«Феноменология

духа» — вершина философии йенского

периода. Работа делится на три главных

раздела: сознание, самосознание,

абсолютный субъект. В разделе «сознание»,

речь идет о чувственной достоверности,

мнении, восприятии, рассудке. В «Абсолютном

субъекте» — о достоверностях и истине

разума, где героем становится именно

разум. —Понятия духа, истинного духа,

нравственности, религии, абсолютного

знания также присутствуют в «Феноменологии

духа». Гегель пытается создать

произведение, основанное на понятии

являющегося духа. Он продолжает развивать

хорошо известное немецкой классической

философии, но, как представляется,

по-новому понимаемое понятие субъекта

и субъективности. С одной стороны,

идеалист Гегель исходит из того, что

дух образует основу мира. У Гегеля и у

Шеллинга к этому времени уже был развит

принцип тождества бытия и мышления,

принцип субстанциональности духа, т.е.

один из основных принципов идеалистической

и, в частности, объективно-идеалистической

философии. Путь Гегеля состоит в том,

чтобы наука была изложена как система.

Истинное надо выразить «не как

субстанцию только, но равным образом и

как субъект, …то, что истинное действительно

только как система, или то, что субстанция

по существу есть субъект, выражено в

представлении, которое провозглашает

абсолютное духа — самое возвышенное

понятие и притом понятие, которое

принадлежит времени и его религии».

Поразмыслив над сложным сплавом идей

и подходов «Феноменологии духа».

Работа

открывается такими понятиями, как

чувственная достоверность, восприятие,

рассудок. На эти три формы и делится

первый раздел гегелевской феноменологии

духа, а именно, раздел о сознании. Затем

от анализа сознания Гегель переходит

к самосознанию. Самосознание же и есть

исследование рассудка. Затем на сцену

выступит разум, который будет

рассматриваться Гегелем в разделе

«абсолютный субъект». Таким образом,

«Феноменология духа» является критическим

анализом предшествующей философии.

Так, в первом разделе, где речь идет о

сознании, Гегель рассматривает формы

сознания, которые связаны с осознанием

вещи, с чувственной достоверностью.

«Феноменология

духа» предстает не просто как

гносеологическое произведение или

рассказ о формах являющегося сознания:

это не просто теория познания и сознания.

Гегель исходит из того, что любая форма

являющегося сознания как бы вступает

на живую, движущуюся, но постоянно

сохраняющуюся сцену взаимодействия

индивидов в истории. Человек может

каким-то образом переживать свое

отношение к форме чувственной

достоверности, но это переживание не

есть просто и только его индивидуальное

переживание, возникающее и тут же

исчезающее. Оно как бы выступает на

сцену форм являющегося духа. Это особенно

очевидно в других разделах «Феноменологии

духа», например, посвященных самосознанию.

Здесь Гегель анализирует диалектику

господского и рабского сознания,

рассматривает так называемое несчастное

сознание, не скрывая связи форм являющегося

знания и сознания с некоторыми

легкоузнаваемыми историческими

прототипами, например теми, которые

выступили в период Французской революции.

Одна из глав «Феноменологии духа»,

которая называется «Свобода и ужас»,

посвящена анализу таких выступающих

на сцене духа форм сознания, которые

связаны с пониманием свободы как ничем

не ограниченной. Результат этой свободы

— абсолютный ужас. Здесь, по-видимому,

речь идет о терроре, сопутствующем

Французской революции (и всякой иной

революции).

Что

касается диалектики господского и

рабского сознания, то это — одна из

самых блестящих глав «Феноменологии

духа». Анализируется диалектика

господского и рабского сознания. Гегель

показывает, что в основе отношения

господства и рабства лежит особый тип

сознания, когда, с одной стороны, раб

признает в господине именно господина,

т. е. существо, которое вправе распоряжаться

его волей, его судьбой, им как человеческим

существом. С другой стороны, господское

сознание тоже признает свою зависимость

от раба, от труда раба, от его покорности.

В

других разделах «Феноменологии духа»,

речь идет о просвещении и добродетели,

нравственности сознания, мудрости,

религии и т.д. Все они «портретируются»

Гегелем, и тем самым ставится множество

проблем, которые связаны с совершенно

необычным прояснением понятий рассудка,

разума, духа.

Значение

и направленность «Феноменологии

духа»

Из

всего вышесказанного вытекает тот факт,

что в момент философствования человек

поднимается над уровнем обыденного

сознания, а точнее, на высоту чистого

разума в абсолютной перспективе (т. е.

он обретает точку зрения Абсолюта).

Чтобы «построить абсолют в сознании»,

требуется устранить и преодолеть

конечность сознания и возвести

эмпирическое «я» в «я»

трансцендентальное, в степень Разума

и Духа.

«Феноменология

духа» была задумана и написана Гегелем

как раз с целью очистить эмпирическое

сознание и «опосредованно» возвысить

его до абсолютного Знания и Духа. Согласно

Гегелю, философия есть познание Абсолюта

в двух смыслах: а) Абсолют как объект и

б) Абсолют как субъект. Ведь философия

— это Абсолют, познающий сам себя

(самопознание через философию). Если

это так, то Абсолют не только цель, к

которой стремится феноменология, но,

по мнению многих ученых, также и сила,

возвышающая сознание.

Можно

утверждать, что «Феноменология»

отводит человеку не менее значимую

роль, чем самому Абсолюту. Действительно,

у Гегеля не существует конечного в

отрыве от бесконечного, частного —

отдельно от всеобщего. Стало быть, и

человек неотделим от Абсолюта, являясь

определяющей частью его структуры, ведь

гегелевское Бесконечное есть

бесконечно-саморазвивающееся-по-средством-конечного.

Абсолют же есть «сущее, вечно

возвращающееся к себе из инобытия».

Вышеизложенное

облегчает понимание гегелевской

трактовки термина «феноменология»,

что обозначает определенное

движение философской мысли.

Термин происходит от греческого

«phainomenon», что означает «проявляющееся»,

«являющееся», и, соответственно,

подразумевает «науку о явлениях и

проявлениях». Это проявления самого

Духа на различных этапах, который,

начиная от эмпирического сознания,

поднимается шаг за шагом на все более

высокие уровни. Следовательно,

феноменология — это наука о Духе, который

проявляется в форме как определенного

бытия, так и множественного бытия, и

который через ряд последовательных

воплощений (фигур), иначе говоря через

ряд диалектически связанных между собой

моментов, достигает аболютного Знания.

В

«Феноменологии духа» имеются два

сопряженных и взаимопересекающихся

плана: 1) план движения Духа в русле

самопостижения через все исторические

перипетии окружающего мира, который,

согласно Гегелю, есть путь самоосуществления

и самопознания Духа; 2) план, относящийся

к отдельному эмпирическому индивиду,

который должен пройти и освоить тот же

путь. Поэтому история сознания индивида

есть не что иное, как повторное прохождение

истории Духа. Феноменологическое

введение в философию — освоение этого

пути.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

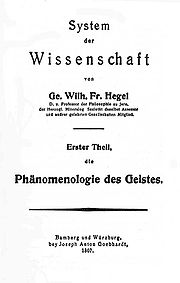

Title page of the first edition |

|

| Author | Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel |

|---|---|

| Original title | Phänomenologie des Geistes |

| Translator | James Black Baillie |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Philosophy |

| Published | 1807 |

|

Published in English |

1910 |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 929308074 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

193 |

| LC Class | B2928 .E5 |

|

Original text |

Phänomenologie des Geistes at Project Gutenberg |

| Translation | The Phenomenology of Spirit at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign |

The Phenomenology of Spirit (German: Phänomenologie des Geistes) is the most widely-discussed philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel; its German title can be translated as either The Phenomenology of Spirit or The Phenomenology of Mind. Hegel described the work, published in 1807, as an «exposition of the coming to be of knowledge».[1] This is explicated through a necessary self-origination and dissolution of «the various shapes of spirit as stations on the way through which spirit becomes pure knowledge».[1]

The book marked a significant development in German idealism after Immanuel Kant. Focusing on topics in metaphysics, epistemology, ontology, ethics, history, religion, perception, consciousness, existence, logic, and political philosophy, it is where Hegel develops his concepts of dialectic (including the lord-bondsman dialectic), absolute idealism, ethical life, and Aufhebung. It had a profound effect in Western philosophy, and «has been praised and blamed for the development of existentialism, communism, fascism, death of God theology, and historicist nihilism».[2]

Historical context[edit]

Hegel was putting the finishing touches to this book as Napoleon engaged Prussian troops on October 14, 1806, in the Battle of Jena on a plateau outside the city. On the day before the battle, Napoleon entered the city of Jena. Later that same day, Hegel wrote a letter to his friend, the theologian Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

I saw the Emperor – this world-soul – riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it … this extraordinary man, whom it is impossible not to admire.[3]

In 2000, Terry Pinkard notes that Hegel’s comment to Niethammer «is all the more striking since at that point he had already composed the crucial section of the Phenomenology in which he remarked that the Revolution had now officially passed to another land (Germany) that would complete ‘in thought’ what the Revolution had only partially accomplished in practice.»[4]

Publication history[edit]

The Phenomenology of Spirit was published with the title “System of Science: First Part: The Phenomenology of Spirit”.[5] Some copies contained either «Science of the Experience of Consciousness», or «Science of the Phenomenology of Spirit» as a subtitle between the «Preface» and the «Introduction».[5] On its initial publication, the work was identified as Part One of a projected «System of Science», which would have contained the Science of Logic «and both the two real sciences of philosophy, the Philosophy of Nature and the Philosophy of Spirit”[6] as its second part. The Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, in its third section (Philosophy of Spirit), contains a second subsection (The Encyclopedia Phenomenology) that recounts in briefer and somewhat altered form the major themes of the original Phenomenology.

Structure[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: coverage of the content of the book, which currently stops at the beginning of ch. 1. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) |

The book consists of a Preface (written after the rest was completed), an Introduction, and six major divisions (of greatly varying size).[a]

- (A) Consciousness is divided into three chapters:

- (I) Sensuous-Certainty,

- (II) Perceiving, and

- (III) Force and the Understanding.

- (B) Self-Consciousness contains one chapter:

- (IV) The Truth of Self-Certainty which contains a preliminary discussion of Life and Desire, followed by two subsections: (A) Self-Sufficiency and Non-Self-Sufficiency of Self-Consciousness; Mastery and Servitude and (B) Freedom of Self-Consciousness: Stoicism, Skepticism, and the Unhappy Consciousness. Notable is the presence of the discussion of the dialectic of the lord and bondsman.[to whom?]

- (C), (AA) Reason contains one chapter:

- (V) The Certainty and Truth of Reason which is divided into three chapters: (A) Observing Reason, (B) The Actualization of Rational Self-Consciousness Through Itself, and (C) Individuality, Which, to Itself, is Real in and for Itself.

- (BB) Spirit contains one chapter:

- (VI) Spirit or Geist which is again divided into three chapters: (A) True Spirit, Ethical Life, (B) Spirit Alienated from Itself: Cultural Formation, and (C) Spirit Certain of Itself: Morality.

- (CC) Religion contains one chapter:

- (VII) Religion, which is divided into three chapters: (A) Natural Religion, (B) The Art-Religion, and (C) Revealed Religion.

- (DD) Absolute Knowing contains one chapter:

- (VIII) Absolute Knowing.[b]

Due to its obscure nature and the many works by Hegel that followed its publication, even the structure or core theme of the book itself remains contested. First, Hegel wrote the book under close time constraints with little chance for revision (individual chapters were sent to the publisher before others were written). Furthermore, according to some readers, Hegel may have changed his conception of the project over the course of the writing. Secondly, the book abounds with both highly technical argument in philosophical language, and concrete examples, either imaginary or historical, of developments by people through different states of consciousness. The relationship between these is disputed: whether Hegel meant to prove claims about the development of world history, or simply used it for illustration; whether or not the more conventionally philosophical passages are meant to address specific historical and philosophical positions; and so forth.

Jean Hyppolite famously interpreted the work as a Bildungsroman that follows the progression of its protagonist, Spirit, through the history of consciousness,[9] a characterization that remains prevalent among literary theorists. However, others contest this literary interpretation and instead read the work as a «self-conscious reflective account»[10] that a society must give of itself in order to understand itself and therefore become reflective. Martin Heidegger saw it as the foundation of a larger «System of Science» that Hegel sought to develop,[11] while Alexandre Kojève saw it as akin to a «Platonic Dialogue … between the great Systems of history.»[12] It has also been called «a philosophical roller coaster … with no more rhyme or reason for any particular transition than that it struck Hegel that such a transition might be fun or illuminating.»[13]

Preface[edit]

The Preface to the text is a preamble to the scientific system and cognition in general. Paraphrased “on scientific cognition» in the table of contents, its intent is to offer a rough idea on scientific cognition, while at the same time aiming «to rid ourselves of a few forms which are only impediments to philosophical cognition».[14] As Hegel’s own announcement noted, it was to explain «what seems to him the need of philosophy in its present state; also about the presumption and mischief of the philosophical formulas that are currently degrading philosophy, and about what is altogether crucial in it and its study».[15] It can thus be seen as a heuristic attempt at creating the need of philosophy (in the present state) and of what philosophy itself in its present state needs. This involves an exposition on the content and standpoint of philosophy, i.e, the true shape of truth and the element of its existence, that is interspersed with polemics aimed at the presumption and mischief of philosophical formulas and what distinguishes it from that of any previous philosophy, especially that of his German Idealist predecessors (Kant, Fichte, and Schelling).[16]

The Hegelian method consists of actually examining consciousness’ experience of both itself and of its objects and eliciting the contradictions and dynamic movement that come to light in looking at this experience. Hegel uses the phrase «pure looking at» (reines Zusehen) to describe this method. If consciousness just pays attention to what is actually present in itself and its relation to its objects, it will see that what looks like stable and fixed forms dissolve into a dialectical movement. Thus, philosophy, according to Hegel, cannot just set out arguments based on a flow of deductive reasoning. Rather, it must look at actual consciousness, as it really exists.

Hegel also argues strongly against the epistemological emphasis of modern philosophy from Descartes through Kant, which he describes as having to first establish the nature and criteria of knowledge prior to actually knowing anything, because this would imply an infinite regress, a foundationalism that Hegel maintains is self-contradictory and impossible. Rather, he maintains, we must examine actual knowing as it occurs in real knowledge processes. This is why Hegel uses the term «phenomenology». «Phenomenology» comes from the Greek word for «to appear», and the phenomenology of mind is thus the study of how consciousness or mind appears to itself. In Hegel’s dynamic system, it is the study of the successive appearances of the mind to itself, because on examination each one dissolves into a later, more comprehensive and integrated form or structure of mind.

Introduction[edit]

Whereas the Preface was written after Hegel completed the Phenomenology, the Introduction was written beforehand.

In the Introduction, Hegel addresses the seeming paradox that we cannot evaluate our faculty of knowledge in terms of its ability to know the Absolute without first having a criterion for what the Absolute is, one that is superior to our knowledge of the Absolute. Yet, we could only have such a criterion if we already had the improved knowledge that we seek.

To resolve this paradox, Hegel adopts a method whereby the knowing that is characteristic of a particular stage of consciousness is evaluated using the criterion presupposed by consciousness itself. At each stage, consciousness knows something, and at the same time distinguishes the object of that knowledge as different from what it knows. Hegel and his readers will simply «look on» while consciousness compares its actual knowledge of the object—what the object is «for consciousness»—with its criterion for what the object must be «in itself». One would expect that, when consciousness finds that its knowledge does not agree with its object, consciousness would adjust its knowledge to conform to its object. However, in a characteristic reversal, Hegel explains that under his method, the opposite occurs.

As just noted, consciousness’ criterion for what the object should be is not supplied externally but rather by consciousness itself. Therefore, like its knowledge, the «object» that consciousness distinguishes from its knowledge is really just the object «for consciousness»—it is the object as envisioned by that stage of consciousness. Thus, in attempting to resolve the discord between knowledge and object, consciousness inevitably alters the object as well. In fact, the new «object» for consciousness is developed from consciousness’ inadequate knowledge of the previous «object». Thus, what consciousness really does is to modify its «object» to conform to its knowledge. Then the cycle begins anew as consciousness attempts to examine what it knows about this new «object».

The reason for this reversal is that, for Hegel, the separation between consciousness and its object is no more real than consciousness’ inadequate knowledge of that object. The knowledge is inadequate only because of that separation. At the end of the process, when the object has been fully «spiritualized» by successive cycles of consciousness’ experience, consciousness will fully know the object and at the same time fully recognize that the object is none other than itself.

At each stage of development, Hegel, adds, «we» (Hegel and his readers) see this development of the new object out of the knowledge of the previous one, but the consciousness that we are observing does not. As far as it is concerned, it experiences the dissolution of its knowledge in a mass of contradictions, and the emergence of a new object for knowledge, without understanding how that new object has been born.

Important concepts[edit]

Hegelian dialectic[edit]

The famous dialectical process of thesis–antithesis–synthesis has been controversially attributed to Hegel.

Whoever looks for the stereotype of the allegedly Hegelian dialectic in Hegel’s Phenomenology will not find it. What one does find on looking at the table of contents is a very decided preference for triadic arrangements. … But these many triads are not presented or deduced by Hegel as so many theses, antitheses, and syntheses. It is not by means of any dialectic of that sort that his thought moves up the ladder to absolute knowledge.

— Walter Kaufmann (1965). Hegel. Reinterpretation, Texts, and Commentary. p. 168.

Regardless of (ongoing) academic controversy regarding the significance of a unique dialectical method in Hegel’s writings, it is true, as Professor Howard Kainz (1996) affirms, that there are «thousands of triads» in Hegel’s writings. Importantly, instead of using the famous terminology that originated with Kant and was elaborated by J. G. Fichte, Hegel used an entirely different and more accurate terminology for dialectical (or as Hegel called them, «speculative») triads.

Hegel used two different sets of terms for his triads, namely, «abstract–negative–concrete» (especially in his Phenomenology of 1807), as well as «immediate–mediate–concrete» (especially in his Science of Logic of 1812), depending on the scope of his argumentation.

When one looks for these terms in his writings, one finds so many occurrences that it may become clear that Hegel employed the Kantian using a different terminology.

Hegel explained his change of terminology. The triad terms «abstract–negative–concrete» contain an implicit explanation for the flaws in Kant’s terms. The first term, «thesis», deserves its anti-thesis simply because it is too abstract. The third term, «synthesis», has completed the triad, making it concrete and no longer abstract by absorbing the negative.

Sometimes Hegel used the terms «immediate–mediate–concrete, to describe his triads. The most abstract concepts are those that present themselves to our consciousness immediately. For example, the notion of Pure Being for Hegel was the most abstract concept of all. The negative of this infinite abstraction would require an entire Encyclopedia, building category by category, dialectically, until it culminated in the category of Absolute Mind or Spirit (since the German word Geist can mean either ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’).

Unfolding of species[edit]

Hegel describes a sequential progression from inanimate objects to animate creatures to human beings. This is frequently compared to Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory.[citation needed] However, unlike Darwin, Hegel thought that organisms had agency in choosing to develop along this progression by collaborating with other organisms.[17][18] Hegel understood this to be a linear process of natural development with a predetermined end. He viewed this end teleologically as its ultimate purpose and destiny.[17][19][20]

Criticism[edit]

Walter Kaufmann, on the question of organisation, argued that Hegel’s arrangement, «over half a century before Darwin published his Origin of Species and impressed the idea of evolution on almost everybody’s mind, was developmental.»[21] The idea is supremely suggestive but, in the end, untenable according to Kaufmann: «The idea of arranging all significant points of view in such a single sequence, on a ladder that reaches from the crudest to the most mature, is as dazzling to contemplate as it is mad to try seriously to implement it».[22] While Kaufmann viewed Hegel as right in seeing that the way a view is reached is not necessarily external to the view itself, since, on the contrary, a knowledge of the development, including the prior positions through which a human being passed before adopting a position may make all the difference when it comes to comprehending his or her position, some aspects of the conception are still somewhat absurd and some of the details bizarre.[23] Kaufmann also remarks that the very table of contents of the Phenomenology may be said to «mirror confusion» and that «faults are so easy to find in it that it is not worth while to adduce heaps of them.»[citation needed] However, he excuses Hegel since he understands that the author of the Phenomenology, «finished the book under an immense strain».[24]

The feminist philosopher Kelly Oliver argues that Hegel’s discussion of women in The Phenomenology of Spirit undermines the entirety of the text. Oliver points out that for Hegel, every element of consciousness must be conceptualizable, but that in Hegel’s discussion of the family, woman is established as in principle unconceptualizable. Oliver writes that “unlike the master or slave, the feminine or woman does not contain the dormant seed of its opposite.”. This means that Hegel’s feminine is nothing other than the negation of the masculine and as such it must be excluded from the story of masculine consciousness. Thus, Oliver argues, the Phenomenology of Spirit is a phenomenology of masculine consciousness; the universalist pretensions of the text are not achieved, as it leaves out the phenomenology of feminine consciousness.[25]

Referencing[edit]

The work is usually abbreviated as PdG (Phänomenologie des Geistes), followed by the pagination or paragraph number of the German original edition. It is also abbreviated as PS (The Phenomenology of Spirit) or as PM (The Phenomenology of Mind), followed by the pagination or paragraph number of the English translation used by each author.

English translations[edit]

- G. W. F. Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by Peter Fuss and John Dobbins (University of Notre Dame Press, 2019)

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit (Cambridge Hegel Translations), translated by Terry Pinkard (Cambridge University Press, 2018) ISBN 0-52185579-9

- Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit: Translated with introduction and commentary, translated by Michael Inwood (Oxford University Press, 2018) ISBN 0-19879062-7

- Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by A. V. Miller with analysis of the text and foreword by J. N. Findlay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) ISBN 0-19824597-1

- Phenomenology of Mind, translated by J. B. Baillie (London: Harper & Row, 1967)

- Hegel’s Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit, translated with introduction, running commentary and notes by Yirmiyahu Yovel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004) ISBN 0-69112052-8.

- Texts and Commentary: Hegel’s Preface to His System in a New Translation With Commentary on Facing Pages, and «Who Thinks Abstractly?», translated by Walter Kaufmann (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1977) ISBN 0-26801069-2.

- «Introduction», «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, in Martin Heidegger, «Hegel’s Concept of Experience» (New York: Harper & Row, 1970)

- «Sense-Certainty», Chapter I, «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, «The Philosophical Forum», Vol. 32, No 4

- «Stoicism», Chapter IV, B, «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, «The Philosophical Forum», Vol. 37, No 3

- «Absolute Knowing», Chapter VIII, «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, «The Philosophical Forum», Vol. 32, No 4

- Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit: Selections Translated and Annotated by Howard P. Kainz. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-27101076-2

- Phenomenology of Spirit selections translated by Andrea Tschemplik and James H. Stam, in Steven M. Cahn, ed., Classics of Western Philosophy (Hackett, 2007)

- Hegel’s Phenomenology of Self-consciousness: text and commentary [A translation of Chapter IV of the Phenomenology, with accompanying essays and a translation of «Hegel’s summary of self-consciousness from ‘The Phenomenology of Spirit’ in the Philosophical Propaedeutic»], by Leo Rauch and David Sherman. State University of New York Press, 1999.

See also[edit]

- Process theology

- Sittlichkeit

- The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology

- Weltgeist

- De divisione naturae

Notes[edit]

- ^ The following table of contents follows the Pinkard Translation.[7] Some versions of the book’s table of contents also group the last four together as a single section on a level with the first two.

- ^ «Absolute Knowing,» for Hegel, is not to be confused with foundational knowledge, which is oxymoronic in Hegelian philosophy, instead, the Absolute is an endpoint of History, «spirit knowing itself as spirit» [8]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Hegel 2018, p. 468, Appendix.

- ^ Pinkard 1996, p. 2.

- ^ «Hegel to Niethammer; October 13, 1806». marxists.org. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Pinkard 2000, p. 228–9.

- ^ a b Hegel 2018, p. xvi.

- ^ Hegel 2015, p. 21.9.

- ^ Hegel 2018.

- ^ Hegel 2018, p. 467, §807.

- ^ Hyppolite 1979, p. 11–12.

- ^ Pinkard 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit.

- ^ Kojève, Alexandre, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, § 1.

- ^ Pinkard 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Hegel 2018, p. 12, §16.

- ^ Harris 1997, p. 30.

- ^ Hegel 2018, p. 6, §6.

- ^ a b Solomon 1985, p. 233.

- ^ Lawler 2014, p. 139.

- ^ Rorty 1998, p. 300.

- ^ Magee 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 148.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 149.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 149.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 152.

- ^ Oliver, Kelly (1996). ««Antigone’s Ghost: Undoing Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit»«. Hypatia. 11 (1): 67–90. doi:10.2979/HYP.1996.11.1.67. JSTOR 3810356.

References[edit]

Primary[edit]

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (2018) [1807]. The phenomenology of spirit. Cambridge Hegel Translations. Translated by Pinkard, Terry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139050494.

- G. W. Hegel (2015). Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Science of Logic

Secondary[edit]

- Lawler, James (2014). «Chapter 8: They’re Not Just Goddamn Trees: Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature and the Avatar of Spirit». In Dunn, G.A.; Irwin, W. (eds.). Avatar and Philosophy: Learning to See. The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series. Wiley. pp. 104–114. ISBN 978-1-118-88676-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - H. S. Harris (1997). Hegel’s Ladder (Vol 1 & 2)

- Hyppolite, Jean (1979) [1974]. Genesis and Structure of Hegel’s «Phenomenology of Spirit». John Heckman, Samuel Cherniak (trans.) (reprint ed.). Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-81010594-2.

- Kaufmann, Walter Arnold (1965). Hegel. Reinterpretation, Texts, and Commentary. New York City: Doubleday.

- Magee, G.A. (2010). «Evolution». The Hegel Dictionary. Bloomsbury Philosophy Dictionaries. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-847-06591-9.

- Pinkard, Terry (1996). Hegel’s Phenomenology. The Sociality of Reason. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56834-0.

- Pinkard, Terry (2001) [2000]. Hegel. A Biography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00387-2.

- Rorty, R. (1998). Truth and Progress: Philosophical Papers. Philosophical papers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55686-6.

- Russon, John Edward (2004). Reading Hegel’s Phenomenology. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21692-2.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1974). «Sketch of a History of the Doctrine of the Ideal and the Real, Appendix». Parerga and Paralipomena, Volume 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19824508-4.

- Solomon, R.C. (1985). In the Spirit of Hegel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-36512-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Davis, Walter A., 1989. Inwardness and Existence: Subjectivity in/and Hegel, Heidegger, Marx and Freud. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-29912014-7.

- Doull, James (2000). «Hegel’s «Phenomenology» and Postmodern Thought» (PDF). Animus. 5. ISSN 1209-0689.

- Doull, James; Jackson, F. L. (2003). «The Idea of a Phenomenology of Spirit» (PDF). Animus. 8. ISSN 1209-0689.

- Heidegger, Martin, 1988. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-25332766-0.

- Kojève, Alexandre. Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. ISBN 0-80149203-3.

- Taylor, Charles, 1975. Hegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52129199-2.

- Pippin, Robert B., 1989. Hegel’s Idealism: the Satisfactions of Self-Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-52137923-7.

- Forster, Michael N., 1998. Hegel’s Idea of a Phenomenology of Spirit. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-22625742-8.

- Harris, H. S., 1995. Hegel: Phenomenology and System. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220281-X.

- Kadvany, John, 2001, Imre Lakatos and the Guises of Reason. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-82232659-0.

- Loewenberg, J., 1965. Hegel’s Phenomenology. Dialogues on the Life of Mind. La Salle IL.

- Pahl, Katrin (2012). Tropes of Transport: Hegel and Emotion. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810165670. OCLC 867784716.

- Stern, Robert, 2002. Hegel and the Phenomenology of Spirit London: Routledge. ISBN 0-41521788-1 An introduction for students.

- Stewart, Jon, 2000. The Unity of Hegel’s «Phenomenology of Spirit»: A Systematic Interpretation Evanston, Illinois : Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-810-11693-1

- Yovel, Yirmiyahu, Hegel’s Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit: Translation and Running Commentary, Princeton and Oxford : Princeton University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-69112052-8

- Westphal, Kenneth R., 2003. Hegel’s Epistemology: A Philosophical Introduction to the Phenomenology of Spirit. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220645-9.

- Westphal, Merold, 1998. History and Truth in Hegel’s Phenomenology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-25321221-9.

- Kalkavage, Peter, 2007. The Logic of Desire: An Introduction to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. Paul Dry Books. ISBN 978-1-589-88037-5.

External links[edit]

Electronic versions of the English translation of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind are available at:

- Marxists Internet Archive: Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind

- Translating Hegel blog, including a running translation of the Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit

- Phenomenology of Spirit. Bilingual, with Dictionary

The Phenomenology of Mind public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Detailed audio commentary by an academic:

- The Bernstein Tapes: Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind

- Gregory Sadler, Half Hour Hegel: The Complete Phenomenology of Spirit on YouTube

Title page of the first edition |

|

| Author | Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel |

|---|---|

| Original title | Phänomenologie des Geistes |

| Translator | James Black Baillie |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Philosophy |

| Published | 1807 |

|

Published in English |

1910 |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 929308074 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

193 |

| LC Class | B2928 .E5 |

|

Original text |

Phänomenologie des Geistes at Project Gutenberg |

| Translation | The Phenomenology of Spirit at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign |

The Phenomenology of Spirit (German: Phänomenologie des Geistes) is the most widely-discussed philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel; its German title can be translated as either The Phenomenology of Spirit or The Phenomenology of Mind. Hegel described the work, published in 1807, as an «exposition of the coming to be of knowledge».[1] This is explicated through a necessary self-origination and dissolution of «the various shapes of spirit as stations on the way through which spirit becomes pure knowledge».[1]

The book marked a significant development in German idealism after Immanuel Kant. Focusing on topics in metaphysics, epistemology, ontology, ethics, history, religion, perception, consciousness, existence, logic, and political philosophy, it is where Hegel develops his concepts of dialectic (including the lord-bondsman dialectic), absolute idealism, ethical life, and Aufhebung. It had a profound effect in Western philosophy, and «has been praised and blamed for the development of existentialism, communism, fascism, death of God theology, and historicist nihilism».[2]

Historical context[edit]

Hegel was putting the finishing touches to this book as Napoleon engaged Prussian troops on October 14, 1806, in the Battle of Jena on a plateau outside the city. On the day before the battle, Napoleon entered the city of Jena. Later that same day, Hegel wrote a letter to his friend, the theologian Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

I saw the Emperor – this world-soul – riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it … this extraordinary man, whom it is impossible not to admire.[3]

In 2000, Terry Pinkard notes that Hegel’s comment to Niethammer «is all the more striking since at that point he had already composed the crucial section of the Phenomenology in which he remarked that the Revolution had now officially passed to another land (Germany) that would complete ‘in thought’ what the Revolution had only partially accomplished in practice.»[4]

Publication history[edit]

The Phenomenology of Spirit was published with the title “System of Science: First Part: The Phenomenology of Spirit”.[5] Some copies contained either «Science of the Experience of Consciousness», or «Science of the Phenomenology of Spirit» as a subtitle between the «Preface» and the «Introduction».[5] On its initial publication, the work was identified as Part One of a projected «System of Science», which would have contained the Science of Logic «and both the two real sciences of philosophy, the Philosophy of Nature and the Philosophy of Spirit”[6] as its second part. The Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, in its third section (Philosophy of Spirit), contains a second subsection (The Encyclopedia Phenomenology) that recounts in briefer and somewhat altered form the major themes of the original Phenomenology.

Structure[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: coverage of the content of the book, which currently stops at the beginning of ch. 1. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) |

The book consists of a Preface (written after the rest was completed), an Introduction, and six major divisions (of greatly varying size).[a]

- (A) Consciousness is divided into three chapters:

- (I) Sensuous-Certainty,

- (II) Perceiving, and

- (III) Force and the Understanding.

- (B) Self-Consciousness contains one chapter:

- (IV) The Truth of Self-Certainty which contains a preliminary discussion of Life and Desire, followed by two subsections: (A) Self-Sufficiency and Non-Self-Sufficiency of Self-Consciousness; Mastery and Servitude and (B) Freedom of Self-Consciousness: Stoicism, Skepticism, and the Unhappy Consciousness. Notable is the presence of the discussion of the dialectic of the lord and bondsman.[to whom?]

- (C), (AA) Reason contains one chapter:

- (V) The Certainty and Truth of Reason which is divided into three chapters: (A) Observing Reason, (B) The Actualization of Rational Self-Consciousness Through Itself, and (C) Individuality, Which, to Itself, is Real in and for Itself.

- (BB) Spirit contains one chapter:

- (VI) Spirit or Geist which is again divided into three chapters: (A) True Spirit, Ethical Life, (B) Spirit Alienated from Itself: Cultural Formation, and (C) Spirit Certain of Itself: Morality.

- (CC) Religion contains one chapter:

- (VII) Religion, which is divided into three chapters: (A) Natural Religion, (B) The Art-Religion, and (C) Revealed Religion.

- (DD) Absolute Knowing contains one chapter:

- (VIII) Absolute Knowing.[b]

Due to its obscure nature and the many works by Hegel that followed its publication, even the structure or core theme of the book itself remains contested. First, Hegel wrote the book under close time constraints with little chance for revision (individual chapters were sent to the publisher before others were written). Furthermore, according to some readers, Hegel may have changed his conception of the project over the course of the writing. Secondly, the book abounds with both highly technical argument in philosophical language, and concrete examples, either imaginary or historical, of developments by people through different states of consciousness. The relationship between these is disputed: whether Hegel meant to prove claims about the development of world history, or simply used it for illustration; whether or not the more conventionally philosophical passages are meant to address specific historical and philosophical positions; and so forth.

Jean Hyppolite famously interpreted the work as a Bildungsroman that follows the progression of its protagonist, Spirit, through the history of consciousness,[9] a characterization that remains prevalent among literary theorists. However, others contest this literary interpretation and instead read the work as a «self-conscious reflective account»[10] that a society must give of itself in order to understand itself and therefore become reflective. Martin Heidegger saw it as the foundation of a larger «System of Science» that Hegel sought to develop,[11] while Alexandre Kojève saw it as akin to a «Platonic Dialogue … between the great Systems of history.»[12] It has also been called «a philosophical roller coaster … with no more rhyme or reason for any particular transition than that it struck Hegel that such a transition might be fun or illuminating.»[13]

Preface[edit]

The Preface to the text is a preamble to the scientific system and cognition in general. Paraphrased “on scientific cognition» in the table of contents, its intent is to offer a rough idea on scientific cognition, while at the same time aiming «to rid ourselves of a few forms which are only impediments to philosophical cognition».[14] As Hegel’s own announcement noted, it was to explain «what seems to him the need of philosophy in its present state; also about the presumption and mischief of the philosophical formulas that are currently degrading philosophy, and about what is altogether crucial in it and its study».[15] It can thus be seen as a heuristic attempt at creating the need of philosophy (in the present state) and of what philosophy itself in its present state needs. This involves an exposition on the content and standpoint of philosophy, i.e, the true shape of truth and the element of its existence, that is interspersed with polemics aimed at the presumption and mischief of philosophical formulas and what distinguishes it from that of any previous philosophy, especially that of his German Idealist predecessors (Kant, Fichte, and Schelling).[16]

The Hegelian method consists of actually examining consciousness’ experience of both itself and of its objects and eliciting the contradictions and dynamic movement that come to light in looking at this experience. Hegel uses the phrase «pure looking at» (reines Zusehen) to describe this method. If consciousness just pays attention to what is actually present in itself and its relation to its objects, it will see that what looks like stable and fixed forms dissolve into a dialectical movement. Thus, philosophy, according to Hegel, cannot just set out arguments based on a flow of deductive reasoning. Rather, it must look at actual consciousness, as it really exists.

Hegel also argues strongly against the epistemological emphasis of modern philosophy from Descartes through Kant, which he describes as having to first establish the nature and criteria of knowledge prior to actually knowing anything, because this would imply an infinite regress, a foundationalism that Hegel maintains is self-contradictory and impossible. Rather, he maintains, we must examine actual knowing as it occurs in real knowledge processes. This is why Hegel uses the term «phenomenology». «Phenomenology» comes from the Greek word for «to appear», and the phenomenology of mind is thus the study of how consciousness or mind appears to itself. In Hegel’s dynamic system, it is the study of the successive appearances of the mind to itself, because on examination each one dissolves into a later, more comprehensive and integrated form or structure of mind.

Introduction[edit]

Whereas the Preface was written after Hegel completed the Phenomenology, the Introduction was written beforehand.

In the Introduction, Hegel addresses the seeming paradox that we cannot evaluate our faculty of knowledge in terms of its ability to know the Absolute without first having a criterion for what the Absolute is, one that is superior to our knowledge of the Absolute. Yet, we could only have such a criterion if we already had the improved knowledge that we seek.

To resolve this paradox, Hegel adopts a method whereby the knowing that is characteristic of a particular stage of consciousness is evaluated using the criterion presupposed by consciousness itself. At each stage, consciousness knows something, and at the same time distinguishes the object of that knowledge as different from what it knows. Hegel and his readers will simply «look on» while consciousness compares its actual knowledge of the object—what the object is «for consciousness»—with its criterion for what the object must be «in itself». One would expect that, when consciousness finds that its knowledge does not agree with its object, consciousness would adjust its knowledge to conform to its object. However, in a characteristic reversal, Hegel explains that under his method, the opposite occurs.

As just noted, consciousness’ criterion for what the object should be is not supplied externally but rather by consciousness itself. Therefore, like its knowledge, the «object» that consciousness distinguishes from its knowledge is really just the object «for consciousness»—it is the object as envisioned by that stage of consciousness. Thus, in attempting to resolve the discord between knowledge and object, consciousness inevitably alters the object as well. In fact, the new «object» for consciousness is developed from consciousness’ inadequate knowledge of the previous «object». Thus, what consciousness really does is to modify its «object» to conform to its knowledge. Then the cycle begins anew as consciousness attempts to examine what it knows about this new «object».

The reason for this reversal is that, for Hegel, the separation between consciousness and its object is no more real than consciousness’ inadequate knowledge of that object. The knowledge is inadequate only because of that separation. At the end of the process, when the object has been fully «spiritualized» by successive cycles of consciousness’ experience, consciousness will fully know the object and at the same time fully recognize that the object is none other than itself.

At each stage of development, Hegel, adds, «we» (Hegel and his readers) see this development of the new object out of the knowledge of the previous one, but the consciousness that we are observing does not. As far as it is concerned, it experiences the dissolution of its knowledge in a mass of contradictions, and the emergence of a new object for knowledge, without understanding how that new object has been born.

Important concepts[edit]

Hegelian dialectic[edit]

The famous dialectical process of thesis–antithesis–synthesis has been controversially attributed to Hegel.

Whoever looks for the stereotype of the allegedly Hegelian dialectic in Hegel’s Phenomenology will not find it. What one does find on looking at the table of contents is a very decided preference for triadic arrangements. … But these many triads are not presented or deduced by Hegel as so many theses, antitheses, and syntheses. It is not by means of any dialectic of that sort that his thought moves up the ladder to absolute knowledge.

— Walter Kaufmann (1965). Hegel. Reinterpretation, Texts, and Commentary. p. 168.

Regardless of (ongoing) academic controversy regarding the significance of a unique dialectical method in Hegel’s writings, it is true, as Professor Howard Kainz (1996) affirms, that there are «thousands of triads» in Hegel’s writings. Importantly, instead of using the famous terminology that originated with Kant and was elaborated by J. G. Fichte, Hegel used an entirely different and more accurate terminology for dialectical (or as Hegel called them, «speculative») triads.

Hegel used two different sets of terms for his triads, namely, «abstract–negative–concrete» (especially in his Phenomenology of 1807), as well as «immediate–mediate–concrete» (especially in his Science of Logic of 1812), depending on the scope of his argumentation.

When one looks for these terms in his writings, one finds so many occurrences that it may become clear that Hegel employed the Kantian using a different terminology.

Hegel explained his change of terminology. The triad terms «abstract–negative–concrete» contain an implicit explanation for the flaws in Kant’s terms. The first term, «thesis», deserves its anti-thesis simply because it is too abstract. The third term, «synthesis», has completed the triad, making it concrete and no longer abstract by absorbing the negative.

Sometimes Hegel used the terms «immediate–mediate–concrete, to describe his triads. The most abstract concepts are those that present themselves to our consciousness immediately. For example, the notion of Pure Being for Hegel was the most abstract concept of all. The negative of this infinite abstraction would require an entire Encyclopedia, building category by category, dialectically, until it culminated in the category of Absolute Mind or Spirit (since the German word Geist can mean either ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’).

Unfolding of species[edit]

Hegel describes a sequential progression from inanimate objects to animate creatures to human beings. This is frequently compared to Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory.[citation needed] However, unlike Darwin, Hegel thought that organisms had agency in choosing to develop along this progression by collaborating with other organisms.[17][18] Hegel understood this to be a linear process of natural development with a predetermined end. He viewed this end teleologically as its ultimate purpose and destiny.[17][19][20]

Criticism[edit]

Walter Kaufmann, on the question of organisation, argued that Hegel’s arrangement, «over half a century before Darwin published his Origin of Species and impressed the idea of evolution on almost everybody’s mind, was developmental.»[21] The idea is supremely suggestive but, in the end, untenable according to Kaufmann: «The idea of arranging all significant points of view in such a single sequence, on a ladder that reaches from the crudest to the most mature, is as dazzling to contemplate as it is mad to try seriously to implement it».[22] While Kaufmann viewed Hegel as right in seeing that the way a view is reached is not necessarily external to the view itself, since, on the contrary, a knowledge of the development, including the prior positions through which a human being passed before adopting a position may make all the difference when it comes to comprehending his or her position, some aspects of the conception are still somewhat absurd and some of the details bizarre.[23] Kaufmann also remarks that the very table of contents of the Phenomenology may be said to «mirror confusion» and that «faults are so easy to find in it that it is not worth while to adduce heaps of them.»[citation needed] However, he excuses Hegel since he understands that the author of the Phenomenology, «finished the book under an immense strain».[24]

The feminist philosopher Kelly Oliver argues that Hegel’s discussion of women in The Phenomenology of Spirit undermines the entirety of the text. Oliver points out that for Hegel, every element of consciousness must be conceptualizable, but that in Hegel’s discussion of the family, woman is established as in principle unconceptualizable. Oliver writes that “unlike the master or slave, the feminine or woman does not contain the dormant seed of its opposite.”. This means that Hegel’s feminine is nothing other than the negation of the masculine and as such it must be excluded from the story of masculine consciousness. Thus, Oliver argues, the Phenomenology of Spirit is a phenomenology of masculine consciousness; the universalist pretensions of the text are not achieved, as it leaves out the phenomenology of feminine consciousness.[25]

Referencing[edit]

The work is usually abbreviated as PdG (Phänomenologie des Geistes), followed by the pagination or paragraph number of the German original edition. It is also abbreviated as PS (The Phenomenology of Spirit) or as PM (The Phenomenology of Mind), followed by the pagination or paragraph number of the English translation used by each author.

English translations[edit]

- G. W. F. Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by Peter Fuss and John Dobbins (University of Notre Dame Press, 2019)

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit (Cambridge Hegel Translations), translated by Terry Pinkard (Cambridge University Press, 2018) ISBN 0-52185579-9

- Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit: Translated with introduction and commentary, translated by Michael Inwood (Oxford University Press, 2018) ISBN 0-19879062-7

- Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by A. V. Miller with analysis of the text and foreword by J. N. Findlay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) ISBN 0-19824597-1

- Phenomenology of Mind, translated by J. B. Baillie (London: Harper & Row, 1967)

- Hegel’s Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit, translated with introduction, running commentary and notes by Yirmiyahu Yovel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004) ISBN 0-69112052-8.

- Texts and Commentary: Hegel’s Preface to His System in a New Translation With Commentary on Facing Pages, and «Who Thinks Abstractly?», translated by Walter Kaufmann (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1977) ISBN 0-26801069-2.

- «Introduction», «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, in Martin Heidegger, «Hegel’s Concept of Experience» (New York: Harper & Row, 1970)

- «Sense-Certainty», Chapter I, «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, «The Philosophical Forum», Vol. 32, No 4

- «Stoicism», Chapter IV, B, «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, «The Philosophical Forum», Vol. 37, No 3

- «Absolute Knowing», Chapter VIII, «The Phenomenology of Spirit», translated by Kenley R. Dove, «The Philosophical Forum», Vol. 32, No 4

- Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit: Selections Translated and Annotated by Howard P. Kainz. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-27101076-2

- Phenomenology of Spirit selections translated by Andrea Tschemplik and James H. Stam, in Steven M. Cahn, ed., Classics of Western Philosophy (Hackett, 2007)

- Hegel’s Phenomenology of Self-consciousness: text and commentary [A translation of Chapter IV of the Phenomenology, with accompanying essays and a translation of «Hegel’s summary of self-consciousness from ‘The Phenomenology of Spirit’ in the Philosophical Propaedeutic»], by Leo Rauch and David Sherman. State University of New York Press, 1999.

See also[edit]

- Process theology

- Sittlichkeit

- The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology

- Weltgeist

- De divisione naturae

Notes[edit]

- ^ The following table of contents follows the Pinkard Translation.[7] Some versions of the book’s table of contents also group the last four together as a single section on a level with the first two.

- ^ «Absolute Knowing,» for Hegel, is not to be confused with foundational knowledge, which is oxymoronic in Hegelian philosophy, instead, the Absolute is an endpoint of History, «spirit knowing itself as spirit» [8]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Hegel 2018, p. 468, Appendix.

- ^ Pinkard 1996, p. 2.

- ^ «Hegel to Niethammer; October 13, 1806». marxists.org. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Pinkard 2000, p. 228–9.

- ^ a b Hegel 2018, p. xvi.

- ^ Hegel 2015, p. 21.9.

- ^ Hegel 2018.

- ^ Hegel 2018, p. 467, §807.

- ^ Hyppolite 1979, p. 11–12.

- ^ Pinkard 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit.

- ^ Kojève, Alexandre, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, § 1.

- ^ Pinkard 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Hegel 2018, p. 12, §16.

- ^ Harris 1997, p. 30.

- ^ Hegel 2018, p. 6, §6.

- ^ a b Solomon 1985, p. 233.

- ^ Lawler 2014, p. 139.

- ^ Rorty 1998, p. 300.

- ^ Magee 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 148.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 149.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 149.

- ^ Kaufmann 1965, p. 152.

- ^ Oliver, Kelly (1996). ««Antigone’s Ghost: Undoing Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit»«. Hypatia. 11 (1): 67–90. doi:10.2979/HYP.1996.11.1.67. JSTOR 3810356.

References[edit]

Primary[edit]

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (2018) [1807]. The phenomenology of spirit. Cambridge Hegel Translations. Translated by Pinkard, Terry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139050494.

- G. W. Hegel (2015). Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Science of Logic

Secondary[edit]

- Lawler, James (2014). «Chapter 8: They’re Not Just Goddamn Trees: Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature and the Avatar of Spirit». In Dunn, G.A.; Irwin, W. (eds.). Avatar and Philosophy: Learning to See. The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series. Wiley. pp. 104–114. ISBN 978-1-118-88676-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - H. S. Harris (1997). Hegel’s Ladder (Vol 1 & 2)

- Hyppolite, Jean (1979) [1974]. Genesis and Structure of Hegel’s «Phenomenology of Spirit». John Heckman, Samuel Cherniak (trans.) (reprint ed.). Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-81010594-2.

- Kaufmann, Walter Arnold (1965). Hegel. Reinterpretation, Texts, and Commentary. New York City: Doubleday.

- Magee, G.A. (2010). «Evolution». The Hegel Dictionary. Bloomsbury Philosophy Dictionaries. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-847-06591-9.

- Pinkard, Terry (1996). Hegel’s Phenomenology. The Sociality of Reason. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56834-0.

- Pinkard, Terry (2001) [2000]. Hegel. A Biography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00387-2.

- Rorty, R. (1998). Truth and Progress: Philosophical Papers. Philosophical papers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55686-6.

- Russon, John Edward (2004). Reading Hegel’s Phenomenology. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21692-2.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1974). «Sketch of a History of the Doctrine of the Ideal and the Real, Appendix». Parerga and Paralipomena, Volume 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19824508-4.

- Solomon, R.C. (1985). In the Spirit of Hegel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-36512-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Davis, Walter A., 1989. Inwardness and Existence: Subjectivity in/and Hegel, Heidegger, Marx and Freud. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-29912014-7.

- Doull, James (2000). «Hegel’s «Phenomenology» and Postmodern Thought» (PDF). Animus. 5. ISSN 1209-0689.

- Doull, James; Jackson, F. L. (2003). «The Idea of a Phenomenology of Spirit» (PDF). Animus. 8. ISSN 1209-0689.

- Heidegger, Martin, 1988. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-25332766-0.

- Kojève, Alexandre. Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. ISBN 0-80149203-3.

- Taylor, Charles, 1975. Hegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52129199-2.

- Pippin, Robert B., 1989. Hegel’s Idealism: the Satisfactions of Self-Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-52137923-7.

- Forster, Michael N., 1998. Hegel’s Idea of a Phenomenology of Spirit. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-22625742-8.

- Harris, H. S., 1995. Hegel: Phenomenology and System. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220281-X.

- Kadvany, John, 2001, Imre Lakatos and the Guises of Reason. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-82232659-0.

- Loewenberg, J., 1965. Hegel’s Phenomenology. Dialogues on the Life of Mind. La Salle IL.

- Pahl, Katrin (2012). Tropes of Transport: Hegel and Emotion. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810165670. OCLC 867784716.

- Stern, Robert, 2002. Hegel and the Phenomenology of Spirit London: Routledge. ISBN 0-41521788-1 An introduction for students.

- Stewart, Jon, 2000. The Unity of Hegel’s «Phenomenology of Spirit»: A Systematic Interpretation Evanston, Illinois : Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-810-11693-1

- Yovel, Yirmiyahu, Hegel’s Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit: Translation and Running Commentary, Princeton and Oxford : Princeton University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-69112052-8

- Westphal, Kenneth R., 2003. Hegel’s Epistemology: A Philosophical Introduction to the Phenomenology of Spirit. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220645-9.

- Westphal, Merold, 1998. History and Truth in Hegel’s Phenomenology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-25321221-9.

- Kalkavage, Peter, 2007. The Logic of Desire: An Introduction to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. Paul Dry Books. ISBN 978-1-589-88037-5.

External links[edit]

Electronic versions of the English translation of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind are available at:

- Marxists Internet Archive: Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind

- Translating Hegel blog, including a running translation of the Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit

- Phenomenology of Spirit. Bilingual, with Dictionary

The Phenomenology of Mind public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Detailed audio commentary by an academic:

- The Bernstein Tapes: Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind

- Gregory Sadler, Half Hour Hegel: The Complete Phenomenology of Spirit on YouTube

Феноменология духа (Гегель)

- Феноменология духа (Гегель)

-

Феноменология духа (нем. Phänomenologie des Geistes) — первая из крупных работ Гегеля, явившаяся в то же время первым выражением всей его системы абсолютного идеализма. Представляет собой исследование форм существования cознания. Методом движения выбрана критика являющегося (естественного, неподлинного, обыденного, нереального — термины Гегеля) знания со стороны науки. Согласно Гегелю (см. Введение) наука тем, что выступает на сцену сама есть только некоторое явление наряду с другим знанием. Наука не может просто отвергнуть неподлинное знание под тем предлогом, что она является истиной, а неподлинное, обыденное знание для него ничего не значит. Ведь последнее, напротив, заявляет, что она истинна и для нее наука ничто. Одно голое уверение имеет одинаковый вес, как и другое. Именно поэтому, наука должна выступить, излагая являющееся знание, чтобы в нем самом показать его неистинность. Последовательность формообразований, которое сознание проходит на этом пути, есть история образования самого сознания до уровня науки. Более того, в этом последовательном движении от одной формы являющегося знания к другой, мы проходим полноту форм существования сознания. Тем самым, критика являющегося знания есть одновременно изложение самой науки об опыте сознания. Научным дополнением к изложению различных форм существования сознания, Гегель считает необходимую (логическую) связь, при котором от одной формы сознания мы переходим к другой. Этот переход Гегель и называет опытом сознания. В чем состоит эта связь? Гегель указывает, что «к какому бы результату не привела критика неподлинного знания, его нельзя сводить к пустому ничто, а необходимо понимать как ничто того, чего он — результат, в коем содержится то, что является истинным в предшествующем знании». Эта связь различных форм существования сознания и определяет необходимость последовательного движения. У этого движения со своей стороны есть цель — она там, где знание выдерживает критику опытом, или как пишет Гегель, где «знанию нет необходимости выходить за пределы самого себя, где оно находит само себя и понятие соотвествует своему предмету, а предмет — понятию». «Поступательное движение к этой цели оказывается безостановочно, и ни на какой более ранней стадии нельзя найти удовлетворения». Именно поэтому «Феноменология Духа» осуществляет одну из главных идей Гегеля состоящих в том, что истинное знание должно быть системой знания, а истинная наука — системой взаимосвязанных наук.

Подготовлена к печати в 1805—1806, опубликована в 1807 под названием «Система наук. Первая часть. Феноменология духа» (одним из предварительных заголовков книги была также «Наука об опыте сознания»).

Титульный лист, 1807

Содержание

- 1 Содержание

- 2 Переводчики

- 3 См. также

- 4 Внешние ссылки

Содержание

- Предисловие

- I. Научная задача нашего времени

- II. Развитие сознания до уровня науки

- III. Философское познание

- IV. Требования, предъявляемые к философскому изучению

- Часть Первая НАУКА ОБ ОПЫТЕ СОЗНАНИЯ

Введение

- [A. Сознание]

- I. ЧУВСТВЕННАЯ ДОСТОВЕРНОСТЬ ИЛИ «ЭТО» И МНЕНИЕ

- II. ВОСПРИЯТИЕ ИЛИ ВЕЩЬ И ИЛЛЮЗИЯ

- III. СИЛА И РАССУДОК, ЯВЛЕНИЕ И СВЕРХЧУВСТВЕННЫЙ МИР

- [B. Самосознание]

- IV. ИСТИНА ДОСТОВЕРНОСТИ СЕБЯ САМОГО

- A. Самостоятельность и несамостоятельность самосознания; господство и рабство

- B. Свобода самосознания; стоицизм, скептицизм и несчастное сознание

- IV. ИСТИНА ДОСТОВЕРНОСТИ СЕБЯ САМОГО

- [С. Абсолютный субъект]

(А. А.) Разум (В. В.) Дух (С. С.) Религия (D. D.) Абсолютное знание

- V. ДОСТОВЕРНОСТЬ И ИСТИНА РАЗУМА

- A. Наблюдающий разум

- a. Наблюдение природы

- b. Наблюдение самосознания в его чистоте и в его отношении к внешней действительности; логические и психологические законы

- c. Наблюдение самосознания в его отношении к своей непосредственной действительности; физиогномика и френология

- B.Претворение разумного самосознания в действительность им самим

- a. Удовольствие и необходимость

- b. Закон сердца и безумие самомнения

- c. Добродетель и общий ход вещей

- C.Индивидуальность, которая видит себя реальной в себе самой и для себя самой

- a. Духовное животное царство и обман или сама суть дела

- b. Разум, предписывающий законы

- c. Разум, проверяющий законы

- A. Наблюдающий разум

- VI. ДУХ

- A. Истинный дух, нравственность

- a. Нравственный мир, человеческий и божественный закон, мужчина и женщина

- b. Нравственное действие, человеческое и божественное знание, вина и судьба

- c. Правовое состояние

- A. Истинный дух, нравственность

-

- B. Отчужденный от себя дух; Образованность

- I. Мир отчужденного от себя духа

- a. Образованность и её царство действительности

- b. Вера и чистое здравомыслие

- II. Просвещение

- a. Борьба просвещения с суеверием

- b. Истина просвещения

- I. Мир отчужденного от себя духа

- III. Абсолютная свобода и ужас

- B. Отчужденный от себя дух; Образованность

-

- C. Дух, обладающий достоверностью себя самого. Моральность

- a. Моральное мировоззрение

- b. Перестановка

- c. Совесть, прекрасная душа, зло и его прощение

- C. Дух, обладающий достоверностью себя самого. Моральность

- VII. РЕЛИГИЯ

- A. Естественная религия

- a. Светлое существо

- b. Растение и животное

- c. Мастер

- B. Художественная религия

- a. Абстрактное произведение искусства

- b. Живое произведение искусства

- c. Духовное произведение искусства

- C. Религия откровения

- A. Естественная религия

- VII. АБСОЛЮТНОЕ ЗНАНИЕ

Переводчики

- На русский язык

- Густав Шпет

- На французский язык

- Ипполит, Жан

См. также

- Наука логики (Гегель)

Внешние ссылки

- Текст книги в переводе Густава Шпета

- Оригинальный текст (на немецком языке) Phänomenologie des Geistes

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «Феноменология духа (Гегель)» в других словарях:

-

ФЕНОМЕНОЛОГИЯ ДУХА — ’ФЕНОМЕНОЛОГИЯ ДУХА ‘ (‘Phénoménologie des Geistes’) первая из крупных работ Гегеля, явившаяся в то же время первым выражением всей его системы абсолютного идеализма. Посвящена анализу форм развития или явлений (феноменов) знания. Подготовлена к… … История Философии: Энциклопедия

-

“ФЕНОМЕНОЛОГИЯ ДУХА” — “ФЕНОМЕНОЛОГИЯ ДУХА” раннее произведение Гегеля. Впервые вышло под заголовком “System der Wissenschaft. Erster Teil, die Phänomenologie des Geistes” в 1807. Следующее издание Гегель начал готовить только в 1831, но смерть помешала этому. В… … Философская энциклопедия

-

Феноменология духа — «ФЕНОМЕНОЛОГИЯ ДУХА» («Phanomenologie des Geistes») одно из основных сочинений Г.В.Ф. Гегеля, написанное в 1805 1806 гг. в Йене и задуманное как первая часть будущей «системы науки». Издано в 1807. Состоит из предисловия, введения и трех… … Энциклопедия эпистемологии и философии науки

-

Феноменология Духа — (нем. Phänomenologie des Geistes) первая из крупных работ Гегеля, явившаяся в то же время первым выражением всей его системы абсолютного идеализма. Представляет собой исследование форм существования cознания. Методом движения выбрана критика… … Википедия

-

ФЕНОМЕНОЛОГИЯ ДУХА — одно из основных сочинений Г.В.Ф. Гегеля, написанное в 1805 1806 в Йене (опубликовано в 1807) и задуманное как первая часть будущей «системы науки». Состоит из предисловия, введения и трех отделов: «Сознание», «Самосознание» и отдела с условным… … Философская энциклопедия

-

ФЕНОМЕНОЛОГИЯ ДУХА — ( Phenomenologie des Geistes ) первая из крупных работ Гегеля, явившаяся в то же время первым выражением всей его системы абсолютного идеализма. Посвящена анализу форм развития или явлений (феноменов) знания. Подготовлена к печати в 1805 1806,… … История Философии: Энциклопедия

-

Феноменология духа — Титульный лист, 1807 Феноменология духа (нем. Phänomenologie des Geistes … Википедия

-

ГЕГЕЛЬ — (Hegel) Георг Вильгельм Фридрих (1770 1831) немецкий философ, создатель философской системы, являющейся не только завершающим звеном в развитии немецкой трансцендентально критической философии, но и одной из последних всеобъемлющих систем… … История Философии: Энциклопедия

-

ГЕГЕЛЬ Георг Вильгельм Фридрих (1770 — 1831) — немецкий философ, создатель философской системы, являющейся не только завершающим звеном в развитии немецкой трансцендентально критической философии, но и одной из последних всеобъемлющих систем классического новоевропейского рационализма. Г.… … История Философии: Энциклопедия

-

ГЕГЕЛЬ — (Hegel) Георг Вильгельм Фридрих (1770 1831) нем. философ, создатель развернутой филос. системы, построенной на принципах «абсолютного идеализма», диалектики, системности, историзма. Учился в гимназии Штутгарта, затем в Тюбингенском теологическом… … Философская энциклопедия