|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Zinc white, calamine, philosopher’s wool, Chinese white, flowers of zinc |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

CAS Number |

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| DrugBank |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.839 |

| EC Number |

|

|

Gmelin Reference |

13738 |

| KEGG |

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 3077 |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

InChI

|

|

|

SMILES

|

|

| Properties | |

|

Chemical formula |

ZnO |

| Molar mass | 81.406 g/mol[1] |

| Appearance | White solid[1] |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 5.606 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 1,974 °C (3,585 °F; 2,247 K) (decomposes)[1][5] |

| Boiling point | 2,360 °C (4,280 °F; 2,630 K) (decomposes) |

|

Solubility in water |

0.0004% (17.8°C)[2] |

| Band gap | 3.3 eV (direct) |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

−27.2·10−6 cm3/mol[3] |

|

Refractive index (nD) |

n1=2.013, n2=2.029[4] |

| Structure[6] | |

|

Crystal structure |

Wurtzite |

|

Space group |

C6v4—P63mc |

|

Lattice constant |

a = 3.2495 Å, c = 5.2069 Å |

|

Formula units (Z) |

2 |

|

Coordination geometry |

Tetrahedral |

| Thermochemistry[7] | |

|

Heat capacity (C) |

40.3 J·K−1mol−1 |

|

Std molar |

43.7±0.4 J·K−1mol−1 |

|

Std enthalpy of |

-350.5±0.3 kJ mol−1 |

|

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

-320.5 kJ mol−1 |

| Pharmacology | |

|

ATCvet code |

QA07XA91 (WHO) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Warning |

|

Hazard statements |

H400, H401 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P273, P391, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

2 1 0 |

| Flash point | 1,436 °C (2,617 °F; 1,709 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

|

LD50 (median dose) |

240 mg/kg (intraperitoneal, rat)[8] 7950 mg/kg (rat, oral)[9] |

|

LC50 (median concentration) |

2500 mg/m3 (mouse)[9] |

|

LCLo (lowest published) |

2500 mg/m3 (guinea pig, 3–4 h)[9] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 5 mg/m3 (fume) TWA 15 mg/m3 (total dust) TWA 5 mg/m3 (resp dust)[2] |

|

REL (Recommended) |

Dust: TWA 5 mg/m3 C 15 mg/m3

Fume: TWA 5 mg/m3 ST 10 mg/m3[2] |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

500 mg/m3[2] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0208 |

| Related compounds | |

|

Other anions |

Zinc sulfide Zinc selenide Zinc telluride |

|

Other cations |

Cadmium oxide Mercury(II) oxide |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Zinc oxide is an inorganic compound with the formula ZnO. It is a white powder that is insoluble in water. ZnO is used as an additive in numerous materials and products including cosmetics, food supplements, rubbers, plastics, ceramics, glass, cement, lubricants,[10] paints, ointments, adhesives, sealants, pigments, foods, batteries, ferrites, fire retardants, and first-aid tapes. Although it occurs naturally as the mineral zincite, most zinc oxide is produced synthetically.[11]

ZnO is a wide-band gap semiconductor of the II-VI semiconductor group. The native doping of the semiconductor due to oxygen vacancies or zinc interstitials is n-type.[12] Other favorable properties include good transparency, high electron mobility, wide band gap, and strong room-temperature luminescence. Those properties make ZnO valuable for a variety of emerging applications: transparent electrodes in liquid crystal displays, energy-saving or heat-protecting windows, and electronics as thin-film transistors and light-emitting diodes.

Chemical properties[edit]

Pure ZnO is a white powder, but in nature it occurs as the rare mineral zincite, which usually contains manganese and other impurities that confer a yellow to red color.[13]

Crystalline zinc oxide is thermochromic, changing from white to yellow when heated in air and reverting to white on cooling.[14] This color change is caused by a small loss of oxygen to the environment at high temperatures to form the non-stoichiometric Zn1+xO, where at 800 °C, x = 0.00007.[14]

Zinc oxide is an amphoteric oxide. It is nearly insoluble in water, but it will dissolve in most acids, such as hydrochloric acid:[15]

- ZnO + 2 HCl → ZnCl2 + H2O

Solid zinc oxide will also dissolve in alkalis to give soluble zincates:

- ZnO + 2 NaOH + H2O → Na2[Zn(OH)4]

ZnO reacts slowly with fatty acids in oils to produce the corresponding carboxylates, such as oleate or stearate. When mixed with a strong aqueous solution of zinc chloride, ZnO forms cement-like products best described as zinc hydroxy chlorides.[16] This cement was used in dentistry.[17]

ZnO also forms cement-like material when treated with phosphoric acid; related materials are used in dentistry.[17] A major component of zinc phosphate cement produced by this reaction is hopeite, Zn3(PO4)2·4H2O.[18]

ZnO decomposes into zinc vapor and oxygen at around 1975 °C with a standard oxygen pressure. In a carbothermic reaction, heating with carbon converts the oxide into zinc vapor at a much lower temperature (around 950 °C).[15]

- ZnO + C → Zn(Vapor) + CO

Physical properties[edit]

Structure[edit]

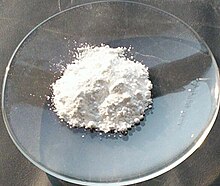

Zinc oxide crystallizes in two main forms, hexagonal wurtzite[19] and cubic zincblende. The wurtzite structure is most stable at ambient conditions and thus most common. The zincblende form can be stabilized by growing ZnO on substrates with cubic lattice structure. In both cases, the zinc and oxide centers are tetrahedral, the most characteristic geometry for Zn(II). ZnO converts to the rocksalt motif at relatively high pressures about 10 GPa.[12] The many remarkable medical properties of creams containing ZnO can be explained by its elastic softness, which is characteristic of tetrahedral coordinated binary compounds close to the transition to octahedral structures.[20]

Hexagonal and zincblende polymorphs have no inversion symmetry (reflection of a crystal relative to any given point does not transform it into itself). This and other lattice symmetry properties result in piezoelectricity of the hexagonal and zincblende ZnO, and pyroelectricity of hexagonal ZnO.

The hexagonal structure has a point group 6 mm (Hermann–Mauguin notation) or C6v (Schoenflies notation), and the space group is P63mc or C6v4. The lattice constants are a = 3.25 Å and c = 5.2 Å; their ratio c/a ~ 1.60 is close to the ideal value for hexagonal cell c/a = 1.633.[21] As in most group II-VI materials, the bonding in ZnO is largely ionic (Zn2+O2−) with the corresponding radii of 0.074 nm for Zn2+ and 0.140 nm for O2−. This property accounts for the preferential formation of wurtzite rather than zinc blende structure,[22] as well as the strong piezoelectricity of ZnO. Because of the polar Zn−O bonds, zinc and oxygen planes are electrically charged. To maintain electrical neutrality, those planes reconstruct at atomic level in most relative materials, but not in ZnO – its surfaces are atomically flat, stable and exhibit no reconstruction.[23] However, studies using wurtzoid structures explained the origin of surface flatness and the absence of reconstruction at ZnO wurtzite surfaces[24] in addition to the origin of charges on ZnO planes.

Mechanical properties[edit]

ZnO is a relatively soft material with approximate hardness of 4.5 on the Mohs scale.[10] Its elastic constants are smaller than those of relevant III-V semiconductors, such as GaN. The high heat capacity and heat conductivity, low thermal expansion and high melting temperature of ZnO are beneficial for ceramics.[25] The E2 optical phonon in ZnO exhibits an unusually long lifetime of 133 ps at 10 K.[26]

Among the tetrahedrally bonded semiconductors, it has been stated that ZnO has the highest piezoelectric tensor, or at least one comparable to that of GaN and AlN.[27] This property makes it a technologically important material for many piezoelectrical applications, which require a large electromechanical coupling. Therefore, ZnO in the form of thin film has been one of the most studied resonator materials for thin-film bulk acoustic resonators.

Electrical and optical properties[edit]

ZnO has a relatively large direct band gap of ~3.3 eV at room temperature. Advantages associated with a large band gap include higher breakdown voltages, ability to sustain large electric fields, lower electronic noise, and high-temperature and high-power operation. The band gap of ZnO can further be tuned to ~3–4 eV by its alloying with magnesium oxide or cadmium oxide.[12]

Most ZnO has n-type character, even in the absence of intentional doping. Nonstoichiometry is typically the origin of n-type character, but the subject remains controversial.[28] An alternative explanation has been proposed, based on theoretical calculations, that unintentional substitutional hydrogen impurities are responsible.[29] Controllable n-type doping is easily achieved by substituting Zn with group-III elements such as Al, Ga, In or by substituting oxygen with group-VII elements chlorine or iodine.[30]

Reliable p-type doping of ZnO remains difficult. This problem originates from low solubility of p-type dopants and their compensation by abundant n-type impurities. This problem is observed with GaN and ZnSe. Measurement of p-type in «intrinsically» n-type material is complicated by the inhomogeneity of samples.[31]

Current limitations to p-doping limit electronic and optoelectronic applications of ZnO, which usually require junctions of n-type and p-type material. Known p-type dopants include group-I elements Li, Na, K; group-V elements N, P and As; as well as copper and silver. However, many of these form deep acceptors and do not produce significant p-type conduction at room temperature.[12]

Electron mobility of ZnO strongly varies with temperature and has a maximum of ~2000 cm2/(V·s) at 80 K.[32] Data on hole mobility are scarce with values in the range 5–30 cm2/(V·s).[33]

ZnO discs, acting as a varistor, are the active material in most surge arresters.[34][35]

Zinc oxide is noted for its strongly nonlinear optical properties, especially in bulk. The nonlinearity of ZnO nanoparticles can be fine-tuned according to their size.[36]

Production[edit]

For industrial use, ZnO is produced at levels of 105 tons per year[13] by three main processes:[25]

Indirect process[edit]

In the indirect or French process, metallic zinc is melted in a graphite crucible and vaporized at temperatures above 907 °C (typically around 1000 °C). Zinc vapor reacts with the oxygen in the air to give ZnO, accompanied by a drop in its temperature and bright luminescence. Zinc oxide particles are transported into a cooling duct and collected in a bag house. This indirect method was popularized by LeClaire (France) in 1844 and therefore is commonly known as the French process. Its product normally consists of agglomerated zinc oxide particles with an average size of 0.1 to a few micrometers. By weight, most of the world’s zinc oxide is manufactured via French process.

Direct process[edit]

The direct or American process starts with diverse contaminated zinc composites, such as zinc ores or smelter by-products. The zinc precursors are reduced (carbothermal reduction) by heating with a source of carbon such as anthracite to produce zinc vapor, which is then oxidized as in the indirect process. Because of the lower purity of the source material, the final product is also of lower quality in the direct process as compared to the indirect one.

Wet chemical process[edit]

A small amount of industrial production involves wet chemical processes, which start with aqueous solutions of zinc salts, from which zinc carbonate or zinc hydroxide is precipitated. The solid precipitate is then calcined at temperatures around 800 °C.

Laboratory synthesis[edit]

The red and green colors of these synthetic ZnO crystals result from different concentrations of oxygen vacancies.[37]

Numerous specialised methods exist for producing ZnO for scientific studies and niche applications. These methods can be classified by the resulting ZnO form (bulk, thin film, nanowire), temperature («low», that is close to room temperature or «high», that is T ~ 1000 °C), process type (vapor deposition or growth from solution) and other parameters.

Large single crystals (many cubic centimeters) can be grown by the gas transport (vapor-phase deposition), hydrothermal synthesis,[23][37][38] or melt growth.[5] However, because of the high vapor pressure of ZnO, growth from the melt is problematic. Growth by gas transport is difficult to control, leaving the hydrothermal method as a preference.[5] Thin films can be produced by chemical vapor deposition, metalorganic vapour phase epitaxy, electrodeposition, pulsed laser deposition, sputtering, sol–gel synthesis, atomic layer deposition, spray pyrolysis, etc.

Ordinary white powdered zinc oxide can be produced in the laboratory by electrolyzing a solution of sodium bicarbonate with a zinc anode. Zinc hydroxide and hydrogen gas are produced. The zinc hydroxide upon heating decomposes to zinc oxide:

- Zn + 2 H2O → Zn(OH)2 + H2

- Zn(OH)2 → ZnO + H2O

ZnO nanostructures[edit]

Nanostructures of ZnO can be synthesized into a variety of morphologies including nanowires, nanorods, tetrapods, nanobelts, nanoflowers, nanoparticles etc. Nanostructures can be obtained with most above-mentioned techniques, at certain conditions, and also with the vapor–liquid–solid method.[23][39][40] The synthesis is typically carried out at temperatures of about 90 °C, in an equimolar aqueous solution of zinc nitrate and hexamine, the latter providing the basic environment. Certain additives, such as polyethylene glycol or polyethylenimine, can improve the aspect ratio of the ZnO nanowires.[41] Doping of the ZnO nanowires has been achieved by adding other metal nitrates to the growth solution.[42] The morphology of the resulting nanostructures can be tuned by changing the parameters relating to the precursor composition (such as the zinc concentration and pH) or to the thermal treatment (such as the temperature and heating rate).[43]

Aligned ZnO nanowires on pre-seeded silicon, glass, and gallium nitride substrates have been grown using aqueous zinc salts such as zinc nitrate and zinc acetate in basic environments.[44] Pre-seeding substrates with ZnO creates sites for homogeneous nucleation of ZnO crystal during the synthesis. Common pre-seeding methods include in-situ thermal decomposition of zinc acetate crystallites, spincoating of ZnO nanoparticles and the use of physical vapor deposition methods to deposit ZnO thin films.[45][46] Pre-seeding can be performed in conjunction with top down patterning methods such as electron beam lithography and nanosphere lithography to designate nucleation sites prior to growth. Aligned ZnO nanowires can be used in dye-sensitized solar cells and field emission devices.[47][48]

History[edit]

Zinc compounds were probably used by early humans, in processed[11] and unprocessed forms, as a paint or medicinal ointment, but their composition is uncertain. The use of pushpanjan, probably zinc oxide, as a salve for eyes and open wounds, is mentioned in the Indian medical text the Charaka Samhita, thought to date from 500 BC or before.[49] Zinc oxide ointment is also mentioned by the Greek physician Dioscorides (1st century AD).[50] Galen suggested treating ulcerating cancers with zinc oxide,[51] as did Avicenna in his The Canon of Medicine. It is used as an ingredient in products such as baby powder and creams against diaper rashes, calamine cream, anti-dandruff shampoos, and antiseptic ointments.[52]

The Romans produced considerable quantities of brass (an alloy of zinc and copper) as early as 200 BC by a cementation process where copper was reacted with zinc oxide.[53] The zinc oxide is thought to have been produced by heating zinc ore in a shaft furnace. This liberated metallic zinc as a vapor, which then ascended the flue and condensed as the oxide. This process was described by Dioscorides in the 1st century AD.[54] Zinc oxide has also been recovered from zinc mines at Zawar in India, dating from the second half of the first millennium BC.[50]

From the 12th to the 16th century zinc and zinc oxide were recognized and produced in India using a primitive form of the direct synthesis process. From India, zinc manufacture moved to China in the 17th century. In 1743, the first European zinc smelter was established in Bristol, United Kingdom.[55] Around 1782 Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau proposed replacing lead white with zinc oxide.[56]

The main usage of zinc oxide (zinc white) was in paints and as an additive to ointments. Zinc white was accepted as a pigment in oil paintings by 1834 but it did not mix well with oil. This problem was solved by optimizing the synthesis of ZnO. In 1845, LeClaire in Paris was producing the oil paint on a large scale, and by 1850, zinc white was being manufactured throughout Europe. The success of zinc white paint was due to its advantages over the traditional white lead: zinc white is essentially permanent in sunlight, it is not blackened by sulfur-bearing air, it is non-toxic and more economical. Because zinc white is so «clean» it is valuable for making tints with other colors, but it makes a rather brittle dry film when unmixed with other colors. For example, during the late 1890s and early 1900s, some artists used zinc white as a ground for their oil paintings. All those paintings developed cracks over the years.[57]

In recent times, most zinc oxide was used in the rubber industry to resist corrosion. In the 1970s, the second largest application of ZnO was photocopying. High-quality ZnO produced by the «French process» was added to photocopying paper as a filler. This application was soon displaced by titanium.[25]

Applications[edit]

The applications of zinc oxide powder are numerous, and the principal ones are summarized below. Most applications exploit the reactivity of the oxide as a precursor to other zinc compounds. For material science applications, zinc oxide has high refractive index, high thermal conductivity, binding, antibacterial and UV-protection properties. Consequently, it is added into materials and products including plastics, ceramics, glass, cement,[58] rubber, lubricants,[10] paints, ointments, adhesive, sealants, concrete manufacturing, pigments, foods, batteries, ferrites, fire retardants, etc.[59]

Rubber manufacture[edit]

Between 50% and 60% of ZnO use is in the rubber industry.[60] Zinc oxide along with stearic acid is used in the vulcanization of rubber[25][61] ZnO additives also protect rubber from fungi (see medical applications) and UV light.

Ceramic industry[edit]

Ceramic industry consumes a significant amount of zinc oxide, in particular in ceramic glaze and frit compositions. The relatively high heat capacity, thermal conductivity and high temperature stability of ZnO coupled with a comparatively low coefficient of expansion are desirable properties in the production of ceramics. ZnO affects the melting point and optical properties of the glazes, enamels, and ceramic formulations. Zinc oxide as a low expansion, secondary flux improves the elasticity of glazes by reducing the change in viscosity as a function of temperature and helps prevent crazing and shivering. By substituting ZnO for BaO and PbO, the heat capacity is decreased and the thermal conductivity is increased. Zinc in small amounts improves the development of glossy and brilliant surfaces. However, in moderate to high amounts, it produces matte and crystalline surfaces. With regard to color, zinc has a complicated influence.[60]

Medicine[edit]

Zinc oxide as a mixture with about 0.5% iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3) is called calamine and is used in calamine lotion. Two minerals, zincite and hemimorphite, have been historically called calamine. When mixed with eugenol, a ligand, zinc oxide eugenol is formed, which has applications as a restorative and prosthodontic in dentistry.[17][62]

Reflecting the basic properties of ZnO,[further explanation needed] fine particles of the oxide have deodorizing and antibacterial[63] properties and for that reason are added into materials including cotton fabric, rubber, oral care products,[64][65] and food packaging.[66][67] Enhanced antibacterial action of fine particles compared to bulk material is not exclusive to ZnO and is observed for other materials, such as silver.[68] This property results from the increased surface area of the fine particles.

Zinc oxide is used in mouthwash products and toothpastes as an anti-bacterial agent proposed to prevent plaque and tartar formation,[69] and to control bad breath by reducing the volatile gases and volatile sulfur compounds (VSC) in the mouth.[70] Along with zinc oxide or zinc salts, these products also commonly contain other active ingredients, such as cetylpyridinium chloride,[71] xylitol,[72] hinokitiol,[73] essential oils and plant extracts.[74][75]

Zinc oxide is widely used to treat a variety of skin conditions, including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, itching due to eczema, diaper rash and acne.[76] Zinc oxide is also often added into sunscreens.[76]

It is used in products such as baby powder and barrier creams to treat diaper rashes, calamine cream, anti-dandruff shampoos, and antiseptic ointments.[52][77] It is also a component in tape (called «zinc oxide tape») used by athletes as a bandage to prevent soft tissue damage during workouts.[78]

Zinc oxide can be used[79] in ointments, creams, and lotions to protect against sunburn and other damage to the skin caused by ultraviolet light (see sunscreen). It is the broadest spectrum UVA and UVB absorber[80][81] that is approved for use as a sunscreen by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[82] and is completely photostable.[83] When used as an ingredient in sunscreen, zinc oxide blocks both UVA (320–400 nm) and UVB (280–320 nm) rays of ultraviolet light. Zinc oxide and the other most common physical sunscreen, titanium dioxide, are considered to be nonirritating, nonallergenic, and non-comedogenic.[84] Zinc from zinc oxide is, however, slightly absorbed into the skin.[85]

Many sunscreens use nanoparticles of zinc oxide (along with nanoparticles of titanium dioxide) because such small particles do not scatter light and therefore do not appear white. The nanoparticles are not absorbed into the skin more than regular-sized zinc oxide particles are,[86] and are only absorbed into the outermost layer of the skin but not into the body.[86]

Zinc oxide nanoparticles can enhance the antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin. It has been shown that nano ZnO that has an average size between 20 nm and 45 nm can enhance the antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in vitro. The enhancing effect of this nanomaterial is concentration dependent against all test strains. This effect may be due to two reasons. First, zinc oxide nanoparticles can interfere with NorA protein, which is developed for conferring resistance in bacteria and has pumping activity that mediates the effluxing of hydrophilic fluoroquinolones from a cell. Second, zinc oxide nanoparticles can interfere with Omf protein, which is responsible for the permeation of quinolone antibiotics into the cell.[87]

Cigarette filters[edit]

Zinc oxide is a component of cigarette filters. A filter consisting of charcoal impregnated with zinc oxide and iron oxide removes significant amounts of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from tobacco smoke without affecting its flavor.[59]

Food additive[edit]

Zinc oxide is added to many food products, including breakfast cereals, as a source of zinc,[88] a necessary nutrient. (Zinc sulfate is also used for the same purpose.) Some prepackaged foods also include trace amounts of ZnO even if it is not intended as a nutrient.

Zinc oxide was linked to dioxin contamination in pork exports in the 2008 Chilean pork crisis. The contamination was found to be due to dioxin contaminated zinc oxide used in pig feed.[89]

Pigment[edit]

Zinc oxide (zinc white) is used as a pigment in paints and is more opaque than lithopone, but less opaque than titanium dioxide.[11] It is also used in coatings for paper. Chinese white is a special grade of zinc white used in artists’ pigments.[90] The use of zinc white as a pigment in oil painting started in the middle of 18th century.[91] It has partly replaced the poisonous lead white and was used by painters such as Böcklin, Van Gogh,[92] Manet, Munch and others. It is also a main ingredient of mineral makeup (CI 77947).[93]

UV absorber[edit]

Micronized and nano-scale zinc oxide provides strong protection against UVA and UVB ultraviolet radiation, and are consequently used in sunscreens,[94] and also in UV-blocking sunglasses for use in space and for protection when welding, following research by scientists at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).[95]

Coatings[edit]

Paints containing zinc oxide powder have long been utilized as anticorrosive coatings for metals. They are especially effective for galvanized iron. Iron is difficult to protect because its reactivity with organic coatings leads to brittleness and lack of adhesion. Zinc oxide paints retain their flexibility and adherence on such surfaces for many years.[59]

ZnO highly n-type doped with aluminium, gallium, or indium is transparent and conductive (transparency ~90%, lowest resistivity ~10−4 Ω·cm[96]). ZnO:Al coatings are used for energy-saving or heat-protecting windows. The coating lets the visible part of the spectrum in but either reflects the infrared (IR) radiation back into the room (energy saving) or does not let the IR radiation into the room (heat protection), depending on which side of the window has the coating.[13]

Plastics, such as polyethylene naphthalate (PEN), can be protected by applying zinc oxide coating. The coating reduces the diffusion of oxygen through PEN.[97] Zinc oxide layers can also be used on polycarbonate in outdoor applications. The coating protects polycarbonate from solar radiation, and decreases its oxidation rate and photo-yellowing.[98]

Corrosion prevention in nuclear reactors[edit]

Zinc oxide depleted in 64Zn (the zinc isotope with atomic mass 64) is used in corrosion prevention in nuclear pressurized water reactors. The depletion is necessary, because 64Zn is transformed into radioactive 65Zn under irradiation by the reactor neutrons.[99]

Methane reforming[edit]

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is used as a pretreatment step to remove hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from natural gas following hydrogenation of any sulfur compounds prior to a methane reformer, which can poison the catalyst. At temperatures between about 230–430 °C (446–806 °F), H2S is converted to water by the following reaction:[100]

- H2S + ZnO → H2O + ZnS

Potential applications[edit]

Electronics[edit]

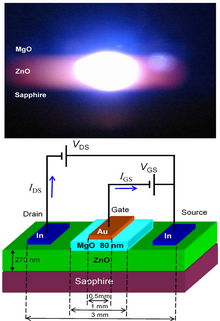

Photograph of an operating ZnO UV laser diode and the corresponding device structure.[101]

ZnO has wide direct band gap (3.37 eV or 375 nm at room temperature). Therefore, its most common potential applications are in laser diodes and light emitting diodes (LEDs).[103] Moreover, ultrafast nonlinearities and photoconductive functions have been reported in ZnO.[104] Some optoelectronic applications of ZnO overlap with that of GaN, which has a similar band gap (~3.4 eV at room temperature). Compared to GaN, ZnO has a larger exciton binding energy (~60 meV, 2.4 times of the room-temperature thermal energy), which results in bright room-temperature emission from ZnO. ZnO can be combined with GaN for LED-applications. For instance, a transparent conducting oxide layer and ZnO nanostructures provide better light outcoupling.[105] Other properties of ZnO favorable for electronic applications include its stability to high-energy radiation and its ability to be patterned by wet chemical etching.[106] Radiation resistance[107] makes ZnO a suitable candidate for space applications. ZnO is the most promising candidate in the field of random lasers to produce an electronically pumped UV laser source.

The pointed tips of ZnO nanorods result in a strong enhancement of an electric field. Therefore, they can be used as field emitters.[108]

Aluminium-doped ZnO layers are used as transparent electrodes. The components Zn and Al are much cheaper and less toxic compared to the generally used indium tin oxide (ITO). One application which has begun to be commercially available is the use of ZnO as the front contact for solar cells or of liquid crystal displays.[109]

Transparent thin-film transistors (TTFT) can be produced with ZnO. As field-effect transistors, they do not need a p–n junction,[110] thus avoiding the p-type doping problem of ZnO. Some of the field-effect transistors even use ZnO nanorods as conducting channels.[111]

Zinc oxide nanorod sensor[edit]

Zinc oxide nanorod sensors are devices detecting changes in electric current passing through zinc oxide nanowires due to adsorption of gas molecules. Selectivity to hydrogen gas was achieved by sputtering palladium clusters on the nanorod surface. The addition of palladium appears to be effective in the catalytic dissociation of hydrogen molecules into atomic hydrogen, increasing the sensitivity of the sensor device. The sensor detects hydrogen concentrations down to 10 parts per million at room temperature, whereas there is no response to oxygen.[112][113] ZnO have been used as immobilization layers in immunosensors enabling the distribution of antibodies across the entire region probed by the measuring electric field applied to the microelectrodes.[114]

Piezoelectricity[edit]

The piezoelectricity in textile fibers coated in ZnO have been shown capable of fabricating «self-powered nanosystems» with everyday mechanical stress from wind or body movements.[115][116]

In 2008 the Center for Nanostructure Characterization at the Georgia Institute of Technology reported producing an electricity generating device (called flexible charge pump generator) delivering alternating current by stretching and releasing zinc oxide nanowires. This mini-generator creates an oscillating voltage up to 45 millivolts, converting close to seven percent of the applied mechanical energy into electricity. Researchers used wires with lengths of 0.2–0.3 mm and diameters of three to five micrometers, but the device could be scaled down to smaller size.[117]

ZnO as anode of Li-ion battery

In form of a thin film ZnO has been demonstrated in miniaturised high frequency thin film resonators, sensors and filters.

Li-ion battery and supercapacitors[edit]

ZnO is a promising anode material for lithium-ion battery because it is cheap, biocompatible, and environmentally friendly. ZnO has a higher theoretical capacity (978 mAh g−1) than many other transition metal oxides such as CoO (715 mAh g−1), NiO (718 mAh g−1) and CuO (674 mAh g−1).[118] ZnO is also used as an electrode in supercapacitors.[119]

Safety[edit]

As a food additive, zinc oxide is on the U.S. FDA’s list of generally recognized as safe, or GRAS, substances.[120]

Zinc oxide itself is non-toxic; it is hazardous, however, to inhale zinc oxide fumes, such as generated when zinc or zinc alloys are melted and oxidized at high temperature. This problem occurs while melting alloys containing brass because the melting point of brass is close to the boiling point of zinc.[121] Exposure to zinc oxide in the air, which also occurs while welding galvanized (zinc plated) steel, can result in a malady called metal fume fever. For this reason, typically galvanized steel is not welded, or the zinc is removed first.[122][dubious – discuss]

In sunscreen formulations containing zinc oxide and other UV absorbers, zinc oxide was found to cause photodegradation of small-molecule UV absorbers, which exhibited toxicity in embryonic zebrafish assays.[123]

See also[edit]

- Depleted zinc oxide

- Zinc oxide nanoparticle

- Gallium(III) nitride

- List of inorganic pigments

- Zinc

- Zinc oxide eugenol

- Zinc peroxide

- Zinc smelting

- Zinc–air battery

- Zinc–zinc oxide cycle

- ZnO nanostructures

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Haynes, p. 4.100

- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0675». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.136

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.144

- ^ a b c Takahashi K, Yoshikawa A, Sandhu A (2007). Wide bandgap semiconductors: fundamental properties and modern photonic and electronic devices. Springer. p. 357. ISBN 978-3-540-47234-6.

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.152

- ^ Haynes, pp. 5.3, 5.16

- ^ Zinc oxide. Chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved on 2015-11-17.

- ^ a b c «Zinc oxide». Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c Battez AH, González R, Viesca JL, Fernández JE, Fernández JD, Machado A, Chou R, Riba J (2008). «CuO, ZrO2 and ZnO nanoparticles as antiwear additive in oil lubricants». Wear. 265 (3–4): 422–428. doi:10.1016/j.wear.2007.11.013.

- ^ a b c De Liedekerke M (2006). «2.3. Zinc Oxide (Zinc White): Pigments, Inorganic, 1». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_243.pub2.

- ^ a b c d Özgür Ü, Alivov YI, Liu C, Teke A, Reshchikov M, Doğan S, Avrutin VC, Cho SJ, Morkoç AH (2005). «A comprehensive review of ZnO materials and devices». Journal of Applied Physics. 98 (4): 041301–041301–103. Bibcode:2005JAP….98d1301O. doi:10.1063/1.1992666.

- ^ a b c Klingshirn C (April 2007). «ZnO: material, physics and applications». ChemPhysChem. 8 (6): 782–803. doi:10.1002/cphc.200700002. PMID 17429819.

- ^ a b Wiberg E, Holleman AF (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ a b Greenwood NN, Earnshaw A (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Nicholson JW (1998). «The chemistry of cements formed between zinc oxide and aqueous zinc chloride». Journal of Materials Science. 33 (9): 2251–2254. Bibcode:1998JMatS..33.2251N. doi:10.1023/A:1004327018497. S2CID 94700819.

- ^ a b c Ferracane JL (2001). Materials in Dentistry: Principles and Applications. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 70, 143. ISBN 978-0-7817-2733-4.

- ^ Park CK, Silsbee MR, Roy DM (1998). «Setting reaction and resultant structure of zinc phosphate cement in various orthophosphoric acid cement-forming liquids». Cement and Concrete Research. 28 (1): 141–150. doi:10.1016/S0008-8846(97)00223-8.

- ^ Fierro JL (2006). Metal Oxides: Chemistry & Applications. CRC Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0824723712.

- ^ Phillips JC (1970). «Ionicity of the Chemical Bond in Crystals». Reviews of Modern Physics. 42 (3): 317–356. Bibcode:1970RvMP…42..317P. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.42.317.

- ^ Rossler U, ed. (1999). Landolt-Bornstein, New Series, Group III. Vol. 17B, 22, 41B. Springer, Heidelberg.

- ^ Klingshirn CF, Waag A, Hoffmann A, Geurts J (2010). Zinc Oxide: From Fundamental Properties Towards Novel Applications. Springer. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-3-642-10576-0.

- ^ a b c Baruah S, Dutta J (February 2009). «Hydrothermal growth of ZnO nanostructures». Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 10 (1): 013001. Bibcode:2009STAdM..10a3001B. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/10/1/013001. PMC 5109597. PMID 27877250.

- ^ Abdulsattar MA (2015). «Capped ZnO (3, 0) nanotubes as building blocks of bare and H passivated wurtzite ZnO nanocrystals». Superlattices and Microstructures. 85: 813–819. Bibcode:2015SuMi…85..813A. doi:10.1016/j.spmi.2015.07.015.

- ^ a b c d Porter F (1991). Zinc Handbook: Properties, Processing, and Use in Design. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8247-8340-2.

- ^ Millot M, Tena-Zaera R, Munoz-Sanjose V, Broto JM, Gonzalez J (2010). «Anharmonic effects in ZnO optical phonons probed by Raman spectroscopy». Applied Physics Letters. 96 (15): 152103. Bibcode:2010ApPhL..96o2103M. doi:10.1063/1.3387843. hdl:10902/23620.

- ^ Posternak M, Resta R, Baldereschi A (October 1994). «Ab initio study of piezoelectricity and spontaneous polarization in ZnO». Physical Review B. 50 (15): 10715–10721. Bibcode:1994PhRvB..5010715D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.50.10715. PMID 9975171.

- ^ Look DC, Hemsky JW, Sizelove JR (1999). «Residual Native Shallow Donor in ZnO». Physical Review Letters. 82 (12): 2552–2555. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82.2552L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.2552. S2CID 53476471.

- ^ Janotti A, Van de Walle CG (January 2007). «Hydrogen multicentre bonds». Nature Materials. 6 (1): 44–7. Bibcode:2007NatMa…6…44J. doi:10.1038/nmat1795. PMID 17143265.

- ^ Kato H, Sano M, Miyamoto K, Yao T (2002). «Growth and characterization of Ga-doped ZnO layers on a-plane sapphire substrates grown by molecular beam epitaxy». Journal of Crystal Growth. 237–239: 538–543. Bibcode:2002JCrGr.237..538K. doi:10.1016/S0022-0248(01)01972-8.

- ^ Ohgaki T, Ohashi N, Sugimura S, Ryoken H, Sakaguchi I, Adachi Y, Haneda H (2008). «Positive Hall coefficients obtained from contact misplacement on evident n-type ZnO films and crystals». Journal of Materials Research. 23 (9): 2293–2295. Bibcode:2008JMatR..23.2293O. doi:10.1557/JMR.2008.0300.

- ^ Wagner P, Helbig R (1974). «Halleffekt und anisotropie der beweglichkeit der elektronen in ZnO». Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 35 (3): 327–335. Bibcode:1974JPCS…35..327W. doi:10.1016/S0022-3697(74)80026-0.

- ^ Ryu YR, Lee TS, White HW (2003). «Properties of arsenic-doped p-type ZnO grown by hybrid beam deposition». Applied Physics Letters. 83 (1): 87. Bibcode:2003ApPhL..83…87R. doi:10.1063/1.1590423.

- ^

René Smeets, Lou van der Sluis, Mirsad Kapetanovic, David F. Peelo, Anton Janssen.

«Switching in Electrical Transmission and Distribution Systems».

2014.

p. 316. - ^

Mukund R. Patel.

«Introduction to Electrical Power and Power Electronics».

2012.

p. 247. - ^ Irimpan L, Krishnan Deepthy BA, Nampoori VPN, Radhakrishnan P (2008). «Size-dependent enhancement of nonlinear optical properties in nanocolloids of ZnO» (PDF). Journal of Applied Physics. 103 (3): 033105–033105–7. Bibcode:2008JAP…103c3105I. doi:10.1063/1.2838178.

- ^ a b Schulz D, Ganschow S, Klimm D, Struve K (2008). «Inductively heated Bridgman method for the growth of zinc oxide single crystals». Journal of Crystal Growth. 310 (7–9): 1832–1835. Bibcode:2008JCrGr.310.1832S. doi:10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2007.11.050.

- ^ Baruah S, Thanachayanont C, Dutta J (April 2008). «Growth of ZnO nanowires on nonwoven polyethylene fibers». Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (2): 025009. Bibcode:2008STAdM…9b5009B. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/2/025009. PMC 5099741. PMID 27877984.

- ^ Miao L, Ieda Y, Tanemura S, Cao YG, Tanemura M, Hayashi Y, Toh S, Kaneko K (2007). «Synthesis, microstructure and photoluminescence of well-aligned ZnO nanorods on Si substrate». Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 8 (6): 443–447. Bibcode:2007STAdM…8..443M. doi:10.1016/j.stam.2007.02.012.

- ^ Xu S, Wang ZL (2011). «One-dimensional ZnO nanostructures: Solution growth and functional properties». Nano Res. 4 (11): 1013–1098. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.654.3359. doi:10.1007/s12274-011-0160-7. S2CID 137014543.

- ^ Zhou Y, Wu W, Hu G, Wu H, Cui S (2008). «Hydrothermal synthesis of ZnO nanorod arrays with the addition of polyethyleneimine». Materials Research Bulletin. 43 (8–9): 2113–2118. doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2007.09.024.

- ^ Cui J, Zeng Q, Gibson UJ (2006-04-15). «Synthesis and magnetic properties of Co-doped ZnO nanowires». Journal of Applied Physics. 99 (8): 08M113. Bibcode:2006JAP….99hM113C. doi:10.1063/1.2169411.

- ^ Elen K, Van den Rul H, Hardy A, Van Bael MK, D’Haen J, Peeters R, et al. (February 2009). «Hydrothermal synthesis of ZnO nanorods: a statistical determination of the significant parameters in view of reducing the diameter». Nanotechnology. 20 (5): 055608. Bibcode:2009Nanot..20e5608E. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/20/5/055608. PMID 19417355. S2CID 206056816.

- ^ Greene LE, Law M, Goldberger J, Kim F, Johnson JC, Zhang Y, et al. (July 2003). «Low-temperature wafer-scale production of ZnO nanowire arrays». Angewandte Chemie. 42 (26): 3031–4. doi:10.1002/anie.200351461. PMID 12851963.

- ^ Wu W (2009). «Effects of Seed Layer Characteristics on the Synthesis of ZnO Nanowires». Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 92 (11): 2718–2723. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03022.x.

- ^ Greene LE, Law M, Tan DH, Montano M, Goldberger J, Somorjai G, Yang P (July 2005). «General route to vertical ZnO nanowire arrays using textured ZnO seeds». Nano Letters. 5 (7): 1231–6. Bibcode:2005NanoL…5.1231G. doi:10.1021/nl050788p. PMID 16178216.

- ^ Hua G (2008). «Fabrication of ZnO nanowire arrays by cycle growth in surfactantless aqueous solution and their applications on dye-sensitized solar cells». Materials Letters. 62 (25): 4109–4111. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2008.06.018.

- ^ Lee JH, Chung YW, Hon MH, Leu C (2009-05-07). «Density-controlled growth and field emission property of aligned ZnO nanorod arrays». Applied Physics A. 97 (2): 403–408. Bibcode:2009ApPhA..97..403L. doi:10.1007/s00339-009-5226-y. S2CID 97205678.

- ^ Craddock PT (1998). «Zinc in India». 2000 years of zinc and brass. British Museum. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-86159-124-4.

- ^ a b Craddock PT (2008). «Mining and Metallurgy, chapter 4». In Oleson JP (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1.

- ^ Winchester DJ, Winchester DP, Hudis CA, Norton L (2005). Breast Cancer (Atlas of Clinical Oncology). PMPH USA. p. 3. ISBN 978-1550092721.

- ^ a b Harding FJ (2007). Breast Cancer: Cause – Prevention – Cure. Tekline Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-9554221-0-2.

- ^ «Zinc». Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 March 2009.

- ^ Craddock PT (2009). «The origins and inspirations of zinc smelting». Journal of Materials Science. 44 (9): 2181–2191. Bibcode:2009JMatS..44.2181C. doi:10.1007/s10853-008-2942-1. S2CID 135523239.

- ^ General Information of Zinc from the National Institute of Health, WHO, and International Zinc Association. Retrieved 10 March 2009

- ^ «Zinc White».

- ^ «Zinc white: History of use». Pigments through the ages. webexhibits.org.

- ^ Sanchez-Pescador R, Brown JT, Roberts M, Urdea MS (February 1988). «The nucleotide sequence of the tetracycline resistance determinant tetM from Ureaplasma urealyticum». Nucleic Acids Research. 16 (3): 1216–7. doi:10.1093/nar/16.3.1216. PMC 334766. PMID 3344217.

- ^ a b c Ambica Dhatu Private Limited. Applications of ZnO. Archived December 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Access date January 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Moezzi A, McDonagh AM, Cortie MB (2012). «Review: Zinc oxide particles: Synthesis, properties and applications». Chemical Engineering Journal. 185–186: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2012.01.076.

- ^ Brown HE (1957). Zinc Oxide Rediscovered. New York: The New Jersey Zinc Company.

- ^ van Noort R (2002). Introduction to Dental Materials (2d ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-7234-3215-9.

- ^ Padmavathy N, Vijayaraghavan R (July 2008). «Enhanced bioactivity of ZnO nanoparticles-an antimicrobial study». Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (3): 035004. Bibcode:2008STAdM…9c5004P. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/3/035004. PMC 5099658. PMID 27878001.

- ^ ten Cate JM (February 2013). «Contemporary perspective on the use of fluoride products in caries prevention». British Dental Journal. 214 (4): 161–7. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.162. PMID 23429124.

- ^ Rošin-Grget K, Peroš K, Sutej I, Bašić K (November 2013). «The cariostatic mechanisms of fluoride». Acta Medica Academica. 42 (2): 179–88. doi:10.5644/ama2006-124.85. PMID 24308397.

- ^ Li Q, Chen S, Jiang W (2007). «Durability of nano ZnO antibacterial cotton fabric to sweat». Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 103: 412–416. doi:10.1002/app.24866.

- ^ Saito M (1993). «Antibacterial, Deodorizing, and UV Absorbing Materials Obtained with Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Coated Fabrics». Journal of Industrial Textiles. 23 (2): 150–164. doi:10.1177/152808379302300205. S2CID 97726945.

- ^ Akhavan O, Ghaderi E (February 2009). «Enhancement of antibacterial properties of Ag nanorods by electric field». Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 10 (1): 015003. Bibcode:2009STAdM..10a5003A. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/10/1/015003. PMC 5109610. PMID 27877266.

- ^ Lynch, Richard J.M. (August 2011). «Zinc in the mouth, its interactions with dental enamel and possible effects on caries; a review of the literature». International Dental Journal. 61: 46–54. doi:10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00049.x. PMC 9374993. PMID 21762155.

- ^ Cortelli, José Roberto; Barbosa, Mônica Dourado Silva; Westphal, Miriam Ardigó (August 2008). «Halitosis: a review of associated factors and therapeutic approach». Brazilian Oral Research. 22 (suppl 1): 44–54. doi:10.1590/S1806-83242008000500007. PMID 19838550.

- ^ «SmartMouth Clinical DDS Activated Mouthwash». smartmouth.com.

- ^ «Oxyfresh». Oxyfresh.com.

- ^ «Dr ZinX». drzinx.com.

- ^ Steenberghe, Daniel Van; Avontroodt, Pieter; Peeters, Wouter; Pauwels, Martine; Coucke, Wim; Lijnen, An; Quirynen, Marc (September 2001). «Effect of Different Mouthrinses on Morning Breath». Journal of Periodontology. 72 (9): 1183–1191. doi:10.1902/jop.2000.72.9.1183. PMID 11577950.

- ^ Harper, D. Scott; Mueller, Laura J.; Fine, James B.; Gordon, Jeffrey; Laster, Larry L. (June 1990). «Clinical Efficacy of a Dentifrice and Oral Rinse Containing Sanguinaria Extract and Zinc Chloride During 6 Months of Use». Journal of Periodontology. 61 (6): 352–358. doi:10.1902/jop.1990.61.6.352. PMID 2195152.

- ^ a b Gupta, Mrinal; Mahajan, Vikram K.; Mehta, Karaninder S.; Chauhan, Pushpinder S. (2014). «Zinc Therapy in Dermatology: A Review». Dermatology Research and Practice. 2014: 709152. doi:10.1155/2014/709152. PMC 4120804. PMID 25120566.

- ^ British National Formulary (2008). «Section 13.2.2 Barrier Preparations».

- ^ Hughes G, McLean NR (December 1988). «Zinc oxide tape: a useful dressing for the recalcitrant finger-tip and soft-tissue injury». Archives of Emergency Medicine. 5 (4): 223–7. doi:10.1136/emj.5.4.223. PMC 1285538. PMID 3233136.

- ^ Dhatu A (10 October 2019). «Zinc oxide as the chemical for skin care». Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ «Critical Wavelength & Broad Spectrum UV Protection». mycpss.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ More BD (2007). «Physical sunscreens: on the comeback trail». Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 73 (2): 80–5. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.31890. PMID 17456911.

- ^ «Sunscreen». U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ Mitchnick MA, Fairhurst D, Pinnell SR (January 1999). «Microfine zinc oxide (Z-cote) as a photostable UVA/UVB sunblock agent». Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 40 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70532-3. PMID 9922017.

- ^ «What to Look for in a Sunscreen». The New York Times. June 10, 2009.

- ^ Agren MS (2009). «Percutaneous absorption of zinc from zinc oxide applied topically to intact skin in man». Dermatologica. 180 (1): 36–9. doi:10.1159/000247982. PMID 2307275.

- ^ a b Burnett ME, Wang SQ (April 2011). «Current sunscreen controversies: a critical review». Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 27 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00557.x. PMID 21392107. S2CID 29173997.

- ^ Banoee M, Seif S, Nazari ZE, Jafari-Fesharaki P, Shahverdi HR, Moballegh A, et al. (May 2010). «ZnO nanoparticles enhanced antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli». Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 93 (2): 557–61. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.31615. PMID 20225250.

- ^ Quaker cereals content. quakeroats.com

- ^ Kim M, Kim DG, Choi SW, Guerrero P, Norambuena J, Chung GS (February 2011). «Formation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins/dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) from a refinery process for zinc oxide used in feed additives: a source of dioxin contamination in Chilean pork». Chemosphere. 82 (9): 1225–9. Bibcode:2011Chmsp..82.1225K. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.12.040. PMID 21216436.

- ^ St Clair K (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 40. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ^ Kuhn, H. (1986) «Zinc White», pp. 169–186 in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 1. L. Feller (ed.). Cambridge University Press, London. ISBN 978-0521303743

- ^ Vincent van Gogh, ‘Wheatfield with Cypresses, 1889, pigment analysis at ColourLex

- ^ Bouchez C. «The Lowdown on Mineral Makeup». WebMD. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ^ US Environment Protection Agency: Sunscreen What are the active Ingredients in Sunscreen – Physical Ingredients:»The physical compounds titanium dioxide and zinc oxide reflect, scatter, and absorb both UVA and UVB rays.» A table lists them as providing extensive physical protection against UVA and UVB

- ^ Look Sharp While Seeing Sharp. NASA Scientific and Technical Information (2006). Retrieved 17 October 2009. JPL scientists developed UV-protective sunglasses using dyes and «zinc oxide, which absorbs ultraviolet light»

- ^ Schmidtmende L, MacManusdriscoll J (2007). «ZnO – nanostructures, defects, and devices». Materials Today. 10 (5): 40–48. doi:10.1016/S1369-7021(07)70078-0.

- ^ Guedri-Knani L, Gardette JL, Jacquet M, Rivaton A (2004). «Photoprotection of poly(ethylene-naphthalate) by zinc oxide coating». Surface and Coatings Technology. 180–181: 71–75. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2003.10.039.

- ^ Moustaghfir A, Tomasella E, Rivaton A, Mailhot B, Jacquet M, Gardette JL, Cellier J (2004). «Sputtered zinc oxide coatings: structural study and application to the photoprotection of the polycarbonate». Surface and Coatings Technology. 180–181: 642–645. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2003.10.109.

- ^ Cowan RL (2001). «BWR water chemistry?a delicate balance». Nuclear Energy. 40 (4): 245–252. doi:10.1680/nuen.40.4.245.39338.

- ^ Robinson, Victor S. (1978) «Process for desulfurization using particulate zinc oxide shapes of high surface area and improved strength» U.S. Patent 4,128,619

- ^ Liu XY, Shan CX, Zhu H, Li BH, Jiang MM, Yu SF, Shen DZ (September 2015). «Ultraviolet Lasers Realized via Electrostatic Doping Method». Scientific Reports. 5: 13641. Bibcode:2015NatSR…513641L. doi:10.1038/srep13641. PMC 4555170. PMID 26324054.

- ^ Zheng ZQ, Yao JD, Wang B, Yang GW (June 2015). «Light-controlling, flexible and transparent ethanol gas sensor based on ZnO nanoparticles for wearable devices». Scientific Reports. 5: 11070. Bibcode:2015NatSR…511070Z. doi:10.1038/srep11070. PMC 4468465. PMID 26076705.

- ^ Bakin A, El-Shaer A, Mofor AC, Al-Suleiman M, Schlenker E, Waag A (2007). «ZnMgO-ZnO quantum wells embedded in ZnO nanopillars: Towards realisation of nano-LEDs». Physica Status Solidi C. 4 (1): 158–161. Bibcode:2007PSSCR…4..158B. doi:10.1002/pssc.200673557.

- ^ Torres-Torres, C.; Castro-Chacón, J. H.; Castañeda, L.; Rojo, R. Rangel; Torres-Martínez, R.; Tamayo-Rivera, L.; Khomenko, A. V. (2011-08-15). «Ultrafast nonlinear optical response of photoconductive ZnO films with fluorine nanoparticles». Optics Express. 19 (17): 16346–16355. Bibcode:2011OExpr..1916346T. doi:10.1364/OE.19.016346. ISSN 1094-4087. PMID 21934998.

- ^ Bakin A (2010). «ZnO – GaN Hybrid Heterostructures as Potential Cost Efficient LED Technology». Proceedings of the IEEE. 98 (7): 1281–1287. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2009.2037444. S2CID 20442190.

- ^ Look D (2001). «Recent advances in ZnO materials and devices». Materials Science and Engineering B. 80 (1–3): 383–387. doi:10.1016/S0921-5107(00)00604-8.

- ^ Kucheyev SO, Williams JS, Jagadish C, Zou J, Evans C, Nelson AJ, Hamza AV (2003-03-31). «Ion-beam-produced structural defects in ZnO» (PDF). Physical Review B. 67 (9): 094115. Bibcode:2003PhRvB..67i4115K. doi:10.1103/physrevb.67.094115.

- ^ Li YB, Bando Y, Golberg D (2004). «ZnO nanoneedles with tip surface perturbations: Excellent field emitters». Applied Physics Letters. 84 (18): 3603. Bibcode:2004ApPhL..84.3603L. doi:10.1063/1.1738174.

- ^ Oh BY, Jeong MC, Moon TH, Lee W, Myoung JM, Hwang JY, Seo DS (2006). «Transparent conductive Al-doped ZnO films for liquid crystal displays». Journal of Applied Physics. 99 (12): 124505–124505–4. Bibcode:2006JAP….99l4505O. doi:10.1063/1.2206417.

- ^ Nomura K, Ohta H, Ueda K, Kamiya T, Hirano M, Hosono H (May 2003). «Thin-film transistor fabricated in single-crystalline transparent oxide semiconductor». Science. 300 (5623): 1269–72. Bibcode:2003Sci…300.1269N. doi:10.1126/science.1083212. PMID 12764192. S2CID 20791905.

- ^ Heo YW, Tien LC, Kwon Y, Norton DP, Pearton SJ, Kang BS, Ren F (2004). «Depletion-mode ZnO nanowire field-effect transistor». Applied Physics Letters. 85 (12): 2274. Bibcode:2004ApPhL..85.2274H. doi:10.1063/1.1794351.

- ^ Wang HT, Kang BS, Ren F, Tien LC, Sadik PW, Norton DP, Pearton SJ, Lin J (2005). «Hydrogen-selective sensing at room temperature with ZnO nanorods». Applied Physics Letters. 86 (24): 243503. Bibcode:2005ApPhL..86x3503W. doi:10.1063/1.1949707.

- ^ Tien LC, Sadik PW, Norton DP, Voss LF, Pearton SJ, Wang HT, et al. (2005). «Hydrogen sensing at room temperature with Pt-coated ZnO thin films and nanorods». Applied Physics Letters. 87 (22): 222106. Bibcode:2005ApPhL..87v2106T. doi:10.1063/1.2136070.

- ^ Sanguino, P.; Monteiro, Tiago; Bhattacharyya, S. R.; Dias, C. J.; Igreja, Rui; Franco, Ricardo (1 December 2014). «ZnO nanorods as immobilization layers for interdigitated capacitive immunosensors». Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 204: 211–217. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2014.06.141. ISSN 0925-4005.

- ^ Keim B (February 13, 2008). «Piezoelectric Nanowires Turn Fabric Into Power Source». Wired News. CondéNet. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008.

- ^ Qin Y, Wang X, Wang ZL (February 2008). «Microfibre-nanowire hybrid structure for energy scavenging». Nature. 451 (7180): 809–13. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..809Q. doi:10.1038/nature06601. PMID 18273015. S2CID 4411796.

- ^ «New Small-scale Generator Produces Alternating Current By Stretching Zinc Oxide Wires». Science Daily. November 10, 2008.

- ^ Zheng X, Shen G, Wang C, Li Y, Dunphy D, Hasan T, et al. (April 2017). «Bio-inspired Murray materials for mass transfer and activity». Nature Communications. 8: 14921. Bibcode:2017NatCo…814921Z. doi:10.1038/ncomms14921. PMC 5384213. PMID 28382972.

- ^ Sreejesh, M.; Dhanush, S.; Rossignol, F.; Nagaraja, H. S. (2017-04-15). «Microwave assisted synthesis of rGO/ZnO composites for non-enzymatic glucose sensing and supercapacitor applications». Ceramics International. 43 (6): 4895–4903. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.12.140. ISSN 0272-8842.

- ^ «Zinc oxide». Database of Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Reviews. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Gray T. «The Safety of Zinc Casting». The Wooden Periodic Table Table.

- ^ Calvert JB. «Introduction to Zinc and its Uses». Archived from the original on 2006-08-27.

- ^ Ginzburg AL, Blackburn RS, Santillan C, Truong L, Tanguay RL, Hutchison JE (2021). «Zinc oxide-induced changes to sunscreen ingredient efficacy and toxicity under UV irradiation». Photochem Photobiol Sci. 20 (10): 1273–1285. doi:10.1007/s43630-021-00101-2. PMC 8550398. PMID 34647278.

Cited sources[edit]

- Haynes WM, ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1439855119.

Reviews[edit]

- Özgür Ü, Alivov YI, Liu C, Teke A, Reshchikov M, Doğan S, et al. (2005). «A comprehensive review of ZnO materials and devices». Journal of Applied Physics. 98 (4): 041301–041301–103. Bibcode:2005JAP….98d1301O. doi:10.1063/1.1992666.

- Bakin A, Waag A (29 March 2011). «ZnO Epitaxial Growth». In Bhattacharya P, Fornari R, Kamimura H (eds.). Comprehensive Semiconductor Science and Technology 6 Volume Encyclopaedia. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53143-8.

- Baruah S, Dutta J (February 2009). «Hydrothermal growth of ZnO nanostructures». Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 10 (1): 013001. Bibcode:2009STAdM..10a3001B. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/10/1/013001. PMC 5109597. PMID 27877250.

- Janisch R (2005). «Transition metal-doped TiO 2 and ZnO—present status of the field». Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 17 (27): R657–R689. Bibcode:2005JPCM…17R.657J. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/17/27/R01. S2CID 118610509.

- Heo YW (2004). «ZnO nanowire growth and devices». Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 47 (1–2): 1–47. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2004.09.001.

- Klingshirn C (2007). «ZnO: From basics towards applications». Physica Status Solidi B. 244 (9): 3027–3073. Bibcode:2007PSSBR.244.3027K. doi:10.1002/pssb.200743072. S2CID 97461963.

- Klingshirn C (April 2007). «ZnO: material, physics and applications». ChemPhysChem. 8 (6): 782–803. doi:10.1002/cphc.200700002. PMID 17429819.

- Lu JG, Chang P, Fan Z (2006). «Quasi-one-dimensional metal oxide materials—Synthesis, properties and applications». Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 52 (1–3): 49–91. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.125.7559. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2006.04.002.

- Xu S, Wang ZL (2011). «One-dimensional ZnO nanostructures: Solution growth and functional properties». Nano Research. 4 (11): 1013–1098. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.654.3359. doi:10.1007/s12274-011-0160-7. S2CID 137014543.

- Xu S, Wang ZL (2011). «Oxide nanowire arrays for light-emitting diodes and piezoelectric energy harvesters». Pure and Applied Chemistry. 83 (12): 2171–2198. doi:10.1351/PAC-CON-11-08-17. S2CID 18770461.

External links[edit]

- Zincite properties

- International Chemical Safety Card 0208.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards.

- Zinc oxide in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

- Zinc white pigment at ColourLex

|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Zinc white, calamine, philosopher’s wool, Chinese white, flowers of zinc |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

CAS Number |

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| DrugBank |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.839 |

| EC Number |

|

|

Gmelin Reference |

13738 |

| KEGG |

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 3077 |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

InChI

|

|

|

SMILES

|

|

| Properties | |

|

Chemical formula |

ZnO |

| Molar mass | 81.406 g/mol[1] |

| Appearance | White solid[1] |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 5.606 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 1,974 °C (3,585 °F; 2,247 K) (decomposes)[1][5] |

| Boiling point | 2,360 °C (4,280 °F; 2,630 K) (decomposes) |

|

Solubility in water |

0.0004% (17.8°C)[2] |

| Band gap | 3.3 eV (direct) |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

−27.2·10−6 cm3/mol[3] |

|

Refractive index (nD) |

n1=2.013, n2=2.029[4] |

| Structure[6] | |

|

Crystal structure |

Wurtzite |

|

Space group |

C6v4—P63mc |

|

Lattice constant |

a = 3.2495 Å, c = 5.2069 Å |

|

Formula units (Z) |

2 |

|

Coordination geometry |

Tetrahedral |

| Thermochemistry[7] | |

|

Heat capacity (C) |

40.3 J·K−1mol−1 |

|

Std molar |

43.7±0.4 J·K−1mol−1 |

|

Std enthalpy of |

-350.5±0.3 kJ mol−1 |

|

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

-320.5 kJ mol−1 |

| Pharmacology | |

|

ATCvet code |

QA07XA91 (WHO) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Warning |

|

Hazard statements |

H400, H401 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P273, P391, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

2 1 0 |

| Flash point | 1,436 °C (2,617 °F; 1,709 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

|

LD50 (median dose) |

240 mg/kg (intraperitoneal, rat)[8] 7950 mg/kg (rat, oral)[9] |

|

LC50 (median concentration) |

2500 mg/m3 (mouse)[9] |

|

LCLo (lowest published) |

2500 mg/m3 (guinea pig, 3–4 h)[9] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 5 mg/m3 (fume) TWA 15 mg/m3 (total dust) TWA 5 mg/m3 (resp dust)[2] |

|

REL (Recommended) |

Dust: TWA 5 mg/m3 C 15 mg/m3

Fume: TWA 5 mg/m3 ST 10 mg/m3[2] |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

500 mg/m3[2] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0208 |

| Related compounds | |

|

Other anions |

Zinc sulfide Zinc selenide Zinc telluride |

|

Other cations |

Cadmium oxide Mercury(II) oxide |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Zinc oxide is an inorganic compound with the formula ZnO. It is a white powder that is insoluble in water. ZnO is used as an additive in numerous materials and products including cosmetics, food supplements, rubbers, plastics, ceramics, glass, cement, lubricants,[10] paints, ointments, adhesives, sealants, pigments, foods, batteries, ferrites, fire retardants, and first-aid tapes. Although it occurs naturally as the mineral zincite, most zinc oxide is produced synthetically.[11]

ZnO is a wide-band gap semiconductor of the II-VI semiconductor group. The native doping of the semiconductor due to oxygen vacancies or zinc interstitials is n-type.[12] Other favorable properties include good transparency, high electron mobility, wide band gap, and strong room-temperature luminescence. Those properties make ZnO valuable for a variety of emerging applications: transparent electrodes in liquid crystal displays, energy-saving or heat-protecting windows, and electronics as thin-film transistors and light-emitting diodes.

Chemical properties[edit]

Pure ZnO is a white powder, but in nature it occurs as the rare mineral zincite, which usually contains manganese and other impurities that confer a yellow to red color.[13]

Crystalline zinc oxide is thermochromic, changing from white to yellow when heated in air and reverting to white on cooling.[14] This color change is caused by a small loss of oxygen to the environment at high temperatures to form the non-stoichiometric Zn1+xO, where at 800 °C, x = 0.00007.[14]

Zinc oxide is an amphoteric oxide. It is nearly insoluble in water, but it will dissolve in most acids, such as hydrochloric acid:[15]

- ZnO + 2 HCl → ZnCl2 + H2O

Solid zinc oxide will also dissolve in alkalis to give soluble zincates:

- ZnO + 2 NaOH + H2O → Na2[Zn(OH)4]

ZnO reacts slowly with fatty acids in oils to produce the corresponding carboxylates, such as oleate or stearate. When mixed with a strong aqueous solution of zinc chloride, ZnO forms cement-like products best described as zinc hydroxy chlorides.[16] This cement was used in dentistry.[17]

ZnO also forms cement-like material when treated with phosphoric acid; related materials are used in dentistry.[17] A major component of zinc phosphate cement produced by this reaction is hopeite, Zn3(PO4)2·4H2O.[18]

ZnO decomposes into zinc vapor and oxygen at around 1975 °C with a standard oxygen pressure. In a carbothermic reaction, heating with carbon converts the oxide into zinc vapor at a much lower temperature (around 950 °C).[15]

- ZnO + C → Zn(Vapor) + CO

Physical properties[edit]

Structure[edit]

Zinc oxide crystallizes in two main forms, hexagonal wurtzite[19] and cubic zincblende. The wurtzite structure is most stable at ambient conditions and thus most common. The zincblende form can be stabilized by growing ZnO on substrates with cubic lattice structure. In both cases, the zinc and oxide centers are tetrahedral, the most characteristic geometry for Zn(II). ZnO converts to the rocksalt motif at relatively high pressures about 10 GPa.[12] The many remarkable medical properties of creams containing ZnO can be explained by its elastic softness, which is characteristic of tetrahedral coordinated binary compounds close to the transition to octahedral structures.[20]

Hexagonal and zincblende polymorphs have no inversion symmetry (reflection of a crystal relative to any given point does not transform it into itself). This and other lattice symmetry properties result in piezoelectricity of the hexagonal and zincblende ZnO, and pyroelectricity of hexagonal ZnO.

The hexagonal structure has a point group 6 mm (Hermann–Mauguin notation) or C6v (Schoenflies notation), and the space group is P63mc or C6v4. The lattice constants are a = 3.25 Å and c = 5.2 Å; their ratio c/a ~ 1.60 is close to the ideal value for hexagonal cell c/a = 1.633.[21] As in most group II-VI materials, the bonding in ZnO is largely ionic (Zn2+O2−) with the corresponding radii of 0.074 nm for Zn2+ and 0.140 nm for O2−. This property accounts for the preferential formation of wurtzite rather than zinc blende structure,[22] as well as the strong piezoelectricity of ZnO. Because of the polar Zn−O bonds, zinc and oxygen planes are electrically charged. To maintain electrical neutrality, those planes reconstruct at atomic level in most relative materials, but not in ZnO – its surfaces are atomically flat, stable and exhibit no reconstruction.[23] However, studies using wurtzoid structures explained the origin of surface flatness and the absence of reconstruction at ZnO wurtzite surfaces[24] in addition to the origin of charges on ZnO planes.

Mechanical properties[edit]

ZnO is a relatively soft material with approximate hardness of 4.5 on the Mohs scale.[10] Its elastic constants are smaller than those of relevant III-V semiconductors, such as GaN. The high heat capacity and heat conductivity, low thermal expansion and high melting temperature of ZnO are beneficial for ceramics.[25] The E2 optical phonon in ZnO exhibits an unusually long lifetime of 133 ps at 10 K.[26]

Among the tetrahedrally bonded semiconductors, it has been stated that ZnO has the highest piezoelectric tensor, or at least one comparable to that of GaN and AlN.[27] This property makes it a technologically important material for many piezoelectrical applications, which require a large electromechanical coupling. Therefore, ZnO in the form of thin film has been one of the most studied resonator materials for thin-film bulk acoustic resonators.

Electrical and optical properties[edit]

ZnO has a relatively large direct band gap of ~3.3 eV at room temperature. Advantages associated with a large band gap include higher breakdown voltages, ability to sustain large electric fields, lower electronic noise, and high-temperature and high-power operation. The band gap of ZnO can further be tuned to ~3–4 eV by its alloying with magnesium oxide or cadmium oxide.[12]

Most ZnO has n-type character, even in the absence of intentional doping. Nonstoichiometry is typically the origin of n-type character, but the subject remains controversial.[28] An alternative explanation has been proposed, based on theoretical calculations, that unintentional substitutional hydrogen impurities are responsible.[29] Controllable n-type doping is easily achieved by substituting Zn with group-III elements such as Al, Ga, In or by substituting oxygen with group-VII elements chlorine or iodine.[30]

Reliable p-type doping of ZnO remains difficult. This problem originates from low solubility of p-type dopants and their compensation by abundant n-type impurities. This problem is observed with GaN and ZnSe. Measurement of p-type in «intrinsically» n-type material is complicated by the inhomogeneity of samples.[31]

Current limitations to p-doping limit electronic and optoelectronic applications of ZnO, which usually require junctions of n-type and p-type material. Known p-type dopants include group-I elements Li, Na, K; group-V elements N, P and As; as well as copper and silver. However, many of these form deep acceptors and do not produce significant p-type conduction at room temperature.[12]

Electron mobility of ZnO strongly varies with temperature and has a maximum of ~2000 cm2/(V·s) at 80 K.[32] Data on hole mobility are scarce with values in the range 5–30 cm2/(V·s).[33]

ZnO discs, acting as a varistor, are the active material in most surge arresters.[34][35]

Zinc oxide is noted for its strongly nonlinear optical properties, especially in bulk. The nonlinearity of ZnO nanoparticles can be fine-tuned according to their size.[36]

Production[edit]

For industrial use, ZnO is produced at levels of 105 tons per year[13] by three main processes:[25]

Indirect process[edit]

In the indirect or French process, metallic zinc is melted in a graphite crucible and vaporized at temperatures above 907 °C (typically around 1000 °C). Zinc vapor reacts with the oxygen in the air to give ZnO, accompanied by a drop in its temperature and bright luminescence. Zinc oxide particles are transported into a cooling duct and collected in a bag house. This indirect method was popularized by LeClaire (France) in 1844 and therefore is commonly known as the French process. Its product normally consists of agglomerated zinc oxide particles with an average size of 0.1 to a few micrometers. By weight, most of the world’s zinc oxide is manufactured via French process.

Direct process[edit]

The direct or American process starts with diverse contaminated zinc composites, such as zinc ores or smelter by-products. The zinc precursors are reduced (carbothermal reduction) by heating with a source of carbon such as anthracite to produce zinc vapor, which is then oxidized as in the indirect process. Because of the lower purity of the source material, the final product is also of lower quality in the direct process as compared to the indirect one.

Wet chemical process[edit]

A small amount of industrial production involves wet chemical processes, which start with aqueous solutions of zinc salts, from which zinc carbonate or zinc hydroxide is precipitated. The solid precipitate is then calcined at temperatures around 800 °C.

Laboratory synthesis[edit]

The red and green colors of these synthetic ZnO crystals result from different concentrations of oxygen vacancies.[37]

Numerous specialised methods exist for producing ZnO for scientific studies and niche applications. These methods can be classified by the resulting ZnO form (bulk, thin film, nanowire), temperature («low», that is close to room temperature or «high», that is T ~ 1000 °C), process type (vapor deposition or growth from solution) and other parameters.

Large single crystals (many cubic centimeters) can be grown by the gas transport (vapor-phase deposition), hydrothermal synthesis,[23][37][38] or melt growth.[5] However, because of the high vapor pressure of ZnO, growth from the melt is problematic. Growth by gas transport is difficult to control, leaving the hydrothermal method as a preference.[5] Thin films can be produced by chemical vapor deposition, metalorganic vapour phase epitaxy, electrodeposition, pulsed laser deposition, sputtering, sol–gel synthesis, atomic layer deposition, spray pyrolysis, etc.

Ordinary white powdered zinc oxide can be produced in the laboratory by electrolyzing a solution of sodium bicarbonate with a zinc anode. Zinc hydroxide and hydrogen gas are produced. The zinc hydroxide upon heating decomposes to zinc oxide:

- Zn + 2 H2O → Zn(OH)2 + H2

- Zn(OH)2 → ZnO + H2O

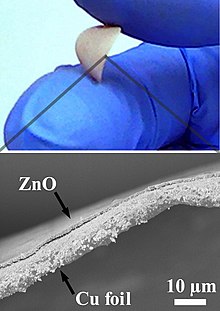

ZnO nanostructures[edit]

Nanostructures of ZnO can be synthesized into a variety of morphologies including nanowires, nanorods, tetrapods, nanobelts, nanoflowers, nanoparticles etc. Nanostructures can be obtained with most above-mentioned techniques, at certain conditions, and also with the vapor–liquid–solid method.[23][39][40] The synthesis is typically carried out at temperatures of about 90 °C, in an equimolar aqueous solution of zinc nitrate and hexamine, the latter providing the basic environment. Certain additives, such as polyethylene glycol or polyethylenimine, can improve the aspect ratio of the ZnO nanowires.[41] Doping of the ZnO nanowires has been achieved by adding other metal nitrates to the growth solution.[42] The morphology of the resulting nanostructures can be tuned by changing the parameters relating to the precursor composition (such as the zinc concentration and pH) or to the thermal treatment (such as the temperature and heating rate).[43]

Aligned ZnO nanowires on pre-seeded silicon, glass, and gallium nitride substrates have been grown using aqueous zinc salts such as zinc nitrate and zinc acetate in basic environments.[44] Pre-seeding substrates with ZnO creates sites for homogeneous nucleation of ZnO crystal during the synthesis. Common pre-seeding methods include in-situ thermal decomposition of zinc acetate crystallites, spincoating of ZnO nanoparticles and the use of physical vapor deposition methods to deposit ZnO thin films.[45][46] Pre-seeding can be performed in conjunction with top down patterning methods such as electron beam lithography and nanosphere lithography to designate nucleation sites prior to growth. Aligned ZnO nanowires can be used in dye-sensitized solar cells and field emission devices.[47][48]

History[edit]

Zinc compounds were probably used by early humans, in processed[11] and unprocessed forms, as a paint or medicinal ointment, but their composition is uncertain. The use of pushpanjan, probably zinc oxide, as a salve for eyes and open wounds, is mentioned in the Indian medical text the Charaka Samhita, thought to date from 500 BC or before.[49] Zinc oxide ointment is also mentioned by the Greek physician Dioscorides (1st century AD).[50] Galen suggested treating ulcerating cancers with zinc oxide,[51] as did Avicenna in his The Canon of Medicine. It is used as an ingredient in products such as baby powder and creams against diaper rashes, calamine cream, anti-dandruff shampoos, and antiseptic ointments.[52]

The Romans produced considerable quantities of brass (an alloy of zinc and copper) as early as 200 BC by a cementation process where copper was reacted with zinc oxide.[53] The zinc oxide is thought to have been produced by heating zinc ore in a shaft furnace. This liberated metallic zinc as a vapor, which then ascended the flue and condensed as the oxide. This process was described by Dioscorides in the 1st century AD.[54] Zinc oxide has also been recovered from zinc mines at Zawar in India, dating from the second half of the first millennium BC.[50]

From the 12th to the 16th century zinc and zinc oxide were recognized and produced in India using a primitive form of the direct synthesis process. From India, zinc manufacture moved to China in the 17th century. In 1743, the first European zinc smelter was established in Bristol, United Kingdom.[55] Around 1782 Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau proposed replacing lead white with zinc oxide.[56]

The main usage of zinc oxide (zinc white) was in paints and as an additive to ointments. Zinc white was accepted as a pigment in oil paintings by 1834 but it did not mix well with oil. This problem was solved by optimizing the synthesis of ZnO. In 1845, LeClaire in Paris was producing the oil paint on a large scale, and by 1850, zinc white was being manufactured throughout Europe. The success of zinc white paint was due to its advantages over the traditional white lead: zinc white is essentially permanent in sunlight, it is not blackened by sulfur-bearing air, it is non-toxic and more economical. Because zinc white is so «clean» it is valuable for making tints with other colors, but it makes a rather brittle dry film when unmixed with other colors. For example, during the late 1890s and early 1900s, some artists used zinc white as a ground for their oil paintings. All those paintings developed cracks over the years.[57]

In recent times, most zinc oxide was used in the rubber industry to resist corrosion. In the 1970s, the second largest application of ZnO was photocopying. High-quality ZnO produced by the «French process» was added to photocopying paper as a filler. This application was soon displaced by titanium.[25]

Applications[edit]

The applications of zinc oxide powder are numerous, and the principal ones are summarized below. Most applications exploit the reactivity of the oxide as a precursor to other zinc compounds. For material science applications, zinc oxide has high refractive index, high thermal conductivity, binding, antibacterial and UV-protection properties. Consequently, it is added into materials and products including plastics, ceramics, glass, cement,[58] rubber, lubricants,[10] paints, ointments, adhesive, sealants, concrete manufacturing, pigments, foods, batteries, ferrites, fire retardants, etc.[59]

Rubber manufacture[edit]

Between 50% and 60% of ZnO use is in the rubber industry.[60] Zinc oxide along with stearic acid is used in the vulcanization of rubber[25][61] ZnO additives also protect rubber from fungi (see medical applications) and UV light.

Ceramic industry[edit]