Тест по разделу

«Мир народной сказки»

1 вариант

1. Народная сказка

– это сказка, автором которой является:

А. Народ.

Б. Один автор.

2. Действующие

персонажи русской сказки «Лисичка-сестричка

и волк» — это:

А. Дед, баба,

морские животные, лиса.

Б. Дед, баба,

морские животные, лиса, волк.

В. Дед, баба, лиса,

волк.

3. Что искала лиса

из корякской сказки «Хитрая лиса» в

лесу?

А. Шубку.

Б. Глаз.

В. Хвост.

Г. Лапы.

4. В русской сказке

«Зимовье» зимовье – это:

А. Дом.

Б. Холодная погода.

5. Пословица «У

страха глаза велики: чего нет – и то

увидят» является основной мыслью

произведений:

А. «Пых».

Б. «Лисичка-сестричка

и волк».

В. «У страха глаза

велики».

Г. «Идэ».

Д. «Айога».

6. «Человек –

везде хозяин. Теперь ты ничего бояться

не будешь» — это строки из сказки:

А. «Айога».

Б. «Кукушка».

В. «Идэ».

7. Сколько детей

было у бедной женщины в ненецкой сказке

«Кукушка»?

А. 5

Б. 4

В. 3

Тест по разделу

«Мир народной сказки»

2 вариант

1. Действующие

персонажи русской сказки «Лисичка-сестричка

и волк» — это:

А. Дед, баба,

морские животные, лиса.

Б. Дед, баба,

морские животные, лиса, волк.

В. Дед, баба, лиса,

волк.

2. Что искала лиса

из корякской сказки «Хитрая лиса» в

лесу?

А. Шубку.

Б. Глаз.

В. Хвост.

Г. Лапы.

3. Народная сказка

– это сказка, автором которой является:

А. Народ.

Б. Один автор.

4. Пословица «У

страха глаза велики: чего нет – и то

увидят» является основной мыслью

произведений:

А. «Пых».

Б. «Лисичка-сестричка

и волк».

В. «У страха глаза

велики».

Г. «Идэ».

Д. «Айога».

5. В русской сказке

«Зимовье» зимовье – это:

А. Дом.

Б. Холодная погода.

6. Сколько детей

было у бедной женщины в ненецкой сказке

«Кукушка»?

А. 5

Б. 4

В. 3

7. «Человек –

везде хозяин. Теперь ты ничего бояться

не будешь» — это строки из сказки:

А. «Айога».

Б. «Кукушка».

В. «Идэ».

Соседние файлы в папке Лит. чтение

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Тесты и проверочные работы по литературному чтению (2 класс, УМК «Перспектива»).

|

Ф.И. ____________________________

|

Ф.И. __________________________

|

|

Ф.И. ___________________________________ Тест к сказке «Зимовье».

————————————————————— Тест к сказке «Пых».

———————————————————— Сказка «Идэ».

|

Тест по сказке «У страха глаза велики».

А) из колодца. Б) из речки. В) из колоды. 2. Где сидел зайка? А) в лесу. Б) под яблонькой. В) на скамейке. 3. Кого испугалась курочка? А) лису. Б) медведя. В) волка. 4. А внучке кто привиделся? А) медведище. Б) лиса. В) волк. 5. Кто, показалось бабке, напал на неё? А) волк. Б) лесник. В) медведище. 6. Откуда брала воду бабушка? А) из речки. Б) из моря. В) из водопровода. Г) из колодца. 7. Откуда брала воду мышка? А) из лужицы. Б) из следа от поросячьего копытца. В) из кружки. 8. Мышка спряталась под печь от кого? А) от лисы. Б) от кота. В) от бабки. 9. Что попало зайке в лоб? А) мяч. Б) шишка. В) яблоко. 10. Сколько персонажей в сказке? А) 5. Б) 3. В) 4. 11. Кого испугался зайчик? А) лису. Б) медведя. В) бабку, внучку. Г) четырех охотников. 12. Сколько людей ходило за водой? А) 3. Б) 4. В) 2. |

|

Тест к сказке «Сестрица Алёнушка и братец Иванушка». 1. Почему сестрица и братец остались одни – одинёшеньки? А) родители их прогнали. Б) родители умерли. В) дети потерялись. 2. Куда пошла Алёнушка? А) на работу. В) играть с подругами. Б) за грибами. Г) за дровами. 3. Откуда Иванушка хотел попить в третий раз? А) из козьего копытца. В) из речки. Б) из лошадиного копытца. Г) из волшебного колодца. 4. Что случилось с Иванушкой? А) попал в жилище ведьмы. В) стал телёночком. Б) стал жеребёночком. Г) стал козлёночком. 5. Что предложил Алёнушке купец? А) спасти Иванушку. Б) убить ведьму. В) выйти за него замуж. 6. Что сделала с Алёнушкой ведьма? А) превратила в лягушку. Б) надела на шею камень и бросила в реку. В) заперла в подвале. 7. Как ведьма попала в дом к купцу? А) околдовала купца. Б) оборотилась мышкой. В) оборотилась Алёнушкой. 8. Почему ведьма упросила купца зарезать козлёнка? А) козлёнок ей не понравился. Б) козлёнок всё знал. В) козлёнок казался ей очень вкусным. 9. Как купец узнал правду? А) его слуга подслушал разговор козлёнка с Алёнушкой. Б) купец подслушал разговор ведьмы. В) козлёнок всё рассказал купцу. |

Тест к сказке «Айога». 1. Как звали отца Айоги?

2. Какой была Айога?

3. Чем девочка стала заниматься целыми днями?

4. Почему девочка отказалась идти за водой?

5. Что придумала девушка, чтобы руки лепешкой не обжечь?

6. Кому отдала лепёшку мать?

7. Во что превратились руки Айоги, когда она разозлилась?

8. В кого превратилась девочка?

9. Что случилось с девочкой после превращения?

10. Что не забыла девушка?

|

Проверочная работа по теме: «Весна, весна! И всё ей радо!» ФИ ______________________________

- Прочитай.

|

Растопило солнце снег, Радость на душе у всех, Птицы весело запели, Слышен звонкий стук капели, |

И ручьи бурлят, и птички В гнёзда сели на яички. Небо чисто – голубое, Что с природою такое? |

- Определи жанр произведения. Выбери из предложенных вариантов и пометь «V».

А. Стихотворение В. Песенка

Б. Загадка Г. Закличка

- О каком времени года идет речь? Выбери из предложенных вариантов и пометь «V».

А. Зима В. Весна

Б. Лето Г. Осень

- Выпиши из прочитанного произведения все признаки весны.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

5. Соедини стрелками темы стихотворений с их названиями.

Борьба Зимы с Весной. «Подснежники»

Возвращение птиц на родину. «Апрель»

В душу уже просится весна. «Весна»

Первоцветы. «Зима недаром злится…»»

Цветение вербы. «Полюбуйся! Весна наступает…»»

6. Допиши авторов к названиям стихотворений.

«Апрель» — _____________________________________________________________________________

«Христос воскрес» — _____________________________________________________________________

«Двенадцать месяцев» — __________________________________________________________________

«Зима недаром злится» — _________________________________________________________________

|

Ф. И. _____________________________________ Проверочная работа по разделу «Здравствуй, матушка – зима!»

«Вот север, тучи нагоняя…» С. Маршак «Поёт зима – аукает…» А. Барто «В декабре, в декабре…» С. Есенин «Дело было в январе» А. Пушкин

В сонной тишине, И горят снежинки В золотом огне. _________________________________________

Ковром шелковым стелется, Но больно холодна. Воробышки игривые, Как детки сиротливые, Прижались у окна. ________________________________________

И соломою шурша, На упругое коленце Засмотрелся, чуть дыша. _______________________________________ |

Ф. И. _____________________________________ Проверочная работа по разделу «Здравствуй, матушка – зима!»

«Вот север, тучи нагоняя…» С. Маршак «Поёт зима – аукает…» А. Барто «В декабре, в декабре…» С. Есенин «Дело было в январе» А. Пушкин

В сонной тишине, И горят снежинки В золотом огне. _________________________________________

Ковром шелковым стелется, Но больно холодна. Воробышки игривые, Как детки сиротливые, Прижались у окна. ________________________________________

И соломою шурша, На упругое коленце Засмотрелся, чуть дыша. _______________________________________ |

|

Ф. И. _____________________________________ Проверочная работа по разделу «Здравствуй, матушка – зима!»

«Вот север, тучи нагоняя…» С. Маршак «Поёт зима – аукает…» А. Барто «В декабре, в декабре…» С. Есенин «Дело было в январе» А. Пушкин

В сонной тишине, И горят снежинки В золотом огне. _________________________________________

Ковром шелковым стелется, Но больно холодна. Воробышки игривые, Как детки сиротливые, Прижались у окна. ________________________________________

И соломою шурша, На упругое коленце Засмотрелся, чуть дыша. _______________________________________ |

Ф. И. _____________________________________ Проверочная работа по разделу «Здравствуй, матушка – зима!»

«Вот север, тучи нагоняя…» С. Маршак «Поёт зима – аукает…» А. Барто «В декабре, в декабре…» С. Есенин «Дело было в январе» А. Пушкин

В сонной тишине, И горят снежинки В золотом огне. _________________________________________

Ковром шелковым стелется, Но больно холодна. Воробышки игривые, Как детки сиротливые, Прижались у окна. ________________________________________

И соломою шурша, На упругое коленце Засмотрелся, чуть дыша. _______________________________________ |

Ф. И. _____________________________________________________

Проверочная работа по литературному чтению по разделу «Чудеса случаются».

- Какой писатель сочинил сборник сказок «Алёнушкины сказки»? ____________________________________________________________________

- Кому посвятил автор эти сказки (для кого их писал)? ____________________________________________________________________

- Что такое присказка? Выбери правильный ответ.

А) Присказка – это устное народное творчество.

Б) Присказка — шутливое вступление или концовка сказки, рассказа, иногда в виде прибаутки, поговорки.

В) Присказка – это стихотворное литературное произведение нравоучительного характера.

- Соедини стрелками, что относится к литературной сказке, а что к народной сказке.

а) Автор высказывает своё отношение к героям Литературная сказка

б) Сочинил народ

в) Герои сказки наделены индивидуальностью

г) Текст сказки неизменный Народная сказка

д) Подробно описано место действия, события,

внешний облик персонажей

е) Текст сказки изменяется в течение времени

ж) Сочинил автор

- Соотнеси названия произведений и автора (соедини стрелками).

«Братец Лис и «Братец Кролик» Д. Мамин-Сибиряк

«Бибигон и пчела» А. Пушкин

«Сказка про храброго зайца – длинные уши, К. Чуковский

косые глаза, короткий хвост»

«Чудесный олень» Дж. Харри

«Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» Э. Распе

«Как цыплёнок впервые сочинил сказку» Г. Цыферов

- Объясни смысл пословицы.

Искать большего счастья – малое потерять. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Объясни значение фразеологизма.

«Держать ухо востро». ___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

- Какая сказка из раздела «Чудеса случаются» тебе понравилась больше всего? Напиши её название и автора.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Чему учит эта сказка? __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

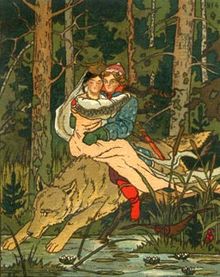

Ivan Tsarevich and the Grey Wolf (Zvorykin)

A Russian fairy tale or folktale (Russian: ска́зка; skazka; «story»; plural Russian: ска́зки, romanized: skazki) is a fairy tale from Russia.

Various sub-genres of skazka exist. A volshebnaya skazka [волше́бная ска́зка] (literally «magical tale») is considered a magical tale.[1][need quotation to verify] Skazki o zhivotnykh are tales about animals and bytovye skazki are tales about household life. These variations of skazki give the term more depth and detail different types of folktales.

Similarly to Western European traditions, especially the German-language collection published by the Brothers Grimm, Russian folklore was first collected by scholars and systematically studied in the 19th century. Russian fairy tales and folk tales were cataloged (compiled, grouped, numbered and published) by Alexander Afanasyev in his 1850s Narodnye russkie skazki. Scholars of folklore still refer to his collected texts when citing the number of a skazka plot. An exhaustive analysis of the stories, describing the stages of their plots and the classification of the characters based on their functions, was developed later, in the first half of the 20th century, by Vladimir Propp (1895-1970).

History[edit]

Appearing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fairy tales became widely popular as they spread throughout the country. Literature was considered an important factor in the education of Russian children who were meant to grow from the moral lessons in the tales. During the 18th Century Romanticism period, poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Pyotr Yershov began to define the Russian folk spirit with their stories. Throughout the 1860s, despite the rise of Realism, fairy tales still remained a beloved source of literature which drew inspiration from writers such as Hans Christian Andersen.[2] The messages in the fairy tales began to take a different shape once Joseph Stalin rose to power under the Communist movement.[3]

Popular fairy tale writer, Alexander Afanasyev

Effects of Communism[edit]

Fairy tales were thought to have a strong influence over children which is why Joseph Stalin decided to place restrictions upon the literature distributed under his rule. The tales created in the mid 1900s were used to impose Socialist beliefs and values as seen in numerous popular stories.[3] In comparison to stories from past centuries, fairy tales in the USSR had taken a more modern spin as seen in tales such as in Anatoliy Mityaev’s Grishka and the Astronaut. Past tales such as Alexander Afanasyev’s The Midnight Dance involved nobility and focused on romance.[4] Grishka and the Astronaut, though, examines modern Russian’s passion to travel through space as seen in reality with the Space Race between Russia and the United States.[5] The new tales included a focus on innovations and inventions that could help characters in place of magic which was often used as a device in past stories.

Influences[edit]

Russian kids listening to a new fairy tale

In Russia, the fairy tale is one sub-genre of folklore and is usually told in the form of a short story. They are used to express different aspects of the Russian culture. In Russia, fairy tales were propagated almost exclusively orally, until the 17th century, as written literature was reserved for religious purposes.[6] In their oral form, fairy tales allowed the freedom to explore the different methods of narration. The separation from written forms led Russians to develop techniques that were effective at creating dramatic and interesting stories. Such techniques have developed into consistent elements now found in popular literary works; They distinguish the genre of Russian fairy tales. Fairy tales were not confined to a particular socio-economic class and appealed to mass audiences, which resulted in them becoming a trademark of Russian culture.[7]

Cultural influences on Russian fairy tales have been unique and based on imagination. Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Polish-American author and Nobel Prize winner, claims that, “You don’t ask questions about a tale, and this is true for the folktales of all nations. They were not told as fact or history but as a means to entertain the listener, whether he was a child or an adult. Some contain a moral, others seem amoral or even antimoral, Some constitute fables on man’s follies and mistakes, others appear pointless.» They were created to entertain the reader.[8]

Russian fairy tales are extremely popular and are still used to inspire artistic works today. The Sleeping Beauty is still played in New York at the American Ballet Theater and has roots to original Russian fairy tales from 1890. Mr. Ratmansky’s, the artist-in-residence for the play, gained inspiration for the play’s choreography from its Russian background.[9]

Formalism[edit]

From the 1910s through the 1930s, a wave of literary criticism emerged in Russia, called Russian formalism by critics of the new school of thought.[10]

Analysis[edit]

Many different approaches of analyzing the morphology of the fairy tale have appeared in scholarly works. Differences in analyses can arise between synchronic and diachronic approaches.[11][12] Other differences can come from the relationship between story elements. After elements are identified, a structuralist can propose relationships between those elements. A paradigmatic relationship between elements is associative in nature whereas a syntagmatic relationship refers to the order and position of the elements relative to the other elements.[12]

A Russian Garland of Fairy Tales

Motif[edit]

Before the period of Russian formalism, beginning in 1910, Alexander Veselovksky called the motif the «simplest narrative unit.»[13] Veselovsky proposed that the different plots of a folktale arise from the unique combinations of motifs.

Motif analysis was also part of Stith Thompson’s approach to folkloristics.[14] Thompson’s research into the motifs of folklore culminated in the publication of the Motif-Index of Folk Literature.[15]

Structural[edit]

In 1919, Viktor Shklovsky published his essay titled «The Relationship Between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style».[13] As a major proponent during Russian formalism,[16] Shklovsky was one of the first scholars to criticize the failing methods of literary analysis and report on a syntagmatic approach to folktales. In his essay he claims, «It is my purpose to stress not so much the similarity of motifs, which I consider of little significance, as the similarity in the plot schemata.»[13]

Syntagmatic analysis, championed by Vladimir Propp, is the approach in which the elements of the fairy tale are analyzed in the order that they appear in the story. Wanting to overcome what he thought was arbitrary and subjective analysis of folklore by motif,[17] Propp published his book Morphology of the Folktale in 1928.[16] The book specifically states that Propp finds a dilemma in Veselovsky’s definition of a motif; it fails because it can be broken down into smaller units, contradicting its definition.[7] In response, Propp pioneered a specific breakdown that can be applied to most Aarne-Thompson type tales classified with numbers 300-749.[7][18] This methodology gives rise to Propp’s 31 functions, or actions, of the fairy tale.[18] Propp proposes that the functions are the fundamental units the story and that there are exactly 31 distinct functions. He observed in his analysis of 100 Russian fairy tales that tales almost always adhere to the order of the functions. The traits of the characters, or dramatis personae, involved in the actions are second to the action actually being carried out. This also follows his finding that while some functions may be missing between different stories, the order is kept the same for all the Russian fairy tales he analyzed.[7]

Alexander Nikiforov, like Shklovsky and Propp, was a folklorist in 1920s Soviet Russia. His early work also identified the benefits of a syntagmatic analysis of fairy tale elements. In his 1926 paper titled «The Morphological Study of Folklore», Nikiforov states that «Only the functions of the character, which constitute his dramatic role in the folk tale, are invariable.»[13] Since Nikiforov’s essay was written almost 2 years before Propp’s publication of Morphology of the Folktale[19], scholars have speculated that the idea of the function, widely attributed to Propp, could have first been recognized by Nikiforov.[20] One source claims that Nikiforov’s work was «not developed into a systematic analysis of syntagmatics» and failed to «keep apart structural principles and atomistic concepts».[17] Nikiforov’s work on folklore morphology was never pursued beyond his paper.[19]

Writers and collectors[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev began writing fairy tales at a time when folklore was viewed as simple entertainment. His interest in folklore stemmed from his interest in ancient Slavic mythology. During the 1850s, Afanasyev began to record part of his collection from tales dating to Boguchar, his birthplace. More of his collection came from the work of Vladimir Dhal and the Russian Geographical Society who collected tales from all around the Russian Empire.[21] Afanasyev was a part of the few who attempted to create a written collection of Russian folklore. This lack in collections of folklore was due to the control that the Church Slavonic had on printed literature in Russia, which allowed for only religious texts to be spread. To this, Afanasyev replied, “There is a million times more morality, truth and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness!”[22]

Between 1855 and 1863, Afanasyev edited Popular Russian Tales[Narodnye russkie skazki], which had been modeled after the Grimm’s Tales. This publication had a vast cultural impact over Russian scholars by establishing a desire for folklore studies in Russia. The rediscovery of Russian folklore through written text led to a generation of great Russian authors to come forth. Some of these authors include Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Folktales were quickly produced in written text and adapted. Since the production of this collection, Russian tales remain understood and recognized all over Russia.[21]

Alexander Pushkin[edit]

Alexander Pushkin is known as one of Russia’s leading writers and poets.[23] He is known for popularizing fairy tales in Russia and changed Russian literature by writing stories no one before him could.[24] Pushkin is considered Russia’s Shakespeare as, during a time when most of the Russian population was illiterate, he gave Russian’s the ability to desire in a less-strict Christian and a more pagan way through his fairy tales.[25]

Pushkin gained his love for Russian fairy tales from his childhood nurse, Ariana Rodionovna, who told him stories from her village when he was young.[26] His stories served importance to Russians past his death in 1837, especially during times political turmoil during the start of the 20th century, in which, “Pushkin’s verses gave children the Russian language in its most perfect magnificence, a language which they may never hear or speak again, but which will remain with them as an eternal treasure.”[27]

The value of his fairy tales was established a hundred years after Pushkin’s death when the Soviet Union declared him a national poet. Pushkin’s work was previously banned during the Czarist rule. During the Soviet Union, his tales were seen acceptable for education, since Pushkin’s fairy tales spoke of the poor class and had anti-clerical tones.[28]

Corpus[edit]

According to scholarship, some of «most popular or most significant» types of Russian Magic Tales (or Wonder Tales) are the following:[a][30]

| Tale number | Russian classification | Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index Grouping | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | The Winner of the Snake | The Dragon-Slayer | ||

| 301 | The Three Kingdoms | The Three Stolen Princesses | The Norka; Dawn, Midnight and Twilight | [b] |

| 302 | Kashchei’s Death in an Egg | Ogre’s (Devil’s) Heart in the Egg | The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

| 307 | The Girl Who Rose from the Grave | The Princess in the Coffin | Viy | [c] |

| 313 | Magic Escape | The Magic Flight | The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise | [d] |

| 315 | The Feigned Illness (beast’s milk) | The Faithless Sister | ||

| 325 | Crafty Knowledge | The Magician and his Pupil | [e] | |

| 327 | Children at Baba Yaga’s Hut | Children and the Ogre | ||

| 327C | Ivanusha and the Witch | The Devil (Witch) Carries the Hero Home in a Sack | [f] | |

| 400 | The husband looks for his wife, who has disappeared or been stolen (or a wife searches for her husband) | The Man on a Quest for The Lost Wife | The Maiden Tsar | |

| 461 | Mark the Rich | Three Hairs of the Devil’s Beard | The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars (Serbian); Vassili The Unlucky | [g] |

| 465 | The Beautiful Wife | The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | [h] |

| 480 | Stepmother and Stepdaughter | The Kind and Unkind Girls | Vasilissa the Beautiful | |

| 519 | The Blind Man and the Legless Man | The Strong Woman as Bride (Brunhilde) | [i][j][k] | |

| 531 | The Little Hunchback Horse | The Clever Horse | The Humpbacked Horse; The Firebird and Princess Vasilisa | [l] |

| 545B | Puss in Boots | The Cat as Helper | ||

| 555 | Kitten-Gold Forehead (a gold fish, a magical tree) | The Fisherman and His Wife | The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish | [m][n] |

| 560 | The Magic Ring | The Magic Ring | [o][p] | |

| 567 | The Marvelous Bird | The Magic Bird-Heart | ||

| 650A | Ivan the Bear’s Ear | Strong John | ||

| 706 | The Handless | The Maiden Without Hands | ||

| 707 | The Tale of Tsar Saltan [Marvelous Children] | The Three Golden Children | Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Wicked Sisters | [q] |

| 709 | The Dead Tsarina or The Dead Tsarevna | Snow White | The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights | [r] |

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Propp’s The Russian Folktale lists types 301, 302, 307, 315, 325, 327, 400, 461, 465, 519, 545B, 555, 560, 567 and 707.[29]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 301, «The Three Kingdoms and the Stolen Princesses», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 45 variants. The type was also the second «most frequently collected in Ukraine», with 31 texts.[31]

- ^ French folklorist Paul Delarue noticed that the tale type, despite existing «throughout Europe», is well known in Russia, where it found «its favorite soil».[32] Likewise, Jack Haney stated that type 307 was «most common» among East Slavs.[33]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 313, «The Magic Flight», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 41 variants. The type was also the «most frequently collected» in Ukraine, with 37 texts.[34]

- ^ Commenting on a Russian tale collected in the 20th century, Richard Dorson stated that the type was «one of the most widespread Russian Märchen».[35] In the East Slavic populations, scholarship registers 42 Russian variants, 25 Ukrainian and 10 Belarrussian.[36]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type of a fishing boy and a witch «[is] common among the various East European peoples.»[37]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type is popular among the East Slavs[38]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type, including previous type AaTh 465A, is «especially common in Russia».[39]

- ^ Russian researcher Dobrovolskaya Varvara Evgenievna stated that tale type ATU 519 (SUS 519) «belongs to the core of» the Russian tale corpus, due to «the presence of numerous variants».[40]

- ^ Following Löwis de Menar’s study, Walter Puchner concluded on its diffusion especially in the East Slavic area.[41]

- ^ Stith Thompson also located this tale type across Russia and the Baltic regions.[42]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type «is extremely popular in all three branches of East Slavic».[43]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type is «common among the East Slavs».[44]

- ^ The variation on the wish-giving entity is also attested in Estonia, whose variants register a golden fish, crayfish, or a sacred tree.[45]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «very common in all the East Slavic traditions».[46]

- ^ Wolfram Eberhard reported «45 variants in Russia alone».[47]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «a very common East Slavic type».[48]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «especially common in Russian and Ukrainian».[49]

References[edit]

- ^ «Magic tale (volshebnaia skazka), also called fairy tale». Kononenko, Natalie (2007). Slavic Folklore: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-313-33610-2.

- ^ Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories : the History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574-2010). Brill, 2013.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. “Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union.” Slavic Review, vol. 32, no. 1, 1973, pp. 45–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494072.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. “The Midnight Dance.” The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces, 1855, www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0306.html.

- ^ Mityayev, Anatoli. Grishka and the Astronaut. Translated by Ronald Vroon, Progress, 1981.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service». Marvels & Tales. 16 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1353/mat.2002.0024. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 41388626. S2CID 163086804.

- ^ a b c d Propp, V. I︠A︡. Morphology of the folktale. ISBN 9780292783768. OCLC 1020077613.

- ^ Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1975-11-16). «Russian Fairy Tales». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Greskovic, Robert (2015-06-02). «‘The Sleeping Beauty’ Review: Back to Its Russian Roots». Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Erlich, Victor (1973). «Russian Formalism». Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (4): 627–638. doi:10.2307/2708893. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708893.

- ^ Saussure, Ferdinand de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Baskin, Wade., Meisel, Perry., Saussy, Haun, 1960-. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231527958. OCLC 826479070.

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur Asa (February 2018). Media analysis techniques. ISBN 9781506366210. OCLC 1000297853.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Terence Patrick (2015). The Fairytale and Plot Structure. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781137547088. OCLC 944065310.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1997). «The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique». Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 3814885.

- ^ Kuehnel, Richard; Lencek, Rado. «What is a Folklore Motif?». www.aktuellum.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ a b Propp, V. I︠A︡.; Пропп, В. Я. (Владимир Яковлевич), 1895-1970 (2012). The Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337219. OCLC 843208720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maranda, Pierre (1974). Soviet structural folkloristics. Meletinskiĭ, E. M. (Eleazar Moiseevich), Jilek, Wolfgang. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 978-9027926838. OCLC 1009096.

- ^ a b Aguirre, Manuel (October 2011). «AN OUTLINE OF PROPP’S MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF FAIRYTALES» (PDF). Tools and Frames – via The Northanger Library Project.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. (2019). The Study of Russian Folklore. Soudakoff, Stephen. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 9783110813913. OCLC 1089596763.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1973). «Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union». Slavic Review. 32 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2494072. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494072.

- ^ a b Levchin, Sergey (2014-04-28). «Russian Folktales from the Collection of A. Afanasyev : A Dual-Language Book».

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1991). Alexander Pushkin : a critical study. The Bristol Press. ISBN 978-1853991721. OCLC 611246966.

- ^ Alexander S. Pushkin, Zimniaia Doroga, ed. by Irina Tokmakova (Moscow: Detskaia Literatura, 1972).

- ^ Bethea, David M. (2010). Realizing Metaphors : Alexander Pushkin and the Life of the Poet. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299159733. OCLC 929159387.

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Akhmatova, “Pushkin i deti,” radio broadcast script prepared in 1963, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, May 1, 1974.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria. «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service.» Marvels & Tales (2002): 171-187.

- ^ The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 215. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Delarue, Paul. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 386.

- ^ Haney, Jack V.; with Sibelan Forrester. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume III. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2021. p. 536.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Горяева, Б. Б. (2011). «Сюжет «Волшебник и его ученик» (at 325) в калмыцкой сказочной традиции». In: Oriental Studies (2): 153. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-volshebnik-i-ego-uchenik-at-325-v-kalmytskoy-skazochnoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 554. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Добровольская Варвара Евгеньевна (2018). «Сказка «слепой и безногий» (сус 519) в репертуаре русских сказочников: фольклорная реализация литературного сюжета». Вопросы русской литературы, (4 (46/103)): 93-113 (111). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-slepoy-i-beznogiy-sus-519-v-repertuare-russkih-skazochnikov-folklornaya-realizatsiya-literaturnogo-syuzheta (дата обращения: 01.09.2021).

- ^ Krauss, Friedrich Salomo; Volkserzählungen der Südslaven: Märchen und Sagen, Schwänke, Schnurren und erbauliche Geschichten. Burt, Raymond I. and Puchner, Walter (eds). Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2002. p. 615. ISBN 9783205994572.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2015 [2001]. p. 434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. p. 718. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram. Folktales of China. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1956. p. 143.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

Further reading[edit]

- Лутовинова, Е.И. (2018). Тематические группы сюжетов русских народных волшебных сказок. Педагогическое искусство, (2): 62-68. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tematicheskie-gruppy-syuzhetov-russkih-narodnyh-volshebnyh-skazok (дата обращения: 27.08.2021). (in Russian)

The Three Kingdoms (ATU 301):

- Лызлова Анастасия Сергеевна (2019). Cказки о трех царствах (медном, серебряном и золотом) в лубочной литературе и фольклорной традиции [FAIRY TALES ABOUT THREE KINGDOMS (THE COPPER, SILVER AND GOLD ONES) IN POPULAR LITERATURE AND RUSSIAN FOLK TRADITION]. Проблемы исторической поэтики, 17 (1): 26-44. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ckazki-o-treh-tsarstvah-mednom-serebryanom-i-zolotom-v-lubochnoy-literature-i-folklornoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Матвеева, Р. П. (2013). Русские сказки на сюжет «Три подземных царства» в сибирском репертуаре [RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES ON THE PLOT « THREE UNDERGROUND KINGDOMS» IN THE SIBERIAN REPERTOIRE]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Философия, (10): 170-175. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkie-skazki-na-syuzhet-tri-podzemnyh-tsarstva-v-sibirskom-repertuare (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Терещенко Анна Васильевна (2017). Фольклорный сюжет «Три царства» в сопоставительном аспекте: на материале русских и селькупских сказок [COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FOLKLORE PLOT “THREE STOLEN PRINCESSES”: RUSSIAN AND SELKUP FAIRY TALES DATA]. Вестник Томского государственного педагогического университета, (6 (183)): 128-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/folklornyy-syuzhet-tri-tsarstva-v-sopostavitelnom-aspekte-na-materiale-russkih-i-selkupskih-skazok (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

Crafty Knowledge (ATU 325):

- Трошкова Анна Олеговна (2019). «Сюжет «Хитрая наука» (сус 325) в русской волшебной сказке» [THE PLOT “THE MAGICIAN AND HIS PUPIL” (NO. 325 OF THE COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS) IN THE RUSSIAN FAIRY TALE]. Вестник Марийского государственного университета, 13 (1 (33)): 98-107. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-hitraya-nauka-sus-325-v-russkoy-volshebnoy-skazke (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Troshkova, A.O. «Plot CIP 325 Crafty Lore / ATU 325 «The Magician and His Pupil» in Catalogues of Tale Types by A. Aarne (1910), Aarne — Thompson (1928, 1961), G. Uther (2004), N. P. Andreev (1929) and L. G. Barag (1979)». In: Traditional culture. 2019. Vol. 20. No. 5. pp. 85—88. DOI: 10.26158/TK.2019.20.5.007 (In Russian).

- Troshkova, A (2019). «The tale type ‘The Magician and His Pupil’ in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)». Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376. (In Russian)

Mark the Rich or Marko Bogatyr (ATU 461):

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2017). Легенда о Христе в составе сказки о Марко Богатом: устные и книжные источники славянских повествований [LEGEND OF CHRIST WITHIN THE FOLKTALE ABOUT MARKO THE RICH: ORAL AND BOOK SOURCES OF SLAVIC NARRATIVES]. Вестник славянских культур, 46 (4): 122-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/legenda-o-hriste-v-sostave-skazki-o-marko-bogatom-ustnye-i-knizhnye-istochniki-slavyanskih-povestvovaniy (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2019). Разновидности сюжета о Марко Богатом (AaTh 930) в восточно- и южнославянских записях [VERSIONS OF THE PLOT ABOUT MARKO THE RICH (AATH 930) IN THE EAST- AND SOUTH SLAVIC TEXTS]. Вестник славянских культур, 52 (2): 104-116. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/raznovidnosti-syuzheta-o-marko-bogatom-aath-930-v-vostochno-i-yuzhnoslavyanskih-zapisyah (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

External links[edit]

Ivan Tsarevich and the Grey Wolf (Zvorykin)

A Russian fairy tale or folktale (Russian: ска́зка; skazka; «story»; plural Russian: ска́зки, romanized: skazki) is a fairy tale from Russia.

Various sub-genres of skazka exist. A volshebnaya skazka [волше́бная ска́зка] (literally «magical tale») is considered a magical tale.[1][need quotation to verify] Skazki o zhivotnykh are tales about animals and bytovye skazki are tales about household life. These variations of skazki give the term more depth and detail different types of folktales.

Similarly to Western European traditions, especially the German-language collection published by the Brothers Grimm, Russian folklore was first collected by scholars and systematically studied in the 19th century. Russian fairy tales and folk tales were cataloged (compiled, grouped, numbered and published) by Alexander Afanasyev in his 1850s Narodnye russkie skazki. Scholars of folklore still refer to his collected texts when citing the number of a skazka plot. An exhaustive analysis of the stories, describing the stages of their plots and the classification of the characters based on their functions, was developed later, in the first half of the 20th century, by Vladimir Propp (1895-1970).

History[edit]

Appearing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fairy tales became widely popular as they spread throughout the country. Literature was considered an important factor in the education of Russian children who were meant to grow from the moral lessons in the tales. During the 18th Century Romanticism period, poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Pyotr Yershov began to define the Russian folk spirit with their stories. Throughout the 1860s, despite the rise of Realism, fairy tales still remained a beloved source of literature which drew inspiration from writers such as Hans Christian Andersen.[2] The messages in the fairy tales began to take a different shape once Joseph Stalin rose to power under the Communist movement.[3]

Popular fairy tale writer, Alexander Afanasyev

Effects of Communism[edit]

Fairy tales were thought to have a strong influence over children which is why Joseph Stalin decided to place restrictions upon the literature distributed under his rule. The tales created in the mid 1900s were used to impose Socialist beliefs and values as seen in numerous popular stories.[3] In comparison to stories from past centuries, fairy tales in the USSR had taken a more modern spin as seen in tales such as in Anatoliy Mityaev’s Grishka and the Astronaut. Past tales such as Alexander Afanasyev’s The Midnight Dance involved nobility and focused on romance.[4] Grishka and the Astronaut, though, examines modern Russian’s passion to travel through space as seen in reality with the Space Race between Russia and the United States.[5] The new tales included a focus on innovations and inventions that could help characters in place of magic which was often used as a device in past stories.

Influences[edit]

Russian kids listening to a new fairy tale

In Russia, the fairy tale is one sub-genre of folklore and is usually told in the form of a short story. They are used to express different aspects of the Russian culture. In Russia, fairy tales were propagated almost exclusively orally, until the 17th century, as written literature was reserved for religious purposes.[6] In their oral form, fairy tales allowed the freedom to explore the different methods of narration. The separation from written forms led Russians to develop techniques that were effective at creating dramatic and interesting stories. Such techniques have developed into consistent elements now found in popular literary works; They distinguish the genre of Russian fairy tales. Fairy tales were not confined to a particular socio-economic class and appealed to mass audiences, which resulted in them becoming a trademark of Russian culture.[7]

Cultural influences on Russian fairy tales have been unique and based on imagination. Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Polish-American author and Nobel Prize winner, claims that, “You don’t ask questions about a tale, and this is true for the folktales of all nations. They were not told as fact or history but as a means to entertain the listener, whether he was a child or an adult. Some contain a moral, others seem amoral or even antimoral, Some constitute fables on man’s follies and mistakes, others appear pointless.» They were created to entertain the reader.[8]

Russian fairy tales are extremely popular and are still used to inspire artistic works today. The Sleeping Beauty is still played in New York at the American Ballet Theater and has roots to original Russian fairy tales from 1890. Mr. Ratmansky’s, the artist-in-residence for the play, gained inspiration for the play’s choreography from its Russian background.[9]

Formalism[edit]

From the 1910s through the 1930s, a wave of literary criticism emerged in Russia, called Russian formalism by critics of the new school of thought.[10]

Analysis[edit]

Many different approaches of analyzing the morphology of the fairy tale have appeared in scholarly works. Differences in analyses can arise between synchronic and diachronic approaches.[11][12] Other differences can come from the relationship between story elements. After elements are identified, a structuralist can propose relationships between those elements. A paradigmatic relationship between elements is associative in nature whereas a syntagmatic relationship refers to the order and position of the elements relative to the other elements.[12]

A Russian Garland of Fairy Tales

Motif[edit]

Before the period of Russian formalism, beginning in 1910, Alexander Veselovksky called the motif the «simplest narrative unit.»[13] Veselovsky proposed that the different plots of a folktale arise from the unique combinations of motifs.

Motif analysis was also part of Stith Thompson’s approach to folkloristics.[14] Thompson’s research into the motifs of folklore culminated in the publication of the Motif-Index of Folk Literature.[15]

Structural[edit]

In 1919, Viktor Shklovsky published his essay titled «The Relationship Between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style».[13] As a major proponent during Russian formalism,[16] Shklovsky was one of the first scholars to criticize the failing methods of literary analysis and report on a syntagmatic approach to folktales. In his essay he claims, «It is my purpose to stress not so much the similarity of motifs, which I consider of little significance, as the similarity in the plot schemata.»[13]

Syntagmatic analysis, championed by Vladimir Propp, is the approach in which the elements of the fairy tale are analyzed in the order that they appear in the story. Wanting to overcome what he thought was arbitrary and subjective analysis of folklore by motif,[17] Propp published his book Morphology of the Folktale in 1928.[16] The book specifically states that Propp finds a dilemma in Veselovsky’s definition of a motif; it fails because it can be broken down into smaller units, contradicting its definition.[7] In response, Propp pioneered a specific breakdown that can be applied to most Aarne-Thompson type tales classified with numbers 300-749.[7][18] This methodology gives rise to Propp’s 31 functions, or actions, of the fairy tale.[18] Propp proposes that the functions are the fundamental units the story and that there are exactly 31 distinct functions. He observed in his analysis of 100 Russian fairy tales that tales almost always adhere to the order of the functions. The traits of the characters, or dramatis personae, involved in the actions are second to the action actually being carried out. This also follows his finding that while some functions may be missing between different stories, the order is kept the same for all the Russian fairy tales he analyzed.[7]

Alexander Nikiforov, like Shklovsky and Propp, was a folklorist in 1920s Soviet Russia. His early work also identified the benefits of a syntagmatic analysis of fairy tale elements. In his 1926 paper titled «The Morphological Study of Folklore», Nikiforov states that «Only the functions of the character, which constitute his dramatic role in the folk tale, are invariable.»[13] Since Nikiforov’s essay was written almost 2 years before Propp’s publication of Morphology of the Folktale[19], scholars have speculated that the idea of the function, widely attributed to Propp, could have first been recognized by Nikiforov.[20] One source claims that Nikiforov’s work was «not developed into a systematic analysis of syntagmatics» and failed to «keep apart structural principles and atomistic concepts».[17] Nikiforov’s work on folklore morphology was never pursued beyond his paper.[19]

Writers and collectors[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev[edit]

Alexander Afanasyev began writing fairy tales at a time when folklore was viewed as simple entertainment. His interest in folklore stemmed from his interest in ancient Slavic mythology. During the 1850s, Afanasyev began to record part of his collection from tales dating to Boguchar, his birthplace. More of his collection came from the work of Vladimir Dhal and the Russian Geographical Society who collected tales from all around the Russian Empire.[21] Afanasyev was a part of the few who attempted to create a written collection of Russian folklore. This lack in collections of folklore was due to the control that the Church Slavonic had on printed literature in Russia, which allowed for only religious texts to be spread. To this, Afanasyev replied, “There is a million times more morality, truth and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness!”[22]

Between 1855 and 1863, Afanasyev edited Popular Russian Tales[Narodnye russkie skazki], which had been modeled after the Grimm’s Tales. This publication had a vast cultural impact over Russian scholars by establishing a desire for folklore studies in Russia. The rediscovery of Russian folklore through written text led to a generation of great Russian authors to come forth. Some of these authors include Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Folktales were quickly produced in written text and adapted. Since the production of this collection, Russian tales remain understood and recognized all over Russia.[21]

Alexander Pushkin[edit]

Alexander Pushkin is known as one of Russia’s leading writers and poets.[23] He is known for popularizing fairy tales in Russia and changed Russian literature by writing stories no one before him could.[24] Pushkin is considered Russia’s Shakespeare as, during a time when most of the Russian population was illiterate, he gave Russian’s the ability to desire in a less-strict Christian and a more pagan way through his fairy tales.[25]

Pushkin gained his love for Russian fairy tales from his childhood nurse, Ariana Rodionovna, who told him stories from her village when he was young.[26] His stories served importance to Russians past his death in 1837, especially during times political turmoil during the start of the 20th century, in which, “Pushkin’s verses gave children the Russian language in its most perfect magnificence, a language which they may never hear or speak again, but which will remain with them as an eternal treasure.”[27]

The value of his fairy tales was established a hundred years after Pushkin’s death when the Soviet Union declared him a national poet. Pushkin’s work was previously banned during the Czarist rule. During the Soviet Union, his tales were seen acceptable for education, since Pushkin’s fairy tales spoke of the poor class and had anti-clerical tones.[28]

Corpus[edit]

According to scholarship, some of «most popular or most significant» types of Russian Magic Tales (or Wonder Tales) are the following:[a][30]

| Tale number | Russian classification | Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index Grouping | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | The Winner of the Snake | The Dragon-Slayer | ||

| 301 | The Three Kingdoms | The Three Stolen Princesses | The Norka; Dawn, Midnight and Twilight | [b] |

| 302 | Kashchei’s Death in an Egg | Ogre’s (Devil’s) Heart in the Egg | The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

| 307 | The Girl Who Rose from the Grave | The Princess in the Coffin | Viy | [c] |

| 313 | Magic Escape | The Magic Flight | The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise | [d] |

| 315 | The Feigned Illness (beast’s milk) | The Faithless Sister | ||

| 325 | Crafty Knowledge | The Magician and his Pupil | [e] | |

| 327 | Children at Baba Yaga’s Hut | Children and the Ogre | ||

| 327C | Ivanusha and the Witch | The Devil (Witch) Carries the Hero Home in a Sack | [f] | |

| 400 | The husband looks for his wife, who has disappeared or been stolen (or a wife searches for her husband) | The Man on a Quest for The Lost Wife | The Maiden Tsar | |

| 461 | Mark the Rich | Three Hairs of the Devil’s Beard | The Story of Three Wonderful Beggars (Serbian); Vassili The Unlucky | [g] |

| 465 | The Beautiful Wife | The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | [h] |

| 480 | Stepmother and Stepdaughter | The Kind and Unkind Girls | Vasilissa the Beautiful | |

| 519 | The Blind Man and the Legless Man | The Strong Woman as Bride (Brunhilde) | [i][j][k] | |

| 531 | The Little Hunchback Horse | The Clever Horse | The Humpbacked Horse; The Firebird and Princess Vasilisa | [l] |

| 545B | Puss in Boots | The Cat as Helper | ||

| 555 | Kitten-Gold Forehead (a gold fish, a magical tree) | The Fisherman and His Wife | The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish | [m][n] |

| 560 | The Magic Ring | The Magic Ring | [o][p] | |

| 567 | The Marvelous Bird | The Magic Bird-Heart | ||

| 650A | Ivan the Bear’s Ear | Strong John | ||

| 706 | The Handless | The Maiden Without Hands | ||

| 707 | The Tale of Tsar Saltan [Marvelous Children] | The Three Golden Children | Tale of Tsar Saltan, The Wicked Sisters | [q] |

| 709 | The Dead Tsarina or The Dead Tsarevna | Snow White | The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights | [r] |

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Propp’s The Russian Folktale lists types 301, 302, 307, 315, 325, 327, 400, 461, 465, 519, 545B, 555, 560, 567 and 707.[29]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 301, «The Three Kingdoms and the Stolen Princesses», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 45 variants. The type was also the second «most frequently collected in Ukraine», with 31 texts.[31]

- ^ French folklorist Paul Delarue noticed that the tale type, despite existing «throughout Europe», is well known in Russia, where it found «its favorite soil».[32] Likewise, Jack Haney stated that type 307 was «most common» among East Slavs.[33]

- ^ A preliminary report by Nikolai P. Andreyev declared that type 313, «The Magic Flight», was among the «most popular types» in Russia, with 41 variants. The type was also the «most frequently collected» in Ukraine, with 37 texts.[34]

- ^ Commenting on a Russian tale collected in the 20th century, Richard Dorson stated that the type was «one of the most widespread Russian Märchen».[35] In the East Slavic populations, scholarship registers 42 Russian variants, 25 Ukrainian and 10 Belarrussian.[36]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type of a fishing boy and a witch «[is] common among the various East European peoples.»[37]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type is popular among the East Slavs[38]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type, including previous type AaTh 465A, is «especially common in Russia».[39]

- ^ Russian researcher Dobrovolskaya Varvara Evgenievna stated that tale type ATU 519 (SUS 519) «belongs to the core of» the Russian tale corpus, due to «the presence of numerous variants».[40]

- ^ Following Löwis de Menar’s study, Walter Puchner concluded on its diffusion especially in the East Slavic area.[41]

- ^ Stith Thompson also located this tale type across Russia and the Baltic regions.[42]

- ^ According to Jack Haney, the tale type «is extremely popular in all three branches of East Slavic».[43]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, this type is «common among the East Slavs».[44]

- ^ The variation on the wish-giving entity is also attested in Estonia, whose variants register a golden fish, crayfish, or a sacred tree.[45]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «very common in all the East Slavic traditions».[46]

- ^ Wolfram Eberhard reported «45 variants in Russia alone».[47]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «a very common East Slavic type».[48]

- ^ According to professor Jack V. Haney, the tale type is «especially common in Russian and Ukrainian».[49]

References[edit]

- ^ «Magic tale (volshebnaia skazka), also called fairy tale». Kononenko, Natalie (2007). Slavic Folklore: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-313-33610-2.

- ^ Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories : the History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574-2010). Brill, 2013.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. “Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union.” Slavic Review, vol. 32, no. 1, 1973, pp. 45–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494072.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. “The Midnight Dance.” The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces, 1855, www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0306.html.

- ^ Mityayev, Anatoli. Grishka and the Astronaut. Translated by Ronald Vroon, Progress, 1981.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service». Marvels & Tales. 16 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1353/mat.2002.0024. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 41388626. S2CID 163086804.

- ^ a b c d Propp, V. I︠A︡. Morphology of the folktale. ISBN 9780292783768. OCLC 1020077613.

- ^ Singer, Isaac Bashevis (1975-11-16). «Russian Fairy Tales». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Greskovic, Robert (2015-06-02). «‘The Sleeping Beauty’ Review: Back to Its Russian Roots». Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Erlich, Victor (1973). «Russian Formalism». Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (4): 627–638. doi:10.2307/2708893. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708893.

- ^ Saussure, Ferdinand de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Baskin, Wade., Meisel, Perry., Saussy, Haun, 1960-. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231527958. OCLC 826479070.

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur Asa (February 2018). Media analysis techniques. ISBN 9781506366210. OCLC 1000297853.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Terence Patrick (2015). The Fairytale and Plot Structure. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781137547088. OCLC 944065310.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1997). «The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique». Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 3814885.

- ^ Kuehnel, Richard; Lencek, Rado. «What is a Folklore Motif?». www.aktuellum.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ a b Propp, V. I︠A︡.; Пропп, В. Я. (Владимир Яковлевич), 1895-1970 (2012). The Russian folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337219. OCLC 843208720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maranda, Pierre (1974). Soviet structural folkloristics. Meletinskiĭ, E. M. (Eleazar Moiseevich), Jilek, Wolfgang. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 978-9027926838. OCLC 1009096.

- ^ a b Aguirre, Manuel (October 2011). «AN OUTLINE OF PROPP’S MODEL FOR THE STUDY OF FAIRYTALES» (PDF). Tools and Frames – via The Northanger Library Project.

- ^ a b Oinas, Felix J. (2019). The Study of Russian Folklore. Soudakoff, Stephen. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 9783110813913. OCLC 1089596763.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1973). «Folklore and Politics in the Soviet Union». Slavic Review. 32 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2494072. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494072.

- ^ a b Levchin, Sergey (2014-04-28). «Russian Folktales from the Collection of A. Afanasyev : A Dual-Language Book».

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. (1991). Alexander Pushkin : a critical study. The Bristol Press. ISBN 978-1853991721. OCLC 611246966.

- ^ Alexander S. Pushkin, Zimniaia Doroga, ed. by Irina Tokmakova (Moscow: Detskaia Literatura, 1972).

- ^ Bethea, David M. (2010). Realizing Metaphors : Alexander Pushkin and the Life of the Poet. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299159733. OCLC 929159387.

- ^ Davidson, H. R. Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A companion to the fairy tale. ISBN 9781782045519. OCLC 960947251.

- ^ Akhmatova, “Pushkin i deti,” radio broadcast script prepared in 1963, published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, May 1, 1974.

- ^ Nikolajeva, Maria. «Fairy Tales in Society’s Service.» Marvels & Tales (2002): 171-187.

- ^ The Russian Folktale by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp. Edited and Translated by Sibelan Forrester. Foreword by Jack Zipes. Wayne State University Press, 2012. p. 215. ISBN 9780814334669.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Delarue, Paul. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 386.

- ^ Haney, Jack V.; with Sibelan Forrester. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume III. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2021. p. 536.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. p. 68. ISBN 0-226-15874-8.

- ^ Горяева, Б. Б. (2011). «Сюжет «Волшебник и его ученик» (at 325) в калмыцкой сказочной традиции». In: Oriental Studies (2): 153. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-volshebnik-i-ego-uchenik-at-325-v-kalmytskoy-skazochnoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 554. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Добровольская Варвара Евгеньевна (2018). «Сказка «слепой и безногий» (сус 519) в репертуаре русских сказочников: фольклорная реализация литературного сюжета». Вопросы русской литературы, (4 (46/103)): 93-113 (111). URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/skazka-slepoy-i-beznogiy-sus-519-v-repertuare-russkih-skazochnikov-folklornaya-realizatsiya-literaturnogo-syuzheta (дата обращения: 01.09.2021).

- ^ Krauss, Friedrich Salomo; Volkserzählungen der Südslaven: Märchen und Sagen, Schwänke, Schnurren und erbauliche Geschichten. Burt, Raymond I. and Puchner, Walter (eds). Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2002. p. 615. ISBN 9783205994572.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2015 [2001]. p. 434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. Accessed August 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. p. 718. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. p. 538. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram. Folktales of China. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1956. p. 143.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536-556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

Further reading[edit]

- Лутовинова, Е.И. (2018). Тематические группы сюжетов русских народных волшебных сказок. Педагогическое искусство, (2): 62-68. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/tematicheskie-gruppy-syuzhetov-russkih-narodnyh-volshebnyh-skazok (дата обращения: 27.08.2021). (in Russian)

The Three Kingdoms (ATU 301):

- Лызлова Анастасия Сергеевна (2019). Cказки о трех царствах (медном, серебряном и золотом) в лубочной литературе и фольклорной традиции [FAIRY TALES ABOUT THREE KINGDOMS (THE COPPER, SILVER AND GOLD ONES) IN POPULAR LITERATURE AND RUSSIAN FOLK TRADITION]. Проблемы исторической поэтики, 17 (1): 26-44. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ckazki-o-treh-tsarstvah-mednom-serebryanom-i-zolotom-v-lubochnoy-literature-i-folklornoy-traditsii (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Матвеева, Р. П. (2013). Русские сказки на сюжет «Три подземных царства» в сибирском репертуаре [RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES ON THE PLOT « THREE UNDERGROUND KINGDOMS» IN THE SIBERIAN REPERTOIRE]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Философия, (10): 170-175. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkie-skazki-na-syuzhet-tri-podzemnyh-tsarstva-v-sibirskom-repertuare (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Терещенко Анна Васильевна (2017). Фольклорный сюжет «Три царства» в сопоставительном аспекте: на материале русских и селькупских сказок [COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FOLKLORE PLOT “THREE STOLEN PRINCESSES”: RUSSIAN AND SELKUP FAIRY TALES DATA]. Вестник Томского государственного педагогического университета, (6 (183)): 128-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/folklornyy-syuzhet-tri-tsarstva-v-sopostavitelnom-aspekte-na-materiale-russkih-i-selkupskih-skazok (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

Crafty Knowledge (ATU 325):

- Трошкова Анна Олеговна (2019). «Сюжет «Хитрая наука» (сус 325) в русской волшебной сказке» [THE PLOT “THE MAGICIAN AND HIS PUPIL” (NO. 325 OF THE COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS) IN THE RUSSIAN FAIRY TALE]. Вестник Марийского государственного университета, 13 (1 (33)): 98-107. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/syuzhet-hitraya-nauka-sus-325-v-russkoy-volshebnoy-skazke (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Troshkova, A.O. «Plot CIP 325 Crafty Lore / ATU 325 «The Magician and His Pupil» in Catalogues of Tale Types by A. Aarne (1910), Aarne — Thompson (1928, 1961), G. Uther (2004), N. P. Andreev (1929) and L. G. Barag (1979)». In: Traditional culture. 2019. Vol. 20. No. 5. pp. 85—88. DOI: 10.26158/TK.2019.20.5.007 (In Russian).

- Troshkova, A (2019). «The tale type ‘The Magician and His Pupil’ in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)». Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376. (In Russian)

Mark the Rich or Marko Bogatyr (ATU 461):

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2017). Легенда о Христе в составе сказки о Марко Богатом: устные и книжные источники славянских повествований [LEGEND OF CHRIST WITHIN THE FOLKTALE ABOUT MARKO THE RICH: ORAL AND BOOK SOURCES OF SLAVIC NARRATIVES]. Вестник славянских культур, 46 (4): 122-134. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/legenda-o-hriste-v-sostave-skazki-o-marko-bogatom-ustnye-i-knizhnye-istochniki-slavyanskih-povestvovaniy (дата обращения: 24.09.2021). (In Russian)

- Кузнецова Вера Станиславовна (2019). Разновидности сюжета о Марко Богатом (AaTh 930) в восточно- и южнославянских записях [VERSIONS OF THE PLOT ABOUT MARKO THE RICH (AATH 930) IN THE EAST- AND SOUTH SLAVIC TEXTS]. Вестник славянских культур, 52 (2): 104-116. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/raznovidnosti-syuzheta-o-marko-bogatom-aath-930-v-vostochno-i-yuzhnoslavyanskih-zapisyah (дата обращения: 24.09.2021).

External links[edit]

В России особой любовью читателей пользуются скандинавские сказки из-под пера Г. Х. х Андерсен, А. Линдгрен, С. Лагерлёф, Т. Янссон, а в XXI веке Свен Нордквист и его школа.

Сказки любят как дети, так и взрослые. Они дают людям все то, чего не хватает в реальной жизни, — волшебство, долгие путешествия и то, что добро всегда побеждает зло.

С древних времен люди придумывали сказки. Они выражали мечты, надежды и желания. Так возникли популярные сказки. Невозможно узнать, кто именно придумал эти истории и кто настоящие авторы произведений. Эти истории передавались из поколения в поколение. Некоторые из них остались неизменными, другие были придуманы и добавлены к уже существующим историям.

У каждой страны своя история. И хотя герои историй были разными, смысл и суть историй были очень похожи. Добро всегда должно побеждать зло. Отрицательные персонажи в сказках наказываются, а положительные герои вознаграждаются.

Самые распространенные и популярные сказки — это сказки о животных и сказки о сказках. Лисы, волки, зайцы, медведи, кошки, собаки, Баба Яга, Кощей Бессмертный, императоры, мужчины и другие персонажи пользуются наибольшей популярностью. Персонализированные специфические характеристики и недостатки — лиса для развязки, медведь для силы, кошка для оригинальности.

Популярные сказки были средством для простых людей, которые не могли открыто выступать против богатых. Только в сказках бедные крестьяне могли обмануть императора и заработать большие деньги. Обычные юноши могли жениться на принцессах и сами становились королями. Когда людям не хватало еды, они делали сказки для скатертей. У бедных людей не было возможности путешествовать по миру. В то время в сказках изобретались скоростные космические корабли и сапоги, которые могли переносить людей в любую страну.

Самыми захватывающими были рассказы о магии. Каждый хотел иметь волшебную палочку или цветок семи разных цветов. В конце концов, как здорово получить желаемое и не работать для этого долго?

Сказки любимы и нравятся всем. Потому что они дают вам возможность погрузиться в волшебство и на время избавиться от трудностей человеческой жизни.

Литература 3, 5 класс, для детей

Содержание

- Народные сказки

- Сказка ложь, да в ней намёк

- Что зашифровано в сказке о Колобке

- Пушкин – поэт или пророк

- Чему учат русские народные сказки?

- Какая главная мысль и мораль?

- Характеристики героев

- Сказки о животных и бытовые

Народные сказки

Бахнур — небольшой город на юге Западной Сибири, на берегу реки. Существует несколько версий того, как возникло название города. По словам одного из них, это слово с казахского языка переводится как «хороший лагерь».

Образ этого благородного разбойника обладает необычным даром и в основном ассоциируется с правосудием. Это и понятно, ведь он скрывается в Шервудском лесу вместе со своими спутниками.

Созвездие Рыб — одно из 12 созвездий, составляющих зодиак, через которые проходит Солнце в своем годовом цикле. Солнце входит в созвездие Рыб 12 марта и покидает его 18 апреля. В настоящее время видимое движение

Многие, но не все, русские народные сказки помимо обучающего имеют и другой, более глубокий смысл. Дети не могут их воспринимать, но они откладываются в их подсознании.

Сказка ложь, да в ней намёк

Но давайте вернемся к сказкам. Почему отношение зрителей к сказкам такое сочувственное? Глядя на сегодняшнее общество, можно с уверенностью сказать, что большинству людей не помешало бы прочитать многие русские сказки.

Сказки, истории — это своего рода повествование. Что такое «сказка»? Он подчинен термину «история». Иными словами, само название уже указывает на некое светло-пустое отношение к феномену сказок. В данном случае мы видим типичную замену концепции. Всего 200 лет назад термин «сказка» не относился к детским историям. В середине XIX века «сказки» были серьезными документами, такими как «Ревизвестка». Обзорные каталоги» — это инвентаризационные списки, используемые для учета популяций. А в дипломатических приказах сказки назывались фактической информацией, а не сказками для детей.

Следует отметить, что в то время существовали сказки в обычном понимании этого термина. Около 150 лет назад начался процесс записи русских народных сказок. И сравнение этих двух событий — «сказок» и серьезной документации с названием термина «русский фольклор» — показывает, что отношение к русскому фольклору тогда было более серьезным, чем сейчас. Почему? Давайте попробуем понять это.

Айсберг можно сравнить с айсбергом. Над ними находится лишь часть их реальной массы. Большинство айсбергов скрыто под водой. То же самое можно сказать и о сказках — наивные на первый взгляд фантастические истории содержат важную закодированную информацию. Это может быть доступно посвященным или это или детальное и глубокое изучение сказки.

Другими словами, сказки — это послания наших предков будущим поколениям, содержащие мудрость и другую жизненно важную информацию. И это крайнее невежество — смотреть на сказки как на детскую забаву. Мы видим только верхушку айсберга и не замечаем главной сути сказки.

Сказки веками передавали глубокую мудрость людей. Вторая концепция важна в сказках: они являются образом жизни. И достаточно вникнуть чуть глубже обычных поверхностных слоев информации в каждую историю, и исследователям открывается глубокая мудрость веков. Самый поверхностный слой восприятия — это, казалось бы, равнодушная обыденная история. Глубокое восприятие, доступное даже маленькому ребенку, позволяет этосу его сказки, его воспитательному элементу. Например, старая история о золотой рыбке и золотых рыбках учит, что жадность может привести к «разбитому корыту». Однако уровень осознания в сказках глубже.

Проблема в том, что мы перестаем читать сказки, когда они вырастают. На самом деле, в этом народном искусстве содержится мудрость, полезная для большинства взрослых. И по мере того, как мы становимся старше, все народные сказки раскрывают все новые и новые аспекты. Сказки не только объясняют тайны Вселенной, но и отсылают к конкретным историческим событиям, которые когда-то происходили на Земле.

Кроме того, колыбельные — это еще и форма рассказывания историй. Колыбельная — это способ передачи информации от матери к ребенку, уровень осознания, доступный младенцу. В этом, казалось бы, примитивном тексте содержится основная человеческая мудрость. К ним относятся призыв быть честным и правдивым и жить в гармонии со Вселенной.

Что зашифровано в сказке о Колобке

Чтобы показать, как мудрость наших предков может быть зашифрована в простой детской сказке, давайте рассмотрим историю о Коробочке.

Это выглядело достаточно просто. Слай Пэн убежал от бабушки и дедушки, упал в лесу и, что еще хуже, попал в когти лисы. Это забавно и увлекательно, но не более того. Но мы не должны делать поспешных выводов. Давайте рассмотрим вторую линию рассуждений в этой истории.

Начните с самого начала. Как был создан «Колобок»? Сначала он был просто тканью. Но в процессе творения он обретает личность, сердце и, возможно, душу. Таким образом, мы можем наблюдать возникновение жизни из ничего. Не символизирует ли это воплощение души в материальном мире?

Мы можем рассматривать сюжет этой истории с точки зрения структуры Вселенной. Предположим, что Колобок — это символ луны. Затем в рассказе о Колобке мы можем увидеть объяснение того, как Луна движется в небесных созвездиях. Чтобы заметить сходство между описанием путешествия Колобка и движением луны в небесных созвездиях, обратимся к более древней версии сказки.

В старой версии Коробок встретил сначала ворона, потом ворона, потом медведя, потом волка и, наконец, лису. И что мы видим? Кабаны, вороны, медведи, волки и лисы — это созвездия славянского зодиака, Сварожьего круга. И что самое интересное, Луна уменьшается по мере продвижения к созвездиям. А в сказке каждый из зверей, которых встречает Корёвок, кусает его. Забавное совпадение, не правда ли? Или это не совпадение?

Поэтому весьма вероятно, что в рассказе о Колобочке содержится описание движения луны по небосводу — луна уменьшается в каждом созвездии, пока полностью не исчезнет в созвездии Лисы. Можно предположить, что история Коробочки — это учебник по изучению астрологии, зашифрованный в простые детские картинки для лучшего запоминания. Это стандартный прием, известный нам еще со школьных времен. Чтобы эффективно научить ребенка чему-либо, процесс обучения должен проходить в форме игры.

Пушкин – поэт или пророк

Обратимся к другому пушкинскому произведению, «Руслану и Людмиле». После прочтения этой истории изучение Рамаяны, древнего ведического писания, показывает, что эти истории почти полностью совпадают. Стоит отметить, что Пушкин написал «Руслана и Людмилу» в возрасте 20 лет. Мог ли он знать древние ведические писания в столь юном возрасте?