Александр Милн — биография

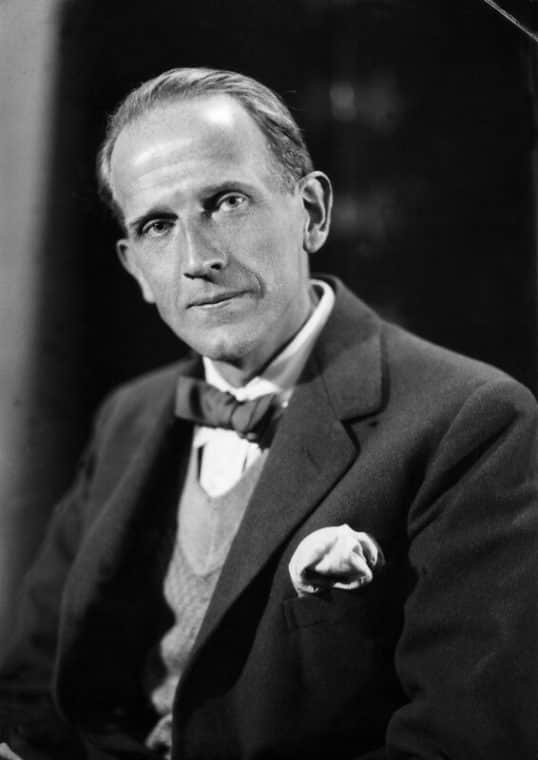

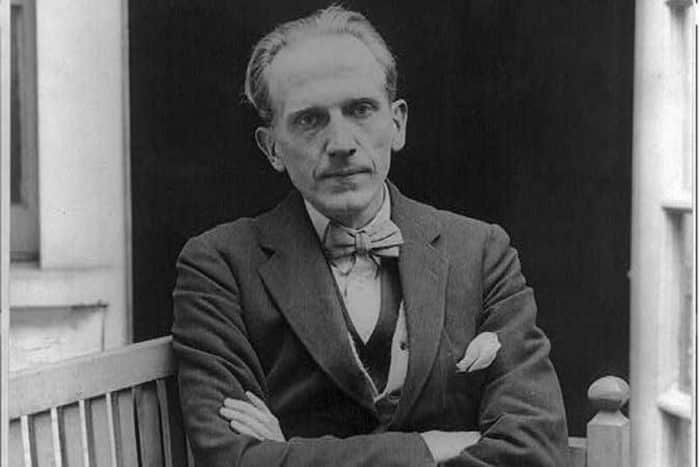

Создатель Винни-Пуха Алан А. Милн – английский писатель, журналист и драматург. Среди его произведений сказки, рассказы, романы, стихи и пьесы. Но самую большую популярность ему принесла детская книга о приключениях сказочных зверей – «Винни-Пух». Сказка об игрушечном мишке полностью затмила другие произведения Милна.

Детские годы

А. А. Милн родился в Лондоне в 1882 году. Детям в семье всячески помогали заниматься творчеством и поощряли эти занятия. Сам Алан с юных лет сочинял стихи, когда стал студентом начал писать статьи совместно со своим братом.

Писателю очень повезло с хорошим образованием: у его отца была частная школа, в которую Милн — младший и ходил. Об уровне обучения в школе можно судить по тому факту, что одним из ее учителей был Герберт Уэллс, знаменитый на весь мир писатель и журналист.

Затем Милн поступил в престижный Кембридж, изучать математику. Юноша имел к точным наукам большие способности, но надо отметить, что математические формулы будущего писателя не привлекали настолько, чтобы заниматься ими всю жизнь. А больше все-таки привлекала литературная деятельность. Он начал писать заметки для университетской газеты.

Его заметили и высоко оценили талант: молодого журналиста пригласили в известнейший британский юмористический журнал «Панч». Для начинающего литератора это был большой успех.

Кстати, будущая жена писателя читала его фельетоны в журнале и заочно им заинтересовалась.

Зрелые годы

В 1913 году Алан женился на Дороти де Селинкур. А на следующий год началась 1-я Мировая война. Милн пошел на войну добровольцем. В основном во время войны он работал в отделе пропаганды.

Еще во время войны Алан Милн писал пьесы, которые имели большой успех. Его стали называть одним из наиболее известных и успешных драматургов Англии.

В 1920 году у четы Милнов родился сын.

Могут быть знакомы

Медвежонок Пух и все-все-все

Как говорил впоследствии сам писатель, сказку он не сочинял специально, а просто перенес на бумагу приключения игрушечных друзей его сына Кристофера Робина.

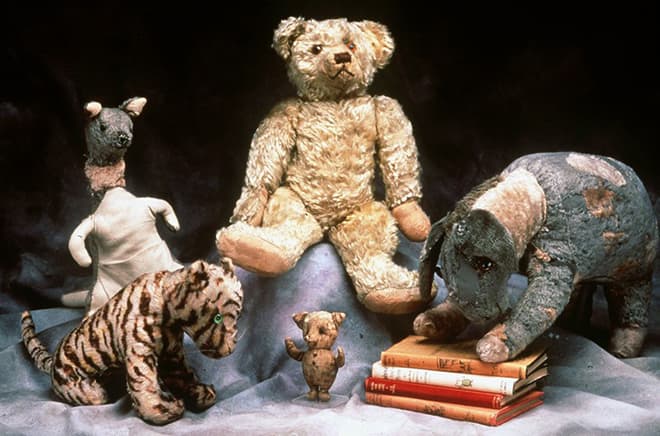

Ребенку дарили разные игрушки, а перед сном папа обычно рассказывал сыну истории, которые приключились с его игрушками. А еще члены семьи разыгрывали спектакли, участниками которых были игрушки Кристофера. Так и рождалась сказка про плюшевого медвежонка и его приятелей.

Персонажи сказки появляются на ее страницах как раз в том порядке, в каком они появлялись в жизни самого ребенка. Лес, в котором жили Винни-Пух и его друзья очень похож на тот лес, в котором любила гулять семья Милнов.

А прототипом самого Винни-Пуха стала реальная медведица. Полное ее имя Виннипег, она была выкуплена еще маленьким медвежонком у канадского охотника и попала в Лондонский зоопарк.

В 1924 году Милны посетили зоопарк, увидели медведицу и маленький Кристофер переименовал ее в Винни. Точно так же он назвал и своего любимого плюшевого мишку.

В конце 1924 года начало истории про медвежонка напечатала одна лондонская газета. Именно эту дату и можно считать «рождением» Винни-Пуха.

Оригинальная сказка так понравилась читателям, что они стали просить продолжение. И Алан Милн начал записывать свои истории про сказочных героев. В 1926 году уже вышла целая книжка о них.

Почему Милны не любили Винни-Пуха?

Сказочная повесть о медвежонке Пухе принесла Алану Милну невиданную славу. Эту историю много раз переводили на разные языки, переиздавали и экранизировали. Есть полнометражный мультфильм, снятый на студии Уолта Диснея. В нем художники-мультипликаторы постарались воспроизвести первые иллюстрации к книге.

Союзмультфильм тоже выпустил свой вариант по этой сказке. Мультфильм полюбился всем зрителям и стал в Советском Союзе классикой детского жанра.

Но самим Милнам, отцу и сыну, эта сказочная история доставила немало реальных неприятностей. Дело в том, что сказка буквально закрыла Алану Милну дальнейший путь в литературу. Его рассказы и пьесы, написанные ранее, уже стали забываться, а новые книги критики не воспринимали. Все произведения отныне начали проходить «проверку Винни-Пухом».

Писатель прекрасно это понимал и с горечью говорил, что если литератор один раз напишет произведение на определенную тему, то от него в дальнейшем будут требовать только эту же тему.

В свое время с подобным же отношением столкнулся и Конан Дойль. Читающая публика настойчиво требовала только продолжения историй о Шерлоке Холмсе, а другие произведения писателя практически игнорировала. Писатель даже возненавидел своего, такого популярного, героя.

Читателей понять можно: если произведение хорошее, то хочется все нового и нового продолжения.

Но и точку зрения писателя тоже можно понять: никому не улыбается на всю жизнь оставаться писателем одного произведения, хочется достичь творческой реализации и в других жанрах.

Конан Дойлю это удалось, наряду с рассказами о Шерлоке Холмсе он продолжал писать и на другие темы. И другие его книги тоже были востребованы. В случае же с Аланом Милном все оказалось куда трагичнее.

Пьесы, рассказы и стихи талантливого писателя оказались почти полностью забыты. Востребованным и популярным был и остается только Винни-Пух. И это при том, что сам Милн не считал себя детским писателем!

В 1938 году провалилась его театральная пьеса. И Милн перестал писать для театра. Его юмористические рассказы тоже потеряли былую популярность. Книги для взрослых больше не переиздавались, росли только тиражи Винни-Пуха. Травила писателя и жена, ядовито называя писателишкой с опилками в голове.

Умер Алан Александр Милн в 1956 году от продолжительной болезни.

От Винни-Пуха немало пострадал и сын писателя. В книге он выведен под собственным именем и сверстникам не составило труда догадаться, что он и есть тот самый Кристофер Робин. Мальчика много лет дразнили и травили, а поддержки от родителей он не получил. Мать никогда не интересовалась сыном, отец, когда Кристофер подрос – тоже.

Даже во взрослой жизни Кристофер так и не смог избавиться от негативного влияния Винни-Пуха.

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

First edition cover |

|

| Author | A. A. Milne |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | E. H. Shepard |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children’s literature |

| Publisher | Methuen (London) Dutton (US) |

|

Publication date |

14 October 1926 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Followed by | The House at Pooh Corner |

Winnie-the-Pooh is a 1926 children’s book by English author A. A. Milne and English illustrator E. H. Shepard. The book is set in the fictional Hundred Acre Wood, with a collection of short stories following the adventures of an anthropomorphic teddy bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, and his friends Christopher Robin, Piglet, Eeyore, Owl, Rabbit, Kanga, and Roo. It is the first of two story collections by Milne about Winnie-the-Pooh, the second being The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Milne and Shepard collaborated previously for English humour magazine Punch, and in 1924 created When We Were Very Young, a poetry collection. Among the characters in the poetry book was a teddy bear Shepard modelled after his son’s toy. Following this, Shepard encouraged Milne to write about his son Christopher Robin Milne’s toys, and so they became the inspiration for the characters in Winnie-the-Pooh.

The book was published on October 14, 1926, and was both well-received by critics and a commercial success, selling 150,000 copies before the end of the year. Critical analysis of the book has held that it represents a rural Arcadia, separated from real-world issues or problems, and is without purposeful subtext. More recently, criticism has been levelled at the lack of positive female characters (i.e. that the only female character, Kanga, is depicted as a bad mother).

Winnie-the-Pooh has been translated into over fifty languages; a 1958 Latin translation, Winnie ille Pu, was the first foreign-language book to be featured on the New York Times Best Seller List, and the only book in Latin ever to have been featured. The stories and characters in the book have been adapted in other media, most notably into a franchise by The Walt Disney Company, beginning with Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, released on February 4, 1966 as a double feature with The Ugly Dachshund. On January 1, 2022, the original Winnie-the-Pooh book entered the public domain in the United States, but remains protected under copyright in other countries, including the UK.

Background and publication

Before writing Winnie-the-Pooh, A. A. Milne was already a successful writer. He wrote for English humour magazine Punch, had published a mystery novel, The Red House Mystery (1922), and was a playwright.[1] Milne began writing poetry for children after being asked by fellow Punch contributor, Rose Fyleman.[2] Milne compiled his first verses for publishing, and though his publishers were initially hesitant to publish children’s poetry, the poetry collection When We Were Very Young (1924) was a success.[1] The illustrations were done by artist and fellow Punch staff E. H. Shepard.[1]

Among the characters in When We Were Very Young was a teddy bear that Shepard modelled after one belonging to his son.[1] With the book’s success, Shepard encouraged Milne to write stories about Milne’s young son, Christopher Robin Milne, and his stuffed toys.[1] Among Christopher’s toys was a teddy bear he called «Winnie-the-Pooh». Christopher got the name «Winnie» from a bear at the London Zoo, Winnipeg. «Pooh» was the name of a swan in When We Were Very Young.[1] Milne used Christopher and his toys as inspiration for a series of short stories, which were compiled and published as Winnie-the-Pooh. The model for Pooh remained the bear belonging to Shepard’s son.[1]

Winnie-the-Pooh was published on 14 October 1926 by Methuen & Co. in England and E. P. Dutton in the United States.[1] As a work first published in 1926, the book entered the public domain in the United States on 1 January 2022. British copyright of the text expires on 1 January 2027 (70 calendar years after Milne’s death) while British copyright of the illustrations expires on 1 January 2047 (70 calendar years after Shepard’s death).

Stories

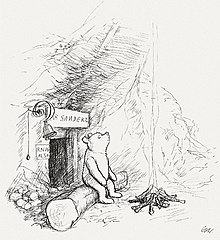

Winnie-the-Pooh in an illustration by E. H. Shepard

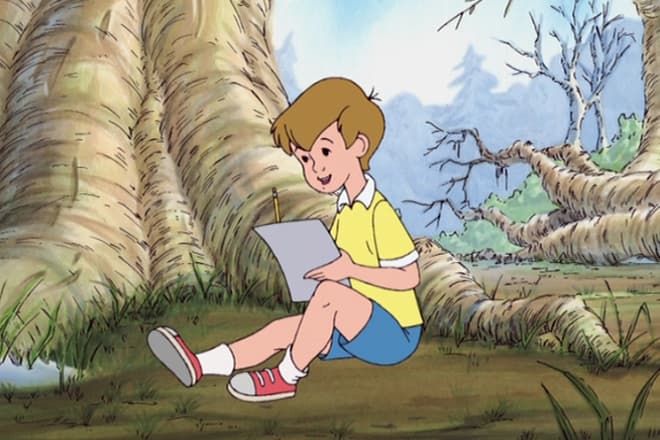

Illustration from Chapter 10: In Which Christopher Robin Gives Pooh a Party and We Say Goodbye.

Some of the stories in Winnie-the-Pooh were adapted by Milne from previous published writings in Punch, St. Nicholas Magazine, Vanity Fair and other periodicals.[3] The first chapter, for instance, was adapted from «The Wrong Sort of Bees», a story published in the London Evening News in its issue for Christmas Eve 1925.[4] Classics scholar Ross Kilpatrick contended in 1998 that Milne adapted the first chapter from «Teddy Bear’s Bee Tree», published in 1912 in Babes in the Woods by Charles G. D. Roberts.[5][6]

The stories in the book can be read independently. The plots do not carry over between stories (with the exception of Stories 9 and 10).

- In Which We Are Introduced to Winnie the Pooh and Some Bees and the Stories Begin:

- Winnie-the-Pooh is out of honey, so he tries to climb a tree to get some, but falls off, bouncing on branches on his way down. He meets with his friend Christopher Robin and floats up with a balloon of Christopher’s, only to discover they are not the right sort of bees for honey. Christopher then shoots the balloon with his gun, letting Pooh slowly float back down.

- In Which Pooh Goes Visiting and Gets into a Tight Place:

- Pooh visits Rabbit, but eats so much while in Rabbit’s house that he gets stuck in Rabbit’s door on the way out. Christopher Robin reads him a book for a week and, having not had any meals, Pooh is slim enough to be pulled out by Christopher, Rabbit, and Rabbit’s friends and extended family.

- In Which Pooh and Piglet Go Hunting and Nearly Catch a Woozle:

- Pooh and Piglet track increasing numbers of footsteps round and round a spinney of trees, only to realise, when Christopher Robin points it out, that they are their own.

- In Which Eeyore Loses a Tail and Pooh Finds One:

- Pooh sets out to find Eeyore’s missing tail, and visits Owl’s place. Owl suggests putting up posters and offering a reward, before asking what Pooh thinks about his bell-rope. They realise that Owl has taken Eeyore’s tail by accident and Christopher Robin nails it back on.

- In Which Piglet Meets a Heffalump:

- Piglet and Pooh try to trap a Heffalump, using honey as a bait, but Pooh ends up getting stuck in the hole himself with the honey jar on his head. Piglet is convinced that Pooh is a Heffalump and calls Christopher Robin, who quickly realises it is Pooh and laughs.

- In Which Eeyore has a Birthday and Gets Two Presents:

- Pooh feels bad that no one has gotten Eeyore anything for his birthday, so he and Piglet try their best to get him presents. Piglet accidentally pops Eeyore’s balloon and Pooh brings Eeyore a honey jar which Owl has written Happy Birthday on. Eeyore ends up being happy with this present.

- In Which Kanga and Baby Roo Come to the Forest and Piglet has a Bath:

- Rabbit convinces Pooh and Piglet to try to kidnap newcomer Baby Roo to convince newcomer Kanga to leave the forest. They switch Roo for Piglet and Kanga mistakes Piglet for Roo and gives him a bath, before Christopher Robin points out the mistake she has made.

- In Which Christopher Robin Leads an Expotition to the North Pole:

- Christopher Robin and all of the animals in the forest go on a quest to find the North Pole in the Hundred Acre Wood. Roo falls into the river and Pooh helps him out using a pole. Christopher Robin announces Pooh has found the North Pole and puts a sign down dedicated to him.

- In Which Piglet is Entirely Surrounded by Water:

- Piglet is trapped in his home by a flood, so he sends a message out in a bottle in hope of rescue. Pooh stays at home, eventually runs out of honey, and then uses the empty jars as a makeshift boat. After Pooh meets Christopher Robin, they set off in a boat made of an umbrella and rescue Piglet.

- In Which Christopher Robin Gives Pooh a Party and We Say Goodbye:

- Christopher Robin gives Pooh a party for helping to rescue Piglet during the flood. Pooh gets a pencil case as a present.

Reception

The book was a critical and commercial success; Dutton sold 150,000 copies before the end of the year.[1] First editions of Winnie-the-Pooh were published in low numbers. Methuen & Co. published 100 copies in large size, signed and numbered. E. P. Dutton issued 500 copies of which only 100 were signed by Milne.[2] The book is Milne’s best-selling work;[7] the author and literary critic John Rowe Townsend described Winnie-the-Pooh and its sequel The House at Pooh Corner as «the spectacular British success of the 1920s» and praised its light, readable prose.[8]

Contemporary reviews of the book were generally positive. A review in The Elementary English Review reviewed the book positively, describing it as containing «delightful nonsense» and «unbelievably funny» illustrations.[9] In 2003, Winnie the Pooh was listed at number 7 on the BBC’s survey The Big Read, a survey of the British public to determine their favourite books.[10] In 2012 it was ranked number 26 on a list of the top 100 children’s novels published by School Library Journal.[11]

Analysis

Townsend describes Milne’s Pooh works as being «as totally without hidden significance as anything written.» In 1963 Frederick Crews published The Pooh Perplex, a satire of literary criticism that contains essays by fake authors on Winnie-the-Pooh.[8] The book is introduced as trying to make sense of «one of the greatest books ever written» on the meaning of which «nobody can quite agree».[12] Crews’ book had a chilling effect on any substantive analysis of the book, particularly for the ten years following its publication.[13]

Although Winnie-the-Pooh was published shortly after the end of the First World War, it takes place in a isolated world free from major issues, which scholar Paula T. Connolly describes as «largely Edenic» and later as an Arcadia standing in stark contrast to the world in which the book was created. She goes on to describe the book as nostalgic for a «rural and innocent world». The book was published towards the end of an era when writing fantasy works for children was very popular, sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Children’s Literature.[14]

In Alison Lurie’s 1990 essay on Winnie-the-Pooh, she argues that its popularity, despite its simplicity, comes from its «universal appeal» to people who find themselves at a «social disadvantage,» and gives kids as one obvious example of this. The power and wise status that Christopher Robin receives, she claims, also appeals to children. Lurie draws a parallel from the setting of an environment that feels small and is devoid of aggression, with most of the activities involving exploring, to Milne’s childhood, which he spent at a small suburban same-sex school. In addition, the rural backdrop without cars and roads is similar to his life as a child in Essex and Kent, before the start of the 20th century. She argues that the characters have widespread appeal because they draw from Milne’s own life, and contain common feelings and personalities found in childhood, such as gloominess (Eeyore) and shyness (Piglet).[13]

In Carol Stranger’s feminist analysis of the book, she criticises this idea, arguing that, since every character other than Kanga is male, Lurie must believe that the «male experience is universal.» The main critique, however, that Stranger levels is that Kanga, the only female character and the mother of Roo, is consistently made out as negative and a bad mother, citing a passage in which Kanga mistakes Piglet for Roo and threatens to put soap in his mouth if he resists taking a cold bath. This, she claims, forces female readers either to identify themselves with Kanga, and «call up the dependency, the pain, vulnerability and disappointment» many babies feel towards their caregivers, or to identify with the male characters, and see Kanga as cruel. She also notes that Christopher Robin’s mother is mentioned only in the dedication.[15]

Translations

The work has been translated into 72 languages,[16] including Afrikaans, Czech, Finnish and Yiddish.[1] The Latin translation by the Hungarian Lénárd Sándor (Alexander Lenard), Winnie ille Pu, was first published in 1958, and, in 1960, became the first foreign-language book to be featured on the New York Times Best Seller List, and the only book in Latin ever to have been featured therein.[17] It was also translated into Esperanto in 1972, by Ivy Kellerman Reed and Ralph A. Lewin, Winnie-La-Pu.[18] The work was featured in the iBooks app for Apple’s iOS as the «starter» book for the app.

Winnie-the-Pooh also received two Polish translations, which vastly differed in their interpretation of the work. Irena Tuwim published the first translation of the work in 1938, titled Kubuś Puchatek. This version prioritized adopting Polish language and culture over a direct translation, which was well received by readers.[19] The second translation, titled Fredzia Phi-Phi, was published by Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska in 1986. Adamczyk-Garbowska’s version was more faithful to the original text, but was widely criticized by Polish readers and scholars, including Robert Stiller and Stanisław Lem.[19] Lem harshly described Tuwim’s easy-to-read translation as being «castrated» by Adamczyk-Garbowska.[19] The titular character’s new Polish name, Fredzia Phi-Phi, also drew criticism from readers who assumed Adamczyk-Garbowska had changed Pooh’s gender by using a female name.[20][21][22] Many of the new character names were also seen as being overly complicated compared to Tuwim’s version.[19] Adamczyk-Garbowska defended her translation, stating that she simply wanted to convey Milne’s linguistic subtleties that were not present in the first translation.[20]

Legacy

In 2018, five works of original art from the book sold for £917,500, including a map of the Hundred Acre Wood that sold for £430,000 and set a record for the most expensive book illustration.[23]

Sequels

Milne and Shepard went on to collaborate on two more books: Now We Are Six (1927) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928).[1] Now We Are Six is a poetry volume like When We Were Very Young, and includes some poetry about Winnie-the-Pooh. The House at Pooh Corner is a second volume of stories about Pooh, and introduces the character Tigger.[1] Milne never wrote another Pooh book, and died in 1956. Penguin Books has called When We Were Very Young, Winnie-the-Pooh, Now We Are Six, and The House At Pooh Corner «the basis of the entire Pooh canon.»[1]

The first authorized Pooh book after Milne’s death was Return to the Hundred Acre Wood in 2009, by David Benedictus. It was written with the full backing of Milne’s estate, which took the trustees ten years to agree to.[24] In the story, a new character, Lottie the Otter, is introduced.[25] The illustrations are by Mark Burgess.[26] The next authorized sequel, The Best Bear in All The World, was published in 2016 by Egmont.[27] It was written by Paul Bright, Jeanne Willis, Kate Saunders and Brian Sibley with illustrations again by Mark Burgess. The four authors each wrote a short story about one of the seasons: Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall.[28][29]

Adaptations

Following The Walt Disney Company’s licensing of certain rights to Pooh from Stephen Slesinger and the A. A. Milne Estate in the 1960s, the Milne storylines were used by Disney in its cartoon featurette Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree.[30] The «look» of Pooh was adapted by Disney from Stephen Slesinger’s distinctive American Pooh with his famous red shirt that had been created and used in commerce by Slesinger since the 1930s.[31]

Parts of the book were adapted to three Russian-language short animated films directed by Fyodor Khitruk: Winnie-the-Pooh (based on chapter 1), Winnie-the-Pooh Pays a Visit (based on chapter 2), and Winnie-the-Pooh and a Busy Day (based on chapters 4 and 6).[32]

In 2022, Jagged Edge Prodictions announced that a horror film starring the character was put in production, and is set for release on February 15, 2023.[33]

Passage into the public domain

Winnie-the-Pooh‘s entrance into the public domain in the United States on January 1, 2022 was noted by several news publications, generally in the context of a greater Public Domain Day article.[34][35][36][37] The book entered the public domain in Canada in 2007.[38][39][40] The UK copyright will expire at the end of 2026, the 70th year since Milne’s death.

See also

- Woozle effect

- List of Winnie-the-Pooh characters

- Public domain in the United States

- Winnie the Pooh (franchise), a media franchise produced by The Walt Disney Company, based on A. A. Milne and E. H. Shepard’s original Winnie-the-Pooh books.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m «A Short History of Winnie-the-Pooh». Penguin Group. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015.

- ^ a b Olsson, Mary (29 June 2020). «The Story Behind A.A. Milne’s Pooh Books». Bauman Rare Books. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Yarbrough, Wynn William (2011). Masculinity in children’s animal stories, 1888–1928 : a critical study of anthropomorphic tales by Wilde, Kipling, Potter, Grahame and Milne. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7864-5943-8. OCLC 689522274.

- ^ «A Real Pooh Timeline». The New York Public Library. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Ross Kilpatrick, «Winnie the Pooh and the Canadian Connection», Queens Quarterly (105/5)

- ^ Shanahan, Noreen (25 March 2012). «From Vergil to Winnie-the-Pooh, Ross Kilpatrick had wide-ranging interests». Globe and Mail. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Connolly 1995, p. xiv.

- ^ a b Townsend, John Rowe (1 May 1996). Written for Children: An Outline of English-Language Children’s Literature. Scarecrow Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-1-4617-3104-7.

- ^ Murdoch, Clarissa (1927). «Review of Winnie-The-Pooh». The Elementary English Review. 4 (1): 30. ISSN 0888-1030. JSTOR 41382198.

- ^ «The Big Read», BBC, April 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2013

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (7 July 2012). «Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results». A Fuse #8 Production. Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com).

- ^ Crews 1965, p. iv.

- ^ a b Lurie, Alison (1990). Don’t tell the grown-ups: subversive children’s literature. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 144–155. ISBN 978-0-316-53722-3 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Connolly 1995, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Stanger, Carol A. (1987). «Winnie The Pooh Through a Feminist Lens». The Lion and the Unicorn. 11 (2): 34–50. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0299. ISSN 1080-6563. S2CID 144046525.

- ^ «Winnie-the-Pooh prequel celebrates Sussex locations». Sussex World. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ McDowell, Edwin (18 November 1984). «‘Winnie Ille Pu’ Nearly XXV Years Later». The New York Times. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ (Milne), Reed and Lewin, trs., Winnie-La-Pooh, foreword by Humphrey Tonkin (Dutton), 1972, 2nd edition UEA, Rotterdam, 1992.

- ^ a b c d Misior-Mroczkowska, Aleksandra (2016). «The Fuss about the Pooh: On Two Polish Translations of a Story about a Little Bear». Styles of Communication. University of Bucharest Publishing House. 8: 28–36.

- ^ a b Reaves, Joseph A. (17 September 1989). «Poland’s New Pooh Spills Honey of a Controversy». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Poland switches sexes on Winnie-the-Pooh». United Press International. 31 December 1986. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Legierska, Anna (11 April 2017). «Od Kubusia Puchatka do Andersena: polskie przekłady baśni świata». Culture.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 6 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Original 1926 Winnie-the-Pooh map sells for record £430,000». BBC News. 10 July 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ «First new Winnie-the-Pooh book in 80 years goes on sale». The Daily Telegraph. 5 October 2009. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ «New friend joins Winnie-the-Pooh». 30 September 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Flood, Alison (10 January 2009). «After 90 years, Pooh returns to Hundred Acre Wood in sequel». The Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ «Egmont Reveals the Four Writers of the Next Winnie-the-Pooh Sequel: The Best Bear in All the World» (Press release). Egmont. 24 November 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016.

- ^ Flood, Alison (19 September 2016). «Winnie-the-Pooh makes friends with a penguin to mark anniversary». The Guardian. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Pequenino, Karla (14 October 2016). «Winnie-the-Pooh gets a new friend». CNN. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (7 April 1966). «A Disney Package: Don’t Miss the Short». The New York Times. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Sauer, Patrick (6 November 2017). «How Winnie-the-Pooh Became a Household Name». Smithsonian. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ Fessenden, Marissa. «Russia Has Its Own Classic Version of an Animated Winnie-the-Pooh». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Ritman, Alex (4 November 2022). «How an Online Frenzy Lit a Fuse Under Microbudget Slasher ‘Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey’«. The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (1 January 2022). «‘Winnie the Pooh,’ Hemingway’s ‘The Sun Also Rises’ and 400,000 Sound Recordings Enter the Public Domain». Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ «Winnie-the-Pooh, Bambi among works entering public domain in 2022». KSTU. 2 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ «Public Domain Day 2022». Duke University School of Law. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hiltzik, Michael (3 January 2022). «Column: ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ (born 1926) is now in the public domain, a reminder that our copyright system is absurd». Los Angeles Times.

- ^ «Winnie the Pooh in the public domain». Copibec. 7 January 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

Even though the copyright on Winnie-the-Pooh expired only this year in the U.S., the book actually entered the public domain in Canada 15 years ago (2007), which was 50 years after Milne’s death in 1956.

- ^ «How Winnie-the-Pooh highlights flaws in U.S. copyright law — and what that could mean for Canada». CBC. CBC Radio. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Hugh Stephens (17 January 2022). «Winnie the Pooh, the Public Domain and Winnie’s Canadian Connection». Hugh Stephens Blog. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

Bibliography

- Crews, Frederick C. (1965). The Pooh perplex : a freshman casebook. New York : Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-47160-8.

- Connolly, Paula T. (1995). Winnie-the-Pooh and The house at Pooh corner. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-8810-5.

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Winnie-the-Pooh at Standard Ebooks

- Winnie-the-Pooh at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Winnie-the-Pooh at Internet Archive

Winnie-the-Pooh public domain audiobook at LibriVox

First edition cover |

|

| Author | A. A. Milne |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | E. H. Shepard |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children’s literature |

| Publisher | Methuen (London) Dutton (US) |

|

Publication date |

14 October 1926 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Followed by | The House at Pooh Corner |

Winnie-the-Pooh is a 1926 children’s book by English author A. A. Milne and English illustrator E. H. Shepard. The book is set in the fictional Hundred Acre Wood, with a collection of short stories following the adventures of an anthropomorphic teddy bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, and his friends Christopher Robin, Piglet, Eeyore, Owl, Rabbit, Kanga, and Roo. It is the first of two story collections by Milne about Winnie-the-Pooh, the second being The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Milne and Shepard collaborated previously for English humour magazine Punch, and in 1924 created When We Were Very Young, a poetry collection. Among the characters in the poetry book was a teddy bear Shepard modelled after his son’s toy. Following this, Shepard encouraged Milne to write about his son Christopher Robin Milne’s toys, and so they became the inspiration for the characters in Winnie-the-Pooh.

The book was published on October 14, 1926, and was both well-received by critics and a commercial success, selling 150,000 copies before the end of the year. Critical analysis of the book has held that it represents a rural Arcadia, separated from real-world issues or problems, and is without purposeful subtext. More recently, criticism has been levelled at the lack of positive female characters (i.e. that the only female character, Kanga, is depicted as a bad mother).

Winnie-the-Pooh has been translated into over fifty languages; a 1958 Latin translation, Winnie ille Pu, was the first foreign-language book to be featured on the New York Times Best Seller List, and the only book in Latin ever to have been featured. The stories and characters in the book have been adapted in other media, most notably into a franchise by The Walt Disney Company, beginning with Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, released on February 4, 1966 as a double feature with The Ugly Dachshund. On January 1, 2022, the original Winnie-the-Pooh book entered the public domain in the United States, but remains protected under copyright in other countries, including the UK.

Background and publication

Before writing Winnie-the-Pooh, A. A. Milne was already a successful writer. He wrote for English humour magazine Punch, had published a mystery novel, The Red House Mystery (1922), and was a playwright.[1] Milne began writing poetry for children after being asked by fellow Punch contributor, Rose Fyleman.[2] Milne compiled his first verses for publishing, and though his publishers were initially hesitant to publish children’s poetry, the poetry collection When We Were Very Young (1924) was a success.[1] The illustrations were done by artist and fellow Punch staff E. H. Shepard.[1]

Among the characters in When We Were Very Young was a teddy bear that Shepard modelled after one belonging to his son.[1] With the book’s success, Shepard encouraged Milne to write stories about Milne’s young son, Christopher Robin Milne, and his stuffed toys.[1] Among Christopher’s toys was a teddy bear he called «Winnie-the-Pooh». Christopher got the name «Winnie» from a bear at the London Zoo, Winnipeg. «Pooh» was the name of a swan in When We Were Very Young.[1] Milne used Christopher and his toys as inspiration for a series of short stories, which were compiled and published as Winnie-the-Pooh. The model for Pooh remained the bear belonging to Shepard’s son.[1]

Winnie-the-Pooh was published on 14 October 1926 by Methuen & Co. in England and E. P. Dutton in the United States.[1] As a work first published in 1926, the book entered the public domain in the United States on 1 January 2022. British copyright of the text expires on 1 January 2027 (70 calendar years after Milne’s death) while British copyright of the illustrations expires on 1 January 2047 (70 calendar years after Shepard’s death).

Stories

Winnie-the-Pooh in an illustration by E. H. Shepard

Illustration from Chapter 10: In Which Christopher Robin Gives Pooh a Party and We Say Goodbye.

Some of the stories in Winnie-the-Pooh were adapted by Milne from previous published writings in Punch, St. Nicholas Magazine, Vanity Fair and other periodicals.[3] The first chapter, for instance, was adapted from «The Wrong Sort of Bees», a story published in the London Evening News in its issue for Christmas Eve 1925.[4] Classics scholar Ross Kilpatrick contended in 1998 that Milne adapted the first chapter from «Teddy Bear’s Bee Tree», published in 1912 in Babes in the Woods by Charles G. D. Roberts.[5][6]

The stories in the book can be read independently. The plots do not carry over between stories (with the exception of Stories 9 and 10).

- In Which We Are Introduced to Winnie the Pooh and Some Bees and the Stories Begin:

- Winnie-the-Pooh is out of honey, so he tries to climb a tree to get some, but falls off, bouncing on branches on his way down. He meets with his friend Christopher Robin and floats up with a balloon of Christopher’s, only to discover they are not the right sort of bees for honey. Christopher then shoots the balloon with his gun, letting Pooh slowly float back down.

- In Which Pooh Goes Visiting and Gets into a Tight Place:

- Pooh visits Rabbit, but eats so much while in Rabbit’s house that he gets stuck in Rabbit’s door on the way out. Christopher Robin reads him a book for a week and, having not had any meals, Pooh is slim enough to be pulled out by Christopher, Rabbit, and Rabbit’s friends and extended family.

- In Which Pooh and Piglet Go Hunting and Nearly Catch a Woozle:

- Pooh and Piglet track increasing numbers of footsteps round and round a spinney of trees, only to realise, when Christopher Robin points it out, that they are their own.

- In Which Eeyore Loses a Tail and Pooh Finds One:

- Pooh sets out to find Eeyore’s missing tail, and visits Owl’s place. Owl suggests putting up posters and offering a reward, before asking what Pooh thinks about his bell-rope. They realise that Owl has taken Eeyore’s tail by accident and Christopher Robin nails it back on.

- In Which Piglet Meets a Heffalump:

- Piglet and Pooh try to trap a Heffalump, using honey as a bait, but Pooh ends up getting stuck in the hole himself with the honey jar on his head. Piglet is convinced that Pooh is a Heffalump and calls Christopher Robin, who quickly realises it is Pooh and laughs.

- In Which Eeyore has a Birthday and Gets Two Presents:

- Pooh feels bad that no one has gotten Eeyore anything for his birthday, so he and Piglet try their best to get him presents. Piglet accidentally pops Eeyore’s balloon and Pooh brings Eeyore a honey jar which Owl has written Happy Birthday on. Eeyore ends up being happy with this present.

- In Which Kanga and Baby Roo Come to the Forest and Piglet has a Bath:

- Rabbit convinces Pooh and Piglet to try to kidnap newcomer Baby Roo to convince newcomer Kanga to leave the forest. They switch Roo for Piglet and Kanga mistakes Piglet for Roo and gives him a bath, before Christopher Robin points out the mistake she has made.

- In Which Christopher Robin Leads an Expotition to the North Pole:

- Christopher Robin and all of the animals in the forest go on a quest to find the North Pole in the Hundred Acre Wood. Roo falls into the river and Pooh helps him out using a pole. Christopher Robin announces Pooh has found the North Pole and puts a sign down dedicated to him.

- In Which Piglet is Entirely Surrounded by Water:

- Piglet is trapped in his home by a flood, so he sends a message out in a bottle in hope of rescue. Pooh stays at home, eventually runs out of honey, and then uses the empty jars as a makeshift boat. After Pooh meets Christopher Robin, they set off in a boat made of an umbrella and rescue Piglet.

- In Which Christopher Robin Gives Pooh a Party and We Say Goodbye:

- Christopher Robin gives Pooh a party for helping to rescue Piglet during the flood. Pooh gets a pencil case as a present.

Reception

The book was a critical and commercial success; Dutton sold 150,000 copies before the end of the year.[1] First editions of Winnie-the-Pooh were published in low numbers. Methuen & Co. published 100 copies in large size, signed and numbered. E. P. Dutton issued 500 copies of which only 100 were signed by Milne.[2] The book is Milne’s best-selling work;[7] the author and literary critic John Rowe Townsend described Winnie-the-Pooh and its sequel The House at Pooh Corner as «the spectacular British success of the 1920s» and praised its light, readable prose.[8]

Contemporary reviews of the book were generally positive. A review in The Elementary English Review reviewed the book positively, describing it as containing «delightful nonsense» and «unbelievably funny» illustrations.[9] In 2003, Winnie the Pooh was listed at number 7 on the BBC’s survey The Big Read, a survey of the British public to determine their favourite books.[10] In 2012 it was ranked number 26 on a list of the top 100 children’s novels published by School Library Journal.[11]

Analysis

Townsend describes Milne’s Pooh works as being «as totally without hidden significance as anything written.» In 1963 Frederick Crews published The Pooh Perplex, a satire of literary criticism that contains essays by fake authors on Winnie-the-Pooh.[8] The book is introduced as trying to make sense of «one of the greatest books ever written» on the meaning of which «nobody can quite agree».[12] Crews’ book had a chilling effect on any substantive analysis of the book, particularly for the ten years following its publication.[13]

Although Winnie-the-Pooh was published shortly after the end of the First World War, it takes place in a isolated world free from major issues, which scholar Paula T. Connolly describes as «largely Edenic» and later as an Arcadia standing in stark contrast to the world in which the book was created. She goes on to describe the book as nostalgic for a «rural and innocent world». The book was published towards the end of an era when writing fantasy works for children was very popular, sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Children’s Literature.[14]

In Alison Lurie’s 1990 essay on Winnie-the-Pooh, she argues that its popularity, despite its simplicity, comes from its «universal appeal» to people who find themselves at a «social disadvantage,» and gives kids as one obvious example of this. The power and wise status that Christopher Robin receives, she claims, also appeals to children. Lurie draws a parallel from the setting of an environment that feels small and is devoid of aggression, with most of the activities involving exploring, to Milne’s childhood, which he spent at a small suburban same-sex school. In addition, the rural backdrop without cars and roads is similar to his life as a child in Essex and Kent, before the start of the 20th century. She argues that the characters have widespread appeal because they draw from Milne’s own life, and contain common feelings and personalities found in childhood, such as gloominess (Eeyore) and shyness (Piglet).[13]

In Carol Stranger’s feminist analysis of the book, she criticises this idea, arguing that, since every character other than Kanga is male, Lurie must believe that the «male experience is universal.» The main critique, however, that Stranger levels is that Kanga, the only female character and the mother of Roo, is consistently made out as negative and a bad mother, citing a passage in which Kanga mistakes Piglet for Roo and threatens to put soap in his mouth if he resists taking a cold bath. This, she claims, forces female readers either to identify themselves with Kanga, and «call up the dependency, the pain, vulnerability and disappointment» many babies feel towards their caregivers, or to identify with the male characters, and see Kanga as cruel. She also notes that Christopher Robin’s mother is mentioned only in the dedication.[15]

Translations

The work has been translated into 72 languages,[16] including Afrikaans, Czech, Finnish and Yiddish.[1] The Latin translation by the Hungarian Lénárd Sándor (Alexander Lenard), Winnie ille Pu, was first published in 1958, and, in 1960, became the first foreign-language book to be featured on the New York Times Best Seller List, and the only book in Latin ever to have been featured therein.[17] It was also translated into Esperanto in 1972, by Ivy Kellerman Reed and Ralph A. Lewin, Winnie-La-Pu.[18] The work was featured in the iBooks app for Apple’s iOS as the «starter» book for the app.

Winnie-the-Pooh also received two Polish translations, which vastly differed in their interpretation of the work. Irena Tuwim published the first translation of the work in 1938, titled Kubuś Puchatek. This version prioritized adopting Polish language and culture over a direct translation, which was well received by readers.[19] The second translation, titled Fredzia Phi-Phi, was published by Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska in 1986. Adamczyk-Garbowska’s version was more faithful to the original text, but was widely criticized by Polish readers and scholars, including Robert Stiller and Stanisław Lem.[19] Lem harshly described Tuwim’s easy-to-read translation as being «castrated» by Adamczyk-Garbowska.[19] The titular character’s new Polish name, Fredzia Phi-Phi, also drew criticism from readers who assumed Adamczyk-Garbowska had changed Pooh’s gender by using a female name.[20][21][22] Many of the new character names were also seen as being overly complicated compared to Tuwim’s version.[19] Adamczyk-Garbowska defended her translation, stating that she simply wanted to convey Milne’s linguistic subtleties that were not present in the first translation.[20]

Legacy

In 2018, five works of original art from the book sold for £917,500, including a map of the Hundred Acre Wood that sold for £430,000 and set a record for the most expensive book illustration.[23]

Sequels

Milne and Shepard went on to collaborate on two more books: Now We Are Six (1927) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928).[1] Now We Are Six is a poetry volume like When We Were Very Young, and includes some poetry about Winnie-the-Pooh. The House at Pooh Corner is a second volume of stories about Pooh, and introduces the character Tigger.[1] Milne never wrote another Pooh book, and died in 1956. Penguin Books has called When We Were Very Young, Winnie-the-Pooh, Now We Are Six, and The House At Pooh Corner «the basis of the entire Pooh canon.»[1]

The first authorized Pooh book after Milne’s death was Return to the Hundred Acre Wood in 2009, by David Benedictus. It was written with the full backing of Milne’s estate, which took the trustees ten years to agree to.[24] In the story, a new character, Lottie the Otter, is introduced.[25] The illustrations are by Mark Burgess.[26] The next authorized sequel, The Best Bear in All The World, was published in 2016 by Egmont.[27] It was written by Paul Bright, Jeanne Willis, Kate Saunders and Brian Sibley with illustrations again by Mark Burgess. The four authors each wrote a short story about one of the seasons: Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall.[28][29]

Adaptations

Following The Walt Disney Company’s licensing of certain rights to Pooh from Stephen Slesinger and the A. A. Milne Estate in the 1960s, the Milne storylines were used by Disney in its cartoon featurette Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree.[30] The «look» of Pooh was adapted by Disney from Stephen Slesinger’s distinctive American Pooh with his famous red shirt that had been created and used in commerce by Slesinger since the 1930s.[31]

Parts of the book were adapted to three Russian-language short animated films directed by Fyodor Khitruk: Winnie-the-Pooh (based on chapter 1), Winnie-the-Pooh Pays a Visit (based on chapter 2), and Winnie-the-Pooh and a Busy Day (based on chapters 4 and 6).[32]

In 2022, Jagged Edge Prodictions announced that a horror film starring the character was put in production, and is set for release on February 15, 2023.[33]

Passage into the public domain

Winnie-the-Pooh‘s entrance into the public domain in the United States on January 1, 2022 was noted by several news publications, generally in the context of a greater Public Domain Day article.[34][35][36][37] The book entered the public domain in Canada in 2007.[38][39][40] The UK copyright will expire at the end of 2026, the 70th year since Milne’s death.

See also

- Woozle effect

- List of Winnie-the-Pooh characters

- Public domain in the United States

- Winnie the Pooh (franchise), a media franchise produced by The Walt Disney Company, based on A. A. Milne and E. H. Shepard’s original Winnie-the-Pooh books.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m «A Short History of Winnie-the-Pooh». Penguin Group. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015.

- ^ a b Olsson, Mary (29 June 2020). «The Story Behind A.A. Milne’s Pooh Books». Bauman Rare Books. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Yarbrough, Wynn William (2011). Masculinity in children’s animal stories, 1888–1928 : a critical study of anthropomorphic tales by Wilde, Kipling, Potter, Grahame and Milne. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7864-5943-8. OCLC 689522274.

- ^ «A Real Pooh Timeline». The New York Public Library. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Ross Kilpatrick, «Winnie the Pooh and the Canadian Connection», Queens Quarterly (105/5)

- ^ Shanahan, Noreen (25 March 2012). «From Vergil to Winnie-the-Pooh, Ross Kilpatrick had wide-ranging interests». Globe and Mail. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Connolly 1995, p. xiv.

- ^ a b Townsend, John Rowe (1 May 1996). Written for Children: An Outline of English-Language Children’s Literature. Scarecrow Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-1-4617-3104-7.

- ^ Murdoch, Clarissa (1927). «Review of Winnie-The-Pooh». The Elementary English Review. 4 (1): 30. ISSN 0888-1030. JSTOR 41382198.

- ^ «The Big Read», BBC, April 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2013

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (7 July 2012). «Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results». A Fuse #8 Production. Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com).

- ^ Crews 1965, p. iv.

- ^ a b Lurie, Alison (1990). Don’t tell the grown-ups: subversive children’s literature. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 144–155. ISBN 978-0-316-53722-3 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Connolly 1995, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Stanger, Carol A. (1987). «Winnie The Pooh Through a Feminist Lens». The Lion and the Unicorn. 11 (2): 34–50. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0299. ISSN 1080-6563. S2CID 144046525.

- ^ «Winnie-the-Pooh prequel celebrates Sussex locations». Sussex World. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ McDowell, Edwin (18 November 1984). «‘Winnie Ille Pu’ Nearly XXV Years Later». The New York Times. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ (Milne), Reed and Lewin, trs., Winnie-La-Pooh, foreword by Humphrey Tonkin (Dutton), 1972, 2nd edition UEA, Rotterdam, 1992.

- ^ a b c d Misior-Mroczkowska, Aleksandra (2016). «The Fuss about the Pooh: On Two Polish Translations of a Story about a Little Bear». Styles of Communication. University of Bucharest Publishing House. 8: 28–36.

- ^ a b Reaves, Joseph A. (17 September 1989). «Poland’s New Pooh Spills Honey of a Controversy». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Poland switches sexes on Winnie-the-Pooh». United Press International. 31 December 1986. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Legierska, Anna (11 April 2017). «Od Kubusia Puchatka do Andersena: polskie przekłady baśni świata». Culture.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 6 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Original 1926 Winnie-the-Pooh map sells for record £430,000». BBC News. 10 July 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ «First new Winnie-the-Pooh book in 80 years goes on sale». The Daily Telegraph. 5 October 2009. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ «New friend joins Winnie-the-Pooh». 30 September 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Flood, Alison (10 January 2009). «After 90 years, Pooh returns to Hundred Acre Wood in sequel». The Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ «Egmont Reveals the Four Writers of the Next Winnie-the-Pooh Sequel: The Best Bear in All the World» (Press release). Egmont. 24 November 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016.

- ^ Flood, Alison (19 September 2016). «Winnie-the-Pooh makes friends with a penguin to mark anniversary». The Guardian. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Pequenino, Karla (14 October 2016). «Winnie-the-Pooh gets a new friend». CNN. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (7 April 1966). «A Disney Package: Don’t Miss the Short». The New York Times. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Sauer, Patrick (6 November 2017). «How Winnie-the-Pooh Became a Household Name». Smithsonian. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ Fessenden, Marissa. «Russia Has Its Own Classic Version of an Animated Winnie-the-Pooh». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Ritman, Alex (4 November 2022). «How an Online Frenzy Lit a Fuse Under Microbudget Slasher ‘Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey’«. The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (1 January 2022). «‘Winnie the Pooh,’ Hemingway’s ‘The Sun Also Rises’ and 400,000 Sound Recordings Enter the Public Domain». Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ «Winnie-the-Pooh, Bambi among works entering public domain in 2022». KSTU. 2 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ «Public Domain Day 2022». Duke University School of Law. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hiltzik, Michael (3 January 2022). «Column: ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ (born 1926) is now in the public domain, a reminder that our copyright system is absurd». Los Angeles Times.

- ^ «Winnie the Pooh in the public domain». Copibec. 7 January 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

Even though the copyright on Winnie-the-Pooh expired only this year in the U.S., the book actually entered the public domain in Canada 15 years ago (2007), which was 50 years after Milne’s death in 1956.

- ^ «How Winnie-the-Pooh highlights flaws in U.S. copyright law — and what that could mean for Canada». CBC. CBC Radio. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Hugh Stephens (17 January 2022). «Winnie the Pooh, the Public Domain and Winnie’s Canadian Connection». Hugh Stephens Blog. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

Bibliography

- Crews, Frederick C. (1965). The Pooh perplex : a freshman casebook. New York : Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-47160-8.

- Connolly, Paula T. (1995). Winnie-the-Pooh and The house at Pooh corner. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-8810-5.

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Winnie-the-Pooh at Standard Ebooks

- Winnie-the-Pooh at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Winnie-the-Pooh at Internet Archive

Winnie-the-Pooh public domain audiobook at LibriVox

На самом деле, автор у книги есть, даже 2. Первый, кто написал Винни Пуха – Милн, а к нам книга пришла благодаря Заходеру, случайно увидевшему оригинальное произведение и решившему его перевести.

Кто написал английского Винни Пуха

Автор оригинальной сказки про Винни Пуха – Алан Александр Милн. Это английский писатель, родившийся в 1882 году в Лондоне. Его отец был хозяином частной школы, а сам мальчик учился у Герберта Уэллса. В годы Первой Мировой Войны Милн был на фронте, служил офицером. А в 1920 году у него появился сын – Кристофер Робин. Именно для него писатель написал серию сказок про медвежонка. В качестве прототипа медведя автор использовал образ плюшевого медвежонка Кристофера, а мальчик стал прототипом самого себя. Кстати, медведя Кристофера звали Эдуардом – как полное имя «Тедди», плюшевого медвежонка, но потом он переименовал и назвал знакомым именем персонажа книги, в честь медведицы из местного зоопарка. Остальные герои – тоже игрушки Кристофера, купленные ему отцом в подарок, или подаренные соседями, как Пятачок. У ослика, кстати, действительно не было хвоста. Его оторвал Кристофер во время игр.

Милн написал свою сказку в 1925 году и опубликовал ее в 1926, хотя сам образ мишутки появился 21 августа 1921 года, в первый день рождения сына. После этой книги было еще множество произведений, но ни одно из них не стало столь популярным, как история про мишку.

Кто написал русского Винни Пуха

13 июля 1960 года была подписана в печать русская версия Винни Пуха. А в 1958 году в журнале «Мурзилка» впервые вышел рассказ о «Мишке-Плюхе». Ктоже написал русского Винни Пуха? Детский писатель и переводчик Борис Заходер. Именно этому автору принадлежат переводы истории про мишку «с опилками в голове». Естественно, это был не просто перевод, а адаптация образа английских персонажей на советский лад. Еще автор добавил образности речи герою. В оригинале, конечно, не было сопелок, кричалок и пыхтелок. Причем в первом варианте книга называлась «Винни Пух и все остальные», а потом уже она приобрела привычное нам имя «Винни Пух и все-все-все». Интересно, что главное детское издательство страны отказалось печатать эту сказку, поэтому автор обратился в новое издательство «Детский мир», которое впоследствии и стало первым ее издателем. Иллюстрации рисовали различные художники. Один из них, Виктор Чижиков, нарисовал еще одного известного мишку – олимпийского. К слову, на первый гонорар, полученный от выпуска книги, Заходер купил «Москвич».

Советский мультфильм

Сценаристом советского мультика, естественно, был Борис Заходер. Федор Хитрук выступал в роли постановщика. Работа над мультфильмом началась в конце 1960-х годов. В экранизацию вошло 3 серии, хотя изначально планировалось нарисовать все главы книги. Произошло это из-за того, что Заходер и Хитрук не смогли договориться о том, как должен выглядеть конечный результат. Например, русский автор не хотел изображать главного персонажа как толстого медвежонка, ведь оригинальная игрушка была худой. Не был он согласен и с характером героя, который, по его мнению, должен быть поэтическим, а не веселым прыгающим и глуповатым. А Хитрук захотел снять обычную детскую историю про веселых зверей. Главного персонажа озвучивал Евгений Леонов, пятачка – Ия Саввина, а ослика – Эраст Гарин, музыку для песенки Винни пуха написал Моисей Вайнберг. Сценарий мультфильма несколько отличался от книги, хотя и максимально к ней приближен, но именно 20 фраз из сценария вошли в разговорную речь советских зрителей, и используются до сих пор как старым, так и новым поколением.

Диснеевский мультфильм

В 1929 году Милн продал права на использование образа Винни Пуха продюсеру Стивену Слезингеру. Тот выпустил несколько спектаклей на пластинках, а после его смерти, в 1961 году, вдова продюсера перепродала его Диснеевской студии. Студия выпустила несколько серий мультика по книге, а дальше занялась самостоятельным творчеством, придумывая сценарий «от себя». Это очень не понравилось семье Милна, потому что они считали, что ни сюжет, ни даже стиль мультсериала не передают дух книги. Но благодаря этой экранизации, образ Винни Пуха стал популярным во всем мире, и сейчас его используют наравне с Микки Маусом и другими диснеевскими героями.

Популярность в мире

Популярность рассказа и его персонажей не угасают. Сборник рассказов переведен на десятки языков. В Оксфордшире до сих пор проводят чемпионат по «Пустякам» — участники кидают палочки в воду и следят за тем, чья приплыла до финиша первой. А в честь главного персонажа названо несколько улиц по всему миру. Памятники этому медведю стоят в центре Лондона, в зоопарке и в Подмосковье. Изображают Винни Пуха и на марках, причем не только наших стран, но и еще 16. А оригинальные игрушки, с которых были описаны герои и по сей день хранятся в музее США, но Великобритания пытается забрать их на родину.

Кто написал Винни Пуха

- История создания сказки

- Советский Винни Пух

- Отличительные черты советского и оригинального Винни Пуха

- Интересные и неизвестные факты о Пухе

Многие смотрели мультфильм или читали сказку в плюшевом медведе. Но далеко не каждый знает, кто первый написал историю, известную детям и взрослым.

Человек, создавший повесть, желал войти в историю серьезным писателем. Им создан цикл стихотворений и повестей, но каждый человек ассоциирует его имя с милым медведем из плюша, голова которого набита опилками.

История создания сказки

Алан Александр Милн подарил миру историю о приключениях Винни Пуха. Сказку английский писатель сочинил для собственного сына, который также стал одним из главных героев – Кристофером Робином.

Почти все персонажи истории имели прототипы в реальном мире. Плюшевые игрушки мальчика носили имена схожие с теми, что у медвежонка и его друзей.

Главный герой истории назван в честь медведицы, проживавшей в 1924 году на территории зоопарка в Лондоне. За три года до посещения отцом и сыном зоопарка малыш получил в подарок на день рождения плюшевого зверя. До эпохальной встречи Кристофер Робин так и не смог подобрать ему подходящее имя.

Называли медведя из плюша, как принято в Англии, просто Тедди. Познакомившись с лондонской медведицей, Кристофер Робин принял решение назвать своего игрушечного друга Винни.

Любящий папа регулярно радовал сына новыми игрушками. Так у Винни Пуха появлялись друзья. Поросенка, которого назвали Пяточком, принесли мальчику соседи. Реальных прототипов нет только у Кролика и Совы. Их Милн придумал, чтобы развивать ход событий в истории.

Начало книги – написание первой главы – произошло в 1925 году под Рождество. С этого и началась счастливая жизнь плюшевого медвежонка Винни и его верных друзей. Продолжается она и в настоящее время.

Английский писатель создал про медведя два сборника стихотворений и 2 прозаические книги. Последние Милн посвятил собственной супруге.

Рассуждая о том, кто написал Винни Пуха, нельзя оставить без внимания еще одного человека, который играет важную роль. Это художник, работавший в редакции журнала «Панч». Эрнест Шепард выступил в роли соавтора. Художник-карикатурист создал образы игрушечных героев повести такими, какими видят их современные дети и взрослые.

Книга о приключениях медвежонка и его друзей пользуется огромной популярностью, потому что история напоминает те рассказы, которые слышит ребенок от мамы и папы, ложась в постель.

В семье Милна сына окружали заботой и любовью, он рос в особой атмосфере. Каждая страница книги пропитана ей.

Одной из основных причин популярности повести о медведе является стиль изложения. Книга пестрит каламбурами, забавными фразеологизмами и пародиями. История приходится по душе взрослым и детям во всем мире.

Книга о Винни Пухе уникальна. Лучшие писатели из разных уголков света переводили ее, чтобы их сограждане смогли познакомиться с плюшевым медведем и окунуться в удивительный мир.

Советский Винни Пух

Впервые переведенная на русский язык история о медвежонке и его друзьях появилась в Литве. Произошло событие в 1958 году. Двумя годами позже повесть перевел Борис Заходер. Именно его перевод получил огромную популярность.

Однажды в библиотеке писатель просматривал английскую энциклопедию. В книге увидел изображение плюшевого героя сказки Милна. Повесть о приключениях медведя Винни и его друзей заинтересовала советского писателя, что он решил пересказать сказку, созданную англичанином.

Заходер постоянно говорил о том, что не стремился сделать перевод дословным. Скорее история представляет собой вольный пересказ, переосмысление оригинальной версии. Именно Заходер добавил разные сопелки, шумелки, пыхтелки, вопелки и кричалки, благодаря которым советские зрители так полюбили знаменитого Пуха.

Отличительные черты советского и оригинального Винни Пуха

Чем отличается оригинальный Винни Пух от советского? Борис Заходер иначе подошел к переводу истории. Основные отличия двух повестей состоят в следующем:

- По версии Милна медвежонок из плюша имел «маленькие мозги», а советский Винни Пух весело распевал песенку о том, что в его голове содержатся опилки;

- Имя главного героя Заходером несколько изменено. В оригинальной версии персонаж назывался Winnie-the-Pooh. При дословном переводе с английского языка это означает Винни-Фу. Незвучное имя героя не прижилось в переводной версии, Борис Заходер назвал медвежонка Винни Пух. Название схоже с транслитерацией. Кристофер Робин подзывал к себе лебедей, говоря «пух». Поэтому такое название отлично вписалось в историю;

- Имена других героев мультика в оригинальном варианте звучали тоже иначе. Пятачок в английской версии — Поросенок, ослик Иа у Милна именовался Eeyore. Другие персонажи истории сохранили имена, данные автором.

- Кардинальные отличия наблюдаются между советским мультфильмом и английской книгой. По версии создателя Винни Пух – игрушка Кристофера Робина. А в телевизионной версии – медвежонок самостоятельный персонаж.

- В советском мультфильме Пух не носит одежду, а в оригинальном варианте – одет в кофточку.

- Количество героев тоже различается. У Милна в повести присутствуют Тигра, Кенга и ее малыш Ру. В советском мультике эти герои отсутствуют.

Отличий между версией Заходера и Милна много. Но несмотря на это, дети и взрослые одинаково любят мультфильмы, созданные компанией Дисней и Хитруком.

Интересные и неизвестные факты о Пухе

Число 18 символично для плюшевого медведя. Ежегодно 18 января празднуется его день рождения. Дата не случайна – она совпадает с именинами английского писателя, придумавшего эту историю для сына. В оригинальной версии повести ровно 18 глав.

Еще интересные факты о Винни Пухе:

- Созданное Милном произведение вошло в историю английской литературы. В 2017 году книга, повествующая о приключениях Винни Пуха и его друзей, стала самой продаваемой в мире. Она переведена на десятки языков и отпечатана на каждом из них.

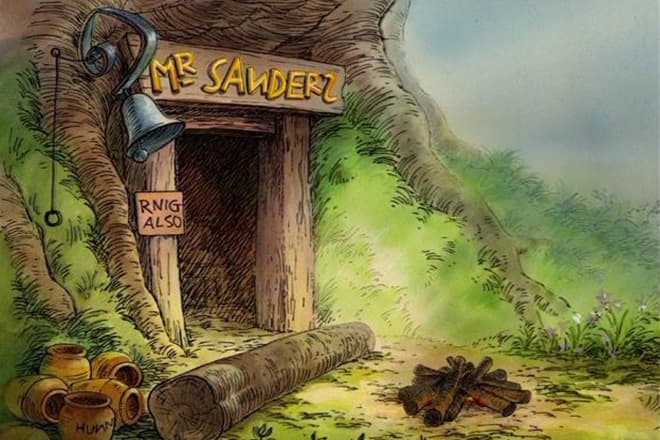

- В диснеевском мультике можно увидеть табличку над дверью домика Винни Пуха, на которой написано «Мистер Сандерс». На самом деле это не фамилия главного героя повести Милна. Согласно истории, медвежонок слишком ленив, чтобы сменить табличку, оставшуюся от предыдущего хозяина дома.

- Суслика автор добавил в повесть не сразу. Этот герой впервые упоминается с 1977 года. В оригинальной версии книги персонажа не существует. Создатели диснеевского мультфильма добавили суслика. Он стал одним из героев мультипликационного сериала с названием «Новые приключения Винни Пуха».

- Места, про которые говорится в книге, можно посетить в реальной жизни. Знаменитый Дремучий лес имеет реальный прототип – лес, расположенный неподалеку от загородного дома английского писателя.

- Отправившись в публичную библиотеку, расположенную в Нью-Йорке, можно своими глазами увидеть настоящие игрушки сына Алана Александра Милна. В коллекции присутствуют все персонажи истории, кроме крошки Ру. В 1930 году Кристофер Робин потерял игрушку.

- Советская версия мультика максимально раскрывает смысл оригинальной версии повести. Экранизация английской книги компанией Дисней сильно изменила историю о Винни Пухе. Бренд плюшевого медвежонка также популярен как Микки Маус или Плуто.

- Каждый год в Оксфордшире проходит чемпионат по «Пустякам». Эта игра взята из оригинального варианта повести. Герой книги бросал в воду палочки и наблюдал, какая из них доберется быстрее до определенной точки. Развлечение прижилось.

Винни Пух – интересный и уникальный герой. Создавая истории для собственного сына, Милн не предполагал, что его сказки перескажут не только многие писатели, но и обычные родители.