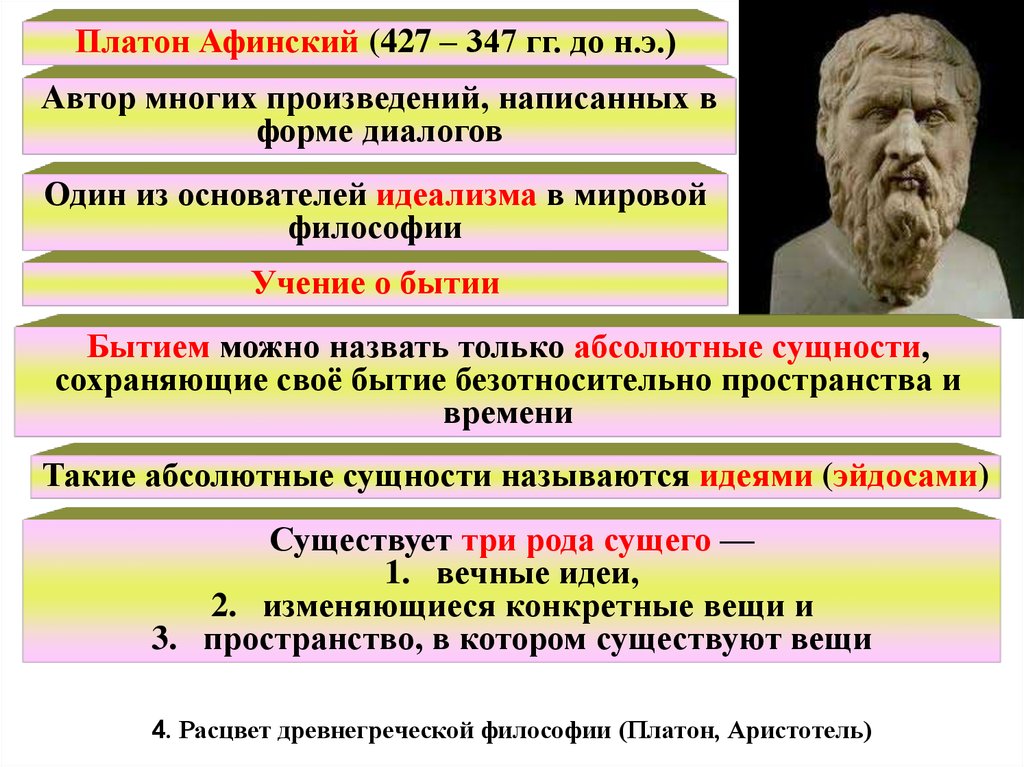

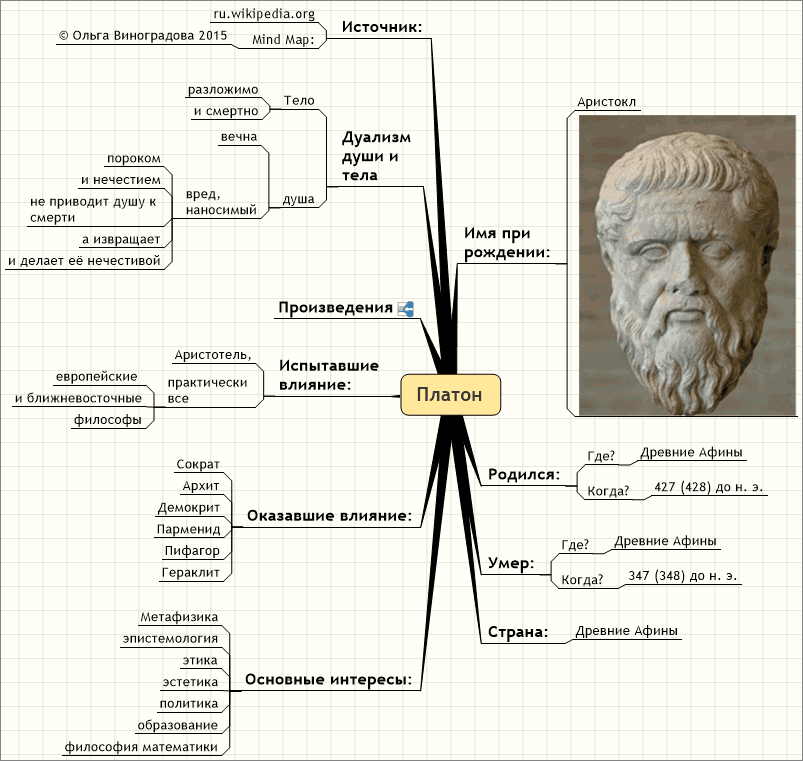

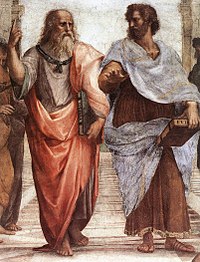

Платон

(427 – 347 гг. до н.э.) – ученик Сократа. Его

подлинное имя – Аристокл (Платон –

«широкоплечий»).

После смерти

учителя он покинул Афины, долго

странствовал по Средиземноморью, общался

с крупнейшими учеными и философами. За

это время он изведал и почести, и уважение,

и даже был продан в рабство. После того

как его выкупили, он вернулся в Афины и

основал свою школу – Академию,

просуществовавшую более 900 лет. Название

свое школа получила по месту своего

расположения (она находилась в роще,

посаженной в честь героя Академа), а ее

ученики стали называться академиками.

До нас дошло более

20 сочинений Платона. Его произведения

написаны в форме диалогов,

главным действующим лицом большинства

из них является Сократ. Форма диалога

близка к художественной, Платон активно

использует мифологические сюжеты как

аллегорический способ подачи сложных

философских идей. Наиболее известные

диалоги Платона: «Государство», «Пир»,

диалоги «Софист» и «Федр» посвящены

проблеме души, «Тимей» – вопросу

возникновения Космоса, «Протагор» –

проблеме добродетели.

Основное значение

философии Платона заключается в том,

что он является создателем системы

объективного

идеализма,

суть которого состоит в том, что мир

идей признается им в качестве первичного

по отношению к миру вещей.

Платон говорит о

существовании двух

миров:

1) мир

вещей

– изменчивый, преходящий – воспринимается

органами чувств;

2) мир

идей –

вечный, бесконечный и неизменный –

постигается только умом.

Идеи – идеальный

прообраз вещей, их совершенный образец.

Вещи – лишь несовершенные копии идей.

Это доказывается им с помощью образа

пещеры (см. диалог «Государство», кн.7 –

«Миф о пещере»). Материальный мир

создается Творцом (Демиургом) по идеальным

образцам (идеям). Этим Демиургом является

разум, творческий ум, а исходный материал

для создания мира вещей – материя.

(Демиург не творит ни материю, ни идеи,

он только оформляет материю по идеальным

образам).

Мир идей, по Платону,

это иерархически организованная система,

идеи находятся в отношении подчинения

и соподчинения, могут быть более или

менее общими. На вершине =- самая общая

идея – Благо,

которая проявляется в прекрасном и

истинном.

Теория познания

Платона

построена на том, что человек имеет

врожденные идеи, которые он «припоминает»

в процессе своего развития. При этом

чувственный опыт является лишь толчком

к воспоминанию, а основным средством

воспоминания является диалог, беседа.

Платон развил диалектику Сократа как

искусство правильного мышления,

приводящего к истине.

Важное место в

философии Платона занимает проблема

человека.

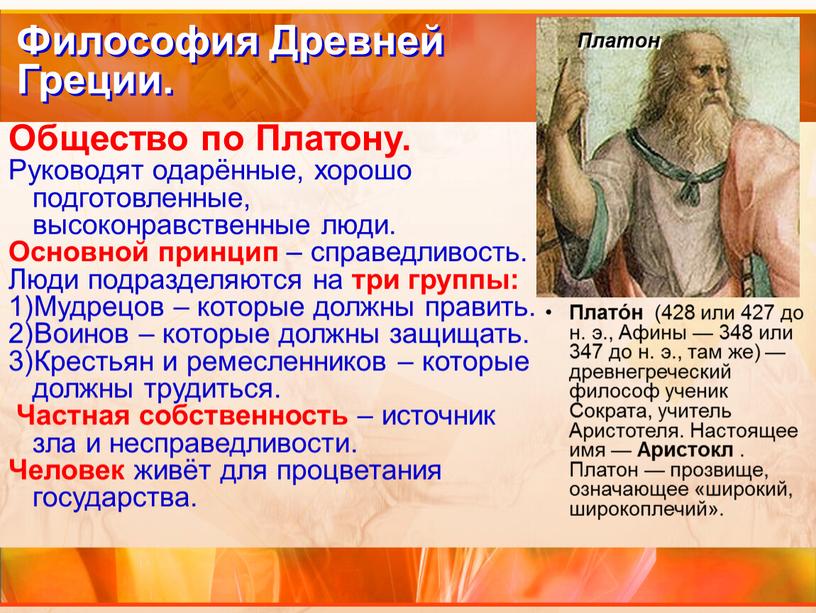

Человек, по Платону, — единство души и

тела, которые в то же время противоположны.

Основу человека составляет его душа,

которая бессмертна и возвращается в

мир много раз. Смертное тело – только

тюрьма для души, оно источник страданий,

причина всех зол; душа гибнет, если она

слишком срослась с телом в процессе

удовлетворения своих страстей.

Стимулом к

совершенствованию души является любовь

к прекрасному. Вообще тема

любви – одна

из центральных в диалогах Платона (см.

диалог «Пир» — «Миф об андрогинах»). Виды

любви, по Платону, также иерархически

организованы:

1)фундаментом всех

видов любви является эротическая любовь,

или любовь к прекрасному телу с целью

породить в нем другое тело и тем самым

удовлетворить стремление к бессмертию;

2)любовь к душе,

т.е. стремление к справедливости,

увлеченность искусством и наукой;

3)любовь к знанию,

т.е. к миру идей – это высшее проявление

любви, которая «восхитительно сладостна»,

т.к. приводит человека к познанию идеи

Блага (эта разновидность любви получила

название платонической).

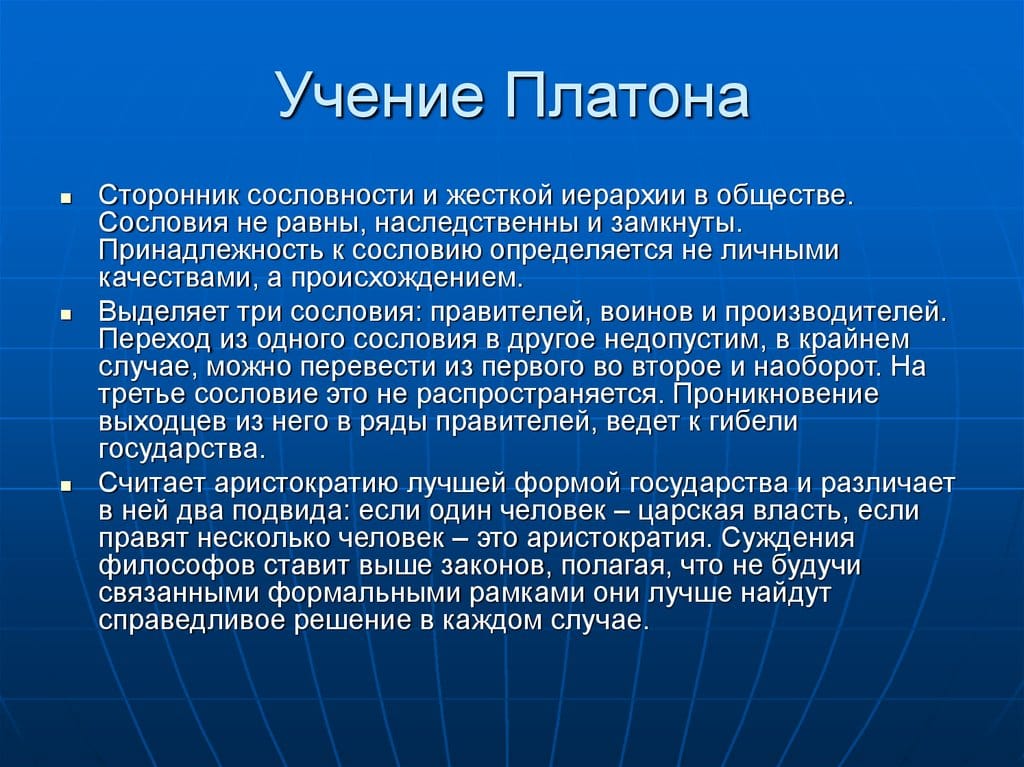

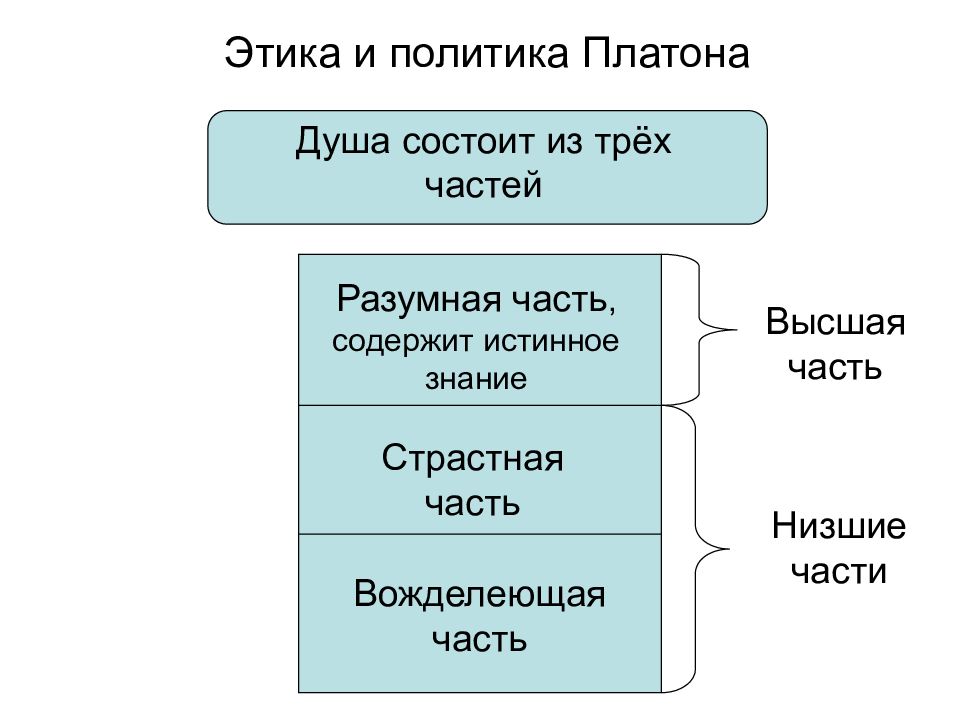

Платон делит души

людей на три разновидности в зависимости

от того, какое начало в них преобладает:

душа разумная (разум), воинственная

(воля), страждущая (вожделение). Обладатели

разумной души – мудрецы, философы. Их

функция – познание истины, написание

законов и управление государством. Душа

воинственная принадлежит воинам,

стражникам. Их функция – охранять

государство и обеспечивать соблюдение

законов. Третий тип души – страждущая

– стремится к материальным, чувственным

благам. Этой душой обладают крестьяне,

торговцы, ремесленники, функция которых

– обеспечение материальных потребностей

людей. Таким образом, Платон предложил

структуру идеального

государства

(см. диалог «Государство»), где три

сословия в зависимости от типа души

выполняют присущие только им функции.

Т.е. Платон связывает социальные функции

человека с его природными наклонностями,

а надлежащее выполнение этих функций

рассматривает как гарантию справедливости

и гармоничных отношений в обществе.

Соседние файлы в предмете Философия

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Диалог — жанр по преимуществу эллинский, античный. Свою классическую форму он принял в IV в. до Р. Х. как один из видов так называемой “сократической” литературы — тех письменных воспоминаний об афинском философе, которые после его казни в 399 г. служили для его почитателей средством защиты и оправдания памяти наставника. Сократовская педагогика не знала ни авторитетного вещания истины типа наших лекций, ни пособий типа наших учебников. Сократ собирал слушателей прямо на улице и завязывал с согражданами беседы, напоминавшие по своему методу расспросы, обычные при судебных разбирательствах. Такой способ философствования при помощи наводящих вопросов принято называть “сократовской майевтикой”1, а записи подобных бесед — “сократическими разговорами”.

Наше знакомство с классическим диалогом ограничено в сущности творчеством двух авторов, Ксенофонта и Платона, произведения которых сохранились целиком. Их диалоги, близкие по тематике, но разные по методу, кладут начало двум традициям, во многом противоположным друг другу. В диалогах Ксенофонта персонажи показаны как носители постоянных, “профессиональных” свойств, что отражено в их речах и поступках; они говорят о вещах конкретных, практических: домохозяин — о том, как он распоряжается в своем семействе, философ (Сократ) — о своей бедности. Они выступают с позитивными утверждениями и сомнения в их правоте оказываются несостоятельными.

Иную картину наблюдаем мы в диалогах Платона. В каждом из них обсуждается какой-то один вопрос, и притом совсем иначе, чем у Ксенофонта. Внимание сосредоточено тут не на конкретных примерах той или иной добродетели, а на той жизненной установке, от которой зависит человеческая деятельность. Платон не сообщает практических сведений, а ставит вопрос о ценности общепринятых мнений, спрашивая устами персонажей: “действительно ли люди знают, что такое справедливость, мужество, благоразумие и т. п.?”.

Интонация недоумения определяет собой своеобразие платоновских диалогов, “незнание” становится объединяющей чертой платоновских героев, и сам Сократ не выпадает из этой роли. Он не вещатель истины, а ее искатель, вечно спрашивающий, неуверенный, стремящийся обрести знание. Гораздо большее значение, чем у Ксенофонта, получает здесь контекст беседы, ее бытовой фон. Философское обсуждение носит у Платона “личный” характер”: собеседники как бы наблюдают друг за другом со стороны, оценивают поведение партнеров и рассматривают ход собственных мыслей, гонятся за правильным определением понятия, как охотники за добычей.

В своей дальнейшей эволюции этот жанр в значительно большей мере усвоил ксенофонтовские, а не платоновские черты, превратившись в вид назидательной и развлекательной литературы. Изменилось и содержание диалогов: они стали описывать отдельные стороны жизни, а не исследовать принципы, на которых она строится. Вместо гимнов любви, подобных платоновскому “Пиру”, появились “любовные диалоги” с рассказами о любовных приключениях.

Временем наивысшего расцвета такого диалога были первые века по Р. Х., эпоха сознательной архаизации, когда античная культура стремилась сохранить себя путем возрождения своих классических форм. С одной стороны, огромную популярность приобрел платоновский текст. Он был заново издан Фрасиллом в первом веке по Р. Х. и входил в культурный обиход образованного грека, о чем говорят его переделки в так называемом “Романе о Сократе”2 и реминисценции у разных авторов. С другой стороны, к жанру диалога стали обращаться такие крупные писатели того времени, как Плутарх и Лукиан. Как пишет Гирцель, в литературу переносилась атмосфера ученых бесед и дискуссий, и письменные диалоги отражали беседы в собраниях философов и риторов3.

С середины II в. по Р. Х. жанр диалога в греческой литературе получил новую сферу приложения: им начали пользоваться христианские писатели главным образом в своих спорах с инакомыслящими. Именно в это время расширялся кругозор христианства, от евангельской проповеди и пастырских наставлений отдельным общинам оно переходило к более планомерным формам миссионерства, обращаясь уже не просто к иудеям, собравшимся в такой-то синагоге, или к афинянам в ареопаге, а к иудеям вообще, к греко-римскому миру в целом. Соответственно обогащались и его языковые и стилистические средства: наряду с проповедью и посланием стали употребительны такие словесные формы, как апология и диалог; апология — для обращения к официальному греко-римскому миру, диалог — для разговора в собственной среде и с иудейством. В значительно большей мере, чем в I веке, в обиход христианства входили теперь тексты не только библейские, но и языческие4.

Языческие тексты, составлявшие общепринятую норму знакомства с классическими авторами, не только служили источником сведений об античной культуре, источником доводов для полемики и защиты, но и снабжали христианскую литературу речевыми оборотами и риторическими приемами, были образцом для подражания. Жанр диалога — любопытный пример того, как христианское содержание облекалось в античную литературную форму. Уже в самом начале христианский диалог принял два вида, которые мы условно позволим себе назвать “неплатоновским” и “платоновским”. Под “неплатоновскими” мы подразумеваем сочинения, не подражающие классическому диалогу, под “платоновскими” — те, в которых удается обнаружить текстуальную и композиционную близость к диалогам Платона. Количественно их сохранилось меньше, чем “неплатоновских”, но именно они позволяют ставить вопрос об эволюции классической формы в новых условиях, о том, как происходило освоение христианством античного литературного наследия, как найденные эллинской культурой экспрессивные средства ставились на службу новым смысловым задачам. Наиболее яркие образцы “платоновского” типа относятся ко II–III вв. В посленикейскую эпоху они встречаются у писателей Газской школы и исчезают после закрытия афинской академии в 529 году5.

Впервые платоновский текст был введен в христианскую литературу святым Иустином6 — апологетом II века, философом и мучеником. Современная критика признает подлинность двух его апологий и “Диалога с иудеем Трифоном”. В определенном смысле эти сочинения в большей степени ориентировались на подлинного Платона, чем то, что создавалось античной культурой того времени. Весьма показательна в этом отношении та новая окраска, какую получил у святого Иустина образ Сократа. От того Сократа, который известен нам по диалогам Плутарха и эпистолярному роману о Сократе, — Сократа, наделенного чертами киника и моралиста, врага власть имущих и друга своих учеников, — христианский апологет вернулся к образу непоколебимого защитника своих убеждений, каким рисует его Платон. Для святого Иустина Сократ стал борцом с заблуждениями языческой религии, мучеником за правду, и этот угол зрения позволил говорить об аналогии исторической роли Сократа и христиан. Вот что читаем мы в первой апологии: “В древности злые демоны являлись <…> и наводили на людей страх, так что те, кто разумом не распознавал случавшихся вещей <…> не ведая, что это злые демоны, называли их богами <…> когда же Сократ словом истинным и тщательно попытался вывести это наружу и отклонить людей от демонов, то демоны, при посредстве людей порочных, заставили убить его как безбожника и нечестивца, говоря, что он вводит новые божества. И так же поступают они с нами, потому что не только у эллинов они были обличаемы словом Сократа, но и среди варваров самим Словом, Которое воплотилось и стало человеком и звалось Иисусом Христом <…> поэтому нас и зовут «безбожниками»” (I Апология, 5, 6)7.

Облик Сократа, нарисованный в приведенной цитате, совмещает в себе черты того портрета, который знаком нам по сочинениям Ксенофонта и Платона (“убить как безбожника и нечестивца, говоря, что он вводит новые божества”), с чертами, ему неприсущими (противостояние демонам) и введенными для полноты аргументации. В гораздо большей мере, чем в подобных эпизодических штрихах, тяготение святого Иустина к платоновскому тексту проявилось в той композиционной технике, которая лежит в основе его “Диалога с иудеем Трифоном”.

“Диалог” написан в форме адресованного некоему Марку Помпею пересказа духовной беседы, которую вел автор с эллинизированным иудеем Трифоном и его спутниками. Основная ее часть сводилась к тому, что святой Иустин истолковывал ветхозаветные тексты, и его речь изредка прерывалась вопросами партнеров. Этой почти монологической беседе предпослано вступление, которое, с одной стороны, наполнено оборотами речи, почерпнутыми у Платона, и, с другой стороны, в какой-то мере воспроизводит отдельные приемы композиции, характерные для платоновских диалогов. Подобно Платону, святой Иустин указывал время и место беседы, обрисовывал персонажей и вводил в разговор философскую тему, задавая личный, интимный вопрос. “Диалог с Трифоном” начинался словами:

“Я гулял утром по аллеям Ксиста, и вот какой-то человек, с ним были и другие люди, встретив меня, сказал мне: «Здравствуй, философ!», и, отклонившись от своего пути, стал прогуливаться вместе со мной. Изменили путь и его друзья. Тут и я, в свою очередь, обратился к нему с вопросом, чем могу служить. Он ответил: «Я узнал в Аргосе от сократика Коринфа, что одетых в такую одежду [как ты] не следует ни презирать, ни оставлять без внимания, но надо всячески благоволить к ним и вступать с ними в беседу, чтобы разговор принес пользу ему или мне. Если бы и один получил пользу, то это благо для обоих. Вот почему, когда вижу человека в такой одежде, с удовольствием приближаюсь к нему; поэтому и к тебе мне приятно было сейчас обратиться. И мои спутники тоже ждут услышать от тебя что-либо полезное».

— А ты кто таков, храбрый из смертных?8 — сказал я ему шутя. Он же совсем просто назвал мне свой род и имя.

— Зовут меня Трифоном, — ответил он, — я — еврей, обрезанный. Я беженец последней войны9 и большую часть времени провожу в Элладе и Коринфе.

— А разве от философии можешь ты получить столько пользы, как от твоего законодателя и пророков? — спросил я его” (гл. 1)10.

В приведенной сцене в самой ситуации разговора намечен мотив личностного контакта персонажей: их внешние характеристики (одежда философа у Иустина, иудейское происхождение и эллинское образование Трифона) обусловливают тему завязавшейся беседы. И затем сугубо лично, конкретно, как вопрос сдержанного Трифона по поводу слов увлекшегося своею речью Иустина ставится вопрос о том, что есть подлинная философия. Обмен репликами показан на фоне той интонации, с какой он произносится: Иустин спрашивает о роде и имени Трифона “шутя”, ответ дан “просто”. И реакцией на этот доверчивый тон служат слова Иустина о философии, произносимые столь же доверительно и открыто. На реплику Трифона: “Не философы ли все рассуждение сосредоточивают на Боге?”, Иустин возражает, заявляя, что философы “говорят и действуют с бесстрашной свободой и не страшатся кары за свои слова и не надеются получить что-либо доброе от Бога…” (гл. 1). Сдержанного Иустина теперь как бы “прорвало”, и это подчеркнуто в тексте реакцией Трифона: “улыбнувшись, он вежливо сказал…”. Трифон еще раз задает вопрос о философии, но уже как вопрос о личном мнении Иустина: “А как ты об этом думаешь, какое у тебя мнение о Боге и какова твоя философия? Скажи нам”. И столь же интимно звучит ответ: “Я тебе скажу, — ответил я, — как мне это видится” (глл. 1, 2).

Намеченная таким путем нить личных отношений между персонажами тянется через весь диалог и обусловливает его композиционное единство. Интимную окраску беседе придают два основных приема: 1. указание на реакцию действующих лиц (жест, интонация, мимика, движение); 2. рассматривание предмета в его отношении к говорящему. Все содержание диалога сводится в сущности к раскрытию авторской мысли по поводу вышеприведенного вопроса Трифона (“Какова твоя философия?”), и мысль эта не декларируется как неоспоримая доктрина, а показывается как результат длительного искания истины. Прежде чем знакомить собеседников с христианским толкованием ветхозаветных текстов, Иустин рассказывал им о своей жизни, об увлечении эллинской философией, об ученичестве у разных наставников и невозможности найти у них истину (гл. 2). Эта часть автобиографии построена как цепь неудачных попыток обрести философию, как внутренний путь разочарований, который завершается, наконец, надеждой на получение искомого. Вопрос Трифона “Какова твоя философия?” получает пока что ответ в сугубо личном плане как изображение Иустином своих жизненных перипетий, связанных с философией. В таком же личном плане как неожиданное событие своей жизни рисует Иустин разрыв с философией и обращение к христианству. Резкость перехода от рационалистических поисков истины к признанию религиозного откровения подчеркнута чисто композиционными средствами: за описанием уроков у платоника, вселяющих в Иустина уверенность в том, что он и сам станет философом, следует рассказ о неожиданной встрече со старцем, который развенчивает надежду Иустина на философию и призывает его обратиться к библейскому авторитету. Этот второй этап автобиографии представлен подробнее первого: тут упомянуты место встречи и внешние приметы незнакомца и воспроизведен разговор с ним:

“В таком расположении духа я отправился как-то в одно местечко неподалеку от моря, решив предаться полному уединению там, где не ступает нога человеческая. Я уже приближался туда, где собирался побыть с самим собой, как вдруг ко мне присоединился некий древний старец, не невзрачный видом, с наружностью кроткой и величественной. Обернувшись, я остановился и в упор посмотрел на него. Он спросил меня:

— Я знаком тебе?

Я отрекся, тогда он сказал:

— А почему ты так в меня вглядываешься?

— Меня удивляет, — ответил я, — эта встреча здесь, ведь я не ждал увидеть тут человека.

На что тот возразил:

— У меня забота о домашних. Некоторые из них сейчас находятся на чужой стороне, и я прихожу сюда, наблюдая, не покажутся ли они откуда-либо. А ты зачем здесь? — задал он мне вопрос, и я ответил:

— Люблю такие прогулки, когда ничто не мешает мне беседовать с самим собой, ничто меня не прерывает. Такие местности самые удобные для умственных занятий.

— Так ты любитель умствований, — возразил он, — а не любитель дела и не любитель истины? И даже не пытаешься быть деятелем больше, чем софистом?” (гл. 3).

В научной литературе уже отмечалось сходство этой встречи со старцем с той встречей Иустина и Трифона, которая открывает собой диалог11. И там и тут знакомство происходит неожиданно, в уединенном месте во время прогулки, и партнеры занимают сходные позиции: с одной стороны — мудрец, с другой — поклонник философии. В обоих случаях этот поклонник отстаивает ценность философии пред лицом собеседника. Роль, которая в начальной сцене отведена Трифону, теперь передана Иустину, соответственно и роль Иустина из начальной сцены возложена на старца. Поставя себя в такое же отношение к старцу, в каком к нему самому стоит Трифон, Иустин начинает устами старца разбивать то доверие к эллинской философии, какое присуще и Иустину-слушателю старца и Трифону-слушателю Иустина. Мы не можем не вспомнить в этой связи те ситуации платоновских диалогов, когда Сократ ведет свое рассуждение устами вымышленного собеседника и выступает в двойной роли говорящего и слушающего. Наиболее полно и красочно эта роль стороннего вещателя истины воплощена в “Пире” в образе таинственной Диотимы. В “Диалоге с Трифоном” композиционную роль Диотимы играет старец и его словами Иустин опровергает мысли Трифона. Обсуждение вопроса ведется методом сократовской майевтики:

“— Философия, стало быть, доставляет счастье? — спросил он.

— Да, самое большое, и только она, — ответил я.

— А что такое философия, — спросил он, — и каково подаваемое ею счастье, объясни это, если ничто не мешает объяснить.

— Философия, — сказал я, — это знание сущего и ведение истинного. Счастье же — награда за такое знание и мудрость.

— Богом же ты что называешь? — спросил он.

— То, что всегда пребывает одинаковым и тождественным и есть причина существования всего остального. — Так я ответил, и ему приятно было это слышать…” (гл. 3).

Подобно платоновскому Сократу, старец обрушивает на своего собеседника град вопросов:

“— Какое, скажи, у нас родство с Богом? Божественна ли и бессмертна ли душа и есть ли она часть владычественного ума? Как он видит Бога, так и для нас доступно своим умом постичь Божество и в этом обрести счастье?

— Именно так, — ответил я на это.

— А все ли души, — спросил он, — проходят через всех животных, или одна бывает у человека, а у лошади и осла — другая?

— Нет, — ответил я, — но одни и те же у всех.

— Значит, — сказал он, — лошади и ослы видят или уже видели Бога.

— Нет, — возразил я, — ведь даже большинство людей [не видят его], а лишь те, кто живет по правде, усердствуя в справедливости и во всякой другой добродетели…

— Так что же? Разве козы или овцы в чем-то попирают справедливость?

— Никак нет, — сказал я.

— Тогда, по твоим словам, — возразил он, — и эти животные увидят Бога?

— Нет, их тело мешает этому…” (гл. 4).

Как и Сократ, своими вопросами старец открывает собеседнику глаза на его незнание и делает вывод о противоречивости исходного утверждения, тем самым разоблачая некомпетентность философов:

“— Значит, души не видят Бога и не переселяются в другие тела. Ведь если бы они знали, что наказываются таким путем, то боялись бы и впредь не совершали бы и малого греха…

— Ты правильно говоришь, — сказал я ему.

— Ничего, выходит, не знают про это те философы, поскольку они не могут даже сказать, что такое душа” (глл. 4, 5).

Возложив на “старца” миссию разоблачения эллинской философии, автор диалога сохраняет тем самым интимно доверительный тон беседы и не превращает обличения в инвективу: адресованное Трифону, оно формально отнесено к Иустину и не может вызвать обиды у Трифона. Дружеские отношения, установившиеся между персонажами в начале диалога, здесь не разрушаются, однако между ними происходит идейное размежевание. Отвечая на вопрос Трифона “какова твоя философия”, Иустин устами старца развенчивает эллинскую философию, то есть позицию, занимаемую Трифоном, и в качестве новой духовной программы предлагает вместо нее учение, опирающееся на библейские тексты. Вот как рисует Иустин заключительную проповедь старца, противопоставившего авторитет Ветхого Завета рационализму эллинской философии:

“— Мне нет дела, — сказал он, — ни до Платона, ни до Пифагора, ни до кого вообще, кто размышлял подобным образом <…> Были в древности, намного раньше всех этих так называемых философов, некие люди, блаженные, праведные, боголюбезные, говорившие по вдохновению Божественного Духа, предсказавшие о будущем то, что происходит сейчас. Их зовут пророками <…> Сочинения их целы и поныне. И в них читатель, поверив им, найдет много полезного и про начала, и про цель, и про те вещи, которые надо знать философу. Речи свои они ведь строили не с помощью доказательств, так как стояли выше всякого доказательства и были достоверными свидетелями истины…” (глл. 6, 7).

Конец беседы со старцем показан как обращение Иустина в христианство: “сказав еще многое <…> он ушел <…> у меня же в душе внезапно вспыхнул огонь, и объяла меня любовь к пророкам и к тем людям, кои суть други Христовы. Беседуя сам с собой о его речах, я нашел, что только тут и есть незыблемая и полезная философия. Вот по каким причинам и какой я философ…” (гл. 8).

Ответив этими словами на вопрос Трифона “какова твоя философия?”, Иустин снова входит в роль собеседника, противостоящего Трифону, и начинает вести себя по отношению к Трифону так, как вел себя старец по отношению к нему, Иустину. Речь старца заканчивалась призывом: “Молись прежде всего о том, чтобы открылись для тебя врата света, ибо не все могут увидеть и понять эти вещи, если Бог и Христос не дадут уразуметь их” (гл. 7). Рассказ Иустина о встрече со старцем завершался аналогичным призывом к Трифону: “Я хотел бы, чтобы все, исполнившись одинакового со мною духа, не отступали от слов Спасителя <…> те, кто следуют им, получают сладчайшее успокоение. Вот и ты, если заботишься о себе, стремишься к спасению и полагаешься на Бога, то, как не вовсе чуждый этому, можешь, познав Христа Божия и став совершенным, насладиться счастьем” (гл. 8).

Слова старца в рассказе Иустина нашли живой отклик в душе его собеседника. Слова Иустина, обращенные к Трифону, тоже вызывают бурную, но уже иную по своему характеру реакцию слушателей. Если в душе Иустина “вспыхнул огонь”, то спутники Трифона “стали смеяться”. Упомянутые мельком в начале диалога и заставляющие нас вспомнить о хоре поклонников софиста в платоновских диалогах, спутники Трифона выполняют смысловую функцию, близкую к функции старца. Подобно тому, как фигура старца как бы расщепляла надвое роль Иустина и позволяла автору показывать одновременно два “Иустиновских лица” — его прошлую приверженность к эллинству и его настоящее преклонение пред христианством, так и спутники расщепляли надвое роль Трифона: их неблагопристойное поведение разделяло Иустина и Трифона и как бы символизировало неприятие Трифоном христианства, а показанная в виде контраста вежливость его самого сглаживала этот разрыв. В итоге между персонажами сохранялось то отношение “разъединения (идейного) — соединения (личного)”, которое лежит в основе диалога. Вот как изображена реакция Трифона и его последователей на слова Иустина: “После того как я, возлюбленный, произнес это, люди, бывшие вместе с Трифоном, рассмеялись, сам же он, улыбнувшись, сказал: «Я принимаю кое-что из твоей речи и восхищаюсь твоим рвением к божественному, но лучше было бы тебе держаться платоновской или другой какой-либо философии <…> чем обманываться лживыми словами и следовать людям никчемным <…> Если хочешь меня послушать, — я ведь уже признал тебя своим другом, — то прежде всего прими обрезание, затем соблюдай положенное законом…»” (гл. 8).

Эта сцена как бы ставит собеседников в равноправные позиции, противоположные по содержанию, но не враждебные. Оба признают неправоту партнера, и оба “протягивают ему руку”, стремясь перетянуть на свою сторону. Тон благожелательности и твердого отстаивания своих убеждений звучит в ответе Иустина Трифону:

“— Тебе простительно это, человек, — возразил я, — и да не вменится тебе этого. Ведь ты не ведаешь, что говоришь, доверяя учителям, которые не понимают Писания <…> А если бы ты пожелал услышать рассуждение о том, что мы не заблуждаемся и не прекращаем нашего исповедания, даже если люди навлекают на нас позор, даже если злейший тиран принуждает к отречению, то я покажу тебе здесь, что мы не пустым басням поверили и речам не бездоказательным, а исполненным силы и благодати Божественного Духа” (гл. 9).

В следующем затем эпизоде ситуация “разъединения-соединения” наглядно выражена движением, жестами и мимикой действующих лиц. Несогласие Трифона с верой Иустина подчеркнуто насмешливым поведением его спутников и желанием Иустина прекратить беседу, стремление же Трифона и Иустина найти общий язык — тем, что они не доводят дело до разрыва. Приведенные выше слова Иустина наталкиваются на такого рода реакцию слушателей: “И вот снова захохотали его спутники и непристойно закричали. Я поднялся и приготовился уйти, Трифон же, взяв меня за плащ, сказал, что не отпустит прежде, чем я не выполню обещанного.

— Так пусть твои товарищи не шумят, — сказал я, — и не бесчинствуют, пусть слушают спокойно, если хотят. А если им очень мешает какое-то дело, пусть уходят. Мы ж, давай, удалимся куда-нибудь и спокойно продолжим там наш разговор. Трифон согласился поступить так, и вот мы удалились <…> Когда же мы пришли туда, где по обеим сторонам стоят каменные скамьи, то спутники Трифона сели на одну из них. Кто-то из них обронил слово о последней иудейской войне, и они завели о ней речь.

Дав им кончить, я снова заговорил: «Не за то ли вы презираете нас, друзья, что мы живем не по закону, не обрезываем плоти? <…> Или у вас пользуется дурной славой наша жизнь, наш нрав? Я говорю о том, не поверили ли и вы тому, что мы едим человеческое мясо и после пиршества при потушенных светильниках предаемся беззаконным смешениям?»” (глл. 9, 10).

Спор о преимуществах христианства и иудейства служит прелюдией к главной части диалога, в которой защищается христианская интерпретация библейских текстов. В ней рассмотрены три темы:

1) завершение обрядовых постановлений (глл. 11–43),

2) вера в Христа (глл. 43–118),

3) Церковь (глл. 119–141).

Речам Иустина отведено здесь наибольшее место и очень малое — возражениям его партнеров. Те личные, доверительные отношения, которые установились между двумя собеседниками в начале их диалога, теперь как бы перенесены на сам обсуждаемый предмет: в основу своих толкований Иустин кладет примиряющую схему, схему непротиворечивости и единства Ветхого и Нового Заветов. В этой перекличке мотивов обрамляющего сценария и основной философской темы мы вправе усмотреть еще одно подражание классическому образцу. Подобно тому, как Платон в “Лисиде” сначала показывал персонажей в их интимных отношениях (дружба Менексена и Лисида, любовь Гиппотала к Лисиду), а затем ставил на обсуждение вопрос, какое надо дать определение понятию “друг”, так и Иустин в “Диалоге с Трифоном” сначала воспроизводил вежливый и заинтересованный разговор христианина с эллинизированным иудеем, а потом раскрывал сущность христианских объяснений иудейской обрядности. Вводная часть заканчивалась недоуменной репликой-вопросом Трифона: “Нас больше всего приводит в недоумение то, что вы, говорящие о благочестии, полагающие, что превосходите других, ни в чем от них не отличаетесь и своею жизнью уподобляетесь язычникам, не храня ни праздников, ни суббот <…> Если можешь в этом оправдаться и показать, каким образом, даже не соблюдая закона, вы на что-то надеетесь, я с большим удовольствием послушал бы тебя…” (гл. 10). И ответом на этот вопрос служило выступление Иустина, которое одновременно признавало и уместность традиции, и неизбежность ее преодоления.

Национальной замкнутости иудейства Иустин противопоставлял новозаветный универсализм, заявляя, что “закон, данный на Хориве, уже обветшал и касается только вас, а этот — всех людей вообще. Закон, наложенный на закон, прекратил действие первого…” (гл. 11). Размежевание с иудейством не доводилось, однако, Иустином до полного отвержения. Он находил средство включить ветхозаветную традицию в одну систему с христианством, и этим средством было понятие знака. События Ветхого и Нового Завета получили в системе Иустина свое историческое место как предшествующее и последующее, как прообраз (знак) и свершение.

Быть “знаком” означало иметь смысл условный и в то же время иносказательный, то есть указывать на другие явления. Иустин заявлял, что все обрядовые предписания иудейского закона (посты, омовения, обрезание, хранение субботы) — это знаки, которые не имеют непреходящей ценности, но условны и вызваны необходимостью воспитательных мер и исторической ситуацией; как знаки они служат образами других отношений, всеобщих, нематериальных, вечно ценных. Христианская интерпретация тем самым превращалась не в зачеркивание ветхозаветного смысла, а в переход от “знака” к “обозначаемому”, от чувственного смысла к духовному. Вот какими словами говорил об этом Иустин: “Какая польза в омовении, которое очищает плоть и одно тело? Омойте душу от гнева и любостяжания, от зависти и ненависти. И тело станет чистым. Знаком (sЪmbolon) этого и служат бесквасные хлебы, чтобы вы не совершали ветхих дел худой закваски. Вы же все поняли в плотском смысле и почитаете себя благочестивыми, если выполняете это, тогда как души у вас стали вместилищем коварства и всякого зла” (гл. 14). Обряд, утративший таким образом свое прямое значение, сохранял в глазах Иустина свою ценность как метафора, как название новых явлений: “Вы видите, — заявлял он, — Бог не хочет того обрезания, которое дано как знак (e„j shme‹on), ведь оно не приносит пользы ни египтянам, ни сынам Моава, ни сынам Едома. Но будь то скиф или перс, если он имеет знание о Боге и Христе Его и верен вечной правде, то он обрезан прекрасным и полезным обрезанием” (гл. 28).

С помощью “небуквального” толкования Библии Иустин оправдывал и защищал христианское учение пред лицом своего собеседника. Вопросы и возражения последнего служили импульсом для все более подробного исследования темы. Интонация реплик Трифона, которые произносились по поводу высказываний Иустина, менялась на протяжении диалога от недоуменно-враждебной до примирительно-дружеской. Подобно тому, как в апоретических диалогах Платона персонажи сталкивались с трудностями, бывали готовы бросить обсуждение и искали выхода из тупика, в иустиновском диалоге разговор шел в первой своей части при нарастающем недоверии Трифона, доходил почти до разлада между партнерами, затем получал новый оборот и продолжал вестись уже с благожелательного согласия Трифона. Упорное неприятие иудеем христианского отношения к обряду создавало конфликтную ситуацию, которую писатель использовал как прием композиции при переходе к новой теме. Это неприятие выражено словами Трифона: “Нам нужно слушаться наших учителей, законоположивших ни с кем из вас не общаться, ибо много кощунств произносишь ты, стремясь убедить нас в том, что Распятый был вместе с Моисеем и Аароном и говорил с ними в столпе облачном…” (гл. 38). Отвечая ему, Иустин начинал раскрывать еще один аспект христианства — его парадоксальность, заявляя: “Знаю, что по слову Божию скрыта от вас великая премудрость Бога Вседержителя и Творца мира, поэтому из сострадания к вам я прилагаю все усилия, чтобы вы уразумели эти наши странные (‘парадоксальные’ — parЈdoxa) утверждения. Если вы не послушаетесь, то пусть хотя бы я буду свободен от наказания в день суда. Внемлите и другим речам, по-видимому еще более странным (‘парадоксальным’)” (гл. 38).

Последующая просьба Трифона: “Вернись туда, где остановился, продолжи свое слово, ведь оно вообще кажется мне странным (‘парадоксальным’) и неприемлемым…” (гл. 48) опять сближала персонажей и служила толчком для более детальной аргументации.

Если рассматривание иудейских обрядов имело до некоторой степени вид спора, когда Иустин утверждал тезис, а Трифон возражал и занимал непреклонную позицию, то “парадокс” сам по себе не мог быть предметом препирательств, и реплики Трифона, продвигающие вперед ход беседы, строились тут совсем иначе, они звучали не враждебно, а дружески, в них не отстаивались взгляды, а выражалось желание понять суть вопроса, решить недоумение. В таком же духе высказывались теперь и спутники Трифона. Приводим примеры:

“После моих слов Трифон сказал:

— Не подумай, что я пытаюсь опровергнуть твои слова, если спрошу то, о чем спрошу. Нет, я хочу знать то, о чем задаю вопрос <…> И я ответил:

— Ты задал вопрос очень разумно и понятно. И на самом деле, по-видимому, это вызывает недоумение (ўpТrhma), но чтобы увидеть и тот смысл, который тут заключен, послушай, что я скажу” (гл. 87).

“И другой из тех, кто пришел на второй день, сказал:

— Ты сказал правду, мы не можем привести доводов. Ведь и я часто вопрошал об этом учителей, и никто не разъяснил мне, так что продолжай говорить, что говоришь…” (гл. 94).

Поведение спутников Трифона подчеркивает ситуацию “соединения”, которая установилась между партнерами. Обсуждение темы “парадокс Христа” и переход к новой теме “христиане — новый Израиль” осуществляется теперь без конфликтов, в доверительной беседе. Однако соединение не доведено до конца, и размежевание иудейского национализма и христианского универсализма осталось в силе. И здесь опять автор использовал фигуры спутников Трифона, чтобы показать его несогласие с Иустином, как и во введении он заставил их громко шуметь и кричать:

“Как в театре закричали некоторые из пришедших на второй день:

— Что это? Разве не про закон говорит он, не про тех ли, кто просвещается им? <…>

Я увидел, что они пришли в смятение от сказанного мною, что и мы — дети Божии” (глл. 122, 124).

Как и во введении, разлад не привел к разрыву, и в конце диалога Иустин и Трифон мирно прощались друг с другом:

“Помолчав немного Трифон сказал:

— Видишь, не по долгу службы вступили мы в этот разговор, и, признаюсь, я получил большое удовольствие и мои спутники, думаю, тоже. Мы нашли больше, чем ожидали и чем можно было ожидать. Вот если бы такие встречи могли происходить чаще, то мы бы получили еще большую пользу, исследуя сами слова [Писаний]. Но раз ты готовишься к отплытию и каждый день у тебя на счету, то будь добр, когда уедешь, вспоминай нас, как друзей” (гл. 142). Так же, не придя к единомыслию, но и без вражды, расходятся в разные стороны платоновские Протагор и Сократ (“Протагор” 361D–362А).

Итак, рассмотрев содержание “Диалога с Трифоном”, мы можем представить себе его композицию в следующем виде:

1. обрамляющая бытовая ситуация инсценирует место беседы в аллеях Ксиста;

2. на этом месте происходит неожиданное соединение двух участвующих в разговоре сторон, из которых одна — сам автор, другая — эллинизированный иудей Трифон со своими спутниками;

3. между встретившимися завязывается беседа на тему “какова твоя философия?”;

4. в ходе беседы между персонажами устанавливаются личные отношения — доверительно дружеские со стороны автора и недоверчиво настороженные со стороны его партнеров. Эти взаимоотношения принимают вид “соединения-разъединения”;

5. принцип “соединения-разъединения” использован не только при изображении персонажей, но и при раскрытии философской темы;

6. в первом случае нить личных взаимоотношений имеет такой вид:

-

a. встреча партнеров во время прогулки; b. враждебная реакция спутников Трифона на слова Иустина, желание Иустина расстаться с ними и препятствие со стороны Трифона; c. нарастающее доверие Трифона к Иустину, которое, однако, не приводит к полному согласию; насмешливая реакция спутников Трифона как бы вновь разъединяет партнеров; d. расставание дружески настроенных друг к другу собеседников;

7. во втором случае, при исследовании вопроса “какова твоя философия?”, “соединение-разъединение” осуществляется следующим образом:

-

a. ответ на поставленный вопрос дается сначала как утверждение ценности христианства в форме биографического экскурса, где Иустин рисует свое приятие христианства как “находку”, как неожиданный выход из недоуменного состояния, как откровение, решившее проблемы, волновавшие автора. При этом Иустин, описывая свое собственное развитие, как бы встает в позицию своего собеседника (Трифона), соединяется с ним в одно лицо, а потом отмежевывается от него, рассказывая о своем обращении в христианство. Трифон — это то, кем был Иустин раньше, это и он, и не он. b. При рассматривании самого христианского учения в нем обнаруживаются черты сходства и несходства с иудейством: сходно приятие библейских текстов, но различна их интерпретация. Теория знака (символа) позволяет автору связать христианское и иудейское толкование в одну непротиворечивую систему, в которой христианство соединено с иудейством и одновременно отделено от него. Такое “соединение-разъединение” заставляет признать христианское учение парадоксальным, благодаря чему решается то недоумение, которое оно вызывает в нехристианском мире.

В филологической литературе в качестве платоновских черт “Диалога с Трифоном” рассматриваются обычно текстуальные заимствования12 из платоновских сочинений и сходство персонажей у святого Иустина и Платона13. Все сказанное выше по поводу этого диалога позволяет говорить о более тонком и глубоком подражании Платону у святого Иустина, чем это принято думать: о сходстве не только деталей, но и функций, не только слов и выражений, но и композиции. К уже отмеченным исследователями чертам близости у обоих писателей мы должны добавить еще и такие:

1. единство темы (“что такое христианская философия”), которая анализируется не с функциональной стороны, как набор признаков, а онтологически — как принцип мирообъяснения (теория знаков);

2. мотив недоумения и парадокса, приводящий в движение беседу, а также мотив конфликта и его преодоления;

3. интонация личной близости партнеров, рассматривание обсуждаемой темы как личностной (“какова твоя философия?”);

4. прием стороннего собеседника (аналогичная функция старца у святого Иустина и Диотимы у Платона);

5. соотношение вводной и основной части диалога: то, что в вводной намечено как личная тема (“какова твоя философия?”), в основной части раскрывается как общая доктрина.

Персонажи не только описаны с помощью цитат из Платона, но и поставлены в некие “платоновские” ситуации. Они ведут свой диспут путем наводящих вопросов, напоминающих сократовскую майевтику, они попадают в затруднительное положение (“апорию”, столь обычную для Сократа и его собеседников), говорят о том, что стремятся найти истину, что опять вызывает в нашей памяти образ афинского философа. Спор этих персонажей приобретает характерную черту одновременного размежевания идейных позиций и объединения совместных усилий в общем искании правды (соединение-разъединение) и тем самым отличается как от простой дружеской беседы, в которой нет антагонистов (наподобие Плутархова диалога “о любви”), так и от резко враждебной полемики. Христианское подражание Платону неизменно окрашено тоном вежливости и благожелательности.

Однако при всей близости к платоновским сочинениям “Диалог с Трифоном” противостоит своему классическому прототипу как учение об откровении противостоит рационализму; христианское учение в глазах святого Иустина вовсе не похоже на то вечно искомое рассудком знание, к которому стремятся платоновские герои. Если для Платона искание истины — это прежде всего логическое исследование понятий, то для святого Иустина оно есть усвоение библейских текстов, библейского откровения.

На фоне языческой литературы первых веков по Р. Х. христианское подражание платоновскому диалогу было несомненно более полным и своеобразным использованием классического образца. При всей невозможности создать нечто, стоящее в одном ряду с “сократовскими разговорами” IV века до Р. Х., это была попытка поставить на обсуждение общие вопросы о смысле жизни, которые не дерзал поднимать тогдашний языческий мир. И в качестве художественных средств христианский писатель взял у эллинства тот древний материал, который был всем хорошо знаком, но не находил применения у современных ему писателей-язычников. Там, где шла ломка античных представлений о мире, разработанные Платоном художественные приемы оказывались наиболее применимыми. “Платон-художник” использовался как средство борьбы с “Платоном-мыслителем”.

1Майевтика — повивальное искусство; этим именем Сократ называет свой метод в платоновском “Теэтете” (149–150).

2“Роман о Сократе” — сборник (псевдо)писем Сократа и его учеников. Сборник составлен в эпоху поздней античности на основе сократической литературы.

3См. Hirzel R. Der Dialog. Bd. 2. Leipzig, 1895. — SS. 83 ff.

4Об отношении раннего христианства к античной литературе см. Kennedy G. A. Greek Rhetoric under Christian Emperors. Princeton Univ. Press. 1983. — Pp. 180–186.

5От доникейского периода сохранились “Диалог с иудеем Трифоном” святого Иустина (II в.), “Пир” священномученика Мефодия Патарского (III–IV вв.); остальные сочинения священномученика Мефодия дошли в отрывках. От газских риторов V в. сохранились “Феофраст” Энея Газского и “О сотворении мира” Захарии Схоластика. О раннехристианском диалоге см. Hoffmann M. Der Dialog bei den christlichen Schriftstellern der ersten vier Jahrhunderte. Berlin, 1966.

6Биографические сведения о святом мученике Иустине Философе содержатся в его житии (Ausgewдhlte Martyracten / Hrs. v. O. Gebracht. Leipzig, 1902. — SS. 18 ff), в “Церковной истории” Евсевия (IV, 16–18) и в его собственных произведениях. Из этих источников мы знаем, что святой Иустин Философ был уроженцем Флавия Неаполиса (бывшего Сихема) в Самарии, по принятии крещения жил в Риме и держал там школу; казнен был при Марке Аврелии (163–167).

7Перевод выполнен по изданию: The Apologies of Iustin Martyr / An intr. by B. Gildersleeve. New York, 1904.

8Цитата из “Илиады” VI, 123.

9Речь идет о войне 132–135 гг., антиримском восстании в Палестине под предводительством Бар-Кохбы.

10Перевод отрывков “Диалога с Трифоном” выполнен по изданию: Patrologiae cursus completus. Series graeca. T. 6. Cols. 472–800.

11См. Hoffman M. Указ. соч. — SS. 24–27.

12Буквальные совпадения с “Протагором” Платона исследованы в статье Keseling R. Iustin’s Dialog gegen Trypho (cap. 1–10) und Platon’s “Protagoras” // Rheinisches Museum fur Philosophie. Bd. 75 (1926). — SS. 223–229; близость речи старца к речи Диотимы в “Пире” Платона отмечена в статье Schmid W. Frьhe Apologetik und Platonismus. Ein Beitrag zur Interpretation des Proцms von Iustin’s Dialogs / `Ermhne…a. Festschrift Otto Regenbogen. Heidelberg, 1952. — SS. 177, 178); о заимствованиях из платоновского “Федра” пишет Гирцель (Указ. соч. Т. 2. — С. 369); влияние “Тимея” Платона устанавливает де Фрэ: De Fraye E. De l’influance du Time de Platon sur la theologie de Iustin Martyr. Paris, 1896.

13В книге Hubik K. Die Apologien des Hl. Iustins. Wien, 1912 отмечено сходство фигуры Трифона и его спутников с фигурой софиста в платоновском “Протагоре”; Гофман (Указ. соч. — Сc. 20, 21) усматривает влияние платоновского диалога в той “наталкивающей” роли реплик Трифона, какую они играют в основной части диалога, способствуя “продвижению вперед” речи Иустина, а также в сократовском методе разговора Иустина со старцем во вводной части.

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

Всю свою жизнь Платон боялся, что его произведения попадут в руки неподготовленных читателей. И опасения оказались ненапрасны. За те две с половиной тысячи лет (с редкими перерывами), что мыслитель присутствует в нашем интеллектуальном поле, его философия покрылась слоем самых разных, а иногда и прямо противоположных толкований.

Добраться до подлинных идей Платона через эти наслоения — сложная задача. Во-первых, они намертво затвердели в нашей традиции. А во-вторых, из-за специфики его философии найти однозначный ответ на вопрос, чему же он всё-таки учил, очень непросто. По крайней мере так считают последователи Тюбингенской школы, совершившие несколько десятилетий назад революцию в платоноведении.

Но для начала поговорим о том, как читали Платона раньше и продолжают читать сегодня.

Платон — это кто?

Уже в эпоху Античности существовало два подхода к чтению Платона, которые в том или ином виде сохраняются до сих пор.

Способ 1: Платон-скептик. Адепты первого из них считают философа скептиком и непримиримым критиком любых догм, верований и представлений.

Самое известное изречение Сократа, героя почти всех диалогов Платона, в полной мере демонстрирует стремление отрешиться от каких бы то ни было убеждений: «Я знаю, что ничего не знаю». За афористичным категоричным утверждением следует еще более острый вопрос — как возможно знание вообще и что оно собой представляет?

Эта традиция толкования Платона впоследствии развилась в учение скептиков, призывавших воздерживаться от любых суждений. В их методологии также явно прослеживается критическое и аналитическое начало, ставшее одним из краеугольных камней европейской мысли.

Способ 2: Платон-догматик. Второй подход основан на предположении, что у Платона было собственное чуть ли не догматическое учение, которое он «спрятал» в своих диалогах. Задача читающих — путем усердной, вдумчивой работы с текстами выцедить из них его философию.

Этим стали заниматься неоплатоники, в III веке н. э. оформившиеся в отдельную школу. Ее основателем считается египетский философ Плотин, чьи ученики составляли очень подробные, скрупулезные комментарии к текстам Платона и сводили его мысли в единую систему. Позже эта школа окажет огромное влияние на христианство.

В Академии самого Платона в разные периоды был популярен то один, то другой подход. Она просуществовала тысячу лет и закрылась по приказу христианского императора Юстиниана в 529 году н. э., как языческое учреждение. В долгую, растянувшуюся на десять веков эпоху Средневековья один из отцов мировой философии, чьи оригинальные рукописи оказались утрачены, будет известен в основном только по сочинениям неоплатоников. И то скорее как искусный литератор, нежели глубокий мыслитель.

Интерес к настоящему Платону, Платону-философу, возникает в эпоху Возрождения, когда его тексты, сохранившиеся благодаря византийским монахам, переводят на язык ученой Европы — латынь. Однако первая монография о Платоне появляется лишь в XVIII веке, а в университетах его начинают изучать только в следующем столетии.

Лекция о Платоне доцента МГИМО, кандидата философских наук Николая Бирюкова

Как принято читать Платона сейчас: акцент на тексте

В 1804 году немецкий теолог и один из основателей герменевтики Фридрих Шлейермахер предложил способ чтения Платона, которым большинство исследователей пользуется до сих пор.

Во вступительной статье к своему переводу платоновских диалогов на немецкий язык он утверждал, что содержание этих произведений неразрывно связано с их формой, то есть жанром прозаической драмы, и отделять философию Платона от его текстов — значит просто не понимать греческого мыслителя. Диалогическая форма была для него естественным способом передачи знаний.

Шлейермахеру было известно, что Платон презрительно отзывался о любом виде письменности как способе передачи знаний вообще. Однако он верил, что философ, учитывая недостатки письма, смог организовать свои диалоги таким образом, что они почти не уступали устной беседе, которой Платон отдавал предпочтение.

Шлейермахер полагал, что внимательного, вдумчивого чтения достаточно, чтобы пережить то, что переживали в личных беседах с великим мыслителем его ученики, и открыть для себя философию Платона.

Конечно, отыскать и понять идеи автора с первого раза удается далеко не всегда. Но тем лучше: при каждом новом прочтении будут открываться более глубокие смыслы, а неподготовленные читатели по мере возрастания сложности идей начнут «отсеиваться». Но даже для них это не приговор — через несколько лет можно вернуться к диалогам и постичь сокрытую в них философию.

Благодаря Шлейермахеру каждая буква, написанная Платоном, на два следующих столетия становится объектом пристального внимания со стороны многочисленных философов и исследователей. Тут и выходят на сцену наши герои — Ганс Кремер и Конрад Гайзер.

Тюбингенская школа, или Минусы демократии

По мнению этих ученых, выступивших со своей теорией в 1950-х годах, одних текстов для понимания философии Платона всё же недостаточно. Они стали утверждать, что так называемое «неписаное учение» Платона, от которого до этого просто отмахивались, действительно существовало, и что его содержание отличается от того, что мыслитель оставил нам в диалогах.

Кремер и Гайзер утверждают, что Платон выработал свои взгляды в более или менее строгом виде еще до основания Академии. Его философия существовала только в устной форме и преподавалась в кругу последователей как «теория первопринципов всего существующего». Кроме этой глобальной темы, она также затрагивала и более частные области: идеальные числа, математические объекты, душа, космос.

Платон не скрывал само наличие у него «устного учения» (о том, что у него это учение было, мы знаем по нескольким внешним источникам, самый известный из них – «Метафизика» Аристотеля).

Но философ принципиально не делился его содержанием в письменной форме, поскольку считал, что книга легко попадает в руки не подготовленного к ней читателя, которому ничто не помешает понять превратно изложенные в ней знания.

Задача диалогов в таком случае сводилась к тому, чтобы привлекать к платоновской философии неофитов. Периодически эти сочинения также выполняли прикладную функцию — служили в качестве упражнений для припоминания уже пройденных тезисов или пособия для обсуждения конкретных вопросов, поставленных в связи с устным учением.

В своих предположениях Кремер и Гайзер опираются на свидетельства самого Платона. Их можно найти в конце диалога «Федр» и его так называемом «Седьмом письме», где автор выступает со своей знаменитой суровой критикой письменной формы передачи мыслей.

Исследователи долгое время отказывались рассматривать всерьез устное учение Платона в том числе и потому, что у них возникали сомнения в авторстве упомянутого «Седьмого письма». А делать выводы на основании одного лишь диалога, конечно, нельзя: мы не можем утверждать, что слова, вложенные в уста персонажа, были выражением взглядов самого философа.

Концепция Кремера и Гайзера устраняет многочисленные противоречия в прочтении Платона и отлично согласуется с его устным учением. А «Седьмое письмо» в этом случае выступает лишь как еще одно доказательство, и, даже если предположить, что оно действительно написано другим автором, их теория всё равно остается стройной и логичной.

Но главная причина заключается в том, что академическое, университетское изучение Платона в Европе началось как раз в тот период, когда стали набирать популярность демократические ценности и неразрывно связанное с ними стремление к свободному распространению информации.

Зачем Платону утаивать мудрость и почему беседа лучше книги

В нашем представлении человек, утаивающий какое-то ценное знание, — злодей. Каждый ученый сегодня стремится как можно скорее поделиться своими открытиями, поскольку верит, что они способны принести благо обществу. А сокрытие информации мы подспудно воспринимаем как претензию на власть, на политическое могущество (так, главный герой сериала «Молодой Папа» долгое время скрывал самого себя).

Для подобных опасений, действительно, есть основания. В той же Древней Греции, например, сокрытие знаний практиковалась сторонниками пифагорейской школы. Это большое тайное общество, чем-то напоминающее масонские ложи, оказывало влияние на политику Южной Италии. За раскрытие какой-либо информации или самого учения провинившегося проклинали и изгоняли, а иногда карали смертью. Однако в этом случае утаивание знаний было обусловлено политическими, а не собственно философскими соображениями.

Платон же, в отличие от пифагорейцев, скрывал содержание своего устного учения по причинам, которые касались самой философии, и уж точно не наказывал тех, кто «проговорился» (а такие случаи были). Причину, по которой Платон скрывал содержание своего «устного» учения, объяснил в своей книге «Как читать Платона» Томас Слезак. В ней он суммировал и развил основные положения Тюбингенской школы.

Такая позиция Платона была обусловлена его представлениями о задаче философа и философии вообще. Он всегда настаивал на том, что живая мысль, развивающаяся в устной беседе, во много раз превосходит мысль записанную, а следовательно – мертвую. И настоящий философ, или диалектик, никогда не сможет смириться с недостатками, которыми обладает письменное сочинение.

Задача мыслителя, по Платону, не проинформировать всех людей о том или ином предмете, но открыть человеку глаза на его образ жизни, чтобы он усомнился в собственных знаниях не только об окружающем мире, но и о себе самом, и обратился в философию, — то есть жизнь, подчиненную разуму. Книга для этих целей совершенно не годится.

Первый недостаток книги

Письменное сочинение, в отличие от живого человека, не может выбирать себе собеседника. Оно легко попадает в руки неподготовленного читателя и быстро становится предметом неверного толкования. Опасность здесь заключается в том, что человек таким образом наносит вред не только самому себе, но и другим людям, лишая их возможности обратиться в философию.

Кроме того, есть такие области, о которых говорить письменно просто невозможно. Простая фиксация на бумаге ничего не проясняет, и драгоценная мысль остается непонятой, а следовательно — бесполезной.

Настоящий философ должен тщательно подходить к выбору собеседника и открывать ему лишь те знания, которые доступны человеку. Причем важен не только интеллектуальный уровень слушателя, но еще и его нравственная, духовная зрелость.

Если кто-то не готов услышать о себе правду, быстро впадает в гнев и отвергает любые, даже самые верные мысли, то философ потратит свои усилия и время впустую.

Второй недостаток книги

Она «всегда передает одно и то же». В ходе живого общения, если у собеседника возникли неверные установки или трудности с пониманием того или иного вопроса, настоящий философ это заметит и попробует привести дополнительные примеры, подойти к объяснению с другой стороны. Книга же не способна дать читателю новые ответы на его новые вопросы. И что хуже всего, она не замолчит, когда это необходимо.

Третий недостаток книги

Письменное сочинение никогда не сможет себя «защитить». Этот тезис очень важен для понимания механики как устной, так и письменной философии Платона. Если в прошлом пункте речь шла о тех, кто всецело открыт к знанию, то здесь имеются в виду собеседники, которым нужны «более веские аргументы». В их число входят критики и люди, требующие повышенной интеллектуальной нагрузки. Первые сочтут книгу плохо обоснованной, а вторые — слишком поверхностной.

Чтобы защитить свою речь, «живой» философ всегда может сменить тему, выбрать другой способ аргументации, «помочь себе», перейдя к более устойчивым основаниям и положениям своей философии. Всё это недоступно тому, кто пользуется «мертвыми знаками».

Конечно, приведенные доводы против письма были известны исследователям давно. Но почти никто из них не придавал этому большого значения, веря, что и письменное сочинение способно открыть человеку необходимые знания при вдумчивой, правильной работе с ним. И действительно, прочитывая текст раз за разом, мы открываем в нем новые смыслы.

Однако Платон исходил из того, что наше восприятие письменной речи субъективно, а следовательно, неизбежно возникают множественные и не всегда верные интерпретации. Именно этого он сторонился, поскольку цель настоящего философа — помочь своему собеседнику, оказать ему содействие на пути к разумной жизни, а не предложить два равновероятных решения отвлеченной проблемы. И книга, как мы знаем по собственному опыту, с этой задачей не справляется.

Но есть и хорошая новость. Устная философия Платона отличается от его же диалогов только уровнем сложности затрагиваемых в ней предметов. А вместе две эти формы выражения мысли составляют единое целое, и противопоставлять их было бы большой ошибкой. Диалоги Платона хотя и не передают содержание устного обучения, но в полной мере демонстрируют все его перечисленные выше особенности.

Платон-драматург

Известно, что до своей знаменательной встречи с Сократом в 407 году до н. э. Платон был прежде всего выдающимся драматургом и поэтом. Неудивительно, что его диалоги до сих пор привлекают внимание читателей яркими образами и силой поэтического воображения. Однако литературный талант Платона проявился не только в изящном слоге, но и в композиции его сочинений.

Вообще, нехудожественные произведения-диалоги не совсем привычный для нас жанр. Обычно ученый или философ излагает свои взгляды в форме трактата — одного большого монолога. Но в европейской культуре долгое время существовала традиция использовать в сочинениях подобного рода драматический принцип организации текста. Николай Кузанский, Джордано Бруно, Коперник, Галилей, Декарт — многие их открытия записаны в форме беседы. Ее хотел использовать даже советский философ Владимир Библер — создатель учения о диалоге культур.

Дело в том, что такая форма лучше всего отражает процесс мышления, который, как правило, тоже поступателен: вопрос — ответ, вопрос — ответ… Это мы обычно и называем «рефлексией». Признанный мастер диалектики, Платон стал первым, кто «перенес» этот процесс мышления «на бумагу».

Но кроме непривычной формы, в диалогах есть и другие черты, которые могут раздражать читателя и даже порой вызывать у нас внутреннее сопротивление. Например, часто возникает ощущение, что беседа обрывается посреди какого-то более важного разговора или перед ним: Сократ — главный герой и «модератор» большинства диалогов Платона — просто заявляет, что предпочитает отложить ту или иную тему на потом, но «потом» мы ее, конечно, не находим.

Еще сильнее раздражает, что тот же Сократ, если он главное действующее лицо, всегда выходит из споров победителем. В такие моменты хочется стать на сторону его соперника, которого всё это время, оказывается, просто водили за нос.

И вообще складывается впечатление, что автор, не умея ничего толком сказать, прячется в своих диалогах за персонажем.

Но приступая к чтению Платона (как и любых великих произведений), необходимо держать в уме, что те детали, которые часто кажутся нам недостатками, на самом деле могут выполнять важную функцию. Нужно помнить, что мы, люди своей эпохи, живем в привычном для нас культурном контексте и сами порой выступаем искажающим фактором, мешающим прорваться за уровень поверхностного понимания. То же самое и здесь: при чтении Платона следует запастись терпением, проницательностью и занять позицию активного читателя.

Так, украинский философ Андрей Баумейстер для начала предлагает следить за тем, как герои Платона аргументируют свои тезисы, представить всю обстановку диалога в деталях, не спешить прокручивать в голове каждое положение и каждый новый поворот в разговоре, стараться предугадывать ответ. Можно даже подумать над тем, какой вопрос лично вы задали бы Сократу.

Лекция Андрея Баумейстера «Почему Платон — мастер мышления и почему он актуален именно сегодня?»

Лекция Андрея Баумейстера «Философия Платона в простом изложении»

Но Томас Слезак идет еще дальше: неустанно подчеркивая, что Платон избрал форму прозаической драмы для своих сочинений неспроста, немецкий филолог показывает, как все вышеназванные «недостатки» диалогов связаны с философией их автора.

Защита логоса, или Отвечаем за свои слова

Слезак отмечает, что центральная ситуация диалогов — это такой момент в беседе, когда от собеседника требуется более глубокое обоснование его философской позиции, как бы отчет (так называемая «помощь логосу»). В этой ситуации диалог может прерваться или перескочить к другому диалогу (форма «диалога в диалоге» часто встречается у Платона). Нередко Сократ просто меняет тему и начинает говорить о других вещах.

Функция этих прерываний — привлечь внимание читающего к тому, что произойдет дальше, и обозначить переход на следующий уровень аргументации — к «более ценному логосу», к рассуждениям «более высокого достоинства».

С помощью такого приема Платон показывает, что настоящий философ должен выдерживать критику своей речи, прибегая каждый раз к более фундаментальным положениям своего учения, затрагивая всё более серьезные темы. И на вершине этой воображаемой лестницы, по которой он постоянно поднимается, — то самое устное учение, затрагивающее первопринципы всего сущего. Как мы уже поняли, излагать его на письме Платон не собирается, а вот более простые темы — может быть.

Если диалог приближается на «опасную дистанцию» к содержанию устного учения, Сократ отказывается говорить, аргументируя это тем, что его собеседник просто не поймет, о чем пойдет речь: он еще не готов.

Слушатели Платона прекрасно знали, что эти сцены в диалогах отсылают к устному учению вообще или к отдельным вопросам, которые они уже обсуждали. Ту же функцию выполняют и эпизоды умолчания, когда собеседники сразу решают отложить рассмотрение какой-то проблемы. Продолжения мы не находим, но это вовсе не «расплывчатые обещания» или загадки, которые предлагается разгадать читателю. На самом деле это «совершенно конкретные отсылки к четко очерченным теоремам» Платона, которые он уже разбирал в устной беседе со слушателями (если те, конечно, были готовы).

Причем «помощь своему логосу» для Платона — вопрос правильной философской позиции, а не вопрос софистики и не демонстрация риторической изворотливости.

По Платону, по-настоящему ответить за свои слова может только диалектик — человек, знакомый с его учением об идеях и способный рассуждать согласно строгим законам мышления.

На этот «длинный обходной путь» и должен стать читатель, встретивший препятствие в виде недоговоренностей и умолчаний и ощутивший нехватку собственных знаний.

Искусство правильно мыслить

Именно Платон первым заявил, что бо́льшая часть наших «знаний» на самом деле представляет собой простые верования и убеждения. Они могут соответствовать истине, но от этого всё равно не становятся «знаниями» в подлинном смысле слова. Последние необходимо логически и самостоятельно вывести, тщательно проработать и согласовать с остальной системой знаний.

Попасть под влияние неотрефлексированных сведений очень легко — мы не замечаем, как они начинают управлять нашими поступками и решениями. Об этом предупреждает и Библия: «Берегись, чтобы в сердце твое не вошла беззаконная мысль». На борьбу с «беззаконной мыслью» и была направлена диалектика Платона.

Смысл слова «идея» несколько изменился за пару тысяч лет, но во времена философа им называли суть вещей, которую можно ухватить умом и взглядом. Выражение «я вижу» в значении «я понимаю» хорошо передает указанный смысл; кроме того, русское существительное «вид» и глагол «ведать» однокоренные с древнегреческим «эйдос». Иначе говоря, диалектик — это человек, понимающий суть вещей и способный мыслить на уровне их идей.

Задачей философа, по Платону, было как раз диалектическое осмысление действительности. Такое познание мира невозможно на эмпирическом уровне, и простой человеческой сообразительности здесь тоже недостаточно. Оно осуществляется только в аргументирующем логосе — упорядоченном, строгом, отдающем самому себе отчет рассуждении. Его результатом оказываются «законные» мысли.

Конечно, содержание умозаключений можно изложить на бумаге. Но для Платона важнее всего было «живое мышление, процесс в душе, который в этом качестве не передается мертвым знакам письма». Потому философ и настаивал на устном обучении, когда мысль рождается у собеседников на виду. Он считал, что люди уподобляются самим богам в ходе этого «великого и величайшего» акта и в сравнении с ним остальные наши занятия просто смехотворны.

Зачем читать Платона?

Итак, мы выяснили, что диалоги Платона не рассчитаны на то, чтобы полностью изложить его философию — скорее, они выполняют отсылающую функцию. Возникает логичный вопрос: а зачем тогда их читать?

Несмотря на всю свою нелюбовь к «мертвым знакам», Платон осознавал, что даже на письме настоящий философ может продемонстрировать то живое и захватывающее движение мысли, которым он увлекает слушателей при устном общении.

Конечная цель любых его бесед, независимо от их формы, — обратить человека в философию, заставить его жить в согласии с разумом. И как сказал Томас Слезак, «кто начинает философствовать с Платоном, может быть уверен, что находится на правильном пути».

Однако нас от Платона отделяет огромное расстояние, которое исчисляется не только двумя десятками веков, но и гигантским количеством интерпретаций, предлагавшихся другими великими умами прошлого. Часть из них была неверна, кое-кому удалось подобраться ближе к истине. Но все они так или иначе оказали влияние на культуру, определяющую наш мир и нас в нем.

И чтобы невольно не попасть под ее влияние, стоит прежде всего обратиться к самому Платону — философу, который первым поставил вопрос «Что значит „знать“?».

Платон — биография

Платон – философ Древней Греции, ученик Сократа, автор многочисленных трудов. Основатель собственной Академии, первого на территории Европы высшего учебного заведения.

Ранние годы

Платон появился на свет предположительно в 428-427 или в 424-423 году до нашей эры, в знатной семье, имевшей большое влияние в обществе. Его отцом был Аристон, потомок афинского царя Кодра, считавшегося сыном божества Посейдона, и правителя Мессении Меланта. Мать Платона носила имя Периктиона, происходила из знатного рода, состояла в родстве с видными государственными деятелями Древней Греции.

О знакомстве родителей будущего философа доподлинных свидетельств не сохранилось. По некоторым сведениям, Периктиона сначала отвергла ухаживания Аристона. И сын у пары родился в результате непорочного зачатия. Но в более поздних источниках указывается на наличие у пары четверых детей – Адейманта, Главкона, Платона и Потон. Младшей в семье стала единственная дочь.

Место рождения Платона также вызывает споры. Но большинство историков сходится во мнении, что это произошло в Афинах или на Эгине. Дата тоже неизвестна. Но, из трудов самого философа, следует, что ему исполнилось 20 лет в год прихода к власти Тридцати тиранов (двое из которых были его родственниками). А значит, он предположительно родился в 424 году.

В античной традиции дата появления на свет Платона указывается как 7 таргелиона, что соответствует дню 21 мая в современном календаре. В древнегреческие времена это был большой праздник, посвященный рождению Аполлона на Делосе. Насколько достоверны такие утверждения – неизвестно.

Аристон умер, когда Платон находился еще в детском возрасте. Периктиона недолго горевала по супругу, и вскоре вступила в брак со своим дядей Пирилампием. От этого союза на свет появился еще один сын.

Имя философа тоже вызывает споры. Предположительно, Платон – это прозвище, образованное от прилагательного «широкий». Семейным имя точно не было. Вероятно, юноша взял его сам, по мере взросления. Существуют упоминания о том, что так называл Платона его тренер по борьбе, за ширину грудной клетки. Другие исследователи указывают на размеры лба философа. Настоящее же имя Платона, как предполагают историки, было Аристокл, в честь одного из дедов.

Платон получал классическое для того времени образование. В воспоминаниях о его юношеских года указывается на скромность, и даже замкнутость мальчика, его склонность к размышлениям. При этом интеллектуальные способности юноши всегда оценивались очень высоко.

Известно, что в юности Платон изучал искусство и музыку, грамматику, гимнастику, занимался борьбой. По некоторым свидетельствам его биографии, молодой человек даже участвовал в Истмийских играх. Философия также была важной частью образовательной программы. Платон изучал доктрины Гераклита, труды Кратила.

Среди учителей этого выдающегося философа в разные годы были и другие знаменитые исторические личности. Известно, что свое учение Платон во многом сформировал под влиянием Пифагора и его последователей. А с Сократом и вовсе встречался многократно, высоко ценил его мнение. И даже вывел философа центральной фигурой своих диалогов.

Среди учителей Платона упоминается и Феодор Киренский, знаменитый математик. Этот предмет философ знал прекрасно. Более того, мог преподавать его. И даже вывел различие между теорией чисел и логистикой.

Зрелость

О жизни Платона по окончанию обучения больше известно из свидетельств очевидцев. Сам он упоминал, что в возрасте 40 лет совершал путешествие по Сицилии и Италии. И не был доволен поездкой, поскольку в тех краях чувственной стороне жизни уделялось слишком много внимания.

По возвращению в Афины из этой поездки Платон основал собственное учебное заведение – первое организованное в Западной цивилизации. Место, где происходил образовательный процесс, располагалось в роще Академус, названной так в честь одного из мифологических героев Аттики. Здесь росли платаны и оливы, царила красота и гармония.

Академия Платона занимала обширное пространство около 1 км2, за пределами Афин, на огороженном участке. Она просуществовала до 84 года до н. э. Была прославлена многими учениками самым известным из которых является философ Аристотель.

Академия представляла собой объединение, где происходили дискуссии, а также осуществлялось служение музам и Аполлону, как их покровителю. В заведение не допускались «негометры» — люди, отрицающие математические и геометрические основы. Главой академии был сколарх. Образование давалось общее – с преподаванием математики и астрономии, ботаники, права, литературы, а также углубленное, индивидуальное.

В академии Платона был установлен строгий распорядок дня. Все учащиеся жили на ее территории в специальных зданиях. Следовали принципам общественного – вместе питались, занимались делами, но находили время и на размышления, которым принято было предаваться в тишине. Первыми преподавателями в академии стали сам Платон и его последователи.

Основав собственную школу, Платон отправился странствовать дальше, оставив управлять ей своего племянника. В Сиракузах он обрел ученика Диона, родственника правителя этих мест Дионисия. Тиран не был доволен деятельностью философа. Его объявили врагом, хотели предать смертной казни, но обошлись продажей в рабство. В этом статусе Платон пробыл, пока его не выкупил философ из Кирены Анникерис.

После смерти Дионисия преследования окончились. Дион обратился к Платону, прося его о помощи в воспитании будущего царя. Юный Дионисий II поначалу прислушивался к учителю. Но затем восстал против Диона. А Платона силой удерживал в Сиракузах еще некоторое время.

Могут быть знакомы

Философия

В философии Платона смешано много разных течений, в том числе метафизического характера. Известно, что он верил в идею переселения душ, и одновременно в числовые принципы Пифагора. Мистицизм как подоплека явлений тоже встречается в трудах философа достаточно часто. Есть даже свидетельства того, что он был участником Элевсинских мистерий.

Сама философия того времени рождалась в бесконечных спорах о природе вещей. В диалогах Платон рассуждает о человеке и религии, науке и мистицизме, любви духовной и плотской.

В своей теории Идей, философ отрицает, что материальный мир реален. По мнению Платона, он лишь копирует или отображает то, что существует на самом деле. То есть, философ верил в существование сразу двух миров: тот, что ощущается чистым разумом, и осязаемый, воспринимаемый через органы чувств.

Платона считают одним из основоположников теории идеализма. Он верил исключительно в абсолютные сущности, не меняющиеся во времени или пространстве. Их философ именовал эйдосами – идеями. По теории Платона, эти явления существуют автономно, наравне с пространством и меняющимися, конкретными предметами или объектами. Так возникает принцип единства дуализма. В нем существование единого без многого признается невозможным.

Развивает в своей философии Платон и идею блага, как высшего стремления, совершенства, подобного Солнцу.

Принципы дуализма он применяет и в исследовании природы человека. Душу и тело философ нередко противопоставляет друг другу, при этом указывая на бессмертие первой и бренность второго. Эту тему он развивает во многих своих произведениях. И даже выводит 4 аргумента в пользу того, что душа бессмертна. При этом указывая, что пребывание в земном теле является для нее скорее наказанием.

В диалогах Платона затрагивается и вопрос того, из чего состоит душа. Это 3 компонента: разум, воля (ярость) и чувства (страсть).

Познание сути вещей Платон производит черед диалектику. Она заключается в попытках рассуждения, работе разума, спорах, в которых собеседники пытаются найти истину.

Диалоги

Самым известным из сохранившихся трудов Платона называют его Диалоги – сочинения, в которых между собой ведут дискуссии реальные и вымышленные персонажи, в том числе исторические. Известно, что в жизни их автор не слишком жаловал письменную форму изложения мыслей. Отсюда и родились Диалоги, имитирующие устную беседу. Они позволяли автору не просто смиренно принимать критику, но и отвечать на нее.

Особенностью диалогов является наличие преимущественно двух центральных персонажей: героя и его оппонента. Имя главного из них обычно выносится в заголовок. Также в Диалогах хорошо заметно неравенство – это всегда беседа невежды с мудрецом. Оно позволяет привести повествование к логическому финалу не превращая его в бесконечную борьбу аргументов.

Существует теория «умолчания», согласно которой, далеко не все свои идеи Платон представлял в письменном виде. В Диалогах они упоминаются лишь косвенно. Но часто развиваются в трудах учеников философа. К примеру, их довольно часто приводит Аристотель.

Еще одним приемом Платона в Диалогах является временное отклонение от темы. Он используется для поисков опоры в спорах, где уже начала развиваться позиция одного из участников дискуссии. Кроме того, в этих трудах философа хорошо прослеживается его литературное дарование. В Диалогах Платон мастерски применяет приемы сквозного действия, и другие элементы, позволяющие судить о его высокообразованности.

Все произведения этого цикла поделены на 9 тетралогий. И если ранние их части посвящены скорее теологическим размышлениям, более поздние открывают видение философа в отношении более бытовых, приземленных вещей. А некоторые из них и вовсе автобиографичны.

Письма Платона

Входящие в состав последней, девятой тетралогии Диалогов Платона 13 писем приписывают его авторству, но достоверного подтверждения этому нет. По умолчанию, философ считается их создателем. Но некоторые из них исследователи считают подложными.

Письма представляют собой личные послания, отправленные Платоном. Среди адресатов – тиран Сиракуз Дионисий Младший, ему адресованы 4 из 13 отправлений. Также Платон, по-видимому состоял в переписке с царем Македонии Пердиккой III, Дионом. А в поздних его посланиях упоминаются Гермий, Корсик и Эраст. На русский язык Письма были переведены С. П. Кондратьевым.

Corpus Platoncum