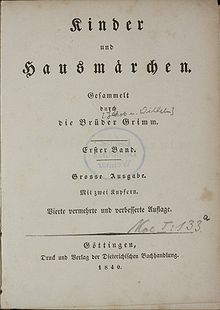

Title page of first volume of Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1819) 2nd Ed. |

|

| Author | Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm |

|---|---|

| Original title | Kinder- und Hausmärchen (lit. Children’s and Household Tales) |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Genre |

|

| Published | 1812–1858 |

| Text | Grimms’ Fairy Tales at Wikisource |

Grimms’ Fairy Tales, originally known as the Children’s and Household Tales (German: Kinder- und Hausmärchen, pronounced [ˌkɪndɐ ʔʊnt ˈhaʊsmɛːɐ̯çən]), is a German collection of fairy tales by the Grimm brothers or «Brothers Grimm», Jacob and Wilhelm, first published on 20 December 1812. Vol. 1 of the first editionedition contained 86 stories, which were followed by 70 more tales, numbered consecutively, in the 1st edition, Vol. 2, in 1815. By the seventh edition in 1857, the corpus of tales had expanded to 200 tales and 10 «Children’s Legends». It is listed by UNESCO in its Memory of the World Registry.

Origin[edit]

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were two of 10 children from Dorothea (née Zimmer) and Philipp Wilhelm Grimm. Philipp was a highly regarded district magistrate in Steinau an der Straße, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Hanau. Jacob and Wilhelm were sent to school for a classical education once they were of age, while their father was working. They were very hard-working pupils throughout their education. They followed in their father’s footsteps and started to pursue a degree in law, and German history. However, in 1796, their father died at the age of 44 from pneumonia. This was a tragic time for the Grimms because the family lost all financial support and relied on their aunt, Henriette Zimmer, and grandfather, Johann Hermann Zimmer. At the age of 11, Jacob was compelled to be head of the household and provide for his family. After downsizing their home because of financial reasons, Henriette sent Jacob and Wilhelm to study at the prestigious high school, Lyzeum, in Kassel. In school, their grandfather wrote to them saying that because of their current situation, they needed to apply themselves industriously to secure their future welfare.[1]

Shortly after attending Lyzeum, their grandfather died and they were again left to themselves to support their family in the future. The two became intent on becoming the best students at Lyzeum, since they wanted to live up to their deceased father. They studied more than twelve hours a day and established similar work habits. They also shared the same bed and room at school. After four years of rigorous schooling, Jacob graduated head of his class in 1802. Wilhelm contracted asthma and scarlet fever, which delayed his graduation by one year although he was also head of his class. Both were given special dispensations for studying law at the University of Marburg. They particularly needed this dispensation because their social standing at the time was not high enough to have normal admittance. University of Marburg was a small, 200-person university where most students were more interested in activities other than schooling. Most of the students received stipends even though they were the richest in the state. The Grimms did not receive any stipends because of their social standing; however, they were not upset by it since it kept the distractions away.[1]

Professor Friedrich Carl von Savigny[edit]

Jacob attended the university first and showed proof of his hard work ethic and quick intelligence. Wilhelm joined Jacob at the university, and Jacob drew the attention of Professor Friedrich Carl von Savigny, founder of its historical school of law. He became a prominent personal and professional influence on the brothers. Throughout their time at university, the brothers became quite close with Savigny and were able to use his personal library as they became interested in German law, history, and folklore. Savigny asked Jacob to join him in Paris as an assistant, and Jacob went with him for a year. While he was gone, Wilhelm became very interested in German literature and started collecting books. Once Jacob returned to Kassel in 1806, he adopted his brother’s passion and changed his focus from law to German literature. While Jacob studied literature and took care of their siblings, Wilhelm continued on to receive his degree in law at Marburg.[1] During the Napoleonic Wars, Jacob interrupted his studies to serve the Hessian War Commission.[2]

In 1808, their mother died, and this was especially hard on Jacob as he took the position of father figure, while also trying to be a brother. From 1806 to 1810, the Grimm family had barely enough money to properly feed and clothe themselves. During this time, Jacob and Wilhelm were concerned about the stability of the family.

Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano were good friends of the brothers and wanted to publish folk tales, so they asked the brothers to collect oral tales for publication. The Grimms collected many old books and asked friends and acquaintances in Kassel to tell tales and to gather stories from others. Jacob and Wilhelm sought to collect these stories in order to write a history of old German Poesie and to preserve history.[1]

Composition[edit]

The first volume of the first edition was published in 1812, containing 86 stories; the second volume of 70 stories followed in 1815. For the second edition, two volumes containing the KHM texts were issued in 1819 and the appendix was removed and published separately in the third volume in 1822, totaling 170 tales. The third edition appeared in 1837, the fourth edition in 1840, the fifth edition in 1843, the sixth edition in 1850, and the seventh edition in 1857. Stories were added, and also removed, from one edition to the next, until the seventh held 210 tales. Some later editions were extensively illustrated, first by Philipp Grot Johann and, after his death in 1892, by German illustrator Robert Leinweber.[citation needed]

The first volumes were much criticized because, although they were called «Children’s Tales», they were not regarded as suitable for children, both for the scholarly information included and the subject matter.[3] Many changes through the editions – such as turning the wicked mother of the first edition in Snow White and Hansel and Gretel (shown in original Grimm stories as Hänsel and Grethel) to a stepmother, were probably made with an eye to such suitability. Jack Zipes believes that the Grimms made the change in later editions because they «held motherhood sacred».[4]

They removed sexual references—such as Rapunzel’s innocently asking why her dress was getting tight around her belly, and thus naively revealing to the witch Dame Gothel her pregnancy and the prince’s visits—but, in many respects, violence, particularly when punishing villains, become more prevalent.[5]

Popularity[edit]

The brothers’ initial intention of their first book, Children’s and Household Tales, was to establish a name for themselves in the world. After publishing the first KHM in 1812, they published a second, augmented and re-edited, volume in 1815. In 1816 Volume I of the German Legends (German: Deutsche Sagen) was published, followed in 1818, Volume II. However, the book that established their international success was not any of their tales, but Jacob’s German Grammar in 1819. In 1825, the Brothers published their Kleine Ausgabe or «small edition», a selection of 50 tales designed for child readers. This children’s version went through ten editions between 1825 and 1858.

In 1830, Jacob became a professor at University of Göttingen and in 1835, Wilhelm also became a professor. During these years Jacob wrote a third volume of German Grammar and Wilhelm prepared the third revision of the Children’s and Household Tales.[1]

In 1837, King Ernst August II revoked the constitution of 1833 and was attempting to restore absolutism in the Kingdom of Hanover. Since Göttingen was a part of Hanover, the brothers were expected to take an oath of allegiance. However, the brothers and five other professors led a protest against this and were heavily supported by the student body since all of these professors were well renowned. Jacob left Göttingen immediately and Wilhelm followed him to Kassel a few months later.[6]

In Kassel, the Grimms devoted themselves to researching and studying. A close friend of theirs, Bettina von Arnim, was also a talented writer. Savigny and others convinced the King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, to allow the brothers to teach and conduct research at the University of Berlin. In March 1841, the brothers did just this and also continued to work on the German Dictionary.[6]

Influence[edit]

Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children and Household Tales) is listed by UNESCO in its Memory of the World Registry.[2]

The Grimms believed that the most natural and pure forms of culture were linguistic and based in history.[2] The work of the Brothers Grimm influenced other collectors, both inspiring them to collect tales and leading them to similarly believe, in a spirit of romantic nationalism, that the fairy tales of a country were particularly representative of it, to the neglect of cross-cultural influence.[7] Among those influenced were the Russian Alexander Afanasyev, the Norwegians Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, the English Joseph Jacobs, and Jeremiah Curtin, an American who collected Irish tales.[8] There was not always a pleased reaction to their collection. Joseph Jacobs was in part inspired by his complaint that English children did not read English fairy tales;[9] in his own words, «What Perrault began, the Grimms completed».

W. H. Auden praised the collection during World War II as one of the founding works of Western culture.[10] The tales themselves have been put to many uses. Adolf Hitler praised them so strongly that the Allies of World War II warned against them, as Hitler thought they were folkish tales showing children with sound racial instincts seeking racially pure marriage partners;[11] for instance, Cinderella with the heroine as racially pure, the stepmother as an alien, and the prince with an unspoiled instinct being able to distinguish.[12] Writers who have written about the Holocaust have combined the tales with their memoirs, as Jane Yolen in her Briar Rose.[13]

Three individual works of Wilhelm Grimm include Altdänische Heldenlieder, Balladen und Märchen (‘Old Danish Heroic Songs, Ballads, and Folktales’) in 1811, Über deutsche Runen (‘On German Runes’) in 1821, and Die deutsche Heldensage (‘The German Heroic Saga’) in 1829.

The Grimm anthology has been a source of inspiration for artists and composers. Arthur Rackham, Walter Crane, and Rie Cramer are among the artists who have created illustrations based on the stories.

English-language collections[edit]

«Grimms’ Fairy Tales in English» by D.L. Ashliman provides a hyperlinked list of 50 to 100 English-language collections that have been digitized and made available online. They were published in print from the 1820s to 1920s. Listings may identify all translators and illustrators who were credited on the title pages, and certainly identify some others.[14]

Translations of the 1812 edition[edit]

These are some translations of the original collection, also known as the first edition of Volume I.

- Zipes, Jack, ed., tr. (2014) The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: the complete first edition.[15]

- Loo, Oliver ed., tr. (2014) The Original 1812 Grimm Fairy Tales. A New Translation of the 1812 First Edition Kinder- und Hausmärchen Collected through the Brothers Grimm[16][self-published source?]

Translations of the 1857 edition[edit]

These are some translations of the two-volume seventh edition (1857):

- Hunt, Margaret, ed., tr. (2014) Grimm’s Household Tales, with Author’s Notes, 2 vols (1884).[17][a]

- Manheim, Ralph, tr. (1977) Grimms’ Tales for Young and Old: The Complete Stories. New York: Doubleday.[b]

- Luke, David; McKay, Gilbert; Schofield, Philip tr. (1982) Brothers Grimm: Selected Tales.[20][c]

List of stories by the Brothers Grimm[edit]

The code «KHM» stands for Kinder- und Hausmärchen. The titles are those as of 1857. Some titles in 1812 were different. All editions from 1812 until 1857 split the stories into two volumes.

This section contains 201 listings, as «KHM 1» to «KHM 210» in numerical sequence plus «KHM 151a».

The next section «No longer included in the last edition» contains 30 listings including 18 that are numbered in series «1812 KHM ###» and 12 without any label.

Volume 1[edit]

Monument to brothers Grimm in the market place in Hanau. (Hessen, Germany)

Frontispiece used for the first volume of the 1840 4th edition

- The Frog King, or Iron Heinrich (Der Froschkönig oder der eiserne Heinrich): KHM 1

- Cat and Mouse in Partnership (Katze und Maus in Gesellschaft): KHM 2

- Mary’s Child (Marienkind): KHM 3

- The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was (Märchen von einem, der auszog das Fürchten zu lernen): KHM 4

- The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids (Der Wolf und die sieben jungen Geißlein): KHM 5

- Faithful John or Trusty John (Der treue Johannes): KHM 6

- The Good Bargain (Der gute Handel): KHM 7

- The Wonderful Musician or The Strange Musician (Der wunderliche Spielmann): KHM 8

- The Twelve Brothers (Die zwölf Brüder): KHM 9

- The Pack of Ragamuffins (Das Lumpengesindel): KHM 10

- Little Brother and Little Sister (Brüderchen und Schwesterchen): KHM 11

- Rapunzel: KHM 12

- The Three Little Men in the Wood (Die drei Männlein im Walde): KHM 13

- The Three Spinning Women (Die drei Spinnerinnen): KHM 14

- Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel): KHM 15

- The Three Snake-Leaves (Die drei Schlangenblätter): KHM 16

- The White Snake (Die weiße Schlange): KHM 17

- The Straw, the Coal, and the Bean (Strohhalm, Kohle und Bohne): KHM 18

- The Fisherman and His Wife (Von dem Fischer und seiner Frau): KHM 19

- The Brave Little Tailor or The Valiant Little Tailor or The Gallant Tailor (Das tapfere Schneiderlein): KHM 20

- Cinderella (Aschenputtel): KHM 21

- The Riddle (Das Rätsel): KHM 22

- The Mouse, the Bird, and the Sausage (Von dem Mäuschen, Vögelchen und der Bratwurst): KHM 23

- Mother Holle or Mother Hulda or Old Mother Frost (Frau Holle): KHM 24

- The Seven Ravens (Die sieben Raben): KHM 25

- Little Red Cap or Little Red Riding Hood (Rotkäppchen): KHM 26

- The Bremen Town Musicians (Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten): KHM 27

- The Singing Bone (Der singende Knochen): KHM 28

- The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs (Der Teufel mit den drei goldenen Haaren): KHM 29

- The Louse and the Flea (Läuschen und Flöhchen): KHM 30

- The Girl Without Hands or The Handless Maiden (Das Mädchen ohne Hände): KHM 31

- Clever Hans (Der gescheite Hans): KHM 32

- The Three Languages (Die drei Sprachen): KHM 33

- Clever Elsie (Die kluge Else): KHM 34

- The Tailor in Heaven (Der Schneider im Himmel): KHM 35

- The Magic Table, the Gold-Donkey, and the Club in the Sack («Tischchen deck dich, Goldesel und Knüppel aus dem Sack» also known as «Tischlein, deck dich!»): KHM 36

- Thumbling (Daumesdick) (see also Tom Thumb): KHM 37

- The Wedding of Mrs. Fox (Die Hochzeit der Frau Füchsin): KHM 38

- The Elves (Die Wichtelmänner): KHM 39

- The Elves and the Shoemaker (Erstes Märchen)

- Second Story (Zweites Märchen)

- Third Story (Drittes Märchen)

- The Robber Bridegroom (Der Räuberbräutigam): KHM 40

- Herr Korbes: KHM 41

- The Godfather (Der Herr Gevatter): KHM 42

- Mother Trudy (Frau Trude): KHM 43

- Godfather Death (Der Gevatter Tod): KHM 44

- Thumbling’s Travels (see also Tom Thumb) (Daumerlings Wanderschaft): KHM 45

- Fitcher’s Bird (Fitchers Vogel): KHM 46

- The Juniper Tree (Von dem Machandelboom): KHM 47

- Old Sultan (Der alte Sultan): KHM 48

- The Six Swans (Die sechs Schwäne): KHM 49

- Briar Rose (Dornröschen): KHM 50

- Foundling-Bird (Fundevogel): KHM 51

- King Thrushbeard (König Drosselbart): KHM 52

- Snow White (Schneewittchen): KHM 53

- The Knapsack, the Hat, and the Horn (Der Ranzen, das Hütlein und das Hörnlein): KHM 54

- Rumpelstiltskin (Rumpelstilzchen): KHM 55

- Sweetheart Roland (Der Liebste Roland): KHM 56

- The Golden Bird (Der goldene Vogel): KHM 57

- The Dog and the Sparrow (Der Hund und der Sperling): KHM 58

- Frederick and Catherine (Der Frieder und das Katherlieschen): KHM 59

- The Two Brothers (Die zwei Brüder): KHM 60

- The Little Peasant (Das Bürle): KHM 61

- The Queen Bee (Die Bienenkönigin): KHM 62

- The Three Feathers (Die drei Federn): KHM 63

- The Golden Goose (Die goldene Gans): KHM 64

- All-Kinds-of-Fur (Allerleirauh): KHM 65

- The Hare’s Bride (Häsichenbraut): KHM 66

- The Twelve Huntsmen (Die zwölf Jäger): KHM 67

- The Thief and His Master (De Gaudeif un sien Meester): KHM 68

- Jorinde and Joringel (Jorinde und Joringel): KHM 69

- The Three Sons of Fortune (Die drei Glückskinder): KHM 70

- How Six Men got on in the World (Sechse kommen durch die ganze Welt): KHM 71

- The Wolf and the Man (Der Wolf und der Mensch): KHM 72

- The Wolf and the Fox (Der Wolf und der Fuchs): KHM 73

- Gossip Wolf and the Fox (Der Fuchs und die Frau Gevatterin): KHM 74

- The Fox and the Cat (Der Fuchs und die Katze): KHM 75

- The Pink (Die Nelke): KHM 76

- Clever Gretel (Das kluge Gretel): KHM 77

- The Old Man and his Grandson (Der alte Großvater und der Enkel): KHM 78

- The Water Nixie (Die Wassernixe): KHM 79

- The Death of the Little Hen (Von dem Tode des Hühnchens): KHM 80

- Brother Lustig (Bruder Lustig) KHM 81

- Gambling Hansel (De Spielhansl): KHM 82

- Hans in Luck (Hans im Glück): KHM 83

- Hans Married (Hans heiratet): KHM 84

- The Gold-Children (Die Goldkinder): KHM 85

- The Fox and the Geese (Der Fuchs und die Gänse): KHM 86

Volume 2[edit]

- The Poor Man and the Rich Man (Der Arme und der Reiche): KHM 87

- The Singing, Springing Lark (Das singende springende Löweneckerchen): KHM 88

- The Goose Girl (Die Gänsemagd): KHM 89

- The Young Giant (Der junge Riese): KHM 90

- The Gnome (Dat Erdmänneken): KHM 91

- The King of the Gold Mountain (Der König vom goldenen Berg): KHM 92

- The Raven (Die Raben): KHM 93

- The Peasant’s Wise Daughter (Die kluge Bauerntochter): KHM 94

- Old Hildebrand (Der alte Hildebrand): KHM 95

- The Three Little Birds (De drei Vügelkens): KHM 96

- The Water of Life (Das Wasser des Lebens): KHM 97

- Doctor Know-all (Doktor Allwissend): KHM 98

- The Spirit in the Bottle (Der Geist im Glas): KHM 99

- The Devil’s Sooty Brother (Des Teufels rußiger Bruder): KHM 100

- Bearskin (Bärenhäuter): KHM 101

- The Willow Wren and the Bear (Der Zaunkönig und der Bär): KHM 102

- Sweet Porridge (Der süße Brei): KHM 103

- Wise Folks (Die klugen Leute): KHM 104

- Tales of the Paddock (Märchen von der Unke): KHM 105

- The Poor Miller’s Boy and the Cat (Der arme Müllerbursch und das Kätzchen): KHM 106

- The Two Travelers (Die beiden Wanderer): KHM 107

- Hans My Hedgehog (Hans mein Igel): KHM 108

- The Shroud (Das Totenhemdchen): KHM 109

- The Jew Among Thorns (Der Jude im Dorn): KHM 110

- The Skillful Huntsman (Der gelernte Jäger): KHM 111

- The Flail from Heaven (Der Dreschflegel vom Himmel): KHM 112

- The Two Kings’ Children (Die beiden Königskinder): KHM 113

- The Cunning Little Tailor or The Story of a Clever Tailor (vom klugen Schneiderlein): KHM 114

- The Bright Sun Brings it to Light (Die klare Sonne bringt’s an den Tag): KHM 115

- The Blue Light (Das blaue Licht): KHM 116

- The Willful Child (Das eigensinnige Kind): KHM 117

- The Three Army Surgeons (Die drei Feldscherer): KHM 118

- The Seven Swabians (Die sieben Schwaben): KHM 119

- The Three Apprentices (Die drei Handwerksburschen): KHM 120

- The King’s Son Who Feared Nothing (Der Königssohn, der sich vor nichts fürchtete): KHM 121

- Donkey Cabbages (Der Krautesel): KHM 122

- The Old Woman in the Wood (Die Alte im Wald): KHM 123

- The Three Brothers (Die drei Brüder): KHM 124

- The Devil and His Grandmother (Der Teufel und seine Großmutter): KHM 125

- Ferdinand the Faithful and Ferdinand the Unfaithful (Ferenand getrü und Ferenand ungetrü): KHM 126

- The Iron Stove (Der Eisenofen): KHM 127

- The Lazy Spinner (Die faule Spinnerin): KHM 128

- The Four Skillful Brothers (Die vier kunstreichen Brüder): KHM 129

- One-Eye, Two-Eyes, and Three-Eyes (Einäuglein, Zweiäuglein und Dreiäuglein): KHM 130

- Fair Katrinelje and Pif-Paf-Poltrie (Die schöne Katrinelje und Pif Paf Poltrie): KHM 131

- The Fox and the Horse (Der Fuchs und das Pferd): KHM 132

- The Shoes that were Danced to Pieces (Die zertanzten Schuhe): KHM 133

- The Six Servants (Die sechs Diener): KHM 134

- The White and the Black Bride (Die weiße und die schwarze Braut): KHM 135

- Iron John (Eisenhans): KHM 136

- The Three Black Princesses (De drei schwatten Prinzessinnen): KHM 137

- Knoist and his Three Sons (Knoist un sine dre Sühne): KHM 138

- The Maid of Brakel (Dat Mäken von Brakel): KHM 139

- My Household (Das Hausgesinde): KHM 140

- The Lambkin and the Little Fish (Das Lämmchen und das Fischchen): KHM 141

- Simeli Mountain (Simeliberg): KHM 142

- Going a Traveling (Up Reisen gohn): KHM 143, appeared in the 1819 edition

- KHM 143 in the 1812/1815 edition was Die Kinder in Hungersnot (The Starving Children)

- The Donkey or The Little Donkey (Das Eselein): KHM 144[d]

- The Ungrateful Son (Der undankbare Sohn): KHM 145

- The Turnip (Die Rübe): KHM 146

- The Old Man Made Young Again (Das junggeglühte Männlein): KHM 147

- The Lord’s Animals and the Devil’s (Des Herrn und des Teufels Getier): KHM 148

- The Beam (Der Hahnenbalken): KHM 149

- The Old Beggar Woman (Die alte Bettelfrau): KHM 150

- The Three Sluggards (Die drei Faulen): KHM 151

- The Twelve Idle Servants (Die zwölf faulen Knechte): KHM 151a

- The Shepherd Boy (Das Hirtenbüblein): KHM 152

- The Star Money (Die Sterntaler): KHM 153

- The Stolen Farthings (Der gestohlene Heller): KHM 154

- Looking for a Bride (Die Brautschau): KHM 155

- The Hurds (Die Schlickerlinge): KHM 156

- The Sparrow and His Four Children (Der Sperling und seine vier Kinder): KHM 157

- The Story of Schlauraffen Land (Das Märchen vom Schlaraffenland): KHM 158

- The Ditmarsch Tale of Lies (Das dietmarsische Lügenmärchen): KHM 159

- A Riddling Tale (Rätselmärchen): KHM 160

- Snow-White and Rose-Red (Schneeweißchen und Rosenrot): KHM 161

- The Wise Servant (Der kluge Knecht): KHM 162

- The Glass Coffin (Der gläserne Sarg): KHM 163

- Lazy Henry (Der faule Heinz): KHM 164

- The Griffin (Der Vogel Greif): KHM 165

- Strong Hans (Der starke Hans): KHM 166

- The Peasant in Heaven (Das Bürle im Himmel): KHM 167

- Lean Lisa (Die hagere Liese): KHM 168

- The Hut in the Forest (Das Waldhaus): KHM 169

- Sharing Joy and Sorrow (Lieb und Leid teilen): KHM 170

- The Willow Wren (Der Zaunkönig): KHM 171

- The Sole (Die Scholle): KHM 172

- The Bittern and the Hoopoe (Rohrdommel und Wiedehopf): KHM 173

- The Owl (Die Eule): KHM 174

- The Moon (Brothers Grimm) (Der Mond): KHM 175

- The Duration of Life (Die Lebenszeit): KHM 176

- Death’s Messengers (Die Boten des Todes): KHM 177

- Master Pfreim (Meister Pfriem): KHM 178

- The Goose-Girl at the Well (Die Gänsehirtin am Brunnen): KHM 179

- Eve’s Various Children (Die ungleichen Kinder Evas): KHM 180

- The Nixie of the Mill-Pond (Die Nixe im Teich): KHM 181

- The Gifts of the Little People[23][24]/The Little Folks’ Presents[25](Die Geschenke des kleinen Volkes): KHM 182[e]

- The Giant and the Tailor (Der Riese und der Schneider): KHM 183

- The Nail (Brothers Grimm) (Der Nagel): KHM 184

- The Poor Boy in the Grave (Der arme Junge im Grab): KHM 185

- The True Bride (Die wahre Braut): KHM 186

- The Hare and the Hedgehog (Der Hase und der Igel): KHM 187

- Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle (Spindel, Weberschiffchen und Nadel): KHM 188

- The Peasant and the Devil (Der Bauer und der Teufel): KHM 189

- The Crumbs on the Table (Die Brosamen auf dem Tisch): KHM 190

- The Sea-Hare (Das Meerhäschen): KHM 191

- The Master Thief (Der Meisterdieb): KHM 192

- The Drummer (Der Trommler): KHM 193

- The Ear of Corn (Die Kornähre): KHM 194

- The Grave Mound (Der Grabhügel): KHM 195

- Old Rinkrank (Oll Rinkrank): KHM 196

- The Crystal Ball (Die Kristallkugel): KHM 197

- Maid Maleen (Jungfrau Maleen): KHM 198

- The Boots of Buffalo Leather (Der Stiefel von üffelleder): KHM 199

- The Golden Key (Der goldene Schlüssel): KHM 200

The children’s legends (Kinder-legende)

First appeared in the G. Reimer 1819 edition at the end of volume 2.

- Saint Joseph in the Forest (Der heilige Joseph im Walde): KHM 201

- The Twelve Apostles (Brothers Grimm) (Die zwölf Apostel): KHM 202

- The Rose (Die Rose): KHM 203

- Poverty and Humility Lead to Heaven (Armut und Demut führen zum Himmel): KHM 204

- God’s Food (Gottes Speise): KHM 205

- The Three Green Twigs (Die drei grünen Zweige): KHM 206

- The Blessed Virgin’s Little Glass (Muttergottesgläschen) or Our Lady’s Little Glass: KHM 207

- The Little Old Lady (Das alte Mütterchen) or The Aged Mother: KHM 208

- The Heavenly Marriage (Die himmlische Hochzeit) or The Heavenly Wedding: KHM 209

- The Hazel Branch (Die Haselrute): KHM 210

Removed from final edition[edit]

- 1812 KHM 6 Von der Nachtigall und der Blindschleiche (The Nightingale and the Slow Worm) also (The Nightingale and the Blindworm)

- 1812 KHM 8 Die Hand mit dem Messer (The Hand with the Knife)

- 1812 KHM 22 Wie Kinder Schlachtens miteinander gespielt haben (The Children Who Played Slaughtering)

- 1812 KHM 27 Der Tod und der Gänsehirt (Death and the Goose Keeper)

- 1812 KHM 33 Der gestiefelte Kater (Puss in Boots)

- 1812 KHM 37 Von der Serviette, dem Tornister, dem Kanonenhütlein und dem Horn (The Napkin, the Knapsack, the Cannon Shell, and the Horn)

- 1812 KHM 43 Die wunderliche Gasterei (The Strange Inn/The Wonderly Guesting Manor)

- 1812 KHM 54 Hans Dumm (Hans Stupid)

- 1812 KHM 62 Blaubart (Bluebeard)

- 1812 KHM 66 Hurleburlebutz

- 1812 KHM 70 Der Okerlo (The Okerlo)

- 1812 KHM 71 Prinzessin Mäusehaut (Princess Mouse Skin)

- 1812 KHM 72 Das Birnli will nit fallen (The Pear Doesn’t Want to Fall)

- 1812 KHM 73 Das Mörderschloss (The Murder Castle)

- 1812 KHM 77 Vom Schreiner und Drechsler (The Carpenter and the Turner)

- 1812 KHM 82 Die drei Schwestern (The Three Sisters)

- 1812 KHM 85A Schneeblume (Snow Flower)

- 1812 KHM 85D Vom Prinz Johannes (Fragment) (Prince Johannes)

- Die Prinzessin auf der Erbse (The Princess and the Pea)

- Der Faule und der Fleißige (The Sluggard and the Diligent)

- Der gute Lappen (Fragment) (The Good Rag)

- Die heilige Frau Kummernis (The Holy Woman Kummernis)

- Die Krähen (The Crows)

- Der Löwe und der Frosch (The Lion and the Frog)

- Der Räuber und seine Söhne (The Robber and His Sons)

- Der Soldat und der Schreiner (The Soldier and the Carpenter)

- Die treuen Tiere (The Faithful Animals)

- Das Unglück (The Accident)

- Der wilde Mann (The Wild Man)

- Der Schmied und der Teufel (The Smith and the Devil)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ A derivative work is Grimm’s Fairy Tales, with 212 Illustrations by Josef Scharl (New York: Pantheon Books, 1944) [repr. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1948][18]

- ^ Translated from Kinder- und Hausmärchen gesammelt durch die Brüder Grimm (Munich: Winkler, 1949). Manheim believed this to be a reprint of the second, 1819 edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen, but it was in fact a reprint of the 7th, 1857 edition[19]

- ^ See Luke&McKay&Gilbert tr. (1982), p. 41 for details of the edition used.

- ^ «The Little Donkey»[21][22] is the more precisely translated title.

- ^ Aliases: «The Gifts of the Little People»;[26] «The Little Folks’ Presents».[25] This is the type tale of AT 503, and «The Gifts of the Little People» is its official English title, insofar as Hans-Jörg Uther has published it,[24] and most folklorists tend to follow it.

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Zipes, Jack (2002). The Brothers Grimm : from enchanted forests to the modern world. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312293801. OCLC 49698876.

- ^ a b c Zipes, Jack. «How the Grimm Brothers Saved the Fairy Tale», Humanities, March/April 2015

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales, p15-17, ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ^ «Grimm brothers’ fairytales have blood and horror restored in new translation». the Guardian. 2014-11-12. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ Maria Tatar, «Reading the Grimms’ Children’s Stories and Household Tales» p. xxvii-iv, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm., ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ a b Zipes, Jack (2002). The Brothers Grimm : from enchanted forests to the modern world. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312293801. OCLC 49698876.

- ^ Acocella, Joan (16 July 2012). «Once Upon a Time». The New Yorker. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 846, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 345-5, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ Maria Tatar, «Reading the Grimms’ Children’s Stories and Household Tales» p. xxx, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Maria Tatar, «-xxxix, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p 77-8 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ Maria Tatar, «Reading the Grimms’ Fairy Stories and Household Tales» p. xlvi, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ D. L. Ashliman, «Grimms’ Fairy Tales in English: An Internet Bibliography», ©2012-2017. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Zipes tr. (2014).

- ^ Loo, Oliver (2014). The Original 1812 Grimm Fairy Tales. A New Translation of the 1812 First Edition Kinder- und Hausmärchen Collected through the Brothers Grimm. Vol. 2 vols. (200 Year Anniversary ed.). ISBN 9781312419049.

- ^ Hunt tr. (1884).

- ^ Luke&McKay&Gilbert tr. (1982), p. 43.

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987), pp. xxii, 238 n. 22.

- ^ Luke&McKay&Gilbert tr. (1982).

- ^ Zipes tr. (2014), 2: 456ff.

- ^ Ashliman (1998–2020). #144 «The Little Donkey»

- ^ Turpin tr. (1907), p. 17–21.

- ^ a b Uther (2004), p. 288.

- ^ a b Hunt tr. (1884), pp. 298–301.

- ^ Zipes tr. (2003).

- Bibliography

- (Translations)

- Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm (1884). Grimm’s Household Tales: With the Author’s Notes. Vol. 1. Translated by Margaret Hunt. London: George Bell and Sons.; volume 2; vol. 1, vol. 2 via Internet Archive

- —— (2015) [1982]. Luke, David; McKay, Gilbert; Schofield, Philip, tr. (eds.). Brothers Grimm: Selected Tales. London: Penguin. ISBN 0241245052.

- —— (1903). Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Translated by Edna Henry Lee Turpin. New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co. ISBN 9781438158952.

- —— (2003). Zipes, Jack (ed.). The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm All-New Third Edition. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 0553897403.

- —— (2016) [2014]. Zipes, Jack (ed.). The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691173222. OCLC 879662315.

- (Other)

- Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: Animal tales, tales of magic, religious tales, and realistic tales, with an introduction. FF Communications. p. 263.

External links[edit]

- Household Tales, the complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales at Standard Ebooks

- Ashliman, D. L. (1998–2020). «The Grimm Brothers’ Children’s and Household Tales (Grimms’ Fairy Tales)». University of Pittsburgh.

- The Original 1812 Grimm A web site for the Original 1812 Kinder und Hausmärchen featuring references and other useful information related to the 1812 book in English.

Grimms’ Fairy Tales public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Title page of first volume of Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1819) 2nd Ed. |

|

| Author | Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm |

|---|---|

| Original title | Kinder- und Hausmärchen (lit. Children’s and Household Tales) |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Genre |

|

| Published | 1812–1858 |

| Text | Grimms’ Fairy Tales at Wikisource |

Grimms’ Fairy Tales, originally known as the Children’s and Household Tales (German: Kinder- und Hausmärchen, pronounced [ˌkɪndɐ ʔʊnt ˈhaʊsmɛːɐ̯çən]), is a German collection of fairy tales by the Grimm brothers or «Brothers Grimm», Jacob and Wilhelm, first published on 20 December 1812. Vol. 1 of the first editionedition contained 86 stories, which were followed by 70 more tales, numbered consecutively, in the 1st edition, Vol. 2, in 1815. By the seventh edition in 1857, the corpus of tales had expanded to 200 tales and 10 «Children’s Legends». It is listed by UNESCO in its Memory of the World Registry.

Origin[edit]

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were two of 10 children from Dorothea (née Zimmer) and Philipp Wilhelm Grimm. Philipp was a highly regarded district magistrate in Steinau an der Straße, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Hanau. Jacob and Wilhelm were sent to school for a classical education once they were of age, while their father was working. They were very hard-working pupils throughout their education. They followed in their father’s footsteps and started to pursue a degree in law, and German history. However, in 1796, their father died at the age of 44 from pneumonia. This was a tragic time for the Grimms because the family lost all financial support and relied on their aunt, Henriette Zimmer, and grandfather, Johann Hermann Zimmer. At the age of 11, Jacob was compelled to be head of the household and provide for his family. After downsizing their home because of financial reasons, Henriette sent Jacob and Wilhelm to study at the prestigious high school, Lyzeum, in Kassel. In school, their grandfather wrote to them saying that because of their current situation, they needed to apply themselves industriously to secure their future welfare.[1]

Shortly after attending Lyzeum, their grandfather died and they were again left to themselves to support their family in the future. The two became intent on becoming the best students at Lyzeum, since they wanted to live up to their deceased father. They studied more than twelve hours a day and established similar work habits. They also shared the same bed and room at school. After four years of rigorous schooling, Jacob graduated head of his class in 1802. Wilhelm contracted asthma and scarlet fever, which delayed his graduation by one year although he was also head of his class. Both were given special dispensations for studying law at the University of Marburg. They particularly needed this dispensation because their social standing at the time was not high enough to have normal admittance. University of Marburg was a small, 200-person university where most students were more interested in activities other than schooling. Most of the students received stipends even though they were the richest in the state. The Grimms did not receive any stipends because of their social standing; however, they were not upset by it since it kept the distractions away.[1]

Professor Friedrich Carl von Savigny[edit]

Jacob attended the university first and showed proof of his hard work ethic and quick intelligence. Wilhelm joined Jacob at the university, and Jacob drew the attention of Professor Friedrich Carl von Savigny, founder of its historical school of law. He became a prominent personal and professional influence on the brothers. Throughout their time at university, the brothers became quite close with Savigny and were able to use his personal library as they became interested in German law, history, and folklore. Savigny asked Jacob to join him in Paris as an assistant, and Jacob went with him for a year. While he was gone, Wilhelm became very interested in German literature and started collecting books. Once Jacob returned to Kassel in 1806, he adopted his brother’s passion and changed his focus from law to German literature. While Jacob studied literature and took care of their siblings, Wilhelm continued on to receive his degree in law at Marburg.[1] During the Napoleonic Wars, Jacob interrupted his studies to serve the Hessian War Commission.[2]

In 1808, their mother died, and this was especially hard on Jacob as he took the position of father figure, while also trying to be a brother. From 1806 to 1810, the Grimm family had barely enough money to properly feed and clothe themselves. During this time, Jacob and Wilhelm were concerned about the stability of the family.

Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano were good friends of the brothers and wanted to publish folk tales, so they asked the brothers to collect oral tales for publication. The Grimms collected many old books and asked friends and acquaintances in Kassel to tell tales and to gather stories from others. Jacob and Wilhelm sought to collect these stories in order to write a history of old German Poesie and to preserve history.[1]

Composition[edit]

The first volume of the first edition was published in 1812, containing 86 stories; the second volume of 70 stories followed in 1815. For the second edition, two volumes containing the KHM texts were issued in 1819 and the appendix was removed and published separately in the third volume in 1822, totaling 170 tales. The third edition appeared in 1837, the fourth edition in 1840, the fifth edition in 1843, the sixth edition in 1850, and the seventh edition in 1857. Stories were added, and also removed, from one edition to the next, until the seventh held 210 tales. Some later editions were extensively illustrated, first by Philipp Grot Johann and, after his death in 1892, by German illustrator Robert Leinweber.[citation needed]

The first volumes were much criticized because, although they were called «Children’s Tales», they were not regarded as suitable for children, both for the scholarly information included and the subject matter.[3] Many changes through the editions – such as turning the wicked mother of the first edition in Snow White and Hansel and Gretel (shown in original Grimm stories as Hänsel and Grethel) to a stepmother, were probably made with an eye to such suitability. Jack Zipes believes that the Grimms made the change in later editions because they «held motherhood sacred».[4]

They removed sexual references—such as Rapunzel’s innocently asking why her dress was getting tight around her belly, and thus naively revealing to the witch Dame Gothel her pregnancy and the prince’s visits—but, in many respects, violence, particularly when punishing villains, become more prevalent.[5]

Popularity[edit]

The brothers’ initial intention of their first book, Children’s and Household Tales, was to establish a name for themselves in the world. After publishing the first KHM in 1812, they published a second, augmented and re-edited, volume in 1815. In 1816 Volume I of the German Legends (German: Deutsche Sagen) was published, followed in 1818, Volume II. However, the book that established their international success was not any of their tales, but Jacob’s German Grammar in 1819. In 1825, the Brothers published their Kleine Ausgabe or «small edition», a selection of 50 tales designed for child readers. This children’s version went through ten editions between 1825 and 1858.

In 1830, Jacob became a professor at University of Göttingen and in 1835, Wilhelm also became a professor. During these years Jacob wrote a third volume of German Grammar and Wilhelm prepared the third revision of the Children’s and Household Tales.[1]

In 1837, King Ernst August II revoked the constitution of 1833 and was attempting to restore absolutism in the Kingdom of Hanover. Since Göttingen was a part of Hanover, the brothers were expected to take an oath of allegiance. However, the brothers and five other professors led a protest against this and were heavily supported by the student body since all of these professors were well renowned. Jacob left Göttingen immediately and Wilhelm followed him to Kassel a few months later.[6]

In Kassel, the Grimms devoted themselves to researching and studying. A close friend of theirs, Bettina von Arnim, was also a talented writer. Savigny and others convinced the King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, to allow the brothers to teach and conduct research at the University of Berlin. In March 1841, the brothers did just this and also continued to work on the German Dictionary.[6]

Influence[edit]

Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children and Household Tales) is listed by UNESCO in its Memory of the World Registry.[2]

The Grimms believed that the most natural and pure forms of culture were linguistic and based in history.[2] The work of the Brothers Grimm influenced other collectors, both inspiring them to collect tales and leading them to similarly believe, in a spirit of romantic nationalism, that the fairy tales of a country were particularly representative of it, to the neglect of cross-cultural influence.[7] Among those influenced were the Russian Alexander Afanasyev, the Norwegians Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, the English Joseph Jacobs, and Jeremiah Curtin, an American who collected Irish tales.[8] There was not always a pleased reaction to their collection. Joseph Jacobs was in part inspired by his complaint that English children did not read English fairy tales;[9] in his own words, «What Perrault began, the Grimms completed».

W. H. Auden praised the collection during World War II as one of the founding works of Western culture.[10] The tales themselves have been put to many uses. Adolf Hitler praised them so strongly that the Allies of World War II warned against them, as Hitler thought they were folkish tales showing children with sound racial instincts seeking racially pure marriage partners;[11] for instance, Cinderella with the heroine as racially pure, the stepmother as an alien, and the prince with an unspoiled instinct being able to distinguish.[12] Writers who have written about the Holocaust have combined the tales with their memoirs, as Jane Yolen in her Briar Rose.[13]

Three individual works of Wilhelm Grimm include Altdänische Heldenlieder, Balladen und Märchen (‘Old Danish Heroic Songs, Ballads, and Folktales’) in 1811, Über deutsche Runen (‘On German Runes’) in 1821, and Die deutsche Heldensage (‘The German Heroic Saga’) in 1829.

The Grimm anthology has been a source of inspiration for artists and composers. Arthur Rackham, Walter Crane, and Rie Cramer are among the artists who have created illustrations based on the stories.

English-language collections[edit]

«Grimms’ Fairy Tales in English» by D.L. Ashliman provides a hyperlinked list of 50 to 100 English-language collections that have been digitized and made available online. They were published in print from the 1820s to 1920s. Listings may identify all translators and illustrators who were credited on the title pages, and certainly identify some others.[14]

Translations of the 1812 edition[edit]

These are some translations of the original collection, also known as the first edition of Volume I.

- Zipes, Jack, ed., tr. (2014) The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: the complete first edition.[15]

- Loo, Oliver ed., tr. (2014) The Original 1812 Grimm Fairy Tales. A New Translation of the 1812 First Edition Kinder- und Hausmärchen Collected through the Brothers Grimm[16][self-published source?]

Translations of the 1857 edition[edit]

These are some translations of the two-volume seventh edition (1857):

- Hunt, Margaret, ed., tr. (2014) Grimm’s Household Tales, with Author’s Notes, 2 vols (1884).[17][a]

- Manheim, Ralph, tr. (1977) Grimms’ Tales for Young and Old: The Complete Stories. New York: Doubleday.[b]

- Luke, David; McKay, Gilbert; Schofield, Philip tr. (1982) Brothers Grimm: Selected Tales.[20][c]

List of stories by the Brothers Grimm[edit]

The code «KHM» stands for Kinder- und Hausmärchen. The titles are those as of 1857. Some titles in 1812 were different. All editions from 1812 until 1857 split the stories into two volumes.

This section contains 201 listings, as «KHM 1» to «KHM 210» in numerical sequence plus «KHM 151a».

The next section «No longer included in the last edition» contains 30 listings including 18 that are numbered in series «1812 KHM ###» and 12 without any label.

Volume 1[edit]

Monument to brothers Grimm in the market place in Hanau. (Hessen, Germany)

Frontispiece used for the first volume of the 1840 4th edition

- The Frog King, or Iron Heinrich (Der Froschkönig oder der eiserne Heinrich): KHM 1

- Cat and Mouse in Partnership (Katze und Maus in Gesellschaft): KHM 2

- Mary’s Child (Marienkind): KHM 3

- The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was (Märchen von einem, der auszog das Fürchten zu lernen): KHM 4

- The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids (Der Wolf und die sieben jungen Geißlein): KHM 5

- Faithful John or Trusty John (Der treue Johannes): KHM 6

- The Good Bargain (Der gute Handel): KHM 7

- The Wonderful Musician or The Strange Musician (Der wunderliche Spielmann): KHM 8

- The Twelve Brothers (Die zwölf Brüder): KHM 9

- The Pack of Ragamuffins (Das Lumpengesindel): KHM 10

- Little Brother and Little Sister (Brüderchen und Schwesterchen): KHM 11

- Rapunzel: KHM 12

- The Three Little Men in the Wood (Die drei Männlein im Walde): KHM 13

- The Three Spinning Women (Die drei Spinnerinnen): KHM 14

- Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel): KHM 15

- The Three Snake-Leaves (Die drei Schlangenblätter): KHM 16

- The White Snake (Die weiße Schlange): KHM 17

- The Straw, the Coal, and the Bean (Strohhalm, Kohle und Bohne): KHM 18

- The Fisherman and His Wife (Von dem Fischer und seiner Frau): KHM 19

- The Brave Little Tailor or The Valiant Little Tailor or The Gallant Tailor (Das tapfere Schneiderlein): KHM 20

- Cinderella (Aschenputtel): KHM 21

- The Riddle (Das Rätsel): KHM 22

- The Mouse, the Bird, and the Sausage (Von dem Mäuschen, Vögelchen und der Bratwurst): KHM 23

- Mother Holle or Mother Hulda or Old Mother Frost (Frau Holle): KHM 24

- The Seven Ravens (Die sieben Raben): KHM 25

- Little Red Cap or Little Red Riding Hood (Rotkäppchen): KHM 26

- The Bremen Town Musicians (Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten): KHM 27

- The Singing Bone (Der singende Knochen): KHM 28

- The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs (Der Teufel mit den drei goldenen Haaren): KHM 29

- The Louse and the Flea (Läuschen und Flöhchen): KHM 30

- The Girl Without Hands or The Handless Maiden (Das Mädchen ohne Hände): KHM 31

- Clever Hans (Der gescheite Hans): KHM 32

- The Three Languages (Die drei Sprachen): KHM 33

- Clever Elsie (Die kluge Else): KHM 34

- The Tailor in Heaven (Der Schneider im Himmel): KHM 35

- The Magic Table, the Gold-Donkey, and the Club in the Sack («Tischchen deck dich, Goldesel und Knüppel aus dem Sack» also known as «Tischlein, deck dich!»): KHM 36

- Thumbling (Daumesdick) (see also Tom Thumb): KHM 37

- The Wedding of Mrs. Fox (Die Hochzeit der Frau Füchsin): KHM 38

- The Elves (Die Wichtelmänner): KHM 39

- The Elves and the Shoemaker (Erstes Märchen)

- Second Story (Zweites Märchen)

- Third Story (Drittes Märchen)

- The Robber Bridegroom (Der Räuberbräutigam): KHM 40

- Herr Korbes: KHM 41

- The Godfather (Der Herr Gevatter): KHM 42

- Mother Trudy (Frau Trude): KHM 43

- Godfather Death (Der Gevatter Tod): KHM 44

- Thumbling’s Travels (see also Tom Thumb) (Daumerlings Wanderschaft): KHM 45

- Fitcher’s Bird (Fitchers Vogel): KHM 46

- The Juniper Tree (Von dem Machandelboom): KHM 47

- Old Sultan (Der alte Sultan): KHM 48

- The Six Swans (Die sechs Schwäne): KHM 49

- Briar Rose (Dornröschen): KHM 50

- Foundling-Bird (Fundevogel): KHM 51

- King Thrushbeard (König Drosselbart): KHM 52

- Snow White (Schneewittchen): KHM 53

- The Knapsack, the Hat, and the Horn (Der Ranzen, das Hütlein und das Hörnlein): KHM 54

- Rumpelstiltskin (Rumpelstilzchen): KHM 55

- Sweetheart Roland (Der Liebste Roland): KHM 56

- The Golden Bird (Der goldene Vogel): KHM 57

- The Dog and the Sparrow (Der Hund und der Sperling): KHM 58

- Frederick and Catherine (Der Frieder und das Katherlieschen): KHM 59

- The Two Brothers (Die zwei Brüder): KHM 60

- The Little Peasant (Das Bürle): KHM 61

- The Queen Bee (Die Bienenkönigin): KHM 62

- The Three Feathers (Die drei Federn): KHM 63

- The Golden Goose (Die goldene Gans): KHM 64

- All-Kinds-of-Fur (Allerleirauh): KHM 65

- The Hare’s Bride (Häsichenbraut): KHM 66

- The Twelve Huntsmen (Die zwölf Jäger): KHM 67

- The Thief and His Master (De Gaudeif un sien Meester): KHM 68

- Jorinde and Joringel (Jorinde und Joringel): KHM 69

- The Three Sons of Fortune (Die drei Glückskinder): KHM 70

- How Six Men got on in the World (Sechse kommen durch die ganze Welt): KHM 71

- The Wolf and the Man (Der Wolf und der Mensch): KHM 72

- The Wolf and the Fox (Der Wolf und der Fuchs): KHM 73

- Gossip Wolf and the Fox (Der Fuchs und die Frau Gevatterin): KHM 74

- The Fox and the Cat (Der Fuchs und die Katze): KHM 75

- The Pink (Die Nelke): KHM 76

- Clever Gretel (Das kluge Gretel): KHM 77

- The Old Man and his Grandson (Der alte Großvater und der Enkel): KHM 78

- The Water Nixie (Die Wassernixe): KHM 79

- The Death of the Little Hen (Von dem Tode des Hühnchens): KHM 80

- Brother Lustig (Bruder Lustig) KHM 81

- Gambling Hansel (De Spielhansl): KHM 82

- Hans in Luck (Hans im Glück): KHM 83

- Hans Married (Hans heiratet): KHM 84

- The Gold-Children (Die Goldkinder): KHM 85

- The Fox and the Geese (Der Fuchs und die Gänse): KHM 86

Volume 2[edit]

- The Poor Man and the Rich Man (Der Arme und der Reiche): KHM 87

- The Singing, Springing Lark (Das singende springende Löweneckerchen): KHM 88

- The Goose Girl (Die Gänsemagd): KHM 89

- The Young Giant (Der junge Riese): KHM 90

- The Gnome (Dat Erdmänneken): KHM 91

- The King of the Gold Mountain (Der König vom goldenen Berg): KHM 92

- The Raven (Die Raben): KHM 93

- The Peasant’s Wise Daughter (Die kluge Bauerntochter): KHM 94

- Old Hildebrand (Der alte Hildebrand): KHM 95

- The Three Little Birds (De drei Vügelkens): KHM 96

- The Water of Life (Das Wasser des Lebens): KHM 97

- Doctor Know-all (Doktor Allwissend): KHM 98

- The Spirit in the Bottle (Der Geist im Glas): KHM 99

- The Devil’s Sooty Brother (Des Teufels rußiger Bruder): KHM 100

- Bearskin (Bärenhäuter): KHM 101

- The Willow Wren and the Bear (Der Zaunkönig und der Bär): KHM 102

- Sweet Porridge (Der süße Brei): KHM 103

- Wise Folks (Die klugen Leute): KHM 104

- Tales of the Paddock (Märchen von der Unke): KHM 105

- The Poor Miller’s Boy and the Cat (Der arme Müllerbursch und das Kätzchen): KHM 106

- The Two Travelers (Die beiden Wanderer): KHM 107

- Hans My Hedgehog (Hans mein Igel): KHM 108

- The Shroud (Das Totenhemdchen): KHM 109

- The Jew Among Thorns (Der Jude im Dorn): KHM 110

- The Skillful Huntsman (Der gelernte Jäger): KHM 111

- The Flail from Heaven (Der Dreschflegel vom Himmel): KHM 112

- The Two Kings’ Children (Die beiden Königskinder): KHM 113

- The Cunning Little Tailor or The Story of a Clever Tailor (vom klugen Schneiderlein): KHM 114

- The Bright Sun Brings it to Light (Die klare Sonne bringt’s an den Tag): KHM 115

- The Blue Light (Das blaue Licht): KHM 116

- The Willful Child (Das eigensinnige Kind): KHM 117

- The Three Army Surgeons (Die drei Feldscherer): KHM 118

- The Seven Swabians (Die sieben Schwaben): KHM 119

- The Three Apprentices (Die drei Handwerksburschen): KHM 120

- The King’s Son Who Feared Nothing (Der Königssohn, der sich vor nichts fürchtete): KHM 121

- Donkey Cabbages (Der Krautesel): KHM 122

- The Old Woman in the Wood (Die Alte im Wald): KHM 123

- The Three Brothers (Die drei Brüder): KHM 124

- The Devil and His Grandmother (Der Teufel und seine Großmutter): KHM 125

- Ferdinand the Faithful and Ferdinand the Unfaithful (Ferenand getrü und Ferenand ungetrü): KHM 126

- The Iron Stove (Der Eisenofen): KHM 127

- The Lazy Spinner (Die faule Spinnerin): KHM 128

- The Four Skillful Brothers (Die vier kunstreichen Brüder): KHM 129

- One-Eye, Two-Eyes, and Three-Eyes (Einäuglein, Zweiäuglein und Dreiäuglein): KHM 130

- Fair Katrinelje and Pif-Paf-Poltrie (Die schöne Katrinelje und Pif Paf Poltrie): KHM 131

- The Fox and the Horse (Der Fuchs und das Pferd): KHM 132

- The Shoes that were Danced to Pieces (Die zertanzten Schuhe): KHM 133

- The Six Servants (Die sechs Diener): KHM 134

- The White and the Black Bride (Die weiße und die schwarze Braut): KHM 135

- Iron John (Eisenhans): KHM 136

- The Three Black Princesses (De drei schwatten Prinzessinnen): KHM 137

- Knoist and his Three Sons (Knoist un sine dre Sühne): KHM 138

- The Maid of Brakel (Dat Mäken von Brakel): KHM 139

- My Household (Das Hausgesinde): KHM 140

- The Lambkin and the Little Fish (Das Lämmchen und das Fischchen): KHM 141

- Simeli Mountain (Simeliberg): KHM 142

- Going a Traveling (Up Reisen gohn): KHM 143, appeared in the 1819 edition

- KHM 143 in the 1812/1815 edition was Die Kinder in Hungersnot (The Starving Children)

- The Donkey or The Little Donkey (Das Eselein): KHM 144[d]

- The Ungrateful Son (Der undankbare Sohn): KHM 145

- The Turnip (Die Rübe): KHM 146

- The Old Man Made Young Again (Das junggeglühte Männlein): KHM 147

- The Lord’s Animals and the Devil’s (Des Herrn und des Teufels Getier): KHM 148

- The Beam (Der Hahnenbalken): KHM 149

- The Old Beggar Woman (Die alte Bettelfrau): KHM 150

- The Three Sluggards (Die drei Faulen): KHM 151

- The Twelve Idle Servants (Die zwölf faulen Knechte): KHM 151a

- The Shepherd Boy (Das Hirtenbüblein): KHM 152

- The Star Money (Die Sterntaler): KHM 153

- The Stolen Farthings (Der gestohlene Heller): KHM 154

- Looking for a Bride (Die Brautschau): KHM 155

- The Hurds (Die Schlickerlinge): KHM 156

- The Sparrow and His Four Children (Der Sperling und seine vier Kinder): KHM 157

- The Story of Schlauraffen Land (Das Märchen vom Schlaraffenland): KHM 158

- The Ditmarsch Tale of Lies (Das dietmarsische Lügenmärchen): KHM 159

- A Riddling Tale (Rätselmärchen): KHM 160

- Snow-White and Rose-Red (Schneeweißchen und Rosenrot): KHM 161

- The Wise Servant (Der kluge Knecht): KHM 162

- The Glass Coffin (Der gläserne Sarg): KHM 163

- Lazy Henry (Der faule Heinz): KHM 164

- The Griffin (Der Vogel Greif): KHM 165

- Strong Hans (Der starke Hans): KHM 166

- The Peasant in Heaven (Das Bürle im Himmel): KHM 167

- Lean Lisa (Die hagere Liese): KHM 168

- The Hut in the Forest (Das Waldhaus): KHM 169

- Sharing Joy and Sorrow (Lieb und Leid teilen): KHM 170

- The Willow Wren (Der Zaunkönig): KHM 171

- The Sole (Die Scholle): KHM 172

- The Bittern and the Hoopoe (Rohrdommel und Wiedehopf): KHM 173

- The Owl (Die Eule): KHM 174

- The Moon (Brothers Grimm) (Der Mond): KHM 175

- The Duration of Life (Die Lebenszeit): KHM 176

- Death’s Messengers (Die Boten des Todes): KHM 177

- Master Pfreim (Meister Pfriem): KHM 178

- The Goose-Girl at the Well (Die Gänsehirtin am Brunnen): KHM 179

- Eve’s Various Children (Die ungleichen Kinder Evas): KHM 180

- The Nixie of the Mill-Pond (Die Nixe im Teich): KHM 181

- The Gifts of the Little People[23][24]/The Little Folks’ Presents[25](Die Geschenke des kleinen Volkes): KHM 182[e]

- The Giant and the Tailor (Der Riese und der Schneider): KHM 183

- The Nail (Brothers Grimm) (Der Nagel): KHM 184

- The Poor Boy in the Grave (Der arme Junge im Grab): KHM 185

- The True Bride (Die wahre Braut): KHM 186

- The Hare and the Hedgehog (Der Hase und der Igel): KHM 187

- Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle (Spindel, Weberschiffchen und Nadel): KHM 188

- The Peasant and the Devil (Der Bauer und der Teufel): KHM 189

- The Crumbs on the Table (Die Brosamen auf dem Tisch): KHM 190

- The Sea-Hare (Das Meerhäschen): KHM 191

- The Master Thief (Der Meisterdieb): KHM 192

- The Drummer (Der Trommler): KHM 193

- The Ear of Corn (Die Kornähre): KHM 194

- The Grave Mound (Der Grabhügel): KHM 195

- Old Rinkrank (Oll Rinkrank): KHM 196

- The Crystal Ball (Die Kristallkugel): KHM 197

- Maid Maleen (Jungfrau Maleen): KHM 198

- The Boots of Buffalo Leather (Der Stiefel von üffelleder): KHM 199

- The Golden Key (Der goldene Schlüssel): KHM 200

The children’s legends (Kinder-legende)

First appeared in the G. Reimer 1819 edition at the end of volume 2.

- Saint Joseph in the Forest (Der heilige Joseph im Walde): KHM 201

- The Twelve Apostles (Brothers Grimm) (Die zwölf Apostel): KHM 202

- The Rose (Die Rose): KHM 203

- Poverty and Humility Lead to Heaven (Armut und Demut führen zum Himmel): KHM 204

- God’s Food (Gottes Speise): KHM 205

- The Three Green Twigs (Die drei grünen Zweige): KHM 206

- The Blessed Virgin’s Little Glass (Muttergottesgläschen) or Our Lady’s Little Glass: KHM 207

- The Little Old Lady (Das alte Mütterchen) or The Aged Mother: KHM 208

- The Heavenly Marriage (Die himmlische Hochzeit) or The Heavenly Wedding: KHM 209

- The Hazel Branch (Die Haselrute): KHM 210

Removed from final edition[edit]

- 1812 KHM 6 Von der Nachtigall und der Blindschleiche (The Nightingale and the Slow Worm) also (The Nightingale and the Blindworm)

- 1812 KHM 8 Die Hand mit dem Messer (The Hand with the Knife)

- 1812 KHM 22 Wie Kinder Schlachtens miteinander gespielt haben (The Children Who Played Slaughtering)

- 1812 KHM 27 Der Tod und der Gänsehirt (Death and the Goose Keeper)

- 1812 KHM 33 Der gestiefelte Kater (Puss in Boots)

- 1812 KHM 37 Von der Serviette, dem Tornister, dem Kanonenhütlein und dem Horn (The Napkin, the Knapsack, the Cannon Shell, and the Horn)

- 1812 KHM 43 Die wunderliche Gasterei (The Strange Inn/The Wonderly Guesting Manor)

- 1812 KHM 54 Hans Dumm (Hans Stupid)

- 1812 KHM 62 Blaubart (Bluebeard)

- 1812 KHM 66 Hurleburlebutz

- 1812 KHM 70 Der Okerlo (The Okerlo)

- 1812 KHM 71 Prinzessin Mäusehaut (Princess Mouse Skin)

- 1812 KHM 72 Das Birnli will nit fallen (The Pear Doesn’t Want to Fall)

- 1812 KHM 73 Das Mörderschloss (The Murder Castle)

- 1812 KHM 77 Vom Schreiner und Drechsler (The Carpenter and the Turner)

- 1812 KHM 82 Die drei Schwestern (The Three Sisters)

- 1812 KHM 85A Schneeblume (Snow Flower)

- 1812 KHM 85D Vom Prinz Johannes (Fragment) (Prince Johannes)

- Die Prinzessin auf der Erbse (The Princess and the Pea)

- Der Faule und der Fleißige (The Sluggard and the Diligent)

- Der gute Lappen (Fragment) (The Good Rag)

- Die heilige Frau Kummernis (The Holy Woman Kummernis)

- Die Krähen (The Crows)

- Der Löwe und der Frosch (The Lion and the Frog)

- Der Räuber und seine Söhne (The Robber and His Sons)

- Der Soldat und der Schreiner (The Soldier and the Carpenter)

- Die treuen Tiere (The Faithful Animals)

- Das Unglück (The Accident)

- Der wilde Mann (The Wild Man)

- Der Schmied und der Teufel (The Smith and the Devil)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ A derivative work is Grimm’s Fairy Tales, with 212 Illustrations by Josef Scharl (New York: Pantheon Books, 1944) [repr. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1948][18]

- ^ Translated from Kinder- und Hausmärchen gesammelt durch die Brüder Grimm (Munich: Winkler, 1949). Manheim believed this to be a reprint of the second, 1819 edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen, but it was in fact a reprint of the 7th, 1857 edition[19]

- ^ See Luke&McKay&Gilbert tr. (1982), p. 41 for details of the edition used.

- ^ «The Little Donkey»[21][22] is the more precisely translated title.

- ^ Aliases: «The Gifts of the Little People»;[26] «The Little Folks’ Presents».[25] This is the type tale of AT 503, and «The Gifts of the Little People» is its official English title, insofar as Hans-Jörg Uther has published it,[24] and most folklorists tend to follow it.

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Zipes, Jack (2002). The Brothers Grimm : from enchanted forests to the modern world. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312293801. OCLC 49698876.

- ^ a b c Zipes, Jack. «How the Grimm Brothers Saved the Fairy Tale», Humanities, March/April 2015

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales, p15-17, ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ^ «Grimm brothers’ fairytales have blood and horror restored in new translation». the Guardian. 2014-11-12. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ Maria Tatar, «Reading the Grimms’ Children’s Stories and Household Tales» p. xxvii-iv, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm., ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ a b Zipes, Jack (2002). The Brothers Grimm : from enchanted forests to the modern world. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312293801. OCLC 49698876.

- ^ Acocella, Joan (16 July 2012). «Once Upon a Time». The New Yorker. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 846, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 345-5, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ Maria Tatar, «Reading the Grimms’ Children’s Stories and Household Tales» p. xxx, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Maria Tatar, «-xxxix, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p 77-8 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ Maria Tatar, «Reading the Grimms’ Fairy Stories and Household Tales» p. xlvi, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ D. L. Ashliman, «Grimms’ Fairy Tales in English: An Internet Bibliography», ©2012-2017. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Zipes tr. (2014).

- ^ Loo, Oliver (2014). The Original 1812 Grimm Fairy Tales. A New Translation of the 1812 First Edition Kinder- und Hausmärchen Collected through the Brothers Grimm. Vol. 2 vols. (200 Year Anniversary ed.). ISBN 9781312419049.

- ^ Hunt tr. (1884).

- ^ Luke&McKay&Gilbert tr. (1982), p. 43.

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987), pp. xxii, 238 n. 22.

- ^ Luke&McKay&Gilbert tr. (1982).

- ^ Zipes tr. (2014), 2: 456ff.

- ^ Ashliman (1998–2020). #144 «The Little Donkey»

- ^ Turpin tr. (1907), p. 17–21.

- ^ a b Uther (2004), p. 288.

- ^ a b Hunt tr. (1884), pp. 298–301.

- ^ Zipes tr. (2003).

- Bibliography

- (Translations)

- Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm (1884). Grimm’s Household Tales: With the Author’s Notes. Vol. 1. Translated by Margaret Hunt. London: George Bell and Sons.; volume 2; vol. 1, vol. 2 via Internet Archive

- —— (2015) [1982]. Luke, David; McKay, Gilbert; Schofield, Philip, tr. (eds.). Brothers Grimm: Selected Tales. London: Penguin. ISBN 0241245052.

- —— (1903). Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Translated by Edna Henry Lee Turpin. New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co. ISBN 9781438158952.

- —— (2003). Zipes, Jack (ed.). The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm All-New Third Edition. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 0553897403.

- —— (2016) [2014]. Zipes, Jack (ed.). The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691173222. OCLC 879662315.

- (Other)

- Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: Animal tales, tales of magic, religious tales, and realistic tales, with an introduction. FF Communications. p. 263.

External links[edit]

- Household Tales, the complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales at Standard Ebooks

- Ashliman, D. L. (1998–2020). «The Grimm Brothers’ Children’s and Household Tales (Grimms’ Fairy Tales)». University of Pittsburgh.

- The Original 1812 Grimm A web site for the Original 1812 Kinder und Hausmärchen featuring references and other useful information related to the 1812 book in English.

Grimms’ Fairy Tales public domain audiobook at LibriVox

ЯКОБ

И ВИЛЬГЕЛЬМ ГРИММ (1785-1863), (1786-1859)

ДРУЖБА

ЯКОБА И ВИЛЬГЕЛЬМА

Братья

с детства дружили, в школьные годы жили

в одной комнате, работали за одним

столом. В студенческие годы в одной

комнате стояли две кровати и два стола.

Под одной крышей и при полной общности

их имущества и книг, за исключением

лишь некоторых изданий, которые должны

были быть под рукой, поэтому покупались

в двух экземплярах. Братья всегда были

вместе, а если и расставались, то

ненадолго. Даже похоронены они вместе

на Берлинском кладбище. На скромных

надгробьях – их имена без всяких

титулов. КЕМ

ЖЕ БЫЛИ БРАТЬЯ ГРИММ?

Оба

получили юридическое образование в

Маргутском университете в Геттингеме.

Переехав в Берлин, оба преподавали в

университете. С детства проявляли

большие способности к наукам. Увлекались

ориологией – их интересовала немецкая

история и культура, язык, литература

Германии, мифы и фольклор.

Братья

очень много работали. Якоб вспоминал:

«все, что мы сделали может занять целый

книжный шкаф». Список их трудов огромный,

выпущены сотни книг, собраний легенд

и мифов, книги по грамматике и

юриспруденции. Но мировую известность

принесли братьям собранные ими сказки.

Якоб вспоминал: «Наши сказки – любимые

книги Вильгельма, когда я беру её в

руки, у меня сжимается сердце – за

каждой страницей я вижу образ брата».

ИСТОРИЯ

СОЗДАНИЯ СКАЗОК

В

1806 году братья Гримм пустились

странствовать по всей Германии, чтобы

услышать сказки из народных уст и

записать их. С большим терпением и

усердием выслушивали они рассказчиков

и дословно записывали их сказки

(крестьян, дворян, баронов, портных,

солдат). На первый взгляд задача братьев

была простой – слушай и пиши, но на это

уходило много времени. Дороги были

плохие, кареты ездили медленно, людям

их занятие казалось странным. Нередко

приходилось уходить с пустыми руками

несмотря на всю их дипломатичность и

убедительность. Сказки решили издать

в виде обычной книги для народа. Якоб

настаивал на доскональном сохранении

устного текста, а Вильгельм предлагал

художественно обработать записи. В

итоге родился особый стиль литературной

обработки народных сказок – гриммовский.

Братья Гримм сократили объём сказок,

освободили их от диалектизмов и

устаревших слов, но сохранили композицию,

меткость и образность народной речи.

Первый

том вышел в 1812 г. – «Детские семейные

сказки, собранные братьями Гримм» (86

сказок). В предисловии Вильгельм написал:

«с каждой сказкой для нас связанно ещё

и приятные воспоминания – немногие

книги создавались с такой радостью».

Успех был огромным. В Германии стали

образовываться целые кружки сказочников.

Над

вторым томом Вильгельм работал без

Якоба, он занимался дипломатической

работой за границей. Второй том вышел

в 1815 г., в него вошли 70 новых сказок.

Когда руки Якоба попал первый экземпляр,

он остался недоволен (бумага и печать

были хуже, книга тоньше, а цена выше).Якоб

считал недостаточным, что Вильгельм в

ссылках и примечаниях поместил не всю

информацию. Эти замечания свидетельствуют

о более выраженных научных склонностях

старшего брата.

Третий

том, изданный в 1822 г. был томом примечаний.

Здесь были опубликованы сведения о

происхождении сказок (правда, без

указания, т.к. изначально братья не

собирались публиковать сказки, поэтому

не всегда записывали имена рассказчиков).

В третьем томе приводились варианты

существующих сюжетов, этим были заложены

основы

научного подхода к публикациям

произведений устного народного

творчества. Братья

Гримм собрали и издали наиболее типичные

и распространенные сюжеты («Волк и

семеро козлят», «Золушка», «Красная

шапочка», «Снегурочка», «Братец и

сестрица»).

При

жизни братьев Гримм в 1825 году было

выпущено отдельное издание избранных

сказок для детей – самая

популярная немецкая книга для детей.

При их жизни вышло ещё 7 новых изданий

сказок, последнее – в 1857 г. и содержало

210 сказок.

.

Сказки о животных, волшебные и бытовые

в творческом наследии братьев Гримм.

Сказка

о животных

(животный эпос) — это сказка, в которой,

преимущественно, действуют животные.

Сказки этого жанра имеют различные

жанровые формы. Большинство из них

обладает кумулятивной композицией

(Рекурсивная или Кумулятивная сказка).

Принцип такой композиции заключается

в многократном повторении единицы

сюжета.

Волшебная

сказка

— такая сказка имеет в своей основе

сложную композицию, которая имеет

экспозицию, завязку, развитие сюжета,

кульминацию и развязку. В основе сюжета

волшебной сказки находится повествование

о преодолении потери или недостачи,

при помощи чудесных средств, или

волшебных помощников. В экспозиции

сказки рассказывается обо всех причинах,

которые породили завязку: запрещение

и нарушение запрета на какие-то действия.

Завязка сказки состоит в том, что главный

герой или героиня обнаруживают потерю

или недостачу. Развитие сюжета — это

поиск потерянного или недостающего.

Кульминация волшебной сказки состоит

в том, что главный герой, или героиня

сражаются с противоборствующей силой

и всегда побеждают её. Развязка — это

преодоление потери, или недостачи.

Герой или героиня в конце «воцаряются»

— то есть приобретают более высокий

социальный статус, чем у них был в

начале.

Волшебные

сказки, как подчеркивал В.Я.Пропп,

«выделяются не по признаку волшебности

или чудесности… а по совершенно четкой

композиции». В основе волшебной сказки

лежит образ инициации (инициации –

разновидность обряда перехода, посвящения

юношей в разряд взрослых мужчин) –

отсюда «иное царство», куда следует

попасть герою, чтобы приобрести невесту

или сказочные ценности, после чего он

должен вернуться домой. Повествование

«вынесено целиком за пределы реальной

жизни». Характерные

особенности волшебной сказки:

словесный орнамент, присказки, концовки,

устойчивые формулы.

Сказки

о животных, растениях (война грибов и

т. д.), о неживой природе (ветер, мороз,

солнце) и предметах (лапоть, соломинка,

пузырь, уголек) составляют небольшую

часть русских и западноевропейских

сказок, тогда как у народов Севера,

Северной Америки и Африки сказки о

животных широко распространены (наиболее

популярные герои – ловкие обманщики-трикстеры

(шуты) заяц, паук, лиса, койот).

Бытование

сказки. Народные

сказки исполнялись особыми рассказчиками

– сказочниками. Одна и та же сказка в

устах исполнителей могла трансформироваться,

как по субъективным причинам (пристрастия

самого сказочника, его одаренность),

так и по причинам объективным, например,

в зависимости от характера аудитории.

Ярчайшими

представителями школы были немецкие

филологи и фольклористы братья Якоб

Гримм

(1785–1863) и

Вильгельм Гримм

(1786–1859). Авторы интересных научных

работ, среди которых Германские

героические сказания (1829), прославились

они, в первую очередь, изданием немецкого

фольклора – преданий (1816–1818) и появившихся

чуть раньше сказок. Книга Детские и

семейные сказки, выходившая отдельными

выпусками с 1812 по 1814, не только с большой

полнотой представила публике памятники

немецкой народной словесности (последнее

прижизненное издание включает 210

сказок), отношение фольклористов к

материалу определило подход к народной

сказке других исследователей.

Братья

Гримм стремились к точности, сохраняя,

по возможности, черты, характерные для

устного повествования. Их собрание

отличают ясность и простота, в примечаниях

даны варианты сюжета и параллели,

почерпнутые из фольклора различных

европейских народов. Подготовленное

ими издание не свободно и от слабостей:

последовательность сказок случайна,

для публикации выбраны сказки наиболее

типичные, что помешало представить

материал во всем разнообразии, кроме

того, правке подверглись язык и стиль

издаваемых текстов, что особенно заметно

сейчас, когда издана так называемая

Эленбергская рукопись, где тексты даны

без правки.

Возникает

вопрос: сказки братьев Гримм — это

оригинальные произведения или записи

народных преданий?

Ответ на него сложен, неоднозначен.

Гриммы, особенно Якоб, — чрезвычайно

строго относились к тому, чтобы сказки

оставались подлинными, народными, чтобы

в их пересказ не вкрались никакое

искажение, никакая переделка на

современный лад, на собственный вкус.

Строгий до педантизма Якоб настаивал

на полнейшей фольклорной достоверности.

Вильгельм, более поэт, чем ученый,

считал, что нужна художественная

обработка материала. Впрочем, разногласия

эти были даже полезны: благодаря им

тексты гриммовских сказок совмещают

в себе добросовестнейшую научную

достоверность с авторским поэтическим

стилем. Записывая сказки со слов разных

людей, Гриммы не могли, да и не хотели,

дословно воспроизводить манеру

рассказчиков. Они оставляли в

неприкосновенности строй языка,

композицию, самый дух сказки, но

пересказывали ее по-своему, не рабски,

но творчески. Братья нашли свой единый

стиль — живой, простодушный, степенный,

иногда лукавый. Благодаря этому стилю

их сказочные сборники стали не просто

этнографическим научным трудом, но

великим явлением немецкой романтической

литературы.

Романтики

видели в произведениях устного народного

творчества свои эстетические образцы,

источники современной литературы и

основу ее национального характера.

Литературным

сказкам романтиков свойственно сочетание

волшебного, фантастического, призрачного

и мистического с современной

действительностью.

«Немецкие

предания» братьев Гримм, как и «Детские

и семейные сказки», вызвали к жизни

оживленную собирательскую деятельность

во многих странах. Понятие «сказка»

закрепилось за сказкой народной, но

вместе с тем обозначало и литературную

сказку. В то же время предпринимались

попытки дать определение литературной

сказке. Приоритет принадлежит Я. Гримму,

видевшему отличие литературной сказки

от народной в осознанном авторстве и

в свойственном первой юмористическом

начале.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Начнем с того, что великие братья пришли к сказкам в общем-то, случайно. Они вовсе не считали сказки главной своей книгой. Это бывает.Бывает, что великие писатели не знают, что именно их прославят. Бывает, что авторы не ведают, что останутся от них в веках именно произведения, которые они считали второстепенными. Так, например, Петрарка очень удивился бы, если бы узнал, что войдет в сокровищницу мировой литературы именно своими сонетами, которые он писал на досуге, относился к ним с пренебрежением, как к «пустякам», «безделкам», написанным не для публики, а для себя, чтобы «как-нибудь, не ради славы, облегчить скорбное сердце». Он то видел главным делом своей жизни не легкие итальянские стишки, а произведения на благородной латыни. Но в историю вошел сонетами, а не монументальной эпической поэмой «Африка», где воспеваются подвиги Сципиона…