Пожалуй, никто не поспорит с утверждением, что самый известный на свете разбойник – это Робин Гуд. В нашем представлении этот герой сугубо положительный, он ярый сторонник бедных и обманутых, готовый всегда восстановить справедливость. При помощи своей ловкости, хитрости, изворотливости он множество раз избегал смерти, хотя поймать и отправить на виселицу его желали многие из числа богатых англичан. В этой статье рассказывается о том, кто написал «Робин Гуда» и почему писатели часто делают этого разбойника и его друзей главными персонажами в своих историях. Попробуем вместе найти на эти вопросы правильные ответы.

Робин Гуд. Книга. Автор

Пишущих о Робин Гуде — легион, ведь образ этого героя влечет к себе со страшной силой, как приключения манят авантюристов. Почему же эти труженики пера делают именно его героем своих романов? Ответ, видимо, можно дать такой: Робин Гуд – сложившийся, очень популярный персонаж, черты и характер его известны каждому, а значит, писателю упрощается работа и ему не нужно утруждать себя прорисовыванием образа. Это значительно облегчает процесс создания произведения. Необязательно также особо ломать голову, придумывая врагов и друзей главного героя. Первыми являются богачи, вторыми – бедняки.

Существовал ли он

Если задаваться вопросом о том, кто написал «Робин Гуда» нужно сначала понять, что это за герой, был ли он на самом деле. Английские историки давно занимаются проблемой идентификации Робина Гуда. Они поднимают документы, изучают фольклор, судебные записи тех далеких времен. Пока что работа в этом направлении не дала результата и человек, с которого был списан образ Робин Гуда, на данный момент все еще не обнаружен. Сегодня ученые сходятся уже в том, что Гуд – это все-таки литературная фигура, хоть и вобравшая в себя черты множества реальных людей – от преступников до праведников. Кстати сказать, Робин Гуд – образ достаточно расплывчатый и разносторонний, хотя основные определения и поведенческие мотивы героя почти всегда оставались прежними (благородство и помощь обездоленным, борьба с нечестными богачами и так далее), простолюдины и писатели все же меняли его в соответствии с эпохой, в которой они проживали. Робин Гуд века XX мало, чем схож с Робином Гудом века XIX, а уже тем более – века XVIII или XVII.

Первоисточник

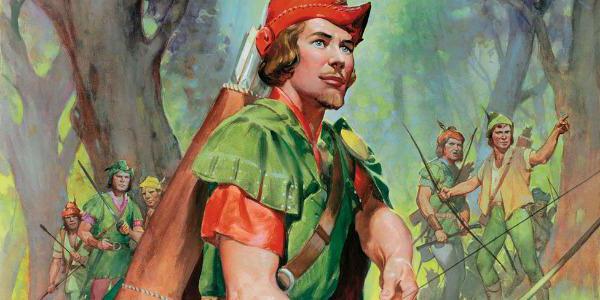

Если спросить англичанина о том, кто написал «Робин Гуда» он, скорее всего, ответит, что это Говард Пайл. Писатель выпустил книгу «The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood» в 1883 году. При работе над произведением он взял за основу легенды и баллады об этом благородном разбойнике и его команде сподвижников. Шервудский лес, который обозначен как обиталище разбойников во всех его историях о Робин Гуде, в представлении Пайла – это очаровательное и светлое место. Здесь Робин и его друзья чувствуют себя вольготно и раскрепощено, оттого и читатель ощущает себя также, открывая книгу и погружаясь в мир этого прославленного героя. Книга Пайла читается непросто, так как написана в несколько архаичной манере, но именно она является основой для создания новых произведений и фильмов о Робине Гуде.

Робин Гуд – книга, автор которой всегда менее известен, чем его герой. К примеру, Роджер Ланселин Грин, выпустивший в 1956 году книгу «Приключения Робин Гуда». Это детище – усовершенствованная версия произведения Пайла, здесь уже появляется любовная линия вместе с героиней Мэрион – избранницей нашего смелого героя.

Гуд не первый

Вообще, писателям сложно не соблазниться созданием своей собственной истории о разбойниках из Шервудского леса. И совсем не обязательно главным героем должен быть Робин, часто его задвигают на задний план, а вперед выбираются другие, хотя и знакомые лица. Майкла Кэднама, к примеру, нельзя причислить к тем авторам, кто написал «Робин Гуда», так как своим героем он сделал на «грозу богачей», а его верного помощника – Малютку Джона в книге «Forbidden Forest». В другом произведении этот же писатель вновь оставил не у дел Гуда, предложив посмотреть на мир глазами Джеффри, шерифа, ему противостоящего. Так что этого автора можно внести в список избранных, неординарных писателей — тех, кто написал книгу «Робин Гуд и шериф», в которой последний играет главную роль, а первый – герой второго плана. Видимо, писатель решил, что отношение читателей изменится к Робину, если посмотреть на него со стороны его главного противника, антипода. Не менее вальяжно с Робином поступают и представительницы прекрасного пола, которых также можно по праву включить в список тех, кто написал«Робин Гуда». Автор цикла книг «The Forestwife» Тереза Томлинсон, к примеру, выводит на первый план Мэрион. Если посмотреть на Робина Гуда с точки зрения этой писательницы, то приходит понимание того, что как герой он сформировался лишь благодаря положительному влиянию своей возлюбленной.

Гуд и мир фантастики

Некоторые из тех, кто написал «Робин Гуда», позволяют себе перебросить героя во времени. Вот у Парка Годвина в книге «Sherwood» Робин борется с шерифом в эпоху Вильгельма Рыжего. Есть и те, кому интересен не сам Робин, а его потомки. Писательница Нэнси Спрингер знакомит читателей с отважной девочкой — его дочерью(в книге «Роуэн Гуд»).

И в жанре фантастики не обошлось без участия Робина Гуда. В книге «The Sherwood Game», написанной Эстер Фризнер, программисту Карлу Фишнеру удалось как-то игру превратить в реальность, и его виртуальный Робин Гуд вдруг оживает.

Весьма плодотворно поработала над образом героя Джейн Йолен, создавшая цикл «Sherwood», состоящий из девяти книг. В одной из своих историй автор отправила дух Робина Гуда в паутину интернета, где тот с ловкостью паука начал прибирать к рукам мировые богатства.

Благороден ли Робин Гуд

Самый ранний по времени Робин Гуд не был замечен в передаче награбленных денег именно бедным. Этот герой забирал богатства у нечестивцев, но отдавал их не бедным, а тем, кто ему был близок и дорог. В первых легендах о Робине Гуде рассказывается, что он действовал почти всегда достаточно просто при грабеже: звал путника на трапезу, за которую требовал взамен оплату. И тому, кто принял предложение отужинать или отобедать приходилось выкладывать все, что было у него в карманах. Впрочем, осуждать Гуда не стоит — все-таки позже он исправился и преобразился в настоящего героя, самоотверженного, благородного, отдающего всего себя ради помощи беднякам. За это его и любим мы с вами, а потому всегда рады увидеть на телеэкранах или прочитать новые приключения Робина Гуда – разбойника с сердцем рыцаря. И неважно, кто написал книгу. Робин Гуда будут помнить всегда, а вот авторов произведений о нем?

| Robin Hood | |

|---|---|

| Tales of Robin Hood and his Merry Men character | |

Woodcut of Robin Hood, from a 17th-century broadside |

|

| First appearance | 13th/14th century AD |

| Created by | anonymous balladeers |

| Portrayed by |

|

| Voiced by |

|

| In-universe information | |

| Alias |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Affiliation | Loyal to Richard the Lionheart |

| Significant other | Maid Marian (wife in some versions) |

| Religion | Catholic (pre-Reformation) |

| Nationality | English |

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman.[1] In some versions of the legend, he is depicted as being of noble birth, and in modern retellings he is sometimes depicted as having fought in the Crusades before returning to England to find his lands taken by the Sheriff. In the oldest known versions, he is instead a member of the yeoman class. Traditionally depicted dressed in Lincoln green, he is said to have robbed from the rich and given to the poor.

Through retellings, additions, and variations, a body of familiar characters associated with Robin Hood has been created. These include his lover, Maid Marian; his band of outlaws, the Merry Men; and his chief opponent, the Sheriff of Nottingham. The Sheriff is often depicted as assisting Prince John in usurping the rightful but absent King Richard, to whom Robin Hood remains loyal. His partisanship of the common people and his hostility to the Sheriff of Nottingham are early recorded features of the legend, but his interest in the rightfulness of the king is not, and neither is his setting in the reign of Richard I. He became a popular folk figure in the Late Middle Ages. The earliest known ballads featuring him are from the 15th century.

There have been numerous variations and adaptations of the story over the subsequent years, and the story continues to be widely represented in literature, film, and television. Robin Hood is considered one of the best-known tales of English folklore. In popular culture, the term «Robin Hood» is often used to describe a heroic outlaw or rebel against tyranny.

The origins of the legend as well as the historical context have been debated for centuries. There are numerous references to historical figures with similar names that have been proposed as possible evidence of his existence, some dating back to the late 13th century. At least eight plausible origins to the story have been mooted by historians and folklorists, including suggestions that «Robin Hood» was a stock alias used by or in reference to bandits.

Ballads and tales

The first clear reference to «rhymes of Robin Hood» is from the alliterative poem Piers Plowman, thought to have been composed in the 1370s, followed shortly afterwards by a quotation of a later common proverb,[2] «many men speak of Robin Hood and never shot his bow»,[3] in Friar Daw’s Reply (c. 1402)[4] and a complaint in Dives and Pauper (1405–1410) that people would rather listen to «tales and songs of Robin Hood» than attend Mass.[5] Robin Hood is also mentioned in a famous Lollard tract[6] dated to the first half of the fifteenth century[7] (thus also possibly predating his other earliest historical mentions)[8] alongside several other folk heroes such as Guy of Warwick, Bevis of Hampton, and Sir Lybeaus.[9]

However, the earliest surviving copies of the narrative ballads that tell his story date to the second half of the 15th century, or the first decade of the 16th century. In these early accounts, Robin Hood’s partisanship of the lower classes, his devotion to the Virgin Mary and associated special regard for women, his outstanding skill as an archer, his anti-clericalism, and his particular animosity towards the Sheriff of Nottingham are already clear.[10] Little John, Much the Miller’s Son, and Will Scarlet (as Will «Scarlok» or «Scathelocke») all appear, although not yet Maid Marian or Friar Tuck. The latter has been part of the legend since at least the later 15th century, when he is mentioned in a Robin Hood play script.[11]

In modern popular culture, Robin Hood is typically seen as a contemporary and supporter of the late-12th-century king Richard the Lionheart, Robin being driven to outlawry during the misrule of Richard’s brother John while Richard was away at the Third Crusade. This view first gained currency in the 16th century.[12] It is not supported by the earliest ballads. The early compilation, A Gest of Robyn Hode, names the king as ‘Edward’; and while it does show Robin Hood accepting the King’s pardon, he later repudiates it and returns to the greenwood.[13][14] The oldest surviving ballad, Robin Hood and the Monk, gives even less support to the picture of Robin Hood as a partisan of the true king. The setting of the early ballads is usually attributed by scholars to either the 13th century or the 14th, although it is recognised they are not necessarily historically consistent.[15]

The early ballads are also quite clear on Robin Hood’s social status: he is a yeoman. While the precise meaning of this term changed over time, including free retainers of an aristocrat and small landholders, it always referred to commoners. The essence of it in the present context was «neither a knight nor a peasant or ‘husbonde’ but something in between».[16] Artisans (such as millers) were among those regarded as ‘yeomen’ in the 14th century.[17] From the 16th century on, there were attempts to elevate Robin Hood to the nobility, such as in Richard Grafton’s Chronicle at Large;[18] Anthony Munday presented him at the very end of the century as the Earl of Huntingdon in two extremely influential plays, as he is still commonly presented in modern times.[19]

As well as ballads, the legend was also transmitted by ‘Robin Hood games’ or plays that were an important part of the late medieval and early modern May Day festivities. The first record of a Robin Hood game was in 1426 in Exeter, but the reference does not indicate how old or widespread this custom was at the time. The Robin Hood games are known to have flourished in the later 15th and 16th centuries.[20] It is commonly stated as fact that Maid Marian and a jolly friar (at least partly identifiable with Friar Tuck) entered the legend through the May Games.[21]

Early ballads

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, woodcut print, Thomas Bewick, 1832

The earliest surviving text of a Robin Hood ballad is the 15th-century «Robin Hood and the Monk».[22] This is preserved in Cambridge University manuscript Ff.5.48. Written after 1450,[23] it contains many of the elements still associated with the legend, from the Nottingham setting to the bitter enmity between Robin and the local sheriff.

The first printed version is A Gest of Robyn Hode (c. 1500), a collection of separate stories that attempts to unite the episodes into a single continuous narrative.[24] After this comes «Robin Hood and the Potter»,[25] contained in a manuscript of c. 1503. «The Potter» is markedly different in tone from «The Monk»: whereas the earlier tale is «a thriller»[26] the latter is more comic, its plot involving trickery and cunning rather than straightforward force.

Other early texts are dramatic pieces, the earliest being the fragmentary Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham[27] (c. 1475). These are particularly noteworthy as they show Robin’s integration into May Day rituals towards the end of the Middle Ages; Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham, among other points of interest, contains the earliest reference to Friar Tuck.

The plots of neither «the Monk» nor «the Potter» are included in the Gest; and neither is the plot of «Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne», which is probably at least as old as those two ballads although preserved in a more recent copy. Each of these three ballads survived in a single copy, so it is unclear how much of the medieval legend has survived, and what has survived may not be typical of the medieval legend. It has been argued that the fact that the surviving ballads were preserved in written form in itself makes it unlikely they were typical; in particular, stories with an interest for the gentry were by this view more likely to be preserved.[28] The story of Robin’s aid to the ‘poor knight’ that takes up much of the Gest may be an example.

The character of Robin in these first texts is rougher edged than in his later incarnations. In «Robin Hood and the Monk», for example, he is shown as quick tempered and violent, assaulting Little John for defeating him in an archery contest; in the same ballad Much the Miller’s Son casually kills a ‘little page’ in the course of rescuing Robin Hood from prison.[29] No extant early ballad actually shows Robin Hood ‘giving to the poor’, although in «A Gest of Robyn Hode» Robin does make a large loan to an unfortunate knight, which he does not in the end require to be repaid;[30] and later in the same ballad Robin Hood states his intention of giving money to the next traveller to come down the road if he happens to be poor.

- Of my good he shall haue some,

- Yf he be a por man.[31]

As it happens the next traveller is not poor, but it seems in context that Robin Hood is stating a general policy. The first explicit statement to the effect that Robin Hood habitually robbed from the rich to give the poor can be found in John Stow’s Annales of England (1592), about a century after the publication of the Gest.[32][33] But from the beginning Robin Hood is on the side of the poor; the Gest quotes Robin Hood as instructing his men that when they rob:

- loke ye do no husbonde harme

- That tilleth with his ploughe.

- No more ye shall no gode yeman

- That walketh by gren-wode shawe;

- Ne no knyght ne no squyer

- That wol be a gode felawe.[13][14]

And in its final lines the Gest sums up:

- he was a good outlawe,

- And dyde pore men moch god.

Within Robin Hood’s band, medieval forms of courtesy rather than modern ideals of equality are generally in evidence. In the early ballad, Robin’s men usually kneel before him in strict obedience: in A Gest of Robyn Hode the king even observes that ‘His men are more at his byddynge/Then my men be at myn.‘ Their social status, as yeomen, is shown by their weapons: they use swords rather than quarterstaffs. The only character to use a quarterstaff in the early ballads is the potter, and Robin Hood does not take to a staff until the 17th-century Robin Hood and Little John.[34]

The political and social assumptions underlying the early Robin Hood ballads have long been controversial. J. C. Holt influentially argued that the Robin Hood legend was cultivated in the households of the gentry, and that it would be mistaken to see in him a figure of peasant revolt. He is not a peasant but a yeoman, and his tales make no mention of the complaints of the peasants, such as oppressive taxes.[35] He appears not so much as a revolt against societal standards as an embodiment of them, being generous, pious, and courteous, opposed to stingy, worldly, and churlish foes.[36] Other scholars have by contrast stressed the subversive aspects of the legend, and see in the medieval Robin Hood ballads a plebeian literature hostile to the feudal order.[37]

Early plays, May Day games, and fairs

By the early 15th century at the latest, Robin Hood had become associated with May Day celebrations, with revellers dressing as Robin or as members of his band for the festivities. This was not common throughout England, but in some regions the custom lasted until Elizabethan times, and during the reign of Henry VIII, was briefly popular at court.[38] Robin was often allocated the role of a May King, presiding over games and processions, but plays were also performed with the characters in the roles,[39] sometimes performed at church ales, a means by which churches raised funds.[40]

A complaint of 1492, brought to the Star Chamber, accuses men of acting riotously by coming to a fair as Robin Hood and his men; the accused defended themselves on the grounds that the practice was a long-standing custom to raise money for churches, and they had not acted riotously but peaceably.[41]

It is from the association with the May Games that Robin’s romantic attachment to Maid Marian (or Marion) apparently stems. A «Robin and Marion» figured in 13th-century French ‘pastourelles’ (of which Jeu de Robin et Marion c. 1280 is a literary version) and presided over the French May festivities, «this Robin and Marion tended to preside, in the intervals of the attempted seduction of the latter by a series of knights, over a variety of rustic pastimes».[42] In the Jeu de Robin and Marion, Robin and his companions have to rescue Marion from the clutches of a «lustful knight».[43] This play is distinct from the English legends.[38] although Dobson and Taylor regard it as ‘highly probable’ that this French Robin’s name and functions travelled to the English May Games where they fused with the Robin Hood legend.[44] Both Robin and Marian were certainly associated with May Day festivities in England (as was Friar Tuck), but these may have been originally two distinct types of performance – Alexander Barclay in his Ship of Fools, writing in c. 1500, refers to ‘some merry fytte of Maid Marian or else of Robin Hood‘ – but the characters were brought together.[45] Marian did not immediately gain the unquestioned role; in Robin Hood’s Birth, Breeding, Valor, and Marriage, his sweetheart is «Clorinda the Queen of the Shepherdesses».[46] Clorinda survives in some later stories as an alias of Marian.[47]

The earliest preserved script of a Robin Hood play is the fragmentary Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham[27] This apparently dates to the 1470s and circumstantial evidence suggests it was probably performed at the household of Sir John Paston. This fragment appears to tell the story of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne.[48] There is also an early playtext appended to a 1560 printed edition of the Gest. This includes a dramatic version of the story of Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar and a version of the first part of the story of Robin Hood and the Potter. (Neither of these ballads are known to have existed in print at the time, and there is no earlier record known of the «Curtal Friar» story). The publisher describes the text as a ‘playe of Robyn Hood, verye proper to be played in Maye games‘, but does not seem to be aware that the text actually contains two separate plays.[49] An especial point of interest in the «Friar» play is the appearance of a ribald woman who is unnamed but apparently to be identified with the bawdy Maid Marian of the May Games.[50] She does not appear in extant versions of the ballad.

Early modern stage

James VI of Scotland was entertained by a Robin Hood play at Dirleton Castle produced by his favourite the Earl of Arran in May 1585, while there was plague in Edinburgh.[51]

In 1598, Anthony Munday wrote a pair of plays on the Robin Hood legend, The Downfall and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington (published 1601). These plays drew on a variety of sources, including apparently «A Gest of Robin Hood», and were influential in fixing the story of Robin Hood to the period of Richard I. Stephen Thomas Knight has suggested that Munday drew heavily on Fulk Fitz Warin, a historical 12th century outlawed nobleman and enemy of King John, in creating his Robin Hood.[52] The play identifies Robin Hood as Robert, Earl of Huntingdon, following in Richard Grafton’s association of Robin Hood with the gentry,[18] and identifies Maid Marian with «one of the semi-mythical Matildas persecuted by King John».[53] The plays are complex in plot and form, the story of Robin Hood appearing as a play-within-a-play presented at the court of Henry VIII and written by the poet, priest and courtier John Skelton. Skelton himself is presented in the play as acting the part of Friar Tuck. Some scholars have conjectured that Skelton may have indeed written a lost Robin Hood play for Henry VIII’s court, and that this play may have been one of Munday’s sources.[54] Henry VIII himself with eleven of his nobles had impersonated «Robyn Hodes men» as part of his «Maying» in 1510. Robin Hood is known to have appeared in a number of other lost and extant Elizabethan plays. In 1599, the play George a Green, the Pinner of Wakefield places Robin Hood in the reign of Edward IV.[55] Edward I, a play by George Peele first performed in 1590–91, incorporates a Robin Hood game played by the characters. Llywelyn the Great, the last independent Prince of Wales, is presented playing Robin Hood.[56]

Fixing the Robin Hood story to the 1190s had been first proposed by John Major in his Historia Majoris Britanniæ (1521), (and he also may have been influenced in so doing by the story of Warin);[52] this was the period in which King Richard was absent from the country, fighting in the Third Crusade.[57]

William Shakespeare makes reference to Robin Hood in his late-16th-century play The Two Gentlemen of Verona. In it, the character Valentine is banished from Milan and driven out through the forest where he is approached by outlaws who, upon meeting him, desire him as their leader. They comment, «By the bare scalp of Robin Hood’s fat friar, This fellow were a king for our wild faction!»[58] Robin Hood is also mentioned in As You Like It. When asked about the exiled Duke Senior, the character of Charles says that he is «already in the forest of Arden, and a many merry men with him; and there they live like the old Robin Hood of England». Justice Silence sings a line from an unnamed Robin Hood ballad, the line is «Robin Hood, Scarlet, and John» in Act 5 scene 3 of Henry IV, part 2. In Henry IV part 1 Act 3 scene 3, Falstaff refers to Maid Marian implying she is a by-word for unwomanly or unchaste behaviour.

Ben Jonson produced the incomplete masque The Sad Shepherd, or a Tale of Robin Hood[59] in part as a satire on Puritanism. It is about half finished and his death in 1637 may have interrupted writing. Jonson’s only pastoral drama, it was written in sophisticated verse and included supernatural action and characters.[60] It has had little impact on the Robin Hood tradition but earns mention as the work of a major dramatist.

The 1642 London theatre closure by the Puritans interrupted the portrayal of Robin Hood on the stage. The theatres would reopen with the Restoration in 1660. Robin Hood did not appear on the Restoration stage, except for «Robin Hood and his Crew of Souldiers» acted in Nottingham on the day of the coronation of Charles II in 1661. This short play adapts the story of the king’s pardon of Robin Hood to refer to the Restoration.[61]

However, Robin Hood appeared on the 18th-century stage in various farces and comic operas.[62] Alfred, Lord Tennyson would write a four-act Robin Hood play at the end of the 19th century, «The Forrestors». It is fundamentally based on the Gest but follows the traditions of placing Robin Hood as the Earl of Huntingdon in the time of Richard I and making the Sheriff of Nottingham and Prince John rivals with Robin Hood for Maid Marian’s hand.[63] The return of King Richard brings a happy ending.

Broadside ballads and garlands

With the advent of printing came the Robin Hood broadside ballads. Exactly when they displaced the oral tradition of Robin Hood ballads is unknown but the process seems to have been completed by the end of the 16th century. Near the end of the 16th century an unpublished prose life of Robin Hood was written, and included in the Sloane Manuscript. Largely a paraphrase of the Gest, it also contains material revealing that the author was familiar with early versions of a number of the Robin Hood broadside ballads.[64] Not all of the medieval legend was preserved in the broadside ballads, there is no broadside version of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne or of Robin Hood and the Monk, which did not appear in print until the 18th and 19th centuries respectively. However, the Gest was reprinted from time to time throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

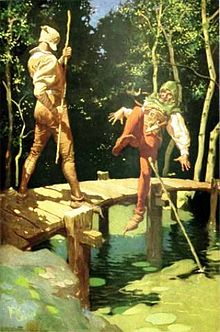

No surviving broadside ballad can be dated with certainty before the 17th century, but during that century, the commercial broadside ballad became the main vehicle for the popular Robin Hood legend.[65] These broadside ballads were in some cases newly fabricated but were mostly adaptations of the older verse narratives. The broadside ballads were fitted to a small repertoire of pre-existing tunes resulting in an increase of «stock formulaic phrases» making them «repetitive and verbose»,[66] they commonly feature Robin Hood’s contests with artisans: tinkers, tanners, and butchers. Among these ballads is Robin Hood and Little John telling the famous story of the quarter-staff fight between the two outlaws.

Dobson and Taylor wrote, ‘More generally the Robin of the broadsides is a much less tragic, less heroic and in the last resort less mature figure than his medieval predecessor’.[67] In most of the broadside ballads Robin Hood remains a plebeian figure, a notable exception being Martin Parker’s attempt at an overall life of Robin Hood, A True Tale of Robin Hood, which also emphasises the theme of Robin Hood’s generosity to the poor more than the broadsheet ballads do in general.

The 17th century introduced the minstrel Alan-a-Dale. He first appeared in a 17th-century broadside ballad, and unlike many of the characters thus associated, managed to adhere to the legend.[46] The prose life of Robin Hood in Sloane Manuscript contains the substance of the Alan-a-Dale ballad but tells the story about Will Scarlet.

In the 18th century, the stories began to develop a slightly more farcical vein. From this period there are a number of ballads in which Robin is severely ‘drubbed’ by a succession of tradesmen including a tanner, a tinker, and a ranger.[57] In fact, the only character who does not get the better of Hood is the luckless Sheriff. Yet even in these ballads Robin is more than a mere simpleton: on the contrary, he often acts with great shrewdness. The tinker, setting out to capture Robin, only manages to fight with him after he has been cheated out of his money and the arrest warrant he is carrying. In Robin Hood’s Golden Prize, Robin disguises himself as a friar and cheats two priests out of their cash. Even when Robin is defeated, he usually tricks his foe into letting him sound his horn, summoning the Merry Men to his aid. When his enemies do not fall for this ruse, he persuades them to drink with him instead (see Robin Hood’s Delight).

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Robin Hood ballads were mostly sold in «Garlands» of 16 to 24 Robin Hood ballads; these were crudely printed chap books aimed at the poor. The garlands added nothing to the substance of the legend but ensured that it continued after the decline of the single broadside ballad.[68] In the 18th century also, Robin Hood frequently appeared in criminal biographies and histories of highwaymen compendia.[69]

Rediscovery: Percy and Ritson

In 1765, Thomas Percy (bishop of Dromore) published Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, including ballads from the 17th-century Percy Folio manuscript which had not previously been printed, most notably Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne which is generally regarded as in substance a genuine late medieval ballad.

In 1795, Joseph Ritson published an enormously influential edition of the Robin Hood ballads Robin Hood: A collection of all the Ancient Poems Songs and Ballads now extant, relative to that celebrated Outlaw.[70][71] ‘By providing English poets and novelists with a convenient source book, Ritson gave them the opportunity to recreate Robin Hood in their own imagination,’[72] Ritson’s collection included the Gest and put the Robin Hood and the Potter ballad in print for the first time. The only significant omission was Robin Hood and the Monk which would eventually be printed in 1806. In all, Ritson printed 33 Robin Hood ballads [73] (and a 34th, now commonly known as Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon that he included as the second part of Robin Hood Newly Revived which he had retitled “Robin Hood and the Stranger”).[74] Ritson’s interpretation of Robin Hood was also influential, having influenced the modern concept of stealing from the rich and giving to the poor as it exists today.[75][76][77][78] Himself a supporter of the principles of the French Revolution and admirer of Thomas Paine, Ritson held that Robin Hood was a genuinely historical, and genuinely heroic, character who had stood up against tyranny in the interests of the common people.[72] J. C. Holt has been quick to point out, however, that Ritson «began as a Jacobite and ended as a Jacobin,» and «certainly reconstructed him [Robin] in the image of a radical.»[79]

In his preface to the collection, Ritson assembled an account of Robin Hood’s life from the various sources available to him, and concluded that Robin Hood was born in around 1160, and thus had been active in the reign of Richard I. He thought that Robin was of aristocratic extraction, with at least ‘some pretension’ to the title of Earl of Huntingdon, that he was born in an unlocated Nottinghamshire village of Locksley and that his original name was Robert Fitzooth. Ritson gave the date of Robin Hood’s death as 18 November 1247, when he would have been around 87 years old. In copious and informative notes Ritson defends every point of his version of Robin Hood’s life.[80] In reaching his conclusion Ritson relied or gave weight to a number of unreliable sources, such as the Robin Hood plays of Anthony Munday and the Sloane Manuscript. Nevertheless, Dobson and Taylor credit Ritson with having ‘an incalculable effect in promoting the still continuing quest for the man behind the myth’, and note that his work remains an ‘indispensable handbook to the outlaw legend even now’.[81]

Ritson’s friend Walter Scott used Ritson’s anthology collection as a source for his picture of Robin Hood in Ivanhoe, written in 1818, which did much to shape the modern legend.[82]

Child ballads

In the decades following the publication of Ritson’s book, other ballad collections would occasionally publish stray Robin Hood ballads Ritson had missed. In 1806, Robert Jamieson published the earliest known Robin Hood ballad, Robin Hood and the Monk in Volume II of his Popular Ballads and Songs From Tradition. In 1846, the Percy Society included The Bold Pedlar and Robin Hood in its collection, Ancient Poems, Ballads, and Songs of the Peasantry of England. In 1850, John Mathew Gutch published his own collection of Robin Hood ballads, Robin Hood Garlands and Ballads, with the tale of the lytell Geste, that in addition to all of Ritson’s collection, also included Robin Hood and the Pedlars and Robin Hood and the Scotchman.

In 1858, Francis James Child published his English and Scottish Ballads which included a volume grouping all the Robin Hood ballads in one volume, including all the ballads published by Ritson, the four stray ballads published since then, as well as some ballads that either mentioned Robin Hood by name or featured characters named Robin Hood but weren’t traditional Robin Hood stories. For his more scholarly work, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, in his volume dedicated to the Robin Hood ballads, published in 1888, Child removed the ballads from his earlier work that weren’t traditional Robin Hood stories, gave the ballad Ritson titled Robin Hood and the Stranger back its original published title Robin Hood Newly Revived, and separated what Ritson had printed as the second part of Robin Hood and the Stranger as its own separate ballad, Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon. He also included alternate versions of ballads that had distinct, alternate versions. He numbered these 38 Robin Hood ballads among the 305 ballads in his collection as Child Ballads Nos 117–154, which is how they’re often referenced in scholarly works.

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood

The title page of Howard Pyle’s 1883 novel, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood

In the 19th century, the Robin Hood legend was first specifically adapted for children. Children’s editions of the garlands were produced and in 1820, a children’s edition of Ritson’s Robin Hood collection was published. Children’s novels began to appear shortly thereafter. It is not that children did not read Robin Hood stories before, but this is the first appearance of a Robin Hood literature specifically aimed at them.[83] A very influential example of these children’s novels was Pierce Egan the Younger’s Robin Hood and Little John (1840).[84][85] This was adapted into French by Alexandre Dumas in Le Prince des Voleurs (1872) and Robin Hood Le Proscrit (1873). Egan made Robin Hood of noble birth but raised by the forestor Gilbert Hood.

Another very popular version for children was Howard Pyle’s The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, which influenced accounts of Robin Hood through the 20th century.[86] Pyle’s version firmly stamp Robin as a staunch philanthropist, a man who takes from the rich to give to the poor. Nevertheless, the adventures are still more local than national in scope: while King Richard’s participation in the Crusades is mentioned in passing, Robin takes no stand against Prince John, and plays no part in raising the ransom to free Richard. These developments are part of the 20th-century Robin Hood myth. Pyle’s Robin Hood is a yeoman and not an aristocrat.

The idea of Robin Hood as a high-minded Saxon fighting Norman lords also originates in the 19th century. The most notable contributions to this idea of Robin are Jacques Nicolas Augustin Thierry’s Histoire de la Conquête de l’Angleterre par les Normands (1825) and Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819). In this last work in particular, the modern Robin Hood—’King of Outlaws and prince of good fellows!’ as Richard the Lionheart calls him—makes his debut.[87]

Forresters Manuscript

In 1993, a previously unknown manuscript of 21 Robin Hood ballads (including 2 versions of The Jolly Pinder of Wakefield) turned up in an auction house and eventually wound up in the British Library. Called The Forresters Manuscript, after the first and last ballads, which are both titled Robin Hood and the Forresters, it was published in 1998 as Robin Hood: The Forresters Manuscript. It appears to have been written in the 1670s.[88] While all the ballads in the Manuscript had already been known and published during the 17th and 18th centuries (although most of the ballads in the Manuscript have different titles then ones they have listed under the Child Ballads), 13 of the ballads in Forresters are noticeably different from how they appeared in the broadsides and garlands. 9 of these ballads are significantly longer and more elaborate than the versions of the same ballads found in the broadsides and garlands. For 4 of these ballads, the Forresters Manuscript versions are the earliest known versions.

20th century onwards

The 20th century grafted still further details on to the original legends. The 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, portrayed Robin as a hero on a national scale, leading the oppressed Saxons in revolt against their Norman overlords while Richard the Lionheart fought in the Crusades; this movie established itself so definitively that many studios resorted to movies about his son (invented for that purpose) rather than compete with the image of this one.[89]

In 1953, during the McCarthy era, a Republican member of the Indiana Textbook Commission called for a ban of Robin Hood from all Indiana school books for promoting communism because he stole from the rich to give to the poor.[90]

Films, animations, new concepts, and other adaptations

Walt Disney’s Robin Hood

In the 1973 animated Disney film Robin Hood, the title character is portrayed as an anthropomorphic fox voiced by Brian Bedford. Years before Robin Hood had even entered production, Disney had considered doing a project on Reynard the Fox; however, due to concerns that Reynard was unsuitable as a hero, animator Ken Anderson adapted some elements from Reynard into Robin Hood, making the title character a fox.[91]

Robin and Marian

The 1976 British-American film Robin and Marian, starring Sean Connery as Robin Hood and Audrey Hepburn as Maid Marian, portrays the figures in later years after Robin has returned from service with Richard the Lionheart in a foreign crusade and Marian has gone into seclusion in a nunnery. This is the first in popular culture to portray King Richard as less than perfect.

Muslim Merry Men

Since the 1980s, it has become commonplace to include a Saracen (Arab/Muslim) among the Merry Men, a trend that began with the character Nasir in the 1984 ITV Robin of Sherwood television series. Later versions of the story have followed suit: a version of Nasir appears in the 1991 movie Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (Azeem) and the 2006 BBC TV series Robin Hood (Djaq).[89] Spoofs have also followed this trend, with the 1990s BBC sitcom Maid Marian and her Merry Men parodying the Moorish character with Barrington, a Rastafarian rapper played by Danny John-Jules,[92] and Mel Brooks comedy Robin Hood: Men in Tights featuring Isaac Hayes as Asneeze and Dave Chappelle as his son Ahchoo. The 2010 movie version Robin Hood, did not include a Saracen character. The 2018 adaptation Robin Hood portrays the character of Little John as a Muslim named Yahya, played by Jamie Foxx.

France

Between 1963 and 1966, French television broadcast a medievalist series entitled Thierry La Fronde (Thierry the Sling). This successful series, which was also shown in Canada, Poland (Thierry Śmiałek), Australia (The King’s Outlaw), and the Netherlands (Thierry de Slingeraar), transposes the English Robin Hood narrative into late medieval France during the Hundred Years’ War.[93]

The original ballads and plays, including the early medieval poems and the latter broadside ballads and garlands have been edited and translated for the very first time in French in 2017[94] by Jonathan Fruoco. Until then, the texts had been unavailable in France.

Historicity

The historicity of Robin Hood has been debated for centuries. A difficulty with any such historical research is that Robert was a very common given name in medieval England, and ‘Robin’ (or Robyn) was its very common diminutive, especially in the 13th century;[95] it is a French hypocorism,[96] already mentioned in the Roman de Renart in the 12th century. The surname Hood (by any spelling) was also fairly common because it referred either to a hooder, who was a maker of hoods, or alternatively to somebody who wore a hood as a head-covering. It is therefore unsurprising that medieval records mention a number of people called «Robert Hood» or «Robin Hood», some of whom are known criminals.

Another view on the origin of the name is expressed in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica which remarks that «hood» was a common dialectical form of «wood» (compare Dutch hout, pronounced /hʌut/, also meaning «wood»), and that the outlaw’s name has been given as «Robin Wood».[97] There are a number of references to Robin Hood as Robin Wood, or Whood, or Whod, from the 16th and 17th centuries. The earliest recorded example, in connection with May games in Somerset, dates from 1518.[98]

Early references

The oldest references to Robin Hood are not historical records, or even ballads recounting his exploits, but hints and allusions found in various works. From 1261 onward, the names «Robinhood», «Robehod», or «Robbehod» occur in the rolls of several English Justices as nicknames or descriptions of malefactors. The majority of these references date from the late 13th century. Between 1261 and 1300, there are at least eight references to «Rabunhod» in various regions across England, from Berkshire in the south to York in the north.[26]

Leaving aside the reference to the «rhymes» of Robin Hood in Piers Plowman in the 1370s,[99][100] and the scattered mentions of his «tales and songs» in various religious tracts dating to the early 15th century,[3][5][7] the first mention of a quasi-historical Robin Hood is given in Andrew of Wyntoun’s Orygynale Chronicle, written in about 1420. The following lines occur with little contextualisation under the year 1283:

- Lytil Jhon and Robyne Hude

- Wayth-men ware commendyd gude

- In Yngil-wode and Barnysdale

- Thai oysyd all this tyme thare trawale.[101]

In a petition presented to Parliament in 1439, the name is used to describe an itinerant felon. The petition cites one Piers Venables of Aston, Derbyshire,[a] «who having no liflode, ne sufficeante of goodes, gadered and assembled unto him many misdoers, beynge of his clothynge, and, in manere of insurrection, wente into the wodes in that countrie, like as it hadde be Robyn Hude and his meyne.»[102]

The next historical description of Robin Hood is a statement in the Scotichronicon, composed by John of Fordun between 1377 and 1384, and revised by Walter Bower in about 1440. Among Bower’s many interpolations is a passage that directly refers to Robin. It is inserted after Fordun’s account of the defeat of Simon de Montfort and the punishment of his adherents, and is entered under the year 1266 in Bower’s account. Robin is represented as a fighter for de Montfort’s cause.[103] This was in fact true of the historical outlaw of Sherwood Forest Roger Godberd, whose points of similarity to the Robin Hood of the ballads have often been noted.[104][105]

- Then arose the famous murderer, Robert Hood, as well as Little John, together with their accomplices from among the disinherited, whom the foolish populace are so inordinately fond of celebrating both in tragedies and comedies, and about whom they are delighted to hear the jesters and minstrels sing above all other ballads.[106]

The word translated here as ‘murderer’ is the Latin sicarius (literally ‘dagger-man’ but actually meaning, in classical Latin, ‘assassin’ or ‘murderer’), from the Latin sica for ‘dagger’, and descends from its use to describe the Sicarii, assassins operating in Roman Judea. Bower goes on to relate an anecdote about Robin Hood in which he refuses to flee from his enemies while hearing Mass in the greenwood, and then gains a surprise victory over them, apparently as a reward for his piety; the mention of «tragedies» suggests that some form of the tale relating his death, as per A Gest of Robyn Hode, might have been in currency already.[107]

Another reference, discovered by Julian Luxford in 2009, appears in the margin of the «Polychronicon» in the Eton College library. Written around the year 1460 by a monk in Latin, it says:

- Around this time [i.e., reign of Edward I], according to popular opinion, a certain outlaw named Robin Hood, with his accomplices, infested Sherwood and other law-abiding areas of England with continuous robberies.[108]

Following this, John Major mentions Robin Hood within his Historia Majoris Britanniæ (1521), casting him in a positive light by mentioning his and his followers’ aversion to bloodshed and ethos of only robbing the wealthy; Major also fixed his floruit not to the mid-13th century but the reigns of Richard I of England and his brother, King John.[52] Richard Grafton, in his Chronicle at Large (1569) went further when discussing Major’s description of «Robert Hood», identifying him for the first time as a member of the gentry, albeit possibly «being of a base stock and linaege, was for his manhood and chivalry advanced to the noble dignity of an Earl» and not the yeomanry, foreshadowing Anthony Munday’s casting of him as the dispossed Earl of Huntingdon.[18] The name nevertheless still had a reputation of sedition and treachery in 1605, when Guy Fawkes and his associates were branded «Robin Hoods» by Robert Cecil. In 1644, jurist Edward Coke described Robin Hood as a historical figure who had operated in the reign of King Richard I around Yorkshire; he interpreted the contemporary term «roberdsmen» (outlaws) as meaning followers of Robin Hood.[109]

Robert Hod of York

The earliest known legal records mentioning a person called Robin Hood (Robert Hod) are from 1226, found in the York Assizes, when that person’s goods, worth 32 shillings and 6 pence, were confiscated and he became an outlaw. Robert Hod owed the money to St Peter’s in York. The following year, he was called «Hobbehod», and also came to known as «Robert Hood». Robert Hod of York is the only early Robin Hood known to have been an outlaw. In 1936, L.V.D. Owen floated the idea that Robin Hood might be identified with an outlawed Robert Hood, or Hod, or Hobbehod, all apparently the same man, referred to in nine successive Yorkshire Pipe Rolls between 1226 and 1234.[110][111] There is no evidence however that this Robert Hood, although an outlaw, was also a bandit.[112]

Robert and John Deyville

Historian Oscar de Ville discusses the career of John Deyville and his brother Robert, along with their kinsmen Jocelin and Adam, during the Second Barons’ War, specifically their activities after the Battle of Evesham. John Deyville was granted authority by the faction led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester over York Castle and the Northern Forests during the war in which they sought refuge after Evesham. John, along with his relatives, led the remaining rebel faction on the Isle of Ely following the Dictum of Kenilworth.[113] De Ville connects their presence there with Bower’s mention of «Robert Hood» during the aftermath of Evesham in his annotations to the Scotichronicon.

While John was eventually pardoned and continued his career until 1290, his kinsmen are no longer mentioned by historical records after the events surrounding their resistance at Ely, and de Ville speculates that Robert remained an outlaw. Other points de Ville raises in support of John and his brothers’ exploits forming the inspiration for Robin Hood include their properties in Barnsdale, John’s settlement of a mortgage worth £400 paralleling Robin Hood’s charity of identical value to Sir Richard at the Lee, relationship with Sir Richard Foliot, a possible inspiration for the former figure, and ownership of a fortified home at Hood Hill, near Kilburn, North Yorkshire. The last of these is suggested to be the inspiration for Robin Hood’s second name as opposed to the more common theory of a head covering.[114] Perhaps not coincidentally, a «Robertus Hod» is mentioned in records among the holdouts at Ely.[115]

Although de Ville does not explicitly connect John and Robert Deyville to Robin Hood, he discusses these parallels in detail and suggests that they formed prototypes for this ideal of heroic outlawry during the tumultuous reign of Henry III’s grandson and Edward I’s son, Edward II of England.[116]

Roger Godberd

David Baldwin identifies Robin Hood with the historical outlaw Roger Godberd, who was a die-hard supporter of Simon de Montfort, which would place Robin Hood around the 1260s.[117][118] There are certainly parallels between Godberd’s career and that of Robin Hood as he appears in the Gest. John Maddicott has called Godberd «that prototype Robin Hood».[119] Some problems with this theory are that there is no evidence that Godberd was ever known as Robin Hood and no sign in the early Robin Hood ballads of the specific concerns of de Montfort’s revolt.[120]

Robin Hood of Wakefield

The antiquarian Joseph Hunter (1783–1861) believed that Robin Hood had inhabited the forests of Yorkshire during the early decades of the fourteenth century. Hunter pointed to two men whom, believing them to be the same person, he identified with the legendary outlaw:

- Robert Hood who is documented as having lived in the city of Wakefield at the start of the fourteenth century.

- «Robyn Hode» who is recorded as being employed by Edward II of England during 1323.

Hunter developed a fairly detailed theory implying that Robert Hood had been an adherent of the rebel Earl of Lancaster, who was defeated by Edward II at the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322. According to this theory, Robert Hood was thereafter pardoned and employed as a bodyguard by King Edward, and in consequence he appears in the 1323 court roll under the name of «Robyn Hode». Hunter’s theory has long been recognised to have serious problems, one of the most serious being that recent research has shown that Hunter’s Robyn Hood had been employed by the king before he appeared in the 1323 court roll, thus casting doubt on this Robyn Hood’s supposed earlier career as outlaw and rebel.[121]

Alias

It has long been suggested, notably by John Maddicott, that «Robin Hood» was a stock alias used by thieves.[122] What appears to be the first known example of «Robin Hood» as a stock name for an outlaw dates to 1262 in Berkshire, where the surname «Robehod» was applied to a man apparently because he had been outlawed.[123] This could suggest two main possibilities: either that an early form of the Robin Hood legend was already well established in the mid-13th century; or alternatively that the name «Robin Hood» preceded the outlaw hero that we know; so that the «Robin Hood» of legend was so called because that was seen as an appropriate name for an outlaw.

Mythology

There is at present little or no scholarly support for the view that tales of Robin Hood have stemmed from mythology or folklore, from fairies or other mythological origins, any such associations being regarded as later development.[124][125] It was once a popular view, however.[97] The «mythological theory» dates back at least to 1584, when Reginald Scot identified Robin Hood with the Germanic goblin «Hudgin» or Hodekin and associated him with Robin Goodfellow.[126] Maurice Keen[127] provides a brief summary and useful critique of the evidence for the view Robin Hood had mythological origins. While the outlaw often shows great skill in archery, swordplay and disguise, his feats are no more exaggerated than those of characters in other ballads, such as Kinmont Willie, which were based on historical events.[128]

Robin Hood has also been claimed for the pagan witch-cult supposed by Margaret Murray to have existed in medieval Europe, and his anti-clericalism and Marianism interpreted in this light.[129] The existence of the witch cult as proposed by Murray is now generally discredited.

Associated locations

Sherwood Forest

The early ballads link Robin Hood to identifiable real places. In popular culture, Robin Hood and his band of «merry men» are portrayed as living in Sherwood Forest, in Nottinghamshire.[130] Notably, the Lincoln Cathedral Manuscript, which is the first officially recorded Robin Hood song (dating from approximately 1420), makes an explicit reference to the outlaw that states that «Robyn hode in scherewode stod».[131] In a similar fashion, a monk of Witham Priory (1460) suggested that the archer had ‘infested shirwode’. His chronicle entry reads:

- ‘Around this time, according to popular opinion, a certain outlaw named Robin Hood, with his accomplices, infested Sherwood and other law-abiding areas of England with continuous robberies’.[132]

Nottinghamshire

Specific sites in the county of Nottinghamshire directly linked to the Robin Hood legend include Robin Hood’s Well, near Newstead Abbey (within the boundaries of Sherwood Forest), the Church of St. Mary in the village of Edwinstowe and most famously of all, the Major Oak also in the village of Edwinstowe.[133] The Major Oak, which resides in the heart of Sherwood Forest, is popularly believed to have been used by the Merry Men as a hide-out. Dendrologists have contradicted this claim by estimating the tree’s true age at around eight hundred years; it would have been relatively a sapling in Robin’s time, at best.[134]

Yorkshire

Nottinghamshire’s claim to Robin Hood’s heritage is disputed, with Yorkists staking a claim to the outlaw. In demonstrating Yorkshire’s Robin Hood heritage, the historian J. C. Holt drew attention to the fact that although Sherwood Forest is mentioned in Robin Hood and the Monk, there is little information about the topography of the region, and thus suggested that Robin Hood was drawn to Nottinghamshire through his interactions with the city’s sheriff.[135] Moreover, the linguist Lister Matheson has observed that the language of the Gest of Robyn Hode is written in a definite northern dialect, probably that of Yorkshire.[136] In consequence, it seems probable that the Robin Hood legend actually originates from the county of Yorkshire. Robin Hood’s Yorkshire origins are generally accepted by professional historians.[137]

Barnsdale

Blue Plaque commemorating Wentbridge’s Robin Hood connections

A tradition dating back at least to the end of the 16th century gives Robin Hood’s birthplace as Loxley, Sheffield, in South Yorkshire. The original Robin Hood ballads, which originate from the fifteenth century, set events in the medieval forest of Barnsdale. Barnsdale was a wooded area covering an expanse of no more than thirty square miles, ranging six miles from north to south, with the River Went at Wentbridge near Pontefract forming its northern boundary and the villages of Skelbrooke and Hampole forming the southernmost region. From east to west the forest extended about five miles, from Askern on the east to Badsworth in the west.[138] At the northernmost edge of the forest of Barnsdale, in the heart of the Went Valley, resides the village of Wentbridge. Wentbridge is a village in the City of Wakefield district of West Yorkshire, England. It lies around 3 miles (5 km) southeast of its nearest township of size, Pontefract, close to the A1 road. During the medieval age Wentbridge was sometimes locally referred to by the name of Barnsdale because it was the predominant settlement in the forest.[139] Wentbridge is mentioned in an early Robin Hood ballad, entitled, Robin Hood and the Potter, which reads, «Y mete hem bot at Went breg,’ syde Lyttyl John». And, while Wentbridge is not directly named in A Gest of Robyn Hode, the poem does appear to make a cryptic reference to the locality by depicting a poor knight explaining to Robin Hood that he ‘went at a bridge’ where there was wrestling’.[140] A commemorative Blue Plaque has been placed on the bridge that crosses the River Went by Wakefield City Council.

Saylis

The Gest makes a specific reference to the Saylis at Wentbridge. Credit is due to the nineteenth-century antiquarian Joseph Hunter, who correctly identified the site of the Saylis.[141] From this location it was once possible to look out over the Went Valley and observe the traffic that passed along the Great North Road. The Saylis is recorded as having contributed towards the aid that was granted to Edward III in 1346–47 for the knighting of the Black Prince. An acre of landholding is listed within a glebe terrier of 1688 relating to Kirk Smeaton, which later came to be called «Sailes Close».[142] Professor Dobson and Mr. Taylor indicate that such evidence of continuity makes it virtually certain that the Saylis that was so well known to Robin Hood is preserved today as «Sayles Plantation».[143] It is this location that provides a vital clue to Robin Hood’s Yorkshire heritage. One final locality in the forest of Barnsdale that is associated with Robin Hood is the village of Campsall.

Church of Saint Mary Magdalene at Campsall

The historian John Paul Davis wrote of Robin’s connection to the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene at Campsall in South Yorkshire.[144] A Gest of Robyn Hode states that the outlaw built a chapel in Barnsdale that he dedicated to Mary Magdalene:

- I made a chapel in Bernysdale,

- That seemly is to se,

- It is of Mary Magdaleyne,

- And thereto wolde I be.[145]

Davis indicates that there is only one church dedicated to Mary Magdalene within what one might reasonably consider to have been the medieval forest of Barnsdale, and that is the church at Campsall. The church was built in the early twelfth century by Robert de Lacy, the 2nd Baron of Pontefract.[146][147] Local legend suggests that Robin Hood and Maid Marion were married at the church.

Abbey of Saint Mary at York

The backdrop of St Mary’s Abbey, York plays a central role in the Gest as the poor knight whom Robin aids owes money to the abbot.

Grave at Kirklees

At Kirklees Priory in West Yorkshire stands an alleged grave with a spurious inscription, which relates to Robin Hood. The fifteenth-century ballads relate that before he died, Robin told Little John where to bury him. He shot an arrow from the Priory window, and where the arrow landed was to be the site of his grave. The Gest states that the Prioress was a relative of Robin’s. Robin was ill and staying at the Priory where the Prioress was supposedly caring for him. However, she betrayed him, his health worsened, and he eventually died there. The inscription on the grave reads,

- Hear underneath dis laitl stean

- Laz robert earl of Huntingtun

- Ne’er arcir ver as hie sa geud

- An pipl kauld im robin heud

- Sick [such] utlawz as he an iz men

- Vil england nivr si agen

- Obiit 24 kal: Dekembris, 1247

Despite the unconventional spelling, the verse is in Modern English, not the Middle English of the 13th century. The date is also incorrectly formatted – using the Roman calendar, «24 kal Decembris» would be the twenty-third day before the beginning of December, that is, 8 November. The tomb probably dates from the late eighteenth century.[148]

The grave with the inscription is within sight of the ruins of the Kirklees Priory, behind the Three Nuns pub in Mirfield, West Yorkshire. Though local folklore suggests that Robin is buried in the grounds of Kirklees Priory, this theory has now largely been abandoned by professional historians.

All Saints’ Church at Pontefract

Another theory is that Robin Hood died at Kirkby, Pontefract. Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion Song 28 (67–70), published in 1622, speaks of Robin Hood’s death and clearly states that the outlaw died at ‘Kirkby’.[149] This is consistent with the view that Robin Hood operated in the Went Valley, located three miles to the southeast of the town of Pontefract. The location is approximately three miles from the site of Robin’s robberies at the now famous Saylis. In the Anglo-Saxon period, Kirkby was home to All Saints’ Church, Pontefract. All Saints’ Church had a priory hospital attached to it. The Tudor historian Richard Grafton stated that the prioress who murdered Robin Hood buried the outlaw beside the road,

Where he had used to rob and spoyle those that passed that way … and the cause why she buryed him there was, for that common strangers and travailers, knowing and seeing him there buryed, might more safely and without feare take their journeys that way, which they durst not do in the life of the sayd outlaes.[150]

All Saints’ Church at Kirkby, modern Pontefract, which was located approximately three miles from the site of Robin Hood’s robberies at the Saylis, is consistent with Richard Grafton’s description because a road ran directly from Wentbridge to the hospital at Kirkby.[151]

Place-name locations

Within close proximity of Wentbridge reside several notable landmarks relating to Robin Hood. One such place-name location occurred in a cartulary deed of 1422 from Monkbretton Priory, which makes direct reference to a landmark named Robin Hood’s Stone, which resided upon the eastern side of the Great North Road, a mile south of Barnsdale Bar.[152] The historians Barry Dobson and John Taylor suggested that on the opposite side of the road once stood Robin Hood’s Well, which has since been relocated six miles north-west of Doncaster, on the south-bound side of the Great North Road. Over the next three centuries, the name popped-up all over the place, such as at Robin Hood’s Bay, near Whitby in Yorkshire, Robin Hood’s Butts in Cumbria, and Robin Hood’s Walk at Richmond, Surrey.

Robin Hood type place-names occurred particularly everywhere except Sherwood. The first place-name in Sherwood does not appear until the year 1700.[153] The fact that the earliest Robin Hood type place-names originated in West Yorkshire is deemed to be historically significant because, generally, place-name evidence originates from the locality where legends begin.[154] The overall picture from the surviving early ballads and other early references[155] indicate that Robin Hood was based in the Barnsdale area of what is now South Yorkshire, which borders Nottinghamshire.

Other place-names and references

The Sheriff of Nottingham also had jurisdiction in Derbyshire that was known as the «Shire of the Deer», and this is where the Royal Forest of the Peak is found, which roughly corresponds to today’s Peak District National Park. The Royal Forest included Bakewell, Tideswell, Castleton, Ladybower and the Derwent Valley near Loxley. The Sheriff of Nottingham possessed property near Loxley, among other places both far and wide including Hazlebadge Hall, Peveril Castle and Haddon Hall. Mercia, to which Nottingham belonged, came to within three miles of Sheffield City Centre. But before the Law of the Normans was the Law of the Danes, The Danelaw had a similar boundary to that of Mercia but had a population of Free Peasantry that were known to have resisted the Norman occupation. Many outlaws could have been created by the refusal to recognise Norman Forest Law.[156] The supposed grave of Little John can be found in Hathersage, also in the Peak District.

Further indications of the legend’s connection with West Yorkshire (and particularly Calderdale) are noted in the fact that there are pubs called the Robin Hood in both nearby Brighouse and at Cragg Vale; higher up in the Pennines beyond Halifax, where Robin Hood Rocks can also be found. Robin Hood Hill is near Outwood, West Yorkshire, not far from Lofthouse. There is a village in West Yorkshire called Robin Hood, on the A61 between Leeds and Wakefield and close to Rothwell and Lofthouse. Considering these references to Robin Hood, it is not surprising that the people of both South and West Yorkshire lay some claim to Robin Hood, who, if he existed, could easily have roamed between Nottingham, Lincoln, Doncaster and right into West Yorkshire.

A British Army Territorial (reserves) battalion formed in Nottingham in 1859 was known as The Robin Hood Battalion through various reorganisations until the «Robin Hood» name finally disappeared in 1992. With the 1881 Childers Reforms that linked regular and reserve units into regimental families, the Robin Hood Battalion became part of The Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment).

A Neolithic causewayed enclosure on Salisbury Plain has acquired the name Robin Hood’s Ball, although had Robin Hood existed it is doubtful that he would have travelled so far south.

List of traditional ballads

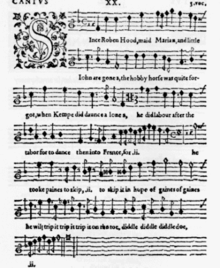

Elizabethan song of Robin Hood

Ballads dating back to the 15th century are the oldest existing form of the Robin Hood legends, although none of them were recorded at the time of the first allusions to him, and many are from much later. They share many common features, often opening with praise of the greenwood and relying heavily on disguise as a plot device, but include a wide variation in tone and plot.[157] The ballads are sorted into four groups, very roughly according to date of first known free-standing copy. Ballads whose first recorded version appears (usually incomplete) in the Percy Folio may appear in later versions[158] and may be much older than the mid-17th century when the Folio was compiled. Any ballad may be older than the oldest copy that happens to survive, or descended from a lost older ballad. For example, the plot of Robin Hood’s Death, found in the Percy Folio, is summarised in the 15th-century A Gest of Robyn Hode, and it also appears in an 18th-century version.[159]

In 15th- or early 16th-century copies

- A Gest of Robyn Hode (Child Ballad 117)

- Robin Hood and the Monk (Child Ballad 119)

- Robin Hood and the Potter (Child Ballad 121)

In 17th-century Percy Folio

NB. The first two ballads listed here (the «Death» and «Gisborne»), although preserved in 17th-century copies, are generally agreed to preserve the substance of late medieval ballads. The third (the «Curtal Friar») and the fourth (the «Butcher»), also probably have late medieval origins.[160] An * before a ballad’s title indicates there’s also a version of this ballad in the Forresters Manuscript.

- Robin Hood’s Death (Child Ballad 120)

- Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (Child Ballad 118)

- *Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar (Child Ballad 123,in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Fryer)

- *Robin Hood and the Butcher (Child Ballad 122)

- *Little John a Begging (Child Ballad 142, in Forresters titled Little Johns Begging)

- Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires (Child Ballad 140)

- *The Jolly Pinder of Wakefield (Child Ballad 124, two versions in Forresters, titled there Robin Hood and the Pinder of Wakefield)

- *Robin Hood and Queen Katherine (Child Ballad 145)

In 17th-century Forresters Manuscript

NB: An * before a ballad’s title indicates that the Forresters version of this ballad is the earliest known version.

- Robin Hood and the Tinker (Child Ballad 127)

- Robin Hood and the Beggar, I (Child Ballad 133)

- Robin Hood’s Progress to Nottingham (Child Ballad 139,in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Forresters I)

- Robin Hood Rescuing Will Stutly (Child Ballad 141, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and Will Scathlock)

- Robin Hood and the Bishop (Child Ballad 143, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Old Wife)

- Robin Hood’s Chase (Child Ballad 146)

- The Noble Fisherman (Child Ballad 148, in Forresters titled Robin Hood’s Fishing)

- Robin Hood and the Tanner (Child Ballad 126)

- Robin Hood and the Shepherd (Child Ballad 135)

- Robin Hood’s Delight (Child Ballad 136, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Forresters II)

- Robin Hood’s Golden Prize (Child Ballad 147, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Preists)

- Robin Hood Newly Revived (Child Ballad 128, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Stranger)

- *Robin Hood and Allan-a-Dale (Child Ballad 138, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Bride)

- *Robin Hood and the Bishop of Hereford (Child Ballad 144, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Bishopp)

- *Robin Hood and the Golden Arrow (Child Ballad 152, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the Sheriffe)

- *The King’s Disguise, and Friendship with Robin Hood (Child Ballad 151, in Forresters titled Robin Hood and the King)

Other ballads

- A True Tale of Robin Hood (Child Ballad 154)

- Robin Hood and the Scotchman (Child Ballad 130)

- Robin Hood and Maid Marian (Child Ballad 150)

- Robin Hood and Little John (Child Ballad 125)

- Robin Hood and the Prince of Aragon (Child Ballad 129)

- Robin Hood’s Birth, Breeding, Valor, and Marriage (Child Ballad 149)

- Robin Hood and the Ranger (Child Ballad 131)

- Robin Hood and the Valiant Knight (Child Ballad 153)

- The Bold Pedlar and Robin Hood (Child Ballad 132)

- Robin Hood and the Beggar, II (Child Ballad 134)

- Robin Hood and the Pedlars (Child Ballad 137)

Some ballads, such as Erlinton, feature Robin Hood in some variants, where the folk hero appears to be added to a ballad pre-existing him and in which he does not fit very well.[161] He was added to one variant of Rose Red and the White Lily, apparently on no more connection than that one hero of the other variants is named «Brown Robin».[162] Francis James Child indeed retitled Child ballad 102; though it was titled The Birth of Robin Hood, its clear lack of connection with the Robin Hood cycle (and connection with other, unrelated ballads) led him to title it Willie and Earl Richard’s Daughter in his collection.[163]

In popular culture

Main characters

- Robin Hood (a.k.a. Robin of Loxley or Locksley)

- The band of «Merry Men»

- Little John

- Friar Tuck

- Will Scarlet

- Alan-a-Dale

- Much the Miller’s Son

- Maid Marian

- King Richard the Lionheart

- Prince John

- Sir Guy of Gisbourne

- The Sheriff of Nottingham

See also

- Barons’ Revolt

- Ishikawa Goemon

- Jesús Malverde

- Joaquin Murrieta

- Juraj Jánošík

- Kayamkulam Kochunni

- Kobus van der Schlossen

- Redistribution of wealth

- Redmond O’Hanlon

- Robin Hood tax

- Schinderhannes

- Wat Tyler

- William Tell

Footnotes

- ^ There are three settlements in Derbyshire called Aston, Aston, Derbyshire Dales, Aston, High Peak and Aston-on-Trent. It is unclear which one this was.

References

- ^ Victor Rouă (20 April 2017). «The Tale Of Robin Hood Of Sherwood Forest: Between Fact And Fiction». The Dockyards. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Brockman 1983, p.69

- ^ a b Dean (1991). «Friar Daw’s Reply». Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Dean (1991). «Friar Daw’s Reply: Introduction». Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ a b Blackwood 2018, p.59

- ^ Cambridge University Library MS Ii.6.26

- ^ a b James 2019, p.204

- ^ «Robin Hood – The Facts and the Fiction » Updates». 28 June 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Hanna 2005, p.151

- ^ A Gest of Robin Hood stanzas 10–15, stanza 292 (archery) 117A: The Gest of Robyn Hode Archived 7 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, p. 203. Friar Tuck is mentioned in the play fragment Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham dated to c. 1475.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, pp. 5, 16.

- ^ a b «The Child Ballads: 117. The Gest of Robyn Hode». sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ a b «A Gest of Robyn Hode». lib.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, p. 34.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c Knight and Ohlgren, 1997.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, pp. 33, 44, and 220–223.

- ^ Singmam, 1998, Robin Hood; The Shaping of the Legend p. 62.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, p. 41. ‘It was here [the May Games] that he encountered and assimilated into his own legend the jolly friar and Maid Marian, almost invariably among the performers in the 16th century morris dance,’ Dobson and Taylor have suggested that theories on the origin of Friar Tuck often founder on a failure to recognise that ‘he was the product of the fusion between two very different friars,’ a ‘bellicose outlaw’, and the May Games figure.

- ^ «Robin Hood and the Monk». Lib.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Introduction Archived 3 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine accompanying Knight and Ohlgren’s 1997 ed.

- ^ Ohlgren, Thomas, Robin Hood: The Early Poems, 1465–1560, (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007), From Script to Print: Robin Hood and the Early Printers, pp. 97–134.

- ^ «Robin Hood and the Potter». Lib.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ a b Holt

- ^ a b «Robyn Hod and the Shryff off Notyngham». Lib.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Singman, Jeffrey L. Robin Hood: The Shaping of the Legend (1998), Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 51. ISBN 0-313-30101-8.

- ^ Robin Hood and the Monk. From Child’s edition of the ballad, online at Sacred Texts, 119A: Robin Hood and the Monk Archived 19 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Stanza 16:

- Then Robyn goes to Notyngham,

- Hym selfe mornyng allone,

- And Litull John to mery Scherwode,

- The pathes he knew ilkone.

- ^ Holt, p. 11.

- ^ Child Ballads 117A:210, ie «A Gest of Robyn Hode» stanza 210.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Knight 2003 Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography p. 43 quoting John Stow, 1592,Annales of England ‘poor men’s goodes hee spared, aboundantly releeving them with that, which by thefte he gote from Abbeyes and the houses of riche Carles‘.

- ^ for it being the earliest clear statement see Dobson and Taylor (1997), Rhymes of Robyn Hood p. 290.

- ^ Holt, p. 36.

- ^ Holt, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Holt, p. 10.

- ^ Singman, Jeffrey L Robin Hood: The Shaping of the Legend, 1998, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 46, and first chapter as a whole. ISBN 0-313-30101-8.

- ^ a b Hutton, 1997, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Hutton (1996), p. 32.

- ^ Hutton (1996), p. 31.

- ^ Holt, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, p. 42.

- ^ Maurice Keen The Outlaws of Medieval England Appendix 1, 1987, Routledge, ISBN 0-7102-1203-8.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), p. 42.

- ^ Jeffrey Richards, Swordsmen of the Screen: From Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York, p. 190, Routledge & Kegan Paul, Lond, Henly and Boston (1988).

- ^ a b Holt, p. 165

- ^ Allen W. Wright, «A Beginner’s Guide to Robin Hood» Archived 4 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), «Rhymes of Robyn Hood», p. 204.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), «Rhymes of Robyn Hood», p. 215.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, «Rhymes of Robyn Hood», p. 209.

- ^ David Masson, Register of the Privy Council of Scotland: 1578-1585, vol. 3 (Edinburgh, 1880), p. 744.

- ^ a b c Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography p. 63.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), p. 44.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), «Rhymes of Robin Hood», pp. 43, 44, and 223.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography, p. 51.

- ^ a b Holt, p. 170.

- ^ Act IV, Scene 1, line 36–37.

- ^ «Johnson’s «The Sad Shepherd»«. Lib.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), p. 231.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, pp. 45, 247

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, p. 45

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, p. 243

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, «Rhymes of Robyn Hood», p. 286.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor (1997), «Rhymes of Robin Hood», p. 47.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, «Rhymes of Robyn Hood», p. 49.

- ^ «Rhymes of Robyn Hood» (1997), p. 50.

- ^ Dobson and Taylor, «Rhymes of Robin Hood», pp. 51–52.

- ^ Basdeo, Stephen (2016). «Robin Hood the Brute: Representations of the Outlaw in Eighteenth Century Criminal Biography». Law, Crime and History. 6: 2: 54–70.

- ^ Bewick, et al. Robin Hood : a Collection of All the Ancient Poems, Songs, and Ballads, Now Extant Relative to That Celebrated English Outlaw; to Which Are Prefixed Historical Anecdotes of His Life / by Joseph Ritson. 2nd ed., W. Pickering, 1832, online at State Library of New South Wales, DSM/821.04/R/v. 1

- ^ 1887 reprint, publisher J.C. Nimmo, https://archive.org/details/robinhoodcollect01ritsrich Archived 26 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine accessed 18 January 2016, digitized 2008 from book provided by University of California Libraries.

- ^ a b Dobson and Taylor (1997), p. 54.

- ^ In his table of contents, he separated the longer ballads from the shorter ballads into two parts; Part 1 containing the longer ballads were numbered I-V while the shorter ballads in Part 2 were numbered I-XXVIII

- ^ Ritson, ‘’ Robin Hood: A collection of all the Ancient Poems Songs and Ballads now extant, relative to that celebrated Outlaw’’. p. 155, 1820 edition.

- ^ J.C. Holt, Robin Hood, 1982, pp. 184, 185

- ^ Robin Hood, Volume 1, Joseph Ritson

- ^ «Robin Hood, Doctor Who, and the emergence of the a modern rogue!». 11 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2020.