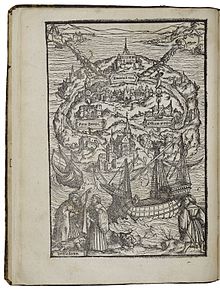

Illustration for the 1516 first edition of Utopia |

|

| Author | Thomas More |

|---|---|

| Original title | Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia |

| Translator | Ralph Robinson Gilbert Burnet |

| Illustrator | Ambrosius Holbein |

| Country | Habsburg Netherlands |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Political philosophy, satire |

| Publisher | More |

|

Publication date |

1516 |

|

Published in English |

1551 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 359 |

| OCLC | 863744174 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

335.02 |

| LC Class | HX810.5 .E54 |

| Preceded by | A Merry Jest |

| Followed by | Latin Poems |

|

Original text |

Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia at Latin Wikisource |

| Translation | Utopia at Wikisource |

Utopia (Latin: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia,[1] «A little, true book, not less beneficial than enjoyable, about how things should be in a state and about the new island Utopia») is a work of fiction and socio-political satire by Thomas More (1478–1535), written in Latin and published in 1516. The book is a frame narrative primarily depicting a fictional island society and its religious, social and political customs. Many aspects of More’s description of Utopia are reminiscent of life in monasteries.[2]

Title[edit]

The title De optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia literally translates, «Of a republic’s best state and of the new island Utopia».

It is variously rendered as any of the following:

- On the Best State of a Republic and on the New Island of Utopia

- Concerning the Highest State of the Republic and the New Island Utopia

- On the Best State of a Commonwealth and on the New Island of Utopia

- Concerning the Best Condition of the Commonwealth and the New Island of Utopia

- On the Best Kind of a Republic and About the New Island of Utopia

- About the Best State of a Commonwealth and the New Island of Utopia

The first created original name was even longer: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia. That translates, «A truly golden little book, no less beneficial than entertaining, of a republic’s best state and of the new island Utopia».

Utopia is derived from the Greek prefix «ou-» (οὔ), meaning «not», and topos (τόπος), «place», with the suffix -iā (-ίᾱ) that is typical of toponyms; the name literally means «nowhere», emphasizing its fictionality. In early modern English, Utopia was spelled «Utopie», which is today rendered Utopy in some editions.[3]

In fact, More’s very first name for the island was Nusquama, the Latin equivalent of «no-place», but he eventually opted for the Greek-influenced name.[4]

In English, Utopia is pronounced the same as Eutopia (the latter word, in Greek Εὐτοπία [Eutopiā], meaning “good place,” contains the prefix εὐ- [eu-], «good», with which the οὔ of Utopia has come to be confused in the English pronunciation).[5] That is something that More himself addresses in an addendum to his book: Wherfore not Utopie, but rather rightely my name is Eutopie, a place of felicitie.[a][7]

Contents[edit]

Preliminary matter[edit]

The first edition contained a woodcut map of the island of Utopia, the Utopian alphabet, verses by Pieter Gillis, Gerard Geldenhouwer, and Cornelius Grapheus, and Thomas More’s epistle dedicating the work to Gillis.[8]

Book 1: Dialogue of Counsel[edit]

The work begins with written correspondence between Thomas More and several people he had met in Europe: Peter Gilles, town clerk of Antwerp, and Hieronymus van Busleyden, counselor to Charles V. More chose those letters, which are communications between actual people, to further the plausibility of his fictional land. In the same spirit, the letters also include a specimen of the Utopian alphabet and its poetry. The letters also explain the lack of widespread travel to Utopia; during the first mention of the land, someone had coughed during announcement of the exact longitude and latitude. The first book tells of the traveller Raphael Hythlodaeus, to whom More is introduced in Antwerp, and it also explores the subject of how best to counsel a prince, a popular topic at the time.

The first discussions with Raphael allow him to discuss some of the modern ills affecting Europe such as the tendency of kings to start wars and the subsequent loss of money on fruitless endeavours. He also criticises the use of execution to punish theft by saying that thieves might as well murder whom they rob, to remove witnesses, if the punishment is going to be the same. He lays most of the problems of theft on the practice of enclosure, the enclosing of common land, and the subsequent poverty and starvation of people who are denied access to land because of sheep farming.

More tries to convince Raphael that he could find a good job in a royal court to advise monarchs, but Raphael says that his views are too radical and would not be listened to. Raphael sees himself in the tradition of Plato: he knows that for good governance, kings must act philosophically. He, however, points out:

Plato doubtless did well foresee, unless kings themselves would apply their minds to the study of philosophy, that else they would never thoroughly allow the council of philosophers, being themselves before, even from their tender age, infected and corrupt with perverse and evil opinions.

More seems to contemplate the duty of philosophers to work around and in real situations and, for the sake of political expediency, work within flawed systems to make them better, rather than hoping to start again from first principles.

… for in courts they will not bear with a man’s holding his peace or conniving at what others do: a man must barefacedly approve of the worst counsels and consent to the blackest designs, so that he would pass for a spy, or, possibly, for a traitor, that did but coldly approve of such wicked practices.

Book 2: Discourse on Utopia[edit]

| Utopia | |

|---|---|

| Utopia location | |

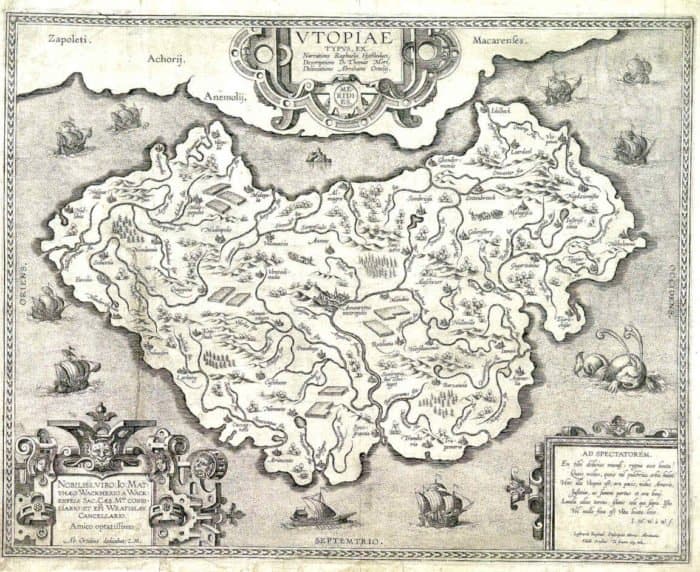

Map by Ortelius, ca. 1595. |

|

| Created by | Thomas More |

| Genre | Utopian fiction |

| In-universe information | |

| Other name(s) | Abraxa (former name) |

| Type | Republic/elective monarchy |

| Ruler | Prince (a.k.a. ademus) |

| Location | New World |

| Locations | Amaurot (capital), Anyder River |

Utopia is placed in the New World and More links Raphael’s travels in with Amerigo Vespucci’s real life voyages of discovery. He suggests that Raphael is one of the 24 men Vespucci, in his Four Voyages of 1507, says he left for six months at Cabo Frio, Brazil. Raphael then travels farther and finds the island of Utopia, where he spends five years observing the customs of the natives.

According to More, the island of Utopia is

…two hundred miles across in the middle part, where it is widest, and nowhere much narrower than this except towards the two ends, where it gradually tapers. These ends, curved round as if completing a circle five hundred miles in circumference, make the island crescent-shaped, like a new moon.[9]

The island was originally a peninsula but a 15-mile wide channel was dug by the community’s founder King Utopos to separate it from the mainland. The island contains 54 cities. Each city is divided into four equal parts. The capital city, Amaurot, is located directly in the middle of the crescent island.

Each city has not more than 6000 households, each family consisting of between 10 and 16 adults. Thirty households are grouped together and elect a Syphograntus (whom More says is now called a phylarchus). Every ten Syphogranti have an elected Traniborus (more recently called a protophylarchus) ruling over them. The 200 Syphogranti of a city elect a Prince in a secret ballot. The Prince stays for life unless he is deposed or removed for suspicion of tyranny.

People are redistributed around the households and towns to keep numbers even. If the island suffers from overpopulation, colonies are set up on the mainland. Alternatively, the natives of the mainland are invited to be part of the Utopian colonies, but if they dislike them and no longer wish to stay, they may return. In the case of underpopulation, the colonists are recalled.

There is no private property on Utopia, with goods being stored in warehouses and people requesting what they need. There are also no locks on the doors of the houses, and the houses are rotated between the citizens every ten years. Agriculture provides the most important occupation on the island. Every person is taught it and must live in the countryside, farming for two years at a time, with women doing the same work as men. Parallelly, every citizen must learn at least one of the other essential trades: weaving (mainly done by the women), carpentry, metalsmithing and masonry. There is deliberate simplicity about the trades; for instance, all people wear the same types of simple clothes, and there are no dressmakers making fine apparel. All able-bodied citizens must work; thus, unemployment is eradicated, and the length of the working day can be minimized: the people have to work only six hours a day although many willingly work for longer. More does allow scholars in his society to become the ruling officials or priests, people picked during their primary education for their ability to learn. All other citizens, however, are encouraged to apply themselves to learning in their leisure time.

Slavery is a feature of Utopian life, and it is reported that every household has two slaves. The slaves are either from other countries (prisoners of war, people condemned to die, or poor people) or are the Utopian criminals. The criminals are weighed down with chains made out of gold. The gold is part of the community wealth of the country, and fettering criminals with it or using it for shameful things like chamber pots gives the citizens a healthy dislike of it. It also makes it difficult to steal, as it is in plain view. The wealth, though, is of little importance and is good only for buying commodities from foreign nations or bribing the nations to fight each other. Slaves are periodically released for good behaviour. Jewels are worn by children, who finally give them up as they mature.

Other significant innovations of Utopia include a welfare state with free hospitals, euthanasia permissible by the state, priests being allowed to marry, divorce permitted, premarital sex punished by a lifetime of enforced celibacy and adultery being punished by enslavement. Meals are taken in community dining halls and the job of feeding the population is given to a different household in turn. Although all are fed the same, Raphael explains that the old and the administrators are given the best of the food. Travel on the island is permitted only with an internal passport, and any people found without a passport are, on a first occasion, returned in disgrace, but after a second offence, they are placed in slavery. In addition, there are no lawyers, and the law is made deliberately simple, as all should understand it and not leave people in any doubt of what is right and wrong.

There are several religions on the island: moon-worshipers, sun-worshipers, planet-worshipers, ancestor-worshipers and monotheists, but each is tolerant of the others. Only atheists are despised (but allowed) in Utopia, as they are seen as representing a danger to the state: since they do not believe in any punishment or reward after this life, they have no reason to share the communistic life of Utopia and so will break the laws for their own gain. They are not banished, but are encouraged to talk out their erroneous beliefs with the priests until they are convinced of their error. Raphael says that through his teachings Christianity was beginning to take hold in Utopia. The toleration of all other religious ideas is enshrined in a universal prayer all the Utopians recite.

…but, if they are mistaken, and if there is either a better government, or a religion more acceptable to God, they implore His goodness to let them know it.

Wives are subject to their husbands and husbands are subject to their wives although women are restricted to conducting household tasks for the most part. Only few widowed women become priests. While all are trained in military arts, women confess their sins to their husbands once a month. Gambling, hunting, makeup and astrology are all discouraged in Utopia. The role allocated to women in Utopia might, however, have been seen as being more liberal from a contemporary point of view.

Utopians do not like to engage in war. If they feel countries friendly to them have been wronged, they will send military aid, but they try to capture, rather than kill, enemies. They are upset if they achieve victory through bloodshed. The main purpose of war is to achieve what over which, if they had achieved already, they would not have gone to war.

Privacy is not regarded as freedom in Utopia; taverns, ale houses and places for private gatherings are nonexistent for the effect of keeping all men in full view and so they are obliged to behave well.

Framework[edit]

The story is written from the perspective of More himself. That was common at the time, and More uses his own name and background to create the narrator.[10] The book is written in two parts: “Book one: Dialogue of Council,” and “Book two: Discourse on Utopia.”

The first book is told from the perspective of More, the narrator, who is introduced by his friend Peter Giles to a fellow traveller named Raphael Hythloday, whose name translates as “expert of nonsense” in Greek. In an amicable dialogue with More and Giles, Hythloday expresses strong criticism of then-modern practices in England and other Catholicism-dominated countries, such as the crime of theft being punishable by death, and the over-willingness of kings to start wars (Getty, 321).

Book two has Hythloday tell his interlocutors about Utopia, where he has lived for five years, with the aim of convincing them about its superior state of affairs. Utopia turns out to be a socialist state. Interpretations about this important part of the book vary. Gilbert notes that while some experts[who?] believe that More supports socialism, others believe that he demonstrates a belief that socialism is impractical. The former would argue that More used book two to show how socialism would work in practice: individual cities are run by privately elected princes and families are made up of ten to sixteen adults living in a single household. It is unknown if More truly believed in socialism, or if he printed Utopia to argue that true socialism was impractical (Gilbert). More printed many writings involving socialism, some seemingly in defense of it and others apparently scathing satires against it. Some scholars believe that More uses the structure to show the perspective of something as an idea against something put into practice. Hythloday describes the city as perfect and ideal, and believes the society thrives and is perfect. As such, he is used to represent the more fanatic socialists and radical reformists of his day. When More arrives he describes the social and cultural norms put into practice, citing a city thriving and idealistic. While some believe that is More’s ideal society, some believe the book’s title, which translates to “Nowhere” from Greek, is a way to describe that the practices used in Utopia are impractical and could not be used in a modern world successfully (Gilbert). Either way, Utopia has become one of the most talked about works both in defense of socialism and against it.

Interpretation[edit]

One of the most troublesome questions about Utopia is Thomas More’s reason for writing it. Most scholars see it as a comment on or criticism of 16th-century Catholicism since the evils of More’s day are laid out in Book I and in many ways apparently solved in Book II.[11] Indeed, Utopia has many of the characteristics of satire, and there are many jokes and satirical asides such as how honest people are in Europe, but these are usually contrasted with the simple, uncomplicated society of the Utopians.

Yet, the puzzle is that some of the practices and institutions of the Utopians, such as the ease of divorce, euthanasia and both married priests and female priests, seem to be polar opposites of More’s beliefs and the teachings of the Catholic Church of which he was a devout member.[12] Another often cited[by whom?] apparent contradiction is that of the religious tolerance of Utopia contrasted with his alleged persecution of Protestants as Lord Chancellor.[citation needed] Similarly, the criticism of lawyers comes from a writer who, as Lord Chancellor, was arguably the most influential lawyer in England. It can be answered, however, that as a pagan society Utopians had the best ethics that could be reached through reason alone, or that More changed from his early life to his later when he was Lord Chancellor.[11]

One highly influential interpretation of Utopia is that of the intellectual historian Quentin Skinner.[13] He has argued that More was taking part in the Renaissance humanist debate over true nobility, and that he was writing to prove the perfect commonwealth could not occur with private property. Crucially, Skinner sees Raphael Hythlodaeus as embodying the Platonic view that philosophers should not get involved in politics, but the character of More embodies the more pragmatic Ciceronian view. Thus, the society Raphael proposes is the ideal that More would want. However, without communism, which he saw no possibility of occurring, it was wiser to take a more pragmatic view.

Quentin Skinner’s interpretation of Utopia is consistent with the speculation that Stephen Greenblatt made in The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. There, Greenblatt argued that More was under the Epicurean influence of Lucretius’s On the Nature of Things and the people that live in Utopia were an example of how pleasure has become their guiding principle of life.[14] Although Greenblatt acknowledged that More’s insistence on the existence of an afterlife and punishment for people holding contrary views were inconsistent with the essentially materialist view of Epicureanism, Greenblatt contended that it was the minimum conditions for what the pious More would have considered as necessary to live a happy life.[14]

Another complication comes from the Greek meanings of the names of people and places in the work. Apart from Utopia, meaning «Noplace,» several other lands are mentioned: Achora meaning «Nolandia», Polyleritae meaning «Muchnonsense», Macarenses meaning «Happiland,» and the river Anydrus meaning «Nowater». Raphael’s last name, Hythlodaeus means «dispenser of nonsense» surely implying that the whole of the Utopian text is ‘nonsense’. Additionally the Latin rendering of More’s name, Morus, is similar to the word for a fool in Greek (μωρός). It is unclear whether More is simply being ironic, an in-joke for those who know Greek, seeing as the place he is talking about does not actually exist or whether there is actually a sense of distancing of Hythlodaeus’ and the More’s («Morus») views in the text from his own.

The name Raphael, though, may have been chosen by More to remind his readers of the archangel Raphael who is mentioned in the Book of Tobit (3:17; 5:4, 16; 6:11, 14, 16, 18; also in chs. 7, 8, 9, 11, 12). In that book the angel guides Tobias and later cures his father of his blindness. While Hythlodaeus may suggest his words are not to be trusted, Raphael meaning (in Hebrew) «God has healed» suggests that Raphael may be opening the eyes of the reader to what is true. The suggestion that More may have agreed with the views of Raphael is given weight by the way he dressed; with «his cloak… hanging carelessly about him», a style that Roger Ascham reports that More himself was wont to adopt. Furthermore, more recent criticism has questioned the reliability of both Gile’s annotations and the character of «More» in the text itself. Claims that the book only subverts Utopia and Hythlodaeus are possibly oversimplistic.

In Humans and Animals in Thomas More’s Utopia, Christopher Burlinson argues that More intended to produce a fictional space in which ethical concerns of humanity and bestial inhumanity could be explored.[15] Burlinson regards the Utopian criticisms of finding pleasure in the spectacle of bloodshed as reflective of More’s own anxieties about the fragility of humanity and the ease in which humans fall to beast-like ways.[15] According to Burlinson, More interprets that decadent expression of animal cruelty as a causal antecedent for the cruel intercourse present within the world of Utopia and More’s own.[15] Burlinson does not argue that More explicitly equates animal and human subjectivities, but is interested in More’s treatment of human-animal relations as significant ethical concerns intertwined with religious ideas of salvation and the divine qualities of souls.[15]

In Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World, Jack Weatherford asserts that native American societies played an inspirational role for More’s writing. For example, indigenous Americans, although referred to as «noble savages» in many circles, showed the possibility of living in social harmony [with nature] and prosperity without the rule a king…». The early British and French settlers in the 1500 and 1600s were relatively shocked to see how the native Americans moved around so freely across the untamed land, not beholden by debt, «lack of magistrates, forced services, riches, poverty or inheritance».[16] Arthur Morgan hypothesized that Utopia was More’s description of the Inca Empire, although it is implausible that More was aware of them when he wrote the book.[17]

In Utopian Justifications: More’s Utopia, Settler Colonialism, and Contemporary Ecocritical Concerns, Susan Bruce juxtaposes Utopian justifications for the violent dispossession of idle peoples unwilling to surrender lands that are underutilized with Peter Kosminsky’s The Promise, a 2011 television drama centered around Zionist settler colonialism in modern-day Palestine.[18] Bruce’s treatment of Utopian foreign policy, which mirrored European concerns in More’s day, situates More’s text as an articulation of settler colonialism.[18] Bruce identifies an isomorphic relationship between Utopian settler logic and the account provided by The Promise’s Paul, who recalls his father’s criticism of Palestinians as undeserving, indolent, and animalistic occupants of the land.[18] Bruce interprets the Utopian fixation with material surplus as foundational for exploitative gift economies, which ensnare Utopia’s bordering neighbors into a subservient relationship of dependence in which they remain in constant fear of being subsumed by the superficially generous Utopians.[18]

Reception[edit]

Utopia was begun while More was an envoy in the Low Countries in May 1515. More started by writing the introduction and the description of the society that would become the second half of the work, and on his return to England, he wrote the «dialogue of counsel». He completed the work in 1516. In the same year, it was printed in Leuven under Erasmus’s editorship and after revisions by More it was printed in Basel in November 1518. It was not until 1551, sixteen years after More’s execution, that it was first published in England as an English translation by Ralph Robinson. Gilbert Burnet’s translation of 1684 is probably the most commonly cited version.

The work seems to have been popular, if misunderstood, since the introduction of More’s Epigrams of 1518 mentions a man who did not regard More as a good writer.

Influence[edit]

The word ‘utopia’, invented by Moore as the name of his fictional island and used as the title of his book, has since entered the English language to describe any imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect. Also, the antonym ‘dystopia’ for an imagined state of suffering or injustice, derives from utopia.

Although he may not have directly founded the contemporary notion of what has since become known as Utopian and dystopian fiction, More certainly popularised the idea of imagined parallel realities, and some of the early works that owe a debt to Utopia must include The City of the Sun by Tommaso Campanella, Description of the Republic of Christianopolis by Johannes Valentinus Andreae, New Atlantis by Francis Bacon and Candide by Voltaire.

Utopian socialism was used to describe the first concepts of socialism, but later Marxist theorists tended to see the ideas as too simplistic and not grounded on realistic principles.[citation needed] The religious message in the work and its uncertain, possibly satiric, tone has also alienated some theorists from the work.[citation needed]

An applied example of More’s Utopia can be seen in Vasco de Quiroga’s implemented society in Michoacán, Mexico, which was directly inspired by More’s work.

During the opening scene in the film A Man for All Seasons, Utopia is mentioned in a conversation. The alleged amorality of England’s priests is compared to that of the more highly principled behaviour of the fictional priests in More’s Utopia when a character observes wryly that «every second person born in England is fathered by a priest.»

In 2006, the artist Rory Macbeth inscribed all 40,000 words on the side of an old electricity factory in Norwich, England.[19]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Felicitie means «happiness».[6]

References[edit]

- ^ BAKER-SMITH, DOMINIC (2000). More’s Utopia. University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442677395. ISBN 9781442677395. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442677395.

- ^ J. C. Davis (28 July 1983). Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516–1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-27551-4.

- ^ «utopia: definition of utopia in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)». Archived from the original on 19 December 2012.

- ^ FROM DREAMLAND «HUMANISM» TO CHRISTIAN POLITICAL REALITY OR FROM «NUSQUAMA» TO «UTOPIA» https://www.jstor.org/stable/44806868?seq=1

- ^ John Wells. «John Wells’s phonetic blog». www.phon.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ «felicity | Origin and meaning of felicity by Online Etymology Dictionary». www.etymonline.com.

- ^ More’s Utopia: The English Translation thereof by Raphe Robynson. second edition, 1556, «Eutopism».

- ^ Paniotova, Taissia Sergeevna (2016). «The Real and The Fantastic in Utopia by Thomas More». Valla. 2 (4–5): 48–54. ISSN 2412-9674.

- ^ More, Thomas (2002). George M. Logan; Robert M. Adams; Raymond Geuss; Quentin Skinner (eds.). Utopia (Revised ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81925-3.

- ^ Baker-Smith, Dominic. «Thomas More.» The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2014 Edition, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/thomas-more/.

- ^ a b Manuel and Manuel (1979). Utopian Thought in the Western World.

- ^ Huddleston, Gilbert. «St. Thomas More.» The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 10 Sept. 2018 www.newadvent.org/cathen/14689c.htm.

- ^ Pagden. The Languages of Political Theory in Early Modern Europe. pp. 123–157.

- ^ a b Greenblatt, Stephen. «Chapter 10: Swerves». The Swerve: How the World Became Modern.

- ^ a b c d Burlinson, Christopher (2008). «Humans and Animals in Thomas More’s Utopia». Utopian Studies. 19 (1): 25–47. doi:10.5325/utopianstudies.19.1.0025. ISSN 1045-991X. JSTOR 20719890. S2CID 150207061.

- ^ Weatherford, Jack (1988). Indian Givers:How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World. ISBN 0-449-90496-2.

- ^ Donner, H. W. (1 July 1949). «Review of Nowhere was Somewhere. How History Makes Utopias and How Utopias Make History by Arthur E. Morgan». The Review of English Studies. os–XXV (99): 259–261. doi:10.1093/res/os-XXV.99.259.

- ^ a b c d Bruce, Susan (2015). «Utopian Justifications: More’s Utopia, Settler Colonialism, and Contemporary Ecocritical Concerns». College Literature. 42 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1353/lit.2015.0009. ISSN 1542-4286.

- ^ Saunt, Raven (16 January 2019). «Do you know the real story behind one of Norwich’s most noticeable graffiti works?». Norwich Evening News. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- More, Thomas (1516/1967), «Utopia», trans. John P. Dolan, in James J. Greene and John P. Dolan, edd., The Essential Thomas More, New York: New American Library.

- Sullivan, E. D. S. (editor) (1983) The Utopian Vision: Seven Essays on the Quincentennial of Sir Thomas More San Diego State University Press, San Diego, California, ISBN 0-916304-51-5

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- The Open Utopia A complete edition (including all of the letters and commendations, as well as the marginal notes, that were included in the first four printings of 1516–18) translated in 2012. Licensed as Creative Commons BY-SA and published in multiple electronic formats (HTML, PDF, TXT, ODF, EPUB, and as a Social Book).

- English translation of Utopia by Gilbert Burnet at Project Gutenberg

Utopia public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Thomas More and his Utopia by Karl Kautsky

- Andre Schuchardt: Freiheit und Knechtschaft. Die dystopische Utopia des Thomas Morus. Eine Kritik am besten Staat

- «Utopia» . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Utopia – Images photocopied the 1518 edition of Utopia, from the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library

- Utopia 2016, a commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the book centered in London.

Illustration for the 1516 first edition of Utopia |

|

| Author | Thomas More |

|---|---|

| Original title | Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia |

| Translator | Ralph Robinson Gilbert Burnet |

| Illustrator | Ambrosius Holbein |

| Country | Habsburg Netherlands |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Political philosophy, satire |

| Publisher | More |

|

Publication date |

1516 |

|

Published in English |

1551 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 359 |

| OCLC | 863744174 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

335.02 |

| LC Class | HX810.5 .E54 |

| Preceded by | A Merry Jest |

| Followed by | Latin Poems |

|

Original text |

Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia at Latin Wikisource |

| Translation | Utopia at Wikisource |

Utopia (Latin: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia,[1] «A little, true book, not less beneficial than enjoyable, about how things should be in a state and about the new island Utopia») is a work of fiction and socio-political satire by Thomas More (1478–1535), written in Latin and published in 1516. The book is a frame narrative primarily depicting a fictional island society and its religious, social and political customs. Many aspects of More’s description of Utopia are reminiscent of life in monasteries.[2]

Title[edit]

The title De optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia literally translates, «Of a republic’s best state and of the new island Utopia».

It is variously rendered as any of the following:

- On the Best State of a Republic and on the New Island of Utopia

- Concerning the Highest State of the Republic and the New Island Utopia

- On the Best State of a Commonwealth and on the New Island of Utopia

- Concerning the Best Condition of the Commonwealth and the New Island of Utopia

- On the Best Kind of a Republic and About the New Island of Utopia

- About the Best State of a Commonwealth and the New Island of Utopia

The first created original name was even longer: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia. That translates, «A truly golden little book, no less beneficial than entertaining, of a republic’s best state and of the new island Utopia».

Utopia is derived from the Greek prefix «ou-» (οὔ), meaning «not», and topos (τόπος), «place», with the suffix -iā (-ίᾱ) that is typical of toponyms; the name literally means «nowhere», emphasizing its fictionality. In early modern English, Utopia was spelled «Utopie», which is today rendered Utopy in some editions.[3]

In fact, More’s very first name for the island was Nusquama, the Latin equivalent of «no-place», but he eventually opted for the Greek-influenced name.[4]

In English, Utopia is pronounced the same as Eutopia (the latter word, in Greek Εὐτοπία [Eutopiā], meaning “good place,” contains the prefix εὐ- [eu-], «good», with which the οὔ of Utopia has come to be confused in the English pronunciation).[5] That is something that More himself addresses in an addendum to his book: Wherfore not Utopie, but rather rightely my name is Eutopie, a place of felicitie.[a][7]

Contents[edit]

Preliminary matter[edit]

The first edition contained a woodcut map of the island of Utopia, the Utopian alphabet, verses by Pieter Gillis, Gerard Geldenhouwer, and Cornelius Grapheus, and Thomas More’s epistle dedicating the work to Gillis.[8]

Book 1: Dialogue of Counsel[edit]

The work begins with written correspondence between Thomas More and several people he had met in Europe: Peter Gilles, town clerk of Antwerp, and Hieronymus van Busleyden, counselor to Charles V. More chose those letters, which are communications between actual people, to further the plausibility of his fictional land. In the same spirit, the letters also include a specimen of the Utopian alphabet and its poetry. The letters also explain the lack of widespread travel to Utopia; during the first mention of the land, someone had coughed during announcement of the exact longitude and latitude. The first book tells of the traveller Raphael Hythlodaeus, to whom More is introduced in Antwerp, and it also explores the subject of how best to counsel a prince, a popular topic at the time.

The first discussions with Raphael allow him to discuss some of the modern ills affecting Europe such as the tendency of kings to start wars and the subsequent loss of money on fruitless endeavours. He also criticises the use of execution to punish theft by saying that thieves might as well murder whom they rob, to remove witnesses, if the punishment is going to be the same. He lays most of the problems of theft on the practice of enclosure, the enclosing of common land, and the subsequent poverty and starvation of people who are denied access to land because of sheep farming.

More tries to convince Raphael that he could find a good job in a royal court to advise monarchs, but Raphael says that his views are too radical and would not be listened to. Raphael sees himself in the tradition of Plato: he knows that for good governance, kings must act philosophically. He, however, points out:

Plato doubtless did well foresee, unless kings themselves would apply their minds to the study of philosophy, that else they would never thoroughly allow the council of philosophers, being themselves before, even from their tender age, infected and corrupt with perverse and evil opinions.

More seems to contemplate the duty of philosophers to work around and in real situations and, for the sake of political expediency, work within flawed systems to make them better, rather than hoping to start again from first principles.

… for in courts they will not bear with a man’s holding his peace or conniving at what others do: a man must barefacedly approve of the worst counsels and consent to the blackest designs, so that he would pass for a spy, or, possibly, for a traitor, that did but coldly approve of such wicked practices.

Book 2: Discourse on Utopia[edit]

| Utopia | |

|---|---|

| Utopia location | |

Map by Ortelius, ca. 1595. |

|

| Created by | Thomas More |

| Genre | Utopian fiction |

| In-universe information | |

| Other name(s) | Abraxa (former name) |

| Type | Republic/elective monarchy |

| Ruler | Prince (a.k.a. ademus) |

| Location | New World |

| Locations | Amaurot (capital), Anyder River |

Utopia is placed in the New World and More links Raphael’s travels in with Amerigo Vespucci’s real life voyages of discovery. He suggests that Raphael is one of the 24 men Vespucci, in his Four Voyages of 1507, says he left for six months at Cabo Frio, Brazil. Raphael then travels farther and finds the island of Utopia, where he spends five years observing the customs of the natives.

According to More, the island of Utopia is

…two hundred miles across in the middle part, where it is widest, and nowhere much narrower than this except towards the two ends, where it gradually tapers. These ends, curved round as if completing a circle five hundred miles in circumference, make the island crescent-shaped, like a new moon.[9]

The island was originally a peninsula but a 15-mile wide channel was dug by the community’s founder King Utopos to separate it from the mainland. The island contains 54 cities. Each city is divided into four equal parts. The capital city, Amaurot, is located directly in the middle of the crescent island.

Each city has not more than 6000 households, each family consisting of between 10 and 16 adults. Thirty households are grouped together and elect a Syphograntus (whom More says is now called a phylarchus). Every ten Syphogranti have an elected Traniborus (more recently called a protophylarchus) ruling over them. The 200 Syphogranti of a city elect a Prince in a secret ballot. The Prince stays for life unless he is deposed or removed for suspicion of tyranny.

People are redistributed around the households and towns to keep numbers even. If the island suffers from overpopulation, colonies are set up on the mainland. Alternatively, the natives of the mainland are invited to be part of the Utopian colonies, but if they dislike them and no longer wish to stay, they may return. In the case of underpopulation, the colonists are recalled.

There is no private property on Utopia, with goods being stored in warehouses and people requesting what they need. There are also no locks on the doors of the houses, and the houses are rotated between the citizens every ten years. Agriculture provides the most important occupation on the island. Every person is taught it and must live in the countryside, farming for two years at a time, with women doing the same work as men. Parallelly, every citizen must learn at least one of the other essential trades: weaving (mainly done by the women), carpentry, metalsmithing and masonry. There is deliberate simplicity about the trades; for instance, all people wear the same types of simple clothes, and there are no dressmakers making fine apparel. All able-bodied citizens must work; thus, unemployment is eradicated, and the length of the working day can be minimized: the people have to work only six hours a day although many willingly work for longer. More does allow scholars in his society to become the ruling officials or priests, people picked during their primary education for their ability to learn. All other citizens, however, are encouraged to apply themselves to learning in their leisure time.

Slavery is a feature of Utopian life, and it is reported that every household has two slaves. The slaves are either from other countries (prisoners of war, people condemned to die, or poor people) or are the Utopian criminals. The criminals are weighed down with chains made out of gold. The gold is part of the community wealth of the country, and fettering criminals with it or using it for shameful things like chamber pots gives the citizens a healthy dislike of it. It also makes it difficult to steal, as it is in plain view. The wealth, though, is of little importance and is good only for buying commodities from foreign nations or bribing the nations to fight each other. Slaves are periodically released for good behaviour. Jewels are worn by children, who finally give them up as they mature.

Other significant innovations of Utopia include a welfare state with free hospitals, euthanasia permissible by the state, priests being allowed to marry, divorce permitted, premarital sex punished by a lifetime of enforced celibacy and adultery being punished by enslavement. Meals are taken in community dining halls and the job of feeding the population is given to a different household in turn. Although all are fed the same, Raphael explains that the old and the administrators are given the best of the food. Travel on the island is permitted only with an internal passport, and any people found without a passport are, on a first occasion, returned in disgrace, but after a second offence, they are placed in slavery. In addition, there are no lawyers, and the law is made deliberately simple, as all should understand it and not leave people in any doubt of what is right and wrong.

There are several religions on the island: moon-worshipers, sun-worshipers, planet-worshipers, ancestor-worshipers and monotheists, but each is tolerant of the others. Only atheists are despised (but allowed) in Utopia, as they are seen as representing a danger to the state: since they do not believe in any punishment or reward after this life, they have no reason to share the communistic life of Utopia and so will break the laws for their own gain. They are not banished, but are encouraged to talk out their erroneous beliefs with the priests until they are convinced of their error. Raphael says that through his teachings Christianity was beginning to take hold in Utopia. The toleration of all other religious ideas is enshrined in a universal prayer all the Utopians recite.

…but, if they are mistaken, and if there is either a better government, or a religion more acceptable to God, they implore His goodness to let them know it.

Wives are subject to their husbands and husbands are subject to their wives although women are restricted to conducting household tasks for the most part. Only few widowed women become priests. While all are trained in military arts, women confess their sins to their husbands once a month. Gambling, hunting, makeup and astrology are all discouraged in Utopia. The role allocated to women in Utopia might, however, have been seen as being more liberal from a contemporary point of view.

Utopians do not like to engage in war. If they feel countries friendly to them have been wronged, they will send military aid, but they try to capture, rather than kill, enemies. They are upset if they achieve victory through bloodshed. The main purpose of war is to achieve what over which, if they had achieved already, they would not have gone to war.

Privacy is not regarded as freedom in Utopia; taverns, ale houses and places for private gatherings are nonexistent for the effect of keeping all men in full view and so they are obliged to behave well.

Framework[edit]

The story is written from the perspective of More himself. That was common at the time, and More uses his own name and background to create the narrator.[10] The book is written in two parts: “Book one: Dialogue of Council,” and “Book two: Discourse on Utopia.”

The first book is told from the perspective of More, the narrator, who is introduced by his friend Peter Giles to a fellow traveller named Raphael Hythloday, whose name translates as “expert of nonsense” in Greek. In an amicable dialogue with More and Giles, Hythloday expresses strong criticism of then-modern practices in England and other Catholicism-dominated countries, such as the crime of theft being punishable by death, and the over-willingness of kings to start wars (Getty, 321).

Book two has Hythloday tell his interlocutors about Utopia, where he has lived for five years, with the aim of convincing them about its superior state of affairs. Utopia turns out to be a socialist state. Interpretations about this important part of the book vary. Gilbert notes that while some experts[who?] believe that More supports socialism, others believe that he demonstrates a belief that socialism is impractical. The former would argue that More used book two to show how socialism would work in practice: individual cities are run by privately elected princes and families are made up of ten to sixteen adults living in a single household. It is unknown if More truly believed in socialism, or if he printed Utopia to argue that true socialism was impractical (Gilbert). More printed many writings involving socialism, some seemingly in defense of it and others apparently scathing satires against it. Some scholars believe that More uses the structure to show the perspective of something as an idea against something put into practice. Hythloday describes the city as perfect and ideal, and believes the society thrives and is perfect. As such, he is used to represent the more fanatic socialists and radical reformists of his day. When More arrives he describes the social and cultural norms put into practice, citing a city thriving and idealistic. While some believe that is More’s ideal society, some believe the book’s title, which translates to “Nowhere” from Greek, is a way to describe that the practices used in Utopia are impractical and could not be used in a modern world successfully (Gilbert). Either way, Utopia has become one of the most talked about works both in defense of socialism and against it.

Interpretation[edit]

One of the most troublesome questions about Utopia is Thomas More’s reason for writing it. Most scholars see it as a comment on or criticism of 16th-century Catholicism since the evils of More’s day are laid out in Book I and in many ways apparently solved in Book II.[11] Indeed, Utopia has many of the characteristics of satire, and there are many jokes and satirical asides such as how honest people are in Europe, but these are usually contrasted with the simple, uncomplicated society of the Utopians.

Yet, the puzzle is that some of the practices and institutions of the Utopians, such as the ease of divorce, euthanasia and both married priests and female priests, seem to be polar opposites of More’s beliefs and the teachings of the Catholic Church of which he was a devout member.[12] Another often cited[by whom?] apparent contradiction is that of the religious tolerance of Utopia contrasted with his alleged persecution of Protestants as Lord Chancellor.[citation needed] Similarly, the criticism of lawyers comes from a writer who, as Lord Chancellor, was arguably the most influential lawyer in England. It can be answered, however, that as a pagan society Utopians had the best ethics that could be reached through reason alone, or that More changed from his early life to his later when he was Lord Chancellor.[11]

One highly influential interpretation of Utopia is that of the intellectual historian Quentin Skinner.[13] He has argued that More was taking part in the Renaissance humanist debate over true nobility, and that he was writing to prove the perfect commonwealth could not occur with private property. Crucially, Skinner sees Raphael Hythlodaeus as embodying the Platonic view that philosophers should not get involved in politics, but the character of More embodies the more pragmatic Ciceronian view. Thus, the society Raphael proposes is the ideal that More would want. However, without communism, which he saw no possibility of occurring, it was wiser to take a more pragmatic view.

Quentin Skinner’s interpretation of Utopia is consistent with the speculation that Stephen Greenblatt made in The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. There, Greenblatt argued that More was under the Epicurean influence of Lucretius’s On the Nature of Things and the people that live in Utopia were an example of how pleasure has become their guiding principle of life.[14] Although Greenblatt acknowledged that More’s insistence on the existence of an afterlife and punishment for people holding contrary views were inconsistent with the essentially materialist view of Epicureanism, Greenblatt contended that it was the minimum conditions for what the pious More would have considered as necessary to live a happy life.[14]

Another complication comes from the Greek meanings of the names of people and places in the work. Apart from Utopia, meaning «Noplace,» several other lands are mentioned: Achora meaning «Nolandia», Polyleritae meaning «Muchnonsense», Macarenses meaning «Happiland,» and the river Anydrus meaning «Nowater». Raphael’s last name, Hythlodaeus means «dispenser of nonsense» surely implying that the whole of the Utopian text is ‘nonsense’. Additionally the Latin rendering of More’s name, Morus, is similar to the word for a fool in Greek (μωρός). It is unclear whether More is simply being ironic, an in-joke for those who know Greek, seeing as the place he is talking about does not actually exist or whether there is actually a sense of distancing of Hythlodaeus’ and the More’s («Morus») views in the text from his own.

The name Raphael, though, may have been chosen by More to remind his readers of the archangel Raphael who is mentioned in the Book of Tobit (3:17; 5:4, 16; 6:11, 14, 16, 18; also in chs. 7, 8, 9, 11, 12). In that book the angel guides Tobias and later cures his father of his blindness. While Hythlodaeus may suggest his words are not to be trusted, Raphael meaning (in Hebrew) «God has healed» suggests that Raphael may be opening the eyes of the reader to what is true. The suggestion that More may have agreed with the views of Raphael is given weight by the way he dressed; with «his cloak… hanging carelessly about him», a style that Roger Ascham reports that More himself was wont to adopt. Furthermore, more recent criticism has questioned the reliability of both Gile’s annotations and the character of «More» in the text itself. Claims that the book only subverts Utopia and Hythlodaeus are possibly oversimplistic.

In Humans and Animals in Thomas More’s Utopia, Christopher Burlinson argues that More intended to produce a fictional space in which ethical concerns of humanity and bestial inhumanity could be explored.[15] Burlinson regards the Utopian criticisms of finding pleasure in the spectacle of bloodshed as reflective of More’s own anxieties about the fragility of humanity and the ease in which humans fall to beast-like ways.[15] According to Burlinson, More interprets that decadent expression of animal cruelty as a causal antecedent for the cruel intercourse present within the world of Utopia and More’s own.[15] Burlinson does not argue that More explicitly equates animal and human subjectivities, but is interested in More’s treatment of human-animal relations as significant ethical concerns intertwined with religious ideas of salvation and the divine qualities of souls.[15]

In Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World, Jack Weatherford asserts that native American societies played an inspirational role for More’s writing. For example, indigenous Americans, although referred to as «noble savages» in many circles, showed the possibility of living in social harmony [with nature] and prosperity without the rule a king…». The early British and French settlers in the 1500 and 1600s were relatively shocked to see how the native Americans moved around so freely across the untamed land, not beholden by debt, «lack of magistrates, forced services, riches, poverty or inheritance».[16] Arthur Morgan hypothesized that Utopia was More’s description of the Inca Empire, although it is implausible that More was aware of them when he wrote the book.[17]

In Utopian Justifications: More’s Utopia, Settler Colonialism, and Contemporary Ecocritical Concerns, Susan Bruce juxtaposes Utopian justifications for the violent dispossession of idle peoples unwilling to surrender lands that are underutilized with Peter Kosminsky’s The Promise, a 2011 television drama centered around Zionist settler colonialism in modern-day Palestine.[18] Bruce’s treatment of Utopian foreign policy, which mirrored European concerns in More’s day, situates More’s text as an articulation of settler colonialism.[18] Bruce identifies an isomorphic relationship between Utopian settler logic and the account provided by The Promise’s Paul, who recalls his father’s criticism of Palestinians as undeserving, indolent, and animalistic occupants of the land.[18] Bruce interprets the Utopian fixation with material surplus as foundational for exploitative gift economies, which ensnare Utopia’s bordering neighbors into a subservient relationship of dependence in which they remain in constant fear of being subsumed by the superficially generous Utopians.[18]

Reception[edit]

Utopia was begun while More was an envoy in the Low Countries in May 1515. More started by writing the introduction and the description of the society that would become the second half of the work, and on his return to England, he wrote the «dialogue of counsel». He completed the work in 1516. In the same year, it was printed in Leuven under Erasmus’s editorship and after revisions by More it was printed in Basel in November 1518. It was not until 1551, sixteen years after More’s execution, that it was first published in England as an English translation by Ralph Robinson. Gilbert Burnet’s translation of 1684 is probably the most commonly cited version.

The work seems to have been popular, if misunderstood, since the introduction of More’s Epigrams of 1518 mentions a man who did not regard More as a good writer.

Influence[edit]

The word ‘utopia’, invented by Moore as the name of his fictional island and used as the title of his book, has since entered the English language to describe any imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect. Also, the antonym ‘dystopia’ for an imagined state of suffering or injustice, derives from utopia.

Although he may not have directly founded the contemporary notion of what has since become known as Utopian and dystopian fiction, More certainly popularised the idea of imagined parallel realities, and some of the early works that owe a debt to Utopia must include The City of the Sun by Tommaso Campanella, Description of the Republic of Christianopolis by Johannes Valentinus Andreae, New Atlantis by Francis Bacon and Candide by Voltaire.

Utopian socialism was used to describe the first concepts of socialism, but later Marxist theorists tended to see the ideas as too simplistic and not grounded on realistic principles.[citation needed] The religious message in the work and its uncertain, possibly satiric, tone has also alienated some theorists from the work.[citation needed]

An applied example of More’s Utopia can be seen in Vasco de Quiroga’s implemented society in Michoacán, Mexico, which was directly inspired by More’s work.

During the opening scene in the film A Man for All Seasons, Utopia is mentioned in a conversation. The alleged amorality of England’s priests is compared to that of the more highly principled behaviour of the fictional priests in More’s Utopia when a character observes wryly that «every second person born in England is fathered by a priest.»

In 2006, the artist Rory Macbeth inscribed all 40,000 words on the side of an old electricity factory in Norwich, England.[19]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Felicitie means «happiness».[6]

References[edit]

- ^ BAKER-SMITH, DOMINIC (2000). More’s Utopia. University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442677395. ISBN 9781442677395. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442677395.

- ^ J. C. Davis (28 July 1983). Utopia and the Ideal Society: A Study of English Utopian Writing 1516–1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-27551-4.

- ^ «utopia: definition of utopia in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)». Archived from the original on 19 December 2012.

- ^ FROM DREAMLAND «HUMANISM» TO CHRISTIAN POLITICAL REALITY OR FROM «NUSQUAMA» TO «UTOPIA» https://www.jstor.org/stable/44806868?seq=1

- ^ John Wells. «John Wells’s phonetic blog». www.phon.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ «felicity | Origin and meaning of felicity by Online Etymology Dictionary». www.etymonline.com.

- ^ More’s Utopia: The English Translation thereof by Raphe Robynson. second edition, 1556, «Eutopism».

- ^ Paniotova, Taissia Sergeevna (2016). «The Real and The Fantastic in Utopia by Thomas More». Valla. 2 (4–5): 48–54. ISSN 2412-9674.

- ^ More, Thomas (2002). George M. Logan; Robert M. Adams; Raymond Geuss; Quentin Skinner (eds.). Utopia (Revised ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81925-3.

- ^ Baker-Smith, Dominic. «Thomas More.» The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2014 Edition, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/thomas-more/.

- ^ a b Manuel and Manuel (1979). Utopian Thought in the Western World.

- ^ Huddleston, Gilbert. «St. Thomas More.» The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 10 Sept. 2018 www.newadvent.org/cathen/14689c.htm.

- ^ Pagden. The Languages of Political Theory in Early Modern Europe. pp. 123–157.

- ^ a b Greenblatt, Stephen. «Chapter 10: Swerves». The Swerve: How the World Became Modern.

- ^ a b c d Burlinson, Christopher (2008). «Humans and Animals in Thomas More’s Utopia». Utopian Studies. 19 (1): 25–47. doi:10.5325/utopianstudies.19.1.0025. ISSN 1045-991X. JSTOR 20719890. S2CID 150207061.

- ^ Weatherford, Jack (1988). Indian Givers:How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World. ISBN 0-449-90496-2.

- ^ Donner, H. W. (1 July 1949). «Review of Nowhere was Somewhere. How History Makes Utopias and How Utopias Make History by Arthur E. Morgan». The Review of English Studies. os–XXV (99): 259–261. doi:10.1093/res/os-XXV.99.259.

- ^ a b c d Bruce, Susan (2015). «Utopian Justifications: More’s Utopia, Settler Colonialism, and Contemporary Ecocritical Concerns». College Literature. 42 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1353/lit.2015.0009. ISSN 1542-4286.

- ^ Saunt, Raven (16 January 2019). «Do you know the real story behind one of Norwich’s most noticeable graffiti works?». Norwich Evening News. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- More, Thomas (1516/1967), «Utopia», trans. John P. Dolan, in James J. Greene and John P. Dolan, edd., The Essential Thomas More, New York: New American Library.

- Sullivan, E. D. S. (editor) (1983) The Utopian Vision: Seven Essays on the Quincentennial of Sir Thomas More San Diego State University Press, San Diego, California, ISBN 0-916304-51-5

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- The Open Utopia A complete edition (including all of the letters and commendations, as well as the marginal notes, that were included in the first four printings of 1516–18) translated in 2012. Licensed as Creative Commons BY-SA and published in multiple electronic formats (HTML, PDF, TXT, ODF, EPUB, and as a Social Book).

- English translation of Utopia by Gilbert Burnet at Project Gutenberg

Utopia public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Thomas More and his Utopia by Karl Kautsky

- Andre Schuchardt: Freiheit und Knechtschaft. Die dystopische Utopia des Thomas Morus. Eine Kritik am besten Staat

- «Utopia» . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Utopia – Images photocopied the 1518 edition of Utopia, from the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library

- Utopia 2016, a commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the book centered in London.

Страна: Ангола

Год: 2000

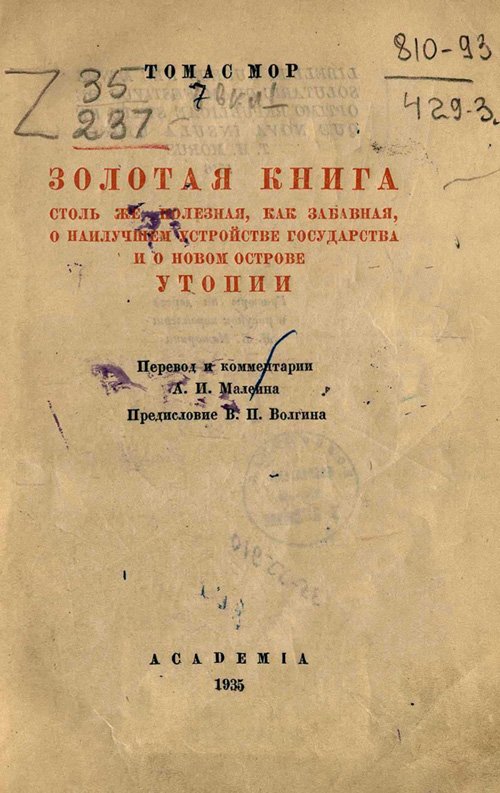

Одно из первых фантастических произведений в истории литературы написал не какой-нибудь щелкопер, а ближайший друг английского Генриха VIII, будущий лорд-канцлер Томас Мор. Как и многие писатели до и после него, Мор хотел в литературной форме описать казавшееся ему идеальным устройство государства. Для этого он придумал остров Утопия, затерянный где-то в Атлантическом океане.

Марка, изданная в серии «События тысячелетия». (личная коллекция автора)

Порядки государства, расположенного на этом острове, Мор записал якобы со слов путешественника Рафаэля Хитлодеуса, встреченного им в Антверпене. То, что там творилось, мало чем напоминало европейские страны. На острове царила демократия: почти все государственные должности были избираемыми. Правда, при этом страной правил несменяемый король. Все граждане были равны между собой. Правда, при этом существовали рабы, осужденные на неволю за собственные проступки. Утопийцы могли заниматься чем угодно. Правда, обязанностью являлся семичасовой ежедневный труд. Все религии были равны между собой. Правда, неверие в бога каралось изгнанием с острова. Денег на острове не существовало. Правда, непонятно чем платили наемной армии, к которой утопийцы прибегали в случае необходимости.

На все эти нестыковки Мор не обращал внимания — так нравилась автору выдуманная им страна. У Мора даже существовал гипотетический шанс воплотить свои мечты в жизнь: в 1529 году он стал лорд-канцлером Англии. Однако шанс этот остался нереализованным. Через три года писатель разошелся во взглядах на религию с другом детства, королем Генрихом, отправился сначала в отставку, а потом — в Тауэр. В 1535 году он был обезглавлен на плахе.

«Утопию» впервые напечатали в 1516 году на латыни, и вскоре она была переведена на несколько европейских языков. В Англии её издали лишь через 16 лет после казни автора. «Утопия» так и осталась лишь литературной фантастикой, а само название придуманного Мором острова стало означать нечто идеальное и недостижимое.

Приблизительное время чтения: 8 мин.

Не один и не два раза человечество в своей истории «штурмовало небо», пытаясь здесь, на Земле построить замену Небесному раю. Таких попыток в истории было на самом деле множество. Всякий раз из этого ничего не выходило, но каждая попытка по-своему поучительна. В нашем цикле “История идей, великих и ужасных”, посвященном истории человеческих попыток построить рай на Земле, рассказываем об итальянском ересиархе Дольчино, собиравшемся построить Царство Божие на земле с оружием.

Время и место действия

Англия, XVI век.

Почему нам это интересно сегодня

Слово «утопия», которое изобрел член парламента, помощник городского шерифа Лондона адвокат Томас Мор, дало имя не только литературному жанру, но и целому направлению общественно-политической мысли. Образовано оно из греческих слов «топос» (место) и «у» (нет) – «место, которого нет», или «Нигдея». Утопия – это дерзкое конструирование идеального общества, фантастика, претендующая на роль социального и нравственного маяка. Таким было «Государство» Платона. Такими станут труды последователей Мора — «Новая Атлантида» Бэкона, «Город Солнца» Томмазо Кампанеллы и многие другие сочинения.

Вслед за Платоном Томас Мор утверждал, что там, где существует частная собственность и все меряется деньгами, правильное течение государственных и общественных дел невозможно, что государство и люди могут быть счастливы, только если между ними будет имущественное равенство. Все должно быть общим, тогда незачем будет завидовать, стараться приобрести побольше, обманывать ближнего.

Но Мор пошел дальше Платона. Он впервые заговорил о коммунизме в масштабах уже всего общества, а не отдельных общин или сословий, и распространил его не только на сферу потребления, как Платон, но и на производство. Поэтому многие идеологи коммунизма именно Мора считали родоначальником современного социализма.

Главные действующие лица

Ганс Гольбейн Младший. Портрет Томаса Мора. 1527

Томас Мор (1478–1535) был не только знаменитым писателем, историком и выдающимся гуманистом эпохи позднего Возрождения, но и высокопоставленным вельможей. В 1529 году он даже стал лорд-канцлером Англии — вторым человеком в государстве после короля.

При этом Мор был глубоко верующим католиком. Казнили его за отказ признать законной церковную реформу, делавшую короля главой Церкви Англии, а также развод Генриха VIII с Екатериной Арагонской и его женитьбу на Анне Болейн. При дворе его противниками стали не только сторонники новой королевы, но и влиятельная партия главного министра Томаса Кромвеля, идеолога английской Реформации, чей потомок Оливер спустя столетие возглавит пуританскую парламентскую «революцию» и станет лордом-протектором – фактическим правителем страны.

Ганс Гольбейн Младший. Портрет Генриха VIII. Около 1539-1540

Мора арестовали и заключили в Тауэр, а 6 июля 1535 года он был обезглавлен. В 1886 году Римско-католическая церковь провозгласила его «блаженным мучеником», а в 1935 году, когда исполнилось 400 лет со дня его казни, папа Пий XI причислил его к лику святых.

Золотая книжечка

Обложка американского издания в 1997 году

Свой знаменитый труд Мор опубликовал в 1516 году под названием «Золотая книжечка, столь же полезная, сколь и забавная о наилучшем устройстве государства и о новом острове Утопия».

Первая часть книги — литературно-политический памфлет, беспощадная критика тогдашней Англии, например, практики огораживания, когда землевладельцы сгоняли крестьян с пахотных земель, чтобы можно было пасти там овец, шерсть которых тогда очень ценилась. Именно оттуда взят афоризм о том, что «в Англии овцы пожирают людей»:

«Ваши овцы, обычно такие кроткие, довольные очень немногим, теперь, говорят, стали такими прожорливыми и неукротимыми, что поедают даже людей, разоряют и опустошают поля, дома и города».

Карта «Утопии» работы Авраама Ортелиуса (14 апреля 1527 — 28 июня 1598), издателя и продавца карт. Он нарисовал ее для удовольствия своих друзей, чтобы снабдить их экземпляры «Утопий»

В первой книге Мор пишет о том, насколько несовершенна социальная и политическая система, критикует смертную казнь, законы о рабочих, иронически высмеивает несовершенства духовенства и предлагает программу реформ, призванных исправить положение.

А во второй части он приглашает читателя на таинственный вымышленный остров Утопия, где нет частной собственности, все общее, люди счастливы и живут в справедливости и довольстве.

Как устроена Утопия Мора

Книга написана в форме диалога, что позволило не отождествлять высказанные в ней коммунистические рецепты устроения общества с мнением самого Мора. Недаром некоторые ученые считают «Утопию» не непосредственным выражением мировоззрения Мора, а некой литературной игрой.

Об идеальном острове рассказывает в книге некий моряк-путешественник по имени Рафаил Гитлодей, якобы спутник самого Америго Веспуччи, попавший на Утопию во время одного из своих плаваний.

Там он обнаружил возглавляемую мудрым монархом федерацию 54 городов со столицей – городом Амауротом. Все островитяне жили в хороших трехэтажных похожих друг на друга домах, которыми менялись каждые 10 лет. С тыльной стороны к каждому дому примыкали прекрасные сады: как сказано в книге, ничему другому основатель идеального государства Утоп не уделял столько трудов, времени и внимания, как устройству этих садов. Это, вероятно, должно подчеркнуть райскую природу Утопии, ведь рай часто понимают как прекрасный сад.

Все люди на острове обязаны были трудиться — как мужчины, так и женщины. Все они занимались земледелием, попеременно проживая то в городе, то в деревне, а также обязаны были владеть еще хотя бы одним ремеслом. Работали утопийцы лишь шесть часов в день – три часа до обеда и после двухчасового перерыва еще три. В остальное время они занимались музыкой, а в предрассветные часы слушали научные лекции. В этом собственно и были цель и счастье их жизни — в свободном досуге и образовании:

«Очень часто также, когда не встречается надобности ни в какой подобной работе, государство объявляет меньшее количество рабочих часов. Власти отнюдь не хотят принуждать граждан к излишним трудам. Учреждение этой повинности имеет прежде всего только ту цель, чтобы обеспечить, насколько это возможно с точки зрения общественных нужд, всем гражданам наибольшее количество времени после телесного рабства для духовной свободы и образования. В этом, по их мнению, заключается счастье жизни».

Деньги использовались только для торговли с другими странами, монополия на которую принадлежала государству, а продукты между островитянами распределялись по потребностям.

Мор всячески подчеркивает разумность жизни и привычек утопийцев, их естественную склонность следовать разумному порядку. Их интересует суть вещей, а не то, как они выглядят. Поэтому, например, золото и серебро у них ценится ниже железа, ведь железо – гораздо более подходящий для разных хозяйственных нужд металл. Игрой в золотые украшения и драгоценные камни у утопийцев забавляются только дети.

Более того, из золота и серебра в его Утопии делают ночные горшки и цепи и кандалы для рабов. Да-да, в Утопии Мора есть и рабы, надо же кому-то выполнять грязные работы — до роботов и автоматики человеческая мысль тогда еще не дошла. Впрочем, с рабами утопийцы обращаются столь милостиво, что часто в них по собственной воле идут жители соседних народов, потому что рабство у утопийцев лучше, чем свободная жизнь за пределами Утопии.

Утопизм автора «Утопии»

Но именно в рационализме автора «Утопии» главная слабость его конструкции. Он совершенно не берет в расчет человеческую природу с ее неподвластными разуму страстями.

Мор считает, что стоит дать каждому причитающуюся ему долю естественных удовольствий, и люди станут счастливы. Но кто будет определять, какие удовольствия согласны с природой, а какие нет? Например, в «Утопии» верхняя одежда у всех одного цвета, поэтому незачем иметь по 4-6 платьев — так экономятся общественные усилия по шитью одежды.

«В результате этого у них каждый довольствуется одним платьем, и притом обычно на два года, в других же местах одному человеку не хватает четырех или пяти верхних шерстяных одежд, да еще разноцветных, а вдобавок требуется столько же шелковых рубашек, иным же неженкам мало и десяти. Для утопийца нет никаких оснований претендовать на большее количество платья: добившись его, он не получит большей защиты от холода, и его одежда не будет ни на волос наряднее других».

Но согласятся ли люди, особенно женщины, одеваться так рационально, безыскусно и разумно?

Интересные факты

1. Большим другом Томаса Мора был великий просветитель и деятель Возрождения Эразм Роттердамский, который посвятил ему свою знаменитую «Похвалу глупости», написанную в доме Мора в Лондоне. Восхищаясь Мором, Эразм в одном из своих писем задает риторический вопрос: «Создавала ли природа когда-либо что-нибудь более светлое, достойное любви, чем гений Томаса Мора»?

Ганс Гольбейн Младший. Портрет Эразма Роттердамского. 1523

2. В юности Мор вовсе не собирался посвятить всю жизнь юридической (довольно долго он был адвокатом) и государственной карьере и долго не мог сделать выбор между гражданской и церковной службой. Одно время он даже решил стать монахом и потом до конца жизни придерживался почти монашеского образа жизни с постоянными молитвами и постами. Однако политическое призвание взяло верх — в 1504 году Мор был избран в парламент, а в 1505 году женился.

Семья Томаса Мора (Портрет семьи Томаса Мора (копия с утраченной картины Ганса Гольбейна Младшего). Сэр Томас Мор, его отец, его семья и его потомки. 1593

3. Мор отстаивал необходимость образования женщин, что было крайне необычным для того времени. Он считал, что женщины столь же способны к наукам, как и мужчины, и настаивал, чтобы его дочери, как и его сын, получили высшее образование.

Эдвард Уорд. «Сэр Томас Мор прощается со своей дочерью»

4. Несмотря на признание мученического подвига Мора, к его «Утопии» Римско-католическая церковь благосклонна не была. Какое-то время книга была даже запрещена, а потом печаталась с купюрами. Действительно, в ней содержится осуждение и монашества как сословия бездельников, и изнуряющих тело постов. Конечно, искренне верующий в Бога Мор не отвергает религии, но одновременно рассуждает о «матери-природе» и ее «ласках», о том, что не стоит отвергать природные наслаждения, лишь бы они были в согласии с разумом. Более того, в его «Утопии» есть даже оправдание эвтаназии. Не удивительно, что некоторые католические авторы утверждают, что если бы Генрих не отрубил Мору голову, его, вполне возможно, сожгли бы по приговору папы.

Трейлер фильма о Томасе Море «Человек на все времена» (1966)

5. Русский перевод «Утопии» вышел почти одновременно с книгой А. Н. Радищева «Путешествие из Петербурга в Москву». Как отмечал советский историк и литературовед И. Н. Осиновский, это, по-видимому, «явления общественной мысли, органически близкие друг к другу. И, по понятным причинам, восприятие их русской читающей публикой было далеко не однозначным. С одной стороны, они вызывали интерес и сочувствие либерально настроенных читателей, с другой — содействовали усилению охранительных настроений и страха перед “французской заразой” у ярых приверженцев самодержавия».

:

Идеальное устройство острова Утопия, где упразднены деньги и частная собственность, а правителей выбирают граждане, противопоставляется европейским державам XVI века, где ведутся войны за чужие земли.

Книга начинается своеобразным вступлением — письмом Томаса Мора к другу Петру Эгидию с просьбой прочесть «Утопию» и написать, не ускользнули ли от Мора какие-то важные детали.

Первая книга

Повествование ведётся от лица Томаса Мора. Он прибывает во Фландрию в качестве посла и встречает там Петра. Тот знакомит друга с опытным мореплавателем Рафаилом, который много путешествовал. Рафаил, узнав множество обычаев и законов других стран, выделяет такие, которые можно использовать во благо в европейских государствах. Пётр советует мореплавателю употребить свои знания, устроившись на службу к государю советником, но тот не желает заниматься этим — цари много внимания уделяют военному делу и стремятся приобрести всё новые земли вместо того, чтобы заботится о своих собственных. Все советники, как правило, поддерживают в этом владыку, дабы не испортить свою репутацию и не впасть в немилость. Рафаил же осуждает войну и считает её бессмысленной. Мелкое воровство и убийство караются одинаково: смертной казнью. Богачи купаются в роскоши, проводя своё время в праздности, а простой люд тяжко работает, нищенствуя, что и способствует преступности.

Каждая держава считает нужным иметь армию и неограниченное количество золота для содержания войска, война же необходима хотя бы для того, чтобы дать опыт солдатам в резне.

Как истинный философ, Рафаил хочет говорить правду, поэтому стоит воздержаться от занятий государственными делами. Мореплаватель рассказывает о государстве, чьи обычаи и законы пришлись ему по душе.

Вторая книга

Остров Утопия назван в честь основателя этого государства, Утопа. На острове пятьдесят четыре города. Нравы, учреждения и законы везде одинаковы. Центром является город Амаурот. Поля равномерно распределены межу всеми областями. Городские и сельские жители каждые два года меняются местами: в деревни прибывают те семьи, которые ещё здесь не работали.

Амаурот окружён глубоким рвом, бойницами и башнями. Это чистый и красивый город. Возле каждого дома есть прекрасный сад. Частная собственность настолько упразднена, что каждые десять лет утопийцы по жребию меняют свои дома.

Каждые тридцать семейств выбирают себе филарха (или сифогранта), над десятью филархами и их семействами стоит протофиларх (или транибор). Все двести протофилархов выбирают князя, который руководит страной. Его избирают на всю жизнь. На других должностях лица меняются ежегодно.

Все мужчины и женщины в стране занимаются земледелием. Помимо этого каждый изучает какое-то ремесло, которое передаётся по наследству. Если кто-то тяготеет не к семейному делу, его переводят в семейство, которое занимается нужным ремеслом. Рабочий день длится шесть часов. Свободное время, как правило, посвящают наукам или своему делу. Наиболее усердные в науках продвигаются в разряд учёных. Из них выбирают духовенство, послов, траниборов и главу государства — адема.

Во время работы утопийцы одеты в шкуры, по улицам они ходят в плащах (крой и цвет одинаков на всём острове). У каждого одно платье на два года.

В семьях повинуются старейшему. Если города перенаселены, то граждан Утопии переселяют в колонии, и наоборот. В центре каждого города есть рынок, куда свозят товары и продовольствие. Там каждый может взять себе сколько нужно: всё имеется в достаточном изобилии. Во дворцах собирается вся сифогрантия для общественных обедов и ужинов.

Утопийцы могут перемещаться между городами с позволения траниборов и сифогрантов. За произвольное передвижение утопийца ждёт наказание, при повторном нарушении — рабство.

Всё необходимое в Утопии есть в таком количестве, что часть отдают малоимущим других стран, остальное продают. Деньги утопийцы используют только во внешней торговле и хранят на случай войны. Золото и серебро они презирают: в кандалы из этих металлов заковывают рабов, утопийцы им вообще не пользуются. Драгоценные камни служат детям игрушками. Взрослея, они оставляют их.

В науках и искусстве утопийцы достигли больших высот. Если у них гостят иностранцы, граждане Утопии детально знакомятся с их культурой и науками, быстро их постигают и развивают у себя.

Жизнь утопийцев состоит из добродетели и удовольствий тела и духа. Отношения строятся на честности и справедливости, граждане помогают слабым и заботятся о больных. Здоровье — одно из главных удовольствий, также ценится красота, сила и проворство.

В рабство обращают за позорное деяние утопийцев или приговорённых к казни представителей других народов. Труд рабов приносит больше пользы, чем казнь.

Тяжело больным даётся право прервать свои мучения: ведь жизнь — это удовольствие, такой поступок не считается грехом. Прелюбодеяние тяжко карается.

Утопийцы считают войну зверством, поэтому для победы, прежде всего, используют хитрость, подкуп приближённых государя-врага и так далее. Если этот метод не помогает, они делают ставку на военные сражения. Утопийцы нанимают иноземных солдат и щедро им платят. Своих граждан ставят лишь на руководящие должности. Они могут вступить в войну для защиты угнетённых народов, но никогда не допускают сражений на своих землях.