Биография Ньютона

4 Января 1643 – 31 Марта 1727 гг. (84 года)

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 625.

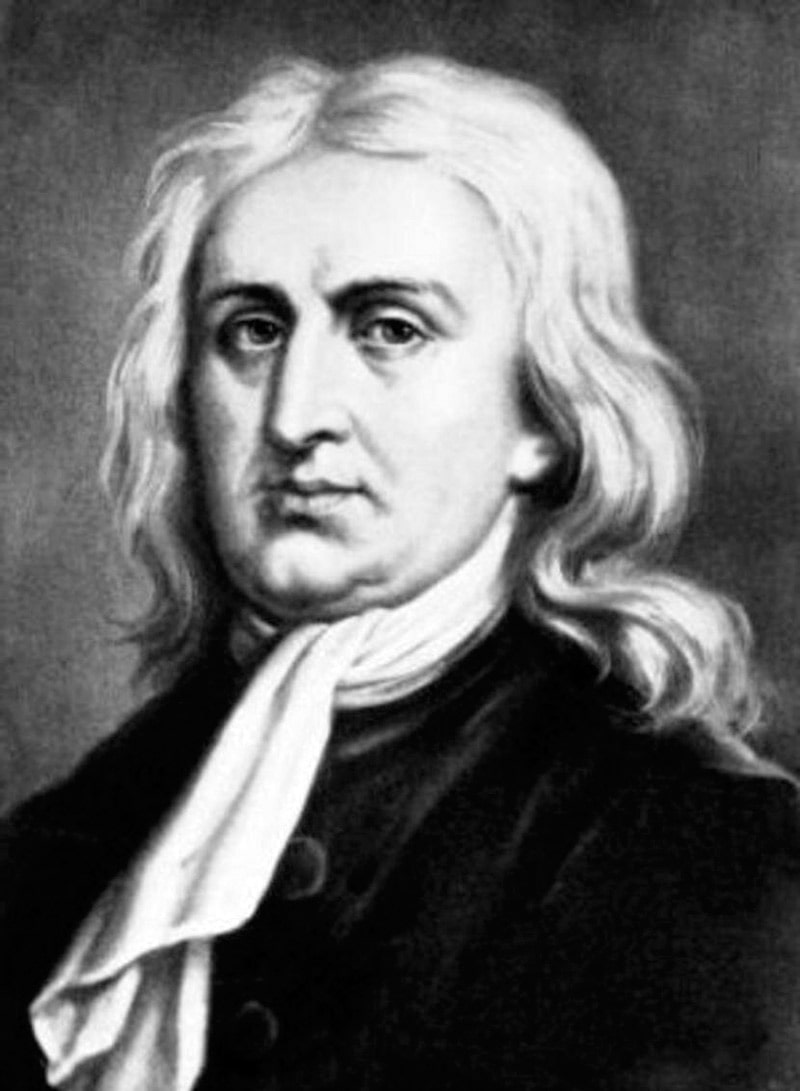

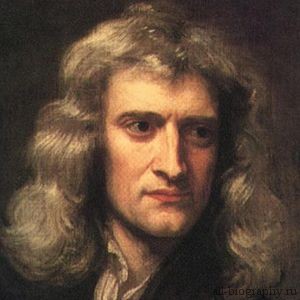

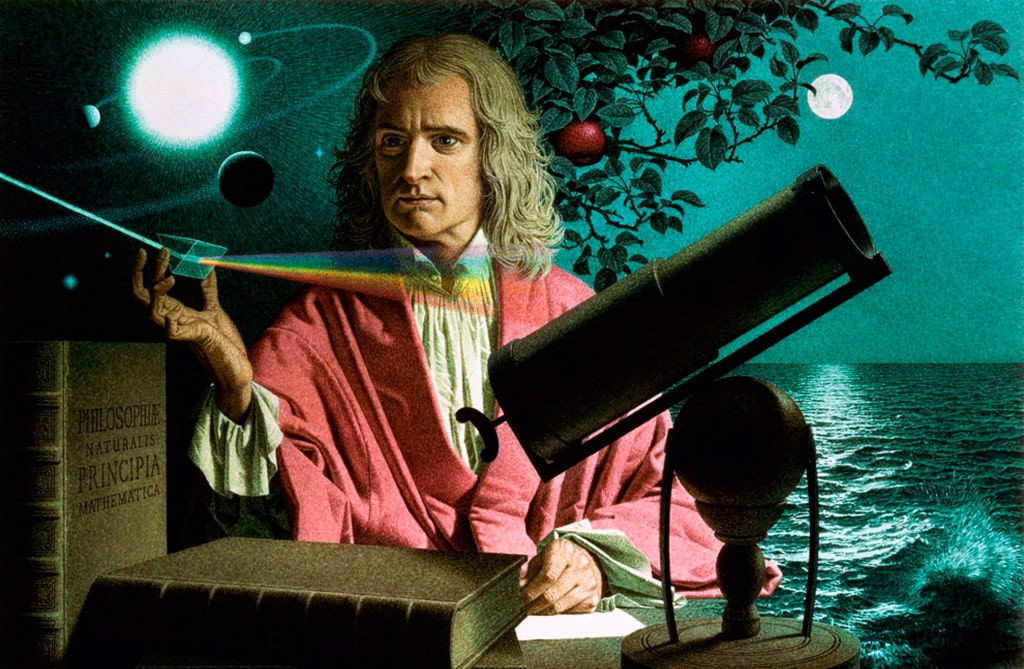

Исаак Ньютон (1642–1727 гг.) – выдающийся английский ученый, один из создателей классической физики. Биография Ньютона богата во всех смыслах этого слова. Он сделал немало открытий в области физики, астрономии, механики и математики, в том числе открыл закон всемирного тяготения.

Детские и юные годы

Исаак Ньютон родился 25 декабря 1642 (или 4 января 1643 г. по грегорианскому календарю) в деревне Вулсторп, графство Линкольншир.

Юный Исаак, по свидетельству современников, отличался мрачным, замкнутым характером. Мальчишеским шалостям и проказам он предпочитал чтение книг и изготовление примитивных технических игрушек.

Когда Исааку исполнилось 12 лет, он поступил на обучение в Грэнтемскую школу. Незаурядные способности будущего ученого обнаружились именно там.

В 1659 г., по настоянию матери, Ньютон был вынужден вернуться домой, чтобы вести фермерское хозяйство. Но благодаря усилиям учителей, сумевших разглядеть будущий гений, он вернулся в школу. В 1661 г. Ньютон продолжил образование в Кембриджском университете.

Обучение в колледже

В апреле 1664 г. Ньютон успешно сдал экзамены и приобрел более высокую студенческую ступень. Во время обучения он активно интересовался работами Г. Галилея, Н. Коперника, а также атомистической теорией Гассенди.

Весной 1663 г. на новой, математической кафедре начались лекции И. Барроу. Известный математик и крупный ученый позже стал близким другом Ньютона. Именно благодаря ему у Исаака возрос интерес к математике.

Во время обучения в колледже Ньютон пришел к своему основному математическому методу – разложению функции в бесконечный ряд. В конце этого же года И. Ньютон получил бакалаврскую степень.

Известные открытия

Изучая краткую биографию Исаака Ньютона, следует знать, что именно ему принадлежит изложение закона всемирного тяготения. Еще одним важнейшим открытием ученого является теория движения небесных тел. Открытые Ньютоном 3 закона механики легли в основу классической механики.

Ньютон сделал немало открытий в области оптики и теории цвета. Им были разработаны многие физические и математические теории. Научные труды выдающегося ученого во многом определяли время и часто были непонятны современникам.

Его гипотезы относительно сплюснутости полюсов Земли, явления поляризации света и отклонения света в поле тяготения и сегодня вызывают удивление ученых.

В 1668 г. Ньютон получил степень магистра. Еще через год он стал доктором математических наук. После создания им рефлектора, предтечи телескопа, в астрономии были сделаны важнейшие открытия.

Общественная деятельность

В 1689 г., в результате переворота, был свергнут король Яков II, с которым у Ньютона был конфликт. После этого ученого избрали в парламент от Кембриджского университета, в котором он заседал около 12 мес.

В 1679 г. произошло знакомство Ньютона с Ч. Монтегю, будущим графом Галифаксом. По протекции Монтегю Ньютон был назначен хранителем Монетного двора.

Последние годы жизни

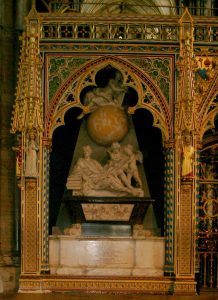

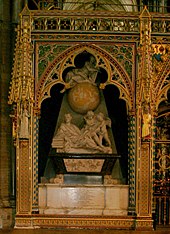

В 1725 г. здоровье великого ученого стало стремительно ухудшаться. Он ушел из жизни 20 (31) марта 1727 г., в Кенсингтоне. Смерть наступила во сне. Похоронен Исаак Ньютон был в Вестминстерском аббатстве.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

- В самом начале своего школьного обучения, Ньютон считался весьма посредственным, едва ли не худшим учеником. В лучшие его заставила выбиться моральная травма, когда он был избит своим рослым и намного более сильным одноклассником.

- В последние годы жизни великий ученый писал некую книгу, которая, по его мнению, должна была стать неким откровением. К сожалению, рукописи горят. По вине любимой собаки ученого, опрокинувшей лампу, книга исчезла в огне.

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Кристина Малышева

9/10

-

Наиль Галямов

10/10

-

Алексей Коваленко

7/10

-

Ами Магомедова

6/10

-

Михаил Калугин

10/10

-

Диана Сергеева

7/10

-

Александр Котков

9/10

Оценка по биографии

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 625.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Исаак Ньютон — биография

Исаак Ньютон – математик, физик, астроном, механик. Сформулировал закон о всемирном тяготении, автор трех законов механики, вошедших в основу классической механики. Ему принадлежит разработка интегрального и дифференциального исчисления и теория цвета.

Исаака Ньютона считают величайшим светилом научного мира. Он прославился в физике и математике, открыл закон гравитации, движения и исчисления. И это кроме основной деятельности. Родившись в семье неграмотных крестьян, он собственным умом постиг тайны Вселенной, стал одним из создателей классической физики. Отличался скрытностью и замкнутым характером, некоторые свои открытия он так и не продемонстрировал своим современникам.

Детство

Родился Исаак Ньютон 4 января 1643 года (по юлианскому календарю) в деревне Вулсторп, расположенной в графстве Линкольншир в Великобритании. Мальчик родился недоношенным в самый канун Рождества, и потом считал это хорошей приметой. А пока он был хилым и слабым ребенком, у которого было мало шансов на выживание. Его долго не крестили, потому что не были уверены, что он вообще выживет. Однако мальчишка оказался на удивление живучим, он не только выкарабкался, но и сумел дожить до глубокой старости. Ньютон умер в 84, и это было скорее исключением, чем правилом в семнадцатом веке.

Своего отца мальчик не знал, Исаак Ньютон-старший умер за несколько месяцев до рождения сына. Новорожденного назвали в честь отца, достаточно состоятельного и успешного мелкого фермера. После того, как он умер, жена унаследовала поля и лесные угодия с плодородной землей. А еще ей досталась баснословная по тем временам сумма – пятьсот фунтов стерлингов.

Мама мальчика – Анна Эйскоу, вскоре устроила свою личную жизнь. Ее мужем стал богатый священник Варнава Смит, который не питал нежных чувств к своему трехлетнему пасынку. Мать с ее новым мужем переехали в другую деревню, а Исаак остался на попечении бабушки, а потом дяди Уильяма Эйскоу. Вскоре один за другим у Анны и Варнавы родилось трое детей.

Исаак рос разносторонне развитым ребенком. Ему нравилась поэзия, живопись, он трудился над изобретением ветряной мельницы и водяных часов, часами возился с бумажными змеями. Мальчик по-прежнему не отличался богатырским здоровьем и не любил общаться со сверстниками. Вместо веселых игр во дворе он проводил время в уединении, предпочитая заниматься тем, что представляло для него интерес.

В школе Исаак никак не мог подружиться со сверстниками, к тому же часто болел и пропускал занятия. Все это раздражало его одноклассников, и однажды они избили его до полусмерти. Это было большим унижением, и ответить кулаками своим обидчикам Ньютон не мог, потому что никогда не был силачом. Тогда он решил завоевать уважение своим умом.

До этого происшествия Исаак учился очень плохо, из-за чего его не любили учителя. После драки он всерьез взялся за учебу, постепенно приобрел себе славу лучшего ученика. Теперь его все больше интересовала математика, техника и необъяснимые явления в природе.

К шестнадцатилетию старшего сына мать снова овдовела, и ей самой было трудно управляться с хозяйством. Она привезла Исаака в родное поместье, в надежде на то, что он поможет ей вести домашние дела. Но, в то время Ньютон уже был серьезно увлечен конструированием разных механизмов, много читал и даже сочинял стихи.

Мать это очень раздражало, а тут еще друзья и родственники начали уговаривать ее дать согласие на то, чтобы парень продолжал учебу. Так, с помощью школьного учителя мистера Стокса, родного дяди Уильяма Эйскоу и знакомого Хэмфри Бабингтона, Исаак смог в 1661-м окончить школу и стать студентом Кембриджского университета.

Научная карьера

В вузе Исаак учился в статусе «sizar». Это человек, который учится бесплатно, но за это задействуется в разноплановых работах, в том числе и в помощи обеспеченным студентам. Ньютону не нравилось его положение, но он собрал все свое мужество и справился. Он был таким же нелюдимым, как и раньше, у него абсолютно не было друзей.

В те времена в Кембриджском университете учили естествознание и философию, опираясь на учения Аристотеля, несмотря на то, что уже было известно об открытиях Галлилея, Коперника и Кеплера. Ньютон много читал, он живо интересовался всеми новинками в мире астрономии, математики, фонетики и оптики. Молодой человек изучал даже теорию музыки, в общем, все, что было новым и попадалось ему под руку. Ему так нравилось это занятие, что он иногда не мог вспомнить, спал ли он, и что ел.

В 1664-м Исаак Ньютон начал самостоятельно трудиться. Он выделил основные проблемы человека и природы, которых насчитывалось сорок пять, и которые никто до него не пытался решить. Биография студента изменилась в том же году, после того, как в его жизни появился талантливый математик Исаак Барроу, преподаватель математической кафедры вуза. Спустя некоторое время Барроу стал учителем Ньютона и по совместительству одним из малочисленных друзей ученого.

Барроу сумел привить Ньютону любовь к математике, он стал серьезно заниматься этой наукой. Вскоре он уже мог похвастаться своим первым открытием в области математики – биноминальным разложением для производного рационального показателя. В это же время Ньютон стал бакалавром.

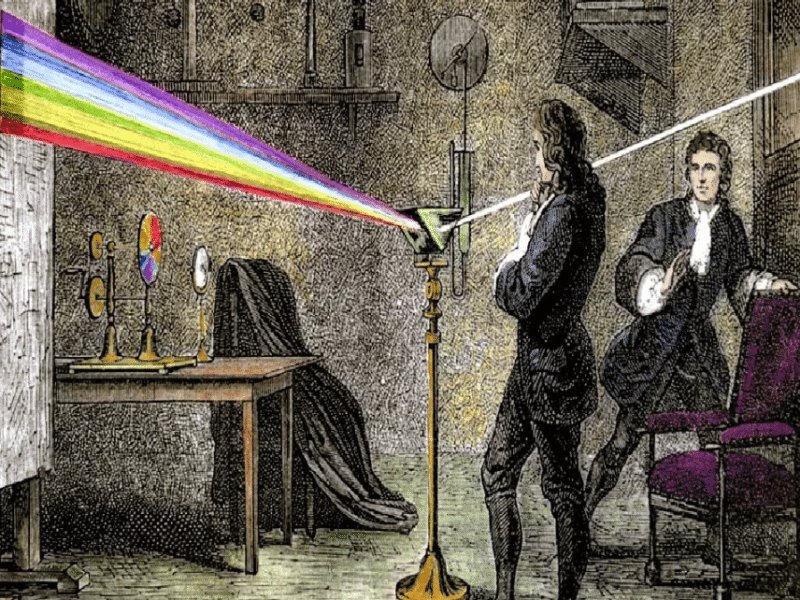

С 1665 по 1667 годы Исаак жил в родовом поместье в Вусторпе. Тогда Англия находилась во власти бубонной чумы, воевала с Голландией, и поэтому университет закрыли. Однако и дома он не прекращает своих научных изысканий. Основной интерес в те годы для Ньютона представляла оптика. Его интересовал вопрос преодоления хроматической аберрации в линзовых телескопах, и изучение этого явления привело его к открытию дисперсии. Он ставил эксперименты для познания физической природы света. Его опыты и сейчас проводят во многих вузах.

В итоге Исаак открыл корпускулярную модель света, он понял, что это поток частиц, вылетающий из источника света и прямолинейно двигающийся к ближайшему препятствию. Эта модель была очень далека от объективности, но стала основой в классической физике. Именно благодаря ей, потом сформировались современные понятия о физике явлений.

В то же время Ньютон открыл свой самый известный закон – о всемирном тяготении. Однако опубликован он был спустя несколько десятилетий, потому что Ньютона больше интересовал сам процесс, а не слава.

Любители любопытных фактов придерживаются мнения, что в открытии этого закона Ньютону помогло упавшее на голову яблоко. На самом деле ученый долго шел к этому открытию, проделывал опыты, записывал все в журнал.

Результатом долгого и кропотливого труда и стало это открытие. А вот легенда об упавшем на голову ученого яблоке принадлежит перу философа Вольтера.

Могут быть знакомы

Светило науки

После возвращения в конце 1660-х в Кембридж, Исаак Ньютон стал магистром. Теперь ему полагалась собственная комната и группа молодых студентов, которым он преподавал математику. Однако Исаак не очень любил преподавательскую деятельность, его больше интересовали научные разработки. Студенты это быстро «просекли» и стали прогуливать его лекции. Случалось такое, что аудитория была абсолютно пустой во время его урока. Зато Ньютон отметился изобретением телескопа-рефлектора, благодаря которому стал членом Лондонского королевского общества. Благодаря его изобретению, стали возможными большие открытия в астрономии.

В 1687-м в печать попала самая важная из всех работ ученого – книга, которую он назвал «Математические начала натуральной философии». Ньютон и до этого уже печатался, но именно этот труд имел очень большое значение – благодаря ему возникла рациональная механика и все математическое естествознание. Этот труд состоял из закона всемирного тяготения, трех уже знакомых законов механики, которые стали основой классической физики, ключевых понятий в физике.

Математический и физический уровень труда Ньютона превосходили все то, что до него открыли другие ученые в этой области. Работа не содержала недоказанную метафизику, в ней отсутствовали пространные рассуждения, необоснованные законы и расплывчатые формулировки, которых придерживались в своих трудах Декарт и Аристотель.

В 1699-м в Кембриджском университете студентов учили по системе мира Ньютона. В это время ученый занимал административные должности.

Личная жизнь и смерть

Выдающийся ученый был слишком занят своими изысканиями, он иногда забывал поесть и поспать, не говоря уже о женщинах. У него полностью отсутствовала личная жизнь, только бесконечное служение науке. Ученый не был женат, и наследников после себя не оставил.

Здоровье Ньютона резко пошатнулось в 1725 году. Он переехал в Кенсингтон рядом с Лондоном, где и умер 31 марта 1727 года. Ученый не оставил письменное завещание, но буквально перед смертью большую часть своего состояния отдал близким родственникам. Хоронили Ньютона с большими почестями. Местом его упокоения стало Вестминстерское аббатство, по соседству с королями и выдающимися общественными деятелями.

Основные труды

- «Новая теория света и цветов»

- «Движение тел по орбите»

- «Математические начала натуральной философии»

- «Оптика или трактат об отражениях, преломлениях, изгибаниях и цветах света»

- «О квадратуре кривых»

- «Перечисление линий третьего порядка»

- «Универсальная арифметика»

- «Анализ с помощью уравнений с бесконечным числом членов»

- «Метод разностей»

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Знаменитый английский ученый Исаак Ньютон не случайно признан одним из выдающихся умов мировой науки. Этот человек сделал бесценный вклад в развитие физики и математики, разработал множество уникальных теорий, большинство которых было подтверждено более поздними научными исследованиями. Его гениальность проявилась во многих научных сферах, включая астрономию и философию. Ньютона по праву считают основоположником классической физики.

Происхождение и ранние годы

Родина Исаака Ньютона – усадьба Вулсторп, где он родился 4 января 1643 года немного раньше положенного срока. Его отец, Исаак Ньютон, довольно зажиточный фермер, умер, не дождавшись появления сына на свет. Новорожденный Исаак был настолько слабеньким, что доктора не давали никаких гарантий, но, вопреки их прогнозам, мальчику удалось выжить.

Дом, где родился Ньютон. Вулсторп

Мать Ньютона звали Анна Эйскоу. После смерти мужа она получила в наследство 500 фунтов стерлингов и несколько сотен акров земли, что по тем временам считалось неплохим состоянием. Вскоре женщина снова вышла замуж, и через некоторое время в семье появилось еще трое детей. Из-за ухода за малышами у матери совсем не оставалось времени на воспитание Исаака, поэтому эту заботу взяли на себя его бабушка и дядя, Уильям Эйскоу. Ньютон часто болел, рос молчаливым и замкнутым, предпочитал в полном уединении читать или мастерить какие-нибудь игрушки. Так, еще в детстве он сконструировал водяные часы и ветряную мельницу. Когда Исааку исполнилось десять лет, его мать овдовела во второй раз. В двенадцать лет он поступил в школу, которая находилась недалеко от Грэнтема.

Образование

Ньютон оказался хорошим учеником и с легкостью осваивал новые дисциплины. Также у него проснулся талант к сочинительству стихов, а чтение продолжало оставаться любимым занятием подростка. Когда Исаак достиг шестнадцатилетия, мать решила забрать его в поместье, потому что ей понадобился помощник по хозяйству. Только благодаря уговорам дяди и знакомого семьи, Хэмфри Бабингтона, она согласилась оставить Ньютона в школе. В 1661 году юноша успешно окончил учебное заведение и поступил в Кембриджский университет.

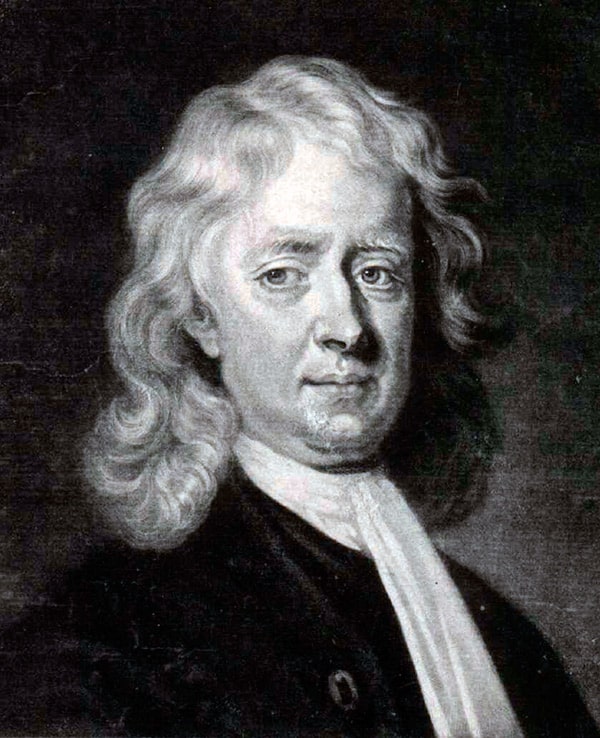

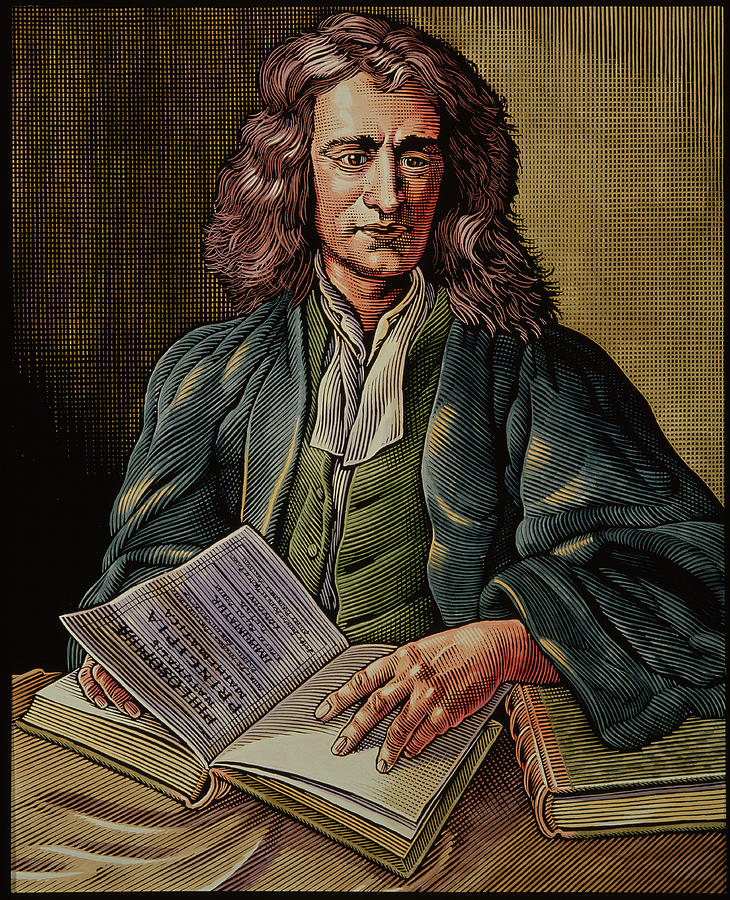

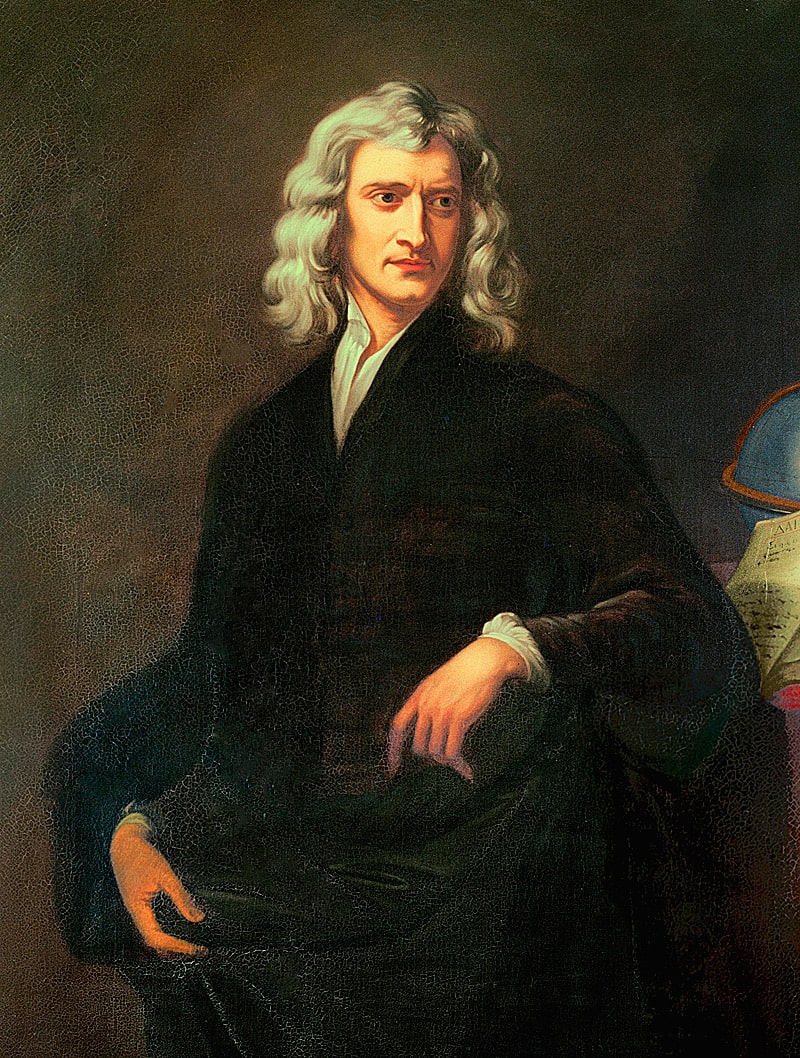

Г. Кнеллер. Портрет Ньютона. 1689

В университете Ньютон получил статус «sizar», так как не оплачивал свое обучение. Взамен этого он должен был помогать в уборке и выполнять другие работы в университете. Всё это ущемляло самолюбие Исаака, но он преодолел это испытание, так как тяга к науке не позволяла ему показывать свое раздражение. Молодой человек все так же предпочитал одиночество и не пытался завести друзей.

В основе университетских программ по философии и естествознанию лежали труды Аристотеля, хотя весь научный мир того времени уже знал об открытиях Галилея и других ученых. По этой причине Ньютон самостоятельно, после основных занятий штудировал труды Коперника, Кеплера, уже упомянутого Галилея, чтобы получить более обширные знания в области физики, астрономии, математики.

Научная деятельность

Ньютону повезло попасть под покровительство английского математика Исаака Барроу, который смог рассмотреть в юноше огромный потенциал. Именно Барроу одобрительно принял первое открытие молодого ученого, которое легло в основу математического метода, и за которое Ньютон получил степень бакалавра.

После этого Исаак приступил к разработке новой теории, которая впоследствии получила название Закона всемирного тяготения. Это была очень кропотливая работа, так как Ньютону пришлось обобщить знания таких ученых, как Галилией, Декарт и Кеплер. Исследования прервала начавшаяся в 1665 году эпидемия чумы, и Ньютон был вынужден вернуться в Вулсторп, прихватив с собой учебники и инструменты.

В своем поместье, в полном уединении Ньютон вновь занялся научными исследованиями. В 1666 году

Потомок дерева, вдохновившего Ньютона на Закон о гравитации

молодой ученый сделал важное открытие, что белый солнечный свет, пропущенный через призму – это комбинация всех видимых цветов спектра. Если же сложить все цвета и пропустить их через установленные определенным образом призмы, то в итоге можно снова получить белый свет. Окончание работы над Законом всемирного тяготения также пришлось на этот период. Ньютон был напрочь лишен тщеславия, поэтому о его открытиях стало известно лишь через двадцать лет. В 1667 году Ньютон вернулся в Кембридж и получил степень магистра Тринити-колледжа. Ему была предоставлена отдельная комната, назначено небольшое содержание и дана возможность читать лекции. Студенты без особого желания посещали его занятия, так как у Ньютона так и не развился талант педагога, а его лекции оставляли желать лучшего. В этот период Ньютон заинтересовался алхимией, но основной акцент его исследований был направлен на математику и оптику.

В 1672 году Ньютон стал членом Королевского общества. Его знаменитый телескоп, над которым он трудился, находясь в своем имении во время эпидемии, был продемонстрирован самому королю Карлу II. Изобретение Ньютона произвело фурор в научных кругах и стало предметом национальной гордости Англии.

В конце семидесятых годов в жизни Ньютона произошла череда печальных событий. Умер его наставник, ученый Исаак Барроу, Люди, сменившие старое руководство Королевского общества, относились к Ньютону весьма недоброжелательно. Через некоторое время в доме ученого произошел пожар, в результате которого сгорело много ценных рукописей. Наконец, тяжело заболела и вскоре умерла мать Исаака. Но, несмотря ни на что, ученый продолжал работать.

Рефлектор Ньютона

Ньютону удалось закончить свою фундаментальную работу «Математические начала натуральной философии», которую он начал в 1682 году. В ней был сформулирован закон всемирного тяготения и законы движения планет с описанием их орбит, даны основные определения механики, введены новые физические величины. Сначала Ньютон отказался от публикации этого труда, несмотря на многочисленные просьбы ученых, но затем, вопреки своим принципам, все же согласился. Средства для этого предоставил Эдмонд Галлей, так как у Королевского общества на тот момент не было денег. В 1687 году в свет вышло трехтомное издание общим, огромным для того времени тиражом три тысячи экземпляров, которое было моментально раскуплено. Труд Ньютона имел такой успех, что еще при его жизни переиздавался несколько раз.

В 1696 году Ньютона назначили хранителем Тауэрского монетного двора. Вникнув в технологию отливки монет, он разработал способ, позволяющий отличать фальшивые деньги от настоящих, а также стал участником проводимой в то время денежной реформы. Через некоторое время на Ньютона начали поступать доносы. Как оказалось, их писали фальшивомонетчики, которые очень боялись быть разоблаченными при помощи методов Ньютона. В 1703 году Ньютон был избран президентом Королевского Общества, в 1705 году он подошел к завершению своего научного труда «Оптика», который на целых два столетия определил направление развития этой науки. Идеи ученого приобретали все больше последователей, а его теорию движения небесных тел ввели в учебную программу университетов.

Тринити-колледж

В том же 1705 году Ньютону было присвоено звание рыцаря, которое давало сэру Исааку Ньютону право принимать участие в правительственных организациях. В этот период у ученого проснулся интерес к истории, и на этой волне им была написана «Хронология древних царств». В это же время готовилась к выходу в свет третья книга его «Начал» с правками и дополнениями, а также рассчитанной орбитой кометы Галлея.

Научные достижения Ньютона

Исааком Ньютоном сделано много важных открытий, послуживших дальнейшему развитию науки. Многие из его физических законов не потеряли своей актуальности и на сегодняшний день.

Три закона движения

Этот труд по праву считается одним из важнейших открытий Ньютона. Работу, которая появились в 1687 году под названием «Математические начала натуральной философии», можно назвать основой классической механики и огромным вкладом в развитие физики. Три ньютоновских закона были разработаны на основе теории движения планет Иоганна Кеплера и сформулированы следующим образом:

- Тело будет оставаться в покое до тех пор, пока на него не начнет воздействовать сила, лишенная баланса. Движущийся объект будет иметь те же изначальные скорость и направление, если не встретит на своем пути несбалансированную силу. Этот закон Ньютона также называют Законом инерции.

- Второй закон Ньютона гласит о взаимозависимости массы тела, ускорения и силы. Ускорение начинает проявляться во время действия силы на массу. Ускорение тела прямо пропорционально приложенной к нему силе и обратно пропорционально массе.

- В формулировке самого Ньютона его третий закон выглядит так: «Действию всегда есть равное и противоположное противодействие, иначе, взаимодействия двух тел друг на друга между собою равны и направлены в противоположные стороны. Для каждого действия существует равное противодействие».

Универсальная гравитация

Закон всемирного тяготения был открыт Ньютоном в 1667 году. В своем труде он обобщил результаты, полученные Галилеем, и впоследствии Кеплером. В итоге он пришел к выводу, что все тела во Вселенной притягиваются друг к другу, при этом можно рассчитать силу, с которой это притяжение происходит. Это и есть Закон всемирного тяготения, а сила притяжения называется гравитацией. Согласно легенде, во время прогулки в саду в своей усадьбе на голову Ньютона упало яблоко, и в этот момент к нему пришло озарение: если луна остается неподвижной, а яблоко падает, это означает, что какая-то сила воздействует и на Луну и на яблоко. Многие историки считают этот случай не иначе, как выдумкой. Однако, не суть важно, действительно ли падало яблоко на голову ученого, важно то, что он первый понял, что гравитация только одна и ее действие можно описать универсальным физическим законом.

Форма Земли

Раньше было принято считать, что Земля имеет идеально круглую форму шара. Это доказывали великие ученые древности: Пифагор, Аристотель и др. В 1687 году Ньютон, опираясь на открытый им закон всемирного тяготения, выдвинул теорию о том, что Земля сплюснута у полюсов. Впоследствии эта гипотеза получила безусловное подтверждение.

Оптика

Ньютон пропускает свет через призму

В начале 18 века Ньютон написал фундаментальный научный труд под названием «Оптика». На ближайшее столетие эта книга стала базовой в развитии этого раздела физики. Ньютоном был создан первый зеркальный телескоп (рефлектор Ньютона) с особым расположением зеркал, что позволяло получить изображение в хорошем качестве. В 1672 году ученым была открыта дисперсия света. Установив, что при прохождении через призму белый свет раскладывается в радужный спектр, Ньютон стал одним из основателей теории цвета.

Много работ Ньютона посвящено термодинамике, звуку, изучению солнечной энергии, им был сформулирован закон Ньютона-Рихмана, который касался вопросов тепловой передачи, а также выведена математическая формула, известная как Бином Ньютона.

Последние годы

Могила Ньютона в Вестминстерском аббатстве

К середине двадцатых годов здоровье Ньютона стало ухудшаться, и он перебрался в пригород Лондона Кенсингтон. В 1725 году ученый уже не мог ходить на службу и 31 марта 1727 года тихо скончался во сне в своей постели. В день похорон в Лондоне был объявлен общенациональный траур, а проводить рыцаря английской науки пришел весь город. Похоронили Ньютона в Вестминстерском аббатстве, где покоятся короли и другие великие люди Англии. На могиле сэра Исаака Ньютона установлен необычный памятник, на котором изображены главные открытия ученого.

Личная жизнь

Главным в жизни Ньютона была наука, и всего себя он посвящал только ей. Возможно, по этой причине ученый так и не создал семью и не оставил после себя наследников.

Хронологическая таблица

| Год (годы) | Событие |

| 25.12.1642 | Дата рождения Исаака Ньютона |

| 1648 | Поступление в школу |

| 1655 | Поступление в Королевскую школу в Грэнтэме |

| 1664 | Становится стипендиатом Тринити-колледжа |

| 1665 | Присвоение звания бакалавра искусств. Отъезд в Вулсторп |

| 1667 | Возвращение в Кембридж |

| 1669 | Назначение лукасианским профессором математики |

| 1671 | Демонстрация телескопа в Королевском обществе |

| 1672 | Избрание в члены Королевского общества. Наброски книги «Оптика» |

| 1677 | Смерть И. Барроу. Пожар в квартире Ньютона |

| 1679 | Смерть матери |

| 1685 | Формулировка закона всемирного тяготения |

| 1687 | Выход первого издания книги «Математические начала натуральной философии» |

| 1689 | Трактат «О природе кислот» |

| 1696 | Назначение смотрителем Монетного двора. Переезд в Лондон |

| 1698 | Избрание членом Парижской академии наук |

| 1703 | Избрание президентом Королевского общества |

| 1704 | Выход первого издания «Оптики» |

| 1705 | Возведение в рыцарское звание |

| 1713 | Второе издание «Начал» |

| 1717 | Второе издание «Оптики» |

| 31.03.1727 | Дата смерти Исаака Ньютона |

Интересные факты

- Исаак Ньютон назван в честь своего отца, умершего до его рождения;

- всю жизнь ученый считал своими предками шотландских дворян, но его биографы позже установили, что он имеет крестьянское происхождение;

- в юном возрасте будущий ученый увлекался стихосложением;

- уже в возрасте 23 лет Ньютон совершил ряд важных открытий в области математики;

- Ньютона редко можно было увидеть смеющимся, он был очень сдержан в эмоциях;

- ученый был близорук, но никогда не пользовался очками;

- Ньютон был равнодушен к любым видам искусства, не проявлял он интереса и к путешествиям;

- очень не любил публиковать свои труды, поэтому многие из них мир увидел только через два-три десятка лет;

- несколько лет последнего периода жизни Ньютон посвятил написанию богословской книги, которая сгорела при пожаре;

- Ньютону принадлежит идея делать край монеты ребристым, так как мошенники часто срезали с них кусочки металла;

- несмотря на то, что врачи пророчили Ньютону смерть еще в детстве, ученый прожил долгую жизнь и умер в 84 года.

Память

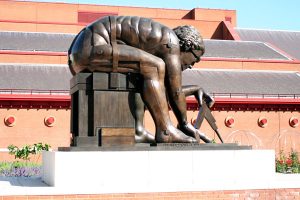

Памятник Ньютону в Оксфорде

Существует международная награда в области физики в виде Медали Исаака Ньютона. К ней прилагается денежная премия в размере 1000 фунтов стерлингов и сертификат.

В честь Ньютона назван так называемый элемент «х» – мировой эфир. По мнению Д.И. Менделеева, этот гипотетический элемент должен был располагаться в самом начале всей Таблицы (нулевая группа нулевого ряда).

Имя Ньютона носит горная вершина на острове Западный Шпицберген, высшая точка одноименного архипелага.

В Эльдорадо штата Арканзас работает Дом-музей Исаака Ньютона.

Скульптура у здания Британской библиотеки

В честь великого ученого воздвигнуты памятники. В частности, статуя Ньютона расположена над входом в Тринити-колледж Кембриджского университета. В Музее национальной истории Оксфордского университета установлен памятник Ньютону. Необычная скульптура установлена во дворе Британской библиотеки в Лондоне. Она представляет собой Ньютона с циркулем в руках, склонившегося к земле, словно измеряющего бесконечность Вселенной.

Цитаты

«То, что мы знаем, это капля, а то, что мы не знаем, это океан».

«Природа проста и не роскошествует излишними причинами».

«При изучении наук примеры полезнее правил».

«Гений есть терпение мысли, сосредоточенной в известном направлении».

«Опыт – это не то, что происходит с вами; это то, что вы делаете с тем, что происходит с вами».

«Действию всегда есть равное и противоположное противодействие».

«Природа неистощима в своих выдумках».

Литература

- Вавилов С. И. Исаак Ньютон. — 2-е доп. изд. — М.—Л.: Изд. АН СССР, 1945.

- Кобзарев И. Ю. Ньютон и его время. — М.: Знание, 1978.

- Акройд П. Исаак Ньютон. Биография. — М.: КоЛибри, Азбука-Аттикус, 2011.

- Храмов Ю. А. Ньютон Исаак (Newton Isaac) // Физики : Биографический справочник / Под ред. А. И. Ахиезера. — Изд. 2-е, испр. и доп. — М. : Наука, 1983.

- Кузнецов Б. Г. Ньютон. — М.: Мысль, 1982.

Ирина Зарицкая | Просмотров: 2.3k

Содержание

- Семья и детство

- Университет, чума и открытия

- Рождение физики как науки

- Признание и успех

- Личная жизнь

- Последние годы и смерть

- Основные достижения Ньютона

- Интересные факты

Сэр Исаак Ньютон — английский физик, математик, механик и астроном, один из создателей классической физики. Автор фундаментального труда «Математические начала натуральной философии», в котором он изложил закон всемирного тяготения и три закона механики, ставшие основой классической механики. Разработал дифференциальное и интегральное исчисления, теорию цвета, заложил основы современной физической оптики, создал многие другие математические и физические теории.

Семья и детство

Исаак Ньютон появился на свет 4 января 1643 года в небольшой британской деревушке Вулсторп, располагавшейся на территории графства Линкольншир. Его отец был из небогатых крестьян, которые волею случая нажили землю и благодаря этому преуспели. Но до рождения Исаака его отец не дожил — и умер за несколько недель до этого. Мальчика назвали в его честь.

Исаак Ньютон в детстве

Когда Ньютону было три года, его мать снова вышла замуж — за почти втрое старшего за себя богатого фермера. После рождение ещё троих детей в новом браке, Исааком начал заниматься брат его матери — Уильям Эйскоу. Но дать хоть какое-либо образование дядя Ньютону не мог, поэтому мальчик был предоставлен сам себе — играл собственноручно сделанными механическими игрушками, кроме того он был немного замкнутым.

Новый муж матери Исаака прожил с ней всего семь лет и умер. Половина наследства досталась вдове, и та сразу переписала всё на Исаака. Несмотря на то, что мать вернулась домой, внимания мальчику она почти не уделяла, поскольку младшие дети требовали его ещё больше, а помощниц у неё не было.

Двенадцатилетним Ньютон пошёл учиться в школу в соседнем городке Грэнтем. Чтобы каждый день не возвращаться несколько миль домой, его поселили в доме у местного аптекаря мистера Кларка. В школе мальчик «расцвёл»: он жадно хватался за новые знания, учителя были в восторге от его ума и способностей. Но уже через четыре года матери потребовался помощник и она решила, что 16-летний сын вполне сможет справиться с фермой.

Но даже вернувшись домой, Исаак не спешит решать хозяйственные проблемы, а читает книги, пишет стихи и продолжает заниматься придумыванием различных механизмов. Поэтому знакомые обратились к его матери, чтобы та вернула парня в школу. Был среди них и преподаватель Тринити-колледжа, знакомый того самого аптекаря, у которого Исаак жил во время учёбы. Общими усилиями Ньютон поехал поступать в Кембридж.

Университет, чума и открытия

В 1661 году парень успешно прошёл экзамен с латыни, и его зачислили в колледж Святой Троицы при Кембриджском университете как студента, который вместо оплаты за учёбу выполняет разные поручение и работы на благо альма матер.

Поскольку жизнь в Англии в те годы была весьма тяжёлой, то не лучшим делом обстояли дела и в Кембридже. Биографы сходятся на мысли, что именно годы в колледже закалили характер учёного и его желание доходить до сути предмета собственными усилиями. Через три года он уже добился стипендии.

В 1664 году одним из преподавателей Ньютона стал Исаак Барроу, который привил ему любовь к математике. В те годы Ньютон делает своё первое открытие в математике, известное сейчас как Бином Ньютона.

Через несколько месяцев учёбу в Кембридже прекратили из-за эпидемии чумы, которая разрасталась в Англии. Ньютон вернулся домой, где продолжал свои научные труды. Именно в те годы он начал разрабатывать закон, который со времен получил имя Ньютона-Лейбница; в родном доме он открыл, что белый цвет — не что иное, как смесь всех цветов, и назвал явление «спектром». Тогда же он открыл свой известный закон всемирного тяготения.

То, что было чертой Ньютоновского характера, и было не слишком полезно для науки — это его излишняя скромность. Некоторые свои исследования он публиковал лишь через 20-30 лет после их открытий. Некоторые нашлись спустя три столетия после его смерти.

В 1667 Ньютон вернулся в колледж, а через год стал магистром, его пригласили поработать преподавателем. Но читать лекции Исааку было не слишком по душе, да и особенной популярностью среди учеников он не пользовался.

В 1669 году разные математики начали публиковать свои варианты разложений в бесконечные ряды. Несмотря на то, что Ньютон разработал свою теорию на эту тему уже много лет назад, он её нигде не публиковал. Опять-таки из-за скромности. Но его бывший преподаватель, а теперь уже и друг Барроу уговорил Исаака. И тот написал «Анализ с помощью уравнений с бесконечным числом членов», где изложил коротко и по сути свои открытия. И хотя Ньютон просил не называть своего имени, Барроу не удержался. Так о Ньютоне впервые узнали ученые всего мира.

В этом же году он переходит на место Барроу и становится профессором математики и оптики в колледже Святой Троицы. А поскольку Барроу оставил ему свою лабораторию, Исаак увлекается алхимией и проводит много опытов на эту тему. Но не оставил он и исследование со светом. Так, он разработал свой первый телескоп-рефлектор, который давал увеличение в 40 раз. Новой разработкой заинтересовались при дворе короля, и после презентации перед учёными, механизм оценили как революционный и очень необходимый, особенно для мореплавателей. А Ньютона в 1672 году приняли в Королевское научное общество. Но уже после первой полемики о спектре, Исаак решил покинуть организацию — его утомляли споры и дискуссии, он привык работать в одиночку и без лишней суеты. Его едва удалось уговорить остаться в Королевском обществе, но контакты с ними у учёного стали минимальными.

Рождение физики как науки

В 1684-1686 годах Ньютон писал свой первый великий печатный труд — «Математические начала натуральной философии». Опубликовать её его уговорил ещё один учёный — Эдмонд Галлей, который сперва предложил разработать формулу эллиптического движение по орбите планет, используя формулу закона тяготения. И тут оказалось, что Ньютон уже всё давно решил. Галлей не отступил, пока не выбил из Исаака обещание опубликовать работу, и тот согласился.

Писал её два года, финансировать публикацию согласился сам Галлей, и в 1686 году она наконец увидела мир.

В этой книге учёный впервые использовал понятия «внешняя сила», «масса» и «количество движения». Ньютон давал три базовые закона механики, делал выводы из законов Кеплера.

Первый тираж в 300 экземпляров раскупили за четыре года, что по тогдашним меркам было триумфом. Всего книгу переиздавали трижды ещё при жизни учёного.

Признание и успех

В 1689 Ньютона избирают членом парламента университета Кембриджа. Ещё через год его перебирают вторично.

В 1696, благодаря содействию своего бывшего ученика, а сейчас президента Королевского общества и канцлера Казначейства Монтегю, Ньютон становится хранителем Монетного двора, для чего переезжает в Лондон. Вместе они приводят в порядок дела Монетного двора и проводят денежную реформу с перечеканкой монет.

В 1699 году в его родном Кембридже начали преподавать Ньютоновскую систему мира, ещё через пять лет такой же курс лекций появился и в Оксфорде.

Его также приняли в Парижский научный клуб, сделав Ньютона почётным иностранным членом общества.

Личная жизнь

Ньютон не оставил после себя потомков, так как никогда не был женат: всё своё свободное время он посвящал науке, а его заурядная, серая внешность делала его неприметным для женщин. Биографы упоминают лишь одну симпатию, промелькнувшую в юности Ньютона: учась в Грэнтэме, он был влюблён в мисс Сторей, свою сверстницу, с которой поддерживал тёплые, дружеские отношения до конца своих дней.

Последние годы и смерть

В 1704 Ньютон издал свой труд «Об оптике», через год королева Анна возвела его в рыцари.

Последние годы жизни Ньютона ушли на допечатку «Начал» и подготовку обновлений для следующих изданий. Кроме того он писал «Хронологию древних царств».

В 1725 году его здоровье серьёзно ухудшилось и он переехал из шумного Лондона в Кенсингтон. Умер там же, во сне. Его тело похоронили в Вестминстерском аббатстве.

Основные достижения Ньютона

- Ньютон — основатель механики, важного раздела физики.

- Ему принадлежат три закона, названные его же именем.

- Открыл закон всемирного тяготения.

- Разложил солнечный свет на спектр и обратно.

- Стал автором популярной корпускулярной теории света.

- Открыл «кольца Ньютона», изучая интерференцию света.

- В математике Ньютон стал основателем интегрального счисления.

- Автор бинома, который также носит его имя.

- Построил зеркальный телескоп.

- Объяснил с научной точки зрения движение Луны вокруг Земли и планет вокруг Солнца.

Интересные факты

- Возведение Ньютона в рыцари было первым в английской истории, когда звание рыцаря было присвоено за научные заслуги. Ньютон обзавёлся собственным гербом и не очень достоверной родословной.

- К концу жизни Ньютон рассорился с Лейбницем, что пагубно сказалось на науке британской и европейской в частности — не было сделано много открытий из-за этих ссор.

- В честь Ньютона назвали единицу силы в Международной системе единиц (СИ).

Легенда о яблоке Ньютона широко распространилась благодаря Вольтеру.

Видео

Источники

- https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9D%D1%8C%D1%8E%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%BD,_%D0%98%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%B0%D0%BA

https://24smi.org/celebrity/3876-isaak-niuton.html

https://theperson.pro/isaak-nyuton/

https://stuki-druki.com/authors/Newton.php

http://biografix.ru/isaak-nyuton

Исаак Ньютон (1643-1727) – английский физик, математик, механик и астроном, один из создателей классической физики. Автор фундаментального труда «Математические начала натуральной философии», в котором он представил закон всемирного тяготения и 3 закона механики.

Разработал дифференциальное и интегральное исчисления, теорию цвета, заложил основы современной физической оптики и создал множество математических и физических теорий.

В биографии Ньютона есть много интересных фактов, о которых мы расскажем в данной статье.

Итак, перед вами краткая биография Исаака Ньютона.

Биография Ньютона

Исаак Ньютон появился на свет 4 января 1643 г. в деревне Вулсторп, находящейся на территории английского графства Линкольншир. Он родился в семье небедного фермера Исаака Ньютона-старшего, который умер еще до рождения сына.

Детство и юность

У матери Исаака, Анны Эйскоу, начались преждевременные роды, вследствие чего мальчик родился недоношенным. Ребенок был настолько слаб, что врачи не надеялись на то, что он выживет.

Тем не менее, Ньютону удалось выкарабкаться и прожить долгую жизнь. После смерти главы семейства, матери будущего ученого досталось несколько сотен акров земли и 500 фунтов стерлингов, что на тот момент составляло немалую сумму.

В скором времени Анна вновь вступила в брак. Ее избранником стал 63-летний мужчина, которому она родила троих детей.

В тот момент биографии Исаак был обделен вниманием мамы, поскольку та заботилась о своих младших детях.

В результате, воспитанием Ньютона занималась его бабушка, а позже и его дядя Уильям Эйскоу. В тот период мальчик предпочитал находиться в одиночестве. Он был весьма молчалив и замкнут.

В свободное время Исаак любил читать книги, а также конструировать различные игрушки, включая водяные часы и ветряную мельницу. При этом он продолжал часто болеть.

Когда Ньютону было около 10 лет скончался его отчим. Спустя пару лет он начал учиться в школе, расположенной вблизи Грэнтема.

Мальчик получал высокие отметки по всем дисциплинам. Кроме этого он пробовал сочинять стихи, продолжая при этом читать разную литературу.

Позже мать забрала 16-летнего сына обратно в поместье, решив переложить на него ряд обязанностей по хозяйственной части. Однако Ньютон с неохотой брался за физическую работу, предпочитая ей все то же чтение книг и конструирование различных механизмов.

Школьный учитель Исаака, его дядя Уильям Эйскоу и знакомый Хэмфри Бабингтон, смогли уговорить Анну разрешить талантливому юноше продолжить учебу.

Благодаря этому парень смог успешно окончить школу в 1661 г. и поступить в Кембриджский университет.

Начало научной карьеры

Как студент Исаак находился в статусе «sizar», что позволяло ему получать бесплатное образование.

Однако взамен ученик был обязан выполнять различные работы в университете, а также помогать состоятельным студентам. И хотя такое положение дел вызывало у него раздражение, ради учебы он был готов выполнять любые просьбы.

В тот период биографии Исаак Ньютон по-прежнему предпочитал вести обособленный образ жизни, не имея близких друзей.

Студентов обучали философии и естествознанию по трудам Аристотеля, несмотря на то, что к тому времени уже были известны открытия Галилея и других ученых.

В связи с этим, Ньютон занимался самообразованием, тщательно изучая труды все того же Галилея, Коперника, Кеплера и прочих известных ученых. Его интересовали математика, физика, оптика, астрономия и теория музыки.

Исаак настолько много работал, что часто недоедал и недосыпал.

Когда молодому человеку был 21 год он начал самостоятельно проводить исследования. Вскоре он вывел 45 проблем в человеческой жизни и природе, которые не имели решений.

Позднее Ньютон познакомился с выдающимся математиком Исааком Барроу, который стал его учителем и одним из немногих друзей. Вследствие этого студент заинтересовался математикой еще больше.

В скором времени Исаак сделал свое первое серьезное открытие – биномиальное разложение для произвольного рационального показателя, посредством которого пришел к уникальному методу разложения функции в бесконечный ряд. В том же году он удостоился звания бакалавра.

В 1665-1667 гг., когда в Англии свирепствовала чума и велась затратная война с Голландией, ученый на время обосновался в Вусторпе.

В тот период Ньютон изучал оптику, пытаясь объяснить физическую природу света. В итоге, он пришел к корпускулярной модели, рассматривая свет в виде потока частиц, вылетающих из определенного источника света.

Именно тогда Исаак Ньютон представил, пожалуй, свое самое знаменитое открытие – Закон всемирного тяготения.

Интересен факт, что история, связанная с яблоком, упавшим на голову исследователя, является мифом. На самом деле, Ньютон постепенно приближался к своему открытию.

Автором легенды о яблоке был известный философ Вольтер.

Научная известность

В конце 1660-х годов Исаак Ньютон возвратился в Кембридж, где получил степень магистра, отдельное жилье и группу учеников, которым преподавал разные науки.

В то время физик сконструировал телескоп-рефлектор, который прославил его и позволил ему стать членом Лондонского королевского общества.

С помощью рефлектора было сделано огромное количество важных астрономических открытий.

В 1687 г. Ньютон завершил писать свой главный труд «Математические начала натуральной философии». Он стал основной рациональной механики и всего математического естествознания.

В книге были изложены закон всемирного тяготения, 3 закона механики, гелиоцентрическая система Коперника, и прочие важные сведения.

Данная работа изобиловала точными доказательствами и формулировками. В ней не было каких-либо абстрактных выражений и размытых трактовок, которые встречались у предшественников Ньютона.

В 1699 г., когда исследователь занимал высокие административные должности, в университете Кембриджа начали преподавать изложенную им систему мира.

Вдохновителями Ньютона в наибольшей степени были физики: Галилей, Декарт и Кеплер. Кроме этого он высоко ценил труды Евклида, Ферма, Гюйгенса, Валлиса и Барроу.

Личная жизнь

Всю свою жизнь Ньютон прожил холостяком. Он был сосредоточен исключительно на науке.

До конца жизни физик почти никогда не носил очков, хотя имел небольшую близорукость. Он редко смеялся, практически никогда не выходил из себя и был сдержан в эмоциях.

Исаак знал счет деньгам, однако не был скуп. Он не проявлял никакого интереса к спорту, музыке, театру и путешествиям.

Все свободное время Ньютон посвящал науке. Его помощник вспоминал, что ученый не разрешал себе даже отдыхать полагая, что каждая свободная минута должна проходить с пользой.

Исаака даже огорчало то, что ему приходилось тратить столько много времени на сон. Он установил для себя ряд правил и самоограничений, которых всегда строго придерживался.

Ньютон с теплотой относился к родственникам и коллегам, однако никогда не стремился развить дружеские отношения, предпочитая им одиночество.

Смерть

За пару лет до смерти здоровье Ньютона стало ухудшаться, вследствие чего он переехал в Кенсингтон. Именно здесь он и скончался.

Исаак Ньютон умер 20 (31) марта 1727 года в возрасте 84 лет. Проститься с великим ученым пришел весь Лондон.

Фото Ньютона

Если вам понравилась краткая биография Исаака Ньютона – поделитесь ею в соцсетях. Если же вам нравятся биографии великих людей вообще, или интересные истории из их жизни, – подписывайтесь на сайт InteresnyeFakty.org.

Понравился пост? Нажми любую кнопку:

This article is about the scientist and mathematician. For the American agriculturalist, see Isaac Newton (agriculturalist).

|

Sir Isaac Newton PRS |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Newton at 46 by Godfrey Kneller, 1689 |

|

| Born | 4 January 1643 [O.S. 25 December 1642][a]

Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 31 March 1727 (aged 84) [O.S. 20 March 1726][a]

Kensington, Middlesex, Great Britain |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Education | Trinity College, Cambridge (M.A., 1668)[2] |

| Known for |

List

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors |

|

| Notable students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Influenced |

List

|

| Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge | |

| In office 1689–1690 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Brady |

| Succeeded by | Edward Finch |

| In office 1701–1702 |

|

| Preceded by | Anthony Hammond |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Annesley, 5th Earl of Anglesey |

| 12th President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1703–1727 |

|

| Preceded by | John Somers |

| Succeeded by | Hans Sloane |

| Master of the Mint | |

| In office 1699–1727 |

|

| 1696–1699 | Warden of the Mint |

| Preceded by | Thomas Neale |

| Succeeded by | John Conduitt |

| 2nd Lucasian Professor of Mathematics | |

| In office 1669–1702 |

|

| Preceded by | Isaac Barrow |

| Succeeded by | William Whiston |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Whig |

| Signature | |

|

Sir Isaac Newton PRS (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27)[a] was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a «natural philosopher»), widely recognised as one of the greatest mathematicians and physicists and among the most influential scientists of all time. He was a key figure in the philosophical revolution known as the Enlightenment. His book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687, established classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for developing infinitesimal calculus.

In the Principia, Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation that formed the dominant scientific viewpoint for centuries until it was superseded by the theory of relativity. Newton used his mathematical description of gravity to derive Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, account for tides, the trajectories of comets, the precession of the equinoxes and other phenomena, eradicating doubt about the Solar System’s heliocentricity. He demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and celestial bodies could be accounted for by the same principles. Newton’s inference that the Earth is an oblate spheroid was later confirmed by the geodetic measurements of Maupertuis, La Condamine, and others, convincing most European scientists of the superiority of Newtonian mechanics over earlier systems.

Newton built the first practical reflecting telescope and developed a sophisticated theory of colour based on the observation that a prism separates white light into the colours of the visible spectrum. His work on light was collected in his highly influential book Opticks, published in 1704. He also formulated an empirical law of cooling, made the first theoretical calculation of the speed of sound, and introduced the notion of a Newtonian fluid. In addition to his work on calculus, as a mathematician Newton contributed to the study of power series, generalised the binomial theorem to non-integer exponents, developed a method for approximating the roots of a function, and classified most of the cubic plane curves.

Newton was a fellow of Trinity College and the second Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. He was a devout but unorthodox Christian who privately rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. He refused to take holy orders in the Church of England, unlike most members of the Cambridge faculty of the day. Beyond his work on the mathematical sciences, Newton dedicated much of his time to the study of alchemy and biblical chronology, but most of his work in those areas remained unpublished until long after his death. Politically and personally tied to the Whig party, Newton served two brief terms as Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge, in 1689–1690 and 1701–1702. He was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705 and spent the last three decades of his life in London, serving as Warden (1696–1699) and Master (1699–1727) of the Royal Mint, as well as president of the Royal Society (1703–1727).

Early life

Early life

Isaac Newton was born (according to the Julian calendar in use in England at the time) on Christmas Day, 25 December 1642 (NS 4 January 1643[a]), «an hour or two after midnight»,[17] at Woolsthorpe Manor in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, a hamlet in the county of Lincolnshire. His father, also named Isaac Newton, had died three months before. Born prematurely, Newton was a small child; his mother Hannah Ayscough reportedly said that he could have fit inside a quart mug.[18] When Newton was three, his mother remarried and went to live with her new husband, the Reverend Barnabas Smith, leaving her son in the care of his maternal grandmother, Margery Ayscough (née Blythe). Newton disliked his stepfather and maintained some enmity towards his mother for marrying him, as revealed by this entry in a list of sins committed up to the age of 19: «Threatening my father and mother Smith to burn them and the house over them.»[19] Newton’s mother had three children (Mary, Benjamin, and Hannah) from her second marriage.[20]

The King’s School

From the age of about twelve until he was seventeen, Newton was educated at The King’s School in Grantham, which taught Latin and Ancient Greek and probably imparted a significant foundation of mathematics.[21] He was removed from school and returned to Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth by October 1659. His mother, widowed for the second time, attempted to make him a farmer, an occupation he hated.[22] Henry Stokes, master at The King’s School, persuaded his mother to send him back to school. Motivated partly by a desire for revenge against a schoolyard bully, he became the top-ranked student,[23] distinguishing himself mainly by building sundials and models of windmills.[24]

University of Cambridge

In June 1661, Newton was admitted to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. His uncle Reverend William Ayscough, who had studied at Cambridge, recommended him to the university. At Cambridge, Newton started as a subsizar, paying his way by performing valet duties until he was awarded a scholarship in 1664, which covered his university costs for four more years until the completion of his MA.[25] At the time, Cambridge’s teachings were based on those of Aristotle, whom Newton read along with then more modern philosophers, including Descartes and astronomers such as Galileo Galilei and Thomas Street. He set down in his notebook a series of «Quaestiones» about mechanical philosophy as he found it. In 1665, he discovered the generalised binomial theorem and began to develop a mathematical theory that later became calculus. Soon after Newton obtained his BA degree at Cambridge in August 1665, the university temporarily closed as a precaution against the Great Plague. Although he had been undistinguished as a Cambridge student,[26] Newton’s private studies at his home in Woolsthorpe over the next two years saw the development of his theories on calculus,[27] optics, and the law of gravitation.

In April 1667, Newton returned to the University of Cambridge, and in October he was elected as a fellow of Trinity.[28][29] Fellows were required to be ordained as priests, although this was not enforced in the restoration years and an assertion of conformity to the Church of England was sufficient. However, by 1675 the issue could not be avoided and by then his unconventional views stood in the way.[30] Nevertheless, Newton managed to avoid it by means of special permission from Charles II.

His academic work impressed the Lucasian professor Isaac Barrow, who was anxious to develop his own religious and administrative potential (he became master of Trinity College two years later); in 1669, Newton succeeded him, only one year after receiving his MA. Newton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1672.[3]

Work

Calculus

Newton’s work has been said «to distinctly advance every branch of mathematics then studied».[31] His work on the subject, usually referred to as fluxions or calculus, seen in a manuscript of October 1666, is now published among Newton’s mathematical papers.[32] His work De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas, sent by Isaac Barrow to John Collins in June 1669, was identified by Barrow in a letter sent to Collins that August as the work «of an extraordinary genius and proficiency in these things».[33]

Newton later became involved in a dispute with Leibniz over priority in the development of calculus (the Leibniz–Newton calculus controversy). Most modern historians believe that Newton and Leibniz developed calculus independently, although with very different mathematical notations. Occasionally it has been suggested that Newton published almost nothing about it until 1693, and did not give a full account until 1704, while Leibniz began publishing a full account of his methods in 1684. Leibniz’s notation and «differential Method», nowadays recognised as much more convenient notations, were adopted by continental European mathematicians, and after 1820 or so, also by British mathematicians.[citation needed]

His work extensively uses calculus in geometric form based on limiting values of the ratios of vanishingly small quantities: in the Principia itself, Newton gave demonstration of this under the name of «the method of first and last ratios»[34] and explained why he put his expositions in this form,[35] remarking also that «hereby the same thing is performed as by the method of indivisibles.»[36]

Because of this, the Principia has been called «a book dense with the theory and application of the infinitesimal calculus» in modern times[37] and in Newton’s time «nearly all of it is of this calculus.»[38] His use of methods involving «one or more orders of the infinitesimally small» is present in his De motu corporum in gyrum of 1684[39] and in his papers on motion «during the two decades preceding 1684».[40]

Newton had been reluctant to publish his calculus because he feared controversy and criticism.[41] He was close to the Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier. In 1691, Duillier started to write a new version of Newton’s Principia, and corresponded with Leibniz.[42] In 1693, the relationship between Duillier and Newton deteriorated and the book was never completed.[43]

Starting in 1699, other members[who?] of the Royal Society accused Leibniz of plagiarism.[44] The dispute then broke out in full force in 1711 when the Royal Society proclaimed in a study that it was Newton who was the true discoverer and labelled Leibniz a fraud; it was later found that Newton wrote the study’s concluding remarks on Leibniz. Thus began the bitter controversy which marred the lives of both Newton and Leibniz until the latter’s death in 1716.[45]

Newton is generally credited with the generalised binomial theorem, valid for any exponent. He discovered Newton’s identities, Newton’s method, classified cubic plane curves (polynomials of degree three in two variables), made substantial contributions to the theory of finite differences, and was the first to use fractional indices and to employ coordinate geometry to derive solutions to Diophantine equations. He approximated partial sums of the harmonic series by logarithms (a precursor to Euler’s summation formula) and was the first to use power series with confidence and to revert power series. Newton’s work on infinite series was inspired by Simon Stevin’s decimals.[46]

When Newton received his MA and became a Fellow of the «College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity» in 1667, he made the commitment that «I will either set Theology as the object of my studies and will take holy orders when the time prescribed by these statutes [7 years] arrives, or I will resign from the college.»[47] Up until this point he had not thought much about religion and had twice signed his agreement to the thirty-nine articles, the basis of Church of England doctrine.

He was appointed Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in 1669, on Barrow’s recommendation. During that time, any Fellow of a college at Cambridge or Oxford was required to take holy orders and become an ordained Anglican priest. However, the terms of the Lucasian professorship required that the holder not be active in the church – presumably,[weasel words] so as to have more time for science. Newton argued that this should exempt him from the ordination requirement, and Charles II, whose permission was needed, accepted this argument; thus, a conflict between Newton’s religious views and Anglican orthodoxy was averted.[48]

Optics

In 1666, Newton observed that the spectrum of colours exiting a prism in the position of minimum deviation is oblong, even when the light ray entering the prism is circular, which is to say, the prism refracts different colours by different angles.[50][51] This led him to conclude that colour is a property intrinsic to light – a point which had, until then, been a matter of debate.

From 1670 to 1672, Newton lectured on optics.[52] During this period he investigated the refraction of light, demonstrating that the multicoloured image produced by a prism, which he named a spectrum, could be recomposed into white light by a lens and a second prism.[53] Modern scholarship has revealed that Newton’s analysis and resynthesis of white light owes a debt to corpuscular alchemy.[54]

He showed that coloured light does not change its properties by separating out a coloured beam and shining it on various objects, and that regardless of whether reflected, scattered, or transmitted, the light remains the same colour. Thus, he observed that colour is the result of objects interacting with already-coloured light rather than objects generating the colour themselves. This is known as Newton’s theory of colour.[55]

Illustration of a dispersive prism separating white light into the colours of the spectrum, as discovered by Newton

From this work, he concluded that the lens of any refracting telescope would suffer from the dispersion of light into colours (chromatic aberration). As a proof of the concept, he constructed a telescope using reflective mirrors instead of lenses as the objective to bypass that problem.[56][57] Building the design, the first known functional reflecting telescope, today known as a Newtonian telescope,[57] involved solving the problem of a suitable mirror material and shaping technique. Newton ground his own mirrors out of a custom composition of highly reflective speculum metal, using Newton’s rings to judge the quality of the optics for his telescopes. In late 1668,[58] he was able to produce this first reflecting telescope. It was about eight inches long and it gave a clearer and larger image. In 1671, the Royal Society asked for a demonstration of his reflecting telescope.[59] Their interest encouraged him to publish his notes, Of Colours,[60] which he later expanded into the work Opticks. When Robert Hooke criticised some of Newton’s ideas, Newton was so offended that he withdrew from public debate. Newton and Hooke had brief exchanges in 1679–80, when Hooke, appointed to manage the Royal Society’s correspondence, opened up a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions,[61] which had the effect of stimulating Newton to work out a proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector. But the two men remained generally on poor terms until Hooke’s death.[62]

Facsimile of a 1682 letter from Newton to William Briggs, commenting on Briggs’ A New Theory of Vision

Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles, which were refracted by accelerating into a denser medium. He verged on soundlike waves to explain the repeated pattern of reflection and transmission by thin films (Opticks Bk.II, Props. 12), but still retained his theory of ‘fits’ that disposed corpuscles to be reflected or transmitted (Props.13). However, later physicists favoured a purely wavelike explanation of light to account for the interference patterns and the general phenomenon of diffraction. Today’s quantum mechanics, photons, and the idea of wave–particle duality bear only a minor resemblance to Newton’s understanding of light.

In his Hypothesis of Light of 1675, Newton posited the existence of the ether to transmit forces between particles. The contact with the Cambridge Platonist philosopher Henry More revived his interest in alchemy.[63] He replaced the ether with occult forces based on Hermetic ideas of attraction and repulsion between particles. John Maynard Keynes, who acquired many of Newton’s writings on alchemy, stated that «Newton was not the first of the age of reason: He was the last of the magicians.»[64] Newton’s contributions to science cannot be isolated from his interest in alchemy.[63] This was at a time when there was no clear distinction between alchemy and science, and had he not relied on the occult idea of action at a distance, across a vacuum, he might not have developed his theory of gravity.

In 1704, Newton published Opticks, in which he expounded his corpuscular theory of light. He considered light to be made up of extremely subtle corpuscles, that ordinary matter was made of grosser corpuscles and speculated that through a kind of alchemical transmutation «Are not gross Bodies and Light convertible into one another, … and may not Bodies receive much of their Activity from the Particles of Light which enter their Composition?»[65] Newton also constructed a primitive form of a frictional electrostatic generator, using a glass globe.[66]

In his book Opticks, Newton was the first to show a diagram using a prism as a beam expander, and also the use of multiple-prism arrays.[67] Some 278 years after Newton’s discussion, multiple-prism beam expanders became central to the development of narrow-linewidth tunable lasers. Also, the use of these prismatic beam expanders led to the multiple-prism dispersion theory.[67]

Subsequent to Newton, much has been amended. Young and Fresnel discarded Newton’s particle theory in favour of Huygens’ wave theory to show that colour is the visible manifestation of light’s wavelength. Science also slowly came to realise the difference between perception of colour and mathematisable optics. The German poet and scientist, Goethe, could not shake the Newtonian foundation but «one hole Goethe did find in Newton’s armour, … Newton had committed himself to the doctrine that refraction without colour was impossible. He, therefore, thought that the object-glasses of telescopes must forever remain imperfect, achromatism and refraction being incompatible. This inference was proved by Dollond to be wrong.»[68]

Gravity

In 1679, Newton returned to his work on celestial mechanics by considering gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets with reference to Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. This followed stimulation by a brief exchange of letters in 1679–80 with Hooke, who had been appointed to manage the Royal Society’s correspondence, and who opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions.[61] Newton’s reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–1681, on which he corresponded with John Flamsteed.[69] After the exchanges with Hooke, Newton worked out a proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector. Newton communicated his results to Edmond Halley and to the Royal Society in De motu corporum in gyrum, a tract written on about nine sheets which was copied into the Royal Society’s Register Book in December 1684.[70] This tract contained the nucleus that Newton developed and expanded to form the Principia.

The Principia was published on 5 July 1687 with encouragement and financial help from Halley. In this work, Newton stated the three universal laws of motion. Together, these laws describe the relationship between any object, the forces acting upon it and the resulting motion, laying the foundation for classical mechanics. They contributed to many advances during the Industrial Revolution which soon followed and were not improved upon for more than 200 years. Many of these advances continue to be the underpinnings of non-relativistic technologies in the modern world. He used the Latin word gravitas (weight) for the effect that would become known as gravity, and defined the law of universal gravitation.[71]

In the same work, Newton presented a calculus-like method of geometrical analysis using ‘first and last ratios’, gave the first analytical determination (based on Boyle’s law) of the speed of sound in air, inferred the oblateness of Earth’s spheroidal figure, accounted for the precession of the equinoxes as a result of the Moon’s gravitational attraction on the Earth’s oblateness, initiated the gravitational study of the irregularities in the motion of the Moon, provided a theory for the determination of the orbits of comets, and much more.[71] Newton’s biographer David Brewster reported that the complexity of applying his theory of gravity to the motion of the moon was so great it affected Newton’s health: «[H]e was deprived of his appetite and sleep» during his work on the problem in 1692-3, and told the astronomer John Machin that «his head never ached but when he was studying the subject». According to Brewster Edmund Halley also told John Conduitt that when pressed to complete his analysis Newton «always replied that it made his head ache, and kept him awake so often, that he would think of it no more«. [Emphasis in original][72]

Newton made clear his heliocentric view of the Solar System—developed in a somewhat modern way because already in the mid-1680s he recognised the «deviation of the Sun» from the centre of gravity of the Solar System.[73] For Newton, it was not precisely the centre of the Sun or any other body that could be considered at rest, but rather «the common centre of gravity of the Earth, the Sun and all the Planets is to be esteem’d the Centre of the World», and this centre of gravity «either is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a right line» (Newton adopted the «at rest» alternative in view of common consent that the centre, wherever it was, was at rest).[74]

Newton’s postulate of an invisible force able to act over vast distances led to him being criticised for introducing «occult agencies» into science.[75] Later, in the second edition of the Principia (1713), Newton firmly rejected such criticisms in a concluding General Scholium, writing that it was enough that the phenomena implied a gravitational attraction, as they did; but they did not so far indicate its cause, and it was both unnecessary and improper to frame hypotheses of things that were not implied by the phenomena. (Here Newton used what became his famous expression «hypotheses non-fingo»[76]).

With the Principia, Newton became internationally recognised.[77] He acquired a circle of admirers, including the Swiss-born mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier.[78]

In 1710, Newton found 72 of the 78 «species» of cubic curves and categorised them into four types.[79] In 1717, and probably with Newton’s help, James Stirling proved that every cubic was one of these four types. Newton also claimed that the four types could be obtained by plane projection from one of them, and this was proved in 1731, four years after his death.[80]

Later life

Royal Mint

In the 1690s, Newton wrote a number of religious tracts dealing with the literal and symbolic interpretation of the Bible. A manuscript Newton sent to John Locke in which he disputed the fidelity of 1 John 5:7—the Johannine Comma—and its fidelity to the original manuscripts of the New Testament, remained unpublished until 1785.[81]

Newton was also a member of the Parliament of England for Cambridge University in 1689 and 1701, but according to some accounts his only comments were to complain about a cold draught in the chamber and request that the window be closed.[82] He was, however, noted by Cambridge diarist Abraham de la Pryme to have rebuked students who were frightening locals by claiming that a house was haunted.[83]

Newton moved to London to take up the post of warden of the Royal Mint in 1696, a position that he had obtained through the patronage of Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax, then Chancellor of the Exchequer. He took charge of England’s great recoining, trod on the toes of Lord Lucas, Governor of the Tower, and secured the job of deputy comptroller of the temporary Chester branch for Edmond Halley. Newton became perhaps the best-known Master of the Mint upon the death of Thomas Neale in 1699, a position Newton held for the last 30 years of his life.[84][85] These appointments were intended as sinecures, but Newton took them seriously. He retired from his Cambridge duties in 1701, and exercised his authority to reform the currency and punish clippers and counterfeiters.

As Warden, and afterwards as Master, of the Royal Mint, Newton estimated that 20 percent of the coins taken in during the Great Recoinage of 1696 were counterfeit. Counterfeiting was high treason, punishable by the felon being hanged, drawn and quartered. Despite this, convicting even the most flagrant criminals could be extremely difficult, but Newton proved equal to the task.[86]

Disguised as a habitué of bars and taverns, he gathered much of that evidence himself.[87] For all the barriers placed to prosecution, and separating the branches of government, English law still had ancient and formidable customs of authority. Newton had himself made a justice of the peace in all the home counties. A draft letter regarding the matter is included in Newton’s personal first edition of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which he must have been amending at the time.[88] Then he conducted more than 100 cross-examinations of witnesses, informers, and suspects between June 1698 and Christmas 1699. Newton successfully prosecuted 28 coiners.[89]

Newton was made president of the Royal Society in 1703 and an associate of the French Académie des Sciences. In his position at the Royal Society, Newton made an enemy of John Flamsteed, the Astronomer Royal, by prematurely publishing Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica, which Newton had used in his studies.[91]

Knighthood

In April 1705, Queen Anne knighted Newton during a royal visit to Trinity College, Cambridge. The knighthood is likely to have been motivated by political considerations connected with the parliamentary election in May 1705, rather than any recognition of Newton’s scientific work or services as Master of the Mint.[92] Newton was the second scientist to be knighted, after Francis Bacon.[93]

As a result of a report written by Newton on 21 September 1717 to the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty’s Treasury, the bimetallic relationship between gold coins and silver coins was changed by royal proclamation on 22 December 1717, forbidding the exchange of gold guineas for more than 21 silver shillings.[94] This inadvertently resulted in a silver shortage as silver coins were used to pay for imports, while exports were paid for in gold, effectively moving Britain from the silver standard to its first gold standard. It is a matter of debate as to whether he intended to do this or not.[95] It has been argued that Newton conceived of his work at the Mint as a continuation of his alchemical work.[96]

Newton was invested in the South Sea Company and lost some £20,000 (£4.4 million in 2020[97]) when it collapsed in around 1720.[98]

Toward the end of his life, Newton took up residence at Cranbury Park, near Winchester, with his niece and her husband, until his death.[99] His half-niece, Catherine Barton,[100] served as his hostess in social affairs at his house on Jermyn Street in London; he was her «very loving Uncle»,[101] according to his letter to her when she was recovering from smallpox.

Death

Newton died in his sleep in London on 20 March 1727 (OS 20 March 1726; NS 31 March 1727).[a] He was given a ceremonial funeral, attended by nobles, scientists, and philosophers, and was buried in Westminster Abbey among kings and queens. He is also the first scientist to be buried in the abbey.[102] Voltaire may have been present at his funeral.[103] A bachelor, he had divested much of his estate to relatives during his last years, and died intestate.[104] His papers went to John Conduitt and Catherine Barton.[105]

After his death, Newton’s hair was examined and found to contain mercury, probably resulting from his alchemical pursuits. Mercury poisoning could explain Newton’s eccentricity in late life.[104]

Personality

Although it was claimed that he was once engaged,[b] Newton never married. The French writer and philosopher Voltaire, who was in London at the time of Newton’s funeral, said that he «was never sensible to any passion, was not subject to the common frailties of mankind, nor had any commerce with women—a circumstance which was assured me by the physician and surgeon who attended him in his last moments».[107] There exists a widespread belief that Newton died a virgin, and writers as diverse as mathematician Charles Hutton,[108] economist John Maynard Keynes,[109] and physicist Carl Sagan each have commented on it.[110]

Newton had a close friendship with the Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, who he met in London around 1689[78]—some of their correspondence has survived.[111][112] Their relationship came to an abrupt and unexplained end in 1693, and at the same time Newton suffered a nervous breakdown,[113] which included sending wild accusatory letters to his friends Samuel Pepys and John Locke. His note to the latter included the charge that Locke «endeavoured to embroil me with woemen».[114]

Newton was relatively modest about his achievements, writing in a letter to Robert Hooke in February 1676, «If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.»[115] Two writers think that the sentence, written at a time when Newton and Hooke were in dispute over optical discoveries, was an oblique attack on Hooke (said to have been short and hunchbacked), rather than—or in addition to—a statement of modesty.[116][117] On the other hand, the widely known proverb about standing on the shoulders of giants, published among others by seventeenth-century poet George Herbert (a former orator of the University of Cambridge and fellow of Trinity College) in his Jacula Prudentum (1651), had as its main point that «a dwarf on a giant’s shoulders sees farther of the two», and so its effect as an analogy would place Newton himself rather than Hooke as the ‘dwarf’.