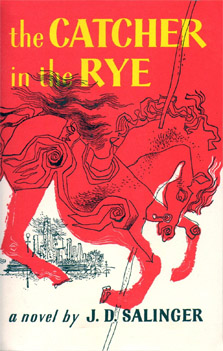

First edition cover |

|

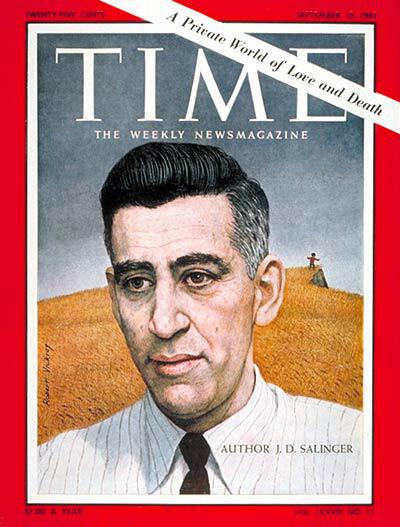

| Author | J. D. Salinger |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | E. Michael Mitchell[1][2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Realistic fiction, Coming-of-age fiction |

| Published | July 16, 1951[3] |

| Publisher | Little, Brown and Company |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 234 (may vary) |

| OCLC | 287628 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

813.54 |

The Catcher in the Rye is an American novel by J. D. Salinger that was partially published in serial form from 1945–46 before being novelized in 1951. Originally intended for adults, it is often read by adolescents for its themes of angst and alienation, and as a critique of superficiality in society.[4][5] The novel also deals with complex issues of innocence, identity, belonging, loss, connection, sex, and depression. The main character, Holden Caulfield, has become an icon for teenage rebellion.[6] Caulfield, nearly of age, gives his opinion on just about everything as he narrates his recent life events.

The Catcher has been translated widely.[7] About one million copies are sold each year, with total sales of more than 65 million books.[8] The novel was included on Time‘s 2005 list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923,[9] and it was named by Modern Library and its readers as one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[10][11][12] In 2003, it was listed at number 15 on the BBC’s survey «The Big Read».

Plot[edit]

Holden Caulfield recalls the events of a weekend (Saturday afternoon to Monday afternoon) shortly before the previous year’s Christmas, beginning at Pencey Preparatory Academy, a boarding school in Pennsylvania that Salinger may have based on the Valley Forge Military Academy and College.[13] Holden has just been expelled from Pencey because he had failed all of his classes except English. After causing the fencing team to forfeit a fencing match in New York because he accidentally lost the team’s equipment on the subway, he says goodbye to his history teacher, Mr. Spencer, who is a well-meaning but long-winded old man. Spencer offers him advice and simultaneously embarrasses Holden by criticizing his history exam.

Back at his dorm, Holden’s dorm neighbor, Robert Ackley, who is unpopular among his peers, disturbs Holden with his impolite questioning and mannerisms. Holden, who feels sorry for Ackley, tolerates his presence. Later, Holden agrees to write an English composition for his roommate, Ward Stradlater, who is leaving for a date. Holden and Stradlater normally hang out well together, and Holden admires Stradlater’s physique. He is distressed to learn that Stradlater’s date is Jane Gallagher, with whom Holden was infatuated and whom he feels the need to protect. That night, Holden decides to go to a Cary Grant comedy with Mal Brossard and Ackley. Since Ackley and Mal had already seen the film, they ended up eating food, playing pinball for a while, and returning to Pencey. When Stradlater returns hours later, he fails to appreciate the deeply personal composition Holden wrote for him about the baseball glove of Holden’s late brother Allie who died from leukemia a few years prior, and refuses to say whether he had sex with Jane. Enraged, Holden punches him, and Stradlater easily wins the fight. When Holden continues insulting him, Stradlater leaves him lying on the floor with a bloody nose. Fed up with the «phonies» at Pencey Prep, Holden decides to leave Pencey early and catches a train to New York. Holden intends to stay away from his home until Wednesday, when his parents will have received notification of his expulsion. Aboard the train, Holden meets the mother of a wealthy, obnoxious Pencey student, Ernest Morrow, and makes up nice but false stories about her son.

In a taxicab, Holden asks the driver whether the ducks in the Central Park lagoon migrate during winter, a subject he brings up often, but the man barely responds. Holden checks into the Edmont Hotel and spends an evening dancing with three tourists at the hotel lounge. Holden is disappointed that they are unable to hold a conversation. Following an unpromising visit to a nightclub, Holden becomes preoccupied with his internal angst and agrees to have a prostitute named Sunny visit his room. His attitude toward the girl changes when she enters the room and takes off her clothes. Holden, who is a virgin, says he only wants to talk, which annoys her and causes her to leave. Even though he maintains that he paid her the right amount for her time, she returns with her pimp Maurice and demands more money. Holden insults Maurice, Sunny takes money from Holden’s wallet, and Maurice snaps his fingers on Holden’s groin and punches him in the stomach. Afterward, Holden imagines that he has been shot by Maurice and pictures murdering him with an automatic pistol.

The next morning, Holden, becoming increasingly depressed and needing personal connection, calls Sally Hayes, a familiar date. Although Holden claims that she is «the queen of all phonies,» they agree to meet that afternoon to attend a play at the Biltmore Theater. Holden shops for a special record, «Little Shirley Beans», for his 10-year-old sister Phoebe. He spots a small boy singing «If a body catch a body coming through the rye», which lifts his mood. After the play, Holden and Sally go ice skating at Rockefeller Center, where Holden suddenly begins ranting against society and frightens Sally. He impulsively invites Sally to run away with him that night to live in the wilderness of New England, but she is uninterested in his hastily conceived plan and declines. The conversation turns sour, and the two angrily part ways.

Holden decides to meet his old classmate, Carl Luce, for drinks at the Wicker Bar. Holden annoys Carl, whom Holden suspects of being gay, by insistently questioning him about his sex life. Before leaving, Luce says that Holden should go see a psychiatrist, to understand himself better. After Luce leaves, Holden gets drunk, awkwardly flirts with several adults, and calls an icy Sally. Exhausted and out of money, Holden wanders over to Central Park to investigate the ducks, accidentally breaking Phoebe’s record on the way. Nostalgic, he heads home to see his sister Phoebe. He sneaks into his parents’ apartment while they are out and wakes up Phoebe — the only person with whom he seems to be able to communicate his true feelings. Although Phoebe is happy to see Holden, she quickly infers that he has been expelled and chastises him for his aimlessness and his apparent disdain for everything. When asked if he cares about anything, Holden shares a selfless fantasy he has been thinking about (based on a mishearing of Robert Burns’s Comin’ Through the Rye), in which he imagines himself as making a job of saving children running through a field of rye by catching them before they fell off a nearby cliff (a «catcher in the rye»). Phoebe points out that the actual poem says, «when a body meet a body, comin through the rye.» Holden breaks down in tears, and his sister tries to console him.

When his parents return home, Holden slips out and visits his former and much-admired English teacher, Mr. Antolini, who expresses concern that Holden is headed for «a terrible fall». Mr. Antolini advises him to begin applying himself and provides Holden with a place to sleep. Holden is upset when he wakes up to find Mr. Antolini patting his head, which he interprets as a sexual advance. He leaves and spends the rest of the night in a waiting room at Grand Central Terminal, where he sinks further into despair and expresses regret over leaving Mr. Antolini. He spends most of the morning wandering Fifth Avenue.

Losing hope of finding belonging or companionship in the city, Holden impulsively decides that he will head out West and live a reclusive lifestyle as a deaf-mute gas station attendant living in a log cabin. He decides to see Phoebe at lunchtime to explain his plan and say goodbye. While visiting Phoebe’s school, Holden sees graffiti containing a curse word and becomes distressed by the thought of children learning the word’s meaning and tarnishing their innocence. When he meets Phoebe at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she arrives with a suitcase and asks to go with him, even though she was looking forward to acting as Benedict Arnold in a play that Friday. Holden refuses to let her come with him, which upsets Phoebe. He tries to cheer her up by allowing her to skip school and taking her to the Central Park Zoo, but she remains angry. They eventually reach the zoo’s carousel, where Phoebe reconciles with Holden after he buys her a ticket. Holden is finally filled with happiness and joy at the sight of Phoebe riding the carousel.

Holden finally alludes to encountering his parents that night and «getting sick», mentioning that he will be attending another school in September. Holden says he doesn’t want to tell anything more because talking about them has made him miss his former classmates.

History[edit]

Various older stories by Salinger contain characters similar to those in The Catcher in the Rye. While at Columbia University, Salinger wrote a short story called «The Young Folks» in Whit Burnett’s class; one character from this story has been described as a «thinly penciled prototype of Sally Hayes». In November 1941 he sold the story «Slight Rebellion off Madison», which featured Holden Caulfield, to The New Yorker, but it wasn’t published until December 21, 1946, due to World War II. The story «I’m Crazy», which was published in the December 22, 1945 issue of Collier’s, contained material that was later used in The Catcher in the Rye.

In 1946, The New Yorker accepted a 90-page manuscript about Holden Caulfield for publication, but Salinger later withdrew it.[14]

Writing style[edit]

The Catcher in the Rye is narrated in a subjective style from the point of view of Holden Caulfield, following his exact thought processes. There is flow in the seemingly disjointed ideas and episodes; for example, as Holden sits in a chair in his dorm, minor events, such as picking up a book or looking at a table, unfold into discussions about experiences.

Critical reviews affirm that the novel accurately reflected the teenage colloquial speech of the time.[15] Words and phrases that appear frequently include:

- «Old» – term of familiarity or endearment

- «Phony» – superficially acting a certain way only to change others’ perceptions

- «That killed me» – one found that hilarious or astonishing

- «Flit» – homosexual

- «Crumbum» or «crumby» – inadequate, insufficient, disappointing

- «Snowing» – sweet-talking

- «I got a bang out of that» – one found it hilarious or exciting

- «Shoot the bull» «bull session» – have a conversation containing false elements

- «Give her the time» – sexual intercourse

- «Necking» – passionate kissing especially on the neck (clothes on)

- «Chew the fat» or «chew the rag» – small-talk

- «Rubbering» or «rubbernecks» – idle onlooking/onlookers

- «The can» – the bathroom

- «Prince of a guy» – fine fellow (however often used sarcastically)

- «Prostitute» – sellout or phony (e.g. in regard to his brother D.B. who is a writer: «Now he’s out in Hollywood being a prostitute»)

Interpretations[edit]

Bruce Brooks held that Holden’s attitude remains unchanged at story’s end, implying no maturation, thus differentiating the novel from young adult fiction.[16]

In contrast, Louis Menand thought that teachers assign the novel because of the optimistic ending, to teach adolescent readers that «alienation is just a phase.»[17] While Brooks maintained that Holden acts his age, Menand claimed that Holden thinks as an adult, given his ability to accurately perceive people and their motives. Others highlight the dilemma of Holden’s state, in between adolescence and adulthood.[18][19] Holden is quick to become emotional. «I felt sorry as hell for…» is a phrase he often uses. It is often said that Holden changes at the end, when he watches Phoebe on the carousel, and he talks about the golden ring and how it’s good for kids to try and grab it.[18]

Peter Beidler in his A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s «The Catcher in the Rye», identifies the movie that the prostitute «Sunny» refers to. In chapter 13 she says that in the movie a boy falls off a boat. The movie is Captains Courageous (1937), starring Spencer Tracy. Sunny says that Holden looks like the boy who fell off the boat. Beidler shows a still of the boy, played by child-actor Freddie Bartholomew.[20]

Each Caulfield child has literary talent. D.B. writes screenplays in Hollywood;[21] Holden also reveres D.B. for his writing skill (Holden’s own best subject), but he also despises Hollywood industry-based movies, considering them the ultimate in «phony» as the writer has no space for his own imagination and describes D.B.’s move to Hollywood to write for films as «prostituting himself»; Allie wrote poetry on his baseball glove;[22] and Phoebe is a diarist.[23]

This «catcher in the rye» is an analogy for Holden, who admires in children attributes that he often struggles to find in adults, like innocence, kindness, spontaneity, and generosity. Falling off the cliff could be a progression into the adult world that surrounds him and that he strongly criticizes. Later, Phoebe and Holden exchange roles as the «catcher» and the «fallen»; he gives her his hunting hat, the catcher’s symbol, and becomes the fallen as Phoebe becomes the catcher.[24]

In their biography of Salinger, David Shields and Shane Salerno argue that: «The Catcher in the Rye can best be understood as a disguised war novel.» Salinger witnessed the horrors of World War II, but rather than writing a combat novel, Salinger, according to Shields and Salerno, «took the trauma of war and embedded it within what looked to the naked eye like a coming-of-age novel.»[25]

Reception[edit]

The Catcher in the Rye has been consistently listed as one of the best novels of the twentieth century. Shortly after its publication, in an article for The New York Times, Nash K. Burger called it «an unusually brilliant novel,»[3] while James Stern wrote an admiring review of the book in a voice imitating Holden’s.[26] George H. W. Bush called it a «marvelous book,» listing it among the books that inspired him.[27] In June 2009, the BBC’s Finlo Rohrer wrote that, 58 years since publication, the book is still regarded «as the defining work on what it is like to be a teenager.»[28] Adam Gopnik considers it one of the «three perfect books» in American literature, along with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby, and believes that «no book has ever captured a city better than Catcher in the Rye captured New York in the fifties.»[29] In an appraisal of The Catcher in the Rye written after the death of J. D. Salinger, Jeff Pruchnic says the novel has retained its appeal for many generations. Pruchnic describes Holden as a «teenage protagonist frozen midcentury but destined to be discovered by those of a similar age in every generation to come.»[30] Bill Gates said that The Catcher in the Rye is one of his favorite books.[31]

Not all reception has been positive. The book has had its share of naysayers, including the longtime Washington Post book critic Jonathan Yardley, who, in 2004, wrote that the experience of rereading the novel after several decades proved to be «a painful experience: The combination of Salinger’s execrable prose and Caulfield’s jejune narcissism produced effects comparable to mainlining castor oil.» Yardley described the novel as among the worst popular books in the annals of American literature. «Why,» Yardley asked, «do English teachers, whose responsibility is to teach good writing, repeatedly and reflexively require students to read a book as badly written as this one?»[32] According to Rohrer, many contemporary readers, as Yardley found, «just cannot understand what the fuss is about…. many of these readers are disappointed that the novel fails to meet the expectations generated by the mystique it is shrouded in. J. D. Salinger has done his part to enhance this mystique. That is to say, he has done nothing.»[28] Rohrer assessed the reasons behind both the popularity and criticism of the book, saying that it «captures existential teenage angst» and has a «complex central character» and «accessible conversational style»; while at the same time some readers may dislike the «use of 1940s New York vernacular» and the excessive «whining» of the «self-obsessed character.»

Censorship and use in schools[edit]

In 1960, a teacher in Tulsa, Oklahoma was fired for assigning the novel in class. She was later reinstated.[33] Between 1961 and 1982, The Catcher in the Rye was the most censored book in high schools and libraries in the United States.[34] The book was briefly banned in the Issaquah, Washington, high schools in 1978 when three members of the School Board alleged the book was part of an «overall communist plot.»[35] This ban did not last long, and the offended board members were immediately recalled and removed in a special election.[36] In 1981, it was both the most censored book and the second most taught book in public schools in the United States.[37] According to the American Library Association, The Catcher in the Rye was the 10th most frequently challenged book from 1990 to 1999.[10] It was one of the ten most challenged books of 2005,[38] and although it had been off the list for three years, it reappeared in the list of most challenged books of 2009.[39]

The challenges generally begin with Holden’s frequent use of vulgar language;[40][41] other reasons include sexual references,[42] blasphemy, undermining of family values[41] and moral codes,[43] encouragement of rebellion,[44] and promotion of drinking, smoking, lying, promiscuity, and sexual abuse.[43] This book was written for an adult audience, which often forms the foundation of many challengers’ arguments against it.[45] Often the challengers have been unfamiliar with the plot itself.[34] Shelley Keller-Gage, a high school teacher who faced objections after assigning the novel in her class, noted that «the challengers are being just like Holden… They are trying to be catchers in the rye.»[41] A Streisand effect has been that this incident caused people to put themselves on the waiting list to borrow the novel, when there was no waiting list before.[46][47]

Violent reactions[edit]

Several shootings have been associated with Salinger’s novel, including Robert John Bardo’s murder of Rebecca Schaeffer and John Hinckley Jr.’s assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan. Additionally, after fatally shooting John Lennon, Mark David Chapman was arrested with a copy of the book that he had purchased that same day, inside of which he had written: «To Holden Caulfield, From Holden Caulfield, This is my statement».[48][49]

Attempted adaptations[edit]

In film[edit]

Early in his career, Salinger expressed a willingness to have his work adapted for the screen.[50] In 1949, a critically panned film version of his short story «Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut» was released; renamed My Foolish Heart, the film took great liberties with Salinger’s plot and is widely considered to be among the reasons that Salinger refused to allow any subsequent film adaptations of his work.[18][51] The enduring success of The Catcher in the Rye, however, has resulted in repeated attempts to secure the novel’s screen rights.[52]

When The Catcher in the Rye was first released, many offers were made to adapt it for the screen, including one from Samuel Goldwyn, producer of My Foolish Heart.[51] In a letter written in the early 1950s, Salinger spoke of mounting a play in which he would play the role of Holden Caulfield opposite Margaret O’Brien, and, if he couldn’t play the part himself, to «forget about it.» Almost 50 years later, the writer Joyce Maynard definitively concluded, «The only person who might ever have played Holden Caulfield would have been J. D. Salinger.»[53]

Salinger told Maynard in the 1970s that Jerry Lewis «tried for years to get his hands on the part of Holden,»[53] the protagonist in the novel which Lewis had not read until he was in his thirties.[46] Film industry figures including Marlon Brando, Jack Nicholson, Ralph Bakshi, Tobey Maguire and Leonardo DiCaprio have tried to make a film adaptation.[54] In an interview with Premiere, John Cusack commented that his one regret about turning 21 was that he had become too old to play Holden Caulfield. Writer-director Billy Wilder recounted his abortive attempts to snare the novel’s rights:

Of course I read The Catcher in the Rye… Wonderful book. I loved it. I pursued it. I wanted to make a picture out of it. And then one day a young man came to the office of Leland Hayward, my agent, in New York, and said, «Please tell Mr. Leland Hayward to lay off. He’s very, very insensitive.» And he walked out. That was the entire speech. I never saw him. That was J. D. Salinger and that was Catcher in the Rye.[55]

In 1961, Salinger denied Elia Kazan permission to direct a stage adaptation of Catcher for Broadway.[56] Later, Salinger’s agents received bids for the Catcher film rights from Harvey Weinstein and Steven Spielberg, neither of which was even passed on to Salinger for consideration.[57]

In 2003, the BBC television program The Big Read featured The Catcher in the Rye, interspersing discussions of the novel with «a series of short films that featured an actor playing J. D. Salinger’s adolescent antihero, Holden Caulfield.»[56] The show defended its unlicensed adaptation of the novel by claiming to be a «literary review», and no major charges were filed.

In 2008, the rights of Salinger’s works were placed in the JD Salinger Literary Trust where Salinger was the sole trustee. Phyllis Westberg, who was Salinger’s agent at Harold Ober Associates in New York, declined to say who the trustees are now that the author is dead. After Salinger died in 2010, Phyllis Westberg stated that nothing has changed in terms of licensing film, television, or stage rights of his works.[58] A letter written by Salinger in 1957 revealed that he was open to an adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye released after his death. He wrote: «Firstly, it is possible that one day the rights will be sold. Since there’s an ever-looming possibility that I won’t die rich, I toy very seriously with the idea of leaving the unsold rights to my wife and daughter as a kind of insurance policy. It pleasures me no end, though, I might quickly add, to know that I won’t have to see the results of the transaction.» Salinger also wrote that he believed his novel was not suitable for film treatment, and that translating Holden Caulfield’s first-person narrative into voice-over and dialogue would be contrived.[59]

In 2020, Don Hahn revealed that Disney had almost made an animated movie titled Dufus which would have been an adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye «with German shepherds», most likely akin to Oliver & Company. The idea came from then CEO Michael Eisner who loved the book and wanted to do an adaptation. After being told that J. D. Salinger would not agree to sell the film rights, Eisner stated «Well, let’s just do that kind of story, that kind of growing up, coming of age story.»[60]

Banned fan sequel[edit]

In 2009, the year before he died, Salinger successfully sued to stop the U.S. publication of a novel that presents Holden Caulfield as an old man.[28][61] The novel’s author, Fredrik Colting, commented: «call me an ignorant Swede, but the last thing I thought possible in the U.S. was that you banned books».[62] The issue is complicated by the nature of Colting’s book, 60 Years Later: Coming Through the Rye, which has been compared to fan fiction.[63] Although commonly not authorized by writers, no legal action is usually taken against fan fiction, since it is rarely published commercially and thus involves no profit.[64]

Legacy and use in popular culture[edit]

See also[edit]

- Book censorship in the United States

- Le Monde‘s 100 Books of the Century

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «CalArts Remembers Beloved Animation Instructor E. Michael Mitchell». Calarts.edu. Archived from the original on September 28, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ «50 Most Captivating Covers». Onlineuniversities.com. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Burger, Nash K. (July 16, 1951). «Books of The Times». The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Costello, Donald P., and Harold Bloom. «The Language of «The Catcher in the Rye..» Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations: The Catcher in the Rye (2000): 11–20. Literary Reference Center. EBSCO. Web. December 1, 2010.

- ^ «Carte Blanche: Famous Firsts». Booklist. November 15, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Allusions By Elizabeth Webber, Mike Feinsilber p.105

- ^ Magill, Frank N. (1991). «J. D. Salinger». Magill’s Survey of American Literature. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 1803. ISBN 1-85435-437-X.

- ^ According to List of best-selling books. An earlier article says more than 20 million: Yardley, Jonathan (October 19, 2004). «J. D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, Aging Gracelessly». The Washington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

It isn’t just a novel, it’s a dispatch from an unknown, mysterious universe, which may help explain the phenomenal sales it enjoys to this day: about 250,000 copies a year, with total worldwide sales over – probably way over – 10 million.

- ^ Grossman, Lev; Lacayo, Richard (October 16, 2005). «All-Time 100 Novels: The Complete List». Time.

- ^ a b «The 100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999». American Library Association. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ List of most commonly challenged books from the list of the one hundred most important books of the 20th century by Radcliffe Publishing Course

- ^ Guinn, Jeff (August 10, 2001). «‘Catcher in the Rye’ still influences 50 years later» (fee required). Erie Times-News. Retrieved December 18, 2007. Alternate URL

- ^ «Hazing, Fighting, Sexual Assaults: How Valley Forge Military Academy Devolved Into «Lord of the Flies» – Mother Jones». Motherjones.com. October 30, 2005. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Salzman, Jack (1991). New essays on the Catcher in the Rye. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521377980.

- ^ Costello, Donald P. (October 1959). «The Language of ‘The Catcher in the Rye’«. American Speech. 34 (3): 172–182. doi:10.2307/454038. JSTOR 454038.

Most critics who glared at The Catcher in the Rye at the time of its publication thought that its language was a true and authentic rendering of teenage colloquial speech.

- ^ Brooks, Bruce (May 1, 2004). «Holden at sixteen». Horn Book Magazine. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Menand, Louis (September 27, 2001). «Holden at fifty». The New Yorker. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ a b c Onstad, Katrina (February 22, 2008). «Beholden to Holden». CBC News. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008.

- ^ Graham, 33.

- ^ Press, Coffeetown (June 16, 2011). «A Reader’s Companion to J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (Second Edition), by Peter G. Beidler». Coffeetown Press. p. 28. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Salinger (1969, p. 67)

- ^ Salinger (1969, p. 38)

- ^ Salinger (1969, p. 160)

- ^ Yasuhiro Takeuchi (Fall 2002). «The Burning Carousel and the Carnivalesque: Subversion and Transcendence at the Close of The Catcher in the Rye«. Studies in the Novel. Vol. 34, no. 3. pp. 320–337.

- ^ Shields, David; Salerno, Shane (2013). Salinger (Hardcover ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. xvi. ASIN 1476744831.

The Catcher in the Rye can best be understood as a disguised war novel. Salinger emerged from the war incapable of believing in the heroic, noble ideals we like to think our cultural institutions uphold. Instead of producing a combat novel, like Norman Mailer, James Jones, and Joseph Heller did, Salinger took the trauma of war and embedded it within what looked to the naked eye like a coming-of-age novel.

- ^ Stern, James (July 15, 1951). «Aw, the World’s a Crumby Place». The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ «Academy of Achievement – George H. W. Bush». The American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on February 13, 1997. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c Rohrer, Finlo (June 5, 2009). «The why of the Rye». BBC News Magazine. BBC. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ Gopnik, Adam. The New Yorker, February 8, 2010, p. 21

- ^ Pruchnic, Jeff. «Holden at Sixty: Reading Catcher After the Age of Irony.» Critical Insights: ————The Catcher in The Rye (2011): 49–63. Literary Reference Center. Web. February 2, 2015.

- ^ Gates, Bill. «The Best Books I Read in 2013». gatesnotes.com. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (October 19, 2004). «J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, Aging Gracelessly». The Washington Post. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Dutra, Fernando (September 25, 2006). «U. Connecticut: Banned Book Week celebrates freedom». The America’s Intelligence Wire. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

In 1960 a teacher in Tulsa, Okla. was fired for assigning «The Catcher in the Rye». After appealing, the teacher was reinstated, but the book was removed from the itinerary in the school.

- ^ a b «In Cold Fear: ‘The Catcher in the Rye’, Censorship, Controversies and Postwar American Character. (Book Review)». Modern Language Review. April 1, 2003. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Reiff, Raychel Haugrud (2008). J.D. Salinger: The Catcher in the Rye and Other Works. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7614-2594-6.

- ^ Jenkinson, Edward (1982). Censors in the Classroom. Avon Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0380597901.

- ^ Andrychuk, Sylvia (February 17, 2004). «A History of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye» (PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007.

During 1981, The Catcher in the Rye had the unusual distinction of being the most frequently censored book in the United States, and, at the same time, the second-most frequently taught novel in American public schools.

- ^ ««It’s Perfectly Normal» tops ALA’s 2005 list of most challenged books». American Library Association. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ^ «Top ten most frequently challenged books of 2009». American Library Association. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ «Art or trash? It makes for endless, unwinnable debate». The Topeka Capital-Journal. October 6, 1997. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

Another perennial target, J.D. Salinger’s «Catcher in the Rye,» was challenged in Maine because of the «f» word.

- ^ a b c Mydans, Seth (September 3, 1989). «In a Small Town, a Battle Over a Book». The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ MacIntyre, Ben (September 24, 2005). «The American banned list reveals a society with serious hang-ups». The Times. London. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Frangedis, Helen (November 1988). «Dealing with the Controversial Elements in The Catcher in the Rye«. The English Journal. 77 (7): 72–75. doi:10.2307/818945. JSTOR 818945.

The foremost allegation made against Catcher is… that it teaches loose moral codes; that it glorifies… drinking, smoking, lying, promiscuity, and more.

- ^ Yilu Zhao (August 31, 2003). «Banned, But Not Forgotten». The New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

The Catcher in the Rye, interpreted by some as encouraging rebellion against authority…

- ^ «Banned from the classroom: Censorship and The Catcher in the Rye – English and Drama blog». blogs.bl.uk. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Whitfield, Stephen (December 1997). «Cherished and Cursed: Toward a Social History of The Catcher in the Rye» (PDF). The New England Quarterly. 70 (4): 567–600. doi:10.2307/366646. JSTOR 366646. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ J.D. Salinger. Philadelphia: Chelsea House. 2001. pp. 77–105. ISBN 0-7910-6175-2.

- ^ Weeks, Linton (September 10, 2000). «Telling on Dad». Amarillo Globe-News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ Doyle, Aidan (December 15, 2003). «When books kill». Salon.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2007.

- ^ Hamilton, Ian (1988). In Search of J. D. Salinger. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-53468-9. p. 75.

- ^ a b Berg, A. Scott. Goldwyn: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. ISBN 1-57322-723-4. p. 446.

- ^ See Dr. Peter Beidler’s A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s the Catcher in the Rye, Chapter 7.

- ^ a b Maynard, Joyce (1998). At Home in the World. New York: Picador. p. 93. ISBN 0-312-19556-7.

- ^ «News & Features». IFILM: The Internet Movie Guide. 2004. Archived from the original on September 6, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ^ Crowe, Cameron, ed. Conversations with Wilder. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. ISBN 0-375-40660-3. p. 299.

- ^ a b McAllister, David (November 11, 2003). «Will J. D. Salinger sue?». The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ «Spielberg wanted to film Catcher In The Rye». Irish Examiner. December 5, 2003. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ «Slim chance of Catcher in the Rye movie – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)». ABC News. ABCnet.au. January 29, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ Connelly, Sherryl (January 29, 2010). «Could ‘Catcher in the Rye’ finally make it to the big screen? Salinger letter suggests yes». Daily News. New York. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (August 3, 2020). «Disney Once Tried to Make an Animated ‘Catcher in the Rye’ — But Wait, There’s More». Collider. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Gross, Doug (June 3, 2009). «Lawsuit targets ‘rip-off’ of ‘Catcher in the Rye’«. CNN. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Fogel, Karl. Looks like censorship, smells like censorship… maybe it IS censorship?. QuestionCopyright.org. July 7, 2009.

- ^ Sutherland, John. How fanfic took over the web London Evening Standard. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Rebecca Tushnet (1997). «Fan Fiction and a New Common Law». Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Journal. 17.

Bibliography[edit]

- Graham, Sarah (2007). J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34452-4.

- Rohrer, Finlo (June 5, 2009). «The why of the Rye». BBC News Magazine. BBC.

- Salinger, J. D. (1969), The Catcher in the Rye, New York: Bantam

- Wahlbrinck, Bernd (2021). Looking Back after 70 Years: J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye Revisited. ISBN 978-3-9821463-7-9.

Further reading[edit]

- Steinle, Pamela Hunt (2000). In Cold Fear: The Catcher in the Rye Censorship Controversies and Postwar American Character. Ohio State University Press. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

External links[edit]

- Book Drum illustrated profile of The Catcher in the Rye Archived September 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Photos of the first edition of Catcher in the Rye

- Lawsuit targets «rip-off» of «Catcher in the Rye» – CNN

First edition cover |

|

| Author | J. D. Salinger |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | E. Michael Mitchell[1][2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Realistic fiction, Coming-of-age fiction |

| Published | July 16, 1951[3] |

| Publisher | Little, Brown and Company |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 234 (may vary) |

| OCLC | 287628 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

813.54 |

The Catcher in the Rye is an American novel by J. D. Salinger that was partially published in serial form from 1945–46 before being novelized in 1951. Originally intended for adults, it is often read by adolescents for its themes of angst and alienation, and as a critique of superficiality in society.[4][5] The novel also deals with complex issues of innocence, identity, belonging, loss, connection, sex, and depression. The main character, Holden Caulfield, has become an icon for teenage rebellion.[6] Caulfield, nearly of age, gives his opinion on just about everything as he narrates his recent life events.

The Catcher has been translated widely.[7] About one million copies are sold each year, with total sales of more than 65 million books.[8] The novel was included on Time‘s 2005 list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923,[9] and it was named by Modern Library and its readers as one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[10][11][12] In 2003, it was listed at number 15 on the BBC’s survey «The Big Read».

Plot[edit]

Holden Caulfield recalls the events of a weekend (Saturday afternoon to Monday afternoon) shortly before the previous year’s Christmas, beginning at Pencey Preparatory Academy, a boarding school in Pennsylvania that Salinger may have based on the Valley Forge Military Academy and College.[13] Holden has just been expelled from Pencey because he had failed all of his classes except English. After causing the fencing team to forfeit a fencing match in New York because he accidentally lost the team’s equipment on the subway, he says goodbye to his history teacher, Mr. Spencer, who is a well-meaning but long-winded old man. Spencer offers him advice and simultaneously embarrasses Holden by criticizing his history exam.

Back at his dorm, Holden’s dorm neighbor, Robert Ackley, who is unpopular among his peers, disturbs Holden with his impolite questioning and mannerisms. Holden, who feels sorry for Ackley, tolerates his presence. Later, Holden agrees to write an English composition for his roommate, Ward Stradlater, who is leaving for a date. Holden and Stradlater normally hang out well together, and Holden admires Stradlater’s physique. He is distressed to learn that Stradlater’s date is Jane Gallagher, with whom Holden was infatuated and whom he feels the need to protect. That night, Holden decides to go to a Cary Grant comedy with Mal Brossard and Ackley. Since Ackley and Mal had already seen the film, they ended up eating food, playing pinball for a while, and returning to Pencey. When Stradlater returns hours later, he fails to appreciate the deeply personal composition Holden wrote for him about the baseball glove of Holden’s late brother Allie who died from leukemia a few years prior, and refuses to say whether he had sex with Jane. Enraged, Holden punches him, and Stradlater easily wins the fight. When Holden continues insulting him, Stradlater leaves him lying on the floor with a bloody nose. Fed up with the «phonies» at Pencey Prep, Holden decides to leave Pencey early and catches a train to New York. Holden intends to stay away from his home until Wednesday, when his parents will have received notification of his expulsion. Aboard the train, Holden meets the mother of a wealthy, obnoxious Pencey student, Ernest Morrow, and makes up nice but false stories about her son.

In a taxicab, Holden asks the driver whether the ducks in the Central Park lagoon migrate during winter, a subject he brings up often, but the man barely responds. Holden checks into the Edmont Hotel and spends an evening dancing with three tourists at the hotel lounge. Holden is disappointed that they are unable to hold a conversation. Following an unpromising visit to a nightclub, Holden becomes preoccupied with his internal angst and agrees to have a prostitute named Sunny visit his room. His attitude toward the girl changes when she enters the room and takes off her clothes. Holden, who is a virgin, says he only wants to talk, which annoys her and causes her to leave. Even though he maintains that he paid her the right amount for her time, she returns with her pimp Maurice and demands more money. Holden insults Maurice, Sunny takes money from Holden’s wallet, and Maurice snaps his fingers on Holden’s groin and punches him in the stomach. Afterward, Holden imagines that he has been shot by Maurice and pictures murdering him with an automatic pistol.

The next morning, Holden, becoming increasingly depressed and needing personal connection, calls Sally Hayes, a familiar date. Although Holden claims that she is «the queen of all phonies,» they agree to meet that afternoon to attend a play at the Biltmore Theater. Holden shops for a special record, «Little Shirley Beans», for his 10-year-old sister Phoebe. He spots a small boy singing «If a body catch a body coming through the rye», which lifts his mood. After the play, Holden and Sally go ice skating at Rockefeller Center, where Holden suddenly begins ranting against society and frightens Sally. He impulsively invites Sally to run away with him that night to live in the wilderness of New England, but she is uninterested in his hastily conceived plan and declines. The conversation turns sour, and the two angrily part ways.

Holden decides to meet his old classmate, Carl Luce, for drinks at the Wicker Bar. Holden annoys Carl, whom Holden suspects of being gay, by insistently questioning him about his sex life. Before leaving, Luce says that Holden should go see a psychiatrist, to understand himself better. After Luce leaves, Holden gets drunk, awkwardly flirts with several adults, and calls an icy Sally. Exhausted and out of money, Holden wanders over to Central Park to investigate the ducks, accidentally breaking Phoebe’s record on the way. Nostalgic, he heads home to see his sister Phoebe. He sneaks into his parents’ apartment while they are out and wakes up Phoebe — the only person with whom he seems to be able to communicate his true feelings. Although Phoebe is happy to see Holden, she quickly infers that he has been expelled and chastises him for his aimlessness and his apparent disdain for everything. When asked if he cares about anything, Holden shares a selfless fantasy he has been thinking about (based on a mishearing of Robert Burns’s Comin’ Through the Rye), in which he imagines himself as making a job of saving children running through a field of rye by catching them before they fell off a nearby cliff (a «catcher in the rye»). Phoebe points out that the actual poem says, «when a body meet a body, comin through the rye.» Holden breaks down in tears, and his sister tries to console him.

When his parents return home, Holden slips out and visits his former and much-admired English teacher, Mr. Antolini, who expresses concern that Holden is headed for «a terrible fall». Mr. Antolini advises him to begin applying himself and provides Holden with a place to sleep. Holden is upset when he wakes up to find Mr. Antolini patting his head, which he interprets as a sexual advance. He leaves and spends the rest of the night in a waiting room at Grand Central Terminal, where he sinks further into despair and expresses regret over leaving Mr. Antolini. He spends most of the morning wandering Fifth Avenue.

Losing hope of finding belonging or companionship in the city, Holden impulsively decides that he will head out West and live a reclusive lifestyle as a deaf-mute gas station attendant living in a log cabin. He decides to see Phoebe at lunchtime to explain his plan and say goodbye. While visiting Phoebe’s school, Holden sees graffiti containing a curse word and becomes distressed by the thought of children learning the word’s meaning and tarnishing their innocence. When he meets Phoebe at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she arrives with a suitcase and asks to go with him, even though she was looking forward to acting as Benedict Arnold in a play that Friday. Holden refuses to let her come with him, which upsets Phoebe. He tries to cheer her up by allowing her to skip school and taking her to the Central Park Zoo, but she remains angry. They eventually reach the zoo’s carousel, where Phoebe reconciles with Holden after he buys her a ticket. Holden is finally filled with happiness and joy at the sight of Phoebe riding the carousel.

Holden finally alludes to encountering his parents that night and «getting sick», mentioning that he will be attending another school in September. Holden says he doesn’t want to tell anything more because talking about them has made him miss his former classmates.

History[edit]

Various older stories by Salinger contain characters similar to those in The Catcher in the Rye. While at Columbia University, Salinger wrote a short story called «The Young Folks» in Whit Burnett’s class; one character from this story has been described as a «thinly penciled prototype of Sally Hayes». In November 1941 he sold the story «Slight Rebellion off Madison», which featured Holden Caulfield, to The New Yorker, but it wasn’t published until December 21, 1946, due to World War II. The story «I’m Crazy», which was published in the December 22, 1945 issue of Collier’s, contained material that was later used in The Catcher in the Rye.

In 1946, The New Yorker accepted a 90-page manuscript about Holden Caulfield for publication, but Salinger later withdrew it.[14]

Writing style[edit]

The Catcher in the Rye is narrated in a subjective style from the point of view of Holden Caulfield, following his exact thought processes. There is flow in the seemingly disjointed ideas and episodes; for example, as Holden sits in a chair in his dorm, minor events, such as picking up a book or looking at a table, unfold into discussions about experiences.

Critical reviews affirm that the novel accurately reflected the teenage colloquial speech of the time.[15] Words and phrases that appear frequently include:

- «Old» – term of familiarity or endearment

- «Phony» – superficially acting a certain way only to change others’ perceptions

- «That killed me» – one found that hilarious or astonishing

- «Flit» – homosexual

- «Crumbum» or «crumby» – inadequate, insufficient, disappointing

- «Snowing» – sweet-talking

- «I got a bang out of that» – one found it hilarious or exciting

- «Shoot the bull» «bull session» – have a conversation containing false elements

- «Give her the time» – sexual intercourse

- «Necking» – passionate kissing especially on the neck (clothes on)

- «Chew the fat» or «chew the rag» – small-talk

- «Rubbering» or «rubbernecks» – idle onlooking/onlookers

- «The can» – the bathroom

- «Prince of a guy» – fine fellow (however often used sarcastically)

- «Prostitute» – sellout or phony (e.g. in regard to his brother D.B. who is a writer: «Now he’s out in Hollywood being a prostitute»)

Interpretations[edit]

Bruce Brooks held that Holden’s attitude remains unchanged at story’s end, implying no maturation, thus differentiating the novel from young adult fiction.[16]

In contrast, Louis Menand thought that teachers assign the novel because of the optimistic ending, to teach adolescent readers that «alienation is just a phase.»[17] While Brooks maintained that Holden acts his age, Menand claimed that Holden thinks as an adult, given his ability to accurately perceive people and their motives. Others highlight the dilemma of Holden’s state, in between adolescence and adulthood.[18][19] Holden is quick to become emotional. «I felt sorry as hell for…» is a phrase he often uses. It is often said that Holden changes at the end, when he watches Phoebe on the carousel, and he talks about the golden ring and how it’s good for kids to try and grab it.[18]

Peter Beidler in his A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s «The Catcher in the Rye», identifies the movie that the prostitute «Sunny» refers to. In chapter 13 she says that in the movie a boy falls off a boat. The movie is Captains Courageous (1937), starring Spencer Tracy. Sunny says that Holden looks like the boy who fell off the boat. Beidler shows a still of the boy, played by child-actor Freddie Bartholomew.[20]

Each Caulfield child has literary talent. D.B. writes screenplays in Hollywood;[21] Holden also reveres D.B. for his writing skill (Holden’s own best subject), but he also despises Hollywood industry-based movies, considering them the ultimate in «phony» as the writer has no space for his own imagination and describes D.B.’s move to Hollywood to write for films as «prostituting himself»; Allie wrote poetry on his baseball glove;[22] and Phoebe is a diarist.[23]

This «catcher in the rye» is an analogy for Holden, who admires in children attributes that he often struggles to find in adults, like innocence, kindness, spontaneity, and generosity. Falling off the cliff could be a progression into the adult world that surrounds him and that he strongly criticizes. Later, Phoebe and Holden exchange roles as the «catcher» and the «fallen»; he gives her his hunting hat, the catcher’s symbol, and becomes the fallen as Phoebe becomes the catcher.[24]

In their biography of Salinger, David Shields and Shane Salerno argue that: «The Catcher in the Rye can best be understood as a disguised war novel.» Salinger witnessed the horrors of World War II, but rather than writing a combat novel, Salinger, according to Shields and Salerno, «took the trauma of war and embedded it within what looked to the naked eye like a coming-of-age novel.»[25]

Reception[edit]

The Catcher in the Rye has been consistently listed as one of the best novels of the twentieth century. Shortly after its publication, in an article for The New York Times, Nash K. Burger called it «an unusually brilliant novel,»[3] while James Stern wrote an admiring review of the book in a voice imitating Holden’s.[26] George H. W. Bush called it a «marvelous book,» listing it among the books that inspired him.[27] In June 2009, the BBC’s Finlo Rohrer wrote that, 58 years since publication, the book is still regarded «as the defining work on what it is like to be a teenager.»[28] Adam Gopnik considers it one of the «three perfect books» in American literature, along with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby, and believes that «no book has ever captured a city better than Catcher in the Rye captured New York in the fifties.»[29] In an appraisal of The Catcher in the Rye written after the death of J. D. Salinger, Jeff Pruchnic says the novel has retained its appeal for many generations. Pruchnic describes Holden as a «teenage protagonist frozen midcentury but destined to be discovered by those of a similar age in every generation to come.»[30] Bill Gates said that The Catcher in the Rye is one of his favorite books.[31]

Not all reception has been positive. The book has had its share of naysayers, including the longtime Washington Post book critic Jonathan Yardley, who, in 2004, wrote that the experience of rereading the novel after several decades proved to be «a painful experience: The combination of Salinger’s execrable prose and Caulfield’s jejune narcissism produced effects comparable to mainlining castor oil.» Yardley described the novel as among the worst popular books in the annals of American literature. «Why,» Yardley asked, «do English teachers, whose responsibility is to teach good writing, repeatedly and reflexively require students to read a book as badly written as this one?»[32] According to Rohrer, many contemporary readers, as Yardley found, «just cannot understand what the fuss is about…. many of these readers are disappointed that the novel fails to meet the expectations generated by the mystique it is shrouded in. J. D. Salinger has done his part to enhance this mystique. That is to say, he has done nothing.»[28] Rohrer assessed the reasons behind both the popularity and criticism of the book, saying that it «captures existential teenage angst» and has a «complex central character» and «accessible conversational style»; while at the same time some readers may dislike the «use of 1940s New York vernacular» and the excessive «whining» of the «self-obsessed character.»

Censorship and use in schools[edit]

In 1960, a teacher in Tulsa, Oklahoma was fired for assigning the novel in class. She was later reinstated.[33] Between 1961 and 1982, The Catcher in the Rye was the most censored book in high schools and libraries in the United States.[34] The book was briefly banned in the Issaquah, Washington, high schools in 1978 when three members of the School Board alleged the book was part of an «overall communist plot.»[35] This ban did not last long, and the offended board members were immediately recalled and removed in a special election.[36] In 1981, it was both the most censored book and the second most taught book in public schools in the United States.[37] According to the American Library Association, The Catcher in the Rye was the 10th most frequently challenged book from 1990 to 1999.[10] It was one of the ten most challenged books of 2005,[38] and although it had been off the list for three years, it reappeared in the list of most challenged books of 2009.[39]

The challenges generally begin with Holden’s frequent use of vulgar language;[40][41] other reasons include sexual references,[42] blasphemy, undermining of family values[41] and moral codes,[43] encouragement of rebellion,[44] and promotion of drinking, smoking, lying, promiscuity, and sexual abuse.[43] This book was written for an adult audience, which often forms the foundation of many challengers’ arguments against it.[45] Often the challengers have been unfamiliar with the plot itself.[34] Shelley Keller-Gage, a high school teacher who faced objections after assigning the novel in her class, noted that «the challengers are being just like Holden… They are trying to be catchers in the rye.»[41] A Streisand effect has been that this incident caused people to put themselves on the waiting list to borrow the novel, when there was no waiting list before.[46][47]

Violent reactions[edit]

Several shootings have been associated with Salinger’s novel, including Robert John Bardo’s murder of Rebecca Schaeffer and John Hinckley Jr.’s assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan. Additionally, after fatally shooting John Lennon, Mark David Chapman was arrested with a copy of the book that he had purchased that same day, inside of which he had written: «To Holden Caulfield, From Holden Caulfield, This is my statement».[48][49]

Attempted adaptations[edit]

In film[edit]

Early in his career, Salinger expressed a willingness to have his work adapted for the screen.[50] In 1949, a critically panned film version of his short story «Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut» was released; renamed My Foolish Heart, the film took great liberties with Salinger’s plot and is widely considered to be among the reasons that Salinger refused to allow any subsequent film adaptations of his work.[18][51] The enduring success of The Catcher in the Rye, however, has resulted in repeated attempts to secure the novel’s screen rights.[52]

When The Catcher in the Rye was first released, many offers were made to adapt it for the screen, including one from Samuel Goldwyn, producer of My Foolish Heart.[51] In a letter written in the early 1950s, Salinger spoke of mounting a play in which he would play the role of Holden Caulfield opposite Margaret O’Brien, and, if he couldn’t play the part himself, to «forget about it.» Almost 50 years later, the writer Joyce Maynard definitively concluded, «The only person who might ever have played Holden Caulfield would have been J. D. Salinger.»[53]

Salinger told Maynard in the 1970s that Jerry Lewis «tried for years to get his hands on the part of Holden,»[53] the protagonist in the novel which Lewis had not read until he was in his thirties.[46] Film industry figures including Marlon Brando, Jack Nicholson, Ralph Bakshi, Tobey Maguire and Leonardo DiCaprio have tried to make a film adaptation.[54] In an interview with Premiere, John Cusack commented that his one regret about turning 21 was that he had become too old to play Holden Caulfield. Writer-director Billy Wilder recounted his abortive attempts to snare the novel’s rights:

Of course I read The Catcher in the Rye… Wonderful book. I loved it. I pursued it. I wanted to make a picture out of it. And then one day a young man came to the office of Leland Hayward, my agent, in New York, and said, «Please tell Mr. Leland Hayward to lay off. He’s very, very insensitive.» And he walked out. That was the entire speech. I never saw him. That was J. D. Salinger and that was Catcher in the Rye.[55]

In 1961, Salinger denied Elia Kazan permission to direct a stage adaptation of Catcher for Broadway.[56] Later, Salinger’s agents received bids for the Catcher film rights from Harvey Weinstein and Steven Spielberg, neither of which was even passed on to Salinger for consideration.[57]

In 2003, the BBC television program The Big Read featured The Catcher in the Rye, interspersing discussions of the novel with «a series of short films that featured an actor playing J. D. Salinger’s adolescent antihero, Holden Caulfield.»[56] The show defended its unlicensed adaptation of the novel by claiming to be a «literary review», and no major charges were filed.

In 2008, the rights of Salinger’s works were placed in the JD Salinger Literary Trust where Salinger was the sole trustee. Phyllis Westberg, who was Salinger’s agent at Harold Ober Associates in New York, declined to say who the trustees are now that the author is dead. After Salinger died in 2010, Phyllis Westberg stated that nothing has changed in terms of licensing film, television, or stage rights of his works.[58] A letter written by Salinger in 1957 revealed that he was open to an adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye released after his death. He wrote: «Firstly, it is possible that one day the rights will be sold. Since there’s an ever-looming possibility that I won’t die rich, I toy very seriously with the idea of leaving the unsold rights to my wife and daughter as a kind of insurance policy. It pleasures me no end, though, I might quickly add, to know that I won’t have to see the results of the transaction.» Salinger also wrote that he believed his novel was not suitable for film treatment, and that translating Holden Caulfield’s first-person narrative into voice-over and dialogue would be contrived.[59]

In 2020, Don Hahn revealed that Disney had almost made an animated movie titled Dufus which would have been an adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye «with German shepherds», most likely akin to Oliver & Company. The idea came from then CEO Michael Eisner who loved the book and wanted to do an adaptation. After being told that J. D. Salinger would not agree to sell the film rights, Eisner stated «Well, let’s just do that kind of story, that kind of growing up, coming of age story.»[60]

Banned fan sequel[edit]

In 2009, the year before he died, Salinger successfully sued to stop the U.S. publication of a novel that presents Holden Caulfield as an old man.[28][61] The novel’s author, Fredrik Colting, commented: «call me an ignorant Swede, but the last thing I thought possible in the U.S. was that you banned books».[62] The issue is complicated by the nature of Colting’s book, 60 Years Later: Coming Through the Rye, which has been compared to fan fiction.[63] Although commonly not authorized by writers, no legal action is usually taken against fan fiction, since it is rarely published commercially and thus involves no profit.[64]

Legacy and use in popular culture[edit]

See also[edit]

- Book censorship in the United States

- Le Monde‘s 100 Books of the Century

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «CalArts Remembers Beloved Animation Instructor E. Michael Mitchell». Calarts.edu. Archived from the original on September 28, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ «50 Most Captivating Covers». Onlineuniversities.com. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Burger, Nash K. (July 16, 1951). «Books of The Times». The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Costello, Donald P., and Harold Bloom. «The Language of «The Catcher in the Rye..» Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations: The Catcher in the Rye (2000): 11–20. Literary Reference Center. EBSCO. Web. December 1, 2010.

- ^ «Carte Blanche: Famous Firsts». Booklist. November 15, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Allusions By Elizabeth Webber, Mike Feinsilber p.105

- ^ Magill, Frank N. (1991). «J. D. Salinger». Magill’s Survey of American Literature. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 1803. ISBN 1-85435-437-X.

- ^ According to List of best-selling books. An earlier article says more than 20 million: Yardley, Jonathan (October 19, 2004). «J. D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, Aging Gracelessly». The Washington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

It isn’t just a novel, it’s a dispatch from an unknown, mysterious universe, which may help explain the phenomenal sales it enjoys to this day: about 250,000 copies a year, with total worldwide sales over – probably way over – 10 million.

- ^ Grossman, Lev; Lacayo, Richard (October 16, 2005). «All-Time 100 Novels: The Complete List». Time.

- ^ a b «The 100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999». American Library Association. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ List of most commonly challenged books from the list of the one hundred most important books of the 20th century by Radcliffe Publishing Course

- ^ Guinn, Jeff (August 10, 2001). «‘Catcher in the Rye’ still influences 50 years later» (fee required). Erie Times-News. Retrieved December 18, 2007. Alternate URL

- ^ «Hazing, Fighting, Sexual Assaults: How Valley Forge Military Academy Devolved Into «Lord of the Flies» – Mother Jones». Motherjones.com. October 30, 2005. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Salzman, Jack (1991). New essays on the Catcher in the Rye. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521377980.

- ^ Costello, Donald P. (October 1959). «The Language of ‘The Catcher in the Rye’«. American Speech. 34 (3): 172–182. doi:10.2307/454038. JSTOR 454038.

Most critics who glared at The Catcher in the Rye at the time of its publication thought that its language was a true and authentic rendering of teenage colloquial speech.

- ^ Brooks, Bruce (May 1, 2004). «Holden at sixteen». Horn Book Magazine. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Menand, Louis (September 27, 2001). «Holden at fifty». The New Yorker. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ a b c Onstad, Katrina (February 22, 2008). «Beholden to Holden». CBC News. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008.

- ^ Graham, 33.

- ^ Press, Coffeetown (June 16, 2011). «A Reader’s Companion to J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (Second Edition), by Peter G. Beidler». Coffeetown Press. p. 28. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Salinger (1969, p. 67)

- ^ Salinger (1969, p. 38)

- ^ Salinger (1969, p. 160)

- ^ Yasuhiro Takeuchi (Fall 2002). «The Burning Carousel and the Carnivalesque: Subversion and Transcendence at the Close of The Catcher in the Rye«. Studies in the Novel. Vol. 34, no. 3. pp. 320–337.

- ^ Shields, David; Salerno, Shane (2013). Salinger (Hardcover ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. xvi. ASIN 1476744831.

The Catcher in the Rye can best be understood as a disguised war novel. Salinger emerged from the war incapable of believing in the heroic, noble ideals we like to think our cultural institutions uphold. Instead of producing a combat novel, like Norman Mailer, James Jones, and Joseph Heller did, Salinger took the trauma of war and embedded it within what looked to the naked eye like a coming-of-age novel.

- ^ Stern, James (July 15, 1951). «Aw, the World’s a Crumby Place». The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ «Academy of Achievement – George H. W. Bush». The American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on February 13, 1997. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c Rohrer, Finlo (June 5, 2009). «The why of the Rye». BBC News Magazine. BBC. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ Gopnik, Adam. The New Yorker, February 8, 2010, p. 21

- ^ Pruchnic, Jeff. «Holden at Sixty: Reading Catcher After the Age of Irony.» Critical Insights: ————The Catcher in The Rye (2011): 49–63. Literary Reference Center. Web. February 2, 2015.

- ^ Gates, Bill. «The Best Books I Read in 2013». gatesnotes.com. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (October 19, 2004). «J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, Aging Gracelessly». The Washington Post. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Dutra, Fernando (September 25, 2006). «U. Connecticut: Banned Book Week celebrates freedom». The America’s Intelligence Wire. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

In 1960 a teacher in Tulsa, Okla. was fired for assigning «The Catcher in the Rye». After appealing, the teacher was reinstated, but the book was removed from the itinerary in the school.

- ^ a b «In Cold Fear: ‘The Catcher in the Rye’, Censorship, Controversies and Postwar American Character. (Book Review)». Modern Language Review. April 1, 2003. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Reiff, Raychel Haugrud (2008). J.D. Salinger: The Catcher in the Rye and Other Works. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7614-2594-6.

- ^ Jenkinson, Edward (1982). Censors in the Classroom. Avon Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0380597901.

- ^ Andrychuk, Sylvia (February 17, 2004). «A History of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye» (PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007.

During 1981, The Catcher in the Rye had the unusual distinction of being the most frequently censored book in the United States, and, at the same time, the second-most frequently taught novel in American public schools.

- ^ ««It’s Perfectly Normal» tops ALA’s 2005 list of most challenged books». American Library Association. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ^ «Top ten most frequently challenged books of 2009». American Library Association. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ «Art or trash? It makes for endless, unwinnable debate». The Topeka Capital-Journal. October 6, 1997. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

Another perennial target, J.D. Salinger’s «Catcher in the Rye,» was challenged in Maine because of the «f» word.

- ^ a b c Mydans, Seth (September 3, 1989). «In a Small Town, a Battle Over a Book». The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ MacIntyre, Ben (September 24, 2005). «The American banned list reveals a society with serious hang-ups». The Times. London. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Frangedis, Helen (November 1988). «Dealing with the Controversial Elements in The Catcher in the Rye«. The English Journal. 77 (7): 72–75. doi:10.2307/818945. JSTOR 818945.

The foremost allegation made against Catcher is… that it teaches loose moral codes; that it glorifies… drinking, smoking, lying, promiscuity, and more.

- ^ Yilu Zhao (August 31, 2003). «Banned, But Not Forgotten». The New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

The Catcher in the Rye, interpreted by some as encouraging rebellion against authority…

- ^ «Banned from the classroom: Censorship and The Catcher in the Rye – English and Drama blog». blogs.bl.uk. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Whitfield, Stephen (December 1997). «Cherished and Cursed: Toward a Social History of The Catcher in the Rye» (PDF). The New England Quarterly. 70 (4): 567–600. doi:10.2307/366646. JSTOR 366646. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ J.D. Salinger. Philadelphia: Chelsea House. 2001. pp. 77–105. ISBN 0-7910-6175-2.

- ^ Weeks, Linton (September 10, 2000). «Telling on Dad». Amarillo Globe-News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ Doyle, Aidan (December 15, 2003). «When books kill». Salon.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2007.

- ^ Hamilton, Ian (1988). In Search of J. D. Salinger. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-53468-9. p. 75.

- ^ a b Berg, A. Scott. Goldwyn: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. ISBN 1-57322-723-4. p. 446.

- ^ See Dr. Peter Beidler’s A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s the Catcher in the Rye, Chapter 7.

- ^ a b Maynard, Joyce (1998). At Home in the World. New York: Picador. p. 93. ISBN 0-312-19556-7.

- ^ «News & Features». IFILM: The Internet Movie Guide. 2004. Archived from the original on September 6, 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ^ Crowe, Cameron, ed. Conversations with Wilder. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. ISBN 0-375-40660-3. p. 299.

- ^ a b McAllister, David (November 11, 2003). «Will J. D. Salinger sue?». The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ «Spielberg wanted to film Catcher In The Rye». Irish Examiner. December 5, 2003. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ «Slim chance of Catcher in the Rye movie – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)». ABC News. ABCnet.au. January 29, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ Connelly, Sherryl (January 29, 2010). «Could ‘Catcher in the Rye’ finally make it to the big screen? Salinger letter suggests yes». Daily News. New York. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (August 3, 2020). «Disney Once Tried to Make an Animated ‘Catcher in the Rye’ — But Wait, There’s More». Collider. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Gross, Doug (June 3, 2009). «Lawsuit targets ‘rip-off’ of ‘Catcher in the Rye’«. CNN. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Fogel, Karl. Looks like censorship, smells like censorship… maybe it IS censorship?. QuestionCopyright.org. July 7, 2009.

- ^ Sutherland, John. How fanfic took over the web London Evening Standard. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Rebecca Tushnet (1997). «Fan Fiction and a New Common Law». Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Journal. 17.

Bibliography[edit]

- Graham, Sarah (2007). J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34452-4.

- Rohrer, Finlo (June 5, 2009). «The why of the Rye». BBC News Magazine. BBC.

- Salinger, J. D. (1969), The Catcher in the Rye, New York: Bantam

- Wahlbrinck, Bernd (2021). Looking Back after 70 Years: J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye Revisited. ISBN 978-3-9821463-7-9.

Further reading[edit]

- Steinle, Pamela Hunt (2000). In Cold Fear: The Catcher in the Rye Censorship Controversies and Postwar American Character. Ohio State University Press. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

External links[edit]

- Book Drum illustrated profile of The Catcher in the Rye Archived September 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Photos of the first edition of Catcher in the Rye

- Lawsuit targets «rip-off» of «Catcher in the Rye» – CNN

Семнадцатилетний Холден Колфилд, находящийся в санатории, вспоминает «ту сумасшедшую историю, которая случилась прошлым Рождеством», после чего он «чуть не отдал концы», долго болел, а теперь вот проходит курс лечения и вскоре надеется вернуться домой.

Его воспоминания начинаются с того самого дня, когда он ушёл из Пэнси, закрытой средней школы в Эгерстауне, штат Пенсильвания. Собственно ушёл он не по своей воле — его отчислили за академическую неуспеваемость — из девяти предметов в ту четверть он завалил пять. Положение осложняется тем, что Пэнси — не первая школа, которую оставляет юный герой. До этого он уже бросил Элктон-хилл, поскольку, по его убеждению, «там была одна сплошная липа». Впрочем, ощущение того, что вокруг него «липа» — фальшь, притворство и показуха, — не отпускает Колфилда на протяжении всего романа. И взрослые, и сверстники, с которыми он встречается, вызывают в нем раздражение, но и одному ему оставаться невмоготу.

Последний день в школе изобилует конфликтами. Он возвращается в Пэнси из Нью-Йорка, куда ездил в качестве капитана фехтовальной команды на матч, который не состоялся по его вине — он забыл в вагоне метро спортивное снаряжение. Сосед по комнате Стрэдлейтер просит его написать за него сочинение — описать дом или комнату, но Колфилд, любящий делать все по-своему, повествует о бейсбольной перчатке своего покойного брата Алли, который исписал её стихами и читал их во время матчей. Стрэдлейтер, прочитав текст, обижается на отклонившегося от темы автора, заявляя, что тот подложил ему свинью, но и Колфилд, огорчённый тем, что Стрэдлейтер ходил на свидание с девушкой, которая нравилась и ему самому, не остаётся в долгу. Дело кончается потасовкой и разбитым носом Колфилда.

Оказавшись в Нью-Йорке, он понимает, что не может явиться домой и сообщить родителям о том, что его исключили. Он садится в такси и едет в отель. По дороге он задаёт свой излюбленный вопрос, который не даёт ему покоя: «Куда деваются утки в Центральном парке, когда пруд замерзает?» Таксист, разумеется, удивлён вопросом и интересуется, не смеётся ли над ним пассажир. Но тот и не думает издеваться, впрочем, вопрос насчёт уток, скорее, проявление растерянности Холдена Колфилда перед сложностью окружающего мира, нежели интерес к зоологии.

Этот мир и гнетёт его, и притягивает. С людьми ему тяжело, без них — невыносимо. Он пытается развлечься в ночном клубе при гостинице, но ничего хорошего из этого не выходит, да и официант отказывается подать ему спиртное как несовершеннолетнему. Он отправляется в ночной бар в Гринич-Виллидж, где любил бывать его старший брат Д. Б., талантливый писатель, соблазнившийся большими гонорарами сценариста в Голливуде. По дороге он задаёт вопрос про уток очередному таксисту, снова не получая вразумительного ответа. В баре он встречает знакомую Д. Б. с каким-то моряком. Девица эта вызывает в нем такую неприязнь, что он поскорее покидает бар и отправляется пешком в отель.

Лифтёр отеля интересуется, не желает ли он девочку — пять долларов на время, пятнадцать на ночь. Холден договаривается «на время», но когда девица появляется в его номере, не находит в себе сил расстаться со своей невинностью. Ему хочется поболтать с ней, но она пришла работать, а коль скоро клиент не готов соответствовать, требует с него десять долларов. Тот напоминает, что договор был насчёт пятёрки. Та удаляется и вскоре возвращается с лифтёром. Очередная стычка заканчивается очередным поражением героя.

Наутро он договаривается о встрече с Салли Хейс, покидает негостеприимный отель, сдаёт чемоданы в камеру хранения и начинает жизнь бездомного. В красной охотничьей шапке задом наперёд, купленной в Нью-Йорке в тот злосчастный день, когда он забыл в метро фехтовальное снаряжение, Холден Колфилд слоняется по холодным улицам большого города. Посещение театра с Салли не приносит ему радости. Пьеса кажется дурацкой, публика, восхищающаяся знаменитыми актёрами Лантами, кошмарной. Спутница тоже раздражает его все больше и больше.

Вскоре, как и следовало ожидать, случается ссора. После спектакля Холден и Салли отправляются покататься на коньках, и потом, в баре, герой даёт волю переполнявшим его истерзанную душу чувствам. Объясняясь в нелюбви ко всему, что его окружает: «Я ненавижу… Господи, до чего я все это ненавижу! И не только школу, все ненавижу. Такси ненавижу, автобусы, где кондуктор орёт на тебя, чтобы ты выходил через заднюю площадку, ненавижу знакомиться с ломаками, которые называют Лантов „ангелами“, ненавижу ездить в лифтах, когда просто хочется выйти на улицу, ненавижу мерить костюмы у Брукса…»

Его порядком раздражает, что Салли не разделяет его негативного отношения к тому, что ему столь немило, а главное, к школе. Когда же он предлагает ей взять машину и уехать недельки на две покататься по новым местам, а она отвечает отказом, рассудительно напоминая, что «мы, в сущности, ещё дети», происходит непоправимое: Холден произносит оскорбительные слова, и Салли удаляется в слезах.

Новая встреча — новые разочарования. Карл Льюс, студент из Принстона, слишком сосредоточен на своей особе, чтобы проявить сочувствие к Холдену, и тот, оставшись один, напивается, звонит Салли, просит у неё прощения, а потом бредёт по холодному Нью-Йорку и в Центральном парке, возле того самого пруда с утками, роняет пластинку, купленную в подарок младшей сестрёнке Фиби.

Вернувшись-таки домой — и к своему облегчению, обнаружив, что родители ушли в гости, — он вручает Фиби лишь осколки. Но она не сердится. Она вообще, несмотря на свои малые годы, отлично понимает состояние брата и догадывается, почему он вернулся домой раньше срока. Именно в разговоре с Фиби Холден выражает свою мечту: «Я себе представляю, как маленькие ребятишки играют вечером в огромном поле во ржи. Тысячи малышей, а кругом ни души, ни одного взрослого, кроме меня… И моё дело — ловить ребятишек, чтобы они не сорвались в пропасть».

Впрочем, Холден не готов к встрече с родителями, и, одолжив у сестрёнки деньги, отложенные ею на рождественские подарки, он отправляется к своему прежнему преподавателю мистеру Антолини. Несмотря на поздний час, тот принимает его, устраивает на ночь. Как истинный наставник, он пытается дать ему ряд полезных советов, как строить отношения с окружающим миром, но Холден слишком устал, чтобы воспринимать разумные изречения. Затем вдруг он просыпается среди ночи и обнаруживает у своей кровати учителя, который гладит ему лоб. Заподозрив мистера Антолини в дурных намерениях, Холден покидает его дом и ночует на Центральном вокзале.

Впрочем, он довольно скоро понимает, что неверно истолковал поведение педагога, свалял дурака, и это ещё больше усиливает его тоску.

Размышляя, как жить дальше, Холден принимает решение податься куда-нибудь на Запад и там в соответствии с давней американской традицией постараться начать все сначала. Он посылает Фиби записку, где сообщает о своём намерении уехать, и просит её прийти в условленное место, так как хочет вернуть одолженные у неё деньги. Но сестрёнка появляется с чемоданом и заявляет, что едет на Запад с братом. Вольно или невольно маленькая Фиби разыгрывает перед Холденом его самого — она заявляет, что и в школу больше не пойдёт, и вообще эта жизнь ей надоела. Холдену, напротив, приходится поневоле стать на точку зрения здравого смысла, забыв на время о своём всеотрицании. Он проявляет благоразумие и ответственность и убеждает сестрёнку отказаться от своего намерения, уверяя её, что сам никуда не поедет. Он ведёт Фиби в зоосад, и там она катается на карусели, а он любуется ею.

Пересказал С. Б. Белов.

Источник: Все шедевры мировой литературы в кратком изложении. Сюжеты и характеры. Зарубежная литература XX века / Ред. и сост. В. И. Новиков. — М. : Олимп : ACT, 1997.

Краткое содержание «Над пропастью во ржи»

4

Средняя оценка: 4

Всего получено оценок: 1856.

Обновлено 29 Сентября, 2022