Время чтения: 4 мин.

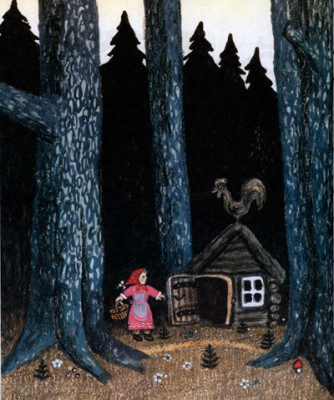

Одна девочка ушла из дома в лес. В лесу она заблудилась и стала искать дорогу домой, да не нашла, а пришла в лесу к домику.

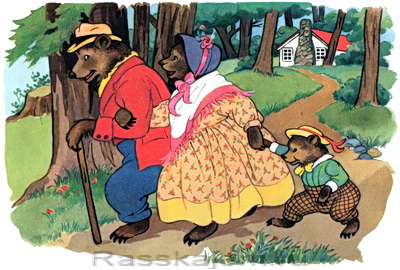

Дверь была отворена; она посмотрела в дверь, видит: в домике никого нет, и вошла. В домике этом жили три медведя. Один медведь был отец, звали его Михайло Иванович. Он был большой и лохматый. Другой была медведица. Она была поменьше, и звали ее Настасья Петровна. Третий был маленький медвежонок, и звали его Мишутка. Медведей не было дома, они ушли гулять по лесу.

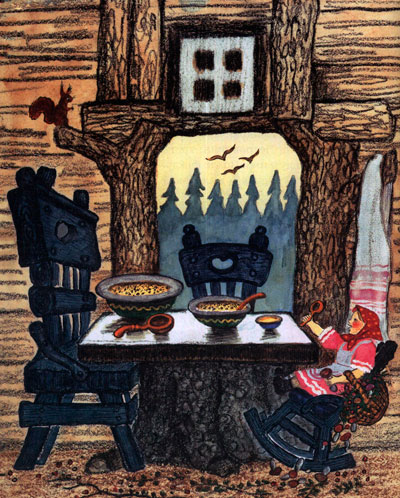

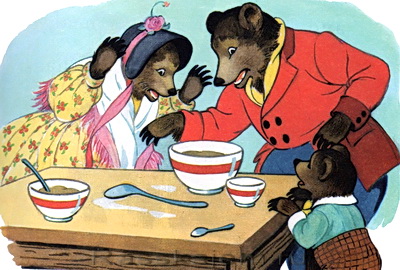

В домике было две комнаты: одна столовая, другая спальня. Девочка вошла в столовую и увидела на столе три чашки с похлебкой. Первая чашка, очень большая, была Михайлы Иваныча. Вторая чашка, поменьше, была Настасьи Петровнина; третья, синенькая чашечка, была Мишуткина. Подле каждой чашки лежала ложка: большая, средняя и маленькая.

Девочка взяла самую большую ложку и похлебала из самой большой чашки; потом взяла среднюю ложку и похлебала из средней чашки; потом взяла маленькую ложечку и похлебала из синенькой чашечки; и Мишуткина похлебка ей показалась лучше всех.

Девочка захотела сесть и видит у стола три стула: один большой — Михайлы Иваныча; другой поменьше — Настасьи Петровнин, а третий, маленький, с синенькой подушечкой — Мишуткин. Она полезла на большой стул и упала; потом села на средний стул, на нем было неловко; потом села на маленький стульчик и засмеялась — так было хорошо.

Она взяла синенькую чашечку на колени и стала есть. Поела всю похлебку и стала качаться на стуле.

Стульчик проломился, и она упала на пол.

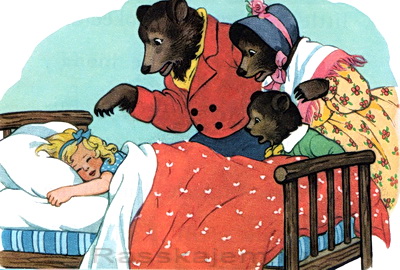

Она встала, подняла стульчик и пошла в другую горницу. Там стояли три кровати: одна большая — Михайлы Иваныча; другая средняя — Настасьи Петровнина; третья маленькая — Мишенькина.

Девочка легла в большую, ей было слишком просторно; легла в среднюю — было слишком высоко; легла в маленькую — кроватка пришлась ей как раз впору, и она заснула.

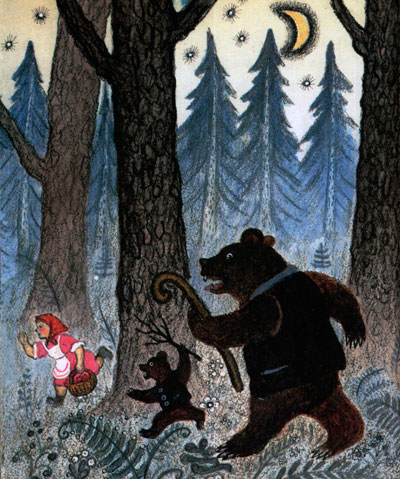

А медведи пришли домой голодные и захотели обедать.

Большой медведь взял чашку, взглянул и заревел страшным голосом:

— КТО ХЛЕБАЛ В МОЕЙ ЧАШКЕ?

Настасья Петровна посмотрела на свою чашку и зарычала не так громко:

— КТО ХЛЕБАЛ В МОЕЙ ЧАШКЕ?

А Мишутка увидал свою пустую чашечку и запищал тонким голосом:

— КТО ХЛЕБАЛ В МОЕЙ ЧАШКЕ И ВСЕ ВЫХЛЕБАЛ?

Михаиле Иваныч взглянул на свой стул и зарычал страшным голосом:

— КТО СИДЕЛ НА МОЕМ СТУЛЕ И СДВИНУЛ ЕГО С МЕСТА?

Настасья Петровна взглянула на свой стул и зарычала не так громко:

— КТО СИДЕЛ НА МОЕМ СТУЛЕ И СДВИНУЛ ЕГО С МЕСТА?

Мишутка взглянул на свой сломанный стульчик и пропищал:

— КТО СИДЕЛ НА МОЕМ СТУЛЕ И СЛОМАЛ ЕГО?

Медведи пришли в другую горницу.

— КТО ЛОЖИЛСЯ В МОЮ ПОСТЕЛЬ И СМЯЛ ЕЕ? — заревел Михаиле Иваныч страшным голосом.

— КТО ЛОЖИЛСЯ В МОЮ ПОСТЕЛЬ И СМЯЛ ЕЕ? — зарычала Настасья Петровна не так громко.

А Мишенька подставил скамеечку, полез в свою кроватку и запищал тонким голосом:

— КТО ЛОЖИЛСЯ В МОЮ ПОСТЕЛЬ?

И вдруг он увидал девочку и завизжал так, как будто его режут:

— Вот она! Держи, держи! Вот она! Ай-я-яй! Держи!

Он хотел ее укусить.

Девочка открыла глаза, увидела медведей и бросилась к окну. Оно было открыто, она выскочила в окно и убежала. И медведи не догнали ее.

Все категории

- Фотография и видеосъемка

- Знания

- Другое

- Гороскопы, магия, гадания

- Общество и политика

- Образование

- Путешествия и туризм

- Искусство и культура

- Города и страны

- Строительство и ремонт

- Работа и карьера

- Спорт

- Стиль и красота

- Юридическая консультация

- Компьютеры и интернет

- Товары и услуги

- Темы для взрослых

- Семья и дом

- Животные и растения

- Еда и кулинария

- Здоровье и медицина

- Авто и мото

- Бизнес и финансы

- Философия, непознанное

- Досуг и развлечения

- Знакомства, любовь, отношения

- Наука и техника

6

Как звали трёх медведей из сказки Л.Толстого «Три медведя»?

10 ответов:

3

0

Вопрос довольно легкий и простой, ведь наверняка каждый из нас перечитывал эту сказку несколько раз и нам так же читали ее в детстве. В сказке «Три Медведя»:

- самого старшего и большого медведя папу звали Михаил Иваныч;

- маму-медведицу в сказке звали Настатья Петровна;

- а маленького медвежонка сына — Мишутка.

2

0

Буквально вчера читала эту сказку своей младшей внучке. Книга советских времён хранилась ещё с моего детства и я помню, кого как звали:

Отца-медведя звали Михайло Иванович

Мать-медвеицу — Настасья Петровна

Сынишку — Мишутка

И, хотя Л.Н.Толстой в роли сказочника мне не очень нравится, «Три медведя» — сказка, которая лучше современных пересказов.

2

0

Скриншот только одного медведя с его именем подтверждает — младшего, которого Мишуткой звали, остальных пришлось искать в самой сказке, т.е. перечитывать-). Итак, отец семейства — самый главный и грозный медведь — это Михайло Иваныч (не путать с человеческим написанием Михаил Иванович-). Мама Мишутки — Настасья Петровна (опять же не Анастасия, а такое сказочное сокращение имени). А вот когда девочка Машей стала — непонятно. Что-то у Льва Николаевича не нашла ее имени, девочка и девочка, без опознавательных имен, потому считаю имя Маша уже мультипликационной версией книжного оригинала-)

Мне этот вопрос под другим ракурсом попался в одной игре, где надо было угадать как звали самого молодого медвежонка, чья ложка, кровать и стул подошли девочке. Ответом же, как понятно, стал Мишутка, с которого и вся эта моя ответная эпопея по героям сказки началась.

2

0

Добрая, красивая, старая сказка, которую часто читал мне Отец перед сном.

Главные герои сказки:

1 Папа Медведь (Михаил или Михайло «Потапович» или «Иваныч»).

2 Мама Медведь (Настасья Петровна).

3 Сын Папы Медведя и Мамы Медведя (Мишутка).

Сказку написал Лев Толстой.

1

0

В сказке «Три медведя» присутствует по сути целая семья медведей. Есть мама и папа, а также их сынишка. Так вот отца зовут Михаило Иванович, медведица — Настасья, по отчеству тоже Ивановна, ну а сын просто Мишутка.

1

0

Очень часто читаю сынули эту сказку. Она она из самых любимых. Поэтому запомнила их имена наизусть.

Папу-медведя зовут Михаил Иваныч,

маму-медведицу зовут Настасья Петровна,

а сына-медведя — просто Мишутка.

1

0

В сказке Льва Толстого «Три медведя» все медведи имеют имена, причем человеческие, вот только имя девочки не названо, но в народе окрестили ее Машей.

Большого медведя-папу автор назвал Михаило Иванович.

Второго медведя поменьше, или медведицу — Настасья Петровна.

И самый маленький медведь, сын-медвежонок по имени Мишутка.

1

0

Как звали трёх медведей из сказки Л. Толстого «Три медведя»? В этой сказке «Три медведя» медведей звали Михайло Иванович, Настасья Петровна, Мишутка. Где в этой семье медведей Михайло Иванович был отцом, Настасья Петровна была матерью, а Мишутка был сыном.

1

0

Сказка, которую читали многим советским детям их родители. Книжка была большого формата с яркими цветными картинками, маленький медвежонок носит имя Мишутка , ласковое имя подчеркивает его озорной характер. Родителей медвежонка зовут Михаило Иванович и Настасья Петровна. Медведи были добрыми, но очень разозлились, когда увидели, что в их доме кто-то по хозяйничал. Девочка сама сильно испугалась и убежала, ей повезло, что медведи ее не догнали

0

0

В России данная сказка является очень популярной, особенно в версии Льва Толстого. Отца зовут Михаил Иванович, жену медведя Настасья Петровна, а маленький умный медвежонок их сыночек, его зовут Мишутка.

Читайте также

В свой читательский дневник можно так коротко написать о сказке про «пятерых из 1-го стручка»:

- Жил на свете один стручок, в котором сидело пять сестриц горошин. Стручок рос, а вместе с ним и горошинки. Однако, скоро горошины стали подумывать, что их мир — это не только стручок, что должно что-то быть и за его пределами. Впрочем попыток предпринять что-либо горошины не предприняли, а дождались того момента, когда стручок сорвали…

- Оказался стручок в руках одного мальчишки, который быстро открыв его и увидав горошины сразу нашел им применение. У мальчика была бузинная трубочка, через которую он и отправил каждую горошинку в свое «путешествие».

- Четыре сестрицы перед вылетом из трубочки почти все сказали, что дальше остальных пойдут. И только самая маленькая, пятам подумала: «будь, что будет,» — положившись на судьбу…

- Последняя-то горошинка и оказалась самой «далеко» сошедшей сестрой, потому что попав в дом на крышу бедной женщины, она не погибла, а стала расти. Мох ее водичкой напоил и накормил.

- У женщины была больная дочка. Мать думала, что дитя умрет. Однако, девочка, увидав растущую горошину, стала наблюдать за ней, и по мере того, как рос горошек, выздоравливала и сама, как бы подпитывающаяся энергией растения.

<hr />

Вывод: одна жизнь породила/подарили/пр<wbr />одлила другую жизнь!

В сказке Андерсена про горошинки, стручок и девочку, на мой взгляд, всего два главных персонажа:

- Пятая, последняя, горошина, которая, вылетев из бузинной трубочки, угодила в дом бедной женщины.

- Больная девочка, сумевшая поправиться, благодаря горошинке, которая не завяла и не затерялась на крыше, а пустила ростки и превратилась в прекрасное растение.

<hr />

Вообще, очень много идет в сказке описанием самого процесса произрастания горошка, что не плохо, т.к. по отдельной теме даже пришлось делать другое задание. Впрочем и «взаимоотношениям» девочки с горошиной Андерсен уделили достаточно внимания.

<hr />

Герои 2-го плана

- Четыре горошинки, которые канули в небытие, одна так точно лопнула в канаве, разбухнув от воды…

- Мама девочки: добрая, ласковая, трудолюбивая женщина, безмерно любящая свое дитя.

- Мальчик с бузинной трубочкой, отправивший горошины по их жизненным дорожкам. Хотя, вы знаете, наверное мальчишку можно посчитать также главным персонажем, ведь не сорви он стручок и не стрельни горошинами, они могли бы все просто завянуть вместе со стручком, а девочка умереть, не встретившись со своим горошком.

В связи с тем, что научно-познавательны<wbr />й рассказ — это не просто пересказ сказки или короткое ее изложение, а уже научные факты или сведения о природе, то мой рассказ будет сконцентрирован на конкретном предмете — на горохе, который стал одним из главных персонажей этой истории.

<hr />

В сказке Андерсена про горошинку и девочку, кроме нравственных и моральных выводов, можно узнать (если внимательно читать книгу) много о том, как растет горошек.

Что нового для себя я узнал о горохе?

1-я часть сказки.

- Плод этого растения представляет из себя стручок, внутри которого находятся горошинки, растущие рядком. Т.е. стручок продолговатой формы. Если горошинок содержится около пяти штук, то получается, что размер стручка составляет примерно 6-8 см.

- Горошинки не высыпаются из стручка, пока он зеленый. Только созрев до желтого состояния, стручок лопается и выпускает горошины из своего хранилища.

- Горошина — это семена для высадки и получения нового растения.

<hr />

2-я часть сказки.

- Для прорастания гороху необходима вода и «еда». В сказке написано, что мох может заменить два эти компонента собой. Достаточно положить горошинку во влажный мох и поставить на солнце, чтобы горошинка пустила корни и дала ростки.

- Стебелек гороха напоминает вьющуюся нитку, и чтобы растение хорошо развивалось, ему ставят подпорку к основанию, а сам стебель пускают по натянутой веревке от земли до, например, крыши.

- Перед тем, как обзавестись стручком, горох цветет.

<hr />

Чтобы полностью осмыслить процесс роста горошка, следует начинать читать доклад/рассказ со второй его части.

<hr />

П.С. Кроме гороха в сказке есть интересный факт о другом растении — бузине. Если мальчик сделал из нее трубочку, значит, ствол бузины полый (пустой). Можно через него не только плевать горохом, но и на звезды ночные смотреть.

«Хвост Феи» — это название гильдии в которой состоят герои вокруг которых и движется сюжет. Само аниме о кампании друзей состоящих в этой гильдии и выполняющих разные задания или попадающие в разные передряги.

Мне думается, что основная/главная мысль этой сказки Андерсена заключена в финальных строках:

Ведь пока чайник не прошел весь свой жизненный путь, ему не было открыто то счастье, которое получает человек (чайник — это олицетворение человеческой натуры, по обыкновению Андерсенского стиля) от дарения себя другим… И как бы это не воспринималось высокопарно или насыщенно, но многие порой задумываются о том, зачем и для чего они (мы или я) пришли в этот мир. А чайник, будучи в молодости и зрелости — напыщенным гордецом, сумел, пройдя через испытания, поймать тот самый миг перехода в иное душевное состояние, которое показало ему новый мир (по большому счету!).

Как говорят, что лучше любить и не быть любимым, чем вовсе не испытать любви. Потому что счастье — это не только настоящее, это по большей части прошлое, наши воспоминания, благодаря которым многие продолжают жить…

Три медведя

Русская народная сказка

В одной деревне жила-была маленькая девочка. И звали её Машенька.

Машенька была девочкой хорошей, да вот беда – не очень-то послушной. Однажды родители Машеньки поехали на базар в город, а ей велели никуда из дома не отлучаться, хлопотать по хозяйству. А Машенька не послушала их, и убежала в лес. Гуляла она, гуляла по лесу, бегала по полянкам, рвала цветочки. Собирала ягоды да грибы, и не заметила, как заблудилась в лесу. Она, конечно, очень расстроилась, но не расплакалась. Потому как слезами горю не поможешь. И стала Машенька искать дорогу домой. Ходила она по лесу, ходила, и набрела на какую-то избушку.

Если бы Машенька знала, кто в этой избушке живёт — нипочём бы к ней не подошла, а побежала бы скорее в другую сторону. Да вот только не ведомо ей было, что набрела она на домик, в котором проживали три медведя. Медведя папу звали Михаил Потапович. Был он огромным и лохматым. Медведицу маму звали Настасья Петровна, она была размером поменьше и не такая косматая. А маленький медвежонок, которого звали Мишуткой, и вовсе был смешным и безобидным.

Мама Настасья Петровна сварила вкусную манную кашу. Медведям захотелось поесть её с малинкой. Они и пошли все в лес, собирать к обеду ягоды. И дома в это время никого не было.

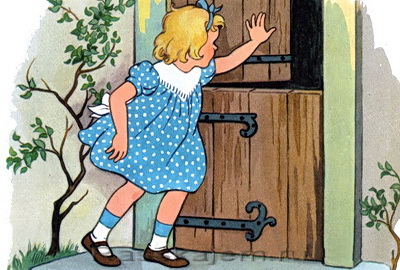

Подошла Машенька к избушке, постучала в дверь. А ей никто не отвечает и двери не открывает. Дома-то никого не было, медведи все в лес ушли. Тогда Машенька зашла в дом сама и стала осматриваться. В избушке было две комнаты. В первой комнате стоял огромный стол. У стола стояли стулья. На столе расстелена белоснежная скатерть, а на ней тарелки расставлены. Когда Машенька увидела на столе тарелки, ей очень захотелось кушать, ведь она долго плутала по лесу и очень давно не ела. Она, конечно, знала, что без спроса нельзя брать ничего чужого. Но каша в тарелках так вкусно пахла… И Машенька не смогла удержаться.

Машенька уселась на самый большой стул, взяла самую большую ложку, и попробовала кашу из самой большой тарелки. Каша Машеньке очень понравилась, только уж очень неудобной оказалась ложка. Тогда Машенька перебралась на средний стул. И стала есть кашу из средней тарелки, средней ложкой. Каша и тут была очень вкусная. Только сидеть на среднем стуле Машеньке было очень неудобно. И тогда она пересела на самый маленький стульчик, взяла самую маленькую ложку и съела всю кашу из маленькой голубой тарелочки. И так ей эта каша понравилась, что когда она всё доела, то стала остатки каши из тарелки вылизывать языком. Хоть и знала, что так делать нельзя. А маленькая, голубенькая тарелочка у Машеньки из рук выскользнула, на пол упала, и разбилась!

Машенька наклонилась под стол, чтобы посмотреть, что с тарелочкой, а в это время у стульчика ножки подломились, и она вслед за тарелочкой оказалась на полу.

Поднялась Машенька с пола и пошла посмотреть, что в другой комнате находится. А во второй комнате у трёх медведей была спальня. Увидела Машенька, что в комнате стоят три кровати. Большая, поменьше и совсем маленькая.

Решила она поваляться сначала на большой кровати. Подушки на большой кровати показались ей неудобными. Тогда Машенька перебралась на среднюю кровать. Но там одеяло оказалось для неё слишком большим. Наконец, Машенька улеглась на маленькую кроватку. Там её всё устраивало. И она крепко заснула.

А в это время медведи возвратились домой. Они насобирали малины, нагуляли аппетит. Вошли в дом, помыли лапы и стали садиться за стол — обедать. Смотрят: а у них, похоже, кто-то был в гостях!

Михаил Потапович взглянул на свой стул, да как заревёт:

— Кто сидел на моём стуле и сдвинул его с места?

Настасья Петровна посмотрела на свой стул, и вслед за мужем заголосила:

— А кто сидел на моём стуле и сдвинул его с места?

А маленький Мишутка увидел свой сломанный стульчик, и заплакал тоненьким голоском:

— А кто сидел на моём стульчике и сломал его???

Михаил Потапович взглянул на свою тарелку, да как заревёт:

— Кто ел кашу из моей тарелки?

Настасья Петровна посмотрела в свою чашку, и тоже давай голосить:

— А кто ел кашу из моей тарелки?

А маленький Мишутка увидел на полу разбитую свою любимую голубенькую тарелочку и ещё сильнее заплакал:

— А кто съел всю мою кашу и разбил мою любимую тарелочку?

Пошли три медведя в спальню.

Михаил Потапович посмотрел на свою кровать, да как заревёт:

— Кто лежал на моей кровати и помял её?

И Настасья Петровна за ним следом:

— А кто лежал на моей кровати и помял её?

И только маленький Мишутка ничего не сказал. Потому что увидел на своей кроватке Машеньку. Машенька в это время проснулась, увидела трёх медведей и очень сильно испугалась. Тогда Мишутка ей и говорит:

— Ты, девочка, нас не бойся, мы медведи добрые, людей не обижаем. Машенька успокоилась, перестала бояться медведей. Ей стало стыдно, и она попросила у медведей прощения за съеденную кашу, разбитую тарелочку, сломанный стульчик и помятые кровати. Попросила прощения и сама стала свои ошибки исправлять. Осколки тарелочки с пола подмела, кровати заправила. А потом Михаилу Потаповичу помогла отремонтировать Мишуткин стульчик.

После этого три медведя угостили Машеньку малиной и помогли ей найти дорогу к дому. Машенька поблагодарила их, попрощалась, и побежала скорее домой, к маме с папой, чтобы те не волновались. А на следующий день Машенька подарила Мишутке новую тарелочку. Красивую. Мишутке эта тарелочка очень понравилась.

— КОНЕЦ —

Категория: Uncategorized

Метки: базар, девочка, изба, медведица, медведь, народные сказки, народные сказки для детей, русские народные сказки, русские сказки, сказки, сказки для детей

Вы можете следить за комментариями с помощью RSS 2.0-ленты.

Вы можете оставить комментарий, или Трекбэк с вашего сайта.

Впервые сказка про трёх медведей была опубликована в 1837 году в сборнике «The Doctor» в литературной обработке английского писателя и поэта Роберта Саути под названием «The Story of the Three Bears».

Медведи — большой, средний и маленький — были в этой истории не семейством, а просто тремя друзьями, жившими вместе. Но самое интересное, что незваной гостьей, вторгшейся в их дом, была вовсе не маленькая девочка, а отвратительная грязная старуха.

Идея использовать шрифт разного размера для передачи разной высоты и силы голоса медведей принадлежит Саути. Вот копия первого издания «The Doctor» из библиотеки Четэма с пометками и исправлениями самого Саути и его зятя Джона Вуда Уортера:

Все симпатии Саути совершенно очевидно на стороне медведей. Он придумывает им забавные имена и описывает их как добродушных, добропорядочных и аккуратных хозяев, чья спокойная жизнь грубо нарушается вторжением наглой бродяжки. Саути не скупится на подробности, призванные вызвать у читателя неприязнь к нарушительнице: грязная и уродливая старушка не только незаконно проникает в дом к безобидным доверчивым медведям и учиняет там беспорядок, но и гадко ругается. В конце сказки ей предоставлена весьма суровая альтернатива: если она не сломала себе шею, выпрыгнув из окна, и не сгинула в лесу, то её, несомненно, схватил констебль и отправил в Исправительный дом.

Впрочем, это не самая жестокая версия. В Публичной библиотеке Торонто хранится рукописный альбом Элинор Мюр с акварельными иллюстрациями, сделанный в подарок её племяннику Хорасу Броуку на четырёхлетие. Рукопись датирована 1831 годом и содержит стихотворное изложение «Истории о трёх медведях» в оригинальной интерпретации. Считается, что сказку Элинор узнала от Саути, но творчески её переработала. Три медведя, устав от дикой лесной жизни в неблагоустроенной берлоге, перебираются в город и покупают дом. Дальше следует знакомая история.

Медведи в этой, напомним, женской версии, отличаются жуткой кровожадностью. Схватив преступную старушку, они решают предать её лютой смерти. Сначала медведи предпринимают безуспешные попытки сжечь и утопить несчастную, но она оказывается необыкновенно устойчивой — в огне не горит и в воде не тонет. Тогда они на глазах изумлённой публики подбрасывают старушку вверх, и она насаживается на шпиль колокольни собора Святого Павла:

On the fire they throw her, but burn her they couldn’t,

In the water they put her, but drown there she wouldn’t.

They seize her before all the wondering people

And chuck her aloft on St Paul’s church-yard steeple.

х

х

Сначала старушку бросают в камин:

х

На этой акварели, как можно предположить, изображена попытка утопления:

х

Боюсь даже представить, как выглядит заключительная из 13 иллюстраций. Уж не знаю, какими разрушительными наклонностями отличался малыш Хорас, что заботливой тётушке представилось необходимым устрашать его подобными ужасами. Современные психологи, несомненно, предали бы её анафеме.

Версия Саути как будто разрешает загадку появления незваной гостьи у лесного дома медведей: скитания бездомной старушки выглядят более естественными, чем одинокие прогулки маленькой девочки. Однако она высвечивает новую проблему: почему в этой сказке ярко выраженный отрицательный персонаж воплощён в человеческом образе, в то время как положительные герои, в которых угадываются черты скорее мирных сельских жителей, чем диких зверей, предстают в облике медведей?

Как бы то ни было, ясно, что никаких «инициаций» и прочих мифических подтекстов в этой истории обнаружить не удаётся. Пафос сказки Саути полностью направлен на защиту частной собственности добропорядочных обывателей от посягательств маргинальных элементов.

Но этот эффект был практически уничтожен всего через 12 лет, когда английский писатель Джозеф Кандэлл включил «Историю о трёх медведях» в сборник «Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children», произведя при этом некоторые изменения:

««Сказка про трёх медведей» — очень старая сказка, но никем она не была столь хорошо рассказана, как великим поэтом Саути, чьей версией (с его разрешения) я делюсь с вами. Только у меня в дом вторгается маленькая девочка, а не старуха. Я сделал так, потому что нахожу версию с Сереброволосой более известной, — и потому что уже есть столько других историй про старух». (х)

Все отрицательные характеристики нарушительницы вычищены из текста — оставлено только поучительное замечание «Если бы она была хорошей маленькой девочкой, она бы дождалась, пока медведи вернутся домой». И, разумеется, она не ругается, как скверная старуха.

Художник Harrison Weir, иллюстрации раскрашены вручную:

«На подушке лежала хорошенькая головка Сребровласки — и она была не на своём месте, потому что ей нечего было там делать».

Конец сказки приобретает известную нам лаконичность: «Наша маленькая Сребровласка выпрыгнула из окна и убежала в лес, и медведи никогда больше не видели её». Именно так заканчивается сказка и у Толстого.

Ещё одна озадачивающая подробность. У Толстого и Спирина сказано: «девочка пошла в другую комнату…» (спальню). Но в английском оригинале везде ясно указано, что старушка или девочка «поднялась наверх, в спальню». Медведи были зажиточными, дом у них был двухэтажным, и спальня, как водится, располагалась на втором этаже. Получается, что и старушка, и Сребровласка обладали поражающей воображение паркурной подготовкой, и им ничего не стоило вот так запросто сигануть в окно с полноценного второго этажа! В мультфильмах, кстати, этот момент часто убирают, и девочка просто сбегает вниз по лестнице, пока ошарашенные медведи стоят разинув варежку.

Считается, что в серебристом цвете волос девочки ещё сохранялся намёк на седые волосы старушки, но со временем она превратилась в Златовласку (Golden Hair в издании 1868; с 1904 за ней закрепилось имя Goldilocks — Золотистые локоны).

По ходу дела любопытным образом менялась и ситуация с медведями.

Как утверждается в Википедии, на иллюстрации к сказке «Три медведя» в книге «Истории тётушки Фанни», изданной в 1852 году, медведи впервые были изображены как семейство (папа, мама и сын), хотя в тексте на это нет никаких намёков — более того, медведи там вообще живут отдельно, каждый в своём доме соответствующего размера. Но в оцифрованной версии иллюстрации к этой сказке нет (возможно, вклеенный лист с иллюстрацией в экземпляре, с которого делали оцифровку, был утрачен). Зато там есть забавное примечание под звёздочкой: сказку рекомендуется читать вслух с соответствующими изменениями голоса, когда рассказчик читает от имени медведей.

Здесь к медведям снова вторгается не девочка, а грязная оборванка-старушка. Войдя сначала в самый большой дом, она ограничивается тем, что пробует кашу, потом переходит в стоящий рядом средний дом, и наконец, в маленький. Там она и творит дальнейшие безобразия. Таким образом, стулья и постели большого и среднего медведей остаются в неприкосновенности, а всё разорение выпадает на долю маленького медведя. Он приходит в ярость и зовёт своих соседей; втроём они поднимаются в спальню и обнаруживают там старушку с испачканным кашей ртом, которая «храпела как трубач». Проснувшись и увидев трёх медведей, старушка «обезумела от страха» и выскочила в открытое окно возле кровати.

В этом варианте медведи изображены уже не столь благостно, как у Саути: они кубарем скатываются по лестнице сломя голову и пытаются догнать старушку, намереваясь съесть её, но это им не удаётся из-за того, что они были слишком толстыми и не могли бегать так же быстро, как бодрая старая оборванка, которая лишь слегка запыхалась, но осталась целой и невредимой )

Известна версия, в которой два больших медведя являются братом и сестрой и дружат с маленьким медведем. Но в конце концов, в 1860, они превращаются в традиционную семью: папа-медведь, мама-медведица и маленький медвежонок-сын. В таком виде сказку и заимствует Лев Толстой.

Что же послужило источником для истории, рассказанной Робертом Саути?

В 1894 году вышел сборник «More English Fairy Tales» с иллюстрациями Джона Д. Баттена. Автор сборника, фольклорист Джозеф Джейкобс, считал, что одна из включённых в него сказок, которую ему сообщил Баттен, является оригинальной устной версией «Истории о трёх медведях».

х

В этой шотландской сказке в дом к медведям вторгается не девочка и не старушка, а внезапно лис по имени Scrapefoot (Лапка-Царапка). Делает он это из чистого любопытства.

Медведи тут предстают не добродушными увальнями, а грозными хозяевами леса, даже живут они не просто в доме, а в замке. Лис очень их боится, но любопытство всё же пересиливает, и убедившись, что медведей нет дома, он осторожно забирается внутрь. А дальше всё идёт по известной схеме.

Когда медведи обнаруживают наглеца, они задаются вопросом, как же с ним поступить. Большой медведь предлагает его повесить, средний — утопить, а маленький — попросту выбросить из окна, что они и делают, видимо, решив, что это наименее энергозатратный способ.

Как видно уже из названия, в этой версии главным героем является лис. Медведи здесь обезличены и практически лишены характеристик (за исключением размера), об их действиях говорится предельно скупо: жили, пришли домой, вошли в зал, сказали, стали думать, что с ним делать. Зато всё, что касается лиса, описывается так ярко и забавно, что этому легкомысленному проказнику невозможно не симпатизировать. Перед взором читателя встают уморительные картины: как он озирается, чтобы убедиться, нет ли кого поблизости; как подкрадывается к дверям и, обнаружив, к своей радости, что они не заперты, опасливо просовывает туда сначала нос, а потом лапы — по одной; как вертится на неудобных сиденьях и кроватях; как пытается собрать развалившийся стульчик; как забывает об осторожности, разомлев в тепле и уюте. В финале бедолага в ужасе потряхивает лапами, чтобы убедиться, что они не переломаны, и улепётывает домой со всех ног. Приключение закончилось для него относительно благополучно, но он так перепуган, что больше и не думает приближаться к медвежьему дому.

Остаётся последняя загадка: каким же образом лис превратился в неопрятную маленькую старушку?

Установлено, что Роберт Саути мог в детстве услышать историю о лисе и медведях от своего дяди Уильяма Тайлера, который был превосходным рассказчиком и умел непревзойдённо изображать голоса животных (возможно, Саути вспоминал его живую манеру, когда пытался шрифтом передать различие голосов медведей). Если Тайлер рассказывал сказку, в которой фигурировал не лис, а лисица — vixen, то маленький Роберт мог понять это слово в его переносном значении — сварливая баба. Разрешается и загадка старушки-паркурщицы: сделав медведей однозначно положительными персонажами, Саути уже не мог заставить их выбрасывать из окна старую женщину, несмотря на все её прегрешения, и ей, а вслед за ней и сменившей её девочке, пришлось прыгать со второго этажа самостоятельно.

Таким образом, всё становится на свои места. Изначально это сказка о проныре и плуте лисе, попадающем в переделки, но удачно из них выпутывающемся, вполне в русле фольклорной традиции. Саути изрядно переработал её, сместив акценты и превратив в назидательную историю с явным выделением положительных и отрицательных персонажей. Замена неприятной старухи маленькой девочкой вернула сказке интригующую амбивалентность: несмотря на сочувствие пострадавшему медвежьему семейству, особенно маленькому медвежонку, читатели не могут не сопереживать и невоспитанной девочке — ведь она всего лишь ребёнок, угодивший в беду по неопытности.

Наконец, в этой сказке есть ещё один интересный момент, на который давно обратили внимание западные исследователи. Когда девочка пробует кашу, в первой миске она оказывается слишком горячей, во второй — слишком холодной, и только в третьей, маленькой — не горячей и не холодной, а «в самый раз» — «just right». Хотя, казалось бы, одновременно разлитая в миски каша должна остывать с примерно одинаковой скоростью. Но дело в принципе, который работает и с другими объектами: один стул оказывается слишком жёстким, второй — слишком мягким, и только третий, маленький — в самый раз. То же самое происходит с кроватями.

Этот эффект наибольшей комфортности среднего по показателям объекта так и называют — принцип Златовласки. Он применяется в разных областях многих наук: экономики, медицины, астробиологии, психологии, теории коммуникаций. Например, для того, чтобы на планете были благоприятные условия для возникновения жизни, она не должна находиться ни слишком близко, ни слишком далеко от звезды, а на том расстоянии, которое будет just right. Этот принцип используется в обучении: для того, чтобы у детей, да и у взрослых тоже, поддерживался наибольший уровень заинтересованности, нужно вводить новое знание умеренными порциями. Никому не интересно пережёвывать уже усвоенное, но и полностью незнакомый материал может отпугнуть, показаться слишком сложным и непонятным, поэтому новое даётся элементами, с опорой на хорошо известное. Сказка про Златовласку помогает английским малышам усвоить понятие just right.

Любопытно, что впервые «принцип Златовласки» зафиксирован в версии Саути: в сказке про лиса его нет, как и в варианте Толстого. Так что нашим детям приходится получать представление о золотой середине из других источников.

Русский текст «The Story of the Three Bears» и «Scrapefoot»

Коллекция иллюстраций к разным вариантам сказки

Собрание современных интерпретаций

Анализ сказки «Три медведя» для читательского дневника

04.08.2021

В этой статье мы разберем детскую сказку «Три медведя» для читательского дневника. В анализ вошли: сюжет (краткое содержание сказки, буквально несколько предложений), главная мысль (мораль), список главных героев и отзыв (личные впечатления от сказки).

Автор – часто эту сказку ошибочно считают русской народной. Но это не так. Сказку придумал английский народ, а на русский язык перевел известный писатель Лев Толстой.

Краткое содержание (о чем сказка)

Маленькая девочка заблудилась в лесу и нашла медвежий домик. В домике она увидела накрытый стол с 3-мя мисками и поела похлебку из каждой (Мишуткину еду съела всю). Потом стала качаться на стульях и сломала самый маленький стульчик (опять же Мишуткин). Затем в спальне уснула на самой маленькой кроватке. Когда пришли медведи, они очень рассердились, увидев съеденную еду и сломанный стульчик. Найдя спящую девочку, они своими голосами разбудили ее. Девочка испугалась, выскочила в окно и убежала.

Главные герои

Маленькая девочка (в некоторых версиях ее называют Машей) – потерялась в лесу и похозяйничала в медвежьей избушке

Михайло Иванович – папа-медведь

Настасья Петровна – мама-медведь

Мишутка – маленький медвежонок, сын Михаила Ивановича и Настасьи Петровны

Мораль (главная мысль, чему учит сказка)

Сказка показывает, как не нужно вести себя в гостях. Нельзя брать без спроса чужую еду, нельзя ломать мебель и вести себя по-хозяйски в чужом доме. А если набедокурил, то нужно извиниться, а не убегать. Так что, медведи рассердились вполне справедливо 🙂 На более глубоком уровне это произведение учит уважать других.

Отзыв (личные впечатления)

Мне было жалко медведей, в доме которых похозяйничала наглая девочка. Им теперь придется убираться в доме, чинить стульчик, мыть посуду и готовить новую еду. А ведь возможно, что они устали после прогулки по лесу. А девочка вызывает неприязнь своей наглостью, невоспитанностью и неблагодарностью. И еще сказка показалась мне слишком короткой – непонятно, что стало с непослушной девочкой, нашла ли она свой дом.

Читайте другие отзывы и впечатления от произведения в комментариях к статье.

Анализ других сказок для читательского дневника:

Пушкин «Сказка о золотом петушке»

Андерсен «Гадкий утенок»

Морозко

| «Goldilocks and the Three Bears» | |

|---|---|

| by Robert Southey | |

Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1918, in English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel |

|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Genre(s) | Fairy tale |

| Published in | The Doctor |

| Publication type | Essay and story collection |

| Publisher | Longman, Rees, etc. |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 1837 |

«Goldilocks and the Three Bears» (originally titled «The Story of the Three Bears«) is a 19th-century English fairy tale of which three versions exist. The original version of the tale tells of an obscene old woman who enters the forest home of three anthropomorphic bachelor bears while they are away. She eats some of their porridge, sits down on one of their chairs and breaks it, and sleeps in one of their beds. When the bears return and discover her, she wakes up, jumps out of the window, and is never seen again. The second version replaces the old woman with a young girl named Goldilocks, and the third and by far best-known version replaces the bachelor trio with a family of three.

What was originally a frightening oral tale became a cosy family story with only a hint of menace. The story has elicited various interpretations and has been adapted to film, opera, and other media. «Goldilocks and the Three Bears» is one of the most popular fairy tales in the English language.[1]

Original plot[edit]

Illustration in «The Story of the Three Bears» second edition, 1839, published by W. N. Wright of 60 Pall Mall, London

In Robert Southey’s version of the tale («The Story of the Three Bears»), three anthropomorphic bears – «a little, small, wee bear, a middle-sized bear, and a great, huge bear» – live together in a house in the woods. Southey describes them as very good-natured, trusting, harmless, tidy, and hospitable. Each of these «bachelor» bears has his own porridge bowl, chair, and bed. One day they make porridge for breakfast, but it is too hot to eat, so they decide to take a walk in the woods while their porridge cools. An old woman approaches the bears’ house. She has been sent out by her family because she is a disgrace to them. She is impudent, bad-mannered, foul-mouthed, ugly, dirty, and a vagrant deserving of a stint in the House of Correction. She looks through a window, peeps through the keyhole, and lifts the latch. Assured that no one is home, she walks in. The old woman eats the Wee Bear’s porridge, then settles into his chair and breaks it. Prowling about, she finds the bears’ beds and falls asleep in Wee Bear’s bed. The end of the tale is reached when the bears return. Wee Bear finds his empty bowl, his broken chair, and the old woman sleeping in his bed and cries, «Somebody has been lying in my bed, and here she is!» The old woman wakes, is chased out of the house by the huge bear and is never seen again.

Origins[edit]

The story was first recorded in narrative form by English writer and poet Robert Southey, and first published anonymously as «The Story of the Three Bears» in 1837 in a volume of his writings called The Doctor.[2][3] The same year Southey’s tale was published, the story was versified by editor George Nicol, who acknowledged the anonymous author of The Doctor as «the great, original concocter» of the tale.[4][5] Southey was delighted with Nicol’s effort to bring more exposure to the tale, concerned children might overlook it in The Doctor.[6] Nicol’s version was illustrated with engravings by B. Hart (after «C.J.»), and was reissued in 1848 with Southey identified as the story’s author.[7]

The story of the three bears was in circulation before the publication of Southey’s tale.[8] In 1813, for example, Southey was telling the story to friends, and in 1831 Eleanor Mure fashioned a handmade booklet about the three bears and the old woman for her nephew Horace Broke’s birthday.[4] Southey and Mure differ in details. Southey’s bears have porridge, but Mure’s have milk;[4] Southey’s old woman has no motive for entering the house, but Mure’s old woman is piqued when her courtesy visit is rebuffed;[9] Southey’s old woman runs away when discovered, but Mure’s old woman is impaled on the steeple of St Paul’s Cathedral.[10]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie point out in The Classic Fairy Tales (1999) that the tale has a «partial analogue» in «Snow White»: the lost princess enters the dwarfs’ house, tastes their food, and falls asleep in one of their beds. In a manner similar to the three bears, the dwarfs cry, «Someone’s been sitting in my chair!», «Someone’s been eating off my plate!», and «Someone’s been sleeping in my bed!» The Opies also point to similarities in a Norwegian tale about a princess who takes refuge in a cave inhabited by three Russian princes dressed in bearskins. She eats their food and hides under a bed.[11]

In 1865, Charles Dickens referenced a similar tale in Our Mutual Friend, but in that story the house belongs to hobgoblins rather than bears. Dickens’ reference however suggests a yet-to-be-discovered analogue or source.[12] Hunting rituals and ceremonies have been suggested and dismissed as possible origins.[13][14]

«Scrapefoot» illustration by John D. Batten in More English Fairy Tales (1895)

In 1894, «Scrapefoot», a tale with a fox as antagonist that bears striking similarities to Southey’s story, was uncovered by the folklorist Joseph Jacobs and may predate Southey’s version in the oral tradition. Some sources state that it was illustrator John D. Batten who in 1894 reported a variant of the tale at least 40 years old. In this version, the three bears live in a castle in the woods and are visited by a fox called Scrapefoot who drinks their milk, sits in their chairs, and rests in their beds.[4] This version belongs to the early Fox and Bear tale-cycle.[15] Southey possibly heard «Scrapefoot», and confused its «vixen» with a synonym for an unpleasant malicious old woman. Some maintain however that the story as well as the old woman originated with Southey.[3]

Southey most likely learned the tale as a child from his uncle William Tyler. Uncle Tyler may have told a version with a vixen (female fox) as the intruder, and then Southey may have later confused «vixen» with another common meaning of «a crafty old woman».[4] P. M. Zall writes in «The Gothic Voice of Father Bear» (1974) that «it was no trick for Southey, a consummate technician, to recreate the improvisational tone of an Uncle William through rhythmical reiteration, artful alliteration (‘they walked into the woods, while’), even bardic interpolation (‘She could not have been a good, honest Old Woman’)».[16] Ultimately, it is uncertain where Southey or his uncle learned the tale.

Later variations: Goldilocks[edit]

London based writer and publisher Joseph Cundall changed the antagonist from an old woman to a girl

Twelve years after the publication of Southey’s tale, Joseph Cundall transformed the antagonist from an ugly old woman to a pretty little girl in his Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children. He explained his reasons for doing so in a dedicatory letter to his children, dated November 1849, which was inserted at the beginning of the book:

The «Story of the Three Bears» is a very old Nursery Tale, but it was never so well told as by the great poet Southey, whose version I have (with permission) given you, only I have made the intruder a little girl instead of an old woman. This I did because I found that the tale is better known with Silver-Hair, and because there are so many other stories of old women.[11]

Once the little girl entered the tale, she remained – suggesting children prefer an attractive child in the story rather than an ugly old woman.[6] The juvenile antagonist saw a succession of names:[17] Silver Hair in the pantomime Harlequin and The Three Bears; or, Little Silver Hair and the Fairies by J. B. Buckstone (1853); Silver-Locks in Aunt Mavor’s Nursery Tales (1858); Silverhair in George MacDonald’s The Golden Key (1867); Golden Hair in Aunt Friendly’s Nursery Book (ca. 1868);[11] Silver-Hair and Goldenlocks at various times; Little Golden-Hair (1889);[15] and finally Goldilocks in Old Nursery Stories and Rhymes (1904).[11] Tatar credits English author Flora Annie Steel with naming the child in English Fairy Tales (1918).[3]

Goldilocks’s fate varies in the many retellings: in some versions, she runs into the forest, in some she is almost eaten by the bears but her mother rescues her, in some she vows to be a good child, and in some she returns home. Whatever her fate, Goldilocks fares better than Southey’s vagrant old woman who, in his opinion, deserved a stint in the House of Correction, and far better than Miss Mure’s old woman who is impaled upon a steeple in St Paul’s church-yard.[18]

Southey’s all-male ursine trio has not been left untouched over the years. The group was re-cast as Papa, Mama, and Baby Bear, but the date of this change is disputed. Tatar indicates it occurred by 1852,[18] while Katherine Briggs suggests the event occurred in 1878 with Mother Goose’s Fairy Tales published by Routledge.[15][17] With the publication of the tale by «Aunt Fanny» in 1852, the bears became a family in the illustrations to the tale but remained three bachelor bears in the text.

In Dickens’ version of 1858, the two larger bears are brother and sister, and friends to the little bear. This arrangement represents the evolution of the ursine trio from the traditional three male bears to a family of father, mother, and child.[19] In a publication c. 1860, the bears have become a family at last in both text and illustrations: «the old papa bear, the mama bear, and the little boy bear».[20] In a Routledge publication c. 1867, Papa Bear is called Rough Bruin, Mama Bear is Mammy Muff, and Baby Bear is called Tiny. Inexplicably, the illustrations depict the three as male bears.[21]

In publications subsequent to Aunt Fanny’s of 1852, Victorian nicety required editors to routinely and silently alter Southey’s «[T]here she sate till the bottom of the chair came out, and down came her’s, plump upon the ground» to read «and down she came», omitting any reference to the human bottom. The cumulative effect of the several changes to the tale since its original publication was to transform a fearsome oral tale into a cosy family story with an unrealised hint of menace.[17]

Interpretations[edit]

Maria Tatar, in The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales (2002), notes that Southey’s tale is sometimes viewed as a cautionary tale that imparts a lesson about the hazards of wandering off and exploring unknown territory. Like «The Tale of the Three Little Pigs», the story uses repetitive formulas to engage the child’s attention and to reinforce the point about safety and shelter.[18] Tatar points out that the tale is typically framed today as a discovery of what is «just right», but for earlier generations, it was a tale about an intruder who could not control herself when encountering the possessions of others.[22]

Illustration by John Batten, 1890

In The Uses of Enchantment (1976), the child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim describes Goldilocks as «poor, beautiful, and charming», and notes that the story does not describe her positively except for her hair.[23] Bettelheim mainly discussed the tale in terms of Goldilocks’ struggle to move past Oedipal issues to confront adolescent identity problems.[24]

In Bettelheim’s view, the tale fails to encourage children «to pursue the hard labour of solving, one at a time, the problems which growing up presents», and does not end as fairy tales should with the «promise of future happiness awaiting those who have mastered their Oedipal situation as a child». He believes the tale is an escapist one that thwarts the child reading it from gaining emotional maturity.

Tatar criticises Bettelheim’s views: «[His] reading is perhaps too invested in instrumentalizing fairy tales, that is, in turning them into vehicles that convey messages and set forth behavioural models for the child. While the story may not solve Oedipal issues or sibling rivalry as Bettelheim believes «Cinderella» does, it suggests the importance of respecting property and the consequences of just ‘trying out’ things that do not belong to you.»[18]

Elms suggests Bettelheim may have missed the anal aspect of the tale that would make it helpful to the child’s personality development.[23] In Handbook of Psychobiography Elms describes Southey’s tale not as one of Bettelheimian post-Oedipal ego development but as one of Freudian pre-Oedipal anality.[24] He believes the story appeals chiefly to preschoolers who are engaged in «cleanliness training, maintaining environmental and behavioural order, and distress about disruption of order». His own experience and his observation of others lead him to believe children align themselves with the tidy, organised ursine protagonists rather than the unruly, delinquent human antagonist. In Elms’s view, the anality of «The Story of the Three Bears» can be traced directly to Robert Southey’s fastidious, dirt-obsessed aunt who raised him and passed her obsession to him in a milder form.[24]

Literary elements[edit]

The story makes extensive use of the literary rule of three, featuring three chairs, three bowls of porridge, three beds, and the three title characters who live in the house. There are also three sequences of the bears discovering in turn that someone has been eating from their porridge, sitting in their chairs, and finally, lying in their beds, at which point is the climax of Goldilocks being discovered. This follows three earlier sequences of Goldilocks trying the bowls of porridge, chairs, and beds successively, each time finding the third «just right». Author Christopher Booker characterises this as the «dialectical three», where «the first is wrong in one way, the second in another or opposite way, and only the third, in the middle, is just right». Booker continues: «This idea that the way forward lies in finding an exact middle path between opposites is of extraordinary importance in storytelling».[25] This concept has spread across many other disciplines, particularly developmental psychology, biology, economics, and engineering where it is called the «Goldilocks principle».[26][27] In planetary astronomy, a planet orbiting its sun at just the right distance for liquid water to exist on its surface, neither too hot nor too cold, is referred to as being in the ‘Goldilocks Zone’. As Stephen Hawking put it, «like Goldilocks, the development of intelligent life requires that planetary temperatures be ‘just right‘«.[28]

Adaptations[edit]

Animated shorts[edit]

Looney Tunes’ Three Bears[edit]

Bugs Bunny and the Three Bears is a 1944 Merrie Melodies cartoon short directed by Chuck Jones.[29]: 148 The short was released on February 26, 1944, and features Bugs Bunny.[30] Later Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies shorts continued the use of the same Three Bears family, distinguished by a short, irascible father named Henry, a deadpan mother, and a huge, oafish seven-year-old «baby,» still in diapers. Jones first brought back the Bears for his 1948 cartoon What’s Brewin’, Bruin?.[29]: 182 Here, Papa Bear decides that it’s time for the Bears to hibernate; however, various disturbances interfere. Junior’s voice is here supplied by Stan Freberg. Other Three Bears cartoons included Bear Feat (1948) and The Bee-Deviled Bruin (1949).

The final golden-age cartoon with this bear family, A Bear for Punishment (1951), parodies cultural values surrounding the celebration of Father’s Day. Looney Tunes comic books and more modern TV cartoons have now and then continued the use of the characters, occasionally in starring roles.

Terrytoons’ The Three Bears[edit]

A short film by Terrytoons titled The Three Bears was released in 1934 and remade in 1939. The remake famously adds stereotypical Italian accents and mannerisms to the bears; instead of eating porridge (as in the 1934 original), they eat spaghetti. The 1939 scene in which Papa Bear says «Somebody toucha my spaghet!» («somebody touched my spaghetti») became a viral Internet meme on YouTube in late 2017. While the 1939 bears are brown, not black, the commonly seen print is faded in such a way that they appear to have black fur, and so are often depicted in artwork based on the meme.

Others[edit]

- The MGM cartoons of the late 1930s included a Bear Family sub-series by Hugh Harman based on the story, starting with Goldilocks and the Three Bears (1939), then continuing on to A Rainy Day with the Bear Family (1940) and Papa Gets the Bird (1941). The MGM character of Barney Bear, originating concurrently, was at times advertised as being this Bear Family’s Papa, though creator Rudolf Ising appears to have always intended him as a separate character.

- Goldilocks and the Jivin’ Bears is a 1944 Merrie Melodies cartoon directed by Friz Freleng.[29]: 154 The cartoon depicts the Bears as an all-male trio of Black musicians, with Goldilocks as a teenage jitterbug.

- Now Hare This is a 1958 Looney Tunes cartoon directed by Robert McKimson whose second act of this short was based on «Goldilocks and Three Bears». The short was released on May 31, 1958, and stars Bugs Bunny.[29]: 308

- Goldimouse and the Three Cats is a 1960 Warner Bros. Looney Tunes animated cartoon directed by Friz Freleng.[29]: 323

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears/Rumpelstiltskin/Little Red Riding Hood/Sleeping Beauty (1984), a direct-to-video featurette produced by Lee Mendelson Film Productions.

- The Goldilocks and the 3 Bears Show (aka Goldilocks and the 3 Bears) is the third and final animated film in the Unstable Fables series. The film is a twisted retelling of the story of Goldilocks. The direct-to-DVD film was released on December 16, 2008.

Television animation[edit]

- Goldilocks is a half-hour musical animated film, the audio tracks for which were recorded in the summer of 1969, produced strictly for television in 1970 by DePatie-Freleng Enterprises (known for their work on The Pink Panther Show, of which the animation style is strongly reminiscent) and produced with the assistance of Mirisch-Geoffrey Productions.

- The three bears may or may not have been the inspiration for Stan and Jan Berenstain’s Berenstain Bears.

- In Rooster Teeth Productions RWBY, Yang Xiao Long is a carefree, reckless yellow-haired girl.[31] She is a «rule-breaker» who likes teddy bears. She is an allusion to Goldilocks which is reflected in her name, translated from Chinese as «sun», referring to the colour yellow.[32] Also, in her trailer, Yang confronts Hei «Junior» Xiong, whose name is Chinese for «black bear.» Combining this with his nickname, he alludes to the Baby Bear.

- The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child featured an adaption of «Goldilocks and the Three Bears» in a Jamaican setting which featured the voices of Raven-Symoné as Goldilocks, Tone Loc as Desmond Bear, Alfre Woodard as Winsome Bear, and David Alan Grier as Dudley Bear.

- In the Simpsons episode «Bart’s New Friend,» the couch gag is based on Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

- In a Simpsons Halloween themed episode titled Treehouse of Horror XI, Bart and Lisa, who are fairy tale characters, enter the three bears house and follow the same route Goldilocks make in the original tale. But when they walk out of the house, they inadvertently lock the real Goldilocks inside the house who proceeds to get violently mauled to death by the bears.

- A fractured version of the story was made for Jay Ward’s Fractured Fairy Tales, in which Goldilocks had a winter resort and the three bears invade for hibernation purposes; Papa Bear was short and short-tempered, Mama Bear was more even-tempered, and Baby Bear was a huge, oversized dope who was «not sleepy».

- In the television show Hello Kitty’s Furry Tale Theater, the episode «Kittylocks and the Three Bears» is an adaptation of the story.

- A commercial for the 2005 Hummer portrayed the Three Bears returning from a family trip to their very upscale home to discover all the elements of the traditional story. They race to their garage to check on the status of the family Hummers. Mama Bear and Papa Bear are relieved that both vehicles are still in place, but Baby Bear is distraught to find his missing as the camera cuts away to Goldilocks (in this version portrayed by a very attractive young woman) rakishly smiling as she makes her getaway in Baby Bear’s Hummer down a scenic mountain road.

- Disney Junior’s Goldie & Bear premiered in 2016. The tale is set after the events of the story where Goldilocks (voiced by Natalie Lander) and Jack Bear (voiced by Georgie Kidder) eventually became best friends.

Live-action television[edit]

- «Goldilocks and the Three Bears» is the 9th episode of the television anthology Faerie Tale Theatre. It stars Tatum O’Neal as Goldilocks. Released in 1984

- In an episode of Sesame Street, a reversed version of the story titled «Baby Bear and the Three Goldilocks» was told (and written) by Telly and Elmo.

Video games[edit]

- The 1993 PC game Sesame Street: Numbers features a Sesame Street-esque twist on the story, and it is found in one of the three books in the game. Titled Count Goldilocks and the 3 Bears, it features the Count von Count taking the role of Goldilocks, as «Count Goldilocks». Instead of arriving after Papa, Mama, and Baby Bear go on their picnic, he arrives before they go out. He then proceeds to count them, their picnic baskets, wooden chairs, and beds. Each time he is done counting one of them, he asks why they have three of what he counted. At the end, Baby Bear says that they have three of everything because they are three bears. Then, they finally go on their picnic in the woods.

Music and audio[edit]

- Goldilocks is a musical with a book by Jean and Walter Kerr, music by Leroy Anderson, and lyrics by the Kerrs and Joan Ford.

- Songwriter Bobby Troup’s hipster interpretation titled «The Three Bears», first recorded by Page Cavanaugh in 1946, is often erroneously credited to «anonymous» and re-titled «Three Bears Rap», «Three Bears with a Beat», etc.

- Kurt Schwertsik’s 35-minute opera Roald Dahl’s Goldilocks premiered in 1997 at the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall. The opera’s setting is the Forest Assizes where Baby Bear stands accused of assaulting Miss Goldie Locks. The tables are turned when the defence limns the trauma suffered by the bears at the hands of that «brazen little crook», Goldilocks.[33]

- Goldilocks is a 12″ soundtrack vinyl album taken from the TV film Goldilocks shown on NBC on 31 March 1970. It was first released in 1970 as DL-3511 by Decca Custom Records for a special promotion of Evans-Black Carpets by Armstrong. When the promotion period had expired, the album was re-released by Disneyland Records as ST-3889 with an accompanying 12-page storybook. The recording is particularly important to the Bing Crosby career as he recorded commercial tracks in every year from 1926 to 1977 and this album represents his only recording work for 1969.[34]

- In 2014, MC Frontalot released a hip-hop rendition of the story as part of the album, Question Bedtime, in which the narrator warns the three bears of a ruthless woman called Gold Locks who hunts and eats bear cubs. An official music video was uploaded in 2015.[35]

- In 2016, professional wrestler Bray Wyatt read a dark version to Edge and Christian.[36]

Other references[edit]

- «Goldilocks Eats Grits» has the bears living in a cave in Georgia in the United States.[37]

See also[edit]

- Little Red Riding Hood

- Goldilocks principle

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Elms 1977, p. 257

- ^ Southey, Robert (1837). «The Story of the Three Bears». The Doctor & C. Vol. 4. London, England: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman. pp. 318–326.

- ^ a b c Tatar 2002, p. 245

- ^ a b c d e Opie 1992, p. 199

- ^ Ober 1981, p. 47

- ^ a b Curry 1921, p. 65

- ^ Ober 1981, p. 48

- ^ Dorson 2001, p. 94

- ^ Ober 1981, pp. 2,10

- ^ Opie 1992, pp. 199–200

- ^ a b c d Opie 1992, p. 200

- ^ Ober 1981, p. xii

- ^ Ober 1981, p. x

- ^ Elms 1977, p. 259

- ^ a b c Briggs 2002, pp. 128–129

- ^ Quoted in: Ober 1981, p. ix

- ^ a b c Seal 2001, p. 91

- ^ a b c d Tatar 2002, p. 246

- ^ Ober 1981, p. 142

- ^ Ober 1981, p. 178

- ^ Ober 1981, p. 190

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 251

- ^ a b Elms 1977, p. 264

- ^ a b c Schultz 2005, p. 93

- ^ Booker 2005, pp. 229–32

- ^ Martin, S J (August 2011). «Oncogene-induced autophagy and the Goldilocks principle». Autophagy. 7 (8): 922–3. doi:10.4161/auto.7.8.15821. PMID 21552010.

- ^ Boulding, K.E. (1981). Evolutionary Economics. Sage Publications. p. 200. ISBN 9780803916487.

- ^ S Hawking, The Grand Design (London 2011) p. 194

- ^ a b c d e Beck, Jerry; Friedwald, Will (1989). Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies: A Complete Illustrated Guide to the Warner Bros. Cartoons. Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-0894-2.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 60-61. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Webb, Charles (1 June 2013). «EXCLUSIVE: Rooster Teeth’s ‘RWBY’ Yellow Trailer». MTV. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Rush, Amanda (12 July 2013). «FEATURE: Inside Rooster Teeth’s «RWBY»«. Crunchyroll. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Roald Dahl’s Goldilocks

- ^ Reynolds, Fred. The Crosby Collection 1927-1977 (Part Five: 1961-1977 ed.). John Joyce. p. 127.

- ^ MC Frontalot (23 September 2014), MC Frontalot — Gold Locks (ft. Jean Grae) [OFFICIAL VIDEO], archived from the original on 21 December 2021, retrieved 11 March 2019

- ^ «Bray Wyatt tells a twisted fairy tale on the Edge & Christian Show, only on WWE Network». YouTube. 2 May 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021.

Bray Wyatt puts a diabolical spin on ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ on The Edge & Christian Show

- ^ Friedman, Amy; Johnson, Meredith (25 January 2015). «Goldilocks Eats Grits». Universal Uclick. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

General sources[edit]

- The Seven Basic Plots. Booker, Christopher (2005). «The Rule of Three». The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-5209-4.

- Briggs, Katherine Mary (2002) [1977]. British Folk Tales and Legends. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28602-6.

- «Coronet: Goldilocks and the Three Bears». Internet Archive. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- Curry, Charles Madison (1921). Children’s Literature. Rand McNally & Company. p. 179. ISBN 9781344646789.

three bears.

- «Disney: Goldilocks and the Three Bears». The Encyclopedia of Disney Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- Dorson, Richard Mercer (2001) [1968]. The British Folklorists. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-20426-7.

- Elms, Alan C. (July–September 1977). ««The Three Bears»: Four Interpretations». The Journal of American Folklore. 90 (357): 257–273. doi:10.2307/539519. JSTOR 539519.

- «MGM: Goldilocks and the Three Bears». Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- Ober, Warren U. (1981). The Story of the Three Bears. Scholars Facsimiles & Reprints. ISBN 0-8201-1362-X.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1992) [1974]. The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211559-6.

- «Roald Dahl’s Goldilocks (1997)». Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- Schultz, William Todd (2005). Handbook of Psychobiography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516827-5.

- Seal, Graham (2001). Encyclopedia of Folk Heroes. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-216-9.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-05163-3.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- «The Story of the Three Bears», manuscript by Eleanor Mure, 1831 — first recorded version

- «The Story of the Three Bears» by Robert Southey, 1837 – first published version

- «The Story of the Three Bears», versified by George Nicol, 2nd edition, 1839 (text)

- «The Three Bears» by Robert Southey – later version with «Silver-hair», a «little girl»

- «Goldilocks and the Three Bears», by Katharine Pyle, 1918 – later version with father, mother and baby bear

| «Goldilocks and the Three Bears» | |

|---|---|

| by Robert Southey | |

Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1918, in English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel |

|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Genre(s) | Fairy tale |

| Published in | The Doctor |

| Publication type | Essay and story collection |

| Publisher | Longman, Rees, etc. |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 1837 |

«Goldilocks and the Three Bears» (originally titled «The Story of the Three Bears«) is a 19th-century English fairy tale of which three versions exist. The original version of the tale tells of an obscene old woman who enters the forest home of three anthropomorphic bachelor bears while they are away. She eats some of their porridge, sits down on one of their chairs and breaks it, and sleeps in one of their beds. When the bears return and discover her, she wakes up, jumps out of the window, and is never seen again. The second version replaces the old woman with a young girl named Goldilocks, and the third and by far best-known version replaces the bachelor trio with a family of three.

What was originally a frightening oral tale became a cosy family story with only a hint of menace. The story has elicited various interpretations and has been adapted to film, opera, and other media. «Goldilocks and the Three Bears» is one of the most popular fairy tales in the English language.[1]

Original plot[edit]

Illustration in «The Story of the Three Bears» second edition, 1839, published by W. N. Wright of 60 Pall Mall, London

In Robert Southey’s version of the tale («The Story of the Three Bears»), three anthropomorphic bears – «a little, small, wee bear, a middle-sized bear, and a great, huge bear» – live together in a house in the woods. Southey describes them as very good-natured, trusting, harmless, tidy, and hospitable. Each of these «bachelor» bears has his own porridge bowl, chair, and bed. One day they make porridge for breakfast, but it is too hot to eat, so they decide to take a walk in the woods while their porridge cools. An old woman approaches the bears’ house. She has been sent out by her family because she is a disgrace to them. She is impudent, bad-mannered, foul-mouthed, ugly, dirty, and a vagrant deserving of a stint in the House of Correction. She looks through a window, peeps through the keyhole, and lifts the latch. Assured that no one is home, she walks in. The old woman eats the Wee Bear’s porridge, then settles into his chair and breaks it. Prowling about, she finds the bears’ beds and falls asleep in Wee Bear’s bed. The end of the tale is reached when the bears return. Wee Bear finds his empty bowl, his broken chair, and the old woman sleeping in his bed and cries, «Somebody has been lying in my bed, and here she is!» The old woman wakes, is chased out of the house by the huge bear and is never seen again.

Origins[edit]

The story was first recorded in narrative form by English writer and poet Robert Southey, and first published anonymously as «The Story of the Three Bears» in 1837 in a volume of his writings called The Doctor.[2][3] The same year Southey’s tale was published, the story was versified by editor George Nicol, who acknowledged the anonymous author of The Doctor as «the great, original concocter» of the tale.[4][5] Southey was delighted with Nicol’s effort to bring more exposure to the tale, concerned children might overlook it in The Doctor.[6] Nicol’s version was illustrated with engravings by B. Hart (after «C.J.»), and was reissued in 1848 with Southey identified as the story’s author.[7]

The story of the three bears was in circulation before the publication of Southey’s tale.[8] In 1813, for example, Southey was telling the story to friends, and in 1831 Eleanor Mure fashioned a handmade booklet about the three bears and the old woman for her nephew Horace Broke’s birthday.[4] Southey and Mure differ in details. Southey’s bears have porridge, but Mure’s have milk;[4] Southey’s old woman has no motive for entering the house, but Mure’s old woman is piqued when her courtesy visit is rebuffed;[9] Southey’s old woman runs away when discovered, but Mure’s old woman is impaled on the steeple of St Paul’s Cathedral.[10]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie point out in The Classic Fairy Tales (1999) that the tale has a «partial analogue» in «Snow White»: the lost princess enters the dwarfs’ house, tastes their food, and falls asleep in one of their beds. In a manner similar to the three bears, the dwarfs cry, «Someone’s been sitting in my chair!», «Someone’s been eating off my plate!», and «Someone’s been sleeping in my bed!» The Opies also point to similarities in a Norwegian tale about a princess who takes refuge in a cave inhabited by three Russian princes dressed in bearskins. She eats their food and hides under a bed.[11]

In 1865, Charles Dickens referenced a similar tale in Our Mutual Friend, but in that story the house belongs to hobgoblins rather than bears. Dickens’ reference however suggests a yet-to-be-discovered analogue or source.[12] Hunting rituals and ceremonies have been suggested and dismissed as possible origins.[13][14]

«Scrapefoot» illustration by John D. Batten in More English Fairy Tales (1895)

In 1894, «Scrapefoot», a tale with a fox as antagonist that bears striking similarities to Southey’s story, was uncovered by the folklorist Joseph Jacobs and may predate Southey’s version in the oral tradition. Some sources state that it was illustrator John D. Batten who in 1894 reported a variant of the tale at least 40 years old. In this version, the three bears live in a castle in the woods and are visited by a fox called Scrapefoot who drinks their milk, sits in their chairs, and rests in their beds.[4] This version belongs to the early Fox and Bear tale-cycle.[15] Southey possibly heard «Scrapefoot», and confused its «vixen» with a synonym for an unpleasant malicious old woman. Some maintain however that the story as well as the old woman originated with Southey.[3]

Southey most likely learned the tale as a child from his uncle William Tyler. Uncle Tyler may have told a version with a vixen (female fox) as the intruder, and then Southey may have later confused «vixen» with another common meaning of «a crafty old woman».[4] P. M. Zall writes in «The Gothic Voice of Father Bear» (1974) that «it was no trick for Southey, a consummate technician, to recreate the improvisational tone of an Uncle William through rhythmical reiteration, artful alliteration (‘they walked into the woods, while’), even bardic interpolation (‘She could not have been a good, honest Old Woman’)».[16] Ultimately, it is uncertain where Southey or his uncle learned the tale.

Later variations: Goldilocks[edit]

London based writer and publisher Joseph Cundall changed the antagonist from an old woman to a girl

Twelve years after the publication of Southey’s tale, Joseph Cundall transformed the antagonist from an ugly old woman to a pretty little girl in his Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children. He explained his reasons for doing so in a dedicatory letter to his children, dated November 1849, which was inserted at the beginning of the book:

The «Story of the Three Bears» is a very old Nursery Tale, but it was never so well told as by the great poet Southey, whose version I have (with permission) given you, only I have made the intruder a little girl instead of an old woman. This I did because I found that the tale is better known with Silver-Hair, and because there are so many other stories of old women.[11]

Once the little girl entered the tale, she remained – suggesting children prefer an attractive child in the story rather than an ugly old woman.[6] The juvenile antagonist saw a succession of names:[17] Silver Hair in the pantomime Harlequin and The Three Bears; or, Little Silver Hair and the Fairies by J. B. Buckstone (1853); Silver-Locks in Aunt Mavor’s Nursery Tales (1858); Silverhair in George MacDonald’s The Golden Key (1867); Golden Hair in Aunt Friendly’s Nursery Book (ca. 1868);[11] Silver-Hair and Goldenlocks at various times; Little Golden-Hair (1889);[15] and finally Goldilocks in Old Nursery Stories and Rhymes (1904).[11] Tatar credits English author Flora Annie Steel with naming the child in English Fairy Tales (1918).[3]

Goldilocks’s fate varies in the many retellings: in some versions, she runs into the forest, in some she is almost eaten by the bears but her mother rescues her, in some she vows to be a good child, and in some she returns home. Whatever her fate, Goldilocks fares better than Southey’s vagrant old woman who, in his opinion, deserved a stint in the House of Correction, and far better than Miss Mure’s old woman who is impaled upon a steeple in St Paul’s church-yard.[18]

Southey’s all-male ursine trio has not been left untouched over the years. The group was re-cast as Papa, Mama, and Baby Bear, but the date of this change is disputed. Tatar indicates it occurred by 1852,[18] while Katherine Briggs suggests the event occurred in 1878 with Mother Goose’s Fairy Tales published by Routledge.[15][17] With the publication of the tale by «Aunt Fanny» in 1852, the bears became a family in the illustrations to the tale but remained three bachelor bears in the text.

In Dickens’ version of 1858, the two larger bears are brother and sister, and friends to the little bear. This arrangement represents the evolution of the ursine trio from the traditional three male bears to a family of father, mother, and child.[19] In a publication c. 1860, the bears have become a family at last in both text and illustrations: «the old papa bear, the mama bear, and the little boy bear».[20] In a Routledge publication c. 1867, Papa Bear is called Rough Bruin, Mama Bear is Mammy Muff, and Baby Bear is called Tiny. Inexplicably, the illustrations depict the three as male bears.[21]

In publications subsequent to Aunt Fanny’s of 1852, Victorian nicety required editors to routinely and silently alter Southey’s «[T]here she sate till the bottom of the chair came out, and down came her’s, plump upon the ground» to read «and down she came», omitting any reference to the human bottom. The cumulative effect of the several changes to the tale since its original publication was to transform a fearsome oral tale into a cosy family story with an unrealised hint of menace.[17]

Interpretations[edit]

Maria Tatar, in The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales (2002), notes that Southey’s tale is sometimes viewed as a cautionary tale that imparts a lesson about the hazards of wandering off and exploring unknown territory. Like «The Tale of the Three Little Pigs», the story uses repetitive formulas to engage the child’s attention and to reinforce the point about safety and shelter.[18] Tatar points out that the tale is typically framed today as a discovery of what is «just right», but for earlier generations, it was a tale about an intruder who could not control herself when encountering the possessions of others.[22]

Illustration by John Batten, 1890

In The Uses of Enchantment (1976), the child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim describes Goldilocks as «poor, beautiful, and charming», and notes that the story does not describe her positively except for her hair.[23] Bettelheim mainly discussed the tale in terms of Goldilocks’ struggle to move past Oedipal issues to confront adolescent identity problems.[24]

In Bettelheim’s view, the tale fails to encourage children «to pursue the hard labour of solving, one at a time, the problems which growing up presents», and does not end as fairy tales should with the «promise of future happiness awaiting those who have mastered their Oedipal situation as a child». He believes the tale is an escapist one that thwarts the child reading it from gaining emotional maturity.

Tatar criticises Bettelheim’s views: «[His] reading is perhaps too invested in instrumentalizing fairy tales, that is, in turning them into vehicles that convey messages and set forth behavioural models for the child. While the story may not solve Oedipal issues or sibling rivalry as Bettelheim believes «Cinderella» does, it suggests the importance of respecting property and the consequences of just ‘trying out’ things that do not belong to you.»[18]

Elms suggests Bettelheim may have missed the anal aspect of the tale that would make it helpful to the child’s personality development.[23] In Handbook of Psychobiography Elms describes Southey’s tale not as one of Bettelheimian post-Oedipal ego development but as one of Freudian pre-Oedipal anality.[24] He believes the story appeals chiefly to preschoolers who are engaged in «cleanliness training, maintaining environmental and behavioural order, and distress about disruption of order». His own experience and his observation of others lead him to believe children align themselves with the tidy, organised ursine protagonists rather than the unruly, delinquent human antagonist. In Elms’s view, the anality of «The Story of the Three Bears» can be traced directly to Robert Southey’s fastidious, dirt-obsessed aunt who raised him and passed her obsession to him in a milder form.[24]

Literary elements[edit]

The story makes extensive use of the literary rule of three, featuring three chairs, three bowls of porridge, three beds, and the three title characters who live in the house. There are also three sequences of the bears discovering in turn that someone has been eating from their porridge, sitting in their chairs, and finally, lying in their beds, at which point is the climax of Goldilocks being discovered. This follows three earlier sequences of Goldilocks trying the bowls of porridge, chairs, and beds successively, each time finding the third «just right». Author Christopher Booker characterises this as the «dialectical three», where «the first is wrong in one way, the second in another or opposite way, and only the third, in the middle, is just right». Booker continues: «This idea that the way forward lies in finding an exact middle path between opposites is of extraordinary importance in storytelling».[25] This concept has spread across many other disciplines, particularly developmental psychology, biology, economics, and engineering where it is called the «Goldilocks principle».[26][27] In planetary astronomy, a planet orbiting its sun at just the right distance for liquid water to exist on its surface, neither too hot nor too cold, is referred to as being in the ‘Goldilocks Zone’. As Stephen Hawking put it, «like Goldilocks, the development of intelligent life requires that planetary temperatures be ‘just right‘«.[28]

Adaptations[edit]

Animated shorts[edit]

Looney Tunes’ Three Bears[edit]

Bugs Bunny and the Three Bears is a 1944 Merrie Melodies cartoon short directed by Chuck Jones.[29]: 148 The short was released on February 26, 1944, and features Bugs Bunny.[30] Later Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies shorts continued the use of the same Three Bears family, distinguished by a short, irascible father named Henry, a deadpan mother, and a huge, oafish seven-year-old «baby,» still in diapers. Jones first brought back the Bears for his 1948 cartoon What’s Brewin’, Bruin?.[29]: 182 Here, Papa Bear decides that it’s time for the Bears to hibernate; however, various disturbances interfere. Junior’s voice is here supplied by Stan Freberg. Other Three Bears cartoons included Bear Feat (1948) and The Bee-Deviled Bruin (1949).