История персонажа

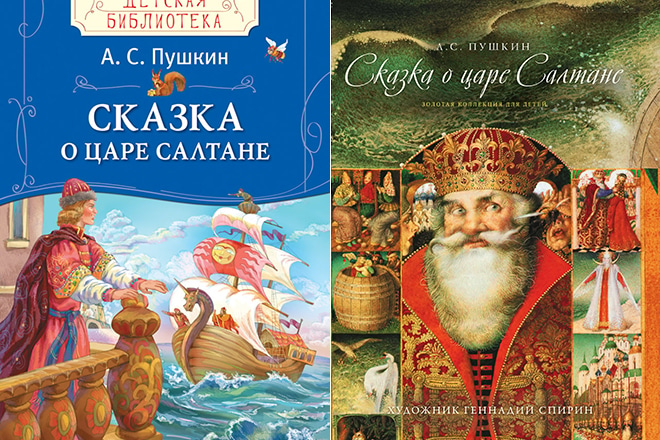

Царь Салтан – великодушный и наивный правитель, появившийся в сказке Александра Сергеевича Пушкина. Автор создал образ большого ребенка, топающего ногами, слепо верящего придворной лижи и мечтающего о простом счастье.

История создания

К одной из самых знаменитых своих сказок Александр Пушкин шел несколько лет, набрасывая в тетради заметки для будущего произведения и раздумывая над формой подачи. Писатель даже помышлял о том, чтобы историю о царе Салтане изложить в прозе. В качестве художественного каркаса автор взял народную сказку «По колена ноги в золоте, по локоть руки в серебре», добавил рассказы няни Арины Родионовны и былички, подслушанные у простого люда. В томительные годы ссылки в Михайловском лишенный свободы выбирать место жительства поэт много общался с народом – коротал вечера в обществе крестьян и дворовых.

К лету 1831 года Пушкин принял участие в затее Василия Жуковского, который предложил нескольким писателям попробовать силы в народном творчестве. Александр Сергеевич выставил на «конкурс» «Сказку о царе Салтане», правда, потом снова ее переписал. Первым, кто услышал творение из уст автора, оказался Николай I. В 1932 году оно появилось в составе сборника сочинений писателя.

Торжественное и длинное название «Сказка о царе Салтане, о сыне его славном и могучем богатыре князе Гвидоне Салтановиче и о прекрасной царевне Лебеди» было выбрано в подражание лубочным повествованиям. Придумывая имя главному герою, Пушкин остроумно переделал двойной титул «царь-султан», получилось колоритное, указывающее на восточные корни, но со славянским оттенком имя.

Славный сын Салтана Гвидон назван на западноевропейский манер. Имена отца и сына символичны, олицетворяют противостояние запада и востока. Еще один яркий персонаж произведения – царевна Лебедь – полностью взят из русского фольклора: Александр Сергеевич наделил ее чертами Василисы Премудрой.

Критики встретили произведение холодно, среди них нашлись и такие, которые заподозрили, что Пушкин теряет талант. На поэта обрушился шквал обвинений в том, что тот не сумел передать колорит русского фольклора, выдав лишь жалкое подобие народного образца. Только в 20 веке критики начали петь хвалебные оды в адрес произведения.

Сюжет

Однажды царь Салтан подслушивает мечтательный разговор на тему «если б я была царица» трех сестриц, прявших вечерком около окна. Обещание одной девушки особенно понравилось государю, ведь она собралась родить ему богатыря. На радостях Салтан женится на ней, оставшихся двух мечтательниц отправляет служить ко двору и уезжает в дальние страны на войну.

В его отсутствие на свет появился обещанный богатырь – сын Гвидон, но завистливые сестры роженицы хитростью избавились от царицы и ее отпрыска. Гвидона вместе с матерью закрыли в бочке и выбросили в море. Это необычное судно доставило героев к берегам необитаемого острова Буяна, который и стал новым местом жительства. Здесь юноша основал чудесный город, а помогла ему в этом прекрасная лебедь, спасенная Гвидоном от коршуна.

Гвидон, желающий увидеть отца, с помощью побывавших в его владениях купцов зовет царя Салтана в гости. Однако государя больше привлекает весть о чудо-белке, которая грызет золотые и изумрудные орехи и умеет петь. Тогда царевич решает поселить на своем острове это сказочное животное, построив для него хрустальный дом.

Во второй раз царь вновь отказался от приглашения, узнав о тридцати трех богатырях, и тогда морское войско во главе с дядькой Черномором появляется на острове Буян.

И в третий раз Гвидону не удалось заманить отца в гости – тот прознал о красавице-царевне Лебеди, которая своим ликом затмевает божий свет. Гвидон настолько проникся новостью, что собрался жениться на девушке. Бросившись за помощью к лебеди, с удивлением обнаружил, что она и есть та самая царевна.

Царь Салтан, наконец, прибыл на остров, где ждала его вся семья – жена, сын и невестка. Пушкин закончил сказку на позитивной ноте – строившие козни женщины прощены, а государь закатил пир на весь мир.

Характеристика царя Салтана

Главный персонаж произведения представлен в комическом ключе. Внешность у героя царская – солидная борода, подобающее одеяние, состоящее из красных сапог и длинного плаща с изящными узорами, вышитого золотом. Однако характер – совсем не самодержца.

Царь Салтан, доверчивый, добродушный и справедливый, – идеал царя-батюшки для русского народа. Его легко обманывает окружение, но врожденная способность прощать заставляет героя закрывать на все глаза и жить в мире иллюзий.

В культуре

В конце 19 века композитор Николай Римский-Корсаков написал по мотивам сказки великолепную оперу, пережившую множество постановок.

В наше время музыку использовала олимпийская чемпионка Мария Киселева в авторском спектакле на воде «Сказка о царе Салтане», который до сих пор колесит с гастролями по России. Водная сказка – это микс спорта и искусства, где участвуют актеры цирка, хореографы, чемпионы по синхронному плаванию, по прыжкам в воду и аквабайку. В интервью Мария Киселева отмечала:

«Для каждого спектакля мы пишем оригинальную музыку. Теперь мы пошли дальше – в новом шоу прозвучит классическая музыка Римского-Корсакова, которая была специально написана для «Сказки о царе Салтане», но в оригинальной обработке. Она будет идеально сочетаться с действием на площадке».

Произведение вошло и в кинематографическое наследие. Впервые пушкинское творение запечатлели на пленке в 1943 году. Режиссеры Валентина и Зинаида Брумберг создали черно-белый мультфильм, в котором Салтан говорит голосом актера Михаила Жарова. Цветной мультик увидел свет намного позже – в 1984 году. Эта картина стала последней работой легендарного режиссерского тандема Ивана Иванова-Вано и Льва Мильчина. Салтана озвучил Михаил Зимин.

В 1966 году за сюжет сказки взялся Александр Птушко, сняв художественный фильм. На съемочной площадке трудились Лариса Голубкина (царица), Олег Видов (Гвидон), Ксения Рябинкина (царевна Лебедь). Роль Салтана досталась Владимиру Андрееву.

ЦАРЬ САЛТАН

- ЦАРЬ САЛТАН

-

ЦАРЬ САЛТАН — герой сказки А.С.Пушкина «Сказка о царе Салтане, о сыне его славном и могучем богатыре князе Гвидоне Салтано-виче и о прекрасной царевне Лебеди» (1831), написанной на основе сказки, поведанной поэту Ариной Родионовной. В передаче Арины Родионовны С. вовсе не имя, а как бы удвоение титула: царь-султан. Пушкин остроумно переделывает его в С. Получилось весьма колоритное, подлинно сказочное имя, сохраняющее славянскую окраску и намек на несметные «султанские» богатства. С.- царь идеальный, олицетворение мечты русского народа, отец-батюшка. Такой царь может запросто простоять весь вечер «позадь забора» и ненароком подслушать беседу трех девиц за пряжей. Царство С.- вполне домашнее, с хорошо протопленной печью в морозный крещенский вечер. Мысли царя самые простые. Три сестрицы пообещали ему разное и несбыточное, и он уверен, что стоит ему лишь пожелать, и все это сбудется. А главное, «к исходу сентября» у него будет сын-богатырь. Гвидон становится воплощением благополучной, подчиняющейся действительности. С. верит в чудеса. Идеальный образ С. разрушается под влиянием прозы жизни. Затягивается война, в которой С. «бьется долго и жестоко». Интригуют ткачиха с поварихой, с сватьей бабой Бабарихой и добиваются изгнания любимой жены с младенцем. Но чем сильнее одурманивают они царя слухами о чудесах, тем слабее становится их власть над ним. Наконец чаша любопытства переполнена, и С. разрывает паутину своего безволия. Реальность, ожидающая его, оказывается богаче самых заманчивых снов. Царь С. обретает даже больше того, о чем мечтал. Главное же — семейное счастье восстановлено. Справедливость торжествует, недобрые чары развеяны. «Царь для радости такой» всех прощает и его, конечно, «уложили спать вполпьяна».

На сюжет пушкинской сказки написана одноименная опера Н.А.Римского-Корсакова (соч. 1900).

В.В.Макаров

Литературные герои. — Академик.

2009.

Смотреть что такое «ЦАРЬ САЛТАН» в других словарях:

-

царь Салтан — (сказочный персонаж) … Орфографический словарь русского языка

-

САЛТАН — (царь С.; сказочный персонаж) Дети это вечер, вечер на диване, Сквозь окно, в тумане, блестки фонарей, Мерный голос сказки о царе Салтане, О русалках сестрах сказочных морей. Цв908 (I,13.1) … Собственное имя в русской поэзии XX века: словарь личных имён

-

Сказка о царе Салтане (опера) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Сказка о царе Салтане (значения). Опера Сказка о царе Салтане … Википедия

-

Диподия — см. Стихосложение метрическое и Двудольные размеры. Литературная энциклопедия. В 11 т.; М.: издательство Коммунистической академии, Советская энциклопедия, Художественная литература. Под редакцией В. М. Фриче, А. В. Луначарского. 1929 1939 … Литературная энциклопедия

-

Диподия — ДИПОДИЯ есть объединение двух стоп с таким расчетом, что ударение одной стопы сильнее ударения другой, напр., в строке «Царь Салтан сидит на троне» первая диподия есть «царь Салтан», вторая «сидит на троне». Диподия объединяется в свою… … Словарь литературных терминов

-

ЦАРИЦА — ЦАРИЦА, царицы, жен. 1. Жена царя. «Царь Салтан за пир честной сел с царицей молодой.» Пушкин. 2. женск. к царь в 1 знач. Царица Екатерина II. 3. женск. к царь во 2 знач. «Для вас, души моей царицы, красавицы, для вас одних.» Пушкин. «Царица… … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

Правовая культура — является одной из приоритетных составлющих теоретической конструкции ( теоретическим телом (проф. Ю.М.Дмитриенко) более сложных форм правовых культур (например, религиозной, политической, национальной и др. (асп. И.В. Дмитриенко), которые чаще… … Википедия

-

Тихонов, Павел Ильич — [15(27).2.1877, Петербург 23.3.1944, Москва] арт. оперы (бас), камерный певец и педагог. Засл. деятель искусств БССР (1940). Род. в бедной многодетной семье. В 1900 окончил юридический ф т Петерб. ун та. В студенческие годы был солистом хора А.… … Большая биографическая энциклопедия

-

ПРЕСТОЛ — ПРЕСТОЛ, престола, муж. 1. Трон монарха (преим. как символ его власти). «Царь Салтан сидит в палате, на престоле и в венце.» Пушкин. Взойти на престол (стать монархом). Свергнуть с престола (лишить власти монарха). Наследник престола (лицо, к… … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

Красная плесень — В этой статье не хватает ссылок на источники информации. Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть поставлена под сомнение и удалена. Вы можете … Википедия

Билибинские Гвидон, Салтан и Дадон

Имена князя Гвидона, царя Салтана , царя Дадона и воеводы Полкана у нас прочно связаны со сказками Пушкина и операми Римского -Корсакова. И вряд ли кому придет в голову сказать, что это русские имена, ну кроме собачьей клички Полкан или Салтанa, который коверканый «султан»,и совсем не русский титул. Откуда же взялись в сказках Пушкина такие странные имена?

А взялись они из самой популярной в дореволюционной России былины под названием «Повесть о Бове Королевиче»

Это сейчас мы считаем самыми популярными былинными героями Илью Муромца, Добрыню Никитича и Алёшу Поповича, а до революции эти три богатыря уступали пальму первенства Бове Гвидоновичу

В основу повести о Бове лег рыцарский роман Андреа да Барберино «Французские короли» (итал. I reali di Francia), написанный ок. 1400 года. Одна из частей романа посвящена Бэву из Антона или Буово Антонскому (итал. Bovo d’Antona), основателю домов Кьярамонте и Монграны и прототипу русского Бовы Королевича.

И в этой «Bovo d’Antona» действующии героями являются некие герои Duodo di Maganza (будущий Дoдон / Дaдон) и герцог Guido d’Antoni (будущий Гвидон). Салтана (султана) там нет, это уже была русская доработка. Еще в этом романе есть персонаж Пуликане (Pulicane) — полупёс, получеловек.

Текст «Bovo d’Antona» был переведен в Княжестве Литовском, а уже оттуда через северные русские княжества распространился на русских землях

Попав в Россию, история о Бове трансформировалась в большое количество местных былин и сказаний, дополнилась местными персонажами, некоторые персонажи или трансформировались, или заменили каких-то более древних персонажей (Полкан, например, с одной стороны в повести о Бове из полупса стал полуконем, заменив более древнее существо Китовраса, а с другой стороны в южных былинах стал одним из богатырей киевского князя или, наоборот, стал ассоциириваться с Идолищем Поганым).

Кроме того, персонажи историй о Бове разбрелись по русским народным сказкам. Hе то, чтобы имена типа Дадона стали общеупотребительными и распространенными, но встречались иногда.

В XVII — начале XX века герои «Повести и Бове Королевиче» стали источником огромного пласта народного искусства, в первую очередь лубочного. и некоторые из этих образов сохранились (лучше всего сохранялся лубок на мебели, всяких сундуках)

Слева «Король Гвидон» 1700-1725 Ксилография (резьба по дереву) 1700-1725 гг. Российская национальная библиотека Спб. Справа раскрашенный лубок XIX века по этой картинке.

Как видим, сплошные битвы. И Гвидон с Салтаном в этой истории самые настоящие воины. А вот Дадон нет, Дадон своего добивается не в честном бою, а обманом и предательством.

1881 Салтан Салтанович. Лист № 29 (слева) и Лист № 28 (справа) из I тома сборника Д.А. Ровинского «Русские народные картинки» 1881 год. Государственный музей истории российской литературы имени В.И. Даля

Бова Королевич и Полкан (сказочный лубок) 1860 г.

Былины и повесть о Бове были популярны не только в русском лубке и в народной среде, но и у русской знати. Пушкин безусловно знал эту историю, он в 14-летнем возрасте написал стихотворение «Сон» (1813 г) и там Бову упомянул. Стихотворение очень длинное, вот отрывок:

Я сам не рад болтливости своей,

Но детских лет люблю воспоминанье.

Ах! умолчу ль о мамушке моей,

О прелести таинственных ночей,

Когда в чепце, в старинном одеянье,

Она, духов молитвой уклони,

С усердием перекрестит меня

И шепотом рассказывать мне станет

О мертвецах, о подвигах Бовы…

От ужаса не шелохнусь, бывало,

Едва дыша, прижмусь под одеяло,

Не чувствуя ни ног, ни головы.

И вот в 1831 году Пушкин пишет «Сказку о царе Салтане, о сыне его славном и могучем богатыре князе Гвидоне Салтановиче и о прекрасной царевне Лебеди», которую кратко принято называть «Сказкой о царе Салтане». Но вообще-то слово богатырь там не просто так упомянуто, для Пушкина Салтан и Гвидон были некими рыцарями-витязями-богатырями, которые умели воевать и побеждать. И визуально они, наверное, даже были в доспехах, а не в одежде XVII века с полуметровыми шапками, шубами и кафтанами в цветочек и ягодки и рукавами до пола.

А в 1834 году Пушкин пишет «Сказку о золотом петушке», главный герой которой царь Дадон хоть и мерзкий старикашка, лгун и обманщик, но в молодости любил повоевать и был успешен, иначе враги со всех сторон на его царство не ходили бы, пытаясь отбитое обратно отбить. Сюжет «Сказки о золотом петушке» с приключениями Бовы ничего общего не имеет, но вот по характеру и личным качествам Дадоны похожи.

Во времена Пушкина книги печатали в основном неиллюстрированные, даже сказки, поэтому первые сказочные изображения пушкинских героев относятся к 1880-м годам, откуда они постепенно начинают эволюционировать в лубок и шубы с розочками (смотри верхние картинки, на которых изображены вроде как «могучие богатыри» согласно Пушкину)

О том, как и почему так получилось, в следующий раз.

Продолжение следует (на следующей неделе)

Предки А.С. Пушкина по мужской линии особенно громко заявили о себе в русской истории в XVIIв. Как пишет сам поэт в своих автобиографических материалах и воспоминаниях, «в числе знатных родов историограф именует и Пушкиных. Гаврило Гаврилович Пушкин принадлежит к числу самых замечательных лиц в эпоху самозванцев. Четверо Пушкиных подписались под грамотою об избрании на царство Романовых, а один из них, окольничий Матвей Степанович, — под соборным уложением об уничтожении местничества. При Петре Первом сын его, стольник Федор Матвеевич, уличен был в заговоре против государя и казнен» (Пушкин, т.VII, с.134-135). По материнской линии прадед Пушкина Ибрагим Петрович Ганнибал — знаменитый «арап Петра Первого».

Столь яркая родословная не могла не вызвать в А.С.Пушкине обостренное сознание причастности к жизни страны на самом решающем изломе ее истории. Общность судьбы собственных предков с судьбой русской самодержавной власти настраивала на образное восприятие самой этой власти в зримой художественной форме. Это ощущение и получило свое законченное выражение в сюжетной интриге «Сказки о царе Салтане».

Образ бочки — царь Петр открыл окно в Европу

Взять, к примеру, произносимые Гвидоном перед выходом из бочки слова:

Как бы здесь на двор окошко

Нам проделать?

Сразу же вспоминается, что той же «оконной» метафорой отмечены у Пушкина и слова Петра I во вступлении к поэме «Медный всадник»:

Природой здесь нам суждено

В Европу прорубить окно.

Символика выхода из тесной и темной бочки на вольный простор острова Буяна тоже могла бы стать предметом самостоятельного разговора, особенно в контексте известного высказывания Петра I: «Мы от тьмы к свету вышли..».

Образ острова Буяна — город Санкт-Петербург

Смысловой центр «Сказки о царе Салтане» после выхода Гвидона из бочки — это остров Буян. Петербург тоже был заложен на острове: «14-го царское величество изволил осматривать на взморье устья Невы острова, и усмотрел удобный остров к строению города <…> 24 мая на острову, которой ныне именуется Санкт-петербургской, царское величество повелел рубить лес и изволил обложить дворец» (из документа «О зачатии и здании Царствующего града Санкт-Петербурга»).

Значение имени «Буян» включает в себя, по словарю В.И.Даля, не только понятия «отваги», «удали», «дерзости», но и понятия «торговой площади», «базара», «рынка», «пристани как места погрузки и выгрузки товаров». В этом смысле новоявленный Петербург был, по сути своей, не чем иным как огромным единым Буяном.

Самое же интересное: понимание Санкт-Петербурга как Буяна, оказывается, реально отразилось в первоначальной островной топономике города: «буянами», как известно, назывались многие мелкие острова в дельте Невы, и именно на них располагались первоначальные пристани складские помещения для хранения товаров. Сейчас эти острова отошли частью к территории Петровского острова, а частью — к территории Петроградской стороны, Васильевского и некоторых других островов; но еще в первой половине XX века память о них бытовала в живом употреблении названий «Тучков буян», «Сельдяной буян» и т.д. В предпушкинские же времена понятие «остров Буян» существовало как повседневная санкт-петербургская реалия.

Так, в труде самого первого историка города А.Богданова читаем: «Остров Буян, новопрозванной, лежит на Малой Невке…. А какой ради причины назван Буян, того знать нельзя..»; «На Буяне острове построены были пеньковые амбары; оные ныне, в в 1761 году июня 27 дня, сгорели, и на место оных начинаются в 1762 году новые амбары строится каменные». (Титов А.А. Дополнения к историческому, географическому и топографическому описанию Санкт-Петербурга с 1751 по 1762 год, сочиненному А.Богдановым. М.. 1903, с.21-22).

Образ дуба — на островах Санкт-Петербурга росло множество дубов, нетипичных для этой полосы

Гвидон с матерью вышли из бочки и видят:

Море синее кругом,

Дуб зеленый над холмом.

Описание острова Буяна корабельщиками:

В море остров был крутой,

Не привальный, не жилой;

Он лежал пустой равниной,

Рос на нем дубок единый.

Спрашивается: откуда здесь, в краю березы, ели и сосны, не характерный для данного климатического пояса дуб? Но оказывается, что «все острова, составляемые протоками Невы при ее устьях, у новгородцев носили название Фомени, от испорченного финского слова Tamminen — дубовый. В старину в здешних лесах дуб составлял редкость; на петербургских же островах он встречался во множестве, о чем свидетельствуют еще до сего времени растущие на Елагином и Каменном островах пятисотлетние огромные дубы» (Пыляев М.И. Старый Петербург: рассказы из былой жизни столицы. Спб., 1889, с.4)

Гвидон убивает коршуна — реальный исторический факт

Тот уж когти распустил,

Клёв кровавый навострил…

Но как раз стрела запела,

В шею коршуна задела —

Коршун в море кровь пролил,

Лук царевич опустил;

Эта деталь прямо соотносится с легендой об основании Петербурга. 16 мая 1703г. при закладке памятного камня на острове, Петр I вырезал из земли два курска дерна, сложил их крестообразно и сказал: «Здесь быть городу». В это время в воздухе появился орел и стал парить над царем, сооружавшим из двух тонких длинных берез, связанных верхушками, нечто вроде арки. Парящий в небе орел опустился с высоты и сел на эту арку, а один из солдат снял его выстрелом из ружья. «Петр был очень рад этому, видя в нем доброе презнаменование, перевязал у орла ноги платком, посадил себе на руку и, сев на яхту с орлом в руке, отплыл к Канцам; в этот день все чины были пожалованы столом, веселье продолжалось до двух часов ночи, при пушечной пальбе». (Пыляев М.И. Старый Петербург: рассказы из былой жизни столицы. Спб.. 1889. с.10). Н.Анциферов так комментирует легенду: «Перед нами основатель города в понимании античной религии. Невольно вспоминается Ромул в момент основания Рима на Палатинском холме, когда 12 коршунов парило над его головою» (Анциферов Н.П. Быль и миф Петербурга. С.28).

Город за одну ночь — метафора о стремительном строительстве Санкт-Петербурга

Вот открыл царевич очи;

Отрясая грезы ночи

И дивясь, перед собой

Видит город он большой,

Стены с частыми зубцами,

И за белыми стенами

Блещут маковки церквей

И святых монастырей.

И эта деталь целиком соотносима с историей Петербурга, строившегося «с такой быстротою, что скоро все совершенно кишело людьми, местность необычайно быстро заселялась, и по числу домов и людей теперь едва ли уступит какому-нибудь германскому городу» (Беспятых Ю.Н. Петербург Петра I в иностранных описаниях. Л., 1991, с.104).

Еще деталь. Корабельщики описывают остров Буян:

Все в том острове богаты,

Изоб нет, везде палаты;

Как же тут не вспомнить о строжайших указах Петра I, направленных на усиленное снабжение новой российской столицы строительным камнем. В анонимной брошюре, изданной в Германии в самом начале VIIIв. под названием «Краткое описание большого императорского города Санкт-Петербурга», говорится, что «дома в городе прежде были деревянными, а теперь в большинстве своем каменные» (Беспятых Ю.Н. Петербург Петра I в иностранных описаниях. Л., 1991, с.264).

20 октября 1714 года царь Петр I издал Указ о запрещении каменного строительства по всей России, кроме Санкт-Петербурга. В городе же на Неве строго предписывалось возведение исключительно каменных «образцовых домов». Отныне во всех городах, кроме Санкт-Петербурга, строительство каменных домов стало строго караться. Легким росчерком пера царь оставил без работы тысячи каменщиков по всей России.

Расчет был прост: каменщики в поисках способа прокормить семью будут вынуждены отправиться на поиски лучшей доли в новую столицу, где и продолжат заниматься любимым делом. А их опыт и мастерство позволит новой российской столице как можно быстрее стать вровень со столицами других европейских городов.

Гвидона венчают на царство — Петра I провозглашают императором

Лишь ступили за ограду,

Оглушительный трезвон

Поднялся со всех сторон:

К ним народ навстречу валит,

Хор церковный бога хвалит;

В колымагах золотых

Пышный двор встречает их;

Все их громко величают

И царевича венчают

Княжей шапкой, и главой

Возглашают над собой;

И среди своей столицы,

С разрешения царицы,

В тот же день стал княжить он

И нарекся: князь Гвидон.

Здесь просто неизбежна аналогия с заметками Пушкина к «Истории Петра Великого»: «Сенат и Синод подносят ему титул отца отечества, всероссийского императора и Петра Великого. Петр недолго церемонился и принял его» (Пушкин, т.IX, с.287).

Образ Ткачихи — это Англия «ткацкая мастерская всего мира». Повариха — Франция. Бабариха — Австрия

Три девицы под окном

Пряли поздно вечерком.

«Кабы я была царица, —

Говорит одна девица, —

То на весь крещеный мир

Приготовила б я пир».

«Кабы я была царица, —

Говорит ее сестрица, —

То на весь бы мир одна

Наткала я полотна».

Ткачиха, Повариха и сватья баба Бабариха — в этих образах легко узнаются «визитки» главных европейских держав предпушкинской и пушкинской поры. В самом деле: Ткачиха — это, вне всякого сомнения, Англия, «ткацкая мастерская всего мира», каковой она обычно изображается во всех изданиях всемирной истории. Достаточно напомнить, что первый прибывший в Санкт-Петербург английский торговый корабль был нагружен исключительно полотном.

Повариха — это Франция, слывшая в Европе XVII-XIXвв. законодательницей кулинарной моды и заполнившая французскими поварами (образ, известный и по русской классической литературе) весь цивилизованный мир того времени.

А сватья баба Бабариха — это третья главная держава Европы XVII-XIXвв. — Священная Римская империя германской нации. Почему «сватья»? Потому что ядро империи — Австрийское владение Габсбургов — «соединилось в одно целое посредством ряда наследств и брачных договоров» (Данилевский Н.Я. Россия и Европа. М., 1991, с.335), а его история — это история «сцепления разных выморочных имений, отдаваемых в приданое» (там же с.330). Известен был даже посвященный этому «ядру» латинский стих, так звучавший в переводе на русский: «Пускай другие воюют; ты же, блаженная Австрия, заключай браки» (там же). Да и выбор имени Бабариха был несомненно продиктован его очевидным звуковым сходством с названием Боварии — страны, положившей историческое начало всей данной политической кристаллизации (выделением из Боварии в 1156г. была впервые образована как самостоятельное герцогство и сама Австрия). Хотя само по себе имя «Бабариха» восходит к русской фольклорной традиции — оно заимствовано Пушкиным из опубликованного в 1818г сборника Кирши Данилова.

Если все эти аналогии верны, то в избраннице царя Салтана придется признать Россию.

Чудеса в сказке: Белочка, 33 богатыря, Царевна-Лебедь — это болевые точки главных европейских держав

Интересно, что тетки Гвидона реагируют на новость о чудном острове в полном соответствии с со своей специфической ролью в политическом раскладе Европы начала XVIIIв. Как говориться, «у кого что болит, тот о том и говорит».

Повариха — Франция — Финансы — Белочка

Что «болит» у Поварихи-Франции? Известно, что самым актуальным вопросом для этого королевства в начале XVIIIв. был финансовый: экономика страны, ожившая после недавнего глубокого кризиса под воздействием только что проведенной денежной реформы, переживала так называемое «экономическое чудо». Правда, оно длилось недолго: уже в 1720г. страна, злоупотребившая эмиссией бумажных денег, снова вошла в полосу жестокого кризиса. Поэтому Повариха говорит, что настоящим чудом следует считать не новый город, а лишь волшебную белку, способную приносить ее владельцу сказочный доход.

«Уж диковинка, ну право, —

Подмигнув другим лукаво,

Повариха говорит, —

Город у моря стоит!

Знайте, вот что не безделка:

Ель в лесу, под елью белка,

Белка песенки поет

И орешки всё грызет,

А орешки не простые,

Всё скорлупки золотые,

Ядра — чистый изумруд;

Вот что чудом-то зовут».

Ткачиха — Англия — Морской флот — 33 богатыря

По аналогии можно интерпретировать образ Ткачихи. У Англии начала XVIIIв имелось только одно больное место — опасение, что кто-то может оспорить ее статус «владычицы морей». Соответственно, «идея фикс» Ткачихи — это морской флот, с которым мы ассоциируем образ тридцати трех богатырей. Поэтому Ткачиха говорит, что чудом следует считать не Белочку с золотыми орехами, а только лишь военную стражу, обитающую в море и охраняющую сушу.

Усмехнувшись исподтиха,

Говорит царю ткачиха:

«Что тут дивного? ну, вот!

Белка камушки грызет,

Мечет золото и в груды

Загребает изумруды;

Этим нас не удивишь,

Правду ль, нет ли говоришь.

В свете есть иное диво:

Море вздуется бурливо,

Закипит, подымет вой,

Хлынет на берег пустой,

Разольется в шумном беге,

И очутятся на бреге,

В чешуе, как жар горя,

Тридцать три богатыря,

Все красавцы удалые,

Великаны молодые,

Все равны, как на подбор,

С ними дядька Черномор.

Это диво, так уж диво,

Можно молвить справедливо!»

Реакция Гвидона на слова Ткачихи — около острова Буяна появляется морская стража. Прообраз этой метафоры очевиден. При Петре I русский флот и армия стали считаться одними из сильнейших во всем мире. Создание флота оказало сильное влияние на развитие торговли. Так как стало возможно осуществлять торговлю по морским путям. Также создание северных портов и флота на Балтике позволило осуществлять сообщение с Европой. Флот расширил и укрепил границы Российской империи.

С того времени, как Россия создала военно-морской флот, появилась возможность обезопасить торговые морские пути, развивать новые порты и прежде всего Петербургский. В 1725 году в город на Неве прибыло 450 иностранных кораблей. Таким образом, город, сотворенный Петром, стал не только политическим, но и международным экономическим центром.

Под дядькой Черномором скрывается, конечно, Федор Матвеевич Апраксин (1671-1728), генерал-адмирал русского флота, знаменитый сподвижник Петра. «Черномором» он назван потому, что был главным распорядителем работ по созданию первого русского, так называемого черноморского флота в Воронеже и Азове. А «дядькой» — потому, что этот термин официально означал в допетровской и петровской Руси должность «опекуна».

Бабариха — Австрия — Народ — Царевна-Лебедь

Повариха и ткачиха

Ни гугу — но Бабариха

Усмехнувшись говорит:

«Кто нас этим удивит?

Люди из моря выходят

И себе дозором бродят!

Правду ль бают, или лгут,

Дива я не вижу тут.

В свете есть такие ль дива?

Вот идет молва правдива:

За морем царевна есть,

Что не можно глаз отвесть:

Днем свет божий затмевает,

Ночью землю освещает,

Месяц под косой блестит,

А во лбу звезда горит.

А сама-то величава,

Выплывает, будто пава;

А как речь-то говорит,

Словно реченька журчит.

Молвить можно справедливо,

Это диво, так уж диво»

Решающий тест на тождество Бабарихи и Австрии — это утверждение Бабарихи, что настоящим чудом следует считать не морскую стражу, а заморскую царевну неслыханной красоты.

Но чтобы понять скрытый смысл этого утверждения, нужно знать, в чем заключалась основная «головная боль» Австрии как государственно-управленческой системы. А заключалась она в том, что собственно австрийская часть империи Габсбургов была не органически возникшей и естественно развивающейся формой государственного самовыражения немецкого народа, а рыхлым эклектическим соединением германских, славянских, венгерских и других земель разного политического статуса и веса. Самое же главное противоречие заключалось не просто в разнородном национальном составе населения страны, но и в чисто искусственной организации отношений между ее господствующим немецким меньшинством и бесправным многонациональным большинством. Особенно напряженные отношения сложились у Австрийского правительства со своими славянскими подданными (с народами Богемии, Моравии, Галиции, Ладомирии, Буковины, Каринтии, Крайны, Далмации, Истрии, Хорватии, Словении), которые хотя и образовывали подавляющее большинство населения империи (почти 50%), но были разобщены и потому бесправны.

При таких заведомо антагонистических отношениях со своими «варварскими» подданными австрийское правительство могло лелеять одну-единственную политическую «идею фикс» — мечту об «идеальном» для своей власти народе, то есть мечту о таких «цивилизованных» подданных, с которыми у правительства не возникало бы никаких проблем. И Бабариха говорит о Царевне-лебеди.

Нужно иметь в виду, что олицетворение «идеального (для власти) народа» в образе «царевны» вовсе не является личным художественным изобретением Пушкина. Поэт воспользовался здесь очень древним фольклорно-мифологическим архетипом, трактующим «народ» как «царскую половину» или «супругу» (в русском языке такая трактовка «народа» до сих пор живет в выражении «венчаться на царство», то есть в представлении о «венце» как о символе обладания не только «супругой», но и «царством» — совокупностью царских подданных.

Ответ на вызов «сватьи» известен: импульс, приданный петровскими реформами России, если и не навсегда покончил с западным представлением о ней как о стране «варваров», то существенно умерил пренебрежительное отношение Европы к России. А то, что образ царевны Лебеди служит в сказке символическим олицетворением русского народа, доказывается словами царевны: «Ты найдешь меня повсюду».

Действительно, и строительством города в устье Невы, и средствами на войну, и флотом, и победами — всем этим Петр I был обязан русскому народу. «Никогда ни один народ не совершал такого подвига, который был совершен русским народом под руководством Петра; история ни одного народа не представляет такого великого, многостороннего, даже всенародного преобразования, сопровождавшегося столь великими последствиями как для внутренней жизни народа, так и для его значения в общей жизни народов. во всемирной истории» (Ключевский, т.IV, с.187).

Можно, конечно, оспаривать превосходные степени данного утверждения («никогда», «ни один») как извинительное на почве национальной гордости преувеличение. Можно также оспаривать ценность петровских преобразований или качество их последствий для русского народа. Но невозможно оспорить тот главный факт, что все совершенное русским народом при Петре I и под его руководством — действительно похоже на чудо.

Образы Комара, Мухи и Шмеля — это заграничные путешествия Петра I

Чрезвычайно многообещающе выглядит сюжетная аналогия «Сказки о царе Салтане», где Гвидон, принимая облик комара, мухи и шмеля, посещает заморские страны с их обитателями — Ткачихой, Поварихой и сватьей бабой Бабарихой.

Будь же, князь, ты комаром».

И крылами замахала,

Воду с шумом расплескала

И обрызгала его

С головы до ног всего.

Тут он в точку уменьшился,

Комаром оборотился

Совершенно очевидно, что здесь напрашивается аналогия с неоднократными заграничными путешествиями Петра I: в Германию, Голландию, Англию и Австрию — во время Великого посольства 1697-1698гг., и в Голландию и Францию — в 1717г. Оправдывается аналогия прежде всего манерой поведения Петра во время этих путешествий — его постоянным стремлением умалиться (в первом путешествии он вообще присутствовал в посольстве инкогнито — под именем урядника Петра Михайлова, а во втором, хотя уже и не скрывал своего имени и достоинства, но тоже поражал европейцев равнодушием к роскоши и церемониалу).

И опять она его

Вмиг обрызгала всего.

Тут он очень уменьшился,

Шмелем князь оборотился

Образ белочки — это финансовая и налоговая реформы Петра I

В «Сказке о Царе Салтане» образ белки, грызущей чудесные орешки и тем самым приносящей князю прибыль, обнаруживает явное отношение к финансово-экономической проблематике.

Князь Гвидон ей отвечает:

«Грусть-тоска меня съедает;

Чудо чудное завесть

Мне б хотелось. Где-то есть

Ель в лесу, под елью белка;

Диво, право, не безделка —

Белка песенки поет,

Да орешки всё грызет,

А орешки не простые,

Всё скорлупки золотые,

Ядра — чистый изумруд;

Но, быть может, люди врут».

Ответом Гвидона на вызов Поварихе явилась, как мы знаем, кардинальная перестройка налоговой системы страны. «Новый оклад подушной (о оброчной) подати с огромным излишком заменил все старые оклады прямых податей — табельных, погодных, запросных. Все они вместе составляли 1.8 млн руб., тогда как подушная (и оброчная) подать давала 4.6 миллиона; общий же итог государственных доходов по окладу поднялся с 6 до 8,5 миллионов. Почти теми же цифрами выражалось и увеличение текущих годичных поступлений. Такая прибавка к старым доходам развязала руки правительству для более правильного обеспечения главных государственных расходов» (Милюков П.Н. Государственное хозяйство России в первой четверти XVIII столетия и Реформа Петра Великого. СПб, 1892, с.726).

Князь для белочки потом

Выстроил хрустальный дом,

Караул к нему приставил

И притом дьяка заставил

Строгий счет орехам весть.

Князю прибыль, белке честь.

Если принять во внимание, что «дьяк» — это древнерусское терминологическое обозначение государственного чиновника, то едва ли придется усомниться, о каком «доме» идет речь. Финансовая реформа, предполагавшая перестройку всего правительственного аппарата, вызвала к жизни, в частности, появление такого небывалого прежде на Руси государственного учреждения, как Сенат с 12ю коллегиями.

В указе Петра об учреждении Сената говорится: «Смотреть во всем государстве расходов, и ненужные, а особливо напрасные, отставить. Денег как можно собирать, понеже деньги суть артерии войны» (Якобсон Н. Русский Сенат (в первое время по учреждении). СПб. 1897. с.10). Сенат задуман Петром как учреждение, осуществляющее высший надзор за расходами, заботу об умножении доходов, об улучшении качества казенных товаров, о векселях, торговле и т.д.

У Пушкина не случайно сказано, что хрустальный дом для белочки был выстроен «потом». Самый первый размещался, как известно, в Москве, потом переехал в Санкт-Петербург, где тоже долго не имел постоянного адреса. И наконец, получил постоянную «Квартиру» во дворце Бестужева. Интересная деталь: открытая аркада вдоль фасада этого здания была остеклена (по одним данным, при Екатерине II, а по другим при Николае I). Не это ли, необычное для того времени, архитектурное решение дало Пушкину назвать дом для белки хрустальным? Хотя скорее всего речь идет об указе Петра от 1715 года, согласно которому в Петербурге были заведены хрустальная и стекольная фабрики (Пушкин, т.X, с.247). Как символ новых российских технологий, это заведение вполне могло вдохновить творческое воображение Пушкина на создание образа «хрустального дома».

Работа с художественным текстом на продвинутом этапе обучения РКИ.

Советский филолог Дмитрий Сергеевич Лихачев так вспоминал о своем обучении в университете: «Пропагандистом медленного чтения был академик Щерба. Мы с ним за год успевали прочесть только несколько строк из „Медного всадника“. Каждое слово представлялось нам как остров, который нам надо было открыть и описать со всех сторон».

Лихачев Д.С.: «Самое печальное, когда люди читают и незнакомые слова их не заинтересовывают, они пропускают их, следят только за движением интриги, за сюжетом, но не читают вглубь. Надо учиться не скоростному, а медленному чтению. У Щербы я научился ценить наслаждение от медленного чтения»

Учебный центр русского языка готовит преподавателей русского языка как иностранного (РКИ). Посмотрите запись Лектория для преподавателей РКИ. В этой лекции мы поговорили об одном из самых востребованных, интересных, но при этом непростых видов работы на занятиях по РКИ — чтению художественного текста с иностранцами, владеющими русским языком на уровнях В2-С1. Лектор Ольга Эдуардовна Чубарова, доцент кафедры РКИ Московского государственного лингвистического университета.

Программа «Методика преподавания русского языка как иностранного»

В программе очного курса «Методика преподавания РКИ» 4 лекции отведены изучению художественного текста. Эти лекции читает Елена Вячеславовна Макеева – кандидат филологических наук, доцент кафедры русского языка как иностранного в профессиональном обучении института филологии МПГУ

Раздел «Художественный текст на занятиях по РКИ» включает темы:

- Учебные пособия по работе с художественным текстом.

- Методики работы с художественным текстом. Цель – контингент – среда.

- Виды чтения. Типы заданий и упражнений.

- Адаптация и комментирование художественного текста.

- Технологии самостоятельной подготовки материалов по обучению чтению художественного текста в иностранной аудитории.

- И уникальный блок. Художественный текст во внеаудиторных формах работы: технологии проведения экскурсий по литературным местам, викторины и квесты. Разработка внеаудиторного занятия. Слушатели очного курса приглашаются на живые экскурсии с иностранцами.

Интересно стать преподавателем русского языка как иностранного? Регистрируйтесь на очную программу.

Источники:

- Горюнков Сергей «Герменевтика пушкинских сказок». СПб, Алетейя, 2009

- «Я живу с ощущением расставания…». Газета «Комсомольская правда». 1996. 5 марта.

Содержание:

- Кем является персонаж и где живет?

- Внешность и характер

- Поступки царя Салтана и их оценка

- Отношение автора к своему герою

Кем является персонаж и где живет?

Салтан считается главенствующей фигурой в царстве, где проходят основные события детской сказки именитого русского писателя. Известно, что его владения широкие, глубокие и бескрайние. Народ его любит за справедливость и честность, и каждого великий правитель готов принять в собственном дворце, в котором живет вместе с семьей и слугами.

Внешность и характер

К сожалению, в стихотворных началах детского произведения не дается точное описание внешности великого правителя, любимого всеми поданными, однако исходя из его поступков, достижений и деяний можно поговорить о его основных внутренних характерных чертах.

Царя Салтана, безусловно, можно назвать добросердечным, праведным, открытым, искренним и наивным человеком, который старается в каждом отыскать светлые образы.

Поступки царя Салтана и их оценка

Читая Сказку о царе Салтане, можно составить краткий пересказ основных деяний главного героя:

-

он простил сестер царицы, несмотря на то, что они привнесли зло в дорогое царство — этот поступок является демонстрацией его доброты;

-

он принимал участие в устроенных военных походах наравне с собственной дружиной — этот поступок является демонстрацией его смелости;

-

он с легкостью верил приближенным лицам, что привело к бедам и трагедиям в царстве — этот поступок является демонстрацией его слабохарактерности и наивности.

Отношение автора к своему герою

Русский поэт и прозаик в положительном ключе рассказывает о царе Салтане. Безусловно, он принес немало страданий людям, которые его любили, из-за наивности и легкой необразованности. Однако он с чуткостью и справедливостью относился ко всем, кто его окружает. Это преимущество, бесспорно, перекрывает его недостатки.

Образ царя Салтана — творческая работа, которая зачастую задается в качестве домашнего задания ученикам младших классов. Мы надеемся, что наш пример позволит вам получить высокие результаты и впечатлить классного руководителя.

| The Tale of Tsar Saltan | |

|---|---|

The mythical island of Buyan (illustration by Ivan Bilibin). |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Tale of Tsar Saltan |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 707, «The Three Golden Children» |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Сказка о царе Салтане (1831), by Александр Сергеевич Пушкин (Alexander Pushkin) |

| Related | The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird |

The Tale of Tsar Saltan, of His Son the Renowned and Mighty Bogatyr Prince Gvidon Saltanovich, and of the Beautiful Princess-Swan (Russian: «Сказка о царе Салтане, о сыне его славном и могучем богатыре князе Гвидоне Салтановиче и о прекрасной царевне Лебеди», tr. Skazka o tsare Saltane, o syne yevo slavnom i moguchem bogatyre knyaze Gvidone Saltanoviche i o prekrasnoy tsarevne Lebedi listen (help·info)) is an 1831 fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin. As a folk tale it is classified as Aarne–Thompson type 707, «The Three Golden Children», for it being a variation of The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.[1]

Synopsis[edit]

The story is about three sisters. The youngest is chosen by Tsar Saltan (Saltán) to be his wife. He orders the other two sisters to be his royal cook and weaver. They become jealous of their younger sister. When the tsar goes off to war, the tsaritsa gives birth to a son, Prince Gvidon (Gvidón). The older sisters arrange to have the tsaritsa and the child sealed in a barrel and thrown into the sea.

The sea takes pity on them and casts them on the shore of a remote island, Buyan. The son, having quickly grown while in the barrel, goes hunting. He ends up saving an enchanted swan from a kite bird.

The swan creates a city for Prince Gvidon to rule, which some merchants, on the way to Tsar Saltan’s court, admire and go to tell Tsar Saltan. Gvidon is homesick, so the swan turns him into a mosquito to help him. In this guise, he visits Tsar Saltan’s court. In his court, his middle aunt scoffs at the merchant’s narration about the city in Buyan, and describes a more interesting sight: in an oak lives a squirrel that sings songs and cracks nuts with a golden shell and kernel of emerald. Gvidon, as a mosquito, stings his aunt in the eye and escapes.

Back in his realm, the swan gives Gvidon the magical squirrel. But he continues to pine for home, so the swan transforms him again, this time into a fly. In this guise Prince Gvidon visits Saltan’s court again and overhears his elder aunt telling the merchants about an army of 33 men led by one Chernomor that march in the sea. Gvidon stings his older aunt in the eye and flies back to Buyan. He informs the swan of the 33 «sea-knights», and the swan tells him they are her brothers. They march out of the sea, promise to be guards and watchmen of Gvidon’s city, and vanish.

The third time, the Prince is transformed into a bumblebee and flies to his father’s court. There, his maternal grandmother tells the merchants about a beautiful princess that outshine both the sun in the morning and the moon at night, with crescent moons in her braids and a star on her brow. Gvidon stings her nose and flies back to Buyan.

Back to Buyan, he sighs over not having a bride. The swan inquires the reason, and Gvidon explains about the beautiful princess his grandmother described. The swan promises to find him the maiden and bids him await until the next day. The next day, the swan reveals she is the same princess his grandmother described and turns into a human princess. Gvidon takes her to his mother and introduces her as his bride. His mother gives her blessing to the couple and they are wed.

At the end of the tale, the merchants go to Tsar Saltan’s court and, impressed by their narration, decides to visit this fabled island kingdom at once, despite protests from his sisters- and mother-in-law. He and the court sail away to Buyan, and are welcomed by Gvidon. The prince guides Saltan to meet his lost Tsaritsa, Gvidon’s mother, and discovers her family’s ruse. He is overjoyed to find his newly married son and daughter-in-law.

Translation[edit]

The tale was given in prose form by American journalist Post Wheeler, in his book Russian Wonder Tales (1917).[2] It was translated in verse by Louis Zellikoff in the book The Tales of Alexander Pushkin (The Tale of the Golden Cockerel & The Tale of Tsar Saltan) (1981).[3]

Analysis[edit]

Classification[edit]

The versified fairy tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as tale type ATU 707, «The Three Golden Children». It is also the default form by which the ATU 707 is known in Russian and Eastern European academia.[4][5] Folklore scholar Christine Goldberg identifies three main forms of this tale type: a variation found «throughout Europe», with the quest for three magical items (as shown in The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird); «an East Slavic form», where mother and son are cast in a barrel and later the sons build a palace; and a third one, where the sons are buried and go through a transformation sequence, from trees to animals to humans again.[6]

In a late 19th century article, Russian ethnographer Grigory Potanin identified a group of Russian fairy tales with the following characteristics: three sisters boast about grand accomplishments, the youngest about giving birth to wondrous children; the king marries her and makes her his queen; the elder sisters replace their nephews for animals, and the queen is cast in the sea with her son in a barrel; mother and son survive and the son goes after strange and miraculous items; at the end of the tale, the deceit is revealed and the queen’s sisters are punished.[7]

French scholar Gédeon Huet considered this format as «the Slavic version» of Les soeurs jalouses and suggested that this format «penetrated into Siberia», brought by Russian migrants.[8]

Russian tale collections attest to the presence of Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore, as the antagonist in many of the stories.[9]

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva suggests that this format must have developed during the period of the Kievan Rus, a period where an intense fluvial trade network developed, since this «East Slavic format» emphasizes the presence of foreign merchants and traders. She also argues for the presence of the strange island full of marvels as another element.[10]

Rescue of brothers from transformation[edit]

In some variants of this format, the castaway boy sets a trap to rescue his brothers and release them from a transformation curse. For example, in Nád Péter («Schilf-Peter«), a Hungarian variant,[11] when the hero of the tale sees a flock of eleven swans flying, he recognizes them as their brothers, who have been transformed into birds due to divine intervention by Christ and St. Peter.

In another format, the boy asks his mother to prepare a meal with her «breast milk» and prepares to invade his brothers’ residence to confirm if they are indeed his siblings. This plot happens in a Finnish variant, from Ingermanland, collected in Finnische und Estnische Volksmärchen (Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne, or «Brother and Sister, and the golden-haired sons of the King»).[12] The mother gives birth to six sons with special traits who are sold to a devil by the old midwife. Some time later, their youngest brother enters the devil’s residence and succeeds in rescuing his siblings.

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva argues that the use of «mother’s milk» or «breast milk» as the key to the reversal of the transformation can be explained by the ancient belief that it has curse-breaking properties.[10] Likewise, scholarship points to an old belief connecting breastmilk and «natal blood», as observed in the works of Aristotle and Galen. Thus, the use of mother’s milk serves to reinforce the hero’s blood relation with his brothers.[13] Russian professor Khemlet Tatiana Yurievna describes that this is the version of the tale type in East Slavic, Scandinavian and Baltic variants,[14] although Russian folklorist Lev Barag [ru] claimed that this motif is «characteristic» of East Slavic folklore, not necessarily related to variants of tale type 707.[15]

Mythological parallels[edit]

This «Slavic» narrative (mother and child or children cast into a chest) recalls the motif of «The Floating Chest», which appears in narratives of Greek mythology about the legendary birth of heroes and gods.[16][17] The motif also appears in the Breton legend of saint Budoc and his mother Azénor: Azénor was still pregnant when cast into the sea in a box by her husband, but an angel led her to safety and she gave birth to future Breton saint Budoc.[18]

Central Asian parallels[edit]

Following professor Marat Nurmukhamedov’s (ru) study on Pushkin’s verse fairy tale,[19] professor Karl Reichl (ky) argues that the dastan (a type of Central Asian oral epic poetry) titled Šaryar, from the Turkic Karakalpaks, is «closely related» to the tale type of the Calumniated Wife, and more specifically to The Tale of Tsar Saltan.[20][21]

Variants[edit]

Distribution[edit]

Russian folklorist Lev Barag [ru] attributed the diffusion of this format amongst the East Slavs to the popularity of Pushkin’s versified tale.[15]

Professor Jack Haney stated that the tale type registers 78 variants in Russia and 30 tales in Belarus.[22]

In Ukraine, a previous analysis by professor Nikolai Andrejev noted an amount between 11 and 15 variants of type «The Marvelous Children».[23] A later analysis by Haney gave 23 variants registered.[22]

Predecessors[edit]

The earliest version of tale type 707 in Russia was recorded in «Старая погудка на новый лад» (1794–1795), with the name «Сказка о Катерине Сатериме» (Skazka o Katyerinye Satyerimye; «The Tale of Katarina Saterima»).[24][25][26] In this tale, Katerina Saterima is the youngest princess, and promises to marry the Tsar of Burzhat and bear him two sons, their arms of gold to the elbow, their legs of silver to the knee, and pearls in their hair. The princess and her two sons are put in a barrel and thrown in the sea.

The same work collected a second variant: Сказка о Труде-королевне («The Tale of Princess Trude»), where the king and queen consult with a seer and learn of the prophecy that their daughter will give birth to the wonder-children: she is to give birth to nine sons in three gestations, and each of them shall have arms of gold up to the elbow, legs of silver up to the knee, pearls in their hair, a shining moon on the front and a red sun on the back of the neck. This prediction catches the interest of a neighboring king, who wishes to marry the princess and father the wonder-children.[27][28]

Another compilation in the Russian language that precedes both The Tale of Tsar Saltan and Afanasyev’s tale collection was «Сказки моего дедушки» (1820), which recorded a variant titled «Сказка о говорящей птице, поющем дереве и золо[то]-желтой воде» (Skazka o govoryashchyey ptitse, poyushchyem dyeryevye i zolo[to]-zhyeltoy vodye).[26]

Early-20th century Russian scholarship also pointed that Arina Rodionovna, Pushkin’s nanny, may have been one of the sources of inspiration to his versified fairy tale Tsar Saltan. Rodionovna’s version, heard in 1824, contains the three sisters; the youngest’s promise to bear 33 children, and a 34th born «of a miracle» — all with silver legs up to the knee, golden arms up to the elbows, a star on the front, a moon on the back; the mother and sons cast in the water; the quest for the strange sights the sisters mention to the king in court. Rodionovna named the prince «Sultan Sultanovich», which may hint at a foreign origin for her tale.[29]

East Slavic languages[edit]

Russia[edit]

Russian folklorist Alexander Afanasyev collected seven variants, divided in two types: The Children with Calves of Gold and Forearms of Silver (in a more direct translation: Up to the Knee in Gold, Up to the Elbow in Silver),[30][31] and The Singing Tree and The Speaking Bird.[32][33] Two of his tales have been translated into English: The Singing-Tree and the Speaking-Bird[34] and The Wicked Sisters. In the later, the children are male triplets with astral motifs on their bodies, but there is no quest for the wondrous items.

Another Russian variant follows the format of The Brother Quests for a Bride. In this story, collected by Russian folklorist Ivan Khudyakov [ru] with the title «Иванъ Царевичъ и Марья Жолтый Цвѣтъ» or «Ivan Tsarevich and Maria the Yellow Flower», the tsaritsa is expelled from the imperial palace, after being accused of giving birth to puppies. In reality, her twin children (a boy and a girl) were cast in the sea in a barrel and found by a hermit. When they reach adulthood, their aunts send the brother on a quest for the lady Maria, the Yellow Flower, who acts as the speaking bird and reveals the truth during a banquet with the tsar.[35][36]

One variant of the tale type has been collected in «Priangarya» (Irkutsk Oblast), in East Siberia.[37]

In a tale collected in Western Dvina (Daugava), «Каровушка-Бялонюшка», the stepdaughter promises to give birth to «three times three children», all with arms of gold, legs of silver and stars on their heads. Later in the story, her stepmother dismisses her stepdaughter’s claims to the tsar, by telling him of strange and wondrous things in a distant kingdom.[38] This tale was also connected to Pushkin’s Tsar Saltan, along with other variants from Northwestern Russia.[39]

Russian ethnographer Grigory Potanin gave the summary of variant collected by Romanov about a «Сын Хоробор» («Son Horobor»): a king has three daughters, the other has an only son, who wants to marry the youngest sister. The other two try to impress him by flaunting their abilities in weaving (sewing 30 shirts with only one «kuzhalinka», a fiber) and cooking (making 30 pies with only a bit of wheat), but he insists on marrying the third one, who promises to bear him 30 sons and a son named «Horobor», all with a star on the front, the moon on the back, with golden up to the waist and silver up to knees. The sisters replace the 30 sons for animals, exchange the prince’s letters and write a false order for the queen and Horobor to be cast into the sea in a barrel. Horobor (or Khyrobor) prays to god for the barrel to reach safe land. He and his mother build a palace on the island, which is visited by merchants. Horobor gives the merchants a cat that serves as his spy on the sisters’ extraordinary claims.[40]

Another version given by Potanin was collected in Biysk by Adrianov: a king listens to the conversations of three sisters, and marries the youngest, who promises to give birth to three golden-handed boys. However, a woman named Yagishna replaces the boys for a cat, a dog and a «korosta». The queen and the three animals are thrown in the sea in a barrel. The cat, the dog and the korosta spy on Yagishna telling about the three golden-handed boys hidden in a well and rescue them.[41]

In a Siberian tale collected by A. A. Makarenko in Kazachinskaya Volost, «О царевне и её трех сыновьях» («The Tsarevna and her three children»), two girls – a peasant’s daughter and Baba Yaga’s daughter – talk about what they would do to marry the king. The girl promises to give birth to three sons: one with legs of silver, the second with legs of gold, and the third with a red sun on the front, a bright moon on the neck, and stars braided in his hair. The king marries her. Near the sons’ delivery (in three consecutive pregnancies), Baba Yaga is brought to be the queen’s midwife. After each boy’s birth, she replaces them with a puppy, a kitten, and a block of wood. The queen is cast into the sea in a barrel with the animals and the object until they reach the shore. The puppy and the kitten act as the queen’s helper and rescue the three biological sons sitting on an oak tree.[42]

Another tale was collected from a 70-year-old teller named Elizaveta Ivanovna Sidorova, in Tersky District, Murmansk Oblast, in 1957, by Dimitri M. Balashov. In her tale, «Девять богатырей — по колен ноги в золоте, по локоть руки в серебре» («Nine bogatyrs — up to the knees in gold, up to the elbows in silver»), a girl promises to give birth to 9 sons with arms of silver and legs of gold, and the sun, moon, stars and a «dawn» adorning their heads and hair. A witch named yaga-baba replaced the boys with animals and things to trick the king. The queen is thrown in the sea with the animals, which act as her helpers. When yaga-baba, on the third visit, tells the king of a place where there are nine boys just as the queen described, the animals decide to rescue them.[43]

In a tale collected from teller A. V. Chuprov with the title «Федор-царевич, Иван-царевич и их оклеветанная мать» («Fyodor Tsarevich, Ivan Tsarevich and their Calumniated Mother»), a king passes by three servants and inquires them about their skills: the first says she can work with silk, the second can bake and cook, and the third says whoever marries her, she will bear him two sons, one with hands covered in gold and legs in silver, a sun on the front, stars on the sides and a moon on the back, and another with arms of a golden color and legs with a silvery tint. The king takes the third servant as his wife. The queen writes a letter to be delivered to the king, but the messenger stops by a bath house and its contents are altered to tell the king his wife gave birth to two puppies. The children are baptized and given the named Fyodor and Ivan. Ivan is given to another king, while the mother is cast in a barrel with Fyodor; both wash ashore on Buyan. Fyodor tries to make contact with some merchants on a ship. Fyodor reaches his father’s kingdom and overhears the conversation about the wondrous sights: a talking squirrel on a tree that tells fairy tales and a similar looking youth (his brother Ivan) on a distant kingdom. Fyodor steals a magic carpet, rescues Ivan and flies back to Buyan with his brother, a princess and an old woman.[44] The tale was also classified as type 707, thus related to Russian tale «Tsar Saltan».[45]

In a tale collected by Chudjakov with the title Der weise Iwan («The Wise Ivan»), Ivan Tsarevich, the son of a tsar, pays a visit to a king and his three daughters. He listens to their conversation: the elder sister promises to weave trousers and shirts for the tsar’s son with a single flax; the middle one that she can weave the same with only a spool of thread, and the youngest that she can bear him six sons, the seventh a «wise Ivan», and all of them with arms of gold up to the elbow, legs of silver up the knee and pearls in their hair. The tsar’s son marries the youngest sister, to the jealousy of the elder sisters. While Ivan Tsarevich goes to war, the jealous sisters join with a sorceress to defame the queen, by taking the children as soon as they are born and replace them for animals. After the third pregnancy, the queen and her son, wise Ivan, are cast in the sea in a barrel. The barrel washes ashore on an island and they live there. Some time later, merchants come to the island and later visit Ivan Tsarevich’s court to tell of strange sights they have seen: exotic felines (sables and martens); singing birds of paradise from the jealous sisters’ aunt’s garden; and six sons with arms of gold, legs of silver and pearls in their hair. Wise Ivan returns to his mother and asks his mother to bake six cakes. Wise Ivan flies to the sorceress’s hut and rescues his brothers.[46]

Belarus[edit]

In a Belarusian tale collected by Evdokim Romanov (ru) with the name «Дуб Дорохвей» or «Дуб Дарахвей» («The Dorokhveï Oak») (fr), a widowed old man marries another woman, who detests his three daughters and orders her husband to dispose of them. The old man takes them to the swamp and abandons the girls there. They notice that their father is not with them, take refuge under a pine tree and begin to cry over their situation, their tears producing a river. The tsar, seeing the river, orders their servants to find its source.[a] They find the three maidens and take them to the king, who inquires about their origin: they say they were expelled from home. The tsar asks each maiden what they can do, and the youngest says she will give birth to 12 sons, their legs of gold, their waist of silver, the moon on the forehead and a small star on the back of the neck. The tsar chooses the third sister, and she bears the 12 sons while he is away. The sisters falsify a letter with a lie that she gave birth to animals and she should be thrown in the sea in a barrel. Eleven of her sons are put in a leather bag and thrown in the sea, but they wash ashore on an island where the Dorokhveï Oak lies. The oak is hollowed, so they make their residence there. Meanwhile, mother and her 12th son are thrown in the sea in a barrel, but leave the barrel as soon as it washes ashore on another island. The son tells her he will rescue his eleven brothers by asks her to bake cakes with her breastmilk. After the siblings are reunited, the son turns into an insect to spy on his aunts and eavesdrop on the conversation about the kingdom of wonders, one of them, a cat that walks and tells stories and tales [fr].[47]

Ukraine[edit]

In a Ukrainian tale, «Песинський, жабинський, сухинський і золотокудрії сини цариці» («Pesinsky, Zhabinsky, Sukhinsky[b] and the golden-haired sons of the queen»), three sisters are washing clothes in the river when they see in the distance a man rowing a boat. The oldest says it might be God, and if it is, may He take her, because she can feed many with a piece of bread. The second says it might be a prince, so she says she wants him to take her, because she will be able to weave clothes for a whole army with just a yarn. The third recognizes him as the tsar, and promises that, after they marry, she will give birth to twelve sons with golden curls. When the girl, now queen, gives birth, the old midwife takes the children, tosses them in a well and replaces them with animals. After the third birth, the tsar consults his ministers and they advise him to cast the queen and her animal children in the sea in a barrel. The barrel washes ashore an island and the three animals build a castle and a glass bridge to mainland. When some sailors visit the island, they visit the tsar to report on the strange sights on the island. The old midwife, however, interrupts their narration by revealing somewhere else there is something even more fantastical. Pesinsky, Zhabinsky and Sukhinsky spy on their audience and run away to fetch these things and bring them to their island. At last, the midwife reveals that there is a well with three golden-curled sons inside, and Pesinsky, Zhabinsky and Sukhinsky rescue them. The same sailors visit the strange island (this time the true sons of the tsar are there) and report their findings to the tsar, who discovers the truth and orders the midwife to be punished.[48][49] According to scholarship, professor Lev Grigorevich Barag noted that this sequence (dog helping the calumniated mother in finding the requested objects) appears as a variation of the tale type 707 only in Ukraine, Russia, Bashkir and Tuvan.[50]

In a tale summarized by folklorist Mykola Sumtsov with the title «Завистливая жена» («The Envious Wife»), the girl promises to bear a son with a golden star on the forehead and a moon on his navel. She is persecuted by her sister-in-law.[51][52]

In a South Russian (Ukrainian) variant collected by Ukrainian folklorist Ivan Rudchenko [ru], «Богатырь з бочки» («The Bogatyr in a barrel»), after the titular bogatyr is thrown in the sea with his mother, he spies on the false queen to search the objects she describes: a cat that walks on a chain, a golden bridge near a magical church and a stone-grinding windmill that produces milk and eight falcon-brothers with golden arms up to the elbow, silver legs up to the knees, golden crown, a moon on the front and stars on the temples.[53][54]

Baltic languages[edit]

Latvia[edit]

According to the Latvian Folktale Catalogue, tale type 707, «The Three Golden Children», is known in Latvia as Brīnuma bērni («Wonderful Children»), comprising 4 different redactions. Its first redaction registers the highest number of tales and follows The Tale of Tsar Saltan: the king marries the youngest of three sisters, because she promises to bear him many children with wonderful traits, her sisters replace the children for animals and their youngest is cast into the sea in a barrel with one of her sons; years later, her son seeks the strange wonders the sisters mention (a cat that dances and tells stories, and a group of male brothers that appear somewhere on a certain place).[55]

Lithuania[edit]

According to professor Bronislava Kerbelyte [lt], the tale type is reported to register 244 (two hundred and forty-four) Lithuanian variants, under the banner Three Extraordinary Babies, with and without contamination from other tale types.[56] However, only 39 variants in Lithuania contain the quest for the strange sights and animals described to the king. Kerbelytė also remarks that many Lithuanian versions of this format contain the motif of baking bread with the hero’s mother’s breastmilk to rescue the hero’s brothers.[57]

In a variant published by Fr. Richter in Zeitschrift für Volkskunde with the title Die drei Wünsche («The Three Wishes»), three sisters spend an evening talking and weaving, the youngest saying she would like to have a son, bravest of all and loyal to the king. The king appears, takes the sisters, and marries the youngest. Her son is born and grows up exceptionally fast, much to the king’s surprise. One day, he goes to war and sends a letter to his wife to send their son to the battlefield. The queen’s jealous sisters intercept the letter and send him a frog dressed in fine clothes. The king is enraged and replies with a written order to cast his wife in the water. The sisters throw the queen and her son in the sea in a barrel, but they wash ashore in an island. The prince saves a hare from a fox. The prince asks the hare about recent events. Later, the hare is disenchanted into a princess with golden eyes and silver hair, who marries the prince.[58]

Finnic languages[edit]

Estonia[edit]

The tale type is known in Estonia as Imelised lapsed («The Miraculous Children»). Estonian folklorists identified two opening episodes: either the king’s son finds the three sisters, or the three sisters are abandoned in the woods and cry so much their tears create a river that flows to the king’s palace.[a] The third sister promises to bear the wonder children with astronomical motifs on their bodies. The story segues into the Tale of Tsar Saltan format: the mother and the only child she rescued are thrown into the sea; the son grows up and seeks the wonders the evil aunts tell his father about: «a golden pig, a wonderous cat, miraculous children».[59]

Regional tales[edit]

Folklorist William Forsell Kirby translated an Estonian version first collected by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald,[60] with the name The Prince who rescued his brothers: a king with silver-coated legs and golden-coated arms marries a general’s daughter with the same attributes. When she gives birth to her sons, her elder sister sells eleven of her nephews to «Old Boy» (a devil-like character) while the queen is banished with her twelfth son and cast adrift into the sea in a barrel. At the end of the tale, the youngest prince releases his brothers from Old Boy and they transform into doves to reach their mother.[61]

In a tale from the Lutsi Estonians collected by linguist Oskar Kallas with the name Kuningaemand ja ta kakstõistkümmend poega («The Queen and her Twelve Sons»), a man remarries and, on orders of his new wife, takes his three daughters to the forest on the pretext of picking up berries, and abandons them there. The king’s bird flies through the woods and finds the girls. The animal inquires them about their skills: the elder one says she can feed the whole world with an ear of wheat; the middle one that she can clothe the whole world with a single linen thread, and the third that she will bear 12 sons, each with a moon on the head, the sun, and stars on their bodies. The bird carries each one to the king, who takes them in. Years later, the king marries the third girl, and she gives birth to three sons in her first pregnancy. Her elder sister takes the boys and drops them in a swamp, replacing them with kittens. This happens again with the next pregnancies: as soon as they are born, the triplets are replaced for animals (puppies in the second, piglets in the third, and lambs in the fourth). However, in the fourth pregnancy, the queen hides one of her sons with her. The king orders her to cast his wife in the sea in an iron boat with her son. The son begs for an island to receive them, and his mother blesses his prayer. After they wash ashore on the island, the boy wishes the island is filled with golden and silver trees, with apples with half of gold and half of silver. His mother blesses his wish, and it happens. He next wishes for a palace larger than his father’s, an army greater than his, and finally for a bridge to connect the island to the continent. Later, he asks his mother to bake 12 cakes with her breastmilk, for he intends to rescue his older brothers. He crosses the bridge and reaches a swamp, then finds a moss-covered hut. He enters the hut and places the 12 cakes on the table. His eleven brothers — everyone shining due to their birthmarks — come to the hut and eat the cakes. Their younger brother appears and convinces them to join their mother on the island. Later, the son wishes for instruments to play, which draws the attention of his father, the king. The king comes to the island and learns of the whole truth.[62]

Kallas published a homonymous variant from the Lutsi Estonians in abbreviated form. In this tale, a king meets three maidens on the road; the third promises to bear him 12 sons with the sun and the moon on the head, a star on their breast, hands of gold and feet of silver. The king and the maiden marry; the children are replaced by animals as soon as they are born, and the mother and her last son are cast into the sea in a sack. The first thing her son does is find his brothers. Later, after he rescues his brothers, he flies back to his father’s court to spy on him and the other maidens, and learns of the sights: a cat that lives in oak and provides clothes for its owner; a cow with a lake between its horns; and a boar that sows his own fields and bakes his own bread.[63]

In another tale from the Lutsi, published with the title Kolm õde («Three Sisters»), a tsar has three daughters and is a great musician. One day, he leaves home and does not return. His daughters go looking for him and find him dead. They begin to cry, their tears creating a river that flows to another kingdom. The son of another tsar orders his servant to discover its origin and finds the girls. The sisters are brought to the prince’s presence and are questioned about their skills: the elder promises to feed the entire country with one pea, the middle one that she can feed the country’s horses with one grain of oat, and the youngest promises to give birth to 12 sons. The prince marries the third sister. In time, she gives birth to 12 sons. A sequence of falsified letters lies that she gave birth to animal-headed children, and must be punished by being cast in the sea. The prince’s wife and a son are thrown into the sea in a barrel and wash ashore on an island. The son grows up and goes hunting around the island. He prepares to shoot at a swan, but the swan pleads to be spared, and helps the boy three times: the first, to pull a thread by the seashore (which guides his father’s ship to the island); secondly, to throw 11 pebbles on the sea (which summons his 11 brothers to the island); finally, to fish a goldfish (which leads his father’s ship again to the island).[64]

Karelia[edit]

Karelian researchers register that the tale type is «widely reported» in Karelia, with 55 variants collected,[65] apart from tales considered to be fragments or summaries of The Tale of Tsar Saltan.[66] According to their research, at least 50 of them follow the Russian redaction (see above), while 5 of them are closer to the Western European tales.[65]

According to Karelian scholarship, the witch Syöjätär is the recurrent antagonist in Karelian variants of tale type 707,[67] especially in tales from South Karelia.[68]

Regional tales[edit]

In a Karelian tale, «Девять золотых сыновей» («Nine Golden Sons»), the third sister promises to give birth to «three times three» children, their arms of gold up to the elbow, the legs of silver up to the knees, a moon on the temples, a sun on the front and stars in their hair. The king overhears their conversation and takes the woman as his wife. On their way, they meet a woman named Syöjätär, who insists to be the future queen’s midwife. She gives birth to triplets in three consecutive pregnancies, but Syöjätär replaces them for rats, crows and puppies. The queen saves one of her children and is cast into a sea in a barrel. The remaining son asks his mother to bake bread with her breastmilk to rescue his brothers.[69][70]

Author Eero Salmelainen collected a tale titled Veljiensä etsijät ja joutsenina lentäjät («One who seeks brothers flying as swans»), which poet Emmy Schreck translated as Die neun Söhne des Weibes («The woman’s nine children») and indicated a Russian-Karelian source for this tale. In this variant, three sisters walk in the forest and talk to each other, the youngest promising to bear nine children in three pregnancies. The king’s son overhears them and decides to marry the youngest, and she bears the wonder children with hands of gold, legs of silver, sunlight in their hair, moonlight shining around it, the «celestial chariot» (Himmelswagen, or Ursa Major) on their shoulder, and stars in their underarms. The king dispatches a servant to look for a washerwoman and a witch offers her services. The witch replaces the boys for animals, takes them to the woods and hides them under a white stone. After the third pregnancy, the mother hides two of her sons «on her sleeve» and is banished with them on a barrel cast in the sea. The barrel washes ashore on an island. Both boys grow up in days, and capture a talking pike that tells them to cut it open to find magical objects inside its entrails. They use the objects to build a grand house on the island for themselves and their mother. After a merchant visits the island and reports to their father, the king’s son arrives on the island and makes peace with his wife. Sometime later, both sons ask his mother to prepare some cakes with her breastmilk, so they can look for their remaining brothers, still missing. Both brothers spare a seagull who carries them across the sea to another country, where they find their seven brothers under an avian transformation curse.[71]

In a tale from Pudozh, collected in 1939 and published in 1982 with the title «Про кота-пахаря» («About the Pakharya Cat»), three sisters promise great things if they marry Ivan, the merchant’s son; the youngest sister, named Barbara (Varvara), promises to bear three sons with golden arms and a red sun on the front. She marries Ivan and bears three sons, in three consecutive pregnancies, but the sons are replaced for puppies and the third is cast in barrel along with his mother. The son grows up in hours, becomes a young man, and both wash ashore on a deserted island. Whatever he wishes for, his mother blesses him so that his prayers go «from his lips to God’s ears». And so appear a magical cat that sings poems and a bath house that rejuvenates people.[72]