Биография Толстого

9 Сентября 1828 – 20 Ноября 1910 гг. (82 года)

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 15148.

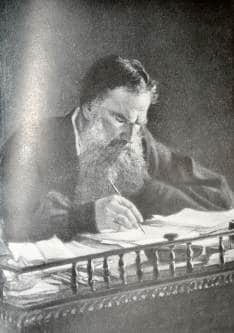

Лев Николаевич Толстой (1828–1910 гг.) — выдающийся русский писатель, публицист, мыслитель, один из великих романистов в мировой литературе. Биография Толстого Льва Николаевича полна интересных фактов и событий, он был необыкновенной, уникальной личностью. Изучение его жизни и творчества будет полезно для учеников всех классов.

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 36 лет.

Детские годы

Дата рождения Льва Николаевича — 28 августа (9 сентября) 1828 года. Будущий писатель появился на свет в имении матери Ясная Поляна, расположенном в Тульской губернии. Родители будущего писателя принадлежали к графской ветви старинного дворянского рода Толстых.

Маленький Лев рано остался без материнской любви и заботы: причиной смерти матери были тяжелые роды, и двухлетний Лев со старшими братьями и сестрой воспитывался родственниками-опекунами. После смерти отца осиротевшие дети переехали в Казань к родной тёте, П. И. Юшковой.

Дом Юшковых был очень веселым и гостеприимным, тётя всем сердцем любила племянников, заботилась об их образовании, и детство Льва Толстого было по-настоящему счастливым. Позже он описал эти годы в автобиографической повести «Детство».

Юность

Лев Николаевич получил прекрасное домашнее образование и в 1843 году поступил в Императорский Казанский университет, где учился его старший брат Николай. Поначалу это был факультет восточных языков, но из-за низкой успеваемости юному графу пришлось бросить его и поступить на юридический факультет. Однако и здесь Толстой учился не более двух лет. Он бросил университет, так и не получив высшее образование.

Лев Николаевич вернулся в Ясную Поляну, предприняв попытку управлять имением и жить как помещик. Но жизнь в деревне разочаровала юношу, и он отправился в Москву, затем в Петербург. Он принялся вести дневник, куда записывал все важное, чего должен достичь в жизни. Толстой занялся самовоспитанием и самообразованием, много читал. Он ставил перед собой высокие цели, часть из которых воплотил в жизнь, а часть так и не смог осуществить. Он изучал историю, музыку, рисование, медицину и естественные науки, сельское хозяйство, иностранные языки. В итоге в зрелом возрасте он свободно говорил на английском, французском, немецком, читал на итальянском, некоторых славянских языках, знал латынь, греческий, татарский и другие языки.

Это был период духовного поиска и метаний. Желание быть «лучше и чище» сменялось кутежами с цыганами и картами. В итоге Лев Толстой, выдержав экзамен в Петербургский университет, не стал учиться, а в звании юнкера отправился на Кавказ, где в то время служил его брат Николай.

Литература

Творческий путь Толстого берет свое начало на Кавказе, где Толстой провел три года. Именно там он сочинил повесть «Детство», вслед за которой последовали повести «Отрочество» и «Юность», составившие автобиографическую трилогию.

Литературный дебют в журнале «Современник» оказался удачным, и Лев Николаевич решил полностью посвятить себя литературе. Вскоре из-под его пера вышел цикл «Севастопольские рассказы», посвящённый Крымской войне и обороне Севастополя, в которой он лично участвовал.

Вернувшись в Петербург, Толстой стал членом литературного кружка «Современник», где им искренне восхищались. Однако писатель быстро устал от столичной суеты и отправился в путешествие по Европе. По возвращении в Ясную Поляну он занялся обустройством школ для крестьянских детей. Им была написана «Азбука», а также сотни добрых и поучительных сказок для самых маленьких.

Самыми главными работами Толстого стали романы «Анна Каренина» и «Война и мир», содержание которых знает практически каждый. Это глубокие психологические произведения, в которых писатель филигранно раскрыл не только внутренний мир героев, но и отразил важнейшие социальные проблемы общества.

В 1880-х годах в сознании писателя наметился перелом, который нашёл своё отражение в произведениях: «Крейцерова соната», «Смерть Ивана Ильича», «После бала», «Отец Сергий». Посредством своих повестей и рассказов Толстой выступал против социального неравенства, праздности дворян, безнравственности и пустоты жизни правящего класса.

Личная жизнь

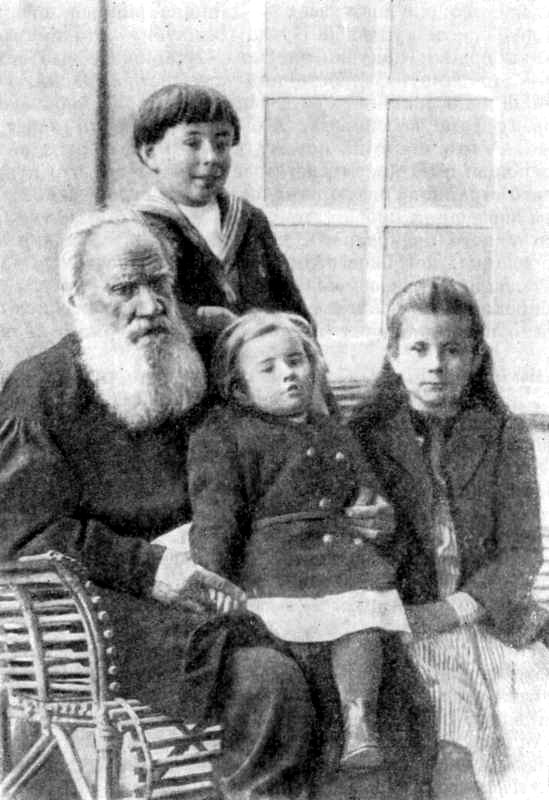

В краткой биографии Льва Толстого важно отметить, что его избранницей стала 18-летняя Софья Берс, которая была младше супруга на 16 лет. Этот брак оказался удачным, хотя между супругами не раз возникали разногласия.

В 1863 году в семье произошло пополнение: родился первенец четы Толстых. Есть сведения, что всего Софья Андреевна родила 13 детей, пятеро из которых не дожили до взрослого возраста. Долгие годы она была верной подругой и соратницей Льва Николаевича, всячески помогала и поддерживала, полностью оградила от решения бытовых вопросов.

Скончался Лев Николаевич Толстой 7 (20) ноября 1910 года, на 83-м году жизни. Причиной смерти стала банальная простуда, которая дала тяжелейшее осложнение — крупозное воспаление легких. Писатель был похоронен, как он сам завещал, в Ясной Поляне, на краю оврага в лесу. Здесь прошли его счастливые годы, и здесь они с братьями в детстве искали «зелёную палочку», способную сделать всех людей счастливыми.

Хронологическая таблица

Интересные факты

- Лев Толстой известен не только как автор серьезных произведений. Он также написал «Азбуку» и «Книгу для чтения» для детей.

- Самое свое большое и значимое произведение «Война и мир» Толстой в конце жизни называл «многословной дребеденью».

- Лев Николаевич Толстой имел дворянский титул графа.

- Толстой увлекался светской жизнью и игрой в карты. Играл всегда очень азартно и часто проигрывал, что негативно сказывалось на его финансовом положении.

- Толстой подверг резкой критике талант Шекспира как драматурга и даже выпустил очерк «О Шекспире и о драме» с подробным разбором некоторых его работ.

- После смерти у Толстого осталась жена и 8 детей. Всего супруги дали жизнь 13 детям.

Все интересные факты из жизни Толстого

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Квест

Мы подготовили интересный квест о жизни Льва Николаевича – пройти.

Тест по биографии

Насколько хорошо вы знаете краткую биографию Толстого – проверьте свои знания:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Никита Петров

10/10

-

Азамат Андадиков

9/10

-

Драконья Сага

5/10

-

Татьяна Дёмкина

8/10

-

Дарья Федоренко

9/10

-

Светлана Грунина

7/10

-

Амин Хайирбеков

10/10

-

Эльдар Дуденин

9/10

-

Samandar Kodirjonov

10/10

-

Константин Красновид

10/10

Оценка по биографии

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 15148.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Лев Толстой — биография

Лев Толстой – русский писатель и мыслитель, участвовал в обороне Севастополя, занимался просветительской и публицистической деятельностью. Стоял у истоков толстовства – нового религиозного течения.

Когда-то вождь пролетариата Владимир Ленин сказал об этом человеке: «Какая глыба! Какой матерый человечище!». Эти слова относились к Льву Толстому – величайшему мировому писателю-романисту. Но он проявил себя не только в области литературы, он выдающийся философ, просветитель, религиозный мыслитель. Он пропагандировал здоровый образ жизни. Никогда не злоупотреблял спиртным, не курил, к сорока годам отказался от кофе, а к старости перестал есть мясо. Он стал автором комплекса упражнений, которые актуальны и для сегодняшнего дня. Был настоящим образцом для подражания, хотя не все в его биографии было ровно и гладко.

Детство и юность

Родился Лев Толстой 28 августа(по новому стилю 9 сентября) 1828 года в родовом имении матери Ясная Поляна Тульской губернии. Его отец – граф Николай Толстой, выходец из старинного рода Толстых, которые были в услужении у Ивана Грозного и Петра I. Мама принадлежала к семейству Волконских, потомков Рюриков. Лев Толстой и поэт Александр Пушкин имели общего предка – Ивана Головина, адмирала царского флота.

Мама Льва умерла вскоре после того, как родила дочь, Льву в то время не исполнилось и два года. Лев был четвертым ребенком в дворянской семье. Отец ненамного пережил мать, он умер через 7 лет после ее кончины.

Дети осиротели, и их воспитанием занялась тетя – Т.А.Ергольская. Спустя некоторое время обязанности опекуна перешли ко второй тетушке – А.М.Остен-Сакен, носившей графский титул. Когда она умерла, дети поселились в Казани в семье отцовской сестры П.И.Юшковой, которая стала их новой опекуншей. Шел 1840 год. Тетушка имела большое влияние на Льва Толстого, годы, проведенные у нее, он назвал самым счастливым периодом своей жизни. Ее дом всегда был полон гостей, его считали самым гостеприимным и веселым в Казани. Детские впечатления от проживания в этой семье нашли отображение в его произведении «Детство».

Программу начальной школы Лев Толстой прошел дома. Его учили французские и немецкие преподаватели. В 1843-м Толстой стал студентом факультета восточных языков Казанского университета. Он не особо интересовался языками, поэтому успеваемость была очень низкой. Это послужило стимулом сменить факультет. Толстой отдал предпочтение юридическому. Однако и эта перемена не дала результата, спустя два года он вообще ушел из университета, так и оставшись без ученой степени.

Толстой вернулся в свое родовое гнездо – Ясную Поляну. У него появился план наладить свою жизнь по-новому, жить в ладах с крестьянством. Из этой затеи ничего не получилось, но в этот период он записывал все наблюдения в дневник, делал выводы. Кроме этого молодого графа Толстого часто видели на светских раутах, и за занятием музыкой. Он мог часами слушать любимых композиторов, среди которых были Фредерик Шопен, Иоганн Бах, Вольфганг Амадей Моцарт.

Лев провел в родном имении лето, понял, что жизнь помещика ему не по нраву. Он оставил деревню и сразу поселился в Москве, а потом перебрался в Петербург. В это время он пытался определиться в жизни, поэтому усердно готовился сдавать кандидатские экзамены в университете, занимался музыкой, играл в карты и кутил с цыганами. Ему одновременно хотелось то в чиновники, то в юнкера конного полка. Родственники видели в нем исключительно «пустяшного малого», который ни на что не годен, и едва успевали рассчитываться по его долгам.

Литература

В 1851-м Лев прислушался к совету своего брата Николая, который на то время уже имел чин офицера, и уехал на Кавказ. На протяжении трех лет он жил в станице, раскинувшейся вдоль реки Терек. Местная природа и образ жизни казаков Толстой потом красочно описал в своих произведениях – «Хаджи-Мурат», «Казаки», «Рубка леса», «Набег».

Именно во время проживания на Кавказе родилась его повесть под названием «Детство», которую напечатал журнал «Современник». Толстой не подписался своей фамилией, под публикацией стояли инициалы Л.Н. Вслед за этим молодой литератор создал продолжение истории, которые получили название «Отрочество» и «Юность». Эти повести были объединены в трилогию. Дебют в литературе удался, и дал мощный толчок к развитию творческой биографии. Лев Толстой стал известным писателем.

Вскоре Лев Толстой был назначен в Бухарест, потом оказался в осажденном Севастополе, где командовал батареей. Эти события в жизни не прошли незамеченными, писатель отобразил их в своих сочинениях. В свет вышли «Севастопольские рассказы», которые получили высокую оценку критиков. Они нашли в цикле рассказов смелый психологический анализ. По мнению Николая Чернышевского, этим рассказам была присуща «диалектика души». Сам император Александр Второй восхитился творческими способностями писателя, особенно ему понравился рассказ «Севастополь в декабре месяце».

В 1855 году Лев Толстой снова поселился в Петербурге и стал членом кружка под названием «Современник». 28-летнего писателя приняли очень радушно, его называли не иначе, как «великая надежда русской литературы». На протяжении года Лев посещал все заседания кружка, присутствовал на литературных чтениях, вступал в споры и конфликты, посещал литературные обеды. До тех пор, пока не понял, что эти люди ему противны, да и он сам себе уже был не рад.

В 1856 году он бросил Петербург и снова поселился в Ясной Поляне. Но пробыл там всего до января 1857 года, и отправился за границу. На протяжении шести месяцев он посетил Италию, Германию, Швейцарию, Францию. По возвращении Толстой недолго пожил в Москве, а потом снова поселился в Ясной Поляне. У него появилась идея учить детей крестьян, и Лев с большим рвением занялся открытием для них учебных заведений. Благодаря усилиям писателя вскоре в окрестностях его имения заработало два десятка школ.

В 1860 году Толстой снова отправился за границу. Он побывал в Бельгии, Германии, Швейцарии, изучал тонкости педагогики этих стран, чтобы потом использовать увиденное на родине.

Толстой любил детей, и создал для них немало поучительных сказок и рассказов, которые так и дышали добротой. Из под его пера вышли сказочные истории под названием «Два брата», «Котенок», «Лев и собачка», «Еж и заяц».

Лев Толстой стал автором школьного пособия «Азбука», в состав которого вошли четыре книги. По ним дети легко могли научиться писать, считать и читать. Пособие состоит из былин, историй, басен. Кроме этого там есть и советы педагогам. Третья книга содержит рассказ «Кавказский пленник».

Помимо обучения детей крестьян, Толстой продолжал свою литературную деятельность. В 1870-м он сел за написание романа «Анна Каренина», который состоял из двух основных сюжетных линий. На фоне разыгравшейся семейной драмы супругов Карениных, очень разительно выглядела идиллия помещика Левина, которого писатель написал практически с себя. С первого взгляда может показаться, что роман – просто любовная история. На самом деле в нем затронута тема смысла жизни богатых и образованных, особенно в сравнении с жизнью простого народа. Роман «Анна Каренина» получил высокую оценку Федора Достоевского.

Постепенно мировоззрение писателя меняется, он все чаще начинает говорить о социальном неравенстве, о праздности жизни господствующего класса – дворян. Это видно из произведений, которые Толстой написал в 1880-х годах. Среди них особо хочется выделить «Крейцерову сонату», «Смерть Ивана Ильича», «После бала», «Отец Сергий».

Лев Толстой все чаще стал задумываться о смысле человеческой жизни, он пытался найти ответ у православных священников, однако получил сплошное разочарование. Он решил, что церковью правит коррупция, и что священники только прикрываются верой, а на самом деле занимаются продвижением ложного учения. В 1883-м Толстой стал основателем издания «Посредник», в котором подробно изложил свои убеждения, и где нещадно критиковал Русскую православную церковь. Это послужило поводом отлучения его от церкви и установки за ним пристального наблюдения со стороны тайной полиции.

В 1898-м вышел еще один роман Льва Толстого – «Воскресение», который тоже высоко оценили критики. Однако это произведение не произвело такой фурор, как «Анна Каренина» и «Война и мир».

Впоследствии Толстой разработал учение ненасильственного сопротивления злу, и последние три десятка лет его жизни его почитали, как духовного и религиозного лидера.

Могут быть знакомы

«Война и мир»

Сам писатель был не в восторге от своего романа «Война и мир». Он называл его не иначе, как многословная дребедень, хотя читателям произведение пришлось по душе. Роман был написан в 1860-х годах, когда Толстой и его семья жили в Ясной Поляне. В 1865-м на страницах «Русского вестника» были напечатаны две первые главы, получившие название «1805 год». В 1868 году писатель смог представить еще три главы, завершившие роман. Роман писался в те годы, когда сам писатель жил счастливой семейной жизнью и ощущал прилив душевных сил. Многие герои его произведения имели прототипов в реальной жизни, или соответствовали хотя бы некоторым характеристикам родных и знакомых самого Толстого. Так княжну Марью Болконскую писатель точно «срисовал» со своей матери – женщины с блестящим образованием и творческими наклонностями. Персонаж Николай Ростов очень напоминал отца Льва Николаевича, он получился такой же насмешливый, любитель охоты и чтения.

Во время работы над романом, Толстой проделал титанический труд. Ему пришлось изучать архивы, читать переписку между Толстыми и Волконскими, даже выезжать на Бородинское поле. К процессу Лев привлек и молодую супругу – в ее обязанности входило переписывание черновиков набело.

От чтения романа невозможно было оторваться, читатели были просто поражены описанием массовых сцен и раскрытием тонкостей человеческих душ. Сам писатель говорил, что он пытался написать историю русского народа.

Спустя столетие, литературовед Лев Аннинский сделал попытку подсчитать, сколько раз произведения Толстого были экранизированы. Оказалось, что к концу 70-х годов двадцатого столетия только за границей вышло сорок экранизаций. До 1980 года роман «Война и мир» вышел на экраны четыре раза. Шестнадцать лент были сняты по «Анне Карениной», двадцать два раза экранизировали «Воскресение». Причем эти фильмы вышли не только в России, но и далеко за ее пределами.

В России первый раз картина «Война и мир» вышла на экраны в 1913 году. Режиссером ленты стал Петр Чардынин. В 1965-м за масштабную экранизацию романа принялся режиссер Сергей Бондарчук, и эта лента пользуется популярностью и в наши дни.

Личная жизнь

Супругой Льва Толстого стала 18-летняя девушка Софья Берс. Их бракосочетание состоялось в 1862 году, когда писателю было уже 34. Семейная жизнь супругов длилась почти полвека, но безоблачного счастья в личной жизни писателя не получилось.

Отцом Софьи был врач Андрей Берс, который служил при Московской дворцовой конторе. Они постоянно жили в столице, но каждое лето выезжали на отдых в тульское имение, расположенное рядом с Ясной Поляной. Лев знал Софью с детства. Сразу она училась дома, потом в Московском университете, знала толк в искусстве и была достаточно начитанной девицей.

Вскоре после свадьбы Толстой дал жене прочесть свой дневник – он хотел, чтобы супруга знала о нем все. Софью поразили описания похождений мужа, его разгульная жизнь и увлечение игрой в карты. Узнала она и о существовании крестьянки Аксиньи, которая была беременна от Толстого.

В 1863-м родился их первый ребенок – сын Сергей. Когда Толстой начал работу над романом «Война и мир», то Софья, хоть и была беременна, всеми силами помогала ему работать. В общей сложности у супругов родилось тринадцать детей, но пять из них скончались младенцами. Всем им Софья Андреевна дала домашнее обучение.

Первый кризис в семейных отношениях начался после того, как Толстой написал «Анну Каренину». У него началась депрессия, он был всем недоволен. Его раздражал налаженный быт, который с любовью обустраивала супруга. Депрессивное состояние выражалось в том, что он бросил курить, пить и есть мясо, и этого требовал от своей семьи. Толстой заставлял родных одеваться по-крестьянски, причем наряды всем изготавливал своими руками. Лев Николаевич собирался раздать все имущество семьи крестьянам, и только один Бог знает, каких усилий стоило Софье отговорить его от необдуманного шага.

Толстой согласился, но супруги поссорились, и он ушел из дома. После возвращения он заставил дочерей переписывать черновики его рукописи.

Супруги ненадолго помирились, когда умер их последний ребенок — сын Ваня. Однако полное взаимопонимание в семье так и не наступило. Софья пыталась утешиться музыкой, и даже ходила на уроки к московскому преподавателю. Между ними возникла симпатия, но дальше этого дело не пошло. Они остались друзьями, но Толстой назвал это «полуизменой» и супругу не простил.

Окончательно супруги рассорились в октябре 1910-го. Писатель ушел, оставив для жены прощальное послание, в котором признавался ей в любви, но говорил, что вынужден оставить ее.

Смерть

В конце октября Толстой и сопровождавший его личный доктор Д.Маковицкий уехали из Ясной Поляны. Писателю на тот момент исполнилось 82 года. В поезде он заболел и был вынужден сойти на станции под названием Астапово. Последним приютом перед смертью ему стал домик станционного смотрителя, в котором он пролежал семь дней.

Жена с детьми приехали к Толстому, но он отказался с ними встречаться. Лев Толстой умер 7 ноября 1910 года. Причиной смерти стало воспаление легких. Местом упокоения писателя стала Ясная Поляна. Софья Андреевна скончалась спустя девять лет.

Творчество

Романы

- 1863—1869 — Война и мир

- 1873—1877 — Анна Каренина

- 1889—1899 — Воскресение

Слушать сказки Толстого

Повести

- 1852 — Детство

- 1854- Отрочество

- 1857 — Юность

- 1856 — Два гусара

- 1856 — Утро помещика

- 1858 — Альберт

- 1859 — Семейное счастие

- 1861—1862 — Идиллия

- 1862 — Поликушка

- 1863 — Казаки

- 1880-х—1904 — Фальшивый купон

- 1884—1886 — Смерть Ивана Ильича

- 1884—1903 — Записки сумасшедшего

- 1887—1889 — Крейцерова соната

- 1889—1890 — Дьявол

- 1890—1898 — Отец Сергий

- 1895 — Хозяин и работник

- 1896—1904 — Хаджи-Мурат

Рассказы

- 1851 — История вчерашнего дня

- 1853 — Набег

- 1853 — Святочная ночь

- 1854 — Как умирают русские солдаты

- 1855 — Записки маркёра

- 1855 — Рубка леса

- 1855—1856 — Севастопольские рассказы

- 1856 — Метель

- 1856 — Разжалованный

- Люцерн

- 1859 — Три смерти

- 1860—1862 — Отрывки рассказов из деревенской жизни

- 1863—1885 — Холстомер

- 1872 — Бог правду видит, да не скоро скажет

- 1872 — Кавказский пленник

- 1880 — Две лошади

- 1880 Прыжок

- 1880 Рассказ Аэронавта

- 1887 — Суратская кофейная

- 1890 — Дорого стоит

- 1891 — Франсуаза

- 1891—1893 — Кто прав?

- 1894 — Карма

- 1894 — Сон молодого царя

- 1903 — После бала

- 1905 — Алёша Горшок

- 1905 — Бедные люди

- 1906 — Божеское и человеческое

- 1906 — За что?

- 1906 — Корней Васильев

- 1906 — Ягоды

- 1906 — Что я видел во сне

- 1906 — Отец Василий

- 1908 — Сила детства

- 1909 — Разговор с прохожим

- 1909 — Проезжий и крестьянин

- 1909 — Песни на деревне

- 1909 — Три дня в деревне

- 1910 — Ходынка

- 1910 — Нечаянно

- 1910 — Благодарная почва

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Детство

Лев Толстой родился 28 августа (9 сентября) 1828 года в именитой дворянской семье в родовой усадьбе матери Ясная Поляна Тульской губернии. Он был четвертым ребенком в семье. Но в уже в детстве будущий великий писатель осиротел. После очередных родов, когда Льву не было и двух лет, умерла мать. Еще через семь лет, уже в Москве, внезапно умер отец. Опекуном над детьми была назначена их тетя – графиня Александра Остен-Сакен, но и ее скоро не стало. В 1840 году Лев Николаевич вместе с братьями и сестрой Марией переехал в Казань к другой тете – Пелагее Юшковой.

Обучение

В 1843 году повзрослевший Лев Николаевич поступает учиться в престижный и один из самых известных Императорский Казанский университет по разряду восточной словесности. Однако после успешных вступительных экзаменов будущий светило русской литературы посчитал обучение и экзамены формальностью и провалил итоговую аттестацию за первый курс. Чтобы заново не проходить обучение, молодой Лев Толстой перевелся на юридический факультет, где он не без проблем, но все-таки перешел на второй курс. Однако здесь он увлекся французской философской литературой и, не доучившись на втором курсе, покинул университет. Но обучение не прервал – поселившись в доставшейся ему по наследству усадьбе Ясная Поляна, он занялся самообучением. Каждый день он ставил перед собой задачи и пытался их выполнять, анализируя проделанное за день. Кроме того, в распорядок дня Толстого входили работа с крестьянами и налаживание быта в поместье. Чувствуя вину перед крепостными, он в 1849 году открыл школу для крестьянских детей. Но самовоспитание молодого Толстого не задалось, далеко не все науки его интересовали и давались ему. Решить эту проблему он собирался в Москве, готовясь к кандидатским экзаменам, но вместо них увлекся светской жизнью. То же самое повторилось и в Петербурге, куда он уехал в феврале 1849 года. Не досдав экзамены на кандидата прав, он вновь уехал в Ясную Поляну. Оттуда он часто приезжал в Москву, где много времени уделял азартным играм. Единственным полезным навыком, который он приобрел в эти годы, была музыка. Будущий писатель научился неплохо играть на рояле, результатом чего стало сочинение вальса и последующее написание «Крейцеровой сонаты».

Военная служба

В 1850 году Лев Толстой начал написание автобиографической повести «Детство» – далеко не первого, но достаточно крупного и значимого своего литературного произведения. В 1851 году к нему в имение приехал старший брат Николай, служивший на Кавказе. Необходимость перемен и финансовые трудности заставили Льва Николаевича присоединиться к брату и отправиться с ним на войну. И к осени того же года он был зачислен юнкером в 4-ю батарею 20-й артиллерийской бригады, стоявшей на берегу Терека под Кизляром. Здесь у Толстого вновь появилась возможность писать, и он, наконец, закончил первую часть своей трилогии «Детство», которую летом 1852 года отправил в журнал «Современник». В издании оценили работу молодого автора, и с публикацией повести к Льву Николаевичу пришел первый успех.

Но и о службе Лев Николаевич не забывал. За два года на Кавказе он не раз участвовал в стычках с неприятелем и даже отличился в бою. С началом Крымской войны он перевелся в Дунайскую армию, вместе с которой оказался в гуще войны, пройдя и Сражение у Черной речки, и отбивая атаки врага на Малаховом кургане в Севастополе. Но даже в окопах Толстой продолжал писать, опубликовав первый из трех «Севастопольских рассказов» – «Севастополь в декабре 1854 года», который также был благосклонно принят читателями и высоко оценен самим императором Александром II. Вместе с этим артиллерист-писатель пытался добиться разрешения на издание простенького журнала под названием «Военный листок», где могли бы публиковаться склонные к литературе военные, но эта идея не получила поддержки у властей.

Творческий путь и признание

В августе 1855 года Льва Николаевича отправили курьером в Петербург, где он дописал оставшиеся два «Севастопольских рассказа» и остался, пока в ноябре 1856 года окончательно не оставил службу. В столице писателя приняли очень хорошо, он стал желанным гостем в литературных салонах и кружках, где сдружился с И.С. Тургеневым, Н.А. Некрасовым, И.С. Гончаровым. Однако Толстому это все быстро наскучило, и в начале 1857 года он отправляется в заграничное путешествие. В последующие четыре года он побывал во многих странах Западной Европы, но так и не нашел того, что искал. Европейский образ жизни ему категорически не подходил.

Между этими поездками Лев Николаевич продолжал писать. Результатом этого творчества стали, в частности, рассказ «Три смерти» и роман «Семейное счастие». Кроме того, он, наконец, закончил повесть «Казаки», которую с перерывами писал почти 10 лет. Однако вскоре популярность Толстого пошла на спад, что было вызвано размолвкой с Тургеневым и отказом от продолжения светской жизни. К этому добавилось общее разочарование писателя, а также смерть старшего брата Николая, которого он считал лучшим другом и который умер буквально у него на руках от туберкулеза. Однако после лечения от депрессии в башкирском хуторе Каралык Толстой вновь возвращается к творчеству, а также определяется с семейной жизнью. В 1862 году он посватался к одной из дочерей своей старой знакомой Любови Александровны Иславиной (в замужестве Берс) – Софье. В ту пору его будущей супруге было 18 лет, а графу – уже 34 года. В браке у Толстых родилось девять мальчиков и четыре девочки, но пятеро детей умерли еще в детстве.

Жена стала для писателя настоящей спутницей жизни. С ее помощью он приступает к созданию своего самого знаменитого романа «Война и мир» о российском обществе в период с 1805-го по 1812-й годы, отрывки и главы которого он публиковал с 1865-го по 1869-й годы.

Творческий и философский перелом

Следующим великим произведением автора стал роман «Анна Каренина», над которым Толстой начал трудиться в 1873 году. После этого романа в творчестве Льва Николаевича наступил идейный перелом, выразившийся в новых взглядах писателя на жизнь, отношении к религии, критике власти, внимании к социальным аспектам устройства общества. Произведения на сюжеты светской жизни больше его не интересовали. Все это нашло свое отражение в автобиографическом произведении «Исповедь» (1884). Далее последовали религиозно-философский трактат «В чем моя вера?», «Краткое изложение Евангелия», а позже – роман «Воскресение», повесть «Хаджи-Мурат» и драма «Живой труп».

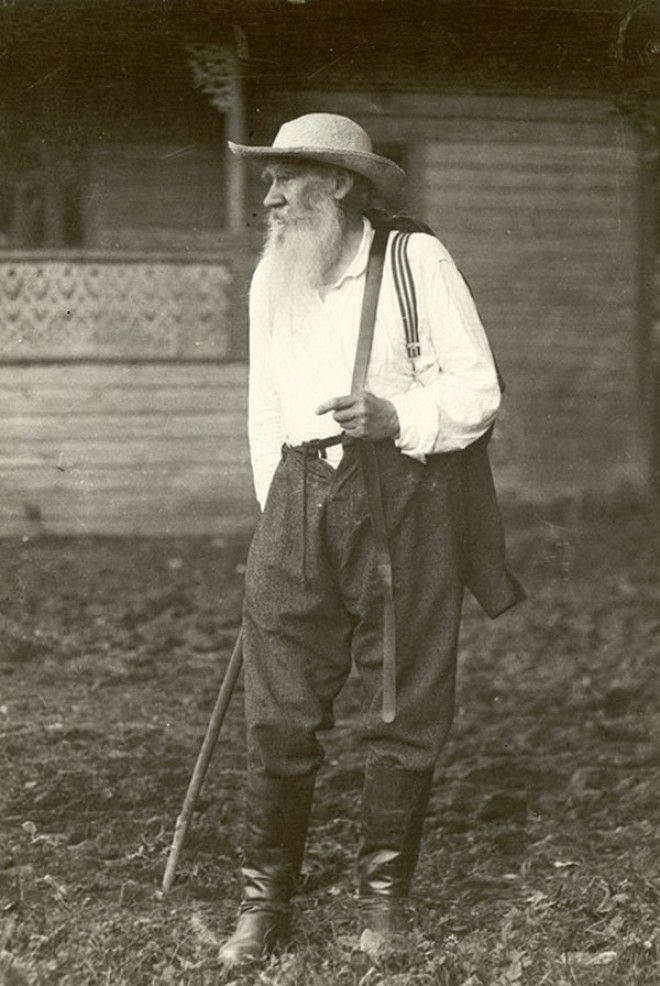

Вместе со своим творчеством изменился и сам Лев Николаевич. Он отказывается от богатств, одевается просто, занимается физической работой, отделяя себя от остального мира. Огромное внимание Толстой уделяет вопросам веры, но эта философия уводит его далеко от лона Русской православной церкви. К тому же церковные устои активно критикуются в таких произведениях писателя, как роман «Воскресение», из-за чего Священный синод в 1901 году отлучает его от Церкви, хотя данное решение скорее было констатацией факта, нежели какой-то мерой.

Вместе с тем Толстой много времени уделяет помощи крестьянам, заботится об их образовании и пропитании. Во время голода в Рязанской губернии Лев Николаевич открывал для нуждающихся столовые, где кормились тысячи крестьян.

Последние дни

28 октября (10 ноября) 1910 года Толстой тайно покидает Ясную Поляну и случайными поездами направляется в сторону границы, но на станции Астапово (ныне Липецкая область) он вынужден покинуть поезд из-за начавшегося воспаления легких. 7 (20) ноября великого писателя не стало. Умер он в доме начальника станции на 83-м году жизни. Льва Николаевича Толстого похоронили в его имении Ясная Поляна в лесу на краю оврага. На похороны приехали несколько тысяч человек. Дань памяти писателю отдали и в Москве, и в Петербурге, и даже за рубежом. По случаю траура были отменены некоторые развлекательные мероприятия, приостанавливалась работа заводов и фабрик, люди выходили на уличные демонстрации с портретами Льва Николаевича.

Связанные объекты (21)

Этот старый мощный дом надежно укрылся за соседними домами, словно за ширмой.

ЦАО, Никитская Б. ул., дом 19/16, строение 1

3.8

Открыть аудиогид

Как ни странно, мы точно знаем, что 25 марта 1851 года в Сивцевом Вражке была «ночь тихая, ясная; молодой месяц виднелся напротив из-за красной крыши большого белого дома; снегу уже мало». Все это благодаря обитателю дома 34.

ЦАО, Сивцев Вражек пер., дом 34, строение 1

Смоленская

3.9

Открыть аудиогид

Воздвиженка, 9 — адрес не только литературный, но и исторический. Этот дом пережил войну 1812 года, здесь неоднократно бывал писатель Л. Н. Толстой. Этот дом выведен в романах «Война и мир» и «Анна Каренина». Сейчас ведется надстройка дома.

ул. Воздвиженка, 9

Арбатская

4.2

Открыть аудиогид

Это загородная усадьба очень богатой семьи Юшковых. В 1812 году здесь расположился маршал Даву после Бородино.

ЦАО, Погодинская ул., дом 22, строение 1

ЛужникиСпортивная

4

Открыть аудиогид

На Большом Афанасьевском переулке, д. 24 расположен жилой дом XVII–XVIII века Зиновьевых–Юсуповых. Дом связан также с историей семьи Толстых. В 2012 году полуразрушенный дом был талантливо отреставрирован.

ЦАО, Афанасьевский Б. пер., дом 24

3.8

Открыть аудиогид

С 1990 года в бывшем усадебном павильоне Трубецких проходили съемки телепередачи «Что? Где? Когда?».

ЦАО, Крымский Вал ул., дом 9, строение 29

ФрунзенскаяШаболовскаяПлощадь ГагаринаЛенинский проспект

4.2

Открыть аудиогид

Мимо этого дома почти все проходят, не останавливаясь. И зря. Дом №4 – в прошлом известная гостиница «Шевалье».

ЦАО, Камергерский пер., дом 4, строение 1

Охотный ряд

3.7

Открыть аудиогид

С 1839 по 1909 год здесь располагался знаменитый Купеческий клуб. Сюда съезжались со всей Москвы, и не только…

ПушкинскаяТверскаяЧеховская

4

Открыть аудиогид

Предание о связи этого дома с масонами нашло отражение в романе в стихах Пастернака «Спекторский»: «Когда-то дом был ложею масонской/ Лет сто назад он отошел в казну».

ЦАО, Мясницкая ул., дом 21, строение 1

ТургеневскаяЧистые пруды

4.2

Открыть аудиогид

О винном магазине Леве упоминает Толстой в романе «Анна Каренина».

ЦАО, Столешников пер., дом 7, строение 1

ПушкинскаяТверскаяЧеховская

4

Открыть аудиогид

Выпускники этой гимназии известны были по всей России и – даже – по всему миру!

ЦАО, Пречистенка ул., дом 32/1, строение 2

Парк Культуры

3.9

Открыть аудиогид

г. Москва, ул. Пречистенка, д. 30/2

Парк КультурыКропоткинская

Пречистенских Ворот пл.

Кропоткинская

Арбат, 33

АрбатскаяСмоленская

3.2

г. Москва, Гоголевский б-р., д. 14

АрбатскаяКропоткинская

Подарок писателей Украины московским собратьям по перу.

Ул. Поварская, д. 52

БеговаяКраснопресненская

3.6

г. Москва, пер. Зачатьевский 1-й, д. 10

Парк КультурыКропоткинская

Здание Щукинского училища было построено в конце 1930-х годов архитектором Н.А. Кругловым в лаконичном стиле с элементами ар-деко. Центральный ризалит выделен высокими окнами и декоративными карнизами с сухариками, а подчеркнутый мощный цоколь придает монументальность и основательность всему строению. Со своего рождения и по сей день дом неизменно служит актерам и режиссерам.

ЦАО, Николопесковский Б. пер., дом 12А, строение 1

АрбатскаяСмоленская

3.4

Открыть аудиогид

В хитросплетениях арбатских переулков есть множество настоящих архитектурных жемчужин. Одна из них — усадьба Н. П. Михайловой-В. Э. Тальгрен, расположенная в Малом Николопесковском переулке, 5. История этого дома уходит своими корнями в начало XIX века. Левая часть особняка более старая, она была построена в 1819 году в стиле ампир, а в 1901 году здание было перестроено архитекторами П. А. Заруцким и А. Е. Антоновым.

ЦАО, Николопесковский М. пер., дом 5, строение 1

АрбатскаяСмоленская

3.3

Открыть аудиогид

Церковь Афанасия и Кирилла, патриархов Александрийских стоит между Большим Афанасьевским и Филипповским переулками, занимая всю ширину квартала. Сейчас церковь отделена от Сивцева Вражка одним домом, построенным на церковной земле в 1914 году по проекту М. Д. Холмогорова.

ЦАО, Филипповский пер., дом 3/16А, строение 1

Кропоткинская

2.9

Открыть аудиогид

Граф Лев Николаевич Толстой — зачинатель нового этапа в развитии русской литературы. Он много путешествовал, воевал, создал философское течение и занял почетное место в списке классиков мировой литературы. Потомкам великий писатель оставил более 150 произведений, которые изучают во всем мире.

Детство, юность и обучение Льва Толстого

Лев Толстой прожил долгую, насыщенную и непростую жизнь. Многие этапы легли в основу его произведений. Чтобы лучше понять творчество писателя, нужно исследовать его биографию.

Какого числа родился Лев Толстой? Лев Толстой родился 28 августа 1828 г. в графской усадьбе Ясной Поляне (Тульская губерния). Спустя полтора года мать Толстого скончалась. Несмотря на то что Лев практически ее не помнил, в мемуарах он отзывался о ней с любовью. Строки писателя о матери в трехтомнике «Биография Л. Н. Толстого» привел публицист и современник писателя П. Бирюков.

Льва с братьями и сестрой растили тетки. Отец Николай Ильич занимался делами и бывал с ними мало, но это не мешало их теплым отношениям. В воспоминаниях писатель указывал, как читал отцу Пушкина наизусть, чем вызывал его большой восторг. В 1837 г. отец Толстого скончался.

Образованием писателя занимался сначала немецкий учитель Фридрих Рессель. Его образ стал прототипом Карла Ивановича в повести «Детство». Следующим был французский гувернер Проспер Сен-Тома. Его можно узнать в Сен-Жероме в следующей части трилогии «Отрочество». Большинство людей, сыгравших важную роль в жизни Толстого, стали прообразами персонажей его произведений.

Воспитательницы Толстого

Наибольшее влияние на духовное воспитание Льва Толстого оказала его троюродная тетка по линии отца Татьяна Александровна Ергольская. Она приехала в графское имение после смерти матери писателя, осталась там жить, фактически заменив ее. Литературовед И. Пахомова приводит слова Толстого о том, что Ергольская научила его духовной любви и прелести неторопливой одинокой жизни. Черты ее характера прослеживаются в образе Сони («Война и мир»).

Еще одной родственницей, которая растила Толстого, была родная сестра его отца Александра Остен-Сакен. Переписка графини Остен-Сакен с Татьяной Ергольской легла в основу писем Болконской и Жюли Карагиной в «Войне и мире». В 1841-м графиня умерла, а на ее могильной плите нанесли стихотворную эпитафию авторства Льва Толстого. С этого момента отсчитывают его путь в литературе.

Третьей опекуншей детей Толстых была младшая сестра их отца Пелагея Ильинична Юшкова. Она приняла решение перевезти детей в Казань, где Лев Толстой начал профильное обучение.

Обучение Льва Толстого

В 1844 г. Льва Толстого зачислили в Императорский Казанский университет на контрактную форму на отделение арабско-турецкой словесности. Такой выбор связан с тем, что еще в 14 лет писатель в частном порядке начал изучать татарский и арабский языки, в чем весьма преуспел.

Толстой был не самым прилежным учеником. Уже по окончанию первого года он не сдал несколько экзаменов, ему назначили повторно пройти курс. Однако он перевелся на юридический. Несмотря на успешную сдачу сессии, проблемы с учебой продолжились, и в 1847 г. Толстой окончательно уходит из университета.

В первом томе автобиографического сборника «Л. Н. Толстой в воспоминаниях современников» сказано, что писателя в то время увлекла философия. Вернувшись в родную усадьбу, он продолжил изучать ее самостоятельно.

Увлечения Льва Толстого

Писатель часто посещал светские мероприятия — балы и званые ужины. Толстой любил праздный образ жизни и мог его себе позволить.

Каким человеком был Лев Толстой? Лев Толстой был любознательным и азартным человеком. В наследство от отца ему досталась слабость к карточным играм, которая неоднократно определяла его жизненный путь. Однако писатель никогда не прекращал развиваться. Он владел более чем восемью языками, самостоятельно изучил греческий за 3 месяца, чтобы читать греческих философов в оригинале.

Чем увлекался Лев Толстой? Лев Толстой увлекался философией, изучением языков, музыкой, юриспруденцией, педагогикой, а также светскими раутами и игрой в карты. Играл он азартно и часто проигрывал. Чтобы скрыться от последствий одного такого проигрыша, в 1851 г. писатель отправился на войну вслед за своим старшим братом Николаем.

Творчество Льва Толстого

Первой пробой пера писателя стал дневник, который он начал вести в 1847 г. В этом дневнике он ставил перед собой цели, обсуждал их пути достижения, отмечал успехи и неудачи. Он вел его до конца жизни.

Произведения периода военной службы

На рубеже 1850–1851 гг. Лев Толстой начал работать над первой повестью знаменитой трилогии «Детство. Отрочество. Юность». «Детство» было опубликовано в 1852 г. в журнале «Современник». Это произведение произвело фурор в литературном мире и было оценено самим Тургеневым. Но ни он, ни кто либо другой не знали, кто его автор, поскольку Толстой публиковался под инициалами Л. Н.

Военная служба давалась писателю лучше, чем учеба. Он успешно сдал экзамен и был прикомандирован к Кавказскому артиллерийскому полку. Толстой участвовал во многих сражениях, несколько раз удостаивался наград за военные заслуги. Участие в двух войнах послужили вдохновением для написания таких произведений, как «Кавказский пленник», «Хаджи Мурат», «Рубка леса», «Набег» «Казаки» и «Севастопольские рассказы». В этот период он работал над «Отрочеством» — продолжением трилогии. Лев Толстой в звании поручика покинул военную службу навсегда в 1856 г.

Творческий кризис

В послевоенное время Толстой тесно общался со многими писателями золотого фонда русской литературы. В его круг входил:

- И. Тургенев;

- И. Гончаров;

- Н. Некрасов;

- И. Панаев;

- А. Дружинин.

В период 1856–1857 гг. он работал над «Юностью» — финальной частью трилогии, продолжал писать «Казаков», издал повесть «Два гусара».

Беспечная жизнь в Петербурге быстро опротивела писателю, и он отправился в путешествие по Европе. В это время написал несколько незначимых произведений. Одной из причин глубокой депрессии писателя была смерть его брата Николая.

В 1859–1860 гг. в преддверии отмены крепостного права в России Толстой активно занимался педагогической и общественной деятельностью. Он создал много крестьянских школ, преподавал и представлял интересы крестьян в уезде Тульской губернии. Писатель приобрел авторитет среди простых людей, но был раскритикован аристократией.

Расцвет творчества

В 1862 г. после излечения от затяжной депрессии Лев Толстой женился на 18-летней дворянке Софье Берс. Семейная жизнь вдохновила писателя на новые свершения, он создает главные свои произведения.

Какие произведения написал Лев Толстой? Лев Толстой написал романы:

- «Семейное счастие».

- «Война и мир».

- «Анна Каренина».

- «Декабристы».

- «Воскресение».

В биографической книге «Лев Толстой» В. Шкловский говорит, что Софья Андреевна стала не только спасением для писателя, но и его редактором.

Личная жизнь и смерть Льва Толстого

У Льва Толстого было много мимолетных увлечений, но единственной настоящей любовью была Софья Андреевна Берс. С ней в браке он прожил 48 лет, она родила ему 13 детей.

На протяжении всей жизни писатель задавался глубокими и сложными вопросами мироздания. Он исследовал институт семьи, читал философские лекции и параллельно изучал устройство души.

К 1900 году Толстой окончательно разочаровался во власти и духовенстве, все больше заботился о судьбе простых крестьян. Он воздвиг физический труд в ранг высшего стремления человека, много работал в этом направлении сам, отказался от материальных благ, носил простую одежду. Все это вызывало возмущение у представителей дворянства и церкви.

В 1901 г. Святейший синод отлучил Льва Толстого от церкви. Писатель прокомментировал, что его нельзя отлучить от Бога. Толстой по-своему трактовал веру, чтил существующие религии и говорил, что Бог един, а миссия верующего в том, чтобы находить в вере то, что объединит его с остальными.

В 1910 г., 28-го октября, Лев Толстой тайно покинул имение в Ясной Поляне в сопровождении врача, оставив записку с извинениями для жены. Седьмого ноября писатель скончался от воспаления легких. Сколько лет прожил Лев Толстой? Лев Толстой прожил 82 года.

Жизнь и творчество Льва Николаевича Толстого имеют большое историческое значение. Он сыграл одну из ключевых ролей в отмене крепостного права в России. Его произведения вошли в золотой фонд классической литературы. Их читают и по ним учатся в ХХІ веке.

Оригинал статьи: https://www.nur.kz/family/school/1860470-lev-tolstoj-biografia-pisatela-zizn-tvorcestvo/

Лев Толстой — писатель, философ и поэт. Родился в Российской империи 9 сентября (28 августа по старому стилю) 1828 года и умер 20 ноября (7 ноября по старому стилю) 1910 года (в возрасте 82 года).

Краткая биография

Лев Николаевич родился в большой дворянской семье в усадьбе Ясная Поляна. Тогда этот район носил название Тульская губерния, а сейчас это Щёкинский район Тульской области. На этой усадьбе он провёл большую часть жизни и был похоронен там же. В 1921 г. Ясная Поляна получила статус музея и на данный момент является природным музеем-заповедником.

Его отцом был граф Николай Ильич Толстой, а матерью — княжна Мария Николаевна Волконская (после бракосочетания стала графиней Толстой). В семье было пятеро детей, у него было три брата и одна сестра.

Он стал сиротой совсем ребёнком — мать умерла когда ему было 1,5 года, а в девять лет он потерял и отца. Его тётка графиня Александра Ильинична Остен-Сакен (урождённая Толстая) стала опекуншей всех пятерых детей.

В 1844 году он поступил в Казанский университет, тогда он назывался Императорским Казанским университетом. Сначала Толстой учился на восточном факультете (изучал арабский и турецкий языки), потом перешёл на юридический. Спустя 2,5 года после начала обучения, в 1847 г., он бросил университет и вернулся в Ясную Поляну.

В 1851 он едет на Кавказ со старшим братом Николаем Николаевичем Толстым (место службы брата). Там он участвовал в военных действиях сначала как волонтёр, а потом в качестве артиллерийского офицера.

В 1852 г. он послал свою рукопись повести «Детство» Н. А. Некрасову. Тогда Толстой сделал запись в своём журнале: «Он или поощрит меня к продолжению любимых занятий, или заставит сжечь всё начатое». Знаменитый писатель оценил его работу, которая была опубликована в сентябре того же года.

В 1854 Лев Николаевич был отправлен в Дунайскую армию. После начала Крымской войны (1853–1856), по собственному желанию, его перевели в Севастополь.

В 1862 г. он женился на Софье Андреевне Берс, они были женаты до самой его смерти, на протяжении 48 лет. От этого брака родилось 13 наследников.

В 82 года писатель тайно покинул дом (Ясную Поляну). По дороге он заболел воспалением лёгких и вынужден был сделать остановку на маленькой станции Астапово, и вскоре умер. Это и считается причиной смерти писателя.

До конца никто не знает, что именно произошло в те последние дни: вокруг него было много людей, каждый шаг писателя был задокументирован, но до сих пор неизвестны причины его ухода из дома.

Его творчество и самые знаменитые работы

Среди его работ более 300 статей и открытых писем (например: «Что такое искусство?», «Великий грех» и «Пора понять»). В 1872 году он опубликовал Азбуку. До нас дошли и его дневники, которые он вёл со студенческих времён (1854 г.) и почти до самой смерти (последняя запись была сделана за 4 дня до смерти в 1910 г.). Возможно, самыми знаменитыми его работами являются:

- Детство (первая опубликованная работа, 1852 г.)

- Отрочество (1854)

- Севастопольские рассказы (1855)

- Юность (1857)

- Семейное счастье (1859)

- Война и мир (1867 г.)

- Кавказский пленник (рассказ, 1872)

- Анна Каренина (1873–77)

- Декабристы (публ. 1884)

- Благодатная почва (последняя опубликованная работа, 1910 г.)

Толстовство

Существует религиозно-философское течение под названием «толстовство», созданное на основе его идей. Очень кратко, основной смысл течения: человеку полезно всё простое, и неверно всё сложное.

Нобелевская премия

Ему никогда не присуждалась Нобелевская премия, потому как сам писатель не хотел её получать.

Лев Николаевич был номинирован на Нобелевскую премию несколько раз:

- премию мира в 1901, 1902 и 1909 годах

- премию по литературе каждый год в 1902–1906 годах.

Лев Николаевич попросил своего знакомого финского писателя и переводчика (по имени Арвид Ярнефельт) сделать так, чтобы эту премию ему не присуждали

Он объяснил это таким образом: «если бы это случилось, мне было бы очень неприятно отказываться» и «всякие деньги, по моему убеждению, могут приносить только зло». Финский писатель выполнил его просьбу.

Мудрые цитаты Льва Николаевича

«Без любви жить легче. Но без неё нет смысла».

«Хочешь жить спокойно и свободно — не приучай себя к лишнему, а сколько можешь отучай себя от того, без чего можешь обойтись».

«Трусливый друг страшнее врага, ибо врага опасаешься, а на друга надеешься».

«В минуту нерешительности действуй быстро и старайся сделать первый шаг, хотя бы и неправильный».

«Часто люди гордятся чистотой своей совести только потому, что они обладают короткой памятью».

«Счастье не в том, чтобы делать всегда, что хочешь, а в том, чтобы всегда хотеть того, что делаешь».

Узнайте также про Некрасова, Чехова, Лермонтова и Пушкина.

|

Leo Tolstoy |

|

|---|---|

![Tolstoy on 23 May 1908 at Yasnaya Polyana,[1] Lithograph print by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/L.N.Tolstoy_Prokudin-Gorsky.jpg/220px-L.N.Tolstoy_Prokudin-Gorsky.jpg)

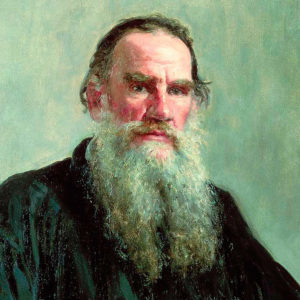

Tolstoy on 23 May 1908 at Yasnaya Polyana,[1] Lithograph print by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky |

|

| Native name |

Лев Николаевич Толстой |

| Born | 9 September 1828 Yasnaya Polyana, Krapivensky Uyezd, Tula Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 20 November 1910 (aged 82) Astapovo, Ranenburgsky Uyezd, Ryazan Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Yasnaya Polyana, Tula |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, playwright, essayist |

| Language | Russian |

| Period | 1847–1910 |

| Literary movement | Realism |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

Sophia Behrs (m. ) |

| Children | 13 |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

|

recorded 1908 |

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy[note 1] (;[2] Russian: Лев Николаевич Толстой,[note 2] IPA: [ˈlʲef nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tɐlˈstoj] (listen); 9 September [O.S. 28 August] 1828 – 20 November [O.S. 7 November] 1910), usually referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time.[3] He received nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906 and for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902, and 1909; the fact that he never won is a major controversy.[4][5][6][7]

Born to an aristocratic Russian family in 1828,[3] Tolstoy’s notable works include the novels War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1878),[8] often cited as pinnacles of realist fiction.[3] He first achieved literary acclaim in his twenties with his semi-autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), and Sevastopol Sketches (1855), based upon his experiences in the Crimean War. His fiction includes dozens of short stories and several novellas such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), Family Happiness (1859), «After the Ball» (1911), and Hadji Murad (1912). He also wrote plays and numerous philosophical essays.

In the 1870s, Tolstoy experienced a profound moral crisis, followed by what he regarded as an equally profound spiritual awakening, as outlined in his non-fiction work A Confession (1882). His literal interpretation of the ethical teachings of Jesus, centering on the Sermon on the Mount, caused him to become a fervent Christian anarchist and pacifist.[3] His ideas on nonviolent resistance, expressed in such works as The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), had a profound impact on such pivotal 20th-century figures as Mahatma Gandhi[9] and Martin Luther King Jr.[10] He also became a dedicated advocate of Georgism, the economic philosophy of Henry George, which he incorporated into his writing, particularly Resurrection (1899).

Origins

The Tolstoys were a well-known family of old Russian nobility who traced their ancestry to a mythical nobleman named Indris described by Pyotr Tolstoy as arriving «from Nemec, from the lands of Caesar» to Chernigov in 1353 along with his two sons Litvinos (or Litvonis) and Zimonten (or Zigmont) and a druzhina of 3000 people.[11][12] While the word «Nemec» has been long used to describe Germans only, at that time it was applied to any foreigner who didn’t speak Russian (from the word nemoy meaning mute).[13] Indris was then converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, under the name of Leonty, and his sons as Konstantin and Feodor. Konstantin’s grandson Andrei Kharitonovich was nicknamed Tolstiy (translated as fat) by Vasily II of Moscow after he moved from Chernigov to Moscow.[11][12]

Because of the pagan names and the fact that Chernigov at the time was ruled by Demetrius I Starshy, some researchers concluded that they were Lithuanians who arrived from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[11][14][15] At the same time, no mention of Indris was ever found in the 14th-to-16th-century documents, while the Chernigov Chronicles used by Pyotr Tolstoy as a reference were lost.[11] The first documented members of the Tolstoy family also lived during the 17th century, thus Pyotr Tolstoy himself is generally considered the founder of the noble house, being granted the title of count by Peter the Great.[16][17]

Life and career

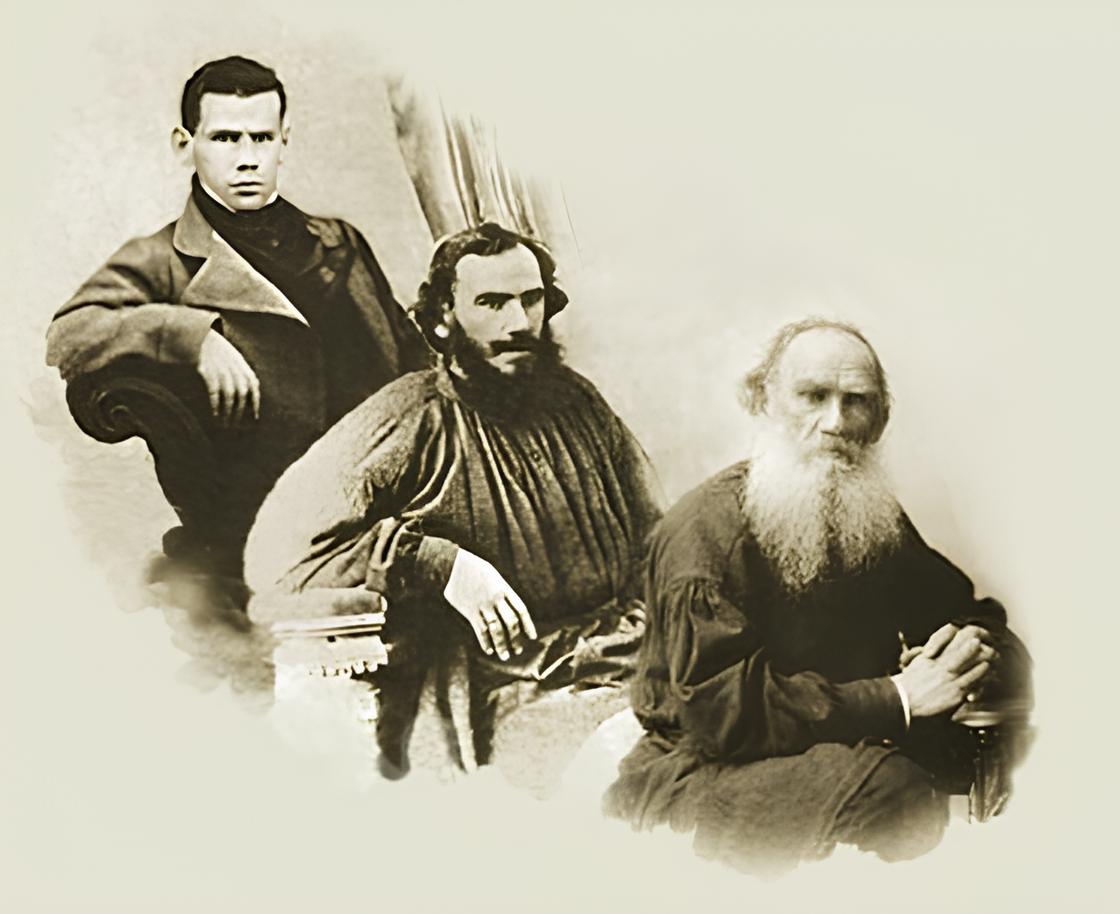

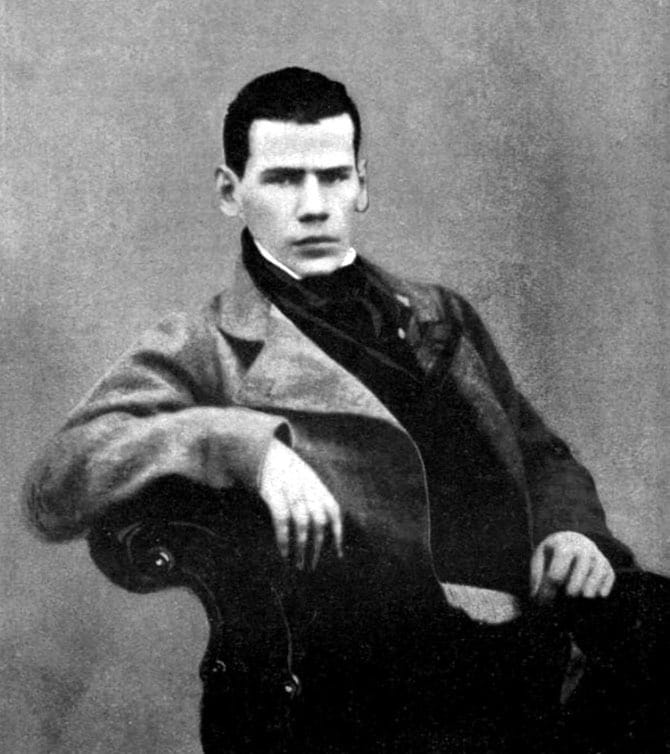

Leo Tolstoy at age 20, c. 1848

Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana, a family estate 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) southwest of Tula, and 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of Moscow. He was the fourth of five children of Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy (1794–1837), a veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812, and Princess Mariya Tolstaya (née Volkonskaya; 1790–1830). His mother died when he was two and his father when he was nine. Tolstoy and his siblings were brought up by relatives.[3] In 1844, he began studying law and oriental languages at Kazan University, where teachers described him as «both unable and unwilling to learn».[18] Tolstoy left the university in the middle of his studies,[18] returned to Yasnaya Polyana and then spent much time in Moscow, Tula and Saint Petersburg, leading a lax and leisurely lifestyle.[3] He began writing during this period,[18] including his first novel Childhood, a fictitious account of his own youth, which was published in 1852.[3] In 1851, after running up heavy gambling debts, he went with his older brother to the Caucasus and joined the army. Tolstoy served as a young artillery officer during the Crimean War and was in Sevastopol during the 11-month-long siege of Sevastopol in 1854–55,[19] including the Battle of the Chernaya. During the war he was recognised for his courage and promoted to lieutenant.[19] He was appalled by the number of deaths involved in warfare,[18] and left the army after the end of the Crimean War.[3]

His experience in the army, and two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860–61 converted Tolstoy from a dissolute and privileged society author to a non-violent and spiritual anarchist. Others who followed the same path were Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that marked the rest of his life. In a letter to his friend Vasily Botkin, Tolstoy wrote: «The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens … Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere.»[20] Tolstoy’s concept of non-violence or ahimsa was bolstered when he read a German version of the Tirukkural.[21][22] He later instilled the concept in Mahatma Gandhi through his A Letter to a Hindu when young Gandhi corresponded with him seeking his advice.[22][23][24]

His European trip in 1860–61 shaped both his political and literary development when he met Victor Hugo. Tolstoy read Hugo’s newly finished Les Misérables. The similar evocation of battle scenes in Hugo’s novel and Tolstoy’s War and Peace indicates this influence. Tolstoy’s political philosophy was also influenced by a March 1861 visit to French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, then living in exile under an assumed name in Brussels. Tolstoy reviewed Proudhon’s forthcoming publication, La Guerre et la Paix («War and Peace» in French), and later used the title for his masterpiece. The two men also discussed education, as Tolstoy wrote in his educational notebooks: «If I recount this conversation with Proudhon, it is to show that, in my personal experience, he was the only man who understood the significance of education and of the printing press in our time.»

Fired by enthusiasm, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded 13 schools for the children of Russia’s peasants, who had just been emancipated from serfdom in 1861. Tolstoy described the schools’ principles in his 1862 essay «The School at Yasnaya Polyana».[25] His educational experiments were short-lived, partly due to harassment by the Tsarist secret police. However, as a direct forerunner to A.S. Neill’s Summerhill School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana[26] can justifiably be claimed the first example of a coherent theory of democratic education.

Personal life

The death of his brother Nikolay in 1860 had an impact on Tolstoy, and led him to a desire to marry.[18] On 23 September 1862, Tolstoy married Sophia Andreevna Behrs, who was sixteen years his junior and the daughter of a court physician. She was called Sonya, the Russian diminutive of Sofia, by her family and friends.[27] They had 13 children, eight of whom survived childhood:[28]

- Count Sergei Lvovich Tolstoy (1863–1947), composer and ethnomusicologist

- Countess Tatyana Lvovna Tolstaya (1864–1950), wife of Mikhail Sergeevich Sukhotin

- Count Ilya Lvovich Tolstoy (1866–1933), writer

- Count Lev Lvovich Tolstoy (1869–1945), writer and sculptor

- Countess Maria Lvovna Tolstaya (1871–1906), wife of Nikolai Leonidovich Obolensky

- Count Peter Lvovich Tolstoy (1872–1873), died in infancy

- Count Nikolai Lvovich Tolstoy (1874–1875), died in infancy

- Countess Varvara Lvovna Tolstaya (1875–1875), died in infancy

- Count Andrei Lvovich Tolstoy (1877–1916), served in the Russo-Japanese War

- Count Michael Lvovich Tolstoy (1879–1944)

- Count Alexei Lvovich Tolstoy (1881–1886)

- Countess Alexandra Lvovna Tolstaya (1884–1979)

- Count Ivan Lvovich Tolstoy (1888–1895)

The marriage was marked from the outset by sexual passion and emotional insensitivity when Tolstoy, on the eve of their marriage, gave her his diaries detailing his extensive sexual past and the fact that one of the serfs on his estate had borne him a son.[27] Even so, their early married life was happy and allowed Tolstoy much freedom and the support system to compose War and Peace and Anna Karenina with Sonya acting as his secretary, editor, and financial manager. Sonya was copying and hand-writing his epic works time after time. Tolstoy would continue editing War and Peace and had to have clean final drafts to be delivered to the publisher.[27][29]

However, their later life together has been described by A.N. Wilson as one of the unhappiest in literary history. Tolstoy’s relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical. This saw him seeking to reject his inherited and earned wealth, including the renunciation of the copyrights on his earlier works.

Some of the members of the Tolstoy family left Russia in the aftermath of the 1905 Russian Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the Soviet Union, and many of Leo Tolstoy’s relatives and descendants today live in Sweden, Germany, the United Kingdom, France and the United States. Tolstoy’s son, Count Lev Lvovich Tolstoy, settled in Sweden and married a Swedish woman. Leo Tolstoy’s last surviving grandchild, Countess Tatiana Tolstoy-Paus, died in 2007 at Herresta manor in Sweden, which is owned by Tolstoy’s descendants.[30] Swedish jazz singer Viktoria Tolstoy is also descended from Leo Tolstoy.[31]

One of his great-great-grandsons, Vladimir Tolstoy (born 1962), is a director of the Yasnaya Polyana museum since 1994 and an adviser to the President of Russia on cultural affairs since 2012.[32][33] Ilya Tolstoy’s great-grandson, Pyotr Tolstoy, is a well-known Russian journalist and TV presenter as well as a State Duma deputy since 2016. His cousin Fyokla Tolstaya (born Anna Tolstaya in 1971), daughter of the acclaimed Soviet Slavist Nikita Tolstoy (ru) (1923–1996), is also a Russian journalist, TV and radio host.[34]

Novels and fictional works

Tolstoy is considered one of the giants of Russian literature; his works include the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina and novellas such as Hadji Murad and The Death of Ivan Ilyich.

Tolstoy’s earliest works, the autobiographical novels Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), tell of a rich landowner’s son and his slow realization of the chasm between himself and his peasants. Though he later rejected them as sentimental, a great deal of Tolstoy’s own life is revealed. They retain their relevance as accounts of the universal story of growing up.

Tolstoy served as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment during the Crimean War, recounted in his Sevastopol Sketches. His experiences in battle helped stir his subsequent pacifism and gave him material for realistic depiction of the horrors of war in his later work.[35]

His fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived.[36] The Cossacks (1863) describes the Cossack life and people through a story of a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. Anna Karenina (1877) tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy), who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives. Tolstoy not only drew from his own life experiences but also created characters in his own image, such as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei in War and Peace, Levin in Anna Karenina and to some extent, Prince Nekhlyudov in Resurrection. Richard Pevear, who translated many of Tolstoy’s works, said of Tolstoy’s signature style, «His works are full of provocation and irony, and written with broad and elaborately developed rhetorical devices.»[37]

War and Peace is generally thought to be one of the greatest novels ever written, remarkable for its dramatic breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical with others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of Napoleon, from the court of Alexander I of Russia to the battlefields of Austerlitz and Borodino. Tolstoy’s original idea for the novel was to investigate the causes of the Decembrist revolt, to which it refers only in the last chapters, from which can be deduced that Andrei Bolkonsky’s son will become one of the Decembrists. The novel explores Tolstoy’s theory of history, and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. Somewhat surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions written at that time to be novels). This view becomes less surprising if one considers that Tolstoy was a novelist of the realist school who considered the novel to be a framework for the examination of social and political issues in nineteenth-century life.[38] War and Peace (which is to Tolstoy really an epic in prose) therefore did not qualify. Tolstoy thought that Anna Karenina was his first true novel.[39]

After Anna Karenina, Tolstoy concentrated on Christian themes, and his later novels such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and What Is to Be Done? develop a radical anarcho-pacifist Christian philosophy which led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901.[40] For all the praise showered on Anna Karenina and War and Peace, Tolstoy rejected the two works later in his life as something not as true of reality.[41]

In his novel Resurrection, Tolstoy attempts to expose the injustice of man-made laws and the hypocrisy of an institutionalized church. Tolstoy also explores and explains the economic philosophy of Georgism, of which he had become a very strong advocate towards the end of his life.

Tolstoy also tried himself in poetry, with several soldier songs written during his military service, and fairy tales in verse such as Volga-bogatyr and Oaf stylized as national folk songs. They were written between 1871 and 1874 for his Russian Book for Reading, a collection of short stories in four volumes (total of 629 stories in various genres) published along with the New Azbuka textbook and addressed to schoolchildren. Nevertheless, he was skeptical about poetry as a genre. As he famously said, «Writing poetry is like ploughing and dancing at the same time.» According to Valentin Bulgakov, he criticised poets, including Alexander Pushkin, for their «false» epithets used «simply to make it rhyme.»[42][43]

Critical appraisal by other authors

Captioned «War and Peace», caricature of Tolstoy in the London magazine Vanity Fair, February 1901

Tolstoy’s contemporaries paid him lofty tributes. Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who died thirty years before Tolstoy, admired and was delighted by Tolstoy’s novels (and, conversely, Tolstoy also admired Dostoyevsky’s work).[44] Gustave Flaubert, on reading a translation of War and Peace, exclaimed, «What an artist and what a psychologist!» Anton Chekhov, who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote, «When literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature.» The 19th-century British poet and critic Matthew Arnold opined that «A novel by Tolstoy is not a work of art but a piece of life.»[3] Isaac Babel said that «if the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy.»[3]

Later novelists continued to appreciate Tolstoy’s art, but sometimes also expressed criticism. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote, «I am attracted by his earnestness and by his power of detail, but I am repelled by his looseness of construction and by his unreasonable and impracticable mysticism.»[45] Virginia Woolf declared him «the greatest of all novelists.»[3] James Joyce noted that, «He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical!» Thomas Mann wrote of Tolstoy’s seemingly guileless artistry: «Seldom did art work so much like nature.» Vladimir Nabokov heaped superlatives upon The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Anna Karenina; he questioned, however, the reputation of War and Peace, and sharply criticized Resurrection and The Kreutzer Sonata. Critic Harold Bloom called Hadji Murat «my personal touchstone for the sublime in prose fiction, to me the best story in the world.»[46]

Religious and political beliefs

Tolstoy dressed in peasant clothing, by Ilya Repin (1901)

After reading Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation, Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ascetic morality upheld in that work as the proper spiritual path for the upper classes. In 1869 he writes: «Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I’ve never experienced before….no student has ever studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer.»[47]

In Chapter VI of A Confession, Tolstoy quoted the final paragraph of Schopenhauer’s work. It explains how a complete denial of self causes only a relative nothingness which is not to be feared. Tolstoy was struck by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer’s ethical chapters, the Russian nobleman chose poverty and formal denial of the will:

But this very necessity of involuntary suffering (by poor people) for eternal salvation is also expressed by that utterance of the Savior (Matthew 19:24): «It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.» Therefore, those who were greatly in earnest about their eternal salvation, chose voluntary poverty when fate had denied this to them and they had been born in wealth. Thus Buddha Sakyamuni was born a prince, but voluntarily took to the mendicant’s staff; and Francis of Assisi, the founder of the mendicant orders who, as a youngster at a ball, where the daughters of all the notabilities were sitting together, was asked: «Now Francis, will you not soon make your choice from these beauties?» and who replied: «I have made a far more beautiful choice!» «Whom?» «La povertà (poverty)»: whereupon he abandoned every thing shortly afterwards and wandered through the land as a mendicant.[48]

In 1884, Tolstoy wrote a book called What I Believe, in which he openly confessed his Christian beliefs. He affirmed his belief in Jesus Christ’s teachings and was particularly influenced by the Sermon on the Mount, and the injunction to turn the other cheek, which he understood as a «commandment of non-resistance to evil by force» and a doctrine of pacifism and nonviolence. In his work The Kingdom of God Is Within You, he explains that he considered mistaken the Church’s doctrine because they had made a «perversion» of Christ’s teachings. Tolstoy also received letters from American Quakers who introduced him to the non-violence writings of Quaker Christians such as George Fox, William Penn, and Jonathan Dymond. Tolstoy believed being a Christian required him to be a pacifist; the apparently inevitable waging of war by governments is why he is considered a philosophical anarchist.

Later, various versions of «Tolstoy’s Bible» were published, indicating the passages Tolstoy most relied on, specifically, the reported words of Jesus himself.[49]

Tolstoy believed that a true Christian could find lasting happiness by striving for inner perfection through following the Great Commandment of loving one’s neighbor and God, rather than guidance from the Church or state. Another distinct attribute of his philosophy based on Christ’s teachings is nonresistance during conflict. This idea in Tolstoy’s book The Kingdom of God Is Within You directly influenced Mahatma Gandhi and therefore also nonviolent resistance movements to this day.

Tolstoy believed that the aristocracy was a burden on the poor.[50] He opposed private land ownership and the institution of marriage, and valued chastity and sexual abstinence (discussed in Father Sergius and his preface to The Kreutzer Sonata), ideals also held by the young Gandhi. Tolstoy’s passion from the depth of his austere moral views is reflected in his later work.[51] One example is the sequence of the temptation of Sergius in Father Sergius. Maxim Gorky relates how Tolstoy once read this passage before him and Chekhov, and Tolstoy was moved to tears by the end of the reading. Later passages of rare power include the personal crises faced by the protagonists of The Death of Ivan Ilyich, and of Master and Man, where the main character in the former and the reader in the latter are made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists’ lives.

In 1886, Tolstoy wrote to the Russian explorer and anthropologist Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay, who was one of the first anthropologists to refute polygenism, the view that the different races of mankind belonged to different species: «You were the first to demonstrate beyond question by your experience that man is man everywhere, that is, a kind, sociable being with whom communication can and should be established through kindness and truth, not guns and spirits.»[52]

Tolstoy had a profound influence on the development of Christian anarchist thought.[53] The Tolstoyans were a small Christian anarchist group formed by Tolstoy’s companion, Vladimir Chertkov (1854–1936), to spread Tolstoy’s religious teachings. From 1892 he regularly met with the student-activist Vasily Maklakov who would defend several Tolstoyans; they discussed the fate of the Doukhobors. Philosopher Peter Kropotkin wrote of Tolstoy in the article on anarchism in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica:

Without naming himself an anarchist, Leo Tolstoy, like his predecessors in the popular religious movements of the 15th and 16th centuries, Chojecki, Denk and many others, took the anarchist position as regards the state and property rights, deducing his conclusions from the general spirit of the teachings of Jesus and from the necessary dictates of reason. With all the might of his talent, Tolstoy made (especially in The Kingdom of God Is Within You) a powerful criticism of the church, the state and law altogether, and especially of the present property laws. He describes the state as the domination of the wicked ones, supported by brutal force. Robbers, he says, are far less dangerous than a well-organized government. He makes a searching criticism of the prejudices which are current now concerning the benefits conferred upon men by the church, the state, and the existing distribution of property, and from the teachings of Jesus he deduces the rule of non-resistance and the absolute condemnation of all wars. His religious arguments are, however, so well combined with arguments borrowed from a dispassionate observation of the present evils, that the anarchist portions of his works appeal to the religious and the non-religious reader alike.[54]

Tolstoy denounced the intervention by the Eight-Nation Alliance in the Boxer Rebellion in China,[55][56] the Filipino-American War, and the Second Boer War.[57]

Tolstoy praised the Boxer Rebellion and harshly criticized the atrocities of the Russian, German, American, Japanese, and other troops of the Eight-Nation alliance. He heard about the looting, rapes, and murders, and accused the troops of slaughter and «Christian brutality.» He named the monarchs most responsible for the atrocities as Tsar Nicholas II and Kaiser Wilhelm II.[58][59] He described the intervention as «terrible for its injustice and cruelty».[60] The war was also criticized by other intellectuals such as Leonid Andreyev and Gorky. As part of the criticism, Tolstoy wrote an epistle called To the Chinese people.[61] In 1902, he wrote an open letter describing and denouncing Nicholas II’s activities in China.[62]

The Boxer Rebellion stirred Tolstoy’s interest in Chinese philosophy.[63] He was a famous sinophile, and read the works of Confucius[64][65][66] and Lao Zi. Tolstoy wrote Chinese Wisdom and other texts about China. Tolstoy corresponded with the Chinese intellectual Gu Hongming and recommended that China remain an agrarian nation, and not reform like Japan. Tolstoy and Gu opposed the Hundred Day’s Reform by Kang Youwei and believed that the reform movement was perilous.[67] Tolstoy’s ideology of non-violence shaped the thought of the Chinese anarchist group Society for the Study of Socialism.[68]

Film by Aleksandr Osipovich Drankov of Tolstoy’s 80th birthday (1908) at Yasnaya Polyana, showing his wife Sofya (picking flowers in the garden) daughter Aleksandra (sitting in the carriage in the white blouse); his aide and confidante V. Chertkov (bald man with the beard and mustache); and students.

In hundreds of essays over the last 20 years of his life, Tolstoy reiterated the anarchist critique of the state and recommended books by Kropotkin and Proudhon to his readers, while rejecting anarchism’s espousal of violent revolutionary means. In the 1900 essay, «On Anarchy,” he wrote: «The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without Authority, there could not be worse violence than that of Authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require the protection of governmental power … There can be only one permanent revolution – a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man.» Despite his misgivings about anarchist violence, Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of anarchist thinkers in Russia, and corrected the proofs of Kropotkin’s «Words of a Rebel», illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906.[69]

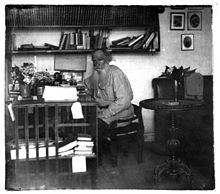

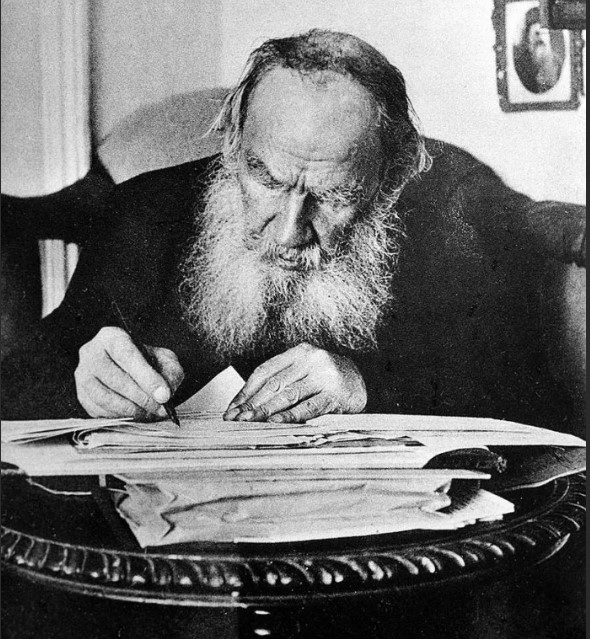

Tolstoy in his study in 1908 (age 80)

In 1908, Tolstoy wrote A Letter to a Hindu[70] outlining his belief in non-violence as a means for India to gain independence from colonial rule. In 1909, Gandhi read a copy of the letter when he was becoming an activist in South Africa. He wrote to Tolstoy seeking proof that he was the author, which led to further correspondence.[21] Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You also helped to convince Gandhi of nonviolent resistance, a debt Gandhi acknowledged in his autobiography, calling Tolstoy «the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced». Their correspondence lasted only a year, from October 1909 until Tolstoy’s death in November 1910, but led Gandhi to give the name Tolstoy Colony to his second ashram in South Africa.[71] Both men also believed in the merits of vegetarianism, the subject of several of Tolstoy’s essays.[72]

Tolstoy also became a major supporter of the Esperanto movement. He was impressed by the pacifist beliefs of the Doukhobors and brought their persecution to the attention of the international community, after they burned their weapons in peaceful protest in 1895. He aided the Doukhobors to migrate to Canada.[73] He also provided inspiration to the Mennonites, another religious group with anti-government and anti-war sentiments.[74][75] In 1904, Tolstoy condemned the ensuing Russo-Japanese War and wrote to the Japanese Buddhist priest Soyen Shaku in a failed attempt to make a joint pacifist statement.

Towards the end of his life, Tolstoy become occupied with the economic theory and social philosophy of Georgism.[76][77][78] He incorporated it approvingly into works such as Resurrection (1899), the book that was a major cause for his excommunication.[79] He spoke with great admiration of Henry George, stating once that «People do not argue with the teaching of George; they simply do not know it. And it is impossible to do otherwise with his teaching, for he who becomes acquainted with it cannot but agree.»[80] He also wrote a preface to George’s journal Social Problems.[81] Tolstoy and George both rejected private property in land (the most important source of income for Russian aristocracy that Tolstoy heavily criticized). They also rejected a centrally planned socialist economy. Because Georgism requires an administration to collect land rent and spend it on infrastructure, some assume that this embrace moved Tolstoy away from his anarchist views. However, anarchist versions of Georgism have been proposed since then.[82] Tolstoy’s 1899 novel Resurrection explores his thoughts on Georgism and hints that Tolstoy had such a view. It suggests small communities with local governance to manage the collective land rents for common goods, while still heavily criticising state institutions such as the justice system.

Death