История создания знаменитых книг, фантазии автора и трактовки учёных.

Чуть больше полутора веков назад вышла одна из самых неоднозначных сказок в истории литературы — «Алиса в Стране чудес» Льюиса Кэрролла. Редко какое произведение, предназначенное для детской аудитории, вызывало столько споров и обсуждений. Конечно, нередки случаи, когда писатели закладывали в сказочные истории вполне взрослые мысли — достаточно вспомнить «Маленького принца» Антуана де Сент-Экзюпери или «Муми-троллей» Туве Янссон.

Но всё же «Алиса в Стране чудес» и её продолжение, «Алиса в Зазеркалье», уникальны. Их обсуждали лингвисты, физики, математики, философы, историки, психологи, в общем, представители самых разных наук. И каждый видел в отдельных сценах какой-то глубокий смысл. Причём сейчас уже доподлинно трудно сказать, в каких моментах подтекст действительно присутствует, а где учёные выдают свои мысли за идеи Кэрролла.

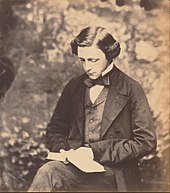

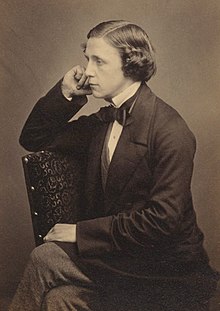

Льюис Кэрролл: математик, сказочник, фотограф, изобретатель

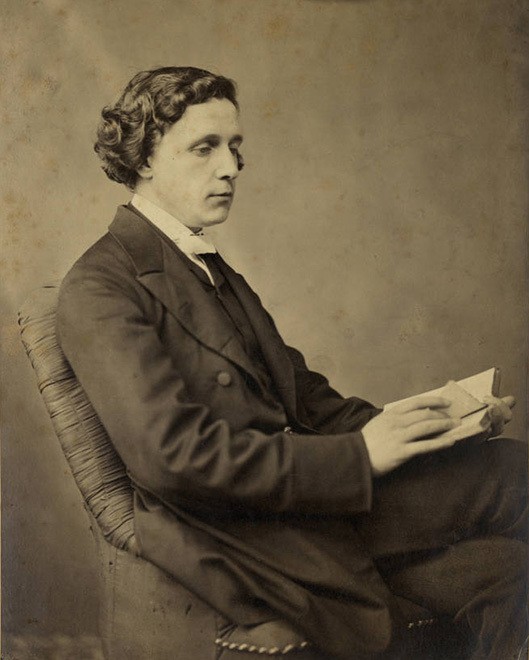

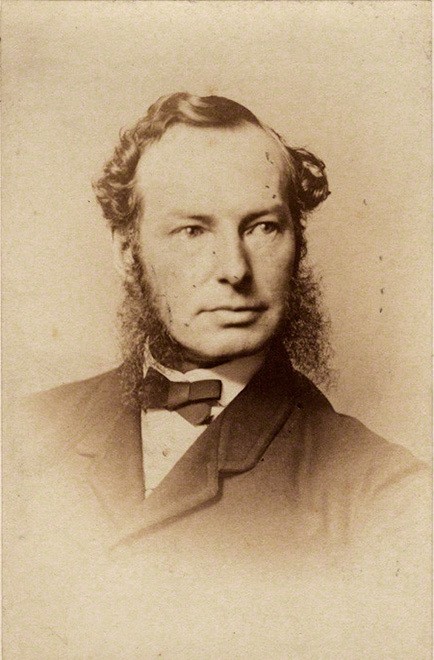

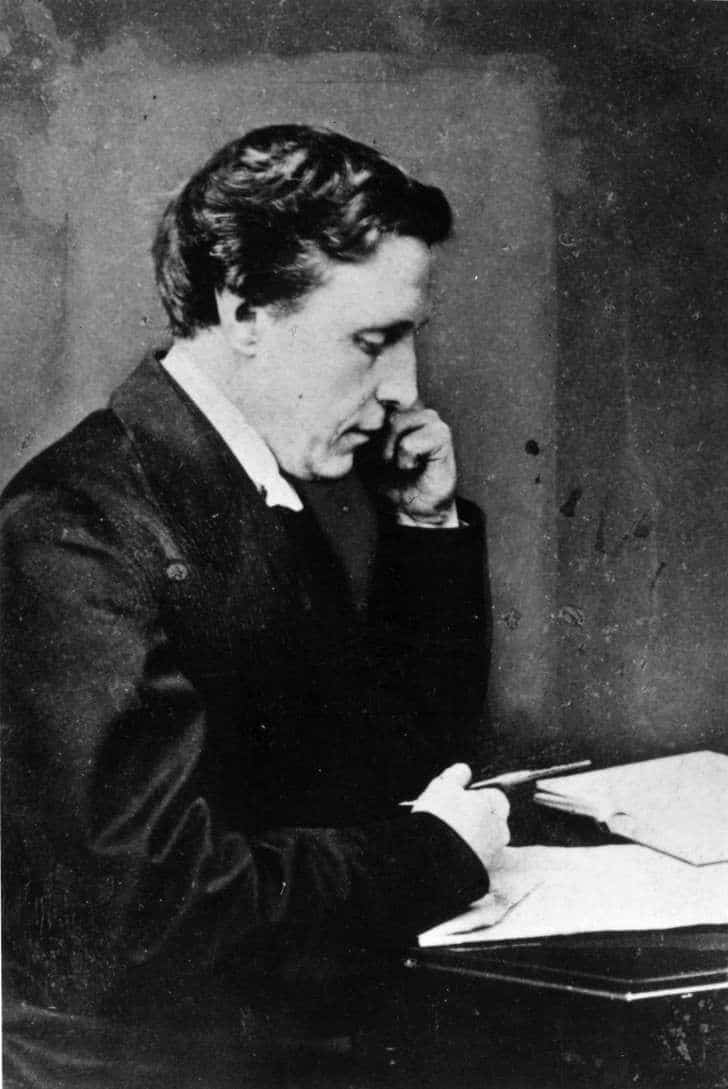

Чарльз Лютвидж Доджсон, как на самом деле звали писателя (хотя сам он произносил свою фамилию как Додсон), был известен не только благодаря литературному таланту. Сначала его знали как выдающегося учёного и просто неординарную личность.

Родился Доджсон 27 января 1832 года в семье приходского священника в одной из деревушек графства Чешир. С самого детства он проявлял сообразительность и изобретательность: придумывал игры с подробными правилами, строил театр марионеток и показывал фокусы. Но главное, он очень любил сочинять истории и стихи и даже «издавал» (то есть писал от руки) домашний журнал.

Когда Чарльз подрос, он отправился учиться в колледж Крайст-Чёрч в Оксфорде. С этим учебным заведением впоследствии была связана большая часть его жизни. Несмотря на посредственные успехи в учёбе, Доджсон проявлял незаурядные способности к математике и вскоре начал зарабатывать чтением лекций. Правда, для этого ему пришлось принять духовный сан и обет безбрачия. Но многие считают, что брак Чарльза и так не очень волновал.

Доджсона можно назвать ярким примером поговорки «талантливый человек талантлив во всём». Помимо лекций и серьёзных математических трудов он придумывал задачи для детей и взрослых и хорошо играл в шахматы. Именно он изобрёл упрощённый метод перевода денег в банке, когда отправитель заполняет два бланка и сообщает код получателю.

А ещё Доджсон придумал «никтограф» — устройство для быстрой записи в темноте — и много других любопытных приспособлений. Кроме того, он любил фотографировать, в основном природу или детей. Многие из тех, кто знал Чарльза, говорили, что если бы он не прославился как писатель, то точно вошёл бы в историю благодаря какой-нибудь другой деятельности.

Но всё же людям запомнился именно литературный талант Доджсона. Он с детства любил «играть словами», позже придумал игру в «дуплеты» — когда в исходном слове меняется одна буква, пока оно не превращается в заданное (например, сделать из «мухи» — «слона»). А потом его стихи и прозу начали печатать и в журналах.

Именно тогда и «родился» Льюис Кэрролл. Всё-таки видному учёному, да ещё и с духовным саном, не пристало печататься под своим именем. И писатель занялся своим любимым делом — игрой в слова.

Псевдоним появился следующим образом: Доджсон взял свои имена Чарльз Лютвидж (первое он получил в честь отца, второе — девичья фамилия матери) и перевёл их на латынь. Получилось Carolus Ludovicus. Потом поменял местами и перевёл обратно, выбрав другие соответствия — Льюис Кэрролл. Под этим псевдонимом он и издал свои главные работы.

Кэрролл и Алиса

Льюис Кэрролл всегда любил общаться с маленькими девочками. Однако все разговоры о педофилии смело можно считать спекуляцией: нет ни одного упоминания о его непристойном поведении ни от самих девочек, ни от их родителей. Подобные слухи во многом связаны с тем, что семья Кэрролла после его смерти избавлялась от излишних упоминаний о его связи со взрослыми женщинами (видимо, из-за обета безбрачия). Так и возник миф о его увлечении исключительно детьми.

Скорее всего, дело совершенно в другом. Кэрролла всегда описывают, как застенчивого человека. Он очень смущался в обществе взрослых и серьёзных людей. А учитывая врождённое заикание, часто стеснялся даже заговорить. Только в обществе детей он чувствовал себя свободно, ведь с ними Кэрролл мог раскрыть свой талант сказочника, придумывая на ходу истории, которые приводили их в восторг.

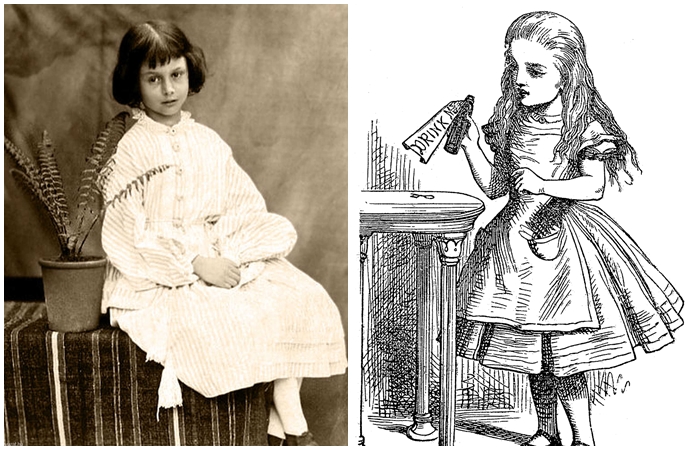

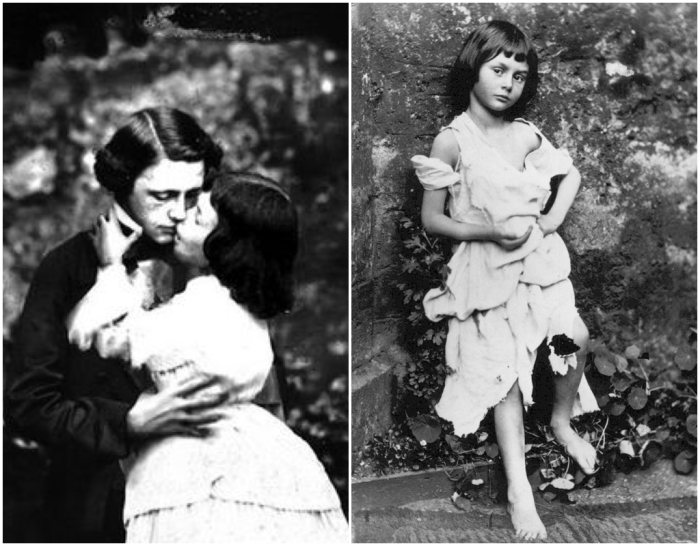

С Алисой Лидделл, которая и стала главным (но не единственным) прообразом героини легендарной книги, писатель познакомился в 1856 году, когда в колледж, где он читал лекции, приехал новый декан Генри Лидделл со своей семьёй. В апреле 1856 года Кэрролл случайно столкнулся с Лидделлом, когда фотографировал собор. Они заговорили и вскоре подружились.

Льюис Кэрролл часто бывал в гостях у Лидделлов, там он и познакомился с юной дочкой декана Алисой. На момент приезда ей было всего четыре года. Вскоре Алиса стала любимой моделью Кэрролла. Наиболее известна её фотография «Алиса Лидделл в образе нищенки». На самом деле, это часть диптиха, но почему-то второй кадр, где девочка практически в той же позе, но хорошо одета, менее знаменит.

Как всё началось

По словам самих участников событий, история легендарной «Алисы в Стране чудес» берёт своё начало 4 июля 1862 года, когда Льюис Кэрролл и его друг Робинсон Дакворт отправились на лодочную прогулку с тремя дочерьми Лидделлов: десятилетней Алисой, её старшей сестрой Лориной Шарлоттой и младшей Эдит Мери.

Дети упрашивали Кэрролла рассказать какую-нибудь сказку, и он на ходу придумал историю девочки Алисы, которая провалилась в глубокую яму и попала в причудливое подземное царство.

Как ни странно, позже многие высказывали сомнения, что Кэрролл придумал сказку именно 4 июля. В первую очередь стали проверять слова писателя и самой Алисы — те говорили, что день был очень жаркий и солнечный. А если судить по архивам синоптиков, именно 4 июля было прохладно и пасмурно.

На самом деле, подобные факты наверняка волнуют только самих историков. Возможно, они перепутали этот день с какой-то другой прогулкой, возможно, в архивах есть ошибка. А скорее всего Кэрролл начал придумывать какие-то отрывки ещё раньше — есть упоминания о чтении отдельных строк ещё в 1850-х.

Но точно одно: во время одной из прогулок Кэрролл рассказал Алисе и её сёстрам сказку о приключениях семилетней девочки под землёй. Позже сёстры неоднократно просили продолжить историю, а Алиса требовала записать сказку.

И пусть там будет побольше всяких глупостей.

Алиса Лидделл

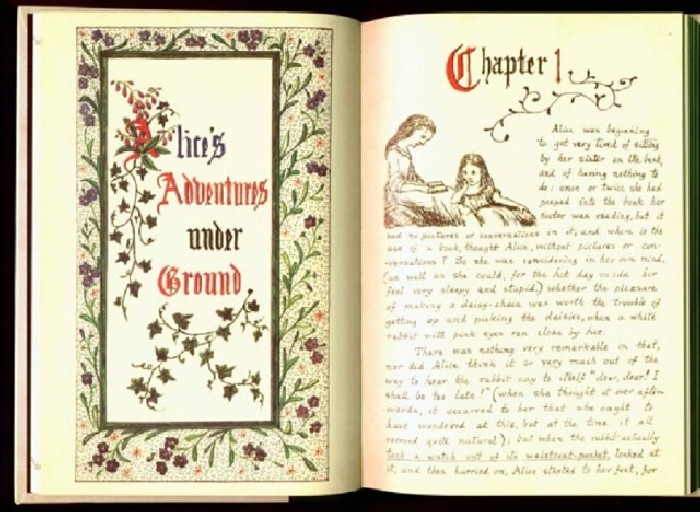

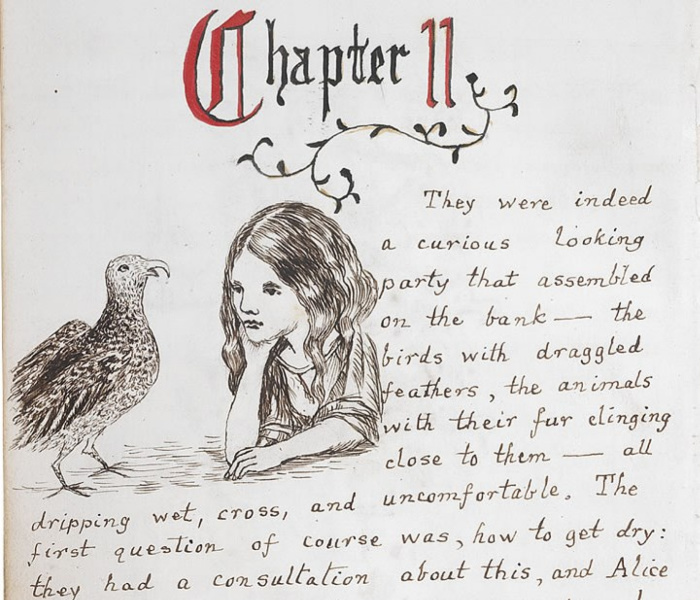

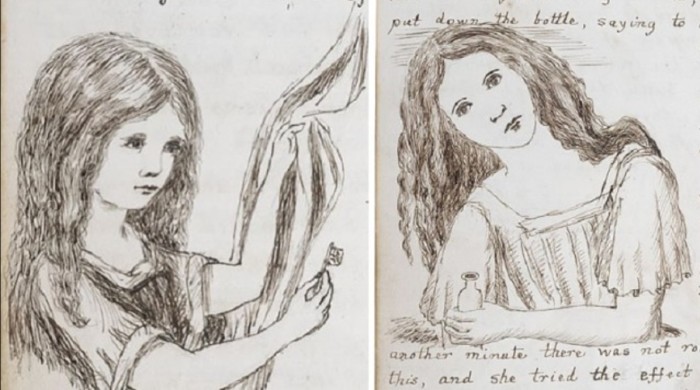

Разумеется, изначально история была значительно короче, и в сказке не было части событий и даже многих героев. Подаренная Алисе спустя два года на рождество рукопись «Приключение Алисы под землёй» насчитывала всего четыре главы. Зато в конце Кэрролл добавил фотографию Алисы в семилетнем возрасте как главную иллюстрацию.

Потом он неоднократно дорабатывал сюжет. Со временем в нём появились «безумное чаепитие» и его участники, Чеширский Кот, суд над Валетом и некоторые другие сцены. Но неуверенный в себе Кэрролл всё ещё сомневался, стоит ли издавать книгу.

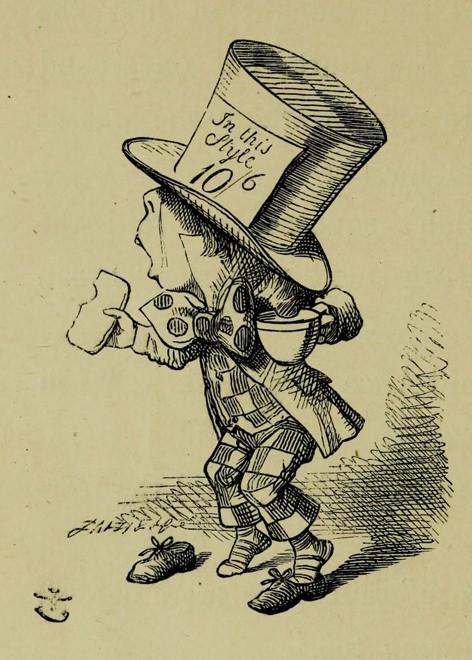

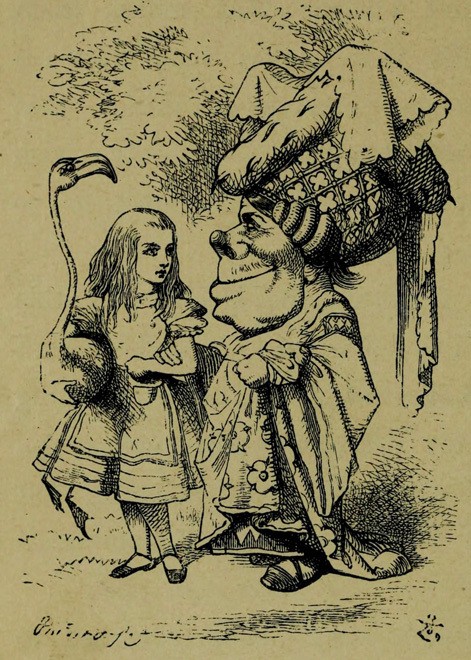

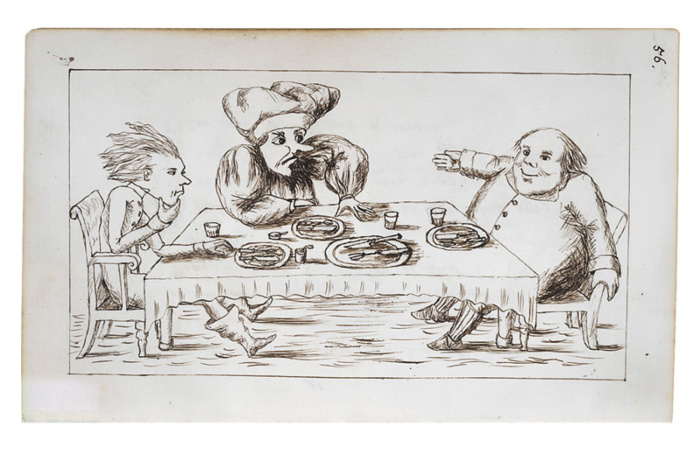

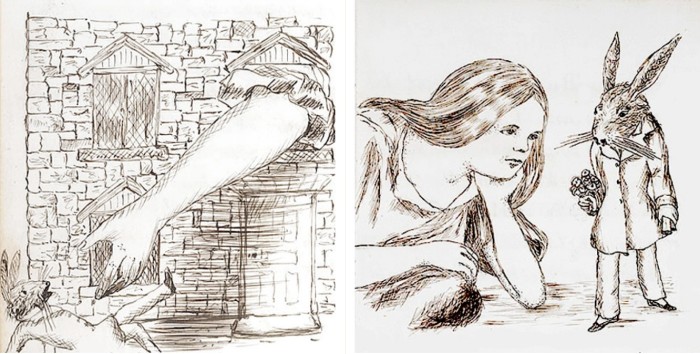

Тогда он решил провести своеобразную проверку: попросил своего друга Джорджа Макдональда зачитать сказку детям. Те остались в полном восторге. А Макдональд посоветовал Кэрроллу ещё и напечатать собственные иллюстрации. Но тот не верил в свой талант художника и обратился к Джону Тенниелу.

Интересно, что в качестве примера образа главной героини автор отправил художнику фотографию не Алисы Лидделл, а другой своей юной подруги — Мэри Хилтон Бэдкок. Однако доподлинно неизвестно, использовал ли Тенниел хоть какие-то рекомендации Кэрролла при создании рисунков. Скорее всего, он ориентировался исключительно на своё воображение.

Но, похоже, Кэрролл не слишком заботился о портретном сходстве. В книге описание Алисы даётся только в общих чертах, автору были важнее эмоции и фантазии, а не описание героини. Ведь он и так знал, кому посвящена книга.

Традиционная сказка

Если разбирать действие «Алисы» поверхностно, как это сделали бы дети, то перед нами простейшая сказка. Её действие развивается абсолютно линейно: девочка просто переходит из одной локации в другую, проходя различные метаморфозы и встречая сказочных персонажей.

После падения она сталкивается с группой животных, которые рассказывают друг другу истории. Потом попадает в дом Белого Кролика, получает мудрый совет от Гусеницы, проводит время на «безумном чаепитии», играет в крокет с Королевой и слушает историю черепахи Квази.

Всё действие легко запомнить и пересказать. Как принято в сказках, добрые герои помогают Алисе и дают советы, злые — мешают и чаще всего сами попадают впросак. Структуру сказки можно сравнить практически с любой классической историей для детей. Хотя есть и несколько отличий.

Во-первых, Кэрролл не выводит какой-либо морали. Здесь нет конкретной победы добра над злом. Скорее всего, это связано как раз с тем, что автор придумывал сюжет «на ходу», не заботясь о финале.

Во-вторых, Кэрролл связал действие сказки с играми. Часть персонажей представляет из себя колоду карт: Король и Королева управляют страной, а мелкие карты им подчиняются. Это связано с любовью автора выдумывать различные новые правила для игр.

То же самое прослеживается в сцене с крокетом. У Кэрролла был свой вариант этой забавы под названием «Крокетный замок», и он даже опубликовал новую версию правил. Кстати, в изначальном варианте книги, вместо молотков герои пользовались не фламинго, а страусами.

Ну а в-третьих, значительная часть шуток в «Алисе» построена на различной игре слов, каламбурах и пародиях на старые стихи и песни.

Беда лингвистов и переводчиков

Именно из-за своей «языковой» особенности «Алиса в стране чудес» быстро привлекла внимание лингвистов, филологов и прочих гуманитариев. В повествовании Кэрролл использовал старые и редкие слова, которые уже на тот момент не употребляли в речи. А заодно он придумывал новые — различить, где использовано действительно устаревшее понятие, а где выдумка автора, получается не сразу.

Кроме того, Кэрролл нередко прибегал к игре слов, причём зачастую шутки предназначались явно не для детей. Думая, что она скоро пролетит сквозь землю, Алиса пыталась вспомнить, как называют людей из Австралии: «Как их там зовут?.. Антипатии, кажется». Вряд ли маленькие читатели без пояснений поймут, что на самом деле имелись в виду «антиподы».

Во время «безумного чаепития» Шляпник загадывает Алисе загадку: «Чем ворон похож на письменный стол?» Этот вопрос чуть не стал камнем преткновения среди любителей языка и философии. Появились варианты «[Эдгар Алан] По писал о/на них обоих», «У обоих есть перья, смоченные в чернилах». А Олдос Хаксли даже предложил на безумный вопрос ещё более безумный ответ: because there’s a ‘b’ in both, and because there’s an ‘n’ in neither (вряд ли это можно понятно перевести на русский).

Сам же Кэрролл впоследствии признался, что он специально сочинил загадку без ответа и даже не собирался её как-то объяснять. Но после шквала вопросов писатель всё-таки придумал свой вариант: «Because it can produce a few notes, tho they are very flat, and it is nevar put with the wrong end in front». Опять же, на русский это просто так перевести не получится. Условно, Кэрролл говорит, что и от стола, и от ворона можно получить несколько notes, которые будут flat. Это словосочетание можно перевести двояко: «записи» — в случае со столом, и «ноты» — в случае с вороном (а flat — это бемоль в переводе, то есть понижение ноты на полутон).

А уж переводчиков эта книга и вовсе ставила в тупик. Ведь им нужно было постараться передать и содержание, и юмор, и игру слов. Зачастую это было совсем непросто. В первой же сцене есть самый простой пример. Падая, Алиса от скуки задумывается: «Do cats eat bats?» — то есть: «Едят ли кошки летучих мышей?» А потом, засыпая, произносит: «Do bats eat cats?»

Это один из самых простых примеров игры слов от Кэрролла, но с ним уже возникают трудности при переводе. В результате автор наиболее популярной русской версии, Нина Демурова (в данной статье приведены примеры из её перевода), предложила вариант: «Едят ли мошки кошек?» — поскольку «летучие мыши» уже разрушают лёгкость речи. Автор ещё одного известного перевода — Борис Заходер — в предисловии к своей версии даже писал, что долгое время планировал издать книгу «К вопросу о причинах непереводимости на русский язык сказки Льюиса Кэрролла».

Дальше всё становится только запутаннее. Например, почти вся глава «Повесть Черепахи Квази» построена только на игре слов. Причём таких, что на русском у них просто нет аналогов. Например, Черепаха произносит фразу: «The master was an old Turtle — we used to call him Tortoise», — то есть их учителем была морская черепаха, которую они называли сухопутной (в английском языке это два разных слова).

А на вопрос Алисы, почему они так поступали, Квази ответил: «We called him Tortoise because he taught us», — здесь используется созвучие слов. В итоге Демурова написала в переводе, что учителя звали Спрутиком, потому что он ходил с прутиком. А Заходер превратил его из черепахи в Удава, которого называли Питоном, потому что ученики были его «питонцами».

А уж различные «науки», о которых говорит Квази, каждый переводил на свой лад, ведь все они созвучны с реальными школьными предметами: «Reeling, Writhing […] and then the different branches of Arithmetic — Ambition, Distraction, Uglification, and Derision». В переводе Демуровой это звучит как: «Чихали и Пищали […], а потом принялись за четыре действия Арифметики: Скольжение, Причитание, Умиление и Изнеможение».

Ещё сложнее обстояли дела со стихами и песенками. Кэрролл сочинял их не просто так: почти все они основаны на каких-то классических английских стихах. Видимо, автору было легче придумывать шутки, отталкиваясь от уже имеющейся структуры.

При этом Алиса, читая стихи, нередко путает их друг с другом, вставляя строчки из других произведений. В результате чего филологам приходилось разбирать, что же легло в основу того или иного отрывка. Переводчикам же это добавило новых проблем, ведь нужно сохранить и смысл, и размерность стиха. А иногда ещё и форму — в главе «Бег по кругу» появляются и «фигурные стихи» в форме мышиного хвоста.

При этом ни русские, ни английские дети даже не пытались анализировать построение языка или точность перевода. Их просто развлекали смешные слова и абсурдные ситуации. И уж тем более они не вдумывались в вероятный научный подтекст произведения.

Научная страна чудес

«Алиса» привлекла внимание не только лингвистов и филологов. Зная, что Кэрролл был ещё и математиком, и изобретателем, в книге ищут намёки на различные реальные и мысленные физические опыты, отсылки к космологии, истории и десяткам других наук.

Здесь можно вернуться всё к тому же падению Алисы под землю и её мыслям, что она пролетит планету насквозь. Эта тема нередко фигурировала в научной и фантастической литературе. Рассуждали даже о возможности создания тоннеля, по которому будет двигаться «гравитационный поезд» под действием одной только силы тяжести. Правда, чтобы это реализовать, придётся как-то исключить силу трения, сопротивление воздуха и силу Кориолиса. Кэрролл, кстати, и сам более серьёзно писал об этой теме в другой своей книге — «Сильвия и Бруно».

Хотя иногда учёные, будто соревнуясь друг с другом, пытаются придумывать всё более сложные трактовки слов Кэрролла даже там, где этого делать не стоит. Например, во время полёта Алиса хватает с полки пустую банку из-под апельсинового джема, но боится уронить её кому-нибудь на голову, а потом ставит на полку. Здесь одни увидели предсказание «Лифта Эйнштейна» — Кэрролл наверняка знал, что банка не может полететь вниз быстрее Алисы. Другие рассуждали о «двойном чуде», одно из которых произошло (Алиса на лету поставила банку на полку), а другое — нет (банка не полетела вниз).

Но если это кажется странным, то следует обратиться к книге Шана Лесли «Льюис Кэрролл и Оксфордское движение», где он пытается доказать, что апельсиновое варенье здесь выступает в роли символа протестантизма (оранжевые апельсины, по его мнению, связаны с Вильгельмом Оранским).

И точно так же простейшие ошибки Алисы, когда она вспоминает таблицу умножения, некоторые математики подводят под операции в восемнадцатеричной системе счисления.

Значит так: четырежды пять — двенадцать, четырежды шесть — тринадцать, четырежды семь… Так я до двадцати никогда не дойду!

Алиса

Действительно, это укладывается в вычисления при основании 18. Но, быть может, девочка просто перепутала слова «двенадцать» и «двадцать» и вообще плохо знала, как перемножать числа. Книга, всё-таки, детская.

В книге находят и намёки на расширение и сужение вселенной в сценах, где Алиса начинает есть и пить всё подряд, из-за чего то растёт, то уменьшается. Бег животных по кругу (с целью просохнуть после вынужденного купания) связывают с теорией эволюции.

А когда дело доходит до «безумного чаепития», учёные вспоминают об остановившихся часах Шляпника. Астрофизик Эддингтон увидел в этом намёк на модель той части космоса, где время остановилось. Именно поэтому герои остались ровно во времени чаепития, и бесконечно повторяют одни и те же действия, а мышка Соня никак не может проснуться.

Реальные герои сказки

Обо всех этих темах учёные могут спорить бесконечно. А вот о чём можно говорить с уверенностью, так это о реальных прообразах многих персонажей — и речь здесь не только об Алисе. Хотя, несмотря на перемену во внешности, автор явно намекает на юную Лидделл: действие происходит 7 мая — ровно в её день рождения, а Дина, о которой девочка вспоминает — её кошка.

Второстепенные герои и даже ситуации в «Алисе» явно списаны с реальности. Например, после того, как Алиса, увеличившись в размерах, наплакала целое море, вокруг неё собралось множество забавных животных. Это воспоминания о другой совместной прогулке Кэрролла и Лидделлов, когда они попали под дождь и сильно вымокли.

А необычные существа — участники этого похода. Робин Гусь — уже упомянутый друг автора Робинсон Дакворт (в оригинале он был просто the Duck, но переводчикам пришлось добавить имя для узнаваемости). Птица Додо — сам Кэрролл. Из-за заикания он иногда произносил свою фамилию «До-до-дожсон», что было поводом для шуток. Попугайчик Лори и орлёнок Эд — сестры Алисы Лорина и Эдит.

Не менее интересны и герои «безумного чаепития». Шляпник и Мартовский заяц скорее выступают ожившими поговорками «безумен, как шляпник» и, соответственно, «безумен, как мартовский заяц». Причём с происхождением второй всё ясно — в марте зайцы скачут по полям, как сумасшедшие. А вот насчёт первого историки так и не пришли к однозначному выводу. То ли фраза произошла от того, что шляпники травились парами ртути при работе с фетром. То ли просто с годами в поговорке «Безумен, как гадюка» слово adder (гадюка) сменилось на hatter (шляпник).

Хотя многие ещё вспоминают некоего торговца мебелью и очень эксцентричного человека Теофилиуса Картера, жившего неподалеку от Оксфорда. Его также прозвали «Безумным Шляпником» из-за привычки носить цилиндр и множества эксцентричных идей. Например, Картер придумал «кровать-будильник», которая сбрасывала спящего на пол в нужное время. Не оттого ли Шляпник в книге так хочет разбудить Соню?

Что же касается Сони, то, скорее всего, это намёк на ручного вомбата одного из друзей Кэрролла Данте Габриэля Росетти. Писатель часто бывал в гостях у этой семьи и периодически заставал животное спящим на столе. А традиция держать мышек-сонь в чайниках с сеном была вполне привычной для Англии тех времён.

А вот происхождение Чеширского Кота остаётся загадкой. Его имя и внешность явно произошли от поговорки «Улыбается как Чеширский кот». Но вот появление самой этой фразы неясно. Есть версии, что в графстве Чешир, где родился Кэрролл, на сырных головах вырезали морды улыбающихся котов. Также есть легенда о художнике, который рисовал подобных котов на тавернах. Получается, что здесь автор от реальных героев снова переходит к фольклору.

Критика сна

Странное смешение сказки, личных воспоминаний и сложных каламбуров Кэрролл объяснил в книге самым простым образом: на самом деле, всё происходящее — сон девочки, задремавшей в саду. Разумеется, это сразу исключает любые претензии к логике повествования. Причём в самом финале автор ещё больше усложняет действие: сестра Алисы начинает видеть её сон.

Как понятно из дневников Кэрролла, его очень интересовала тема реальности во сне. Он писал: «Сон имеет свой собственный мир, и зачастую он так же реалистичен, как и сама жизнь». Вероятно, это во многом связано и с его пристрастием к фантазиям и сказкам. Достаточно вспомнить, что Кэрролл любил придумывать новые правила к старым играм. Точно так же, создавая сказочные миры, он мог добавить в них свои правила, которые сильно отличаются от обычных. Нужно лишь принять их.

Но критики далеко не сразу оценили попытки Льюиса Кэрролла. Книгу стали считать кладезем мудрости лишь спустя десятилетия, а в первые годы отзывы о ней были в лучшем случае сдержанными. Автора хвалили лишь за владение языком, а вот сюжет называли «слишком запутанным» и «перегруженным». Парадоксально, но сказке, которая впоследствии станет эталоном абсурдного юмора, ставили в вину бессмысленность сюжета и отсутствие логики.

Однако Льюиса Кэрролла это не остановило: спустя шесть лет вышло продолжение под заголовком «Сквозь зеркало, и что там нашла Алиса» или, как чаще его называют, «Алиса в Зазеркалье».

Зеркала и шахматы

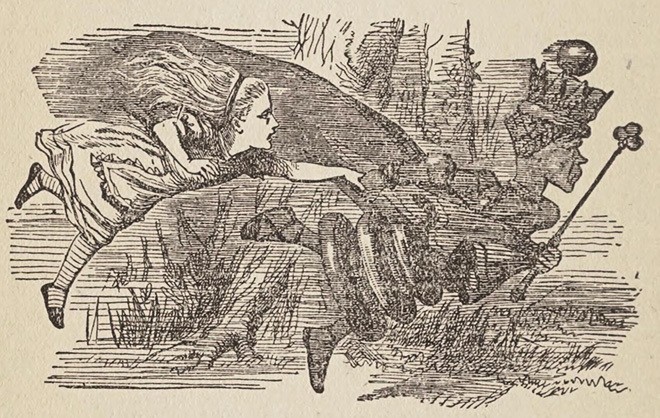

Придумывая вторую книгу, Кэрролл во многом использовал те же приёмы, но удивительным образом сумел не уйти в самоповторы. Здесь ему вновь помогли любимые занятия — в первую очередь, шахматы. Автор построил сюжет в виде шахматной партии, а оглавление книги сделал в виде описания ходов.

Правда шахматисты могут заметить, что многие ходы нелогичны, а их порядок порой нарушается. Но это снова придирки, ведь по сюжету всё та же Алиса сидит за шахматной доской со своим котёнком и засыпает. Вполне ожидаемо, что ребёнок может что-то перепутать.

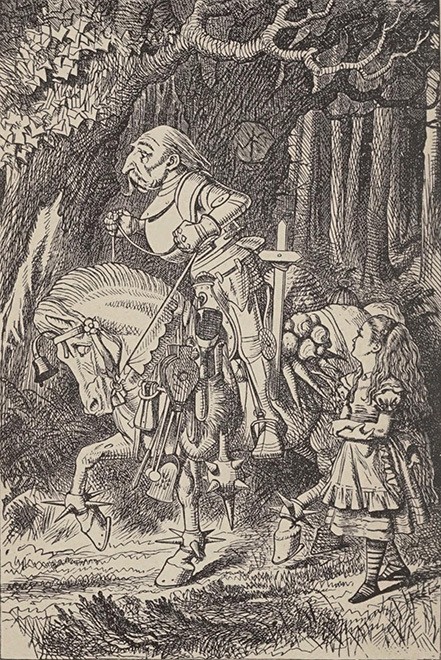

Главное, что сохранена основа. В первой книге героями были игральные карты, в продолжении же Кэрролл заменил их шахматными фигурами, а саму Алису сделал пешкой. При этом все они двигаются по доске строго по правилам шахмат, а главная героиня может разговаривать только с теми, кто находится на соседней с ней клетке. И логично, что она играет за белых — всё-таки этот цвет связан с добром и детской невинностью.

Тут есть интересная тонкость, которая не очень заметна русскому читателю. В оригинале принятые у нас чёрные фигуры были красными. И поэтому Король и Королева вполне коррелировали с главными злодеями из Страны чудес.

Сюжет снова очень прост: Алиса должна пройти до конца шахматного поля, чтобы из пешки превратиться в королеву. Белые фигуры ей помогают, чёрные — мешают. А заодно девочка общается со всякими причудливыми существами и слушает интересные истории.

Эта книга, как и «Страна чудес» получилась почти случайно: Кэролл учил Алису Лидделл и её сестёр шахматам, а для лучшего запоминания ходов придумывал различные шутки и сказки.

Но писатель увидел в шахматах не только возможность построения сюжета. Он взял за основу само изначальное расположение фигур напротив друг друга. И тогда ему пришла мысль о Зазеркалье — месте, где всё симметрично, но при этом наоборот. К этому можно прибавить распространённое мнение, что вторая книга посвящена не одной, а сразу двум девочкам. Кроме уже подросшей Алисы Лидделл музой Кэрролла называли его дальнюю родственницу Алису Рейкс.

— Сначала скажи мне, — проговорил он, подавая мне апельсин, — в какой руке ты его держишь.

— В правой, — ответила я.

— А теперь, — сказал он, — подойди к зеркалу и скажи мне, в какой руке держит апельсин девочка в зеркале.

Воспоминания Алисы Рейкс о Льюисе Кэрролле

Хотя вступительное стихотворение, где автор грустит о том, что героиня выросла и забыла его, всё же намекает на воспоминания о временах создания первой книги. Тем более, что в фантазии Кэрролла Алиса повзрослела всего лишь на полгода.

Симметрия и отражения

Симметрию и двойственность можно заметить ещё до начала самого сюжета. Новая книга кажется полной противоположностью «Алисе в стране чудес». В первой сказке действие начиналось в жаркий день на лугу, а теперь Алиса сидит дома, пока на улице холодно. С её дня рождения прошло ровно полгода — на дворе 5 ноября.

И снова учёные начинают выискивать в словах юной героини намёки на научные открытия. На сей раз речь идёт даже о химии. Ещё не пройдя сквозь зеркало, Алиса спрашивает: «Впрочем, не знаю, можно ли пить зазеркальное молоко?» Здесь усматривают предсказание скорого открытия асимметричного строения атомов. Так, например, молекулы декстрозы и фруктозы представляют собой зеркальные отражения. В этом случае, действительно, Кэрролл мог предполагать, что молоко из Зазеркалья несъедобно. Или же это просто был вопрос девочки, которая боится навредить котёнку.

Ну а после того, как Алиса оказывается в Зазеркалье, отражения и двойники попадаются ей повсеместно. Труляля и Траляля — «зеркальные» близнецы. Для рукопожатия один протягивает Алисе правую руку, а другой — левую. Белый рыцарь появляется сразу после Чёрного, а потом поёт песню о попытке засунуть левую ногу в правый ботинок. Морж и Плотник тоже появляются парой и ведут себя ровно противоположно друг другу.

Последние, кстати, стали ещё одной причиной философских споров. По сюжету, они безжалостно пожирают устриц. Морж их немного жалеет, но съедает больше. А Плотник и хотел бы съесть столько же, но не успел. И здесь возникает традиционная дилемма: что важнее, поступки или намерения? Но Кэрролл не даёт конкретного ответа, оставляя это философам.

«Зеркальность» касается не только героев, но и самого действия. Когда Алиса встречает Чёрную Королеву, им приходится бежать только для того, чтобы оставаться на месте. Белая Королева сначала кричит от боли, а потом уже протыкает палец заколкой. Труляля и Траляля сначала поют песню о своей драке, и только после дерутся. И ровно то же происходит с Шалтаем-Болтаем.

В мире Зазеркалья Кэрролл сумел придать абсурдному сюжету какое-то подобие логического обоснования. Конечно, история точно так же безумна, но в «Стране чудес» автор просто поддавался этой глупости, а здесь придумывает структуру, где всё происходит задом наперёд, а то и вообще хаотично.

Кстати, находили в этом произведении и намёки на квантовую физику. А именно в сцене, где Алиса заходит в лавку и никак не может рассмотреть ни одну вещь, потому что они все «текучие». Возможно, это намёк на невозможность определить положение электрона. Или же просто очередная мысль о хаотичности всего происходящего в мире.

Настоящие герои

В «Алисе в Зазеркалье» Кэрролл продолжил свои эксперименты с языком и пародиями. Он брал за основу стишков и песен старые мотивы, но на этот раз, возможно, добавлял к ним исторический и политический подтекст.

Так, споры между Труляля и Траляля (в оригинале Tweedledum and Tweedledee) отсылают к конфликту композиторов Генделя и Бонончини. Имена героев взяты из эпиграммы Байрона о композиторах, где он приходит к выводу, что не видит разницы между «Труляля и Траляля» — то есть их мелодиями.

Ну а в Морже и Плотнике некоторые видят аллюзию на две политические партии Великобритании. И эта же тема более ярко прослеживается в противостоянии Льва и Единорога — на гербе страны изображены именно эти животные. Хотя, возможно, автор просто ссылался на старинную детскую песенку об этих существах. Ведь точно так же из старой песни появился и Шалтай-Болтай.

Но не забывал Кэрролл и о личном. Среди героев проскакивают персонажи, явно списанные с реальных людей. Чёрная Королева здесь похожа на мисс Прикетт — гувернантку семьи Лидделлов, которую дети прозвали «Колючкой». По некоторым предположениям, она же была прообразом вечно недовольной мыши в «Стране чудес».

А Белый Рыцарь — конечно же, снова сам Кэрролл. У него добрые голубые глаза, взлохмаченные волосы. А ещё он постоянно что-то выдумывает и очень стесняется.

По сути, Рыцарь — единственный, кто действительно помог Алисе в её путешествии. И в его грусти, когда девочка превращается в Королеву, можно заметить аналогию с эмоциями Кэрролла в начале книги, где он печалится, что юная подруга выросла и забыла его.

В финале же книги автор очень трогательно прощается с героиней. Это можно заметить не сразу. Но первые буквы каждой строчки заключительного стихотворения складываются в «Алиса Плезенс Лидделл» — полное имя девочки.

Ненастоящий язык

Игры слов в «Алисе в Зазеркалье» ничуть не меньше, чем в «Стране чудес». Но в этой книге есть, можно сказать, апофеоз любви Кэрролла к шуткам над языком. Это, конечно же, знаменитое стихотворение Jabberwocky, получившее в самом популярном русском переводе название «Бармаглот». Всё дело в том, что первое четверостишие этого стихотворения полностью состоит из несуществующих слов, которые, при этом, подчиняются всем законам языка.

Варкалось. Хливкие шорьки

Пырялись по наве,

И хрюкотали зелюки,

Как мюмзики в мове.

Перевод Дины Орловской

На самом деле, «Бармаглот» появился ещё за десять лет до «Алисы в Стране чудес». Тогда Кэрролл назвал его «Англосаксонский стих», пародируя старую речь. Изначально это просто бессмысленный набор слов, о котором автор иронично писал: «Смысл этой древней Поэзии неясен, но всё же он глубоко трогает сердце». Позже в «Алисе в Зазеркалье» главная героиня практически повторит его слова.

Наводят на всякие мысли — хоть я и не знаю, на какие.

Алиса

Объяснение всех слов появилось у автора уже в 1863 году, когда друзья попросили его в очередной раз прочитать стихотворение, а потом рассказать о его значении. Как ни странно, он действительно сумел его чётко истолковать. Хотя, возможно, снова придумывал на ходу.

В книге устами Шалтая-Болтая Кэрролл рассказывает о смысле стихотворения, приводя в пример «слова-бумажники» — то есть, целые фразы, собранные в одно слово. Например, «хливкий» это одновременно, хлипкий и ловкий, а «хрюкотать» — хрюкать и хохотать. В оригинале, конечно всё звучит совсем иначе, но Дина Орловская, автор наиболее известной русской версии, попыталась передать именно значение и игру слов. Что у Кэрролла очень непросто.

Остальная же часть стихотворения была дописана специально для книги. И она уже состоит, по большей части, из обычных слов. Правда, и здесь можно узнать, как «в глуше рымит исполин — Злопастный Брандашмыг». Как выглядят эти животные, было ведомо одному лишь Кэрроллу.

Сон о снах

Конечно же, всё происходящее во второй книге — тоже сон. Но Кэрролл здесь сумел ещё больше усложнить структуру истории. В финале «Алисы в Стране чудес» сестра героини начинала видеть её сон. Здесь же Алиса ещё в середине действия встречает спящего Белого Короля, а все окружающие утверждают, что она ему снится.

Это во многом напоминает буддистскую притчу о монахе, который видит себя во сне бабочкой, которая, в свою очередь, видит себя во сне монахом. Только Кэрролл идёт ещё дальше, делая структуру не цикличной, а скорее спиральной. Ведь Алиса не считает себя Королём, а видит его. При этом она сама может оказаться «сном во сне». И так до бесконечности — словно бесконечный коридор отражающихся друг в друге зеркал.

Сказка для детей и взрослых

Споры вокруг истинного значения книг Кэрролла стали разгораться значительно позже. Тем более, что после Алисы автор написал «Охоту на Снарка», ещё больше наполненную аллюзиями и неоднозначностью. По словам Кэрролла, эта книга создана «с конца». Он придумал последнюю строчку: «Ибо Снарк был Буджумом, увы», — а потом дописал к ней остальные строфы. И это снова очень похоже на правила зазеркального мира.

В «Охоте на Снарка» некоторые исследователи находили даже намёки на ядерную бомбу как противовес мирному использованию атома. Но кто знает, может это не имело вовсе никакого смысла.

Хотя в пользу теорий учёных о скрытых значениях «Алисы» свидетельствует тот факт, что в 1890 году Кэрролл выпустил «детскую версию» своих книг. Вряд ли обычным сказкам нужны отдельные версии для детей. А значит, как минимум часть исследований была не напрасна.

На сегодняшний день об «Алисе в Стране чудес» и «Алисе в Зазеркалье» написаны десятки научных работ. Сюжет неоднократно пересказывали в детских и взрослых экранизациях. Кто-то по сей день пытается найти в сказках предсказания научных открытий.

Другие же уверены, что попытки изучать эти сказки слишком серьёзно лишь вредят произведениям. Возможно, так оно и есть.

Бедная, бедная Алиса! Мало того, что её поймали и заставили учить уроки; её еще заставляют поучать других. Алиса теперь не только школьница, но и классная наставница.

Г. К. Честертон, писатель

2 октября 2017Литература

Как читать «Алису в Стране чудес»

Какие люди, события и выражения угадываются в книгах об Алисе и кем был Льюис Кэрролл

Сказки про Алису — одни из самых известных книг, написанных на английском языке: по цитируемости они уступают только Библии и пьесам Шекспира. Время идет, эпоха, описанная Кэрроллом, все глубже уходит в прошлое, но интерес к «Алисе» не уменьшается, а, напротив, растет. Что же такое «Алиса в Стране чудес»? Сказка для детей, сборник логических парадоксов для взрослых, аллегория английской истории или богословских споров? Чем больше проходит времени, тем большим количеством самых невероятных интерпретаций обрастают эти тексты.

Кто такой Льюис Кэрролл

Писательская судьба Кэрролла — это история человека, попавшего в литературу по случайности. Чарльз Доджсон (а именно так на самом деле звали автора «Алисы») рос среди многочисленных сестер и братьев: он был третьим из 11 детей. Младших надо было уметь занять, а у Чарльза был прирожденный дар изобретать самые разнообразные игры. Сохранился сделанный им в 11-летнем возрасте кукольный театр, а в семейных бумагах можно найти рассказы, сказки и стихотворные пародии, сочиненные им в 12 и 13 лет. В юности Доджсон любил изобретать слова и словесные игры — спустя годы он будет вести еженедельную колонку, посвященную играм, в Vanity Fair. Слова galumph Согласно определению Оксфордского словаря английского языка, глагол to galumph ранее трактовался как «двигаться беспорядочными скачками», а в современном языке стал означать шумное и неуклюжее движение. и chortle To chortle — «громко и радостно смеяться»., придуманные им для стихотворения «Бармаглот», вошли в словари английского языка.

Доджсон был личностью парадоксальной и загадочной. С одной стороны, застенчивый, педантичный, страдающий заиканием преподаватель математики в оксфордском колледже Крайст-Чёрч и исследователь евклидовой геометрии и символической логики, чопорный джентльмен и священнослужитель Доджсон принял сан дьякона, но стать священником, как было положено членам колледжа, так и не решился.; с другой — человек, водивший компанию со всеми знаменитыми писателями, поэтами и художниками своего времени, автор романтических стихов, любитель театра и общества — в том числе детского. Он умел рассказывать детям истории; его многочисленные child-friends Кэрролловское определение детей, с которыми он дружил и переписывался. вспоминали, что он всегда готов был развернуть перед ними какой-нибудь сюжет, хранившийся в его памяти, снабдив его новыми деталями и изменив действие. То, что одна из этих историй (сказка-импровизация, рассказанная 4 июля 1862 года), в отличие от многих других, была записана, а потом отдана в печать, — удивительное стечение обстоятельств.

Дневник Льюиса Кэрролла

Автор «Алисы в Стране чудес» — о путешествии в Россию летом 1867 года

Как возникла сказка про Алису

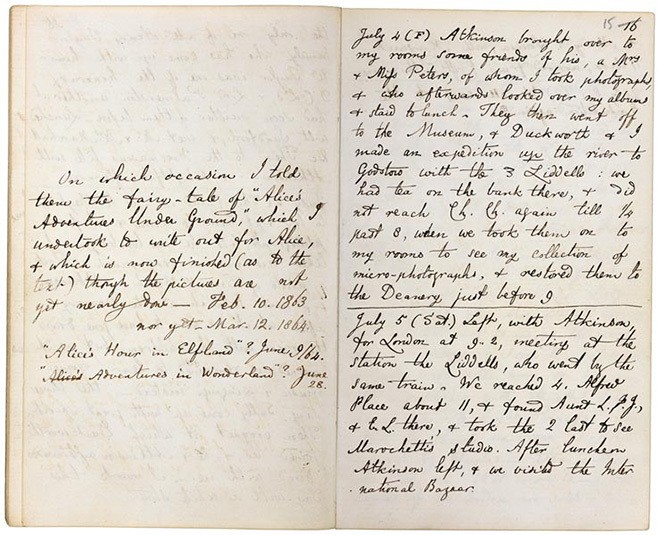

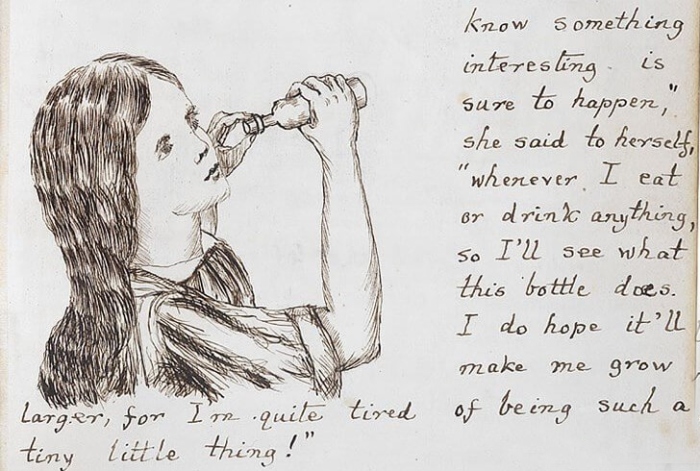

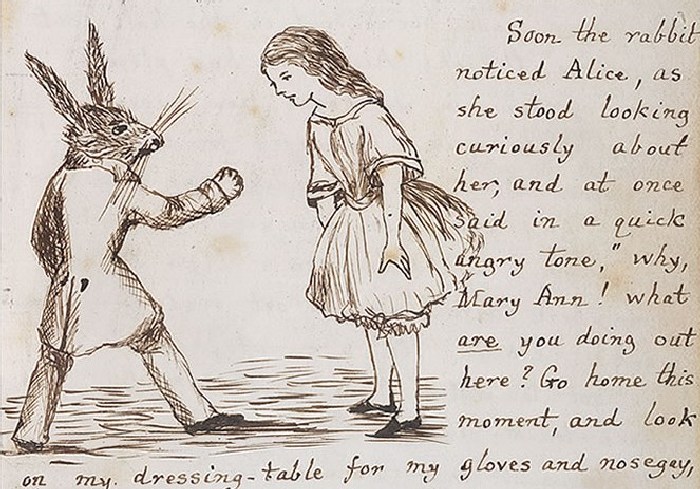

1 / 2

Алиса Лидделл. Фотография Льюиса Кэрролла. Лето 1858 годаNational Media Museum

2 / 2

Алиса Лидделл. Фотография Льюиса Кэрролла. Май-июнь 1860 годаThe Morgan Library & Museum

Летом 1862 года Чарльз Доджсон рассказал дочерям ректора Лидделла Генри Лидделл известен не только как отец Алисы: вместе с Робертом Скоттом он составил знаменитый словарь древнегреческого языка — так называемый «Лидделл — Скотт». Филологи-классики по всему миру пользуются им и сегодня. сказку-импровизацию. Девочки настойчиво просили ее записать. Зимой следующего года Доджсон закончил рукопись под названием «Приключения Алисы под землей» и подарил ее одной из сестер Лидделл, Алисе. Среди других читателей «Приключений» были дети писателя Джорджа Макдональда, с которым Доджсон познакомился, когда лечился от заикания. Макдональд убедил его задуматься о публикации, Доджсон серьезно переработал текст, и в декабре 1865 года Издательство датировало тираж 1866 годом. вышли «Приключения Алисы в Стране чудес», подписанные псевдонимом Льюис Кэрролл. «Алиса» неожиданно получила невероятный успех, и в 1867 году ее автор начал работу над продолжением. В декабре 1871 года вышла книга «Сквозь зеркало и что там увидела Алиса».

1 / 6

Страница рукописной книги Льюиса Кэрролла «Приключения Алисы под землей». 1862–1864 годыThe British Library

2 / 6

Страница рукописной книги Льюиса Кэрролла «Приключения Алисы под землей». 1862–1864 годыThe British Library

3 / 6

Страница рукописной книги Льюиса Кэрролла «Приключения Алисы под землей». 1862–1864 годыThe British Library

4 / 6

Страница рукописной книги Льюиса Кэрролла «Приключения Алисы под землей». 1862–1864 годыThe British Library

5 / 6

Страница рукописной книги Льюиса Кэрролла «Приключения Алисы под землей». 1862–1864 годыThe British Library

6 / 6

Страница рукописной книги Льюиса Кэрролла «Приключения Алисы под землей». 1862–1864 годыThe British Library

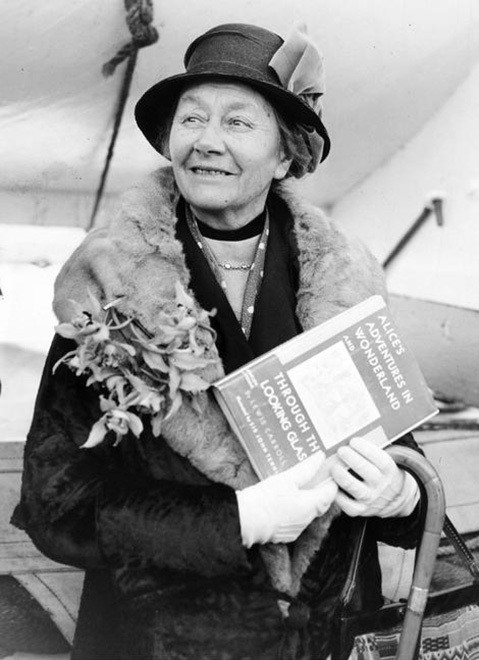

В 1928 году Алиса Харгривз, урожденная Лидделл, оказавшись после смерти мужа стесненной в средствах, выставила рукопись на аукционе Sotheby’s и продала ее за невероятные для того времени 15 400 фунтов. Через 20 лет рукопись снова попала на аукцион, где уже за 100 тысяч долларов ее по инициативе главы Библиотеки Конгресса США купила группа американских благотворителей, чтобы подарить Британскому музею — в знак благодарности британскому народу, который удерживал Гитлера, пока США готовились к войне. Позже рукопись была передана в Британскую библиотеку, на сайте которой ее теперь может полистать любой желающий.

На сегодняшний день вышло более ста английских изданий «Алисы», она переведена на 174 языка, на основе сказок созданы десятки экранизаций и тысячи театральных постановок.

Как выглядел рукописный оригинал «Алисы в Стране чудес»

Оригинал «Алисы», подаренный Льюисом Кэрроллом Алисе Лидделл, — из архива Британской библиотеки

Что такое «Алиса в Стране чудес»

1 / 5

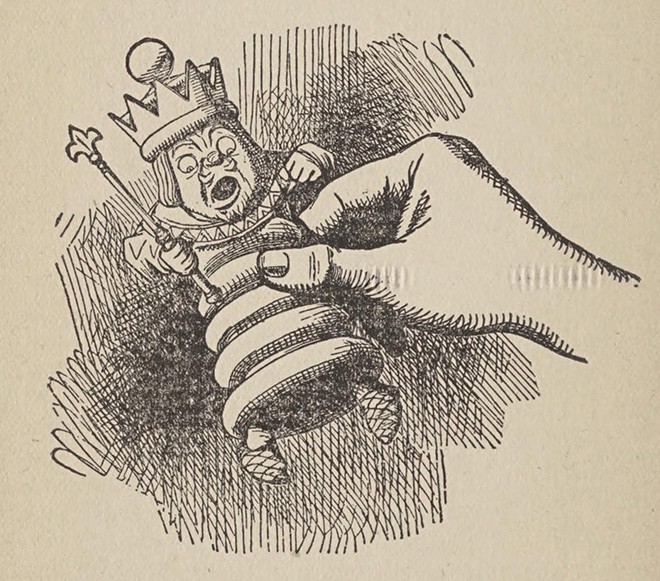

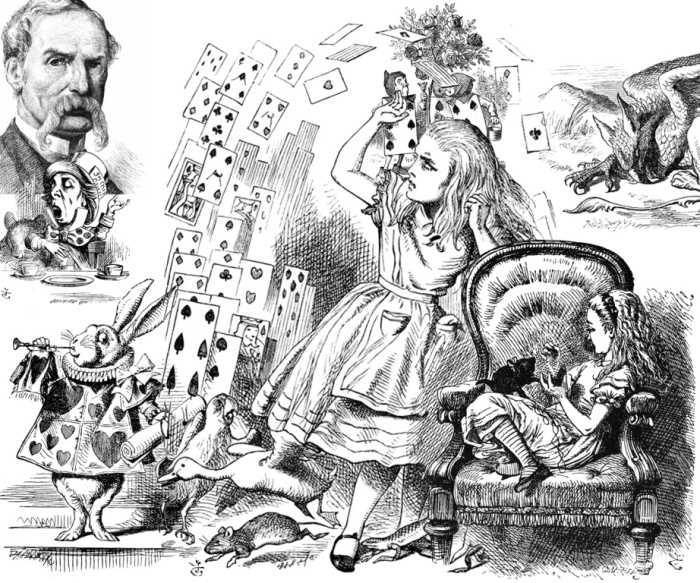

Иллюстрация Джона Тенниела к «Алисе в Стране чудес». Лондон, 1867 год Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

2 / 5

Иллюстрация Джона Тенниела к «Алисе в Стране чудес». Лондон, 1867 год Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

3 / 5

Иллюстрация Джона Тенниела к «Алисе в Зазеркалье». Чикаго, 1900 год Library of Congress

4 / 5

Льюис Кэрролл с семьей писателя Джорджа Макдональда. 1863 год George MacDonald Society

5 / 5

Иллюстрация Джона Тенниела к «Алисе в Стране чудес». Лондон, 1867 год Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

Чтобы верно понимать «Алису в Стране чудес», важно иметь в виду, что эта книга появилась на свет случайно. Автор двигался туда, куда его вела фантазия, ничего не желая этим сказать читателю и не подразумевая никаких разгадок. Возможно, именно поэтому текст стал идеальным полем для поиска смыслов. Вот далеко не полный список истолкований книг об Алисе, предложенных читателями и исследователями.

История Англии

Младенец-герцог, превращающийся в поросенка, — это Ричард III, на гербе которого был изображен белый кабан, а требование Королевы перекрасить белые розы в красный цвет, конечно же, отсылка к противостоянию Алой и Белой розы — Ланкастеров и Йорков. По другой версии, в книге изображен двор королевы Виктории: по легенде, королева сама написала «Алису», а потом попросила неизвестного оксфордского профессора подписать сказки своим именем.

История Оксфордского движения Оксфордское движение — движение за приближение англиканского богослужения и догматики к католической традиции, развивавшееся в Оксфорде в 1830–40-х годах.

Высокие и низкие двери, в которые пытается войти Алиса, меняющая рост, — это Высокая и Низкая церкви (тяготеющие, соответственно, к католической и протестантской традиции) и колеблющийся между этими течениями верующий. Кошка Дина и скотчтерьер, упоминания которых так боится Мышь (простой прихожанин), — это католичество и пресвитерианство, Белая и Черная королевы — кардиналы Ньюмен и Мэннинг, а Бармаглот — папство.

Шахматная задача

Чтобы ее решить, нужно использовать, в отличие от обычных задач, не только шахматную технику, но и «шахматную мораль», выводящую читателя на широкие морально-этические обобщения.

Энциклопедия психозов и сексуальности

В 1920–50-х годах стали особенно популярны психоаналитические толкования «Алисы», а дружбу Кэрролла с детьми стали пытаться представить как свидетельство его противоестественных наклонностей.

Энциклопедия употребления «веществ»

В 1960-х, на волне интереса к различным способам «расширения сознания», в сказках об Алисе, которая все время меняется, отпивая из склянок и откусывая от гриба, и ведет философские беседы с Гусеницей, курящей огромную трубку, стали видеть энциклопедию употребления «веществ». Манифест этой традиции — написанная в 1967 году песня «White Rabbit» группы Jefferson Airplane:

One pill makes you larger

And one pill makes you small

And the ones that mother gives you

Don’t do anything at all «Одна таблетка — и ты вырастаешь, // Другая — и ты уменьшаешься. // А от тех, что дает тебе мама, // Нет никакого толку»..

Откуда что взялось

Кэрролловская фантазия удивительна тем, что в «Стране чудес» и «Зазеркалье» нет ничего выдуманного. Метод Кэрролла напоминает аппликацию: элементы реальной жизни причудливо перемешаны между собой, поэтому в героях сказки ее первые слушатели легко угадывали себя, рассказчика, общих знакомых, привычные места и ситуации.

4 июля 1862 года

«Июльский полдень золотой» из стихотворного посвящения, предваряющего текст книги, — это вполне конкретная пятница, 4 июля 1862 года. По словам Уистена Хью Одена, день «столь же памятный в истории литературы, сколь в истории американского государства». Именно 4 июля Чарльз Доджсон, а также его друг, преподаватель Тринити-колледжа А позже — воспитатель принца Леопольда и каноник Вестминстерского аббатства. Робинсон Дакворт, и три дочери ректора — 13-летняя Лорина Шарлотта, 10-летняя Алиса Плезенс и Эдит Мэри восьми лет — отправились на лодочную прогулку по Айсису (так называется протекающая по Оксфорду Темза).

Строго говоря, это была уже вторая попытка отправиться на летнюю речную прогулку. Семнадцатого июня та же компания, а также две сестры и тетушка Доджсона сели в лодку, но вскоре пошел дождь, и гуляющим пришлось изменить свои планы Этот эпизод лег в основу глав «Море слез» и «Бег по кругу».. Но 4 июля погода была прекрасная, и компания устроила пикник в Годстоу, у развалин древнего аббатства. Именно там Доджсон рассказал девочкам Лидделл первую версию сказки про Алису. Это был экспромт: на недоуменные вопросы друга о том, где он услышал эту сказку, автор отвечал, что «сочиняет на ходу». Прогулки продолжались до середины августа, и девочки просили рассказывать дальше и дальше.

Алиса, Додо, Орленок Эд, Черная Королева и другие

Прототипом главной героини была средняя сестра, Алиса, любимица Доджсона. Лорина стала прототипом попугайчика Лори, а Эдит — Орленка Эда. Отсылка к сестрам Лидделл есть также в главе «Безумное чаепитие»: «кисельных барышень» из рассказа Сони зовут Элси, Лэси и Тилли. «Элси» — воспроизведение инициалов Лорины Шарлотты (L. C., то есть Lorina Charlotte); «Тилли» — сокращение от Матильды, домашнего имени Эдит, а «Лэси» (Lacie) — анаграмма имени Алисы (Alice). Сам Доджсон — это Додо. Представляясь, он выговаривал свою фамилию с характерным заиканием: «До-до-доджсон». Дакворт был изображен в виде Селезня (Робин Гусь в переводе Нины Демуровой), а мисс Прикетт, гувернантка сестер Лидделл (они звали ее Колючкой — Pricks), стала прообразом Мыши и Черной Королевы.

Дверь, сад удивительной красоты и безумное чаепитие

1 / 5

Сад ректора. Фотография Льюиса Кэрролла. 1856–1857 годыHarry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

2 / 5

Калитка в саду ректора в наши дниФотография Николая Эппле

3 / 5

«Кошачье дерево» в саду ректора в наши дниФотография Николая Эппле

4 / 5

Вид на сад ректора из кабинета Доджсона в библиотеке в наши дниФотография Николая Эппле

5 / 5

Колодец Фридесвиды в наши дниФотография Николая Эппле

Заглядывая в дверцу, Алиса видит «сад удивительной красоты» — это дверь, ведущая из сада дома ректора в сад при соборе (детям было запрещено заходить в церковный сад, и они могли видеть его только через калитку). Здесь Доджсон и девочки играли в крокет, а на раскидистом дереве, растущем в саду, сидели кошки. Нынешние жильцы ректорского дома считают, что среди них был и Чеширский Кот.

Даже безумное чаепитие, для участников которого всегда шесть часов и время пить чай, имеет реальный прообраз: когда бы сестры Лидделл ни пришли к Доджсону, у него всегда был готов для них чай. «Патоковый колодец» из сказки, которую во время чаепития рассказывает Соня, превращается в «кисель», а живущие на дне сестрицы — в «кисельных барышень». Это целебный источник в местечке Бинзи, которое находилось по дороге из Оксфорда в Годстоу.

Первая версия «Алисы в Стране чудес» представляла собой именно собрание таких отсылок, тогда как нонсенсы и словесные игры всем известной «Алисы» появились лишь при переработке сказки для публикации.

Шахматы, говорящие цветы и Зазеркалье

В «Алисе в Зазеркалье» тоже содержится огромное количество отсылок к реальным людям и ситуациям. Доджсон любил играть с сестрами Лидделл в шахматы — отсюда шахматная основа сказки. Снежинкой звали котенка Мэри Макдональд, дочери Джорджа Макдональда, а в образе белой пешки Доджсон вывел его старшую дочь Лили. Роза и фиалка из главы «Сад, где цветы говорили» — младшие сестры Лидделл Рода и Вайолет Violet (англ.) — фиалка.. Сам сад и последующий бег на месте были, очевидно, навеяны прогулкой автора с Алисой и мисс Прикетт 4 апреля 1863 года. Кэрролл приехал навестить детей, гостивших у бабушки с дедушкой в Чарлтон-Кингс (в их доме находилось то самое зеркало, через которое проходит Алиса). Эпизод с путешествием на поезде (глава «Зазеркальные насекомые») — отзвук путешествия обратно в Оксфорд 16 апреля 1863 года. Возможно, именно во время этой поездки Доджсон придумал топографию Зазеркалья: железнодорожная линия между Глостером и Дидкотом пересекает шесть ручьев — это очень похоже на шесть ручейков-горизонталей, которые в «Зазеркалье» преодолевает Алиса-пешка, чтобы стать королевой.

Из чего состоит книга

Слова, пословицы, народные стихи и песни

Элементы реальности, из которых сконструирован ирреальный мир Страны чудес и Зазеркалья, не ограничиваются людьми, местами и ситуациями. В гораздо большей степени этот мир создан из элементов языка. Впрочем, эти пласты тесно переплетаются. Например, на роль прототипа Шляпника В переводе Демуровой — Болванщик. претендуют как минимум два реальных человека: оксфордский изобретатель и коммерсант Теофил Картер Считается, что Джон Тенниел, иллюстрировавший «Алису», специально приезжал в Оксфорд, чтобы делать с него наброски. и Роджер Крэб, шляпник, живший в XVII веке. Но в первую очередь своим происхождением этот персонаж обязан языку. Шляпник — это визуализация английской пословицы «Mad as a hatter» — «Безумен как шляпник». В Англии XIX века при производстве фетра, из которого делали шляпы, использовалась ртуть. Шляпники вдыхали ее пары, а симптомами ртутного отравления являются спутанная речь, потеря памяти, тики и искажение зрения.

Персонаж, созданный из языкового образа, — очень характерный прием для Кэрролла. Мартовский Заяц — тоже из поговорки: «Mad as a March hare» в переводе означает «Безумен как мартовский заяц»: в Англии считается, что зайцы в период размножения, то есть с февраля по сентябрь, сходят с ума.

Чеширский Кот появился из выражения «To grin like a Cheshire cat» «Ухмыляться как Чеширский Кот».. Происхождение этой фразы не вполне очевидно. Возможно, оно возникло потому, что в графстве Чешир было много молочных ферм и коты чувствовали себя там особенно вольготно, или потому, что на этих фермах изготавливали сыр в форме котов с улыбающимися мордами (причем есть их полагалось с хвоста, так что последнее, что от них оставалось, — это морда без туловища). Или потому, что местный художник рисовал над входами в пабы львов с разинутой пастью, но получались у него улыбающиеся коты. Реплика Алисы «Котам на королей смотреть не возбраняется» в ответ на недовольство Короля пристальным взглядом Чеширского Кота тоже отсылка к старой пословице «A cat may look at a king», означающей, что даже у стоящих в самом низу иерархической лестницы есть права.

Но лучше всего этот прием виден на примере Черепахи Квази, с которой Алиса встречается в девятой главе. В оригинале ее зовут Mock Turtle. И на недоуменный вопрос Алисы, что же она такое, Королева сообщает ей: «It’s the thing Mock Turtle Soup is made from» — то есть то, из чего делают «как бы черепаший суп». Mock turtle soup — имитация традиционного деликатесного супа из зеленой черепахи, готовившаяся из телятины Именно поэтому на иллюстрации Тенниела Mock Turtle — это существо с головой теленка, задними копытами и телячьим хвостом.. Такое создание персонажей из игры слов очень типично для Кэрролла В первоначальной редакции перевода Нины Демуровой Mock Turtle называется Под-Котиком, то есть существом, из шкуры которого изготавливаются шубы «под котика»..

Язык у Кэрролла управляет и развитием сюжета. Так, Бубновый Валет похищает крендели, за что его судят в 11-й и 12-й главах «Страны чудес». Это «драматизация» английской народной песенки «The Queen of Hearts, she made some tarts…» («Король Червей, пожелав кренделей…»). Из народных песен выросли также эпизоды о Шалтае-Болтае, Льве и Единороге.

Теннисон, Шекспир и английская народная поэзия

В книгах Кэрролла можно найти множество отсылок к литературным произведениям. Самое очевидное — это откровенные пародии, прежде всего переиначенные известные стихотворения, главным образом нравоучительные («Папа Вильям», «Малютка крокодил», «Еда вечерняя» и так далее). Пародии не ограничиваются стихами: Кэрролл иронически обыгрывает пассажи из учебников (в главе «Бег по кругу») и даже стихи поэтов, к которым относился с большим уважением (эпизод в начале главы «Сад, где цветы говорили» обыгрывает строки из поэмы Теннисона «Мод»). Сказки об Алисе настолько наполнены литературными реминисценциями, цитатами и полуцитатами, что одно их перечисление составляет увесистые тома. Среди цитируемых Кэрроллом авторов — Вергилий, Данте, Мильтон, Грей, Кольридж, Скотт, Китс, Диккенс, Макдональд и многие другие. Особенно часто в «Алисе» цитируется Шекспир: так, реплика «Голову ему (ей) долой», которую постоянно повторяет Королева, — прямая цитата из «Ричарда III».

Как логика и математика повлияли на «Алису»

Специальностью Чарльза Доджсона были евклидова геометрия, математический анализ и математическая логика. Кроме того, он увлекался фотографией, изобретением логических и математических игр и головоломок. Этот логик и математик становится одним из создателей литературы нонсенса, в которой абсурд представляет собой строгую систему.

Пример нонсенса — часы Шляпника, которые показывают не час, а число. Алисе это кажется странным — ведь в часах, не показывающих время, нет смысла. Но в них нет смысла в ее системе координат, тогда как в мире Шляпника, в котором всегда шесть часов и время пить чай, смысл часов именно в указании дня. Внутри каждого из миров логика не нарушена — она сбивается при их встрече. Точно так же идея смазывать часы сливочным маслом — не бред, а понятный сбой логики: и механизм, и хлеб полагается чем-то смазывать, главное — не перепутать, чем именно.

Инверсия — еще одна черта писательского метода Кэрролла. В изобретенном им графическом методе умножения множитель записывался задом наперед и над множимым. По воспоминаниям Доджсона, задом наперед была сочинена «Охота на Снарка»: сначала последняя строчка, потом последняя строфа, а потом все остальное. Изобретенная им игра «Дуплеты» состояла в перестановке местами букв в слове. Его псевдоним Lewis Carroll — тоже инверсия: сначала он перевел свое полное имя — Чарльз Латвидж — на латынь, получилось Carolus Ludovicus. А потом обратно на английский — имена при этом поменялись местами.

Инверсия в «Алисе» встречается на самых разных уровнях — от сюжетного (на суде над Валетом Королева требует сначала вынести приговор, а потом установить виновность подсудимого) до структурного (встречая Алису, Единорог говорит, что всегда считал детей сказочными существами). Принцип зеркального отражения, которому подчинена логика существования Зазеркалья, — тоже разновидность инверсии (и «отраженное» расположение фигур на шахматной доске делает шахматную игру идеальным продолжением темы игры карточной из первой книги). Чтобы утолить жажду, здесь нужно отведать сухого печенья; чтобы стоять на месте, нужно бежать; из пальца сначала идет кровь, а уже потом его колют булавкой.

Умные раскраски

Иллюстрация к «Алисе в Стране чудес», гравюра с единорогами, волна Хокусая и другие картины, которые можно разрисовать

Кто создал первые иллюстрации к «Алисе»

Одна из важнейших составляющих сказок об Алисе — иллюстрации, с которыми ее увидели первые читатели и которых нет в большинстве переизданий. Речь об иллюстрациях Джона Тенниела (1820–1914), которые важны не меньше реальных прообразов героев и ситуаций, описанных в книге.

Сначала Кэрролл собирался опубликовать книгу с собственными иллюстрациями и даже перенес некоторые из рисунков на самшитовые дощечки, использовавшиеся типографами для изготовления гравюр. Но друзья из круга прерафаэлитов убедили его пригласить профессионального иллюстратора. Кэрролл остановил свой выбор на самом известном и востребованном: Тенниел тогда был главным иллюстратором влиятельного сатирического журнала «Панч» и одним из самых занятых художников.

Работа над иллюстрациями под дотошным и часто навязчивым контролем Кэрролла (70 % иллюстраций отталкиваются от авторских рисунков) надолго затормозила выпуск книги. Тенниел был недоволен качеством тиража, поэтому Кэрролл потребовал у издателей изъять его из продажи Интересно, что сейчас именно он дороже всего ценится у коллекционеров. и напечатать новый. И все же, готовясь к публикации «Алисы в Зазеркалье», Кэрролл вновь пригласил Тенниела. Сначала тот наотрез отказался (работа с Кэрроллом требовала слишком много сил и времени), но автор был настойчив и в конце концов уговорил художника взяться за работу.

Иллюстрации Тенниела — не дополнение к тексту, но его полноправный партнер, и именно поэтому Кэрролл так требовательно к ним относился. Даже на уровне сюжета многое можно понять только благодаря иллюстрациям — например, что Королевский Гонец из пятой и седьмой глав «Зазеркалья» — это Шляпник из «Страны чудес». Некоторые оксфордские реалии стали связываться с «Алисой» из-за того, что послужили прообразами не для Кэрролла, а для Тенниела: например, на рисунке из главы «Вода и вязание» изображен «овечий» магазин на Сент-Олдейтc, 83. Сегодня это магазин сувениров, посвященный книгам Льюиса Кэрролла.

Где мораль

Одна из причин успеха «Алисы» — отсутствие привычной для детских книжек того времени нравоучительности. Назидательные детские истории были мейнстримом тогдашней детской литературы (их публиковали в огромных количествах в изданиях вроде «Журнал тетушки Джуди»). Сказки про Алису выбиваются из этого ряда: их героиня ведет себя естественно, как живой ребенок, а не образец добродетели. Она путается в датах и словах, плохо помнит хрестоматийные стихи и исторические примеры. Да и сам пародийный подход Кэрролла, делающий хрестоматийные стихотворения предметом легкомысленной игры, не слишком способствует морализаторству. Более того, морализаторство и назидательность в «Алисе» — прямой объект насмешек: достаточно вспомнить абсурдные замечания Герцогини («А мораль отсюда такова…») и кровожадность Черной Королевы, образ которой сам Кэрролл называл «квинтэссенцией всех гувернанток». Успех «Алисы» показал, что именно такой детской литературы больше всего не хватало как детям, так и взрослым.

Дальнейшая литературная судьба Кэрролла подтвердила уникальность «Алисы» как результата невероятного стечения обстоятельств. Мало кто знает, что, помимо «Алисы в Стране чудес», он написал «Сильвию и Бруно» — назидательный роман о волшебной стране, сознательно (но совершенно безрезультатно) разрабатывающий темы, присутствующие в «Алисе». В общей сложности Кэрролл работал над этим романом 20 лет и считал его делом своей жизни.

Как переводить «Алису»

Главный герой «Приключений Алисы в Стране чудес» и «Алисы в Зазеркалье» — язык, что делает перевод этих книг невероятно сложным, а подчас невозможным. Вот только один из многочисленных примеров непереводимости «Алисы»: варенье, которое по «твердому правилу» Королевы горничная получает только «на завтра», в русском переводе не более чем очередной случай странной зазеркальной логики «Тебя я взяла бы [в горничные] с удовольствием, — откликнулась Королева. — Два

пенса в неделю и варенье на завтра!

Алиса рассмеялась.

— Нет, я в горничные не пойду, — сказала она. — К тому же варенье я не люблю!

— Варенье отличное, — настаивала Королева.

— Спасибо, но сегодня мне, право, не хочется!

— Сегодня ты бы его все равно не получила, даже если б очень захотела, — ответила Королева. — Правило у меня твердое: варенье на завтра! И только на завтра!

— Но ведь завтра когда-нибудь будет сегодня!

— Нет, никогда! Завтра никогда не бывает сегодня! Разве можно проснуться поутру и сказать: „Ну, вот, сейчас, наконец, завтра?“» (пер. Нины Демуровой).. Но в оригинале фраза «The rule is, jam to-morrow and jam yesterday — but never jam to-day» не просто странная. Как обычно это бывает у Кэрролла, у этой странности есть система, которая строится из элементов реальности. Слово jam, по-английски означающее «варенье», в латыни используется для передачи значения «сейчас», «теперь», но только в прошлом и будущем временах. В настоящем же времени для этого используется слово nunc. Вложенная Кэрроллом в уста Королевы фраза использовалась на уроках латыни в качестве мнемонического правила. Таким образом, «варенье на завтра» — не только зазеркальная странность, но и изящная языковая игра и еще один пример обыгрывания Кэрроллом школьной рутины.

«Алису в Стране чудес» невозможно перевести, но можно пересоздать на материале другого языка. Именно такие переводы Кэрролла оказываются удачными. Так произошло с русским переводом, сделанным Ниной Михайловной Демуровой. Подготовленное Демуровой издание «Алисы» в серии «Литературные памятники» (1979) — образец книгоиздания, соединяющий талант и глубочайшую компетентность редактора-переводчика с лучшими традициями советской академической науки. Помимо перевода, издание включает классический комментарий Мартина Гарднера из его «Аннотированной Алисы» (в свою очередь, откомментированный для русского читателя), статьи о Кэрролле Гилберта Честертона, Вирджинии Вулф, Уолтера де ла Мара и другие материалы — и, конечно, воспроизводит иллюстрации Тенниела.

Демурова не просто перевела Алису, а совершила чудо, сделав эту книгу достоянием русскоязычной культуры. Свидетельств тому довольно много; одно из самых красноречивых — сделанный Олегом Герасимовым на основе этого перевода музыкальный спектакль, который вышел на пластинках студии «Мелодия» в 1976 году. Песни к спектаклю написал Владимир Высоцкий — и выход пластинок стал первой его официальной публикацией в СССР в качестве поэта и композитора. Спектакль оказался настолько живым, что слушатели находили в нем политические подтексты («Много неясного в странной стране», «Нет-нет, у народа не трудная роль: // Упасть на колени — какая проблема?»), а худсовет даже пытался запретить выход пластинок. Но пластинки все же вышли и переиздавались вплоть до 1990-х годов миллионными тиражами.

Читайте также материал Николая Эппле о том, как устроены «Хроники Нарнии»

микрорубрики

Ежедневные короткие материалы, которые мы выпускали последние три года

Архив

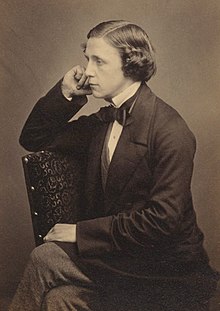

|

Lewis Carroll |

|

|---|---|

Carroll in June 1857 |

|

| Born | Charles Lutwidge Dodgson 27 January 1832 Daresbury, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 14 January 1898 (aged 65) Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Resting place | Mount Cemetery, Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Education |

|

| Genre |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass (1871). He was noted for his facility with word play, logic, and fantasy. His poems Jabberwocky (1871) and The Hunting of the Snark (1876) are classified in the genre of literary nonsense.

Carroll came from a family of high-church Anglicans, and developed a long relationship with Christ Church, Oxford, where he lived for most of his life as a scholar and teacher. Alice Liddell, the daughter of Christ Church’s dean Henry Liddell, is widely identified as the original inspiration for Alice in Wonderland, though Carroll always denied this.

An avid puzzler, Carroll created the word ladder puzzle (which he then called «Doublets»), which he published in his weekly column for Vanity Fair magazine between 1879 and 1881. In 1982 a memorial stone to Carroll was unveiled at Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works.[1][2]

Early life[edit]

Dodgson’s family was predominantly northern English, conservative, and high-church Anglican. Most of his male ancestors were army officers or Anglican clergymen. His great-grandfather, Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin in rural Ireland.[3] His paternal grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies.[4] The older of these sons, yet another Charles Dodgson, was Carroll’s father. He went to Westminster School and then to Christ Church, Oxford.[5] He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead, he married his first cousin Frances Jane Lutwidge in 1830 and became a country parson.[6][7]

Dodgson was born on 27 January 1832 at All Saints’ Vicarage in Daresbury, Cheshire,[8] the oldest boy and the third oldest of 11 children. When he was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees, Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next 25 years. Charles’ father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond[9] and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was high-church, inclining toward Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instil such views in his children. However, Charles developed an ambivalent relationship with his father’s values and with the Church of England as a whole.[10]

During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His «reading lists» preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven, he was reading books such as The Pilgrim’s Progress. He also spoke with a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings[11] – that often inhibited his social life throughout his years. At the age of twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School) in Richmond, North Yorkshire.

Lewis Carroll self-portrait c. 1856, aged 24 at that time

In 1846 Dodgson entered Rugby School, where he was evidently unhappy, as he wrote some years after leaving: «I cannot say … that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again … I can honestly say that if I could have been … secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear.»[12] He did not claim he suffered from bullying, but cited little boys as the main targets of older bullies at Rugby.[13] Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, Dodgson’s nephew, wrote that «even though it is hard for those who have only known him as the gentle and retiring don to believe it, it is nevertheless true that long after he left school, his name was remembered as that of a boy who knew well how to use his fists in defence of a righteous cause», which is the protection of the smaller boys.[13]

Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. «I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby», observed mathematics master R. B. Mayor.[14] Francis Walkingame’s The Tutor’s Assistant; Being a Compendium of Arithmetic – the mathematics textbook that the young Dodgson used – still survives and it contained an inscription in Latin, which translates to: «This book belongs to Charles Lutwidge Dodgson: hands off!»[15] Some pages also included annotations such as the one found on p. 129, where he wrote «Not a fair question in decimals» next to a question.[16]

He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at the University of Oxford in May 1850 as a member of his father’s old college, Christ Church.[17] After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851.[18] He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of «inflammation of the brain» – perhaps meningitis or a stroke – at the age of 47.[18]

His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted, and achievement came easily to him. In 1852, he obtained first-class honours in Mathematics Moderations and was soon afterwards nominated to a Studentship by his father’s old friend Canon Edward Pusey.[19][20] In 1854, he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, standing first on the list, and thus graduated as Bachelor of Arts.[21][22] He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship exam through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study.[23][24] Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855,[25] which he continued to hold for the next 26 years.[26] Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson remained at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death, including that of Sub-Librarian of the Christ Church library, where his office was close to the Deanery, where Alice Liddell lived.[27]

Character and appearance[edit]

Health problems[edit]

The young adult Charles Dodgson was about 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, although this might be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of 17, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. In early childhood, he acquired a stammer, which he referred to as his «hesitation»; it remained throughout his life.[27]

The stammer has always been a significant part of the image of Dodgson. While one apocryphal story says that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, there is no evidence to support this idea.[28] Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer, while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people whom he met; it is said that he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many supposed facts often repeated for which no first-hand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as a dodo, but whether or not this reference was to his stammer is simply speculation.[27]

Dodgson’s stammer did trouble him, but it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. He lived in a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, and the young Dodgson was well equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He could reportedly sing at a passable level and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was also adept at mimicry and storytelling, and reputedly quite good at charades.[27]

[edit]

In the interim between his early published writings and the success of the Alice books, Dodgson began to move in the pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. Around 1863, he developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family. He would often take pictures of the family in the garden of the Rossetti’s house in Chelsea, London. He also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He knew fairy-tale author George MacDonald well – it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that persuaded him to submit the work for publication.[27][29]

Politics, religion, and philosophy[edit]

In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative. Martin Gardner labels Dodgson as a Tory who was «awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors».[30] William Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as «austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice’s landscape».[31] Dodgson was ordained a deacon in the Church of England on 22 December 1861. In The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, the editor states that «his Diary is full of such modest depreciations of himself and his work, interspersed with earnest prayers (too sacred and private to be reproduced here) that God would forgive him the past, and help him to perform His holy will in the future.»[32] When a friend asked him about his religious views, Dodgson wrote in response that he was a member of the Church of England, but «doubt[ed] if he was fully a ‘High Churchman'». He added:

I believe that when you and I come to lie down for the last time, if only we can keep firm hold of the great truths Christ taught us—our own utter worthlessness and His infinite worth; and that He has brought us back to our one Father, and made us His brethren, and so brethren to one another—we shall have all we need to guide us through the shadows. Most assuredly I accept to the full the doctrines you refer to—that Christ died to save us, that we have no other way of salvation open to us but through His death, and that it is by faith in Him, and through no merit of ours, that we are reconciled to God; and most assuredly I can cordially say, «I owe all to Him who loved me, and died on the Cross of Calvary.»

— Carroll (1897)[33]

Dodgson also expressed interest in other fields. He was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research, and one of his letters suggests that he accepted as real what was then called «thought reading».[34] Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article «What the Tortoise Said to Achilles», which appeared in one of the early volumes of Mind.[35] The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled «Practical Tortoise Raising».[36]

Artistic activities[edit]

One of Carroll’s own illustrations

Literature[edit]

From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines such as the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. «I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so someday,» he wrote in July 1855.[27] Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet plays for his siblings’ entertainment, of which one has survived: La Guida di Bragia.[37]

In March 1856, he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called «Solitude» appeared in The Train under the authorship of «Lewis Carroll». This pseudonym was a play on his real name: Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which comes the name Charles.[7] The transition went as follows:

«Charles Lutwidge» translated into Latin as «Carolus Ludovicus». This was then translated back into English as «Carroll Lewis» and then reversed to make «Lewis Carroll».[38] This pseudonym was chosen by editor Edmund Yates from a list of four submitted by Dodgson, the others being Edgar Cuthwellis, Edgar U. C. Westhill, and Louis Carroll.[39]

Alice books[edit]

«The chief difficulty Alice found at first was in managing her flamingo». Illustration by John Tenniel, 1865.

The Jabberwock, as illustrated by John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, including the poem «Jabberwocky».

In 1856, Dean Henry Liddell arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson’s life over the following years, and would greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell’s wife Lorina and their children, particularly the three sisters Lorina, Edith, and Alice Liddell. He was widely assumed for many years to have derived his own «Alice» from Alice Liddell; the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking-Glass spells out her name in full, and there are also many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been noted that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his «little heroine» was based on any real child,[40][41] and he frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway’s name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and it is not suggested that this means that any of the characters in the narrative are based on her.[41]

Information is scarce (Dodgson’s diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), but it seems clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children on rowing trips (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) accompanied by an adult friend[42] to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow.[43]

It was on one such expedition on 4 July 1862 that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and greatest commercial success. He told the story to Alice Liddell and she begged him to write it down, and Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground in November 1864.[43]

Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson’s incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles were rejected – Alice Among the Fairies and Alice’s Golden Hour – the work was finally published as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier.[29] The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. Annotated versions provide insights into many of the ideas and hidden meanings that are prevalent in these books.[44][45] Critical literature has often proposed Freudian interpretations of the book as «a descent into the dark world of the subconscious», as well as seeing it as a satire upon contemporary mathematical advances.[46][47]

The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson’s life in many ways.[48][49][50] The fame of his alter ego «Lewis Carroll» soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice in Wonderland so much that she commanded that he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants.[51][52] Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting «… It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred»;[52][53] and it is unlikely for other reasons. As T. B. Strong comments in a Times article, «It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify [the] author of Alice with the author of his mathematical works».[54][55] He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church.[29]

Late in 1871, he published the sequel Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives «1872» as the date of publication.[56]) Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects changes in Dodgson’s life. His father’s death in 1868 plunged him into a depression that lasted some years.[29]

The Hunting of the Snark[edit]