На чтение 6 мин Просмотров 33.5к. Опубликовано 29.03.2020

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ «Медный всадник» за 30 секунд и подробно по частям за 3 минуты.

Очень краткий пересказ поэмы «Медный всадник»

Наводнение на улицах Петербурга, о котором говорит автор поэмы, было серьёзнейшим испытанием для его жителей за всю историю города. Оно принесло разрушения и гибель множества людей. В числе жертв оказалась невеста скромного чиновника Евгения. Герой на фоне своего горя сошёл с ума. Ему казалось, что оживший памятник Петру преследует его на улицах города. В конце повествования рыбаки находят бездыханное тело Евгения.

Главные герои и их характеристика:

- Евгений — главный герой поэмы, чиновник скромного достатка и самых простых планов на жизнь. Он мечтает жениться на любимой девушке и построить с ней спокойный, размеренный быт. Со смертью невесты жизнь героя теряет всякий смысл. Он лишается рассудка, и вскоре сам погибает.

- Петр I — в начале повествования — самодержец, решивший воздвигнуть новую столицу своей державы. К концу — оживший в воспаленном от горя мозгу Евгения памятник на коне.

Второстепенный герой и его характеристика:

- Параша — любимая девушка главного героя. О ней читатель узнает из уст и мыслей Евгения.

Краткое содержание «Медный всадник» подробно по частям

Поэма «Медный всадник» включает в себя предисловие, вступление и две части повествования. С их содержанием можно ознакомиться ниже.

Предисловие

Здесь автор объясняет читателю, что его история основывается на реальных событиях, сведения о которых были им почерпнуты из архивов.

Вступление

Читатель знакомится с величественным Петром I, который размышляет о возведении города. Спустя сто лет на задуманном месте вырос молодой и величавый Петербург. Автор искренне восхищен его красотой и признаётся городу в любви: «Люблю тебя, Петра творенье..».

Часть I

Ноябрь. Поздний вечер. Евгений возвращается из гостей. Его одолевают мысли о бедном существовании, долгом пути к выслуге. Погода портится, черные думы сгущаются. Но лучиком в этом «тёмном царстве» для героя становится мечта о будущем рядом с любимой девушкой Парашей.

Она живёт на другом конце города, у залива. Из-за непогоды вряд ли Евгений сможет увидеть её в ближайшее время. Герой засыпает с мыслями о возлюбленной.

Новый день приносит настоящий кошмар. Нева «взбесилась» и буквально набросилась на город. На месте площадей — озёра, улиц — реки. Кругом обломки, страх, смерть. Герой в этом хаосе словно застыл на пороге богатого особняка.

Он сел возле мраморной статуи льва и глядел в ту сторону, где живёт его невеста. В тех краях буря была особенно безжалостна. Евгений понимал, что его девушка в страшной опасности. Но что он мог сделать? Он лишь видел перед собой тонны разбушевавшейся воды и медную спину всадника — памятника Петру I.

Часть II

Буря утихла. Вода стала отступать. Евгений спешит к месту, где стоял ветхий домишко его невесты. Но домик смыло страшными волнами. Осознав, что его любимой больше нет, Евгений теряет рассудок.

С наступлением нового дня, жизнь возвращается в город. Люди спешат на службу, открываются лавки. Но для героя поэмы потерян смысл существования. Он бесцельно скитается по городу, он бросает и службу, и дом.

Спит где придётся, ест что попало, дети швыряют в него камнями, возницы бьют плетями, прогоняя с дороги.

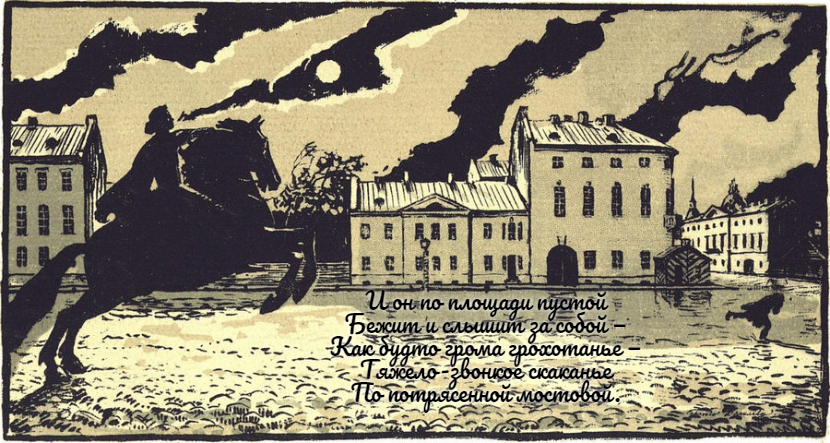

В конце лета, когда над городом разразилась гроза, Евгений оказался на том самом месте, где был во время потопа. Он видит памятник Петру и винит его в своём горе. Затем герой бросается бежать.

Ему кажется, что медный всадник ожил и преследует его по пятам. С той минуты, он в страхе, смиренно опускал глаза при виде памятника. А по весне бездыханное тело Евгения нашли рыбаки на одном из островов. Там беднягу и похоронили, как неизвестного.

Кратко об истории создания произведения

В сюжет поэмы легла реальная история наводнения в Петербурге в 1824 году. Сам автор наводнения не видел, но основывался на показания очевидцев, статьи журналов того времени, архивы.

Меньше чем за месяц написал Пушкин свою поэму в 1833 году в Болдино. Однако процесс создания требовал от поэта полной самоотдачи, он переписывал каждый стих чуть десятки раз, добиваясь, таким образом, идеальной формы.

Идея об «оживающем памятнике», возможно, была почерпнута классиком из истории о том, как Александр I помышлял перевезти памятник Петру из города. Он передумал, после того, как ему рассказали о сне одного майора, который видел скачущего медного всадника на улицах Петербурга и слышал грозные слова Петра Великого, обращенные к императору: «Молодой человек! До чего ты довел мою Россию! Но покамест я на месте, моему городу нечего опасаться». Есть и другое предположение. Возможно, Пушкин вдохновился идеей «оживить» памятник из произведения «Дон Жуан».

Поэма «Медный всадник» по объёму относится к самым небольшим произведениям великого русского поэта, при этом она вмещает в себя благоговение перед мощью самодержца и его бессмертного творения Петербурга, историю любви, жуткие сцены страшного потопа и раскрытие проблемы «маленького человека» на фоне большого жестокого мира.

Осень всегда вдохновляла Александра Сергеевича Пушкина. В 1833 году золотая пора стала для него особенно плодотворной. Результат размышлений поэта во время пребывания в Болдино — произведение «Медный всадник», краткое содержание которого, а также детальный анализ представлены ниже.

«Медный всадник»: краткое содержание

Поэма «Медный всадник», краткое содержание которой известно каждому школьнику, — это не просто вершина стихотворного искусства, но и содержательные размышления о государственности, нравственности и роли правителя в жизни населения.

Несомненно, Александр Сергеевич Пушкин, гений которого известен и за рубежом, умело воплотил в жизнь образ легендарного Петра Первого, отобразил тогдашнее настроение людей:

Вступление

Ищете краткий пересказ? «Медный всадник» начинается с описания экспозиции: на берегу Невы стоит государь Петр Великий и думает о том, какое будущее ждет это место. Тяжелое настроение передают детализированные пейзажи:

- огромные валуны волн разбиваются о крутые берега;

- холодный ноябрьский ветер забирается под теплую шинель;

- взор поражает масштабность просторов, усыпанных редкими деревьями;

- в другой стороне Невы раскинулись топкие опасные болота, на месте которых скоро возвысятся башни Петербурга.

События, которые далее происходят, связаны с главным героем — Евгением. Мелкого чиновника из обедневшего рода делает главным героем Пушкин. «Медный всадник», краткое содержание которого помогает восстановить сюжет, рассказывает о судьбе маленького человека в большом городе.

Завязка и развитие сюжета

Описывая завязку сюжета «Медный всадник» кратко, отметим, что автор так характеризует Евгения:

- мрачный и неказистый;

- мелкий и незначительный;

- безликий и серый.

Александр Сергеевич нарочно не упоминает ни фамилию, ни возраст, ни другие детали жизни главного героя. Евгений — образ собирательный. Он часть толпы, он и есть народ, угнетенный машиной государственности. Произведение «Медный всадник» начинается картиной кручины Евгения, который в непогоду добрался до своего темного жилища в Коломне.

Главный герой влачит свое жалкое существование на посредственной работе, с посредственной платой за труды и в посредственном окружении. Но единственная его радость, отрада в этой душной серости — пылкое чувство к девушке Параше, живущей по ту сторону Невы.

Кульминация

Краткое содержание «Медного всадника» обязательно включает рассказ о непогоде, что пришла в город в ноябре. Нева вышла из берегов и затопила все поселения, что находились неподалеку. Ничто не могло унять стихию, и людям оставалось только прятаться и молить Бога о спасении. Правительство не смогло предотвратить страшную трагедию, заявив: «С Божией стихией царям не совладать».

Катастрофа уносит жизнь возлюбленной Евгения Параши, а также ее старушки-матери. Это приводит героя в шок, делает его жизнь бессмысленной.

Развязка

Поэму «Медный всадник» читать рекомендуем внимательно, ведь каждая деталь, описанная Александром Сергеевичем, играет важную роль и создает особое настроение. После смерти Параши Евгений не мог найти себе места, его существование потеряло всякий смысл.

Только спустя год, кое-как оправившись от горя, главный герой решается выразить всю свою боль, как ему кажется, виновнику трагедии — памятнику Петру Первому. Мужчина сгоряча проклинает и Петра Великого, и созданный им город, который стал трагической точкой на карте его любви. Но, конечно же, статуя беспристрастно направляет взор вдаль, не снисходя к проблеме простого смертного.

Лейтмотив поэмы «Медный всадник» — внутренняя тревога, которая нарастает. Она вынуждает Евгения слышать топот копыт коня Петра: герою кажется, что государь преследует его. В конечном итоге это погубило мелкого чиновника: рыбаки выловили его труп возле пустынного острова и похоронили.

Поэма Пушкина «Медный всадник» — яркий пример трагической судьбы маленького человека, раздавленного безжалостной машиной государства.

«Медный всадник»: анализ произведения

«Медный всадник»: о чем это произведение, каков его жанр и что пытался сказать в повествовании автор? Чтобы найти ответы на эти вопросы, внимательно изучите следующее:

«Медный всадник»: история создания

Поэма «Медный всадник», история создания которой связана с непростыми временами в жизни Пушкина, отразила антигуманную природу российской государственности. Держава переживала внутренний раскол. В России возникли два лагеря: одни всячески превозносили Петра Первого, а другие искренне считали, что в его натуре есть что-то нечистое и бесовское.

Охваченный всеобщими настроениями, Александр Сергеевич отбыл в 1833 году в поместье жены Болдино. Произведение «Медный всадник» Пушкин написал в том же сезоне, завершив произведением болдинский период творчества. Поэма — квинтэссенция размышлений автора о политике, самодержавии и государственности в целом.

Тема и конфликт поэмы

«Медный всадник» — поэма, посвященная острой социальной теме отношений маленького человека и государства. Страна представляется читателю огромной безжалостной машиной, не замечающей проблем маленьких людей.

Фундаментальность государства и его масштабы отображены в названии произведения. Хоть статуя изготовлена из бронзы, автор представляет ее из меди — более тяжелого материала. Статуя масштабная и необъятная, а человек возле нее непропорционально мал и жалок.

К сожалению, конфликт человека с властью исчерпывается уже к концу поэмы, поскольку громадная машина перемалывает человека, не заметив потери.

«Медный всадник»: жанр, особенности композиции

«Медный всадник», жанр которого определяют как стихотворная реалистическая поэма, — это работа чрезвычайно глубокая в смысловом аспекте. Тут встречаются:

- философские размышления автора;

- исторические зарисовки;

- великолепные пейзажи;

- детализированный анализ личности самого Петра Первого.

Важно отметить композицию произведения. Она кардинально отличается от похожих произведений тем, что поэма имеет открытый финал:

- Каждый читатель сам делает выводы и рисует тот эпилог, который, на его взгляд, уместен.

- Эксперты говорят о масштабе повествования: рассказ о личности Петра Великого, его деяниях и основании города на Неве — произведение в произведении.

Отметим легкий, незатейливый, простой слог автора в рассказе о жизни маленького чиновника Евгения. Это добавляет атмосферность повествованию. Как только вектор внимания перемещается на личность Петра, то речь становится пафосной, витиеватой и величавой.

Поэма Пушкина «Медный всадник»: главные герои

Вся поэма строится на контрасте двух главных героев:

- Петра Великого;

- мелкого чиновника Евгения.

Петр — могущественный, одиозный самодержец, одержимый идеей величия Российской империи. Он мыслит масштабно, амбициозно, смело и порой поступает жестоко. Он идет на риск, пренебрегая нуждами маленьких людей, своего народа. Он делает это для развития России, но не во благо обычных людей.

Личность Евгения — полная противоположность Петру. Он жалкий, ничтожный и серый. Он частичка безликой массы, но при этом герой переживает личную драму. Судьба маленького человека трагична и жестока, а равнодушие государства и окружающих делает картину еще печальнее.

«Медный всадник» — произведение-загадка, над расшифровкой которой трудятся литературоведы десятилетиями. Статья поможет приблизиться к пониманию авторского замысла.

Оригинал статьи: https://www.nur.kz/family/school/1874338-mednyj-vsadnik-kratkoe-soderzanie-i-analiz-proizvedenia/

Alexandre Benois’s illustration to the poem (1904). |

|

| Author | Alexander Pushkin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Медный Всадник [Mednyi Vsadnik] |

| Translator | C. E. Turner |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Narrative poem |

| Publisher | Sovremennik |

|

Publication date |

1837 |

|

Published in English |

1882 |

The Bronze Horseman: A Petersburg Tale (Russian: Медный всадник: Петербургская повесть Mednyy vsadnik: Peterburgskaya povest) is a narrative poem written by Alexander Pushkin in 1833 about the equestrian statue of Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg and the great flood of 1824. While the poem was written in 1833, it was not published, in its entirety, until after his death as his work was under censorship due to the political nature of his other writings. Widely considered to be Pushkin’s most successful narrative poem, The Bronze Horseman has had a lasting impact on Russian literature. The Pushkin critic A. D. P. Briggs praises the poem «as the best in the Russian language, and even the best poem written anywhere in the nineteenth century».[1] It is considered one of the most influential works in Russian literature, and is one of the reasons Pushkin is often called the “founder of modern Russian literature.”

The statue became known as The Bronze Horseman due to the great influence of the poem.[2]

Plot summary[edit]

The poem is divided into three sections: a shorter introduction (90 lines) and two longer parts (164 and 222 lines). The introduction opens with a mythologized history of the establishment of the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703. In the first two stanzas, Peter the Great stands at the edge of the River Neva and conceives the idea for a city which will threaten the Swedes and open a «window to Europe». The poem describes the area as almost uninhabited: Peter can only see one boat and a handful of dark houses inhabited by Finnish peasants. Saint Petersburg was in fact constructed on territory newly gained from the Swedes in the Great Northern War, and Peter himself chose the site for the founding of a major city because it provided Russia with a corner of access to the Baltic Sea, and thus to the Atlantic and Europe.

The rest of the introduction is in the first person and reads as an ode to the city of Petersburg. The poet-narrator describes how he loves Petersburg, including the city’s «stern, muscular appearance» (l. 44), its landmarks such as the Admiralty (ll. 50–58), and its harsh winters and long summer evenings (ll. 59 – ll. 84). He encourages the city to retain its beauty and strength and stand firm against the waves of the Neva (ll. 85–91).

Part I opens with an image of the Neva growing rough in a storm: the river is «tossing and turning like a sick man in his troubled bed» (ll. 5–6). Against this backdrop, a young poor man in the city, Evgenii, is contemplating his love for a young woman, Parasha, and planning to spend the rest of his life with her (ll. 49–62). Evgenii falls asleep, and the narrative then turns back to the Neva, with a description of how the river floods and destroys much of the city (ll. 72–104). The frightened and desperate Evgenii is left sitting alone on top of two marble lions on Peter’s Square, surrounded by water and with the Bronze Horseman statue looking down on him (ll. 125–164).

In Part II, Evgenii finds a ferryman and commands him to row to where Parasha’s home used to be (ll. 26 – ll. 56). However, he discovers that her home has been destroyed (ll. 57–60), and falls into a crazed delirium and breaks into laughter (ll. 61–65). For a year, he roams the street as a madman (ll. 89–130), but the following autumn, he is reminded of the night of the storm (ll. 132–133) and the source of his troubles. In a fit of rage, he curses the statue of Peter (ll. 177–179), which brings the statue to life, and Peter begins pursuing Evgenii (ll. 180–196). The narrator does not describe Evgenii’s death directly, but the poem closes with the discovery of his corpse in a ruined hut floating on the water (ll. 219–222).

Genre[edit]

Formally, the poem is an unusual mix of genres: the sections dealing with Tsar Peter are written in a solemn, odic, 18th-century style, while the Evgenii sections are prosaic, playful and, in the latter stages, filled with pathos.[3] This mix of genres is anticipated by the title: «The Bronze Horseman» suggested a grandiose ode, but the subtitle «A Petersburg Tale» leads one to expect an unheroic protagonist[4] Metrically, the entire poem is written in using the four-foot iamb, one of Pushkin’s preferred meters, a versatile form which is able to adapt to the changing mood of the poem. The poem has a varied rhyme scheme and stanzas of varying length.[5]

The critic Michael Watchel has suggested that Pushkin intended to produce a national epic in this poem, arguing that the Peter sections have many of the typical features of epic poetry.[6] He points to Pushkin’s extensive use of Old Testament language and allusions when describing both the founding of St Petersburg and the flood and argues that they draw heavily on the Book of Genesis. Further evidence for the categorization of Pushkin’s poem as an epic can be seen in its rhyme scheme and stanza structure which allow the work to convey its meaning in a very concise yet artistic manner.[7] Another parallel to the classical epic tradition can be drawn in the final scenes of Evgenii’s burial described as “for God’s sake.” In Russian, this phrase is not one of “chafing impatience, but of the kind of appeal to Christian sentiment which a beggar might make” according to Newman.[8] Therefore, it is a lack of empathy and charity in Petersburg that ultimately causes Evgenii’s death. The requirement that civilization must have a moral order is a theme also found in the writings of Virgil.[8] However, he adds that the Evgenii plot runs counter to the epic mode, and praises Pushkin for his «remarkable ability to synthesize diverse materials, styles and genres».[9] What is particularly unusual is that Pushkin focuses on a protagonist that is humble as well as one that is ostensibly great. There are more questions than answers in this new type of epic, where “an agnostic irony can easily find a place” while “the unbiased reader would be forced to recognize as concerned with the profoundest issues which confront humanity”.[10] He concludes that if the poem is to be labeled a national epic, it is a «highly idiosyncratic» one.[9]

Historical and cultural context[edit]

Several critics have suggested that the immediate inspiration for «The Bronze Horseman» was the work of the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz.[11][12] Before beginning work on «The Bronze Horseman», Pushkin had read Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve (1823–32), which contains a poem entitled «To My Muscovite Friends», a thinly-veiled attack on Pushkin and Vasily Zhukovsky for their failure to join the radical Decembrist revolt of 1825. Forefather’s Eve contains poems where Peter I is described as a despot who created the city because of autocratic whim, and a poem mocks the Falconet statue as looking as though he is about to jump off a precipice. Pushkin’s poem can be read in part as a retort to Mickiewicz, although most critics agree that its concerns are much broader than answering a political enemy.[13]

There are distinct similarities between Pushkin’s protagonist in The Bronze Horseman, and that of his other work “Evgeni Onegin.” Originally, Pushkin wanted to continue “Evgeni Onegin” in this narrative, and instead chose to make a new Evgenii, with a different family name but that was still a “caricature of Pushkin’s own character”.[14] Both were descendants of the old regime of Boyars that now found itself socially insignificant in a society where family heritage wasn’t esteemed.

The statue[edit]

The Bronze Horseman of the title was sculpted by Étienne Maurice Falconet and completed in 1782. Catherine the Great, a German princess that married into the Romanov family, commissioned the construction of the statue to legitimize

her rule and claim to the throne to the Russian people. Catherine came to power through an illegal palace coup. She had the statue inscribed with the phrase, Петру перьвому Екатерина вторая, лѣта 1782, in both Latin and Russian, meaning «To Peter the first, from Catherine the second,» to show reverence to the ruler and indicate where she saw her place among Russia’s rulers.

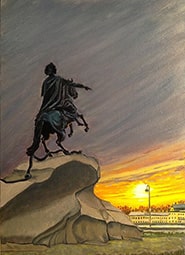

The statue took 12 years to create. It depicts Peter the Great astride his horse, his outstretched arm reaching toward the Neva River in the western part of the country. The statue is lauded for its ambiguity; it is said Pushkin felt the ambiguous message of the statue and was inspired to pen the poem. In a travelogue about Petersburg in 1821, the French statesman Joseph de Maistre commented that he did not know «whether Peter’s bronze hand protects or threatens».[3]

The city of St. Petersburg[edit]

St. Petersburg was built by Peter the Great at the beginning of the 18th century, on the swampy shores and islands of the Neva. The difficulties of construction were numerous, but Peter was unperturbed by the expenditure of human life required to fulfil his vision of a city on the coast. Of the artisans whom he compelled to come north to lay the foundations of the city, thousands died of hardship and disease; and the city, in its unnatural location, was at the mercy of terrible floods caused by the breaking-up of the ice of the Lake Ladoga just east of it or – as on the occasion described in the poem – by the west wind blowing back the Neva. There had been one such devastating flood in 1777 and again in 1824, during Pushkin’s time and the flood modeled in the poem, and they continued until the Saint Petersburg Dam was built.

Themes[edit]

Statue vs. Evgenii[edit]

The conflict between Tsar and citizen, or empire and individual, is a key theme of «The Bronze Horseman».[15] Critics differ as to whether Pushkin ultimately sides with Evgenii — the little man — or Peter and historical necessity. The radical 19th-century critic Vissarion Belinsky considered the poem a vindication of Peter’s policies, while the writer Dmitri Merezhkovsky thought it a poem of individual protest.[16]

Another interpretation of the poem suggests that the statue does not actually come to life, but that Evgenii loses his sanity. Pushkin makes Evgenii go mad to create “a terrifying dimension to even the most humdrum personality and at the same time show the abyss hidden in the most apparently common-place human soul”.[17] In this regard, Evgenii is seen to become a disinherited man of the time in much the same vein as a traditional epic hero.[18]

Perhaps Evgenii is not Peter’s enemy at all. According to Newman, “[Evgenii] is too small for that.”[19] Instead, the heroic conflict of the poem is between Peter the Great and the elements while Evgenii is merely its “impotent victim.»[20] As Evgenii becomes more and more distressed at the disappearance of his fiancée, his increasing anxiety is juxtaposed with the indifference of the ferryman who rows him across the river. Newman thus calls into question whether or not Evgenii is justified in these feelings and how these feelings reflect his non-threatening position in relation to the statue.[7]

Man’s position in relation to nature[edit]

In the very act of conceiving and creating his city in the northern swamps, Peter has imposed order on the primeval natural scene depicted at the beginning of the poem. The city itself, «graceful yet austere» in its classical design, is, as much as the Falconet statue, Peter’s living monument, carrying on his struggle against the «wild, tumultuous» Finnish waves. Its granite banks may hold the unruly elements in check for most of the time, but even they are helpless against such a furious rebellion as the flood of 1824. The waves’ victory is, admittedly, short-lived: the flood soon recedes and the city returns to normal. Even so, it is clear that they can never be decisively defeated; they live to fight another day.

A psychoanalytical reading by Daniel Rancour-Laferriere suggests that there is an underlying concern with couvade syndrome or male birthing in the poem. He argues that the passages of the creation of Petersburg resemble the Greek myth of Zeus giving birth to Athena, and suggests that the flood corresponds to the frequent use of water as a metaphor for birth in many cultures. He suggests that the imagery describing Peter and the Neva is gendered: Peter is male and the Neva female.[21]

Immortality[edit]

Higher authority is represented most clearly by Peter. What is more, he represents it in a way which sets him apart from the mass of humanity and even (so Pushkin hints, as we shall see) from such run-of-the-mill autocrats as Alexander I. Only in the first twenty lines of the poem does Peter appear as a living person. The action then shifts forward abruptly by a hundred years, and the rest of the poem is set in a time when Peter is obviously long since dead. Yet despite this we have a sense throughout of Peter’s living presence, as if he had managed to avoid death in a quite unmortal way. The section evoking contemporary St Petersburg– Peter’s youthful creation, in which his spirit lives on–insinuates the first slight suggestion of this. Then comes a more explicit hint, as Pushkin voices the hope that the Finnish waves will not ‘disturb great Peter’s ageless sleep’. Peter, we must conclude, is not dead after all: he will awake from his sleep if danger should at any time threaten his capital city, the heart of the nation. Peter appears not as an ordinary human being but as an elemental force: he is an agent in the historical process, and even beyond this he participates in a wider cosmic struggle between order and disorder.

Evgenii is accorded equal status with Peter in purely human terms, and his rebellion against state power is shown to be as admirable and significant in its way as that of the Decembrists. Yet turning now to the question of Evgenii’s role in the wider scheme of things, we have to admit that he seems an insignificant third factor in the equation when viewed against the backdrop of the titanic struggle taking place between Peter and the elements. Evgenii is utterly and completely helpless against both. The flood sweeps away all his dreams of happiness, and it is in the river that he meets his death. Peter’s statue, which at their first «encounter» during the flood had its back turned to Evgenii as if ignoring him, late hounds him mercilessly when he dares to protest at Peter’s role in his suffering. The vast, impersonal forces of order and chaos, locked in an unending struggle – these, Pushkin seems to be saying, are the reality: these are the millstones of destiny or of the historical process to which Evgenii and his kind are but so much grist.

Symbolism[edit]

The river[edit]

Peter the Great chose the river and all of its elemental forces as an entity worth combating.[19] Peter «harnesses it, dresses it up, and transforms it into the centerpiece of his imperium.”[22] However, the river cannot be tamed for long. It brings floods to Peter’s orderly city as “It seethes up from below, manifesting itself in uncontrolled passion, illness, and violence. It rebels against order and tradition. It wanders from its natural course.”[23] “Before Peter, the river lived in an uneventful but primeval existence” and though Peter tries to impose order, the river symbolizes what is natural and tries to return to its original state. “The river resembles Evgenii not as an initiator of violence but as a reactant. Peter has imposed his will on the people (Evgenii) and nature (the Neva) as a means of realizing his imperialistic ambitions” [22] and both Evgenii and the river try to break away from the social order and world that Peter has constructed.

The Bronze Horseman[edit]

The Bronze Horseman symbolizes «Tsar Peter, the city of St Petersburg, and the uncanny reach of autocracy over the lives of ordinary people.»[24] When Evgenii threatens the statue, he is threatening “everything distilled in the idea of Petersburg.”[23] At first, Evgenii was just a lowly clerk that the Bronze Horseman could not deign to recognize because Evgenii was so far beneath him. However, when Evgenii challenges him, «Peter engages the world of Evgenii» as a response to Evgenii’s arrogance.[25] The «statue stirs in response to his challenge» and gallops after him to crush his rebellion.[24] Before, Evgenii was just a little man that the Bronze Horseman would not bother to respond to. Upon Evgenii’s challenge, however, he becomes an equal and a rival that the Bronze Horseman must crush in order to protect the accomplishments he stands for.

Soviet analysis[edit]

Alexander Pushkin on Soviet poster

Pushkin’s poem became particularly significant during the Soviet era. Pushkin depicted Peter as a strong leader, so allowing Soviet citizens to praise their own Peter, Joseph Stalin.[26] Stalin himself was said to be “most willingly compared” to Peter the Great.[27] A poll in Literaturnyi sovremennik in March 1936 reported praise for Pushkin’s portrayal of Peter, with comments in favour of how The Bronze Horseman depicted the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public in favour of the public. This was in keeping with the Stalinist emphasis of how the achievements of Soviet society as a whole were to be extolled over the sufferings of the individual.[26] Soviet thinkers also read deeper meanings into Pushkin’s works. Andrei Platonov wrote two essays to commemorate the centenary of Pushkin’s death, both published in Literaturnyi kritik. In Pushkin, Our Comrade, Platonov expanded upon his view of Pushkin as a prophet of the later rise of socialism.[28] Pushkin not only ‘divined the secret of the people’, wrote Platonov, he depicted it in The Bronze Horseman, where the collision between Peter the Great’s ruthless quest to build an empire, as expressed in the construction of Saint Petersburg, and Evgenii’s quest for personal happiness will eventually come together and be reconciled by the advent of socialism.[28] Josef Brodsky’s A Guide to a Renamed City «shows both Lenin and the Horseman to be equally heartless arbiters of other’s fates,» connecting the work to another great Soviet leader.[29]

Soviet literary critics could however use the poem to subvert those same ideals. In 1937 the Red Archive published a biographical account of Pushkin, written by E. N. Cherniavsky. In it Cherniavsky explained how The Bronze Horseman could be seen as Pushkin’s attack on the repressive nature of the autocracy under Tsar Nicholas I.[26] Having opposed the government and suffered his ruin, Evgenii challenges the symbol of Tsarist authority but is destroyed by its terrible, merciless power.[26] Cherniavsky was perhaps also using the analysis to attack the Soviet system under Stalin. By 1937 the Soviet intelligentsia was faced with many of the same issues that Pushkin’s society had struggled with under Nicholas I.[30] Cherniavsky set out how Evgenii was a symbol for the downtrodden masses throughout Russia. By challenging the statue, Evgenii was challenging the right of the autocracy to rule over the people. Whilst in keeping with Soviet historiography of the late Tsarist period, Cherniavsky subtly hinted at opposition to the supreme power presently ruling Russia.[30] He assessed the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public with praise for the triumph of socialism, but couched it in terms that left his work open to interpretation, that while openly praising Soviet advances, he was using Pushkin’s poem to criticise the methods by which this was achieved.[30]

Legacy and adaptations[edit]

The work has had enormous influence in Russian culture. The setting of Evgenii’s defiance, Senate Square, was coincidentally also the scene of the Decembrist revolt of 1825.[31] Within the literary realm, Dostoevsky’s The Double: A Petersburg Poem [Двойник] (1846) directly engages with «The Bronze Horseman», treating Evgenii’s madness as parody.[32] The theme of madness parallels many of Gogol’s works and became characteristic of 19th- and 20th-century Russian literature.[17] Andrei Bely’s novel Petersburg [Петербург] (1913; 1922) uses the Bronze Horseman as a metaphor for the centre of power in the city of Petersburg, which is itself a living entity and the main character of Bely’s novel.[33] The bronze horseman, representing Peter the Great, chases the novel’s protagonist, Nikolai Ableukhov. He is thus forced to flee the statue just like Evgenii. In this context, Bely implies that Peter the Great is responsible for Russia’s national identity that is torn between Western and Eastern influences.[29]

Other literary references to the poem include Anna Akmatova’s «Poem Without a Hero», which mentions the Bronze Horseman «first as the thudding of unseen hooves». Later on, the epilogue describes her escape from the pursuing Horseman.[24] In Valerii Briusov’s work “To the Bronze Horseman” published in 1906, the author suggests that the monument is a «representation of eternity, as indifferent to battles and slaughter as it was Evgenii’s curses».[34]

Nikolai Myaskovsky’s 10th Symphony (1926–7) was inspired by the poem.

In 1949 composer Reinhold Glière and choreographer Rostislav Zakharov adapted the poem into a ballet premiered at the Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre in Leningrad. This production was restored, with some changes, by Yuri Smekalov ballet (2016) at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. The ballet has re-established its place in the Mariinsky repertoire.

References[edit]

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. «Mednyy vsadnik [The Bronze Horseman]». The Literary Encyclopedia. 26 April 2005.accessed 30 November 2008.

- ^ For general comments on the poem’s success and influence, see Binyon, T. J. (2002), Pushkin: A Biography. London: Harper Collins, p. 437; Rosenshield, Gary. (2003), Pushkin and the Genres of Madness. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, p. 91; Cornwell, Neil (ed.) (1998), Reference Guide to Russian Literature. London: Taylor and Francis, p. 677.

- ^ a b See V. Ia. Briusov’s 1929 essay on «The Bronze Horseman», available here (in Russian).

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 91.

- ^ Little, p. xiv.

- ^ Wachtel, Michael. (2006) «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: CUP, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): p. 187.JSTOR. Penn State University Press.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 190

- ^ a b Wachtel, p. 86.

- ^ Newman, p. 176

- ^ Pushkin’s own footnotes refer to Mickiewicz’s poem ‘Oleskiewicz’ which describe the 1824 flood in Petersburg. See also Little, p. xiii; Binyon, pp. 435–6

- ^ Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ See Binyon, p. 435; Little, p. xiii; Bayley, John (1971), Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 128.

- ^ Wilson, p. 67.

- ^ Little, p. xix; Bayley, p. 131.

- ^ Cited in Banjeree, Maria. (1978) «Pushkin’s ‘The Bronze Horseman’: An Agonistic Vision». Modern Languages Studies, 8, no. 2, Spring, p. 42.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Newman, p. 189.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 175,

- ^ Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.), Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 73–85.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 141.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Weinstock, p. 60.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 143.

- ^ Newman, p. 175.

- ^ a b Debreczany. «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. pp. 60–1.

- ^ a b Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew (2014). The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. Central Michigan University. p. 60.

- ^ a b c Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 144.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (1938). The Triple Thinkers; Ten Essays on Literature. New York: Harcourt, Brace. p. 71.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 5.

- ^ Cornwell, p. 160.

- ^ Weinstock, p. 59.

Sources[edit]

- Basker, Michael (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bristol Classical Press, 2000

- Binyon, T. J. Pushkin: A Biography. Harper Collins, 2002

- Briggs, A. D. P. Aleksandr Pushkin: A Critical Study. Barnes and Noble, 1982

- Debreczany, Paul (1993). «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». In Lahusen, Thomas; Kuperman, Gene (eds.). Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1324-3., 1993

- Kahn, Andrew (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Pushkin. Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Kahn, Andrew, Pushkin’s «Bronze Horseman»: Critical Studies in Russian Literature. Bristol Classical Press, 1998

- Little, T. E. (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bradda Books, 1974

- Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): JSTOR. Penn State University Press

- Petrone, Karen (2000). Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades: Celebrations in the Time of Stalin. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33768-2., 2000

- Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.). Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington

- Rosenshield, Gary. Pushkin and the Genres of Madness: The Masterpieces of 1833. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 2003.

- Schenker, Alexander M. The Bronze Horseman: Falconet’s Monument to Peter the Great. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003

- Wachtel, Michael. «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew. «The Bronze Horseman.» The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters: Central Michigan University, 2014

- Wilson, Edmund. The Triple Thinkers; Ten Essays on Literature. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1938.

External links[edit]

- (in Russian) The text of The Bronze Horseman at Russian Wikisource

- (in Russian) The Bronze Horseman: Russian Text

- (in Russian) Listen to Russian version of The Bronze Horseman, courtesy of Cornell University

- Information about English translations of the poem

- The Bronze Horseman: an English verse translation

Alexandre Benois’s illustration to the poem (1904). |

|

| Author | Alexander Pushkin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Медный Всадник [Mednyi Vsadnik] |

| Translator | C. E. Turner |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Narrative poem |

| Publisher | Sovremennik |

|

Publication date |

1837 |

|

Published in English |

1882 |

The Bronze Horseman: A Petersburg Tale (Russian: Медный всадник: Петербургская повесть Mednyy vsadnik: Peterburgskaya povest) is a narrative poem written by Alexander Pushkin in 1833 about the equestrian statue of Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg and the great flood of 1824. While the poem was written in 1833, it was not published, in its entirety, until after his death as his work was under censorship due to the political nature of his other writings. Widely considered to be Pushkin’s most successful narrative poem, The Bronze Horseman has had a lasting impact on Russian literature. The Pushkin critic A. D. P. Briggs praises the poem «as the best in the Russian language, and even the best poem written anywhere in the nineteenth century».[1] It is considered one of the most influential works in Russian literature, and is one of the reasons Pushkin is often called the “founder of modern Russian literature.”

The statue became known as The Bronze Horseman due to the great influence of the poem.[2]

Plot summary[edit]

The poem is divided into three sections: a shorter introduction (90 lines) and two longer parts (164 and 222 lines). The introduction opens with a mythologized history of the establishment of the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703. In the first two stanzas, Peter the Great stands at the edge of the River Neva and conceives the idea for a city which will threaten the Swedes and open a «window to Europe». The poem describes the area as almost uninhabited: Peter can only see one boat and a handful of dark houses inhabited by Finnish peasants. Saint Petersburg was in fact constructed on territory newly gained from the Swedes in the Great Northern War, and Peter himself chose the site for the founding of a major city because it provided Russia with a corner of access to the Baltic Sea, and thus to the Atlantic and Europe.

The rest of the introduction is in the first person and reads as an ode to the city of Petersburg. The poet-narrator describes how he loves Petersburg, including the city’s «stern, muscular appearance» (l. 44), its landmarks such as the Admiralty (ll. 50–58), and its harsh winters and long summer evenings (ll. 59 – ll. 84). He encourages the city to retain its beauty and strength and stand firm against the waves of the Neva (ll. 85–91).

Part I opens with an image of the Neva growing rough in a storm: the river is «tossing and turning like a sick man in his troubled bed» (ll. 5–6). Against this backdrop, a young poor man in the city, Evgenii, is contemplating his love for a young woman, Parasha, and planning to spend the rest of his life with her (ll. 49–62). Evgenii falls asleep, and the narrative then turns back to the Neva, with a description of how the river floods and destroys much of the city (ll. 72–104). The frightened and desperate Evgenii is left sitting alone on top of two marble lions on Peter’s Square, surrounded by water and with the Bronze Horseman statue looking down on him (ll. 125–164).

In Part II, Evgenii finds a ferryman and commands him to row to where Parasha’s home used to be (ll. 26 – ll. 56). However, he discovers that her home has been destroyed (ll. 57–60), and falls into a crazed delirium and breaks into laughter (ll. 61–65). For a year, he roams the street as a madman (ll. 89–130), but the following autumn, he is reminded of the night of the storm (ll. 132–133) and the source of his troubles. In a fit of rage, he curses the statue of Peter (ll. 177–179), which brings the statue to life, and Peter begins pursuing Evgenii (ll. 180–196). The narrator does not describe Evgenii’s death directly, but the poem closes with the discovery of his corpse in a ruined hut floating on the water (ll. 219–222).

Genre[edit]

Formally, the poem is an unusual mix of genres: the sections dealing with Tsar Peter are written in a solemn, odic, 18th-century style, while the Evgenii sections are prosaic, playful and, in the latter stages, filled with pathos.[3] This mix of genres is anticipated by the title: «The Bronze Horseman» suggested a grandiose ode, but the subtitle «A Petersburg Tale» leads one to expect an unheroic protagonist[4] Metrically, the entire poem is written in using the four-foot iamb, one of Pushkin’s preferred meters, a versatile form which is able to adapt to the changing mood of the poem. The poem has a varied rhyme scheme and stanzas of varying length.[5]

The critic Michael Watchel has suggested that Pushkin intended to produce a national epic in this poem, arguing that the Peter sections have many of the typical features of epic poetry.[6] He points to Pushkin’s extensive use of Old Testament language and allusions when describing both the founding of St Petersburg and the flood and argues that they draw heavily on the Book of Genesis. Further evidence for the categorization of Pushkin’s poem as an epic can be seen in its rhyme scheme and stanza structure which allow the work to convey its meaning in a very concise yet artistic manner.[7] Another parallel to the classical epic tradition can be drawn in the final scenes of Evgenii’s burial described as “for God’s sake.” In Russian, this phrase is not one of “chafing impatience, but of the kind of appeal to Christian sentiment which a beggar might make” according to Newman.[8] Therefore, it is a lack of empathy and charity in Petersburg that ultimately causes Evgenii’s death. The requirement that civilization must have a moral order is a theme also found in the writings of Virgil.[8] However, he adds that the Evgenii plot runs counter to the epic mode, and praises Pushkin for his «remarkable ability to synthesize diverse materials, styles and genres».[9] What is particularly unusual is that Pushkin focuses on a protagonist that is humble as well as one that is ostensibly great. There are more questions than answers in this new type of epic, where “an agnostic irony can easily find a place” while “the unbiased reader would be forced to recognize as concerned with the profoundest issues which confront humanity”.[10] He concludes that if the poem is to be labeled a national epic, it is a «highly idiosyncratic» one.[9]

Historical and cultural context[edit]

Several critics have suggested that the immediate inspiration for «The Bronze Horseman» was the work of the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz.[11][12] Before beginning work on «The Bronze Horseman», Pushkin had read Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve (1823–32), which contains a poem entitled «To My Muscovite Friends», a thinly-veiled attack on Pushkin and Vasily Zhukovsky for their failure to join the radical Decembrist revolt of 1825. Forefather’s Eve contains poems where Peter I is described as a despot who created the city because of autocratic whim, and a poem mocks the Falconet statue as looking as though he is about to jump off a precipice. Pushkin’s poem can be read in part as a retort to Mickiewicz, although most critics agree that its concerns are much broader than answering a political enemy.[13]

There are distinct similarities between Pushkin’s protagonist in The Bronze Horseman, and that of his other work “Evgeni Onegin.” Originally, Pushkin wanted to continue “Evgeni Onegin” in this narrative, and instead chose to make a new Evgenii, with a different family name but that was still a “caricature of Pushkin’s own character”.[14] Both were descendants of the old regime of Boyars that now found itself socially insignificant in a society where family heritage wasn’t esteemed.

The statue[edit]

The Bronze Horseman of the title was sculpted by Étienne Maurice Falconet and completed in 1782. Catherine the Great, a German princess that married into the Romanov family, commissioned the construction of the statue to legitimize

her rule and claim to the throne to the Russian people. Catherine came to power through an illegal palace coup. She had the statue inscribed with the phrase, Петру перьвому Екатерина вторая, лѣта 1782, in both Latin and Russian, meaning «To Peter the first, from Catherine the second,» to show reverence to the ruler and indicate where she saw her place among Russia’s rulers.

The statue took 12 years to create. It depicts Peter the Great astride his horse, his outstretched arm reaching toward the Neva River in the western part of the country. The statue is lauded for its ambiguity; it is said Pushkin felt the ambiguous message of the statue and was inspired to pen the poem. In a travelogue about Petersburg in 1821, the French statesman Joseph de Maistre commented that he did not know «whether Peter’s bronze hand protects or threatens».[3]

The city of St. Petersburg[edit]

St. Petersburg was built by Peter the Great at the beginning of the 18th century, on the swampy shores and islands of the Neva. The difficulties of construction were numerous, but Peter was unperturbed by the expenditure of human life required to fulfil his vision of a city on the coast. Of the artisans whom he compelled to come north to lay the foundations of the city, thousands died of hardship and disease; and the city, in its unnatural location, was at the mercy of terrible floods caused by the breaking-up of the ice of the Lake Ladoga just east of it or – as on the occasion described in the poem – by the west wind blowing back the Neva. There had been one such devastating flood in 1777 and again in 1824, during Pushkin’s time and the flood modeled in the poem, and they continued until the Saint Petersburg Dam was built.

Themes[edit]

Statue vs. Evgenii[edit]

The conflict between Tsar and citizen, or empire and individual, is a key theme of «The Bronze Horseman».[15] Critics differ as to whether Pushkin ultimately sides with Evgenii — the little man — or Peter and historical necessity. The radical 19th-century critic Vissarion Belinsky considered the poem a vindication of Peter’s policies, while the writer Dmitri Merezhkovsky thought it a poem of individual protest.[16]

Another interpretation of the poem suggests that the statue does not actually come to life, but that Evgenii loses his sanity. Pushkin makes Evgenii go mad to create “a terrifying dimension to even the most humdrum personality and at the same time show the abyss hidden in the most apparently common-place human soul”.[17] In this regard, Evgenii is seen to become a disinherited man of the time in much the same vein as a traditional epic hero.[18]

Perhaps Evgenii is not Peter’s enemy at all. According to Newman, “[Evgenii] is too small for that.”[19] Instead, the heroic conflict of the poem is between Peter the Great and the elements while Evgenii is merely its “impotent victim.»[20] As Evgenii becomes more and more distressed at the disappearance of his fiancée, his increasing anxiety is juxtaposed with the indifference of the ferryman who rows him across the river. Newman thus calls into question whether or not Evgenii is justified in these feelings and how these feelings reflect his non-threatening position in relation to the statue.[7]

Man’s position in relation to nature[edit]

In the very act of conceiving and creating his city in the northern swamps, Peter has imposed order on the primeval natural scene depicted at the beginning of the poem. The city itself, «graceful yet austere» in its classical design, is, as much as the Falconet statue, Peter’s living monument, carrying on his struggle against the «wild, tumultuous» Finnish waves. Its granite banks may hold the unruly elements in check for most of the time, but even they are helpless against such a furious rebellion as the flood of 1824. The waves’ victory is, admittedly, short-lived: the flood soon recedes and the city returns to normal. Even so, it is clear that they can never be decisively defeated; they live to fight another day.

A psychoanalytical reading by Daniel Rancour-Laferriere suggests that there is an underlying concern with couvade syndrome or male birthing in the poem. He argues that the passages of the creation of Petersburg resemble the Greek myth of Zeus giving birth to Athena, and suggests that the flood corresponds to the frequent use of water as a metaphor for birth in many cultures. He suggests that the imagery describing Peter and the Neva is gendered: Peter is male and the Neva female.[21]

Immortality[edit]

Higher authority is represented most clearly by Peter. What is more, he represents it in a way which sets him apart from the mass of humanity and even (so Pushkin hints, as we shall see) from such run-of-the-mill autocrats as Alexander I. Only in the first twenty lines of the poem does Peter appear as a living person. The action then shifts forward abruptly by a hundred years, and the rest of the poem is set in a time when Peter is obviously long since dead. Yet despite this we have a sense throughout of Peter’s living presence, as if he had managed to avoid death in a quite unmortal way. The section evoking contemporary St Petersburg– Peter’s youthful creation, in which his spirit lives on–insinuates the first slight suggestion of this. Then comes a more explicit hint, as Pushkin voices the hope that the Finnish waves will not ‘disturb great Peter’s ageless sleep’. Peter, we must conclude, is not dead after all: he will awake from his sleep if danger should at any time threaten his capital city, the heart of the nation. Peter appears not as an ordinary human being but as an elemental force: he is an agent in the historical process, and even beyond this he participates in a wider cosmic struggle between order and disorder.

Evgenii is accorded equal status with Peter in purely human terms, and his rebellion against state power is shown to be as admirable and significant in its way as that of the Decembrists. Yet turning now to the question of Evgenii’s role in the wider scheme of things, we have to admit that he seems an insignificant third factor in the equation when viewed against the backdrop of the titanic struggle taking place between Peter and the elements. Evgenii is utterly and completely helpless against both. The flood sweeps away all his dreams of happiness, and it is in the river that he meets his death. Peter’s statue, which at their first «encounter» during the flood had its back turned to Evgenii as if ignoring him, late hounds him mercilessly when he dares to protest at Peter’s role in his suffering. The vast, impersonal forces of order and chaos, locked in an unending struggle – these, Pushkin seems to be saying, are the reality: these are the millstones of destiny or of the historical process to which Evgenii and his kind are but so much grist.

Symbolism[edit]

The river[edit]

Peter the Great chose the river and all of its elemental forces as an entity worth combating.[19] Peter «harnesses it, dresses it up, and transforms it into the centerpiece of his imperium.”[22] However, the river cannot be tamed for long. It brings floods to Peter’s orderly city as “It seethes up from below, manifesting itself in uncontrolled passion, illness, and violence. It rebels against order and tradition. It wanders from its natural course.”[23] “Before Peter, the river lived in an uneventful but primeval existence” and though Peter tries to impose order, the river symbolizes what is natural and tries to return to its original state. “The river resembles Evgenii not as an initiator of violence but as a reactant. Peter has imposed his will on the people (Evgenii) and nature (the Neva) as a means of realizing his imperialistic ambitions” [22] and both Evgenii and the river try to break away from the social order and world that Peter has constructed.

The Bronze Horseman[edit]

The Bronze Horseman symbolizes «Tsar Peter, the city of St Petersburg, and the uncanny reach of autocracy over the lives of ordinary people.»[24] When Evgenii threatens the statue, he is threatening “everything distilled in the idea of Petersburg.”[23] At first, Evgenii was just a lowly clerk that the Bronze Horseman could not deign to recognize because Evgenii was so far beneath him. However, when Evgenii challenges him, «Peter engages the world of Evgenii» as a response to Evgenii’s arrogance.[25] The «statue stirs in response to his challenge» and gallops after him to crush his rebellion.[24] Before, Evgenii was just a little man that the Bronze Horseman would not bother to respond to. Upon Evgenii’s challenge, however, he becomes an equal and a rival that the Bronze Horseman must crush in order to protect the accomplishments he stands for.

Soviet analysis[edit]

Alexander Pushkin on Soviet poster

Pushkin’s poem became particularly significant during the Soviet era. Pushkin depicted Peter as a strong leader, so allowing Soviet citizens to praise their own Peter, Joseph Stalin.[26] Stalin himself was said to be “most willingly compared” to Peter the Great.[27] A poll in Literaturnyi sovremennik in March 1936 reported praise for Pushkin’s portrayal of Peter, with comments in favour of how The Bronze Horseman depicted the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public in favour of the public. This was in keeping with the Stalinist emphasis of how the achievements of Soviet society as a whole were to be extolled over the sufferings of the individual.[26] Soviet thinkers also read deeper meanings into Pushkin’s works. Andrei Platonov wrote two essays to commemorate the centenary of Pushkin’s death, both published in Literaturnyi kritik. In Pushkin, Our Comrade, Platonov expanded upon his view of Pushkin as a prophet of the later rise of socialism.[28] Pushkin not only ‘divined the secret of the people’, wrote Platonov, he depicted it in The Bronze Horseman, where the collision between Peter the Great’s ruthless quest to build an empire, as expressed in the construction of Saint Petersburg, and Evgenii’s quest for personal happiness will eventually come together and be reconciled by the advent of socialism.[28] Josef Brodsky’s A Guide to a Renamed City «shows both Lenin and the Horseman to be equally heartless arbiters of other’s fates,» connecting the work to another great Soviet leader.[29]

Soviet literary critics could however use the poem to subvert those same ideals. In 1937 the Red Archive published a biographical account of Pushkin, written by E. N. Cherniavsky. In it Cherniavsky explained how The Bronze Horseman could be seen as Pushkin’s attack on the repressive nature of the autocracy under Tsar Nicholas I.[26] Having opposed the government and suffered his ruin, Evgenii challenges the symbol of Tsarist authority but is destroyed by its terrible, merciless power.[26] Cherniavsky was perhaps also using the analysis to attack the Soviet system under Stalin. By 1937 the Soviet intelligentsia was faced with many of the same issues that Pushkin’s society had struggled with under Nicholas I.[30] Cherniavsky set out how Evgenii was a symbol for the downtrodden masses throughout Russia. By challenging the statue, Evgenii was challenging the right of the autocracy to rule over the people. Whilst in keeping with Soviet historiography of the late Tsarist period, Cherniavsky subtly hinted at opposition to the supreme power presently ruling Russia.[30] He assessed the resolution of the conflict between the personal and the public with praise for the triumph of socialism, but couched it in terms that left his work open to interpretation, that while openly praising Soviet advances, he was using Pushkin’s poem to criticise the methods by which this was achieved.[30]

Legacy and adaptations[edit]

The work has had enormous influence in Russian culture. The setting of Evgenii’s defiance, Senate Square, was coincidentally also the scene of the Decembrist revolt of 1825.[31] Within the literary realm, Dostoevsky’s The Double: A Petersburg Poem [Двойник] (1846) directly engages with «The Bronze Horseman», treating Evgenii’s madness as parody.[32] The theme of madness parallels many of Gogol’s works and became characteristic of 19th- and 20th-century Russian literature.[17] Andrei Bely’s novel Petersburg [Петербург] (1913; 1922) uses the Bronze Horseman as a metaphor for the centre of power in the city of Petersburg, which is itself a living entity and the main character of Bely’s novel.[33] The bronze horseman, representing Peter the Great, chases the novel’s protagonist, Nikolai Ableukhov. He is thus forced to flee the statue just like Evgenii. In this context, Bely implies that Peter the Great is responsible for Russia’s national identity that is torn between Western and Eastern influences.[29]

Other literary references to the poem include Anna Akmatova’s «Poem Without a Hero», which mentions the Bronze Horseman «first as the thudding of unseen hooves». Later on, the epilogue describes her escape from the pursuing Horseman.[24] In Valerii Briusov’s work “To the Bronze Horseman” published in 1906, the author suggests that the monument is a «representation of eternity, as indifferent to battles and slaughter as it was Evgenii’s curses».[34]

Nikolai Myaskovsky’s 10th Symphony (1926–7) was inspired by the poem.

In 1949 composer Reinhold Glière and choreographer Rostislav Zakharov adapted the poem into a ballet premiered at the Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre in Leningrad. This production was restored, with some changes, by Yuri Smekalov ballet (2016) at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. The ballet has re-established its place in the Mariinsky repertoire.

References[edit]

- ^ Briggs, A. D. P. «Mednyy vsadnik [The Bronze Horseman]». The Literary Encyclopedia. 26 April 2005.accessed 30 November 2008.

- ^ For general comments on the poem’s success and influence, see Binyon, T. J. (2002), Pushkin: A Biography. London: Harper Collins, p. 437; Rosenshield, Gary. (2003), Pushkin and the Genres of Madness. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, p. 91; Cornwell, Neil (ed.) (1998), Reference Guide to Russian Literature. London: Taylor and Francis, p. 677.

- ^ a b See V. Ia. Briusov’s 1929 essay on «The Bronze Horseman», available here (in Russian).

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 91.

- ^ Little, p. xiv.

- ^ Wachtel, Michael. (2006) «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: CUP, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): p. 187.JSTOR. Penn State University Press.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 190

- ^ a b Wachtel, p. 86.

- ^ Newman, p. 176

- ^ Pushkin’s own footnotes refer to Mickiewicz’s poem ‘Oleskiewicz’ which describe the 1824 flood in Petersburg. See also Little, p. xiii; Binyon, pp. 435–6

- ^ Czesław Miłosz (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ See Binyon, p. 435; Little, p. xiii; Bayley, John (1971), Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 128.

- ^ Wilson, p. 67.

- ^ Little, p. xix; Bayley, p. 131.

- ^ Cited in Banjeree, Maria. (1978) «Pushkin’s ‘The Bronze Horseman’: An Agonistic Vision». Modern Languages Studies, 8, no. 2, Spring, p. 42.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Newman, p. 189.

- ^ a b Newman, p. 175,

- ^ Newman, p. 180.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.), Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 73–85.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 141.

- ^ a b Rosenshield, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Weinstock, p. 60.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 143.

- ^ Newman, p. 175.

- ^ a b Debreczany. «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. pp. 60–1.

- ^ a b Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew (2014). The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. Central Michigan University. p. 60.

- ^ a b c Petrone. Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. p. 144.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (1938). The Triple Thinkers; Ten Essays on Literature. New York: Harcourt, Brace. p. 71.

- ^ Rosenshield, p. 5.

- ^ Cornwell, p. 160.

- ^ Weinstock, p. 59.

Sources[edit]

- Basker, Michael (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bristol Classical Press, 2000

- Binyon, T. J. Pushkin: A Biography. Harper Collins, 2002

- Briggs, A. D. P. Aleksandr Pushkin: A Critical Study. Barnes and Noble, 1982

- Debreczany, Paul (1993). «»Zhitie Aleksandra Boldinskogo«: Pushkin’s Elevation to Sainthood in Soviet Culture». In Lahusen, Thomas; Kuperman, Gene (eds.). Late Soviet Culture: From Perestroika to Novostroika. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1324-3., 1993

- Kahn, Andrew (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Pushkin. Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Kahn, Andrew, Pushkin’s «Bronze Horseman»: Critical Studies in Russian Literature. Bristol Classical Press, 1998

- Little, T. E. (ed.), The Bronze Horseman. Bradda Books, 1974

- Newman, John Kevin. «Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman and the Epic Tradition.» Comparative Literature Studies 9.2 (1972): JSTOR. Penn State University Press

- Petrone, Karen (2000). Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades: Celebrations in the Time of Stalin. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33768-2., 2000

- Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. «The Couvade of Peter the Great: A Psychoanalytic Aspect of The Bronze Horseman», D. Bethea (ed.). Pushkin Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington

- Rosenshield, Gary. Pushkin and the Genres of Madness: The Masterpieces of 1833. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 2003.

- Schenker, Alexander M. The Bronze Horseman: Falconet’s Monument to Peter the Great. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003

- Wachtel, Michael. «Pushkin’s long poems and the epic impulse». In Andrew Kahn (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Puskhin, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew. «The Bronze Horseman.» The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters: Central Michigan University, 2014

- Wilson, Edmund. The Triple Thinkers; Ten Essays on Literature. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1938.

External links[edit]

- (in Russian) The text of The Bronze Horseman at Russian Wikisource

- (in Russian) The Bronze Horseman: Russian Text

- (in Russian) Listen to Russian version of The Bronze Horseman, courtesy of Cornell University

- Information about English translations of the poem

- The Bronze Horseman: an English verse translation

Скачать обзор:

О чем поэма «Медный всадник»

Поэма «Медный всадник» рассказывает о противоречии между интересами государства и счастьем отдельной личности. Противоречие в поэме усугубляет контраст: мелкий чиновник взбунтовался против императора — основателя Петербурга.

Очень краткое содержание «Медный всадник»

Во вступлении автор рассказывает об истории возникновения Санкт-Петербурга, который появился на свет благодаря военным успехам и дальновидности Петра I. У Евгения — мелкого служащего стихия (наводнение) забрала любимую девушку. Евгений не может пережить несчастья, которые обрушились на его голову. Молодой человек сходит с ума и грозит изваянию Петра как виновнику своих бед.

Время и место сюжета

Персонажи повести — современники Пушкина. Местом сюжета является Санкт-Петербург — новая столица Российской империи. Как многие современники, автор любил этот город и восхищался им.

Время было выбрано не случайно — в 1824 году непогода стала причиной большого наводнения, которое унесло десятки жизней петербуржцев. Эта трагедия легла в основу сюжета поэмы.

Главные герои поэмы

Число персонажей поэмы невелико — композиция произведения основана на мыслях и поступках трех действующих лиц.

Евгений — мелкий чиновник, род которого был когда-то знатным. Он мечтал о тихом семейном счастье с любимой девушкой Парашей. Из-за её гибели сошёл с ума.

Петр I — олицетворение государства в поэме, главный строитель Петербурга. В прологе Пушкин прославляет «великие думы» Петра и новую столицу русского государства, выстроенную из военно-стратегических и экономических соображений. Поэт прямо восхваляет великое дело Петра. Однако государственные соображения стали причиной трагедии обыкновенного человека.

Медный всадник — памятник Петру Первому, царю-реформатору. Памятник императору на вздыбленном коне символизирует государство.

Второстепенные герои

Параша — возлюбленная Евгения, которая погибла во время наводнения.

Краткое содержание поэмы Пушкина «Медный всадник» по частям с цитатами

Сюжет поэмы разворачивается в Санкт-Петербурге, во временной шкале он разделен на две части. Первая относится к моменту возникновения замысла о строительстве новой столицы новой империи и занимает пятую часть всего сюжета. Вторая часть разворачивается осенью 1824 года.

Предисловие

Предисловие имеет следующее содержание:

Происшествие, описанное в сей повести, основано на истине. Подробности наводнения заимствованы из тогдашних журналов. Любопытные могут справиться с известием, составленным В. Н. Берхом.

Вступление

В начале поэмы перед читателем разворачивается сцена, где главным героем выступает Петр I. После того, как русским войскам удалось отбить балтийский берег, царь стоит «на берегу пустынных волн».

На берегу пустынных волн

Стоял он, дум великих полн,

И вдаль глядел

Молодой император решил возвести здесь новый город, который стал бы торговым и промышленным центром России. Замысел удалось воплотить в жизнь, и Петербург «Вознёсся пышно, горделиво», стал одним из красивейших европейских городов.

Часть 1. Знакомство с главным персонажем

Осень 1824 год петербуржцев не радовала — дождило неделями, а штормовой ветер пронизывал насквозь. Евгений возвратился из гостей в свою холостяцкую квартиру. Здесь было пусто и неуютно. Молодой человека не мог заснуть, думал о будущем.

Редеет мгла ненастной ночи

И бледный день уж настает…

Он надеялся сделать предложение любимой девушке, мечтал о своей Параше. Евгений представлял, как девушка примет его предложение, и они будут жить долго и счастливо. Но для женитьбы не хватало денег. Молодой человека надеялся, что Параша подождет, пока он сможет накопить нужную сумму. А дождь за окном усиливался.

Наступал канун страшного события. Из-за обильного дождя Нева стала выходить из берегов. Евгений начал беспокоиться о своей невесте и ее матери. Женщины жили на острове и были беззащитны перед стихией.

Молодой человек сидел на каменном изваянии льва и не мог сдвинуться с места. За его спиной «стоит с простёртою рукою кумир на бронзовом коне». Душа Евгения болела, но он был бессилен помочь своей невесте. Оставалось лишь надеяться, что все обойдется.

Часть 2. Последствия стихийного бедствия

Черезнекоторое время ненастье стало утихать, Нева вернулась в свои берега. Дождь прекратился. Среди хаоса и разрушения Евгению удалось раздобыть лодку.

Перевозчик согласился отвезти молодого человека на остров, где жила его невеста с матерью. Но на острове домик любимой Евгений не нашел. Строение просто смыло мутной водой Невы, и от жильцов не осталось никаких следов. Невеста Евгения и ее мать утонули, их тела похоронила река.

Жители острова постепенно навели порядок, жизнь стала идти своим чередом. Но для Евгения мир разрушился. Молодой человек испытал сильнейшее потрясение, он не мог принять утрату самых близких ему людей. Главный герой постепенно теряет разум. Он перестал ходить на службу, потерял квартиру и стал питаться объедками.

Прошло время. Евгений все также скитается по улицам столицы без цели и смысла. Он забредает на площадь, где установлен памятник основателю города — Петру I. Царь горделиво восседает на коне, а сама скульптура сделана из меди. Измученный Евгений узнает правителя, «чьей волей роковой / Под морем город основался…», и решает, что царь виноват в его бедах. Именно Петр I повелел построить город в таком опасном месте, где потопы случаются очень часто, а река ведет себя непредсказуемо. Безумец высказывает памятнику все свои беды.

Евгению вдруг кажется, что самодержец хмурится, выслушивая оскорбления, молодой человек пугается и бежит прочь. Герою слышится за спиной громоподобный топот копыт, сотрясающий мостовую. С того времени Евгений, проходя мимо памятника, боялся поднять голову и заглянуть в глаза медному всаднику.

Домик погибшей невесты прибило к берегу. Рядом с развалинами находят тело Евгения. Несчастного тихо «похоронили, ради Бога».

Заключение. Главная мысль поэмы

Неразрешимость противоречия между благом государства и счастьем простого человека. Пушкин полностью признаёт правоту Петра I, не могущего учитывать в своих государственных делах интересы отдельной личности. В то же время поэт совершенно уверен в праве всякого человека требовать соблюдения его интересов.

Автор глубоко сострадает своему герою, поэтому в поэме нет эпилога, который возвратил бы читателя к величию Петербурга и примирил бы его с трагедией Евгения, оправданной исторически.

Как писать сочинение

Сочинение по произведению Пушкина «Медный всадник» должно включать в себя краткую историю создания произведения, основную мысль и заключение. Все тезисы можно свести к такому плану.

- Вступление и история возникновения города на Неве.

- «Здесь будет город заложен».

- «люблю тебя, Петра творенье…» — прославление новой столицы.

- Знакомство с Евгением.

- Образ жизни и мечты главного героя.

- Наводнение.

- Последствия стихийного бедствия. Сообщение о трагедии.

- Медный всадник.

- Образ жизни Евгения после наводнения.

- Встреча с Медным всадником.

- Побег и гибель главного героя.

- Заключение и суть произведения.

При раскрытии каждого пункта плана следует внимательно изучать отрывки из поэмы, ставить себя на место главного героя. В сочинении желательно дать ответы на такие вопросы, как:

- почему именно Медный Всадник стал для Евгения воплощением собственных несчастий?

- как поэт обыгрывает контраст между величием царя и ничтожностью маленького человека?

- чем могла бы закончиться поэма, если бы Параша осталась жива?

Поиск ответов на эти и другие вопросы помогут лучше понять смысл поэмы и поступки ее главного героя.

История создания поэмы «Медный всадник»

А.С. Пушкин приступил к созданию поэмы в 1833 году, в период знаменитой «болдинской осени». Идея об ожившем монументе могла прийти из бессмертного произведения Мольера «Дон Жуан». По другой версии, поэт взял за основу рассказ о том, как сон одного майора помешал Александру I вывезти монумент из Петербурга. При работе Пушкин использовал документальные хроники наводнения и изучал рассказы очевидцев, переживших это стихийное бедствие. Каждый стих поэт переписывал по нескольку раз, добиваясь идеальной рифмы и звучания.

Несмотря на личную протекцию царя, цензоры не пропустили публикацию поэмы, и вернули ее Пушкину с множеством правок. Поэт справедливо оценил присланные замечания, как цензуру, о чем и написал в своем дневнике. Автор попытался внести в произведение правки с учетом пометок царя, но вскоре оставил эту затею: «Медный Всадник» был написан настолько хорошо, что любые изменения лишь портили четкий слог.

При жизни А.С. Пушкина поэма оставалась неопубликованной и была известна только узкому кругу друзей.

После смерти поэта в журнале «Современник» был опубликован полный текст «Медного всадника» с переработками Жуковского. Так, были вырезаны сцены бунта и прочие стихи, которые могли бы не понравиться цензорам. В урезанном виде поэму публиковали до начала XX века.

Медный всадник — памятник в Санкт-Петербурге

История создания монумента также интересна. На самом деле памятник выполнен из бронзы. «Медным» его сделала только поэма А.С. Пушкина.

Памятник был воздвигнут по распоряжению Екатерины II. Интересно, что главным скульптором был Морис Фальконе, а вот голову царя было поручено выполнить помощнице скульптора Мари-Анн Коло. Императрице настолько понравилась работа , что она выделила женщине пожизненное содержание.

Для того, чтобы верно воспроизвести в металле конскую стать, скульптору позировали два лучших жеребца императрицы. Гвардейцы специально ставили коней на дыбы, а Фальконе делал зарисовки.

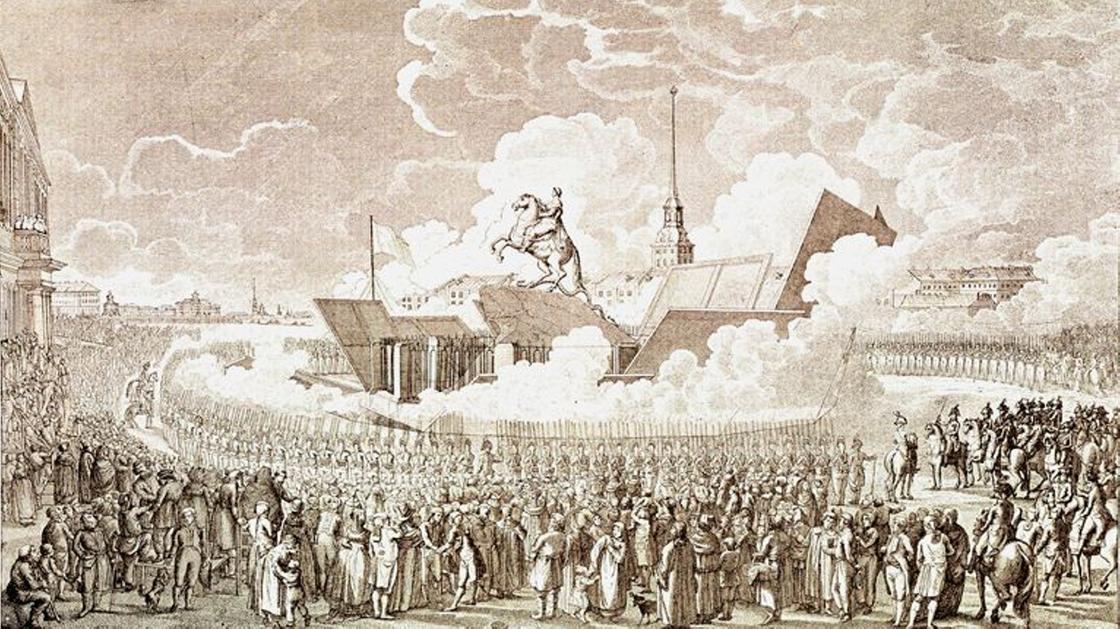

Гранитная глыба для постамента искалась по всей стране. Нужный камень нашелся в 12 верстах от столицы. До реки волокли камень по бревнам, на огромной платформе из дерева. В Петербург его доставили на барже. Инженер Маринос Карбури, придумавший технологию перевозки валуна, получил крупную денежную премию.

Змея на постаменте создана руками русского скульптора Федора Гордеева. Она придает бронзовому изваянию устойчивость.

Интересно, что рука Петра I направлена на границы Швеции. В Стокгольме есть аналогичный памятник Карлу XII. Шведский король указывает рукой на берег России.

Экранизация

На большие экраны поэму удалось перенести еще сто лет назад. Первую ленту по мотивам поэмы снял А.Алексеев и называлась она «На берегу пустынных вод». Фильм, к сожалению, не сохранился. Известно лишь, что большая часть картины была посвящена именно строительству Петербурга, а не переживаниям главного героя.

Вторая попытка экранизировать поэму состоялась в 1915 году. Фильм назывался «В волнах безумия». Здесь речь шла о странностях убитого горем человека. Попытки снять сцены наводнения в Ярославле не состоялись — съемочная группа приехала слишком поздно. Снятые кадры не сохранились.

Историю создания бронзовой скульптуры экранизировали несколько раз. Последняя лента вышла в 2019 году. Фильм повествует о том, как был возведен монумент первому российскому императору.

Аудиокнига

Скачать обзор:

- Начало

- Галерея

- Артклуб

- Магазин

- Новости

- Форум

«Медный всадник», краткое содержание 674 слова читать ~4 мин.

- 0

«Медный всадник: Петербургская повесть» – это повествовательная поэма русского поэта, драматурга и романиста XIX века Александра Пушкина, который считается величайшим поэтом России. Она была написана в 1833 году, но была опубликована только в 1841-м, после смерти Пушкина, из-за цензуры произведений Пушкина российским правительством.