|

E. T. A. Hoffmann |

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait |

|

| Born | Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann 24 January 1776 Königsberg, Kingdom of Prussia, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 25 June 1822 (aged 46) Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation |

| Pen name | E. T. A. Hoffmann |

| Occupation | Jurist, author, composer, music critic, artist |

| Period | 1809–1822 |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Signature | |

|

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; 24 January 1776 – 25 June 1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist.[1][2][3] His stories form the basis of Jacques Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann, in which Hoffmann appears (heavily fictionalized) as the hero. He is also the author of the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker is based. The ballet Coppélia is based on two other stories that Hoffmann wrote, while Schumann’s Kreisleriana[4] is based on Hoffmann’s character Johannes Kreisler.

Hoffmann’s stories highly influenced 19th-century literature, and he is one of the major authors of the Romantic movement.

Life[edit]

Youth[edit]

Hoffmann’s ancestors, both maternal and paternal, were jurists. His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736–97), was a barrister in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), as well as a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba. In 1767 he married his cousin, Lovisa Albertina Doerffer (1748–96). Ernst Theodor Wilhelm, born on 24 January 1776, was the youngest of three children, of whom the second died in infancy.

When his parents separated in 1778, his father went to Insterburg (now Chernyakhovsk) with his elder son, Johann Ludwig Hoffmann (1768–1822), while Ernst’s mother stayed in Königsberg with her relatives: two aunts, Johanna Sophie Doerffer (1745–1803) and Charlotte Wilhelmine Doerffer (c. 1754–79) and their brother, Otto Wilhelm Doerffer (1741–1811), who were all unmarried. The trio raised the youngster.

The household, dominated by the uncle (whom Ernst nicknamed O Weh—»Oh dear!»—in a play on his initials), was pietistic and uncongenial. Hoffmann was to regret his estrangement from his father. Nevertheless, he remembered his aunts with great affection, especially the younger, Charlotte, whom he nicknamed Tante Füßchen («Aunt Littlefeet»). Although she died when he was only three years old, he treasured her memory (e.g. see Kater Murr) and embroidered stories about her to such an extent that later biographers sometimes assumed her to be imaginary, until proof of her existence was found after World War II.[5]

Between 1781 and 1792 he attended the Lutheran school or Burgschule, where he made good progress in classics. He was taught drawing by one Saemann, and counterpoint by a Polish organist named Podbileski, who was to be the prototype of Abraham Liscot in Kater Murr. Ernst showed great talent for piano-playing, and busied himself with writing and drawing. The provincial setting was not, however, conducive to technical progress, and despite his many-sided talents he remained rather ignorant of both classical forms and of the new artistic ideas that were developing in Germany. He had, however, read Schiller, Goethe, Swift, Sterne, Rousseau and Jean Paul, and wrote part of a novel titled Der Geheimnisvolle.

Around 1787 he became friends with Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Younger (1775–1843), the son of a pastor, and nephew of Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Elder, the well-known writer friend of Immanuel Kant. During 1792, both attended some of Kant’s lectures at the University of Königsberg. Their friendship, although often tested by an increasing social difference, was to be lifelong.

In 1794, Hoffmann became enamored of Dora Hatt, a married woman to whom he had given music lessons. She was ten years older, and gave birth to her sixth child in 1795.[6] In February 1796, her family protested against his attentions and, with his hesitant consent, asked another of his uncles to arrange employment for him in Glogau (Głogów), Prussian Silesia.[7]

The provinces[edit]

From 1796, Hoffmann obtained employment as a clerk for his uncle, Johann Ludwig Doerffer, who lived in Glogau with his daughter Minna. After passing further examinations he visited Dresden, where he was amazed by the paintings in the gallery, particularly those of Correggio and Raphael. During the summer of 1798, his uncle was promoted to a court in Berlin, and the three of them moved there in August—Hoffmann’s first residence in a large city. It was there that Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia. The official reply advised to him to write to the director of the Royal Theatre, a man named Iffland. By the time the latter responded, Hoffmann had passed his third round of examinations and had already left for Posen (Poznań) in South Prussia in the company of his old friend Hippel, with a brief stop in Dresden to show him the gallery.

From June 1800 to 1803, he worked in Prussian provinces in the area of Greater Poland and Masovia. This was the first time he had lived without supervision by members of his family, and he started to become «what school principals, parsons, uncles, and aunts call dissolute.»[8]

His first job, at Posen, was endangered after Carnival on Shrove Tuesday 1802, when caricatures of military officers were distributed at a ball. It was immediately deduced who had drawn them, and complaints were made to authorities in Berlin, who were reluctant to punish the promising young official. The problem was solved by «promoting» Hoffmann to Płock in New East Prussia, the former capital of Poland (1079–1138), where administrative offices were relocated from Thorn (Toruń). He visited the place to arrange lodging, before returning to Posen where he married Mischa (Maria or Marianna Thekla Michalina Rorer, whose Polish surname was Trzcińska). They moved to Płock in August 1802.

Hoffmann despaired because of his exile, and drew caricatures of himself drowning in mud alongside ragged villagers. He did make use, however, of his isolation, by writing and composing. He started a diary on 1 October 1803. An essay on the theatre was published in Kotzebue’s periodical, Die Freimüthige, and he entered a competition in the same magazine to write a play. Hoffmann’s was called Der Preis («The Prize»), and was itself about a competition to write a play. There were fourteen entries, but none was judged worthy of the award: 100 Friedrichs d’or. Nevertheless, his entry was singled out for praise.[9] This was one of the few good times of a sad period of his life, which saw the deaths of his uncle J. L. Hoffmann in Berlin, his Aunt Sophie, and Dora Hatt in Königsberg.

At the beginning of 1804, he obtained a post at Warsaw. On his way there, he passed through his hometown and met one of Dora Hatt’s daughters. He was never to return to Königsberg.

Warsaw[edit]

Hoffmann assimilated well with Polish society; the years spent in Prussian Poland he recognized as the happiest of his life. In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin, renewing his friendship with Zacharias Werner, and meeting his future biographer, a neighbour and fellow jurist called Julius Eduard Itzig (who changed his name to Hitzig after his baptism). Itzig had been a member of the Berlin literary group called the Nordstern, or «North Star», and he gave Hoffmann the works of Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Carlo Gozzi and Calderón. These relatively late introductions marked his work profoundly.

He moved in the circles of August Wilhelm Schlegel, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Rahel Levin and David Ferdinand Koreff.

But Hoffmann’s fortunate position was not to last: on 28 November 1806, during the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops captured Warsaw, and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their jobs. They divided the contents of the treasury between them and fled. In January 1807, Hoffmann’s wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia returned to Posen, while he pondered whether to move to Vienna or go back to Berlin. A delay of six months was caused by severe illness. Eventually the French authorities demanded that all former officials swear allegiance or leave the country. As they refused to grant Hoffmann a passport to Vienna, he was forced to return to Berlin.

He visited his family in Posen before arriving in Berlin on 18 June 1807, hoping to further his career there as an artist and writer.

Berlin and Bamberg[edit]

The next fifteen months were some of the worst in Hoffmann’s life.

The city of Berlin was also occupied by Napoleon’s troops. Obtaining only meagre allowances, he had frequent recourse to his friends, constantly borrowing money and still going hungry for days at a time; he learned that his daughter had died. Nevertheless, he managed to compose his Six Canticles for a cappella choir: one of his best compositions, which he would later attribute to Kreisler in Lebensansichten des Katers Murr.

Hoffmann’s portrait of Kapellmeister Kreisler

On 1 September 1808 he arrived with his wife in Bamberg, where he began a job as theatre manager. The director, Count Soden, left almost immediately for Würzburg, leaving a man named Heinrich Cuno in charge. Hoffmann was unable to improve standards of performance, and his efforts caused intrigues against him which resulted in him losing his job to Cuno. He began work as music critic for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, a newspaper in Leipzig, and his articles on Beethoven were especially well received, and highly regarded by the composer himself. It was in its pages that the «Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler» character made his first appearance.

Hoffmann’s breakthrough came in 1809, with the publication of Ritter Gluck, a story about a man who meets, or believes he has met, the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–87) more than twenty years after the latter’s death. The theme alludes to the work of Jean Paul, who invented the term Doppelgänger the previous decade, and continued to exact a powerful influence over Hoffmann, becoming one of his earliest admirers. With this publication, Hoffmann began to use the pseudonym E. T. A. Hoffmann, telling people that the «A» stood for Amadeus, in homage to the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91). However, he continued to use Wilhelm in official documents throughout his life, and the initials E. T. W. also appear on his gravestone.

The next year, he was employed at the Bamberg Theatre as stagehand, decorator, and playwright, while also giving private music lessons.

He became so enamored of a young singing student, Julia Marc, that his feelings were obvious whenever they were together, and Julia’s mother quickly found her a more suitable match. When Joseph Seconda offered Hoffmann a position as musical director for his opera company (then performing in Dresden), he accepted, leaving on 21 April 1813.

Dresden and Leipzig[edit]

Prussia had declared war against France on 16 March during the War of the Sixth Coalition, and their journey was fraught with difficulties. They arrived on the 25th, only to find that Seconda was in Leipzig; on the 26th, they sent a letter pleading for temporary funds. That same day Hoffmann was surprised to meet Hippel, whom he had not seen for nine years.

The situation deteriorated, and in early May Hoffmann tried in vain to find transport to Leipzig. On 8 May, the bridges were destroyed, and his family were marooned in the city. During the day, Hoffmann would roam, watching the fighting with curiosity. Finally, on 20 May, they left for Leipzig, only to be involved in an accident which killed one of the passengers in their coach and injured his wife.

They arrived on 23 May, and Hoffmann started work with Seconda’s orchestra, which he found to be of the best quality. On 4 June an armistice began, which allowed the company to return to Dresden. But on 22 August, after the end of the armistice, the family was forced to relocate from their pleasant house in the suburbs into the town, and during the next few days the Battle of Dresden raged. The city was bombarded; many people were killed by bombs directly in front of him. After the main battle was over, he visited the gory battlefield. His account can be found in Vision auf dem Schlachtfeld bei Dresden. After a long period of continued disturbance, the town surrendered on 11 November, and on 9 December the company travelled to Leipzig.

On 25 February, Hoffmann quarrelled with Seconda, and the next day he was given notice of twelve weeks. When asked to accompany them on their journey to Dresden in April, he refused, and they left without him. But during July his friend Hippel visited, and soon he found himself being guided back into his old career as a jurist.

Berlin[edit]

Grave of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated, the inscription reads: E. T. W. Hoffmann, born on 24 January 1776, in Königsberg, died on 25 June 1822, in Berlin, Councillor of the Court of Justice, excellent in his office, as a poet, as a musician, as a painter, dedicated by his friends.

At the end of September 1814, in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat, Hoffmann returned to Berlin and succeeded in regaining a job at the Kammergericht, the chamber court. His opera Undine was performed by the Berlin Theatre. Its successful run came to an end only after a fire on the night of the 25th performance. Magazines clamoured for his contributions, and after a while his standards started to decline. Nevertheless, many masterpieces date from this time.

During the period from 1819, Hoffmann was involved with legal disputes, while fighting ill health. Alcohol abuse and syphilis eventually caused weakening of his limbs during 1821, and paralysis from the beginning of 1822. His last works were dictated to his wife or to a secretary.

Prince Metternich’s anti-liberal programs began to put Hoffmann in situations that tested his conscience. Thousands of people were accused of treason for having certain political opinions,

and university professors were monitored during their lectures.

King Frederick William III of Prussia appointed an Immediate Commission for the investigation of political dissidence; when he found its observance of the rule of law too frustrating, he established a Ministerial Commission to interfere with its processes. The latter was greatly influenced by Commissioner Kamptz. During the trial of «Turnvater» Jahn, the founder of the gymnastics association movement, Hoffmann found himself annoying Kamptz, and became a political target. When Hoffmann caricatured Kamptz in a story (Meister Floh), Kamptz began legal proceedings. These ended when Hoffmann’s illness was found to be life-threatening. The King asked for a reprimand only, but no action was ever taken. Eventually Meister Floh was published with the offending passages removed.

Hoffmann died of syphilis in Berlin on 25 June 1822 at the age of 46. His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof III der Jerusalems- und Neuen Kirchengemeinde (Cemetery No. III of the congregations of Jerusalem Church and New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, south of Hallesches Tor at the underground station Mehringdamm.

Works[edit]

Literary[edit]

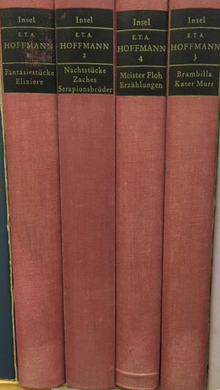

Four volume set of Hoffmann’s writings

- Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (collection of previously published stories, 1814)[10]

- «Ritter Gluck», «Kreisleriana», «Don Juan», «Nachricht von den neuesten Schicksalen des Hundes Berganza»

- «Der Magnetiseur», «Der goldne Topf» (revised in 1819), «Die Abenteuer der Silvesternacht»

- Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815)

- Nachtstücke (1817)

- «Der Sandmann», «Das Gelübde», «Ignaz Denner», «Die Jesuiterkirche in G.»

- «Das Majorat», «Das öde Haus», «Das Sanctus», «Das steinerne Herz»

- Seltsame Leiden eines Theater-Direktors (1819)

- Little Zaches (1819)

- Die Serapionsbrüder (1819)

- «Der Einsiedler Serapion», «Rat Krespel», «Die Fermate», «Der Dichter und der Komponist»

- «Ein Fragment aus dem Leben dreier Freunde», «Der Artushof», «Die Bergwerke zu Falun», «Nußknacker und Mausekönig» (1816)

- «Der Kampf der Sänger», «Eine Spukgeschichte», «Die Automate», «Doge und Dogaresse»

- «Alte und neue Kirchenmusik», «Meister Martin der Küfner und seine Gesellen», «Das fremde Kind»

- «Nachricht aus dem Leben eines bekannten Mannes», «Die Brautwahl», «Der unheimliche Gast»

- «Das Fräulein von Scuderi», «Spielerglück» (1819), «Der Baron von B.»

- «Signor Formica», «Zacharias Werner», «Erscheinungen»

- «Der Zusammenhang der Dinge», «Vampirismus», «Die ästhetische Teegesellschaft», «Die Königsbraut»

- Prinzessin Brambilla (1820)

- Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820)

- «Die Irrungen» (1820)

- «Die Geheimnisse» (1821)

- «Die Doppeltgänger» (1821)

- Meister Floh (1822)

- «Des Vetters Eckfenster» (1822)

- Letzte Erzählungen (1825)

Musical[edit]

Vocal music[edit]

- Messa d-moll (1805)

- Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807)

- 6 Canzoni per 4 voci alla capella (1808)

- Miserere b-moll (1809)

- In des Irtisch weiße Fluten (Kotzebue), Lied (1811)

- Recitativo ed Aria „Prendi l’acciar ti rendo» (1812)

- Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812)

- Nachtgesang, Türkische Musik, Jägerlied, Katzburschenlied für Männerchor (1819–21)

Works for stage[edit]

- Die Maske (libretto by Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799)

- Die lustigen Musikanten (libretto: Clemens Brentano), Singspiel (1804)

- Incidental music to Zacharias Werner’s tragedy Das Kreuz an der Ostsee (1805)

- Liebe und Eifersucht (libretto by Hoffmann after Calderón, translated by August Wilhelm Schlegel) (1807)

- Arlequin, ballet (1808)

- Der Trank der Unsterblichkeit (libretto: Julius von Soden), romantic opera (1808)

- Wiedersehn! (libretto by Hoffmann), prologue (1809)

- Dirna (libretto: Julius von Soden), melodrama (1809)

- Incidental music to Julius von Soden’s drama Julius Sabinus (1810)

- Saul, König von Israel (libretto: Joseph von Seyfried), melodrama (1811)

- Aurora (libretto: Franz von Holbein), heroic opera (1812)

- Undine (libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué), Zauberoper (1816)

- Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode (unfinished)

Instrumental[edit]

- Rondo für Klavier (1794/95)

- Ouvertura. Musica per la chiesa d-moll (1801)

- Klaviersonaten: A-Dur, f-moll, F-Dur, f-moll, cis-moll (1805–1808)

- Große Fantasie für Klavier (1806)

- Sinfonie Es-Dur (1806)

- Harfenquintett c-moll (1807)

- Grand Trio E-Dur (1809)

- Walzer zum Karolinentag (1812)

- Teutschlands Triumph in der Schlacht bei Leipzig, (by «Arnulph Vollweiler», 1814; lost)

- Serapions-Walzer (1818–1821)

Assessment[edit]

Statue of «E. T. A. Hoffmann and his cat» in Bamberg

Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, and a pioneer of the fantasy genre, with a taste for the macabre combined with realism that influenced such authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Nikolai Gogol[11][12] (1809–1852), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), George MacDonald (1824–1905),[13] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), Vernon Lee (1856–1935),[14] Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980). Hoffmann’s story Das Fräulein von Scuderi is sometimes cited as the first detective story and a direct influence on Poe’s «The Murders in the Rue Morgue»;[15] Characters from it also appear in the opera Cardillac by Paul Hindemith.

The twentieth-century Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin characterised Hoffmann’s works as Menippea, essentially satirical and self-parodying in form, thus including him in a tradition that includes Cervantes, Diderot and Voltaire.

Robert Schumann’s piano suite Kreisleriana (1838) takes its title from one of Hoffmann’s books (and according to Charles Rosen’s The Romantic Generation, is possibly also inspired by «The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr», in which Kreisler appears).[4] Jacques Offenbach’s masterwork, the opera Les contes d’Hoffmann («The Tales of Hoffmann», 1881), is based on the stories, principally «Der Sandmann» («The Sandman», 1816), «Rat Krespel» («Councillor Krespel», 1818), and «Das verlorene Spiegelbild» («The Lost Reflection») from Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year’s Eve, 1814). Klein Zaches genannt Zinnober (Little Zaches called Cinnabar, 1819) inspired an aria as well as the operetta Le Roi Carotte, 1872). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker (1892) is based on «The Nutcracker and the Mouse King», and the ballet Coppélia, with music by Delibes, is based on two eerie Hoffmann stories.

Hoffmann also influenced 19th-century musical opinion directly through his music criticism. His reviews of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) and other important works set new literary standards for writing about music, and encouraged later writers to consider music as «the most Romantic of all the arts.»[16] Hoffmann’s reviews were first collected for modern readers by Friedrich Schnapp, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann: Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese (1963) and have been made available in an English translation in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume (2004).

Hoffmann’s drawing of himself, riding on Tomcat Murr and fighting «Prussian bureaucracy»

Hoffmann strove for artistic polymathy. He created far more in his works than mere political commentary achieved through satire. His masterpiece novel Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr, 1819–1821) deals with such issues as the aesthetic status of true artistry and the modes of self-transcendence that accompany any genuine endeavour to create. Hoffmann’s portrayal of the character Kreisler (a genius musician) is wittily counterpointed with the character of the tomcat Murr – a virtuoso illustration of artistic pretentiousness that many of Hoffmann’s contemporaries found offensive and subversive of Romantic ideals.

Hoffmann’s literature indicates the failings of many so-called artists to differentiate between the superficial and the authentic aspects of such Romantic ideals. The self-conscious effort to impress must, according to Hoffmann, be divorced from the self-aware effort to create. This essential duality in Kater Murr is conveyed structurally through a discursive ‘splicing together’ of two biographical narratives.

Science fiction[edit]

While disagreeing with E. F. Bleiler’s claim that Hoffmann was «one of the two or three greatest writers of fantasy», Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction said that he «did lay down the groundwork for some of our most enduring themes».[17]

Historian Martin Willis argues that Hoffmann’s impact on science fiction has been overlooked, saying «his work reveals a writer dynamically involved in the important scientific debates of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.» Willis points out that Hoffmann’s work is contemporary with Frankenstein (1818) and with «the heated debates and the relationship between the new empirical science and the older forms of natural philosophy that held sway throughout the eighteenth century.» His «interest in the machine culture of his time is well represented in his short stories, of which the critically renowned The Sandman (1816) and Automata (1814) are the best examples. …Hoffmann’s work makes a considerable contribution to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early years of the nineteenth century and to the conflict between science and magic, centred mainly on the ‘truths’ available to the advocates of either practice. …Hoffmann’s balancing of mesmerism, mechanics, and magic reflects the difficulty in categorizing scientific knowledge in the early nineteenth century.»[18]

In popular culture[edit]

- Robertson Davies invokes Hoffmann as a character (with the pet name of ‘ETAH’) trapped in Limbo, in his novel The Lyre of Orpheus (1988).

- Alexandre Dumas, père translated The Nutcracker into French, which aided in making the tale popular and widespread.

- The exotic and supernatural elements in the storyline of Ingmar Bergman’s 1982 film Fanny and Alexander derive largely from the stories of Hoffmann.[19]

- Freud gives an extensive psychoanalytic analysis of Hoffmann’s «The Sandman» in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche.[citation needed]

- Coppelius is a German classical metal band whose name is taken from a character in Hoffmann’s «The Sandman». The band’s 2010 album Zinnober includes a track titled «Klein Zaches».[20][citation needed]

- The Russian show Puppets was cancelled by government officials after an episode in which Vladimir Putin was portrayed as Hoffmann’s Klein Zaches.[21][1][22]

See also[edit]

- The Tales of Hoffmann for Offenbach’s opera.

- The Tales of Hoffmann for the film

- Gofmaniada, a Russian puppet-animated feature film about Hoffmann and several of his stories.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Penrith Goff, «E.T.A. Hoffmann» in E. F. Bleiler, Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror. New York: Scribner’s, 1985. pp. 111–120. ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ Mike Ashley, «Hoffmann, E(rnst) T(heodor) A(madeus) «, in St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost, and Gothic Writers, ed. David Pringle. Detroit: St. James Press/Gale, 1998. ISBN 9781558622067 (pp. 668-69).

- ^ «Ludwig Tieck, Heinrich von Kleist, and E. T. A. Hoffmann also profoundly influenced the development of European Gothic horror in the nineteenth century….» Heide Crawford, The Origins of the Literary Vampire. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2016. ISBN 9781442266742 (p. xiii).

- ^ a b Schumann, Robert (2004). Herttrich, Ernst (ed.). Kreisleriana (PDF) (in German, English, and French). G. Henle Verlag. pp. III.

- ^ Friedrich Schnapp. «Hoffmanns Verwandte aus der Familie Doerffer in Königsberger Kirchenbüchern der Jahre 1740–1811.» Mitteilungen der E. T. A. Hoffmann-Gesellschaft. 23 (1977), 1–11.

- ^ Zipes, Jack (2007) [1816]. «The ‘Merry’ Dance of the Nutcracker: Discovering the World through Fairy Tales». Nutcracker & Mouse King & The Tale of the Nutcracker. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0143104834. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

He began writing novels and musical compositions as a young man and had his first love affair in 1794 with Cora (Dora) Hatt, a woman ten years older

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Das Leben eines skeptischen Phantasten. Carl Hanser, Munich, 1984. ISBN 3-446-13822-6

Gerhard R. Kaiser. E. T. A. Hoffmann. J. B. Metzlersche, Stuttgart, 1988. ISBN 3-476-10243-2 - ^ Hoffmann, E. T. A. (1977). Sahlin, Johanna C. (ed.). Selected Letters of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated by Sahlin, Johanna C. University of Chicago Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-226-34790-7.

- ^ Die Freimüthige, 11 February 1804. Volume II, no. 6, pages xxi–xxiv.

- ^ «Fantasy pieces in the manner of Jacques Callot»

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Intertextual Parallels Between Gogol’ and Hoffmann: A Case Study of Vij and The Devil’s Elixirs.» Canadian-American Slavic Studies (CASS) 47.1 (2013): 1-20. (20 pages)

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Allusions to Hoffmann in Gogol’s Ukrainian Horror Stories from the Dikan’ka Collection.» Canadian Slavonic Papers: Special Issue, devoted to the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol’s birth (1809–1852) 51.2-3 (June–September 2009): 243-266. (23 pages)

- ^ Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife London: Allen and Unwin, 1924 (p. 297-8).

- ^ «Another major influence for Lee is unmistakably E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann…» Christa Zorn, Vernon Lee : aesthetics, history, and the Victorian female intellectual. Athens : Ohio University Press, 2003. ISBN 0821414976 (p. 142).

- ^ The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker, Continuum, 2004, page 507

- ^ See also Fausto Cercignani, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Italien und die romantische Auffassung der Musik, in S. M. Moraldo (ed.), Das Land der Sehnsucht. E. T. A. Hoffmann und Italien, Heidelberg, Winter, 2002, S. 191–201.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (July 1968). «Galaxy Bookshelf». Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 161–167.

- ^ Martin Willis (2006). Mesmerists, Monsters, and Machines: Science Fiction and the Cultures of Science in the Nineteenth Century. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 29–30.

- ^ «Fanny and Alexander». www.ingmarbergman.se. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Review of Zinnober, http://www.ice-vajal.com/c/CD/coppelius.htm

- ^ «New Cartoon Show Puts Putin Among Men» http://www.ekaterinburg.com/news/print/news_id-316222.html

- ^ Loiko, Sergei (20 February 2012). «Vladimir Putin is spoofed on the Internet». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

External links[edit]

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about E. T. A. Hoffmann at Internet Archive

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hoffmann’s Life and Opinions of the Tom Cat Murr

- Free scores by E. T. A. Hoffmann in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- T. A. Hoffmann’s Fairy Tales

- Compositions of E. T. A. Hoffmann in the digital collection of the Bamberg State Library

- E. T. A. Hoffmann entry in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

- E. T. A. Hoffmann at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Extensively cross-indexed bibliography of Hoffmann’s works

|

E. T. A. Hoffmann |

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait |

|

| Born | Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann 24 January 1776 Königsberg, Kingdom of Prussia, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 25 June 1822 (aged 46) Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation |

| Pen name | E. T. A. Hoffmann |

| Occupation | Jurist, author, composer, music critic, artist |

| Period | 1809–1822 |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Signature | |

|

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; 24 January 1776 – 25 June 1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist.[1][2][3] His stories form the basis of Jacques Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann, in which Hoffmann appears (heavily fictionalized) as the hero. He is also the author of the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker is based. The ballet Coppélia is based on two other stories that Hoffmann wrote, while Schumann’s Kreisleriana[4] is based on Hoffmann’s character Johannes Kreisler.

Hoffmann’s stories highly influenced 19th-century literature, and he is one of the major authors of the Romantic movement.

Life[edit]

Youth[edit]

Hoffmann’s ancestors, both maternal and paternal, were jurists. His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736–97), was a barrister in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), as well as a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba. In 1767 he married his cousin, Lovisa Albertina Doerffer (1748–96). Ernst Theodor Wilhelm, born on 24 January 1776, was the youngest of three children, of whom the second died in infancy.

When his parents separated in 1778, his father went to Insterburg (now Chernyakhovsk) with his elder son, Johann Ludwig Hoffmann (1768–1822), while Ernst’s mother stayed in Königsberg with her relatives: two aunts, Johanna Sophie Doerffer (1745–1803) and Charlotte Wilhelmine Doerffer (c. 1754–79) and their brother, Otto Wilhelm Doerffer (1741–1811), who were all unmarried. The trio raised the youngster.

The household, dominated by the uncle (whom Ernst nicknamed O Weh—»Oh dear!»—in a play on his initials), was pietistic and uncongenial. Hoffmann was to regret his estrangement from his father. Nevertheless, he remembered his aunts with great affection, especially the younger, Charlotte, whom he nicknamed Tante Füßchen («Aunt Littlefeet»). Although she died when he was only three years old, he treasured her memory (e.g. see Kater Murr) and embroidered stories about her to such an extent that later biographers sometimes assumed her to be imaginary, until proof of her existence was found after World War II.[5]

Between 1781 and 1792 he attended the Lutheran school or Burgschule, where he made good progress in classics. He was taught drawing by one Saemann, and counterpoint by a Polish organist named Podbileski, who was to be the prototype of Abraham Liscot in Kater Murr. Ernst showed great talent for piano-playing, and busied himself with writing and drawing. The provincial setting was not, however, conducive to technical progress, and despite his many-sided talents he remained rather ignorant of both classical forms and of the new artistic ideas that were developing in Germany. He had, however, read Schiller, Goethe, Swift, Sterne, Rousseau and Jean Paul, and wrote part of a novel titled Der Geheimnisvolle.

Around 1787 he became friends with Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Younger (1775–1843), the son of a pastor, and nephew of Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Elder, the well-known writer friend of Immanuel Kant. During 1792, both attended some of Kant’s lectures at the University of Königsberg. Their friendship, although often tested by an increasing social difference, was to be lifelong.

In 1794, Hoffmann became enamored of Dora Hatt, a married woman to whom he had given music lessons. She was ten years older, and gave birth to her sixth child in 1795.[6] In February 1796, her family protested against his attentions and, with his hesitant consent, asked another of his uncles to arrange employment for him in Glogau (Głogów), Prussian Silesia.[7]

The provinces[edit]

From 1796, Hoffmann obtained employment as a clerk for his uncle, Johann Ludwig Doerffer, who lived in Glogau with his daughter Minna. After passing further examinations he visited Dresden, where he was amazed by the paintings in the gallery, particularly those of Correggio and Raphael. During the summer of 1798, his uncle was promoted to a court in Berlin, and the three of them moved there in August—Hoffmann’s first residence in a large city. It was there that Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia. The official reply advised to him to write to the director of the Royal Theatre, a man named Iffland. By the time the latter responded, Hoffmann had passed his third round of examinations and had already left for Posen (Poznań) in South Prussia in the company of his old friend Hippel, with a brief stop in Dresden to show him the gallery.

From June 1800 to 1803, he worked in Prussian provinces in the area of Greater Poland and Masovia. This was the first time he had lived without supervision by members of his family, and he started to become «what school principals, parsons, uncles, and aunts call dissolute.»[8]

His first job, at Posen, was endangered after Carnival on Shrove Tuesday 1802, when caricatures of military officers were distributed at a ball. It was immediately deduced who had drawn them, and complaints were made to authorities in Berlin, who were reluctant to punish the promising young official. The problem was solved by «promoting» Hoffmann to Płock in New East Prussia, the former capital of Poland (1079–1138), where administrative offices were relocated from Thorn (Toruń). He visited the place to arrange lodging, before returning to Posen where he married Mischa (Maria or Marianna Thekla Michalina Rorer, whose Polish surname was Trzcińska). They moved to Płock in August 1802.

Hoffmann despaired because of his exile, and drew caricatures of himself drowning in mud alongside ragged villagers. He did make use, however, of his isolation, by writing and composing. He started a diary on 1 October 1803. An essay on the theatre was published in Kotzebue’s periodical, Die Freimüthige, and he entered a competition in the same magazine to write a play. Hoffmann’s was called Der Preis («The Prize»), and was itself about a competition to write a play. There were fourteen entries, but none was judged worthy of the award: 100 Friedrichs d’or. Nevertheless, his entry was singled out for praise.[9] This was one of the few good times of a sad period of his life, which saw the deaths of his uncle J. L. Hoffmann in Berlin, his Aunt Sophie, and Dora Hatt in Königsberg.

At the beginning of 1804, he obtained a post at Warsaw. On his way there, he passed through his hometown and met one of Dora Hatt’s daughters. He was never to return to Königsberg.

Warsaw[edit]

Hoffmann assimilated well with Polish society; the years spent in Prussian Poland he recognized as the happiest of his life. In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin, renewing his friendship with Zacharias Werner, and meeting his future biographer, a neighbour and fellow jurist called Julius Eduard Itzig (who changed his name to Hitzig after his baptism). Itzig had been a member of the Berlin literary group called the Nordstern, or «North Star», and he gave Hoffmann the works of Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Carlo Gozzi and Calderón. These relatively late introductions marked his work profoundly.

He moved in the circles of August Wilhelm Schlegel, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Rahel Levin and David Ferdinand Koreff.

But Hoffmann’s fortunate position was not to last: on 28 November 1806, during the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops captured Warsaw, and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their jobs. They divided the contents of the treasury between them and fled. In January 1807, Hoffmann’s wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia returned to Posen, while he pondered whether to move to Vienna or go back to Berlin. A delay of six months was caused by severe illness. Eventually the French authorities demanded that all former officials swear allegiance or leave the country. As they refused to grant Hoffmann a passport to Vienna, he was forced to return to Berlin.

He visited his family in Posen before arriving in Berlin on 18 June 1807, hoping to further his career there as an artist and writer.

Berlin and Bamberg[edit]

The next fifteen months were some of the worst in Hoffmann’s life.

The city of Berlin was also occupied by Napoleon’s troops. Obtaining only meagre allowances, he had frequent recourse to his friends, constantly borrowing money and still going hungry for days at a time; he learned that his daughter had died. Nevertheless, he managed to compose his Six Canticles for a cappella choir: one of his best compositions, which he would later attribute to Kreisler in Lebensansichten des Katers Murr.

Hoffmann’s portrait of Kapellmeister Kreisler

On 1 September 1808 he arrived with his wife in Bamberg, where he began a job as theatre manager. The director, Count Soden, left almost immediately for Würzburg, leaving a man named Heinrich Cuno in charge. Hoffmann was unable to improve standards of performance, and his efforts caused intrigues against him which resulted in him losing his job to Cuno. He began work as music critic for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, a newspaper in Leipzig, and his articles on Beethoven were especially well received, and highly regarded by the composer himself. It was in its pages that the «Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler» character made his first appearance.

Hoffmann’s breakthrough came in 1809, with the publication of Ritter Gluck, a story about a man who meets, or believes he has met, the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–87) more than twenty years after the latter’s death. The theme alludes to the work of Jean Paul, who invented the term Doppelgänger the previous decade, and continued to exact a powerful influence over Hoffmann, becoming one of his earliest admirers. With this publication, Hoffmann began to use the pseudonym E. T. A. Hoffmann, telling people that the «A» stood for Amadeus, in homage to the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91). However, he continued to use Wilhelm in official documents throughout his life, and the initials E. T. W. also appear on his gravestone.

The next year, he was employed at the Bamberg Theatre as stagehand, decorator, and playwright, while also giving private music lessons.

He became so enamored of a young singing student, Julia Marc, that his feelings were obvious whenever they were together, and Julia’s mother quickly found her a more suitable match. When Joseph Seconda offered Hoffmann a position as musical director for his opera company (then performing in Dresden), he accepted, leaving on 21 April 1813.

Dresden and Leipzig[edit]

Prussia had declared war against France on 16 March during the War of the Sixth Coalition, and their journey was fraught with difficulties. They arrived on the 25th, only to find that Seconda was in Leipzig; on the 26th, they sent a letter pleading for temporary funds. That same day Hoffmann was surprised to meet Hippel, whom he had not seen for nine years.

The situation deteriorated, and in early May Hoffmann tried in vain to find transport to Leipzig. On 8 May, the bridges were destroyed, and his family were marooned in the city. During the day, Hoffmann would roam, watching the fighting with curiosity. Finally, on 20 May, they left for Leipzig, only to be involved in an accident which killed one of the passengers in their coach and injured his wife.

They arrived on 23 May, and Hoffmann started work with Seconda’s orchestra, which he found to be of the best quality. On 4 June an armistice began, which allowed the company to return to Dresden. But on 22 August, after the end of the armistice, the family was forced to relocate from their pleasant house in the suburbs into the town, and during the next few days the Battle of Dresden raged. The city was bombarded; many people were killed by bombs directly in front of him. After the main battle was over, he visited the gory battlefield. His account can be found in Vision auf dem Schlachtfeld bei Dresden. After a long period of continued disturbance, the town surrendered on 11 November, and on 9 December the company travelled to Leipzig.

On 25 February, Hoffmann quarrelled with Seconda, and the next day he was given notice of twelve weeks. When asked to accompany them on their journey to Dresden in April, he refused, and they left without him. But during July his friend Hippel visited, and soon he found himself being guided back into his old career as a jurist.

Berlin[edit]

Grave of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated, the inscription reads: E. T. W. Hoffmann, born on 24 January 1776, in Königsberg, died on 25 June 1822, in Berlin, Councillor of the Court of Justice, excellent in his office, as a poet, as a musician, as a painter, dedicated by his friends.

At the end of September 1814, in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat, Hoffmann returned to Berlin and succeeded in regaining a job at the Kammergericht, the chamber court. His opera Undine was performed by the Berlin Theatre. Its successful run came to an end only after a fire on the night of the 25th performance. Magazines clamoured for his contributions, and after a while his standards started to decline. Nevertheless, many masterpieces date from this time.

During the period from 1819, Hoffmann was involved with legal disputes, while fighting ill health. Alcohol abuse and syphilis eventually caused weakening of his limbs during 1821, and paralysis from the beginning of 1822. His last works were dictated to his wife or to a secretary.

Prince Metternich’s anti-liberal programs began to put Hoffmann in situations that tested his conscience. Thousands of people were accused of treason for having certain political opinions,

and university professors were monitored during their lectures.

King Frederick William III of Prussia appointed an Immediate Commission for the investigation of political dissidence; when he found its observance of the rule of law too frustrating, he established a Ministerial Commission to interfere with its processes. The latter was greatly influenced by Commissioner Kamptz. During the trial of «Turnvater» Jahn, the founder of the gymnastics association movement, Hoffmann found himself annoying Kamptz, and became a political target. When Hoffmann caricatured Kamptz in a story (Meister Floh), Kamptz began legal proceedings. These ended when Hoffmann’s illness was found to be life-threatening. The King asked for a reprimand only, but no action was ever taken. Eventually Meister Floh was published with the offending passages removed.

Hoffmann died of syphilis in Berlin on 25 June 1822 at the age of 46. His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof III der Jerusalems- und Neuen Kirchengemeinde (Cemetery No. III of the congregations of Jerusalem Church and New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, south of Hallesches Tor at the underground station Mehringdamm.

Works[edit]

Literary[edit]

Four volume set of Hoffmann’s writings

- Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (collection of previously published stories, 1814)[10]

- «Ritter Gluck», «Kreisleriana», «Don Juan», «Nachricht von den neuesten Schicksalen des Hundes Berganza»

- «Der Magnetiseur», «Der goldne Topf» (revised in 1819), «Die Abenteuer der Silvesternacht»

- Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815)

- Nachtstücke (1817)

- «Der Sandmann», «Das Gelübde», «Ignaz Denner», «Die Jesuiterkirche in G.»

- «Das Majorat», «Das öde Haus», «Das Sanctus», «Das steinerne Herz»

- Seltsame Leiden eines Theater-Direktors (1819)

- Little Zaches (1819)

- Die Serapionsbrüder (1819)

- «Der Einsiedler Serapion», «Rat Krespel», «Die Fermate», «Der Dichter und der Komponist»

- «Ein Fragment aus dem Leben dreier Freunde», «Der Artushof», «Die Bergwerke zu Falun», «Nußknacker und Mausekönig» (1816)

- «Der Kampf der Sänger», «Eine Spukgeschichte», «Die Automate», «Doge und Dogaresse»

- «Alte und neue Kirchenmusik», «Meister Martin der Küfner und seine Gesellen», «Das fremde Kind»

- «Nachricht aus dem Leben eines bekannten Mannes», «Die Brautwahl», «Der unheimliche Gast»

- «Das Fräulein von Scuderi», «Spielerglück» (1819), «Der Baron von B.»

- «Signor Formica», «Zacharias Werner», «Erscheinungen»

- «Der Zusammenhang der Dinge», «Vampirismus», «Die ästhetische Teegesellschaft», «Die Königsbraut»

- Prinzessin Brambilla (1820)

- Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820)

- «Die Irrungen» (1820)

- «Die Geheimnisse» (1821)

- «Die Doppeltgänger» (1821)

- Meister Floh (1822)

- «Des Vetters Eckfenster» (1822)

- Letzte Erzählungen (1825)

Musical[edit]

Vocal music[edit]

- Messa d-moll (1805)

- Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807)

- 6 Canzoni per 4 voci alla capella (1808)

- Miserere b-moll (1809)

- In des Irtisch weiße Fluten (Kotzebue), Lied (1811)

- Recitativo ed Aria „Prendi l’acciar ti rendo» (1812)

- Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812)

- Nachtgesang, Türkische Musik, Jägerlied, Katzburschenlied für Männerchor (1819–21)

Works for stage[edit]

- Die Maske (libretto by Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799)

- Die lustigen Musikanten (libretto: Clemens Brentano), Singspiel (1804)

- Incidental music to Zacharias Werner’s tragedy Das Kreuz an der Ostsee (1805)

- Liebe und Eifersucht (libretto by Hoffmann after Calderón, translated by August Wilhelm Schlegel) (1807)

- Arlequin, ballet (1808)

- Der Trank der Unsterblichkeit (libretto: Julius von Soden), romantic opera (1808)

- Wiedersehn! (libretto by Hoffmann), prologue (1809)

- Dirna (libretto: Julius von Soden), melodrama (1809)

- Incidental music to Julius von Soden’s drama Julius Sabinus (1810)

- Saul, König von Israel (libretto: Joseph von Seyfried), melodrama (1811)

- Aurora (libretto: Franz von Holbein), heroic opera (1812)

- Undine (libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué), Zauberoper (1816)

- Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode (unfinished)

Instrumental[edit]

- Rondo für Klavier (1794/95)

- Ouvertura. Musica per la chiesa d-moll (1801)

- Klaviersonaten: A-Dur, f-moll, F-Dur, f-moll, cis-moll (1805–1808)

- Große Fantasie für Klavier (1806)

- Sinfonie Es-Dur (1806)

- Harfenquintett c-moll (1807)

- Grand Trio E-Dur (1809)

- Walzer zum Karolinentag (1812)

- Teutschlands Triumph in der Schlacht bei Leipzig, (by «Arnulph Vollweiler», 1814; lost)

- Serapions-Walzer (1818–1821)

Assessment[edit]

Statue of «E. T. A. Hoffmann and his cat» in Bamberg

Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, and a pioneer of the fantasy genre, with a taste for the macabre combined with realism that influenced such authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Nikolai Gogol[11][12] (1809–1852), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), George MacDonald (1824–1905),[13] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), Vernon Lee (1856–1935),[14] Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980). Hoffmann’s story Das Fräulein von Scuderi is sometimes cited as the first detective story and a direct influence on Poe’s «The Murders in the Rue Morgue»;[15] Characters from it also appear in the opera Cardillac by Paul Hindemith.

The twentieth-century Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin characterised Hoffmann’s works as Menippea, essentially satirical and self-parodying in form, thus including him in a tradition that includes Cervantes, Diderot and Voltaire.

Robert Schumann’s piano suite Kreisleriana (1838) takes its title from one of Hoffmann’s books (and according to Charles Rosen’s The Romantic Generation, is possibly also inspired by «The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr», in which Kreisler appears).[4] Jacques Offenbach’s masterwork, the opera Les contes d’Hoffmann («The Tales of Hoffmann», 1881), is based on the stories, principally «Der Sandmann» («The Sandman», 1816), «Rat Krespel» («Councillor Krespel», 1818), and «Das verlorene Spiegelbild» («The Lost Reflection») from Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year’s Eve, 1814). Klein Zaches genannt Zinnober (Little Zaches called Cinnabar, 1819) inspired an aria as well as the operetta Le Roi Carotte, 1872). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker (1892) is based on «The Nutcracker and the Mouse King», and the ballet Coppélia, with music by Delibes, is based on two eerie Hoffmann stories.

Hoffmann also influenced 19th-century musical opinion directly through his music criticism. His reviews of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) and other important works set new literary standards for writing about music, and encouraged later writers to consider music as «the most Romantic of all the arts.»[16] Hoffmann’s reviews were first collected for modern readers by Friedrich Schnapp, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann: Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese (1963) and have been made available in an English translation in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume (2004).

Hoffmann’s drawing of himself, riding on Tomcat Murr and fighting «Prussian bureaucracy»

Hoffmann strove for artistic polymathy. He created far more in his works than mere political commentary achieved through satire. His masterpiece novel Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr, 1819–1821) deals with such issues as the aesthetic status of true artistry and the modes of self-transcendence that accompany any genuine endeavour to create. Hoffmann’s portrayal of the character Kreisler (a genius musician) is wittily counterpointed with the character of the tomcat Murr – a virtuoso illustration of artistic pretentiousness that many of Hoffmann’s contemporaries found offensive and subversive of Romantic ideals.

Hoffmann’s literature indicates the failings of many so-called artists to differentiate between the superficial and the authentic aspects of such Romantic ideals. The self-conscious effort to impress must, according to Hoffmann, be divorced from the self-aware effort to create. This essential duality in Kater Murr is conveyed structurally through a discursive ‘splicing together’ of two biographical narratives.

Science fiction[edit]

While disagreeing with E. F. Bleiler’s claim that Hoffmann was «one of the two or three greatest writers of fantasy», Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction said that he «did lay down the groundwork for some of our most enduring themes».[17]

Historian Martin Willis argues that Hoffmann’s impact on science fiction has been overlooked, saying «his work reveals a writer dynamically involved in the important scientific debates of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.» Willis points out that Hoffmann’s work is contemporary with Frankenstein (1818) and with «the heated debates and the relationship between the new empirical science and the older forms of natural philosophy that held sway throughout the eighteenth century.» His «interest in the machine culture of his time is well represented in his short stories, of which the critically renowned The Sandman (1816) and Automata (1814) are the best examples. …Hoffmann’s work makes a considerable contribution to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early years of the nineteenth century and to the conflict between science and magic, centred mainly on the ‘truths’ available to the advocates of either practice. …Hoffmann’s balancing of mesmerism, mechanics, and magic reflects the difficulty in categorizing scientific knowledge in the early nineteenth century.»[18]

In popular culture[edit]

- Robertson Davies invokes Hoffmann as a character (with the pet name of ‘ETAH’) trapped in Limbo, in his novel The Lyre of Orpheus (1988).

- Alexandre Dumas, père translated The Nutcracker into French, which aided in making the tale popular and widespread.

- The exotic and supernatural elements in the storyline of Ingmar Bergman’s 1982 film Fanny and Alexander derive largely from the stories of Hoffmann.[19]

- Freud gives an extensive psychoanalytic analysis of Hoffmann’s «The Sandman» in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche.[citation needed]

- Coppelius is a German classical metal band whose name is taken from a character in Hoffmann’s «The Sandman». The band’s 2010 album Zinnober includes a track titled «Klein Zaches».[20][citation needed]

- The Russian show Puppets was cancelled by government officials after an episode in which Vladimir Putin was portrayed as Hoffmann’s Klein Zaches.[21][1][22]

See also[edit]

- The Tales of Hoffmann for Offenbach’s opera.

- The Tales of Hoffmann for the film

- Gofmaniada, a Russian puppet-animated feature film about Hoffmann and several of his stories.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Penrith Goff, «E.T.A. Hoffmann» in E. F. Bleiler, Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror. New York: Scribner’s, 1985. pp. 111–120. ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ Mike Ashley, «Hoffmann, E(rnst) T(heodor) A(madeus) «, in St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost, and Gothic Writers, ed. David Pringle. Detroit: St. James Press/Gale, 1998. ISBN 9781558622067 (pp. 668-69).

- ^ «Ludwig Tieck, Heinrich von Kleist, and E. T. A. Hoffmann also profoundly influenced the development of European Gothic horror in the nineteenth century….» Heide Crawford, The Origins of the Literary Vampire. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2016. ISBN 9781442266742 (p. xiii).

- ^ a b Schumann, Robert (2004). Herttrich, Ernst (ed.). Kreisleriana (PDF) (in German, English, and French). G. Henle Verlag. pp. III.

- ^ Friedrich Schnapp. «Hoffmanns Verwandte aus der Familie Doerffer in Königsberger Kirchenbüchern der Jahre 1740–1811.» Mitteilungen der E. T. A. Hoffmann-Gesellschaft. 23 (1977), 1–11.

- ^ Zipes, Jack (2007) [1816]. «The ‘Merry’ Dance of the Nutcracker: Discovering the World through Fairy Tales». Nutcracker & Mouse King & The Tale of the Nutcracker. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0143104834. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

He began writing novels and musical compositions as a young man and had his first love affair in 1794 with Cora (Dora) Hatt, a woman ten years older

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Das Leben eines skeptischen Phantasten. Carl Hanser, Munich, 1984. ISBN 3-446-13822-6

Gerhard R. Kaiser. E. T. A. Hoffmann. J. B. Metzlersche, Stuttgart, 1988. ISBN 3-476-10243-2 - ^ Hoffmann, E. T. A. (1977). Sahlin, Johanna C. (ed.). Selected Letters of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated by Sahlin, Johanna C. University of Chicago Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-226-34790-7.

- ^ Die Freimüthige, 11 February 1804. Volume II, no. 6, pages xxi–xxiv.

- ^ «Fantasy pieces in the manner of Jacques Callot»

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Intertextual Parallels Between Gogol’ and Hoffmann: A Case Study of Vij and The Devil’s Elixirs.» Canadian-American Slavic Studies (CASS) 47.1 (2013): 1-20. (20 pages)

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Allusions to Hoffmann in Gogol’s Ukrainian Horror Stories from the Dikan’ka Collection.» Canadian Slavonic Papers: Special Issue, devoted to the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol’s birth (1809–1852) 51.2-3 (June–September 2009): 243-266. (23 pages)

- ^ Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife London: Allen and Unwin, 1924 (p. 297-8).

- ^ «Another major influence for Lee is unmistakably E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann…» Christa Zorn, Vernon Lee : aesthetics, history, and the Victorian female intellectual. Athens : Ohio University Press, 2003. ISBN 0821414976 (p. 142).

- ^ The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker, Continuum, 2004, page 507

- ^ See also Fausto Cercignani, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Italien und die romantische Auffassung der Musik, in S. M. Moraldo (ed.), Das Land der Sehnsucht. E. T. A. Hoffmann und Italien, Heidelberg, Winter, 2002, S. 191–201.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (July 1968). «Galaxy Bookshelf». Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 161–167.

- ^ Martin Willis (2006). Mesmerists, Monsters, and Machines: Science Fiction and the Cultures of Science in the Nineteenth Century. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 29–30.

- ^ «Fanny and Alexander». www.ingmarbergman.se. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Review of Zinnober, http://www.ice-vajal.com/c/CD/coppelius.htm

- ^ «New Cartoon Show Puts Putin Among Men» http://www.ekaterinburg.com/news/print/news_id-316222.html

- ^ Loiko, Sergei (20 February 2012). «Vladimir Putin is spoofed on the Internet». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

External links[edit]

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about E. T. A. Hoffmann at Internet Archive

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hoffmann’s Life and Opinions of the Tom Cat Murr

- Free scores by E. T. A. Hoffmann in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- T. A. Hoffmann’s Fairy Tales

- Compositions of E. T. A. Hoffmann in the digital collection of the Bamberg State Library

- E. T. A. Hoffmann entry in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

- E. T. A. Hoffmann at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Extensively cross-indexed bibliography of Hoffmann’s works

Поиск ответов на кроссворды и сканворды

Ответ на вопрос «Автор сказки «Щелкунчик» «, 6 (шесть) букв:

гофман

Альтернативные вопросы в кроссвордах для слова гофман

Определение слова гофман в словарях

Энциклопедический словарь, 1998 г.

Значение слова в словаре Энциклопедический словарь, 1998 г.

ГОФМАН (Hofman) Фриц (1866-1956) немецкий химик-технолог. Труды посвящены химии синтетического каучука. Совместно с сотрудниками осуществил в 1909 первый синтез метилкаучука продукта полимеризации диметилбутадиена. Организовал (1916) фабрику по производству …

Википедия

Значение слова в словаре Википедия

Гофман — фамилия немецкого или еврейского происхождения. В латинском написании может иметь вид Hofman, Hoffman, Hoffmann, Hofmann. В русском языке передаётся как Хофман или Гофман (с одинарными или удвоенными ф или н ). Известные носители:

Примеры употребления слова гофман в литературе.

Без больших надежд он собирался обсуждать этот вопрос с Гофманом, который в тот момент как раз готовил советской делегации ультиматум о немедленном подписании аннексионистского мира на германских условиях.

Ах, опять это городской викарий Гофман, восхваляющий благодать аугсбургского исповедания.

Но в тот момент, когда я входил в кабинет Горынина, совместной фантазии Кафки и Борхеса при участии Гофмана не хватило бы, чтобы вообразить себе этот коврик лежащим перед порогом.

У нее были всякие неожиданные прибаутки и огромный запас второстепенных стихов,— тут были и Жадовская, и Виктор Гофман, и К.

В автомобиле Тонио, пользуясь тем, что киноартистки были заняты оживленным разговором с Гофманом, тихо спросил Эллен: — Когда же вы дадите мне ответ, Эллен?

Однажды Эллен в обществе Престо, Гофмана и двух киноартисток подъехала к фешенебельному кинотеатру.

Источник: библиотека Максима Мошкова

Гофман Эрнст Теодор Амадей

Гофман Эрнст Теодор Амадей (24.01.1776 – 25.06.1822) – немецкий писатель, открывший целое направление в литературе, названное романтическим. Самое известное произведение – сказка «Щелкунчик и Мышиный король».

«Если у тебя есть глаза, то ты способен увидеть и прозрачные марципановые замки, и сверкающие цукатные рощи. И они будут повсюду. Другими словами, ты способен видеть чудеса»

Детство

В 24 года Гофман окончил Кенингсбергский университет и поступил на государственную службу. Но при этом сама работа юноше никогда не нравилась. Все свое свободное время он отдавал музыке и живописи. И так хорошо выучился игре на пианино, что даже стал давать уроки. В это время он пишет свои первые крупные произведения – фортепианные сонаты для скрипок, арфы и виолончели.

Начало творческой карьеры

В 1802 году Гофман попал в немилость у начальства после того как в шутку нарисовал несколько злобных политических карикатур. Его не арестовали, но решили сослать подальше – в отдаленную провинцию Плоцк. Сам писатель называл ее «гнусным местечком», но именно там его творческие способности стали раскрываться все больше. Он активно занялся музыкой, живописью, изучал итальянский язык.

И когда его «помиловали» и перевели на работу в Варшаву, за плечами Гофмана был уже солидный творческий багаж. Были написаны серьезные драматические произведения – зингшпиль «Веселые музыканты», музыка к драме «Крест на Балтийском море» и опера «Любовь и ревность».

Тогда же Гофман начинает активно интересоваться литературой. Он взахлеб читает немецких романтиков – Шлегеля, Фридриха фон Харденберга, Тика, Бретано и других. Под впечатлением от большинства произведений, и сам Эрнст Теодор решает написать нечто подобное.

Литературная деятельность

В 1806 году в Варшаву вторгается Наполеон. Все учреждения в городе были закрыты, и Гофман остался практически без средств к существованию. Но друзья помогли ему переправиться в Берлин. Там он познакомился с известным музыкальным критиком И.Ф.Рохлицем. И тот предложил написать ему вымышленную историю о творческом человеке, который дошел до крайней нищеты. Так появилось известное произведение «Крейслериана». А вслед за ним были написаны музыкальные новеллы «Дон-Жуан» и «Кавалер Глюк».

Через несколько лет нашелся еще один старый друг Гофмана – Франц Гольбейн. Он позвал писателя и композитора работать в Бамберский театр, где творческая натура Эрнста Теодора смогла развернуться на полную катушку. Он писал музыку к спектаклям, участвовал в постановках, создавал декорации и даже занимался архитектурным украшением здания театра.

С 1816 года Гофман решил закончить со своим музыкальным творчеством. Последнее созданное им произведение – опера «Ундина», которая была очень тепло принята зрителями и критиками. Но после этого Эрнст Теодор полностью сосредоточился на литературе. Причем писал в основном сказки и мистические романы. Среди самых значимых произведений того времени – «Элексир дьявола», «Золотой горшок», «Принцесса Брамбилла», «Серапиновы братья» и, конечно, «Щелкунчик и Мышиный король».

Создание Щелкунчика

Эта легендарная сказка была задумана Гофманом, когда он нянчился с детьми своего друга и биографа Юлиуса Гитцига. Даже имена главных героев – Фриц и Мари – не вымышлены, а персонажи точно передают черты их характера.

Само произведение написано осенью 1816 года. После этого Гофман передал рукопись издателю Георгу Раймеру. И сказка тут же была напечатана в сборнике «Детских новелл», который вышел как раз накануне Рождества. «Щелкунчик и Мышиный король» стал настоящей сенсацией среди читателей и критиков.

Произведение оценили даже военные. Так, один прусский военачальник говорил, что Гофман очень ярко описал сцены батальной битвы Щелкунчика с мышиной армией и «убедительно и по всей военной науке рассказал о каждом этапе сражения».

Смерть писателя

Знаменитый немецкий писатель и композитор Эрнст Теодор Амадей Гофман скончался 25 июня 1822 года. Перед этим полгода он сильно болел, простудившись еще в январе. Правда, болезнь усугубилась еще и разбирательствами с прусским правительством. Именно в это время против Гофмана были выдвинуты серьезные обвинения в насмешках над высокими чиновниками и даже в нарушении служебной тайны. В доме писателя проводили регулярные обыски, его рукописи изымали для изучения. Естественно, в такой атмосфере было очень тяжело лечиться. И состояние здоровья Гофмана только ухудшалось.

Писателя даже несколько раз пытались вызвать на допрос, но врачи вставали на его защиту и запрещали куда-либо ездить. Со временем Эрнсту Теодору стало совсем плохо. Он уже не мог держать в руках перо, но продолжал творить. По диктовку автора друзья сумели закончить несколько его произведений. Среди них «Повелитель блох», «Угловое окно» и «Наивность». Но к 24 июня паралич сковал все тело Гофмана, а утром следующего дня немецкий писатель умер.

Популярные сказки:

- Щелкунчик и Мышиный король

- Золотой горшок

- Песочный Человек

- Повелитель блох

- Приключения в новогоднюю ночь

Все сказки Гофмана Э.Т.А.

| История Щелкунчика | |

|---|---|

| фр. (b) Histoire d’un casse-noisette | |

Обложка издания 1860 года |

|

| Жанр | Сказка (b) |

| Автор | Александр Дюма-отец (b) |

| Язык оригинала | французский (b) |

| Дата написания | 1844 |

| Дата первой публикации | 1844 |

«История Щелкунчика» (фр. (b) Histoire d’un casse-noisette) — переложение сказки Э. Т. А. Гофмана (b) «Щелкунчик и мышиный король (b) », сделанное в 1844 году Александром Дюма-отцом (b) и опубликованное в том же году. Несмотря на сохранение основной сюжетной линии сказки, вольный перевод Дюма представлял собой новый её вариант, отличный от оригинала. В варианте французского писателя смещены смысловые акценты, изменена атмосфера и манера изложения. Основной идеей стало всепобеждающее чувство любви, превратившее деревянного Щелкунчика в человека, что является упрощением философской концепции сказки Гофмана.

Переработка Дюма послужила первоисточником для либретто последнего балета П. И. Чайковского (b) «Щелкунчик (b) » (1892), которое создал балетмейстер Мариус Петипа (b) . В связи с частичным изменением сюжета сказки Гофмана сюжетная версия либретто этого балета-феерии предстаёт в более сглаженном, сказочно-символическом виде, что продиктовано вариантом французского писателя.

Сюжет

Действие сказки начинается в канун Рождества (b) в немецком городе Нюрнберге (b) , знаменитом производством детских игрушек. В этом городе жил господин президент Зильберхауз, у которого были сын и дочь. Сыну было девять лет и его звали Фриц, а его сестре Мари было семь с половиной лет. В отличие от своего толстого, хвастливого и проказливого брата, Мари была изящная, скромная, мечтательная и сострадательная девочка. Также в городе проживал их крёстный Дроссельмейер, советник медицины, занимавший такое же видное положение, как и их отец. Он увлекался изготовлением механических кукол и, невзирая на их недостатки, уверял, что рано или поздно ему удастся создать настоящих людей и животных.

Весь день 24 декабря Фрица и Мари не пускали в гостиную, где родители поставили и украсили рождественскую ёлку. Когда уже совсем стемнело, их наконец-то пригласили в гостиную, где дети получили многочисленные подарки, в том числе замок с движущимися фигурками от крёстного. Среди подарков Мари обнаружила красиво одетого маленького человечка с длинным туловищем и непропорциональной головой. От отца дети узнали, что этот подарок предназначен им обоим и представляет собой механическое приспособление для колки орехов, раскалывающее орех своими «зубами». Фриц практически сразу поломал Щелкунчику зубы, и за ним стала «ухаживать» Мари. Перед сном дети расставили свои новые подарки в специальный стеклянный шкаф, где хранились все их игрушки. Мари осталась в гостиной одна, занятая заботами о Щелкунчике, и в это время часы прозвонили о наступлении полуночи. После чего начались чудеса: игрушки стали оживать, а в комнату проникли полчища мышей под предводительством мышиного короля (b) , у которого было семь коронованных голов. Мари стала пятиться к шкафу, при этом разбив стекло локтем и поранившись. Куклы и игрушки начали готовиться к бою, а во главе их стал Щелкунчик, под командованием которого образовалась целая армия с артиллерией, регулярными частями и ополчением. Однако игрушечное войско заметно уступало в численности и понесло поражение. Щелкунчик был прижат противниками к шкафу, и когда мышиный король уже было хотел с ним расправиться, в это мгновение Мари бросила в предводителя мышей свою туфельку и сбила его с ног. Она ощутила сильную боль в руке и после этого противоборствующие стороны разом пропали, а она упала без чувств.

Мари очнулась после забытья в своей кровати, узнав, что потеряла много крови от ранения. Когда она стала говорить о битве, никто ей не поверил, подумав, что она бредит. Девочку навещает Дроссельмейер, который рассказывает ей сказку об орехе Кракатук и принцессе Пирлипат. Последняя родилась в королевской семье, которой противостояли госпожа Мышильда и её мышиное племя. Чтобы избавиться от мышей, королём был приглашён Кристиан Элиас Дроссельмейер; он изготовил мышеловки и переловил всех мышей, кроме их королевы и немногих её приближённых. Мышильда покинула эти края, но прокляла королеву и её детей. Позже в результате козней Мышильды принцесса превратилась в уродца. Король возложил вину на Дроссельмейера, заявив, что если тот не вернёт его дочери прежнего облика, то будет казнён. Механик понимал, что ему не удаётся вылечить ребёнка, но он обратил внимание, что после превращения она необычайно полюбила орехи. При помощи звездочёта он выяснил, что для того чтобы вернуть её былую красоту, она должна съесть ядро ореха Кракатук, обладавшего необычайно твёрдой скорлупой. При этом этот орех должен был разгрызть «молодой человек, ещё ни разу не брившийся и всю жизнь носивший сапоги». Другим условием было то, что он должен передать ядрышко ореха принцессе, зажмурив глаза, а затем, не открывая их, отступить на семь шагов и не споткнуться при этом. Механик и звездочёт обошли весь свет в поисках соблюдения необходимых условий, но так и не смогли этого сделать, пока не побывали в Нюрнберге, где проживал брат Дроссельмейера — Кристоф Захариас, у которого был нужный им орех. Также выяснилось, что его сын Натаниэль, которого прозвали Щелкунчиком, подходит для миссии по спасению принцессы. К его голове ему приделали специальную деревянную косичку, приводящую в действие механизм для раскалывания орехов. При выполнении их замысла Натаниэлю, которому пообещали выдать за него принцессу, почти всё удалось сделать в точности, и принцесса, которой исполнилось пятнадцать лет, вновь стала красавицей. Однако когда он пятился назад, между его ног пробежала Мышильда, и он споткнулся, после чего превратился в такое же безобразное чудовище, каким только что была принцесса. При этом королева мышей была им раздавлена и издохла. Принцесса захотела увидеть своего спасителя, но король и она, увидев, что он стал безобразен, прогнали его. С ним покинули двор и Дроссельмейер со звездочётом, которые при помощи гадания выяснили, что несмотря на нынешнее положение юноша может стать принцем, если будет противостоять в битве семиголовому мышиному королю (сыну Мышильды), и при этом, несмотря на его уродство, его сможет полюбить «прекрасная дама». Они вернулись в Нюрнберг и стали ожидать свершения пророчества.

После того как Дроссельмейер рассказал Мари сказку об орехе Кракатук и принцессе Пирлипат, его крестница ещё неделю пролежала в кровати. Она рассказала домашним свою историю, но ей опять не поверили. Несколько ночей подряд к ней являлся мышиный король и угрожал загрызть Щелкунчика. Щелкунчик попросил Мари достать ему шпагу, с чем им помог Фриц, отдав саблю одного из своих солдатиков. Ночью произошла битва, в которой Щелкунчик убил мышиного короля, после чего он попросил Мари отправиться с ним в путешествие по его королевству кукол, где они увидели множество волшебных мест. В этом королевстве девочка сказала, что не отвергла бы Щелкунчика, если бы, оказывая ей услугу, он стал бы уродом. Утром Мари просыпается и рассказывает домочадцам, что с ней случилось, но ей опять не верят, прозвав «маленькой мечтательницей». В один из дней Мари узнаёт, что в город после многолетних странствий вернулся племянник его крёстного — красивый молодой человек небольшого роста. Натаниэль делает предложение руки и сердца Мари и она соглашается. С одобрения родителей они в тот же день были помолвлены, с условием, что свадьба пройдёт через год. По истечении этого срока принц приехал за Мари в великолепной карете и забрал её в Марципановый дворец, где и состоялась свадьба. По словам автора, скорее всего Мари и поныне является государыней чудесного королевства, где можно увидеть «сверкающие Рождественские леса, реки лимонада, оранжада, миндального молока и розового масла, просвечивающие насквозь дворцы из сахара чище снега и прозрачнее льда, и где, короче, можно увидеть всякого рода чудеса и диковинки, если, разумеется, твои глаза способны увидеть их»[1].

Создание

Французский писатель Александр Дюма (b) наиболее известен как романист и драматург, но в огромной библиографии (b) писателя имеются сказки и сказочные повести, как оригинальные, так и переработки произведений известных сказочников (Х. К. Андерсена (b) , братьев Гримм (b) и др.)[2][3][4]. Чаще всего сказки писателя первоначально публиковались в периодической печати. В 1857—1860 годах, ещё при жизни автора, они вышли в составе четырёх сборников, которые, впрочем, не охватывают все сочинения автора в этом жанре литературы[5]. Исследователи отмечают, что литературные сказки Дюма несут отпечаток его оригинального стиля, и даже те из них, которые являются адаптациями известных сказок, «сохраняя основные сюжетные линии оригиналов, вполне могут, тем не менее, рассматриваться как самостоятельные произведения»[5].

Об истории создания литературной переработки сказки немецкого писателя-романтика Э. Т. А. Гофмана (b) «Щелкунчик и мышиный король (b) » Александр Дюма (b) подробно рассказывает в предисловии своей версии, названной им «История Щелкунчика». По словам французского писателя, однажды он вместе со своей дочерью Мари Александрин (b) присутствовал в гостях у «графа де М.», который устроил у себя дома большой детский праздник, где были дети в возрасте от восьми до десяти лет. От производимого ими шума у писателя разболелась голова, и он решил уединиться в одном из пустующих кабинетов, где, сев в вольтеровское кресло, минут через десять задремал[6]. Чуть позже он проснулся от детских криков и смеха и увидел, что привязан к креслу, как Гулливер (b) в стране Лилипутов (b) . Дюма решил откупиться от детей, пообещав сводить их в кондитерский магазин или устроить фейерверк (b) , но эти предложения были отвергнуты. Тогда его дочь предложила ему рассказать какую-нибудь «занятную сказку», на что Дюма возразил, что нет ничего сложнее, чем сочинить сказку. Но дети настаивали, и он согласился, предупредив их, что не он является автором истории, которую он им поведает. Дети охотно согласились, в связи с чем Дюма несколько обиделся: «Признаться, я был немного оскорблён тем, сколь мало настаивала моя аудитория на том, чтобы услышать моё собственное сочинение»[7]. Когда у него спросили, кто автор и как называется сказка, то писатель ответил, что сказочника зовут Гофман, а называется эта история «Щелкунчик из Нюрнберга». Анри, сын хозяев дома, в ответ сказал, что если сказка им не понравится, то писатель должен будет рассказать им другую сказку, до тех пор, пока их пленник не поведает им историю, которая их «позабавит», иначе его ждёт «пожизненное заключение»[8]. Дюма пообещал, что если его освободят, то он сделает всё, что дети пожелают. После этого дети дружно отвязали его от кресла, и он согласился рассказать сказочную историю, так как «надо держать слово, даже если даёшь его детям». После этого он пригласил своих юных слушателей усесться поудобнее, чтобы они «могли легко перейти от слушания сказки ко сну», и после этого стал рассказывать историю про Щелкунчика[8].

Сказка впервые была опубликована в 1844 году в «Новом журнале для детей» (фр. (b) Le Nouveau Magasin des enfants), а первое её отдельное издание вышло во Франции в 1845 году в издательстве Этцеля[9].

Художественные особенности