Всего найдено: 5

Есть ли исключения для имён собственных в § 154 Правил русской орфографии и пунктуации под ред. Лопатина? В имени собственном «Папуа — Новая Гвинея» должен стоять дефис или тире? В названии «Кривой Рог — Сортировочный»? (То есть правильно «Кривой Рог-Сортировочный» или «Кривой Рог — Сортировочный»?) В названии земель «Северный Рейн — Вестфалия» и «Мекленбург — Передняя Померания» (учитывая, что «Северный» относится только к «Рейну», а «Передняя» к «Померании»)? Дефис или тире? «Мекленбург-Передняя Померания» или «Мекленбург — Передняя Померания»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Везде требуется тире: Папуа — Новая Гвинея, Кривой Рог — Сортировочный, Северный Рейн — Вестфалия» и Мекленбург — Передняя Померания.

Добрый день!

Склоняется ли название государства Папуа – Новая Гвинея, например, достопримечательности Папуа – Новая(ой) Гвинея(и)?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, вторая часть названия склоняется. Правильно: достопримечательности Папуа – Новой Гвинеи.

Уважаемые сотрудники «Грамоты»! Как правильно пишется название государства: Папуа (-) Новая Гвинея? Через тире с пробелами или через дефис без пробелов? Различные авторитетные источники дают написание по-разному: БЭС — чере тире, фундаментальный «Атлас мира» / Федеральная служба геодезии и картографии России — через дефис. Помогите, пожалуйста, очень срочно узнать правду об этом, иначе мне придется написать как в «Атласе», который в нашей организации считается эталоном по географическим названиям. А мне кажется, что там ошибка и надо через тире. (Может быть «тайна» написания — в переводе слова «Папуа«?) Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Следует писать через тире с пробелами: Папуа – Новая Гвинея (если написать через дефис, получится сложное слово Папуа-Новая, т. е. будут нарушены смысловые отношения между единицами). Написание через тире Папуа – Новая Гвинея зафиксировано нормативными словарями русского языка, в том числе «Русским орфографическим словарем» Российской академии наук.

Здравствуйте! 1. Папуа — Новая Гвинея: правильно дефис или тире? С пробелами? В словаре имен собственных на Вашем сайте указан дефис, а в ответах здесь в справке Вы указывате тире. Какая последняя верная информация? 2. Склоняются ли здесь слова «Новая» и «Гвинея»: как правильно: шоколад с какао из Папуа — Новая Гвинея или шоколад с какао из Папуа — Новой Гвинеи? (и тот же вопрос: дефис или тире? С пробелами?)

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. Правильно тире с пробелами. 2. Правильно склонять: из Папуа – Новой Гвинеи.

здравствуйте. объясните мне , пожалуйста, формулировку » склоняется, если топоним русского, славянского происхождения или представляет собой давно заимствованное и освоенное наименование». Как можно знать происхождение названий населённых пунктов? Освоенное кем? Каким количеством людей? В городе Казани? В городе Уренгое? Но это не русскообразованные названия… Если Казани 1000 лет, то Уренгою гораздо меньше — освоено название или нет? А потом, почему такие сложности только по отношению к населённым пунктам? На планете Земле?…Спасибо. Сергей.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Под освоенностью в данном случае понимается то, что название является привычным для носителя языка вследствие более или менее частого употребления в устной и письменной речи; четких критериев (дата заимствования, количество словоупотреблений и др.) нет. Например, такие названия, как Вевак, Наматанай, Маданг (Папуа – Новая Гвинея), вряд ли известны большому числу носителей языка, поэтому при употреблении с родовым словом город их целесообразно не склонять. А такие названия, как Казань и Уренгой, давно употребляются в русском языке, они известны (или, по крайней мере, должны быть известны) большинству говорящих и пишущих по-русски, поэтому их можно назвать освоенными русским языком.

Что касается названия нашей планеты, то оно не склоняется при употреблении с родовым словом. Правильно: на Земле, но: на планете Земля.

Coordinates: 6°S 147°E / 6°S 147°E

|

Independent State of Papua New Guinea

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag National emblem |

|

| Motto: ‘Unity in diversity’[1] | |

| Anthem: «O Arise, All You Sons»[2]

Royal anthem: «God Save the King» |

|

Location of Papua New Guinea (green) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Port Moresby 09°28′44″S 147°08′58″E / 9.47889°S 147.14944°E |

| Official languages[3][4] |

|

|

Indigenous languages |

851 languages[5] |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion

(2011 census)[6] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Papua New Guinean |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

|

• Monarch |

Charles III |

|

• Governor-General |

Bob Dadae |

|

• Prime Minister |

James Marape |

| Legislature | National Parliament |

| Independence

from Australia |

|

|

• Papua and New Guinea Act 1949 |

1 July 1949 |

|

• Declared and recognised |

16 September 1975 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

462,840 km2 (178,700 sq mi) (54th) |

|

• Water (%) |

2 |

| Population | |

|

• 2020 estimate |

|

|

• 2011 census |

7,275,324[7] |

|

• Density |

15/km2 (38.8/sq mi) (201st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

|

• Total |

$32.382 billion[8] (124th) |

|

• Per capita |

$3,764[8] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

|

• Total |

$21.543 billion[8] (110th) |

|

• Per capita |

$2,504[8] |

| Gini (2009) | 41.9[9] medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 156th |

| Currency | Kina (PGK) |

| Time zone | UTC+10, +11 (PNGST) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +675 |

| ISO 3166 code | PG |

| Internet TLD | .pg |

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , also ;[11] Tok Pisin: Papua Niugini; Hiri Motu: Papua Niu Gini), officially[12] the Independent State of Papua New Guinea (Tok Pisin: Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; Hiri Motu: Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country in Oceania that comprises the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and its offshore islands in Melanesia (a region of the southwestern Pacific Ocean north of Australia). Its capital, located along its southeastern coast, is Port Moresby. The country is the world’s third largest island country, with an area of 462,840 km2 (178,700 sq mi).[13]

At the national level, after being ruled by three external powers since 1884, including nearly 60 years of Australian administration starting during World War I, Papua New Guinea established its sovereignty in 1975. It became an independent Commonwealth realm in 1975 with Elizabeth II as its queen. It also became a member of the Commonwealth of Nations in its own right.

There are 839 known languages of Papua New Guinea, one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world.[5] As of 2019, it is also the most rural, as only 13.25% of its people live in urban centres.[14] Most of the population of more than 8 million people live in customary communities.[15] Although government estimates have placed the country’s population at 9.4 million, it was reported in December 2022 that a yet-to-be-published study suggests the true population is close to 17 million.[16][17]

The country is believed to be the home of many undocumented species of plants and animals.[18]

The sovereign state is classified as a developing economy by the International Monetary Fund;[19] nearly 40% of the population are subsistence farmers, living relatively independently of the cash economy.[20] Their traditional social groupings are explicitly acknowledged by the Papua New Guinea Constitution, which expresses the wish for «traditional villages and communities to remain as viable units of Papua New Guinean society»[21] and protects their continuing importance to local and national community life. Papua New Guinea has been an observer state in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) since 1976, and has filed its application for full membership status.[22] It is a full member of the Commonwealth of Nations,[23] the Pacific Community, and the Pacific Islands Forum.[24]

Etymology[edit]

The word papua is derived from an old local term of uncertain origin.[25] «New Guinea» (Nueva Guinea) was the name coined by the Spanish explorer Yñigo Ortiz de Retez. In 1545, he noted the resemblance of the people to those he had earlier seen along the Guinea coast of Africa. Guinea, in its turn, is etymologically derived from the Portuguese word Guiné. The name is one of several toponyms sharing similar etymologies, ultimately meaning «land of the blacks» or similar meanings, in reference to the dark skin of the inhabitants.

History[edit]

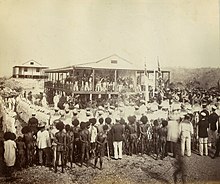

Kerepunu women at the marketplace of Kalo, British New Guinea, 1885

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans first arrived in Papua New Guinea around 42,000 to 45,000 years ago. They were descendants of migrants out of Africa, in one of the early waves of human migration.[26] A 2016 study at the University of Cambridge by Christopher Klein et al. suggests that it was about 50,000 years ago that these peoples reached Sahul (the supercontinent consisting of present-day Australia and New Guinea). The sea levels rose and isolated New Guinea about 10,000 years ago, but Aboriginal Australians and Papuans diverged from each other genetically earlier, about 37,000 years BP.[27] Evolutionary Geneticist Svante Pääbo found that people of New Guinea share 4%–7% of their genome with the Denisovans, indicating that the ancestors of Papuans interbred in Asia with these archaic hominins.[28]

Agriculture was independently developed in the New Guinea highlands around 7000 BC, making it one of the few areas in the world where people independently domesticated plants.[29] A major migration of Austronesian-speaking peoples to coastal regions of New Guinea took place around 500 BC. This has been correlated with the introduction of pottery, pigs, and certain fishing techniques.

In the 18th century, traders brought the sweet potato to New Guinea, where it was adopted and became a staple food. Portuguese traders had obtained it from South America and introduced it to the Moluccas.[30] The far higher crop yields from sweet potato gardens radically transformed traditional agriculture and societies. Sweet potato largely supplanted the previous staple, taro, and resulted in a significant increase in population in the highlands.

Although by the late 20th century headhunting and cannibalism had been practically eradicated, in the past they were practised in many parts of the country as part of rituals related to warfare and taking in enemy spirits or powers.[31][32] In 1901, on Goaribari Island in the Gulf of Papua, missionary Harry Dauncey found 10,000 skulls in the island’s long houses, a demonstration of past practices.[33] According to Marianna Torgovnick, writing in 1991, «The most fully documented instances of cannibalism as a social institution come from New Guinea, where head-hunting and ritual cannibalism survived, in certain isolated areas, into the Fifties, Sixties, and Seventies, and still leave traces within certain social groups.»[34]

European encounters[edit]

Little was known in Europe about the island until the 19th century, although Portuguese and Spanish explorers, such as Dom Jorge de Menezes and Yñigo Ortiz de Retez, had encountered it as early as the 16th century. Traders from Southeast Asia had visited New Guinea beginning 5,000 years ago to collect bird-of-paradise plumes.[35]

Colonialism[edit]

New Guinea from 1884 to 1919. Germany and Britain controlled the eastern half of New Guinea.

The country’s dual name results from its complex administrative history before independence. In the nineteenth century, Germany ruled the northern half of the country for some decades, beginning in 1884, as a colony named German New Guinea. In 1914 after the outbreak of World War I, Australian forces captured German New Guinea and occupied it throughout the war. After the war, in which Germany and the Central Powers were defeated, the League of Nations authorised Australia to administer this area as a League of Nations mandate territory that became the Territory of New Guinea.

Also in 1884, the southern part of the country became a British protectorate. In 1888 it was annexed, together with some adjacent islands, by Britain as British New Guinea. In 1902, Papua was effectively transferred to the authority of the new British dominion of Australia. With the passage of the Papua Act 1905, the area was officially renamed the Territory of Papua, and Australian administration became formal in 1906. In contrast to establishing an Australian mandate in former German New Guinea, the League of Nations determined that Papua was an external territory of the Australian Commonwealth; as a matter of law it remained a British possession. The difference in legal status meant that until 1949, Papua and New Guinea had entirely separate administrations, both controlled by Australia. These conditions contributed to the complexity of organising the country’s post-independence legal system.

World War II[edit]

During World War II, the New Guinea campaign (1942–1945) was one of the major military campaigns and conflicts between Japan and the Allies. Approximately 216,000 Japanese, Australian, and U.S. servicemen died.[36] After World War II and the victory of the Allies, the two territories were combined into the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. This was later referred to as «Papua New Guinea.»

The natives of Papua appealed to the United Nations for oversight and independence. The nation established independence from Australia on 16 September 1975, becoming a Commonwealth realm, continuing to share the British monarch as its head of state. It maintains close ties with Australia, which continues to be its largest aid donor. Papua New Guinea was admitted to membership in the United Nations on 10 October 1975.[37]

Bougainville[edit]

A secessionist revolt in 1975–76 on Bougainville Island resulted in an eleventh-hour modification of the draft Constitution of Papua New Guinea to allow for Bougainville and the other eighteen districts to have quasi-federal status as provinces. A renewed uprising on Bougainville started in 1988 and claimed 20,000 lives until it was resolved in 1997. Bougainville had been the primary mining region of the country, generating 40% of the national budget. The native peoples felt they were bearing the adverse environmental effects of the mining, which contaminated the land, water and air, without gaining a fair share of the profits.[38]

The government and rebels negotiated a peace agreement that established the Bougainville Autonomous District and Province. The autonomous Bougainville elected Joseph Kabui as president in 2005, who served until his death in 2008. He was succeeded by his deputy John Tabinaman as acting president while an election to fill the unexpired term was organised. James Tanis won that election in December 2008 and served until the inauguration of John Momis, the winner of the 2010 elections. As part of the current peace settlement, a non-binding independence referendum was held, between 23 November and 7 December 2019. The referendum question was a choice between greater autonomy within Papua New Guinea and full independence for Bougainville, and voters voted overwhelmingly (98.31%) for independence.[39] Negotiations between the Bougainville government and national Papua New Guinea on a path to Bougainville independence began after the referendum, and are ongoing.

Chinese minority[edit]

Numerous Chinese have worked and lived in Papua New Guinea, establishing Chinese-majority communities. Anti-Chinese rioting involving tens of thousands of people broke out in May 2009. The initial spark was a fight between ethnic Chinese and indigenous workers at a nickel factory under construction by a Chinese company. Native resentment against Chinese ownership of numerous small businesses and their commercial monopoly in the islands led to the rioting.[40][41]

[edit]

There is existing collaboration between Papua New Guinea and African countries. Papua New Guinea is part of the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) forum.[42] There is a thriving community of Africans who live and work in the country.

Earthquakes[edit]

Papua New Guinea is also famous for its frequent seismic activity, being on the Ring of Fire. On 17 July 1998, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck north of Aitape. It triggered a 50 foot high tsunami, which killed over 2,180 people in one of the worst natural disasters in the country.

In September 2002, a magnitude 7.6 earthquake struck off the coast of Wewak, Sandaun Province, killing six people.[43]

From March to April 2018, a chain of earthquakes hit Hela Province, causing widespread landslides and the deaths of 200 people. Various nations from Oceania and Southeast Asia immediately sent aid to the country.[44][45]

Another severe earthquake occurred on 11 September 2022, killing seven people and causing damaging shaking in some of the country’s largest cities, such as Lae and Madang, it was also felt in the capital Port Moresby.[46]

Government and politics[edit]

Papua New Guinea is a Commonwealth realm with Charles III as King of Papua New Guinea. The constitutional convention, which prepared the draft constitution, and Australia, the outgoing metropolitan power, had thought that Papua New Guinea would not remain a monarchy. The founders, however, considered that imperial honours had a cachet.[47] The monarch is represented by the Governor-General of Papua New Guinea, currently Bob Dadae. Papua New Guinea, and Solomon Islands, are unusual among Commonwealth realms in that governors-general are appointed by the Sovereign, the Head of State, upon nomination by the National Parliament, which nomination the Head of State is not obliged to accept.

The Prime Minister heads the cabinet, which consists of 31 members of Parliament from the ruling coalition, which make up the government. The current prime minister is James Marape. The unicameral National Parliament has 111 seats, of which 22 are occupied by the governors of the 22 provinces and the National Capital District. Candidates for members of parliament are voted upon when the prime minister asks the governor-general to call a national election, a maximum of five years after the previous national election.

In the early years of independence, the instability of the party system led to frequent votes of no confidence in parliament, with resulting changes of the government, but with referral to the electorate, through national elections only occurring every five years. In recent years, successive governments have passed legislation preventing such votes sooner than 18 months after a national election and within 12 months of the next election. In 2012, the first two (of three) readings were passed to prevent votes of no confidence occurring within the first 30 months. This restriction on votes of no confidence has arguably resulted in greater stability, although perhaps at a cost of reducing the accountability of the executive branch of government.

Elections in PNG attract numerous candidates. After independence in 1975, members were elected by the first-past-the-post system, with winners frequently gaining less than 15% of the vote. Electoral reforms in 2001 introduced the Limited Preferential Vote system (LPV), a version of the alternative vote. The 2007 general election was the first to be conducted using LPV.

Under a 2002 amendment, the leader of the party winning the largest number of seats in the election is invited by the governor-general to form the government, if they can muster the necessary majority in parliament. The process of forming such a coalition in PNG, where parties do not have much ideology, involves considerable «horse-trading» right up until the last moment. Peter O’Neill emerged as Papua New Guinea’s prime minister after the July 2012 election, and formed a government with Leo Dion, the former Governor of East New Britain Province, as deputy prime minister.

In 2011 there was a constitutional crisis between the parliament-elect Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill (voted into office by a large majority of MPs), and Sir Michael Somare, who was deemed by the supreme court to retain office. The stand-off between parliament and the supreme court continued until the July 2012 national elections, with legislation passed effectively removing the chief justice and subjecting the supreme court members to greater control by the legislature, as well as a series of other laws passed, for example limiting the age for a prime minister. The confrontation reached a peak, with the deputy prime minister entering the supreme court during a hearing, escorted by police, ostensibly to arrest the chief justice. There was strong pressure among some MPs to defer the national elections for a further six months to one year, although their powers to do that were highly questionable. The parliament-elect prime minister and other cooler-headed MPs carried the votes for the writs for the new election to be issued, slightly late, but for the election itself to occur on time, thereby avoiding a continuation of the constitutional crisis.

During the 10th Parliament (2017-2022) there were no women Members, one of only 3 countries worldwide (4 since the Taliban regained control in Afghanistan).

In May 2019, O’Neill resigned as prime minister and was replaced through a vote of Parliament by James Marape. Marape was a key minister in O’Neill’s government and his defection from the government to the opposition camp had finally led to O’Neill’s resignation from office.[48] Davis Steven was appointed deputy prime minister, justice Minister and Attorney General.[49] After an election widely criticised by observers for its inadequate preparation (including failure to update the electoral roll), abuses and violence, in July 2022, Prime Minister James Marape’s PANGU Party secured the most seats of any party in the election, enabling James Marape to be invited to form a coalition government, which he succeeded in doing and he continued as PNG’s Prime Minister.[50] In the 2022 Election two women were elected into the eleventh Parlaiment, one, Rufina Peter, also became Provincial governor of Central Province.[51]

Law[edit]

The unicameral Parliament enacts legislation in the same manner as in other Commonwealth realms that use the Westminster system of government. The cabinet collectively agrees on government policy, then the relevant minister introduces bills to Parliament, depending on which government department is responsible for implementation of a particular law. Back bench members of parliament can also introduce bills. Parliament debates bills, and (section 110.1 of the Constitution) they become enacted laws when the Speaker certifies that Parliament has passed them. There is no Royal assent.

All ordinary statutes enacted by Parliament must be consistent with the Constitution. The courts have jurisdiction to rule on the constitutionality of statutes, both in disputes before them and on a reference where there is no dispute but only an abstract question of law. Unusually among developing countries, the judicial branch of government in Papua New Guinea has remained remarkably independent, and successive executive governments have continued to respect its authority.

The «underlying law» (Papua New Guinea’s common law) consists of principles and rules of common law and equity in English[52] common law as it stood on 16 September 1975 (the date of independence), and thereafter the decisions of PNG’s own courts. The courts are directed by the Constitution and, latterly, the Underlying Law Act, to take note of the «custom» of traditional communities. They are to determine which customs are common to the whole country and may be declared also to be part of the underlying law. In practice, this has proved difficult and has been largely neglected. Statutes are largely adapted from overseas jurisdictions, primarily Australia and England. Advocacy in the courts follows the adversarial pattern of other common-law countries. This national court system, used in towns and cities, is supported by a village court system in the more remote areas. The law underpinning the village courts is ‘customary law’.

Foreign relations[edit]

APEC 2018 in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, Pacific Community, Pacific Islands Forum, and the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) of countries. It was accorded observer status within ASEAN in 1976, followed later by special observer status in 1981. It is also a member of APEC and an ACP country, associated with the European Union.

Papua New Guinea supported Indonesia’s control of Western New Guinea:[53] the focus of the Papua conflict where numerous human rights violations have reportedly been committed by the Indonesian security forces.[54][55][56]

Military[edit]

The Papua New Guinea Defence Force[57] is the military organisation responsible for the defence of Papua New Guinea. It consists of three wings. The Land Element has 7 units: the Royal Pacific Islands Regiment, a special forces unit, a battalion of engineers, three other small units primarily dealing with signals and health, and a military academy. The Air Element consists of one aircraft squadron, which transports the other military wings. The Maritime Element consists of four Pacific-class patrol boats, three ex-Australian Balikpapan-class landing craft, and one Guardian-class patrol boat. One of the landing craft is used as a training ship. Three more Guardian-class patrol boats are under construction in Australia, to replace the old Pacific-class vessels. The main tasks of the Maritime Element are to patrol inshore waters and to transport the Land Element. Papua New Guinea has a very large exclusive economic zone because of its extensive coastline. The Maritime Element relies heavily on satellite imagery to surveil the country’s waters. Patrolling is generally ineffective because underfunding often leaves the patrol boats unserviceable. This problem will be partially corrected when the larger Guardian-class patrol boats enter service.

Crime and human rights[edit]

Papua New Guinean children, men and women show their support for putting an end to violence against women during a White Ribbon Day march

Papua New Guinea is often ranked as likely the worst place in the world for violence against women.[58][59] A 2013 study in The Lancet found that 27% of men on Bougainville Island reported having raped a non-partner, while 14.1% reported having committed gang rape.[60] According to UNICEF, nearly half of reported rape victims are under 15 years old, and 13% are under 7 years old.[61] A report by ChildFund Australia, citing former Parliamentarian Dame Carol Kidu, claimed 50% of those seeking medical help after rape are under 16, 25% are under 12, and 10% are under 8.[62] Under Dame Carol’s term as Minister for Community Development, Parliament passed the Family Protection Act (2013) and the Lukautim Pikini Act (2015), although the Family Protection Regulation was not approved until 2017, delaying its application in the Courts.[63][64]

The 1971 Sorcery Act imposed a penalty of up to 2 years in prison for the practice of «black» magic, until the act was repealed in 2013.[65] An estimated 50–150 alleged witches are killed each year in Papua New Guinea.[66] A Sorcery and Witchcraft Accusation Related National Action Plan (SNAP) was approved by the Government in 2015, although funding and application has been deficient.[67] There are also no protections given to LGBT citizens in the country. Homosexual acts are prohibited by law in Papua New Guinea.[68]

Royal PNG Constabulary[edit]

The Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary has been troubled in recent years by infighting, political interference and corruption. It was recognised from early after Independence (and hitherto) that a national police force alone could never have the capacity to administer law and order across the country, and that it would also require effective local level systems of policing and enforcement, notably the village court magisterial service.[69] The weaknesses of police capacity, poor working conditions and recommendations to address them were the subject of the 2004 Royal PNG Constabulary Administrative Review to the Minister for Internal Security.[70]

In 2011, Commissioner for Police Anthony Wagambie took the unusual step of asking the public to report police asking for payments for performing their duties.[71]

In September 2020, Minister for Police Bryan Jared Kramer launched a broadside on Facebook against his own police department,[72] which was subsequently reported in the international media.[73] In the post, Kramer accused the Royal PNG Constabulary of widespread corruption, claiming that «Senior officers based in Police Headquarters in Port Moresby were stealing from their own retired officers’ pension funds. They were implicated in organised crime, drug syndicates, smuggling firearms, stealing fuel, insurance scams, and even misusing police allowances. They misused tens of millions of kina allocated for police housing, resources, and welfare. We also uncovered many cases of senior officers facilitating the theft of Police land.»[72] Commissioner for Police David Manning, in a separate statement, said that his force included «criminals in uniform.»[73]

Administrative divisions[edit]

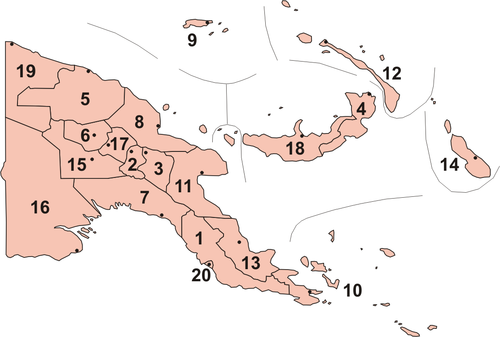

Papua New Guinea is divided into four regions, which are not the primary administrative divisions but are quite significant in many aspects of government, commercial, sporting and other activities. The nation has 22 province-level divisions: twenty provinces, the Autonomous Region of Bougainville and the National Capital District. Each province is divided into one or more districts, which in turn are divided into one or more Local-Level Government areas. Provinces[74] are the primary administrative divisions of the country. Provincial governments are branches of the national government as Papua New Guinea is not a federation of provinces. The province-level divisions are as follows:

|

|

Provinces of Papua New Guinea. |

In 2009, Parliament approved the creation of two additional provinces: Hela Province, consisting of part of the existing Southern Highlands Province, and Jiwaka Province, formed by dividing Western Highlands Province.[75] Jiwaka and Hela officially became separate provinces on 17 May 2012.[76] The declaration of Hela and Jiwaka is a result of the largest liquefied natural gas[77] project in the country that is situated in both provinces. The government set 23 November 2019[78] as the voting date for a non-binding[79] independence referendum in the Bougainville autonomous region.[80] In December 2019, the autonomous region voted overwhelmingly for independence, with 97.7% voting in favour of obtaining full independence and around 1.7% voting in favour of greater autonomy.[81]

Geography[edit]

Map of Papua New Guinea

At 462,840 km2 (178,704 sq mi), Papua New Guinea is the world’s 54th-largest country and the third-largest island country.[13] Papua New Guinea is part of the Australasian realm, which also includes Australia, New Zealand, eastern Indonesia, and several Pacific island groups, including the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. Including all its islands, it lies between latitudes 0° and 12°S, and longitudes 140° and 160°E. It has an exclusive economic zone of 2,402,288 km2 (927,529 sq mi). The mainland of the country is the eastern half of New Guinea island, where the largest towns are also located, including Port Moresby (capital) and Lae; other major islands within Papua New Guinea include New Ireland, New Britain, Manus and Bougainville.

Located north of the Australian mainland, the country’s geography is diverse and, in places, extremely rugged. A spine of mountains, the New Guinea Highlands, runs the length of the island of New Guinea, forming a populous highlands region mostly covered with tropical rainforest, and the long Papuan Peninsula, known as the ‘Bird’s Tail’. Dense rainforests can be found in the lowland and coastal areas as well as very large wetland areas surrounding the Sepik and Fly rivers. This terrain has made it difficult for the country to develop transportation infrastructure. Some areas are accessible only on foot or by aeroplane.[citation needed] The highest peak is Mount Wilhelm at 4,509 metres (14,793 ft). Papua New Guinea is surrounded by coral reefs which are under close watch, in the interests of preservation. Papua New Guinea’s largest rivers are in New Guinea and include Sepik, Ramu, Markham, Musa, Purari, Kikori, Turama, Wawoi and Fly.

The country is situated on the Pacific Ring of Fire, at the point of collision of several tectonic plates. Geologically, the island of New Guinea is a northern extension of the Indo-Australian tectonic plate, forming part of a single land mass which is Australia-New Guinea (also called Sahul or Meganesia). It is connected to the Australian segment by a shallow continental shelf across the Torres Strait, which in former ages lay exposed as a land bridge, particularly during ice ages when sea levels were lower than at present. As the Indo-Australian Plate (which includes landmasses of India, Australia, and the Indian Ocean floor in between) drifts north, it collides with the Eurasian Plate. The collision of the two plates pushed up the Himalayas, the Indonesian islands, and New Guinea’s Central Range. The Central Range is much younger and higher than the mountains of Australia, so high that it is home to rare equatorial glaciers.

There are several active volcanoes, and eruptions are frequent. Earthquakes are relatively common, sometimes accompanied by tsunamis. On 25 February 2018, an earthquake of magnitude 7.5 and depth of 35 kilometres struck the middle of Papua New Guinea.[82] The worst of the damage was centred around the Southern Highlands region.[83] Papua New Guinea is one of the few regions close to the equator that experience snowfall, which occurs in the most elevated parts of the mainland.

The border between Papua New Guinea and Indonesia was confirmed by treaty with Australia before independence in 1974.[84] The land border comprises a segment of the 141° E meridian from the north coast southwards to where it meets the Fly River flowing east, then a short curve of the river’s thalweg to where it meets the 141°01’10» E meridian flowing west, then southwards to the south coast.[84] The 141° E meridian formed the entire eastern boundary of Dutch New Guinea according to its 1828 annexation proclamation.[85] By the Treaty of The Hague (1895) the Dutch and British agreed to a territorial exchange, bringing the entire left bank of the Fly River into British New Guinea and moving the southern border east to the Torasi Estuary.[85] The maritime boundary with Australia was confirmed by a treaty in 1978.[86] In the Torres Strait it runs close to the mainland of New Guinea, keeping the adjacent North Western Torres Strait Islands (Dauan, Boigu and Saibai) under Australian sovereignty. Maritime boundaries with the Solomon Islands were confirmed by a 1989 treaty.

Biodiversity[edit]

Papua New Guinea’s highlands

Many species of birds and mammals found on New Guinea have close genetic links with corresponding species found in Australia. One notable feature in common for the two landmasses is the existence of several species of marsupial mammals, including some kangaroos and possums, which are not found elsewhere. Papua New Guinea is a megadiverse country.

Many of the other islands within PNG territory, including New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, the Admiralty Islands, the Trobriand Islands, and the Louisiade Archipelago, were never linked to New Guinea by land bridges. As a consequence, they have their own flora and fauna; in particular, they lack many of the land mammals and flightless birds that are common to New Guinea and Australia.

Australia and New Guinea are portions of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, which started to break into smaller continents in the Cretaceous period, 65–130 million years ago. Australia finally broke free from Antarctica about 45 million years ago. All the Australasian lands are home to the Antarctic flora, descended from the flora of southern Gondwana, including the coniferous podocarps and Araucaria pines, and the broad-leafed southern beech (Nothofagus). These plant families are still present in Papua New Guinea. New Guinea is part of the humid tropics, and many Indomalayan rainforest plants spread across the narrow straits from Asia, mixing together with the old Australian and Antarctic floras. New Guinea has been identified as the world’s most floristically diverse island in the world, with 13,634 known species of vascular plants.[87]

PNG includes a number of terrestrial ecoregions:

- Admiralty Islands lowland rain forests – forested islands to the north of the mainland, home to a distinct flora.

- Central Range montane rain forests

- Huon Peninsula montane rain forests

- Louisiade Archipelago rain forests

- New Britain-New Ireland lowland rain forests

- New Britain-New Ireland montane rain forests

- New Guinea mangroves

- Northern New Guinea lowland rain and freshwater swamp forests

- Northern New Guinea montane rain forests

- Solomon Islands rain forests (includes Bougainville Island and Buka)

- Southeastern Papuan rain forests

- Southern New Guinea freshwater swamp forests

- Southern New Guinea lowland rain forests

- Trobriand Islands rain forests

- Trans-Fly savanna and grasslands

- Central Range sub-alpine grasslands

Three new species of mammals were discovered in the forests of Papua New Guinea by an Australian-led expedition in the early 2010s. A small wallaby, a large-eared mouse and shrew-like marsupial were discovered. The expedition was also successful in capturing photographs and video footage of some other rare animals such as the Tenkile tree kangaroo and the Weimang tree kangaroo.[88] Nearly one quarter of Papua New Guinea’s rainforests were damaged or destroyed between 1972 and 2002.[89] Papua New Guinea had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.84/10, ranking it 17th globally out of 172 countries.[90] Mangrove swamps stretch along the coast, and in the inland it is inhabited by nipa palm (Nypa fruticans), and deeper in the inland the sago palm tree inhabits areas in the valleys of larger rivers. Trees such as oaks, red cedars, pines, and beeches are becoming predominant in the uplands above 3,300 feet. Papua New Guinea is rich in various species of reptiles, indigenous freshwater fish and birds, but it is almost devoid of large mammals.[91]

Climate[edit]

The climate on the island is essentially tropical, but it varies by region. The maximum mean temperature in the lowlands is 30 to 32 °C, and the minimum 23-24 °C. In the highlands above 2100 meters, colder conditions prevail and night frosts are common there, while the daytime temperature exceeds 22 °C, regardless of the season.[91]

Economy[edit]

A proportional representation of Papua New Guinea exports, 2019

Papua New Guinea is richly endowed with natural resources, including mineral and renewable resources, such as forests, marine resources (including a large portion of the world’s major tuna stocks), and in some parts agriculture. The rugged terrain—including high mountain ranges and valleys, swamps and islands—and high cost of developing infrastructure, combined with other factors (including law and order problems in some centres and the system of customary land title) makes it difficult for outside developers. Local developers are hindered by years of deficient investment in education, health, and access to finance. Agriculture, for subsistence and cash crops, provides a livelihood for 85% of the population and continues to provide some 30% of GDP. Mineral deposits, including gold, oil, and copper, account for 72% of export earnings. Oil palm production has grown steadily over recent years (largely from estates and with extensive outgrower output), with palm oil now the main agricultural export. Coffee remains the major export crop (produced largely in the Highlands provinces); followed by cocoa and coconut oil/copra from the coastal areas, each largely produced by smallholders; tea, produced on estates; and rubber. The Iagifu/Hedinia Field was discovered in 1986 in the Papuan fold and thrust belt.[92]: 471

Former Prime Minister Sir Mekere Morauta tried to restore integrity to state institutions, stabilise the kina, restore stability to the national budget, privatise public enterprises where appropriate, and ensure ongoing peace on Bougainville following the 1997 agreement which ended Bougainville’s secessionist unrest. The Morauta government had considerable success in attracting international support, specifically gaining the backing of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in securing development assistance loans.

As of 2019, PNG’s real GDP growth rate was 3.8%, with an inflation rate of 4.3%[93] This economic growth has been primarily attributed to strong commodity prices, particularly mineral but also agricultural, with the high demand for mineral products largely sustained even during the crisis by the buoyant Asian markets, a booming mining sector and by a buoyant outlook and the construction phase for natural gas exploration, production, and exportation in liquefied form (liquefied natural gas or «LNG») by LNG tankers, all of which will require multibillion-dollar investments (exploration, production wells, pipelines, storage, liquefaction plants, port terminals, LNG tanker ships).

The first major gas project was the PNG LNG joint venture. ExxonMobil is operator of the joint venture, also comprising PNG company Oil Search, Santos, Kumul Petroleum Holdings (Papua New Guinea’s national oil and gas company), JX Nippon Oil and Gas Exploration, the PNG government’s Mineral Resources Development Company and Petromin PNG Holdings.[94] The project is an integrated development that includes gas production and processing facilities in the Hela, Southern Highlands and Western Provinces of Papua New Guinea, including liquefaction and storage facilities (located northwest of Port Moresby) with capacity of 6.9 million tonnes per year. There are over 700 kilometres (430 mi) of pipelines connecting the facilities.[94] It is the largest private-sector investment in the history of PNG.[95] A second major project is based on initial rights held by the French oil and gas major TotalEnergies and the U.S. company InterOil Corp. (IOC), which have partly combined their assets after TotalEnergies agreed in December 2013 to purchase 61.3% of IOC’s Antelope and Elk gas field rights, with the plan to develop them starting in 2016, including the construction of a liquefaction plant to allow export of LNG. TotalEnergies has separately another joint operating agreement with Oil Search.

Further gas and mineral projects are proposed (including the large Wafi-Golpu copper-gold mine), with extensive exploration ongoing across the country.[96]

The PNG government’s long-term Vision 2050 and shorter-term policy documents, including the 2013 Budget and the 2014 Responsible Sustainable Development Strategy, emphasise the need for a more diverse economy, based upon sustainable industries and avoiding the effects of Dutch disease from major resource extraction projects undermining other industries, as has occurred in many countries experiencing oil or other mineral booms, notably in Western Africa, undermining much of their agriculture sector, manufacturing and tourism, and with them broad-based employment prospects. Measures have been taken to mitigate these effects, including through the establishment of a sovereign wealth fund, partly to stabilise revenue and expenditure flows, but much will depend upon the readiness to make real reforms to effective use of revenue, tackling rampant corruption and empowering households and businesses to access markets, services and develop a more buoyant economy, with lower costs, especially for small to medium-size enterprises. One major project conducted through the PNG Department for Community Development suggested that other pathways to sustainable development should be considered.[97]

The Institute of National Affairs, a PNG independent policy think tank, provides a report on the business and investment environment of Papua New Guinea every five years, based upon a survey of large and small, local and overseas companies, highlighting law and order problems and corruption, as the worst impediments, followed by the poor state of transport, power and communications infrastructure.[98][99]

Land tenure[edit]

The PNG legislature has enacted laws in which a type of tenure called «customary land title» is recognised, meaning that the traditional lands of the indigenous peoples have some legal basis to inalienable tenure. This customary land notionally covers most of the usable land in the country (some 97% of total land area);[100] alienated land is either held privately under state lease or is government land. Freehold title (also known as fee simple) can only be held by Papua New Guinean citizens.[101]

Only some 3% of the land of Papua New Guinea is in private hands; this is privately held under 99-year state lease, or it is held by the State. There is virtually no freehold title; the few existing freeholds are automatically converted to state lease when they are transferred between vendor and purchaser. Unalienated land is owned under customary title by traditional landowners. The precise nature of the seisin varies from one culture to another. Many writers portray land as in the communal ownership of traditional clans; however, closer studies usually show that the smallest portions of land whose ownership cannot be further divided are held by the individual heads of extended families and their descendants or their descendants alone if they have recently died.[citation needed]

This is a matter of vital importance because a problem of economic development is identifying the membership of customary landowning groups and the owners. Disputes between mining and forestry companies and landowner groups often devolve on the issue of whether the companies entered into contractual relations for the use of land with the true owners. Customary property—usually land—cannot be devised by will. It can only be inherited according to the custom of the deceased’s people.[citation needed] The Lands Act was amended in 2010 along with the Land Group Incorporation Act, intended to improve the management of state land, mechanisms for dispute resolution over land, and to enable customary landowners to be better able to access finance and possible partnerships over portions of their land, if they seek to develop it for urban or rural economic activities. The Land Group Incorporation Act requires more specific identification of the customary landowners than hitherto and their more specific authorisation before any land arrangements are determined; (a major issue in recent years has been a land grab, using, or rather misusing, the Lease-Leaseback provision under the Land Act, notably using ‘Special Agricultural and Business Leases’ (SABLs) to acquire vast tracts of customary land, purportedly for agricultural projects, but in an almost all cases as a back-door mechanism for securing tropical forest resources for logging—circumventing the more exacting requirements of the Forest Act, for securing Timber Permits (which must comply with sustainability requirements and be competitively secured, and with the customary landowners approval). Following a national outcry, these SABLs have been subject to a Commission of Inquiry, established in mid-2011, for which the report is still awaited for initial presentation to the Prime Minister and Parliament.

Gold discovery[edit]

Traces of gold were first found in 1852, in pottery from Redscar Bay on the Papuan Peninsula.[102]

Demographics[edit]

| Population[103][104] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Million |

| 1950 | 1.7 |

| 2000 | 5.6 |

| 2021 | 9.9 |

Papua New Guinea is one of the most heterogeneous nations in the world[105] with an estimated 8.95 million inhabitants as of 2020.[106] There are hundreds of ethnic groups indigenous to Papua New Guinea, the majority being from the group known as Papuans, whose ancestors arrived in the New Guinea region tens of thousands of years ago. The other indigenous peoples are Austronesians, their ancestors having arrived in the region less than four thousand years ago.

There are also numerous people from other parts of the world now resident, including Chinese,[107] Europeans, Australians, Indonesians, Filipinos, Polynesians, and Micronesians (the last four belonging to the Austronesian family). Around 40,000 expatriates, mostly from Australia and China, were living in Papua New Guinea in 1975.[108] 20,000 people from Australia currently live in Papua New Guinea.[109] They represent 0.25% of the total population of Papua New Guinea.

With the National Census deferred during 2020/2021, ostensibly on the grounds of the Covid-19 pandemic, an interim assessment was conducted using satellite imagery. In December 2022, a report by the UN, based upon this survey was conducted with the University of Southampton using satellite imagery and ground-truthing, suggested a new population estimate of 17 million, nearly double the country’s official estimate.[16]

Urbanisation[edit]

According to the CIA World Factbook (2018),[110] Papua New Guinea has the second lowest urban population percentage in the world, with 13.2%, only behind Burundi. The geography and economy of Papua New Guinea are the main factors behind the low percentage. Papua New Guinea has an urbanisation rate of 2.51%, measured as the projected change in urban population from 2015 to 2020.

|

Largest cities and towns in Papua New Guinea www.geonames.org/PG/largest-cities-in-papua-new-guinea.html |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | |

Port Moresby  Lae |

1 | Port Moresby | National capital district | 283,733 |

| 2 | Lae | Morobe | 76,255 | |

| 3 | Arawa | Bougainville | 40,266 | |

| 4 | Mount Hagen | Western Highlands | 33,623 | |

| 5 | Popondetta | Northern Province | 28,198 | |

| 6 | Madang | Madang | 27,419 | |

| 7 | Kokopo | East New Britain | 26,273 | |

| 8 | Mendi | Southern Highlands | 26,252 | |

| 9 | Kimbe | West New Britain | 18,847 | |

| 10 | Goroka | Eastern Highlands | 18,503 |

Languages[edit]

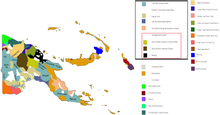

The language families of Papua New Guinea, according to Timothy Usher

The language families in Ross’s conception of the Trans-New Guinea language family. The affiliation of some Eastern branches is not universally accepted.

Papua New Guinea has more languages than any other country,[111] with over 820 indigenous languages, representing 12% of the world’s total, but most have fewer than 1,000 speakers. With an average of only 7,000 speakers per language, Papua New Guinea has a greater density of languages than any other nation on earth except Vanuatu.[112][113] The most widely spoken indigenous language is Enga, with about 200,000 speakers, followed by Melpa and Huli.[114] Indigenous languages are classified into two large groups, Austronesian languages and non-Austronesian, or Papuan, languages. There are four languages in Papua New Guinea with some statutory recognition: English, Tok Pisin, Hiri Motu,[115] and, since 2015, sign language (which in practice means Papua New Guinean Sign Language).

English is the language of government and the education system, but it is not spoken widely. The primary lingua franca of the country is Tok Pisin (commonly known in English as New Guinean Pidgin or Melanesian Pidgin), in which much of the debate in Parliament is conducted, many information campaigns and advertisements are presented, and a national weekly newspaper, Wantok, is published. The only area where Tok Pisin is not prevalent is the southern region of Papua, where people often use the third official language, Hiri Motu. Although it lies in the Papua region, Port Moresby has a highly diverse population which primarily uses Tok Pisin, and to a lesser extent English, with Motu spoken as the indigenous language in outlying villages.

Health[edit]

Life expectancy in Papua New Guinea at birth was 64 years for men in 2016 and 68 for women.[116] Government expenditure health in 2014 accounted for 9.5% of total government spending, with total health expenditure equating to 4.3% of GDP.[117] There were five physicians per 100,000 people in the early 2000s.[118] The 2010 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Papua New Guinea was 250. This is compared with 311.9 in 2008 and 476.3 in 1990. The under-5 mortality rate, per 1,000 births is 69 and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under-5s’ mortality is 37. In Papua New Guinea, the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is 1 and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women is 1 in 94.[119]

Religion[edit]

Citizen population in Papua New Guinea by religion, based on the 2011 census[120]

Kwato Church (0.2%)

Other Christian (5.1%)

Non Christian (1.4%)

Not stated (3.1%)

The government and judiciary uphold the constitutional right to freedom of speech, thought, and belief, and no legislation to curb those rights has been adopted. The 2011 census found that 95.6% of citizens identified themselves as Christian, 1.4% were not Christian, and 3.1% gave no answer. Virtually no respondent identified as being nonreligious. Religious syncretism is high, with many citizens combining their Christian faith with some traditional indigenous religious practices.[121] Most Christians in Papua New Guinea are Protestants, constituting roughly 70% of the total population. They are mostly represented by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, diverse Pentecostal denominations, the United Church in Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands, the Evangelical Alliance Papua New Guinea, and the Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea. Apart from Protestants, there is a notable Roman Catholic minority with approximately 25% of the population.

There are approximately 5,000 Muslims in the country. The majority belong to the Sunni group, while a small number are Ahmadi. Non-traditional Christian churches and non-Christian religious groups are active throughout the country. The Papua New Guinea Council of Churches has stated that both Muslim and Confucian missionaries are highly active.[122][123] Traditional religions are often animist. Some also tend to have elements of veneration of the dead, though generalisation is suspect given the extreme heterogeneity of Melanesian societies. Prevalent among traditional tribes is the belief in masalai, or evil spirits, which are blamed for «poisoning» people, causing calamity and death, and the practice of puripuri (sorcery).[124][125]

The first Bahá’í in PNG was Violete Hoenke who arrived at Admiralty Island, from Australia, in 1954. The PNG Bahá’í community grew so quickly that in 1969 a National Spiritual Assembly (administrative council) was elected. As of 2020 there are over 30,000 members of the Bahá’í Faith in PNG. In 2012 the decision was made to erect the first Bahá’í House of Worship in PNG. Its design is that of a woven basket, a common feature of all groups and cultures in PNG. It is, therefore, hoped to be a symbol for the entire country. Its nine entrances are inspired by the design of Haus Tambaran (Spirit House). Construction began in Port Moresby in 2018.

Culture[edit]

A resident of Boga-Boga, a village on the southeast coast of mainland Papua New Guinea

A 20th-century wooden Abelam ancestor figure (nggwalndu)

It is estimated that more than one thousand cultural groups exist in Papua New Guinea. Because of this diversity, many styles of cultural expression have emerged. Each group has created its own expressive forms in art, dance, weaponry, costumes, singing, music, architecture and much more. Most of these cultural groups have their own language. People typically live in villages that rely on subsistence farming. In some areas people hunt and collect wild plants (such as yam roots and karuka) to supplement their diets. Those who become skilled at hunting, farming and fishing earn a great deal of respect.

Seashells are no longer the currency of Papua New Guinea, as they were in some regions—sea shells were abolished as currency in 1933. This tradition is still present in local customs. In some cultures, to get a bride, a groom must bring a certain number of golden-edged clam shells[126] as a bride price. In other regions, the bride price is paid in lengths of shell money, pigs, cassowaries or cash. Elsewhere, it is brides who traditionally pay a dowry.

People of the highlands engage in colourful local rituals that are called «sing sings.» They paint themselves and dress up with feathers, pearls and animal skins to represent birds, trees or mountain spirits. Sometimes an important event, such as a legendary battle, is enacted at such a musical festival.

The country possesses one UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Kuk Early Agricultural Site, which was inscribed in 2008. The country, however, has no elements inscribed yet in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists, despite having one of the widest array of intangible cultural heritage elements in the world.[127][128]

Sport[edit]

Sport is an important part of Papua New Guinean culture, and rugby league is by far the most popular sport.[129] In a nation where communities are far apart and many people live at a minimal subsistence level, rugby league has been described as a replacement for tribal warfare as a way of explaining the local enthusiasm for the game. Many Papua New Guineans have become celebrities by representing their country or playing in an overseas professional league. Even Australian rugby league players who have played in the annual State of Origin series, which is celebrated every year in PNG, are among the most well-known people throughout the nation. State of Origin is a highlight of the year for most Papua New Guineans, although the support is so passionate that many people have died over the years in violent clashes supporting their team.[130] The Papua New Guinea national rugby league team usually plays against the Australian Prime Minister’s XIII (a selection of NRL players) each year, normally in Port Moresby.

Although not as popular, Australian rules football is more significant in another way, as the national team is ranked second, only after Australia. Other major sports which have a part in the Papua New Guinea sporting landscape are association football, rugby union, basketball and, in eastern Papua, cricket.

Education[edit]

A large proportion of the population is illiterate,[131] with women predominating in this area.[131] Much of the education in PNG is provided by church institutions.[132] This includes 500 schools of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea.[133] Papua New Guinea has six universities as well as other tertiary institutions. The two founding universities are the University of Papua New Guinea, based in the National Capital District,[134] and the Papua New Guinea University of Technology, based outside of Lae, in Morobe Province.

The four other universities were once colleges but have since been recognized by the government. These are the University of Goroka in the Eastern Highlands province, Divine Word University (run by the Catholic Church’s Divine Word Missionaries) in Madang Province, Vudal University in East New Britain Province, and Pacific Adventist University (run by the Seventh-day Adventist Church) in the National Capital District.

Science and technology[edit]

Papua New Guinea’s National Vision 2050 was adopted in 2009. This has led to the establishment of the Research, Science and Technology Council. At its gathering in November 2014, the Council re-emphasised the need to focus on sustainable development through science and technology.[135]

Vision 2050‘s medium-term priorities are:[135]

- emerging industrial technology for downstream processing;

- infrastructure technology for the economic corridors;

- knowledge-based technology;

- science and engineering education; and

- to reach the target of investing 5% of GDP in research and development by 2050. (Papua New Guinea invested 0.03% of GDP in research and development in 2016.[136])

In 2016, women accounted for 33.2% of researchers in Papua New Guinea.[136]

According to Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science, Papua New Guinea had the largest number of publications (110) among Pacific Island states in 2014, followed by Fiji (106). Nine out of ten scientific publications from Papua New Guinea focused on immunology, genetics, biotechnology and microbiology. Nine out of ten were also co-authored by scientists from other countries, mainly Australia, the United States of America, United Kingdom, Spain and Switzerland.[135]

In 2019, Papua New Guinea took second place among Pacific Island states with 253 publications, behind Fiji with 303 publications, in the Scopus (Elsevier) database of scientific publications.[136] Health sciences accounted for 49% of these publications.[136] Papua New Guinea’s top scientific collaborators over 2017 to 2019 were Australia, the United States of America, United Kingdom, France and India.[136]

Forestry is an important economic resource for Papua New Guinea, but the industry uses low and semi-intensive technological inputs. As a result, product ranges are limited to sawed timber, veneer, plywood, block board, moulding, poles and posts and wood chips. Only a few limited finished products are exported. Lack of automated machinery, coupled with inadequately trained local technical personnel, are some of the obstacles to introducing automated machinery and design.[135]

Renewable energy sources represent two-thirds of the total electricity supply.[135] In 2015, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community observed that, ‘while Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and Samoa are leading the way with large-scale hydropower projects, there is enormous potential to expand the deployment of other renewable energy options such as solar, wind, geothermal and ocean-based energy sources’.[137] The European Union funded the Renewable Energy in Pacific Island Countries Developing Skills and Capacity programme (EPIC) over 2013 to 2017. The programme developed a master’s programme in renewable energy management, accredited in 2016, at the University of Papua New Guinea and helped to establish a Centre of Renewable Energy at the same university.[136]

Papua New Guinea is one of the 15 beneficiaries of a programme on Adapting to Climate Change and Sustainable Energy worth €37.26 million. The programme resulted from the signing of an agreement in February 2014 between the European Union and the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. The other beneficiaries are the Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu.[135]

Transport[edit]

The country’s mountainous terrain impedes transport. Aeroplanes opened up the country during its colonial period and continue to be used for most travel and for most high density/value freight. The capital, Port Moresby, has no road links to any of PNG’s other major towns. Similarly, many remote villages are reachable only by light aircraft or on foot.

Jacksons International Airport is the major international airport in Papua New Guinea, located 8 kilometres (5 mi) from Port Moresby. In addition to two international airfields, Papua New Guinea has 578 airstrips, most of which are unpaved.[3]

See also[edit]

- Economy of Papua New Guinea

- Outline of Papua New Guinea

- Western New Guinea

References[edit]

- ^ Somare, Michael (6 December 2004). «Stable Government, Investment Initiatives, and Economic Growth». Keynote address to the 8th Papua New Guinea Mining and Petroleum Conference. Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ «Never more to rise». The National. 6 February 2006. Archived from the original on 13 July 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2005.

- ^ a b «Papua New Guinea». The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ «Sign language becomes an official language in PNG». Radio New Zealand. 21 May 2015.

- ^ a b Papua New Guinea, Ethnologue

- ^ Koloma. Kele, Roko. Hajily. «PAPUA NEW GUINEA 2011 NATIONAL REPORT-NATIONAL STATISTICAL OFFICE». sdd.spc.int.

- ^ «2011 National Population and Housing Census of Papua New Guinea – Final Figures». National Statistical Office of Papua New Guinea. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d «World Economic Outlook Database, October 2018». IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ «GINI index (World Bank estimate)». data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ «Human Development Report 2021/2022» (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- ^ «Constitution of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea» (PDF).

- ^ a b «Island Countries of the World». WorldAtlas.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ «Urban population (% of total population) — Papua New Guinea». data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ James, Paul; Nadarajah, Yaso; Haive, Karen; Stead, Victoria (2012). Sustainable Communities, Sustainable Development: Other Paths for Papua New Guinea. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ a b Lagan, Bernard (5 December 2022). «Papua New Guinea finds real population is almost double official estimates». The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Fildes, Nic (5 December 2022). «Papua New Guinea’s population size puzzles prime minister and experts». Financial Times. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Gelineau, Kristen (26 March 2009). «Spiders and frogs identified among 50 new species». The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ World Economic Outlook Database, October 2015, International Monetary Fund. Database updated on 6 October 2015. Accessed on 6 October 2015.

- ^ World Bank. 2010. World Development Indicators. Washington DC.

- ^ «Constitution of Independent State of Papua New Guinea (consol. to amendment #22)». Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 16 July 2005.

- ^ «Papua New Guinea keen to join ASEAN». The Brunei Times. 7 March 2016. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^ «Profile: The Commonwealth». 1 February 2012 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ «About Us – Forum Sec».

- ^ Pickell, David & Müller, Kal (2002). Between the Tides: A Fascinating Journey among the Kamoro of New Guinea. Tuttle Publishing. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-7946-0072-3.

- ^ O’Connell, J. F., and J. Allen. «Pre-LGM Sahul (Australia-New Guinea) and the archaeology of early modern humans», Rethinking the human revolution: new behavioural and biological perspectives on the origin and dispersal of modern humans (2007): 395–410.

- ^ Klein, Christopher (23 September 2016). «DNA Study Finds Aboriginal Australians World’s Oldest Civilization». History.

Updated Aug 22, 2018

- ^ Carl Zimmer (22 December 2010). «Denisovans Were Neanderthals’ Cousins, DNA Analysis Reveals». NYTimes.com.

- ^ Diamond, J. (March 1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03891-2.

- ^ Swadling, p. 282

- ^ Knauft, Bruce M. (1999) From Primitive to Postcolonial in Melanesia and Anthropology. University of Michigan Press. p. 103. ISBN 0-472-06687-0

- ^ «Cannibalism Normal For Early Humans?.» National Geographic News. 10 April 2003.

- ^ Goldman, Laurence (1999).The Anthropology of Cannibalism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 19. ISBN 0-89789-596-7

- ^ Torgovnick, Marianna (1991). Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives, University of Chicago Press. p. 258 ISBN 0-226-80832-7

- ^ Swadling: «Such trade links and the nominal claim of the Sultan of Ceram over New Guinea constituted the legal basis for the Netherlands’ claim over West New Guinea and ultimately that of Indonesia over what is new West Papua.»

- ^ Fenton, Damien. «How many died? (QnA)». Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Australian War Memorial. - ^ «United Nations Official Document». www.un.org.

- ^ «New report doubles death toll on Bougainville to 20,000.» Radio Australia. 19 March 2012.

- ^ Lyons, Kate (11 December 2019). «Bougainville referendum: region votes overwhelmingly for independence from Papua New Guinea». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Callick, Rowan (23 May 2009). «Looters shot dead amid chaos of Papua New Guinea’s anti-Chinese riots». The Australian. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ «Overseas and under siege», The Economist, 11 August 2009

- ^ «Leaders of African, Caribbean and Pacific Countries to meet in Papua New Guinea for pivotal summit this month | ACP». www.acp.int. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ «Earthquake leaves 3,000 homeless». smh.com.au. 10 September 2002.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (5 April 2018). «Papua New Guinea earthquake: UN pulls out aid workers from violence-hit region». the Guardian.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (8 March 2018). «Papua New Guinea earthquake: anger grows among ‘forgotten victims’«. the Guardian.

- ^ «Volunteers lead desperate bid to reach Papua New Guinea quake victims». Agence France-Presse. CNA. 13 September 2022. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Bradford, Sarah (1997). Elizabeth: A Biography of Britain’s Queen. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1-57322-600-4.

- ^ «Papua New Guinea MPs elect James Marape to be next prime minister». The Guardian. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ «Davis Steven named Deputy PM». PNG Report. 9 June 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ «James Marape returned as PNG’s prime minister after tense election». ABC News. 9 August 2022.

- ^ «highlights of general Election 2022». the National. 30 December 2022.

- ^ Papua New Guinea Constitution Schedule 2.2.2

- ^ Namorong, Martyn (3 March 2017). «Can the next #PNG Government do better on West Papua?».

- ^ Doherty, Ben; Lamb, Kate (30 September 2017). «West Papua independence petition is rebuffed at UN». The Guardian.

- ^ Gawler, Virginia (19 August 2005). «Report claims secret genocide in Indonesia». University of Sydney.

- ^ «Goodbye Indonesia». Al-Jazeera. 31 January 2013.

- ^ Mench, Paul (1975). The Role of the Papua New Guinea Defence Force. Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-909150-10-5.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (5 July 2013). «Médecins Sans Frontières opens Papua New Guinea clinic for abuse victims». Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (19 July 2013). «Papua New Guinea: a country suffering spiralling violence». Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Jewkes, Rachel; Fulu, Emma; Roselli, Tim; Garcia-Moreno, Claudia (2013). «Prevalence of and factors associated with non-partner rape perpetration: findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific». The Lancet. 323 (4): e208-18. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70069-X. PMID 25104346.

- ^ «UNICEF strives to help Papua New Guinea break cycle of violence». UNICEF. 18 August 2008. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Wiseman H (August 2013). «Stop Violence Against Women and Children in Papua New Guinea» (PDF). ChildFund. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ «No. 45 of 2015 Lukautim Pikinini Act 2015» (PDF). National Parliament of Papua New Guinea. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ «Survivors have legal rights: Family Protection Act». Loop PNG. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ «PNG repeals sorcery law and expands death penalty». BBC News. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ Oakford, Samuel (6 January 2015). «Papua New Guinea’s ‘Sorcery Refugees’: Women Accused of Witchcraft Flee Homes to Escape Violence». Vice News. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ Kuku, Rebecca (14 November 2020). «‘They just slaughter them’: how sorcery violence spreads fear across Papua New Guinea». The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ ««The state of gay rights around the world». The Washington Post. 14 June 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ Clifford, William; Morauta, Louise; Stuart, Barry (September 1984). Law and Order in Papua New Guinea. Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea: Institute of National Affairs. ISBN 9980770023.

- ^ «RPNGC Administrative Review» (PDF). Government of Papua New Guinea and the Institute of National Affairs. September 2004.

- ^ Fox, Liam (18 July 2011). «PNG top cop says no to bribe police». ABC News (Australia). Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ a b «One year in — why so quiet?». Facebook. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ a b Doherty, Ben (18 September 2020). «Papua New Guinea police accused of gun running and drug smuggling by own Minister». The Guardian. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ The Constitution of Papua New Guinea sets out the names of the 19 provinces at the time of Independence. Several provinces have changed their names; such changes are not strictly speaking official without a formal constitutional amendment, though «Oro,» for example, is universally used in reference to that province.

- ^ Kolo, Pearson (15 July 2009). «Jiwaka, Hela set to go!». Postcourier.com.pg. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011.

- ^ «Hela, Jiwaka declared». The National (Papua New Guinea). 17 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ LNG

- ^ Gorethy, Kenneth (5 August 2019). «B’ville Referendum Dates Changed». Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ «Bougainville referendum not binding — PM». Radio New Zealand. 11 March 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Westbrook, Tom (1 March 2019). «Bougainville independence vote delayed to October». Reuters. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ «Bougainville referendum: PNG region votes overwhelmingly for independence». BBC News. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ «Major earthquake strikes Papua New Guinea». CBC News. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ «State of Emergency declared as PNG earthquake toll rises to 31». SBS News. Sydney, NSW. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ a b «Agreement between Australia and Indonesia concerning Certain Boundaries between Papua New Guinea and Indonesia (1974) ATS 26». www3.austlii.edu.au. Austraasian Legal Information Institute, Australian Treaties Library. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ a b Van der Veur, Paul W. (2012) [1966]. Documents and Correspondence on New Guinea’s Boundaries. Springer Science & Business Media. §§ A1, D1–D5. ISBN 9789401537063.

- ^ «Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the area between the two Countries, including the area known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters [1985] ATS 4». www3.austlii.edu.au. Australasian Legal Information Institute, Australian Treaties Library. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ Cámara-Leret; Frodin; Adema (2020). «New Guinea has the world’s richest island flora». Nature. 584 (7822): 579–583. Bibcode:2020Natur.584..579C. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2549-5. PMID 32760001. S2CID 220980697.

- ^ Australian Geographic (July 2014). «New and rare species found in remote PNG».

- ^ «Satellite images uncover rapid PNG deforestation.» ABC News. 2 June 2008.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). «Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity — Supplementary Material». Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ a b «Papua New Guinea — Climate». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Matzke, R.H., Smith, J.G., and Foo, W.K., 1992, Iagifu/Hedinia Field, In Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade, 1978–1988, AAPG Memoir 54, Halbouty, M.T., editor, Tulsa: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, ISBN 0-89181-333-0

- ^ «Data». www.imf.org. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ a b «Papua New Guinea». ExxonMobil. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ «Voters in Papua New Guinea head to the polls». The Economist. 29 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ «Project Overview». pnglng.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ James, P.; Nadarajah, Y.; Haive, K. and Stead, V. (2012) Sustainable Communities, Sustainable Development: Other Paths for Papua New Guinea, Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ [1] Institute of National Affairs (2013)

- ^ [2] Institute of National Affairs (2018).

- ^ Armitage, Lynne. «Customary Land Tenure in Papua New Guinea: Status and Prospects». Queensland University of Technology. Retrieved 15 July 2005.

- ^ HBW International Inc. (10 September 2003). «Facilitating Foreign Investment through Property Lease Options» (PDF). p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

- ^ Exploration for gold / Papua New Guinea: forty years of independence, State Library of NSW, Australia, 16 December 2019, retrieved 16 June 2022,