Фортепиано музыкальный инструмент

Пианино — струнно-клавишный музыкальный инструмент с клавиатурой. Обычное пианино имеет 88 клавиш. Хотя основные принципы работы фортепиано просты, утонченность, необходимая для разработки мощного, но чувствительного современного фортепиано, делает его также самым сложным из всех механических инструментов, кроме органа. Струны фортепиано ударяет войлочный молоток, который должен отскочить от струн мгновенно, иначе это ослабит их вибрации в самом процессе их инициации. Таким образом, молоток должен свободно лететь к струнам. Чтобы пианист сохранил максимальный контроль над громкостью, расстояние свободного полета молотка должно быть как можно меньше.

Инструмент бывает двух основных типов: рояль и фортепиано. Фортепиано — клавишный струнный инструмент с горизонтальным (рояль) или вертикальным (пианино) расположением струн. Пианино было чрезвычайно популярным инструментом в западной классической музыке с конца 18-го века. Человек, который играет на пианино, называется пианистом.

История происхождения пианино

Фортепиано было изобретено в 18-ом веке Бартоломео Кристофори из Падуи, Италия. Свой первый рояль он сделал в 1709 году. Он происходил от клавесина, который выглядит как пианино. В фортепьяно на струны ударяет кусок дерева, называемый молотком.

Ранние инструменты с клавиатурой, такие как клавикорды, клавесины и органы, которые использовались в то время, имели гораздо более короткую клавиатуру, чем сегодня. Постепенно клавиатура стала длиннее, пока в ней не стало 88 нот (7 октав плюс три ноты) современного пианино.

Сначала инструмент назывался «фортепиано». Это означает «громко-тихо» по-итальянски. Ему было дано это имя, потому что его можно было играть громко или тихо, в зависимости от того, как сильно была нажата нота.

Хотя пианино было изобретено в начале 18-го века, только спустя 50 лет оно стало популярным. Первый раз на пианино было сыграно на публичном концерте в Лондоне, это было в 1768 году, когда на нем сыграл Иоганн Кристиан Бах. Вертикальное пианино было изобретено в 1800 году Джоном Исааком Хокингсом. Семь лет спустя Т. Саутвелл изобрел «перетягивание». Это означает, что струны для низких нот проходят по диагонали через деки, чтобы они могли быть длиннее и издавать гораздо больший звук.

У ранних фортепиано были струны, которые были прикреплены к деревянной раме. Они были не очень тяжелыми, но они были не очень сильными или громкими, поэтому их не очень хорошо слышали в большом концертном зале. В 1825 году чугунная рама была изобретена в Америке. Это сделало пианино намного сильнее, чтобы оно могло издавать больший звук, и струны вряд ли бы сломались.

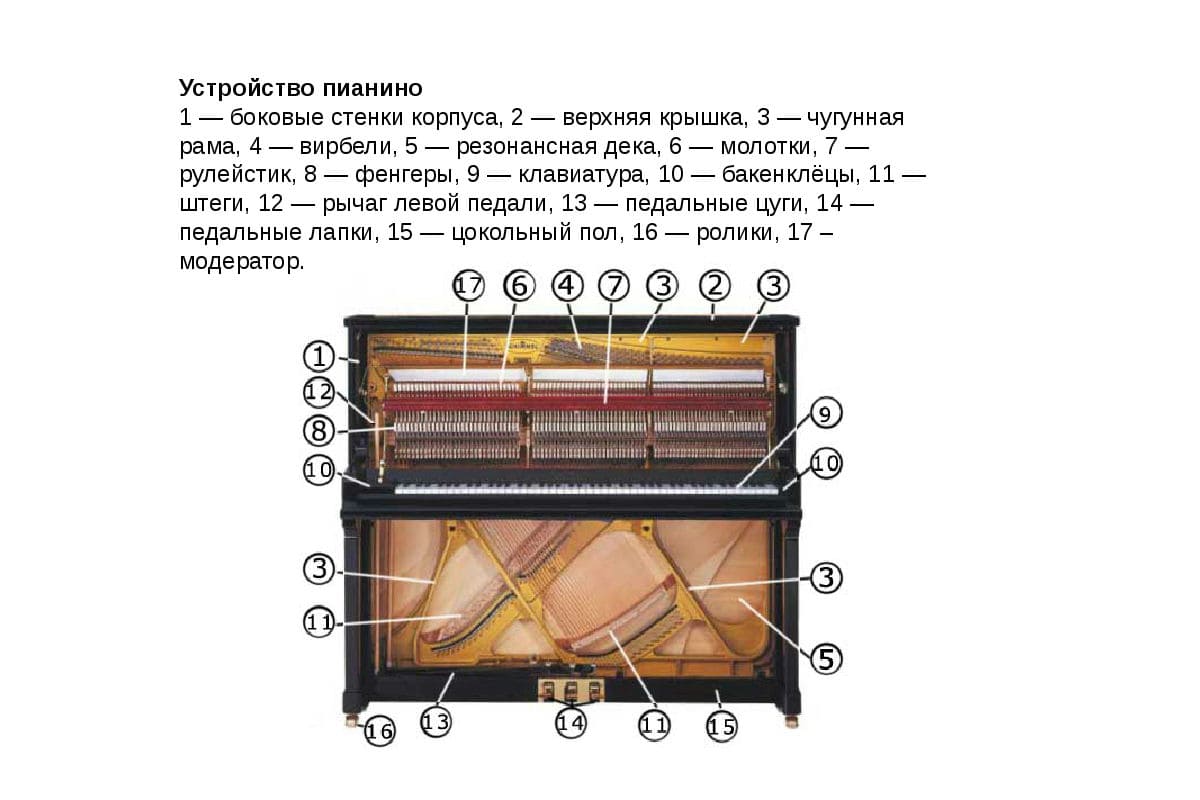

Устройство фортепиано

У пианино есть клавиатура с белыми клавишами и черными. Когда клавиша нажата, демпфер отрывается от струны, и молоток ударяет струну. Он ударяет его очень быстро и отскакивает, так что струна может свободно вибрировать и издавать звук. Когда пианист убирает палец с ключа, демпфер падает обратно на струну, и звук прекращается. Струны натянуты очень плотно по раме, проходя по мосту на пути. Мост касается деки. Это означает, что вибрации отправляются на деки. Дека является очень важной частью фортепиано. Если он поврежден, пианино не издаст звука.

Механизм, который заставляет молот отскочить от струны очень быстро, называется «спуск». В 1821 году Себастьян Эрар изобрел своего рода двойной спуск. Молоток касается струны только около одной тысячной секунды. Молотки покрыты войлоком, который представляет собой смесь шерсти, шелка и волос.

Стандартные пианино имеет две педали, но есть разновидности с тремя.

- Педаль демпфера — эта педаль находится справа. Когда пианист прижимает его правой ногой, любые ноты, которые он играет, будут звучать, даже если он уберет палец с ноты. Это потому, что есть демпферы (они немного похожи на молотки), которые опираются на все струны. Когда пианист удерживает правую педаль, все демпферы отрываются от струн, так что струны могут свободно вибрировать. При воспроизведении ноты эта нота продолжит звучать. Некоторые другие струны также будут вибрировать очень легко (это называется «сочувствующей вибрацией»). Это сделает звук более гладким и богатым. Пианисты должны научиться правильно пользоваться педалью. Это будет зависеть от таких вещей, как стиль музыки, размер пианино, размер комнаты и много ли там обстановки.

- Вторая педаль — мягкая педаль находится слева. Когда пианист прижимает его левой ногой, ноты звучат тише. На рояле вся клавиатура и действие немного смещены влево, так что молотки бьют только по двум струнам вместо трех. Также части войлока, которые поражают нить, мягче, потому что они не стали твердыми при большом количестве использования.

- Средняя педаль, как и правая педаль, она поддерживает звучание, но влияет только на ноты, которые уже воспроизводятся в момент нажатия средней педали. Это позволяет сохранить один аккорд во время исполнения других нот, которые не будут продолжаться. У всех концертных роялей есть такая педаль, а также у некоторых современных пианино.

Знаменитые композиторы и пианисты

Как только пианино стало популярным в конце 18 века, многие композиторы писали музыку для фортепиано. Вольфганг Амадей Моцарт начал учиться игре на клавесине, когда был очень маленьким, но пианино становилось популярным, когда он был молодым, и он написал много сонат и концертов для фортепиано. Франц Йозеф Гайдн также написал много фортепианной музыки. Людвиг ван Бетховен был очень известным пианистом, прежде чем он стал очень известным как композитор. Его фортепианные композиции включают 5 концертов и 32 сонаты. В романтический период многие композиторы писали для фортепиано. Среди них Франц Шуберт, Роберт Шуман, Иоганнес Брамс, Ференц Лист и Фридерик Шопен. Позднее композиторы — Сергей Рахманинов, Клод Дебюсси, Морис Равель, Сергей Прокофьев, Дмитрий Шостакович и Бела Барток.

Одни из первых известных пианистов игры на фортепиано Дюссек, Моцарт, Муцио Клементи, Джон Филд и Шопен. В 19 веке Ференц Лист очень сильно повлиял на фортепиано, сочиняя и исполняя очень сложную музыку. Другими великими пианистами являются Клара Шуман и Антон Рубинштейн. Пианисты 20-го века Артур Шнабель, Владимир Горовиц, Иосиф Гофман, Вильгельм Кемпф, Дину Липатти, Клаудио Аррау, Артур Рубинштейн, Святослав Рихтер и Альфред Брендель. Среди величайших пианистов сегодня Владимир Ашкенази, Даниэль Баренбойм, Лейф Ове Андснес, Борис Березовский и Евгений Кисин.

Пианисты, играющие популярную музыку, Либераче, Джерри Ли Льюис, Литтл Ричард, Элтон Джон, Билли Джоэл, Телониус Монах, Тори Эймос и Рэй Чарльз. Возможно, величайшим джазовым пианистом был Фэтс Уоллер.

Пианино было очень популярным инструментом с середины 18-го века, когда вскоре он заменил клавикорд и клавесин. К началу 19-го века звучание фортепиано было достаточно большим, чтобы заполнить большие концертные залы. Маленькие пианино были сделаны для использования в домах людей.

Пианино не часто используются в оркестрах (если они есть, они являются частью секции ударных). Они могут использоваться для концертов фортепьяно (пьесы для сольного пианиста в сопровождении оркестра). Существует огромное количество музыки, написанной для фортепиано соло. Пианино также можно использовать вместе с другими инструментами, в джазовых группах и для сопровождения пения.

Видео

Посмотрите видео ниже чтобы послушать и насладиться звучанием инструмента.

Фортепиано – общее название для клавишно-струнных инструментов, имеющих молоточковую механику. Умение играть на нем – признак хорошего вкуса. Образ старательного, талантливого музыканта столетия сопровождает каждого пианиста. Можно сказать, это – инструмент для избранных, хотя владение игрой на нем является составной частью любого музыкального образования.

Изучение истории помогает глубже понять устройство и специфику сочинений прошлой эпохи.

История пианино

Самыми распространенными являются «кабинетные пианино». У них стандартный размер корпуса 1400Х1200 мм, диапазон из 7 октав, педальный механизм, установленный на цокольном полу, вертикальная консоль, соединяющаяся с ножкой и балкой пианино. Таким образом, история создания пианино почти на сто лет короче эпохи развития данного инструментов типа.

Предки современного инструмента

Самыми древними представителями данного класса считаются клавикорд и клавесин. Кто и в каком году придумал или изобрел эти клавишно-щипковые инструменты, предшествующие фортепиано, не известно. Возникнув примерно в XIV веке, они получили широкое распространение в Европе в XVI-XVIII веках.

Отличие клавесина – выразительный звук. Он получается благодаря прикрепленному к концу клавиши стержню с перышком. Это приспособление дергает струну, вызывая звучание. Особенность в малой певучести, что не позволяет развить динамическое разнообразие, обуславливая необходимость устройства двух клавиатур, громкой и тихой. Особенности внешней отделки клавесина: изящество и своеобразная окраска клавиш. Верхняя клавиатура имеет белый, нижняя – черный цвет.

Другой предшественник фортепиано – клавикорд. Относится к инструментам камерного типа. Язычки заменены металлическими пластинами, не дергающими, а касающимися струн. Это определяет певучее звучание, дает возможность исполнять динамически насыщенное произведение.

Сила и яркость звучания ниже, поэтому инструмент по преимуществу применялся в домашнем музицировании, а не на концертах.

История создания нового инструмента и его эволюция

Флорентинец Барталамео Кристофори

С течением времени музыкальное искусство стало требовательно к качеству динамики. Старые клавишные инструменты постепенно модернизировались. Так появилось фортепиано. Его изобретателем считается флорентинец Барталамео Кристофори. Около 1709 года итальянский создатель фортепиано разместил под струнами молоточки. Эта конструкция получила наименование gravicembalo col piano e forte. Во Франции подобное новшество было разработано Ж. Мариусом в 1716 году, в Германии К. Г. Шретером в 1717 году. Благодаря изобретению двойной репетиции Эраром появилась возможность быстро повторно нажимать клавиши, вызывая более совершенное и мощное звучание. С конца XVIII века оно уверенно вытеснило распространенные до этого клавесины и клавикорды. При этом возникли своеобразные гибриды, сочетающие органные, клавесинные и фортепианные механизмы.

Отличие нового инструмента в наличии металлических пластин вместо язычков. Это повлияло на звучание, позволив изменять громкость. Сочетание громких (forte) и тихих (piano) звуков на одной клавиатуре дало название инструменту. Постепенно возникли фабрики, производящие фортепиано. Самые популярные предприятия – Штрейхера и Штейна.

В Российской империи его развитием занимались в 1818-1820-х годах Тишнер и Вирта.

Благодаря специализированному производству началось усовершенствование инструмента, прочно занявшего свое место в музыкальной культуре девятнадцатого столетия. Его конструкция несколько раз менялась. В течение всего века итальянские, немецкие, английские мастера вносили улучшения в устройство. Значительным вкладом стала работа Зильберманна, Цумпе, Шретера и Штейна. В настоящее время сложились отдельные традиции производства фортепиано, отличающиеся механикой. Также на основе классического инструмента появились новые: синтезаторы, электронные пианино.

Выпуск инструментов в СССР, несмотря на большое количество, не отличался высоким качеством. Фабрики «Красный Октябрь», «Заря», «Аккорд», «Лира», «Кама», «Ростов-Дон», «Ноктюрн», «Ласточка» производили недорогие добротные изделия из натуральных материалов, уступающие европейским аналогам. После распада Союза практически исчезло производство фортепиано в России.

Значения инструмента в истории

Развитие фортепиано стало поворотным моментом в музыкальной истории. Благодаря его появлению изменились концерты, в которых он занял ведущее положение. Это определило быстрый рост популярности в период классицизма и романтизма. Возникла плеяда композиторов, посвятивших свое творчество исключительно этому инструменту. Одними из первых его освоили В. А. Моцарт, Й Гайдн, Л. Бетховен, Р. Шуман, Ш. Гуно. Известны многочисленные шедевры фортепианной музыки. Даже не предназначенные для фортепиано произведения звучат именно на нем значительно интереснее, чем на других инструментах.

Фортепиано В. А. Моцарта

Вывод

Появление фортепиано – своеобразный технический ответ на назревшую в музыкальной культуре потребность в новом клавишном инструменте с сильным звучанием и широкой гаммой динамических оттенков. Будучи подходящим для воспроизведения лучших и сложных мелодий, оно стало неизменным атрибутом дворянских усадеб и квартир современной интеллигенции. А история создания фортепиано – триумфальное шествие идеального инструмента.

История пианино

в Клавишные инструменты

Каждый советский ребенок помнит огромный музыкальный инструмент, занимающий полкомнаты в наших небольших квартирах — пианино. Оно считалось и роскошью, и необходимостью, для многих семей. В прошлом же веке, каждая девушка или девочка, просто обязана была уметь играть на этом инструменте.

Может показаться что в наш век интерес к нему иссяк, но возможно кто-то пересмотрит свой взгляд на пианино, узнав сколько труда и времени понадобилось, чтобы создать привычное современное звучание и его внешний удобный вид. А так же то, сколько произведений не только полюбившихся классиков, но и современных шедевров, созданы, используя звучание именно пианино, этого громоздкого, казалось бы, устаревшего инструмента.

Как и для чего создавалось пианино?

Пианино — меньшая по размеру разновидность фортепиано. В свою очередь предшественниками фортепиано считаются клавикорды и клавесины. Создавался этот инструмент специально для комнатного музицирования в небольших помещениях.

В 1800 году американец Дж. Хокинс изобрел первое в мире пианино. В 1801 году похожую конструкцию, но уже с педалями, придумал М. Мюллер из Австралии. Вот так, два разных человека, не зная друг друга, живя на разных континентах создали это чудо!

В России о фортепиано узнали в 1818—1820 годах благодаря мастерам Тишнеру и Вирты. Вот так…почти через сто лет существования фортепиано узнали о нем и мы. И полюбили. Полюбилось пианино настолько, что этот инструмент продолжали усовершенствовать на протяжении почти трехсот лет. В 20 веке появляются знакомые многим электронные пианино и синтезаторы. Если копнуть историю, инструмент, который возможно кто-то считает древним, а его произведения не интересными по звучанию, на самом деле — плод не только таланта, но и усиленного труда, даже в те времена, когда для пианино не было таких электронных «конкурентов» как сейчас.

Видимо, когда был рожден этот инструмент, с ним вместе родились и умельцы создавать шедевры на нем. Как бы то ни было, чтобы музыка этого необычного инструмента доставляла наслаждение, его нужно любить, чувствовать, понимать.

Популярные в конце XVII века клавесин и клавикорд претерпели ряд принципиальных конструктивных изменений. В результате произошло возникновение нового инструмента – фортепиано, обладающего великолепными техническими возможностями, обширным диапазоном звучания, тембровой выразительностью. В советские годы пианино было почти в каждом доме, игре на нем обучали в музыкальных школах, а умение играть на фортепиано считалось частью хорошего образования.

Что такое фортепиано

Музыкальный струнный ударно-клавишный инструмент – так классифицируется фортепиано. Он появился более трех столетий назад, по прошествии времени не теряет актуальность, используется, как сольно, так и в сопровождении оркестров.

Старинное название фортепиано – клавир. До изобретения инструмента существовали и другие ударно-клавишные струнные виды – клавесин и клавикорд. Объединяет их то, что все они состоят из корпуса и внутреннего ударно-струнного механизма. Клавесины и клавикорды утратили свое значение из-за негромкого затихающего звука, недостаточно динамичного звучания, невозможности менять громкость.

Устройство

В элегантном корпусе инструмента прячется «начинка», отвечающая за звукоизвлечение. На тяжелой чугунной раме располагаются колки. На них натягиваются струны. Под струнами располагаются штеги. Взаимодействуя с резонансной декой, они усиливают струнные колебания, звуки воспроизводятся громко с выразительным тембром.

Фортепьяно имеет клавиатуру из 88 клавиш-полутонов. Под ней располагаются две или три педали. При нажатии правой педали происходит неразрывное звучание «legato». При нажатии средней педали музыкант удерживает избранные демпферы, а левая педаль используется для ослабления звука.

Конструкция фортепиано сложная. Но, благодаря ей, инструмент имеет богатые выразительные возможности и диапазон звучания целого оркестра. Звукоизвлечение происходит, когда пианист ударяет по клавишам. В это время деревянные молоточки, обтянутые войлоком, ударяют по струнам. В нижнем регистре «работает» одна струна, в среднем и верхнем молоточки ударяют сразу по двум или трем.

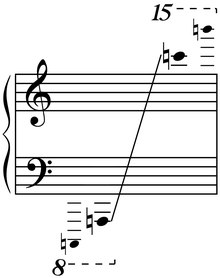

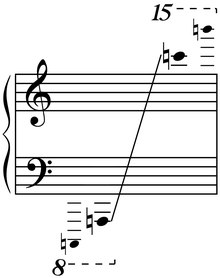

Диапазон звучания инструмента семь с четвертью октав от «ля» субконтроктавы до ноты «до» пятой октавы. Наиболее популярны две основные октавы – малая и первая. Контроктава представлена тремя самыми низкими нотами, а пятая – всего одной самой высокой нотой.

Вес пианино внушительный – 250-350 килограммов. Некоторые концертные экземпляры весят около полтонны.

История

Далекий предок фортепиано – монохорд. Этот инструмент использовался в Древней Греции во времена Пифагора. Представлял собой узкий длинный деревянный ящик с натянутой над ним струной. При помощи специальной подставки, которую музыкант передвигал по длине, извлекался звук разной высоты, воспроизводимый молоточками.

Со временем струн стало больше, ящик увеличился в размерах, появилась клавиатура. Нажатием клавиш приводились в движение тангеты – пластинки из металла. Конструкция получила название клавикорд от сочетания латинских слов «clavis» и «chorde», которое означает «клавиша» и «струна». В 17 столетии он был украшением гостиных и музыкальных салонов, являлся роскошью, украшался позолотой, перламутром, драгоценными камнями.

В это же время происходило создание и развитие другого предшественника фортепиано – клавесина. От клавикорда он отличался длиной струн, вследствие чего и имел другую форму, которая позднее перешла к роялю. На струны воздействовали щипковые язычки из птичьих перышек. Звук, извлекаемый таким способом, был мощным, но невыразительным.

В начале 18 века итальянский мастер Бартоломео Кристофори изобрел новый инструмент, в механизм которого заложил все составляющие современного фортепиано: демпфер, молоточек, шультер, шпиллер. Его создание стало началом происхождения пианино.

Первое фортепиано миру представил американский изобретатель Дж. Хаккинс в 1800 году. Через год конструкцию усовершенствовал другой мастер М. Мюллер, добавив к ней педали. Выглядело пианино не так, как сегодня. Фортепиано в том виде, в каком мы привыкли видеть его сегодня, появилось только в 19 веке. В это время он стал популярным и в России. В Петербурге работало несколько десятков мастеров, развивалось фабричное производство.

Разновидности фортепьяно

Пианино и рояль – два вида одного инструмента с разными конструкционными особенностями. Их строение отличается расположением струн. Пианино – разновидность фортепиано, у которой они лежат перпендикулярно клавиатуре, у рояля – в одной плоскости с ней. Поэтому размеры рояля больше, звук громче, насыщеннее.

Отличаются типы инструмента и количеством педалей – у пианино их две, а у более крупного представителя ударных струнно-клавишных – три. В семействе фортепиано эти инструменты называют «младшим» и «старшим» братьями.

Пианино имеет меньшие габариты, является инструментом для домашнего или камерного музицирования, «старший брат» – для концертного. В свою очередь пианино и рояль имеют разновидности, которые отличаются размерами.

Игра на инструменте

Овладение инструментом – сложный, долгий, кропотливый процесс. Поэтому обучение игре на фортепиано начинается с раннего возраста. Среди выдающихся пианистов прошлого века выделяются Артур Рубинштейн, Сергей Рахманинов, Святослав Рихтер. В современной музыкальной культуре место непревзойденного виртуоза занимает Денис Мацуев.

Инструмент позволяет реализовать многогранные задачи в музыке. Он используется для аккомпанемента сольным вокальным исполнителям. Широко распространены концерты для фортепиано с оркестром. Используются рояль или пианино и в камерных ансамблях в сочетании со струнными или духовыми инструментами.

Интересные факты

- До 50-х годов прошлого века клавиши фортепьяно изготавливались исключительно из слоновой кости. Позднее их заменили на пластиковые и деревянные.

- Японская игрушечная корпорация выпустила мини-пианино шириной всего 25 сантиметров. Это полностью функциональная модель. Она выглядит реалистично, а строение конструктивно правильное, настрой точный. Клавиши пианино всего полсантиметра в ширину.

- В советское время фортепиано было признаком самодостаточности, статусности, особого отношения к культуре. Его дарили за заслуги перед государством. Такой подарок после полета в космос получил Юрий Гагарин.

- На одном из концертов пианист-виртуоз Денис Мацуев настолько рьяно играл на инструменте, что у рояля сломалась ножка, а сам музыкант повредил палец.

- Особое отношение к пианино проявляли техасские ковбои. Даже во время перестрелок, которые часто случались в салунах, пианист продолжал играть, а даже самые отъявленные негодяи не осмеливались стрелять в музыканта.

- Рояль «Challen» – самый габаритный концертный инструмент. Весит знаменитый экземпляр более полутоны, длина корпуса составляет 3 метра 30 сантиметров.

- В истории аукционов отмечен рояль, проданный за баснословную сумму – 2,1 миллиона долларов. Он принадлежал Джону Леннону.

Фортепиано – универсальный инструмент с беспрецедентной популярностью, открывающий многогранное звучание. Для него написано бессчетное количество произведений, а музыкальная литература по художественному значению и ценности граничит с симфонической. Пианино используется в концертах, написанных для фортепиано, но и находит применение в джазовой музыке, применяется для сопровождения вокальных партий.

Фортепиано – популярный и универсальный музыкальный инструмент, с помощью которого можно исполнить множество мелодий. Отдельного фортепьяно как такового нет, это собирательное название для двух типов инструмента – рояля и пианино.

Что такое фортепиано

Фортепиано – музыкальный ударно-клавишный струнный инструмент. Несколько столетий назад был известен клавир – это старинное название фортепиано. Сменившее его наименование фортепиано происходит от соединения итальянских терминов “форте”, что обозначает “быстро”, и пиано – “тихо”. Его назвали так за возможность регулирования высоты звучания.

История создания

Два старинных инструмента – клавикорд и клавесин – являются предшественниками фортепиано. Данные “предки” клавишного инструмента имели негромкий затихающий звук и недостаточно динамично звучали, поэтому появилась необходимость их усовершенствования. От них было перенято внешнее устройство корпуса и внутренний ударно-струнный механизм.

Механизм будущего фортепиано был изобретен Бартоломео Кристофори (1655-1731), мастером из Италии. В 1709 году изобретатель разработал “пианофорте”. В дальнейшем у инструмента появились металлические рамы и изменилось расположение струн.

В 1721 году Готтлиб Шретер, немецкий композитор и педагог, сконструировал новый механизм. В нем прикрепленный к клавише молоточек подскакивал, ударяя по струне.

В 1770 году Иоганн Штайн усовершенствовал механизм и фортепьяно оставалось таким без изменений до середины XIX века.

В начале XIX века Джон Айзек Хокинс сконструировал пианино, поместив струнный механизм вертикально. В 1842 году Роберт Уорнум получил патент на детально разработанный им механизм пианино. Данная система используется в современном инструменте.

С середины XIX века устройство фортепьяно усовершенствуется еще больше.

Строение фортепиано

Разные модели фортепиано отличаются по размерам. Но длина должна быть не менее 1,8 м, а ширина – не менее 1,5 м. Устройство фортепиано сложное, поэтому настройка фортепиано считается кропотливой и трудной.

Инструмент состоит из:

- Акустического аппарата, включающего в себя резонансную деку и струнные переплетения.

- Дека для резонирования представляет собой расположенный под струнами деревянный щит. На ней расположены подставки для струн, которые передают ей колебания.

- Струны натягиваются на чугунную раму, находящейся над деревянной резонансной декой. С одного края они крепятся на металлические стержни, а с другого – на металлические колки, с помощью которых регулируется натяжение струн.

- Клавишного механизма. Фортепиано имеет 88 клавиш и 220 струн. Белых клавиш 56, а черных 32. Звук извлекается, когда пианист касается клавиш. При этом молоточки, головки которых обтянуты войлоком, бьют по струнам. Вместе с нажатием клавиш и ударом молоточка отделяется особое приспособление для прекращения колебаний – демпфер.

- Корпуса из различных пород древесины, совмещенных в несколько слоев. Верхний слой полированный. Корпус также имеет деревянную основу, к которой крепятся резонансная дека и чугунная рама.

- Педального механизма. В основном, устройство имеет две педали. При нажатии на правую отделяются все демпферы, поэтому все звуки усиливаются и становятся более продолжительными.

Нажатие левой педали ослабляет звучание и изменяет тембр. У рояля это происходит за счет смещения молоточков вправо, у пианино – приближения молоточков к струнам.

В некоторых моделях имеется средняя педаль. Она продолжает задерживать демпферы еще некоторое время после того, как клавиша будет опущена. Таким образом ноты продолжают звучать независимо от дальнейшей игры.

Как звучит фортепиано

На фортепиано можно сыграть практически любую мелодию как в сольных произведениях, так и в оркестровых.

Диапазон фортепьяно – 7 с четвертью октав: от ноты ля субконтроктавы до ноты до пятой октавы. Белые ноты называются по нотам, которые они извлекают, и повторяются на клавишах несколько раз, каждый раз в новом регистре. Черные клавиши соответствуют тем же нотам, что и белые, но только с повышением (диез) или понижением (бемоль) на полутон. К названиям добавляются соответствующие обозначения – диез или бемоль.

Каждая клавиша имеет по 3 струны в верхнем и среднем регистрах, по 2 – в басовом и по одной в самом низком регистрах. Высота звука возрастает слева направо: в левой части находятся самые низкие звуки, в правой – самые высокие.

Виды фортепиано

Фортепиано – общее название для группы подобных музыкальных инструментов. К ним относятся пианино и рояль.

Рояль образовано от французского “королевский”. В рояле, как и в фортепиано, струны имеют горизонтальное расположение. Сам инструмент имеет большие размеры и по форме напоминает птичье крыло. Во время исполнения крышка рояля приоткрыта, что усиливает мощность звука.

Рояль отличается размерами от малых (длина 1,2-1,5 м) до концертных видов инструмента (2,2-2,7 м).

Пианино на итальянском языке означает “маленькое фортепиано”. Струны и весь механизм расположены в нем вертикально. Это дало инструменту малые габариты и позволило добиться компактности, чтобы расположить пианино в любом помещении. Также уменьшилась стоимость инструмента.

Пианино находит применение не только на концертах вместо рояля, но и в джазовой музыке, для аккомпанемента вокальных партий, домашних занятий музыкой и обучения игры на фортепиано.

Наиболее распространенный вид – это пианино-консоль, высотой 1,1 м. Профессиональные и большие пианино по звуку равнозначны роялю, их высота достигает более 1,15 м.

Интересные факты

Несколько примечательных фактов о музыкальном инструменте:

- Первое произведение для фортепиано была соната “12 Sonate da cimbalo di piano e forte”, написанная Людовико Джустини в 1732 году.

- До середины XX века клавиши фортепиано изготавливались из слоновой кости. Позже их заменили на деревянные и пластиковые.

- Белые и черные клавиши фортепьяно не всегда имели расположение как в современном виде. В XVIII веке они размещались наоборот.

- Каждая струна имеет натяжение в 70 кг. Общее натяжение всех струн – примерно 18 тонн, у концертного рояля достигает 30 тонн.

- В общей сложности сумма всех деталей фортепиано составляет около 12 000 деталей. Из них 7500 деталей составляют механизм, приводящий фортепиано в действие.

- Самый большой концертный инструмент – рояль Challen. Он весит более полутонны, а корпус в длину достигает 3 м 30 см.

- Самыми взыскательными слушателями пианистов были техасские ковбои XIX- начала XX века. В одном из салунов Остина была надпись “Не стреляйте в пианиста, он играет, как умеет”. Из-за риска попасть под горячую руку ковбоя или стать невольной жертвой перестрелки американский инженер Э. С. Воти разработал механическую пианолу. Аппаратура проигрывателя сама регулировала клавиши с педалями. Мелодия выбиралась с помощью съемных барабанов.

У каждой вещи есть своя история, есть она и у клавишных инструментоов. Знать ее, несомненно, не только интересно, но и полезно. Это позволяет лучше разбираться в музыкальных стилях и понимать содержание того или иного произведения

Клавишные инструменты существовали еще в Средние Века. Орган, самый старый из них, — это духовой клавишный инструмент. У него нет струн, а есть множество труб.

Первый клавишный инструмент, у которого были струны, — клавикорд. Он появился в позднее Средневековье. Его звук был слишком мягким и тихим для того, чтобы на нем можно было играть перед большим количеством людей.

Клавикорд, будучи намного меньше по размеру и проще, чем его родственник клавесин, был достаточно популярным инструментом домашнего музицирования, и его наверняка можно было найти в домах композиторов эпохи барокко, включая Баха.

Клавикорд имел очень простое устройство. При нажатии на клавишу маленький медный квадратик под названием тангент ударял струну. В то же время поднятый демпфер позволял струне вибрировать. Будучи очень тихим инструментом, клавикорд все же позволял делать крещендо и диминуэндо.

Другой клавишный инструмент – клавесин. Звук у клавесина извлекается птичьими перышками или кусочками кожи (наподобие медиатора). К тому же струны клавесина расположены параллельно клавишам, как у современного рояля, а не перпендикулярно, как у клавикорда и современного пианино. Звук клавесина — блестящий, но малопевучий (отрывистый) – значит, не поддающийся динамическим изменениям (он более громкий, но менее выразительный, чем у клавикорда), изменение силы и тембра звука не зависит от характера удара по клавишам. В 17—18 вв. для придания клавесину динамически более разнообразного звучания изготовлялись инструменты с 2 (иногда 3) ручными клавиатурами (мануалами), которые располагались террасообразно одна над другой (обычно верхний мануал настраивался на октаву выше). В пьесы для клавесина композиторы вставляли множество мелизмов (украшений) для того, чтобы длинные ноты могли звучать достаточно протяженно.

На рубеже XVIII века композиторы и музыканты стали остро ощущать потребность в новом клавишном инструменте, который не уступал бы по выразительности скрипке.

Более того, был необходим инструмент с большим динамическим диапазоном, способным на громовое фортиссимо, нежнейшее пианиссимо и тончайшие динамические переходы. Эти мечты стали реальностью, когда в 1709 году итальянец Бартоломео Кристофори, изобрел первое фортепиано.

Он назвал свое изобретение «gravicembalo col piano e forte», что означает «клавишный инструмент, играющий нежно и громко». Это название затем было сокращено, и появилось слово «фортепиано».

Самое замечательное в фортепиано — это способность резонировать и динамический диапазон. Деревянный корпус и стальная рама позволяют инструменту достигать почти колокольного звучания на форте. Другое отличие фортепиано от его предшественников — это способность звучать не только тихо и громко, но и делать крещендо и диминуэндо, менять динамику внезапно или постепенно.

В период классицизма фортепиано стало популярным инструментом домашнего музицирования и концертного исполнения. Фортепиано как нельзя более подходило для исполнения появившегося в это время жанра сонаты, ярким образцом которого являются произведения Гайдна, Моцарта, Бетховена

Появление фортепиано также вызвало изменение репертуара ансамблей и оркестров. Концерт для фортепиано с оркестром — новый жанр, ставший весьма популярным в период классицизма. Динамические возможности позволили фортепиано встать в ряд сольных инструментов, таких, как скрипка и труба, и занять центральное место в концертных залах Европы.

На смену классицизму приходит эпоха романтизма, когда в музыке, да и в искусстве в целом, основную роль стало играть выражение эмоций. Это выразилось, в частности, в фортепианном творчестве Шумана, Листа, Шопена.

И здесь выразительные возможности фортепиано оказались очень кстати.

Произведения для фортепиано в четыре руки стали очень популярными в этот период, когда из фортепиано одновременно извлекали до двадцати звуков, порождая новые краски.

В период романтизма фортепиано было популярным инструментом домашнего музицирования. Любители музыки предпочитали именно фортепиано, потому что оно давало возможность исполнять одновременно и мелодию, и гармонию.

Очевидно, что появление фортепиано стало поворотным моментом в истории искусства. Это изобретение изменило характер всей европейской музыки, которая является важной частью всей мировой культуры.

За прошедшие триста лет почти все великие композиторы писали для фортепиано, и многие из них знамениты именно своими фортепианными произведениями. Сегодня нельзя найти музыканта — будь то певец или композитор, кларнетист или скрипач — у которого в доме не было бы фортепиано.

Несмотря на его молодость, фортепиано оказывает на общество в целом большее воздействие, чем какой-либо другой инструмент, и надо полагать, что его славе еще очень далеко до заката.

Часто спрашивают, чем отличается пианино от рояля или чем отличается пианино от фортепиано?

Фортепиано и пианино – это один и тот же инструмент. Рояль и фортепиано это тоже один и тот же инструмент. Фортепиано – общее название для них. Так же, как под духовыми подразумевают саксофоны, тромбоны, трубы. Кроме формы мало кто может понять, в чем же состоит разница между роялем и пианино, но мало кто задумывается, почему же они имеют различную форму.

Пианино – инструмент с вертикальным построением струн, это построение обеспечивает компактность (относительную, конечно) инструмента.

У рояля же построение горизонтальное, он имеет дугообразную форму и,

- Помимо размера имеется еще одно ключевое отличие. В рояле существует особый механизм,

- называющийся «механизмом двойной репетиции» («репетиция» – повторение) – он создан для того, чтобы легко можно было бы проигрывать быстро повторяющиеся нажатия на клавиши, что также незаменимо на концертах, где требуется максимально продемонстрировать своё мастерство.

- Все мы прекрасно знаем, что фортепиано очень многогранно как инструмент, и синтезатор как раз является одной из его граней, которая смогла в корне поменять всю музыку, расширить её возможности до пределов, которые себе и представить не могли классические композиторы.

Корень слова «синтезатор» — «синтез», то есть создание чего-либо из ранее разрозненных частей. Одной из его ключевых особенностей является то, что синтезатор способен воспроизводить не только звуки классического пианино, но и имитировать звучание многих других инструментов. В них заложены и электронные звуки, которые смогут воспроизвести только синтезаторы.

Своё начало создание электронных инструментов берёт еще в конце XIX века, русский учёный Лев Термен изобрёл один из первых полноценных инструментов, использующих законы физики и электрическое питание, известный как терменвокс.

Он представлял собой довольно простую и мобильную конструкцию, аналогов которой нет до сих пор – это единственный инструмент, на котором играют, даже не касаясь его.

Музыкант, перемещая руки в пространстве между антеннами инструмента, меняет колебательные волны и тем самым изменяет и ноты, которые выдает терменвокс.

Один из первых электронных инструментов, на этот раз уже клавишных, назывался Теллармониум и был изобретен Таддеусом Кэхилом из Айовы.

Инструмент, целью которого было заменить церковный орган, вышел воистину масштабным: он весил около 200 тонн, состоял из 145 огромных электрогенераторов, а, чтобы перевезти его в Нью-Йорк, понадобилось 30 железнодорожных вагонов.

Но сам факт его создания показал, куда двигаться музыке, показал, насколько еще может технический прогресс помочь развитию искусства. Говорили, что Кэхил опередил своё время, называли его невоспетым гением.

Однако, несмотря на все прелести инструмента, ему еще было куда развиваться: дело в том, что он вызывал помехи на телефонных линиях, да и качество звука его было достаточно посредственным даже по меркам начала XX века.

Во время Первой мировой войны, когда на долгое время гул разрывающихся снарядов, свист пуль, скрежет гусениц танков наполняли окружающий мир, французский радист Морис Мартено (Maurice Martenot), сидя в окопах, мечтал найти новое звучание, которое бы заглушило звуки войны.

Экспериментируя с военной радиостанцией, он заинтересовался необычным «поющим» звуком, который издавали лампы оборудования.

Будучи музыкантом по призванию (он в совершенстве играл на скрипке), ему не составило труда превратить случайные электрические звуки радиостанции в незатейливые мелодии.

После окончания войны, увлеченный электрическим звучанием, Морис Мартено продолжил свои эксперименты. Почти десять лет он работал над своим проектом и только лишь в 1928 году достиг желаемого результата.

В этом же году на Парижской выставке он представил мировому сообществу свое изобретение, назвав его «Волны Мартено» (Ondes Martenot).

Поскольку это был один из первых подобных инструментов, изобретение Мартено вызвало оживленный интерес.

В тридцатые годы композиторы, ищущие новое звучание, пишут музыку для Волн Мартено. Среди них были такие известные композиторы, как Оливье Мессиан, Богуслав Мартину, Дариюс Мийо, Артюр Онеггер, Шарль Кёклен и другие. Широкое применение этот инструмент нашел в кино-индустрии при создании музыки к фантастическим фильмам.

RCA (Radio Corporation of America) приняла первую попытку создать синтезаторы, которые стали бы шагом вперёд после органа Хаммонда, но созданные корпорацией модели Mark I иMark II не снискали успеха из-за, опять же, болезни всех электронных устройств того времени – габаритов (синтезатор занимал целую комнату!) и астрономической цены, однако определенно стали новой вехой в развитии технологий звукового синтеза.

С начала 1960х появилось множество компаний, каждая из которых заняла свою нишу в создании синтезаторов: Sequential Circuits, E-mu, Roland, ARP, Korg, Oberheim, Yamaha и это еще не весь список.

Аналоговые синтезаторы с тех времен не подверглись кардинальным изменениям, они до сих пор ценимы и очень дороги – модели представляли собой тот классический вид синтезаторов, к которому мы привыкли.

Между прочим, советские производители тоже не отставали. Советские синтезаторы являются очень интересными в плане звучания, в СССР даже были свои маэстро электронной музыки, такие как, Эдуард Артемьев. Самыми известными сериями были Аэлита, Юность, Лель, Электроника ЭМ.

К середине 80-х годов в музыкальную индустрию стали уверенно входить цифровые технологии.

Оказалось, что в ряде случаев сложный и неповторимый процесс аналогового синтеза можно просто и быстро заменить цифровым запоминанием полученного результата — сэмпла.

Появились простые и дешёвые клавишные инструменты, которые используют библиотеку сэмплов, записанных в ROM-памяти, их назвали ромплерами.

Источник: https://www.sites.google.com/site/muzlomteva/iz-istorii-klavisnyh-instrumentov

Древние родственники пианино: история развития инструмента

Пианино само по себе является разновидностью фортепиано.

Под фортепиано можно подразумевать не только инструмент с вертикальным расположением струн, но и рояль, у которого струны натянуты горизонтально.

Но это – современное пианино, которое мы привыкли видеть, а до него существовали другие разновидности струнно-клавишных инструментов, имеющие с привычным нам инструментом мало чего общего.

Давным-давно можно было встретить такие инструменты, как пирамидальное фортепиано, пиано-лира, пиано-бюро, пиано-арфа и некоторые другие.

В какой-то степени предшественником современного пианино можно назвать клавикорд и клавесин. Но последний имел лишь постоянную динамику звука, который к тому же быстро затухал.

В шестнадцатом веке был создан так называемый «клавицитерий» – клавикорд с вертикальным расположением струн. Итак, начнем по порядку…

Клавикорд

За это стоит благодарить Себастьяна Баха, который и проделал этуогромнейшую работу. Он же известен и как автор сорока восьми произведений, написанных специально для клавикорда.

По сути, написаны они были для домашнего воспроизведения: клавикорд был слишком тихим для концертных залов. Зато для дома он был поистине бесценным инструментом, а потому довольно долгое время оставался популярным.

Отличительной особенностью клавишных инструментов того времени были струны одинаковой длины. Это значительно усложняло настройку инструмента, а потому стали разрабатываться конструкции со струнами различной длины.

Клавесин

Мало какие клавишные обладают столь же необычной конструкцией, как клавесин. В нем вы могли бы увидеть и струны, и клавиатуру, но вот звук извлекался не ударами молоточка, а медиаторами.

По форме клавесин уже больше напоминает современное фортепиано, так как содержит струны различной длины.

Но, как и в истории с фортепиано, крыловидный вид клавесина был лишь одной из распространенных конструкций.

Другой вид был похож на прямоугольный, иногда квадратный, ящик. Были как горизонтальные клавесины, так и вертикальные, которые могли иметь размер значительно больший, чем у горизонтальной конструкции.

Как и клавикорд, клавесин не был инструментом больших концертных залов, – это был домашний или салонный инструмент. Тем не менее, со временем он снискал репутацию отличного ансамблевого инструмента.

Постепенно к клавесину стали относиться, как к шикарной игрушке дорогих людей. Инструмент изготавливался из ценных пород дерева и был богато украшен.

Некоторые клавесины имели по две клавиатуры с разной силой звука, к ним приделывали педали – эксперименты ограничивались лишь фантазией мастеров, которые стремились любыми путями разнообразить суховатое звучание клавесина. Но в то же время подобное отношение побудило выше ценить музыку, написанную для клавесина.

Сейчас этот инструмент хоть и не пользуется такой же популярностью, что и прежде, но все же иногда встречается.

Его можно услышать на концертах старинной и авангардной музыки. Хотя стоит признать, что современные музыканты куда вероятней будут использовать цифровой синтезатор с семплами, имитирующими звук клавесина, чем сам инструмент. Все-таки это сейчас редкость.

Подготовленное фортепиано

Точнее, препарированное. Или тюнингованное. Суть не меняется: для изменения характера звучания струн несколько дорабатывают конструкцию современного пианино, подкладывая под струны разнообразные предметы и устройства или извлекая звуки уже не столько клавишами, сколько подручными средствами: иногда медиатором, а в особо запущенных случаях – пальцами.

Словно повторяется история клавесина, но уже на современный лад. Вот только современное пианино, если особо не вмешиваться в его конструкцию, способно служить столетиями.

Отдельные экземпляры, сохранившиеся с середины девятнадцатого века (к примеру, фирмы «Смит энд Вегнер», англ. “Smidt&Wegener”), и сейчас обладают на редкость богатым и насыщенным звучанием, практически недоступным современным инструментам.

Абсолютная экзотика – кошачье пианино

Когда слышишь название «кошачье пианино», то сперва кажется, что это – метафорическое название. Ан нет, такое пианино действительно состояло из клавиатуры и…. котов.

Зверство, конечно, и надо обладать изрядной долей садизма, чтобы верно оценить юмор того времени. Коты были рассажены по голосам, из деки торчали их головы, а с другой стороны виднелись их хвосты.

Вот за них-то и дергали, чтобы извлечь звуки нужной высоты.

Сейчас, конечно, такое фортепиано в принципе возможно, но лучше пусть об этом не будет известно обществу защиты животных. Сойдут с ума заочно.

Но вы можете расслабиться, этот инструмент имел место в далеком шестнадцатом веке, а именно в 1549-м году, во время одной из процессий испанского короля в Брюсселе. Несколько описаний встречается и в более позднее время, но уже не так понятно, существовали ли эти инструменты дальше, или о них остались лишь сатирические воспоминания.

Хотя ходил слух, что однажды его использовал некий И.Х. Рейль, чтобы вылечить от меланхолии итальянского принца. По его версии, подобный забавный инструмент должен был отвлечь принца от его грустных мыслей.

Так что может это и было жестоким обращением с животными, но одновременно и серьезным прогрессом в обращении с душевнобольными, что ознаменовало рождение психотерапии в ее зачаточном виде.

На этом видео клавесинистка исполняет сонату ре-минор Domenico Scarlatti (Доменико Скарлатти):

(1

Источник: https://ProPianino.ru/drevnie-rodstvenniki-pianino

История фортепиано

История создания фортепиано уходит корнями в далекую эпоху Средневековья. Именно тогда появились первые прообразы современных клавишных инструментов — портативные органы. Однако все-таки следует отнести их к классу клавишно-духовых инструментов. В те времена на них играли бродячие артисты и таким образом увеселяли публику и зарабатывали себе на хлеб. Далее портативный орган видоизменился, стал больше по размеру, а применять его начали в основном в церковной музыке.

Другими близкими «родственниками» фортепиано можно назвать клавикорд и клавесин. Первые упоминания о них появляются в 16 веке. Однако самый старый клавикорд был изготовлен в 15 веке. Основное отличие данных инструментов — в их звучании, обусловленном разной конструкцией.

Клавикорд относится к группе клавишно-ударных, а клавесин — клавишно-щипковых инструментов, к тому же последний обладает более сложным механизмом. В свое время эти инструменты использовали для создания своих шедевров Моцарт, Бах, Бетховен и многие другие известные композиторы.

В начале 18 века итальянский клавесинный мастер Бартоломео Кристофори изобрел инструмент, называемый «пианофорте», за которым в дальнейшем закрепилось название фортепиано.

Основными его достоинствами можно назвать динамическую свободу и резонанс, за счет которого удавалось получать звук любой протяженности, благодаря наличию у инструмента специальных педалей для отрывистого звука и для более протяженного.

Кроме того, фортепиано обладало более сложной молоточковой системой по сравнению со своими предшественниками.

В дальнейшем фортепиано совершенствовалось: улучшился клавишный механизм, увеличился диапазон, произошли изменения расположения струн и многое другое. Проблему слабой репетиции удалось решить в 1823 году Себастьяну Эрару. Это позволило вывести фортепианную музыку на новый уровень.

В 19 веке фортепиано стало пользоваться большой популярностью в Европе, а затем дошло и до России. Многие компании начали заниматься изготовлением данного инструмента. В настоящее время таких фирм около 20 000.

В первую очередь, рост популярности фортепиано был связан с тем, что его предшественник клавесин издавал быстро затихающий звук, а это не позволяло играть legato.

Тем не менее, клавесинная музыка не вышла из употребления, а, наоборот, пережила свое возрождение в начале 20 столетия.

В 20 веке на смену фортепиано пришли синтезаторы и электронные пианино, позволяющие создавать различные композиции с элементами электронной музыки.

В целом же современные фортепиано делятся на две группы: рояль и пианино, диапазон которых в большинстве случаев составляет 88 полутонов (52 белых и 36 черных ключей). Они отличаются друг от друга как по форме и размерам, так и по способу звучания. У рояля струны расположены горизонтально, а у пианино – вертикально.

Если вы хотите освоить игру на фортепиано или синтезаторе, начните свой путь в музыкальной школе Jam’s cool. Благодаря проверенным методикам обучения и качественной подготовке преподавателей, уже через несколько месяцев вы сможете исполнить первые несложные композиции.

18 октября — Трибьют Antonio Jobim (ударный)

Подробнее

Розыгрыш бесплатного месяца в Jam’s cool

Подробнее

28-29.09 — Мастер-класс Раза Кеннеди в Jam’s cool

Подробнее

Источник: https://jamschool.ru/istoriya-fortepiano/

История фортепиано

В современном мире существует огромное количество различных музыкальных инструментов, любой из которых имеет свою неповторимую историю. История фортепиано стоит особняком хотя бы потому, что именно фортепиано является одним из самых популярных музыкальных инструментов.

Уникальный диапазон звучания, широчайший спектр динамических оттенков, возможность плавно переходить от forte к piano и обратно, извлекать одновременно 10 и более звуков, ровность тембра во всех регистрах, исключительная способность подражать другим инструментам, возможность исполнять на нем все, что можно назвать музыкой, все это стало причиной, по которой музыкальный инструмент, под названием фортепиано, вот уже на протяжении двух с лишним столетий, стал основным инструментом, как для профессионального, так и для любительского музицирования. Занять лидирующие позиции фортепиано помогли труды многих мастеров и изобретателей, а также богатая предыстория.

Предки современного фортепиано

Орган

Первым инструментом, в котором начали использовать клавиши, был орган.

Изобретение органа с трубами принадлежит александрийцу Ктесибию (III в. до н. э.).

Правда, его гидравлос был не столько музыкальным инструментом, сколько эффективным приспособлением для демонстрации принципов гидравлики.

В первое время органы служили дипломатическими подарками и знаками королевской власти; только лишь в X веке, с оживлением деятельности монастырей, они начали проникать в церковную службу.

Первое время клавиши органа были похожи на те, которые использовались в клавишных карийонах XVI века. Их ширина составляла 10-12 см, и их не нажимали пальцами, а ударяли по ним кулаками. Так же следует заметить, что приблизительно до конца X века клавиатуры были исключительно диатоническими.

Монохорд

Ранним предшественником фортепиано был монохорд (от греческого monos – «один» и chorda – «струна»). Первое упоминание о монохорде относится к V в. до н. э. По преданию монохорд был изобретен Пифагором, и использовался им для исследования музыкальных интервалов.

То есть опять же не столько как музыкальный инструмент, сколько инструмент для исследования музыки. Таким монохорд оставался до XIX в., по большей части он использовался в опытах по акустике, при настройке инструментов и при обучении теории музыки и пению, а еще как прибор для проектирования и измерения колоколов и органных труб.

Правда, в греческих и средневековых источниках монохорд иногда упоминается также как ансамблевый инструмент.

Состоял монохорд из продолговатого корпуса длиной порядка метра, вдоль которого сверху натягивалась струна.

Помещенная под струной нефиксированная подставка (порожек) делила струну на 2 части; передвижение этой подставки давало возможность извлекать (щипком или молоточками) звуки различной высоты.

Позже монохорд снабдили несколькими струнами, что увеличило его диапазон примерно до двух октав. Именно из многострунного монохорда позже возник клавикорд.

Клавикорд

Клавикорд (от латинского clavis – «ключ» или «клавиша», chorda – «струна»). Струнный клавишный ударный инструмент XV-XVIII вв. Диапазон инструмента как правило составлял 4 октавы (до большой – до третьей), при этом мог варьироваться от 1 до 5 октав.

Когда играющий на клавикорде нажимает на клавишу, укрепленный на ее задней части металлический штифт – тангент – ударяет по струне. Чем сильнее исполнитель ударяет по клавише (и, соответственно, чем сильнее тангент давит на струну), тем громче звук.

Пока тангент остается прижатым к струне, исполнитель может варьировать высоту звука, добиваясь эффекта вибрато («бебунг») и даже иллюзии crescendo.

На протяжении большей части своей истории клавир использовался преимущественно для домашнего музицирования. В XVI в. его рекомендовали в качестве возможной замены клавесину. Отношение к клавиру изменилось в середине XVIII века т.е. в эпоху чувствительного стиля.

Немецкие авторы этой поры считали клавир идеальным инструментом для излияния нежных чувств. Так К. Ф. Э. Бах высоко отозвался о клавире в своем «Руководстве к истинному искусству игры на клавире». Тем не менее, к концу XVIII в.

интерес к клавиру исчезает – с появлением фортепиано эта участь становится неизбежной не только для него одного.

Клавесин

Современником и одновременно конкурентом клавикорда и еще одним дальним предком фортепиано является клавесин, возникший в пятнадцатом веке в Италии.

Главное отличие этого струнного клавишного инструмента, заключается в том, что его струны не ударяются, а защипываются. Клавесин имеет форму продолговатого треугольника, чем-то напоминающую современный рояль. Его струны расположены горизонтально на разных высотных уровнях.

Позади каждой клавиши находится деревянный стерженек, так называемый толкачик, на верхнем конце которого помещен плектр из птичьего пера или кожи. При нажатии клавиши толкачик поднимается, и плектр зацепляется за струну, таким образом извлекается звук.

Вибрация струны заглушается кусочком войлока, прикрепленным к верхней части толкачика. Для изменения силы и тембра звука, используются ручные и ножные переключатели.

Конечно, если сравнивать клавесин и клавикорд, у первого был гораздо более ясный и сильных звук, однако изменять громкость на клавесине было практически невозможно.

Для того, чтобы обойти это ограничение создавались инструменты с большим количеством мануалов и с несколькими регистрами, это частично решало проблему, хотя плавное увеличение или уменьшение звука на клавесине невозможно в принципе.

Уже к XVI в. существовало несколько разновидностей клавесина:1) крылообразный инструмент с клавиатурой на короткой стороне, струны которого расположены горизонтально, параллельно клавишам – собственно клавесин, cembalo.

2) вертикально стоящий инструмент крылообразной формы – клавицитериум (clavicytherium).3) горизонтальный крылообразный инструмент с клавиатурой на большой стороне, часто трапецивидный, струны которого протянуты по диагонали слева направо – спинет (итал.

spinetta, от – spina – «колючка»). 4) горизонтальный инструмент, похожий на спинет, но прямоугольной формы, струны которого идут параллельно клавиатуре — вёрджинел (англ. virginal, от virgin – «дева», «барышня»). В XV в. диапазон инструмента составлял 3 октавы, в XVI в.

он расширился до 4 октав (до большой – до третьей), в XVIII в. – до 5 октав (фа контроктавы – фа третьей).

Изобретение нового инструмента

Настоящая история фортепиано началась в XVII веке в Европе, когда многие думали над конструкцией, легшей в основу молоточкового фортепиано. Прорыв совершил итальянский мастер клавишных инструментов Бартоломео Кристофори (1655 Падуя — 1731 Флоренция). Собственно он и изобрел около 1698 года фортепианную механику. Причем молоточковое фортепиано Кристофори стало не только первым, но и надолго лучшим. Гениальную механику этого инструмента смогли усовершенствовать лишь в во второй половине XVIII века.

Сам Бартоломео Кристофори назвал свое изобретение Gravecembalo col piano e forte (т.е. «клавесин с тихим и громким [звучанием]»). Позже сокращенное до «Piano forte» . Инструмент уже в то время имел все сущностные качества более поздних разновидностей фортепиано, в том числе сложный механизм подбрасывания молоточка с одновременным отходом демпферов от струн.

Эволюция

Сразу после того, как Бартоломео Кристофори изобрел свое «Пианофорте», оно было оценено и музыкантами, и композиторами.

Потому в восемнадцатом многие другие европейские мастера стали работать над развитием нового инструмента, тем самым определяя развитие его конструкции и механизма на годы вперед.

Фортепиано развивали Готфрид Зильберман, Цумпе, Штейн, Бродвуд, Эрар и многие другие. Уже к девятнадцатому веку возникла целая индустрия производства фортепиано.

Из всего спектра всевозможных конструктивных нововведений в истории фортепиано, можно выделить следующие наиболее значимые. В 1808 году Французский мастер Себастьян Эрар изобрел механизм так называемой двойной репетиции (что запатентовано, правда, было лишь в 1822 году).

В результате чего стало возможно не только более быстрое повторение звука, что само по себе способствовало повышению динамичности игры и как следствие придавало мощь и силу звучанию инструмента, но также появлялась возможность связанного извлечения звуков при непрерывно поднятом демпфере, что давало эффект схожий с игрой на грифе струнного инструмента.

В конце XVIII века в Англии и США началось производство фортепиано с металлической рамой, которая долго выдерживала натяжение струн без изменения настройки. На рубеже XVIII-XIX веков филадельфийский мастер Джон Айзек Хокинс изобрел пианино современного типа.

В 1825 году Алфеус Бэбкок, работавший в Бостоне и Филадельфии, запатентовал цельнолитую металлическую раму. Одно из последних крупных нововведений стало использование чугунной рамы, позволившей дополнительно повысить натяжение струн, увеличив их толщину, и тем самым добиться более сильного и полного тона.

Позднее для равномерного распределения натяжения по поверхности рамы струны стали располагать крест-накрест друг над другом.

Сегодня фортепиано делится на два основных вида: рояль и пианино. Рояль (франц. royal – «королевский») стал прямым продолжением развития молоточкового фортепиано, вобрав в себя все конструктивные нововведения прежних столетий, и став по сути олицетворением самого понятия фортепиано.

Внешне он сохранил отличительные признаки своих предшественников: крыловидный корпус и горизонтальное расположение деки, механики и струн. В XIX- XX веках среди ведущих производителей роялей были такие фирмы как: Бёзендорфер, Бехштейн, Эрар, Блютнер, Бродвуд, Стейнуэй, Ибах, Плейель, Штрейхер, Штейн, Ямаха.

В XX веке появился также малый (кабинетный) рояль.

Пианино (итал. pianino – уменьш. от piano[forte] – «фортепиано»), в отличие от своего старшего брата рояля, который создан для концертного исполнения, применяется главным образом для занятий и музицирования в домашних условиях. Главное конструктивное отличие заключается в вертикальном расположении струн, деки и механики. Со временем появляются всевозможные малые разновидности пианино.

В XX веке появляются различные новшества. В первой трети века популярностью пользовалось механическое пианино, инструмент способный автоматически играть музыку, записанную на перфорированной бумажной ленте.

В наши дни существует аналог такой самоиграющей системы, но уже компьютеризированный.

Появляются различного рода электрические фортепиано, как модифицированные, то есть обычные фортепиано с электронным усилением звука, так и полностью электронные клавишные инструменты.

История фортепиано насчитывает более четырех сотен лет. Начиная с Иоганна Себастьяна Баха (1685 — 1750) фортепиано стало определяющим музыкальным инструментом в истории музыкальной культуры. Нет ни одного инструмента, который в истории музыки имел бы настолько сильное влияние на целые эпохи.

Забавное видео про историю музыки, которую писали для фортепиано в последние два столетия:

Источник: http://My-Piano.ru/instrument/istoriya-fortepiano.html

Статья на тему «Из истории создания фортепиано»

Из истории создания фортепиано

Фортепиано – это удивительный музыкальный инструмент; пожалуй, самый совершенный. Существует он в двух разновидностях –рояль, что означает «королевский», и пианино.

История создания этого удивительного инструмента уходит своими корнями в глубокую древность.

С тех пор, как первобытный человек стал использовать для охоты лук и стрелы, он заметил, что момент спуска стрелы сопровождается гудящим звуком, возникающим от колебания тетивы.

Заинтересовавшись этим, человек стал использовать лук как орудие для звукоизвлечения; таким образом, появился первый струнный музыкальный инструмент.

Струны современного фортепиано приводятся в колебание ударами молоточков. Исходя из этого, связь с прошлым очевидна. Конечно, фортепиано в том виде, в котором мы видим его сегодня, изобрели не сразу. Это был довольно долгий путь.

После рождения струны был изобретён монохорд,представлявший собой деревянный прямоугольный ящик-резонатор, над верхней плоскостью которого крепилась сначала одна струна, а затем и несколько десятков струн.

Звук появлялся в момент защипывания струны, либо от удара по ним специальной пластинкой – плектром. Но управляться с большим количеством струн — дело вовсе не простое. И в эпоху раннего средневековья появляются инструменты с клавиатурой.

Первые клавишные потомки монохорда уступили место инструменту клавикорду.

Клавикорд появился в позднее Средневековье, хотя никто не знает, когда именно. Это был достаточно простой и небольшой по конструкции музыкальный инструмент с тихим звучанием, выполненный в виде небольшого плоского ящика без подставки и ножек.

Струны у клавикорда располагались перпендикулярно клавишам, как у современного пианино, и их количество было часто меньшим, чем количество клавиш. В этом случае одна струна обслуживала несколько клавиш. Отдельная для каждой ноты струна была только в басовой октаве.

Диапазон первых клавикордов охватывал всего 2,5 октавы, к 17 веку он расширился до 4-х октав, а в 18 веке достиг 5-6 октав, и для каждой ноты была своя струна. Поскольку клавикорд был небольшим, он предназначался исключительно для домашнего музицирования.

В отличие от тонкого и нежного звука клавикорда,клавесин обладает игрой более звучной и блестящей, звук у него более резкий.

При нажатии на клавишу клавесина плектр из гусиного пера цеплялся за струну и она звучала.

В клавесине могли звучать от одной до четырех струн одновременно и располагались они параллельно клавишам, как у современного рояля. И ещё одна особенность клавесина – у него было две клавиатуры.

Таким образом, прямыми предшественниками фортепиано считаются клавесиныиклавикорды.

В 17-18 веках многие мастера трудились над тем, чтобы создать достаточно громко звучащий инструмент.

И в 1709 году клавесинный мастер Бартоломео Кристофори изобрел клавишный инструмент, в котором молоточки ударяли непосредственно по струнам, чутко откликаясь на прикосновение пальца к клавише.

Специальный механизм позволял молоточку после удара по струне быстро возвращаться в исходную позицию, даже если при этом исполнитель продолжал держать палец на клавише.

Этот новый инструмент сначала получил название «клавишный инструмент, играющий тихо и громко», затем это название сократилось до пьянофорте и только позже обрел современное название фортепиано.

Первое музыкальное произведение, написанное специально для фортепиано, появилось в 1732 г. (соната Лодовико Джустини).

Фортепианообладает огромным преимуществом перед клавикордом и клавесином — это возможность изменять динамику звучания, способность воспроизводить различные музыкальные оттенки от pp и p до нескольких f, но эта возможность появилась уже позже. А в начале фортепиано, на котором играл И.-Х.

Бах в 1768 году, звучал совершенно не так, как звучит современный рояль. Сегодня Бетховен и Моцарт могли бы просто не узнать собственную музыку, поскольку «современное» звучание рояль обрёл только приблизительно к 1850 году.

Это объясняется тем, что фортепианные струны в начале 19 века были по сравнению с современными струнами очень тонкими и лёгкими, и натянуты они были намного слабее, — ведь струны на современных роялях напоминают скорее жёсткие неподвижные бруски.

Тонкие струны, которые устанавливались на ранних фортепиано, издавали массу обертонов, поэтому такие инструменты показались бы нам, современным слушателям, плохо настроенными.

Еще один ключевой момент в истории пианино, —клавиши. Раньше клавиатура состояла из одних только белых клавиш, называвшихся по первым буквам латинского алфавита. Как правило, эти же буквы наносились и на клавиши самого инструмента – это делалось для того, чтобы помочь музыканту ориентироваться в сплошном ряду одинаковых клавиш.

Да и классическая система семи нот, которую мы сейчас используем, тоже родилась не сразу. Немало музыкантов, имена которых остались неизвестны, бились над тем, чтобы понять, какой же все-таки должна быть ее структура.

И начиная с 13 века уже создается привычное нашим глазам и пальцам построение клавиш – 7 белых и 5 черных в октаве, всего 88 клавиш.

Итак, изобретенный Бартоломео Кристофори инструмент с годами менялся, совершенствовался разными мастерами. И в 1783 году были изобретены ножные педали. Одна педаль использовалась для игры f, а вторая – для того, чтобы приглушить струну. Многие мастера экспериментировали с другими видами педалей, количество которых на некоторых инструментах доходило до 4-х и даже 6-и.

В начале 18 века новый инструмент – фортепиано – не сразу был принят публикой. Ведь механика первых фортепиано была не совершенна, а звук, хотя и менялся по силе, был резким и сухим.

Вторая половина 18 века является переломным моментом в истории фортепиано. Отныне крыловидное фортепианополучило название рояль, что означает «королевский».

Главной особенностью этого инструмента был певучий звук.

Динамические возможности позволили фортепиано встать в ряд сольных инструментов и занять центральное место в концертных залах Европы. В 19 веке роялю, завоевавшему большие залы, не хватало силы звука. Для этого струны сделали толще, длиннее и больше натянули их. Но деревянные корпуса роялей не выдерживали большого натяжения струн, которое исчислялось сотнями килограммов.

На помощь дереву пришёл металл – чугунная рама, позволявшая увеличить силу натяжения струн до 20 с лишним тонн! А сами струны стали располагаться перекрёстно в два яруса. В результате звук стал ярче, полнее, громче.

Изменились не только сила, но и качество звука. Раньше молоточки обтягивали лосиной кожей, но она была жёсткая и не долговечная, а теперь стали использовать прессованный войлок – фильц.

Но самым удивительным усовершенствованием рояля стало изобретение педали.

Одна педаль использовалась для задержания звука, для его продления после того, как клавиша отпущена, а вторая – для того, чтобы приглушить струну и сделать звук особо тихим и мягким.

Всего фортепиано понадобилось более 200 лет на то, чтобы окончательно сформироваться в тот инструмент, который мы с вами привыкли видеть и слышать.

Источник: https://infourok.ru/statya-na-temu-iz-istorii-sozdaniya-fortepiano-1561999.html

Клавикорд и клавесин — предшественники пианино

Клавикорды берут свое начало от XIV-XV вв.

Изначально небольшие и легкие переносные клавикорды в Западной Европы использовались исключительно бродячими музыкантами, из чего можно сделать вывод о крайне невысокой стоимости инструментов.

Клавикорд представлял собой деревянный ящик, в которой размещались узкая клавиатура и набор металлических струн. Так как все струны имели идентичные длину, клавикорды были прямоугольной формы.

Позже мастера пришли к выводы, что из-за струн одной длины существует много проблем и неудобств, даже в настройке, поэтому началось производство инструментов, обладавших разной длиной струн, а также бóльшими размерами и наличием ножек.

В связи со схожей с фортепиано механикой, клавикорд располагал, говоря современным языком, «динамической» клавиатурой, благодаря чему сила звука имела зависимость от силы удара по клавише.

Специально под этот инструмент создавались шедевры такими композиторами, как Бах, Гендель, Моцарт, Гайдн, Телеман и даже Бетховен в своих ранних сонатах.

Кстати говоря, именно под клавикорд, на базе которого мастерами, наконец, был решен вопрос искусственного уравнивания полутонов, а также равенства бемолей и диезов, Иоганн Себастьян Бах написал целых сорок восемь бесценных для мировой музыкальной культуры фуг и прелюдий, получивших легендарное название «Wohltemperierte Klavier».

И все-таки звук клавикорда был слишком тихим и мягким, чтобы на нем можно было проводить выступления в залах перед большим количеством слушателей. Поэтому потом клавикорд широко применялся в домашнем музицировании.

Вторым видом струнно-клавишного инструмента, пользовавшегося популярностью в XV, XVI и XVII веках, является спинет. Фактически, спинет представляет собой мини-версию (слегка упрощенную) клавесина, обладающего одной или двумя клавиатурами с размерностью в четыре или пять октав. Отличительной чертой клавесина, как правило, было богатое декорирование.

Но гораздо большую популярность снискал третий и, наверное, самый необычный музыкальный инструмент – сам клавесин. Его даже по-разному называли: и вёрджинел, и чембало, и клавичембало. Если расцвет искусства игры на клавикорде относится к Германии, то клавесин с его разновидностями широко применялся в Англии, Франции и Скандинавии.

Клавесин напоминает спинет, у него та же щипковая механика, но размеры крупнее.

Внутри корпуса находились натянутые струны, имевшие идентичную толщину, но разную длину: именно этим объясняется его характерная форма – по внешнему виду он напоминает современный рояль.

Извлечение звука осуществлялось при помощи упругих язычков из кусочков кожи или ороговевших кончиков птичьих перьев, которые, будучи закрепленными на специальных тангентах, которые приводились в движение клавишами, щипали струны.

Клавесины делятся на два типа: прямоугольный или квадратный среднего размера и крыловидный горизонтальный или вертикальный размером побольше.

Инструмент пользовался особой популярностью в эпоху барокко, когда модными были пышные наряды с кринолинами и оборками, и даже архитектура и живопись отражала салонное искусство во всех своих проявлениях.

Клавесин являлся уже настоящим концертным инструментом.

Первоначально музицирование на клавесине можно было проводить только в гостиных и светских салонах. В крупных залах его звонкий голос затухал, как и у клавикорда. Клавесин издает достаточно специфичный звук – слегка суховатый, «стеклянный», не выдающий достаточной протяженности, которой отличался клавикорд.

Но это был добротный, сравнительно звучный музыкальный инструмент, на котором при условии определенного умения можно было играть подвижные пьесы, легкие композиции и аккомпанемент, сопровождающий речитатив и пение. Отличная гармония достигалась при дополнении друг другом коротких звуков клавесина и плавно тянущихся звуков голоса, скрипки или виолы.

Таким образом, клавесин постепенно превратился в прекрасный ансамблевый инструмент.

В оркестре его роль была двоякой: партия сопровождения (дирижер музицировал за клавесином, левой рукой исполняя аккорды, а правой руководя оркестром), генерал-бас, и параллельно – партия звеняще-шелестящих ударных. Именно благодаря этим свойствам клавесина, мы можем наблюдать, как почти во всей музыке эпохи барокко партия виолы, а позднее и виолончели, дублируется клавесином.

С течением времени клавесин появился во всех богатых домах. Инструмент уже изготавливался из самых драгоценных пород дерева.

Проводилась инкрустация бронзой, слоновой костью, золотом, а на стенках и крыловидных крышках клавесина модными салонными живописцами писались разнообразные картины. Клавиши обзаводились покрытием из самоцветных пластинок.

Никогда прежде музыкальный инструмент не становился столь дорогой, ценимой и почитаемой… игрушкой.

Роскошный вид клавесина заставлял придворных вельмож ценить и музыку, которую на нем исполняли. Расцвет клавесинной музыки, наравне с Германией, приходится на Англию (Гендель, Пёрселл) и Францию (Люли, Куперен, Рамо).

Мастера, разумеется, не хотели смиряться с тем, что звучание клавесина стало слишком однообразным, поэтому начали изобретать различные усовершенствования, призванные разнообразить его звучание.

К примеру, устанавливались несколько клавиатур, как на органных мануалах, обладающих разной силой звука; приделывалась педаль, нажатие на которой приглушал звук – но все они не отличались удобством.

Несмотря на то, что популярность клавесина упала, сам инструмент насовсем не исчез – услышать его можно и в настоящее время на концертах как старинной, так и современной авангардной музыки.

Источник: http://www.pianinoff.ru/vse-o-pianino/klavesin-i-klavikord

«Хорошо темперированный клавир», «Осенний вальс, «Весенняя рапсодия», «Аппассионата», «Лунная соната»… Бах, Шопен, Бетховен… Все бывшие и нынешние ученики музыкальной школы знают, о чем речь. Но теперь гениальными сочинениями для фортепиано мы можем наслаждаться, просто подключившись к интернету. С легкостью можно найти современные вариации в клавишном исполнении на различные песни. Их не сосчитать. Почти во всех группах разных направлений клавишный инструмент обязателен. Часто это синтезатор ー навороченный потомок пианино. Лет 15 назад в каждой второй семье обязательно стояло фортепиано, и хотя бы один из членов семьи обязан был уметь играть на нем. Это было модным. Даже сейчас можно встретить такие семьи.

Пианино никогда не утратит своих позиций. В его звучании есть что-то чарующее. Веселящее и воодушевляющее при мажоре, навевающее на грустные, но серьезные мысли при миноре. Можете себе представить, что пианино не изобрели? А знаете историю его возникновения? Нет? Вы здесь, значит, уже можете считать, что знаете.

Первые версии

Самый первый предок пианино ー орган. Его изобрел александриец Ктесибий в III веке н. э. Вот как это было. Отличительная черта органа ー это трубы вместо струн. Этот инструмент нам известен тем, что его использовали в католических церквях. До этого орган был дипломатическим подарком и знаком королевской власти. Музыкальным инструментом он не был.

В V веке на мир появился монохорд. Создал его Пифагор. Как и орган, в начале своей истории, этот инструмент не был музыкальным. Пифагор использовал его для изучения и исследования музыки. Часто монохорд использовали в опытах по акустике.

Интересно: Некоторые средневековые источники утверждают, что монохорд в Греции был ансамблевым инструментом.

Монохорд и орган ー первые клавишные инструменты, как рассказывает нам история создания пианино, потомка клавесина и клавикорда. Именно их когда-то вытеснил известный нам инструмент.

В XV веке в Италии появился клавесин. По своей форме он чем-то похож на современное фортепиано.

клавесин

Само строение клавесина было довольно сложным. Струны защипываются, а не ударяются. Звук извлекался чем-то вроде медиатора: перышками или кусочками кожи и был достаточно громким, но невыразительным. Со временем для улучшения тембра звука клавесин изменяли, и к концу XVI века существовало несколько видов инструмента:

- Спинет. Горизонтальный и крылообразный. Клавиатура на большой стороне.

- Клавицитериум. Крылообразный и вертикально стоящий.

- Оригинальный клавесин. Крылообразный, клавиатура на короткой стороне.

- Верджинел. Он похож на спинет, но прямоугольной формы.

Диапазон клавесина достигал 5 октав.

Кто и когда изобрел клавикорд — неизвестно. Это произошло примерно в XIV веке. В его диапазоне было 4 октавы. На задней части клавиши клавикорда был укреплен тангент ー это такой небольшой медный квадратик. Когда нажимали на клавишу клавикорда, тангент ударял по струне. Пока тангент прижат к струне, у играющего была возможность менять громкость звука.

клавикорд

Недостаток клавикорда заключался в его звучании. Звук был слишком мягким и тихим. Это не позволяло играть на клавикорде для большой аудитории. Поэтому инструмент использовали для домашнего музицирования.

XVIII век ー это век стиля рококо. Время популярности клавикорда у именитых немецких авторов. К. Ф. Э. Бах выпустил свое «Руководство к истинному искусству игры на клавире», в котором очень высоко и трепетно отозвался о клавикорде. Но конец XVIII века ー конец истории клавикорда. Появилось первое пианино.

Кто, как и когда создал пианино?

Современное фортепиано ー потомок клавикорда, как рассказывает нам история происхождения. Пианино начали создавать еще в XVII веке. В Европе многие ломали голову над тем, как сделать молоточковое фортепиано.

Представитель одной нации смог прорваться вперед и внести свой вклад в историю. В какой стране? Создали пианино в Италии, во Флоренции. Этот человек превосходно разбирался в устройстве клавесина, так как сам создавал эти инструменты. Он разработал инновации, которые добавил к клавесину и в итоге получил молоточковый клавишный инструмент. Кто? Создал пианино Бартоломео Кристофори.

Остается открытым один вопрос: когда? Создали пианино ближе к концу XVII века. К сожалению, более подробного ответа история изобретения пианино нам дать не может.

Почему в создании фортепиано преуспел именно Кристофори? Об этом мы можем только догадываться, но, возможно, ответ кроется где-то в изначальной идеи итальянца: создать клавесин, который звучит громко и мягко.

Развитие инструмента

Сейчас мы хорошо знаем историю возникновения. Пианино, однако, точнее само его существование в XVII веке, долго оставалось в тайне. За ее открытие стоит поблагодарить Щипионе Мэффеи ー итальянского журналиста. Его статья об «усовершенствованном клавесине” не на шутку взбудоражила общество и гениальные умы изобретателей.

Всем знакомы педальки на современном фортепиано. Левая педалька заглушает звук, правая ー создает вибрацию, удлиняя звучание. Этот механизм много лет совершенствовали, но создал его основу органный мастер ー Готтфрид Зильберман. Главным критиком творения Зильбермана выступал Бах. Сначала великому композитору инструмент не нравился, но Готтфрид прислушивался к критике и постоянно улучшал свое творение.

В итоге Бах не только на словах был в восторге от окончательного результата. Музыкант активно помогал в продаже и продвижении инструмента.

Интересные факты

Вот некоторые интересные факты из истории пианино, которым стоит уделить особое внимание:

- Некоторые люди не понимают, в чем схожесть или разница между роялем, пианино и фортепиано. Секрет прост: это все один инструмент, просто фортепиано ー обобщенное название. У рояля горизонтальная, дугообразная форма, он на трех ножках и именно его используют на больших концертах, так как его звук более громкий.