|

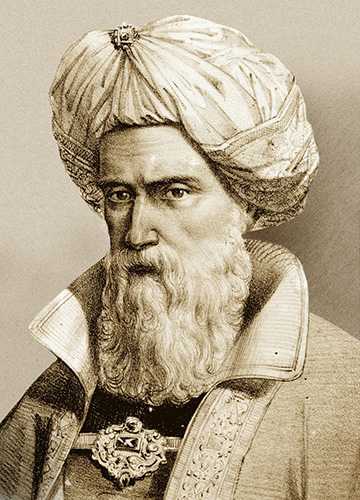

Avicenna |

|

|---|---|

|

ابن سینا |

|

Portrait of Avicenna on an Iranian postage stamp |

|

| Born | 980

Afshana, Transoxiana, Samanid Empire |

| Died | 22 June 1037 (aged 56–57)[1]

Hamadan, Kakuyid dynasty |

| Monuments | Avicenna Mausoleum |

| Other names |

|

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Middle Eastern philosophy

|

| School | Aristotelianism, Avicennism |

|

Main interests |

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

Ibn Sina (Persian: ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian[4] polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic Golden Age,[5] and the father of early modern medicine.[6][7][8] Sajjad H. Rizvi has called Avicenna «arguably the most influential philosopher of the pre-modern era».[9] He was a Muslim Peripatetic philosopher influenced by Greek Aristotelian philosophy. Of the 450 works he is believed to have written, around 240 have survived, including 150 on philosophy and 40 on medicine.[10]

His most famous works are The Book of Healing, a philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and The Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia[11][12][13] which became a standard medical text at many medieval universities[14] and remained in use as late as 1650.[15] Besides philosophy and medicine, Avicenna’s corpus includes writings on astronomy, alchemy, geography and geology, psychology, Islamic theology, logic, mathematics, physics, and works of poetry.[16]

Name

Avicenna is a Latin corruption of the Arabic patronym Ibn Sīnā (ابن سينا),[17] meaning «Son of Sina». However, Avicenna was not the son but the great-great-grandson of a man named Sina.[18] His formal Arabic name was Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn bin ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Ḥasan bin ʿAlī bin Sīnā al-Balkhi al-Bukhari (أبو علي الحسين بن عبد الله بن الحسن بن علي بن سينا البلخي البخاري).[19][20]

Circumstances

Avicenna created an extensive corpus of works during what is commonly known as the Islamic Golden Age, in which the translations of Byzantine Greco-Roman, Persian and Indian texts were studied extensively. Greco-Roman (Mid- and Neo-Platonic, and Aristotelian) texts translated by the Kindi school were commented, redacted and developed substantially by Islamic intellectuals, who also built upon Persian and Indian mathematical systems, astronomy, algebra, trigonometry and medicine.[21]

The Samanid dynasty in the eastern part of Persia, Greater Khorasan and Central Asia as well as the Buyid dynasty in the western part of Persia and Iraq provided a thriving atmosphere for scholarly and cultural development. Under the Samanids, Bukhara rivaled Baghdad as a cultural capital of the Islamic world.[22] There, Avicenna had access to the great libraries of Balkh, Khwarezm, Gorgan, Rey, Isfahan and Hamadan.

Various texts (such as the ‘Ahd with Bahmanyar) show that Avicenna debated philosophical points with the greatest scholars of the time. Aruzi Samarqandi describes how before Avicenna left Khwarezm he had met Al-Biruni (a famous scientist and astronomer), Abu Nasr Iraqi (a renowned mathematician), Abu Sahl Masihi (a respected philosopher) and Abu al-Khayr Khammar (a great physician). The study of the Quran and the Hadith also thrived, and Islamic philosophy, fiqh and theology (kalaam) were all further developed by Avicenna and his opponents at this time.

Biography

Early life and education

Avicenna was born in c. 980 in the village of Afshana in Transoxiana to a family of Persian stock.[23] The village was near the Samanid capital of Bukhara, which was his mother’s hometown.[24] His father Abd Allah was a native of the city of Balkh in Tukharistan.[25] An official of the Samanid bureaucracy, he had served as the governor of a village of the royal estate of Harmaytan (near Bukhara) during the reign of Nuh II (r. 976–997).[25] Avicenna also had a younger brother. A few years later, the family settled in Bukhara, a center of learning, which attracted many scholars. It was there that Avicenna was educated, which early on was seemingly administered by his father.[26][27][28] Although both Avicenna’s father and brother had converted to Ismailism, he himself did not follow the faith.[29][30] He was instead an adherent of the Sunni Hanafi school, which was also followed by the Samanids.[31]

Avicenna was first schooled in the Quran and literature, and by the age of 10, he had memorized the entire Quran.[27] He was later sent by his father to an Indian greengrocer, who taught him arithmetic.[32] Afterwards, he was schooled in Jurisprudence by the Hanafi jurist Ismail al-Zahid. Some time later, Avicenna’s father invited the physician and philosopher Abu Abdallah al-Natili to their house to educate Avicenna.[27][28] Together, they studied the Isagoge of Porphyry (died 305) and possibly the Categories of Aristotle (died 322 BC) as well. After Avicenna had read the Almagest of Ptolemy (died 170) and Euclid’s Elements, Natili told him to continue his research independently.[28] By the time Avicenna was eighteen, he was well-educated in Greek sciences. Although Avicenna only mentions Natili as his teacher in his autobiography, he most likely had other teachers as well, such as the physicians Abu Mansur Qumri and Abu Sahl al-Masihi.[26][32]

Career

In Bukhara and Gurganj

At the age of seventeen, Avicenna was made a physician of Nuh II. By the time Avicenna was at least 21 years old, his father died. He was subsequently given an administrative post, possibly succeeding his father as the governor of Harmaytan. Avicenna later moved to Gurganj, the capital of Khwarazm, which he reports that he did due to «necessity». The date he went to the place is uncertain, as he reports that he served the Khwarazmshah (ruler) of the region, the Ma’munid Abu al-Hasan Ali. The latter ruled from 997 to 1009, which indicates that Avicenna moved sometime during that period. He may have moved in 999, the year which the Samanid state fell after the Turkic Qarakhanids captured Bukhara and imprisoned the Samanid ruler Abd al-Malik II. Due to his high position and strong connection with the Samanids, Avicenna may have found himself in an unfavorable position after the fall of his suzerain.[26] It was through the minister of Gurganj, Abu’l-Husayn as-Sahi, a patron of Greek sciences, that Avicenna entered into the service of Abu al-Hasan Ali.[33] Under the Ma’munids, Gurganj became a centre of learning, attracting many prominent figures, such as Avicenna and his former teacher Abu Sahl al-Masihi, the mathematician Abu Nasr Mansur, the physician Ibn al-Khammar, and the philologist al-Tha’alibi.[34][35]

In Gurgan

Avicenna later moved due to «necessity» once more (in 1012), this time to the west. There he travelled through the Khurasani cities of Nasa, Abivard, Tus, Samangan and Jajarm. He was planning to visit the ruler of the city of Gurgan, the Ziyarid Qabus (r. 977–981, 997–1012), a cultivated patron of writing, whose court attracted many distinguished poets and scholars. However, when Avicenna eventually arrived, he discovered that the ruler had been dead since the winter of 1013.[26][36] Avicenna then left Gurgan for Dihistan, but returned after becoming ill. There he met Abu ‘Ubayd al-Juzjani (died 1070) who became his pupil and companion.[26][37] Avicenna stayed briefly in Gurgan, reportedly serving Qabus’ son and successor Manuchihr (r. 1012–1031) and resided in the house of a patron.[26]

In Ray and Hamadan

In c. 1014, Avicenna went to the city of Ray, where he entered into the service of the Buyid amir (ruler) Majd al-Dawla (r. 997–1029) and his mother Sayyida Shirin, the de facto ruler of the realm. There he served as the physician at the court, treating Majd al-Dawla, who was suffering from melancholia. Avicenna reportedly later served as the «business manager» of Sayyida Shirin in Qazvin and Hamadan, though details regarding this tenure are unclear.[26][38] During this period, Avicenna finished his Canon of Medicine, and started writing his Book of Healing.[38]

In 1015, during Avicenna’s stay in Hamadan, he participated in a public debate, as was custom for newly arrived scholars in western Iran at that time. The purpose of the debate was to examine one’s reputation against a prominent local resident.[39] The person whom Avicenna debated against was Abu’l-Qasim al-Kirmani, a member of the school of philosophers of Baghdad.[40] The debate became heated, resulting in Avicenna accusing Abu’l-Qasim of lack of basic knowledge in logic, while Abu’l-Qasim accused Avicenna of impoliteness.[39] After the debate, Avicenna sent a letter to the Baghdad Peripatetics, asking if Abu’l-Qasim’s claim that he shared the same opinion as them was true. Abu’l-Qasim later retaliated by writing a letter to an unknown person, in which he made accusations so serious, that Avicenna wrote to a deputy of Majd al-Dawla, named Abu Sa’d, to investigate the matter. The accusation made towards Avicenna may have been the same as he had received earlier, in which he was accused by the people of Hamadan of copying the stylistic structures of the Quran in his Sermons on Divine Unity.[41] The seriousness of this charge, in the words of the historian Peter Adamson, «cannot be underestimated in the larger Muslim culture.»[42]

Not long afterwards, Avicenna shifted his allegiance to the rising Buyid amir Shams al-Dawla (the younger brother of Majd al-Dawla), which Adamson suggests was due to Abu’l-Qasim also working under Sayyida Shirin.[43][44] Avicenna had been called upon by Shams al-Dawla to treat him, but after the latters campaign in the same year against his former ally, the Annazid ruler Abu Shawk (r. 1010–1046), he forced Avicenna to become his vizier.[45] Although Avicenna would sometimes clash with Shams al-Dawla’s troops, he remained vizier until the latter died of colic in 1021. Avicenna was asked by Shams al-Dawla’s son and successor Sama’ al-Dawla (r. 1021–1023) to stay as vizier, but instead went into hiding with his patron Abu Ghalib al-Attar, to wait for better opportunities to emerge. It was during this period that Avicenna was secretly in contact with Ala al-Dawla Muhammad (r. 1008–1041), the Kakuyid ruler of Isfahan and uncle of Sayyida Shirin.[26][46][47]

It was during his stay at Attar’s home that Avicenna completed his Book of Healing, writing 50 pages a day.[48] The Buyid court in Hamadan, particularly the Kurdish vizier Taj al-Mulk, suspected Avicenna of correspondence with Ala al-Dawla, and as result had the house of Attar ransacked and Avicenna imprisoned in the fortress of Fardajan, outside Hamadan. Juzjani blames one of Avicenna’s informers for his capture. Avicenna was imprisoned for four months, until Ala al-Dawla captured Hamadan, thus putting an end to Sama al-Dawla’s reign.[26][49]

In Isfahan

Avicenna was subsequently released, and went to Isfahan, where he was well received by Ala al-Dawla. In the words of Juzjani, the Kakuyid ruler gave Avicenna «the respect and esteem which someone like him deserved.»[26] Adamson also says that Avicenna’s service under Ala al-Dawla «proved to be the most stable period of his life.»[50] Avicenna served as the advisor, if not vizier of Ala al-Dawla, accompanying him in many of his military expeditions and travels.[26][50] Avicenna dedicated two Persian works to him, a philosophical treatise named Danish-nama-yi Ala’i («Book of Science for Ala»), and a medical treatise about the pulse.[51]

During the brief occupation of Isfahan by the Ghaznavids in January 1030, Avicenna and Ala al-Dawla relocated to the southwestern Iranian region of Khuzistan, where they stayed until the death of the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud (r. 998–1030), which occurred two months later. It was seemingly when Avicenna returned to Isfahan that he started writing his Pointers and Reminders.[52] In 1037, while Avicenna was accompanying Ala al-Dawla to a battle near Isfahan, he was hit by a severe colic, which he had been constantly suffering from throughout his life. He died shortly afterwards in Hamadan, where he was buried.[53]

Philosophy

Avicenna wrote extensively on early Islamic philosophy, especially the subjects logic, ethics and metaphysics, including treatises named Logic and Metaphysics. Most of his works were written in Arabic—then the language of science in the Middle East—and some in Persian. Of linguistic significance even to this day are a few books that he wrote in nearly pure Persian language (particularly the Danishnamah-yi ‘Ala’, Philosophy for Ala’ ad-Dawla’). Avicenna’s commentaries on Aristotle often criticized the philosopher,[54] encouraging a lively debate in the spirit of ijtihad.

Avicenna’s Neoplatonic scheme of «emanations» became fundamental in the Kalam (school of theological discourse) in the 12th century.[55]

His Book of Healing became available in Europe in partial Latin translation some fifty years after its composition, under the title Sufficientia, and some authors have identified a «Latin Avicennism» as flourishing for some time, paralleling the more influential Latin Averroism, but suppressed by the Parisian decrees of 1210 and 1215.[56]

Avicenna’s psychology and theory of knowledge influenced William of Auvergne, Bishop of Paris[57] and Albertus Magnus,[57] while his metaphysics influenced the thought of Thomas Aquinas.[57]

Metaphysical doctrine

Early Islamic philosophy and Islamic metaphysics, imbued as it is with Islamic theology, distinguishes more clearly than Aristotelianism between essence and existence. Whereas existence is the domain of the contingent and the accidental, essence endures within a being beyond the accidental. The philosophy of Avicenna, particularly that part relating to metaphysics, owes much to al-Farabi. The search for a definitive Islamic philosophy separate from Occasionalism can be seen in what is left of his work.

Following al-Farabi’s lead, Avicenna initiated a full-fledged inquiry into the question of being, in which he distinguished between essence (Mahiat) and existence (Wujud). He argued that the fact of existence cannot be inferred from or accounted for by the essence of existing things, and that form and matter by themselves cannot interact and originate the movement of the universe or the progressive actualization of existing things. Existence must, therefore, be due to an agent-cause that necessitates, imparts, gives, or adds existence to an essence. To do so, the cause must be an existing thing and coexist with its effect.[58]

Avicenna’s consideration of the essence-attributes question may be elucidated in terms of his ontological analysis of the modalities of being; namely impossibility, contingency and necessity. Avicenna argued that the impossible being is that which cannot exist, while the contingent in itself (mumkin bi-dhatihi) has the potentiality to be or not to be without entailing a contradiction. When actualized, the contingent becomes a ‘necessary existent due to what is other than itself’ (wajib al-wujud bi-ghayrihi). Thus, contingency-in-itself is potential beingness that could eventually be actualized by an external cause other than itself. The metaphysical structures of necessity and contingency are different. Necessary being due to itself (wajib al-wujud bi-dhatihi) is true in itself, while the contingent being is ‘false in itself’ and ‘true due to something else other than itself’. The necessary is the source of its own being without borrowed existence. It is what always exists.[59][60]

The Necessary exists ‘due-to-Its-Self’, and has no quiddity/essence (mahiyya) other than existence (wujud). Furthermore, It is ‘One’ (wahid ahad)[61] since there cannot be more than one ‘Necessary-Existent-due-to-Itself’ without differentia (fasl) to distinguish them from each other. Yet, to require differentia entails that they exist ‘due-to-themselves’ as well as ‘due to what is other than themselves’; and this is contradictory. However, if no differentia distinguishes them from each other, then there is no sense in which these ‘Existents’ are not one and the same.[62] Avicenna adds that the ‘Necessary-Existent-due-to-Itself’ has no genus (jins), nor a definition (hadd), nor a counterpart (nadd), nor an opposite (did), and is detached (bari) from matter (madda), quality (kayf), quantity (kam), place (ayn), situation (wad) and time (waqt).[63][64][65]

Avicenna’s theology on metaphysical issues (ilāhiyyāt) has been criticized by some Islamic scholars, among them al-Ghazali, Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn al-Qayyim.[66][page needed] While discussing the views of the theists among the Greek philosophers, namely Socrates, Plato and Aristotle in Al-Munqidh min ad-Dalal («Deliverance from Error»), al-Ghazali noted that the Greek philosophers «must be taxed with unbelief, as must their partisans among the Muslim philosophers, such as Avicenna and al-Farabi and their likes.» He added that «None, however, of the Muslim philosophers engaged so much in transmitting Aristotle’s lore as did the two men just mentioned. […] The sum of what we regard as the authentic philosophy of Aristotle, as transmitted by al-Farabi and Avicenna, can be reduced to three parts: a part which must be branded as unbelief; a part which must be stigmatized as innovation; and a part which need not be repudiated at all.»[67]

Argument for God’s existence

Avicenna made an argument for the existence of God which would be known as the «Proof of the Truthful» (Arabic: burhan al-siddiqin). Avicenna argued that there must be a «necessary existent» (Arabic: wajib al-wujud), an entity that cannot not exist[68] and through a series of arguments, he identified it with the Islamic conception of God.[69] Present-day historian of philosophy Peter Adamson called this argument one of the most influential medieval arguments for God’s existence, and Avicenna’s biggest contribution to the history of philosophy.[68]

Al-Biruni correspondence

Correspondence between Avicenna (with his student Ahmad ibn ‘Ali al-Ma’sumi) and Al-Biruni has survived in which they debated Aristotelian natural philosophy and the Peripatetic school. Abu Rayhan began by asking Avicenna eighteen questions, ten of which were criticisms of Aristotle’s On the Heavens.[70]

Theology

Avicenna was a devout Muslim and sought to reconcile rational philosophy with Islamic theology. His aim was to prove the existence of God and His creation of the world scientifically and through reason and logic.[71] Avicenna’s views on Islamic theology (and philosophy) were enormously influential, forming part of the core of the curriculum at Islamic religious schools until the 19th century.[72] Avicenna wrote a number of short treatises dealing with Islamic theology. These included treatises on the prophets (whom he viewed as «inspired philosophers»), and also on various scientific and philosophical interpretations of the Quran, such as how Quranic cosmology corresponds to his own philosophical system. In general these treatises linked his philosophical writings to Islamic religious ideas; for example, the body’s afterlife.

There are occasional brief hints and allusions in his longer works, however, that Avicenna considered philosophy as the only sensible way to distinguish real prophecy from illusion. He did not state this more clearly because of the political implications of such a theory, if prophecy could be questioned, and also because most of the time he was writing shorter works which concentrated on explaining his theories on philosophy and theology clearly, without digressing to consider epistemological matters which could only be properly considered by other philosophers.[73]

Later interpretations of Avicenna’s philosophy split into three different schools; those (such as al-Tusi) who continued to apply his philosophy as a system to interpret later political events and scientific advances; those (such as al-Razi) who considered Avicenna’s theological works in isolation from his wider philosophical concerns; and those (such as al-Ghazali) who selectively used parts of his philosophy to support their own attempts to gain greater spiritual insights through a variety of mystical means. It was the theological interpretation championed by those such as al-Razi which eventually came to predominate in the madrasahs.[74]

Avicenna memorized the Quran by the age of ten, and as an adult, he wrote five treatises commenting on suras from the Quran. One of these texts included the Proof of Prophecies, in which he comments on several Quranic verses and holds the Quran in high esteem. Avicenna argued that the Islamic prophets should be considered higher than philosophers.[75]

Avicenna is generally understood to have been aligned with the Sunni Hanafi school of thought.[76][77] Avicenna studied Hanafi law, many of his notable teachers were Hanafi jurists, and he served under the Hanafi court of Ali ibn Mamun.[78][76] Avicenna said at an early age that he remained «unconvinced» by Ismaili missionary attempts to convert him.[76] Medieval historian Ẓahīr al-dīn al-Bayhaqī (d. 1169) also believed Avicenna to be a follower of the Brethren of Purity.[77]

Thought experiments

While he was imprisoned in the castle of Fardajan near Hamadhan, Avicenna wrote his famous «floating man»—literally falling man—a thought experiment to demonstrate human self-awareness and the substantiality and immateriality of the soul. Avicenna believed his «Floating Man» thought experiment demonstrated that the soul is a substance, and claimed humans cannot doubt their own consciousness, even in a situation that prevents all sensory data input. The thought experiment told its readers to imagine themselves created all at once while suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argued that, in this scenario, one would still have self-consciousness. Because it is conceivable that a person, suspended in air while cut off from sense experience, would still be capable of determining his own existence, the thought experiment points to the conclusions that the soul is a perfection, independent of the body, and an immaterial substance.[79] The conceivability of this «Floating Man» indicates that the soul is perceived intellectually, which entails the soul’s separateness from the body. Avicenna referred to the living human intelligence, particularly the active intellect, which he believed to be the hypostasis by which God communicates truth to the human mind and imparts order and intelligibility to nature. Following is an English translation of the argument:

One of us (i.e. a human being) should be imagined as having been created in a single stroke; created perfect and complete but with his vision obscured so that he cannot perceive external entities; created falling through air or a void, in such a manner that he is not struck by the firmness of the air in any way that compels him to feel it, and with his limbs separated so that they do not come in contact with or touch each other. Then contemplate the following: can he be assured of the existence of himself? He does not have any doubt in that his self exists, without thereby asserting that he has any exterior limbs, nor any internal organs, neither heart nor brain, nor any one of the exterior things at all; but rather he can affirm the existence of himself, without thereby asserting there that this self has any extension in space. Even if it were possible for him in that state to imagine a hand or any other limb, he would not imagine it as being a part of his self, nor as a condition for the existence of that self; for as you know that which is asserted is different from that which is not asserted and that which is inferred is different from that which is not inferred. Therefore the self, the existence of which has been asserted, is a unique characteristic, in as much that it is not as such the same as the body or the limbs, which have not been ascertained. Thus that which is ascertained (i.e. the self), does have a way of being sure of the existence of the soul as something other than the body, even something non-bodily; this he knows, this he should understand intuitively, if it is that he is ignorant of it and needs to be beaten with a stick [to realize it].

— Ibn Sina, Kitab Al-Shifa, On the Soul[62][80]

However, Avicenna posited the brain as the place where reason interacts with sensation. Sensation prepares the soul to receive rational concepts from the universal Agent Intellect. The first knowledge of the flying person would be «I am,» affirming his or her essence. That essence could not be the body, obviously, as the flying person has no sensation. Thus, the knowledge that «I am» is the core of a human being: the soul exists and is self-aware.[81] Avicenna thus concluded that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms, but as a primary given, a substance. The body is unnecessary; in relation to it, the soul is its perfection.[82][83][84] In itself, the soul is an immaterial substance.[85]

Principal works

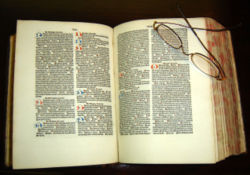

The Canon of Medicine

Avicenna authored a five-volume medical encyclopedia: The Canon of Medicine (Al-Qanun fi’t-Tibb). It was used as the standard medical textbook in the Islamic world and Europe up to the 18th century.[86][87] The Canon still plays an important role in Unani medicine.[88]

Liber Primus Naturalium

Avicenna considered whether events like rare diseases or disorders have natural causes.[89] He used the example of polydactyly to explain his perception that causal reasons exist for all medical events. This view of medical phenomena anticipated developments in the Enlightenment by seven centuries.[90]

The Book of Healing

Earth sciences

Avicenna wrote on Earth sciences such as geology in The Book of Healing.[91] While discussing the formation of mountains, he explained:

Either they are the effects of upheavals of the crust of the earth, such as might occur during a violent earthquake, or they are the effect of water, which, cutting itself a new route, has denuded the valleys, the strata being of different kinds, some soft, some hard … It would require a long period of time for all such changes to be accomplished, during which the mountains themselves might be somewhat diminished in size.[91]

Philosophy of science

In the Al-Burhan (On Demonstration) section of The Book of Healing, Avicenna discussed the philosophy of science and described an early scientific method of inquiry. He discussed Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics and significantly diverged from it on several points. Avicenna discussed the issue of a proper methodology for scientific inquiry and the question of «How does one acquire the first principles of a science?» He asked how a scientist would arrive at «the initial axioms or hypotheses of a deductive science without inferring them from some more basic premises?» He explained that the ideal situation is when one grasps that a «relation holds between the terms, which would allow for absolute, universal certainty». Avicenna then added two further methods for arriving at the first principles: the ancient Aristotelian method of induction (istiqra), and the method of examination and experimentation (tajriba). Avicenna criticized Aristotelian induction, arguing that «it does not lead to the absolute, universal, and certain premises that it purports to provide.» In its place, he developed a «method of experimentation as a means for scientific inquiry.»[92]

Logic

An early formal system of temporal logic was studied by Avicenna.[93] Although he did not develop a real theory of temporal propositions, he did study the relationship between temporalis and the implication.[94] Avicenna’s work was further developed by Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī and became the dominant system of Islamic logic until modern times.[95][96] Avicennian logic also influenced several early European logicians such as Albertus Magnus[97] and William of Ockham.[98][99] Avicenna endorsed the law of non-contradiction proposed by Aristotle, that a fact could not be both true and false at the same time and in the same sense of the terminology used. He stated, «Anyone who denies the law of non-contradiction should be beaten and burned until he admits that to be beaten is not the same as not to be beaten, and to be burned is not the same as not to be burned.»[100]

Physics

In mechanics, Avicenna, in The Book of Healing, developed a theory of motion, in which he made a distinction between the inclination (tendency to motion) and force of a projectile, and concluded that motion was a result of an inclination (mayl) transferred to the projectile by the thrower, and that projectile motion in a vacuum would not cease.[101] He viewed inclination as a permanent force whose effect is dissipated by external forces such as air resistance.[102]

The theory of motion presented by Avicenna was probably influenced by the 6th-century Alexandrian scholar John Philoponus. Avicenna’s is a less sophisticated variant of the theory of impetus developed by Buridan in the 14th century. It is unclear if Buridan was influenced by Avicenna, or by Philoponus directly.[103]

In optics, Avicenna was among those who argued that light had a speed, observing that «if the perception of light is due to the emission of some sort of particles by a luminous source, the speed of light must be finite.»[104] He also provided a wrong explanation of the rainbow phenomenon. Carl Benjamin Boyer described Avicenna’s («Ibn Sīnā») theory on the rainbow as follows:

Independent observation had demonstrated to him that the bow is not formed in the dark cloud but rather in the very thin mist lying between the cloud and the sun or observer. The cloud, he thought, serves as the background of this thin substance, much as a quicksilver lining is placed upon the rear surface of the glass in a mirror. Ibn Sīnā would change the place not only of the bow, but also of the color formation, holding the iridescence to be merely a subjective sensation in the eye.[105]

In 1253, a Latin text entitled Speculum Tripartitum stated the following regarding Avicenna’s theory on heat:

Avicenna says in his book of heaven and earth, that heat is generated from motion in external things.[106]

Psychology

Avicenna’s legacy in classical psychology is primarily embodied in the Kitab al-nafs parts of his Kitab al-shifa (The Book of Healing) and Kitab al-najat (The Book of Deliverance). These were known in Latin under the title De Anima (treatises «on the soul»).[dubious – discuss] Notably, Avicenna develops what is called the Flying Man argument in the Psychology of The Cure I.1.7 as defence of the argument that the soul is without quantitative extension, which has an affinity with Descartes’s cogito argument (or what phenomenology designates as a form of an «epoche«).[82][83]

Avicenna’s psychology requires that connection between the body and soul be strong enough to ensure the soul’s individuation, but weak enough to allow for its immortality. Avicenna grounds his psychology on physiology, which means his account of the soul is one that deals almost entirely with the natural science of the body and its abilities of perception. Thus, the philosopher’s connection between the soul and body is explained almost entirely by his understanding of perception; in this way, bodily perception interrelates with the immaterial human intellect. In sense perception, the perceiver senses the form of the object; first, by perceiving features of the object by our external senses. This sensory information is supplied to the internal senses, which merge all the pieces into a whole, unified conscious experience. This process of perception and abstraction is the nexus of the soul and body, for the material body may only perceive material objects, while the immaterial soul may only receive the immaterial, universal forms. The way the soul and body interact in the final abstraction of the universal from the concrete particular is the key to their relationship and interaction, which takes place in the physical body.[107]

The soul completes the action of intellection by accepting forms that have been abstracted from matter. This process requires a concrete particular (material) to be abstracted into the universal intelligible (immaterial). The material and immaterial interact through the Active Intellect, which is a «divine light» containing the intelligible forms.[108] The Active Intellect reveals the universals concealed in material objects much like the sun makes colour available to our eyes.

Other contributions

Astronomy and astrology

Avicenna wrote an attack on astrology titled Resāla fī ebṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm, in which he cited passages from the Quran to dispute the power of astrology to foretell the future.[109] He believed that each planet had some influence on the earth, but argued against astrologers being able to determine the exact effects.[110]

Avicenna’s astronomical writings had some influence on later writers, although in general his work could be considered less developed than Alhazen or Al-Biruni. One important feature of his writing is that he considers mathematical astronomy as a separate discipline to astrology.[111] He criticized Aristotle’s view of the stars receiving their light from the Sun, stating that the stars are self-luminous, and believed that the planets are also self-luminous.[112] He claimed to have observed Venus as a spot on the Sun. This is possible, as there was a transit on 24 May 1032, but Avicenna did not give the date of his observation, and modern scholars have questioned whether he could have observed the transit from his location at that time; he may have mistaken a sunspot for Venus. He used his transit observation to help establish that Venus was, at least sometimes, below the Sun in Ptolemaic cosmology,[111] i.e. the sphere of Venus comes before the sphere of the Sun when moving out from the Earth in the prevailing geocentric model.[113][114]

He also wrote the Summary of the Almagest, (based on Ptolemy’s Almagest), with an appended treatise «to bring that which is stated in the Almagest and what is understood from Natural Science into conformity». For example, Avicenna considers the motion of the solar apogee, which Ptolemy had taken to be fixed.[111]

Chemistry

Avicenna was first to derive the attar of flowers from distillation[115] and used steam distillation to produce essential oils such as rose essence, which he used as aromatherapeutic treatments for heart conditions.[116][117]

Unlike al-Razi, Avicenna explicitly disputed the theory of the transmutation of substances commonly believed by alchemists:

Those of the chemical craft know well that no change can be effected in the different species of substances, though they can produce the appearance of such change.[118]

Four works on alchemy attributed to Avicenna were translated into Latin as:[119]

- Liber Aboali Abincine de Anima in arte Alchemiae

- Declaratio Lapis physici Avicennae filio sui Aboali

- Avicennae de congelatione et conglutinatione lapidum

- Avicennae ad Hasan Regem epistola de Re recta

Liber Aboali Abincine de Anima in arte Alchemiae was the most influential, having influenced later medieval chemists and alchemists such as Vincent of Beauvais. However, Anawati argues (following Ruska) that the de Anima is a fake by a Spanish author. Similarly the Declaratio is believed not to be actually by Avicenna. The third work (The Book of Minerals) is agreed to be Avicenna’s writing, adapted from the Kitab al-Shifa (Book of the Remedy).[119] Avicenna classified minerals into stones, fusible substances, sulfurs and salts, building on the ideas of Aristotle and Jabir.[120] The epistola de Re recta is somewhat less sceptical of alchemy; Anawati argues that it is by Avicenna, but written earlier in his career when he had not yet firmly decided that transmutation was impossible.[119]

Poetry

Almost half of Avicenna’s works are versified.[121] His poems appear in both Arabic and Persian. As an example, Edward Granville Browne claims that the following Persian verses are incorrectly attributed to Omar Khayyám, and were originally written by Ibn Sīnā:[122]

|

از قعر گل سیاه تا اوج زحل |

From the depth of the black earth up to Saturn’s apogee, |

Legacy

Classical Islamic civilization

Robert Wisnovsky, a scholar of Avicenna attached to McGill University, says that «Avicenna was the central figure in the long history of the rational sciences in Islam, particularly in the fields of metaphysics, logic and medicine» but that his works didn’t only have an influence in these «secular» fields of knowledge alone, as «these works, or portions of them, were read, taught, copied, commented upon, quoted, paraphrased and cited by thousands of post-Avicennian scholars—not only philosophers, logicians, physicians and specialists in the mathematical or exact sciences, but also by those who specialized in the disciplines of ʿilm al-kalām (rational theology, but understood to include natural philosophy, epistemology and philosophy of mind) and usūl al-fiqh (jurisprudence, but understood to include philosophy of law, dialectic, and philosophy of language).»[124]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Inside view of the Avicenna Mausoleum, designed by Hooshang Seyhoun in 1945–1950

As early as the 14th century when Dante Alighieri depicted him in Limbo alongside the virtuous non-Christian thinkers in his Divine Comedy such as Virgil, Averroes, Homer, Horace, Ovid, Lucan, Socrates, Plato and Saladin. Avicenna has been recognized by both East and West as one of the great figures in intellectual history. Johannes Kepler cites Avicenna’s opinion when discussing the causes of planetary motions in Chapter 2 of Astronomia Nova.

[125]

George Sarton, the author of The History of Science, described Avicenna as «one of the greatest thinkers and medical scholars in history»[126] and called him «the most famous scientist of Islam and one of the most famous of all races, places, and times». He was one of the Islamic world’s leading writers in the field of medicine.

Along with Rhazes, Abulcasis, Ibn al-Nafis and al-Ibadi, Avicenna is considered an important compiler of early Muslim medicine. He is remembered in the Western history of medicine as a major historical figure who made important contributions to medicine and the European Renaissance. His medical texts were unusual in that where controversy existed between Galen and Aristotle’s views on medical matters (such as anatomy), he preferred to side with Aristotle, where necessary updating Aristotle’s position to take into account post-Aristotelian advances in anatomical knowledge.[127] Aristotle’s dominant intellectual influence among medieval European scholars meant that Avicenna’s linking of Galen’s medical writings with Aristotle’s philosophical writings in the Canon of Medicine (along with its comprehensive and logical organisation of knowledge) significantly increased Avicenna’s importance in medieval Europe in comparison to other Islamic writers on medicine. His influence following translation of the Canon was such that from the early fourteenth to the mid-sixteenth centuries he was ranked with Hippocrates and Galen as one of the acknowledged authorities, princeps medicorum («prince of physicians»).[128]

Modern reception

In present-day Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, he is considered a national icon, and is often regarded as among the greatest Persians. A monument was erected outside the Bukhara museum.[year needed] The Avicenna Mausoleum and Museum in Hamadan was built in 1952. Bu-Ali Sina University in Hamadan (Iran), the biotechnology Avicenna Research Institute in Tehran (Iran), the ibn Sīnā Tajik State Medical University in Dushanbe, Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences at Aligarh, India, Avicenna School in Karachi and Avicenna Medical College in Lahore, Pakistan,[129] Ibn Sina Balkh Medical School in his native province of Balkh in Afghanistan, Ibni Sina Faculty Of Medicine of Ankara University Ankara, Turkey, the main classroom building (the Avicenna Building) of the Sharif University of Technology, and Ibn Sina Integrated School in Marawi City (Philippines) are all named in his honour. His portrait hangs in the Hall of the Avicenna Faculty of Medicine in the University of Paris. There is a crater on the Moon named Avicenna and a mangrove genus.

In 1980, the Soviet Union, which then ruled his birthplace Bukhara, celebrated the thousandth anniversary of Avicenna’s birth by circulating various commemorative stamps with artistic illustrations, and by erecting a bust of Avicenna based on anthropological research by Soviet scholars.[130] Near his birthplace in Qishlak Afshona, some 25 km (16 mi) north of Bukhara, a training college for medical staff has been named for him.[year needed] On the grounds is a museum dedicated to his life, times and work.[131][self-published source?]

The Avicenna Prize, established in 2003, is awarded every two years by UNESCO and rewards individuals and groups for their achievements in the field of ethics in science.[132] The aim of the award is to promote ethical reflection on issues raised by advances in science and technology, and to raise global awareness of the importance of ethics in science.

The Avicenna Directories (2008–15; now the World Directory of Medical Schools) list universities and schools where doctors, public health practitioners, pharmacists and others, are educated. The original project team stated «Why Avicenna? Avicenna … was … noted for his synthesis of knowledge from both east and west. He has had a lasting influence on the development of medicine and health sciences. The use of Avicenna’s name symbolises the worldwide partnership that is needed for the promotion of health services of high quality.»[133]

In June 2009, Iran donated a «Persian Scholars Pavilion» to United Nations Office in Vienna which is placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the Vienna International Center.[134] The «Persian Scholars Pavilion» at United Nations in Vienna, Austria is featuring the statues of four prominent Iranian figures. Highlighting the Iranian architectural features, the pavilion is adorned with Persian art forms and includes the statues of renowned Iranian scientists Avicenna, Al-Biruni, Zakariya Razi (Rhazes) and Omar Khayyam.[135][136]

The 1982 Soviet film Youth of Genius (Russian: Юность гения, romanized: Yunost geniya) by Elyor Ishmukhamedov [ru] recounts Avicenna’s younger years. The film is set in Bukhara at the turn of the millennium.[137]

In Louis L’Amour’s 1985 historical novel The Walking Drum, Kerbouchard studies and discusses Avicenna’s The Canon of Medicine.

In his book The Physician (1988) Noah Gordon tells the story of a young English medical apprentice who disguises himself as a Jew to travel from England to Persia and learn from Avicenna, the great master of his time. The novel was adapted into a feature film, The Physician, in 2013. Avicenna was played by Ben Kingsley.

List of works

The treatises of Avicenna influenced later Muslim thinkers in many areas including theology, philology, mathematics, astronomy, physics and music. His works numbered almost 450 volumes on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived. In particular, 150 volumes of his surviving works concentrate on philosophy and 40 of them concentrate on medicine.[10]

His most famous works are The Book of Healing, and The Canon of Medicine.

Avicenna wrote at least one treatise on alchemy, but several others have been falsely attributed to him. His Logic, Metaphysics, Physics, and De Caelo, are treatises giving a synoptic view of Aristotelian doctrine,[138] though Metaphysics demonstrates a significant departure from the brand of Neoplatonism known as Aristotelianism in Avicenna’s world; Arabic philosophers[who?][year needed] have hinted at the idea that Avicenna was attempting to «re-Aristotelianise» Muslim philosophy in its entirety, unlike his predecessors, who accepted the conflation of Platonic, Aristotelian, Neo- and Middle-Platonic works transmitted into the Muslim world.

The Logic and Metaphysics have been extensively reprinted, the latter, e.g., at Venice in 1493, 1495 and 1546. Some of his shorter essays on medicine, logic, etc., take a poetical form (the poem on logic was published by Schmoelders in 1836).[139] Two encyclopedic treatises, dealing with philosophy, are often mentioned. The larger, Al-Shifa’ (Sanatio), exists nearly complete in manuscript in the Bodleian Library and elsewhere; part of it on the De Anima appeared at Pavia (1490) as the Liber Sextus Naturalium, and the long account of Avicenna’s philosophy given by Muhammad al-Shahrastani seems to be mainly an analysis, and in many places a reproduction, of the Al-Shifa’. A shorter form of the work is known as the An-najat (Liberatio). The Latin editions of part of these works have been modified by the corrections which the monastic editors confess that they applied. There is also a حكمت مشرقيه (hikmat-al-mashriqqiyya, in Latin Philosophia Orientalis), mentioned by Roger Bacon, the majority of which is lost in antiquity, which according to Averroes was pantheistic in tone.[138]

Avicenna’s works further include:[140][141]

- Sirat al-shaykh al-ra’is (The Life of Avicenna), ed. and trans. WE. Gohlman, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1974. (The only critical edition of Avicenna’s autobiography, supplemented with material from a biography by his student Abu ‘Ubayd al-Juzjani. A more recent translation of the Autobiography appears in D. Gutas, Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition: Introduction to Reading Avicenna’s Philosophical Works, Leiden: Brill, 1988; second edition 2014.)[140]

- Al-isharat wa al-tanbihat (Remarks and Admonitions), ed. S. Dunya, Cairo, 1960; parts translated by S.C. Inati, Remarks and Admonitions, Part One: Logic, Toronto, Ont.: Pontifical Institute for Mediaeval Studies, 1984, and Ibn Sina and Mysticism, Remarks and Admonitions: Part 4, London: Kegan Paul International, 1996.[140]

- Al-Qanun fi’l-tibb (The Canon of Medicine), ed. I. a-Qashsh, Cairo, 1987. (Encyclopedia of medicine.)[140] manuscript,[142][143] Latin translation, Flores Avicenne,[144] Michael de Capella, 1508,[145] Modern text.[146] Ahmed Shawkat Al-Shatti, Jibran Jabbur.[147]

- Risalah fi sirr al-qadar (Essay on the Secret of Destiny), trans. G. Hourani in Reason and Tradition in Islamic Ethics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.[140]

- Danishnama-i ‘ala’i (The Book of Scientific Knowledge), ed. and trans. P. Morewedge, The Metaphysics of Avicenna, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973.[140]

- Kitab al-Shifa’ (The Book of Healing). (Avicenna’s major work on philosophy. He probably began to compose al-Shifa’ in 1014, and completed it in 1020.) Critical editions of the Arabic text have been published in Cairo, 1952–83, originally under the supervision of I. Madkour.[140]

- Kitab al-Najat (The Book of Salvation), trans. F. Rahman, Avicenna’s Psychology: An English Translation of Kitab al-Najat, Book II, Chapter VI with Historical-philosophical Notes and Textual Improvements on the Cairo Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952. (The psychology of al-Shifa’.) (Digital version of the Arabic text)

- Risala fi’l-Ishq (A Treatise on Love). Translated by Emil L. Fackenheim.

Persian works

Avicenna’s most important Persian work is the Danishnama-i ‘Alai (دانشنامه علائی, «the Book of Knowledge for [Prince] ‘Ala ad-Daulah»). Avicenna created new scientific vocabulary that had not previously existed in Persian. The Danishnama covers such topics as logic, metaphysics, music theory and other sciences of his time. It has been translated into English by Parwiz Morewedge in 1977.[148] The book is also important in respect to Persian scientific works.

Andar Danesh-e Rag (اندر دانش رگ, «On the Science of the Pulse») contains nine chapters on the science of the pulse and is a condensed synopsis.

Persian poetry from Avicenna is recorded in various manuscripts and later anthologies such as Nozhat al-Majales.

See also

- Al-Qumri (possibly Avicenna’s teacher)

- Abdol Hamid Khosro Shahi (Iranian theologian)

- Mummia (Persian medicine)

- Eastern philosophy

- Iranian philosophy

- Islamic philosophy

- Contemporary Islamic philosophy

- Science in the medieval Islamic world

- List of scientists in medieval Islamic world

- Sufi philosophy

- Science and technology in Iran

- Ancient Iranian medicine

- List of pre-modern Iranian scientists and scholars

Namesakes of Ibn Sina

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences in Aligarh

- Avicenna Bay in Antarctica

- Avicenna (crater) on the far side of the Moon

- Avicenna Cultural and Scientific Foundation

- Avicenne Hospital in Paris, France

- Avicenna International College in Budapest, Hungary

- Avicenna Mausoleum (complex dedicated to Avicenna) in Hamadan, Iran

- Avicenna Research Institute in Tehran, Iran

- Avicenna Tajik State Medical University in Dushanbe, Tajikistan

- Bu-Ali Sina University in Hamedan, Iran

- Ibn Sina Peak – named after the Scientist, on the Kyrgyzstan–Tajikistan border

- Ibn Sina Foundation in Houston, Texas[149]

- Ibn Sina Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq

- Ibn Sina Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey[150]

- Ibn Sina Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- Ibn Sina University Hospital of Rabat-Salé at Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco

- Ibne Sina Hospital, Multan, Punjab, Pakistan[151]

- International Ibn Sina Clinic, Dushanbe, Tajikistan

References

Citations

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam: Vol 1, p. 562, Edition I, 1964, Lahore, Pakistan

- ^ The Sheed & Ward Anthology of Catholic Philosophy. Rowman & Littlefield. 2005. ISBN 978-0-7425-3198-7.

- ^ Ramin Jahanbegloo, In Search of the Sacred : A Conversation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought, ABC-CLIO (2010), p. 59

- ^

- Corbin 2016, Overview. «In this work a distinguished scholar of Islamic religion examines the mysticism and psychological thought of the great eleventh-century Persian philosopher and physician Avicenna (Ibn Sina), author of over a hundred works on theology, logic, medicine, and mathematics.»

- Pasnau & Dyke 2010, p. 52. «Most important of these initially was the massive Book of Healing (Al-Shifa) of the eleventh-century Persian Avicenna, the parts of which labeled in Latin as De anima and De generatione having been translated in the second half of the twelfth century.»

- Daly 2013, p. 18. «The Persian polymath Ibn Sina (981–1037) consolidated all of this learning, along with Ancient Greek and Indian knowledge, into his The Canon of Medicine (1025), a work still taught in European medical schools in the seventeenth century.»

- ^

- Adamson 2016, pp. 113, 117, 206.

(page 113) «For one thing, it means that he[Avicenna] had a Persian cultural background…he spoke Persian natively and did use it to write philosophy.»

(page 117) «But for the time being, it was a Persian from Khurasan who would have commentaries lavished upon him. Avicenna would be known by the honorific of «leading master» (al-shaykh al-raʾis).»

(page 206) «Persians like Avicenna» - Bennison 2009, p. 195. «Avicenna was a Persian whose father served the Samanids of Khurasan and Transoxania as the administrator of a rural district outside Bukhara.»

- Paul Strathern (2005). A brief history of medicine: from Hippocrates to gene therapy. Running Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7867-1525-1.

- Brian Duignan (2010). Medieval Philosophy. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-61530-244-4.

- Michael Kort (2004). Central Asian republics. Infobase Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8160-5074-1.

- Goichon 1986, p. 941. «He was born in 370/980 in Afshana, his mother’s home, near Bukhara. His native language was Persian.»

- «Avicenna was the greatest of all Persian thinkers; as physician and metaphysician …» (excerpt from A.J. Arberry, Avicenna on Theology, Kazi Publications Inc, 1995).

- Corbin 1998, p. 74. «Whereas the name of Avicenna (Ibn Sina, died 1037) is generally listed as chronologically first among noteworthy Iranian philosophers, recent evidence has revealed previous existence of Ismaili philosophical systems with a structure no less complete than of Avicenna.»

- Adamson 2016, pp. 113, 117, 206.

- ^ Saffari, Mohsen; Pakpour, Amir (1 December 2012). «Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine: A Look at Health, Public Health, and Environmental Sanitation». Archives of Iranian Medicine. 15 (12): 785–9. PMID 23199255.

Avicenna was a well-known Persian and a Muslim scientist who was considered to be the father of early modern medicine.

- ^ Colgan, Richard (19 September 2009). Advice to the Young Physician: On the Art of Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4419-1034-9.

Avicenna is known as the father of early modern medicine.

- ^ Roudgari, Hassan (28 December 2018). «Ibn Sina or Abu Ali Sina (ابن سینا c. 980 –1037) is often known by his Latin name of Avicenna (ævɪˈsɛnə/)». Journal of Iranian Medical Council. 1 (2). ISSN 2645-338X.

Avicenna was a Persian polymath and one of the most famous physicians from the Islamic Golden Age. He is known as the father of early modern medicine and his most famous work in Medicine called «The Book of Healing», which became a standard medical textbook at many European universities and remained in use up to the recent centuries.

- ^ «Avicenna (Ibn Sina)». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., «Avicenna», MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). «Avicenna». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ Edwin Clarke, Charles Donald O’Malley (1996), The human brain and spinal cord: a historical study illustrated by writings from antiquity to the twentieth century, Norman Publishing, p. 20 (ISBN 0-930405-25-0).

- ^ Iris Bruijn (2009), Ship’s Surgeons of the Dutch East India Company: Commerce and the progress of medicine in the eighteenth century, Amsterdam University Press, p. 26 (ISBN 90-8728-051-3).

- ^ «Avicenna 980–1037». Hcs.osu.edu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ e.g. at the universities of Montpellier and Leuven (see «Medicine: an exhibition of books relating to medicine and surgery from the collection formed by J.K. Lilly». Indiana.edu. 31 August 2004. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2010.).

- ^ «Avicenna», in Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Version 2006″. Iranica.com. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2012), «Avicenna», Encyclopedia of the Black Death, Vol. I, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-253-1.

- ^ Van Gelder, Geert Jan, ed. (2013), «Introduction», Classical Arabic Literature, Library of Arabic Literature, New York: New York University Press, p. xxii, ISBN 978-0-8147-7120-4

- ^ «Avicenna», Consortium of European Research Libraries

- ^ Avicenna (1935), «Majmoo’ rasaa’il al-sheikh al-ra’iis abi Ali al-Hussein ibn Abdullah ibn Sina al-Bukhari» مجموع رسائل الشيخ الرئيس اب علي الحسين ابن عبدالله ابن سينا البخاري [The Grand Sheikh Ibn Sina’s Collection of Treatises], World Digital Library (first ed.), Haydarabad Al-Dakan: Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Press

- ^ «Major periods of Muslim education and learning». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ Afary, Janet (2007). «Iran». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ According to El-Bizri 2006, p. 369, Avicenna was «of Persian descent». According to Khalidi 2005, p. xviii, Avicenna was «born of Persian parentage». According to Copleston 1993, p. 190, Avicenna was «Persian by birth». Gutas 2014, pp. xi, 310, mentions Avicenna as an example for «Persian-born authors» and speaks of «presumed Persian origins» for Avicenna. Glick, Livesey & Wallis 2005, p. 256, states «An ethnic Persian, he[Avicenna] was born in Kharmaithen, near Bukhara».

- ^ Goichon 1986, p. 941.

- ^ a b Gutas 2014, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gutas 1987, pp. 67–70.

- ^ a b c Gutas 2014, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Adamson 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Daftary 2017, p. 191.

- ^ Daftary 2007, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Gutas 1988, pp. 330–331.

- ^ a b Gutas 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Gutas 2014, p. 19 (see also note 28).

- ^ Bosworth 1978, p. 1066.

- ^ Bosworth 1984a, pp. 762–764.

- ^ Madelung 1975, p. 215.

- ^ Gutas 2014, pp. 19, 29.

- ^ a b Adamson 2013, p. 14.

- ^ a b Adamson 2013, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 15.

- ^ Adamson 2013, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Madelung 1975, p. 293.

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 18 (see also note 45).

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Bosworth 1984b, pp. 773–774.

- ^ Adamson 2013, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 23.

- ^ a b Adamson 2013, p. 25.

- ^ Lazard 1975, p. 630.

- ^ Gutas 2014, p. 133.

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 26.

- ^ Stroumsa, Sarah (1992). «Avicenna’s Philosophical Stories: Aristotle’s Poetics Reinterpreted». Arabica. 39 (2): 183–206. doi:10.1163/157005892X00166. ISSN 0570-5398. JSTOR 4057059.

- ^ Nahyan A.G. Fancy (2006), pp. 80–81, «Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)», Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame Archived 4 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine[page needed]

- ^

c.f. e.g.

Henry Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, Routledge, 2014, p. 174.

Henry Corbin, Avicenna and the Visionary Recital, Princeton University Press, 2014, p. 103. - ^ a b c «The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Avicenna (Ibn Sina) (c. 980–1037)». Iep.utm.edu. 6 January 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ «Islam». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- ^ Avicenna, Kitab al-shifa’, Metaphysics II, (eds.) G.C. Anawati, Ibrahim Madkour, Sa’id Zayed (Cairo, 1975), p. 36

- ^ Nader El-Bizri, «Avicenna and Essentialism,» Review of Metaphysics, Vol. 54 (2001), pp. 753–778

- ^ Avicenna, Metaphysica of Avicenna, trans. Parviz Morewedge (New York, 1973), p. 43.

- ^ a b Nader El-Bizri, The Phenomenological Quest between Avicenna and Heidegger (Binghamton, N.Y.: Global Publications SUNY, 2000)

- ^ Avicenna, Kitab al-Hidaya, ed. Muhammad ‘Abdu (Cairo, 1874), pp. 262–263

- ^ Salem Mashran, al-Janib al-ilahi ‘ind Ibn Sina (Damascus, 1992), p. 99

- ^ Nader El-Bizri, «Being and Necessity: A Phenomenological Investigation of Avicenna’s Metaphysics and Cosmology,» in Islamic Philosophy and Occidental Phenomenology on the Perennial Issue of Microcosm and Macrocosm, ed. Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2006), pp. 243–261

- ^ Ibn al-Qayyim, Eghaathat al-Lahfaan, Published: Al Ashqar University (2003) Printed by International Islamic Publishing House: Riyadh.

- ^ Ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad (1980). al-Munqidh min al-Dalal (PDF). Boston: American University of Beirut. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b Adamson 2013, p. 170.

- ^ Adamson 2013, p. 171.

- ^ Rafik Berjak and Muzaffar Iqbal, «Ibn Sina—Al-Biruni correspondence», Islam & Science, June 2003.

- ^ Lenn Evan Goodman (2003), Islamic Humanism, pp. 8–9, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513580-6.

- ^ James W. Morris (1992), «The Philosopher-Prophet in Avicenna’s Political Philosophy», in C. Butterworth (ed.), The Political Aspects of Islamic Philosophy, ISBN 978-0-932885-07-4, Chapter 4, Cambridge Harvard University Press, pp. 152–198 [p. 156].

- ^ James W. Morris (1992), «The Philosopher-Prophet in Avicenna’s Political Philosophy», in C. Butterworth (ed.), The Political Aspects of Islamic Philosophy, Chapter 4, Cambridge Harvard University Press, pp. 152–198 [pp. 160–161].

- ^ James W. Morris (1992), «The Philosopher-Prophet in Avicenna’s Political Philosophy», in C. Butterworth (ed.), The Political Aspects of Islamic Philosophy, Chapter 4, Cambridge Harvard University Press, pp. 152–198 [pp. 156–158].

- ^ Jules Janssens (2004), «Avicenna and the Qur’an: A Survey of his Qur’anic commentaries», MIDEO 25, p. 177–192.

- ^ a b c Aisha Khan (2006). Avicenna (Ibn Sina): Muslim physician and philosopher of the eleventh century. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4042-0509-3.

- ^ a b Janssens, Jules L. (1991). An annotated bibliography on Ibn Sînâ (1970–1989): including Arabic and Persian publications and Turkish and Russian references. Leuven University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-90-6186-476-9. excerpt: «… Dimitri Gutas’s Avicenna’s maḏhab convincingly demonstrates that I.S. was a sunnî-Ḥanafî.»[1]

- ^ DIMITRI GUTAS (1987), «Avicenna’s «maḏhab» with an Appendix on the Question of His Date of Birth», Quaderni di Studi Arabi, Istituto per l’Oriente C. A. Nallino, 5/6: 323–336, JSTOR 25802612

- ^ See a discussion of this in connection with an analytic take on the philosophy of mind in: Nader El-Bizri, ‘Avicenna and the Problem of Consciousness’, in Consciousness and the Great Philosophers, eds. S. Leach and J. Tartaglia (London: Routledge, 2016), 45–53

- ^ Ibn Sina, الفن السادس من الطبيعيات من كتاب الشفاء القسم الأول (Beirut, Lebanon.: M.A.J.D Enterprise Universitaire d’Etude et de Publication S.A.R.L)

يجب أن يتوهم الواحد منا كأنه خلق دفعةً وخلق كاملاً لكنه حجب بصره عن مشاهدة الخارجات وخلق يهوى في هواء أو خلاء هوياً لا يصدمه فيه قوام الهواء صدماً ما يحوج إلى أن يحس وفرق بين أعضائه فلم تتلاق ولم تتماس ثم يتأمل هل أنه يثبت وجود ذاته ولا يشكك في إثباته لذاته موجوداً ولا يثبت مع ذلك طرفاً من أعضائه ولا باطناً من أحشائه ولا قلباً ولا دماغاً ولا شيئاً من الأشياء من خارج بل كان يثبت ذاته ولا يثبت لها طولاً ولا عرضاً ولا عمقاً ولو أنه أمكنه في تلك الحالة أن يتخيل يداً أو عضواً آخر لم يتخيله جزء من ذاته ولا شرطاً في ذاته وأنت تعلم أن المثبت غير الذي لم يثبت والمقربه غير الذي لم يقربه فإذن للذات التي أثبت وجودها خاصية على أنها هو بعينه غير جسمه وأعضائه التي لم تثبت فإذن المثبت له سبيل إلى أن يثبته على وجود النفس شيئاً غير الجسم بل غير جسم وأنه عارف به مستشعر له وإن كان ذاهلاً عنه يحتاج إلى أن يقرع عصاه.

— Ibn Sina, Kitab Al-Shifa, On the Soul

- ^ Hasse, Dag Nikolaus (2000). Avicenna’s De Anima in the Latin West. London: Warburg Institute. p. 81.

- ^ a b Nader El-Bizri, The Phenomenological Quest between Avicenna and Heidegger (Binghamton, NY: Global Publications SUNY, 2000), pp. 149–171.

- ^ a b Nader El-Bizri, «Avicenna’s De Anima between Aristotle and Husserl,» in The Passions of the Soul in the Metamorphosis of Becoming, ed. Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003), pp. 67–89.

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Leaman, Oliver (1996). History of Islamic philosophy. Routledge. pp. 315, 1022–1023. ISBN 978-0-415-05667-0.

- ^ Hasse, Dag Nikolaus (2000). Avicenna’s De Anima in the Latin West. London: Warburg Institute. p. 92.

- ^ McGinnis, Jon (2010). Avicenna. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-19-533147-9.

- ^ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet’s Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-78074-420-9.

- ^ Indian Studies on Ibn Sina’s Works by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Avicenna (Scientific and Practical International Journal of Ibn Sino International Foundation, Tashkent/Uzbekistan. 1–2; 2003: 40–42

- ^ Avicenna Latinus. 1992. Liber Primus Naturalium: Tractatus Primus, De Causis et Principiis Naturalium. Leiden (The Netherlands): E.J. Brill.

- ^ Axel Lange and Gerd B. Müller. Polydactyly in Development, Inheritance, and Evolution. The Quarterly Review of Biology Vol. 92, No. 1, Mar. 2017, pp. 1–38. doi:10.1086/690841.

- ^ a b Stephen Toulmin and June Goodfield (1965), The Ancestry of Science: The Discovery of Time, p. 64, University of Chicago Press (cf. The Contribution of Ibn Sina to the development of Earth sciences Archived 14 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ McGinnis, Jon (July 2003). «Scientific Methodologies in Medieval Islam». Journal of the History of Philosophy. 41 (3): 307–327. doi:10.1353/hph.2003.0033. S2CID 30864273.

- ^ History of logic: Arabic logic, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Peter Øhrstrøm; Per Hasle (1995). Temporal Logic: From Ancient Ideas to Artificial Intelligence. Springer. p. 72.

- ^ Street, Tony (2000), «Toward a History of Syllogistic After Avicenna: Notes on Rescher’s Studies on Arabic Modal Logic», Journal of Islamic Studies, 11 (2): 209–228, doi:10.1093/jis/11.2.209

- ^ Street, Tony (1 January 2005). «Logic». In Peter Adamson & Richard C. Taylor (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 247–265. ISBN 978-0-521-52069-0.

- ^ Richard F. Washell (1973), «Logic, Language, and Albert the Great», Journal of the History of Ideas 34 (3), pp. 445–450 [445].

- ^ Kneale p. 229

- ^ Kneale: p. 266; Ockham: Summa Logicae i. 14; Avicenna: Avicennae Opera Venice 1508 f87rb

- ^ Avicenna, Metaphysics, I; commenting on Aristotle, Topics I.11.105a4–5

- ^ Fernando Espinoza (2005). «An analysis of the historical development of ideas about motion and its implications for teaching», Physics Education 40 (2), p. 141.

- ^ A. Sayili (1987), «Ibn Sīnā and Buridan on the Motion of the Projectile», Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500 (1), pp. 477–482: «It was a permanent force whose effect got dissipated only as a result of external agents such as air resistance. He is apparently the first to conceive such a permanent type of impressed virtue for non-natural motion.»

- ^ Jack Zupko, «John Buridan» in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2014

(fn. 48)

«We do not know precisely where Buridan got the idea of impetus, but a less sophisticated notion of impressed forced can be found in Avicenna’s doctrine of mayl (inclination). In this he was possibly influenced by Philoponus, who was developing the Stoic notion of hormé (impulse). For discussion, see Zupko (1997) [‘What Is the Science of the Soul? A Case Study in the Evolution of Late Medieval Natural Philosophy,’ Synthese, 110(2): 297–334].» - ^ George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science, Vol. 1, p. 710.

- ^ Carl Benjamin Boyer (1954). «Robert Grosseteste on the Rainbow», Osiris 11, pp. 247–258 [248].

- ^ Gutman, Oliver (1997). «On the Fringes of the Corpus Aristotelicum: the Pseudo-Avicenna Liber Celi Et Mundi». Early Science and Medicine. 2 (2): 109–128. doi:10.1163/157338297X00087.

- ^ Avicenna (1952). F. Rahman (ed.). Avicenna’s Psychology. An English translation of Kitāb al-Najāt, Book II, Chapter VI, with Historico-Philosophical Notes and Textual Improvements on the Cairo edition. London: Oxford University Press, Geoffrey Cumberlege. p. 41.

- ^ Avicenna (1952). F. Rahman (ed.). Avicenna’s Psychology. An English translation of Kitāb al-Najāt, Book II, Chapter VI, with Historico-Philosophical Notes and Textual Improvements on the Cairo edition. London: Oxford University Press, Geoffrey Cumberlege. pp. 68–69.

- ^ George Saliba (1994), A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam, pp. 60, 67–69. New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-8023-7.

- ^ Saliba, George (2011). «Avicenna». Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition.

- ^ a b c Sally P. Ragep (2007). «Ibn Sīnā: Abū ʿAlī al‐Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbdallāh ibn Sīnā». In Thomas Hockey (ed.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 570–572.

- ^ Ariew, Roger (March 1987). «The phases of venus before 1610». Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 18 (1): 81–92. Bibcode:1987SHPSA..18…81A. doi:10.1016/0039-3681(87)90012-4.

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (1969). «Some Medieval Reports of Venus and Mercury Transits». Centaurus. 14 (1): 49–59. Bibcode:1969Cent…14…49G. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1969.tb00135.x.

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (March 1972). «Theory and Observation in Medieval Astronomy». Isis. 63 (1): 39–47 [44]. Bibcode:1972Isis…63…39G. doi:10.1086/350839. S2CID 120700705.

- ^ Essa, Ahmed; Ali, Othman (2010). Studies in Islamic Civilization: The Muslim Contribution to the Renaissance. International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT). p. 70. ISBN 978-1-56564-350-5.

- ^ Marlene Ericksen (2000). Healing with Aromatherapy, p. 9. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-658-00382-8.

- ^ Ghulam Moinuddin Chishti (1991). The Traditional Healer’s Handbook: A Classic Guide to the Medicine of Avicenna. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-89281-438-1.

- ^ Robert Briffault (1938). The Making of Humanity, p. 196–197.

- ^ a b c Georges C. Anawati (1996), «Arabic alchemy», in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 3, pp. 853–885 [875]. Routledge, London and New York.

- ^ Leicester, Henry Marshall (1971), The Historical Background of Chemistry, Courier Dover Publications, p. 70, ISBN 978-0-486-61053-5,

There was one famous Arab physician who doubted even the reality of transmutation. This was ‘Abu Ali al-Husain ibn Abdallah ibn Sina (980–1037), called Avicenna in the West, the greatest physician of Islam. … Many of his observations on chemistry are included in the Kitab al-Shifa, the «Book of the Remedy». In the physical section of this work he discusses the formation of minerals, which he classifies into stones, fusible substances, sulfurs, and salts. Mercury is classified with the fusible substances, metals

- ^ E.G. Browne, Islamic Medicine (sometimes also printed under the title Arabian medicine), 2002, Goodword Pub., ISBN 81-87570-19-9, p61

- ^ E.G. Browne, Islamic Medicine (sometimes also printed under the title Arabian medicine), 2002, Goodword Pub., ISBN 81-87570-19-9, pp. 60–61)

- ^ Gabrieli, F. (1950). Avicenna’s Millenary. East and West, 1(2), 87–92.

- ^ Robert Wisnovsky, «Indirect Evidence for Establishing the Text of the Shifā» in Oriens, volume 40, issue 2 (2012), pp. 257–258

- ^ , Johannes Kepler, New Astronomy, translated by William H. Donahue, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1992. ISBN 0-521-30131-9

- ^ George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science.

(cf. Dr. A. Zahoor and Dr. Z. Haq (1997). Quotations From Famous Historians of Science, Cyberistan.) - ^ Musallam, B. (2011). «Avicenna Medicine and Biology». Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Weisser, U. (2011). «Avicenna The influence of Avicenna on medical studies in the West». Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ «Home Page». amch.edu.pk. 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013.

- ^ Thought Experiments: Popular Thought Experiments in Philosophy, Physics, Ethics, Computer Science & Mathematics by Fredrick Kennard, p. 114

- ^ Kennard, Fredrick. Thought Experiments: Popular Thought Experiments in Philosophy, Physics, Ethics, Computer Science & Mathematics. Lulu.com. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-1-329-00342-2.[self-published source]

- ^ «UNESCO: The Avicenna Prize for Ethics in Science». 4 September 2019.

- ^ «Educating health professionals: the Avicenna project» The Lancet, March 2008. Volume 371 pp. 966–967.

- ^ «Monument to Be Inaugurated at the Vienna International Centre, ‘Scholars Pavilion’ donated to International Organizations in Vienna by Iran». unvienna.org.

- ^ «Permanent mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations office – Vienna». mfa.ir. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Hosseini, Mir Masood. «Negareh: Persian Scholars Pavilion at United Nations Vienna, Austria». parseed.ir. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016.

- ^ «Youth of Genius» (USSR, Uzbekfilm and Tajikfilm, 1982): 1984 – State Prize of the USSR (Elyer Ishmuhamedov); 1983 – VKF (All-Union Film Festival) Grand Prize (Elyer Ishmuhamedov); 1983 – VKF (All-Union Film Festival) Award for Best Cinematography (Tatiana Loginov). See annotation on kino-teatr.ru.

- ^ a b

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Avicenna». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–63.

- ^ Thought Experiments: Popular Thought Experiments in Philosophy, Physics, Ethics, Computer Science & Mathematics by Fredrick Kennard, p. 115

- ^ a b c d e f g «Ibn Sina Abu ‘Ali Al-Husayn». Muslimphilosophy.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ Tasaneef lbn Sina by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Tabeeb Haziq, Gujarat, Pakistan, 1986, pp. 176–198

- ^ «The Canon of Medicine». Wdl.org. 1 January 1597.

- ^ «The Canon of Medicine». World Digital Library. 1597. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Flowers of Avicenna. Wdl.org. Printed by Claude Davost alias de Troys, for Bartholomeus Trot. 1 January 1508.

- ^ «Flowers of Avicenna – Flores Avicenne». World Digital Library. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ «The Book of Simple Medicine and Plants» from «The Canon of Medicine». Wdl.org. Knowledge Foundation. 1 January 1900.

- ^ Avicenna. «The Canon of Medicine». World Digital Library. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Avicenna, Danish Nama-i ‘Alai. trans. Parviz Morewedge as The Metaphysics of Avicenna (New York: Columbia University Press), 1977.

- ^ «Our Story». Ibn Sina Foundation. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ «Ibn Sina Hospital». Ibn Sina Hospital, Turkey. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ «Ibne Sina Hospital». Ibn e Siena. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

Sources

- Adamson, Peter (2013). Interpreting Avicenna: Critical Essays Search in this book. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-0-521-19073-2.

- Adamson, Peter (2016). Philosophy in the Islamic World: A history of philosophy without any gaps, Volume 3. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957749-1.

- Bennison, Amira K. (2009). The great caliphs: the golden age of the ‘Abbasid Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15227-2.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1978). «K̲h̲wārazm-S̲h̲āhs». In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 758278456.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1984a). «Āl-e Maʾmūn». Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7. pp. 762–764.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1984b). «ʿAlāʾ-al-dawla Moḥammad». Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7. pp. 773–774.

- Copleston, Frederick (1993). A History of Philosophy, Volume 2: Medieval Philosophy – From Augustine to Duns Scotus. Image Books. ISBN 978-0-385-46844-2.

- Corbin, Henry (1998). The Voyage and the messenger: Iran and philosophy. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781556432699.

- Corbin, Henry (19 April 2016). Avicenna and the Visionary Recital. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-63054-0. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). Ismaili History and Intellectual Traditions. The Isma’ilis: Their History and Doctrines. ISBN 978-0-521-85084-1.

- Daftary, Farhad (2017). Ismaili History and Intellectual Traditions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-28810-2.

- Daly, Jonathan (19 December 2013). The Rise of Western Power: A Comparative History of Western Civilization. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-1851-6.

- El-Bizri, Nader (2006). «Ibn Sina, or Avicenna». In Meri, Josef W. (ed.). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge. pp. 369–370. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

- Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-138-05670-1.

- Goichon, A.M (1986). «Ibn Sīnā». In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469525.

- Gutas, Dimitri (1987). «Avicenna ii. Biography». In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume III/1: Ātaš–Awāʾel al-Maqālāt. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 67–70. ISBN 978-0-71009-113-0.

- Gutas, Dimitri (1988). «Avicenna’s Maḏhab with an appendix on the question of his date of Birth». Quaderni di Studi Arabi. 6: 323–336. JSTOR 25802612. (registration required)

- Gutas, Dimitri (2014). Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition: Introduction to Reading Avicenna’s Philosophical Works. Second, Revised and Enlarged Edition, Including an Inventory of Avicenna’s Authentic Works. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004201729.

- Khalidi, Muhammad Ali (2005). Medieval Islamic Philosophical Writings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82243-5.

- Lazard, G. (1975). «The Rise of the New Persian Language». In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 595–633. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1975). «The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran». In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 595–633. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Pasnau, Robert; Dyke, Christina Van (2010). Cambridge History of Medieval Philosophy, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

Encyclopedic articles

- Syed Iqbal, Zaheer (2010). An Educational Encyclopedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Bangalore: Iqra Publishers. p. 1280. ISBN 978-603-90004-4-0.

- Flannery, Michael. «Avicenna». Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Goichon, A.-M. (1999). «Ibn Sina, Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn b. ‘Abd Allah b. Sina, known in the West as Avicenna». Encyclopedia of Islam. Brill Publishers.

- Mahdi, M.; Gutas, D; Abed, Sh.B.; Marmura, M.E.; Rahman, F.; Saliba, G.; Wright, O.; Musallam, B.; Achena, M.; Van Riet, S.; Weisser, U. (1987). «Avicenna». Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Avicenna» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.