Миф о пещере из диалога Платона «Государство» — это одна из главных историй в европейской теории познания, капитально повлиявшая на всю последующую традицию философской мысли. Даже в XXI веке люди регулярно его вспоминают, хотя давно миновали времена, когда пещеры были актуальной частью ландшафта. С концептуальной точки зрения этот миф стал началом дискуссии о том, насколько наши представления о вещах позволяют судить о самих вещах.

Вот о чём идёт речь в этом фрагменте «Государства». Сократ, неизменный персонаж платоновских диалогов и поставщик всяческой мудрости, беседует с братом Платона Главконом. Речь заходит о том, каких успехов можно достичь на пути познания, о просвещённости и непросвещённости. Здесь-то Сократ и прибегает к знаменитой аллегории.

Он рассказывает Главкону о людях, которые находятся в подземной пещере, в то время как перед ними на стене проходят тени от проносимых за границей их поля видения предметов.

Именно эти тени люди и считают подлинными вещами, даже не задумываясь, что их отбрасывает нечто другое.

— Люди как бы находятся в подземном жилище наподобие пещеры, где во всю её длину тянется широкий просвет. С малых лет у них там на ногах и на шее оковы, так что людям не двинуться с места, и видят они только то, что у них прямо перед глазами, ибо повернуть голову они не могут из-за этих оков. Люди обращены спиной к свету, исходящему от огня, который горит далеко в вышине, а между огнем и узниками проходит верхняя дорога, ограждённая невысокой стеной вроде той ширмы, за которой фокусники помещают своих помощников, когда поверх ширмы показывают кукол.

За этой стеной другие люди несут различную утварь, держа её так, что она видна поверх стены; проносят они и статуи, и всяческие изображения живых существ, сделанные из камня и дерева. При этом, как водится, одни из несущих разговаривают, другие молчат.

— Странный ты рисуешь образ и странных узников!

— Подобных нам. Прежде всего, разве ты думаешь, что, находясь в таком положении, люди что-нибудь видят, своё ли или чужое, кроме теней, отбрасываемых огнём на расположенную перед ними стену пещеры?

— Как же им видеть что-то иное, раз всю свою жизнь они вынуждены держать голову неподвижно?

— Если бы в их темнице отдавалось эхом всё, что бы ни произнес любой из проходящих мимо, думаешь ты, они приписали бы эти звуки чему-нибудь иному, а не проходящей тени?.. Такие узники целиком и полностью принимали бы за истину тени проносимых мимо предметов.

(Платон, «Государство»)

Учение об идеях и Благе

Миф о пещере посвящён относительности перцептивного восприятия и его продуктов (то есть, данных, получаемых с помощью органов чувств). К тому же, как отмечает Платон, увиденным смутным теням люди ещё и «дают имена» — считают их подлинными явлениями, которые обозначаются терминологически и подлежат интерпретации.

Чтобы разобраться в том, что именно искажается, превращаясь в тень на стене пещеры, нужно обратиться с платоновскому учению об эйдосах.

Эйдосы (идеи вещей) в представлении Платона существуют сами по себе, то есть обладают онтологической самостоятельностью. А вот реальные вещи, с которыми люди имеют дело в повседневной жизни — отражения идей.

Идеи неразрушимы и вечны, тогда как вещи могут разрушаться. Но это не страшно, ведь имея представление о том, что из себя представляет стол, можно воссоздать его, а то и запустить целую мебельную фабрику.

Какие-то вещи соответствуют своим идеям меньше, какие-то — больше. Нетрудно догадаться, что, согласно Платону, вторые — лучше, потому что более полно передают бытие вещи в качестве себя самой. Скажем, кривой и колченогий стол далеко ушёл от своей идеи, а вот стол красивый и устойчивый справляется со стольностью хорошо. Тем не менее, они оба являются столами. Признать стол в таких разных объектах, как, скажем, такой и такой, нам, согласно платоновскому учению, помогает именно объединяющая их идея.

Идея предполагает не только общее представление о той или иной вещи, но и сам смысл её существования. Чем больше бытийственая определённость, а заодно добротность, «правильность» конкретной вещи (например, стольность стола), тем больше в ней Блага. Это ещё одно краеугольное понятие платоновской философии. Благое у Платона — это, скорее, не «что-то хорошее», а что-то, точно соответствующее своему онтологическому статусу.

Благо, которое является главным и высшим предметом познания, Платон сравнивает с Солнцем, освещающим предметы.

Таким же образом, как солнце освещает предметы, Благо позволяет познавать идеи. В мифе о пещере это свет, который освещает предметы (а заодно и создаёт тени, доступные людскому восприятию). Благо — это причина, по которой возможно познание, при этом само оно — абсолют, максимум того, что вообще можно познать.

Объективный и субъективный идеализм

Разобравшись с мифом о пещере, можно заодно понять, что такое философский идеализм как таковой.

Сформированное Платоном представление о том, как обстоят дела с идеями, стало каноническим для объективного идеализма. Согласно этому философскому мировоззрению, кроме чувственно воспринимаемой реальности и познающего её субъекта (то есть, всякого человека, который взаимодействует с миром) существует и сверхчувственная, внематериальная реальность. Её генерирует объективное сознание — бог, одухотворённая Вселенная или мировой разум. Только этой высшей духовной сущности доступно видение мира «как он есть», а вот человеку остаётся довольствоваться данными органов чувств и априорными суждениями.

Кроме объективного идеализма, существует также идеализм субъективный. Тут речь идёт о том, что реальность в принципе не существует за пределами разума субъекта. Все те данные, которые тот получает на основе своих ощущений, впечатлений и суждений, признаются единственным содержанием мира. При таком подходе реальность и вовсе может существовать только в сознании человека.

Представим себе, что мы обучаем алгоритм распознаванию объектов. Он способен запомнить большое количество конкретных объектов, как и их признаки, комбинация которых позволяет определить автомобиль как автомобиль, а собаку — как собаку. Но доступна ли такому роботу идея этого объекта?

Согласно Платону, алгоритм, который мог бы действительно видеть все эйдосы, и на их основе «генерировать» вещи, и был бы «божественным умозрением», работающем вместо электричества на Благе. Мнение, что такое первоначало существует, являясь гарантом всех форм и вещей (в том числе тех, которые люди не могут познать и понять), и является идеализмом.

Копии копий: картины как двойное искажение

Чтобы оценить масштаб вклада платоновской аллегории в историю мысли, не обязательно быть идеалистом. Платон описывает принцип человеческого познания, пытаясь разобраться в соотношении кажимости и истины.

В 1929 году французский сюрреалист Рене Магритт, который любил играть со смыслами и образами, написал картину «Вероломство образов». На ней нет ничего, кроме реалистичного изображения курительной трубки с подписью «Это не трубка».

«Вероломство образов».

Сочетание изображения и подписи кажется на первый взгляд простой нелогичностью, но технически Магритт не обманывает — перед нами действительно не трубка, а изображение трубки. Мало того, в нашем случае есть ещё как минимум одна итерация: оригинал картины «Вероломство образов» находится в Художественном музее Лос-Анджелеса, а вы сейчас смотрите на цифровую копию репродукции, которая была размещена в «Википедии». Своей работой Магритт запустил новый виток дискуссий о соотношении вещей и художественных образов в искусстве.

В рамках учения, выраженного в мифе о пещере, вещи являются всего лишь копиями эйдосов. Само собой, в процессе «отбрасывания тени» возникают неточности и ошибки.

Создавая картину, скульптуру или просто пересказывая что-то в меру своих возможностей и словаря, люди создают дополнительные искажения, как случается, если засунуть в ксерокс ксерокопию. Искусство, таким образом, является «копией копии»: Платон относился к изображениям настороженно, полагая, что они умножают погрешности и «неистинность».

Можно ли выйти из пещеры?

Согласно Платону, человек, снявший оковы в пещере и взглянувший на вещи в ярком сиянии Солнца (то есть, увидевший истинную сущность вещей), запаникует или даже откажется от истинного знания, потому что «правильный взгляд» с непривычки окажется болезненным. Такому человеку будет проще вернуться в пещеру — к прежним представлениям, потому что свет может опалить глаза.

Тут нужно учитывать, что Платон полагал, будто «правильный взгляд» в принципе возможен — за него отвечает абсолют. Из всех людей плотнее всего приблизиться к постижению вечных идей могут только мыслители, способные снять «оковы неразумения».

Кстати, сразу после растолковывания идеи Блага Платон устами Сократа объясняет, почему философы кажутся людьми не от мира сего, а окружающие часто советуют им пересмотреть приоритеты: «Не удивляйся, что пришедшие ко всему этому не хотят заниматься человеческими делами; их души всегда стремятся ввысь. А удивительно разве, по-твоему, если кто-нибудь, перейдя от божественных созерцаний к человеческому убожеству, выглядит неважно и кажется крайне смешным?».

Тем не менее, даже человек, который стремится к познанию Блага с помощью философии, всё ещё остаётся человеком. Согласно платоновскому учению о бессмертной душе, кроме «разумной» и «волевой» частей у неё есть также «страстная», которая тянется к плотским наслаждениям и отвлекает от высоких побуждений.

Проблемы познания: от Платона до Хокинга

За тысячелетия, которые прошли со времени жизни Платона, исследовательский аппарат человечества необыкновенно расширился, но нельзя сказать, что проблемы, которые философ когда-то сформулировал, были решены.

Насколько наша способность ощущать и понимать отражает реальное положение дел, и есть ли это «реальное положение», а если да, то кто его подтверждает? Сегодня мы можем назвать в качестве такой подтверждающей инстанции науку. Однако даже доказывая нечто математически, мы должны учитывать, что «фундаментальные принципы» могут быть сформулированы только в рамках наших естественных ограничений — как биологических (человеческое описание физических законов напрямую связано с нашими органами чувств), так и определённых свойствами среды (за пределами планеты законы будут иными, не говоря уже о том, что физики-теоретики могут предположить существование вселенных, скажем, с десятками измерений).

«Невозможно познать истинную природу реальности: мы считаем, что чётко представляем себе окружающий мир, но, говоря метафорически, мы обречены всю жизнь провести в аквариуме, так как возможности нашего тела не дают нам выбраться из него», — пишет Стивен Хокинг, сравнивая познающего человека с аквариумной рыбкой.

Возможно, вы помните эпопею с синим-или-золотым платьем, которая расколола интернет на два лагеря. Одним казалось, что оно золотое с белым, другим — что синее с чёрным.

Оригинал в центре. Не у всех, но получается: если особым образом расфокусировать глаза, можно заставить изображение менять свой цвет.

На деле платье было чёрно-синим, а противоречия вызвали особенности хроматической адаптации разных людей, из-за которых у некоторых голубой цвет может «не читаться» (другие таким же образом игнорировали золотые оттенки). Платье оказалось одним из самых ярких известных примеров индивидуальных различий в цветовом восприятии, однако случаев таких оптических иллюзий немало. Кроме особенностей строения сетчатки (количества колбочек и палочек) роль играет то, как именно и под воздействием каких факторов мозг будет «подправлять» картинку, достраивая восприятие.

Якоб фон Икскюль обозначал индивидуальный мир, который создаёт каждое живое существо в меру своих познавательных способностей, словом «умвельт». Наш умвельт будет отличаться, скажем, от собачьего, где существуют целые картины из запахов, но нет отвлечённых понятий. А вот мир какого-нибудь червяка и вовсе будет состоять из нескольких простейших регистрируемых состояний. Различие в восприятии между разными видами велико, однако неверно было бы считать, будто умвельты двух представителей одного вида идентичны друг другу — мы ведь даже не можем договориться по поводу цвета платья.

Так можно ли выйти из пещеры?

«Истинной» картины мира не видит никто, однако каждый воспринимает её в меру своих познавательных возможностей. Вопрос в том, можно ли в принципе её увидеть, и нужно ли это нам?

Согласно теории когнитивиста Дональда Хоффмана, то, что мы считаем реальностью, на деле больше похоже на рабочий стол со значками — систему для обозначения и взаимодействия.

На основании расчётов и лабораторных исследований Хоффман сделал вывод, что приспособленность организмов к выживанию не связана с умением воспринимать «подлинную реальность». Тесты показали, что способность видеть вещи такими, какие они есть, менее важна, чем приспособленность. Эволюция не способствует подлинному восприятию. Звучит нелогично, ведь, казалось бы, чем точнее живые существа видят мир, тем выше должны быть шансы на выживание.

Однако животные используют простые подсказки, чтобы выжить. Например, австралийские жуки опознают самок как что-то коричневое и гладкое, и потому пытаются спариться даже с пивными бутылками, которые местные жители кидают в кусты. Даниел Канеман называет путь простых решений «Системой 1» — она, в противовес рефлексирующей «Системе 2», принимает самые простые и очевидные решения, которые чаще всего действительно работают.

Дональд Хоффман приводит в пример иконку на рабочем столе компьютера — если она синяя и квадратная, это ведь не значит, что сам файл синий и квадратный? Это всего лишь пользовательский интерфейс, который позволяет нам ничего не знать о резисторах и диодах, оптоволоконных кабелях и программном обеспечении. Таким образом, умвельт-интерфейс, через который живые существа познают мир, скорее прячет реальность. Получается, что выбраться из пещеры невозможно — в неё нас отправляет сама эволюция.

Впрочем, по словам Хоффмана всё это не должно разочаровывать или намекать, что всякое научное познание бессмысленно. Просто представление о том, что наша перцептивная способность поставляет нам «настоящую реальность» оказалось неверным.

С уверенностью можно сказать одно: вопрос границ познания и относительности познавательных способностей, поставленный когда-то Платоном с помощью мифа о пещере, пронизывает все современные науки от нейробиологии до физики. В этой истории впервые в истории европейской мысли была так глубоко и образно сформулирована разница между «реальной реальностью» и представлениями о ней.

Нашли опечатку? Выделите фрагмент и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Пещера Платона

Люди как бы находятся в подземном жилище наподобие пещеры, где во всю ее длину тянется широкий просвет. С малых лет у них там на ногах и на шее оковы, так что людям не двинуться с места, и видят они только то, что у них прямо перед глазами, ибо повернуть голову они не могут из-за этих оков. Люди обращены спиной к свету, исходящему от огня, который горит далеко в вышине, а между огнем и узниками проходит верхняя дорога, огражденная невысокой стеной. И за этой стеной другие люди несут различную утварь, держа ее так, что она видна поверх стены; проносят они и статуи, и всяческие изображения живых существ, сделанные из камня и дерева. Тени, отбрасываемые этими предметами на стену пещеры, — единственное зрелище, доступное узникам, единственное, о чем они могут думать и говорить.

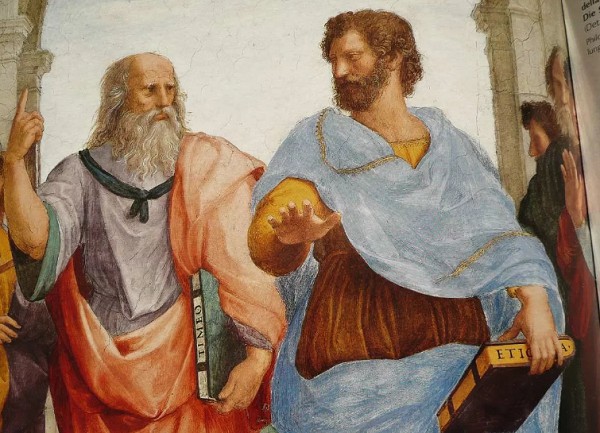

«Платон и Аристотель» (Рафаэль, нач. XVII века) Платону придано портретное сходство с Леонардо да Винчи

Аллегория Пещеры, описанная Платоном в 7-м томе «Государства», монументального трактата о формах государственного устройства и идеальном правителе, вероятно, самая известная из множества образов и аналогий, предложенных этим великим греческим философом. Идея передать управление обществом философам зиждется на тщательном изучении природы истины и знания, и именно в этом контексте Платон использует аллегорию Пещеры.

Платоновская концепция познания сложна и многослойна, и раскрывается она по мере изложения мифа о пещере.

Теперь представь, что с тебя сняли оковы и позволили свободно ходить по пещере. Сначала ты сощуришься от света огня, но постепенно поймешь, каково происхождение теней, которые ты прежде считал подлинными предметами. А потом ты выйдешь из пещеры в залитый светом внешний мир, где вся полнота реальности освещена ярчайшим небесным светилом, Солнцем.

Толкование притчи о Пещере

Интерпретация платоновской пещеры вызывала массу споров, но общий смысл вполне ясен. Сама пещера олицетворяет «чувственный мир» — видимый мир повседневного опыта, где все неопределенно и постоянно изменяется. Скованные узники (обычные люди) живут в мире догадок и иллюзий, в то время как бывшие заключенные, которым позволено бродить по пещере, придерживаются самого точного взгляда на реальность, возможного в переменчивом мире восприятия и опыта. Мир за пределами пещеры — это «истинное бытие», постигаемый мир, наполненный объектами познания, идеальный, вечный и неизменный.

«Смотри, человеческие существа, живущие в подземной пещере… подобно нам… они видят лишь собственную тень либо тени друг друга, отбрасываемые на стену этой пещеры» Платон, около 375 г. до н. э.

Теория Форм

По мнению Платона, знание должно быть не только истинным, но еще идеальным и неизменным. Однако ничто в эмпирическом мире (представленном жизнью внутри пещеры) не соответствует этому описанию: высокий человек по сравнению с деревом мал; яблоко, красное в полдень, в сумерках кажется черным и т. п. Поскольку ничто в эмпирическом мире не может быть объектом познания, Платон предполагает, что должна быть иная реальность (мир за пределами пещеры) совершенного и неизменного бытия, которое он назвал миром Форм (или Идей). Так, например, посредством имитации или копирования Формы Правосудия все отдельные акты справедливости являются справедливыми. В аллегории пещеры описана иерархия Форм, высшей из которых является Форма Добра (представляемая Солнцем), придающая смысл всем остальным и лежащая в основе их существования.

Проблема универсалий

Теория Форм и метафизическая основа, на которой она строится, может показаться чересчур замысловатой и надуманной, но проблема, которую она породила, — так называемая проблема универсалий — стала основной в философии и в том или ином виде существует до сих пор. В Средневековье философская линия фронта пролегла между реалистами (сторонниками Платона), которые полагали, что универсалии, подобные «красноте» и «высоте», существуют независимо от красных и высоких предметов и номиналистами, считавшими эти понятия всего лишь названиями, ярлыками, прикрепленными к объектам, чтобы подчеркнуть сходство между ними.

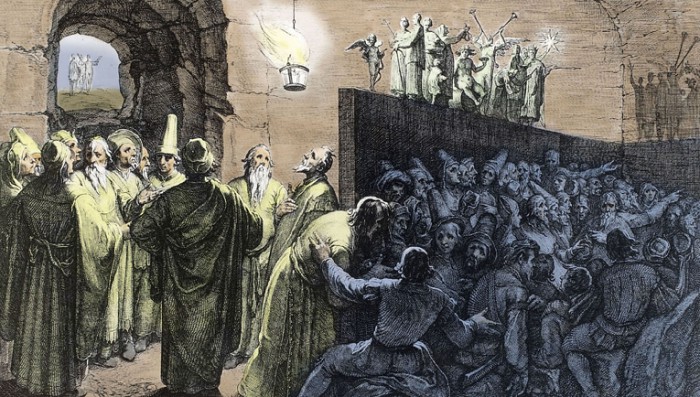

Картина 1604 года н. э. изображает Пещеру Платона и ее жителей — простой народ, обреченный на жизнь в невежестве, пока стоящие вкруг философы обсуждают, что есть истина, чтобы предложить разъяснения менее одаренным.

Такое же различие, обычно выраженное терминами «реализм» и «антиреализм», присутствует во многих областях современной философии. Согласно реалистической позиции, во «внешнем мире» есть сущности — физические объекты, нормы морали, математические формулы, — которые существуют независимо от нашего знания или ощущения их. Противоположная концепция, известная как антиреалистическая, предполагает, что необходимо наличие связи между объектом и нашим знанием о нем. Основные аргументы этой дискуссии были сформулированы более двух тысяч лет назад великим Платоном, одним из первых философов-реалистов.

В защиту Сократа

В аллегории Пещеры Платон не только прояснил собственный взгляд на реальность и наше знание о ней. В самом конце притчи узник, выйдя во внешний мир и познав природу истины и подлинной реальности, стремится вернуться в пещеру и освободить своих томящихся во мраке товарищей. Но, привыкнув к яркому свету, в темноте пещеры он поначалу спотыкается, тычется в разные стороны, и потому прочие узники считают его глуповатым. Они полагают, что путешествие вовне дурно повлияло на него, не желают слушать захватывающих рассказов и даже пытаются убить несчастного, когда тот становится чересчур настойчив. В этом фрагменте Платон намекает на обычную участь мыслителя — насмешки и отверженность, — пытающегося просвещать обычных людей и указывать им путь к знаниям и мудрости.

Особое место в трудах Платона занимает судьба его учителя, Сократа (его устами он излагает собственные взгляды в «Государстве» и большинстве других диалогов), который всю жизнь отказывался смягчать свои философские концепции в угоду публике и в итоге был казнен по приговору афинских властей в 339 г. до н. э.

Платоническая любовь

Идея, с которой сегодня чаще всего ассоциируют имя Платона, — так называемая платоническая любовь — естественным образом рождается из аллегории Пещеры, где вступают в противоречие мир разума и мир ощущений. Классическое объяснение этой идеи, состоящее в том, что идеальная любовь выражается не физически, но интеллектуально, сформулировано в знаменитом диалоге «Симпосий».

В массовой культуре

Эхо платоновских размышлений ясно слышится в творчестве К. С. Льюиса, автора семи романов, образующих единый цикл «Хроники Нарнии». В финале завершающей части, «Последней битвы», дети — герои книги становятся свидетелями разрушения Нарнии и вступают в земли Аслана, чудесную страну, в которой соединилось лучшее, что было в прежней Нарнии, с той Англией, которую они помнят. В конце концов дети обнаруживают, что в действительности они умерли и покинули «Землю теней», которая была лишь бледной копией вечного и неизменного мира, где они отныне поселились.

Несмотря на откровенно христианские реминисценции, влияние Платона не менее очевидно — и это лишь один из многочисленных примеров огромного (и порой неожиданного) влияния великого греческого философа на всю западную культуру, религиозную мысль и искусство.

Поделиться ссылкой

Платоновские идеи,

стало быть, не есть просто понятия, т.е.

чисто умственные представления (это

позже термин принял такой смысл), это,

скорее, целостность, сущность. Идеи — не

мысли, а то, по поводу чего мысль думает,

когда она свободна от чувственного, это

подлинное бытие, бытие в превосходной

степени. Идеи — сущность вещей, т.е.

то, что каждую из них делает тем, что она

есть. Платон

употребляет термин «парадигма«,

указывая, что идеи образуют перманентную

модель каждой вещи (чем она должна быть).

Комплекс Идей с

вышеописанными чертами вошел в историю

под названием «Гиперурания»

Миф

о пещере.

Представим себе

людей, которые живут в подземелье, в

пещере со входом, направленным к свету,

который освещает во всю длину одну из

стен входа. Представим также, что

обитатели пещеры к тому же связаны по

ногам и по рукам, и будучи недвижными,

они обращают свои взоры вглубь пещеры.

Вообразим еще, что как раз у самого входа

в пещеру есть вал из камней ростом в

человека, по ту сторону которого двигаются

люди, нося на плечах статуи из камня и

дерева, всевозможные изображения. В

довершение всего нужно увидеть позади

этих людей огромный костер, а еще выше

— сияющее солнце. Вне пещеры кипит жизнь,

люди что-то говорят, и их говор эхом

отдается в чреве пещеры.

Так узники пещеры

не в состоянии видеть ничего, кроме

теней, отбрасываемых статуэтками на

стены их мрачного обиталища, они слышат

лишь эхо чьих-то голосов. Однако они

полагают, что эти тени — единственная

реальность, и не зная, не видя и не слыша

ничего другого, они принимают за чистую

монету отголоски эха и теневые проекции.

Теперь предположим, что один из узников

решается сбросить с себя оковы, и после

изрядных усилий он осваивается с новым

видением вещей, скажем, узрев статуэтки,

движущиеся снаружи, он понял бы, что

реальны они, а не тени, прежде им виденные.

Наконец, предположим, что некто осмелился

бы вывести узника на волю. И после первой

минуты ослепления от лучей солнца и

костра наш узник увидел бы вещи как

таковые, а затем солнечные лучи, сперва

отраженные, а потом их чистый свет сам

по себе; тогда, поняв, что такое подлинная

реальность, он понял бы, что именно

солнце — истинная

причина всех видимых вещей.

Четыре значения

мифа о пещере

Во-первых,

это представление об онтологической

градации бытия, о типах реальности —

чувственном и сверхчувственном — и их

подвидах: тени на стенах — это простая

кажимость вещей; статуи — вещи чувственно

воспринимаемые; каменная стена —

демаркационная линия, разделяющая два

рода бытия; предметы и люди вне пещеры

— это истинное бытие, ведущее к идеям;

ну а солнце — Идея Блага.

Во-вторых,

миф символизирует ступени познания:

созерцание теней — воображение (eikasia),

видение статуй — (pistis), т.е. верования, от

которых мы переходим к пониманию

предметов как таковых и к образу солнца,

сначала опосредованно, потом

непосредственно, — это фазы диалектики

с различными ступенями, последняя из

которых — чистое созерцание, интуитивное

умопостижение.

В-третьих,

мы имеем также аспекты: аскетический,

мистический и теологический. Жизнь под

знаком чувства и только чувства — это

пещерная жизнь. Жизнь в духе — это жизнь

в чистом свете правды. Путь восхождения

от чувственного к интеллигибельному

есть «освобождение от оков», т.е.

преображение; наконец, высшее познание

солнца-Блага — это созерцание божественного.

Впрочем,

у этого мифа есть и политический аспект

с истинно платоновским изыском. Платон

говорит о возможном возвращении в пещеру

того, кто однажды был освобожден.

Вернуться с целью освободить и вывести

к свободе тех, с которыми провел долгие

годы рабства. Несомненно, это возвращение

философа-политика, единственное желание

которого — созерцание истины, преодолевающего

себя в поисках других, нуждающихся в

его помощи и спасении. Вспомним, что, по

Платону, настоящий политик — не тот, кто

любит власть и все с ней связанное, но

кто, используя власть, занят лишь

воплощением Блага. Возникает вопрос:

что ждет спустившегося вновь из царства

света в царство теней? Он не увидит

ничего, пока не привыкнет к темноте. Его

не поймут, пока он не адаптируется к

старым привычкам. Принеся с собой

возмущение, он рискует навлечь на себя

гнев людей, предпочитающих блаженное

неведение. Он рискует и большим, — быть

убитым, как Сократ.

Но человек, который

знает Благо, может и должен избежать

этого риска, лишь исполненный долг

придаст смысл его существованию…

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The Allegory of the Cave, or Plato’s Cave, is an allegory presented by the Greek philosopher Plato in his work Republic (514a–520a) to compare «the effect of education (παιδεία) and the lack of it on our nature». It is written as a dialogue between Plato’s brother Glaucon and his mentor Socrates, narrated by the latter. The allegory is presented after the analogy of the sun (508b–509c) and the analogy of the divided line (509d–511e).

In the allegory «The Cave,» Plato describes a group of people who have lived chained to the wall of a cave all their lives, facing a blank wall. The people watch shadows projected on the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them and give names to these shadows. The shadows are the prisoners’ reality, but are not accurate representations of the real world. The shadows represent the fragment of reality that we can normally perceive through our senses, while the objects under the sun represent the true forms of objects that we can only perceive through reason. Three higher levels exist: the natural sciences; mathematics, geometry, and deductive logic; and the theory of forms.

Socrates explains how the philosopher is like a prisoner who is freed from the cave and comes to understand that the shadows on the wall are actually not the direct source of the images seen. A philosopher aims to understand and perceive the higher levels of reality. However, the other inmates of the cave do not even desire to leave their prison, for they know no better life.[1]

Socrates remarks that this allegory can be paired with previous writings, namely the analogy of the sun and the analogy of the divided line.

Summary[edit]

Allegory of the cave. From top to bottom:

- The sun («the Good»)

- Natural things (ideas)

- Reflections of natural things (mathematical objects)

- Fire (doctrine)

- Artificial objects (creatures and objects)

- Shadows of artificial objects, allegory (image, analogy of the sun and of the divided line)

Imprisonment in the cave[edit]

Plato begins by having Socrates ask Glaucon to imagine a cave where people have been imprisoned from childhood, but not from birth. These prisoners are chained so that their legs and necks are fixed, forcing them to gaze at the wall in front of them and not to look around at the cave, each other, or themselves (514a–b).[2] Behind the prisoners is a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway with a low wall, behind which people walk carrying objects or puppets «of men and other living things» (514b).[2]

The people walk behind the wall so their bodies do not cast shadows for the prisoners to see, but the objects they carry do («just as puppet showmen have screens in front of them at which they work their puppets» (514a).[2] The prisoners cannot see any of what is happening behind them, they are only able to see the shadows cast upon the cave wall in front of them. The sounds of the people talking echo off the walls, and the prisoners believe these sounds come from the shadows (514c).[2]

Socrates suggests that the shadows are reality for the prisoners because they have never seen anything else; they do not realize that what they see are shadows of objects in front of a fire, much less that these objects are inspired by real things outside the cave which they do not see (514b–515a).[2]

The fire, or human-made light, and the puppets, used to make shadows, are done by the artists. Plato, however, indicates that the fire is also the political doctrine that is taught in a nation state. The artists use light and shadows to teach the dominant doctrines of a time and place.

Also, few humans will ever escape the cave. This is not some easy task, and only a true philosopher, with decades of preparation, would be able to leave the cave, up the steep incline. Most humans will live at the bottom of the cave, and a small few will be the major artists that project the shadows with the use of human-made light.

Departure from the cave[edit]

Plato then supposes that one prisoner is freed. This prisoner would look around and see the fire. The light would hurt his eyes and make it difficult for him to see the objects casting the shadows. If he were told that what he is seeing is real instead of the other version of reality he sees on the wall, he would not believe it. In his pain, Plato continues, the freed prisoner would turn away and run back to what he is accustomed to (that is, the shadows of the carried objects). He writes «… it would hurt his eyes, and he would escape by turning away to the things which he was able to look at, and these he would believe to be clearer than what was being shown to him.»[2]

Plato continues: «Suppose… that someone should drag him… by force, up the rough ascent, the steep way up, and never stop until he could drag him out into the light of the sun.»[2] The prisoner would be angry and in pain, and this would only worsen when the radiant light of the sun overwhelms his eyes and blinds him.[2]

«Slowly, his eyes adjust to the light of the sun. First he can see only shadows. Gradually he can see the reflections of people and things in water and then later see the people and things themselves. Eventually, he is able to look at the stars and moon at night until finally he can look upon the sun itself (516a).»[2] Only after he can look straight at the sun «is he able to reason about it» and what it is (516b).[2] (See also Plato’s analogy of the sun, which occurs near the end of The Republic, Book VI.[3][4])

Return to the cave[edit]

Plato continues, saying that the freed prisoner would think that the world outside the cave was superior to the world he experienced in the cave and attempt to share this with the prisoners remaining in the cave attempting to bring them onto the journey he had just endured; «he would bless himself for the change, and pity [the other prisoners]» and would want to bring his fellow cave dwellers out of the cave and into the sunlight (516c).[2]

The returning prisoner, whose eyes have become accustomed to the sunlight, would be blind when he re-enters the cave, just as he was when he was first exposed to the sun (516e).[2] The prisoners, according to Plato, would infer from the returning man’s blindness that the journey out of the cave had harmed him and that they should not undertake a similar journey. Plato concludes that the prisoners, if they were able, would therefore reach out and kill anyone who attempted to drag them out of the cave (517a).[2]

Themes in the allegory appearing elsewhere in Plato’s work[edit]

The allegory is related to Plato’s theory of Forms, according to which the «Forms» (or «Ideas»), and not the material world known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality. Knowledge of the Forms constitutes real knowledge or what Socrates considers «the Good».[5] Socrates informs Glaucon that the most excellent people must follow the highest of all studies, which is to behold the Good. Those who have ascended to this highest level, however, must not remain there but must return to the cave and dwell with the prisoners, sharing in their labors and honors.

Plato’s Phaedo contains similar imagery to that of the allegory of the cave; a philosopher recognizes that before philosophy, his soul was «a veritable prisoner fast bound within his body… and that instead of investigating reality of itself and in itself is compelled to peer through the bars of a prison.»[6]

Scholarly discussion[edit]

Scholars debate the possible interpretations of the allegory of the cave, either looking at it from an epistemological standpoint—one based on the study of how Plato believes we come to know things—or through a political (politeia) lens.[7] Much of the scholarship on the allegory falls between these two perspectives, with some completely independent of either. The epistemological view and the political view, fathered by Richard Lewis Nettleship and A. S. Ferguson, respectively, tend to be discussed most frequently.[7]

Nettleship interprets the allegory of the cave as representative of our innate intellectual incapacity, in order to contrast our lesser understanding with that of the philosopher, as well as an allegory about people who are unable or unwilling to seek truth and wisdom.[8][7] Ferguson, on the other hand, bases his interpretation of the allegory on the claim that the cave is an allegory of human nature and that it symbolizes the opposition between the philosopher and the corruption of the prevailing political condition.[1]

Cleavages have emerged within these respective camps of thought, however. Much of the modern scholarly debate surrounding the allegory has emerged from Martin Heidegger’s exploration of the allegory, and philosophy as a whole, through the lens of human freedom in his book The Essence of Human Freedom: An Introduction to Philosophy and The Essence of Truth: On Plato’s Cave Allegory and Theaetetus.[9] In response, Hannah Arendt, an advocate of the political interpretation of the allegory, suggests that through the allegory, Plato «wanted to apply his own theory of ideas to politics».[10] Conversely, Heidegger argues that the essence of truth is a way of being and not an object.[11] Arendt criticised Heidegger’s interpretation of the allegory, writing that «Heidegger … is off base in using the cave simile to interpret and ‘criticize’ Plato’s theory of ideas».[10]

Various scholars also debate the possibility of a connection between the work in the allegory and the cave and the work done by Plato considering the analogy of the divided line and the analogy of the sun. The divided line is a theory presented to us in Plato’s work the Republic. This is displayed through a dialogue given between Socrates and Glaucon. In which they explore the possibility of a visible and intelligible world. With the visible world consisting of items such as shadows and reflections (displayed as AB) then elevating to the physical item itself (displayed as BC) while the intelligible world consists of mathematical reasoning (displayed by CD) and philosophical understanding (displayed by DE).[12]

Many seeing this as an explanation to the way in which the prisoner in the allegory of the cave goes through the journey. First in the visible world with shadows such as those on the wall. Socrates suggests that the shadows are reality for the prisoners because they have never seen anything else; they do not realize that what they see are shadows of objects in front of a fire, much less that these objects are inspired by real things outside the cave which they do not see[12] then the realization of the physical with the understanding of concepts such as the tree being separate from its shadow. It enters the intelligible world as the prisoner looks at the sun.[13]

The divided line – (AC) is generally taken as representing the visible world and (CE) as representing the intelligible world[14]

The Analogy of the Sun refers to the moment in book six in which Socrates after being urged by Glaucon to define goodness, proposes instead an analogy through a «child of goodness». Socrates reveals this «child of goodness» to be the sun, proposing that just as the sun illuminates, bestowing the ability to see and be seen by the eye,[15]: 169 with its light so the idea of goodness illumines the intelligible with truth, leading some scholars to believe this forms a connection of the sun and the intelligible world within the realm of the allegory of the cave.

Influence[edit]

The themes and imagery of Plato’s cave have appeared throughout Western thought and culture. Some examples include:

- Francis Bacon used the term «Idols of the Cave» to refer to errors of reason arising from the idiosyncratic biases and preoccupations of individuals.

- Thomas Browne in his 1658 discourse Urn Burial stated: «A Dialogue between two Infants in the womb concerning the state of this world, might handsomely illustrate our ignorance of the next, whereof methinks we yet discourse in Platoes denne, and are but Embryon Philosophers».

- Evolutionary biologist Jeremy Griffith’s book A Species In Denial includes the chapter «Deciphering Plato’s Cave Allegory».[16]

- The films The Conformist, The Matrix, Cube, Dark City, 1899 (TV series),The Truman Show, Us and City of Ember model Plato’s allegory of the cave.[17]

- The 2013 movie After the Dark has a segment where Mr. Zimit likens James’ life to the Allegory of the Cave.

- The Cave by José Saramago culminates in the discovery of Plato’s Cave underneath the center, «an immense complex fusing the functions of an office tower, a shopping mall and a condominium.»[18]

- Emma Donoghue acknowledges the influence of Plato’s allegory of the cave on her novel Room.[19]

- Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 explores the themes of reality and perception also explored in Plato’s allegory of the cave and Bradbury references Plato’s work in the novel.[20][21]

- José Carlos Somoza’s novel The Athenian Murders is presented as a murder mystery but features many references to Plato’s philosophy including the allegory of the cave.[22]

- Novelist James Reich argues Nicholas Ray’s film Rebel Without a Cause, starring James Dean, Natalie Wood, and Sal Mineo as John «Plato» Crawford is influenced by and enacts aspects of the allegory of the cave.[23]

- In an episode of the television show Legion, titled «Chapter 16», the narrator uses Plato’s Cave to explain «the most alarming delusion of all», narcissism.

- H. G. Wells’ short novel The Country of the Blind has a similar «Return to the Cave» situation when a man accidentally discovers a village of blind people and wherein he tries to explain how he can «see», only to be ridiculed.

- Daniel F. Galouye’s post-apocalyptic novel Dark Universe describes the Survivors, who live underground in total darkness, using echolocation to navigate. Another race of people evolve, who are able to see using infrared.

- C. S. Lewis’ novels The Silver Chair and The Last Battle both reference the ideas and imagery of the Cave. In the former in Chapter 12, the Witch dismisses the idea of a greater reality outside the bounds of her Underworld. In The Last Battle most of the characters learn that the Narnia which they have known is but a «shadow» of the true Narnia. Lord Digory says in Chapter 15, «It’s all in Plato, all in Plato».

- In season 1, episode 2 of the 2015 Catalan television series Merlí, titled «Plato», a high school philosophy teacher demonstrates the allegory using household objects for a non-verbal, agoraphobic student, and makes a promise to him that «I’ll get you out of the cave».

- In the 2016 season 1, episode 1 of The Path, titled «What the Fire Throws», a cult leader uses the allegory in a sermon to inspire the members to follow him «up out of the world of shadows … into the light».

See also[edit]

- Allegorical interpretations of Plato

- Anekantavada

- Archetype

- Brain in a vat

- Experience machine

- Flatland

- The Form of the Good

- Intelligibility (philosophy)

- Nous – Noumenon

- Phaneron

- Plato’s Republic in popular culture

- Simulation hypothesis

- Holographic principle

- Blind men and an elephant, a rough equivalent in Eastern Philosophy

- Maya (illusion)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Ferguson, A. S. (1922). «Plato’s Simile of Light. Part II. The Allegory of the Cave (Continued)». The Classical Quarterly. 16 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1017/S0009838800001956. JSTOR 636164. S2CID 170982104.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Plato. Rouse, W.H.D. (ed.). The Republic Book VII. Penguin Group Inc. pp. 365–401.

- ^ Jowett, B. (ed.) (1941). Plato’s The Republic. New York: The Modern Library. OCLC 964319.

- ^ Malcolm, John (1962-01-01). «The Line and the Cave». Phronesis. 7 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1163/156852862×00025. ISSN 0031-8868.

- ^ Watt, Stephen (1997), «Introduction: The Theory of Forms (Books 5–7)», Plato: Republic, London: Wordsworth Editions, pp. xiv–xvi, ISBN 978-1-85326-483-2

- ^ Elliott, R. K. (1967). «Socrates and Plato’s Cave». Kant-Studien. 58 (2): 138. doi:10.1515/kant.1967.58.1-4.137. S2CID 170201374.

- ^ a b c Hall, Dale (January 1980). «Interpreting Plato’s Cave as an Allegory of the Human Condition». Apeiron. 14 (2): 74–86. doi:10.1515/APEIRON.1980.14.2.74. JSTOR 40913453. S2CID 170372013. ProQuest 1300369376.

- ^ Nettleship, Richard Lewis (1955). «Chapter 4 — The four stages of intelligence». Lectures On The Republic Of Plato (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan & Co.

- ^ McNeill, William (5 January 2003). «The Essence of Human Freedom: An Introduction to Philosophy and The Essence of Truth: On Plato’s Cave Allegory and Theaetetus». Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

- ^ a b Abensour, Miguel (2007). «Against the Sovereignty of Philosophy over Politics: Arendt’s Reading of Plato’s Cave Allegory». Social Research: An International Quarterly. 74 (4): 955–982. doi:10.1353/sor.2007.0064. JSTOR 40972036. Gale A174238908 Project MUSE 527590 ProQuest 209671578.

- ^ Powell, Sally (1 January 2011). «Discovering the unhidden: Heidegger’s Interpretation of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and its Implications for Psychotherapy». Existential Analysis. 22 (1): 39–50. Gale A288874147.

- ^ a b Plato, The Republic, Book 6, translated by Benjamin Jowett, online Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Raven, J. E. (1953). «Sun, Divided Line, and Cave». The Classical Quarterly. 3 (1/2): 22–32. doi:10.1017/S0009838800002573. JSTOR 637158. S2CID 170803513.

- ^ «divided line,» The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-63722-8, p. 239.

- ^ Pojman, Louis & Vaughn, L. (2011). Classics of Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

- ^ Griffith, Jeremy (2003). A Species in Denial. Sydney: WTM Publishing & Communications. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-74129-000-4. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ^ The Matrix and Philosophy: Welcome to the Desert of the Real by William Irwin. Open Court Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-8126-9501-1. «Written for those fans of the film who are already philosophers.»

- ^ Keates, Jonathan. «Shadows on the Wall». The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2002.

- ^ «Q & A with Emma Donoghue – Spoiler-friendly Discussion of Room (showing 1–50 of 55)». www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ «Parallels between Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 69 and Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’«. Archived from the original on 2019-06-06.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (1953). Fahrenheit 451. The Random House Publishing Group. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-758-77616-7.

- ^ Somoza, Jose Carlos (2003). The Athenian Murders. ABACUS. ISBN 978-0349116181.

- ^ «Plato’s Cave: Rebel Without a Cause and Platonic Allegory – OUTSIDER ACADEMY». Retrieved 2017-06-25.[permanent dead link]

Further reading[edit]

The following is a list of supplementary scholarly literature on the allegory of the cave that includes articles from epistemological, political, alternative, and independent viewpoints on the allegory:

- Kim, A. (2004). «Shades of Truth: Phenomenological Perspectives on the Allegory of the Cave». Idealistic Studies. 34 (1): 1–24. doi:10.5840/idstudies200434118. INIST:16811501.

- Zamosc, Gabriel (2017). «The Political Significance of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave». Ideas y Valores. 66 (165). doi:10.15446/ideasyvalores.v66n165.55201. ProQuest 1994433580.

- Mitta, Dimitra (1 January 2003). «Reading Platonic Myths from a Ritualistic Point of View: Gyges’ Ring and the Cave Allegory». Kernos (16): 133–141. doi:10.4000/kernos.815.

- McNeill, William (5 January 2003). «The Essence of Human Freedom: An Introduction to Philosophy and The Essence of Truth: On Plato’s Cave Allegory and Theaetetus». Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

- Eckert, Maureen (2012). «Cinematic Spelunking Inside Plato’s Cave». Glipmse Journal. 9: 42–49.

- Tsabar, Boaz (1 January 2014). «‘Poverty and Resourcefulness’: On the Formative Significance of Eros in Educational Practice». Studies in Philosophy and Education. 33 (1): 75–87. doi:10.1007/s11217-013-9364-5. S2CID 144408538.

- Malcolm, J. (May 1981). «The Cave Revisited». The Classical Quarterly. 31 (1): 60–68. doi:10.1017/S0009838800021078. S2CID 170697508.

- Murphy, N. R. (April 1932). «The ‘Simile Of Light’ In Plato’S Republic». The Classical Quarterly. 26 (2): 93–102. doi:10.1017/S0009838800002366. S2CID 170223655.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Allegory of the cave at PhilPapers

- Ted-ed: Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

- Animated interpretation of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

- Plato: The Republic at Project Gutenberg

- Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic at University of Washington – Faculty

- Plato: Book VII of The Republic, Allegory of the Cave at Shippensburg University

- 2019 translation of the Allegory of the Cave

The Allegory of the Cave, or Plato’s Cave, is an allegory presented by the Greek philosopher Plato in his work Republic (514a–520a) to compare «the effect of education (παιδεία) and the lack of it on our nature». It is written as a dialogue between Plato’s brother Glaucon and his mentor Socrates, narrated by the latter. The allegory is presented after the analogy of the sun (508b–509c) and the analogy of the divided line (509d–511e).

In the allegory «The Cave,» Plato describes a group of people who have lived chained to the wall of a cave all their lives, facing a blank wall. The people watch shadows projected on the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them and give names to these shadows. The shadows are the prisoners’ reality, but are not accurate representations of the real world. The shadows represent the fragment of reality that we can normally perceive through our senses, while the objects under the sun represent the true forms of objects that we can only perceive through reason. Three higher levels exist: the natural sciences; mathematics, geometry, and deductive logic; and the theory of forms.

Socrates explains how the philosopher is like a prisoner who is freed from the cave and comes to understand that the shadows on the wall are actually not the direct source of the images seen. A philosopher aims to understand and perceive the higher levels of reality. However, the other inmates of the cave do not even desire to leave their prison, for they know no better life.[1]

Socrates remarks that this allegory can be paired with previous writings, namely the analogy of the sun and the analogy of the divided line.

Summary[edit]

Allegory of the cave. From top to bottom:

- The sun («the Good»)

- Natural things (ideas)

- Reflections of natural things (mathematical objects)

- Fire (doctrine)

- Artificial objects (creatures and objects)

- Shadows of artificial objects, allegory (image, analogy of the sun and of the divided line)

Imprisonment in the cave[edit]

Plato begins by having Socrates ask Glaucon to imagine a cave where people have been imprisoned from childhood, but not from birth. These prisoners are chained so that their legs and necks are fixed, forcing them to gaze at the wall in front of them and not to look around at the cave, each other, or themselves (514a–b).[2] Behind the prisoners is a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway with a low wall, behind which people walk carrying objects or puppets «of men and other living things» (514b).[2]

The people walk behind the wall so their bodies do not cast shadows for the prisoners to see, but the objects they carry do («just as puppet showmen have screens in front of them at which they work their puppets» (514a).[2] The prisoners cannot see any of what is happening behind them, they are only able to see the shadows cast upon the cave wall in front of them. The sounds of the people talking echo off the walls, and the prisoners believe these sounds come from the shadows (514c).[2]

Socrates suggests that the shadows are reality for the prisoners because they have never seen anything else; they do not realize that what they see are shadows of objects in front of a fire, much less that these objects are inspired by real things outside the cave which they do not see (514b–515a).[2]

The fire, or human-made light, and the puppets, used to make shadows, are done by the artists. Plato, however, indicates that the fire is also the political doctrine that is taught in a nation state. The artists use light and shadows to teach the dominant doctrines of a time and place.

Also, few humans will ever escape the cave. This is not some easy task, and only a true philosopher, with decades of preparation, would be able to leave the cave, up the steep incline. Most humans will live at the bottom of the cave, and a small few will be the major artists that project the shadows with the use of human-made light.

Departure from the cave[edit]

Plato then supposes that one prisoner is freed. This prisoner would look around and see the fire. The light would hurt his eyes and make it difficult for him to see the objects casting the shadows. If he were told that what he is seeing is real instead of the other version of reality he sees on the wall, he would not believe it. In his pain, Plato continues, the freed prisoner would turn away and run back to what he is accustomed to (that is, the shadows of the carried objects). He writes «… it would hurt his eyes, and he would escape by turning away to the things which he was able to look at, and these he would believe to be clearer than what was being shown to him.»[2]

Plato continues: «Suppose… that someone should drag him… by force, up the rough ascent, the steep way up, and never stop until he could drag him out into the light of the sun.»[2] The prisoner would be angry and in pain, and this would only worsen when the radiant light of the sun overwhelms his eyes and blinds him.[2]

«Slowly, his eyes adjust to the light of the sun. First he can see only shadows. Gradually he can see the reflections of people and things in water and then later see the people and things themselves. Eventually, he is able to look at the stars and moon at night until finally he can look upon the sun itself (516a).»[2] Only after he can look straight at the sun «is he able to reason about it» and what it is (516b).[2] (See also Plato’s analogy of the sun, which occurs near the end of The Republic, Book VI.[3][4])

Return to the cave[edit]

Plato continues, saying that the freed prisoner would think that the world outside the cave was superior to the world he experienced in the cave and attempt to share this with the prisoners remaining in the cave attempting to bring them onto the journey he had just endured; «he would bless himself for the change, and pity [the other prisoners]» and would want to bring his fellow cave dwellers out of the cave and into the sunlight (516c).[2]

The returning prisoner, whose eyes have become accustomed to the sunlight, would be blind when he re-enters the cave, just as he was when he was first exposed to the sun (516e).[2] The prisoners, according to Plato, would infer from the returning man’s blindness that the journey out of the cave had harmed him and that they should not undertake a similar journey. Plato concludes that the prisoners, if they were able, would therefore reach out and kill anyone who attempted to drag them out of the cave (517a).[2]

Themes in the allegory appearing elsewhere in Plato’s work[edit]

The allegory is related to Plato’s theory of Forms, according to which the «Forms» (or «Ideas»), and not the material world known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality. Knowledge of the Forms constitutes real knowledge or what Socrates considers «the Good».[5] Socrates informs Glaucon that the most excellent people must follow the highest of all studies, which is to behold the Good. Those who have ascended to this highest level, however, must not remain there but must return to the cave and dwell with the prisoners, sharing in their labors and honors.

Plato’s Phaedo contains similar imagery to that of the allegory of the cave; a philosopher recognizes that before philosophy, his soul was «a veritable prisoner fast bound within his body… and that instead of investigating reality of itself and in itself is compelled to peer through the bars of a prison.»[6]

Scholarly discussion[edit]

Scholars debate the possible interpretations of the allegory of the cave, either looking at it from an epistemological standpoint—one based on the study of how Plato believes we come to know things—or through a political (politeia) lens.[7] Much of the scholarship on the allegory falls between these two perspectives, with some completely independent of either. The epistemological view and the political view, fathered by Richard Lewis Nettleship and A. S. Ferguson, respectively, tend to be discussed most frequently.[7]

Nettleship interprets the allegory of the cave as representative of our innate intellectual incapacity, in order to contrast our lesser understanding with that of the philosopher, as well as an allegory about people who are unable or unwilling to seek truth and wisdom.[8][7] Ferguson, on the other hand, bases his interpretation of the allegory on the claim that the cave is an allegory of human nature and that it symbolizes the opposition between the philosopher and the corruption of the prevailing political condition.[1]

Cleavages have emerged within these respective camps of thought, however. Much of the modern scholarly debate surrounding the allegory has emerged from Martin Heidegger’s exploration of the allegory, and philosophy as a whole, through the lens of human freedom in his book The Essence of Human Freedom: An Introduction to Philosophy and The Essence of Truth: On Plato’s Cave Allegory and Theaetetus.[9] In response, Hannah Arendt, an advocate of the political interpretation of the allegory, suggests that through the allegory, Plato «wanted to apply his own theory of ideas to politics».[10] Conversely, Heidegger argues that the essence of truth is a way of being and not an object.[11] Arendt criticised Heidegger’s interpretation of the allegory, writing that «Heidegger … is off base in using the cave simile to interpret and ‘criticize’ Plato’s theory of ideas».[10]

Various scholars also debate the possibility of a connection between the work in the allegory and the cave and the work done by Plato considering the analogy of the divided line and the analogy of the sun. The divided line is a theory presented to us in Plato’s work the Republic. This is displayed through a dialogue given between Socrates and Glaucon. In which they explore the possibility of a visible and intelligible world. With the visible world consisting of items such as shadows and reflections (displayed as AB) then elevating to the physical item itself (displayed as BC) while the intelligible world consists of mathematical reasoning (displayed by CD) and philosophical understanding (displayed by DE).[12]

Many seeing this as an explanation to the way in which the prisoner in the allegory of the cave goes through the journey. First in the visible world with shadows such as those on the wall. Socrates suggests that the shadows are reality for the prisoners because they have never seen anything else; they do not realize that what they see are shadows of objects in front of a fire, much less that these objects are inspired by real things outside the cave which they do not see[12] then the realization of the physical with the understanding of concepts such as the tree being separate from its shadow. It enters the intelligible world as the prisoner looks at the sun.[13]

The divided line – (AC) is generally taken as representing the visible world and (CE) as representing the intelligible world[14]

The Analogy of the Sun refers to the moment in book six in which Socrates after being urged by Glaucon to define goodness, proposes instead an analogy through a «child of goodness». Socrates reveals this «child of goodness» to be the sun, proposing that just as the sun illuminates, bestowing the ability to see and be seen by the eye,[15]: 169 with its light so the idea of goodness illumines the intelligible with truth, leading some scholars to believe this forms a connection of the sun and the intelligible world within the realm of the allegory of the cave.

Influence[edit]

The themes and imagery of Plato’s cave have appeared throughout Western thought and culture. Some examples include:

- Francis Bacon used the term «Idols of the Cave» to refer to errors of reason arising from the idiosyncratic biases and preoccupations of individuals.

- Thomas Browne in his 1658 discourse Urn Burial stated: «A Dialogue between two Infants in the womb concerning the state of this world, might handsomely illustrate our ignorance of the next, whereof methinks we yet discourse in Platoes denne, and are but Embryon Philosophers».

- Evolutionary biologist Jeremy Griffith’s book A Species In Denial includes the chapter «Deciphering Plato’s Cave Allegory».[16]

- The films The Conformist, The Matrix, Cube, Dark City, 1899 (TV series),The Truman Show, Us and City of Ember model Plato’s allegory of the cave.[17]

- The 2013 movie After the Dark has a segment where Mr. Zimit likens James’ life to the Allegory of the Cave.

- The Cave by José Saramago culminates in the discovery of Plato’s Cave underneath the center, «an immense complex fusing the functions of an office tower, a shopping mall and a condominium.»[18]

- Emma Donoghue acknowledges the influence of Plato’s allegory of the cave on her novel Room.[19]

- Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 explores the themes of reality and perception also explored in Plato’s allegory of the cave and Bradbury references Plato’s work in the novel.[20][21]

- José Carlos Somoza’s novel The Athenian Murders is presented as a murder mystery but features many references to Plato’s philosophy including the allegory of the cave.[22]

- Novelist James Reich argues Nicholas Ray’s film Rebel Without a Cause, starring James Dean, Natalie Wood, and Sal Mineo as John «Plato» Crawford is influenced by and enacts aspects of the allegory of the cave.[23]

- In an episode of the television show Legion, titled «Chapter 16», the narrator uses Plato’s Cave to explain «the most alarming delusion of all», narcissism.

- H. G. Wells’ short novel The Country of the Blind has a similar «Return to the Cave» situation when a man accidentally discovers a village of blind people and wherein he tries to explain how he can «see», only to be ridiculed.

- Daniel F. Galouye’s post-apocalyptic novel Dark Universe describes the Survivors, who live underground in total darkness, using echolocation to navigate. Another race of people evolve, who are able to see using infrared.

- C. S. Lewis’ novels The Silver Chair and The Last Battle both reference the ideas and imagery of the Cave. In the former in Chapter 12, the Witch dismisses the idea of a greater reality outside the bounds of her Underworld. In The Last Battle most of the characters learn that the Narnia which they have known is but a «shadow» of the true Narnia. Lord Digory says in Chapter 15, «It’s all in Plato, all in Plato».

- In season 1, episode 2 of the 2015 Catalan television series Merlí, titled «Plato», a high school philosophy teacher demonstrates the allegory using household objects for a non-verbal, agoraphobic student, and makes a promise to him that «I’ll get you out of the cave».

- In the 2016 season 1, episode 1 of The Path, titled «What the Fire Throws», a cult leader uses the allegory in a sermon to inspire the members to follow him «up out of the world of shadows … into the light».

See also[edit]

- Allegorical interpretations of Plato

- Anekantavada

- Archetype

- Brain in a vat

- Experience machine

- Flatland

- The Form of the Good

- Intelligibility (philosophy)

- Nous – Noumenon

- Phaneron

- Plato’s Republic in popular culture

- Simulation hypothesis

- Holographic principle

- Blind men and an elephant, a rough equivalent in Eastern Philosophy

- Maya (illusion)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Ferguson, A. S. (1922). «Plato’s Simile of Light. Part II. The Allegory of the Cave (Continued)». The Classical Quarterly. 16 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1017/S0009838800001956. JSTOR 636164. S2CID 170982104.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Plato. Rouse, W.H.D. (ed.). The Republic Book VII. Penguin Group Inc. pp. 365–401.

- ^ Jowett, B. (ed.) (1941). Plato’s The Republic. New York: The Modern Library. OCLC 964319.

- ^ Malcolm, John (1962-01-01). «The Line and the Cave». Phronesis. 7 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1163/156852862×00025. ISSN 0031-8868.

- ^ Watt, Stephen (1997), «Introduction: The Theory of Forms (Books 5–7)», Plato: Republic, London: Wordsworth Editions, pp. xiv–xvi, ISBN 978-1-85326-483-2

- ^ Elliott, R. K. (1967). «Socrates and Plato’s Cave». Kant-Studien. 58 (2): 138. doi:10.1515/kant.1967.58.1-4.137. S2CID 170201374.

- ^ a b c Hall, Dale (January 1980). «Interpreting Plato’s Cave as an Allegory of the Human Condition». Apeiron. 14 (2): 74–86. doi:10.1515/APEIRON.1980.14.2.74. JSTOR 40913453. S2CID 170372013. ProQuest 1300369376.

- ^ Nettleship, Richard Lewis (1955). «Chapter 4 — The four stages of intelligence». Lectures On The Republic Of Plato (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan & Co.

- ^ McNeill, William (5 January 2003). «The Essence of Human Freedom: An Introduction to Philosophy and The Essence of Truth: On Plato’s Cave Allegory and Theaetetus». Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

- ^ a b Abensour, Miguel (2007). «Against the Sovereignty of Philosophy over Politics: Arendt’s Reading of Plato’s Cave Allegory». Social Research: An International Quarterly. 74 (4): 955–982. doi:10.1353/sor.2007.0064. JSTOR 40972036. Gale A174238908 Project MUSE 527590 ProQuest 209671578.

- ^ Powell, Sally (1 January 2011). «Discovering the unhidden: Heidegger’s Interpretation of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and its Implications for Psychotherapy». Existential Analysis. 22 (1): 39–50. Gale A288874147.

- ^ a b Plato, The Republic, Book 6, translated by Benjamin Jowett, online Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Raven, J. E. (1953). «Sun, Divided Line, and Cave». The Classical Quarterly. 3 (1/2): 22–32. doi:10.1017/S0009838800002573. JSTOR 637158. S2CID 170803513.

- ^ «divided line,» The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-63722-8, p. 239.

- ^ Pojman, Louis & Vaughn, L. (2011). Classics of Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

- ^ Griffith, Jeremy (2003). A Species in Denial. Sydney: WTM Publishing & Communications. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-74129-000-4. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ^ The Matrix and Philosophy: Welcome to the Desert of the Real by William Irwin. Open Court Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-8126-9501-1. «Written for those fans of the film who are already philosophers.»

- ^ Keates, Jonathan. «Shadows on the Wall». The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2002.

- ^ «Q & A with Emma Donoghue – Spoiler-friendly Discussion of Room (showing 1–50 of 55)». www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ «Parallels between Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 69 and Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’«. Archived from the original on 2019-06-06.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (1953). Fahrenheit 451. The Random House Publishing Group. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-758-77616-7.

- ^ Somoza, Jose Carlos (2003). The Athenian Murders. ABACUS. ISBN 978-0349116181.

- ^ «Plato’s Cave: Rebel Without a Cause and Platonic Allegory – OUTSIDER ACADEMY». Retrieved 2017-06-25.[permanent dead link]

Further reading[edit]

The following is a list of supplementary scholarly literature on the allegory of the cave that includes articles from epistemological, political, alternative, and independent viewpoints on the allegory:

- Kim, A. (2004). «Shades of Truth: Phenomenological Perspectives on the Allegory of the Cave». Idealistic Studies. 34 (1): 1–24. doi:10.5840/idstudies200434118. INIST:16811501.

- Zamosc, Gabriel (2017). «The Political Significance of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave». Ideas y Valores. 66 (165). doi:10.15446/ideasyvalores.v66n165.55201. ProQuest 1994433580.

- Mitta, Dimitra (1 January 2003). «Reading Platonic Myths from a Ritualistic Point of View: Gyges’ Ring and the Cave Allegory». Kernos (16): 133–141. doi:10.4000/kernos.815.

- McNeill, William (5 January 2003). «The Essence of Human Freedom: An Introduction to Philosophy and The Essence of Truth: On Plato’s Cave Allegory and Theaetetus». Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

- Eckert, Maureen (2012). «Cinematic Spelunking Inside Plato’s Cave». Glipmse Journal. 9: 42–49.

- Tsabar, Boaz (1 January 2014). «‘Poverty and Resourcefulness’: On the Formative Significance of Eros in Educational Practice». Studies in Philosophy and Education. 33 (1): 75–87. doi:10.1007/s11217-013-9364-5. S2CID 144408538.

- Malcolm, J. (May 1981). «The Cave Revisited». The Classical Quarterly. 31 (1): 60–68. doi:10.1017/S0009838800021078. S2CID 170697508.

- Murphy, N. R. (April 1932). «The ‘Simile Of Light’ In Plato’S Republic». The Classical Quarterly. 26 (2): 93–102. doi:10.1017/S0009838800002366. S2CID 170223655.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Allegory of the cave at PhilPapers

- Ted-ed: Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

- Animated interpretation of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

- Plato: The Republic at Project Gutenberg

- Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic at University of Washington – Faculty

- Plato: Book VII of The Republic, Allegory of the Cave at Shippensburg University

- 2019 translation of the Allegory of the Cave

Платон родился в 428 году до нашей эры, в месяце Фаргилион (май), он происходил из знатного рода. В молодом возрасте, будущий философ получил хорошее музыкальное и гимнастическое образование и имел превосходные математические знания.

Платон. Академия Платона в Афинах, читайте здесь

Платон был учеником Сократа и того, что в 399 г. до н.э. его Учитель был осуждён и казнён. Это стало шокирующим ударом для его свободной и беспокойной души. В тот момент он понял, что политика его страны создает препятствия для философского и свободного мышления, которое он отстаивал.

После этого Платон начал путешествовать, чтобы узнать как живут люди в других странах.

В Южной Италии Платон встретил Пифагора, в Египте он был посвящен в Мистерии пирамид и был главным архидьяконом в Элевсинских мистериях. В Сиракузах он попытался установить свое идеальное государство, но пал жертвой происков королевского двора и едва не избежал казни.

В Афинах он основал свою школу-академию, просуществовавшую почти тысячу лет, до 529 года нашей эры.

Некоторые из работ Платона сохранились, такие как «Законы», «Симпозиум», «Государство» и несколько других, которые повлияли на всех его более поздних философов и ученых.

В 7-й главе «Государства», Платон сравнивает мир, в котором мы живем, с темной пещерой.

Кратко рассмотрим эту древнюю притчу, которая очень похожа на то, как работает сегодняшняя система, хотя с момента ее написания прошло 2500 лет.

Платон сравнивает нашу жизнь с пещерой, где Сократ, в форме диалога, ведёт беседу с братом Платона.

Пещера Платона

Есть большая темная пещера, в которой живет много людей, они называются пленниками. Они привязаны на месте и не могут смотреть по сторонам. За ними идут разные люди, которые несут какие-то предметы, одушевленные и неодушевленные. Свет, идущий от входа в пещеру, проходит через эти объекты и создает тени перед глазами связанных людей. Таким образом, поскольку они не могут смотреть по сторонам или за собой из-за скрепляющих их связей, они принимают за реальность только то, что видят перед собой, а именно тени. Вся эта сцена устроена таким образом, что пленники живут в темноте, имея ложное представление о реальности. И их узы настолько сильны, что они удерживают их неподвижно, не имея возможности сделать ни малейшего движения свободы, чтобы открыть истинную правду.

Пророчества Платона для 21 века

Эта картина очень похожа на сегодняшнюю картину нашего общества. Человек формируется и растет с единственной целью приобретения материальных благ (теней), не имея возможности развивать добродетели и ценности, чтобы иметь возможность мечтать о великих идеалах и духовных идеалах.

Добродетели и Человеческие ценности представлены таким образом и настолько хорошо покрыты красочной и роскошной оберткой, которая их окружает, что человек 21 века остается совершенно поверхностным. Он так много занимается этой оберткой, что не ставит высоких целей и не видит реальности. Он живет жизнью в ловушке теней, которые принимает за реальность и думает, что за этой красивой оберткой ничего нет. Таким образом, он остается рабом хозяев пещеры и становится тенью своего настоящего «я».

Продолжая, Платон упоминает, что бывают такие случая, когда человеку удается разорвать свои узы и посмотреть назад, откуда исходит свет. Сначала он будет ослеплен этим светом. И если бы кто-то заставил этого человека жить под ярким светом за пределами пещеры, он бы сошел с ума.

Поэтому ему нужно двигаться медленно, чтобы он привык к этому состоянию, чтобы понять, что реальный мир находится за пределами пещеры и что тени, которые он считал реальностью, являются просто отражением солнечного света. Это открытие превратит его в счастливого человека, мудрого человека и он не захочет возвращаться в пещеру.

Но если он решит из любви к человечеству вернуться к пленникам, находящимся внутри пещеры, то ему снова потребуется некоторое время, чтобы привыкнуть к темноте, а его глаза смогли бы приспособиться к ней. Затем, конечно, он попытается объяснить правду связанным людям. Но, как пишет Платон, они подумают, что он пытается их обмануть и будут преследовать его или постараются убить.

Платон объясняет в своей книге, что тот, кто преуспеет, разорвет свои узы и будет освобожден — это тот, кто культивирует пробужденное сознание. Основываясь на человеческих ценностях и добродетелях, ему удается стать Свободным и Творческим и покорить высшую часть себя, следуя истинному Философскому Пути. Конечно, это трудный путь с множеством препятствий из-за многолетних связей, но он ведет к настоящему Счастью.

Тот, кто из истинной любви к человечеству возвращается в пещеру, чтобы помочь пленникам освободиться, осознает Политический Путь. Другими словами, настоящий политик — это тот, кто первым сумел освободиться от своих оков, взять под контроль свои недостатки и культивировать человеческие ценности и добродетели, а затем мудро вести за собой других людей. Настоящий Политик основан не на мнении многих, а на Знаниях и Этике, которые он культивировал в себе.

Из этой столь древней, но столь же актуальной притчи мы можем сделать много выводов. Выводы, основанные не на психологических желаниях и неудовлетворенных отвращениях, а на тысячелетней Мудрости, оставленной многими великими философами и учеными во многих культурах, в разное время и по всей Земле.

Когда мы не посвящаем время поиску Истины и не культивируем глобальную и свободную мысль, тогда мы остаемся в ловушке тьмы невежества и дезинформации. В то же время, не осознавая этого, мы легко становимся жертвами «промывания мозгов», навязываемого нам, тем, кто перемещает нити для ориентации исключительно на материю.

Только тот, кому удастся сбросить оковы своих слабостей и ложных впечатлений, наложенных на него, только тот, кто идет Дорогой в гору к своей вершине и преуспевает и преодолевает трудности и препятствия, делая положительные выводы, только он осознает тщетность движущихся перед ним теней.