| Pinocchio | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Supervising Directors

Sequence Directors

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on | The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Starring |

|

| Music by |

|

|

Production |

Walt Disney Productions |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.6 million[3] |

| Box office | $164 million |

Pinocchio is a 1940 American animated musical fantasy film produced by Walt Disney Productions and based on the 1883 Italian children’s novel The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi. It was the second animated feature film produced by Disney, made after the first animated success Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).

The plot involves an old Italian woodcarver named Geppetto who carves a wooden puppet named Pinocchio and wishes that he might be a real boy. The puppet is brought to life by a blue fairy, who informs him that he can become a real boy if he proves himself to be «brave, truthful, and unselfish». The key character of Jiminy Cricket, who takes the role of Pinocchio’s conscience, attempts to guide Pinocchio in matters of right and wrong. Pinocchio’s efforts to become a real boy involve encounters with a host of unsavory characters, representing the temptations and consequences of wrongdoing.

The film was adapted by several storyboard artists from Collodi’s book. The production was supervised by Ben Sharpsteen and Hamilton Luske, and the film’s sequences were directed by Norman Ferguson, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Jack Kinney, and Bill Roberts. Pinocchio was a groundbreaking achievement in the area of effects animation, giving realistic movement to vehicles, machinery and natural elements such as rain, lightning, smoke, shadows and water. Pinocchio was released to theatres by RKO Radio Pictures on February 23, 1940.

Although it received critical acclaim and became the first animated feature to win a competitive Academy Award — winning two for Best Music, Original Score and for Best Music, Original Song for «When You Wish Upon a Star» — it was initially a box office bomb, mainly due to World War II cutting off the European and Asian markets overseas. It eventually made a profit in its 1945 reissue, and is considered one of the greatest animated films ever made, with a 100% rating on the website Rotten Tomatoes. The film and characters are still prevalent in popular culture, featuring at various Disney parks and in other forms of entertainment. In 1994, Pinocchio was added to the United States National Film Registry for being deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».[4]

A 2000 live-action movie titled Geppetto, told from Geppetto’s perspective, was released direct to television.[5] In April 2015, a live-action adaptation of the same name officially entered development; filming began in March 2021 and ended that April, and it was released on Disney+ on September 8, 2022.

Plot[edit]

Jiminy Cricket addresses the audience as the narrator and begins to tell a story. Jiminy came to a village in Italy sometime in the late 19th century, where he arrived at the shop of a woodworker and toymaker named Geppetto, who creates a marionette whom he names Pinocchio. Falling asleep, Geppetto wishes upon a star for Pinocchio to be a real boy. Late that night, a Blue Fairy visits the workshop and brings Pinocchio to life, although he remains a puppet. She informs him that if he proves himself brave, truthful, and unselfish, he will become a real boy. When Jiminy reveals himself, the Blue Fairy assigns him to be Pinocchio’s conscience. Geppetto wakes up upon hearing a commotion from Pinocchio falling, and is overjoyed to discover that his puppet is alive and will become a real boy.

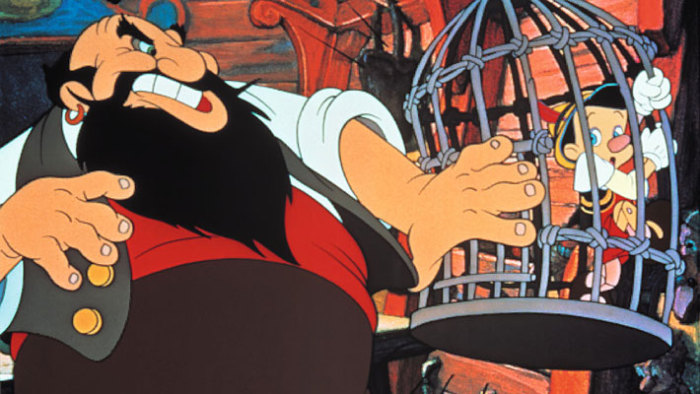

The next morning on his way to school, Pinocchio is led astray by con artist fox Honest John and his sidekick Gideon the Cat. Honest John convinces him to join Stromboli’s puppet show, despite Jiminy’s objections. Pinocchio becomes Stromboli’s star attraction, but when he tries to go home, Stromboli locks him in a bird cage and leaves to tour the world with Pinocchio. After Jiminy unsuccessfully tries to free his friend, the Blue Fairy appears, and an anxious Pinocchio lies about what happened, causing his nose to grow. The Blue Fairy restores his nose and frees him when Pinocchio promises to make amends, but she warns him that she can offer no further help.

Meanwhile, Honest John is hired by a mysterious coachman to find disobedient boys for him to take to Pleasure Island. Though Honest John and Gideon are frightened by the Coachman’s implication of what happens to the boys, the former reluctantly accepts the job and finds Pinocchio, convincing him to take a vacation on Pleasure Island. On the way, Pinocchio befriends Lampwick, a delinquent boy. At Pleasure Island, without rules or authority to enforce their activity, Pinocchio, Lampwick, and countless other boys soon engage in vices such as smoking and drinking. Jiminy eventually discovers that the island hides a horrible curse, turning boys into donkeys, which the Coachman plans to sell as slave labor to salt mines and circuses. Pinocchio witnesses Lampwick transform into a donkey, and with Jiminy’s help, Pinocchio escapes, partially transformed with a donkey’s ears and tail.

Returning home, Pinocchio and Jiminy find Geppetto’s workshop deserted. They get a letter from the Blue Fairy in the form of a dove, stating that Geppetto had gone out looking for Pinocchio and sailed to Pleasure Island. After learning that Pinocchio had left, he was then swallowed by Monstro, a terrible sperm whale, and is now living in the belly of the beast. Determined to rescue his father, Pinocchio jumps into the ocean, accompanied by Jiminy. Pinocchio is soon swallowed by Monstro, where he reunites with Geppetto. Pinocchio devises a scheme to make Monstro sneeze, giving them a chance to escape. The scheme works, but the enraged whale chases them and smashes their raft with his tail. Pinocchio selflessly pulls Geppetto to safety in a cove just as Monstro crashes into it and Pinocchio is seemingly killed.

Back home, Geppetto, Jiminy, Figaro, and Cleo mourn the loss of Pinocchio. However, having proven himself brave, truthful, and unselfish, Pinocchio is revived and turned into a real human boy by the Blue Fairy, getting rid of the Pleasure Island curse in the process, much to everyone’s joy. As the group celebrates, Jiminy steps outside to thank the Fairy and is rewarded with a solid gold badge that certifies him as an official conscience.

Voice cast[edit]

- Dick Jones as Pinocchio, an exuberant and endearing wooden puppet carved by Geppetto, and brought to life by the Blue Fairy.

- Cliff Edwards as Jiminy Cricket, a cheerful, intelligent, wisecracking, optimistic and wise cricket, who acts as Pinocchio’s «conscience», and the partial narrator of the story.

- Christian Rub as Geppetto, a kind and elderly wood-carver, who creates Pinocchio, and wishes for him to become a real boy. He speaks with an Austrian accent.

- Clarence Nash as Figaro, Geppetto’s spoiled pet cat who is prone to jealousy. Cleo, Geppetto’s flirty pet goldfish with a habit of being Figaro’s counselor, is unvoiced. Figaro and Cleo were original characters added to the script by the Disney team.[6]

- Walter Catlett as «Honest» John Worthington Foulfellow, an anthropomorphic red fox con artist who swindles Pinocchio twice.

- Gideon the Cat, Honest John’s mute, dimwitted and bumbling anthropomorphic feline partner and sidekick who serves as the film’s comic relief. He was originally intended to be voiced by Mel Blanc of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies fame (in his second work for Disney until his final work in Who Framed Roger Rabbit), but the filmmakers removed his dialogue from the script in favor of a mute performance just like Dopey in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the circus elephant title character Dumbo;[7] however, Gideon’s hiccups were provided by Blanc.[7]

- Charles Judels as Stromboli, a greedy and abusive puppeteer, who intends to force Pinocchio to perform onstage in order to make money and to use him as «firewood» once he gets «too old» to perform, revealing also his sadistic attitude. He speaks English with an Italian accent, and curses in an Italian gibberish when he gets angry, though he is called «Gypsy» by Honest John, probably due to his theatre and caravan always traveling, along with other names like «rascal» and «faker». Due to his popularity, he has been for long the only character of the film to be part of the official Disney Villains line-up.

- Judels also voiced the nefarious and cunning Coachman, owner and operator of Pleasure Island, where unruly boys are turned into donkeys and sold. This latter is the only antagonist of the film which is not an official member of the aforementioned Disney Villains line-up/franchise.

- Evelyn Venable as the Blue Fairy, who brings Pinocchio to life, and promises to turn him into a real boy if he proves himself brave, truthful, and selfless. Live-action references for the Blue Fairy were provided by Marge Champion, who did live-action references for the titular heroine in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

- Frankie Darro as Lampwick, a naughty and spoiled boy who Pinocchio befriends on his way to Pleasure Island. He is turned into a donkey on Pleasure Island for his mischief.

- Stuart Buchanan as the Carnival Barker, the announcer heard on Pleasure Island. In a book adaptation of the film, «Barker» is how the Coachman is named.

- Thurl Ravenscroft as Monstro, the terrible sperm whale. He swallows Pinocchio, Geppetto, Figaro and Cleo, then tries to kill them after they escape from his belly by making him sneeze.

(The voice cast were all uncredited as was the practice at the time for many animated films.)

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

In September 1937, during the production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, animator Norman Ferguson brought a translated version of Carlo Collodi’s 1883 Italian children’s novel The Adventures of Pinocchio to the attention of Walt Disney. After reading the book, «Walt was busting his guts with enthusiasm» as Ferguson later recalled. Disney then commissioned storyboard artist Bianca Majolie to write a new story outline for the book, but after reading it, he felt her outline was too faithful.[8] Pinocchio was intended to be the studio’s third feature, after Bambi (1942). However, due to difficulties with Bambi (adapting the story and animating the animals realistically), Disney announced that Bambi would be postponed while Pinocchio would move ahead in production. Ben Sharpsteen was then re-assigned to supervise the production while Jack Kinney was given directional reins.[9][8]

Writing and design[edit]

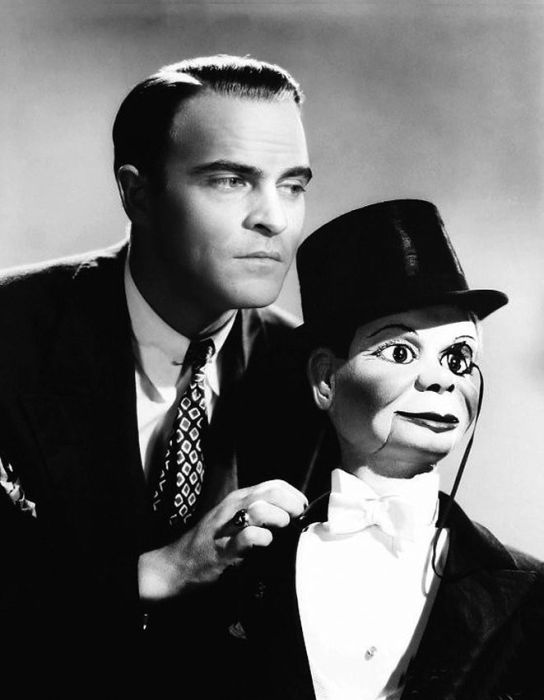

Unlike Snow White, which was a short story that the writers could expand and experiment with, Pinocchio was based on a novel with a very fixed, although episodic, story. Therefore, the story went through drastic changes before reaching its final incarnation.[7] In the original novel, Pinocchio is a cold, rude, ungrateful, inhuman brat that often repels sympathy and only learns his lessons the hard way.[10] The writers decided to modernize the character and depict him similar to Edgar Bergen’s dummy Charlie McCarthy,[11] but equally as rambunctious as the puppet in the book. The story was still being developed in the early stages of animation.[10]

Early scenes animated by Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas show that Pinocchio’s design was exactly like that of a real wooden puppet with a long pointed nose, a peaked cap and bare wooden hands.[7]

Early scenes animated by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston show that Pinocchio’s design was exactly like that of a real wooden puppet with a long pointed nose, a peaked cap and bare wooden hands.[12] Disney, however, was not impressed with the work that was being done on the film. He felt that no one could really sympathize with such a character and called for an immediate halt in production.[10][11] Fred Moore redesigned the character slightly to make him more appealing, but the design still retained a wooden feel.[13]

Young and upcoming animator Milt Kahl felt that Thomas, Johnston, and Moore were «rather obsessed with the idea of this boy being a wooden puppet» and felt that they should «forget that he was a puppet and get a cute little boy; you can always draw the wooden joints and make him a wooden puppet afterwards». Co-supervising director Hamilton Luske suggested to Kahl that he should demonstrate his beliefs by animating a test sequence.[14]

Kahl then showed Disney an animation test scene in which Pinocchio is underwater looking for his father.[15] From this scene, Kahl re-envisioned the character by making him look more like a real boy, with a child’s Tyrolean hat and standard cartoon character four-fingered (or three and a thumb) hands with Mickey Mouse-type gloves on them.[16] The only parts of Pinocchio that still looked more or less like a puppet were his arms, legs and his little button wooden nose. Disney embraced Kahl’s scene and immediately urged the writers to evolve Pinocchio into a more innocent, naïve, somewhat coy personality that reflected Kahl’s design.[17]

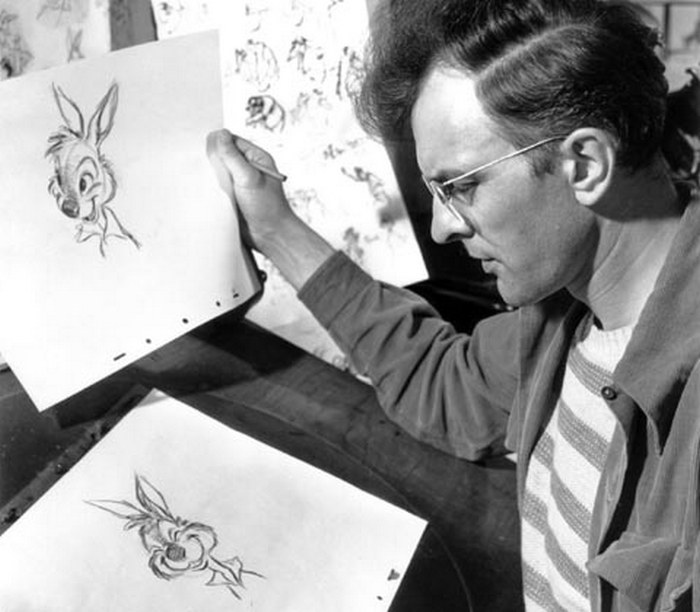

However, Disney discovered that the new Pinocchio was too helpless and was far too often led astray by deceiving characters. Therefore, in the summer of 1938, Disney and his story team established the character of the cricket. Originally, the talking cricket was only a minor character that Pinocchio abruptly killed by squashing him with a mallet and that later returned as a ghost. Disney dubbed the cricket «Jiminy», and made him into a character that would try to guide Pinocchio into the right decisions.[18] Once the character was expanded, he was depicted as a realistic cricket with toothed legs and waving antennae, but Disney wanted something more likable. Ward Kimball had spent several months animating two sequences—a soup-eating musical number and a bed-building sequence—in Snow White, which was cut from the film due to pacing reasons. Kimball was about to quit until Disney rewarded him for his work by promoting him to the supervising animator of Jiminy Cricket.[19] Kimball then conjured up the design for Jiminy Cricket, whom he described as a little man with an egg head and no ears.[20] Jiminy «was a cricket because we called him a cricket,» Kimball later joked.[18]

Casting[edit]

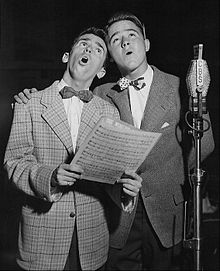

Dickie Jones (right, as an adult) voices Pinocchio in the film.

Due to the huge success of Snow White, Walt Disney wanted more famous voices for Pinocchio, which marked the first time an animated film had used celebrities as voice actors.[21] He cast popular singer Cliff Edwards, also known as «Ukulele Ike», as Jiminy Cricket.[22] Disney rejected the idea of having an adult play Pinocchio and insisted that the character be voiced by a real child. He cast 11-year-old child actor Dickie Jones, who had previously been in Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).[23] He also cast Frankie Darro as Lampwick, Walter Catlett as «Honest» John Foulfellow the Fox, Evelyn Venable as the Blue Fairy, Charles Judels as both the villainous Stromboli and the Coachman, and Christian Rub as Geppetto, whose design was even a caricature of Rub.[24]

Another voice actor recruited was Mel Blanc, best remembered for voicing many of the characters in Warner Bros. cartoon shorts, including Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. Blanc recorded the voice of Gideon the Cat in sixteen days. However, it was eventually decided that Gideon would be mute, so all of Blanc’s recorded dialogue was subsequently deleted except for a solitary hiccup,[25] which was heard three times in the finished film.

Animation[edit]

Animation on the film began in January 1938, but work on Pinocchio’s animation was discontinued as the writers sought to re-work his characterization and the film’s narrative structure. However, animation on the film’s supporting characters started in April 1938.[12] Animation would not resume again with the revised story until September.[17]

During the production of the film, story artist Joe Grant formed a character model department, which would be responsible for building three-dimensional clay models of the characters in the film, known as maquettes. These models were then given to the staff to observe how a character should be drawn from any given angle desired by the artists.[15] The model makers also built working models of Geppetto’s elaborate cuckoo clocks designed by Albert Hurter, as well as Stromboli’s gypsy wagon and wooden cage, and the Coachman’s carriage. However, owing to the difficulty of animating a realistic moving vehicle, the artists filmed the carriage maquettes on a miniature set using stop motion animation. Then, each frame of the animation was transferred onto animation cels using an early version of a Xerox. The cels were then painted on the back and overlaid on top of background images with the cels of the characters to create the completed shot on the rostrum camera. Like Snow White, live-action footage was shot for Pinocchio with the actors playing the scenes in pantomime, supervised by Luske.[26] Rather than tracing, which would result in stiff unnatural movement, the animators used the footage as a guide for animation by studying human movement and then incorporating some poses into the animation (though slightly exaggerated).[26]

Pinocchio was a groundbreaking achievement in the area of effects animation, led by Joshua Meador. In contrast to the character animators who concentrate on the acting of the characters, effects animators create everything that moves other than the characters. This includes vehicles, machinery and natural effects such as rain, lightning, snow, smoke, shadows and water, as well as the fantasy or science-fiction type effects like the pixie dust of Peter Pan (1953). The influential abstract animator Oskar Fischinger, who mainly worked on Fantasia (1940), contributed to the effects animation of the Blue Fairy’s wand.[27] Effects animator Sandy Strother kept a diary about his year-long animation of the water effects, which included splashes, ripples, bubbles, waves and the illusion of being underwater. To help give depth to the ocean, the animators put more detail into the waves on the water surface in the foreground, and put in less detail as the surface moved further back. After the animation was traced onto cels, the assistant animators would trace it once more with blue and black pencil leads to give the waves a sculptured look.[28] To save time and money, the splashes were kept impressionistic. These techniques enabled Pinocchio to be one of the first animated films to have highly realistic effects animation. Ollie Johnston remarked «I think that’s one of the finest things the studio’s ever done, as Frank Thomas said, ‘The water looks so real a person can drown in it, and they do.'»[29]

Music[edit]

The songs in Pinocchio were composed by Leigh Harline with lyrics by Ned Washington. Harline and Paul J. Smith composed the incidental music score.[30] The underscore for the Monstro chase sequence was orchestrated by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer composer Leo Arnaud. The soundtrack was first released on February 9, 1940.[30] Jiminy Cricket’s song, «When You Wish Upon A Star», became a major hit and is still identified with the film, and later as the theme song of The Walt Disney Company itself.[31] The soundtrack won an Academy Award for Best Original Score.[31]

Themes[edit]

Commentator Nicholas Sammond considers Pinocchio to be a metaphor for American child rearing in the mid-20th century.

M. Keith Booker considers the film to be the most down-to-earth of the Disney animated films despite its theme song and magic, and notes that the film’s protagonist has to work to prove his worth, which he remarked seemed «more in line with the ethos of capitalism» than most of the Disney films.[32] Claudia Mitchell and Jacqueline Reid-Walsh believe that the male protagonists of films like Pinocchio and Bambi (1942) were purposefully constructed by Disney to appeal to both boys and girls.[33] Mark I. Pinsky said that it is «a simple morality tale—cautionary and schematic—ideal for moral instruction, save for some of its darker moments», and noted that the film is a favorite of parents of young children.[34]

Nicolas Sammond argues that the film is «an apt metaphor for the metaphysics of midcentury American child-rearing» and that the film is «ultimately an assimilationist fable».[35] He considered it to be the central Disney film and the most strongly middle class, intended to relay the message that indulging in «the pleasures of the working class, of vaudeville, or of pool halls and amusement parks, led to a life as a beast of burden». For Sammond, the purpose of Pinocchio is to help convey to children the «middle-class virtues of deferred gratification, self-denial, thrift, and perseverance, naturalized as the experience of the most average American».[36]

Author and illustrator Maurice Sendak, who saw the film in theaters in 1940, called the film superior to Collodi’s novel in its depiction of children and growing up. «The Pinocchio in the film is not the unruly, sulking, vicious, devious (albeit still charming) marionette that Collodi created. Neither is he an innately evil, doomed-to-calamity child of sin. He is, rather, both lovable and loved. Therein lies Disney’s triumph. His Pinocchio is a mischievous, innocent and very naive little wooden boy. What makes our anxiety over his fate endurable is a reassuring sense that Pinocchio is loved for himself — and not for what he should or shouldn’t be. Disney has corrected a terrible wrong. Pinocchio, he says, is good; his «badness» is only a matter of inexperience,» and also that «Pinocchio’s wish to be a real boy remains the film’s underlying theme, but «becoming a real boy» now signifies the wish to grow up, not the wish to be good.»[37]

Home media[edit]

On July 16, 1985, it was released on VHS, Betamax, CED, and LaserDisc in North America for the first time as part of the Walt Disney Classics label, the second title with the Classics label after Robin Hood (1973) which was released the previous December.[38] It would become the best-selling home video title of the year selling 130–150,000 units at $80 each.[39] It was re-issued on October 14, 1986 to advertise the home video debut of Sleeping Beauty (1959), this release also helped leave out the preview of The Black Cauldron from the original 1985 VHS release due to the preview being too dark and scary for kids. Then, for the first time, it was released on VHS in the UK in 1988, 1995, and 2000.[40] The digital restoration that was completed for the 1992 cinema re-issue was released on VHS and Laserdisc on March 26, 1993,[41] followed by its fourth VHS release and first release on Disney DVD as the 60th Anniversary Edition on October 25, 1999.[42]

The film was re-issued on DVD and one final time on VHS as part of the Walt Disney Gold Classics Collection release on March 7, 2000.[43] Along the film, the VHS edition also contained a making-of documentary while the DVD had the film’s original theatrical trailer as supplemental features.[44] The Gold Classic Collection release was returned to the Disney Vault on January 31, 2002.[45]

A special edition VHS and DVD of the film was released in the United Kingdom on March 3, 2003.[46] The fourth DVD release and first Blu-ray Disc release (the second Blu-ray in the Walt Disney Platinum Editions series) was released on March 10, 2009.[47] Like the 2008 Sleeping Beauty Blu-ray release, the Pinocchio Blu-ray package featured a new restoration by Lowry Digital in a two-disc Blu-ray set, with a bonus DVD version of the film also included.[48] This set returned to the Disney Vault on April 30, 2011.[49] A Signature Edition was released on Digital HD on January 10, 2017 and was followed by a Blu-ray/DVD combo pack on January 31, 2017.[50][51]

Reception[edit]

Initial release[edit]

Frank S. Nugent of The New York Times gave the film five out of five stars, saying «Pinocchio is here at last, is every bit as fine as we had prayed it would be—if not finer—and that it is as gay and clever and delightful a fantasy as any well-behaved youngster or jaded oldster could hope to see.»[52] Time magazine gave the film a positive review, stating «In craftsmanship and delicacy of drawing and coloring, in the articulation of its dozens of characters, in the greater variety and depth of its photographic effects, it tops the high standard Snow White set. The charm, humor and loving care with which it treats its inanimate characters puts it in a class by itself.»[53]

Variety praised the animation as superior to Snow White‘s writing the «[a]nimation is so smooth that cartoon figures carry impression of real persons and settings rather than drawings to onlooker.» In summary, they felt Pinocchio «will stand on [its] own as a substantial piece of entertainment for young and old, providing attention through its perfection in animation and photographic effects.[54] The Hollywood Reporter wrote «Pinocchio is entertainment for every one of every age, so completely charming and delightful that there is profound regret when it reaches the final fade-out. Since comparisons will be inevitable, it may as well be said at once that, from a technical standpoint, conception and production, this picture is infinitely superior to Snow White.»[55]

Initially, Pinocchio was not a box-office success.[56] The box office returns from the film’s initial release were both below Snow White’s unprecedented success and below studio expectations.[57] Of the film’s $2.6 million negative cost—twice the cost of Snow White[3]—Disney only recouped $1 million by late 1940, with studio reports of the film’s final original box office take varying between $1.4 million and $1.9 million.[58] Animation historian Michael Barrier notes that Pinocchio returned rentals of less than one million by September 1940, and in its first public annual report, Walt Disney Productions charged off a $1 million loss to the film.[59] Barrier relays that a 1947 Pinocchio balance sheet listed total receipts to the studio of $1.4 million. This was primarily due to the fact that World War II and its aftermath had cut off the European and Asian markets overseas, and hindered the international success of Pinocchio and other Disney releases during the early and mid-1940s.[60] Joe Grant recalled Walt Disney being «very, very depressed» about Pinocchio’s initial returns at the box office.[57] The distributor RKO recorded a loss of $94,000 for the film from worldwide rentals of $3,238,000.[61]

Accolades[edit]

The film was nominated and won two Academy Awards for Best Original Score and Best Original Song (for «When You Wish Upon a Star»), the first Disney film to win either category.[31]

To date, only six other Disney films have made this achievement: Mary Poppins (1964), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994), and Pocahontas (1995).

Reissues[edit]

With the re-release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1944 came the tradition of re-releasing Disney films every seven to ten years.[68] Pinocchio was theatrically re-released in 1945, 1954, 1962, 1971, 1978, 1984, and 1992. RKO handled the first two reissues in 1945 and 1954, while Disney itself reissued the film from 1962 on through its Buena Vista Distribution division. The 1992 re-issue was digitally restored by cleaning and removing scratches from the original negatives one frame at a time, eliminating soundtrack distortions, and revitalizing the colour.[69]

Despite its initial struggles at the box office, a series of reissues in the years after World War II proved more successful, and allowed the film to turn a profit. By 1973, the film had earned rentals of $13 million in the United States and Canada from the initial 1940 release and four reissues.[70][71] After the 1978 reissue, the rentals had increased to $19.9 million[72] from a total gross of $39 million.[73] The 1984 reissue grossed $26.4 million in the U.S. and Canada,[74] bringing its total gross there to $65.4 million[73] and $145 million worldwide.[38] The 1992 reissue grossed $18.9 million in the U.S. and Canada bringing Pinocchio’s lifetime gross to $84.3 million at the U.S. and Canadian box office.[73]

Modern acclaim[edit]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has the website’s highest rating of 100%, meaning every single one of the 60 reviews of the reviews from contemporary, to modern re-appraisals, on the site are positive, with an average rating of 9.1/10.[75] The general consensus of the film on the site is «Ambitious, adventurous, and sometimes frightening, Pinocchio arguably represents the pinnacle of Disney’s collected works – it’s beautifully crafted and emotionally resonant.».[75] On Metacritic, Pinocchio has a weighted score of 99 out of 100 based on 17 critics, indicating «universal acclaim». It is currently the highest-rated animated film on the site, as well as the highest-rated Disney animated film.[76]

Many film historians consider this to be the film that most closely approaches technical perfection of all the Disney animated features.[77] Film critic Leonard Maltin said, «with Pinocchio, Disney reached not only the height of his powers, but the apex of what many critics consider to be the realm of the animated cartoon.»[78]

In 1994, Pinocchio was added to the United States National Film Registry as being deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».[4] Filmmaker Terry Gilliam selected it as one of the ten best animated films of all time in a 2001 article written for The Guardian[79] and in 2005, Time magazine named it one of the 100 best films of the last 80 years, and then in June 2011 named it the best animated movie of «The 25 All-TIME Best Animated Films».[80]

In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its «Ten top Ten»—the best ten films in ten «classic» American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Pinocchio was acknowledged as the second best film in the medium of animation, after Snow White.[81] It was nominated for the AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies,[82]

and received further nominations for their Thrills[83] and Heroes and Villains (Stromboli in the villains category) lists.[84] The song «When You Wish Upon A Star» ranked number 7 on their 100 Songs list,[85] and the film ranked 38th in the 100 Cheers list.[86] The quote «A lie keeps growing and growing until it’s as plain as the nose on your face» was nominated for the Movie Quotes list,[87] and the film received further nomination in the AFI’s Greatest Movie Musicals list.[88]

On June 29, 2018, Pinocchio was named the 13th best Disney animated film by IGN.[89] Film critic Roger Ebert, adding it to his list of «Great Movies», wrote that the movie «isn’t just a concocted fable or a silly fairy tale, but a narrative with deep archetypal reverberations.»[90]

Legacy[edit]

Figaro, the petulant and jealous kitten character, primarily animated by Eric Larson, has been described as a «hit with the audiences», which resulted in him making appearances in several subsequent Disney short films in the 1940s.[91]

Many of Pinocchio‘s characters are costumed characters at Disney parks.[92] Pinocchio’s Daring Journey is a popular ride at the original Disneyland,[92] Tokyo Disneyland,[93] and Disneyland Park in Paris.[94] Pinocchio Village Haus is a quick service restaurant at Walt Disney World that serves pizza and macaroni and cheese.[95] There are similar quick-service restaurants at the Disneyland parks in Anaheim and Paris as well, with almost identical names.[95]

Disney on Ice starring Pinocchio, toured internationally from 1987 to 1992.[96] A shorter version of the story is also presented in the current Disney on Ice production «One Hundred Years of Magic».[96]

Cancelled sequel[edit]

In the mid-2000s, Disneytoon Studios began development on a sequel to Pinocchio. Robert Reece co-wrote the film’s screenplay, which saw Pinocchio on a «strange journey» for the sake of something dear to him. «It’s a story that leads Pinocchio to question why life appears unfair sometimes,» said Reece.[97] John Lasseter cancelled Pinocchio II soon after being named Chief Creative Officer of Walt Disney Animation Studios in 2006.[98]

Live-action adaptations[edit]

Geppetto[edit]

A Disney’s made-for-television movie titled Geppetto was released in 2000. It was based on a book by David Stern, which was a re-telling of the original 1883 original Pinocchio book but told from Geppetto’s perspective.[99][5] While not a direct adaptation of the 1940 animated film, it features few commons elements such as the character of Figaro, the song «I’ve Got No Strings», and Pleasure Island. It stars Drew Carey as Geppetto and Seth Adkins as Pinocchio, and features music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz.[5]

The movie was in turn adapted into a musical, Disney’s My Son Pinocchio: Geppetto’s Musical Tale, which premiered at The Coterie Theatre, Kansas City, Missouri in 2006.[100]

2022 remake[edit]

A live-action adaptation[101][102] directed by Robert Zemeckis who also co-produced and co-written with Chris Weitz,[103][104][105] and stars Tom Hanks as Geppetto, Benjamin Evan Ainsworth as Pinocchio, Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Jiminy Cricket, Cynthia Erivo as the Blue Fairy, Keegan-Michael Key as Honest John, Luke Evans as the Coachman and Lorraine Bracco as a new character named Sofia the Seagull.[106][107][108] The film was released to the streaming service Disney+ on September 8, 2022.[109]

In other media[edit]

The Silly Symphony Sunday comic strip published an adaptation of Pinocchio from December 24, 1939 to April 7, 1940. The sequences were scripted by Merrill De Maris and drawn by Hank Porter.[110]

Video games[edit]

Aside from the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive, Game Boy, and SNES games based on the animated film, the characters appear in several Disney video games.

Jiminy Cricket appears as a main character in Disney’s Villains’ Revenge, being player’s guide during the progress of the game.

In the Kingdom Hearts series, Jiminy Cricket appears acting as a recorder, keeping a journal of the game’s progress in Kingdom Hearts, Kingdom Hearts: Chain of Memories, Kingdom Hearts II, and Kingdom Hearts III.[111] Pinocchio, Geppetto and Cleo also appear as characters in Kingdom Hearts.[112] and the inside of Monstro is also featured as one of the worlds.[111] Pinocchio’s home world was slated to appear in Kingdom Hearts 358/2 Days, but was omitted due to time restrictions, although talk-sprites of Pinocchio, Geppetto, Honest John and Gideon have been revealed.[113] As compensation, this world appears in Kingdom Hearts 3D: Dream Drop Distance, under the name «Prankster’s Paradise», with Dream world versions of Pinocchio, Jiminy Cricket, Geppetto, Monstro and the Blue Fairy appearing.[113]

Pinocchio, Jiminy Cricket, Geppetto, Figaro, the Blue Fairy, Honest John and Stromboli appear as playable characters in the video game Disney Magic Kingdoms, along with some attractions based on locations of the film. Monstro also appeared temporarily as a non-player character for a Boss Battle during the limited time «Pinocchio Event» in which the characters and material related to the film were included. In the game, the characters are involved in new storylines that serve as a continuation of the film.[114]

See also[edit]

- 1940 in film

- List of American films of 1940

- List of Walt Disney Pictures films

- List of Disney theatrical animated features

- List of animated feature films of the 1940s

- List of highest-grossing animated films

- List of Disney animated films based on fairy tales

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

- List of films considered the best

References[edit]

- ^ Williams, Pat; Denney, Jim (January 1, 2010). How to Be Like Walt: Capturing the Disney Magic Every Day of Your Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-7573-9446-1.

- ^ «Pinocchio: Detail View». American Film Institute. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ^ a b Barrier 1999, p. 266.

- ^ a b «25 Films Added to National Registry». The New York Times. November 15, 1994. p. C20. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c «Disney’s My Son Pinocchio: Geppetto’s Musical Tale». www.musicalschwartz.com.

- ^ Cryer, Max (February 1, 2015). The Cat’s Out of the Bag: Truth and lies about cats. Exisle Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-77559-207-5.

- ^ a b c d No Strings Attached: The Making of Pinocchio (DVD, Blu-Ray). Pinocchio Platinum Edition: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 291.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 236.

- ^ a b c Barrier 1999, p. 237.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 294.

- ^ a b Barrier 1999, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 238.

- ^ Canemaker 2001, p. 137.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 306.

- ^ Barrier 2008, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b Barrier 1999, p. 239.

- ^ a b Gabler 2006, p. 305.

- ^ Canemaker 2001, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 240.

- ^ Gabler 2006, p. 304.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. «Cliff «Ukelele [sic] Ike» Edwards | Biography». AllMusic. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ «Almanac: «Pinocchio»«. CBS News. February 23, 1940. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Barrier 1999, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Blanc, Mel; Bashe, Philip (1988). That’s Not All Folks: My Life in the Golden Age of Cartoons and Radio. New York: Warner Books. p. 60. ISBN 0446512443 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Barrier 1999, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Moritz 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 262.

- ^ Shadowline2000 (March 26, 2016). «Animation Collection: Original Courvoisier Production Cel Setup of Pinocchio, Geppetto, Figaro, Cleo, and Water Effects Cels from «Pinocchio,» 1940″. Animation Collection. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ a b «Pinocchio [RCA] — Original Soundtrack | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards». AllMusic. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c Roberts 2006, p. 134.

- ^ Booker 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Mitchell & Reid-Walsh 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Pinsky 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Honeyman 2013, p. 29.

- ^ Booker 2010, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Sendak, Maurice (October 7, 1988). «Walt Disney’s Triumph — The Art of Pinocchio». The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Bierbaum, Tom (May 9, 1985). «Disney Goes To Vault For Its ‘Pinocchio’ HV». Variety. p. 1.

- ^ «Disney Vid Points ‘Sword’ At March Release Schedule». Variety. January 29, 1986. p. 10.

- ^ «Disney Releases ‘Pinocchio’ Video». Chicago Tribune. July 12, 1985. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ Stevens, Mary (March 19, 1993). «‘Pinocchio’ Is The Winner by a Nose». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ «Pinocchio (Gold Classic Collection) [VHS]: Dickie Jones, Christian Rub, Mel Blanc, Don Brodie, Walter Catlett, Marion Darlington, Frankie Darro, Cliff Edwards, Charles Judels, Patricia Page, Evelyn Venable, Ben Sharpsteen, Bill Roberts, Hamilton Luske, Jack Kinney, Norman Ferguson, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Aurelius Battaglia, Bill Peet: Movies & TV». Amazon.com. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «Imagination for a Lifetime — Disney Titles All the Time; Walt Disney Home Video Debuts the «Gold Classic Collection»; An Animated Masterpiece Every Month in 2000″ (Press release). Burbank, California. Business Wire. January 6, 2000. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2020 – via TheFreeLibrary.com.

- ^ «Pinocchio — Disney Gold Collection». Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ «Time Is Running Out … Four of Disney’s Greatest Animated Classics Are Disappearing into the Vault» (Press release). Walt Disney Press Release. PR Newswire. January 23, 2002. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2017 – via TheFreeLibrary.com.

- ^ Sharpsteen, Ben; Luske, Hamilton (supervising directors) (March 3, 2003). Pinocchio Special Edition (Animated film). Lebanon: Disney.

- ^ Brevet, Brad (March 10, 2009). «This Week On DVD and Blu-ray: March 10, 2009». ComingSoon.net. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «Pinocchio: 70th Anniversary — Platinum Edition (DVD 1940)». DVD Empire. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «Pinocchio | Disney Movies». Disneydvd.disney.go.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Knopp, JeniLynn (November 19, 2016). «D23: Pinocchio is joining the Walt Disney Signature Collection on January 10». Inside the Magic. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ «Breaking: Pinocchio To Join the Walt Disney Signature Collection». Oh My Disney. November 19, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (February 8, 1940). «The Screen in Review; ‘Pinocchio,’ Walt Disney’s Long-Awaited Successor to ‘Snow White,’ Has Its Premiere at the Center Theatre». The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ «Cinema: The New Pictures». Time. February 26, 1940. pp. 64, 66. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ «Film Reviews: Pinocchio». Variety. January 31, 1940. p. 14. Retrieved September 16, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ «‘Pinocchio’ Screen Triumph; Walt Disney’s Masterpiece». The Hollywood Reporter. January 30, 1940. p. 3. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Barrier 1999, pp. 269–273.

- ^ a b Thomas 1994, p. 161.

- ^ Barrier 1999, pp. 318, 602.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. 272.

- ^ Barrier 1999, pp. 269–273, 602.

- ^ Sedgwick, John (1994). «Richard B. Jewell’s RKO film grosses, 1929–51: The C. J. Trevlin Ledger: A comment». Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 14 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1080/01439689400260041 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ «The 13th Academy Awards (1941) Nominees and Winners». Oscars.org (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ^ «1941 Retro-Hugo Awards». Hugo Awards. July 26, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ «National Film Registry». D23. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ «Complete National Film Registry Listing». Library of Congress. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ «Film Hall of Fame Productions». Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ «Film Hall of Fame Inductees: Songs». Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ «Pinocchio (1940) — Release Summary». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Hunter, Stephen (June 25, 1992). «‘Pinocchio’ returns The restored print looks better than the original». The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Wasko 2013, p. 137.

- ^ «Updated All-Time Film Rental Champs». Variety. January 9, 1974. p. 23.

- ^ «All-Time Film Rental Champs». Variety. January 11, 1983. p. 16.

- ^ a b c «Pinocchio». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ Harris, Kathryn (June 12, 1992). «A Nose for Profit: ‘Pinocchio’ Release to Test Truth of Video Sales Theory». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ a b «Pinocchio (1940)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ «Pinocchio (1940)». Metacritic. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- ^ «Pinocchio – Disney Movies History». Disney.go.com. August 4, 2003. Archived from the original on August 4, 2003. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1973). «Pinocchio». The Disney Films. New York: Crown Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 978-0517177419.

- ^ Gilliam, Terry (April 27, 2001). «Terry Gilliam Picks the Ten Best Animated Films of All Time». The Guardian. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (June 21, 2011). «Pinocchio | The 25 All-TIME Best Animated Films». Time. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’s 10 Top 10». American Film Institute. June 17, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ «Movies_Ballot_06» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «400 Nominees for AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Thrills». Listology. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’S 100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains» (PDF). American Film Institute. June 20, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 YEARS…100 SONGS». American Film Institute. June 22, 2004. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’S 100 Years… 100 Cheers» (PDF). American Film Institute. June 20, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’S 100 Years… 100 Movie Quotes» (PDF). American Film Institute. June 20, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 YEARS OF MUSICALS». American Film Institute. September 3, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «The 25 Best Disney Animated Movies». IGN. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 22, 1998). «Pinocchio movie review». RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Max Cryer (February 1, 2015). The Cat’s Out of the Bag: Truth and lies about cats. Exisle Publishing. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-1-77559-207-5.

- ^ a b «Pinocchio’s Daring Journey | Rides & Attractions | Disneyland Park | Disneyland Resort». Disneyland.disney.go.com. May 25, 1983. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «Tokyo Disney Resort». Tokyodisneyresort.co.jp. Archived from the original on August 19, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «Disneyland Paris Rides | Les Voyages de Pinocchio». Parks.disneylandparis.co.uk. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b «Pinocchio Village Haus | Walt Disney World Resort». Disneyworld.disney.go.com. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Blankenship, Bill (December 1, 2013). «Disney on Ice brings back ‘100 Years of Magic’ to Expocentre». CJOnline.com. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Armstrong, Josh (April 22, 2013). «From Snow Queen to Pinocchio II: Robert Reece’s animated adventures in screenwriting». Animated Views. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ «DisneyToon Studios to be Restructured and Will Operate as a Separate Unit Within Walt Disney Animation Studios» (Press release). Walt Disney Studios. June 22, 2007. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ «Disney’s My Son Pinocchio: Geppetto’s Musical Tale — Share Photos, Videos, Costume, and Sets, Theatrical Advice». MTIShowspace.

- ^ «Home Coterie Theatre».

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (April 8, 2015). «‘Pinocchio’-Inspired Live-Action Pic in the Works at Disney». Deadline Hollywood.

- ^ McNary, Dave (April 8, 2015). «Disney Developing Live-Action ‘Pinocchio’ Movie». Variety. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ «Robert Zemeckis in Talks to Direct Live-Action ‘Pinocchio’ for Disney (EXCLUSIVE)». Variety. October 18, 2019.

- ^ Medina, Joseph Jammer (August 21, 2018). «Disney’s Live-Action Pinocchio Writer Chris Weitz Says They’re Still Developing The Script (Exclusive)». LRM Online. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ D’Alessandro, Anthony (January 24, 2020). «Robert Zemeckis Closes Deal To Direct & Co-Write Disney’s Live-Action ‘Pinocchio’«. Deadline Hollywood.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca (December 10, 2020). «‘Pinocchio’ With Tom Hanks, ‘Peter Pan and Wendy’ to Skip Theaters for Disney Plus». Variety. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ D’Alessandro, Anthony (January 26, 2021). «‘Beauty And The Beast’ Star Luke Evans Joins Disney’s Tom Hanks ‘Pinocchio’ Movie». Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Radish, Christina (February 16, 2021). «Luke Evans on ‘The Pembrokeshire Murders’ and Why Disney’s ‘Pinocchio’ Remake Will Be Unique». Collider. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Petski, Denise (May 31, 2022). «‘Pinocchio’: Robert Zemeckis’ Live-Action Remake Gets Disney+ Premiere Date, Teaser Trailer». Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Karp, Hubie; Grant, Bob; De Maris, Merrill; Taliaferro, Al; Porter, Hank (2018). Silly Symphonies: The Complete Disney Classics, vol 3. San Diego: IDW Publishing. ISBN 978-1631409882.

- ^ a b «Jiminy Cricket — Kingdom Hearts 3D Wiki Guide». IGN. July 31, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ «Disney’s Pinocchio (Mega Drive): Amazon.co.uk: PC & Video Games». Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b «Prankster’s Paradise (Riku) — Kingdom Hearts 3D Wiki Guide». IGN. July 31, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ «Update 55: Pinocchio | Livestream». YouTube. December 10, 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons : American Animation in Its Golden Age: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802079-0.

- Barrier, Michael (2008). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52-025619-4.

- Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-222-6.

- Booker, M. Keith (2010). Disney, Pixar, and the Hidden Messages of Children’s Films. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37672-6.

- Canemaker, John (2001). Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0786864966.

- Gabler, Neal (2006). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-75747-4.

- Honeyman, Susan (2013). Consuming Agency in Fairy Tales, Childlore, and Folkliterature. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-60395-2.

- Mitchell, Claudia; Reid-Walsh, Jacqueline (2008). Girl Culture: Studying girl culture : a readers’ guide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-33909-7.

- Moritz, William (2004). Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34348-8.

- Pinsky, Mark I. (2004). «4». The Gospel According to Disney: Faith, Trust, and Pixie Dust. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23467-6.

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles and Albums. Guinness World Records Limited. ISBN 978-1-904994-10-7.

- Thomas, Bob (1994) [1976]. Walt Disney: An American Original. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7857-5515-9.

- Wasko, Janet (2013). Understanding Disney: The Manufacture of Fantasy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-6904-5.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Pinocchio at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Pinocchio at AllMovie

- Pinocchio at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- Pinocchio at Box Office Mojo

- Pinocchio at IMDb

- Pinocchio at Rotten Tomatoes

- Pinocchio at Metacritic

- Pinocchio at the TCM Movie Database

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). «Pinocchio». America’s Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. A & C Black. pp. 311–313. ISBN 978-0826429773.

- Kaufman, J.B. (2014). «Pinocchio» (PDF). National Film Registry.

| Pinocchio | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Supervising Directors

Sequence Directors

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on | The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Starring |

|

| Music by |

|

|

Production |

Walt Disney Productions |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.6 million[3] |

| Box office | $164 million |

Pinocchio is a 1940 American animated musical fantasy film produced by Walt Disney Productions and based on the 1883 Italian children’s novel The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi. It was the second animated feature film produced by Disney, made after the first animated success Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).

The plot involves an old Italian woodcarver named Geppetto who carves a wooden puppet named Pinocchio and wishes that he might be a real boy. The puppet is brought to life by a blue fairy, who informs him that he can become a real boy if he proves himself to be «brave, truthful, and unselfish». The key character of Jiminy Cricket, who takes the role of Pinocchio’s conscience, attempts to guide Pinocchio in matters of right and wrong. Pinocchio’s efforts to become a real boy involve encounters with a host of unsavory characters, representing the temptations and consequences of wrongdoing.

The film was adapted by several storyboard artists from Collodi’s book. The production was supervised by Ben Sharpsteen and Hamilton Luske, and the film’s sequences were directed by Norman Ferguson, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Jack Kinney, and Bill Roberts. Pinocchio was a groundbreaking achievement in the area of effects animation, giving realistic movement to vehicles, machinery and natural elements such as rain, lightning, smoke, shadows and water. Pinocchio was released to theatres by RKO Radio Pictures on February 23, 1940.

Although it received critical acclaim and became the first animated feature to win a competitive Academy Award — winning two for Best Music, Original Score and for Best Music, Original Song for «When You Wish Upon a Star» — it was initially a box office bomb, mainly due to World War II cutting off the European and Asian markets overseas. It eventually made a profit in its 1945 reissue, and is considered one of the greatest animated films ever made, with a 100% rating on the website Rotten Tomatoes. The film and characters are still prevalent in popular culture, featuring at various Disney parks and in other forms of entertainment. In 1994, Pinocchio was added to the United States National Film Registry for being deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».[4]

A 2000 live-action movie titled Geppetto, told from Geppetto’s perspective, was released direct to television.[5] In April 2015, a live-action adaptation of the same name officially entered development; filming began in March 2021 and ended that April, and it was released on Disney+ on September 8, 2022.

Plot[edit]

Jiminy Cricket addresses the audience as the narrator and begins to tell a story. Jiminy came to a village in Italy sometime in the late 19th century, where he arrived at the shop of a woodworker and toymaker named Geppetto, who creates a marionette whom he names Pinocchio. Falling asleep, Geppetto wishes upon a star for Pinocchio to be a real boy. Late that night, a Blue Fairy visits the workshop and brings Pinocchio to life, although he remains a puppet. She informs him that if he proves himself brave, truthful, and unselfish, he will become a real boy. When Jiminy reveals himself, the Blue Fairy assigns him to be Pinocchio’s conscience. Geppetto wakes up upon hearing a commotion from Pinocchio falling, and is overjoyed to discover that his puppet is alive and will become a real boy.

The next morning on his way to school, Pinocchio is led astray by con artist fox Honest John and his sidekick Gideon the Cat. Honest John convinces him to join Stromboli’s puppet show, despite Jiminy’s objections. Pinocchio becomes Stromboli’s star attraction, but when he tries to go home, Stromboli locks him in a bird cage and leaves to tour the world with Pinocchio. After Jiminy unsuccessfully tries to free his friend, the Blue Fairy appears, and an anxious Pinocchio lies about what happened, causing his nose to grow. The Blue Fairy restores his nose and frees him when Pinocchio promises to make amends, but she warns him that she can offer no further help.

Meanwhile, Honest John is hired by a mysterious coachman to find disobedient boys for him to take to Pleasure Island. Though Honest John and Gideon are frightened by the Coachman’s implication of what happens to the boys, the former reluctantly accepts the job and finds Pinocchio, convincing him to take a vacation on Pleasure Island. On the way, Pinocchio befriends Lampwick, a delinquent boy. At Pleasure Island, without rules or authority to enforce their activity, Pinocchio, Lampwick, and countless other boys soon engage in vices such as smoking and drinking. Jiminy eventually discovers that the island hides a horrible curse, turning boys into donkeys, which the Coachman plans to sell as slave labor to salt mines and circuses. Pinocchio witnesses Lampwick transform into a donkey, and with Jiminy’s help, Pinocchio escapes, partially transformed with a donkey’s ears and tail.

Returning home, Pinocchio and Jiminy find Geppetto’s workshop deserted. They get a letter from the Blue Fairy in the form of a dove, stating that Geppetto had gone out looking for Pinocchio and sailed to Pleasure Island. After learning that Pinocchio had left, he was then swallowed by Monstro, a terrible sperm whale, and is now living in the belly of the beast. Determined to rescue his father, Pinocchio jumps into the ocean, accompanied by Jiminy. Pinocchio is soon swallowed by Monstro, where he reunites with Geppetto. Pinocchio devises a scheme to make Monstro sneeze, giving them a chance to escape. The scheme works, but the enraged whale chases them and smashes their raft with his tail. Pinocchio selflessly pulls Geppetto to safety in a cove just as Monstro crashes into it and Pinocchio is seemingly killed.

Back home, Geppetto, Jiminy, Figaro, and Cleo mourn the loss of Pinocchio. However, having proven himself brave, truthful, and unselfish, Pinocchio is revived and turned into a real human boy by the Blue Fairy, getting rid of the Pleasure Island curse in the process, much to everyone’s joy. As the group celebrates, Jiminy steps outside to thank the Fairy and is rewarded with a solid gold badge that certifies him as an official conscience.

Voice cast[edit]

- Dick Jones as Pinocchio, an exuberant and endearing wooden puppet carved by Geppetto, and brought to life by the Blue Fairy.

- Cliff Edwards as Jiminy Cricket, a cheerful, intelligent, wisecracking, optimistic and wise cricket, who acts as Pinocchio’s «conscience», and the partial narrator of the story.

- Christian Rub as Geppetto, a kind and elderly wood-carver, who creates Pinocchio, and wishes for him to become a real boy. He speaks with an Austrian accent.

- Clarence Nash as Figaro, Geppetto’s spoiled pet cat who is prone to jealousy. Cleo, Geppetto’s flirty pet goldfish with a habit of being Figaro’s counselor, is unvoiced. Figaro and Cleo were original characters added to the script by the Disney team.[6]

- Walter Catlett as «Honest» John Worthington Foulfellow, an anthropomorphic red fox con artist who swindles Pinocchio twice.

- Gideon the Cat, Honest John’s mute, dimwitted and bumbling anthropomorphic feline partner and sidekick who serves as the film’s comic relief. He was originally intended to be voiced by Mel Blanc of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies fame (in his second work for Disney until his final work in Who Framed Roger Rabbit), but the filmmakers removed his dialogue from the script in favor of a mute performance just like Dopey in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the circus elephant title character Dumbo;[7] however, Gideon’s hiccups were provided by Blanc.[7]

- Charles Judels as Stromboli, a greedy and abusive puppeteer, who intends to force Pinocchio to perform onstage in order to make money and to use him as «firewood» once he gets «too old» to perform, revealing also his sadistic attitude. He speaks English with an Italian accent, and curses in an Italian gibberish when he gets angry, though he is called «Gypsy» by Honest John, probably due to his theatre and caravan always traveling, along with other names like «rascal» and «faker». Due to his popularity, he has been for long the only character of the film to be part of the official Disney Villains line-up.

- Judels also voiced the nefarious and cunning Coachman, owner and operator of Pleasure Island, where unruly boys are turned into donkeys and sold. This latter is the only antagonist of the film which is not an official member of the aforementioned Disney Villains line-up/franchise.

- Evelyn Venable as the Blue Fairy, who brings Pinocchio to life, and promises to turn him into a real boy if he proves himself brave, truthful, and selfless. Live-action references for the Blue Fairy were provided by Marge Champion, who did live-action references for the titular heroine in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

- Frankie Darro as Lampwick, a naughty and spoiled boy who Pinocchio befriends on his way to Pleasure Island. He is turned into a donkey on Pleasure Island for his mischief.

- Stuart Buchanan as the Carnival Barker, the announcer heard on Pleasure Island. In a book adaptation of the film, «Barker» is how the Coachman is named.

- Thurl Ravenscroft as Monstro, the terrible sperm whale. He swallows Pinocchio, Geppetto, Figaro and Cleo, then tries to kill them after they escape from his belly by making him sneeze.

(The voice cast were all uncredited as was the practice at the time for many animated films.)

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

In September 1937, during the production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, animator Norman Ferguson brought a translated version of Carlo Collodi’s 1883 Italian children’s novel The Adventures of Pinocchio to the attention of Walt Disney. After reading the book, «Walt was busting his guts with enthusiasm» as Ferguson later recalled. Disney then commissioned storyboard artist Bianca Majolie to write a new story outline for the book, but after reading it, he felt her outline was too faithful.[8] Pinocchio was intended to be the studio’s third feature, after Bambi (1942). However, due to difficulties with Bambi (adapting the story and animating the animals realistically), Disney announced that Bambi would be postponed while Pinocchio would move ahead in production. Ben Sharpsteen was then re-assigned to supervise the production while Jack Kinney was given directional reins.[9][8]

Writing and design[edit]

Unlike Snow White, which was a short story that the writers could expand and experiment with, Pinocchio was based on a novel with a very fixed, although episodic, story. Therefore, the story went through drastic changes before reaching its final incarnation.[7] In the original novel, Pinocchio is a cold, rude, ungrateful, inhuman brat that often repels sympathy and only learns his lessons the hard way.[10] The writers decided to modernize the character and depict him similar to Edgar Bergen’s dummy Charlie McCarthy,[11] but equally as rambunctious as the puppet in the book. The story was still being developed in the early stages of animation.[10]

Early scenes animated by Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas show that Pinocchio’s design was exactly like that of a real wooden puppet with a long pointed nose, a peaked cap and bare wooden hands.[7]

Early scenes animated by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston show that Pinocchio’s design was exactly like that of a real wooden puppet with a long pointed nose, a peaked cap and bare wooden hands.[12] Disney, however, was not impressed with the work that was being done on the film. He felt that no one could really sympathize with such a character and called for an immediate halt in production.[10][11] Fred Moore redesigned the character slightly to make him more appealing, but the design still retained a wooden feel.[13]

Young and upcoming animator Milt Kahl felt that Thomas, Johnston, and Moore were «rather obsessed with the idea of this boy being a wooden puppet» and felt that they should «forget that he was a puppet and get a cute little boy; you can always draw the wooden joints and make him a wooden puppet afterwards». Co-supervising director Hamilton Luske suggested to Kahl that he should demonstrate his beliefs by animating a test sequence.[14]

Kahl then showed Disney an animation test scene in which Pinocchio is underwater looking for his father.[15] From this scene, Kahl re-envisioned the character by making him look more like a real boy, with a child’s Tyrolean hat and standard cartoon character four-fingered (or three and a thumb) hands with Mickey Mouse-type gloves on them.[16] The only parts of Pinocchio that still looked more or less like a puppet were his arms, legs and his little button wooden nose. Disney embraced Kahl’s scene and immediately urged the writers to evolve Pinocchio into a more innocent, naïve, somewhat coy personality that reflected Kahl’s design.[17]

However, Disney discovered that the new Pinocchio was too helpless and was far too often led astray by deceiving characters. Therefore, in the summer of 1938, Disney and his story team established the character of the cricket. Originally, the talking cricket was only a minor character that Pinocchio abruptly killed by squashing him with a mallet and that later returned as a ghost. Disney dubbed the cricket «Jiminy», and made him into a character that would try to guide Pinocchio into the right decisions.[18] Once the character was expanded, he was depicted as a realistic cricket with toothed legs and waving antennae, but Disney wanted something more likable. Ward Kimball had spent several months animating two sequences—a soup-eating musical number and a bed-building sequence—in Snow White, which was cut from the film due to pacing reasons. Kimball was about to quit until Disney rewarded him for his work by promoting him to the supervising animator of Jiminy Cricket.[19] Kimball then conjured up the design for Jiminy Cricket, whom he described as a little man with an egg head and no ears.[20] Jiminy «was a cricket because we called him a cricket,» Kimball later joked.[18]

Casting[edit]

Dickie Jones (right, as an adult) voices Pinocchio in the film.

Due to the huge success of Snow White, Walt Disney wanted more famous voices for Pinocchio, which marked the first time an animated film had used celebrities as voice actors.[21] He cast popular singer Cliff Edwards, also known as «Ukulele Ike», as Jiminy Cricket.[22] Disney rejected the idea of having an adult play Pinocchio and insisted that the character be voiced by a real child. He cast 11-year-old child actor Dickie Jones, who had previously been in Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).[23] He also cast Frankie Darro as Lampwick, Walter Catlett as «Honest» John Foulfellow the Fox, Evelyn Venable as the Blue Fairy, Charles Judels as both the villainous Stromboli and the Coachman, and Christian Rub as Geppetto, whose design was even a caricature of Rub.[24]

Another voice actor recruited was Mel Blanc, best remembered for voicing many of the characters in Warner Bros. cartoon shorts, including Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. Blanc recorded the voice of Gideon the Cat in sixteen days. However, it was eventually decided that Gideon would be mute, so all of Blanc’s recorded dialogue was subsequently deleted except for a solitary hiccup,[25] which was heard three times in the finished film.

Animation[edit]

Animation on the film began in January 1938, but work on Pinocchio’s animation was discontinued as the writers sought to re-work his characterization and the film’s narrative structure. However, animation on the film’s supporting characters started in April 1938.[12] Animation would not resume again with the revised story until September.[17]

During the production of the film, story artist Joe Grant formed a character model department, which would be responsible for building three-dimensional clay models of the characters in the film, known as maquettes. These models were then given to the staff to observe how a character should be drawn from any given angle desired by the artists.[15] The model makers also built working models of Geppetto’s elaborate cuckoo clocks designed by Albert Hurter, as well as Stromboli’s gypsy wagon and wooden cage, and the Coachman’s carriage. However, owing to the difficulty of animating a realistic moving vehicle, the artists filmed the carriage maquettes on a miniature set using stop motion animation. Then, each frame of the animation was transferred onto animation cels using an early version of a Xerox. The cels were then painted on the back and overlaid on top of background images with the cels of the characters to create the completed shot on the rostrum camera. Like Snow White, live-action footage was shot for Pinocchio with the actors playing the scenes in pantomime, supervised by Luske.[26] Rather than tracing, which would result in stiff unnatural movement, the animators used the footage as a guide for animation by studying human movement and then incorporating some poses into the animation (though slightly exaggerated).[26]

Pinocchio was a groundbreaking achievement in the area of effects animation, led by Joshua Meador. In contrast to the character animators who concentrate on the acting of the characters, effects animators create everything that moves other than the characters. This includes vehicles, machinery and natural effects such as rain, lightning, snow, smoke, shadows and water, as well as the fantasy or science-fiction type effects like the pixie dust of Peter Pan (1953). The influential abstract animator Oskar Fischinger, who mainly worked on Fantasia (1940), contributed to the effects animation of the Blue Fairy’s wand.[27] Effects animator Sandy Strother kept a diary about his year-long animation of the water effects, which included splashes, ripples, bubbles, waves and the illusion of being underwater. To help give depth to the ocean, the animators put more detail into the waves on the water surface in the foreground, and put in less detail as the surface moved further back. After the animation was traced onto cels, the assistant animators would trace it once more with blue and black pencil leads to give the waves a sculptured look.[28] To save time and money, the splashes were kept impressionistic. These techniques enabled Pinocchio to be one of the first animated films to have highly realistic effects animation. Ollie Johnston remarked «I think that’s one of the finest things the studio’s ever done, as Frank Thomas said, ‘The water looks so real a person can drown in it, and they do.'»[29]

Music[edit]

The songs in Pinocchio were composed by Leigh Harline with lyrics by Ned Washington. Harline and Paul J. Smith composed the incidental music score.[30] The underscore for the Monstro chase sequence was orchestrated by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer composer Leo Arnaud. The soundtrack was first released on February 9, 1940.[30] Jiminy Cricket’s song, «When You Wish Upon A Star», became a major hit and is still identified with the film, and later as the theme song of The Walt Disney Company itself.[31] The soundtrack won an Academy Award for Best Original Score.[31]

Themes[edit]

Commentator Nicholas Sammond considers Pinocchio to be a metaphor for American child rearing in the mid-20th century.

M. Keith Booker considers the film to be the most down-to-earth of the Disney animated films despite its theme song and magic, and notes that the film’s protagonist has to work to prove his worth, which he remarked seemed «more in line with the ethos of capitalism» than most of the Disney films.[32] Claudia Mitchell and Jacqueline Reid-Walsh believe that the male protagonists of films like Pinocchio and Bambi (1942) were purposefully constructed by Disney to appeal to both boys and girls.[33] Mark I. Pinsky said that it is «a simple morality tale—cautionary and schematic—ideal for moral instruction, save for some of its darker moments», and noted that the film is a favorite of parents of young children.[34]

Nicolas Sammond argues that the film is «an apt metaphor for the metaphysics of midcentury American child-rearing» and that the film is «ultimately an assimilationist fable».[35] He considered it to be the central Disney film and the most strongly middle class, intended to relay the message that indulging in «the pleasures of the working class, of vaudeville, or of pool halls and amusement parks, led to a life as a beast of burden». For Sammond, the purpose of Pinocchio is to help convey to children the «middle-class virtues of deferred gratification, self-denial, thrift, and perseverance, naturalized as the experience of the most average American».[36]

Author and illustrator Maurice Sendak, who saw the film in theaters in 1940, called the film superior to Collodi’s novel in its depiction of children and growing up. «The Pinocchio in the film is not the unruly, sulking, vicious, devious (albeit still charming) marionette that Collodi created. Neither is he an innately evil, doomed-to-calamity child of sin. He is, rather, both lovable and loved. Therein lies Disney’s triumph. His Pinocchio is a mischievous, innocent and very naive little wooden boy. What makes our anxiety over his fate endurable is a reassuring sense that Pinocchio is loved for himself — and not for what he should or shouldn’t be. Disney has corrected a terrible wrong. Pinocchio, he says, is good; his «badness» is only a matter of inexperience,» and also that «Pinocchio’s wish to be a real boy remains the film’s underlying theme, but «becoming a real boy» now signifies the wish to grow up, not the wish to be good.»[37]

Home media[edit]

On July 16, 1985, it was released on VHS, Betamax, CED, and LaserDisc in North America for the first time as part of the Walt Disney Classics label, the second title with the Classics label after Robin Hood (1973) which was released the previous December.[38] It would become the best-selling home video title of the year selling 130–150,000 units at $80 each.[39] It was re-issued on October 14, 1986 to advertise the home video debut of Sleeping Beauty (1959), this release also helped leave out the preview of The Black Cauldron from the original 1985 VHS release due to the preview being too dark and scary for kids. Then, for the first time, it was released on VHS in the UK in 1988, 1995, and 2000.[40] The digital restoration that was completed for the 1992 cinema re-issue was released on VHS and Laserdisc on March 26, 1993,[41] followed by its fourth VHS release and first release on Disney DVD as the 60th Anniversary Edition on October 25, 1999.[42]

The film was re-issued on DVD and one final time on VHS as part of the Walt Disney Gold Classics Collection release on March 7, 2000.[43] Along the film, the VHS edition also contained a making-of documentary while the DVD had the film’s original theatrical trailer as supplemental features.[44] The Gold Classic Collection release was returned to the Disney Vault on January 31, 2002.[45]

A special edition VHS and DVD of the film was released in the United Kingdom on March 3, 2003.[46] The fourth DVD release and first Blu-ray Disc release (the second Blu-ray in the Walt Disney Platinum Editions series) was released on March 10, 2009.[47] Like the 2008 Sleeping Beauty Blu-ray release, the Pinocchio Blu-ray package featured a new restoration by Lowry Digital in a two-disc Blu-ray set, with a bonus DVD version of the film also included.[48] This set returned to the Disney Vault on April 30, 2011.[49] A Signature Edition was released on Digital HD on January 10, 2017 and was followed by a Blu-ray/DVD combo pack on January 31, 2017.[50][51]

Reception[edit]

Initial release[edit]

Frank S. Nugent of The New York Times gave the film five out of five stars, saying «Pinocchio is here at last, is every bit as fine as we had prayed it would be—if not finer—and that it is as gay and clever and delightful a fantasy as any well-behaved youngster or jaded oldster could hope to see.»[52] Time magazine gave the film a positive review, stating «In craftsmanship and delicacy of drawing and coloring, in the articulation of its dozens of characters, in the greater variety and depth of its photographic effects, it tops the high standard Snow White set. The charm, humor and loving care with which it treats its inanimate characters puts it in a class by itself.»[53]

Variety praised the animation as superior to Snow White‘s writing the «[a]nimation is so smooth that cartoon figures carry impression of real persons and settings rather than drawings to onlooker.» In summary, they felt Pinocchio «will stand on [its] own as a substantial piece of entertainment for young and old, providing attention through its perfection in animation and photographic effects.[54] The Hollywood Reporter wrote «Pinocchio is entertainment for every one of every age, so completely charming and delightful that there is profound regret when it reaches the final fade-out. Since comparisons will be inevitable, it may as well be said at once that, from a technical standpoint, conception and production, this picture is infinitely superior to Snow White.»[55]

Initially, Pinocchio was not a box-office success.[56] The box office returns from the film’s initial release were both below Snow White’s unprecedented success and below studio expectations.[57] Of the film’s $2.6 million negative cost—twice the cost of Snow White[3]—Disney only recouped $1 million by late 1940, with studio reports of the film’s final original box office take varying between $1.4 million and $1.9 million.[58] Animation historian Michael Barrier notes that Pinocchio returned rentals of less than one million by September 1940, and in its first public annual report, Walt Disney Productions charged off a $1 million loss to the film.[59] Barrier relays that a 1947 Pinocchio balance sheet listed total receipts to the studio of $1.4 million. This was primarily due to the fact that World War II and its aftermath had cut off the European and Asian markets overseas, and hindered the international success of Pinocchio and other Disney releases during the early and mid-1940s.[60] Joe Grant recalled Walt Disney being «very, very depressed» about Pinocchio’s initial returns at the box office.[57] The distributor RKO recorded a loss of $94,000 for the film from worldwide rentals of $3,238,000.[61]

Accolades[edit]

The film was nominated and won two Academy Awards for Best Original Score and Best Original Song (for «When You Wish Upon a Star»), the first Disney film to win either category.[31]

To date, only six other Disney films have made this achievement: Mary Poppins (1964), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994), and Pocahontas (1995).

Reissues[edit]