Not to be confused with Magnesium (Mg).

Pure manganese cube and oxidized manganese chips |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manganese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (MANG-gə-neez) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Mn) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manganese in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

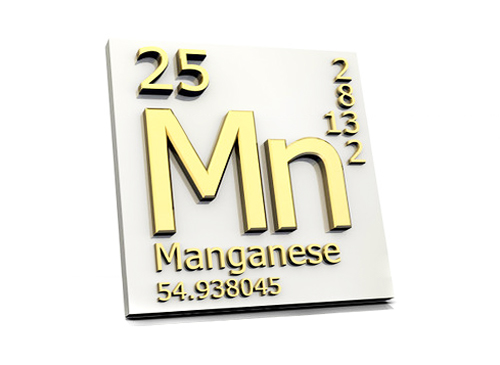

| Atomic number (Z) | 25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d5 4s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 13, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1519 K (1246 °C, 2275 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2334 K (2061 °C, 3742 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 7.21 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 5.95 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 12.91 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 221 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.32 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

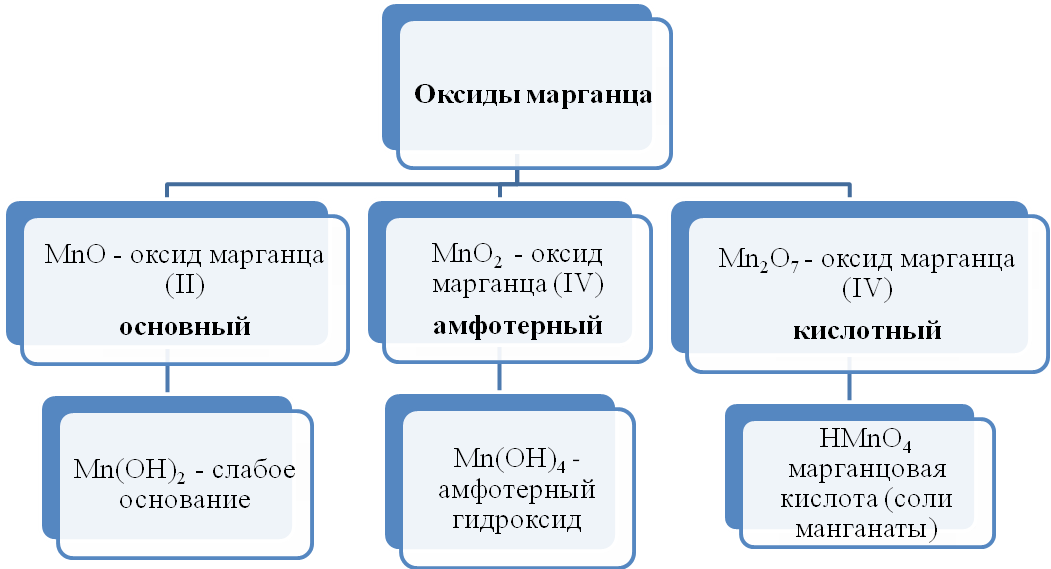

| Oxidation states | −3, −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6, +7 (depending on the oxidation state, an acidic, basic, or amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.55 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 127 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | Low spin: 139±5 pm High spin: 161±8 pm |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of manganese |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 5150 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 21.7 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 7.81 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 1.44 µΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | (α) +529.0×10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 198 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 120 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 6.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 196 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-96-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1774) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Johann Gottlieb Gahn (1774) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of manganese

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy uses, particularly in stainless steels. It improves strength, workability, and resistance to wear. Manganese oxide is used as an oxidising agent; as a rubber additive; and in glass making, fertilisers, and ceramics. Manganese sulfate can be used as a fungicide.

Manganese is also an essential human dietary element, important in macronutrient metabolism, bone formation, and free radical defense systems. It is a critical component in dozens of proteins and enzymes.[3] It is found mostly in the bones, but also the liver, kidneys, and brain.[4] In the human brain, the manganese is bound to manganese metalloproteins, most notably glutamine synthetase in astrocytes.

Manganese was first isolated in 1774. It is familiar in the laboratory in the form of the deep violet salt potassium permanganate. It occurs at the active sites in some enzymes.[5] Of particular interest is the use of a Mn-O cluster, the oxygen-evolving complex, in the production of oxygen by plants.

Characteristics[edit]

Physical properties[edit]

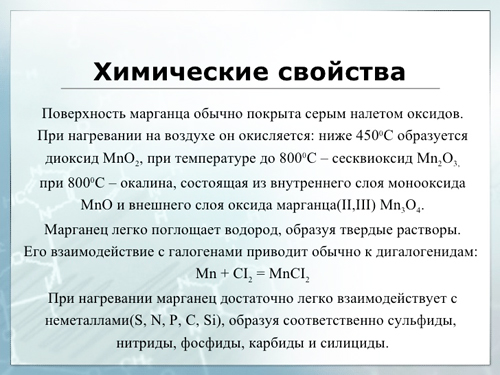

Manganese is a silvery-gray metal that resembles iron. It is hard and very brittle, difficult to fuse, but easy to oxidize.[6] Manganese metal and its common ions are paramagnetic.[7] Manganese tarnishes slowly in air and oxidizes («rusts») like iron in water containing dissolved oxygen.

Isotopes[edit]

Naturally occurring manganese is composed of one stable isotope, 55Mn. Several radioisotopes have been isolated and described, ranging in atomic weight from 44 u (44Mn) to 69 u (69Mn). The most stable are 53Mn with a half-life of 3.7 million years, 54Mn with a half-life of 312.2 days, and 52Mn with a half-life of 5.591 days. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives of less than three hours, and the majority of less than one minute. The primary decay mode in isotopes lighter than the most abundant stable isotope, 55Mn, is electron capture and the primary mode in heavier isotopes is beta decay.[8] Manganese also has three meta states.[8]

Manganese is part of the iron group of elements, which are thought to be synthesized in large stars shortly before the supernova explosion.[9] 53Mn decays to 53Cr with a half-life of 3.7 million years. Because of its relatively short half-life, 53Mn is relatively rare, produced by cosmic rays impact on iron.[10] Manganese isotopic contents are typically combined with chromium isotopic contents and have found application in isotope geology and radiometric dating. Mn–Cr isotopic ratios reinforce the evidence from 26Al and 107Pd for the early history of the Solar System. Variations in 53Cr/52Cr and Mn/Cr ratios from several meteorites suggest an initial 53Mn/55Mn ratio, which indicate that Mn–Cr isotopic composition must result from in situ decay of 53Mn in differentiated planetary bodies. Hence, 53Mn provides additional evidence for nucleosynthetic processes immediately before coalescence of the Solar System.

Chemical compounds[edit]

Common oxidation states of manganese are +2, +3, +4, +6, and +7, although all oxidation states from −3 to +7 have been observed. Manganese in oxidation state +7 is represented by salts of the intensely purple permanganate anion MnO4−. Potassium permanganate is a commonly used laboratory reagent because of its oxidizing properties; it is used as a topical medicine (for example, in the treatment of fish diseases). Solutions of potassium permanganate were among the first stains and fixatives to be used in the preparation of biological cells and tissues for electron microscopy.[12]

Aside from various permanganate salts, Mn(VII) is represented by the unstable, volatile derivative Mn2O7. Oxyhalides (MnO3F and MnO3Cl) are powerful oxidizing agents.[6] The most prominent example of Mn in the +6 oxidation state is the green anion manganate, [MnO4]2-. Manganate salts are intermediates in the extraction of manganese from its ores. Compounds with oxidation states +5 are somewhat elusive, one example is the blue anion hypomanganate [MnO4]3-.

Compounds with Mn in oxidation state +5 are rarely encountered and often found associated with an oxide (O2-) or nitride (N3-) ligand.[13][14]

Mn(IV) is somewhat enigmatic because it is common in nature but far rarer in synthetic chemistry. The most common Mn ore, pyrolusite, is MnO2. It is the dark brown pigment of many cave drawings but is also a common ingredient in dry cell batteries. Complexes of Mn(IV) are well known, but they require elaborate ligands. Mn(IV)-OH complexes are an intermediate in some enzymes, including the oxygen evolving center (OEC) in plants.[15]

Simple derivatives Mn+3 are rarely encountered but can be stabilized by suitably basic ligands. Manganese(III) acetate is an oxidant useful in organic synthesis. Solid compounds of manganese(III) are characterized by its strong purple-red color and a preference for distorted octahedral coordination resulting from the Jahn-Teller effect.

Aqueous solution of KMnO4 illustrating the deep purple of Mn(VII) as it occurs in permanganate

A particularly common oxidation state for manganese in aqueous solution is +2, which has a pale pink color. Many manganese(II) compounds are known, such as the aquo complexes derived from manganese(II) sulfate (MnSO4) and manganese(II) chloride (MnCl2). This oxidation state is also seen in the mineral rhodochrosite (manganese(II) carbonate). Manganese(II) commonly exists with a high spin, S = 5/2 ground state because of the high pairing energy for manganese(II). There are no spin-allowed d–d transitions in manganese(II), which explain its faint color.[16]

| Oxidation states of manganese[17] | |

|---|---|

| 0 | Mn 2(CO) 10 |

| +1 | MnC 5H 4CH 3(CO) 3 |

| +2 | MnCl 2, MnCO 3, MnO |

| +3 | MnF 3, Mn(OAc) 3, Mn 2O 3 |

| +4 | MnO 2 |

| +5 | K 3MnO 4 |

| +6 | K 2MnO 4 |

| +7 | KMnO 4, Mn 2O 7 |

| Common oxidation states are in bold. |

Organomanganese compounds[edit]

Manganese forms a large variety of organometallic derivatives, i.e., compounds with Mn-C bonds. The organometallic derivatives include numerous examples of Mn in its lower oxidation states, i.e. Mn(-III) up through Mn(I). This area of organometallic chemistry is attractive because Mn is inexpensive and of relatively low toxicity.

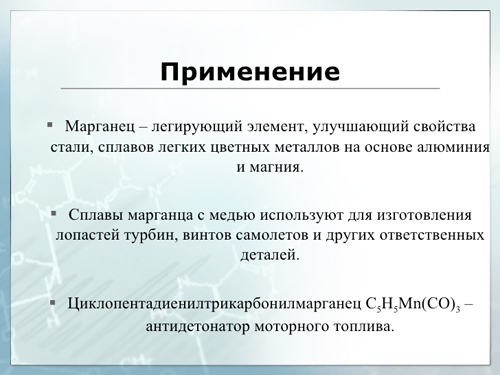

Of greatest commercial interest is «MMT», methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl, which is used as an anti-knock compound added to gasoline (petrol) in some countries. It features Mn(I). Consistent with other aspects of Mn(II) chemistry, manganocene (Mn(C5H5)2) is high-spin. In contrast, its neighboring metal iron forms an air-stable, low-spin derivative in the form of ferrocene (Fe(C5H5)2). When conducted under an atmosphere of carbon monoxide, reduction of Mn(II) salts gives dimanganese decacarbonyl Mn2(CO)10, an orange and volatile solid. The air-stability of this Mn(0) compound (and its many derivatives) reflects the powerful electron-acceptor properties of carbon monoxide. Many alkene complexes and alkyne complexes are derived from Mn2(CO)10.

In Mn(CH3)2(dmpe)2, Mn(II) is low spin, which contrasts with the high spin character of its precursor, MnBr2(dmpe)2 (dmpe = (CH3)2PCH2CH2P(CH3)2).[18] Polyalkyl and polyaryl derivatives of manganese often exist in higher oxidation states, reflecting the electron-releasing properties of alkyl and aryl ligands. One example is [Mn(CH3)6]2-.

History[edit]

The origin of the name manganese is complex. In ancient times, two black minerals were identified from the regions of the Magnetes (either Magnesia, located within modern Greece, or Magnesia ad Sipylum, located within modern Turkey).[19]

They were both called magnes from their place of origin, but were considered to differ in sex. The male magnes attracted iron, and was the iron ore now known as lodestone or magnetite, and which probably gave us the term magnet. The female magnes ore did not attract iron, but was used to decolorize glass. This female magnes was later called magnesia, known now in modern times as pyrolusite or manganese dioxide.[citation needed] Neither this mineral nor elemental manganese is magnetic. In the 16th century, manganese dioxide was called manganesum (note the two Ns instead of one) by glassmakers, possibly as a corruption and concatenation of two words, since alchemists and glassmakers eventually had to differentiate a magnesia nigra (the black ore) from magnesia alba (a white ore, also from Magnesia, also useful in glassmaking). Michele Mercati called magnesia nigra manganesa, and finally the metal isolated from it became known as manganese (German: Mangan). The name magnesia eventually was then used to refer only to the white magnesia alba (magnesium oxide), which provided the name magnesium for the free element when it was isolated much later.[20]

Some of the cave paintings in Lascaux, France, use manganese-based pigments.[21]

Manganese dioxide, which is abundant in nature, has long been used as a pigment. The cave paintings in Gargas that are 30,000 to 24,000 years old are made from the mineral form of MnO2 pigments.[22]

Manganese compounds were used by Egyptian and Roman glassmakers, either to add to, or remove, color from glass.[23] Use as «glassmakers soap» continued through the Middle Ages until modern times and is evident in 14th-century glass from Venice.[24]

Because it was used in glassmaking, manganese dioxide was available for experiments by alchemists, the first chemists. Ignatius Gottfried Kaim (1770) and Johann Glauber (17th century) discovered that manganese dioxide could be converted to permanganate, a useful laboratory reagent.[25] By the mid-18th century, the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele used manganese dioxide to produce chlorine. First, hydrochloric acid, or a mixture of dilute sulfuric acid and sodium chloride was made to react with manganese dioxide, and later hydrochloric acid from the Leblanc process was used and the manganese dioxide was recycled by the Weldon process. The production of chlorine and hypochlorite bleaching agents was a large consumer of manganese ores.

Scheele and others were aware that pyrolusite (mineral form of manganese dioxide) contained a new element. Johan Gottlieb Gahn was the first to isolate an impure sample of manganese metal in 1774, which he did by reducing the dioxide with carbon.

The manganese content of some iron ores used in Greece led to speculations that steel produced from that ore contains additional manganese, making the Spartan steel exceptionally hard.[26] Around the beginning of the 19th century, manganese was used in steelmaking and several patents were granted. In 1816, it was documented that iron alloyed with manganese was harder but not more brittle. In 1837, British academic James Couper noted an association between miners’ heavy exposure to manganese and a form of Parkinson’s disease.[27] In 1912, United States patents were granted for protecting firearms against rust and corrosion with manganese phosphate electrochemical conversion coatings, and the process has seen widespread use ever since.[28]

The invention of the Leclanché cell in 1866 and the subsequent improvement of batteries containing manganese dioxide as cathodic depolarizer increased the demand for manganese dioxide. Until the development of batteries with nickel-cadmium and lithium, most batteries contained manganese. The zinc–carbon battery and the alkaline battery normally use industrially produced manganese dioxide because naturally occurring manganese dioxide contains impurities. In the 20th century, manganese dioxide was widely used as the cathodic for commercial disposable dry batteries of both the standard (zinc–carbon) and alkaline types.[29]

Occurrence[edit]

Manganese comprises about 1000 ppm (0.1%) of the Earth’s crust, the 12th most abundant of the crust’s elements.[4] Soil contains 7–9000 ppm of manganese with an average of 440 ppm.[4] The atmosphere contains 0.01 μg/m3.[4] Manganese occurs principally as pyrolusite (MnO2), braunite (Mn2+Mn3+6)SiO12),[30] psilomelane (Ba,H2O)2Mn5O10, and to a lesser extent as rhodochrosite (MnCO3).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Manganese ore | Psilomelane (manganese ore) | Spiegeleisen is an iron alloy with a manganese content of approximately 15% | Manganese oxide dendrites on limestone from Solnhofen, Germany – a kind of pseudofossil. Scale is in mm | Mineral rhodochrosite (manganese(II) carbonate) |

Percentage of manganese output in 2006 by countries[31]

The most important manganese ore is pyrolusite (MnO2). Other economically important manganese ores usually show a close spatial relation to the iron ores, such as sphalerite.[6][32] Land-based resources are large but irregularly distributed. About 80% of the known world manganese resources are in South Africa; other important manganese deposits are in Ukraine, Australia, India, China, Gabon and Brazil.[31] According to 1978 estimate, the ocean floor has 500 billion tons of manganese nodules.[33] Attempts to find economically viable methods of harvesting manganese nodules were abandoned in the 1970s.[34]

In South Africa, most identified deposits are located near Hotazel in the Northern Cape Province, with a 2011 estimate of 15 billion tons. In 2011 South Africa produced 3.4 million tons, topping all other nations.[35]

Manganese is mainly mined in South Africa, Australia, China, Gabon, Brazil, India, Kazakhstan, Ghana, Ukraine and Malaysia.[36]

Production[edit]

For the production of ferromanganese, the manganese ore is mixed with iron ore and carbon, and then reduced either in a blast furnace or in an electric arc furnace.[37] The resulting ferromanganese has a manganese content of 30 to 80%.[6] Pure manganese used for the production of iron-free alloys is produced by leaching manganese ore with sulfuric acid and a subsequent electrowinning process.[38]

Process flow diagram for a manganese refining circuit.

A more progressive extraction process involves directly reducing (a low grade) manganese ore by heap leaching. This is done by percolating natural gas through the bottom of the heap; the natural gas provides the heat (needs to be at least 850 °C) and the reducing agent (carbon monoxide). This reduces all of the manganese ore to manganese oxide (MnO), which is a leachable form. The ore then travels through a grinding circuit to reduce the particle size of the ore to between 150 and 250 μm, increasing the surface area to aid leaching. The ore is then added to a leach tank of sulfuric acid and ferrous iron (Fe2+) in a 1.6:1 ratio. The iron reacts with the manganese dioxide (MnO2) to form iron hydroxide (FeO(OH)) and elemental manganese (Mn):

This process yields approximately 92% recovery of the manganese. For further purification, the manganese can then be sent to an electrowinning facility.[39]

In 1972 the CIA’s Project Azorian, through billionaire Howard Hughes, commissioned the ship Hughes Glomar Explorer with the cover story of harvesting manganese nodules from the sea floor.[40] That triggered a rush of activity to collect manganese nodules, which was not actually practical. The real mission of Hughes Glomar Explorer was to raise a sunken Soviet submarine, the K-129, with the goal of retrieving Soviet code books.[41]

An abundant resource of manganese in the form of Mn nodules found on the ocean floor.[42][43] These nodules, which are composed of 29% manganese,[44] are located along the ocean floor and the potential impact of mining these nodules is being researched. Physical, chemical, and biological environmental impacts can occur due to this nodule mining disturbing the seafloor and causing sediment plumes to form. This suspension includes metals and inorganic nutrients, which can lead to contamination of the near-bottom waters from dissolved toxic compounds. Mn nodules are also the grazing grounds, living space, and protection for endo- and epifaunal systems. When theses nodules are removed, these systems are directly affected. Overall, this can cause species to leave the area or completely die off.[45] Prior to the commencement of the mining itself, research is being conducted by United Nations affiliated bodies and state-sponsored companies in an attempt to fully understand environmental impacts in the hopes of mitigating these impacts.[46]

Oceanic environment[edit]

Many trace elements in the ocean come from metal-rich hydrothermal particles from hydrothermal vents.[47] Dissolved manganese (dMn) is found throughout the world’s oceans, 90% of which originates from hydrothermal vents.[48] Particulate Mn develops in buoyant plumes over an active vent source, while the dMn behaves conservatively.[47] Mn concentrations vary between the water columns of the ocean. At the surface, dMn is elevated due to input from external sources such as rivers, dust, and shelf sediments. Coastal sediments normally have lower Mn concentrations, but can increase due to anthropogenic discharges from industries such as mining and steel manufacturing, which enter the ocean from river inputs. Surface dMn concentrations can also be elevated biologically through photosynthesis and physically from coastal upwelling and wind-driven surface currents. Internal cycling such as photo-reduction from UV radiation can also elevate levels by speeding up the dissolution of Mn-oxides and oxidative scavenging, preventing Mn from sinking to deeper waters.[49] Elevated levels at mid-depths can occur near mid-ocean ridges and hydrothermal vents. The hydrothermal vents release dMn enriched fluid into the water. The dMn can then travel up to 4,000 km due to the microbial capsules present, preventing exchange with particles, lowing the sinking rates. Dissolved Mn concentrations are even higher when oxygen levels are low. Overall, dMn concentrations are normally higher in coastal regions and decrease when moving offshore.[49]

Soils[edit]

Manganese occurs in soils in three oxidation states: the divalent cation, Mn2+ and as brownish-black oxides and hydroxides containing Mn (III,IV), such as MnOOH and MnO2. Soil pH and oxidation-reduction conditions affect which of these three forms of Mn is dominant in a given soil. At pH values less than 6 or under anaerobic conditions, Mn(II) dominates, while under more alkaline and aerobic conditions, Mn(III,IV) oxides and hydroxides predominate. These effects of soil acidity and aeration state on the form of Mn can be modified or controlled by microbial activity. Microbial respiration can cause both the oxidation of Mn2+ to the oxides, and it can cause reduction of the oxides to the divalent cation.[50]

The Mn(III,IV) oxides exist as brownish-black stains and small nodules on sand, silt, and clay particles. These surface coatings on other soil particles have high surface area and carry negative charge. The charged sites can adsorb and retain various cations, especially heavy metals (e.g., Cr3+, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Pb2+). In addition, the oxides can adsorb organic acids and other compounds. The adsorption of the metals and organic compounds can then cause them to be oxidized while the Mn(III,IV) oxides are reduced to Mn2+ (e.g., Cr3+ to Cr(VI) and colorless hydroquinone to tea-colored quinone polymers).[51]

Applications[edit]

Manganese has no satisfactory substitute in its major applications in metallurgy.[31] In minor applications (e.g., manganese phosphating), zinc and sometimes vanadium are viable substitutes.

Steel[edit]

Manganese is essential to iron and steel production by virtue of its sulfur-fixing, deoxidizing, and alloying properties, as first recognized by the British metallurgist Robert Forester Mushet (1811–1891) who, in 1856, introduced the element, in the form of Spiegeleisen, into steel for the specific purpose of removing excess dissolved oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus in order to improve its malleability. Steelmaking,[52] including its ironmaking component, has accounted for most manganese demand, presently in the range of 85% to 90% of the total demand.[38] Manganese is a key component of low-cost stainless steel.[53][54] Often ferromanganese (usually about 80% manganese) is the intermediate in modern processes.

Small amounts of manganese improve the workability of steel at high temperatures by forming a high-melting sulfide and preventing the formation of a liquid iron sulfide at the grain boundaries. If the manganese content reaches 4%, the embrittlement of the steel becomes a dominant feature. The embrittlement decreases at higher manganese concentrations and reaches an acceptable level at 8%. Steel containing 8 to 15% of manganese has a high tensile strength of up to 863 MPa.[55][56] Steel with 12% manganese was discovered in 1882 by Robert Hadfield and is still known as Hadfield steel (mangalloy). It was used for British military steel helmets and later by the U.S. military.[57]

Aluminium alloys[edit]

Manganese is used in production of alloys with aluminium. Aluminium with roughly 1.5% manganese has increased resistance to corrosion through grains that absorb impurities which would lead to galvanic corrosion.[58] The corrosion-resistant aluminium alloys 3004 and 3104 (0.8 to 1.5% manganese) are used for most beverage cans.[59] Before 2000, more than 1.6 million tonnes of those alloys were used; at 1% manganese, this consumed 16,000 tonnes of manganese.[failed verification][59]

Batteries[edit]

Manganese(IV) oxide was used in the original type of dry cell battery as an electron acceptor from zinc, and is the blackish material in carbon–zinc type flashlight cells. The manganese dioxide is reduced to the manganese oxide-hydroxide MnO(OH) during discharging, preventing the formation of hydrogen at the anode of the battery.[60]

- MnO2 + H2O + e− → MnO(OH) + OH−

The same material also functions in newer alkaline batteries (usually battery cells), which use the same basic reaction, but a different electrolyte mixture. In 2002, more than 230,000 tons of manganese dioxide was used for this purpose.[29][60]

World-War-II-era 5-cent coin (1942-5 identified by mint mark P, D or S above dome) made from a 56% copper-35% silver-9% manganese alloy

Resistors[edit]

Copper alloys of manganese, such as Manganin, are commonly found in metal element shunt resistors used for measuring relatively large amounts of current. These alloys have very low temperature coefficient of resistance and are resistant to sulfur. This makes the alloys particularly useful in harsh automotive and industrial environments.[61]

Niche[edit]

Methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl is an additive in some unleaded gasoline to boost octane rating and reduce engine knocking.

Manganese(IV) oxide (manganese dioxide, MnO2) is used as a reagent in organic chemistry for the oxidation of benzylic alcohols (where the hydroxyl group is adjacent to an aromatic ring). Manganese dioxide has been used since antiquity to oxidize and neutralize the greenish tinge in glass from trace amounts of iron contamination.[24] MnO2 is also used in the manufacture of oxygen and chlorine and in drying black paints. In some preparations, it is a brown pigment for paint and is a constituent of natural umber.

Tetravalent manganese is used as an activator in red-emitting phosphors. While many compounds are known which show luminescence,[62] the majority are not used in commercial application due to low efficiency or deep red emission.[63][64] However, several Mn4+ activated fluorides were reported as potential red-emitting phosphors for warm-white LEDs.[65][66] But to this day, only K2SiF6:Mn4+ is commercially available for use in warm-white LEDs.[67]

The metal is occasionally used in coins; until 2000, the only United States coin to use manganese was the «wartime» nickel from 1942 to 1945.[68] An alloy of 75% copper and 25% nickel was traditionally used for the production of nickel coins. However, because of shortage of nickel metal during the war, it was substituted by more available silver and manganese, thus resulting in an alloy of 56% copper, 35% silver and 9% manganese. Since 2000, dollar coins, for example the Sacagawea dollar and the Presidential $1 coins, are made from a brass containing 7% of manganese with a pure copper core.[69] In both cases of nickel and dollar, the use of manganese in the coin was to duplicate the electromagnetic properties of a previous identically sized and valued coin in the mechanisms of vending machines. In the case of the later U.S. dollar coins, the manganese alloy was intended to duplicate the properties of the copper/nickel alloy used in the previous Susan B. Anthony dollar.

Manganese compounds have been used as pigments and for the coloring of ceramics and glass. The brown color of ceramic is sometimes the result of manganese compounds.[70] In the glass industry, manganese compounds are used for two effects. Manganese(III) reacts with iron(II) to reduce strong green color in glass by forming less-colored iron(III) and slightly pink manganese(II), compensating for the residual color of the iron(III).[24] Larger quantities of manganese are used to produce pink colored glass. In 2009, Professor Mas Subramanian and associates at Oregon State University discovered that manganese can be combined with yttrium and indium to form an intensely blue, non-toxic, inert, fade-resistant pigment, YInMn blue, the first new blue pigment discovered in 200 years.

Biological role[edit]

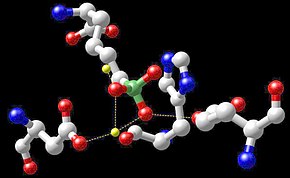

Reactive center of arginase with boronic acid inhibitor – the manganese atoms are shown in yellow.

Biochemistry[edit]

The classes of enzymes that have manganese cofactors include oxidoreductases, transferases, hydrolases, lyases, isomerases and ligases. Other enzymes containing manganese are arginase and Mn-containing superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD). Also the enzyme class of reverse transcriptases of many retroviruses (though not lentiviruses such as HIV) contains manganese. Manganese-containing polypeptides are the diphtheria toxin, lectins and integrins.[71]

Biological role in humans[edit]

Manganese is an essential human dietary element. It is present as a coenzyme in several biological processes, which include macronutrient metabolism, bone formation, and free radical defense systems. It is a critical component in dozens of proteins and enzymes.[3] The human body contains about 12 mg of manganese, mostly in the bones. The soft tissue remainder is concentrated in the liver and kidneys.[4] In the human brain, the manganese is bound to manganese metalloproteins, most notably glutamine synthetase in astrocytes.[72]

Nutrition[edit]

| Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | AI (mg/day) | Age | AI (mg/day) |

| 1–3 | 1.2 | 1–3 | 1.2 |

| 4–8 | 1.5 | 4–8 | 1.5 |

| 9–13 | 1.9 | 9–13 | 1.6 |

| 14–18 | 2.2 | 14–18 | 1.6 |

| 19+ | 2.3 | 19+ | 1.8 |

| pregnant: 2 | |||

| lactating: 2.6 |

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) updated Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for minerals in 2001. For manganese there was not sufficient information to set EARs and RDAs, so needs are described as estimates for Adequate Intakes (AIs). As for safety, the IOM sets Tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of manganese the adult UL is set at 11 mg/day. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).[73] Manganese deficiency is rare.[74]

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL defined the same as in United States. For people ages 15 and older the AI is set at 3.0 mg/day. AIs for pregnancy and lactation is 3.0 mg/day. For children ages 1–14 years the AIs increase with age from 0.5 to 2.0 mg/day. The adult AIs are higher than the U.S. RDAs.[75] The EFSA reviewed the same safety question and decided that there was insufficient information to set a UL.[76]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For manganese labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 2.0 mg, but as of 27 May 2016 it was revised to 2.3 mg to bring it into agreement with the RDA.[77][78] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Excessive exposure or intake may lead to a condition known as manganism, a neurodegenerative disorder that causes dopaminergic neuronal death and symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease.[4][79]

Deficiency[edit]

Manganese deficiency in humans, which is rare, results in a number of medical problems. A deficiency of manganese causes skeletal deformation in animals and inhibits the production of collagen in wound healing.[citation needed]

Toxicity in marine life[edit]

Many enzymatic systems need Mn to function, but in high levels, Mn can become toxic. One environmental reason Mn levels can increase in seawater is when hypoxic periods occur.[80] Since 1990 there have been reports of Mn accumulation in marine organisms including fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and echinoderms. Specific tissues are targets in different species, including the gills, brain, blood, kidney, and liver/hepatopancreas. Physiological effects have been reported in these species. Mn can affect the renewal of immunocytes and their functionality, such as phagocytosis and activation of pro-phenoloxidase, suppressing the organisms’ immune systems. This causes the organisms to be more susceptible to infections. As climate change occurs, pathogen distributions increase, and in order for organisms to survive and defend themselves against these pathogens, they need a healthy, strong immune system. If their systems are compromised from high Mn levels, they will not be able to fight off these pathogens and die.[48]

Biological role in bacteria[edit]

Mn-SOD is the type of SOD present in eukaryotic mitochondria, and also in most bacteria (this fact is in keeping with the bacterial-origin theory of mitochondria). The Mn-SOD enzyme is probably one of the most ancient, for nearly all organisms living in the presence of oxygen use it to deal with the toxic effects of superoxide (O−

2), formed from the 1-electron reduction of dioxygen. The exceptions, which are all bacteria, include Lactobacillus plantarum and related lactobacilli, which use a different nonenzymatic mechanism with manganese (Mn2+) ions complexed with polyphosphate, suggesting a path of evolution for this function in aerobic life.

Biological role in plants[edit]

Manganese is also important in photosynthetic oxygen evolution in chloroplasts in plants. The oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) is a part of photosystem II contained in the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts; it is responsible for the terminal photooxidation of water during the light reactions of photosynthesis, and has a metalloenzyme core containing four atoms of manganese.[81][82] To fulfill this requirement, most broad-spectrum plant fertilizers contain manganese.

Precautions[edit]

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Hazard statements |

H401 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P273, P501[83] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

0 0 0 |

Manganese compounds are less toxic than those of other widespread metals, such as nickel and copper.[84] However, exposure to manganese dusts and fumes should not exceed the ceiling value of 5 mg/m3 even for short periods because of its toxicity level.[85] Manganese poisoning has been linked to impaired motor skills and cognitive disorders.[86]

Permanganate exhibits a higher toxicity than manganese(II) compounds. The fatal dose is about 10 g, and several fatal intoxications have occurred. The strong oxidative effect leads to necrosis of the mucous membrane. For example, the esophagus is affected if the permanganate is swallowed. Only a limited amount is absorbed by the intestines, but this small amount shows severe effects on the kidneys and on the liver.[87][88]

Manganese exposure in United States is regulated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).[89] People can be exposed to manganese in the workplace by breathing it in or swallowing it. OSHA has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for manganese exposure in the workplace as 5 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 1 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday and a short term limit of 3 mg/m3. At levels of 500 mg/m3, manganese is immediately dangerous to life and health.[90]

Generally, exposure to ambient Mn air concentrations in excess of 5 μg Mn/m3 can lead to Mn-induced symptoms. Increased ferroportin protein expression in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells is associated with decreased intracellular Mn concentration and attenuated cytotoxicity, characterized by the reversal of Mn-reduced glutamate uptake and diminished lactate dehydrogenase leakage.[91]

Environmental health concerns[edit]

In drinking water[edit]

Waterborne manganese has a greater bioavailability than dietary manganese. According to results from a 2010 study,[92] higher levels of exposure to manganese in drinking water are associated with increased intellectual impairment and reduced intelligence quotients in school-age children. It is hypothesized that long-term exposure due to inhaling the naturally occurring manganese in shower water puts up to 8.7 million Americans at risk.[93] However, data indicates that the human body can recover from certain adverse effects of overexposure to manganese if the exposure is stopped and the body can clear the excess.[94]

In gasoline[edit]

Methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT) is a gasoline additive used to replace lead compounds for unleaded gasolines to improve the octane rating of low octane petroleum distillates. It reduces engine knock agent through the action of the carbonyl groups. Fuels containing manganese tend to form manganese carbides, which damage exhaust valves. Compared to 1953, levels of manganese in air have dropped.[95]

In tobacco smoke[edit]

The tobacco plant readily absorbs and accumulates heavy metals such as manganese from the surrounding soil into its leaves. These are subsequently inhaled during tobacco smoking.[96] While manganese is a constituent of tobacco smoke,[97] studies have largely concluded that concentrations are not hazardous for human health.[98]

Role in neurological disorders[edit]

Manganism[edit]

Manganese overexposure is most frequently associated with manganism, a rare neurological disorder associated with excessive manganese ingestion or inhalation. Historically, persons employed in the production or processing of manganese alloys[99][100] have been at risk for developing manganism; however, current health and safety regulations protect workers in developed nations.[89] The disorder was first described in 1837 by British academic John Couper, who studied two patients who were m.[27]

Manganism is a biphasic disorder. In its early stages, an intoxicated person may experience depression, mood swings, compulsive behaviors, and psychosis. Early neurological symptoms give way to late-stage manganism, which resembles Parkinson’s disease. Symptoms include weakness, monotone and slowed speech, an expressionless face, tremor, forward-leaning gait, inability to walk backwards without falling, rigidity, and general problems with dexterity, gait and balance.[27][101] Unlike Parkinson’s disease, manganism is not associated with loss of the sense of smell and patients are typically unresponsive to treatment with L-DOPA.[102] Symptoms of late-stage manganism become more severe over time even if the source of exposure is removed and brain manganese levels return to normal.[101]

Chronic manganese exposure has been shown to produce a parkinsonism-like illness characterized by movement abnormalities.[103] This condition is not responsive to typical therapies used in the treatment of PD, suggesting an alternative pathway than the typical dopaminergic loss within the substantia nigra.[103] Manganese may accumulate in the basal ganglia, leading to the abnormal movements.[104] A mutation of the SLC30A10 gene, a manganese efflux transporter necessary for decreasing intracellular Mn, has been linked with the development of this Parkinsonism-like disease.[105] The Lewy bodies typical to PD are not seen in Mn-induced parkinsonism.[104]

Animal experiments have given the opportunity to examine the consequences of manganese overexposure under controlled conditions. In (non-aggressive) rats, manganese induces mouse-killing behavior.[106]

Childhood developmental disorders[edit]

Several recent studies attempt to examine the effects of chronic low-dose manganese overexposure on child development. The earliest study was conducted in the Chinese province of Shanxi. Drinking water there had been contaminated through improper sewage irrigation and contained 240–350 μg Mn/L. Although Mn concentrations at or below 300 μg Mn/L were considered safe at the time of the study by the US EPA and 400 μg Mn/L by the World Health Organization, the 92 children sampled (between 11 and 13 years of age) from this province displayed lower performance on tests of manual dexterity and rapidity, short-term memory, and visual identification, compared to children from an uncontaminated area. More recently, a study of 10-year-old children in Bangladesh showed a relationship between Mn concentration in well water and diminished IQ scores. A third study conducted in Quebec examined school children between the ages of 6 and 15 living in homes that received water from a well containing 610 μg Mn/L; controls lived in homes that received water from a 160 μg Mn/L well. Children in the experimental group showed increased hyperactive and oppositional behavior.[92]

The current maximum safe concentration under EPA rules is 50 μg Mn/L.[107]

Neurodegenerative diseases[edit]

A protein called DMT1 is the major transporter in manganese absorption from the intestine, and may be the major transporter of manganese across the blood–brain barrier. DMT1 also transports inhaled manganese across the nasal epithelium. The proposed mechanism for manganese toxicity is that dysregulation leads to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, and aggregation of proteins.[108]

See also[edit]

- Manganese exporter, membrane transport protein

- List of countries by manganese production

- Parkerizing

References[edit]

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Manganese». CIAAW. 2017.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ a b Erikson, Keith M.; Ascher, Michael (2019). «Chapter 10. Manganese: Its Role in Disease and Health». In Sigel, Astrid; Freisinger, Eva; Sigel, Roland K. O.; Carver, Peggy L. (eds.). Essential Metals in Medicine:Therapeutic Use and Toxicity of Metal Ions in the Clinic. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 19. Berlin: de Gruyter GmbH. pp. 253–266. doi:10.1515/9783110527872-016. ISBN 978-3-11-052691-2. PMID 30855111. S2CID 73725546.

- ^ a b c d e f Emsley, John (2001). «Manganese». Nature’s Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 249–253. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- ^ Roth, Jerome; Ponzoni, Silvia; Aschner, Michael (2013). «Chapter 6 Manganese Homeostasis and Transport». In Banci, Lucia (ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Springer. pp. 169–201. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_6. ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4. PMC 6542352. PMID 23595673. Electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1.

- ^ a b c d Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). «Mangan». Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1110–1117. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ Lide, David R. (2004). Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ a b Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S. (2017). «The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties» (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- ^ Clery, Daniel (4 June 2020). «The galaxy’s brightest explosions go nuclear with an unexpected trigger: pairs of dead stars». Science. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Schaefer, Jeorg; Faestermann, Thomas; Herzog, Gregory F.; Knie, Klaus; Korschinek, Gunther; Masarik, Jozef; Meier, Astrid; Poutivtsev, Michail; Rugel, Georg; Schlüchter, Christian; Serifiddin, Feride; Winckler, Gisela (2006). «Terrestrial manganese-53 – A new monitor of Earth surface processes». Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 251 (3–4): 334–345. Bibcode:2006E&PSL.251..334S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.09.016.

- ^ «Ch. 20». Shriver and Atkins’ Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-923617-6.

- ^ Luft, J. H. (1956). «Permanganate – a new fixative for electron microscopy». Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 2 (6): 799–802. doi:10.1083/jcb.2.6.799. PMC 2224005. PMID 13398447.

- ^ Man, Wai-Lun; Lam, William W. Y.; Lau, Tai-Chu (2014). «Reactivity of Nitrido Complexes of Ruthenium(VI), Osmium(VI), and Manganese(V) Bearing Schiff Base and Simple Anionic Ligands». Accounts of Chemical Research. 47 (2): 427–439. doi:10.1021/ar400147y. PMID 24047467.

- ^ Goldberg, David P. (2007). «Corrolazines: New Frontiers in High-Valent Metalloporphyrinoid Stability and Reactivity». Accounts of Chemical Research. 40 (7): 626–634. doi:10.1021/ar700039y. PMID 17580977.

- ^ Yano, Junko; Yachandra, Vittal (2014). «Mn4Ca Cluster in Photosynthesis: Where and How Water is Oxidized to Dioxygen». Chemical Reviews. 114 (8): 4175–4205. doi:10.1021/cr4004874. PMC 4002066. PMID 24684576.

- ^ Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey and Overton, Tina (2003) Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry, Macmillan, p. 491, ISBN 0-7167-4620-4.

- ^ Schmidt, Max (1968). «VII. Nebengruppe». Anorganische Chemie II (in German). Wissenschaftsverlag. pp. 100–109.

- ^ Girolami, Gregory S.; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Thornton-Pett, Mark; Hursthouse, Michael B. (1983). «Hydrido, alkyl, and ethylene 1,2-bis(dimethylphosphino)ethane complexes of manganese and the crystal structures of MnBr2(dmpe)2, [Mn(AlH4)(dmpe)2]2 and MnMe2(dmpe)2». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 105 (22): 6752–6753. doi:10.1021/ja00360a054.

- ^ languagehat (28 May 2005). «MAGNET». languagehat.com. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Calvert, J. B. (24 January 2003). «Chromium and Manganese». Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^

- ^ Chalmin, E.; Vignaud, C.; Salomon, H.; Farges, F.; Susini, J.; Menu, M. (2006). «Minerals discovered in paleolithic black pigments by transmission electron microscopy and micro-X-ray absorption near-edge structure» (PDF). Applied Physics A. 83 (12): 213–218. Bibcode:2006ApPhA..83..213C. doi:10.1007/s00339-006-3510-7. hdl:2268/67458. S2CID 9221234.

- ^ Sayre, E. V.; Smith, R. W. (1961). «Compositional Categories of Ancient Glass». Science. 133 (3467): 1824–1826. Bibcode:1961Sci…133.1824S. doi:10.1126/science.133.3467.1824. PMID 17818999. S2CID 25198686.

- ^ a b c Mccray, W. Patrick (1998). «Glassmaking in renaissance Italy: The innovation of venetian cristallo». JOM. 50 (5): 14–19. Bibcode:1998JOM….50e..14M. doi:10.1007/s11837-998-0024-0. S2CID 111314824.

- ^ Rancke-Madsen, E. (1975). «The Discovery of an Element». Centaurus. 19 (4): 299–313. Bibcode:1975Cent…19..299R. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1975.tb00329.x.

- ^ Alessio, L.; Campagna, M.; Lucchini, R. (2007). «From lead to manganese through mercury: mythology, science, and lessons for prevention». American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 50 (11): 779–787. doi:10.1002/ajim.20524. PMID 17918211.

- ^ a b c Couper, John (1837). «On the effects of black oxide of manganese when inhaled into the lungs». Br. Ann. Med. Pharm. Vital. Stat. Gen. Sci. 1: 41–42.

- ^ Olsen, Sverre E.; Tangstad, Merete; Lindstad, Tor (2007). «History of omanganese». Production of Manganese Ferroalloys. Tapir Academic Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-82-519-2191-6.

- ^ a b Preisler, Eberhard (1980). «Moderne Verfahren der Großchemie: Braunstein». Chemie in unserer Zeit (in German). 14 (5): 137–148. doi:10.1002/ciuz.19800140502.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, P. K.; Dasgupta, Somnath; Fukuoka, M.; Roy Supriya (1984). «Geochemistry of braunite and associated phases in metamorphosed non-calcareous manganese ores of India». Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 87 (1): 65–71. Bibcode:1984CoMP…87…65B. doi:10.1007/BF00371403. S2CID 129495326.

- ^ a b c USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2009

- ^ Cook, Nigel J.; Ciobanu, Cristiana L.; Pring, Allan; Skinner, William; Shimizu, Masaaki; Danyushevsky, Leonid; Saini-Eidukat, Bernhardt; Melcher, Frank (2009). «Trace and minor elements in sphalerite: A LA-ICPMS study». Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 73 (16): 4761–4791. Bibcode:2009GeCoA..73.4761C. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2009.05.045.

- ^ Wang, X; Schröder, HC; Wiens, M; Schlossmacher, U; Müller, WEG (2009). «Manganese/polymetallic nodules: micro-structural characterization of exolithobiontic- and endolithobiontic microbial biofilms by scanning electron microscopy». Micron. 40 (3): 350–358. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2008.10.005. PMID 19027306.

- ^ United Nations (1978). Manganese Nodules: Dimensions and Perspectives. Marine Geology. Natural Resources Forum Library. Vol. 41. Springer. p. 343. Bibcode:1981MGeol..41..343C. doi:10.1016/0025-3227(81)90092-X. ISBN 978-90-277-0500-6. OCLC 4515098.

- ^ «Manganese Mining in South Africa – Overview». MBendi Information Services. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Elliott, R; Coley, K; Mostaghel, S; Barati, M (2018). «Review of Manganese Processing for Production of TRIP/TWIP Steels, Part 1: Current Practice and Processing Fundamentals». JOM. 70 (5): 680–690. Bibcode:2018JOM…tmp…63E. doi:10.1007/s11837-018-2769-4. S2CID 139950857.

- ^ Corathers, L. A.; Machamer, J. F. (2006). «Manganese». Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses (7th ed.). SME. pp. 631–636. ISBN 978-0-87335-233-8.

- ^ a b Zhang, Wensheng; Cheng, Chu Yong (2007). «Manganese metallurgy review. Part I: Leaching of ores/secondary materials and recovery of electrolytic/chemical manganese dioxide». Hydrometallurgy. 89 (3–4): 137–159. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2007.08.010.

- ^ Chow, Norman; Nacu, Anca; Warkentin, Doug; Aksenov, Igor & Teh, Hoe (2010). «The Recovery of Manganese from low grade resources: bench scale metallurgical test program completed» (PDF). Kemetco Research Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2012.

- ^ «The CIA secret on the ocean floor». BBC News. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ «Project Azorian: The CIA’s Declassified History of the Glomar Explorer». National Security Archive at George Washington University. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ Hein, James R. (January 2016). Encyclopedia of Marine Geosciences — Manganese Nodules. Springer. pp. 408–412. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Hoseinpour, Vahid; Ghaemi, Nasser (1 December 2018). «Green synthesis of manganese nanoparticles: Applications and future perspective–A review». Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 189: 234–243. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.10.022. PMID 30412855. S2CID 53248245. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ International Seabed Authority. «Polymetallic Nodules» (PDF). isa.org. International Seabed Authority. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Oebius, Horst U; Becker, Hermann J; Rolinski, Susanne; Jankowski, Jacek A (January 2001). «Parametrization and evaluation of marine environmental impacts produced by deep-sea manganese nodule mining». Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 48 (17–18): 3453–3467. Bibcode:2001DSRII..48.3453O. doi:10.1016/s0967-0645(01)00052-2. ISSN 0967-0645.

- ^ Thompson, Kirsten F.; Miller, Kathryn A.; Currie, Duncan; Johnston, Paul; Santillo, David (2018). «Seabed Mining and Approaches to Governance of the Deep Seabed». Frontiers in Marine Science. 5. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00480. S2CID 54465407.

- ^ a b Ray, Durbar; Babu, E. V. S. S. K.; Surya Prakash, L. (1 January 2017). «Nature of Suspended Particles in Hydrothermal Plume at 3°40’N Carlsberg Ridge:A Comparison with Deep Oceanic Suspended Matter». Current Science. 112 (1): 139. doi:10.18520/cs/v112/i01/139-146. ISSN 0011-3891.

- ^ a b Hernroth, Bodil; Tassidis, Helena; Baden, Susanne P. (March 2020). «Immunosuppression of aquatic organisms exposed to elevated levels of manganese: From global to molecular perspective». Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 104: 103536. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2019.103536. ISSN 0145-305X. PMID 31705914. S2CID 207935992.

- ^ a b Sim, Nari; Orians, Kristin J. (October 2019). «Annual variability of dissolved manganese in Northeast Pacific along Line-P: 2010–2013». Marine Chemistry. 216: 103702. doi:10.1016/j.marchem.2019.103702. ISSN 0304-4203. S2CID 203151735.

- ^ Bartlett, Richmond; Ross, Donald (2005). «Chemistry of Redox Processes in Soils». In Tabatabai, M.A.; Sparks, D.L. (eds.). Chemical Processes in Soils. SSSA Book Series, no. 8. Madison, Wisconsin: Soil Science Society of America. pp. 461–487. LCCN 2005924447.

- ^ Dixon, Joe B.; White, G. Norman (2002). «Manganese Oxides». In Dixon, J.B.; Schulze, D.G. (eds.). Soil Mineralogy with Environmental Applications. SSSA Book Series no. 7. Madison, Wisconsin: Soil Science Society of America. pp. 367–386. LCCN 2002100258.

- ^ Verhoeven, John D. (2007). Steel metallurgy for the non-metallurgist. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-87170-858-8.

- ^ Manganese USGS 2006

- ^ Dastur, Y. N.; Leslie, W. C. (1981). «Mechanism of work hardening in Hadfield manganese steel». Metallurgical Transactions A. 12 (5): 749–759. Bibcode:1981MTA….12..749D. doi:10.1007/BF02648339. S2CID 136550117.

- ^ Stansbie, John Henry (2007). Iron and Steel. Read Books. pp. 351–352. ISBN 978-1-4086-2616-0.

- ^ Brady, George S.; Clauser, Henry R.; Vaccari. John A. (2002). Materials Handbook: an encyclopedia for managers, technical professionals, purchasing and production managers, technicians, and supervisors. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 585–587. ISBN 978-0-07-136076-0.

- ^ Tweedale, Geoffrey (1985). «Sir Robert Abbott Hadfield F.R.S. (1858–1940), and the Discovery of Manganese Steel Geoffrey Tweedale». Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 40 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1985.0004. JSTOR 531536.

- ^ «Chemical properties of 2024 aluminum allow». Metal Suppliers Online, LLC. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ a b Kaufman, John Gilbert (2000). «Applications for Aluminium Alloys and Tempers». Introduction to aluminum alloys and tempers. ASM International. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-87170-689-8.

- ^ a b Dell, R. M. (2000). «Batteries fifty years of materials development». Solid State Ionics. 134 (1–2): 139–158. doi:10.1016/S0167-2738(00)00722-0.

- ^ «WSK1216» (PDF). vishay. Vishay Intertechnology. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Chen, Daquin; Zhou, Yang; Zhong, Jiasong (2016). «A review on Mn4+ activators in solids for warm white light-emitting diodes». RSC Advances. 6 (89): 86285–86296. Bibcode:2016RSCAd…686285C. doi:10.1039/C6RA19584A.

- ^ Baur, Florian; Jüstel, Thomas (2016). «Dependence of the optical properties of Mn4+ activated A2Ge4O9 (A=K,Rb) on temperature and chemical environment». Journal of Luminescence. 177: 354–360. Bibcode:2016JLum..177..354B. doi:10.1016/j.jlumin.2016.04.046.

- ^ Jansen, T.; Gorobez, J.; Kirm, M.; Brik, M. G.; Vielhauer, S.; Oja, M.; Khaidukov, N. M.; Makhov, V. N.; Jüstel, T. (1 January 2018). «Narrow Band Deep Red Photoluminescence of Y2Mg3Ge3O12:Mn4+,Li+ Inverse Garnet for High Power Phosphor Converted LEDs». ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology. 7 (1): R3086–R3092. doi:10.1149/2.0121801jss. S2CID 103724310.

- ^ Jansen, Thomas; Baur, Florian; Jüstel, Thomas (2017). «Red emitting K2NbF7:Mn4+ and K2TaF7:Mn4+ for warm-white LED applications». Journal of Luminescence. 192: 644–652. Bibcode:2017JLum..192..644J. doi:10.1016/j.jlumin.2017.07.061.

- ^ Zhou, Zhi; Zhou, Nan; Xia, Mao; Yokoyama, Meiso; Hintzen, H. T. (Bert) (6 October 2016). «Research progress and application prospects of transition metal Mn4+-activated luminescent materials». Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 4 (39): 9143–9161. doi:10.1039/c6tc02496c.

- ^ «TriGain LED phosphor system using red Mn4+-doped complex fluorides» (PDF). GE Global Research. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Kuwahara, Raymond T.; Skinner III, Robert B.; Skinner Jr., Robert B. (2001). «Nickel coinage in the United States». Western Journal of Medicine. 175 (2): 112–114. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.2.112. PMC 1071501. PMID 11483555.

- ^ «Design of the Sacagawea dollar». United States Mint. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ Shepard, Anna Osler (1956). «Manganese and Iron–Manganese Paints». Ceramics for the Archaeologist. Carnegie Institution of Washington. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-0-87279-620-1.

- ^ Rice, Derek B.; Massie, Allyssa A.; Jackson, Timothy A. (2017). «Manganese–Oxygen Intermediates in O–O Bond Activation and Hydrogen-Atom Transfer Reactions». Accounts of Chemical Research. 50 (11): 2706–2717. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00343. PMID 29064667.

- ^ Takeda, A. (2003). «Manganese action in brain function». Brain Research Reviews. 41 (1): 79–87. doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(02)00234-5. PMID 12505649. S2CID 1922613.

- ^ a b Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Micronutrients (2001). «Manganese». Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Chromium, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Chromium. National Academy Press. pp. 394–419. ISBN 978-0-309-07279-3. PMID 25057538.

- ^ See «Manganese». Micronutrient Information Center. Oregon State University Linus Pauling Institute. 23 April 2014.

- ^ «Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies» (PDF). 2017.

- ^ Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals (PDF), European Food Safety Authority, 2006

- ^ «Federal Register May 27, 2016 Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. FR page 33982» (PDF).

- ^ «Daily Value Reference of the Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD)». Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Silva Avila, Daiana; Luiz Puntel, Robson; Aschner, Michael (2013). «Chapter 7. Manganese in Health and Disease». In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 199–227. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_7. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMC 6589086. PMID 24470093.

- ^ Hernroth, Bodil; Krång, Anna-Sara; Baden, Susanne (February 2015). «Bacteriostatic suppression in Norway lobster (Nephrops norvegicus) exposed to manganese or hypoxia under pressure of ocean acidification». Aquatic Toxicology. 159: 217–224. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.11.025. ISSN 0166-445X. PMID 25553539.

- ^ Umena, Yasufumi; Kawakami, Keisuke; Shen, Jian-Ren; Kamiya, Nobuo (May 2011). «Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å» (PDF). Nature. 473 (7345): 55–60. Bibcode:2011Natur.473…55U. doi:10.1038/nature09913. PMID 21499260. S2CID 205224374.

- ^ Dismukes, G. Charles; Willigen, Rogier T. van (2006). «Manganese: The Oxygen-Evolving Complex & Models». Manganese: The Oxygen-Evolving Complex & Models Based in part on the article Manganese: Oxygen-Evolving Complex & Models by Lars-Erik Andréasson & Tore Vänngård which appeared in the Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry, First Edition, First Edition. Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. doi:10.1002/0470862106.ia128. ISBN 978-0470860786.

- ^ «Safety Data Sheet». Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Hasan, Heather (2008). Manganese. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4042-1408-8.

- ^ «Manganese Chemical Background». Metcalf Institute for Marine and Environmental Reporting University of Rhode Island. April 2006. Archived from the original on 28 August 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ^ «Risk Assessment Information System Toxicity Summary for Manganese». Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ Ong, K. L.; Tan, T. H.; Cheung, W. L. (1997). «Potassium permanganate poisoning – a rare cause of fatal self poisoning». Emergency Medicine Journal. 14 (1): 43–45. doi:10.1136/emj.14.1.43. PMC 1342846. PMID 9023625.

- ^ Young, R.; Critchley, J. A.; Young, K. K.; Freebairn, R. C.; Reynolds, A. P.; Lolin, Y. I. (1996). «Fatal acute hepatorenal failure following potassium permanganate ingestion». Human & Experimental Toxicology. 15 (3): 259–61. doi:10.1177/096032719601500313. PMID 8839216. S2CID 8993404.

- ^ a b «Safety and Health Topics: Manganese Compounds (as Mn)». U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

- ^ «NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Manganese compounds and fume (as Mn)». Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Yin, Z.; Jiang, H.; Lee, E. S.; Ni, M.; Erikson, K. M.; Milatovic, D.; Bowman, A. B.; Aschner, M. (2010). «Ferroportin is a manganese-responsive protein that decreases manganese cytotoxicity and accumulation» (PDF). Journal of Neurochemistry. 112 (5): 1190–8. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06534.x. PMC 2819584. PMID 20002294.

- ^ a b Bouchard, M. F; Sauvé, S; Barbeau, B; Legrand, M; Bouffard, T; Limoges, E; Bellinger, D. C; Mergler, D (2011). «Intellectual impairment in school-age children exposed to manganese from drinking water». Environmental Health Perspectives. 119 (1): 138–143. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002321. PMC 3018493. PMID 20855239.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald; Barceloux, Donald (1999). «Manganese». Clinical Toxicology. 37 (2): 293–307. doi:10.1081/CLT-100102427. PMID 10382563.

- ^ Devenyi, A. G; Barron, T. F; Mamourian, A. C (1994). «Dystonia, hyperintense basal ganglia, and high whole blood manganese levels in Alagille’s syndrome». Gastroenterology. 106 (4): 1068–71. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(94)90769-2. PMID 8143974. S2CID 2711273.

- ^ Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (2012) 6. Potential for human exposure, in Toxicological Profile for Manganese, Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- ^ Pourkhabbaz, A; Pourkhabbaz, H (2012). «Investigation of Toxic Metals in the Tobacco of Different Iranian Cigarette Brands and Related Health Issues». Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 15 (1): 636–644. PMC 3586865. PMID 23493960.

- ^ Talhout, Reinskje; Schulz, Thomas; Florek, Ewa; Van Benthem, Jan; Wester, Piet; Opperhuizen, Antoon (2011). «Hazardous Compounds in Tobacco Smoke». International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 8 (12): 613–628. doi:10.3390/ijerph8020613. PMC 3084482. PMID 21556207.

- ^ Bernhard, David; Rossmann, Andrea; Wick, Georg (2005). «Metals in cigarette smoke». IUBMB Life. 57 (12): 805–9. doi:10.1080/15216540500459667. PMID 16393783. S2CID 35694266.

- ^ Baselt, R. (2008) Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, pp. 883–886, ISBN 0-9626523-7-7.

- ^ Normandin, Louise; Hazell, A. S. (2002). «Manganese neurotoxicity: an update of pathophysiologic mechanisms». Metabolic Brain Disease. 17 (4): 375–87. doi:10.1023/A:1021970120965. PMID 12602514. S2CID 23679769.

- ^ a b Cersosimo, M. G.; Koller, W.C. (2007). «The diagnosis of manganese-induced parkinsonism». NeuroToxicology. 27 (3): 340–346. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.006. PMID 16325915.

- ^ Lu, C. S.; Huang, C.C; Chu, N.S.; Calne, D.B. (1994). «Levodopa failure in chronic manganism». Neurology. 44 (9): 1600–1602. doi:10.1212/WNL.44.9.1600. PMID 7936281. S2CID 38040913.

- ^ a b Guilarte TR, Gonzales KK (August 2015). «Manganese-Induced Parkinsonism Is Not Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease: Environmental and Genetic Evidence». Toxicological Sciences (Review). 146 (2): 204–12. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfv099. PMC 4607750. PMID 26220508.

- ^ a b Kwakye GF, Paoliello MM, Mukhopadhyay S, Bowman AB, Aschner M (July 2015). «Manganese-Induced Parkinsonism and Parkinson’s Disease: Shared and Distinguishable Features». Int J Environ Res Public Health (Review). 12 (7): 7519–40. doi:10.3390/ijerph120707519. PMC 4515672. PMID 26154659.

- ^ Peres TV, Schettinger MR, Chen P, Carvalho F, Avila DS, Bowman AB, Aschner M (November 2016). «Manganese-induced neurotoxicity: a review of its behavioral consequences and neuroprotective strategies». BMC Pharmacology & Toxicology (Review). 17 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/s40360-016-0099-0. PMC 5097420. PMID 27814772.

- ^ Lazrishvili, I.; et al. (2016). «Manganese loading induces mouse-killing behaviour in nonaggressive rats». Journal of Biological Physics and Chemistry. 16 (3): 137–141. doi:10.4024/31LA14L.jbpc.16.03.

- ^ «Drinking Water Contaminants». US EPA. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Prabhakaran, K.; Ghosh, D.; Chapman, G.D.; Gunasekar, P.G. (2008). «Molecular mechanism of manganese exposure-induced dopaminergic toxicity». Brain Research Bulletin. 76 (4): 361–367. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.03.004. ISSN 0361-9230. PMID 18502311. S2CID 206339744.

External links[edit]

- National Pollutant Inventory – Manganese and compounds Fact Sheet

- International Manganese Institute

- NIOSH Manganese Topic Page

- Manganese at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- All about Manganese Dendrites

Not to be confused with Magnesium (Mg).

Pure manganese cube and oxidized manganese chips |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manganese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (MANG-gə-neez) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Mn) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manganese in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d5 4s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 13, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1519 K (1246 °C, 2275 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2334 K (2061 °C, 3742 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 7.21 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 5.95 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 12.91 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 221 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.32 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −3, −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6, +7 (depending on the oxidation state, an acidic, basic, or amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.55 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 127 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | Low spin: 139±5 pm High spin: 161±8 pm |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of manganese |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 5150 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 21.7 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 7.81 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 1.44 µΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | (α) +529.0×10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 198 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 120 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||