The music of the United States reflects the country’s multi-ethnic population through a diverse array of styles. It is a mixture of music influenced by the music of Europe, Indigenous peoples, West Africa, Latin America, Middle East, North Africa, amongst many other places. The country’s most internationally renowned genres are traditional pop, jazz, blues, country, bluegrass, rock, rock and roll, R&B, pop, hip hop, soul, funk, gospel, disco, house, techno, ragtime, doo-wop, folk music, americana, boogaloo, tejano, reggaeton, surf, and salsa. American music is heard around the world. Since the beginning of the 20th century, some forms of American popular music have gained a near global audience.[1]

Native Americans were the earliest inhabitants of the land that is today known as the United States and played its first music. Beginning in the 17th century, settlers from the United Kingdom, Ireland, Spain, Germany, and France began arriving in large numbers, bringing with them new styles and instruments. Slaves from West Africa brought their musical traditions, and each subsequent wave of immigrants contributed to a melting pot.

There are also some African-American influences in the musical tradition of the European-American settlers, such as jazz, blues, rock, country and bluegrass. The United States has also seen documented folk music and recorded popular music produced in the ethnic styles of the Ukrainian, Irish, Scottish, Polish, Hispanic, and Jewish communities, among others.

Many American cities and towns have vibrant music scenes which, in turn, support a number of regional musical styles. Musical centers around the country have all have produced and contributed to the many distinctive styles of American music. The Cajun and Creole traditions in Louisiana music, the folk and popular styles of Hawaiian music, and the bluegrass and old time music of the Southeastern states are a few examples of diversity in American music.

Characteristics[edit]

Raymond Carlos Nakai is an American Indian of Navajo/Ute heritage. His Earth Spirit and Canyon Trilogy albums are the only Native American albums to be certified gold and platinum, respectively, by the RIAA.

The music of the United States can be characterized by the use of syncopation and asymmetrical rhythms, long, irregular melodies, which are said to «reflect the wide open geography of (the American landscape)» and the «sense of personal freedom characteristic of American life».[2] Some distinct aspects of American music, like the call-and-response format, are derived from African techniques and instruments.

Throughout the later part of American history, and into modern times, the relationship between American and European music has been a discussed topic among scholars of American music. Some have urged for the adoption of more purely European techniques and styles, which are sometimes perceived as more refined or elegant, while others have pushed for a sense of musical nationalism that celebrates distinctively American styles. Modern classical music scholar John Warthen Struble has contrasted American and European, concluding that the music of the United States is inherently distinct because the United States has not had centuries of musical evolution as a nation. Instead, the music of the United States is that of dozens or hundreds of indigenous and immigrant groups, all of which developed largely in regional isolation until the American Civil War, when people from across the country were brought together in army units, trading musical styles and practices. Struble deemed the ballads of the Civil War «the first American folk music with discernible features that can be considered unique to America: the first ‘American’ sounding music, as distinct from any regional style derived from another country.»[3]

The Civil War, and the period following it, saw a general flowering of American art, literature and music. Amateur musical ensembles of this era can be seen as the birth of American popular music. Music author David Ewen describes these early amateur bands as combining «the depth and drama of the classics with undemanding technique, eschewing complexity in favor of direct expression. If it was vocal music, the words would be in English, despite the snobs who declared English an unsingable language. In a way, it was part of the entire awakening of America that happened after the Civil War, a time in which American painters, writers, and ‘serious’ composers addressed specifically American themes.»[4] During this period the roots of blues, gospel, jazz, and country music took shape; in the 20th century, these became the core of American popular music, which further evolved into the styles like rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and hip hop music.

[edit]

Music intertwines with aspects of American social and cultural identity, including through social class, race and ethnicity, geography, religion, language, gender, and sexuality. The relationship between music and race is perhaps the most potent determiner of musical meaning in the United States. The development of an African American musical identity, out of disparate sources from Africa and Europe, has been a constant theme in the music history of the United States. Little documentation exists of colonial-era African American music, when styles, songs, and instruments from across West Africa commingled with European styles and instruments, leading to the creation of new genres and self expression from enslaved people. By the mid-19th century, a distinctly African American folk tradition was well-known and widespread, and African American musical techniques, instruments, and images became a part of mainstream American music through spirituals, minstrel shows, and slave songs.[6] African American musical styles became an integral part of American popular music through blues, jazz, rhythm and blues, and then rock and roll, soul, and hip hop; all of these styles were consumed by Americans of all races, but were created in African American styles and idioms before eventually becoming common in performance and consumption across racial lines. In contrast, country music derives from both African and European, as well as Native American and Hawaiian, traditions and has long been perceived as a form of white music.[7]

Economic and social classes separates American music through the creation and consumption of music, such as the upper-class patronage of symphony-goers, and the generally poor performers of rural and ethnic folk musics. Musical divisions based on class are not absolute, however, and are sometimes as much perceived as actual;[8] popular American country music, for example, is a commercial genre designed to «appeal to a working-class identity, whether or not its listeners are actually working class».[9] Country music is also intertwined with geographic identity, and is specifically rural in origin and function; other genres, like R&B and hip hop, are perceived as inherently urban.[10] For much of American history, music-making has been a «feminized activity».[11] In the 19th century, amateur piano and singing were considered proper for middle- and upper-class women. Women were also a major part of early popular music performance, though recorded traditions quickly become more dominated by men. Most male-dominated genres of popular music include female performers as well, often in a niche appealing primarily to women; these include gangsta rap and heavy metal.[12]

History[edit]

|

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (May 2021) |

Diversity[edit]

The United States is often said to be a cultural melting pot, taking in influences from across the world and creating distinctively new methods of cultural expression. Though aspects of American music can be traced back to specific origins, claiming any particular original culture for a musical element is inherently problematic, due to the constant evolution of American music through transplanting and hybridizing techniques, instruments and genres. Elements of foreign musics arrived in the United States both through the formal sponsorship of educational and outreach events by individuals and groups, and through informal processes, as in the incidental transplantation of West African music through slavery, and Irish music through immigration. The most distinctly American musics are a result of cross-cultural hybridization through close contact. Slavery, for example, mixed persons from numerous tribes in tight living quarters, resulting in a shared musical tradition that was enriched through further hybridizing with elements of indigenous, Latin, and European music.[13] American ethnic, religious, and racial diversity has also produced such intermingled genres as the French-African music of the Louisiana Creoles, the Native, Mexican and European fusion Tejano music, and the thoroughly hybridized slack-key guitar and other styles of modern Hawaiian music.

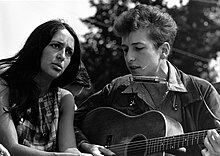

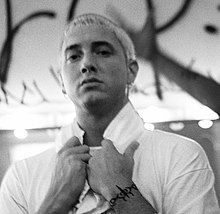

The process of transplanting music between cultures is not without criticism. The folk revival of the mid-20th century, for example, appropriated the musics of various rural peoples, in part to promote certain political causes, which has caused some to question whether the process caused the «commercial commodification of other peoples’ songs … and the inevitable dilution of mean» in the appropriated musics. The use of African American musical techniques, images, and conceits in popular music largely by and for white Americans has been widespread since at least the mid-19th century songs of Stephen Foster and the rise of minstrel shows. The American music industry has actively attempted to popularize white performers of African American music because they are more palatable to mainstream and middle-class Americans.[citation needed] This process has been related to the rise of stars as varied as Benny Goodman, Eminem, and Elvis Presley, as well as popular styles like blue-eyed soul and rockabilly.[13]

Folk music[edit]

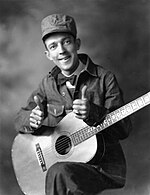

Singer Elvis Presley was one of the most successful music artists of the 20th century, he is often referred to as «the King of Rock and Roll», or simply, «the King».

Folk music in the US is varied across the country’s numerous ethnic groups. The Native American tribes each play their own varieties of folk music, most of it spiritual in nature. African American music includes blues and gospel, descendants of West African music brought to the Americas by slaves and mixed with Western European music. During the colonial era, English, French and Spanish styles and instruments were brought to the Americas. By the early 20th century, the United States had become a major center for folk music from around the world, including polka, Ukrainian and Polish fiddling, Ashkenazi, Klezmer, and several kinds of Latin music.

The Native Americans played the first folk music in what is now the United States, using a wide variety of styles and techniques. Some commonalities are near universal among Native American traditional music, however, especially the lack of harmony and polyphony, and the use of vocables and descending melodic figures. Traditional instrumentations use the flute and many kinds of percussion instruments, like drums, rattles, and shakers.[14] Since European and African contact was established, Native American folk music has grown in new directions, into fusions with disparate styles like European folk dances and Tejano music. Modern Native American music may be best known for pow wows, pan-tribal gatherings at which traditionally styled dances and music are performed.[15]

This is an 1897 recording of a traditional Omaha courtship song.

This is a British tune recorded in Florida in 1940 by Bob Hall, Walter van Bass, Ned Hugh Bass, and J. C. King.

This is old-time Appalachian folk music from 1925. Performed by Bascam Lamar Lunsford.

The Thirteen Colonies of the original United States were all former English possessions, and Anglo culture became a major foundation for American folk and popular music. Many American folk songs are identical to British songs in arrangements, but with new lyrics, often as parodies of the original material. American-Anglo songs are also characterized as having fewer pentatonic tunes, less prominent accompaniment (but with heavier use of drones) and more melodies in major.[16] Anglo-American traditional music also includes a variety of broadside ballads, humorous stories and tall tales, and disaster songs regarding mining, shipwrecks, and murder. Legendary heroes like Joe Magarac, John Henry, and Jesse James are part of many songs. Folk dances of British origin include the square dance, descended from the quadrille, combined with the American innovation of a caller instructing the dancers.[17] The religious communal society known as the Shakers emigrated from England during the 18th century and developed their own folk dance style. Their early songs can be dated back to British folk song models.[18] Other religious societies established their own unique musical cultures early in American history, such as the music of the Amish, the Harmony Society, and the Ephrata Cloister in Pennsylvania.[19]

The ancestors of today’s African American population were brought to the United States as slaves, working primarily in the plantations of the South. They were from hundreds of tribes across West Africa, and they brought with them certain traits of West African music including call and response vocals and complexly rhythmic music,[20] as well as syncopated beats and shifting accents.[21] The African musical focus on rhythmic singing and dancing was brought to the New World, where it became part of a distinct folk culture that helped Africans «retain continuity with their past through music». The first slaves in the United States sang work songs, field hollers[22] and, following Christianization, hymns. In the 19th century, a Great Awakening of religious fervor gripped people across the country, especially in the South. Protestant hymns written mostly by New England preachers became a feature of camp meetings held among devout Christians across the South. When blacks began singing adapted versions of these hymns, they were called Negro spirituals. It was from these roots, of spiritual songs, work songs, and field hollers, that blues, jazz, and gospel developed.

Blues and spirituals[edit]

Ethnographic recordings collected for the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Song. Performed by Bertha Houston.

Spirituals were primarily expressions of religious faith, sung by slaves on southern plantations.[23] In the mid to late 19th century, spirituals spread out of the U.S. South. In 1871 Fisk University became home to the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a pioneering group that popularized spirituals across the country. In imitation of this group, gospel quartets arose, followed by increasing diversification with the early 20th-century rise of jackleg and singing preachers, from whence came the popular style of gospel music.

Blues is a combination of African work songs, field hollers, and shouts.[24] It developed in the rural South in the first decade of the 20th century. The most important characteristics of the blues is its use of the blue scale, with a flatted or indeterminate third, as well as the typically lamenting lyrics; though both of these elements had existed in African American folk music prior to the 20th century, the codified form of modern blues (such as with the AAB structure) did not exist until the early 20th century.[25]

Other immigrant communities[edit]

The United States is a melting pot consisting of numerous ethnic groups. Many of these peoples have kept alive the folk traditions of their homeland, often producing distinctively American styles of foreign music. Some nationalities have produced local scenes in regions of the country where they have clustered, like Cape Verdean music in New England,[26] Armenian music in California,[27] and Italian and Ukrainian music in New York City.[28]

The Creoles are a community with varied non-Anglo ancestry, mostly descendant of people who lived in Louisiana before its purchase by the U.S. The Cajuns are a group of Francophones who arrived in Louisiana after leaving Acadia in Canada.[29] The city of New Orleans, Louisiana, being a major port, has acted as a melting pot for people from all over the Caribbean basin. The result is a diverse and syncretic set of styles of Cajun music and Creole music.

Spain and subsequently Mexico controlled much of what is now the western United States until the Mexican–American War, including the entire state of Texas. After Texas joined the United States, the native Tejanos living in the state began culturally developing separately from their neighbors to the south, and remained culturally distinct from other Texans. Central to the evolution of early Tejano music was the blend of traditional Mexican forms such as mariachi and the corrido, and Continental European styles introduced by German and Czech settlers in the late 19th century.[30] In particular, the accordion was adopted by Tejano folk musicians around the start of the 20th century, and it became a popular instrument for amateur musicians in Texas and Northern Mexico.

Classical music[edit]

Classical music was brought to the United States with some of the first colonists. European classical music is rooted in the traditions of European art, ecclesiastical and concert music. The central norms of this tradition developed between 1550 and 1825, centering on what is known as the common practice period. Many American classical composers attempted to work entirely within European models until late in the 19th century. When Antonín Dvořák, a prominent Czech composer, visited the United States from 1892 to 1895, he iterated the idea that American classical music needed its own models instead of imitating European composers; he helped to inspire subsequent composers to make a distinctly American style of classical music.[31] By the beginning of the 20th century, many American composers were incorporating disparate elements into their work, ranging from jazz and blues to Native American music.

Early classical music[edit]

Aaron Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as «the Dean of American Composers»

During the colonial era, there were two distinct fields of what is now considered classical music. One was associated with amateur composers and pedagogues, whose style was originally drawn from simple hymns and gained sophistication over time. The other colonial tradition was that of the mid-Atlantic cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore, which produced a number of prominent composers who worked almost entirely within the European model; these composers were mostly English in origin, and worked specifically in the style of prominent English composers of the day.[32]

Classical music was brought to the United States during the colonial era. Many American composers of this period worked exclusively with European models, while others, such as William Billings, Supply Belcher, and Justin Morgan, also known as the First New England School, developed a style almost entirely independent of European models.[33] Of these composers, Billings is the most well-remembered; he was also influential «as the founder of the American church choir, as the first musician to use a pitch pipe, and as the first to introduce a violoncello into church service».[34] Many of these composers were amateur singers who developed new forms of sacred music suitable for performance by amateurs, and often using harmonic methods which would have been considered bizarre by contemporary European standards.[35] These composers’ styles were untouched by «the influence of their sophisticated European contemporaries», using modal or pentatonic scales or melodies and eschewing the European rules of harmony.[36]

In the early 19th century, America produced diverse composers such as Anthony Heinrich, who composed in an idiosyncratic, intentionally American style and was the first American composer to write for a symphony orchestra. Many other composers, most famously William Henry Fry and George Frederick Bristow, supported the idea of an American classical style, though their works were very European in orientation. It was John Knowles Paine, however, who became the first American composer to be accepted in Europe. Paine’s example inspired the composers of the Second New England School, which included such figures as Amy Beach, Edward MacDowell, and Horatio Parker.[37]

Louis Moreau Gottschalk is perhaps the best-remembered American composer of the 19th century, said by music historian Richard Crawford to be known for «bringing indigenous or folk, themes and rhythms into music for the concert hall». Gottschalk’s music reflected the cultural mix of his home city, New Orleans, Louisiana, which was home to a variety of Latin, Caribbean, African American, Cajun, and Creole music. He was well acknowledged as a talented pianist in his lifetime, and was also a known composer who remains admired though little performed.[38]

20th century[edit]

Philip Glass in Florence, 1993

The New York classical music scene included Charles Griffes, originally from Elmira, New York, who began publishing his most innovative material in 1914. His early collaborations were attempts to use non-Western musical themes. The best-known New York composer was George Gershwin. Gershwin was a songwriter with Tin Pan Alley and the Broadway theatres, and his works were strongly influenced by jazz, or rather the precursors to jazz that were extant during his time. Gershwin’s work made American classical music more focused, and attracted an unheard of amount of international attention. Following Gershwin, the first major composer was Aaron Copland from Brooklyn, who used elements of American folk music, though it remained European in technique and form. Later, he turned to the ballet and then serial music.[39] Charles Ives was one of the earliest American classical composers of enduring international significance, producing music in a uniquely American style, though his music was mostly unknown until after his death in 1954.

Many of the later 20th-century composers, such as John Cage, John Corigliano, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, John Adams, and Miguel del Aguila, used modernist and minimalist techniques. Reich discovered a technique known as phasing, in which two musical activities begin simultaneously and are repeated, gradually drifting out of sync, creating a natural sense of development. Reich was also very interested in non-Western music, incorporating African rhythmic techniques in his compositions.[40] Recent composers and performers are strongly influenced by the minimalist works of Philip Glass, a Baltimore native based out of New York, Meredith Monk, and others.[41]

Popular music[edit]

The United States has produced many popular musicians and composers in the modern world. Beginning with the birth of recorded music, American performers have continued to lead the field of popular music, which out of «all the contributions made by Americans to world culture… has been taken to heart by the entire world».[42] Most histories of popular music start with American ragtime or Tin Pan Alley; others, however, trace popular music to the Renaissance and through broadsheets, ballads, and other popular traditions.[43] Other authors typically look at popular sheet music, tracing American popular music to spirituals, minstrel shows, vaudeville, and the patriotic songs of the Civil War.

Early popular song[edit]

The patriotic lay songs of the American Revolution constituted the first kind of mainstream popular music. These included «The Liberty Tree» by Thomas Paine. Cheaply printed as broadsheets, early patriotic songs spread across the colonies and were performed at home and at public meetings.[44] Fife songs were especially celebrated, and were performed on fields of battle during the American Revolution. The longest lasting of these fife songs is «Yankee Doodle», still well known today. The melody dates back to 1755 and was sung by both American and British troops.[45] Patriotic songs were based mostly on English melodies, with new lyrics added to denounce British colonialism; others, however, used tunes from Ireland, Scotland or elsewhere, or did not utilize a familiar melody. The song «Hail, Columbia» was a major work[46] that remained an unofficial national anthem until the adoption of «The Star-Spangled Banner». Much of this early American music still survives in Sacred Harp. Although relatively unknown outside of Shaker Communities, Simple Gifts was written in 1848 by Elder Joseph Brackett and the tune has since become internationally famous.[47]

During the Civil War, when soldiers from across the country commingled, the multifarious strands of American music began to cross-fertilize each other, a process that was aided by the burgeoning railroad industry and other technological developments that made travel and communication easier. Army units included individuals from across the country, and they rapidly traded tunes, instruments and techniques. The war was an impetus for the creation of distinctly American songs that became and remained wildly popular.[3] The most popular songs of the Civil War era included «Dixie», written by Daniel Decatur Emmett. The song, originally titled «Dixie’s Land», was made for the closing of a minstrel show; it spread to New Orleans first, where it was published and became «one of the great song successes of the pre-Civil War period».[48] In addition to popular patriotic songs, the Civil War era also produced a great body of brass band pieces.[49]

Al Jolson, circa 1916, is credited with being America’s most famous and highest-paid star of the 1920s.

Following the Civil War, minstrel shows became the first distinctively American form of music expression. The minstrel show was an indigenous form of American entertainment consisting of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music, usually performed by white people in blackface. Minstrel shows used African American elements in musical performances, but only in simplified ways; storylines in the shows depicted blacks as natural-born slaves and fools, before eventually becoming associated with abolitionism.[50] The minstrel show was invented by Daniel Decatur Emmett and the Virginia Minstrels.[51] Minstrel shows produced the first well-remembered popular songwriters in American music history: Thomas D. Rice, Daniel Decatur Emmett, and, most famously, Stephen Foster. After minstrel shows’ popularity faded, coon songs, a similar phenomenon, became popular.

The composer John Philip Sousa is closely associated with the most popular trend in American popular music just before the start of the 20th century. Formerly the bandmaster of the United States Marine Band, Sousa wrote military marches like «The Stars and Stripes Forever» that reflected his «nostalgia for [his] home and country», giving the melody a «stirring virile character».[52]

In the early 20th century, American musical theater was a major source for popular songs, many of which influenced blues, jazz, country, and other extant styles of popular music. The center of development for this style was in New York City, where the Broadway theatres became among the most renowned venues in the city. Theatrical composers and lyricists like the brothers George and Ira Gershwin created a uniquely American theatrical style that used American vernacular speech and music. Musicals featured popular songs and fast-paced plots that often revolved around love and romance.[53]

Blues and gospel[edit]

Ragtime composition by Scott Joplin

The blues is a genre of African American folk music that is the basis for much of modern American popular music. Blues can be seen as part of a continuum of musical styles like country, jazz, ragtime, and gospel; though each genre evolved into distinct forms, their origins were often indistinct. Early forms of the blues evolved in and around the Mississippi Delta in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The earliest blues music was primarily call and response vocal music, without harmony or accompaniment and without any formal musical structure. Slaves and their descendants created the blues by adapting the field shouts and hollers, turning them into passionate solo songs.[54] When mixed with the Christian spiritual songs of African American churches and revival meetings, blues became the basis of gospel music. Modern gospel began in African American churches in the 1920s, in the form of worshipers proclaiming their faith in an improvised, often musical manner (testifying). Composers like Thomas A. Dorsey composed gospel works that used elements of blues and jazz in traditional hymns and spiritual songs.[55]

Ragtime was originally a piano style, featuring syncopated rhythms and chromaticisms.[25] It is primarily a form of dance music utilizing the walking bass, and is generally composed in sonata form. Ragtime is a refined and evolved form of the African American cakewalk dance, mixed with styles ranging from European marches[56] and popular songs to jigs and other dances played by large African American bands in northern cities during the end of the 19th century. The most famous ragtime performer and composer was Scott Joplin, known for works such as «Maple Leaf Rag».[57]

Blues became a part of American popular music in the 1920s, when classic female blues singers like Bessie Smith grew popular. At the same time, record companies launched the field of race music, which was mostly blues targeted at African American audiences. The most famous of these acts went on to inspire much of the later popular development of the blues and blues-derived genres, including the legendary delta blues musician Robert Johnson and Piedmont blues musician Blind Willie McTell. By the end of the 1940s, however, pure blues was only a minor part of popular music, having been subsumed by offshoots like rhythm & blues and the nascent rock and roll style. Some styles of electric, piano-driven blues, like boogie-woogie, retained a large audience. A bluesy style of gospel also became popular in mainstream America in the 1950s, led by singer Mahalia Jackson.[58] The blues genre experienced major revivals in the 1950s with Chicago blues musicians such as Muddy Waters and Little Walter,[59] as well as in the 1960s in the British Invasion and American folk music revival when country blues musicians like Mississippi John Hurt and Reverend Gary Davis were rediscovered. The seminal blues musicians of these periods had tremendous influence on rock musicians such as Chuck Berry in the 1950s, as well as on the British blues and blues rock scenes of the 1960s and 1970s, including Eric Clapton in Britain and Johnny Winter in Texas.

Jazz[edit]

Main article: Jazz

Jazz is a kind of music characterized by swung and blue notes, call and response vocals, polyrhythms and improvisation. Though originally a kind of dance music, jazz has been a major part of popular music, and has also become a major element of Western classical music. Jazz has roots in West African cultural and musical expression, and in African American music traditions including blues and ragtime, as well as European military band music.[60] Early jazz was closely related to ragtime, with which it could be distinguished by the use of more intricate rhythmic improvisation. The earliest jazz bands adopted much of the vocabulary of the blues, including bent and blue notes and instrumental «growls» and smears otherwise not used on European instruments. Jazz’s roots come from the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, populated by Cajuns and black Creoles, who combined the French-Canadian culture of the Cajuns with their own styles of music in the 19th century. Large Creole bands that played for funerals and parades became a major basis for early jazz, which spread from New Orleans to Chicago and other northern urban centers.

Though jazz had long since achieved some limited popularity, it was Louis Armstrong who became one of the first popular stars and a major force in the development of jazz, along with his friend pianist Earl Hines. Armstrong, Hines, and their colleagues were improvisers, capable of creating numerous variations on a single melody. Armstrong also popularized scat singing, an improvisational vocal technique in which nonsensical syllables (vocables) are sung. Armstrong and Hines were influential in the rise of a kind of pop big band jazz called swing. Swing is characterized by a strong rhythm section, usually consisting of double bass and drums, medium to fast tempo, and rhythmic devices like the swung note, which is common to most jazz. Swing is primarily a fusion of 1930s jazz fused with elements of the blues and Tin Pan Alley.[57] Swing used bigger bands than other kinds of jazz, leading to bandleaders tightly arranging the material which discouraged improvisation, previously an integral part of jazz. Swing became a major part of African American dance, and came to be accompanied by a popular dance called the swing dance.

Jazz influenced many performers of all the major styles of later popular music, though jazz itself never again became such a major part of American popular music as during the swing era. The later 20th-century American jazz scene did, however, produce some popular crossover stars, such as Miles Davis. In the middle of the 20th century, jazz evolved into a variety of subgenres, beginning with bebop. Bebop is a form of jazz characterized by fast tempos, improvisation based on harmonic structure rather than melody, and use of the flatted fifth. Bebop was developed in the early and mid-1940s, later evolving into styles like hard bop and free jazz. Innovators of the style included Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, who arose from small jazz clubs in New York City.[61]

Country music[edit]

Johnny Cash was considered one of the most influential musicians of his generation.

Country music is primarily a fusion of African American blues and spirituals with Appalachian folk music, adapted for pop audiences and popularized beginning in the 1920s. The origins of country are in rural Southern folk music, which was primarily Irish and British, with African and continental European musics.[62] Anglo-Celtic tunes, dance music, and balladry were the earliest predecessors of modern country, then known as hillbilly music. Early hillbilly also borrowed elements of the blues and drew upon more aspects of 19th-century pop songs as hillbilly music evolved into a commercial genre eventually known as country and western and then simply country.[63] The earliest country instrumentation revolved around the European-derived fiddle and the African-derived banjo, with the guitar later added.[64] String instruments like the ukulele and steel guitar became commonplace due to the popularity of Hawaiian musical groups in the early 20th century.[65]

The roots of commercial country music are generally traced to 1927, when music talent scout Ralph Peer recorded Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family.[66] Popular success was very limited, though a small demand spurred some commercial recording. After World War II, there was increased interest in specialty styles like country music, producing a few major pop stars.[67] The most influential country musician of the era was Hank Williams, a bluesy country singer from Alabama.[58][68] He remains renowned as one of country music’s greatest songwriters and performers, viewed as a «folk poet» with a «honky-tonk swagger» and «working-class sympathies».[69] Throughout the decade the roughness of honky-tonk gradually eroded as the Nashville sound grew more pop-oriented. Producers like Chet Atkins created the Nashville sound by stripping the hillbilly elements of the instrumentation and using smooth instrumentation and advanced production techniques.[70] Eventually, most records from Nashville were in this style, which began to incorporate strings and vocal choirs.[71]

By the early part of the 1960s, however, the Nashville sound had become perceived as too watered-down by many more traditionalist performers and fans, resulting in a number of local scenes like the Bakersfield sound. A few performers retained popularity, however, such as the long-standing cultural icon Johnny Cash.[72] The Bakersfield sound began in the mid to late 1950s when performers like Wynn Stewart and Buck Owens began using elements of Western swing and rock, such as the breakbeat, in their music.[73] In the 1960s performers like Merle Haggard popularized the sound. In the early 1970s, Haggard was also part of outlaw country, alongside singer-songwriters such as Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings.[61] Outlaw country was rock-oriented and lyrically focused on the criminal antics of the performers, in contrast to the clean-cut country singers of the Nashville sound.[74] By the middle of the 1980s, the country music charts were dominated by pop singers, alongside a nascent revival of honky-tonk-style country with the rise of performers like Dwight Yoakam. The 1980s also saw the development of alternative country performers like Uncle Tupelo, who were opposed to the more pop-oriented style of mainstream country. At the beginning of the 2000s, rock-oriented country acts remained among the best-selling performers in the United States, especially Garth Brooks.[75]

Soul, R&B and funk[edit]

The classic soul song by Sam Cooke became a civil rights anthem.

The groundbreaking hit by James Brown marked the beginning of the development of funk.

Singer James Brown was critical in the transition of rhythm and blues to soul music and pioneering funk music.[76]

R&B, an abbreviation for rhythm and blues, is a style that arose in the 1930s and 1940s. Early R&B consisted of large rhythm units «smashing away behind screaming blues singers (who) had to shout to be heard above the clanging and strumming of the various electrified instruments and the churning rhythm sections».[77] R&B was not extensively recorded and promoted because record companies felt that it was not suited for most audiences, especially middle-class whites, because of the suggestive lyrics and driving rhythms.[78] Bandleaders like Louis Jordan innovated the sound of early R&B, using a band with a small horn section and prominent rhythm instrumentation. By the end of the 1940s, he had had several hits, and helped pave the way for contemporaries like Wynonie Harris and John Lee Hooker. Many of the most popular R&B songs were not performed in the rollicking style of Jordan and his contemporaries; instead they were performed by white musicians like Pat Boone in a more palatable mainstream style, which turned into pop hits.[79] By the end of the 1950s, however, there was a wave of popular black blues rock and country-influenced R&B performers like Chuck Berry gaining unprecedented fame among white listeners.[80][81]

Motown Records became highly successful during the early and mid-1960s for producing music of black American roots that defied racial segregation in the music industry and consumer market. Music journalist Jerry Wexler (who coined the phrase «rhythm and blues») once said of Motown: «[They] did something that you would have to say on paper is impossible. They took black music and beamed it directly to the white American teenager.» Berry Gordy founded Motown in 1959 in Detroit, Michigan. It was one of few R&B record labels that sought to transcend the R&B market (which was definitively black in the American mindset) and specialize in crossover music. The company emerged as the leading producer (or «assembly line,» a reference to its motor-town origins) of black popular music by the early 1960s and marketed its products as «The Motown Sound» or «The Sound of Young America»—which combined elements of soul, funk, disco and R&B.[82] Notable Motown acts include the Four Tops, the Temptations, the Supremes, Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder, and the Jackson 5. Visual representation was central to Motown’s rise; they placed greater emphasis on visual media than other record labels. Many people’s first exposure to Motown was by television and film. Motown artists’ image of successful black Americans who held themselves with grace and aplomb broadcast a distinct form of middle-class blackness to audiences, which was particularly appealing to whites.[83]

Soul music is a combination of rhythm and blues and gospel which began in the late 1950s in the United States. It is characterized by its use of gospel-music devices, with a greater emphasis on vocalists and the use of secular themes. The 1950s recordings of Ray Charles, Sam Cooke,[84] and James Brown are commonly considered the beginnings of soul. Charles’ Modern Sounds (1962) records featured a fusion of soul and country music, country soul, and crossed racial barriers in music at the time.[85] One of Cooke’s most well-known songs «A Change Is Gonna Come» (1964) became accepted as a classic and an anthem of the American Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s.[86] According to AllMusic, James Brown was critical, through «the gospel-impassioned fury of his vocals and the complex polyrhythms of his beats», in «two revolutions in black American music. He was one of the figures most responsible for turning R&B into soul and he was, most would agree, the figure most responsible for turning soul music into the funk of the late ’60s and early ’70s.»[76]

Singer Michael Jackson, nicknamed the »King of Pop», was a leading figure of popular music crossover in the 1980s. His 1983 music video for «Thriller» broke racial boundaries for pop music on television.[87]

Pure soul was popularized by Otis Redding and the other artists of Stax Records in Memphis, Tennessee. By the late 1960s, Atlantic recording artist Aretha Franklin had emerged as the most popular female soul star in the country.[88][89] Also by this time, soul had splintered into several genres,[90] influenced by psychedelic rock and other styles. The social and political ferment of the 1960s inspired artists like Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield to release albums with hard-hitting social commentary, while another variety became more dance-oriented music, evolving into funk. Despite his previous affinity with politically and socially-charged lyrical themes, Gaye helped popularize sexual and romance-themed music and funk,[91] while his 70s recordings, including Let’s Get It On (1973) and I Want You (1976) helped develop the quiet storm sound and format.[92] One of the most influential albums ever recorded, Sly & the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971) has been considered among the first and best examples of the matured version of funk music, after prototypical instances of the sound in the group’s earlier work.[93] Artists such as Gil Scott-Heron and The Last Poets practiced an eclectic blend of poetry, jazz-funk, and soul, featuring critical political and social commentary with afrocentric sentiment. Scott-Heron’s Proto-rap work, including «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised» (1971) and Winter in America (1974), has had a considerable impact on later hip hop artists,[94] while his unique sound with Brian Jackson influenced neo soul artists.[95]

During the mid-1970s, highly slick and commercial bands such as Philly soul group The O’Jays and blue-eyed soul group Hall & Oates achieved mainstream success. By the end of the 1970s, most music genres, including soul, had been disco-influenced. With the introduction of influences from electro music and funk in the late 1970s and early 1980s, soul music became less raw and more slickly produced, resulting in a genre of music that was once again called R&B, usually distinguished from the earlier rhythm and blues by identifying it as contemporary R&B.

The first contemporary R&B stars arose in the 1980s, with the dance-pop star Michael Jackson, funk-influenced singer Prince, and a wave of female vocalists like Tina Turner and Whitney Houston.[75] Michael Jackson and Prince have been described as the most influential figures in contemporary R&B and popular music because of their eclectic use of elements from a variety of genres.[97] Prince was largely responsible for creating the Minneapolis sound: «a blend of horns, guitars, and electronic synthesizers supported by a steady, bouncing rhythm.»[98] Jackson’s work focused on smooth balladry or disco-influenced dance music; as an artist, he «pulled dance music out of the disco doldrums with his 1979 adult solo debut, Off the Wall, merged R&B with rock on Thriller, and introduced stylized steps such as the robot and moonwalk over the course of his career.»[99] Jackson is often recognized as the «King of Pop» for his achievements.

Beyoncé was one of the most popular American R&B singers in the 2000s.

By 1983, the concept of popular music crossover became inextricably associated with Michael Jackson. Thriller saw unprecedented success, selling over 10 million copies in the United States alone. By 1984, the album captured over 140 gold and platinum awards and was recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the best-selling record of all-time, a title it still holds today.[87] MTV’s broadcast of «Billie Jean» was the first for any black artist, thereby breaking the «color barrier» of pop music on the small screen.[87] Thriller remains the only music video recognized by the National Film Registry.

Singer Ariana Grande became the first solo artist to hold the top three spots on the Hot 100 simultaneously.

Janet Jackson collaborated with former Prince associates Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis on her third studio album Control (1986); the album’s second single «Nasty» has been described as the origin of the new jack swing sound, a genre innovated by Teddy Riley.[97] Riley’s work on Keith Sweat’s Make It Last Forever (1987), Guy’s Guy (1988), and Bobby Brown’s Don’t Be Cruel (1998) made new jack swing a staple of contemporary R&B into the mid-1990s.[97] New jack swing was a style and trend of vocal music, often featuring rapped verses and drum machines.[58] The crossover appeal of early contemporary R&B artists in mainstream popular music, including works by Prince, Michael and Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, Tina Turner, Anita Baker, and The Pointer Sisters became a turning point for black artists in the industry, as their success «was perhaps the first hint that the greater cosmopolitanism of a world market might produce some changes in the complexion of popular music.»[100]

The use of melisma, a gospel tradition adapted by vocalists Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey would become a cornerstone of contemporary R&B singers beginning in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s.[97] Whitney Houston’s R&B hits included «All the Man That I Need» (1990) and «I Will Always Love You» (1992), later became the best-selling physical single by a female act of all time, with sales of over 20 million copies worldwide. Her 1992 hit soundtrack The Bodyguard, spent 20 weeks on top of the Billboard Hot 200, sold over 45 million copies worldwide and remains the best-selling soundtrack album of all time.

Hip hop came to influence contemporary R&B later in the 1980s, first through new jack swing and then in a related series of subgenres called hip hop soul and neo soul. Hip hop soul and neo soul developed later, in the 1990s. Typified by the work of Mary J. Blige, R. Kelly and Bobby Brown, the former is a mixture of contemporary R&B with hip hop beats, while the images and themes of gangsta rap may be present. The latter is a more experimental, edgier, and generally less mainstream combination of 1960s and 1970s-style soul vocals with some hip hop influence, and has earned some mainstream recognition through the work of D’Angelo, Erykah Badu, Alicia Keys, and Lauryn Hill.[101] D’Angelo’s critically acclaimed album Voodoo (2000) has been recognized by music writers as a masterpiece and the cornerstone of the neo soul genre.[102][103][104]

Pop music[edit]

Madonna has been nicknamed the «Queen of Pop» since the 1980s.[105] She is noted for her continual reinvention and versatility in music and visual presentation.

Pop Music is a genre of popular music that originated in its modern form during the mid-1950s in the United States and the United Kingdom. During the 1950s and 1960s, pop music encompassed rock and roll and the youth-oriented styles it influenced. Rock and pop remained roughly synonymous until the late 1960s, after which pop became associated with music that was more commercial, ephemeral, and accessible. Although much of the music that appears on record charts is seen as pop music, the genre is distinguished from chart music. Bing Crosby was one of the first artists to be nicknamed «King of Song» or «King of Popular Music». Indie pop, which developed in the late 1970s, marked another departure from the glamour of contemporary pop music, with guitar bands formed on the then-novel premise that one could record and release their own music without having to procure a record contract from a major label.[106] By the early 1980s, the promotion of pop music had been greatly affected by the rise of music television channels like MTV, which «favoured those artists such as Michael Jackson and Madonna who had a strong visual appeal». The 1980s are commonly remembered for an increase in the use of digital recording, associated with the usage of synthesizers, with synth-pop music and other electronic genres featuring non-traditional instruments increasing in popularity.[107] By 2014, pop music worldwide had been permeated by electronic dance music. In 2018, researchers at the University of California, Irvine, concluded that pop music has become ‘sadder’ since the 1980s. The elements of happiness and brightness have eventually been replaced with the electronic beats making the pop music more ‘sad yet danceable’.[108] Kelly Clarkson is the only American singer to be a two-time winners of the Grammy Award for Best Pop Vocal Album as of 2021, Clarkson being the first to win twice. Clarkson and Justin Timberlake have both been nominated five times, more than any other artist, though Clarkson is the only artist to have the most solo albums nominated. Three of Timberlake’s are solo, two are from NSYNC.

Rock, metal, and punk[edit]

Rock and roll developed out of country, blues, and R&B. Rock’s exact origins and early influences have been hotly debated, and are the subjects of much scholarship. Though squarely in the blues tradition, rock took elements from Afro-Caribbean and Latin musical techniques.[111] Rock was an urban style, formed in the areas where diverse populations resulted in the mixtures of African American, Latin and European genres ranging from the blues and country to polka and zydeco.[112] Rock and roll first entered popular music through a style called rockabilly,[113] which fused the nascent sound with elements of country music. Black-performed rock and roll had previously had limited mainstream success, but it was the white performer Elvis Presley who first appealed to mainstream audiences with a black style of music, becoming one of the best-selling musicians in history, and brought rock and roll to audiences across the world.[114]

The 1960s saw several important changes in popular music, especially rock. Many of these changes took place through the British Invasion where bands such as The Beatles, The Who, and The Rolling Stones,[115] became immensely popular and had a profound effect on American culture and music. These changes included the move from professionally composed songs to the singer-songwriter, and the understanding of popular music as an art, rather than a form of commerce or pure entertainment.[116] These changes led to the rise of musical movements connected to political goals, such as the American Civil Rights Movement and the opposition to the Vietnam War. Rock was at the forefront of this change.

In the early 1960s, rock spawned several subgenres, beginning with surf. Surf was an instrumental guitar genre characterized by a distorted sound, associated with the Southern California surfing youth culture.[117][118] Inspired by the lyrical focus of surf, The Beach Boys began recording in 1961 with an elaborate, pop-friendly, and harmonic sound.[119][120] As their fame grew, The Beach Boys’ songwriter Brian Wilson experimented with new studio techniques and became associated with the counterculture. The counterculture was a movement that embraced political activism, and was closely connected to the hippie subculture. The hippies were associated with folk rock, country rock, and psychedelic rock.[121] Folk and country rock were associated with the rise of politicized folk music, led by Pete Seeger and others, especially at the Greenwich Village music scene in New York.[122] Folk rock entered the mainstream in the middle of the 1960s, when the singer-songwriter Bob Dylan began his career. AllMusic editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine attributes The Beatles’ shift toward introspective songwriting in the mid-1960s to Bob Dylan’s influence at the time.[110] He was followed by a number of country-rock bands and soft, folky singer-songwriters. Psychedelic rock was a hard-driving kind of guitar-based rock, closely associated with the city of San Francisco. Though Jefferson Airplane was the only local band to have a major national hit, the Grateful Dead, a country and bluegrass-flavored jam band, became an iconic part of the psychedelic counterculture, associated with hippies, LSD and other symbols of that era.[121] Some say that the Grateful Dead were truly the most American patriotic rock band to have ever existed; forming and molding a culture that defines Americans today.[123]

The Eagles with five number-one singles, six Grammy Awards, five American Music Awards, and six number one albums, the Eagles were one of the most successful musical acts of the 1970s..

Following the turbulent political, social and musical changes of the 1960s and early 1970s, rock music diversified. What was formerly a discrete genre known as rock and roll evolved into a catchall category called simply rock music, which came to include diverse styles developed in the US like punk rock. During the 1970s most of these styles were evolving in the underground music scene, while mainstream audiences began the decade with a wave of singer-songwriters who drew on the deeply emotional and personal lyrics of 1960s folk rock. The same period saw the rise of bombastic arena rock bands, bluesy Southern rock groups and mellow soft rock stars. Beginning in the later 1970s, the rock singer and songwriter Bruce Springsteen became a major star, with anthemic songs and dense, inscrutable lyrics that celebrated the poor and working class.[75]

Aerosmith is an American rock band, sometimes referred to as «the Bad Boys from Boston» and «America’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band».

Punk was a form of rebellious rock that began in the 1970s, and was loud, aggressive, and often very simple. Punk began as a reaction against the popular music of the period, especially disco and arena rock. American bands in the field included, most famously, The Ramones and Talking Heads, the latter playing a more avant-garde style that was closely associated with punk before evolving into mainstream new wave.[75] Other major acts include Blondie, Patti Smith, and Television. In the 1980s some punk fans and bands became disillusioned with the growing popularity of the style, resulting in an even more aggressive style called hardcore punk. Hardcore was a form of sparse punk, consisting of short, fast, intense songs that spoke to disaffected youth, with such influential bands as Bad Religion, Bad Brains, Black Flag, Dead Kennedys, and Minor Threat. Hardcore began in metropolises like Washington, D.C., though most major American cities had their own local scenes in the 1980s.[124]

Hardcore, punk, and garage rock were the roots of alternative rock, a diverse grouping of rock subgenres that were explicitly opposed to mainstream music, and that arose from the punk and post-punk styles. In the United States, many cities developed local alternative rock scenes, including Minneapolis and Seattle.[126] Seattle’s local scene produced grunge music, a dark and brooding style inspired by hardcore, psychedelia, and alternative rock.[127] With the addition of a more melodic element to the sound of bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains, grunge became wildly popular across the United States[128] in 1991. Three years later, bands like Green Day, The Offspring, Rancid, Bad Religion, and NOFX hit the mainstream (with their respective then-new albums Dookie, Smash, Let’s Go, Stranger than Fiction and Punk in Drublic) and brought the California punk scene exposure worldwide.

Metallica was one of the most influential bands in heavy metal, as they bridged the gap between commercial and critical success for the genre.[129] The band became the best-selling rock act of the 1990s.[130]

Heavy metal is characterized by aggressive, driving rhythms, amplified and distorted guitars, grandiose lyrics, and virtuosic instrumentation. Heavy metal’s origins lie in the hard rock bands who took blues and rock and created a heavy sound built on guitar and drums. The first major American bands came in the early 1970s, like Blue Öyster Cult, KISS, and Aerosmith. Heavy metal remained, however, a largely underground phenomenon. During the 1980s the first major pop-metal style arose and dominated the charts for several years kicked off by metal act Quiet Riot and dominated by bands such as Mötley Crüe and Ratt; this was glam metal, a hard rock and pop fusion with a raucous spirit and a glam-influenced visual aesthetic. Some of these bands, like Bon Jovi, became international stars. The band Guns N’ Roses rose to fame near the end of the decade with an image that was a reaction against the glam metal aesthetic.

By the mid-1980s heavy metal had branched in so many different directions that fans, record companies, and fanzines created numerous subgenres. The United States was especially known for one of these subgenres, thrash metal, which was innovated by bands like Metallica, Megadeth, Slayer, and Anthrax, with Metallica being the most commercially successful.[131] The United States was known as one of the birthplaces of death metal during the mid to late 1980s. The Florida scene was the most well-known, featuring bands like Death, Cannibal Corpse, Morbid Angel, Deicide, and many others. There are now countless death metal and deathgrind bands across the country.

Hip hop[edit]

Hip hop is a cultural movement, of which music is a part. Hip hop music for the most part is itself composed of two parts: rapping, the delivery of swift, highly rhythmic and lyrical vocals; and DJing and/or producing, the production of instrumentation through sampling, instrumentation, turntablism, or beatboxing, the production of musical sounds through vocalized tones.[132] Hip hop arose in the early 1970s in The Bronx, New York City. Jamaican immigrant DJ Kool Herc is widely regarded as the progenitor of hip hop; he brought with him from Jamaica the practice of toasting over the rhythms of popular songs. Emcees originally arose to introduce the soul, funk, and R&B songs that the DJs played, and to keep the crowd excited and dancing; over time, the DJs began isolating the percussion break of songs (when the rhythm climaxes), producing a repeated beat that the emcees rapped over.

Eminem in 1999. He was the best-selling music artist of the 2000s in the United States.

Unlike Motown which predicated its mainstream success on the class appeal of its acts that rendered racial identity irrelevant, hip hop of 1980s, particularly hip hop that crossed over to rock-and-roll, was predicated on its (implicit but emphatic) primary identification with black identity.[133] By the beginning of the 1980s, there were popular hip hop songs, and the celebrities of the scene, like LL Cool J, gained mainstream renown. Other performers experimented with politicized lyrics and social awareness, or fused hip hop with jazz, heavy metal, techno, funk and soul. New styles appeared in the latter part of the 1980s, like alternative hip hop and the closely related jazz rap fusion, pioneered by rappers like De La Soul.

Gangsta rap is a kind of hip hop, most importantly characterized by a lyrical focus on macho sexuality, physicality, and a dangerous criminal image.[134] Though the origins of gangsta rap can be traced back to the mid-1980s style of Philadelphia’s Schoolly D and the West Coast’s Ice-T, the style broadened and came to apply to many different regions in the country, to rappers from New York, such as Notorious B.I.G. and influential hip hop group Wu-Tang Clan, and to rappers on the West Coast, such as Too Short and N.W.A. A distinctive West Coast rap scene spawned the early 1990s G-funk sound, which paired gangsta rap lyrics with a thick and hazy sound, often from 1970s funk samples; the best-known proponents were the rappers 2Pac, Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, and Snoop Dogg. Gangsta rap continued to exert a major presence in American popular music through the end of the 1990s and early into the 21st century.

The dominance of gangsta rap in mainstream hip-hop was supplanted in the late-2000s, largely due to the mainstream success of hip-hop artists such as Kanye West.[135] The outcome of a highly publicized sales competition between the simultaneous release of his and gangsta rapper 50 Cent’s third studio albums, Graduation and Curtis respectively, has since been accredited to the decline.[136] The competition resulted in record-breaking sales performances by both albums and West outsold 50 Cent, selling nearly a million copies of Graduation in the first week alone.[137] Industry observers remark that West’s victory over 50 Cent proved that rap music did not have to conform to gangsta-rap conventions in order to be commercially successful.[138] West effectively paved the way for a new wave of hip-hop artists, including Drake, Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole, who did not follow the hardcore-gangster mold and became platinum-selling artists.[139][140]

Jay-Z became an internationally renowned hip hop icon in the wake of the deaths of The Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur in the mid-1990s.[141] Kanye West was mentored by Jay-Z and produced for him,[142] before attaining a similar level of success.[143]

Cardi B during an interview with Vogue

Female rappers Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, Saweetie, Doja Cat, Iggy Azalea, City Girls and Megan Thee Stallion also entered the mainstream.[144] There are many women that have notably influenced the hip hop culture. However, a few names that cannot go unsaid are MC Sha-rock, MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, Lauryn Hill, Missy Elliot, Lil Kim, Erykah Badu, Foxy Brown, and many more. Of this list MC Sha-rock is considered the historian/pioneer of female hip-hop culture. She started her career as a break-dancer in the Bronx, New York and later became «The hip-hop’s culture’s first female emcee/rapper».[145] Her career has been long-lived. From being a former member of the Funky 4+1 more to having MC rhyming battles with groups such as Grandmaster Flash and Furious 5. Another notable pioneer of female hip-hop is the famous Queen Latifah, Born Dana Elaine Owens in Newark,NJ. Queen Latifah started her career from a young age, as early as 17. But, not long after it began it soon took-off. She released her first full length album, All Hail the Queen in 1989.[146] As she continued to release music she grew more and more popular, and her fame increased amidst the hip-hop culture. However, Queen Latifah was not an ordinary rapper. She rapped about the issues surrounding being a black woman and overall social injustice issues that appear in the music industry. These early pioneers have led female rap culture and impacted today’s popular female hip-hop artists. For example, such popular artists may include Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion, Miss Mulatto, Flo Milli, Cupcakke and many others. Each artists has their own identity in the rap game, however as hip-hop evolves so does the style of music. Cardi B’s first studio album, Invasion of Privacy (2018), debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 and was named the number-one female rap album of the 2010s by Billboard. Critically acclaimed, it made Cardi B the only woman to win the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album as a solo artist, and marked the first female rap album in fifteen years to be nominated for Album of the Year.

Other niche styles and Latin American music[edit]

Christina Aguilera’s album Mi Reflejo peaked at number-one on the Billboard Top Latin Albums and Latin Pop Albums charts where it spent 19 weeks at the top of both charts. The album was the best-selling Latin pop album of 2000.

The American music industry is dominated by large companies that produce, market, and distribute certain kinds of music. Generally, these companies do not produce, or produce in only very limited quantities, recordings in styles that do not appeal to very large audiences. Smaller companies often fill in the void, offering a wide variety of recordings in styles ranging from polka to salsa. Many small music industries are built around a core fanbase who may be based largely in one region, such as Tejano or Hawaiian music, or they may be widely dispersed, such as the audience for Jewish klezmer.

Among the Hispanic American musicians who were pioneers in the early stages of rock and roll were Ritchie Valens, who scored several hits, most notably «La Bamba» and Herman Santiago wrote the lyrics to the iconic rock and roll song «Why Do Fools Fall in Love». Songs that became popular in the United States and are heard during the Holiday/Christmas season are «¿Dónde Está Santa Claus?» is a novelty Christmas song with 12-year-old Augie Ríos was a record hit in 1959 which featured the Mark Jeffrey Orchestra. «Feliz Navidad»(1970) by José Feliciano is another famous Latin song.

Demi Lovato rose to prominence in 2008 when they starred in the Disney Channel television film Camp Rock and signed a recording contract with Hollywood Records.

The single largest niche industry is based on Latin music. Latin music has long influenced American popular music, and was an especially crucial part of the development of jazz. Modern pop Latin styles include a wide array of genres imported from across Latin America, including Colombian cumbia, Puerto Rican reggaeton, and Mexican corrido. Latin popular music in the United States began with a wave of dance bands in the 1930s and 1950s. The most popular styles included the conga, rumba, and mambo. In the 1950s Perez Prado made the cha-cha-cha famous, and the rise of Afro-Cuban jazz opened many ears to the harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic possibilities of Latin music. The most famous American form of Latin music, however, is salsa. Salsa incorporates many styles and variations; the term can be used to describe most forms of popular Cuban-derived genres. Most specifically, however, salsa refers to a particular style that was developed by mid-1970s groups of New York City-area Cuban and Puerto Rican immigrants, and stylistic descendants like 1980s salsa romantica.[147] Salsa rhythms are complicated, with several patterns played simultaneously. The clave rhythm forms the basis of salsa songs and is used by the performers as a common rhythmic ground for their own phrases.[148]

Latin American music has long influenced American popular music, jazz, rhythm and blues, and even country music. This includes music from Spanish, Portuguese, and (sometimes) French-speaking countries and territories of Latin America.[149]

Today, the American record industry defines Latin music as any type of release with lyrics mostly in Spanish.[150][151] Mainstream artists and producers tend to feature more on songs from Latin artists and it’s also become more likely that English language songs crossover to Spanish radio and vice versa.

The United States played a significant role in the development of electronic dance music, specifically house and techno, which originated in Chicago and Detroit, respectively.

Today Latin American music has become a term for music performed by Latinos regardless of whether it has a Latin element or not. Acts such as Shakira, Jennifer Lopez, Enrique Iglesias, Pitbull, Selena Gomez, Christina Aguilera, Gloria Estefan, Demi Lovato, Mariah Carey, Becky G, Paulina Rubio, and Camila Cabello are prominent on the pop charts. Iglesias who holds the record for most #1s on Billboard’s Hot Latin Tracks released a bilingual album, inspired by urban acts he releases two completely different songs to Latin and pop formats at the same time.

Government, politics and law[edit]

The government of the United States regulates the music industry, enforces intellectual property laws, and promotes and collects certain kinds of music. Under American copyright law, musical works, including recordings and compositions, are protected as intellectual property as soon as they are fixed in a tangible form. Copyright holders often register their work with the Library of Congress, which maintains a collection of the material. In addition, the Library of Congress has actively sought out culturally and musicologically significant materials since the early 20th century, such as by sending researchers to record folk music. These researchers include the pioneering American folk song collector Alan Lomax, whose work helped inspire the roots revival of the mid-20th century. The federal government also funds the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, which allocate grants to musicians and other artists, the Smithsonian Institution, which conducts research and educational programs, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which funds non-profit and television broadcasters.[152]

Music has long affected the politics of the United States. Political parties and movements frequently use music and song to communicate their ideals and values, and to provide entertainment at political functions. The presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison was the first to greatly benefit from music, after which it became standard practice for major candidates to use songs to create public enthusiasm. In more recent decades, politicians often chose theme songs, some of which have become iconic; the song «Happy Days Are Here Again», for example, has been associated with the Democratic Party since the 1932 campaign of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Since the 1950s, however, music has declined in importance in politics, replaced by televised campaigning with little or no music. Certain forms of music became more closely associated with political protest, especially in the 1960s. Gospel stars like Mahalia Jackson became important figures in the Civil Rights Movement, while the American folk revival helped spread the counterculture of the 1960s and opposition to the Vietnam War.[153]

Industry and economics[edit]

Sinatra in 1947, at the Liederkranz Hall. He is one of the best-selling music artists of all time, having sold more than 150 million records worldwide.

The United States has the world’s largest music market with a total retail value of 4.9 billion dollars in 2014,[154] The American music industry includes a number of fields, ranging from record companies to radio stations and community orchestras. Total industry revenue is about $40 billion worldwide, and about $12 billion in the United States.[155] Most of the world’s major record companies are based in the United States; they are represented by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The major record companies produce material by artists that have signed to one of their record labels, a brand name often associated with a particular genre or record producer. Record companies may also promote and market their artists, through advertising, public performances and concerts, and television appearances. Record companies may be affiliated with other music media companies, which produce a product related to popular recorded music. These include television channels like MTV, magazines like Rolling Stone and radio stations. In recent years the music industry has been embroiled in turmoil over the rise of the Internet downloading of copyrighted music; many musicians and the RIAA have sought to punish fans who illegally download copyrighted music.[156]

Katy Perry has received many awards, including four Guinness World Records, a Brit Award, and a Juno Award, and been included in the Forbes list of «Top-Earning Women In Music» (2011–2016).

Radio stations in the United States often broadcast popular music. Each music station has a format, or a category of songs to be played; these are generally similar to but not the same as ordinary generic classification. Many radio stations in the United States are locally owned and operated, and may offer an eclectic assortment of recordings; many other stations are owned by large companies like Clear Channel, and are generally formatted on smaller, more repetitive playlists. Commercial sales of recordings are tracked by Billboard magazine, which compiles a number of music charts for various fields of recorded music sales. The Billboard Hot 100 is the top pop music chart for singles, a recording consisting of a handful of songs; longer pop recordings are albums, and are tracked by the Billboard 200.[157] Though recorded music is commonplace in American homes, many of the music industry’s revenue comes from a small number of devotees; for example, 62% of album sales come from less than 25% of the music-buying audience.[158] Total CD sales in the United States topped 705 million units sold in 2005, and singles sales just under three million.[159]

Though the major record companies dominate the American music industry, an independent music industry (indie music) does exist. Most indie record labels have limited, if any, retail distribution outside a small region. Artists sometimes record for an indie label and gain enough acclaim to be signed to a major label; others choose to remain at an indie label for their entire careers. Indie music may be in styles generally similar to mainstream music, but is often inaccessible, unusual, or otherwise unappealing to many people. Indie musicians often release some or all of their songs over the Internet for fans and others to download and listen.[156] In addition to recording artists of many kinds, there are numerous fields of professional musicianship in the United States, many of whom rarely record, including community orchestras, wedding singers and bands, lounge singers, and nightclub DJs. The American Federation of Musicians is the largest American labor union for professional musicians. However, only 15% of the Federation’s members have steady music employment.[160]

Education and scholarship[edit]

Music is an important part of education in the United States, and is a part of most or all school systems in the country. Music education is generally mandatory in public elementary schools, and is an elective in later years.[161]

Britney Spears is regarded as a pop icon and credited with influencing the revival of teen pop during the late 1990s. She became the ‘best-selling teenage artist of all time’ and garnered honorific titles including the «Princess of Pop».

The scholarly study of music in the United States includes work relating music to social class, racial, ethnic and religious identity, gender and sexuality, as well as studies of music history, musicology, and other topics. The academic study of American music can be traced back to the late 19th century, when researchers like Alice Fletcher and Francis La Flesche studied the music of the Omaha peoples, working for the Bureau of American Ethnology and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. In the 1890s and into the early 20th century, musicological recordings were made among indigenous, Hispanic, African-American and Anglo-American peoples of the United States. Many worked for the Library of Congress, first under the leadership of Oscar Sonneck, chief of the Library’s Music Divisions.[162] These researchers included Robert W. Gordon, founder of the Archive of American Folk Song, and John and Alan Lomax; Alan Lomax was the most prominent of several folk song collectors who helped to inspire the 20th century roots revival of American folk culture.[163]

Early 20th scholarly analysis of American music tended to interpret European-derived classical traditions as the most worthy of study, with the folk, religious, and traditional musics of the common people denigrated as low-class and of little artistic or social worth. American music history was compared to the much longer historical record of European nations, and was found wanting, leading writers like the composer Arthur Farwell to ponder what sorts of musical traditions might arise from American culture, in his 1915 Music in America. In 1930, John Tasker Howard’s Our American Music became a standard analysis, focusing on largely on concert music composed in the United States.[164] Since the analysis of musicologist Charles Seeger in the mid-20th century, American music history has often been described as intimately related to perceptions of race and ancestry. Under this view, the diverse racial and ethnic background of the United States has both promoted a sense of musical separation between the races, while still fostering constant acculturation, as elements of European, African, and indigenous musics have shifted between fields.[162] Gilbert Chase’s America’s Music, from the Pilgrims to the Present, was the first major work to examine the music of the entire United States, and recognize folk traditions as more culturally significant than music for the concert hall. Chase’s analysis of a diverse American musical identity has remained the dominant view among the academic establishment.[164] Until the 1960s and 1970s, however, most musical scholars in the United States continued to study European music, limiting themselves only to certain fields of American music, especially European-derived classical and operatic styles, and sometimes African American jazz. More modern musicologists and ethnomusicologists have studied subjects ranging from the national musical identity to the individual styles and techniques of specific communities in a particular time of American history.[162] Prominent recent studies of American music include Charles Hamm’s Music in the New World from 1983 and Richard Crawford’s America’s Musical Life from 2001.[165]

Holidays and festivals[edit]