| «Puss in Boots» | |

|---|---|

| by Giovanni Francesco Straparola Giambattista Basile Charles Perrault |

|

Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer |

|

| Country | Italy (1550–1553) France (1697) |

| Language | Italian (originally) |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

«Puss in Boots» (Italian: Il gatto con gli stivali) is an Italian[1][2] fairy tale, later spread throughout the rest of Europe, about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand of a princess in marriage for his penniless and low-born master.

The oldest written telling is by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola, who included it in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–1553) in XIV–XV. Another version was published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile with the title Cagliuso, and a tale was written in French at the close of the seventeenth century by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a retired civil servant and member of the Académie française. There is a version written by Girolamo Morlini, from whom Straparola used various tales in The Facetious Nights of Straparola.[3] The tale appeared in a handwritten and illustrated manuscript two years before its 1697 publication by Barbin in a collection of eight fairy tales by Perrault called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[4][5] The book was an instant success and remains popular.[3]

Perrault’s Histoires has had considerable impact on world culture. The original Italian title of the first edition was Costantino Fortunato, but was later known as Il gatto con gli stivali (lit. The cat with the boots); the French title was «Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités» with the subtitle «Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye» («Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times with Morals», subtitled «Mother Goose Tales»). The frontispiece to the earliest English editions depicts an old woman telling tales to a group of children beneath a placard inscribed «MOTHER GOOSE’S TALES» and is credited with launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4]

«Puss in Boots» has provided inspiration for composers, choreographers, and other artists over the centuries. The cat appears in the third act pas de caractère of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty.[6] Puss in Boots appears in DreamWorks’ Shrek franchise, appearing in all three sequels to the original film, as well as two spin-off films, Puss in Boots (2011) and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish (2022), where he is voiced by Antonio Banderas. The character is signified in the logo of Japanese anime studio Toei Animation, and is also a popular pantomime in the UK.

Plot[edit]

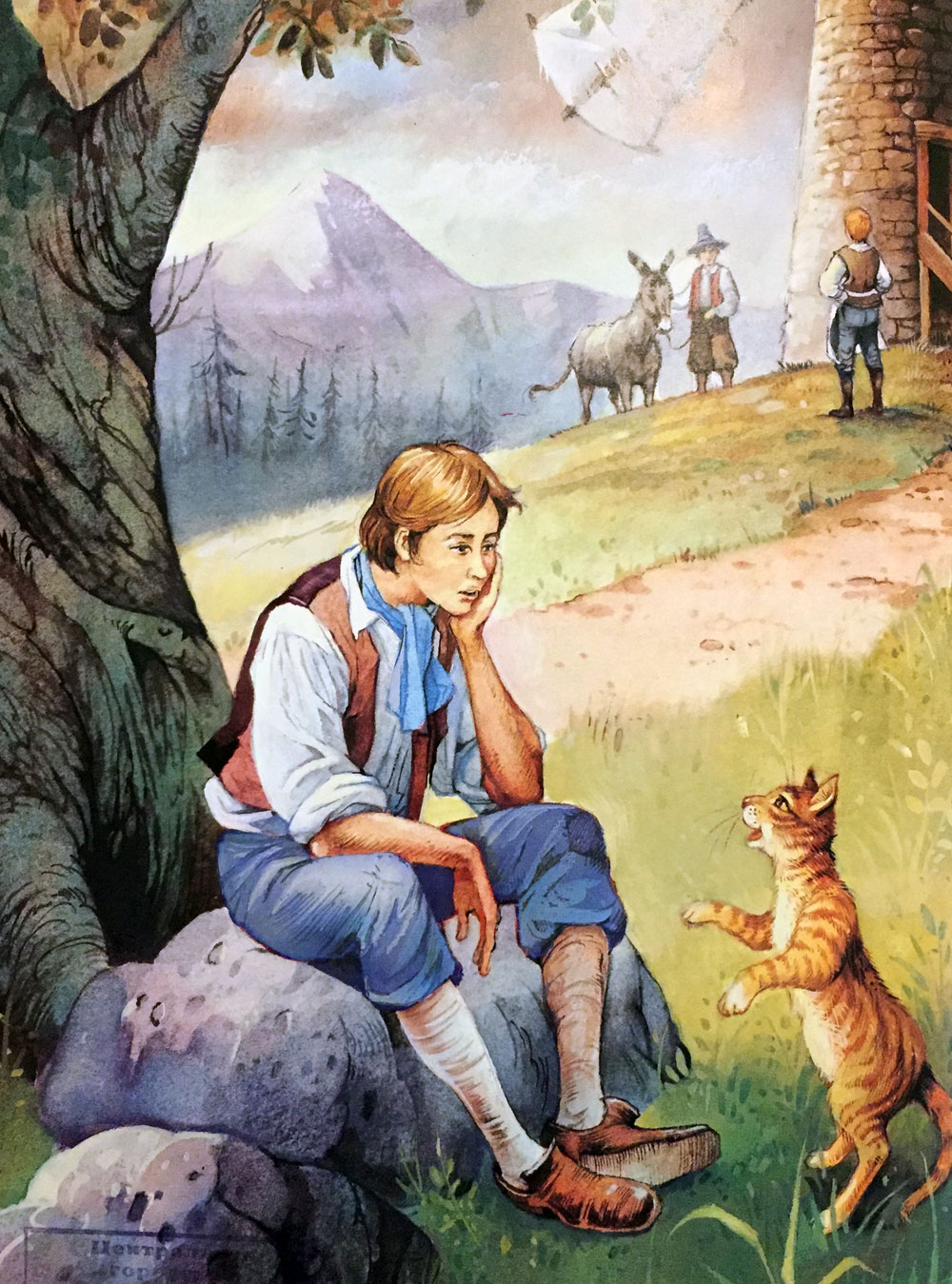

The tale opens with the third and youngest son of a miller receiving his inheritance — a cat. At first, the youngest son laments, as the eldest brother gains their father’s mill, and the middle brother gets the mule-and-cart. However, the feline is no ordinary cat, but one who requests and receives a pair of boots. Determined to make his master’s fortune, the cat bags a rabbit in the forest and presents it to the king as a gift from his master, the fictional Marquis of Carabas. The cat continues making gifts of game to the king for several months, for which he is rewarded.

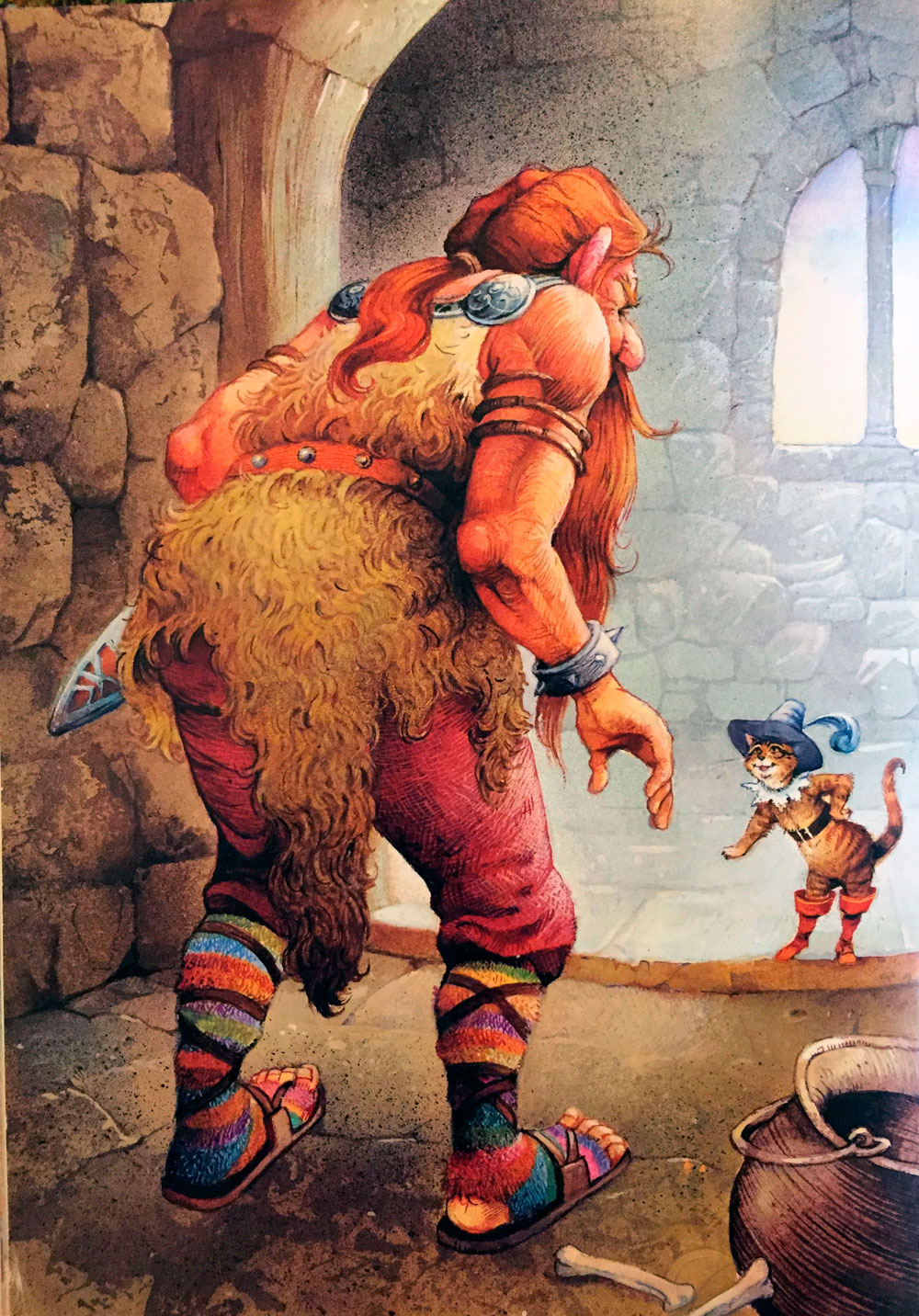

Puss meets the ogre in a nineteenth-century illustration by Gustave Doré

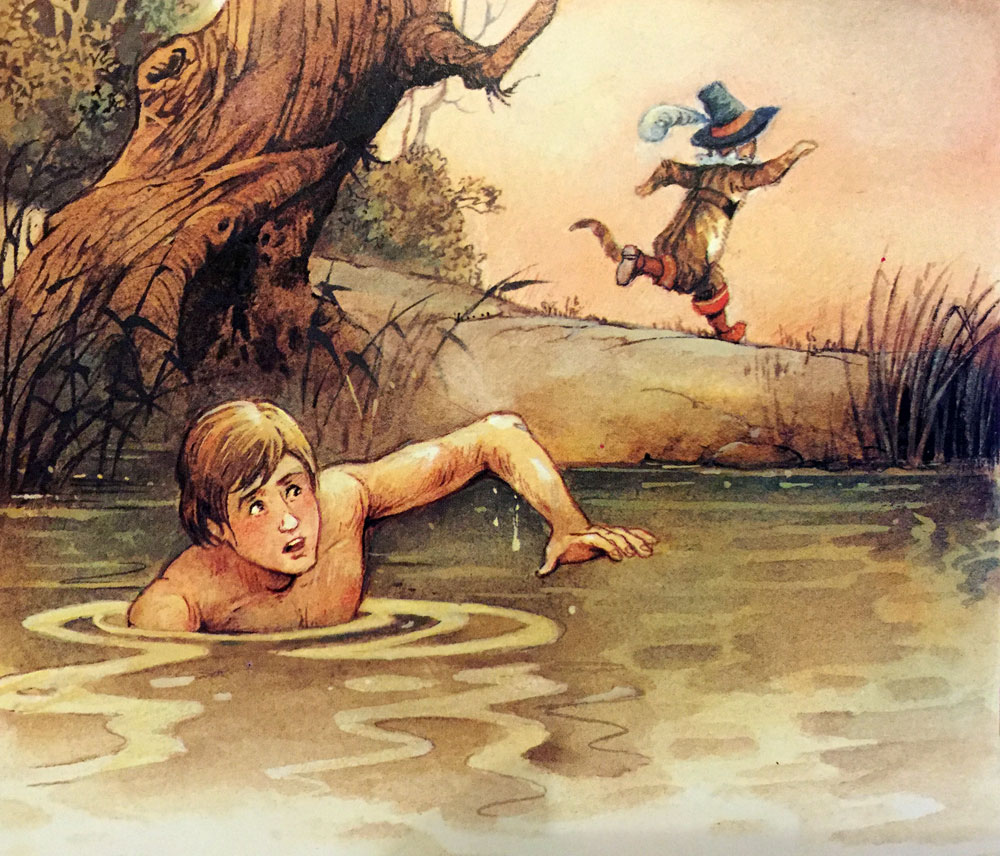

One day, the king decides to take a drive with his daughter. The cat persuades his master to remove his clothes and enter the river which their carriage passes. The cat disposes of his master’s clothing beneath a rock. As the royal coach nears, the cat begins calling for help in great distress. When the king stops to investigate, the cat tells him that his master the Marquis has been bathing in the river and robbed of his clothing. The king has the young man brought from the river, dressed in a splendid suit of clothes, and seated in the coach with his daughter, who falls in love with him at once.

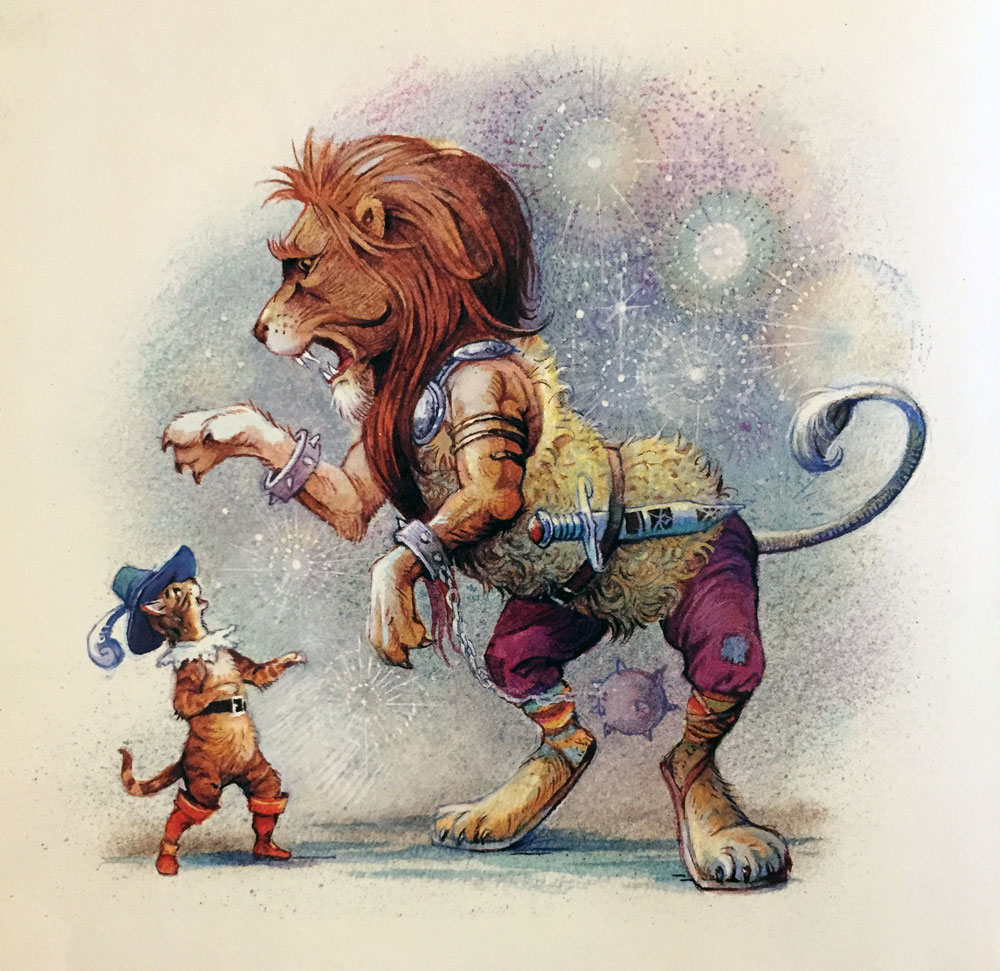

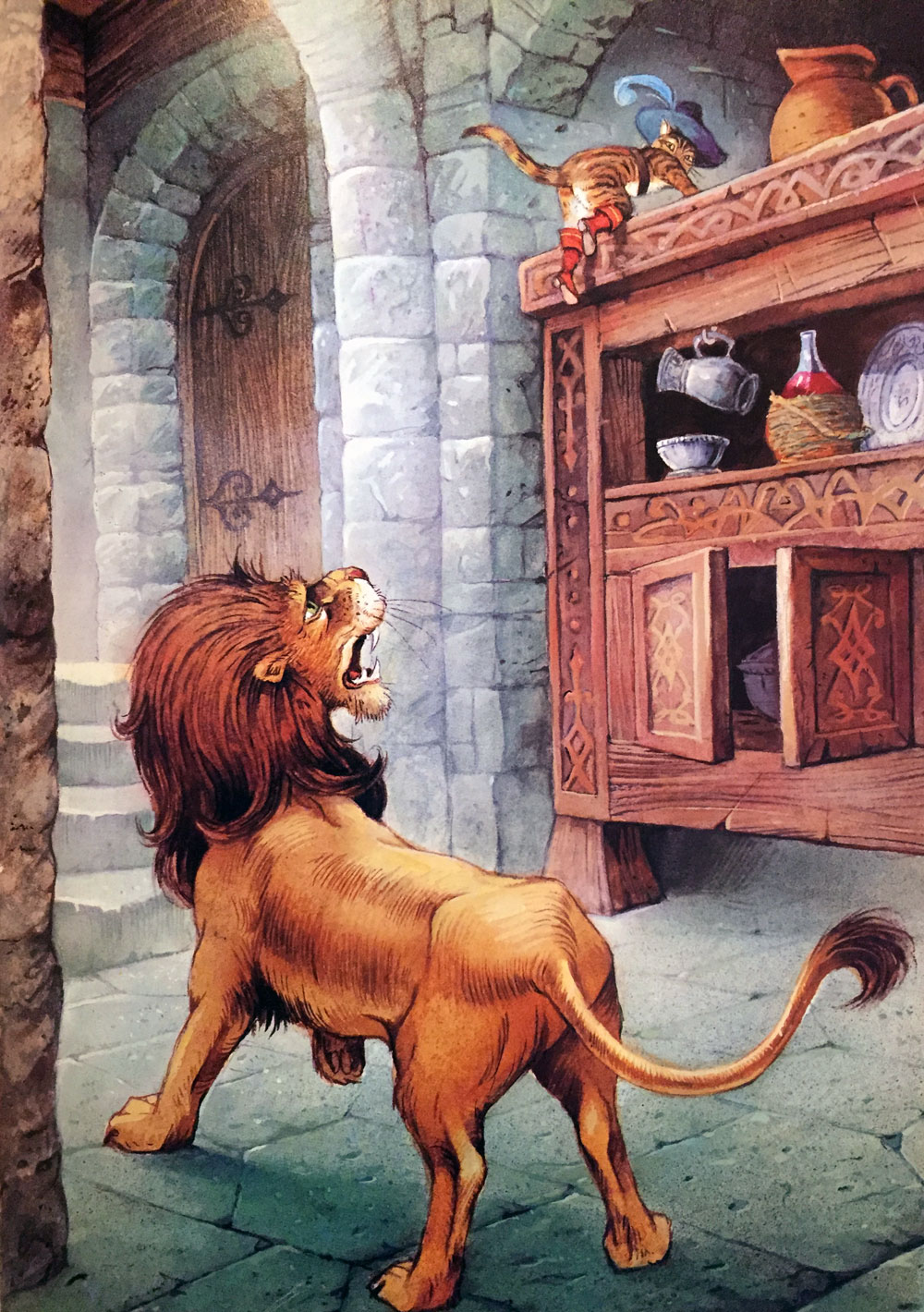

The cat hurries ahead of the coach, ordering the country folk along the road to tell the king that the land belongs to the «Marquis of Carabas», saying that if they do not he will cut them into mincemeat. The cat then happens upon a castle inhabited by an ogre who is capable of transforming himself into a number of creatures. The ogre displays his ability by changing into a lion, frightening the cat, who then tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse. The cat then pounces upon the mouse and devours it. The king arrives at the castle that formerly belonged to the ogre, and impressed with the bogus Marquis and his estate, gives the lad the princess in marriage. Thereafter; the cat enjoys life as a great lord who runs after mice only for his own amusement.[7]

The tale is followed immediately by two morals; «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie and savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess».[8] The Italian translation by Carlo Collodi notes that the tale gives useful advice if you happen to be a cat or a Marquis of Carabas.

This is the theme in France, but other versions of this theme exist in Asia, Africa, and South America.[9]

Background[edit]

Handwritten and illustrated manuscript of Perrault’s «Le Maître Chat» dated 1695

Perrault’s the «Master Cat or Puss in Boots» is the most renowned tale in all of Western folklore of the animal as helper.[10] However, the trickster cat did not originate with Perrault.[11] Centuries before the publication of Perrault’s tale, Somadeva, a Kashmir Brahmin, assembled a vast collection of Indian folk tales called Kathā Sarit Sāgara (lit. «The ocean of the streams of stories») that featured stock fairy tale characters and trappings such as invincible swords, vessels that replenish their contents, and helpful animals. In the Panchatantra (lit. «Five Principles»), a collection of Hindu tales from the second century BC., a tale follows a cat who fares much less well than Perrault’s Puss as he attempts to make his fortune in a king’s palace.[12]

In 1553, «Costantino Fortunato», a tale similar to «Le Maître Chat», was published in Venice in Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s Le Piacevoli Notti (lit. The Facetious Nights),[13] the first European storybook to include fairy tales.[14] In Straparola’s tale however, the poor young man is the son of a Bohemian woman, the cat is a fairy in disguise, the princess is named Elisetta, and the castle belongs not to an ogre but to a lord who conveniently perishes in an accident. The poor young man eventually becomes King of Bohemia.[13] An edition of Straparola was published in France in 1560.[10] The abundance of oral versions after Straparola’s tale may indicate an oral source to the tale; it also is possible Straparola invented the story.[15]

In 1634, another tale with a trickster cat as hero was published in Giambattista Basile’s collection Pentamerone although neither the collection nor the tale were published in France during Perrault’s lifetime. In Basile’s version, the lad is a beggar boy called Gagliuso (sometimes Cagliuso) whose fortunes are achieved in a manner similar to Perrault’s Puss. However, the tale ends with Cagliuso, in gratitude to the cat, promising the feline a gold coffin upon his death. Three days later, the cat decides to test Gagliuso by pretending to be dead and is mortified to hear Gagliuso tell his wife to take the dead cat by its paws and throw it out the window. The cat leaps up, demanding to know whether this was his promised reward for helping the beggar boy to a better life. The cat then rushes away, leaving his master to fend for himself.[13] In another rendition, the cat performs acts of bravery, then a fairy comes and turns him to his normal state to be with other cats.

It is likely that Perrault was aware of the Straparola tale, since ‘Facetious Nights’ was translated into French in the sixteenth century and subsequently passed into the oral tradition.[3]

Publication[edit]

The oldest record of written history was published in Venice by the Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–53) in XIV-XV. His original title was Costantino Fortunato (lit. Lucky Costantino).

The story was published under the French title Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté (‘Master Cat, or the Booted Cat’) by Barbin in Paris in January 1697 in a collection of tales called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[3] The collection included «La Belle au bois dormant» («The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood»), «Le petit chaperon rouge» («Little Red Riding Hood»), «La Barbe bleue» («Blue Beard»), «Les Fées» («The Enchanted Ones», or «Diamonds and Toads»), «Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre» («Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper»), «Riquet à la Houppe» («Riquet with the Tuft»), and «Le Petit Poucet» («Hop o’ My Thumb»).[3] The book displayed a frontispiece depicting an old woman telling tales to a group of three children beneath a placard inscribed «CONTES DE MA MERE L’OYE» (Tales of Mother Goose).[4] The book was an instant success.[3]

Le Maître Chat first was translated into English as «The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots» by Robert Samber in 1729 and published in London for J. Pote and R. Montagu with its original companion tales in Histories, or Tales of Past Times, By M. Perrault.[note 1][16] The book was advertised in June 1729 as being «very entertaining and instructive for children».[16] A frontispiece similar to that of the first French edition appeared in the English edition launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4] Samber’s translation has been described as «faithful and straightforward, conveying attractively the concision, liveliness and gently ironic tone of Perrault’s prose, which itself emulated the direct approach of oral narrative in its elegant simplicity.»[17] Since that publication, the tale has been translated into various languages and published around the world.

[edit]

Perrault’s son Pierre Darmancour was assumed to have been responsible for the authorship of Histoires with the evidence cited being the book’s dedication to Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans, the youngest niece of Louis XIV, which was signed «P. Darmancour». Perrault senior, however, was known for some time to have been interested in contes de veille or contes de ma mère l’oye, and in 1693 published a versification of «Les Souhaits Ridicules» and, in 1694, a tale with a Cinderella theme called «Peau d’Ane».[4] Further, a handwritten and illustrated manuscript of five of the tales (including Le Maistre Chat ou le Chat Botté) existed two years before the tale’s 1697 Paris publication.[4]

Pierre Darmancour was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time the manuscript was prepared and, as scholars Iona and Peter Opie note, quite unlikely to have been interested in recording fairy tales.[4] Darmancour, who became a soldier, showed no literary inclinations, and, when he died in 1700, his obituary made no mention of any connection with the tales. However, when Perrault senior died in 1703, the newspaper alluded to his being responsible for «La Belle au bois dormant», which the paper had published in 1696.[4]

Analysis[edit]

In folkloristics, Puss in Boots is classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots», a subtype of ATU 545, «The Cat as Helper».[18] Folklorists Joseph Jacobs and Stith Thompson point that the Perrault’s tale is the possible source of the Cat Helper story in later European folkloric traditions.[19][20] The tale has also spread to the Americas, and is known in Asia (India, Indonesia and Philippines).[21]

Variations of the feline helper across cultures replace the cat with a jackal or fox.[22][23][24] For instance, the helpful animal is a monkey «in all Philippine variants» according to Damiana Eugenio.[25]

Greek scholar Marianthi Kaplanoglou states that the tale type ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots» (or, locally, «The Helpful Fox»), is an «example» of «widely known stories (…) in the repertoires of Greek refugees from Asia Minor».[26]

Adaptations[edit]

Perrault’s tale has been adapted to various media over the centuries. Ludwig Tieck published a dramatic satire based on the tale, called Der gestiefelte Kater,[27] and, in 1812, the Brothers Grimm inserted a version of the tale into their Kinder- und Hausmärchen.[28] In ballet, Puss appears in the third act of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty in a pas de caractère with The White Cat.[6]

The phrase «enough to make a cat laugh» dates from the mid-1800s and is associated with the tale of Puss in Boots.[29]

The Bibliothèque de Carabas[30] book series was published by David Nutt in London in the late 19th century, in which the front cover of each volume depicts Puss in Boots reading a book.

In film and television, Walt Disney produced an animated black and white silent short based on the tale in 1922.[31]

It was also adapted by Toei as anime feature film in 1969, It followed by two sequels. Hayao Miyazaki made manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film. The title character, Pero, named after Perrault, has since then become the mascot of Toei Animation, with his face appearing in the studio’s logo.

In the mid-1980s, Puss in Boots was televised as an episode of Faerie Tale Theatre with Ben Vereen and Gregory Hines in the cast.[32]

1987’s anime Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics features Puss in Boots, This version of Puss cheats his good-natured master out of money to buy his boots and his hat, hunts the king’s favorite thrush for introduced his master to the king.

Another version from the Cannon Movie Tales series features Christopher Walken as Puss, who in this adaptation is a cat who turns into a human when wearing the boots.

The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child features the story in a Hawaiian setting. The episode stars the voices of David Hyde Pierce as Puss in Boots, Dean Cain as Kuhio, Pat Morita as King Makahana, and Ming-Na Wen as Lani. In addition, the shapeshifting ogre is replaced with a shapeshifting giant (voiced by Keone Young).

Another adaptation of the character with little relation to the story was in the Pokémon anime episode «Like a Meowth to a Flame,» where a Meowth owned by the character Tyson wore boots, a hat, and a neckerchief.

DreamWorks Animation’s 2004 animated film Shrek 2 features a version of the character voiced by Antonio Banderas (and modeled after Banderas’ performance as Zorro). An assassin initially hired to kill Shrek, Puss becomes one of Shrek’s most loyal allies following his defeat. Banderas also voices Puss in the third and fourth films in the Shrek franchise, and in a 2011 spin-off animated feature Puss in Boots, which spawned a 2022 sequel Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. Puss also appears in the Netflix/DreamWorks series The Adventures of Puss in Boots where he is voiced by Eric Bauza.

[edit]

Jacques Barchilon and Henry Pettit note in their introduction to The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes that the main motif of «Puss in Boots» is the animal as helper and that the tale «carries atavistic memories of the familiar totem animal as the father protector of the tribe found everywhere by missionaries and anthropologists.» They also note that the title is original with Perrault as are the boots; no tale prior to Perrault’s features a cat wearing boots.[33]

Woodcut frontispiece copied from the 1697 Paris edition of Perrault’s tales and published in the English-speaking world.

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie observe that «the tale is unusual in that the hero little deserves his good fortune, that is if his poverty, his being a third child, and his unquestioning acceptance of the cat’s sinful instructions, are not nowadays looked upon as virtues.» The cat should be acclaimed the prince of ‘con’ artists, they declare, as few swindlers have been so successful before or since.[11]

The success of Histoires is attributed to seemingly contradictory and incompatible reasons. While the literary skill employed in the telling of the tales has been recognized universally, it appears the tales were set down in great part as the author heard them told. The evidence for that assessment lies first in the simplicity of the tales, then in the use of words that were, in Perrault’s era, considered populaire and du bas peuple, and finally, in the appearance of vestigial passages that now are superfluous to the plot, do not illuminate the narrative, and thus, are passages the Opies believe a literary artist would have rejected in the process of creating a work of art. One such vestigial passage is Puss’s boots; his insistence upon the footwear is explained nowhere in the tale, it is not developed, nor is it referred to after its first mention except in an aside.[34]

According to the Opies, Perrault’s great achievement was accepting fairy tales at «their own level.» He recounted them with neither impatience nor mockery, and without feeling that they needed any aggrandisement such as a frame story—although he must have felt it useful to end with a rhyming moralité. Perrault would be revered today as the father of folklore if he had taken the time to record where he obtained his tales, when, and under what circumstances.[34]

Bruno Bettelheim remarks that «the more simple and straightforward a good character in a fairy tale, the easier it is for a child to identify with it and to reject the bad other.» The child identifies with a good hero because the hero’s condition makes a positive appeal to him. If the character is a very good person, then the child is likely to want to be good too. Amoral tales, however, show no polarization or juxtaposition of good and bad persons because amoral tales such as «Puss in Boots» build character, not by offering choices between good and bad, but by giving the child hope that even the meekest can survive. Morality is of little concern in these tales, but rather, an assurance is provided that one can survive and succeed in life.[35]

Small children can do little on their own and may give up in disappointment and despair with their attempts. Fairy stories, however, give great dignity to the smallest achievements (such as befriending an animal or being befriended by an animal, as in «Puss in Boots») and that such ordinary events may lead to great things. Fairy stories encourage children to believe and trust that their small, real achievements are important although perhaps not recognized at the moment.[36]

In Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion Jack Zipes notes that Perrault «sought to portray ideal types to reinforce the standards of the civilizing process set by upper-class French society».[8] A composite portrait of Perrault’s heroines, for example, reveals the author’s idealized female of upper-class society is graceful, beautiful, polite, industrious, well groomed, reserved, patient, and even somewhat stupid because for Perrault, intelligence in womankind would be threatening. Therefore, Perrault’s composite heroine passively waits for «the right man» to come along, recognize her virtues, and make her his wife. He acts, she waits. If his seventeenth century heroines demonstrate any characteristics, it is submissiveness.[37]

A composite of Perrault’s male heroes, however, indicates the opposite of his heroines: his male characters are not particularly handsome, but they are active, brave, ambitious, and deft, and they use their wit, intelligence, and great civility to work their way up the social ladder and to achieve their goals. In this case of course, it is the cat who displays the characteristics and the man benefits from his trickery and skills. Unlike the tales dealing with submissive heroines waiting for marriage, the male-centered tales suggest social status and achievement are more important than marriage for men. The virtues of Perrault’s heroes reflect upon the bourgeoisie of the court of Louis XIV and upon the nature of Perrault, who was a successful civil servant in France during the seventeenth century.[8]

According to fairy and folk tale researcher and commentator Jack Zipes, Puss is «the epitome of the educated bourgeois secretary who serves his master with complete devotion and diligence.»[37] The cat has enough wit and manners to impress the king, the intelligence to defeat the ogre, and the skill to arrange a royal marriage for his low-born master. Puss’s career is capped by his elevation to grand seigneur[8] and the tale is followed by a double moral: «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie et savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess.»[8]

The renowned illustrator of Dickens’ novels and stories, George Cruikshank, was shocked that parents would allow their children to read «Puss in Boots» and declared: «As it stood the tale was a succession of successful falsehoods—a clever lesson in lying!—a system of imposture rewarded with the greatest worldly advantages.»

Another critic, Maria Tatar, notes that there is little to admire in Puss—he threatens, flatters, deceives, and steals in order to promote his master. She further observes that Puss has been viewed as a «linguistic virtuoso», a creature who has mastered the arts of persuasion and rhetoric to acquire power and wealth.[5]

«Puss in Boots» has successfully supplanted its antecedents by Straparola and Basile and the tale has altered the shapes of many older oral trickster cat tales where they still are found. The morals Perrault attached to the tales are either at odds with the narrative, or beside the point. The first moral tells the reader that hard work and ingenuity are preferable to inherited wealth, but the moral is belied by the poor miller’s son who neither works nor uses his wit to gain worldly advantage, but marries into it through trickery performed by the cat. The second moral stresses womankind’s vulnerability to external appearances: fine clothes and a pleasant visage are enough to win their hearts. In an aside, Tatar suggests that if the tale has any redeeming meaning, «it has something to do with inspiring respect for those domestic creatures that hunt mice and look out for their masters.»[38]

Briggs does assert that cats were a form of fairy in their own right having something akin to a fairy court and their own set of magical powers. Still, it is rare in Europe’s fairy tales for a cat to be so closely involved with human affairs. According to Jacob Grimm, Puss shares many of the features that a household fairy or deity would have including a desire for boots which could represent seven-league boots. This may mean that the story of «Puss and Boots» originally represented the tale of a family deity aiding an impoverished family member.[39][self-published source]

Stefan Zweig, in his 1939 novel, Ungeduld des Herzens, references Puss in Boots’ procession through a rich and varied countryside with his master and drives home his metaphor with a mention of Seven League Boots.

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ The distinction of being the first to translate the tales into English was long questioned. An edition styled Histories or Tales of Past Times, told by Mother Goose, with Morals. Written in French by M. Perrault, and Englished by G.M. Gent bore the publication date of 1719, thus casting doubt upon Samber being the first translator. In 1951, however, the date was proven to be a misprint for 1799 and Samber’s distinction as the first translator was assured.

- Footnotes

- ^ W. G. Waters, The Mysterious Giovan Francesco Straparola, in Jack Zipes, a c. di, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974 Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Opie & Opie 1974, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Opie & Opie 1974, p. 23.

- ^ a b Tatar 2002, p. 234

- ^ a b Brown 2007, p. 351

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 113–116

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 1991, p. 26

- ^ Darnton, Robert (1984). The Great Cat Massacre. New York, NY: Basic Books, Ink. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-465-01274-9.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Zipes 2001, p. 877

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 24.

- ^ Gillespie & Hopkins 2005, p. 351

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 58-59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 239-240.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2006). «The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a ‘Fictional Animal’«. Asian Folklore Studies. 65 (2): 133–160. JSTOR 30030396.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Eugenio, Damiana L. (1985). «Philippine Folktales: An Introduction». Asian Folklore Studies. 44 (2): 155–177. doi:10.2307/1178506. JSTOR 1178506.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (December 2010). «Two Storytellers from the Greek-Orthodox Communities of Ottoman Asia Minor. Analyzing Some Micro-data in Comparative Folklore». Fabula. 51 (3–4): 251–265. doi:10.1515/fabl.2010.024. S2CID 161511346.

- ^ Paulin 2002, p. 65

- ^ Wunderer 2008, p. 202

- ^ «https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/enough+to+make+a+cat+laugh»>enough to make a cat laugh

- ^ «Nutt, Alfred Trübner». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Puss in Boots». The Disney Encyclopedia of Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Zipes 1997, p. 102

- ^ Barchilon 1960, pp. 14, 16

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 10

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 73

- ^ a b Zipes 1991, p. 25

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 235

- ^ Nukiuk H. 2011 Grimm’s Fairies: Discover the Fairies of Europe’s Fairy Tales, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Works cited

- Barchilon, Jacques (1960), The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes, Denver, CO: Alan Swallow

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977) [1975, 1976], The Uses of Enchantment, New York: Random House: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-394-72265-5

- Brown, David (2007), Tchaikovsky, New York: Pegasus Books LLC, ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9

- Gillespie, Stuart; Hopkins, David, eds. (2005), The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English: 1660–1790, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924622-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Paulin, Roger (2002) [1985], Ludwig Tieck, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815852-1

- Tatar, Maria (2002), The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Wunderer, Rolf (2008), «Der gestiefelte Kater» als Unternehmer, Weisbaden: Gabler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8349-0772-1

- Zipes, Jack David (1991) [1988], Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90513-3

- Zipes, Jack David (2001), The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Zipes, Jack David (1997), Happily Ever After, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-91851-0

Further reading[edit]

- Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- Neuhaus, Mareike (2011). «The Rhetoric of Harry Robinson’s ‘Cat With the Boots On’«. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 44 (2): 35–51. JSTOR 44029507. Project MUSE 440541 ProQuest 871355970.

- Nikolajeva, Maria (2009). «Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats». Marvels & Tales. 23 (2): 248–267. JSTOR 41388926.

- Blair, Graham (2019). «Jack Ships to the Cat». Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat: Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition. University Press of Colorado. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-1-60732-919-0. JSTOR j.ctvqc6hwd.11.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Origin of the Story of ‘Puss in Boots’

- «Puss in Boots» – English translation from The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- «Puss in Boots» – Beautifully illustrated in The Colorful Story Book (1941)

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox

| «Puss in Boots» | |

|---|---|

| by Giovanni Francesco Straparola Giambattista Basile Charles Perrault |

|

Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer |

|

| Country | Italy (1550–1553) France (1697) |

| Language | Italian (originally) |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

«Puss in Boots» (Italian: Il gatto con gli stivali) is an Italian[1][2] fairy tale, later spread throughout the rest of Europe, about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand of a princess in marriage for his penniless and low-born master.

The oldest written telling is by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola, who included it in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–1553) in XIV–XV. Another version was published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile with the title Cagliuso, and a tale was written in French at the close of the seventeenth century by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a retired civil servant and member of the Académie française. There is a version written by Girolamo Morlini, from whom Straparola used various tales in The Facetious Nights of Straparola.[3] The tale appeared in a handwritten and illustrated manuscript two years before its 1697 publication by Barbin in a collection of eight fairy tales by Perrault called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[4][5] The book was an instant success and remains popular.[3]

Perrault’s Histoires has had considerable impact on world culture. The original Italian title of the first edition was Costantino Fortunato, but was later known as Il gatto con gli stivali (lit. The cat with the boots); the French title was «Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités» with the subtitle «Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye» («Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times with Morals», subtitled «Mother Goose Tales»). The frontispiece to the earliest English editions depicts an old woman telling tales to a group of children beneath a placard inscribed «MOTHER GOOSE’S TALES» and is credited with launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4]

«Puss in Boots» has provided inspiration for composers, choreographers, and other artists over the centuries. The cat appears in the third act pas de caractère of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty.[6] Puss in Boots appears in DreamWorks’ Shrek franchise, appearing in all three sequels to the original film, as well as two spin-off films, Puss in Boots (2011) and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish (2022), where he is voiced by Antonio Banderas. The character is signified in the logo of Japanese anime studio Toei Animation, and is also a popular pantomime in the UK.

Plot[edit]

The tale opens with the third and youngest son of a miller receiving his inheritance — a cat. At first, the youngest son laments, as the eldest brother gains their father’s mill, and the middle brother gets the mule-and-cart. However, the feline is no ordinary cat, but one who requests and receives a pair of boots. Determined to make his master’s fortune, the cat bags a rabbit in the forest and presents it to the king as a gift from his master, the fictional Marquis of Carabas. The cat continues making gifts of game to the king for several months, for which he is rewarded.

Puss meets the ogre in a nineteenth-century illustration by Gustave Doré

One day, the king decides to take a drive with his daughter. The cat persuades his master to remove his clothes and enter the river which their carriage passes. The cat disposes of his master’s clothing beneath a rock. As the royal coach nears, the cat begins calling for help in great distress. When the king stops to investigate, the cat tells him that his master the Marquis has been bathing in the river and robbed of his clothing. The king has the young man brought from the river, dressed in a splendid suit of clothes, and seated in the coach with his daughter, who falls in love with him at once.

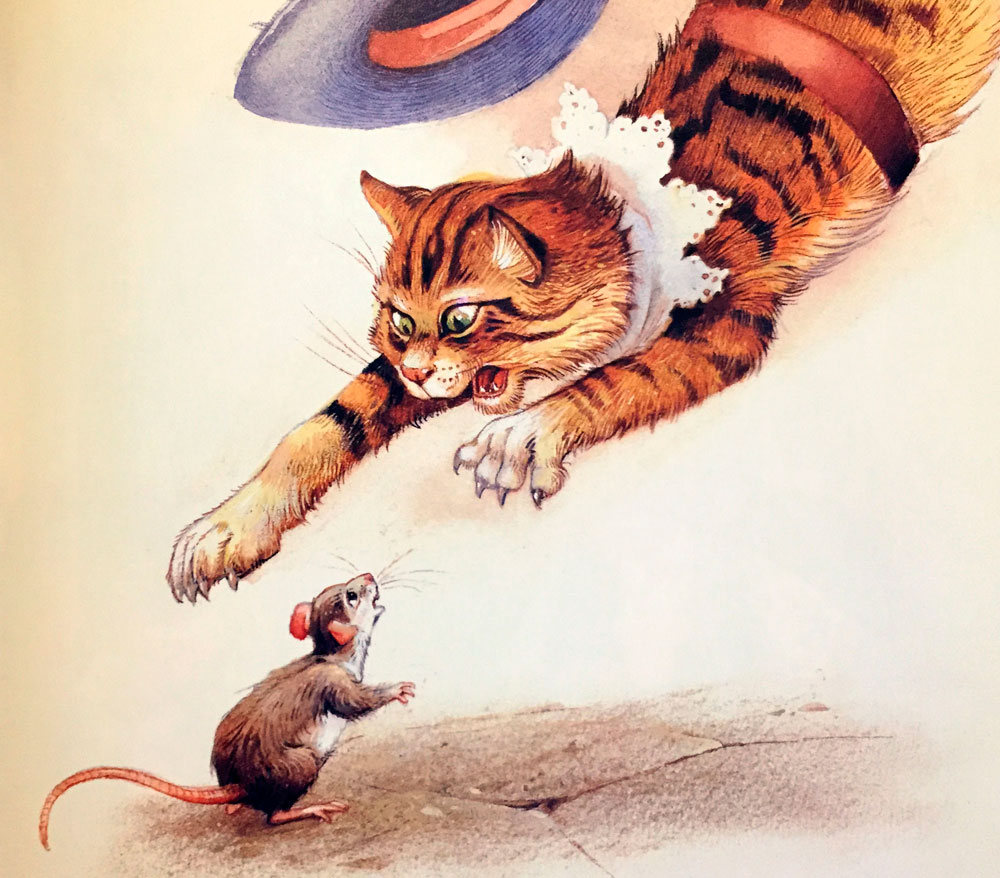

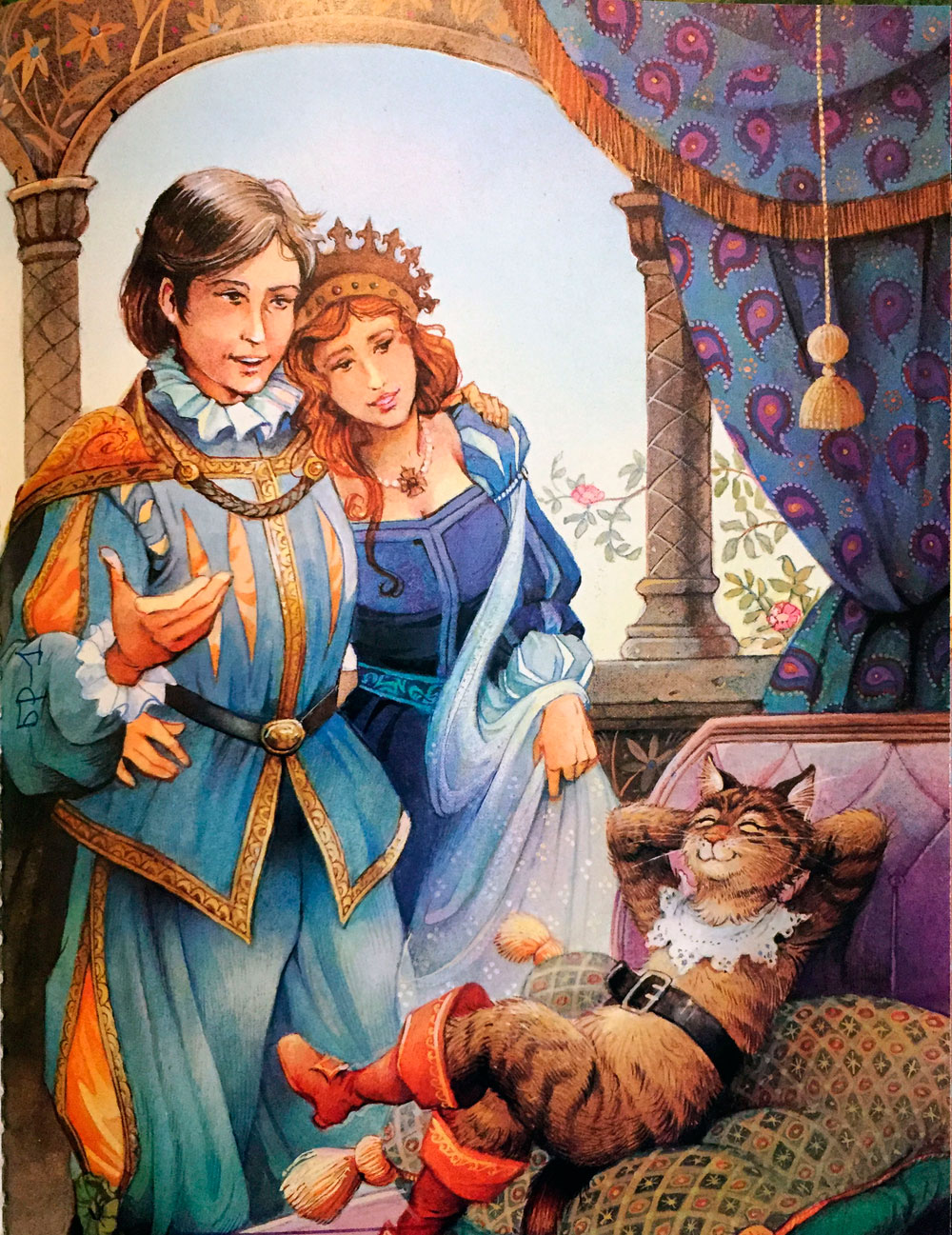

The cat hurries ahead of the coach, ordering the country folk along the road to tell the king that the land belongs to the «Marquis of Carabas», saying that if they do not he will cut them into mincemeat. The cat then happens upon a castle inhabited by an ogre who is capable of transforming himself into a number of creatures. The ogre displays his ability by changing into a lion, frightening the cat, who then tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse. The cat then pounces upon the mouse and devours it. The king arrives at the castle that formerly belonged to the ogre, and impressed with the bogus Marquis and his estate, gives the lad the princess in marriage. Thereafter; the cat enjoys life as a great lord who runs after mice only for his own amusement.[7]

The tale is followed immediately by two morals; «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie and savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess».[8] The Italian translation by Carlo Collodi notes that the tale gives useful advice if you happen to be a cat or a Marquis of Carabas.

This is the theme in France, but other versions of this theme exist in Asia, Africa, and South America.[9]

Background[edit]

Handwritten and illustrated manuscript of Perrault’s «Le Maître Chat» dated 1695

Perrault’s the «Master Cat or Puss in Boots» is the most renowned tale in all of Western folklore of the animal as helper.[10] However, the trickster cat did not originate with Perrault.[11] Centuries before the publication of Perrault’s tale, Somadeva, a Kashmir Brahmin, assembled a vast collection of Indian folk tales called Kathā Sarit Sāgara (lit. «The ocean of the streams of stories») that featured stock fairy tale characters and trappings such as invincible swords, vessels that replenish their contents, and helpful animals. In the Panchatantra (lit. «Five Principles»), a collection of Hindu tales from the second century BC., a tale follows a cat who fares much less well than Perrault’s Puss as he attempts to make his fortune in a king’s palace.[12]

In 1553, «Costantino Fortunato», a tale similar to «Le Maître Chat», was published in Venice in Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s Le Piacevoli Notti (lit. The Facetious Nights),[13] the first European storybook to include fairy tales.[14] In Straparola’s tale however, the poor young man is the son of a Bohemian woman, the cat is a fairy in disguise, the princess is named Elisetta, and the castle belongs not to an ogre but to a lord who conveniently perishes in an accident. The poor young man eventually becomes King of Bohemia.[13] An edition of Straparola was published in France in 1560.[10] The abundance of oral versions after Straparola’s tale may indicate an oral source to the tale; it also is possible Straparola invented the story.[15]

In 1634, another tale with a trickster cat as hero was published in Giambattista Basile’s collection Pentamerone although neither the collection nor the tale were published in France during Perrault’s lifetime. In Basile’s version, the lad is a beggar boy called Gagliuso (sometimes Cagliuso) whose fortunes are achieved in a manner similar to Perrault’s Puss. However, the tale ends with Cagliuso, in gratitude to the cat, promising the feline a gold coffin upon his death. Three days later, the cat decides to test Gagliuso by pretending to be dead and is mortified to hear Gagliuso tell his wife to take the dead cat by its paws and throw it out the window. The cat leaps up, demanding to know whether this was his promised reward for helping the beggar boy to a better life. The cat then rushes away, leaving his master to fend for himself.[13] In another rendition, the cat performs acts of bravery, then a fairy comes and turns him to his normal state to be with other cats.

It is likely that Perrault was aware of the Straparola tale, since ‘Facetious Nights’ was translated into French in the sixteenth century and subsequently passed into the oral tradition.[3]

Publication[edit]

The oldest record of written history was published in Venice by the Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–53) in XIV-XV. His original title was Costantino Fortunato (lit. Lucky Costantino).

The story was published under the French title Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté (‘Master Cat, or the Booted Cat’) by Barbin in Paris in January 1697 in a collection of tales called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[3] The collection included «La Belle au bois dormant» («The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood»), «Le petit chaperon rouge» («Little Red Riding Hood»), «La Barbe bleue» («Blue Beard»), «Les Fées» («The Enchanted Ones», or «Diamonds and Toads»), «Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre» («Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper»), «Riquet à la Houppe» («Riquet with the Tuft»), and «Le Petit Poucet» («Hop o’ My Thumb»).[3] The book displayed a frontispiece depicting an old woman telling tales to a group of three children beneath a placard inscribed «CONTES DE MA MERE L’OYE» (Tales of Mother Goose).[4] The book was an instant success.[3]

Le Maître Chat first was translated into English as «The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots» by Robert Samber in 1729 and published in London for J. Pote and R. Montagu with its original companion tales in Histories, or Tales of Past Times, By M. Perrault.[note 1][16] The book was advertised in June 1729 as being «very entertaining and instructive for children».[16] A frontispiece similar to that of the first French edition appeared in the English edition launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4] Samber’s translation has been described as «faithful and straightforward, conveying attractively the concision, liveliness and gently ironic tone of Perrault’s prose, which itself emulated the direct approach of oral narrative in its elegant simplicity.»[17] Since that publication, the tale has been translated into various languages and published around the world.

[edit]

Perrault’s son Pierre Darmancour was assumed to have been responsible for the authorship of Histoires with the evidence cited being the book’s dedication to Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans, the youngest niece of Louis XIV, which was signed «P. Darmancour». Perrault senior, however, was known for some time to have been interested in contes de veille or contes de ma mère l’oye, and in 1693 published a versification of «Les Souhaits Ridicules» and, in 1694, a tale with a Cinderella theme called «Peau d’Ane».[4] Further, a handwritten and illustrated manuscript of five of the tales (including Le Maistre Chat ou le Chat Botté) existed two years before the tale’s 1697 Paris publication.[4]

Pierre Darmancour was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time the manuscript was prepared and, as scholars Iona and Peter Opie note, quite unlikely to have been interested in recording fairy tales.[4] Darmancour, who became a soldier, showed no literary inclinations, and, when he died in 1700, his obituary made no mention of any connection with the tales. However, when Perrault senior died in 1703, the newspaper alluded to his being responsible for «La Belle au bois dormant», which the paper had published in 1696.[4]

Analysis[edit]

In folkloristics, Puss in Boots is classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots», a subtype of ATU 545, «The Cat as Helper».[18] Folklorists Joseph Jacobs and Stith Thompson point that the Perrault’s tale is the possible source of the Cat Helper story in later European folkloric traditions.[19][20] The tale has also spread to the Americas, and is known in Asia (India, Indonesia and Philippines).[21]

Variations of the feline helper across cultures replace the cat with a jackal or fox.[22][23][24] For instance, the helpful animal is a monkey «in all Philippine variants» according to Damiana Eugenio.[25]

Greek scholar Marianthi Kaplanoglou states that the tale type ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots» (or, locally, «The Helpful Fox»), is an «example» of «widely known stories (…) in the repertoires of Greek refugees from Asia Minor».[26]

Adaptations[edit]

Perrault’s tale has been adapted to various media over the centuries. Ludwig Tieck published a dramatic satire based on the tale, called Der gestiefelte Kater,[27] and, in 1812, the Brothers Grimm inserted a version of the tale into their Kinder- und Hausmärchen.[28] In ballet, Puss appears in the third act of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty in a pas de caractère with The White Cat.[6]

The phrase «enough to make a cat laugh» dates from the mid-1800s and is associated with the tale of Puss in Boots.[29]

The Bibliothèque de Carabas[30] book series was published by David Nutt in London in the late 19th century, in which the front cover of each volume depicts Puss in Boots reading a book.

In film and television, Walt Disney produced an animated black and white silent short based on the tale in 1922.[31]

It was also adapted by Toei as anime feature film in 1969, It followed by two sequels. Hayao Miyazaki made manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film. The title character, Pero, named after Perrault, has since then become the mascot of Toei Animation, with his face appearing in the studio’s logo.

In the mid-1980s, Puss in Boots was televised as an episode of Faerie Tale Theatre with Ben Vereen and Gregory Hines in the cast.[32]

1987’s anime Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics features Puss in Boots, This version of Puss cheats his good-natured master out of money to buy his boots and his hat, hunts the king’s favorite thrush for introduced his master to the king.

Another version from the Cannon Movie Tales series features Christopher Walken as Puss, who in this adaptation is a cat who turns into a human when wearing the boots.

The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child features the story in a Hawaiian setting. The episode stars the voices of David Hyde Pierce as Puss in Boots, Dean Cain as Kuhio, Pat Morita as King Makahana, and Ming-Na Wen as Lani. In addition, the shapeshifting ogre is replaced with a shapeshifting giant (voiced by Keone Young).

Another adaptation of the character with little relation to the story was in the Pokémon anime episode «Like a Meowth to a Flame,» where a Meowth owned by the character Tyson wore boots, a hat, and a neckerchief.

DreamWorks Animation’s 2004 animated film Shrek 2 features a version of the character voiced by Antonio Banderas (and modeled after Banderas’ performance as Zorro). An assassin initially hired to kill Shrek, Puss becomes one of Shrek’s most loyal allies following his defeat. Banderas also voices Puss in the third and fourth films in the Shrek franchise, and in a 2011 spin-off animated feature Puss in Boots, which spawned a 2022 sequel Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. Puss also appears in the Netflix/DreamWorks series The Adventures of Puss in Boots where he is voiced by Eric Bauza.

[edit]

Jacques Barchilon and Henry Pettit note in their introduction to The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes that the main motif of «Puss in Boots» is the animal as helper and that the tale «carries atavistic memories of the familiar totem animal as the father protector of the tribe found everywhere by missionaries and anthropologists.» They also note that the title is original with Perrault as are the boots; no tale prior to Perrault’s features a cat wearing boots.[33]

Woodcut frontispiece copied from the 1697 Paris edition of Perrault’s tales and published in the English-speaking world.

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie observe that «the tale is unusual in that the hero little deserves his good fortune, that is if his poverty, his being a third child, and his unquestioning acceptance of the cat’s sinful instructions, are not nowadays looked upon as virtues.» The cat should be acclaimed the prince of ‘con’ artists, they declare, as few swindlers have been so successful before or since.[11]

The success of Histoires is attributed to seemingly contradictory and incompatible reasons. While the literary skill employed in the telling of the tales has been recognized universally, it appears the tales were set down in great part as the author heard them told. The evidence for that assessment lies first in the simplicity of the tales, then in the use of words that were, in Perrault’s era, considered populaire and du bas peuple, and finally, in the appearance of vestigial passages that now are superfluous to the plot, do not illuminate the narrative, and thus, are passages the Opies believe a literary artist would have rejected in the process of creating a work of art. One such vestigial passage is Puss’s boots; his insistence upon the footwear is explained nowhere in the tale, it is not developed, nor is it referred to after its first mention except in an aside.[34]

According to the Opies, Perrault’s great achievement was accepting fairy tales at «their own level.» He recounted them with neither impatience nor mockery, and without feeling that they needed any aggrandisement such as a frame story—although he must have felt it useful to end with a rhyming moralité. Perrault would be revered today as the father of folklore if he had taken the time to record where he obtained his tales, when, and under what circumstances.[34]

Bruno Bettelheim remarks that «the more simple and straightforward a good character in a fairy tale, the easier it is for a child to identify with it and to reject the bad other.» The child identifies with a good hero because the hero’s condition makes a positive appeal to him. If the character is a very good person, then the child is likely to want to be good too. Amoral tales, however, show no polarization or juxtaposition of good and bad persons because amoral tales such as «Puss in Boots» build character, not by offering choices between good and bad, but by giving the child hope that even the meekest can survive. Morality is of little concern in these tales, but rather, an assurance is provided that one can survive and succeed in life.[35]

Small children can do little on their own and may give up in disappointment and despair with their attempts. Fairy stories, however, give great dignity to the smallest achievements (such as befriending an animal or being befriended by an animal, as in «Puss in Boots») and that such ordinary events may lead to great things. Fairy stories encourage children to believe and trust that their small, real achievements are important although perhaps not recognized at the moment.[36]

In Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion Jack Zipes notes that Perrault «sought to portray ideal types to reinforce the standards of the civilizing process set by upper-class French society».[8] A composite portrait of Perrault’s heroines, for example, reveals the author’s idealized female of upper-class society is graceful, beautiful, polite, industrious, well groomed, reserved, patient, and even somewhat stupid because for Perrault, intelligence in womankind would be threatening. Therefore, Perrault’s composite heroine passively waits for «the right man» to come along, recognize her virtues, and make her his wife. He acts, she waits. If his seventeenth century heroines demonstrate any characteristics, it is submissiveness.[37]

A composite of Perrault’s male heroes, however, indicates the opposite of his heroines: his male characters are not particularly handsome, but they are active, brave, ambitious, and deft, and they use their wit, intelligence, and great civility to work their way up the social ladder and to achieve their goals. In this case of course, it is the cat who displays the characteristics and the man benefits from his trickery and skills. Unlike the tales dealing with submissive heroines waiting for marriage, the male-centered tales suggest social status and achievement are more important than marriage for men. The virtues of Perrault’s heroes reflect upon the bourgeoisie of the court of Louis XIV and upon the nature of Perrault, who was a successful civil servant in France during the seventeenth century.[8]

According to fairy and folk tale researcher and commentator Jack Zipes, Puss is «the epitome of the educated bourgeois secretary who serves his master with complete devotion and diligence.»[37] The cat has enough wit and manners to impress the king, the intelligence to defeat the ogre, and the skill to arrange a royal marriage for his low-born master. Puss’s career is capped by his elevation to grand seigneur[8] and the tale is followed by a double moral: «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie et savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess.»[8]

The renowned illustrator of Dickens’ novels and stories, George Cruikshank, was shocked that parents would allow their children to read «Puss in Boots» and declared: «As it stood the tale was a succession of successful falsehoods—a clever lesson in lying!—a system of imposture rewarded with the greatest worldly advantages.»

Another critic, Maria Tatar, notes that there is little to admire in Puss—he threatens, flatters, deceives, and steals in order to promote his master. She further observes that Puss has been viewed as a «linguistic virtuoso», a creature who has mastered the arts of persuasion and rhetoric to acquire power and wealth.[5]

«Puss in Boots» has successfully supplanted its antecedents by Straparola and Basile and the tale has altered the shapes of many older oral trickster cat tales where they still are found. The morals Perrault attached to the tales are either at odds with the narrative, or beside the point. The first moral tells the reader that hard work and ingenuity are preferable to inherited wealth, but the moral is belied by the poor miller’s son who neither works nor uses his wit to gain worldly advantage, but marries into it through trickery performed by the cat. The second moral stresses womankind’s vulnerability to external appearances: fine clothes and a pleasant visage are enough to win their hearts. In an aside, Tatar suggests that if the tale has any redeeming meaning, «it has something to do with inspiring respect for those domestic creatures that hunt mice and look out for their masters.»[38]

Briggs does assert that cats were a form of fairy in their own right having something akin to a fairy court and their own set of magical powers. Still, it is rare in Europe’s fairy tales for a cat to be so closely involved with human affairs. According to Jacob Grimm, Puss shares many of the features that a household fairy or deity would have including a desire for boots which could represent seven-league boots. This may mean that the story of «Puss and Boots» originally represented the tale of a family deity aiding an impoverished family member.[39][self-published source]

Stefan Zweig, in his 1939 novel, Ungeduld des Herzens, references Puss in Boots’ procession through a rich and varied countryside with his master and drives home his metaphor with a mention of Seven League Boots.

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ The distinction of being the first to translate the tales into English was long questioned. An edition styled Histories or Tales of Past Times, told by Mother Goose, with Morals. Written in French by M. Perrault, and Englished by G.M. Gent bore the publication date of 1719, thus casting doubt upon Samber being the first translator. In 1951, however, the date was proven to be a misprint for 1799 and Samber’s distinction as the first translator was assured.

- Footnotes

- ^ W. G. Waters, The Mysterious Giovan Francesco Straparola, in Jack Zipes, a c. di, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974 Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Opie & Opie 1974, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Opie & Opie 1974, p. 23.

- ^ a b Tatar 2002, p. 234

- ^ a b Brown 2007, p. 351

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 113–116

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 1991, p. 26

- ^ Darnton, Robert (1984). The Great Cat Massacre. New York, NY: Basic Books, Ink. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-465-01274-9.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Zipes 2001, p. 877

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 24.

- ^ Gillespie & Hopkins 2005, p. 351

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 58-59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 239-240.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2006). «The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a ‘Fictional Animal’«. Asian Folklore Studies. 65 (2): 133–160. JSTOR 30030396.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Eugenio, Damiana L. (1985). «Philippine Folktales: An Introduction». Asian Folklore Studies. 44 (2): 155–177. doi:10.2307/1178506. JSTOR 1178506.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (December 2010). «Two Storytellers from the Greek-Orthodox Communities of Ottoman Asia Minor. Analyzing Some Micro-data in Comparative Folklore». Fabula. 51 (3–4): 251–265. doi:10.1515/fabl.2010.024. S2CID 161511346.

- ^ Paulin 2002, p. 65

- ^ Wunderer 2008, p. 202

- ^ «https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/enough+to+make+a+cat+laugh»>enough to make a cat laugh

- ^ «Nutt, Alfred Trübner». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Puss in Boots». The Disney Encyclopedia of Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Zipes 1997, p. 102

- ^ Barchilon 1960, pp. 14, 16

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 10

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 73

- ^ a b Zipes 1991, p. 25

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 235

- ^ Nukiuk H. 2011 Grimm’s Fairies: Discover the Fairies of Europe’s Fairy Tales, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Works cited

- Barchilon, Jacques (1960), The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes, Denver, CO: Alan Swallow

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977) [1975, 1976], The Uses of Enchantment, New York: Random House: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-394-72265-5

- Brown, David (2007), Tchaikovsky, New York: Pegasus Books LLC, ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9

- Gillespie, Stuart; Hopkins, David, eds. (2005), The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English: 1660–1790, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924622-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Paulin, Roger (2002) [1985], Ludwig Tieck, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815852-1

- Tatar, Maria (2002), The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Wunderer, Rolf (2008), «Der gestiefelte Kater» als Unternehmer, Weisbaden: Gabler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8349-0772-1

- Zipes, Jack David (1991) [1988], Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90513-3

- Zipes, Jack David (2001), The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Zipes, Jack David (1997), Happily Ever After, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-91851-0

Further reading[edit]

- Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- Neuhaus, Mareike (2011). «The Rhetoric of Harry Robinson’s ‘Cat With the Boots On’«. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 44 (2): 35–51. JSTOR 44029507. Project MUSE 440541 ProQuest 871355970.

- Nikolajeva, Maria (2009). «Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats». Marvels & Tales. 23 (2): 248–267. JSTOR 41388926.

- Blair, Graham (2019). «Jack Ships to the Cat». Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat: Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition. University Press of Colorado. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-1-60732-919-0. JSTOR j.ctvqc6hwd.11.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Origin of the Story of ‘Puss in Boots’

- «Puss in Boots» – English translation from The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- «Puss in Boots» – Beautifully illustrated in The Colorful Story Book (1941)

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox

|

[Эта сказка] содержит атавистические воспоминания о духе тотемного животного как отце-защитнике племени, которых повсюду находят миссионеры и антропологи. |

| Жак Баршилон и Анри Петтит, «Настоящая Матушка Гусыня: Сказки и прибаутки» |

Скотт Густафсон, «Кот в сапогах»

«Господин Кот, или Кот в сапогах» (Le Maître chat ou le chat botté) — знаменитая французская сказка, записанная Шарлем Перро в 1695 году. Через два года сказка была опубликована в книге «Сказки Матушки Гусыни», имела невероятный успех и остаётся популярной до сих пор.

«Кот в сапогах» (как и другие сказки Перро) внесла заметный вклад в мировую культуру. Эта книга на протяжении веков становилась источником вдохновения для композиторов, танцоров, художников и литераторов. Например, кот в сапогах появляется в третьем акте балета Чайковского «Спящая красавица».

По большому счёту, «Кот в сапогах», как и многие знаменитые классические сказки, основан на определённым архетипе: в данном случае, это образ мудрого помощника героя, благодаря своей смекалке и расторопности выходящего на первый план повествования, становясь протагонистом. Очень, к слову популярный приём нарратива: эдакий серый кардинал зачастую прописан автором гораздо более живо, нежели номинальный главный герой текста.

Сюжет[править]

Сказка начинается с того, что третий сын мельника после смерти отца в наследство получает только пару сапог и кота. Кот просит у хозяина сапоги, и расстроенный хозяин покорно с ними расстается. Но всё не так просто, как кажется: у смекалистого животного наготове хитрый план — и кот отправляется в лес, где ловит кролика и преподносит его королю в качестве подарка от вымышленного маркиза Карабаса. Вымышленный маркиз действует затем в том же роде в течение нескольких месяцев.

Узнав, что король готовится объезжать свои владения, кот заставляет нищего хозяина отправиться купаться в реку. Когда король проезжает по мосту, кот убеждает его, что сын мельника и есть легендарный маркиз Карабас, одежду которого украли разбойники. Фальшивый маркиз извлекается из реки, получает одежду из королевских сундуков и с почестями усаживается в королевскую карету. Пока он забалтывает короля и принцессу (которая, разумеется, влюбляется в него с первого взгляда), кот бежит впереди кареты и договаривается с крестьянами, убирающими урожай, что они сообщат королю о хозяине этих плодородных нив и весей — маркизе, естественно, Карабасе.

Пока король расспрашивает крестьян, кот прибывает в замок огра-волшебника, который умеет превращаться в любое существо по своему желанию (многофункциональный анимаг). Хитростью кот заставляет огра превратиться в мышь и съедает его. Таким образом, замок оказывается в полном его распоряжении. Когда король со свитой и маркизом Карабасом прибывают в замок, кот объявляет его собственностью маркиза. Пораженный богатством маркиза король предлагает ему немедленно жениться на королевской дочери. Влюбленные счастливы, король счастлив, а коту теперь даже не нужно ловить мышей — разве что только для развлечения.

Анализ[править]

Кот-трикстер определенно не является изобретением Шарля Перро: по крайней мере до «Кота в сапогах» было опубликовано несколько подобных сказок; однако среди исследователей преобладает уверенность, что Перро не был знаком ни с одной из них.

Ценность работы Перро состоит еще и в том, что он не стал добавлять в свои сказки мораль, а записал их так, как услышал.

Можно точно утверждать, что сказки Перро действительно были сначала ему рассказаны, а потом записаны — например, он использовал некоторые слова, считавшиеся тогда простонародными. Кроме того, остались рудиментарные признаки устного рассказа, которые не участвуют в сюжете и не являются ценными для повествования. Это значит, что в процессе обработки рассказа писатель убирал лишние детали, но за какими-то все-таки не уследил. Если обратить внимание на сапоги кота, то нигде не объясняется, зачем они ему понадобились, и они нигде не упоминаются после того, как кот получил их в подарок от хозяина.

Известные фольклористы Иона и Питер Опи считают, что сказка о коте в сапогах необычна тем, что герой не слишком-то заслуживает богатства, которое получил в конце: он беден, он третий ребенок в семье, он беспрекословно подчиняется коту и помогает ему обманывать. Все это не является добродетелями, за которые герои должны вознаграждаются. С этой точки зрения, кот должен быть провозглашен королем мошенников — немногим удавалось безнаказанно заполучить такое богатство.

Исследователь Бруно Беттельхейм отмечает, что аморальные сказки вроде «Кота в сапогах» нравятся маленьким детям, потому что они дают надежду, что даже самое кроткое существо может выжить и преуспеть в жизни. Дети часто чувствуют себя беспомощными по сравнению со взрослыми, а в сказках даже небольшим достижениям воздаются большие почести. Такая простая вещь, как дружба с животным, может привести к неожиданным результатам. Сказки позволяют детям увидеть, что их маленькие, но настоящие достижения действительно важны, хотя в данную минуту может казаться наоборот.

Джек Зайпс пишет, что кот в сапогах является «миниатюрным воплощением образованного секретаря-буржуа, который служит своему хозяину с полной самоотдачей и усердием». У кота достаточно ума и манер, чтобы впечатлить короля, хитрости, чтобы победить огра, и ловкости, чтобы устроить свадьбу своего бедного господина с принцессой. Но карьера кота ограничена карьерой вельможи, которому он служит — таковы реалии французского высшего общества XVII века, в котором вращался Шарль Перро.

Что здесь есть[править]

- Говорящее животное и Умён, как человек — собственно Кот.

- Стереотипы о кошках — кодификатор всех стереотипов о рыжих котах. Рыжий — значит, сообразительный и бесстрашный. Одним словом — герой.

- Ради фишки или ради красного словца — сапоги Кота. Зачем ему сапоги, если они нигде не фигурируют? Обоснуй: без сапог (и псевдомушкетёрского наряда) Кота будут воспринимать не как слугу уважаемого дворянина, а как обычного кота, т. е. это неправдоподобно убедительная маскировка.

- В фильме 1988 г. кот может превращаться в человека, а сапоги ему нужны как раз для солидности.

- А в мультфильме 1995-го сапоги волшебные.

- Человеко-звериный сеттинг.

- Младший сын — хозяин кота. Старшему досталась мельница, среднему — осел.

- Огр, переименованный In Translation просто в людоеда. Как людоед он и запомнился русскоязычной аудитории. Т. к. людоеды за редким исключением всегда плохие, у целевой аудитории и их родителей не должно возникать вопросов «что за фигня, кот?»

- Чудовище на троне — он же.

- Однокрылый ангел и Однокрылый ангел не взлетел — превращения огра-людоеда в льва и в мышь соответственно.

- Прекрасная принцесса — дочь короля.

- Дочь в жёны и полцарства в придачу — в финале сказки.

Адаптации[править]

Если не указано другое, название адаптаций — «Кот в сапогах»

Кино[править]

- «Про кота…» — телефильм. Режиссер Святослав Чекин. Актеры: Леонид Ярмольник (Кот), Альберт Филозов (король), Марина Левтова (принцесса), Петр Щербаков (канцлер), Валентин Гафт (Людоед), Сергей Проханов (лжемаркиз, младший сын мельника), Вадим Ермолаев (повар), Игорь Суровцев (старший сын мельника), Вячеслав Логинов (средний сын мельника), Александр Иншаков (старший косарь), Елена Ольшанская (старшая жница). Производство ТО «Экран», 1985 г. Импровизация на тему сказки Перро с использованием пьесы Д. Самойлова.

- Фильм Юджина Марнера (США, 1988). Принцесса здесь девчушка-попрыгушка, и из-за непосредственности у нее не получается усвоить дворцовый этикет.

- «Кот в сапогах» (1979), телефильм-телеспектакль основан на театральной постановке театра им. Е. Вахтангова.

- Музыкальный триппер — «Surfin’ Bird» здесь прозвучала задолго до этих ваших «Гриффинов».

Мультфильмы[править]

Характерна Крутая шляпа во многих экранизациях, особенно в советской, анимешной и из Шрека.

- «Кот в сапогах» (1938, «Союзмультфильм», сёстры Брумберг) — снят в т. н. диснеевской манере

- Ещё «Кот в сапогах» — тоже сестёр Брумберг, тоже «Союзмультфильм», но 1968 г. Римейк мультфильма 1938 (некоторые сцены пересняты один в один, но в новой стилистике), тоже с опорой на пародийную драматургию Самойлова. А финал (битва с Людоедом и то, что было после неё) — эталон фэнтези. Подробнее в статье про режиссёров.

- Тупая блондинка, Младший сын, Бездельник — собственно, сын Мельника.

- Рыжее солнышко, Девчушка-попрыгушка — Принцесса.

- Отвратительный толстяк и монобровь — Людоед.

- Музыкальный триппер — песня Кота «Мяу-мяу-мяу, тебя я пониМЯУ».

- Ещё «Кот в сапогах» — тоже сестёр Брумберг, тоже «Союзмультфильм», но 1968 г. Римейк мультфильма 1938 (некоторые сцены пересняты один в один, но в новой стилистике), тоже с опорой на пародийную драматургию Самойлова. А финал (битва с Людоедом и то, что было после неё) — эталон фэнтези. Подробнее в статье про режиссёров.

- Пластилиново-кукольный мультфильм Гарри Бардина. ООО «Стайер», 1995. Несколько новаторское прочтение; хлёсткая политическая сатира (Бардин любит такие вещи). Кот при первом знакомстве с Карабасовым представляется — «My name is Cat».

- Живой вертолёт — кот, используя хвост в качестве пропеллера, пытался вывезти своего хозяина-забулдыгу на ПМЖ в Америку, но долететь получилось только до средневековой Франции.

- Австралия, режиссер Рик Хеберт, 1993. В ролях: Рик Херберт, Рэйчел Кинг, Ли Перри и др.

- Мультфильм Александра Давыдова, Аргус Интернейшнл, 1997. Вариации на тему сказки (не слишком далеко ушли от оригинала).

- Мультсериал Festival of Family Classics (по классическим сказкам), серия Puss in Boots.

- «Правдивая история кота в сапогах» — весьма вольная экранизация 2000-х.

- Немеций (ГДР) куольный 1966 г. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3we4cxmzbeA

Аниме и театр[править]

- Аниме 1969 г. по мотивам Перро и «Трех мушкетёров». Вместо людоеда — Дьявол.

- Есть еще и два сиквела — «Возвращение Кота в сапогах» (1972) и «Кругосветное путешествие Кота в сапогах» (1976).

- В последнем главным противником Кота и компании является Грумон, самый богатый житель города, который изображён в виде здоровенного кабана. Его хамство, злоба и агрессивность, наряду с немалой физической силой, показываются на протяжении всего фильма. Достаточно сказать, что по условию пари Перро (главный герой-кот) в случае проигрыша на всю жизнь стал бы его рабом. Гоняясь за ГГ, проломал не одну дверь (дикий кабан, чтоб его!). А в финале вообще педаль в пол: Перро близок к своей цели — а Грумон преследует его, как какой-то монстр из фильма ужасов, и кричит «Хвост оторву!».

- Там же «свинская» тема отыграна шутки ради: Грумон, связываясь по видеотелефону со своим подельником-волком Гари-Гари (нанятым, чтобы помешать Перро успеть в срок), в гневе вопрошает: «За что я тебе плачу деньги, свинья?!» Волк, услышав такое обращение, приходит в бешенство, и Грумон, сообразив, что ляпнул что-то не то, вынужден умерить пыл.

- А ещё в нём есть злобный слон — механический мамонт профессора Гари-Гари, едва не убивший главных героев.

- Собственно пьеса Д. Самойлова.

- Мелкий жемчуг — субверсия. Поначалу кажется, что троп:

Ах, у нас королей дело плохо.

Где достать сто рублей, вот эпоха?

Где бы денег набрать, чтоб кормить эту рать?

Министров, камергеров, солдат и лекарей,

Героев да курьеров, писцов, секретарей,

Плохо, плохо дело у нас, королей.- Только не «героев да курьеров», а «герольдов, курьеров».

А потом:

Король: Эй, повар, готов ли обед?

Повар: Ваше величество, продуктов нет. В королевских подвалах остался один бульонный кубик и одна картофельная котлета.- Телеверсия от ТО «Экран» кукольного спектакля Центрального театра кукол (1979).

- Телеспектакль по пьесе Г. Калау в постановке Государственного академического театра имени Вахтангова (тоже 1979).

- Телеспектакль, Петербургское телевидение, 1996 г., реж. В. Обгорелов.

- Немецкая постановка (запись 1990 г.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RPaqvm6eb2g&list=PL9CCHSQbqyjC-UTDIvtmOC23mF4yeIk7o&index=22&t=0s

Прочие одноимённые адаптации[править]

- Книжка-раскладушка (официально именовалась книжка-игрушка) Художник-конструктор Т. Шеварёва, автор перевода М. Булатов. Изд-во «Малыш» три переиздания: 1980, 1984 и 1986 гг. См. пример (http://samoe-vazhnoe.blogspot.ru/2015/12/kot-v-sapogah.html).

- Диафильмы:

- художник К. Сапегин, 1978 г. (http://diafilm-nsk.ru/skachat_diafilmy/kot_v_sapogah).

- художник Е. Н. Евган (Рапопорт) 1949 г. (http://diafilmy.su/472-kot-v-sapogah.html).

- художники А. А. Кокорин и А. В. Кокорин (http://diafilmy.su/3400-kot-v-sapogah.html).

- художник Ю.Скирда 1987 г. (http://diafilmy.su/4498-kot-v-sapogah.html)

- Аудиоспектакли:

- Пластинка из серии «Сказка за сказкой» по пьесе Д. Самойлова. В роли кота Н.Литвинов.

- Версия В. Монюкова. В роли кота В. Шиловский. 1968 г.

- Настольные игры:

- Кинь-двинь 2000-х гг. (http://www.intelkot.ru/kot-v-sapogah-nastolnaya-igra-dlya-detey-disk-s-pesenkami-v-komplekte).

- Аналогично (http://www.10kor.ru/catalog/nastolno_pechatnye_igry/nastolnaya_igra_khodilka_s_zhestkim_polem_zolushka_kot_v_sapogakh_dve_igry_v_korobke). Два поля в комплекте — помимо «Кота» есть игра «Золушка».

- Еще одна современная «кинь-двинь» (http://www.umniza.de/Nastolnaya-igra-Kot-v-sapogaha).

- Современная «кинь двинь», но уже с карточками-сюрпризами, по мультфильму сестер Брумберг (http://www.labirint.ru/screenshot/goods/488725/1).

- Еще одна современная, но с кубиком и фишками под советские (http://www.kupitoys.ru/products/nastolnaja-igra-kot-v-sapogakh-dobrye-igrushki).

- Советская «кинь-двинь» 1970-х гг. (http://novaya-beresta.ru/load/nastolnye_igry/nastolnaja_igra_kot_v_sapogakh/13-1-0-851).

- Игра О. Емельяновой. Художники А. Шахгельдян, В. Голубев, О. Вакурова. ООО «Русский Стиль», 1999 г. (http://olesya-emelyanova.ru/nastoljnye_igry-kot_v_sapogah.html).

- «Собери сказку» из карточек (http://www.vesnushka89.ru/tovar/kot-v-sapogah) и (http://товаромания.рф/product_info.php?products_id=843483)

Кот в сапогах, гуляющий сам по себе[править]

Литература[править]

- Е. Шварц, сказка «Новые приключения кота в сапогах». Не путать с фильмом А. А. Роу.

- В пьесах по европейским сказкам могут вспомнить про Кота: на днях заходил и т. п.

- К. Булычев, «Заповедник сказок» — Кот присутствует и играет не последнюю роль.

- «Королева пиратов на планете сказок» — кот мелькает эпизодически. Если разобраться, то это разные Коты в сапогах (тем более, что эта повесть — неканон от К. Булычева).

- В сказке А. Зарецкого и А. Труханова «А я был в компьютерном городе» анимированное изображение Кота в сапогах является приветствием операционной системы компьютера (при этом оно еще и озвучено — кот приветственно мяукает).

- Нил Гейман, «Никогде» — в Нижнем Лондон исторические лохмотья вполне в ходу, но де Карабас одевается так не из любви к моде, он просто косплеит Кота в сапогах.

Кино[править]

- «Новые похождения Кота в сапогах» (1958), постановка Александра Роу по сценарию С. Михалкова. Основной сюжет о Коте (с продвижением сына мельника в зятья к королю и поеданием главгада в виде мыши) встроен в сюжет пьесы Михалкова о Шахматно-Карточном королевстве по мотивам «Любви к трём апельсинам» К. Гоцци (она же позже была экранизирована в телефильме «Весёлое сновидение, или Смех и слёзы» (1976), где Кота уже не было). И всё это был сон девочки, которая должна была участвовать в школьной постановке (кроссовера «Кота в сапогах» со «Смехом и слезами» Михалкова?)…

- Шут шахматного королевства в исполнении Георгия Милляра, погрустневший и поникший от болезни принцессы и методов лечения — чтения страшных «Рассказок», которые ему и приходится читать.

- Милляр сыграл там также Колдунью в старом обличье. Подсвечивается, когда на празднике Колдунья появляется (в молодом облике, сыгранном Лидией Вертинской) вместо исчезнувшего Шута.

- Тот же шут в «Весёлом сновидении» был сыгран Валентином Никулиным (с неплохими и местами более глубокими, чем сам фильм, песнями-зонгами).

- Шут шахматного королевства в исполнении Георгия Милляра, погрустневший и поникший от болезни принцессы и методов лечения — чтения страшных «Рассказок», которые ему и приходится читать.

Мультфильмы[править]

- Фильмы про Шрека, где он «знаменитый охотник на огров», пародия на образ Зорро. Стал настолько популярным персонажем, что про него вышел отдельный фильм «Кот в сапогах» (Puss in Boots), но тоже почти не имеющий отношения к исходной сказке (сюжет даже больше связан со сказкой о Джеке и бобовом стебле), и мультсериал «Приключения Кота в сапогах» (The Adventures of Puss in Boots).

- От неприязни до любви — знакомство Кота и Киски началось с того, что они не поделили бобы, а потом во время танцевальной битвы устроили дуэль на шпагах, в финале которой Кот ударил Мягколапку гитарой по голове. Впрочем, Кот не знал, что сражается с девушкой.

- «Приключения Кота в сапогах»: Белый — цвет женственности — Дульсинея.

- А в короткометражном продолжении «Кот в сапогах: Три дьяволёнка» (Puss in Boots: The Three Diablos) Коту приходится противостоять трём довольно вредным и опасным котятам. Однако те под влиянием Кота ближе к финалу перевоспитались и стали защитниками принцессы.

- Отечественный «Мальчик из Неаполя» по мотивам сказки Джанни Родари — комендант волшебного леса. Сапог не носит — жмут.

- Отечественный «Золушка» 1979 — Золушка, попав на бал, поправила перекошенный портрет Кота в сапогах, он снял шляпу и поклонился.

- «Кошкин дом» (1958) — портрет Кошкиного прадеда очень похож на Кота в сапогах.

- В некотором роде мультфильм «Слонёнок заболел» (1985 г.) Кот пытается вести себя как Кот в сапогах (даже представляет себя в его костюме), обманывая слонёнка и верблюжонка. Но те выводят кота на чистую воду.

- Автором сценария был тот же Д. Самойлов.

- В «Красной шапочке» сестёр Брумберг (Союзмультфильм, 1937 г.) есть отсылка к Коту в сапогах. Кот, сражаясь с волком, обувает сапоги, надевает берет и использует стрелку от часов вместо шпаги.

- Забыл название — девочка болеет, а её игрушки пытаются её развеселить. Среди игрушек — Кот в сапогах.

- Появлялся как кучер кареты Зайца в серии «Ну, погоди!» про сказочные «глюки» Волка. После двенадцатого удара часов стал обычным котом.

- «Зай и Чик» (1952 г.) Среди прохожих был Кот в сапогах (хотя это не тот, а сделанный на игрушечной фабрике, наверное там не один такой). Сделал Чику замечание, хотя по его манере говорить казалось, что кот вызовет зайца на дуэль здесь и сейчас.

Аниме[править]

- Продолжение аниме 1969 г., а именно «Возвращение кота в сапогах» (вестерн) и «Кругосветное путешествие кота в сапогах» (по мотивам «Вокруг света за 80 дней»).

- Бонусные баллы: стал маскотом студии Тоэй.

В изобразительном искусстве[править]

- В журнале «Весёлые картинки» — частый персонаж иллюстраций. Обычно встречался на большой кроссоверной картинке, подписанной в духе «назовите героев представленных сказок». Хотя бывали и другие его появления — например, на последней странице январского номера за 1988 год в мини-самоделке с украшением ёлки.

- В принципе, делая роспись для детского учреждения, создавая коробочки для новогодних подарков или ещё что-то подобное, художник может нарисовать и сабж. Правда, в современных творениях сейчас больше похожих на кота из «Шрека».

- Если на детской площадке есть фигуры сказочных героев, то там можно встретить и Кота в сапогах.

- На советских открытках встречался (см. http://panizosya.com/Koski_otkritki_sovetskie.html последние две или http://www.davno.ru/cards/m8/vosmoe-marta-613.html). На современных тоже встречается.

В прочих товарах народного потребления[править]

- Производители игрушек также обратили внимание на персонажа. Современный пример http://www.kosh-ka.ru/toysql.php?cat=mult&num=6013, советские варианты ([1]), ([2], [3]).

- Целый набор см. https://zen.yandex.ru/media/neskuchnye_melochi/sovetskoe-detstvo-miniigrushki-5e37397f53de5721ccf788e2 после поросят

- Конфеты «Кот в сапогах» ([4]), ([[5]]) и даже дореволюционные.