among the East Slavs».[44]

- ^ The variation on the wish-giving entity is also attested in Estonia, whose variants register a golden fish, crayfish, or a sacred tree.[45]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «very common in all the East Slavic traditions».[46]

- ^ Wolfram Eberhard reported «45 variants in Russia alone».[47]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «a very common East Slavic type».[48]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «especially common in Russian and Ukrainian».[49]

References[edit]

- ^ «Magic tale (volshebnaia skazka), also called fairy tale». Kononenko, Natalie (2007). Slavic Folklore: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-313-33610-2.

- ^ Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories : the History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574-2010). Brill, 2013.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. “Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union.” Slavic Review, vol. 32, no. 1, 1973, pp. 45–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494072.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. “The Midnight Dance.” The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces, 1855, www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0306.html.

- ^ Mityayev, Anatoli. Grishka and the Astronaut. Translated by Ronald Vroon, Progress, 1981.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service». Marvels & Tales. 16 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1353/mat.2002.0024. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 41388626. S2CID 163086804.

- ^ a b c d Propp, V. I︠A︡. Morphology of the folktale. ISBN 9780292783768. OCLC 1020077613.

- ^ Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1975-11-16). «Russian Fairy Tales». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Greskovic, Robert (2015-06-02). «‘The Sleeping Beauty’ Review: Back to Its Russian Roots». Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Erlich, Victor (1973). «Russian Formalism». Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (4): 627–638. doi:10.2307/2708893. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708893.

- ^ Saussure, Ferdinand de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Baskin, Wade., Meisel, Perry., Saussy, Haun, 1960-. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231527958. OCLC 826479070.

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur Asa (February 2018). Media analysis techniques. ISBN 9781506366210. OCLC 1000297853.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Terence Patrick (2015). The Fairytale and Plot Structure. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781137547088. OCLC 944065310.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1997). «The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique». Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 3814885.

- ^ Kuehnel, Richard; Lencek, Rado. «What is a Folklore Motif?». www.aktuellum.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ a b Propp, V. I︠A︡.; Пропп, В. Я. (Владимир Яковлевич), 1895-1970 (2012). The Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337219. OCLC 843208720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maranda, Pierre (1974). Soviet structural folkloristics. Meletinskiĭ, E. M. (Eleazar Moiseevich), Jilek, Wolfgang. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 978-9027926838. OCLC 1009096.

- ^ a b Aguirre, Manuel (October 2011). «AN OUTLINE OF PROPP’S MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF FAIRYTALES» (PDF). Tools and Frames – via The Northanger Library Project.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. (2019). The Study of Russian Folklore. Soudakoff, Stephen. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 9783110813913. OCLC 1089596763.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1973). «Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union». Slavic Review. 32 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2494072. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494072.

- ^ a b Levchin, Sergey (2014-04-28). «Russian Folktales from the Collection of A. Afanasyev : A Dual-Language Book».

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1991). Alexander Pushkin : a critical study. The Bristol Press. ISBN 978-1853991721. OCLC 611246966.

- ^ Alexander S. Pushkin, Zimniaia Doroga, ed. by Irina Tokmakova (Moscow: Detskaia Literatura, 1972).

- ^ Bethea, David M. (2010). Realizing Metaphors : Alexander Pushkin and the Life of the Poet. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299159733. OCLC 929159387.

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Akhmatova, “Pushkin i deti,” radio broadcast script prepared in 1963, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, May 1, 1974.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria. «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service.» Marvels & Tales (2002): 171-187.

- ^ The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 215. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Delarue, Paul. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 386.

- ^ Haney, Jack V.; with Sibelan Forrester. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume III. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2021. p. 536.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Горяева, Б. Б. (2011). «Сюжет «Волшебник и его ученик» (at 325) в калмыцкой сказочной традиции». In: Oriental Studies (2): 153. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-volshebnik-i-ego-uchenik-at-325-v-kalmytskoy-skazochnoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 554. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Добровольская Варвара Евгеньевна (2018). «Сказка «слепой и безногий» (сус 519) в репертуаре русских сказочников: фольклорная реализация литературного сюжета». Вопросы русской литературы, (4 (46/103)): 93-113 (111). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-slepoy-i-beznogiy-sus-519-v-repertuare-russkih-skazochnikov-folklornaya-realizatsiya-literaturnogo-syuzheta (дата обращения: 01.09.2021).

- ^ Krauss, Friedrich Salomo; Volkserzählungen der Südslaven: Märchen und Sagen, Schwänke, Schnurren und erbauliche Geschichten. Burt, Raymond I. and Puchner, Walter (eds). Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2002. p. 615. ISBN 9783205994572.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2015 [2001]. p. 434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. p. 718. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram. Folktales of China. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1956. p. 143.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

Further reading[edit]

- Лутовинова, Е.И. (2018). Тематические группы сюжетов русских народных волшебных сказок. Педагогическое искусство, (2): 62-68. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tematicheskie-gruppy-syuzhetov-russkih-narodnyh-volshebnyh-skazok (дата обращения: 27.08.2021). (in Russian)

The Three Kingdoms (ATU 301):

- Лызлова Анастасия Сергеевна (2019). Cказки о трех царствах (медном, серебряном и золотом) в лубочной литературе и фольклорной традиции [FAIRY TALES ABOUT THREE KINGDOMS (THE COPPER, SILVER AND GOLD ONES) IN POPULAR LITERATURE AND RUSSIAN FOLK TRADITION]. Проблемы исторической поэтики, 17 (1): 26-44. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ckazki-o-treh-tsarstvah-mednom-serebryanom-i-zolotom-v-lubochnoy-literature-i-folklornoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Матвеева, Р. П. (2013). Русские сказки на сюжет «Три подземных царства» в сибирском репертуаре [RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES ON THE PLOT « THREE UNDERGROUND KINGDOMS» IN THE SIBERIAN REPERTOIRE]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Философия, (10): 170-175. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkie-skazki-na-syuzhet-tri-podzemnyh-tsarstva-v-sibirskom-repertuare (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Терещенко Анна Васильевна (2017). Фольклорный сюжет «Три царства» в сопоставительном аспекте: на материале русских и селькупских сказок [COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FOLKLORE PLOT “THREE STOLEN PRINCESSES”: RUSSIAN AND SELKUP FAIRY TALES DATA]. Вестник Томского государственного педагогического университета, (6 (183)): 128-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/folklornyy-syuzhet-tri-tsarstva-v-sopostavitelnom-aspekte-na-materiale-russkih-i-selkupskih-skazok (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

Crafty Knowledge (ATU 325):

- Трошкова Анна Олеговна (2019). «Сюжет «Хитрая наука» (сус 325) в русской волшебной сказке» [THE PLOT “THE MAGICIAN AND HIS PUPIL” (NO. 325 OF THE COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS) IN THE RUSSIAN FAIRY TALE]. Вестник Марийского государственного университета, 13 (1 (33)): 98-107. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-hitraya-nauka-sus-325-v-russkoy-volshebnoy-skazke (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Troshkova, A.O. «Plot CIP 325 Crafty Lore / ATU 325 «The Magician and His Pupil» in Catalogues of Tale Types by A. Aarne (1910), Aarne — Thompson (1928, 1961), G. Uther (2004), N. P. Andreev (1929) and L. G. Barag (1979)». In: Traditional culture. 2019. Vol. 20. No. 5. pp. 85—88. DOI: 10.26158/TK.2019.20.5.007 (In Russian).

- Troshkova, A (2019). «The tale type ‘The Magician and His Pupil’ in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)». Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376. (In Russian)

Mark the Rich or Marko Bogatyr (ATU 461):

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2017). Легенда о Христе в составе сказки о Марко Богатом: устные и книжные источники славянских повествований [LEGEND OF CHRIST WITHIN THE FOLKTALE ABOUT MARKO THE RICH: ORAL AND BOOK SOURCES OF SLAVIC NARRATIVES]. Вестник славянских культур, 46 (4): 122-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/legenda-o-hriste-v-sostave-skazki-o-marko-bogatom-ustnye-i-knizhnye-istochniki-slavyanskih-povestvovaniy (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2019). Разновидности сюжета о Марко Богатом (AaTh 930) в восточно- и южнославянских записях [VERSIONS OF THE PLOT ABOUT MARKO THE RICH (AATH 930) IN THE EAST- AND SOUTH SLAVIC TEXTS]. Вестник славянских культур, 52 (2): 104-116. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/raznovidnosti-syuzheta-o-marko-bogatom-aath-930-v-vostochno-i-yuzhnoslavyanskih-zapisyah (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

External links[edit]

Ivan Tsarevich and the Grey Wolf (Zvorykin)

A Russian fairy tale or folktale (Russian: ска́зка; skazka; «story»; plural Russian: ска́зки, romanized: skazki) is a fairy tale from Russia.

Various sub-genres of skazka exist. A volshebnaya skazka [волше́бная ска́зка] (literally «magical tale») is considered a magical tale.[1][need quotation to verify] Skazki o zhivotnykh are tales about animals and bytovye skazki are tales about household life. These variations of skazki give the term more depth and detail different types of folktales.

Similarly to Western European traditions, especially the German-language collection published by the Brothers Grimm, Russian folklore was first collected by scholars and systematically studied in the 19th century. Russian fairy tales and folk tales were cataloged (compiled, grouped, numbered and published) by Alexander Afanasyev in his 1850s Narodnye russkie skazki. Scholars of folklore still refer to his collected texts when citing the number of a skazka plot. An exhaustive analysis of the stories, describing the stages of their plots and the classification of the characters based on their functions, was developed later, in the first half of the 20th century, by Vladimir Propp (1895-1970).

History[edit]

Appearing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fairy tales became widely popular as they spread throughout the country. Literature was considered an important factor in the education of Russian children who were meant to grow from the moral lessons in the tales. During the 18th Century Romanticism period, poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Pyotr Yershov began to define the Russian folk spirit with their stories. Throughout the 1860s, despite the rise of Realism, fairy tales still remained a beloved source of literature which drew inspiration from writers such as Hans Christian Andersen.[2] The messages in the fairy tales began to take a different shape once Joseph Stalin rose to power under the Communist movement.[3]

Popular fairy tale writer, Alexander Afanasyev

Effects of Communism[edit]

Fairy tales were thought to have a strong influence over children which is why Joseph Stalin decided to place restrictions upon the literature distributed under his rule. The tales created in the mid 1900s were used to impose Socialist beliefs and values as seen in numerous popular stories.[3] In comparison to stories from past centuries, fairy tales in the USSR had taken a more modern spin as seen in tales such as in Anatoliy Mityaev’s Grishka and the Astronaut. Past tales such as Alexander Afanasyev’s The Midnight Dance involved nobility and focused on romance.[4] Grishka and the Astronaut, though, examines modern Russian’s passion to travel through space as seen in reality with the Space Race between Russia and the United States.[5] The new tales included a focus on innovations and inventions that could help characters in place of magic which was often used as a device in past stories.

Influences[edit]

Russian kids listening to a new fairy tale

In Russia, the fairy tale is one sub-genre of folklore and is usually told in the form of a short story. They are used to express different aspects of the Russian culture. In Russia, fairy tales were propagated almost exclusively orally, until the 17th century, as written literature was reserved for religious purposes.[6] In their oral form, fairy tales allowed the freedom to explore the different methods of narration. The separation from written forms led Russians to develop techniques that were effective at creating dramatic and interesting stories. Such techniques have developed into consistent elements now found in popular literary works; They distinguish the genre of Russian fairy tales. Fairy tales were not confined to a particular socio-economic class and appealed to mass audiences, which resulted in them becoming a trademark of Russian culture.[7]

Cultural influences on Russian fairy tales have been unique and based on imagination. Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Polish-American author and Nobel Prize winner, claims that, “You don’t ask questions about a tale, and this is true for the folktales of all nations. They were not told as fact or history but as a means to entertain the listener, whether he was a child or an adult. Some contain a moral, others seem amoral or even antimoral, Some constitute fables on man’s follies and mistakes, others appear pointless.» They were created to entertain the reader.[8]

Russian fairy tales are extremely popular and are still used to inspire artistic works today. The Sleeping Beauty is still played in New York at the American Ballet Theater and has roots to original Russian fairy tales from 1890. Mr. Ratmansky’s, the artist-in-residence for the play, gained inspiration for the play’s choreography from its Russian background.[9]

Formalism[edit]

From the 1910s through the 1930s, a wave of literary criticism emerged in Russia, called Russian formalism by critics of the new school of thought.[10]

Analysis[edit]

Many different approaches of analyzing the morphology of the fairy tale have appeared in scholarly works. Differences in analyses can arise between synchronic and diachronic approaches.[11][12] Other differences can come from the relationship between story elements. After elements are identified, a structuralist can propose relationships between those elements. A paradigmatic relationship between elements is associative in nature whereas a syntagmatic relationship refers to the order and position of the elements relative to the other elements.[12]

A Russian Garland of Fairy Tales

Motif[edit]

Before the period of Russian formalism, beginning in 1910, Alexander Veselovksky called the motif the «simplest narrative unit.»[13] Veselovsky proposed that the different plots of a folktale arise from the unique combinations of motifs.

Motif analysis was also part of Stith Thompson’s approach to folkloristics.[14] Thompson’s research into the motifs of folklore culminated in the publication of the Motif-Index of Folk Literature.[15]

Structural[edit]

In 1919, Viktor Shklovsky published his essay titled «The Relationship Between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style».[13] As a major proponent during Russian formalism,[16] Shklovsky was one of the first scholars to criticize the failing methods of literary analysis and report on a syntagmatic approach to folktales. In his essay he claims, «It is my purpose to stress not so much the similarity of motifs, which I consider of little significance, as the similarity in the plot schemata.»[13]

Syntagmatic analysis, championed by Vladimir Propp, is the approach in which the elements of the fairy tale are analyzed in the order that they appear in the story. Wanting to overcome what he thought was arbitrary and subjective analysis of folklore by motif,[17] Propp published his book Morphology of the Folktale in 1928.[16] The book specifically states that Propp finds a dilemma in Veselovsky’s definition of a motif; it fails because it can be broken down into smaller units, contradicting its definition.[7] In response, Propp pioneered a specific breakdown that can be applied to most Aarne-Thompson type tales classified with numbers 300-749.[7][18] This methodology gives rise to Propp’s 31 functions, or actions, of the fairy tale.[18] Propp proposes that the functions are the fundamental units the story and that there are exactly 31 distinct functions. He observed in his analysis of 100 Russian fairy tales that tales almost always adhere to the order of the functions. The traits of the characters, or dramatis personae, involved in the actions are second to the action actually being carried out. This also follows his finding that while some functions may be missing between different stories, the order is kept the same for all the Russian fairy tales he analyzed.[7]

Alexander Nikiforov, like Shklovsky and Propp, was a folklorist in 1920s Soviet Russia. His early work also identified the benefits of a syntagmatic analysis of fairy tale elements. In his 1926 paper titled «The Morphological Study of Folklore», Nikiforov states that «Only the functions of the character, which constitute his dramatic role in the folk tale, are invariable.»[13] Since Nikiforov’s essay was written almost 2 years before Propp’s publication of Morphology of the Folktale[19], scholars have speculated that the idea of the function, widely attributed to Propp, could have first been recognized by Nikiforov.[20] One source claims that Nikiforov’s work was «not developed into a systematic analysis of syntagmatics» and failed to «keep apart structural principles and atomistic concepts».[17] Nikiforov’s work on folklore morphology was never pursued beyond his paper.[19]

Writers and collectors[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev began writing fairy tales at a time when folklore was viewed as simple entertainment. His interest in folklore stemmed from his interest in ancient Slavic mythology. During the 1850s, Afanasyev began to record part of his collection from tales dating to Boguchar, his birthplace. More of his collection came from the work of Vladimir Dhal and the Russian Geographical Society who collected tales from all around the Russian Empire.[21] Afanasyev was a part of the few who attempted to create a written collection of Russian folklore. This lack in collections of folklore was due to the control that the Church Slavonic had on printed literature in Russia, which allowed for only religious texts to be spread. To this, Afanasyev replied, “There is a million times more morality, truth and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness!”[22]

Between 1855 and 1863, Afanasyev edited Popular Russian Tales[Narodnye russkie skazki], which had been modeled after the Grimm’s Tales. This publication had a vast cultural impact over Russian scholars by establishing a desire for folklore studies in Russia. The rediscovery of Russian folklore through written text led to a generation of great Russian authors to come forth. Some of these authors include Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Folktales were quickly produced in written text and adapted. Since the production of this collection, Russian tales remain understood and recognized all over Russia.[21]

Alexander Pushkin[edit]

Alexander Pushkin is known as one of Russia’s leading writers and poets.[23] He is known for popularizing fairy tales in Russia and changed Russian literature by writing stories no one before him could.[24] Pushkin is considered Russia’s Shakespeare as, during a time when most of the Russian population was illiterate, he gave Russian’s the ability to desire in a less-strict Christian and a more pagan way through his fairy tales.[25]

Pushkin gained his love for Russian fairy tales from his childhood nurse, Ariana Rodionovna, who told him stories from her village when he was young.[26] His stories served importance to Russians past his death in 1837, especially during times political turmoil during the start of the 20th century, in which, “Pushkin’s verses gave children the Russian language in its most perfect magnificence, a language which they may never hear or speak again, but which will remain with them as an eternal treasure.”[27]

The value of his fairy tales was established a hundred years after Pushkin’s death when the Soviet Union declared him a national poet. Pushkin’s work was previously banned during the Czarist rule. During the Soviet Union, his tales were seen acceptable for education, since Pushkin’s fairy tales spoke of the poor class and had anti-clerical tones.[28]

Corpus[edit]

According to scholarship, some of «most popular or most significant» types of Russian Magic Tales (or Wonder Tales) are the following:[a][30]

| Tale number | Russian classification | Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index Grouping | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | The Winner of the Snake | The Dragon-Slayer | ||

| 301 | The Three Kingdoms | The Three Stolen Princesses | The Norka; Dawn, Midnight and Twilight | [b] |

| 302 | Kashchei’s Death in an Egg | Ogre’s (Devil’s) Heart in the Egg | The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

| 307 | The Girl Who Rose from the Grave | The Princess in the Coffin | Viy | [c] |

| 313 | Magic Escape | The Magic Flight | The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise | [d] |

| 315 | The Feigned Illness (beast’s milk) | The Faithless Sister | ||

| 325 | Crafty Knowledge | The Magician and his Pupil | [e] | |

| 327 | Children at Baba Yaga’s Hut | Children and the Ogre | ||

| 327C | Ivanusha and the Witch | The Devil (Witch) Carries the Hero Home in a Sack | [f] | |

| 400 | The husband looks for his wife, who has disappeared or been stolen (or a wife searches for her husband) | The Man on a Quest for The Lost Wife | The Maiden Tsar | |

| 461 | Mark the Rich | Three Hairs of the Devil’s Beard | The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars (Serbian); Vassili The Unlucky | [g] |

| 465 | The Beautiful Wife | The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | [h] |

| 480 | Stepmother and Stepdaughter | The Kind and Unkind Girls | Vasilissa the Beautiful | |

| 519 | The Blind Man and the Legless Man | The Strong Woman as Bride (Brunhilde) | [i][j][k] | |

| 531 | The Little Hunchback Horse | The Clever Horse | The Humpbacked Horse; The Firebird and Princess Vasilisa | [l] |

| 545B | Puss in Boots | The Cat as Helper | ||

| 555 | Kitten-Gold Forehead (a gold fish, a magical tree) | The Fisherman and His Wife | The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish | [m][n] |

| 560 | The Magic Ring | The Magic Ring | [o][p] | |

| 567 | The Marvelous Bird | The Magic Bird-Heart | ||

| 650A | Ivan the Bear’s Ear | Strong John | ||

| 706 | The Handless | The Maiden Without Hands | ||

| 707 | The Tale of Tsar Saltan [Marvelous Children] | The Three Golden Children | Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Wicked Sisters | [q] |

| 709 | The Dead Tsarina or The Dead Tsarevna | Snow White | The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights | [r] |

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Propp’s The Russian Folktale lists types 301, 302, 307, 315, 325, 327, 400, 461, 465, 519, 545B, 555, 560, 567 and 707.[29]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 301, «The Three Kingdoms and the Stolen Princesses», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 45 variants. The type was also the second «most frequently collected in Ukraine», with 31 texts.[31]

- ^ French folklorist Paul Delarue noticed that the tale type, despite existing «throughout Europe», is well known in Russia, where it found «its favorite soil».[32] Likewise, Jack Haney stated that type 307 was «most common» among East Slavs.[33]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 313, «The Magic Flight», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 41 variants. The type was also the «most frequently collected» in Ukraine, with 37 texts.[34]

- ^ Commenting on a Russian tale collected in the 20th century, Richard Dorson stated that the type was «one of the most widespread Russian Märchen».[35] In the East Slavic populations, scholarship registers 42 Russian variants, 25 Ukrainian and 10 Belarrussian.[36]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type of a fishing boy and a witch «[is] common among the various East European peoples.»[37]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type is popular among the East Slavs[38]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type, including previous type AaTh 465A, is «especially common in Russia».[39]

- ^ Russian researcher Dobrovolskaya Varvara Evgenievna stated that tale type ATU 519 (SUS 519) «belongs to the core of» the Russian tale corpus, due to «the presence of numerous variants».[40]

- ^ Following Löwis de Menar’s study, Walter Puchner concluded on its diffusion especially in the East Slavic area.[41]

- ^ Stith Thompson also located this tale type across Russia and the Baltic regions.[42]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type «is extremely popular in all three branches of East Slavic».[43]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type is «common among the East Slavs».[44]

- ^ The variation on the wish-giving entity is also attested in Estonia, whose variants register a golden fish, crayfish, or a sacred tree.[45]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «very common in all the East Slavic traditions».[46]

- ^ Wolfram Eberhard reported «45 variants in Russia alone».[47]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «a very common East Slavic type».[48]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «especially common in Russian and Ukrainian».[49]

References[edit]

- ^ «Magic tale (volshebnaia skazka), also called fairy tale». Kononenko, Natalie (2007). Slavic Folklore: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-313-33610-2.

- ^ Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories : the History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574-2010). Brill, 2013.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. “Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union.” Slavic Review, vol. 32, no. 1, 1973, pp. 45–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494072.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. “The Midnight Dance.” The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces, 1855, www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0306.html.

- ^ Mityayev, Anatoli. Grishka and the Astronaut. Translated by Ronald Vroon, Progress, 1981.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service». Marvels & Tales. 16 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1353/mat.2002.0024. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 41388626. S2CID 163086804.

- ^ a b c d Propp, V. I︠A︡. Morphology of the folktale. ISBN 9780292783768. OCLC 1020077613.

- ^ Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1975-11-16). «Russian Fairy Tales». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Greskovic, Robert (2015-06-02). «‘The Sleeping Beauty’ Review: Back to Its Russian Roots». Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Erlich, Victor (1973). «Russian Formalism». Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (4): 627–638. doi:10.2307/2708893. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708893.

- ^ Saussure, Ferdinand de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Baskin, Wade., Meisel, Perry., Saussy, Haun, 1960-. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231527958. OCLC 826479070.

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur Asa (February 2018). Media analysis techniques. ISBN 9781506366210. OCLC 1000297853.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Terence Patrick (2015). The Fairytale and Plot Structure. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781137547088. OCLC 944065310.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1997). «The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique». Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 3814885.

- ^ Kuehnel, Richard; Lencek, Rado. «What is a Folklore Motif?». www.aktuellum.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ a b Propp, V. I︠A︡.; Пропп, В. Я. (Владимир Яковлевич), 1895-1970 (2012). The Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337219. OCLC 843208720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maranda, Pierre (1974). Soviet structural folkloristics. Meletinskiĭ, E. M. (Eleazar Moiseevich), Jilek, Wolfgang. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 978-9027926838. OCLC 1009096.

- ^ a b Aguirre, Manuel (October 2011). «AN OUTLINE OF PROPP’S MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF FAIRYTALES» (PDF). Tools and Frames – via The Northanger Library Project.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. (2019). The Study of Russian Folklore. Soudakoff, Stephen. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 9783110813913. OCLC 1089596763.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1973). «Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union». Slavic Review. 32 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2494072. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494072.

- ^ a b Levchin, Sergey (2014-04-28). «Russian Folktales from the Collection of A. Afanasyev : A Dual-Language Book».

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1991). Alexander Pushkin : a critical study. The Bristol Press. ISBN 978-1853991721. OCLC 611246966.

- ^ Alexander S. Pushkin, Zimniaia Doroga, ed. by Irina Tokmakova (Moscow: Detskaia Literatura, 1972).

- ^ Bethea, David M. (2010). Realizing Metaphors : Alexander Pushkin and the Life of the Poet. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299159733. OCLC 929159387.

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Akhmatova, “Pushkin i deti,” radio broadcast script prepared in 1963, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, May 1, 1974.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria. «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service.» Marvels & Tales (2002): 171-187.

- ^ The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 215. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Delarue, Paul. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 386.

- ^ Haney, Jack V.; with Sibelan Forrester. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume III. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2021. p. 536.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Горяева, Б. Б. (2011). «Сюжет «Волшебник и его ученик» (at 325) в калмыцкой сказочной традиции». In: Oriental Studies (2): 153. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-volshebnik-i-ego-uchenik-at-325-v-kalmytskoy-skazochnoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 554. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Добровольская Варвара Евгеньевна (2018). «Сказка «слепой и безногий» (сус 519) в репертуаре русских сказочников: фольклорная реализация литературного сюжета». Вопросы русской литературы, (4 (46/103)): 93-113 (111). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-slepoy-i-beznogiy-sus-519-v-repertuare-russkih-skazochnikov-folklornaya-realizatsiya-literaturnogo-syuzheta (дата обращения: 01.09.2021).

- ^ Krauss, Friedrich Salomo; Volkserzählungen der Südslaven: Märchen und Sagen, Schwänke, Schnurren und erbauliche Geschichten. Burt, Raymond I. and Puchner, Walter (eds). Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2002. p. 615. ISBN 9783205994572.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2015 [2001]. p. 434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. p. 718. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram. Folktales of China. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1956. p. 143.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

Further reading[edit]

- Лутовинова, Е.И. (2018). Тематические группы сюжетов русских народных волшебных сказок. Педагогическое искусство, (2): 62-68. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tematicheskie-gruppy-syuzhetov-russkih-narodnyh-volshebnyh-skazok (дата обращения: 27.08.2021). (in Russian)

The Three Kingdoms (ATU 301):

- Лызлова Анастасия Сергеевна (2019). Cказки о трех царствах (медном, серебряном и золотом) в лубочной литературе и фольклорной традиции [FAIRY TALES ABOUT THREE KINGDOMS (THE COPPER, SILVER AND GOLD ONES) IN POPULAR LITERATURE AND RUSSIAN FOLK TRADITION]. Проблемы исторической поэтики, 17 (1): 26-44. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ckazki-o-treh-tsarstvah-mednom-serebryanom-i-zolotom-v-lubochnoy-literature-i-folklornoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Матвеева, Р. П. (2013). Русские сказки на сюжет «Три подземных царства» в сибирском репертуаре [RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES ON THE PLOT « THREE UNDERGROUND KINGDOMS» IN THE SIBERIAN REPERTOIRE]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Философия, (10): 170-175. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkie-skazki-na-syuzhet-tri-podzemnyh-tsarstva-v-sibirskom-repertuare (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Терещенко Анна Васильевна (2017). Фольклорный сюжет «Три царства» в сопоставительном аспекте: на материале русских и селькупских сказок [COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FOLKLORE PLOT “THREE STOLEN PRINCESSES”: RUSSIAN AND SELKUP FAIRY TALES DATA]. Вестник Томского государственного педагогического университета, (6 (183)): 128-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/folklornyy-syuzhet-tri-tsarstva-v-sopostavitelnom-aspekte-na-materiale-russkih-i-selkupskih-skazok (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

Crafty Knowledge (ATU 325):

- Трошкова Анна Олеговна (2019). «Сюжет «Хитрая наука» (сус 325) в русской волшебной сказке» [THE PLOT “THE MAGICIAN AND HIS PUPIL” (NO. 325 OF THE COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS) IN THE RUSSIAN FAIRY TALE]. Вестник Марийского государственного университета, 13 (1 (33)): 98-107. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-hitraya-nauka-sus-325-v-russkoy-volshebnoy-skazke (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Troshkova, A.O. «Plot CIP 325 Crafty Lore / ATU 325 «The Magician and His Pupil» in Catalogues of Tale Types by A. Aarne (1910), Aarne — Thompson (1928, 1961), G. Uther (2004), N. P. Andreev (1929) and L. G. Barag (1979)». In: Traditional culture. 2019. Vol. 20. No. 5. pp. 85—88. DOI: 10.26158/TK.2019.20.5.007 (In Russian).

- Troshkova, A (2019). «The tale type ‘The Magician and His Pupil’ in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)». Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376. (In Russian)

Mark the Rich or Marko Bogatyr (ATU 461):