Музыка была всегда, она сопровождала человека на протяжении всего его существования: ритуальные обряды, досуг, религия, творчество и самовыражение не обходились без музыкального сопровождения. Менялись века, инструменты, речь, развивалась цивилизация, но музыка передавалась из поколения в поколения, претерпевая естественные изменения. Эти изменения были связаны не только с появлением новых музыкальных инструментов, но и с тем, что музыку никак не записывали, а запоминали «на слух», воспроизводя ее иногда очень приблизительно. Так как музыкальный слух исполнителя мог подвести его, то воспроизведение музыки было подобно «пересказу близко к тексту», что, конечно, вносило авторский «акцент», при этом оригинал мог измениться до неузнаваемости.

Сложность также заключалась в том, что при обучении исполнения определенной мелодии, требовалось много времени, и чаще всего было индивидуальным.

Первые шаги к нотной записи

Попытки записать мелодию предпринимались еще в Древнем Египте. Во времена Древнего и Среднего царства (IV-II вв. до н.э.) музыку записывали при помощи простейших рисунков (так называемая пиктографическая нотация).

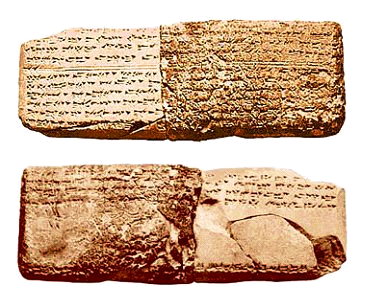

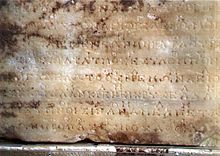

На территории современной Сирии во втором тысячелетии до нашей эры также существовала нотация в виде символов. В древнем городе Угарит была найдена глиняная табличка с музыкальными символами, расположенными горизонтально, слева направо, на хурритском языке (древний язык Сирии). Уникальность находки заключается не только в ее возрасте, но и в том, что ученым удалось расшифровать данные записи. Удивительно, что на табличке написаны отдельно музыка и слова, а также подробная инструкция о том, как совмещать их. Найденный материал посвящался жене бога Луны и назывался «Гимн Никале».

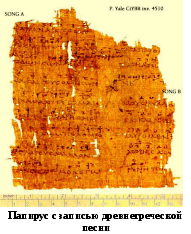

Музыкальное наследие Древней Греции удалось обнаружить на каменных колоннах и гробницах. Археологи обнаружили на месте раскопок древнегреческого города каменные пластины, относящиеся ко II в. до н.э., на которых были высечены гимны Аполлону. Их отличительной особенностью были символы, располагающиеся между строками гимнов, именно они и являются самыми ранними партитурами в культуре Древней Греции. Также образцы древнегреческих записей музыкальных произведений были найдены на папирусах, плохо сохранившихся и представляющих собой лишь кусочки записей.

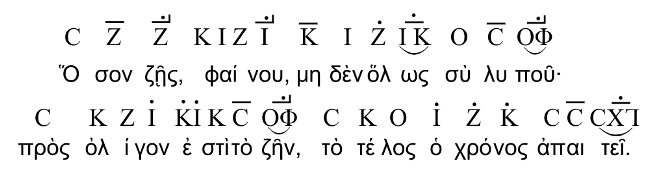

В III-IV веках н.э. древнегреческий теоретик музыки Алипий создал нотную систему, которая впоследствии стала классической для греческой музыки. Каждому из используемых в записи музыки символов (а это были алфавитные и псевдоалфавитные знаки) он определил четкое значение и дал подробное описание. Работы Алипия сохранились благодаря частому их переписыванию и активному использованию в музыке. Греки использовали буквенную нотацию, обозначая ступени музыкальных ладов буквами алфавита, которая в Средние века была забыта. Однако в X веке вновь стали использовать буквенную нотацию, но уже в усовершенствованном виде с указанием особенностей ритма и темпа.

Греческая нотация была представлена двумя вариантами: диатоническая (более древняя), которая представляла собой инструментальную нотацию, и энгармонически-хроматическая (более поздняя), которая использовалась для пения.

Также изображения, напоминающие запись мелодий, встречались в древних культурах Индии, Месопотамии, Персии и т.д.

Невмы

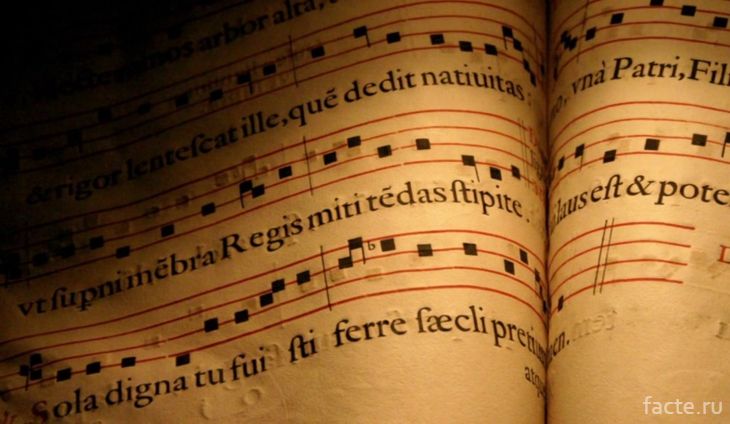

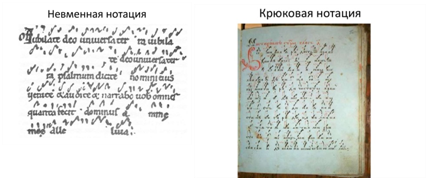

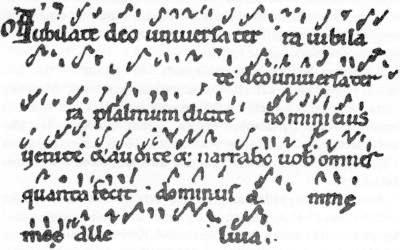

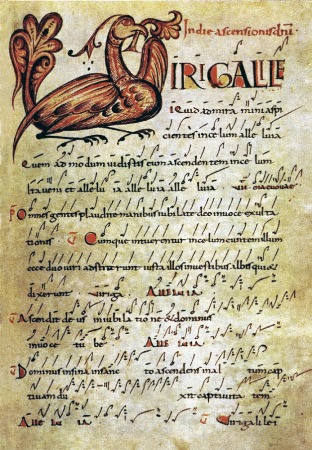

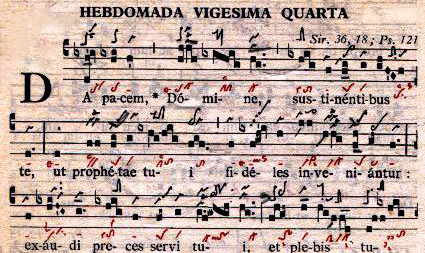

В Средние века (VI-XII в. н.э.) в григорианской музыке использовали так называемые невмы – некие значки-подсказки, которые наглядно показывали интонацию воспроизведения мелодии. В дословном переводе слово «невмы» означает «знак» или «намек».

Невмы помогали обозначить мелодические обороты, повторение звука, повышение или понижение высоты тона, но не указывали точной высоты. Цель обозначений сводилась к указанию числа звуков в одном слоге и незначительном украшении мелодии, при этом другие детали музыкального произведения исполнитель придумывал сам. Невмы использовали исключительно для записи вокальной музыки. Внешне они выглядели как точки, запятые и различной длины черточки, расположенные над текстом псалмов, в кажущемся на первый взгляд беспорядке, что часто приводило к путанице и замешательству певцов, особенно юных и неопытных.

Хоральная нотация

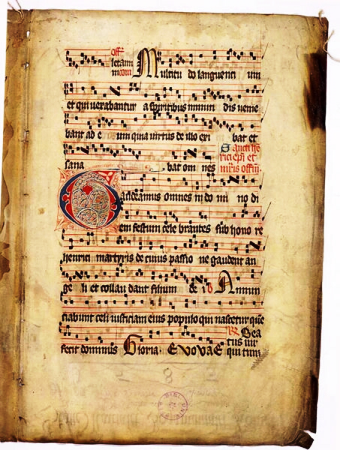

В IX веке были предприняты попытки усовершенствовать невменную нотацию, добавив обозначения высоты звука при помощи букв, а затем и с помощью размещения невм на специальных линейках. Это привело к возникновению квадратного нотописания, получившего название хоральной нотации, которая легла в основу современного нотного письма. Хоральная нотация взяла свое название от слова «хорал», что означает «церковное песнопение», т.е. литургическое пение на латыни в католических церквях, без инструментального сопровождения.

В Средневековье хорал имел широкое распространение, в результате чего существовало несколько его типов:

-

римский (Рим);

-

галльский – (Франция);

-

староиспанский или мозарабский –(Испания);

-

амвросианский – (Милане);

-

беневентский – (южная Италия).

Григорианский хорал произошел в результате слияния вышеперечисленных видов. Отличительной особенностью григорианского хорала была его одноголосность, что не исключает хорового исполнения.

Для современных ученых невменная нотация григорианского хорала до сих пор представляет некоторую загадку, так как не позволяет достоверно судить о точной длительности, громкости и высоте звуков.

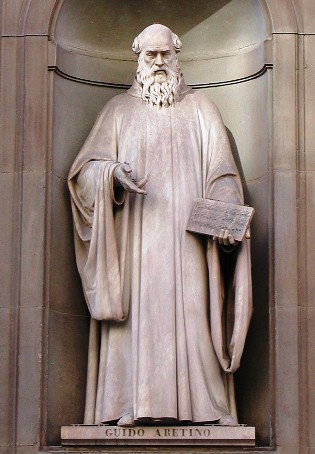

Гвидо д’Ареццо – реформатор в записи музыки

В Х веке для лучшей ориентации в высоте исполняемых звуков к невмам, помимо букв латинского алфавита, добавили горизонтальную линию для обозначения тона F.

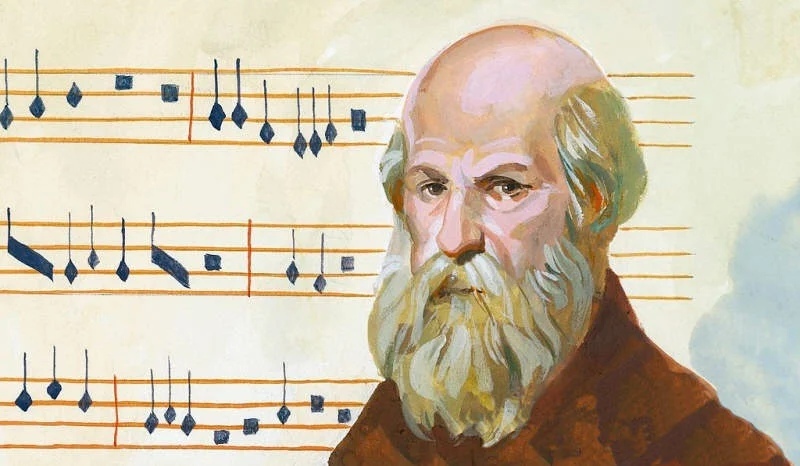

Но настоящую революцию в нотной записи в XI веке совершил музыкант и теоретик Гвидо д’Ареццо (или Гвидо Аретинский), который считается изобретателем нотного стана.

Д’Ареццо обучал пению в церковном хоре, и его утомляло то, что юные певцы путались в невмах. К тому же индивидуальное обучение занимало много времени. Сначала д’Ареццо ввёл две линейки, которые соответствовали ключам F и C, что позволило нотировать высоту звука более точно, а затем разработал систему сольмизации: ему пришла в голову идея располагать невмы на четырех линиях, а также между ними, что позволило более детально указывать высоту тона.

Со временем буквенные обозначения высоты линий преобразились в ключи – условные графические знаки, указывающие на высоту нот.

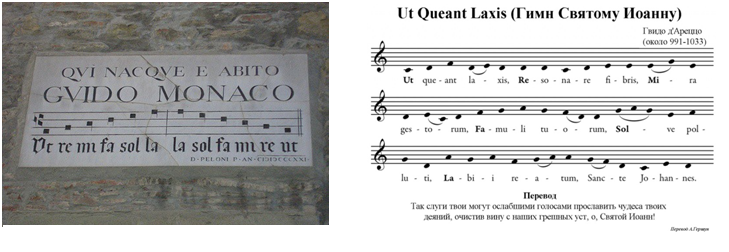

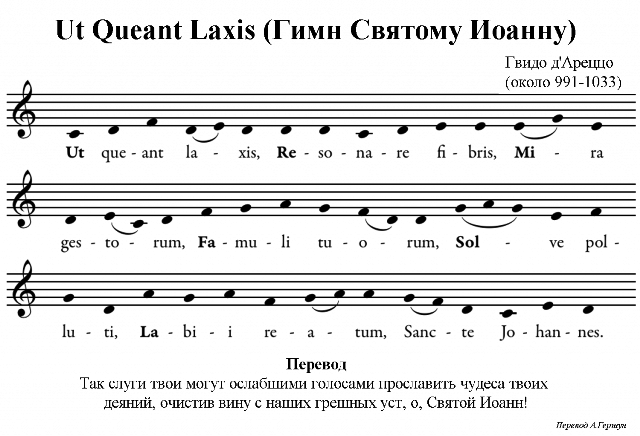

Чтобы облегчить певцам считывание музыки с листа, Гвидо предложил шестиступенный звукоряд с определённым соотношением интервалов (гексахорд). Ступени данного ряда он назвал в соответствии со слогами молитвы святому Иоанну: Ut(do), Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La. Каждая строка в этом гимне поется на один тон выше предыдущей. Таким образом, Ареццо в XI веке заложил основы сольмизационной теории, которая практиковалась в вокальной музыке XVIII века.

Ut queant laxis,

Resonare fibris,

Mira gestorum,

Famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti,

Labii reatum,

Sancte Ioannes!.

Интересно, что названия всех нот, помимо первой, заканчиваются на гласный звук, поэтому их удобно петь. А вот первый слог ut отличается закрытостью, поэтому его в XVI веке его заменили на звук do (от латинского слова Dominus – Господь). Последняя нота si произошла от сокращения двух слов последней строки гимна, причем в англоязычных странах ее название заменили на «ти», чтобы не путать с буквой С.

Д’Ареццо применил на практике свое изобретение, научив певчих в хоре разбираться в нотной грамоте и петь по нотам. Теперь не нужно было каждого певца обучать индивидуально и заучивать с ним мелодии. Достаточно было записать мелодию на бумаге, а затем каждый певчий мог пропеть ее. Это существенно сократило срок обучения.

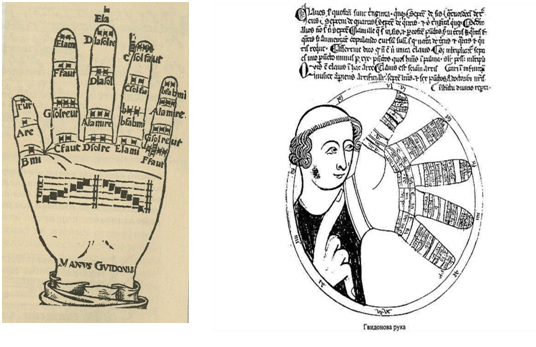

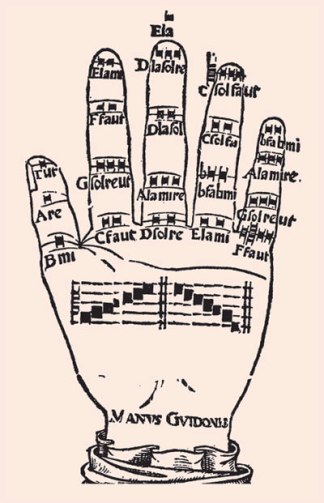

Также авторству д’Ареццо приписывают изобретение особой техники, которая позволяет облегчить чтение нот, так называемой «гвидоновой руки», когда названия нот располагают на пальцах.

Нотация, придуманная Гвидо д’Ареццо оказались самой простой и удобной системой записи музыки. Поэтому распространение нотной грамоты по всему мира – его заслуга. Именно тогда, в XI веке музыка «вышла» из стен соборов и распространилась по домам вельмож, театрам и далее стала доступна всем.

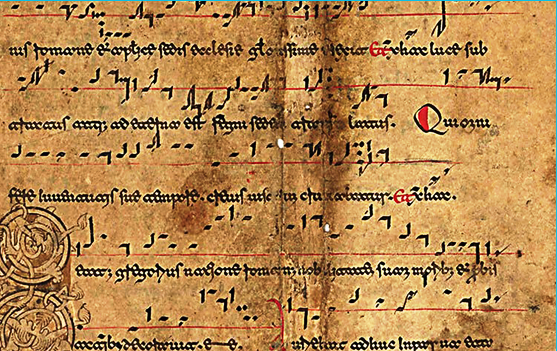

Что же было на Руси?

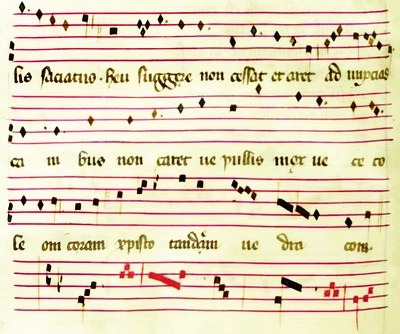

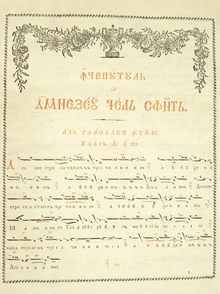

Было древнерусское музыкальное письмо, состоящее из крюков и знамён, в котором можно выделить три периода: ранний (XI-XIV в.в.), средний (XV-начало XVII в. в.) и поздний (с середины XVII в.). К сожалению нотация первых двух периодов не расшифрована. Она пришла из Византии, использовалась преимущественно в церковном пении и представляла собой знаки (киноварные пометы), показывающие повышение или понижение тона, замедление, ускорение или паузу. Самой совершенной из сохранившихся является азбука знаменного пения, созданная в 1604 году, под названием «Ключ знаменной» авторства Христофора – инока Кирилло-Белозёрского монастыря. В данной азбуке расшифрованы более сотен знамён и попевок.

Переход от крюкового письма к 5-линейной нотации с квадратными нотами и цефаутным ключом произошел в России лишь в XVII веке. При помощи цефаутного ключа записывались все звуки церковного звукоряда. Внешне ключ напоминал квадратную ноту со штилем и располагался на третьей линии нотного стана, соответствуя ноте «до» первой октавы.

Мензуральная нотация

Долгое время ноты не имели чётких длительностей. Решение этой проблемы привело к возникновению Мензуральной нотации (XIII-XV вв.), которая определяла длительность каждого звука. К концу XV века сформировались виды ритмического деления — трёхдольность или двухдольность каждой нотной длительности, которые располагались в начале нотной строки и назывались мензурами. Со временем понятие «мензура» стало соответствовать понятию «такт». К концу XVI века было окончательно утверждено соотношение длительностей 1:2 и округлая запись нот.

Современная нотация

Современная нотация удобна, универсальна, международна и понятна всем, кто ее когда-либо изучал. Современное нотное письмо включает в себя следующие элементы.

-

Пятилинейный нотный стан.

-

Ключи.

-

Нотные знаки и их длительности.

-

Знаки альтерации при ключе и при нотах.

-

Метр.

-

Дополнительные знаки (точка, фермата, лига).

-

Объединение нескольких нотных станов.

-

Систему дополнительных обозначений (темповые, динамические, указывающие характер выразительности).

Современная нотация позволяет максимально точно записать любое музыкальное произведение. Более того, существует специальная нотная система для слепых. И так как человечество постоянно стремится к комфорту и упрощению своих временных и энергетических затрат, то, возможно, и современная нотная грамота когда-то подвергнется реформации.

Нотная грамота существовала не всегда. Сначала музыку пели и играли по памяти, и так она переходила от одного музыканта к другому. Но со временем произведение искажалось, и люди искали способ, как передать музыку такой, какой сочинил ее автор.

К 900 году н.э. придумали более удобный способ. Знаки стали писать на определенном расстоянии выше или ниже горизонтальной красной черты, которая означала по высоте звука ноту «фа». Такая запись показывала, где нужно петь высоко, а где — низко.

У разных народов были свои способы записи музыки. В Древней Греции нотами служили буквы, а в григорианской музыке сложилась особая система записи звуков – невма.

Невмы передавали только музыкальное направление произведения и точная высота звука не указывалась. Они обозначали число звуков в одном слоге и незначительное украшение мелодии, а все детали музыкального произведения исполнитель мог придумывать сам. Такой нотной грамотой записывали только вокальную музыку. Невмы напоминали точки, запятые и разные черточки, в беспорядке разбросанные по бумаге и певцы нередко путались из-за неразборчивости символов.

Вся эта путаница прекратилась в начале XI века. Итальянский монах, музыкант и учитель пения Гвидо Аретинский — Гвидо д’ Ареццо нарисовал линии, на которых разместились ноты.

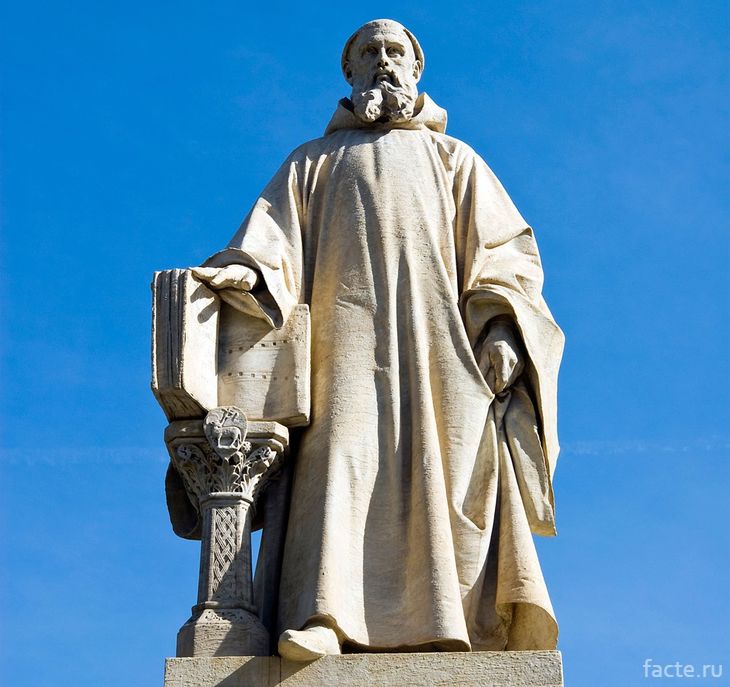

Статуя Гвидо Аретинского во Флоренции неподалеку от галереи Уффици

Изобретатель современной системы нотной записи – бенедиктинский монах Гвидо Аретинский (Гвидо д’Ареццо) (990-1050). Ареццо – небольшой городок в Тоскане, неподалеку от Флоренции. В здешнем монастыре брат Гвидо обучал певчих исполнению церковных песнопений. Дело это было нелегким и долгим. Все знания и умения передавались устно в непосредственном общении. Певчие под руководством преподавателя и с его голоса последовательно разучивали каждый гимн и каждое песнопение католической мессы. Поэтому полный «курс обучения» занимал около 10 лет.

Гвидо Ареттинский начал отмечать звуки нотами (от латинского слова nota – знак). Ноты, заштрихованные квадратики, размещались на нотном стане, состоящем из четырех параллельных линий. Сейчас этих линий пять, и ноты изображают кружочками, но принцип, введенный Гвидо, остался без изменений. Более высокие ноты изображаются на более высокой линейке. Нот семь, они образуют октаву.

Каждой из семи нот октавы Гвидо дал название: ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si. Это – первые слоги гимна св. Иоанну. Каждая строка этого гимна поется на тон выше предыдущей.

Ut queant laxis,

Resonare fibris,

Mira gestorum,

Famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti,

Labii reatum,

Sancte Ioannes!

(В переводе с латинского:

Чтобы слуги твои

голосами своими

смогли воспеть

чудные деяния твои,

очисти грех

с наших опороченных уст,

о, Святой Иоанн»)

Ноты следующей октавы называются так же, но поются более высоким или более низким голосом. При переходе от одной октавы к другой частота звука, обозначаемого одной и той же нотой, увеличивается или уменьшается вдвое. Например, музыкальные инструменты настраивают по ноте ля первой октавы. Этой ноте соответствует частота 440 Гц. Ноте ля следующей, второй, октавы будет соответствовать частота 880 Гц.

Об этой деятельности Гвидо свидетельствуют четыре трактата, дошедшие до нас: «Микролог», «Пролог к Антифонарию», «Правила в стихах» и «Послание о незнакомом пении».

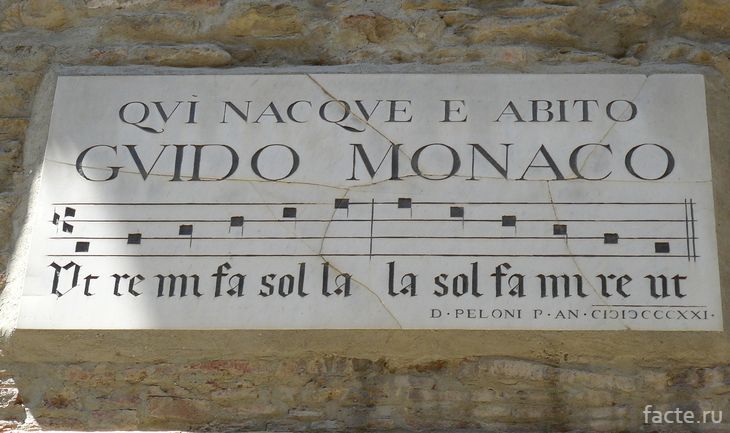

Мемориальная доска в Ареццо на улице Рикасолли на доме, в котором родился Гвидо. На ней изображены квадратные ноты.

Названия всех нот, кроме первой, заканчиваются на гласный звук, их удобно петь. Слог ut – закрытый и пропеть его подобно прочим невозможно. Поэтому название первой ноты октавы, ut, в шестнадцатом веке заменили на do (скорее всего, от латинского слова Dominus – Господь). Этот переход традиционно приписывается итальянскому теоретику музыки Дж.Б. Дони в его труде (на французском языке) «Nouvelle introduction de musique» (1640). Последняя нота октавы, si – сокращение двух слов последней строки гимна, Sancte Ioannes. В англоязычных странах название ноты «си» заменили на «ти», чтобы не путать с буквой С, также используемой в нотной записи.

Изобретя ноты, Гвидо обучил певчих этой своеобразной азбуке, а также научил их петь по нотам. То есть тому, что в современных музыкальных школах называется сольфеджио. Теперь достаточно было записать нотами всю мессу, и певчие могли уже сами пропеть нужную мелодию. Отпала необходимость учить каждого каждой песне лично. Гвидо должен был только контролировать процесс. Время обучения певчих сократилось в пять раз. Вместо десяти лет – два года.

Гвидо также неточно приписывается изобретение, названное в честь него — гвидонова рука – механический способ облегчить чтение нот, обозначив их названия на суставах и конечностях пальцев.

Надо сказать, что монах Гвидо из Ареццо был не первым, кто придумал записывать музыку при помощи знаков. До него в Западной Европе уже существовала система невмов (от греческого слова «пневмо» – дыхание), значков, проставляемых над текстом псалмов, чтобы обозначить подъем или понижение тона песни. На Руси для той же цели употребляли собственную систему «крюков» или «знамен».

Квадратные ноты Гвидо Аретинского, размещаемые на четырех линиях нотного стана, оказались самой простой и удобной системой записи музыки. Благодаря ей нотная грамота распространилась по всему миру. Музыка покинула пределы церкви и ушла сперва во дворцы владык и вельмож, а потом в театры, концертные залы и на городские площади, став всеобщим достоянием.

Давайте вспомним еще какие нибудь истории создания чего либо: давайте вспомним, кто сделал Первый в мире пароход, а так же Когда что появилось в автомобиле. Ну и интереснейшая История знаков

Оригинал статьи находится на сайте ИнфоГлаз.рф Ссылка на статью, с которой сделана эта копия — http://infoglaz.ru/?p=31382

Музыка и ноты

Музыка всегда была с человеком. С древних времён женщины успокаивали своих детей тихими простыми мелодиями. Песни сопутствовали ритуалам, обрядам. Тембры звучания пытались передать не только человеческим голосом, но и стуком, скрипом, используя подручные материалы. Тихие напевы помогали «скрасить» будничные обязанности, а шумные песни возвещали о победах в сражениях, походах, охоте и празднествах.

С давних пор музыка именовалась высочайшей формой искусства. Древнегреческий философ Платон полагал, что музыка возбуждает в человеке все его лучшие качества, способствует развитию воображения и позволяет человеческой душе воспарить над бытом.

Итак, каждая мелодия состоит из нот. Но что это значит? Само слово «нота» (nōta) произошло из латинского языка и буквально означает «знак», «метка». Действительно, нота является графическим символом, знаком звука музыкального произведения. Кроме самих нот существуют дополнительные обозначения — диез и бемоль. С помощью них звук изменяется по высоте, звучанию и длительности.

Немецкая нотация

Хорошо известные нам ноты в других языках звучат и обозначаются совсем не так, как мы привыкли. Одна из самых распространённых буквенных нотаций — немецкая. В ней ноты записываются следующим образом: C, D, E, F, G, A, Н, где С соответственно «До», а Н — «Си».

Остальные символы также отличаются от привычных нам. Так, диез обозначается не отдельным знаком, а окончанием -is. Получается, повышение звука До на полтона будет выглядеть, как Сis.

Бемоль обозначается окончанием -еs. Соответственно, понижение звука для ноты До записывается, как Ces. Также существуют исключения. Например, по правилу нота А с понижением тона должна была бы записываться Aes, но лишнюю букву сократили и оставили As. То же произошло и с Ees = Es. А нота Си вообще поменяла букву: Нes = B.

Символом бекара стало обозначение нужной ноты со строчной буквы.

Музыка.4кл. Рабочая тетрадь.РИТМ

Рабочая тетрадь является дидактическим дополнением к учебнику, содержит творческие задания, которые помогут понять и закрепить материал учебника.

Купить

Английская нотация

В странах, где английский является государственным языком, принята английская нотация. Любопытным является то, что последовательность нот соответствует начальным буквам английского алфавита. Правда, «начинается» этот алфавит с ноты Ля (то есть Ля — А, Си — В, До — С и так далее до G). Дополнительное обозначение диеза воплотилось в sharp, бемоль стал flat, бекар — идентичная нота.

Что такое «нотный стан»?

Нотный стан представляет собой пять линий, где первая линия — нижняя. Ноты пишут слева направо. Если для записи более низкого или высокого звука не хватило пяти линий, то дополнительные линии дорисовывают самостоятельно.

Первый знак на нотном стане — скрипичный или басовый ключ. Он задаёт общую тональность музыкального произведения. Если есть дополнительные обозначения, действующие на определённые ноты на протяжении всего произведения (диез, бемоль, бекар), то они обозначаются после ключа. Далее рисуют ноты.

Ноты представляют собой овал — «пустой» или заштрихованный. Заполненность овала, а также дополнительные линии (штиль), дорисованные к ноте, обозначают её длительность. Например, пустой овал без штиля — это стандартная нота, исполняющаяся четыре полных счёта. Но как только к такой ноте добавляется штиль, целая нота превращается в половинную и играется уже два счёта. Теперь закрасим овал — наша нота стала четвертной. Если же ко всему перечисленному добавить флажок на штиле, нота превратится в 1/8 счёта. Добавляя флажки далее, мы продолжаем уменьшать длительность звучания ноты.

Что было до нот?

Ноты, какими мы их знаем, были записаны лишь в XI веке. До этого звуки обозначались буквами греческого или латинского алфавита. Однако подобная запись была неудовлетворительной — пропеть буквы было сложно, записать же несколько партий одновременно вообще не представлялось возможным.

Спустя некоторое время для записи нот в церковных хорах стали использовать невмы — особые крючки и завитушки. Ими отмечались общие положения произведения — повышение или понижение звучания. Однако такая запись не подходила для описания всех тонкостей песни, а запоминать хористам множество отдельных нюансов было почти невозможно.

Линейная нотация

Так как невмы не позволяли подробно описать реальную мелодию, в записи нот требовались изменения. К невмам стали добавлять буквы, отражающие тональность. Вследствие этого записи становились слишком запутанными, читать их становилось сложно.

Кардинально изменить вид записей музыкальной нотации смог итальянский теоретик музыки и педагог Гвидо д’Ареццо. Он заменил бесчисленное множество букв и крючков линиями. Сначала таких линий было две, затем четыре. Невмы стали записываться на них или между ними. Так как Гвидо был монахом, то и музыкальные нововведения предназначались, в основном, для хористов. Теперь во время службы исполнители понимали, какой диапазон нужен для конкретного произведения. С течением времени на смену невмам пришли квадратные аналоги, позднее превратившиеся в овалы.

Больше интересных материалов:

- Интересные факты о библиотеках

- Как горит лампочка?

- Как предотвратить пропажу ребенка? (материал для родительского собрания)

- Как собрать рюкзак в школу

- Что такое дождь?

Гвидо д’Ареццо — автор нот

Точная дата рождения Гвидо Аретинского неизвестна, считается, что это 991 или 992 год. Будучи монахом, Гвидо сначала жил в аббатстве Помпоза и руководил там певческой школой. Затем он переехал в Ареццо и работал уже в кафедральном соборе. Именно там Гвидо и написал свои самые значимые работы, став музыкальным теоретиком — одним из крупнейших в Средние века.

Именно Гвидо д’Ареццо дал названия нотам. Своим вдохновением он был обязан акростиху молитвы Иоанну Крестителю. «Ut queant laxis» — гимн Иоанну Крестителю, написанный на латинском языке, автором музыки которого считается Гвидо. Начальные слоги каждой строки и стали названиями шести нот: Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La. Сам гимн состоял из семи строк, и каждая строка первой строфы исполнялась на тон выше.

Искусство. Музыка. 7 класс. Нотное приложение

Нотное приложение адресовано учителям, работающим по учебнику «Искусство. Музыка. 7 класс». Учебник соответствует Федеральному государственному образовательному стандарту основного общего образования, рекомендован Министерством образования и науки РФ, включён в Федеральный перечень. Нотное приложение содержит музыкальные произведения (академический и песенный репертуар), представленные в точном соответствии с тематическим планированием рабочей программы и материалами учебника. В учебно-методический комплекс входят также рабочая программа, учебник с аудиоприложением, рабочая тетрадь «Дневник музыкальных размышлений» и методическое пособие.

Купить

Несмотря на то что имена нотам дал Гвидо Аретинский, Ut на знакомое нам Do изменил не он. Существует множество версий появления названия этой ноты. Самая известная теория происхождения гласит о том, что Do появилось в честь Бога (лат. Dominus — Господь).

Седьмая нота также появилась позже. Своё имя она получила из начальных букв седьмой строки: Sancte Ioannes — Si (Святой Иоанн — Си).

Осторожно, подделка!

На просторах интернета существует множество необычных теорий о происхождении названий нот. Чаще всего, авторы статей (как и авторы нот) не указываются, зато материалы изобилуют невероятными вариантами. Подбираются латинские слова с нужными начальными буквами, чаще всего это случайный перечень красивых слов: материя (rem), чудо (signum), Солнце (sol) и т.п.

Однако только одна информация остаётся верной — именно Гвидо Аретинский изобрёл и дал названия нотам! И развитие «нотной грамоты» до Гвидо, и изменения уже после его «музыкальной революции» представляют собой запутанную, но весьма интересную историю. Чтобы осмыслить действительную необходимость трансформации нот до привычного нам вида, необходимо знать реального автора нот и смысл, что стоит за их названиями.

#ADVERTISING_INSERT#

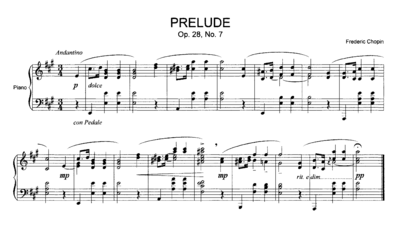

This article is about a notation for music. For the «musical» notation in mathematics, see Musical isomorphism.

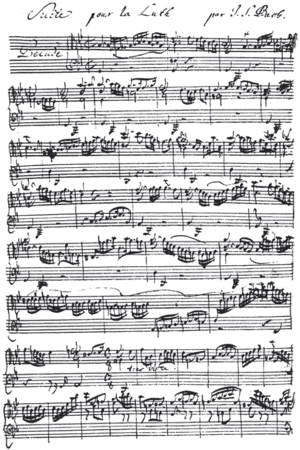

Hand-written musical notation by J. S. Bach (1685–1750). This is the beginning of the Prelude from the Suite for Lute in G minor, BWV 995 (transcription of Cello Suite No. 5, BWV 1011).

Music notation or musical notation is any system used to visually represent aurally perceived music played with instruments or sung by the human voice through the use of written, printed, or otherwise-produced symbols, including notation for durations of absence of sound such as rests.

The types and methods of notation have varied between cultures and throughout history, and much information about ancient music notation is fragmentary. Even in the same time period, such as in the 2010s, different styles of music and different cultures use different music notation methods; for example, for professional classical music performers, sheet music using staves and noteheads is the most common way of notating music, but for professional country music session musicians, the Nashville Number System is the main method.

The symbols used include ancient symbols and modern symbols made upon any media such as symbols cut into stone, made in clay tablets, made using a pen on papyrus or parchment or manuscript paper; printed using a printing press (c. 1400s), a computer printer (c. 1980s) or other printing or modern copying technology.

Although many ancient cultures used symbols to represent melodies and rhythms, none of them was particularly comprehensive, which has limited today’s understanding of their music. The seeds of what would eventually become modern Western notation were sown in medieval Europe, starting with the Christian Church’s goal for ecclesiastical uniformity. The church began notating plainchant melodies so that the same chants could be used throughout the church. Music notation developed further during the Renaissance and Baroque music eras. In the classical period (1750–1820) and the Romantic music era (1820–1900), notation continued to develop as new musical instrument technologies were developed. In the contemporary classical music of the 20th and 21st century, music notation has continued to develop, with the introduction of graphical notation by some modern composers and the use, since the 1980s, of computer-based score writer programs for notating music. Music notation has been adapted to many kinds of music, including classical music, popular music, and traditional music.

History[edit]

Ancient Near East[edit]

A tablet with the Hymn to Nikkal inscribed[1]

The earliest form of musical notation can be found in a cuneiform tablet that was created at Nippur, in Babylonia (today’s Iraq), in about 1400 BCE. The tablet represents fragmentary instructions for performing music, that the music was composed in harmonies of thirds, and that it was written using a diatonic scale.[2] A tablet from about 1250 BCE shows a more developed form of notation.[3] Although the interpretation of the notation system is still controversial, it is clear that the notation indicates the names of strings on a lyre, the tuning of which is described in other tablets.[4] Although they are fragmentary, these tablets represent the earliest notated melodies found anywhere in the world.[5]

A photograph of the original stone at Delphi containing the second of the two Delphic Hymns to Apollo. The music notation is the line of occasional symbols above the main, uninterrupted line of Greek lettering.

Ancient Greece[edit]

Ancient Greek musical notation was in use from at least the 6th century BCE until approximately the 4th century CE; only one complete composition (Seikilos epitaph) and a number of fragments using this notation survive. The notation for sung music consists of letter symbols for the pitches, placed above text syllables. Rhythm is indicated in a rudimentary way only, with long and short symbols. The Seikilos epitaph has been variously dated between the 2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE.

Three hymns by Mesomedes of Crete exist in manuscript. The Delphic Hymns, dated to the 2nd century BCE also use this notation, but they are not completely preserved. Ancient Greek notation appears to have fallen out of use around the time of the Decline of the Western Roman Empire.

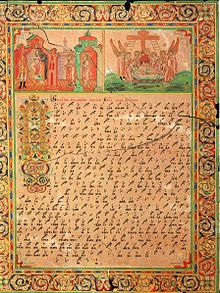

Byzantine Empire[edit]

Byzantine music notation in the first edition (1823) of Macarie Ieromonahul’s anastasimatarion, a hymnal with daily chant (including resurrection troparia called apolytikia anastasima) in oktoechos order, each section began with the evening psalm 140 (here section of echos protos with Romanian transliterated in Cyrillic script)

Byzantine music once included music for court ceremonies, but has only survived as vocal church music within various Orthodox traditions of monodic (monophonic) chant written down in Byzantine round notation (see Macarie’s anastasimatarion with the Greek text translated into Romanian and transliterated into Cyrillic script).[6]

Since the 6th century, Greek theoretical categories (melos, genos, harmonia, systema) played a key role to understand and transmit Byzantine music, especially the tradition of Damascus had a strong impact on the pre-Islamic Near East comparable to the impact coming from Persian music. The earliest evidence are papyrus fragments of Greek tropologia. These fragments just present the hymn text following a modal signature or key (like «ΠΛ Α» for echos plagios protos or «Β» for echos devteros).

Unlike Western notation, Byzantine neumes used since the 10th century were always related to modal steps (same modal degree, one degree lower, two degrees higher, etc.) in relation to such a clef or modal key (modal signatures). Originally this key or the incipit of a common melody was enough to indicate a certain melodic model given within the echos. Next to ekphonetic notation, only used in lectionaries to indicate formulas used during scriptural lessons, melodic notation developed not earlier than between the 9th and the 10th century, when a theta (θ), oxeia (/) or diple (//) were written under a certain syllable of the text, whenever a longer melisma was expected. This primitive form was called «theta» or «diple notation».

Today, one can study the evolution of this notation in Greek monastic chant books like those of the sticherarion and the heirmologion (Chartres notation was rather used on Mount Athos and Constantinople, Coislin notation within the patriarchates of Jerusalem and Alexandria), while there was another gestic notation originally used for the asmatikon (choir book) and kontakarion (book of the soloist or monophonaris) of the Constantinopolitan cathedral rite. The earliest books which have survived, are «kondakars» in Slavonic translation which already show a notation system known as Kondakarian notation.[7] Like the Greek alphabet notational signs are ordered left to right (though the direction could be adapted like in certain Syriac manuscripts). The question of rhythm was entirely based on cheironomia (the interpretation of so-called great signs which derived from different chant books). These great signs (μεγάλα σῃμάδια) indicated well-known melodic phrases given by gestures of the choirleaders of the cathedral rite. They existed once as part of an oral tradition, developed Kondakarian notation and became, during the 13th century, integrated into Byzantine round notation as a kind of universal notation system.[8]

Today the main difference between Western and Eastern neumes is that Eastern notation symbols are «differential» rather than absolute, i.e., they indicate pitch steps (rising, falling or at the same step), and the musicians know to deduce correctly, from the score and the note they are singing presently, which correct interval is meant. These step symbols themselves, or better «phonic neumes», resemble brush strokes and are colloquially called gántzoi (‘hooks’) in modern Greek.

Notes as pitch classes or modal keys (usually memorised by modal signatures) are represented in written form only between these neumes (in manuscripts usually written in red ink). In modern notation they simply serve as an optional reminder and modal and tempo directions have been added, if necessary. In Papadic notation medial signatures usually meant a temporary change into another echos.

The so-called «great signs» were once related to cheironomic signs; according to modern interpretations they are understood as embellishments and microtonal attractions (pitch changes smaller than a semitone), both essential in Byzantine chant.[9]

Chrysanthos’ Kanonion with a comparison between Ancient Greek tetraphonia (column 1), Western Solfeggio, the Papadic Parallage (ascending: column 3 and 4; descending: column 5 and 6) according to the trochos system, and his heptaphonic parallage according to the New Method (syllables in the fore-last and martyriai in the last column)[10])

Since Chrysanthos of Madytos there are seven standard note names used for «solfège» (parallagē) pá, vú, ghá, dhi, ké, zō, nē, while the older practice still used the four enechemata or intonation formulas of the four echoi given by the modal signatures, the authentic or kyrioi in ascending direction, and the plagal or plagioi in descending direction (Papadic Octoechos).[11] With exception of vú and zō they do roughly correspond to Western solmization syllables as re, mi, fa, sol, la, si, do. Byzantine music uses the eight natural, non-tempered scales whose elements were identified by Ēkhoi, «sounds», exclusively, and therefore the absolute pitch of each note may slightly vary each time, depending on the particular Ēkhos used. Byzantine notation is still used in many Orthodox Churches. Sometimes cantors also use transcriptions into Western or Kievan staff notation while adding non-notatable embellishment material from memory and «sliding» into the natural scales from experience, but even concerning modern neume editions since the reform of Chrysanthos a lot of details are only known from an oral tradition related to traditional masters and their experience.

13th-century Near East[edit]

In 1252, Safi al-Din al-Urmawi developed a form of musical notation, where rhythms were represented by geometric representation. Many subsequent scholars of rhythm have sought to develop graphical geometrical notations. For example, a similar geometric system was published in 1987 by Kjell Gustafson, whose method represents a rhythm as a two-dimensional graph.[12]

Early Europe[edit]

Music notation from an early 14th-century English Missal

The scholar and music theorist Isidore of Seville, while writing in the early 7th century, considered that «unless sounds are held by the memory of man, they perish, because they cannot be written down.»[13] By the middle of the 9th century, however, a form of neumatic notation began to develop in monasteries in Europe as a mnemonic device for Gregorian chant, using symbols known as neumes; the earliest surviving musical notation of this type is in the Musica disciplina of Aurelian of Réôme, from about 850. There are scattered survivals from the Iberian Peninsula before this time, of a type of notation known as Visigothic neumes, but its few surviving fragments have not yet been deciphered.[14] The problem with this notation was that it only showed melodic contours and consequently the music could not be read by someone who did not know the music already.

Notation had developed far enough to notate melody, but there was still no system for notating rhythm. A mid-13th-century treatise, De Mensurabili Musica, explains a set of six rhythmic modes that were in use at the time,[15] although it is not clear how they were formed. These rhythmic modes were all in triple time and rather limited rhythm in chant to six different repeating patterns. This was a flaw seen by German music theorist Franco of Cologne and summarised as part of his treatise Ars cantus mensurabilis (the art of measured chant, or mensural notation). He suggested that individual notes could have their own rhythms represented by the shape of the note. Not until the 14th century did something like the present system of fixed note lengths arise.[citation needed] The use of regular measures (bars) became commonplace by the end of the 17th century.[citation needed]

The founder of what is now considered the standard music staff was Guido d’Arezzo,[16] an Italian Benedictine monk who lived from about 991 until after 1033. He taught the use of solmization syllables based on a hymn to Saint John the Baptist, which begins Ut Queant Laxis and was written by the Lombard historian Paul the Deacon. The first stanza is:

- Ut queant laxis

- resonare fibris,

- Mira gestorum

- famuli tuorum,

- Solve polluti

- labii reatum,

- Sancte Iohannes.

Guido used the first syllable of each line, Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, and Si, to read notated music in terms of hexachords; they were not note names, and each could, depending on context, be applied to any note. In the 17th century, Ut was changed in most countries except France to the easily singable, open syllable Do, believed to have been taken either from the name of the Italian theorist Giovanni Battista Doni, or from the Latin word Dominus, meaning Lord.[17]

Christian monks developed the first forms of modern European musical notation in order to standardize liturgy throughout the worldwide Church,[18] and an enormous body of religious music has been composed for it through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of European classical music, and its many derivatives. The Baroque style, which encompassed music, art, and architecture, was particularly encouraged by the post-Reformation Catholic Church as such forms offered a means of religious expression that was stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.[19]

Modern staff notation[edit]

Modern music notation is used by musicians of many different genres throughout the world. The staff (or stave, in British English) consists of 5 parallel horizontal lines which acts as a framework upon which pitches are indicated by placing oval note-heads on (ie crossing) the staff lines, between the lines (ie in the spaces) or above and below the staff using small additional lines called ledger lines. Notation is read from left to right, which makes setting music for right-to-left scripts difficult. The pitch of a note is indicated by the vertical position of the note-head within the staff, and can be modified by accidentals. The duration (note length or note value) is indicated by the form of the note-head or with the addition of a note-stem plus beams or flags. A stemless hollow oval is a whole note or semibreve, a hollow rectangle or stemless hollow oval with one or two vertical lines on both sides is a double whole note or breve. A stemmed hollow oval is a half note or minim. Solid ovals always use stems, and can indicate quarter notes (crotchets) or, with added beams or flags, smaller subdivisions. Additional symbols such as dots and ties can lengthen the duration of a note.

A staff of written music generally begins with a clef, which indicates the pitch-range of the staff. The treble clef or G clef was originally a letter G and it identifies the second line up on the five line staff as the note G above middle C. The bass clef or F clef identifies the second line down as the note F below middle C. While the treble and bass clef are the most widely used, other clefs, which identify middle C, are used for some instruments, such as the alto clef (for viola and alto trombone) and the tenor clef (used for some cello, bassoon, tenor trombone, and double bass music). Some instruments use mainly one clef, such as violin and flute which use treble clef, and double bass and tuba which use bass clef. Some instruments, such as piano and pipe organ, regularly use both treble and bass clefs.

Following the clef, the key signature is a group of from 0 to 7 sharp (♯) or flat (♭) signs placed on the staff to indicate the key of the piece or song by specifying that certain notes are sharp or flat throughout the piece, unless otherwise indicated with accidentals added before certain notes. When a flat (♭) sign is placed before a note, the pitch of the note is lowered by one semitone. Similarly, a sharp sign (♯) raises the pitch by one semitone. For example, a sharp on the note D would raise it to D♯ while a flat would lower it to D♭. Double sharps and double flats are less common, but they are used. A double sharp is placed before a note to make it two semitones higher, a double flat — two semitones lower. A natural sign placed before a note renders that note in its «natural» form, which means that any sharp or flat applied to that note from the key signature or an accidental, is cancelled. Sometimes a courtesy accidental is used in music where it is not technically required, to remind the musician of what pitch is required.

Following the key signature is the time signature. The time signature typically consists of two numbers, with one of the most common being 4

4. The top «4» indicates that there are four beats per measure (also called bar). The bottom «4» indicates that each of those beats are quarter notes. Measures divide the piece into groups of beats, and the time signatures specify those groupings. 4

4 is used so often that it is also called «common time», and it may be indicated with rather than numbers. Other frequently used time signatures are 3

4 (three beats per bar, with each beat being a quarter note); 2

4 (two beats per bar, with each beat being a quarter note); 6

8 (six beats per bar, with each beat being an eighth note) and 12

8 (twelve beats per bar, with each beat being an eighth note; in practice, the eighth notes are typically put into four groups of three eighth notes. 12

8 is a compound time type of time signature). Many other time signatures exist, such as 3

8, 5

8, 5

4, 7

4, 9

8, and so on.

Many short classical music pieces from the classical era and songs from traditional music and popular music are in one time signature for much or all of the piece. Music from the Romantic music era and later, particularly contemporary classical music and rock music genres such as progressive rock and the hardcore punk subgenre mathcore, may use mixed meter; songs or pieces change from one meter to another, for example alternating between bars of 5

4 and 7

8.

Directions to the player regarding matters such as tempo (e.g., Allegro, Andante, Largo, Vif, Lent, Modérément, Presto, etc.), dynamics (pianississimo, pianissimo, piano, mezzopiano, mezzoforte, forte, fortissimo, fortississimo, etc.) appear above or below the staff. Terms indicating the musical expression or «feel» to a song or piece are indicated at the beginning of the piece and at any points where the mood changes (e.g., «Slow March», «Fast Swing», «Medium Blues», «Fougueux», «Feierlich», «Gelassen», «Piacevole», «Con slancio», «Majestic», «Hostile» etc.) For vocal music, lyrics are written near the pitches of the melody. For short pauses (breaths), retakes (retakes are indicated with a ‘ mark) are added.

In music for ensembles, a «score» shows music for all players together, with the staves for the different instruments and/or voices stacked vertically. The conductor uses the score while leading an orchestra, concert band, choir or other large ensemble. Individual performers in an ensemble play from «parts» which contain only the music played by an individual musician. A score can be constructed from a complete set of parts and vice versa. The process was laborious and time consuming when parts were hand-copied from the score, but since the development of scorewriter computer software in the 1980s, a score stored electronically can have parts automatically prepared by the program and quickly and inexpensively printed out using a computer printer.

Variations on staff notation[edit]

- Percussion notation conventions are varied because of the wide range of percussion instruments. Percussion instruments are generally grouped into two categories: pitched (e.g. glockenspiel or tubular bells) and non-pitched (e.g. bass drum and snare drum). The notation of non-pitched percussion instruments is less standardized. Pitched instruments use standard Western classical notation for the pitches and rhythms. In general, notation for unpitched percussion uses the five line staff, with different lines and spaces representing different drum kit instruments. Standard Western rhythmic notation is used to indicate the rhythm.

- Figured bass notation originated in Baroque basso continuo parts. It is also used extensively in accordion notation. The bass notes of the music are conventionally notated, along with numbers and other signs that determine which chords the harpsichordist, organist or lutenist should improvise. It does not, however, specify the exact pitches of the harmony, leaving that for the performer to improvise.

- A lead sheet specifies only the melody, lyrics and harmony, using one staff with chord symbols placed above and lyrics below. It is used to capture the essential elements of a popular song without specifying how the song should be arranged or performed.

- A chord chart or «chart» contains little or no melodic or voice-leading information at all, but provides basic harmonic information about the chord progression. Some chord charts also contain rhythmic information, indicated using slash notation for full beats and rhythmic notation for rhythms. This is the most common kind of written music used by professional session musicians playing jazz or other forms of popular music and is intended primarily for the rhythm section (usually containing piano, guitar, bass and drums).

- Simpler chord charts for songs may contain only the chord changes, placed above the lyrics where they occur. Such charts depend on prior knowledge of the melody, and are used as reminders in performance or informal group singing. Some chord charts intended for rhythm section accompanists contain only the chord progression.

- The shape note system is found in some church hymnals, sheet music, and song books, especially in the Southern United States. Instead of the customary elliptical note head, note heads of various shapes are used to show the position of the note on the major scale. The Sacred Harp is one of the most popular tune books using shape notes.

In various countries[edit]

Korea[edit]

Jeongganbo musical notation system

Jeongganbo is a unique traditional musical notation system created during the time of Sejong the Great that was the first East Asian system to represent rhythm, pitch, and time.[20][21] Among various kinds of Korean traditional music, Jeong-gan-bo targets a particular genre, Jeong-ak (정악, 正樂).

Jeong-gan-bo tells the pitch by writing the pitch’s name down in a box called ‘jeong-gan’ (this is where the name comes from). One jeong-gan is one beat each, and it can be split into two, three or more to hold half beats and quarter beats, and more. This makes it easy for the reader to figure out the beat.

Also, there are many markings indicating things such as ornaments. Most of these were later created by Ki-su Kim.

India[edit]

Indian music, early 20th century.

The Samaveda text (1200 BCE – 1000 BCE) contains notated melodies, and these are probably the world’s oldest surviving ones.[22] The musical notation is written usually immediately above, sometimes within, the line of Samaveda text, either in syllabic or a numerical form depending on the Samavedic Sakha (school).[23] The Indian scholar and musical theorist Pingala (c. 200 BCE), in his Chanda Sutra, used marks indicating long and short syllables to indicate meters in Sanskrit poetry.

A rock inscription from circa 7th–8th century CE at Kudumiyanmalai, Tamil Nadu contains an early example of a musical notation. It was first identified and published by archaeologist/epigraphist D. R. Bhandarkar.[24] Written in the Pallava-grantha script of the 7th century, it contains 38 horizontal lines of notations inscribed on a rectangular rock face (dimension of around 13 by 14 feet). Each line of the notation contains 64 characters (characters representing musical notes), written in groups of four notes. The basic characters for the seven notes, ‘sa ri ga ma pa dha ni’, are seen to be suffixed with the vowels a, i, u, e. For example, in the place of ‘sa’, any one of ‘sa’, ‘si’, ‘su’ or ‘se’ is used. Similarly, in place of ri, any one of ‘ra’, ‘ri’, ‘ru’ or ‘re’ is used. Horizontal lines divide the notation into 7 sections. Each section contains 4 to 7 lines of notation, with a title indicating its musical ‘mode’. These modes may have been popular at least from the 6th century CE and were incorporated into the Indian ‘raga’ system that developed later. But some of the unusual features seen in this notation have been given several non-conclusive interpretations by scholars.[25]

In the notation of Indian rāga, a solfege-like system called sargam is used. As in Western solfege, there are names for the seven basic pitches of a major scale (Shadja, Rishabha, Gandhara, Madhyama, Panchama, Dhaivata and Nishada, usually shortened to Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni). The tonic of any scale is named Sa, and the dominant Pa. Sa is fixed in any scale, and Pa is fixed at a fifth above it (a Pythagorean fifth rather than an equal-tempered fifth). These two notes are known as achala swar (‘fixed notes’).

Each of the other five notes, Re, Ga, Ma, Dha and Ni, can take a ‘regular’ (shuddha) pitch, which is equivalent to its pitch in a standard major scale (thus, shuddha Re, the second degree of the scale, is a whole-step higher than Sa), or an altered pitch, either a half-step above or half-step below the shuddha pitch. Re, Ga, Dha and Ni all have altered partners that are a half-step lower (Komal-«flat») (thus, komal Re is a half-step higher than Sa).

Ma has an altered partner that is a half-step higher (teevra-«sharp») (thus, tivra Ma is an augmented fourth above Sa). Re, Ga, Ma, Dha and Ni are called vikrut swar (‘movable notes’). In the written system of Indian notation devised by Ravi Shankar, the pitches are represented by Western letters. Capital letters are used for the achala swar, and for the higher variety of all the vikrut swar. Lowercase letters are used for the lower variety of the vikrut swar.

Other systems exist for non-twelve-tone equal temperament and non-Western music, such as the Indian Swaralipi.

Russia[edit]

An example of Znamenny notation with so-called «red marks», Russia, 1884. «Thy Cross we honour, oh Lord, and Thy holy Resurrection we praise.»

Hand-drawn lubok featuring ‘hook and banner notation’

Znamenny Chant is a singing tradition used in the Russian Orthodox Church which uses a «hook and banner» notation. Znamenny Chant is unison, melismatic liturgical singing that has its own specific notation, called the stolp notation. The symbols used in the stolp notation are called kryuki (Russian: крюки, ‘hooks’) or znamena (Russian: знамёна, ‘signs’). Often the names of the signs are used to refer to the stolp notation. Znamenny melodies are part of a system, consisting of Eight Modes (intonation structures; called glasy); the melodies are characterized by fluency and well-balancedness (Kholopov 2003, 192). There exist several types of Znamenny Chant: the so-called Stolpovoy, Malyj (Little) and Bolshoy (Great) Znamenny Chant. Ruthenian Chant (Prostopinije) is sometimes considered a sub-division of the Znamenny Chant tradition, with the Muscovite Chant (Znamenny Chant proper) being the second branch of the same musical continuum.

Znamenny Chants are not written with notes (the so-called linear notation), but with special signs, called Znamëna (Russian for «marks», «banners») or Kryuki («hooks»), as some shapes of these signs resemble hooks. Each sign may include the following components: a large black hook or a black stroke, several smaller black ‘points’ and ‘commas’ and lines near the hook or crossing the hook. Some signs may mean only one note, some 2 to 4 notes, and some a whole melody of more than 10 notes with a complicated rhythmic structure. The stolp notation was developed in Kievan Rus’ as an East Slavic refinement of the Byzantine neumatic musical notation.

The most notable feature of this notation system is that it records transitions of the melody, rather than notes. The signs also represent a mood and a gradation of how this part of melody is to be sung (tempo, strength, devotion, meekness, etc.) Every sign has its own name and also features as a spiritual symbol. For example, there is a specific sign, called «little dove» (Russian: голубчик (golubchik)), which represents two rising sounds, but which is also a symbol of the Holy Ghost. Gradually the system became more and more complicated. This system was also ambiguous, so that almost no one, except the most trained and educated singers, could sing an unknown melody at sight. The signs only helped to reproduce the melody, not coding it in an unambiguous way.

(See Byzantine Empire)

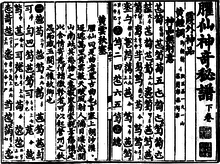

China[edit]

The earliest known examples of text referring to music in China are inscriptions on musical instruments found in the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (d. 433 B.C.). Sets of 41 chimestones and 65 bells bore lengthy inscriptions concerning pitches, scales, and transposition. The bells still sound the pitches that their inscriptions refer to. Although no notated musical compositions were found, the inscriptions indicate that the system was sufficiently advanced to allow for musical notation. Two systems of pitch nomenclature existed, one for relative pitch and one for absolute pitch. For relative pitch, a solmization system was used.[26]

Gongche notation used Chinese characters for the names of the scale.

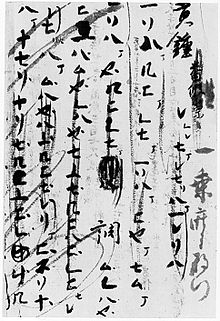

Japan[edit]

Tempyō Biwa Fu 天平琵琶譜 (circa 738 AD), musical notation for Biwa. (Shōsōin, at Nara, Japan)

Japanese music is highly diversified, and therefore requires various systems of notation. In Japanese shakuhachi music, for example, glissandos and timbres are often more significant than distinct pitches, whereas taiko notation focuses on discrete strokes.

Ryukyuan sanshin music uses kunkunshi, a notation system of kanji with each character corresponding to a finger position on a particular string.

Indonesia[edit]

Notation plays a relatively minor role in the oral traditions of Indonesia. However, in Java and Bali, several systems were devised beginning at the end of the 19th century, initially for archival purposes. Today the most widespread are cipher notations («not angka» in the broadest sense) in which the pitches are represented with some subset of the numbers 1 to 7, with 1 corresponding to either highest note of a particular octave, as in Sundanese gamelan, or lowest, as in the kepatihan notation of Javanese gamelan.

Notes in the ranges outside the central octave are represented with one or more dots above or below the each number. For the most part, these cipher notations are mainly used to notate the skeletal melody (the balungan) and vocal parts (gerongan), although transcriptions of the elaborating instrument variations are sometimes used for analysis and teaching. Drum parts are notated with a system of symbols largely based on letters representing the vocables used to learn and remember drumming patterns; these symbols are typically laid out in a grid underneath the skeletal melody for a specific or generic piece.

The symbols used for drum notation (as well as the vocables represented) are highly variable from place to place and performer to performer. In addition to these current systems, two older notations used a kind of staff: the Solonese script could capture the flexible rhythms of the pesinden with a squiggle on a horizontal staff, while in Yogyakarta a ladder-like vertical staff allowed notation of the balungan by dots and also included important drum strokes. In Bali, there are a few books published of Gamelan gender wayang pieces, employing alphabetical notation in the old Balinese script.

Composers and scholars both Indonesian and foreign have also mapped the slendro and pelog tuning systems of gamelan onto the western staff, with and without various symbols for microtones. The Dutch composer Ton de Leeuw also invented a three line staff for his composition Gending. However, these systems do not enjoy widespread use.

In the second half of the twentieth century, Indonesian musicians and scholars extended cipher notation to other oral traditions, and a diatonic scale cipher notation has become common for notating western-related genres (church hymns, popular songs, and so forth). Unlike the cipher notation for gamelan music, which uses a «fixed Do» (that is, 1 always corresponds to the same pitch, within the natural variability of gamelan tuning), Indonesian diatonic cipher notation is «moveable-Do» notation, so scores must indicate which pitch corresponds to the number 1 (for example, «1=C»).

-

A short melody in slendro notated using the Surakarta method.[27]

-

The same notated using the Yogyakarta method or ‘chequered notation’.[27]

-

The same notated using Kepatihan notation.[27]

-

The same approximated using Western notation.[27]

Play (help·info)

Other systems and practices[edit]

Cipher notation[edit]

Cipher notation systems assigning Arabic numerals to the major scale degrees have been used at least since the Iberian organ tablatures of the 16th-century and include such exotic adaptations as Siffernotskrift. The one most widely in use today is the Chinese Jianpu, discussed in the main article. Numerals can also be assigned to different scale systems, as in the Javanese kepatihan notation described above.

Solfège[edit]

Solfège is a way of assigning syllables to names of the musical scale. In order, they are today: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do‘ (for the octave). The classic variation is: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Si Do‘. The first Western system of functional names for the musical notes was introduced by Guido of Arezzo (c. 991 – after 1033), using the beginning syllables of the first six musical lines of the Latin hymn Ut queant laxis. The original sequence was Ut Re Mi Fa Sol La, where each verse started a scale note higher. «Ut» later became «Do». The equivalent syllables used in Indian music are: Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni. See also: solfège, sargam, Kodály hand signs.

Tonic sol-fa is a type of notation using the initial letters of solfège.

Letter notation[edit]

The notes of the 12-tone scale can be written by their letter names A–G, possibly with a trailing sharp or flat symbol, such as A♯ or B♭.

Tablature[edit]

Tablature was first used in the Middle Ages for organ music and later in the Renaissance for lute music.[28] In most lute tablatures, a staff is used, but instead of pitch values, the lines of the staff represent the strings of the instrument. The frets to finger are written on each line, indicated by letters or numbers. Rhythm is written separately with one or another variation of standard note values indicating the duration of the fastest moving part. Few seem to have remarked on the fact that tablature combines in one notation system both the physical and technical requirements of play (the lines and symbols on them and in relation to each other representing the actual performance actions) with the unfolding of the music itself (the lines of tablature taken horizontally represent the actual temporal unfolding of the music). In later periods, lute and guitar music was written with standard notation. Tablature caught interest again in the late 20th century for popular guitar music and other fretted instruments, being easy to transcribe and share over the internet in ASCII format.

Klavar notation[edit]

Klavarskribo (sometimes shortened to klavar) is a music notation system that was introduced in 1931 by the Dutchman Cornelis Pot. The name means «keyboard writing» in Esperanto. It differs from conventional music notation in a number of ways and is intended to be easily readable. Many klavar readers are from the Netherlands.

Piano-roll-based notations[edit]

Some chromatic systems have been created taking advantage of the layout of black and white keys of the standard piano keyboard. The «staff» is most widely referred to as «piano roll», created by extending the black and white piano keys.

Chromatic staff notations[edit]

Over the past three centuries, hundreds of music notation systems have been proposed as alternatives to traditional western music notation. Many of these systems seek to improve upon traditional notation by using a «chromatic staff» in which each of the 12 pitch classes has its own unique place on the staff. An example is Jacques-Daniel Rochat’s Dodeka music notation.[29][30] These notation systems do not require the use of standard key signatures, accidentals, or clef signs. They also represent interval relationships more consistently and accurately than traditional notation, e.g. major 3rds appear wider than minor 3rds. Many of these systems are described and illustrated in Gardner Read’s «Source Book of Proposed Music Notation Reforms».

Graphic notation[edit]

The term ‘graphic notation’ refers to the contemporary use of non-traditional symbols and text to convey information about the performance of a piece of music. Composers such as Johanna Beyer. Christian Wolff, Carmen Barradas, Earle Brown, Yoko Ono, Anthony Braxton, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Cathy Berberian, Graciela Castillo, Krzysztof Penderecki, Cornelius Cardew, Pauline Oliveros and Roger Reynolds are among the early generation of practitioners. The book Notations, by John Cage and Alison Knowles, is another example of this kind of notation.

Simplified music notation[edit]

Simplified Music Notation is an alternative form of musical notation designed to make sight-reading easier. It is based on classical staff notation, but incorporates sharps and flats into the shape of the note heads. Notes such as double sharps and double flats are written at the pitch they are actually played at, but preceded by symbols called history signs that show they have been transposed.

Modified Stave Notation[edit]

Modified Stave Notation (MSN) is an alternative way of notating music for people who cannot easily read ordinary musical notation even if it is enlarged.

Parsons code[edit]

Parsons code is used to encode music so that it can be easily searched.

Braille music[edit]

Braille music is a complete, well developed, and internationally accepted musical notation system that has symbols and notational conventions quite independent of print music notation. It is linear in nature, similar to a printed language and different from the two-dimensional nature of standard printed music notation. To a degree Braille music resembles musical markup languages[31] such as MusicXML[32] or NIFF.

Integer notation[edit]

In integer notation, or the integer model of pitch, all pitch classes and intervals between pitch classes are designated using the numbers 0 through 11.

Rap notation[edit]

The standard form of rap notation is the «flow diagram», where rappers line up their lyrics underneath «beat numbers».[33] Hip-hop scholars also make use of the same flow diagrams that rappers use: the books How to Rap and How to Rap 2 extensively use the diagrams to explain rap’s triplets, flams, rests, rhyme schemes, runs of rhyme, and breaking rhyme patterns, among other techniques.[34] Similar systems are used by musicologists Adam Krims in his book Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity[35] and Kyle Adams in his work on rap’s flow.[36] As rap usually revolves around a strong 4/4 beat,[37] with certain syllables aligned to the beat, all the notational systems have a similar structure: they all have four beat numbers at the top of the diagram, so that syllables can be written in-line with the beat.[37]

ABC[edit]

ABC notation is a compact format using plain text characters, readable by computers and by humans. More than 100,000 tunes are now transcribed in this format.[38]

Music notation on computers[edit]

Unicode[edit]

The Musical Symbols Unicode block encodes an extensive system of formal musical notation.

The Miscellaneous Symbols block has a few of the more common symbols:

- U+2669 ♩ QUARTER NOTE

- U+266A ♪ EIGHTH NOTE

- U+266B ♫ BEAMED EIGHTH NOTES

- U+266C ♬ BEAMED SIXTEENTH NOTES

- U+266D ♭ MUSIC FLAT SIGN

- U+266E ♮ MUSIC NATURAL SIGN

- U+266F ♯ MUSIC SHARP SIGN

The Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs block has three emoji that may include depictions of musical notes:

- U+1F3A7 🎧 HEADPHONE

- U+1F3B5 🎵 MUSICAL NOTE

- U+1F3B6 🎶 MULTIPLE MUSICAL NOTES

Software[edit]

Many computer programs have been developed for creating music notation (called scorewriters or music notation software). Music may also be stored in various digital file formats for purposes other than graphic notation output.

Perspectives of musical notation in composition and musical performance[edit]

According to Philip Tagg and Richard Middleton, musicology and to a degree European-influenced musical practice suffer from a ‘notational centricity’, a methodology slanted by the characteristics of notation.[39][40] A variety of 20th- and 21st-century composers have dealt with this problem, either by adapting standard Western musical notation or by using graphic notation.[clarification needed] These include George Crumb, Luciano Berio, Krzystof Penderecki, Earl Brown, John Cage, Witold Lutoslawski, and others.[41][42]

See also[edit]

- List of musical symbols of modern notation.

- Hebrew cantillation

- Colored music notation

- Eye movement in music reading

- Guido of Arezzo, inventor of modern musical notation

- History of music publishing

- List of scorewriters

- Mensural notation

- Modal notation

- Music engraving, drawing music notation for the purpose of mechanical reproduction

- Music OCR, the application of optical character recognition to interpret sheet music

- Neume (plainchant notation)

- Pitch class

- Rastrum, a five-pointed writing implement used to draw parallel staff lines across a blank piece of sheet music

- Scorewriter

- Semasiography

- Sheet music

- Time unit box system, a notation system useful for polyrhythms

- Tongan music notation, a subset of standard music notation

- Tonnetz

- Znamenny chant

Notes[edit]

- ^ Giorgio Buccellati, «Hurrian Music», associate editor and webmaster Federico A. Buccellati Urkesh website (n.p.: IIMAS, 2003).

- ^ Kilmer & Civil (1986), p. [page needed].

- ^ Kilmer (1965), p. [page needed].

- ^ West (1994), pp. 161–163.

- ^ West (1994), p. 161.

- ^ Printed chant books with a modern simplified version of round notation were published since the 1820s and also used in Greece and Constantinople and in Old Church Slavonic translation within the slavophone Balkans and later on the territory of the autocephalous foundation of Bulgaria.

- ^ Only one Greek asmatikon written during the 14th century (Kastoria, Metropolitan Library, Ms.

preserved this gestic notation based on the practice of cheironomia, and transcribed the gestic signs into sticherarion notation in a second row. For more about kondakar, see Floros & Moran (2009) and Myers (1998).

- ^ After the decline of the Constantinopolitan cathedral rite during the fourth crusade (1201), its books kontakarion and asmatikon had been written in monastic scriptoria using Byzantine round notation. For more, see Byzantine music.

- ^ See Alexandru (2000) for a historical discussion of the great signs and their modern interpretations.

- ^ Chrysanthos (1832), p. 33.

- ^ Chrysanthos (1832) made a difference between his monosyllabic and the traditional polysyllabic parallage.

- ^ Toussaint (2004), 3.

- ^ Isidore of Seville (2006), p. 95.

- ^ Zapke (2007), p. [page needed].

- ^ Christensen (2002), p. 628.

- ^ Otten (1910).

- ^ McNaught (1893), p. 43.

- ^ Hall, Neitz & Battani (2003), p. 100.

- ^ Murray (1994), p. 45.

- ^ Gnanadesikan (2011), p. [page needed].

- ^ «Gukak». The DONG-A ILBO. dongA.com. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Bruno Nettl, Ruth M. Stone, James Porter and Timothy Rice (1999), The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Routledge, ISBN 978-0824049461, pages 242–245

- ^ KR Norman (1979), Sāmavedic Chant by Wayne Howard (Book Review), Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3, page 524;

Wayne Howard (1977), Samavedic Chant, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300019568

- ^ Bhandarkar (1913–1914).

- ^ Widdess (1979).

- ^ Bagley (2004).

- ^ a b c d Lindsay (1992), pp. 43–45.

- ^ Apel (1961), pp. xxiii, 22.

- ^ Dodeka Alternative Music Notation

- ^ Rochat (2018).

- ^ «musicmarkup.info». Archived from the original on 24 June 2004. Retrieved 1 June 2004.

- ^ emusician.com Archived 1 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Edwards (2009), p. 67.

- ^ Edwards (2013), p. 53.

- ^ Krims (2001), pp. 59–60.

- ^ Adams (2009).

- ^ a b Edwards (2009), p. 69.

- ^ «abc». www.music-notation.info. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Tagg (1979), pp. 28–32.

- ^ Middleton (1990), pp. 104–106.

- ^ Pierce (1973), p. [page needed].

- ^ Cogan (1976), p. [page needed].

Sources[edit]

- Adams, Kyle (October 2009). «On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music». Music Theory Online. 5 (9). Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Alexandru, Maria (2000). Studie über die ‘großen Zeichen’ der byzantinischen musikalischen Notation unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Periode vom Ende des 12. bis Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts [Study of the ‘great signs’ of Byzantine musical notation with special reference to the period from the end of the 12th to the beginning of the 19th century] (in German). Copenhagen: Københavns Universitet, Det Humanistiske Fakultet.[full citation needed]

- Apel, Willi (1961). The Notation of Polyphonic Music, 900–1600. Publications of the Mediaeval Academy of America, no. 38 (5th revised and with commentary ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Mediaeval Academy of America.

- Bagley, Robert (26 October 2004). The Prehistory of Chinese Music Theory (Speech). Elsley Zeitlyn Lecture on Chinese Archaeology and Culture. British Academy’s Autumn 2004 Lecture Programme. London: British Academy. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- Bhandarkar, D. R. (1913–1914). «28. Kudimiyamalai inscription on music». In Konow, Sten (ed.). Epigraphia Indica. Vol. 12. pp. 226–237.

- Christensen, Thomas (2002). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Chrysanthos of Madytos (1832). Theoritikón méga tís Mousikís Θεωρητικὸν μέγα τῆς Μουσικῆς [Great Theory of Music]. Tergeste: Michele Weis. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Cogan, Robert (1976). Sonic Design The Nature of Sound and Music. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13822726-8.

- Edwards, Paul (2009). How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC. foreword by Kool G. Rap. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Edwards, Paul (2013). How to Rap 2: Advanced Flow and Delivery Techniques. foreword by Gift of Gab. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Floros, Constantin; Moran, Neil K. (2009). The Origins of Russian Music: Introduction to the Kondakarian Notation. Frankfurt am Main etc.: Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631595534.

- Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. (2011). The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444359855. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Hall, John; Neitz, Mary Jo; Battani, Marshall (2003). Sociology on Culture. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28484-4.

- Isidore of Seville (2006). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (PDF). Translated with introduction and notes by Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof, with the collaboration of Muriel Hall. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83749-1.

- Kholopov, Yuri (2003). Гармония. Теоретический курс [Harmony: A Theoretical Course] (2nd ed.). Moscow; Saint Petersburg: Lan. ISBN 5-8114-0516-2.

- Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn (1965). «The Strings of Musical Instruments: Their Names, Numbers, and Significance». In Güterbock, Hans G.; Jacobsen, Thorkild (eds.). Studies in Honor of Benno Landsberger on His Seventy-fifth Birthday, April 21, 1965. Assyriological Studies. Vol. 16. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 261–268.

- Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn; Civil, Miguel (1986). «Old Babylonian Musical Instructions Relating to Hymnody». Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 38 (1): 94–98. doi:10.2307/1359953. JSTOR 1359953. S2CID 163942248.

- Krims, Adam (2001). Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lindsay, Jennifer (1992). Javanese Gamelan. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-588582-1.

- McNaught, W. G. (January 1893). «The History and Uses of the Sol-fa Syllables». Proceedings of the Musical Association. 19: 35–51. doi:10.1093/jrma/19.1.35. ISSN 0958-8442.

- Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- Murray, Chris (1994). Dictionary of the Arts. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-3205-1.

- Myers, Gregory (1998). «The medieval Russian Kondakar and the choirbook from Kastoria: a palaeographic study in Byzantine and Slavic musical relations». Plainsong and Medieval Music. 7 (1): 21–46. doi:10.1017/S0961137100001406.

- Otten, J. (1910). «Guido of Arezzo». The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- Pierce, Brent (1973). New Choral Notation (A Handbook). New York: Walton Music Corporation.

- Rochat, Jacques-Daniel (2018). Dodeka: la révolution musicale (in French). Chexbres: Crea 7. ISBN 9782970127505. OCLC 1078658738.

- Tagg, Philip (1979). Kojak—50 Seconds of Television Music: Toward the Analysis of Affect in Popular Music. Skrifter från Musikvetenskapliga Institutionen, Göteborg 2. Göteborg: Musikvetenskapliga Institutionen, Göteborgs Universitet. ISBN 91-7222-235-2. English translation of «Kojak—50 sekunders tv-musik».

- Toussaint, Godfried (2004). A Comparison of Rhythmic Similarity Measures (PDF). Technical Report SOCS-TR-2004.6. Montréal: School of Computer Science, McGill University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2012.

- West, Martin Litchfield (May 1994). «The Babylonian Musical Notation and the Hurrian Melodic Texts». Music & Letters. 75 (2): 161–179. doi:10.1093/ml/75.2.161.

- Widdess, D. R (1979). «The Kudumiyamalai inscription: a source of early Indian music in notation». Musica Asiatica. Oxford University Press. 2: 115–150.

- Zapke, Susana, ed. (2007). Hispania Vetus: Musical-Liturgical Manuscripts from Visigothic Origins to the Franco-Roman Transition (9th–12th Centuries). Foreword by Anscario M Mundó. Bilbao: Fundación BBVA. ISBN 978-84-96515-50-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Gayou, Évelyne (August 2010). «Transcrire les musiques électroacoustiques». EContact! (in French). Montréal: Canadian Electroacoustic Community. 12 (4 Perspectives on the Electroacoustic Work / Perspectives sur l’œuvre électroacoustique).

- Gould, Elaine (2011). Behind Bars – The Definitive Guide to Music Notation. London: Faber Music.

- Hall, Rachael (2005). Math for Poets and Drummers (PDF). Saint Joseph’s University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- Karakayali, Nedim (2010). «Two Assemblages of Cultural Transmission: Musicians, Political Actors and Educational Techniques in the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe». Journal of Historical Sociology. 23 (3): 343–71. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2010.01377.x. hdl:11693/22234.

- Lieberman, David (2006). «Game Enhanced Music Manuscript». In Y Tina Lee; Siti Mariyam Shamsuddin; Diego Gutierrez; Norhaida Mohd Suaib (eds.). Graphite ’06: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques in Australasia and South East Asia, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), 29 November–2 December 2006. 4th International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques in Australasia and South East Asia. New York: ACM Press. pp. 245–50. ISBN 1-59593-564-9.

- Read, Gardner (1978). Modern Rhythmic Notation. Victor Gollance.

- Read, Gardner (1987). Source Book of Proposed Music Notation Reforms. Greenwood Press.

- Reisenweaver, Anna (2012). «Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning». Musical Offerings. 3 (1): 37–59. doi:10.15385/jmo.2012.3.1.4.

- Savas, Savas I. (1965). Byzantine Music in Theory and Practice (PDF). Boston: Hercules. ISBN 0-916586-24-3. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Schneider, Albrecht (1987). «Musik, Sound, Sprache, Schrift: Transkription und Notation in der Vergleichenden Musikwissenschaft und Musikethnologie» [Music, sound, language, writing: Transcription and notation in comparative musicology and music ethnology]. Zeitschrift für Semiotik (in German). 9 (3–4): 317–43.

- Sotorrio, José A. (1997). Bilinear Music Notation: A New Notation System for the Modern Musician. Spectral Music. ISBN 978-0-9548498-2-5.

- Stone, Kurt (1980). Music Notation in the Twentieth Century: A Practical Guidebook. W. W. Norton.

- Strayer, Hope R. (2013). «From Neumes to Notes: The Evolution of Music Notation». Musical Offerings. 4 (1): 1–14. doi:10.15385/jmo.2013.4.1.1.

- Touma, Habib Hassan (1996). The Music of the Arabs (book with accompanying CD recording). Translated by Laurie Schwartz (new expanded ed.). Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

- Williams, Charles Francis Abdy (1903). The Story of Notation. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

External links[edit]

- Byzantine Music Notation. Contains a Guide to Byzantine Music Notation (neumes).