- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

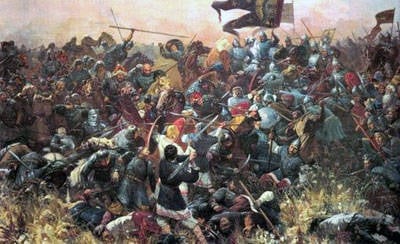

The Battle of Kulikovo (Russian: Мамаево побоище, Донское побоище, Куликовская битва, битва на Куликовом поле) was fought between the armies of the Golden Horde, under the command of Mamai, and various Russian principalities, under the united command of Prince Dmitry of Moscow. The battle took place on 8 September 1380, at the Kulikovo Field near the Don River (now Tula Oblast, Russia) and was won by Dmitry, who became known as Donskoy, ‘of the Don’ after the battle.

Although the victory did not end Mongol domination over Rus, it is widely regarded by Russian historians as the turning point at which Mongol influence began to wane and Moscow’s power began to rise. The process eventually led to Grand Duchy of Moscow independence and the formation of the modern Russian state.[7]

BackgroundEdit

After the Mongol-Tatar conquest, the territories of the disintegrating Kievan Rus became part of the western region of the Mongol Empire (also known as the Golden Horde), centered in the lower Volga region. The numerous Rus principalities became the Horde’s tributaries. During this period, the small regional principality of Moscow was growing in power and was often challenging its neighbors over territory, including clashing with the Grand Duchy of Ryazan. Thus, in 1300, Moscow seized the city of Kolomna from Ryazan, and the Ryazan Prince was killed after several years in captivity.[8]

After the killing of Khan Berdi Beg of the Golden Horde at 1359, a civil war had arisen there. Warlord (temnik) Mamai, who was son-in-law and beylerbey of Berdi Beg, soon took power in the western part of the Golden Horde. Mamai enthroned Abdullah Khan in 1361 and after his mysterious death in 1370 immature Khan Muhammad Bolak was enthroned.[9] Mamai was not a Genghisid (descendant of Genghis Khan), and as such his grip on power was tenuous, as there were true Genghisids with claims to mastery. Therefore, he had to constantly fight for supreme power and at the same time struggle against separatism. While there was a civil war in the falling Golden Horde, the new political powers were appearing, such as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, and the Grand Duchy of Ryazan.

Meanwhile, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania continued its expansion. It competed with Moscow for supremacy over Tver and in 1368–1372 made three campaigns against Moscow. After the death of Algirdas in 1377, his eldest sons Andrei of Polotsk and Dmitri of Bryansk began to struggle with their step-brother Jogaila for their legitimate right to the throne and entered into an alliance with the Grand Prince of Moscow.[10]

Simultaneously with the beginning of the Great Troubles in the Horde in 1359, Prince of Moscow Ivan II died and the new Khan of the Horde by his jarliq (law pronouncement) transferred the throne of the Grand Duchy of Vladimir to the Prince of Nizhny Novgorod. But the Moscow elite (in 1359, new Prince Dmitry was only 9 years old) did not accept this. They used equally armed force and bribes to various Khans and as a result, in 1365, forced the princes of Nizhny Novgorod to finally give up claims to the Grand Duchy of Vladimir.[9] In 1368, the conflict between Moscow and Tver began. Prince of Tver Mikhail used the help of Lithuania, and in addition, in 1371 Mamai gave him a jarliq to the Grand Duchy of Vladimir. But the Moscow troops simply did not let the new «Grand Prince» enter to Vladimir, despite the presence of the Tatar ambassador. The campaigns of the Lithuanian army also ended in failure and so the jarliq returned to Dmitry. According to the results of the truce with Lithuania in 1372, the Grand Duchy of Vladimir was now recognized as the hereditary possession of the Moscow Princes.[11] In 1375 the Prince of Tver once again received a jarliq for the Grand Duchy from Mamai. Then Dmitri with a strong army (larger than it was in the Kulikovo battle) quickly moved to Tver and forced it to capitulate. Mikhail recognized himself as the «little brother» of the Moscow Prince and ensure to participate in wars with the Tatars.[12]

The open conflict between Dmitry and Mamai began in 1374, the exact reasons are unknown. It is believed that the illegitimacy of the puppet khans of Mamai was by that time too obvious, and he demanded more and more money, as he lost the war for the throne of the Golden Horde.[13] In the following years the Tatars raided Dmitry’s allies and the Moscow troops made campaign against Tatars over the Oka River in 1376 and seized the city Bolghar in 1377. In the same year «Mamai’s tatars» defeated the army of Nizhny Novgorodl with an auxiliary detachment left by Dmitry at the Battle on Pyana River. The Tatars then began to raid Nizhniy Novgorod and Ryazan.[14]

Mamai continued attempts to re-affirm his control over the tributary lands of the Golden Horde. In 1378, he sent forces led by the warlord Murza Begich to ensure Prince Dmitri’s obedience, but this army suffered crushing defeat at the Battle of the Vozha River. Meanwhile, another khan, Tokhtamysh, seized power in the eastern part of the Golden Horde. He enjoyed the support of Tamerlane and was ready to unite the entire Horde under his rule. In 1380, despite the threat from Tokhtamysh, Mamai chose to personally lead his army against the forces of Moscow. In preparation for the invasion, he entered into an alliance with Prince Jogaila of Lithuania. Ryazan Prince Oleg was defeated by Mamai in 1378 (and his capital was burnt), he had no strength to resist Mamai, and Ryazan’s relationship with Moscow had long been hostile. Therefore, in the campaign of 1380 Oleg took the side of Mamai, although this fact is sometimes challenged. Mamai camped his army on the bank of the Don River, waiting for the arrival of his allies.[15][16]

PreludeEdit

CampaignEdit

In August 1380 Prince Dmitri learned of the approaching army of Mamai. It is alleged that Oleg Ryazansky sent a message to him. The interpretations of such an act are different. Some believe that he did this, because in fact he was not a supporter of Mamai, others believe that he expected to intimidate Dmitry — earlier none of the Russian princes dared to meet in battle with the Khan himself. Nevertheless, Dmitry quickly assembled an army in Kolomna. There he was visited by the ambassadors of Mamai. They demanded an increased tribute, «as under the Khan Jani Beg». Dmitry agreed to pay tribute, but only in the amount provided for by his previous contract with Mamai.[17] In Kolomna, Dmitry received updated information about the Mamai itinerary and about approaching forces of Jogaila. So, after reviewing the army, on August 20 he moved west along the Oka River, crossed it at the town Lopasnya on August 24–25 and moved south towards Mamai. On September 6 Russian army reached the Don River where it was reorganized taking into account the units that joined during the movement from Kolomna. At the council it was decided to cross the Don before the enemies could combine their forces, although this step cut off the path to retreat in case of defeat.[18]

ForcesEdit

The earliest chronicle tales do not provide details on the composition of the Russian army. Among the dead in the battle there are named only Princes of Beloozero (which by that time were in strong submission to Moscow), noble Moscow boyars, and Alexander Peresvet.[19] The latter, according to some sources, was from Lithuania (rather from Bryansk). The poetic story «Zadonshchina», along with a figure of 253,000 fallen in the battle, gives dozens of dead princes, boyars, «Lithuanian pans» and «Novgorod posadniks» from all over North-Eastern Rus’, but all this data is doubtful. There are mentioned even 70 fallen Ryazan boyars, although according to all other sources the Duchy of Ryazan was the forced ally of Tatars. According to the Russian historian Gorskii, the list of princes and commanders (according to which one can estimate the composition of the army), cited in «The Tale of the Rout of Mamai» and the sources derived from it, is completely untrustworthy. However, he identified two chronicles with a sufficiently high level of reliability. According to his reconstruction, detachments from most of North-Eastern Russia, part of the Princes of the Smolensk Land and part of the Upper Oka Principalities were represented in the army of Dmitry, but there were no troops from Nizhny Novgorod and from the Principality of Tver (except for Kashin, who became independent under the treaty of 1375). The probability of the presence of a detachment from Veliky Novgorod is quite high (although in the early Novgorod chronicles such information is not available). Grand Duchy of Ryazan could be represented by the troops of the appanage Principality of Pronsk, whose rulers have long rivaled their Grand Princes. Also, the presence of small detachments from the border lands of Murom, Yelets and Meshchera is «not excluded». Probably, the army of Dmitri was enforced by Jogaila’s rebellious brothers Andrei of Polotsk and Dmitri of Bryansk.[1]

The first data on the total number of troops collected by Dmitry appeared in the Expanded Chronicle Tale, which estimates them in 150–200,000. This number is completely unreliable, as such masses of people simply could not physically fit on the field; even the number of 100,000 seems overestimated. Late literature sources determine the number of Russian troops at 300 or even 400 thousand armored soldiers only. Thus, there is no exact data on the number of the army of Dmitry. It can only be said that by the standards of that time it was a very large army, and even in the 15th century the Moscow princes could not assemble an equally powerful force, which led to fantastic stories about hundreds of thousands of warriors.[20] The definition of the real size of the medieval armies on the basis of chronicles is a difficult task.[21]

Estimates of the number of the Russian army by historians gradually departed from the hundreds of thousands of soldiers described in the chronicles and medieval literature. Military historian General Maslovsky in the work of 1881 estimated it to be 100–150,000. The historian of military art Razin in the book of 1957 estimated it to be 50–60,000. The historian and archaeologist, medieval warfare expert Kirpchinikov, in the book of 1966 argues that the maximum strength of the army of six regiments on Kulikovo Field could not exceed 36,000. Archaeologist Dvurechensky, an employee of the «Kulikovo field» museum, in his report of 2014 determined the number of the Russian army in 6-7 thousand warriors. Close assessments are given by modern Russian historians Penskoy and Bulychev. The main impetus for reducing the estimates of the strength of the army was the analysis of demography and mobilization potential. It was noted that even a much larger and densely populated Russia of the 16th century rarely could expose 30–40,000 soldiers at a time. It was also noted that the timeframe for mobilization (about two weeks) was too small to mobilize a huge army of unskilled militiamen (even apart from the fact that this approach was completely contrary to all the military traditions of that time).[22][23][24][25][26] Attempts to reduce the size of the army are criticized by some authors.[27]

Estimates of the forces of the Tatars in Russian sources are equally unreliable, they only show an overwhelming numerical superiority. So, in one variant of «The Tale» the number of Russians troops was boldly given at 1,320,000 but the Tatar army was named «innumerable».[28] There were no medieval sources from the Tatar side.[29] Mamai’s allies, Grand Prince Oleg II of Ryazan and Grand Prince Jogaila of Lithuania, were late to the battle and the number of their troops can be ignored.

LocationEdit

Ancient sources do not give a precise description of the site of the battle, but they mention a large clear field beyond the Don River and near the mouth of the Nepryadva River. In the 19th century Stepan Nechaev came up with what he believed was the exact location of the battle and his hypothesis was accepted. Studies of ancient soils in the 20th century showed that the left bank of Nepryadva near its influx in the Don was covered with dense forests, while on the right there was a wooded steppe with vast openings. On one of them, between the rivers Nepryadva and Smolka, the place of the battle was finally localized by archeologists.[30]

The historian Azbelev subjected this localization to sharp criticism. Trying to prove that 400,000 people were involved in the battle on both sides, he assumed that the real battlefield was not at the mouth, but at the source of Nepryadva, since the Old Russian word ust’e had also designated the place where the river flows from the lake.[31] As early as the beginning of the 20th century it was believed that Nepryadva derived from Lake Volovo [ru] (Volosovo).[32]

BattleEdit

IntroEdit

The early sources contain few details about the course of the battle. «The Tale of the Rout of Mamai», which dates back to the 16th century, gives a complete picture detailing the alignment of forces and the events on the field, and adds many colorful details. It is unknown whether «The Tale» is based on an unknown earlier source, or whether it reflects a retrospective attempt to describe the battle based on tactics and practices of the 16th century. Due to the absence of other sources, the course of the battle according to «The Tale» was adopted as a basis for subsequent reconstructions of the battle.[33]

On 7 September, Prince Dmitri was told that Mamai’s army was approaching. On the morning of 8 September, in a thick fog, the army crossed the Don River. According to the Nikon Chronicle, after that the bridges were destroyed. The day of 8 September was very special, as it was the feast of the Nativity of the Theotokos, who was considered a patron Saint of Russia. According to chronology adopted in Russia it was the year 6888 Anno Mundi, which also had a numerological value.[34] The army came to the «clean field» near Nepryadva mouth and assumed a battle formation. After some time, Tatars appeared and began to form their order of battle against the «Christians».[35]

The beginningEdit

The Russian army was organized into six «regiments» — a Patrol, a Forward, two regiments of «Right» and «Left Hand,» a Large regiment and an Ambush regiment. In turn, each of the regiments was divided into smaller tactical units — «banners» (a total of about 23).[36] On the field the army was arranged in multiple lines, and probably, the location of the regiments did not match their names (there is no evidence that the regiments of the Left and Right Hand disposed in line with the Large Regiment). The terrain did not allow for a broad front; probably, the units entered into battle gradually. The army’s flanks were protected by ravines with dense thickets which excluded any chance for a surprise flank attack of a Horde. The Ambush regiment under the command of Vladimir the Bold and Dmitry Bobrok (brother-in-law of the Grand Prince) was hidden behind the line of Russian troops in an oak grove.[a] The Grand Prince himself went to the front lines, leaving his trusted boyar Mikhail Brenok as the head of the Large Regiment under the great banner. He also exchanged with the boyar horses and gave him a coat and a helmet, so the Grand Prince could fight like an ordinary boyar, remaining unrecognized.[b] The battle opened with a single combat between two champions.[c] The Russian champion was Alexander Peresvet and The Horde’s champion was Temir-murza (also Chelubey or Cheli-bey, also Tovrul or Chrysotovrul). During the first pass of the contest each champion killed the other with his spear and both fell to the ground. Thus, it remained unclear whose victory was predicted by the outcome of the duel.[37]

The main clashEdit

Dmitri Donskoy in the thick of the fray; painting by Adolphe Yvon.

«The Field of Kulikovo» (1890s). A large-scale hand-drawn lubok by I.G. Blinov (ink, tempera, gold).

After the fights of the advanced detachments, the main forces of both armies clashed. According to the «Expanded Chronicle Tale» it happened «at the sixth hour of the day» (the daylight was divided into twelve hours, the duration of which changed throughout the year).[d] «The sixth hour of the day» approximately corresponds to 10.35 am. According to one of the later sources, the Tatars met the first blow of the Russian cavalry on foot, exposing the spears in two rows, which gave rise to stories about the «hired Genovese infantry.» Russian sources, even the earliest ones, unanimously tell us that after the clash of the main forces, a cruel melee began, which lasted a long time and in which the «innumerable multitude of people» perished on both sides.[38] The medieval German historian Albert Krantz describe this battle in his book «Vandalia»: «both of these people do not fight standing in large detachments, but in their usual way they rush to throw missiles, strike and then retreat backwards». An expert on the medieval warfare Kirpichnikov assumed that the armies on the Kulikovo field fought by a number of separate consolidated units, that tried to keep the battle order. As soon as this order was disrupted, the survivors from the unit fled and a new detachment was put in their place. Gradually, more and more units were drawn into the battle. As described in the «Expanded Chronicle Tale»: «And a corpse fell on a corpse, a Tatar body fell on a Christian body; then here, it was possible to see how a Rusyn pursued a Tatar, and a Tatar pursued a Rusyn.» The tightness of the field did not allow the Tatars to realize their mobility and use their tactics of flanking. Nevertheless, in a fierce battle the Tatars began to gradually overcome. They broke through to the banner of the Large Regiment, threw it down and killed boyar Brenok. The regiment of the «Left Hand» was also overturned and some «Moscow recruits» fell into a panic.[e] It seemed that the rout of the Russian army was close and the Tatars put all their forces into action.[39]

At that time, the cavalry of the ambush regiment launched a surprise counterstrike on the Horde’s flank, which led to the collapse of the Horde’s line. People and horses, tired from a long battle, could not resist the blow of fresh forces. After the horde was routed, the Russians chased the Tatars for over 50 kilometers, until they reached Krasivaya Mecha River.[40]

The endEdit

An exhausted Dmitri having his wounds cared for after the battle. By Vasily Sazonov

The losses in the battle were great. A third of the commanders of 23 «banners» were killed in action. Grand Prince Dmitry himself survived, although wounded and fainted from exhaustion. His entire escort died or scattered and he was hardly found among the corpses. For six days the victorious army stood «on the bones».[41]

AftermathEdit

Upon learning of Mamai’s defeat, Prince Jogaila turned his army back to Lithuania. People of the Ryazan Land attacked separate detachments coming from the battlefield, plundered them and taken prisoners (the question of the return of prisoners remained actual for twenty years, it was mentioned in the Moscow–Ryazan Treaties of 1381 and 1402). Prince Dmitry of Moscow began to prepare for reprisal, but Prince Oleg of Ryazan fled (according to the Nikon Chronicle, «to Lithuania») and the Ryazan boyars received Moscow governors. Soon Prince Oleg returned to power, but he was forced to accept Prince Dmitry as his sovereign («older brother») and to sign a treaty of peace.[42]

Mukhammad-Bulek, Mamai’s figurehead Khan, was killed in battle. Mamai escaped to the Genoese stronghold Caffa in Crimea. He assembled a new army, but now he did not have a «legitimate khan» and his nobles defected to his rival Tokhtamysh khan. Mamai again fled to Caffa and was killed there.[43] The war with Moscow had led Mamai’s Horde to a complete crash. With one stroke Tokhtamysh received full power, thus eliminating the 20-year split of the Golden Horde. According to historian Gorsky, it was Tokhtamysh who received the most concrete political benefit from the defeat of Mamai.[44]

Prince Dmitri, who became known as Donskoy (of the Don) after the battle, did not manage to become fully independent from the Golden Horde, however. In 1382, Khan Tokhtamysh launched another campaign against the Grand Duchy of Moscow. He captured and burned down Moscow, forcing Dmitri to accept him as sovereign. However, the victory at Kulikovo was an early sign of the decline of Mongol power. In the century that followed, Moscow’s power rose, solidifying control over the other Russian principalities. Russian vassalage to the Golden Horde officially ended in 1480, a century after the battle, following the defeat of the Horde’s invasion at the great stand on the Ugra River.

LegacyEdit

The site of the battle is commemorated by a memorial church, built from a design by Aleksey Shchusev.

A minor planet, 2869 Nepryadva, discovered in 1980 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named in honor of the Russian victory over the Tataro-Mongols.[45]

LiteratureEdit

The Battle of Kulikovo gave rise to an unprecedentedly large stratum of medieval Russian literature; no other historical event has received such wide coverage. Russian historians singled out a body of «Literary Works of the Kulikovo Cycle».[46] The most important works are:[47]

- Short Chronicle Tale (Kratkaia letopisnaia povest’)

- Expanded Chronicle Tale (Prostrannaia letopisnaia povest’)

- Zadonshchina

- The Tale of the Rout of Mamai (Skazanie o Mamaevom poboishche)

ArtEdit

The paintings on the theme of the battle were created by many Russian and Soviet artists such as Orest Kiprensky, Vasily Sazonov, Mikhail Nesterov, Alexander Bubnov, Mikhail Avilov. The French painter Adolphe Yvon, later known for his works on the Napoleonic Wars, in 1850 wrote the monumental painting «The Battle of the Kulikovo Field» by order of Nicholas I.[48]

Archaeological findsEdit

A collection of artifacts related to the battle is present in the state museum Kulikovo Polye, and a significant amount of finds is open to the public in other Russian museums. The first relics were discovered on the Kulikovo field in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, though their fate is hitherto unknown; fragments of weapons were reported to have been frequently discovered by 18th-century peasants during plowing, and it is known that at the time some of the finds were collected by economist Vasily Lyovshin, who had a personal interest in the history of the battle. A large number of antiquities were discovered in the 19th century and their relatively large number led to the publication of the first catalogue of Kulikovo artifacts by Ivan Sakharov, Secretary of the Department of Russian and Slavic Archaeology of the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society. Historian Stepan Nechayev noted in his writings that during their agricultural operations local peasants discovered old weapons, crosses, chainmails, and used to find human bones before; some of those finds were purchased by him, and their description appeared on the pages of Vestnik Evropy. In 1825, it was reported by a famous Russian adventurer that the «precious things» from the field, once numerous, were «scattered across Russia» and formed private collections, such as those of Nechayev, Countess Bobrinskaya and other noble persons. The fate of these collections is not always clear and not all of them have been preserved to this day; General Governor Alexander Balashov and educator Dmitri Tikhomirov [ru] pointed to the fact that in their time iron objects were often collected, melted down by peasants and used for their purposes. One of such cases occurred recently, in 2009, when a Persian blade dug out from the field was discovered in the house of a local family and transferred to the Kulikovo field museum. After visiting the field and the village of Monastyrschina, Tikhomirov noted that «swords, axes, arrows, spears, crosses, coins and other similar things» that were of value were frequently found there and owned by private persons. Numerous fragments of weapons, crosses and armour were also noted by the famous 19th-century Tula historian Ivan Afremov [ru], who suggested building a museum for these artifacts. Some of the finds are known to have been sent as gifts to government officials and members of the Imperial family; in 1839 and 1843, the head of a mace and the blade of a sword were gifted to Emperor Nicholas I by a Kulikovo nobleman. While preparing his work «Parishes and Churches of the Tula Diocese» (1895), editor Pavel Malitsky received reports from inhabitants of the Tula Oblast, who had found spearheads, poleaxes and crosses on the field. Spears and arrows dug out by the locals are also mentioned in the worksheets of the Tula provincial academic archival commission. Many artifacts were collected by noble families that owned Kulikovo, such the Oltufyevs, the Safonovs, the Nechayevs and the Chebyshevs, whose rich collections were still remembered by local citizens in the 1920–1930s. Their estates were situated around the village of Monastyrschina, close to the site of the battle, but during the Civil War most of their collections were lost and only a significant part of the Nechayevs’ collection survived the revolutionary period, whereas the extensive use of agricultural machinery in the field contributed to a loss of remaining artifacts. A number of antiquities, however, were found and transferred to museums in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[49]

Works on relics from Kulikovo were published in the 1920s and 1930s by local lore specialists Vladimir Narcissov and Vadim Ashurkov [ru]. Most recent descriptions of Kulikovo weaponry and other artifacts have been presented in publications by Vasily Putsko, Oleg Dvurechensky [ru] and other historians.[50][51][49]

The 2008 book presents a catalog of findings at the Kulikovo field. According to the compilers, the following items of weapons belong to the time of the battle:

four spearheads (and two fragments), a tip of a javelin, two fragments of ax blades, a fragment of an armor plate, a fragment of chain mail, and several arrowheads. Many weapons found in the vicinity of the Kulikovo field (such as bardiches, firearms), date back to the 16–18 centuries and cannot in any way relate to the Kulikovo battle of 1380.[50]

PerspectivesEdit

The historical evaluation of the battle has many theories as to its significance in the course of history.

- The traditional slavophile Russian point of view sees the battle as the first step in the liberation of the Russian lands from the Golden Horde dependency. It should however be noted that approximately a half of the old Kievan Rus at this time were controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania,

- Some historians within the Eastern Orthodox tradition view the battle as a stand-off between the Christian Rus and non-Christians of the steppe.

- Russian historian Sergey Solovyov saw the battle as critical for the history of Eastern Europe in stopping another invasion from Asia, similar to the Battle of Châlons in the 5th century and the Battle of Tours in the 8th century in Western Europe.

- Other historians believe that the meaning of the battle is overstated, viewing it as nothing more than a simple regional conflict within the Golden Horde.

- Another Russian historian, Lev Gumilev, sees in Mamai a representative of economic and political interests from outside, particularly Western Europe, which in the battle were represented by numerous Genoese mercenaries, while the Moscow army stood in support of the rightful ruler of the Golden Horde Tuqtamış xan. According to the Russian historian Lev Gumilev, «Russians went to the Kulikovo field as citizens of various principalities and returned as a united Russian nation».[52]

- The battle is perhaps the earliest example of the Russian tactic of deception, or maskirovka, and it is taught as such at Russian military schools.

See alsoEdit

PersonsEdit

- Dmitri Donskoy

- Alexander Peresvet

- Oslyabya

- Bobrok

- Stepan Nechaev

Edit

- Battle of the Vozha River

- Great stand on the Ugra river

- Tatar invasions

- Russo-Kazan Wars

- Mongol invasion of Rus

- Timeline of the Tataro-Mongol Yoke in Russia

NotesEdit

- ^ A detailed account of the location and actions of the Ambush Regiment is contained only in «The Tale of the Rout of Mamai», but with an important note that it was written by the words of a spectator and participant. In addition, the formation and command structure of this regiment is described in credible chronicles (Amel’kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 235)

- ^ The episode with disguise appears only in «The Tale of the Rout of Mamai», but already in the «Expanded Tale» it is said about how Dmitry drove off to the Patrol Regiment and took part in the attack in the first line. Then he returned to his place in the Large Regiment and his retinue tried to dissuade him from such reckless behavior. But he refused and again fought in the front ranks and his armor was damaged in many places. This behavior was not something exceptional for the rulers of that time. Dmitry Donskoy’s grandson Vasily II in one of the battles with the Tatars was surrounded and taken prisoner after a brutal melee, although armor saved his life, like his grandfather.

- ^ This episode appears only in «The Tale of the Rout of Mamai» and there are serious suspicions that this is the product of literary fiction. The book of Amel’kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 238 lists 6 arguments in favor of this. In «Zadonschina» Peresvet does not fight in a duel, but in the thick of the battle, and not as a monk, but as a noble boyar in a gold-plated armor.

- ^ According to «The Tale of the Rout of Mamai» it happened «at the third hour», but this information is doubtful. Chronicle data are more reliable, and, in addition, «The Tale» mentions earlier that the formation of regiments continued until «the sixth hour of the day» (Rybakov 1998, pp. 215–216, 218).

- ^ Reconstructions of the battle traditionally draw a breakthrough of the Tatars on the left flank of the Russian troops, but there is no direct indication of such a course of events in the medieval sources. The description that the battle line of the Russian army was broken and the regiment of the Left Hand was cut off appears only in the work of the historian of the 18th century Tatischev.

ReferencesEdit

- ^ a b Gorskii, Anton (2001). «К вопросу о составе русского войска на Куликовом поле» (PDF). Древняя Русь. Вопросы медиевистики. 6: 1–9.

- ^ Janet Martin, Medieval Russia 980–1584, (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 214.

- ^ a b L. Podhorodecki, Kulikowe Pole 1380, Warszawa 2008, s. 106

- ^ Разин Е. А. История военного искусства VI–XVI вв. С.-Пб.: ООО «Издательство Полигон», 1999. 656 с. Тираж 7000 экз. ISBN 5-89173-040-5 (VI–XVI вв.). ISBN 5-89173-038-3. (Военно-историческая библиотека)[1]

- ^ Карнацевич В. Л. 100 знаменитых сражений. Харьков., 2004. стр. 139

- ^ Мерников А. Г., Спектор А. А. Всемирная история войн. Минск., 2005.

- ^ Timofeychev, A. (2017-07-19). «The Battle of Kulikovo: When the Russian Nation Was Born». Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- ^ Gorskii 2000, pp. 28–29, 44.

- ^ a b Gorskii 2000, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Auty, Robert; Obolensky, Dimitri (1981). A Companion to Russian Studies: An Introduction to Russian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-521-28038-9.

- ^ Gorskii 2000, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Gorskii 2000, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Gorskii 2000, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Gorskii 2000, pp. 90, 92–93.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. p. 543. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- ^ Robert O. Crummey (2014). The Formation of Muscovy 1300–1613. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-317-87200-9.

- ^ Gorskii 2000, p. 97.

- ^ Kirpichnikov 1980, p. 37-43.

- ^ Rybakov 1998, p. 18.

- ^ Rybakov 1998, p. 51-52.

- ^ Christian Raffensperger (26 April 2018). Conflict, Bargaining, and Kinship Networks in Medieval Eastern Europe. Lexington Books. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-1-4985-6853-1.

- ^ Масловский Д.М. Из истории военного искусства России: Опыт критического разбора похода Дмитрия Донского 1380 г. до Куликовской битвы включительно // Военный сборник. СПб., 1881. № 8. Отд. 1.

- ^ Разин, Е. А. История военного искусства в 3 т. Т. 2 : История военного искусства VI—XVI вв. — СПб. : Полигон, 1999. — 656 с. — ISBN 5-89173-040-5

- ^ Кирпичников А.Н. Военное дело на Руси в XIII-XV вв. — Л.: Наука, 1966, с.16

- ^ Двуреченский О.В. Масштабы Донского побоища по данным палеографии и военной археологии // Воинские традиции в археологическом контексте. От позднего латена до позднего средневековья. — Тула: Куликово поле, 2014. С. 124-129

- ^ Пенской В.В. О численности войска Дмитрия Ивановича на Куликовом поле // Военное дело Золотой Орды: проблемы и перспективы изучения. Казань, 2011, стр. 157-161

- ^ Азбелев С.Н. Куликовская битва по летописным данным //Исторический формат, 2016

- ^ Rybakov 1998, p. 277,308.

- ^ Amel’kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Где была Куликовская битва. В поисках Куликова поля — интервью с руководителем отряда Верхне-Донской археологической экспедиции Государственный исторический музей Олегом Двуреченским. Журнал «Нескучный Сад» № 4 (15) 15.08.05

- ^ Azbelev, Sergey (2016). «Место сражения на Куликовом поле по летописным данным» (PDF). Древняя Русь. Вопросы медиевистики. 3 (65): 17–29.

- ^ https://ru.wikisource.org/wiki/ЭСБЕ/Непрядва

- ^ Parppei 2017, p. 57,80-83,231.

- ^ Рудаков, Владимир (1998). «Духъ южны» и «осьмый час» в «Сказании о Мамаевом побоище» (К вопросу о восприятии победы над «погаными» в памятниках «куликовского цикла»). Герменевтика древнерусской литературы (in Russian). 9: 135–157.

- ^ Kirpichnikov 1980, p. 88.

- ^ Kirpichnikov 1980, p. 51.

- ^ Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 89–92.

- ^ Rybakov 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 94–99.

- ^ Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 100–104.

- ^ Amel’kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 248-249.

- ^ Amel’kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 246.

- ^ Gorskii 2000, p. 100.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 236. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- ^ Rybakov 1998, p. 5.

- ^ Parppei 2017, pp. ix, 20.

- ^ «Куликово поле: 12 картин».

- ^ a b The history of research of relics of the Battle of Kulikovo // State Military–Historical and National Museum “The Kulikovo Field” (in Russian)

- ^ a b Двуреченский О. В., Егоров В. Л., Наумов А. Н. Реликвии Донского побоища. Находки на Куликовом поле / авт.-сост. О. В. Двуреченский. М.: Квадрига, 2008. 88 с. (Реликвии ратных полей / Гос. ист. музей, Военно-ист. и природный музей-заповедник «Куликово поле»). ISBN 978-5-904162-01-6

- ^ М. В. Фехнер Находки на Куликовом поле // Куликово поле: Материалы и исследования. Труды ГИМ. М., 1990. Вып. 73

- ^ Lev Gumilev. From Rus to Russia

SourcesEdit

- Amel’kin, Andrei; Seleznev, Yuri (2011). Куликовская битва в свидетельствах современников и памяти потомков [The Battle of Kulikovo in the Testimonies of Contemporaries and Memory of Posterity)] (in Russian). Moscow: Квадрига. pp. 384, illus. ISBN 978-5-91791-074-1.

- Gorskii, Anton (2000). Москва и Орда [Moscow and the Horde] (in Russian). Moscow: Наука. p. 214. ISBN 5-02-010202-4.

- Kirpichnikov, Anatoly (1980). Куликовская битва [Battle of Kulikovo (in Russian)] (in Russian). Leningrad: Наука.

- Rybakov, Boris (1998). Памятники Куликовского цикла [Literary Works of the Kulikovo Cycle] (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. ISBN 5-8678-9-033-3.

- Parppei, Kati (2017). The Battle of Kulikovo Refought: «The First National Feat». Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-33794-7.

Further readingEdit

- Galeotti, Mark (2019): Kulikovo 1380; The battle that made Russia. Osprey Campaign Series #332; Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1472831217

External linksEdit

- (in Ukrainian) Unveiling the myths (Kulikovo battle)

- The Zadonshchina

- The Battle of Kulikovo

- History of Kulikovo Battle

Coordinates: 53°39.15′N 38°39.21′E / 53.65250°N 38.65350°E

- Текст

- Веб-страница

The battle of Kulikovo Field is one of the most important events in the history of Russia. It took place in 1380 during the reign of Dmitry Donskoy, the Prince of Muscovy. At that time Russia was under the yoke of the Tatarts. This battle signalized the beginning of the liberation of the Russian people from the yoke of the Golden Horde. Although the end of the yoke occurred only in 1480, the battle of Kulikovo Field was the first and the main victory in the process of the liberation of Russia. This event determined the future development of the Russian state. The role of this event can not be underestimated.

0/5000

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

The battle of Kulikovo Field is one of the most important events in the history of Russia. It took place in 1380 during the reign of Dmitry Donskoy, the Prince of Muscovy. At that time Russia was under the yoke of the Tatarts. This battle signalized the beginning of the liberation of the Russian people from the yoke of the Golden Horde. Although the end of the yoke occurred only in 1480, the battle of Kulikovo Field was the first and the main victory in the process of the liberation of Russia. This event determined the future development of the Russian state. The role of this event can not be underestimated.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Куликовская битва является одним из самых важных событий в истории России. Это произошло в 1380 году во время правления Дмитрия Донского, князя Московии. В то время Россия была под гнетом Tatarts. Это сражение ознаменовало начало освобождения русского народа от ига Золотой Орды. Хотя конец ярма произошло только в 1480 году, битва Куликовская была первая и главная победа в процессе освобождения России. Это событие определило дальнейшее развитие Российского государства. Роль этого события нельзя недооценивать.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 3:[копия]

Скопировано!

битва куликово поле является одним из наиболее важных событий в истории россии.она состоялась в 1380 году, во время правления дмитрий донской, князя московского государства.в это время россия была под игом в tatarts.эта битва сообщил об начало освобождения россиян из игом золотой орды.хотя в конце игом произошел только в 1480 — битва куликово поле была первой и главной победы в процессе освобождения россии.это событие определило будущего развития российского государства.роль это событие нельзя недооценивать.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- Секретарь ест бутерброды в 12 часов.

- Huile essentielle

- nautae

- fractura claviculoae

- Success at what price?Better Prices, a l

- Холагол

- Customs clearance: Released by custom ho

- Russia is the largest country in the wor

- Applicatio est vita regŭlae

- take off

- Poetae

- в воскресенье с двух до четырех мы работ

- Success at what price?Better Prices, a l

- палец

- Hi Daniel,My name’s Alessandra. It’s an

- The guide told us a lot of stories and l

- Mein Mann und ich zusammen gearbeitet. A

- our family is not very big. We are only

- Mein Mann und ich zusammen gearbeitet. A

- our family is not very big. We are only

- в воскресенье с двух до четырех мы работ

- Mən təhqir edirəm

- теперь мы закончили школу,она выбрала пр

- Алекс в субботу в школу не идет.

According to the legend, the duel between the two strongmen preceded the battle. Pictured: Mikhail Avilov, Single Combat on the Kulikovo Field, 1943.

Global Look Press

For Russians the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 is what the Battle of Patay is for the French, or the Battle of Britain is for the British. This is the first in a series of articles by RBTH describing great battles of Russia’s history and their significance.

“Russians went to Kulikovo Field as citizens of various principalities and returned as a united Russian nation” — famous Russian historian of the 20th century Lev Gumilev wrote.

Two generations without fear

In 1380, Russians from different parts of the Russian territory under the command of the Prince of Moscow Dmitry defeated the troops of Khan Mamai. He was a powerful commander and a claimant to the throne of the Golden Horde — a huge state created by the Mongols in the 13th century. Russian principalities had been reigned over by Mongolian rulers from the Horde for 150 years. They had to pay tribute and had limited sovereignty.

The brutal Mongolian invasion in the middle of the 13th century devastated Russian. However, as historian Vasily Klyuchevsky put it, by 1380 time had subdued the memory of terror — two generations had grown up without experiencing the horrors of the invasion.

‘Triumph over Asia’

As with many events from the distant past there is some uncertainty hovering over the Battle of Kulikovo, with many historians debating what actually happened — and its significance. The mainstream approach claims that at Kulikovo Field, Russia — for the first time in 150 years — fought against the Mongolian invaders, marking the beginning of the national liberation process.

There is also a view that Prince Dmitry didn’t want to challenge the Mongols’ suzerainty over Russian principalities. “His main goal was not an overthrow of the Yoke, how it is traditionally perceived (which was not achieved, since Russia was subjugated to the Horde for 100 further years).

“He wanted to bring the title of the Grand Prince of Vladimir (it gave the city the status of the main Russian principality) to Moscow on a permanent basis”, historian Anton Gorsky argued. Before Dmitry’s rule it was the Horde who chose the main Russian principality. In the spirit of this approach Dmitry fought with Mamai because the latter did not want to give the title to Moscow’s ruler. Dmitry’s victory made this title a hereditary possession of Moscow’s future princes, thus making Moscow principality a major entity in the Russian territory.

How Dmitry won the battle

A ferocious battle followed, with tens of thousands of soldiers on each side. The Mongols were assisted by Genoese infantry from Crimea and Mamai managed to break the Russian ranks to the left and started attacking the main bulk of the Russian troops from the rear. Just as the Mongols thought they were on the brink of a historical victory, a reserve regiment (that Dmitry has positioned as backup) moved in and took the Mongols by surprise, forcing Mamai to retreat in panic. Dmitry himself has been fighting on the front line wearing the armor of one of his noblemen, and was named Donskoy after that victory.

Moscow and the fate of Russia

According to Lev Gumilev, the Battle of Kulikovo was more than a fight for territory — it was about protecting culture and traditions. He says Mamai embodied the threat from both Islamism (Mongols) and Catholicism (Genovese and Lithuanians).

The victory at Kulikovo Field provided Russia with the foundation for unification throughout the ages. The battle changed Russia. “Because of the act of valor and self-sacrifice, Moscow rose up against the Horde and its allies”, Gumilev wrote, adding that the battle changed the way people thought; they started to perceive themselves as an entity, as Russia.

100 years later, in 1480, Dmitry’s descendent Ivan III, who is credited with creating the centralized Russian state, put Mongolia’s domination over Russia to bed. As chronicles say, he did it with the memory of the Battle of Kulikovo in mind.

Read more: Myths of Russian History: Does the word ‘Slavs’ derive from the ‘slave’?

If using any of Russia Beyond’s content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Get the week’s best stories straight to your inbox

In 1380, Prince Dmitry Donskoy defeated the Mongol army under the leadership of Khan Mamai at the Kulikovo field. In some historical In his writings, you can read that Dmitry Donskoy did not lead the battle, that he gave up command altogether and went to the front ranks to fight like a simple warrior. Others in the description of the battle place the main emphasis on the heroism of the Russian army, thanks to him, they say, they won. At the same time, it is overlooked that the course of the battle was largely predetermined by the strategic moves of the Moscow prince.

Those who focus on heroism lose sight of the fact that the heroism of some is often a consequence of the stupidity of others. So in 1237, the Ryazan prince with his squad went into the open field to meet Batu, there, in fact, there was no battle, just the beating of the heroic Ryazan army. And the battle on Kalka, when almost the 90 thousandth Russian army met the 30 thousandth Tatar army, half of the Russian army was killed, and nothing good. So in the story with Dmitry Donskoy, a great role was played not by his personal heroism and not by the courage of the Russian army, but, first of all, by Dmitry’s genius and strategic talent, who won the battle before it even began.

Strategic deception

Throughout history, any army, especially the defending one, has tried to rise in the heights. It is always more convenient to defend from a height, especially against cavalry troops. The prince was the first to enter the Kulikovo field, but did not occupy the height, he left it to Mamai. Mamai accepted this “sacrifice” and already then lost the battle. It is even strange that such an experienced commander did not think about why he was presented with the dominant height. Dmitry did this so that Mamai could watch and was sure that he could see. And he did not see the main things: the ravines in front of the Russian right flank, the ambush regiment sheltered by the forest, did not understand the asymmetry and weakness of the flanks of the Russian rati.

The effect of advanced shelf

For the first time in history before the head regiment, Dmitry Donskoy put forward an advanced regiment slightly ahead, a very dubious at first glance protection in 3-5 thousand people. What role should he perform? Was it worth it to attach to the head?

In order to understand this, you can refer to the circus number. Its essence is as follows: the hero knocks the stone with a hammer, it cracks or splits under the blow. Dale is put on the table of a man and covered with a thin stone slab, the same Hammer striker now beats the slab, it shatters into pieces, and the man rises from under it unscathed. At the moment of impact, the plate evenly distributes the impact force over its entire area. Instead of a powerful blow, only some uniform pressure is transmitted to a person.

We don’t know how Dmitriy thought of turning the Mongolian cavalry’s swift strike into the usual weakened pressure on the center of the Russian army, without violating its structure. But we have to admit, he applied this technique very skillfully.

Mamai — Dmitri’s ally?

Mamai thought he saw everything from the hill. And he clearly saw that the weakest flank of the Russian army was the right one. He was not numerous and stretched for quite a long distance. In the center, on the contrary, there was the bulk of the Russian army: the forward, head and spare regiments.

The battle plan was born by itself: to break through the right flank and go to the rear of the main Russian forces, surround them, bring panic into the ranks and destroy. And Mamai originally sent his cavalry to the regiment of his right hand. And then he ran into the first “gift” that Dmitry had prepared for him. The positions of the Russian troops were two rows of ravines, which simply could not be seen from the hill. Moreover, even the horsemen themselves noticed the ravines, only standing in front of them closely.

Thousands of cavalry in a broad front at a decent speed flies into a ravine. Rear horsemen are pushing at the front, it is impossible to step aside — the offensive is going on a broad front. Already before the collision with the Russian Tatars suffer losses. Instead of a swift raid, cavalry is slowly moving up to … the second row of ravines.

And this is a small victory. Horsemen first descend into a ravine, then slowly rise one by one from it and stumble upon a squad of princely squads, who calmly one by one, methodically beating up these emerging riders. Mamai’s army suffers heavy losses, its best batyrs die, the tempo of attack is lost. After 1-2 hours of such beatings, Mamai takes the second point of Dmitry Donskoy’s plan to “get stuck” in a critical mass in the center of the Russian army.

Trick prince

After that, none of the historians really could not explain why the prince, before the battle, wore a simple chainmail war, and gave his cloak and banner to the boyar Mikhail Brenko. But this was one of the moments that later led to the first turning point in the course of the battle: the balancing of forces in the center and the loss of the offensive outburst here by the Tatars.

The prince knew the Horde army well, the methods of conducting the battle, and the generals of the enemy. He was confident that the tactical offensive impulse, each individual commander will be sent to him, the Russian commander, to his banner. That is exactly what happened, the Tatars, regardless of the losses, were hacked to the flag, and it was impossible to stop their outburst, the boyar was hacked up, and the banner was knocked down.

Historically, the loss of the commander and the flag, death or flight led to a psychological change, followed by the defeat of the army. It turned out differently; the Tatars turned out to be paralyzed. Thinking that they killed the commander, they published victorious shouts, many even chopped off, their pressure began to fade. But the Russians did not even think about stopping the battle, they knew that the Tatars were wrong!

Outfit troops

Let’s return to the advanced regiment. He took upon himself the very first and most terrible blow of the Mongolian cavalry, but this did not mean that all his warriors were doomed to death. Foot soldiers can resist cavalry. For example, you can put a «wall» of copies. Several rows of warriors, armed with spears of different lengths (at the front they are shorter, at the back — longer) that end at the same distance in front of the line. In this case, the advancing cavalry encounters not one spear, which he can deflect with a shield or chop, but stumbles upon 3-4 and one of them can achieve his goal. The warriors’ bodies were also well protected. The so-called “blue armor” of the squad from Veliky Ustyug was not inferior in its qualities to the armor of the Genoese knights who fought on the side of the Horde.

The prince himself during the battle was not even wounded, although he fought in the front ranks of the troops. And it’s not just in the skill and power of Dmitry Donskoy. The enemy simply could not hit him when he took a sword or spear. His mail was forged from the best grades of metal. A plate of metal plates was worn over the chain mail, and a simple warrior was disguised over all this chain mail. He was hacked, stabbed, beaten, but no one was able to cut through all three layers of his armor.

But any blows are blows. The prince’s helmet was dented in several places; by the end of the battle, Dmitry was in a state of deep concussion, perhaps it was the cause of his early death at the age of 39. But at the same time not one Russian soldier did not see that the prince was bleeding, he did not give such a psychological loss to the Tatars.

Mamai gets trapped

The battle is already 4-5 hours. Mamai sees that there is a dead end in the center, a wall of the dead is formed between the living, a critical mass has worked, Mamai sees this from a hill and gives the order to transfer the blow to the left flank. And even in spite of the fatigue factor, the Tatars are already offensive for several hours, both people and horses are tired, their pressure is still strong. The numerical advantage affects, and the regiment of the left hand begins to retreat, bend under the onslaught of the Tatars, retreat to the oak grove. The numerical advantage on the side of the attackers, it seems to Mamai from the hill, he does not see the Ambush regiment beyond the oak grove.

But it is from the top that you can see how the Russian regiments are moving farther and farther back, how a gap appears, into which you can throw troops and go around the Russians to the left and strike them to the rear. And Mamai makes his last mistake. Directs to the breakthrough all the reserves at his disposal. The regiment of the left hand is rejected, the Tatars rush forward, accumulate and unfold to strike at the flank and rear of the central regiments, leaving the rear for the Ambush regiment open. The prince’s plan was completely successful; the Tatars turned back to the main strike force of the Russian troops. The strike of the fresh cavalry of the ambush regiment was fatal for the Tatars. Army Mamaia turns into uncontrollable flight.

Куликовская битва

(кратко)

Знаменитое сражение в 1380 г. войска

московского князя Дмитрия и его союзников

с одной стороны против полчищ

татаро-монгольского хана Мамая и его

союзников – с другой получило название

Куликовской битвы.

Краткая предыстория Куликовской битвы

такова: отношения князя Дмитрия Ивановича

и Мамая начали обостряться еще в 1371

году, когда последний дал ярлык на

великое владимирское княжение Михаилу

Александровичу Тверскому, а московский

князь тому воспротивился и не пустил

ордынского ставленника во Владимир. А

спустя несколько лет, 11 августа 1378 года

войска Дмитрия Ивановича нанесли

сокрушительное поражение монголо-татарскому

войску под предводительством мурзы

Бегича в битве на реке Воже. Потом князь

отказался от повышения уплачиваемой

Золотой Орде дани и Мамай собрал новое

большое войско и двинул его в сторону

Москвы.

Перед выступлением в поход

Дмитрий Иванович побывал у святого

преподобного Сергия Радонежского,

который благословил князя и все русское

войско на битву с иноземцами. Мамай же

надеялся соединиться со своими союзниками:

Олегом Рязанским и литовским князем

Ягайло, но не успел: московский правитель,

вопреки ожиданиям, 26 августа переправился

через Оку, а позднее перешел на южный

берег Дона. Численность русских войск

перед Куликовской битвой оценивается

от 40 до 70 тысяч человек, монголо-татарских

– 100-150 тысяч человек. Большую помощь

москвичам оказали Псков, Переяславль-Залесский,

Новгород, Брянск, Смоленск и другие

русские города, правители которых

прислали князю Дмитрию войска.

Битва состоялась на южном берегу Дона,

на Куликовом поле 8 сентября 1380 года.

После нескольких стычек передовых

отрядов перед войсками выехали от

татарского войска – Челубей, а от

русского – инок Пересвет, и состоялся

поединок, в котором они оба погибли.

После это началось основное сражение.

Русские полки шли в бой под красным

знаменем с золотым изображением Иисуса

Христа.

Кратко говоря, Куликовская

битва закончилась победой русских войск

во многом благодаря военной хитрости:

в расположенной рядом с полем боя дубраве

спрятался засадный полк под командованием

князя Владимира Андреевича Серпуховского

и Дмитрия Михайловича Боброка-Волынского.

Мамай основные усилия сосредоточил на

левом фланге, русские несли потери,

отступали и, казалось, что победа близка.

Но в это самое время в Куликовскую битву

вступил засадный полк и ударил в тыл

ничего не подозревающим монголо-татарам.

Этот маневр оказался решающим: войска

хана Золотой Орды были разгромлены и

обратились в бегство.

Потери русских сил в Куликовской битве

составили порядка 20 тысяч человек,

войска Мамая погибли почти полностью.

Сам князь Дмитрий, впоследствии прозванный

Донским, поменялся конем и доспехами с

московским боярином Михаилом Андреевичем

Бренком и принимал в сражении активное

участие. Боярин в битве погиб, а сбитого

с коня князя нашли под срубленной березой

без сознания.

Это сражение имело большое значение

для дальнейшего хода русской истории.

Кратко говоря, Куликовская битва, хотя

и не освободила Русь от монголо-татарского

ига, но создала предпосылки для того,

чтобы это произошло в будущем. Кроме

того, победа над Мамаем значительно

усилила Московское княжество.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

КУЛИКОВСКАЯ+БИТВА

-

1

битваж

алыш, ҡаты (хәл иткес) һуғыш

Русско-башкирский словарь > битва

См. также в других словарях:

-

Куликовская битва — Монголо татарское иго … Википедия

-

Куликовская Битва — Монголо татарское иго миниатюра из летописи XVII века Дата … Википедия

-

Куликовская битва — Куликовская битва. А.П. Бубнов. Утро на Куликовом поле . 1943 47. Третьяковская галерея. КУЛИКОВСКАЯ БИТВА, 8.9.1380 на Куликовом поле (между реками Дон и Непрядва, ныне в Куркинском районе Тульской области). Русское войско (участвовали воины… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

КУЛИКОВСКАЯ БИТВА — Битва русского войска во главе с великим князем Дмитрием Ивановичем (см. Дмитрий Донской*) и монголо татарского войска под началом ордынского темника (военачальника, командовавшего «тьмою», то есть 10 000 войска) Мамая, узурпировавшего в Золотой… … Лингвострановедческий словарь

-

КУЛИКОВСКАЯ БИТВА — КУЛИКОВСКАЯ БИТВА, русских полков во главе с великим князем московским и владимирским Дмитрием Ивановичем (см. ДМИТРИЙ ДОНСКОЙ) и ордынским войском под началом Мамая 8.9.1380 на Куликовом поле (на правом берегу Дона, в районе впадения в него реки … Русская история

-

Куликовская битва — КУЛИКОВСКАЯ БИТВА, произошла 8 снт. 1380 г. между рус. ратями Дмитрія Донского и татар. полчищами Мамая, при впаденіи р. Непрядвы въ Донъ, въ предѣлахъ нынѣш. Епифанск. у., Тульск. губ. Пораженіе татаръ на р. Вожѣ (см. это слово) ожесточило орду… … Военная энциклопедия

-

КУЛИКОВСКАЯ БИТВА — русских полков во главе с великим князем московским и владимирским Дмитрием Донским и монголо татарских войск под началом Мамая 8 сентября 1380 на Куликовом поле. В Куликовской битве участвовали воины многих русских княжеств. Борьбу с врагом… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Куликовская битва — русских полков во главе с великим князем московским и владимирским Дмитрием Донским и монголо татарских войск под началом Мамая 8 сентября 1380 на Куликовом поле. В Куликовской битве участвовали воины многих русских княжеств. Борьбу с врагом… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Куликовская битва 1380 — сражение русских войск под предводительством великого князя владимирского и московского Дмитрия Ивановича Донского (См. Дмитрий Иванович Донской) с монголо татарами, возглавляемыми правителем Золотой Орды темником Мамаем (См. Мамай) на… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

КУЛИКОВСКАЯ БИТВА 1380 — сражение рус. войск под предводительством вел. кн. Дмитрия Ивановича Донского с монголо татарами, к рых возглавлял фактич. правитель Золотой Орды темник Мамай. К. б. явилась поворотным пунктом в борьбе рус. народа против монголо тат. ига. Борьбу… … Советская историческая энциклопедия

-

Куликовская битва — происходила 8 сентября 1380 г. на Куликовом поле, между рр. Доном, Непрядвой и Красивой Мечей, в юго зап. части нынешнего Епифанского у. Тульской губ., на протяжении 10 кв. в. Рассерженный поражением татарского отряда на бер. р. Вожи, Мамай… … Энциклопедический словарь Ф.А. Брокгауза и И.А. Ефрона