This article is about the American boxer and media personality. For other people named Mike Tyson, see Mike Tyson (disambiguation).

Michael Gerard Tyson (born June 30, 1966) is an American former professional boxer who competed from 1985 to 2005. Nicknamed «Iron Mike«[4] and «Kid Dynamite» in his early career, and later known as «The Baddest Man on the Planet«,[5] Tyson is considered to be one of the greatest heavyweight boxers of all time.[6] He reigned as the undisputed world heavyweight champion from 1987 to 1990. Tyson won his first 19 professional fights by knockout, 12 of them in the first round. Claiming his first belt at 20 years, four months, and 22 days old, Tyson holds the record as the youngest boxer ever to win a heavyweight title.[7] He was the first heavyweight boxer to simultaneously hold the WBA, WBC and IBF titles, as well as the only heavyweight to unify them in succession. The following year, Tyson became the lineal champion when he knocked out Michael Spinks in 91 seconds of the first round.[8] In 1990, Tyson was knocked out by underdog Buster Douglas[9] in one of the biggest upsets in history.

|

Mike Tyson |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

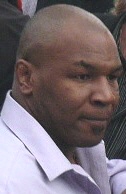

Tyson in 2019 |

|||||||||||||

| Born |

Michael Gerard Tyson June 30, 1966 (age 56) Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

||||||||||||

| Spouses |

|

||||||||||||

| Children | 7[a] | ||||||||||||

| Boxing career | |||||||||||||

| Statistics | |||||||||||||

| Nickname(s) |

|

||||||||||||

| Weight(s) | Heavyweight | ||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 10 in (178 cm)[1][2] | ||||||||||||

| Reach | 71 in (180 cm)[3] | ||||||||||||

| Stance | Orthodox | ||||||||||||

| Boxing record | |||||||||||||

| Total fights | 58 | ||||||||||||

| Wins | 50 | ||||||||||||

| Wins by KO | 44 | ||||||||||||

| Losses | 6 | ||||||||||||

| No contests | 2 | ||||||||||||

|

Medal record

|

|||||||||||||

| Website | miketyson.com |

In 1992, Tyson was convicted of rape and sentenced to six years in prison, although he was released on parole after three years.[10][11][12] After his release in 1995, he engaged in a series of comeback fights, regaining the WBA and WBC titles in 1996 to join Floyd Patterson, Muhammad Ali, Tim Witherspoon, Evander Holyfield and George Foreman as the only men in boxing history to have regained a heavyweight championship after losing it. After being stripped of the WBC title in the same year, Tyson lost the WBA title to Evander Holyfield by an eleventh round stoppage. Their 1997 rematch ended when Tyson was disqualified for biting Holyfield’s ears, one bite notoriously being strong enough to remove a portion of his right ear. In 2002, Tyson fought for the world heavyweight title, losing by knockout to Lennox Lewis.

Tyson was known for his ferocious and intimidating boxing style as well as his controversial behavior inside and outside the ring. With a knockout-to-win percentage of 88%,[13] he was ranked 16th on The Ring magazine’s list of 100 greatest punchers of all time,[14] and first on ESPN’s list of «The Hardest Hitters in Heavyweight History».[15] Sky Sports described him as «perhaps the most ferocious fighter to step into a professional ring».[16] He has been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the World Boxing Hall of Fame.

Early life

Michael Gerard Tyson was born into a Catholic family in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, New York City on June 30, 1966.[17][18] He has an older brother named Rodney (born c. 1961)[19] and an older sister named Denise, who died of a heart attack at age 24 in February 1990.[20] Tyson’s mother, born in Charlottesville, Virginia[21] was described as a promiscuous woman who might have been a prostitute.[22] Tyson’s biological father is listed as «Purcell Tyson», a «humble cab driver» (who was from Jamaica) on his birth certificate[23][24] but the man Tyson had known as his father was a pimp named Jimmy Kirkpatrick. Kirkpatrick was from Grier Town, North Carolina (a predominantly black neighborhood that was annexed by the city of Charlotte),[25] where he was one of the neighborhood’s top baseball players. Kirkpatrick married and had a son, Tyson’s half-brother Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick, who would help to integrate Charlotte high school football in 1965. In 1959, Jimmy Kirkpatrick left his family and moved to Brooklyn, where he met Tyson’s mother, Lorna Mae (Smith) Tyson. Kirkpatrick frequented pool halls, gambled and hung out on the streets. «My father was just a regular street guy caught up in the street world,» Tyson said. Kirkpatrick abandoned the Tyson family around the time Mike was born, leaving Tyson’s mother to care for the children on her own.[26] Kirkpatrick died in 1992.[27]

The family lived in Bedford-Stuyvesant until their financial burdens necessitated a move to Brownsville when Tyson was 10 years old.[28] Tyson’s mother died six years later, leaving 16-year-old Tyson in the care of boxing manager and trainer Cus D’Amato, who would become his legal guardian. Tyson later said, «I never saw my mother happy with me and proud of me for doing something: she only knew me as being a wild kid running the streets, coming home with new clothes that she knew I didn’t pay for. I never got a chance to talk to her or know about her. Professionally, it has no effect, but it’s crushing emotionally and personally.»[29]

Throughout his childhood, Tyson lived in and around neighborhoods with a high rate of crime. According to an interview in Details, his first fight was with a bigger youth who had pulled the head off one of Tyson’s pigeons.[30] Tyson was repeatedly caught committing petty crimes and fighting those who ridiculed his high-pitched voice and lisp. By the age of 13, he had been arrested 38 times.[31] He ended up at the Tryon School for Boys in Johnstown, New York. Tyson’s emerging boxing ability was discovered there by Bobby Stewart, a juvenile detention center counselor and former boxer. Stewart considered Tyson to be an outstanding fighter and trained him for a few months before introducing him to Cus D’Amato.[26] Tyson dropped out of high school as a junior.[32] He would be awarded an honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters from Central State University in 1989.[33] Kevin Rooney also trained Tyson, and he was occasionally assisted by Teddy Atlas, although Atlas was dismissed by D’Amato when Tyson was 15. Rooney eventually took over all training duties for the young fighter.[34]

Amateur career

As an amateur, Tyson won gold medals at the 1981 and 1982 Junior Olympic Games, defeating Joe Cortez in 1981 and beating Kelton Brown in 1982. Brown’s corner threw in the towel in the first round. In 1984 Tyson won the gold medal at the Nation Golden Gloves held in New York, beating Jonathan Littles.[35] He fought Henry Tillman twice as an amateur, losing both bouts by decision. Tillman went on to win heavyweight gold at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.[36]

Professional career

Rise to stardom

Tyson made his professional debut as an 18-year-old on March 6, 1985, in Albany, New York. He defeated Hector Mercedes via first-round TKO.[26] He had 15 bouts in his first year as a professional. Fighting frequently, Tyson won 26 of his first 28 fights by KO or TKO; 16 of those came in the first round.[37] The quality of his opponents gradually increased to journeyman fighters and borderline contenders,[37] like James Tillis, David Jaco, Jesse Ferguson, Mitch Green, and Marvis Frazier. His win streak attracted media attention and Tyson was billed as the next great heavyweight champion. D’Amato died in November 1985, relatively early into Tyson’s professional career, and some speculate that his death was the catalyst to many of the troubles Tyson was to experience as his life and career progressed.[38]

Tyson’s first nationally televised bout took place on February 16, 1986, at Houston Field House in Troy, New York, against journeyman heavyweight Jesse Ferguson, and was carried by ABC Sports. Tyson knocked down Ferguson with an uppercut in the fifth round that broke Ferguson’s nose.[39] During the sixth round, Ferguson began to hold and clinch Tyson in an apparent attempt to avoid further punishment. After admonishing Ferguson several times to obey his commands to box, the referee finally stopped the fight near the middle of the sixth round. The fight was initially ruled a win for Tyson by disqualification (DQ) of his opponent. The ruling was «adjusted» to a win by technical knockout (TKO) after Tyson’s corner protested that a DQ win would end Tyson’s string of knockout victories, and that a knockout would have been the inevitable result.

In July, after recording six more knockout victories, Tyson fought former world title challenger Marvis Frazier in Glens Falls, New York, on another ABC Sports broadcast. Tyson won easily, charging at Frazier at the opening bell and hitting him with an uppercut that knocked Frazier unconscious thirty seconds into the fight.

On November 22, 1986, Tyson was given his first title fight against Trevor Berbick for the World Boxing Council (WBC) heavyweight championship. Tyson won the title by TKO in the second round, and at the age of 20 years and 4 months became the youngest heavyweight champion in history.[40] He added the WBA and IBF titles after defeating James Smith and Tony Tucker in 1987. Tyson’s dominant performance brought many accolades. Donald Saunders wrote: «The noble and manly art of boxing can at least cease worrying about its immediate future, now [that] it has discovered a heavyweight champion fit to stand alongside Dempsey, Tunney, Louis, Marciano, and Ali.»[41]

Tyson intimidated fighters with his strength, combined with outstanding hand speed, accuracy, coordination and timing.[42] Tyson also possessed notable defensive abilities, holding his hands high in the peek-a-boo style taught by his mentor Cus D’Amato[43][44] to slip under and weave around his opponent’s punches while timing his own.[44] Tyson’s explosive punching technique was due in large part to crouching immediately prior to throwing a hook or an uppercut: this allowed the ‘spring’ of his legs to add power to the punch.[45] Among his signature moves was a right hook to his opponent’s body followed by a right uppercut to his opponent’s chin. Lorenzo Boyd, Jesse Ferguson and José Ribalta were each knocked down by this combination.[citation needed]

Undisputed champion

Expectations for Tyson were extremely high, and he was the favorite to win the heavyweight unification series, a tournament designed to establish an undisputed heavyweight champion. Tyson defended his title against James Smith on March 7, 1987, in Las Vegas, Nevada. He won by unanimous decision and added Smith’s World Boxing Association (WBA) title to his existing belt.[46] «Tyson-mania» in the media was becoming rampant.[47] He beat Pinklon Thomas in May by TKO in the sixth round.[48] On August 1 he took the International Boxing Federation (IBF) title from Tony Tucker in a twelve-round unanimous decision 119–111, 118–113, and 116–112.[49] He became the first heavyweight to own all three major belts – WBA, WBC, and IBF – at the same time. Another fight, in October of that year, ended with a victory for Tyson over 1984 Olympic super heavyweight gold medalist Tyrell Biggs by TKO in the seventh round.[50]

During this time, Tyson came to the attention of gaming company Nintendo. After witnessing one of Tyson’s fights, Nintendo of America president Minoru Arakawa was impressed by the fighter’s «power and skill», prompting him to suggest Tyson be included in the upcoming Nintendo Entertainment System port of the Punch Out!! arcade game. In 1987, Nintendo released Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!!, which was well received and sold more than a million copies.[51]

Tyson had three fights in 1988. He faced Larry Holmes on January 22, 1988, and defeated the legendary former champion by KO in the fourth round.[52] This knockout loss was the only loss Holmes had in 75 professional bouts. In March, Tyson then fought contender Tony Tubbs in Tokyo, Japan, fitting in an easy second-round TKO victory amid promotional and marketing work.[53]

On June 27, 1988, Tyson faced Michael Spinks. Spinks, who had taken the heavyweight championship from Larry Holmes via fifteen-round decision in 1985, had not lost his title in the ring but was not recognized as champion by the major boxing organizations. Holmes had previously given up all but the IBF title, and that was eventually stripped from Spinks after he elected to fight Gerry Cooney (winning by TKO in the fifth round) rather than IBF Number 1 Contender Tony Tucker, as the Cooney fight provided him a larger purse. However, Spinks did become the lineal champion by beating Holmes and many (including Ring magazine) considered him to have a legitimate claim to being the true heavyweight champion.[54] The bout was, at the time, the richest fight in history and expectations were very high. Boxing pundits were predicting a titanic battle of styles, with Tyson’s aggressive infighting conflicting with Spinks’s skillful out-boxing and footwork. The fight ended after 91 seconds when Tyson knocked Spinks out in the first round; many consider this to be the pinnacle of Tyson’s fame and boxing ability.[55][56]

Controversy and upset

During this period, Tyson’s problems outside the ring were also beginning to emerge. His marriage to Robin Givens was heading for divorce,[57] and his future contract was being fought over by Don King and Bill Cayton.[58] In late 1988, Tyson parted with manager Bill Cayton and fired longtime trainer Kevin Rooney, the man many credit for honing Tyson’s craft after the death of D’Amato.[44] Following Rooney’s departure, critics alleged that Tyson began to show less head movement and combination punching.[59][60] In 1989, Tyson had only two fights amid personal turmoil. He faced the British boxer Frank Bruno in February. Bruno managed to stun Tyson at the end of the first round,[61] although Tyson went on to knock Bruno out in the fifth round. Tyson then knocked out Carl «The Truth» Williams in the first round in July.[62]

By 1990, Tyson seemed to have lost direction, and his personal life was in disarray amidst reports of less vigorous training prior to the Buster Douglas match.[63] In a fight on February 11, 1990, he lost the undisputed championship to Douglas in Tokyo.[64] Tyson was a huge betting favorite; indeed, the Mirage, the only casino to put out odds for the fight, made Tyson a 42/1 favorite. Tyson failed to find a way past Douglas’s quick jab that had a 12-inch (30 cm) reach advantage over his own.[65] Tyson did catch Douglas with an uppercut in the eighth round and knocked him to the floor, but Douglas recovered sufficiently to hand Tyson a heavy beating in the subsequent two rounds. After the fight, the Tyson camp would complain that the count was slow and that Douglas had taken longer than ten seconds to get back on his feet.[66] Just 35 seconds into the tenth round, Douglas unleashed a brutal uppercut, followed by a four-punch combination of hooks that knocked Tyson down for the first time in his career. He was counted out by referee Octavio Meyran.[64]

The knockout victory by Douglas over Tyson, the previously undefeated «baddest man on the planet» and arguably the most feared boxer in professional boxing at that time, has been described as one of the most shocking upsets in modern sports history.[67][68]

After Douglas

Despite the shocking loss, Tyson has said that losing to Douglas was the greatest moment of his career: «I needed that fight to make me a better person and fighter. I have a broader perspective of myself and boxing.»[69]

After the loss, Tyson recovered with first-round knockouts of Henry Tillman[70] and Alex Stewart[71] in his next two fights. Tyson’s victory over Tillman, the 1984 Olympic heavyweight gold medalist, enabled Tyson to avenge his amateur losses at Tillman’s hands. These bouts set up an elimination match for another shot at the undisputed world heavyweight championship, which Evander Holyfield had taken from Douglas in his first defense of the title.[72]

Tyson, who was the number one contender, faced number two contender Donovan «Razor» Ruddock on March 18, 1991, in Las Vegas. Ruddock was seen as the most dangerous heavyweight around and was thought of as one of the hardest punching heavyweights. Tyson and Ruddock went back and forth for most of the fight, until referee Richard Steele controversially stopped the fight during the seventh round in favor of Tyson. This decision infuriated the fans in attendance, sparking a post-fight melee in the audience. The referee had to be escorted from the ring.[73]

Tyson and Ruddock met again on June 28 that year, with Tyson knocking down Ruddock twice and winning a twelve-round unanimous decision 113–109, 114–108, and 114–108.[74] A fight between Tyson and Holyfield for the undisputed championship was scheduled for November 8, 1991, at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, but Tyson pulled out after sustaining a rib cartilage injury during training.[75]

Rape trial and prison

Tyson was arrested in July 1991 for the rape of 18-year-old Desiree Washington, in an Indianapolis hotel room. Tyson’s rape trial at the Marion County superior court lasted from January 26 to February 10, 1992.[76]

Partial corroboration of Washington’s story came via testimony from Tyson’s chauffeur who confirmed Desiree Washington’s state of shock after the incident. Further testimony came from the emergency room physician who examined Washington more than 24 hours after the incident and confirmed that Washington’s physical condition was consistent with rape.[77]

Under lead defense lawyer Vincent J. Fuller’s direct examination, Tyson claimed that everything had taken place with Washington’s full consent and he claimed not to have forced himself upon her. When he was cross-examined by lead prosecutor Gregory Garrison, Tyson denied claims that he had misled Washington and insisted that she wanted to have sex with him.[78] Tyson was convicted on the rape charge on February 10, 1992, after the jury deliberated for nearly 10 hours.[79]

Alan Dershowitz, acting as Tyson’s counsel, filed an appeal urging error of law in the Court’s exclusion of evidence of the victim’s past sexual conduct (known as the Rape Shield Law), the exclusion of three potential defense witnesses, and the lack of a jury instruction on honest and reasonable mistake of fact.[80] The Indiana Court of Appeals ruled against Tyson in a 2–1 vote.[80] The Indiana Supreme Court let the lower court opinion stand due to a 2–2 split in its review. The tie vote was due to the fact that the Chief Justice of the Indiana Supreme Court recused himself from the case. The Chief Justice later revealed he did so because of a heated argument between his wife and Dershowitz at a Yale Law School reunion concerning the case.[81] On March 26, 1992, Tyson was sentenced to six years in prison along with four years of probation.[82] He was assigned to the Indiana Youth Center (now the Plainfield Correctional Facility) in April 1992,[83] and he was released in March 1995 after serving less than three years of the sentence.[84]

It has been widely reported that while in prison, Tyson converted to Islam and adopted the Muslim name Malik Abdul Aziz;[85] some sources report it as Malik Shabazz.[86] However, Tyson has stated that he converted to Islam before entering prison, but made no efforts to correct the misinformation in the media.[87] Tyson never changed his given name to an Islamic one, despite the rumors.[88] Due to his conviction, Tyson is required to register as a Tier II sex offender under federal law.[89][90][91]

Comeback

After being paroled from prison, Tyson easily won his comeback bouts against Peter McNeeley and Buster Mathis Jr. Tyson’s first comeback fight grossed more than US$96 million worldwide, including a United States record $63 million for PPV television. The viewing of the fight was purchased by 1.52 million homes, setting both PPV viewership and revenue records.[92] The 89-second fight elicited criticism that Tyson’s management lined up «tomato cans» to ensure easy victories for his return.[93] TV Guide included the Tyson–McNeeley fight in their list of the 50 Greatest TV Sports Moments of All Time in 1998.[94]

Tyson regained one belt by easily winning the WBC title against Frank Bruno in March 1996. It was the second fight between the two, and Tyson knocked out Bruno in the third round.[95] In 1996, Lennox Lewis turned down a $13.5 million guarantee to fight Tyson. This would’ve been Lewis’s highest fight purse to date. Lewis then accepted $4 million from Don King to step aside and allow Tyson to fight Bruce Seldon for an expected $30 million instead with the intention that if Tyson defeated Seldon, he would fight Lewis next.[96] Tyson added the WBA belt by defeating champion Seldon in the first round in September that year. Seldon was severely criticized and mocked in the popular press for seemingly collapsing to innocuous punches from Tyson.[97]

Tyson–Holyfield fights

Tyson vs. Holyfield

Tyson attempted to defend the WBA title against Evander Holyfield, who was in the fourth fight of his own comeback. Holyfield had retired in 1994 following the loss of his championship to Michael Moorer. It was said that Don King and others saw former champion Holyfield, who was 34 at the time of the fight and a huge underdog, as a washed-up fighter.[98]

On November 9, 1996, in Las Vegas, Nevada, Tyson faced Holyfield in a title bout dubbed «Finally». In a surprising turn of events, Holyfield, who was given virtually no chance to win by numerous commentators,[99] defeated Tyson by TKO when referee Mitch Halpern stopped the bout in round eleven.[100] Holyfield became the second boxer to win a heavyweight championship belt three times. Holyfield’s victory was marred by allegations from Tyson’s camp of Holyfield’s frequent headbutts[101] during the bout. Although the headbutts were ruled accidental by the referee,[101] they would become a point of contention in the subsequent rematch.[102]

Tyson vs. Holyfield II and aftermath

Tyson and Holyfield fought again on June 28, 1997. Originally, Halpern was supposed to be the referee, but after Tyson’s camp protested, Halpern stepped aside in favor of Mills Lane.[103] The highly anticipated rematch was dubbed The Sound and the Fury, and it was held at the Las Vegas MGM Grand Garden Arena, site of the first bout. It was a lucrative event, drawing even more attention than the first bout and grossing $100 million. Tyson received $30 million and Holyfield $35 million, the highest paid professional boxing purses until 2007.[104][105] The fight was purchased by 1.99 million households, setting a pay-per-view buy rate record that stood until May 5, 2007, being surpassed by Oscar De La Hoya vs. Floyd Mayweather Jr.[105][106]

Soon to become one of the most controversial events in modern sports,[107] the fight was stopped at the end of the third round, with Tyson disqualified[108] for biting Holyfield on both ears. The first time Tyson bit him, the match was temporarily stopped. Referee Mills Lane deducted two points from Tyson and the fight resumed. However, after the match resumed, Tyson bit him again, resulting in his disqualification, and Holyfield won the match. The first bite was severe enough to remove a piece of Holyfield’s right ear, which was found on the ring floor after the fight.[109] Tyson later stated that his actions were retaliation for Holyfield repeatedly headbutting him without penalty.[102] In the confusion that followed the ending of the bout and announcement of the decision, a near riot occurred in the arena and several people were injured.[110] Tyson Holyfield II was the first heavyweight title fight in over 50 years to end in a disqualification.[111]

As a subsequent fallout from the incident, US$3 million was immediately withheld from Tyson’s $30-million purse by the Nevada state boxing commission (the most it could legally hold back at the time).[112] Two days after the fight, Tyson issued a statement,[113] apologizing to Holyfield for his actions and asked not to be banned for life over the incident.[114] Tyson was roundly condemned in the news media but was not without defenders. Novelist and commentator Katherine Dunn wrote a column that criticized Holyfield’s sportsmanship in the controversial bout and charged the news media with being biased against Tyson.[115]

On July 9, 1997, Tyson’s boxing license was rescinded by the Nevada State Athletic Commission in a unanimous voice vote; he was also fined US$3 million and ordered to pay the legal costs of the hearing.[116] As most state athletic commissions honor sanctions imposed by other states, this effectively made Tyson unable to box in the United States. The revocation was not permanent, as the commission voted 4–1 to restore Tyson’s boxing license on October 18, 1998.[117]

During his time away from boxing in 1998, Tyson made a guest appearance at WrestleMania XIV as an enforcer for the main event match between Shawn Michaels and Steve Austin. During this time, Tyson was also an unofficial member of Michaels’s stable, D-Generation X. Tyson was paid $3 million for being guest enforcer of the match at WrestleMania XIV.[118]

1999–2005

«I’m the best ever. I’m the most brutal and vicious, the most ruthless champion there has ever been. There’s no one can stop me. Lennox is a conqueror? No! I’m Alexander! He’s no Alexander! I’m the best ever. There’s never been anyone as ruthless. I’m Sonny Liston. I’m Jack Dempsey. There’s no one like me. I’m from their cloth. There is no one who can match me. My style is impetuous, my defense is impregnable, and I’m just ferocious. I want your heart! I want to eat his children! Praise be to Allah!»

—Tyson’s post-fight interview after knocking out Lou Savarese 38 seconds into the bout in June 2000.[119]

In January 1999, Tyson returned to the ring for a match against the South African Francois Botha. This match also ended in controversy. While Botha initially controlled the fight, Tyson allegedly attempted to break Botha’s arms during a tie-up and both boxers were cautioned by the referee in the ill-tempered bout. Botha was ahead on points on all scorecards and was confident enough to mock Tyson as the fight continued. Nonetheless, Tyson landed a straight right hand in the fifth round that knocked out Botha.[120] Critics noticed Tyson stopped using the bob and weave defense altogether following this return.[121] Promoting the fight on Secaucus, New Jersey television station WWOR-TV, Tyson launched into an expletive-laden tirade that forced sports anchor Russ Salzberg to cut the interview short.[122]

Legal problems arose with Tyson once again. On February 5, 1999, Tyson was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment, fined $5,000, and ordered to serve two years probation along with undergoing 200 hours of community service for assaulting two motorists after a traffic accident on August 31, 1998.[123] He served nine months of that sentence. After his release, he fought Orlin Norris on October 23, 1999. Tyson knocked down Norris with a left hook thrown after the bell sounded to end the first round. Norris injured his knee when he went down and said that he was unable to continue. Consequently, the bout was ruled a no contest.[124]

In 2000, Tyson had three fights. The first match in January was staged at the MEN Arena in Manchester, England against Julius Francis. Following controversy as to whether Tyson was allowed into the country, he took four minutes to knock out Francis, ending the bout in the second round.[125] He also fought Lou Savarese in June 2000 in Glasgow, winning in the first round; the fight lasted only 38 seconds. Tyson continued punching after the referee had stopped the fight, knocking the referee to the floor as he tried to separate the boxers.[126] In October, Tyson fought the similarly controversial Andrew Golota,[127] winning in round three after Gołota was unable to continue due to a broken cheekbone, concussion, and neck injury.[128] The result was later changed to no contest after Tyson refused to take a pre-fight drug test and then tested positive for marijuana in a post-fight urine test.[129] Tyson fought only once in 2001, beating Brian Nielsen in Copenhagen by TKO in the seventh round.[130]

Lewis vs. Tyson

Tyson once again had the opportunity to fight for a heavyweight championship in 2002. Lennox Lewis held the WBC, IBF, IBO and Lineal titles at the time. As promising fighters, Tyson and Lewis had sparred at a training camp in a meeting arranged by Cus D’Amato in 1984.[131] Tyson sought to fight Lewis in Nevada for a more lucrative box-office venue, but the Nevada Boxing Commission refused him a license to box as he was facing possible sexual assault charges at the time.[132]

Two years prior to the bout, Tyson had made several inflammatory remarks to Lewis in an interview following the Savarese fight. The remarks included the statement «I want your heart, I want to eat your children.»[133] On January 22, 2002, the two boxers and their entourages were involved in a brawl at a New York press conference to publicize the planned event.[134] A few weeks later, the Nevada State Athletic Commission refused to grant Tyson a license for the fight, and the promoters had to make alternative arrangements. After multiple states balked at granting Tyson a license, the fight eventually occurred on June 8 at the Pyramid Arena in Memphis, Tennessee. Lewis dominated the fight and knocked out Tyson with a right hand in the eighth round. Tyson was respectful after the fight and praised Lewis on his victory.[135] This fight was the highest-grossing event in pay-per-view history at that time, generating $106.9 million from 1.95 million buys in the US.[105][106]

Later career, bankruptcy, and retirement

Tyson at the Boxing Hall of Fame, 2013

In another Memphis fight on February 22, 2003, Tyson beat fringe contender Clifford Etienne 49 seconds into round one. The pre-fight was marred by rumors of Tyson’s lack of fitness. Some said that he took time out from training to party in Las Vegas and get a new facial tattoo.[136] This eventually proved to be Tyson’s final professional victory in the ring.

In August 2003, after years of financial struggles, Tyson finally filed for bankruptcy.[137][138][139] Tyson earned over $30 million for several of his fights and $300 million during his career. At the time, the media reported that he had approximately $23 million in debt.[140]

On August 13, 2003, Tyson entered the ring for a face-to-face confrontation against K-1 fighting phenom, Bob Sapp, immediately after Sapp’s win against Kimo Leopoldo in Las Vegas. K-1 signed Tyson to a contract with the hopes of making a fight happen between the two, but Tyson’s felony history made it impossible for him to obtain a visa to enter Japan, where the fight would have been most profitable. Alternative locations were discussed, but the fight ultimately failed to happen.[141]

On July 30, 2004, Tyson had a match against British boxer Danny Williams in another comeback fight, and this time, staged in Louisville, Kentucky. Tyson dominated the opening two rounds. The third round was even, with Williams getting in some clean blows and also a few illegal ones, for which he was penalized. In the fourth round, Tyson was unexpectedly knocked out. After the fight, it was revealed that Tyson was trying to fight on one leg, having torn a ligament in his other knee in the first round. This was Tyson’s fifth career defeat.[142] He underwent surgery for the ligament four days after the fight. His manager, Shelly Finkel, claimed that Tyson was unable to throw meaningful right-hand punches since he had a knee injury.[143]

On June 11, 2005, Tyson stunned the boxing world by quitting before the start of the seventh round in a close bout against journeyman Kevin McBride. In the 2008 documentary Tyson, he stated that he fought McBride for a payday, that he did not anticipate winning, that he was in poor physical condition and fed up with taking boxing seriously. After losing three of his last four fights, Tyson said he would quit boxing because he felt he had lost his passion for the sport.[144]

In 2000 Tyson fired everyone working for him and enlisted new accountants, who prepared a statement showing he started the year $3.3 million in debt but earned $65.7 million.[145] In August 2007, Tyson pleaded guilty to drug possession and driving under the influence in an Arizona court, which stemmed from an arrest in December where authorities said Tyson, who has a long history of legal problems, admitted to using cocaine that day and to being addicted to the drug.[146]

Exhibition bouts

Mike Tyson’s World Tour

To help pay off his debts, Tyson announced he would be doing a series of exhibition bouts, calling it Tyson’s World Tour. For his first bout, Tyson returned to the ring in 2006 for a four-round exhibition against journeyman heavyweight Corey Sanders in Youngstown, Ohio.[147] Tyson, without headgear at 5 ft 10.5 in and 216 pounds, was in quality shape, but far from his prime against Sanders, at 6 ft 6 in[148] who wore headgear. Tyson appeared to be «holding back» in the exhibition to prevent an early end to the «show». «If I don’t get out of this financial quagmire there’s a possibility I may have to be a punching bag for somebody. The money I make isn’t going to help my bills from a tremendous standpoint, but I’m going to feel better about myself. I’m not going to be depressed», explained Tyson about the reasons for his «comeback».[149] After the bout was poorly received by fans the remainder of the tour was cancelled.[150]

Tyson vs. Jones

It was announced in July 2020 that Tyson had signed a contract to face former four-division world champion, Roy Jones Jr., in an eight-round exhibition fight. Mixed martial arts coach Rafael Cordeiro was selected to be Tyson’s trainer and cornerman.[151][152] The bout—officially sanctioned by the California State Athletic Commission (CSAC)—was initially scheduled to take place on September 12 at the Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, California,[153] however, the date was pushed back to November 28 in order to maximize revenue for the event. The fight went the full 8 rounds, and was declared a draw.[154] The fight was a split draw and the three judges scored the fight as follows: Chad Dawson (76–76 draw), Christy Martin (79–73 for Tyson), and Vinny Pazienza (76–80 for Jones).[155]

In July 2020, Mike Tyson announced the creation of Mike Tyson’s Legends Only League.[156] Tyson formed the league in partnership with Sophie Watts and her company, Eros Innovations.[157] The league provides retired professional athletes the opportunity to compete in their respective sport.[158] On November 28, 2020, Mike Tyson fought Roy Jones Jr. at the Staples Center in the first event produced under Legends Only League.[159] The event received largely positive reviews and was the highest selling PPV event of 2020, which ranks in the Top-10 for PPV purchased events all-time.[160][161]

Legacy

Tyson was The Ring magazine’s Fighter of the Year in 1986 and 1988.[162] A 1998 ranking of «The Greatest Heavyweights of All-Time» by The Ring magazine placed Tyson at number 14 on the list.[163] Despite criticism of facing underwhelming competition during his run as champion, Tyson’s knockout power and intimidation factor made him the sport’s most dynamic box-office draw.[164] According to Douglas Quenqua of The New York Times, «The [1990s] began with Mike Tyson, considered by many to be the last great heavyweight champion, losing his title to the little-known Buster Douglas. Seven years later, Mr. Tyson bit Evander Holyfield’s ear in a heavyweight champion bout—hardly a proud moment for the sport.»[165]

He is remembered for his attire of black trunks, black shoes with no socks, and a plain white towel fit around his neck in place of a traditional robe, as well as his habit of rapidly pacing the ring before the start of a fight.[164][166] In his prime, Tyson rarely took a step back and had never been knocked down or seriously challenged.[166] According to Martial Arts World Report, it gave Tyson an Honorable Mention in its Ten Greatest Heavyweights of All Time rather than a ranking because longevity is a factor and the peak period of Tyson’s career lasted only about 5 years.[167]

BoxRec currently ranks Tyson at number 13 among the greatest heavyweight boxers of all time.[168] In The Ring magazine’s list of the 80 Best Fighters of the Last 80 Years, released in 2002, Tyson was ranked at number 72.[169] He is ranked number 16 on The Ring magazine’s 2003 list of 100 greatest punchers of all time.[170][171] Tyson has defeated 11 boxers for the world heavyweight title, the seventh-most in history.

On June 12, 2011, Tyson was inducted to the International Boxing Hall of Fame alongside legendary Mexican champion Julio César Chávez, light welterweight champion Kostya Tszyu, and actor/screenwriter Sylvester Stallone.[172] In 2011, Bleacher Report omitted Tyson from its list of top 10 heavyweights, saying that «Mike Tyson is not a top 10 heavyweight. He killed the fighters he was supposed to beat, but when he fought another elite fighter, he always lost. I’m not talking about some of those B-level fighters he took a belt from. I’m talking about the handful of good boxers he fought throughout his career.»[173]

In 2013, Tyson was inducted into the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame and headlined the induction ceremony.[174][175] Tyson was inducted into the Southern Nevada Hall of Fame in 2015 along with four other inductees with ties to Southern Nevada.[176][177]

Tyson reflected on his strongest opponents in ten categories for a 2014 interview with The Ring magazine, including best jab, best defense, fastest hands, fastest feet, best chin, smartest, strongest, best puncher, best boxer, and best overall.[178]

In 2017, The Ring magazine ranked Tyson as number 9 of 20 heavyweight champions based on a poll of panelists that included trainers, matchmakers, media, historians, and boxers, including:[179]

- Trainers: Teddy Atlas, Pat Burns, Virgil Hunter, and Don Turner

- Matchmakers: Eric Bottjer, Don Chargin, Don Elbaum, Bobby Goodman, Ron Katz, Mike Marchionte, Russell Peltz, and Bruce Trampler.

- Media: Al Bernstein, Ron Borges, Gareth A Davies, Norm Frauenheim, Jerry Izenberg, Harold Lederman, Paulie Malignaggi, Dan Rafael, and Michael Rosenthal

- Historians: Craig Hamilton, Steve Lott, Don McRae, Bob Mee, Clay Moyle, Adam Pollack, and Randy Roberts

- Boxers: Lennox Lewis and Mike Tyson participated in the poll, but neither fighter ranked himself. Instead, a weighted average from the other panelists was assigned to their respective slots on their ballots.

In 2020, Bill Caplan of The Ring magazine listed Tyson as number 17 of the 20 greatest heavyweights of all time.[180] Tyson spoke with The Ring magazine in 2020 about his six greatest victories, which included knockouts of Trevor Berbick, Pinklon Thomas, Tony Tucker, Tyrell Biggs, Larry Holmes, and Michael Spinks.[181] In 2020, CBS Sports boxing experts Brian Campbell and Brent Brookhouse ranked the top 10 heavyweights of the last 50 years and Tyson was ranked number 7.[182]

Life after boxing

In an interview with USA Today published on June 3, 2005, Tyson said, «My whole life has been a waste – I’ve been a failure.» He continued: «I just want to escape. I’m really embarrassed with myself and my life. I want to be a missionary. I think I could do that while keeping my dignity without letting people know they chased me out of the country. I want to get this part of my life over as soon as possible. In this country nothing good is going to come of me. People put me so high; I wanted to tear that image down.»[183] Tyson began to spend much of his time tending to his 350 pigeons in Paradise Valley, an upscale enclave near Phoenix, Arizona.[184]

Tyson has stayed in the limelight by promoting various websites and companies.[185] In the past Tyson had shunned endorsements, accusing other athletes of putting on a false front to obtain them.[186] Tyson has held entertainment boxing shows at a casino in Las Vegas[187] and started a tour of exhibition bouts to pay off his numerous debts.[188]

On December 29, 2006, Tyson was arrested in Scottsdale, Arizona, on suspicion of DUI and felony drug possession; he nearly crashed into a police SUV shortly after leaving a nightclub. According to a police probable-cause statement, filed in Maricopa County Superior Court, «[Tyson] admitted to using [drugs] today and stated he is an addict and has a problem.»[189] Tyson pleaded not guilty on January 22, 2007, in Maricopa County Superior Court to felony drug possession and paraphernalia possession counts and two misdemeanor counts of driving under the influence of drugs. On February 8 he checked himself into an inpatient treatment program for «various addictions» while awaiting trial on the drug charges.[190]

On September 24, 2007, Tyson pleaded guilty to possession of cocaine and driving under the influence. He was convicted of these charges in November 2007 and sentenced to 24 hours in jail. After his release, he was ordered to serve three years’ probation and complete 360 hours of community service. Prosecutors had requested a year-long jail sentence, but the judge praised Tyson for seeking help with his drug problems.[191] On November 11, 2009, Tyson was arrested after getting into a scuffle at Los Angeles International airport with a photographer.[192] No charges were filed.

Tyson has taken acting roles in movies and television, most famously playing a fictionalized version of himself in the 2009 film The Hangover.

In September 2011, Tyson gave an interview in which he made comments about former Alaska governor Sarah Palin including crude and violent descriptions of interracial sex. These comments were reprinted on The Daily Caller website. Journalist Greta van Susteren criticized Tyson and The Daily Caller over the comments, which she described as «smut» and «violence against women».[193]

After debuting a one-man show in Las Vegas, Tyson collaborated with film director Spike Lee and brought the show to Broadway in August 2012.[194][195] In February 2013, Tyson took his one-man show Mike Tyson: Undisputed Truth on a 36-city, three-month national tour. Tyson talks about his personal and professional life on stage.[196] The one-man show was aired on HBO on November 16, 2013.

In October 2012, Tyson launched the Mike Tyson Cares Foundation.[197] The mission of the Mike Tyson Cares Foundation is to «give kids a fighting chance» by providing innovative centers that provide for the comprehensive needs of kids from broken homes.

In August 2013, Tyson teamed up with Acquinity Sports to form Iron Mike Productions, a boxing promotions company.[198]

In September 2013, Tyson was featured on a six-episode television series on Fox Sports 1 that documented his personal and private life entitled Being: Mike Tyson.[199][200]

In November 2013, Tyson’s Undisputed Truth was published, which appeared on The New York Times Best Seller list.[201] At the Golden Podium Awards Ceremony, Tyson received the Sportel Special Prize for the best autobiography.[202]

In May 2017, Tyson published his second book, Iron Ambition,[203] which details his time with trainer and surrogate father Cus D’Amato.

In February 2018, Tyson attended the international mixed martial arts (MMA) tournament in the Russian city of Chelyabinsk. Tyson said: «As I have travelled all over the country of Russia I have realised that the people are very sensitive and kind. But most Americans do not have any experience of that.»[204]

On May 12, 2020, Tyson posted a video on his Instagram of him training again. At the end of the video, Tyson hinted at a return to boxing by saying, «I’m back».[205]

On May 23, 2020, at All Elite Wrestling’s Double or Nothing, Tyson helped Cody defeat Lance Archer alongside Jake Roberts and presented him the inaugural AEW TNT Championship. Tyson alongside Henry Cejudo, Rashad Evans, and Vitor Belfort appeared on the May 27 episode of AEW Dynamite facing off against Chris Jericho and his stable The Inner Circle.[206] Tyson returned to AEW on the April 7, 2021 episode of Dynamite and helped Jericho from being attacked by The Pinnacle, beating down Shawn Spears in the process.[207] He was the special guest enforcer on the April 14 episode of Dynamite for a match between Jericho and Dax Harwood of The Pinnacle, a preview of the upcoming Inner Circle vs. Pinnacle match at Blood and Guts.[208]

Tyson made an extended cameo appearance in the Telugu-Hindi movie Liger, which released on August 25, 2022.[209]

Personal life

The gates of Tyson’s mansion in Southington, Ohio, which he purchased and lived in during the 1980s[210]

Tyson resides in Seven Hills, Nevada.[211] He has been married three times, and has seven children, one deceased, with three women; in addition to his biological children, Tyson includes his second wife’s oldest daughter as one of his own.[212]

His first marriage was to actress Robin Givens from February 7, 1988, to February 14, 1989.[57] Givens was known at the time for her role on the sitcom Head of the Class. Tyson’s marriage to Givens was especially tumultuous, with allegations of violence, spousal abuse, and mental instability on Tyson’s part.[213]

Matters came to a head when Tyson and Givens gave a joint interview with Barbara Walters on the ABC TV newsmagazine show 20/20 in September 1988, in which Givens described life with Tyson as «torture, pure hell, worse than anything I could possibly imagine.»[214] Givens also described Tyson as «manic depressive» – which was later confirmed by doctors[215] – on national television while Tyson looked on with an intent and calm expression.[213] A month later, Givens announced that she was seeking a divorce from the allegedly abusive Tyson.[213]

According to the book Fire and Fear: The Inside Story of Mike Tyson, Tyson admitted that he punched Givens and stated, «that was the best punch I’ve ever thrown in my entire life.»[216] Tyson claimed that book was «filled with inaccuracies.»[217] They had no children but she reported having had a miscarriage; Tyson claimed that she was never pregnant and only used that to get him to marry her.[213][218] During their marriage, the couple lived in a mansion in Bernardsville, New Jersey.[219][220]

Tyson’s second marriage was to Monica Turner from April 19, 1997, to January 14, 2003.[221] At the time of the divorce filing, Turner worked as a pediatric resident at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C.[222] She is the sister of Michael Steele, the former Lieutenant Governor of Maryland and former Republican National Committee.[223] Turner filed for divorce from Tyson in January 2002, claiming that he committed adultery during their five-year marriage, an act that «has neither been forgiven nor condoned.»[222] The couple had two children; son Amir and Ramsey who is non-binary.[224]

On May 25, 2009, Tyson’s four-year-old daughter Exodus was found by her seven-year-old brother Miguel unconscious and tangled in a cord, dangling from an exercise treadmill. The child’s mother, Sol Xochitl, untangled her, administered CPR and called for medical attention. Tyson, who was in Las Vegas at the time of the incident, traveled back to Phoenix to be with her. She died of her injuries on May 26, 2009.[225][226][227]

Eleven days after his daughter’s death, Tyson wed for the third time, to longtime girlfriend Lakiha «Kiki» Spicer, age 32, exchanging vows on Saturday, June 6, 2009, in a short, private ceremony at the La Bella Wedding Chapel at the Las Vegas Hilton.[228] They have two children; daughter Milan and son Morocco.[212]

In March 2011, Tyson appeared on The Ellen DeGeneres Show to discuss his new Animal Planet reality series Taking on Tyson. In the interview with DeGeneres, Tyson discussed some of the ways he had improved his life in the past two years, including sober living and a vegan diet.[229] However, in August 2013 he admitted publicly that he had lied about his sobriety and was on the verge of death from alcoholism.[230]

In November 2013, Tyson stated «the more I look at churches and mosques, the more I see the devil».[231] But, just a month later, in a December 2013 interview with Fox News, Tyson said that he is very grateful to be a Muslim and that he needs Allah in his life. In the same interview Tyson talked about his progress with sobriety and how being in the company of good people has made him want to be a better and more humble person.[232]

Tyson also revealed that he is no longer vegan, stating, «I was a vegan for four years but not anymore. I eat chicken every now and then. I should be a vegan. [No red meat] at all, no way! I would be very sick if I ate red meat. That’s probably why I was so crazy before.»[232]

In 2015, Tyson announced that he was supporting Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy.[233]

On April 20, 2022, on a JetBlue flight from San Francisco to Florida, Tyson repeatedly punched a male passenger who was harassing him, including throwing water on Tyson; he did not face criminal charges.[234][235]

In popular culture

At the height of his fame and career in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, Tyson was among the most recognized sports personalities in the world. In addition to his many sporting accomplishments, his outrageous and controversial behavior in the ring and in his private life has kept him in the public eye and in the courtroom.[236] As such, Tyson has been the subject of myriad popular media including movies, television, books and music. He has also been featured in video games and as a subject of parody or satire. Tyson became involved in professional wrestling and has made many cameo appearances in film and television.

The film Tyson was released in 1995 and was directed by Uli Edel. It explores the life of Mike Tyson, from the death of his guardian and trainer Cus D’Amato to his rape conviction. Tyson is played by Michael Jai White.

Published in 2007, author Joe Layden’s book The Last Great Fight: The Extraordinary Tale of Two Men and How One Fight Changed Their Lives Forever, chronicled the lives of Tyson and Douglas before and after their heavyweight championship fight.

In 2008, the documentary Tyson premiered at the annual Cannes Film Festival in France.

In 2013, he appeared in an episode of Law and Order: SVU as a survivor of child-abuse awaiting execution for murder.

He is the titular character in Mike Tyson Mysteries, which started airing on October 27, 2014, on Adult Swim. In the animated series, Tyson voices a fictionalized version of himself, solving mysteries in the style of Scooby-Doo.[237][238][239]

In early March 2015, Tyson appeared on the track «Iconic» on Madonna’s album Rebel Heart. Tyson says some lines at the beginning of the song.[240]

In late March 2015, Ip Man 3 was announced. With Donnie Yen reprising his role as the titular character, Bruce Lee’s martial arts master, Ip Man, while Mike Tyson has been confirmed to join the cast.[241] Principal photography began on March 25, 2015, and was premiered in Hong Kong on December 16, 2015.

In January 2017, Tyson launched his YouTube channel with Shots Studios, a comedy video and comedy music production company with young digital stars like Lele Pons and Rudy Mancuso. Tyson’s channel includes parody music videos and comedy sketches.[242][243]

He hosts the podcast Hotboxin’ with Mike Tyson.[244]

In October 2017, Tyson was announced as the new face of Australian car servicing franchise Ultra Tune. He has taken over from Jean-Claude van Damme in fronting television commercials for the brand, and the first advert is due to air in January 2018 during the Australian Open.[245][246]

A joint Mainland China-Hong Kong-directed film on female friendship titled Girls 2: Girls vs Gangsters (Vietnamese: Girls 2: Những Cô Gái và Găng Tơ) that was shot earlier from July–August 2016 at several locations around Vietnam was released in March 2018, featuring Tyson as «Dragon».[247][248]

Tiki Lau released a dance music single, «Mike Tyson», in October 2020, which includes vocals from Tyson.[249]

In 2021, Mike’s Hard Lemonade Seltzer featured ads with Tyson.[250]

In March 2021, it was announced that Jamie Foxx will star in, and also executive produce the official scripted series Tyson.[251] The limited series will be directed by Antoine Fuqua and executive produced by Martin Scorsese.[252]

A two-part documentary series titled Mike Tyson: The Knockout premiered on May 25, 2021, on ABC.[253]

Hulu is set to release a biographical drama limited series on Tyson, entitled Mike, that will go over the boxer’s life and career.[254] On August 6, 2022 Tyson spoke out about the series saying, «Hulu stole my story» and telling the service that «I’m not a n****r you can sell on the auction block.»[254]

NFTs

Mike Tyson launched several officially licensed NFT projects, including the «Mike Tyson NFT Collection,» created from digital graphic artist Cory Van Lew’s original artwork with creative oversight from Mike Tyson himself. Each one of Tyson’s four initial NFT collections came with varying degrees of ‘utility,’ ranging from an all-expenses paid first-class airfare and lodging package, an all-access tour of Mike Tyson’s personal training facility, and even a potential invitation to visit Tyson Ranch, his 40-acre marijuana resort in Southern California. [255] Since then, Mike Tyson has been involving himself with various other NFT projects including «Iron Pigeons,» which is an NFT Trading Card game that launched on October 20, 2022.[256]

Professional boxing record

| 58 fights | 50 wins | 6 losses |

|---|---|---|

| By knockout | 44 | 5 |

| By decision | 5 | 0 |

| By disqualification | 1 | 1 |

| No contests | 2 |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round, time | Date | Age | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 | Loss | 50–6 (2) | Kevin McBride | RTD | 6 (10), 3:00 | Jun 11, 2005 | 38 years, 346 days | MCI Center, Washington, D.C., U.S. | |

| 57 | Loss | 50–5 (2) | Danny Williams | KO | 4 (10), 2:51 | Jul 30, 2004 | 38 years, 30 days | Freedom Hall, Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. | |

| 56 | Win | 50–4 (2) | Clifford Etienne | KO | 1 (10), 0:49 | Feb 22, 2003 | 36 years, 237 days | The Pyramid, Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. | |

| 55 | Loss | 49–4 (2) | Lennox Lewis | KO | 8 (12), 2:25 | Jun 8, 2002 | 35 years, 343 days | The Pyramid, Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. | For WBC, IBF, IBO, and The Ring heavyweight titles |

| 54 | Win | 49–3 (2) | Brian Nielsen | RTD | 6 (10), 3:00 | Oct 13, 2001 | 35 years, 115 days | Parken Stadium, Copenhagen, Denmark | |

| 53 | NC | 48–3 (2) | Andrew Golota | RTD | 3 (10), 3:00 | Oct 20, 2000 | 34 years, 112 days | The Palace, Auburn Hills, Michigan, U.S. | Originally an RTD win for Tyson, later ruled an NC after he failed a drug test |

| 52 | Win | 48–3 (1) | Lou Savarese | TKO | 1 (10), 0:38 | Jun 24, 2000 | 33 years, 360 days | Hampden Park, Glasgow, Scotland | |

| 51 | Win | 47–3 (1) | Julius Francis | TKO | 2 (10), 1:03 | Jan 29, 2000 | 33 years, 213 days | MEN Arena, Manchester, England | |

| 50 | NC | 46–3 (1) | Orlin Norris | NC | 1 (10), 3:00 | Oct 23, 1999 | 33 years, 115 days | MGM Grand Garden Arena, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | Norris unable to continue after a Tyson foul |

| 49 | Win | 46–3 | Francois Botha | KO | 5 (10), 2:59 | Jan 16, 1999 | 32 years, 200 days | MGM Grand Garden Arena, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | |

| 48 | Loss | 45–3 | Evander Holyfield | DQ | 3 (12), 3:00 | Jun 28, 1997 | 30 years, 363 days | MGM Grand Garden Arena, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | For WBA heavyweight title; Tyson disqualified for biting |

| 47 | Loss | 45–2 | Evander Holyfield | TKO | 11 (12), 0:37 | Nov 9, 1996 | 30 years, 132 days | MGM Grand Garden Arena, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | Lost WBA heavyweight title |

| 46 | Win | 45–1 | Bruce Seldon | TKO | 1 (12), 1:49 | Sep 7, 1996 | 30 years, 69 days | MGM Grand Garden Arena, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | Won WBA heavyweight title |

| 45 | Win | 44–1 | Frank Bruno | TKO | 3 (12), 0:50 | Mar 16, 1996 | 29 years, 260 days | MGM Grand Garden Arena, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | Won WBC heavyweight title |

| 44 | Win | 43–1 | Buster Mathis Jr. | KO | 3 (12), 2:32 | Dec 16, 1995 | 29 years, 169 days | CoreStates Spectrum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 43 | Win | 42–1 | Peter McNeeley | DQ | 1 (10), 1:29 | Aug 19, 1995 | 29 years, 50 days | MGM Grand Garden Arena, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | McNeeley disqualified after his manager entered the ring |

| 42 | Win | 41–1 | Donovan Ruddock | UD | 12 | Jun 28, 1991 | 24 years, 363 days | The Mirage, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | |

| 41 | Win | 40–1 | Donovan Ruddock | TKO | 7 (12), 2:22 | Mar 18, 1991 | 24 years, 261 days | The Mirage, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | |

| 40 | Win | 39–1 | Alex Stewart | TKO | 1 (10), 2:27 | Dec 8, 1990 | 24 years, 161 days | Convention Hall, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 39 | Win | 38–1 | Henry Tillman | KO | 1 (10), 2:47 | Jun 16, 1990 | 23 years, 351 days | Caesars Palace, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | |

| 38 | Loss | 37–1 | Buster Douglas | KO | 10 (12), 1:22 | Feb 11, 1990 | 23 years, 226 days | Tokyo Dome, Tokyo, Japan | Lost WBA, WBC, and IBF heavyweight titles |

| 37 | Win | 37–0 | Carl Williams | TKO | 1 (12), 1:33 | Jul 21, 1989 | 23 years, 21 days | Convention Hall, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | Retained WBA, WBC, IBF, and The Ring heavyweight titles |

| 36 | Win | 36–0 | Frank Bruno | TKO | 5 (12), 2:55 | Feb 25, 1989 | 22 years, 240 days | Las Vegas Hilton, Winchester, Nevada, U.S. | Retained WBA, WBC, IBF, and The Ring heavyweight titles |

| 35 | Win | 35–0 | Michael Spinks | KO | 1 (12), 1:31 | Jun 27, 1988 | 21 years, 363 days | Convention Hall, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | Retained WBA, WBC, and IBF heavyweight titles; Won The Ring heavyweight title |

| 34 | Win | 34–0 | Tony Tubbs | TKO | 2 (12), 2:54 | Mar 21, 1988 | 21 years, 265 days | Tokyo Dome, Tokyo, Japan | Retained WBA, WBC, and IBF heavyweight titles |

| 33 | Win | 33–0 | Larry Holmes | TKO | 4 (12), 2:55 | Jan 22, 1988 | 21 years, 186 days | Convention Hall, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | Retained WBA, WBC, and IBF heavyweight titles |

| 32 | Win | 32–0 | Tyrell Biggs | TKO | 7 (15), 2:59 | Oct 16, 1987 | 21 years, 108 days | Convention Hall, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | Retained WBA, WBC, and IBF heavyweight titles |

| 31 | Win | 31–0 | Tony Tucker | UD | 12 | Aug 1, 1987 | 21 years, 32 days | Las Vegas Hilton, Winchester, Nevada, U.S. | Retained WBA and WBC heavyweight titles; Won IBF heavyweight title; Heavyweight unification series |

| 30 | Win | 30–0 | Pinklon Thomas | TKO | 6 (12), 2:00 | May 30, 1987 | 20 years, 334 days | Las Vegas Hilton, Winchester Nevada, U.S. | Retained WBA and WBC heavyweight titles; Heavyweight unification series |

| 29 | Win | 29–0 | James Smith | UD | 12 | Mar 7, 1987 | 20 years, 250 days | Las Vegas Hilton, Winchester, Nevada, U.S. | Retained WBC heavyweight title; Won WBA heavyweight title; Heavyweight unification series |

| 28 | Win | 28–0 | Trevor Berbick | TKO | 2 (12), 2:35 | Nov 22, 1986 | 20 years, 145 days | Las Vegas Hilton, Winchester, Nevada, U.S. | Won WBC heavyweight title |

| 27 | Win | 27–0 | Alfonso Ratliff | TKO | 2 (10), 1:41 | Sep 6, 1986 | 20 years, 68 days | Las Vegas Hilton, Winchester, Nevada, U.S. | |

| 26 | Win | 26–0 | José Ribalta | TKO | 10 (10), 1:37 | Aug 17, 1986 | 20 years, 48 days | Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 25 | Win | 25–0 | Marvis Frazier | KO | 1 (10), 0:30 | Jul 26, 1986 | 20 years, 26 days | Civic Center, Glens Falls, New York, U.S. | |

| 24 | Win | 24–0 | Lorenzo Boyd | KO | 2 (10), 1:43 | Jul 11, 1986 | 20 years, 11 days | Stevensville Hotel, Swan Lake, New York, U.S. | |

| 23 | Win | 23–0 | William Hosea | KO | 1 (10), 2:03 | Jun 28, 1986 | 19 years, 363 days | Houston Field House, Troy, New York, U.S. | |

| 22 | Win | 22–0 | Reggie Gross | TKO | 1 (10), 2:36 | Jun 13, 1986 | 19 years, 348 days | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 21 | Win | 21–0 | Mitch Green | UD | 10 | May 20, 1986 | 19 years, 324 days | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 20 | Win | 20–0 | James Tillis | UD | 10 | May 3, 1986 | 19 years, 307 days | Civic Center, Glens Falls, New York, U.S. | |

| 19 | Win | 19–0 | Steve Zouski | KO | 3 (10), 2:39 | Mar 10, 1986 | 19 years, 253 days | Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum, Uniondale, New York, U.S. | |

| 18 | Win | 18–0 | Jesse Ferguson | TKO | 6 (10), 1:19 | Feb 16, 1986 | 19 years, 231 days | Houston Field House, Troy, New York, U.S. | Originally a DQ win for Tyson, later ruled a TKO |

| 17 | Win | 17–0 | Mike Jameson | TKO | 5 (8), 0:46 | Jan 24, 1986 | 19 years, 208 days | Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 16 | Win | 16–0 | David Jaco | TKO | 1 (10), 2:16 | Jan 11, 1986 | 19 years, 195 days | Plaza Convention Center, Albany, New York, U.S. | |

| 15 | Win | 15–0 | Mark Young | TKO | 1 (10), 0:50 | Dec 27, 1985 | 19 years, 180 days | Latham Coliseum, Latham, New York, U.S. | |

| 14 | Win | 14–0 | Sammy Scaff | TKO | 1 (10), 1:19 | Dec 6, 1985 | 19 years, 159 days | Felt Forum, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 13 | Win | 13–0 | Conroy Nelson | TKO | 2 (8), 0:30 | Nov 22, 1985 | 19 years, 145 days | Latham Coliseum, Latham, New York, U.S. | |

| 12 | Win | 12–0 | Eddie Richardson | KO | 1 (8), 1:17 | Nov 13, 1985 | 19 years, 136 days | Ramada Hotel, Houston, Texas, U.S. | |

| 11 | Win | 11–0 | Sterling Benjamin | TKO | 1 (8), 0:54 | Nov 1, 1985 | 19 years, 124 days | Latham Coliseum, Latham, New York, U.S. | |

| 10 | Win | 10–0 | Robert Colay | KO | 1 (8), 0:37 | Oct 25, 1985 | 19 years, 117 days | Atlantis Hotel and Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 9 | Win | 9–0 | Donnie Long | TKO | 1 (6), 1:28 | Oct 9, 1985 | 19 years, 101 days | Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 8 | Win | 8–0 | Michael Johnson | KO | 1 (6), 0:39 | Sep 5, 1985 | 19 years, 67 days | Atlantis Hotel and Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 7 | Win | 7–0 | Lorenzo Canady | KO | 1 (6), 1:05 | Aug 15, 1985 | 19 years, 46 days | Steel Pier, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 6 | Win | 6–0 | Larry Sims | KO | 3 (6), 2:04 | Jul 19, 1985 | 19 years, 19 days | Mid-Hudson Civic Center, Poughkeepsie, New York, U.S. | |

| 5 | Win | 5–0 | John Alderson | TKO | 2 (6), 3:00 | Jul 11, 1985 | 19 years, 11 days | Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 4 | Win | 4–0 | Ricardo Spain | TKO | 1 (6), 0:39 | Jun 20, 1985 | 18 years, 355 days | Steel Pier, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 3 | Win | 3–0 | Don Halpin | KO | 4 (6), 1:04 | May 23, 1985 | 18 years, 327 days | Albany, New York, U.S. | |

| 2 | Win | 2–0 | Trent Singleton | TKO | 1 (4), 0:52 | Apr 10, 1985 | 18 years, 284 days | Albany, New York, U.S. | |

| 1 | Win | 1–0 | Hector Mercedes | TKO | 1 (4), 1:47 | Mar 6, 1985 | 18 years, 249 days | Plaza Convention Center, Albany, New York, U.S. |

[257]

Exhibition boxing record

| 4 fights | 0 wins | 0 losses |

|---|---|---|

| Draws | 1 | |

| Non-scored | 3 |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round, time | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Draw | 0–0–1 (3) | Roy Jones Jr. | SD | 8 | Nov 28, 2020 | Staples Center, Los Angeles, California, U.S. | Scored by the WBC |

| 3 | — | 0–0 (3) | Corey Sanders | — | 4 | Oct 20, 2006 | Chevrolet Centre, Youngstown, Ohio, U.S. | Non-scored bout |

| 2 | — | 0–0 (2) | James Tillis | — | 4 | Nov 12, 1987 | DePaul University Alumni Hall, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | Non-scored bout |

| 1 | — | 0–0 (1) | Anthony Davis | — | 1 | Jul 4, 1986 | Liberty State Park, Jersey City, New Jersey, U.S. | Non-scored bout |

Pay-per-view bouts

Boxing

PPV home television

| No. | Date | Fight | Billing | Buys | Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

June 27, 1988 |

Tyson vs. Spinks | Once and For All |

700,000[258] |

King Vision |

| 2 |

March 18, 1991 |

Tyson vs. Ruddock | The Fight of the Year |

960,000[259] |

King Vision |

| 3 |

June 28, 1991 |

Tyson vs. Ruddock II | The Rematch |

1,250,000[260] |

King Vision |

| 4 |

August 19, 1995 |

Tyson vs. McNeeley | He’s Back |

1,600,000[261] |

Showtime/King Vision |

| 5 |

March 16, 1996 |

Tyson vs. Bruno II | The Championship Part I |

1,400,000[261] |

Showtime/King Vision |

| 6 |

September 7, 1996 |

Tyson vs. Seldon | Liberation: Champion vs. Champion |

1,150,000[262] |

Showtime/King Vision |

| 7 |

November 9, 1996 |

Tyson vs. Holyfield | Finally |

1,600,000[261] |

Showtime/King Vision |

| 8 |

June 28, 1997 |

Tyson vs. Holyfield II | The Sound and the Fury |

1,990,000[262] |

Showtime/King Vision |

| 9 |

Jan 16, 1999 |

Tyson vs. Botha | Tyson-Botha |

750,000[262] |

Showtime |

| 10 |

October 20, 2000 |

Tyson vs. Golota | Showdown in Motown |

450,000[262] |

Showtime |

| 11 |

June 8, 2002 |

Lewis vs. Tyson | Lewis–Tyson Is On |

1,970,000[262] |

HBO/Showtime |

| 12 |

February 22, 2003 |

Tyson vs. Etienne | Back to Business |

100,000[263] |

Showtime |

| 13 |

July 30, 2004 |

Tyson vs. Williams | Return for Revenge |

150,000[264] |

Showtime |

| 14 |

June 11, 2005 |

Tyson vs. McBride | Tyson-McBride |

250,000[265] |

Showtime |

| 15 | November 28, 2020 | Tyson vs. Jones | Tyson vs Jones | 1,600,000[266] | Triller |

| Total sales | 15,920,000 |

| Date | Fight | Network | Buys | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 16, 1996 | Frank Bruno vs. Mike Tyson II | Sky Box Office | 600,000 | [267] |

| June 28, 1997 | Evander Holyfield vs. Mike Tyson II | Sky Box Office | 550,000 | [268] |

| January 29, 2000 | Mike Tyson vs. Julius Francis | Sky Box Office | 500,000 | [268] |

| June 8, 2002 | Lennox Lewis vs. Mike Tyson | Sky Box Office | 750,000 | [269] |

| Total sales | 2,400,000 |

Closed-circuit theatre TV

Select pay-per-view boxing buy rates at American closed-circuit theatre television venues:

| Date | Fight | Buys | Revenue | Revenue (inflation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 27, 1988 | Mike Tyson vs. Michael Spinks | 800,000[270] | $32,000,000[270] | $73,320,000 |

| June 28, 1997 | Evander Holyfield vs. Mike Tyson II | 120,000[271] | $9,000,000[272] | $15,190,000 |

| Total sales | 920,000 | $41,000,000 | $79,930,000 |

Professional wrestling

World Wrestling Federation

| Date | Event | Venue | Location | Buys | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 29, 1998 | WrestleMania XIV | FleetCenter | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | 730,000 | [273] |

All Elite Wrestling

| Date | Event | Venue | Location | Buys | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 23, 2020 | Double or Nothing | Daily’s Place TIAA Bank Field |

Jacksonville, Florida | 115,000–120,000 | [274][275] |

Awards and honors

Humane letters

The Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio, in 1989 awarded Tyson an honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters: «Mike demonstrates that hard work, determination and perseverance can enable one to overcome any obstacles.»[33]

Boxing

- Ring magazine Prospect of the Year (1985)

- 2× Ring magazine Fighter of the Year (1986, 1988)

- 2× Sugar Ray Robinson Award winner (1987, 1989)

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year Overseas Personality (1989)

- International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee (Class of 2011)

- «Guirlande d’Honneur» by the FICTS (Milan, 2010) [276]

Professional wrestling

- WWE Hall of Fame (Class of 2012)[277]

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- Faction of the Year (2021) – with The Inner Circle[278]

See also

- List of undisputed boxing champions

- List of heavyweight boxing champions

- World heavyweight boxing championship records and statistics

Notes

- ^ One child is deceased.

References

- ^ Lewis, Darren (November 15, 2005). «Mike Tyson Exclusive: No More Mr Bad Ass». The Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ J, Jenna (August 22, 2013). «Mike Tyson: ‘I always thought of myself as a big guy, as a giant, I never thought I was five foot ten’«. Doghouse Boxing. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ HBO Sports tale of the tape prior to the Lennox Lewis fight.

- ^ McIntyre, Jay (September 1, 2014). ««Iron,» Mike Tyson – At His Sharpest». Boxingnews24.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Boyd, Todd (2008). African Americans and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 235. ISBN 9780313064081. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Eisele, Andrew (2007). «50 Greatest Boxers of All-Time». About.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ «At only 20 years of age, Mike Tyson became the youngest heavyweight boxing champion of the world». Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ ««Iron» Mike Tyson». Cyber Boxing Zone. Archived from the original on February 19, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ Mike Tyson vs Buster Douglas, 1990, archived from the original on May 25, 2021, retrieved May 25, 2021

- ^ Holley, David (September 16, 2005). «Tyson a Heavyweight in Chechnya». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ «Майк Тайсон в гостях у Рамзана Кадырова (видео)» Archived August 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian). NTV. Gazprom-Media. Retrieved July 21, 2017

- ^ «Mike Tyson». biography.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ «BoxRec: Mike Tyson». boxrec.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Eisele, Andrew (2003). «Ring Magazine’s 100 Greatest Punchers». About.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Houston, Graham (2007). «The hardest hitters in heavyweight history». ESPN. Bristol, Connecticut. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ «Mike Tyson? Sonny Liston? Who is the scariest boxer ever?». Sky Sports. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ «Local Black History Spotlight: Cumberland Hosptial [sic]». myrtleavenue.org. February 20, 2014. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ McNeil, William F. (2014). The Rise of Mike Tyson, Heavyweight. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4766-1802-9. OCLC 890981745.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (May 21, 2002). «Boxing: Tyson Remains an Object of Fascination». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ «Tyson’s Sister Is Dead at 24». The New York Times. February 22, 1990. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ «Mike Tyson Pens Heartbreaking Tribute To His Late Mother: «I Know Nothing About Her»«. fromthestage.net. June 7, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ «Mike Tyson: ‘I’m ashamed of so many things I’ve done’«. The Guardian. March 21, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Costello, Mike (December 18, 2013). «Mike Tyson staying clean but still sparring with temptation». BBC Sport. Archived from the original on December 23, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ «Mike Tyson on his one-man Las Vegas act: Raw, revealing, poignant». USA Today. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ «Charlotte, North Carolina, Annexation history» (PDF), Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Department, archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2013, retrieved September 4, 2013

- ^ a b c Puma, Mike., Sportscenter Biography: ‘Iron Mike’ explosive in and out of ring Archived April 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, ESPN.com, October 10, 2005. Retrieved March 27, 2007

- ^ «Where are they now?». The Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ Mike Tyson Biography. BookRags. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ Mike Tyson Quotes Archived April 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Kjkolb.tripod.com. Retrieved on November 25, 2011.

- ^ «Mike Tyson Interview, Details magazine». Archived from the original on July 9, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Rob (December 4, 2013). «Mike Tyson on Ditching Club Life and Getting Sober». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ^ Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company. 1989. p. 28. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b «Sports People: Boxing; A Doctorate for Tyson». The New York Times. April 25, 1989. Archived from the original on December 27, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ Mike Tyson Net Worth Archived June 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, NetWorthCity.com. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ «Mike Tyson». www.ibhof.com. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Foreman and Tyson Book a Doubleheader Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, N.Y. Times article, 1990-05-01, Retrieved on August 10, 2013

- ^ a b «Iron» Mike Tyson Archived February 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Cyberboxingzone.com Boxing record. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ Hornfinger, Cus D’Amato Archived September 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, SaddoBoxing.com. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Oates, Joyce C., Mike Tyson Archived June 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Life Magazine via author’s website, November 22, 1986. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ Pinnington, Samuel., Trevor Berbick – The Soldier of the Cross Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Britishboxing.net, January 31, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ Houston, Graham. «Which fights will Tyson be remembered for?». ESPN. Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ Para, Murali., «Iron» Mike Tyson – His Place in History Archived April 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Eastsideboxing.com, September 25. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ «The Science of Mike Tyson and Elements of Peek-A-Boo: part II». SugarBoxing.com. February 1, 2014. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Richmann What If Mike Tyson And Kevin Rooney Reunited? Archived March 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Saddoboxing.com, February 24, 2006. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ «Mike Tyson’s Arching Uppercuts & Leaping Left Hooks Explained». themodernmartialartist.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), «Tyson Unifies W.B.C.-W.B.A. Titles», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 5, Page 1, Column 4, March 8, 1987.

- ^ Bamonte, Bryan (June 10, 2005). «Bad man rising» (PDF). The Daily Iowan. pp. 12, 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), «Tyson Retains Title On Knockout In Sixth», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 5, Page 1, Column 2, May 31, 1987.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), «Boxing — Tyson Undisputed And Unanimous Titlist», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 1, Page 51, Column 1, August 2, 1987.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), «Tyson Retains Title In 7 Rounds», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 1, Page 51, Column 1, October 17, 1987.

- ^ «Profile: Minoru Arakawa». N-Sider. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1988), «Tyson Keeps Title With 3 Knockdowns in Fourth», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 1, Page 47, Column 5, January 23, 1988.

- ^ Shapiro, Michael. (1988), «Tubbs’s Challenge Was Brief and Sad», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section A, Page 29, Column 1, March 22, 1988.

- ^ Jake Donovan. «Crowning and Recognizing A Lineal Champion». BoxingScene. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ Berger, Phil. (1988), «Tyson Knocks Out Spinks at 1:31 of Round 1», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section B, Page 7, Column 5, June 28, 1988.

- ^ Simmons, Bill (June 11, 2002). «Say ‘goodbye’ to our little friend». ESPN. Archived from the original on July 19, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ a b Sports People: Boxing; Tyson and Givens: Divorce Is Official Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, AP via New York Times, June 2, 1989. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Sports People: Boxing; King Accuses Cayton Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, January 20, 1989. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (June 24, 1991). «Tyson Failed to Make Adjustments». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Hoffer, Richard (June 24, 1991). «Where’s the fire?». Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Bruno vs Tyson Archived August 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, BBC TV. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1989), «Tyson Stuns Williams With Knockout in 1:33», The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late Edition-Final, Section 1, Page 45, Column 2, July 22, 1989.