| «Puss in Boots» | |

|---|---|

| by Giovanni Francesco Straparola Giambattista Basile Charles Perrault |

|

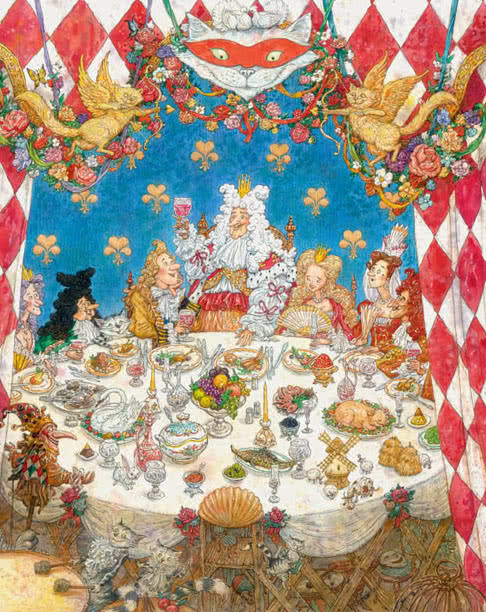

Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer |

|

| Country | Italy (1550–1553) France (1697) |

| Language | Italian (originally) |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

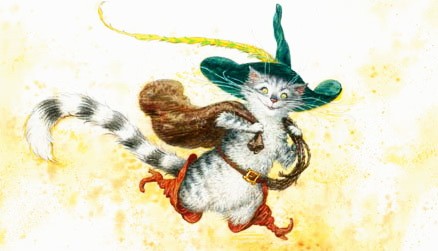

«Puss in Boots» (Italian: Il gatto con gli stivali) is an Italian[1][2] fairy tale, later spread throughout the rest of Europe, about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand of a princess in marriage for his penniless and low-born master.

The oldest written telling is by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola, who included it in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–1553) in XIV–XV. Another version was published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile with the title Cagliuso, and a tale was written in French at the close of the seventeenth century by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a retired civil servant and member of the Académie française. There is a version written by Girolamo Morlini, from whom Straparola used various tales in The Facetious Nights of Straparola.[3] The tale appeared in a handwritten and illustrated manuscript two years before its 1697 publication by Barbin in a collection of eight fairy tales by Perrault called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[4][5] The book was an instant success and remains popular.[3]

Perrault’s Histoires has had considerable impact on world culture. The original Italian title of the first edition was Costantino Fortunato, but was later known as Il gatto con gli stivali (lit. The cat with the boots); the French title was «Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités» with the subtitle «Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye» («Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times with Morals», subtitled «Mother Goose Tales»). The frontispiece to the earliest English editions depicts an old woman telling tales to a group of children beneath a placard inscribed «MOTHER GOOSE’S TALES» and is credited with launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4]

«Puss in Boots» has provided inspiration for composers, choreographers, and other artists over the centuries. The cat appears in the third act pas de caractère of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty.[6] Puss in Boots appears in DreamWorks’ Shrek franchise, appearing in all three sequels to the original film, as well as two spin-off films, Puss in Boots (2011) and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish (2022), where he is voiced by Antonio Banderas. The character is signified in the logo of Japanese anime studio Toei Animation, and is also a popular pantomime in the UK.

Plot[edit]

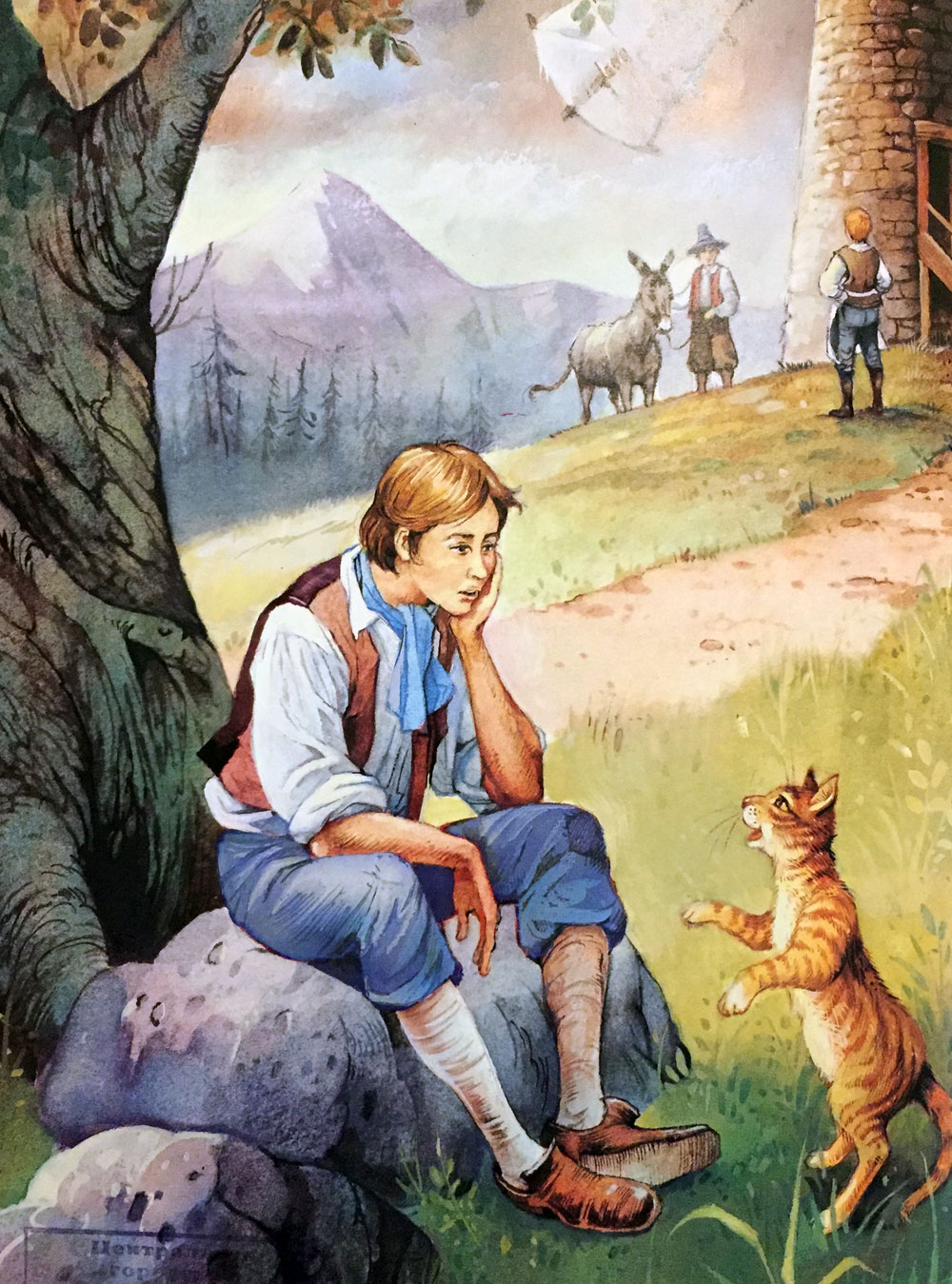

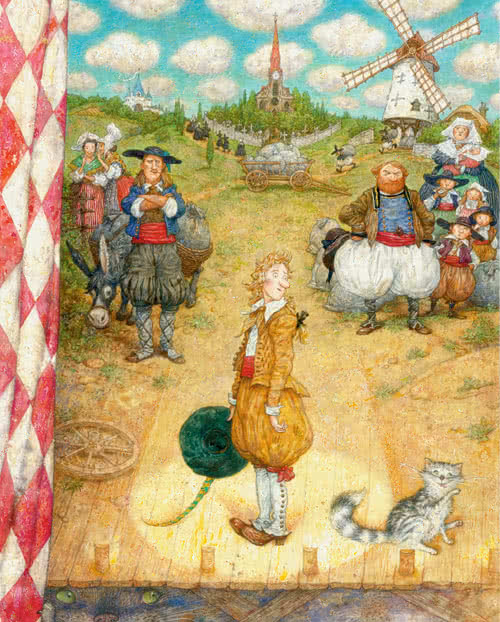

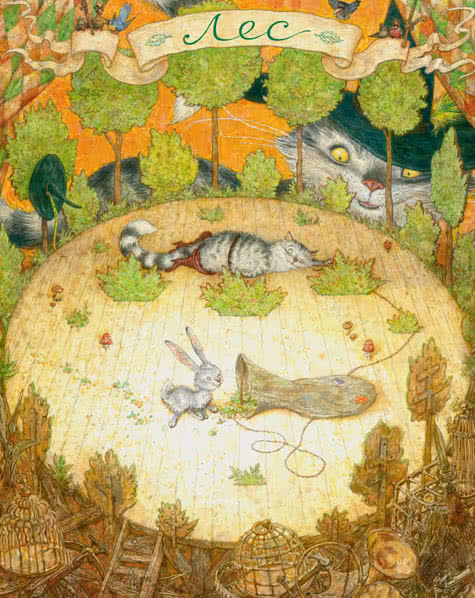

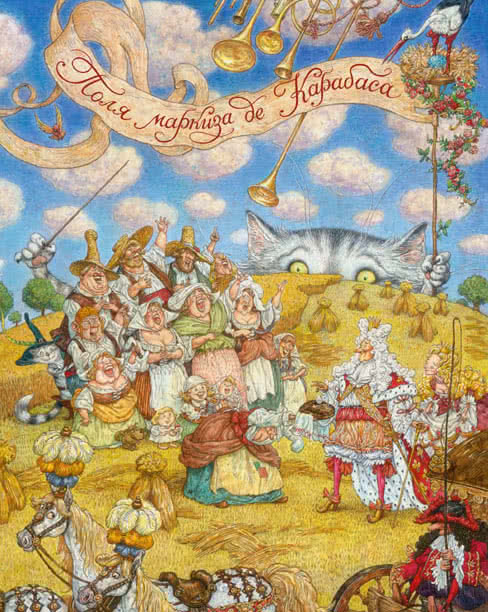

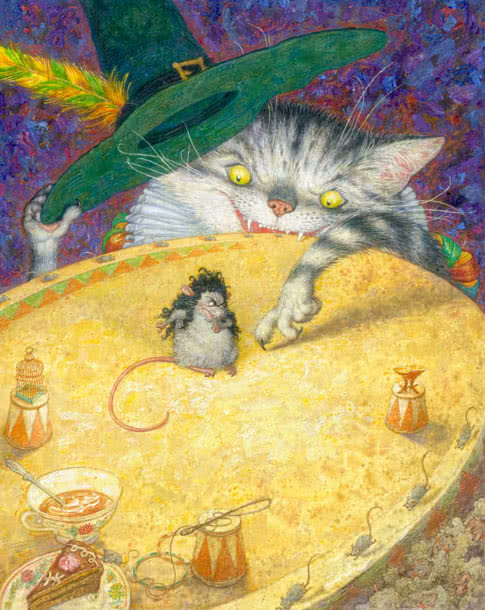

The tale opens with the third and youngest son of a miller receiving his inheritance — a cat. At first, the youngest son laments, as the eldest brother gains their father’s mill, and the middle brother gets the mule-and-cart. However, the feline is no ordinary cat, but one who requests and receives a pair of boots. Determined to make his master’s fortune, the cat bags a rabbit in the forest and presents it to the king as a gift from his master, the fictional Marquis of Carabas. The cat continues making gifts of game to the king for several months, for which he is rewarded.

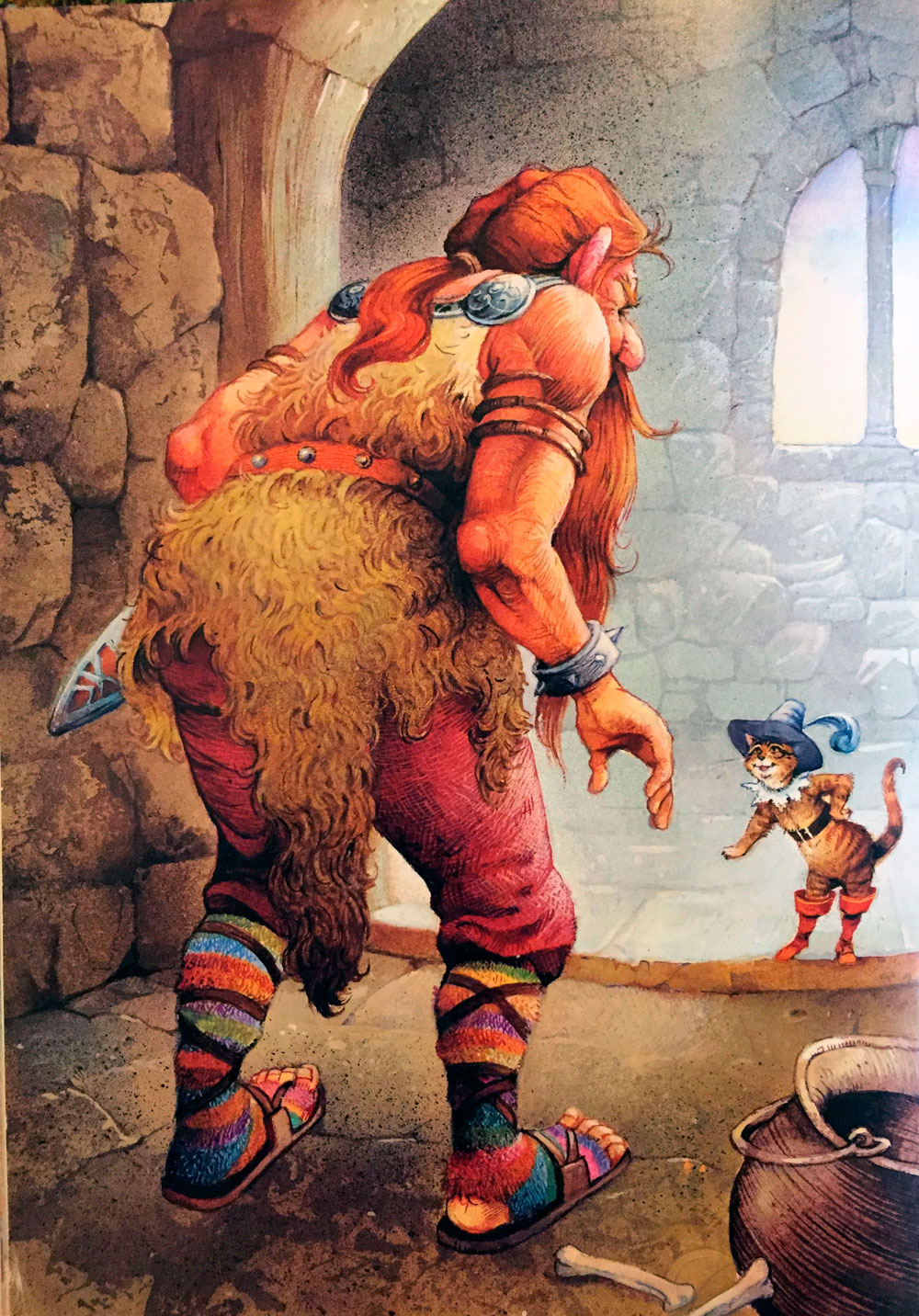

Puss meets the ogre in a nineteenth-century illustration by Gustave Doré

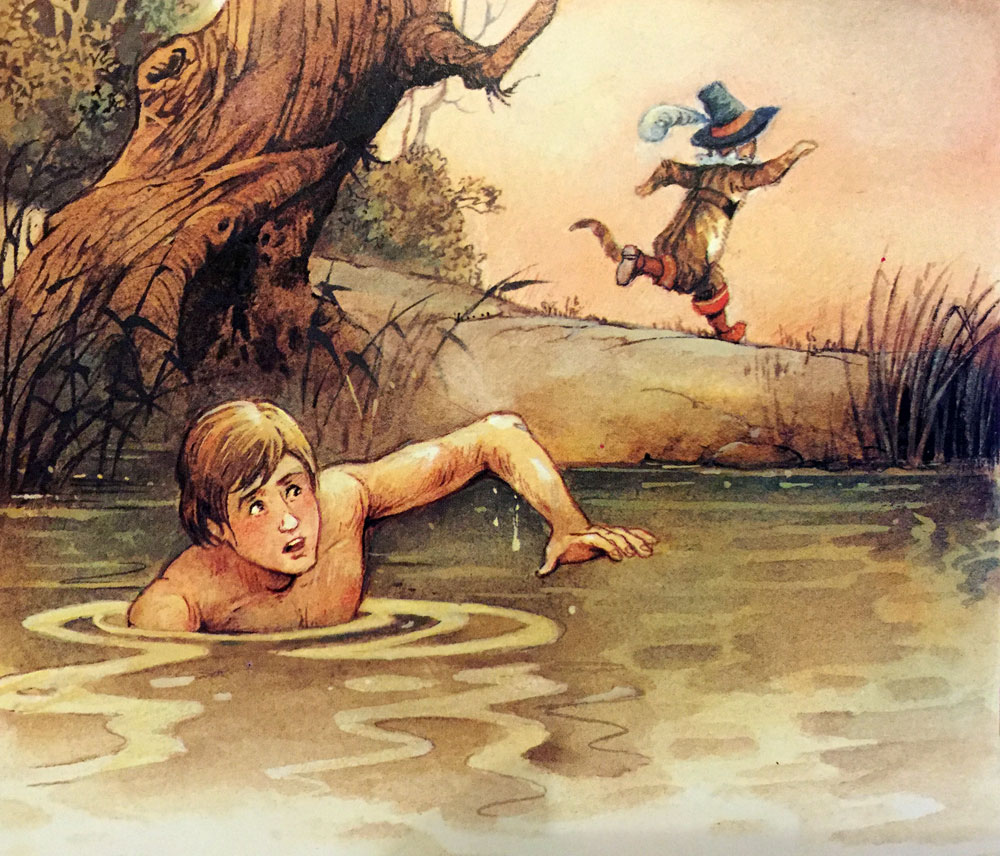

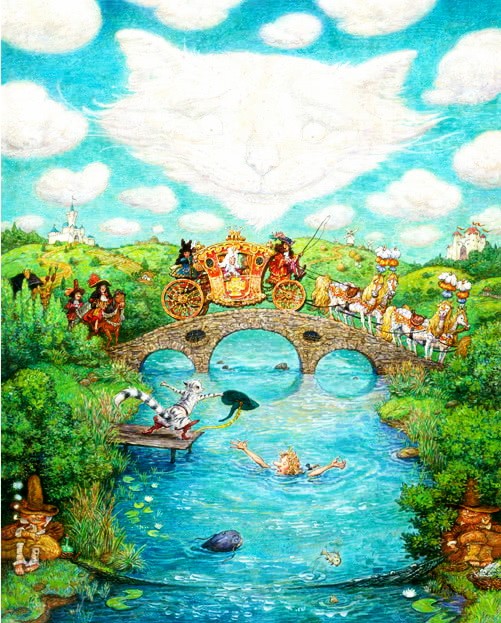

One day, the king decides to take a drive with his daughter. The cat persuades his master to remove his clothes and enter the river which their carriage passes. The cat disposes of his master’s clothing beneath a rock. As the royal coach nears, the cat begins calling for help in great distress. When the king stops to investigate, the cat tells him that his master the Marquis has been bathing in the river and robbed of his clothing. The king has the young man brought from the river, dressed in a splendid suit of clothes, and seated in the coach with his daughter, who falls in love with him at once.

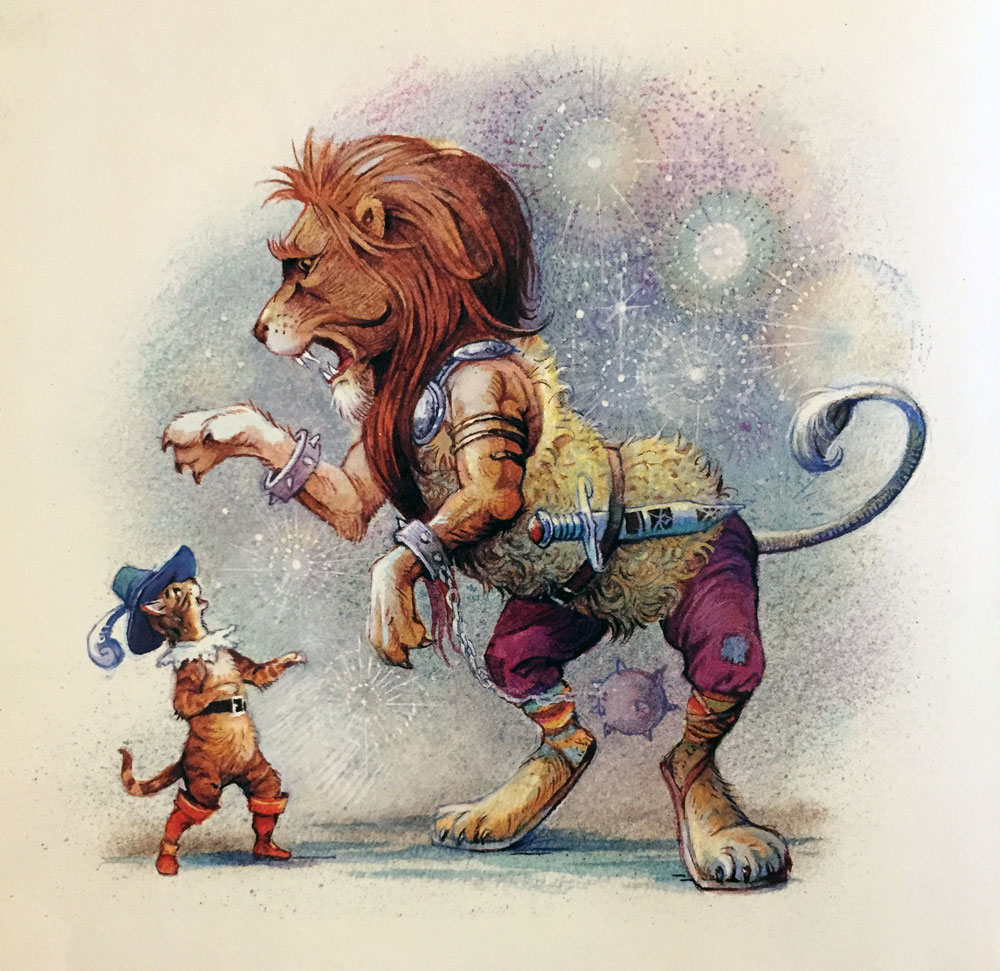

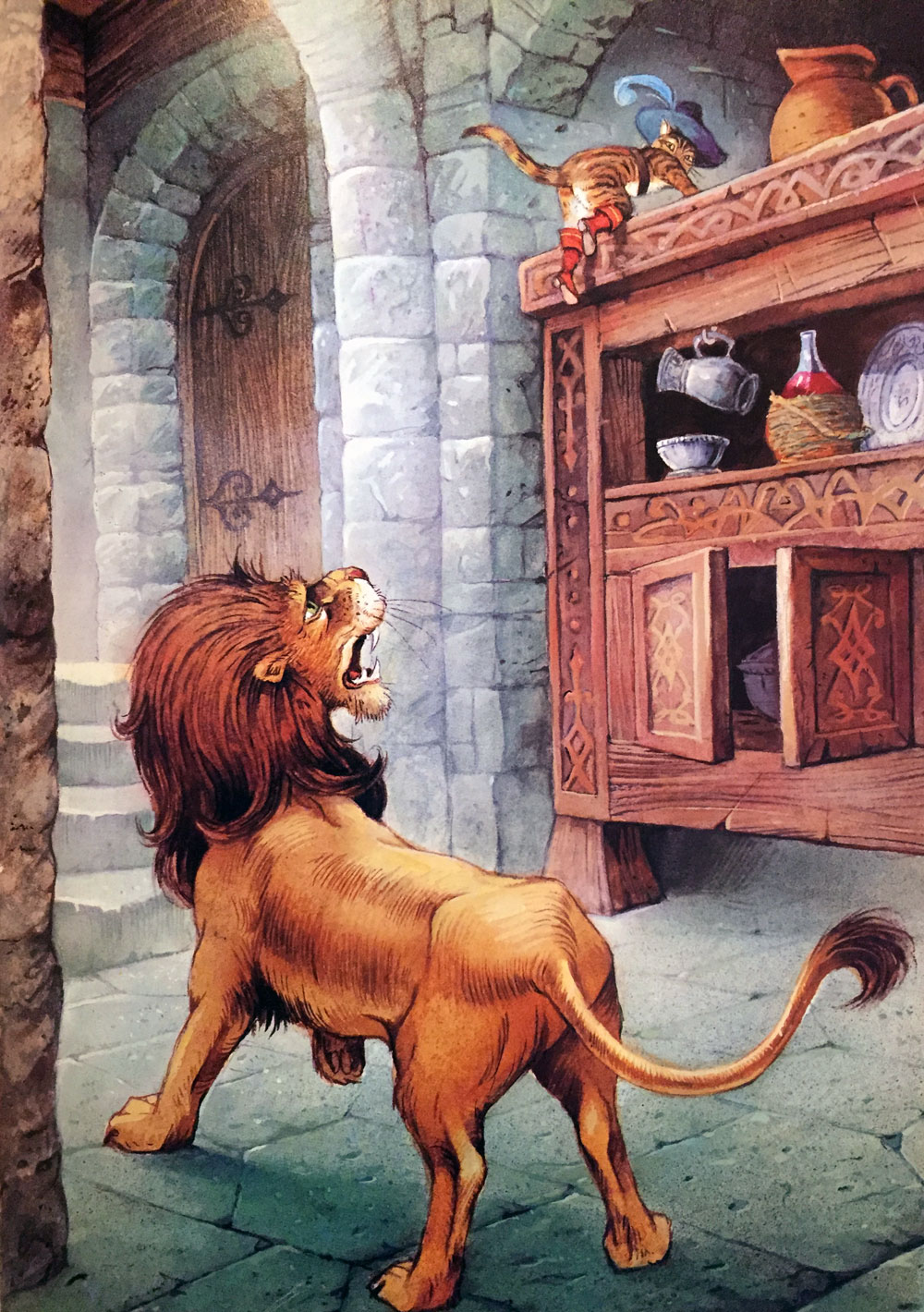

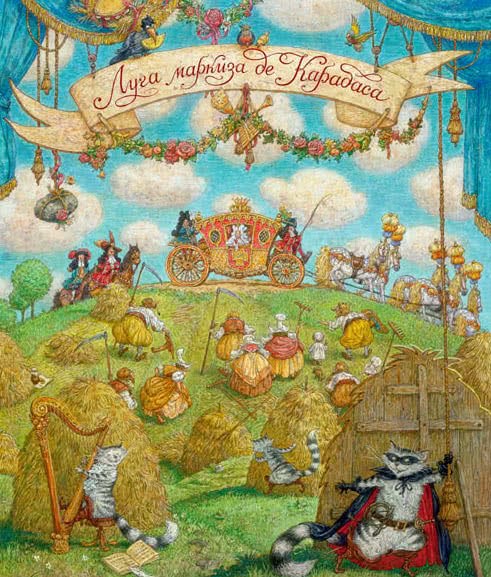

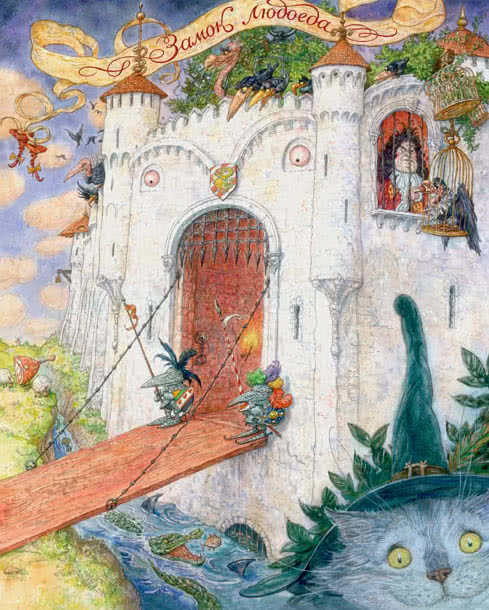

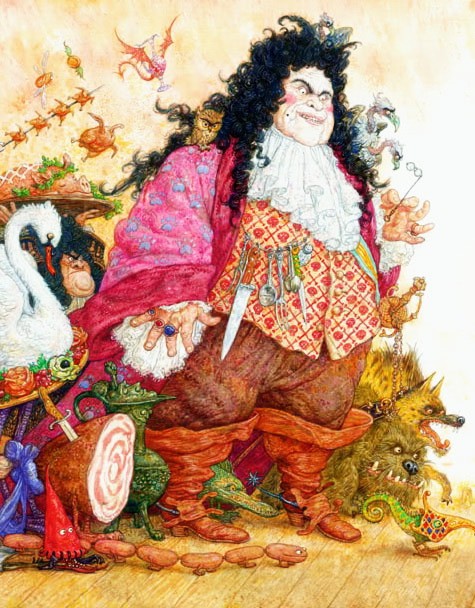

The cat hurries ahead of the coach, ordering the country folk along the road to tell the king that the land belongs to the «Marquis of Carabas», saying that if they do not he will cut them into mincemeat. The cat then happens upon a castle inhabited by an ogre who is capable of transforming himself into a number of creatures. The ogre displays his ability by changing into a lion, frightening the cat, who then tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse. The cat then pounces upon the mouse and devours it. The king arrives at the castle that formerly belonged to the ogre, and impressed with the bogus Marquis and his estate, gives the lad the princess in marriage. Thereafter; the cat enjoys life as a great lord who runs after mice only for his own amusement.[7]

The tale is followed immediately by two morals; «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie and savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess».[8] The Italian translation by Carlo Collodi notes that the tale gives useful advice if you happen to be a cat or a Marquis of Carabas.

This is the theme in France, but other versions of this theme exist in Asia, Africa, and South America.[9]

Background[edit]

Handwritten and illustrated manuscript of Perrault’s «Le Maître Chat» dated 1695

Perrault’s the «Master Cat or Puss in Boots» is the most renowned tale in all of Western folklore of the animal as helper.[10] However, the trickster cat did not originate with Perrault.[11] Centuries before the publication of Perrault’s tale, Somadeva, a Kashmir Brahmin, assembled a vast collection of Indian folk tales called Kathā Sarit Sāgara (lit. «The ocean of the streams of stories») that featured stock fairy tale characters and trappings such as invincible swords, vessels that replenish their contents, and helpful animals. In the Panchatantra (lit. «Five Principles»), a collection of Hindu tales from the second century BC., a tale follows a cat who fares much less well than Perrault’s Puss as he attempts to make his fortune in a king’s palace.[12]

In 1553, «Costantino Fortunato», a tale similar to «Le Maître Chat», was published in Venice in Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s Le Piacevoli Notti (lit. The Facetious Nights),[13] the first European storybook to include fairy tales.[14] In Straparola’s tale however, the poor young man is the son of a Bohemian woman, the cat is a fairy in disguise, the princess is named Elisetta, and the castle belongs not to an ogre but to a lord who conveniently perishes in an accident. The poor young man eventually becomes King of Bohemia.[13] An edition of Straparola was published in France in 1560.[10] The abundance of oral versions after Straparola’s tale may indicate an oral source to the tale; it also is possible Straparola invented the story.[15]

In 1634, another tale with a trickster cat as hero was published in Giambattista Basile’s collection Pentamerone although neither the collection nor the tale were published in France during Perrault’s lifetime. In Basile’s version, the lad is a beggar boy called Gagliuso (sometimes Cagliuso) whose fortunes are achieved in a manner similar to Perrault’s Puss. However, the tale ends with Cagliuso, in gratitude to the cat, promising the feline a gold coffin upon his death. Three days later, the cat decides to test Gagliuso by pretending to be dead and is mortified to hear Gagliuso tell his wife to take the dead cat by its paws and throw it out the window. The cat leaps up, demanding to know whether this was his promised reward for helping the beggar boy to a better life. The cat then rushes away, leaving his master to fend for himself.[13] In another rendition, the cat performs acts of bravery, then a fairy comes and turns him to his normal state to be with other cats.

It is likely that Perrault was aware of the Straparola tale, since ‘Facetious Nights’ was translated into French in the sixteenth century and subsequently passed into the oral tradition.[3]

Publication[edit]

The oldest record of written history was published in Venice by the Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–53) in XIV-XV. His original title was Costantino Fortunato (lit. Lucky Costantino).

The story was published under the French title Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté (‘Master Cat, or the Booted Cat’) by Barbin in Paris in January 1697 in a collection of tales called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[3] The collection included «La Belle au bois dormant» («The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood»), «Le petit chaperon rouge» («Little Red Riding Hood»), «La Barbe bleue» («Blue Beard»), «Les Fées» («The Enchanted Ones», or «Diamonds and Toads»), «Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre» («Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper»), «Riquet à la Houppe» («Riquet with the Tuft»), and «Le Petit Poucet» («Hop o’ My Thumb»).[3] The book displayed a frontispiece depicting an old woman telling tales to a group of three children beneath a placard inscribed «CONTES DE MA MERE L’OYE» (Tales of Mother Goose).[4] The book was an instant success.[3]

Le Maître Chat first was translated into English as «The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots» by Robert Samber in 1729 and published in London for J. Pote and R. Montagu with its original companion tales in Histories, or Tales of Past Times, By M. Perrault.[note 1][16] The book was advertised in June 1729 as being «very entertaining and instructive for children».[16] A frontispiece similar to that of the first French edition appeared in the English edition launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4] Samber’s translation has been described as «faithful and straightforward, conveying attractively the concision, liveliness and gently ironic tone of Perrault’s prose, which itself emulated the direct approach of oral narrative in its elegant simplicity.»[17] Since that publication, the tale has been translated into various languages and published around the world.

[edit]

Perrault’s son Pierre Darmancour was assumed to have been responsible for the authorship of Histoires with the evidence cited being the book’s dedication to Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans, the youngest niece of Louis XIV, which was signed «P. Darmancour». Perrault senior, however, was known for some time to have been interested in contes de veille or contes de ma mère l’oye, and in 1693 published a versification of «Les Souhaits Ridicules» and, in 1694, a tale with a Cinderella theme called «Peau d’Ane».[4] Further, a handwritten and illustrated manuscript of five of the tales (including Le Maistre Chat ou le Chat Botté) existed two years before the tale’s 1697 Paris publication.[4]

Pierre Darmancour was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time the manuscript was prepared and, as scholars Iona and Peter Opie note, quite unlikely to have been interested in recording fairy tales.[4] Darmancour, who became a soldier, showed no literary inclinations, and, when he died in 1700, his obituary made no mention of any connection with the tales. However, when Perrault senior died in 1703, the newspaper alluded to his being responsible for «La Belle au bois dormant», which the paper had published in 1696.[4]

Analysis[edit]

In folkloristics, Puss in Boots is classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots», a subtype of ATU 545, «The Cat as Helper».[18] Folklorists Joseph Jacobs and Stith Thompson point that the Perrault’s tale is the possible source of the Cat Helper story in later European folkloric traditions.[19][20] The tale has also spread to the Americas, and is known in Asia (India, Indonesia and Philippines).[21]

Variations of the feline helper across cultures replace the cat with a jackal or fox.[22][23][24] For instance, the helpful animal is a monkey «in all Philippine variants» according to Damiana Eugenio.[25]

Greek scholar Marianthi Kaplanoglou states that the tale type ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots» (or, locally, «The Helpful Fox»), is an «example» of «widely known stories (…) in the repertoires of Greek refugees from Asia Minor».[26]

Adaptations[edit]

Perrault’s tale has been adapted to various media over the centuries. Ludwig Tieck published a dramatic satire based on the tale, called Der gestiefelte Kater,[27] and, in 1812, the Brothers Grimm inserted a version of the tale into their Kinder- und Hausmärchen.[28] In ballet, Puss appears in the third act of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty in a pas de caractère with The White Cat.[6]

The phrase «enough to make a cat laugh» dates from the mid-1800s and is associated with the tale of Puss in Boots.[29]

The Bibliothèque de Carabas[30] book series was published by David Nutt in London in the late 19th century, in which the front cover of each volume depicts Puss in Boots reading a book.

In film and television, Walt Disney produced an animated black and white silent short based on the tale in 1922.[31]

It was also adapted by Toei as anime feature film in 1969, It followed by two sequels. Hayao Miyazaki made manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film. The title character, Pero, named after Perrault, has since then become the mascot of Toei Animation, with his face appearing in the studio’s logo.

In the mid-1980s, Puss in Boots was televised as an episode of Faerie Tale Theatre with Ben Vereen and Gregory Hines in the cast.[32]

1987’s anime Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics features Puss in Boots, This version of Puss cheats his good-natured master out of money to buy his boots and his hat, hunts the king’s favorite thrush for introduced his master to the king.

Another version from the Cannon Movie Tales series features Christopher Walken as Puss, who in this adaptation is a cat who turns into a human when wearing the boots.

The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child features the story in a Hawaiian setting. The episode stars the voices of David Hyde Pierce as Puss in Boots, Dean Cain as Kuhio, Pat Morita as King Makahana, and Ming-Na Wen as Lani. In addition, the shapeshifting ogre is replaced with a shapeshifting giant (voiced by Keone Young).

Another adaptation of the character with little relation to the story was in the Pokémon anime episode «Like a Meowth to a Flame,» where a Meowth owned by the character Tyson wore boots, a hat, and a neckerchief.

DreamWorks Animation’s 2004 animated film Shrek 2 features a version of the character voiced by Antonio Banderas (and modeled after Banderas’ performance as Zorro). An assassin initially hired to kill Shrek, Puss becomes one of Shrek’s most loyal allies following his defeat. Banderas also voices Puss in the third and fourth films in the Shrek franchise, and in a 2011 spin-off animated feature Puss in Boots, which spawned a 2022 sequel Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. Puss also appears in the Netflix/DreamWorks series The Adventures of Puss in Boots where he is voiced by Eric Bauza.

[edit]

Jacques Barchilon and Henry Pettit note in their introduction to The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes that the main motif of «Puss in Boots» is the animal as helper and that the tale «carries atavistic memories of the familiar totem animal as the father protector of the tribe found everywhere by missionaries and anthropologists.» They also note that the title is original with Perrault as are the boots; no tale prior to Perrault’s features a cat wearing boots.[33]

Woodcut frontispiece copied from the 1697 Paris edition of Perrault’s tales and published in the English-speaking world.

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie observe that «the tale is unusual in that the hero little deserves his good fortune, that is if his poverty, his being a third child, and his unquestioning acceptance of the cat’s sinful instructions, are not nowadays looked upon as virtues.» The cat should be acclaimed the prince of ‘con’ artists, they declare, as few swindlers have been so successful before or since.[11]

The success of Histoires is attributed to seemingly contradictory and incompatible reasons. While the literary skill employed in the telling of the tales has been recognized universally, it appears the tales were set down in great part as the author heard them told. The evidence for that assessment lies first in the simplicity of the tales, then in the use of words that were, in Perrault’s era, considered populaire and du bas peuple, and finally, in the appearance of vestigial passages that now are superfluous to the plot, do not illuminate the narrative, and thus, are passages the Opies believe a literary artist would have rejected in the process of creating a work of art. One such vestigial passage is Puss’s boots; his insistence upon the footwear is explained nowhere in the tale, it is not developed, nor is it referred to after its first mention except in an aside.[34]

According to the Opies, Perrault’s great achievement was accepting fairy tales at «their own level.» He recounted them with neither impatience nor mockery, and without feeling that they needed any aggrandisement such as a frame story—although he must have felt it useful to end with a rhyming moralité. Perrault would be revered today as the father of folklore if he had taken the time to record where he obtained his tales, when, and under what circumstances.[34]

Bruno Bettelheim remarks that «the more simple and straightforward a good character in a fairy tale, the easier it is for a child to identify with it and to reject the bad other.» The child identifies with a good hero because the hero’s condition makes a positive appeal to him. If the character is a very good person, then the child is likely to want to be good too. Amoral tales, however, show no polarization or juxtaposition of good and bad persons because amoral tales such as «Puss in Boots» build character, not by offering choices between good and bad, but by giving the child hope that even the meekest can survive. Morality is of little concern in these tales, but rather, an assurance is provided that one can survive and succeed in life.[35]

Small children can do little on their own and may give up in disappointment and despair with their attempts. Fairy stories, however, give great dignity to the smallest achievements (such as befriending an animal or being befriended by an animal, as in «Puss in Boots») and that such ordinary events may lead to great things. Fairy stories encourage children to believe and trust that their small, real achievements are important although perhaps not recognized at the moment.[36]

In Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion Jack Zipes notes that Perrault «sought to portray ideal types to reinforce the standards of the civilizing process set by upper-class French society».[8] A composite portrait of Perrault’s heroines, for example, reveals the author’s idealized female of upper-class society is graceful, beautiful, polite, industrious, well groomed, reserved, patient, and even somewhat stupid because for Perrault, intelligence in womankind would be threatening. Therefore, Perrault’s composite heroine passively waits for «the right man» to come along, recognize her virtues, and make her his wife. He acts, she waits. If his seventeenth century heroines demonstrate any characteristics, it is submissiveness.[37]

A composite of Perrault’s male heroes, however, indicates the opposite of his heroines: his male characters are not particularly handsome, but they are active, brave, ambitious, and deft, and they use their wit, intelligence, and great civility to work their way up the social ladder and to achieve their goals. In this case of course, it is the cat who displays the characteristics and the man benefits from his trickery and skills. Unlike the tales dealing with submissive heroines waiting for marriage, the male-centered tales suggest social status and achievement are more important than marriage for men. The virtues of Perrault’s heroes reflect upon the bourgeoisie of the court of Louis XIV and upon the nature of Perrault, who was a successful civil servant in France during the seventeenth century.[8]

According to fairy and folk tale researcher and commentator Jack Zipes, Puss is «the epitome of the educated bourgeois secretary who serves his master with complete devotion and diligence.»[37] The cat has enough wit and manners to impress the king, the intelligence to defeat the ogre, and the skill to arrange a royal marriage for his low-born master. Puss’s career is capped by his elevation to grand seigneur[8] and the tale is followed by a double moral: «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie et savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess.»[8]

The renowned illustrator of Dickens’ novels and stories, George Cruikshank, was shocked that parents would allow their children to read «Puss in Boots» and declared: «As it stood the tale was a succession of successful falsehoods—a clever lesson in lying!—a system of imposture rewarded with the greatest worldly advantages.»

Another critic, Maria Tatar, notes that there is little to admire in Puss—he threatens, flatters, deceives, and steals in order to promote his master. She further observes that Puss has been viewed as a «linguistic virtuoso», a creature who has mastered the arts of persuasion and rhetoric to acquire power and wealth.[5]

«Puss in Boots» has successfully supplanted its antecedents by Straparola and Basile and the tale has altered the shapes of many older oral trickster cat tales where they still are found. The morals Perrault attached to the tales are either at odds with the narrative, or beside the point. The first moral tells the reader that hard work and ingenuity are preferable to inherited wealth, but the moral is belied by the poor miller’s son who neither works nor uses his wit to gain worldly advantage, but marries into it through trickery performed by the cat. The second moral stresses womankind’s vulnerability to external appearances: fine clothes and a pleasant visage are enough to win their hearts. In an aside, Tatar suggests that if the tale has any redeeming meaning, «it has something to do with inspiring respect for those domestic creatures that hunt mice and look out for their masters.»[38]

Briggs does assert that cats were a form of fairy in their own right having something akin to a fairy court and their own set of magical powers. Still, it is rare in Europe’s fairy tales for a cat to be so closely involved with human affairs. According to Jacob Grimm, Puss shares many of the features that a household fairy or deity would have including a desire for boots which could represent seven-league boots. This may mean that the story of «Puss and Boots» originally represented the tale of a family deity aiding an impoverished family member.[39][self-published source]

Stefan Zweig, in his 1939 novel, Ungeduld des Herzens, references Puss in Boots’ procession through a rich and varied countryside with his master and drives home his metaphor with a mention of Seven League Boots.

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ The distinction of being the first to translate the tales into English was long questioned. An edition styled Histories or Tales of Past Times, told by Mother Goose, with Morals. Written in French by M. Perrault, and Englished by G.M. Gent bore the publication date of 1719, thus casting doubt upon Samber being the first translator. In 1951, however, the date was proven to be a misprint for 1799 and Samber’s distinction as the first translator was assured.

- Footnotes

- ^ W. G. Waters, The Mysterious Giovan Francesco Straparola, in Jack Zipes, a c. di, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974 Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Opie & Opie 1974, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Opie & Opie 1974, p. 23.

- ^ a b Tatar 2002, p. 234

- ^ a b Brown 2007, p. 351

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 113–116

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 1991, p. 26

- ^ Darnton, Robert (1984). The Great Cat Massacre. New York, NY: Basic Books, Ink. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-465-01274-9.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Zipes 2001, p. 877

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 24.

- ^ Gillespie & Hopkins 2005, p. 351

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 58-59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 239-240.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2006). «The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a ‘Fictional Animal’«. Asian Folklore Studies. 65 (2): 133–160. JSTOR 30030396.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Eugenio, Damiana L. (1985). «Philippine Folktales: An Introduction». Asian Folklore Studies. 44 (2): 155–177. doi:10.2307/1178506. JSTOR 1178506.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (December 2010). «Two Storytellers from the Greek-Orthodox Communities of Ottoman Asia Minor. Analyzing Some Micro-data in Comparative Folklore». Fabula. 51 (3–4): 251–265. doi:10.1515/fabl.2010.024. S2CID 161511346.

- ^ Paulin 2002, p. 65

- ^ Wunderer 2008, p. 202

- ^ «https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/enough+to+make+a+cat+laugh»>enough to make a cat laugh

- ^ «Nutt, Alfred Trübner». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Puss in Boots». The Disney Encyclopedia of Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Zipes 1997, p. 102

- ^ Barchilon 1960, pp. 14, 16

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 10

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 73

- ^ a b Zipes 1991, p. 25

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 235

- ^ Nukiuk H. 2011 Grimm’s Fairies: Discover the Fairies of Europe’s Fairy Tales, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Works cited

- Barchilon, Jacques (1960), The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes, Denver, CO: Alan Swallow

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977) [1975, 1976], The Uses of Enchantment, New York: Random House: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-394-72265-5

- Brown, David (2007), Tchaikovsky, New York: Pegasus Books LLC, ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9

- Gillespie, Stuart; Hopkins, David, eds. (2005), The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English: 1660–1790, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924622-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Paulin, Roger (2002) [1985], Ludwig Tieck, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815852-1

- Tatar, Maria (2002), The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Wunderer, Rolf (2008), «Der gestiefelte Kater» als Unternehmer, Weisbaden: Gabler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8349-0772-1

- Zipes, Jack David (1991) [1988], Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90513-3

- Zipes, Jack David (2001), The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Zipes, Jack David (1997), Happily Ever After, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-91851-0

Further reading[edit]

- Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- Neuhaus, Mareike (2011). «The Rhetoric of Harry Robinson’s ‘Cat With the Boots On’«. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 44 (2): 35–51. JSTOR 44029507. Project MUSE 440541 ProQuest 871355970.

- Nikolajeva, Maria (2009). «Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats». Marvels & Tales. 23 (2): 248–267. JSTOR 41388926.

- Blair, Graham (2019). «Jack Ships to the Cat». Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat: Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition. University Press of Colorado. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-1-60732-919-0. JSTOR j.ctvqc6hwd.11.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Origin of the Story of ‘Puss in Boots’

- «Puss in Boots» – English translation from The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- «Puss in Boots» – Beautifully illustrated in The Colorful Story Book (1941)

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox

| «Puss in Boots» | |

|---|---|

| by Giovanni Francesco Straparola Giambattista Basile Charles Perrault |

|

Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer |

|

| Country | Italy (1550–1553) France (1697) |

| Language | Italian (originally) |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

«Puss in Boots» (Italian: Il gatto con gli stivali) is an Italian[1][2] fairy tale, later spread throughout the rest of Europe, about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand of a princess in marriage for his penniless and low-born master.

The oldest written telling is by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola, who included it in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–1553) in XIV–XV. Another version was published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile with the title Cagliuso, and a tale was written in French at the close of the seventeenth century by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a retired civil servant and member of the Académie française. There is a version written by Girolamo Morlini, from whom Straparola used various tales in The Facetious Nights of Straparola.[3] The tale appeared in a handwritten and illustrated manuscript two years before its 1697 publication by Barbin in a collection of eight fairy tales by Perrault called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[4][5] The book was an instant success and remains popular.[3]

Perrault’s Histoires has had considerable impact on world culture. The original Italian title of the first edition was Costantino Fortunato, but was later known as Il gatto con gli stivali (lit. The cat with the boots); the French title was «Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités» with the subtitle «Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye» («Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times with Morals», subtitled «Mother Goose Tales»). The frontispiece to the earliest English editions depicts an old woman telling tales to a group of children beneath a placard inscribed «MOTHER GOOSE’S TALES» and is credited with launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4]

«Puss in Boots» has provided inspiration for composers, choreographers, and other artists over the centuries. The cat appears in the third act pas de caractère of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty.[6] Puss in Boots appears in DreamWorks’ Shrek franchise, appearing in all three sequels to the original film, as well as two spin-off films, Puss in Boots (2011) and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish (2022), where he is voiced by Antonio Banderas. The character is signified in the logo of Japanese anime studio Toei Animation, and is also a popular pantomime in the UK.

Plot[edit]

The tale opens with the third and youngest son of a miller receiving his inheritance — a cat. At first, the youngest son laments, as the eldest brother gains their father’s mill, and the middle brother gets the mule-and-cart. However, the feline is no ordinary cat, but one who requests and receives a pair of boots. Determined to make his master’s fortune, the cat bags a rabbit in the forest and presents it to the king as a gift from his master, the fictional Marquis of Carabas. The cat continues making gifts of game to the king for several months, for which he is rewarded.

Puss meets the ogre in a nineteenth-century illustration by Gustave Doré

One day, the king decides to take a drive with his daughter. The cat persuades his master to remove his clothes and enter the river which their carriage passes. The cat disposes of his master’s clothing beneath a rock. As the royal coach nears, the cat begins calling for help in great distress. When the king stops to investigate, the cat tells him that his master the Marquis has been bathing in the river and robbed of his clothing. The king has the young man brought from the river, dressed in a splendid suit of clothes, and seated in the coach with his daughter, who falls in love with him at once.

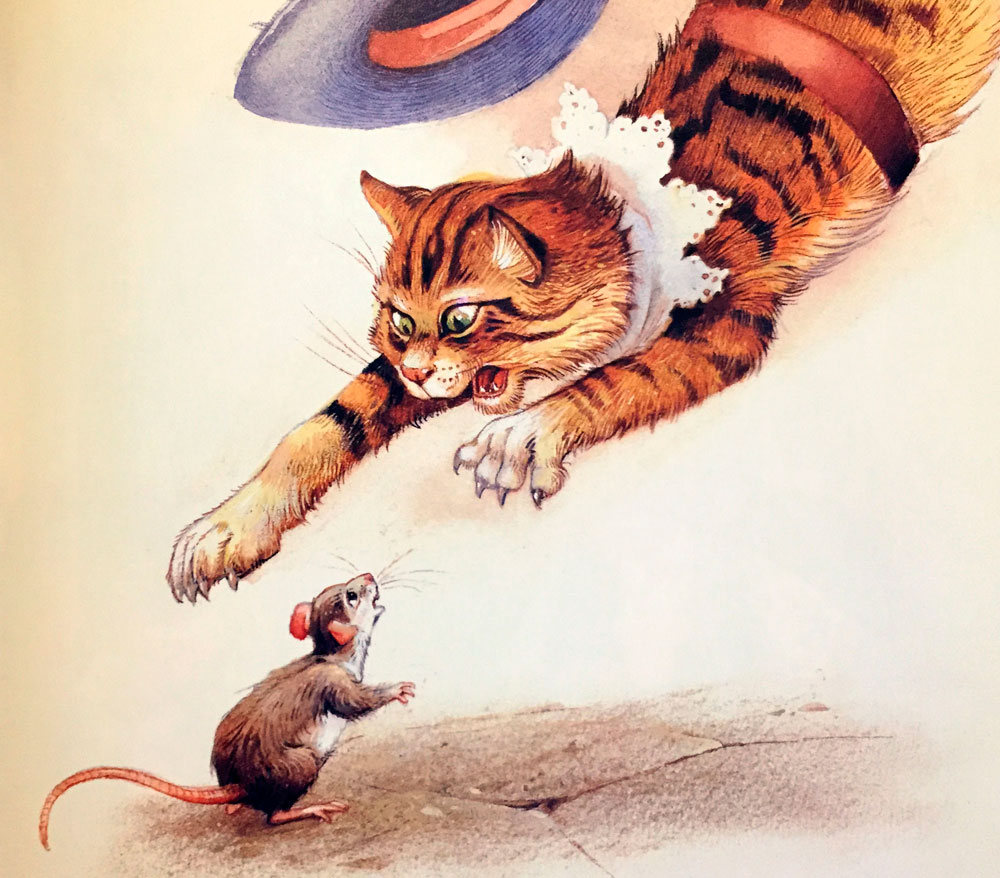

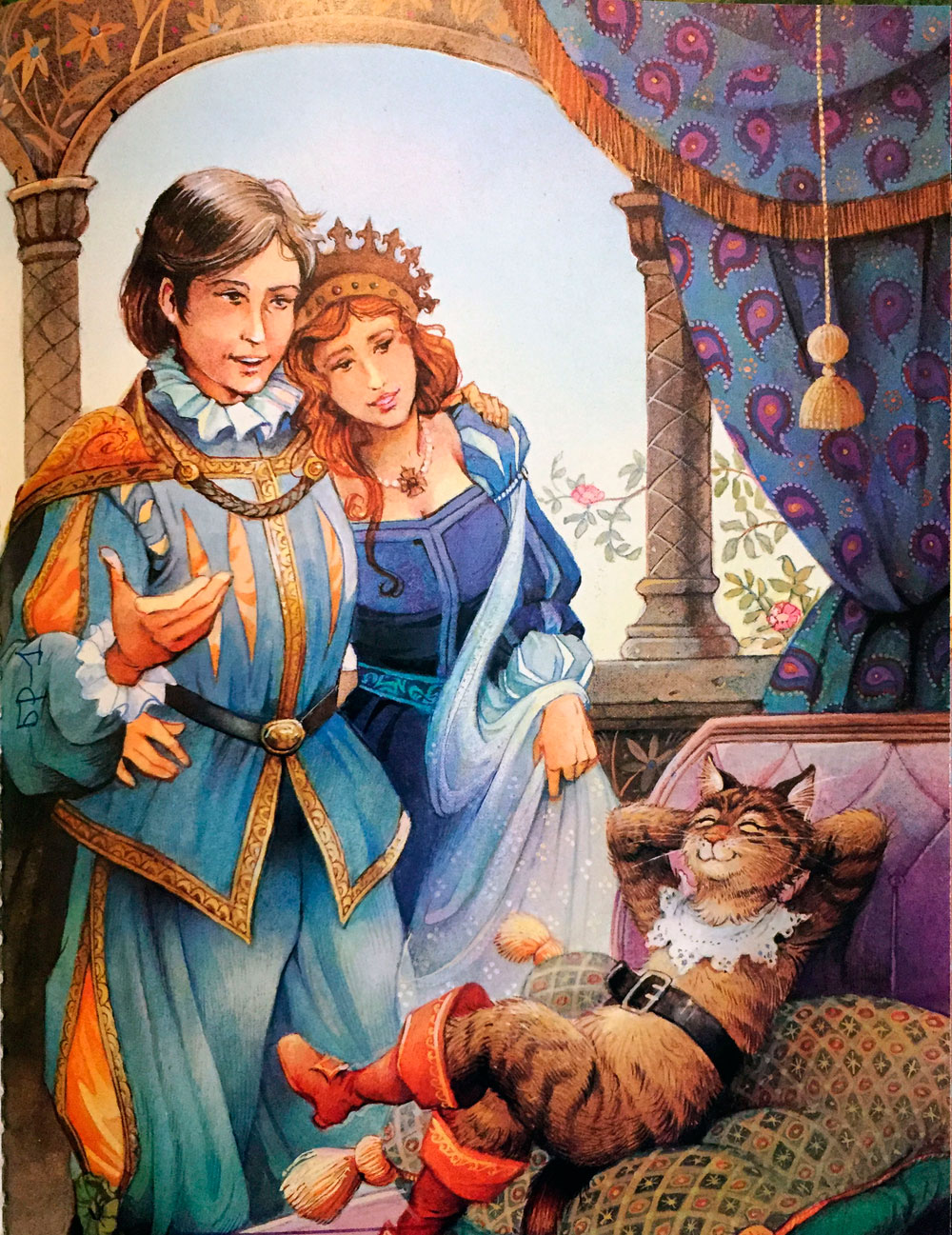

The cat hurries ahead of the coach, ordering the country folk along the road to tell the king that the land belongs to the «Marquis of Carabas», saying that if they do not he will cut them into mincemeat. The cat then happens upon a castle inhabited by an ogre who is capable of transforming himself into a number of creatures. The ogre displays his ability by changing into a lion, frightening the cat, who then tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse. The cat then pounces upon the mouse and devours it. The king arrives at the castle that formerly belonged to the ogre, and impressed with the bogus Marquis and his estate, gives the lad the princess in marriage. Thereafter; the cat enjoys life as a great lord who runs after mice only for his own amusement.[7]

The tale is followed immediately by two morals; «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie and savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess».[8] The Italian translation by Carlo Collodi notes that the tale gives useful advice if you happen to be a cat or a Marquis of Carabas.

This is the theme in France, but other versions of this theme exist in Asia, Africa, and South America.[9]

Background[edit]

Handwritten and illustrated manuscript of Perrault’s «Le Maître Chat» dated 1695

Perrault’s the «Master Cat or Puss in Boots» is the most renowned tale in all of Western folklore of the animal as helper.[10] However, the trickster cat did not originate with Perrault.[11] Centuries before the publication of Perrault’s tale, Somadeva, a Kashmir Brahmin, assembled a vast collection of Indian folk tales called Kathā Sarit Sāgara (lit. «The ocean of the streams of stories») that featured stock fairy tale characters and trappings such as invincible swords, vessels that replenish their contents, and helpful animals. In the Panchatantra (lit. «Five Principles»), a collection of Hindu tales from the second century BC., a tale follows a cat who fares much less well than Perrault’s Puss as he attempts to make his fortune in a king’s palace.[12]

In 1553, «Costantino Fortunato», a tale similar to «Le Maître Chat», was published in Venice in Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s Le Piacevoli Notti (lit. The Facetious Nights),[13] the first European storybook to include fairy tales.[14] In Straparola’s tale however, the poor young man is the son of a Bohemian woman, the cat is a fairy in disguise, the princess is named Elisetta, and the castle belongs not to an ogre but to a lord who conveniently perishes in an accident. The poor young man eventually becomes King of Bohemia.[13] An edition of Straparola was published in France in 1560.[10] The abundance of oral versions after Straparola’s tale may indicate an oral source to the tale; it also is possible Straparola invented the story.[15]

In 1634, another tale with a trickster cat as hero was published in Giambattista Basile’s collection Pentamerone although neither the collection nor the tale were published in France during Perrault’s lifetime. In Basile’s version, the lad is a beggar boy called Gagliuso (sometimes Cagliuso) whose fortunes are achieved in a manner similar to Perrault’s Puss. However, the tale ends with Cagliuso, in gratitude to the cat, promising the feline a gold coffin upon his death. Three days later, the cat decides to test Gagliuso by pretending to be dead and is mortified to hear Gagliuso tell his wife to take the dead cat by its paws and throw it out the window. The cat leaps up, demanding to know whether this was his promised reward for helping the beggar boy to a better life. The cat then rushes away, leaving his master to fend for himself.[13] In another rendition, the cat performs acts of bravery, then a fairy comes and turns him to his normal state to be with other cats.

It is likely that Perrault was aware of the Straparola tale, since ‘Facetious Nights’ was translated into French in the sixteenth century and subsequently passed into the oral tradition.[3]

Publication[edit]

The oldest record of written history was published in Venice by the Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–53) in XIV-XV. His original title was Costantino Fortunato (lit. Lucky Costantino).

The story was published under the French title Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté (‘Master Cat, or the Booted Cat’) by Barbin in Paris in January 1697 in a collection of tales called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[3] The collection included «La Belle au bois dormant» («The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood»), «Le petit chaperon rouge» («Little Red Riding Hood»), «La Barbe bleue» («Blue Beard»), «Les Fées» («The Enchanted Ones», or «Diamonds and Toads»), «Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre» («Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper»), «Riquet à la Houppe» («Riquet with the Tuft»), and «Le Petit Poucet» («Hop o’ My Thumb»).[3] The book displayed a frontispiece depicting an old woman telling tales to a group of three children beneath a placard inscribed «CONTES DE MA MERE L’OYE» (Tales of Mother Goose).[4] The book was an instant success.[3]

Le Maître Chat first was translated into English as «The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots» by Robert Samber in 1729 and published in London for J. Pote and R. Montagu with its original companion tales in Histories, or Tales of Past Times, By M. Perrault.[note 1][16] The book was advertised in June 1729 as being «very entertaining and instructive for children».[16] A frontispiece similar to that of the first French edition appeared in the English edition launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4] Samber’s translation has been described as «faithful and straightforward, conveying attractively the concision, liveliness and gently ironic tone of Perrault’s prose, which itself emulated the direct approach of oral narrative in its elegant simplicity.»[17] Since that publication, the tale has been translated into various languages and published around the world.

[edit]

Perrault’s son Pierre Darmancour was assumed to have been responsible for the authorship of Histoires with the evidence cited being the book’s dedication to Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans, the youngest niece of Louis XIV, which was signed «P. Darmancour». Perrault senior, however, was known for some time to have been interested in contes de veille or contes de ma mère l’oye, and in 1693 published a versification of «Les Souhaits Ridicules» and, in 1694, a tale with a Cinderella theme called «Peau d’Ane».[4] Further, a handwritten and illustrated manuscript of five of the tales (including Le Maistre Chat ou le Chat Botté) existed two years before the tale’s 1697 Paris publication.[4]

Pierre Darmancour was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time the manuscript was prepared and, as scholars Iona and Peter Opie note, quite unlikely to have been interested in recording fairy tales.[4] Darmancour, who became a soldier, showed no literary inclinations, and, when he died in 1700, his obituary made no mention of any connection with the tales. However, when Perrault senior died in 1703, the newspaper alluded to his being responsible for «La Belle au bois dormant», which the paper had published in 1696.[4]

Analysis[edit]

In folkloristics, Puss in Boots is classified as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots», a subtype of ATU 545, «The Cat as Helper».[18] Folklorists Joseph Jacobs and Stith Thompson point that the Perrault’s tale is the possible source of the Cat Helper story in later European folkloric traditions.[19][20] The tale has also spread to the Americas, and is known in Asia (India, Indonesia and Philippines).[21]

Variations of the feline helper across cultures replace the cat with a jackal or fox.[22][23][24] For instance, the helpful animal is a monkey «in all Philippine variants» according to Damiana Eugenio.[25]

Greek scholar Marianthi Kaplanoglou states that the tale type ATU 545B, «Puss in Boots» (or, locally, «The Helpful Fox»), is an «example» of «widely known stories (…) in the repertoires of Greek refugees from Asia Minor».[26]

Adaptations[edit]

Perrault’s tale has been adapted to various media over the centuries. Ludwig Tieck published a dramatic satire based on the tale, called Der gestiefelte Kater,[27] and, in 1812, the Brothers Grimm inserted a version of the tale into their Kinder- und Hausmärchen.[28] In ballet, Puss appears in the third act of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty in a pas de caractère with The White Cat.[6]

The phrase «enough to make a cat laugh» dates from the mid-1800s and is associated with the tale of Puss in Boots.[29]

The Bibliothèque de Carabas[30] book series was published by David Nutt in London in the late 19th century, in which the front cover of each volume depicts Puss in Boots reading a book.

In film and television, Walt Disney produced an animated black and white silent short based on the tale in 1922.[31]

It was also adapted by Toei as anime feature film in 1969, It followed by two sequels. Hayao Miyazaki made manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film. The title character, Pero, named after Perrault, has since then become the mascot of Toei Animation, with his face appearing in the studio’s logo.

In the mid-1980s, Puss in Boots was televised as an episode of Faerie Tale Theatre with Ben Vereen and Gregory Hines in the cast.[32]

1987’s anime Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics features Puss in Boots, This version of Puss cheats his good-natured master out of money to buy his boots and his hat, hunts the king’s favorite thrush for introduced his master to the king.

Another version from the Cannon Movie Tales series features Christopher Walken as Puss, who in this adaptation is a cat who turns into a human when wearing the boots.

The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child features the story in a Hawaiian setting. The episode stars the voices of David Hyde Pierce as Puss in Boots, Dean Cain as Kuhio, Pat Morita as King Makahana, and Ming-Na Wen as Lani. In addition, the shapeshifting ogre is replaced with a shapeshifting giant (voiced by Keone Young).

Another adaptation of the character with little relation to the story was in the Pokémon anime episode «Like a Meowth to a Flame,» where a Meowth owned by the character Tyson wore boots, a hat, and a neckerchief.

DreamWorks Animation’s 2004 animated film Shrek 2 features a version of the character voiced by Antonio Banderas (and modeled after Banderas’ performance as Zorro). An assassin initially hired to kill Shrek, Puss becomes one of Shrek’s most loyal allies following his defeat. Banderas also voices Puss in the third and fourth films in the Shrek franchise, and in a 2011 spin-off animated feature Puss in Boots, which spawned a 2022 sequel Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. Puss also appears in the Netflix/DreamWorks series The Adventures of Puss in Boots where he is voiced by Eric Bauza.

[edit]

Jacques Barchilon and Henry Pettit note in their introduction to The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes that the main motif of «Puss in Boots» is the animal as helper and that the tale «carries atavistic memories of the familiar totem animal as the father protector of the tribe found everywhere by missionaries and anthropologists.» They also note that the title is original with Perrault as are the boots; no tale prior to Perrault’s features a cat wearing boots.[33]

Woodcut frontispiece copied from the 1697 Paris edition of Perrault’s tales and published in the English-speaking world.

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie observe that «the tale is unusual in that the hero little deserves his good fortune, that is if his poverty, his being a third child, and his unquestioning acceptance of the cat’s sinful instructions, are not nowadays looked upon as virtues.» The cat should be acclaimed the prince of ‘con’ artists, they declare, as few swindlers have been so successful before or since.[11]

The success of Histoires is attributed to seemingly contradictory and incompatible reasons. While the literary skill employed in the telling of the tales has been recognized universally, it appears the tales were set down in great part as the author heard them told. The evidence for that assessment lies first in the simplicity of the tales, then in the use of words that were, in Perrault’s era, considered populaire and du bas peuple, and finally, in the appearance of vestigial passages that now are superfluous to the plot, do not illuminate the narrative, and thus, are passages the Opies believe a literary artist would have rejected in the process of creating a work of art. One such vestigial passage is Puss’s boots; his insistence upon the footwear is explained nowhere in the tale, it is not developed, nor is it referred to after its first mention except in an aside.[34]

According to the Opies, Perrault’s great achievement was accepting fairy tales at «their own level.» He recounted them with neither impatience nor mockery, and without feeling that they needed any aggrandisement such as a frame story—although he must have felt it useful to end with a rhyming moralité. Perrault would be revered today as the father of folklore if he had taken the time to record where he obtained his tales, when, and under what circumstances.[34]

Bruno Bettelheim remarks that «the more simple and straightforward a good character in a fairy tale, the easier it is for a child to identify with it and to reject the bad other.» The child identifies with a good hero because the hero’s condition makes a positive appeal to him. If the character is a very good person, then the child is likely to want to be good too. Amoral tales, however, show no polarization or juxtaposition of good and bad persons because amoral tales such as «Puss in Boots» build character, not by offering choices between good and bad, but by giving the child hope that even the meekest can survive. Morality is of little concern in these tales, but rather, an assurance is provided that one can survive and succeed in life.[35]

Small children can do little on their own and may give up in disappointment and despair with their attempts. Fairy stories, however, give great dignity to the smallest achievements (such as befriending an animal or being befriended by an animal, as in «Puss in Boots») and that such ordinary events may lead to great things. Fairy stories encourage children to believe and trust that their small, real achievements are important although perhaps not recognized at the moment.[36]

In Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion Jack Zipes notes that Perrault «sought to portray ideal types to reinforce the standards of the civilizing process set by upper-class French society».[8] A composite portrait of Perrault’s heroines, for example, reveals the author’s idealized female of upper-class society is graceful, beautiful, polite, industrious, well groomed, reserved, patient, and even somewhat stupid because for Perrault, intelligence in womankind would be threatening. Therefore, Perrault’s composite heroine passively waits for «the right man» to come along, recognize her virtues, and make her his wife. He acts, she waits. If his seventeenth century heroines demonstrate any characteristics, it is submissiveness.[37]

A composite of Perrault’s male heroes, however, indicates the opposite of his heroines: his male characters are not particularly handsome, but they are active, brave, ambitious, and deft, and they use their wit, intelligence, and great civility to work their way up the social ladder and to achieve their goals. In this case of course, it is the cat who displays the characteristics and the man benefits from his trickery and skills. Unlike the tales dealing with submissive heroines waiting for marriage, the male-centered tales suggest social status and achievement are more important than marriage for men. The virtues of Perrault’s heroes reflect upon the bourgeoisie of the court of Louis XIV and upon the nature of Perrault, who was a successful civil servant in France during the seventeenth century.[8]

According to fairy and folk tale researcher and commentator Jack Zipes, Puss is «the epitome of the educated bourgeois secretary who serves his master with complete devotion and diligence.»[37] The cat has enough wit and manners to impress the king, the intelligence to defeat the ogre, and the skill to arrange a royal marriage for his low-born master. Puss’s career is capped by his elevation to grand seigneur[8] and the tale is followed by a double moral: «one stresses the importance of possessing industrie et savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess.»[8]

The renowned illustrator of Dickens’ novels and stories, George Cruikshank, was shocked that parents would allow their children to read «Puss in Boots» and declared: «As it stood the tale was a succession of successful falsehoods—a clever lesson in lying!—a system of imposture rewarded with the greatest worldly advantages.»

Another critic, Maria Tatar, notes that there is little to admire in Puss—he threatens, flatters, deceives, and steals in order to promote his master. She further observes that Puss has been viewed as a «linguistic virtuoso», a creature who has mastered the arts of persuasion and rhetoric to acquire power and wealth.[5]

«Puss in Boots» has successfully supplanted its antecedents by Straparola and Basile and the tale has altered the shapes of many older oral trickster cat tales where they still are found. The morals Perrault attached to the tales are either at odds with the narrative, or beside the point. The first moral tells the reader that hard work and ingenuity are preferable to inherited wealth, but the moral is belied by the poor miller’s son who neither works nor uses his wit to gain worldly advantage, but marries into it through trickery performed by the cat. The second moral stresses womankind’s vulnerability to external appearances: fine clothes and a pleasant visage are enough to win their hearts. In an aside, Tatar suggests that if the tale has any redeeming meaning, «it has something to do with inspiring respect for those domestic creatures that hunt mice and look out for their masters.»[38]

Briggs does assert that cats were a form of fairy in their own right having something akin to a fairy court and their own set of magical powers. Still, it is rare in Europe’s fairy tales for a cat to be so closely involved with human affairs. According to Jacob Grimm, Puss shares many of the features that a household fairy or deity would have including a desire for boots which could represent seven-league boots. This may mean that the story of «Puss and Boots» originally represented the tale of a family deity aiding an impoverished family member.[39][self-published source]

Stefan Zweig, in his 1939 novel, Ungeduld des Herzens, references Puss in Boots’ procession through a rich and varied countryside with his master and drives home his metaphor with a mention of Seven League Boots.

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ The distinction of being the first to translate the tales into English was long questioned. An edition styled Histories or Tales of Past Times, told by Mother Goose, with Morals. Written in French by M. Perrault, and Englished by G.M. Gent bore the publication date of 1719, thus casting doubt upon Samber being the first translator. In 1951, however, the date was proven to be a misprint for 1799 and Samber’s distinction as the first translator was assured.

- Footnotes

- ^ W. G. Waters, The Mysterious Giovan Francesco Straparola, in Jack Zipes, a c. di, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974 Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Opie & Opie 1974, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Opie & Opie 1974, p. 23.

- ^ a b Tatar 2002, p. 234

- ^ a b Brown 2007, p. 351

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 113–116

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 1991, p. 26

- ^ Darnton, Robert (1984). The Great Cat Massacre. New York, NY: Basic Books, Ink. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-465-01274-9.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110.

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Zipes 2001, p. 877

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 24.

- ^ Gillespie & Hopkins 2005, p. 351

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 58-59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 239-240.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2006). «The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a ‘Fictional Animal’«. Asian Folklore Studies. 65 (2): 133–160. JSTOR 30030396.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Eugenio, Damiana L. (1985). «Philippine Folktales: An Introduction». Asian Folklore Studies. 44 (2): 155–177. doi:10.2307/1178506. JSTOR 1178506.

- ^ Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (December 2010). «Two Storytellers from the Greek-Orthodox Communities of Ottoman Asia Minor. Analyzing Some Micro-data in Comparative Folklore». Fabula. 51 (3–4): 251–265. doi:10.1515/fabl.2010.024. S2CID 161511346.

- ^ Paulin 2002, p. 65

- ^ Wunderer 2008, p. 202

- ^ «https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/enough+to+make+a+cat+laugh»>enough to make a cat laugh

- ^ «Nutt, Alfred Trübner». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Puss in Boots». The Disney Encyclopedia of Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Zipes 1997, p. 102

- ^ Barchilon 1960, pp. 14, 16

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 10

- ^ Bettelheim 1977, p. 73

- ^ a b Zipes 1991, p. 25

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 235

- ^ Nukiuk H. 2011 Grimm’s Fairies: Discover the Fairies of Europe’s Fairy Tales, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Works cited

- Barchilon, Jacques (1960), The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes, Denver, CO: Alan Swallow

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977) [1975, 1976], The Uses of Enchantment, New York: Random House: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-394-72265-5

- Brown, David (2007), Tchaikovsky, New York: Pegasus Books LLC, ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9

- Gillespie, Stuart; Hopkins, David, eds. (2005), The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English: 1660–1790, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924622-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Paulin, Roger (2002) [1985], Ludwig Tieck, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815852-1

- Tatar, Maria (2002), The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Wunderer, Rolf (2008), «Der gestiefelte Kater» als Unternehmer, Weisbaden: Gabler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8349-0772-1

- Zipes, Jack David (1991) [1988], Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90513-3

- Zipes, Jack David (2001), The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Zipes, Jack David (1997), Happily Ever After, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-91851-0

Further reading[edit]

- Kaplanoglou, Marianthi (January 1999). «AT 545B ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘The Fox-Matchmaker’: From the Central Asian to the European Tradition». Folklore. 110 (1–2): 57–62. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1999.9715981. JSTOR 1261067.

- Neuhaus, Mareike (2011). «The Rhetoric of Harry Robinson’s ‘Cat With the Boots On’«. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 44 (2): 35–51. JSTOR 44029507. Project MUSE 440541 ProQuest 871355970.

- Nikolajeva, Maria (2009). «Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats». Marvels & Tales. 23 (2): 248–267. JSTOR 41388926.

- Blair, Graham (2019). «Jack Ships to the Cat». Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat: Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition. University Press of Colorado. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-1-60732-919-0. JSTOR j.ctvqc6hwd.11.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Origin of the Story of ‘Puss in Boots’

- «Puss in Boots» – English translation from The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- «Puss in Boots» – Beautifully illustrated in The Colorful Story Book (1941)

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Время чтения: 9 мин.

Один мельник, умирая, оставил трем своим сыновьям мельницу, осла да кота. Братья наследство сами поделили, в суд не пошли: жадные судьи последнее отберут. Старший получил мельницу, средний — осла, а самый младший — кота. Долго не мог утешиться младший брат: жалкое наследство ему досталось.

— Хорошо братьям, — говорил он. — Заживут они вместе, будут честно на хлеб зарабатывать. А я? Ну, съем кота, ну, сошью рукавицы из его шкурки. А дальше что? С голоду помирать?

Кот эти слова услышал, но виду не подал, а сказал:

— Хватит горевать. Дайте мне мешок, да закажите пару сапог, чтобы легче было ходить по лесам и полям, и вы увидите, что не так уж вас обидели, как вам сейчас кажется.

Хозяин сделал все, как велел кот. И едва кот получил все необходимое, как быстро обулся, перекинул через плечо мешок и отправился в ближайший заповедный лес.

Из мешка, в котором находились отруби и заячья капуста, кот устроил хитрую западню, а сам, растянувшись на траве и притворившись мертвым, стал поджидать добычу. Долго ждать ему не пришлось: какой-то глупый молодой кролик сразу же прыгнул в мешок. Кот, недолго думая, затянул мешок и отправился в королевский дворец. Когда кота ввели в королевские покои, он отвесил королю почтительный поклон и сказал:

— Ваше величество, вот кролик из лесов маркиза де Карабаса (такое имя выдумал он для своего хозяина). Мой господин велел мне преподнести вам этот скромный подарок.

— Поблагодари своего господина, — ответил король, — и скажи ему, что он доставил мне большое удовольствие.

Через несколько дней кот отправился на поле и снова расставил свою ловушку. На этот раз ему попались две жирные куропатки. Он проворно затянул шнурки на мешке и понес их королю. Король с радостью принял и этот подарок и даже приказал наградить кота. С тех пор так и повелось: кот то и дело приносил королю дичь, будто бы убитую на охоте его хозяином. И вот как-то раз кот узнал, что король вместе со своей дочкой, прекрасной принцессой, собирается совершить прогулку в карете по берегу реки. Кот сразу же побежал к своему хозяину.

— Хозяин, если вы послушаетесь моего совета, — сказал кот, — то считайте, что счастье у вас уже в руках. Все, что от вас требуется, — это пойти купаться на реку, в то место, куда я вам укажу. Остальное предоставьте мне. Хозяин послушно исполнил все, что посоветовал кот, хоть он совсем и не понимал, для чего все это нужно.

Как раз, когда он купался, королевская карета выехала на берег реки. Кот со всех ног кинулся к карете и закричал:

— Сюда! Скорее! Помогите! Маркиз де Карабас тонет!

Король, услышав эти крики, приоткрыл дверцу кареты. Он сразу же узнал кота, который так часто приносил ему подарки, и сейчас же послал своих слуг выручать маркиза де Карабаса. В то время, как бедного маркиза вытаскивали из реки, кот рассказал королю, что во время купания у его господина воры украли всю одежду. (На самом же деле хитрец припрятал бедное платье хозяина под большим камнем).

Король немедленно приказал принести для маркиза де Карабаса один из лучших нарядов королевского гардероба. Все вышло как нельзя лучше. Король отнесся к сыну мельника очень ласково и даже пригласил сесть в карету и принять участие в прогулке. Да и королевской дочери юноша приглянулся. Уж очень королевское платье было ему к лицу. Кот, радуясь, что все идет, как он задумал, весело побежал перед каретой. По дороге он увидел крестьян, косивших на лугу траву.

— Кому принадлежит этот луг?

— Страшному людоеду, который живет в замке, — ответили косари.

— Сейчас сюда приедет король, — крикнул кот, — и если вы не скажете, что этот луг принадлежит маркизу де Карабасу, вас всех изрубят на мелкие кусочки!

Тут как раз подъехала королевская карета и король, выглянув из окна, спросил, кому принадлежит этот луг.

— Маркизу де Карабасу! — ответили в один голос косари, испуганные угрозами кота. Сын мельника не поверил своим ушам, зато король остался доволен и сказал:

— Дорогой маркиз! У вас замечательный луг!

А между тем кот бежал все дальше и дальше, пока не увидел жнецов, работающих в поле.

— Кому принадлежит это поле? — спросил их кот.

— Страшному людоеду, — ответили они.

— Сейчас сюда приедет король, — опять крикнул кот, — и если вы не скажете, что это поле принадлежит маркизу де Карабасу, вас изрубят на мелкие кусочки!

Через минуту к жнецам подъехал король и спросил, чьи это поля они жнут.

— Поля маркиза де Карабаса, — был ответ.

Король от удовольствия захлопал в ладоши и сказал:

— Дорогой маркиз! У вас замечательные поля!

А кот все бежал и бежал впереди кареты, и всем, кто попадался навстречу, велел говорить одно и то же: «Это дом маркиза де Карабаса, это мельница маркиза де Карабаса, это сад маркиза де Карабаса…»

И вот, наконец, кот прибежал к воротам прекрасного замка, где жил очень богатый и страшный людоед, тот самый, которому принадлежали все земли, по которым проехала королевская карета.

Кот заранее разузнал все об этом великане. Его сила была в том, что он мог превращаться в различных зверей — слона, льва, мышь…

Кот подошел к замку и попросил допустить его к хозяину.

Людоед принял кота со всей учтивостью, на какую был только способен: ведь он никогда не видел, чтобы кот разгуливал в сапогах, да еще и говорил человеческим голосом.

— Мне говорили, — промурлыкал кот, — что вы умеете превращаться в любого зверя. Ну, скажем, в льва или слона…

— Могу! — засмеялся людоед. — И, чтобы доказать тебе это, сейчас же обернусь львом. Смотри же!

Кот так испугался, увидев перед собой льва, что в мгновение ока взобрался на крышу прямо по водосточной трубе. Это было не только трудно, но даже и опасно, потому что в сапогах не так-то просто ходить по гладкой черепице. Лишь когда великан вновь принял свое прежнее обличие, кот спустился с крыши и признался людоеду, что едва не умер от страха.

— А еще меня уверяли, — сказал кот, — но этому-то я уж никак не поверю, что будто бы вы можете превратиться даже в самых маленьких животных. Например, обернуться крысой или мышкой. Должен признаться, что считаю это совершенно невозможным.

— Ах, вот как! Считаешь невозможным? — заревел великан. — Так смотри же!

В то же мгновение великан превратился в очень маленькую мышку. Мышка проворно побежала по полу. И тут кот, на то ведь он и кот, кинулся на мышку, поймал ее и съел. Так и не стало страшного людоеда.

Тем временем король проезжал мимо прекрасного замка и пожелал посетить его.

Кот услышал, как на подъездном мосту стучат колеса кареты, и выбежал навстречу королю.

— Милости просим пожаловать в замок маркиза де Карабаса, ваше величество! — сказал кот.

— Неужели и этот замок тоже ваш, господин маркиз! — воскликнул король. — Трудно представить себе что-нибудь более красивое. Это настоящий дворец! А внутри он наверное еще лучше, и если вы не возражаете, мы сейчас же пойдем и осмотрим его.

— Король пошел впереди, а маркиз подал руку прекрасной принцессе.

— Все втроем они вошли в великолепную залу, где был уже приготовлен отменный ужин. (В тот день людоед ждал в гости приятелей, но они не посмели явиться, узнав, что в замке король.)

Король был так очарован достоинствами и богатством маркиза де Карабаса, что, осушив несколько кубков, сказал:

— Вот что, господин маркиз. Только от вас зависит, женитесь вы на моей дочери или нет.

Маркиз обрадовался этим словам еще больше, чем неожиданному богатству, поблагодарил короля за великую честь и, конечно же, согласился жениться на прекраснейшей в мире принцессе.

Свадьбу отпраздновали в тот же день.

После этого кот в сапогах сделался очень важным господином и ловит мышей только для забавы.

Сказка о необычном коте, который достался младшему брату в наследство от отца мельника. Юноша сначала не очень обрадовался своей доле наследства, но хитрый и умный кот сделал его богатейшим человеком и зятем короля…

Было у мельника три сына, и оставил он им, умирая, всего только мельницу, осла и кота.

Братья поделили между собой отцовское добро без нотариуса и судьи, которые бы живо проглотили всё их небогатое наследство.

Старшему досталась мельница. Среднему осёл. Ну а уж младшему пришлось взять себе кота.

Бедняга долго не мог утешиться, получив такую жалкую долю наследства.

Братья, говорил он, – могут честно зарабатывать себе на хлеб, если только будут держаться вместе. А что станется со мною после того, как я съем своего кота и сделаю из его шкурки муфту? Прямо хоть с голоду помирай!

Кот слышал эти слова, но и виду не подал, а сказал спокойно и рассудительно:

– Не печальтесь, хозяин. Дайте-ка мне мешок да закажите пару сапог, чтобы было легче бродить по кустарникам, и вы сами увидите, что вас не так уж обидели, как это вам сейчас кажется.

Хозяин кота и сам не знал, верить этому или нет, но он хорошо помнил, на какие хитрости пускался кот, когда охотился на крыс и мышей, как ловко он прикидывался мёртвым, то повиснув на задних лапах, то зарывшись чуть ли не с головой в муку. Кто его знает, а вдруг и в самом деле он чем-нибудь поможет в беде!

Едва только кот получил всё, что ему было надобно, он живо обулся, молодецки притопнул, перекинул через плечо мешок и, придерживая его за шнурки передними лапами, зашагал в заповедный лес, где водилось множество кроликов. А в мешке у него были отруби и заячья капуста.

Растянувшись на траве и притворившись мёртвым, он стал поджидать, когда какой-нибудь неопытный кролик, ещё не успевший испытать на собственной шкуре, как зол и коварен свет, заберётся в мешок, чтобы полакомиться припасённым для него угощением.

Долго ждать ему не пришлось: какой-то молоденький доверчивый простачок кролик сразу же прыгнул к нему в мешок.

Недолго думая, дядюшка-кот затянул шнурки и покончил с кроликом безо всякого милосердия.

После этого, гордый своей добычей, он отправился прямо во дворец и попросил приёма у короля. Его ввели в королевские покои. Он отвесил его величеству почтительный поклон и сказал:

– Государь, вот кролик из лесов маркиза де Карабаса (такое имя выдумал он для своего хозяина). Мой господин приказал мне преподнести вам этот скромный подарок.

– Поблагодари своего господина, – ответил король, – и скажи ему, что он доставил мне большое удовольствие.

Несколько дней спустя кот пошёл на поле и там, спрятавшись среди колосьев, опять открыл свой мешок.

На этот раз к нему в ловушку попались две куропатки. Он живо затянул шнурки и понёс обеих королю.

Король охотно принял и этот подарок и приказал дать коту на чай.

Так прошло два или три месяца. Кот то и дело приносил королю дичь, будто бы убитую на охоте его хозяином, маркизом де Карабасом.

И вот как-то раз узнал кот, что король вместе со своей дочкой, самой прекрасной принцессой на свете, собирается совершить прогулку в карете по берегу реки.

Согласны вы послушаться моего совета? – спросил он своего хозяина. – В таком случае счастье у нас в руках. Всё, что от вас требуется, это пойти купаться на реку, туда, куда я вам укажу. Остальное предоставьте мне.

Маркиз де Карабас послушно исполнил все, что посоветовал ему кот, хоть он вовсе и не догадывался, для чего это нужно. В то время как он купался, королевская карета выехала на берег реки.

Кот со всех ног бросился и закричал, что было мочи:

– Сюда, сюда! Помогите! Маркиз де Карабас тонет!

Король услыхал этот крик, приоткрыл дверцу кареты и, узнав кота, который столько раз приносил ему в подарок дичь, сейчас же послал свою стражу выручать маркиза де Карабаса.

Пока бедного маркиза вытаскивали из воды, кот успел рассказать королю, что у господина во время купания воры украли всё до нитки. (А на самом деле хитрец собственными лапами припрятал хозяйское платье под большим камнем.)

Король немедленно приказал своим придворным принести для маркиза де Карабаса один из лучших нарядов королевского гардероба.

Наряд оказался и в пору, и к лицу, а так как маркиз и без того был малый хоть куда – красивый и статный, то, приодевшись, он, конечно, стал ещё лучше, и королевская дочка, поглядев на него, нашла, что он как раз в её вкусе.

Когда же маркиз де Карабас бросил в её сторону два-три взгляда, очень почтительных и в то же время нежных, она влюбилась в него без памяти.

Отцу её молодой маркиз тоже пришёлся по сердцу. Король был с ним очень ласков и даже пригласил сесть в карету и принять участие в прогулке.

Кот был в восторге оттого, что все идёт как по маслу, и весело побежал перед каретой.

По пути он увидел крестьян, косивших на лугу сено.

Эй, люди добрые, – крикнул он на бегу, – если вы не скажете королю, что этот луг принадлежит маркизу де Карабасу, вас всех изрубят в куски, словно начинку для пирога! Так и знайте!

Тут как раз подъехала королевская карета, и король спросил, выглянув из окна:

– Чей это луг вы косите?

– Маркиза де Карабаса! – в один голос отвечали косцы, потому что кот до смерти напугал их своими угрозами.

– Однако, маркиз, у вас тут славное имение! – сказал король.

– Да, государь, этот луг каждый год даёт отличное сено, – скромно ответил маркиз.

Между тем дядюшка-кот бежал всё вперёд и вперёд, пока не увидел по дороге жнецов, работающих на поле.

– Эй, люди добрые, – крикнул он, – если вы не скажете королю, что все эти хлеба принадлежат маркизу де Карабасу, так и знайте: всех вас изрубят в куски, словно начинку для пирога!

Через минуту к жнецам подъехал король и захотел узнать, чьи поля они жнут.

– Поля маркиза де Карабаса, – ответили жнецы. И король опять порадовался за господина маркиза. А кот всё бежал вперёд и всем, кто попадался ему навстречу, приказывал говорить одно и то же: “Это дом маркиза де Карабаса”, “это мельница маркиза де Карабаса”, “это сад маркиза де Карабаса”. Король не мог надивиться богатству молодого маркиза.

И вот, наконец, кот прибежал к воротам прекрасного замка. Тут жил один очень богатый великан-людоед. Никто на свете никогда не видел великана богаче этого. Все земли, по которым проехала королевская карета, были в его владении.

Кот заранее разузнал, что это был за великан, в чем его сила, и попросил допустить его к хозяину. Он, дескать, не может и не хочет пройти мимо, не засвидетельствовав своего почтения.

Людоед принял его со всей учтивостью, на какую способен людоед, и предложил отдохнуть.

– Меня уверяли, – сказал кот, – что вы умеете превращаться в любого зверя. Ну, например, вы будто бы можете превратиться во льва или слона…

– Могу! – рявкнул великан. – И чтобы доказать это, сейчас же сделаюсь львом! Смотри!

Кот до того испугался, увидев перед собой льва, что в одно мгновение взобрался по водосточной трубе на крышу, хотя это было трудно и даже опасно, потому что в сапогах не так-то просто ходить по черепице.

Только когда великан опять принял свой прежний облик, кот спустился с крыши и признался хозяину, что едва не умер со страху.

А ещё меня уверяли, – сказал он, – но уж этому-то я никак не могу поверить, что вы будто бы умеете превращаться даже в самых мелких животных. Ну, например, сделаться крысой или даже мышкой. Должен сказать по правде, что считаю это совершенно невозможным.

– Ах, вот как! Невозможным? – переспросил великан. – А ну-ка, погляди!

И в то же мгновение превратился в мышь. Мышка проворно забегала по полу, но кот погнался за ней и разом проглотил.

Тем временем король, проезжая мимо, заметил по пути прекрасный замок и пожелал войти туда.

Кот услыхал, как гремят на подъёмном мосту колёса королевской кареты, и, выбежав навстречу, сказал королю:

– Добро пожаловать в замок маркиза де Карабаса, ваше величество! Милости просим!

– Как, господин маркиз?! – воскликнул король. – Этот замок тоже ваш? Нельзя себе представить ничего красивее, чем этот двор и постройки вокруг. Да это прямо дворец! Давайте же посмотрим, каков он внутри, если вы не возражаете.

Маркиз подал руку прекрасной принцессе и повёл её вслед за королём, который, как полагается, шёл впереди.

Все втроём они вошли в большой зал, где был приготовлен великолепный ужин.

Как раз в этот день людоед пригласил к себе приятелей, но они не посмели явиться, узнав, что в замке гостит король.

Король был очарован достоинствами господина маркиза де Карабаса почти так же, как его дочка, которая была от маркиза просто без ума.

Кроме того, его величество не мог, конечно, не оценить прекрасных владений маркиза и, осушив пять-шесть кубков, сказал:

– Если хотите стать моим зятем, господин маркиз, это зависит только от вас. А я согласен.

Маркиз почтительным поклоном поблагодарил короля за честь, оказанную ему, и в тот же день женился на принцессе.

А кот стал знатным вельможей и с тех пор охотился на мышей только изредка – для собственного удовольствия.

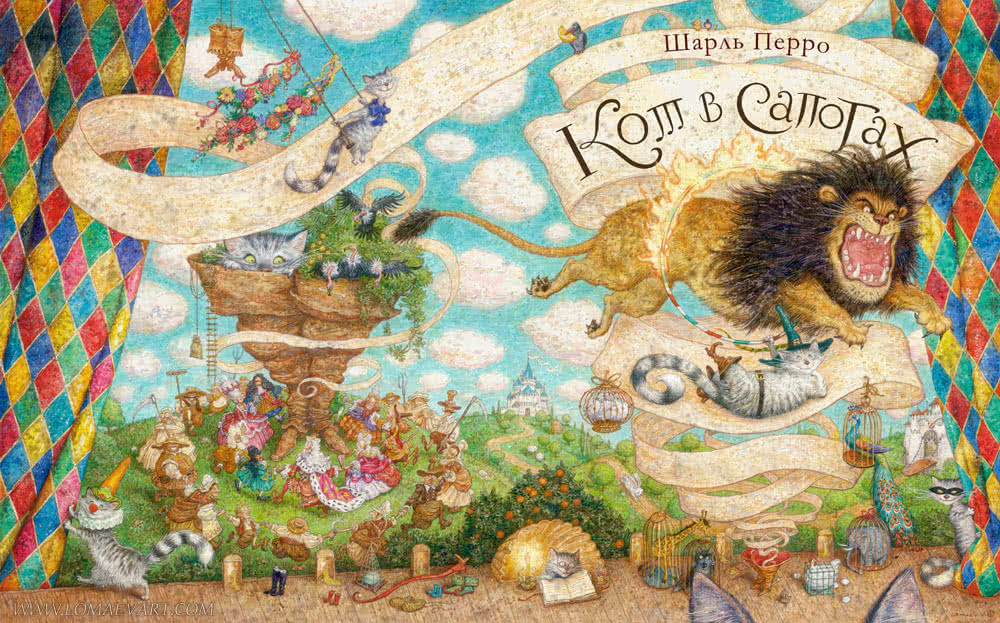

(Перевод Т.Габбе, илл. А.Ломаева, изд. Азбука, 2014 г.)

❤️ 343

🔥 260

😁 250

😢 152

👎 178

🥱 198

Добавлено на полку

Удалено с полки

Достигнут лимит

Один мельник оставил своим трем сыновьям небольшое наследство – мельницу, осла и кота.

Братья сразу же поделили отцовское наследство: старший взял себе мельницу, средний – осла, а младшему дали кота. Младший брат очень горевал, что ему досталось такое плохое наследство.

– Братья могут честно зарабатывать себе кусок хлеба, если будут жить вместе, – говорил он. – А мне, когда я съем своего кота и сошью из его шкурки рукавицы, придётся умирать с голоду.

Кот услышал эти слова, но не обиделся.

– Не горюй, хозяин, – сказал он важно и серьёзно, – дай мне лучше мешок да пару сапог, чтобы удобнее было ходить по кустарникам. Увидишь тогда, что ты получил не такое уж плохое наследство, как думаешь.

Хозяин Кота не очень-то поверил его словам. Но вспомнил о разных его хитростях и подумал: «Может быть. Кот и в самом деле чем-нибудь поможет мне!»

Как только Кот получил от хозяина сапоги, он ловко надел их. Потом положил в мешок капусты, закинул мешок на спину и пошел в лес, где водилось много кроликов.

Пришёл он в лес, притаился за кустами и стал поджидать, чтобы какой-нибудь молодой, глупенький кролик сунулся в мешок за капустой.

Не успел он спрятаться, как ему сразу повезло: молоденький, доверчивый кролик забрался в мешок. Кот быстро кинулся к мешку и крепко-накрепко затянул завязки.

Очень гордый, что охота была такой удачной. Кот пошёл во дворец и попросил допустить его к королю.

Его ввели в королевские покои. Войдя туда. Кот низко поклонился королю и сказал:

– Великий король! Маркиз Карабас (так Коту вздумалось назвать своего хозяина) приказал мне поднести вам в подарок этого кролика.

– Скажи своему хозяину, – ответил король, – что я очень доволен его подарком и благодарю его.

Кот откланялся и ушёл из дворца.

В другой раз он спрятался в поле, среди колосьев пшеницы, и открыл мешок с приманкой.

Когда в мешок попали две куропатки. Кот сейчас же отнёс куропаток королю. Король с удовольствием принял и куропаток и приказал угостить Кота вином.

Так месяца два или три подряд Кот носил королю разную дичь от имени маркиза Карабаса.

Однажды Кот узнал, что король собирался ехать по берегу реки в карете на прогулку со своей дочерью, самой прекрасной принцессой на свете. Он сказал своему хозяину:

– Если послушаешь меня, будешь счастлив всю жизнь. Ступай сегодня купаться на реку в том месте, которое я укажу, остальное я уж устрою сам!

Хозяин послушался Кота и пошёл на реку, хоть и не понимал, какая ему будет от этого польза.

В то время как он купался, по берегу реки проезжал король.

Кот уже поджидал его, и, как только карета приблизилась, он закричал изо всех сил:

– Помогите! Помогите! Тонет маркиз Карабас! Король услышал крик и выглянул из кареты. Он узнал Кота, который уже столько раз приносил ему дичь, и приказал слугам бежать скорее на помощь маркизу Карабасу.

Пока маркиза вытаскивали из реки. Кот подошёл к карете и рассказал королю, что, когда маркиз купался, воры унесли всю его одежду, хоть он, Кот, изо всех сил звал на помощь и громко кричал: «Воры! Воры!»

А на самом деле плут сам же спрятал одежду своего хозяина под большим камнем.

Король приказал придворным сейчас же принести маркизу Карабасу один из самых лучших своих нарядов.