Краткое содержание «Вий»

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 1434.

Обновлено 7 Мая, 2022

О произведении

Мистическую повесть «Вий» Гоголь написал в конце 1834 года. Произведение вошло в сборник писателя «Миргород» (1835 г.). В повести объединены романтизм и реализм, фантастика и реальность.

Произведение основано на народных преданиях и имеет много фольклорных элементов, например приём троекратного повторения. Сам Вий в славянской мифологии — персонаж из преисподней со смертоносным взглядом.

На нашем сайте можно читать онлайн краткое содержание «Вий» по главам. Представленный пересказ подойдёт для читательского дневника, подготовки к уроку литературы.

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 30 лет.

Место и время действия

События повести происходят в первой половине XIX века на хуторе под Киевом.

Главные герои

- Хома Брут – семинарист, философ. Читал три ночи молитвы над умершей панночкой-ведьмой;

«был нрава веселого»

. - Панночка – ведьма, дочь сотника, над ее умершим телом Хома читал молитвы.

- Сотник – богач, отец панночки-ведьмы,

«уже престарелый»

, около 50-ти лет.

Другие персонажи

- Халява – богослов (затем звонарь), приятель Хомы.

- Тиберий Горобець – ритор (затем философ), приятель Хомы.

- Вий – славянское демоническое существо с веками до земли.

Краткое содержание

Самым торжественным событием для киевской семинарии были вакансии (каникулы), когда всех семинаристов распускали по домам. Бурсаки шли толпой по дороге, постепенно разбредаясь в стороны. Как-то «во время подобного странствования три бурсака»

– богослов Халява, философ Хома Брут и ритор Тиберий Горобець решили по дороге зайти в ближайший хутор, чтобы запастись провиантом. Семинаристов впустила к себе старуха и разместила отдельно.

Философ Хома собирался уже спать, как к нему вошла хозяйка. Ее глаза горели «каким-то необыкновенным блеском»

. Хома понял, что не может пошевелиться. Старуха же вскочила на спину философу, «ударила его метлой по боку, и он, подпрыгивая, как верховой конь, понес ее на плечах своих»

. Хома понял, что старуха – ведьма, и начал читать молитвы и заклятья против духов. Когда старуха ослабла, он выпрыгнул из-под нее, вскочил ей на спину и начал бить поленом. Ведьма закричала, постепенно ослабла и упала на землю. Начинало светать, и философ увидел перед собой вместо ведьмы красавицу. «Затрепетал, как древесный лист, Хома»

и пустился бежать во весь дух в Киев.

Распространились слухи, что дочь богатого сотника вернулась домой вся избитая и перед смертью «изъявила желание, чтобы отходную по ней и молитвы»

три дня читал киевский семинарист Хома Брут. За философом прямо в семинарию прислали экипаж и шесть козаков. По приезду Хому сразу отвели к сотнику. На расспросы пана философ ответил, что не знает ни его дочь, ни причин такой ее воли. Сотник показал философу умершую. Брут к своему ужасу понял, что это «была та самая ведьма, которую убил он»

.

После ужина Хому отвели в церковь, где был гроб с покойной, и заперли за Брутом двери. Философу показалось, словно панночка «глядит на него закрытыми глазами»

. Неожиданно мертвая приподняла голову, затем вышла из гроба и с закрытыми глазами последовала к философу. В страхе Хома очертил вокруг себя круг и начал читать молитвы и заклинания против нечисти. Панночка не смогла переступить через круг и снова легла в гроб. Вдруг гроб поднялся и начал летать по церкви, но даже так ведьма не пересекла очерченного круга. «Гроб грянулся на середине церкви»

, из него поднялся «синий, позеленевший»

труп, но тут послышался крик петуха. Труп опустился в гроб, и гроб захлопнулся.

Вернувшись в поселение, Хома лег спать и после обеда «был совершенно в духе»

. «Но чем более время близилось к вечеру, тем задумчивее становился философ»

– «страх загорался в нем»

.

Ночью Хому снова отвели в церковь. Философ сразу очертил вокруг себя круг и начал читать. Через час он поднял глаза и увидел, что «труп уже стоял перед ним на самой черте»

. Умершая начала произносить какие-то страшные слова – философ понял, что «она творила заклинания»

. По церкви пошел ветер, и что-то забилось в стекла церковных окон, пыталось попасть внутрь. Наконец вдали послышался крик петуха и все прекратилось.

Вошедшие сменить философа нашли его едва живого – за ночь Хома весь поседел. Брут попросил у сотника разрешения не идти в церковь на третью ночь, но пан ему пригрозил и распорядился продолжать.

Придя в церковь, философ снова очертил круг и начал читать молитвы. Вдруг в тишине железная крышка гроба с треском лопнула. Умершая поднялась и начала читать заклинания. «Вихорь поднялся по церкви, попадали на землю иконы»

, двери сорвались с петель, и в церковь влетела «несметная сила чудовищ»

. По призыву ведьмы в церковь вошел «приземистый, дюжий, косолапый человек», весь в черной земле и с железным лицом. Его длинные веки были опущены до самой земли. Вий сказал: «Подымите мне веки: не вижу!»

Внутренний голос шепнул философу не смотреть, но Хома глянул. Вий тут же закричал: «Вот он!»

и указал на философа железным пальцем. Вся нечисть бросилась на Брута. «Бездыханный грянулся он на землю, и тут же вылетел дух из него от страха»

.

Раздался второй петушиный крик – первый нечисть прослушала. Духи бросились убегать, но не смогли выбраться. «Так навеки и осталась церковь с завязнувшими в дверях и окнах чудовищами»

, обросла лесом и сорняками, «и никто не найдет теперь к ней дороги»

.

Слухи о случившемся дошли до Киева. Халява и Горобець пошли помянуть душу Хомы в шинок. Во время беседы Горобець высказался, что Хома пропал «оттого, что побоялся»

.

И что в итоге?

Хома Брут – взглянув на Вия, становится для него видимым; умирает от страха, когда на него кинулась вся толпа нечисти.

Панночка – призывает Вия в церковь, вместе с остальной нечистью остаётся навеки в церкви.

Халява и Горобець – поминают душу Хомы после его смерти.

Вий – вместе с остальной нечистью остаётся навеки в заброшенной церкви.

Заключение

Повесть Н. В. Гоголя «Вий» принято относить к прозе романтизма. В рассказе фантастический, романтический мир представляется исключительно ночным, тогда как реальный мир – дневным. При этом и сам Хома не является классическим романтическим героем – в нем много от обывателя, он не противопоставляется толпе.

Советуем не ограничиваться кратким пересказом «Вия», а прочитать повесть Н. В. Гоголя в полном варианте.

Тест по повести

Проверьте запоминание краткого содержания тестом:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Данил Ким

10/11

-

Александр Чалдушкин

10/11

-

Александр Белый

11/11

-

Лия Раинская

11/11

-

Исмаилова Азиза

11/11

-

Павел Авдеев

8/11

-

Максим Ирвачёв

11/11

-

Александр Антипов

9/11

-

Женя Гаврилов

11/11

-

Настя Гудкова

11/11

Рейтинг пересказа

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 1434.

А какую оценку поставите вы?

- Краткие содержания

- Гоголь

- Вий

Краткое содержание Вий Гоголя

Хома Брут являлся слушателем-философом киевского церковного заведения, как-то был выпущен на каникулы. Домой он добирался пешим ходом. В дороге его застал вечер, и он попросился на ночлег к старухе. Ночью он проснулся от того, что ночью к нему пришла старуха с дико блестящим взором. Она прыгнула ему на спину и начала подгонять метлой. Хому охватила паника, ведь это была ведьма.

Брут прыгал в пространстве, мча ведьму на своей спине. Читая молитвы, ему удалось скинуть старуху. После чего он сам прыгнул на ее спину, и принялся бить ее поленом. Старуха жутко кричала, охрипшим голосом. Спустя какое-то время ее голос стал привлекательнее и настоящим. Когда ведьма свалилась на землю, он увидел, что на земле распростерлась не старуха, а бессознательная, очень красивая молодая девушка.

Уже совсем близко были видны златоглавые купола киевских храмов. Хома оставил девушку лежать на земле, а сам стремглав понесся к городу. В ближайшее время он уже почти забыл о происшедшем. В то же время было вестимо о дочери самого богатого сотника. Его дочь, возвращаясь с гуляния, была побита до смерти. Ее последним желанием было, чтобы после ее смерти все три ночи отходную молитву по ней читал Хома.

Семинарист почуял неладное, но делать нечего. Ему пришлось ехать к сотнику, но он думал убежать при первом удобном случае.

Сотник был удивлен, в честь чего его дочка доверила справить отходную молитву какому-то незнакомому Хоме. Однако отец решил выполнить ее волю. Философа препроводили к гробу с телом молодой панночки. Взглянув, Хома сразу распознал в ней ведьму, оседлавшую его в ночи.

Гроб поместили в храме на окраине деревни. Когда Хома сел вечером кушать вместе с казаками, он услышал, как все сказывали, что умершая была ведьмой. Очень много зла повидали от нее односельчане.

Несколько казаков препроводили философа в храм, где покоилось тело молодой панночки. Он очень робел, не смотря на то, что выпил горилки. Во время молитвы Хома не сводил взгляд с гроба. Внезапно панночка поднялась и начала ходить по храму.

В испуге, Хома, нарисовал вокруг своего места круг и начал еще громче молиться. Ведьма хотела поймать его, однако переступить через черту круга мертвая панночка не имела возможности, она постоянно тормозила на этой черте. Панночка вернулась в гроб лишь после того, как пропели первые петухи.

Утром, отворив двери, казаки увидели, сильно уставшего, Хому. Вечером его снова препроводили в церковь и закрыли там.

Перед началом молитвы, философ опять нарисовал круг. Бездыханное тело девушки вновь встало из гроба и остановилось прямо перед ним на черте. Она цокотала зубами, повторяя невнятные заклятия. В храме стало твориться, что-то невероятное – подул сильный ветер, в окна бились гадкие, крылатые существа… Закончилось все вновь после пения первых петухов. За эту ночь Хома был едва живым и седым.

Встретившись с паном, он сказал ему, что больше не пойдет молиться в церковь. Однако пан был настойчив. Он требовал провести оставшуюся ночь в храме, обещая за невыполнение высечь Хому плетьми. Хома попытался сбежать, но был пойман и возвращен назад.

Хому с покойницей заперли в храме последний раз. Он, как и в предыдущие ночи нарисовал вокруг себя круг и начал молиться. Покойница вновь встала и начала призывать разных чудовищ ей в помощь. Прилетевшая нечисть повыбивала в храме окна и двери, носилась вокруг Хомы. Однако никто из них не видел молящегося философа. Тогда панночка закричала, чтобы к ней привели Вия.

Появившийся Вий выглядел очень жутко. Его тело было покрыто землей, а руки и ноги были словно сильные корни, веки спускались до самой земли. Вий жутким голосом потребовал поднять ему веки. Что-то внутри Хомы шептало ему – «Не смотри!», однако он не выдержал и посмотрел. «Он тут!»- прокричал Вий указывая на Хому. Нечистая сила тут же набросилась на Хому. И несчастный помер со страху.

Товарищи Хомы узнав о том, что случилось. Пришли к выводу, что смерть его произошла из-за боязни.

Главная мысль

Этот рассказ учит вере в Бога, в свои силы. Ответственно относится к начатому делу, пусть даже не по собственной воле. Как говорится «На Бога надейся, а сам не плошай!»

Можете использовать этот текст для читательского дневника

Гоголь. Все произведения

- Вечер накануне Ивана Купала

- Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки

- Вий

- Девяносто третий год

- Женитьба

- Заколдованное место

- Записки сумасшедшего

- Иван Фёдорович Шпонька и его тётушка

- Игроки

- История создания комедии Ревизор

- История создания повести Тарас Бульба

- История создания поэмы Мертвые души

- Как поссорился Иван Иванович с Иваном Никифоровичем

- Коляска

- Король забавляется

- Майская ночь или Утопленница

- Мёртвые души

- Мертвые души по главам

- Миргород

- Невский проспект

- Нос

- Ночь перед Рождеством

- Петербургские повести

- Повесть о капитане Копейкине

- Портрет

- Пропавшая грамота

- Ревизор

- Рим

- Сорочинская ярмарка

- Старосветские помещики

- Страшная месть

- Тарас Бульба

- Шинель

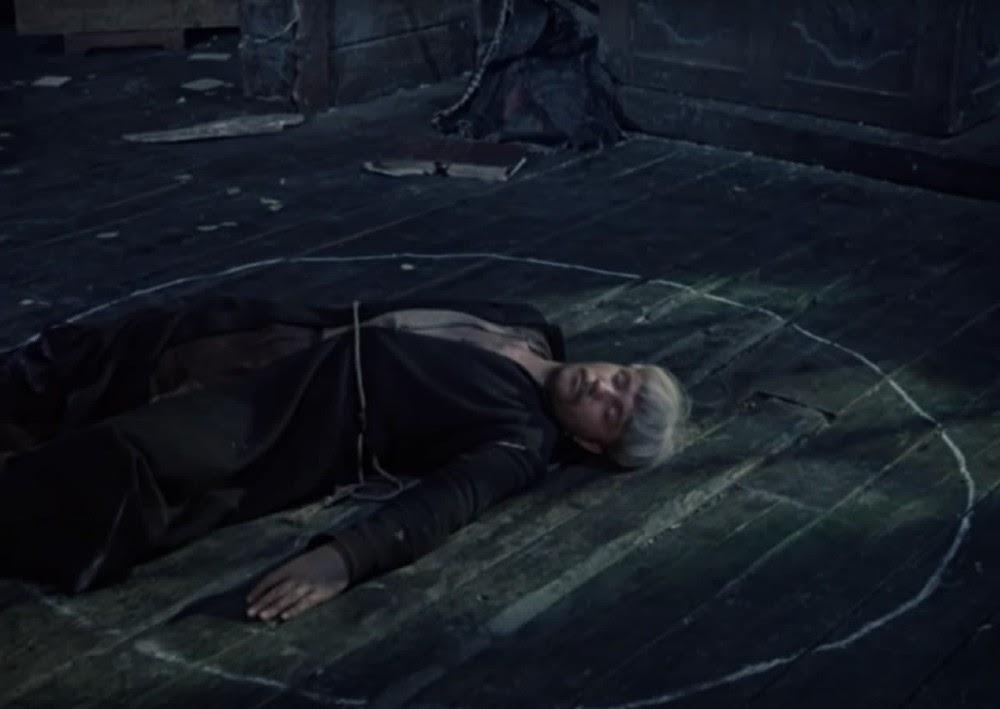

Вий. Картинка к рассказу

Сейчас читают

- Краткое содержание Горький На дне кратко и по актам

В подвале, больше похожем на пещеру, ютились люди. Девять человек жили здесь, занимаясь каждый своим делом: столяр Клещ, картузник Бубнов, вор Васька Пепел, торговка пельменями Квашня

- Краткое содержание Сказка Листопадничек Соколов-Микитов

Все происходит осенью, именно тогда и родила зайчиха маленьких зайчат. По лесу постоянно бродят охотники, поэтому зайчиха вместе с зайчатами должны прятаться в норе и сидеть там тихо-тихо.

- Краткое содержание Вересаев Состязание

Очень глубокая сказка «Состязание» посвящена вечной теме всех видов искусства- красоте. В данном произведении оба персонажа, Дважды-Венчанный и его подмастерья Единорог, по средством написания картин, устраивают состязание

- Краткое содержание Житие Сергия Радонежского

Произведение повествует о жизненном пути преподобного Сергия Радонежского, который родился во время правления князя Твери Дмитрия в семье глубоко верующих людей.

- Краткое содержание Журавль и цапля (сказка)

Вздумал как-то одинокий журавль к цапле посвататься. А жила цапля далеко – на другом конце болота. Долго пришлось ему к ней топать. Пока дотопал – всю грязь болотную перемесил. Приходит он к цапле, и, едва поздоровавшись

На чтение 7 мин Просмотров 7.5к. Опубликовано 04.04.2020

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ «Вий» менее 1 минуты и подробно по главам за 5 минут.

Очень краткий пересказ повести «Вий»

Сюжет разворачивается на одном из хуторов в окрестностях Киева. Ученик бурсы Хома Брут и его двое товарищей решили заняться репетиторской подработкой. Хома сталкивается со странной старухой, усмиряет ведьму, и она превращается в прекрасную девушку. После данного случая она умирает, но перед смертью просит своего отца пана, чтобы бурсак Хома читал над её гробом молитвы три ночи подряд. Получив задание от пана, Хома принимается за дело, но закончить начатое у него не получается, в конце третьей ночи, взглянув на страшного Вия, Хома погибает.

Главные герои и их характеристика:

- Хома Брут – ученик киевской бурсы, любитель «забить» на науки. Весельчак, любитель хорошей компании. Отправился на один из хуторов Киевской губернии, чтобы заняться репетиторством. Усмирил ведьму, под личиной коей скрывалась красавица-девушка. После её смерти читал над гробом молитвы. В конце третьей ночи погиб.

- Панночка – дочь пана-сотника и заглавная злодейка повести. Ведьма, погубившая многих жителей хутора. После смерти преследует Хому, и в конце третьей ночи ведьме помогает нечисть во главе с Вием.

- Вий – один из главных противников Хомы Брута. Могущественный мифический гном-злодей, предводитель гномьей страны. Отличительная черта – опускающиеся до земли веки, кои поднимает нечисть. Если кто-нибудь посмотрит на Вия – несчастного глупца ждёт смерть.

Второстепенные герои и их характеристика:

- Богослов по прозвищу Халява – один из товарищей и соучеников Хомы Брута. Получил работу звонаря. Жалеет о смерти Хомы.

- Ритор Тиберий по прозвищу Горобець (Воробей) – товарищ и соученик Хомы. Стал философом. Именно Тиберий высказал мнение, что Хома мог выжить, если бы не посмотрел в глаза Вию.

- Пан-сотник – хозяин хутора. Хотя и косо посматривал на Хому, однако сделал то, о чём просила дочь перед смертью: отправил философа в церковь, дабы тот читал молитвы над гробом.

Краткое содержание повести «Вий» подробно по главам

Глава 1

Читатель знакомится с бытом и нравами киевской бурсы и семинарии. Не обходилось без традиционных драк, из-за коих у риторов оставались знаки на лице вроде распухшей губы или «фонаря» под глазом. Без воровства не обходилось – ибо бурсаки и семинаристы были бедны, как церковные мыши.

Когда же начиналось лето, учёба заканчивалась, и бурсаки с семинаристами начинали искать себе работу. Обычно это было репетиторство.

Глава 2

Три товарища-бурсака – философ-весельчак Хома Брут, ритор Тиберий по прозвищу Горобець, богослов по прозвищу Халява – свернули с наезженной дороги и отправились на поиски хутора, где можно было заниматься репетитором. Ритор был отчаянным забиякой, богослов – клептоманом, кравшим всё, что подворачивалось под руку, а Хома – философом, чей девиз звучал так: «чему быть – того не миновать».

Постепенно догорела вечерняя заря, а хутора всё не видно. И когда уже была глубокая ночь, приятели наконец-то дошли до хутора. Там была всего лишь пара хат, а когда бурсаки постучали в ворота – появилась старуха. Сумев-таки уломать её, приятели получили возможность нормально переночевать под крышей. Правда, в разных местах.

Глава 3

Хому ждал тот ещё сюрприз: старуха вошла в хлев, и так посмотрела, что несчастный философ оказался заколдован. Оседлав его, как коня, ведьма пришпорила Брута метлой. И лишь во время бега, когда остановиться было невозможно, понял Хома, что попал под хватку настоящей ведьмы. Правда, с помощью фраз-заклятий философ сумел усмирить несносную наездницу, а затем сам оседлал её. Однако неприятности лишь продолжались, и кончились в тот момент, когда невольный наездник отдубасил ведьму поленом. Настал рассвет, и старуха превратилась в молодую прекрасную девушку. Перепуганный Хома бежал со всех ног в хуторок.

Сумев нормально поесть и завалившись в трактир, молодой философ позабыл о ночном приключении, как вдруг услышал новость: дочь богатого сотника вернулась в отцовский дом, причём девушка была до полусмерти избита. Девушка при смерти, и её последнее желание – пусть её отпоёт Хома Брут, и пусть он же молится три ночи после её кончины. Сотник дал задание казакам: привести Хому.

Глава 4

По дороге Хома узнал о том, что девушка умерла. На душе философа скребли кошки, и Брут понимал, что дело плохо. И когда он увидел умершую панночку и внимательно присмотрелся – с ужасом узнал в ней ведьму. Сам сотник жалел о том, что не знает, кто именно погубил его дочь. Да только читатели догадались, что именно Хома Брут и стал тем самым убийцей.

Узнав о том, какие страшные злодейства творила роковая красавица, сколько людей погибло от её каверз, философ изрядно нервничал перед ночной службой. Когда церковь заперли, Хома зажёг свечи, и начал читать молитвы. Вскоре стряслась напасть: ведьма вылезла из гроба, и Хома очертил мелом круг, встав внутри него, и начал говорить заклятия. Не прорвавшись через круг, ведьма вернулась в гроб. И тут вдруг началась свистопляска: гроб летал по всей церкви.

Запели петухи, и наваждение закончилось. Гроб падает, крышка закрывается. Но это была только первая ночь.

Глава 5

На вторую ночь главный герой столкнулся с новой напастью: ведьма своими заклинаниями призывала нечистую силу и одновременно проклинала Хому, голос ведьмы наводил ужас. Когда всё закончилось, философ едва дышал. Когда двери церкви открылись, и казаки довели Брута до поместья сотника, Хома узнал о том, что поседел из-за проклятия ведьмы. Решил бурсак вернуться в Киев, однако суровый сотник чётко объяснил, что у парня нет выбора: либо по-хорошему отслужит третью ночь, либо будет выпорот и насильно загнан в церковь.

Попытка бегства оказалась напрасной, и в конце концов пришлось читать службу. И в этот раз в церковь ворвалась нечистая сила, а затем ведьма приказала позвать Вия. Привели чудовище, невысокого роста, который ступал по-медвежьи. Это и был Вий. И когда ему подняли веки, Хома не смог бороться с опасным искушением и посмотрел на чудовище. Увидел Вий противника и указал на него, напала нечисть, и Хома умер от страха.

Глава 6

Халява и Тиберий Горобець узнали о гибели Хомы Брута и пошли в кабак помянуть товарища. Обменялись они мнениями, и Тиберий сделал вывод, что именно страх и погубил Хому Брута.

Кратко об истории создания произведения

Говоря об истории этой жуткой повести, стоит вспомнить балладу Жуковского «Старушка» («Баллада о том, как одна старушка ехала на чёрном коне вдвоём и кто сидел впереди»). Именно там была умершая ведьма, служение над гробов в течение трёх ночей, появление на третью ночь нечисти и катастрофа. Причём изначально в названии баллады старушка была родом из Киева, что отсылало к малороссийскому фольклору.

«Вий» Гоголя: краткое содержание повести. Текст, аудиокнига и фильм

2 года назад · 1777 просмотров

Повесть «Вий» Н.В. Гоголя. Читать полный текст, слушать аудиокнигу. Кратчайшее изложение и подробный пересказ произведения. Советский фильм «Вий».

Обложка третьего издания повести / Кадр из фильма «Вий» 1967 года

«Вий» — повесть Н.В. Гоголя, впервые опубликованная в 1835 году в сборнике «Миргород». Это мистическое произведение рассказывает о столкновении киевского семинариста Хомы Брута с нечистой силой.

Содержание

-

Кратчайшее содержание

-

Полный текст и аудиокнига

-

Подробное изложение с цитатами

-

Фильм «Вий» 1967 года

Кратчайшее содержание

Киевский семинарист Хома Брут, на которого ночью нападает ведьма и катается на нём верхом, до смерти избивает её поленом. Умирая, ведьма превращается в красивую девушку, а парень сбегает.

Вскоре семинариста вызывает к себе богатый пан — сотник, который велит Хоме три ночи подряд читать молитвы над своей умершей дочерью. Покойная девушка оказывается той самой ведьмой. По словам пана, это была её последняя воля.

В первую же ночь мёртвая ведьма встаёт из гроба, но не может увидеть Хому, который очертил подле себя защитный круг и читает молитвы. Во вторую она призывает на помощь нечистую силу. Хома вновь спасается.

На третью ночь чудовища приводят Вия — страшное существо с веками до земли. Вию поднимают веки. Хома не выдерживает и смотрит на монстра. Тогда Вий указывает нечистой силе на семинариста. Утром юношу находят в церкви мёртвым.

Полный текст и аудиокнига

Полный текст повести Н.В. Гоголя «Вий» доступен в «Викитеке».

В формате аудиокниги произведение можно бесплатно послушать на YouTube.

Подробное изложение с цитатами

Повесть начинается с описания жизни в киевской семинарии. В июне бурсаки-семинаристы расходятся на каникулы по домам или давать уроки детям из богатых семей.

Философ Хома Брут — круглый сирота, он отправляется на каникулы с двумя товарищами. Ночь застает путешественников в поле, но им удается в темноте отыскать одинокий хутор. Хозяйка-старуха нехотя впускает незваных гостей, Брут ложится спать в хлеву.

Ночью к нему приходит старуха. Брут решает, что та добивается от него любви, и пытается отказать. На самом деле хозяйка хутора оказывается ведьмой. Она вскакивает на спину семинаристу, бьёт его метлой, и вот тот несёт её по полям, словно конь.

Кадр из фильма «Вий»

Измученный гонкой Хома припоминает всевозможные молитвы, сбрасывает с себя старуху и сам влезает ей на спину.

Он схватил лежавшее на дороге полено и начал им со всех сил колотить старуху. Дикие вопли издала она; сначала были они сердиты и угрожающи, потом становились слабее, приятнее, чаще, и потом уже тихо, едва звенели, как тонкие серебряные колокольчики, и заронялись ему в душу; и невольно мелькнула в голове мысль: точно ли это старуха? «Ох, не могу больше!» — произнесла она в изнеможении и упала на землю.

Умирающая ведьма превращается в прекрасную молодую девушку. Хома Брут бросается бежать. Он возвращается в семинарию.

Кадр из фильма «Вий»

Спустя некоторое время незнакомый сотник присылает к ректору бурсы своих людей, требуя срочно прислать философа Брута. Выясняется, что его дочь умирает и хочет, чтобы молитвы над ней читал именно Хома Брут.

Хома отказывается ехать, но его заставляют. По дороге он крепко выпивает с сопровождающими казаками и едва не уговаривает отпустить его. Тем не менее, его привозят на хутор сотника. Там выясняется, что панночка — дочь пана сотника — умерла.

Сотник велит Бруту три ночи читать молитвы над гробом покойной дочери, потому что так просила перед кончиной она сама:

«Уж как ты себе хочешь, только я всё, что завещала мне моя голубка, исполню, ничего не пожалея. И когда ты с сего дня три ночи совершишь, как следует, над нею молитвы, то я награжу тебя; а не то — и самому черту не советую рассердить меня».

Хоме страшно, но делать нечего. Он утешает себя тем, что получит награду: «Три ночи как-нибудь отработаю, — подумал философ, — зато пан набьёт мне оба кармана чистыми червонцами».

Кадр из фильма «Вий»

Взглянув на гроб покойницы, семинарист узнаёт в ней девушку-ведьму, которую убил поленом. Ночью гроб с телом относят в деревянную церковь на краю хутора. Казаки рассказывают, что панночка была ведьмой: погубила псаря Микиту, катаясь на нём верхом, и загрызла казачку Шепчиху с ребёнком, обернувшись собакой.

Хома Брут идет к покойнице. Он расставляет свечи по всей церкви и успокаивает себя словами, что молитвы защитят его от нечистой силы. Но всё же в голове у него крутится мысль: а вдруг панночка сейчас встанет из гроба? И она встает.

Она приподняла голову…

Он дико взглянул и протёр глаза. Но она точно уже не лежит, а сидит в своём гробе. Он отвёл глаза свои и опять с ужасом обратил на гроб. Она встала… идёт по церкви с закрытыми глазами, беспрестанно расправляя руки, как бы желая поймать кого-нибудь.

Хома Брут очерчивает подле себя круг, читает молитвы и заклинания, которым его однажды научил знающий монах. Ведьма подходит к самому кругу, но не может переступить черту, не может увидеть семинариста. Разозлённая, она ложится обратно в гроб. На заре Брут покидает церковь.

Кадр из фильма «Вий» 1967 года

После обеда Хома приходит в хорошее расположение духа, но к вечеру вновь становится мрачен. Пора возвращаться в церковь на вторую ночь.

Брут вновь очерчивает круг и читает молитвы. Когда он поднимает глаза, то видит: «Труп уже стоял перед ним на самой черте и вперил на него мёртвые, позеленевшие глаза».

Ведьма начинает произносить заклятия, к церкви слетается нечистая сила и ломится внутрь. Хома Брут, зажмурив глаза, читает молитвы до первых криков петуха. На рассвете его находят едва живым от страха. Волосы на голове парня за ночь поседели.

Кадр из фильма «Вий» 1967 года

Брут идет к пану и рассказывает, что покойница «пустила к себе сатану», отказывается читать молитвы дальше. Но непреклонный сотник велит читать и в третью ночь, грозя страшным наказанием и суля большие деньги. Тогда Хома Брут пытается бежать, но его догоняет и возвращает на хутор один из казаков.

Вернувшись на панский хутор, Брут требует музыкантов и долго пляшет, а затем, обессилев, засыпает.

Наступает третья ночь. Хома снова в церкви, он очерчивает круг и читает молитвы. Сорвав железную крышку, из гроба поднимается покойница-ведьма. Церковь наполняется нечистой силой:

Двери сорвались с петлей, и несметная сила чудовищ влетела в божью церковь. Страшный шум от крыл и от царапанья когтей наполнил всю церковь. Всё летало и носилось, ища повсюду философа.

Но никто из чудовищ не может обнаружить Хому, защищённого молитвами и волшебным кругом. Тогда ведьма велит: «Приведите Вия! ступайте за Вием!»

В церковь входит главный из монстров с железным лицом и веками до самой земли — Вий. «Подымите мне веки: не вижу!» — требует он. Внутренний голос велит Хоме Бруту: «Не гляди!». Но он не выдерживает и смотрит. В этот миг Вий железным пальцем указывает чудовищам на семинариста: «Вот он!».

Нечистая сила кидается на Брута, и он умирает от страха.

Кадр из фильма «Вий» 1967 года

Чудовища пропускают второй крик петуха и не успевают покинуть церковь до рассвета. Они пытаются бежать, но застревают в дверях и окнах навсегда. Священник не решается более служить в посрамлённом храме. Церковь так навеки и остаётся брошенной, заросшей лесом и бурьяном; «и никто не найдёт теперь к ней дороги».

Два друга Хомы Брута из киевской семинарии, узнав о случившемся, обсуждают смерть товарища:

— Славный был человек Хома! Знатный был человек! А пропал ни за что.

— А я знаю, почему пропал он: оттого, что побоялся. А если бы не боялся, то бы ведьма ничего не могла с ним сделать.

Кадр из фильма «Вий» 1967 года

Фильм «Вий» 1967 года

В 1967 году по повести Гоголя был снят фильм «Вий» (режиссеры — Константин Ершов и Георгий Кропачёв). Картина стала одним из популярнейших фильмов 1968 года: в советских кинотеатрах её посмотрели 32,6 миллиона раз.

Роль Хомы Брута исполнил Леонид Куравлёв, роль ведьмы-панночки — Наталья Варлей.

Illustration for Viy by R.Shteyn (1901)

«Viy» (Russian: Вий, IPA: [ˈvʲij]), also translated as «The Viy«, is a horror novella by the writer Nikolai Gogol, first published in volume 2 of his collection of tales entitled Mirgorod (1835).

Despite an author’s note alluding to folklore, the title character is generally conceded to be wholly Gogol’s invention.

Plot summary[edit]

Students at Bratsky Monastery in Kyiv break for summer vacation.[1][2] The impoverished students must find food and lodging along their journey home. They stray from the high road at the sight of a farmstead, hoping its cottagers would provide them.

A group of three, the kleptomaniac theologian Khalyava, the merry-making philosopher Khoma Brut, and the younger-aged rhetorician Tiberiy Gorobets, attracted by a false target of wheat fields suggesting a nearby village, must walk extra distance before finally reaching a farm with two cottages, as night drew near. The old woman begrudgingly lodges the three travelers separately.

The witch rides Khoma.

—Constantin Kousnetzoff, a study for his colour illustration in the French edition of Viy (1930)

At night, the woman calls on Khoma, and begins grabbing at him. This is no amorous embrace; the flashy-eyed woman leaps on his back and rides him like a horse. When she broom-whips him, his legs begin to motion beyond his control. He sees the black forest part before them, and realizes she is a witch (Russian: ведьма, ved’ma). He is strangely envisioning himself galloping over the surface of a glass-mirror like sea: he sees his own reflection in it, and the grass grows deep underneath; he bears witness to a sensually naked water-nymph (rusalka).[3]

By chanting prayers and exorcisms, he slows himself down, and his vision is back to seeing ordinary grass. He now throws off the witch, and rides on her back instead. He picks up a piece of log,[a] and beats her. The older woman collapses, and transforms into a beautiful girl with «long, pointy eyelashes».[4]

Later, rumour circulates that a Cossack chief (sotnik[5])’s daughter was found crawling home, beaten near death, her last wish being for Khoma the seminary student to come pray for her at her deathbed, and for three successive nights after she dies.

Khoma learns of this from the seminary’s rector who orders him to go. Khoma wants to flee, but the bribed rector is in league with the Cossack henchmen,[b] who are already waiting with the kibitka wagon to transport him.

- At the Cossack community

The Cossack chief Yavtukh (nicknamed Kovtun) explains that his daughter expired before she finished revealing how she knew Khoma; at any rate he swears horrible vengeance upon her killer. Khoma turns sympathetic, and swears to discharge his duty (hoping for a handsome reward), but the daughter killed turns out to be the witch he had fatally beaten.

The Cossacks start relating stories about comrades, revealing all sorts of terrible exploits by the chief’s daughter, whom they know is a witch. One comrade was charmed by her, ridden like a horse, and did not survive long; another had his infant child’s blood sucked out at the throat, and his wife killed by the blue necrotic witch who growled like a dog. Inexhaustible episodes about the witch-daughter follow.

The first night, Khoma is escorted to the gloomy church to hold vigil alone with the girl’s body. Just as he wonders if it may come alive, the girl is reanimated and walks towards him. Frightened, Khoma draws a magic circle of protection around himself, and she is unable to cross the line.[c] She turns cadaverously blue, and reenters her coffin making it fly around wildly, but the barrier holds until the rooster crows.

The next night, he draws the magic circle again and recites prayer, which render him invisible, and she is seen clawing at empty space. The witch summons unseen, winged demons and monsters, that bang and rattle and screech at the windows and door from the outside, trying to enter. He endures until the rooster’s crow. He is brought back, and the people notice half his hair had turned gray.

Khoma’s attempted escape into the brambles fails. The third and most terrifying night, the winged «unclean powers» (нечистая сила nechistaya sila) are all audibly darting around him, and the witch-corpse calls on these spirits to bring the Viy, the one who can see everything. The squat Viy is hairy with an iron face, bespattered all over with black earth, its limbs like fibrous roots. The Viy orders its long-dangling eyelids reaching the floor to be lifted so it can see. Khoma, despite his warning instinct, cannot resist the temptation to watch. The Viy is able to see Khoma’s whereabouts, the spirits all attack, and Khoma falls dead. The cock crows, but this is already its second morning call, and the «gnomes» who are unable to flee get trapped forever in the church, which eventually becomes overgrown by weeds and trees.

The story ends with Khoma’s two friends commenting on his death and how it was his lot in life to die in such a way, agreeing that if his courage held he would have survived.

Analysis[edit]

Scholars attempting to identify elements from folklore tradition represents perhaps the largest group.[8]

Others seek to reconstruct how Gogol may have put together the pieces from (Russian translations of) European literary works.[8] There is also a contingent of religious interpretation present,[8] but also a considerable number of scholars delving in psychology-based interpretation, Freudian and Jungian.[9]

Folkloric sources[edit]

Among scholars delving into the folkloric aspects of the novella, Viktor P. Petrov tries to match individual motifs in the plot with folktales from Afanasyev’s collection or elsewhere.[8]

Viacheslav V. Ivanov’s studies concentrate on the Viy creature named in the title, and the themes of death and vision associated around it; Ivanov also undertakes a broader comparative analysis which references non-Slavic traditions as well.[8]

Hans-Jörg Uther classified the story of «Viy», by Gogol, as Aarne–Thompson–Uther tale type ATU 307, «The Princess in the Coffin».[10]

The witch[edit]

The witch (Russian: ведьма, ved’ma or панночка, pannochka[d][11]) who attempts to ride her would-be husband is echoed in Ukrainian (or Russian) folktale.

The Malorussian folktale translated as «The Soldier’s Midnight Watch», set in Kiev, was identified as a parallel in this respect by its translator, W. R. S. Ralston (1873); it was taken from Afanasyev’s collection and the Russian original bore no special title, except «Stories about Witches», variant c.[12][13]

The «Vid’ma ta vid’mak» (Відьма та видьмак), another tale or version from Ukraine, also features a «ride» of similar nature according to Vladimir Ivanovich Shenrok [ru] (1893)’s study of Gogol; this tale was edited by Drahomanov.[14]

A listing of a number of folktales exhibiting parallels on this, as well as other motifs, was given by Viktor Petrov (pen names V. Domontovych)[15] and paraphrase of it can be found in Frederik C. Driessen’s study (avail. in English translation).[16][e]

Viy[edit]

Viy (Russian: Вий) was the name given to the «chief of the gnomes» (Russian: нача́льник гно́мов, nachál’nik gnómov) by the «Little Russians», or so Gogol has insisted in his author’s note.[19][20]

However, given that the gnome is not a part of native Ukrainian folklore, or of Eastern Slavonic lore in general,[21][22][20] the viy has come to be considered a product of Gogol’s own imagination rather than folklore.[21][23]

The fact that viy itself shows little sign of existing in the region’s folklore record is an additional plain reason for the skepticism.[21][22] Thus, Gogol’s contrivance of the viy is the consensus opinion of other modern commentators also, who refer to the viy as a literary device,[22] and so forth.[f]

In the past, the viy creature had been an assumed part of genuine Malorussian (Ukrainian) lore. For instance, Scottish folklorist Charlotte Dempster mentions the «vie» of Little Russia in passing, and floats the idea of the phonetic similarity to the vough or vaugh of the Scottish Highlands.[24] Ralston suggested Viy was known to the Serbians, but clarification as to any attestation is wanting.[25]

There is a tantalizing claim that a Gogol acquaintance Aleksandra Osipovna Rosset (later Smirnova) wrote c. 1830 that she heard from a nurse, but this informant’s reliability has been questioned,[27] as well as her actual authorship at such a date,[g] So the story was probably something Smirnova had heard or read from Gogol, but reshuffled as a remote past memory.[29]

Heavy eyebrow motif[edit]

The witch’s husband in the Russian folk tale «Ivan Bykovich (Ivan the Bull’s Son)», needed to have his eyebrows and eyelashes lifted with a «pitchfork» (Russian: вилы).[30][31] The aforementioned Viacheslav V. Ivanov (1971) is credited, in modern times, with drawing the parallel between Gogol’s viy and the witch’s husband, called the «old, old man» or «Old Oldster» (Russian: старый старик; staryĭ starik).[32] However, this was perhaps anticipated by Ralston, who stated that the witch-husband («Aged One») bore physical resemblance to what, he claimed, the Serbians called a «Vy»,[25] though he did not address resemblance with Gogol’s viy directly.

There also exists an old folk tradition surrounding St. Cassian the Unmerciful, who was said in some tales to have eyebrows that descended to his knees and which were raised only on Leap Year.[33] Some scholars believe that the conception of Viy may have been at least partially based on it, as it is likely that Gogol had heard about the character and designed Viy on his various forms.[citation needed]

Psychological interpretations[edit]

Hugh McLean (Slavicist) (1958) is a noted example of a psychological study of this novella;[34] he identifies the running motif of sexual fulfillment resulting in punishment in this Gogol collection, so that when the student Khoma engages in the ride of the witch, «an obviously sexual act», death is meted out as punishment.[35] A supplementary understanding of this schema using Lacanian analysis is undertaken by Romanchuk (2009), where Khoma’s resistance using prayer is an enactment of his perversion, defined as Perversion is «a wish for a father’s Law that reveals its absence».[36] McLean’s analysis was poorly received by Soviet scholars at the time.[37]

- Psychoanalysis

Due to the psychosexual nature of the central plot, namely Khoma’s killing of the witch and her subsequent transformation into a beautiful girl, the novella has become open to various psychoanalytical (Freudian) interpretations,[38] thus the attempt by some, to interpret Khoma’s strife with the witch in terms of Oedipal desires and carnal relations with the mother.[39][h][40]

Viy was proclaimed «the image of an inexorable father who comes to avenge his son’s incest», in a comment near the end given without underlying reasoning, by Driessen (1965)[i][41] This was modified to «a condensation of the [witch] who was ravished by [Khoma] Brut and the sotnik/father who has vowed to take revenge against the ravisher of his daughter» by Rancour-Laferriere (1978),[42] though Rancour-Laferriere’s approach has been characterized as «an interesting extreme» elsewhere.[34]

- Vision

Leon Stilman has stayed clear of such psychoanalytic interpretations, and opted to take the eye motif as symbolic of Gogol’s own quest for gaining visionary power (an «absolute vision» or «all-seeing eye»).[43][44] However, his study is still characterized as «psychosexual» in some quarters.[34]

- Viy and the witch’s eye

The close relationship between the witch and the Viy has been suggested, based on the similarity of her long-eyelashes with the Viy’s long-eyelids.[45] And the Ukrainian word viy glossed as ‘eyelid’[46] incorrectly, has been connected with a hypothetical viya or viia meaning ‘eyelash’.[47][49][j]

Further proposed etymology entwines connection with the word vuy (Ukr. ‘maternal uncle’), suggested by Semyon Karlinsky [ru][53] This establishes the blood relationship between the two for some commentators.[54]

Adaptations[edit]

- Viy (1909 film), silent film adaptation by Vasily Goncharov. The film is lost.

- Viy (1967 film), a faithful Soviet adaptation by Georgi Kropachyov, Konstantin Yershov, and Aleksandr Ptushko.

- A Holy Place (1990 film), a Serbian (Yugoslav) horror film based on the story.

- Viy (1996 animated short) ‘Вій’ by Leonid Zarubin, Alla Grachyova

- The Power of Fear (2006 film), a Russian horror film very loosely based on the story.

- Evil Spirit; VIY (2008 film), a South Korean horror film by Park Jin-seong based on the story.

- Viy (2014 film), internationally known as Forbidden Empire, and in the UK as Forbidden Kingdom. A Russian dark fantasy film by Oleg Stepchenko very loosely based on the story. A young, British map maker stumbles onto a rural Transylvanian town steeped in the myth.

- Gogol. Viy, 2018 film, serialized for TV as Gogol (film series); Viy is episode 6

Several other works draw on the short story:

- Mario Bava’s film Black Sunday is loosely based on «Viy».

- In the 1978 film Piranha, a camp counselor retells Viy’s climactic identification of Khoma as a ghost story.

- Russian heavy metal band Korrozia Metalla are believed to have recorded a demo tape in 1982 titled Vii, however, nothing about the tape has surfaced.

- In the adventure-platformer video game La-Mulana, Viy serves as the boss of the Inferno Cavern area.

- In Catherynne M. Valente’s novel Deathless, Viy is the Tsar of Death, a Grim Reaper-like figure who embodies gloom and decay in Russia.

- In the mobile game Fate/Grand Order, Viy appears as Anastasia Nikolaevna’s familiar and the source of her powers.

See also[edit]

- Rusalka

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Or «billet» (полено).

- ^ Khoma overhears the rector thanking the gifts and advising the Cossack to bind Khoma so he does not flee.

- ^ In Gogol’s works, the magic protective circle is a reference to «chur [ru]«, a magical boundary that evil cannot cross, according to Christopher R. Putney.[6] However, «chur» is a magic protective word according to other sources.[7]

- ^ Transliterated as «ved’ma/pannočka» in Rancour-Laferriere’s paper.

- ^ The other motifs being the killing of the witch, dueling with corpse,[17] three nights of prayer over dead girl, evil spirits attacking hero at night.[18]

- ^ For example, «attempt at mystification», Setchkarev (1965), p. 147) or «a typical Gogolian mystification» Erlich (1969), p. 68, cited by Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 214; «a Ukrainian name for a metonymically displaced nothing» (Romanchuk (2009), p. 308–309).

- ^ Aleksandra’s «Memoirs» were not of her own making, but actually assembled by her daughter Olga (who wasn’t born until 1834).[28]

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere’s analysis (p. 227, loc. cit.) is philological (as elsewhere). The Cossack sotnik interrogates what the young man’s relationship was with his daughter, because the girl’s dying words which trailed off was «He [Khoma] knows..» Rancour-Laferriere then seizes on the word ved’ma for ‘witch’, which has been glossed as synonym with spoznavshayasya(спознавшаяся) that contains a {-znaj} (знай) ‘know’ root.

- ^ Driessen stipulated that a psychoanalytic interpretation could be undertaken, but was not delving into this himself.

- ^ Ivanov (1971) suggested connection with the Ukrainian vyty (вити, cog. вити ‘twist’) as root.[50] This has resulted in Rancour-Laferriere stating the «Ukrainian vyty can theoretically yield viy«,[51] and Romanchuk discovering the existence of a Ukrainian word viy though it only means «bundle (of brush, etc.)», and tying it to the vyty root.[52]

Citations[edit]

- Footnotes

- ^ Gogol, Pevear (tr.) & Volokhonsky (tr.) (1999), pp. 155–193.

- ^ Gogol, Nikolai (142). «Вий Viy» . Миргород Mirgorod – via Wikisource.

- ^ Gogol & English (ed.) (1994), p. xii: «the mirror motif», etc.

- ^ Gogol, Pevear (tr.) & Volokhonsky (tr.) (1999), p. 165.

- ^ сотник in Gogol’s original text, designated «sotnik» by Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 215, etc.

- ^ Putney, Christopher (1984). Russian Devils and Diabolic Conditionality in Nikolai Gogol’s Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka. Harvard University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780820437705.

- ^ Putney, W. F. (William Francis) (1999). Russian Devils and Diabolic Conditionality in Nikolai Gogol’s Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka. Penn State Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780271019673.

- ^ a b c d e Connolly (2002), p. 253.

- ^ Connolly (2002), p. 254–255.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. 2004. The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Based on the system of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. FF Communications no. 284 (Vol. 1). Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. p. 189. ISBN 951-41-0955-4

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 217.

- ^ Ralston (1873), tr., «The Soldier’s Midnight Watch», pp. 273–282.

- ^ Cited by Ralston as Vol. VII, No. 36c: Afanasyev, Alexander, ed. (1863). «36: Razskazy o Ved’makh» разсказы о ВедЬмахЪ [Stories about witches]. Narodnyi͡a︡ russkīi͡a︡ skazki Народные русские сказки. Vol. 7. pp. 247–253. Cf.

The full text of Рассказы о ведьмах at Wikisource

- ^ Cited by Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 221 as exhibiting a «similar ride»: Shenrok, Vladimir Ivanovich (1893). Materialy dlia biografii Gogolia Материалы для биографии Гоголя. Vol. 2. p. 74.

- ^ Petrov; Gogol (1937), 2: 735–743 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n7.

- ^ Driessen (1965), pp. 138–139 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n7.

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n7.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 212.

- ^ Gogol, Kent (ed.) & Garnett (tr.) (1985), 2: 132; Gogol (1937), 2: 175 apud Connolly (2002), pp. 263–264

- ^ a b Romanchuk (2009), p. 308.

- ^ a b c Stilman (1976) p. 377: «However, Viy is unknown in Ukrainian folklore; so, in fact are gnomes.. Viy therefore is a creation not of the imagination of ‘the folk’ but rather of Gogol himself», requoted by Maguire (1996), pp. 360–361, n5

- ^ a b c Rancour-Laferriere (1978), pp. 214–215: «There is, evidently, no «Vij» known to exist in ‘Little Russian’ folklore2 nor are there any ‘gnomes’ in Slavic folklore in general. The footnote is thus likely to be a pseudo-documentary device..»

- ^ Karlinsky (1976), p. 87 p. 87: «the mythology of‘Viy’is not that of the Ukrainian people, but that of Nikolai Gogol’s subconscious», requoted by Rancour-Laferriere (1978)

- ^ Dempster, Charlotte H. (1888), «Folk-Lore of Sutherlandshire», The Folk-Lore Journal, 6: 223; text @ Internet Archive

- ^ a b Ralston (1873), p. 72

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 214 n2

- ^ Aleksandra Osipovna Rosset (later Smirnova) wrote, ca. 1830, that she heard the story of the Vij from her nurse, and then ostensibly met Gogol shortly after, but the veracity of the statement is inconclusive «given Aleksandra Osipovna’s questionable ability to report the facts».[26]

- ^ Eichenbaum, Boris (1976), Maguire, Robert A. (ed.), «How the Overcoat is Made», Gogol from the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, p. 274, n10, ISBN 9780691013268

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n8 on Smirnova: «chronologically jumbled reminiscences…» «all of which are doubtless reflexes of Gogol’s story itself».

- ^

Russian Wikisource has original text related to this article: Иван Быкович

- ^ Afanasʹev, Aleksandr Nikolaevich (1985). Ivan the Bull’s Son. Russian Folk Tales from Alexander Afanasiev’s Collection: Words of wisdom. illustrated by Aleksandr Kurkin. Raduga. p. 59. ISBN 9785050000545.

- ^ Ivanov (1971), p. 136 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 308 and Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 212, the latter quoting a passage from the Russian tale.

- ^ Ivantis, Linda. Russian Folk Belief pp. 35–36

- ^ a b c Maguire (1996), p. 360, n1.

- ^ McLean (1958), repr. at McLean (1987), pp. 110–111

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), pp. 305–306.

- ^ McLean (1987), pp. 119–111.

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 306.

- ^ e.g. Driessen (1965), p. 164 and Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 227 apud Connolly (2002), p. 263

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 227.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 227, citing Driessen (1965), p. 165

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 232.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 218.

- ^ Nemoianu, Virgil (1984). The Taming of Romanticism: European Literature and the Age of Biedermeier. Harvard University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780674868021.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 217: «Note that the most salient characteristic of Vij, his (twice-mentioned) «dlinnye veki . . . opušĉeny do samoj zemli» relates in an especially direct way to the following descriptions of the ved’ma/pannočka: «Перед ним лежала красавица, с растрепанною роскошною косою, с длинными, как стрелы, ресницами (arrow-like eyelashes).«.

- ^ Commentary to Gogol (1937), 2: 742 apud Stilman (1976), p. 377, n2.

- ^ Stilman (1976), p. 377, n2.

- ^ Trubachev, Oleg N. (1967), «Iz slaviano-iranskikh leksicheskikh otnoshenii» Из славяно-иранских лексических отношений, Etimologiia Этимология, Moscow: Nauka, no. 1965, Materialy i issledovaniia po indoevropeiskim i drugim iazykam, pp. 3–81

- ^ Trubachev (1967), pp. 42–43[48] apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 309: «Trubachev.. and Stilman.. arrived at this derivation independently».

- ^ Ivanov (1971) Ob odnoi p. 137, n19 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 309, n12

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 218, n3.

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 309.

- ^ Karlinsky (1976), pp. 98–103. Cited by Romanchuk (2009), p. 309 and Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 218, n3

- ^ Kutik, Ilʹi︠a︡ (2005). Writing as Exorcism: The Personal Codes of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Gogol. Northwestern University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780810120518.

- References

Russian Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Connolly, Julian W. (Summer 2002), «The Quest for Self-Discovery in Gogol’s’Vii’«, The Slavic and East European Journal, 46 (2): 253–267, doi:10.2307/3086175, JSTOR 3086175

- Driessen, F. C. (1965). Gogol as a Short-Story Writer: A Study of His Technique of Composition. Translated by Ian F. Finlay. Hague: Mouton. ISBN 9783111035680.

- Gogol, Nikolai (1937). «Viy» Вий. Polnoe Sobranie Sochineniĭ Полное собрание сочинений. Vol. 2. Akademii nauk SSSR. pp. 175–.

- ——— (1985). «Viy». In Kent (ed.). The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol. Vol. 2. Translated by Garnett, Constance. University of Chicago Press. pp. 132–.

- ——— (1994). «Viy». In English, Christopher (ed.). Village Evenings Near Dikanka; And, Mirgorod. Oxford University Press. pp. 367–. ISBN 9780192828804.

- ——— (1999) [1998]. The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol. Translated by Pevear, Richard; Volokhonsky, Larissa. Vintage Books. pp. 155–193. ISBN 9780307803368.

- Ivanov, Viacheslav V. (1971), «Ob odnoi paralleli k gogolevskomu’Viiu’» Об одной параллели к гоголевскому ‘Вию’ [On a Parallel to Gogol’s Viy], Uchenye zapiski Tartuskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta (in Russian), 284: 133–142; Reprinted p. 151ff in van der Eng & Grygar edd. (2018) Structure of Texts and Semiotics of Culture.

- Karlinsky, Simon (1976). The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolai Gogol. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674802810.

- Kent, Leonard J «The Collected Tales and Plays of Nikolai Gogol.» Toronto: Random House of Canada Limited. 1969. Print.

- Krys, Svitlana, “Intertextual Parallels Between Gogol’ and Hoffmann: A Case Study of Vij and The Devil’s Elixirs.” Canadian-American Slavic Studies (CASS) 47.1 (2013): 1-20.

- Maguire, Robert A. (1996). Exploring Gogol. Stanford University Press. pp. 360–361, n5. ISBN 9780804765329.

- McLean, Hugh (September 1958), «Gogol’s Retreat From Love: Toward an Interpretation of Mirgorod», American Contributions to the Fourth International Congress of Slavicists, Moscow, The Hague: Mouton, pp. 225–244

- ——— (1987), «Gogol’s Retreat From Love: Toward an Interpretation of Mirgorod», Russian Literature and Psychoanalysis, pp. 101–122, ISBN 9027215367

- Putney, Christopher. «Russian Devils and Diabolical Conditionality in Nikolai Gogol’s Evenings on a farm near Dikanka.» New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. 1999. Print.

- Ralston, W. R. S. (1873). «Ivan Popyalof». Russian Folk Tales. p. 72. Archived from the original on 2007-07-09.

- Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel (June 1978), «The Identity of Gogol’s Vij», Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 2 (2): 211–234, JSTOR 41035781

- Romanchuk, Robert (June–September 2009), «Back to ‘Gogol’s Retreat from Love’: Mirgorod as a Locus of Gogolian Perversion (Part II: ‘Viĭ’)», Canadian Slavonic Papers, 51 (2/3): 305–331, doi:10.1080/00085006.2009.11092615, JSTOR 40871412, S2CID 144872675

- Stilman, Leon (1976), Maguire, Robert A. (ed.), «The ‘All-Seeing Eye’ in Gogol», Gogol from the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, pp. 376–389, ISBN 9780691013268

External links[edit]

- An omnibus collection of Gogol’s short fiction at Standard Ebooks

Illustration for Viy by R.Shteyn (1901)

«Viy» (Russian: Вий, IPA: [ˈvʲij]), also translated as «The Viy«, is a horror novella by the writer Nikolai Gogol, first published in volume 2 of his collection of tales entitled Mirgorod (1835).

Despite an author’s note alluding to folklore, the title character is generally conceded to be wholly Gogol’s invention.

Plot summary[edit]

Students at Bratsky Monastery in Kyiv break for summer vacation.[1][2] The impoverished students must find food and lodging along their journey home. They stray from the high road at the sight of a farmstead, hoping its cottagers would provide them.

A group of three, the kleptomaniac theologian Khalyava, the merry-making philosopher Khoma Brut, and the younger-aged rhetorician Tiberiy Gorobets, attracted by a false target of wheat fields suggesting a nearby village, must walk extra distance before finally reaching a farm with two cottages, as night drew near. The old woman begrudgingly lodges the three travelers separately.

The witch rides Khoma.

—Constantin Kousnetzoff, a study for his colour illustration in the French edition of Viy (1930)

At night, the woman calls on Khoma, and begins grabbing at him. This is no amorous embrace; the flashy-eyed woman leaps on his back and rides him like a horse. When she broom-whips him, his legs begin to motion beyond his control. He sees the black forest part before them, and realizes she is a witch (Russian: ведьма, ved’ma). He is strangely envisioning himself galloping over the surface of a glass-mirror like sea: he sees his own reflection in it, and the grass grows deep underneath; he bears witness to a sensually naked water-nymph (rusalka).[3]

By chanting prayers and exorcisms, he slows himself down, and his vision is back to seeing ordinary grass. He now throws off the witch, and rides on her back instead. He picks up a piece of log,[a] and beats her. The older woman collapses, and transforms into a beautiful girl with «long, pointy eyelashes».[4]

Later, rumour circulates that a Cossack chief (sotnik[5])’s daughter was found crawling home, beaten near death, her last wish being for Khoma the seminary student to come pray for her at her deathbed, and for three successive nights after she dies.

Khoma learns of this from the seminary’s rector who orders him to go. Khoma wants to flee, but the bribed rector is in league with the Cossack henchmen,[b] who are already waiting with the kibitka wagon to transport him.

- At the Cossack community

The Cossack chief Yavtukh (nicknamed Kovtun) explains that his daughter expired before she finished revealing how she knew Khoma; at any rate he swears horrible vengeance upon her killer. Khoma turns sympathetic, and swears to discharge his duty (hoping for a handsome reward), but the daughter killed turns out to be the witch he had fatally beaten.

The Cossacks start relating stories about comrades, revealing all sorts of terrible exploits by the chief’s daughter, whom they know is a witch. One comrade was charmed by her, ridden like a horse, and did not survive long; another had his infant child’s blood sucked out at the throat, and his wife killed by the blue necrotic witch who growled like a dog. Inexhaustible episodes about the witch-daughter follow.

The first night, Khoma is escorted to the gloomy church to hold vigil alone with the girl’s body. Just as he wonders if it may come alive, the girl is reanimated and walks towards him. Frightened, Khoma draws a magic circle of protection around himself, and she is unable to cross the line.[c] She turns cadaverously blue, and reenters her coffin making it fly around wildly, but the barrier holds until the rooster crows.

The next night, he draws the magic circle again and recites prayer, which render him invisible, and she is seen clawing at empty space. The witch summons unseen, winged demons and monsters, that bang and rattle and screech at the windows and door from the outside, trying to enter. He endures until the rooster’s crow. He is brought back, and the people notice half his hair had turned gray.

Khoma’s attempted escape into the brambles fails. The third and most terrifying night, the winged «unclean powers» (нечистая сила nechistaya sila) are all audibly darting around him, and the witch-corpse calls on these spirits to bring the Viy, the one who can see everything. The squat Viy is hairy with an iron face, bespattered all over with black earth, its limbs like fibrous roots. The Viy orders its long-dangling eyelids reaching the floor to be lifted so it can see. Khoma, despite his warning instinct, cannot resist the temptation to watch. The Viy is able to see Khoma’s whereabouts, the spirits all attack, and Khoma falls dead. The cock crows, but this is already its second morning call, and the «gnomes» who are unable to flee get trapped forever in the church, which eventually becomes overgrown by weeds and trees.

The story ends with Khoma’s two friends commenting on his death and how it was his lot in life to die in such a way, agreeing that if his courage held he would have survived.

Analysis[edit]

Scholars attempting to identify elements from folklore tradition represents perhaps the largest group.[8]

Others seek to reconstruct how Gogol may have put together the pieces from (Russian translations of) European literary works.[8] There is also a contingent of religious interpretation present,[8] but also a considerable number of scholars delving in psychology-based interpretation, Freudian and Jungian.[9]

Folkloric sources[edit]

Among scholars delving into the folkloric aspects of the novella, Viktor P. Petrov tries to match individual motifs in the plot with folktales from Afanasyev’s collection or elsewhere.[8]

Viacheslav V. Ivanov’s studies concentrate on the Viy creature named in the title, and the themes of death and vision associated around it; Ivanov also undertakes a broader comparative analysis which references non-Slavic traditions as well.[8]

Hans-Jörg Uther classified the story of «Viy», by Gogol, as Aarne–Thompson–Uther tale type ATU 307, «The Princess in the Coffin».[10]

The witch[edit]

The witch (Russian: ведьма, ved’ma or панночка, pannochka[d][11]) who attempts to ride her would-be husband is echoed in Ukrainian (or Russian) folktale.

The Malorussian folktale translated as «The Soldier’s Midnight Watch», set in Kiev, was identified as a parallel in this respect by its translator, W. R. S. Ralston (1873); it was taken from Afanasyev’s collection and the Russian original bore no special title, except «Stories about Witches», variant c.[12][13]

The «Vid’ma ta vid’mak» (Відьма та видьмак), another tale or version from Ukraine, also features a «ride» of similar nature according to Vladimir Ivanovich Shenrok [ru] (1893)’s study of Gogol; this tale was edited by Drahomanov.[14]

A listing of a number of folktales exhibiting parallels on this, as well as other motifs, was given by Viktor Petrov (pen names V. Domontovych)[15] and paraphrase of it can be found in Frederik C. Driessen’s study (avail. in English translation).[16][e]

Viy[edit]

Viy (Russian: Вий) was the name given to the «chief of the gnomes» (Russian: нача́льник гно́мов, nachál’nik gnómov) by the «Little Russians», or so Gogol has insisted in his author’s note.[19][20]

However, given that the gnome is not a part of native Ukrainian folklore, or of Eastern Slavonic lore in general,[21][22][20] the viy has come to be considered a product of Gogol’s own imagination rather than folklore.[21][23]

The fact that viy itself shows little sign of existing in the region’s folklore record is an additional plain reason for the skepticism.[21][22] Thus, Gogol’s contrivance of the viy is the consensus opinion of other modern commentators also, who refer to the viy as a literary device,[22] and so forth.[f]

In the past, the viy creature had been an assumed part of genuine Malorussian (Ukrainian) lore. For instance, Scottish folklorist Charlotte Dempster mentions the «vie» of Little Russia in passing, and floats the idea of the phonetic similarity to the vough or vaugh of the Scottish Highlands.[24] Ralston suggested Viy was known to the Serbians, but clarification as to any attestation is wanting.[25]

There is a tantalizing claim that a Gogol acquaintance Aleksandra Osipovna Rosset (later Smirnova) wrote c. 1830 that she heard from a nurse, but this informant’s reliability has been questioned,[27] as well as her actual authorship at such a date,[g] So the story was probably something Smirnova had heard or read from Gogol, but reshuffled as a remote past memory.[29]

Heavy eyebrow motif[edit]

The witch’s husband in the Russian folk tale «Ivan Bykovich (Ivan the Bull’s Son)», needed to have his eyebrows and eyelashes lifted with a «pitchfork» (Russian: вилы).[30][31] The aforementioned Viacheslav V. Ivanov (1971) is credited, in modern times, with drawing the parallel between Gogol’s viy and the witch’s husband, called the «old, old man» or «Old Oldster» (Russian: старый старик; staryĭ starik).[32] However, this was perhaps anticipated by Ralston, who stated that the witch-husband («Aged One») bore physical resemblance to what, he claimed, the Serbians called a «Vy»,[25] though he did not address resemblance with Gogol’s viy directly.

There also exists an old folk tradition surrounding St. Cassian the Unmerciful, who was said in some tales to have eyebrows that descended to his knees and which were raised only on Leap Year.[33] Some scholars believe that the conception of Viy may have been at least partially based on it, as it is likely that Gogol had heard about the character and designed Viy on his various forms.[citation needed]

Psychological interpretations[edit]

Hugh McLean (Slavicist) (1958) is a noted example of a psychological study of this novella;[34] he identifies the running motif of sexual fulfillment resulting in punishment in this Gogol collection, so that when the student Khoma engages in the ride of the witch, «an obviously sexual act», death is meted out as punishment.[35] A supplementary understanding of this schema using Lacanian analysis is undertaken by Romanchuk (2009), where Khoma’s resistance using prayer is an enactment of his perversion, defined as Perversion is «a wish for a father’s Law that reveals its absence».[36] McLean’s analysis was poorly received by Soviet scholars at the time.[37]

- Psychoanalysis

Due to the psychosexual nature of the central plot, namely Khoma’s killing of the witch and her subsequent transformation into a beautiful girl, the novella has become open to various psychoanalytical (Freudian) interpretations,[38] thus the attempt by some, to interpret Khoma’s strife with the witch in terms of Oedipal desires and carnal relations with the mother.[39][h][40]

Viy was proclaimed «the image of an inexorable father who comes to avenge his son’s incest», in a comment near the end given without underlying reasoning, by Driessen (1965)[i][41] This was modified to «a condensation of the [witch] who was ravished by [Khoma] Brut and the sotnik/father who has vowed to take revenge against the ravisher of his daughter» by Rancour-Laferriere (1978),[42] though Rancour-Laferriere’s approach has been characterized as «an interesting extreme» elsewhere.[34]

- Vision

Leon Stilman has stayed clear of such psychoanalytic interpretations, and opted to take the eye motif as symbolic of Gogol’s own quest for gaining visionary power (an «absolute vision» or «all-seeing eye»).[43][44] However, his study is still characterized as «psychosexual» in some quarters.[34]

- Viy and the witch’s eye

The close relationship between the witch and the Viy has been suggested, based on the similarity of her long-eyelashes with the Viy’s long-eyelids.[45] And the Ukrainian word viy glossed as ‘eyelid’[46] incorrectly, has been connected with a hypothetical viya or viia meaning ‘eyelash’.[47][49][j]

Further proposed etymology entwines connection with the word vuy (Ukr. ‘maternal uncle’), suggested by Semyon Karlinsky [ru][53] This establishes the blood relationship between the two for some commentators.[54]

Adaptations[edit]

- Viy (1909 film), silent film adaptation by Vasily Goncharov. The film is lost.

- Viy (1967 film), a faithful Soviet adaptation by Georgi Kropachyov, Konstantin Yershov, and Aleksandr Ptushko.

- A Holy Place (1990 film), a Serbian (Yugoslav) horror film based on the story.

- Viy (1996 animated short) ‘Вій’ by Leonid Zarubin, Alla Grachyova

- The Power of Fear (2006 film), a Russian horror film very loosely based on the story.

- Evil Spirit; VIY (2008 film), a South Korean horror film by Park Jin-seong based on the story.

- Viy (2014 film), internationally known as Forbidden Empire, and in the UK as Forbidden Kingdom. A Russian dark fantasy film by Oleg Stepchenko very loosely based on the story. A young, British map maker stumbles onto a rural Transylvanian town steeped in the myth.

- Gogol. Viy, 2018 film, serialized for TV as Gogol (film series); Viy is episode 6

Several other works draw on the short story:

- Mario Bava’s film Black Sunday is loosely based on «Viy».

- In the 1978 film Piranha, a camp counselor retells Viy’s climactic identification of Khoma as a ghost story.

- Russian heavy metal band Korrozia Metalla are believed to have recorded a demo tape in 1982 titled Vii, however, nothing about the tape has surfaced.

- In the adventure-platformer video game La-Mulana, Viy serves as the boss of the Inferno Cavern area.

- In Catherynne M. Valente’s novel Deathless, Viy is the Tsar of Death, a Grim Reaper-like figure who embodies gloom and decay in Russia.

- In the mobile game Fate/Grand Order, Viy appears as Anastasia Nikolaevna’s familiar and the source of her powers.

See also[edit]

- Rusalka

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Or «billet» (полено).

- ^ Khoma overhears the rector thanking the gifts and advising the Cossack to bind Khoma so he does not flee.

- ^ In Gogol’s works, the magic protective circle is a reference to «chur [ru]«, a magical boundary that evil cannot cross, according to Christopher R. Putney.[6] However, «chur» is a magic protective word according to other sources.[7]

- ^ Transliterated as «ved’ma/pannočka» in Rancour-Laferriere’s paper.

- ^ The other motifs being the killing of the witch, dueling with corpse,[17] three nights of prayer over dead girl, evil spirits attacking hero at night.[18]

- ^ For example, «attempt at mystification», Setchkarev (1965), p. 147) or «a typical Gogolian mystification» Erlich (1969), p. 68, cited by Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 214; «a Ukrainian name for a metonymically displaced nothing» (Romanchuk (2009), p. 308–309).

- ^ Aleksandra’s «Memoirs» were not of her own making, but actually assembled by her daughter Olga (who wasn’t born until 1834).[28]

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere’s analysis (p. 227, loc. cit.) is philological (as elsewhere). The Cossack sotnik interrogates what the young man’s relationship was with his daughter, because the girl’s dying words which trailed off was «He [Khoma] knows..» Rancour-Laferriere then seizes on the word ved’ma for ‘witch’, which has been glossed as synonym with spoznavshayasya(спознавшаяся) that contains a {-znaj} (знай) ‘know’ root.

- ^ Driessen stipulated that a psychoanalytic interpretation could be undertaken, but was not delving into this himself.

- ^ Ivanov (1971) suggested connection with the Ukrainian vyty (вити, cog. вити ‘twist’) as root.[50] This has resulted in Rancour-Laferriere stating the «Ukrainian vyty can theoretically yield viy«,[51] and Romanchuk discovering the existence of a Ukrainian word viy though it only means «bundle (of brush, etc.)», and tying it to the vyty root.[52]

Citations[edit]

- Footnotes

- ^ Gogol, Pevear (tr.) & Volokhonsky (tr.) (1999), pp. 155–193.

- ^ Gogol, Nikolai (142). «Вий Viy» . Миргород Mirgorod – via Wikisource.

- ^ Gogol & English (ed.) (1994), p. xii: «the mirror motif», etc.

- ^ Gogol, Pevear (tr.) & Volokhonsky (tr.) (1999), p. 165.

- ^ сотник in Gogol’s original text, designated «sotnik» by Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 215, etc.

- ^ Putney, Christopher (1984). Russian Devils and Diabolic Conditionality in Nikolai Gogol’s Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka. Harvard University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780820437705.

- ^ Putney, W. F. (William Francis) (1999). Russian Devils and Diabolic Conditionality in Nikolai Gogol’s Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka. Penn State Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780271019673.

- ^ a b c d e Connolly (2002), p. 253.

- ^ Connolly (2002), p. 254–255.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. 2004. The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Based on the system of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. FF Communications no. 284 (Vol. 1). Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. p. 189. ISBN 951-41-0955-4

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 217.

- ^ Ralston (1873), tr., «The Soldier’s Midnight Watch», pp. 273–282.

- ^ Cited by Ralston as Vol. VII, No. 36c: Afanasyev, Alexander, ed. (1863). «36: Razskazy o Ved’makh» разсказы о ВедЬмахЪ [Stories about witches]. Narodnyi͡a︡ russkīi͡a︡ skazki Народные русские сказки. Vol. 7. pp. 247–253. Cf.

The full text of Рассказы о ведьмах at Wikisource

- ^ Cited by Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 221 as exhibiting a «similar ride»: Shenrok, Vladimir Ivanovich (1893). Materialy dlia biografii Gogolia Материалы для биографии Гоголя. Vol. 2. p. 74.

- ^ Petrov; Gogol (1937), 2: 735–743 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n7.

- ^ Driessen (1965), pp. 138–139 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n7.

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n7.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 212.

- ^ Gogol, Kent (ed.) & Garnett (tr.) (1985), 2: 132; Gogol (1937), 2: 175 apud Connolly (2002), pp. 263–264

- ^ a b Romanchuk (2009), p. 308.

- ^ a b c Stilman (1976) p. 377: «However, Viy is unknown in Ukrainian folklore; so, in fact are gnomes.. Viy therefore is a creation not of the imagination of ‘the folk’ but rather of Gogol himself», requoted by Maguire (1996), pp. 360–361, n5

- ^ a b c Rancour-Laferriere (1978), pp. 214–215: «There is, evidently, no «Vij» known to exist in ‘Little Russian’ folklore2 nor are there any ‘gnomes’ in Slavic folklore in general. The footnote is thus likely to be a pseudo-documentary device..»

- ^ Karlinsky (1976), p. 87 p. 87: «the mythology of‘Viy’is not that of the Ukrainian people, but that of Nikolai Gogol’s subconscious», requoted by Rancour-Laferriere (1978)

- ^ Dempster, Charlotte H. (1888), «Folk-Lore of Sutherlandshire», The Folk-Lore Journal, 6: 223; text @ Internet Archive

- ^ a b Ralston (1873), p. 72

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 214 n2

- ^ Aleksandra Osipovna Rosset (later Smirnova) wrote, ca. 1830, that she heard the story of the Vij from her nurse, and then ostensibly met Gogol shortly after, but the veracity of the statement is inconclusive «given Aleksandra Osipovna’s questionable ability to report the facts».[26]

- ^ Eichenbaum, Boris (1976), Maguire, Robert A. (ed.), «How the Overcoat is Made», Gogol from the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, p. 274, n10, ISBN 9780691013268

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 308, n8 on Smirnova: «chronologically jumbled reminiscences…» «all of which are doubtless reflexes of Gogol’s story itself».

- ^

Russian Wikisource has original text related to this article: Иван Быкович

- ^ Afanasʹev, Aleksandr Nikolaevich (1985). Ivan the Bull’s Son. Russian Folk Tales from Alexander Afanasiev’s Collection: Words of wisdom. illustrated by Aleksandr Kurkin. Raduga. p. 59. ISBN 9785050000545.

- ^ Ivanov (1971), p. 136 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 308 and Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 212, the latter quoting a passage from the Russian tale.

- ^ Ivantis, Linda. Russian Folk Belief pp. 35–36

- ^ a b c Maguire (1996), p. 360, n1.

- ^ McLean (1958), repr. at McLean (1987), pp. 110–111

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), pp. 305–306.

- ^ McLean (1987), pp. 119–111.

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 306.

- ^ e.g. Driessen (1965), p. 164 and Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 227 apud Connolly (2002), p. 263

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 227.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 227, citing Driessen (1965), p. 165

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 232.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 218.

- ^ Nemoianu, Virgil (1984). The Taming of Romanticism: European Literature and the Age of Biedermeier. Harvard University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780674868021.

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 217: «Note that the most salient characteristic of Vij, his (twice-mentioned) «dlinnye veki . . . opušĉeny do samoj zemli» relates in an especially direct way to the following descriptions of the ved’ma/pannočka: «Перед ним лежала красавица, с растрепанною роскошною косою, с длинными, как стрелы, ресницами (arrow-like eyelashes).«.

- ^ Commentary to Gogol (1937), 2: 742 apud Stilman (1976), p. 377, n2.

- ^ Stilman (1976), p. 377, n2.

- ^ Trubachev, Oleg N. (1967), «Iz slaviano-iranskikh leksicheskikh otnoshenii» Из славяно-иранских лексических отношений, Etimologiia Этимология, Moscow: Nauka, no. 1965, Materialy i issledovaniia po indoevropeiskim i drugim iazykam, pp. 3–81

- ^ Trubachev (1967), pp. 42–43[48] apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 309: «Trubachev.. and Stilman.. arrived at this derivation independently».

- ^ Ivanov (1971) Ob odnoi p. 137, n19 apud Romanchuk (2009), p. 309, n12

- ^ Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 218, n3.

- ^ Romanchuk (2009), p. 309.

- ^ Karlinsky (1976), pp. 98–103. Cited by Romanchuk (2009), p. 309 and Rancour-Laferriere (1978), p. 218, n3

- ^ Kutik, Ilʹi︠a︡ (2005). Writing as Exorcism: The Personal Codes of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Gogol. Northwestern University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780810120518.

- References

Russian Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Connolly, Julian W. (Summer 2002), «The Quest for Self-Discovery in Gogol’s’Vii’«, The Slavic and East European Journal, 46 (2): 253–267, doi:10.2307/3086175, JSTOR 3086175

- Driessen, F. C. (1965). Gogol as a Short-Story Writer: A Study of His Technique of Composition. Translated by Ian F. Finlay. Hague: Mouton. ISBN 9783111035680.

- Gogol, Nikolai (1937). «Viy» Вий. Polnoe Sobranie Sochineniĭ Полное собрание сочинений. Vol. 2. Akademii nauk SSSR. pp. 175–.

- ——— (1985). «Viy». In Kent (ed.). The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol. Vol. 2. Translated by Garnett, Constance. University of Chicago Press. pp. 132–.

- ——— (1994). «Viy». In English, Christopher (ed.). Village Evenings Near Dikanka; And, Mirgorod. Oxford University Press. pp. 367–. ISBN 9780192828804.

- ——— (1999) [1998]. The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol. Translated by Pevear, Richard; Volokhonsky, Larissa. Vintage Books. pp. 155–193. ISBN 9780307803368.

- Ivanov, Viacheslav V. (1971), «Ob odnoi paralleli k gogolevskomu’Viiu’» Об одной параллели к гоголевскому ‘Вию’ [On a Parallel to Gogol’s Viy], Uchenye zapiski Tartuskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta (in Russian), 284: 133–142; Reprinted p. 151ff in van der Eng & Grygar edd. (2018) Structure of Texts and Semiotics of Culture.

- Karlinsky, Simon (1976). The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolai Gogol. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674802810.

- Kent, Leonard J «The Collected Tales and Plays of Nikolai Gogol.» Toronto: Random House of Canada Limited. 1969. Print.

- Krys, Svitlana, “Intertextual Parallels Between Gogol’ and Hoffmann: A Case Study of Vij and The Devil’s Elixirs.” Canadian-American Slavic Studies (CASS) 47.1 (2013): 1-20.

- Maguire, Robert A. (1996). Exploring Gogol. Stanford University Press. pp. 360–361, n5. ISBN 9780804765329.

- McLean, Hugh (September 1958), «Gogol’s Retreat From Love: Toward an Interpretation of Mirgorod», American Contributions to the Fourth International Congress of Slavicists, Moscow, The Hague: Mouton, pp. 225–244

- ——— (1987), «Gogol’s Retreat From Love: Toward an Interpretation of Mirgorod», Russian Literature and Psychoanalysis, pp. 101–122, ISBN 9027215367

- Putney, Christopher. «Russian Devils and Diabolical Conditionality in Nikolai Gogol’s Evenings on a farm near Dikanka.» New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. 1999. Print.

- Ralston, W. R. S. (1873). «Ivan Popyalof». Russian Folk Tales. p. 72. Archived from the original on 2007-07-09.

- Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel (June 1978), «The Identity of Gogol’s Vij», Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 2 (2): 211–234, JSTOR 41035781