Действие романа происходит в губернском городе ранней осенью. О событиях повествует хроникёр Г-в, который также является участником описываемых событий. Его рассказ начинается с истории Степана Трофимовича Верховенского, идеалиста сороковых годов, и описания его сложных платонических отношений с Варварой Петровной Ставрогиной, знатной губернской дамой, покровительством которой он пользуется.

Вокруг Верховенского, полюбившего «гражданскую роль» и живущего «воплощённой укоризной» отчизне, группируется местная либерально настроенная молодёжь. В нем много «фразы» и позы, однако достаточно также ума и проницательности. Он был воспитателем многих героев романа. Прежде красивый, теперь он несколько опустился, обрюзг, играет в карты и не отказывает себе в шампанском.

Ожидается приезд Николая Ставрогина, чрезвычайно «загадочной и романической» личности, о которой ходит множество слухов. Он служил в элитном гвардейском полку, стрелялся на дуэли, был разжалован, выслужился. Затем известно, что закутил, пустился в самую дикую разнузданность. Побывав четыре года назад в родном городе, он много накуролесил, вызвав всеобщее возмущение: оттаскал за нос почтенного человека Гаганова, больно укусил за ухо тогдашнего губернатора, публично поцеловал чужую жену… В конце концов все как бы объяснилось белой горячкой. Выздоровев, Ставрогин уехал за границу.

Его мать Варвара Петровна Ставрогина, женщина решительная и властная, обеспокоенная вниманием сына к её воспитаннице Дарье Шатовой и заинтересованная в его браке с дочерью приятельницы Лизой Тушиной, решает женить на Дарье своего подопечного Степана Трофимовича. Тот в некотором ужасе, хотя и не без воодушевления, готовится сделать предложение.

В соборе на обедне к Варваре Петровне неожиданно подходит Марья Тимофеевна Лебядкина, она же Хромоножка, и целует её руку. Заинтригованная дама, получившая недавно анонимное письмо, где сообщалось, что в её судьбе будет играть серьёзную роль хромая женщина, приглашает её к себе, с ними же едет и Лиза Тушина. Там уже ждёт взволнованный Степан Трофимович, так как именно на этот день намечено его сватовство к Дарье. Вскоре здесь же оказывается и прибывший за сестрой капитан Лебядкин, в туманных речах которого, перемежающихся стихами его собственного сочинения, упоминается некая страшная тайна и намекается на какие-то особенные его права.

Внезапно объявляют о приезде Николая Ставрогина, которого ожидали только через месяц. Сначала появляется суетливый Петр Верховенский, а за ним уже и сам бледный и романтичный красавец Ставрогин. Варвара Петровна с ходу задаёт сыну вопрос, не является ли Марья Тимофеевна его законной супругой. Ставрогин молча целует у матери руку, затем благородно подхватывает под руку Лебядкину и выводит её. В его отсутствие Верховенский сообщает красивую историю о том, как Ставрогин внушил забитой юродивой красивую мечту, так что она даже вообразила его своим женихом. Тут же он строго спрашивает Лебядкина, правда ли это, и капитан, трепеща от страха, все подтверждает.

Варвара Петровна в восторге и, когда её сын появляется снова, просит у него прощения. Однако происходит неожиданное: к Ставрогину вдруг подходит Шатов и даёт ему пощёчину. Бесстрашный Ставрогин в гневе хватает его, но тут же внезапно убирает руки за спину. Как выяснится позже, это ещё одно свидетельство его огромной силы, ещё одно испытание. Шатов беспрепятственно выходит. Лиза Тушина, явно неравнодушная к «принцу Гарри», как называют Ставрогина, падает в обморок.

Проходит восемь дней. Ставрогин никого не принимает, а когда его затворничество заканчивается, к нему тут же проскальзывает Петр Верховенский. Он изъявляет готовность на все для Ставрогина и сообщает про тайное общество, на собрании которого они должны вместе появиться. Вскоре после его визита Ставрогин направляется к инженеру Кириллову. Инженер, для которого Ставрогин много значит, сообщает, что по-прежнему исповедует свою идею. Её суть — в необходимости избавиться от Бога, который есть не что иное, как «боль страха смерти», и заявить своеволие, убив самого себя и таким образом став человекобогом.

Затем Ставрогин поднимается к живущему в том же доме Шатову, которому сообщает, что действительно некоторое время назад в Петербурге официально женился на Лебядкиной, а также о своём намерении в ближайшее время публично объявить об этом. Он великодушно предупреждает Шатова, что его собираются убить. Шатов, на которого Ставрогин прежде имел огромное влияние, раскрывает ему свою новую идею о народе-богоносце, каковым считает русский народ, советует бросить богатство и мужицким трудом добиться Бога. Правда, на встречный вопрос, а верит ли он сам в Бога, Шатов несколько неуверенно отвечает, что верит в православие, в Россию, что он… будет веровать в Бога.

Той же ночью Ставрогин направляется к Лебядкину и по дороге встречает беглого Федьку Каторжного, подосланного к нему Петром Верховенским. Тот изъявляет готовность исполнить за плату любую волю барина, но Ставрогин гонит его. Лебядкину он сообщает, что собирается объявить о своём браке с Марьей Тимофеевной, на которой женился «…после пьяного обеда, из-за пари на вино…». Марья Тимофеевна встречает Ставрогина рассказом о зловещем сне. Он спрашивает её, готова ли она уехать вместе с ним в Швейцарию и там уединённо прожить оставшуюся жизнь. Возмущённая Хромоножка кричит, что Ставрогин не князь, что её князя, ясного сокола, подменили, а он — самозванец, у него нож в кармане. Сопровождаемый её визгом и хохотом, взбешённый Ставрогин ретируется. На обратном пути он бросает Федьке Каторжному деньги.

На следующий день происходит дуэль Ставрогина и местного дворянина Артемия Гаганова, вызвавшего его за оскорбление отца. Кипящий злобой Гаганов трижды стреляет и промахивается. Ставрогин же объявляет, что не хочет больше никого убивать, и трижды демонстративно стреляет в воздух. История эта сильно поднимает Ставрогина в глазах общества.

Между тем в городе наметились легкомысленные настроения и склонность к разного рода кощунственным забавам: издевательство над новобрачными, осквернение иконы и пр. В губернии неспокойно, свирепствуют пожары, порождающие слухи о поджогах, в разных местах находят призывающие к бунту прокламации, где-то свирепствует холера, проявляют недовольство рабочие закрытой фабрики Шпигулиных, некий подпоручик, не вынеся выговора командира, бросается на него и кусает за плечо, а до того им были изрублены два образа и зажжены церковные свечки перед сочинениями Фохта, Молешотта и Бюхнера… В этой атмосфере готовится праздник по подписке в пользу гувернанток, затеянный женой губернатора Юлией Михайловной.

Варвара Петровна, оскорблённая слишком явным желанием Степана Трофимовича жениться и его слишком откровенными письмами к сыну Петру с жалобами, что его, дескать, хотят женить «на чужих грехах», назначает ему пенсион, но вместе с тем объявляет и о разрыве.

Младший Верховенский в это время развивает бурную деятельность. Он допущен в дом к губернатору и пользуется покровительством его супруги Юлии Михайловны. Она считает, что он связан с революционным движением, и мечтает раскрыть с его помощью государственный заговор. На свидании с губернатором фон Лембке, чрезвычайно озабоченным происходящим, Верховенский умело выдаёт ему несколько имён, в частности Шатова и Кириллова, но при этом просит у него шесть дней, чтобы раскрыть всю организацию. Затем он забегает к Кириллову и Шатову, уведомляя их о собрании «наших» и прося быть, после чего заходит за Ставрогиным, у которого только что побывал Маврикий Николаевич, жених Лизы Тушиной, с предложением, чтобы Николай Всеволодович женился на ней, поскольку она хоть и ненавидит его, но в то же время и любит. Ставрогин признается ему, что никак этого сделать не может, поскольку уже женат. Вместе с Верховенским они отправляются на тайное собрание.

На собрании выступает мрачный Шигалев со своей программой «конечного разрешения вопроса». Её суть в разделении человечества на две неравные части, из которых одна десятая получает свободу и безграничное право над остальными девятью десятыми, превращёнными в стадо. Затем Верховенский предлагает провокационный вопрос, донесли ли бы участники собрания, если б узнали о намечающемся политическом убийстве. Неожиданно поднимается Шатов и, обозвав Верховенского подлецом и шпионом, покидает собрание. Это и нужно Петру Степановичу, который уже наметил Шатова в жертвы, чтобы кровью скрепить образованную революционную группу-«пятёрку». Верховенский увязывается за вышедшим вместе с Кирилловым Ставрогиным и в горячке посвящает их в свои безумные замыслы. Его цель — пустить большую смуту. «Раскачка такая пойдёт, какой мир ещё не видал… Затуманится Русь, заплачет земля по старым богам…» Тогда-то и понадобится он, Ставрогин. Красавец и аристократ. Иван-Царевич.

События нарастают как снежный ком. Степана Трофимовича «описывают» — приходят чиновники и забирают бумаги. Рабочие со шпигулинской фабрики присылают просителей к губернатору, что вызывает у фон Лембке приступ ярости и выдаётся чуть ли не за бунт. Попадает под горячую руку градоначальника и Степан Трофимович. Сразу вслед за этим в губернаторском доме происходит также вносящее смуту в умы объявление Ставрогина, что Лебядкина — его жена.

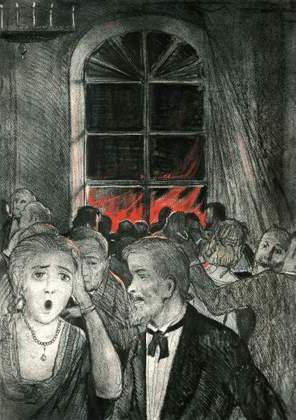

Наступает долгожданный день праздника. Гвоздь первой части — чтение известным писателем Кармазиновым своего прощального сочинения «Merci», а затем обличительная речь Степана Трофимовича. Он страстно защищает от нигилистов Рафаэля и Шекспира. Его освистывают, и он, проклиная всех, гордо удаляется со сцены. Становится известно, что Лиза Тушина среди бела дня пересела внезапно из своей кареты, оставив там Маврикия Николаевича, в карету Ставрогина и укатила в его имение Скворешники. Гвоздь второй части праздника — «кадриль литературы», уродливо-карикатурное аллегорическое действо. Губернатор и его жена вне себя от возмущения. Тут-то и сообщают, что горит Заречье, якобы подожжённое шпигулинскими, чуть позже становится известно и об убийстве капитана Лебядкина, его сестры и служанки. Губернатор едет на пожар, где на него падает бревно.

В Скворешниках меж тем Ставрогин и Лиза Тушина вместе встречают утро. Лиза намерена уйти и всячески старается уязвить Ставрогина, который, напротив, пребывает в нехарактерном для него сентиментальном настроении. Он спрашивает, зачем Лиза к нему пришла и зачем было «столько счастья». Он предлагает ей вместе уехать, что она воспринимает с насмешкой, хотя в какое-то мгновение глаза её вдруг загораются. Косвенно в их разговоре всплывает и тема убийства — пока только намёком. В эту минуту и появляется вездесущий Петр Верховенский. Он сообщает Ставрогину подробности убийства и пожара в Заречье. Лизе Ставрогин говорит, что не он убил и был против, но знал о готовящемся убийстве и не остановил. В истерике она покидает ставрогинский дом, неподалёку её ждёт просидевший всю ночь под дождём преданный Маврикий Николаевич. Они направляются к месту убийства и встречают по дороге Степана Трофимовича, бегущего, по его словам, «из бреду, горячечного сна, <…> искать Россию» В толпе возле пожарища Лизу узнают как «ставрогинскую», поскольку уже пронёсся слух, что дело затеяно Ставрогиным, чтобы избавиться от жены и взять другую. Кто-то из толпы бьёт её, она падает. Отставший Маврикий Николаевич успевает слишком поздно. Лизу уносят ещё живую, но без сознания.

А Петр Верховенский продолжает хлопотать. Он собирает пятёрку и объявляет, что готовится донос. Доносчик — Шатов, его нужно непременно убрать. После некоторых сомнений сходятся, что общее дело важнее всего. Верховенский в сопровождении Липутина идёт к Кириллову, чтобы напомнить о договорённости, по которой тот должен, прежде чем покончить с собой в соответствии со своей идеей, взять на себя и чужую кровь. У Кириллова на кухне сидит выпивающий и закусывающий Федька Каторжный. В гневе Верховенский выхватывает револьвер: как он мог ослушаться и появиться здесь? Федька неожиданно бьёт Верховенского, тот падает без сознания, Федька убегает. Свидетелю этой сцены Липутину Верховенский заявляет, что Федька в последний раз пил водку. Утром действительно становится известно, что Федька найден с проломленной головой в семи верстах от города. Липутин, уже было собравшийся бежать, теперь не сомневается в тайном могуществе Петра Верховенского и остаётся.

К Шатову тем же вечером приезжает жена Марья, бросившая его после двух недель брака. Она беременна и просит временного пристанища. Чуть позже к нему заходит молодой офицерик Эркель из «наших» и сообщает о завтрашней встрече. Ночью у жены Шатова начинаются роды. Он бежит за акушеркой Виргинской и потом помогает ей. Он счастлив и чает новой трудовой жизни с женой и ребёнком. Измотанный, Шатов засыпает под утро и пробуждается уже затемно. За ним заходит Эркель, вместе они направляются в ставрогинский парк. Там уже ждут Верховенский, Виргинский, Липутин, Лямшин, Толкаченко и Шигалев, который внезапно категорически отказывается принимать участие в убийстве, потому что это противоречит его программе.

На Шатова нападают. Верховенский выстрелом из револьвера в упор убивает его. К телу привязывают два больших камня и бросают в пруд. Верховенский спешит к Кириллову. Тот хоть и негодует, однако обещание выполняет — пишет под диктовку записку и берет на себя вину за убийство Шатова, а затем стреляется. Верховенский собирает вещи и уезжает в Петербург, оттуда за границу.

Отправившись в своё последнее странствование, Степан Трофимович умирает в крестьянской избе на руках примчавшейся за ним Варвары Петровны. Перед смертью случайная попутчица, которой он рассказывает всю свою жизнь, читает ему Евангелие, и он сравнивает одержимого, из которого Христос изгнал бесов, вошедших в свиней, с Россией. Этот пассаж из Евангелия взят хроникёром одним из эпиграфов к роману.

Все участники преступления, кроме Верховенского, вскоре арестованы, выданные Лямшиным. Дарья Шатова получает письмо-исповедь Ставрогина, который признается, что из него «вылилось одно отрицание, без всякого великодушия и безо всякой силы». Он зовёт Дарью с собой в Швейцарию, где купил маленький домик в кантоне Ури, чтобы поселиться там навечно. Дарья даёт прочесть письмо Варваре Петровне, но тут обе узнают, что Ставрогин неожиданно появился в Скворешниках. Они торопятся туда и находят «гражданина кантона Ури» повесившимся в мезонине.

Действие романа происходит в губернском городе ранней осенью. О событиях повествует хроникёр Г-в, который также является участником описываемых событий. Его рассказ начинается с истории Степана Трофимовича Верховенского, идеалиста сороковых годов, и описания его сложных платонических отношений с Варварой Петровной Ставрогиной, знатной губернской дамой, покровительством которой он пользуется.

Вокруг Верховенского, полюбившего «гражданскую роль» и живущего «воплощённой укоризной» отчизне, группируется местная либерально настроенная молодёжь. В нем много «фразы» и позы, однако достаточно также ума и проницательности. Он был воспитателем многих героев романа. Прежде красивый, теперь он несколько опустился, обрюзг, играет в карты и не отказывает себе в шампанском.

Ожидается приезд Николая Ставрогина, чрезвычайно «загадочной и романической» личности, о которой ходит множество слухов. Он служил в элитном гвардейском полку, стрелялся на дуэли, был разжалован, выслужился. Затем известно, что закутил, пустился в самую дикую разнузданность. Побывав четыре года назад в родном городе, он много накуролесил, вызвав всеобщее возмущение: оттаскал за нос почтенного человека Гаганова, больно укусил за ухо тогдашнего губернатора, публично поцеловал чужую жену… В конце концов все как бы объяснилось белой горячкой. Выздоровев, Ставрогин уехал за границу.

Его мать Варвара Петровна Ставрогина, женщина решительная и властная, обеспокоенная вниманием сына к её воспитаннице Дарье Шатовой и заинтересованная в его браке с дочерью приятельницы Лизой Тушиной, решает женить на Дарье своего подопечного Степана Трофимовича. Тот в некотором ужасе, хотя и не без воодушевления, готовится сделать предложение.

В соборе на обедне к Варваре Петровне неожиданно подходит Марья Тимофеевна Лебядкина, она же Хромоножка, и целует её руку. Заинтригованная дама, получившая недавно анонимное письмо, где сообщалось, что в её судьбе будет играть серьёзную роль хромая женщина, приглашает её к себе, с ними же едет и Лиза Тушина. Там уже ждёт взволнованный Степан Трофимович, так как именно на этот день намечено его сватовство к Дарье. Вскоре здесь же оказывается и прибывший за сестрой капитан Лебядкин, в туманных речах которого, перемежающихся стихами его собственного сочинения, упоминается некая страшная тайна и намекается на какие-то особенные его права.

Внезапно объявляют о приезде Николая Ставрогина, которого ожидали только через месяц. Сначала появляется суетливый Петр Верховенский, а за ним уже и сам бледный и романтичный красавец Ставрогин. Варвара Петровна с ходу задаёт сыну вопрос, не является ли Марья Тимофеевна его законной супругой. Ставрогин молча целует у матери руку, затем благородно подхватывает под руку Лебядкину и выводит её. В его отсутствие Верховенский сообщает красивую историю о том, как Ставрогин внушил забитой юродивой красивую мечту, так что она даже вообразила его своим женихом. Тут же он строго спрашивает Лебядкина, правда ли это, и капитан, трепеща от страха, все подтверждает.

Варвара Петровна в восторге и, когда её сын появляется снова, просит у него прощения. Однако происходит неожиданное: к Ставрогину вдруг подходит Шатов и даёт ему пощёчину. Бесстрашный Ставрогин в гневе хватает его, но тут же внезапно убирает руки за спину. Как выяснится позже, это ещё одно свидетельство его огромной силы, ещё одно испытание. Шатов беспрепятственно выходит. Лиза Тушина, явно неравнодушная к «принцу Гарри», как называют Ставрогина, падает в обморок.

Проходит восемь дней. Ставрогин никого не принимает, а когда его затворничество заканчивается, к нему тут же проскальзывает Петр Верховенский. Он изъявляет готовность на все для Ставрогина и сообщает про тайное общество, на собрании которого они должны вместе появиться. Вскоре после его визита Ставрогин направляется к инженеру Кириллову. Инженер, для которого Ставрогин много значит, сообщает, что по-прежнему исповедует свою идею. Её суть — в необходимости избавиться от Бога, который есть не что иное, как «боль страха смерти», и заявить своеволие, убив самого себя и таким образом став человекобогом.

Затем Ставрогин поднимается к живущему в том же доме Шатову, которому сообщает, что действительно некоторое время назад в Петербурге официально женился на Лебядкиной, а также о своём намерении в ближайшее время публично объявить об этом. Он великодушно предупреждает Шатова, что его собираются убить. Шатов, на которого Ставрогин прежде имел огромное влияние, раскрывает ему свою новую идею о народе-богоносце, каковым считает русский народ, советует бросить богатство и мужицким трудом добиться Бога. Правда, на встречный вопрос, а верит ли он сам в Бога, Шатов несколько неуверенно отвечает, что верит в православие, в Россию, что он… будет веровать в Бога.

Той же ночью Ставрогин направляется к Лебядкину и по дороге встречает беглого Федьку Каторжного, подосланного к нему Петром Верховенским. Тот изъявляет готовность исполнить за плату любую волю барина, но Ставрогин гонит его. Лебядкину он сообщает, что собирается объявить о своём браке с Марьей Тимофеевной, на которой женился «…после пьяного обеда, из-за пари на вино…». Марья Тимофеевна встречает Ставрогина рассказом о зловещем сне. Он спрашивает её, готова ли она уехать вместе с ним в Швейцарию и там уединённо прожить оставшуюся жизнь. Возмущённая Хромоножка кричит, что Ставрогин не князь, что её князя, ясного сокола, подменили, а он — самозванец, у него нож в кармане. Сопровождаемый её визгом и хохотом, взбешённый Ставрогин ретируется. На обратном пути он бросает Федьке Каторжному деньги.

На следующий день происходит дуэль Ставрогина и местного дворянина Артемия Гаганова, вызвавшего его за оскорбление отца. Кипящий злобой Гаганов трижды стреляет и промахивается. Ставрогин же объявляет, что не хочет больше никого убивать, и трижды демонстративно стреляет в воздух. История эта сильно поднимает Ставрогина в глазах общества.

Между тем в городе наметились легкомысленные настроения и склонность к разного рода кощунственным забавам: издевательство над новобрачными, осквернение иконы и пр. В губернии неспокойно, свирепствуют пожары, порождающие слухи о поджогах, в разных местах находят призывающие к бунту прокламации, где-то свирепствует холера, проявляют недовольство рабочие закрытой фабрики Шпигулиных, некий подпоручик, не вынеся выговора командира, бросается на него и кусает за плечо, а до того им были изрублены два образа и зажжены церковные свечки перед сочинениями Фохта, Молешотта и Бюхнера… В этой атмосфере готовится праздник по подписке в пользу гувернанток, затеянный женой губернатора Юлией Михайловной.

Варвара Петровна, оскорблённая слишком явным желанием Степана Трофимовича жениться и его слишком откровенными письмами к сыну Петру с жалобами, что его, дескать, хотят женить «на чужих грехах», назначает ему пенсион, но вместе с тем объявляет и о разрыве.

Младший Верховенский в это время развивает бурную деятельность. Он допущен в дом к губернатору и пользуется покровительством его супруги Юлии Михайловны. Она считает, что он связан с революционным движением, и мечтает раскрыть с его помощью государственный заговор. На свидании с губернатором фон Лембке, чрезвычайно озабоченным происходящим, Верховенский умело выдаёт ему несколько имён, в частности Шатова и Кириллова, но при этом просит у него шесть дней, чтобы раскрыть всю организацию. Затем он забегает к Кириллову и Шатову, уведомляя их о собрании «наших» и прося быть, после чего заходит за Ставрогиным, у которого только что побывал Маврикий Николаевич, жених Лизы Тушиной, с предложением, чтобы Николай Всеволодович женился на ней, поскольку она хоть и ненавидит его, но в то же время и любит. Ставрогин признается ему, что никак этого сделать не может, поскольку уже женат. Вместе с Верховенским они отправляются на тайное собрание.

На собрании выступает мрачный Шигалев со своей программой «конечного разрешения вопроса». Её суть в разделении человечества на две неравные части, из которых одна десятая получает свободу и безграничное право над остальными девятью десятыми, превращёнными в стадо. Затем Верховенский предлагает провокационный вопрос, донесли ли бы участники собрания, если б узнали о намечающемся политическом убийстве. Неожиданно поднимается Шатов и, обозвав Верховенского подлецом и шпионом, покидает собрание. Это и нужно Петру Степановичу, который уже наметил Шатова в жертвы, чтобы кровью скрепить образованную революционную группу-«пятёрку». Верховенский увязывается за вышедшим вместе с Кирилловым Ставрогиным и в горячке посвящает их в свои безумные замыслы. Его цель — пустить большую смуту. «Раскачка такая пойдёт, какой мир ещё не видал… Затуманится Русь, заплачет земля по старым богам…» Тогда-то и понадобится он, Ставрогин. Красавец и аристократ. Иван-Царевич.

События нарастают как снежный ком. Степана Трофимовича «описывают» — приходят чиновники и забирают бумаги. Рабочие со шпигулинской фабрики присылают просителей к губернатору, что вызывает у фон Лембке приступ ярости и выдаётся чуть ли не за бунт. Попадает под горячую руку градоначальника и Степан Трофимович. Сразу вслед за этим в губернаторском доме происходит также вносящее смуту в умы объявление Ставрогина, что Лебядкина — его жена.

Наступает долгожданный день праздника. Гвоздь первой части — чтение известным писателем Кармазиновым своего прощального сочинения «Merci», а затем обличительная речь Степана Трофимовича. Он страстно защищает от нигилистов Рафаэля и Шекспира. Его освистывают, и он, проклиная всех, гордо удаляется со сцены. Становится известно, что Лиза Тушина среди бела дня пересела внезапно из своей кареты, оставив там Маврикия Николаевича, в карету Ставрогина и укатила в его имение Скворешники. Гвоздь второй части праздника — «кадриль литературы», уродливо-карикатурное аллегорическое действо. Губернатор и его жена вне себя от возмущения. Тут-то и сообщают, что горит Заречье, якобы подожжённое шпигулинскими, чуть позже становится известно и об убийстве капитана Лебядкина, его сестры и служанки. Губернатор едет на пожар, где на него падает бревно.

В Скворешниках меж тем Ставрогин и Лиза Тушина вместе встречают утро. Лиза намерена уйти и всячески старается уязвить Ставрогина, который, напротив, пребывает в нехарактерном для него сентиментальном настроении. Он спрашивает, зачем Лиза к нему пришла и зачем было «столько счастья». Он предлагает ей вместе уехать, что она воспринимает с насмешкой, хотя в какое-то мгновение глаза её вдруг загораются. Косвенно в их разговоре всплывает и тема убийства — пока только намёком. В эту минуту и появляется вездесущий Петр Верховенский. Он сообщает Ставрогину подробности убийства и пожара в Заречье. Лизе Ставрогин говорит, что не он убил и был против, но знал о готовящемся убийстве и не остановил. В истерике она покидает ставрогинский дом, неподалёку её ждёт просидевший всю ночь под дождём преданный Маврикий Николаевич. Они направляются к месту убийства и встречают по дороге Степана Трофимовича, бегущего, по его словам, «из бреду, горячечного сна, <…> искать Россию» В толпе возле пожарища Лизу узнают как «ставрогинскую», поскольку уже пронёсся слух, что дело затеяно Ставрогиным, чтобы избавиться от жены и взять другую. Кто-то из толпы бьёт её, она падает. Отставший Маврикий Николаевич успевает слишком поздно. Лизу уносят ещё живую, но без сознания.

А Петр Верховенский продолжает хлопотать. Он собирает пятёрку и объявляет, что готовится донос. Доносчик — Шатов, его нужно непременно убрать. После некоторых сомнений сходятся, что общее дело важнее всего. Верховенский в сопровождении Липутина идёт к Кириллову, чтобы напомнить о договорённости, по которой тот должен, прежде чем покончить с собой в соответствии со своей идеей, взять на себя и чужую кровь. У Кириллова на кухне сидит выпивающий и закусывающий Федька Каторжный. В гневе Верховенский выхватывает револьвер: как он мог ослушаться и появиться здесь? Федька неожиданно бьёт Верховенского, тот падает без сознания, Федька убегает. Свидетелю этой сцены Липутину Верховенский заявляет, что Федька в последний раз пил водку. Утром действительно становится известно, что Федька найден с проломленной головой в семи верстах от города. Липутин, уже было собравшийся бежать, теперь не сомневается в тайном могуществе Петра Верховенского и остаётся.

К Шатову тем же вечером приезжает жена Марья, бросившая его после двух недель брака. Она беременна и просит временного пристанища. Чуть позже к нему заходит молодой офицерик Эркель из «наших» и сообщает о завтрашней встрече. Ночью у жены Шатова начинаются роды. Он бежит за акушеркой Виргинской и потом помогает ей. Он счастлив и чает новой трудовой жизни с женой и ребёнком. Измотанный, Шатов засыпает под утро и пробуждается уже затемно. За ним заходит Эркель, вместе они направляются в ставрогинский парк. Там уже ждут Верховенский, Виргинский, Липутин, Лямшин, Толкаченко и Шигалев, который внезапно категорически отказывается принимать участие в убийстве, потому что это противоречит его программе.

На Шатова нападают. Верховенский выстрелом из револьвера в упор убивает его. К телу привязывают два больших камня и бросают в пруд. Верховенский спешит к Кириллову. Тот хоть и негодует, однако обещание выполняет — пишет под диктовку записку и берет на себя вину за убийство Шатова, а затем стреляется. Верховенский собирает вещи и уезжает в Петербург, оттуда за границу.

Отправившись в своё последнее странствование, Степан Трофимович умирает в крестьянской избе на руках примчавшейся за ним Варвары Петровны. Перед смертью случайная попутчица, которой он рассказывает всю свою жизнь, читает ему Евангелие, и он сравнивает одержимого, из которого Христос изгнал бесов, вошедших в свиней, с Россией. Этот пассаж из Евангелия взят хроникёром одним из эпиграфов к роману.

Все участники преступления, кроме Верховенского, вскоре арестованы, выданные Лямшиным. Дарья Шатова получает письмо-исповедь Ставрогина, который признается, что из него «вылилось одно отрицание, без всякого великодушия и безо всякой силы». Он зовёт Дарью с собой в Швейцарию, где купил маленький домик в кантоне Ури, чтобы поселиться там навечно. Дарья даёт прочесть письмо Варваре Петровне, но тут обе узнают, что Ставрогин неожиданно появился в Скворешниках. Они торопятся туда и находят «гражданина кантона Ури» повесившимся в мезонине.

Пересказал Е. А. Шкловский.

Источник: Все шедевры мировой литературы в кратком изложении. Сюжеты и характеры. Русская литература XIX века / Ред. и сост. В. И. Новиков. — М. : Олимп : ACT, 1996. — 832 с.

Содержание

- Смысл названия «Бесы»

- Смысл произведения Бесы

- Смысл финала

Шестой по счету роман Фёдора Михайловича Достоевского «Бесы» был написан в 1872 году. Автор находился под впечатлениями от событий 1869 года, когда группа молодых людей под предводительством анархиста Нечаева убила студента Иванова, подозревая его в предательстве идей революционного кружка.

Достоевский не планировал грандиозную вещь: ему хотелось на нескольких страницах высказаться на тему возникшей «нечаевщины» и подобных политических явлений. И даже не в художественном стиле задумывалось произведение, но в итоге из-под пера вышел роман-предсказание, не теряющий свою актуальность до сих пор.

Смысл названия «Бесы»

Лаконичное название говорит само за себя: автор жестко и категорично оценивает происходящее. Анархию он не поддерживает, террор его ужасает. А потому неудивительно, что Достоевский называет революционеров бесами. Книжный прообраз Нечаева – сын учителя Пётр Верховенский. Убитый Иванов на страницах романа становится Иваном Шатовым, пострадавшим за «измену идеалам». Но не одни только нигилисты получают нелестную характеристику.

«Бесы» и «бесенята» живут в каждом персонаже произведения. Властолюбивая Варвара Ставрогина, либерал и идеалист Степан Трофимович, «пятёрка Верховенского», – все они в той или иной степени покорны своим страстям, по-своему одержимы. Как токи электростанции проходят по всему городу, так и через весь роман скользит душевная борьба, тоска по абсолюту главного героя Николая Всеволодовича Ставрогина.

Главным «бесом» Фёдор Михайлович называл именно духовный упадок, распад личности всего народа Российской империи, как нельзя лучше проявившихся в лице Ставрогина. Внутренняя гниль неминуемо приведёт к внешней: собирательный образ Николая Всеволодовича несёт в себе мысль о грядущей исторической катастрофе.

Смысл произведения Бесы

Начав писать документальное эссе, Достоевский за пару лет пишет пророчество: меньше, чем через полвека «верховенские» и «нечаевы» станут во главе его родины.

В середине XIX века набирали силу нигилистические настроения среди интеллигенции и разночинцев. То там, то здесь возникали кружки единомышленников, где критиковали не только монархию, но и бытовой уклад в целом. На примере Верховенского и его «пятёрки» писатель показывает своё отношение к революционному движению. Петр предстает перед читателем не только хитрым и коварным, но и изощренно-жестоким. И это выражается даже не в хладнокровном убийстве Шатова. Молодой анархист считает, что только десятая часть народа достойна перемен и лучшей жизни, остальные могут довольствоваться услужением элите. Грош-цена высокопарным идеям и словам «нечаевцев», если в человеке они видят только пушечное мясо, средство к достижению целей.

Фёдор Михайлович выводит в главном герое основную проблему революционных настроений. Персонаж с символической фамилией Ставрогин («ставр» по-гречески «крест») на протяжении всего роман раздираемый противоречиями. С одной стороны – отход от традиций и преданий (а значит, и от веры, от жизни простого народа), с другой – внутренняя борьба за обретение Бога. Но силы не равны: Николай ищет ответы умом, а не сердцем, что приводит к искаженному восприятию. Именно этот душевный хаос главного героя (в частности) и каждого персонажа (в целом) и подводит к событиям начала следующего столетия. Достоевский «Бесами» предостерегал об опасности, как оказалось в дальнейшем, слишком поздно.

Смысл финала

Сестра Шатова получает от Ставрогина письмо, в котором он приглашает ее к себе в Швейцарию. В это же время доходи слух, что Николай вернулся в Скворешники. Дарья и Варвара Петровна обнаруживают несчастного повесившимся в мезонине. Предсмертная записка гласит: «Я сам». Финал оставляет леденящее, жуткое ощущение. Главный герой, не нашедший в себе силы и духовный ориентир, самостоятельно подписывает приговор всей своей жизни.

Эпизод в книге, где вспоминается евангельская притча, делает концовку ясней: Степан Трофимович сравнивает Россию с бесноватым, из которого Христос изгнал легион. Страсти Ставрогина в конце концов одерживают над ним победу: Николай не встречает Бога, не находит правду, мечется по собственной внутренней пустоте. Писатель таким многострадальным «ставрогиным» видит и свой народ, также не сумевший противостоять «легиону».

На чтение 24 мин Просмотров 7.8к. Опубликовано 20.12.2020

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ «Бесы» менее 3 минут и подробно по частям и главам за 19 минут.

Роман «Бесы» Федор Михайлович Достоевский написал в 1872 году, находясь под впечатлением от революционных веяний в Российской Империи. Сюжет произведения основывается на том, что автор осуждает анархию и террор, показывая различного рода жизненные испытания и душевные терзания героев. Именно поэтому роман считается одним из наиболее политизированных творений писателя.

Очень краткий пересказ романа «Бесы»

Степан Трофимович Верховенский – дважды овдовевший мужчина средних лет, принимает предложение своей старой знакомой Варвары Петровны Ставрогиной, стать наставником и воспитателем для ее юного сына Николая.

Повзрослев, Николай Ставрогин отправляется в Петербург на учебу. А вскоре по родному городу начинают расползаться слухи о том, что там он ведет разгульный и безответственный образ жизни. Спустя несколько лет он возвращается домой, где на удивление всем производит впечатление воспитанного и благородного господина.

Однако, спустя совсем немного времени дебоширит и ведет себя неподобающе в обществе. Это поведение списывают на белую горячку и отправляют Николая на лечение. Поправившись, молодой человек уезжает в путешествие заграницу.

Там у юноши случается знакомство и дружба с Лизаветой Тушиной, дочерью старой подруги его матери. По приезде Лизы в город, Варвара Петровна понимает, что они с Николаем из-за чего-то поссорились.

Замечая, что между Николаем и ее воспитанницей Дашей завязалось общение, Варвара Петровна спешит выдать девушку замуж за Степана Трофимовича, опасаясь начала отношений между Дарьей и сыном.

В стране начинаются беспокойства, вызванные недовольством существующего порядка. И городок, где происходит действие романа – не исключение, там тоже растут революционные волнения.

В день губернаторского праздника всеобщее веселье омрачает убийство брата и сестры Лебядкиных и поджог на месте преступления. Многие в городе подозревают, что это дело рук Николая. Толпа, не разобравшись, отыгрывается на Лизе, оказавшейся в пекле событий в неподходящее время, обвинив ее в связи со Ставрогиным и убивая.

Члены революционной пятерки, под предводительством внезапно явившегося в город Петра Верховенского, родного сына Степана Трофимовича, убивают Шатова, бывшего местного революционера, из-за того, что он предал веру в их общие идеи и попытался изолироваться от общества. Бывший друг Шатова, Кириллов берет вину на себя, а затем, согласно собственно разработанной теории, совершает самоубийство. Петр, тем временем, спешит уехать заграницу.

В имении Скворешники Варвара Петровна и Дарья находят повешенного Николая и записку, в которой он просит никого не винить в своей смерти, он ушел самостоятельно.

Главные герои и их характеристика:

- Варвара Петровна Ставрогина – знатная и богатая помещица, владеющая имением Скворешники и занимающая влиятельное положение в губернии. Обладает большим наследством, оставленным отцом – богатым откупщиком, и связями со многими людьми, благодаря покойному мужу. Она приходится матерью Николаю, покровительствует Степану Трофимовичу и благосклонна к Дарье Шатовой. Она умна и добра, но у нее злопамятный характер.

- Лизавета Николаевна Тушина –молодая, образованная и очень красивая девушка. Она помолвлена с Маврикием Николаевичем, но влюблена в Николая. За границей у них завязывается роман, который в итоге ни к чему не приводит. Значительно позже они проводят ночь вместе, тогда девушка понимает, что Николай ее никогда не любил.

- Петр Степанович Верховенский – главный «бес», сын Степана Трофимовича, основатель тайной революционной «пятерки». По его внешнему виду казалось, что его ничего не может смутить. Хитрый, продуманный, самодовольный и одержимый дикими идеями. Из-за своего характера почти никому не нравится, хотя обладает приятной внешностью.

- Николай Всеволодович Ставрогин – воспитанник Верховенского, единственный сын Варвары Петровны. По глупости, будучи пьяным, женился на Марии Лебядкиной. Хорош собой, отлично воспитан, но равнодушный ко многому, дамский угодник.

- Степан Трофимович Верховенский – близкий друг Варвары Ставрогиной, пользуется ее благосклонностью, живет за ее счет, учит ее сына Николая. Идеалист и либерал старой закалки. Несмотря на немолодой возраст, сохраняет былую красоту, щеголяет солидностью своих лет. Умен и проницателен, обладает добрым нравом, но достаточно безволен.

Второстепенные герои и их характеристика:

- Алексей Нилыч Кириллов – инженер-строитель, философ и революционер. Друг Шатова. Раньше был глубоко верующим, стал атеистом. Разрабатывает собственную концепцию избавления от бога и обретения свободы воли путем самоубийства, считая его высшим проявлением своеволия. Юноша одержим идеями революции и самопожертвования, этим пользуется Верховенский.

- Виргинский – чиновник лет тридцати, входящий в революционную «пятерку», причастный к убийству Шатова. Имеет спокойный и скромный характер. Женат на Арине Прохоровне Виргинской. Часто присутствует на слушаниях Степана Трофимовича.

- Сергей Васильевич Липутин – участник революционной «пятерки», губернский чиновник, ярый либерал и атеист, подчиненные его не уважают, а светское общество от него отворачивается и считает странным. Он уже в возрасте, женат на девушке значительно младше его, от первого брака имеет трех взрослых дочерей. Строг со всеми членами семьи. Скупой и мелочный человек, но благодаря этим качествам сколотил целое состояние. Довольно умный и образованный мужчина, любит пошутить и повеселиться. Любит послушать сплетни, очень любопытен и пытлив.

- Эркель – член тайной организации Верховенского. Принимает участие в убийстве Шатова, за что его арестовывают. Невероятно молчаливый человек, безусловно преданный общему делу и конкретно Петру Степановичу.

- Маврикий Николаевич – артиллерийский капитан пятидесяти лет, высокий, статный, благородный и симпатичный мужчина. С виду строг и хладнокровен, но на самом деле обладает очень добрым нравом. Помолвлен с Лизаветой Николаевной Тушиной. Знает, что у ней тайный роман с Николаем, но любит Лизавету и все ей прощает.

- Андрей Антонович фон Лембке – губернатор, муж Юлии Михайловны, обязанный ей своей высокой должностью. Имеет немецкое происхождение, сочиняет романы, имеет тихий и спокойный характер, подчиняется супруге.

- Мария Тимофеевна Лебядкина – городская сумасшедшая, которую прозвали Хромоножкой. Является супругой Николая Ставрогина, женившегося на ней на спор и теперь не знавшего, как от нее избавится. Живет с братом – капитаном Лебядкиным, он ее избивает и все деньги, посланные Николаем супруге на содержание, тратит на выпивку.

- Лямшин – входит в революционную «пятерку» Верховенского. Один из убийц Шатова, во время преступления у него случается срыв. Спустя несколько дней мучений он идет в полицию и сдается. Любит мерзко шутить, по натуре невероятно труслив.

- Игнат Тимофеевич Лебядкин – спившийся капитан, поэт. Брат психически нездоровой Марии Тимофеевны, использует сестру, чтобы получать деньги от ее мужа. Жестоко обращается с сестрой, пользуясь ее тяжелым положением.

- Федька Каторжный – скрывающийся от закона преступник, вор и убийца. Сотрудничает с Петром Верховенским, чтобы получить паспорт. Его обвинили в убийстве Лебядкиных, вскоре после этого он был найден с проломленным черепом.

- Отец Тихон – священнослужитель, у которого исповедается Николай Ставрогин перед тем, как наложить на себя руки.

- Дарья Павловна Шатова – сестра Ивана Шатова, живет у своей наставницы – Варвары Петровны. Девушке около двадцати, характер у нее тихий, мягкий и покладистый, она скромна и рассудительна, но ради любви готова многим пожертвовать. Находится в романтических отношениях с Николаем, Варвара Петровна, недовольная этим, пожелала выдать ее замуж за старшего Верховенского, но тот не захотел этого.

- Антон Лаврентьевич Г-в – рассказчик, от имени которого идет повествование, друг Степана Трофимовича. Молодой служащий, честен и всегда готов помочь нуждающимся.

- Юлия Михайловна – жена губернатора. Сорокалетняя женщина с жестким и властным характером, но одновременно немного наивная. Хочет раскрыть революционный заговор.

- Толкаченко – сорокалетний мужчина, член тайной организации и «пятерки» Верховенского, хорошо знает народ. Участвует в убийстве Шатова. Позже его арестовывают при попытке бегства.

- Шигалев — член «пятерки» Верховенского, один из организаторов убийства Шатова, впоследствии отказавшийся в нем участвовать, благодаря этому после раскрытия преступления ему удается оправдаться. Всегда хмурится и выглядит озлобленно. Приехал в город за два месяца до основных событий романа. Много философствует, у него есть собственная рукопись – «Система», в которой он описывает возможное устройство общества. По его мнению, нужно разделить людей на две группы: правящая элита и рабы. Ходят слухи, что Шигалев публикуется в известном журнале.

- Семён Егорович Кармазинов – известный писатель. На балу читает свою рукопись, основанную на нигилистическом учении, которая не производит впечатления на зрителей, и он бесславно уходит.

- Иван Павлович Шатов – член тайной организации Верховенского, разочаровавшийся в революционной идеологии. Был крепостным у Ставрогиной, потом обучался у Степана Трофимовича, поступил в университет, но был отчислен. В людях больше всего ценит честность, не представляет, что его может полюбить хоть одна женщина, считает себя уродом. Часто омрачен и молчит, полностью отдается своим идеям, иногда доходя до фанатизма.

- Артемий Павлович Гаганов – отставной гвардейский капитан, злопамятный, гордый и мстительный. Враждует с Николаем Ставрогиным, который как-то схватил его отца за нос и протащил так несколько шагов. Отказывается разобраться мирно и вызывает Николая на дуэль, которая заканчивается ничем.

Краткое содержание романа «Бесы» подробно по частям и главам

Часть первая

Глава 1. Вместо введения несколько подробностей из биографии многочтимого Степана Трофимовича Верховенского

Рассказчиком в романе «Бесы» выступает некий Антон Лаврентьевич Г-в, близкий друг одного из героев и непосредственный участник событий.

Действие происходит в губернском городе, в котором живет знатная и богатая дама – Варвара Петровна Ставрогина, занимающая отличное положение в обществе. Она умна и рассудительна, но иногда до крайности властна и своенравна.

По соседству со Ставрогиной живет Степан Трофимович Верховенский –мужчина, которому с годами удалось не потерять юношеской наивности. Несмотря на свою чрезмерную доверчивость, он был очень умен и проницателен. В губернском городе вокруг него собирался кружок либерально настроенных людей, которые были готовы его слушать.

Отношения между Варварой и Степаном были непростыми. Что-то между крепкой товарищеской любовью и мучительной ненавистью. Варвара Петровна испытывала к Верховенскому сильную, почти материнскую привязанность, но взамен ждала от него полного подчинения. Степан Трофимович пользовался попечительством своей влиятельной подруги, он уважал и, скорее всего, даже терпел ее, но тяжело переносил ее, время от времени впадающую в крайность, деспотизм.

Дважды овдовев и живя один, Верхоенский с радостью принимает предложение Варвары Петровны, и становится наставником и воспитателем для ее единственного сына Николая. Между героями завязывается настоящая крепкая дружба.

Глава 2. Принц Гарри. Сватовство

Сильнее, чем к Верховенскому, Варвара Петровна была привязана только к Николаю – Принцу Гарри, как его называли в детстве.

Николай уже совсем повзрослел и уехал учиться в столицу, где дослужился до звания офицера, но из-за участия в дуэли был разжалован в рядовые. Почти сразу Николаю удалось выслужиться, но неожиданно он уходит в отставку и пускает свою жизнь на самотек.

После отъезда молодого человека по городку начали расползаться слухи о его щегольском и безответственном образе жизни – все это длилось на протяжении нескольких лет. И каково же было всеобщее удивление, когда Ставрогин вернулся в родные края в наилучшем виде, производя впечатление вполне приличного человека.

Однако, Николай быстро показал свое истинное «Я», совершив несколько скандальных и совершенно непозволительных в приличном обществе поступков. Он повздорил с почетным членом клуба и, схватив его за нос, протащил несколько метров, набросился и поранил губернатора, целует чужую жен Ставрогин был окрещен психически нездоровым и направлен в лечебницу. Поправившись, Николай поспешил уехать заграницу и побывать в разных европейских странах.

За границей Николай познакомился с Лизой Тушиной, дочерью давней приятельницы его матери. Вскоре Лиза вернулась в город, и Ставрогиной стало понятно, что они с Николаем крупно повздорили.

Одновременно с этим Варвара Петровна заподозрила взаимный интерес между сыном и ее воспитанницей Дашей Шатовой, которая путешествовала вместе с Лизаветой и ее матерью. Опасаясь того, что сын может жениться на Дарье, не подходящей ему по статусу, она собралась выдать девушку за Степана Трофимовича.

Глава 3. Чужие грехи

Верховенский выслушал эту идею с некоторым опасением, но в то же время и с немалым воодушевлением. Сватовство было запланировано на ближайшее воскресенье.

Неожиданно появился инженер Липутин, старый знакомый Ставрогина и предупредил новоиспеченного жениха о том, что эта женитьба происходит совсем не из добрых помыслов, а чтобы скрыть что-то неприятное, напрямую связанное с Николаем.

Лизавета Тушина, подруга Николая, с которой они вместе путешествовали по Европе, тем временем тоже приехала в поместье – ее интересует Иван Шатов, в совершенстве владеющий несколькими языками.

Глава 4. Хромоножка

К Ивану Павловичу у дамы чисто профессиональный интерес. Она собирается начать работу над книгой и ей необходима помощь. Шатов сначала проявляет отзывчивость, но позже, узнав о связи Лизы с Лебядкиным (он сватался к девушке в письме), решительно отказывается от сотрудничества.

Как-то раз возле собора Ставрогину останавливает стоящая на коленях Мария Лебядкина, она смотрит на даму то робким благоговейным взглядом, то глупо смеется и все норовит поцеловать Варваре Петровне руку. Ставрогина спрашивает у девушки, кто она и откуда, нужна ли ей помощь, а потом дает 10 рублей и приглашает к себе. К ним присоединяется Лизавета. Подходя к карете, Варвара Петровна замечает хромоту Марии, женщина бледнеет и меняется в лице. Всю дорогу она находится в задумчивости – недавно ей пришло письмо от неизвестного отправителя, в котором говорилось о некой тайне и о том, что Варваре Петровне следует обратить внимание на хромую незнакомку.

Глава 5. Премудрый змей

В доме Варвару Петровну нетерпеливо ожидает Степан Трофимович – сегодня у него запланировано сватовство к Шатовой.

Мария Тимофеевна, только увидев Дашу, обвиняет ее в краже, якобы она передала сумму меньше, чем обещал Ставрогин. Хозяйка дома, разозлившись, встает на защиту воспитанницы. Тем временем в глазах Лизаветы всякий раз при виде Даши появляются огоньки злобы.

В усадьбу за сестрой заявляется Игнат Лебядкин. Он объявляет всем, что Мария сошла с ума, и, цитируя авторские стихи, намекает Варваре Петровне о страшной тайне, касающейся ее сына.

В это время, неожиданно для всех, домой из заграничного путешествия возвращается Николай Ставрогин, его сопровождает Петр Верховенский – молодые люди ехали в одном вагоне из Женевы. Пока Петр холодно здоровается с отцом, Варвара Петровна прямо спрашивает сына о его связи с Марией Тимофеевной. Николай вместо ответа целует у матери руку, аккуратно берет под руку Марию и отводит ее к карете.

Тем временем Петр рассказывает всем трогательную историю о том, как милосердный Николай Всеволодович помогал бесприютным Лебядкиным, Ставрогин внушил доверие Марии и так сильно поразил бедную Хромоножку, что та начала воображать Николая своим женихом. Он со скрытой угрозой просит подтвердить эту историю капитана Лебядкина, тот, испугавшись, говорит, что все это правда.

Варвара Петровна с облегчением умиляется такой доброте сына и, когда тот заходит в дом, просит прощения за незаслуженные упреки. Тем временем с Лизаветой что-то происходит — у нее начинается истерика, от избытка эмоций она падает в обморок. Шатов подходит к Ставрогину и дает ему пощечину, Николай Всеволодович хватает его, но тут же отпускает, после чего Иван беспрепятственно покидает дом.

Часть вторая

Глава 1. Ночь

По городу ползут слухи о том, что же происходит между Лизой и Ставрогиным. В то же время последний получает оскорбительное письмо от некого Гаганова, сына старшины, которого Николай, будучи не в себе, в шутку протащил за нос несколько метров. Гаганов решительно намерен стреляться, и Ставрогин ищет секунданта. Выбор падает на Алексея Нилыча.

Попутно Алексей Кириллов поведал товарищу свою идею. Она заключалась в избавлении от Бога и полного самосовершенствования путем самоубийства.

В этот же день Николай навещает Ивана Шатова и признается ему, что Марья на самом деле его жена, он согласился на свадьбу будучи пьяным, но пока ему удается это скрывать. Николай объяснил, что ударил молодого человека из-за того, что поступок Ставрогина по отношению к Лебядкиной его сильно разочаровал. Николай предупредил Ивана о том, что местные революционеры планируют убить его в отместку за то, что он предал их общие убеждения и практически полностью открестился от общества. Иван не придал этому предостережению большого значения.

Идя от Шатова, Николай встречает Федьку Каторжного – укрывающегося от закона преступника. Он, за определенную плату, готов оказать совершенно любую услугу. Однако, Николай отвечает, что это его не интересует и угрожает сдать Федьку властям.

Глава 2. Ночь (продолжение)

Капитан Лебядкин был трезв и постоянно пытался намекнуть шурину, что будет молчать о его браке с Марьей, если тот ему заплатит. Но Ставрогин объяснил, что скоро сам во всем признается. Марья была не в себе: кричала и хохотала, обзывая Николая самозванцем. Рассерженный молодой человек не стал этого долго терпеть и ушел.

Направляясь домой, он снова натыкается на Федьку, который снова озвучивает свое предложение. На этот раз Ставрогин ничего не говорит, а заливисто смеется и бросает мужчине кошелек с деньгами.

Глава 3. Поединок

Вскоре состоялась дуэль Ставрогина и Артемия Гаганова, который не согласился на примирение и изъявил желание стреляться. Гаганов стреляет первым и все три раза промахивается – ему удается только задеть пулей палец противника да прострелить шляпу. Ставрогин трижды стреляет в воздух, объясняя это тем, что больше не хочет никого убивать. Соперники расходятся. Николай, очевидно, рассчитывал на свою гибель на дуэли, поэтому уезжает домой в плохом расположении духа.

Вернувшись с дуэли, Николай посещает Дашу и просит ее быть осторожнее, чтобы мать не узнала о том, что между молодыми людьми был роман.

Глава 4. Все в ожидании

В городе узнают о благородном поведении Николая на дуэли и благодаря этому укрепляется его репутация чистой души человека.

Степан Трофимович Верховенский, поверив словам Липутина из местной революционной организации, всерьез забеспокоился о том, что женитьба, навязанная ему Ставрогиной, действительно скрывает какой-то нечистый замысел. Узнав об этом из писем Степана Трофимовича к сыну, Варвара Петровна была так возмущена, что объявила о прекращении любых взаимоотношений со старшим Верховенским, назначив ему при этом пенсионное жалование.

Глава 5. Пред праздником

В городе, как и во всей губернии, стало неспокойно. Повсюду устраивали поджоги, оскверняли иконы, рабочие с ближайшей разорившейся фабрики стали открыто показывать свое недовольство.

В это время жена губернатора, Юлия Михайловна, решает устроить праздник для того, чтобы оказать поддержку бедным гувернанткам. А младший Верховенский начал плести собственные интриги. Обзаведясь расположением губернаторши, желающей раскрыть революционный заговор.

Глава 6. Петр Степанович в хлопотах.

Во время беседы с губернатором и его женой Петр выдал Шатова, Кириллова и других заговорщиков и попросил несколько дней, чтобы разузнать об остальных.

Затем Петр зашел к Николаю Ставрогину, предложив посетить заседание тайного сообщества. В это время у него присутствовал некий Маврикий Николаевич, влюбленный в Лизу, с просьбой взять девушку в жены. Этот человек был уверен, что девушка испытывает к нему нежные чувства и презирает одновременно. Николай отвечает ему, что уже женат на Лебядкиной.

Глава 7. У наших

На собрании присутствуют около 15 человек, среди которых основные учредители и самые ярые борцы либерализма, так называемая «пятерка» Верховенского: Виргинский, Шигалев, Лямшин, Толкаченко и Липутин.

Мрачный профессор Щегалев высказывает свою идею о разделении общества на две неравные части: одна, которая значительно меньше, должна править, а та, что больше подчиняться.

Неожиданно Петр задал присутствующим провокационный вопрос: если бы они узнали о намечающемся политическом убийстве, совершили бы они донос? Все ответили отрицательно, но Шатов поднялся, оскорбил выступавшего и ушел с собрания. Петр на это и рассчитывал: он выбрал Ивана жертвой убийства, которое кровью скрепит его с сообщниками. Кириллов и Ставрогин тоже покинули собрание, отказавшись отвечать.

Глава 8. Иван-царевич

Петр догнал их и посвятил в свои идеи о том, что планирует создать великую смуту, а затем представить народу спасителя Ивана-царевича в лице Ставрогина.

Николай не хотел его слушать, а после и вовсе обвинил в том, что Верховенский намеревается подтолкнуть Ставрогина к расправе над Лебядкиными, чтобы иметь над ним власть. Испугавшись, Петр умоляет товарища пойти на примирение и не выдавать никому его плана убийства Шатова. В замен он обещает самостоятельно решить вопрос с Лебядкиными и наладить отношения Николая с Лизой.

Глава 9. Степана Трофимовича описали

К Степану Трофимовичу нагрянули чиновники. Обыскав его жилье, они нашли некоторые бумаги и прокламации и изъяли их. Мужчина был довольно сильно напуган, но собрав свое мужество и гордость в кулак, он решительно направился в гости к фон Лембке, где проходил праздник.

Глава 10. Флибустьеры. Роковое утро.

Недовольные рабочие фабрики нагрянули к губернатору. Тот счел это за мятеж и ужасно разозлился. Не вовремя пришедший объясниться, Степан Трофимович попал под его горячую руку, но Юлия Михайловна, возмущенная поведением мужа, пригласила старшего Верховенского к себе в салон, где уже собрались другие гости, в том числе Ставрогин и Лиза.

Когда разговор зашел о Лебядкиных, Николай решил, что пришло время во всем признаться и заявил, что уже пять лет женат на Хромоножке, что потрясло всех присутствующих.

Часть третья

Глава 1. Праздник. Отдел первый

Вскоре состоялся, организованный женой губернатора, праздник. Вечер начался с выступления известного писателя Кармазинова, читавшего свое сочинение о нигилизме. Выступил с обличительной речью и Степан Трофимович, объявивший Шекспира и Рафаэля выше социализма, а красоту – важнейшим условием существования человечества. Публика не поняла ни одного из выступающих и освистала.

Глава 2. Окончание праздника

Не дожидаясь окончания праздника, Лиза уехала вместе с Николаем в семейное имение Ставрогиных, а ночью стало известно о жестоком убийстве брата и сестры Лебядкиных и о поджоге, который устроили недовольные рабочие.

Лиза и Николай провели вместе ночь. Наутро Ставрогин предложил девушке уехать с ним заграницу, но та отказалась. Раздосадованный молодой человек проговорился, что заплатил за нее жизнью, но Лизавета не придала значения этим словам.

Тем временем пришел Петр и рассказал о ночном происшествии. Ставрогину пришлось признаться Лизе в том, что он знал об организации убийства, но не осмелился его остановить.

Глава 3. Законченный роман

В отчаянии девушка убежала и встретила преданного Маврикия Николаевича, который ждал ее всю ночь. Лиза и ее утешитель решили посетить место страшного ночного убийства. По пути они встретили старшего Верховенского, который собирался в путешествие – он поставил себе цель найти настоящую Россию.

На пожарище собралась толпа. Люди думали, что в случившемся виноват Ставрогин. Подошедшую Лизу узнали и решили, что она тоже причастна к смерти Лебядкиных, ведь она была в близких отношениях с Николаем. Кто-то из толпы ударил ее, а затем подключились остальные и стали наносить удар за ударом. Маврикий Николаевич хотел вступиться за возлюбленную, но не совладал с толпой – его тут же оттолкнули. Набросившаяся толпа забивает Лизавету до потери сознания, и вскоре девушка умирает.

Глава 4. Последнее решение

Петр продолжает развивать ранее начатые интриги. Собрав пятерку своих сообщников, он сообщает, что Шатов собирается предать их, совершив донос, и предлагает расправится с Иваном за это. Заговорщики соглашаются, что это необходимо ради общего дела.

Затем Верховенский обращается к Кириллову, чтобы тот взял вину за убийство на себя, ведь он все равно собирается совершить самоубийство из личных помыслов. В доме Кириллова Верховенский натыкается на Федьку Каторжного. Эта нежеланная встреча приводит Петра в ярость, в гневе он выхватывает револьвер и целится в Федьку, но тому удается сбежать.

Верховенский загадочно заявляет, что больше преступнику пить не придется. На следующий день Каторжного находят с проломленным черепом. Липутин, сторонник Верховенского, удостоверился, что его покровитель обладает действительно большим могуществом и теперь намеревается бежать из города.

Глава 5. Путешественница

Шатова навещает его бывшая жена, которая ушла от него несколько лет назад к другому мужчине. Она беременна и ей негде жить, поэтому девушка надеется на помощи у единственного близкого для нее человека. Шатов все еще испытывает к ней чувства, поэтому разрешает остаться. Ночью у несчастной начинаются схватки, и Иван отправляется за акушеркой, а позже даже помогает принять роды.

Тайно Шатов мечтает о спокойной и размеренной жизни простого рабочего человека. Ему хочется быть рядом с женой и ребенком, которого он назвал своим сыном. Но для начала нужно окончательно разобраться с прежней революционной жизнью.

Этой же ночью к Шатову заходит офицер Эркель из революционной пятерки и приглашает на собрание. Вместе они направляются в парк, где уже поджидает свита заговорщиков.

Глава 6. Многотрудная ночь

Эркель занимает в «пятерке» место Шигалева, который является одним из главных организаторов нападения, но в последний момент наотрез отказывается от участия, посчитав, что так он отклонится от правильного пути.

Верховенский в упор стреляет в Ивана, а затем вся пятерка привязывает к телу камни в качестве груза и топит в пруду. После совершения убийства Петр направляется к Киррилову, чтобы проконтролировать его самоубийство и заставить написать предсмертную записку с признанием. Кириллов выполняет указание, а затем стреляет в себя.

Петр скоропостижно уезжает в Петербург, а затем и вовсе покидает страну.

Глава 7. Последнее странствование Степана Трофимовича

В дороге Степан Трофимович встречает незнакомку и выдает ей всю историю своей жизни, а она в ответ приводит ему цитату из Евангелия, где говорится о бесах, изгнанных из человека и вселившихся в свиней.

После долгих странствий он находит свое последнее пристанище в крестьянской избе, где умирает от случившегося с ним приступа на руках у Варвары Петровны, примчавшейся к нему в последний момент. В последние минуты жизни он продолжает историю незнакомки и сравнивает Россию с тем самым одержимым из которого Иисус изгнал бесов.

Глава 8. Заключение

Один из революционеров, Лямшин, не выдержав душевных мук, сдает всех участников преступления, кроме Петра Верховенского. Всех арестовывают, но Шигалеву, в последний момент передумавшему убивать Шатова, удается оправдаться.

Отчаявшийся Николай Ставрогин пишет письмо Дарье, в котором предлагает уехать в Швейцарию и искренне раскаивается. Дарью беспокоит такое известие, и она делится своими переживаниями с матерью Николая. Вместе женщины едут в Скворешники, где находят молодого человека повесившимся. Перед смертью юноша исповедовался у Отца Тихона и оставляет короткую записку: «Никого не винить, я сам…»

Кратко об истории создания произведения

На создание этой книги Ф. М. Достоевского вдохновило «нечаевское дело». Оно заключалось в убийстве слушателя Петровской земельной академии И. П. Иванова пятью заговорщиками из тайного общества под названием «Народная расправа».

Подробности убийства на идеологической почве, политические взгляды и нравы преступников, личность их предводителя и стали основой для создания «Бесов». Автор преследовал идею не только погрузить читателя в суть конкретного события, но и показать свое видение причин того, что толкает людей на подобного рода поступки.

В 1869 году это произведение было задумано как роман о Нечаеве и его последователях. Достоевский предполагал сделать террориста-революционера главным героем в образе Петра Верховенского.Роман впервые был напечатан в «Русском вестнике» в 1872 году, а спустя год вышел в отдельном издании.

Несмотря на то, что произведение, казалось бы, повествует о бесе, как о конкретной личности, главным бесом Достоевский всегда считал духовный упадок. Суть произведения в необходимости веры в нечто лучшее и стремлении к духовному просветлению.

Анализ романа «Бесы» (Ф. М. Достоевский)

Предпосылкой к написанию романа «Бесы» для Федора Михайловича послужили материалы из уголовного дела Нечаева – организатора тайного общества, целью которого были подрывные политические акции. Во времена автора это событие прогремело на всю империю. Однако ему удалось из небольшой газетной вырезки сделать глубокое и насыщенное произведение, которое считают эталоном не только русские, но и зарубежные писатели.

Содержание:

- 1 История создания

- 2 Жанр, направление

- 3 Суть

- 4 Главные герои и их характеристика

- 5 Темы и настроение

- 6 Главная мысль

- 7 Чему учит?

- 8 Критика

История создания

Федор Михайлович Достоевский отличался упорством и требовательностью. В один миг, пережив очередной эпилептический припадок, автор пришел к выводу, что новое произведение его совершенно не устраивает. Тогда он полностью уничтожил свое творение, но оставил нетронутой идею романа – историю о нигилистах, чье отрицание зашло слишком далеко.

Далее Достоевский заново берется за написание «Бесов» — так свет увидел вторую версию произведения. Писатель не успевал сдать работу к назначенному издателем сроку, но и не хотел предавать себя и отдавать публике произведение, которое его не устраивает. Катков, издатель автора, только разводил руками, ведь писатель обеспечивал себя и семью только авансами за книги, но готов был жить впроголодь, лишь бы не выпускать сырой материал.

Жанр, направление

В романе «Бесы» необычайно переплетаются такие качества, как хроникальность, суровый историзм мышления, философичность, но при этом писатель смотрел в будущее и говорил о том, что будет волновать и его потомков. Именно за данным романом надежно закрепилось обозначение: «роман-пророчество».

Действительно, большинство читателей отмечает провидческий дар Достоевского, ведь в романе отражены проблемы не только того времени, но и вопросы сегодняшнего информационного общества. Автор проникновенно изображает основную угрозу для будущего общественности – замещение устоявшихся понятий на неестественные бесовские догмы.

Направление творчества писателя – реализм, так как он изображает действительность во всем ее многообразии.

Суть

События происходят в провинциальном городке во владениях Варвары Петровны Ставрогиной. Ребенок вольнодумца Степана Трофимовича Верховенского, Петр Верховенский — основной идейный наставник революционного движения. Петр старается привлечь к революционерам Николая Всеволодовича Стравогина, который является сыном Варвары Петровны.

Петр Верховенский созывает «сочувствующих» перевороту молодых людей: военного в отставке Виргинского, эксперта народных масс Толкаченко, философа Шигалева и др. Лидер организации Верховенский планирует убийство бывшего студента Ивана Шатова, который решает расстаться с революционным движением. Он покидает организацию из-за интереса к мысли народа-«богоносца». Однако убийство героя нужно компании не для мести, реальный мотив, которого не знают рядовые члены кружка, — сплочение организации кровью, единым преступлением.

Далее события развиваются стремительно: маленький городок потрясают невиданные доселе происшествия. Всему виной тайная организация, но о ней горожане не имеют понятия. Однако самые жуткие и пугающие вещи происходят в душе героя, Николая Ставрогина. Автор подробно описывает процесс ее разложения под влиянием вредоносные идей.

Главные герои и их характеристика

- Варвара Ставрогина — известная губернская дама, выдающаяся помещица. Героиня обладает имением, унаследованным от обеспеченного откупщика-родителя. Муж Всеволод Николаевич, по профессии генерал-лейтенант, не владел огромным состоянием, но обладал большими связями, которые Варвара Петровна, после его ухода из этой жизни, всеми возможными способами стремится восстановить, но безуспешно. В губернии она очень влиятельная женщина. По своей природе она высокомерна и деспотична. Однако героиня часто чувствует сильную зависимость от людей, порой даже жертвенную, но и взамен ждет такого же поведения. В общении с людьми Варвара Петровна всегда придерживается лидирующей позиции, не исключение и старые друзья.

- Николай Всеволодович Ставрогин – обладал демонической привлекательностью, имел превосходный вкус и благовоспитанное поведение. Общество на его появление реагировало бурно, но, при всей живости и насыщенности его образа, герой вел себя довольно скромно и не особо разговорчиво. Всё женское светское общество было в него влюблено. Николай Всеволодович встречался с супругой Шатова – Машей, с его сестрой – Дашей, со своей знакомой из детства – Елизаветой Тушиной. Возвратившись из Европы, он принимал участие в возрождении тайного общества. В этот же период он ставил опыт по воздействию на Шатова и Кириллова. Прямое участие в смерти Шатова Николай Всеволодович не принимал и даже относился к этому отрицательно, но мысль о сплочении участников объединения исходила именно от него. Подробнее о характере Ставрогина

- Кириллов Алексей Нилыч – один из ведущих персонажей произведения Ф. М. Достоевского «Бесы», по профессии инженер-строитель, он придумал теорию самоубийства, как потребность рассуждающего человека. Кириллов преодолел быстрый путь от религии к отрицанию существования кого-то свыше, был одержим маниакальными мыслями, идеями о революции и готовности к самоотречению. Всё это в Алексее Нилыче вовремя увидел Петр Верховенский – персона хитрая и безжалостная. Петр был осведомлен о намерении Кириллова совершить самоубийство, и принудил его написать признание, что Шатов, которого убил Петр, погиб от рук Кириллова.

- Петр Степанович Верховенский – предводитель революционеров, скользкий и коварный персонаж. В произведении это главный «бес» — он управляет тайным обществом, продвигающим атеистские прокламации. Вдохновленный безумными мыслями, он старается очаровать ими и Николая Всеволодовича Ставрогина – друга детства. Внешностью Верховенский неплох, но не вызывает ни у кого симпатии.

- Степан Трофимович Верховенский – человек старой закалки, преданный высоким идеалам и проживающий на содержании известной губернской особы. В молодости обладал красивой внешностью, отголоски которой можно заметить и в старости. В его поведении много притворства, но он достаточно образованный и проницательный. Был женат два раза. В какое-то время он был уважаем почти как Белинский и Герцен, но после обнаружения у него поэмы двусмысленного содержания, был вынужден уехать из Петербурга и скрыться в поместье Варвары Петровны Ставрогиной. С тех пор он заметно деградировал.

- Шигалёв – участвовал в организации убийства Шатова, но отказался от этого. О Шигалёве известно немного. Сотрудник отдела хроники говорит, что он приехал в город за пару месяцев до происшествия, ходил слух, что он публиковался в известном петербургском издании. Создавалось впечатление, словно Шигалёву известно время, место и событие, которое должно произойти. По мнению этого персонажа, все люди должны быть разделены на две неравноценные половины. Только одна десятая должна обладать властью. Оставшаяся часть – стадо без мнения, рабы. В подобной манере предстояло перевоспитать целые поколения, потому как это было более чем естественно.

- Эркель, Виргинский, Липутин, Толкаченко – члены тайного общества, которых завербовал Верховенский.

Темы и настроение

- Отношения отцов и детей. Очевидно, в романе «Бесы» автор описывает столкновение разных эпох и потерю связи разных поколений. Родители совсем не понимают детей, они как будто с разных планет. Поэтому молодежи никто не может вовремя помочь, так как утеряны те драгоценные семейные узы, которые могли бы удержать юношей от морального падения.

- Нигилизм. В романе «Бесы» четко видна связь с произведением «Отцы и дети», так как именно Тургенев первым заговорил о нигилизме. Читатель узнает героев Достоевского, как и тургеневских персонажей, через идеологические споры, в которых открываются возможные направления совершенствования общества. В незначительном количестве наблюдается связь со стихотворением Александра Сергеевича Пушкина, с одноименным названием «Бесы»: мысль о потерявших свой путь людях, которые блуждают кругами в словесном тумане русского общества.

- Отсутствие единых нравственных ориентиров. Духовный общественный недуг, показанный автором, спровоцирован полным отсутствием высоких ценностей. Ни развитие техники, ни скачек образования, ни жалкие попытки уничтожить общественные разногласия при помощи власти не приведут к положительному результату, пока не появятся единые нравственные ориентиры. «Великого ничего нет» — вот главная причина печального состояния русского народа.

- Религиозность и атеизм. Достигнет ли человек гармонии после жизненных страданий, и имеет ли ценность эта гармония? Если не существует бессмертия – можно делать всё, что придет в голову, не задумываясь о последствиях. В этом умозаключении, которое может возникнуть у любого атеиста, автор видит опасность безверия. Однако Достоевский понимает, что и вера не может быть абсолютной, пока у религиозной философии есть неразрешенные вопросы, по которым нет единого мнения. Мысли писателя следующие: справедлив ли Бог, если позволяет страдать невинным людям? И если это — его справедливость, то как можно судить тех, кто проливает кровь на дороге к общественному счастью? По мнению автора, нужно отказаться от всеобщего счастья, если ради него понадобится хоть одна человеческая жертва.

- Реальность и мистика постоянно сталкиваются в произведениях Федора Михайловича Достоевского, порой до такой степени, что грань между повествованием писателя и иллюзиями самого персонажа исчезает. События развиваются стремительно, они происходят стихийно в небольшие временные отрезки, они мчатся вперед, не позволяя человеку, по ту сторону книги, сосредоточится на обыденных вещах. Приковывая всё внимание читателя к психологическим моментам, автор лишь по крупицам дает бытовой материал.

Главная мысль

Федор Михайлович Достоевский старался описать болезнь нигилистов-революционеров, которая засела или постепенно наводит свои порядки в головах людей, рассеивает около себя хаос. Его идея (упрощенно) сводится к тому, что нигилистические настроения отрицательно влияют на русское общество – как беснование на человека.

Федор Михайлович установил причину и значение революционного движения. Оно сулит счастье в будущем, но цена в настоящем слишком велика, на нее нельзя соглашаться, иначе люди утратят моральные ценности, которые делают их совместную жизнь возможной. Без них народ распадется и самоуничтожится. И только преодолев это непостоянное явление (как беснование души), Россия станет сильнее, станет на ноги и будет жить с новой силой – силой единого общества, где человек и его права должны быть на первом месте.

Чему учит?

Духовное здоровье нации зависит от морального благосостояния и приумножения тепла и любви во всех людях по отдельности. Если у всего общества есть единые нравственные каноны и ориентиры, оно пройдет через все тернии и достигнет процветания. А вот разнузданность идей и отрицание основы основ приведет к постепенной деградации народа.

Созидательный опыт «Бесов» показывает: во всем необходимо находить нравственный центр, определять уровень ценностей, руководящий мыслями и поступками человека, решать, какие отрицательные или положительные стороны души полагаются на различные жизненные явления.

Критика

Естественно, русская критика, в частности либерально-демократическая, отрицательно отреагировала на выход «Бесов», усмотрев в сюжете острую сатиру. Глубокое философское наполнение было рассмотрено как идеологическое предупреждение нечаевщины. Рецензенты писали о том, что исчезновение революционной инициативы повергнет общество в оцепенение и сон, а власть перестанет слышать голос народа. Тогда трагическая судьба русского народа никогда не изменится к лучшему.

В работе «Духи русской революции» Бердяев выражает мнение о том, что нигилизм в понимании Достоевского можно трактовать как определённый религиозный взгляд. По Бердяеву, русский нигилист может представить вместо Бога самого себя. И хотя у самого Достоевского нигилизм больше связан с атеизмом, но в знаменитом монологе Ивана Карамазова о слезе ребёнка чувствуется острая необходимость человека в вере.

Автор: Дарья Попова

Интересно? Сохрани у себя на стенке!

Читайте также:

Приблизительное время чтения: 11 мин.

В нашей рубрике друзья «Фомы» выбирают и советуют читателям книги, которые – Стоит перечитать.

Книгу рекомендует Владимир Хотиненко

Автор

Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский (1821–1881) — писатель, критик, публицист.

Время написания и история создания

Работа над романом проходила в 1870–1871 годах за границей. В основу романа Достоевский положил громкое дело 1869 года об убийстве студента Ивана Иванова членами одного из революционных кружков во главе с нигилистом и революционером Сергеем Нечаевым с целью укрепления своей власти в террористическом кружке, против идей которого выступил Иванов. Программным документом кружка был «Катехизис революционера», где впервые была сформулирована программа беспощадного террора ради «светлого будущего всего человечества».

Достоевский узнал о деле из газет, внимательно читал статьи, корреспонденции, касающиеся Нечаева и его помощников. Сначала прозаик замыслил небольшой злободневный памфлет. Однако в процессе работы усложнились сюжет и идея текста. В итоге получился трагический многостраничный роман, который был опубликован в 1872 году в журнале «Русский вестник».

Смысл романа

«Бесы» — роман о трагедии русского общества, в котором революционные настроения, по мнению Достоевского, являются следствием утраты веры. Говоря о «нечаевщине» и убийстве Иванова, писатель признавался: «В моем романе “Бесы” я попытался изобразить те многоразличные и разнообразные мотивы, по которым даже чистейшие сердцем и простодушнейшие люди могут быть привлечены к совершению такого же чудовищного злодейства».

Одна из главных мыслей романа: человеку необходима свобода. Однако на путях свободы его подстерегают соблазны своеволия. Главным героем романа, Николаем Ставрогиным одновременно владеют и жажда веры, и поразительное безверие, утверждение себя вне Бога. Духовное омертвение главного героя-«беса» «порождает» остальных, которые, в свою очередь, создают «мелких бесов». «Бесовщина» у Достоевского — это одержимость идеей, которая отделяет человека от реальности, поглощает его целиком. Таков революционер Петр Верховенский, который под лозунгом «все для человека» разрабатывает программу развращения и уничтожения людей («…Мы сначала пустим смуту… Мы проникнем в самый народ… Мы пустим пьянство, сплетни, доносы; мы пустим неслыханный разврат, мы всякого гения потушим в младенчестве… Мы провозгласим разрушение… Мы пустим пожары… Мы пустим легенды… Ну-с, и начнется смута! Раскачка такая пойдет, какой еще мир не видал»). Таков инженер Кириллов, который решил доказать истинность своих убеждений с помощью самоубийства («Если нет Бога, то я Бог… Если Бог есть, то вся воля Его, и без воли Его я не могу. Если нет, то вся воля моя, и я обязан заявить своеволие… Я обязан себя застрелить, потому что самый полный пункт моего своеволия — это убить себя самому…»). Таков и студент Шатов, проповедующий свою веру в богоносность русского народа. Все они становятся рабами своей идеи.

В то же время «Бесы» — это великая христианская книга, в которой утверждается возможность противостоять «бесам» и их деяниям. Одна из героинь, юродивая Марья Тимофеевна, которая обладает даром видеть истинную сущность людей и событий, говорит, что «всякая тоска земная и всякая слеза земная — радость нам есть». Эта радость — напоминание о грядущей правде и победе Христа над «бесами» и их властными идеями.

Достоевский обращается к евангельской притче об исцелении Христом бесноватого, чтобы показать — мир может излечиться от «бесов», и даже самый опасный и падший человек может исправиться и сохранить в себе образ Божий. Роман заканчивается светлым пророчеством о России одного из героев, которому прочли упомянутую притчу. «Эти бесы, — произнес Степан Трофимович в большом волнении… — это все язвы, все миазмы, вся нечистота, все бесы и бесенята, накопившиеся в великом и малом нашем больном, в нашей России, за века, за века!.. Но великая мысль и великая воля осенят ее свыше, как и того безумного бесноватого, и выйдут все эти бесы. Вся нечистота… Но больной исцелится и “сядет у ног Иисусовых”… и будут все глядеть с изумлением…»

Интересные факты

1. «Бесы» — третий роман так называемого «великого пятикнижия Достоевского». В него также входят романы «Преступление и наказание», «Идиот», «Игрок» и «Братья Карамазовы».