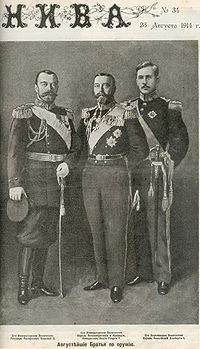

| Nicholas II | ||

|---|---|---|

Nicholas II in 1912 |

||

| Emperor of Russia | ||

| Reign | 1 November 1894[a] – 15 March 1917[b] | |

| Coronation | 26 May 1896[c] | |

| Predecessor | Alexander III | |

| Successor | Monarchy abolished | |

| Prime Minister | See list | |

| Born | 18 May [O.S. 6 May] 1868 Alexander Palace, Tsarskoye Selo, Russian Empire |

|

| Died | 17 July 1918 (aged 50) Ipatiev House, Yekaterinburg, Russian SFSR |

|

| Burial | 17 July 1998

Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation |

|

| Spouse |

Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse) (m. ; died ) |

|

| Issue |

|

|

|

||

| House | Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov | |

| Father | Alexander III of Russia | |

| Mother | Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark) | |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox | |

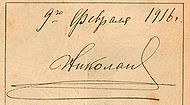

| Signature |  |

|

Saint Nicholas II of Russia |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Saint, Passion-Bearer, Tsar | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodoxy |

| Canonized |

|

| Major shrine | Church on Blood, Yekaterinburg, Russia |

| Feast | 17 July |

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov[d] (18 May [O.S. 6 May] 1868 – 17 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,[e] was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland and Grand Duke of Finland, ruling from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. During his reign, Nicholas gave support to the economic and political reforms promoted by his prime ministers, Sergei Witte and Pyotr Stolypin. He advocated modernization based on foreign loans and close ties with France, but resisted giving the new parliament (the Duma) major roles.[1][2] Ultimately, progress was undermined by Nicholas’s commitment to autocratic rule,[2][3] strong aristocratic opposition and defeats sustained by the Russian military in the Russo-Japanese War and World War I.[4][5][6] By March 1917, public support for Nicholas had collapsed and he was forced to abdicate the throne, thereby ending the Romanov dynasty’s 304-year rule of Russia (1613–1917).

Nicholas signed the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which was designed to counter Germany’s attempts to gain influence in the Middle East; it ended the Great Game of confrontation between Russia and the British Empire. He aimed to strengthen the Franco-Russian Alliance and proposed the unsuccessful Hague Convention of 1899 to promote disarmament and solve international disputes peacefully.[7] Domestically, he was criticised for his government’s repression of political opponents and his perceived fault or inaction during the Khodynka Tragedy, anti-Jewish pogroms, Bloody Sunday and the violent suppression of the 1905 Russian Revolution. His popularity was further damaged by the Russo-Japanese War, which saw the Russian Baltic Fleet annihilated at the Battle of Tsushima, together with the loss of Russian influence over Manchuria and Korea and the Japanese annexation of the south of Sakhalin Island.[8]

During the July Crisis, Nicholas supported Serbia and approved the mobilization of the Russian Army on 30 July 1914. In response, Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August 1914 and its ally France on 3 August 1914,[9] starting the Great War, later known as the First World War. The severe military losses led to a collapse of morale at the front and at home; a general strike and a mutiny of the garrison in Petrograd sparked the February Revolution and the disintegration of the monarchy’s authority. After abdicating for himself and his son, Nicholas and his family were imprisoned by the Russian Provisional Government and exiled to Siberia. After the Bolsheviks took power in the October Revolution, the family was held in Yekaterinburg, where they were executed on 17 July 1918.[5][6]

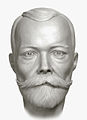

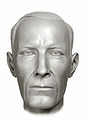

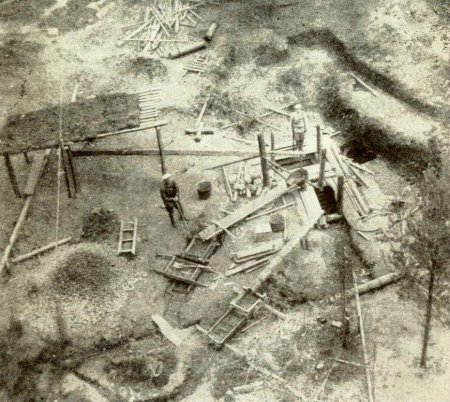

In 1981, Nicholas, his wife, and their children were recognized as martyrs by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, based in New York City.[10] Their gravesite was discovered in 1979, but this was not acknowledged until 1989. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the remains of the imperial family were exhumed, identified by DNA analysis, and re-interred with an elaborate state and church ceremony in St. Petersburg on 17 July 1998, exactly 80 years after their deaths. They were canonized in 2000 by the Russian Orthodox Church as passion bearers.[11] In the years following his death, Nicholas was reviled by Soviet historians and state propaganda as a «callous tyrant» who «persecuted his own people while sending countless soldiers to their deaths in pointless conflicts».[12] Despite being viewed more positively in recent years, the majority view among historians is that Nicholas was a well-intentioned yet poor ruler who proved incapable of handling the challenges facing his nation.[13][14][15][16]

Early life

Birth and family background

Nicholas II, unbreeched at two years old, with his mother, Maria Feodorovna, in 1870

Grand Duke Nicholas was born on 18 May [O.S. 6 May] 1868, in the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo south of Saint Petersburg, during the reign of his grandfather Emperor Alexander II. He was the eldest child of then-Tsesarevich Alexander Alexandrovich and his wife, Tsesarevna Maria Feodorovna (née Princess Dagmar of Denmark). Grand Duke Nicholas’ father was heir apparent to the Russian throne as the second but eldest surviving son of Emperor Alexander II of Russia. His paternal grandparents were Emperor Alexander II and Empress Maria Alexandrovna (née Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine). His maternal grandparents were King Christian IX and Queen Louise of Denmark.

The young grand duke was christened in the Chapel of the Resurrection of the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoye Selo on 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1868 by the confessor of the imperial family, protopresbyter Vasily Borisovich Bazhanov. His godparents were Emperor Alexander II (his paternal grandfather), Queen Louise of Denmark (his maternal grandmother), Crown Prince Frederick of Denmark (his maternal uncle), and Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (his great great-aunt).[17] The boy received the traditional Romanov name Nicholas and was named in memory of his father’s older brother and mother’s first fiancé, Tsesarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich of Russia, who had died young in 1865.[18] Informally, he was known as «Nikki» throughout his life.

Nicholas was of primarily German and Danish descent, his last ethnically Russian ancestor being Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna of Russia (1708–1728), daughter of Peter the Great. On the other hand, Nicholas was related to several monarchs in Europe. His mother’s siblings included Kings Frederick VIII of Denmark and George I of Greece, as well as the United Kingdom’s Queen Alexandra (consort of King Edward VII). Nicholas, his wife Alexandra, and German emperor Wilhelm II were all first cousins of King George V of the United Kingdom. Nicholas was also a first cousin of both King Haakon VII and Queen Maud of Norway, as well as King Christian X of Denmark and King Constantine I of Greece. Nicholas and Wilhelm II were in turn second cousins once-removed, as each descended from King Frederick William III of Prussia, as well as third cousins, as they were both great-great-grandsons of Tsar Paul I of Russia. In addition to being second cousins through descent from Louis II, Grand Duke of Hesse and his wife Princess Wilhelmine of Baden, Nicholas and Alexandra were also third cousins once-removed, as they were both descendants of King Frederick William II of Prussia.

Tsar Nicholas II was the first cousin once-removed of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich. To distinguish between them, the Grand Duke was often known within the imperial family as «Nikolasha» and «Nicholas the Tall», while the Tsar was «Nicholas the Short».

Childhood

Grand Duke Nicholas was to have five younger siblings: Alexander (1869–1870), George (1871–1899), Xenia (1875–1960), Michael (1878–1918) and Olga (1882–1960). Nicholas often referred to his father nostalgically in letters after Alexander’s death in 1894. He was also very close to his mother, as revealed in their published letters to each other.[19]

In his childhood, Nicholas, his parents and siblings made annual visits to the Danish royal palaces of Fredensborg and Bernstorff to visit his grandparents, the king and queen. The visits also served as family reunions, as his mother’s siblings would also come from the United Kingdom, Germany and Greece with their respective families.[20] It was there in 1883, that he had a flirtation with one of his British first cousins, Princess Victoria. In 1873, Nicholas also accompanied his parents and younger brother, two-year-old George, on a two-month, semi-official visit to the United Kingdom.[21] In London, Nicholas and his family stayed at Marlborough House, as guests of his «Uncle Bertie» and «Aunt Alix», the Prince and Princess of Wales, where he was spoiled by his uncle.[22]

Tsesarevich

On 1 March 1881,[23] following the assassination of his grandfather, Tsar Alexander II, Nicholas became heir apparent upon his father’s accession as Alexander III. Nicholas and his other family members bore witness to Alexander II’s death, having been present at the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg, where he was brought after the attack.[24] For security reasons, the new Tsar and his family relocated their primary residence to the Gatchina Palace outside the city, only entering the capital for various ceremonial functions. On such occasions, Alexander III and his family occupied the nearby Anichkov Palace.

In 1884, Nicholas’s coming-of-age ceremony was held at the Winter Palace, where he pledged his loyalty to his father. Later that year, Nicholas’s uncle, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, married Princess Elizabeth, daughter of Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and his late wife Princess Alice of the United Kingdom (who had died in 1878), and a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. At the wedding in St. Petersburg, the sixteen-year-old Tsesarevich met with and admired the bride’s youngest surviving sister, twelve-year-old Princess Alix. Those feelings of admiration blossomed into love following her visit to St. Petersburg five years later in 1889. Alix had feelings for him in turn. As a devout Lutheran, she was initially reluctant to convert to Russian Orthodoxy to marry Nicholas, but later relented.[25]

In 1890 Nicholas, his younger brother George, and their cousin Prince George of Greece, set out on a world tour, although Grand Duke George fell ill and was sent home partway through the trip. Nicholas visited Egypt, India, Singapore, and Siam (Thailand), receiving honors as a distinguished guest in each country. During his trip through Japan, Nicholas had a large dragon tattooed on his right forearm by Japanese tattoo artist Hori Chyo.[26] His cousin George V of the United Kingdom had also received a dragon tattoo from Hori in Yokohama years before. It was during his visit to Otsu, that Tsuda Sanzō, one of his escorting policemen, swung at the Tsesarevich’s face with a sabre, an event known as the Ōtsu incident. Nicholas was left with a 9 centimeter long scar on the right side of his forehead, but his wound was not life-threatening. The incident cut his trip short.[27] Returning overland to St. Petersburg, he was present at the ceremonies in Vladivostok commemorating the beginning of work on the Trans-Siberian Railway. In 1893, Nicholas traveled to London on behalf of his parents to be present at the wedding of his cousin the Duke of York to Princess Mary of Teck. Queen Victoria was struck by the physical resemblance between the two cousins, and their appearances confused some at the wedding. During this time, Nicholas had an affair with St. Petersburg ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska.[28]

Though Nicholas was heir-apparent to the throne, his father failed to prepare him for his future role as Tsar. He attended meetings of the State Council; however, as his father was only in his forties, it was expected that it would be many years before Nicholas succeeded to the throne.[29] Sergei Witte, Russia’s finance minister, saw things differently and suggested to the Tsar that Nicholas be appointed to the Siberian Railway Committee.[30] Alexander argued that Nicholas was not mature enough to take on serious responsibilities, having once stated «Nikki is a good boy, but he has a poet’s soul…God help him!» Witte stated that if Nicholas was not introduced to state affairs, he would never be ready to understand them.[30] Alexander’s assumptions that he would live a long life and had years to prepare Nicholas for becoming Tsar proved wrong, as by 1894, Alexander’s health was failing.[31]

Engagement and marriage

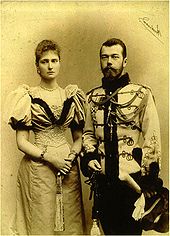

Official engagement photograph of Nicholas II and Alexandra, April 1894

In April 1894, Nicholas joined his Uncle Sergei and Aunt Elizabeth on a journey to Coburg, Germany, for the wedding of Elizabeth’s and Alix’s brother, Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse, to their mutual first cousin Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Other guests included Queen Victoria, Kaiser Wilhelm II, the Empress Frederick (Kaiser Wilhelm’s mother and Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter), Nicholas’s uncle, the Prince of Wales, and the bride’s parents, the Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Once in Coburg Nicholas proposed to Alix, but she rejected his proposal, being reluctant to convert to Orthodoxy. But the Kaiser later informed her she had a duty to marry Nicholas and to convert, as her sister Elizabeth had done in 1892. Thus once she changed her mind, Nicholas and Alix became officially engaged on 20 April 1894. Nicholas’s parents initially hesitated to give the engagement their blessing, as Alix had made poor impressions during her visits to Russia. They gave their consent only when they saw Tsar Alexander’s health deteriorating.

That summer, Nicholas travelled to England to visit both Alix and the Queen. The visit coincided with the birth of the Duke and Duchess of York’s first child, the future King Edward VIII. Along with being present at the christening, Nicholas and Alix were listed among the child’s godparents.[32] After several weeks in England, Nicholas returned home for the wedding of his sister, Xenia, to a cousin, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich («Sandro»).[33]

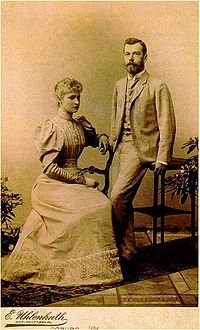

Nicholas II and family in 1904

By that autumn, Alexander III lay dying. Upon learning that he would live only a fortnight, the Tsar had Nicholas summon Alix to the imperial palace at Livadia.[34] Alix arrived on 22 October; the Tsar insisted on receiving her in full uniform. From his deathbed, he told his son to heed the advice of Witte, his most capable minister. Ten days later, Alexander III died at the age of forty-nine, leaving twenty-six-year-old Nicholas as Emperor of Russia. That evening, Nicholas was consecrated by his father’s priest as Tsar Nicholas II and, the following day, Alix was received into the Russian Orthodox Church, taking the name Alexandra Feodorovna with the title of Grand Duchess and the style of Imperial Highness.[35]

Nicholas may have felt unprepared for the duties of the crown, for he asked his cousin and brother-in-law, Grand Duke Alexander,[36] «What is going to happen to me and all of Russia?»[37] Though perhaps under-prepared and unskilled, Nicholas was not altogether untrained for his duties as Tsar. Nicholas chose to maintain the conservative policies favoured by his father throughout his reign. While Alexander III had concentrated on the formulation of general policy, Nicholas devoted much more attention to the details of administration.[38]

Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra with their first child, Grand Duchess Olga, 1896

Leaving Livadia on 7 November, Tsar Alexander’s funeral procession—which included Nicholas’s maternal aunt through marriage and paternal first cousin once removed Queen Olga of Greece, and the Prince and Princess of Wales—arrived in Moscow. After lying in state in the Kremlin, the body of the Tsar was taken to St. Petersburg, where the funeral was held on 19 November.[39]

Nicholas and Alix’s wedding was originally scheduled for the spring of 1895, but it was moved forward at Nicholas’s insistence. Staggering under the weight of his new office, he had no intention of allowing the one person who gave him confidence to leave his side.[40] Instead, Nicholas’s wedding to Alix took place on 26 November 1894, which was the birthday of the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, and court mourning could be slightly relaxed. Alexandra wore the traditional dress of Romanov brides, and Nicholas a hussar’s uniform. Nicholas and Alexandra, each holding a lit candle, faced the palace priest and were married a few minutes before one in the afternoon.[41]

Nicholas (left) and his family on a boat trip in the Finnish archipelago in 1909

Accession and reign

Coronation

Despite a visit to the United Kingdom in 1893, where he observed the House of Commons in debate and was seemingly impressed by the machinery of constitutional monarchy, Nicholas turned his back on any notion of giving away any power to elected representatives in Russia. Shortly after he came to the throne, a deputation of peasants and workers from various towns’ local assemblies (zemstvos) came to the Winter Palace proposing court reforms, such as the adoption of a constitutional monarchy,[42] and reform that would improve the political and economic life of the peasantry, in the Tver Address.[43][44]

Although the addresses they had sent in beforehand were couched in mild and loyal terms, Nicholas was angry and ignored advice from an Imperial Family Council by saying to them:

… it has come to my knowledge that during the last months there have been heard in some assemblies of the zemstvos the voices of those who have indulged in a senseless dream that the zemstvos be called upon to participate in the government of the country. I want everyone to know that I will devote all my strength to maintain, for the good of the whole nation, the principle of absolute autocracy, as firmly and as strongly as did my late lamented father.[45]

On 26 May 1896, Nicholas’s formal coronation as Tsar was held in Uspensky Cathedral located within the Kremlin.[46]

Nicholas as Tsesarevich in 1892

In a celebration on 27 May 1896, a large festival with food, free beer and souvenir cups was held in Khodynka Field outside Moscow. Khodynka was chosen as the location as it was the only place near Moscow large enough to hold all of the Moscow citizens.[47] Khodynka was primarily used as a military training ground and the field was uneven with trenches. Before the food and drink was handed out, rumours spread that there would not be enough for everyone. As a result, the crowd rushed to get their share and individuals were tripped and trampled upon, suffocating in the dirt of the field.[48] Of the approximate 100,000 in attendance, it is estimated that 1,389 individuals died[46] and roughly 1,300 were injured.[47] The Khodynka Tragedy was seen as an ill omen and Nicholas found gaining popular trust difficult from the beginning of his reign. The French ambassador’s gala was planned for that night. The Tsar wanted to stay in his chambers and pray for the lives lost, but his uncles believed that his absence at the ball would strain relations with France, particularly the 1894 Franco-Russian Alliance. Thus Nicholas attended the party; as a result the mourning populace saw Nicholas as frivolous and uncaring.

During the autumn after the coronation, Nicholas and Alexandra made a tour of Europe. After making visits to the emperor and empress of Austria-Hungary, the Kaiser of Germany, and Nicholas’s Danish grandparents and relatives, Nicholas and Alexandra took possession of their new yacht, the Standart, which had been built in Denmark.[49] From there, they made a journey to Scotland to spend some time with Queen Victoria at Balmoral Castle. While Alexandra enjoyed her reunion with her grandmother, Nicholas complained in a letter to his mother about being forced to go shooting with his uncle, the Prince of Wales, in bad weather, and was suffering from a bad toothache.[50]

The first years of his reign saw little more than continuation and development of the policy pursued by Alexander III. Nicholas allotted money for the All-Russia exhibition of 1896. In 1897 restoration of gold standard by Sergei Witte, Minister of Finance, completed the series of financial reforms, initiated fifteen years earlier. By 1902 the Trans-Siberian Railway was nearing completion; this helped the Russians trade in the Far East but the railway still required huge amounts of work.

Ecclesiastical affairs

Nicholas always believed God chose him to be the tsar and therefore the decisions of the tsar reflected the will of God and could not be disputed. He was convinced that the simple people of Russia understood this and loved him, as demonstrated by the display of affection he perceived when he made public appearances. His old-fashioned belief made for a very stubborn ruler who rejected constitutional limitations on his power. It put the tsar at variance with the emerging political consensus among the Russian elite. It was further belied by the subordinate position of the Church in the bureaucracy. The result was a new distrust between the tsar and the church hierarchy and between those hierarchs and the people. Thereby the tsar’s base of support was conflicted.[51]

In 1903, Nicholas threw himself into an ecclesiastical crisis regarding the canonisation of Seraphim of Sarov. The previous year, it had been suggested that if he were canonised, the imperial couple would beget a son and heir to throne. While Alexandra demanded in July 1902 that Seraphim be canonised in less than a week, Nicholas demanded that he be canonised within a year. Despite a public outcry, the Church bowed to the intense imperial pressure, declaring Seraphim worthy of canonisation in January 1903. That summer, the imperial family travelled to Sarov for the canonisation.[52]

Initiatives in foreign affairs

According to his biographer:

- His tolerance if not preference for charlatans and adventurers extended to grave matters of external policy, and his vacillating conduct and erratic decisions aroused misgivings and occasional alarm among his more conventional advisers. The foreign ministry itself was not a bastion of diplomatic expertise. Patronage and «connections» were the keys to appointment and promotion.[53]

Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary paid a state visit in April 1897 that was a success. It produced a «gentlemen’s agreement» to keep the status quo in the Balkans, and a somewhat similar commitment became applicable to Constantinople and the Straits. The result was years of peace that allowed for rapid economic growth.[54]

Nicholas followed the policies of his father, strengthening the Franco-Russian Alliance and pursuing a policy of general European pacification, which culminated in the famous Hague peace conference. This conference, suggested and promoted by Nicholas II, was convened with the view of terminating the arms race, and setting up machinery for the peaceful settlement of international disputes. The results of the conference were less than expected due to the mutual distrust existing between great powers. Nevertheless, the Hague conventions were among the first formal statements of the laws of war.[55][56] Nicholas II became the hero of the dedicated disciples of peace. In 1901 he and the Russian diplomat Friedrich Martens were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for the initiative to convene the Hague Peace Conference and contributing to its implementation.[57] However historian Dan L. Morrill states that «most scholars» agree that the invitation was «conceived in fear, brought forth in deceit, and swaddled in humanitarian ideals…Not from humanitarianism, not from love for mankind.»[58]

Russo-Japanese War

A clash between Russia and the Empire of Japan was almost inevitable by the turn of the 20th century. Russia had expanded in the Far East, and the growth of its settlement and territorial ambitions, as its southward path to the Balkans was frustrated, conflicted with Japan’s own territorial ambitions on the Asian mainland. Nicholas pursued an aggressive foreign policy with regards to Manchuria and Korea, and strongly supported the scheme for timber concessions in these areas as developed by the Bezobrazov group.[59][60]

Before the war in 1901, Nicholas told Prince Henry of Prussia «I do not want to seize Korea but under no circumstances can I allow Japan to become firmly established there. That will be a casus belli.»[61]

War began in February 1904 with a preemptive Japanese attack on the Russian fleet in Port Arthur, prior to a formal declaration of war.[59]

With the Russian Far East fleet trapped at Port Arthur, the only other Russian Fleet was the Baltic Fleet; it was half a world away, but the decision was made to send the fleet on a nine-month voyage to the East. The United Kingdom would not allow the Russian navy to use the Suez Canal, due to its alliance with the Empire of Japan, and due to the Dogger Bank incident where the Baltic Fleet mistakenly fired on British fishing boats in the North Sea. The Baltic Fleet traversed the world to lift the blockade on Port Arthur, but after many misadventures on the way, was nearly annihilated by the Japanese in the Battle of the Tsushima Strait.[59] On land the Imperial Russian Army experienced logistical problems. While commands and supplies came from St. Petersburg, combat took place in east Asian ports with only the Trans-Siberian Railway for transport of supplies as well as troops both ways.[59] The 9,200-kilometre (5,700 mi) rail line between St. Petersburg and Port Arthur was single-track, with no track around Lake Baikal, allowing only gradual build-up of the forces on the front. Besieged Port Arthur fell to the Japanese, after nine months of resistance.[59]

As Russia faced imminent defeat by the Japanese, the call for peace grew. Nicholas’s mother, as well as his cousin Emperor Wilhelm II, urged Nicholas to negotiate for peace. Despite the efforts, Nicholas remained evasive, sending a telegram to the Kaiser on 10 October that it was his intent to keep on fighting until the Japanese were driven from Manchuria.[59] It was not until 27–28 May 1905 and the annihilation of the Russian fleet by the Japanese, that Nicholas finally decided to sue for peace.[62] Nicholas II accepted American mediation, appointing Sergei Witte chief plenipotentiary for the peace talks. The war was ended by the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth.[59]

Tsar’s confidence in victory

Nicholas’s stance on the war was so at variance with the obvious facts that many observers were baffled. He saw the war as an easy God-given victory that would raise Russian morale and patriotism. He ignored the financial repercussions of a long-distance war.[63] Rotem Kowner argues that during his visit to Japan in 1891, where Nicholas was attacked by a Japanese policeman, he regarded the Japanese as small of stature, feminine, weak, and inferior. He ignored reports of the prowess of Japanese soldiers in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) and reports on the capabilities of the Japanese fleet, as well as negative reports on the lack of readiness of Russian forces.[27]

Before the Japanese attack on Port Arthur, Nicholas held firm to the belief that there would be no war. Despite the onset of the war and the many defeats Russia suffered, Nicholas still believed in, and expected, a final victory, maintaining an image of the racial inferiority and military weakness of the Japanese.[64] Throughout the war, the tsar demonstrated total confidence in Russia’s ultimate triumph. His advisors never gave him a clear picture of Russia’s weaknesses. Despite the continuous military disasters Nicholas believed victory was near at hand. Losing his navy at Tsushima finally persuaded him to agree to peace negotiations. Even then he insisted on the option of reopening hostilities if peace conditions were unfavorable. He forbade his chief negotiator Count Witte to agree to either indemnity payments or loss of territory. Nicholas remained adamantly opposed to any concessions. Peace was made, but Witte did so by disobeying the tsar and ceding southern Sakhalin to Japan.[60][better source needed]

Anti-Jewish pogroms of 1903–1906

The Kishinev newspaper Bessarabets, which published anti-Semitic materials, received funds from Viacheslav Plehve, Minister of the Interior.[65] These publications served to fuel the Kishinev pogrom (rioting). The government of Nicholas II formally condemned the rioting and dismissed the regional governor, with the perpetrators arrested and punished by the court.[66] Leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church also condemned anti-Semitic pogroms. Appeals to the faithful condemning the pogroms were read publicly in all churches of Russia.[67] In private Nicholas expressed his admiration for the mobs, viewing anti-Semitism as a useful tool for unifying the people behind the government;[68] however in 1911, following the assassination of Pyotr Stolypin by the Jewish revolutionary Dmitry Bogrov, he approved of government efforts to prevent anti-Semitic pogroms.[69]

Bloody Sunday (1905)

A few days prior to Bloody Sunday (9 (22) January 1905), priest and labor leader Georgy Gapon informed the government of the forthcoming procession to the Winter Palace to hand a workers’ petition to the Tsar. On Saturday, 8 (21) January, the ministers convened to consider the situation. There was never any thought that the Tsar, who had left the capital for Tsarskoye Selo on the advice of the ministers, would actually meet Gapon; the suggestion that some other member of the imperial family receive the petition was rejected.[70]

Finally informed by the Prefect of Police that he lacked the men to pluck Gapon from among his followers and place him under arrest, the newly appointed Minister of the Interior, Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky, and his colleagues decided to bring additional troops to reinforce the city. That evening Nicholas wrote in his diary, «Troops have been brought from the outskirts to reinforce the garrison. Up to now the workers have been calm. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of their union is a kind of socialist priest named Gapon. Mirsky came this evening to present his report on the measures taken.»[70]

On Sunday, 9 (22) January 1905, Gapon began his march. Locking arms, the workers marched peacefully through the streets. Some carried religious icons and banners, as well as national flags and portraits of the Tsar. As they walked, they sang hymns and God Save The Tsar. At 2 pm all of the converging processions were scheduled to arrive at the Winter Palace. There was no single confrontation with the troops. Throughout the city, at bridges on strategic boulevards, the marchers found their way blocked by lines of infantry, backed by Cossacks and Hussars; and the soldiers opened fire on the crowd.[71]

The official number of victims was 92 dead and several hundred wounded. Gapon vanished and the other leaders of the march were seized. Expelled from the capital, they circulated through the empire, increasing the casualties. As bullets riddled their icons, their banners and their portraits of Nicholas, the people shrieked, «The Tsar will not help us!»[71] Outside Russia, the future British Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald attacked the Tsar, calling him a «blood-stained creature and a common murderer».[72]

That evening Nicholas wrote in his diary:

Difficult day! In St. Petersburg there were serious disturbances due to the desire of workers to get to the Winter Palace. The troops had to shoot in different places of the city, there were many dead and wounded. Lord, how painful and bad![72][73]

His younger sister, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, wrote afterwards:

Nicky had the police report a few days before. That Saturday he telephoned my mother at the Anitchkov and said that she and I were to leave for Gatchina at once. He and Alicky went to Tsarskoye Selo. Insofar as I remember, my Uncles Vladimir and Nicholas were the only members of the family left in St. Petersburg, but there may have been others. I felt at the time that all those arrangements were hideously wrong. Nicky’s ministers and the Chief of Police had it all their way. My mother and I wanted him to stay in St. Petersburg and to face the crowd. I am positive that, for all the ugly mood of some of the workmen, Nicky’s appearance would have calmed them. They would have presented their petition and gone back to their homes. But that wretched Epiphany incident had left all the senior officials in a state of panic. They kept on telling Nicky that he had no right to run such a risk, that he owed it to the country to leave the capital, that even with the utmost precautions taken there might always be some loophole left. My mother and I did all we could to persuade him that the ministers’ advice was wrong, but Nicky preferred to follow it and he was the first to repent when he heard of the tragic outcome.[74]

From his hiding place Gapon issued a letter, stating «Nicholas Romanov, formerly Tsar and at present soul-murderer of the Russian empire. The innocent blood of workers, their wives and children lies forever between you and the Russian people … May all the blood which must be spilled fall upon you, you Hangman. I call upon all the socialist parties of Russia to come to an immediate agreement among themselves and bring an armed uprising against Tsarism.»[72]

1905 Revolution

Confronted with growing opposition and after consulting with Witte and Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky, the Tsar issued a reform ukase on 25 December 1904 with vague promises.[75]

In hopes of cutting the rebellion short, many demonstrators were shot on Bloody Sunday (1905) as they tried to march to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov was ordered to take drastic measures to stop the revolutionary activity. Grand Duke Sergei was killed in February by a revolutionary’s bomb in Moscow as he left the Kremlin. On 3 March the Tsar condemned the revolutionaries. Meanwhile, Witte recommended that a manifesto be issued.[76] Schemes of reform would be elaborated by Goremykin and a committee consisting of elected representatives of the zemstvos and municipal councils under the presidency of Witte. In June the battleship Potemkin, part of the Black Sea Fleet, mutinied.

Around August/September, after his diplomatic success on ending the Russo-Japanese War, Witte wrote to the Tsar stressing the urgent need for political reforms at home. The Tsar remained quite impassive and indulgent; he spent most of that autumn hunting.[77] With the defeat of Russia by a non-Western power, the prestige and authority of the autocratic regime fell significantly.[78] Tsar Nicholas II, taken by surprise by the events, reacted with anger and bewilderment. He wrote to his mother after months of disorder:

It makes me sick to read the news! Nothing but strikes in schools and factories, murdered policemen, Cossacks and soldiers, riots, disorder, mutinies. But the ministers, instead of acting with quick decision, only assemble in council like a lot of frightened hens and cackle about providing united ministerial action… ominous quiet days began, quiet indeed because there was complete order in the streets, but at the same time everybody knew that something was going to happen — the troops were waiting for the signal, but the other side would not begin. One had the same feeling, as before a thunderstorm in summer! Everybody was on edge and extremely nervous and of course, that sort of strain could not go on for long…. We are in the midst of a revolution with an administrative apparatus entirely disorganized, and in this lies the main danger.[79]

In October a railway strike developed into a general strike which paralysed the country. In a city without electricity, Witte told Nicholas II «that the country was at the verge of a cataclysmic revolution».[80] The Tsar accepted the draft, hurriedly outlined by Aleksei D. Obolensky.[81][82] The Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias was forced to sign the October Manifesto agreeing to the establishment of the Imperial Duma, and to give up part of his unlimited autocracy. The freedom of religion clause outraged the Church because it allowed people to switch to evangelical Protestantism, which they denounced as heresy.[83]

For the next six months, Witte was the Prime Minister. According to Harold Williams: «That government was almost paralyzed from the beginning.» On 26 October (O.S.) the Tsar appointed Trepov Master of the Palace (without consulting Witte), and had daily contact with the Emperor; his influence at court was paramount. On 1 November 1905 (O.S.), Princess Milica of Montenegro presented Grigori Rasputin to Tsar Nicholas and his wife (who by then had a hemophiliac son) at Peterhof Palace.[84]

Relationship with the Duma

Silver coin: 1 ruble Nikolai II_Romanov Dynasty – 1913 – On the obverse of the coin features two rulers: left Emperor Nikolas II in military uniform of the life guards of the 4th infantry regiment of the Imperial family, right Michael I in Royal robes and Monomakh’s Cap. Portraits made in a circular frame around of a Greek ornament.

Nicholas II’s opening speech before the two chambers of the State Duma in the Winter Palace, 1906.

One ruble silver coin of Nicholas II, dated 1898, with the Imperial coat-of-arms on the reverse. The Russian inscription reads:

B[ozheyu] M[ilostyu] Nikolay Imperator i Samoderzhets Vse[ya] Ross[ii].[iyskiy].

The English translation is, «By the grace of God, Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias.»

Under pressure from the attempted 1905 Russian Revolution, on 5 August of that year Nicholas II issued a manifesto about the convocation of the State Duma, known as the Bulygin Duma, initially thought to be an advisory organ. In the October Manifesto, the Tsar pledged to introduce basic civil liberties, provide for broad participation in the State Duma, and endow the Duma with legislative and oversight powers. He was determined, however, to preserve his autocracy even in the context of reform. This was signalled in the text of the 1906 constitution. He was described as the supreme autocrat, and retained sweeping executive powers, also in church affairs. His cabinet ministers were not allowed to interfere with nor assist one another; they were responsible only to him.

Nicholas’s relations with the Duma were poor. The First Duma, with a majority of Kadets, almost immediately came into conflict with him. Scarcely had the 524 members sat down at the Tauride Palace when they formulated an ‘Address to the Throne’. It demanded universal suffrage, radical land reform, the release of all political prisoners and the dismissal of ministers appointed by the Tsar in favour of ministers acceptable to the Duma.[85] Grand Duchess Olga, Nicholas’s sister, later wrote:

There was such gloom at Tsarskoye Selo. I did not understand anything about politics. I just felt everything was going wrong with the country and all of us. The October Constitution did not seem to satisfy anyone. I went with my mother to the first Duma. I remember the large group of deputies from among peasants and factory people. The peasants looked sullen. But the workmen were worse: they looked as though they hated us. I remember the distress in Alicky’s eyes.[74]

Minister of the Court Count Vladimir Frederiks commented, «The Deputies, they give one the impression of a gang of criminals who are only waiting for the signal to throw themselves upon the ministers and cut their throats. I will never again set foot among those people.»[86] The Dowager Empress noticed «incomprehensible hatred.»[86]

Although Nicholas initially had a good relationship with his prime minister, Sergei Witte, Alexandra distrusted him as he had instigated an investigation of Grigori Rasputin and, as the political situation deteriorated, Nicholas dissolved the Duma. The Duma was populated with radicals, many of whom wished to push through legislation that would abolish private property ownership, among other things. Witte, unable to grasp the seemingly insurmountable problems of reforming Russia and the monarchy, wrote to Nicholas on 14 April 1906 resigning his office (however, other accounts have said that Witte was forced to resign by the Emperor). Nicholas was not ungracious to Witte and an Imperial Rescript was published on 22 April creating Witte a Knight of the Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky with diamonds (the last two words were written in the Emperor’s own hand, followed by «I remain unalterably well-disposed to you and sincerely grateful, for ever more Nicholas.»).

A second Duma met for the first time in February 1907. The leftist parties—including the Social Democrats and the Social Revolutionaries, who had boycotted the First Duma—had won 200 seats in the Second, more than a third of the membership. Again Nicholas waited impatiently to rid himself of the Duma. In two letters to his mother he let his bitterness flow:

A grotesque deputation is coming from England to see liberal members of the Duma. Uncle Bertie informed us that they were very sorry but were unable to take action to stop their coming. Their famous «liberty», of course. How angry they would be if a deputation went from us to the Irish to wish them success in their struggle against their government.[87]

A little while later he further wrote:

All would be well if everything said in the Duma remained within its walls. Every word spoken, however, comes out in the next day’s papers which are avidly read by everyone. In many places the populace is getting restive again. They begin to talk about land once more and are waiting to see what the Duma is going to say on the question. I am getting telegrams from everywhere, petitioning me to order a dissolution, but it is too early for that. One has to let them do something manifestly stupid or mean and then — slap! And they are gone![88]

Nicholas II, Stolypin and the Jewish delegation during the Tsar’s visit to Kiev in 1911

After the Second Duma resulted in similar problems, the new prime minister Pyotr Stolypin (whom Witte described as «reactionary») unilaterally dissolved it, and changed the electoral laws to allow for future Dumas to have a more conservative content, and to be dominated by the liberal-conservative Octobrist Party of Alexander Guchkov. Stolypin, a skilful politician, had ambitious plans for reform. These included making loans available to the lower classes to enable them to buy land, with the intent of forming a farming class loyal to the crown. Nevertheless, when the Duma remained hostile, Stolypin had no qualms about invoking Article 87 of the Fundamental Laws, which empowered the Tsar to issue ‘urgent and extraordinary’ emergency decrees ‘during the recess of the State Duma’. Stolypin’s most famous legislative act, the change in peasant land tenure, was promulgated under Article 87.[88]

The third Duma remained an independent body. This time the members proceeded cautiously. Instead of hurling themselves at the government, opposing parties within the Duma worked to develop the body as a whole. In the classic manner of the British Parliament, the Duma reached for power grasping for the national purse strings. The Duma had the right to question ministers behind closed doors as to their proposed expenditures. These sessions, endorsed by Stolypin, were educational for both sides, and, in time, mutual antagonism was replaced by mutual respect. Even the sensitive area of military expenditure, where the October Manifesto clearly had reserved decisions to the throne, a Duma commission began to operate. Composed of aggressive patriots no less anxious than Nicholas to restore the fallen honour of Russian arms, the Duma commission frequently recommended expenditures even larger than those proposed.

With the passage of time, Nicholas also began to have confidence in the Duma. «This Duma cannot be reproached with an attempt to seize power and there is no need at all to quarrel with it,» he said to Stolypin in 1909.[89] Nevertheless, Stolypin’s plans were undercut by conservatives at court. Although the tsar at first supported him, he finally sided with the arch critics.[90] Reactionaries such as Prince Vladimir Nikolayevich Orlov never tired of telling the tsar that the very existence of the Duma was a blot on the autocracy. Stolypin, they whispered, was a traitor and secret revolutionary who was conniving with the Duma to steal the prerogatives assigned the Tsar by God. Witte also engaged in constant intrigue against Stolypin. Although Stolypin had had nothing to do with Witte’s fall, Witte blamed him. Stolypin had unwittingly angered the Tsaritsa. He had ordered an investigation into Rasputin and presented it to the Tsar, who read it but did nothing. Stolypin, on his own authority, ordered Rasputin to leave St. Petersburg. Alexandra protested vehemently but Nicholas refused to overrule his Prime Minister,[91] who had more influence with the Emperor.

By the time of Stolypin’s assassination in September 1911, Stolypin had grown weary of the burdens of office. For a man who preferred clear decisive action, working with a sovereign who believed in fatalism and mysticism was frustrating. As an example, Nicholas once returned a document unsigned with the note:

Despite most convincing arguments in favour of adopting a positive decision in this matter, an inner voice keeps on insisting more and more that I do not accept responsibility for it. So far my conscience has not deceived me. Therefore I intend in this case to follow its dictates. I know that you, too, believe that «a Tsar’s heart is in God’s hands.» Let it be so. For all laws established by me I bear a great responsibility before God, and I am ready to answer for my decision at any time.[91]

Alexandra, believing that Stolypin had severed the bonds that her son depended on for life, hated the Prime Minister.[91] In March 1911, in a fit of anger stating that he no longer commanded the imperial confidence, Stolypin asked to be relieved of his office. Two years earlier when Stolypin had casually mentioned resigning to Nicholas he was informed: «This is not a question of confidence or lack of it. It is my will. Remember that we live in Russia, not abroad…and therefore I shall not consider the possibility of any resignation.»[92] He was assassinated in September 1911.

In 1912, a fourth Duma was elected with almost the same membership as the third. «The Duma started too fast. Now it is slower, but better, and more lasting,» stated Nicholas to Sir Bernard Pares.[89]

The First World War developed badly for Russia. By late 1916, Romanov family desperation reached the point that Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich, younger brother of Alexander III and the Tsar’s only surviving uncle, was deputed to beg Nicholas to grant a constitution and a government responsible to the Duma. Nicholas sternly and adamantly refused, reproaching his uncle for asking him to break his coronation oath to maintain autocratic power for his successors. In the Duma on 2 December 1916, Vladimir Purishkevich, a fervent patriot, monarchist and war worker, denounced the dark forces which surrounded the throne in a thunderous two-hour speech which was tumultuously applauded. «Revolution threatens,» he warned, «and an obscure peasant shall govern Russia no longer!»[93]

Tsarevich Alexei’s illness and Rasputin

Further complicating domestic matters was the matter of the succession. Alexandra bore Nicholas four daughters, the Grand Duchess Olga in 1895, the Grand Duchess Tatiana in 1897, Grand Duchess Maria in 1899, and Grand Duchess Anastasia in 1901, before their son Alexei was born on 12 August 1904. The young heir was afflicted with Hemophilia B, a hereditary disease that prevents blood from clotting properly, which at that time was untreatable and usually led to an untimely death. As a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, Alexandra carried the same gene mutation that afflicted several of the major European royal houses, such as Prussia and Spain. Hemophilia, therefore, became known as «the royal disease». Through Alexandra, the disease had passed on to her son. As all of Nicholas and Alexandra’s daughters were assassinated with their parents and brother in Yekaterinburg in 1918, it is not known whether any of them inherited the gene as carriers.

Before Rasputin’s arrival, the tsarina and the tsar had consulted numerous mystics, charlatans, «holy fools», and miracle workers. The royal behavior was not some odd aberration, but a deliberate retreat from the secular social and economic forces of his time – an act of faith and vote of confidence in a spiritual past. They had set themselves up for the greatest spiritual advisor and manipulator in Russian history.[94]

Because of the fragility of the autocracy at this time, Nicholas and Alexandra chose to keep secret Alexei’s condition. Even within the household, many were unaware of the exact nature of the Tsarevich’s illness. At first Alexandra turned to Russian doctors and medics to treat Alexei; however, their treatments generally failed, and Alexandra increasingly turned to mystics and holy men (or starets as they were called in Russian). One of these starets, an illiterate Siberian named Grigori Rasputin, gained amazing success. Rasputin’s influence over Empress Alexandra, and consequently the Tsar himself, grew even stronger after 1912 when the Tsarevich nearly died from an injury. His bleeding grew steadily worse as doctors despaired, and priests administered the Last Sacrament. In desperation, Alexandra called upon Rasputin, to which he replied, «God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much.»[95] The hemorrhage stopped the very next day and the boy began to recover. Alexandra took this as a sign that Rasputin was a starets and that God was with him; for the rest of her life she would fervently defend him and turn her wrath against anyone who dared to question him.

European affairs

Nicholas II and his son Alexei aboard the Imperial yacht Standart, during King Edward VII’s state visit to Russia in Reval, 1908

In 1907, to end longstanding controversies over central Asia, Russia and the United Kingdom signed the Anglo-Russian Convention that resolved most of the problems generated for decades by The Great Game.[96] The UK had already entered into the Entente cordiale with France in 1904, and the Anglo-Russian convention led to the formation of the Triple Entente. The following year, in May 1908, Nicholas and Alexandra’s shared «Uncle Bertie» and «Aunt Alix», Britain’s King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, made a state visit to Russia, being the first reigning British monarchs to do so. However, they did not set foot on Russian soil. Instead, they stayed aboard their yachts, meeting off the coast of modern-day Tallinn. Later that year, Nicholas was taken off guard by the news that his foreign minister, Alexander Izvolsky, had entered into a secret agreement with the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister, Count Alois von Aehrenthal, agreeing that, in exchange for Russian naval access to the Dardanelles and the Bosporus Strait, Russia would not oppose the Austrian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a revision of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. When Austria-Hungary did annex this territory that October, it precipitated the diplomatic crisis. When Russia protested about the annexation, the Austrians threatened to leak secret communications between Izvolsky and Aehernthal, prompting Nicholas to complain in a letter to the Austrian emperor, Franz Joseph, about a breach of confidence. In 1909, in the wake of the Anglo-Russian convention, the Russian imperial family made a visit to England, staying on the Isle of Wight for Cowes Week. In 1913, during the Balkan Wars, Nicholas personally offered to arbitrate between Serbia and Bulgaria. However, the Bulgarians rejected his offer. Also in 1913, Nicholas, albeit without Alexandra, made a visit to Berlin for the wedding of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s daughter, Princess Victoria Louise, to a maternal cousin of Nicholas, Ernest Augustus, the Duke of Brunswick.[97] Nicholas was also joined by his cousin, King George V and his wife, Queen Mary.

Tercentenary

In February 1913, Nicholas presided over the tercentenary celebrations for the Romanov Dynasty. On 21 February, a Te Deum took place at Kazan Cathedral, and a state reception at the Winter Palace.[98] In May, Nicholas and the imperial family made a pilgrimage across the empire, retracing the route down the Volga River that was made by the teenage Michael Romanov from the Ipatiev Monastery in Kostroma to Moscow in 1613 when he finally agreed to become Tsar.[99]

In Finland, Nicholas had become associated with deeply unpopular Russification measures. These began with the February Manifesto proclaimed by Nicholas II in 1899,[100] which restricted Finland’s autonomy and instigated a period of censorship and political repression.[101] A petition of protest signed by more than 500,000 Finns was collected against the manifesto and delivered to St. Petersburg by a delegation of 500 people, but they were not received by Nicholas. Russification measures were reintroduced in 1908 after a temporary suspension in the aftermath of the 1905 Revolution, and Nicholas received an icy reception when he made his only visit to Helsinki on 10 March 1915.[102][103][104]

First World War

On 28 June 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated by a Bosnian Serb nationalist in Sarajevo, who opposed Austria-Hungary’s annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The outbreak of war was not inevitable, but leaders, diplomats and nineteenth-century alliances created a climate for large-scale conflict. The concept of Pan-Slavism and shared religion created strong public sympathy between Russia and Serbia. Territorial conflict created rivalries between Germany and France and between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, and as a consequence alliance networks developed across Europe. The Triple Entente and Triple Alliance networks were set before the war. Nicholas wanted neither to abandon Serbia to the ultimatum of Austria, nor to provoke a general war. In a series of letters exchanged with Wilhelm of Germany (the «Willy–Nicky correspondence») the two proclaimed their desire for peace, and each attempted to get the other to back down. Nicholas desired that Russia’s mobilization be only against Austria-Hungary, in the hopes of preventing war with Germany.

Nicholas II (right) with Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany in 1905. Nicholas is wearing a German Army uniform, while Wilhelm wears that of a Russian hussar regiment.

On 25 July 1914, at his council of ministers, Nicholas decided to intervene in the Austro-Serbian conflict, a step toward general war. He put the Russian army on «alert»[105] on 25 July. Although this was not general mobilization, it threatened the German and Austro-Hungarian borders and looked like military preparation for war.[105] However, his army had no contingency plans for a partial mobilization, and on 30 July 1914 Nicholas took the fateful step of confirming the order for general mobilization, despite being strongly counselled against it.

On 28 July, Austria-Hungary formally declared war against Serbia. On 29 July 1914, Nicholas sent a telegram to Wilhelm with the suggestion to submit the Austro-Serbian problem to the Hague Conference (in Hague tribunal). Wilhelm did not address the question of the Hague Conference in his subsequent reply.[106][107] Count Witte told the French Ambassador, Maurice Paléologue that from Russia’s point of view the war was madness, Slav solidarity was simply nonsense and Russia could hope for nothing from the war.[108] On 30 July, Russia ordered general mobilization, but still maintained that it would not attack if peace talks were to begin. Germany, reacting to the discovery of partial mobilization ordered on 25 July, announced its own pre-mobilization posture, the Imminent Danger of War. Germany requested that Russia demobilize within the next twelve hours.[109] In Saint Petersburg, at 7 pm, with the ultimatum to Russia having expired, the German ambassador to Russia met with the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov, asked three times if Russia would reconsider, and then with shaking hands, delivered the note accepting Russia’s war challenge and declaring war on 1 August. Less than a week later, on 6 August, Franz Joseph signed the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Russia.

The outbreak of war on 1 August 1914 found Russia grossly unprepared. Russia and her allies placed their faith in her army, the famous ‘Russian steamroller’.[110] Its pre-war regular strength was 1,400,000; mobilization added 3,100,000 reserves and millions more stood ready behind them. In every other respect, however, Russia was unprepared for war. Germany had ten times as much railway track per square mile, and whereas Russian soldiers travelled an average of 1,290 kilometres (800 mi) to reach the front, German soldiers traveled less than a quarter of that distance. Russian heavy industry was still too small to equip the massive armies the Tsar could raise, and her reserves of munitions were pitifully small; while the German army in 1914 was better equipped than any other, man-for-man, the Russians were severely short on artillery pieces, shells, motorized transports, and even boots. With the Baltic Sea barred by German U-boats and the Dardanelles by the guns of Germany’s ally, the Ottoman Empire, Russia initially could receive help only via Archangel, which was frozen solid in winter, or via Vladivostok, which was over 6,400 kilometres (4,000 mi) from the front line. By 1915, a rail line was built north from Petrozavodsk to the Kola Gulf and this connection laid the foundation of the ice-free port of what eventually was called Murmansk. The Russian High Command was moreover greatly weakened by the mutual contempt between Vladimir Sukhomlinov, the Minister of War, and the incompetent Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolayevich who commanded the armies in the field.[111] In spite of all of this, an immediate attack was ordered against the German province of East Prussia. The Germans mobilised there with great efficiency and completely defeated the two Russian armies which had invaded. The Battle of Tannenberg, where an entire Russian army was annihilated, cast an ominous shadow over Russia’s future. Russia had great success against both the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman armies from the very beginning of the war, but they never succeeded against the might of the German Army. In September 1914, to relieve pressure on France, the Russians were forced to halt a successful offensive against Austria-Hungary in Galicia to attack German-held Silesia.[112]

Gradually a war of attrition set in on the vast Eastern Front, where the Russians were facing the combined forces of the German and Austro-Hungarian armies, and they suffered staggering losses. General Denikin, retreating from Galicia wrote, «The German heavy artillery swept away whole lines of trenches, and their defenders with them. We hardly replied. There was nothing with which we could reply. Our regiments, although completely exhausted, were beating off one attack after another by bayonet … Blood flowed unendingly, the ranks became thinner and thinner and thinner. The number of graves multiplied.»[113] On 5 August, with the Russian army in retreat, Warsaw fell. Defeat at the front bred disorder at home. At first, the targets were German, and for three days in June shops, bakeries, factories, private houses and country estates belonging to people with German names were looted and burned.[citation needed] The inflamed mobs then turned on the government, declaring the Empress should be shut up in a convent, the Tsar deposed and Rasputin hanged. Nicholas was by no means deaf to these discontents. An emergency session of the Duma was summoned and a Special Defense Council established, its members drawn from the Duma and the Tsar’s ministers.

In July 1915, King Christian X of Denmark, first cousin of the Tsar, sent Hans Niels Andersen to Tsarskoye Selo with an offer to act as a mediator. He made several trips between London, Berlin and Petrograd and in July saw the Dowager Empress Maria Fyodorovna. Andersen told her they should conclude peace. Nicholas chose to turn down King Christian’s offer of mediation, as he felt it would be a betrayal for Russia to form a separate peace treaty with the Central Powers when its allies Britain and France were still fighting.[114]

The energetic and efficient General Alexei Polivanov replaced Sukhomlinov as Minister of War, which failed to improve the strategic situation.[110] In the aftermath of the Great Retreat and the loss of the Kingdom of Poland, Nicholas assumed the role of commander-in-chief after dismissing his cousin, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolayevich, in September 1915. This was a mistake, as the Tsar came to be personally associated with the continuing losses at the front. He was also away at the remote HQ at Mogilev, far from the direct governance of the empire, and when revolution broke out in Petrograd he was unable to halt it. In reality the move was largely symbolic, since all important military decisions were made by his chief-of-staff General Michael Alexeiev, and Nicholas did little more than review troops, inspect field hospitals, and preside over military luncheons.[115]

The Duma was still calling for political reforms and political unrest continued throughout the war. Cut off from public opinion, Nicholas could not see that the dynasty was tottering. With Nicholas at the front, domestic issues and control of the capital were left with his wife Alexandra. However, Alexandra’s relationship with Grigori Rasputin, and her German background, further discredited the dynasty’s authority. Nicholas had been repeatedly warned about the destructive influence of Rasputin but had failed to remove him. Rumors and accusations about Alexandra and Rasputin appeared one after another; Alexandra was even accused of harboring treasonous sympathies towards Germany. Anger at Nicholas’s failure to act and the extreme damage that Rasputin’s influence was doing to Russia’s war effort and to the monarchy led to Rasputin’s eventual murder by a group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Yusupov and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, a cousin of the Tsar, in the early morning of Saturday 17 December 1916 (O.S.) / 30 December 1916 (N.S.).

Collapse

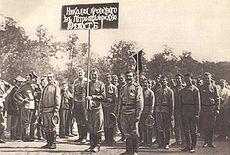

Nicholas with members of the Stavka at Mogilev in April 1916.

As the government failed to produce supplies, mounting hardship resulted in massive riots and rebellions. With Nicholas away at the front from 1915 through 1916, authority appeared to collapse and the capital was left in the hands of strikers and mutineering soldiers. Despite efforts by the British Ambassador Sir George Buchanan to warn the Tsar that he should grant constitutional reforms to fend off revolution, Nicholas continued to bury himself away at the Staff HQ (Stavka) 600 kilometres (400 mi) away at Mogilev, leaving his capital and court open to intrigues and insurrection.[116]

Ideologically the tsar’s greatest support came from the right-wing monarchists, who had recently gained strength. However they were increasingly alienated by the tsar’s support of Stolypin’s Westernizing reforms taken early in the Revolution of 1905 and especially by the political power the tsar had bestowed on Rasputin.[117]

By early 1917, Russia was on the verge of total collapse of morale. An estimated 1.7 million Russian soldiers were killed in World War I.[118] The sense of failure and imminent disaster was everywhere. The army had taken 15 million men from the farms and food prices had soared. An egg cost four times what it had in 1914, butter five times as much. The severe winter dealt the railways, overburdened by emergency shipments of coal and supplies, a crippling blow.[116]

Russia entered the war with 20,000 locomotives; by 1917, 9,000 were in service, while the number of serviceable railway wagons had dwindled from half a million to 170,000. In February 1917, 1,200 locomotives burst their boilers and nearly 60,000 wagons were immobilized. In Petrograd, supplies of flour and fuel had all but disappeared.[116] War-time prohibition of alcohol was enacted by Nicholas to boost patriotism and productivity, but instead damaged the funding of the war, due to the treasury now being deprived of alcohol taxes.[119]

On 23 February 1917 in Petrograd, a combination of very severe cold weather and acute food shortages caused people to break into shops and bakeries to get bread and other necessities. In the streets, red banners appeared and the crowds chanted «Down with the German woman! Down with Protopopov! Down with the war! Down with the Tsar!»[116]

Police shot at the populace which incited riots. The troops in the capital were poorly motivated and their officers had no reason to be loyal to the regime, with the bulk of the tsar’s loyalists away fighting World War I. In contrast, the soldiers in Petrograd were angry, full of revolutionary fervor and sided with the populace.[120]

The Tsar’s Cabinet begged Nicholas to return to the capital and offered to resign completely. The Tsar, 800 kilometres (500 mi) away, misinformed by the Minister of the Interior Alexander Protopopov that the situation was under control, ordered that firm steps be taken against the demonstrators. For this task, the Petrograd garrison was quite unsuitable. The cream of the old regular army had been destroyed in Poland and Galicia. In Petrograd, 170,000 recruits, country boys or older men from the working-class suburbs of the capital itself, were available under the command of officers at the front and cadets not yet graduated from the military academies. The units in the capital, although many bore the names of famous Imperial Guard regiments, were in reality rear or reserve battalions of these regiments, the regular units being away at the front. Many units, lacking both officers and rifles, had never undergone formal training.[120]

General Khabalov attempted to put the Tsar’s instructions into effect on the morning of Sunday, 11 March 1917. Despite huge posters ordering people to keep off the streets, vast crowds gathered and were only dispersed after some 200 had been shot dead, though a company of the Volinsky Regiment fired into the air rather than into the mob, and a company of the Pavlovsky Life Guards shot the officer who gave the command to open fire. Nicholas, informed of the situation by Rodzianko, ordered reinforcements to the capital and suspended the Duma.[120] However, it was too late.

On 12 March, the Volinsky Regiment mutinied and was quickly followed by the Semenovsky, the Ismailovsky, the Litovsky Life Guards and even the legendary Preobrazhensky Regiment of the Imperial Guard, the oldest and staunchest regiment founded by Peter the Great. The arsenal was pillaged and the Ministry of the Interior, Military Government building, police headquarters, Law Courts and a score of police buildings were set on fire. By noon, the fortress of Peter and Paul, with its heavy artillery, was in the hands of the insurgents. By nightfall, 60,000 soldiers had joined the revolution.[120]

Order broke down and Prime Minister Nikolai Golitsyn resigned; members of the Duma and the Soviet formed a Provisional Government to try to restore order. They issued a demand that Nicholas must abdicate. Faced with this demand, which was echoed by his generals, deprived of loyal troops, with his family firmly in the hands of the Provisional Government, and fearful of unleashing civil war and opening the way for German conquest, Nicholas had little choice but to submit.

Revolution

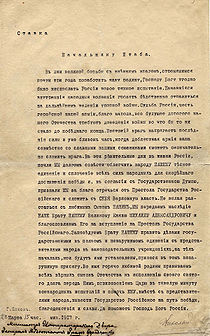

Abdication (1917)

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Nicholas had suffered a coronary occlusion only four days before his abdication.[121] At the end of the «February Revolution», Nicholas II chose to abdicate on 2 March (O.S.) / 15 March (N.S.) 1917. He first abdicated in favor of Alexei, but a few hours later changed his mind after advice from doctors that Alexei would not live long enough while separated from his parents, who would be forced into exile. Nicholas thus abdicated on behalf of his son, and drew up a new manifesto naming his brother, Grand Duke Michael, as the next Emperor of all Russias. He issued a statement but it was suppressed by the Provisional Government. Michael declined to accept the throne until the people were allowed to vote through a Constituent Assembly for the continuance of the monarchy or a republic. The abdication of Nicholas II and Michael’s deferment of accepting the throne brought three centuries of the Romanov dynasty’s rule to an end. The fall of Tsarist autocracy brought joy to liberals and socialists in Britain and France. The United States was the first foreign government to recognize the Provisional government. In Russia, the announcement of the Tsar’s abdication was greeted with many emotions, including delight, relief, fear, anger and confusion.[122]

Possibility of exile

Both the Provisional Government and Nicholas wanted the royal family to go into exile following his abdication, with the United Kingdom being the preferred option.[123] The British government reluctantly offered the family asylum on 19 March 1917, although it was suggested that it would be better for the Romanovs to go to a neutral country. News of the offer provoked uproar from the Labour Party and many Liberals, and the British ambassador Sir George Buchanan advised the government that the extreme left would use the ex-Tsar’s presence «as an excuse for rousing public opinion against us».[124] The Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George preferred that the family went to a neutral country, and wanted the offer to be announced as at the request of the Russian government.[125] The offer of asylum was withdrawn in April following objections by King George V, who, acting on the advice of his secretary Arthur Bigge, 1st Baron Stamfordham, was worried that Nicholas’s presence might provoke an uprising like the previous year’s Easter Rising in Ireland. However, later the king defied his secretary and went to the Romanov memorial service at the Russian Church in London.[126] In the early summer of 1917, the Russian government approached the British government on the issue of asylum and was informed the offer had been withdrawn due to the considerations of British internal politics.[127]

The French government declined to accept the Romanovs in view of increasing unrest on the Western Front and on the home front as a result of the ongoing war with Germany.[128][129] The British ambassador in Paris, Lord Francis Bertie, advised the Foreign Secretary that the Romanovs would be unwelcome in France as the ex-Empress was regarded as pro-German.[124]

Even if an offer of asylum had been forthcoming, there would have been other obstacles to be overcome. The Provisional Government only remained in power through an uneasy alliance with the Petrograd Soviet, an arrangement known as «The Dual power». An initial plan to send the royal family to the northern port of Murmansk had to be abandoned when it was realised that the railway workers and the soldiers guarding them were loyal to the Petrograd Soviet, which opposed the escape of the tsar; a later proposal to send the Romanovs to a neutral port in the Baltic Sea via the Grand Duchy of Finland faced similar difficulties.[130]

Imprisonment

Nicholas II under guard in the grounds at Tsarskoye Selo in the summer of 1917.

Tsarskoye Selo

On 20 March 1917, the Provisional Government decreed that the royal family should be held under house arrest in the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. Nicholas joined the rest of the family there two days later, having traveled from the wartime headquarters at Mogilev.[131] The family had total privacy inside the palace, but walks in the grounds were strictly regulated.[132] Members of their domestic staff were allowed to stay if they wished and culinary standards were maintained.[133] Colonel Eugene Kobylinsky was appointed to command the military garrison at Tsarskoye Selo,[134] which increasingly had to be done through negotiation with the committees or soviets elected by the soldiers.[135]

The Governor’s Mansion in Tobolsk, where the Romanov family was held in captivity between August 1917 and April 1918

Nicholas and Alexei sawing wood at Tobolsk in late 1917; a favourite pastime.

Tobolsk

That summer, the failure of the Kerensky Offensive against Austro-Hungarian and German forces in Galicia led to anti-government rioting in Petrograd, known as the July Days. The government feared that further disturbances in the city could easily reach Tsarskoye Selo and it was decided to move the royal family to a safer location.[136] Alexander Kerensky, who had taken over as prime minister, selected the town of Tobolsk in Western Siberia, since it was remote from any large city and 150 miles (240 km) from the nearest rail station.[137] Some sources state that there was an intention to send the family abroad in the spring of 1918 via Japan,[138] but more recent work suggests that this was just a Bolshevik rumour.[139] The family left the Alexander Palace late on 13 August, reached Tyumen by rail four days later and then by two river ferries finally reached Tobolsk on 19 August.[140] There they lived in the former Governor’s Mansion in considerable comfort. In October 1917, however, the Bolsheviks seized power from Kerensky’s Provisional Government; Nicholas followed the events in October with interest but not yet with alarm. Boris Soloviev, the husband of Maria Rasputin, attempted to organize a rescue with monarchical factions, but it came to nothing. Rumors persist that Soloviev was working for the Bolsheviks or the Germans, or both.[141] Separate preparations for a rescue by Nikolai Yevgenyevich Markov were frustrated by Soloviev’s ineffectual activities.[142] Nicholas continued to underestimate Lenin’s importance. In the meantime he and his family occupied themselves with reading books, exercising and playing games; Nicholas particularly enjoyed chopping firewood.[143] However, in January 1918, the guard detachment’s committee grew more assertive, restricting the hours that the family could spend in the grounds and banning them from walking to church on a Sunday as they had done since October.[144] In a later incident, the soldiers tore the epaulettes from Kobylinsky’s uniform, and he asked Nicholas not to wear his uniform outside for fear of provoking a similar event.[145]

In February 1918, the Council of People’s Commissars (abbreviated to «Sovnarkom») in Moscow, the new capital, announced that the state subsidy for the family would be drastically reduced, starting on 1 March. This meant parting with twelve devoted servants and giving up butter and coffee as luxuries, even though Nicholas added to the funds from his own resources.[146] Nicholas and Alexandra were appalled by news of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, whereby Russia agreed to give up Poland, Finland, the Baltic States, most of Belarus, Ukraine, the Crimea, most of the Caucasus, and small parts of Russia proper including areas around Pskov and Rostov-on-Don.[147] What kept the family’s spirits up was the belief that help was at hand.[148] The Romanovs believed that various plots were underway to break them out of captivity and smuggle them to safety. The Western Allies lost interest in the fate of the Romanovs after Russia left the war. The German government wanted the monarchy restored in Russia to crush the Bolsheviks and maintain good relations with the Central Powers.[149]

The situation in Tobolsk changed for the worse on 26 March, when 250 ill-disciplined Red Guards arrived from the regional capital, Omsk. Not to be outdone, the soviet in Yekaterinburg, the capital of the neighbouring Ural region, sent 400 Red Guards to exert their influence on the town.[150] Disturbances between these rival groups and the lack of funds to pay the guard detachment caused them to send a delegation to Moscow to plead their case. The result was that Sovnarkom appointed their own commissar to take charge of Tobolsk and remove the Romanovs to Yekaterinburg, with the intention of eventually bringing Nicholas to a show trial in Moscow.[151] The man selected was Vasily Yakovlev, a veteran Bolshevik,[152] Recruiting a body of loyal men en route, Yakovlev arrived in Tobolsk on 22 April; he imposed his authority on the competing Red Guards factions, paid-off and demobilized the guard detachment, and placed further restrictions on the Romanovs.[153] The next day, Yakovlev informed Kobylinsky that Nicholas was to be transferred to Yekaterinburg. Alexei was too ill to travel, so Alexandra elected to go with Nicholas along with Maria, while the other daughters would remain at Tobolsk until they were able to make the journey.[154]

Yekaterinburg

At 3 am on 25 April, the three Romanovs, their retinue, and the escort of Yakovlev’s detachment, left Tobolsk in a convoy of nineteen tarantasses (four-wheeled carriages), as the river was still partly frozen which prevented the use of the ferry.[155] After an arduous journey which included two overnight stops, fording rivers, frequent changes of horses and a foiled plot by the Yekaterinburg Red Guards to abduct and kill the prisoners, the party arrived at Tyumen and boarded a requisitioned train. Yakovlev was able to communicate securely with Moscow by means of a Hughes’ teleprinter and obtained agreement to change their destination to Omsk, where it was thought that the leadership were less likely to harm the Romanovs.[156] Leaving Tyumen early on 28 April, the train left towards Yekaterinburg, but quickly changed direction towards Omsk. This led the Yekaterinburg leaders to believe that Yakovlev was a traitor who was trying to take Nicholas to exile by way of Vladivostok; telegraph messages were sent, two thousand armed men were mobilized and a train was dispatched to arrest Yakovlev and the Romanovs. The Romanovs’ train was halted at Omsk station and after a frantic exchange of cables with Moscow, it was agreed that they should go to Yekaterinburg in return for a guarantee of safety for the royal family; they finally arrived there on the morning of 30 April.[157]