| Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp | |

|---|---|

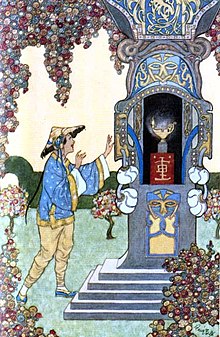

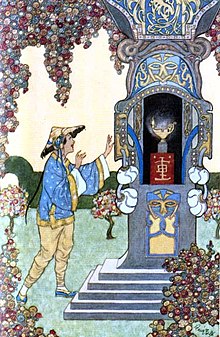

Aladdin finds the wonderful lamp inside the cave. A c. 1898 illustration by Rene Bull. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 561 (Aladdin) |

| Region | Middle East |

| Published in | One Thousand and One Nights, compiled and translated by Antoine Galland |

Aladdin ( ə-LAD-in; Arabic: علاء الدين, ʻAlāʼ ud-Dīn/ ʻAlāʼ ad-Dīn, IPA: [ʕalaːʔ adˈdiːn], ATU 561, ‘Aladdin’) is a Middle-Eastern folk tale. It is one of the best-known tales associated with The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (The Arabian Nights), despite not being part of the original text; it was added by the Frenchman Antoine Galland, based on a folk tale that he heard from the Syrian Maronite storyteller Hanna Diyab.[1]

Sources[edit]

Known along with Ali Baba as one of the «orphan tales», the story was not part of the original Nights collection and has no authentic Arabic textual source, but was incorporated into the book Les mille et une nuits by its French translator, Antoine Galland.[2]

John Payne quotes passages from Galland’s unpublished diary: recording Galland’s encounter with a Maronite storyteller from Aleppo, Hanna Diyab.[1] According to Galland’s diary, he met with Hanna, who had travelled from Aleppo to Paris with celebrated French traveller Paul Lucas, on March 25, 1709. Galland’s diary further reports that his transcription of «Aladdin» for publication occurred in the winter of 1709–10. It was included in his volumes ix and x of the Nights, published in 1710, without any mention or published acknowledgment of Hanna’s contribution.

Payne also records the discovery in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris of two Arabic manuscripts containing Aladdin (with two more of the «interpolated» tales). One was written by a Syrian Christian priest living in Paris, named Dionysios Shawish, alias Dom Denis Chavis. The other is supposed to be a copy Mikhail Sabbagh made of a manuscript written in Baghdad in 1703. It was purchased by the Bibliothèque Nationale at the end of the nineteenth century.[3] As part of his work on the first critical edition of the Nights, Iraq’s Muhsin Mahdi has shown[4] that both these manuscripts are «back-translations» of Galland’s text into Arabic.[5][6]

Ruth B. Bottigheimer[7] and Paulo Lemos Horta[8][9] have argued that Hanna Diyab should be understood as the original author of some of the stories he supplied, and even that several of Diyab’s stories (including Aladdin) were partly inspired by Diyab’s own life, as there are parallels with his autobiography.[10]

Plot summary[edit]

The Sorcerer traps Aladdin in the magic cave.

The story is often retold with variations. The following is a précis of the Burton translation of 1885.[11]

Aladdin is an impoverished young ne’er-do-well, dwelling in «one of the cities of China». He is recruited by a sorcerer from the Maghreb, who passes himself off as the brother of Aladdin’s late father, Mustapha the tailor, convincing Aladdin and his mother of his good will by pretending to set up the lad as a wealthy merchant. The sorcerer’s real motive is to persuade young Aladdin to retrieve a wonderful oil lamp (chirag) from a booby-trapped magic cave. After the sorcerer attempts to double-cross him, Aladdin finds himself trapped in the cave. Aladdin is still wearing a magic ring the sorcerer has lent him. When he rubs his hands in despair, he inadvertently rubs the ring and a genie appears and releases him from the cave, allowing him to return to his mother while in possession of the lamp. When his mother tries to clean the lamp, so they can sell it to buy food for their supper, a second far more powerful genie appears who is bound to do the bidding of the person holding the lamp.

With the aid of the genie of the lamp, Aladdin becomes rich and powerful and marries Princess Badroulbadour, the sultan’s daughter (after magically foiling her marriage to the vizier’s son). The genie builds Aladdin and his bride a wonderful palace, far more magnificent than the sultan’s.

The sorcerer hears of Aladdin’s good fortune, and returns; he gets his hands on the lamp by tricking Aladdin’s wife (who is unaware of the lamp’s importance) by offering to exchange «new lamps for old». He orders the genie of the lamp to take the palace, along with all its contents, to his home in the Maghreb. Aladdin still has the magic ring and is able to summon the lesser genie. The genie of the ring cannot directly undo any of the magic of the genie of the lamp, but he is able to transport Aladdin to the Maghreb where, with the help of the «woman’s wiles» of the princess, he recovers the lamp and slays the sorcerer, returning the palace to its proper place.

The sorcerer’s more powerful and evil brother plots to destroy Aladdin for killing his brother by disguising himself as an old woman known for her healing powers. Badroulbadour falls for his disguise and commands the «woman» to stay in her palace in case of any illnesses. Aladdin is warned of this danger by the genie of the lamp and slays the impostor.

Aladdin eventually succeeds to his father-in-law’s throne.

Setting[edit]

The opening sentences of the story, in both the Galland and the Burton versions, set it in «one of the cities of China».[12] On the other hand, there is practically nothing in the rest of the story that is inconsistent with a Middle Eastern setting. For instance, the ruler is referred to as «Sultan» rather than «Emperor», as in some retellings, and the people in the story are Muslims and their conversation is filled with Muslim platitudes. A Jewish merchant buys Aladdin’s wares, but there is no mention of Buddhists, Daoists or Confucians.

Notably, ethnic groups in Chinese history have long included Muslim groups, including large populations of Uighurs, and the Hui people as well as the Tajiks whose origins go back to Silk Road travelers. Islamic communities have been known to exist in the region since the Tang dynasty (which rose to power simultaneously with the prophet Muhammad’s career.) Some have suggested that the intended setting may be Turkestan (encompassing Central Asia and the modern-day Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang in Western China).[13]

For all this, speculation about a «real» Chinese setting depends on a knowledge of China that the teller of a folk tale (as opposed to a geographic expert) might well not possess.[14] In early Arabic usage, China is known to have been used in an abstract sense to designate an exotic, faraway land.[15][16]

Motifs and variants[edit]

Tale type[edit]

The story of Aladdin is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as tale type ATU 561, «Aladdin», after the character. In the Index, the Aladdin story is situated next to two similar tale types: ATU 560, The Magic Ring, and ATU 562, The Spirit in the Blue Light.[17] All stories deal with a down-on-his-luck and impoverished boy or soldier, who finds a magical item (ring, lamp, tinderbox) that grants his wishes. In this tale type, the magical item is stolen, but eventually recovered thanks to the use of another magical object.[18]

Distribution[edit]

Since its appearance in The One Thousand and One Nights, the tale has integrated into oral tradition. Scholars Ton Deker and Theo Meder located variants across Europe and the Middle East.[19]

An Indian variant has been attested, titled The Magic Lamp and collected among the Santal people.[20][21]

Adaptations[edit]

Adaptations vary in their faithfulness to the original story. In particular, difficulties with the Chinese setting are sometimes resolved by giving the story a more typical Arabian Nights background.

Books[edit]

- One of the many literary retellings of the tale appears in A Book of Wizards (1966) and A Choice of Magic (1971), by Ruth Manning-Sanders. Another is the early Penguin version for children, Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp, illustrated by John Harwood with many Chinese details: the translator or re-teller is not acknowledged: this was a «Porpoise» imprint printed in 1947 and released in 1948.

- Aladdin: Master of the Lamp (1992), edited by Mike Resnick and Martin H. Greenberg, is an anthology containing 43 original short stories inspired by the tale.

- «The Nobility of Faith» by Jonathan Clements in the anthology Doctor Who Short Trips: The Ghosts of Christmas (2007) is a retelling of the Aladdin story in the style of the Arabian Nights, but featuring the Doctor in the role of the genie.

Comics[edit]

Western comics[edit]

- In 1962 the Italian branch of Walt Disney Productions published the story Paperino e la grotta di Aladino (Donald and Aladdin’s Cave), written by Osvaldo Pavese and drawn by Pier Lorenzo De Vita. As in many pantomimes, the plot is combined with elements of the Ali Baba story: Uncle Scrooge leads Donald Duck and their nephews on an expedition to find the treasure of Aladdin and they encounter the Middle Eastern counterparts of the Beagle Boys. Scrooge describes Aladdin as a brigand who used the legend of the lamp to cover the origins of his ill-gotten gains. They find the cave holding the treasure—blocked by a huge rock requiring a magic password («open sesame») to open.[22]

- The original version of the comic book character Green Lantern was partly inspired by the Aladdin myth; the protagonist discovers a «lantern-shaped power source and a ‘power ring‘» which gives him power to create and control matter.[23]

- In the Elseworlds series, there was even a story that combined the Green Lantern mythos with that of Aladdin called Green Lantern: 1001 Emerald Nights.

Manga[edit]

- The Japanese manga series Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic is not a direct adaptation, but features Aladdin as the main character of the story and includes many characters from other One Thousand and One Nights stories. An adaptation of this comic to an anime television series was made in October 2012 in which Aladdin is voiced by Kaori Ishihara in Japanese and Erica Mendez in English.

Pantomimes[edit]

An 1886 theatre poster advertising a production of the pantomime Aladdin.

- In the United Kingdom, the story of Aladdin was dramatised in 1788 by John O’Keefe for the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden.[24] It has been a popular subject for pantomime for over 200 years.[25]

- The traditional Aladdin pantomime is the source of the well-known pantomime character Widow Twankey (Aladdin’s mother). In pantomime versions, changes in the setting and story are often made to fit it better into «China» (albeit a China situated in the East End of London rather than medieval Baghdad), and elements of other Arabian Nights tales (in particular Ali Baba) are often introduced into the plot. One version of the «pantomime Aladdin» is Sandy Wilson’s musical Aladdin, from 1979.

- Since the early 1990s, Aladdin pantomimes have tended to be influenced by the Disney animation. For instance, the 2007/8 production at the Birmingham Hippodrome starring John Barrowman featured songs from the Disney movies Aladdin and Mulan.

Other musical theatre[edit]

New Crowns for Old, a 19th-century British cartoon based on the Aladdin story (Disraeli as Abanazer from the pantomime version of Aladdin offering Queen Victoria an Imperial crown (of India) in exchange for a Royal one)

- The New Aladdin was a successful Edwardian musical comedy in 1906.

- Adam Oehlenschläger wrote his verse drama Aladdin in 1805. Carl Nielsen wrote incidental music for this play in 1918–19. Ferruccio Busoni set some verses from the last scene of Oehlenschläger’s Aladdin in the last movement of his Piano Concerto, Op. 39.

- In 1958, a musical comedy version of Aladdin was written especially for US television with a book by S. J. Perelman and music and lyrics by Cole Porter. A London stage production followed in 1959 in which a 30-year-old Bob Monkhouse played the part of Aladdin at the Coliseum Theatre.[26]

- Aladdin; Prince Street Players version; book by Jim Eiler; Music by Jim Eiler and Jeanne Bargy; Lyrics by Jim Eiler.[27]

- Broadway Junior has released Aladdin Jr., a children’s musical based on the music and screenplay of the Disney animation.

- The Disney’s Aladdin: A Musical Spectacular musical stage show ran in Disney California Adventure from January 2003 to January 10, 2016.[28]

- StarKid Productions released the musical «Twisted» on YouTube in 2013, a parody of the 1992 Disney film that is told from the royal vizier’s point of view.

- A Disney Theatrical Production of Aladdin opened in 2011 in Seattle, in Toronto in 2013, and on Broadway at the New Amsterdam Theatre on March 20, 2014.

Theatrical films[edit]

Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (1917)

Animation: Europe and Asia[edit]

- The 1926 animated film The Adventures of Prince Achmed (the earliest surviving animated feature film) combined the story of Aladdin with that of the prince. In this version the princess Aladdin pursues is Achmed’s sister and the sorcerer is his rival for her hand. The sorcerer steals the castle and the princess through his own magic and then sets a monster to attack Aladdin, from which Achmed rescues him. Achmed then informs Aladdin he requires the lamp to rescue his own intended wife, Princess Pari Banou, from the demons of the Island of Wak Wak. They convince the Witch of the Fiery Mountain to defeat the sorcerer, and then all three heroes join forces to battle the demons.

- The animated feature Aladdin et la lampe merveilleuse by Film Jean Image was released in 1970 in France. The story contains many of the original elements of the story as compared to the Disney version.

- A Thousand and One Nights is a 1969 Japanese adult anime feature film directed by Eiichi Yamamoto, conceived by Osamu Tezuka. The film is a first part of Mushi Production’s Animerama, a series of films aimed at an adult audience.

- An elderly version of Aladdin appears as a protagonist in the 1975 anime series Arabian Nights: Sinbad’s Adventures.

- Aladdin and the Magic Lamp was a rendition in Japanese directed by Yoshikatsu Kasai, produced in Japan by Toei Animation and released in the United States by The Samuel Goldwyn Company in 1982.

- Son of Aladdin is a 2003 Indian 3D-animated fantasy-adventure film by Singeetam Srinivasa Rao, produced by Pentamedia Graphics. It follows the adventures of the son of Aladdin and his fight with an evil sorcerer.

Animation: USA[edit]

- In the 1934 short film, Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp, Aladdin is a child laborer who finds a magic lamp and uses it to become a prince.IMDb

- In the 1938 animated film Have You Got Any Castles?, Aladdin makes a brief appearance asking for help but gets punched by one of the Three Musketeers.

- Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp is a 1939 Popeye the Sailor cartoon.

- The 1959 animated film 1001 Arabian Nights starring Mr. Magoo as Aladdin’s uncle and produced by UPA.

- Aladdin is a 48-minute animated film based on the classic Arabian Nights story «Aladdin and the magic lamp», translated by Antoine Galland. Aladdin was produced by Golden Films and the American Film Investment Corporation. Like all other Golden Films productions, the film featured a single theme song, «Rub the Lamp», written and composed by Richard Hurwitz and John Arrias. It was released directly to video on April 27, 1992 by GoodTimes Home Video (months before Disney’s version was released) and was reissued on DVD in 2002 as part of the distributor’s Collectible Classics line of products.

- Aladdin, the 1992 animated feature by Walt Disney Feature Animation (currently the best-known retelling of the story). In this version several characters are renamed or amalgamated. For instance the Sorcerer and the Sultan’s vizier were combined into one character named Jafar while the Princess is renamed Jasmine. They have new motivations for their actions. The Genie of the Lamp only grants three wishes and desires freedom from his role. A sentient magic carpet replaces the ring’s genie while Jafar uses a royal magic ring to find Aladdin. The names «Jafar» and «Abu», the Sultan’s delight in toys, and their physical appearances are borrowed from the 1940 film The Thief of Bagdad. The setting is moved from China to the fictional Arabian city of Agrabah, and the structure of the plot is simplified.

- The Return of Jafar (1994), direct-to-video sequel to the 1992 Walt Disney movie.

- Aladdin and the King of Thieves (1996), direct-to-video second and final sequel to the 1992 Walt Disney movie.

Live-action: English language films[edit]

- Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (1917), directed by Chester M. Franklin and Sidney A. Franklin and released by the Fox Film Corporation, told the story using child actors.[29][30][31] It is the earliest known filmed adaptation of the story.

- The 1940 British movie The Thief of Bagdad borrows elements of the Aladdin story, although it also departs from the original story fairly freely: for instance the genie grants only three wishes and the minor character of the Emperor’s vizier is renamed Jaffar and becomes the main villain, replacing the sorcerer from the original plot.

- Arabian Nights is a 1942 adventure film directed by John Rawlins and starring Sabu, Maria Montez, Jon Hall and Leif Erickson. The film is derived from The Book of One Thousand and One Nights but owes more to the imagination of Universal Pictures than the original Arabian stories. Unlike other films in the genre (The Thief of Bagdad), it features no monsters or supernatural elements.[32]

- A Thousand and One Nights (1945) is a tongue-in-cheek Technicolor fantasy film set in the Baghdad of the One Thousand and One Nights, starring Cornel Wilde as Aladdin, Evelyn Keyes as the genie of the magic lamp, Phil Silvers as Aladdin’s larcenous sidekick, and Adele Jergens as the princess Aladdin loves.

- The Wonders of Aladdin is a 1961 film directed by Mario Bava and Henry Levin and starring Donald O’Connor as Aladdin. This film has a more working-class focus: Aladdin helps the prince (Mario Girotti) and princess (as does a fakir) but never becomes one and ends up in a romantic relationship with his neighbor, Djalma (Noelle Adam). The genie (Vittorio De Sica) can grant only three wishes (although what constitutes as a single wish is quite malleable, probably due to his sympathies with Aladdin) and shrinks with each one, which is leading to his eternal rest after 12,000 years.

- A 1998 direct-to-video movie A Kid in Aladdin’s Palace directed by Robert L. Levy which is a sequel to A Kid in King Arthur’s Court.

- Adventures of Aladdin (2019), a mockbuster produced by The Asylum.[33][34]

- Aladdin, a Disney live-action remake of the 1992 animated film, released in 2019. It stars Mena Massoud as the title character, Naomi Scott as Jasmine, Marwan Kenzari as Jafar, and Will Smith as the Genie.

Live-action: Non-English language films[edit]

- Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp is a 1927 Indian silent film, by Bhagwati Prasad Mishra, based on the folktale.[35]

- Alladin and the Wonderful Lamp is a 1931 Indian silent film, adapted from the folktale, by Jal Ariah.[35]

- Aladdin Aur Jadui Chirag (Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp) is a 1933 Indian Hindi-language fantasy-adventure film by Jal Ariah. A remake of the 1931 film in sound.[35]

- Aaj Ka Aladdin (Today’s Aladdin) is a 1935 Indian Hindi-language film by Nagendra Majumdar. It is a modern retelling of the folktale.[35]

- Aladdin Aur Jadui Chirag (Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp) is a 1937 Indian Hindi-language film adaptation by Navinchandra.[35]

- Aladdin Aur Jadui Chirag (Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp) is a 1952 Indian Hindi-language musical fantasy-adventure film by Homi Wadia, starring Mahipal as Aladdin and Meena Kumari as Princess Badar.

- Alif-Laila is a 1955 Indian Hindi-language fantasy film by K. Amarnath, Vijay Kumar portrays the character of Aladdin with actress Nimmi as the female genie.

- Chirag-e-Cheen (Lamp of China) is a 1955 Indian Hindi-language film adaptation by G.P. Pawar and C. M. Trivedi.[35]

- Alladin Ka Beta (Son of Alladin) is a 1955 Indian Hindi-language action film, it follows the story of the son of Alladin.

- Alladin and the Wonderful Lamp is a 1957 Indian fantasy film by T. R. Raghunath. Based on the story of Aladdin, it was simultaneously filmed in Telugu, Tamil and Hindi with Akkineni Nageshwara Rao portraying the titular character.

- Alladdin Laila is a 1957 Indian Hindi-language film by Lekhraj Bhakri, starring Mahipal, Lalita Pawar and Shakila.[35]

- Sindbad Alibaba and Aladdin is a 1965 Indian Hindi-language musical fantasy-adventure film by Prem Narayan Arora. It features the three most popular characters from the Arabian Nights. Very loosely based on the original, in which the heroes get to meet and share in each other’s adventures. In this version, the lamp’s jinni (genie) is female and Aladdin marries her rather than the princess (she becomes a mortal woman for his sake).

- Main Hoon Aladdin (I am Aladdin) is a 1965 Indian Hindi-language film by Mohammed Hussain, starring Ajit in the titular role.[35]

- A Soviet film Volshebnaia Lampa Aladdina («Aladdin’s Magic Lamp») was released in 1966.

- A Mexican production, Pepito y la Lampara Maravillosa was made en 1972, where comedian Chabelo plays the role of the genie who grant wishes to a young kid called Pepito in 1970s Mexico City.

- Adventures of Aladdin is a 1978 Indian Hindi-language adventure-film based on the tale, by Homi Wadia.

- Allauddinum Albhutha Vilakkum (Aladdin and the Magic Lamp) is a 1979 Indian adventure fantasy-drama film by I. V. Sasi. It was simultaneously filmed in Malayalam and Tamil with Kamal Haasan in the titular role.

- In 1986, an Italian production (under supervision of Golan-Globus) of a modern-day Aladdin was filmed in Miami under the title Superfantagenio, starring actor Bud Spencer as the genie and his daughter Diamante as the daughter of a police sergeant.

- Aladin is a 2009 Indian Hindi-language fantasy action film directed by Sujoy Ghosh. The film stars Ritesh Deshmukh in the titular role, along with Amitabh Bachchan, Jacqueline Fernandez and Sanjay Dutt.

- The New Adventures of Aladdin, France modern retelling of the tale of Aladdin.

- Alad’2, second sequel to the French movie The New Adventures of Aladdin (2018).

- Ashchorjyo Prodeep is a 2013 Indian Bengali-language film by Anik Dutta. This film is based on a Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay novel of the same name and deals with the issues of consumerism. It is a modern adaptation of Aladdin about the story of a middle-class man (played by Saswata Chatterjee) who accidentally finds a magic lamp containing a Jinn (played by Rajatava Dutta).

- Aladin Saha Puduma Pahana was released in 2018 in Sri Lanka in Sinhala language.[36]

Television[edit]

Animation: English language[edit]

- Aladdin is a 1958 musical fantasy written especially for television with a book by S.J. Perelman and music and lyrics by Cole Porter, telecast in color on the DuPont Show of the Month by CBS.

- «Aladdin and the Magic Lamp»,[37] an episode of Rabbit Ears Productions’ We All Have Tales series, televised on PBS in 1991, featuring John Hurt as narrator, with illustrations by Greg Couch and music by Mickey Hart. This version is set in Isfahan, Persia, and closely follows the original plot, including the origin of the sorcerer. The audiobook version was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for Children in 1994.

- Aladdin, an animated series produced by Disney based on their movie adaptation that ran from 1994 to 1995.

- Aladdin featured in an episode of Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child. The story was set in «Ancient China», but otherwise had a tenuous connection with the original plot.

- Magi, Alladin, a young magi, befriends a Jin and goes adventuring with Alibaba. (2013) Japanese, English dub available

Live-action: English language[edit]

- Aladdin appeared in episode 297 of Sesame Street performed by Frank Oz. This version was made from a large lavender live-hand Anything Muppet.

- A segment of the Marty Feldman episode of The Muppet Show retells the story of Aladdin with The Great Gonzo in the role of Aladdin and Marty Feldman playing the genie of the lamp.

- A 1967 TV movie was based on the Prince Street Players stage musical. This version is very close to the touring musical with about 15 minutes cut to be adapted into the 50 minutes tv program. It had Will B. Able as the Genii and Fred Grades as Aladdin.

- In 1986, the program Faerie Tale Theatre based an episode on the story called «Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp», directed by Tim Burton and starring Robert Carradine as Aladdin and James Earl Jones as both the ring Genie and the lamp Genie.

- In 1990 Disney made a direct to TV movie based on the Prince Street Players stage musical, starring Barry Bostwick.[38]

- Aladdin features as one of five stories in the Hallmark Entertainment TV miniseries Arabian Nights in 2000, featuring Jason Scott Lee as Aladdin and John Leguizamo as both of the genies.

- The characters of Aladdin, Jasmine, Jafar and the Sultan, along with Agrabah as the setting and the genie of the lamp were adapted into the sixth season of TV series Once Upon a Time, with Aladdin portrayed by Deniz Akdeniz, Jasmine portrayed by Karen David, and Jafar portrayed by Oded Fehr. Jafar previously appeared in the spin-off Once Upon a Time in Wonderland, portrayed by Naveen Andrews. Both were produced by ABC Television Studios and based on the Disney version of the story.

- Syfy released a made-for-TV horror adaptation called Aladdin and the Death Lamp on September 15, 2012.

Live-action: Non-English language[edit]

- In Kyōryū Sentai Zyuranger, the sixteenth installment of the long-running Super Sentai metaseries, the Djinn (voiced by Eisuke Yoda) that appears in the eleventh episode («My Master!» Transcription: «Goshujin-sama!» (Japanese: ご主人さま!)) reveals that he was the genie from the tale of «Aladdin and the Magic Lamp», which did take place.

- The story of Aladdin was featured in Alif Laila, an Indian TV series directed by Ramanand Sagar in 1994 and telecasted on DD National.

- Aladdin – Jaanbaaz Ek Jalwe Anek (2007–2009), an Indian fantasy television series based on the story of Aladdin that aired on Zee TV, starring Mandar Jadhav in the titular role of Aladdin.

- Aladdin — Naam Toh Suna Hoga (2018–2021), a live-action Indian fantasy television show on SAB TV starring Siddharth Nigam as Aladdin and Avneet Kaur/Ashi Singh as Yasmine.

Video games[edit]

- A number of video games were based on the Disney movie:

- The Genesis version (also on Amiga, MS-DOS, NES, Game Boy, and Game Boy Color) by Virgin Games.

- The SNES version (also on Game Boy Advance) by Capcom.

- The Master System version (also on Game Gear) by SIMS.

- Nasira’s Revenge for the PlayStation and Windows by Argonaut Games.

- The Disney version of Aladdin appears throughout the Disney/Square Enix crossover series Kingdom Hearts, with Agrabah being a visitable world.

- The video game Sonic and the Secret Rings is heavily based on the story of Aladdin, and both genies appear in the story. The genie of the lamp is the main antagonist, known in the game as the Erazor Djinn, and the genie of the ring, known in the game as Shahra, appears as Sonic’s sidekick and guide through the game. Furthermore, the ring genie is notably lesser than the lamp genie in the story.

- In 2010, Anuman Interactive launched Aladin and the Enchanted Lamp, a hidden object game on PC and Mac.[39]

- In 2016 Saturn Animation Studio produced an interactive adaptation of The Magical Lamp of Aladdin for mobile devices.

Pachinko[edit]

Sega Sammy have released a line of pachinko machines based on Aladdin since 1989. Sega Sammy have sold over 570,000 Aladdin pachinko machines in Japan, as of 2017.[40] At an average price of about $5,000,[41] this is equivalent to approximately $2.85 billion in pachinko sales revenue.

Gallery[edit]

-

Aladdin trades the silver plates to a Jew for a piece of gold

-

Aladdin in Disney’s stage show.

See also[edit]

- 54521 Aladdin, asteroid

- Arabian mythology

- Genies in popular culture

- The Bronze Ring

- Jack and His Golden Snuff-Box

- The Tinderbox

- The Blue Light

- Three wishes joke

References[edit]

- ^ a b Razzaque (2017)

- ^ Allen (2005) pp.280–

- ^ Payne (1901) pp. 13-15

- ^ Irwin (1994) pp. 57-58

- ^ Mahdi (1994) pp. 51-71

- ^ Dobie (2008) p.36

- ^ Bottigheimer, Ruth B. «East Meets West» (2014).

- ^ Horta, Paulo Lemos (2018). Aladdin: A New Translation. Liveright Publishing. pp. 8–10. ISBN 9781631495175. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Paulo Lemos Horta, Marvellous Thieves: Secret Authors of the Arabian Nights (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), pp. 24-95.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia B. (May 23, 2019). «Was Aladdin Based on a Real Person? Here’s Why Scholars Are Starting to Think So». Time. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Burton (2009) pp. 1 ff

- ^ Plotz (2001) p. 148–149

- ^ Moon (2005) p. 23

- ^ Honour (1973) — Section I «The Imaginary Continent»

- ^ Arafat A. Razzaque (10 August 2017). «Who was the «real» Aladdin? From Chinese to Arab in 300 Years». Ajam Media Collective.

- ^ Olivia B. Waxman (2019-05-23). «Was Aladdin Based on a Real Person? Here’s Why Scholars Are Starting to Think So». Time. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ^ Ranke, Kurt (1966). Folktales of Germany. Routledge & K. Paul. p. 214. ISBN 978-81-304-0032-7.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 70-73. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Deker, Ton; Meder, Theo. «Aladdin en de wonderlamp». In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sun. 1997. p. 40.

- ^ Campbell, A., of the Santal mission. Santal Folk-Tales. Pokhuria, India : Santal Mission Press. 1891. pp. 1-5.

- ^ Brown, W. Norman (1919). «The Pañcatantra in Modern Indian Folklore». Journal of the American Oriental Society. 39: 1–54. doi:10.2307/592712. JSTOR 592712.

- ^ «Profile of Paperino e la grotta di Aladino«. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Adam Robert, The History of Science Fiction, Palgrave Histories of Literature, ISBN 978-1-137-56959-2, 2016, p. 224

- ^ Witchard (2017)

- ^ «Aladdin». www.its-behind-you.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ «Cole Porter / Aladdin (London Stage Production)». Sondheim Guide. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ «MTIshows.com Music Theatre International». Archived from the original on 2015-05-15. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ^ Slater, Shawn (9 September 2015). «All New ‘Frozen’-Inspired Stage Musical Coming to Disney California Adventure Park in 2016». Disney Parks Blog. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ «Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp». Letterboxd. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ «The Library of Congress American Silent Feature Film Survival Catalog:Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp«. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ^ «Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp». Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Article on Arabian Nights at Turner Classic Movies accessed 10 January 2014

- ^ News, VICE (2019-05-24). «What It Takes to Make a Hollywood Mockbuster, the «Slightly Shittier» Blockbuster». Vice News. Archived from the original on 2019-05-29. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ Adventures of Aladdin (2019), retrieved 2019-05-29

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 9780851706696. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ «Dhananjaya became Aladin». Sarasaviya. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ «Aladdin and the Magic Lamp — Rabbit Ears». www.rabbitears.com. Archived from the original on 2019-04-10. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- ^ Buck, Jerry (February 25, 1990). «Barry Bostwick ‘explores other worlds’ in ‘Challenger’ movie». The Sacramento Bee.

- ^ «Aladin et la Lampe Merveilleuse PC, Mac | 2010». Planete Jeu (in French). Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Beyond Expectations: Integrated Report (PDF). Sega Sammy Holdings. 2017. p. 73. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-26. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ Graser, Marc (2 August 2013). «‘Dark Knight’ Producer Plays Pachinko to Launch Next Franchise (EXCLUSIVE)». Variety. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Allen, Roger (2005). The Arabic Literary Heritage: The Development of Its Genres and Criticism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48525-8.

- Burton, Sir Richard (2009). Aladdin and the Magic Lamp. Digireads.com Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4209-3193-8.

- Dobie, Madeleine (2008). «Translation in the contact zone: Antoine Galland’s Mille et une nuits: contes arabes». In Makdisi, S.; Nussbaum, F. (eds.). The Arabian Nights in Historical Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955415-7.

- El-Shamy, Hasan (2004). «The Oral Connections of the Arabian Nights». The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-204-2.

- Honour, Hugh (1973). Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay. Ican. ISBN 978-0-06-430039-1.

- Horta, Paulo Lemos (2018). «Introduction». Aladdin: A New Translation. Translated by Seale Y. Liveright Publishing. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-1-63149-517-5. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Irwin, Robert (2004). Arabian Nights, The: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 1-86064-983-1.

- Littman (1986). «Alf Layla wa Layla». Encyclopedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill.

- Mahdi, Muhsin (1994). The Thousand and One Nights Part 3. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10106-3.

- Moon, Krystyn (2005). Yellowface. Rutgers University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8135-3507-7.

- Payne, John (1901). Aladdin and the Enchanted Lamp and Other Stories. London.

- Plotz, Judith Ann (2001). Romanticism and the vocation of childhood. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-22735-3.

- «Who ‘wrote’ Aladdin? The Forgotten Syrian Storyteller». Ajam Media Collective. 14 September 2017.

- Witchard, Anne Veronica (2017). Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-5864-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Gaál, E. (1973). «Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp». Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 27 (3): 291–300. JSTOR 23657287.

- Gogiashvili, Elene (3 April 2018). «The Tale of Aladdin in Georgian Oral Tradition». Folklore. 129 (2): 148–160. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2017.1397392. S2CID 165697492.

- Haddawy, Husain (2008). The Arabian Nights. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33166-0.

- Huet, G. (1918). «Les Origines du Conte de Aladdin et la Lampe Merveilleuse». Revue de l’histoire des religions. 77: 1–50. JSTOR 23663317.

- Larzul, Sylvette (2004). «Further Considerations on Galland’s ‘Mille et une Nuits’: A Study of the Tales Told by Hanna». Marvels & Tales. 18 (2): 258–271. doi:10.1353/mat.2004.0043. JSTOR 41388712. S2CID 162289753.

- Marzolph, Ulrich (1 July 2019). «Aladdin Almighty: Middle Eastern Magic in the Service of Western Consumer Culture». Journal of American Folklore. 132 (525): 275–290. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.132.525.0275. S2CID 199268544.

- Nun, Katalin; Stewart, Dr Jon (2014). Volume 16, Tome I: Kierkegaard’s Literary Figures and Motifs: Agamemnon to Guadalquivir. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4724-4136-2.

External links[edit]

- Andrew Lang. The Arabian Nights at Project Gutenberg

- Aladdin, or, The wonderful lamp, by Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger, William Blackwood & Sons, 1863

- «Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp», in John Payne, Oriental Tales vol. 13

- The Thousand Nights and a Night in several classic translations, with additional material, including Payne’s introduction [1] and quotes from Galland’s diary.

| Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp | |

|---|---|

Aladdin finds the wonderful lamp inside the cave. A c. 1898 illustration by Rene Bull. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 561 (Aladdin) |

| Region | Middle East |

| Published in | One Thousand and One Nights, compiled and translated by Antoine Galland |

Aladdin ( ə-LAD-in; Arabic: علاء الدين, ʻAlāʼ ud-Dīn/ ʻAlāʼ ad-Dīn, IPA: [ʕalaːʔ adˈdiːn], ATU 561, ‘Aladdin’) is a Middle-Eastern folk tale. It is one of the best-known tales associated with The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (The Arabian Nights), despite not being part of the original text; it was added by the Frenchman Antoine Galland, based on a folk tale that he heard from the Syrian Maronite storyteller Hanna Diyab.[1]

Sources[edit]

Known along with Ali Baba as one of the «orphan tales», the story was not part of the original Nights collection and has no authentic Arabic textual source, but was incorporated into the book Les mille et une nuits by its French translator, Antoine Galland.[2]

John Payne quotes passages from Galland’s unpublished diary: recording Galland’s encounter with a Maronite storyteller from Aleppo, Hanna Diyab.[1] According to Galland’s diary, he met with Hanna, who had travelled from Aleppo to Paris with celebrated French traveller Paul Lucas, on March 25, 1709. Galland’s diary further reports that his transcription of «Aladdin» for publication occurred in the winter of 1709–10. It was included in his volumes ix and x of the Nights, published in 1710, without any mention or published acknowledgment of Hanna’s contribution.

Payne also records the discovery in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris of two Arabic manuscripts containing Aladdin (with two more of the «interpolated» tales). One was written by a Syrian Christian priest living in Paris, named Dionysios Shawish, alias Dom Denis Chavis. The other is supposed to be a copy Mikhail Sabbagh made of a manuscript written in Baghdad in 1703. It was purchased by the Bibliothèque Nationale at the end of the nineteenth century.[3] As part of his work on the first critical edition of the Nights, Iraq’s Muhsin Mahdi has shown[4] that both these manuscripts are «back-translations» of Galland’s text into Arabic.[5][6]

Ruth B. Bottigheimer[7] and Paulo Lemos Horta[8][9] have argued that Hanna Diyab should be understood as the original author of some of the stories he supplied, and even that several of Diyab’s stories (including Aladdin) were partly inspired by Diyab’s own life, as there are parallels with his autobiography.[10]

Plot summary[edit]

The Sorcerer traps Aladdin in the magic cave.

The story is often retold with variations. The following is a précis of the Burton translation of 1885.[11]

Aladdin is an impoverished young ne’er-do-well, dwelling in «one of the cities of China». He is recruited by a sorcerer from the Maghreb, who passes himself off as the brother of Aladdin’s late father, Mustapha the tailor, convincing Aladdin and his mother of his good will by pretending to set up the lad as a wealthy merchant. The sorcerer’s real motive is to persuade young Aladdin to retrieve a wonderful oil lamp (chirag) from a booby-trapped magic cave. After the sorcerer attempts to double-cross him, Aladdin finds himself trapped in the cave. Aladdin is still wearing a magic ring the sorcerer has lent him. When he rubs his hands in despair, he inadvertently rubs the ring and a genie appears and releases him from the cave, allowing him to return to his mother while in possession of the lamp. When his mother tries to clean the lamp, so they can sell it to buy food for their supper, a second far more powerful genie appears who is bound to do the bidding of the person holding the lamp.

With the aid of the genie of the lamp, Aladdin becomes rich and powerful and marries Princess Badroulbadour, the sultan’s daughter (after magically foiling her marriage to the vizier’s son). The genie builds Aladdin and his bride a wonderful palace, far more magnificent than the sultan’s.

The sorcerer hears of Aladdin’s good fortune, and returns; he gets his hands on the lamp by tricking Aladdin’s wife (who is unaware of the lamp’s importance) by offering to exchange «new lamps for old». He orders the genie of the lamp to take the palace, along with all its contents, to his home in the Maghreb. Aladdin still has the magic ring and is able to summon the lesser genie. The genie of the ring cannot directly undo any of the magic of the genie of the lamp, but he is able to transport Aladdin to the Maghreb where, with the help of the «woman’s wiles» of the princess, he recovers the lamp and slays the sorcerer, returning the palace to its proper place.

The sorcerer’s more powerful and evil brother plots to destroy Aladdin for killing his brother by disguising himself as an old woman known for her healing powers. Badroulbadour falls for his disguise and commands the «woman» to stay in her palace in case of any illnesses. Aladdin is warned of this danger by the genie of the lamp and slays the impostor.

Aladdin eventually succeeds to his father-in-law’s throne.

Setting[edit]

The opening sentences of the story, in both the Galland and the Burton versions, set it in «one of the cities of China».[12] On the other hand, there is practically nothing in the rest of the story that is inconsistent with a Middle Eastern setting. For instance, the ruler is referred to as «Sultan» rather than «Emperor», as in some retellings, and the people in the story are Muslims and their conversation is filled with Muslim platitudes. A Jewish merchant buys Aladdin’s wares, but there is no mention of Buddhists, Daoists or Confucians.

Notably, ethnic groups in Chinese history have long included Muslim groups, including large populations of Uighurs, and the Hui people as well as the Tajiks whose origins go back to Silk Road travelers. Islamic communities have been known to exist in the region since the Tang dynasty (which rose to power simultaneously with the prophet Muhammad’s career.) Some have suggested that the intended setting may be Turkestan (encompassing Central Asia and the modern-day Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang in Western China).[13]

For all this, speculation about a «real» Chinese setting depends on a knowledge of China that the teller of a folk tale (as opposed to a geographic expert) might well not possess.[14] In early Arabic usage, China is known to have been used in an abstract sense to designate an exotic, faraway land.[15][16]

Motifs and variants[edit]

Tale type[edit]

The story of Aladdin is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as tale type ATU 561, «Aladdin», after the character. In the Index, the Aladdin story is situated next to two similar tale types: ATU 560, The Magic Ring, and ATU 562, The Spirit in the Blue Light.[17] All stories deal with a down-on-his-luck and impoverished boy or soldier, who finds a magical item (ring, lamp, tinderbox) that grants his wishes. In this tale type, the magical item is stolen, but eventually recovered thanks to the use of another magical object.[18]

Distribution[edit]

Since its appearance in The One Thousand and One Nights, the tale has integrated into oral tradition. Scholars Ton Deker and Theo Meder located variants across Europe and the Middle East.[19]

An Indian variant has been attested, titled The Magic Lamp and collected among the Santal people.[20][21]

Adaptations[edit]

Adaptations vary in their faithfulness to the original story. In particular, difficulties with the Chinese setting are sometimes resolved by giving the story a more typical Arabian Nights background.

Books[edit]

- One of the many literary retellings of the tale appears in A Book of Wizards (1966) and A Choice of Magic (1971), by Ruth Manning-Sanders. Another is the early Penguin version for children, Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp, illustrated by John Harwood with many Chinese details: the translator or re-teller is not acknowledged: this was a «Porpoise» imprint printed in 1947 and released in 1948.

- Aladdin: Master of the Lamp (1992), edited by Mike Resnick and Martin H. Greenberg, is an anthology containing 43 original short stories inspired by the tale.

- «The Nobility of Faith» by Jonathan Clements in the anthology Doctor Who Short Trips: The Ghosts of Christmas (2007) is a retelling of the Aladdin story in the style of the Arabian Nights, but featuring the Doctor in the role of the genie.

Comics[edit]

Western comics[edit]

- In 1962 the Italian branch of Walt Disney Productions published the story Paperino e la grotta di Aladino (Donald and Aladdin’s Cave), written by Osvaldo Pavese and drawn by Pier Lorenzo De Vita. As in many pantomimes, the plot is combined with elements of the Ali Baba story: Uncle Scrooge leads Donald Duck and their nephews on an expedition to find the treasure of Aladdin and they encounter the Middle Eastern counterparts of the Beagle Boys. Scrooge describes Aladdin as a brigand who used the legend of the lamp to cover the origins of his ill-gotten gains. They find the cave holding the treasure—blocked by a huge rock requiring a magic password («open sesame») to open.[22]

- The original version of the comic book character Green Lantern was partly inspired by the Aladdin myth; the protagonist discovers a «lantern-shaped power source and a ‘power ring‘» which gives him power to create and control matter.[23]

- In the Elseworlds series, there was even a story that combined the Green Lantern mythos with that of Aladdin called Green Lantern: 1001 Emerald Nights.

Manga[edit]

- The Japanese manga series Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic is not a direct adaptation, but features Aladdin as the main character of the story and includes many characters from other One Thousand and One Nights stories. An adaptation of this comic to an anime television series was made in October 2012 in which Aladdin is voiced by Kaori Ishihara in Japanese and Erica Mendez in English.

Pantomimes[edit]

An 1886 theatre poster advertising a production of the pantomime Aladdin.

- In the United Kingdom, the story of Aladdin was dramatised in 1788 by John O’Keefe for the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden.[24] It has been a popular subject for pantomime for over 200 years.[25]

- The traditional Aladdin pantomime is the source of the well-known pantomime character Widow Twankey (Aladdin’s mother). In pantomime versions, changes in the setting and story are often made to fit it better into «China» (albeit a China situated in the East End of London rather than medieval Baghdad), and elements of other Arabian Nights tales (in particular Ali Baba) are often introduced into the plot. One version of the «pantomime Aladdin» is Sandy Wilson’s musical Aladdin, from 1979.

- Since the early 1990s, Aladdin pantomimes have tended to be influenced by the Disney animation. For instance, the 2007/8 production at the Birmingham Hippodrome starring John Barrowman featured songs from the Disney movies Aladdin and Mulan.

Other musical theatre[edit]

New Crowns for Old, a 19th-century British cartoon based on the Aladdin story (Disraeli as Abanazer from the pantomime version of Aladdin offering Queen Victoria an Imperial crown (of India) in exchange for a Royal one)

- The New Aladdin was a successful Edwardian musical comedy in 1906.

- Adam Oehlenschläger wrote his verse drama Aladdin in 1805. Carl Nielsen wrote incidental music for this play in 1918–19. Ferruccio Busoni set some verses from the last scene of Oehlenschläger’s Aladdin in the last movement of his Piano Concerto, Op. 39.

- In 1958, a musical comedy version of Aladdin was written especially for US television with a book by S. J. Perelman and music and lyrics by Cole Porter. A London stage production followed in 1959 in which a 30-year-old Bob Monkhouse played the part of Aladdin at the Coliseum Theatre.[26]

- Aladdin; Prince Street Players version; book by Jim Eiler; Music by Jim Eiler and Jeanne Bargy; Lyrics by Jim Eiler.[27]

- Broadway Junior has released Aladdin Jr., a children’s musical based on the music and screenplay of the Disney animation.

- The Disney’s Aladdin: A Musical Spectacular musical stage show ran in Disney California Adventure from January 2003 to January 10, 2016.[28]

- StarKid Productions released the musical «Twisted» on YouTube in 2013, a parody of the 1992 Disney film that is told from the royal vizier’s point of view.

- A Disney Theatrical Production of Aladdin opened in 2011 in Seattle, in Toronto in 2013, and on Broadway at the New Amsterdam Theatre on March 20, 2014.

Theatrical films[edit]

Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (1917)

Animation: Europe and Asia[edit]

- The 1926 animated film The Adventures of Prince Achmed (the earliest surviving animated feature film) combined the story of Aladdin with that of the prince. In this version the princess Aladdin pursues is Achmed’s sister and the sorcerer is his rival for her hand. The sorcerer steals the castle and the princess through his own magic and then sets a monster to attack Aladdin, from which Achmed rescues him. Achmed then informs Aladdin he requires the lamp to rescue his own intended wife, Princess Pari Banou, from the demons of the Island of Wak Wak. They convince the Witch of the Fiery Mountain to defeat the sorcerer, and then all three heroes join forces to battle the demons.

- The animated feature Aladdin et la lampe merveilleuse by Film Jean Image was released in 1970 in France. The story contains many of the original elements of the story as compared to the Disney version.

- A Thousand and One Nights is a 1969 Japanese adult anime feature film directed by Eiichi Yamamoto, conceived by Osamu Tezuka. The film is a first part of Mushi Production’s Animerama, a series of films aimed at an adult audience.

- An elderly version of Aladdin appears as a protagonist in the 1975 anime series Arabian Nights: Sinbad’s Adventures.

- Aladdin and the Magic Lamp was a rendition in Japanese directed by Yoshikatsu Kasai, produced in Japan by Toei Animation and released in the United States by The Samuel Goldwyn Company in 1982.

- Son of Aladdin is a 2003 Indian 3D-animated fantasy-adventure film by Singeetam Srinivasa Rao, produced by Pentamedia Graphics. It follows the adventures of the son of Aladdin and his fight with an evil sorcerer.

Animation: USA[edit]

- In the 1934 short film, Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp, Aladdin is a child laborer who finds a magic lamp and uses it to become a prince.IMDb

- In the 1938 animated film Have You Got Any Castles?, Aladdin makes a brief appearance asking for help but gets punched by one of the Three Musketeers.

- Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp is a 1939 Popeye the Sailor cartoon.

- The 1959 animated film 1001 Arabian Nights starring Mr. Magoo as Aladdin’s uncle and produced by UPA.

- Aladdin is a 48-minute animated film based on the classic Arabian Nights story «Aladdin and the magic lamp», translated by Antoine Galland. Aladdin was produced by Golden Films and the American Film Investment Corporation. Like all other Golden Films productions, the film featured a single theme song, «Rub the Lamp», written and composed by Richard Hurwitz and John Arrias. It was released directly to video on April 27, 1992 by GoodTimes Home Video (months before Disney’s version was released) and was reissued on DVD in 2002 as part of the distributor’s Collectible Classics line of products.

- Aladdin, the 1992 animated feature by Walt Disney Feature Animation (currently the best-known retelling of the story). In this version several characters are renamed or amalgamated. For instance the Sorcerer and the Sultan’s vizier were combined into one character named Jafar while the Princess is renamed Jasmine. They have new motivations for their actions. The Genie of the Lamp only grants three wishes and desires freedom from his role. A sentient magic carpet replaces the ring’s genie while Jafar uses a royal magic ring to find Aladdin. The names «Jafar» and «Abu», the Sultan’s delight in toys, and their physical appearances are borrowed from the 1940 film The Thief of Bagdad. The setting is moved from China to the fictional Arabian city of Agrabah, and the structure of the plot is simplified.

- The Return of Jafar (1994), direct-to-video sequel to the 1992 Walt Disney movie.

- Aladdin and the King of Thieves (1996), direct-to-video second and final sequel to the 1992 Walt Disney movie.

Live-action: English language films[edit]

- Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (1917), directed by Chester M. Franklin and Sidney A. Franklin and released by the Fox Film Corporation, told the story using child actors.[29][30][31] It is the earliest known filmed adaptation of the story.

- The 1940 British movie The Thief of Bagdad borrows elements of the Aladdin story, although it also departs from the original story fairly freely: for instance the genie grants only three wishes and the minor character of the Emperor’s vizier is renamed Jaffar and becomes the main villain, replacing the sorcerer from the original plot.

- Arabian Nights is a 1942 adventure film directed by John Rawlins and starring Sabu, Maria Montez, Jon Hall and Leif Erickson. The film is derived from The Book of One Thousand and One Nights but owes more to the imagination of Universal Pictures than the original Arabian stories. Unlike other films in the genre (The Thief of Bagdad), it features no monsters or supernatural elements.[32]

- A Thousand and One Nights (1945) is a tongue-in-cheek Technicolor fantasy film set in the Baghdad of the One Thousand and One Nights, starring Cornel Wilde as Aladdin, Evelyn Keyes as the genie of the magic lamp, Phil Silvers as Aladdin’s larcenous sidekick, and Adele Jergens as the princess Aladdin loves.

- The Wonders of Aladdin is a 1961 film directed by Mario Bava and Henry Levin and starring Donald O’Connor as Aladdin. This film has a more working-class focus: Aladdin helps the prince (Mario Girotti) and princess (as does a fakir) but never becomes one and ends up in a romantic relationship with his neighbor, Djalma (Noelle Adam). The genie (Vittorio De Sica) can grant only three wishes (although what constitutes as a single wish is quite malleable, probably due to his sympathies with Aladdin) and shrinks with each one, which is leading to his eternal rest after 12,000 years.

- A 1998 direct-to-video movie A Kid in Aladdin’s Palace directed by Robert L. Levy which is a sequel to A Kid in King Arthur’s Court.

- Adventures of Aladdin (2019), a mockbuster produced by The Asylum.[33][34]

- Aladdin, a Disney live-action remake of the 1992 animated film, released in 2019. It stars Mena Massoud as the title character, Naomi Scott as Jasmine, Marwan Kenzari as Jafar, and Will Smith as the Genie.

Live-action: Non-English language films[edit]

- Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp is a 1927 Indian silent film, by Bhagwati Prasad Mishra, based on the folktale.[35]

- Alladin and the Wonderful Lamp is a 1931 Indian silent film, adapted from the folktale, by Jal Ariah.[35]

- Aladdin Aur Jadui Chirag (Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp) is a 1933 Indian Hindi-language fantasy-adventure film by Jal Ariah. A remake of the 1931 film in sound.[35]

- Aaj Ka Aladdin (Today’s Aladdin) is a 1935 Indian Hindi-language film by Nagendra Majumdar. It is a modern retelling of the folktale.[35]

- Aladdin Aur Jadui Chirag (Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp) is a 1937 Indian Hindi-language film adaptation by Navinchandra.[35]

- Aladdin Aur Jadui Chirag (Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp) is a 1952 Indian Hindi-language musical fantasy-adventure film by Homi Wadia, starring Mahipal as Aladdin and Meena Kumari as Princess Badar.

- Alif-Laila is a 1955 Indian Hindi-language fantasy film by K. Amarnath, Vijay Kumar portrays the character of Aladdin with actress Nimmi as the female genie.

- Chirag-e-Cheen (Lamp of China) is a 1955 Indian Hindi-language film adaptation by G.P. Pawar and C. M. Trivedi.[35]

- Alladin Ka Beta (Son of Alladin) is a 1955 Indian Hindi-language action film, it follows the story of the son of Alladin.

- Alladin and the Wonderful Lamp is a 1957 Indian fantasy film by T. R. Raghunath. Based on the story of Aladdin, it was simultaneously filmed in Telugu, Tamil and Hindi with Akkineni Nageshwara Rao portraying the titular character.

- Alladdin Laila is a 1957 Indian Hindi-language film by Lekhraj Bhakri, starring Mahipal, Lalita Pawar and Shakila.[35]

- Sindbad Alibaba and Aladdin is a 1965 Indian Hindi-language musical fantasy-adventure film by Prem Narayan Arora. It features the three most popular characters from the Arabian Nights. Very loosely based on the original, in which the heroes get to meet and share in each other’s adventures. In this version, the lamp’s jinni (genie) is female and Aladdin marries her rather than the princess (she becomes a mortal woman for his sake).

- Main Hoon Aladdin (I am Aladdin) is a 1965 Indian Hindi-language film by Mohammed Hussain, starring Ajit in the titular role.[35]

- A Soviet film Volshebnaia Lampa Aladdina («Aladdin’s Magic Lamp») was released in 1966.

- A Mexican production, Pepito y la Lampara Maravillosa was made en 1972, where comedian Chabelo plays the role of the genie who grant wishes to a young kid called Pepito in 1970s Mexico City.

- Adventures of Aladdin is a 1978 Indian Hindi-language adventure-film based on the tale, by Homi Wadia.

- Allauddinum Albhutha Vilakkum (Aladdin and the Magic Lamp) is a 1979 Indian adventure fantasy-drama film by I. V. Sasi. It was simultaneously filmed in Malayalam and Tamil with Kamal Haasan in the titular role.

- In 1986, an Italian production (under supervision of Golan-Globus) of a modern-day Aladdin was filmed in Miami under the title Superfantagenio, starring actor Bud Spencer as the genie and his daughter Diamante as the daughter of a police sergeant.

- Aladin is a 2009 Indian Hindi-language fantasy action film directed by Sujoy Ghosh. The film stars Ritesh Deshmukh in the titular role, along with Amitabh Bachchan, Jacqueline Fernandez and Sanjay Dutt.

- The New Adventures of Aladdin, France modern retelling of the tale of Aladdin.

- Alad’2, second sequel to the French movie The New Adventures of Aladdin (2018).

- Ashchorjyo Prodeep is a 2013 Indian Bengali-language film by Anik Dutta. This film is based on a Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay novel of the same name and deals with the issues of consumerism. It is a modern adaptation of Aladdin about the story of a middle-class man (played by Saswata Chatterjee) who accidentally finds a magic lamp containing a Jinn (played by Rajatava Dutta).

- Aladin Saha Puduma Pahana was released in 2018 in Sri Lanka in Sinhala language.[36]

Television[edit]

Animation: English language[edit]

- Aladdin is a 1958 musical fantasy written especially for television with a book by S.J. Perelman and music and lyrics by Cole Porter, telecast in color on the DuPont Show of the Month by CBS.

- «Aladdin and the Magic Lamp»,[37] an episode of Rabbit Ears Productions’ We All Have Tales series, televised on PBS in 1991, featuring John Hurt as narrator, with illustrations by Greg Couch and music by Mickey Hart. This version is set in Isfahan, Persia, and closely follows the original plot, including the origin of the sorcerer. The audiobook version was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for Children in 1994.

- Aladdin, an animated series produced by Disney based on their movie adaptation that ran from 1994 to 1995.

- Aladdin featured in an episode of Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child. The story was set in «Ancient China», but otherwise had a tenuous connection with the original plot.

- Magi, Alladin, a young magi, befriends a Jin and goes adventuring with Alibaba. (2013) Japanese, English dub available

Live-action: English language[edit]

- Aladdin appeared in episode 297 of Sesame Street performed by Frank Oz. This version was made from a large lavender live-hand Anything Muppet.

- A segment of the Marty Feldman episode of The Muppet Show retells the story of Aladdin with The Great Gonzo in the role of Aladdin and Marty Feldman playing the genie of the lamp.

- A 1967 TV movie was based on the Prince Street Players stage musical. This version is very close to the touring musical with about 15 minutes cut to be adapted into the 50 minutes tv program. It had Will B. Able as the Genii and Fred Grades as Aladdin.

- In 1986, the program Faerie Tale Theatre based an episode on the story called «Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp», directed by Tim Burton and starring Robert Carradine as Aladdin and James Earl Jones as both the ring Genie and the lamp Genie.

- In 1990 Disney made a direct to TV movie based on the Prince Street Players stage musical, starring Barry Bostwick.[38]

- Aladdin features as one of five stories in the Hallmark Entertainment TV miniseries Arabian Nights in 2000, featuring Jason Scott Lee as Aladdin and John Leguizamo as both of the genies.

- The characters of Aladdin, Jasmine, Jafar and the Sultan, along with Agrabah as the setting and the genie of the lamp were adapted into the sixth season of TV series Once Upon a Time, with Aladdin portrayed by Deniz Akdeniz, Jasmine portrayed by Karen David, and Jafar portrayed by Oded Fehr. Jafar previously appeared in the spin-off Once Upon a Time in Wonderland, portrayed by Naveen Andrews. Both were produced by ABC Television Studios and based on the Disney version of the story.

- Syfy released a made-for-TV horror adaptation called Aladdin and the Death Lamp on September 15, 2012.

Live-action: Non-English language[edit]

- In Kyōryū Sentai Zyuranger, the sixteenth installment of the long-running Super Sentai metaseries, the Djinn (voiced by Eisuke Yoda) that appears in the eleventh episode («My Master!» Transcription: «Goshujin-sama!» (Japanese: ご主人さま!)) reveals that he was the genie from the tale of «Aladdin and the Magic Lamp», which did take place.

- The story of Aladdin was featured in Alif Laila, an Indian TV series directed by Ramanand Sagar in 1994 and telecasted on DD National.

- Aladdin – Jaanbaaz Ek Jalwe Anek (2007–2009), an Indian fantasy television series based on the story of Aladdin that aired on Zee TV, starring Mandar Jadhav in the titular role of Aladdin.

- Aladdin — Naam Toh Suna Hoga (2018–2021), a live-action Indian fantasy television show on SAB TV starring Siddharth Nigam as Aladdin and Avneet Kaur/Ashi Singh as Yasmine.

Video games[edit]

- A number of video games were based on the Disney movie:

- The Genesis version (also on Amiga, MS-DOS, NES, Game Boy, and Game Boy Color) by Virgin Games.

- The SNES version (also on Game Boy Advance) by Capcom.

- The Master System version (also on Game Gear) by SIMS.

- Nasira’s Revenge for the PlayStation and Windows by Argonaut Games.

- The Disney version of Aladdin appears throughout the Disney/Square Enix crossover series Kingdom Hearts, with Agrabah being a visitable world.

- The video game Sonic and the Secret Rings is heavily based on the story of Aladdin, and both genies appear in the story. The genie of the lamp is the main antagonist, known in the game as the Erazor Djinn, and the genie of the ring, known in the game as Shahra, appears as Sonic’s sidekick and guide through the game. Furthermore, the ring genie is notably lesser than the lamp genie in the story.

- In 2010, Anuman Interactive launched Aladin and the Enchanted Lamp, a hidden object game on PC and Mac.[39]

- In 2016 Saturn Animation Studio produced an interactive adaptation of The Magical Lamp of Aladdin for mobile devices.

Pachinko[edit]

Sega Sammy have released a line of pachinko machines based on Aladdin since 1989. Sega Sammy have sold over 570,000 Aladdin pachinko machines in Japan, as of 2017.[40] At an average price of about $5,000,[41] this is equivalent to approximately $2.85 billion in pachinko sales revenue.

Gallery[edit]

-

Aladdin trades the silver plates to a Jew for a piece of gold

-

Aladdin in Disney’s stage show.

See also[edit]

- 54521 Aladdin, asteroid

- Arabian mythology

- Genies in popular culture

- The Bronze Ring

- Jack and His Golden Snuff-Box

- The Tinderbox

- The Blue Light

- Three wishes joke

References[edit]

- ^ a b Razzaque (2017)

- ^ Allen (2005) pp.280–

- ^ Payne (1901) pp. 13-15

- ^ Irwin (1994) pp. 57-58

- ^ Mahdi (1994) pp. 51-71

- ^ Dobie (2008) p.36

- ^ Bottigheimer, Ruth B. «East Meets West» (2014).

- ^ Horta, Paulo Lemos (2018). Aladdin: A New Translation. Liveright Publishing. pp. 8–10. ISBN 9781631495175. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Paulo Lemos Horta, Marvellous Thieves: Secret Authors of the Arabian Nights (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), pp. 24-95.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia B. (May 23, 2019). «Was Aladdin Based on a Real Person? Here’s Why Scholars Are Starting to Think So». Time. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Burton (2009) pp. 1 ff

- ^ Plotz (2001) p. 148–149

- ^ Moon (2005) p. 23

- ^ Honour (1973) — Section I «The Imaginary Continent»

- ^ Arafat A. Razzaque (10 August 2017). «Who was the «real» Aladdin? From Chinese to Arab in 300 Years». Ajam Media Collective.

- ^ Olivia B. Waxman (2019-05-23). «Was Aladdin Based on a Real Person? Here’s Why Scholars Are Starting to Think So». Time. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ^ Ranke, Kurt (1966). Folktales of Germany. Routledge & K. Paul. p. 214. ISBN 978-81-304-0032-7.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 70-73. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Deker, Ton; Meder, Theo. «Aladdin en de wonderlamp». In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sun. 1997. p. 40.

- ^ Campbell, A., of the Santal mission. Santal Folk-Tales. Pokhuria, India : Santal Mission Press. 1891. pp. 1-5.

- ^ Brown, W. Norman (1919). «The Pañcatantra in Modern Indian Folklore». Journal of the American Oriental Society. 39: 1–54. doi:10.2307/592712. JSTOR 592712.

- ^ «Profile of Paperino e la grotta di Aladino«. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Adam Robert, The History of Science Fiction, Palgrave Histories of Literature, ISBN 978-1-137-56959-2, 2016, p. 224

- ^ Witchard (2017)

- ^ «Aladdin». www.its-behind-you.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ «Cole Porter / Aladdin (London Stage Production)». Sondheim Guide. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ «MTIshows.com Music Theatre International». Archived from the original on 2015-05-15. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ^ Slater, Shawn (9 September 2015). «All New ‘Frozen’-Inspired Stage Musical Coming to Disney California Adventure Park in 2016». Disney Parks Blog. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ «Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp». Letterboxd. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ «The Library of Congress American Silent Feature Film Survival Catalog:Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp«. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ^ «Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp». Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Article on Arabian Nights at Turner Classic Movies accessed 10 January 2014

- ^ News, VICE (2019-05-24). «What It Takes to Make a Hollywood Mockbuster, the «Slightly Shittier» Blockbuster». Vice News. Archived from the original on 2019-05-29. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ Adventures of Aladdin (2019), retrieved 2019-05-29

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 9780851706696. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ «Dhananjaya became Aladin». Sarasaviya. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ «Aladdin and the Magic Lamp — Rabbit Ears». www.rabbitears.com. Archived from the original on 2019-04-10. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- ^ Buck, Jerry (February 25, 1990). «Barry Bostwick ‘explores other worlds’ in ‘Challenger’ movie». The Sacramento Bee.

- ^ «Aladin et la Lampe Merveilleuse PC, Mac | 2010». Planete Jeu (in French). Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Beyond Expectations: Integrated Report (PDF). Sega Sammy Holdings. 2017. p. 73. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-26. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ Graser, Marc (2 August 2013). «‘Dark Knight’ Producer Plays Pachinko to Launch Next Franchise (EXCLUSIVE)». Variety. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Allen, Roger (2005). The Arabic Literary Heritage: The Development of Its Genres and Criticism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48525-8.

- Burton, Sir Richard (2009). Aladdin and the Magic Lamp. Digireads.com Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4209-3193-8.

- Dobie, Madeleine (2008). «Translation in the contact zone: Antoine Galland’s Mille et une nuits: contes arabes». In Makdisi, S.; Nussbaum, F. (eds.). The Arabian Nights in Historical Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955415-7.

- El-Shamy, Hasan (2004). «The Oral Connections of the Arabian Nights». The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-204-2.

- Honour, Hugh (1973). Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay. Ican. ISBN 978-0-06-430039-1.

- Horta, Paulo Lemos (2018). «Introduction». Aladdin: A New Translation. Translated by Seale Y. Liveright Publishing. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-1-63149-517-5. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Irwin, Robert (2004). Arabian Nights, The: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 1-86064-983-1.

- Littman (1986). «Alf Layla wa Layla». Encyclopedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill.

- Mahdi, Muhsin (1994). The Thousand and One Nights Part 3. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10106-3.

- Moon, Krystyn (2005). Yellowface. Rutgers University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8135-3507-7.

- Payne, John (1901). Aladdin and the Enchanted Lamp and Other Stories. London.

- Plotz, Judith Ann (2001). Romanticism and the vocation of childhood. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-22735-3.

- «Who ‘wrote’ Aladdin? The Forgotten Syrian Storyteller». Ajam Media Collective. 14 September 2017.

- Witchard, Anne Veronica (2017). Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-5864-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Gaál, E. (1973). «Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp». Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 27 (3): 291–300. JSTOR 23657287.

- Gogiashvili, Elene (3 April 2018). «The Tale of Aladdin in Georgian Oral Tradition». Folklore. 129 (2): 148–160. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2017.1397392. S2CID 165697492.

- Haddawy, Husain (2008). The Arabian Nights. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33166-0.

- Huet, G. (1918). «Les Origines du Conte de Aladdin et la Lampe Merveilleuse». Revue de l’histoire des religions. 77: 1–50. JSTOR 23663317.

- Larzul, Sylvette (2004). «Further Considerations on Galland’s ‘Mille et une Nuits’: A Study of the Tales Told by Hanna». Marvels & Tales. 18 (2): 258–271. doi:10.1353/mat.2004.0043. JSTOR 41388712. S2CID 162289753.

- Marzolph, Ulrich (1 July 2019). «Aladdin Almighty: Middle Eastern Magic in the Service of Western Consumer Culture». Journal of American Folklore. 132 (525): 275–290. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.132.525.0275. S2CID 199268544.

- Nun, Katalin; Stewart, Dr Jon (2014). Volume 16, Tome I: Kierkegaard’s Literary Figures and Motifs: Agamemnon to Guadalquivir. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4724-4136-2.

External links[edit]

- Andrew Lang. The Arabian Nights at Project Gutenberg

- Aladdin, or, The wonderful lamp, by Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger, William Blackwood & Sons, 1863

- «Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp», in John Payne, Oriental Tales vol. 13

- The Thousand Nights and a Night in several classic translations, with additional material, including Payne’s introduction [1] and quotes from Galland’s diary.

Вступление[править]

Как известно, этот персонаж пришёл в европейскую культуру с очень вольным переводом «Тысячи и одной ночи» от Антуана Галлана. Но парадокс: в арабских сборниках эта сказка отсутствует, как впрочем и сказка о Али-бабе. Похоже, что то ли переводчик Антуан Галлан добавил от себя какую-то постороннюю сказку, то ли сам её и сочинил, то ли скомпилировал из сказок которые напрочь не проходили французскую цензуру — наиболее вероятный кандидат «Сказка о Джударе»; с теориями и расследованиями можно ознакомиться в Википедии. Кстати, во французском тексте прямо говорится, что Аладдин живёт в Китае, но при этом мусульманин — вероятнее всего, дунганин или уйгур. Во многих переводах на русский добавили ещё отсебятины — назвав страну Персией, а не Китаем, или в лучшем случае просто удалив все упоминания Китая, не называя страну (и герой стал по умолчанию восприниматься арабом). К тому же ни одна деталь окружения не указывает на китайские реалии.

Сюжет[править]

Итак, жил себе в каком-то китайском городе мальчишка по имени Ала ад-Дин. Учиться он ничему не хотел, предпочитая бегать по улицам с другими мальчишками и в целом маяться дурью. Отец Ала ад-Дина, портной, тщетно пытался его научить своему ремеслу и в итоге, отчаявшись, заболел да и умер. Мать, пытаясь прокормить себя и сына, зарабатывала рукоделием, ну а наш главный герой так лоботрясом и остался, ничему не учился и шатался по улицам, хотя в целом всё же был добрый и бесхитростный малый.

Тем временем некий колдун-магрибинец[1] путём астрологии вычислил местонахождение некоего могущественного артефакта, а также узнал, что Ала ад-Дин — как раз такой человек, который может это сокровище взять, поскольку злодею оно не дастся. Прибыв в город нашего героя, колдун представился его пропавшим дядюшкой и, не скупясь на подарки, втёрся в доверие к парню и его матери[2]. На самом деле, злодею это было нужно лишь чтобы отправить Ала ад-Дина на опасное задание без надежды на возвращение. Однажды ночью колдун привёл его к пещере за городом, при помощи колдовства открыл её, выдал парню инструктаж по технике безопасности в волшебных подземельях и какое-то защитное магическое кольцо, а потом велел полезть вниз и найти старую медную лампу. Ала ад-Дин успешно отыскал артефакт и вернулся, но попросил сначала вытащить его наверх. Колдун почему-то занервничал и закрыл пещеру обратно — видимо, надеясь вернуться, когда Ала ад-Дин умрёт с голоду. Несколько дней герой провёл в темноте, а затем случайно повернул кольцо на пальце и обнаружил, что в этом кольце заключён джинн (Дахнаш, сын Кашкаша). Оправившись от испуга, парень попросил вынести его наружу.

К моменту возвращения домой парень почему-то забыл о джинне. Но при попытке почистить старую лампу с целью дальнейшей продажи обнаружился второй джинн (Маймун, сын Шамхураша). Тем не менее, и его помощь была использована поначалу очень скромно. Лишь когда спустя какое-то время Ала ад-Дин случайно увидал дочь местного султана[3] — красавицу Будур и влюбился в неё, он принялся просить у джинна то предоставить драгоценный подарок для султана, то запугать жениха принцессы, а потом и вовсе построить за одну ночь невиданный дворец со штатом слуг. Конечно, впечатлённый султан отдал царевну замуж за Ала ад-Дина, и после этого парень действительно проявил себя, без дальнейшей помощи джинна заслужив всенародную любовь, уважение при дворе и даже одержав несколько военных побед.

Позже колдун, решив всё-таки наверстать упущенное, в отсутствие Ала ад-Дина под видом полоумного торговца пришёл во дворец и хитростью выпросил у царевны «старую ненужную лампу», после чего с помощью джинна перенёс дворец вместе с принцессой и слугами к себе в Магриб. Убитый горем султан потребовал от зятя объяснений и хотел его казнить, но народ едва не поднял восстание. Ала ад-Дин пообещал всё вернуть как было, отправился на поиски и снова случайно повернув кольцо, обнаружил первого джинна[4]. Чужую магию этот джинн отменить не имел права, но перенёс героя к дворцу, а там Ала ад-Дин с женой при помощи хитрости заполучили лампу и убили злодея-колдуна.

Джинн лампы вернул героев и дворец обратно к султану, и все снова зажили счастливо. Правда, чуть позже явился ещё и брат магрибинца, тоже колдун, и попытался убедить Ала ад-Дина загадать джинну оскорбительное желание (см. ниже «Кнопка берсерка»). Однако же, сам джинн разоблачил коварство, после чего герой и второго злодея перехитрил и убил своими руками. А вот после этого уже все жили долго и счастливо.

Что здесь есть[править]

- Ай, молодца, злодей!. Ничто не мешало колдуну сначала вытащить Ала ад-Дина из пещеры, получить лампу, а потом уже расправиться с героем (или не расправляться, лампа-то теперь всё равно его). Вместо этого злодей вообще оставил себя без лампы. А уж что говорить о кольце, способном вытащить героя из подземелья! То ли главгад не знал обо всех свойствах кольца, то ли оно и правда влияет на память.

- А что, так можно было?. Герой проявляет чудеса скромности, не злоупотребляя джинном. Например, он предпочёл продавать оставшуюся после первого заказа еды драгоценную посуду, хотя мог заказывать такую доставку ежедневно или вообще сразу потребовать себе богатство и дворец — в литературном первоисточнике ни разу не сказано, в отличие от адаптаций, что количество желаний ограничено. Впрочем, героя просила не злоупотреблять волшебством его мать, которую начинало трясти от одного упоминания джиннов — очень уж напугалась при первой встрече. Да и, в конце концов, может как раз за потрясающее бескорыстие Аллах герою и помогал столько раз?

- Тут, скорее, другое. Герой просто не привык к тому, что можно жить, не зная нужды.