Марко Поло — биография

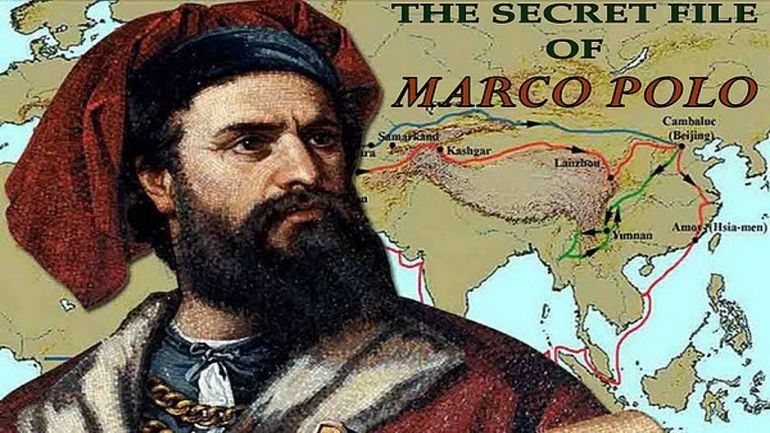

У многих из нас мечты о путешествиях и далеких странах так и остаются мечтами, а некоторые не боятся оторваться от насиженного места и отправиться открывать неведомые страны. К последним точно относится Марко Поло, которого все знают не только как купца и путешественника, но и автора знаменитого произведения «Книга о разнообразии мира». О достоверности данных, изложенных в ней, спорят уже не одно столетие, но то, что она пригодилась в путешествиях многим людям, в том числе и прославленному Колумбу, сомнений не вызывает.

Детство

Точных подтверждений даты и места рождения Марко Поло нет, ими принято считать 15 сентября 1254 года в Венеции. Его отец Никколо Поло принадлежал к дворянскому сословию, был венецианским вельможей с собственным гербом. Он продавал ювелирные изделия и пряности. Марко совершенно не знал свою маму, она умерла во время родов. Поэтому воспитание мальчика легло на плечи отца и родной тети.

По поводу родины путешественника до сих пор ведутся ссоры между Польшей и Хорватией. Поляки уверены, что в пользу их версии указывает фамилия Поло, как сокращенная от слова поляк. Хорваты в свою очередь уверены, что располагают первыми свидетельствами того, что Марко родился на их земле.

Об образовании Марко так ничего и не удалось выяснить. Также неизвестно, обучен ли он был грамоте или нет, потому что свою знаменитую книгу он сумел написать с помощью сокамерника Рустичиано, которому диктовал ее от начала до конца во время пребывания в генуэзской тюрьме. Но, тем не менее, известно, что путешествуя по миру, Поло делал отметки собственной рукой в записной книжке, внимательно изучал все, что происходит вокруг и записывал все, что поразило его внимание. Во время путешествия он постепенно овладел несколькими языками.

Путешествия

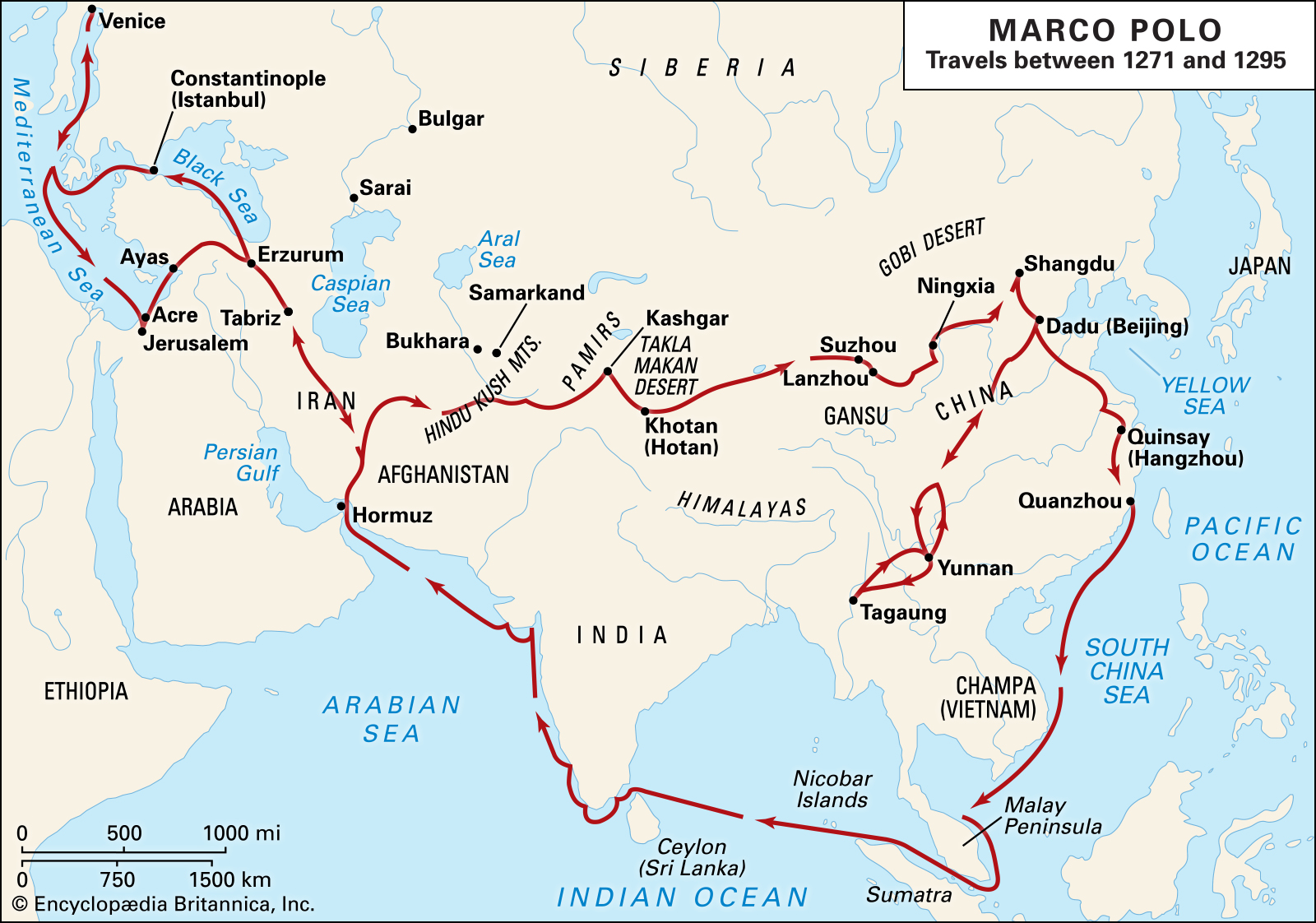

По роду своих занятий, отцу Марко часто приходилось отправляться в путешествия. Он много ездил по всему миру, прокладывал торговые тропы. Благодаря отцу мальчик полюбил путешествия, потому что постоянно слушал рассказы о дальних странах и приключениях моряков. В 1271-м Марко первый раз оказался в путешествии, куда его взял с собой отец. По окончанию странствия, они должны были оказаться в Иерусалиме.

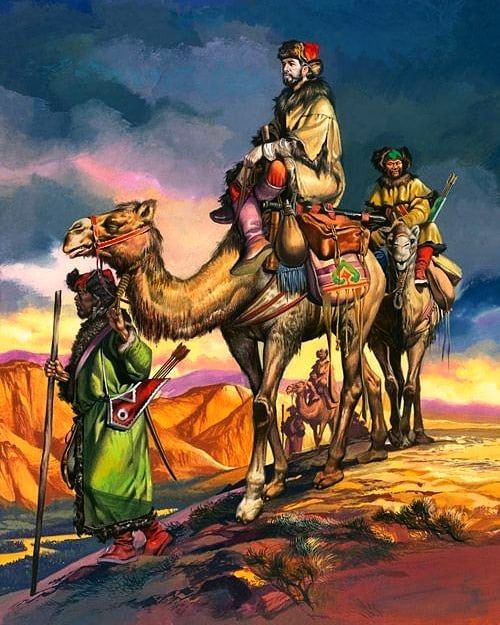

Тогда же прошли выборы нового папы Римского, который в свою очередь удостоил семью Поло честью представлять их интересы в Китае. В то время власть в этой стране принадлежала монгольскому хану. Они отправились по Средиземному морю, сделав первую остановку в порту Лаяс. Именно сюда доставлялись товары из азиатских стран, покупателями которых были генуэзские и венецианские купцы. Потом на очереди путешественников была Малая Азия, Армения, Междуречье. Марко с отцом побывали также в Багдаде и Мосуле.

Далее их путь лежит к персидскому Тебризу, славившемуся своим богатейшим рынком жемчуга. В Персии они подверглись нападению разбойников и потеряли часть сопровождающих.

Семейство Поло выжило только благодаря чуду. Им пришлось преодолевать знойную пустыню, они были сильно ослаблены жаждой. Едва живые, они наконец-то попали в афганский город Балху, и таким образом спаслись.

Дальнейший путь привел путешественников к восточным землям, где в изобилии были фрукты и дичь. Следующий регион на их пути – Бадахшан, поражал многочисленностью рабов, работающих на добыче драгоценных камней. Существует версия, что Марко в это время серьезно заболел, поэтому путешественники провели в этой местности целый год. Потом они переправились через Памир и устремились к Кашмиру. Поло никак не мог скрыть своего восторга от местных колдунов и изобилия красивых женщин.

И вот, наконец, их взору предстал Южный Тянь-Шань, где до этого не ступала нога ни одного европейца. Потом их караван устремился через пустыню Такла-Макан. Путешественники добрались до первого китайского города – Шанчжоу, потом посетили Гуанчжоу и Ланчжоу. Марко очень впечатлили местные обычаи и обряды, он любовался флорой и фауной этой неизвестной ему страны. В это время он сделал свои самые удивительные открытия, путешествовал по разным местам.

Семья Поло воспользовалась гостеприимностью хана Хубилая, и жила у него на протяжении пятнадцати лет. Хан полюбил Марко за его бесстрашие, независимость и отличную память. Правитель приблизил молодого человека к себе, позволял участвовать в жизни государства, набирать армию. Кроме этого Поло выступил с предложением об использовании военных катапульт, и это понравилось хану.

С важными дипломатическими заданиями Марко объездил множество китайских городов, в совершенстве овладел языком. Его удивляли и восторгали невероятные открытия и достижения, сделанные китайцами. Обо всем этом он подробно писал в своем труде. Перед самым возвращением на родину, хан назначил Марко управлять китайскими провинциями Цзяннань.

Хубилай не хотел, чтобы Марко уезжал, но в 1291-м семья Поло отправилась в качестве сопровождения для монгольской принцессы, ставшей женой правителя Персии. Путешественникам предстояло побывать на Цейлоне и Суматре. Спустя три года, когда они еще были в пути, до них дошло известие о смерти хана Хубилая.

Поло решили возвращаться на родину. Для этого им нужно было пересечь воды Индийского океана, а это удавалось далеко не каждому. Возвращение Марко домой состоялось зимой 1295-го, спустя 24 года после начала путешествия.

Могут быть знакомы

Дома

Спустя два года между Венецией и Генуей вспыхнула война, в которой Марко принимал непосредственное участие. Его взяли в плен, и на несколько месяцев заточили в тюрьму. Именно в этом месте он и написал свою знаменитую на весь мир книгу.

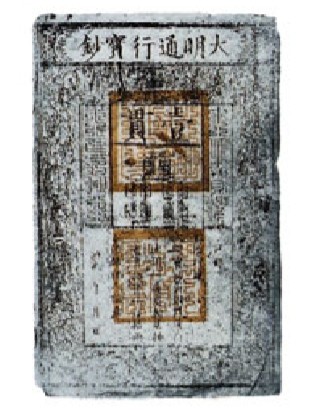

Произведение вышло в ста сорока вариантах, переведено на 12 языков. В книге есть место некоторым домыслам, но зато европейцы расширили свои познания. Они узнали, что существуют бумажные деньги, саговая пальма и каменный уголь, места выращивания пряностей и еще о многих вещах, о существовании которых они никогда не задумывались.

Личная жизнь

После возвращения на родину, отец Марко снова женился, и в этом браке родились три сына. Сам Марко тоже сумел устроить свою личную жизнь. Его женой стала знатная и достаточно богатая венецианка Доната, они приобрели дом и родили трех девочек. В те годы Поло называют господином Миллионом. Жители города видят в нем чудаковатого лжеца, его рассказы о дальних странах не вызывают у них доверия. В целом, жизнь Поло сложилась благополучно, но он очень скучал по Китаю.

Настоящее удовольствие Поло получал от венецианских карнавалов, которые тоже навевали мысли о Китае. После возвращения домой Марко занимался торговлей, и пожинал плоды славы от своей книги.

Марко Поло не стало в 1324 году. Он умер в Венеции, в возрасте 70-ти лет. Местом его упокоения стала церковь Сан Лоренцо, которую разрушили в 19-м веке. От роскошного дома тоже ничего не осталось, он сгорел в конце 16-го века. Биография Марко Поло нашла отражение в кинематографе, в разные годы на экраны выходили сериалы и полнометражные картины, рассказывающие о великом путешественнике.

Интересные факты

- Польша, Хорватия и Италия никак не прекратят борьбу за право называться родиной известного путешественника.

- Перед самой смертью отличался невероятной скупостью, Поло даже судился со своей семьей.

- Марко отпустил на волю одного своего раба и даже оставил ему по завещанию часть наследства. Такой экстравагантный поступок вызвал много предположений о том, чем вызвана такая щедрость.

- В 1888 году имя Марко Поло присвоили бабочке. Ее называют Желтушка Марко Поло

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Биография Марко Поло

15 Сентября 1254 – 8 Января 1324 гг. (69 лет)

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 325.

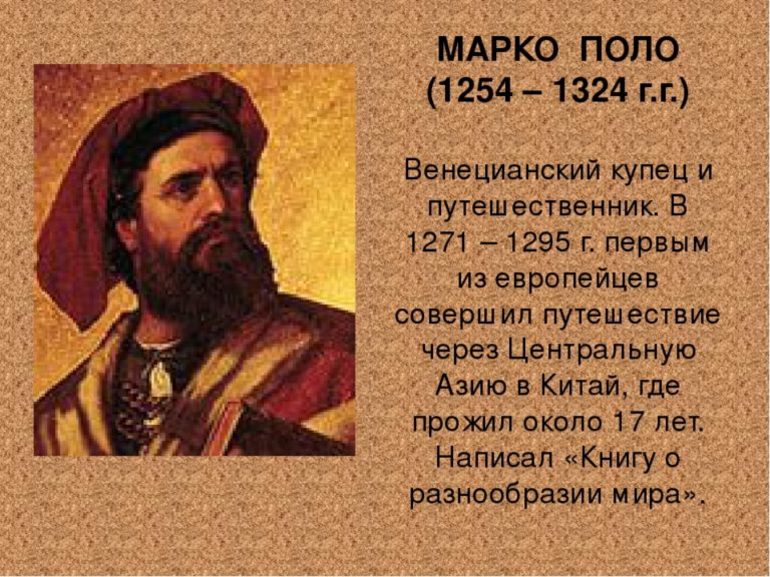

Марко Поло (1254–1324 гг.) – первый великий путешественник. В конце тринадцатого века он совершил, по тем временам, невероятный по дальности и длительности поход на Восток. Монголия, Китай, Япония, Юго-Восточная Азия, Персия – вот неполный перечень стран, в которых он успел побывать. Свои впечатления он описал в своей «Книге о разнообразии мира».

Опыт работы учителем географии — 35 лет.

Рождение и детство

О биографии Марко Поло известно не очень много. Интересно отметить, что нет ни одного его достоверного портрета. В XVI веке некий Джон Баптист Рамусио предпринимает попытку собрать и упорядочить сведения о жизни знаменитого путешественника. Иными словами, с момента рождения и до появления первых упоминаний о нем прошло триста лет. Отсюда неточность, приблизительность фактов и описаний.

Марко Поло родился примерно 15 сентября 1254 года в Венеции. Его семья принадлежала к дворянскому сословию, так называемой венецианской знати, и имела герб. Его отец, Никколо Поло, успешно вел торговлю ювелирными изделиями и пряностями. Мать знаменитого путешественника умерла еще при родах, поэтому его воспитанием занимались отец и родная тётя.

Первые путешествия

Крупнейшим источником дохода Венецианского государства была торговля с дальними странами. Считалось, что чем больше риска, тем выше прибыль. Поэтому не удивительно, что отец Марко Поло много путешествовал в поисках всё новых торговых путей. Сын не отставал от отца: любовь к странствиям и приключениям у него в крови. В 1271 году он отправляется с отцом в свое первое путешествие в Иерусалим.

Китай

В тот же год новоизбранный Папа Римский назначает Никколо Поло, его брата Морфео и родного сына Марко своими официальными представителями в Китай. Семья Поло незамедлительно отправляется в далёкое путешествие к главному правителю Китая – монгольскому хану. Малая Азия, Армения, Мосул, Багдад, Персия, Памир, Кашмир – вот примерный маршрут их следования. В 1275 году, то есть через пять лет после отбытия из итальянского порта, купцы оказываются в резиденции хана Хубилая. Последний принимает их радушно. Особенно ему полюбился молодой Марко. В нем он ценил независимость, бесстрашие и хорошую память. Он не раз предлагал ему участвовать в государственной жизни, доверял важные поручения. В благодарность младший из семьи Поло помогает хану набрать армию, рассказывает об использовании военных катапульт и многое другое. Так прошло 15 лет.

Возвращение

В 1291 году Китайский император решает отдать свою дочь за персидского шаха Аргуна. Переход по суше был невозможен, поэтому снаряжается флотилия из 14 судов. Семья Поло – на первых позициях: они сопровождают и охраняют монгольскую принцессу. Однако, еще во время путешествия приходит печальное известие о скоропостижной смерти хана. И Поло тут же принимают решение о незамедлительном возвращении в родные края. Но путь домой оказался долгим и небезопасным.

Книга и её содержание

В 1295 году Марко Поло возвращается в Венецию. Ровно через два года его сажают в тюрьму за участие в войне между Генуей и Венецией. Те несколько месяцев, что он провел под стражей, нельзя назвать пустыми и бесплодными. Там он встречает Рустикелло – итальянского писателя, родом из Пизы. Именно он обличает в художественную форму рассказы Марко Поло об удивительных землях, их природе, населении, культуре, обычаях и новых открытиях. Книга имела название «Книга о разнообразии мира», которая впоследствии стала настольной для многих первооткрывателей, в том числе и для Христофора Колумба.

Смерть путешественника

Марко Поло скончался у себя на родине, в Венеции. По тем временам он прожил долгую жизнь – 69 лет. Умер путешественник 8 января 1324 года.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

- Знаменитая «Книга» Марко Поло вначале не воспринималась читателями серьезно. Ее использовали не как источник бесценной информации о Китае и других далеких странах, а как легкое, занимательное чтиво с полностью выдуманным сюжетом.

- Христофор Колумб взял «Книгу» с собой в первую экспедицию к «берегам Индии». На её полях он сделал немало пометок. Сегодня «колумбовский» экземпляр бережно хранится в одном из музеев Севильи.

- К концу жизни Марко Поло был до неприличия скуп и не раз судился со своими родными.

- В краткой биографии Марко Поло интересно отметить, что Польша и Хорватия также претендуют на роль его малой родины. Польская сторона утверждает, что фамилия Поло буквально переводится как «поляк». Хорваты же уверены в том, что родился он вовсе не в Венеции, а на их земле – в Корчуле.

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Тамара Михель

9/10

-

Август Мандаринский

10/10

-

Александра Максимова

7/10

-

Михаил Леньшин

8/10

-

Галина Кузьмина

10/10

Оценка по биографии

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 325.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Биография

Марко Поло — венецианский купец, знаменитый путешественник, писатель, автор знаменитой «Книги о разнообразии мира», в которой рассказал историю своего путешествия по странам Азии. С достоверностью фактов, изложенных в сочинении, соглашаются не все исследователи, но до настоящего времени оно остается одним из важных источников по истории, этнографии и географии азиатских государств эпохи Средневековья.

Книгой пользовались мореплаватели, картографы, исследователи, писатели, путешественники и первооткрыватели. Она странствовала с Христофором Колумбом во время его знаменитого плавания в Америку.

Детство и юность

Документы о рождении Марко не сохранились, поэтому информация об этом периоде его биографии неточна. Считается, что он был дворянином, принадлежал к венецианской знати, имел герб. Родился 15 сентября 1254 года в семье венецианского купца Никколо Поло, торговавшего ювелирными изделиями и пряностями. Свою мать он не знал, так как она умерла при родах. Воспитанием мальчика занимались отец и родная тетя.

Родиной знаменитого путешественника могли быть также Польша и Хорватия, которые оспаривают это право, приводя в доказательство те или иные факты, подтверждающие обе версии. Поляки утверждают, что фамилия Поло имеет польское происхождение, хорватские исследователи уверены, что первые свидетельства о жизни знаменитого землепроходца находятся на их земле.

Путешествия и открытия

Отец будущего путешественника в силу своей профессии много перемещался. В поездках по миру он открывал новые торговые пути. Именно Никколо привил Марко любовь к странствиям, рассказывая о своих приключениях. В 1271 году состоялось путешествие, в которое юноша отправился вместе с отцом. Конечным его пунктом был Иерусалим.

В этом же году был выбран новый папа римский, который назначил купеческую семью (Никколо, его брата и Марко) официальными посланниками в Китай, где в то время страной правил монгольский хан Хубилай. Первой остановкой на побережье Средиземного моря был порт Лаяс — место, куда привозились товары из Азии, где их покупали купцы из Венеции и Генуи. Далее их путь проходил через Малую Азию, Армению, Междуречье, где они посетили Мосул и Багдад.

Затем путешественники отправились в персидский Тебриз, где в те времена находился богатейший рынок жемчуга. В Персии часть их сопроводителей была перебита разбойниками, напавшими на караван. Семья Поло чудом уцелела. Мучаясь от жажды в знойной пустыне, на грани жизни и смерти они добрались до афганского города Балха и нашли в нем спасение.

Восточные земли, на которых они оказались, продолжив свое путешествие, изобиловали фруктами и дичью. В Бадахшане — следующем регионе — рабы добывали драгоценные камни. По одной из версий, в этих местах из-за болезни Марко путешественники остановились на год. Затем, преодолевая остроги Памира, отправились в Кашмир. Путник был удивлен местными колдунами, влияющими на погоду, а также красотой местных женщин.

Приключения Марко Поло: факты о знаменитом путешественнике

После этого итальянцы первыми из европейцев оказались в Южном Тянь-Шане. Далее караван направился на северо-восток через оазисы пустыни Такла-Макан. Первым китайским городом на их пути стал Шанчжоу, за ним последовали Гуанчжоу и Ланьчжоу. Купец был под огромным впечатлением от местных обрядов и обычаев, флоры и фауны этой страны. Это было прекрасное время его удивительных путешествий и открытий.

У хана Хубилая семья венецианских купцов прожила около 17 лет. Молодой человек нравился хану независимостью, бесстрашием и хорошей памятью. Он стал приближенным китайского правителя, участвовал в государственной жизни, принятии важных решений, помогал набирать армию, предложил использовать военные катапульты и многое другое.

Выполняя сложнейшие дипломатические поручения, Марко Поло побывал во многих китайских городах, изучил язык и не переставал удивляться достижениям и открытиям этого народа. Все это он описал в своей книге.

Хубилай не хотел отпускать своего помощника и любимца, но в 1291 году отправил его сопровождать монгольскую принцессу, вышедшую замуж за правителя из Персии. Путь проходил через Цейлон и Суматру. В 1294 году, еще во время похода, пришло известие, что хан Хубилай умер.

Поло принял решение о возвращении домой. Путь через Индийский океан был очень опасным, лишь немногим удалось его преодолеть. Путешественник вернулся на родину зимой 1295 года.

На родной земле

Через два года после возвращения началась война Генуи и Венеции, в которой участвовал и Марко Поло. В 1298 году в битве при Курцоле он попал в плен к противнику и пребывал в тюрьме вплоть до мая 1299 года. Здесь по его рассказам о путешествиях и была написана знаменитая книга.

Также руку к произведению приложил сокамерник путешественника Рустикелло (Рустичано). Существует версия, что текст диктовался на венетском наречии, другая гласит, что писание велось на старофранцузском с примечаниями на итальянском языке. Поскольку оригинал рукописи не сохранился, проверить достоверность теорий невозможно.

Личная жизнь

Отец землепроходца женился повторно, и у него появились еще три брата. После плена в личной жизни Марко Поло тоже сложилось все хорошо: он женился на знатной и богатой венецианке Донате Бадоер, купил дом и вырастил трех дочерей. Горожане считали его чудаковатым лжецом, не доверяя рассказам о дальних странствиях. Марко жил благополучной жизнью, но тосковал по путешествиям, особенно по Китаю.

Embed from Getty Images

Единственную радость ему доставляли венецианские карнавалы, так как напоминали великолепные китайские дворцы и роскошные ханские наряды. После возвращения из Азии путешественник прожил почти три десятка лет. На родине он занимался торговлей. «Книга о разнообразии мира», написанная в заключении, сделала его знаменитым еще при жизни.

В последние годы в Марко Поло проснулась скупость, которая привела его к судебным разбирательствам с собственной семьей. Путешественник дал волю одному из своих рабов и завещал ему часть наследства.

Смерть

Умер Поло в 1324 году в Венеции в возрасте 70 лет. Точная причина смерти путешественника неизвестна, однако некоторые источники утверждали, что он на протяжении длительного времени боролся с неизвестной болезнью.

Похоронили его в церкви Сан Лоренцо. Роскошный дом Марко Поло сгорел в огне пожара в конце XIV века. По слухам, там хранились ценные вещи, привезенные из Китая. Церковь, где погребен путешественник, была разрушена в XIX веке.

Память

Именем великого путешественника в 1888 году названа бабочка Желтушка Марко Поло.

Международный аэропорт в Венеции, основанный в 1960 году, назван в честь землепроходца. Российская фолк-группа, лидером и вокалисткой которой является Людмила Савостьянова, также носит его имя.

О Поло, его жизни и путешествиях, снято множество захватывающих фильмов и сериалов, вызывающих неподдельный интерес среди наших современников.

В 2007 году Кевин Коннор срежиссировал ТВ-проект «Марко Поло» с Иэном Сомерхолдером в главной роли. Также в актерский состав вошли Б. Д. Вонг, Дезире Энн Сиахаан и Брайан Деннехи. Работа не произвела впечатления на критиков и зрителей, о чем свидетельствовали неоднозначные и критические рецензии.

По прошествии времени Netflix решился на крупнобюджетный сериал о знаменитом путешественнике, образ которого достался исполнителю Лоренцо Рикельми. Создатели выпустили два сезона по 10 эпизодов в каждом. Шоу имело высокие рейтинги и положительные отзывы. Примечательно, что съемки проходили в Италии, Малайзии и Казахстане.

После концовки первого сезона на стриминговом сервисе вышел короткометражный фильм и по совместительству спецвыпуск ТВ-шоу «Марко Поло: Сотня глаз». За постановку отвечал американский режиссер узбекского происхождения Алик Сахаров.

Интересные факты

- В одной из глав произведения Поло указано, что во время путешествий он вносил заметки в записную книжку, старался быть внимательным к происходящему и фиксировать все новое и необычное, с чем приходилось сталкиваться. В дальнейшем, странствуя по миру, Марко выучил несколько языков.

- Пребывая в Китае, венецианский купец три года занимал пост губернатора Янчжоу.

- Считается, что слово «миллион» придумал Марко Поло. Впервые термин появился в его книге, а затем в печатной арифметике в городе Тревизо в 1478 году.

- Ходит миф, что путешественник завез на родину макароны. В действительности это блюдо упоминалось еще в 1279 году в Генуе.

- Биографы подозревают, что у Марко Поло была четвертая внебрачная дочь Аньезе.

Марко Поло

Краткая биография

Венецианский путешественник Марко Поло родился в 1254 г. в купеческой семье на острове Корчула в Адриатическом море. Его отец Никколо Поло и дядя Маффео не раз совершали коммерческие поездки в азиатские страны, торговали пряностями, тканями, ювелирными изделиями, драгоценными камнями. Их путешествия занимали несколько лет, потому что в те времена добраться из Европы в Индию и Китай можно было исключительно по суше (морской путь в Юго-Восточную Азию Васко да Гама откроет только через 240 лет). Возвращаясь из дальних странствий домой, отец рассказывал мальчику о диковинных городах, необычных народах и сказочных богатствах.

Марко мечтал подрасти и тоже отправиться в путешествие. Так и произошло: он побывал во многих государствах Востока. Его впечатления и воспоминания легли в основу «Книги о разноо бразии мира», в которую вошли не только рассказы о путешествиях и жизни на чужбине, но и описание азиатских государств, местностей, городов, нравов и быта их обитателей, а также исторические очерки и легенды. Она была настольной книгой многих купцов, выдающихся мореплавателей и путешественников и сыграла значительную роль в истории Великих географических открытий. Книга Марко Поло переведена на несколько иностранных языков, она издается и переиздается во многих странах мира.

Марко путешествовал 24 года. Вернувшись в Европу, он женился и прожил долгую и счастливую жизнь. Умер Марко Поло в 1324 г. в возрасте 70 лет.

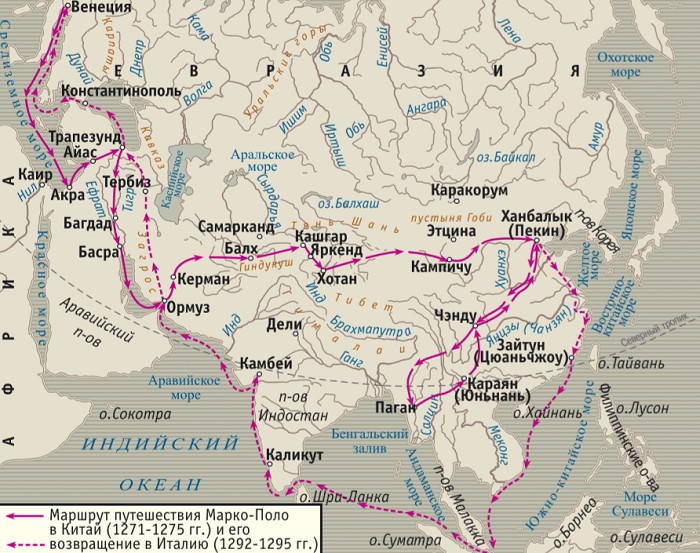

Путешествия Марко-Поло в Китай и его возвращение в Италию

В 1271 г. Марко Поло с отцом и дядей отправился в увлекательное и опасное путешествие на Восток. Опытные венецианские купцы хорошо знали, что торговля в Азии гораздо более выгодна, чем МАРКО ПОЛО И ЕГО ЗНАМЕНИТАЯ «КНИГА О РАЗНООБРАЗИИ МИРА» в любых других странах. Их путь лежал в Даду – «Великую столицу» Китая (по-монгольски – Ханбалык). Монгольский хан Хубилай, самый знаменитый из внуков Чингисхана, к тому времени почти завершил разгром китайской династии Сун и стал правителем монгольской империи и Китая. Во время прежнего торгового путешествия на Восток Никколо и Маффео Поло были представлены Хубилаю, он принял братьев благосклонно и даже пожаловал им верительную золотую бирку пайцзу (или дщицу), она давала право на получение лошадей и эскорта в трудном путешествии обратно в Европу. Тогда Хубилай поручил венецианцам передать римскому папе просьбу прислать ему «сотню ученых, владеющих мастерством семи свободных искусств».

Однако, когда братья вернулись на родину, им не удалось выполнить повеление хана: папа римский скончался, а выборы нового понтифика затянулись. Братья тем временем предприняли новое торговое путешествие на Восток. Шел 1271 год, с караваном судов Никколо, Маффео и Марко добрались до Палестины, затем пересекли полуостров Малая Азия, Армянское нагорье, по реке Тигр спустились до Басры, затем добрались до Ормуза. По пути венецианцы не раз останавливались в городах, где располагались крупнейшие на Востоке рынки.

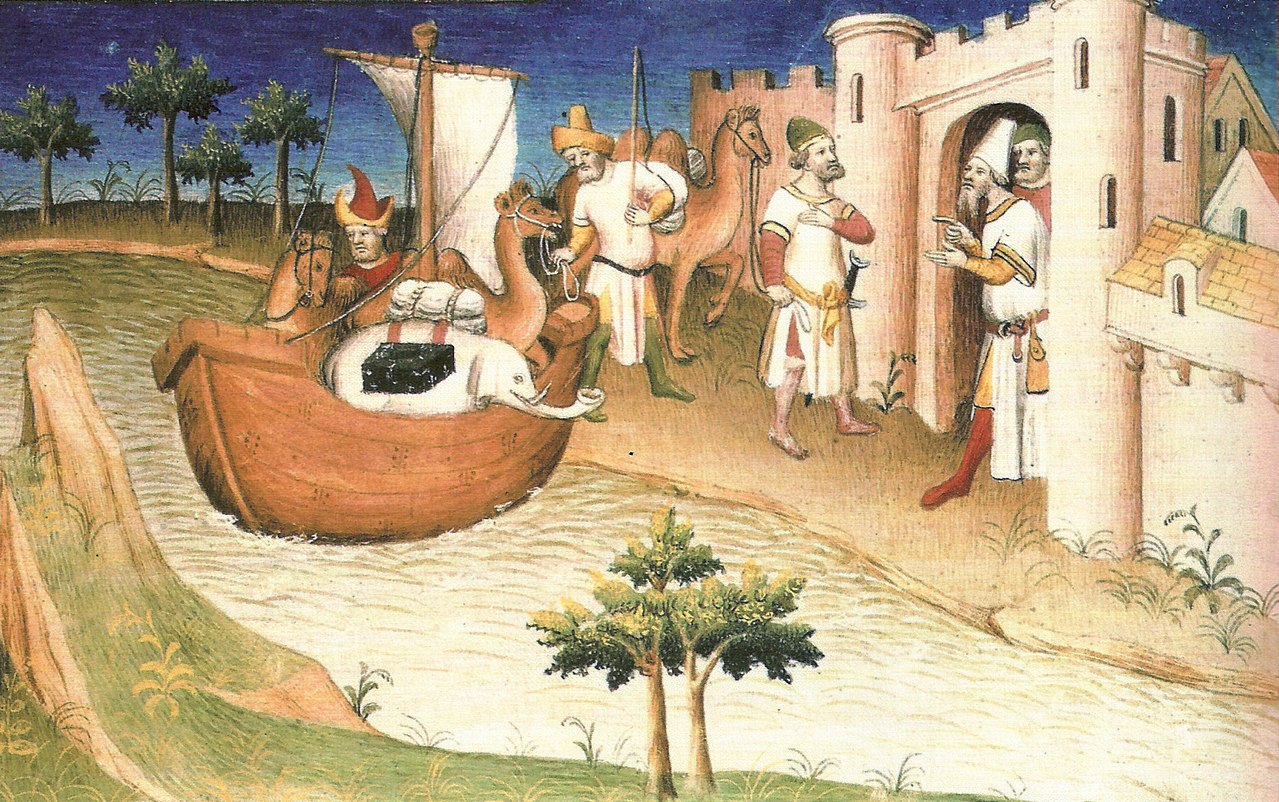

Отплытие Марко Поло из Венеции. Миниатюра из рыцарского «Романа об Александре». XVII в.

В Мосуле Марко поразили шелковые и золотые ткани «мосулины», а также «самые тонкие и красивые в свете ковры», крупнейшим рынком жемчуга славился в те времена Тебриз. Видимо, путешественники собирались плыть в Китай на корабле, но почему-то передумали и направились на северо-восток. Теперь их путь лежал вдоль южных предгорий Гиндукуша к Памиру. По опасным дорогам северо-восточной Персии и Афганистана они добрались, наконец, до древнего города Афганистана – Балха. На Памире Марко Поло побывал на копях, где рабы добывали драгоценные камни: рубины, сапфиры, лазурит.

В городе Ганьчжоу по невыясненным причинам путешественники остановились надолго – прожили целый год. Затем они отправились через перевалы Памира на север и оказались у южных склонов Тянь-Шаня. Много позже в своей «Книге о разнообразии мира» Марко расскажет об этих суровых высокогорных краях и в частности о том, что «птиц тут нет… от великого холода и огонь светится не таким цветом, как в других местах, и пища не так хорошо варится».

Маршрут путешествия Марко-Поло в Китай и его возвращение в Италию

Путники обогнули с юга пустыню Такла-Макан и через безжизненные равнины прошли на северо-восток. Далее по долине реки Хуанхэ – к землям, которыми владели великие монгольские завоеватели. Своим достатком и благополучием особенно понравился путешественникам город Хотан: «Всего вдоволь, хлопку родится много, у жителей есть виноградники и много садов, народ смирный, занимается торговлей и ремеслами». Прошло три с половиной года с тех пор, как Поло отплыли из Венеции.

В начале лета 1275 г. они добрались, наконец, до великой резиденции хана Хубилая – города Ханбалык. Венецианцев встретили радушно, город поразил Марко великолепными дворцами, роскошными пирами, шумными многолюдными рынками, бесконечными торговыми рядами, чайными домами, каменными мостовыми, сторожевыми противопожарными башнями и многим-многим другим. Не оставил равнодушными венецианцев и город Кинсай в Южном Китае – самый густонаселенный город мира, в котором проживал миллион жителей! Он был построен, как и Венеция, на каналах, по ним непрерывно сновали корабли, торговые лодки и прогулочные суда.

Хан Хубилай. Китайская миниатюра. 1294 г.

Хан Хубилай вручает золотую пайцзу братьям Поло. Рисунок конца XIV – начала XV в.

Братья Поло перед великим ханом Хубилаем. Рисунок из «Книги о разнообразии мира». XV в.

Восхищался Марко и правителем – великим ханом Хубилаем, «великим делам и диковинам величайшего государя всех татарских князей… росту он хорошего, толст в меру, лицом бел как роза, глаза черные, славные». Хубилай приближал ко двору талантливых иностранцев, и пока отец и дядя занимались торговлей, Марко изучил монгольский язык. Вскоре способного юношу Хубилай нанял на гражданскую службу. Марко жил в почете и роскоши, много путешествовал по Китаю, его посылали в длительные поездки в отдаленные китайские провинции, а возвращаясь, он докладывал правителю о положении дел.

Купцы Поло прожили в Китае 17 лет, пришло время возвращаться домой. По словам Поло, хан был им восхищен, давал различные поручения, не разрешал ему возвращаться в Венецию. Наконец, представился случай: в 1292 г. Марко вызвался сопровождать в Персию монгольскую принцессу Кокёчин для бракосочетания с сыном персидского короля. Чтобы безопасно доставить ее в Ормуз, а затем в Тебриз, Хубилай снарядил четырнадцать кораблей. Флотилия, в составе которой были и купцы Поло, побывала на Зондских островах, Цейлоне, затем вдоль берегов Индии проследовала до Ормуза. Благополучно доставив принцессу в Тебриз, купцы Поло через Иран и Черное море в 1295 г. вернулись в Венецию.

Семья Марко Поло в составе каравана, путешествующего по пустыне. Фрагмент карты из каталанского атласа. XIV в.

Марко Поло впервые увидел бумажные деньги в Китае. Китайская банкнота. XIII в.

Во время войны Венецианской республики с генуэзцами в 1298 г. Марко Поло оказался на борту торгового судна, захваченного противниками, и год провел в генуэзской тюрьме. Там он надиктовал свои воспоминания о странствиях и жизни на Востоке – знаменитую книгу Марко Поло – заключенному из Пизы – Рустичиано.

Биографы Марко утверждают, что он был способным, энергичным, терпеливым и наблюдательным человеком, хорошим, но увлекающимся рассказчиком. За склонность к преувеличениям Марко еще при жизни получил прозвище «Миллион». Некоторые ученые подвергают сомнению факты, изложенные в книге Марко Поло, и высказывают мнение, что она была лишь талантливым пересказом впечатлений персидских купцов о странствиях по Востоку. Однако обнаруженные неточности могли появиться при многочисленных переводах, к тому же Марко Поло диктовал свои воспоминания по памяти. Можно смело утверждать, что описания Марко Поло вполне соответствуют современным знаниям о природе и истории стран Востока.

Прибытие семьи Марко Поло в Ормуз. Рисунок из «Книги о разнообразии мира». XV в.

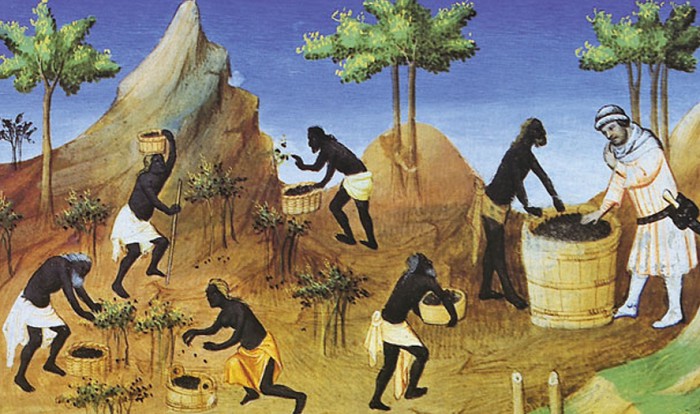

Сбор урожая перца в Южной Индии. Рисунок из «Книги о разнообразии мира». XV в.

Вклад в географию

В XIII в. Марко Поло был, пожалуй, самым известным путешественником в Европе. Он прожил в Китае семнадцать лет, описал неведомые европейцам земли, повседневную жизнь китайцев, типичные ремесла и кулинарные традиции различных областей этой страны. В его книге содержатся сведения о Японии, островах Ява и Суматра, о Цейлоне и Мадагаскаре.

Поделиться ссылкой

|

Marco Polo |

|

|---|---|

Polo wearing a Tartar outfit, print from the 18th century |

|

| Born | 1254

Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Died | 8 January 1324 (aged 69–70)

Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Resting place | Church of San Lorenzo 45°26′14″N 12°20′44″E / 45.4373°N 12.3455°E |

| Occupation(s) | Merchant, explorer, writer |

| Known for | The Travels of Marco Polo |

| Spouse |

Donata Badoer (m. 1300–1324) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

Marco Polo (, Venetian: [ˈmaɾko ˈpolo], Italian: [ˈmarko ˈpɔːlo] (listen); c. 1254 – 8 January 1324)[1] was a Venetian merchant,[2][3] explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in The Travels of Marco Polo (also known as Book of the Marvels of the World and Il Milione, c. 1300), a book that described to Europeans the then mysterious culture and inner workings of the Eastern world, including the wealth and great size of the Mongol Empire and China in the Yuan Dynasty, giving their first comprehensive look into China, Persia, India, Japan and other Asian cities and countries.[4]

Born in Venice, Marco learned the mercantile trade from his father and his uncle, Niccolò and Maffeo, who travelled through Asia and met Kublai Khan. In 1269, they returned to Venice to meet Marco for the first time. The three of them embarked on an epic journey to Asia, exploring many places along the Silk Road until they reached Cathay (China). They were received by the royal court of Kublai Khan, who was impressed by Marco’s intelligence and humility. Marco was appointed to serve as Khan’s foreign emissary, and he was sent on many diplomatic missions throughout the empire and Southeast Asia, such as in present-day Burma, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Vietnam.[5][6] As part of this appointment, Marco also travelled extensively inside China, living in the emperor’s lands for 17 years and seeing many things that had previously been unknown to Europeans.[7] Around 1291, the Polos also offered to accompany the Mongol princess Kököchin to Persia; they arrived around 1293. After leaving the princess, they travelled overland to Constantinople and then to Venice, returning home after 24 years.[7] At this time, Venice was at war with Genoa; Marco was captured and imprisoned by the Genoans after joining the war effort and dictated his stories to Rustichello da Pisa, a cellmate. He was released in 1299, became a wealthy merchant, married, and had three children. He died in 1324 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Venice.

Though he was not the first European to reach China (see Europeans in Medieval China), Marco Polo was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. This account of the Orient provided the Europeans with a clear picture of the East’s geography and ethnic customs, and was the first Western record of porcelain, gunpowder, paper money, and some Asian plants and exotic animals.[8] His travel book inspired Christopher Columbus[9] and many other travellers. There is substantial literature based on Polo’s writings; he also influenced European cartography, leading to the introduction of the Fra Mauro map.

Life

Birthplace and family origin

16th-century portrait of Marco Polo

Marco Polo was born in 1254 in Venice, the capital of the Venetian Republic.[10][11] His father, Niccolò Polo, had his household in Venice and left Marco’s pregnant mother in order to travel to Asia with his brother Maffeo Polo. Their return to Italy in order to «go to Venice and visit their household» is described in The Travels of Marco Polo as follows: «…they departed from Acre and went to Negropont, and from Negropont they continued their voyage to Venice. On their arrival there, Messer Nicolas found that his wife was dead and that she had left behind her a son of fifteen years of age, whose name was Marco».[12]

His first known ancestor was a great uncle, Marco Polo (the older) from Venice, who lent some money and commanded a ship in Constantinople. Andrea, Marco’s grandfather, lived in Venice in «contrada San Felice», he had three sons: Marco «the older», Maffeo and Niccolò (Marco’s father).[13][14] Some old Venetian historical sources considered Polo’s ancestors to be of far Dalmatian origin.[15][16][17]

Nickname Milione

Corte Seconda del Milion, Venice is named after the nickname of Polo, Il Milione

Marco Polo is most often mentioned in the archives of the Republic of Venice as Marco Paulo de confinio Sancti Iohannis Grisostomi,[18] which means Marco Polo of the contrada of St John Chrysostom Church.

However, he was also nicknamed Milione during his lifetime (which in Italian literally means ‘Million’). In fact, the Italian title of his book was Il libro di Marco Polo detto il Milione, which means «The Book of Marco Polo, nicknamed ‘Milione‘«. According to the 15th-century humanist Giovanni Battista Ramusio, his fellow citizens awarded him this nickname when he came back to Venice because he kept on saying that Kublai Khan’s wealth was counted in millions. More precisely, he was nicknamed Messer Marco Milioni (Mr Marco Millions).[19]

However, since also his father Niccolò was nicknamed Milione,[20] 19th-century philologist Luigi Foscolo Benedetto was persuaded that Milione was a shortened version of Emilione, and that this nickname was used to distinguish Niccolò’s and Marco’s branch from other Polo families.[21][22]

Early life and Asian travel

Mosaic of Marco Polo displayed in the Palazzo Doria-Tursi, Genoa, Italy

In 1168, his great-uncle, Marco Polo, borrowed money and commanded a ship in Constantinople.[23][24] His grandfather, Andrea Polo of the parish of San Felice, had three sons, Maffeo, yet another Marco, and the traveller’s father Niccolò.[23] This genealogy, described by Ramusio, is not universally accepted as there is no additional evidence to support it.[25][26]

His father, Niccolò Polo, a merchant, traded with the Near East, becoming wealthy and achieving great prestige.[27][28] Niccolò and his brother Maffeo set off on a trading voyage before Marco’s birth.[29][28] In 1260, Niccolò and Maffeo, while residing in Constantinople, then the capital of the Latin Empire, foresaw a political change; they liquidated their assets into jewels and moved away.[27] According to The Travels of Marco Polo, they passed through much of Asia, and met with Kublai Khan, a Mongol ruler and founder of the Yuan dynasty.[30] Their decision to leave Constantinople proved timely. In 1261 Michael VIII Palaiologos, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea, took Constantinople, promptly burned the Venetian quarter and re-established the Byzantine Empire. Captured Venetian citizens were blinded,[31] while many of those who managed to escape perished aboard overloaded refugee ships fleeing to other Venetian colonies in the Aegean Sea.

Almost nothing is known about the childhood of Marco Polo until he was fifteen years old, except that he probably spent part of his childhood in Venice.[32][33][24] Meanwhile, Marco Polo’s mother died, and an aunt and uncle raised him.[28] He received a good education, learning mercantile subjects including foreign currency, appraising, and the handling of cargo ships;[28] he learned little or no Latin.[27] His father later married Floradise Polo (née Trevisan).[26]

In 1269, Niccolò and Maffeo returned to their families in Venice, meeting young Marco for the first time.[32] In 1271, during the rule of Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo, Marco Polo (at seventeen years of age), his father, and his uncle set off for Asia on the series of adventures that Marco later documented in his book.[34]

They sailed to Acre and later rode on their camels to the Persian port Hormuz. During the first stages of the journey, they stayed for a few months in Acre and were able to speak with Archdeacon Tedaldo Visconti of Piacenza. The Polo family, on that occasion, had expressed their regret at the long lack of a pope, because on their previous trip to China they had received a letter from Kublai Khan to the Pope, and had thus had to leave for China disappointed. During the trip, however, they received news that after 33 months of vacation, finally, the Conclave had elected the new Pope and that he was exactly the archdeacon of Acre. The three of them hurried to return to the Holy Land, where the new Pope entrusted them with letters for the «Great Khan», inviting him to send his emissaries to Rome. To give more weight to this mission he sent with the Polos, as his legates, two Dominican fathers, Guglielmo of Tripoli and Nicola of Piacenza.[35]

They continued overland until they arrived at Kublai Khan’s place in Shangdu, China (then known as Cathay). By this time, Marco was 21 years old.[36] Impressed by Marco’s intelligence and humility, Khan appointed him to serve as his foreign emissary to India and Burma. He was sent on many diplomatic missions throughout his empire and in Southeast Asia, (such as in present-day Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Vietnam),[5][6] but also entertained the Khan with stories and observations about the lands he saw. As part of this appointment, Marco travelled extensively inside China, living in the emperor’s lands for 17 years.[7]

Kublai initially refused several times to let the Polos return to Europe, as he appreciated their company and they became useful to him.[37] However, around 1291, he finally granted permission, entrusting the Polos with his last duty: accompany the Mongol princess Kököchin, who was to become the consort of Arghun Khan, in Persia (see Narrative section).[36][38] After leaving the princess, the Polos travelled overland to Constantinople. They later decided to return to their home.[36]

They returned to Venice in 1295, after 24 years, with many riches and treasures. They had travelled almost 15,000 miles (24,000 km).[28]

Genoese captivity and later life

Marco Polo returned to Venice in 1295 with his fortune converted into gemstones. At this time, Venice was at war with the Republic of Genoa.[39] Polo armed a galley equipped with a trebuchet[40] to join the war. He was probably caught by Genoans in a skirmish in 1296, off the Anatolian coast between Adana and the Gulf of Alexandretta[41] (and not during the battle of Curzola (September 1298), off the Dalmatian coast,[42] a claim which is due to a later tradition (16th century) recorded by Giovanni Battista Ramusio[43][44]).

He spent several months of his imprisonment dictating a detailed account of his travels to a fellow inmate, Rustichello da Pisa,[28] who incorporated tales of his own as well as other collected anecdotes and current affairs from China. The book soon spread throughout Europe in manuscript form, and became known as The Travels of Marco Polo (Italian title: Il Milione, lit. «The Million», deriving from Polo’s nickname «Milione». Original title in Franco-Italian : Livres des Merveilles du Monde). It depicts the Polos’ journeys throughout Asia, giving Europeans their first comprehensive look into the inner workings of the Far East, including China, India, and Japan.[45]

Polo was finally released from captivity in August 1299,[28] and returned home to Venice, where his father and uncle in the meantime had purchased a large palazzo in the zone named contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo (Corte del Milion).[46] For such a venture, the Polo family probably invested profits from trading, and even many gemstones they brought from the East.[46] The company continued its activities and Marco soon became a wealthy merchant. Marco and his uncle Maffeo financed other expeditions, but likely never left Venetian provinces, nor returned to the Silk Road and Asia.[47] Sometime before 1300, his father Niccolò died.[47] In 1300, he married Donata Badoèr, the daughter of Vitale Badoèr, a merchant.[48] They had three daughters, Fantina (married Marco Bragadin), Bellela (married Bertuccio Querini), and Moreta.[49][50]

Pietro d’Abano philosopher, doctor and astrologer based in Padua, reports having spoken with Marco Polo about what he had observed in the vault of the sky during his travels. Marco told him that during his return trip to the South China Sea, he had spotted what he describes in a drawing as a star «shaped like a sack» (in Latin: ut sacco) with a big tail (magna habens caudam), most likely a comet. Astronomers agree that there were no comets sighted in Europe at the end of the thirteenth century, but there are records about a comet sighted in China and Indonesia in 1293.[51] Interestingly, this circumstance does not appear in Polo’s book of Travels. Peter D’Abano kept the drawing in his volume «Conciliator Differentiarum, quæ inter Philosophos et Medicos Versantur». Marco Polo gave Pietro other astronomical observations he made in the Southern Hemisphere, and also a description of the Sumatran rhinoceros, which are collected in the Conciliator.[51]

In 1305 he is mentioned in a Venetian document among local sea captains regarding the payment of taxes.[26] His relation with a certain Marco Polo, who in 1300 was mentioned with riots against the aristocratic government, and escaped the death penalty, as well as riots from 1310 led by Bajamonte Tiepolo and Marco Querini, among whose rebels were Jacobello and Francesco Polo from another family branch, is unclear.[26] Polo is clearly mentioned again after 1305 in Maffeo’s testament from 1309 to 1310, in a 1319 document according to which he became owner of some estates of his deceased father, and in 1321, when he bought part of the family property of his wife Donata.[26]

Death

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness.[52] On 8 January 1324, despite physicians’ efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed.[53] To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices.[53] The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried.[53] He also set free Peter, a Tartar servant, who may have accompanied him from Asia,[54] and to whom Polo bequeathed 100 lire of Venetian denari.[55]

He divided up the rest of his assets, including several properties, among individuals, religious institutions, and every guild and fraternity to which he belonged.[53] He also wrote off multiple debts including 300 lire that his sister-in-law owed him, and others for the convent of San Giovanni, San Paolo of the Order of Preachers, and a cleric named Friar Benvenuto.[53] He ordered 220 soldi be paid to Giovanni Giustiniani for his work as a notary and his prayers.[56]

The will was not signed by Polo, but was validated by the then-relevant «signum manus» rule, by which the testator only had to touch the document to make it legally valid.[55][57] Due to the Venetian law stating that the day ends at sunset, the exact date of Marco Polo’s death cannot be determined, but according to some scholars it was between the sunsets of 8 and 9 January 1324.[58] Biblioteca Marciana, which holds the original copy of his testament, dates the testament on 9 January 1323, and gives the date of his death at some time in June 1324.[57]

The Travels of Marco Polo

Map of Marco Polo’s travels

An authoritative version of Marco Polo’s book does not and cannot exist, for the early manuscripts differ significantly, and the reconstruction of the original text is a matter of textual criticism. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist. Before the availability of printing press, errors were frequently made during copying and translating, so there are many differences between the various copies.[59][60]

Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote Devisement du Monde in Franco-Venetian.[61] The idea probably was to create a handbook for merchants, essentially a text on weights, measures and distances.[62]

The oldest surviving manuscript is in Old French heavily flavoured with Italian;[63] According to the Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, this «F» text is the basic original text, which he corrected by comparing it with the somewhat more detailed Italian of Giovanni Battista Ramusio, together with a Latin manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana. Other early important sources are R (Ramusio’s Italian translation first printed in 1559), and Z (a fifteenth-century Latin manuscript kept at Toledo, Spain). Another Old French Polo manuscript, dating to around 1350, is held by the National Library of Sweden.[64]

One of the early manuscripts Iter Marci Pauli Veneti was a translation into Latin made by the Dominican brother Francesco Pipino [it] in 1302, just a few years after Marco’s return to Venice. Since Latin was then the most widespread and authoritative language of culture, it is suggested that Rustichello’s text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Dominican Order, and this helped to promote the book on a European scale.[18]

The first English translation is the Elizabethan version by John Frampton published in 1579, The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo, based on Santaella’s Castilian translation of 1503 (the first version in that language).[65]

The published editions of Polo’s book rely on single manuscripts, blend multiple versions together, or add notes to clarify, for example in the English translation by Henry Yule. The 1938 English translation by A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot is based on a Latin manuscript found in the library of the Cathedral of Toledo in 1932, and is 50% longer than other versions.[66] The popular translation published by Penguin Books in 1958 by R. E. Latham works several texts together to make a readable whole.[67]

Narrative

Statue of Marco Polo in Hangzhou, China

The book opens with a preface describing his father and uncle travelling to Bolghar where Prince Berke Khan lived. A year later, they went to Ukek[68] and continued to Bukhara. There, an envoy from the Levant invited them to meet Kublai Khan, who had never met Europeans.[69] In 1266, they reached the seat of Kublai Khan at Dadu, present-day Beijing, China. Kublai received the brothers with hospitality and asked them many questions regarding the European legal and political system.[70] He also inquired about the Pope and Church in Rome.[71] After the brothers answered the questions he tasked them with delivering a letter to the Pope, requesting 100 Christians acquainted with the Seven Arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy). Kublai Khan requested also that an envoy bring him back oil of the lamp in Jerusalem.[72] The long sede vacante between the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268 and the election of his successor delayed the Polos in fulfilling Kublai’s request. They followed the suggestion of Theobald Visconti, then papal legate for the realm of Egypt, and returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270 to await the nomination of the new Pope, which allowed Marco to see his father for the first time, at the age of fifteen or sixteen.[73]

In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfil Kublai’s request. They sailed to Acre, and then rode on camels to the Persian port of Hormuz. The Polos wanted to sail straight into China, but the ships there were not seaworthy, so they continued overland through the Silk Road, until reaching Kublai’s summer palace in Shangdu, near present-day Zhangjiakou. In one instance during their trip, the Polos joined a caravan of travelling merchants whom they crossed paths with. Unfortunately, the party was soon attacked by bandits, who used the cover of a sandstorm to ambush them. The Polos managed to fight and escape through a nearby town, but many members of the caravan were killed or enslaved.[74] Three and a half years after leaving Venice, when Marco was about 21 years old, the Polos were welcomed by Kublai into his palace.[28] The exact date of their arrival is unknown, but scholars estimate it to be between 1271 and 1275.[nb 1] On reaching the Yuan court, the Polos presented the sacred oil from Jerusalem and the papal letters to their patron.[27]

Marco knew four languages, and the family had accumulated a great deal of knowledge and experience that was useful to Kublai. It is possible that he became a government official;[28] he wrote about many imperial visits to China’s southern and eastern provinces, the far south and Burma.[75] They were highly respected and sought after in the Mongolian court, and so Kublai Khan decided to decline the Polos’ requests to leave China. They became worried about returning home safely, believing that if Kublai died, his enemies might turn against them because of their close involvement with the ruler. In 1292, Kublai’s great-nephew, then ruler of Persia, sent representatives to China in search of a potential wife, and they asked the Polos to accompany them, so they were permitted to return to Persia with the wedding party—which left that same year from Zaitun in southern China on a fleet of 14 junks. The party sailed to the port of Singapore,[76] travelled north to Sumatra,[77] and around the southern tip of India,[78] eventually crossing the Arabian Sea to Hormuz. The two-year voyage was a perilous one—of the six hundred people (not including the crew) in the convoy only eighteen had survived (including all three Polos).[79] The Polos left the wedding party after reaching Hormuz and travelled overland to the port of Trebizond on the Black Sea, the present-day Trabzon.[28]

A page from Il Milione, from a manuscript believed to date between 1298 and 1299

Role of Rustichello

The British scholar Ronald Latham has pointed out that The Book of Marvels was, in fact, a collaboration written in 1298–1299 between Polo and a professional writer of romances, Rustichello of Pisa.[80] It is believed that Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote Devisement du Monde in Franco-Venetian language, which was the language of culture widespread in northern Italy between the subalpine belt and the lower Po between the 13th and 15th centuries.[61][81]

Latham also argued that Rustichello may have glamorised Polo’s accounts, and added fantastic and romantic elements that made the book a bestseller.[80] The Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto had previously demonstrated that the book was written in the same «leisurely, conversational style» that characterised Rustichello’s other works, and that some passages in the book were taken verbatim or with minimal modifications from other writings by Rustichello. For example, the opening introduction in The Book of Marvels to «emperors and kings, dukes and marquises» was lifted straight out of an Arthurian romance Rustichello had written several years earlier, and the account of the second meeting between Polo and Kublai Khan at the latter’s court is almost the same as that of the arrival of Tristan at the court of King Arthur at Camelot in that same book.[82] Latham believed that many elements of the book, such as legends of the Middle East and mentions of exotic marvels, may have been the work of Rustichello who was giving what medieval European readers expected to find in a travel book.[83]

Role of the Dominican Order

Apparently, from the very beginning, Marco’s story aroused contrasting reactions, as it was received by some with a certain disbelief. The Dominican father Francesco Pipino was the author of a translation into Latin, Iter Marci Pauli Veneti in 1302, just a few years after Marco’s return to Venice. Francesco Pipino solemnly affirmed the truthfulness of the book and defined Marco as a «prudent, honoured and faithful man».[84]

In his writings, the Dominican brother Jacopo d’Acqui explains why his contemporaries were sceptical about the content of the book. He also relates that before dying, Marco Polo insisted that «he had told only a half of the things he had seen».[84]

According to some recent research of the Italian scholar Antonio Montefusco, the very close relationship that Marco Polo cultivated with members of the Dominican Order in Venice suggests that local fathers collaborated with him for a Latin version of the book, which means that Rustichello’s text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Order.[18]

Since Dominican fathers had among their missions that of evangelizing foreign peoples (cf. the role of Dominican missionaries in China[85] and in the Indies[86]), it is reasonable to think that they considered Marco’s book as a trustworthy piece of information for missions in the East. The diplomatic communications between Pope Innocent IV and Pope Gregory X with the Mongols[87] were probably another reason for this endorsement. At the time, there was open discussion of a possible Christian-Mongol alliance with an anti-Islamic function.[88] In fact, a Mongol delegate was solemny baptised at the Second Council of Lyon. At the council, Pope Gregory X promulgated a new Crusade to start in 1278 in liaison with the Mongols.[89]

Authenticity and veracity

Kublai Khan’s court, from the French «Livre des merveilles»

Since its publication, some have viewed the book with skepticism.[90] Some in the Middle Ages regarded the book simply as a romance or fable, due largely to the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck, who portrayed the Mongols as ‘barbarians’ who appeared to belong to ‘some other world’.[90] Doubts have also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo’s narrative of his travels in China, for example for his failure to mention the Great Wall of China, and in particular the difficulties in identifying many of the place names he used[91] (the great majority, however, have since been identified).[92] Many have questioned whether he had visited the places he mentioned in his itinerary, whether he had appropriated the accounts of his father and uncle or other travellers, and some doubted whether he even reached China, or that if he did, perhaps never went beyond Khanbaliq (Beijing).[91][93]

It has, however, been pointed out that Polo’s accounts of China are more accurate and detailed than other travellers’ accounts of the period. Polo had at times refuted the ‘marvellous’ fables and legends given in other European accounts, and despite some exaggerations and errors, Polo’s accounts have relatively few of the descriptions of irrational marvels. In many cases of descriptions of events where he was not present (mostly given in the first part before he reached China, such as mentions of Christian miracles), he made a clear distinction that they are what he had heard rather than what he had seen. It is also largely free of the gross errors found in other accounts such as those given by the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta who had confused the Yellow River with the Grand Canal and other waterways, and believed that porcelain was made from coal.[94]

Modern studies have further shown that details given in Marco Polo’s book, such as the currencies used, salt productions and revenues, are accurate and unique. Such detailed descriptions are not found in other non-Chinese sources, and their accuracy is supported by archaeological evidence as well as Chinese records compiled after Polo had left China. His accounts are therefore unlikely to have been obtained second hand.[95] Other accounts have also been verified; for example, when visiting Zhenjiang in Jiangsu, China, Marco Polo noted that a large number of Christian churches had been built there. His claim is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdian named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand founded six Nestorian Christian churches there in addition to one in Hangzhou during the second half of the 13th century.[96] His story of the princess Kököchin sent from China to Persia to marry the Īl-khān is also confirmed by independent sources in both Persia and China.[97]

Scholarly analyses

Explaining omissions

Sceptics have long wondered whether Marco Polo wrote his book based on hearsay, with some pointing to omissions about noteworthy practices and structures of China as well as the lack of details on some places in his book. While Polo describes paper money and the burning of coal, he fails to mention the Great Wall of China, tea, Chinese characters, chopsticks, or footbinding.[98] His failure to note the presence of the Great Wall of China was first raised in the middle of the seventeenth century, and in the middle of the eighteenth century, it was suggested that he might have never reached China.[91] Later scholars such as John W. Haeger argued that Marco Polo might not have visited Southern China due to the lack of details in his description of southern Chinese cities compared to northern ones, while Herbert Franke also raised the possibility that Marco Polo might not have been to China at all, and wondered if he might have based his accounts on Persian sources due to his use of Persian expressions.[93][99] This is taken further by Frances Wood who claimed in her 1995 book Did Marco Polo Go to China? that at best Polo never went farther east than Persia (modern Iran), and that there is nothing in The Book of Marvels about China that could not be obtained via reading Persian books.[100] Wood maintains that it is more probable that Polo only went to Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey) and some of the Italian merchant colonies around the Black Sea, picking hearsay from those travellers who had been farther east.[100]

Supporters of Polo’s basic accuracy countered on the points raised by sceptics such as footbinding and the Great Wall of China. Historian Stephen G. Haw argued that the Great Walls were built to keep out northern invaders, whereas the ruling dynasty during Marco Polo’s visit were those very northern invaders. They note that the Great Wall familiar to us today is a Ming structure built some two centuries after Marco Polo’s travels; and that the Mongol rulers whom Polo served controlled territories both north and south of today’s wall, and would have no reasons to maintain any fortifications that may have remained there from the earlier dynasties.[101] Other Europeans who travelled to Khanbaliq during the Yuan dynasty, such as Giovanni de’ Marignolli and Odoric of Pordenone, said nothing about the wall either. The Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta, who asked about the wall when he visited China during the Yuan dynasty, could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen it, suggesting that while ruins of the wall constructed in the earlier periods might have existed, they were not significant or noteworthy at that time.[101]

Haw also argued that footbinding was not common even among Chinese during Polo’s time and almost unknown among the Mongols. While the Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone who visited Yuan China mentioned footbinding (it is however unclear whether he was merely relaying something he had heard as his description is inaccurate),[102] no other foreign visitors to Yuan China mentioned the practice, perhaps an indication that the footbinding was not widespread or was not practised in an extreme form at that time.[103] Marco Polo himself noted (in the Toledo manuscript) the dainty walk of Chinese women who took very short steps.[101] It has also been noted by other scholars that many of the things not mentioned by Marco Polo such as tea and chopsticks were not mentioned by other travellers as well.[38] Haw also pointed out that despite the few omissions, Marco Polo’s account is more extensive, more accurate and more detailed than those of other foreign travellers to China in this period.[104] Marco Polo even observed Chinese nautical inventions such as the watertight compartments of bulkhead partitions in Chinese ships, knowledge of which he was keen to share with his fellow Venetians.[105]

In addition to Haw, a number of other scholars have argued in favour of the established view that Polo was in China in response to Wood’s book.[38] The book has been criticized by figures including Igor de Rachewiltz (translator and annotator of The Secret History of the Mongols) and Morris Rossabi (author of Kublai Khan: his life and times).[106] The historian David Morgan points out basic errors made in Wood’s book such as confusing the Liao dynasty with the Jin dynasty, and he found no compelling evidence in the book that would convince him that Marco Polo did not go to China.[107] Haw also argues in his book Marco Polo’s China that Marco’s account is much more correct and accurate than has often been supposed and that it is extremely unlikely that he could have obtained all the information in his book from second-hand sources.[108] Haw also criticizes Wood’s approach to finding mention of Marco Polo in Chinese texts by contending that contemporaneous Europeans had little regard for using surnames and that a direct Chinese transliteration of the name «Marco» ignores the possibility of him taking on a Chinese or even Mongol name with no similarity to his Latin name.[109]

Also in reply to Wood, Jørgen Jensen recalled the meeting of Marco Polo and Pietro d’Abano in the late 13th century. During this meeting, Marco gave to Pietro details of the astronomical observations he had made on his journey. These observations are only compatible with Marco’s stay in China, Sumatra and the South China Sea[110] and are recorded in Pietro’s book Conciliator Differentiarum, but not in Marco’s Book of Travels.

Reviewing Haw’s book, Peter Jackson (author of The Mongols and the West) has said that Haw «must surely now have settled the controversy surrounding the historicity of Polo’s visit to China».[111] Igor de Rachewiltz’s review, which refutes Wood’s points, concludes with a strongly-worded condemnation: «I regret to say that F. W.’s book falls short of the standard of scholarship that one would expect in a work of this kind. Her book can only be described as deceptive, both in relation to the author and to the public at large. Questions are posted that, in the majority of cases, have already been answered satisfactorily … her attempt is unprofessional; she is poorly equipped in the basic tools of the trade, i.e., adequate linguistic competence and research methodology … and her major arguments cannot withstand close scrutiny. Her conclusion fails to consider all the evidence supporting Marco Polo’s credibility.»[112]

Allegations of exaggeration

Some scholars believe that Marco Polo exaggerated his importance in China. The British historian David Morgan thought that Polo had likely exaggerated and lied about his status in China,[113] while Ronald Latham believed that such exaggerations were embellishments by his ghostwriter Rustichello da Pisa.[83]

Et meser Marc Pol meisme, celui de cui trate ceste livre, seingneurie ceste cité por trois anz.

And the same Marco Polo, of whom this book relates, ruled this city for three years.

This sentence in The Book of Marvels was interpreted as Marco Polo was «the governor» of the city of «Yangiu» Yangzhou for three years, and later of Hangzhou. This claim has raised some controversy. According to David Morgan no Chinese source mentions him as either a friend of the Emperor or as the governor of Yangzhou – indeed no Chinese source mentions Marco Polo at all.[113] In fact, in the 1960s the German historian Herbert Franke noted that all occurrences of Po-lo or Bolod in Yuan texts were names of people of Mongol or Turkic extraction.[99]

However, in the 2010s the Chinese scholar Peng Hai identified Marco Polo with a certain «Boluo», a courtier of the emperor, who is mentioned in the Yuanshi («History of Yuan») since he was arrested in 1274 by an imperial dignitary named Saman. The accusation was that Boluo had walked on the same side of the road as a female courtesan, in contravention of the order for men and women to walk on opposite sides of the road inside the city.[114] According to the «Yuanshi» records, Boluo was released at the request of the emperor himself, and was then transferred to the region of Ningxia, in the northeast of present-day China, in the spring of 1275. The date could correspond to the first mission of which Marco Polo speaks.[115]

If this identification is correct, there is a record about Marco Polo in Chinese sources. These conjectures seem to be supported by the fact that in addition to the imperial dignitary Saman (the one who had arrested the official named «Boluo»), the documents mention his brother, Xiangwei. According to sources, Saman died shortly after the incident, while Xiangwei was transferred to Yangzhou in 1282–1283. Marco Polo reports that he was moved to Hangzhou the following year, in 1284. It has been supposed that these displacements are due to the intention to avoid further conflicts between the two.[116]

The sinologist Paul Pelliot thought that Polo might have served as an officer of the government salt monopoly in Yangzhou, which was a position of some significance that could explain the exaggeration.[113]

It may seem unlikely that a European could hold a position of power in the Mongolian empire. However, some records prove he was not the first nor the only one. In his book, Marco mentions an official named «Mar Sarchis» who probably was a Nestorian Christian bishop, and he says he founded two Christian churches in the region of «Caigiu». This official is actually mentioned in the local gazette Zhishun Zhenjian zhi under the name «Ma Xuelijisi» and the qualification of «General of Third Class». Always in the gazette, it is said Ma Xuelijsi was an assistant supervisor in the province of Zhenjiang for three years, and that during this time he founded two Christian churches.[117][118][116] In fact, it is a well-documented fact that Kublai Khan trusted foreigners more than Chinese subjects in internal affairs.[119][116]

Stephen G. Haw challenges this idea that Polo exaggerated his own importance, writing that, «contrary to what has often been said … Marco does not claim any very exalted position for himself in the Yuan empire.»[120] He points out that Polo never claimed to hold high rank, such as a darughachi, who led a tumen – a unit that was normally 10,000 strong. In fact, Polo does not even imply that he had led 1,000 personnel. Haw points out that Polo himself appears to state only that he had been an emissary of the khan, in a position with some esteem. According to Haw, this is a reasonable claim if Polo was, for example, a keshig – a member of the imperial guard by the same name, which included as many as 14,000 individuals at the time.[120]

Haw explains how the earliest manuscripts of Polo’s accounts provide contradicting information about his role in Yangzhou, with some stating he was just a simple resident, others stating he was a governor, and Ramusio’s manuscript claiming he was simply holding that office as a temporary substitute for someone else, yet all the manuscripts concur that he worked as an esteemed emissary for the khan.[121] Haw also objected to the approach to finding mention of Marco Polo in Chinese texts, contending that contemporaneous Europeans had little regard for using surnames, and a direct Chinese transcription of the name «Marco» ignores the possibility of him taking on a Chinese or even Mongol name that had no bearing or similarity with his Latin name.[120]

Another controversial claim is at chapter 145 when the Book of Marvels states that the three Polos provided the Mongols with technical advice on building mangonels during the Siege of Xiangyang,

Adonc distrent les .II. freres et lor filz meser Marc. «Grant Sire, nos avon avech nos en nostre mesnie homes qe firont tielz mangan qe giteront si grant pieres qe celes de la cité ne poront sofrir mes se renderont maintenant.»

Then the two brothers and their son Marc said: «Great Lord, in our entourage we have men who will build such mangonels which launch such great stones, that the inhabitants of the city will not endure it and will immediately surrender.»

Since the siege was over in 1273, before Marco Polo had arrived in China for the first time, the claim cannot be true.[113][122] The Mongol army that besieged Xiangyang did have foreign military engineers, but they were mentioned in Chinese sources as being from Baghdad and had Arabic names.[99] In this respect, Igor de Rachewiltz recalls that the claim that the three Polo were present at the siege of Xiang-yang is not present in all manuscripts, but Niccolò and Matteo could have made this suggestion. Therefore, this claim seems a subsequent addition to give more credibility to the story.[123][38]

Errors

A number of errors in Marco Polo’s account have been noted: for example, he described the bridge later known as Marco Polo Bridge as having twenty-four arches instead of eleven or thirteen.[38] He also said that city wall of Khanbaliq had twelve gates when it had only eleven.[124] Archaeologists have also pointed out that Polo may have mixed up the details from the two attempted invasions of Japan by Kublai Khan in 1274 and 1281. Polo wrote of five-masted ships, when archaeological excavations found that the ships, in fact, had only three masts.[125]

Appropriation

Wood accused Marco Polo of taking other people’s accounts in his book, retelling other stories as his own, or basing his accounts on Persian guidebooks or other lost sources. For example, Sinologist Francis Woodman Cleaves noted that Polo’s account of the voyage of the princess Kököchin from China to Persia to marry the Īl-khān in 1293 has been confirmed by a passage in the 15th-century Chinese work Yongle Encyclopedia and by the Persian historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in his work Jami’ al-tawarikh. However, neither of these accounts mentions Polo or indeed any European as part of the bridal party,[97] and Wood used the lack of mention of Polo in these works as an example of Polo’s «retelling of a well-known tale». Morgan, in Polo’s defence, noted that even the princess herself was not mentioned in the Chinese source and that it would have been surprising if Polo had been mentioned by Rashid-al-Din.[107] Historian Igor de Rachewiltz strongly criticised Wood’s arguments in his review of her book.[126] Rachewiltz argued that Marco Polo’s account, in fact, allows the Persian and Chinese sources to be reconciled – by relaying the information that two of the three envoys sent (mentioned in the Chinese source and whose names accord with those given by Polo) had died during the voyage, it explains why only the third who survived, Coja/Khoja, was mentioned by Rashìd al-Dìn. Polo had therefore completed the story by providing information not found in either source. He also noted that the only Persian source that mentions the princess was not completed until 1310–11, therefore Marco Polo could not have learned the information from any Persian book. According to de Rachewiltz, the concordance of Polo’s detailed account of the princess with other independent sources that gave only incomplete information is proof of the veracity of Polo’s story and his presence in China.[126]

Assessments

Morgan writes that since much of what The Book of Marvels has to say about China is «demonstrably correct», any claim that Polo did not go to China «creates far more problems than it solves», therefore the «balance of probabilities» strongly suggests that Polo really did go to China, even if he exaggerated somewhat his importance in China.[127] Haw dismisses the various anachronistic criticisms of Polo’s accounts that started in the 17th century, and highlights Polo’s accuracy in great part of his accounts, for example on features of the landscape such as the Grand Canal of China.[128] «If Marco was a liar,» Haw writes, «then he must have been an implausibly meticulous one.»[129]

In 2012, the University of Tübingen Sinologist and historian Hans Ulrich Vogel released a detailed analysis of Polo’s description of currencies, salt production and revenues, and argued that the evidence supports his presence in China because he included details which he could not have otherwise known.[95][130] Vogel noted that no other Western, Arab, or Persian sources have given such accurate and unique details about the currencies of China, for example, the shape and size of the paper, the use of seals, the various denominations of paper money as well as variations in currency usage in different regions of China, such as the use of cowry shells in Yunnan, details supported by archaeological evidence and Chinese sources compiled long after the Polos had left China.[131] His accounts of salt production and revenues from the salt monopoly are also accurate, and accord with Chinese documents of the Yuan era.[132] Economic historian Mark Elvin, in his preface to Vogel’s 2013 monograph, concludes that Vogel «demonstrates by specific example after specific example the ultimately overwhelming probability of the broad authenticity» of Polo’s account. Many problems were caused by the oral transmission of the original text and the proliferation of significantly different hand-copied manuscripts. For instance, did Polo exert «political authority» (seignora) in Yangzhou or merely «sojourn» (sejourna) there? Elvin concludes that «those who doubted, although mistaken, were not always being casual or foolish», but «the case as a whole had now been closed»: the book is, «in essence, authentic, and, when used with care, in broad terms to be trusted as a serious though obviously not always final, witness.»[133]

Legacy

Further exploration

Other lesser-known European explorers had already travelled to China, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, but Polo’s book meant that his journey was the first to be widely known. Christopher Columbus was inspired enough by Polo’s description of the Far East to want to visit those lands for himself; a copy of the book was among his belongings, with handwritten annotations.[9] Bento de Góis, inspired by Polo’s writings of a Christian kingdom in the east, travelled 4,000 miles (6,400 km) in three years across Central Asia. He never found the kingdom but ended his travels at the Great Wall of China in 1605, proving that Cathay was what Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) called «China».[134]

Cartography

Marco Polo’s travels may have had some influence on the development of European cartography, ultimately leading to the European voyages of exploration a century later.[135] The 1453 Fra Mauro map was said by Giovanni Battista Ramusio (disputed by historian/cartographer Piero Falchetta, in whose work the quote appears) to have been partially based on the one brought from Cathay by Marco Polo:

That fine illuminated world map on parchment, which can still be seen in a large cabinet alongside the choir of their monastery [the Camaldolese monastery of San Michele di Murano] was by one of the brothers of the monastery, who took great delight in the study of cosmography, diligently drawn and copied from a most beautiful and very old nautical map and a world map that had been brought from Cathay by the most honourable Messer Marco Polo and his father.

Though Marco Polo never produced a map that illustrated his journey, his family drew several maps to the Far East based on the traveller’s accounts. These collections of maps were signed by Polo’s three daughters, Fantina, Bellela and Moreta.[136] Not only did it contain maps of his journey, but also sea routes to Japan, Siberia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, the Bering Strait and even to the coastlines of Alaska, centuries before the rediscovery of the Americas by Europeans.

Pasta myth

There is a legend about Marco Polo importing pasta from China; however, it is actually a popular misconception,[137] originating with the Macaroni Journal, published by a food industry association with the goal of promoting the use of pasta in the United States.[138] Marco Polo describes in his book a food similar to «lasagna», but he uses a term with which he was already familiar. In fact, pasta had already been invented in Italy a long time before Marco Polo’s travels to Asia.[139] According to the newsletter of the National Macaroni Manufacturers Association[139] and food writer Jeffrey Steingarten,[140] the durum wheat was introduced by Arabs from Libya, during their rule over Sicily in the late 9th century, thus predating Marco Polo’s travels by about four centuries.[140] Steingarten also mentioned that Jane Grigson believed the Marco Polo story to have originated in the 1920s or 30s in an advertisement for a Canadian spaghetti company.[140]

Commemoration

Italian banknote issued in 1982, portraying Marco Polo

The Marco Polo sheep, a subspecies of Ovis ammon, is named after the explorer,[141] who described it during his crossing of Pamir (ancient Mount Imeon) in 1271.[nb 2]