Ниже перечислены пьесы Э. Грига из музыки к спектаклю «Пер Гюнт». Какие из них вошли в первую оркестровую сюиту, а какие – во вторую?

Первая сюита |

Вторая сюита |

|---|---|

Кто из поэтов является автором трагедии «Эгмонт»?

|

И. В. Гете |

|

|

Ф. Шиллер |

|

|

Дж. Байрон |

Кто является автором драматической поэмы «Пер Гюнт»?

|

А. Линдрен |

|

|

Г. Ибсен |

|

|

Г. Х. Андерсен |

В большинстве случаев название музыки, созданной к той или иной театральной постановке, повторяет название спектакля. Но из этого правила бывают исключения. Какое из данных музыкальных произведений является таким исключением?

|

Л. ван Бетховен. Увертюра «Эгмонт» |

|

|

Э. Григ. Сюита «Пер Гюнт» |

|

|

А. Шнитке. «Гоголь-сюита» |

К каким музыкальным стилям можно отнести музыку, с которой вы познакомились на этом уроке?

«Гоголь-сюита» Альфреда Шнитке

«Эгмонт» Людвига ван Бетховена

Кто является главным героем этих спектаклей?

Деревенский парень из Норвегии

Благородный граф из Фландрии

Знаменитый писатель из России

Подберите подписи к этим портретам:

Что послужило основой сюжета спектакля «Ревизская сказка»?

|

Комедия Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизор» |

|

|

Рассказ Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизская сказка» |

|

|

Фрагменты из различных произведений Н. В. Гоголя |

Контрольная работа № 1 по музыке по программе Г.П.Сергеевой,

Е.Д.Критской, 8 класс

Вариант 1

Часть I

Выбери правильное утверждение.

1. Какие

произведения искусства называют классикой?

А) Произведения, созданные

много лет назад

Б) Произведения, которые

считают высшим образцом

В) Произведения, которые

всем нравятся

2. Вспомни звучание арии

главного героя. Какой голос исполняет партию князя Игоря?

А) Тенор

Б) Баритон

В) Бас

3. Кто написал тексты для

вокальных номеров оперы «Князь Игорь»?

А) В,В.Стасов

Б) А.С.Пушкин

В) А.П.Бородин

4. В каком из номеров оперы

композитор использовал подлинный русский старинный напев?

А)

Хор «Солнцу красному слава!»

Б)

Ария князя Игоря

В)

Плач Ярославны

5.

В каком номере балета Б. Тищенко «Ярославна» используется подлинный текст

«Слова о полку Игореве»?

А)

Вежи половецкие

Б)

Стон русской земли

В)

Молитва

6.

Какой прием использовал Б. Тищенко для создания образа половецкой конницы,

безжалостно топчущей русскую землю?

А)

Изображение топота копыт барабанной дробью

Б)

Изображение топота копыт женским кордебалетом на пуантах

В)

Изображение топота копыт ударами тарелок и грохотом литавр

7.

Кто является автором драматической поэмы «Пер Гюнт»?

А)

А. Линдрен

Б)

Г. Ибсен

В)

Г. Х. Андерсен

8.

Как называли кинематограф в начале XX века?

А)

великий глухой

Б)

великий немой

В)

великий слепой

9. Кто дал название Симфонии №

8 Ф. Шуберта «Неоконченная»?

А)

Автор

Б)

Первый исполнитель

В)

Слушатели

10.

Какая музыка звучала в фильме Андрея Тарковского «Солярис»?

А)

фортепианная пьеса П. И. Чайковского

Б)

симфоническая увертюра Л. ван Бетховена

В)

органная прелюдия И. С. Баха

11.

В каких областях человеческой деятельности проявился талант А. П. Бородина?(неск.

вар)

А) Музыка

Б) Живопись

В) Медицина

Г) История

Д) Физика

Е) Химия

12. Что

оказало влияние на стилистику оперы «Преступление и наказание»?

А) Сопричастность

композитора прошлому.

Б) Следование традициям

классической оперы.

В) Глубокий интерес к

подлинному русскому фольклору.

Г) Увлечение композитора

электронной музыкой.

Д) Впечатленность

композитора рок-оперой «Иисус Христос – Суперзвезда».

Е) Понимание актуальности

проблем, выдвинутых в романе Ф. Достоевского для современности.

Часть II

1.

Расставь фрагменты балета Б. Тищенко «Ярославна» в правильном порядке.

«Стон Русской Земли»

«Плач Ярославны»

«Молитва»

«Вступление»

«Вежи половецкие»

2. Продолжи название мюзикла Жерара Пресгурвика «Ромео и

Джульетта: от до

».

3.

В начале XX века демонстрация фильмов сопровождалась живой музыкой.

В

кинотеатрах была такая должность — ___________.

Так

называли пианиста, который импровизировал во время сеанса.

4. Сопоставь

музыкальные термины и их значение.

1)

Попытка максимально точно воспроизвести стиль и манеру исполнения, характерную

для прошлых веков.

2)

Создание новой композиции на основе известного музыкального произведения.

3)

Переложение произведения для другого состава музыкальных инструментов.

А)

Аранжировка

Б)

Транскрипция

В)

Аутентичное исполнение

5. Составь

правильные названия номеров оперы А. П. Бородина «Князь Игорь»

6.

Кто из композиторов является автором следующих песен из

кинофильмов?

1)

«Песня о встречном»

А) Тихон Хренников

2) «Я

шагаю по Москве» Б) Андрей

Петров

3) «Песня

о Москве» В) Дмитрий

Шостакович

Сбросить

ответы

Контрольная работа № 1 по музыке 8 класс

Вариант 1I

Часть I

Выбери

правильное утверждение.

1. Как называются переработки сочинений В.А. Моцарта, Ф.

Шуберта, Дж. Верди, которые создавал Ференц Лист?

А)

Аранжировка

Б)

Транскрипция

В)

Аутентичное исполнение

2.

Вспомни, как звучит «Плач Ярославны». Как называется голос, которому композитор

поручил исполнение партии княгини?

А) Сопрано

Б)

Меццо-сопрано

В)

Контральто

3.Какие

древние традиции русской музыки использует композитор в «Плаче Ярославны»?

А)

Интонации колыбельной

Б) Интонации

плача

В) Интонации

заклички

4. Что послужило основой сюжета оперы

«Князь Игорь»?

А) Старинная легенда

Б) Русская народная сказка

В) Памятник древнерусской литературы

5.

Какой национальный образ воссоздает Борис Тищенко через активные ритмоформулы и

свободную пластику босоногих воинов?

А) Национальный

колорит русского стана

Б) Национальный

колорит половецкого стана

В) Образ

Русской земли

6.

Какой

из перечисленных композиторов современности написал музыку к фильму Франко

Дзефирелли «Ромео и Джульетта»?

А) Жерар

Пресгурвик

Б) Нино Рота

В) Леонард

Бернстайн

7. В

большинстве случаев название музыки, созданной к той или иной театральной

постановке, повторяет название спектакля. Но из этого правила бывают

исключения. Какое из данных музыкальных произведений является таким

исключением?

А) Шнитке. «Гоголь-сюита»

Б) Л. ван Бетховен. Увертюра «Эгмонт»

В) Э. Григ. Сюита «Пер Гюнт

8. Что послужило основой сюжета

спектакля «Ревизская сказка»?

А) Комедия Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизор»

Б) Рассказ Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизская сказка»

В) Фрагменты из различных произведений Н. В.

Гоголя

9.

Сколько частей в Симфонии № 8 («Неоконченной») Ф. Шуберта?

А) 4

Б) 3

В) 2

10. Кто из композиторов является автором

музыки к фильмам трилогии «Властелин колец»?

А) Мишель Легран

Б) Говард Лесли Шор

В) Исаак Шварц

11. Что оказало влияние на стилистику

балета «Ярославна»?

А) Сопричастность

композитора прошлому

Б) Следование

традициям классического балета.

В) Глубокий

интерес к подлинному русскому фольклору

Г) Увлечение

композитора японской средневековой музыкой.

Д) Увлечение

композитора западноевропейской музыкой.

Е) Обостренное,

драматическое переживание собственного внутреннего мира.

12.

Музыку к каким отечественным кинофильмам создал Исаак Дунаевский?

А) «Встречный»

Б) «Веселые

ребята»

В) «Солярис»

Г) «Свинарка

и пастух»

Д) «Цирк»

Е) «Понизовая

вольница»

Ж) «Волга-Волга»

З) «Я

шагаю по Москве»

И) «Свой

среди чужих, чужой среди своих»

Часть II

1.

Расставь произведения в порядке их появления.

П.И. Чайковский Увертюра-фантазия «Ромео и Джульетта»

Ж. Пресгурвик «Ромео и Джульетта: от ненависти до любви»

Л. Бернстайн Мюзикл «Вестсайдская история»

С.С. Прокофьев Балет «Ромео и Джульетта

У. Шекспир «Ромео и Джульетта»

2.

Вставьте пропущенное слово:

—

современная хореографическая версия старой театральной постановки.

3. В начале XX века демонстрация фильмов сопровождалась

живой музыкой.

В кинотеатрах была такая должность — ___________.

Так называли пианиста, который импровизировал во время

сеанса.

4. К каким музыкальным стилям можно отнести музыку?

1) «Эгмонт»

Людвига ван Бетховена А) классицизм

2) «Пер

Гюнт» Эдварда Грига Б) полистилистика

3) «Гоголь-сюита»

Альфреда Шнитке В) романтизм

5. В какой момент оперного спектакля звучат эти номера?

1) Хор

«Улетай на крыльях ветра» А) Пролог

2)

Сцена затмения

Б) II действие

3)

Плач Ярославны В)

IV действие

6. Кто является главным героем этих спектаклей?

1) «Ревизская

сказка» А) Деревенский

парень из Норвегии

2) «Пер

Гюнт» Б) Благородный

граф из Фландрии

3) «Эгмонт» В)

Знаменитый писатель из России

Ключи к контрольной работе № 1 по музыке 8 класс

Вариант

I Часть I

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

|

Б |

Б |

В |

А |

Б |

Б |

Б |

Б |

В |

В |

А |

Б |

Часть

II

1. «Вступление»

«Стон Русской

Земли»

«Вежи половецкие»

«Плач

Ярославны»

«Молитва»

2. ненависти

любви

3. тапер

4. 1В, 2А, 3Б

5. 1Б, 2В, 3А

6. 1В, 2Б, 3А

Вариант

II Часть I

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

|

Б |

А |

Б |

В |

А |

Б |

А |

В |

В |

Б |

А |

Б |

Часть

II

1. У. Шекспир

«Ромео и Джульетта»

П.И. Чайковский

Увертюра-фантазия «Ромео и Джульетта»

С.С. Прокофьев

Балет «Ромео и Джульетта

Л. Бернстайн

Мюзикл «Вестсайдская история»

Ж. Пресгурвик

«Ромео и Джульетта: от ненависти до любви»

2. «Ярославна»

3. тапер

4. 1А, 2В, 3Б

5. 1Б, 2А, 3В

6. 1В, 2А, 3Б

Критерии

оценивания

Часть I

С 1 -10 по 1

баллу, всего — 10

11,12 – по 1.5

балла, всего – 3

Часть II

№1 – по 1 баллу, всего – 5

№2 – всего – 2

№3 – всего – 1

№4 — по 1 баллу, всего — 3

№5- по 1 баллу, всего — 3

№6 — по 1 баллу, всего — 3

«5» — 28-30

«4» -22 – 27

«3» — 16 – 21

«2» — до 15

Тест по предмету «Музыка» 8 класс

(по программе Г.П.Сергеевой, Е.Д.Критской)

Составлен учителем музыки

МОУ «СОШ № 20» Казацкой Л.А.

Тест по музыке 8 класс

(по программе Г.П.Сергеевой, Е.Д.Критской)

(полугодовая проверочная работа)

Выполнил(а)__________________________________, 8__класс

Вариант 1

Часть I

Выбери правильное утверждение.

1. Какие произведения искусства называют классикой?

А) Произведения, созданные много лет назад

Б) Произведения, которые считают высшим образцом

В) Произведения, которые всем нравятся

2. Вспомни звучание арии главного героя. Какой голос исполняет партию князя

Игоря?

А) Тенор

Б) Баритон

В) Бас

3. Кто написал тексты для вокальных номеров оперы «Князь Игорь»?

А) В,В.Стасов

Б) А.С.Пушкин

В) А.П.Бородин

4. В каком из номеров оперы композитор использовал подлинный русский старинный

напев?

А) Хор «Солнцу красному слава!»

Б) Ария князя Игоря

В) Плач Ярославны

5. В каком номере балета Б. Тищенко «Ярославна» используется подлинный текст

«Слова о полку Игореве»?

А) Вежи половецкие

Б) Стон русской земли

В) Молитва

6. Какой прием использовал Б. Тищенко для создания образа половецкой конницы,

безжалостно топчущей русскую землю?

А) Изображение топота копыт барабанной дробью

Б) Изображение топота копыт женским кордебалетом на пуантах

В) Изображение топота копыт ударами тарелок и грохотом литавр

7. Кто является автором драматической поэмы «Пер Гюнт»?

А) А. Линдрен

Б) Г. Ибсен

В) Г. Х. Андерсен

8. Как называли кинематограф в начале XX века?

А) великий глухой

Б) великий немой

В) великий слепой

9. Кто дал название Симфонии № 8 Ф. Шуберта «Неоконченная»?

А) Автор

Б) Первый исполнитель

В) Слушатели

10. Какая музыка звучала в фильме Андрея Тарковского «Солярис»?

А) фортепианная пьеса П. И. Чайковского

Б) симфоническая увертюра Л. ван Бетховена

В) органная прелюдия И. С. Баха

11. В каких областях человеческой деятельности проявился талант А. П.

Бородина?(неск. вар)

А) Музыка

Б) Живопись

В) Медицина

Г) История

Д) Физика

Е) Химия

12. Что оказало влияние на стилистику оперы «Преступление и наказание»?

А) Сопричастность композитора прошлому.

Б) Следование традициям классической оперы.

В) Глубокий интерес к подлинному русскому фольклору.

Г) Увлечение композитора электронной музыкой.

Д) Впечатленность композитора рок—оперой «Иисус Христос – Суперзвезда».

Е) Понимание актуальности проблем, выдвинутых в романе Ф. Достоевского для

современности.

Часть II

1. Расставь фрагменты балета Б. Тищенко «Ярославна» в правильном порядке.

«Стон Русской Земли»

«Плач Ярославны»

«Молитва»

«Вступление»

«Вежи половецкие»

2. Продолжи название мюзикла Жерара Пресгурвика «Ромео и Джульетта: от до ».

3. В начале XX века демонстрация фильмов сопровождалась живой музыкой.

В кинотеатрах была такая должность — ___________.

Так называли пианиста, который импровизировал во время сеанса.

4. Сопоставь музыкальные термины и их значение.

1) Попытка максимально точно воспроизвести стиль и манеру исполнения, характерную

для прошлых веков.

2) Создание новой композиции на основе известного музыкального произведения.

3) Переложение произведения для другого состава музыкальных инструментов.

А) Аранжировка

Б) Транскрипция

В) Аутентичное исполнение

5. Составь правильные названия номеров оперы А. П. Бородина «Князь Игорь»

1).Плач

2) Ария

3) Хор

А) «Солнцу красному слава!»

Б) Ярославны

В) Князя Игоря

6. Кто из композиторов является автором следующих песен из кинофильмов?

1) «Песня о встречном» А) Тихон Хренников

2) «Я шагаю по Москве» Б) Андрей Петров

3) «Песня о Москве» В) Дмитрий Шостакович

Сбросить ответы

Тест по музыке 8 класс

(по программе Г.П.Сергеевой, Е.Д.Критской)

(полугодовая проверочная работа)

Выполнил(а)____________________________________, 8__ класс

Вариант 1I

Часть I

Выбери правильное утверждение.

1. Как называются переработки сочинений В.А. Моцарта, Ф. Шуберта, Дж. Верди,

которые создавал Ференц Лист?

А) Аранжировка

Б) Транскрипция

В) Аутентичное исполнение

2. Вспомни, как звучит «Плач Ярославны». Как называется голос, которому

композитор поручил исполнение партии княгини?

А) Сопрано

Б) Меццо—сопрано

В) Контральто

3.Какие древние традиции русской музыки использует композитор в «Плаче

Ярославны»?

А) Интонации колыбельной

Б) Интонации плача

В) Интонации заклички

4. Что послужило основой сюжета оперы «Князь Игорь»?

А) Старинная легенда

Б) Русская народная сказка

В) Памятник древнерусской литературы

5. Какой национальный образ воссоздает Борис Тищенко через активные

ритмоформулы и свободную пластику босоногих воинов?

А) Национальный колорит русского стана

Б) Национальный колорит половецкого стана

В) Образ Русской земли

6. Какой из перечисленных композиторов современности написал музыку к фильму

Франко Дзефирелли «Ромео и Джульетта»?

А) Жерар Пресгурвик

Б) Нино Рота

В) Леонард Бернстайн

7. В большинстве случаев название музыки, созданной к той или иной театральной

постановке, повторяет название спектакля. Но из этого правила бывают

исключения. Какое из данных музыкальных произведений является таким

исключением?

А) Шнитке. «Гоголь—сюита»

Б) Л. ван Бетховен. Увертюра «Эгмонт»

В) Э. Григ. Сюита «Пер Гюнт

8. Что послужило основой сюжета спектакля «Ревизская сказка»?

А) Комедия Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизор»

Б) Рассказ Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизская сказка»

В) Фрагменты из различных произведений Н. В. Гоголя

9. Сколько частей в Симфонии № 8 («Неоконченной») Ф. Шуберта?

А) 4

Б) 3

В) 2

10. Кто из композиторов является автором музыки к фильмам трилогии «Властелин

колец»?

А) Мишель Легран

Б) Говард Лесли Шор

В) Исаак Шварц

11. Что оказало влияние на стилистику балета «Ярославна»?

А) Сопричастность композитора прошлому

Б) Следование традициям классического балета.

В) Глубокий интерес к подлинному русскому фольклору

Г) Увлечение композитора японской средневековой музыкой.

Д) Увлечение композитора западноевропейской музыкой.

Е) Обостренное, драматическое переживание собственного внутреннего мира.

12. Музыку к каким отечественным кинофильмам создал Исаак Дунаевский?

А) «Встречный»

Б) «Веселые ребята»

В) «Солярис»

Г) «Свинарка и пастух»

Д) «Цирк»

Е) «Понизовая вольница»

Ж) «Волга—Волга»

З) «Я шагаю по Москве»

И) «Свой среди чужих, чужой среди своих»

Часть II

1. Расставь произведения в порядке их появления.

П.И. Чайковский Увертюра—фантазия «Ромео и Джульетта»

Ж. Пресгурвик «Ромео и Джульетта: от ненависти до любви»

Л. Бернстайн Мюзикл «Вестсайдская история»

С.С. Прокофьев Балет «Ромео и Джульетта

У. Шекспир «Ромео и Джульетта»

2. Вставьте пропущенное слово:

— современная хореографическая версия старой театральной постановки.

3. В начале XX века демонстрация фильмов сопровождалась живой музыкой.

В кинотеатрах была такая должность — ___________.

Так называли пианиста, который импровизировал во время сеанса.

4. К каким музыкальным стилям можно отнести музыку?

1) «Эгмонт» Людвига ван Бетховена А) классицизм

2) «Пер Гюнт» Эдварда Грига Б) полистилистика

3) «Гоголь—сюита» Альфреда Шнитке В) романтизм

5. В какой момент оперного спектакля звучат эти номера?

1) Хор «Улетай на крыльях ветра» А) Пролог

2) Сцена затмения Б) II действие

3) Плач Ярославны В) IV действие

6. Кто является главным героем этих спектаклей?

1) «Ревизская сказка» А) Деревенский парень из Норвегии

2) «Пер Гюнт» Б) Благородный граф из Фландрии

3) «Эгмонт» В) Знаменитый писатель из России

Ключи к проверочной работе № 1 по музыке 8 класс

Вариант I Часть I

Часть II

1. «Вступление»

«Стон Русской Земли»

«Вежи половецкие»

«Плач Ярославны»

«Молитва»

2. ненависти любви

3. тапер

4. 1В, 2А, 3Б

5. 1Б, 2В, 3А

6. 1В, 2Б, 3А

Вариант II Часть I

Часть II

1. У. Шекспир «Ромео и Джульетта»

П.И. Чайковский Увертюра—фантазия «Ромео и Джульетта»

С.С. Прокофьев Балет «Ромео и Джульетта

Л. Бернстайн Мюзикл «Вестсайдская история»

Ж. Пресгурвик «Ромео и Джульетта: от ненависти до любви»

2. «Ярославна»

3. тапер

4. 1А, 2В, 3Б

5. 1Б, 2А, 3В

6. 1В, 2А, 3Б

Критерии оценивания

Часть I

С 1 —10 по 1 баллу, всего — 10

11,12 – по 1.5 балла, всего – 3

Часть II

№1 – по 1 баллу, всего – 5

№2 – всего – 2

№3 – всего – 1

№4 — по 1 баллу, всего — 3

№5- по 1 баллу, всего — 3

№6 — по 1 баллу, всего — 3

«5» — 28-30

«4» -22 – 27

«3» — 16 – 21

«2» — до 15

! постараюсь !

музыка

по структуре пятая симфония — традиционный четырехчастный цикл. первая часть, воплощающая героико-эпическое начало, начинается с изложения главной партии. мелодия, исполненная простоты и благородства, разворачивается неторопливо. она станет как бы лейтмотивом всей части, носителем героической идеи. ее развитие усиливает драматические черты, нагнетает напряженность. волны этого развития приводят к небольшим (их называют «местными») кульминациям, в которых отдельные мотивы темы превращаются в призывные сигналы. широко развернутая побочная партия не противопоставляется главной, а скорее дополняет ее нотками искренней лирики. заключительная часть экспозиции состоит из двух тем — решительной, волевой, вырастающей из ритмически активных ходов главной партии, и второй — игривой, острой, привносящей в музыку элемент психологической разрядки. в разработке неуклонно нагнетается драматизм, возникают эпизоды батального характера, усиливаются героические черты. не только главная, но и побочная и даже заключительные темы приобретают действенный, активный характер и становятся как бы непосредственным образным продолжением главной. лирика переплавляется в горниле героики и в преображенном виде вливается в образный строй музыки. в репризе слышна качественно новая ступень — лирическое начало оказывается полностью подчиненным героике, достигается высочайшая степень напряжения. заключает часть поистине богатырская кода: плотная оркестровка, замедленный темп и обилие ударных музыке характер торжественной триумфальности.

во второй части, скерцо, совмещены черты токкатности и танцевального движения. его музыкальные темы пластичны и вместе с тем отмечены графической остротой контуров. на фоне остро пульсирующего остинатного движения звучит лаконичная гротескная тема. она перебрасывается от инструмента к инструменту, охватывая огромный диапазон и окрашиваясь в различные темброво-тональные цвета. к концу начального раздела скерцо она словно растворяется в ритмически по- прежнему четком, но постепенно затухающем движении струнных. средний раздел части пронизан энергией танцевального ритма. полетное движение вальса временами переходит в веселый пляс. заключительный раздел трехчастной формы — резкий контраст. в нем господствуют жесткие сухие аккорды, мрачный тембр медных инструментов. темп замедлен, словно заторможен, и все это вместе создает тревожную, порою даже зловещую атмосферу. однако постепенно эти настроения преодолеваются, основная тема становится сначала насмешливой, затем назойливой, еще через несколько тактов — лукавой и, наконец, искрометной. заканчивается скерцо темпераментной пляской, в которой, однако, слышны отзвуки зловещей бури.

третья часть — адажио — сочетает лирику, мягкую, нежную, трепетную, с патетикой, драматизмом, суровой сдержанностью. манера изложения музыкального материала, -повествовательная, объединяет разнородные образы, придавая им некую сюжетную направленность. музыка полна благородства, простоты, мужественной силы. отчетливо проступают черты раздумья, углубленной созерцательности.

финал перекликается с начальными страницами симфонии. его настроение — юношески восторженное, лучезарное. в ритме веселой пляски звучит у солирующего кларнета живая, по-прокофьевски угловатая тема. она то исчезает, то снова «выплывает на поверхность», цементируя форму. а в промежутках появляются другие образы — и лирические, и полные мужественного благородства, и лукаво-грациозные. завершается симфония потоком празднично-ликующих звучаний.

Выбери правильное утверждение.

1. Как называются переработки сочинений В.А. Моцарта, Ф. Шуберта, Дж. Верди, которые создавал Ференц Лист?

А) Аранжировка

Б) Транскрипция

В) Аутентичное исполнение

2. Вспомни, как звучит «Плач Ярославны». Как называется голос, которому композитор поручил исполнение партии княгини?

А) Сопрано

Б) Меццо-сопрано

В) Контральто

3.Какие древние традиции русской музыки использует композитор в «Плаче Ярославны»?

А) Интонации колыбельной

Б) Интонации плача

В) Интонации заклички

4. Что послужило основой сюжета оперы «Князь Игорь»?

А) Старинная легенда

Б) Русская народная сказка

В) Памятник древнерусской литературы

5. Какой национальный образ воссоздает Борис Тищенко через активные ритмоформулы и свободную пластику босоногих воинов?

А) Национальный колорит русского стана

Б) Национальный колорит половецкого стана

В) Образ Русской земли

6. Какой из перечисленных композиторов современности написал музыку к фильму Франко Дзефирелли «Ромео и Джульетта»?

А) Жерар Пресгурвик

Б) Нино Рота

В) Леонард Бернстайн

7. В большинстве случаев название музыки, созданной к той или иной театральной постановке, повторяет название спектакля. Но из этого правила бывают исключения. Какое из данных музыкальных произведений является таким исключением?

А) Шнитке. «Гоголь-сюита»

Б) Л. ван Бетховен. Увертюра «Эгмонт»

В) Э. Григ. Сюита «Пер Гюнт

8. Что послужило основой сюжета спектакля «Ревизская сказка»?

А) Комедия Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизор»

Б) Рассказ Н. В. Гоголя «Ревизская сказка»

В) Фрагменты из различных произведений Н. В. Гоголя

9. Сколько частей в Симфонии № 8 («Неоконченной») Ф. Шуберта?

А) 4

Б) 3

В) 2

10. Кто из композиторов является автором музыки к фильмам трилогии «Властелин колец»?

А) Мишель Легран

Б) Говард Лесли Шор

В) Исаак Шварц

11. Что оказало влияние на стилистику балета «Ярославна»?

А) Сопричастность композитора прошлому

Б) Следование традициям классического балета.

В) Глубокий интерес к подлинному русскому фольклору

Г) Увлечение композитора японской средневековой музыкой.

Д) Увлечение композитора западноевропейской музыкой.

Е) Обостренное, драматическое переживание собственного внутреннего мира.

12. Музыку к каким отечественным кинофильмам создал Исаак Дунаевский?

А) «Встречный»

Б) «Веселые ребята»

В) «Солярис»

Г) «Свинарка и пастух»

Д) «Цирк»

Е) «Понизовая вольница»

Ж) «Волга-Волга»

З) «Я шагаю по Москве»

И) «Свой среди чужих, чужой среди своих»

Часть II

1. Расставь произведения в порядке их появления.

П.И. Чайковский Увертюра-фантазия «Ромео и Джульетта»

Ж. Пресгурвик «Ромео и Джульетта: от ненависти до любви»

Л. Бернстайн Мюзикл «Вестсайдская история»

С.С. Прокофьев Балет «Ромео и Джульетта

У. Шекспир «Ромео и Джульетта»

2. Вставьте пропущенное слово:

— современная хореографическая версия старой театральной постановки.

3. В начале XX века демонстрация фильмов сопровождалась живой музыкой.

В кинотеатрах была такая должность — ___________.

Так называли пианиста, который импровизировал во время сеанса.

4. К каким музыкальным стилям можно отнести музыку?

1) «Эгмонт» Людвига ван Бетховена А) классицизм

2) «Пер Гюнт» Эдварда Грига Б) полистилистика

3) «Гоголь-сюита» Альфреда Шнитке В) романтизм

5. В какой момент оперного спектакля звучат эти номера?

1) Хор «Улетай на крыльях ветра» А) Пролог

2) Сцена затмения Б) II действие

3) Плач Ярославны В) IV действие

6. Кто является главным героем этих спектаклей?

1) «Ревизская сказка» А) Деревенский парень из Норвегии

2) «Пер Гюнт» Б) Благородный граф из Фландрии

3) «Эгмонт» В) Знаменитый писатель из России

Это задание по музыке

Похожие вопросы:

Музыка, 03.03.2019 14:37

Сочинение по произведению «сон снится» гаврилина

Ответов: 3

Музыка, 03.03.2019 18:46

Составить программу концерта камерной музыки , не из инета

Ответов: 1

Музыка, 03.03.2019 22:01

Прослушать произведение баха «шутка» в разных вариантах 1) оригинальная аранжировка 2) скрипка 3) гитара 4) баян 5) валторна 6) вокал 7) рок чем отличаются прослушанные вами варианты произведения? кратко опишите каждый. какой вариант вам нравиться больше всего? почему? у меня уже голова не !

Ответов: 2

Музыка, 10.03.2019 20:05

Прошу с в билете, прошу , 35 , тот кто сделает хоть 3 (из письменных естественно) поставлю лучший ответ.

Ответов: 3

Музыка, 19.03.2019 19:36

Каков был круг общения глинки, когда он жил в петербурге по окончании учебы?

Ответов: 1

Музыка, 20.03.2019 05:11

Сравнить 2 музыкальных произведения по средствам выразительности (какие знаете) и эмоциональному миру. е. крылатов «до чего дошел прогресс» и «ты- человек» из к/ф «приключения электроника»

Ответов: 2

Музыка, 20.03.2019 12:39

Различие и сходство коталической музыки и православной музы́ки

Ответов: 1

Музыка, 21.03.2019 10:00

Напишите обладателей 1 премии в двух последних конкурсах имени п. и.чайковского

Ответов: 2

Музыка, 21.03.2019 11:45

Нужно через 15 ! гарсонический фа мажор, построить в данной тональности интервалы и аккорды.

Ответов: 1

Музыка, 21.03.2019 16:18

Никак не могу решить, это контрольные . прошу скорей

Ответов: 1

Музыка, 24.03.2019 14:19

15 , ! мне на концерт учитель по музыке зада напишите биографию в несколько строчек про андрея эшпая (композитора) отметьте самую важную информацию, типо про него в военное время, про семью, что было перед смертью. заранее .

Ответов: 1

Музыка, 30.03.2019 17:04

Прошу мне: нужно соединить термин с определением. это музыкальной школы, а не обычной, ну да да, легко, но из-за выпускных экзаменов в муз. школе у меня ни времени, ни нервов тем более на подобного рода не хватает.

Ответов: 3

Вопросы по другим предметам:

Українська мова, 23.05.2020 19:15

Алгебра, 23.05.2020 19:15

Русский язык, 23.05.2020 19:15

Биология, 23.05.2020 19:15

Русский язык, 23.05.2020 19:15

Биология, 23.05.2020 19:15

Математика, 23.05.2020 19:15

Русский язык, 23.05.2020 19:15

| Peer Gynt | |

|---|---|

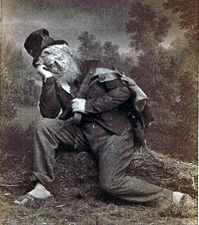

Henrik Klausen as Peer (1876) |

|

| Written by | Henrik Ibsen |

| Date premiered | 24 February 1876 |

| Place premiered | Christiania (now Oslo), Norway |

| Original language | Norwegian |

| Genre | Romantic dramatic poem converted into a play |

Peer Gynt (, Norwegian: [peːr ˈjʏnt, — ˈɡʏnt])[a] is a five-act play in verse by the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen published in 1876. Written in Norwegian,[2] it is one of the most widely performed Norwegian plays. Ibsen believed Per Gynt, the Norwegian fairy tale on which the play is loosely based, to be rooted in fact, and several of the characters are modelled after Ibsen’s own family, notably his parents Knud Ibsen and Marichen Altenburg. He was also generally inspired by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen’s collection of Norwegian fairy tales, published in 1845 (Huldre-Eventyr og Folkesagn).

Peer Gynt chronicles the journey of its title character from the Norwegian mountains to the North African desert and back. According to Klaus Van Den Berg, «its origins are romantic, but the play also anticipates the fragmentations of emerging modernism» and the «cinematic script blends poetry with social satire and realistic scenes with surreal ones.»[3] Peer Gynt has also been described as the story of a life based on procrastination and avoidance.[4] The play was written in Italy and a first edition of 1,250 copies was published on 14 November 1867 by the Danish publisher Gyldendal in Copenhagen.[5] Although the first edition swiftly sold out, a reprint of two thousand copies, which followed after only fourteen days, did not sell out until seven years later.[6]

Peer Gynt was first performed in Christiania (now Oslo) on 24 February 1876, with original music composed by Edvard Grieg that includes some of today’s most recognised classical pieces, «In the Hall of the Mountain King» and «Morning Mood». It was published in German translation in 1881, in English in 1892, and in French in 1896.[7] The contemporary influence of the play continues into the Twenty-First Century; it is widely performed internationally both in traditional and in modern experimental productions.

While Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson admired the play’s «satire on Norwegian egotism, narrowness, and self-sufficiency» and described it as «magnificent»,[8] Hans Christian Andersen, Georg Brandes and Clemens Petersen all joined the widespread hostility, Petersen writing that the play was not poetry.[9] Enraged by Petersen’s criticisms in particular, Ibsen defended his work by arguing that it «is poetry; and if it isn’t, it will become such. The conception of poetry in our country, in Norway, shall shape itself according to this book.»[10] Despite this defense of his poetic achievement in Peer Gynt, the play was his last to employ verse; from The League of Youth (1869) onwards, Ibsen was to write drama only in prose.[11]

Ibsen wrote Peer Gynt in deliberate disregard of the limitations that the conventional stagecraft of the 19th century imposed on drama.[12] Its forty scenes move uninhibitedly in time and space and between consciousness and the unconscious, blending folkloric fantasy and unsentimental realism.[13] Raymond Williams compares Peer Gynt with August Strindberg’s early drama Lucky Peter’s Journey (1882) and argues that both explore a new kind of dramatic action that was beyond the capacities of the theatre of the day; both created «a sequence of images in language and visual composition» that «became technically possible only in film.»[14]

Characters[edit]

- Åse, a peasant’s widow

- Peer Gynt, her son

- Two old women with corn–sacks

- Aslak, a blacksmith

- Wedding guest

- A master cook

- A fiddler

- A man and a wife, newcomers to the district

- Solveig and little Helga, their daughters

- The farmer at Hægstad

- Ingrid, his daughter

- The bridegroom and his parents

- Three alpine dairymaids

- A green-clad woman, a troll princess

- The Old Man of the Mountains, a troll king (Also known as The Mountain King)

- Multiple troll-courtiers, troll-maidens and troll-urchins

- A couple of witches

- Brownies, nixies, gnomes, etc.

- An ugly brat

- The Bøyg, a voice in the darkness

- Kari, a cottar’s wife

- Master Cotton

- Monsieur Ballon

- Herr von Eberkopf

- Herr Trumpeterstrale

- Gentlemen on their travels

- A thief

- A receiver

- Anitra, daughter of a Bedouin chief

- Arabs

- Female slaves

- Dancing girls

- The Memnon statue

- The Sphinx at Giza

- Dr. Begriffenfeldt, director of the madhouse at Cairo

- Huhu, a language reformer from the coast of Malabar

- Hussein, an eastern minister

- A fellow with a royal mother

- Several madmen and their keepers

- A Norwegian skipper

- His crew

- A strange passenger

- A pastor/The Devil (Peer Gynt thinks he is a pastor)

- A funeral party

- A parish-officer

- A button-moulder

- A lean person

Plot[edit]

Act I[edit]

Peer Gynt is the son of the once highly regarded Jon Gynt. Jon Gynt spent all his money on feasting and living lavishly, and had to leave his farm to become a wandering salesman, leaving his wife and son behind in debt. Åse, the mother, wished to raise her son to restore the lost fortune of his father, but Peer is soon to be considered useless. He is a poet and a braggart, not unlike the youngest son from Norwegian fairy tales, the «Ash Lad», with whom he shares some characteristics.

As the play opens, Peer gives an account of a reindeer hunt that went awry, a famous theatrical scene generally known as «the Buckride». His mother scorns him for his vivid imagination, and taunts him because he spoiled his chances with Ingrid, the daughter of the richest farmer. Peer leaves for Ingrid’s wedding, scheduled for the following day, because he may still get a chance with the bride. His mother follows quickly to stop him from shaming himself completely.

Per Gynt, the hero of the folk-story that Ibsen loosely based Peer Gynt on

At the wedding, the other guests taunt and laugh at Peer, especially the local blacksmith, Aslak, who holds a grudge after an earlier brawl. In the same wedding, Peer meets a family of Haugean newcomers from another valley. He instantly notices the elder daughter, Solveig, and asks her to dance. She refuses because her father would disapprove, and because Peer’s reputation has preceded him. She leaves, and Peer starts drinking. When he hears the bride has locked herself in, he seizes the opportunity, runs away with her, and spends the night with her in the mountains.

Act II[edit]

Peer is banished for kidnapping Ingrid. As he wanders the mountains, his mother and Solveig’s father search for him. Peer meets three amorous dairymaids who are waiting to be courted by trolls (a folklore motif from Gudbrandsdalen). He becomes highly intoxicated with them and spends the next day alone suffering from a hangover. He runs head-first into a rock and swoons, and the rest of the second act probably takes place in Peer’s dreams.

He comes across a woman clad in green, who claims to be the daughter of the troll mountain king. Together they ride into the mountain hall, and the troll king gives Peer the opportunity to become a troll if Peer would marry his daughter. Peer agrees to a number of conditions, but declines in the end. He is then confronted with the fact that the green-clad woman has become pregnant. Peer denies this; he claims not to have touched her, but the wise troll king replies that he begat the child in his head. Crucial for the plot and understanding of the play is the question asked by the troll king: «What is the difference between troll and man?»

The answer given by the Old Man of the Mountain is: «Out there, where sky shines, humans say: ‘To thyself be true.’ In here, trolls say: ‘Be true to yourself and to hell with the world.'» Egotism is a typical trait of the trolls in this play. From then on, Peer uses this as his motto, always proclaiming that he is himself. He then meets the Bøyg — a creature who has no real description. Asked the question «Who are you?» the Bøyg answers, «Myself». In time, Peer also takes the Bøyg’s important saying as a motto: «Go around». The rest of his life, he «beats around the bush» instead of facing himself or the truth.

Upon awaking, Peer is confronted by Helga, Solveig’s sister, who gives him food and regards from her sister. Peer gives the girl a silver button for Solveig to keep and asks that she not forget him.

Act III[edit]

As an outlaw, Peer struggles to build his own cottage in the hills. Solveig turns up and insists on living with him. She has made her choice, she says, and there will be no return for her. Peer is delighted and welcomes her, but as she enters the cabin, an old-looking woman in green garments appears with a limping boy at her side.

This is the green-clad woman from the mountain hall, and her half-human brat is the child begotten by Peer from his mind during his stay there. She has cursed Peer by forcing him to remember her and all his previous sins, when facing Solveig. Peer hears a ghostly voice saying «Go roundabout, Peer», and decides to leave. He tells Solveig he has something heavy to fetch. He returns in time for his mother’s death, and then sets off overseas.

Act IV[edit]

Peer is away for many years, taking part in various occupations and playing various roles, including that of a businessman engaged in enterprises on the coast of Morocco. Here, he explains his view of life, and we learn that he is a businessman taking part in unethical transactions, including sending heathen images to China and trading slaves. In his defense, he points out that he has also sent missionaries to China, and he treated his slaves well.

His companions rob him, after he decides to support the Turks in suppressing a Greek revolt, and leave him alone on the shore. He then finds some stolen Bedouin gear, and, in these clothes, he is hailed as a prophet by a local tribe. He tries to seduce Anitra, the chieftain’s daughter, but she steals his money and rings, gets away, and leaves him.

Then he decides to become a historian and travels to Egypt. He wanders through the desert, passing the Colossi of Memnon and the Sphinx. As he addresses the Sphinx, believing it to be the Bøyg, he encounters the keeper of the local madhouse, himself insane, who regards Peer as the bringer of supreme wisdom. Peer comes to the madhouse and understands that all of the patients live in their own worlds, being themselves to such a degree that no one cares for anyone else. In his youth, Peer had dreamt of becoming an emperor. In this place, he is finally hailed as one — the emperor of the «self». Peer despairs and calls for the «Keeper of all fools», i.e., God.

Act V[edit]

Finally, on his way home as an old man, he is shipwrecked. Among those on board, he meets the Strange Passenger, who wants to make use of Peer’s corpse to find out where dreams have their origin. This passenger scares Peer out of his wits. Peer lands on shore bereft of all of his possessions, a pitiful and grumpy old man.

Back home in Norway, Peer Gynt attends a peasant funeral and an auction, where he offers for sale everything from his earlier life. The auction takes place at the very farm where the wedding once was held. Peer stumbles along and is confronted with all that he did not do, his unsung songs, his unmade works, his unwept tears, and his questions that were never asked. His mother comes back and claims that her deathbed went awry; he did not lead her to heaven with his ramblings.

Peer escapes and is confronted with the Button-molder, who maintains that Peer’s soul must be melted down with other faulty goods unless he can explain when and where in life he has been «himself». Peer protests. He has been only that, and nothing else. Then he meets the troll king, who states that Peer has been a troll, not a man, most of his life.

The Button-molder says that he has to come up with something if he is not to be melted down. Peer looks for a priest to whom to confess his sins, and a character named «The Lean One» (who is the Devil) turns up. The Lean One believes Peer cannot be counted a real sinner who can be sent to Hell; he has committed no grave sin.

Peer despairs in the end, understanding that his life is forfeit; he is nothing. But at the same moment, Solveig starts to sing—the cabin Peer built is close at hand, but he dares not enter. The Bøyg in Peer tells him «go around». The Button-molder shows up and demands a list of sins, but Peer has none to give, unless Solveig can vouch for him. Then Peer breaks through to Solveig, asking her to forgive his sins. But she answers: «You have not sinned at all, my dearest boy.»

Peer does not understand—he believes himself lost. Then he asks her: «Where has Peer Gynt been since we last met? Where was I as the one I should have been, whole and true, with the mark of God on my brow?» She answers: «In my faith, in my hope, in my love.» Peer screams, calls his mother, and hides himself in her lap. Solveig sings her lullaby for him, and we might presume he dies in this last scene of the play, although there are neither stage directions nor dialogue to indicate that he actually does.

Behind the corner, the Button-molder, who is sent by God, still waits, with the words: «Peer, we shall meet at the last crossroads, and then we shall see if… I’ll say no more.»

Analysis[edit]

Klaus van den Berg argues that Peer Gynt

… is a stylistic minefield: Its origins are romantic, but the play also anticipates the fragmentations of emerging Modernism. Chronicling Peer’s journey from the Norwegian mountains to the North African desert, the cinematic script blends poetry with social satire, and realistic scenes with surreal ones. The irony of isolated individuals in a mass society infuses Ibsen’s tale of two seemingly incompatible lovers – the deeply committed Solveig and the superficial Peer, who is more a surface for projections than a coherent character.[3] The simplest conclusion one may draw from Peer Gynt, is expressed in the eloquent prose of the author: “If you lie; are you real?”

The literary critic Harold Bloom in his book The Western Canon has challenged the conventional reading of Peer Gynt, stating:

Far more than Goethe’s Faust, Peer is the one nineteenth-century literary character who has the largeness of the grandest characters of Renaissance imaginings. Dickens, Tolstoy, Stendhal, Hugo, even Balzac have no single figure quite so exuberant, outrageous, vitalistic as Peer Gynt. He merely seems initially to be an unlikely candidate for such eminence: What is he, we say, except a kind of Norwegian roaring boy? – marvelously attractive to women, a kind of bogus poet, a narcissist, absurd self-idolator, a liar, seducer, bombastic self-deceiver. But this is paltry moralizing – all too much like the scholarly chorus that rants against Falstaff. True, Peer, unlike Falstaff, is not a great wit. But in the Yahwistic, biblical sense, Peer the scamp bears the blessing: More life.[15]

Writing process[edit]

On 5 January 1867 Ibsen wrote to Frederik Hegel, his publisher, with his plan for the play: it would be «a long dramatic poem, having as its principal a part-legendary, part-fictional character from Norwegian folklore during recent times. It will bear no resemblance to Brand, and will contain no direct polemics or anything of that kind.»[16]

He began to write Peer Gynt on 14 January, employing a far greater variety of metres in its rhymed verse than he had used in his previous verse plays Brand (written 1865) or Love’s Comedy (written 1862).[17] The first two acts were completed in Rome and the third in Casamicciola on the north of the island of Ischia.[18]

During this time, Ibsen told Vilhelm Bergsøe that «I don’t think the play’s for acting» when they discussed the possibility of staging the play’s image of a casting-ladle «big enough to re-cast human beings in.»[19] Ibsen sent the three acts to his publisher on 8 August, with a letter that explains that «Peer Gynt was a real person who lived in Gudbrandsdal, probably around the end of the last century or the beginning of this. His name is still famous among the people up there, but not much more is known about his life than what is to be found in Asbjørnsen’s Norwegian Folktales (in the section entitled ‘Stories from the Mountain’).»[20] In those stories, Peer Gynt rescues the three dairy-maids from the trolls and shoots the Bøyg, who was originally a gigantic worm-shaped troll-being. Peer was known to tell tall tales of his own achievements, a trait Peer in the play inherited. The «buck-ride» story, which Peer tells his mother in the play’s first scene, is also from this source, but, as Åse points out, it was originally Gudbrand Glesne from Vågå who did the tour with the reindeer stag and finally shot it.

Following an earthquake on Ischia on 14 August, Ibsen left for Sorrento, where he completed the final two acts; he finished the play on 14 October.[21] It was published in a first edition of 1,250 copies a month later in Copenhagen.[5]

Background[edit]

Ibsen’s previous play, Brand, preached the philosophy of “All or nothing.” Relentless, cruel, resolute, overriding in will, Brand went through everything that stood in his way toward gaining an ideal. Peer Gynt is a compensating balance, a complementary color to Brand. In contrast to Brand, with his iron will, Peer is willless, insufficient, and irresolute. Peer «goes around» all issues facing him.[22]

Brand had a phenomenal literary success, and people became curious to know what Ibsen’s next play would be. The dramatist, about this time, was relieved of financial worry by two money grants, one from the Norwegian government and the other from the Scientific Society of Trondhjem. This enabled him to give to his work an unfettered mind. He went with his family to Frascati, where, in the Palazzo rooms, he looked many feet down upon the Mediterranean, and pondered his new drama. He preserved a profound silence about the content of the play, and begged his publisher, Hegel, to create as much mystery about it as possible.[22]

The portrayal of the Gynt family is known to be based on Henrik Ibsen’s own family and childhood memories; in a letter to Georg Brandes, Ibsen wrote that his own family and childhood had served «as some kind of model» for the Gynt family. In a letter to Peter Hansen, Ibsen confirmed that the character Åse, Peer Gynt’s mother, was based on his own mother, Marichen Altenburg.[23][24] The character Jon Gynt is considered to be based on Ibsen’s father Knud Ibsen, who was a rich merchant before he went bankrupt.[25] Even the name of the Gynt family’s ancestor, the prosperous Rasmus Gynt, is borrowed from the Ibsen’s family’s earliest known ancestor. Thus, the character Peer Gynt could be interpreted as being an ironic representation of Henrik Ibsen himself. There are striking similarities to Ibsen’s own life; Ibsen himself spent 27 years living abroad and was never able to face his hometown again.

Grieg’s music[edit]

Ibsen asked Edvard Grieg to compose incidental music for the play. Grieg composed a score that plays approximately ninety minutes. Grieg extracted two suites of four pieces each from the incidental music (Opus 46 and Opus 55), which became very popular as concert music. One of the sung parts of the incidental music, «In the Hall of the Mountain King», was included in the first suite with the vocal parts omitted. Originally, the second suite had a fifth number, «The Dance of the Mountain King’s Daughter», but Grieg withdrew it. Grieg himself declared that it was easier to make music «out of his own head» than strictly following suggestions made by Ibsen. For instance, Ibsen wanted music that would characterize the «international» friends in the fourth act, by melding the said national anthems (Norwegian, Swedish, German, French and English). Reportedly, Grieg was not in the right mood for this task.[citation needed]

The music of these suites, especially «Morning Mood» starting the first suite, «In the Hall of the Mountain King», and the string lament «Åse’s Death» later reappeared in numerous arrangements, soundtracks, etc.

Other Norwegian composers who have written theatrical music for Peer Gynt include Harald Sæverud (1947), Arne Nordheim (1969), Ketil Hvoslef (1993) and Jon Mostad (1993–4). Gunnar Sønstevold (1966) wrote music for a ballet version of Peer Gynt.

Notable productions[edit]

In 1906 scenes from the play were given by the Progressive Stage Society of New York.[22] The first US production of Peer Gynt opened at the Chicago Grand Opera House on October 24, 1906, and starred the noted actor Richard Mansfield,[22] in one of his very last roles before his untimely death. In 1923, Joseph Schildkraut played the role on Broadway, in a Theatre Guild production, featuring Selena Royle, Helen Westley, Dudley Digges, and, before he entered films, Edward G. Robinson. In 1944, at the Old Vic, Ralph Richardson played the role, surrounded by some of the greatest British actors of the time in supporting or bit roles, among them Sybil Thorndike as Åse, and Laurence Olivier as the Button Molder. In 1951, John Garfield fulfilled his wish to star in a Broadway production, featuring Mildred Dunnock as Åse. This production was not a success, and is said by some to have contributed to Garfield’s death at age 39.

On film, years before he became a superstar, the seventeen-year-old Charlton Heston starred as Peer in a silent, student-made, low-budget film version of the play produced in 1941. Peer Gynt, however, has never been given a full-blown treatment as a sound film in English on the motion picture screen, although there have been several television productions, and a sound film was produced in German in 1934.

In 1957, Ingmar Bergman produced a five-hour stage version[26] of Peer Gynt, at Sweden’s Malmö City Theatre, with Max von Sydow as Peer Gynt. Bergman produced the play again, 34 years later,[27] in 1991, at Sweden’s Royal Dramatic Theatre, this time with Börje Ahlstedt in the title role. Bergman chose not to use Grieg’s music, nor the more modern Harald Sæverud composition, but rather traditional Norwegian folk music, and little of that either.

In 1993, Christopher Plummer starred in his own concert version of the play,[28] with the Hartford Symphony Orchestra in Hartford, Connecticut. This was a new performing version and a collaboration of Plummer and Hartford Symphony Orchestra Music Director Michael Lankester. Plummer had long dreamed of starring in a fully staged production of the play, but had been unable to. The 1993 production was not a fully staged version, but rather a drastically condensed concert version, narrated by Plummer, who also played the title role, and accompanied by Edvard Grieg’s complete incidental music for the play. This version included a choir and vocal parts for soprano and mezzo-soprano. Plummer performed the concert version again in 1995 with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra with Lankester conducting. The 1995 production was broadcast on Canadian radio. It has never been presented on television nor released on compact disc. In the 1990s Plummer and Lankester also collaborated on and performed similarly staged concert versions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (with music by Mendelssohn) and Ivan the Terrible (an arrangement of a Prokofiev film score with script for narrator). Among the three aforementioned Plummer/Lankester collaborations, all received live concert presentations and live radio broadcasts, but only Ivan the Terrible was released on CD.

Alex Jennings won the Olivier Award for Best Actor 1995/1996 for his performance in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Peer Gynt.

In 1999 Braham Murray directed a production at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester with David Threlfall as Peer Gynt, Josette Bushell-Mingo as Solveig and Espen Skjonberg as Button Moulder.

In 2000, the Royal National Theatre staged a version based on the 1990 translation of the play by Frank McGuinness.[29] The production featured three actors playing Peer, including Chiwetel Ejiofor as the young Peer, Patrick O’Kane as Peer in his adventures in Africa, and Joseph Marcell as the old Peer. Not only was the use of three actors playing one character unusual in itself, but the actors were part of a «color-blind» cast: Ejiofor and Marcell are black, and O’Kane is white.[30]

In 2001 at the BBC Proms, the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers, conducted by Manfred Honeck, performed the complete incidental music in Norwegian with an English narration read by Simon Callow.[31]

In 2005 Chicago’s storefront theater The Artistic Home mounted an acclaimed production (directed by Kathy Scambiatterra and written by Norman Ginsbury) that received two Jeff Nominations for its dynamic staging in a 28-seat house.[32][33] The role of Peer was played by a single actor, John Mossman.[34]

In 2006, Robert Wilson staged a co-production revival with both the National Theater of Bergen and the Norwegian Theatre of Oslo, Norway. Ann-Christin Rommen directed the actors in Norwegian (with English subtitles). This production mixed both Wilson’s minimalist (yet constantly moving) stage designs with technological effects to bring out the play’s expansive potential. Furthermore, they utilized state-of-the-art microphones, sound systems, and recorded acoustic and electronic music to bring clarity to the complex and shifting action and dialogue. From April 11 through the 16th, they performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Howard Gilman Opera House.

In 2006, as part of the Norwegian Ibsen anniversary festival, Peer Gynt was set at the foot of the Great Sphinx of Giza near Cairo, Egypt (an important location in the original play). The director was Bentein Baardson. The performance was the centre of some controversy, with some critics seeing it as a display of colonialist attitudes.

In January 2008 the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis debuted a new translation of Peer Gynt by the poet Robert Bly. Bly learned Norwegian from his grandparents while growing up in rural Minnesota, and later during several years of travel in Norway. This production stages Ibsen’s text rather abstractly, tying it loosely into a modern birthday party for a 50-year-old man. It also significantly cuts the length of the play. (An earlier production of the full-length play at the Guthrie required the audience to return a second night to see the second half of the play.)

In 2009, Dundee Rep with the National Theatre of Scotland toured a production. This interpretation, with much of the dialogue in modern Scots, received mixed reviews.[35][36] The cast included Gerry Mulgrew as the older Peer. Directed by Dominic Hill.

In November 2010 Southampton Philharmonic Choir and the New London Sinfonia performed the complete incidental music using a new English translation commissioned from Beryl Foster. In the performance, the musical elements were linked by an English narrative read by actor Samuel West.[37]

From June 28 through July 24, 2011, La Jolla Playhouse ran a production of Peer Gynt as a co-production with the Kansas City Repertory Theatre, adapted and directed by David Schweizer.

The 2011 Dublin Theatre Festival presented a new version of Peer Gynt by Arthur Riordan, directed by Lynne Parker with music by Tarab.

In November 2013, Basingstoke Choral Society (directed by David Gibson, who also directs Southampton Philharmonic Choir) reprised the earlier performance by their colleagues in Southampton.

In June 2019, Toneelgroep Twister in Nijmegen, The Netherlands

The Peer Gynt Festival[edit]

At Vinstra in Gudbrandsdalen (the Gudbrand valley), Henrik Ibsen and Peer Gynt have been celebrated with an annual festival since 1967. The festival is one of Norway’s largest cultural festivals, and is recognized by the Norwegian Government as a leading institution of presenting culture in nature. The festival has a broad festival program with theatre, concerts, an art exhibition and several debates and literature seminars.

The main event in the festival is the outdoor theatre production of Peer Gynt at Gålå. The play is staged in Peer Gynt‘s birthplace, where Ibsen claims he found inspiration for the character Peer Gynt, and is regarded by many as the most authentic version. The play is performed by professional actors from the national theater institutions, and nearly 80 local amateur actors. The music to the play is inspired by the original theatre music by Edvard Grieg – the «Peer Gynt suite». The play is one of the most popular theater productions in Norway, attracting more than 12,000 people every summer.

The festival also holds the Peer Gynt Prize, which is a national Norwegian honor prize given to a person or institution that has achieved distinction in society and contributed to improving Norway’s international reputation.

Peer Gynt Sculpture Park[edit]

Peer Gynt Sculpture Park (Peer Gynt-parken) is a sculpture park located in Oslo, Norway. Created in honour of Henrik Ibsen, it is a monumental presentation of Peer Gynt, scene by scene. It was established in 2006 by Selvaag, the company behind the housing development in the area. Most of the sculptures in this park are the result of an international sculpture competition.

Adaptations[edit]

Theatre posters for Peer Gynt and an adaptation entitled Peer Gynt-innen? in Ibsen Museum, Oslo

In 1912 German writer Dietrich Eckart adapted the play. In Eckart’s version, the play became «a powerful dramatisation of nationalist and anti-semitic ideas», in which Gynt represents the superior Germanic hero, struggling against implicitly Jewish «trolls».[38] In this racial allegory the trolls and Great Bøyg represented what philosopher Otto Weininger – Eckart’s hero – conceived as the Jewish spirit. Eckart’s version was one of the best attended productions of the age with more than 600 performances in Berlin alone. Eckart later helped to found the Nazi Party and served as a mentor to Adolf Hitler; he was also the first editor of the party’s newspaper, the Völkische Beobachter. He never had another theatrical success after Peer Gynt.[39]

In 1938 German composer Werner Egk finished an opera based on the story.

In 1948, the composer Harald Sæverud made a new score for the nynorsk-production at «the Norwegian Theatre» (Det Norske Teatret) in Oslo. Sæverud incorporated the national music of each of the friends in the fourth act, as per Ibsen’s request, who died in 1906.

In 1951, North Carolinian playwright Paul Green published an American version of the Norwegian play. This is the version in which actor John Garfield starred on Broadway. This version is also the American Version, and features subtle plot differences from Ibsen’s original work, including the omittance of the shipwreck scene near the end, and the Buttonmolder character playing a moderately larger role.[40]

In 1961, Hugh Leonard’s version, The Passion of Peter Ginty, transferred the play to an Irish Civil War setting. It was staged at Dublin’s Gate Theatre.[41]

In 1969, Broadway impresario Jacques Levy (who had previously directed the first version of Oh! Calcutta!) commissioned The Byrds’ Roger McGuinn to write the music for a pop (or country-rock) version of Peer Gynt, to be titled Gene Tryp. The play was apparently never completed, although, as of 2006, McGuinn was preparing a version for release.[citation needed] Several songs from the abortive show appeared on the Byrds’ albums of 1970 and 1971.[citation needed]

In March 1972 Jerry Heymann’s adaptation,[42] called Mr. Gynt, Inc., was performed at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club.[43]

In 1981, Houston Ballet presented Peer Gynt as adapted by Artistic Director Ben Stevenson, OBE.

In 1989, John Neumeier created a ballet «freely based on Ibsen’s play», for which Alfred Schnittke composed the score.

In 1998, the Trinity Repertory Company of Providence, Rhode Island commissioned David Henry Hwang and Swiss director Stephan Muller to do an adaptation of Peer Gynt.

In 1998, playwright Romulus Linney directed his adaptation of the play, entitled Gint, at the Theatre for the New City in New York. This adaptation moved the play’s action to 20th-century Appalachia and California.

In 2001, Rogaland Theatre produced an adaptation entitled Peer Gynt-innen?, loosely translated as Peer the Gyntess? This was a one-act monologue performed by Marika Enstad.[44]

In 2007, St. John’s Prep of Danvers, Massachusetts won the MHSDG Festival with their production starring Bo Burnham.

In 2008, Theater in the Open in Newburyport, Massachusetts, produced a production of Peer Gynt adapted and directed by Paul Wann and the company. Scott Smith, whose great, great grandfather (Ole Bull) was one of the inspirations for the character, was cast as Gynt.

In 2009, a DVD was released of Heinz Spoerli’s ballet, which he had created in 2007. This ballet uses mostly the Grieg music, but adds selections by other composers. Spoken excerpts from the play, in Norwegian, are also included.[45]

In Israel, poet Dafna Eilat (he:דפנה אילת) composed a poem in Hebrew called «Solveig», which she also set to music, its theme derived from the play and emphasizing the named character’s boundless faithful love. It was performed by Hava Alberstein (see [46]).

In 2011, Polarity Ensemble Theatre in Chicago presented another version of Robert Bly’s translation of the play, in which Peer’s mythic journey was envisioned as that of America itself, «a 150-year whirlwind tour of the American psyche.»[47]

On an episode of «Inside the Actors Studio», Elton John spontaneously composed a song based on a passage from Peer Gynt.

The German a cappella metal band Van Canto also made a theatrical a cappella metal adaption of the story, naming it «Peer Returns». The first episode that has been released up until now, called «A Storm to Come», appears on the band’s album Break the Silence.

Will Eno’s adaptation of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt titled Gnit had its world premiere at the 37th Humana Festival of New American Plays in March 2013.[48]

In 2020, a new audio drama adaptation of Peer Gynt by Colin Macnee, written in verse form with original music, was released[49] in podcast form.

Films[edit]

There have been a number of film adaptations including:

- Peer Gynt (1915 film), an American film directed by Oscar Apfel and Raoul Walsh

- Peer Gynt (1919 film), a German film directed by Richard Oswald

- Peer Gynt (1934 film), a German film directed by Fritz Wendhausen

- Peer Gynt (1941 film), notable for being the film debut of Charlton Heston

- Peer Gynt (1971 film), a German language TV film starring Edith Clever

- Peer Gynt (1979 animated film), Russian animation studio Soyuzmultfilm animated film «Пер Гюнт».

- Peer Gynt (1981 film), a French TV film directed by Bernard Sobel

- Peer Gynt (1988 film), a Hungarian TV film directed by István Gaál

- Peer Gynt (2006 film), a German TV film directed by Uwe Janson

- Peer Gynt (2017 film), a Belgian short film directed by Michiel Robberecht

Notes[edit]

- ^ While historically more accurate, the pronunciation [ˈjʏnt], with a soft G, is now uncommon in Norway.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ «Mener vi uttaler Peer Gynts navn feil» (in Norwegian). NRK. 17 November 2017.

- ^ Falkenberg, Ingrid. «Ibsens språk» (in Norwegian). Norwegian Language Council.

- ^ a b Klaus Van Den Berg, «Peer Gynt» (review), Theatre Journal 58.4 (2006) 684–687

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 391) and Meyer (1974, 284).

- ^ a b Meyer (1974, 284).

- ^ Meyer (1974, 288).

- ^ Farquharson Sharp (1936, 9).

- ^ Leverson, Michael, Henrik Ibsen: The farewell to poetry, 1864–1882, Hart-Davis, 1967 p. 67

- ^ Meyer (1974, 284–286). Meyer describes Clemens Petersen as «the most influential critic in Scandinavia» (1974, 285). He reviewed Peer Gynt in the 30 November 1867 edition of the newspaper Faedrelandet. He wrote that the play «is not poetry, because in the transmutation of reality into art it fails to meet the demands of either art or reality.»

- ^ Letter to Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson on 9 December 1867; quoted by Meyer (1974, 287).

- ^ Watts (1966, 10–11).

- ^ Meyer (1974, 288–289).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 391) and Meyer (1974, 288–289).

- ^ Williams (1993, 76).

- ^ Bloom, Harold. The Western Canon. p. 357.

- ^ Quoted by Meyer (1974, 276).

- ^ Peer Gynt employs octosyllabics and decasyllabics, iambic, trochaic, dactylic, anapaestic, as well as amphibrachs. See Meyer (1974, 277).

- ^ Meyer (1974, 277–279).

- ^ Quoted by Meyer (1974, 279).

- ^ See Meyer (1974, 282).

- ^ Meyer (1974, 282). Meyer points out that Ibsen’s fear of subsequent earthquakes in the town, which motivated his swift departure from the island, were not groundless, since it was destroyed by one 16 years later.

- ^ a b c d This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Moses, Montrose J. (1920). «Peer Gynt» . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ «Bumerker i teksten – Om store og små gjengangere i Ibsens samtidsdramaer | Bokvennen Litterært Magasin». Blm.no. 2010-01-24. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Robert Ferguson, Henrik Ibsen. A New Biography, Richard Cohen Books, London 1996

- ^ Templeton, Joan (2009). «Survey of Articles on Ibsen: 2007, 2008» (PDF). IBSEN News and Comment. The Ibsen Society of America. 29: 40. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Ingmar Bergman Foundation. «Ingmar Bergman produces Peer Gynt at Malmö City Theatre, 1957″. Ingmarbergman.se. Archived from the original on 2009-01-11. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ^ Ingmar Bergman Foundation. «Ingmar Bergman produces Peer Gynt at Royal Dramatic Theatre, 1991″. Ingmarbergman.se. Archived from the original on 2010-08-17. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ^ «Christopher-Plummer.com». Christopher-Plummer.com. Archived from the original on 2002-08-03. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ^ «Peer Gynt». National Theatre. Retrieved 30 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Billington, Michael (26 April 2002). «National’s Peer Gynt shambles into life». Guardian UK. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ Jeal, Erica (11 August 2001). «Prom 27: Peer Gynt». Theguardian.com. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ «Peer Gynt». Theartistichome.org. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ «Jeff Awards | CMS». www.jeffawards.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ «John Mossman». IMDb.com. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ «Peer Gynt, Barbican Theatre, London». Independent.co.uk. 7 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Spencer, Charles (5 May 2009). «Peer Gynt at the Barbican, review». Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ «Grieg – Peer Gynt, with Narrator, Samuel West; Mendelssohn – Hebrides Overture (Fingal’s Cave); Delius – Songs of Farewell – Southampton Philharmonic Choir». 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Brown, Kristi (2006) «The Troll Among Us», in Powrie, Phil et al. (ed), Changing Tunes: The Use of Pre-existing Music in Film, Ashgate. ISBN 9780754651376 pp.74–91

- ^ Weber, Thomas (2017). Becoming Hitler: the Making of a Nazi. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03268-6.

- ^ Ibsen, Henrik; Green, Paul (23 December 2017). Ibsen’s Peer Gynt: American Version. Samuel French, Inc. ISBN 9780573613791. Retrieved 23 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ «PlayographyIreland — the Passion of Peter Ginty». www.irishplayography.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ «New Light Theater Project | New York City Collaborative Theater». Archived from the original on 2018-03-08. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- ^ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections, «Production: Mr. Gynt, Inc.». Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ «Sceneweb». sceneweb.no. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- ^ «Peer Gynt: Marijn Rademaker, Philipp Schepmann, Yen Han, Christiane Kohl, Zürcher Ballett, Sarah-Jane Brodbeck, Juliette Brunner, Julie Gardette, Arman Grigoryan, Vahe Martirosyan, Ana Carolina Quaresma, Andy Sommer, Corentin Leconte: Movies & TV». Amazon. 27 October 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ «חוה אלברשטיין סולווג LYRICS». 5 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 April 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ «Polarity Ensemble Theatre’s Peer Gynt at Chicago’s Storefront Theater». petheatre.com. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ «Premiere of Will Eno’s Gnit, Adaptation of Peer Gynt Directed by Les Waters, Opens March 17 at Humana Fest — Playbill.com». 8 January 2014. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ «Announcement of Macnee’s audio drama version of Peer Gynt».

Sources[edit]

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Brockett, Oscar G. & Franklin J. Hildy. 2003. History of the Theatre. 9th, International edition. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-205-41050-2.

- Farquharson Sharp, R., trans. 1936. Peer Gynt: A Dramatic Poem. Henrik Ibsen. Edinburgh: J. M Dent & Sons and Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. Available in online edition.

- McLeish, Kenneth, trans. 1990. Peer Gynt. Henrik Ibsen. Drama Classics ser. London: Nick Hern, 1999. ISBN 1-85459-435-4.

- Meyer, Michael, trans. 1963. Peer Gynt. Henrik Ibsen. In Plays: Six. World Classics ser. London: Methuen, 1987. 29–186. ISBN 0-413-15300-2.

- –––. 1974. Ibsen: A Biography. Abridged. Pelican Biographies ser. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-021772-X.

- Moi, Toril. 2006. Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism: Art, Theater, Philosophy. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP. ISBN 978-0-19-920259-1.

- Oelmann, Klaus Henning. 1993. Edvard Grieg: Versuch einer Orientierung. Egelsbach Cologne New York: Verlag Händel-Hohenhausen. ISBN 3-89349-485-5.

- Schumacher, Meinolf. 2009. «Peer Gynts letzte Nacht: Eschatologische Medialität und Zeitdehnung bei Henrik Ibsen». Figuren der Ordnung: Beiträge zu Theorie und Geschichte literarischer Dispositionsmuster. Ed. Susanne Gramatzki and Rüdiger Zymner. Cologne: Böhlau. pp. 147–162. ISBN 978-3-412-20355-9 Available in online edition.

- Watts, Peter, trans. 1966. Peer Gynt: A Dramatic Poem. By Henrik Ibsen. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044167-0.

- Williams, Raymond. 1966. Modern Tragedy. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-1260-3.

- –––. 1989. The Politics of Modernism: Against the New Conformists. Ed. Tony Pinkney. London and New York: Verso. ISBN 0-86091-955-2.

- –––. 1993. Drama from Ibsen to Brecht. London: Hogarth. ISBN 0-7012-0793-0.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Free Scores of piano arrangements of the two suites.

- Peer Gynt (in Norwegian), freely available at Project Runeberg (in Norwegian)

Peer Gynt public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Peer Gynt: a dramatic poem, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1936. Color illustrations by Arthur Rackham via Internet Archive.

- The Peer Gynt Festival,

| Peer Gynt | |

|---|---|

Henrik Klausen as Peer (1876) |

|

| Written by | Henrik Ibsen |

| Date premiered | 24 February 1876 |

| Place premiered | Christiania (now Oslo), Norway |

| Original language | Norwegian |

| Genre | Romantic dramatic poem converted into a play |

Peer Gynt (, Norwegian: [peːr ˈjʏnt, — ˈɡʏnt])[a] is a five-act play in verse by the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen published in 1876. Written in Norwegian,[2] it is one of the most widely performed Norwegian plays. Ibsen believed Per Gynt, the Norwegian fairy tale on which the play is loosely based, to be rooted in fact, and several of the characters are modelled after Ibsen’s own family, notably his parents Knud Ibsen and Marichen Altenburg. He was also generally inspired by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen’s collection of Norwegian fairy tales, published in 1845 (Huldre-Eventyr og Folkesagn).

Peer Gynt chronicles the journey of its title character from the Norwegian mountains to the North African desert and back. According to Klaus Van Den Berg, «its origins are romantic, but the play also anticipates the fragmentations of emerging modernism» and the «cinematic script blends poetry with social satire and realistic scenes with surreal ones.»[3] Peer Gynt has also been described as the story of a life based on procrastination and avoidance.[4] The play was written in Italy and a first edition of 1,250 copies was published on 14 November 1867 by the Danish publisher Gyldendal in Copenhagen.[5] Although the first edition swiftly sold out, a reprint of two thousand copies, which followed after only fourteen days, did not sell out until seven years later.[6]

Peer Gynt was first performed in Christiania (now Oslo) on 24 February 1876, with original music composed by Edvard Grieg that includes some of today’s most recognised classical pieces, «In the Hall of the Mountain King» and «Morning Mood». It was published in German translation in 1881, in English in 1892, and in French in 1896.[7] The contemporary influence of the play continues into the Twenty-First Century; it is widely performed internationally both in traditional and in modern experimental productions.

While Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson admired the play’s «satire on Norwegian egotism, narrowness, and self-sufficiency» and described it as «magnificent»,[8] Hans Christian Andersen, Georg Brandes and Clemens Petersen all joined the widespread hostility, Petersen writing that the play was not poetry.[9] Enraged by Petersen’s criticisms in particular, Ibsen defended his work by arguing that it «is poetry; and if it isn’t, it will become such. The conception of poetry in our country, in Norway, shall shape itself according to this book.»[10] Despite this defense of his poetic achievement in Peer Gynt, the play was his last to employ verse; from The League of Youth (1869) onwards, Ibsen was to write drama only in prose.[11]

Ibsen wrote Peer Gynt in deliberate disregard of the limitations that the conventional stagecraft of the 19th century imposed on drama.[12] Its forty scenes move uninhibitedly in time and space and between consciousness and the unconscious, blending folkloric fantasy and unsentimental realism.[13] Raymond Williams compares Peer Gynt with August Strindberg’s early drama Lucky Peter’s Journey (1882) and argues that both explore a new kind of dramatic action that was beyond the capacities of the theatre of the day; both created «a sequence of images in language and visual composition» that «became technically possible only in film.»[14]

Characters[edit]

- Åse, a peasant’s widow

- Peer Gynt, her son

- Two old women with corn–sacks

- Aslak, a blacksmith

- Wedding guest

- A master cook

- A fiddler

- A man and a wife, newcomers to the district

- Solveig and little Helga, their daughters

- The farmer at Hægstad

- Ingrid, his daughter

- The bridegroom and his parents

- Three alpine dairymaids

- A green-clad woman, a troll princess

- The Old Man of the Mountains, a troll king (Also known as The Mountain King)