- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

|

Maya Plisetskaya |

|

|---|---|

Plisetskaya in 2011 |

|

| Born |

Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya 20 November 1925 Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 2 May 2015 (aged 89)

Munich, Germany |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse |

Rodion Shchedrin (m. 1958) |

| Awards | Full cavalier of the Order «For Merit to the Fatherland» |

| Former groups | Bolshoi Ballet |

| Dances | Ballet, modern |

| Website | www.shchedrin.de |

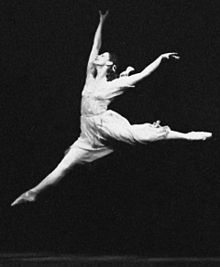

Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya (Russian: Майя Михайловна Плисецкая; 20 November 1925 – 2 May 2015) was a Soviet and Russian ballet dancer, choreographer, ballet director, and actress. In post-Soviet times, she held both Lithuanian and Spanish citizenship.[1][2][3] She danced during the Soviet era at the Bolshoi Theatre under the directorships of Leonid Lavrovsky, then of Yury Grigorovich; later she moved into direct confrontation with him.[citation needed] In 1960, when famed Russian ballerina Galina Ulanova retired, Plisetskaya became prima ballerina assoluta of the company.

Her early years were marked by political repression and loss.[4] Her father, Mikhail Plisetski, a Soviet official, was arrested in 1937 and executed in 1938, during the Great Purge. Her mother, actress Rachel Messerer, was arrested in 1938 and imprisoned for a few years, then held in a concentration camp together with her infant son, Azari [ru]. The older children were faced with the threat of being put in an orphanage but were cared for by maternal relatives. Maya was adopted by their aunt Sulamith Messerer, and Alexander was taken into the family of their uncle Asaf Messerer; both Alexander and Azary eventually became solo dancers of the Bolshoi.

Plisetskaya studied ballet at The Bolshoi Ballet School from age nine, and she first performed at the Bolshoi Theatre when she was eleven. She studied ballet under the direction of Elizaveta Gerdt and also her aunt, Sulamith Messerer. Graduating in 1943 at the age of eighteen, she joined the Bolshoi Ballet company, quickly rising to become their leading soloist. In 1959, during the Thaw Time, she started to tour outside the country with the Bolshoi, then on her own. Her fame as a national ballerina was used to project the Soviet Union’s achievements during the Cold War. Premier Nikita Khrushchev considered her to be «not only the best ballerina in the Soviet Union, but the best in the world».[5]

As an artist, Plisetskaya had an inexhaustible interest in new roles and dance styles, and she liked to experiment on stage. As a member of the Bolshoi until 1990, she had international exposure and her skills as a dancer changed the world of ballet. She set a higher standard for ballerinas, both in terms of technical brilliance and dramatic presence. As a soloist, Plisetskaya created a number of leading roles, including Juliet in Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet; Phrygia in Yakobson’s Spartacus (1958); in Grigorovich’s ballets : Mistress of the Copper Mountain in The Stone Flower (1959); Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty (1963); Mahmene Banu in The Legend of Love [ru] (1965); Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite (1967), choreographed especially for her; and Maurice Bejart’s Isadora (1976). Among her most acclaimed roles were Kitri in Don Quixote, Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, and The Dying Swan, first danced as a pre-graduate student under the guidance of Sulamith Messerer. A fellow dancer said that her dramatic portrayal of Carmen, reportedly her favorite role, «helped confirm her as a legend, and the ballet soon took its place as a landmark in the Bolshoi repertoire». Her husband, composer Rodion Shchedrin, wrote the scores to a number of her ballets.

Having become «an international superstar» and a continuous «box office hit throughout the world», Plisetskaya was treated by the Soviet Union as a favored cultural emissary. Although she toured extensively during the same years that other prominent dancers defected, including Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov, Plisetskaya always refused to defect. In 1991, she published her autobiography, I, Maya Plisetskaya.[6]

Early life[edit]

Plisetskaya was born on 20 November 1925 in Moscow,[7] into a prominent family of Lithuanian Jewish descent,[8] most of whom were involved in the theater or film. Her mother, Rachel Messerer, was a silent-film actress. Bolshoi Ballet principal dancer Asaf Messerer was a maternal uncle and Bolshoi prima ballerina Sulamith Messerer was a maternal aunt. Her father, Mikhail Plisetski (Misha), was a diplomat, engineer and mine director; he was not involved in the arts, although he was a fan of ballet.[9] Her brothers Alexander Plisetski and Azari Plisetski became renowned ballet masters, and her niece Anna Plisetskaya would also become a ballerina. She was the cousin of theater artist Boris Messerer.

In 1938, her father was arrested and later executed during the Stalinist purges, during which thousands of people were murdered.[4] According to ballet scholar Jennifer Homans, her father was a committed Communist, and had earlier been «proclaimed a national hero for his work on behalf of the Soviet coal industry».[10] Soviet leader Vyacheslav Molotov presented him with one of the Soviet Union’s first manufactured cars. Her mother was arrested soon after and together with her seven-month-old baby Azary sent to a labor camp (Gulag) in Kazakhstan for the next three years.[11][12] Maya was taken in by their maternal aunt, ballerina Sulamith Messerer, until her mother was released in 1941.[13]

During the years without her parents, while barely a teenager, Plisetskaya «faced terror, war, and dislocation», writes Homans. As a result, «Maya took refuge in ballet and the Bolshoi Theater.»[10] As her father was stationed at Spitzbergen to supervise the coalmines in Barentsburg, she had stayed there for four years with her family, from 1932 to 1936.[14] She subsequently studied at the Bolshoi School under the ex-ballerina of the Mariinsky imperial ballet, the great Elizaveta Gerdt. Maya first performed at the Bolshoi Theatre when she was eleven. In 1943, at the age of eighteen, Plisetskaya graduated from the Bolshoi School. She joined the Bolshoi Ballet, where she performed until 1990.[13]

Career[edit]

Performing in the Soviet Union[edit]

From the beginning, Plisetskaya was a different kind of ballerina. She spent a very short time in the corps de ballet after graduation and was quickly named a soloist. Her bright red hair and striking looks made her a glamorous figure on and off the stage. «She was a remarkably fluid dancer but also a very powerful one», according to The Oxford Dictionary of Dance.[15] «The robust theatricality and passion she brought to her roles made her an ideal Soviet ballerina.» Her interpretation of The Dying Swan, a short showcase piece made famous by Anna Pavlova, became her calling card. Plisetskaya was known for the height of her jumps, her extremely flexible back, the technical strength of her dancing, and her charisma. She excelled both in adagio and allegro, which is very unusual in dancers.[15]

Plisetskaya performing in Carmen (1974)

Despite her acclaim, Plisetskaya was not treated well by the Bolshoi management. She was Jewish at a time of Soviet anti-Zionist campaigns combined with other oppression of suspected dissidents.[8] Her family had been purged during the Stalinist era, and she had a defiant personality. As a result, Plisetskaya was not allowed to tour outside the country for sixteen years after she had become a member of the Bolshoi.[11]

The Soviet Union used the artistry of such dancers as Plisetskaya to project its achievements during the Cold War period with United States. Historian Christina Ezrahi notes, «In a quest for cultural legitimacy, the Soviet ballet was shown off to foreign leaders and nations.» Plisetskaya recalls that foreigners «were all taken to the ballet. And almost always, Swan Lake … Khrushchev was always with the high guests in the loge», including Mao Zedong and Stalin.[4][16]

Ezrahi writes, «the intrinsic paranoia of the Soviet regime made it ban Plisetskaya, one of the most celebrated dancers, from the Bolshoi Ballet’s first major international tour», as she was considered «politically suspect» and was «non-exportable».[10] In 1948, the Zhdanov Doctrine took effect, and with her family history, and being Jewish, she became a «natural target . . . publicly humiliated and excoriated for not attending political meetings».[10] As a result, dancing roles were continually denied her and for sixteen years she could tour only within the Eastern Bloc. She became a «provincial artist, consigned to grimy, unrewarding bus tours, exclusively for local consumption», writes Homans.[10]

In 1958, Plisetskaya received the title of the People’s Artist of the USSR. That same year, she married the young composer Rodion Shchedrin, whose subsequent fame she shared. Wanting to dance internationally, she rebelled and defied Soviet expectations. On one occasion, to gain the attention and respect from some of the country’s leaders, she gave one of the most powerful performances of her career, in Swan Lake, for her 1956 concert in Moscow. Homans describes that «extraordinary performance»:

We can feel the steely contempt and defiance taking hold of her dancing. When the curtain came down on the first act, the crowd exploded. KGB toughs muffled the audience’s applauding hands and dragged people out of the theater kicking, screaming, and scratching. By the end of the evening the government thugs had retreated, unable (or unwilling) to contain the public enthusiasm. Plisetskaya had won.[10]

International tours[edit]

«Plisetskaya was not only the best ballerina in the Soviet Union, but the best in the world.»

— Nikita Khrushchev[5]

In Swan Lake with the Bolshoi Ballet, 1966

Soviet leader Khrushchev was still concerned, writes historian David Caute, that «her defection would have been useful for the West as anti-Soviet propaganda». She wrote him «a long and forthright expression of her patriotism and her indignation that it should be doubted».[5] Subsequently, the travel ban was lifted in 1959 on Khrushchev’s personal intercession, as it became clear to him that striking Plisetskaya from the Bolshoi’s participants could have serious consequences for the tour’s success.[16] In his memoirs, Khrushchev writes that Plisetskaya «was not only the best ballerina in the Soviet Union, but the best in the world».[5][17]

Able to travel the world as a member of the Bolshoi, Plisetskaya changed the world of ballet by her skills and technique, setting a higher standard for ballerinas both in terms of technical brilliance and dramatic presence. Having allowed her to tour in New York, Khrushchev was immensely satisfied upon reading the reviews of her performances. «He embraced her upon her return: ‘Good girl, coming back. Not making me look like a fool. You didn’t let me down.'»[10]

Within a few years, Plisetskaya was recognized as «an international superstar» and a continuous «box office hit throughout the world».[10] The Soviet Union treated her as a favored cultural emissary, as «the dancer who did not defect».[10] Although she toured extensively during the same years that other dancers defected, including Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov, «Plisetskaya always returned to Russia», wrote historian Tim Scholl.[13]: xiii

Plisetskaya explains that for her generation, and her family in particular, defecting was a moral issue: «He who runs to the enemy’s side is a traitor.» She had once asked her mother why their family didn’t leave the Soviet Union when they had the chance, at the time living in Norway. Her mother said that her father «would have abandoned [her] with the children instantly» for even asking. «Misha would never have been a traitor.»[13]: 239

Style[edit]

Although she lacked the first-rate training and coaching of her contemporaries, Plisetskaya «compensated» by «developing an individual, iconoclastic style that capitalized on her electrifying stage presence», writes historian Tim Scholl. She had a «daring rarely seen on ballet stages today, and a jump of almost masculine power».[13]

Her very personal style was angular, dramatic, and theatrical, exploiting the gifts that everyone in her mother’s family seemed to possess…. Those who saw Plisetskaya’s first performances in the West still speak of her ability to wrap the theater in her gaze, to convey powerful emotions in terse gestures.[13]: xii

Critic and dance historian Vadim Gaevsky said of her influence on ballet that «she began by creating her own style and ended up creating her own theater.»[18] Among her most notable performances was a 1975 free-form dance, in a modern style, set to Ravel’s Boléro. In it, she dances a solo piece on an elevated round stage, surrounded and accompanied by 40 male dancers. One reviewer wrote, «Words cannot compare to the majesty and raw beauty of Plisetskaya’s performance»:[19]

What makes the piece so compelling is that although Plisetskaya may be accompanied by dozens of other dancers mirroring her movement, the first and only focus is on the prima ballerina herself. Her continual rocking and swaying at certain points, rhythmically timed to the syncopation of the orchestra, create a mesmerizing effect that demonstrated an absolute control over every nuance of her body, from the smallest toe to her fingertips, to the top of her head.[19]

Performances[edit]

«She burst like a flame on the American scene in 1959. Instantly she became a darling to the public and a miracle to the critics. She was compared to Maria Callas, Theda Bara and Greta Garbo.»

Sarah Montague[20]

Plisetskaya created a number of leading roles, including ones in Lavrovsky’s Stone Flower (1954), Moiseyev’s Spartacus (1958), Grigorovich’s Moscow version of The Stone Flower (1959), Aurora in Grigorovich’s staging The Sleeping Beauty (1963), Grigorovich’s Moscow version of The Legend of Love (1965), the title role in Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite (1967), Petit’s La Rose malade (Paris, 1973), Bejart’s Isadora (Monte Carlo, 1976) and his Moscow staging of Leda (1979), Granero’s Maria Estuardo (Madrid, 1988), and Julio Lopez’s El Reñidero (Buenos Aires, 1990).[15]

Performing in Don Quixote in 1974

After performing in Spartacus during her 1959 U.S. debut tour, Life magazine, in its issue featuring the Bolshoi, rated her second only to Galina Ulanova.[21] Spartacus became a significant ballet for the Bolshoi, with one critic describing their «rage to perform», personified by Plisetskaya as ballerina, «that defined the Bolshoi».[10] During her travels, she also appeared as guest artist with the Paris Opera Ballet, Ballet National de Marseilles, and Ballet of the 20th Century in Brussels.[15]

By 1962, following Ulanova’s retirement, Plisetskaya embarked on another three-month world tour. As a performer, notes Homans, she «excelled in the hard-edged, technically demanding roles that Ulanova eschewed, including Raymonda, the black swan in Swan Lake, and Kitri in Don Quixote«.[10] In her performances, Plisetskaya was «unpretentious, refreshing, direct. She did not hold back.»[10] Ulanova added that Plisetskaya’s «artistic temperament, bubbling optimism of youth reveal themselves in this ballet with full force».[20] World-famous impresario Sol Hurok said that Plisetskaya was the only ballerina after Pavlova who gave him «a shock of electricity» when she came on stage.[20] Rudolf Nureyev watched her debut as Kitri in Don Quixote and told her afterwards, «I sobbed from happiness. You set the stage on fire.»[4][22]

At the conclusion of one performance at the Metropolitan Opera, she received a half-hour ovation. Choreographer Jerome Robbins, who had just finished the Broadway play, West Side Story, told her that he «wanted to create a ballet especially for her».[5]

Plisetskaya’s most acclaimed roles included Odette-Odile in Swan Lake (1947) and Aurora in Sleeping Beauty (1961). Her dancing partner in Swan Lake states that for twenty years, he and Plisetskaya shared the world stage with that ballet, with her performance consistently producing «the most powerful impression on the audience».[23]

Equally notable were her ballets as The Dying Swan. Critic Walter Terry described one performance: «What she did was to discard her own identity as a ballerina and even as a human and to assume the characteristics of a magical creature. The audience became hysterical, and she had to perform an encore.»[20] She danced that particular ballet until her late 60s, giving one of her last performances of it in the Philippines, where similarly, the applause wouldn’t stop until she came out and performed an encore.[24]

Novelist Truman Capote remembered a similar performance in Moscow, seeing «grown men crying in the aisles and worshiping girls holding crumpled bouquets for her». He saw her as «a white spectre leaping in smooth rainbow arcs», with «a royal head». She said of her style that «the secret of the ballerina is to make the audience say, ‘Yes, I believe.'»[20]

Fashion designers Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Cardin considered Plisetskaya one of their inspirations, with Cardin alone having traveled to Moscow over 30 times just to see Plisetskaya perform.[24][25] She credits Cardin’s costume designs for the success and recognition she received for her ballets of Anna Karenina, The Seagull, and Lady with the Dog. She recalls his reaction when she initially suggested he design one of her costumes: «Cardin’s eyes lit up like batteries. As if an electrical current passed through them.»[13]: 170 Within a week, he had created a design for Anna Karenina, and over the course of her career he created ten different costumes for just Karenina.[26]

«She was, and still is, a star, ballet’s monstre sacré, the final statement about theatrical glamour, a flaring, flaming beacon in a world of dimly twinkling talents, a beauty in the world of prettiness.»

Financial Times. 2005[27]

In 1967, she performed as Carmen in the Carmen Suite, choreographed specifically for her by Cuban choreographer Alberto Alonso. The music was re-scored from Bizet’s original by her husband, Rodion Shchedrin, and its themes were re-worked into a «modernist and almost abstract narrative».[28] Dancer Olympia Dowd, who performed alongside her, writes that Plisetskaya’s dramatic portrayal of Carmen, her favorite role, made her a legend, and soon became a «landmark» in the Bolshoi’s repertoire.[29] Her Carmen, however, at first «rattled the Soviet establishment», which was «shaken with her Latin sensuality».[30] She was aware that her dance style was radical and new, saying that «every gesture, every look, every movement had meaning, was different from all other ballets… The Soviet Union was not ready for this sort of choreography. It was war, they accused me of betraying classical dance.»[31]

Some critics outside of Russia saw her departure from classical styles as necessary to the Bolshoi’s success in the West. New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff observed, «Without her presence, their poverty of movement invention would make them untenable in performance. It is a tragedy of Soviet ballet that a dancer of her singular genius was never extended creatively.»[18] A Russian news commentator wrote, she «was never afraid to bring ardor and vehemence onto the stage», contributing to her becoming a «true queen of the Bolshoi».[30] Her life and work was described by the French ballet critic André Philippe Hersin as «genius, audacity and avant-garde».[32]

Acting and choreography[edit]

After Galina Ulanova left the stage in 1960, Maya Plisetskaya was proclaimed the prima ballerina assoluta of the Bolshoi Theatre. In 1971, her husband Shchedrin wrote a ballet on the same subject, where she would play the leading role. Anna Karenina was also her first attempt at choreography.[33] Other choreographers who created ballets for her include Yury Grigorovich, Roland Petit, Alberto Alonso, and Maurice Béjart with «Isadora». She created The Seagull and Lady with a Lapdog. She starred in the 1961 film, The Humpbacked Horse, and appeared as a straight actress in several films, including the Soviet version of Anna Karenina (1968), which featured music by Shchedrin later reused in his ballet score. Her own ballet of the same name was filmed in 1974.[citation needed]

While on tour in the United States in 1987, Plisetskaya gave master classes at the David Howard Dance Center. A review in New York magazine noted that although she was 61 when giving the classes, «she displayed the suppleness and power of a performer in her physical prime».[34] In October that year, she performed with Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov for the opening night of the season with the Martha Graham Dance Company in New York.[35]

Plisetskaya’s husband, composer Rodion Shchedrin, wrote the score to a number of her ballets, including Anna Karenina, The Sea Gull, Carmen, and Lady with a Small Dog. In the 1980s, he was considered the successor to Shostakovich, and became the Soviet Union’s leading composer.[36] Plisetskaya and Shchedrin spent time abroad, where she worked as the artistic director of the Rome Opera Ballet from 1984 to 85, then the Spanish National Dance Company from 1987 to 1989. She retired as a soloist for the Bolshoi at age 65 in 1990 and on her 70th birthday, she debuted in Maurice Béjart’s piece choreographed for her, «Ave Maya». Since 1994, she has presided over the annual international ballet competitions, called Maya, and in 1996 she was named President of the Imperial Russian Ballet.[37] After the Soviet Union collapsed Plisetskaya and her husband lived mostly in Germany spending summers in their house in Lithuania and occasionally visiting Moscow and St. Petersburg.

She was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts in 2005 with the ballerina Tamara Rojo also. She was awarded the Spanish Gold Medal of Fine Art. In 1996, she danced the Dying Swan, her signature role, at a gala in her honor in St. Petersburg.[15]

On her 80th birthday, the Financial Times wrote:

«She was, and still is, a star, ballet’s monstre sacre, the final statement about theatrical glamour, a flaring, flaming beacon in a world of dimly twinkling talents, a beauty in the world of prettiness.»[38]

In 2006, Emperor Akihito of Japan presented her with the Praemium Imperiale.

Death[edit]

Plisetskaya died in Munich, Germany, on 2 May 2015 from a heart attack.[39][18] According to her last will and testament, she was to be cremated, and after the death of her widower, Rodion Shchedrin, who is also to be cremated, their ashes are to be combined and spread over Russia.[40]

Russian President Vladimir Putin expressed his condolences, and Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said that «a whole era of ballet was gone» with Plisetskaya.[41] Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko extended condolences to her family and friends:

The passing of great Maya Mikhailovna [Plisetskaya] whose creative work embodied the whole cultural era is an irretrievable loss for Russian and world art. Her brilliant choreography and wonderful grace, fantastic power of dramatic identification and outstanding mastery dazzled the audience. Thanks to her selfless service to art and commitment to the stage, she was respected all over the world.[42]

Tributes[edit]

- Brazilian mural artist Eduardo Kobra painted a 12-meter (39 ft) tall mural of Plisetskaya in 2013, located in Moscow’s central theater district, near the Bolshoi Theatre.[43]

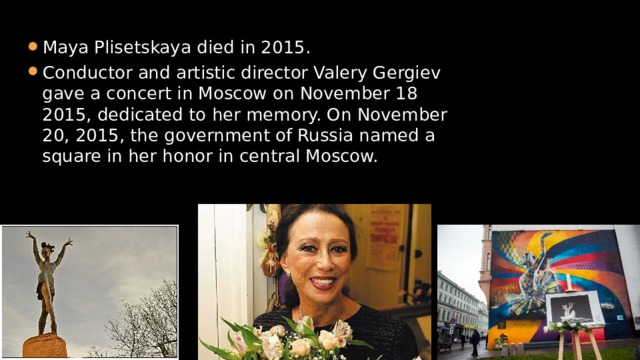

- Conductor and artistic director Valery Gergiev, who was a close friend of Plisetskya, gave a concert in Moscow on 18 November 2015, dedicated to her memory.[44]

- On 20 November 2015, the government of Russia named a square in her honor in central Moscow, on Ulitsa Bolshaya Dmitrovka, near the Bolshoi Theatre. A bronze plaque affixed at the square included an engraving: «Maya Plisetskaya Square is named after the outstanding Russian ballerina. Opened 20 November 2015.»[45]

- In St. Petersburg, the Mariinsky Theater Symphony Orchestra paid homage to Plisetskaya’s memory with a concert on 27 December 2015. It was conducted by Valery Gergiev and included a performance with ballet dancer Diana Vishneva.[44] The Mariinsky Ballet later performed a four-program «Tribute of Maya Plisetskaya» at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in February 2016.[46]

- The Bolshoi Theater performed a concert in memory of Plisetskaya at the London Coliseum on 6 March 2016.[47]

- A monument to Maya Plisetskaya was unveiled in the center of Moscow, on Bolshaya Dmitrovka, in the square named after her. The opening took place on 20 November 2016, the date of her birth, and shows her in a pose from Carmen.[48][49] Describing the monument, one observer commented about sculpturist Viktor Mitroshin and the statue’s design:

In choosing Carmen, Mitroshin emphasized not only Plisetskaya’s physical prowess, grace and beauty, he put a big exclamation point after character… Look at those gorgeous arms, hands, legs. Look at the sassy sway of the dress. Look at the dark, hard eyes and the tight, determined mouth. Look at the sway of the back. Look at that crazy flower on her head. Look at how all of it strains upward into the sky. I’m telling you, the whole thing is beautiful.[50]

Personal life[edit]

Career friendships[edit]

Plisetskaya’s tour manager, Maxim Gershunoff, who also helped promote the Soviet/American Cultural Exchange Program, describes her as «not only a great artist, but also very realistic and earthy … with a very open and honest outlook on life».[51]

During Plisetskaya’s tours abroad, she became friends with a number of other theater and music artists, including composer and pianist Leonard Bernstein, with whom she remained friends until his death. Pianist Arthur Rubinstein, also a friend, was able to converse with her in Russian. She visited him after his concert performance in Russia.[13]: 202 Novelist John Steinbeck, while at their home in Moscow, listened to her stories of the hardship of becoming a ballerina, and told her that the backstage side of ballet could make for a «most interesting novel».[13]: 203

In 1962, the Bolshoi was invited to perform at the White House by president John F. Kennedy, and Plisetskaya recalled that first lady Jacqueline Kennedy greeted her by saying «You’re just like Anna Karenina.»[13]: 222

While in France in 1965, Plisetskaya was invited to the home of Russian artist Marc Chagall and his wife. Chagall had moved to France to study art in 1910. He asked her if she wouldn’t mind creating some ballet poses to help him with his current project, a mural for the new Metropolitan Opera House in New York, which would show various images representing the arts. She danced and posed in various positions as he sketched, and her images were used on the mural, «at the top left corner, a colorful flock of ballerinas».[13]: 250

Plisetskaya made friends with a number of celebrities and notable politicians who greatly admired and followed her work. She met Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman, then living in the U.S., after a performance of Anna Karenina. Bergman told her that both their photographs, taken by noted photographer Richard Avedon, appeared on the same page in Vogue magazine. Bergman suggested she «flee Communism», recalled Plisetskaya, telling her «I will help you.»[13]: 222

Actress Shirley MacLaine once held a party for her and the other members of the Bolshoi. She remembered seeing her perform in Argentina when Plisetskaya was sixty-five, and writes «how humiliating it was that Plisetskaya had to dance on a vaudeville stage in South America to make ends meet».[52] Dancer Daniel Nagrin noted that she was a dancer who «went on to perform to the joy of audiences everywhere while simultaneously defying the myth of early retirement».[53]

MacLaine’s brother, actor Warren Beatty, is said to have been inspired by their friendship, which led him to write and produce his 1981 film Reds, about the Russian Revolution. He directed the film and costarred with Diane Keaton. He first met Plisetskaya at a reception in Beverly Hills, and, notes Beatty’s biographer Peter Biskind, «he was smitten» by her «classic dancer’s» beauty.[54]

Plisetskaya became friends with film star Natalie Wood and her sister, actress Lana Wood. Wood, whose parents immigrated from Russia, greatly admired Plisetskaya, and once had an expensive custom wig made for her to use in the Spartacus ballet. They enjoyed socializing together on Wood’s yacht.[51]

Friendship with Robert F. Kennedy[edit]

U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the younger brother to president John F. Kennedy, befriended Plisetskaya, with whom he shared the birth date of 20 November 1925. She was invited to gatherings with Kennedy and his family at their estate on Cape Cod in 1962. They later named their sailboat Maya, in her honor.[51]

As the Cuban Missile Crisis had ended a few weeks earlier, at the end of October 1962, U.S. and Soviet relations were at a low point. Diplomats of both countries considered her friendship with Kennedy to be a great benefit to warmer relations, after weeks of worrisome military confrontation. Years later, when they met in 1968, he was then campaigning for the presidency, and diplomats again suggested that their friendship would continue to help relations between the two countries. Plisetskaya summarizes Soviet thoughts on the matter:

Maya Plisetskaya should bring the candidate presents worthy of the great moment. Stun the future president with Russian generosity to continue and deepen contacts and friendship.[13]: 265

Of their friendship, Plisetskaya wrote in her autobiography:

With me Robert Kennedy was romantic, elevated, noble, and completely pure. No seductions, no passes.[13]: 265

Robert Kennedy was assassinated just days before he was to see Plisetskaya again in New York. Gershunoff, Plisetskaya’s manager at the time, recalls that on the day of the funeral, most of the theaters and concert halls in New York City went «dark», closed in mourning and respect. The Bolshoi likewise planned to cancel their performance, but they decided instead to do a different ballet than planned, one dedicated to Kennedy. Gershunoff describes that evening:

The most appropriate way to open such an evening would be for the great Plisetskaya to perform The Dying Swan, which normally would close an evening’s program to thunderous applause with stamping feet, and clamors for an encore…. This assignment created an emotional burden for Maya. She really did not want to dance that work that night … I thought it was best for me to remain backstage in the wings. That turned out to be one of the most poignant moments I have ever experienced. Replacing the usual thunderous audience applause at the conclusion, there was complete silence betokening the feelings of a mourning nation in the packed, cavernous Metropolitan Opera House. Maya came off the stage in tears, looked at me, raised her beautiful arms and looked upward. Then disappeared into her dressing room.[51]

Awards and honors[edit]

Plisetskaya receives a governmental award from President of Russia Vladimir Putin on 20 November 2000.

Plisetskaya on a 2017 stamp of Russia

Plisetskaya was honored on numerous occasions for her skills:[37]

Russia[edit]

- Order of Merit for the Fatherland

- 1st class (20 November 2005) – for outstanding contribution to the development of domestic and international choreographic art, many years of creative activity[55]

- 2nd class (18 November 2000) – for outstanding contribution to the development of choreographic art[56]

- 3rd class (21 November 1995) – for outstanding contributions to national culture and a significant contribution to contemporary choreographic art[57]

- 4th class (9 November 2010) – for outstanding contribution to the development of national culture and choreography, many years of creative activity[58]

- Made an honorary professor at Moscow State University in 1993.[59]

Soviet Union[edit]

- Hero of Socialist Labour (1985)

- Three Orders of Lenin (1967, 1976, 1985)

- Lenin Prize (1964)

- People’s Artist of USSR (1959)

- People’s Artist of RSFSR (1956)

- Honoured Artist of the RSFSR (1951)

Other decorations[edit]

- Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (France, 1984)[59]

- Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (Spain)[citation needed]

- Commander of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas[citation needed]

- Great Commander’s Cross of the Order for Merits to Lithuania (2003)[citation needed]

- Gold Medal of Gloria Artis (Poland, 2008)[60]

- Order of the Rising Sun, 3rd class (Japan, 2011)[citation needed]

- Officer of the Légion d’honneur (France, 2012; Knight: 1986)

Awards[edit]

- First prize, Budapest International Competition (1949)

- Anna Pavlova Prize, Paris Academy of Dance (1962)

- Gold Prize, Slovenia, 2000.

- «Doctor of the Sorbonne» in 1985.[59]

- Gold Medal of Fine Arts of Spain (1991)[59]

- Triumph Prize, 2000.

- Premium «Russian National Olympus» (2000)[citation needed]

- Prince of Asturias Award (2005, Spain)

- Imperial Prize of Japan (2006)[59]

See also[edit]

- List of dancers

- List of Russian ballet dancers

References[edit]

- ^ Maya Plisetskaya profile, viola.bz; accessed 2 May 2015.

- ^ Plisetskaya and Shchedrin settle in Lithuania, upi.com; accessed 4 May 2015.

- ^ Two greats of world ballet win Spanish Nobels, expatica.com; accessed 4 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d «Maya Plisetskaya: Ballerina whose charisma and talent helped her fight the Soviet authorities and achieve international fame», The Independent, U.K. 5 May 2015

- ^ a b c d e Caute, David (2003). The Dancer Defects: The Struggle for Cultural Supremacy During the Cold War, Oxford Univ. Press. p. 489. ISBN 978-0-19-155458-2

- ^ «Maya Plisetskaya, ballerina – obituary». Telegraph. 4 May 2015.

- ^ Current Biography Yearbook, H. W. Wilson Co., 1964, p. 331.

- ^ a b Miller, Jack (1984). Jews in Soviet Culture. Transaction Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 0-87855-495-5.

- ^ Popovich, Irina. «Maya Plisetskaya: A Balletic Lethal Weapon» Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Russia Journal, Issue 10, May 1999.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Homans, Jennifer (2010). Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet. Random House. pp. 383–386. ISBN 978-0-8129-6874-3

- ^ a b Eaton, Katherine Bliss (2004). Daily Life in the Soviet Union. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31628-7.

- ^ They were sent to ALZHIR camp, a Russian acronym for the Akmolinskii Camp for Wives of Traitors of the Motherland, «enemies of the people» «Pope_pays_Trebute». Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2008. near Akmolinsk

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Plisetskaya, Maya (2001). I, Maya Plisetskaya. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08857-4.

- ^ Dagens Næringsliv, the article «Svanens død» («Death of the Swan»), p. 19, 9 May 2015

- ^ a b c d e Craine, Debra and Mackrell, Judith (2010). The Oxford Dictionary of Dance, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 352–353. ISBN 978-0-19-956344-9

- ^ a b Ezrahi, Christina (2012) . Swans of the Kremlin. Univ. of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 68, 142. ISBN 978-0-8229-6214-4

- ^ Taubman, William; Khrushchev, Sergei; Gleason, Abbott; Gehrenbeck, David; Kane, Eileen; Bashenko, Alla (2000). Nikita Khrushchev. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07635-5.

- ^ a b c «Maya Plisetskaya, Ballerina Who Embodied Bolshoi, Dies at 89», New York Times, 2 May 2015.

- ^ a b «Master Class: Maya Plisetskaya’s Bolero«, Artful Intel, 25 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Montague, Sarah (1980). The Ballerina, Universe Books, N.Y. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-0-87663-277-2

- ^ Life magazine, 23 February 1959.

- ^ «Maya Plisetskaya in Don Quixote ca 1959» on YouTube

- ^ «Plisetskaya-AVE MAYA-documentary film» on YouTube, translated from Russian

- ^ a b «Remembering The Great Maya Plisetskaya». Inquirer. Philippines. 6 July 2015.

- ^ «Russia mourns its ballet legend rebel Plisetskaya». AFP. 3 May 2015.

- ^ «BALLERINA MAYA PLISETSKAYA AND FASHION AT HER POINTE SHOES». Cassandra Fox. 3 May 2015.

- ^ «Endless dance of Maya Plisetskaya». Russia Beyond the Headlines. 6 May 2015.

- ^ Hutcheon, Linda (2006). A Theory of Adaptation, Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-415-53938-8

- ^ Dowd, Olympia (2003). A Young Dancer’s Apprenticeship: On Tour with the Moscow City Ballet, Twenty-first Century Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7613-2917-6

- ^ a b «Moscow Honors Bolshoi’s ‘True Queen'». Washington Post. 20 November 2005.

- ^ «Russian ballet great Maya Plisetskaya dies – Bolshoi», GMG News, Agence France-Presse, 2 May 2015

- ^ «Endless dance of Maya Plisetskaya»[permanent dead link]. Russia Beyond the Headlines. 6 May 2015.

- ^ Tolstoy, Leo (2003). Anna Karenina. Mandelker, Amy; Garnett, Constance. Spark Educational Publishing. ISBN 1-59308-027-1.

- ^ New York magazine, 22 June 1987, p. 65

- ^ New York magazine, 21 September 1987, p. 100

- ^ New York magazine, 28 March 1988, p. 99

- ^ a b Sleeman, Elizabeth (2001). The International Who’s Who of Women (3rd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-122-7.

- ^ Crisp, Clement (18 November 2005). «Mayan goddess». Financial Times. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- ^ Скончалась балерина Майя Плисецкая (in Russian). ITAR TASS. 2 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Плисецкая завещала развеять ее прах над Россией Info re last will testament of Plisetskaya, interfax.ru, 3 May 2015 (in Russian)

- ^ «Ballerina Maya Plisetskaya dies of heart attack at 89». Pravda. 2 May 2015.

- ^ «Lukashenko extends condolences over passing of Maya Plisetskaya» Archived 7 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Belarusian News, 5 May 2015

- ^ «Gorgeous Mural Honors Russian Ballerina Maya Plisetskaya». My Modern Net. 21 October 2013.

- ^ a b «Gergiev to pay homage to memory of Maya Plisetskaya with concert in Moscow». Tass. 18 November 2015.

- ^ «Moscow Square Named in Honor of Ballerina Plisetskaya». The Moscow Times. 20 November 2015.

- ^ «Review: Mariinsky Celebrates a Prima Ballerina». New York Times. 26 February 2016.

- ^ «London to host gala in memory of Maya Plisetskaya». Russia Beyond the Headlines. 6 May 2015.

- ^ Monument to Maya Plisetskaya unveiled in Moscow on her day of birth. Russian Ministry of Culture. 20 November 2016.

- ^ Photo of Plisetskaya statue unveiling in Moscow

- ^ «Maya Plisetskaya Monument, Moscow». Russian Landmarks. 27 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d Gershunoff, Maxim (2005). It’s Not All Song and Dance: A Life Behind the Scenes in the Performing Arts, Hal Leonard Corp. pp. 61, 65, 74. ISBN 978-0-87910-310-1

- ^ MacLaine, Shirley (2003). Out on a Leash: Exploring the Nature of Reality and Love, Simon & Schuster. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-7434-8506-7

- ^ Nagrin, Daniel (1988). How to Dance Forever: Surviving Against the Odds, HarperCollins. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-688-07479-1

- ^ Biskind, Peter (2010). Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America, Simon & Schuster. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7432-4659-0

- ^ «Putin awarded Maya Plisetskaya with the Order of Merit for the Fatherland». ria.ru (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 20 November 2005. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ «On awarding the Order of Merit to the Fatherland, II degree, Plisetskaya M.M.» docs.cntd.ru (in Russian). Codex. 18 November 2000. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

V. Putin

- ^ «On awarding the Order of Merit to the Fatherland, III degree, Plisetskaya M.M.» docs.cntd.ru (in Russian). Codex. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

B. Yeltsin

- ^ «On awarding the Order of Merit to the Fatherland, IV degree, Plisetskaya M.M.» docs.cntd.ru (in Russian). Codex. 9 November 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

D. Medvedev

- ^ a b c d e «Died ballerina Maya Plisetskaya». TASS. 2 May 2015.

- ^ Warszawa. Urodziny primadonny at the www.e-teatr.pl (in Polish)

External links[edit]

- Maya Plisetskaya at IMDb

- «Maya Plisetskaya Dances Ballet, biographical documentary, 1964» on YouTube, 1 hr. 11 min.

- «Legendary performances: Maya Plisetskaya» on YouTube, documentary biography, 1 hr. 20 min.

- Maya Plisetskaya – «Swan» on YouTube, 3 1/2 min.

- Maya Plisetskaya and Alexander Godunov in «Carmen», at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow

- «Maya Plisetskaya in ‘Spartacus'» on YouTube, 2 1/2 min.

- «Maya Plisetskaya – Bolero, by Ravel», video, 20 min.

- Video: Excerpt from Maya’s «Dance Studies» on YouTube

ANNA GALAYDA SPECIAL TO RBTH

On Nov. 20, ballet lovers around the world celebrate the anniversary of the birth of Maya Plisetskaya, the great ballerina who transcended the boundaries of dance, leaving her mark in literature, fashion, cinema, music, and beyond.

Even during the era of the Cold War and the Iron Curtain, it seemed impossible that the mercurial talent of the great Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya could be contained by any walls. Now, long after the end of the Soviet Union, her life and work continues to unite and inspire admirers of high art in countries and continents around the world.

An example to emulate for dancers starring in Swan Lake or Don Quixote, she is recognized by the whole world as the paragon of Russian ballet. It was thanks to her that the likes of Maurice Béjart and Roland Petit were able to bring their ballets to Russia.

But even if she was half a century ahead of her time in ballet, Plisetskaya was not simply a ballerina – she was a woman of oustanding personality, a star that drew the most remarkable people of her time into her orbit. The stage – even one as great and grand as the Bolshoi – was simply not enough for her.

From stage to silver screen

Plisetskaya’s artistic skill manifested itself very early in her life. As she herself recalled, back when she was too young to even go to school, she was once drawn away from her home by the sounds of a waltz from Léo Delibes’ ballet Coppélia, playing from a PA loudspeaker.

The music enchanted her so much she began twirling in the middle of the street, oblivious to everything around her.

But the most fascinating thing about this story is that her mother (who was a silent film star and a member of one of Moscow’s most prominent stage actor families) found her surrounded by a crowd of fascinated onlookers who were enjoying little Maya’s impromptu dance number.

The girl’s aunt, the Bolshoi star Sulamith Messerer, gave young Maya her first ballet lessons and choreographed her first production of The Dying Swan when she was seven – and even at that time, Messerer praised the girl’s incredibly flexible arms and her huge, dazzling dark eyes.

Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni once broke in backstage after a performance of Swan Lake, just to declare tearfully: «Actors are so poor: All we have is our facial expressions and gestures, but you, Maya, you use your whole body to act.»

A scene from Anna Karenina by Aleksandr Zarkhi

Unsurprisingly, Plisetskaya captivated the minds of numerous film directors. Her Betsy Tverskaya, as performed in the classic Soviet film Anna Karenina by Aleksandr Zarkhi, was a masterpiece of acting, rivaling her ballet roles in emotional expressiveness. And it was not her only film appearance: She also played the role of real-life Belgian singer Désirée Artôt in Tchaikovsky (1969) and the muse of Lithuanian painter Mikalojus Čiurlionis in Zodiac by Jonas Vaitkus. Later, she also gave the great Russian stage director Anatoly Efros the idea to adapt Ivan Turgenev’s Torrents of Spring as a play filmed for TV.

«It was her idea, to perform a stage role and a ballet dance in the same play… As was usual for me, I decided to say yes so as not to offend her, and cop out later on some excuse,» the director himself recalled.

«I always comply only to disappear later, but I never manage to pull it off, and it was definitely out of the question then, since it was impossible to get rid of Plisetskaya. You still think you can back out of it, but somehow you’re already on your way to the ballet school where she’s rehearsing – and how she rehearses!»

Sadly, Plisetskaya had never performed «pure» stage roles. However, she did play a white-socks-and-wooden-sandals-clad celestial fairy in Nagoromo, a Japanese Noh play.

A dance made immortal

If one were to count the number of portraits of Maya Plisetskaya in the fine arts, it would probably turn that no other performing artist has been so frequently painted and sculpted. Her expressiveness, the soft curve of her gorgeous neck, and her long, evocative arms are as easy to detect in masterpieces crafted by geniuses as they are in children’s drawings.

The ballerina once modeled for Mark Chagall, spinning in front of him barefooted to Mendelsohn’s music. Later, she recognized herself on one of the murals Chagall created for the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. «This was most certainly me – hip curved, body tilted, all tight as a string…» she wrote.

The Dying Swan as performed by Plisetskaya became symbolic in and of itself: The portrayal was immortalized in figurines by Soviet sculptor Elena Yanson-Manizer, who drew inspiration from the dancer’s performances for many years, as well as mosaics by Nadia Léger, and even graffiti by Italian artist Eduardo Kobra – one of his works even adorns a house not far from the Bolshoi Theater, in a small park recently renamed after Maya Plisetskaya.

Above: 1. Maya Plisetskaya. 2. ‘Maya Plisetskaya’ — Carving in shell by jeweler Petr Zaltsmas 3. Street mural by Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra

Below: 1. ‘Maya Plisetskaya as Carmen’ — sculpture by D.I.Narodnitsky 2. Portrait by Artur Fonvizin. 3. ‘Swan-Maya Plisetsaya’ — sculpture by Elena Yanson-Manizer

The music of love

Unlike most ballet dancers, Plisetskaya always had a good standing with poets, writers, artists, and musicians, even when she was quite young.

«Today I was at Lilya Brik’s. They invited Gérard Philipe with his wife and Georges Sadoul over. Everyone was very nice and friendly. The couple regretted they had not had an opportunity to see me perform, but I ‘comforted’ them by giving them my photos with some inscriptions (the photos were quite bad since I didn’t have any good ones). There were no other guests (just Shchedrin, the composer),» the ballerina wrote in 1955, describing an evening at Brik’s that Rodion Shchedrin, her future husband, spent playing his music on a Bechstein piano.

The composer himself wrote: «I heard a recording of Plisetskaya singing the music from Prokofiev’s ballet Cinderella, and I was fascinated, primarily because she was a ballerina who had a perfect ear – she reproduced all the melodies and even the supporting harmonies perfectly in the original key, and for the record, Prokofiev’s music could be quite difficult to follow at the time.»

After this aural acquaintance, and later their first meeting, it took them three years to fall in love with each other. Shchedrin’s ballets written for her – like Anna Karenina, The Seagull, and The Lady with the Lapdog, all of which were not just about their respective characters but about Maya Plisetskaya as well – became an integral part of her repertoire.

Maya Plisetskaya and her husband Rodion Schedrin

‘I am galloping through my life’

The Swan – just like Carmen later — became one of Maya Plisetskaya’s trademarks. The iconic character of a strong and fearless bird – proud, lonely and resilient – inspired not only artists, but also poets, with endless lines, extraordinary and amateur alike, dedicated to it.

Incidentally, the ballerina’s own literary talent was considerable – in fact, she could well give a professional writer a run for his money. She wrote two books, I Am Maya Plisetskaya and Thirteen Years Later. Both of them became bestsellers – and not just because of her fame, but also thanks to her impeccable style.

«I am galloping through my life, through my whole hectic life. It becomes increasingly clear that it will be impossible for me to fully describe my experiences. There are only fragments. Blurred silhouettes. Shadows… Did it really happen? Yes, it did…

«Premieres, flowers, struggles, rushes and excursions, disappointments, outbursts, encounters, parties, luggage bags, and the everyday battles…

«What would you like to know about me, my dear reader?

«Is it the fact that I am left-handed and do everything with my left hand? That I only use my right hand to write, and can only write with my left hand in the opposite direction, in an inverted manner?

«Or is it the fact that I have always been confrontational? That I used to look for trouble, often to no particular purpose? I could offend people just because, without thinking, without any reasons. And later, I felt remorse…

«Or maybe that I combined the opposites, that I could be both wasteful and greedy, both brave and cowardly, both a queen and a shy little girl?

«Or that I had a collection of funny surnames, gathering clippings with those from all the print media I could find? That I was as stupidly gullible as I was stupidly impatient – I have never been capable of waiting… I was blunt and impulsive… So, is this just nonsense, trifles? Or do these trifles complement my persona?»

The style queen

Left: Plisetskaya and Yves Saint Laurent; Above right: Plisetskaya and Pierre Cardin

In an era when each and every Soviet woman was supposed to sport a jolly calico dress, Plisetskaya managed to be stunningly flamboyant. She was the first Soviet ballerina to come back from an international tour with elastic leotards for ballet classes and bags full of luxury fabrics for tutus.

During her stay in Paris, she was acquainted with the latest fashion trends by writer Elsa Triolet, the wife of Louis Aragon and Lilya Brik’s sister. Coco Chanel once invited her to her fashion house and offered her any outfit from her latest collection.

Yves Saint Laurent and Jean Paul Gaultier created clothes for her. In the 1960s, she donned furs and jewels to model for famous fashion photographers like Richard Avedon and Sir Cecil Beaton.

At the 1971 Avignon Festival, Nadia Léger introduced Plisetskaya to Pierre Cardin.

«I saw her in Carmen, and I fell in love with her,» the fashion designer later said.

The ballerina became Cardin’s muse for years to come. He created over 30 dresses for her specifically, asking nothing in return but some friendly disposition. And she stayed loyal to him, impressing the public with his incredible dresses with trains.

«It’s not like I am too faithful, it’s just that he is a genius. Cardin was the one to create my outfits for stage and film – and these were truly gifts fit for a queen!» she used to say. These fabulous outfits are now kept in Moscow’s Bakhrushin Museum. In 1998, Plisetskaya and Cardin presented a joint show dubbed «Fashion and Dance» in the Kremlin.

As for Soviet designers, Plisetskaya collaborated with Vyacheslav Zaitsev – she selected him to create outfits for her ballet Anna Karenina.

«Over 20 sketches were made in total,» recalled the designer. «Maya liked many of them, but Shchedrin had doubts about them. The argument eventually reached the Minister of Culture, Yekaterina Furtseva, and she demanded that I agree to a compromise. I didn’t. Pierre Cardin was hired to work on the ballet.»

Swifter, higher, stronger

People who wanted to come across Plisetskya in Munich, where she and her husband made their home several decades ago, stood a better chance of catching her at the local stadium, rather than an opera. Whenever they were in the city, the couple did not miss a single soccer match. And this was probably the only place in the world the great dancer could remain incognito.

«Football fans do not know me,» she said. «I love football, but this love is one-sided.» The ballerina had always been a fan of sports. «All this is delightful. It is the civilization of the human body,» she explained. «And the football players are modern gladiators: They are so fantastic, so powerful, and what technique they possess!»

In Soviet times, she was an avid fan of the CSKA Moscow soccer club. In an album dedicated to the ballerina by Pierre Cardin, there is a photo of her with legendary French attacking midfielder Michel Platini. She passionately argued that the impact of sports could be felt even in ballet. And, remembering Pelé’s words about how footballers had not had modern techniques back in his time, Plisetskaya said ballet had advanced along the same path and modern styles had not been seen in her time either.

Share the story with your friends:

Text by Anna Galayda

Edited by Oleg Krasnov and Alastair Gill

Photo credits: Mikhail Pochuev, Nikolay Kuleshov, Vladimir Kiselev/TASS; Alexander Makarov, V.Malyshev, Dmitry Donskoy, A. Knyayev, Vladimir Rodionov, Igor Mikhalev, Sergey Pyatakov/RIA Novosti; Corbis/East News; Getty Images.

Photo edited by Slava Petrakina

Design and layout by Ekaterina Chipurenko.

© 2015 All Right Reserved. Russia Beyond The Headlines.

info@rbth.com

Инфоурок

›

Другое

›Презентации›Презентация по английскому языку на тему » Человек, оставивший след в истории. Майя Плисецкая.»

Презентация по английскому языку на тему » Человек, оставивший след в истории. Майя Плисецкая.»

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 95 человек из 43 регионов

- Курс добавлен 18.10.2022

- Сейчас обучается 24 человека из 20 регионов

- Сейчас обучается 144 человека из 48 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Maya Plisetskaya

(20 November 1925 – 2 May 2015) -

2 слайд

Her father, Mikhail Plisetsky, was a famous engineer and communist who held a senior position in the country’s coal industry.

Her mother, Rakhil Messerer, was a film actor.Family

-

3 слайд

In 1932 her family lived in Svalbard (Spitsbergen )

Maya Plisetskaya`s career started in that island. Her debute took place in the opera Rusalka by Dargomyzhsky. -

4 слайд

In 1934 Plisetskaya entered the Bolshoi Ballet School.

Plisetskaya was known for the height of her jumps, her extremely flexible back, the technical strength of her dancing, and her charisma.

Plisetskaya studied ballet from age nine and first performed at the Bolshoi Theatre when she was eleven.Education

-

5 слайд

Maya Plisetskaya developed her own style of dancing.

She is an author of such element as «jump rings».

In 1960 she became a prima-ballerina of the Bolshoi Theatre. -

6 слайд

She created a number of leading roles

Lavrovsky’s Stone Flower , Moiseyev’s Spartacus, Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty , the title role in Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite, Odette-Odile in Swan Lake. -

7 слайд

She performed in a number of countries.

Petit’s La Rose malade (Paris, 1973), Bejart’s Isadora (Monte Carlo, 1976) and his Moscow staging of Leda (1979), Granero’s Maria Estuardo (Madrid, 1988), and Lopez’s El Renedero (Buenos Aires, 1990) -

8 слайд

She retired as a soloist for the Bolshoi at age 65

Since 1994, she has presided over the annual international ballet competitions, called Maya.

in 1996 she was named President of the Imperial Russian Ballet. -

9 слайд

Besides her career as a ballet dancer she was a good actress: the film «Anna Karenina»

She was a choreographer in some plays such as «Anna Karenina», «The Seagull», «The lady with the dog» -

10 слайд

Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra painted Plisetskaya in 2013.

Conductor and artistic director Valery Gergiev gave a concert in Moscow on November 18 2015, dedicated to her memory.

On November 20, 2015, the government of Russia named a square in her honor in central Moscow. -

11 слайд

If you want to learn more about Maya Plisetskaya’s biography and her artistic creation you can watch documentary films about her life.For example «Portraits of the Epoque».

If you want to find her as an actress you can watch «Anna Karenina», «The lady with the dog»

If you want to enjoy her dancing you can watch her best performances.“In art it doesn’t matter «what». It is more important «how» ” .

-

12 слайд

What were her parents?

How did Maya Plisetskaya’s career start?

What performances did she take part in?

What did she do besides ballet?

How can we learn about her life?Questions

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 056 432 материала в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 28.12.2015

- 631

- 0

- 28.12.2015

- 420

- 0

Рейтинг:

5 из 5

- 28.12.2015

- 4074

- 59

- 28.12.2015

- 437

- 0

- 28.12.2015

- 897

- 0

- 28.12.2015

- 1153

- 0

- 28.12.2015

- 992

- 3

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Испанский язык: теория и методика обучения иностранному языку в образовательной организации»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Специфика преподавания испанского языка с учетом требований ФГОС»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Теория и методика преподавания иностранных языков в профессиональном образовании: английский, немецкий, французский»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Теория и методика преподавания иностранных языков в начальной школе»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация кросс-культурной адаптации иностранных студентов в образовательных организациях в сфере профессионального образования»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Специфика преподавания русского языка как иностранного»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация деятельности секретаря руководителя со знанием английского языка»

-

Настоящий материал опубликован пользователем Мишуренкова Ольга Владиславовна. Инфоурок является

информационным посредником и предоставляет пользователям возможность размещать на сайте

методические материалы. Всю ответственность за опубликованные материалы, содержащиеся в них

сведения, а также за соблюдение авторских прав несут пользователи, загрузившие материал на сайтЕсли Вы считаете, что материал нарушает авторские права либо по каким-то другим причинам должен быть удален с

сайта, Вы можете оставить жалобу на материал.Удалить материал

-

- На сайте: 7 лет и 3 месяца

- Подписчики: 0

- Всего просмотров: 106566

-

Всего материалов:

36

- Текст

- Веб-страница

Майя Михайловна Плисецкая родилась

Майя Михайловна Плисецкая родилась 20 ноября 1925 в Москве в семье известного советского хозяйственного деятеля Михаила Эммануиловича Плисецкого и актрисы немого кино Рахили Михайловны Мессерер. Была старшей из троих детей — артистка балета, представительница театральной династии Мессерер — Плисецких, прима-балерина Большого театра СССР в 1948—1990 годах. Герой Социалистического Труда (1985), народная артистка СССР (1959)[2]. Полный кавалер ордена «За заслуги перед Отечеством», лауреат премии Анны Павловой Парижской академии танца (1962), Ленинской премии (1964) и множества других наград и премий[⇨], почётный доктор университета Сорбонны, почётный профессор МГУ имени М. В. Ломоносова, почётный гражданин Испании. Всего имеет около 50 орденов и премий.

В октябре 2013 года бразильские художники Эдуардо Кобра и Агналдо Брито посвятили Майе Плисецкой одну из своих работ. Граффити длиной 16 м и шириной 18 м, включающее в себя изображение балерины в образе лебедя, находится на стене дома в Москве по адресу Большая Дмитровка, д. 16, к. 1

Майя Михайловна Плисецкая скончалась 2 мая 2015 года в Мюнхене на 90-м году жизни от обширного инфаркта миокарда. Согласно завещанию, прах Плисецкой будет соединён воедино с прахом Родиона Щедрина после его смерти и развеян над Россией.

0/5000

Результаты (английский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya was born November 20, 1925 in Moscow in the family of famous Soviet economic figure Mikhail Èmmanuiloviča Pliseckogo and silent film actress Rachel Mikhailovna Messerer. Was the eldest of three children, Ballet, theatrical dynasty Messerer-Pliseckih, prima ballerina of the Bolshoi Theatre in 1948-1990. Hero of Socialist Labor (1985), people’s artist of the USSR (1959) [2]. Full Cavalier of the order of merit for the fatherland, Anna Pavlova Prize laureate of the Paris Academy of dance (1962), Lenin Prize (1964) and many other awards and prizes [⇨], honorary doctor of Sorbonne University, Honorary Professor of MOSCOW STATE UNIVERSITY named after m. v. Lomonosov Moscow State University, honorary citizen of Spain. Only has about 50 orders and awards.In October 2013 year Brazilian artists Eduardo Cobra and Agnaldo Brito dedicated Maya Plisetskaya one of her works. Graffiti with a length of 16 meters and a width of 18 m, which includes the image of a ballerina in the guise of a Swan, is on the wall at home in Moscow at Bolshaya Dmitrovka Street, д. 16, c. 1Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya died on May 2, 2015 years in Munich at the 90-year life of a massive heart attack. According to his will, his ashes will be connected together with Plisetskaya ashes Rodion Shchedrin after his death and scattered over Russia.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (английский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Maya Plisetskaya was born November 20, 1925 in Moscow in a family of well-known Soviet economic leader Mikhail Plisetski and silent film actress Rachel Mikhailovna Messerer. Was the eldest of three children — ballet dancer, a spokeswoman for the theatrical dynasty Messerer — Plisetskaya prima ballerina of the Bolshoi Theater in the 1948-1990 years. Hero of Socialist Labor (1985), People’s Artist of the USSR (1959). [2] Holders of the Order «For Merit», winner of the Anna Pavlova Prize of the Paris Academy of Dance (1962), Lenin Prize (1964) and many other awards [⇨], Honorary Doctor of the University of the Sorbonne, honorary professor of Moscow State University named after MV Lomonosov , an honorary citizen of Spain. Total has about 50 awards and prizes.

In October 2013, Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra and Agnaldo Brito dedicated to Maya Plisetskaya one of his works. Graffiti length of 16 m and a width of 18 m, including a ballerina image in the form of a swan, is on the wall of a house in Moscow at Bolshaya Dmitrovka, d. 16, k. 1

Maya Plisetskaya died on May 2, 2015 in Munich on the 90th year life of a massive heart attack. According to the will, Plisetskaya’s ashes will be connected together with the ashes of Rodion Shchedrin after his death and scattered over Russia.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- Bene audi, quod dicunt

- Эти два мальчика родственники?

- поговорить по душам

- ангел хранитель всегда со мной

- поговорить по душам

- fini filtrare

- La bella vita

- What’s Paco’s school day like? When does

- прими настойку валерианы

- Jane and Teds brother is ten

- Cambridge — Nuremburg. joss Langford, 29

- Jane and Teds brother is ten

- What is your fathers job?

- Мен сени кызганам

- hydrogen concentration is set within the

- Library

- senza necessità di modifica dei patti so

- So Many Men so Many Minds. Alexander’s f

- можно ли у вас заказать такой кабель дли

- Его вклад в науку не оценили

- Scitisne theatrum novum in campo Martio

- Эти два мальчика родственники?

- Disce miscere

- Postgraduate

Содержимое разработки

Maya Plisetskaya

Автор: Ярочкина В.В.

- The main difference between the art of the actor and all other arts is that every other [non-performing] artist may create whenever he is in the mood of inspiration. But the artist of the stage must be the master of his own inspiration, and must know how to call it forth at the hour announced on the posters of the theatre. This is the chief secret of our art . Constantin Stanislavski

Theatre

- One of the wonderful ancient kinds of art is theatre. Theatre is a kind of art which consist of many other kinds such as literature, music,choreography, singing, visual art and so on.

- Theatre differs from other kinds of art in that it has ist own peculiarities. Here the centre of all that happens is an actor.

- An actor expresses the dramatic nature of the performance.

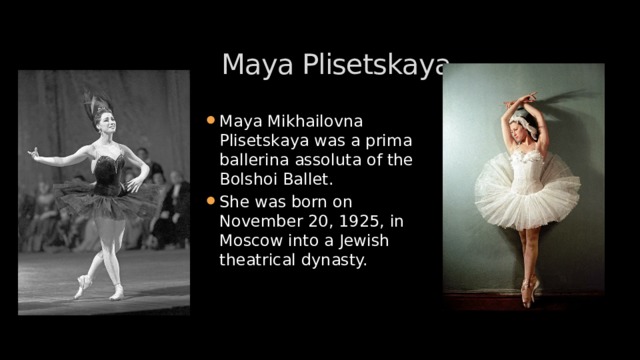

Maya Plisetskaya

- Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya was a prima ballerina assoluta of the Bolshoi Ballet.

- She was born on November 20, 1925, in Moscow into a Jewish theatrical dynasty.

- Her father, Mikhail Plisetsky, was a famous engineer and communist.

- For over 70 years the Messerer family(mother’s family) played a prominent part in the Soviet theater and films, as well as in the ballet world.

- Her mother, Rakhil Messerer, was a well-known silent-film actress .

- Maya’s brother Azari became a dancer.

- Her Aunt Elizaveta was an actress in Moscow.

- Maya’s cousin Boris was a distinguished set designer.

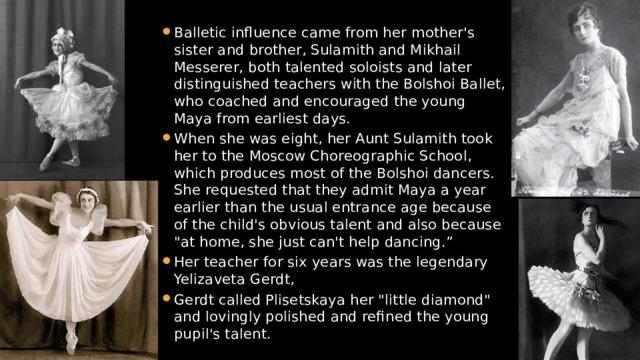

- Balletic influence came from her mother’s sister and brother, Sulamith and Mikhail Messerer, both talented soloists and later distinguished teachers with the Bolshoi Ballet, who coached and encouraged the young Maya from earliest days.

- When she was eight, her Aunt Sulamith took her to the Moscow Choreographic School, which produces most of the Bolshoi dancers. She requested that they admit Maya a year earlier than the usual entrance age because of the child’s obvious talent and also because «at home, she just can’t help dancing.”

- Her teacher for six years was the legendary Yelizaveta Gerdt,

- Gerdt called Plisetskaya her «little diamond» and lovingly polished and refined the young pupil’s talent.

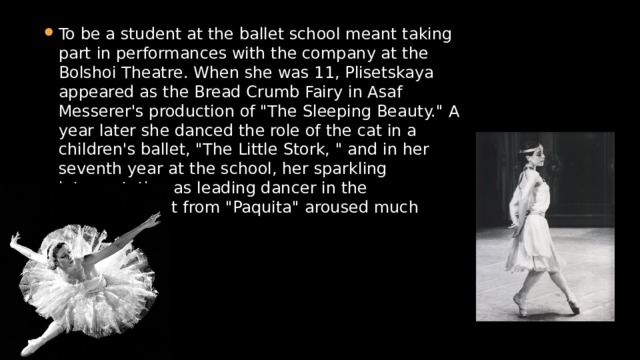

- To be a student at the ballet school meant taking part in performances with the company at the Bolshoi Theatre. When she was 11, Plisetskaya appeared as the Bread Crumb Fairy in Asaf Messerer’s production of «The Sleeping Beauty.» A year later she danced the role of the cat in a children’s ballet, «The Little Stork, » and in her seventh year at the school, her sparkling interpretation as leading dancer in the divertissement from «Paquita» aroused much interest.

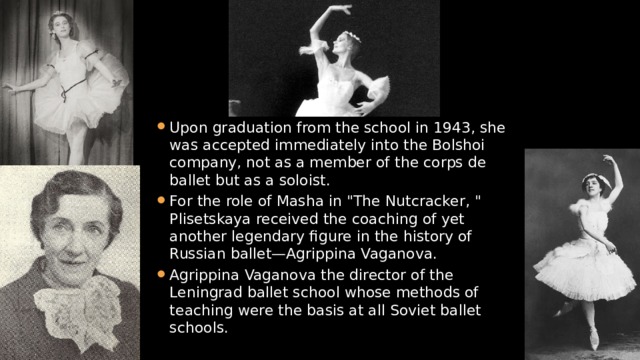

- Upon graduation from the school in 1943, she was accepted immediately into the Bolshoi company, not as a member of the corps de ballet but as a soloist.

- For the role of Masha in «The Nutcracker, » Plisetskaya received the coaching of yet another legendary figure in the history of Russian ballet—Agrippina Vaganova.

- Agrippina Vaganova the director of the Leningrad ballet school whose methods of teaching were the basis at all Soviet ballet schools.

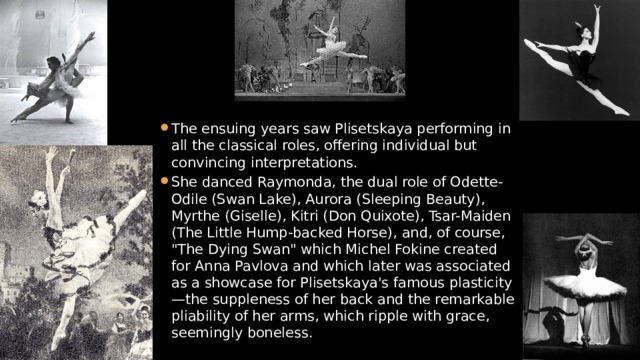

- The ensuing years saw Plisetskaya performing in all the classical roles, offering individual but convincing interpretations.

- She danced Raymonda, the dual role of Odette-Odile (Swan Lake), Aurora (Sleeping Beauty), Myrthe (Giselle), Kitri (Don Quixote), Tsar-Maiden (The Little Hump-backed Horse), and, of course, «The Dying Swan» which Michel Fokine created for Anna Pavlova and which later was associated as a showcase for Plisetskaya’s famous plasticity—the suppleness of her back and the remarkable pliability of her arms, which ripple with grace, seemingly boneless.

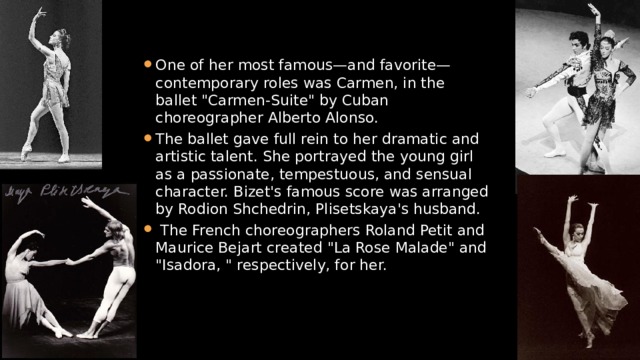

- One of her most famous—and favorite—contemporary roles was Carmen, in the ballet «Carmen-Suite» by Cuban choreographer Alberto Alonso.

- The ballet gave full rein to her dramatic and artistic talent. She portrayed the young girl as a passionate, tempestuous, and sensual character. Bizet’s famous score was arranged by Rodion Shchedrin, Plisetskaya’s husband.

- The French choreographers Roland Petit and Maurice Bejart created «La Rose Malade» and «Isadora, » respectively, for her.

- Another facet of Plisetskaya’s talent was her choreography.

- Her ballets «Anna Karenina, » «The Seagull» and «Lady with a Lapdog» are all based on Russian literature with music especially composed by Shchedrin and created as vehicles for her own star quality.

- Plisetskaya won the top civilian award, the Lenin Prize, in 1964 and the French Pavlova Prize in 1962.

- She taught master classes in many cities, including New York, and was the artistic director of The National Ballet of Spain beginning of 1988.

- After her departure from the Bolshoi Ballet, Plisetskaya continued to astound audiences world wide.

- She was accorded one of the highest tributes that a dancer could receive, an international ballet competition was named for her in 1994.

- When most prima ballerinas would have long retired, Plisetskaya continued to perform on stage. In 1996, at age seventy, she received rave reviews for her remarkable performance of her signature «The Dying Swan» at New York City Hall.

- In 2005 Plisetskaya received Spain’s Prince of Asturias Award for the arts, and the following year she was granted the Japan Art Association’s Praemium Imperiale prize for theatre or film.

- Maya Plisetskaya died in 2015.

- Conductor and artistic director Valery Gergiev gave a concert in Moscow on November 18 2015, dedicated to her memory. On November 20, 2015, the government of Russia named a square in her honor in central Moscow.

Thank you for attention

Reference list:

- https :// www . britannica . com / biography / Maya — Plisetskaya

- https://biography.yourdictionary.com/maya-mikhailovna-plisetskaya

- Internet resources

-80%

Скачать разработку

Сохранить у себя:

Похожие файлы

-

Future for mankind_Starlight 11

-

Survival_Starlight 11

-

Контрольная работа по английскому языку для 5 класса по теме «Здоровье»

-

Творческий проект « Живая лексика интернета ».

-

Презентация на повторение по материалам Spotlight 5 «Game on»

Вы смотрели

Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya (Майя Михайловна Плисецкая, scientific transliteration: Majja Michajlovna Pliseckaja), born is a Russian ballet dancer, frequently cited as one of the greatest ballerinas of the 20th century. Maya danced during the Soviet era at the same time as the great Galina Ulanova, and took over from her as prima ballerina assoluta of the Bolshoi in 1960. Maya Plisetskaya is a naturalized Spanish and Lithuanian citizen.

Contents

- 1 Early life

- 2 Career

- 3 Awards and honors

- 4 External links

Early life

Maya Plisetskaya was born in Moscow into a prominent Jewish family. She went to school in Spitsbergen, where her father worked as an engineer and mine director.

In 1938, her father, Michael Plisetski was executed during the Stalinist purges, possibly because he had hired a friend who had been a secretary to Leon Trotsky. Her mother Rachel Messerer-Plisetskaya (aka Ra Messerer), a silent-film actress, was arrested and sent to a labor camp (Gulag) in Kazakhstan, together with Maya’s seven-month old baby brother. Thereupon Maya was adopted by her maternal aunt, the ballerina Sulamith Messerer, until her mother was released in 1941.

Maya studied under the great ballerina of imperial school, Elizaveta Gerdt. She first performed at the Bolshoi Theatre when she had just turned 11 years of age. In 1943, she graduated from the choreographic school and joined the Bolshoi Ballet, where she would perform until 1990.

Career

From the beginning, Maya was a different kind of ballerina. She spent very short time in the corps de ballet after graduation and was quickly named a soloist. Her bright red hair and striking looks made her a glamorous figure on and off the stage. Her long arms had a fluidity that to this day remains unmatched; her interpretation of The Dying Swan, a short showcase piece made famous by Anna Pavlova, became Maya’s calling card. Maya was known for the height of her jumps, her extremely flexible back, the technical strength of her dancing, and her charisma. She excelled both in adagio and allegro, which is very unusual in dancers.

Despite her acclaim, Maya was not treated well by the Bolshoi management. She was Jewish in an anti-Semitic climate, her family had been purged during the Stalinist era and her personality was defiant, so she was not allowed to tour outside the country for six years after joining the Bolshoi. It wasn’t until 1959 that Nikita Khrushchev permitted her to travel abroad, and Plisetskaya could tour internationally. Her ability changed the world of ballet, setting a higher standard for ballerinas both in terms of technical brilliance and dramatic presence.

Maya’s most acclaimed roles included Odette-Odile in Swan Lake (1947) and Aurora in Sleeping Beauty (1961). In 1958, she was honoured with the title of the People’s Artist of the USSR and married the young composer Rodion Shchedrin, in whose subsequent fame she shared.

After Galina Ulanova left the stage in 1960, Maya Plisetskaya was proclaimed the prima ballerina assoluta of the Bolshoi Theatre. In the Soviet screen version of Anna Karenina, she played Princess Tverskaya. In 1971, her husband the composer Rodion Shchedrin wrote a ballet on the same subject, where she would play the leading role. Anna Karenina was also her first attempt at choreography. Other choreographers who created ballets for her include Yury Grigorovich, Roland Petit, Alberto Alonso, and Maurice Béjart with «Isadora».