Конец 1867 года. Князь Лев Николаевич Мышкин приезжает в Петербург из Швейцарии. Ему двадцать шесть лет, он последний из знатного дворянского рода, рано осиротел, в детстве заболел тяжёлой нервной болезнью и был помещён своим опекуном и благодетелем Павлищевым в швейцарский санаторий. Там он прожил четыре года и теперь возвращается в Россию с неясными, но большими планами послужить ей. В поезде князь знакомится с Парфеном Рогожиным, сыном богатого купца, унаследовавшим после его смерти огромное состояние. От него князь впервые слышит имя Настасьи Филипповны Барашковой, любовницы некоего богатого аристократа Тоцкого, которой страстно увлечён Рогожин.

По приезде князь со своим скромным узелком отправляется в дом генерала Епанчина, дальним родственником жены которого, Елизаветы Прокофьевны, является. В семье Епанчиных три дочери — старшая Александра, средняя Аделаида и младшая, общая любимица и красавица Аглая. Князь поражает всех непосредственностью, доверчивостью, откровенностью и наивностью, настолько необычайными, что поначалу его принимают очень настороженно, однако с все большим любопытством и симпатией. Обнаруживается, что князь, показавшийся простаком, а кое-кому и хитрецом, весьма неглуп, а в каких-то вещах по-настоящему глубок, например, когда рассказывает о виденной им за границей смертной казни. Здесь же князь знакомится и с чрезвычайно самолюбивым секретарём генерала Ганей Иволгиным, у которого видит портрет Настасьи Филипповны. Её лицо ослепительной красоты, гордое, полное презрения и затаённого страдания, поражает его до глубины души.

Узнает князь и некоторые подробности: обольститель Настасьи Филипповны Тоцкий, стремясь освободиться от неё и вынашивая планы жениться на одной из дочерей Епанчиных, сватает её за Ганю Иволгина, давая в качестве приданого семьдесят пять тысяч. Ганю манят деньги. С их помощью он мечтает выбиться в люди и в дальнейшем значительно приумножить капитал, но в то же время ему не даёт покоя унизительность положения. Он бы предпочёл брак с Аглаей Епанчиной, в которую, может быть, даже немного влюблён (хотя и тут тоже его ожидает возможность обогащения). Он ждёт от неё решающего слова, ставя от этого в зависимость дальнейшие свои действия. Князь становится невольным посредником между Аглаей, которая неожиданно делает его своим доверенным лицом, и Ганей, вызывая в том раздражение и злобу.

Между тем князю предлагают поселиться не где-нибудь, а именно в квартире Иволгиных. Не успевает князь занять предоставленную ему комнату и перезнакомиться со всеми обитателями квартиры, начиная с родных Гани и кончая женихом его сестры молодым ростовщиком Птицыным и господином непонятных занятий Фердыщенко, как происходят два неожиданных события. В доме внезапно появляется не кто иной, как Настасья Филипповна, приехавшая пригласить Ганю и его близких к себе на вечер. Она забавляется, выслушивая фантазии генерала Иволгина, которые только накаляют атмосферу. Вскоре появляется шумная компания с Рогожиным во главе, который выкладывает перед Настасьей Филипповной восемнадцать тысяч. Происходит нечто вроде торга, как бы с её насмешливо-презрительным участием: это её-то, Настасью Филипповну, за восемнадцать тысяч? Рогожин же отступать не собирается: нет, не восемнадцать — сорок. Нет, не сорок — сто тысяч!..

Для сестры и матери Гани происходящее нестерпимо оскорбительно: Настасья Филипповна — продажная женщина, которую нельзя пускать в приличный дом. Для Гани же она — надежда на обогащение. Разражается скандал: возмущённая сестра Гани Варвара Ардалионовна плюёт ему в лицо, тот собирается ударить её, но за неё неожиданно вступается князь и получает пощёчину от взбешённого Гани. «О, как вы будете стыдиться своего поступка!» — в этой фразе весь князь Мышкин, вся его бесподобная кротость. Даже в эту минуту он сострадает другому, пусть даже и обидчику. Следующее его слово, обращённое к Настасье Филипповне: «Разве вы такая, какою теперь представлялись», станет ключом к душе гордой женщины, глубоко страдающей от своего позора и полюбившей князя за признание её чистоты.

Покорённый красотой Настасьи Филипповны, князь приходит к ней вечером. Здесь собралось разношёрстное общество, начиная с генерала Епанчина, тоже увлечённого героиней, до шута Фердыщенко. На внезапный вопрос Настасьи Филипповны, выходить ли ей за Ганю, он отвечает отрицательно и тем самым разрушает планы присутствующего здесь же Тоцкого. В половине двенадцатого раздаётся удар колокольчика и появляется прежняя компания во главе с Рогожиным, который выкладывает перед своей избранницей завёрнутые в газету сто тысяч.

И снова в центре оказывается князь, которого больно ранит происходящее, он признается в любви к Настасье Филипповне и выражает готовность взять её, «честную», а не «рогожинскую», в жены. Тут же внезапно выясняется, что князь получил от умершей тётки довольно солидное наследство. Однако решение принято — Настасья Филипповна едет с Рогожиным, а роковой свёрток со ста тысячами бросает в горящий камин и предлагает Гане достать их оттуда. Ганя из последних сил удерживается, чтобы не броситься за вспыхнувшими деньгами, он хочет уйти, но падает без чувств. Настасья Филипповна сама выхватывает каминными щипцами пачку и оставляет деньги Гане в награду за его муки (потом они будут гордо возвращены им).

Проходит шесть месяцев. Князь, поездив по России, в частности и по наследственным делам, и просто из интереса к стране, приезжает из Москвы в Петербург. За это время, по слухам, Настасья Филипповна несколько раз бежала, чуть ли не из-под венца, от Рогожина к князю, некоторое время оставалась с ним, но потом бежала и от князя.

На вокзале князь чувствует на себе чей-то огненный взгляд, который томит его смутным предчувствием. Князь наносит визит Рогожину в его грязно-зелёном мрачном, как тюрьма, доме на Гороховой улице, во время их разговора князю не даёт покоя садовый нож, лежащий на столе, он то и дело берет его в руки, пока Рогожин наконец в раздражении не отбирает его у него (потом этим ножом будет убита Настасья Филипповна). В доме Рогожина князь видит на стене копию картины Ханса Гольбейна, на которой изображён Спаситель, только что снятый с креста. Рогожин говорит, что любит смотреть на неё, князь в изумлении вскрикивает, что «…от этой картины у иного ещё вера может пропасть», и Рогожин это неожиданно подтверждает. Они обмениваются крестами, Парфен ведёт князя к матушке для благословения, поскольку они теперь, как родные братья.

Возвращаясь к себе в гостиницу, князь в воротах неожиданно замечает знакомую фигуру и устремляется вслед за ней на тёмную узкую лестницу. Здесь он видит те же самые, что и на вокзале, сверкающие глаза Рогожина, занесённый нож. В это же мгновение с князем случается припадок эпилепсии. Рогожин убегает.

Через три дня после припадка князь переезжает на дачу Лебедева в Павловск, где находится также семейство Епанчиных и, по слухам, Настасья Филипповна. В тот же вечер у него собирается большое общество знакомых, в том числе и Епанчины, решившие навестить больного князя. Коля Иволгин, брат Гани, поддразнивает Аглаю «рыцарем бедным», явно намекая на её симпатию к князю и вызывая болезненный интерес матери Аглаи Елизаветы Прокофьевны, так что дочь вынуждена объяснить, что в стихах изображён человек, способный иметь идеал и, поверив в него, отдать за этот идеал жизнь, а затем вдохновенно читает и само стихотворение Пушкина.

Чуть позже появляется компания молодых людей во главе с неким молодым человеком Бурдовским, якобы «сыном Павлищева». Они вроде как нигилисты, но только, по словам Лебедева, «дальше пошли-с, потому что прежде всего деловые-с». Зачитывается пасквиль из газетки о князе, а затем от него требуют, чтобы он как благородный и честный человек вознаградил сына своего благодетеля. Однако Ганя Иволгин, которому князь поручил заняться этим делом, доказывает, что Бурдовский вовсе не сын Павлищева. Компания в смущении отступает, в центре внимания остаётся лишь один из них — чахоточный Ипполит Терентьев, который, самоутверждаясь, начинает «ораторствовать». Он хочет, чтобы его пожалели и похвалили, но ему и стыдно своей открытости, воодушевление его сменяется яростью, особенно против князя. Мышкин же всех внимательно выслушивает, всех жалеет и чувствует себя перед всеми виноватым.

Ещё через несколько дней князь посещает Епанчиных, затем все семейство Епанчиных вместе с князем Евгением Павловичем Радомским, ухаживающим за Аглаей, и князем Щ., женихом Аделаиды, отправляются на прогулку. На вокзале неподалёку от них появляется другая компания, среди которой Настасья Филипповна. Она фамильярно обращается к Радомскому, сообщая тому о самоубийстве его дядюшки, растратившего крупную казённую сумму. Все возмущены провокацией. Офицер, приятель Радомского, в негодовании замечает, что «тут просто хлыст надо, иначе ничем не возьмёшь с этой тварью!», в ответ на его оскорбление Настасья Филипповна выхваченной у кого-то из рук тросточкой до крови рассекает его лицо. Офицер собирается ударить Настасью Филипповну, но князь Мышкин удерживает его.

На праздновании дня рождения князя Ипполит Терентьев читает написанное им «Моё необходимое объяснение» — потрясающую по глубине исповедь почти не жившего, но много передумавшего молодого человека, обречённого болезнью на преждевременную смерть. После чтения он совершает попытку самоубийства, но в пистолете не оказывается капсюля. Князь защищает Ипполита, мучительно боящегося показаться смешным, от нападок и насмешек.

Утром на свидании в парке Аглая предлагает князю стать её другом. Князь чувствует, что по-настоящему любит её. Чуть позже в том же парке происходит встреча князя и Настасьи Филипповны, которая встаёт перед ним на колени и спрашивает его, счастлив ли он с Аглаей, а затем исчезает с Рогожиным. Известно, что она пишет письма Аглае, где уговаривает её выйти за князя замуж.

Через неделю князь формально объявлен женихом Аглаи. К Епанчиным приглашены высокопоставленные гости на своего рода «смотрины» князя. Хотя Аглая считает, что князь несравненно выше всех них, герой именно из-за её пристрастности и нетерпимости боится сделать неверный жест, молчит, но потом болезненно воодушевляется, много говорит о католицизме как антихристианстве, объясняется всем в любви, разбивает драгоценную китайскую вазу и падает в очередном припадке, произведя на присутствующих болезненное и неловкое впечатление.

Аглая назначает встречу Настасье Филипповне в Павловске, на которую приходит вместе с князем. Кроме них присутствует только Рогожин. «Гордая барышня» строго и неприязненно спрашивает, какое право имеет Настасья Филипповна писать ей письма и вообще вмешиваться в её и князя личную жизнь. Оскорблённая тоном и отношением соперницы, Настасья Филипповна в порыве мщения призывает князя остаться с ней и гонит Рогожина. Князь разрывается между двумя женщинами. Он любит Аглаю, но он любит и Настасью Филипповну — любовью-жалостью. Он называет её помешанной, но не в силах бросить её. Состояние князя все хуже, все больше и больше погружается он в душевную смуту.

Намечается свадьба князя и Настасьи Филипповны. Событие это обрастает разного рода слухами, но Настасья Филипповна как будто радостно готовится к нему, выписывая наряды и пребывая то в воодушевлении, то в беспричинной грусти. В день свадьбы, по пути к церкви, она внезапно бросается к стоящему в толпе Рогожину, который подхватывает её на руки, садится в экипаж и увозит её.

На следующее утро после её побега князь приезжает в Петербург и сразу отправляется к Рогожину. Того нет дома, однако князю чудится, что вроде бы Рогожин смотрит на него из-за шторы. Князь ходит по знакомым Настасьи Филипповны, пытаясь что-нибудь разузнать про неё, несколько раз возвращается к дому Рогожина, но безрезультатно: того нет, никто ничего не знает. Весь день князь бродит по знойному городу, полагая, что Парфен все-таки непременно появится. Так и случается: на улице его встречает Рогожин и шёпотом просит следовать за ним. В доме он приводит князя в комнату, где в алькове на кровати под белой простыней, обставленная склянками со ждановской жидкостью, чтобы не чувствовался запах тления, лежит мёртвая Настасья Филипповна.

Князь и Рогожин вместе проводят бессонную ночь над трупом, а когда на следующий день в присутствии полиции открывают дверь, то находят мечущегося в бреду Рогожина и успокаивающего его князя, который уже ничего не понимает и никого не узнает. События полностью разрушают психику Мышкина и окончательно превращают его в идиота.

Приблизительное время чтения: 5 мин.

Книги, которые влияют на наше мировоззрение. Книги, которые отвечают на главные вопросы людей своей эпохи. Книги, которые стали частью христианской культуры. Мы знакомим наших читателей с ними в литературном проекте «Фомы» — «Легендарные христианские книги».

Автор:

Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский (1821–1881) — прозаик, критик, публицист.

О книге

Время написания: 1867–1869

Содержание

Молодой человек, князь Лев Николаевич Мышкин, возвращается в Петербург из Швейцарии, где лечился от тяжелой нервной болезни.

После нескольких лет почти затворнической жизни он попадает в эпицентр петербургского общества. Князь жалеет этих людей, видит, что они гибнут, пытается спасти, но, несмотря на все усилия, ничего не может изменить.

В конечном итоге Мышкина доводят до потери рассудка те люди, которым он более всего пытался помочь.

История создания

Роман «Идиот» был написан за границей, куда Достоевский поехал, чтобы поправить здоровье и написать роман, чтобы расплатиться с кредиторами.

Работа над романом шла тяжело, здоровье не улучшалось, а в 1868 году в Женеве умерла трехмесячная дочь Достоевских.

Находясь в Германии и Швейцарии, Достоевский осмысливает нравственные и социально-политические изменения в России 60-х годов XIX века: кружки разночинцев, революционные идеи, умонастроения нигилистов. Все это найдет свое отражение на страницах романа.

Замысел произведения

Достоевский считал, что на свете существует только одно положительно прекрасное лицо — это Христос. Писатель попытался наделить главного героя романа — князя Мышкина — похожими чертами.

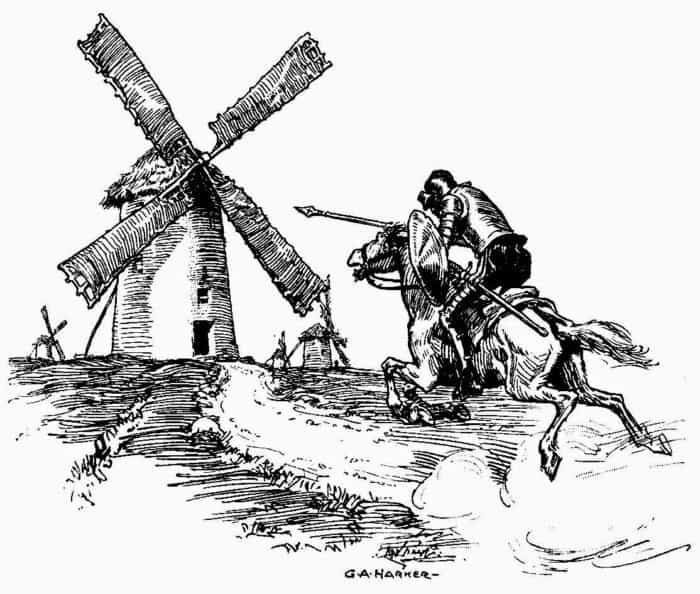

По мнению Достоевского, в литературе ближе всех к идеалу Христа стоит Дон Кихот. Образ князя Мышкина перекликается с героем романа Сервантеса. Как и Сервантес, Достоевский ставит вопрос: что случится с человеком, наделенным качествами святого, если он окажется в современном обществе, как сложатся его отношения с окружающими и какое влияние он окажет на них, а они — на него?

Заглавие

Историческое значение слова «идиот» — человек, живущий в себе, далекий от общества.

В романе обыгрываются различные оттенки значения этого слова, чтобы подчеркнуть сложность образа героя. Мышкина считают странным, его то признают нелепым и смешным, то считают, что он может «насквозь прочитать» другого человека. Он, честный и правдивый, не вписывается в общепринятые нормы поведения. Лишь в самом конце романа актуализируется другое значение — «душевнобольной», «помраченный рассудком».

Подчеркивается детскость облика и поведения Мышкина, его наивность, беззащитность. «Совершенный ребенок», «дитя» — так называют его окружающие, а князь соглашается с этим. Мышкин говорит: «Какие мы еще дети, Коля! и… и… как это хорошо, что мы дети!». В этом совершенно отчетливо звучит евангельский призыв: «будьте как дети» (Мф 18:3).

Еще один оттенок значения слова «идиот» — юродивый. В религиозной традиции блаженные — проводники Божественной мудрости для простых людей.

Смысл произведения

В романе повторяется и подлинная евангельская история, и история Дон Кихота. Мир снова не принимает «положительно прекрасного человека». Лев Мышкин наделен христианской любовью и добром и несет их свет ближним. Однако главные препятствия на этом пути — неверие и бездуховность современного общества.

Люди, которым пытается помочь князь, губят себя на его глазах. Отвергая его, общество отвергает возможность спастись. С сюжетной точки зрения роман предельно трагичен.

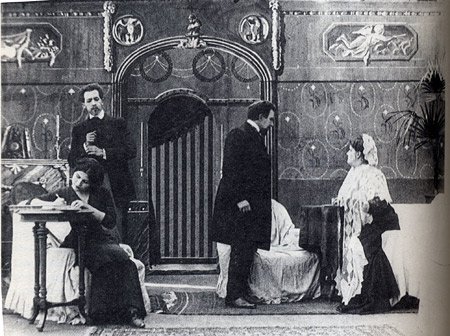

Экранизации и театральные постановки

К сюжету романа роману «Идиот» обращались многие режиссеры кино и театра, композиторы. Драматические инсценировки начинаются уже с 1887 года. Одной из самых значительных театральных постановок версий романа Достоевского стал спектакль 1957 года, поставленный Георгием Товстоноговым в Большом драматическом театре в Петербурге. В роли князя Мышкина выступал Иннокентий Смоктуновский.

Первая экранизация романа относится к 1910 году, периоду немого кино. Автором этого короткометражного фильма стал Петр Чардынин. Выдающейся киноверсией первой части романа стал художественный фильм Ивана Пырьева «Идиот» (1958), где роль Мышкина сыграл Юрий Яковлев.

Одна из лучших зарубежный экранизаций романа — японская чёрно-белая драма «Идиот» (1951) режиссера Акиры Куросавы.

Самой подробной и максимально приближенной к первоисточнику киноверсией романа является многосерийный фильм Владимира Бортко «Идиот» (2002), роль Мышкина исполнил Евгений Миронов.

Интересные факты о романе

1. «Идиот» — второй роман так называемого «великого пятикнижия Достоевского». В него также входят романы «Преступление и наказание», «Игрок», «Бесы» и «Братья Карамазовы».

2. На идею романа сильно повлияло впечатление Достоевского от картины Ганса Гольбейна Младшего «Мертвый Христос в гробу». На полотне предельно натуралистически изображено тело мертвого Спасителя после снятия с Креста. В образе такого Христа не видно ничего божественного, а по преданию Гольбейн и вовсе писал эту картину с утопленника. Приехав в Швейцарию, Достоевский захотел увидеть эту картину. Писатель пришел в такой ужас, что сказал жене: «От такой картины веру потерять можно». Трагическая фабула романа, где большинство героев живет без веры, во многом проистекает из размышлений об этой картине. Не случайно именно в мрачном доме Парфёна Рогожина, который потом совершит страшный грех убийства, висит копия картины «Мертвый Христос».

3. В романе «Идиот» можно встретить всем известную фразу «мир спасет красота». В тексте ее произносят в грустном, ироничном и почти издевательском тоне два героя — Аглая Епанчина и смертельно больной Ипполит Терентьев. Сам Достоевский никогда не считал, что мир спасет некая абстрактная красота. В его дневниках формула спасения звучит так — «мир станет красота Христова». Романом «Идиот» Достоевский доказывает, что красоте присуща не только одухотворяющая, но и губительная сила. Трагическая судьба Настасьи Филипповны, женщины необыкновенной красоты, иллюстрирует мысль о том, что красота способна вызвать невыносимые страдания и погубить.

4. Ужасную сцену в рогожинском доме в финальной части «Идиота» Достоевский считал самой главной в романе, а также сценой «такой силы, которая не повторялась в литературе».

Цитаты:

Нет ничего обиднее человеку нашего времени и племени, чем сказать ему, что он не оригинален, слаб характером, без особенных талантов и человек обыкновенный.

Сострадание есть главнейший и, может быть, единственный закон бытия всего человечества.

Столько силы, столько страсти в современном поколении, и ни во что не веруют!

Читайте также:

Александр Ткаченко. Кто хочет стать идиотом?

Легендарные христианские книги: Александр Мень «Сын Человеческий»

Легендарные христианские книги: Сергей Фудель «У стен Церкви»

Легендарные христианские книги: Сюсаку Эндо «Молчание»

Достоевский пытается изобразить «положительно прекрасного человека» — и пишет роман о судьбе пророка в современном мире, где жгут деньги в камине и руки на свечке, лгут, убивают и сходят с ума.

комментарии: Иван Чувиляев

О чём эта книга?

Из швейцарской клиники в Россию возвращается больной эпилепсией князь Мышкин — человек поразительной доброты, кротости, при этом тонкий психолог, умеющий говорить с любым собеседником и в каждом видеть больше, чем прочие. В Петербурге у князя завязываются отношения с купцом Парфёном Рогожиным, роковой красавицей Настасьей Филипповной Барашковой и прогрессивной барышней Аглаей Епанчиной. Генералы и попрошайки, купцы и нищие аристократы сталкиваются со странным князем — и каждый из них проявляет себя самым неожиданным образом, меняется, по-новому раскрывается. Жулики и вруны оказываются несчастными людьми, пьяницы и горлопаны — униженными и оскорблёнными. Но эти преображения жизни героев изменить не могут, они остаются теми же, кем были, а сам князь в финале окончательно теряет рассудок. Достоевский намеревался показать идеального человека, похожего на Христа; мир, в котором ему приходится существовать, берёт верх над добродетелью, изменить его не удаётся. Роман, плохо встреченный современниками, потомки оценили как одно из самых мощных высказываний Достоевского.

Когда она написана?

О том, как происходила работа над «Идиотом», судить можно только по письмам Достоевского и воспоминаниям его жены Анны Григорьевны: черновики романа не сохранились, перед возвращением в Россию Достоевский все свои рукописи сжёг. Как пишет Анна Григорьевна, он опасался, что «на русской границе его, несомненно, будут обыскивать и бумаги от него отберут, а затем они пропадут, как пропали все его бумаги при его аресте в 1849

году»

1

Достоевская А. Г. Воспоминания. М.: Худ. лит-ра, 1971.

.

Достоевский работал над «Идиотом» с сентября 1867-го по январь 1869 года. Этот период был одним из самых тяжёлых и даже трагических в его жизни. Писатель сбежал от бесчисленных кредиторов из России в Европу, безуспешно пытался побороть свою лудоманию — патологическую зависимость от азартных игр. Наконец, во время работы над «Идиотом», в 1868 году, у него родился первый ребёнок, дочь Соня, — девочка умерла всего через два месяца. Одновременно с работой над «Идиотом» Достоевские постоянно переезжали с места на место: из Дрездена в Женеву, оттуда в Веве, в Милан, Флоренцию.

Все эти события отражались и на работе над романом: уже оконченную первую часть «Идиота» Достоевский уничтожил и переписал начисто. Только после этого он сам сформулировал сложившуюся идею нового романа: изобразить «положительно прекрасного человека». И даже после этого Достоевский постоянно жаловался в письмах, что работа продвигается трудно и медленно: «Романом я недоволен до отвращения. <…> Теперь сделаю последнее усилие на 3-ю часть. Если поправлю роман — поправлюсь сам, если нет, то я

погиб»

2

Из письма Аполлону Майкову 21 июля 1868 года.

. Не был удовлетворён результатом Достоевский и после публикации: «В романе много написано наскоро, много растянуто и не

удалось»

3

Из письма Николаю Страхову 26 февраля 1869 года.

.

Как она написана?

Отличительная черта романа, буквально бросающаяся в глаза, — его театральность. Роман почти полностью состоит из диалогов, авторский текст представляет собой в основном очень подробные описания персонажей и мест действия. Театральна и композиция романа: он фактически разбит на сцены, места действия сменяются крайне неспешно, а все события первой части — от знакомства Мышкина с Рогожиным в поезде до бегства Настасьи Филипповны с тем же Рогожиным — происходят в течение одних суток.

Михаил Бахтин эту диалогичность «Идиота» считал признаком жанра, который он называл мениппеей. Суть мениппеи в том, чтобы создавать «исключительные ситуации для провоцирования и испытания философской идеи — слова, правды, воплощённой в образе мудреца, искателя этой

правды»

4

Бахтин М. М. Проблемы поэтики Достоевского // Бахтин М. М. Собрание сочинений. Т. 6. М.: Русские словари: Языки славянской культуры, 2002.

. В «Идиоте» таким искателем оказывается князь Мышкин — и его голос здесь «построен так, как строится голос самого автора в романе обычного типа. Слово героя… …звучит как бы рядом с авторским словом и особым образом сочетается с ним и с полноценными же голосами других

героев»

5

Бахтин М. М. Проблемы поэтики Достоевского // Бахтин М. М. Собрание сочинений. Т. 6. М.: Русские словари: Языки славянской культуры, 2002.

. Примером такого «раздвоения» может служить эпизод, когда Настасья Филипповна впервые появляется в романе, приходит к Иволгиным. Сначала она — назло хозяевам, осуждающим её, — разыгрывает роль кокотки. Но голос Мышкина, пересекающийся с её внутренним диалогом в другом направлении, заставляет её резко изменить этот тон и почтительно поцеловать руку матери Гани, над которой она только что издевалась.

Что на неё повлияло?

В письме своей племяннице Софье Ивановой (которой роман был посвящён в журнальной публикации) Достоевский прямо называет «прототипов» Мышкина, тех «положительно прекрасных» литературных персонажей, на которых мог бы быть похож его герой. Среди прочих упоминаются Дон Кихот, затем «слабейшая мысль, чем Дон-Кихот, но всё-таки огромная» — Пиквик Диккенса и, наконец, Жан Вальжан из «Отверженных» Гюго.

Леонид Гроссман

Леонид Петрович Гроссман (1888–1965) — литературовед, поэт. В 1919 году выпустил сборник сонетов, посвящённый Пушкину. Преподавал русскую литературу в Высшем литературно-художественном институте им. В. Брюсова, Московском городском педагогическом институте. Автор исследовательских работ о Пушкине и Достоевском. Гроссман написал их биографии для серии «Жизнь замечательных людей».

в своей биографии Достоевского указывает, что важным источником вдохновения для написания «Идиота» была французская романтическая литература. «…Противопоставление гротескных фигур единому святому или нравственному подвижнику, — пишет он, — видимо, восходит к методу романтических антитез Гюго в одной из любимейших книг Достоевского, где подворью уродов противостоит собор Парижской Богоматери, а прелестная Эсмеральда внушает страсть чудовищному Квазимодо». При этом отмечает, что сюжетные схемы и поэтика «Собора Парижской Богоматери» и других романтических произведений сильно видоизменена и осовременена.

Если вы заговорите о чём-нибудь вроде смертной казни, или об экономическом состоянии России, или о том, что «мир спасёт красота», то… я, конечно, порадуюсь и посмеюсь очень, но… предупреждаю вас заранее: не кажитесь мне потом на глаза!

Фёдор Достоевский

Другой источник влияния на «Идиота», на который обращает внимание Гроссман, — бальзаковские романы и повести: это «единственный европейский писатель, которым Достоевский восхищается в своих школьных письмах и к которому он обращается для философской аргументации в своём последнем

произведении»

6

Гроссман Л. Поэтика Достоевского. М.: ГАХН, 1925.

. В частности, в описании дома Рогожина из «Идиота» обнаруживается родство с пассажем о жилище папаши Гранде у Бальзака; здесь стоит учесть, что в молодости Достоевский сам переводил «Евгению Гранде» на русский.

Наконец, некоторые источники влияния на «Идиота» непосредственно упоминаются в самом тексте романа. Князь находит в комнате Настасьи Филипповны «развёрнутую книгу из библиотеки для чтения, французский роман «Madame Bovary». Играя в предложенную Фердыщенко игру с рассказом о своём худшем поступке, Тоцкий, содержанкой которого была Настасья Филипповна, упоминает «Даму с камелиями» Дюма-сына.

Как она была опубликована?

«Идиот» публиковался по частям в одном из наиболее влиятельных журналов своего времени — «Русском вестнике» — с января 1868 года по март 1869-го (там же раньше вышло «Преступление и наказание»).

Одновременно с публикацией последних частей в «Вестнике» Достоевский пытался договориться о выходе романа отдельным изданием — но безуспешно. Александр Базунов, печатавший «Преступление и наказание», покупать «Идиота» отказался. Через своего пасынка Павла Исаева писатель целый год вёл переговоры с

Фёдором Стелловским

Фёдор Тимофеевич Стелловский (1826–1875) — издатель. Был одним из крупнейших нотоиздателей 1850-х годов, способствовал продвижению русской музыки. Издавал журналы «Музыкальный и театральный вестник», «Гудок», газету «Русский мир». В 1860-е годы Стелловский занялся выпуском русской литературы — издавал Достоевского, Толстого, Писемского. Умер в психиатрической лечебнице.

, был даже составлен контракт, но издание так и не вышло в

свет

7

Летопись жизни и творчества Ф. М. Достоевского. СПб.: Академический проект, 1993.

. Выпустить книгу получилось только спустя шесть лет, в 1874 году, когда жена писателя, Анна Григорьевна, решила организовать собственное издательство. Для этой публикации Достоевский отредактировал первоначальную версию «Идиота».

Как её приняли?

«Идиот» был принят критиками, мягко говоря, с недоумением. Характерны в этом смысле письма Достоевскому

Николая Страхова

Николай Николаевич Страхов (1828–1896) — идеолог почвенничества, близкий друг Толстого и первый биограф Достоевского. Страхов написал важнейшие критические статьи о творчестве Толстого, до сих пор мы говорим о «Войне и мире», во многом опираясь именно на них. Страхов активно критиковал нигилизм и западный рационализм, который он презрительно называл «просвещенство». Идеи Страхова о человеке как «центральном узле мироздания» повлияли на развитие русской религиозной философии.

, с которым писателя связывали очень тёплые отношения. В самом начале 1868 года, когда были опубликованы первые главы романа, он пишет автору: «Идиот» интересует меня лично чуть ли не больше всего, что Вы писали», «я не нашёл в первой части «Идиота» никакого недостатка». Но чем дальше, тем лаконичнее отзывы — Страхов только уверяет, что ждёт конца романа, и обещает написать о нём. Только в 1871 году он наконец прямо высказывает своё впечатление от романа: «Всё, что Вы вложили в «Идиота», пропало даром».

Одним из первых рецензентов «Идиота» был Николай Лесков, — во всяком случае, именно ему приписывают авторство анонимной рецензии, опубликованной в первом номере «Вечерней газеты» за 1869 год. В ней «Мышкин, — идиот, как его называют многие; человек крайне ненормально развитый духовно, человек с болезненно развитою рефлексиею, у которого две крайности, наивная непосредственность и глубокий психологический анализ, слиты вместе, не противореча друг другу…». Куда более прямо он высказался уже в другом тексте, «Русских общественных заметках»: «Начни глаголать разными языками г. Достоевский после своего «Идиота»… это, конечно, ещё можно бы, пожалуй, объяснять тем, что на своём языке ему некоторое время конфузно изъясняться».

Но язвительнее всех выступил сатирик Дмитрий Минаев — он отозвался на публикацию не рецензией, а эпиграммой:

У тебя, бедняк, в кармане

Грош в почёте — и в большом,

А в затейливом романе

Миллионы нипочём.

Холод терпим мы, славяне,

В доме месяц не один.

А в причудливом романе

Топят деньгами камин.

От Невы и до Кубани

Идиотов жалок век,

«Идиот» же в том романе

Самый умный человек.

Подобные колкие отзывы появлялись и после публикации романа. Михаил Салтыков-Щедрин в 1871 году вспоминает об «Идиоте» в отзыве на совсем другой роман, «Светлова»

Иннокентия Омулевского

Иннокентий Васильевич Омулевский (настоящая фамилия — Фёдоров; 1836–1883) — прозаик, поэт. Начал заниматься литературой в начале 1860-х годов: печатался в «Современнике» и «Русском слове». Приобрёл известность благодаря роману «Светлов, его взгляды, его жизнь и деятельность» (1871), его переиздание в 1874 году было запрещено цензурой. Публикация второго романа «Попытка — не шутка» тоже была запрещена, автора арестовали за антиправительственные высказывания, но вскоре освободили за недоказанностью обвинений. В конце жизни Омулевский сильно нуждался, в 1883 году умер от разрыва сердца.

. В нём он упоминает о Достоевском как о литераторе исключительном «по глубине замысла, по ширине задач нравственного мира». Но здесь же обвиняет его в том, что эта «ширина задач» в «Идиоте» реализуется не самыми очевидными средствами. «Дешёвое глумление над так называемым нигилизмом и презрение к смуте, которой причины всегда оставляются без разъяснения, — всё это пестрит произведения г. Достоевского пятнами совершенно им не свойственными и рядом с картинами, свидетельствующими о высокой художественной прозорливости, вызывает сцены, которые доказывают какое-то уже слишком непосредственное и поверхностное понимание жизни и её явлений».

Что было дальше?

Несмотря на то что современники оценили «Идиота» не слишком высоко, роман оказал огромное влияние на идеи рубежа XIX–XX веков. Наиболее характерный пример — работы Фридриха Ницше. В «Антихристе» он пишет о «болезненном и странном мире, в который нас вводит евангелие, мире, где, как в одном русском романе, представлены, словно на подбор, отбросы общества, нервные болезни и «детский» идиотизм». Об «Идиоте» подробно писал в своих «Трёх мастерах» Стефан Цвейг и в эссе о Достоевском — Андре Жид. В итоге роман был «реабилитирован» модернистами: в нём увидели не сумбурное и неровное повествование, иллюстрирующее важную для автора идею, а сложный текст о роли пророка в современном мире.

Кроме того, благодаря драматургичности романа, обилию диалогов и готовой разбивке на «сцены» в ХХ веке его неоднократно ставили в театре и экранизировали. Известен спектакль

Георгия Товстоногова

Георгий Александрович Товстоногов (1915–1989) — театральный режиссёр. Был режиссёром Тбилисского русского драматического театра (1938–1946), Центрального детского театра (1946–1949), Ленинградского театра имени Ленинского комсомола (1950–1956) и Большого драматического театра (1956–1989). Преподавал в Ленинградском институте театра, музыки и кинематографии, написал несколько книг о театральной режиссуре.

в ленинградском Большом драматическом театре (1957) с Иннокентием Смоктуновским в роли Мышкина и постановка Театра Вахтангова (1958) с Николаем Гриценко и Юлией Борисовой. Композитор Мечислав Вайнберг написал по роману оперу — премьера её состоялась только в 2013 году, спустя почти тридцать лет после написания. Иван Пырьев снял по мотивам «Идиота» фильм (работа осталась неоконченной, режиссёр перенёс на экран только действие первой части), а Владимир Бортко — сериал.

Знаете, я не понимаю, как можно проходить мимо дерева и не быть счастливым, что видишь его? Говорить с человеком и не быть счастливым, что любишь его!

Фёдор Достоевский

«Идиот» оказался произведением открытым для самых смелых интерпретаций на экране. Акира Куросава в своей ленте 1951 года перенёс действие в послевоенную Японию, князя Мышкина сделал пленным, а высший свет — униженными войной обывателями. В 1985 году Анджей Жулавский снял по мотивам «Идиота» гангстерское кино в декорациях современного Парижа; князь Мышкин здесь натурально безумен, а не просто «не от мира сего». Анджей Вайда в «Настасье» поступил ещё радикальнее: и Мышкина, и Настасью Филипповну у него играет один актёр, патриарх японского театра Бандо Тамасабуро Пятый. Не стоит забывать и хулиганскую версию Романа Качанова, «Даун Хаус», в котором роман Достоевского превратился в фарс (в финале Мышкин и Рогожин съедают Настасью Филипповну).

«Идиот». Режиссёр Иван Пырьев. СССР, 1958 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Иван Пырьев. СССР, 1958 год

«Настасья». Режиссёр Анджей Вайда. Польша, Япония, 1994 год

«Настасья». Режиссёр Анджей Вайда. Польша, Япония, 1994 год

«Даун Хаус». Режиссёр Роман Качанов. Россия, 2001 год

«Даун Хаус». Режиссёр Роман Качанов. Россия, 2001 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Владимир Бортко. Россия, 2003 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Владимир Бортко. Россия, 2003 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Иван Пырьев. СССР, 1958 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Иван Пырьев. СССР, 1958 год

«Настасья». Режиссёр Анджей Вайда. Польша, Япония, 1994 год

«Настасья». Режиссёр Анджей Вайда. Польша, Япония, 1994 год

«Даун Хаус». Режиссёр Роман Качанов. Россия, 2001 год

«Даун Хаус». Режиссёр Роман Качанов. Россия, 2001 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Владимир Бортко. Россия, 2003 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Владимир Бортко. Россия, 2003 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Иван Пырьев. СССР, 1958 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Иван Пырьев. СССР, 1958 год

«Настасья». Режиссёр Анджей Вайда. Польша, Япония, 1994 год

«Настасья». Режиссёр Анджей Вайда. Польша, Япония, 1994 год

«Даун Хаус». Режиссёр Роман Качанов. Россия, 2001 год

«Даун Хаус». Режиссёр Роман Качанов. Россия, 2001 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Владимир Бортко. Россия, 2003 год

«Идиот». Режиссёр Владимир Бортко. Россия, 2003 год

Почему роман так назван?

Слово «идиот» имеет как минимум три очень разных, даже взаимоисключающих значения.

Самое очевидное — бытовое, «дурачок». В этом смысле слово используется в тексте: идиотом называет сам себя Мышкин, в гневе так обзывают его и Ганя Иволгин, и Настасья Филипповна (приняв его за лакея), и Аглая.

Другое — медицинское. Как диагноз идиотия — наиболее тяжёлая форма

олигофрении

Умственная отсталость.

, которая характеризуется отсутствием психических реакций и речи. В этом смысле Мышкин становится идиотом лишь в финале, после убийства Настасьи Филипповны. Строго говоря, Достоевский использует термин неверно: во всяком случае, в медицине олигофрению и эпилепсию не связывают. Кроме того, вылечить идиотию до такой степени, чтобы пациент мог полностью обрести все утраченные навыки, почти невозможно.

Наконец, третье и самое любопытное значение термина — архаическое, не используемое в современном языке. В Древней Греции так называли человека, живущего частной жизнью и не принимающего участия в спорах и собраниях общества. Этому определению Мышкин, в общем, соответствует: он хотя и спорит с обществом, проповедует ему, но существует как бы отдельно от него. На это обращает внимание в «Проблемах поэтики Достоевского» Михаил Бахтин: Мышкин, пишет он, «в особом, высшем смысле не занимает никакого положения в жизни, которое могло бы определить его поведение и ограничить его чистую человечность. С точки зрения обычной жизненной логики всё поведение и все переживания князя Мышкина являются неуместными и крайне

эксцентричными»

8

Бахтин М. М. Проблемы поэтики Достоевского // Бахтин М. М. Собрание сочинений. Т. 6. М.: Русские словари: Языки славянской культуры, 2002.

. В качестве примеров этого «идиотизма» Бахтин приводит два красноречивых эпизода романа: попытку совместить две любви, к Аглае и Настасье Филипповне, и нежные, братские чувства к Рогожину, которые доходят до высшей точки после того, как Парфён убивает Настасью Филипповну. Именно в таком значении парадоксального, или, как это называет Бахтин, карнавализирующего, персонажа и стоит понимать название романа.

Зачем Достоевский наделил Мышкина эпилепсией?

Достоевский, сам страдавший от эпилепсии, несколько раз вводил в свои произведения героев с тем же недугом: девушка Нелли в «Униженных и оскорблённых», Мурин в «Хозяйке». Уже после «Идиота» эпилептиком будет Смердяков в «Братьях Карамазовых», а в «Бесах» перспективой эпилепсии будет угрожать Кириллову Шатов.

В случае с Мышкиным медицинский диагноз — важная составляющая образа. Именно припадки делают его сверхчувствительным, отличным от прочих героев: «…В эпилептическом состоянии его была одна степень почти пред самым припадком… когда вдруг, среди грусти, душевного мрака, давления, мгновениями как бы воспламенялся его мозг и с необыкновенным порывом напрягались разом все жизненные силы его», «Да, за этот момент можно отдать всю жизнь!» и т. д.

Первым на это значение болезни Мышкина обратил внимание в книге «Лев Толстой и Достоевский» Дмитрий Мережковский: «…Болезнь Идиота, как мы видели, — не от скудости, а от какого-то оргийного избытка жизненной силы. Это — особая,

«священная болезнь»

Так в Древней Греции называли эпилепсию — считалось, что эпилепсия связана с магией и волшебством.

, источник не только «низшего», но и «высшего бытия»; это — узкая, опасная стезя над пропастью, переход от низшего, грубого, животного — к новому, высшему, может быть, «сверхчеловеческому» здоровью». В этом смысле эпилепсия — инструмент, с помощью которого «идиотизм» героя может быть описан не только в его поступках и отношениях с окружающими, но и буквально, физиологически. Самый характерный пример — сцена, в которой Рогожин пытается убить Мышкина. Увидев нож в его руках, князь не пытается спастись, а только кричит: «Не верю!» «Затем, — пишет Достоевский, — вдруг как бы что-то разверзлось пред ним: необычайный внутренний свет озарил его душу. Это мгновение продолжалось, может быть, полсекунды; но он, однако же, ясно и сознательно помнил начало, самый первый звук своего страшного вопля, который вырвался из груди его сам собой и который никакою силой он не мог бы остановить. Затем сознание его угасло мгновенно, и наступил полный мрак».

Wellcome Collection gallery

Князь Мышкин — современный Иисус Христос?

Часто в качестве источника даже внешности князя — высокого молодого человека со светлой бородкой и большими глазами — указывается Иисус Христос. Как правило, сторонники этой теории отталкиваются от определения, данного герою самим Достоевским в письмах: «князь-Христос».

Другой источник образа раскрывается, когда завязываются отношения князя и Аглаи Епанчиной. Здесь Достоевский вводит в беседе героев пушкинское стихотворение «Жил на свете рыцарь бедный…». Рассуждая о нём, Аглая фактически признаётся в любви князю:

…В стихах этих прямо изображён человек, способный иметь идеал, во-вторых, раз поставив себе идеал, поверить ему, а поверив, слепо отдать ему всю свою жизнь. Это не всегда в нашем веке случается. Там, в стихах этих, не сказано, в чём, собственно, состоял идеал «рыцаря бедного», но видно, что это был какой-то светлый образ, «образ чистой красоты», и влюблённый рыцарь вместо шарфа даже чётки себе повязал на шею.

Леонид Гроссман обращает внимание на то, что во времена Достоевского по цензурным соображениям пушкинский текст публиковался с купюрами, без строчек, в которых упоминается Дева Мария. Поэтому Аглая и не понимает, какой именно идеал имеется в виду в «рыцаре

бедном»

9

Гроссман Л. П. Достоевский. М.: Молодая гвардия, 1963.

:

Опускалась третья строфа: «Путешествуя в Женеву, / На дороге у креста / Видел он Марию Деву» и прочее. Опускалась и последняя строфа («Но Пречистая сердечно / Заступилась за него»), что делало зашифрованным смысл всего стихотворения. Оставались прекрасные и неясные формулы: «Он имел одно виденье, / Непостижное уму…» Или: «С той поры, сгорев душою, / Он на женщин не смотрел…» Сохранялись таинственные инициалы А. М. Д. или малопонятные читателю наименования литургической латыни: «Lumen coeli, sancta Rosa!..» Но Достоевский безошибочно истолковал этот пушкинский фрагмент, построив свой образ на теме чистой любви».

В этой же сцене появляется ещё один прототип Мышкина: Аглая прячет письмо от князя в томик «Дон Кихота» и, обнаружив это, смеётся совпадению. Именно сочетание князя и героя Сервантеса заставляет её вспомнить о рыцаре бедном.

Наконец, ещё одну трактовку образа Мышкина и другого литературного прототипа предлагает в своих лекциях по русской литературе Владимир Набоков, относившийся к Достоевскому скептически. Он сравнивает Мышкина не с Дон Кихотом и не с Христом, а с фольклорным Иванушкой-дурачком. Более того — встраивает героя в неожиданный контекст: «У князя Мышкина, в свою очередь, есть внук, недавно созданный современным советским писателем Михаилом Зощенко, — тип бодрого дебила, живущего на задворках полицейского тоталитарного государства, где слабоумие стало последним прибежищем человека».

Почему Настасья Филипповна мечется между Рогожиным и Мышкиным?

Бахтин в «Проблемах поэтики Достоевского» обращает внимание на то, что мотивировки поступков героев, в частности Настасьи Филипповны, часто лежат не в плоскости бытовой психологии. Ею метания героини между двумя персонажами объяснить невозможно (или можно, но тогда она окажется просто кокоткой, которая не может определиться со своими желаниями).

Настасья Филипповна, как и князь, чутко откликается на тех, кто её окружает. Только не словом и не разговором, а действием. «Реальные голоса Мышкина и Рогожина переплетаются и пересекаются, — пишет Бахтин, — с голосами внутреннего диалога Настасьи Филипповны. Перебои её голоса превращаются в сюжетные перебои её взаимоотношений с Мышкиным и

Рогожиным»

10

Бахтин М. М. Проблемы поэтики Достоевского // Бахтин М. М. Собрание сочинений. Т. 6. М.: Русские словари: Языки славянской культуры, 2002.

. Каждый из героев провоцирует героиню на то, чтобы она проявляла себя определённым образом, откликалась на их «голоса». Самый характерный пример — смена интонации после монолога Мышкина («…Вы уже до того несчастны, что и действительно виновною себя считаете»). До того говорившая исключительно с вызовом («…Я замуж выхожу, слышали? За князя, у него полтора миллиона, он князь Мышкин и меня берёт!»), она внезапно отвечает: «Спасибо, князь, со мной так никто не говорил до сих пор». С Рогожиным же она называет себя «рогожинской»: «А теперь я гулять хочу, я ведь уличная!» Этой полифоничностью, а не психологией героини стоит объяснять истеричность, неоднородность её образа. Она не столько истеричная, сколько чуткая и готовая поддаться любому импульсу извне.

Почему в любовный треугольник Достоевский вводит Аглаю?

Аглая Епанчина, с одной стороны, выступает «противовесом» Настасье Филипповне — не только в отношениях с Мышкиным, но и как таковая, по природе своей. Она цельная, в ней нет амбивалентности, она не готова меняться каждый раз и откликаться на голоса тех, кто её окружает. Не зря оппонент и критик автора «Идиота» Владимир Набоков в своих лекциях только Аглаю описывает как абсолютно положительного героя: «Непорочно чистая, красивая, искренняя девушка. Она не хочет мириться с

окружающим миром»

11

Набоков В. В. Лекции по русской литературе. М.: Независимая газета, 1999.

и т. д.

Эта инакость по отношению к другим персонажам во многом и определяет роль героини в романе. Она не только «непорочно чистая», но и своенравная, и эгоистичная. Она прямым текстом говорит о том, чего хочет от Мышкина: «Всё расспросить об загранице». «Я ни одного собора готического не видала, я хочу в Риме быть, я хочу все кабинеты учёные осмотреть, я хочу в Париже учиться; я весь последний год готовилась и училась и очень много книг прочла; я все запрещённые книги прочла». То есть признаётся, что хочет им воспользоваться как гарантией своей независимости. С другой стороны, в другой сцене романа она прямо сравнивает его с Дон Кихотом и «рыцарем бедным» — но это не чуткость, а скорее романтизация ухажёра, радость от того, что он может быть похож на литературных персонажей. Наконец, она открыто издевается над князем и хочет его задеть, присылая ему ежа и капризно спрашивая, собирается ли он за неё свататься.

Женщина способна замучить человека жестокостями и насмешками и ни разу угрызения совести не почувствует, потому что про себя каждый раз будет думать, смотря на тебя: «Вот теперь я его измучаю до смерти, да зато потом ему любовью моею наверстаю…»

Фёдор Достоевский

В эпилоге Достоевский превращает Аглаю в героиню почти карикатурную. Она выходит замуж за польского революционера, который пленил её «необычайным благородством своей истерзавшейся страданиями по отчизне души, и до того пленил, что та, ещё до выхода замуж, стала членом какого-то заграничного комитета по восстановлению Польши и, сверх того, попала в католическую исповедальню какого-то знаменитого патера, овладевшего её умом до исступления». Аглая, «западник» и «прогрессивная девушка», спорит с Мышкиным, который говорит в духе славянофилов: «Надо, чтобы воссиял в отпор Западу наш Христос, которого мы сохранили и которого они и не знали!» Некоторую карикатурность её образа усиливает тот факт, что сразу после рассказа о её судьбе следует филиппика в адрес Европы, вложенная Достоевским в уста Лизаветы Прокофьевны: «И всё это, и вся эта заграница, и вся эта ваша Европа, всё это одна фантазия, и все мы, за границей, одна фантазия».

Какую роль в романе играет живопись?

Замысел «Идиота» рождался в Дрездене, где Достоевский бывал в галерее Цвингера, и Анна Григорьевна оставила подробные воспоминания о том, как потрясла его коллекция.

Упоминаются в романе и конкретные полотна. Самое известное среди них — «Мёртвый Христос в гробу» Ганса Гольбейна. Мышкин видит его копию в доме Рогожина и произносит: «Да от этой картины у иного ещё вера может пропасть!» Стоит заметить, что об этом же полотне писал Николай Карамзин в «Письмах русского путешественника» (в нём «не видно ничего божественного, но как умерший человек изображён он весьма естественно»), а Жорж Санд в книге «Чёртово болото» пишет о Гольбейне как о художнике, который проповедовал «беспощадный пессимизм, особенно тяжёлый потому, что сулит одни страдания всем обездоленным жизнью… Перед современным художником та же проблема о голодных и раздетых, о социальной вражде и гуманности

»

12

Гроссман Л. П. Достоевский. М.: Молодая гвардия, 1963.

. По мнению Леонида Гроссмана, Достоевский «предполагал включить в роман трактовку князем Мышкиным гольбейнова шедевра… Вопросы атеизма и веры, реализма и натурализма здесь получили бы широкий простор. Но этот философский комментарий к Гольбейну он так и не написал, хотя картина Базельского музея поразила и восхитила его».

Наконец, и сам по себе «Идиот» — роман, если можно так сказать, живописный, изобразительный ряд играет в нём важную роль. Хотя подробнейшие описания внешности героев, отражающей их характер, в принципе свойственны романам того времени, Достоевский любопытным образом обыгрывает этот приём, например создавая особый эффект постепенного появления Настасьи Филипповны — впервые мы видим её на фотографии дома у Епанчиных: «В чёрном шёлковом платье, чрезвычайно простого и изящного фасона; волосы, по-видимому тёмно-русые, были убраны просто, по-домашнему; глаза тёмные, глубокие, лоб задумчивый; выражение лица страстное и как бы высокомерное. Она была несколько худа лицом, может быть, и бледна…» Наконец, только после двух «заочных» появлений героиня материализуется, происходит её непосредственное знакомство с Мышкиным.

Почему в «Идиоте» так подробно показаны второстепенные персонажи?

Отличительная черта «Идиота» — подробность, с которой описаны в романе герои второстепенные, порой комические. Больной чахоткой Ипполит, плутоватый Келлер, шут Фердыщенко, опустившийся чиновник Лебедев, пьяница и маразматик генерал Иволгин имеют свои детально расписанные «выходы». Каждый из них в определённый момент исповедуется князю.

Суть таких исповедей объясняет в «Проблемах поэтики Достоевского» Михаил Бахтин: он говорит о них как о произнесённых (или написанных) «с напряжённейшей установкой на другого, без которого герой не может обойтись, но которого он в то же время ненавидит и суда которого он не принимает». Каждый из второстепенных комических героев князя обманывает — просит денег или просто морочит голову. Но одновременно каждый из них от этих «исповедей» преображается и раскрывается с неожиданной стороны. Келлер оказывается способным к стыду, Иволгин-старший вовсе превращается в трагическую фигуру (особенно если учесть, что в итоге он сбегает из дома и умирает на улице).

Действительно ли в романе герои оперируют огромными суммами денег?

Современники, в частности остроумный критик Дмитрий Минаев, упрекали Достоевского в том, что его роман не имеет ровным счётом никакой связи с реальностью, его герои оперируют абстрактными понятиями и такими же нереальными суммами. Проверить достоверность быта в «Идиоте» непросто: всё-таки суммы 1860-х в современные рубли (а также доллары и евро) не конвертируются. Но понять, что за деньги оказываются в руках персонажей, можно. Во время знакомства с Мышкиным генерал Епанчин, узнав о таланте князя-каллиграфа, говорит: «Прямо можно тридцать пять рублей в месяц положить, с первого шагу!» На самом деле это деньги крохотные, не случайно тут же Епанчин предлагает Мышкину снять угол в квартире Иволгиных. На 35 рублей арендовать собственное жильё в Петербурге было невозможно, самая скромная квартира в 1860-е годы стоила минимум 50 рублей в месяц. Тем же вечером князь сообщает гостям Настасьи Филипповны, что получил по завещанию тётки наследство, полтора миллиона рублей. Сумма астрономическая: дом в центре Москвы стоил порядка пятидесяти тысяч рублей.

Повели мне в камин: весь влезу, всю голову свою седую в огонь вложу!

Фёдор Достоевский

Но все эти суммы, смущавшие своим размахом современников, в романе относительны. Настасья Филипповна кидает в камин сто тысяч — и этот жест воспринимается как безумие, огромные деньги горят. Когда же князь в очередном объяснении с Аглаей говорит, что его состояние — 135 тысяч, она встречает эту фразу смехом и комментарием: «Только-то?» Деньги здесь — не признак состоятельности героев, как считали Щедрин, Лесков и другие критики, а лишь те условные правила, вроде титулов и званий, среди которых живут персонажи. И которые абсолютно непонятны Мышкину.

список литературы

- Бахтин М. М. Проблемы поэтики Достоевского // Бахтин М. М. Собрание сочинений. Т. 6. М.: Русские словари: Языки славянской культуры, 2002.

- Гроссман Л. П. Достоевский. М.: Молодая гвардия, 1963.

- Гроссман Л. П. Поэтика Достоевского. М.: ГАХН, 1925.

- Достоевская А. Г. Воспоминания. М.: Худ. лит-ра, 1971.

- Летопись жизни и творчества Ф. М. Достоевского. СПб.: Академический проект, 1993.

- Мережковский Д. С. Л. Толстой и Достоевский. М.: Наука, 2000.

- Набоков В. В. Лекции по русской литературе. М.: Независимая газета, 1999.

Электронная книга

Идиот

- Описание

- Обсуждения 3

- Цитаты 21

- Рецензии

- Коллекции 2

Что будет, если человека с открытым сердцем и благими чаяниями, человека вмещающего в себя все христианские добродетели, поместить в наш жестокий мир, в самую гущу страстей? Заразит ли он своей добродетелью окружающих его людей, сделает ли мир лучше? Или же сам сгинет и других затянет туда, куда выстлана дорога хорошими намерениями, под натиском жестокости и циничности реалий, его окружающих?

Вот вопрос, который ставит Федор Михайлович перед читателем, а хуже всего то, что каждый из нас в глубине души уже знает на него ответ. Так есть ли место христианским идеалам на грешной земле, или же нужно быть идиотом, чтобы верить в это? А если так, к чему стремиться и где искать ответы на главные вопросы?.. (с)Kamitake для Librebook

….как легко прививаются привычки роскоши и как трудно потом отставать от них, когда роскошь мало-по-малу обращается в необходимость.

Он чувствовал отчасти, что ему бы надо было про что-то узнать, про что-то спросить, — во всяком случае про что-то посерьезнее того, как пистолет заряжают. Но всё это вылетело у него из ума, кроме одного того, что пред ним сидит она, а он на нее глядит, а о чем бы она ни заговорила, ему в эту минуту было бы почти всё равно.

… не всё же понимать сразу, не прямо же начинать с совершенства! Чтобы достичь совершенства, надо прежде многого не понимать. А слишком скоро поймем, так, пожалуй, и не хорошо поймем.

Подлецы любят честных людей, — вы этого не знали?

Может быть, он безмерно преувеличивал беду; но с тщеславными людьми всегда так бывает.

добавить цитату

Все цитаты из книги Идиот

Иллюстрации

Интересные факты

Балет:

1980 — премьера балета «Идиот» в Ленинграде балетмейстера Бориса Эйфмана по мотивам одноимённого романа Достоевского на музыку Шестой симфонии П. И. Чайковского

2015 — 30 июля премьера балета «Идиот» на музыку П. И. Чайковского в Омском государственном музыкальном театре

Во Флоренции на площади перед палаццо Питти на одном из домов висит мемориальная табличка, сообщающая, что здесь Ф. М. Достоевский написал роман «Идиот».

Произведение Идиот полностью

Видеоанонс

|

Взято c youtube.com. Пожаловаться, не открывается |

|

Взято c youtube.com. Пожаловаться, не открывается |

|

Взято c youtube.com. Пожаловаться, не открывается |

|

Взято c youtube.com. Пожаловаться, не открывается |

Информация об экранизации книги

«Идиот» — фильм Петра Чардынина (Россия, 1910)

«Идиот» — фильм Сальваторе Аверсано (Италия, 1919)

«Князь-идиот» — фильм Эудженио Перего (Италия, 1920)

«Идиот» / L’Idiot — фильм Жоржа Лампена (Франция, 1946). В главной роли Жерар Филип, его роль в немецком переводе озвучил актёр Макс Эккард)

«Идиот» — фильм Ивана Пырьева (СССР, 1958)

«Идиот» — телесериал Алана Бриджеса (Великобритания, 1966)

«Идиот» (ТВ) / L’idiot — фильм Андре Барсака (Франция, 1968)

«Идиот» — фильм Александры Ремизовой (СССР, театр им. Вахтангова, 1979)

«Шальная любовь» — фильм Анджея Жулавского (Франция, 1985)

«Идиот» — телесериал Мани Каула (Индия, 1991)

«Настасья» — фильм Анджея Вайды (Польша, 1994)

«Возвращение идиота» — фильм Саши Гедеона (Германия, Чехия, 1999)

«Даун Хаус» — фильм-пародия Романа Качанова (Россия, 2001)

«Идиот» — телесериал Владимира Бортко (Россия, 2003)

«Идиот» — фильм Пьера Леона (Франция, 2008)

В августе 2010 года эстонский режиссёр Райнер Сарнет приступил к съёмкам фильма «Идиот» по одноимённой книге Достоевского. Премьера состоялась 12 октября 2011 года.

Связанные произведения

Герои

Статьи

Купить онлайн

340 руб

529 руб

567 руб

176 руб

225 руб

Все предложения…

- Похожее

-

Рекомендации

-

Ваши комменты

- Еще от автора

Drawing and handwritten text by Fyodor Dostoevsky |

|

| Author | Fyodor Dostoevsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Идиот |

The Idiot (pre-reform Russian: Идіотъ; post-reform Russian: Идиот, tr. Idiót) is a novel by the 19th-century Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. It was first published serially in the journal The Russian Messenger in 1868–69.

The title is an ironic reference to the central character of the novel, Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin, a young man whose goodness, open-hearted simplicity and guilelessness lead many of the more worldly characters he encounters to mistakenly assume that he lacks intelligence and insight. In the character of Prince Myshkin, Dostoevsky set himself the task of depicting «the positively good and beautiful man.»[1] The novel examines the consequences of placing such a singular individual at the centre of the conflicts, desires, passions and egoism of worldly society, both for the man himself and for those with whom he becomes involved.

Joseph Frank describes The Idiot as «the most personal of all Dostoevsky’s major works, the book in which he embodies his most intimate, cherished, and sacred convictions.»[2] It includes descriptions of some of his most intense personal ordeals, such as epilepsy and mock execution, and explores moral, spiritual and philosophical themes consequent upon them. His primary motivation in writing the novel was to subject his own highest ideal, that of true Christian love, to the crucible of contemporary Russian society.

The artistic method of conscientiously testing his central idea meant that the author could not always predict where the plot was going as he was writing. The novel has an awkward structure, and many critics have commented on its seemingly chaotic organization. According to Gary Saul Morson, «The Idiot violates every critical norm and yet somehow manages to achieve real greatness.»[3] Dostoevsky himself was of the opinion that the experiment was not entirely successful, but the novel remained his favourite among his works. In a letter

to Strakhov he wrote: «Much in the novel was written hurriedly, much is too diffuse and did not turn out well, but some of it did turn out well. I do not stand behind the novel, but I do stand behind the idea.»[4]

Background[edit]

In September 1867, when Dostoevsky began work on what was to become The Idiot, he was living in Switzerland with his new wife Anna Grigoryevna, having left Russia in order to escape his creditors. They were living in extreme poverty, and constantly had to borrow money or pawn their possessions. They were evicted from their lodgings five times for non-payment of rent, and by the time the novel was finished in January 1869 they had moved between four different cities in Switzerland and Italy. During this time Dostoevsky periodically fell into the grip of his gambling addiction and lost what little money they had on the roulette tables. He was subject to regular and severe epileptic seizures, including one while Anna was going into labor with their daughter Sofia, delaying their ability to go for a midwife. The baby died aged only three months, and Dostoevsky blamed himself for the loss.[5]

Dostoevsky’s notebooks of 1867 reveal deep uncertainty as to the direction he was taking with the novel. Detailed plot outlines and character sketches were made, but were quickly abandoned and replaced with new ones. In one early draft, the character who was to become Prince Myshkin is an evil man who commits a series of terrible crimes, including the rape of his adopted sister (Nastasya Filippovna), and who only arrives at goodness by way of his conversion through Christ. By the end of the year, however, a new premise had been firmly adopted. In a letter to Apollon Maykov, Dostoevsky explained that his own desperate circumstances had «forced» him to seize on an idea that he had considered for some time but had been afraid of, feeling himself to be artistically unready for it. This was the idea to «depict a completely beautiful human being».[6] Rather than bring a man to goodness, he wanted to start with a man who was already a truly Christian soul, someone who is essentially innocent and deeply compassionate, and test him against the psychological, social and political complexities of the modern Russian world. It was not only a matter of how the good man responded to that world, but of how it responded to him. Devising a series of scandalous scenes, he would «examine each character’s emotions and record what each would do in response to Myshkin and to the other characters.»[7] The difficulty with this approach was that he himself did not know in advance how the characters were going to respond, and thus he was unable to pre-plan the plot or structure of the novel. Nonetheless, in January 1868 the first chapters of The Idiot were sent off to The Russian Messenger.

Plot[edit]

Part 1[edit]

Prince Myshkin, a young man in his mid-twenties and a descendant of one of the oldest Russian lines of nobility, is on a train to Saint Petersburg on a cold November morning. He is returning to Russia having spent the past four years in a Swiss clinic for treatment of a severe epileptic condition. On the journey, Myshkin meets a young man of the merchant class, Parfyon Semyonovich Rogozhin, and is struck by his passionate intensity, particularly in relation to a woman—the dazzling society beauty Nastasya Filippovna Barashkova—with whom he is obsessed. Rogozhin has just inherited a very large fortune due to the death of his father, and he intends to use it to pursue the object of his desire. Joining in their conversation is a civil servant named Lebedyev—a man with a profound knowledge of social trivia and gossip. Realizing who Rogozhin is, Lebedyev firmly attaches himself to him.

The purpose of Myshkin’s trip is to make the acquaintance of his distant relative Lizaveta Prokofyevna, and to make inquiries about a matter of business. Lizaveta Prokofyevna is the wife of General Epanchin, a wealthy and respected man in his mid-fifties. When the Prince calls on them he meets Gavril Ardalionovich Ivolgin (Ganya), the General’s assistant. The General and his business partner, the aristocrat Totsky, are seeking to arrange a marriage between Ganya and Nastasya Filippovna. Totsky had been the orphaned Nastasya Filippovna’s childhood guardian, but he had taken advantage of his position to groom her for his own sexual gratification. As a grown woman, Nastasya Filippovna has developed an incisive and merciless insight into their relationship. Totsky, thinking the marriage might settle her and free him to pursue his desire for marriage with General Epanchin’s eldest daughter, has promised 75,000 rubles. Nastasya Filippovna, suspicious of Ganya and aware that his family does not approve of her, has reserved her decision, but has promised to announce it that evening at her birthday soirée. Ganya and the General openly discuss the subject in front of Myshkin. Ganya shows him a photograph of her, and he is particularly struck by the dark beauty of her face.

Myshkin makes the acquaintance of Lizaveta Prokofyevna and her three daughters—Alexandra, Adelaida and Aglaya. They are all very curious about him and not shy about expressing their opinion, particularly Aglaya. He readily engages with them and speaks with remarkable candor on a wide variety of subjects—his illness, his impressions of Switzerland, art, philosophy, love, death, the brevity of life, capital punishment, and donkeys. In response to their request that he speak of the time he was in love, he tells a long anecdote from his time in Switzerland about a downtrodden woman—Marie—whom he befriended, along with a group of children, when she was unjustly ostracized and morally condemned. The Prince ends by describing what he divines about each of their characters from studying their faces and surprises them by saying that Aglaya is almost as beautiful as Nastasya Filippovna.

The prince rents a room in the Ivolgin apartment, occupied by Ganya’s family and another lodger called Ferdyschenko. There is much angst within Ganya’s family about the proposed marriage, which is regarded, particularly by his mother and sister (Varya), as shameful. Just as a quarrel on the subject is reaching a peak of tension, Nastasya Filippovna herself arrives to pay a visit to her potential new family. Shocked and embarrassed, Ganya succeeds in introducing her, but when she bursts into a prolonged fit of laughter at the look on his face, his expression transforms into one of murderous hatred. The Prince intervenes to calm him down, and Ganya’s rage is diverted toward him in a violent gesture. The tension is not eased by the entrance of Ganya’s father, General Ivolgin, a drunkard with a tendency to tell elaborate lies. Nastasya Filippovna flirtatiously encourages the General and then mocks him. Ganya’s humiliation is compounded by the arrival of Rogozhin, accompanied by a rowdy crowd of drunks and rogues, Lebedyev among them. Rogozhin openly starts bidding for Nastasya Filippovna, ending with an offer of a hundred thousand rubles. With the scene assuming increasingly scandalous proportions, Varya angrily demands that someone remove the «shameless woman». Ganya seizes his sister’s arm, and she responds, to Nastasya Filippovna’s delight, by spitting in his face. He is about to strike her when the Prince again intervenes, and Ganya slaps him violently in the face. Everyone is deeply shocked, including Nastasya Filippovna, and she struggles to maintain her mocking aloofness as the others seek to comfort the Prince. Myshkin admonishes her and tells her it is not who she really is. She apologizes to Ganya’s mother and leaves, telling Ganya to be sure to come to her birthday party that evening. Rogozhin and his retinue go off to raise the 100,000 rubles.

Among the guests at the party are Totsky, General Epanchin, Ganya, his friend Ptitsyn (Varya’s fiancé), and Ferdyshchenko, who, with Nastasya Filippovna’s approval, plays the role of cynical buffoon. With the help of Ganya’s younger brother Kolya, the Prince arrives, uninvited. To enliven the party, Ferdyshchenko suggests a game where everyone must recount the story of the worst thing they have ever done. Others are shocked at the proposal, but Nastasya Filippovna is enthusiastic. When it comes to Totsky’s turn he tells a long but innocuous anecdote from the distant past. Disgusted, Nastasya Filippovna turns to Myshkin and demands his advice on whether or not to marry Ganya. Myshkin advises her not to, and Nastasya Filippovna, to the dismay of Totsky, General Epanchin and Ganya, firmly announces that she is following this advice. At this point, Rogozhin and his followers arrive with the promised 100,000 rubles. Nastasya Filipovna is preparing to leave with him, exploiting the scandalous scene to humiliate Totsky, when Myshkin himself offers to marry her. He speaks gently and sincerely, and in response to incredulous queries about what they will live on, produces a document indicating that he will soon be receiving a large inheritance. Though surprised and deeply touched, Nastasya Filipovna, after throwing the 100,000 rubles in the fire and telling Ganya they are his if he wants to get them out, chooses to leave with Rogozhin. Myshkin follows them.

Part 2[edit]

For the next six months, Nastasya Filippovna remains unsettled and is torn between Myshkin and Rogozhin. Myshkin is tormented by her suffering, and Rogozhin is tormented by her love for Myshkin and her disdain for his own claims on her. Returning to Petersburg, the Prince visits Rogozhin’s house. Myshkin becomes increasingly horrified at Rogozhin’s attitude to her. Rogozhin confesses to beating her in a jealous rage and raises the possibility of cutting her throat. Despite the tension between them, they part as friends, with Rogozhin even making a gesture of concession. But the Prince remains troubled and for the next few hours he wanders the streets, immersed in intense contemplation. He suspects that Rogozhin is watching him and returns to his hotel where Rogozhin—who has been hiding in the stairway—attacks him with a knife. At the same moment, the Prince is struck down by a violent epileptic seizure, and Rogozhin flees in a panic.

Recovering, Myshkin joins Lebedyev (from whom he is renting a dacha) in the summer resort town Pavlovsk. He knows that Nastasya Filippovna is in Pavlovsk and that Lebedyev is aware of her movements and plans. The Epanchins, who are also in Pavlovsk, visit the Prince. They are joined by their friend Yevgeny Pavlovich Radomsky, a handsome and wealthy military officer with a particular interest in Aglaya. Aglaya, however, is more interested in the Prince, and to Myshkin’s embarrassment and everyone else’s amusement, she recites Pushkin’s poem «The Poor Knight» in a reference to his noble efforts to save Nastasya Filippovna.

The Epanchins’ visit is rudely interrupted by the arrival of Burdovsky, a young man who claims to be the illegitimate son of Myshkin’s late benefactor, Pavlishchev. The inarticulate Burdovsky is supported by a group of insolent young men. These include the consumptive seventeen-year-old Ippolit Terentyev, the nihilist Doktorenko, and Keller, an ex-officer who, with the help of Lebedyev, has written an article vilifying the Prince and Pavlishchev. They demand money from Myshkin as a «just» reimbursement for Pavlishchev’s support, but their arrogant bravado is severely dented when Gavril Ardalionovich, who has been researching the matter on Myshkin’s behalf, proves conclusively that the claim is false and that Burdovsky has been deceived. The Prince tries to reconcile with the young men and offers financial support anyway. Disgusted, Lizaveta Prokofyevna loses all control and furiously attacks both parties. Ippolit laughs, and Lizaveta Prokofyevna seizes him by the arm, causing him to break into a prolonged fit of coughing. But he suddenly becomes calm, informs them all that he is near death, and politely requests that he be permitted to talk to them for a while. He awkwardly attempts to express his need for their love, eventually bringing both himself and Lizaveta Prokofyevna to the point of tears. But as the Prince and Lizaveta Prokofyevna discuss what to do with the invalid, another transformation occurs and Ippolit, after unleashing a torrent of abuse at the Prince, leaves with the other young men. The Epanchins also leave, both Lizaveta Prokofyevna and Aglaya deeply indignant with the Prince. Only Yevgeny Pavlovich remains in good spirits, and he smiles charmingly as he says good-bye. At that moment, a magnificent carriage pulls up at the dacha, and the ringing voice of Nastasya Filippovna calls out to Yevgeny Pavlovich. In a familiar tone, she tells him not to worry about all the IOUs as Rogozhin has bought them up. The carriage departs, leaving everyone, particularly Yevgeny Pavlovich and the Prince, in a state of shock. Yevgeny Pavlovich claims to know nothing about the debts, and Nastasya Filippovna’s motives become a subject of anxious speculation.

Part 3[edit]

Reconciling with Lizaveta Prokofyevna, the Prince visits the Epanchins at their dacha. He is beginning to fall in love with Aglaya, and she likewise appears to be fascinated by him, though she often mocks or angrily reproaches him for his naiveté and excessive humility. Myshkin joins Lizaveta Prokofyevna, her daughters and Yevgeny Pavlovich for a walk to the park to hear the music. While listening to the high-spirited conversation and watching Aglaya in a kind of daze, he notices Rogozhin and Nastasya Filippovna in the crowd. Nastasya Filippovna again addresses herself to Yevgeny Pavlovich, and in the same jolly tone as before loudly informs him that his uncle—a wealthy and respected old man from whom he is expecting a large inheritance—has shot himself and that a huge sum of government money is missing. Yevgeny Pavlovich stares at her in shock as Lizaveta Prokofyevna makes a hurried exit with her daughters. Nastasya Filippovna hears an officer friend of Yevgeny Pavlovich suggest that a whip is needed for women like her, and she responds by grabbing a riding-whip from a bystander and striking the officer across the face with it. He tries to attack her but Myshkin restrains him, for which he is violently pushed. Rogozhin, after making a mocking comment to the officer, leads Nastasya Filippovna away. The officer recovers his composure, addresses himself to Myshkin, politely confirms his name, and leaves.

Myshkin follows the Epanchins back to their dacha, where eventually Aglaya finds him alone on the verandah. To his surprise, she begins to talk to him very earnestly about duels and how to load a pistol. They are interrupted by General Epanchin who wants Myshkin to walk with him. Aglaya slips a note into Myshkin’s hand as they leave. The General is greatly agitated by the effect Nastasya Filippovna’s behavior is having on his family, particularly since her information about Yevgeny Pavlovich’s uncle has turned out to be completely correct. When the General leaves, Myshkin reads Aglaya’s note, which is an urgent request to meet her secretly the following morning. His reflections are interrupted by Keller who has come to offer to be his second at the duel that will inevitably follow from the incident that morning, but Myshkin merely laughs heartily and invites Keller to visit him to drink champagne. Keller departs and Rogozhin appears. He informs the Prince that Nastasya Filippovna wants to see him and that she has been in correspondence with Aglaya. She is convinced that the Prince is in love with Aglaya, and is seeking to bring them together. Myshkin is perturbed by the information, but he remains in an inexplicably happy frame of mind and speaks with forgiveness and brotherly affection to Rogozhin. Remembering it will be his birthday tomorrow, he persuades Rogozhin to join him for some wine.

They find that a large party has assembled at his home and that the champagne is already flowing. Present are Lebedyev, his daughter Vera, Ippolit, Burdovsky, Kolya, General Ivolgin, Ganya, Ptitsyn, Ferdyshchenko, Keller, and, to Myshkin’s surprise, Yevgeny Pavlovich, who has come to ask for his friendship and advice. The guests greet the Prince warmly and compete for his attention. Stimulated by Lebedyev’s eloquence, everyone engages for some time in intelligent and inebriated disputation on lofty subjects, but the good-humoured atmosphere begins to dissipate when Ippolit suddenly produces a large envelope and announces that it contains an essay he has written which he now intends to read to them. The essay is a painfully detailed description of the events and thoughts leading him to what he calls his ‘final conviction’: that suicide is the only possible way to affirm his will in the face of nature’s invincible laws, and that consequently he will be shooting himself at sunrise. The reading drags on for over an hour and by its end the sun has risen. Most of his audience, however, are bored and resentful, apparently not at all concerned that he is about to shoot himself. Only Vera, Kolya, Burdovsky and Keller seek to restrain him. He distracts them by pretending to abandon the plan, then suddenly pulls out a small pistol, puts it to his temple and pulls the trigger. There is a click but no shot: Ippolit faints but is not killed. It turns out that he had taken out the cap earlier and forgotten to put it back in. Ippolit is devastated and tries desperately to convince everyone that it was an accident. Eventually he falls asleep and the party disperses.

The Prince wanders for some time in the park before falling asleep at the green seat appointed by Aglaya as their meeting place. Her laughter wakes him from an unhappy dream about Nastasya Filippovna. They talk for a long time about the letters Aglaya has received, in which Nastasya Filippovna writes that she herself is in love with Aglaya and passionately beseeches her to marry Myshkin. Aglaya interprets this as evidence that Nastasya Filippovna is in love with him herself, and demands that Myshkin explain his feelings toward her. Myshkin replies that Nastasya Filippovna is insane, that he only feels profound compassion and is not in love with her, but admits that he has come to Pavlovsk for her sake. Aglaya becomes angry, demands that he throw the letters back in her face, and storms off. Myshkin reads the letters with dread, and later that day Nastasya Filippovna herself appears to him, asking desperately if he is happy, and telling him she is going away and will not write any more letters. Rogozhin escorts her.

Part 4[edit]

It is clear to Lizaveta Prokofyevna and General Epanchin that their daughter is in love with the Prince, but Aglaya denies this and angrily dismisses talk of marriage. She continues to mock and reproach him, often in front of others, and lets slip that, as far as she is concerned, the problem of Nastasya Filippovna is yet to be resolved. Myshkin himself merely experiences an uncomplicated joy in her presence and is mortified when she appears to be angry with him. Lizaveta Prokofyevna feels it is time to introduce the Prince to their aristocratic circle and a dinner party is arranged for this purpose, to be attended by a number of eminent persons. Aglaya, who does not share her parents’ respect for these people and is afraid that Myshkin’s eccentricity will not meet with their approval, tries to tell him how to behave, but ends by sarcastically telling him to be as eccentric as he likes, and to be sure to wave his arms about when he is pontificating on some high-minded subject and break her mother’s priceless Chinese vase. Feeling her anxiety, Myshkin too becomes extremely anxious, but he tells her that it is nothing compared to the joy he feels in her company. He tries to approach the subject of Nastasya Filippovna again, but she silences him and hurriedly leaves.