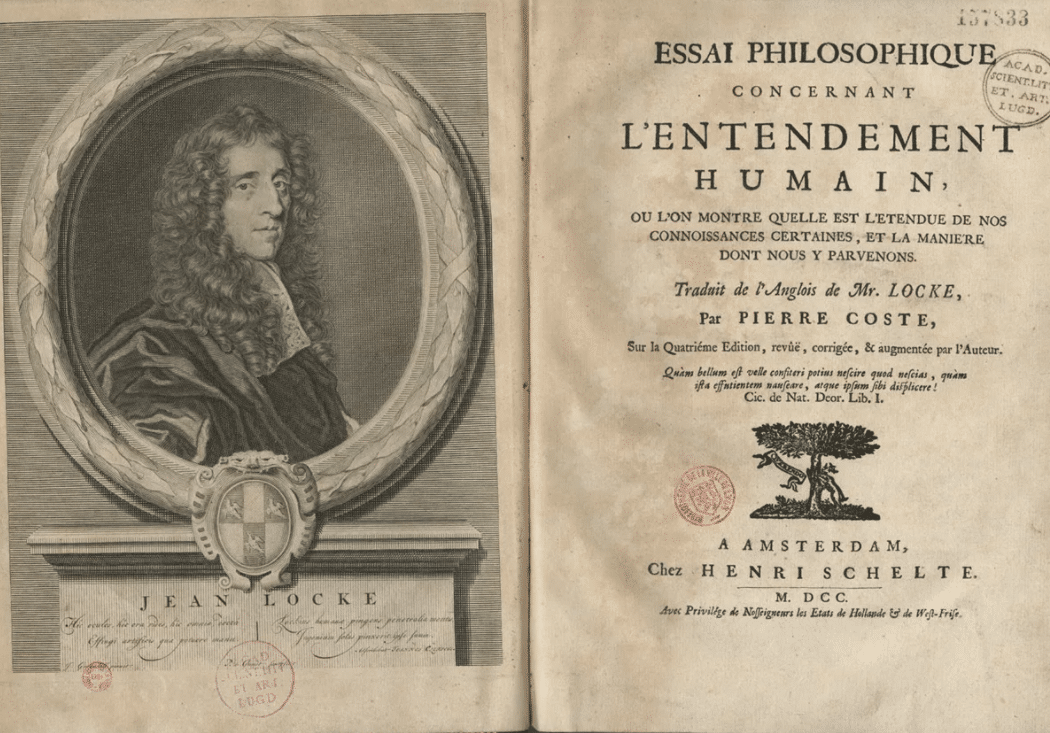

Джон Локк – английский философ, которого современные авторы называют одним из наиболее выдающихся мыслителей эпохи Просвещения. Его работы и идеи существенным образом повлияли на развитие сенсуализма, эмпиризма и либерализма. Кроме того, он считается основоположником экономического либерализма – идеологии, согласно которой государство должно по возможности избегать вмешательства в экономику страны.

Родился философ в небольшой деревне Рингтон (Wrington) в графстве Сомерсетшир 29 августа 1632 года. За свою жизнь он опубликовал немало выдающихся трудов о проблемах из разных сфер жизни, рассматривая такие темы как взаимоотношения внутри семьи, воспитание детей, отношения между религиями, социальное устройство общества, экономика и многое другое.

Сперва кратко пробежимся по его основным идеям и взглядам, после чего рассмотрим каждую теорию более подробно.

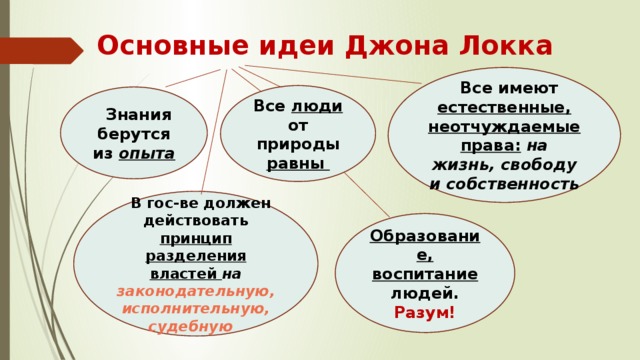

Краткий обзор ключевых идей Джона Локка

Учение Локка строится вокруг человека и его практической жизни. Разделяя основные идеи философии Нового времени, он отказывается от схоластики и делает акцент на связь с практикой. Это отразилось в его работах по воспитанию детей и социальному устройству общества. Философию, как научную дисциплину, Локк считал важным практическим инструментом, позволяющим обеспечить счастье для людей.

Одним из важнейших достижений Локка считается разработанная им теория познания, которая строится на следующих постулатах:

- У человека нет врождённых идей. Все идеи происходят из знаний, полученных посредством чувственного познания в течение жизни. Единственным источником идей является опыт, который можно дополнительно разделить на внешний и внутренний.

- Знание основывается на простых (примитивных) идеях. При этом Локк разделяет идеи первичных и вторичных качеств. Под первичными качествами он подразумевает собственные свойства предметов: форма, размер, количество, движение. Вторичные качества – это воспринимаемые свойства: запах, вкус, звук, цвет. Каждое из этих свойств является простой идеей, которая сама по себе знанием не является, но может служить материалом для знания. Объединение простых идей приводит к появлению сложных и общих идей.

- В зависимости от степени достоверности, можно выделить два типа знания: достоверное и вероятное. Вероятное знание является всего лишь мнением или предположением. Достоверное знание Локк разделил на три вида: созерцательное (интуитивное), демонстративное (доказательное) и чувственное.

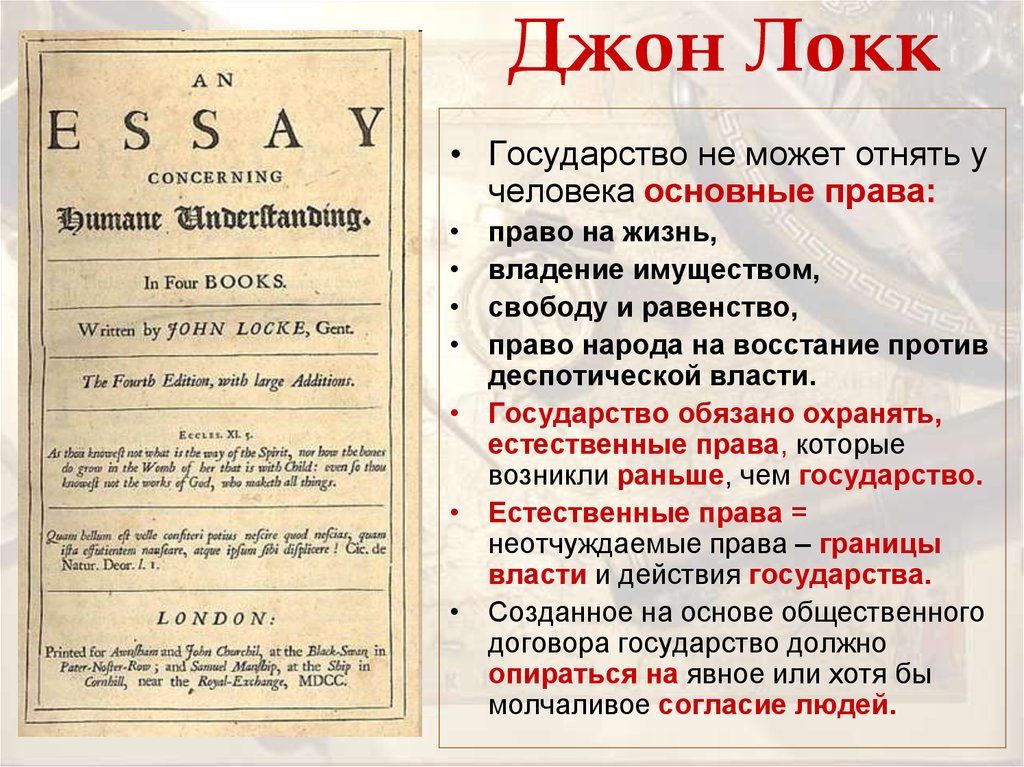

Одной из важнейших идей философа стало разделение властей на три ветви: законодательную, исполнительную (включая судебную) и федеративную (осуществляющую внешнюю политику). Он был первым, кто предложил такое устройство государственной власти, и сегодня эта идея в несколько ином виде воплощена в большинстве стран мира.

Политические взгляды

Локк разделял взгляды Томаса Гоббса и, в частности, был сторонником договорной теории происхождения государства. Всякое государство он считал продуктом негласного соглашения между гражданами и властью, в рамках которого население страны делегирует государству определённые права, получая взамен безопасность и другие блага.

В этом плане он был идеалистом, поскольку считал, что весь состав государственной власти должен быть избран народом (или, по крайней мере, согласован с ним). Если же власть плохо справляется со своими обязанностями, народ имеет право потребовать перевыборы.

Джон Локк был противником абсолютной власти, сосредоточенной в одних руках, независимо от её природы. Такую форму государственного устройства он называл одной из худших угроз для свободы личности. Он считал, что власть должна делиться на 3 ветви:

- законодательную (принятие законов, определение меры ответственности за различные преступления);

- исполнительную (исполнение законов, применение наказания к преступникам);

- федеративную (вопросы внешней политики, дипломатии, войны и мира).

В этой системе монарх (верховный правитель) должен быть главой исполнительной и федеративной власти, однако не может руководить ими напрямую. Он должен вмешиваться в случае возникновения противоречий, не предусмотренных действующим законодательством. По сути, Локк выделил для монарха роль гаранта соблюдения законов.

Благодаря идее о разделении ветвей власти, а также о наделении монарха обязанностями гаранта, современные авторы называют Джона Локка основателем теории конституционализма.

По мнению Локка, истинная цель существования государства заключается в том, чтобы обеспечивать всем гражданам условия жизни, которые их устраивают. При этом правовое государство обязано следить за соблюдением трёх неотъемлемых прав личности:

- на жизнь;

- на свободу;

- на частную собственность.

Это три фундаментальных права, присутствующих у каждого человека, независимо от его происхождения, достатка и заслуг перед обществом. В любом правовом государстве конституция должна создаваться на основе этих трёх прав, а одной из её ключевых целей должна быть их защита. Государство должно пресекать любые попытки насилия, порабощения, принуждения к труду и присвоения чужой собственности.

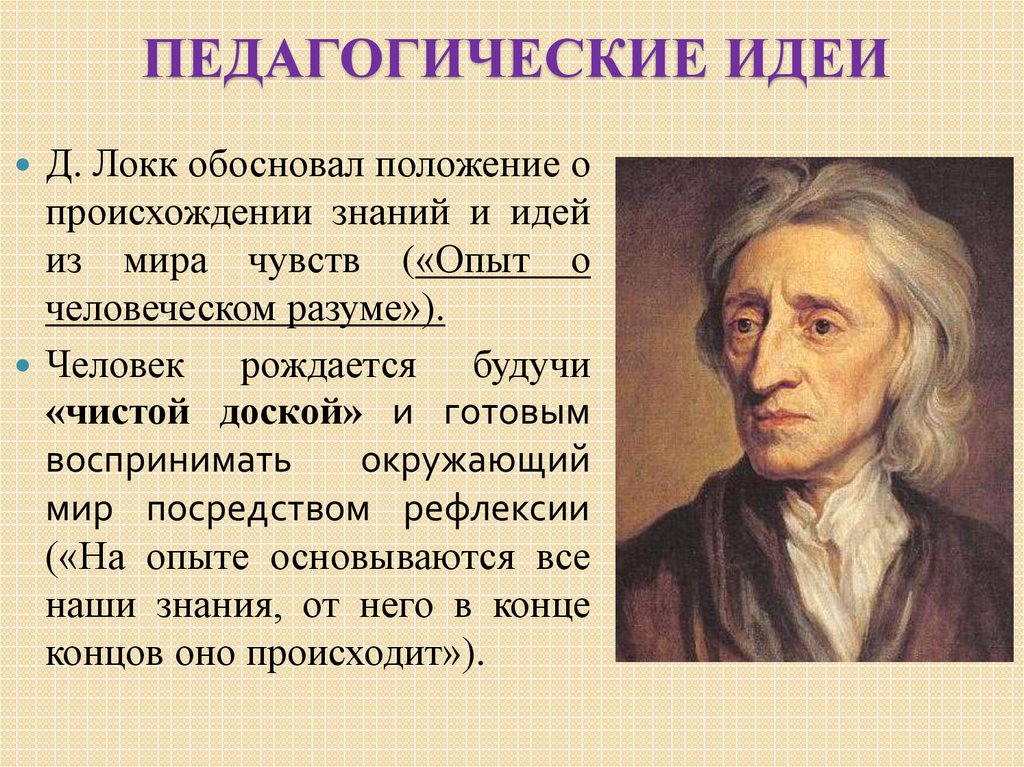

Педагогические идеи

Педагогика была одной из излюбленных тем Джона Локка. Он много писал о воспитании детей, но уделял внимание и воспитанию взрослых людей. В основе его педагогической системы лежит прагматизм и рационализм. В частности, он рекомендует родителям обучать детей уделять значительное внимание таким аспектам как постоянная работа над собой, анализ собственных успехов и неудач. При этом главным воспитательным методом должен служить личный пример родителей, а также помещение детей в правильное окружение.

Основные педагогические постулаты Локка:

- не существует врожденных идей и убеждений;

- все наши знания являются продуктом чувственного познания;

- воспитание определяет, как сложится жизнь человека;

- задача воспитателя – обеспечить ученику счастливое будущее;

- принуждение – недопустимый метод в воспитании детей;

- наглядный пример – самый эффективный метод воспитания.

Локка не устраивала действующая система образования, в рамках которой детей, в частности, заставляли заучивать наизусть огромные тексты на латинском языке, считая, что это закладывает фундамент грамотности. По мнению Локка, такие методы были губительными и не позволяли раскрываться творческому потенциалу детей.

Теория познания

В 1620 году Фрэнсис Бэкон опубликовал трактат «Новый Органон», в котором представил индуктивный (антисхоластический) метод научного познания. Джон Локк был сторонником этого метода, привнёс в него много дополнений и дал ему подробное обоснование. Он последовательно отстаивал утверждение, что знание черпается исключительно из чувственного опыта и не может быть врождённым.

Он выделял два типа чувственного опыта:

- внешний – наблюдения и ощущения, полученные в результате воздействия объектов на органы чувств;

- внутренний – рефлексия и логический анализ ранее полученных эмпирических знаний.

Локк разделил все идеи на два вида: простые и сложные. Простые представляют собой проекцию отдельно взятых свойств внешнего мира. Это пассивные знания, полученные извне в готовом виде, часто против воли человека (мы не выбираем, запоминать ли полученную информацию, и, как правило, не можем предотвратить её получение). Сложные идеи представляют собой комбинацию простых идей, полученную в результате целенаправленной мозговой деятельности.

Основные качества вещей

Знания о любом объекте или явлении Локк сводил к оценке имеющихся у него качеств, среди которых он выделял первичные и вторичные. К первичным он относил такие качества как:

- размер;

- форма;

- количество;

- плотность;

- способность к движению.

Это качества, присущие объектам внешнего мира, но не воспринимаемые напрямую органами чувств. Вторичные качества, наоборот, воспринимаются органами чувств и позволяют сделать выводы о первичных. В эту группу входят такие качества как:

- цвет и свет;

- вкус и запах;

- звуки;

- температура.

Вторичные качества познаются в рамках получения внешнего опыта (эмпирического познания), а первичные – внутреннего (рациональное познание).

Отношение к религии

Будучи сторонником материалистического эмпиризма, Джон Локк всё же придерживался христианских ценностей. Сложно судить, насколько верующим человеком он был, и всё же он одобрительно высказывался о многих постулатах из христианства (при этом подчёркивал, что эти идеи свойственны всем ветвям данной религии). Также он был сторонником толерантности к другим религиям и писал в своих работах, что нельзя считать любую из церквей более правильной, чем другие.

С точки зрения Локка, нравственное и моральное воспитание человека имеет большее значение, чем приверженность к той или иной религии. Он считал, что мусульманин, иудей или язычник может иметь хорошее воспитание и придерживаться строгих моральных норм. Но в то же время он говорил, что христианство, в отличие от других религий, уделяет больше внимания морали и нравственности, следовательно, эти черты наиболее естественны именно для христианина.

Отдельно стоит отметить и то, что Локк последовательно отстаивал необходимость полного разделения церкви и государства. При этом он считал, что судить о совести и вере людей может только церковь, государство же не должно судить людей за отсутствие этих качеств. В деятельность церкви государство может вмешиваться лишь тогда, когда её служители совершают преступления. При этом сам философ не был слишком наивным и не особо верил, что отношения государства и церкви когда-нибудь действительно будут соответствовать представленному им идеалу.

Заключение

Джон Локк – один из самых влиятельных философов эпохи Просвещения, навсегда вписавший своё имя в историю и оказавший влияние на развитие всего мира. В частности, его идеи присутствуют в Конституции США. Также он первым предложил разделить власть на три ветви, а правителя наделить правами и обязанностями гаранта исполнения законов. В дальнейшем его идеи оказали влияние на таких известных мыслителей как Иммануил Кант, Артур Шопенгауэр и Вольтер.

|

John Locke FRS |

|

|---|---|

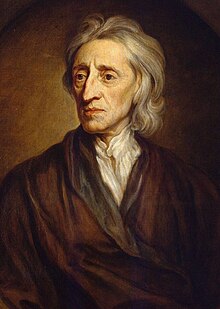

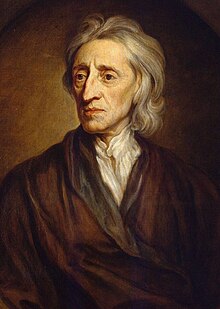

Portrait of Locke in 1697 by Godfrey Kneller |

|

| Born |

John Locke 29 August 1632 Wrington, Somerset, England |

| Died | 28 October 1704 (aged 72)

High Laver, Essex, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Christ Church, Oxford (BA, 1656; MA, 1658; MB, 1675) |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | University of Oxford[7] Royal Society |

|

Main interests |

Metaphysics, epistemology, political philosophy, philosophy of mind, philosophy of education, economics |

|

Notable ideas |

List

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

John Locke’s portrait by Godfrey Kneller, National Portrait Gallery, London

John Locke FRS (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the «father of liberalism».[14][15][16] Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, Locke is equally important to social contract theory. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American Revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence.[17] Internationally, Locke’s political-legal principles continue to have a profound influence on the theory and practice of limited representative government and the protection of basic rights and freedoms under the rule of law.[18]

Locke’s theory of mind is often cited as the origin of modern conceptions of identity and the self, figuring prominently in the work of later philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant. Locke was the first to define the self through a continuity of consciousness.

He postulated that, at birth, the mind was a blank slate, or tabula rasa. Contrary to Cartesian philosophy based on pre-existing concepts, he maintained that we are born without innate ideas, and that knowledge is instead determined only by experience derived from sense perception, a concept now known as empiricism.[19]

Demonstrating the ideology of science in his observations, whereby something must be capable of being tested repeatedly and that nothing is exempt from being disproved, Locke stated that «whatever I write, as soon as I discover it not to be true, my hand shall be the forwardest to throw it into the fire». Such is one example of Locke’s belief in empiricism.

Early life

Locke was born on 29 August 1632, in a small thatched cottage by the church in Wrington, Somerset, about 12 miles from Bristol. He was baptised the same day, as both of his parents were Puritans. Locke’s father, also called John, was an attorney who served as clerk to the Justices of the Peace in Chew Magna[20] and as a captain of cavalry for the Parliamentarian forces during the early part of the English Civil War. His mother was Agnes Keene. Soon after Locke’s birth, the family moved to the market town of Pensford, about seven miles south of Bristol, where Locke grew up in a rural Tudor house in Belluton.

In 1647, Locke was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London under the sponsorship of Alexander Popham, a member of Parliament and John Sr.’s former commander. After completing studies there, he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford, in the autumn of 1652 at the age of 20. The dean of the college at the time was John Owen, vice-chancellor of the university. Although a capable student, Locke was irritated by the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He found the works of modern philosophers, such as René Descartes, more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. Through his friend Richard Lower, whom he knew from the Westminster School, Locke was introduced to medicine and the experimental philosophy being pursued at other universities and in the Royal Society, of which he eventually became a member.[citation needed]

Locke was awarded a bachelor’s degree in February 1656 and a master’s degree in June 1658.[7] He obtained a bachelor of medicine in February 1675,[21] having studied the subject extensively during his time at Oxford and, in addition to Lower, worked with such noted scientists and thinkers as Robert Boyle, Thomas Willis and Robert Hooke. In 1666, he met Anthony Ashley Cooper, Lord Ashley, who had come to Oxford seeking treatment for a liver infection. Ashley was impressed with Locke and persuaded him to become part of his retinue.

Career

Work

Locke had been looking for a career and in 1667 moved into Ashley’s home at Exeter House in London, to serve as his personal physician. In London, Locke resumed his medical studies under the tutelage of Thomas Sydenham. Sydenham had a major effect on Locke’s natural philosophical thinking – an effect that would become evident in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Locke’s medical knowledge was put to the test when Ashley’s liver infection became life-threatening. Locke coordinated the advice of several physicians and was probably instrumental in persuading Ashley to undergo surgery (then life-threatening in itself) to remove the cyst. Ashley survived and prospered, crediting Locke with saving his life.

During this time, Locke served as Secretary of the Board of Trade and Plantations and Secretary to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, which helped to shape his ideas on international trade and economics.[citation needed]

Ashley, as a founder of the Whig movement, exerted great influence on Locke’s political ideas. Locke became involved in politics when Ashley became Lord Chancellor in 1672 (Ashley being created 1st Earl of Shaftesbury in 1673). Following Shaftesbury’s fall from favour in 1675, Locke spent some time travelling across France as a tutor and medical attendant to Caleb Banks.[22] He returned to England in 1679 when Shaftesbury’s political fortunes took a brief positive turn. Around this time, most likely at Shaftesbury’s prompting, Locke composed the bulk of the Two Treatises of Government. While it was once thought that Locke wrote the Treatises to defend the Glorious Revolution of 1688, recent scholarship has shown that the work was composed well before this date.[23] The work is now viewed as a more general argument against absolute monarchy (particularly as espoused by Robert Filmer and Thomas Hobbes) and for individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy. Although Locke was associated with the influential Whigs, his ideas about natural rights and government are today considered quite revolutionary for that period in English history.

The Netherlands

Locke fled to the Netherlands in 1683, under strong suspicion of involvement in the Rye House Plot, although there is little evidence to suggest that he was directly involved in the scheme. The philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in Holland, Locke chose his friends «from among the same freethinking members of dissenting Protestant groups as Spinoza’s small group of loyal confidants. [Baruch Spinoza had died in 1677.] Locke almost certainly met men in Amsterdam who spoke of the ideas of that renegade Jew who… insisted on identifying himself through his religion of reason alone.» While she says that «Locke’s strong empiricist tendencies» would have «disinclined him to read a grandly metaphysical work such as Spinoza’s Ethics, in other ways he was deeply receptive to Spinoza’s ideas, most particularly to the rationalist’s well thought out argument for political and religious tolerance and the necessity of the separation of church and state.»[24] In the Netherlands, Locke had time to return to his writing, spending a great deal of time working on the Essay Concerning Human Understanding and composing the Letter on Toleration.

Return to England

Locke did not return home until after the Glorious Revolution. Locke accompanied Mary II back to England in 1688. The bulk of Locke’s publishing took place upon his return from exile – his aforementioned Essay Concerning Human Understanding, the Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration all appearing in quick succession.

Locke’s close friend Lady Masham invited him to join her at Otes, the Mashams’ country house in Essex. Although his time there was marked by variable health from asthma attacks, he nevertheless became an intellectual hero of the Whigs. During this period he discussed matters with such figures as John Dryden and Isaac Newton.

Death

He died on 28 October 1704, and is buried in the churchyard of the village of High Laver,[25] east of Harlow in Essex, where he had lived in the household of Sir Francis Masham since 1691. Locke never married nor had children.

Events that happened during Locke’s lifetime include the English Restoration, the Great Plague of London, the Great Fire of London, and the Glorious Revolution. He did not quite see the Act of Union of 1707, though the thrones of England and Scotland were held in personal union throughout his lifetime. Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy were in their infancy during Locke’s time.

Philosophy

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke’s Two Treatises were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the book, «except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense debate of the 1690s it made little impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made ‘a great noise’).»[26] John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke’s theories were «mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the [Glorious] Revolution, up to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them» and that «no one, including most Whigs, [was] ready for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated by Locke».[27]: 200 In contrast, Kenyon adds that Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government were «certainly much more influential than Locke’s Two Treatises.«[i][27]: 51

In the 50 years after Queen Anne’s death in 1714, the Two Treatises were reprinted only once (except in the collected works of Locke). However, with the rise of American resistance to British taxation, the Second Treatise of Government gained a new readership; it was frequently cited in the debates in both America and Britain. The first American printing occurred in 1773 in Boston.[28]

Locke exercised a profound influence on political philosophy, in particular on modern liberalism. Michael Zuckert has argued that Locke launched liberalism by tempering Hobbesian absolutism and clearly separating the realms of Church and State. He had a strong influence on Voltaire, who called him «le sage Locke». His arguments concerning liberty and the social contract later influenced the written works of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and other Founding Fathers of the United States. In fact, one passage from the Second Treatise is reproduced verbatim in the Declaration of Independence, the reference to a «long train of abuses». Such was Locke’s influence that Thomas Jefferson wrote:[29][30][31]

Bacon, Locke and Newton… I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences.

However, Locke’s influence may have been even more profound in the realm of epistemology. Locke redefined subjectivity, or self, leading intellectual historians such as Charles Taylor and Jerrold Seigel to argue that Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689/90) marks the beginning of the modern Western conception of the self.[32][33]

Locke’s theory of association heavily influenced the subject matter of modern psychology. At the time, Locke’s recognition of two types of ideas, simple and complex—and, more importantly, their interaction through association—inspired other philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley, to revise and expand this theory and apply it to explain how humans gain knowledge in the physical world.[34]

Religious tolerance

Writing his Letters Concerning Toleration (1689–1692) in the aftermath of the European wars of religion, Locke formulated a classic reasoning for religious tolerance, in which three arguments are central:[35]

- earthly judges, the state in particular, and human beings generally, cannot dependably evaluate the truth-claims of competing religious standpoints;

- even if they could, enforcing a single ‘true religion’ would not have the desired effect, because belief cannot be compelled by violence;

- coercing religious uniformity would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.

With regard to his position on religious tolerance, Locke was influenced by Baptist theologians like John Smyth and Thomas Helwys, who had published tracts demanding freedom of conscience in the early 17th century.[36][37][38][39] Baptist theologian Roger Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island in 1636, where he combined a democratic constitution with unlimited religious freedom. His tract, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644), which was widely read in the mother country, was a passionate plea for absolute religious freedom and the total separation of church and state.[40] Freedom of conscience had had high priority on the theological, philosophical, and political agenda, as Martin Luther refused to recant his beliefs before the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire at Worms in 1521, unless he would be proved false by the Bible.[41]

Slavery and child labour

Locke’s views on slavery were multifaceted and complex. Although he wrote against slavery in general, Locke was an investor and beneficiary of the slave trading Royal Africa Company. In addition, while secretary to the Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke participated in drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which established a quasi-feudal aristocracy and gave Carolinian planters absolute power over their enslaved chattel property; the constitutions pledged that «every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves». Philosopher Martin Cohen notes that Locke, as secretary to the Council of Trade and Plantations and a member of the Board of Trade, was «one of just half a dozen men who created and supervised both the colonies and their iniquitous systems of servitude».[42][43]

According to American historian James Farr, Locke never expressed any thoughts concerning his contradictory opinions regarding slavery, which Farr ascribes to his personal involvement in the slave trade.[44] Locke’s positions on slavery have been described as hypocritical, and laying the foundation for the Founding Fathers to hold similarly contradictory thoughts regarding freedom and slavery.[45]

Historian Holly Brewer has argued, however, that Locke’s role in the Constitution of Carolina has been exaggerated and that he was merely paid to revise and make copies of a document that had already been partially written before he became involved; she compares Locke’s role to a lawyer writing a will.[46] She further says that Locke was paid in Royal African Company stock in lieu of money for his work as a secretary for a governmental sub-committee and that he sold the stock after a few years.[47] Brewer likewise argues that Locke actively worked to undermine slavery in Virginia while heading a Board of Trade created by William of Orange following the Glorious Revolution. He specifically attacked colonial policy granting land to slave owners and encouraged the baptism and Christian education of the children of enslaved Africans to undercut a major justification of slavery—that they were heathens that possessed no rights.[48]

Locke also supported child labour. In his «Essay on the Poor Law», he turns to the education of the poor; he laments that «the children of labouring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labour also is generally lost to the public till they are 12 or 14 years old».[49]: 190 He suggests, therefore, that «working schools» be set up in each parish in England for poor children so that they will be «from infancy [three years old] inured to work».[49]: 190 He goes on to outline the economics of these schools, arguing not only that they will be profitable for the parish, but also that they will instill a good work ethic in the children.[49]: 191

Government

Locke’s political theory was founded upon that of social contract. Unlike Thomas Hobbes, Locke believed that human nature is characterised by reason and tolerance. Like Hobbes, however, Locke believed that human nature allows people to be selfish. This is apparent with the introduction of currency. In a natural state, all people were equal and independent, and everyone had a natural right to defend his «life, health, liberty, or possessions».[50]: 198 Most scholars trace the phrase «Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness» in the American Declaration of Independence to Locke’s theory of rights,[51] although other origins have been suggested.[52]

Like Hobbes, Locke assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not enough, so people established a civil society to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government in a state of society. However, Locke never refers to Hobbes by name and may instead have been responding to other writers of the day.[53] Locke also advocated governmental separation of powers and believed that revolution is not only a right but an obligation in some circumstances. These ideas would come to have profound influence on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

Accumulation of wealth

According to Locke, unused property is wasteful and an offence against nature,[54] but, with the introduction of «durable» goods, men could exchange their excessive perishable goods for those which would last longer and thus not offend the natural law. In his view, the introduction of money marked the culmination of this process, making possible the unlimited accumulation of property without causing waste through spoilage.[55] He also includes gold or silver as money because they may be «hoarded up without injury to anyone»,[56] as they do not spoil or decay in the hands of the possessor. In his view, the introduction of money eliminates limits to accumulation. Locke stresses that inequality has come about by tacit agreement on the use of money, not by the social contract establishing civil society or the law of land regulating property. Locke is aware of a problem posed by unlimited accumulation, but does not consider it his task. He just implies that government would function to moderate the conflict between the unlimited accumulation of property and a more nearly equal distribution of wealth; he does not identify which principles that government should apply to solve this problem. However, not all elements of his thought form a consistent whole. For example, the labour theory of value in the Two Treatises of Government stands side by side with the demand-and-supply theory of value developed in a letter he wrote titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money. Moreover, Locke anchors property in labour but, in the end, upholds unlimited accumulation of wealth.[57]

Ideas

Economics

On price theory

Locke’s general theory of value and price is a supply-and-demand theory, set out in a letter to a member of parliament in 1691, titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money.[58] In it, he refers to supply as quantity and demand as rent: «The price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers» and «that which regulates the price…[of goods] is nothing else but their quantity in proportion to their rent.»

The quantity theory of money forms a special case of this general theory. His idea is based on «money answers all things» (Ecclesiastes) or «rent of money is always sufficient, or more than enough» and «varies very little». Locke concludes that, as far as money is concerned, the demand for it is exclusively regulated by its quantity, regardless of whether the demand is unlimited or constant. He also investigates the determinants of demand and supply. For supply, he explains the value of goods as based on their scarcity and ability to be exchanged and consumed. He explains demand for goods as based on their ability to yield a flow of income. Locke develops an early theory of capitalisation, such as of land, which has value because «by its constant production of saleable commodities it brings in a certain yearly income». He considers the demand for money as almost the same as demand for goods or land: it depends on whether money is wanted as medium of exchange. As a medium of exchange, he states, «money is capable by exchange to procure us the necessaries or conveniences of life» and, for loanable funds, «it comes to be of the same nature with land by yielding a certain yearly income…or interest».

Monetary thoughts

Locke distinguishes two functions of money: as a counter to measure value, and as a pledge to lay claim to goods. He believes that silver and gold, as opposed to paper money, are the appropriate currency for international transactions. Silver and gold, he says, are treated to have equal value by all of humanity and can thus be treated as a pledge by anyone, while the value of paper money is only valid under the government which issues it.

Locke argues that a country should seek a favourable balance of trade, lest it fall behind other countries and suffer a loss in its trade. Since the world money stock grows constantly, a country must constantly seek to enlarge its own stock. Locke develops his theory of foreign exchanges, in addition to commodity movements, there are also movements in country stock of money, and movements of capital determine exchange rates. He considers the latter less significant and less volatile than commodity movements. As for a country’s money stock, if it is large relative to that of other countries, he says it will cause the country’s exchange to rise above par, as an export balance would do.

He also prepares estimates of the cash requirements for different economic groups (landholders, labourers, and brokers). In each group he posits that the cash requirements are closely related to the length of the pay period. He argues the brokers—the middlemen—whose activities enlarge the monetary circuit and whose profits eat into the earnings of labourers and landholders, have a negative influence on both personal and the public economy to which they supposedly contribute.[citation needed]

Theory of value and property

Locke uses the concept of property in both broad and narrow terms: broadly, it covers a wide range of human interests and aspirations; more particularly, it refers to material goods. He argues that property is a natural right that is derived from labour. In Chapter V of his Second Treatise, Locke argues that the individual ownership of goods and property is justified by the labour exerted to produce such goods—»at least where there is enough [land], and as good, left in common for others» (para. 27)—or to use property to produce goods beneficial to human society.[59]

Locke states in his Second Treatise that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of goods gives them their value. From this premise, understood as a labour theory of value,[59] Locke developed a labour theory of property, whereby ownership of property is created by the application of labour. In addition, he believed that property precedes government and government cannot «dispose of the estates of the subjects arbitrarily». Karl Marx later critiqued Locke’s theory of property in his own social theory.[citation needed]

The human mind

The self

Locke defines the self as «that conscious thinking thing, (whatever substance, made up of whether spiritual, or material, simple, or compounded, it matters not) which is sensible, or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so is concerned for itself, as far as that consciousness extends».[60] He does not, however, wholly ignore «substance», writing that «the body too goes to the making the man».[61]

In his Essay, Locke explains the gradual unfolding of this conscious mind. Arguing against both the Augustinian view of man as originally sinful and the Cartesian position, which holds that man innately knows basic logical propositions, Locke posits an ’empty mind’, a tabula rasa, which is shaped by experience; sensations and reflections being the two sources of all of our ideas.[62] He states in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding:

This source of ideas every man has wholly within himself; and though it be not sense, as having nothing to do with external objects, yet it is very like it, and might properly enough be called ‘internal sense.’[63]

Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education is an outline on how to educate this mind. Drawing on thoughts expressed in letters written to Mary Clarke and her husband about their son,[64] he expresses the belief that education makes the man—or, more fundamentally, that the mind is an «empty cabinet»:[65]

I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education.

Locke also wrote that «the little and almost insensible impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting consequences».[65] He argues that the «associations of ideas» that one makes when young are more important than those made later because they are the foundation of the self; they are, put differently, what first mark the tabula rasa. In his Essay, in which both these concepts are introduced, Locke warns, for example, against letting «a foolish maid» convince a child that «goblins and sprites» are associated with the night, for «darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other».[66]

This theory came to be called associationism, going on to strongly influence 18th-century thought, particularly educational theory, as nearly every educational writer warned parents not to allow their children to develop negative associations. It also led to the development of psychology and other new disciplines with David Hartley’s attempt to discover a biological mechanism for associationism in his Observations on Man (1749).

Dream argument

Locke was critical of Descartes’s version of the dream argument, with Locke making the counter-argument that people cannot have physical pain in dreams as they do in waking life.[67]

Religion

Religious beliefs

Some scholars have seen Locke’s political convictions as being based from his religious beliefs.[68][69][70] Locke’s religious trajectory began in Calvinist trinitarianism, but by the time of the Reflections (1695) Locke was advocating not just Socinian views on tolerance but also Socinian Christology.[71] However Wainwright (1987) notes that in the posthumously published Paraphrase (1707) Locke’s interpretation of one verse, Ephesians 1:10, is markedly different from that of Socinians like Biddle, and may indicate that near the end of his life Locke returned nearer to an Arian position, thereby accepting Christ’s pre-existence.[72][71]

Locke was at times not sure about the subject of original sin, so he was accused of Socinianism, Arianism, or Deism.[73] Locke argued that the idea that «all Adam’s Posterity [are] doomed to Eternal Infinite Punishment, for the Transgression of Adam» was «little consistent with the Justice or Goodness of the Great and Infinite God», leading Eric Nelson to associate him with Pelagian ideas.[74] However, he did not deny the reality of evil. Man was capable of waging unjust wars and committing crimes. Criminals had to be punished, even with the death penalty.[75]

With regard to the Bible, Locke was very conservative. He retained the doctrine of the verbal inspiration of the Scriptures.[36] The miracles were proof of the divine nature of the biblical message. Locke was convinced that the entire content of the Bible was in agreement with human reason (The Reasonableness of Christianity, 1695).[76][36] Although Locke was an advocate of tolerance, he urged the authorities not to tolerate atheism, because he thought the denial of God’s existence would undermine the social order and lead to chaos.[77] That excluded all atheistic varieties of philosophy and all attempts to deduce ethics and natural law from purely secular premises.[78] In Locke’s opinion the cosmological argument was valid and proved God’s existence. His political thought was based on Protestant Christian views.[78][79] Additionally, Locke advocated a sense of piety out of gratitude to God for giving reason to men.[80]

Philosophy from religion

Locke’s concept of man started with the belief in creation.[81] Like philosophers Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf, Locke equated natural law with the biblical revelation.[82][83][84] Locke derived the fundamental concepts of his political theory from biblical texts, in particular from Genesis 1 and 2 (creation), the Decalogue, the Golden Rule, the teachings of Jesus, and the letters of Paul the Apostle.[85] The Decalogue puts a person’s life, reputation and property under God’s protection.

Locke’s philosophy on freedom is also derived from the Bible. Locke derived from the Bible basic human equality (including equality of the sexes), the starting point of the theological doctrine of Imago Dei.[86] To Locke, one of the consequences of the principle of equality was that all humans were created equally free and therefore governments needed the consent of the governed.[87] Locke compared the English monarchy’s rule over the British people to Adam’s rule over Eve in Genesis, which was appointed by God.[88]

Following Locke’s philosophy, the American Declaration of Independence founded human rights partially on the biblical belief in creation. Locke’s doctrine that governments need the consent of the governed is also central to the Declaration of Independence.[89]

Library

Manuscripts, books and treatises

Locke’s signature in Bodleian Locke 13.12. Photo taken at the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Locke was an assiduous book collector and notetaker throughout his life. By his death in 1704, Locke had amassed a library of more than 3,000 books, a significant number in the seventeenth century.[90] Unlike some of his contemporaries, Locke took care to catalogue and preserve his library, and his will made specific provisions for how his library was to be distributed after his death. Locke’s will offered Lady Masham the choice of «any four folios, eight quartos and twenty books of less volume, which she shall choose out of the books in my Library.»[91] Locke also gave six titles to his “good friend” Anthony Collins, but Locke bequeathed the majority of his collection to his cousin Peter King (later Lord King) and to Lady Masham’s son, Francis Cudworth Masham.[91]

Francis Masham was promised one “moiety” (half) of Locke’s library when he reached “the age of one and twenty years.”[91] The other “moiety” of Locke’s books, along with his manuscripts, passed to his cousin King.[91] Over the next two centuries, the Masham portion of Locke’s library was dispersed.[92] The manuscripts and books left to King, however, remained with King’s descendants (later the Earls of Lovelace), until most of the collection was bought by the Bodleian Library, Oxford in 1947.[93] Another portion of the books Locke left to King was discovered by the collector and philanthropist Paul Mellon in 1951.[93] Mellon supplemented this discovery with books from Locke’s library which he bought privately, and in 1978, he transferred his collection to the Bodleian.[93] The holdings in the Locke Room at the Bodleian have been a valuable resource for scholars interested in Locke, his philosophy, practices for information management, and the history of the book.

Many of the books still contain Locke’s signature, which he often made on the pastedowns of his books. Many also include Locke’s marginalia.

The printed books in Locke’s library reflected his various intellectual interests as well as his movements at different stages of his life. Locke travelled extensively in France and the Netherlands during the 1670s and 1680s, and during this time he acquired many books from the continent. Only half of the books in Locke’s library were printed in England, while close to 40% came from France and the Netherlands.[94] These books cover a wide range of subjects. According to John Harrison and Peter Laslett, the largest genres in Locke’s library were theology (23.8% of books), medicine (11.1%), politics and law (10.7%), and classical literature (10.1%).[95] The Bodleian library currently holds more than 800 of the books from Locke’s library.[93] These include Locke’s copies of works by several of the most influential figures of the seventeenth century, including

- The Quaker William Penn: An address to Protestants of all perswasions (Bodleian Locke 7.69a)

- The explorer Francis Drake: The world encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (Bodleian Locke 8.37c)

- The scientist Robert Boyle: A discourse of things above reason (Bodleian Locke 7.272)

- The bishop and historian Thomas Sprat: The history of the Royal-Society of London (Bodleian Locke 9.10a)

In addition to books owned by Locke, the Bodleian also possesses more than 100 manuscripts related to Locke or written in his hand. Like the books in Locke’s library, these manuscripts display a range of interests and provide different windows into Locke’s activity and relationships. Several of the manuscripts include letters to and from acquaintances like Peter King (MS Locke b. 6) and Nicolas Toinard (MS Locke c. 45).[96] MS Locke f. 1–10 contain Locke’s journals for most years between 1675 and 1704.[96] Some of the most significant manuscripts include early drafts of Locke’s writings, such as his Essay concerning human understanding (MS Locke f. 26).[96] The Bodleian also holds a copy of Robert Boyle’s General History of the Air with corrections and notes Locke made while preparing Boyle’s work for posthumous publication (MS Locke c. 37 ).[97] Other manuscripts contain unpublished works. Among others, MS. Locke e. 18 includes some of Locke’s thoughts on the Glorious Revolution, which Locke sent to his friend Edward Clarke but never published.[98]

One of the largest categories of manuscript at the Bodleian comprises Locke’s notebooks and commonplace books. The scholar Richard Yeo calls Locke a «Master Note-taker» and explains that «Locke’s methodical note-taking pervaded most areas of his life.»[99] In an unpublished essay “Of Study,” Locke argued that a notebook should work like a “chest-of-drawers” for organizing information, which would be a «great help to the memory and means to avoid confusion in our thoughts.»[100] Locke kept several notebooks and commonplace books, which he organized according to topic. MS Locke c. 43 includes Locke’s notes on theology, while MS Locke f. 18–24 contain medical notes.[96] Other notebooks, such as MS c. 43, incorporate several topics in the same notebook, but separated into sections.[96]

Page 1 of Locke’s unfinished index in Bodleian Locke 13.12. Photo taken at the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

These commonplace books were highly personal and were designed to be used by Locke himself rather than accessible to a wide audience.[101] Locke’s notes are often abbreviated and are full of codes which he used to reference material across notebooks.[102] Another way Locke personalized his notebooks was by devising his own method of creating indexes using a grid system and Latin keywords.[103] Instead of recording entire words, his indexes shortened words to their first letter and vowel. Thus, the word «Epistle» would be classified as «Ei».[104] Locke published his method in French in 1686, and it was republished posthumously in English in 1706.

Some of the books in Locke’s library at the Bodleian are a combination of manuscript and print. Locke had some of his books interleaved, meaning that they were bound with blank sheets in-between the printed pages to enable annotations. Locke interleaved and annotated his five volumes of the New Testament in French, Greek, and Latin (Bodleian Locke 9.103-107). Locke did the same with his copy of Thomas Hyde’s Bodleian Library catalogue (Bodleian Locke 16.17), which Locke used to create a catalogue of his own library.[105]

Writing

List of major works

- 1689. A Letter Concerning Toleration.

- 1690. A Second Letter Concerning Toleration

- 1692. A Third Letter for Toleration

- 1689/90. Two Treatises of Government (published throughout the 18th century by London bookseller Andrew Millar by commission for Thomas Hollis)[106]

- 1689/90. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- 1691. Some Considerations on the consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money

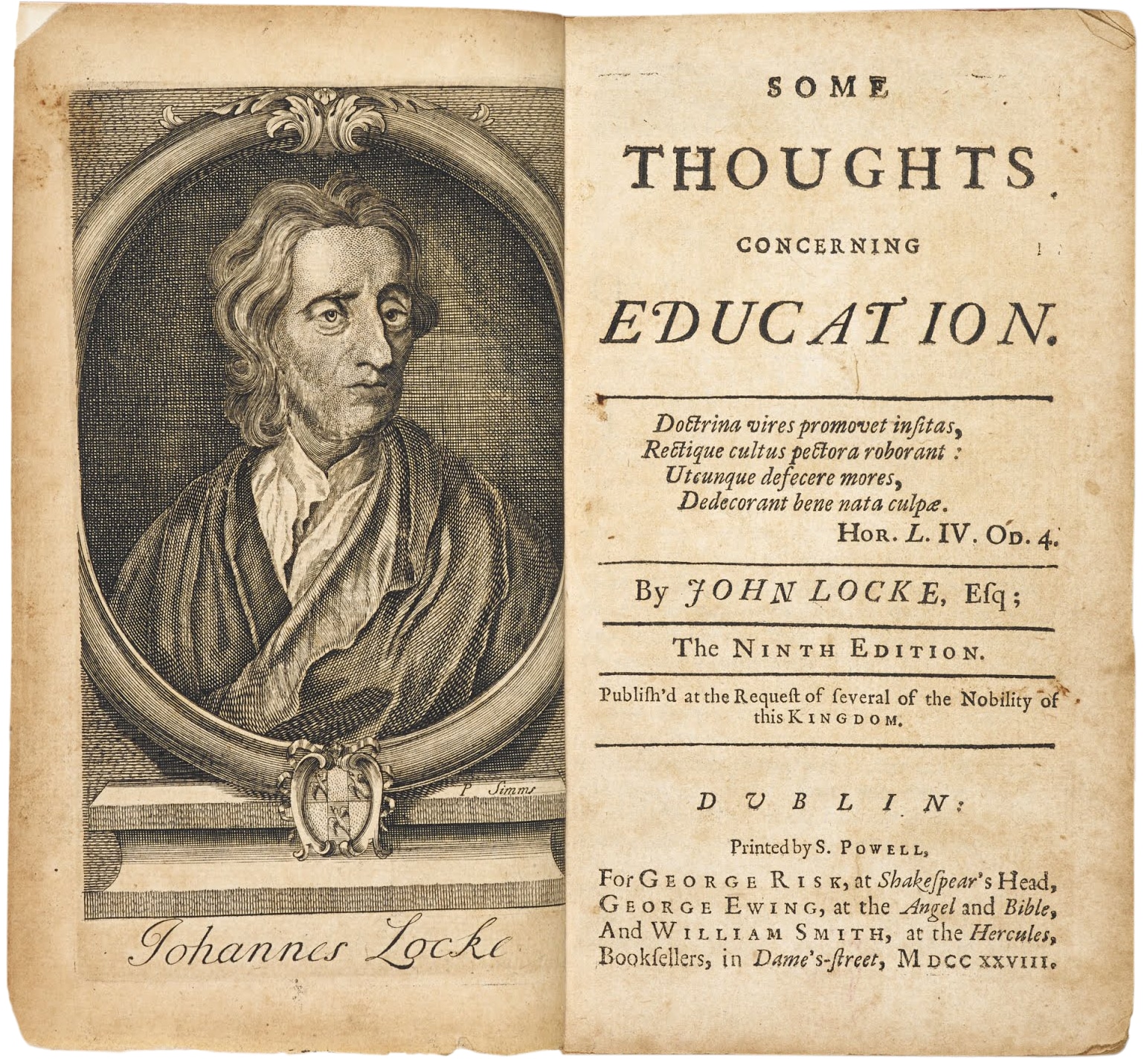

- 1693. Some Thoughts Concerning Education

- 1695. The Reasonableness of Christianity, as Delivered in the Scriptures

- 1695. A Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity

Major posthumous manuscripts

- 1660. First Tract of Government (or the English Tract)

- c.1662. Second Tract of Government (or the Latin Tract)

- 1664. Questions Concerning the Law of Nature.[107]

- 1667. Essay Concerning Toleration

- 1706. Of the Conduct of the Understanding

- 1707. A paraphrase and notes on the Epistles of St. Paul to the Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Ephesians

See also

- List of liberal theorists

References

Notes

- ^ Kenyon (1977) adds: «Any unbiassed study of the position shows in fact that it was Filmer, not Hobbes, Locke or Sidney, who was the most influential thinker of the age» (p. 63).

Citations

- ^ Fumerton, Richard (2000). «Foundationalist Theories of Epistemic Justification». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ David Bostock (2009). Philosophy of Mathematics: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 43.

All of Descartes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume supposed that mathematics is a theory of our ideas, but none of them offered any argument for this conceptualist claim, and apparently took it to be uncontroversial.

- ^ John W. Yolton (2000). Realism and Appearances: An Essay in Ontology. Cambridge University Press. p. 136.

- ^ «The Correspondence Theory of Truth». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2020.

- ^ Grigoris Antoniou; John Slaney, eds. (1998). Advanced Topics in Artificial Intelligence. Springer. p. 9.

- ^ Vere Claiborne Chappell, ed. (1994). The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge University Press. p. 56.

- ^ a b Uzgalis, William (1 May 2018) [September 2, 2001]. «John Locke». In E. N. Zalta (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Fallacies: classical and contemporary readings. Hansen, Hans V., Pinto, Robert C. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. 1995. ISBN 978-0-271-01416-6. OCLC 30624864.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Locke, John (1690). «Book IV, Chapter XVII: Of Reason». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). Two Treatises of Government (10th edition): Chapter II, Section 6. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Broad, Jacqueline (2006). «A Woman’s Influence? John Locke and Damaris Masham on Moral Accountability». Journal of the History of Ideas. 67 (3): 489–510. doi:10.1353/jhi.2006.0022. JSTOR 30141038. S2CID 170381422.

- ^ a b Ducheyne, Steffen (2009). «The Flow of Influence: From Newton to Locke … And Back». Rivista di Storia della Filosofia (1984-). 64 (2): 245–268. doi:10.3280/SF2009-002001. ISSN 0393-2516. JSTOR 44024132.

- ^ a b Rogers, G. A. J. (1978). «Locke’s Essay and Newton’s Principia». Journal of the History of Ideas. 39 (2): 217–232. doi:10.2307/2708776. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708776.

- ^ Hirschmann, Nancy J. (2009). Gender, Class, and Freedom in Modern Political Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 79.

- ^ Sharma, Urmila; S. K. Sharma (2006). Western Political Thought. Washington: Atlantic Publishers. p. 440.

- ^ Korab-Karpowicz, W. Julian (2010). A History of Political Philosophy: From Thucydides to Locke. New York: Global Scholarly Publications. p. 291.

- ^ Becker, Carl Lotus (1922). The Declaration of Independence: a Study in the History of Political Ideas. New York: Harcourt, Brace. p. 27.

- ^ Foreword and study guide to John Locke’s Two Treatises on Government: A Translation into Modern English, ISR Publications, 2013, page ii. ISBN 9780906321690

- ^ Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 527–29. ISBN 978-0-13-158591-1.

- ^ Broad, C. D. (2000). Ethics And the History of Philosophy. UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22530-4.

- ^ Roger Woolhouse (2007). Locke: A Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 116.

- ^ Henning, Basil Duke (1983), The House of Commons, 1660–1690, vol. 1, ISBN 978-0-436-19274-6, retrieved 28 August 2012

- ^ Laslett 1988, III. Two Treatises of Government and the Revolution of 1688.

- ^ Rebecca Newberger Goldstein (2006). Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 260–61.

- ^ Rogers, Graham A. J. «John Locke». Britannica Online. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Hoppit, Julian (2000). A Land of Liberty? England. 1689–1727. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 195.

- ^ a b Kenyon, John (1977). Revolution Principles: The Politics of Party. 1689–1720. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Milton, John R. (2008) [2004]. «Locke, John (1632–1704)». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16885. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «The Three Greatest Men». American Treasures of the Library of Congress. Library of Congress. August 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

Jefferson identified Bacon, Locke, and Newton as «the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception». Their works in the physical and moral sciences were instrumental in Jefferson’s education and world view.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas. «The Letters: 1743–1826 Bacon, Locke, and Newton». Archived from the original on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

Bacon, Locke and Newton, whose pictures I will trouble you to have copied for me: and as I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical & Moral sciences.

- ^ «Jefferson called Bacon, Newton, and Locke, who had so indelibly shaped his ideas, «my trinity of the three greatest men the world had ever produced»«. Explorer. Monticello. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Seigel, Jerrold (2005). The Idea of the Self: Thought and Experience in Western Europe since the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Taylor, Charles (1989). Sources of the Self: The Making of Modern Identity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Schultz, Duane P. (2008). A History of Modern Psychology (ninth ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomas Higher Education. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-495-09799-0.

- ^ McGrath, Alister (1998). Historical Theology, An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 214–15.

- ^ a b c Heussi 1956.

- ^ Olmstead 1960, p. 18.

- ^ Stahl, H. (1957). «Baptisten». Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German). 3 (1), col. 863

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Halbrooks, G. Thomas; Erich Geldbach; Bill J. Leonard; Brian Stanley (2011). «Baptists». Religion Past and Present. doi:10.1163/1877-5888_rpp_COM_01472. ISBN 978-90-04-14666-2. Retrieved 2 June 2020..

- ^ Olmstead 1960, pp. 102–05.

- ^ Olmstead 1960, p. 5.

- ^ Cohen, Martin (2008), Philosophical Tales, Blackwell, p. 101.

- ^ Tully, James (2007), An Approach to Political Philosophy: Locke in Contexts, New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 128, ISBN 978-0-521-43638-0

- ^ Farr, J. (1986). «I. ‘So Vile and Miserable an Estate’: The Problem of Slavery in Locke’s Political Thought». Political Theory. 14 (2): 263–89. doi:10.1177/0090591786014002005. JSTOR 191463. S2CID 145020766..

- ^ Farr, J. (2008). «Locke, Natural Law, and New World Slavery». Political Theory. 36 (4): 495–522. doi:10.1177/0090591708317899. S2CID 159542780..

- ^ Brewer 2017, p. 1052.

- ^ Brewer 2017, pp. 1053–1054.

- ^ Brewer 2017, pp. 1066 & 1072.

- ^ a b c Locke, John (1997a). «An Essay on the Poor Law». In Mark Goldie (ed.). Locke: Political Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Locke, John. [1690] 2017. Second Treatise of Government (10th ed.), digitized by D. Gowan. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Zuckert, Michael (1996), The Natural Rights Republic, Notre Dame University Press, pp. 73–85

- ^ Wills, Garry (2002), Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co

- ^ Skinner, Quentin, Visions of Politics, Cambridge.

- ^ Locke, John (2009), Two Treatises on Government: A Translation into Modern English, Industrial Systems Research, p. 81, ISBN 978-0-906321-47-8

- ^ «John Locke: Inequality is inevitable and necessary». Department of Philosophy The University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original (MS PowerPoint) on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Locke, John. «Second Treatise». The Founders Constitution. §§ 25–51, 123–26. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Cliff, Cobb; Foldvary, Fred. «John Locke on Property». The School of Cooperative Individualism. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Locke, John (1691), Some Considerations on the consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money, Marxists.

- ^ a b Vaughn, Karen (1978). «John Locke and the Labor Theory of Value» (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 2 (4): 311–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Locke 1997b, p. 307.

- ^ Locke 1997b, p. 306.

- ^ The American International Encyclopedia, vol. 9, New York: JJ Little Co, 1954.

- ^ Angus, Joseph (1880). The Handbook of Specimens of English Literature. London: William Clowes and Sons. p. 324.

- ^ «Clarke [née Jepp], Mary». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/66720. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Locke 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Locke 1997b, p. 357.

- ^ «Dreaming, Philosophy of – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy». utm.edu.

- ^ Forster, Greg (2005), John Locke’s politics of moral consensus.

- ^ Parker, Kim Ian (2004), The Biblical Politics of John Locke, Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion.

- ^ Locke, John (2002), Nuovo, Victor (ed.), Writings on religion, Oxford.

- ^ a b Marshall, John (1994), John Locke: resistance, religion and responsibility, Cambridge, p. 426.

- ^ Wainwright, Arthur, W., ed. (1987). The Clarendon Edition of the Works of John Locke: A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistle of St. Paul to the Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Ephesians. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 806. ISBN 978-0-19-824806-4.

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 27, 223.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Henrich, D (1960), «Locke, John», Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German), 3. Auflage, Band IV, Spalte 426

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 217 ff.

- ^ a b Waldron 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Dunn, John (1969), The Political Thought of John Locke: A Historical Account of the Argument of the ‘Two Treatises of Government’, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 99,

[The Two Treatises of Government are] saturated with Christian assumptions.

. - ^ Wolterstorff, Nicholas. 1994. «John Locke’s Epistemological Piety: Reason Is The Candle Of The Lord.» Faith and Philosophy 11(4):572–91.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 142.

- ^ Elze, M (1958), «Grotius, Hugo», Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German) 2(3):1885–86.

- ^ Hohlwein, H (1961), «Pufendorf, Samuel Freiherr von», Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German), 5(3):721.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 22–43, 45–46, 101, 153–58, 195, 197.

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 21–43.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 136.

- ^ Locke, John (1947). Two Treatises of Government. New York: Hafner Publishing Company. pp. 17–18, 35, 38.

- ^ Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. 1922. Google Book Search. Revised edition New York: Vintage Books, 1970. ISBN 978-0-394-70060-1.

- ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Quoted in Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 8.

- ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 57–61.

- ^ a b c d Bodleian Library. «Rare Books Named Collections».

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 20.

- ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Clapinson, M, and TD Rogers. 1991. Summary Catalogue of Post-Medieval Western Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press.

- ^ The works of Robert Boyle, vol. 12. Edited by Michael Hunter and Edward B. Davis. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2000, pp. xviii–xxi.

- ^ James Farr and Clayton Robers. “John Locke on the Glorious Revolution: a Rediscovered Document” Historical Journal 28 (1985): 395–98.

- ^ Richard Yeo, Notebooks, English Virtuosi (University of Chicago Press, 2014), 183.

- ^ John Locke, The Educational Writings of John Locke, ed. James Axtell (Cambridge University Press, 1968), 421.

- ^ Richard Yeo, Notebooks, English Virtuosi (University of Chicago Press, 2014), 218.

- ^ G. G. Meynell, “John Locke’s Method of Common-Placing, as seen in His Drafts and His Medical Notebooks, Bodleian MSS Locke d. 9, f. 21 and f. 23,” The Seventeenth Century 8, no. 2 (1993): 248.

- ^ Michael Stolberg, “John Locke’s ‘New Method of Making Common-Place-Books’: Tradition, Innovation and Epistemic Effects,” Early Science and Medicine 19, no. 5 (2014): 448–70.

- ^ John Locke, A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books (London: Printed for J. Greenood, 1706), 4.

- ^ G. G. Meynell, “A Database for John Locke’s Medical Notebooks and Medical Reading,” Medical History 42 (1997): 478

- ^ «The manuscripts, Letter from Andrew Millar to Thomas Cadell, 16 July, 1765. University of Edinburgh». www.millar-project.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Locke, John. [1664] 1990. Questions Concerning the Law of Nature (definitive Latin text), translated by R. Horwitz, et al. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sources

- Ashcraft, Richard, 1986. Revolutionary Politics & Locke’s Two Treatises of Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Discusses the relationship between Locke’s philosophy and his political activities.

- Ayers, Michael, 1991. Locke. Epistemology & Ontology Routledge (the standard work on Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding.)

- Bailyn, Bernard, 1992 (1967). The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Harvard Uni. Press. Discusses the influence of Locke and other thinkers upon the American Revolution and on subsequent American political thought.

- Brewer, Holly (October 2017). «Slavery, Sovereignty, and «Inheritable Blood»: Reconsidering John Locke and the Origins of American Slavery». American Historical Review. 122 (4): 1038–1078. doi:10.1093/ahr/122.4.1038.

- Cohen, Gerald, 1995. ‘Marx and Locke on Land and Labour’, in his Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality, Oxford University Press.

- Cox, Richard, Locke on War and Peace, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960. A discussion of Locke’s theory of international relations.

- Chappell, Vere, ed., 1994. The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge U.P. excerpt and text search

- Dunn, John, 1984. Locke. Oxford Uni. Press. A succinct introduction.

- ———, 1969. The Political Thought of John Locke: An Historical Account of the Argument of the «Two Treatises of Government». Cambridge Uni. Press. Introduced the interpretation which emphasises the theological element in Locke’s political thought.

- Heussi, Karl (1956), Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte (in German), Tübingen, DE

- Hudson, Nicholas, «John Locke and the Tradition of Nominalism,» in: Nominalism and Literary Discourse, ed. Hugo Keiper, Christoph Bode, and Richard Utz (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997), pp. 283–99.

- Laslett, Peter (1988), Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press to Locke, John, Two Treatises of Government

- Locke, John (1996), Grant, Ruth W; Tarcov, Nathan (eds.), Some Thoughts Concerning Education and of the Conduct of the Understanding, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co, p. 10

- Locke, John (1997b), Woolhouse, Roger (ed.), An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, New York: Penguin Books

- Locke Studies, appearing annually from 2001, formerly The Locke Newsletter (1970–2000), publishes scholarly work on John Locke.

- Mack, Eric (2008). «Locke, John (1632–1704)». In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 305–07. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n184. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Macpherson, C.B. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962). Establishes the deep affinity from Hobbes to Harrington, the Levellers, and Locke through to nineteenth-century utilitarianism.

- Moseley, Alexander (2007), John Locke: Continuum Library of Educational Thought, Continuum, ISBN 978-0-8264-8405-5

- Nelson, Eric (2019). The Theology of Liberalism: Political Philosophy and the Justice of God. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-24094-0.

- Olmstead, Clifton E (1960), History of Religion in the United States, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

- Robinson, Dave; Groves, Judy (2003), Introducing Political Philosophy, Icon Books, ISBN 978-1-84046-450-4

- Rousseau, George S. (2004), Nervous Acts: Essays on Literature, Culture and Sensibility, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-4039-3453-6

- Tully, James, 1980. A Discourse on Property : John Locke and his Adversaries. Cambridge Uni. Press

- Waldron, Jeremy (2002), God, Locke, and Equality: Christian Foundations in Locke’s Political Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-89057-1

- Yolton, John W., ed., 1969. John Locke: Problems and Perspectives. Cambridge Uni. Press.

- Yolton, John W., ed., 1993. A Locke Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Zuckert, Michael, Launching Liberalism: On Lockean Political Philosophy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

External links

Works

- Works by John Locke in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- The Clarendon Edition of the Works of John Locke

- Of the Conduct of the Understanding

- Works by John Locke at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Locke at Internet Archive

- Works by John Locke at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Work by John Locke at Online Books

- The Works of John Locke

- 1823 Edition, 10 volumes on PDF files, and additional resources

- John Locke Manuscripts

- Updated versions of Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Second Treatise of Government, Letter on Toleration and Conduct of the Understanding, edited (i.e. modernized and abridged) by Jonathan Bennett

Resources

- «John Locke». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «John Locke: Epistemology». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «John Locke: Political Philosophy». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Rickless, Samuel. «Locke on Freedom». In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- John Locke Bibliography

- Locke Studies An Annual Journal of Locke Research

- Hewett, Caspar, John Locke’s Theory of Knowledge, UK: The great debate.

- The Digital Locke Project, NL, archived from the original on 1 January 2014, retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Portraits of Locke, UK: NPG.

- Huyler, Jerome, Was Locke a Liberal? (PDF), Independent, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009, retrieved 2 August 2008, a complex and positive answer.

- Kraynak, Robert P. (March 1980). «John Locke: from absolutism to toleration». American Political Science Review. 74 (1): 53–69. doi:10.2307/1955646. JSTOR 1955646. S2CID 146901427.

- Anstey, Peter, John Locke and Natural Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2011.

|

John Locke FRS |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Locke in 1697 by Godfrey Kneller |

|

| Born |

John Locke 29 August 1632 Wrington, Somerset, England |

| Died | 28 October 1704 (aged 72)

High Laver, Essex, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Christ Church, Oxford (BA, 1656; MA, 1658; MB, 1675) |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | University of Oxford[7] Royal Society |

|

Main interests |

Metaphysics, epistemology, political philosophy, philosophy of mind, philosophy of education, economics |

|

Notable ideas |

List

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

John Locke’s portrait by Godfrey Kneller, National Portrait Gallery, London

John Locke FRS (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the «father of liberalism».[14][15][16] Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, Locke is equally important to social contract theory. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American Revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence.[17] Internationally, Locke’s political-legal principles continue to have a profound influence on the theory and practice of limited representative government and the protection of basic rights and freedoms under the rule of law.[18]

Locke’s theory of mind is often cited as the origin of modern conceptions of identity and the self, figuring prominently in the work of later philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant. Locke was the first to define the self through a continuity of consciousness.

He postulated that, at birth, the mind was a blank slate, or tabula rasa. Contrary to Cartesian philosophy based on pre-existing concepts, he maintained that we are born without innate ideas, and that knowledge is instead determined only by experience derived from sense perception, a concept now known as empiricism.[19]

Demonstrating the ideology of science in his observations, whereby something must be capable of being tested repeatedly and that nothing is exempt from being disproved, Locke stated that «whatever I write, as soon as I discover it not to be true, my hand shall be the forwardest to throw it into the fire». Such is one example of Locke’s belief in empiricism.

Early life

Locke was born on 29 August 1632, in a small thatched cottage by the church in Wrington, Somerset, about 12 miles from Bristol. He was baptised the same day, as both of his parents were Puritans. Locke’s father, also called John, was an attorney who served as clerk to the Justices of the Peace in Chew Magna[20] and as a captain of cavalry for the Parliamentarian forces during the early part of the English Civil War. His mother was Agnes Keene. Soon after Locke’s birth, the family moved to the market town of Pensford, about seven miles south of Bristol, where Locke grew up in a rural Tudor house in Belluton.

In 1647, Locke was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London under the sponsorship of Alexander Popham, a member of Parliament and John Sr.’s former commander. After completing studies there, he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford, in the autumn of 1652 at the age of 20. The dean of the college at the time was John Owen, vice-chancellor of the university. Although a capable student, Locke was irritated by the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He found the works of modern philosophers, such as René Descartes, more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. Through his friend Richard Lower, whom he knew from the Westminster School, Locke was introduced to medicine and the experimental philosophy being pursued at other universities and in the Royal Society, of which he eventually became a member.[citation needed]

Locke was awarded a bachelor’s degree in February 1656 and a master’s degree in June 1658.[7] He obtained a bachelor of medicine in February 1675,[21] having studied the subject extensively during his time at Oxford and, in addition to Lower, worked with such noted scientists and thinkers as Robert Boyle, Thomas Willis and Robert Hooke. In 1666, he met Anthony Ashley Cooper, Lord Ashley, who had come to Oxford seeking treatment for a liver infection. Ashley was impressed with Locke and persuaded him to become part of his retinue.

Career

Work

Locke had been looking for a career and in 1667 moved into Ashley’s home at Exeter House in London, to serve as his personal physician. In London, Locke resumed his medical studies under the tutelage of Thomas Sydenham. Sydenham had a major effect on Locke’s natural philosophical thinking – an effect that would become evident in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Locke’s medical knowledge was put to the test when Ashley’s liver infection became life-threatening. Locke coordinated the advice of several physicians and was probably instrumental in persuading Ashley to undergo surgery (then life-threatening in itself) to remove the cyst. Ashley survived and prospered, crediting Locke with saving his life.

During this time, Locke served as Secretary of the Board of Trade and Plantations and Secretary to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, which helped to shape his ideas on international trade and economics.[citation needed]

Ashley, as a founder of the Whig movement, exerted great influence on Locke’s political ideas. Locke became involved in politics when Ashley became Lord Chancellor in 1672 (Ashley being created 1st Earl of Shaftesbury in 1673). Following Shaftesbury’s fall from favour in 1675, Locke spent some time travelling across France as a tutor and medical attendant to Caleb Banks.[22] He returned to England in 1679 when Shaftesbury’s political fortunes took a brief positive turn. Around this time, most likely at Shaftesbury’s prompting, Locke composed the bulk of the Two Treatises of Government. While it was once thought that Locke wrote the Treatises to defend the Glorious Revolution of 1688, recent scholarship has shown that the work was composed well before this date.[23] The work is now viewed as a more general argument against absolute monarchy (particularly as espoused by Robert Filmer and Thomas Hobbes) and for individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy. Although Locke was associated with the influential Whigs, his ideas about natural rights and government are today considered quite revolutionary for that period in English history.

The Netherlands

Locke fled to the Netherlands in 1683, under strong suspicion of involvement in the Rye House Plot, although there is little evidence to suggest that he was directly involved in the scheme. The philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in Holland, Locke chose his friends «from among the same freethinking members of dissenting Protestant groups as Spinoza’s small group of loyal confidants. [Baruch Spinoza had died in 1677.] Locke almost certainly met men in Amsterdam who spoke of the ideas of that renegade Jew who… insisted on identifying himself through his religion of reason alone.» While she says that «Locke’s strong empiricist tendencies» would have «disinclined him to read a grandly metaphysical work such as Spinoza’s Ethics, in other ways he was deeply receptive to Spinoza’s ideas, most particularly to the rationalist’s well thought out argument for political and religious tolerance and the necessity of the separation of church and state.»[24] In the Netherlands, Locke had time to return to his writing, spending a great deal of time working on the Essay Concerning Human Understanding and composing the Letter on Toleration.

Return to England

Locke did not return home until after the Glorious Revolution. Locke accompanied Mary II back to England in 1688. The bulk of Locke’s publishing took place upon his return from exile – his aforementioned Essay Concerning Human Understanding, the Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration all appearing in quick succession.

Locke’s close friend Lady Masham invited him to join her at Otes, the Mashams’ country house in Essex. Although his time there was marked by variable health from asthma attacks, he nevertheless became an intellectual hero of the Whigs. During this period he discussed matters with such figures as John Dryden and Isaac Newton.

Death

He died on 28 October 1704, and is buried in the churchyard of the village of High Laver,[25] east of Harlow in Essex, where he had lived in the household of Sir Francis Masham since 1691. Locke never married nor had children.

Events that happened during Locke’s lifetime include the English Restoration, the Great Plague of London, the Great Fire of London, and the Glorious Revolution. He did not quite see the Act of Union of 1707, though the thrones of England and Scotland were held in personal union throughout his lifetime. Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy were in their infancy during Locke’s time.

Philosophy

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke’s Two Treatises were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the book, «except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense debate of the 1690s it made little impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made ‘a great noise’).»[26] John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke’s theories were «mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the [Glorious] Revolution, up to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them» and that «no one, including most Whigs, [was] ready for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated by Locke».[27]: 200 In contrast, Kenyon adds that Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government were «certainly much more influential than Locke’s Two Treatises.«[i][27]: 51