In chemistry, the amount of substance n in a given sample of matter is defined as the quantity or number of discrete atomic-scale particles in it divided by the Avogadro constant NA. The particles or entities may be molecules, atoms, ions, electrons, or other, depending on the context, and should be specified (e.g. amount of sodium chloride nNaCl). The value of the Avogadro constant NA has been defined as 6.02214076×1023 mol−1. The mole (symbol: mol) is a unit of amount of substance in the International System of Units, defined (since 2019) by fixing the Avogadro constant at the given value.[1] Sometimes, the amount of substance is referred to as the chemical amount.

Role of amount of substance and its unit mole in chemistry[edit]

Historically, the mole was defined as the amount of substance in 12 grams of the carbon-12 isotope. As a consequence, the mass of one mole of a chemical compound, in grams, is numerically equal (for all practical purposes) to the mass of one molecule of the compound, in daltons, and the molar mass of an isotope in grams per mole is equal to the mass number. For example, a molecule of water has a mass of about 18.015 daltons on average, whereas a mole of water (which contains 6.02214076×1023 water molecules) has a total mass of about 18.015 grams.

In chemistry, because of the law of multiple proportions, it is often much more convenient to work with amounts of substances (that is, number of moles or of molecules) than with masses (grams) or volumes (liters). For example, the chemical fact «1 molecule of oxygen (O

2) will react with 2 molecules of hydrogen (H

2) to make 2 molecules of water (H2O)» can also be stated as «1 mole of O2 will react with 2 moles of H2 to form 2 moles of water». The same chemical fact, expressed in terms of masses, would be «32 g (1 mole) of oxygen will react with approximately 4.0304 g (2 moles of H

2) hydrogen to make approximately 36.0304 g (2 moles) of water» (and the numbers would depend on the isotopic composition of the reagents). In terms of volume, the numbers would depend on the pressure and temperature of the reagents and products. For the same reasons, the concentrations of reagents and products in solution are often specified in moles per liter, rather than grams per liter.

The amount of substance is also a convenient concept in thermodynamics. For example, the pressure of a certain quantity of a noble gas in a recipient of a given volume, at a given temperature, is directly related to the number of molecules in the gas (through the ideal gas law), not to its mass.

This technical sense of the term «amount of substance» should not be confused with the general sense of «amount» in the English language. The latter may refer to other measurements such as mass or volume,[2] rather than the number of particles. There are proposals to replace «amount of substance» with more easily-distinguishable terms, such as enplethy[3] and stoichiometric amount.[2]

The IUPAC recommends that «amount of substance» should be used instead of «number of moles», just as the quantity mass should not be called «number of kilograms».[4]

Nature of the particles[edit]

To avoid ambiguity, the nature of the particles should be specified in any measurement of the amount of substance: thus, a sample of 1 mol of molecules of oxygen (O

2) has a mass of about 32 grams, whereas a sample of 1 mol of atoms of oxygen (O) has a mass of about 16 grams.[5][6]

Derived quantities[edit]

Molar quantities (per mole)[edit]

The quotient of some extensive physical quantity of a homogeneous sample by its amount of substance is an intensive property of the substance, usually named by the prefix molar.[7]

For example, the ratio of the mass of a sample by its amount of substance is the molar mass, whose SI unit is kilograms (or, more usually, grams) per mole; which is about 18.015 g/mol for water, and 55.845 g/mol for iron. From the volume, one gets the molar volume, which is about 17.962 milliliter/mol for liquid water and 7.092 mL/mol for iron at room temperature. From the heat capacity, one gets the molar heat capacity, which is about 75.385 J/K/mol for water and about 25.10 J/K/mol for iron.

Amount concentration (moles per liter)[edit]

Another important derived quantity is the amount of substance concentration[8] (also called amount concentration, or substance concentration in clinical chemistry;[9] which is defined as the amount of a specific substance in a sample of a solution (or some other mixture), divided by the volume of the sample.

The SI unit of this quantity is the mole (of the substance) per liter (of the solution). Thus, for example, the amount concentration of sodium chloride in ocean water is typically about 0.599 mol/L.

The denominator is the volume of the solution, not of the solvent. Thus, for example, one liter of standard vodka contains about 0.40 L of ethanol (315 g, 6.85 mol) and 0.60 L of water. The amount concentration of ethanol is therefore (6.85 mol of ethanol)/(1 L of vodka) = 6.85 mol/L, not (6.85 mol of ethanol)/(0.60 L of water), which would be 11.4 mol/L.

In chemistry, it is customary to read the unit «mol/L» as molar, and denote it by the symbol «M» (both following the numeric value). Thus, for example, each liter of a «0.5 molar» or «0.5 M» solution of urea (CH

4N

2O) in water contains 0.5 moles of that molecule. By extension, the amount concentration is also commonly called the molarity of the substance of interest in the solution. However, as of May 2007, these terms and symbols are not condoned by IUPAC.[10]

This quantity should not be confused with the mass concentration, which is the mass of the substance of interest divided by the volume of the solution (about 35 g/L for sodium chloride in ocean water).

Amount fraction (moles per mole)[edit]

Confusingly, the amount concentration, or «molarity», should also be distinguished from «molar concentration», which should be the number of moles (molecules) of the substance of interest divided by the total number of moles (molecules) in the solution sample. This quantity is more properly called the amount fraction.

History[edit]

The alchemists, and especially the early metallurgists, probably had some notion of amount of substance, but there are no surviving records of any generalization of the idea beyond a set of recipes. In 1758, Mikhail Lomonosov questioned the idea that mass was the only measure of the quantity of matter,[11] but he did so only in relation to his theories on gravitation. The development of the concept of amount of substance was coincidental with, and vital to, the birth of modern chemistry.

- 1777: Wenzel publishes Lessons on Affinity, in which he demonstrates that the proportions of the «base component» and the «acid component» (cation and anion in modern terminology) remain the same during reactions between two neutral salts.[12]

- 1789: Lavoisier publishes Treatise of Elementary Chemistry, introducing the concept of a chemical element and clarifying the Law of conservation of mass for chemical reactions.[13]

- 1792: Richter publishes the first volume of Stoichiometry or the Art of Measuring the Chemical Elements (publication of subsequent volumes continues until 1802). The term «stoichiometry» is used for the first time. The first tables of equivalent weights are published for acid–base reactions. Richter also notes that, for a given acid, the equivalent mass of the acid is proportional to the mass of oxygen in the base.[12]

- 1794: Proust’s Law of definite proportions generalizes the concept of equivalent weights to all types of chemical reaction, not simply acid–base reactions.[12]

- 1805: Dalton publishes his first paper on modern atomic theory, including a «Table of the relative weights of the ultimate particles of gaseous and other bodies».[14]

- The concept of atoms raised the question of their weight. While many were skeptical about the reality of atoms, chemists quickly found atomic weights to be an invaluable tool in expressing stoichiometric relationships.

- 1808: Publication of Dalton’s A New System of Chemical Philosophy, containing the first table of atomic weights (based on H = 1).[15]

- 1809: Gay-Lussac’s Law of combining volumes, stating an integer relationship between the volumes of reactants and products in the chemical reactions of gases.[16]

- 1811: Avogadro hypothesizes that equal volumes of different gases (at same temperature and pressure) contain equal numbers of particles, now known as Avogadro’s law.[17]

- 1813/1814: Berzelius publishes the first of several tables of atomic weights based on the scale of O = 100.[12][18][19]

- 1815: Prout publishes his hypothesis that all atomic weights are integer multiple of the atomic weight of hydrogen.[20] The hypothesis is later abandoned given the observed atomic weight of chlorine (approx. 35.5 relative to hydrogen).

- 1819: Dulong–Petit law relating the atomic weight of a solid element to its specific heat capacity.[21]

- 1819: Mitscherlich’s work on crystal isomorphism allows many chemical formulae to be clarified, resolving several ambiguities in the calculation of atomic weights.[12]

- 1834: Clapeyron states the ideal gas law.[22]

- The ideal gas law was the first to be discovered of many relationships between the number of atoms or molecules in a system and other physical properties of the system, apart from its mass. However, this was not sufficient to convince all scientists of the existence of atoms and molecules, many considered it simply being a useful tool for calculation.

- 1834: Faraday states his Laws of electrolysis, in particular that «the chemical decomposing action of a current is constant for a constant quantity of electricity«.[23]

- 1856: Krönig derives the ideal gas law from kinetic theory.[24] Clausius publishes an independent derivation the following year.[25]

- 1860: The Karlsruhe Congress debates the relation between «physical molecules», «chemical molecules» and atoms, without reaching consensus.[26]

- 1865: Loschmidt makes the first estimate of the size of gas molecules and hence of number of molecules in a given volume of gas, now known as the Loschmidt constant.[27]

- 1886: van’t Hoff demonstrates the similarities in behaviour between dilute solutions and ideal gases.

- 1886: Eugen Goldstein observes discrete particle rays in gas discharges, laying the foundation of mass spectrometry, a tool subsequently used to establish the masses of atoms and molecules.

- 1887: Arrhenius describes the dissociation of electrolyte in solution, resolving one of the problems in the study of colligative properties.[28]

- 1893: First recorded use of the term mole to describe a unit of amount of substance by Ostwald in a university textbook.[29]

- 1897: First recorded use of the term mole in English.[30]

- By the turn of the twentieth century, the concept of atomic and molecular entities was generally accepted, but many questions remained, not least the size of atoms and their number in a given sample. The concurrent development of mass spectrometry, starting in 1886, supported the concept of atomic and molecular mass and provided a tool of direct relative measurement.

- 1905: Einstein’s paper on Brownian motion dispels any last doubts on the physical reality of atoms, and opens the way for an accurate determination of their mass.[31]

- 1909: Perrin coins the name Avogadro constant and estimates its value.[32]

- 1913: Discovery of isotopes of non-radioactive elements by Soddy[33] and Thomson.[34]

- 1914: Richards receives the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for «his determinations of the atomic weight of a large number of elements».[35]

- 1920: Aston proposes the whole number rule, an updated version of Prout’s hypothesis.[36]

- 1921: Soddy receives the Nobel Prize in Chemistry «for his work on the chemistry of radioactive substances and investigations into isotopes».[37]

- 1922: Aston receives the Nobel Prize in Chemistry «for his discovery of isotopes in a large number of non-radioactive elements, and for his whole-number rule».[38]

- 1926: Perrin receives the Nobel Prize in Physics, in part for his work in measuring the Avogadro constant.[39]

- 1959/1960: Unified atomic mass unit scale based on 12C = 12 adopted by IUPAP and IUPAC.[40]

- 1968: The mole is recommended for inclusion in the International System of Units (SI) by the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM).[41]

- 1972: The mole is approved as the SI base unit of amount of substance.[41]

- 2019: The mole is redefined in the SI as «the amount of substance of a system that contains 6.02214076×1023 specified elementary entities».[1]

See also[edit]

- Amount fraction

- International System of Quantities

References[edit]

- ^ a b Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (2019): The International System of Units (SI), 9th edition, English version, p. 134. Available at the BIPM website.

- ^ a b Giunta, Carmen J. (2016). «What’s in a Name? Amount of Substance, Chemical Amount, and Stoichiometric Amount». Journal of Chemical Education. 93 (4): 583–86. Bibcode:2016JChEd..93..583G. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00690.

- ^ «E.R. Cohen, T. Cvitas, J.G. Frey, B. Holmström, K. Kuchitsu, R. Marquardt, I. Mills, F. Pavese, M. Quack, J. Stohner, H.L. Strauss, M. Takami, and A.J. Thor, «Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry», IUPAC Green Book, 3rd Edition, 2nd Printing, IUPAC & RSC Publishing, Cambridge (2008)» (PDF). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 4. Electronic version.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «amount of substance, n«. doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00297

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 46. Electronic version.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 7. Electronic version.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «amount-of-substance concentration». doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00298

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1996). «Glossary of Terms in Quantities and Units in Clinical Chemistry» (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 68: 957–1000. doi:10.1351/pac199668040957. S2CID 95196393.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 42 (n. 15). Electronic version.

- ^ Lomonosov, Mikhail (1970). «On the Relation of the Amount of Material and Weight». In Leicester, Henry M. (ed.). Mikhail Vasil’evich Lomonosov on the Corpuscular Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 224–33 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e «Atome». Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle. Paris: Pierre Larousse. 1: 868–73. 1866.. (in French)

- ^ Lavoisier, Antoine (1789). Traité élémentaire de chimie, présenté dans un ordre nouveau et d’après les découvertes modernes. Paris: Chez Cuchet.. (in French)

- ^ Dalton, John (1805). «On the Absorption of Gases by Water and Other Liquids». Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester. 2nd Series. 1: 271–87.

- ^ Dalton, John (1808). A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Manchester: London.

- ^ Gay-Lussac, Joseph Louis (1809). «Memoire sur la combinaison des substances gazeuses, les unes avec les autres». Mémoires de la Société d’Arcueil. 2: 207. English translation.

- ^ Avogadro, Amedeo (1811). «Essai d’une maniere de determiner les masses relatives des molecules elementaires des corps, et les proportions selon lesquelles elles entrent dans ces combinaisons». Journal de Physique. 73: 58–76. English translation.

- ^ Excerpts from Berzelius’ essay: Part II; Part III.

- ^ Berzelius’ first atomic weight measurements were published in Swedish in 1810: Hisinger, W.; Berzelius, J.J. (1810). «Forsok rorande de bestamda proportioner, havari den oorganiska naturens bestandsdelar finnas forenada». Afh. Fys., Kemi Mineral. 3: 162.

- ^ Prout, William (1815). «On the relation between the specific gravities of bodies in their gaseous state and the weights of their atoms». Annals of Philosophy. 6: 321–30.

- ^ Petit, Alexis Thérèse; Dulong, Pierre-Louis (1819). «Recherches sur quelques points importants de la Théorie de la Chaleur». Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 10: 395–413. English translation

- ^ Clapeyron, Émile (1834). «Puissance motrice de la chaleur». Journal de l’École Royale Polytechnique. 14 (23): 153–90.

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1834). «On Electrical Decomposition». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 124: 77–122. doi:10.1098/rstl.1834.0008. S2CID 116224057.

- ^ Krönig, August (1856). «Grundzüge einer Theorie der Gase». Annalen der Physik. 99 (10): 315–22. Bibcode:1856AnP…175..315K. doi:10.1002/andp.18561751008.

- ^ Clausius, Rudolf (1857). «Ueber die Art der Bewegung, welche wir Wärme nennen». Annalen der Physik. 176 (3): 353–79. Bibcode:1857AnP…176..353C. doi:10.1002/andp.18571760302.

- ^ Wurtz’s Account of the Sessions of the International Congress of Chemists in Karlsruhe, on 3, 4, and 5 September 1860.

- ^ Loschmidt, J. (1865). «Zur Grösse der Luftmoleküle». Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften Wien. 52 (2): 395–413. English translation Archived February 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Arrhenius, Svante (1887). Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 1: 631.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) English translation Archived 2009-02-18 at the Wayback Machine. - ^ Ostwald, Wilhelm (1893). Hand- und Hilfsbuch zur ausführung physiko-chemischer Messungen. Leipzig: W. Engelmann.

- ^ Helm, Georg (1897). The Principles of Mathematical Chemistry: The Energetics of Chemical Phenomena. (Transl. Livingston, J.; Morgan, R.). New York: Wiley. pp. 6.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1905). «Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen». Annalen der Physik. 17 (8): 549–60. Bibcode:1905AnP…322..549E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220806.

- ^ Perrin, Jean (1909). «Mouvement brownien et réalité moléculaire». Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 8e Série. 18: 1–114. Extract in English, translation by Frederick Soddy.

- ^ Soddy, Frederick (1913). «The Radio-elements and the Periodic Law». Chemical News. 107: 97–99.

- ^ Thomson, J.J. (1913). «Rays of positive electricity». Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 89 (607): 1–20. Bibcode:1913RSPSA..89….1T. doi:10.1098/rspa.1913.0057.

- ^ Söderbaum, H.G. (November 11, 1915). Statement regarding the 1914 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- ^ Aston, Francis W. (1920). «The constitution of atmospheric neon». Philosophical Magazine. 39 (6): 449–55. doi:10.1080/14786440408636058.

- ^ Söderbaum, H.G. (December 10, 1921). Presentation Speech for the 1921 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- ^ Söderbaum, H.G. (December 10, 1922). Presentation Speech for the 1922 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- ^ Oseen, C.W. (December 10, 1926). Presentation Speech for the 1926 Nobel Prize in Physics.

- ^ Holden, Norman E. (2004). «Atomic Weights and the International Committee – A Historical Review». Chemistry International. 26 (1): 4–7.

- ^ a b International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 114–15, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-04, retrieved 2021-12-16

In chemistry, the amount of substance n in a given sample of matter is defined as the quantity or number of discrete atomic-scale particles in it divided by the Avogadro constant NA. The particles or entities may be molecules, atoms, ions, electrons, or other, depending on the context, and should be specified (e.g. amount of sodium chloride nNaCl). The value of the Avogadro constant NA has been defined as 6.02214076×1023 mol−1. The mole (symbol: mol) is a unit of amount of substance in the International System of Units, defined (since 2019) by fixing the Avogadro constant at the given value.[1] Sometimes, the amount of substance is referred to as the chemical amount.

Role of amount of substance and its unit mole in chemistry[edit]

Historically, the mole was defined as the amount of substance in 12 grams of the carbon-12 isotope. As a consequence, the mass of one mole of a chemical compound, in grams, is numerically equal (for all practical purposes) to the mass of one molecule of the compound, in daltons, and the molar mass of an isotope in grams per mole is equal to the mass number. For example, a molecule of water has a mass of about 18.015 daltons on average, whereas a mole of water (which contains 6.02214076×1023 water molecules) has a total mass of about 18.015 grams.

In chemistry, because of the law of multiple proportions, it is often much more convenient to work with amounts of substances (that is, number of moles or of molecules) than with masses (grams) or volumes (liters). For example, the chemical fact «1 molecule of oxygen (O

2) will react with 2 molecules of hydrogen (H

2) to make 2 molecules of water (H2O)» can also be stated as «1 mole of O2 will react with 2 moles of H2 to form 2 moles of water». The same chemical fact, expressed in terms of masses, would be «32 g (1 mole) of oxygen will react with approximately 4.0304 g (2 moles of H

2) hydrogen to make approximately 36.0304 g (2 moles) of water» (and the numbers would depend on the isotopic composition of the reagents). In terms of volume, the numbers would depend on the pressure and temperature of the reagents and products. For the same reasons, the concentrations of reagents and products in solution are often specified in moles per liter, rather than grams per liter.

The amount of substance is also a convenient concept in thermodynamics. For example, the pressure of a certain quantity of a noble gas in a recipient of a given volume, at a given temperature, is directly related to the number of molecules in the gas (through the ideal gas law), not to its mass.

This technical sense of the term «amount of substance» should not be confused with the general sense of «amount» in the English language. The latter may refer to other measurements such as mass or volume,[2] rather than the number of particles. There are proposals to replace «amount of substance» with more easily-distinguishable terms, such as enplethy[3] and stoichiometric amount.[2]

The IUPAC recommends that «amount of substance» should be used instead of «number of moles», just as the quantity mass should not be called «number of kilograms».[4]

Nature of the particles[edit]

To avoid ambiguity, the nature of the particles should be specified in any measurement of the amount of substance: thus, a sample of 1 mol of molecules of oxygen (O

2) has a mass of about 32 grams, whereas a sample of 1 mol of atoms of oxygen (O) has a mass of about 16 grams.[5][6]

Derived quantities[edit]

Molar quantities (per mole)[edit]

The quotient of some extensive physical quantity of a homogeneous sample by its amount of substance is an intensive property of the substance, usually named by the prefix molar.[7]

For example, the ratio of the mass of a sample by its amount of substance is the molar mass, whose SI unit is kilograms (or, more usually, grams) per mole; which is about 18.015 g/mol for water, and 55.845 g/mol for iron. From the volume, one gets the molar volume, which is about 17.962 milliliter/mol for liquid water and 7.092 mL/mol for iron at room temperature. From the heat capacity, one gets the molar heat capacity, which is about 75.385 J/K/mol for water and about 25.10 J/K/mol for iron.

Amount concentration (moles per liter)[edit]

Another important derived quantity is the amount of substance concentration[8] (also called amount concentration, or substance concentration in clinical chemistry;[9] which is defined as the amount of a specific substance in a sample of a solution (or some other mixture), divided by the volume of the sample.

The SI unit of this quantity is the mole (of the substance) per liter (of the solution). Thus, for example, the amount concentration of sodium chloride in ocean water is typically about 0.599 mol/L.

The denominator is the volume of the solution, not of the solvent. Thus, for example, one liter of standard vodka contains about 0.40 L of ethanol (315 g, 6.85 mol) and 0.60 L of water. The amount concentration of ethanol is therefore (6.85 mol of ethanol)/(1 L of vodka) = 6.85 mol/L, not (6.85 mol of ethanol)/(0.60 L of water), which would be 11.4 mol/L.

In chemistry, it is customary to read the unit «mol/L» as molar, and denote it by the symbol «M» (both following the numeric value). Thus, for example, each liter of a «0.5 molar» or «0.5 M» solution of urea (CH

4N

2O) in water contains 0.5 moles of that molecule. By extension, the amount concentration is also commonly called the molarity of the substance of interest in the solution. However, as of May 2007, these terms and symbols are not condoned by IUPAC.[10]

This quantity should not be confused with the mass concentration, which is the mass of the substance of interest divided by the volume of the solution (about 35 g/L for sodium chloride in ocean water).

Amount fraction (moles per mole)[edit]

Confusingly, the amount concentration, or «molarity», should also be distinguished from «molar concentration», which should be the number of moles (molecules) of the substance of interest divided by the total number of moles (molecules) in the solution sample. This quantity is more properly called the amount fraction.

History[edit]

The alchemists, and especially the early metallurgists, probably had some notion of amount of substance, but there are no surviving records of any generalization of the idea beyond a set of recipes. In 1758, Mikhail Lomonosov questioned the idea that mass was the only measure of the quantity of matter,[11] but he did so only in relation to his theories on gravitation. The development of the concept of amount of substance was coincidental with, and vital to, the birth of modern chemistry.

- 1777: Wenzel publishes Lessons on Affinity, in which he demonstrates that the proportions of the «base component» and the «acid component» (cation and anion in modern terminology) remain the same during reactions between two neutral salts.[12]

- 1789: Lavoisier publishes Treatise of Elementary Chemistry, introducing the concept of a chemical element and clarifying the Law of conservation of mass for chemical reactions.[13]

- 1792: Richter publishes the first volume of Stoichiometry or the Art of Measuring the Chemical Elements (publication of subsequent volumes continues until 1802). The term «stoichiometry» is used for the first time. The first tables of equivalent weights are published for acid–base reactions. Richter also notes that, for a given acid, the equivalent mass of the acid is proportional to the mass of oxygen in the base.[12]

- 1794: Proust’s Law of definite proportions generalizes the concept of equivalent weights to all types of chemical reaction, not simply acid–base reactions.[12]

- 1805: Dalton publishes his first paper on modern atomic theory, including a «Table of the relative weights of the ultimate particles of gaseous and other bodies».[14]

- The concept of atoms raised the question of their weight. While many were skeptical about the reality of atoms, chemists quickly found atomic weights to be an invaluable tool in expressing stoichiometric relationships.

- 1808: Publication of Dalton’s A New System of Chemical Philosophy, containing the first table of atomic weights (based on H = 1).[15]

- 1809: Gay-Lussac’s Law of combining volumes, stating an integer relationship between the volumes of reactants and products in the chemical reactions of gases.[16]

- 1811: Avogadro hypothesizes that equal volumes of different gases (at same temperature and pressure) contain equal numbers of particles, now known as Avogadro’s law.[17]

- 1813/1814: Berzelius publishes the first of several tables of atomic weights based on the scale of O = 100.[12][18][19]

- 1815: Prout publishes his hypothesis that all atomic weights are integer multiple of the atomic weight of hydrogen.[20] The hypothesis is later abandoned given the observed atomic weight of chlorine (approx. 35.5 relative to hydrogen).

- 1819: Dulong–Petit law relating the atomic weight of a solid element to its specific heat capacity.[21]

- 1819: Mitscherlich’s work on crystal isomorphism allows many chemical formulae to be clarified, resolving several ambiguities in the calculation of atomic weights.[12]

- 1834: Clapeyron states the ideal gas law.[22]

- The ideal gas law was the first to be discovered of many relationships between the number of atoms or molecules in a system and other physical properties of the system, apart from its mass. However, this was not sufficient to convince all scientists of the existence of atoms and molecules, many considered it simply being a useful tool for calculation.

- 1834: Faraday states his Laws of electrolysis, in particular that «the chemical decomposing action of a current is constant for a constant quantity of electricity«.[23]

- 1856: Krönig derives the ideal gas law from kinetic theory.[24] Clausius publishes an independent derivation the following year.[25]

- 1860: The Karlsruhe Congress debates the relation between «physical molecules», «chemical molecules» and atoms, without reaching consensus.[26]

- 1865: Loschmidt makes the first estimate of the size of gas molecules and hence of number of molecules in a given volume of gas, now known as the Loschmidt constant.[27]

- 1886: van’t Hoff demonstrates the similarities in behaviour between dilute solutions and ideal gases.

- 1886: Eugen Goldstein observes discrete particle rays in gas discharges, laying the foundation of mass spectrometry, a tool subsequently used to establish the masses of atoms and molecules.

- 1887: Arrhenius describes the dissociation of electrolyte in solution, resolving one of the problems in the study of colligative properties.[28]

- 1893: First recorded use of the term mole to describe a unit of amount of substance by Ostwald in a university textbook.[29]

- 1897: First recorded use of the term mole in English.[30]

- By the turn of the twentieth century, the concept of atomic and molecular entities was generally accepted, but many questions remained, not least the size of atoms and their number in a given sample. The concurrent development of mass spectrometry, starting in 1886, supported the concept of atomic and molecular mass and provided a tool of direct relative measurement.

- 1905: Einstein’s paper on Brownian motion dispels any last doubts on the physical reality of atoms, and opens the way for an accurate determination of their mass.[31]

- 1909: Perrin coins the name Avogadro constant and estimates its value.[32]

- 1913: Discovery of isotopes of non-radioactive elements by Soddy[33] and Thomson.[34]

- 1914: Richards receives the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for «his determinations of the atomic weight of a large number of elements».[35]

- 1920: Aston proposes the whole number rule, an updated version of Prout’s hypothesis.[36]

- 1921: Soddy receives the Nobel Prize in Chemistry «for his work on the chemistry of radioactive substances and investigations into isotopes».[37]

- 1922: Aston receives the Nobel Prize in Chemistry «for his discovery of isotopes in a large number of non-radioactive elements, and for his whole-number rule».[38]

- 1926: Perrin receives the Nobel Prize in Physics, in part for his work in measuring the Avogadro constant.[39]

- 1959/1960: Unified atomic mass unit scale based on 12C = 12 adopted by IUPAP and IUPAC.[40]

- 1968: The mole is recommended for inclusion in the International System of Units (SI) by the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM).[41]

- 1972: The mole is approved as the SI base unit of amount of substance.[41]

- 2019: The mole is redefined in the SI as «the amount of substance of a system that contains 6.02214076×1023 specified elementary entities».[1]

See also[edit]

- Amount fraction

- International System of Quantities

References[edit]

- ^ a b Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (2019): The International System of Units (SI), 9th edition, English version, p. 134. Available at the BIPM website.

- ^ a b Giunta, Carmen J. (2016). «What’s in a Name? Amount of Substance, Chemical Amount, and Stoichiometric Amount». Journal of Chemical Education. 93 (4): 583–86. Bibcode:2016JChEd..93..583G. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00690.

- ^ «E.R. Cohen, T. Cvitas, J.G. Frey, B. Holmström, K. Kuchitsu, R. Marquardt, I. Mills, F. Pavese, M. Quack, J. Stohner, H.L. Strauss, M. Takami, and A.J. Thor, «Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry», IUPAC Green Book, 3rd Edition, 2nd Printing, IUPAC & RSC Publishing, Cambridge (2008)» (PDF). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 4. Electronic version.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «amount of substance, n«. doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00297

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 46. Electronic version.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 7. Electronic version.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «amount-of-substance concentration». doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00298

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1996). «Glossary of Terms in Quantities and Units in Clinical Chemistry» (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 68: 957–1000. doi:10.1351/pac199668040957. S2CID 95196393.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 42 (n. 15). Electronic version.

- ^ Lomonosov, Mikhail (1970). «On the Relation of the Amount of Material and Weight». In Leicester, Henry M. (ed.). Mikhail Vasil’evich Lomonosov on the Corpuscular Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 224–33 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e «Atome». Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle. Paris: Pierre Larousse. 1: 868–73. 1866.. (in French)

- ^ Lavoisier, Antoine (1789). Traité élémentaire de chimie, présenté dans un ordre nouveau et d’après les découvertes modernes. Paris: Chez Cuchet.. (in French)

- ^ Dalton, John (1805). «On the Absorption of Gases by Water and Other Liquids». Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester. 2nd Series. 1: 271–87.

- ^ Dalton, John (1808). A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Manchester: London.

- ^ Gay-Lussac, Joseph Louis (1809). «Memoire sur la combinaison des substances gazeuses, les unes avec les autres». Mémoires de la Société d’Arcueil. 2: 207. English translation.

- ^ Avogadro, Amedeo (1811). «Essai d’une maniere de determiner les masses relatives des molecules elementaires des corps, et les proportions selon lesquelles elles entrent dans ces combinaisons». Journal de Physique. 73: 58–76. English translation.

- ^ Excerpts from Berzelius’ essay: Part II; Part III.

- ^ Berzelius’ first atomic weight measurements were published in Swedish in 1810: Hisinger, W.; Berzelius, J.J. (1810). «Forsok rorande de bestamda proportioner, havari den oorganiska naturens bestandsdelar finnas forenada». Afh. Fys., Kemi Mineral. 3: 162.

- ^ Prout, William (1815). «On the relation between the specific gravities of bodies in their gaseous state and the weights of their atoms». Annals of Philosophy. 6: 321–30.

- ^ Petit, Alexis Thérèse; Dulong, Pierre-Louis (1819). «Recherches sur quelques points importants de la Théorie de la Chaleur». Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 10: 395–413. English translation

- ^ Clapeyron, Émile (1834). «Puissance motrice de la chaleur». Journal de l’École Royale Polytechnique. 14 (23): 153–90.

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1834). «On Electrical Decomposition». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 124: 77–122. doi:10.1098/rstl.1834.0008. S2CID 116224057.

- ^ Krönig, August (1856). «Grundzüge einer Theorie der Gase». Annalen der Physik. 99 (10): 315–22. Bibcode:1856AnP…175..315K. doi:10.1002/andp.18561751008.

- ^ Clausius, Rudolf (1857). «Ueber die Art der Bewegung, welche wir Wärme nennen». Annalen der Physik. 176 (3): 353–79. Bibcode:1857AnP…176..353C. doi:10.1002/andp.18571760302.

- ^ Wurtz’s Account of the Sessions of the International Congress of Chemists in Karlsruhe, on 3, 4, and 5 September 1860.

- ^ Loschmidt, J. (1865). «Zur Grösse der Luftmoleküle». Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften Wien. 52 (2): 395–413. English translation Archived February 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Arrhenius, Svante (1887). Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 1: 631.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) English translation Archived 2009-02-18 at the Wayback Machine. - ^ Ostwald, Wilhelm (1893). Hand- und Hilfsbuch zur ausführung physiko-chemischer Messungen. Leipzig: W. Engelmann.

- ^ Helm, Georg (1897). The Principles of Mathematical Chemistry: The Energetics of Chemical Phenomena. (Transl. Livingston, J.; Morgan, R.). New York: Wiley. pp. 6.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1905). «Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen». Annalen der Physik. 17 (8): 549–60. Bibcode:1905AnP…322..549E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220806.

- ^ Perrin, Jean (1909). «Mouvement brownien et réalité moléculaire». Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 8e Série. 18: 1–114. Extract in English, translation by Frederick Soddy.

- ^ Soddy, Frederick (1913). «The Radio-elements and the Periodic Law». Chemical News. 107: 97–99.

- ^ Thomson, J.J. (1913). «Rays of positive electricity». Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 89 (607): 1–20. Bibcode:1913RSPSA..89….1T. doi:10.1098/rspa.1913.0057.

- ^ Söderbaum, H.G. (November 11, 1915). Statement regarding the 1914 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- ^ Aston, Francis W. (1920). «The constitution of atmospheric neon». Philosophical Magazine. 39 (6): 449–55. doi:10.1080/14786440408636058.

- ^ Söderbaum, H.G. (December 10, 1921). Presentation Speech for the 1921 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- ^ Söderbaum, H.G. (December 10, 1922). Presentation Speech for the 1922 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- ^ Oseen, C.W. (December 10, 1926). Presentation Speech for the 1926 Nobel Prize in Physics.

- ^ Holden, Norman E. (2004). «Atomic Weights and the International Committee – A Historical Review». Chemistry International. 26 (1): 4–7.

- ^ a b International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 114–15, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-04, retrieved 2021-12-16

1

Как в химии обозначается количество вещества?

1 ответ:

2

0

Количество вещества в химии может обозначаться греческой прописной буквой «ню», нет возможности её изобразить, нет ее на клавиатуре, а также прописной латинской «n», но первая считается предпочтительней в соответствии с СИ. Количество вещества имеет единицу измерения — моль.

Читайте также

2CH3COOH+Zn= (CH3COO)2Zn+H2 (реакция идет медленно, ее проводят при нагревании)

CH3COOH+NaOH= CH3COONa+H2O

6CH3COOH + Al2O3 = 2(CH3COO)3Al+3H2O, однако ацетат алюминия (CH3COO)3Al – соль образованная слабой кислотой и слабым основанием, а значит, сразу же после образования подвергнется гидролизу по катиону и аниону:

(CH3COO)3Al+3H2O=3CH3COOH+ Al(OH)3↓

То же самое можно сказать про ацетат цинка образующийся в реакции, написанной выше, и про ацетат аммония, образующийся в реакции уксусной кислоты с гидроксидом аммония:

CH3COOH+ NH4OH= CH3COONH4 + H2O (ацетат аммония образован слабой кислотой и слабым основанием)

CH3COONH4 + H2O = NH4OH + CH3COOH (обратная реакция – гидролиз)

С оксидом фосфора уксусная кислота непосредственно не реагирует, однако в его присутствии протекает реакция:

2CH3COOH= CH3-CO-O-OC-CH3 + H2O (т.к. P2O5 очень гигроскопичен, его используют в качестве водоотнимающего средства)

С карбонатами реагирует с выделением углекислого газа

2CH3COOH+CaCO3= (CH3COO)2Ca+CO2↑+H2O

Я знаю много названий алкадиенов. Непосредственно самому приходилось иметь дело с тремя: 1,3-бутадиеном СН2=СН-СН=СН2, изопреном (2-метил-1,3-бутадиеном СН2=С(СН3)-СН=СН2), пипериленом (1,3-пентадиеном СН2=СН-СН=СН-СН3). Полимеризацией 1,3-бутадиена и изопрена получают львиную долю вырабатываемых сегодня каучуков (сырья для получения резины).

Реакции ионного обмена — это реакции протекающие в полярных растворителях между ионами исходных веществ. При этом степень окисления элементов не изменяется. Пример: водный раствор BaCl2 + Na2SO4= BaSO4 + 2Nacl.

Масса ржавого железа больше массы исходного не ржавого железа потому что в ржавом железе добавлен кислород в соответствии с химической формулой оксида железа Fe2 O3. Атомная масса железа 56, у кислорода 17, следовательно к 112 массам железа прибавляется 51 масса кислорода и ржавое железо тяжелее чистого на 45,5%.

Если бы речной песок растворялся в воде, то на нашей планете, по большому счету не было бы суши,а также пляжей, т.к. диоксид кремния входит не только в речной песок, но является основой всех камней, а песок продукт выветривания горных пород под действием погодных условий: тепло, холод, ветер, вода. Кремний — химический элемент, который входит во все горные породы, занимает второе место по распространенности хим. элементов , где первое место у кислорода. У этого элемента у нас русское название кремний. вспомним поговорку: «Твердые как кремень». Поэтому ответ на вопрос : речной песок никогда не растворяется в воде.

В уроке 8 «Химическое количество вещества и моль» из курса «Химия для чайников» выясним, что такое химическое количество вещества; рассмотрим моль в качестве единицы количества вещества, а также познакомимся с постоянной Авогадро. Напоминаю, что в прошлом уроке «Относительная молекулярная и относительная формульная массы» мы научились вычислять относительную молекулярную массу, а также относительную формульную массу веществ; кроме того, выяснили что такое массовая доля и привели формулу для ее вычисления.

Любое чистое вещество имеет свою химическую формулу, т. е. характеризуется определенным качественным и количественным составом.

Если необходима какая-то порция твердого вещества, то для этого следует взять нужную его массу, т. е. взвесить вещество (рис. 43). Нужный объем жидкого вещества обычно отмеряют с помощью мензурки или мерного цилиндра (рис. 44). Для отбора необходимой порции (объема) газообразных веществ применяют специальные емкости — газометры (рис. 45).

Следовательно, объем и масса — это величины, характеризующие данную порцию вещества.

Химическое количество вещества

В жизни мы часто не различаем понятия «масса» и «количество». А это разные понятия. Когда вы говорите: «Я купил 2 кг груш», то здесь речь идет о массе груш. Но если вы говорите: «Я купил 10 груш», то в этом случае речь идет о количестве груш. Массу вещества измеряют в граммах, килограммах, тоннах, а количество — в штуках.

Груши можно пересчитать поштучно, а если это, например, зерна? Тут уже посчитать каждое зернышко даже в небольшой емкости сложно. Поэтому зерно обычно продают мешками, т. е. определенными порциями. В каждой такой порции — мешке (если они равны по массе и все зерна одинаковы) — будет находиться практически одно и то же число зерен. Подобным образом продают многие товары. Например, яйца — десятками, спички — спичечными коробками, в каждом из которых находится по 45 спичек (рис. 46).

В химической практике, помимо массы или объема, необходимо знать число структурных единиц (атомов, молекул, формульных единиц), которые содержатся в данной порции вещества, поскольку именно они участвуют в химических реакциях. Поэтому в химии, как и в других естественных науках, используют физическую величину, характеризующую число частиц в рассматриваемой порции вещества. Эта физическая величина называется количеством вещества или, как следует называть ее при химических расчетах, — химическое количество вещества.

Химическое количество вещества — физическая величина, пропорциональная числу структурных единиц, содержащихся в данной порции вещества.

Другими словами, химическое количество вещества — это порция данного вещества, содержащая определенное число его структурных единиц. Химическое количество вещества обозначают латинской буквой n. Это одна из семи основных физических величин Международной системы единиц (СИ).

Моль — единица химического количества вещества

Каждая из основных физических величин имеет свою единицу. Например, единица длины — метр (м), массы — килограмм (кг), времени — секунда (с). Единицей химического количества вещества является моль.

Моль — порция вещества (т. е. такое его химическое количество), которая содержит столько же структурных единиц, сколько атомов содержится в углероде массой 0,012 кг.

Сокращенное обозначение единицы химического количества записывается, как и полное, — моль. Поэтому, если слово «моль» стоит после числа, то оно не склоняется, так же, как и другие сокращенные единицы величин: 3 кг, 5 л, 8 моль. При чтении вслух и при записи числительного буквами слово «моль» склоняется: три килограмма, пять литров, восемь молей.

На заметку. Термины «молекула» и «моль», как нетрудно заметить, однокоренные. Они действительно произошли от одного и того же латинского слова «moles». Но это слово имеет, по крайней мере, два значения. Первое — «маленькая масса». Именно в этом смысле в XVII в. оно превратилось в термин «молекула». А понятие «моль» (в смысле кучка, порция) появилось значительно позже, в начале ХХ в. Автор этого термина известный немецкий химик и физик Оствальд толковал его смысл как «большая масса», как бы противопоставляя термину «молекула».

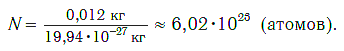

Число (N) атомов в порции углерода массой 0,012 кг легко определить, зная массу одного атома углерода (19,94·10-27 кг):

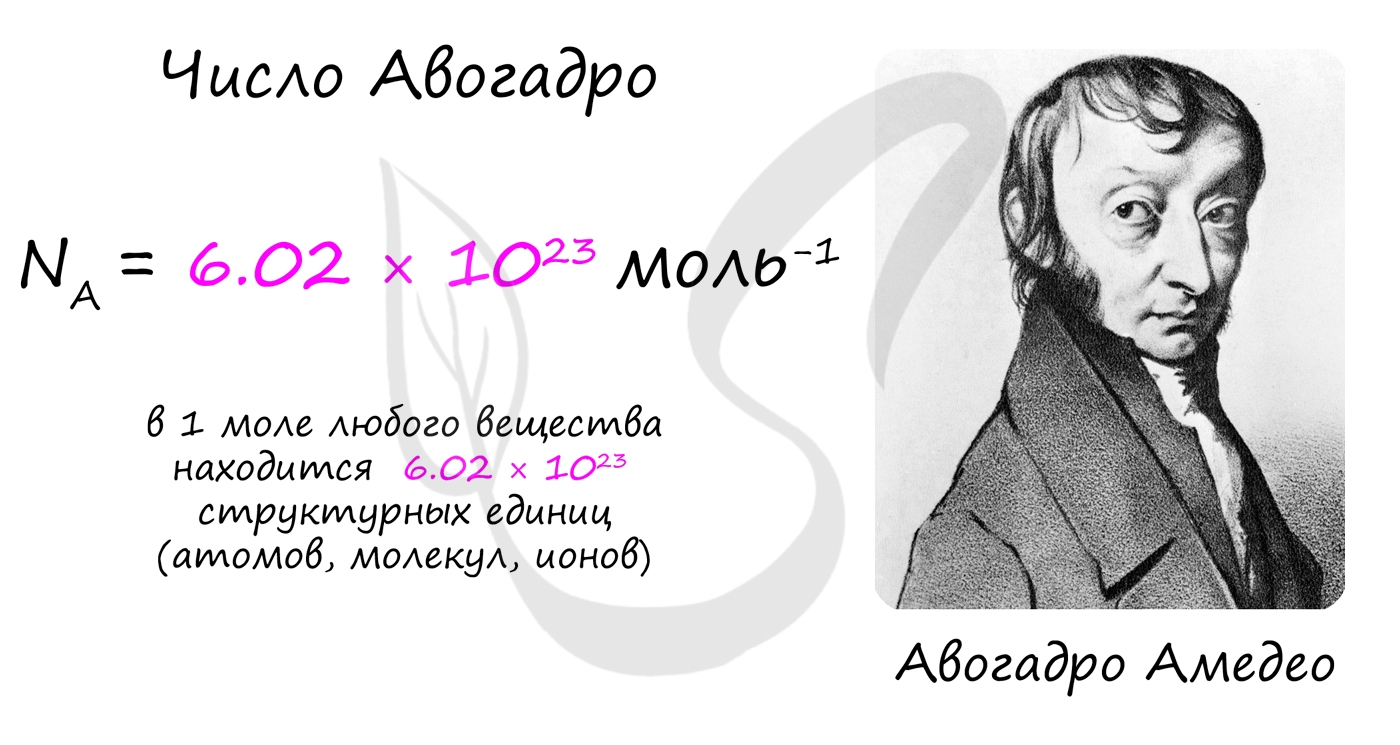

Следовательно, в углероде массой 0,012 кг содержатся 6,02·1023 атомов углерода и эта порция составляет 1 моль. Столько же структурных единиц содержится в 1 моль любого вещества.

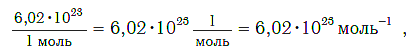

Величина, равная:

получила название постоянной Авогадро. Она является одной из важнейших универсальных постоянных и обозначается символом NA:

Единица в числителе дроби (1/моль) заменяет название структурной единицы.

Если структурной единицей вещества (например, меди, углерода) является атом, то в порции этого вещества количеством 1 моль содержатся 6,02·1023 атомов. В случае веществ молекулярного строения (вода, углекислый газ) их порции количеством 1 моль содержат по 6,02·1023 молекул. Если структурными единицами веществ немолекулярного строения (например, NaCl или CuSO4) являются их формульные единицы, то в порциях этих веществ количеством 1 моль содержатся по 6,02·1023 формульных единиц.

На заметку. Численное значение постоянной Авогадро огромно. О том, насколько велико это число, можно судить по следующему сравнению. Поверхность Земли, включая и водную, равна 510 000 000 км2. Если равномерно рассыпать по всей этой поверхности 6,02·1023 песчинок диаметром 1 мм, то они образуют слой песка толщиной более 1 м.

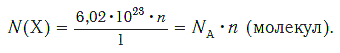

Зная химическое количество n данного вещества Х, легко рассчитать число молекул (атомов, формульных единиц) N(Х) в этой порции:

если 1 моль вещества содержит 6,02·1023 молекул, то n моль вещества содержат N(Х) молекул.

Отсюда:

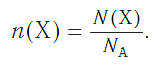

И наоборот, по числу структурных единиц можно рассчитать химическое количество вещества:

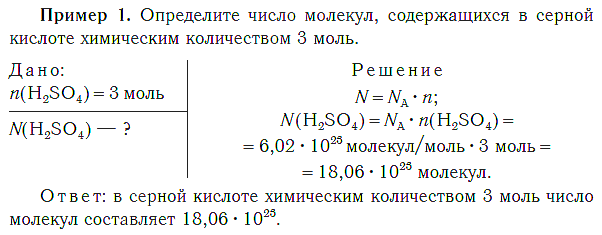

Пример 1. Определите число молекул, содержащихся в серной кислоте химическим количеством 3 моль.

Спойлер

[свернуть]

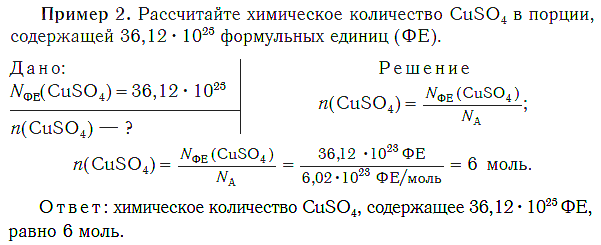

Пример 2. Рассчитайте химическое количество CuSO4 в порции, содержащей 36,12·1023 формульных единиц (ФЕ).

Спойлер

[свернуть]

Краткие выводы урока:

- Химическое количество вещества — физическая величина, пропорциональная числу структурных единиц, содержащихся в данной порции вещества.

- Моль — единица химического количества вещества, т. е. такое его количество, которое содержит 6,02·1023 структурных единиц.

Надеюсь урок 8 «Химическое количество вещества и моль» был понятным и познавательным. Если у вас возникли вопросы, пишите их в комментарии.

В этой статье мы коснемся нескольких краеугольных понятий в химии, без которых совершенно невозможно

решение задач. Старайтесь понять смысл физических величин, чтобы усвоить эту тему.

Я постараюсь приводить как можно больше примеров по ходу этой статьи, в ходе изучения вы увидите множество примеров

по данной теме.

Относительная атомная масса — Ar

Представляет собой массу атома, выраженную в атомных единицах массы. Относительные атомные массы указаны в периодической

таблице Д.И. Менделеева. Так, один атом водорода имеет атомную массу = 1, кислород = 16, кальций = 40.

Относительная молекулярная масса — Mr

Относительная молекулярная масса складывается из суммы относительных атомных масс всех атомов, входящих в состав вещества.

В качестве примера найдем относительные молекулярные массы кислорода, воды, перманганата калия и медного купороса:

Mr (O2) = (2 × Ar(O)) = 2 × 16 = 32

Mr (H2O) = (2 × Ar(H)) + Ar(O) = (2 × 1) + 16 = 18

Mr (KMnO4) = Ar(K) + Ar(Mn) + (4 × Ar(O)) = 39 + 55 + (4 * 16) = 158

Mr (CuSO4*5H2O) = Ar(Cu) + Ar(S) + (4 × Ar(O)) + (5 × ((Ar(H) × 2) +

Ar(O))) = 64 + 32 + (4 × 16) + (5 × ((1 × 2) + 16)) = 160 + 5 * 18 = 250

Моль и число Авогадро

Моль — единица количества вещества (в системе единиц СИ), определяемая как количество вещества, содержащее столько же структурных единиц

этого вещества (молекул, атомов, ионов) сколько содержится в 12 г изотопа 12C, т.е. 6 × 1023.

Число Авогадро (постоянная Авогадро, NA) — число частиц (молекул, атомов, ионов) содержащихся в одном моле любого вещества.

Больше всего мне хотелось бы, чтобы вы поняли физический смысл изученных понятий. Моль — международная единица количества вещества, которая

показывает, сколько атомов, молекул или ионов содержится в определенной массе или конкретном объеме вещества. Один моль любого вещества

содержит 6.02 × 1023 атомов/молекул/ионов — вот самое важное, что сейчас нужно понять.

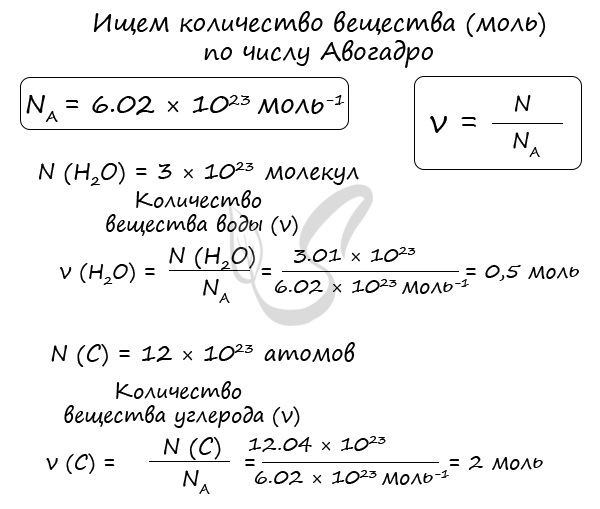

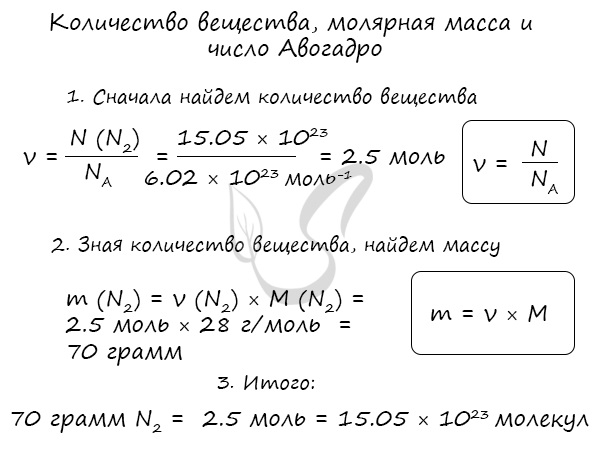

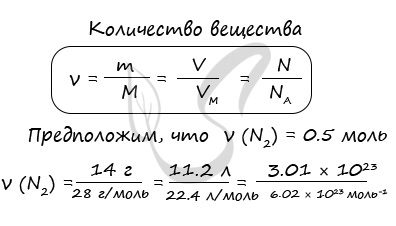

Иногда в задачах бывает дано число Авогадро, и от вас требуется найти, какое вам дали количество вещества (моль). Количество вещества в химии

обозначается N, ν (по греч. читается «ню»).

Рассчитаем по формуле: ν = N/NA количество вещества 3.01 × 1023 молекул воды и 12.04 × 1023 атомов углерода.

Мы нашли количества вещества (моль) воды и углерода. Сейчас это может показаться очень абстрактным, но, иногда не зная, как найти

количество вещества, используя число Авогадро, решение задачи по химии становится невозможным.

Молярная масса — M

Молярная масса — масса одного моля вещества, выражается в «г/моль» (грамм/моль). Численно совпадает с изученной нами ранее

относительной молекулярной массой.

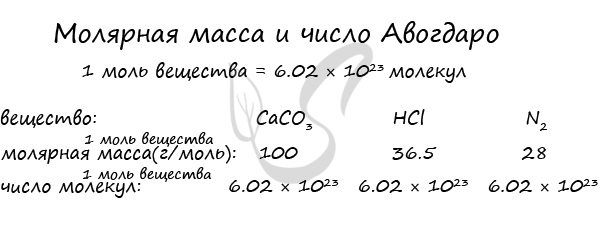

Рассчитаем молярные массы CaCO3, HCl и N2

M (CaCO3) = Ar(Ca) + Ar(C) + (3 × Ar(O)) = 40 + 12 + (3 × 16) = 100 г/моль

M (HCl) = Ar(H) + Ar(Cl) = 1 + 35.5 = 36.5 г/моль

M (N2) = Ar(N) × 2 = 14 × 2 = 28 г/моль

Полученные знания не должны быть отрывочны, из них следует создать цельную систему. Обратите внимание: только что мы рассчитали

молярные массы — массы одного моля вещества. Вспомните про число Авогадро.

Получается, что, несмотря на одинаковое число молекул в 1 моле (1 моль любого вещества содержит 6.02 × 1023 молекул),

молекулярные массы отличаются. Так, 6.02 × 1023 молекул N2 весят 28 грамм, а такое же количество молекул

HCl — 36.5 грамм.

Это связано с тем, что, хоть количество молекул одинаково — 6.02 × 1023, в их состав входят разные атомы, поэтому и

массы получаются разные.

Часто в задачах бывает дана масса, а от вас требуется рассчитать количество вещества, чтобы перейти к другому веществу в реакции.

Сейчас мы определим количество вещества (моль) 70 грамм N2, 50 грамм CaCO3, 109.5 грамм HCl. Их молярные

массы были найдены нам уже чуть раньше, что ускорит ход решения.

ν (CaCO3) = m(CaCO3) : M(CaCO3) = 50 г. : 100 г/моль = 0.5 моль

ν (HCl) = m(HCl) : M(HCl) = 109.5 г. : 36.5 г/моль = 3 моль

Иногда в задачах может быть дано число молекул, а вам требуется рассчитать массу, которую они занимают. Здесь нужно использовать

количество вещества (моль) как посредника, который поможет решить поставленную задачу.

Предположим нам дали 15.05 × 1023 молекул азота, 3.01 × 1023 молекул CaCO3 и 18.06 × 1023 молекул

HCl. Требуется найти массу, которую составляет указанное число молекул. Мы несколько изменим известную формулу, которая поможет нам связать

моль и число Авогадро.

Теперь вы всесторонне посвящены в тему. Надеюсь, что вы поняли, как связаны молярная масса, число Авогадро и количество вещества.

Практика — лучший учитель. Найдите самостоятельно подобные значения для оставшихся CaCO3 и HCl.

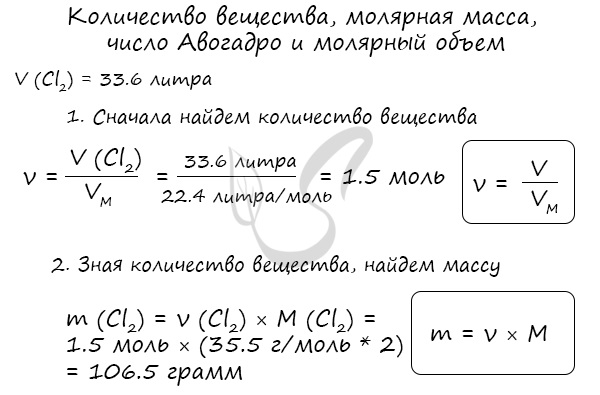

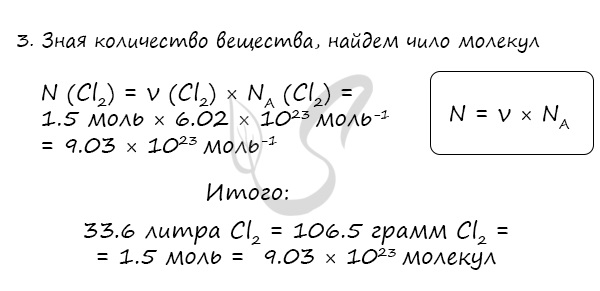

Молярный объем

Молярный объем — объем, занимаемый одним молем вещества. Примерно одинаков для всех газов при стандартной температуре

и давлении составляет 22.4 л/моль. Он обозначается как — VM.

Подключим к нашей системе еще одно понятие. Предлагаю найти количество вещества, количество молекул и массу газа объемом

33.6 литра. Поскольку показательно молярного объема при н.у. — константа (22.4 л/моль), то совершенно неважно, какой газ мы

возьмем: хлор, азот или сероводород.

Запомните, что 1 моль любого газа занимает объем 22.4 литра. Итак, приступим к решению задачи. Поскольку какой-то газ

все же надо выбрать, выберем хлор — Cl2.

Моль (количество вещества) — самое гибкое из всех понятий в химии. Количество вещества позволяет вам перейти и к

числу Авогадро, и к массе, и к объему. Если вы усвоили это, то главная задача данной статьи — выполнена

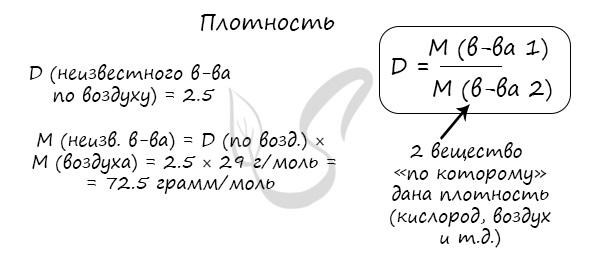

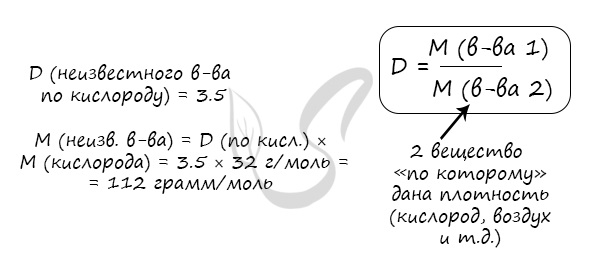

Относительная плотность и газы — D

Относительной плотностью газа называют отношение молярных масс (плотностей) двух газов. Она показывает, во сколько раз одно вещество

легче/тяжелее другого. D = M (1 вещества) / M (2 вещества).

В задачах бывает дано неизвестное вещество, однако известна его плотность по водороду, азоту, кислороду или

воздуху. Для того чтобы найти молярную массу вещества, следует умножить значение плотности на молярную массу

газа, по которому дана плотность.

Запомните, что молярная масса воздуха = 29 г/моль. Лучше объяснить, что такое плотность и с чем ее едят на примере.

Нам нужно найти молярную массу неизвестного вещества, плотность которого по воздуху 2.5

Предлагаю самостоятельно решить следующую задачку (ниже вы найдете решение): «Плотность неизвестного вещества по

кислороду 3.5, найдите молярную массу неизвестного вещества»

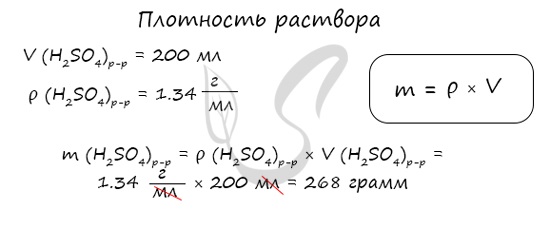

Относительная плотность и водный раствор — ρ

Пишу об этом из-за исключительной важности в решении

сложных задач, высокого уровня, где особенно часто упоминается плотность. Обозначается греческой буквой ρ.

Плотность является отражением зависимости массы от вещества, равна отношению массы вещества к единице его объема. Единицы

измерения плотности: г/мл, г/см3, кг/м3 и т.д.

Для примера решим задачку. Объем серной кислоты составляет 200 мл, плотность 1.34 г/мл. Найдите массу раствора. Чтобы не

запутаться в единицах измерения поступайте с ними как с самыми обычными числами: сокращайте при делении и умножении — так

вы точно не запутаетесь.

Иногда перед вами может стоять обратная задача, когда известна масса раствора, плотность и вы должны найти объем. Опять-таки,

если вы будете следовать моему правилу и относится к обозначенным условным единицам «как к числам», то не запутаетесь.

В ходе ваших действий «грамм» и «грамм» должны сократиться, а значит, в таком случае мы будем делить массу на плотность. В противном случае

вы бы получили граммы в квадрате

К примеру, даны масса раствора HCl — 150 грамм и плотность 1.76 г/мл. Нужно найти объем раствора.

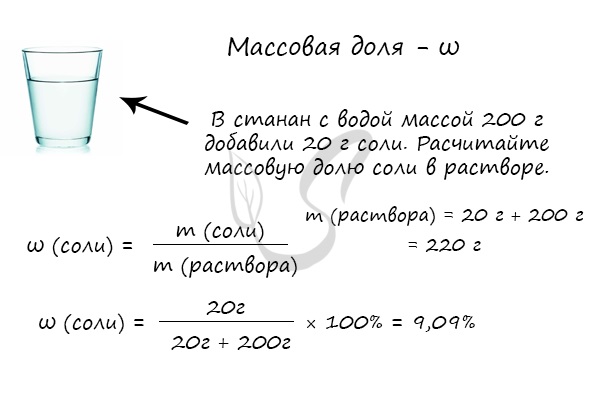

Массовая доля — ω

Массовой долей называют отношение массы растворенного вещества к массе раствора. Важно заметить, что в понятие раствора входит

как растворитель, так и само растворенное вещество.

Массовая доля вычисляется по формуле ω (вещества) = m (вещества) / m (раствора). Полученное число будет показывать массовую долю

в долях от единицы, если хотите получить в процентах — его нужно умножить на 100%. Продемонстрирую это на примере.

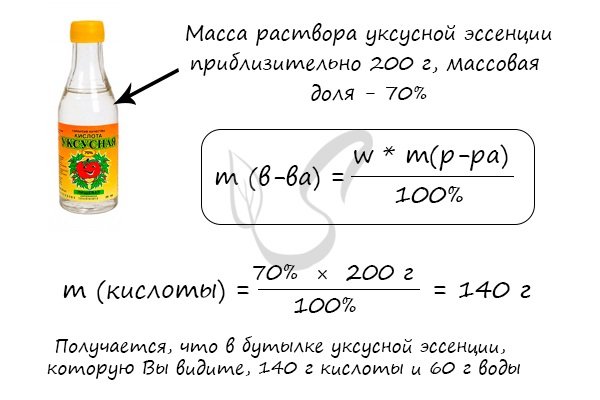

Решим несколько иную задачу и найдем массу чистой уксусной кислоты в широко известной уксусной эссенции.

© Беллевич Юрий Сергеевич 2018-2022

Данная статья написана Беллевичем Юрием Сергеевичем и является его интеллектуальной собственностью. Копирование, распространение

(в том числе путем копирования на другие сайты и ресурсы в Интернете) или любое иное использование информации и объектов

без предварительного согласия правообладателя преследуется по закону. Для получения материалов статьи и разрешения их использования,

обратитесь, пожалуйста, к Беллевичу Юрию.