Иллюстрации Е.Д. Шавиковой

© Матвеев С.А., адаптация текста, коммент., упражнения и словарь, 2019

© Шавикова Е.Д., иллюстрации

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2019

1

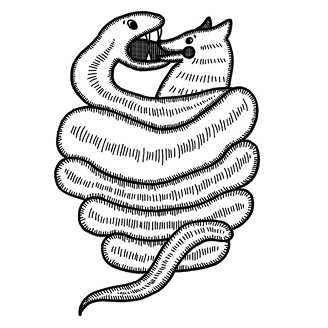

Once when I was six years old I saw a magnificent picture in a book, called True Stories from Nature, about the primeval forest. It was a picture of a boa which was swallowing an animal. Here is a copy of the drawing:

In the book it said: “Boas swallow their prey whole, they do not chew it. After that they are not able to move, and they sleep through the six months that they need for digestion.”

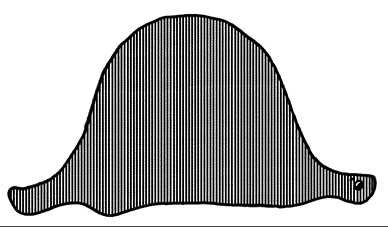

I thought about it. And then I made my first drawing. My Drawing Number One. It looked like this:

I showed my masterpiece to the grown-ups, and asked them whether the drawing frightened them.

But they answered: “Frighten? Why can anyone be frightened by a hat?”

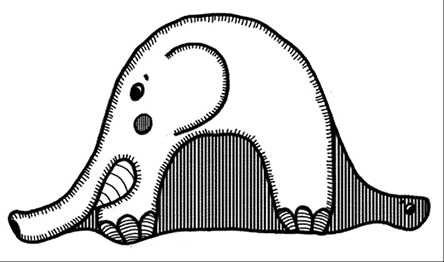

My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa which was digesting an elephant. But the grown-ups were not able to understand it. They always needed explanations. So I made another drawing: I drew the inside of the boa. This time the grown-ups could see it clearly. My Drawing Number Two looked like this:

The grown-ups advised me not to draw the boas from the inside or the outside, and study geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar. That is why, at the age of six, I stopped drawing. So I did not become a famous painter. I was disheartened by the failure of my Drawing Number One and my Drawing Number Two. Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is tiresome for children to explain things to them all the time.

So I chose another profession, and became a pilot. I flew over all parts of the world; and it is true that geography was very useful to me. Now I can distinguish China from Arizona.

I have met many people. I lived among grownups. I saw them intimately, and that did not improve my opinion of them.

When I met one of them who seemed clever enough to me, I tried to show him my Drawing Number One. I tried to learn, so, if this person had true understanding. But he—or she—always said,

“That is a hat.”

Then I did not talk to that person about boas, or forests, or stars. I talked to him about bridge, and golf, and politics, and ties.

↺

Once when I was six years old I saw a magnificent picture in a book, called True Stories from Nature, about the primeval forest.

> — Когда мне было шесть лет, в книге под названием «Правдивые истории», где рассказывалось про девственные леса, я увидел однажды удивительную картинку.

↺

It was a picture of a boa constrictor in the act of swallowing an animal.

На картинке огромная змея — удав — глотала хищного зверя.

↺

Here is a copy of the drawing.

Вот как это было нарисовано:

↺

In the book it said:

В книге говорилось:

↺

«Boa constrictors swallow their prey whole, without chewing it.

«Удав заглатывает свою жертву целиком, не жуя.

↺

After that they are not able to move, and they sleep through the six months that they need for digestion.»

После этого он уже не может шевельнуться и спит полгода подряд, пока не переварит пищу».

↺

I pondered deeply, then, over the adventures of the jungle. And after some work with a colored pencil I succeeded in making my first drawing.

Я много раздумывал о полной приключений жизни джунглей и тоже нарисовал цветным карандашом свою первую картинку.

↺

My Drawing Number One.

Это был мой рисунок №1.

↺

It looked something like this:

Вот что я нарисовал:

↺

I showed my masterpiece to the grown-ups, and asked them whether the drawing frightened them.

Я показал мое творение взрослым и спросил, не страшно ли им.

↺

But they answered: «Frighten? Why should any one be frightened by a hat?»

— Разве шляпа страшная? — возразили мне.

↺

My drawing was not a picture of a hat.

А это была совсем не шляпа.

↺

It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant.

Это был удав, который проглотил слона.

↺

But since the grown-ups were not able to understand it, I made another drawing: I drew the inside of a boa constrictor, so that the grown-ups could see it clearly.

Тогда я нарисовал удава изнутри, чтобы взрослым было понятнее.

↺

They always need to have things explained.

Им ведь всегда нужно все объяснять.

↺

My Drawing Number Two looked like this:

Вот мой рисунок №2:

↺

The grown-ups’ response, this time, was to advise me to lay aside my drawings of boa constrictors, whether from the inside or the outside, and devote myself instead to geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar.

Взрослые посоветовали мне не рисовать змей ни снаружи, ни изнутри, а побольше интересоваться географией, историей, арифметикой и правописанием.

↺

That is why, at the age of six, I gave up what might have been a magnificent career as a painter.

Вот как случилось, что шести лет я отказался от блестящей карьеры художника.

Для перехода между страницами книги вы можете использовать клавиши влево и вправо на клавиатуре.

Конец

Книга закончилась. Надеемся, Вы провели время с удовольствием!

Поделитесь, пожалуйста, своими впечатлениями:

Оглавление:

-

To Leon Werth

1

-

I

1

-

II

1

-

III

1

-

IV

2

-

V

2

-

VI

3

-

VII

3

-

VIII

4

-

IX

4

-

X

4

-

XI

5

-

ХII

5

-

XIII

6

-

XIV

6

-

XV

7

-

XVI

7

-

ХVII

7

-

XVIII

8

-

XIX

8

-

ХX

8

-

XXI

8

-

XXII

9

-

XXIII

9

-

ХXIV

9

-

XXV

10

-

XXVI

10

-

XXVII

11

Настройки:

Ширина: 100%

Выравнивать текст

-

Главная

-

Книги

-

Авторы

-

Антуан де Сент-Экзюпери

-

Маленький принц

-

Стр. 1/66

Once

when

I

was

six

I

saw

a

magnificent

picture

in

a

book

about

the

jungle

,

called

True

Stories

.

It

showed

a

boa

constrictor

swallowing

a

wild

beast

.

Here

is

a

copy

of

the

picture

.

In

the

book

it

said

:

»

Boa

constrictors

swallow

their

prey

whole

,

without

chewing

.

Afterward

they

are

no

longer

able

to

move

,

and

they

sleep

for

six

months

they

need

for

digestion

.

»

In

those

days

I

thought

a

lot

about

jungle

adventures

,

and

eventually

managed

to

make

my

first

drawing

,

with

a

colored

pencil

.

My

drawing

Number

One

looked

like

this

:

I

showed

the

grown-ups

my

masterpiece

,

and

I

asked

them

if

my

drawing

scared

them

.

They

answered

,

»

Why

should

anyone

be

scared

of

a

hat

?

»

My

drawing

was

not

a

picture

of

a

hat

.

It

was

a

picture

of

a

boa

constrictor

digesting

an

elephant

.

Then

I

drew

the

inside

of

the

boa

constrictor

,

so

the

grown-ups

could

understand

.

They

always

need

explanations

.

My

drawing

Number

Two

looked

like

this

:

The

grown-ups

advised

me

to

put

away

my

drawings

of

boa

constrictors

,

outside

or

inside

,

and

apply

myself

instead

to

geography

,

history

,

arithmetic

,

and

grammar

.

That

is

why

I

gave

up

,

at

the

age

of

six

,

a

magnificent

career

as

an

artist

.

I

had

been

discouraged

by

the

failure

of

my

drawing

Number

One

and

of

my

drawing

Number

Two

.

Grown-ups

never

understand

anything

by

themselves

,

and

it

is

exhausting

for

children

to

have

to

explain

over

and

over

again

.

So

then

I

had

to

choose

another

career

.

I

learned

to

pilot

airplanes

.

I

have

flown

almost

everywhere

in

the

world

.

And

,

as

a

matter

of

fact

,

geography

has

been

a

big

help

to

me

.

I

could

tell

China

from

Arizona

at

first

glance

,

which

is

very

useful

if

you

get

lost

during

the

night

.

TO LEON WERTH

ЛЕОНУ ВЕРТУ

I ask the indulgence of the children who may read this book for dedicating it to a grown-up. I have a serious reason: he is the best friend I have in the world. I have another reason: this grown-up understands everything, even books about children. I have a third reason: he lives in France where he is hungry and cold. He needs cheering up.

Прошу детей простить меня за то, что я посвятил эту книжку взрослому. Скажу в оправдание: этот взрослый — мой самый лучший друг. И ещё: он понимает всё на свете, даже детские книжки. И, наконец, он живёт во Франции, а там сейчас голодно и холодно. И он очень нуждается в утешении.

If all these reasons are not enough, I will dedicate the book to the child from whom this grown-up grew. All grown-ups were once children — although few of them remember it. And so I correct my dedication:

Если же всё это меня не оправдывает, я посвящу эту книжку тому мальчику, каким был когда-то мой взрослый друг. Ведь все взрослые сначала были детьми, только мало кто из них об этом помнит. Итак, я исправляю посвящение:

TO LEON WERTH WHEN HE WAS A LITTLE BOY.

ЛЕОНУ ВЕРТУ, КОГДА ОН БЫЛ МАЛЕНЬКИМ

I

ГЛАВА ПЕРВАЯ

Once when I was six years old I saw a magnificent picture in a book, called True Stories from Nature, about the primeval forest. It was a picture of a boa constrictor in the act of swallowing an animal. Here is a copy of the drawing.

Когда мне было шесть лет, в книге под названием «Правдивые истории», где рассказывалось про девственные леса, я увидел однажды удивительную картинку. На картинке огромная змея — удав — глотала хищного зверя. Вот как это было нарисовано:

In the book it said: “Boa constrictors swallow their prey whole, without chewing it. After that they are not able to move, and they sleep through the six months that they need for digestion.”

В книге говорилось: «Удав заглатывает свою жертву целиком, не жуя. После этого он уже не может шевельнуться и спит полгода подряд, пока не переварит пищу».

I pondered deeply, then, over the adventures of the jungle. And after some work with a colored pencil I succeeded in making my first drawing. My Drawing Number One. It looked something like this:

Я много раздумывал о полной приключений жизни джунглей и тоже нарисовал цветным карандашом свою первую картинку. Это был мой рисунок №1. Вот что я нарисовал:

I showed my masterpiece to the grown-ups, and asked them whether the drawing frightened them.

Я показал моё творение взрослым и спросил, не страшно ли им.

But they answered: “Frighten? Why should any one be frightened by a hat?”

— Разве шляпа страшная? — возразили мне.

My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. But since the grown-ups were not able to understand it, I made another drawing: I drew the inside of a boa constrictor, so that the grown-ups could see it clearly. They always need to have things explained. My Drawing Number Two looked like this:

А это была совсем не шляпа. Это был удав, который проглотил слона. Тогда я нарисовал удава изнутри, чтобы взрослым было понятнее. Им ведь всегда нужно всё объяснять. Это мой рисунок №2:

The grown-ups’ response, this time, was to advise me to lay aside my drawings of boa constrictors, whether from the inside or the outside, and devote myself instead to geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar. That is why, at the age of six, I gave up what might have been a magnificent career as a painter.

Взрослые посоветовали мне не рисовать змей ни снаружи, ни изнутри, а побольше интересоваться географией, историей, арифметикой и правописанием. Вот как случилось, что шести лет я отказался от блестящей карьеры художника.

I had been disheartened by the failure of my Drawing Number One and my Drawing Number Two. Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is tiresome for children to be always and forever explaining things to them.

Потерпев неудачу с рисунками №1 и №2, я утратил веру в себя. Взрослые никогда ничего не понимают сами, а для детей очень утомительно без конца им всё объяснять и растолковывать.

So then I chose another profession, and learned to pilot airplanes. I have flown a little over all parts of the world; and it is true that geography has been very useful to me.

Итак, мне пришлось выбирать другую профессию, и я выучился на лётчика. Облетел я чуть ли не весь свет. И география, по правде сказать, мне очень пригодилась.

At a glance I can distinguish China from Arizona. If one gets lost in the night, such knowledge is valuable.

Я умел с первого взгляда отличить Китай от Аризоны. Это очень полезно, если ночью собьёшься с пути.

In the course of this life I have had a great many encounters with a great many people who have been concerned with matters of consequence. I have lived a great deal among grown-ups. I have seen them intimately, close at hand. And that hasn’t much improved my opinion of them.

На своём веку я много встречал разных серьёзных людей. Я долго жил среди взрослых. Я видел их совсем близко. И от этого, признаться, не стал думать о них лучше.

Whenever I met one of them who seemed to me at all clear-sighted, I tried the experiment of showing him my Drawing Number One, which I have always kept. I would try to find out, so, if this was a person of true understanding.

Когда я встречал взрослого, который казался мне разумней и понятливей других, я показывал ему свой рисунок №1 — я его сохранил и всегда носил с собою. Я хотел знать, вправду ли этот человек что-то понимает.

But, whoever it was, he, or she, would always say: “That is a hat.”

Но все они отвечали мне: «Это шляпа».

Then I would never talk to that person about boa constrictors, or primeval forests, or stars. I would bring myself down to his level. I would talk to him about bridge, and golf, and politics, and neckties. And the grown-up would be greatly pleased to have met such a sensible man.

И я уже не говорил с ними ни об удавах, ни о джунглях, ни о звёздах. Я применялся к их понятиям. Я говорил с ними об игре в бридж и гольф, о политике и о галстуках. И взрослые были очень довольны, что познакомились с таким здравомыслящим человеком.

II

ГЛАВА II

So I lived my life alone, without anyone that I could really talk to, until I had an accident with my plane in the Desert of Sahara, six years ago.

Так я жил в одиночестве, и не с кем было мне поговорить по душам. И вот шесть лет тому назад пришлось мне сделать вынужденную посадку в Сахаре.

Something was broken in my engine. And as I had with me neither a mechanic nor any passengers, I set myself to attempt the difficult repairs all alone.

Что-то сломалось в моторе моего самолёта. Со мной не было ни механика, ни пассажиров, и я решил, что попробую сам всё починить, хоть это и очень трудно.

It was a question of life or death for me: I had scarcely enough drinking water to last a week.

Я должен был исправить мотор или погибнуть. Воды у меня едва хватило бы на неделю.

The first night, then, I went to sleep on the sand, a thousand miles from any human habitation. I was more isolated than a shipwrecked sailor on a raft in the middle of the ocean.

Итак, в первый вечер я уснул на песке в пустыне, где на тысячи миль вокруг не было никакого жилья. Человек, потерпевший кораблекрушение и затерянный на плоту посреди океана, — и тот был бы не так одинок.

Thus you can imagine my amazement, at sunrise, when I was awakened by an odd little voice. It said:

Вообразите же моё удивление, когда на рассвете меня разбудил чей-то тоненький голосок. Он сказал:

“If you please — draw me a sheep!”

— Пожалуйста… нарисуй мне барашка!

“What!”

— А?..

“Draw me a sheep!”

— Нарисуй мне барашка…

I jumped to my feet, completely thunderstruck. I blinked my eyes hard. I looked carefully all around me. And I saw a most extraordinary small person, who stood there examining me with great seriousness.

Я вскочил, точно надо мною грянул гром. Протёр глаза. Стал осматриваться. И увидел забавного маленького человечка, который серьёзно меня разглядывал.

Here you may see the best portrait that, later, I was able to make of him.

Вот самый лучший его портрет, какой мне после удалось нарисовать.

But my drawing is certainly very much less charming than its model. That, however, is not my fault. The grown-ups discouraged me in my painter’s career when I was six years old, and I never learned to draw anything, except boas from the outside and boas from the inside.

Но на моём рисунке он, конечно, далеко не так хорош, как был на самом деле. Это не моя вина. Когда мне было шесть лет, взрослые убедили меня, что художник из меня не выйдет, и я ничего не научился рисовать, кроме удавов — снаружи и изнутри.

Now I stared at this sudden apparition with my eyes fairly starting out of my head in astonishment. Remember, I had crashed in the desert a thousand miles from any inhabited region. And yet my little man seemed neither to be straying uncertainly among the sands, nor to be fainting from fatigue or hunger or thirst or fear.

Итак, я во все глаза смотрел на это необычайное явление. Не забудьте, я находился за тысячи миль от человеческого жилья. А между тем ничуть не похоже было, чтобы этот малыш заблудился, или до смерти устал и напуган, или умирает от голода и жажды.

Nothing about him gave any suggestion of a child lost in the middle of the desert, a thousand miles from any human habitation. When at last I was able to speak, I said to him:

По его виду никак нельзя было сказать, что это ребёнок, потерявшийся в необитаемой пустыне, вдалеке от всякого жилья. Наконец ко мне вернулся дар речи, и я спросил:

“But — what are you doing here?”

— Но… что ты здесь делаешь?

And in answer he repeated, very slowly, as if he were speaking of a matter of great consequence:

И он опять попросил тихо и очень серьёзно:

“If you please — draw me a sheep…”

— Пожалуйста… нарисуй барашка…

When a mystery is too overpowering, one dare not disobey. Absurd as it might seem to me, a thousand miles from any human habitation and in danger of death, I took out of my pocket a sheet of paper and my fountain-pen.

Всё это было так таинственно и непостижимо, что я не посмел отказаться. Как ни нелепо это было здесь, в пустыне, на волосок от смерти, я всё-таки достал из кармана лист бумаги и вечное перо.

But then I remembered how my studies had been concentrated on geography, history, arithmetic and grammar, and I told the little chap (a little crossly, too) that I did not know how to draw. He answered me:

Но тут же вспомнил, что учился-то я больше географии, истории, арифметике и правописанию, и сказал малышу (немножко даже сердито сказал), что не умею рисовать. Он ответил:

“That doesn’t matter. Draw me a sheep…”

— Всё равно. Нарисуй барашка.

But I had never drawn a sheep. So I drew for him one of the two pictures I had drawn so often. It was that of the boa constrictor from the outside. And I was astounded to hear the little fellow greet it with:

Так как я никогда в жизни не рисовал баранов, я повторил для него одну из двух старых картинок, которые я только и умею рисовать — удава снаружи. И очень изумился, когда малыш воскликнул:

“No, no, no! I do not want an elephant inside a boa constrictor. A boa constrictor is a very dangerous creature, and an elephant is very cumbersome. Where I live, everything is very small. What I need is a sheep. Draw me a sheep.”

— Нет, нет! Мне не надо слона в удаве! Удав слишком опасен, а слон слишком большой. У меня дома всё очень маленькое. Мне нужен барашек. Нарисуй барашка.

So then I made a drawing.

И я нарисовал.

He looked at it carefully, then he said:

Он внимательно посмотрел на мой рисунок и сказал:

“No. This sheep is already very sickly. Make me another.”

— Нет, этот барашек уже совсем хилый. Нарисуй другого.

So I made another drawing.

Я нарисовал.

My friend smiled gently and indulgently.

Мой новый друг мягко, снисходительно улыбнулся.

“You see yourself,” he said, “that this is not a sheep. This is a ram. It has horns.”

— Ты же сам видишь, — сказал он, — это не барашек. Это большой баран. У него рога…

So then I did my drawing over once more.

Я опять нарисовал по-другому.

But it was rejected too, just like the others.

Но он и от этого рисунка отказался:

“This one is too old. I want a sheep that will live a long time.”

— Этот слишком старый. Мне нужен такой барашек, чтобы жил долго.

By this time my patience was exhausted, because I was in a hurry to start taking my engine apart. So I tossed off this drawing.

Тут я потерял терпение — ведь мне надо было поскорей разобрать мотор — и нацарапал ящик.

And I threw out an explanation with it.

И сказал малышу:

“This is only his box. The sheep you asked for is inside.”

— Вот тебе ящик. А в нём сидит такой барашек, какого тебе хочется.

I was very surprised to see a light break over the face of my young judge:

Но как же я удивился, когда мой строгий судья вдруг просиял:

“That is exactly the way I wanted it! Do you think that this sheep will have to have a great deal of grass?”

— Вот это хорошо! Как ты думаешь, много этому барашку надо травы?

“Why?”

— А что?

“Because where I live everything is very small…”

— Ведь у меня дома всего очень мало…

“There will surely be enough grass for him,” I said. “It is a very small sheep that I have given you.”

— Ему хватит. Я тебе даю совсем маленького барашка.

He bent his head over the drawing.

“Not so small that — Look! He has gone to sleep…”

— Не такой уж он маленький… — сказал он, наклонив голову и разглядывая рисунок. — Смотри-ка! Он уснул…

And that is how I made the acquaintance of the little prince.

Так я познакомился с Маленьким принцем.

III

ГЛАВА III

It took me a long time to learn where he came from. The little prince, who asked me so many questions, never seemed to hear the ones I asked him.

Не скоро я понял, откуда он явился. Маленький принц засыпал меня вопросами, но когда я спрашивал о чём-нибудь, он словно и не слышал.

It was from words dropped by chance that, little by little, everything was revealed to me. The first time he saw my airplane, for instance (I shall not draw my airplane; that would be much too complicated for me), he asked me:

Лишь понемногу, из случайных, мимоходом оброненных слов мне всё открылось. Так, когда он впервые увидел мой самолёт (самолёт я рисовать не стану, мне всё равно не справиться), он спросил:

“What is that object?”

— Что это за штука?

“That is not an object. It flies. It is an airplane. It is my airplane.”

— Это не штука. Это самолёт. Мой самолёт. Он летает.

And I was proud to have him learn that I could fly. He cried out, then:

И я с гордостью объяснил ему, что умею летать. Тогда он воскликнул:

“What! You dropped down from the sky?”

— Как! Ты упал с неба?

“Yes,” I answered, modestly.

— Да, — скромно ответил я.

“Oh! That is funny!”

— Вот забавно!..

And the little prince broke into a lovely peal of laughter, which irritated me very much. I like my misfortunes to be taken seriously. Then he added:

И Маленький принц звонко засмеялся, так что меня взяла досада: я люблю, чтобы к моим злоключениям относились серьёзно. Потом он прибавил:

“So you, too, come from the sky! Which is your planet?”

— Значит, ты тоже явился с неба. А с какой планеты?

At that moment I caught a gleam of light in the impenetrable mystery of his presence; and I demanded, abruptly:

«Так вот разгадка его таинственного появления здесь, в пустыне!» — подумал я и спросил напрямик:

“Do you come from another planet?”

— Стало быть, ты попал сюда с другой планеты?

But he did not reply. He tossed his head gently, without taking his eyes from my plane:

Но он не ответил. Он тихо покачал головой, разглядывая мой самолёт:

“It is true that on that you can’t have come from very far away…”

— Ну, на этом ты не мог прилететь издалека…

And he sank into a reverie, which lasted a long time. Then, taking my sheep out of his pocket, he buried himself in the contemplation of his treasure.

И надолго задумался о чём-то. Потом вынул из кармана моего барашка и погрузился в созерцание этого сокровища.

You can imagine how my curiosity was aroused by this half-confidence about the “other planets.” I made a great effort, therefore, to find out more on this subject.

Можете себе представить, как разгорелось моё любопытство от этого полупризнания о «других планетах». И я попытался разузнать побольше:

“My little man, where do you come from? What is this ‘where I live,’ of which you speak? Where do you want to take your sheep?”

— Откуда же ты прилетел, малыш? Где твой дом? Куда ты хочешь унести моего барашка?

After a reflective silence he answered:

Он помолчал в раздумье, потом сказал:

“The thing that is so good about the box you have given me is that at night he can use it as his house.”

— Очень хорошо, что ты дал мне ящик: барашек будет там спать по ночам.

“That is so. And if you are good I will give you a string, too, so that you can tie him during the day, and a post to tie him to.”

— Ну конечно. И если ты будешь умницей, я дам тебе верёвку, чтобы днём его привязывать. И колышек.

But the little prince seemed shocked by this offer:

Маленький принц нахмурился:

“Tie him! What a queer idea!”

— Привязывать? Для чего это?

“But if you don’t tie him,” I said, “he will wander off somewhere, and get lost.”

— Но ведь если ты его не привяжешь, он забредёт неведомо куда и потеряется.

My friend broke into another peal of laughter:

Тут мой друг опять весело рассмеялся:

“But where do you think he would go?”

— Да куда же он пойдёт?

“Anywhere. Straight ahead of him.”

— Мало ли куда? Всё прямо, прямо, куда глаза глядят.

Then the little prince said, earnestly:

Тогда Маленький принц сказал серьёзно:

“That doesn’t matter. Where I live, everything is so small!”

— Это не страшно, ведь у меня там очень мало места.

And, with perhaps a hint of sadness, he added:

И прибавил не без грусти:

“Straight ahead of him, nobody can go very far…”

— Если идти всё прямо да прямо, далеко не уйдёшь…