— Это его песня, — сказала девочка. — Если её сыграть правильно — уводит навсегда. Но сыграть правильно её можно только на его дудке… Или, может, большим оркестром. Наверное. Если собрать виртуозов со всего мира, чтобы их было несколько тысяч человек… Тогда, наверное, получится. Наверное. Понимаешь?

Марина и Сергей Дяченко «Алёна и Аспирин»

Помните историю о музыканте с волшебной флейтой, который вывел из города Гамельна и утопил всех крыс, а потом, когда скаредные горожане не заплатили ему за услугу, увёл неведомо куда их детей? В детстве её читал или слышал каждый из нас. И каждый наверняка задавался вопросом: кем был этот странный крысолов? Что у него за флейта? Куда он увёл детей? Правда ли они все погибли? Историки и фантасты наперебой предлагают свои варианты ответов.

Легенда о Гамельнском Крысолове — одна из тех, что не теряются в глубине веков, в сказочных «давным-давно, в тридевятом царстве», а напротив, имеют чётко обозначенные время и место действия. Это легенда, весьма убедительно претендующая на правду. Итак, что же на самом деле произошло в немецком городе Гамельне 26 июня 1284 года?

Откуда мы это знаем?

Интересно, что изначально во всей этой истории не было никаких крыс. Самая ранняя версия легенды изложена в хрониках города Гамельна за 1375 год в нескольких строчках:

«В 1284 году в день Иоанна и Павла, что было в 26-й день месяца июня, одетый в пёструю одежду флейтист вывел из города сто и тридцать рождённых в Гамельне детей на Коппен близ Кальварии, где они и пропали».

И всё.

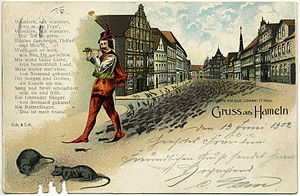

Это событие (если допустить, что оно было в действительности) так потрясло гамельнцев, что некоторое время они даже вели отсчёт времени именно с этой даты — «от ухода детей наших». Ранее — около 1300 года — флейтист, за которым следуют дети, был изображён на витраже городской церкви Маркеткирхе («рыночная церковь»), к сожалению, не сохранившемся, но известном по описаниям и зарисовкам.

Зарисовка XIII века, изображающая витраж с Крысоловом

В начале ХХ века в Гамельне во время ремонта городской ратуши, построенной в 1603 году на месте более ранних домов, была найдена древняя деревянная балка с надписью на старом диалекте:

«В году 1284-м, в День Иоанна и Павла 26 июня был Свистун в пёстрых одеждах, кем 130 детей, в Гамельне рождённых, уведены и в горе потеряны».

Сейчас эта надпись украшает фасад дома, в котором разместились гостиница и ресторан. А на Бунгелозенштрассе («улица молчания»), где стоит здание, законодательно запрещено исполнять любую музыку и танцевать — по преданию, именно по этой улице Флейтист увёл детишек.

Угол «бесшумной улицы»

История кочевала из одной исторической хроники в другую, постепенно обрастая подробностями. Примерно в начале 1560-х годов в хронике вюртенбергских графов фон Циммерн приведена уже полная версия легенды в том виде, в каком она дошла до нас. Правда, точной даты события в этот раз не называют, только приблизительную: «несколько сотен лет назад».

А дело было так. Богатый Гамельн одолело нашествие крыс, с которыми горожане никак не могли справиться. И тут как нельзя кстати появился некий бродячий школяр, который пообещал избавить город от напасти за огромную по тем временам сумму в несколько сот гульденов. С помощью волшебной флейты музыкант вывел крыс к одной из ближайших гор, где и запер их навсегда. А когда магистрат города пошел на попятную и отказался платить обещанную сумму, флейтист точно так же поступил с городскими детьми.

Что характерно, в те годы, когда создавалась хроника, Гамельн был действительно богат и славен. Так что завистливые соседи могли и дополнить легенду, изобразив исчезновение детей как справедливую кару за жадность, а не как нежданное несчастье, каким полагали эту историю гамельнцы.

Старая ратуша, известная как «Дом Крысолова»

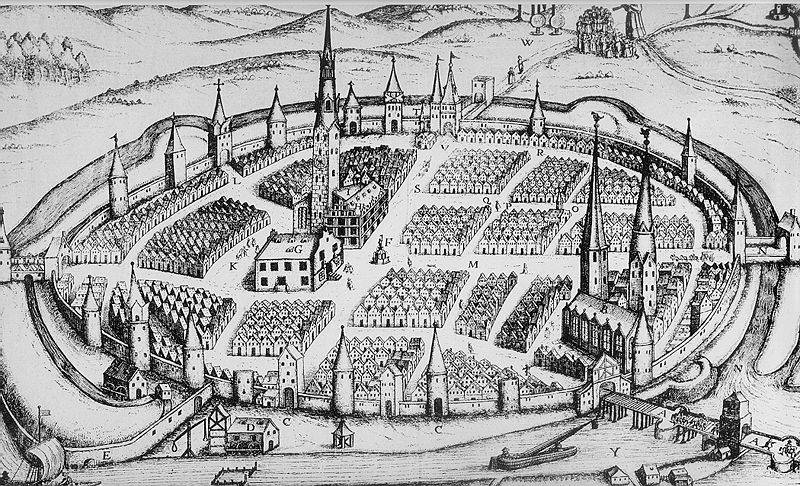

Город Гамельн

Маленький уютный городок Гамельн (Хамельн) находится на востоке Вестфалии, на реке Везер, и является столицей района Хамельн-Пирмонт. Он был основан около 851 года — именно тогда в хрониках впервые упоминается монастырь, у стен которого выросла деревушка, уже к XII столетию превратившаяся во вполне приличный город. Разбогател он благодаря торговле хлебом — окрестные поля были весьма урожайными. С 1277 года — вольный город. В XV—XVI веках Гамельн был членом Ганзейской лиги — влиятельного альянса торговых городов Северной Европы.

Во время Тридцатилетней войны, в 1634 году, город был осаждён шведскими войсками. Правители извлекли урок из этой истории: всего веком позднее Гамельн стал наиболее укреплённым населённым пунктом королевства Ганноверского — его окружали четыре мощные крепости, и подступиться к городу было непросто. Тем не менее войскам Наполеона в 1808 году город сдался без боя. В 1864 году Гамельн стал частью королевства Пруссия, и оставался ею вплоть до 1871 года, когда была создана Германская империя.

В наши дни дудочник уже не бич Гамельна, а его главный источник дохода, привлекающий туристов

Ныне население городка составляет около 58 тысяч человек. Основной источник дохода его жителей — туризм. Помимо мест, связанных с Гамельнским крысоловом, достойна внимания смотровая башня Клуттурм, возведённая в 1843 году. С неё открывается великолепный вид на старый город. Ещё одно примечательное место — отель, переделанный из городской тюрьмы, в которой во время Второй мировой войны фашисты казнили врагов режима, а британские войска впоследствии — нацистских военных преступников.

Легенда распространяется

В начале XVII века Крысолов появляется в «Возрождении угасшего разума», исторической работе англичанина голландского происхождения Ричарда Роланса. Излагая легенду, автор добавляет к ней иную концовку: будто бы уведённые Пёстрым Флейтистом дети прошли сквозь горный туннель в Трансильванию, где и остались жить. С точки зрения географии такой исход, конечно, совершенно невероятен. Роланс приводит иную дату события, почти на сто лет позднее Гамельнской версии: 22 июля 1376 года.

У Роланса заимствуют легенду его соотечественники Роберт Бертон (в книге «Анатомия меланхолии», 1621), Уильям Рэмси и Натаниэль Уонли. Причём первый объясняет эту историю происком тёмных сил, а неведомого музыканта называет «дьяволом в обличье пёстрого флейтиста». И он вновь путается в датах, на сей раз называя 20 июня 1484 года.

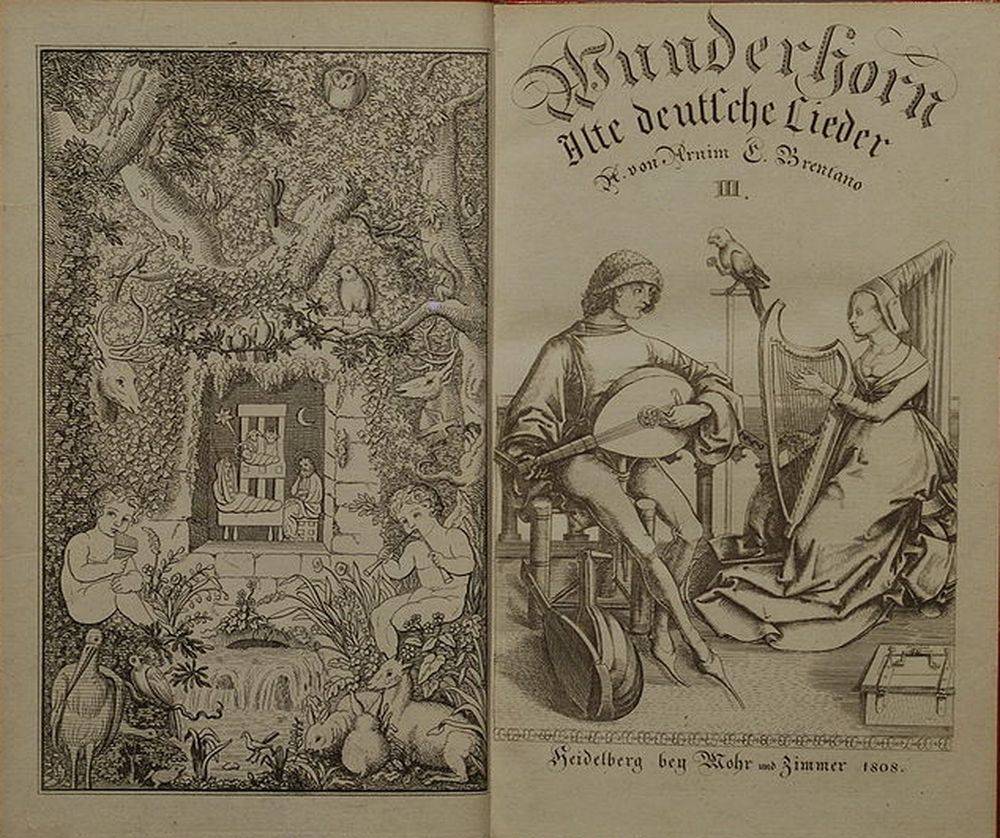

Титульные листы сборника «Волшебный рог мальчика». Многие из этих песен поют в Германии до сих пор

Настоящую популярность старинная легенда обрела сравнительно недавно — в начале XIX века. В 1806 году вышел первый том антологии народной немецкой поэзии «Волшебный рог мальчика», изданной поэтами-романтиками Людвигом Иоахимом фон Арнимом и Клеменсом Брентано. Среди прочих фольклорных баллад здесь есть и песня «Крысолов из Гамельна». Она неприкрыто назидательна, её последние строки: «Людская жадность — вот он, яд, сгубивший гамельнских ребят». Именно эта версия легенды стала хрестоматийной.

Нам легенда о Гамельнском крысолове известна в основном не по этой балладе, а по сказке братьев Гримм. Они тоже не избежали соблазна вывести из этой истории мораль. Флейтист, по версии сказочников, был самим Дьяволом, но детям удалось избежать его наваждения и остаться в живых, основав новый город в Трансильвании.

Крысы и крысоловы

Крысы были настоящим бедствием в Средние века и даже в Новое время. Они так быстро размножались, что способны были за считанные дни сожрать зерно в амбарах целого города. Вдобавок крысиные блохи разносили чуму — об этом не было известно вплоть до конца XIX века, когда открыли чумную бациллу. Положение усугублялось ещё и тем, что европейцы массово истребляли кошек, считавшихся дьявольскими отродьями, и бороться с хвостатыми вредителями было некому.

Между тем методы борьбы применялись самые безумные, вплоть до сжигания города вместе с грызунами. А в бургундском городе Отён, где в начале XVI века грызуны уничтожили весь хлеб, крыс даже вызывали на суд специально составленными повестками и долго ждали в ратуше, когда же пред очи судей и народа явится сам Крысиный Король. Когда тот нахально пренебрёг слушаниями, крысам было приговором велено убраться с бургундских земель. Нужно ли говорить, что и этот приказ они проигнорировали?

«Уж мы их душили-душили!» Крысолов демонстрирует горожанам новейшую ловушку для грызунов. Рисунок начала XVII века

На фоне такого бедственного состояния в амбарах и умах достопочтенных бюргеров стала популярной, хотя и малоуважаемой профессия крысолова. При дворе английского короля Якоба I (1603—1625) в штат Королевской Палаты входил придворный крысолов. Но получить такую хлебную должность удавалось немногим. Большинство крысоловов были бродячими ремесленниками. Они ходили из города в город, таская с собой связки крысиных трупов, приспособления для ловли грызунов и сильнодействующие яды, и расхваливали свой способ избавления от вредителей на улицах и площадях. Если горожанам методика того или иного специалиста казалась эффективной, они заключали с ним договор на уничтожение крыс в отдельном доме или в целом городе. Что интересно, многие крысоловы действительно пользовались музыкальными инструментами — считалось, что правильно подобранные мелодии зачаровывают крыс

Похожие легенды

Наш загадочный Крысолов не одинок: в мифологии и фольклоре разных народов музыкантам, обладающим способностью зачаровывать всё живое, уделено немалое внимание. Сирены, обольщавшие своими песнями древнегреческих моряков, но проколовшиеся на аргонавтах и Одиссее, — одного поля ягоды с Пёстрым Флейтистом. Явно в близком родстве с ним и Орфей, перед искусством которого склонялась вся природа, не исключая диких зверей, и герой «Калевалы» музыкант Вяйнямёйнен.

Нельзя не вспомнить, что волшебные свойства в фольклоре приписывались музыке и пению «маленького народца» — фей и эльфов. Согласно легендам, услышавший это пение либо вскоре умрёт, либо покинет свой дом и будет искать волшебную страну, не зная покоя до конца своих дней. А ещё эльфы очень любили похищать маленьких детей — к крысам они, впрочем, подобной любви не питали.

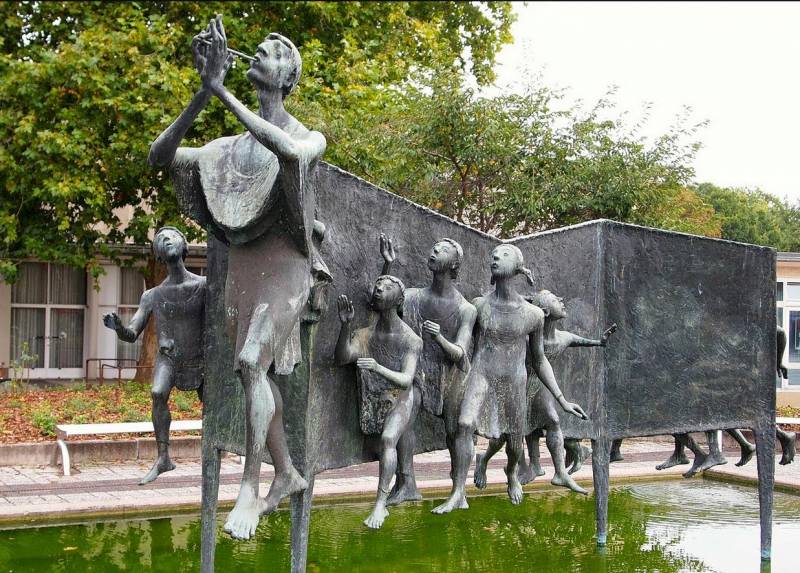

Современная версия витража с крысоловом

Но родословная Крысолова восходит куда выше — к самим богам. Согласно верованиям древних германцев, души умерших принимают облик мышей и крыс, собирающихся по зову бога Смерти — именно его роль и досталась Флейтисту. А Аполлон, божественный (во всех смыслах слова) музыкант, среди прочих своих эпитетов имел и такой, как Сминфей («мышиный» или «истребитель мышей»), потому что избавил многие греческие области от нашествия полёвок.

Легенды, поразительно похожие на историю Гамельнского крысолова, нет-нет, да и встречаются в Европе. Французы рассказывают о некоем монахе, который в отместку за обман магистрата увёл не детей, а домашних животных. В Ирландии есть сказка о волынщике, уведшем за собой неведомо куда юношей и девушек из города. На английском острове Уайт легенду о Гамельнском крысолове повторяют буквально слово в слово — с той незначительной разницей, что детей музыкант уводит не в гору, а в лес. Да и в самой Германии сразу несколько городов претендуют на то, чтобы считаться родиной волшебника с флейтой, которого именуют то монахом-отшельником, то колдуном.

Легенда, которую рассказывают в австрийском городе Корнойбурге, называет позднейшую дату события — 1646 год, — а также имя таинственного Дудочника: Ганс Мышиная Нора. Родом он, по его собственным словам, был из Вены, где занимал должность городского крысолова. История похищения детей здесь заканчивается прозаично: флейтист ведёт их к кораблю на Дунае, который увозит «живой товар» на невольничьи рынки Константинополя.

Так что это было?

Поискам реальной подоплёки легенды о Крысолове посвящено немало научных работ. Большинство версий выглядят достаточно убедительно и подкрепляются фактами — за исключением совсем уж бредовых вроде похищения детей инопланетянами или нападений маньяка-педофила. Но и возражений против них тоже хватает. Можно сказать, что на сегодняшний день тайна Крысолова всё ещё не раскрыта.

Крестовый поход детей?

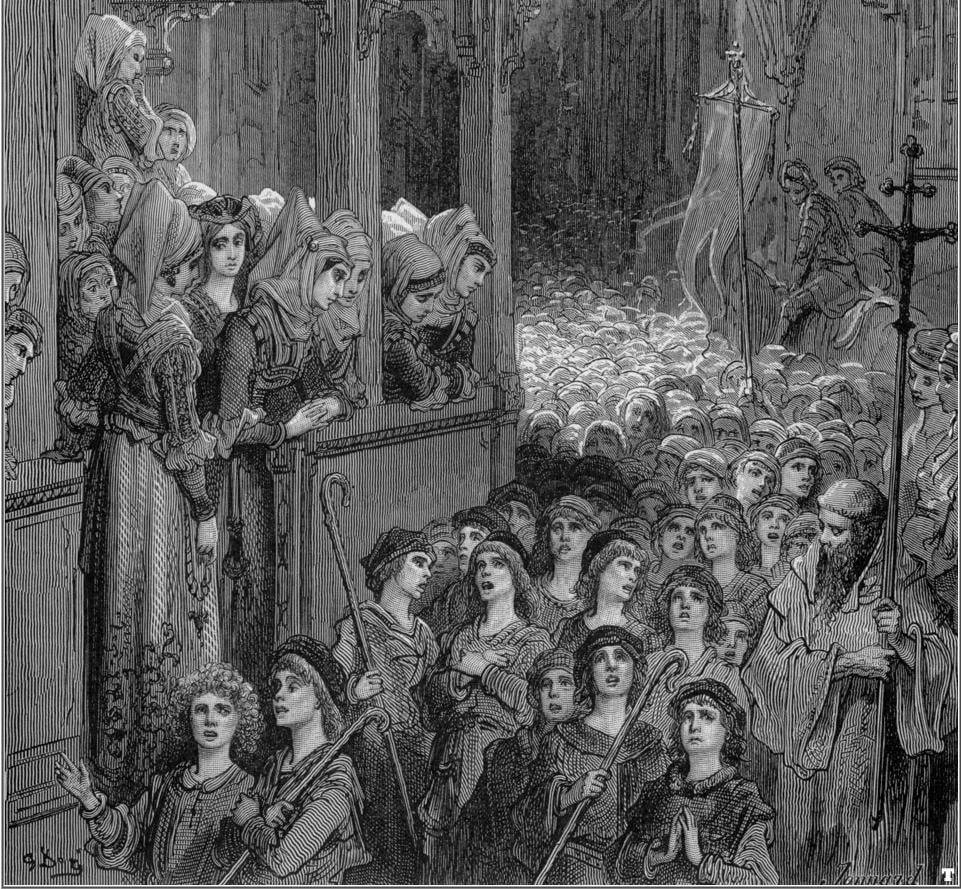

Одна из самых популярных теорий гласит, что ушедшие ребятишки на самом деле последовали за печально известным Крестовым походом детей, произошедшим в 1212 году. Тысячи детей и подростков Германии и Франции пленились речами маленьких пророков — немца Николаса и француза Этьена. Последние утверждали, что Бог не отдаёт Иерусалим в руки взрослых, так как те погрязли в грехе, и лишь невинные дети способны завоевать Гроб Господень.

Сейчас считается, что основную массу паломников составляли не маленькие дети, а подростки и юноши

К детям присоединились и взрослые, в момент наибольшего подъёма паломников было 25 тысяч. Судьба их была печальна: многие умерли в дороге от болезней и голода, те же, кто смог достичь Италии, откуда предполагалось морем переправиться в Иерусалим, были проданы в рабство на невольничьих рынках Туниса. Кое-кто сумел-таки взойти на корабли в Генуе, но они были тут же затоплены. Домой не вернулся никто из детей.

У этой версии есть два настораживающих момента. Во-первых, до указанного в гамельнских хрониках 1284 года оставалось немало времени — крестовый поход детей остался в народной памяти как совершенно отдельное явление. Во-вторых, в такой истории совершенно не находится места Пёстрому Флейтисту: вряд ли мальчики-пророки или их подручные носили разноцветные одеяния.

Чума?

Другая теория происхождения легенды о Гамельнском крысолове не менее зловеща. Она напоминает об эпидемиях чумы, опустошавшей в Средневековье целые города. В пёстрые одежды художники облачали скелет, символизирующий пляску Смерти, иногда этот жуткий танцор принимал и облик музыканта с флейтой, аккомпанирующего самому себе и тем, кто пускается в пляс вместе с ним.

В эту теорию отлично укладывается символизм Флейтиста как бога смерти и мышей как душ умерших. А холмы, за которые музыкант уводит детей, могут символизировать и границу между нашим и загробным мирами. Кроме того, именно крысы являются основными разносчиками чумы — правда, в Средние века об этом не знали.

Смерть аккомпанирует жутким пляскам на дудочке

Вроде всё логично, но в XIII веке, к которому предположительно относится действие легенды, в Германии не было крупных эпидемий чумы. Настоящим бедствием она стала более чем полстолетия спустя — в 1349 году, а на тот момент уже существовал витраж в Маркеткирхе.

Связана с этой версией и теория о другой заразной болезни — пляске Святого Витта. Она может иметь вирусное происхождение, но многие исследователи полагают, что в таких приступах люди выплёскивали ужас, накопившийся во время эпидемий чумы. Больные этим тяжёлым поражением нервной системы могли часами скакать и дёргаться в странном подобии танца, чтобы в конце концов упасть в изнеможении. Известен случай, когда в немецком городе Эрфурте этой безумной пляской оказались одержимы несколько сотен детей, которые в танце сумели дойти до соседнего города, где и упали. Многие из них умерли, другие, даже благополучно вернувшись домой, всю жизнь прожили с последствиями болезни — дрожащими конечностями и неустойчивой походкой.

Великое переселение?

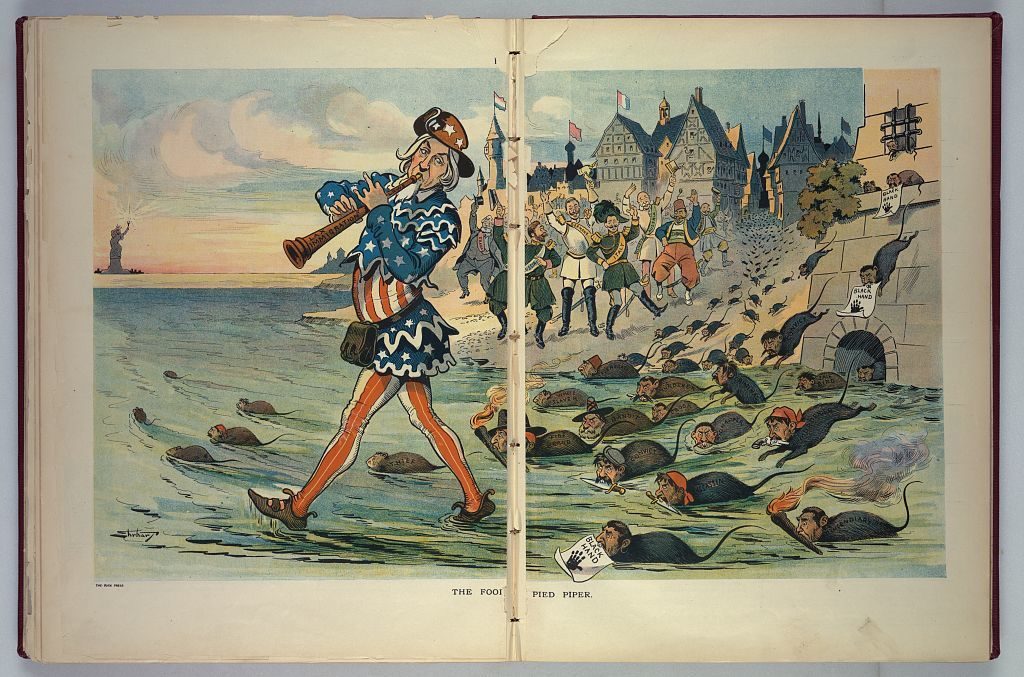

Крысолов подарил художникам неиссякаемую тему для карикатур…

Очень популярна в настоящее время теория, согласно которой ушедшие из города просто отправились обживать новые земли, в том числе Польшу, Моравию и Трансильванию, опустошённые монгольским нашествием. Активно переселялись немцы и в Прибалтику, в которой требовалось ослабить славянское влияние. Эмиграция была не слишком популярна среди горожан, привязанных к родным местам, поэтому сеньоры нанимали специальных вербовщиков, уговаривавших жителей собрать вещи и отправиться на поиски лучшей жизни на востоке. Вербовщики одевались в броскую яркую одежду и носили с собой барабаны и флейты, чтобы привлекать внимание народа.

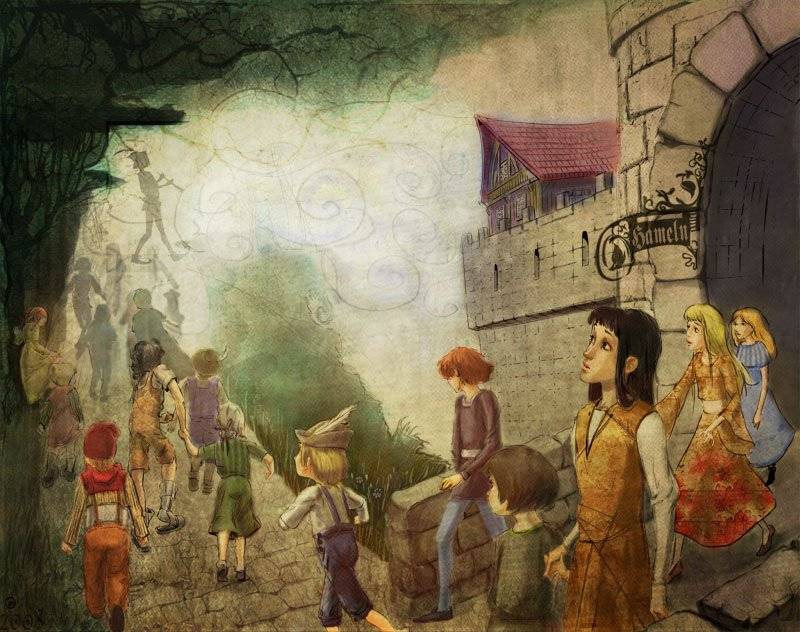

В этом случае дети из легенды исчезают, а появляется лёгкая на подъём молодёжь, в том числе молодые семьи. Косвенное подтверждение этой версии можно найти и на рисунке, скопировавшем витраж в Маркеткирхе: на полянке между Флейтистом и детьми изображены три оленя — герб фон Шпигельбергов, местных дворян, активно участвовавших в колонизации восточных земель. А в современной Польше живут люди с фамилиями Гамелин, Гамель и Гамелинков, да и просто с типично саксонскими фамилиями.

Версия, безусловно, элегантна. Однако совершенно непонятно, зачем гамельнцам понадобилось преображать прозаический рассказ об эмиграции в мистическую легенду. Это событие явно не из тех, что требовалось зашифровывать.

Катастрофа на празднике?

…и даже агитплакатов за здоровый образ жизни

Среди версий легенды о Крысолове есть и такая: якобы один или два ребёнка отстали от общего шествия и видели, как ушедших вперёд поглотила гора. Они-то и передали гамельнцам эту историю. Видимо, рассказывающие легенду в один прекрасный момент смекнули, что событие не может считаться истинным, если все его возможные свидетели сгинули.

Опираясь на эту версию, немецкая исследовательница Вальтраут Вёллер предположила, что причиной гибели детей стал горный оползень, а раскрывшаяся гора померещилась лишь издалека. В пятнадцати километрах от города действительно нашлась подходящая гора, по соседству с которой имеется и ущелье, в котором легко стать жертвой камнепада, и болотистая трясина, где несчастные дети во главе с музыкантом могли утонуть.

Куда они все шли? Возможно, к месту проведения праздника в честь летнего солнцестояния — отсюда и необходимость флейтиста. Одна неувязочка: солнцестояние всё-таки празднуют на несколько дней раньше указанной в хрониках даты…

Битва при Зедемунде?

Некоторые исследователи пытаются возвести легенду о Крысолове к незначительной битве при Зедемунде (1259), в которой гамельнское ополчение выступило против войск епископа Минденского (Минден — городок в Вестфалии) в споре за некое земельное владение. Гамельнцы битву проиграли, многие из них попали в плен — этих-то «детей Гамельна» (то есть уроженцев города) и поминают строки в хронике и надпись на доске. К слову, пленные, согласно летописям, были уведены с поля боя через горы, а домой смогли вернуться только через Трансильванию.

Правда, непонятно, почему составители хроники приписали этому событию другую дату, почему указали иное число пленных (их было 30, а не 130), а главное — откуда в таком случае взялся Пёстрый Флейтист? Словом, вопросов при любой версии остаётся больше, чем ответов…

Пёстрый флейтист в фантастике

Самое интересное в легенде о Гамельнском крысолове — ее неоднозначность. Трудно понять, кто же в этой истории главный злодей: Флейтист или жадные горожане, потерявшие детей. Да и кто такой этот человек с дудочкой — ловкий авантюрист или волшебник, сам Дьявол или гениальный музыкант-гипнотизёр? О чём эта история — только ли о том, что жадничать и обманывать нехорошо, или ещё и о силе искусства, способного служить как на пользу людям, так и во вред? Простор для интерпретации открывается широчайший — потому легенда до сих пор так популярна среди писателей. Не случайно образ Крысолова часто становится символом: например, вполне реалистический роман Невила Шюта «Крысолов» рассказывает о пожилом англичанине, спасающем детей из оккупированной Франции во время Второй мировой войны.

Большинству из нас история о Пёстром Флейтисте известна скорее не из сказки братьев Гримм, а из «Чудесного путешествия Нильса с дикими гусями» Сельмы Лагерлёф и одноимённого советского мультфильма. Это сказка, а значит, объяснений чуду не требуется: если Нильс находит ту самую волшебную дудочку, то крысы непременно его послушаются. Фокус, оказывается, в магическом предмете, а не в музыканте.

Нильс исполняет обязанности крысолова

У взрослой литературы и проблемы взрослые. В пьесе Бертольда Брехта «Правдивая история Крысолова из Гаммельна» финал легенды совсем другой: заблудившийся Крысолов возвращается в город вместе с детьми, и его приговаривают к повешению. Марина Цветаева в поэме «Крысолов» (1925) обличает сытое мещанство, глухое к настоящему искусству, и представляет легенду как историю справедливой мести — но не за жадность, а за тупость и душевную пустоту. Но и Крысолов в её интерпретации — не ангел возмездия, а опасный диктатор, сладкими речами увлекающий за собой на верную гибель, предвестник зловещих тираний ХХ столетия. Александр Грин в рассказе «Крысолов» тоже говорит об опасности тоталитаризма, но его главный страх — не Крысолов, а сами грызуны, превращающиеся в людей и захватывающие власть.

Фантасты, конечно, не могут избавиться от искушения раскинуть Гамельн на всю планету. Харлан Эллисон в повести «Эмиссар из Гаммельна» рассказывает о мальчике по имени Вилли, потомке Крысолова, игрой на дудочке заставившем уйти из города всех тараканов. Однако люди не стали меньше загрязнять Землю — и тогда он убрал с планеты всех взрослых людей, оставив её детям.

У Аркадия и Бориса Стругацких в повести «Жук в муравейнике» фигурирует планета, которую покинуло всё взрослое население, бросив детей, — их же пытаются куда-то заманивать странные человекоподобные существа в пёстрых одеждах.

В романе Андрэ Нортон «Угрюмый дудочник» (в другом переводе — «Тёмный трубач») главный герой, отождествляющийся с Флейтистом, снова выступает как благодетель: он помогает горстке детей колонизированной планеты избежать гибели, постигшей почти всё прочее человечество.

А в книге Ольги Родионовой «Мой ангел Крысолов» загадочный странник с флейтой борется с «отродьями» — детьми-мутантами, обладающими необычными способностями.

Терри Пратчетт в детской повести «Удивительный Морис и его учёные грызуны» отталкивается от одного простого факта — крысы прекрасно плавают, так что утопить их Пёстрый Флейтист не смог бы. Повесть напоминает старый добрый фильм-сказку «Сердце дракона»: разумные крысы объединяются с Крысоловом — мальчиком, инсценируя нашествие на город и их последующее выведение с помощью «волшебной» дудочки. А в «Осеннем лисе» Дмитрия Скирюка Гамельнским Крысоловом и вовсе поневоле становится главный герой цикла.

В рассказе Марины и Сергея Дяченко «Горелая башня» и его непрямом продолжении, романе «Алёна и Аспирин», Флейтист ни разу не назван, но у читателя есть возможность догадаться, что это именно он. Здесь он — нечеловеческое существо, некий высший судия и воплощённый моральный закон, ставящий людей перед сложнейшими выборами. Девочка Алёна — одна из детей, которых Крысолов когда-то увёл в светлый мир, полный радости и счастья, — но её брат сбежал на Землю, и девочка последовала за ним…

Зловещий облик Крысолова в наше несказочное время куда более популярен, чем его светлая сторона. У Гарта Никса в детском цикле «Ключи от Королевства» Дудочник, похищающий детей, — противник главного героя, мальчика по имени Артур, а одна из девочек, уведённых им, становится спутницей Артура. А Чайна Мьевилль в романе «Крысиный король» к Крысолову особенно беспощаден: здесь он — жестокий мегаломаньяк, «белокурая бестия» с жаждой безграничной власти, которую ему дает его музыка.

Пёстрый Флейтист бесчисленное множество раз появлялся в песнях — его упоминали в своих текстах ABBA и Jethro Tull, Queen и Led Zeppelin, Megadeth, Rammstein и In Extremo.

А вот воплощений на киноэкране, особенно оригинальных трактовок, у него не так уж много. Из примечательных моментов: в одной из экранизаций сказки («Пёстрый Флейтист» 1972 года) его сыграл фолк-музыкант Донован, а ещё Крысолов появляется в диснеевском мультфильме «Фантазия» и в «Шреке». Наконец, в одном из эпизодов старого телесериала «Бэтмен» главный герой пародирует Крысолова, заманивая в реку толпу механических грызунов.

Японцы, с их привычкой тащить в аниме и мангу всё, что плохо лежит, тоже не смогли пройти мимо Гамельнского крысолова. Художник Асада Торао изобразил весьма жестокую и кровавую, а-ля «Королевская битва», историю по мотивам легенды: в его манге «Крысолов» описывается мир, в котором бесчинствуют банды школьников, и взрослые ничего не могут с ними сделать — ведь несовершеннолетних нельзя судить по всей строгости закона. Зато со своими сверстниками легко расправляются подростки, некогда бывшие такими же преступниками, а затем создавшие Патруль 357, борющийся с детскими бандами. Тем временем становится ясно, что кто-то зомбирует школьников, присылая им приказы об убийствах. Кем может быть загадочный злоумышленник, если не легендарным Гамельнским флейтистом?

А вот аниме «Гамельнский скрипач» (Hameln no Violin Hiki) не имеет никакого отношения к сюжету легенды. Общего с Пёстрым Флейтистом у главного героя лишь то, что он умеет играть на скрипке музыку, подчиняющую демонов. Во всём остальном это довольно стандартное фэнтези, любопытное разве что тем, что многие герои в нем носят имена в честь музыкальных инструментов (Флейта, Тромбон, Рояль, Кларнет).

Гамельнский скрипач, как ни странно

* * *

Похоже, нам ещё долго следовать за дудочкой Гамельнского Крысолова. Её мелодия зовёт и манит, обещая чудеса, но вместо этого только запутывает всё больше и больше. Легенда о Пёстром Флейтисте жива постольку, поскольку она интригует, заставляя искать и находить всё новые её интерпретации. В этом смысле можно сказать, что Крысолов своё предназначение выполнил, наглядно и убедительно продемонстрировав нам силу искусства, с магией которого спорить невозможно.

Если вы нашли опечатку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Филолог по образованию и книжный червь по призванию. В свободное от чтения и написания текстов время играет в ролевые игры живого действия и преподает исторические танцы. Иногда пишет под псевдонимом «Александра Королёва».

Показать комментарии

1592 painting of the Pied Piper copied from the glass window of Marktkirche in Hamelin

Postcard «Gruss aus Hameln» featuring the Pied Piper of Hamelin, 1902

The Pied Piper of Hamelin (German: der Rattenfänger von Hameln, also known as the Pan Piper or the Rat-Catcher of Hamelin) is the title character of a legend from the town of Hamelin (Hameln), Lower Saxony, Germany.

The legend dates back to the Middle Ages, the earliest references describing a piper, dressed in multicolored («pied») clothing, who was a rat catcher hired by the town to lure rats away[1] with his magic pipe. When the citizens refuse to pay for this service as promised, he retaliates by using his instrument’s magical power on their children, leading them away as he had the rats. This version of the story spread as folklore and has appeared in the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Brothers Grimm, and Robert Browning, among others. The phrase «pied piper» has become a metaphor for a person who attracts a following through charisma or false promises.[2]

There are many contradictory theories about the Pied Piper. Some suggest he was a symbol of hope to the people of Hamelin, which had been attacked by plague; he drove the rats from Hamelin, saving the people from the epidemic.[3]

1909 Maxfield Parrish mural of the Pied Piper of Hamelin at the Palace Hotel, San Francisco

The earliest known record of the story originates from the town of Hamelin itself, depicted in a stained glass window created for the church of Hamelin, which dated to around 1300. Although the church was destroyed in 1660, several written accounts of the tale have survived.[4]

Plot[edit]

In 1284, while the town of Hamelin was suffering from a rat infestation, a piper dressed in multicolored («pied») clothing appeared, claiming to be a rat-catcher. He promised the mayor a solution to their problem with the rats. The mayor, in turn, promised to pay him for the removal of the rats (the promised sum was 1,000 guilders). The piper accepted and played his pipe to lure the rats into the Weser River, where all the rats drowned.[5]

Despite the piper’s success, the mayor reneged on his promise and refused to pay him the full sum (reputedly reduced to a sum of 50 guilders) even going so far as to blame the piper for bringing the rats himself in an extortion attempt. Enraged, the piper stormed out of the town, vowing to return later to take revenge. On Saint John and Paul’s day, while the adults were in church, the piper returned, dressed in green like a hunter and playing his pipe. In so doing, he attracted the town’s children. One hundred and thirty children followed him out of town and into a cave, after which they were never seen again. Depending on the version, at most three children remained behind: one was lame and could not follow quickly enough, the second was deaf and therefore could not hear the music, and the last was blind and therefore unable to see where he was going. These three informed the villagers of what had happened when they came out from church.[5]

Other versions relate that the Pied Piper led the children to the top of Koppelberg Hill, where he took them to a beautiful land,[6] or a place called Koppenberg Mountain,[7] or Transylvania, or that he made them walk into the Weser as he did with the rats, and they all drowned. Some versions state that the Piper returned the children after extorting payment, or that the children were only returned after the villagers paid several times the original payment in gold.[5][8]

The Hamelin street named Bungelosenstrasse («street without drums») is believed to be the last place that the children were seen. Ever since, music or dancing is not allowed on this street.[9][10]

Background[edit]

The earliest mention of the story seems to have been on a stained-glass window placed in the Church of Hamelin c. 1300. The window was described in several accounts between the 14th and 17th centuries.[11] It was destroyed in 1660. Based on the surviving descriptions, a modern reconstruction of the window has been created by historian Hans Dobbertin. It features the colorful figure of the Pied Piper and several figures of children dressed in white.[4]

The window is generally considered to have been created in memory of a tragic historical event for the town; Hamelin town records also apparently start with this event. The earliest written record is from the town chronicles in an entry from 1384 which reportedly states: «It is 100 years since our children left.»[12][13]

Although research has been conducted for centuries, no explanation for the historical event is universally accepted as true. In any case, the rats were first added to the story in a version from c. 1559 and are absent from earlier accounts.[14]

14th-century Decan Lude chorus book[edit]

Decan Lude of Hamelin was reported c. 1384 to have in his possession a chorus book containing a Latin verse giving an eyewitness account of the event.[15][further explanation needed]

15th-century Lüneburg manuscript[edit]

The Lüneburg manuscript (c. 1440–50) gives an early German account of the event.[16] According to the Christmas Eve edition of »The Saturday Evening Post» in 1955, on the back of the last tattered page of a dusty chronicle called The Golden Chain, written in Latin in 1370 by the monk Heinrich of Hereford, is there written in a different handwriting the following account:[17]

Here follows a marvellous wonder, which transpired in the town of Hamelin in the diocese of Minden, in the Year of Our Lord, 1284, on the Feast of Saints John and Paul. A certain young man thirty years of age, handsome and well-dressed, so that all who saw him admired him because of his appearance, crossed the bridges and entered the town by the West Gate. He then began to play all through the town a silver pipe of the most magnificent sort. All the children who heard his pipe, in the number of 130, followed him to the East Gate and out of the town to the so-called execution place or Calvary. There they proceeded to vanish, so that no trace of them could be found. The mothers of the children ran from town to town, but they found nothing. It is written: A voice was heard from on high, and a mother was bewailing her son. And as one counts the years according to the Year of Our Lord or according to the first, second or third year of an anniversary, so do the people in Hamelin reckon the years after the departure and disappearance of their children. This report I found in an old book. And the mother of the Dean Johann von Lüde saw the children depart.[18][19][20][note 1]

Rattenfängerhaus[edit]

It is rendered in the following form in an inscription on a house known as Rattenfängerhaus (English: «Rat Catcher’s House» or Pied Piper’s House) in Hamelin:[16]

|

anno 1284 am dage johannis et pauli war der 26. juni dorch einen piper mit allerley farve bekledet gewesen cxxx kinder verledet binnen hameln geboren to calvarie bi den koppen verloren |

(In the year 1284 on the day of [Saints] John and Paul on 26 June 130 children born in Hamelin were misled by a piper clothed in many colours to Calvary near the Koppen, [and] lost) |

According to author Fanny Rostek-Lühmann this is the oldest surviving account. Koppen (High German Kuppe, meaning a knoll or domed hill) seems to be a reference to one of several hills surrounding Hamelin. Which of them was intended by the manuscript’s author remains uncertain.[21]

The Wedding House[edit]

A similar inscription can be found on the «Wedding- or Hochzeitshaus, a fine structure erected between 1610 and 1617[22] for marriage festivities, but diverted from its purpose since 1721. Behind rises the spire of the parish church of St. Nicholas, which may still enwall stones that witness how the parents prayed, while the Piper wrought sorrow for them without»:[23]

|

Nach Christi Geburt 1284 Jahr Gingen bei den Koppen unter Verwahr Hundert und dreissig Kinder, in Hameln geboren von einem Pfeiffer verfürt und verloren |

In the year of Our Lord 1284 went into the Koppen under custody 130 children born in Hamelin by a piper seduced and lost |

The Town Gate[edit]

Part of the town gate from the year 1556 is today exhibited at the Hamelin Museum. According to Hamelin Museum, this stone is the oldest surviving sculptural evidence for the legend.[24] It bears the following inscription:[25]

|

Anno 1556 / Centu[m] ter denos |

In the year 1556, |

Verses in the monastery at Hamelin[edit]

The Hamelin Museum writes:[26]

In the mid 14th Century, a monk from Minden, Heinrich von Herford, puts together a collection of holy legends called the “Catena Aurea”. It speaks of a “miracle” that took place in 1284 in Hamelin. A youth appeared and played on a strange silver flute. Every child that heard the flute, followed the stranger. They left Hameln by the Eastern gate and disappeared at Kalvarien Hill. This is the oldest known account of this occurrence. Around this time a verse of rhyme is found in “zu Hameln im Kloster”. It tells about the children’s disappearance. It is written in red ink on the title page of a missal. It bewails “the 130 beloved Hamelner children” who were “eaten alive by Calvaria”. The original verses are probably the oldest written source of this legend. It has been missing for hundreds of years.[note 2]

However, different versions of transcriptions of handwritten copies still exist. One was published by Heinrich Meibom in 1688.[27] Another was included by Johann Daniel Gottlieb Herr under the title Passionale Sanctorum in Collectanea zur Geschichte der Stadt Hameln. His manuscript is dated 1761.[28] There are some Latin verses which had a prose version underneath:[29]

|

Maria audi nos, tibi Filius nil negat. Anno millesimo ducentesimo octuagesimo quarto in die Johannis et Pauli perdiderunt Hamelenses centum et triginta pueros, qui intraverunt montem Calvariam. |

Mary, hear us, for your Son denies you nothing. In the year one thousand two hundred and eighty-four, on the day of John and Paul, the Hamelin lost a hundred and thirty children who entered Calvary mount. |

16th- and 17th-century sources[edit]

Somewhere between 1559 and 1565, Count Froben Christoph von Zimmern included a version in his Zimmerische Chronik.[30] This appears to be the earliest account which mentions the plague of rats. Von Zimmern dates the event only as «several hundred years ago» (vor etlichen hundert jarn [sic]), so that his version throws no light on the conflict of dates (see next paragraph). Another contemporary account is that of Johann Weyer in his De praestigiis daemonum (1563).[31]

Theories[edit]

The Pied Piper leads the children out of Hamelin. Illustration by Kate Greenaway for Robert Browning’s «The Pied Piper of Hamelin»

Natural causes[edit]

A number of theories suggest that children died of some natural causes such as disease or starvation,[32] and that the Piper was a symbolic figure of Death. Analogous themes which are associated with this theory include the Dance of Death, Totentanz or Danse Macabre, a common medieval trope. Some of the scenarios that have been suggested as fitting this theory include that the children drowned in the river Weser, were killed in a landslide or contracted some disease during an epidemic. Another modern interpretation reads the story as alluding to an event where Hamelin children were lured away by a pagan or heretic sect to forests near Coppenbrügge (the mysterious Koppen «hills» of the poem) for ritual dancing where they all perished during a sudden landslide or collapsing sinkhole.[33]

Emigration[edit]

Speculation on the emigration theory is based on the idea that, by the 13th century, overpopulation of the area resulted in the oldest son owning all the land and power (majorat), leaving the rest as serfs.[34] It has also been suggested that one reason the emigration of the children was never documented was that the children were sold to a recruiter from the Baltic region of Eastern Europe, a practice that was not uncommon at the time.[citation needed] In his book The Pied Piper: A Handbook, Wolfgang Mieder states that historical documents exist showing that people from the area including Hamelin did help settle parts of Transylvania.[35] Emily Gerard reports in The Land Beyond the Forest an element of the folktale that «popular tradition has averred the Germans who about that time made their appearance in Transylvania to be no other than the lost children of Hameln, who, having performed their long journey by subterranean passages, reissued to the light of day through the opening of a cavern known as the Almescher Höhle, in the north-east of Transylvania.»[36] Transylvania had suffered under lengthy Mongol invasions of Central Europe, led by two grandsons of Genghis Khan and which date from around the time of the earliest appearance of the legend of the piper, the early 13th century.[37]

In the version of the legend posted on the official website for the town of Hamelin, another aspect of the emigration theory is presented:

Among the various interpretations, reference to the colonization of East Europe starting from Low Germany is the most plausible one: The «Children of Hameln» would have been in those days citizens willing to emigrate being recruited by landowners to settle in Moravia, East Prussia, Pomerania or in the Teutonic Land. It is assumed that in past times all people of a town were referred to as «children of the town» or «town children» as is frequently done today. The «Legend of the children’s Exodus» was later connected to the «Legend of expelling the rats». This most certainly refers to the rat plagues being a great threat in the medieval milling town and the more or less successful professional rat catchers.[38]

The theory is provided credence by the fact that family names common to Hamelin at the time «show up with surprising frequency in the areas of Uckermark and Prignitz, near Berlin.»[39]

Historian Ursula Sautter, citing the work of linguist Jürgen Udolph, offers this hypothesis in support of the emigration theory:

«After the defeat of the Danes at the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227,» explains Udolph, «the region south of the Baltic Sea, which was then inhabited by Slavs, became available for colonization by the Germans.» The bishops and dukes of Pomerania, Brandenburg, Uckermark and Prignitz sent out glib «locators,» medieval recruitment officers, offering rich rewards to those who were willing to move to the new lands. Thousands of young adults from Lower Saxony and Westphalia headed east. And as evidence, about a dozen Westphalian place names show up in this area. Indeed there are five villages called Hindenburg running in a straight line from Westphalia to Pomerania, as well as three eastern Spiegelbergs and a trail of etymology from Beverungen south of Hamelin to Beveringen northwest of Berlin to Beweringen in modern Poland.[40]

Udolph favors the hypothesis that the Hamelin youths wound up in what is now Poland.[41] Genealogist Dick Eastman cited Udolph’s research on Hamelin surnames that have shown up in Polish phonebooks:

Linguistics professor Jürgen Udolph says that 130 children did vanish on a June day in the year 1284 from the German village of Hamelin (Hameln in German). Udolph entered all the known family names in the village at that time and then started searching for matches elsewhere. He found that the same surnames occur with amazing frequency in the regions of Prignitz and Uckermark, both north of Berlin. He also found the same surnames in the former Pomeranian region, which is now a part of Poland.

Udolph surmises that the children were actually unemployed youths who had been sucked into the German drive to colonize its new settlements in Eastern Europe. The Pied Piper may never have existed as such, but, says the professor, «There were characters known as lokators who roamed northern Germany trying to recruit settlers for the East.» Some of them were brightly dressed, and all were silver-tongued.

Professor Udolph can show that the Hamelin exodus should be linked with the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227 which broke the Danish hold on Eastern Europe. That opened the way for German colonization, and by the latter part of the thirteenth century there were systematic attempts to bring able-bodied youths to Brandenburg and Pomerania. The settlement, according to the professor’s name search, ended up near Starogard in what is now northwestern Poland. A village near Hamelin, for example, is called Beverungen and has an almost exact counterpart called Beveringen, near Pritzwalk, north of Berlin and another called Beweringen, near Starogard.

Local Polish telephone books list names that are not the typical Slavic names one would expect in that region. Instead, many of the names seem to be derived from German names that were common in the village of Hamelin in the thirteenth century. In fact, the names in today’s Polish telephone directories include Hamel, Hamler and Hamelnikow, all apparently derived from the name of the original village.[42]

Pagan—Christian conflict[edit]

It has been noted that all local reports of the incident date it to the specific date of 26 June, the date of pagan midsummer celebrations and often also place emphasis the children being led away to the «Koppen» meaning hills. It was traditional in some areas of Germany to celebrate midsummer by lighting bonfires in the hills. This has led to speculation that the children may have been led away by a pagan shaman to participate in one of these celebrations and been forced into a monastery or massacred by local Christians.[43]

Other[edit]

Some theories have linked the disappearance of the children to mass psychogenic illness in the form of dancing mania. Dancing mania outbreaks occurred during the 13th century, including one in 1237 in which a large group of children travelled from Erfurt to Arnstadt (about 20 km (12 mi)), jumping and dancing all the way,[44] in marked similarity to the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, which originated at around the same time.[45]

Others have suggested that the children left Hamelin to be part of a pilgrimage, a military campaign, or even a new Children’s Crusade (which is said to have occurred in 1212) but never returned to their parents. These theories see the unnamed Piper as their leader or a recruiting agent. The townspeople made up this story (instead of recording the facts) to avoid the wrath of the church or the king.[46]

William Manchester’s A World Lit Only by Fire places the events in 1484, 100 years after the written mention in the town chronicles that «It is 100 years since our children left», and further proposes that the Pied Piper was a psychopathic paedophile.[47]

Adaptations[edit]

- In 1803, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote a poem based on the story that was later set to music by Hugo Wolf. Goethe also incorporated references to the story in his version of Faust. (The first part of the drama was first published in 1808 and the second in 1832.)

- Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, known as the Brothers Grimm, drawing from 11 sources, included the tale in their collection Deutsche Sagen (first published in 1816). According to their account, two children were left behind, as one was blind and the other lame, so neither could follow the others. The rest became the founders of Siebenbürgen (Transylvania).[21]

- Using the Verstegan version of the tale (1605: the earliest account in English) and adopting the 1376 date, Robert Browning wrote a poem of that name which was published in his Dramatic Lyrics (1842).[48] Browning’s retelling in verse is notable for its humour, wordplay, and jingling rhymes.[citation needed][according to whom?]

- Viktor Dyk’s Krysař (The Rat-Catcher), published in 1915, retells the story in a slightly darker, more enigmatic way. The short novel also features the character of Faust.

- In Marina Tsvetaeva’s long poem liricheskaia satira, The Rat-Catcher (serialized in the émigré journal Volia Rossii in 1925–1926), rats are an allegory of people influenced by Bolshevik propaganda.[according to whom?][49]

- The Pied Piper (16 September 1933) is a short animated film based on the story, produced by Walt Disney Productions, directed by Wilfred Jackson, and released as a part of Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies series. It stars the voice talents of Billy Bletcher as the Mayor of Hamelin.[50]

- ಬೊಮ್ಮನಹಳ್ಳಿಯ ಕಿಂದರ ಜೋಗಿ (Kondara Jogi of Bommanahalli) by the Kannada poet-laureate Kuvempu is a poetic adaptation of the story

- Paying the Piper, starring Porky Pig, is a Looney Tunes parody of the tale of the Pied Piper.

- The Town on the Edge of the End, a comic-book version, was published by Walt Kelly in his 1954 Pogo collection Pogo Stepmother Goose.

- Van Johnson starred as the Piper in NBC studios’ adaptation: The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1957).

- The Pied Piper is a 1972 British film directed by Jacques Demy and starring Jack Wild, Donald Pleasence, and John Hurt and featuring Donovan and Diana Dors.[51]

- «Emissary from Hamelin» is a short story written by Harlan Ellison, published in 1978 in the collection «Strange Wine.»

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin is a 1981 stop-motion animated film by Cosgrove Hall using Robert Browning’s original poem verbatim. This adaptation was later shown as an episode for the PBS series Long Ago and Far Away.

- The paperback horror novel Come, Follow Me by Philip Michaels (Avon Books, 1983) is based on the story.

- In 1985 Robert Browning’s poetic retelling of the story was adapted as an episode of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre starring Eric Idle as the Piper, and as Robert Browning in the prologue and epilogue, who narrates the poem to a young boy.

- In 1986, Jiří Bárta made an animated movie The Pied Piper based more on the above-mentioned story by Viktor Dyk; the movie was accompanied by the rock music by Michal Pavlíček.

- In 1989, W11 Opera premiered Koppelberg, an opera they commissioned from composer Steve Gray and lyricist Norman Brooke; the work was based on the Robert Browning poem.[52]

- In Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter (1997), the myth of the Pied Piper is a metaphor for a town’s failure to protect its children.[53]

- China Miéville’s 1998 London-set novel King Rat centers on the ancient rivalry between the rats (some of whom are portrayed as having humanlike characteristics) and the Pied Piper, who appears in the novel as a mysterious musician named Pete who infiltrates the local club-music scene.

- The cast of Peanuts did their own version of the tale in the direct-to-DVD special It’s the Pied Piper, Charlie Brown (2000), which was the final special to have the involvement of original creator Charles Schulz, who died before it was released.

- Demons and Wizards’ first album, Demons and Wizards (2000), includes a track called «The Whistler» which recounts the tale of the Pied Piper.

- Terry Pratchett’s 2001 young-adult novel, The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents, parodies the legend from the perspective of the rats, the piper, and their handler.

- The 2003 television film The Electric Piper, set in the United States in the 1960s, depicts the piper as a psychedelic rock guitarist modeled after Jimi Hendrix.

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin was adapted in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child where it uses jazz music. The episode featured Wesley Snipes as the Pied Piper and the music performed by Ronnie Laws as well as the voices of Samuel L. Jackson as the Mayor of Hamelin, Grant Shaud as the Mayor’s assistant Toadey, John Ratzenberger and Richard Moll as respective guards Hinky and Dinky.[54]

- The Pied Piper, «voiced» by Jeremy Steig, has a small role (flute only) in the 2010 Dreamworks animated film Shrek Forever After.

- In the anime adaptation of the Japanese light novel series, Problem Children Are Coming from Another World, Aren’t They? (2013), a major story revolves around the «false legend» of Pied Piper of Hamelin. The adaptation speaks in great length about the original source and the various versions of the story that sprang up throughout the years. It is stated that Weser, the representation of Natural Disaster, was the true Piper of Hamelin (meaning the children were killed by drowning or landslides).[55]

- In Ever After High, the Pied Piper has a daughter named Melody.

- In 2015, a South Korean horror movie title The Piper was released. It is a loose adaptation of the Brothers Grimm tale where the Pied Piper uses the rats for his revenge to kill all the villagers except for the children whom he traps in a cave.[56]

- The short story «The Rat King» by John Connolly, first included in the 2016 edition of his novel The Book of Lost Things, is a fairly faithful adaptation of the legend, but with a new ending. It was adapted for BBC Radio 4 and first broadcast on 28 October 2016.

- In 2016, Victorian Opera presented The Pied Piper, an Opera by Richard Mills. At the Playhouse the Art Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

- In the American TV series Once Upon a Time, the Pied Piper is revealed to be Peter Pan, who is using pipes to call out to «lost boys» and take them away from their homes.

- In the Netflix series The Society (TV series), a man named Pfeiffer removes a mysterious smell from the town of West Ham, but is not paid. Two days later he takes the kids on field trip in a school bus and returns them to an alternate version of the town where the adults are not present.

- In the song «Pied Piper» by the boy group BTS, dedicated to their fans to remind them not to get distracted by said group.

- In 2019, the collectible card game Magic: The Gathering, introduced a new set based on European folk and fairy tales. This set contained the first direct reference to the Piper, by being named «Piper of the Swarm.»[1]

- In the 1995 anime film Sailor Moon SuperS: The Movie, one of the film’s antagonists named Poupelin was very similar to the Pied Piper, using his special flute to hypnotize children and follow him into his ship away from their homes where they sailed off to his home planet.

- In Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles there is a villain called the Rat King who uses rats as troops; like the Pied Piper he uses a flute to charm them and even turns Master Splinter on his prized students.

- The HBO series Silicon Valley centers around a compression company called Pied Piper. The denouement of the series depicts the company as benevolent and self-sacrificing as opposed to the extortionist depiction in the fable. One of the characters refers to the company’s eponymous inspiration as «a predatory flautist who murders children in a cave.»

- The Pied Piper An opera in one act based on the poem The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Robert Browning with additional material by Adam Cornford. Music by Daniel Steven Crafts

- Karl Weigl composed a children’s operetta The Pied Piper of Hamelin in 1934, with libretto by Helene Scheu-Riesz. Under the direction of Davide Casali, the Festival Viktor Ullmann mounted a dramatic performance of the operetta in 2021, in Italian rather than the original German.

- Piedmon, from the first season of the animated series “Digimon” (1999), is also based on the Pied Piper. In the show, he played a pipe and was able to lure other people and Digimon to do his bidding, much like mind control.

- Piper, a 2017 liberal adaptation of the original story into a Young Adult graphic novel written by Jay Asher and Jessica Freeburg and illustrated by Jeff Stokely, from Penguin imprint Razorbill.

- Ratcatcher, a 2022 song by GWAR, has GWAR’s lead singer take credit for being the Piper and stealing the children when their bill went unpaid.

Literature[edit]

- The Pied Piper is a central figure in Rainbow Valley and Rilla of Ingleside by Lucy Maud Montgomery, calling, or in hindsight luring, that generation of boys off to war.[57][58]

Allusions in linguistics[edit]

In linguistics, pied-piping is the common name for the ability of question words and relative pronouns to drag other words along with them when brought to the front, as part of the phenomenon called Wh-movement. For example, in «For whom are the pictures?», the word «for» is pied-piped by «whom» away from its declarative position («The pictures are for me»), and in «The mayor, pictures of whom adorn his office walls» both words «pictures of» are pied-piped in front of the relative pronoun, which normally starts the relative clause.

Some researchers believe that the tale has inspired the common English phrase «pay the piper»,[59] although the phrase is potentially a contraction[59] of the English proverb «he who pays the piper calls the tune» which means, contrary to paying a debt such as the modern expression implies, that the person paying for something is the one who gets to say how it should be done.[60]

Modernity[edit]

The present-day city of Hamelin continues to maintain information about the Pied Piper legend and possible origins of the story on its website. Interest in the city’s connection to the story remains so strong that, in 2009, Hamelin held a tourist festival to mark the 725th anniversary of the disappearance of the town’s earlier children.[61] The Rat Catcher’s House is popular with visitors, although it bears no connection to the Rat-Catcher version of the legend. Indeed, the Rattenfängerhaus is instead associated with the story due to the earlier inscription upon its facade mentioning the legend. The house was built much later, in 1602 and 1603. It is now a Hamelin City-owned restaurant with a Pied Piper theme throughout.[62] The city also maintains an online shop with rat-themed merchandise as well as offering an officially licensed Hamelin Edition of the popular board game Monopoly which depicts the legendary Piper on the cover.[63]

In addition to the recent milestone festival, each year the city marks 26 June as «Rat Catcher’s Day». In the United States, a similar holiday for exterminators based on Rat Catcher’s Day is marked on 22 July, but has not caught on.[64]

See also[edit]

- Hamelen (TV series)

- List of literary accounts of the Pied Piper

- Pied Piper of Hamelin in popular culture

- Hamline University, whose mascot is the Pied Piper

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ The Christmas Eve edition of The Saturday Evening Post in 1955 translates also the name «Johann von Lüde», to «John of Luede» (the original Latin sentence goes: «Et mater domini Johannis de Lude decani vidit pueros recedentes»), and uses the description «Calvary Cross» and makes no mention of an execution place. The newspaper also writes that the piper plays on a «magic silver flute». Both The Saturday Evening Post and Wolfgang Wieder write «the Weser Gate» instead of «the West Gate». All the three sources translate decani with «deacon», but he was a Stiftsdechant, which in German can also be written Dekan and Dekant. In English this position is called Dean. Johann von Lüde was a dean, not a deacon.

- ^ Catena Aurea in Latin is the same as The Golden Chain in English

References[edit]

- ^ Hanif, Anees (3 January 2015). «Was the Pied Piper of Hamelin real?». ARY News. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ «Pied piper – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary». Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ «Deutungsansätze zur Sage: Ein Funken Wahrheit mit einer Prise Phantasie». Stadt Hameln (in German). Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b «Kirchenfenster». Marktkirche St. Nicolai Hameln (in German). Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Ashliman, D. L. (ed.). «The Pied Piper of Hameln and related legends from other towns». University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Hameln» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 876.

- ^ Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Irving (1975–1981). «True Story The Pied Piper of Hamelin Never Piped». The People’s Almanac. Trivia-Library.Com. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ^ «Die wohl weltweit bekannteste Version». Stadt Hameln (in German). Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Cuervo, Maria J. Pérez (19 February 2019). «The Lost Children of Hamelin». The Daily Grail. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Pearson, Lizz (18 February 2005). «On the trail of the real Pied Piper». BBC. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Reader’s Digest (2003). Reader’s Digest the Truth about History: How New Evidence is Transforming the Story of the Past. Reader’s Digest Association. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-7621-0523-6.

- ^ Kadushin, Raphael. «The grim truth behind the Pied Piper». www.bbc.com. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Asher, Jay; Freeburg, Jessica (2017). Piper. New York: Razorbill. ISBN 978-0448493688.

Researching earliest mentions of the Piper, we found sources quoting the first words in Hameln’s town records, written in the Chronica ecclesiae Hamelensis of AD 1384: ‘It is 100 years since our children left.’

- ^ «Der Rattenfänger von Hameln». Museum Hameln (in German). Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Krogmann, Willy (1934). Der Rattenfänger von Hameln: Eine Untersuchung über das werden der sage (in German). E. Ebering. p. 67.

- ^ a b Illustrated in Rattenfänger von Hameln

- ^ Richter, John Henry 1919-1994. John H. Richter Collection 1904-1994. Leo Baeck Institute Archives.

- ^ Medievalists.net (8 December 2014). «The Pied Piper of Hamelin: A Medieval Mass Abduction?». Medievalists.net. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Mieder, Wolfgang (11 August 2015). Tradition and Innovation in Folk Literature. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-37685-9.

- ^ «The Lüneburg Manuscript – The original manuscript published digitally. HAB – Handschriftendatenbank – Handschrift lg-rb-theol-2f-25». diglib.hab.de. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

«Et mater domini Johannis de Lude decani vidit pueros recedentes» Notes to the quote: He was a Stiftsdechant, which, in German, can also be written Dekan and Dekant. In English this position is called Dean. He was a dean, not a deacon.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Rostek-Lühmann, Fanny. «Der Rattenfänger von Hameln». Hinrich Lühmann. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ «Museum Hameln – 400 years Hochzeitshaus» (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Folklore Society (Great Britain). Folklore. Robarts — University of Toronto. London, Folk-lore Society.

- ^ «Commemorative stone (New Gate Stone) – Hameln Museum» (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Mieder, Wolfgang (11 August 2015). Tradition and Innovation in Folk Literature. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-37686-6.

- ^ «The Hameln Museum – The Pied Piper in Literatur and Arts: The Children’s Exodus» (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Meibom, Heinrich (1688). RERVM GERMANICARVM TOM. III. Dissertationes Historicas varii argumenti & Chronica Monasteriorum Saxoniae nonnulla continets MEIBOMIIS Auctoribus (in Latin). Typis & Sumptibus Georgii Wolffgangi Hammii, Acad. Typogr.

- ^ a b Scutts, Julian. «Ad fontes: A Timeline of Accounts of the Pied Piper Story».

- ^ Folklore Society (Great Britain). Folklore. Robarts — University of Toronto. London, Folk-lore Society. p. 242.

- ^ F. C. von Zimmern [attr.]: Zimmerische Chronik, ed. K. A. Barack (Stuttgart, 1869), vol. III, pp. 198–200.

- ^ Weyer, Johannes (1568). De Praestigiis Daemonum, Et Incantationibus ac veneficiis. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Wolfers, D. (April 1965). «A Plaguey Piper». The Lancet. 285 (7388): 756–757. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(65)92112-4. PMID 14255255.

- ^ Hüsam, Gernot (1990). Der Koppen-Berg der Rattenfängersage von Hameln [The Koppen hill of Pied Piper of Hamelin legend]. Coppenbrügge Museum Society.

- ^ Borsch, Stuart J (2005). The Black Death in Egypt and England: A Comparative Study. University of Texas Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-292-70617-0..

- ^ Mieder, Wolfgang (2007). The Pied Piper: A Handbook. Greenwood Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-313-33464-1.

- ^ Gerard, Emily (1888). The Land Beyond the Forest: Facts, Figures, and Fancies from Transylvania. Harper & Brothers. p. 30.

- ^ Thompson, Helen (26 May 2016). «Climate probably stopped Mongols cold in Hungary». Science News.

- ^ «The Legend of the Pied Piper». Rattenfängerstadt Hameln. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Kadushin, Raphael. «The grim truth behind the Pied Piper». www.bbc.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Sautter, Ursula (27 April 1998). «Fairy Tale Ending». Time International. p. 58.

- ^ Karacs, Imre (27 January 1998). «Twist in the tale of Pied Piper’s kidnapping». The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022.

- ^ Eastman, Dick (7 February 1998). «Pied Piper of Hamelin». Eastman’s Online Genealogy Newsletter. Vol. 3, no. 6. Ancestry Publishing. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- ^ Kadushin, Raphael (3 September 2020). «The grim truth behind the Pied Piper». www.bbc.com. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ Marks, Robert W. (2005). The Story of Hypnotism. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4191-5424-9.

- ^ Schullian, D. M. (1977). «The Dancing Pilgrims at Muelebeek». Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. Oxford University Press. 32 (3): 315–9. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xxxii.3.315. PMID 326865.

- ^ Bučková, Tamara. «Wie liest man ein Buch, ein Theaterstück oder einen Film?! Rattenfäger von Hameln ‘Nur’ eine Sage aus der Vergangenheit?» (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Manchester, William (2009). A World Lit Only by Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance – Portrait of an Age. Little, Brown. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-316-08279-2.

- ^ Browning, Robert. «The Pied Piper of Hamelin». Lancashire Grid for Learning. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Forrester, Sibelan E.S. (2002). «Review Of «The Ratcatcher: A Lyrical Satire» By M. Tsvetaeva And Translated By A. Livingstone». Slavic and East European Journal. 46 (2): 383–385. doi:10.2307/3086191. JSTOR 3086191.

- ^ «The Pied Piper (1933)». IMDB. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ «The Pied Piper (1972)». British Film Institute. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ «Koppelberg». W11 Opera. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Kelly, Brendan (16 May 1997). «The Sweet Hereafter». Variety. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ «Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child». IMDB. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Diomeda (2 March 2013). «8. It Seems that a Great Disaster will Come with the Playing of a Flute?». Problem Children are Coming from Another World, Aren’t They?. Season 1.

- ^ «The Piper (2015)». IMDB. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ «The Project Gutenberg eBook of Rainbow Valley, by Lucy Maud Montgomery». www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ «The Project Gutenberg E-text of Rilla of Ingleside, by Lucy Maud Montgomery». www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ a b Mieder, Wolfgang (1999). ««To pay the Piper» and the legend of «The Pied Piper of Hamelin»«. De Proverbia Journal. Archived from the original on 17 February 2004. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ «He who pays the piper calls the tune». Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ «Goosebumps and romance in Hamelin». Pied Piper Anniversary. 13 November 2008. Archived from the original on 1 July 2011.

- ^ Page, Helen (June 2012). «Rattenfängerhaus – The Rat Catcher’s House in Hameln». Travelsignposts. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ «Monopoly Hameln» [Hamelin Monopoly Game] (in German). January 2005. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Roach, John (21 July 2004). «Rat Catcher’s Day Eludes Pest Control Industry». National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Marco Bergmann: Dunkler Pfeifer – Die bisher ungeschriebene Lebensgeschichte des «Rattenfängers von Hameln», BoD, 2. Auflage 2009, ISBN 978-3-8391-0104-9.

- Hans Dobbertin: Quellensammlung zur Hamelner Rattenfängersage. Schwartz, Göttingen 1970.

- Hans Dobbertin: Quellenaussagen zur Rattenfängersage. Niemeyer, Hameln 1996 (erw. Neuaufl.). ISBN 3-8271-9020-7.

- Stanisław Dubiski: Ile prawdy w tej legendzie? (How much truth is there behind the Pied Piper Legend?). [In:] «Wiedza i Życie», No 6/1999.

- Radu Florescu: In Search of the Pied Piper. Athena Press 2005. ISBN 1-84401-339-1.

- Norbert Humburg: Der Rattenfänger von Hameln. Die berühmte Sagengestalt in Geschichte und Literatur, Malerei und Musik, auf der Bühne und im Film. Niemeyer, Hameln 2. Aufl. 1990. ISBN 3-87585-122-6.

- Peter Stephan Jungk: Der Rattenfänger von Hameln. Recherchen und Gedanken zu einem sagenhaften Mythos. [In:] «Neue Rundschau», No 105 (1994), vol.2, pp. 67–73.

- Ullrich Junker: Rübezahl – Sage und Wirklichkeit. [In:] „Unser Harz. Zeitschrift für Heimatgeschichte, Brauchtum und Natur». Goslar, December 2000, pp. 225–228.

- Wolfgang Mieder: Der Rattenfänger von Hameln. Die Sage in Literatur, Medien und Karikatur. Praesens, Wien 2002. ISBN 3-7069-0175-7.

- Aleksander R. Michalak: Denar dla Szczurołapa, Replika 2018. ISBN 978-83-7674-703-3

- Heinrich Spanuth: Der Rattenfänger von Hameln. Niemeyer Hameln 1951.

- Izabela Taraszczuk: Die Rattenfängersage: zur Deutung und Rezeption der Geschichte. [In:] Robert Buczek, Carsten Gansel, Paweł Zimniak, eds.: Germanistyka 3. Texte in Kontexten. Zielona Góra: Oficyna Wydawnicza Uniwersytetu Zielonogórskiego 2004, pp. 261–273. ISBN 83-89712-29-6.

- Jürgen Udolph: Zogen die Hamelner Aussiedler nach Mähren? Die Rattenfängersage aus namenkundlicher Sicht. [In:] Niedersächsisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 69 (1997), pp. 125–183. ISSN 0078-0561

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pied piper.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Maria J. Pérez Cuervo: «The Lost Children of Hamelin». Originally published in Fortean Times.

- The Lüneburg Manuscript – The original manuscript published digitally

- Chronica Ecclesiæ Hamelensis (1384) by Joannem de Polda, Seniorem Ecclesiæ, in Rerum Germanicarum tomi III : I. Historicos Germanicos (1688) by Heinrich Meibom

- D. L. Ashliman of the University of Pittsburgh quotes the Grimm’s «Children of Hamelin» in full, as well as a number of similar and related legends.

- An 1888 illustrated version of Robert Browning’s poem (Illustrated by Kate Greenaway)

- The 725th anniversary of the Pied Piper in 2009

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin From the Collections at the Library of Congress

- A Translation of Grimm’s Saga No. 245 «The Children of Hameln»

- A version of the legend from Howel’s Famous Letters

1592 painting of the Pied Piper copied from the glass window of Marktkirche in Hamelin

Postcard «Gruss aus Hameln» featuring the Pied Piper of Hamelin, 1902

The Pied Piper of Hamelin (German: der Rattenfänger von Hameln, also known as the Pan Piper or the Rat-Catcher of Hamelin) is the title character of a legend from the town of Hamelin (Hameln), Lower Saxony, Germany.

The legend dates back to the Middle Ages, the earliest references describing a piper, dressed in multicolored («pied») clothing, who was a rat catcher hired by the town to lure rats away[1] with his magic pipe. When the citizens refuse to pay for this service as promised, he retaliates by using his instrument’s magical power on their children, leading them away as he had the rats. This version of the story spread as folklore and has appeared in the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Brothers Grimm, and Robert Browning, among others. The phrase «pied piper» has become a metaphor for a person who attracts a following through charisma or false promises.[2]

There are many contradictory theories about the Pied Piper. Some suggest he was a symbol of hope to the people of Hamelin, which had been attacked by plague; he drove the rats from Hamelin, saving the people from the epidemic.[3]

1909 Maxfield Parrish mural of the Pied Piper of Hamelin at the Palace Hotel, San Francisco

The earliest known record of the story originates from the town of Hamelin itself, depicted in a stained glass window created for the church of Hamelin, which dated to around 1300. Although the church was destroyed in 1660, several written accounts of the tale have survived.[4]

Plot[edit]

In 1284, while the town of Hamelin was suffering from a rat infestation, a piper dressed in multicolored («pied») clothing appeared, claiming to be a rat-catcher. He promised the mayor a solution to their problem with the rats. The mayor, in turn, promised to pay him for the removal of the rats (the promised sum was 1,000 guilders). The piper accepted and played his pipe to lure the rats into the Weser River, where all the rats drowned.[5]

Despite the piper’s success, the mayor reneged on his promise and refused to pay him the full sum (reputedly reduced to a sum of 50 guilders) even going so far as to blame the piper for bringing the rats himself in an extortion attempt. Enraged, the piper stormed out of the town, vowing to return later to take revenge. On Saint John and Paul’s day, while the adults were in church, the piper returned, dressed in green like a hunter and playing his pipe. In so doing, he attracted the town’s children. One hundred and thirty children followed him out of town and into a cave, after which they were never seen again. Depending on the version, at most three children remained behind: one was lame and could not follow quickly enough, the second was deaf and therefore could not hear the music, and the last was blind and therefore unable to see where he was going. These three informed the villagers of what had happened when they came out from church.[5]

Other versions relate that the Pied Piper led the children to the top of Koppelberg Hill, where he took them to a beautiful land,[6] or a place called Koppenberg Mountain,[7] or Transylvania, or that he made them walk into the Weser as he did with the rats, and they all drowned. Some versions state that the Piper returned the children after extorting payment, or that the children were only returned after the villagers paid several times the original payment in gold.[5][8]

The Hamelin street named Bungelosenstrasse («street without drums») is believed to be the last place that the children were seen. Ever since, music or dancing is not allowed on this street.[9][10]

Background[edit]

The earliest mention of the story seems to have been on a stained-glass window placed in the Church of Hamelin c. 1300. The window was described in several accounts between the 14th and 17th centuries.[11] It was destroyed in 1660. Based on the surviving descriptions, a modern reconstruction of the window has been created by historian Hans Dobbertin. It features the colorful figure of the Pied Piper and several figures of children dressed in white.[4]

The window is generally considered to have been created in memory of a tragic historical event for the town; Hamelin town records also apparently start with this event. The earliest written record is from the town chronicles in an entry from 1384 which reportedly states: «It is 100 years since our children left.»[12][13]

Although research has been conducted for centuries, no explanation for the historical event is universally accepted as true. In any case, the rats were first added to the story in a version from c. 1559 and are absent from earlier accounts.[14]

14th-century Decan Lude chorus book[edit]

Decan Lude of Hamelin was reported c. 1384 to have in his possession a chorus book containing a Latin verse giving an eyewitness account of the event.[15][further explanation needed]

15th-century Lüneburg manuscript[edit]

The Lüneburg manuscript (c. 1440–50) gives an early German account of the event.[16] According to the Christmas Eve edition of »The Saturday Evening Post» in 1955, on the back of the last tattered page of a dusty chronicle called The Golden Chain, written in Latin in 1370 by the monk Heinrich of Hereford, is there written in a different handwriting the following account:[17]

Here follows a marvellous wonder, which transpired in the town of Hamelin in the diocese of Minden, in the Year of Our Lord, 1284, on the Feast of Saints John and Paul. A certain young man thirty years of age, handsome and well-dressed, so that all who saw him admired him because of his appearance, crossed the bridges and entered the town by the West Gate. He then began to play all through the town a silver pipe of the most magnificent sort. All the children who heard his pipe, in the number of 130, followed him to the East Gate and out of the town to the so-called execution place or Calvary. There they proceeded to vanish, so that no trace of them could be found. The mothers of the children ran from town to town, but they found nothing. It is written: A voice was heard from on high, and a mother was bewailing her son. And as one counts the years according to the Year of Our Lord or according to the first, second or third year of an anniversary, so do the people in Hamelin reckon the years after the departure and disappearance of their children. This report I found in an old book. And the mother of the Dean Johann von Lüde saw the children depart.[18][19][20][note 1]

Rattenfängerhaus[edit]

It is rendered in the following form in an inscription on a house known as Rattenfängerhaus (English: «Rat Catcher’s House» or Pied Piper’s House) in Hamelin:[16]

|

anno 1284 am dage johannis et pauli war der 26. juni dorch einen piper mit allerley farve bekledet gewesen cxxx kinder verledet binnen hameln geboren to calvarie bi den koppen verloren |

(In the year 1284 on the day of [Saints] John and Paul on 26 June 130 children born in Hamelin were misled by a piper clothed in many colours to Calvary near the Koppen, [and] lost) |

According to author Fanny Rostek-Lühmann this is the oldest surviving account. Koppen (High German Kuppe, meaning a knoll or domed hill) seems to be a reference to one of several hills surrounding Hamelin. Which of them was intended by the manuscript’s author remains uncertain.[21]

The Wedding House[edit]

A similar inscription can be found on the «Wedding- or Hochzeitshaus, a fine structure erected between 1610 and 1617[22] for marriage festivities, but diverted from its purpose since 1721. Behind rises the spire of the parish church of St. Nicholas, which may still enwall stones that witness how the parents prayed, while the Piper wrought sorrow for them without»:[23]

|

Nach Christi Geburt 1284 Jahr Gingen bei den Koppen unter Verwahr Hundert und dreissig Kinder, in Hameln geboren von einem Pfeiffer verfürt und verloren |

In the year of Our Lord 1284 went into the Koppen under custody 130 children born in Hamelin by a piper seduced and lost |

The Town Gate[edit]

Part of the town gate from the year 1556 is today exhibited at the Hamelin Museum. According to Hamelin Museum, this stone is the oldest surviving sculptural evidence for the legend.[24] It bears the following inscription:[25]

|

Anno 1556 / Centu[m] ter denos |

In the year 1556, |

Verses in the monastery at Hamelin[edit]

The Hamelin Museum writes:[26]

In the mid 14th Century, a monk from Minden, Heinrich von Herford, puts together a collection of holy legends called the “Catena Aurea”. It speaks of a “miracle” that took place in 1284 in Hamelin. A youth appeared and played on a strange silver flute. Every child that heard the flute, followed the stranger. They left Hameln by the Eastern gate and disappeared at Kalvarien Hill. This is the oldest known account of this occurrence. Around this time a verse of rhyme is found in “zu Hameln im Kloster”. It tells about the children’s disappearance. It is written in red ink on the title page of a missal. It bewails “the 130 beloved Hamelner children” who were “eaten alive by Calvaria”. The original verses are probably the oldest written source of this legend. It has been missing for hundreds of years.[note 2]

However, different versions of transcriptions of handwritten copies still exist. One was published by Heinrich Meibom in 1688.[27] Another was included by Johann Daniel Gottlieb Herr under the title Passionale Sanctorum in Collectanea zur Geschichte der Stadt Hameln. His manuscript is dated 1761.[28] There are some Latin verses which had a prose version underneath:[29]

|

Maria audi nos, tibi Filius nil negat. Anno millesimo ducentesimo octuagesimo quarto in die Johannis et Pauli perdiderunt Hamelenses centum et triginta pueros, qui intraverunt montem Calvariam. |

Mary, hear us, for your Son denies you nothing. In the year one thousand two hundred and eighty-four, on the day of John and Paul, the Hamelin lost a hundred and thirty children who entered Calvary mount. |

16th- and 17th-century sources[edit]