Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta ( STEF-ən-ee JUR-mə-NOT-ə; born March 28, 1986), known professionally as Lady Gaga, is an American singer, songwriter, and actress. She is known for her image reinventions and musical versatility. Gaga began performing as a teenager, singing at open mic nights and acting in school plays. She studied at Collaborative Arts Project 21, through the New York University Tisch School of the Arts, before dropping out to pursue a career in music. After Def Jam Recordings canceled her contract, she worked as a songwriter for Sony/ATV Music Publishing, where she signed a joint deal with Interscope Records and KonLive Distribution, in 2007. Gaga had her breakthrough the following year with her debut studio album, The Fame, and its chart-topping singles «Just Dance» and «Poker Face». The album was later reissued to include the extended play The Fame Monster (2009), which yielded the successful singles «Bad Romance», «Telephone», and «Alejandro».

|

Lady Gaga |

|

|---|---|

Gaga at the inauguration of Joe Biden in 2021 |

|

| Born |

Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta March 28, 1986 (age 36) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 2001–present |

| Organizations |

|

| Works |

|

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Natali Germanotta (sister) |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Labels |

|

| Website | ladygaga.com |

Gaga’s five succeeding studio albums all debuted atop the US Billboard 200. Her second full-length album, Born This Way (2011), explored electronic rock and techno-pop and sold more than one million copies in its first week. The title track became the fastest-selling song on the iTunes Store, with over one million downloads in less than a week. Following her EDM-influenced third album, Artpop (2013), and its lead single «Applause», Gaga released the jazz album Cheek to Cheek (2014) with Tony Bennett, and the soft rock album Joanne (2016). She ventured into acting, winning awards for her leading roles in the miniseries American Horror Story: Hotel (2015–2016) and the musical film A Star Is Born (2018). Her contributions to the latter’s soundtrack, which spawned the chart-topping single «Shallow», made her the first woman to win an Academy Award, BAFTA Award, Golden Globe Award, and Grammy Award in one year. Gaga returned to dance-pop with her sixth studio album, Chromatica (2020), which yielded the number-one single «Rain on Me». She followed this with her second collaborative album with Bennett, Love for Sale, and a starring role in the biopic House of Gucci, both in 2021.

Having sold an estimated 170 million records, Gaga is one of the world’s best-selling music artists and the only female artist to achieve four singles that each sold at least 10 million copies globally. Her accolades include 13 Grammy Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, 18 MTV Video Music Awards, awards from the Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Council of Fashion Designers of America, and recognition as Billboard‘s Artist of the Year (2010) and Woman of the Year (2015). She has also been included in several Forbes‘ power rankings and ranked fourth on VH1’s Greatest Women in Music (2012). Time magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2010 and 2019 and placed her on their All-Time 100 Fashion Icons list. Her philanthropy and activism focus on mental health awareness and LGBT rights; she has her own non-profit organization, the Born This Way Foundation, which supports the wellness of young people. Gaga’s business ventures include Haus Labs, a vegan cosmetics brand launched in 2019.

Life and career

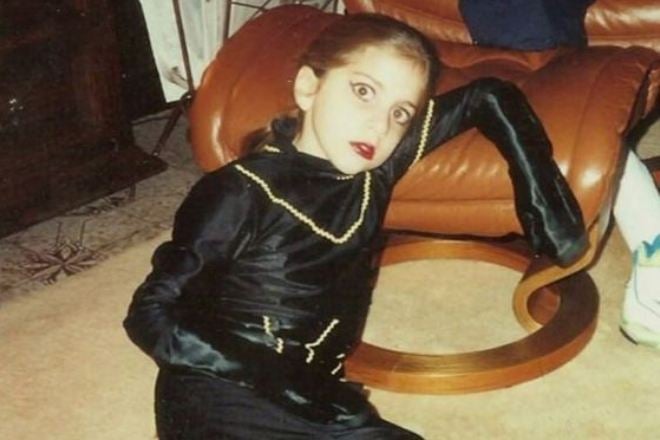

1986–2004: Early life

Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta was born on March 28, 1986, at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, New York City,[1] to an upper middle class Catholic family. Both of her parents have Italian ancestry.[2] Her parents are Cynthia Louise (née Bissett), a philanthropist and business executive, and Internet entrepreneur Joseph Germanotta,[3] and she has a younger sister named Natali.[4] Brought up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, Gaga said in an interview that her parents came from lower-class families and worked hard for everything.[5][6] From age 11, she attended the Convent of the Sacred Heart, a private all-girls Roman Catholic school.[7] Gaga has described her high-school self as «very dedicated, very studious, very disciplined» but also «a bit insecure». She considered herself a misfit and was mocked for «being either too provocative or too eccentric».[8]

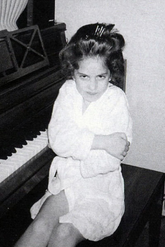

Gaga began playing the piano at age four when her mother insisted she become «a cultured young woman». She took piano lessons and practiced through her childhood. The lessons taught her to create music by ear, which she preferred over reading sheet music. Her parents encouraged her to pursue music and enrolled her in Creative Arts Camp.[9] As a teenager, she played at open mic nights.[10] Gaga played the lead roles of Adelaide in the play Guys and Dolls and Philia in the play A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum at Regis High School.[11] She also studied method acting at the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute for ten years.[12] Gaga unsuccessfully auditioned for New York shows, though she did appear in a small role as a high-school student in a 2001 episode of The Sopranos titled «The Telltale Moozadell».[13][14] She later said of her inclination towards music:

I don’t know exactly where my affinity for music comes from, but it is the thing that comes easiest to me. When I was like three years old, I may have been even younger, my mom always tells this really embarrassing story of me propping myself up and playing the keys like this because I was too young and short to get all the way up there. Just go like this on the low end of the piano … I was really, really good at piano, so my first instincts were to work so hard at practicing piano, and I might not have been a natural dancer, but I am a natural musician. That is the thing that I believe I am the greatest at.[15]

In 2003, at age 17, Gaga gained early admission to Collaborative Arts Project 21, a music school at New York University (NYU)’s Tisch School of the Arts, and lived in an NYU dorm. She studied music there, and improved her songwriting skills by writing essays on art, religion, social issues and politics, including a thesis on pop artists Spencer Tunick and Damien Hirst.[16][17] In 2005, she withdrew from school during the second semester of her second year to focus on her music career.[18] That year, she also played an unsuspecting diner customer for MTV’s Boiling Points, a prank reality television show.[19]

In a 2014 interview, Gaga said she had been raped at age 19, for which she later underwent mental and physical therapy.[20] She has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which she attributes to the incident, and credits support from doctors, family and friends with helping her.[21] Gaga later gave additional details about the rape, including that «the person who raped me dropped me off pregnant on a corner at my parents’ house because I was vomiting and sick. Because I’d been being abused. I was locked away in a studio for months.»[22]

2005–2007: Career beginnings

In 2005, Gaga recorded two songs with hip-hop artist Melle Mel for an audio book accompanying Cricket Casey’s children’s novel The Portal in the Park.[23] She also formed a band called the SGBand with some friends from NYU.[11][24] They played gigs around New York and became a fixture of the downtown Lower East Side club scene.[11] After the 2006 Songwriters Hall of Fame New Songwriters Showcase at the Cutting Room in June, talent scout Wendy Starland recommended her to music producer Rob Fusari.[25] Fusari collaborated with Gaga, who traveled daily to New Jersey, helping to develop her songs and compose new material.[26] The producer said they began dating in May 2006, and claimed to have been the first person to call her «Lady Gaga», which was derived from Queen’s song «Radio Ga Ga».[27] Their relationship lasted until January 2007.[28]

Fusari and Gaga established a company called «Team Lovechild, LLC» to promote her career.[27] They recorded and produced electropop tracks, sending them to music industry executives. Joshua Sarubin, the head of Artists and repertoire (A&R) at Def Jam Recordings, responded positively and, after approval from Sarubin’s boss Antonio «L.A.» Reid, Gaga was signed to Def Jam in September 2006.[29][30] She was dropped from the label three months later[31] and returned to her family home for Christmas. Gaga began performing at neo-burlesque shows, which according to her represented freedom.[32] During this time, she met performance artist Lady Starlight, who helped mold her onstage persona.[33] The pair began performing at downtown club venues like the Mercury Lounge, the Bitter End, and the Rockwood Music Hall. Their live performance art piece, known as «Lady Gaga and the Starlight Revue» and billed as «The Ultimate Pop Burlesque Rockshow», was a tribute to 1970s variety acts.[34][35] They performed at the 2007 Lollapalooza music festival.[34]

Having initially focused on avant-garde electronic dance music, Gaga began to incorporate pop melodies and the glam rock style of David Bowie and Queen into her songs. While Gaga and Starlight were performing, Fusari continued to develop the songs he had created with her, sending them to the producer and record executive Vincent Herbert.[36] In November 2007, Herbert signed Gaga to his label Streamline Records, an imprint of Interscope Records, established that month.[37] Gaga later credited Herbert as the man who discovered her.[38] Having served as an apprentice songwriter during an internship at Famous Music Publishing, Gaga struck a music publishing deal with Sony/ATV. As a result, she was hired to write songs for Britney Spears, New Kids on the Block, Fergie, and the Pussycat Dolls.[39] At Interscope, musician Akon was impressed with her singing abilities when she sang a reference vocal for one of his tracks in studio.[40] Akon convinced Jimmy Iovine, chairman and CEO of Interscope Geffen A&M Records (a brother company for Def Jam), to form a joint deal by having Gaga also sign with his own label KonLive, making her his «franchise player».[31][41]

In late 2007, Gaga met with songwriter and producer RedOne.[42] She collaborated with him in the recording studio for a week on her debut album, signing with Cherrytree Records, an Interscope imprint established by producer and songwriter Martin Kierszenbaum; she also wrote four songs with Kierszenbaum.[39] Despite securing a record deal, she said that some radio stations found her music too «racy», «dance-oriented», and «underground» for the mainstream market, to which she replied: «My name is Lady Gaga, I’ve been on the music scene for years, and I’m telling you, this is what’s next.»[7]

2008–2010: Breakthrough with The Fame and The Fame Monster

By 2008, Gaga had relocated to Los Angeles to work extensively with her record label to complete her debut album, The Fame, and to set up her own creative team called the Haus of Gaga, modeled on Andy Warhol’s The Factory.[43][44] The Fame was released on August 19, 2008,[45] and reached number one in Austria, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Switzerland and the UK, as well as the top five in Australia and the US.[46][47] Its first two singles, «Just Dance» and «Poker Face»,[48] reached number one in the United States,[49] Australia,[50] Canada[51] and the UK.[52] The latter was also the world’s best-selling single of 2009, with 9.8 million copies sold that year, and spent a record 83 weeks on Billboard magazine’s Digital Songs chart.[53][54] Three other singles, «Eh, Eh (Nothing Else I Can Say)», «LoveGame» and «Paparazzi», were released from the album;[55] the lattermost reached number one in Germany.[56] Remixed versions of the singles from The Fame, except «Eh, Eh (Nothing Else I Can Say)», were included on Hitmixes in August 2009.[57] At the 52nd Annual Grammy Awards, The Fame and «Poker Face» won Best Dance/Electronica Album and Best Dance Recording, respectively.[58]

Following her opening act on the Pussycat Dolls’ 2009 Doll Domination Tour in Europe and Oceania, Gaga headlined her worldwide The Fame Ball Tour, which ran from March to September 2009.[60] While traveling the globe, she wrote eight songs for The Fame Monster, a reissue of The Fame.[61] Those new songs were also released as a standalone EP on November 18, 2009.[62] Its first single, «Bad Romance», was released one month earlier[63] and went number one in Canada[51] and the UK,[52] and number two in the US,[49] Australia[64] and New Zealand.[65] «Telephone», with Beyoncé, followed as the second single from the EP and became Gaga’s fourth UK number one.[66][67] Its third single was «Alejandro»,[68] which reached number one in Finland[69] and attracted controversy when its music video was deemed blasphemous by the Catholic League.[70] Both tracks reached the top five in the US.[49] The video for «Bad Romance» became the most watched on YouTube in April 2010, and that October, Gaga became the first person with more than one billion combined views.[71][72] At the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards, she won eight awards from 13 nominations, including Video of the Year for «Bad Romance».[73] She was the most nominated artist for a single year, and the first woman to receive two nominations for Video of the Year at the same ceremony.[74] The Fame Monster won the Grammy Award for Best Pop Vocal Album, and «Bad Romance» won Best Female Pop Vocal Performance and Best Short Form Music Video at the 53rd Annual Grammy Awards.[75]

In 2009, Gaga spent a record 150 weeks on the UK Singles Chart and became the most downloaded female act in a year in the US, with 11.1 million downloads sold, earning an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records.[76][77] Worldwide, The Fame and The Fame Monster together have sold more than 15 million copies, and the latter was 2010’s second best-selling album.[78][79][80] Its success allowed Gaga to start her second worldwide concert tour, The Monster Ball Tour, and release The Remix, her final record with Cherrytree Records[81] and among the best-selling remix albums of all time.[82][83] The Monster Ball Tour ran from November 2009 to May 2011 and grossed $227.4 million, making it the highest-grossing concert tour for a debut headlining artist.[59][84] Concerts performed at Madison Square Garden in New York City were filmed for an HBO television special, Lady Gaga Presents the Monster Ball Tour: At Madison Square Garden.[85] Gaga also performed songs from her albums at the 2009 Royal Variety Performance, the 52nd Annual Grammy Awards, and the 2010 Brit Awards.[86] Before Michael Jackson’s death, Gaga was set to take part in his canceled This Is It concert series at the O2 Arena in the UK.[87]

During this era, Gaga ventured into business, collaborating with consumer electronics company Monster Cable Products to create in-ear, jewel-encrusted headphones called Heartbeats by Lady Gaga.[88] She also partnered with Polaroid in January 2010 as their creative director and announced a suite of photo-capture products called Grey Label.[89][90] Her collaboration with her past record producer and ex-boyfriend Rob Fusari led to a lawsuit against her production team, Mermaid Music LLC.[a] At this time, Gaga was tested borderline positive for lupus, but claimed not to be affected by the symptoms and hoped to maintain a healthy lifestyle.[93][94]

2011–2014: Born This Way, Artpop, and Cheek to Cheek

In February 2011, Gaga released «Born This Way», the lead single from her studio album of the same name. The song sold more than one million copies within five days, earning the Guinness World Record for the fastest selling single on iTunes.[95] It debuted atop the Billboard Hot 100, becoming the 1,000th number-one single in the history of the charts.[96] Its second single «Judas» followed two months later,[97] and «The Edge of Glory» served as its third single.[98] Both reached the top 10 in the US and the UK.[49][52] Her music video for «The Edge of Glory», unlike her previous work, portrays her dancing on a fire escape and walking on a lonely street, without intricate choreography and back-up dancers.[99]

Gaga promoting Born This Way with performances in Sydney, Australia

Born This Way was released on May 23, 2011,[97] and debuted atop the Billboard 200 with first-week sales of 1.1 million copies.[100] The album sold eight million copies worldwide and received three Grammy nominations, including Gaga’s third consecutive nomination for Album of the Year.[101][102] Rolling Stone listed it among «The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time» in 2020.[103] Born This Way‘s following singles were «You and I» and «Marry the Night»,[104] which reached numbers six and 29 in the US, respectively.[49] While filming the former’s music video, Gaga met and started dating actor Taylor Kinney in July 2011, who played her love interest.[105][106] She also embarked on the Born This Way Ball tour in April 2012, which was scheduled to conclude the following March, but ended one month earlier when Gaga canceled the remaining dates due to a labral tear of her right hip that required surgery.[107] While refunds for the cancellations were estimated to be worth $25 million,[108] the tour grossed $183.9 million globally.[109]

In 2011, Gaga also worked with Tony Bennett on a jazz version of «The Lady Is a Tramp»,[110] with Elton John on «Hello Hello» for the animated feature film Gnomeo & Juliet,[111] and with The Lonely Island and Justin Timberlake on «3-Way (The Golden Rule)».[112] She also performed a concert at the Sydney Town Hall in Australia that year to promote Born This Way and to celebrate former US President Bill Clinton’s 65th birthday.[113] In November, she was featured in a Thanksgiving television special titled A Very Gaga Thanksgiving, which attracted 5.7 million American viewers and spawned the release of her fourth EP, A Very Gaga Holiday.[114] In 2012, Gaga guest-starred as an animated version of herself in an episode of The Simpsons called «Lisa Goes Gaga»,[115] and released her first fragrance, Lady Gaga Fame, followed by a second one, Eau de Gaga, in 2014.[b]

Gaga began work on her third studio album, Artpop, in early 2012, during the Born This Way Ball tour; she crafted the album to mirror «a night at the club».[118][119][120] In August 2013, Gaga released the album’s lead single «Applause»,[121] which reached number one in Hungary, number four in the US, and number five in the UK.[52][49][122] A lyric video for Artpop track «Aura» followed in October to accompany Robert Rodriguez’s Machete Kills, where she plays an assassin named La Chameleon.[123] The film received generally mixed reviews and earned less than half of its $33 million budget.[124][125] The second Artpop single, «Do What U Want», featured singer R. Kelly and was released later that month,[126] topping the charts in Hungary and reaching number 13 in the US.[49][127] Artpop was released on November 6, 2013, to mixed reviews.[128] Helen Brown in The Daily Telegraph criticized Gaga for making another album about her fame and doubted the record’s originality, but found it «great for dancing».[129] The album debuted atop the Billboard 200 chart, and sold more than 2.5 million copies worldwide as of July 2014.[130][131] «G.U.Y.» was released as the third single in March 2014 and peaked at number 76 in the US.[49][132]

Gaga hosted an episode of Saturday Night Live in November 2013.[134] After holding her second Thanksgiving Day television special on ABC, Lady Gaga and the Muppets Holiday Spectacular, she performed a special rendition of «Do What U Want» with Christina Aguilera on the fifth season of the American reality talent show The Voice.[135][136] In March 2014, Gaga had a seven-day concert residency commemorating the last performance at New York’s Roseland Ballroom before its closure.[137] Two months later, she embarked on the ArtRave: The Artpop Ball tour, building on concepts from her ArtRave promotional event. Earning $83 million, the tour included cities canceled from the Born This Way Ball tour itinerary.[138] In the meantime, Gaga split from longtime manager Troy Carter over «creative differences»,[139] and by June 2014, she and new manager Bobby Campbell joined Artist Nation, the artist management division of Live Nation Entertainment.[140] She briefly appeared in Rodriguez’s Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, and was confirmed as Versace’s spring-summer 2014 ambassador with a campaign called «Lady Gaga For Versace».[141][142]

In September 2014, Gaga released a collaborative jazz album with Tony Bennett titled Cheek to Cheek. The inspiration behind the album came from her friendship with Bennett, and fascination with jazz music since her childhood.[143] Before the album was released, it produced the singles «Anything Goes» and «I Can’t Give You Anything but Love».[144] Cheek to Cheek received generally favorable reviews;[145] The Guardian‘s Caroline Sullivan praised Gaga’s vocals and Howard Reich of the Chicago Tribune wrote that «Cheek to Cheek serves up the real thing, start to finish».[146][147] The record was Gaga’s third consecutive number-one album on the Billboard 200,[148] and won a Grammy Award for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album.[149] The duo recorded the concert special Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga: Cheek to Cheek Live!,[150] and embarked on the Cheek to Cheek Tour from December 2014 to August 2015.[151]

2015–2017: American Horror Story, Joanne, and Super Bowl performances

In February 2015, Gaga became engaged to Taylor Kinney.[152] After the lukewarm response to Artpop, Gaga began to reinvent her image and style. According to Billboard, this shift started with the release of Cheek to Cheek and the attention she received for her performance at the 87th Academy Awards, where she sang a medley of songs from The Sound of Music in a tribute to Julie Andrews.[133] Considered one of her best performances by Billboard, it triggered more than 214,000 interactions per minute globally on Facebook.[153][154] She and Diane Warren co-wrote the song «Til It Happens to You» for the documentary The Hunting Ground, which earned them the Satellite Award for Best Original Song and an Academy Award nomination in the same category.[155] Gaga won Billboard Woman of the Year and Contemporary Icon Award at the 2015 Annual Songwriters Hall of Fame Awards.[156][157]

Gaga had spent much of her early life wanting to be an actress, and achieved her goal when she starred in American Horror Story: Hotel.[158] Running from October 2015 to January 2016, Hotel is the fifth season of the television anthology horror series, American Horror Story, in which Gaga played a hotel owner named Elizabeth.[159][160] At the 73rd Golden Globe Awards, Gaga received the Best Actress in a Miniseries or Television Film award for her work on the season.[158] She appeared in Nick Knight’s 2015 fashion film for Tom Ford’s 2016 spring campaign[161] and was guest editor for V fashion magazine’s 99th issue in January 2016, which featured 16 different covers.[162] She received Editor of the Year award at the Fashion Los Angeles Awards.[163]

In February 2016, Gaga sang the US national anthem at Super Bowl 50,[164] partnered with Intel and Nile Rodgers for a tribute performance to the late David Bowie at the 58th Annual Grammy Awards,[165] and sang «Til It Happens to You» at the 88th Academy Awards, where she was introduced by Joe Biden and was accompanied on-stage by 50 people who had suffered from sexual assault.[166] She was honored that April with the Artist Award at the Jane Ortner Education Awards by The Grammy Museum, which recognizes artists who have demonstrated passion and dedication to education through the arts.[167] Her engagement to Taylor Kinney ended in July; she later said her career had interfered with their relationship.[168]

Gaga played a witch named Scathach in American Horror Story: Roanoke, the series’ sixth season,[169] which ran from September to November 2016.[170][171] Her role in the fifth season of the show ultimately influenced her future music, prompting her to feature «the art of darkness».[172] In September 2016, she released her fifth album’s lead single, «Perfect Illusion», which topped the charts in France and reached number 15 in the US.[173][174][175] The album, titled Joanne, was named after Gaga’s late aunt, who was an inspiration for the music.[176] It was released on October 21, 2016, and became Gaga’s fourth number one album on the Billboard 200, making her the first woman to reach the US chart’s summit four times in the 2010s.[177] The album’s second single, «Million Reasons», followed the next month and reached number four in the US.[175][178] She later released a piano version of the album’s title track in 2018,[179] which won a Grammy for Best Pop Solo Performance.[180] To promote the album, Gaga embarked on the three-date Dive Bar Tour.[181]

Gaga performed as the headlining act during the Super Bowl LI halftime show on February 5, 2017. Her performance featured a group of hundreds of lighted drones forming various shapes in the sky above Houston’s NRG Stadium—the first time robotic aircraft appeared in a Super Bowl program.[182] It attracted 117.5 million viewers in the United States, exceeding the game’s 111.3 million viewers and making it the second most-watched Super Bowl halftime show to date.[183] The performance led to a surge of 410,000 song downloads in the United States for Gaga and earned her an Emmy nomination in the Outstanding Special Class Program category.[184][185] CBS Sports included her performance as the second best in the history of Super Bowl halftime shows.[186] In April, Gaga headlined the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.[187] She also released a standalone-single, «The Cure», which reached the top 10 in Australia.[188][189] In August, Gaga began the Joanne World Tour, which she announced after the Super Bowl LI halftime show.[190] Gaga’s creation of Joanne and preparation for her halftime show performance were featured in the documentary Gaga: Five Foot Two, which premiered on Netflix that September.[191] Throughout the film, she was seen suffering from chronic pain, which was later revealed to be the effect of a long-term condition called fibromyalgia.[192] In February 2018, it prompted Gaga to cancel the last ten shows of the Joanne World Tour, which ultimately grossed $95 million from 842,000 tickets sold.[193][194]

2018–2019: A Star Is Born and Las Vegas residency

In March 2018, Gaga supported the March for Our Lives gun-control rally in Washington, D.C.,[196] and released a cover of Elton John’s «Your Song» for his tribute album Revamp.[197] Later that year, she starred as struggling singer Ally in Bradley Cooper’s musical romantic drama A Star Is Born, a remake of the 1937 film of the same name. The film follows Ally’s relationship with singer Jackson Maine (played by Cooper), which becomes strained after her career begins to overshadow his. It received acclaim from critics, with a consensus that the movie had «appealing leads, deft direction, and an affecting love story».[198] Cooper approached Gaga after seeing her perform at a cancer research fundraiser. An admirer of Cooper’s work, Gaga agreed to the project due to its portrayal of addiction and depression.[199][200] A Star Is Born premiered at the 2018 Venice Film Festival, and was released worldwide that October.[201] Gaga’s performance was acclaimed by film critics, with Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian labeling the film «outrageously watchable» and stating that «Gaga’s ability to be part ordinary person, part extraterrestrial celebrity empress functions at the highest level»;[202] Stephanie Zacharek of Time magazine similarly highlighted her «knockout performance» and found her to be «charismatic» without her usual makeup, wigs and costumes.[203] For the role, Gaga won the National Board of Review and Critics’ Choice awards for Best Actress, in addition to receiving nominations for the Academy Award, Golden Globe Award, Screen Actors Guild Award and BAFTA Award for Best Actress.[204]

Gaga and Cooper co-wrote and produced most of the songs on the soundtrack for A Star Is Born, which she insisted they perform live in the film.[205] Its lead single, «Shallow», performed by the two, was released on September 27, 2018[206] and topped the charts in various countries including Australia, the UK and the US.[207] The soundtrack contains 34 tracks, including 17 original songs, and received generally positive reviews;[208] Mark Kennedy of The Washington Post called it a «five-star marvel» and Ben Beaumont-Thomas of The Guardian termed it an «instant classics full of Gaga’s emotional might».[209][210] Commercially, the soundtrack debuted at number one in the US, making Gaga the first woman with five US number-one albums in the 2010s, and breaking her tie with Taylor Swift as the most for any female artist this decade;[211] Swift tied with her again in 2019.[212] It additionally topped the charts in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, Switzerland and the UK.[213] As of June 2019, the soundtrack had sold over six million copies worldwide.[214] The album won Gaga four Grammy Awards—Best Compilation Soundtrack for Visual Media and Best Pop Duo/Group Performance and Best Song Written for Visual Media for «Shallow», as well as the latter category for «I’ll Never Love Again»—and a BAFTA Award for Best Film Music.[180][215][216] «Shallow» also won her the Academy Award, Golden Globe Award, and Critics’ Choice Award for Best Original Song.[204]

In October, Gaga announced her engagement to talent agent Christian Carino whom she had met in early 2017.[217] They ended the engagement in February 2019.[218] Gaga signed a concert residency, named Lady Gaga Enigma + Jazz & Piano, to perform at the MGM Park Theater in Las Vegas.[219] The residency consists of two types of shows: Enigma, which focused on theatricality and included Gaga’s biggest hits,[220] and Jazz & Piano, which involved tracks from the Great American Songbook and stripped-down versions of Gaga’s songs. The Enigma show opened in December 2018 and the Jazz & Piano in January 2019.[221] Gaga launched her vegan makeup line, Haus Laboratories, in September 2019 exclusively on Amazon. Consisting of 40 products, including liquid eyeliners, lip glosses and face mask sticker, it reached number-one on Amazon’s list of best-selling lipsticks.[222]

2020–present: Chromatica, Love for Sale, and House of Gucci

In February 2020, Gaga began a relationship with entrepreneur Michael Polansky.[223] Her sixth studio album, Chromatica, was released on May 29, 2020, to positive reviews.[224][225] It debuted atop the US charts, becoming her sixth consecutive number-one album in the country, and reached the top spot in more than a dozen other territories including Australia, Canada, France, Italy and the UK.[226] Chromatica was preceded by two singles, «Stupid Love», on February 28, 2020,[227] and «Rain on Me», with Ariana Grande, on May 22.[228] The latter won the Best Pop Duo/Group Performance at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards, and debuted at number one in the US, making Gaga the third person to top the country’s chart in the 2000s, 2010s and 2020s.[229][230] At the 2020 MTV Video Music Awards, Gaga won five awards, including the inaugural Tricon Award recognizing artists accomplished in different areas of the entertainment industry.[231] In September 2020, she appeared in the video campaign for Valentino’s Voce Viva fragrance, singing a stripped-down version of Chromatica track «Sine from Above», along with a group of models.[232]

During the inauguration of Joe Biden as the 46th President of the United States on January 20, 2021, Gaga sang the US national anthem.[234] In February 2021, her dog walker Ryan Fischer was hospitalized after getting shot in Hollywood. Two of her French Bulldogs, Koji and Gustav, were taken while a third dog named Miss Asia escaped and was subsequently recovered by police. Gaga later offered a $500,000 reward for the return of her pets.[235][236] Two days later, on February 26, a woman brought the dogs to a police station in Los Angeles. Both were unharmed. Los Angeles Police initially said the woman who dropped off the dogs did not appear to be involved with the shooting,[237] but on April 29, she was one of five people charged in connection with the shooting and theft.[238] In December 2022, James Howard Jackson, the man who shot Fischer, was sentenced to 21 years in prison.[239]

In April 2021, Gaga teamed up with Champagne brand Dom Pérignon, and appeared in an ad shot by Nick Knight.[240] On September 3, she released her third remix album, Dawn of Chromatica.[241] This was followed by her second collaborative album with Tony Bennett, titled Love for Sale, on September 30.[242] The record received generally favorable reviews, and debuted at number eight in the US.[243][244] The album’s promotional rollout included the television special One Last Time: An Evening with Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga, released in November 2021, on CBS, which featured select performances from the duo’s August 3 and 5 performances at Radio City Music Hall.[245][246] Another taped performance by the duo recorded for MTV Unplugged was released that December.[247] At the 64th Annual Grammy Awards, Love for Sale won Gaga and Bennett the award for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album.[248]

After an appearance in the television special Friends: The Reunion, in which Gaga sang «Smelly Cat» with Lisa Kudrow,[249] she portrayed Patrizia Reggiani, who was convicted of hiring a hitman to murder her ex-husband and former head of the Gucci fashion house Maurizio Gucci (played by Adam Driver), in Ridley Scott’s biographical crime film titled House of Gucci.[250][251] For the part, Gaga learned to speak with an Italian accent. She also stayed in character for 18 months, speaking with an accent for nine months during that period.[252] Her method acting approach took a toll on her mental wellbeing, and towards the end of filming she had to be accompanied on-set by a psychiatric nurse.[253] The film was released on November 24, 2021, to mixed reviews, though critics praised Gaga’s performance as «note-perfect».[254] She earned the New York Film Critics Circle Award, and nominations for the BAFTA Award, Critics’ Choice Award, Golden Globe Award and Screen Actors Guild Award for Best Actress.[255] Gaga wrote the song «Hold My Hand» for the 2022 film Top Gun: Maverick,[256] and also composed the score alongside Hans Zimmer and Harold Faltermeyer.[257] In July 2022, she embarked on The Chromatica Ball stadium tour,[258] which had twenty dates and grossed $112.4 million from 834,000 tickets sold.[233] By the end of the year, she became the highest grossing female artist of 2022.[259] Gaga is set to star with Joaquin Phoenix in Joker: Folie à Deux, which will be released in 2024.[260]

Artistry

Influences

Gaga grew up listening to artists such as Michael Jackson, the Beatles, Stevie Wonder, Queen, Bruce Springsteen, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Whitney Houston, Elton John, Christina Aguilera and Blondie,[261][262][263] who have all influenced her music.[264][265] Gaga’s musical inspiration varies from dance-pop singers such as Madonna and Michael Jackson to glam rock artists such as David Bowie and Freddie Mercury, as well as the theatrics of the pop artist Andy Warhol and her own performance roots in musical theater.[31][266] She has been compared to Madonna, who has said that she sees herself reflected in Gaga.[267] Gaga says that she wants to revolutionize pop music as Madonna has.[268] Gaga has also cited heavy metal bands as an influence, specifically Iron Maiden, Black Sabbath and Marilyn Manson.[269][270][271][272] She credits Beyoncé as a key inspiration to pursue a musical career.[273]

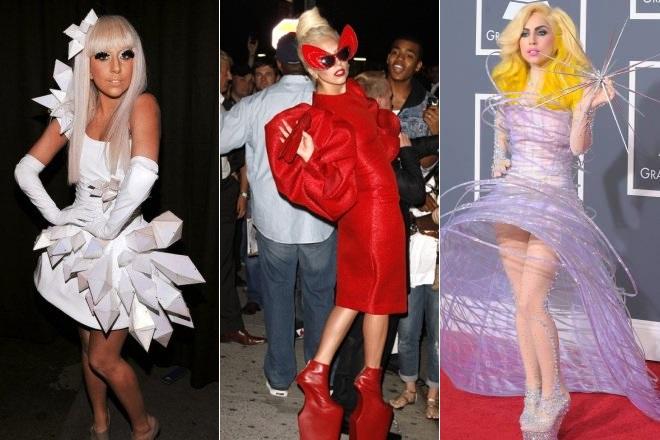

Gaga was inspired by her mother to be interested in fashion, which she now says is a major influence and integrated with her music.[18][274] Stylistically, Gaga has been compared to Leigh Bowery, Isabella Blow, and Cher;[275][276] she once commented that as a child, she absorbed Cher’s fashion sense and made it her own.[276] Gaga became friends with British fashion designer Alexander McQueen shortly before his suicide in 2010, and became known for wearing his designs, particularly his towering armadillo shoes.[93][277] She considers fashion designer Donatella Versace her muse; Versace has called Lady Gaga «the fresh Donatella».[278][279] Gaga has also been influenced by Princess Diana, whom she has admired since her childhood.[280]

Gaga has called the Indian alternative medicine advocate Deepak Chopra a «true inspiration»,[281] and has also quoted Indian leader Osho’s book Creativity on Twitter. Gaga says she was influenced by Osho’s work in valuing rebellion through creativity and equality.[282]

Musical style and themes

Critics have analyzed and scrutinized Gaga’s musical and performance style, as she has experimented with new ideas and images throughout her career. She says the continual reinvention is «liberating» herself, which she has been drawn to since childhood.[283] Gaga combines a variety of music genres, particularly incorporating elements of rock into her pop and dance music. She has also branched out into jazz and other non-pop musical genres.[284] Gaga is a contralto, with a range spanning from B♭2 to B5.[285][286][287] She has changed her vocal style regularly, and considers Born This Way «much more vocally up to par with what I’ve always been capable of».[288][289] In summing up her voice, Entertainment Weekly wrote: «There’s an immense emotional intelligence behind the way she uses her voice. Almost never does she overwhelm a song with her vocal ability, recognizing instead that artistry is to be found in nuance rather than lung power.»[290]

According to Evan Sawdey of PopMatters, Gaga «manage[s] to get you moving and grooving at an almost effortless pace».[291] Gaga believes that «all good music can be played on a piano and still sound like a hit».[292] Simon Reynolds wrote in 2010, «Everything about Gaga came from electroclash, except the music, which wasn’t particularly 1980s, just ruthlessly catchy naughties pop glazed with Auto-Tune and undergirded with R&B-ish beats.»[293]

Gaga’s songs have covered a wide variety of concepts; The Fame discusses the lust for stardom, while the follow-up The Fame Monster expresses fame’s dark side through monster metaphors. The Fame is an electropop and dance-pop album that has influences of 1980s pop and 1990s Europop,[294] whereas The Fame Monster displays Gaga’s taste for pastiche, drawing on «Seventies arena glam, perky ABBA disco, and sugary throwbacks like Stacey Q».[295] Born This Way has lyrics in English, French, German, and Spanish and features themes common to Gaga’s controversial songwriting such as sex, love, religion, money, drugs, identity, liberation, sexuality, freedom, and individualism.[296] The album explores new genres, such as electronic rock and techno.[297]

The themes in Artpop revolve around Gaga’s personal views of fame, love, sex, feminism, self-empowerment, overcoming addiction, and reactions to media scrutiny.[298] Billboard describes Artpop as «coherently channeling R&B, techno, disco and rock music».[299] With Cheek to Cheek, Gaga dabbled in the jazz genre.[300] Joanne, exploring the genres of country, funk, pop, dance, rock, electronic music and folk, was influenced by her personal life.[301] The A Star Is Born soundtrack contains elements of blues rock, country and bubblegum pop.[209] Billboard says its lyrics are about wanting change, its struggle, love, romance, and bonding, describing the music as «timeless, emotional, gritty and earnest. They sound like songs written by artists who, quite frankly, are supremely messed up but hit to the core of the listener.»[302] On Chromatica, Gaga returned to her dance-pop roots, and discussed her struggles with mental health.[303] Her second album with Tony Bennett, Love for Sale, consists of a tribute to Cole Porter.[304]

Videos and stage

Gaga during a «blood soaked» performance in 2010

Featuring constant costume changes and provocative visuals, Gaga’s music videos are often described as short films.[305] The video for «Telephone» earned Gaga the Guinness World Record for Most Product Placement in a Video.[306] According to author Curtis Fogel, she explores bondage and sadomasochism and highlights prevalent feminist themes. The main themes of her music videos are sex, violence, and power. She calls herself «a little bit of a feminist» and asserts that she is «sexually empowering women».[307] Billboard ranked her sixth on its list of «The 100 Greatest Music Video Artists of All Time» in 2020, stating that «the name ‘Lady Gaga’ will forever be synonymous with culture-shifting music videos».[308]

Regarded as «one of the greatest living musical performers» by Rolling Stone,[309] Gaga has called herself a perfectionist when it comes to her elaborate shows.[310] Her performances have been described as «highly entertaining and innovative»;[311] the blood-spurting performance of «Paparazzi» at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards was described as «eye-popping» by MTV News.[312] She continued the blood-soaked theme during The Monster Ball Tour, causing protests in England from family groups and fans in the aftermath of the Cumbria shootings, in which a taxi driver had killed 12 people, then himself.[313] At the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards, Gaga appeared in drag as her male alter ego, Jo Calderone, and delivered a lovesick monologue before a performance of her song «You and I».[314] As Gaga’s choreographer and creative director, Laurieann Gibson provided material for her shows and videos for four years before she was replaced by her assistant Richard Jackson in 2014.[315]

In an October 2018 article for Billboard, Rebecca Schiller traced back Gaga’s videography from «Just Dance» to the release of A Star Is Born. Schiller noted that following the Artpop era, Gaga’s stripped-down approach to music was reflected in the clips for the singles from Joanne, taking the example of the music video of lead single «Perfect Illusion» where she eschewed «the elaborate outfits for shorts and a tee-shirt as she performed the song at a desert party». It continued with her performances in the film as well as her stage persona.[316] Reviewing The Chromatica Ball in 2022, Chris Willman of Variety wrote that Gaga «could have further played the authenticity card for all it’s worth» after the release of Joanne and A Star Is Born, but instead «has determined to keep herself weird — or just weird enough to provide necessarily ballast to her more earnest inclinations».[317]

Public image

In 2010, eight wax figures of Gaga were installed at the museum Madame Tussauds.[318]

Public reception of her music, fashion sense, and persona is polarized. Because of her influence on modern culture, and her rise to global fame, sociologist Mathieu Deflem of the University of South Carolina has offered a course titled «Lady Gaga and the Sociology of the Fame» since early 2011 with the objective of unraveling «some of the sociologically relevant dimensions of the fame of Lady Gaga».[319] When Gaga met briefly with then-president Barack Obama at a Human Rights Campaign fundraiser, he found the interaction «intimidating» as she was dressed in 16-inch heels, making her the tallest woman in the room.[320] When interviewed by Barbara Walters for her annual ABC News special 10 Most Fascinating People in 2009, Gaga dismissed the claim that she is intersex as an urban legend. Responding to a question on this issue, she expressed her fondness for androgyny.[321]

Gaga’s outlandish fashion sense has also served as an important aspect of her character.[275][278] During her early career, members of the media compared her fashion choices to those of Christina Aguilera.[278] In 2011, 121 women gathered at the Grammy Awards dressed in costumes similar to those worn by Gaga, earning the 2011 Guinness World Record for Largest Gathering of Lady Gaga Impersonators.[95] The Global Language Monitor named «Lady Gaga» as the Top Fashion Buzzword with her trademark «no pants» a close third.[322] Entertainment Weekly put her outfits on its end of the decade «best-of» list, saying that she «brought performance art into the mainstream».[323] People ranked her number one on their «Best Dressed Stars of 2021» list, writing that Gaga «strutted the streets in high-fashion designs, from a sculptural seersucker number to a black lace corseted gown—accessorizing each with elegant updos, sky-high heels and retro shades—like it was no sweat.»[324]

Time placed Gaga on their All-Time 100 Fashion Icons list, stating: «Lady Gaga is just as notorious for her outrageous style as she is for her pop hits … [Gaga] has sported outfits made from plastic bubbles, Kermit the Frog dolls, and raw meat.»[325] Gaga wore a dress made of raw beef to the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards, which was supplemented by boots, a purse, and a hat also made out of raw beef.[326] Partly awarded in recognition of the dress, Vogue named her one of the Best Dressed people of 2010 and Time named the dress the Fashion Statement of the year.[327][328] It attracted the attention of worldwide media; the animal rights organization PETA found it offensive.[329] The meat dress was displayed at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in 2012,[330] and entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in September 2015.[331]

Gaga’s fans call her «Mother Monster», and she often refers to them as «Little Monsters», a phrase she had tattooed on herself in dedication.[332] In his article «Lady Gaga Pioneered Online Fandom Culture As We Know It» for Vice, Jake Hall wrote that Gaga inspired several subsequent fan-brandings, such as those of Taylor Swift, Rihanna and Justin Bieber.[333] In July 2012, Gaga also co-founded the social networking service LittleMonsters.com, devoted to her fans.[334] Scott Hardy, CEO of Polaroid, praised Gaga for inspiring fans and for her close interactions with them on social media.[335]

Censorship

In 2011, the Ministry of Culture of the People’s Republic of China acting on behalf of the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, banned Gaga for «being vulgar.»[336] The ban was lifted in 2014. However, conditions for Artpop to go on sale legally in China were placed on the album artwork, covering her almost naked body. Officials also changed the title of the song «Sexxx Dreams» to «X Dreams.»[337]

In 2016, Gaga was banned in China again after she publicly talked with the Dalai Lama.[338][339] The Chinese government added Gaga to a list of hostile foreign forces, and Chinese websites and media organizations were ordered to stop distributing her songs. The Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party also issued an order for state-controlled media to condemn this meeting.[340] In the following years, Gaga’s image was blacked out in reporting of the 91st Academy Awards in China and her appearance was cut from Friends: The Reunion; both incidents received backlash from her Chinese fans.[341][342]

Activism

Philanthropy

After declining an invitation to appear on the single «We Are the World 25 for Haiti», because of rehearsals for her tour, to benefit victims of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, Gaga donated the proceeds of her January 2010 Radio City Music Hall concert to the country’s reconstruction relief fund.[343] All profits from her online store that day were also donated, and Gaga announced that $500,000 was collected for the fund.[344] Hours after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami hit Japan, Gaga tweeted a link to Japan Prayer Bracelets. All revenue from a bracelet she designed in conjunction with the company was donated to relief efforts;[345] these raised $1.5 million.[346] In June 2011, Gaga performed at MTV Japan’s charity show in Makuhari Messe, which benefited the Japanese Red Cross.[347]

In 2012, Gaga joined the campaign group Artists Against Fracking.[348] That October, Yoko Ono gave Gaga and four other activists the LennonOno Grant for Peace in Reykjavík, Iceland.[349] The following month, Gaga pledged to donate $1 million to the American Red Cross to help the victims of Hurricane Sandy. Gaga also contributes in the fight against HIV and AIDS, focusing on educating young women about the risks of the disease. In collaboration with Cyndi Lauper, Gaga joined forces with MAC Cosmetics to launch a line of lipstick under their supplementary cosmetic line, Viva Glam.[350] Sales have raised more than $202 million to fight HIV and AIDS.[351]

In April 2016, Gaga joined Vice President Joe Biden at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas to support Biden’s It’s On Us campaign as he traveled to colleges on behalf of the organization, which has seen 250,000 students from more than 530 colleges sign a pledge of solidarity and activism.[352] Two months later, Gaga attended the 84th Annual US Conference of Mayors in Indianapolis where she joined with the Dalai Lama to talk about the power of kindness and how to make the world a more compassionate place.[353]

In April 2020, Gaga curated the televised benefit concert, One World: Together at Home, a collaboration with Global Citizen to benefit the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund.[354][355] The special raised $127 million, which according to Forbes «puts it on par with the other legendary fundraiser, Live Aid, as the highest grossing charity concert in history.»[356] In recognition of her contribution to the Black Lives Matter movement, Gaga received the Yolanda Denise King High Ground Award from the King Center’s Beloved Community Awards in January 2021. In her acceptance speech, she denounced racism and white supremacy and addressed her social responsibility as a high-profile artist and white woman.[357]

Born This Way Foundation

In 2012, Gaga launched the Born This Way Foundation (BTWF), a non-profit organization that focuses on youth empowerment. It takes its name from her 2011 single and album. Media proprietor Oprah Winfrey, writer Deepak Chopra, and US Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius spoke at the foundation’s inauguration at Harvard University.[358] The foundation’s original funding included $1.2 million from Gaga, $500,000 from the MacArthur Foundation, and $850,000 from Barneys New York.[359] In July 2012, the BTWF partnered with Office Depot, which donated 25% of the sales, a minimum of $1 million of a series of limited edition back-to-school products.[360] The foundation’s initiatives have included the «Born Brave Bus» that followed her on tour as a youth drop-in center as an initiative against bullying.[361][362]

In October 2015, at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, Gaga joined 200 high school students, policy makers, and academic officials, including Peter Salovey, to discuss ways to recognize and channel emotions for positive outcomes.[363] In 2016, the foundation partnered with Intel, Vox Media, and Recode to fight online harassment.[364] The sales revenue of the 99th issue of the V magazine, which featured Gaga and Kinney, was donated to the foundation.[162] Gaga and Elton John released the clothing and accessories line Love Bravery at Macy’s in May. 25% of each purchase support Gaga’s foundation and the Elton John AIDS Foundation.[365] Gaga partnered with Starbucks for a week in June 2017 with the «Cups of Kindness» campaign, where the company donated 25 cents from some of the beverages sold to the foundation.[366] She also appeared in a video by Staples Inc. to raise funds for the foundation and DonorsChoose.org.[367]

On the 2018 World Kindness Day, Gaga partnered with the foundation to bring food and relief to a Red Cross shelter for people who have been forced to evacuate homes due to the California wildfires. The foundation also partnered with Starbucks and SoulCycle to thank California firefighters for their relief work during the crisis. The singer had to previously evacuate her own home during the Woolsey Fire which spread through parts of Malibu.[368]

In March 2019, she penned a letter to supporters of the Born This Way Foundation, announcing the launch of a new pilot program for a teen mental health first aid project with the National Council for Behavioral Health. Gaga revealed her personal struggles with mental health in her letter and how she was able to get support which saved her life: «I know what it means to have someone support me and understand what I’m going through, and every young person in the world should have someone to turn to when they’re hurting. It saved my life, and it will save theirs.»[369][370] In September 2020, Gaga released an anthology book, Channel Kindness: Stories of Kindness and Community, featuring fifty-one stories about kindness, bravery, and resilience from young people all over the world collected by the Born This Way Foundation, and introduced by herself.[371] She had been promoting it with a 21 days of kindness challenge on her social media, using the «BeKind21» hashtag.[372] In 2021, Gaga collaborated with the Champagne house Dom Pérignon to release a limited edition of Rosé Vintage 2005 bottles along with a sculpture designed by her. The 110 exclusive pieces will be sold at private sales, and the profits will benefit the foundation.[373] On the 2021 World Kindness Day, Gaga released a 30-minute special, titled The Power of Kindness, as part of the foundation’s Channel Kindness program, in which together with a mental health expert and a group of eleven young people, she explored the connection between kindness and mental health.[374]

LGBT advocacy

A bisexual woman,[c] Gaga actively supports LGBT rights worldwide.[375] She attributes much of her early success as a mainstream artist to her gay fans and is considered a gay icon.[376][377] Early in her career she had difficulty getting radio airplay, and stated, «The turning point for me was the gay community.»[378] She thanked FlyLife, a Manhattan-based LGBT marketing company with whom her label Interscope works, in the liner notes of The Fame.[379] One of her first televised performances was in May 2008 at the NewNowNext Awards, an awards show aired by the LGBT television network Logo.[380]

Gaga spoke at the 2009 National Equality March in Washington, D.C. to support the LGBT rights movement.[381] She attended the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards accompanied by four gay and lesbian former members of the United States Armed Forces who had been unable to serve openly under the US military’s «don’t ask, don’t tell» policy, which banned open homosexuality in the military.[382] Gaga urged her fans via YouTube to contact their senators in an effort to overturn the policy. In September 2010, she spoke at a Servicemembers Legal Defense Network’s rally in Portland, Maine. Following this event, The Advocate named her a «fierce advocate» for gays and lesbians.[383]

Gaga appeared at Europride, an international event dedicated to LGBT pride, in Rome in June 2011. She criticized the poor state of gay rights in many European countries and described gay people as «revolutionaries of love».[384] Later that year, she was referenced by teenager Jamey Rodemeyer in the hours prior to his death, with Rodemeyer having tweeted «@ladygaga bye mother monster, thank you for all you have done, paws up forever». Rodemeyer’s suicide prompted Gaga to meet with then-President Barack Obama in order to address anti-gay bullying in American schools.[385] In 2011, she was also ordained as a minister by the Universal Life Church Monastery so that she could officiate the wedding of two female friends.[386]

In June 2016, during a vigil held in Los Angeles for victims of the attack at the gay nightclub Pulse in Orlando, Gaga read aloud the names of the 49 people killed in the attack, and gave a speech.[387] Later that month, Gaga appeared in Human Rights Campaign’s tribute video to the victims of the attack.[388] She opposed the presidency of Donald Trump and his military transgender ban.[389][390] She supported former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for president in 2016.[391] In 2018, a leaked memo from Trump’s office revealed that his administration wanted to change the legal definition of sex to exclude transgender Americans. Gaga was one of the many celebrities to call him out and spread the #WontBeErased campaign to her 77 million Twitter followers.[392][393] In January 2019, during one of her Enigma shows, she criticized Vice President Mike Pence for his wife Karen Pence working at an evangelical Christian school where LGBTQ people are turned away, calling him «the worst representation of what it means to be a Christian». Gaga also stated «I am a Christian woman, and what I do know about Christianity is that we bear no prejudice, and everybody is welcome».[394] Gaga made a congratulatory speech commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots and the LGBTQ+ community’s accomplishments at WorldPride NYC 2019 outside the Stonewall Inn, birthplace of the modern gay rights movement.[395]

Impact

Gaga was named the «Queen of Pop» in a 2011 ranking by Rolling Stone based on record sales and social media metrics. In 2012, she ranked fourth in VH1’s Greatest Women in Music[396][397] and became a feature of the temporary exhibition The Elevated. From the Pharaoh to Lady Gaga, which marked the 150th anniversary of the National Museum in Warsaw.[398]

Gaga has often been praised for using controversy to bring attention to various issues.[399][400] According to Frankie Graddon of The Independent, Gaga—who wore a meat dress to highlight her distaste for the US military’s «don’t ask, don’t tell» policy—influenced protest dressing on red carpet.[401] Billboard named her «the Greatest Pop Star of 2009», asserting that «to say that her one-year rise from rookie to MVP was meteoric doesn’t quite cut it, as she wasn’t just successful, but game-changing—thanks to her voracious appetite for reinvention.»[402] Because of The Fame‘s success—it was listed as one of the 100 Greatest Debut Albums of All-Time by Rolling Stone in 2013[403]—Gaga has been credited as one of the musicians that popularized synthpop in the late 2000s and early 2010s.[404]

According to Kelefa Sanneh of The New Yorker, «Lady Gaga blazed a trail for truculent pop stars by treating her own celebrity as an evolving art project.»[405] Including Born This Way as one of the 50 best female albums of all time, Rolling Stone‘s Rob Sheffield considers it «hard to remember a world where we didn’t have Gaga, although we’re pretty sure it was a lot more boring».[406] In 2015, Time also noted that Gaga had «practically invented the current era of pop music as spectacle».[407] A 2017 journal published by Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts studying structural patterns in melodies of earworm songs compiled lists of catchiest tracks from 3,000 participants, in which Gaga’s «Bad Romance», «Alejandro», and «Poker Face» ranked number one, eight, and nine, respectively.[408] In 2018, NPR named her the second most influential female artist of the 21st century, noting her as «one of the first big artists of the ‘Internet age‘«.[409] Gaga and her work have influenced various artists including Miley Cyrus,[410] Nicki Minaj,[411] Ellie Goulding,[412] Halsey,[413] Jennifer Lopez,[414] Beyoncé,[415] Nick Jonas,[416] Sam Smith,[417] Noah Cyrus,[418] Katherine Langford,[419] MGMT,[420] Allie X,[421] Greyson Chance,[422] Cardi B,[423] Rina Sawayama,[424] Blackpink,[425] Madison Beer,[426] Ren,[427] Slayyyter,[428] Bebe Rexha,[429] Bree Runway,[430] Celeste,[431] Kim Petras,[432] Jojo Siwa,[433] Pabllo Vittar,[434] Ava Max,[435] Doja Cat,[436] Chaeyoung of Twice,[437] Kanye West,[438] Rachel Zegler,[439] and SZA.[440]

A new genus of ferns, Gaga, and three species, G. germanotta, G. monstraparva and Kaikaia gaga, have been named in her honor. The name monstraparva alluded to Gaga’s fans, known as Little Monsters, since their symbol is the outstretched «monster claw» hand, which resembles a tightly rolled young fern leaf prior to unfurling.[441][442] Gaga also has an extinct mammal, Gagadon minimonstrum,[443] and a parasitic wasp, Aleiodes gaga, named for her.[444][445]

In Taichung, Taiwan, July 3 is designated as «Lady Gaga Day» marking the first day Gaga visited the country in 2011.[446] In May 2021, to celebrate the tenth anniversary of Born This Way and its cultural impact, West Hollywood mayor, Lindsey P. Horvath, presented a key to the city to Gaga and declared May 23 as «Born This Way Day.» A street painting with the Daniel Quasar’s version of the pride flag featuring the album’s title was also unveiled on Robertson Boulevard as a tribute to the album, and how it has inspired the LGBT community over the years.[447]

Achievements

Gaga has won thirteen Grammy Awards,[448] an Academy Award,[204] two Golden Globe Awards,[449] a BAFTA Award,[204] three Brit Awards,[450] sixteen Guinness World Records,[451] and the inaugural Songwriters Hall of Fame’s Contemporary Icon Award.[157] She received a National Arts Awards’ Young Artist Award, which honors individuals who have shown accomplishments and leadership early in their career,[452] the Jane Ortner Artist Award from the Grammy Museum in 2016,[167] and a National Board of Review Award for Best Actress in 2018.[204] Gaga has also been recognized by the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) with the Fashion Icon award.[453] In 2019, she became the first woman to win an Academy Award, a BAFTA Award, a Golden Globe Award and a Grammy Award in one year for her contribution to A Star Is Born‘s soundtrack.[454] At the 2020 MTV Video Music Awards, she was honored with the inaugural Tricon Award representing achievement in three (or more) fields of entertainment.[231]

Acknowledged by Billboard as the Greatest Pop Star in 2009, with honorable mention in 2010 and 2011, and Woman of the Year in 2015, Gaga has consecutively appeared on the magazine’s Artists of the Year chart (scoring the definitive title in 2010), and ranked 11th on its Top Artists of the 2010s chart.[455][456][457] She is the longest-reigning act of Billboard‘s Dance/Electronic Albums chart with 244 weeks at number one, while The Fame (2008) holds the record for the most time on top in the chart’s history, with 175 non-consecutive weeks.[458][459] Her album Born This Way (2011) featured on Rolling Stone‘s 2020 revision of their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and the song «Bad Romance» and its music video were among Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time and 100 Greatest Music Videos of All Time, respectively, in 2021.[460] In 2023, the magazine included Gaga among the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[461]

With estimated sales of 170 million records as of 2018,[462] Gaga is one of the world’s best-selling music artists, and has produced some of the best-selling singles of all time.[463] As of 2022, she has grossed more than $689.5 million in revenue from concert tours and residencies with attendance of 6.3 million, being the fifth woman to pass the half-billion total as reported to Billboard Boxscore,[233][464] receiving the Pollstar Award for Pop Touring Artist of the Decade (2010s).[465] She is the fourteenth top digital singles artist in the US, with 85.5 million equivalent units certified according to Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA),[d] was the first woman to receive the Digital Diamond Award certification from RIAA, one of three artists with at least two Diamond certified songs («Bad Romance» and «Poker Face»),[467][468] and the first and only artist to have two songs pass seven million downloads («Poker Face» and «Just Dance»).[469] In 2020, she became the first female artist to have four singles («Just Dance», «Poker Face», «Bad Romance» and «Shallow») sell at least 10 million copies globally.[470]

According to Guinness World Records, she was the most followed person on Twitter from 2011 to 2013,[471] the most famous celebrity in 2013,[472] and the most powerful popstar in 2014.[473] She was included on Forbes‘ Celebrity 100 from 2010 to 2015 and then from 2018 to 2020, having topped the list in 2011. She earned $62 million, $90 million, $52 million, $80 million, $33 million, and $59 million from 2010 through 2015, and $50 million, $39 million and $38 million between 2018 and 2020.[474][475] Gaga also appeared on their list of the World’s Most Powerful Women from 2010 to 2014.[476][477] She was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine in 2010 and 2019,[478][479] and ranked second in its most influential people of the past ten years readers’ poll in 2013.[480]

In March 2012, Gaga was ranked fourth on Billboard‘s list of top moneymakers of 2011 with earnings of $25 million, which included sales from Born This Way and her Monster Ball Tour.[481] The following year, she topped Forbes‘ List of Top-Earning Celebs Under 30,[475] which she also topped in 2011,[482] and in February 2016, the magazine estimated her net worth to be $275 million.[483] In December 2019, Gaga placed 10th on Forbes‘ list of Top-Earning Musicians of the Decade with earnings of $500 million in the 2010s. She was the fourth highest-earning female musician on the list.[484]

Discography

Tours and residencies

Filmography

|

Film

|

Television

|

See also

- Artists with the most number-ones on the U.S. Dance Club Songs chart

- Honorific nicknames in popular music

- LGBT culture in New York City

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of LGBT people from New York City

- List of Billboard Social 50 number-one artists

- List of best-selling female artists

- List of most-followed Twitter accounts

- Forbes list of highest-earning musicians

- List of organisms named after famous people (born 1950–present)

Notes

- ^ In 2010, Fusari claimed he was entitled to a 20% share of the company’s earnings, but the New York Supreme Court dismissed both the lawsuit and a counter-suit by Gaga.[91][92]

- ^ Both of the fragrances were released in association with Coty, Inc.[116][117]

- ^ Gaga says that the song «Poker Face» was about her bisexuality, and she openly speaks about how her past boyfriends were uncomfortable with her sexual orientation.[28]

- ^ As of October 2022, Gaga has had cumulative single certifications of 80.5 million digital downloads and on-demand streaming as a solo artist, and 5 million with Bradley Cooper.[466]

References

Citations

- ^ Birth details:

- «Artists: Lady Gaga». NME. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- Spedding, Emma (March 28, 2013). «It’s Lady Gaga’s 27th Birthday! We Celebrate With Her 10 Style Highlights Of The Year». Grazia. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013.

- ^

Family background details:- Graves-Fitzsimmons, Guthrie (February 5, 2017). «The provocative faith of Lady Gaga». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- Kaufman, Gil (January 26, 2012). «Lady Gaga Opens Italian Restaurant With Her Dad». MTV News. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- «Lady Gaga». Elle. December 1, 2009. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ «Lady Gaga’s Universe: Mom Cynthia Germanotta». Rolling Stone. May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on April 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Harman, Justine (September 20, 2011). «Lady Gaga’s Little Sister: I Support the Spectacle». People. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ Reszutek, Dana (March 28, 2017). «Uptown to downtown, see Lady Gaga’s New York». AM New York. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Barber, Lynn (December 6, 2009). «Shady lady: The truth about pop’s Lady Gaga». The Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Sturges, Fiona (May 16, 2009). «Lady Gaga: How the world went crazy for the new queen of pop». The Independent. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ^ Tracy 2013, p. 202.

- ^ Johnson 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Johnson 2012, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Grigoriadis, Vanessa (March 28, 2010). «Growing Up Gaga». New York. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Manelis, Michele (October 12, 2015). «LSTFI Alum Lady Gaga taps into The Lee Strasberg Method». Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Morgan 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Blauvelt, Christian (October 11, 2010). «Lady Gaga fans discover her pre-fame ‘Sopranos’ cameo». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 8, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ «Lady Gaga: Inside the Outside». Interviewed by Davi Russo. MTV News. May 26, 2011. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Florino, Rick (January 30, 2009). «Interview: Lady GaGa». Artistdirect. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ «Lady Gaga Bio». ladygaga.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Harris, Chris (June 9, 2008). «Lady GaGa Brings Her Artistic Vision Of Pop Music To New Album». MTV News. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ Kos, Saimon (August 10, 2009). «‘Boiling Points’ Actress And Producer Talk About Pulling Prank On Not-Yet-Famous Lady Gaga». MTV News. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Bakare, Larney (December 2, 2014). «Lady Gaga reveals she was raped at 19». The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ «Lady Gaga says she has PTSD after being raped at 19». BBC News. December 5, 2016. Archived from the original on December 8, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Rice, Nicholas (May 21, 2021). «Lady Gaga Opens Up About Past Sexual Assault, Says She Became Pregnant After Being Raped at 19». People. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Musto, Michael (January 19, 2010). «Lady Gaga Did a Children’s Book In 2007!». The Village Voice. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ Morgan 2010, p. 31.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (March 19, 2010). «Lady Gaga/ Rob Fusari Lawsuit: A Closer Look». MTV News. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ Morgan 2010, p. 36.

- ^ a b «Lady Gaga Sued By Producer Rob Fusari». Billboard. March 18, 2010. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Hiatt, Brian (May 30, 2009). «The Rise of Lady Gaga». Rolling Stone. Vol. 1080, no. 43. New York. ISSN 0035-791X.

- ^ Resende, Sasha (December 9, 2009). «Lady Gaga unleashes an electro-pop ‘Monster’«. The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Morgan 2010, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Birchmeier, Jason (April 20, 2008). «Lady Gaga». AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ Carlton, Andrew (February 16, 2010). «Lady Gaga: ‘I’ve always been famous, you just didn’t know it’«. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ Montgomery, James (May 25, 2011). «Lady Gaga’s ‘Inside The Outside’: Meet The ‘Perpetual Underdog’«. MTV News. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Hobart, Erika (November 18, 2008). «Lady GaGa: Some Like it Pop». Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ «Lady Gaga». Broadcast Music Incorporated. July 9, 2007. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Haus of GaGa (December 16, 2008). Transmission Gaga-vision: Episode 26. Lady Gaga.

- ^ Mitchell, Gail (November 10, 2007). «Interscope’s New Imprint». Billboard. Vol. 119, no. 45. p. 14. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ «Singer Tamar Braxton files for divorce from husband-manager». Daily Herald. Arlington. October 25, 2017. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Harding, Cortney (August 15, 2009). «Lady Gaga: The Billboard Cover Story». Billboard. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Cowing, Emma (January 20, 2009). «Lady GaGa: Totally Ga-Ga». The Scotsman. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (June 5, 2009). «Akon Calls Lady Gaga His ‘Franchise Player’«. MTV News. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2009.

- ^ «Interview With RedOne». HitQuarters. March 23, 2009. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Lady Gaga Biography». Contactmusic.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ^ «Inspiration». Haus of Gaga. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Gaga, Lady. «The Fame». iTunes Store. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Williams, John (January 14, 2009). «Lady GaGa’s ‘Fame’ rises to No. 1». Jam!. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015.

- ^ «Lady Gaga – The Fame – World Charts». aCharts.co. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Gray II 2012, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Lady Gaga Chart History: Hot 100». Billboard. Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ «Discography Lady GaGa». Hung Medien. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ a b «Lady Gaga Chart History: Billboard Canadian Hot 100». Billboard. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d «Lady Gaga | Official Chart History». Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ «Digital Music Sales Around The World» (PDF). International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ «Most weeks on US Hot Digital Songs chart». Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Single releases from The Fame:

- «Eh Eh (Nothing Else I Can Say) Single». Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- «No 7: Love Game». Capital FM. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- Evans, Morgan (January 31, 2017). «Lady Gaga’s 10 Most Amazing Live Performances». Harper’s Bazaar. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ «Chartverfolgung / Lady Gaga / Single» (in German). GfK Entertainment. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ «Hit Mixes – Lady Gaga». AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ «List of Grammy winners». CNN. February 1, 2010. Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ a b Nestruck, Kelly (November 30, 2009). «Lady Gaga’s Monster Ball, reviewed by a theatre critic». The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Morgan 2010, p. 131.

- ^ «Lady Gaga Returns With 8 New Songs on ‘The Fame Monster’» (Press release). PR Newswire. October 8, 2009. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Cinquemani, Sal (November 18, 2009). «Lady Gaga The Fame Monster». Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ Villa, Lucas (May 16, 2014). «Lady Gaga becomes first woman to earn Digital Diamond Award for ‘Bad Romance’«. AXS. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ «Australian-charts.com – Lady Gaga – Bad Romance». Hung Medien. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ «Charts.org.nz – Lady Gaga – Bad Romance». Hung Medien. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ Daw, Robbie (November 12, 2009). «Lady Gaga-Beyonce Duet ‘Telephone’ Set As Next ‘Fame Monster’ Single». Idolator. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ «Lady Gaga tops UK album and single charts». BBC News. March 22, 2010. Archived from the original on August 19, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ «Lady Gaga releases ‘Alejandro’ remix album». The Independent. May 19, 2010. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ «Lady Gaga – Alejandro (song)». Hung Medien. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ «Lady Gaga Mimics Madonna». Catholic League. June 9, 2010. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ O’Neill, Megan (April 14, 2010). «Lady Gaga’s Bad Romance Is Officially The Most Viewed Video On YouTube Ever». Adweek. Archived from the original on May 14, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ Whitworth, Dan (October 26, 2010). «Lady Gaga beats Justin Bieber to YouTube record». BBC News. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ «MTV Video Music Awards 2010». MTV. September 12, 2010. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (August 3, 2010). «Lady Gaga’s 13 VMA Nominations: How Do They Measure Up?». MTV News. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ «53rd annual Grammy awards: The winners list». CNN. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ «Most cumulative weeks on UK singles chart in one year». Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ «Most downloaded act in a year (USA) – female». Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ «Lady Gaga adds second show in Singapore». AsiaOne. February 27, 2012. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2017.