| Mickey Mouse | |

|---|---|

|

|

| First appearance | Steamboat Willie (1928) |

| Created by | Walt Disney Ub Iwerks |

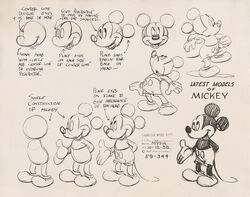

| Designed by | Walt Disney Ub Iwerks (original, 1928 design) Fred Moore (1938 redesign) |

| Voiced by | Walt Disney (1928–1947, 1955–1962) Carl W. Stalling (1929) Jimmy MacDonald (1947–1978) Wayne Allwine (1977–2009)[1] Bret Iwan (2009–present) Chris Diamantopoulos (2013–present) (see voice actors) |

| Developed by | Les Clark Fred Moore Floyd Gottfredson Romano Scarpa |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Mickey Mouse |

| Alias |

|

| Species | Mouse |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Mickey Mouse family |

| Significant other | Minnie Mouse |

| Pets | Pluto (dog) |

Mickey Mouse is an animated cartoon character co-created in 1928 by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks. The longtime mascot of The Walt Disney Company, Mickey is an anthropomorphic mouse who typically wears red shorts, large yellow shoes, and white gloves. Taking inspiration from silent film personalities such as Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp, Mickey is traditionally characterized as a sympathetic underdog who gets by on pluck and ingenuity.[2] The character’s status as a small mouse was personified through his diminutive stature and falsetto voice, the latter of which was originally provided by Disney. Mickey is one of the world’s most recognizable and universally acclaimed fictional characters of all time.

Created as a replacement for a prior Disney character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Mickey first appeared in the short Plane Crazy, debuting publicly in the short film Steamboat Willie (1928), one of the first sound cartoons. The character was originally to be named “Mortimer Mouse”, until Lillian Disney instead suggested “Mickey” during a train ride. The character went on to appear in over 130 films, including The Band Concert (1935), Brave Little Tailor (1938), and Fantasia (1940). Mickey appeared primarily in short films, but also occasionally in feature-length films. Ten of Mickey’s cartoons were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film, one of which, Lend a Paw, won the award in 1941. In 1978, Mickey became the first cartoon character to have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Beginning in 1930, Mickey has also been featured extensively in comic strips and comic books. The Mickey Mouse comic strip, drawn primarily by Floyd Gottfredson, ran for 45 years. Mickey has also appeared in comic books such as Mickey Mouse, Disney Italy’s Topolino and MM – Mickey Mouse Mystery Magazine, and Wizards of Mickey. Mickey also features in television series such as The Mickey Mouse Club (1955–1996) and others. He appears in other media such as video games as well as merchandising and is a meetable character at the Disney parks.

Mickey generally appears alongside his girlfriend Minnie Mouse, his pet dog Pluto, his friends Donald Duck and Goofy, and his nemesis Pete, among others (see Mickey Mouse universe). Though originally characterized as a cheeky lovable rogue, Mickey was rebranded over time as a nice guy, usually seen as an honest and bodacious hero. In 2009, Disney began to rebrand the character again by putting less emphasis on his friendly, well-meaning persona and reintroducing the more adventurous and stubborn sides of his personality, beginning with the video game Epic Mickey.[3]

History

Film

Origin

Mickey Mouse was created as a replacement for Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, an earlier cartoon character that was created by the Disney studio but owned by Universal Pictures.[4] Charles Mintz served as a middleman producer between Disney and Universal through his company, Winkler Pictures, for the series of cartoons starring Oswald. Ongoing conflicts between Disney and Mintz and the revelation that several animators from the Disney studio would eventually leave to work for Mintz’s company ultimately resulted in Disney cutting ties with Oswald. Among the few people who stayed at the Disney studio were animator Ub Iwerks, apprentice artist Les Clark, and Wilfred Jackson. On his train ride home from New York, Walt brainstormed ideas for a new cartoon character.

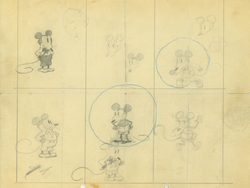

Mickey Mouse was conceived in secret while Disney produced the final Oswald cartoons he contractually owed Mintz. Disney asked Ub Iwerks to start drawing up new character ideas. Iwerks tried sketches of various animals, such as dogs and cats, but none of these appealed to Disney. A female cow and male horse were also rejected. (They would later turn up as Clarabelle Cow and Horace Horsecollar.) A male frog was also rejected, which later showed up in Iwerks’ own Flip the Frog series.[5] Walt Disney got the inspiration for Mickey Mouse from a tame mouse at his desk at Laugh-O-Gram Studio in Kansas City, Missouri.[6] In 1925, Hugh Harman drew some sketches of mice around a photograph of Walt Disney. These inspired Ub Iwerks to create a new mouse character for Disney.[5] «Mortimer Mouse» had been Disney’s original name for the character before his wife, Lillian, convinced him to change it, and ultimately Mickey Mouse came to be.[7][8] The actor Mickey Rooney claimed that, during his Mickey McGuire days, he met cartoonist Walt Disney at the Warner Brothers studio, and that Disney was inspired to name Mickey Mouse after him.[9] This claim, however, has been debunked by Disney historian Jim Korkis, since at the time of Mickey Mouse’s development, Disney Studios had been located on Hyperion Avenue for several years, and Walt Disney never kept an office or other working space at Warner Brothers, having no professional relationship with Warner Brothers.[10][11] Over the years, the name Mortimer Mouse was eventually given to several different characters in the Mickey Mouse universe : Minnie Mouse’s uncle, who appears in several comics stories, one of Mickey’s antagonists who competes for Minnie’s affections in various cartoons and comics, and one of Mickey’s nephews, named Morty.

Debut (1928)

Mickey was first seen in a test screening of the cartoon short Plane Crazy, on May 15, 1928, but it failed to impress the audience and Walt could not find a distributor for the short.[12] Walt went on to produce a second Mickey short, The Gallopin’ Gaucho, which was also not released for lack of a distributor.

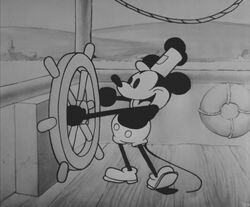

Steamboat Willie was first released on November 18, 1928, in New York. It was co-directed by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks. Iwerks again served as the head animator, assisted by Johnny Cannon, Les Clark, Wilfred Jackson and Dick Lundy. This short was intended as a parody of Buster Keaton’s Steamboat Bill, Jr., first released on May 12 of the same year. Although it was the third Mickey cartoon produced, it was the first to find a distributor, and thus is considered by The Disney Company as Mickey’s debut. Willie featured changes to Mickey’s appearance (in particular, simplifying his eyes to large dots) that established his look for later cartoons and in numerous Walt Disney films.[citation needed]

The cartoon was not the first cartoon to feature a soundtrack connected to the action. Fleischer Studios, headed by brothers Dave and Max Fleischer, had already released a number of sound cartoons using the DeForest system in the mid-1920s. However, these cartoons did not keep the sound synchronized throughout the film. For Willie, Disney had the sound recorded with a click track that kept the musicians on the beat. This precise timing is apparent during the «Turkey in the Straw» sequence when Mickey’s actions exactly match the accompanying instruments. Animation historians have long debated who had served as the composer for the film’s original music. This role has been variously attributed to Wilfred Jackson, Carl Stalling and Bert Lewis, but identification remains uncertain. Walt Disney himself was voice actor for both Mickey and Minnie and would remain the source of Mickey’s voice through 1946 for theatrical cartoons. Jimmy MacDonald took over the role in 1946, but Walt provided Mickey’s voice again from 1955 to 1959 for The Mickey Mouse Club television series on ABC.[citation needed]

Audiences at the time of Steamboat Willie‘s release were reportedly impressed by the use of sound for comedic purposes. Sound films or «talkies» were still considered innovative. The first feature-length movie with dialogue sequences, The Jazz Singer starring Al Jolson, was released on October 6, 1927. Within a year of its success, most United States movie theaters had installed sound film equipment. Walt Disney apparently intended to take advantage of this new trend and, arguably, managed to succeed. Most other cartoon studios were still producing silent products and so were unable to effectively act as competition to Disney. As a result, Mickey would soon become the most prominent animated character of the time. Walt Disney soon worked on adding sound to both Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Gaucho (which had originally been silent releases) and their new release added to Mickey’s success and popularity. A fourth Mickey short, The Barn Dance, was also put into production; however, Mickey does not actually speak until The Karnival Kid in 1929 (see below). After Steamboat Willie was released, Mickey became a close competitor to Felix the Cat, and his popularity would grow as he was continuously featured in sound cartoons. By 1929, Felix would lose popularity among theater audiences, and Pat Sullivan decided to produce all future Felix cartoons in sound as a result.[13] Unfortunately, audiences did not respond well to Felix’s transition to sound and by 1930, Felix had faded from the screen.[14]

Black and white films (1929–1935)

In Mickey’s early films he was often characterized not as a hero, but as an ineffective young suitor to Minnie Mouse. The Barn Dance (March 14, 1929) is the first time in which Mickey is turned down by Minnie in favor of Pete. The Opry House (March 28, 1929) was the first time in which Mickey wore his white gloves. Mickey wears them in almost all of his subsequent appearances and many other characters followed suit. The three lines on the back of Mickey’s gloves represent darts in the gloves’ fabric extending from between the digits of the hand, typical of glove design of the era.

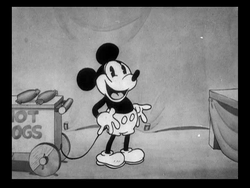

When the Cat’s Away (April 18, 1929), essentially a remake of the Alice Comedy, «Alice Rattled by Rats», was an unusual appearance for Mickey. Although Mickey and Minnie still maintained their anthropomorphic characteristics, they were depicted as the size of regular mice and living with a community of many other mice as pests in a home. Mickey and Minnie would later appear the size of regular humans in their own setting. In appearances with real humans, Mickey has been shown to be about two to three feet high.[15] The next Mickey short was also unusual. The Barnyard Battle (April 25, 1929) was the only film to depict Mickey as a soldier and also the first to place him in combat. The Karnival Kid (1929) was the first time Mickey spoke. Before this he had only whistled, laughed, and grunted. His first words were «Hot dogs! Hot dogs!» said while trying to sell hot dogs at a carnival. Mickey’s Follies (1929) introduced the song «Minnie’s Yoo-Hoo» which would become the theme song for Mickey Mouse films for the next several years. The same song sequence was also later reused with different background animation as its own special short shown only at the commencement of 1930s theater-based Mickey Mouse Clubs.[16][17] Mickey’s dog Pluto first appeared as Mickey’s pet in The Moose Hunt (1931) after previously appearing as Minnie’s dog «Rover» in The Picnic (1930).

The Cactus Kid (April 11, 1930) was the last film to be animated by Ub Iwerks at Disney. Shortly before the release of the film, Iwerks left to start his own studio, bankrolled by Disney’s then-distributor Pat Powers. Powers and Disney had a falling out over money due Disney from the distribution deal. It was in response to losing the right to distribute Disney’s cartoons that Powers made the deal with Iwerks, who had long harbored a desire to head his own studio. The departure is considered a turning point in Mickey’s career, as well as that of Walt Disney. Walt lost the man who served as his closest colleague and confidant since 1919. Mickey lost the man responsible for his original design and for the direction or animation of several of the shorts released till this point. Advertising for the early Mickey Mouse cartoons credited them as «A Walt Disney Comic, drawn by Ub Iwerks». Later Disney Company reissues of the early cartoons tend to credit Walt Disney alone.

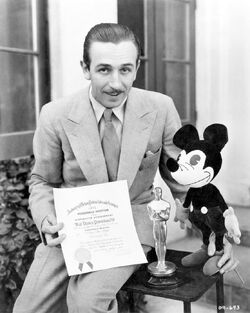

Disney and his remaining staff continued the production of the Mickey series, and he was able to eventually find a number of animators to replace Iwerks. As the Great Depression progressed and Felix the Cat faded from the movie screen, Mickey’s popularity would rise, and by 1932 The Mickey Mouse Club would have one million members.[18] At the 5th Academy Awards in 1932, Mickey received his first Academy Award nomination, received for Mickey’s Orphans (1931). Walt Disney also received an honorary Academy Award for the creation of Mickey Mouse. Despite being eclipsed by the Silly Symphony short the Three Little Pigs in 1933, Mickey still maintained great popularity among theater audiences too, until 1935, when polls showed that Popeye was more popular than Mickey.[19][20][21] By 1934, Mickey merchandise had earned $600,000 a year.[22] In 1935, Disney began to phase out the Mickey Mouse Clubs, due to administration problems.[23]

About this time, story artists at Disney were finding it increasingly difficult to write material for Mickey. As he had developed into a role model for children, they were limited in the types of gags they could present. This led to Mickey taking more of a secondary role in some of his next films, allowing for more emphasis on other characters. In Orphan’s Benefit (1934), Mickey first appeared with Donald Duck who had been introduced earlier that year in the Silly Symphony series. The tempestuous duck would provide Disney with seemingly endless story ideas and would remain a recurring character in Mickey’s cartoons.

Color films (1935–1953)

Mickey first appeared animated in color in Parade of the Award Nominees in 1932; however, the film strip was created for the 5th Academy Awards ceremony and was not released to the public. Mickey’s official first color film came in 1935 with The Band Concert. The Technicolor film process was used in the film production. Here Mickey conducted the William Tell Overture, but the band is swept up by a tornado. It is said that conductor Arturo Toscanini so loved this short that, upon first seeing it, he asked the projectionist to run it again. In 1994, The Band Concert was voted the third-greatest cartoon of all time in a poll of animation professionals. By colorizing and partially redesigning Mickey, Walt would put Mickey back on top once again, and Mickey would reach popularity he never reached before as audiences now gave him more appeal.[24] Also in 1935, Walt would receive a special award from the League of Nations for creating Mickey.

However, by 1938, the more manic Donald Duck would surpass the passive Mickey, resulting in a redesign of the mouse between 1938 and 1940 that put Mickey at the peak of his popularity.[24] The second half of the 1930s saw the character Goofy reintroduced as a series regular. Together, Mickey, Donald Duck, and Goofy would go on several adventures together. Several of the films by the comic trio are some of Mickey’s most critically acclaimed films, including Mickey’s Fire Brigade (1935), Moose Hunters (1937), Clock Cleaners (1937), Lonesome Ghosts (1937), Boat Builders (1938), and Mickey’s Trailer (1938). Also during this era, Mickey would star in Brave Little Tailor (1938), an adaptation of The Valiant Little Tailor, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

Mickey was redesigned by animator Fred Moore which was first seen in The Pointer (1939). Instead of having solid black eyes, Mickey was given white eyes with pupils, a Caucasian skin colored face, and a pear-shaped body. In the 1940s, he changed once more in The Little Whirlwind, where he used his trademark pants for the last time in decades, lost his tail, got more realistic ears that changed with perspective and a different body anatomy. But this change would only last for a short period of time before returning to the one in «The Pointer«, with the exception of his pants. In his final theatrical cartoons in the 1950s, he was given eyebrows, which were removed in the more recent cartoons.

In 1940, Mickey appeared in his first feature-length film, Fantasia. His screen role as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, set to the symphonic poem of the same name by Paul Dukas, is perhaps the most famous segment of the film and one of Mickey’s most iconic roles. The apprentice (Mickey), not willing to do his chores, puts on the sorcerer’s magic hat after the sorcerer goes to bed and casts a spell on a broom, which causes the broom to come to life and perform the most tiring chore—filling up a deep well using two buckets of water. When the well eventually overflows, Mickey finds himself unable to control the broom, leading to a near-flood. After the segment ends, Mickey is seen in silhouette shaking hands with Leopold Stokowski, who conducts all the music heard in Fantasia. Mickey has often been pictured in the red robe and blue sorcerer’s hat in merchandising. It was also featured into the climax of Fantasmic!, an attraction at the Disney theme parks.

After 1940, Mickey’s popularity would decline until his 1955 re-emergence as a daily children’s television personality.[25] Despite this, the character continued to appear regularly in animated shorts until 1943 (winning his only competitive Academy Award—with canine companion Pluto—for a short subject, Lend a Paw) and again from 1946 to 1952. In these later cartoons, Mickey was often just a supporting character in his own shorts, where Pluto would be the main character.

The last regular installment of the Mickey Mouse film series came in 1953 with The Simple Things in which Mickey and Pluto go fishing and are pestered by a flock of seagulls.

Television and later films

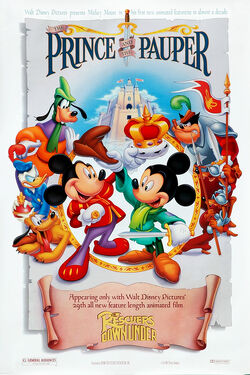

In the 1950s, Mickey became more known for his appearances on television, particularly with The Mickey Mouse Club. Many of his theatrical cartoon shorts were rereleased on television series such as Ink & Paint Club, various forms of the Walt Disney anthology television series, and on home video. Mickey returned to theatrical animation in 1983 with Mickey’s Christmas Carol, an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol in which Mickey played Bob Cratchit. This was followed up in 1990 with The Prince and the Pauper.

Throughout the decades, Mickey Mouse competed with Warner Bros.’ Bugs Bunny for animated popularity. But in 1988, the two rivals finally shared screen time in the Robert Zemeckis Disney/Amblin film Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Disney and Warner signed an agreement stating that each character had the same amount of screen time in the scene.

Similar to his animated inclusion into a live-action film in Roger Rabbit, Mickey made a featured cameo appearance in the 1990 television special The Muppets at Walt Disney World where he met Kermit the Frog. The two are established in the story as having been old friends, although they have not made any other appearance together outside of this.

His most recent theatrical cartoon short was 2013’s Get a Horse! which was preceded by 1995’s Runaway Brain, while from 1999 to 2004, he appeared in direct-to-video features like Mickey’s Once Upon a Christmas, Mickey, Donald, Goofy: The Three Musketeers and the computer-animated Mickey’s Twice Upon a Christmas.

Many television series have centered on Mickey, such as the ABC shows Mickey Mouse Works (1999–2000), Disney’s House of Mouse (2001–2003), Disney Channel’s Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (2006–2016), Mickey Mouse Mixed-Up Adventures (2017–2021) and Mickey Mouse Funhouse (2021–).[26] Prior to all these, Mickey was also featured as an unseen character in the Bonkers episode «You Oughta Be In Toons».

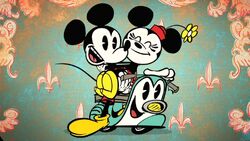

Mickey Mouse, as he appears in the Paul Rudish years, and the modern era.

In 2013, Disney Channel started airing new 3-minute Mickey Mouse shorts, with animator Paul Rudish at the helm, incorporating elements of Mickey’s late twenties-early thirties look with a contemporary twist.[27] The creative team behind the 2017 DuckTales reboot had hoped to have Mickey Mouse in the series, but this idea was rejected by Disney executives.[28] However, this did not stop them from including a watermelon shaped like Mickey Mouse that Donald Duck made and used like a ventriloquist dummy (to the point where he had perfectly replicated his voice (supplied by Chris Diamantopoulos)) while he was stranded on a deserted island during the season two finale.[29] On November 10, 2020, the series was revived as The Wonderful World of Mickey Mouse and premiered on Disney+[30]

In August 2018, ABC television announced a two-hour prime time special, Mickey’s 90th Spectacular, in honor of Mickey’s 90th birthday. The program featured never-before-seen short videos and several other celebrities who wanted to share their memories about Mickey Mouse and performed some of the Disney songs to impress Mickey. The show took place at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles and was produced and directed by Don Mischer on November 4, 2018.[31][32] On November 18, 2018, a 90th anniversary event for the character was celebrated around the world.[33] In December 2019, both Mickey and Minnie served as special co-hosts of Wheel of Fortune for two weeks while Vanna White served as the main host during Pat Sajak’s absence.[34]

Mickey is the subject of the 2022 documentary film Mickey: The Story of a Mouse, directed by Jeff Malmberg. Debuting at the South by Southwest film festival prior to its premiere on the Disney+ streaming service, the documentary examines the history and cultural impact of Mickey Mouse across. The feature is accompanied by an original, hand-drawn animated short film starring Mickey titled Mickey in a Minute.[35]

Comics

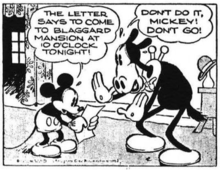

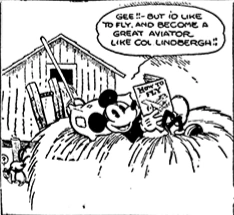

Mickey and Horace Horsecollar from the Mickey Mouse daily strip; created by Floyd Gottfredson and published December 1932

Mickey first appeared in comics after he had appeared in 15 commercially successful animated shorts and was easily recognized by the public. Walt Disney was approached by King Features Syndicate with the offer to license Mickey and his supporting characters for use in a comic strip. Disney accepted and Mickey Mouse made its first appearance on January 13, 1930.[36] The comical plot was credited to Disney himself, art to Ub Iwerks and inking to Win Smith. The first week or so of the strip featured a loose adaptation of «Plane Crazy«. Minnie soon became the first addition to the cast. The strips first released between January 13, 1930, and March 31, 1930, has been occasionally reprinted in comic book form under the collective title «Lost on a Desert Island«. Animation historian Jim Korkis notes «After the eighteenth strip, Iwerks left and his inker, Win Smith, continued drawing the gag-a-day format.»[37]

In early 1930, after Iwerks’ departure, Disney was at first content to continue scripting the Mickey Mouse comic strip, assigning the art to Win Smith. However, Disney’s focus had always been in animation and Smith was soon assigned with the scripting as well. Smith was apparently discontent at the prospect of having to script, draw, and ink a series by himself as evidenced by his sudden resignation.

Disney then searched for a replacement among the remaining staff of the Studio. He selected Floyd Gottfredson, a recently hired employee. At the time Gottfredson was reportedly eager to work in animation and somewhat reluctant to accept his new assignment. Disney had to assure him the assignment was only temporary and that he would eventually return to animation. Gottfredson accepted and ended up holding this «temporary» assignment from May 5, 1930, to November 15, 1975.

Walt Disney’s last script for the strip appeared May 17, 1930.[37] Gottfredson’s first task was to finish the storyline Disney had started on April 1, 1930. The storyline was completed on September 20, 1930, and later reprinted in comic book form as Mickey Mouse in Death Valley. This early adventure expanded the cast of the strip which to this point only included Mickey and Minnie. Among the characters who had their first comic strip appearances in this story were Clarabelle Cow, Horace Horsecollar, and Black Pete as well as the debuts of corrupted lawyer Sylvester Shyster and Minnie’s uncle Mortimer Mouse. The Death Valley narrative was followed by Mr. Slicker and the Egg Robbers, first printed between September 22 and December 26, 1930, which introduced Marcus Mouse and his wife as Minnie’s parents.

Starting with these two early comic strip stories, Mickey’s versions in animation and comics are considered to have diverged from each other. While Disney and his cartoon shorts would continue to focus on comedy, the comic strip effectively combined comedy and adventure. This adventurous version of Mickey would continue to appear in comic strips and later comic books throughout the 20th and into the 21st century.

Floyd Gottfredson left his mark with stories such as Mickey Mouse Joins the Foreign Legion (1936) and The Gleam (1942). He also created the Phantom Blot, Eega Beeva, Morty and Ferdie, Captain Churchmouse, and Butch. Besides Gottfredson artists for the strip over the years included Roman Arambula, Rick Hoover, Manuel Gonzales, Carson Van Osten, Jim Engel, Bill Wright, Ted Thwailes and Daan Jippes; writers included Ted Osborne, Merrill De Maris, Bill Walsh, Dick Shaw, Roy Williams, Del Connell, and Floyd Norman.

The next artist to leave his mark on the character was Paul Murry in Dell Comics. His first Mickey tale appeared in 1950 but Mickey did not become a specialty until Murry’s first serial for Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories in 1953 («The Last Resort»). In the same period, Romano Scarpa in Italy for the magazine Topolino began to revitalize Mickey in stories that brought back the Phantom Blot and Eega Beeva along with new creations such as the Atomo Bleep-Bleep. While the stories at Western Publishing during the Silver Age emphasized Mickey as a detective in the style of Sherlock Holmes, in the modern era several editors and creators have consciously undertaken to depict a more vigorous Mickey in the mold of the classic Gottfredson adventures. This renaissance has been spearheaded by Byron Erickson, David Gerstein, Noel Van Horn, Michael T. Gilbert and César Ferioli.

In Europe, Mickey Mouse became the main attraction of a number of comics magazines, the most famous being Topolino in Italy from 1932 onward, Le Journal de Mickey in France from 1934 onward, Don Miki in Spain and the Greek Miky Maous.

Mickey was the main character for the series MM Mickey Mouse Mystery Magazine, published in Italy from 1999 to 2001.

In 2006, he appeared in the Italian fantasy comic saga Wizards of Mickey.

In 1958, Mickey Mouse was introduced to the Arab world through another comic book called “Sameer”. He became very popular in Egypt and got a comic book with his name. Mickey’s comics in Egypt are licensed by Disney and were published since 1959 by “Dar Al-Hilal” and they were successful, however Dar Al-Hilal stopped the publication in 2003 because of problems with Disney. The comics were re-released by «Nahdat Masr» in 2004 and the first issues were sold out in less than 8 hours.[38]

Portrayal

Design

The silhouette of Mickey Mouse’s head has become an iconic image.

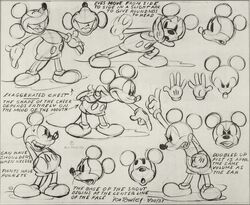

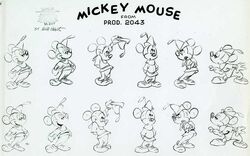

Throughout the earlier years, Mickey’s design bore heavy resemblance to Oswald, save for the ears, nose, and tail.[39][40][41] Ub Iwerks designed Mickey’s body out of circles in order to make the character simple to animate. Disney employees John Hench and Marc Davis believed that this design was part of Mickey’s success as it made him more dynamic and appealing to audiences.

Mickey’s circular design is most noticeable in his ears. In animation in the 1940s, Mickey’s ears were animated in a more realistic perspective. Later, they were drawn to always appear circular no matter which way Mickey was facing. This made Mickey easily recognizable to audiences and made his ears an unofficial personal trademark. The circular rule later created a dilemma for toy creators who had to recreate a three-dimensional Mickey.

In 1938, animator Fred Moore redesigned Mickey’s body away from its circular design to a pear-shaped design. Colleague Ward Kimball praised Moore for being the first animator to break from Mickey’s «rubber hose, round circle» design. Although Moore himself was nervous at first about changing Mickey, Walt Disney liked the new design and told Moore «that’s the way I want Mickey to be drawn from now on.»

Each of Mickey’s hands has only three fingers and a thumb. Disney said that this was both an artistic and financial decision, explaining, «Artistically five digits are too many for a mouse. His hand would look like a bunch of bananas. Financially, not having an extra finger in each of 45,000 drawings that make up a six and one-half minute short has saved the Studio millions.» In the film The Opry House (1929), Mickey was first given white gloves as a way of contrasting his naturally black hands against his black body. The use of white gloves would prove to be an influential design for cartoon characters, particularly with later Disney characters, but also with non-Disney characters such as Bugs Bunny, Woody Woodpecker, Mighty Mouse, Mario, and Sonic The Hedgehog.

Mickey’s eyes, as drawn in Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Gaucho, were large and white with black outlines. In Steamboat Willie, the bottom portion of the black outlines was removed, although the upper edges still contrasted with his head. Mickey’s eyes were later re-imagined as only consisting of the small black dots which were originally his pupils, while what were the upper edges of his eyes became a hairline. This is evident only when Mickey blinks. Fred Moore later redesigned the eyes to be small white eyes with pupils and gave his face a Caucasian skin tone instead of plain white. This new Mickey first appeared in 1938 on the cover of a party program, and in animation the following year with the release of The Pointer.[42] Mickey is sometimes given eyebrows as seen in The Simple Things (1953) and in the comic strip, although he does not have eyebrows in his subsequent appearances.[citation needed]

Originally characters had black hands, but Frank Thomas said this was changed for visibility reasons.[43] According to Disney’s Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, written by former Disney animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, «The characters were in black and white with no shades of grey to soften the contrast or delineate a form. Mickey’s body was black, his arms and his hands- all black. There was no way to stage an action except in silhouette. How else could there be any clarity? A hand in front of a chest would simply disappear.»[44]

Multiple sources state that Mickey’s characteristics, particularly the black body combined with the large white eyes, white mouth, and the white gloves, evolved from blackface caricatures used in minstrel shows.[45][46][47][48][49]

Besides Mickey’s gloves and shoes, he typically wears only a pair of shorts with two large buttons in the front. Before Mickey was seen regularly in color animation, Mickey’s shorts were either red or a dull blue-green. With the advent of Mickey’s color films, the shorts were always red. When Mickey is not wearing his red shorts, he is often still wearing red clothing such as a red bandmaster coat (The Band Concert, The Mickey Mouse Club), red overalls (Clock Cleaners, Boat Builders), a red cloak (Fantasia, Fun and Fancy Free), a red coat (Squatter’s Rights, Mickey’s Christmas Carol), or a red shirt (Mickey Down Under, The Simple Things).

Voice actors

A large part of Mickey’s screen persona is his famously shy, falsetto voice. From 1928 onward, Mickey was voiced by Walt Disney himself, a task in which Disney took great personal pride. Composer Carl W. Stalling was the first person to provide lines for Mickey in the 1929 shorts The Karnival Kid and Wild Waves,[50][51] and J. Donald Wilson and Joe Twerp provided the voice in some 1938 broadcasts of The Mickey Mouse Theater of the Air,[52] although Disney remained Mickey’s official voice during this period. However, by 1946, Disney was becoming too busy with running the studio to do regular voice work which meant he could not do Mickey’s voice on a regular basis anymore. It is also speculated that his cigarette habit had damaged his voice over the years.[53] After recording the Mickey and the Beanstalk section of Fun and Fancy Free, Mickey’s voice was handed over to veteran Disney musician and actor Jimmy MacDonald. Walt would reprise Mickey’s voice occasionally until his passing in 1966, such as in the introductions to the original 1955–1959 run of The Mickey Mouse Club TV series, the «Fourth Anniversary Show» episode of the Walt Disney’s Disneyland TV series that aired on September 11, 1957, and the Disneyland USA at Radio City Music Hall show from 1962.[54]

MacDonald voiced Mickey in most of the remaining theatrical shorts and for various television and publicity projects up until his retirement in 1976.[55] However, other actors would occasionally play the role during this era. Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck, provided the voice in three of Mickey’s theatrical shorts, The Dognapper, R’coon Dawg, and Pluto’s Party.[56] Stan Freberg voiced Mickey in the Freberg-produced record Mickey Mouse’s Birthday Party.

Alan Young voiced Mickey in the Disneyland record album An Adaptation of Dickens’ Christmas Carol, Performed by The Walt Disney Players in 1974.[57][58]

The 1983 short film Mickey’s Christmas Carol marked the theatrical debut of Wayne Allwine as Mickey Mouse, who was the official voice of Mickey from 1977 until his death in 2009,[59] although MacDonald returned to voice Mickey for an appearance at the 50th Academy Awards in 1978.[60] Allwine once recounted something MacDonald had told him about voicing Mickey: «The main piece of advice that Jim gave me about Mickey helped me keep things in perspective. He said, ‘Just remember kid, you’re only filling in for the boss.’ And that’s the way he treated doing Mickey for years and years. From Walt, and now from Jimmy.»[61] In 1991, Allwine married Russi Taylor, the voice of Minnie Mouse from 1986 until her death in 2019.

Les Perkins did the voice of Mickey in two TV specials, «Down and Out with Donald Duck» and «DTV Valentine», in the mid-1980s. Peter Renaday voiced Mickey in the 1980s Disney albums Yankee Doodle Mickey and Mickey Mouse Splashdance.[62][63] He also provided his voice for The Talking Mickey Mouse toy in 1986.[64][65] Quinton Flynn briefly filled in for Allwine as the voice of Mickey in a few episodes of the first season of Mickey Mouse Works whenever Allwine was unavailable to record.[66]

Bret Iwan, a former Hallmark greeting card artist, is one of the current voices of Mickey. Iwan was originally cast as an understudy for Allwine due to the latter’s declining health, but Allwine died before Iwan could get a chance to meet him and Iwan became the new official voice of the character at the time. Iwan’s early recordings in 2009 included work for the Disney Cruise Line, Mickey toys, the Disney theme parks and the Disney on Ice: Celebrations! ice show.[67] He directly replaced Allwine as Mickey for the Kingdom Hearts video game series and the TV series Mickey Mouse Clubhouse. His first video game voice-over of Mickey Mouse can be heard in Kingdom Hearts: Birth by Sleep. Iwan also became the first voice actor to portray Mickey during Disney’s rebranding of the character, providing the vocal effects of Mickey in Epic Mickey as well as his voice in Epic Mickey 2: The Power of Two and the remake of Castle of Illusion.

Chris Diamantopoulos is the first voice of Mickey Mouse to be nominated for two Emmy Awards and two Annie Awards, in the award-winning Mickey Mouse 2013 animated series[68] developed by Paul Rudish, and the 2017 DuckTales reboot (in the form of a watermelon that Donald uses as a ventriloquist dummy), as the producers were looking for a voice closer to Walt Disney’s portrayal of the character in order to match the vintage look of that series.[69]

Diamantopoulos also speaks and sings for Mickey Mouse in the Walt Disney World attraction Mickey and Minnie’s Runaway Railway. Songs featuring Diamantopoulos as Mickey Mouse from that attraction, as well as soundtrack songs from the recent Disney+ series The Wonderful World of Mickey Mouse streaming on various platforms.[70]

Merchandising

Since his early years, Mickey Mouse has been licensed by Disney to appear on many different kinds of merchandise. Mickey was produced as plush toys and figurines, and Mickey’s image has graced almost everything from T-shirts to lunchboxes. Largely responsible for early Disney merchandising was Kay Kamen, Disney’s head of merchandise and licensing from 1932 until his death in 1949, who was called a «stickler for quality.» Kamen was recognized by The Walt Disney Company as having a significant part in Mickey’s rise to stardom and was named a Disney Legend in 1998.[71] At the time of his 80th-anniversary celebration in 2008, Time declared Mickey Mouse one of the world’s most recognized characters, even when compared against Santa Claus.[72] Disney officials have stated that 98% of children aged 3–11 around the world are at least aware of the character.[72]

Disney parks

As the official Walt Disney mascot, Mickey has played a central role in the Disney parks since the opening of Disneyland in 1955. As with other characters, Mickey is often portrayed by a non-speaking costumed actor. In this form, he has participated in ceremonies and countless parades, and poses for photographs with guests. As of the presidency of Barack Obama (who jokingly referred to him as «a world leader who has bigger ears than me»)[73] Mickey has met every U.S. president since Harry Truman, with the exception of Lyndon B. Johnson.[41]

Mickey also features in several specific attractions at the Disney parks. Mickey’s Toontown (Disneyland and Tokyo Disneyland) is a themed land which is a recreation of Mickey’s neighborhood. Buildings are built in a cartoon style and guests can visit Mickey or Minnie’s houses, Donald Duck’s boat, or Goofy’s garage. This is a common place to meet the characters.[74]

Mickey’s PhilharMagic (Magic Kingdom, Tokyo Disneyland, Hong Kong Disneyland) is a 4D film which features Mickey in the familiar role of symphony conductor. At Main Street Cinema several of Mickey’s short films are shown on a rotating basis; the sixth film is always Steamboat Willie. Mickey plays a central role in Fantasmic! (Disneyland Resort, Disney’s Hollywood Studios) a live nighttime show which famously features Mickey in his role as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Mickey was also a central character in the now-defunct Mickey Mouse Revue (Magic Kingdom, Tokyo Disneyland) which was an indoor show featuring animatronic characters. Mickey’s face formerly graced the Mickey’s Fun Wheel (now Pixar Pal-A-Round) at Disney California Adventure Park, where a figure of him also stands on top of Silly Symphony Swings.

Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway at Disney’s Hollywood Studios is a trackless dark ride themed to Mickey Mouse.[75]

In addition to Mickey’s overt presence in the parks, numerous images of him are also subtly included in sometimes unexpected places. This phenomenon is known as «Hidden Mickeys», involving hidden images in Disney films, theme parks, and merchandise.[76]

Video games

Like many popular characters, Mickey has starred in many video games, including Mickey Mousecapade on the Nintendo Entertainment System, Mickey Mania: The Timeless Adventures of Mickey Mouse, Mickey’s Ultimate Challenge, and Disney’s Magical Quest on the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse on the Mega Drive/Genesis, Mickey Mouse: Magic Wands! on the Game Boy, and many others. In the 2000s, the Disney’s Magical Quest series were ported to the Game Boy Advance, while Mickey made his sixth generation era debut in Disney’s Magical Mirror Starring Mickey Mouse, a GameCube title aimed at younger audiences. Mickey plays a major role in the Kingdom Hearts series, as the king of Disney Castle and aided to the protagonist, Sora and his friends. King Mickey wields the Keyblade, a weapon in the form of a key that has the power to open any lock and combat darkness. Epic Mickey, featuring a darker version of the Disney universe, was released in 2010 for the Wii. The game is part of an effort by The Walt Disney Company to re-brand the Mickey Mouse character by moving away from his current squeaky clean image and reintroducing the mischievous side of his personality.[3]

Watches and clock

Mickey was most famously featured on wristwatches and alarm clocks, typically utilizing his hands as the actual hands on the face of the clock. The first Mickey Mouse watches were manufactured in 1933 by the Ingersoll Watch Company. The seconds were indicated by a turning disk below Mickey. The first Mickey watch was sold at the Century of Progress in Chicago, 1933 for $3.75 (equivalent to $78 in 2021). Mickey Mouse watches have been sold by other companies and designers throughout the years, including Timex, Elgin, Helbros, Bradley, Lorus, and Gérald Genta.[77] The fictional character Robert Langdon from Dan Brown’s novels was said to wear a Mickey Mouse watch as a reminder «to stay young at heart.»[78]

Other products

In 1989, Milton Bradley released the electronic talking game titled Mickey Says, with three modes featuring Mickey Mouse as its host. Mickey also appeared in other toys and games, including the Worlds of Wonder released The Talking Mickey Mouse.

Fisher-Price has produced a line of talking animatronic Mickey dolls including «Dance Star Mickey» (2010)[79] and «Rock Star Mickey» (2011).[80]

In total, approximately 40% of Disney’s revenues for consumer products are derived from Mickey Mouse merchandise, with revenues peaking in 1997.[72]

Use in politics

In the United States, protest votes are often made in order to indicate dissatisfaction with the slate of candidates presented on a particular ballot or to highlight the inadequacies of a particular voting procedure. Since most states’ electoral systems do not provide for blank balloting or a choice of «None of the Above», most protest votes take the form of a clearly non-serious candidate’s name entered as a write-in vote. Mickey Mouse is often selected for this purpose.[81][82] As an election supervisor in Georgia observed, «If Mickey Mouse doesn’t get votes in our election, it’s a bad election.»[83] The earliest known mention of Mickey Mouse as a write-in candidate dates back to the 1932 New York City mayoral elections.[84]

Mickey Mouse’s name has also been known to appear fraudulently on voter registration lists, such as in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election.[85][86]

Pejorative use of Mickey’s name

«Mickey Mouse» is a slang expression meaning small-time, amateurish or trivial. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, it also means poor quality or counterfeit.[87] In Poland the phrase «mały Miki», which translates to «small Mickey», means something very simple and trivial — usually used in the comparison between two things.[88] However, in parts of Australia it can mean excellent or very good (rhyming slang for «grouse»).[89] Examples of the negative usages include the following:

- In The Godfather Part II, Fredo’s justification of betraying Michael is that his orders in the family usually were «Send Fredo off to do this, send Fredo off to do that! Let Fredo take care of some Mickey Mouse nightclub somewhere!» as opposed to more meaningful tasks.

- In an early episode of the 1978–82 sitcom Mork & Mindy, Mork stated that Pluto was «a Mickey Mouse planet», referring to the future dwarf planet having the same name as Mickey’s pet dog Pluto.

- On November 19, 1983, just after an ice hockey game in which Wayne Gretzky’s Edmonton Oilers beat the New Jersey Devils 13–4, Gretzky was quoted as saying to a reporter, «Well, it’s time they got their act together, they’re ruining the whole league. They had better stop running a Mickey Mouse organization and put somebody on the ice». Reacting to Gretzky’s comment, Devils fans wore Mickey Mouse apparel when the Oilers returned to New Jersey on January 15, 1984, despite a 5–4 Devils loss.[90]

- In the 1996 Warner Bros. film Space Jam, Bugs Bunny derogatorily comments on Daffy Duck’s idea for the name of their basketball team, asking: «What kind of Mickey Mouse organization would name a team ‘The Ducks?'» (This also referenced the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim, an NHL team that was then owned by Disney, as well as the Disney-made The Mighty Ducks movie franchise. This was referencing the Disney/Warner Brothers rivalry.)

- In schools a «Mickey Mouse course», «Mickey Mouse major», or «Mickey Mouse degree» is a class, college major, or degree where very little effort is necessary in order to attain a good grade (especially an A) or one where the subject matter of such a class is not of any importance in the labor market.[91]

- Musicians often refer to a film score that directly follows each action on screen, sometimes pejoratively, as Mickey Mousing (also mickey-mousing and mickeymousing).[92]

- In the beginning of the 1980s, then-British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher once called the European Parliament a «Mickey Mouse parliament», meaning a discussion club without influence.[93]

Parodies and criticism

Mickey Mouse’s global fame has made him both a symbol of The Walt Disney Company and of the United States itself. For this reason, Mickey has been used frequently in anti-American satire, such as the infamous underground cartoon «Mickey Mouse in Vietnam» (1969). There have been numerous parodies of Mickey Mouse, such as the two-page parody «Mickey Rodent» by Will Elder (published in Mad #19, 1955) in which the mouse walks around unshaven and jails Donald Duck out of jealousy over the duck’s larger popularity.[94] The Simpsons would later become Disney property as its distributor Fox was acquired by Disney. On the Comedy Central series South Park, Mickey is depicted as the sadistic, greedy, foul-mouthed boss of The Walt Disney Company, only interested in money. He also appears briefly with Donald Duck in the comic Squeak the Mouse by the Italian cartoonist Massimo Mattioli. Horst Rosenthal created a comic book, Mickey au Camp de Gurs (Mickey Mouse in the Gurs Internment Camp) while detained in the Gurs internment camp during the Second World War; he added «Publié Sans Autorisation de Walt Disney» («Published without Walt Disney’s Permission») to the front cover.[95]

In the 1969 parody novel Bored of the Rings, Mickey Mouse is satirized as Dickey Dragon.

In the fifth episode of the Japanese anime, Pop Team Epic, Popuko, one of the main characters, attempts an impression of Mickey, but does so poorly.

Legal issues

Like all major Disney characters, Mickey Mouse is not only copyrighted but also trademarked, which lasts in perpetuity as long as it continues to be used commercially by its owner. So, whether or not a particular Disney cartoon goes into the public domain, the characters themselves may not be used as trademarks without authorization.

Because of the Copyright Term Extension Act of the United States (sometimes called the ‘Mickey Mouse Protection Act’ because of extensive lobbying by the Disney corporation) and similar legislation within the European Union and other jurisdictions where copyright terms have been extended, works such as the early Mickey Mouse cartoons will remain under copyright until at least 2024. However, some copyright scholars argue that Disney’s copyright on the earliest version of the character may be invalid due to ambiguity in the copyright notice for Steamboat Willie.[96]

The Walt Disney Company has become well known for protecting its trademark on the Mickey Mouse character—whose likeness is closely associated with the company—with particular zeal. In 1989, Disney threatened legal action against three daycare centers in the Orlando, Florida region (where Walt Disney World is a dominant employer) for having Mickey Mouse and other Disney characters painted on their walls. The characters were removed, and the newly opened rival Universal Studios Florida allowed the centers to use their own cartoon characters with their blessing, to build community goodwill.[97]

Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates

In 1971, a group of underground cartoonists calling themselves the Air Pirates, after a group of villains from early Mickey Mouse films, produced a comic called Air Pirates Funnies. In the first issue, cartoonist Dan O’Neill depicted Mickey and Minnie Mouse engaging in explicit sexual behavior and consuming drugs. As O’Neill explained, «The air pirates were…some sort of bizarre concept to steal the air, pirate the air, steal the media….Since we were cartoonists, the logical thing was Disney.»[98] Rather than change the appearance or name of the character, which O’Neill felt would dilute the parody, the mouse depicted in Air Pirates Funnies looks like and is named «Mickey Mouse». Disney sued for copyright infringement, and after a series of appeals, O’Neill eventually lost and was ordered to pay Disney $1.9 million. The outcome of the case remains controversial among free-speech advocates. New York Law School professor Edward Samuels said, «The Air Pirates set parody back twenty years.»[99][better source needed]

Food product packaging from Myanmar using the image of Mickey Mouse

Copyright status

There have been multiple attempts to argue that certain versions of Mickey Mouse are in fact in the public domain. In the 1980s, archivist George S. Brown attempted to recreate and sell cels from the 1933 short «The Mad Doctor», on the theory that they were in the public domain because Disney had failed to renew the copyright as required by current law.[100] However, Disney successfully sued Brown to prevent such sale, arguing that the lapse in copyright for «The Mad Doctor» did not put Mickey Mouse in the public domain because of the copyright in the earlier films.[100] Brown attempted to appeal, noting imperfections in the earlier copyright claims, but the court dismissed his argument as untimely.[100]

In 1999, Lauren Vanpelt, a law student at Arizona State University, wrote a paper making a similar argument.[100][101] Vanpelt points out that copyright law at the time required a copyright notice specify the year of the copyright and the copyright owner’s name. The title cards to early Mickey Mouse films «Steamboat Willie», «Plane Crazy», and «Gallopin’ Gaucho» do not clearly identify the copyright owner, and also misidentify the copyright year. However, Vanpelt notes that copyright cards in other early films may have been done correctly, which could make Mickey Mouse «protected as a component part of the larger copyrighted films».[101]

A 2003 article by Douglas A. Hedenkamp in the Virginia Sports and Entertainment Law Journal analyzed Vanpelt’s arguments, and concluded that she is likely correct.[100][102] Hedenkamp provided additional arguments, and identified some errors in Vanpelt’s paper, but still found that due to imperfections in the copyright notice on the title cards, Walt Disney forfeited his copyright in Mickey Mouse. He concluded: «The forfeiture occurred at the moment of publication, and the law of that time was clear: publication without proper notice irrevocably forfeited copyright protection.»[102]

Disney threatened to sue Hedenkamp for slander of title, but did not follow through.[100] The claims in Vanpelt and Hedenkamp’s articles have not been tested in court.[citation needed]

Censorship

In 1930, the German Board of Film Censors prohibited any presentations of the 1929 Mickey Mouse cartoon The Barnyard Battle. The animated short, which features the mouse as a kepi-wearing soldier fighting cat enemies in German-style helmets, was viewed by censors as a negative portrayal of Germany.[103] It was claimed by the board that the film would «reawaken the latest anti-German feeling existing abroad since the War».[104] The Barnyard Battle incident did not incite wider anti-Mickey sentiment in Germany in 1930; however, after Adolf Hitler came to power several years later, the Nazi regime unambiguously propagandized against Disney. A mid-1930s German newspaper article read:

Mickey Mouse is the most miserable ideal ever revealed. Healthy emotions tell every independent young man and every honorable youth that the dirty and filth-covered vermin, the greatest bacteria carrier in the animal kingdom, cannot be the ideal type of animal. Away with Jewish brutalization of the people! Down with Mickey Mouse! Wear the Swastika Cross![105][106][107]

American cartoonist and writer Art Spiegelman would later use this quote on the opening page of the second volume of his graphic novel Maus.

In 1935 Romanian authorities also banned Mickey Mouse films from cinemas, purportedly fearing that children would be «scared to see a ten-foot mouse in the movie theatre».[108] In 1938, based on the Ministry of Popular Culture’s recommendation that a reform was necessary «to raise children in the firm and imperialist spirit of the Fascist revolution», the Italian Government banned foreign children’s literature[109] except Mickey; Disney characters were exempted from the decree for the «acknowledged artistic merit» of Disney’s work.[110] Actually, Mussolini’s children were fond of Mickey Mouse, so they managed to delay his ban as long as possible.[111] In 1942, after Italy declared war on the United States, fascism immediately forced Italian publishers to stop printing any Disney stories. Mickey’s stories were replaced by the adventures of Tuffolino, a new human character that looked like Mickey, created by Federico Pedrocchi (script) and Pier Lorenzo De Vita (art). After the downfall of Italy’s fascist government in 1945, the ban was removed.

Filmography

Selected short films

- Steamboat Willie (1928)

- Plane Crazy (1928)

- The Karnival Kid (1929)

- Mickey’s Orphans (1931)

- Building a Building (1933)

- The Mad Doctor (1933)

- The Band Concert (1935)

- Thru the Mirror (1936)

- Moving Day (1936)

- Clock Cleaners (1937)

- Lonesome Ghosts (1937)

- Brave Little Tailor (1938)

- The Pointer (1939)

- The Nifty Nineties (1941)

- Lend a Paw (1941)

- Symphony Hour (1942)

- Squatter’s Rights (1946)

- Mickey and the Seal (1948)

- The Simple Things (1953)

- Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983)

- Runaway Brain (1995)

- Get a Horse! (2013)

Full-length films

- Hollywood Party (cameo, 1934)

- Fantasia (1940)

- Fun and Fancy Free (1947)

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit (cameo, 1988)

- A Goofy Movie (cameo, 1995)

- Mickey’s Once Upon a Christmas (1999) (DTV)

- Fantasia 2000 (1999)

- Mickey’s Magical Christmas (2001) (DTV)

- Mickey’s House of Villains (2002) (DTV)

- Mickey, Donald, Goofy: The Three Musketeers (2004) (DTV)

- Mickey’s Twice Upon a Christmas (2004) (DTV)

(Note: DTV means Direct-to-video)

Television series

- The Mickey Mouse Club (1955–1959; 1977–1979; 1989–1994)

- Mickey Mouse Works (1999–2000)

- Disney’s House of Mouse (2001–2003)

- Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (2006–2016)

- Mickey Mouse (2013–2019)

- Mickey Mouse Mixed-Up Adventures (2017–2021)[note 1]

- The Wonderful World of Mickey Mouse (2020–present)

- Mickey Mouse Funhouse (2021–present)

Awards and honors

Mickey Mouse has received ten nominations for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. These are Mickey’s Orphans (1931), Building a Building (1933), Brave Little Tailor (1938), The Pointer (1939), Lend a Paw (1941), Squatter’s Rights (1946), Mickey and the Seal (1948), Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983), Runaway Brain (1995), and Get a Horse! (2013). Among these, Lend a Paw was the only film to actually win the award. Additionally, in 1932 Walt Disney received an honorary Academy Award in recognition of Mickey’s creation and popularity.

In 1994, four of Mickey’s cartoons were included in the book The 50 Greatest Cartoons which listed the greatest cartoons of all time as voted by members of the animation field. The films were The Band Concert (#3), Steamboat Willie (#13), Brave Little Tailor (#26), and Clock Cleaners (#27).

On November 18, 1978, in honor of his 50th anniversary, Mickey became the first cartoon character to have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The star is located on 6925 Hollywood Blvd.

Melbourne (Australia) runs the annual Moomba festival street procession and appointed Mickey Mouse as their King of Moomba (1977).[112]: 17–22 Although immensely popular with children, there was controversy with the appointment: some Melburnians wanted a ‘home-grown’ choice, e.g. Blinky Bill; when it was revealed that Patricia O’Carroll (from Disneyland’s Disney on Parade show) was performing the mouse, Australian newspapers reported «Mickey Mouse is really a girl!»[112]: 19–20

Mickey was the Grand Marshal of the Tournament of Roses Parade on New Year’s Day 2005. He was the first cartoon character to receive the honor and only the second fictional character after Kermit the Frog in 1996.

See also

- Mickey Mouse Adventures, a short-lived comic starring Mickey Mouse as the protagonist

- Mouse Museum, a Russian museum featuring artifacts and memorabilia relating to Mickey Mouse

- Walt Disney (2015 PBS film)

Notes

- ^ The first two seasons were titled Mickey and the Roadster Racers.

References

Citations

- ^ «Voice of Mickey Mouse dies – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)». Abc.net.au. May 21, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Jackson, Kathy (2003). Mickey and the Tramp: Walt Disney’s Debt to Charlie Chaplin (26th ed.). The Journal of American Culture. pp. 439–444.

- ^ a b Barnes, Brooks (November 4, 2009). «After Mickey’s Makeover, Less Mr. Nice Guy». The New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (2008). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. University of California Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-520-25619-4.

- ^ a b Kenworthy, John (2001). The Hand Behind the Mouse (Disney ed.). New York. pp. 53–54.

- ^ Walt Disney: Conversations (Conversations With Comic Artists Series) by Kathy Merlock Jackson with Walt Disney » ISBN 1-57806-713-8 page 120

- ^ «Mickey Mouse’s Magic- Tweentimes – Indiatimes». The Times of India. Archived from the original on January 13, 2004.

- ^ «Mickey Mouse was going to be Mortimer Mo». Uselessknowledge.co.za. May 8, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Albin, Kira (1995). «Mickey Rooney: Hollywood, Religion and His Latest Show». GrandTimes.com. Senior Magazine. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ Korkis, Jim (April 13, 2011). «The Mickey Rooney-Mickey Mouse Myth». Mouse Planet. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Korkis 2012, pp. 157–161

- ^ «1928: Plane Crazy». Disney Shorts. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ «Felix the Cat». Toontracker.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Gordon, Ian (2002). «Felix the Cat». St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009.

- ^ Mickey was first pictured with a real human in Fantasia in silhouette. Later a famous statue of Mickey and Walt Disney at Disneyland would maintain Mickey’s size.

- ^ «Disney Shorts: 1930: Minnie’s Yoo Hoo». The Encyclopedia of Disney Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Polsson, Ken (June 2, 2010). Chronology of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse (1930–1931) Ken Polsson personal page.

- ^ Polsson, Ken (June 2, 2010). Chronology of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse (1932–1934) Ken Polsson personal page.

- ^ DeMille, William (November 1935). «Mickey vs. Popeye». The Forum.

- ^ Koszarski, Richard (1976). Hollywood directors, 1914–1940, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. (Quotes DeMille. 1935).

- ^ Calma, Gordan (May 17, 2005). Popeye’s Popularity – Article from 1935 Archived July 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine GAC Forums. (Quotes DeMille, 1935).

- ^ Solomon, Charles. «The Golden Age of Mickey Mouse». Disney.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ Polsson, Ken (June 2, 2010). Chronology of the Walt Disney Company (1935–1939). Ken Polsson personal page.

- ^ a b Solomon, Charles. «The Golden Age of Mickey Mouse». Disney.com guest services. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008.

- ^ Solomon, Charles. «Mickey in the Post-War Era». Disney.com guest services. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008.

- ^ ««Jump Into Wow» This Summer on Disney Junior with «Marvel’s Spidey and His Amazing Friends» and «Mickey Mouse Funhouse»» (Press release). Disney Channel. June 16, 2021 – via The Futon Critic.

- ^ «Mickey Mouse’s first new short in 50 years; iconic character gets new retro look for big return to cartoon shorts to be featured on Disney Channel,» Don Kaplan, New York Daily News, December 3, 2013

- ^ «Frank Angones and the Suspenders of Disbelief». January 5, 2017.

- ^ «Moonvasion!». DuckTales. Season 2. Episode 47. September 12, 2019.

- ^ Deitchman, Beth (September 14, 2020). «JUST ANNOUNCED: The Wonderful World of Mickey Mouse Comes to Disney+ in November». D23. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ «ABC to celebrate 90 years of Mickey Mouse». Idaho Statesman. Associated Press. August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ «Mickey’s 90th Spectacular airs on ABC on November 4, 2018». ABC.

- ^ «Global celebrations for Mickey Mouse 90th Anniversary». Samsung Newsroom.

- ^ Bucksbaum, Sydney (December 10, 2019). «Vanna White hosts Wheel of Fortune for first time while Pat Sajak recovers from emergency surgery». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ «Mickey Documentary Film Released Date». Twitter. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ «When Mickey’s Career Turned a Page». D23. January 13, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Korkis, Jim (August 10, 2003). «The Uncensored Mouse». Jim Hill Media.

- ^ «Mickey Mouse In Egypt! Comic Book Guide». Comicbookguide.wordpress.com. March 12, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Luling, Todd Van (December 10, 2015). «Here’s One Thing You Didn’t Know About Disney’s Origin Story». The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Kindelan, Katie (November 29, 2011). «Lost Inspiration for Mickey Mouse Discovered in England Film Archive». ABC News. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Suddath, Claire. «A Brief History of Mickey Mouse.» Time. November 18, 2008.

- ^ Holliss, Richard; Brian Sibley (1986). Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: His Life and Times. New York City: Harper & Row. pp. 40–45. ISBN 0-06-015619-8.

- ^ Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston (2002). Walt Disney Treasures: Wave Two- Mickey Mouse in Black & White (DVD), Disc 1, Bonus Features: Frank and Ollie… and Mickey featurette (2002) (DVD). The Walt Disney Company.

«There was an interesting bit of development there. They drew [Mickey Mouse] with black hands on the black arm against the black body and black feet. And if he said something in here (gestures in front of body), you couldn’t see it and won’t realize. Fairly early they had tried it on him, putting the white gloves on him here, and the white shoes, but it had to clear up.» ~ Frank Thomas

- ^ Thomas and Johnston, Frank and Ollie (1981). «The Principles of Animation«. Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life (1995 ed.). Disney Publishing Worldwide. p. 56. ISBN 0-7868-6070-7.

The characters were in black and white with no shades of grey to soften the contrast or delineate a form. Mickey’s body was black, his arms and his hands- all black. There was no way to stage an action except in silhouette. How else could there be any clarity? A hand in front of a chest would simply disappear.

- ^ Inge, M. Thomas (September 30, 2014). «Mickey Mouse». In Apgar, Garry (ed.). A Mickey Mouse Reader. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 341–342. ISBN 9781626743601 – via Google Books.

- ^ Caswell, Estelle (February 2, 2017). «Why cartoon characters wear gloves». Vox.

- ^ Holt, Patricia (May 21, 1996). «The Minstrel Show Never Faded Away». San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Davis, James C. (January 1, 2007). Commerce in Color: Race, Consumer Culture, and American Literature, 1893–1933. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472069873 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sammond, Nicholas (August 17, 2015). Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822375784 – via Google Books.

Mickey Mouse isn’t like a minstrel; he is a minstrel.

- ^ Barrier, Michael. «Funnyworld Revisited: Carl Stalling». MichaelBarrier.com. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ «Hit the Beach (Part 1)». cartoonresearch.com. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Korkis, Jim (2014). The Book of Mouse: A Celebration of Mickey Mouse. Theme Park Press. ISBN 978-0984341504.

- ^ Littlechild, Chris (September 7, 2021). «Why Walt Disney Stopped Being the Voice of Mickey Mouse». Grunge. Static Media. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ «Your Host, Walt Disney Review». Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ «Interview: Jimmy MacDonald — The Dundee voice of Disney». The Scotsman. December 23, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Gerstein, David; Kaufman, J.B. (2018). Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History. Taschen. ISBN 978-3836552844.

- ^ «DisneylandRecords.com — 3811 An Adaptation Of Dickens’ Christmas Carol». disneylandrecords.com.

- ^ «Dickens’ Christmas Carol by Disneyland Records | MouseVinyl.com». www.mousevinyl.com.

- ^ «Disney Legends – Wayne Allwine». Legends.disney.go.com. May 18, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Korkis, Jim (February 12, 2021). «Animated Characters At the Academy Awards». Cartoon Research. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ «Wayne Allwine, Voice of Mickey Mouse for 32 Years, Passes Away at Age 62 « Disney D23». D23.disney.go.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Major, B.J. «A Disney Discography».

- ^ «Character Records by Steve Burns – StartedByAMouse.com Features Section». Archived from the original on March 9, 2015.

- ^ Dave (October 18, 2008). «Children’s Records & More: TALKING MICKEY MOUSE READALONG BOOKS AND CASSETTES».

- ^ «Talking Mickey Mouse Show, The (1986, Toy) Voice Cast». Voice Chasers. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Korkis, Jim. «A New Mouse Voice In Town by Wade Sampson». Mouseplanet. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ^ «Disney on Ice Celebrations features Princess Tiana and Mickey’s New Voice, Bret Iwan – The Latest». Laughingplace.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Blake (June 27, 2013). «Disney Shorts Debut with New Voice for Mickey Mouse». The Rotoscopers. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Dave (March 6, 2014). «Dave Smith Reveals Where the «33» in Disneyland’s Exclusive and Famed Club 33 Comes From». D23. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ Donald Duck & Mickey Mouse & Goofy. «The Wonderful World of Mickey Mouse». Amazon (Album). Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Kay Kamen at disney.com

- ^ a b c Claire Suddath (November 18, 2008). «A Brief History of Mickey Mouse». time.com. Time, Inc. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Auletta, Kate (January 19, 2012). «Obama Disney World Visit: President Touts Tourism, Mickey’s Big Ears During Speech». The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Mickey’s House and Meet Mickey at disney.com

- ^ «Disney Unveils First-ever Mickey Mouse Ride». Travel + Leisure. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Sponagle, Michele (November 25, 2006). «Exposing hidden world of Mickey Mouse». Toronto Star. Archived from the original on February 24, 2008.

- ^ «THE SYDNEY TARTS: Gérald Genta». Thesydneytarts.blogspot.com. November 29, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ The Original Mickey Mouse Watch: 11,000 Sold in One Day & Robert Langdon’s Choice at hodinkee.com Archived October 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Dance Star Mickey From Fisher-Price». Fisher-price.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ «Rock Star Mickey From Fisher-Price». Fisher-price.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Friedman, Peter (June 10, 2008). «Write in Mickey Mouse for President». Whatisfairuse.blogspot.com. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ «MM among top write-in candidates in Wichita elections». Nbcactionnews.com. Associated Press. January 17, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Rigsby, G.G. (November 15, 2012). «Elvis, Mickey Mouse and God get write-in votes». savannahnow. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Fuller, Jaime (November 5, 2013). «If You Give a Mouse a Vote». The American Prospect. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ «Vote drives defended, despite fake names». St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ «The ACORN investigations». The Economist. October 16, 2008.

- ^ «Mickey Mouse». Dictionary.com. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ «Słownik Miejski — Mały Miki». Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ Miller, John (2009). The lingo dictionary : of favourite Australian words and phrases. Wollombi, N.S.W.: Exisle Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 9781921497049.

- ^ Rosen, Dan. «1983–84: Growing Pains Lead to Promise». New Jersey Devils. Retrieved March 25, 2006.

- ^ «‘Irresponsible’ Hodge under fire». BBC News. January 14, 2003. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ «Film music». BBC. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

When the music is precisely synchronised with events on screen this is known as Mickey-Mousing, eg someone slipping on a banana skin could use a descending scale followed by a cymbal crash. Mickey-Mousing is often found in comedy films.

- ^ «What does Mickey Mouse Have To Do With The European Parliament?». EU-Oplysnigen (Denmark). Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ ««Mickey Rodent!» (Mad #19)». Johnglenntaylor.blogspot.com. January 2009. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Rosenberg, Pnina (2002). «Mickey Mouse in Gurs – humour, irony and criticism in works of art produced in the Gurs internment camp». Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice. 6 (3): 273–292. doi:10.1080/13642520210164508. S2CID 143675622.

- ^ Menn, Joseph (August 22, 2008). «Disney’s rights to young Mickey Mouse may be wrong». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Daycare Center Murals. Snopes.com, updated September 17, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Mann, Ron. Director (1989). Comic Book Confidential. Sphinx Productions.

- ^ Levin, Bob (2003). The Pirates and the Mouse: Disney’s War Against the Counterculture. Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 1-56097-530-X.

- ^ a b c d e f Menn, Joseph (August 22, 2008). «Whose mouse is it anyway?». The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Vanpelt, Lauren (Spring 1999). «Mickey Mouse – A Truly Public Character». Archived from the original on March 20, 2004. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Hedenkamp, Douglas (Spring 2003). «Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works, and the Copyright Act of 1909». Virginia Sports and Entertainment Law Journal. Archived from the original on June 22, 2004. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ The full 1929 cartoon The Barnyard Battle (7:48) is available for viewing on YouTube. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ The Times (July 14, 1930). «Mickey Mouse in Trouble (German Censorship)», The Times Archive (archive.timesonline.co.uk). Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ Hungerford, Amy (January 15, 2003). The Holocaust of Texts. University Of Chicago Press. p. 206. ISBN 0-226-36076-8.

- ^ LaCapra, Dominick (March 1998). History and Memory After Auschwitz. Cornell University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0-8014-8496-0.

- ^ Rosenthal, Jack (August 2, 1992). «On language; Mickey-Mousing». The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ^ Conner, Floyd (2002). Hollywood’s Most Wanted: The Top 10 Book of Lucky Breaks, Prima Donnas, Box Office Bombs, and Other Oddities. illustrated. Brassey’s Inc. p. 243.

- ^ The Times (November 16, 1938). «The Banning of a Mouse». archive.timesonline.co.uk. London: The Times Archive. p. 15. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ «Italian Decree: Mickey Mouse Reprieved». The Evening Post. Vol. CXXVI, no. 151. Wellington, New Zealand. December 23, 1938. p. 16, column 3. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ Francesco De Giacomo, Quando il duce salvò Topolino, IF terza serie, n. 4, 1995.

- ^ a b Craig Bellamy; Gordon Chisholm; Hilary Eriksen (February 17, 2006). «Moomba: A festival for the people» (PDF). City of Melbourne. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2006.

Bibliography

- Korkis, Jim (2012). Who Is Afraid of the Song of the South?: And Other Forbidden Disney Stories. Orlando, Fla.: Theme Park Press. ISBN 978-0984341559. OCLC 823179800.

External links

- Disney’s Mickey Mouse character page

- Mickey Mouse at Inducks

- Mickey Mouse on IMDb

- Mickey Mouse’s Campaign Website (as archived on August 3, 2008)

- Wayne Allwine – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Mickey Mouse comic strip reprints at Creators Syndicate

- Mickey Mouse at Don Markstein’s Toonopedia.

| Mickey Mouse | |

|---|---|

|

|

| First appearance | Steamboat Willie (1928) |

| Created by | Walt Disney Ub Iwerks |

| Designed by | Walt Disney Ub Iwerks (original, 1928 design) Fred Moore (1938 redesign) |

| Voiced by | Walt Disney (1928–1947, 1955–1962) Carl W. Stalling (1929) Jimmy MacDonald (1947–1978) Wayne Allwine (1977–2009)[1] Bret Iwan (2009–present) Chris Diamantopoulos (2013–present) (see voice actors) |

| Developed by | Les Clark Fred Moore Floyd Gottfredson Romano Scarpa |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Mickey Mouse |

| Alias |

|

| Species | Mouse |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Mickey Mouse family |

| Significant other | Minnie Mouse |

| Pets | Pluto (dog) |

Mickey Mouse is an animated cartoon character co-created in 1928 by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks. The longtime mascot of The Walt Disney Company, Mickey is an anthropomorphic mouse who typically wears red shorts, large yellow shoes, and white gloves. Taking inspiration from silent film personalities such as Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp, Mickey is traditionally characterized as a sympathetic underdog who gets by on pluck and ingenuity.[2] The character’s status as a small mouse was personified through his diminutive stature and falsetto voice, the latter of which was originally provided by Disney. Mickey is one of the world’s most recognizable and universally acclaimed fictional characters of all time.

Created as a replacement for a prior Disney character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Mickey first appeared in the short Plane Crazy, debuting publicly in the short film Steamboat Willie (1928), one of the first sound cartoons. The character was originally to be named “Mortimer Mouse”, until Lillian Disney instead suggested “Mickey” during a train ride. The character went on to appear in over 130 films, including The Band Concert (1935), Brave Little Tailor (1938), and Fantasia (1940). Mickey appeared primarily in short films, but also occasionally in feature-length films. Ten of Mickey’s cartoons were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film, one of which, Lend a Paw, won the award in 1941. In 1978, Mickey became the first cartoon character to have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Beginning in 1930, Mickey has also been featured extensively in comic strips and comic books. The Mickey Mouse comic strip, drawn primarily by Floyd Gottfredson, ran for 45 years. Mickey has also appeared in comic books such as Mickey Mouse, Disney Italy’s Topolino and MM – Mickey Mouse Mystery Magazine, and Wizards of Mickey. Mickey also features in television series such as The Mickey Mouse Club (1955–1996) and others. He appears in other media such as video games as well as merchandising and is a meetable character at the Disney parks.

Mickey generally appears alongside his girlfriend Minnie Mouse, his pet dog Pluto, his friends Donald Duck and Goofy, and his nemesis Pete, among others (see Mickey Mouse universe). Though originally characterized as a cheeky lovable rogue, Mickey was rebranded over time as a nice guy, usually seen as an honest and bodacious hero. In 2009, Disney began to rebrand the character again by putting less emphasis on his friendly, well-meaning persona and reintroducing the more adventurous and stubborn sides of his personality, beginning with the video game Epic Mickey.[3]

History

Film

Origin

Mickey Mouse was created as a replacement for Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, an earlier cartoon character that was created by the Disney studio but owned by Universal Pictures.[4] Charles Mintz served as a middleman producer between Disney and Universal through his company, Winkler Pictures, for the series of cartoons starring Oswald. Ongoing conflicts between Disney and Mintz and the revelation that several animators from the Disney studio would eventually leave to work for Mintz’s company ultimately resulted in Disney cutting ties with Oswald. Among the few people who stayed at the Disney studio were animator Ub Iwerks, apprentice artist Les Clark, and Wilfred Jackson. On his train ride home from New York, Walt brainstormed ideas for a new cartoon character.