|

The «surgeon’s photograph» of 1934, now known to have been a hoax[1] |

|

| Sub grouping | Lake monster |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | Nessie, Niseag |

| Country | Scotland |

| Region | Loch Ness, Scottish Highlands |

The Loch Ness Monster (Scottish Gaelic: Uilebheist Loch Nis[3]), affectionately known as Nessie, is a creature in Scottish folklore that is said to inhabit Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands. It is often described as large, long-necked, and with one or more humps protruding from the water. Popular interest and belief in the creature has varied since it was brought to worldwide attention in 1933. Evidence of its existence is anecdotal, with a number of disputed photographs and sonar readings.

The scientific community explains alleged sightings of the Loch Ness Monster as hoaxes, wishful thinking, and the misidentification of mundane objects.[4] The pseudoscience and subculture of cryptozoology has placed particular emphasis on the creature.

Origin of the name

In August 1933, the Courier published the account of George Spicer’s alleged sighting. Public interest skyrocketed, with countless letters being sent in detailing different sightings[5] describing a «monster fish,» «sea serpent,» or «dragon,»[6] with the final name ultimately settling on «Loch Ness monster.»[7] Since the 1940s, the creature has been affectionately called Nessie (Scottish Gaelic: Niseag).[8][9]

Sightings

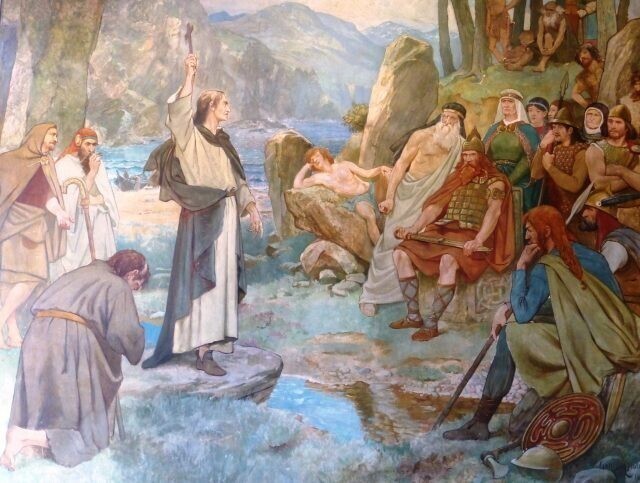

Saint Columba (565)

The earliest report of a monster in the vicinity of Loch Ness appears in the Life of St. Columba by Adomnán, written in the sixth century AD.[10] According to Adomnán, writing about a century after the events described, Irish monk Saint Columba was staying in the land of the Picts with his companions when he encountered local residents burying a man by the River Ness. They explained that the man was swimming in the river when he was attacked by a «water beast» that mauled him and dragged him underwater despite their attempts to rescue him by boat. Columba sent a follower, Luigne moccu Min, to swim across the river. The beast approached him, but Columba made the sign of the cross and said: «Go no further. Do not touch the man. Go back at once.»[11] The creature stopped as if it had been «pulled back with ropes» and fled, and Columba’s men and the Picts gave thanks for what they perceived as a miracle.[11]

Believers in the monster point to this story, set in the River Ness rather than the loch itself, as evidence for the creature’s existence as early as the sixth century.[12] Skeptics question the narrative’s reliability, noting that water-beast stories were extremely common in medieval hagiographies, and Adomnán’s tale probably recycles a common motif attached to a local landmark.[13] According to skeptics, Adomnán’s story may be independent of the modern Loch Ness Monster legend and became attached to it by believers seeking to bolster their claims.[12] Ronald Binns considers that this is the most serious of various alleged early sightings of the monster, but all other claimed sightings before 1933 are dubious and do not prove a monster tradition before that date.[14] Christopher Cairney uses a specific historical and cultural analysis of Adomnán to separate Adomnán’s story about St. Columba from the modern myth of the Loch Ness Monster, but finds an earlier and culturally significant use of Celtic «water beast» folklore along the way. In doing so he also discredits any strong connection between kelpies or water-horses and the modern «media-augmented» creation of the Loch Ness Monster. He also concludes that the story of Saint Columba may have been impacted by earlier Irish myths about the Caoránach and an Oilliphéist.[15]

D. Mackenzie (1871 or 1872)

In October 1871 (or 1872), D. Mackenzie of Balnain reportedly saw an object resembling a log or an upturned boat «wriggling and churning up the water,» moving slowly at first before disappearing at a faster speed.[16][17] The account was not published until 1934, when Mackenzie sent his story in a letter to Rupert Gould shortly after popular interest in the monster increased.[18][17][19][20]

Alexander Macdonald (1888)

In 1888, mason Alexander Macdonald of Abriachan[21] sighted «a large stubby-legged animal» surfacing from the loch and propelling itself within fifty yards of the shore where Macdonald stood.[22] Macdonald reported his sighting to Loch Ness water bailiff Alex Campbell, and described the creature as looking like a salamander.[21]

Aldie Mackay (1933)

The best-known article that first attracted a great deal of attention about a creature was published on 2 May 1933 in The Inverness Courier, about a large «beast» or «whale-like fish». The article by Alex Campbell, water bailiff for Loch Ness and a part-time journalist,[citation needed] discussed a sighting by Aldie Mackay of an enormous creature with the body of a whale rolling in the water in the loch while she and her husband John were driving on the A82 on 15 April 1933. The word «monster» was reportedly applied for the first time in Campbell’s article, although some reports claim that it was coined by editor Evan Barron.[14][23][24]

The Courier in 2017 published excerpts from the Campbell article, which had been titled «Strange Spectacle in Loch Ness».[25]

«The creature disported itself, rolling and plunging for fully a minute, its body resembling that of a whale, and the water cascading and churning like a simmering cauldron. Soon, however, it disappeared in a boiling mass of foam. Both onlookers confessed that there was something uncanny about the whole thing, for they realised that here was no ordinary denizen of the depths, because, apart from its enormous size, the beast, in taking the final plunge, sent out waves that were big enough to have been caused by a passing steamer.»

According to a 2013 article,[18] Mackay said that she had yelled, «Stop! The Beast!» when viewing the spectacle. In the late 1980s, a naturalist interviewed Aldie Mackay and she admitted to knowing that there had been an oral tradition of a «beast» in the loch well before her claimed sighting.[18] Alex Campbell’s 1933 article also stated that «Loch Ness has for generations been credited with being the home of a fearsome-looking monster».[26]

George Spicer (1933)

Modern interest in the monster was sparked by a sighting on 22 July 1933, when George Spicer and his wife saw «a most extraordinary form of animal» cross the road in front of their car.[27] They described the creature as having a large body (about 4 feet (1.2 m) high and 25 feet (8 m) long) and a long, wavy, narrow neck, slightly thicker than an elephant’s trunk and as long as the 10–12-foot (3–4 m) width of the road. They saw no limbs.[28] It lurched across the road toward the loch 20 yards (20 m) away, leaving a trail of broken undergrowth in its wake.[28] Spicer described it as «the nearest approach to a dragon or pre-historic animal that I have ever seen in my life,»[27] and as having «a long neck, which moved up and down in the manner of a scenic railway.»[29] It had «an animal» in its mouth[27] and had a body that «was fairly big, with a high back, but if there were any feet they must have been of the web kind, and as for a tail I cannot say, as it moved so rapidly, and when we got to the spot it had probably disappeared into the loch.»[29]

On 4 August 1933 the Courier published a report of Spicer’s sighting. This sighting triggered a massive amount of public interest and an uptick in alleged sightings, leading to the solidification of the actual name «Loch Ness Monster.»[7]

It has been claimed that sightings of the monster increased after a road was built along the loch in early 1933, bringing workers and tourists to the formerly isolated area.[30] However, Binns has described this as «the myth of the lonely loch», as it was far from isolated before then, due to the construction of the Caledonian Canal. In the 1930s, the existing road by the side of the loch was given a serious upgrade.[14]

Hugh Gray (1933)

Hugh Gray’s photograph taken near Foyers on 12 November 1933 was the first photograph alleged to depict the monster. It was slightly blurred, and it has been noted that if one looks closely the head of a dog can be seen. Gray had taken his Labrador for a walk that day and it is suspected that the photograph depicts his dog fetching a stick from the loch.[31] Others have suggested that the photograph depicts an otter or a swan. The original negative was lost. However, in 1963, Maurice Burton came into «possession of two lantern slides, contact positives from th[e] original negative» and when projected onto a screen they revealed an «otter rolling at the surface in characteristic fashion.»[32]

Arthur Grant (1934)

Sketch of the Arthur Grant sighting.

On 5 January 1934 a motorcyclist, Arthur Grant, claimed to have nearly hit the creature while approaching Abriachan (near the north-eastern end of the loch) at about 1 a.m. on a moonlit night.[33] According to Grant, it had a small head attached to a long neck; the creature saw him, and crossed the road back to the loch. Grant, a veterinary student, described it as a cross between a seal and a plesiosaur. He said he dismounted and followed it to the loch, but saw only ripples.[21][34]

Grant produced a sketch of the creature that was examined by zoologist Maurice Burton, who stated it was consistent with the appearance and behavior of an otter.[35] Regarding the long size of the creature reported by Grant; it has been suggested that this was a faulty observation due to the poor light conditions.[36] Paleontologist Darren Naish has suggested that Grant may have seen either an otter or a seal and exaggerated his sighting over time.[37]

«Surgeon’s photograph» (1934)

The «surgeon’s photograph» is reportedly the first photo of the creature’s head and neck.[38] Supposedly taken by Robert Kenneth Wilson, a London gynaecologist, it was published in the Daily Mail on 21 April 1934. Wilson’s refusal to have his name associated with it led to it being known as the «surgeon’s photograph».[39] According to Wilson, he was looking at the loch when he saw the monster, grabbed his camera and snapped four photos. Only two exposures came out clearly; the first reportedly shows a small head and back, and the second shows a similar head in a diving position. The first photo became well known, and the second attracted little publicity because of its blurriness.

For 60 years the photo was considered evidence of the monster’s existence, although skeptics dismissed it as driftwood,[17] an elephant,[40] an otter or a bird. The photo’s scale was controversial; it is often shown cropped (making the creature seem large and the ripples like waves), while the uncropped shot shows the other end of the loch and the monster in the centre. The ripples in the photo were found to fit the size and pattern of small ripples, rather than large waves photographed up close. Analysis of the original image fostered further doubt. In 1993, the makers of the Discovery Communications documentary Loch Ness Discovered analyzed the uncropped image and found a white object visible in every version of the photo (implying that it was on the negative). It was believed to be the cause of the ripples, as if the object was being towed, although the possibility of a blemish on the negative could not be ruled out. An analysis of the full photograph indicated that the object was small, about 60 to 90 cm (2 to 3 ft) long.[39]

Since 1994, most agree that the photo was an elaborate hoax.[39] It had been described as fake in a 7 December 1975 Sunday Telegraph article that fell into obscurity.[41] Details of how the photo was taken were published in the 1999 book, Nessie – the Surgeon’s Photograph Exposed, which contains a facsimile of the 1975 Sunday Telegraph article.[42] The creature was reportedly a toy submarine built by Christian Spurling, the son-in-law of Marmaduke Wetherell. Wetherell had been publicly ridiculed by his employer, the Daily Mail, after he found «Nessie footprints» that turned out to be a hoax. To get revenge on the Mail, Wetherell perpetrated his hoax with co-conspirators Spurling (sculpture specialist), Ian Wetherell (his son, who bought the material for the fake), and Maurice Chambers (an insurance agent).[43] The toy submarine was bought from F. W. Woolworths, and its head and neck were made from wood putty. After testing it in a local pond the group went to Loch Ness, where Ian Wetherell took the photos near the Altsaigh Tea House. When they heard a water bailiff approaching, Duke Wetherell sank the model with his foot and it is «presumably still somewhere in Loch Ness».[17] Chambers gave the photographic plates to Wilson, a friend of his who enjoyed «a good practical joke». Wilson brought the plates to Ogston’s, an Inverness chemist, and gave them to George Morrison for development. He sold the first photo to the Daily Mail,[44] who then announced that the monster had been photographed.[17]

Little is known of the second photo; it is often ignored by researchers, who believe its quality too poor and its differences from the first photo too great to warrant analysis. It shows a head similar to the first photo, with a more turbulent wave pattern, and possibly taken at a different time and location in the loch. Some believe it to be an earlier, cruder attempt at a hoax,[45] and others (including Roy Mackal and Maurice Burton) consider it a picture of a diving bird or otter that Wilson mistook for the monster.[16] According to Morrison, when the plates were developed, Wilson was uninterested in the second photo; he allowed Morrison to keep the negative, and the photo was rediscovered years later.[46] When asked about the second photo by the Ness Information Service Newsletter, Spurling «… was vague, thought it might have been a piece of wood they were trying out as a monster, but [was] not sure.»[47]

Taylor film (1938)

On 29 May 1938, South African tourist G. E. Taylor filmed something in the loch for three minutes on 16 mm colour film. The film was obtained by popular science writer Maurice Burton, who did not show it to other researchers. A single frame was published in his 1961 book, The Elusive Monster. His analysis concluded it was a floating object, not an animal.[48]

William Fraser (1938)

On 15 August 1938, William Fraser, chief constable of Inverness-shire, wrote a letter that the monster existed beyond doubt and expressed concern about a hunting party that had arrived (with a custom-made harpoon gun) determined to catch the monster «dead or alive». He believed his power to protect the monster from the hunters was «very doubtful». The letter was released by the National Archives of Scotland on 27 April 2010.[49][50]

Sonar readings (1954)

In December 1954, sonar readings were taken by the fishing boat Rival III. Its crew noted a large object keeping pace with the vessel at a depth of 146 metres (479 ft). It was detected for 800 m (2,600 ft) before contact was lost and regained.[51] Previous sonar attempts were inconclusive or negative.

Peter MacNab (1955)

Peter MacNab at Urquhart Castle on 29 July 1955 took a photograph that depicted two long black humps in the water. The photograph was not made public until it appeared in Constance Whyte’s 1957 book on the subject. On 23 October 1958 it was published by the Weekly Scotsman. Author Ronald Binns wrote that the «phenomenon which MacNab photographed could easily be a wave effect resulting from three trawlers travelling closely together up the loch.»[52]

Other researchers consider the photograph a hoax.[53] Roy Mackal requested to use the photograph in his 1976 book. He received the original negative from MacNab, but discovered it differed from the photograph that appeared in Whyte’s book. The tree at the bottom left in Whyte’s was missing from the negative. It is suspected that the photograph was doctored by re-photographing a print.[54]

Dinsdale film (1960)

Aeronautical engineer Tim Dinsdale filmed a hump that left a wake crossing Loch Ness in 1960.[55] Dinsdale, who reportedly had the sighting on his final day of search, described it as reddish with a blotch on its side. He said that when he mounted his camera the object began to move, and he shot 40 feet of film. According to JARIC, the object was «probably animate».[56][third-party source needed] Others were sceptical, saying that the «hump» cannot be ruled out as being a boat[57] and when the contrast is increased, a man in a boat can be seen.[56]

In 1993 Discovery Communications produced a documentary, Loch Ness Discovered, with a digital enhancement of the Dinsdale film. A person who enhanced the film noticed a shadow in the negative that was not obvious in the developed film. By enhancing and overlaying frames, he found what appeared to be the rear body of a creature underwater: «Before I saw the film, I thought the Loch Ness Monster was a load of rubbish. Having done the enhancement, I’m not so sure».[58]

«Loch Ness Muppet» (1977)

On 21 May 1977 Anthony «Doc» Shiels, camping next to Urquhart Castle, took «some of the clearest pictures of the monster until this day».[citation needed] Shiels, a magician and psychic, claimed to have summoned the animal out of the water. He later described it as an «elephant squid», claiming the long neck shown in the photograph is actually the squid’s «trunk» and that a white spot at the base of the neck is its eye. Due to the lack of ripples, it has been declared a hoax by a number of people and received its name because of its staged look.[59][60]

Holmes video (2007)

On 26 May 2007, 55-year-old laboratory technician Gordon Holmes videotaped what he said was «this jet black thing, about 14 metres (46 ft) long, moving fairly fast in the water.»[61] Adrian Shine, a marine biologist at the Loch Ness 2000 Centre in Drumnadrochit, described the footage as among «the best footage [he had] ever seen.»[61] BBC Scotland broadcast the video on 29 May 2007.[62] STV News North Tonight aired the footage on 28 May 2007 and interviewed Holmes. Shine was also interviewed, and suggested that the footage was an otter, seal or water bird.[63]

Sonar image (2011)

On 24 August 2011 Loch Ness boat captain Marcus Atkinson photographed a sonar image of a 1.5-metre-wide (4.9 ft), unidentified object that seemed to follow his boat for two minutes at a depth of 23 m (75 ft), and ruled out the possibility of a small fish or seal. In April 2012, a scientist from the National Oceanography Centre said that the image is a bloom of algae and zooplankton.[64]

George Edwards photograph (2011)

On 3 August 2012, skipper George Edwards claimed that a photo he took on 2 November 2011 shows «Nessie». Edwards claims to have searched for the monster for 26 years, and reportedly spent 60 hours per week on the loch aboard his boat, Nessie Hunter IV, taking tourists for rides on the lake.[65] Edwards said, «In my opinion, it probably looks kind of like a manatee, but not a mammal. When people see three humps, they’re probably just seeing three separate monsters.»[66]

Other researchers have questioned the photograph’s authenticity,[67] and Loch Ness researcher Steve Feltham suggested that the object in the water is a fibreglass hump used in a National Geographic Channel documentary in which Edwards had participated.[68] Researcher Dick Raynor has questioned Edwards’ claim of discovering a deeper bottom of Loch Ness, which Raynor calls «Edwards Deep». He found inconsistencies between Edwards’ claims for the location and conditions of the photograph and the actual location and weather conditions that day. According to Raynor, Edwards told him he had faked a photograph in 1986 that he claimed was genuine in the Nat Geo documentary.[69] Although Edwards admitted in October 2013 that his 2011 photograph was a hoax,[70] he insisted that the 1986 photograph was genuine.[71]

A survey of the literature about other hoaxes, including photographs, published by The Scientific American on 10 July 2013, indicates many others since the 1930s. The most recent photo considered to be «good» appeared in newspapers in August 2012; it was allegedly taken by George Edwards in November 2011 but was «definitely a hoax» according to the science journal.[67]

David Elder video (2013)

On 27 August 2013, tourist David Elder presented a five-minute video of a «mysterious wave» in the loch. According to Elder, the wave was produced by a 4.5 m (15 ft) «solid black object» just under the surface of the water.[72] Elder, 50, from East Kilbride, South Lanarkshire, was taking a picture of a swan at the Fort Augustus pier on the south-western end of the loch,[73] when he captured the movement.[74] He said, «The water was very still at the time and there were no ripples coming off the wave and no other activity on the water.»[74] Sceptics suggested that the wave may have been caused by a wind gust.[75]

Apple Maps photograph (2014)

On 19 April 2014, it was reported[76] that a satellite image on Apple Maps showed what appeared to be a large creature (thought by some to be the Loch Ness Monster) just below the surface of Loch Ness. At the loch’s far north, the image appeared about 30 metres (98 ft) long. Possible explanations were the wake of a boat (with the boat itself lost in image stitching or low contrast), seal-caused ripples, or floating wood.[77][78]

Google Street View (2015)

Google commemorated the 81st anniversary of the «surgeon’s photograph» with a Google Doodle,[79] and added a new feature to Google Street View with which users can explore the loch above and below the water.[80][81] Google reportedly spent a week at Loch Ness collecting imagery with a street-view «trekker» camera, attaching it to a boat to photograph above the surface and collaborating with members of the Catlin Seaview Survey to photograph underwater.[82]

Searches

Edward Mountain expedition (1934)

Loch Ness, reported home of the monster

After reading Rupert Gould’s The Loch Ness Monster and Others,[21] Edward Mountain financed a search. Twenty men with binoculars and cameras positioned themselves around the loch from 9 am to 6 pm for five weeks, beginning on 13 July 1934. Although 21 photographs were taken, none was considered conclusive. Supervisor James Fraser remained by the loch filming on 15 September 1934; the film is now lost.[83] Zoologists and professors of natural history concluded that the film showed a seal, possibly a grey seal.[84]

Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau (1962–1972)

The Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau (LNPIB) was a UK-based society formed in 1962 by Norman Collins, R. S. R. Fitter, politician David James, Peter Scott and Constance Whyte[85] «to study Loch Ness to identify the creature known as the Loch Ness Monster or determine the causes of reports of it».[86] In 1967 it received a grant of $20,000 from World Book Encyclopedia to fund a 2-year programme of daylight watches from May to October. The principal equipment was 35 mm movie cameras on mobile units with 20 inch lenses, and one with a 36 inch lens at Achnahannet, near the midpoint of the loch. With the mobile units in laybys about 80% of the loch surface was covered.[87] The society’s name was later shortened to the Loch Ness Investigation Bureau (LNIB), and it disbanded in 1972.[88] The LNIB had an annual subscription charge, which covered administration. Its main activity was encouraging groups of self-funded volunteers to watch the loch from vantage points with film cameras with telescopic lenses. From 1965 to 1972 it had a caravan camp and viewing platform at Achnahannet, and sent observers to other locations up and down the loch.[89][90] According to the bureau’s 1969 annual report[91] it had 1,030 members, of whom 588 were from the UK.

Sonar study (1967–1968)

D. Gordon Tucker, chair of the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at the University of Birmingham, volunteered his services as a sonar developer and expert at Loch Ness in 1968.[92] His gesture, part of a larger effort led by the LNPIB from 1967 to 1968, involved collaboration between volunteers and professionals in a number of fields. Tucker had chosen Loch Ness as the test site for a prototype sonar transducer with a maximum range of 800 m (2,600 ft). The device was fixed underwater at Temple Pier in Urquhart Bay and directed at the opposite shore, drawing an acoustic «net» across the loch through which no moving object could pass undetected. During the two-week trial in August, multiple targets were identified. One was probably a shoal of fish, but others moved in a way not typical of shoals at speeds up to 10 knots.[93]

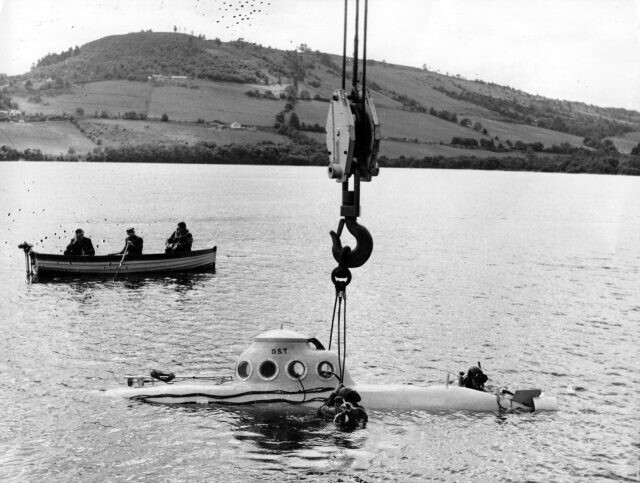

Robert Rines studies (1972, 1975, 2001, 2008)

In 1972, a group of researchers from the Academy of Applied Science led by Robert H. Rines conducted a search for the monster involving sonar examination of the loch depths for unusual activity. Rines took precautions to avoid murky water with floating wood and peat.[citation needed] A submersible camera with a floodlight was deployed to record images below the surface. If Rines detected anything on the sonar, he turned the light on and took pictures.

On 8 August, Rines’ Raytheon DE-725C sonar unit, operating at a frequency of 200 kHz and anchored at a depth of 11 metres (36 ft), identified a moving target (or targets) estimated by echo strength at 6 to 9 metres (20 to 30 ft) in length. Specialists from Raytheon, Simrad (now Kongsberg Maritime), Hydroacoustics, Marty Klein of MIT and Klein Associates (a side-scan sonar producer) and Ira Dyer of MIT’s Department of Ocean Engineering were on hand to examine the data. P. Skitzki of Raytheon suggested that the data indicated a 3-metre (10 ft) protuberance projecting from one of the echoes. According to author Roy Mackal, the shape was a «highly flexible laterally flattened tail» or the misinterpreted return from two animals swimming together.[94]

Concurrent with the sonar readings, the floodlit camera obtained a pair of underwater photographs. Both depicted what appeared to be a rhomboid flipper, although sceptics have dismissed the images as depicting the bottom of the loch, air bubbles, a rock, or a fish fin. The apparent flipper was photographed in different positions, indicating movement.[95] The first flipper photo is better-known than the second, and both were enhanced and retouched from the original negatives. According to team member Charles Wyckoff, the photos were retouched to superimpose the flipper; the original enhancement showed a considerably less-distinct object. No one is sure how the originals were altered.[96] During a meeting with Tony Harmsworth and Adrian Shine at the Loch Ness Centre & Exhibition, Rines admitted that the flipper photo may have been retouched by a magazine editor.[97]

British naturalist Peter Scott announced in 1975, on the basis of the photographs, that the creature’s scientific name would be Nessiteras rhombopteryx (Greek for «Ness inhabitant with diamond-shaped fin»).[98][99] Scott intended that the name would enable the creature to be added to the British register of protected wildlife. Scottish politician Nicholas Fairbairn called the name an anagram for «Monster hoax by Sir Peter S».[100][101][102] However, Rines countered that when rearranged, the letters could also spell «Yes, both pix are monsters – R.»[100]

Another sonar contact was made, this time with two objects estimated to be about 9 metres (30 ft). The strobe camera photographed two large objects surrounded by a flurry of bubbles.[103] Some interpreted the objects as two plesiosaur-like animals, suggesting several large animals living in Loch Ness. This photograph has rarely been published.

A second search was conducted by Rines in 1975. Some of the photographs, despite their obviously murky quality and lack of concurrent sonar readings, did indeed seem to show unknown animals in various positions and lightings. One photograph appeared to show the head, neck, and upper torso of a plesiosaur-like animal,[103] but sceptics argue the object is a log due to the lump on its «chest» area, the mass of sediment in the full photo, and the object’s log-like «skin» texture.[97] Another photograph seemed to depict a horned «gargoyle head», consistent with that of some sightings of the monster;[103] however, sceptics point out that a tree stump was later filmed during Operation Deepscan in 1987, which bore a striking resemblance to the gargoyle head.[97]

In 2001, Rines’ Academy of Applied Science videotaped a V-shaped wake traversing still water on a calm day. The academy also videotaped an object on the floor of the loch resembling a carcass and found marine clamshells and a fungus-like organism not normally found in freshwater lochs, a suggested connection to the sea and a possible entry for the creature.[104]

In 2008, Rines theorised that the creature may have become extinct, citing the lack of significant sonar readings and a decline in eyewitness accounts. He undertook a final expedition, using sonar and an underwater camera in an attempt to find a carcass. Rines believed that the animals may have failed to adapt to temperature changes resulting from global warming.[105]

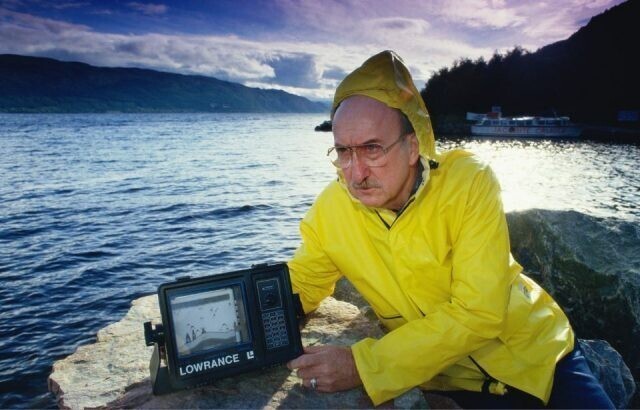

Operation Deepscan (1987)

Operation Deepscan was conducted in 1987.[106] Twenty-four boats equipped with echo sounding equipment were deployed across the width of the loch, and simultaneously sent acoustic waves. According to BBC News the scientists had made sonar contact with an unidentified object of unusual size and strength.[107] The researchers returned, re-scanning the area. Analysis of the echosounder images seemed to indicate debris at the bottom of the loch, although there was motion in three of the pictures. Adrian Shine speculated, based on size, that they might be seals that had entered the loch.[108]

Sonar expert Darrell Lowrance, founder of Lowrance Electronics, donated a number of echosounder units used in the operation. After examining a sonar return indicating a large, moving object at a depth of 180 metres (590 ft) near Urquhart Bay, Lowrance said: «There’s something here that we don’t understand, and there’s something here that’s larger than a fish, maybe some species that hasn’t been detected before. I don’t know.»[109]

Searching for the Loch Ness Monster (2003)

In 2003, the BBC sponsored a search of the loch using 600 sonar beams and satellite tracking. The search had sufficient resolution to identify a small buoy. No animal of substantial size was found and, despite their reported hopes, the scientists involved admitted that this proved the Loch Ness Monster was a myth. Searching for the Loch Ness Monster aired on BBC One.[110]

DNA survey (2018)

An international team consisting of researchers from the universities of Otago, Copenhagen, Hull and the Highlands and Islands, did a DNA survey of the lake in June 2018, looking for unusual species.[111] The results were published in 2019; no DNA of large fish such as sharks, sturgeons and catfish could be found. No otter or seal DNA were obtained either, though there was a lot of eel DNA. The leader of the study, Prof Neil Gemmell of the University of Otago, said he could not rule out the possibility of eels of extreme size, though none were found, nor were any ever caught. The other possibility is that the large amount of eel DNA simply comes from many small eels. No evidence of any reptilian sequences were found, he added, «so I think we can be fairly sure that there is probably not a giant scaly reptile swimming around in Loch Ness», he said.[112][113]

Explanations

A number of explanations have been suggested to account for sightings of the creature. According to Ronald Binns, a former member of the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau, there is probably no single explanation of the monster. Binns wrote two sceptical books, the 1983 The Loch Ness Mystery Solved, and his 2017 The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. In these he contends that an aspect of human psychology is the ability of the eye to see what it wants, and expects, to see.[14] They may be categorised as misidentifications of known animals, misidentifications of inanimate objects or effects, reinterpretations of Scottish folklore, hoaxes, and exotic species of large animals. A reviewer wrote that Binns had «evolved into the author of … the definitive, skeptical book on the subject». Binns does not call the sightings a hoax, but «a myth in the true sense of the term» and states that the «‘monster is a sociological … phenomenon. …After 1983 the search … (for the) possibility that there just might be continues to enthrall a small number for whom eye-witness evidence outweighs all other considerations».[114]

Misidentification of known animals

Bird wakes

Wakes have been reported when the loch is calm, with no boats nearby. Bartender David Munro reported a wake he believed was a creature zigzagging, diving, and reappearing; there were reportedly 26 other witnesses from a nearby car park.[96][better source needed] Although some sightings describe a V-shaped wake similar to a boat’s,[104] others report something not conforming to the shape of a boat.[58]

Eels

A large eel was an early suggestion for what the «monster» was. Eels are found in Loch Ness, and an unusually large one would explain many sightings.[115] Dinsdale dismissed the hypothesis because eels undulate side to side like snakes.[116] Sightings in 1856 of a «sea-serpent» (or kelpie) in a freshwater lake near Leurbost in the Outer Hebrides were explained as those of an oversized eel, also believed common in «Highland lakes».[117]

From 2018 to 2019, scientists from New Zealand undertook a massive project to document every organism in Loch Ness based on DNA samples. Their reports confirmed that European eels are still found in the Loch. No DNA samples were found for large animals such as catfish, Greenland sharks, or plesiosaurs. Many scientists now believe that giant eels account for many, if not most of the sightings.[118][119][120][121]

Elephant

In a 1979 article, California biologist Dennis Power and geographer Donald Johnson claimed that the «surgeon’s photograph» was the top of the head, extended trunk and flared nostrils of a swimming elephant photographed elsewhere and claimed to be from Loch Ness.[40] In 2006, palaeontologist and artist Neil Clark suggested that travelling circuses might have allowed elephants to bathe in the loch; the trunk could be the perceived head and neck, with the head and back the perceived humps. In support of this, Clark provided an example painting.[122]

Greenland shark

Zoologist, angler and television presenter Jeremy Wade investigated the creature in 2013 as part of the series River Monsters, and concluded that it is a Greenland shark. The Greenland shark, which can reach up to 20 feet in length, inhabits the North Atlantic Ocean around Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, and possibly Scotland. It is dark in colour, with a small dorsal fin.[123] According to biologist Bruce Wright, the Greenland shark could survive in fresh water (possibly using rivers and lakes to find food) and Loch Ness has an abundance of salmon and other fish.[124][125]

Wels catfish

In July 2015 three news outlets reported that Steve Feltham, after a vigil at the loch that was recognized by the Guinness Book of Records, theorised that the monster is an unusually large specimen of Wels catfish (Silurus glanis), which may have been released during the late 19th century.[126][127][128]

Other resident animals

It is difficult to judge the size of an object in water through a telescope or binoculars with no external reference. Loch Ness has resident otters, and photos of them and deer swimming in the loch, which were cited by author Ronald Binns[129] may have been misinterpreted. According to Binns, birds may be mistaken for a «head and neck» sighting.[130]

Misidentifications of inanimate objects or effects

Trees

In 1933, the Daily Mirror published a picture with the caption: «This queerly-shaped tree-trunk, washed ashore at Foyers [on Loch Ness] may, it is thought, be responsible for the reported appearance of a ‘Monster‘«.[131]

In a 1982 series of articles for New Scientist, Maurice Burton proposed that sightings of Nessie and similar creatures may be fermenting Scots pine logs rising to the surface of the loch. A decomposing log could not initially release gases caused by decay because of its high resin level. Gas pressure would eventually rupture a resin seal at one end of the log, propelling it through the water (sometimes to the surface). According to Burton, the shape of tree logs (with their branch stumps) closely resembles descriptions of the monster.[132][133][134]

Seiches and wakes

Loch Ness, because of its long, straight shape, is subject to unusual ripples affecting its surface. A seiche is a large oscillation of a lake, caused by water reverting to its natural level after being blown to one end of the lake (resulting in a standing wave); the Loch Ness oscillation period is 31.5 minutes.[135] Earthquakes in Scotland are too weak to cause observable seiches, but extremely massive earthquakes far away could cause large waves. The seiche created in Loch Ness by the catastrophic 1755 Lisbon earthquake was reportedly «so violent as to threaten destruction to some houses built on the sides of it», while the 1761 aftershock caused two-foot (60 cm) waves. However, no sightings of the monster were reported in 1755.[136][137]

Optical effects

Wind conditions can give a choppy, matte appearance to the water with calm patches appearing dark from the shore (reflecting the mountains). In 1979 W. H. Lehn showed that atmospheric refraction could distort the shape and size of objects and animals,[138] and later published a photograph of a mirage of a rock on Lake Winnipeg that resembled a head and neck.[139]

Seismic gas

Italian geologist Luigi Piccardi has proposed geological explanations for ancient legends and myths. Piccardi noted that in the earliest recorded sighting of a creature (the Life of Saint Columba), the creature’s emergence was accompanied «cum ingenti fremitu» («with loud roaring»). The Loch Ness is along the Great Glen Fault, and this could be a description of an earthquake. Many reports consist only of a large disturbance on the surface of the water; this could be a release of gas through the fault, although it may be mistaken for something swimming below the surface.[140]

Folklore

In 1980 Swedish naturalist and author Bengt Sjögren wrote that present beliefs in lake monsters such as the Loch Ness Monster are associated with kelpie legends. According to Sjögren, accounts of loch monsters have changed over time; originally describing horse-like creatures, they were intended to keep children away from the loch. Sjögren wrote that the kelpie legends have developed into descriptions reflecting a modern awareness of plesiosaurs.[141]

The kelpie as a water horse in Loch Ness was mentioned in an 1879 Scottish newspaper,[142] and inspired Tim Dinsdale’s Project Water Horse.[143] A study of pre-1933 Highland folklore references to kelpies, water horses and water bulls indicated that Ness was the loch most frequently cited.[144]

Hoaxes

A number of hoax attempts have been made, some of which were successful. Other hoaxes were revealed rather quickly by the perpetrators or exposed after diligent research. A few examples follow.

In August 1933, Italian journalist Francesco Gasparini submitted what he said was the first news article on the Loch Ness Monster. In 1959, he reported sighting a «strange fish» and fabricated eyewitness accounts: «I had the inspiration to get hold of the item about the strange fish. The idea of the monster had never dawned on me, but then I noted that the strange fish would not yield a long article, and I decided to promote the imaginary being to the rank of monster without further ado.»[145]

In the 1930s, big-game hunter Marmaduke Wetherell went to Loch Ness to look for the monster. Wetherell claimed to have found footprints, but when casts of the footprints were sent to scientists for analysis they turned out to be from a hippopotamus; a prankster had used a hippopotamus-foot umbrella stand.[146]

In 1972 a team of zoologists from Yorkshire’s Flamingo Park Zoo, searching for the monster, discovered a large body floating in the water. The corpse, 4.9–5.4 m (16–18 ft) long and weighing as much as 1.5 tonnes, was described by the Press Association as having «a bear’s head and a brown scaly body with clawlike fins.» The creature was placed in a van to be carried away for testing, but police seized the cadaver under an act of parliament prohibiting the removal of «unidentified creatures» from Loch Ness. It was later revealed that Flamingo Park education officer John Shields shaved the whiskers and otherwise disfigured a bull elephant seal that had died the week before and dumped it in Loch Ness to dupe his colleagues.[147]

On 2 July 2003, Gerald McSorely discovered a fossil, supposedly from the creature, when he tripped and fell into the loch. After examination, it was clear that the fossil had been planted.[148]

Cryptoclidus model used in the Five TV programme, Loch Ness Monster: The Ultimate Experiment

In 2004 a Five TV documentary team, using cinematic special-effects experts, tried to convince people that there was something in the loch. They constructed an animatronic model of a plesiosaur, calling it «Lucy». Despite setbacks (including Lucy falling to the bottom of the loch), about 600 sightings were reported where she was placed.[149][150]

In 2005, two students claimed to have found a large tooth embedded in the body of a deer on the loch shore. They publicised the find, setting up a website, but expert analysis soon revealed that the «tooth» was the antler of a muntjac. The tooth was a publicity stunt to promote a horror novel by Steve Alten, The Loch.[148]

Exotic large-animal species

Plesiosaur

Reconstruction of Nessie as a plesiosaur outside the Museum of Nessie

In 1933 it was suggested that the creature «bears a striking resemblance to the supposedly extinct plesiosaur»,[151] a long-necked aquatic reptile that became extinct during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. A popular explanation at the time, the following arguments have been made against it:

- In an October 2006 New Scientist article, «Why the Loch Ness Monster is no plesiosaur», Leslie Noè of the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge said: «The osteology of the neck makes it absolutely certain that the plesiosaur could not lift its head up swan-like out of the water».[152]

- The loch is only about 10,000 years old, dating to the end of the last ice age. Before then, it was frozen for about 20,000 years.[153]

- If creatures similar to plesiosaurs lived in Loch Ness they would be seen frequently, since they would have to surface several times a day to breathe.[108]

In response to these criticisms, Tim Dinsdale, Peter Scott and Roy Mackal postulate a trapped marine creature that evolved from a plesiosaur directly or by convergent evolution.[154] Robert Rines explained that the «horns» in some sightings function as breathing tubes (or nostrils), allowing it to breathe without breaking the surface. Also new discoveries have shown that Plesiosaurs had the ability to swim in fresh waters, but the cold temperatures would make it hard for it to live.

Long-necked giant amphibian

R. T. Gould suggested a long-necked newt;[21][155] Roy Mackal examined the possibility, giving it the highest score (88 percent) on his list of possible candidates.[156]

Invertebrate

In 1968 F. W. Holiday proposed that Nessie and other lake monsters, such as Morag, may be a large invertebrate such as a bristleworm; he cited the extinct Tullimonstrum as an example of the shape.[157] According to Holiday, this explains the land sightings and the variable back shape; he likened it to the medieval description of dragons as «worms». Although this theory was considered by Mackal, he found it less convincing than eels, amphibians or plesiosaurs.[158]

See also

- Bear Lake monster

- Beithir

- Bunyip

- Chessie (sea monster)

- Gaasyendietha

- Jiaolong

- Lake Tianchi Monster

- Lake Van Monster

- Lariosauro

- Leviathan

- List of reported lake monsters

- List of topics characterised as pseudoscience

- Living fossils

- Loch Ness Monster in popular culture

- Manipogo

- Memphre

- Mishipeshu

- Mokele-mbembe

- Morag

- Nahuel Huapi Lake Monster

- Ogopogo

- Plesiosauria

- Sea monster

- Selma (lake monster)

- Stronsay Beast

- Wani (dragon)

- Zegrze Reservoir Monster

Footnotes

Notes

- ^ The date is inferred from the oldest written source reporting a monster near Loch Ness.[2]

References

- ^ Krystek, Lee. «The Surgeon’s Hoax». unmuseum.org. UNMuseum. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Life of St. Columba Archived 17 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine (chapter 28).

- ^ Mac Farlane, Malcolm (1912). Am Faclair Beag. 43 Murray Place, Stirling: Eneas MacKay, Bookseller. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Carroll, Robert Todd (2011) [2003], The Skeptic’s Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 200–201, ISBN 978-0-471-27242-7, archived from the original on 16 October 2021, retrieved 15 November 2020

- ^ R. Binns The Loch Ness Mystery Solved pp 19–27

- ^ Daily Mirror, 11 August 1933 «Loch Ness, which is becoming famous as the supposed abode of a dragon…»

- ^ a b The Oxford English Dictionary gives 9 June 1933 as the first usage of the exact phrase Loch Ness monster

- ^ Campbell, Elizabeth Montgomery & David Solomon, The Search for Morag (Tom Stacey 1972) ISBN 0-85468-093-4, page 28 gives an-t-Seileag, an-Niseag, a-Mhorag for the monsters of Lochs Shiel, Ness and Morag, adding that they are feminine diminutives

- ^ «Up Again». Edinburgh Scotsman. 14 May 1945. p. 1.

So «Nessie» is at her tricks again. After a long, she has by all accounts bobbed up in home waters…

- ^ J. A Carruth Loch Ness and its Monster, (1950) Abbey Press, Fort Augustus, cited by Tim Dinsdale (1961) Loch Ness Monster pp. 33–35

- ^ a b Adomnán, p. 176 (II:27).

- ^ a b Adomnán p. 330.

- ^ R. Binns The Loch Ness Mystery Solved, pp. 52–57

- ^ a b c d R. Binns The Loch Ness Mystery Solved pp. 11–12

- ^ Bro, Lisa; O’Leary-Davidson, Crystal; Gareis, Mary Ann (2018). Monsters of Film, Fiction and Fable, the Cultural Links Between the Human and Inhuman. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 377–399. ISBN 9781527510890.

- ^ a b Mackal, Roy. The Monsters of Loch Ness.

- ^ a b c d e The Mammoth Encyclopedia of the Unsolved

- ^ a b c Bignell, Paul (14 April 2013). «Monster mania on Nessie’s anniversary». The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Searle, Maddy (3 February 2017). «Adrian Shine on making sense of the Loch Ness monster legend». The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Gareth Williams (12 November 2015). A Monstrous Commotion: The Mysteries of Loch Ness. Orion Publishing Group. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-4091-5875-2. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Gould, Rupert T. (1934). The Loch Ness Monster and Others. London: Geoffrey Bles.

- ^ Delrio, Martin (2002). The Loch Ness Monster. Rosen Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 0-8239-3564-7.

- ^ Inverness Courier 2 May 1933 «Loch Ness has for generations been credited with being the home of a fearsome-looking monster»

- ^ Campbell, Steuart (14 April 2013). «Say goodbye to Loch Ness mystery». The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ «Report of strange spectacle on Loch Ness in 1933 leaves unanswered question — what was it?». The Inverness Courier. 11 September 2017. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020.

- ^ Hoare, Philip (2 May 2013). «Has the internet killed the Loch Ness monster?». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ a b c «Is this the Loch Ness Monster?». Inverness Courier. 4 August 1933.

- ^ a b T. Dinsdale (1961) Loch Ness Monster page 42.

- ^ a b «Are Hunters Closing in on the Loch Ness Monster?». The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ R. Mackal (1976) «The Monsters of Loch Ness» page 85.

- ^ Loxton, Daniel; Prothero, Donald. (2015). Abominable Science! Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids. Columbia University Press. pp. 142–144. ISBN 978-0-231-15321-8

- ^ Burton, Maurice. A Ring of bright water? New Scientist. 24 June 1982. p. 872

- ^ Campbell, Steuart. (1997). The Loch Ness Monster: The Evidence. Prometheus Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-1573921787

- ^ Tim Dinsdale Loch Ness Monster pp. 44–5

- ^ Burton, Maurice. A Fast Moving, Agile Beastie. New Scientist. 1 July 1982. p. 41.

- ^ Burton, Maurice. (1961). Loch Ness Monster: A Burst Bubble? The Illustrated London News. May, 27. p. 896

- ^ Naish, Darren. (2016). «Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths» Archived 5 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Arcturus.

- ^ R. P. Mackal (1976) The Monsters of Loch Ness page 208

- ^ a b c «The Loch Ness Monster and the Surgeon’s Photo». Museumofhoaxes.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ a b A Fresh Look at Nessie, New Scientist, v. 83, pp. 358–359

- ^ Book review of Nessie – The Surgeon’s Photograph – Exposed Archived 14 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Douglas Chapman.

- ^ David S. Martin & Alastair Boyd (1999) Nessie – the Surgeon’s Photograph Exposed (East Barnet: Martin and Boyd). ISBN 0-9535708-0-0

- ^ «Loch Ness Hoax Photo». The UnMuseum. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ «Nessie’s Secret Revealed». yowieocalypse.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Tony Harmsworth. «Loch Ness Monster Surface Photographs. Pictures of Nessie taken by Monster Hunters and Loch Ness Researchers». loch-ness.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ The Loch Ness Story, revised edition, Penguin Books, 1975, pp. 44–45

- ^ Ness Information Service Newsletter, 1991 issue

- ^ Burton, Maurice. (1961). The Elusive Monster: An Analysis of the Evidence From Loch Ness. Hart-Davis. pp. 83–84

- ^ Casciato, Paul (28 April 2010). «Loch Ness Monster is real, says policeman». reuters. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ «Police chief William Fraser demanded protection for Loch Ness Monster». Perth Now. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ «Searching for Nessie». Sansilke.freeserve.co.uk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ Binns, Ronald. (1983). The Loch Ness Mystery Solved. Prometheus Books. p. 102

- ^ Campbell, Steuart. (1991). The Loch Ness Monster: The Evidence. Aberdeen University Press. pp. 43–44.

- ^ «The MacNab Photograph» Archived 19 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Museum of Hoaxes.

- ^ «The Loch Ness Monster». YouTube. 19 January 2007. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ a b «Loch Ness movie film & Loch Ness video evidence». Loch-ness.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Legend of Nessie. «Analysis of the Tim Dinsdale film». Nessie.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ a b Discovery Communications, Loch Ness Discovered, 1993

- ^ Naish, Darren. «Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited». Scientific American. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ «Nessie sightings». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ a b «Tourist Says He’s Shot Video of Loch Ness Monster». Fox News. Associated Press. 1 June 2007. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ «Fabled monster caught on video». 1 June 2007. Archived from the original on 18 June 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ «stv News North Tonight – Loch Ness Monster sighting report and interview with Gordon Holmes – tx 28 May 2007». Scotlandontv.tv. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ Love, David (21 April 2012). «Does sonar image show the Loch Ness Monster?». Daily Record. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ McLaughlin, Erin (15 August 2012). «Scottish Sailor Claims To Have Best Picture Yet of Loch Ness Monster | ABC News Blogs – Yahoo!». Gma.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ McLaughlin, Erin, «Scottish Sailor Claims To Have Best Picture Yet Of Loch Ness Monster Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine», ABC News/Yahoo! News, 16 August 2012

- ^ a b Naish, Darren (10 July 2013). «Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited». Scientific American. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Watson, Roland (20 August 2012). «Follow up to the George Edwards Photo». Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Raynor, Dick. «An examination of the claims and pictures taken by George Edwards». Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Alistair, Munro. «Loch Ness Monster: George Edwards ‘faked’ photo». The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Gross, Jenny (5 October 2013). «Latest Loch Ness ‘Sighting’ Causes a Monstrous Fight». Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Jauregui, Andres (26 August 2013). «Loch Ness Monster Sighting? Photographer Claims ‘Black Object’ Glided Beneath Lake’s Surface». HuffPost. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ «Do new pictures from amateur photographer prove Loch Ness Monster exists?». Metro. 26 August 2013. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ a b Baillie, Claire (27 August 2013). «New photo of Loch Ness Monster sparks debate». The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ «Finally, is this proof the Loch Ness monster exists?». news.com.au. 28 August 2013. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Gander, Kashmira (19 April 2014). «Loch Ness Monster found on Apple Maps?». The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ McKenzie, Steven (21 November 2014). «Fallen branches ‘could explain Loch Ness Monster sightings’«. Archived from the original on 22 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ «Loch Ness Monster on Apple Maps? Why Satellite Images Fool Us». livescience. 22 April 2014. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ «81st Anniversary of the Loch Ness Monster’s most famous photograph». 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Kashmira Gander (21 April 2015). «Loch Ness Monster: Google Maps unveils Nessie Street View and homepage Doodle to mark 81st anniversary of iconic photograph». The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ «Loch Ness monster: iconic photograph commemorated in Google doodle». The Guardian. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Oliver Smith (21 April 2015). «Has Google found the Loch Ness Monster?». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ R. Binns (1983) The Loch Ness Mystery Solved ISBN 0-7291-0139-8, pages 36–39

- ^ The Times 5 October 1934, page 12 Loch Ness «Monster» Film

- ^ Henry H. Bauer, The Enigma of Loch Ness: Making Sense of a Mystery, page 163 (University of Illinois Press, 1986). ISBN 0-252-01284-4

- ^ Rick Emmer, Loch Ness Monster: Fact or Fiction?, page 35 (Infobase Publishing, 2010). ISBN 978-0-7910-9779-3

- ^

Spector, Leo (14 September 1967). «The Great Monster Hunt». Machine Design. Cleveland, Ohio: The Penton Publishing Co. - ^ <!-anonymous letter commenting on news: name and address supplied—> (1 June 1972). «Take a Lesson from Nessie». Daily Mirror. London.

- ^ Holiday, F. W. (1968). The Great Orm of Loch Ness: A Practical Inquiry into the Nature and Habits of Water-monsters. London: Faber & Faber. pp. 30–60, 98–117, 160–173. ISBN 0-571-08473-7.

- ^ Tim Dinsdale (1973) The Story of the Loch Ness Monster Target Books ISBN 0-426-11340-3

- ^ «1969 Annual Report: Loch Ness Investigation» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ «The Glasgow Herald — Google News Archive Search». news.google.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ New Scientist 40 (1968): 564–566; «Sonar Picks Up Stirrings in Loch Ness»

- ^ Roy Mackal (1976) The Monsters of Loch Ness page 307, see also appendix E

- ^ «Photographic image». Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Townend, Lorne (writer/director) (2001). Loch Ness Monster: Search for the Truth.

- ^ a b c Harmsworth, Tony. Loch Ness, Nessie & Me: Loch Ness Understood and Monster Explained.

- ^ Scott, Peter; Rines, Robert (1975). «Naming the Loch Ness monster». Nature. 258 (5535): 466. Bibcode:1975Natur.258..466S. doi:10.1038/258466a0.

- ^ Lawton, John H. (1996). «Nessiteras Rhombopteryx«. Oikos. 77 (3): 378–380. doi:10.2307/3545927. JSTOR 3545927.

- ^ a b Dinsdale, T. «Loch Ness Monster» (Routledge and Kegan paul 1976), p.171.

- ^ Fairbairn, Nicholas (18 December 1975). «Loch Ness monster». Letters to the Editor. The Times. No. 59,581. London. p. 13.

- ^ «Loch Ness Monster Shown a Hoax by Another Name». The New York Times. Vol. 125, no. 43,063. Reuters. 19 December 1975. p. 78.

- ^ a b c «Martin Klein Home» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ a b Dr. Robert H. Rines. Loch Ness Findings Archived 23 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Academy of Applied Science.

- ^ «Veteran Loch Ness Monster Hunter Gives Up – The Daily Record». Dailyrecord.co.uk. 13 February 2008. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ «Operation Deepscan». www.lochnessproject.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ «educational.rai.it (p. 17)» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ a b «What is the Loch Ness Monster?». Firstscience.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ Mysterious Creatures (1988) by the Editors of Time-Life Books, page 90

- ^ «BBC ‘proves’ Nessie does not exist». BBC News. 27 July 2003. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Gemmell, Neil; Rowley, Ellie (28 June 2018). «First phase of hunt for Loch Ness monster complete». University of Otago. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ «Loch Ness Monster may be a giant eel, say scientists». BBC News. 5 September 2019. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew (5 September 2019). «Loch Ness monster could be a giant eel, say scientists». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (2017). «Loch Ness Solved – Even More Fully!». Skeptical Inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. 41 (6): 59, 61.

- ^ R. P. Mackal (1976) The Monsters of Loch Ness page 216, see also chapter 9 and appendix G

- ^ Tim Dinsdale (1961) Loch Ness Monster page 229

- ^ «Varieties». Colonial Times. Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 10 June 1856. p. 3. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ «Loch Ness Monster may be a giant eel, say scientists». BBC News. BBC. 5 September 2019. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ «New DNA evidence may prove what the Loch Ness Monster really is». www.popsci.com. 6 September 2019. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ News, Tom Metcalfe-Live Science Contributor 2019-09-09T15:53:19Z Strange (9 September 2019). «Loch Ness Contains No ‘Monster’ DNA, Say Scientists». livescience.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Knowles. «The Loch Ness Monster is still a mystery». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019.

- ^ «National Geographic News». News.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ «‘River Monsters’ Finale: Hunt For Loch Ness Monster And Greenland Shark (Video)». The Huffington Post. 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ «Scientist wonders if Nessie-like monster in Alaska lake is a sleeper shark». Alaska Dispatch News. 3 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ «‘Alaska lake monster’ may be a sleeper shark, biologist says». Yahoo! News. 9 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ «Loch Ness Monster ‘Most Likely Large Catfish’«. Sky News. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ «Nessie hunter believes Loch Ness monster is ‘giant catfish’«. scotsman.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ «Loch Ness Monster is just a ‘giant catfish’ – says Nessie expert». International Business Times UK. 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ R. Binns (1983) The Loch Ness Mystery Solved plates 15(a)-(f)

- ^ R. Binns (1983) The Loch Ness Mystery Solved plates 16–18

- ^ Daily Mirror 17 August 1933 page 12

- ^ Burton, Maurice (1982). «The Loch Ness Saga». New Scientist. 06–24: 872.

- ^ Burton, Maurice (1982). «The Loch Ness Saga». New Scientist. 07–01: 41–42.

- ^ Burton, Maurice (1982). «The Loch Ness Saga». New Scientist. 07–08: 112–113.

- ^ «Movement of Water in Lakes: Long standing waves (Seiches)». Biology.qmul.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ Muir-Wood, Robert; Mignan, Arnaud (2009). «A Phenomenological Reconstruction of the Mw9 November 1st 1755 Earthquake Source». In Mendes-Victor, Luiz A.; Sousa Oliveira, Carlos; Azevedo, João; Ribeiro, António (eds.). The 1755 Lisbon Earthquake: Revisited. Springer. pp. 130, 138. ISBN 978-1-4020-8608-3.

- ^ Bressan, David (30 June 2013). «The Earth-shattering Loch Ness Monster that wasn’t». Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ W. H. Lehn (1979) Science vol 205. No. 4402 pages 183–185 «Atmospheric Refraction and Lake Monsters»

- ^ Lehn, W. H.; Schroeder, I. (1981). «The Norse merman as an optical phenomenon». Nature. 289 (5796): 362. Bibcode:1981Natur.289..362L. doi:10.1038/289362a0. S2CID 4280555.

- ^ «Seismotectonic Origins of the Monster of Loch Ness». Gsa.confex.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ Sjögren, Bengt (1980). Berömda vidunder (in Swedish). Settern. ISBN 91-7586-023-6.

- ^ Aberdeen Weekly Journal, Wednesday, 11 June 1879 «This kelpie had been in the habit of appearing as a beautiful black horse… No sooner had the weary unsuspecting victim seated himself in the saddle than away darted the horse with more than the speed of the hurricane and plunged into the deepest part of Loch Ness, and the rider was never seen again.»

- ^ Tim Dinsdale (1975) Project Water Horse. The true story of the monster quest at Loch Ness (Routledge & Kegan Paul) ISBN 0-7100-8030-1

- ^ Watson, Roland,The Water Horses of Loch Ness (2011) ISBN 1-4611-7819-3

- ^ «Invention of Loch Ness monster». The Irish Times. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Alt URL Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Birth of a legend: Famous Photo Falsified?». Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ «Loch Ness ‘Monster’ Is an April Fool’s Joke». The New York Times. 2 April 1972. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ a b «Loch Ness Monster Hoaxes». Museumofhoaxes.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ «Loch Ness monster: The Ultimate Experiment». Crawley-creatures.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ «Nessie swims in Loch for TV Show». BBC News. 16 August 2005. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ R. J. Binns (1983) The Loch Ness Mystery Solved, page 22

- ^ «Why the Loch Ness Monster is no plesiosaur». New Scientist. 2576: 17. 2006. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ «Legend of Nessie — Ultimate and Official Loch Ness Monster Site — About Loch Ness». www.nessie.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ Roy P. Mackal (1976) The Monsters of Loch Ness, page 138

- ^ The Times 9 December 1933, page 14

- ^ R. P. Mackal (1976) The Monsters of Loch Ness, pages 138–9, 211–213

- ^ Holiday, F.T. The Great Orm of Loch Ness (Faber and Faber 1968)

- ^ R. P. Mackal (1976) The Monsters of Loch Ness pages 141–142, chapter XIV

Bibliography

- Bauer, Henry H. The Enigma of Loch Ness: Making Sense of a Mystery, Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1986

- Binns, Ronald, The Loch Ness Mystery Solved, Great Britain, Open Books, 1983, ISBN 0-7291-0139-8 and Star Books, 1984, ISBN 0-352-31487-7

- Binns, Ronald, The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, London, Zoilus Press, 2017, ISBN 9781999735906

- Burton, Maurice, The Elusive Monster: An Analysis of the Evidence from Loch Ness, London, Rupert Hart-Davis, 1961

- Campbell, Steuart. The Loch Ness Monster – The Evidence, Buffalo, New York, Prometheus Books, 1985.

- Dinsdale, Tim, Loch Ness Monster, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1961, SBN 7100 1279 9

- Harrison, Paul The encyclopaedia of the Loch Ness Monster, London, Robert Hale, 1999

- Gould, R. T., The Loch Ness Monster and Others, London, Geoffrey Bles, 1934 and paperback, Lyle Stuart, 1976, ISBN 0-8065-0555-9

- Holiday, F. W., The Great Orm of Loch Ness, London, Faber & Faber, 1968, SBN 571 08473 7

- Perera, Victor, The Loch Ness Monster Watchers, Santa Barbara, Capra Press, 1974.

- Whyte, Constance, More Than a Legend: The Story of the Loch Ness Monster, London, Hamish Hamilton, 1957

Documentary

- Secrets of Loch Ness. Produced & Directed by Christopher Jeans (ITN/Channel 4/A&E Network, 1995).

External links

- Nova Documentary On Nessie

- Smithsonian Institution

- Darnton, John (20 March 1994). «Loch Ness: Fiction Is Stranger Than Truth». The New York Times. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

|

The «surgeon’s photograph» of 1934, now known to have been a hoax[1] |

|

| Sub grouping | Lake monster |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | Nessie, Niseag |

| Country | Scotland |

| Region | Loch Ness, Scottish Highlands |

The Loch Ness Monster (Scottish Gaelic: Uilebheist Loch Nis[3]), affectionately known as Nessie, is a creature in Scottish folklore that is said to inhabit Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands. It is often described as large, long-necked, and with one or more humps protruding from the water. Popular interest and belief in the creature has varied since it was brought to worldwide attention in 1933. Evidence of its existence is anecdotal, with a number of disputed photographs and sonar readings.

The scientific community explains alleged sightings of the Loch Ness Monster as hoaxes, wishful thinking, and the misidentification of mundane objects.[4] The pseudoscience and subculture of cryptozoology has placed particular emphasis on the creature.

Origin of the name

In August 1933, the Courier published the account of George Spicer’s alleged sighting. Public interest skyrocketed, with countless letters being sent in detailing different sightings[5] describing a «monster fish,» «sea serpent,» or «dragon,»[6] with the final name ultimately settling on «Loch Ness monster.»[7] Since the 1940s, the creature has been affectionately called Nessie (Scottish Gaelic: Niseag).[8][9]

Sightings

Saint Columba (565)

The earliest report of a monster in the vicinity of Loch Ness appears in the Life of St. Columba by Adomnán, written in the sixth century AD.[10] According to Adomnán, writing about a century after the events described, Irish monk Saint Columba was staying in the land of the Picts with his companions when he encountered local residents burying a man by the River Ness. They explained that the man was swimming in the river when he was attacked by a «water beast» that mauled him and dragged him underwater despite their attempts to rescue him by boat. Columba sent a follower, Luigne moccu Min, to swim across the river. The beast approached him, but Columba made the sign of the cross and said: «Go no further. Do not touch the man. Go back at once.»[11] The creature stopped as if it had been «pulled back with ropes» and fled, and Columba’s men and the Picts gave thanks for what they perceived as a miracle.[11]

Believers in the monster point to this story, set in the River Ness rather than the loch itself, as evidence for the creature’s existence as early as the sixth century.[12] Skeptics question the narrative’s reliability, noting that water-beast stories were extremely common in medieval hagiographies, and Adomnán’s tale probably recycles a common motif attached to a local landmark.[13] According to skeptics, Adomnán’s story may be independent of the modern Loch Ness Monster legend and became attached to it by believers seeking to bolster their claims.[12] Ronald Binns considers that this is the most serious of various alleged early sightings of the monster, but all other claimed sightings before 1933 are dubious and do not prove a monster tradition before that date.[14] Christopher Cairney uses a specific historical and cultural analysis of Adomnán to separate Adomnán’s story about St. Columba from the modern myth of the Loch Ness Monster, but finds an earlier and culturally significant use of Celtic «water beast» folklore along the way. In doing so he also discredits any strong connection between kelpies or water-horses and the modern «media-augmented» creation of the Loch Ness Monster. He also concludes that the story of Saint Columba may have been impacted by earlier Irish myths about the Caoránach and an Oilliphéist.[15]

D. Mackenzie (1871 or 1872)

In October 1871 (or 1872), D. Mackenzie of Balnain reportedly saw an object resembling a log or an upturned boat «wriggling and churning up the water,» moving slowly at first before disappearing at a faster speed.[16][17] The account was not published until 1934, when Mackenzie sent his story in a letter to Rupert Gould shortly after popular interest in the monster increased.[18][17][19][20]

Alexander Macdonald (1888)

In 1888, mason Alexander Macdonald of Abriachan[21] sighted «a large stubby-legged animal» surfacing from the loch and propelling itself within fifty yards of the shore where Macdonald stood.[22] Macdonald reported his sighting to Loch Ness water bailiff Alex Campbell, and described the creature as looking like a salamander.[21]

Aldie Mackay (1933)

The best-known article that first attracted a great deal of attention about a creature was published on 2 May 1933 in The Inverness Courier, about a large «beast» or «whale-like fish». The article by Alex Campbell, water bailiff for Loch Ness and a part-time journalist,[citation needed] discussed a sighting by Aldie Mackay of an enormous creature with the body of a whale rolling in the water in the loch while she and her husband John were driving on the A82 on 15 April 1933. The word «monster» was reportedly applied for the first time in Campbell’s article, although some reports claim that it was coined by editor Evan Barron.[14][23][24]

The Courier in 2017 published excerpts from the Campbell article, which had been titled «Strange Spectacle in Loch Ness».[25]

«The creature disported itself, rolling and plunging for fully a minute, its body resembling that of a whale, and the water cascading and churning like a simmering cauldron. Soon, however, it disappeared in a boiling mass of foam. Both onlookers confessed that there was something uncanny about the whole thing, for they realised that here was no ordinary denizen of the depths, because, apart from its enormous size, the beast, in taking the final plunge, sent out waves that were big enough to have been caused by a passing steamer.»

According to a 2013 article,[18] Mackay said that she had yelled, «Stop! The Beast!» when viewing the spectacle. In the late 1980s, a naturalist interviewed Aldie Mackay and she admitted to knowing that there had been an oral tradition of a «beast» in the loch well before her claimed sighting.[18] Alex Campbell’s 1933 article also stated that «Loch Ness has for generations been credited with being the home of a fearsome-looking monster».[26]

George Spicer (1933)

Modern interest in the monster was sparked by a sighting on 22 July 1933, when George Spicer and his wife saw «a most extraordinary form of animal» cross the road in front of their car.[27] They described the creature as having a large body (about 4 feet (1.2 m) high and 25 feet (8 m) long) and a long, wavy, narrow neck, slightly thicker than an elephant’s trunk and as long as the 10–12-foot (3–4 m) width of the road. They saw no limbs.[28] It lurched across the road toward the loch 20 yards (20 m) away, leaving a trail of broken undergrowth in its wake.[28] Spicer described it as «the nearest approach to a dragon or pre-historic animal that I have ever seen in my life,»[27] and as having «a long neck, which moved up and down in the manner of a scenic railway.»[29] It had «an animal» in its mouth[27] and had a body that «was fairly big, with a high back, but if there were any feet they must have been of the web kind, and as for a tail I cannot say, as it moved so rapidly, and when we got to the spot it had probably disappeared into the loch.»[29]

On 4 August 1933 the Courier published a report of Spicer’s sighting. This sighting triggered a massive amount of public interest and an uptick in alleged sightings, leading to the solidification of the actual name «Loch Ness Monster.»[7]

It has been claimed that sightings of the monster increased after a road was built along the loch in early 1933, bringing workers and tourists to the formerly isolated area.[30] However, Binns has described this as «the myth of the lonely loch», as it was far from isolated before then, due to the construction of the Caledonian Canal. In the 1930s, the existing road by the side of the loch was given a serious upgrade.[14]

Hugh Gray (1933)

Hugh Gray’s photograph taken near Foyers on 12 November 1933 was the first photograph alleged to depict the monster. It was slightly blurred, and it has been noted that if one looks closely the head of a dog can be seen. Gray had taken his Labrador for a walk that day and it is suspected that the photograph depicts his dog fetching a stick from the loch.[31] Others have suggested that the photograph depicts an otter or a swan. The original negative was lost. However, in 1963, Maurice Burton came into «possession of two lantern slides, contact positives from th[e] original negative» and when projected onto a screen they revealed an «otter rolling at the surface in characteristic fashion.»[32]

Arthur Grant (1934)

Sketch of the Arthur Grant sighting.

On 5 January 1934 a motorcyclist, Arthur Grant, claimed to have nearly hit the creature while approaching Abriachan (near the north-eastern end of the loch) at about 1 a.m. on a moonlit night.[33] According to Grant, it had a small head attached to a long neck; the creature saw him, and crossed the road back to the loch. Grant, a veterinary student, described it as a cross between a seal and a plesiosaur. He said he dismounted and followed it to the loch, but saw only ripples.[21][34]

Grant produced a sketch of the creature that was examined by zoologist Maurice Burton, who stated it was consistent with the appearance and behavior of an otter.[35] Regarding the long size of the creature reported by Grant; it has been suggested that this was a faulty observation due to the poor light conditions.[36] Paleontologist Darren Naish has suggested that Grant may have seen either an otter or a seal and exaggerated his sighting over time.[37]

«Surgeon’s photograph» (1934)

The «surgeon’s photograph» is reportedly the first photo of the creature’s head and neck.[38] Supposedly taken by Robert Kenneth Wilson, a London gynaecologist, it was published in the Daily Mail on 21 April 1934. Wilson’s refusal to have his name associated with it led to it being known as the «surgeon’s photograph».[39] According to Wilson, he was looking at the loch when he saw the monster, grabbed his camera and snapped four photos. Only two exposures came out clearly; the first reportedly shows a small head and back, and the second shows a similar head in a diving position. The first photo became well known, and the second attracted little publicity because of its blurriness.